Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1895. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 843. | two dollars a year. |

"It's altogether too absurd!" That was what the schoolmaster said.

"It is a wicked assumption of power!" That was what the minister said.

"It's flying in the face of Providence!" That was what old Mrs. Mehonky said.

"Them two boys is a couple o' fools, an' they'll git drowned!" That was what old Captain Silas Witherbee, formerly commander of the steam oyster-dredge Lotus Lily, said.

And really, when you come to think of it, that was the most sensible remark of the lot. But what people said did not seem to trouble "them two boys."

"We're going to do it," declared Peter Bright.

"That's what," added Randall Frank.

And so they did. What was it? Well, it was this way. Searsbridge was a small sea-coast town situated at the head of a bay some four miles long. There was very little commercial traffic in that bay, for Searsbridge was a tiny place. A schooner occasionally dropped anchor in the bay when head winds and ugly seas were raging outside; and it was said that two or three big ships had run into the shelter of the harbor in days gone by, and there was a legend that a great Russian ironclad had once stopped there for a supply of fresh water. But, as a rule, only the fishermen's boats ran in and out between Porgy Point and Mullet Head. There was no light at the entrance to the harbor, but there were some of the sharpest and most dangerous rocks on the coast scattered about the entrance.

"It'd be a famous place for a wreck," said a visitor one day.

"Why," exclaimed Peter Bright, who was showing him about, "there have been three wrecks there since I was born."

"And is there no life-saving station?"

"Not nearer than Hartwell, and that's three miles away."

"Well, there ought to be a volunteer crew here, then."

"We generally manage to get a crew together when there's a wreck."

"There ought to be a regular crew, well drilled, and prepared for the worst."

And that was what led Peter Bright and Randall Frank[Pg 182] to talk it all over and decide to get up a crew. But the other fellows all laughed at them, and said that there would be a crew on hand when there was any need for it.

"Yes," said Randall, who always spoke briefly and to the point, "and before that crew gets afloat lives will be lost."

But the arguments of the two young men did not prevail, and they therefore came to the determination which called forth the protests of the schoolmaster, the minister, Mrs. Mehonky, and Captain Silas Witherbee. But these protests had no influence with the two friends.

"We're going to brace up my boat, and in suspicious weather we're going to cruise in her off the mouth of the bay to lend aid to vessels in distress," said Peter, with all the dignity he could command.

And Randall proudly and emphatically added, "That's what."

Peter's boat was by no means so despicable a craft as might have been supposed from the comments of the neighbors. She had been the dinghy of a large sailing ship, and was stoutly built for work in lumpy water. The ship had been wrecked on the coast, and the dinghy had been given to Peter in payment for his services in helping to save her cargo. The first thing that the boy did was to put a centre-board in the craft, and to rig her with a stout mast and a mainsail, cat-boat fashion. Then he announced that in his opinion he had a boat that would stay out when some more pretentious vessels would have to go home. Of course she was not very speedy, but for that Peter did not care a great deal. In light weather most of the fishermen could put him in their wake, but when they had to reef he could carry all sail, and drop them to leeward as if they were so many corks. Peter and Randall now went to work to "brace up" the Petrel, as she was called. They put some extra ribs in her, and built a small deck before the mast. Then they put an extra row of reef points in the mainsail, and set up a pair of extra heavy shrouds. Peter also put a socket in the taffrail for a rowlock, so that in case of having to run before a heavy sea an oar could be shipped to steer with.

"You know she'll work a good deal better with an oar in running off than with the rudder," he said.

And Randall sagely answered, "That's what."

By the time the September gales were due the Petrel was ready for business, and whenever the weather looked threatening she was seen pounding her way through the choppy seas near the mouth of the bay. No wrecks occurred, however. Indeed, no vessels of any kind approached the harbor, and the two young men were hard put to it to endure the ridicule that greeted them on their return from each profitless cruise. But Peter pluckily declared that their time would come, and Randall repeated his unshaken opinion that that was what.

Men are still talking about the storm that visited that coast in October of that year. It was the worst that had occurred within the memory of the oldest inhabitant. Even old Tommy Ryddam, who had been around the Horn three times, had weathered the Cape of Good Hope, and had been as far north as Upernavik, said, "I 'ain't never seed it blow no harder." And that was the first time that Tommy had ever made such an admission. It began on a Wednesday night. The day had been oppressively warm for that time of year, and as a result a light fog had set in early in the morning. But before sundown the wind began to come in cold sharp puffs out of the southeast, and the fog was soon cut into swirling shreds and sent skimming and twisting away over the yellow land. Its disappearance revealed a hard brassy-looking sky, and a gray sea running from the horizon in great oily folds that broke upon the rocks outside of Porgy Point and Mullet Head with a noise like the booming of distant guns, and a smother of snowy spray.

"I reckon this'll be the gale that'll bring us a job," said Peter, as he hoisted the mainsail on his boat.

"I shouldn't wonder," said Randall; "but it's going to be a corker."

His slangy prediction proved to be true. He and Peter cruised around inside the mouth of the bay for an hour after sunset; but the great breadth and weight of the swell that came brimming in between the two headlands and the fast-increasing power of the wind sent them to shelter for the night. In the morning they beat down under the lee of the easterly shore, and landed on Mullet Head. Hauling up the boat, they walked to the highest point of observation. So fierce was the wind that they were forced to lie down. The sea was an appalling sight. It was running in great serried ridges of gray and white that hurled themselves against the land in mountainous breakers.

"We couldn't get out there if a dozen wrecks came," said Peter.

"So," answered Randall, "but we might pull some poor fellow out of the sea."

"That's about all we could do."

The boys kept a constant watch all day, but not the faintest sign of a sail hove in sight above the wavering horizon. The gale blew all day Thursday and all day Friday. Such a sea had never been seen on the coast, and many people went down to look at it. The boys maintained their watch all day on Mullet Head, with the boat safe under its lee. They knew they were helpless, yet they could not go away. People tried to persuade or to ridicule them into doing so, but they remained. They were pretty resolute boys, and were not easily turned from their purposes.

On Saturday morning the wind shifted, and the gale showed signs of moderating. By Saturday night it had fallen to a brisk wind, and the sea had gone down somewhat. On Sunday morning the two boys sailed down to Mullet Head to have another look around the horizon. The minister saw them start, and reproved them for not staying at home to go to church. But they said that they might go in the afternoon. As soon as they reached their customary landing-place, they hauled up the boat and walked up the hill.

"Look!" exclaimed Peter; "now that the gale is over a sail is in sight."

"That's a fact," said Randall. "A sloop."

"Yes; but doesn't she look queer to you?"

"No—hold on—yes. Her hull looks too big for her rig."

"That's it. There! Did you see that when she rose on that sea? She's a schooner, but her mainmast is gone close to the deck. I saw the stump. Look now!"

"Yes! I see it, I see it!" cried Randall; "and what's more, she's lost her foretop-mast."

"That's so. It's broken off above the masthead cap."

"She must have had a pretty lively time of it with the gale."

"Sure enough. I wonder where she's bound?"

They watched her in silence for half an hour, and then Peter sprang to his feet with an exclamation:

"Guinea-pigs and dogs! She's trying to make this harbor."

"That's what!" cried Randall, slapping his knee.

They watched her now with more interest than ever. She was not more than two miles off the entrance now, and Peter was intensely interested. Suddenly he started down the hill toward the boat.

"What is it!" cried Randall, following him.

"She's flying the flag union down, and she's so heavy in her movements that I believe she's sinking."

With nervous haste the boys got their boat afloat, and hoisted the mainsail. In a few minutes they were standing out of the mouth of the harbor with the long swells underrunning their light craft. Somehow news of the incoming vessel had reached Searsbridge, and several of the residents had ridden down to the Head to see what was going to happen. Some of them caught sight of the little dinghy running out, and waved at her to return. But the boys were in earnest now, and were not to be turned from their course.

"I knew I was right," said Peter. "She's sinking fast, and they're trying to run her into shallow water."

"Do you think we can get to her in time?"

"We must do our best."

The mainsail ought to have had the last reef taken in, for the mast bent like a whip, and the dinghy plunged heavily; but it was a time for driving, if ever there was one.

"Look! look!" screamed Randall.

"Too late!" cried Peter.

The schooner, now half a mile away from them, made a great lurch forward, threw her stern into the air, and settled down head first. The top of her broken foremast protruded some ten feet above the surface.

"No, we're not too late!" shouted Randall.

"Right you are!" ejaculated Peter.

They had just discovered that two men had managed to clamber up on the foretop-mast stump as the schooner went down, and were now clinging there, waving their arms toward the boys.

"Get the heaving line ready, Randall," said Pete.

"Ay, ay," answered the willing boy.

Peter brought the dinghy broad under the lee of the mast, and getting a good full on her let her luff up straight at the spar, knowing that the sea would quickly kill her way.

"Stand by to catch the line!" he shouted to the men. "Heave!"

Randall hove the line with good judgment, and one of the wrecked sailors catching it took a couple of turns around the mast with it. Randall now hauled the dinghy up close enough to the mast for the two seamen to swing themselves into her. They were gaunt, hollow-eyed, and exhausted, and at Randall's bidding they lay down in the bottom of the dinghy. In three-quarters of an hour the two boys had sailed back to their landing-place inside Mullet Head. There they met the people who had come down to see the wreck, and who now received them with cheers. The two seamen were able to state that they were the sole survivors of a crew of six, the other four having been carried overboard when the mainmast went over Thursday night. Old Mr. Peddie volunteered to take the men up to the town in his carriage, and as they climbed out of the boat he exclaimed to one of them,

"Hold on! let me look at you! Aren't you Joseph Spring?"

"Yes," said the man, hanging his head; "I am."

"Well, boys," said Mr. Peddie, "you've done a fine Sunday-morning's work. This is Joe Spring, who quarrelled with his father and ran away to sea four years ago. There will be a happy reunion in one house to-day."

Peter and Randall have a fine Block Island boat now, the gift of their admiring fellow townsmen.

Washingtonville, Christmas Day.

Dear Mr. Editor:—Why is it that when a fellow tries to have some fun, he always gets into trouble? Take two years ago this Christmas, for instance, when I had a notion that I'd play a little trick on old Santa Claus. My idea was to keep awake till he came down, wedge up the chimney on him, and then go out and help myself to a pair of reindeer—he'd have had enough left. Besides, I wasn't going to steal them, of course—just borrow them for a while and hitch 'em to my double ripper. Now, I call that an innocent and perfectly proper thing for any boy to do, but what was the result? A long, lank, limp, hollow stocking in the morning—and no reindeer stamping their feet and bleating in the wood-shed, either.

Well, this was two years ago, and I haven't been fooling around much about Santa Claus since. Santa Claus can drive a procession of reindeer a mile long if he wants to, and I won't touch one of them. Santa Claus is all right in his way, but I think that Captain Kidd was rather more my kind of a man. Captain Kidd wasn't much on filling anybody's stockings, but when he got alongside and grappled the other fellow there was fun—genuine, innocent fun.

And I can't see that Captain Kidd always got into trouble when he had a little fun, like a boy does now. You see, it was this way: They had a Christmas tree over at the church last night. It was a regular old-fashioned Christmas tree, which was the minister's idea. Last Sunday says he: "Of late years Christmas trees have been too much given up to children and such things. It was not that way when I was a boy up at Hurricane Centre. There were presents for everybody, old and young. Let us have a genuine, plain, old Hurricane Centre tree."

The tree was set for last night, of course, and the committees and folks and things were working on it all day. Fanny (she's my sister) and Aunt Lou were over in the afternoon stringing pop-corn, and falling off of step-ladders, and so forth. My brother Bob is home from college, and he was over too; though Fanny said he didn't do much but talk to the girls. That's just like Bob. The football season has closed, and he has got his hair cut, and kind of exposed his countenance again at last. Bob thinks he's going to be a lawyer, but if he ever tries to prosecute me when I get to be a pirate, he'll be sorry for it.

Along toward night ma asked me to run over to the church, and take a little package of things which she wanted put on the tree.

"What's in it, ma?" I asked.

"A pair of Santa Claus's reindeer for you," says ma. They're always throwing that thing up to me.

So I took the package and started. When I got there I found everybody gone home to supper except Deacon Green, who was just staying to keep the church. He took my package, and I says to him:

"Mr. Green, supper is all ready over at your house."

"How do you know?" asks he.

"I smelt it as I came along," I says. "Apple dumplings, I think."

"My, you don't say so!" says the Deacon. "I'm a good deal fond of dumplings. 'Specially with maple syrup on 'em—and plenty o' butter."

"Yes, ma'am," says I. (I always go and say "Yes, ma'am," to a man.)

"Wish I could go over and get 'em while they're hot," says he.

"I'll stay here while you go, if you'd like," I said.

"Sure you wouldn't snoop 'round the tree?"

"Yes, ma'am," says I.

So the Deacon put on his mittens and went home.

Well, it was sort of lonesome and solemnlike waiting there in that big hollow church, and so I went up and began looking at the tree. It was a big pine, all covered with beautiful things. I guess I jarred the thing a little, and the label off of somebody's present came fluttering down.

"Oh," says I to myself, "that won't do. If I don't put that back somebody will be disappointed. I'll just shin up and fix it." So up I went.

I looked a long time before I could find a package without a label on it, and then after I did find one and got it on, I saw another label on it; so it wasn't right after all. I looked around a little more and found the right one at last, but when I turned to take off the label I had put on, I couldn't for the life of me tell which of the two it was, so I just jerked off one of 'em by guess and stuck it on the present. Probably I got the wrong one—just my luck.

The tree was sort of bendy and wigglesome, and I saw I'd shaken off several more tags, so I went down and got them. I was getting a little tired of roosting up there like a Christmas bird, so I stuck the labels around sort of promiscuouslike, and probably got most of them wrong. I noticed a good many of the big parcels had small labels, and vice versa, as Bob says, so I thought while I was about it I might as well fix things up a little. So I put the big labels on the big things and—vice versa again. Some others I guess I changed without any particular rule, which, I suppose, was a bad thing to do, as my teacher says our actions should always be governed by definite and intelligent rules, but I was tired and I just stuck 'em about, hit or miss. I thought it would be kind of funny, and maybe old-fashioned and Hurricane Centre like. Besides, I wanted to be doing something—the teacher says idleness is a vice, heard her say so more'n a thousand times.

Well, after awhile I heard scrunching in the snow outside. I got down and went over and sat in our pew and tried to look just about as much like a lamb as a boy not having any wool can look.

It was Deacon Green. Says he; "Young man, you were a little mistaken about them apple dumplings. It was just a picked-up cold supper, 'cause Miranda said to-morrow was Christmas, and we could eat then."

"Then it must have been Mr. Doolittle's supper I smelt, ma'am," says I.

"Well, no matter; run along home and get yours," answered the Deacon. So I did so.

After supper we all went over to the church. I sat in the outside end of the pew because, of course, I didn't know what might happen. Well, they had singing and speaking and such stuff. Then Mr. Doty, the Superintendent of the Sunday-school, made a funny speech, with easy jokes for children, and then they began to take down the things and read 'em off to folks. The first few things on the lower branches seemed to fit all right; then Tommy Snyder's great-grandma got a pair of club skates. Folks looked surprised, but the next few things appeared to be right, and nobody said anything. Then somehow the minister got a red tin horn, and a yearling baby a pair of silver-bowed spectacles, and Mrs. Deacon Wilkie a cigar-case, right in succession. This made talk, but Mr. Doty went on. But things seemed to get worse, and two or three old gentlemen got rattle-boxes and such stuff, and a little girl got a gold-headed cane, and Tommy Snyder's poor great-grandma was called again and got a set of boxing gloves. There was a great uproar, and just then Deacon Green got a teething-ring. I saw him rise up and motion for silence. I put my hand on my stomach and says to ma,

"Ma, I don't feel well at all."

"Better run out in the vestibule and get some fresh air," says ma.

I ran. As I went out the door I heard Deacon Green saying something about me. The air seemed to do me good, so I staid out. While I was about it I thought I might as well run home and go to bed, so I did so.

The next morning at breakfast there was some talk. I didn't succeed in resembling a lamb so much as I had expected. But pa stood by me as usual. Then, when it quieted down, I happened to think of something, and I said,

"Ma, wasn't there anything on that tree for me?"

"Well," says ma, "I had understood from trustworthy sources that there was to be a good-sized brass steam-engine on it for you, but the engine was read off to a boy who lives over at Clear Brook, so I suppose I must have been mistaken. Anyhow, I didn't say anything, and he went off with it."

There seemed to be something wrong with my buckwheat cake, and I didn't eat any more of it. I concluded I wasn't much hungry, and left the table.

"Don't mind, Willie," said Bob, "you've got your reindeer yet."

That's the way it goes, you see, when a boy tries to have a little harmless, innocent amusement. A pirate ship can't come along looking for recruits any too soon to suit.

Yours truly,

Willie Tucker.

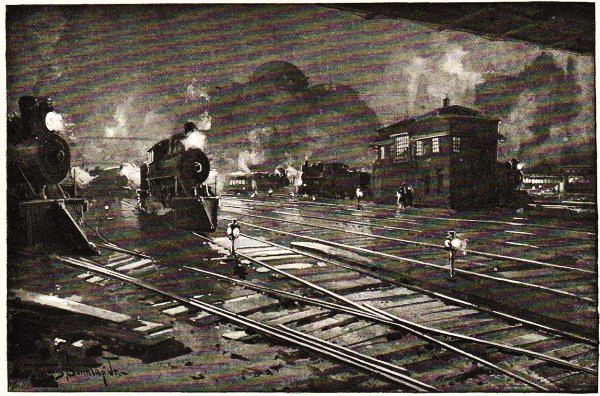

Clickety-click! click! click! go the levers in the narrow brick house at six o'clock. Rapidly yet surely five alert men, clad in blue railroad blouses and trousers, rush about from handle to handle.

"Quick, Jim!" shouts the head man, "49, 61, and 72! There comes the Boston express, and the Croton local only two minutes behind! Shove 'em in there lively!"

"All right," responds Jim.

On the instant this lever is down, the others snapped up, and the express train just out of the tunnel has a clean, clear track into its haven at Forty-second Street. Three hundred yards before the station is reached the flame-throated iron monster, uncoupled from its burden of cars, darts forward on a siding like a spirited horse unharnessed from its load, while the train glides forward with its own momentum, slowly and more slowly as the brakes are applied, until it comes to a stop under the depot shed. Hardly have the passengers poured forth when another train rolls in, and then another, the pathway in each instance cleared by those keen men at the levers in this tower-house of the yards of the Grand Central station in New York city. For they only know the intricacies of this interesting modern labyrinth where more iron paths and by-paths are to be found, in all probability, than in any other place of the same size in the world.

There is a strange fascination about this labyrinth. Business men on their way to work and children on their way from school stop to watch the scene. The light iron foot-bridges which span the tracks for several blocks, saturated and blackened by the steam and smoke of the five hundred engines which pass underneath every day, separate you by barely two feet from the tops of the trains which run in and out of the great union depot, and from the smoke-stacks of the engines which dart about from siding to main track and from main track to round-house, where they sleep and dream fire dreams at night.

And the chief heart-throb of all this incessant activity, the centre of the iron labyrinth, in which Theseus himself, were he alive, would be lost, is the smoke-begrimed tower-house in the middle of the yard, where all the switching for the New York Central, the Harlem, and the New Haven railroads in the vicinity of the tunnel is done. From every train that comes in from or starts out for the West or the East through the long smoky tunnel that leads into the heart of New York a pathway is found by the clear-headed men in this house. Every rail on the many tracks and sidings of the busy yard can be coaxed and compelled from this house to do its part in forming a new wheel path. It is the busiest tower-house in the world, according to the yard-master.

Suppose you enter this rectangular house with one of your railroad friends and go up stairs. Here there is a long "key-board," as the men call it, consisting of one hundred and four numbered iron levers. You see the men in charge grasp lever after lever, apparently at random; you hear the sharp click of these gunlike rods as they move backwards or forwards, and then as you see a red light flash white or a white red two blocks away, you are told by one of the men at the levers that a path has been cleared for the Stamford local or the Empire State express. If you look in the room underneath it seems like the interior of a huge piano-board. Here are stiff-moving wires and bars, each one connected above to its particular iron key. Beneath they spread out in every direction, like the thread-like legs of a spider, each connected with its special rail or switch or light, and never interfering with its neighbor—so delicate the mechanism. As you go up stairs a second time, to hear Mr. Anderson, the man in charge of the great key-board, talk about the arrangements, you cannot help thinking again how like a monster piano it is. To be sure the iron keys are pushed and pulled instead of gently struck. But then what of that? They must be skilful musicians at those keys, these men. Suppose a false note were struck, what a discord would be sounded! It is a human symphony these men play, where a wrong chord might bring death to many people.

But Mr. Anderson, the head operator in the tower-house, doesn't seem to be thinking of these things. It is his duty and his work. He bends his mind to it, and he never makes a mistake. For a few minutes now he gives the direction of the work over to another man and speaks of the work. Over five hundred "pieces of rolling stock"—as the railroad men speak of trains and engines—have to be sent in and out of the depot and yard in a day. These include nearly three hundred regular incoming and outgoing passenger trains, the "stock" and baggage trains which ply between there and Mott Haven, carrying empty cars and station freight, and the "made-up" and "unmade" trains passing to and fro. When a through Western or Boston express starts out of the station, the arrangement of one or two levers by no means insures it a straight track into the tunnel. Oftentimes a combination of ten or fifteen[Pg 185] all over the switch-board is necessary to give a train a straightaway track, and you wonder, as you hear this, how the men ever learn the varying combinations of keys. The train-despatcher in the depot notifies the men in the tower-house on which road each arriving and departing train is—whether New York Central, Harlem River, or New Haven—and they instantly know the answer to the problem.

THE LABYRINTH AND THE TOWER-HOUSE AT GRAND CENTRAL

STATION.

THE LABYRINTH AND THE TOWER-HOUSE AT GRAND CENTRAL

STATION.

It is a noisy piano these men play, noisier and larger than in the switch-house of the Pennsylvania Railroad yards in Jersey City. There the electric pneumatic interlocking switch and signal system of Mr. Westinghouse is in use. In this one man can do the work of several, although many old railroad men believe that the operation of a switch key-board by hand is the only one absolutely safe and reliable. This key-board in the house at the Pennsylvania yards is a glass-topped case about the size of a grand-piano box. The case is apparently full of metal cylinders. About seventy handles project from the front of the case—half of them numbered in black, the other half in red. Each is, or seems to be, the handle of a cylinder. The train-director is in charge of the room, and the young men under him touch the handles as easily as piano keys when the different switch numbers are called out. Suppose he calls out, "29, 21, 23, 20, 17, 13, 12, 7, 8!" One of the men touches the black handles bearing these numbers, then the red. The switches begin to waver up in the yard, though the gush of compressed air which precedes the wavering cannot be heard. Finally, as the last of these numbers is touched, a red signal in the yard droops from its horizontal position to an angle of sixty degrees. Then an empty train comes out of the shed from track 9 to 0 viâ switches 29, 21, 23, 20, 17, 13, 12, 7, and 8, as you note on the yard model—black ground, with bright brass tracks—above the case. Although it seems so simple, it is really as intricate as is the network of wires running down from the glass case through the tower-base to the various switches.

It is early in the morning and late in the afternoon that there is the greatest activity in the yards of the New York Central Railroad. Between seven and nine in the morning so many trains come in that frequently the switching necessary to give them clear ways in and out has meant the moving of 1400 levers in the tower-house. Hardly an engine, as it passes Forty-ninth Street, dragging its train on its way in, but darts away from the cars to a siding, leaving the train to roll in by itself, controlled by the trainmen at the brakes. You are not conscious of this if you are on the incoming cars. But as you get out and walk along the platform you note that yours is an engineless train. It saves time, this swerving of the engine off to right or left, and it is immediately ready to drag another load out. But the alertness of these tower-house men is here called into keenest play, for but a second elapses between the arrival of the engine and its train at the self-same switch, and each must have a separate path.

Although you can plainly see all this rush and bustle on a winter morning just as the sun is creeping over the top of the Grand Central palace, can note so clearly, as you stand on the bridge, which switches are turned for a particular train, and can count exactly the thirty-two tracks from the round-house alongside Lexington Avenue to the "annex sheds" on Madison Avenue, it is far more interesting to visit the yard late in the afternoon, just after dusk. Then you can stand on one of the bridges and see a brilliant panorama—the moving flash-lights of the engines, the quickly shifting red and white signal-lamps, the brilliantly lighted outgoing trains, standing out in relief against the dark narrow bulk of an "unmade" train on a distant siding, and, a short distance away, veiled every now and then by puffs of smoke from an impatient engine, the dazzling arc-burners of the station.

Shut your eyes, then open them, and again almost shut them, and give yourself up to the scene. It is fairy-land, all these moving lights, this brilliant panorama. Close your eyes still more till you can just peep out at the motion around you. It is no longer the iron-threaded yard of the Grand Central station. You are in the midst of some wild, strange region. Great dragons snorting flame and smoke move uneasily about. Black serpents with eyes of flashing fire and long dark bodies trail their way through the flat country past you, and disappear in that cavern of a tunnel above. On all sides are weird noises. But in the midst of it all you half dreamily see, not many feet away from you, the men at the levers in the tower-house, playing their mechanical music so well on the great key-board that every iron monster is charmed, and keeps safely and quietly his own pathway.

The little camp-fire at which Colonel Hewes and some of the officers were sitting was just outside the line of heavy fortifications which the Americans had thrown up some weeks previously.

Colonel Hewes, as soon as he heard George's answer, welcomed the young soldier heartily, and, searching in the saddle-bags that were lying on the ground, he secured some bread and a slice of ham, which George accepted, as he had not tasted food since early in the morning.

For two days nothing was done, but at last Washington's plans were perfected, and under the cover of a heavy fog nine thousand men were ferried across to the city of New York. As George was about to embark with the body of discouraged stragglers in one of the small boats impressed for the service, he heard a familiar voice beside him.

Carter Hewes! He started suddenly. There he stood. A cape was over his shoulder, his left arm was in a sling.

"Oh, Carter, are you wounded?" he exclaimed, before the other had noticed who it was that called to him.

"George, dear friend, you've escaped?" answered Carter, wheeling. Then he noticed the anxious glance. "Merely a scratch," he went on. "Come over with my company, at least what is left of them—it's been bad work. What! a Lieutenant! Hurrah! I told you so."

The soldiers crowded into the flat-boat, and soon the two friends were drifting across the river.

"Your father's proposal has gone to the Convention," said George.

"That relieves me," said Carter. "It is a pet scheme of his, and it was dreadful careless of me to forget and carry it in my pocket. See; do you remember this?" He held out the note-book.

"Why, it's mine!" cried George. "Where did you get it?"

Questions and answers followed in quick succession, and the young officers seemed to forget that they were retreating with a defeated army.

As soon as they had landed they made their way past the Fly Market, near the river.

"It looks as if a plague were in town," thought George to himself. He had just finished relating the incidents that led to his sudden promotion, and had listened to Carter's tale of the adventures in the strange house.

Carter was leaning on his arm as they went up the street, and suddenly he stopped. "Take a good look at this man, here on the right. Who is he?" he asked.

As George turned he saw in the group of spectators a strange figure leaning on a stick. His clothes were ragged, and his hat flopped about his ears; a patch was over his left eye, but despite all this the young Lieutenant recognized him in an instant.

"That's my old schoolmaster, Jabez Anderson. The Tory-hunters haven't found him, evidently," he said, quietly, "and I certainly shall not betray him. Though he's rabid for the crown."

"It seems to me that I have met him some place," returned Carter. "But, come to think, he resembles a portrait I've seen and can't place for the life of me."

What Carter was thinking of was a reflection in an old gilt-framed mirror, although he did not know it.

"He's an odd fish," said George, as they stepped forward again, "and used to give us long lectures on our duty to the King, and all in his own way, for he told minutely the grievances of the colonies, and then admonished us to be steadfast. I often even then felt like taking up cudgels on the opposite side of the question. I owe him no ill-will."

As he spoke he looked in his companion's face. "You are suffering, dear friend," he said. "We must find some place to rest."

"It's nothing. I shall be right in a few days," murmured Carter.

George noticed that he was pale, however, and that during the last half-hour or so he leaned heavily on his arm.

"Courage; I know of just the place," he said.

"We won't be left quietly here very long," responded Carter. "Howe has us on the hip, I fear me. Let me sit down on this step a minute."

"Mr. Frothingham! Mr. Frothingham!" called a voice just at this juncture.

George looked around. There stood Mrs. Mack.

"Thank Dame Fortune," said George to his companion, "here's my old landlady; she will look after us, I'll warrant."

He stepped over to where the honest woman stood. She spoke before he had time to say a word.

"I hev somethin' fer ye to the house, sir," she said; "and shure you lift a foine suit of clothes."

George's heart bounded. He needed clothes badly enough, but had no recollection of having left anything but an old worn coat.

"Won't yez be after comin' ter the house!" continued the woman. "I ken git you a bite to ate, and you kin stay there. Shure ye look that tired."

George easily got permission from his Captain, and dropped out of the ranks. With the help of the widow he succeeded in getting Carter at last tucked away in a great soft bed, where he immediately went to sleep. The last thing he said was, "George, this is the house they took me to, only I had the little room upstairs." George stole away, intending to ask an explanation from the good Irish woman, and solve the mystery.

"Whisper," said Mrs. Mack, taking her old boarder by the arm before he could begin his questioning. "I was on the look fer ye. Here!"

What was George's surprise, and even consternation, when Mrs. Mack handed him an envelope. He opened it. It was heavy with gold coin—English guineas, bright and clinking.

"Where did they come from? Where? Where?" he exclaimed.

"Shure I don't know, sir," said Mrs. Mack. "They wus lift here by a little old man who wus deaf and dumb."

George was puzzled.

"They are shure fer you, sir," she said, "bekase he described you."

"And if he was deaf and dumb, how could he describe me?"

The good woman appeared confused. "And shure, sir, wid signs," she answered. "Oh, I will git the suit of clothes."

She disappeared, but came back immediately. Again was the young soldier almost frightened. He never owned a coat like that, and surely never possessed such a fine pair of buckskin breeches; but there they were.

"Some mistake," said George, looking at the yellow facings, the large brass buttons, and the Lieutenant's shoulder-knots. "I won't take them until I know where they came from," said he, decidedly.

Now may the Recording Angel forgive the good washer-woman, for he must have put down against her name that day a fib of the straightest, whitest kind.

"I made thim fer ye," she said, unblushingly. "If all the army was dressed as foine as that the Ridcoats would take off their hats to ye."

The fact was Mrs. Mack may have referred to the lace trimmings when she said that she had made them, for that was all that she had contributed.

Aunt Clarissa must have relented! At last it dawned on the young soldier. Why had he not written to her? He resolved to do so at once. If he could find some way of sending her the letter.

In a few days Carter was able to move, and Colonel Hewes—who had been ordered to New Jersey to help his cousin mould cannon-balls—took him with him out to the estate. Mrs. Mack had acknowledged the fact that the wounded lad had been her guest before, under certain mysterious circumstances. But she could not or would not explain the method or means of his previous arrival, insisting[Pg 187] that he was brought to her by two "dark men" whose language she could not understand.

Two days after Carter's departure George was leaning against the side of a little brick guard-house—he was officer of the guard—his thoughts far away, busy with the good old times, when he saw down the street some one crossing from a path that led along the common. His heart beat quickly. He would know that shuffling gait, that was yet so strong, amongst a thousand. In half a minute his long young legs were striding in the direction of the retreating figure, and in another he had grasped the man by both shoulders and swung him sharply against a tall board fence.

"Cato, you old rascal!" he exclaimed, shaking his shoulders back and forth roughly, though the tears of joy had gathered in his eyes.

"Why, Mas'r George," came the answer with a jerky emphasis. "How y-y-youse growed, and I done guess you pritty strong too, but you needn't try for to p-prove it no more."

It was not until this that George remembered that he must have changed somewhat, and that he did not know really how strong he had become, for it only seemed yesterday that the old man had been able to lay him across his knee, or carry him by the slack of his little homespun coat.

"Cato," he said, "how are you all at home?"

"Dat's what I's come to tell you, young mas'r," said the old darky. "Dere's a peck of trubble over yander, and I's got a letter fer you from Mistis Grace."

George took the crumpled paper and read it hastily. How she must have changed—his little sister—to write and think such thoughts as these! For the letter told how she prayed every night that he would come back safe and sound, and that the great General Washington would whip the British and drive them from the country. "Aunt Clarissa would not let me write to you," concluded the letter, "and does not know that Cato has gone to look for you. Good-by, dear, dear George.

"From your little Rebel Sister,

"Grace."

"God bless her sweet heart!" said Lieutenant Frothingham, and he paused for a minute. Oh, it seemed so long ago, and William, his dear brother, was in England, and could not understand.

"Cato," he said, suddenly, breaking away from his train of thought, for the old darky had not spoken, "did you bring any money for me some time ago and leave it with Mrs. Mack?"

"No, sah, 'fo' de Lawd, I didn', Mas'r George, but I's got some now," he said, hurriedly, diving into the capacious pockets of his flapping waistcoat. He brought out a worn leather wallet. It contained two gold pieces and a half-handful of silver. "It's yours, sah," he said.

George looked at him earnestly. "Did Mistress Frothingham send it to me?" he asked.

The old darky shifted uneasily. "Yes, sah," he said, faintly.

"Cato, you're telling me a lie," said George, once more laying his hand on the colored man's shoulder. "I don't need the money, and you know that it is yours. I am rich now, Cato." He jingled the gold coins in his own pocket.

The old darky had not replied, but a huge tear rolled down his face.

"T'ank God for dat, honey," he said. "Old Cato didn't know." Then, as if to change the subject, he went on more cheerfully. "Cunel Hewes's cousin is runnin' de big works, sah. Dey is moulding a big chain over dere—biggest you ever seed. Dey done goin' to tro it 'cross de Hudson Ribber to keep dem Redcoat boats from goin' up. He's makin' cannon-balls. I reckon he'd like to use yo' foundry."

"Well, what's to prevent him?" said George.

"'Deed ol' miss' won't let 'im," responded Cato, seriously. "She'd fight 'em toof and nail."

George smiled. "Have you heard her speak of me?" he asked.

"No, Mas'r George," said the old negro, shaking his head. "I heered her tell Mistis Grace dat—dat—"

"Well?" said George.

"Dat you wus dead to her, you 'n' massa."

A drum rolled down the street, and some ragged soldiers were seen leading some thin, unkempt horses from the stable across the way. Two non-commissioned officers came out of the little house before which Cato and his young master had been standing. One was buckling on his heavy leather belt.

"Orders to march, I reckon," he said to his companion. George acknowledged the salute they gave him, and the old darky removed his hat and bowed.

"Wus dat Gineral Washington?" he asked, in an awed whisper, looking at the burly figure of the first speaker, who had a great lump of cheese in his hand, which he was endeavoring to slip into the pocket of his coat.

"No, Cato," said George; "that was a sergeant of artillery."

He was scribbling a few lines, addressed to his sister, on a bit of rough paper. He thrust it into Cato's hands. "Good-by, old friend," he said, and placed his arm about the faithful darky's shoulder and gave him a squeeze, as he had often done in the good old days.

"I's not goin' back," said Cato, shaking his head. "I's goin' wid you as yo' body-sarvant."

"You can't," said George. "Prithee do you think that a Lieutenant is allowed a servant?"

"I don't know," said the old darky. "I spec you'll be a gineral 'fore very long."

"No, no, Cato, you must go back," said his young master. "Good-by—good-by."

He turned quickly and ran off toward the guard-house. Where could the gold have come from? It was puzzling.

Cato looked after him, and placing the note in the crown of his big hat, walked slowly away.

An orderly met the young Lieutenant at the door. "Your presence is requested at headquarters, sir," he said, and hurried off.

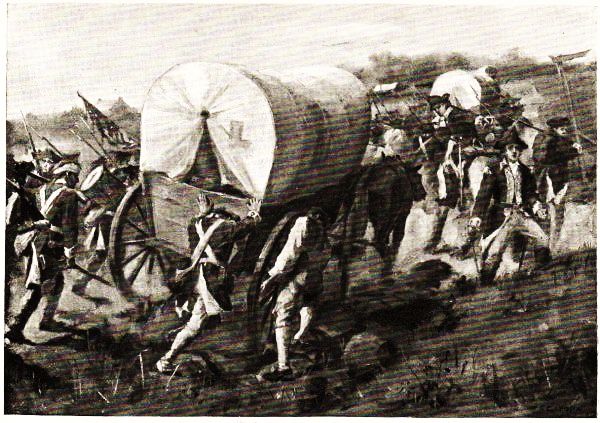

The city was going to be abandoned, and to George Frothingham was given the important charge of conducting the precious powder train through the lanes and by-ways of Manhattan Island to the new position Washington had taken at Harlem Heights.

LUMBERING VANS TRUNDLED AND JOLTED ALONG WITH THE

REAR-GUARD.

LUMBERING VANS TRUNDLED AND JOLTED ALONG WITH THE

REAR-GUARD.

At noon the caravan was ready to start. Besides the lumbering vans, two brass field-pieces trundled and jolted along with the rear-guard. George knew well the best route to take, and gave the orders to push ahead up the old "King's Highway"—the post-road to Boston.

At a street corner as they passed were standing some soldiers of one of the commands that had not received marching orders. Running out into the street, one of the men touched a tall private on the elbow. It was Thomas, the former porter in Mr. Wyeth's office. He held in his hand a buckskin bag of bullets.

"Brother Ralston," he said, "here are some leaden pills. Shoot straight with them." Then he noticed George, and saluted. Pouring something out in his hand, he came up close. "Slip them into your pocket for a keepsake, Mr. Frothingham," he said. "They are some of those that were moulded out of the statue of King George himself."

George took them, and remembered the time when he and his brother had looked at this same statue when they had that first unhappy parting with Carter Hewes three years before. How differently had things terminated. He smiled sadly to himself as he slipped the new shining bullets into the pocket of his coat.

As they trudged along through the hot sun and the dust, a young officer, scarcely nineteen, galloped up and down the line, hurrying on those in the rear, and keeping the column well together to prevent straggling. He did not shout his orders, but talked in a low, intense voice; his movements were quick and nervous, but his graceful figure sat erect on his horse, and he seemed to take in everything with a rapid glance of his handsome deep-set eyes. George saw at once that it was his friend who had lent him his first Lieutenant's uniform, and whose name he had forgotten to ask. Chagrined, he thought that he could only explain that the wet had ruined everything, and the gay coat had been discarded.

"Who is he, that he should assume such airs?" said one of the slouching rear-guard that had been swelled by stragglers from various commands in advance, for the young officer had hastened him on by giving him a sharp dig in the shoulder with his foot as he rode up the line.

"'Tis young Aaron Burr," was the response.

"Humph! the young coxcomb!" had exclaimed the first soldier.

"Coxcomb, perhaps, but a game one, I'll warrant you," had come the answer.

The last time the proud young officer had ridden down the line, his tired horse dotted and blotched with foam, he had caught sight of the young Lieutenant, and had ridden up to him.

"Well met, comrade Frothingham!" he said, with a fascinating smile. "Take charge of these lazybones. Stop their mouths, and make them use their legs."

He cut with apparent playfulness at the shoulder of one of the belated ones nearest to him.

The blow stung, nevertheless, but the man only cringed, and hastened on like a jaded horse, frightened to further exertion. George looked at his face carefully. It was the pale youth with the fishy eyes who had been a clerk in Mr. Wyeth's employ with him. They had cordially disliked each other.

It was good that the rear-guard had hastened, for scarcely had they crossed to the heights at Harlem, where Washington was waiting, when the British appeared from east and west. A battery of Yankee artillery—the two brass pieces—had taken possession of a little knoll, and they roared alternately and held the victors in check. George placed his force along the slope, and took command of the battery. At the sound of the guns and the smell of the white sulphurous smoke our young hero's heart once more began to beat with that strange unaccountable excitement. As he faced his men about, he noticed private Ralston kneel down behind a stump, and soon the bullets made from King George's statue were singing across the meadow. The pursuit stopped at the bottom of the hill.

That night George and his weary companions rested in the hay of a small barn on the hill-side that overlooked the beautiful village of Bloomingdale.

He was too tired to sleep, and his thoughts ran rampant. What must William think of him? What was his brother doing? Why could not he see the right side? Oh, the bitterness of it! When would it end? Perhaps one of those bullets whose sound he now knew so well would settle things for good and all. If only William were here by him!

"Look back at the city!—look!" said a voice from the hay.

Far to the southward great red tongues of flame were leaping against the sky; billows of smoke swept up and caught the reflection of the flames, and sparks filled the air and danced out over the river. The city was on fire.

As George watched the conflagration from the window of the hay-mow, which was now crowded with excited soldiers, some men on horseback passed by beneath him.

"There's a warm reception for them," said a short thick-set man with a round chubby face. His voice had a cheery sound.

"I don't think that it was fired by our directions, General Putnam," came the answer.

"Probably it was done by the British themselves. They're not above it. Gadzooks, it is a grand sight!" said the short man, "and many a Tory heart is thumping with fear against its Tory ribs, I'll warrant ye." There came a pause, and then the speaker added, "What was the name of the lad who saved the powder train?"

"Aaron Burr," was the answer.

"No, not he—the young Lieutenant, I mean—the one who brought the news from Staten Island?"

"His name has slipped me," replied the second officer, "but I heard the General himself speak well of him."

George's heart gave a great leap, and then he murmured a prayer that he might never fail to deserve such commendation. For well-earned praise is balm to wounds and strengthening to the soul and spirit of the soldier, be he young or old, great general or humble private in the ranks.

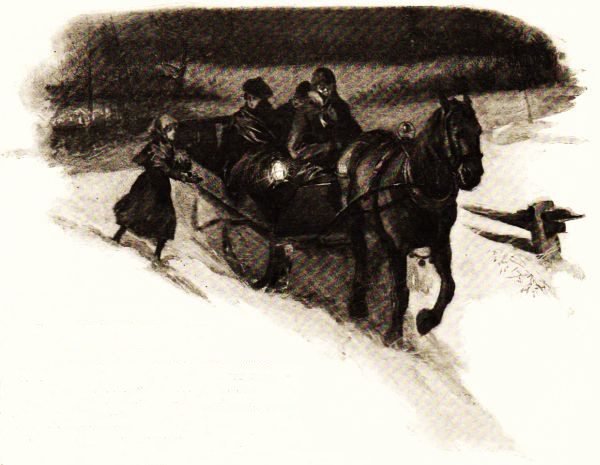

It had begun to look as if no one would go to Viola Pitkin's birthday party; it had been snowing for two days, and the drifts in some places were as high as a man's head. Patty Perley had tried to take an interest in the new lace pattern that she was crocheting, and in the paper lamp-shade she was making, for which Ruby Nutting had taught her to make roses that almost smelled sweet, they were so natural, and it was all in vain; and she quite envied Anson, who was trying to draw the buff kitten stuck into the leg of Uncle Reuben's boot. The kitten's squirming and the old cat's frantic remonstrances were preventing the picture from being a success, but Anson was highly entertained, and didn't seem to care whether he went to the party or not. It was just when Patty was feeling irritated by this indifference that Uncle Reuben came in, and she heard him stamping and shaking his clothes in the entry, and saying, "Whew, this is a night!" Then her spirits went down to zero. But the very first thing that Uncle Reuben said when he opened the door was:

"I've told Pelatiah to get out the big sled and hitch up the black mare, and you'll get to your party if the snow is deep. And the sled is large; you'd better pick up all the youngsters you can along the way."

Now that was like Uncle Reuben as he used to be, not as he had been since Dave, his only son, ran away; since then he had not seemed to think there was anything but gloom and sadness in the world. Indeed, Dave's going had taken the heart out of the good times all over Butternut Corner. He was only sixteen, and a good boy—his mother had meant that he should be a minister—but he got into the company of some wild fellows down at Bymport, and of Alf Coombs, a wild fellow nearer home, and then he had run away from home under circumstances almost too dreadful to tell. Burton's jewelry-store at Bymport had been broken into and robbed of watches and jewelry, and the next morning Dave and Alf Coombs had disappeared. They had been seen around the store that night; Dave had not come home until almost morning. The boys had been gone almost two months now, and the suspicion against them had become almost a certainty in most people's minds, and it was reported that the sheriff had a warrant for their arrest, but as yet had not been able to find them.

With such trouble weighing upon them, Patty had felt as if it were almost wicked to wish to go to Viola Pitkin's party, but Aunt Eunice had said, with the quiver about her patient mouth that always came there when she referred to Dave, that the innocent must not suffer for the guilty; and she had told Barbara, the "hired girl," to roast a pair of chickens and make some of her famous cream-cakes also, for it was to be a surprise party, and each guest was to carry a basket of goodies for the supper.

And now Uncle Reuben had planned for them to go, in spite of the snow-drifts; so Patty began to feel that it was not wrong to be light-hearted under the circumstances.

"Take all the youngsters you can pack on," repeated Uncle Reuben, as Patty and Anson settled themselves on the great sled, and Pelatiah cracked his whip over the old horse; "only I wouldn't stop at the foot of the hill"—Uncle Reuben's face darkened suddenly as he said this—"we've had about enough of Coombses."

Patty's heart sank a little, for she liked Tilly Coombs. They were rough and poor people, the Coombs family—"back folks," who had moved to the Corner only the summer before; the father drank, and the mother was an invalid, and it was the son Alf who was supposed to have had an evil influence over Dave. Patty thought it probable that Tilly had been invited to the surprise party, because Ruby Nutting, the doctor's daughter, who had planned the party, would be sure to ask her. Poor people who would be likely to be slighted, and stray animals that no one wanted, those were the ones that Ruby Nutting thought of first.

Along slid the great sled with its jingling bells, and out of her gate at the foot of the hill ran Tilly Coombs—the very first passenger. Patty couldn't help it. She didn't disobey Uncle Reuben's injunction not to stop; Tilly ran and jumped on.

"YOU'LL LET ME GO WITH YOU, WON'T YOU?"

"YOU'LL LET ME GO WITH YOU, WON'T YOU?"

"You'll let me go with you, won't you?" she panted. "I couldn't bear to miss it when she asked me! Some folks wouldn't, but she did. And I never went to a party in all my life! I couldn't bring anything but some doughnuts." Tilly opened her small basket, and by the light of Pelatiah's great lantern Patty saw that eager face darken suddenly. "I made 'em myself, and I'm afraid they're only middling. Doughnuts will soak fat, though, won't they?" she added, anxiously, as Patty gazed doubtfully at the soggy lumps laid carefully in the folds of a ragged napkin. "I never made any before."

It was altogether an affair of first times with Tilly—a happier thing in the way of party-going than of doughnut-making!

"They're very nicely flavored," said Patty, tasting critically, "and where there are so many things nobody will notice if they're not—not so very light."

Tilly's sharp anxious face brightened a little, but she heaved a sigh and covered her doughnuts quickly as the sled stopped to take on Rilly Parkhurst and her cousins, the Stillman boys, and Kathie Loomis, who was visiting Rilly. The Sage boys came next, and Delia Sage, who was sixteen and had taught school, but was just as full of fun as if she were young. It was a merry company; the jingling of the bells was almost drowned in chatter and laughter, and when Ruby Nutting joined it, she was greeted with a cheering that, as Pelatiah said, "must 'a' cracked the mill-pond."

The crowd increased; the baskets were all huddled together upon the seat with Pelatiah, and under the seat, and in the middle of the sled; no one could keep hold of his own, but there was no fear but that they would all know their own when they reached Viola's house.

Ruby Nutting was missed suddenly. She hadn't been as gay as usual; generally Ruby could be depended upon to stir up every one's wits and make the dullest party merry, but to-night she had been sitting in a corner talking in a low tone with Alvan Sage. Now she had disappeared, and Alvan Sage, looking very much surprised and bewildered himself, said that she had slipped off when they were going a little slowly up the hill, just as Pelatiah had held the lantern down to see if there was anything the matter with the horse's foot; she had said she would wait until Horace Barker's sleigh came along; either she thought the sled was too crowded, or she wanted to see some one who was coming with the Barkers. The latter explanation was probable enough, for Chrissy Barker was on the "committee of arrangements," and had helped Ruby about the preparations.

So no one thought much more about it, although it didn't seem like Ruby to go off without saying anything. The sled party was the first to reach Viola's, and it was great fun to see her perfect surprise and delight when they trooped in. They all thought that Ruby Nutting should have been there then.

Patty had a surprise that was not pleasant. When her basket was carried in the cover was open, the cream-cakes all jammed and half spoiled, and the two fine roast chickens were gone!

"See here, you can catch the thief by his mitten!" cried one of the boys. The rim of the basket was broken, probably by the thief in his haste, and to one sharply jagged end was attached a long, long string of red worsted. "Who has a ravelled mitten?"

The color came and went in Tilly Coombs's sharp, elfish little face; then she thrust her hand into her pocket as if she was thrusting her mittens deep into it. Patty Perley happened to be standing close beside her, and saw her.

Patty was mortified to have come to the surprise party with only a few half-spoiled cream-cakes, but she was kind-hearted, and her first thought was a pitying one.

"They must be so very poor! Tilly wanted them for her sick mother," she said to herself.

How Tilly could have taken the chickens from the basket and where she could have concealed them was a mystery. But Uncle Reuben believed that all the Coombs family were thievish and sly; perhaps he was right, and Tilly was used to doing such things. But even Uncle Reuben would not be very hard upon a girl who had stolen delicate food for her sick mother.

"'Sh!—'sh! don't say anything about it! It is of no consequence," she whispered to some girls and boys who were loudly wondering and guessing about the mysterious theft.

Then they all went into the sitting-room, and the Virginia reel, the old-fashioned dance with which Butternut Corner festivities almost always began, was danced, and no one thought any more of the stolen chickens.

Ruby Nutting had come by this time, and she led the dance, as usual the life of the good time. She had come in Horace Barker's sleigh, and she gayly evaded the wonderings and reproaches of the party she had left. As the dance ended, Berta Treadwell beckoned slyly to Patty. Berta was Viola Pitkin's cousin, who had come all the way from California to visit her; she and Patty had "taken to" each other at once.

"I want you to see such a funny thing!" whispered Berta, drawing Patty out into the back entry. "That queer-looking girl they call Tilly, with the wispy black hair and the faded cotton dress, asked me to lend her a pair of knitting-needles! I got grandma's for her, and she snatched them out of my hands, she was so eager. 'You needn't tell anybody that I asked you for 'em, either,' she said, in that sharp way of hers. I had such a curiosity to know what she was going to do with them that I watched her. After a while, when the reel was begun and she thought no one was looking, she slipped out through the wood-shed into the barn. Come and peep through the crack!"

Patty followed Berta softly through the wood-shed, and looked through a chink in the rough board partition into the barn.

On an inverted bucket, with a lantern hung upon a nail over her head, sat Tilly Coombs diligently knitting. The barn was cold; the cattle's breaths made vapors, and there was a glitter of frost around the beams. Tilly was muffled in a shawl, but her face looked pinched and blue.

"What is she knitting? It looks like a red mitten," whispered Berta. "Is she so industrious? To think of leaving a party on a winter night to go out to the barn and knit! Do you think we ought to leave her there in the cold? I should think she must be crazy!"

Patty was drawing Berta back through the wood-shed eagerly, in silence. Berta had not heard about the ravelled mitten; she did not know that Tilly was trying to knit it into shape again so it would never be known that it was her mitten that was ravelled.

"I know why she is doing it," said Patty, "though I don't see why she couldn't have waited until she got home; but I suppose she is awfully anxious. Berta, don't say that we saw her, or anything about the needles, to anybody. That will be kind to her, and she is so poor. Whatever you hear, don't say anything."

"I'm sure I don't want to say anything to hurt her," answered Berta, a little resentfully, for she did think Patty might have told her all about it. "But I must say I think society in Butternut Corner is a little mixed."

"Ruby asked her," explained Patty. "I think it was right; Tilly never went to a party before."

"Her way of enjoying herself at a party is a little queer," said Berta, unsympathetically.

And Patty thought she did not feel quite so sorry as she had done that Berta was going back to California the next day.

She thought she would tell Ruby Nutting; Ruby would understand, and pity Tilly; but before she had a chance, while Horace Barker was singing a college song and Ruby was playing the accompaniment on the piano, a sudden recollection struck her that sent the color from her face. Aunt Eunice's spoons!

Aunt Eunice had said that there were never spoons enough to go round at a surprise party, and Viola Pitkin's mother was her intimate friend, so she wished to help her[Pg 191] all she could, and she put a dozen spoons into the basket—the solid silver ones that had been Grandmother Oliver's—and charged Patty to take care of them. And it was not until she overheard Mrs. Pitkin whisper to Viola that she wasn't sure that there were sauce-plates enough that Patty remembered the spoons.

She had a struggle to repress a cry of dismay, those spoons were so precious! Uncle Reuben had demurred when they were put into the basket, but Aunt Eunice was proud, and always liked to give and lend of her best. Patty felt as if she must cry out and denounce Tilly when she crept slyly in behind broad-backed Uncle Nathan Pitkin and slyly warmed her benumbed hands at the fire. But Patty held her peace; when she had reflected for a few minutes she knew that this was too grave a matter for fourteen-year-old wits to grapple with, and she must tell Uncle Reuben and Aunt Eunice.

Tilly Coombs was drawn into a merry game—Ruby Nutting took care of that—and before long her queer little sharp face was actually dimpling with fun, and her laugh rang out with the gayest! Patty Perley looked at her, and decided that it was a very queer world indeed; for her the joy of Viola Pitkin's party was done.

When they were all dressing to depart, Patty looked involuntarily at Tilly Coombs's mittens; in fact, many furtive glances were cast around at the red mittens by those who remembered the theft of the roast chickens. There were many of them, red being the fashionable color for mittens at Butternut Corner, but apparently they were all sound and whole. Tommy Barker had one mitten with a white thumb, which his blind grandmother had knitted on in place of a torn thumb, and little Seba Sage had but one mitten; but that one was very dark red, not the vivid scarlet of the ravelling.

Rilly Parkhurst whispered to Patty, as she sat down beside her on the sled: "Tilly Coombs has the ravelled mitten! She is trying to cover it with her shawl; it is only a little more than half a mitten!"

Patty smothered an exclamation of doubt, and then she gazed curiously at Tilly's hands; but they were tightly, carefully covered by her shawl.

Could it be that after spending all that time in the cold barn she had failed to knit up her ravelled mitten? Tilly looked as if she had been having a good time. Under the light of Pelatiah's lantern her eyes were shining, her face rippling with smiles. Patty thought with wonder that she had not seen her look so happy—well, certainly not since her brother Alf ran away.

"I must have grown plump at the party!" laughed Ruby Nutting. "One of my mittens is too tight around the wrist." And Patty saw Tilly Coombs nervously fold her shawl more closely about her mittens.

Just before her own door was reached, Tilly Coombs leaned towards Patty and whispered, so that even Anson or Pelatiah should not hear.

"I didn't know there were such good times in the world!" she said, with her face aglow. "And Viola Pitkin's uncle Nathan ate one of my doughnuts!" But Patty shrank away from her.

The Eve of Epiphany or Twelfth-Night brings to the Roman children very much the same experience which Christmas brings to young Americans. It is the time and opportunity for presents, and sometimes for disappointments and even punishments. Upon this occasion, however, it is a benefactress instead of a benefactor who confers the coveted favor. It is not Santa Claus, who, round, red, and good-natured, comes down the chimney with a gift for every child, but a hideous old woman, lean, dark, and sour-visaged, who descends the chimney with a bell in one hand and a long cane in the other. The bell announces her coming, and the cane is especially for the children who have rebelled against parents and teachers, or have been otherwise forgetful of duty. The name of this old crone is Befana, and she brings plenty of good things, in spite of her forbidding countenance and manner, and the good, obedient child may confidently expect a stocking full of dainties. She fills the stocking of the disobedient too, but with ashes! The Festival of the Befana is one of the most fascinating to the children of Rome. Crowds gather upon the thoroughfares and fill up the streets and piazzas, and the beating drums, squeaking whistles, jingling tambourines, and sonorous trumpets show that Roman children can be quite as noisy in honor of the Befana as American children are when they wish to welcome Christmas or celebrate the glorious Fourth. This festival occurs, of course, on the eve of Twelfth-Night, and in addition to the various noises which assail your ears, your eyes are feasted with the most startling and curious spectacles. Very odd and, we can say, very picturesque toys are exhibited on all sides, and the brilliant display of fireworks gives a fascination to things which are in themselves ridiculous and grotesque. Noise, unceasing noise, is the order of the night, and he who can surprise you with the loudest is greeted with peals of laughter and shouts of applause. A whistle or horn is always at your ears.

Nor is the custom of receiving presents on this happy occasion confined to children. The Pope and the Cardinals take part in the rejoicing. Formerly a chalice of gold containing a hundred ducats was presented to the Pope with a Latin address and great ceremony, and the Pope, in accepting it, made his reply in Latin, and graciously allowed the bearer to kiss his foot. This offering was called the Befana Tribute. The ceremony was discontinued in the year 1802; but the Befana Tribute is still offered and accepted. Of course, there are many traditions concerning the Befana, and it is in honor of a tradition that a burning broom is always carried in the processions which celebrate her festival. According to this tradition she is said to have been an old woman, who was engaged in cleaning the house when the three Kings passed carrying presents to the infant Christ; she was called to the window to see them, but she declined to leave her household duties, and said, "I will see them as they return." But the old woman was denied the blessed sight, for they did not return that way, and hence she is represented as waiting and watching for them continually—always standing in the attitude of expectation, with her broom in her hand.

To disguise themselves as this old woman is one of the pranks of the Roman boys during the Befana Festival. With blackened faces and fantastic caps on their heads they stand in the doors with a broom in one hand and a lantern in the other. Around their necks and suspended to their waists are rows of stockings filled with sweet-meats, and also with the reward of evil-doing—the famous ashes! And what do the Roman children say when they see these representations of the Befana?

Well, very much what the American children say when they see the images of their dearly loved Santa Claus!

Come, draw around the fire,

And watch the sparks that go

All singing like a fairy choir

Into the realms of snow.

Above us evergreen,

With mistletoe in sprays,

And tenderly the leaves between

The holly-berries blaze.

And while the logs burn bright,

Before the day takes wing,

The happy children, gowned in white,

Their merry carols sing.

Then high the stockings lift,

Like hungry beggars dumb.

Good Santa Claus, bring every gift,

And fill them when you come!

he most illustrious name connected with London Tower—high over king, priest, or prince—is the name of Raleigh. There at four different times he was sent, not so much prisoner of England as of Spain. He never lay in the lonesome cell in the crypt called his. His longest term was in the grim fortress Bloody Tower, where his undaunted spirit taught the world

"Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage."

GARDEN INSIDE THE TOWER, WHERE RALEIGH WALKED.

GARDEN INSIDE THE TOWER, WHERE RALEIGH WALKED.

He was allowed the freedom of the garden, with a little lodge for a study—a hen-house of lath and plaster, where he experimented with drugs and chemicals, studied medicine and ship-building, kept his crucibles and apparatus, and the near terrace he paced up and down through weary years is to this day called Raleigh's Walk.

It was in the reign of King James the First—the cruel and cowardly—and never in his peerless prime was Raleigh greater than in the fourteen years that sentence of death hung over his head. His prison was a court to which men crowded with delight. Queen Anne sent gracious messages to him, and Prince Henry rode down from Whitehall to hear the old sailor tell of green isles with waving palms like beckoning hands, hints of wonderful plumage, hissing serpents in tropic jungles, barbarian cities built of precious stones, and of rivers running over sands of gold, all waiting for the English conqueror to come and make them his own.

After a morning of high converse the Prince cried out, "No man but my father would keep such a bird in such a cage," and when the young listener fell ill the Queen would have him take nothing but Raleigh's cordial, which, she said, had saved her life.

His best biographer writes: "Raleigh was a sight to see; not only for his fame and name, but for his picturesque and dazzling figure. Fifty-one years old, tall, tawny, splendid, with the bronze of tropical suns on his leonine cheek, a bushy beard, a round mustache, and a ripple of curling hair which his man Peter took an hour to dress. Apparelled as became such a figure, in scarf and band of richest color and costliest stuff, in cap and plume worth a ransom, in jacket powdered with gems, his whole attire from cap to shoe-strings blazing with rubies, emeralds, and pearls, he was allowed to be one of the handsomest men alive."

In the eleventh year of his bondage he finished the first part of the History of the World. He wrote what men will not let die, invented the modern war-ship, and from the turrets of Bloody Tower looked across the vast blue plain of ocean and directed operations in Virginia and Guiana. He was a guiding light to his beloved England; proud and brilliant heroes deferred to him, sought his advice; charming women were charmed by the most courtly of courtiers, and all felt him to be a man whom the government could not afford to spare. He knew more than any other person living about the New World offering endless riches to the Old, and his services were at the King's command. While prisoner to the crown he sailed with five ships under royal orders for the region of the Orinoco, the land of promise unfulfilled. The golden city lighted by jewels was a vanishing illusion ending in bitter disappointment.

Years before, in 1609, he had written to Shakespeare, whom he called, "My dearest Will":

"Great were our hopes, both of glory and of gold, in the kingdom of Powhatan. But it grieves me much to say that all hath resulted in infelicity, misfortune, and an unhappy end.... As I was blameworthy for thy risk, I send by the messenger your £50, which you shall not lose by my overhopeful vision. For its usance I send a package of a new herb from the Chesapeake, called by the natives tobacco. Make it not into tea, as did one of my kinsmen, but kindle and smoke it in the little tube the messenger will bestow ... it is a balm for all sorrows and griefs, and as a dream of Paradise.... Thou knowest that from my youth up I have adventured for the welfare and glory of our Queen, Elizabeth. On sea and on land and in many climes have I fought the accursed Spaniard, and am honored by our sovereign and among men ... but all this would I give, and more, for a tithe of the honor which in the coming time shall assuredly be thine. Thy kingdom is of the imagination, and hath no limit or end."

The dreams of the Admiral far outran any possibility, and the mines of Guiana proved a cheat equal to the yellow clay of the Roanoke. Peril of life, fortune, and the varied resources of genius and valor were not enough to insure success, and a failure in the paradise of the world probably hastened the sentence for which Philip III. of Spain clamored.

The charges of treason against Raleigh were pure invention; but on his return from South America he was arrested, committed to the Tower, and the warrant for execution was signed without a new trial, while men from the streets and ships came crowding to the wharf, whence they could see him walking on the wall. He was advised to kill himself to escape the shameful sentence of James I., but he solemnly spoke of self-murder, and declared he would die in the light of day and before the face of his countrymen. In the field of battle, on land and on sea, he had looked at death too often to tremble now.

His farewell letter to his wife is one of the sweetest. I wish I had space for it all. It concludes:

"The everlasting God, Infinite, Powerful, Inscrutable; the Almighty God, which is Goodness itself, Mercy itself; the true light and life—keep thee and thine, have mercy on me, and teach me to forgive my persecutors and false witnesses, and send us to meet again in His Glorious Kingdom. My own true wife, farewell. Bless my poor boy. Pray for me, and let the good God fold you both in His arms. Written with the dying hand of sometime thy husband, but now, alas! overthrown.

"Yours that was, but not now my own,

"W. Raleigh."

In his final imprisonment Lady Raleigh was not allowed a share. When she caught his youthful fancy it was as Elizabeth Throckmorton, maid of honor to Queen Elizabeth.

"Sweet Bess" was a favorite there among ladies of gentle blood. The flatterers of the dazzling court fluttered round the lovely young girl, conspicuous for beauty and grace; slender, fair, golden-haired. Her sighs were only for the sea-captain who expected to crown her with glory won by his sword, and riches, the spoil to be fought for in many lands. She was his loyal wife to the end, always pleading for pardon, defiant before King and court, where she appeared daily in her husband's cause, "holding little Wat by the hand." When her petition was refused, she was not afraid to call down curses on the head of the tyrant, who heeded not her wrath or her grief.

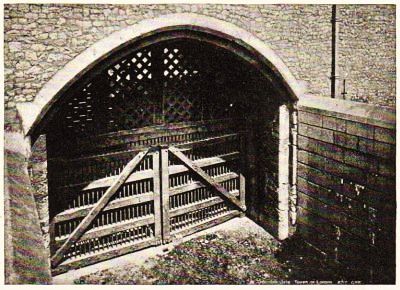

The water-way from the Thames is a dark passage under whose arch a pale procession of ghosts of the murdered may easily be fancied as coming up out of the past. Beneath it went Raleigh from prison to hear his sentence in Westminster Hall; from the King's Bench he was sent to Westminster Abbey. Crowds thronged to watch him pass, and from the carriage window he noticed his old friend Burton, and invited him to Palace Yard next day to see him die.

THE TRAITORS' GATE.

THE TRAITORS' GATE.

The warrant came on a dark October morning, 1618. Raleigh was in bed, but on hearing the Lieutenant's voice he sprang lightly to his feet, threw on hose and doublet, and left his room. At the door he met Peter, his barber, coming in. "Sir," said Peter, "we have not curled your head this morning." His master answered with a smile, "Let them comb it that shall have it." The faithful servant followed him to the gate insisting on the service. "Peter," he asked, "canst thou give me any plaster to set on a man's head when it is off?"

John Eliot wrote: "There is no parallel to the fortitude of Raleigh. Nothing petty disturbed his calm soul in ending a career of constant toil for the greatness and honor of his country. The hero who created a New England for Old England was fearless of death, the most resolute and confident of men, yet with reverence and conscience."

The executioner was deeply moved by the matchless spirit of the martyr. He knelt and prayed forgiveness—the usual formula at the block or scaffold. Raleigh placed both hands on the man's shoulders and said, "I forgive you with all my heart. Now show me the axe." He carefully touched the edge of the blade to feel its keenness, and kissed it. "This gives me no fear. It is a sharp and fair medicine to cure all my ills." Being asked which way he would lie on the block, he answered, "It is no matter which way the head lies, so that the heart be right." Presently he added, "When I stretch forth my hands, despatch me." There were omissions in his last speech, but we may be sure they were noble utterances. He prayed in an unbroken voice, and begged his friends to stand near him on the scaffold so they might better hear his dying words. Which being done, he concluded, "And now I entreat you all to join with me in prayer that the great God of Heaven, whom I have grievously offended—being a man full of vanity, and having lived a sinful life in all sinful callings, having been a soldier, a captain, and a sea-captain, and a courtier, which are all places of wickedness and vice—that God, I say, would forgive me and cast away my sins from me, and that He would receive me into everlasting life. So I take my leave of you making my peace with God.