*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 50693 ***

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

[Pg i]

ILLUSTRATED MICHELIN GUIDES

TO THE BATTLE-FIELDS.

BATTLE-FIELDS

OF

THE MARNE

1914

Published:

in FRANCE; by MICHELIN & Cie,

Clermont-Ferrand.

in ENGLAND; by MICHELIN TYRE Co Ltd,

81 Fulham Road, London, S.W.

in the U.S.A.; by MICHELIN TIRE Co,

Milltown, New Jersey.

[Pg ii]

[Pg iii]

For all Information and Advice—

MOTORISTS MAY APPLY

TO THE 'BUREAU DE TOURISME MICHELIN'

99, Boulevard Pereire—PARIS

Hotels and Motor-agents.

Palatial and luxuriously appointed hotels.

Palatial and luxuriously appointed hotels. Well-appointed, first-class hotels.

Well-appointed, first-class hotels. Comfortable hotels with modern improvements.

Comfortable hotels with modern improvements. Well-managed hotels with good accommodation.

Well-managed hotels with good accommodation. Hotels with good service for luncheon and dinner.

Hotels with good service for luncheon and dinner. Small hotels or inns where good meals are provided.

Small hotels or inns where good meals are provided.

| Compressed Air |

Depôt for 'bouteilles d'air Michelin' for inflation of tyres. |

|

Repair shop. |

| Agt de |

Manufacturer's Agent. |

| 3 |

Garage showing car capacity. |

|

Repair Pit. |

|

Electric installation for recharging accumulators. |

104 104 |

Telephone number. |

|

Telegraphic address. |

- MEAUX (Seine-et-Marne).

de la Sirène, 34 r. St-Nicolas. Ⓑ(wc) Gar 3 Shed 5

de la Sirène, 34 r. St-Nicolas. Ⓑ(wc) Gar 3 Shed 5  Sirène

Sirène  83.

83. des Trois-Rois, 1 r. des Ursulines and 30 r. St-Rémy. (wc) Shed 4

Inner courtyard 10

des Trois-Rois, 1 r. des Ursulines and 30 r. St-Rémy. (wc) Shed 4

Inner courtyard 10  146.

146. MICHELIN STOCK (Compressed Air) Garage Central (A.

Feillée), 17-21 r. du Grand-Cerf. Agt. de: Panhard, Renault,

de Dion. 30

MICHELIN STOCK (Compressed Air) Garage Central (A.

Feillée), 17-21 r. du Grand-Cerf. Agt. de: Panhard, Renault,

de Dion. 30  G Petrol Depôt

G Petrol Depôt  59.

59.- — MICHELIN STOCK Auto-Garage de Meaux (E. Vance),

55-57 pl. du Marché. Agt de: Delahaye. 20

G

G

84.

84.

- SENLIS (Oise).

du Grand-Cerf, 47 r. de la République. Central heating

du Grand-Cerf, 47 r. de la République. Central heating  Ⓑ (wc)

Inner coach-house 6

Ⓑ (wc)

Inner coach-house 6

Grandcerf

Grandcerf  111.

111. des Arènes, 30 r. de Beauvais. (wc) Inner coach-house 7 ott

des Arènes, 30 r. de Beauvais. (wc) Inner coach-house 7 ott  17.

17. MICHELIN STOCK Guinot, 8 pl. de la Halle. Stock: de Dion.

Agt de: Peugeot. 3

MICHELIN STOCK Guinot, 8 pl. de la Halle. Stock: de Dion.

Agt de: Peugeot. 3

46.

46.- — MICHELIN STOCK L. Buat and A. Rémond, 2 r. de Crépy.

Agts de: Panhard, Renault, Cottin-Desgouttes, Delahaye,

Rochet-Schneider, Mors. 10

G

G

38.

38.

- CHANTILLY (Oise).

du Grand-Condé, av. de la Gare. Closed in 1917. Asc Central heating

du Grand-Condé, av. de la Gare. Closed in 1917. Asc Central heating

Ⓑ (wc) Gar 50

Ⓑ (wc) Gar 50

52.

52. d'Angleterre, r. de Paris and pl. de l'Hôpital.

d'Angleterre, r. de Paris and pl. de l'Hôpital.  Ⓑ (wc) Inner

shed 8

Ⓑ (wc) Inner

shed 8  59.

59. Noguey's Family Hotel, 10 av. de la Gare.

Noguey's Family Hotel, 10 av. de la Gare.  Ⓑ (wc) Inner coach-house

5

Ⓑ (wc) Inner coach-house

5  146.

146. MICHELIN STOCK Grigaut, 72 r. du Connétable.

MICHELIN STOCK Grigaut, 72 r. du Connétable.  1.14.

1.14.- — MICHELIN STOCK Garage Bourdeau, 1 bis r. de Gouvieux. 6

G

G

1.90.

1.90.

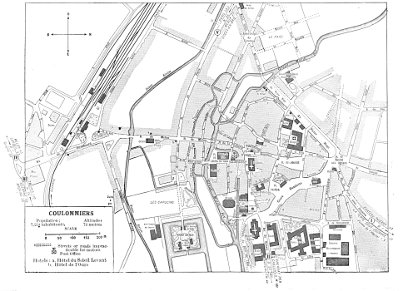

- COULOMMIERS (Seine-et-Marne).

du Soleil-Levant, 62 r. de Melun. Central heating, Inner coach-house

3 courtyard 15

du Soleil-Levant, 62 r. de Melun. Central heating, Inner coach-house

3 courtyard 15  22.

22. de l'Ours, r. de Melun. Central heating. Inner coach-house 3 courtyard

10

de l'Ours, r. de Melun. Central heating. Inner coach-house 3 courtyard

10  27.

27. MICHELIN STOCK Doupé-Lejeune, 42 r. de Paris. Agt de:

Panhard, Delage, Darracq. 10

MICHELIN STOCK Doupé-Lejeune, 42 r. de Paris. Agt de:

Panhard, Delage, Darracq. 10  Petrol Depôt

Petrol Depôt

92.

92.- — Gautier, 6 av. de la Ferté-sous-Jouarre. Agt de: Peugeot, Vinot-Deguingand,

de Dion. 4

Petrol Depôt

Petrol Depôt  1.19.

1.19.

- — P. Fritsch, 51 av. de Strasbourg. Agt de: Brasier, Le Zèbre.

6

Petrol Depôt.

Petrol Depôt.

- — Purson, cycles, 1 r. de Melun. Agt de: Clément-Bayard. 2

Petrol Depôt.

Petrol Depôt.

- — A. Gontier, cycles, Le Martroy.

- — Doupé-Boucher, cycles, 1 r. de la Ferté-sous-Jouarre. Petrol

Depôt.

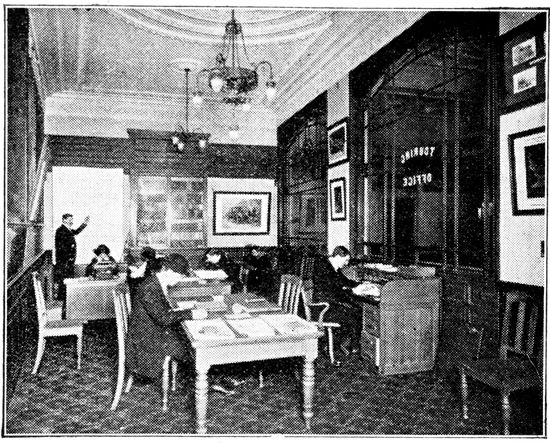

'OFFICE NATIONAL DU TOURISME'

17, Rue de Surène, PARIS (VIIIe)

The 'Office National du Tourisme' was created by

an Act of April 8, 1910, and reorganised in 1917. It

enjoys civil privileges and financial autonomy.

It is directed by an administrative council chosen

by the Minister of Public Works.

Its mission is to seek out every means of developing

travel; to urge and, if necessary, to take any measure

capable of ameliorating the condition of the transport,

circulation and sojourn of tourists.

It co-ordinates the efforts of touring societies and

industries, encourages them in the execution of their

programmes and stimulates legislative and administrative

initiative with regard to the development of travel

in France.

It promotes understanding between the public services,

the great transport companies, the 'Syndicats d'Initiative'

and the 'Syndicats Professionnels.'

It organises propaganda in foreign countries; and

arranges for the creation of travel enquiry offices in

France and abroad, with a view to making known the

scenery and monuments of France as well as the

health-giving powers of French mineral waters, spas

and bathing places.

ALL ENQUIRIES WITH REGARD TO TRAVELLING

SHOULD BE ADDRESSED

TO THE 'TOURING-CLUB DE FRANCE'

65, Avenue de la Grande Armée, 65

PARIS

[Pg iv]

'THE TOURING-CLUB DE FRANCE'

ADVANTAGES OF MEMBERSHIP

The 'Touring-Club de France' (founded in 1890),

is at the present time the largest touring association

in the world. Its principal aim is to introduce

France—one of the loveliest countries on earth—to

the French people themselves and to tourists of other

nations.

It seeks to develop travel in all its forms: on foot,

horseback, bicycle, in carriage, motor, yacht or railway,

and, eventually, by aeroplane.

Every member of the association receives a badge

and an identity ticket, free of charge, and also the

'Revue Mensuelle' every month.

Members have the benefit also of special prices in

a certain number of affiliated hotels; and this advantage

holds good in the purchasing of guide-books and Staff

(Etat-major) maps, as well as those of the 'Ministère de

l'Intérieur,' the T.C.F., etc. They may insert notices

regarding the sale or purchase of travelling requisites,

in the 'Revue' (1 fr. per line). The 'Comité de

Contentieux' is ready to give them council with regard

to travelling, and 3,000 delegates in all the principal

towns are retained to give advice and information

about the curiosities of art or of nature of the neighbourhood,

as well as concerning the roads, hotels, motor-agents,

garages, etc.

Members are accorded free passages across the

frontier for a bicycle or motor-bicycle. For a motor-car

the association gives a 'Triptyque' ensuring free passage

through the 'douane,' etc.

TO TOUR FRANCE IN COMFORT JOIN

THE 'TOURING-CLUB DE FRANCE'[Pg 1]

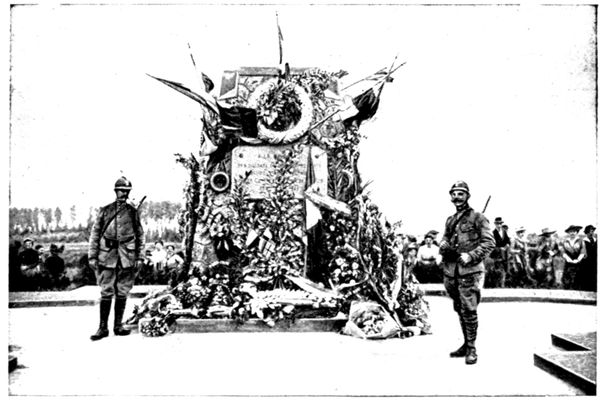

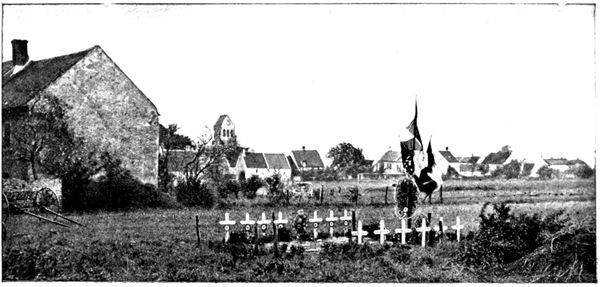

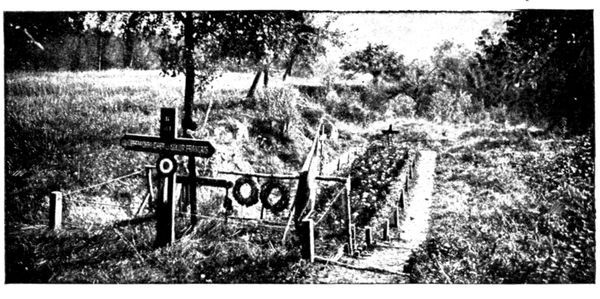

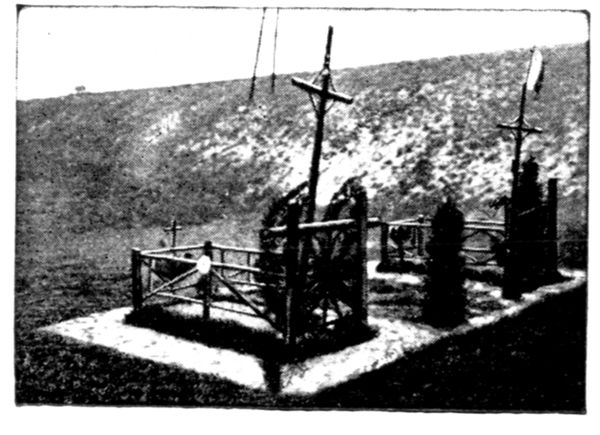

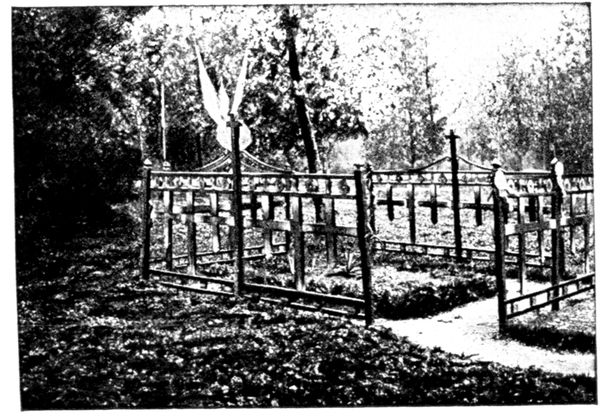

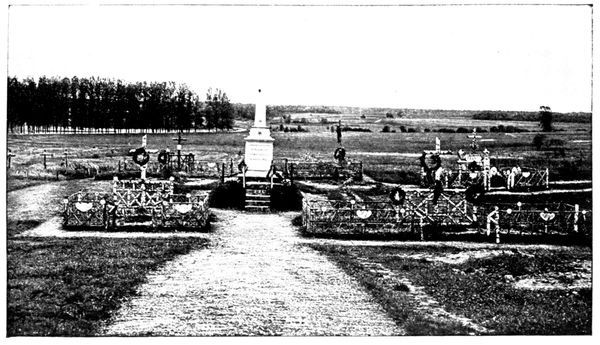

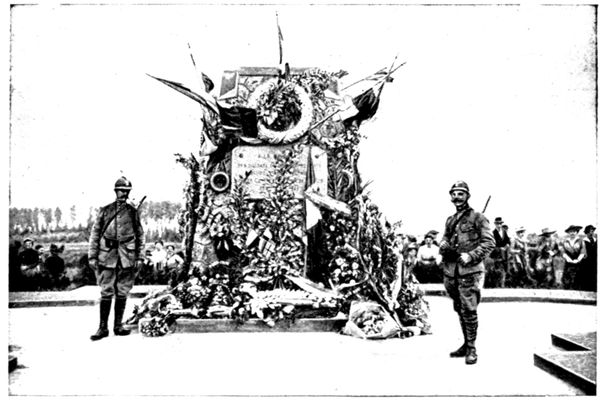

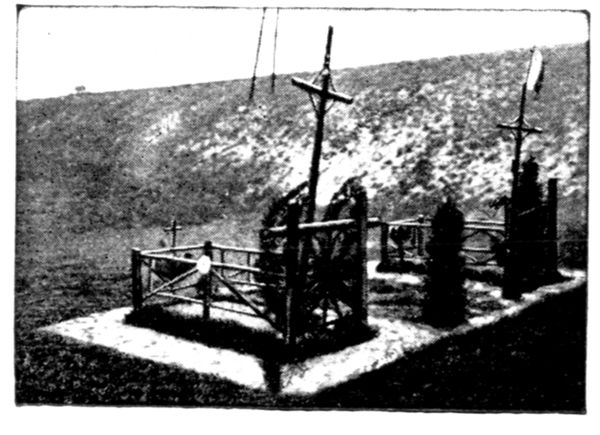

IN MEMORY

OF THE MICHELIN EMPLOYEES

AND WORKMEN WHO DIED GLORIOUSLY

FOR THEIR COUNTRY.

THE MARNE

BATTLE-FIELDS

(1914)

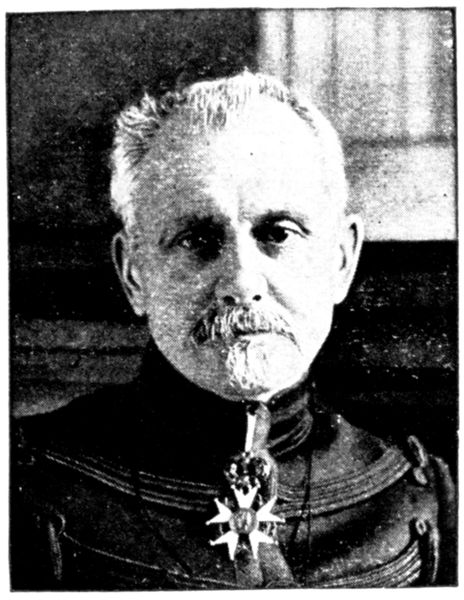

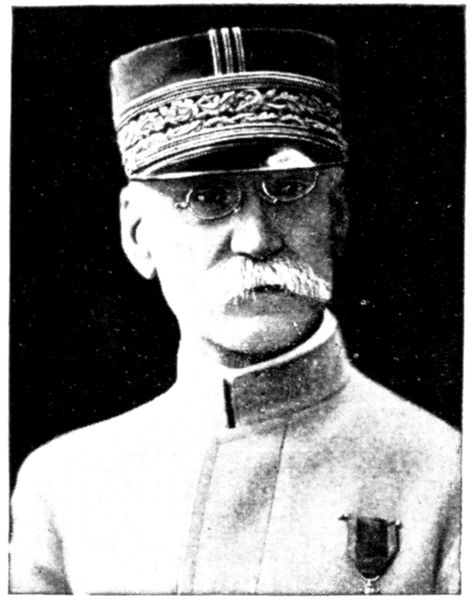

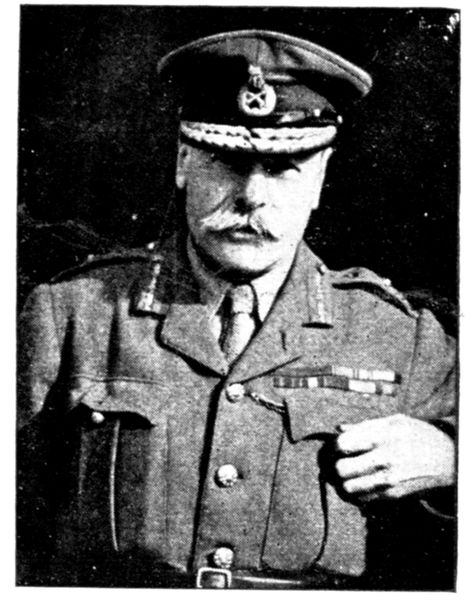

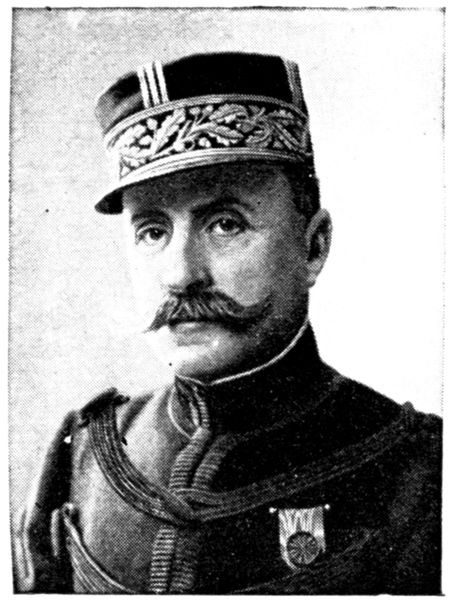

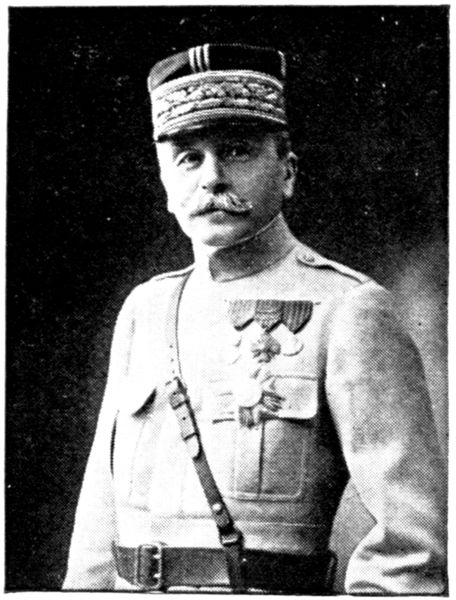

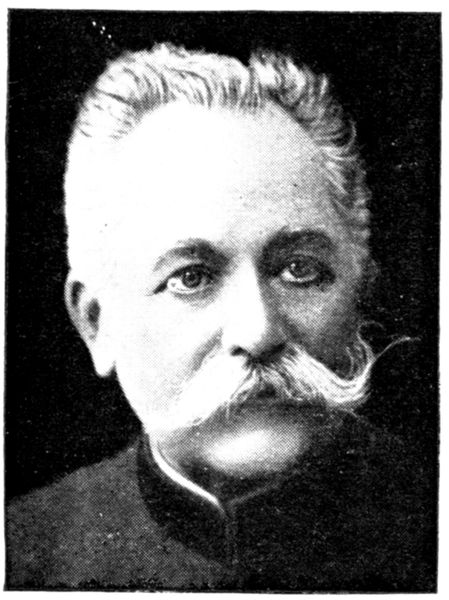

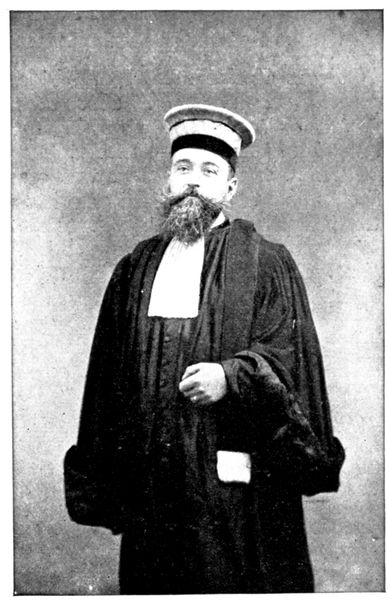

JOFFRE

Commander-in-chief of the French Army

Copyright 1919 by Michelin & Cie.

All rights of translation, adaptation, or reproduction

(in part or whole) reserved in all countries.

[Pg 2]

FOREWORD

For the benefit of tourists who wish to visit the battlefields and

mutilated towns of France we have tried to produce a work combining

a practical guide with a history.

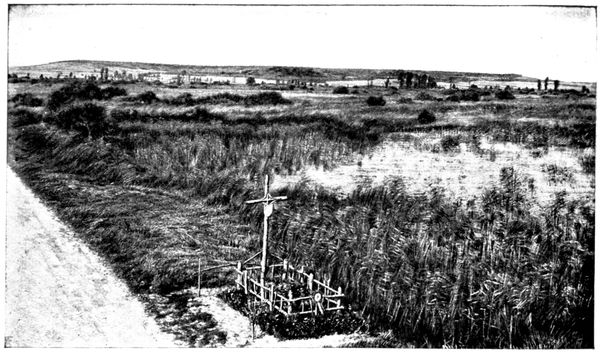

Such a visit should be a pilgrimage, not merely a journey across

a ravaged land. Seeing is not enough, one must understand: a

ruin is more moving when one knows what has caused it; a stretch

of country which might seem dull and uninteresting to the unenlightened

eye, becomes transformed at the thought of the battles which

have raged there.

We have, therefore, prefaced the description of our journeys by a

short account of the events which took place in the vicinity, and we

have done our best to make this account quite clear by the use of

many illustrations and maps.

In the course of the description we give a brief military commentary

on the numerous views and panoramas contained in the

book.

When we come across a place that is interesting either from an

archæological or an artistic point of view, there we halt, even though

the war has passed it by; that the tourist may realise it was to

preserve intact this heritage of history and beauty that so many of

our heroes have fallen.

Our readers will not find any attempt at literary effect in these

pages; the truth is too beautiful and tragic to be altered for the sake

of embellishing the story. We have, therefore, after carefully sifting

the great volume of evidence available, selected only that obtained from

official documents or from reliable eye-witnesses.

This book was written before the end of the war, even then the

country over which it leads the reader had long been freed. The

wealth of illustration in this work allows the intending tourist to

make a preliminary trip in imagination, until such time as circumstances

permit of his undertaking a journey in reality beneath the

sunny skies of France.

[Pg 3]

HISTORICAL PART

IMPORTANT NOTE.—On pages 4 to 16 will be found a brief summarized

account of the Battle of the Marne and of the events which immediately

preceded it. We recommend the reading of these few pages attentively,

and the consultation of the maps annexed to the same, before reading

the descriptive part which commences at page 17.

A clear understanding of the action as a whole is absolutely necessary to

comprehend with interest the description of the separate combats.

[Pg 4]

THE BATTLE OF THE MARNE

(1914)

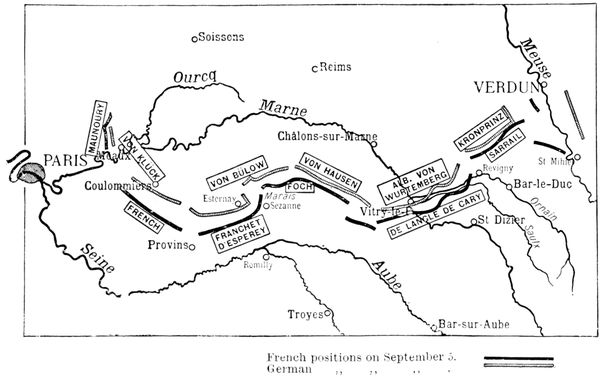

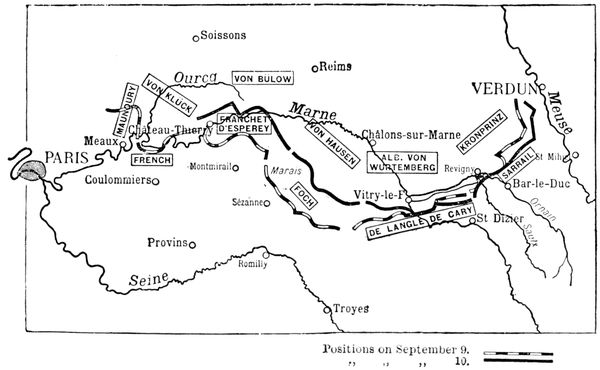

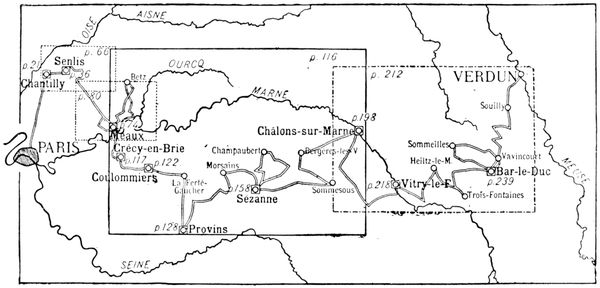

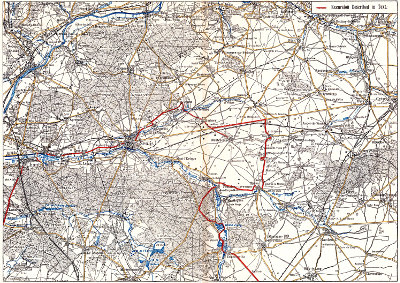

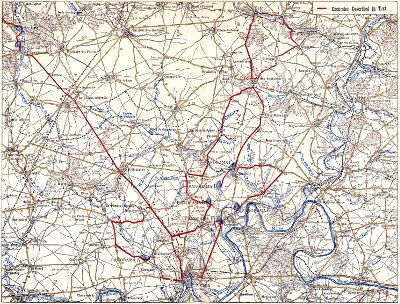

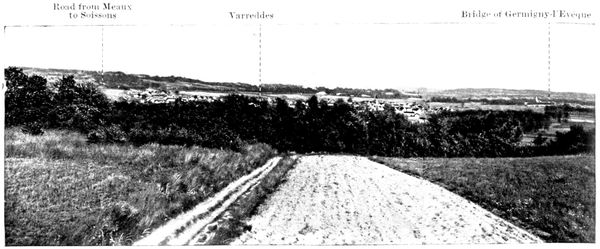

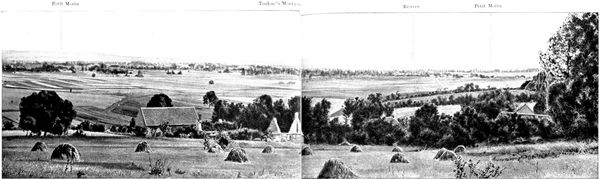

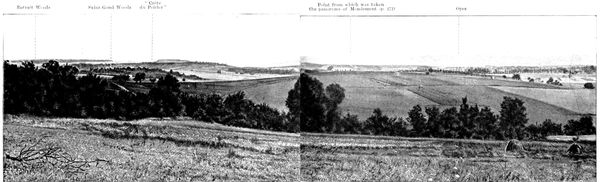

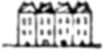

The above map gives a general view of the ground on which took place

successively: the battle of the frontier, the retreat of the Allies, the victorious

stand, and the pursuit of the retreating enemy.

The distance from Paris to Verdun is 140 miles as the crow flies; from

Charleroi to the Marne is 97 miles.

In consequence of the tearing up of that fateful "scrap of paper" which

preceded the invasion of Belgium by Germany, in violation of the common

rights of man, the Battle of the Frontier (also called the Battle of Charleroi) was

fought in August 1914 on the line Mons—Charleroi—Dinant—Saint-Hubert—Longwy—Metz.

[Pg 5]

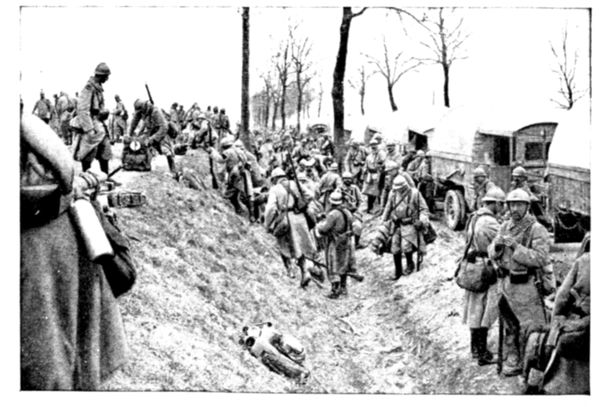

On August 22, 1914, and the two succeeding

days this Allied offensive failed at Charleroi, in

consequence of which the French Commander-in-chief,

General Joffre, broke off contact with the

enemy and ordered a general retreat.

It was impossible to do otherwise as the

enemy forces were greatly superior in numbers.

Moreover, they were well equipped with powerful

artillery and machine-guns, whereas the Franco-British

forces were short of both. Lastly, the

German soldier had long been trained in trench

warfare, whereas the Allies had yet to learn

this art.

To help in readjusting the balance between

the opposing forces, Joffre fell back in the direction

of the French reserves.

The respite thus afforded was utilized to re-arrange the commands, and

to train the reserves in the form of warfare adopted by the Germans. Meanwhile,

the latter greatly extended their line of communications and more or

less tired themselves.

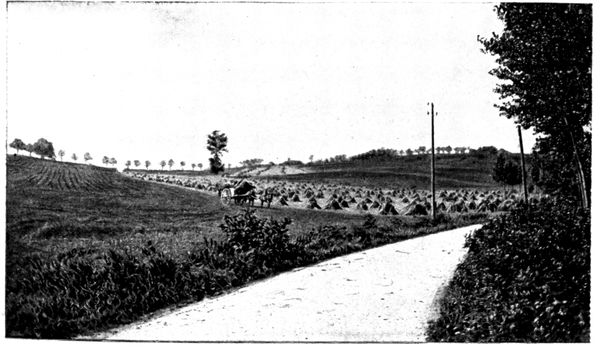

Then began that heroic retreat, without precedent in history, which

attained a depth of 122 miles, and in the course of which the Allied soldiers,

though already fatigued, marched as much as thirty miles a day facing about

from time to time and counter-attacking fiercely, often with success.

The Germans followed in pursuit, overrunning the country like a plague

of locusts. Using their left wing as a pivot, their right undertook a vast

turning movement taking in Valenciennes, Cambrai, Péronne, and Amiens.

By August 27 Joffre had fixed up a plan according to which the offensive

was to be taken again at the first favourable opportunity. In view of the

execution of this plan an important mass of troops, under the orders of

General Maunoury, was formed on the French left.

General Maunoury's task was to outflank at a given moment the German

right wing while, at the same time, a general attack, or at least unflinching

resistance, was to be made along the rest of the front.

This was the Allies' reply to the turning movement of the German general

Von Kluck.

A first line of resistance offered itself on the River Somme, where fierce

fighting took place. It was, however, realized that the battle front could

not be reformed there successfully. Joffre wanted a flanking position not

only for his left wing, but also for his right, which the Somme line did not

offer. He therefore continued the withdrawal of the whole front towards

the River Marne and Paris.

On September 3 German cavalry patrols were signalled at Ecouen, only

eight miles from the gates of Paris. The inhabitants of the latter were

asking themselves anxiously whether they, too, would not have to face the

horrors of a German occupation. The suspense was cruel. Fortunately, a

great man, General Gallieni, was silently watching over their destinies.

This great soldier had just been made Military Governor of Paris, with

General Maunoury's Army, mentioned a moment ago, under his orders.

The entrenched camp of Paris and this army were, in turn, under the authority

of the French Commander-in-Chief, Joffre, who thus had full liberty

of action from Paris to Verdun.

On September 3 General Gallieni issued his stirring proclamation which

put soldiers and civilians alike on their mettle:

"Armies of Paris, Inhabitants of Paris, the Government of the Republic

has left Paris to give a new impulse to the National Defence. I have received

orders to defend Paris against invasion. I shall do this to the end."

The temptation to push straight on to the long-coveted capital must

have been very great for the German High Command. However, in view[Pg 6]

of the danger presented by the Franco-British

forces, which were still unbroken, it was eventually

decided first to crush the Allied armies,

and then to march on Paris, which would fall

like 'a ripe pear.'

Seemingly ignorant of Maunoury's existence,

Von Kluck's Army slanted off eastwards in pursuit

of the British force, which it had received

orders from the Kaiser to exterminate and which

it had been harrying incessantly during its retreat

from the Belgian frontier.

There will be heated arguments for many

years to come as to whether the German High

Command was right or wrong in giving up the

direct advance on Paris, but whatever the consensus

of expert opinion on the point may eventually be, one thing is certain—Von

Kluck did not expect the furious attack by the Army of Paris, which

followed.

Later, he declared: "There was only one general who, against all rules,

would have dared to carry the fight so far from his base. Unluckily for me,

that man was Gallieni."

On September 3, thanks to the Flying Corps, General Gallieni learned

of the change of direction taken by Von Kluck's Army. Realising the

possibilities which this offered, he suggested a flank attack by the Army of

Paris. As previously mentioned, such an attack formed part of Joffre's

general plan, matured on August 27. It was, however, necessary that the

attack should be not merely a local and temporary success, as would have

been the case on the Somme line for instance, where the remainder of the

front was not in a favourable position for resistance, or attack.

On September 4, after conferring with General Gallieni, Joffre decided that

conditions were favourable for a new offensive, and fixed upon September 6

as the date on which the decisive battle should be begun along the whole

front.

[Pg 7]

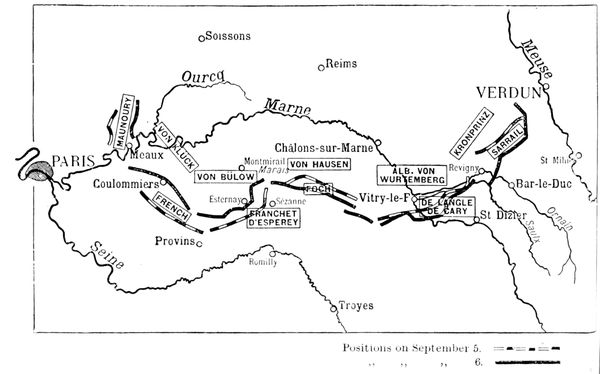

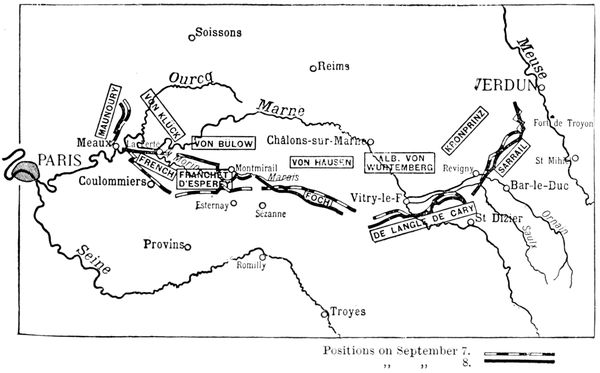

SEPTEMBER 5, 1914

The map before you shows the respective

positions occupied by the opposing armies on

September 5, 1914, the eve of the great battle.

The Allied forces are represented by a thick

black line, those of the Germans by a black and

white line.

Joffre directed the operations first from Bar-sur-Aube

and afterwards from Romilly.

As you see, the half-circle formed by the

Allies, into which the Germans imprudently penetrated,

was supported at the western extremity

by the entrenched camp of Paris and at the

eastern extremity by the fortified position of

Verdun. The River Marne flows through the middle.

Although the battle was only to begin on the 6th, General Maunoury's

Army was already engaged the day before. Its orders were to advance to the

River Ourcq (see map), but, despite furious fighting, it was unable to get there.

The British forces were to occupy a line running north and south, with

Coulommiers as point of support. Unfortunately, the exceedingly fatiguing

retreat it had just accomplished, retarded the execution of the necessary

volte-face. The map shows them on the 5th, still far to the south of Coulommiers.

The fact that neither of these two forces was able to take up its assigned

position greatly increased the difficulties of the turning movement planned

by Joffre.

In front of the forces under Maunoury and French, were the right and

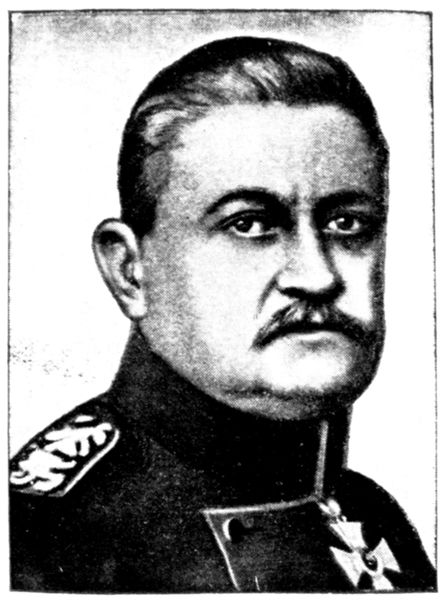

centre of the First German Army, under Von Kluck.

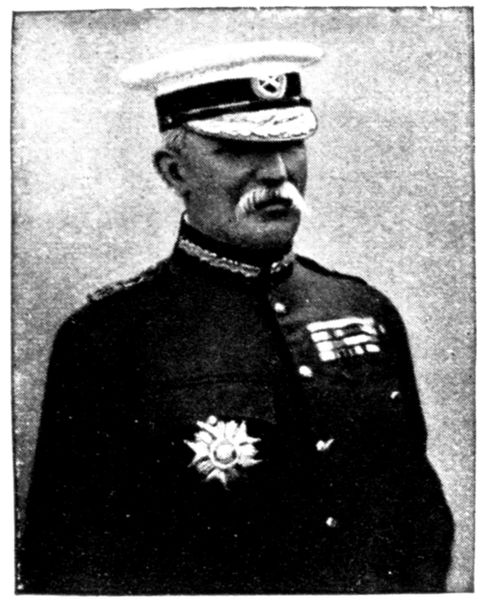

The Fifth French Army, under General Franchet d'Esperey, whose position

extended from the north of Provins to Sézanne, delivered a frontal attack

against the left wing of Von Kluck's army and the right wing of the Second

German army under Von Bulow.

At the right of Franchet d'Esperey's army was the Ninth French Army

under General Foch, whose task it was to cover his neighbour on the left

by holding the issues south of the Marshes of St.-Gond.

Opposing Foch was the left of Von Bulow's army, with the right of the

Third German Army commanded by Von Hausen.

The Fourth French Army, under General Langle de Cary, was minus two

army corps which had helped to form Foch's army. This diminution of

the forces of the Fourth Army prevented the latter from breaking off contact

with the enemy. While, at the extreme left, General Maunoury had already

begun his advance towards the River Ourcq, General Langle de Cary received

orders to hold up the opposing forces under the Duke of Wurtemberg.

Unfortunately, Langle de Cary's forces had not sufficient liberty of movement

to effect the necessary volte-face.

At the extreme right of the Allied front was the Third French Army, under

General Sarrail, established in a position extending from the north-east

of Revigny to Verdun, with a reserve group to the west of Saint-Mihiel,

to be moved either east or west, according to circumstances.

The forces opposing General Sarrail were commanded by the future

"War-Lord": the Crown Prince.

While the French were preparing to thrust back the invader, "War Lord

the Second," drunk with victory, ordered the pursuit to be continued as far as

the line Dijon—Besançon—Belfort: triumphal dreams destined to give place

first to surprise, then to uncertainty, and finally to the bitterness of defeat.

Posterity will compare this arrogant order of the Crown Prince's with the

stirring proclamation which Joffre caused to be made known to the whole

of the French army on the eve of the great battle:

[Pg 8]

"On the eve of the

battle, on which the future

of our country depends, it

is important to remind all

that there must be no looking

back. Every effort

mast be made to attack

and drive back the enemy.

Troops which can no

longer advance must at all

costs keep the ground they

have won, and die rather

than fall back. Under

present circumstances no

weakness can be tolerated."

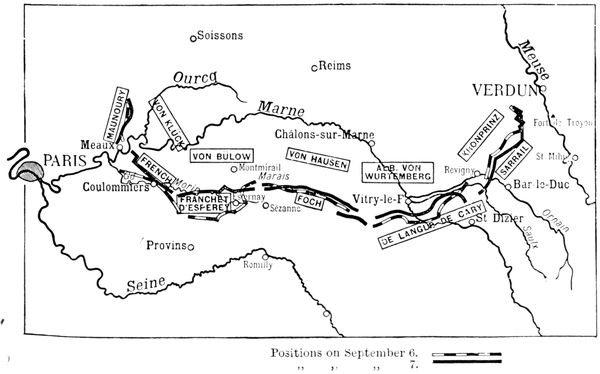

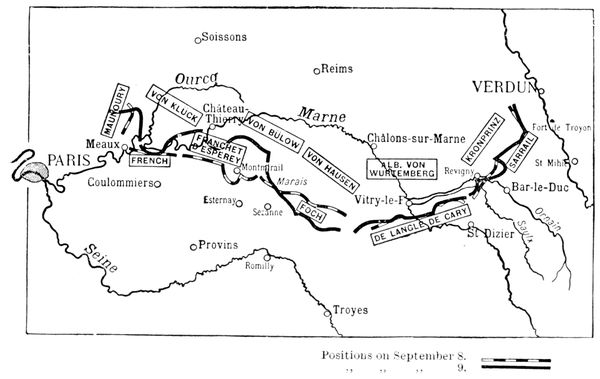

SEPTEMBER 6, 1914

On this and the succeeding maps, the Allied positions of the previous

evening and at the end of the next day are shown.

The German positions are not shown, as too many lines might create

confusion in reading the maps.

Maunoury's Army effected an advance of about six miles, but his left was

unable to accomplish its task, which was to outflank the German right. Von

Kluck who, till then, seeming to ignore Maunoury had concentrated all

his efforts against the British and Franchet d'Esperey's Army, now perceived

this manœuvre. With the promptitude and audacity which particularly

marked his character, he completely changed his plans and rounded

on Maunoury. Taking advantage of the state of extreme fatigue of the

British forces, Von Kluck withdrew one of the army corps which were facing

them and despatched it by forced marches to the help of his right wing.

It was these unexpected reinforcements which enabled Von Kluck to hold

up Maunoury's left.

On this day the British army finally recovered itself, and reached a line

running from the north-west to the south-east of Coulommiers.

[Pg 9]

The armies of Generals Franchet d'Esperey

and Foch fought with great stubbornness. The

former wrested several dominating positions

from the Germans and approached Esternay,

but the latter was able only to maintain himself

on the line of resistance assigned to him south

of the Marshes of Saint-Gond.

General Langle de Cary was eventually able

to hold up the bulk of the troops under the

Duke of Wurtemberg on positions extending

from the south-west of Vitry-le-François to

Revigny.

The general plan of operations included an

attack by the Third Army, under General Sarrail,

against the German left wing, such attack to

coincide with that of General Maunoury at the other end of the line. This

was, however, anticipated by the Germans who, under the Crown Prince,

and in far greater numbers, forced back Sarrail's left and prevented all progress

on his right.

SEPTEMBER 7, 1914

On September 7, Maunoury's army began to feel the effects of the German

heavy artillery, established out of range of the French 75's, and could advance

but very slowly.

However, at the end of the day, Maunoury still hoped to be able to

outflank the German right. Meanwhile, Von Kluck continued his risky

manœuvre, and detached a second army corps from the forces opposed to

the British, adding it to his right. Each was endeavouring to outflank the

other.

Fronting the British, there was now only a thin curtain of troops taken

from two of the German army corps opposed to Franchet d'Esperey.

This small force fought with great stubbornness, in order, if possible, to

give Von Kluck time to crush Maunoury, before the advance by the British

and Franchet d'Esperey could become really dangerous.

[Pg 10]

The slow progress effected in the British sector

is explained by the extreme fierceness of the

struggle.

General Franchet d'Esperey took advantage

of the reduction of the forces opposed to him.

Vigorously pushing back the latter, he continued

his advance northwards, eventually reaching

and crossing the River Grand Morin.

This advance helped to lessen the effects of

the furious attacks that the Germans were then

making against General Foch's army.

In front of the latter, Von Bulow, whose

armies were still intact, realised the danger

which threatened Von Kluck, and, in order to

avert it, endeavoured to pierce the French front.

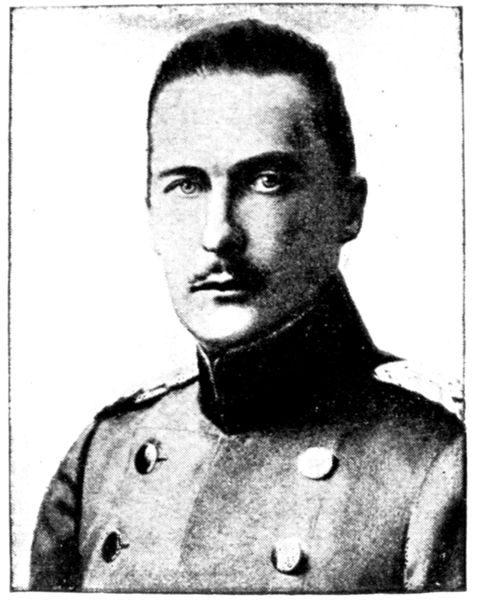

He concentrated the whole of his efforts against the 42nd Division, under

General Grossetti, whose arduous mission it was to maintain the connection

between the Fifth and Ninth Armies, under Franchet d'Esperey and Foch

respectively.

A terrific struggle followed, as a result of which Grossetti was forced to

fall back. Fortunately, as we have just seen, the right of Franchet d'Esperey's

Army was able, thanks to its advance, to come to the rescue and prevent

the French front from being pierced.

Before Von Hausen, the whole line fell back slightly.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Wurtemberg and the Crown Prince attacked

fiercely at the junction of the Fourth and Third French Armies under Langle

de Cary and Sarrail respectively.

The aim of the attack was to separate these two armies and force what

is known as the Revigny Pass. The latter is a hollow through which flow the

Rivers Ornain and Saulx, and the canal from the Marne to the Rhine.

While the Germans under the Duke of Wurtemberg attacked the right

of Langle de Cary's army, in the direction of Saint-Dizier, the Crown Prince

sought to drive back General Sarrail's left towards Bar-le-Duc.

The resistance of Langle de Cary's army began to weaken under the weight

of the greater opposing forces. On the other hand, General Sarrail's army

reinforced by an army corps sent by Joffre stood firm. At this juncture

General Sarrail learned that the Germans were getting very active in his

rear, on the heights above the River Meuse, and was accordingly obliged to

make dispositions to avoid being surprised by German forces who were

preparing to cross the river.

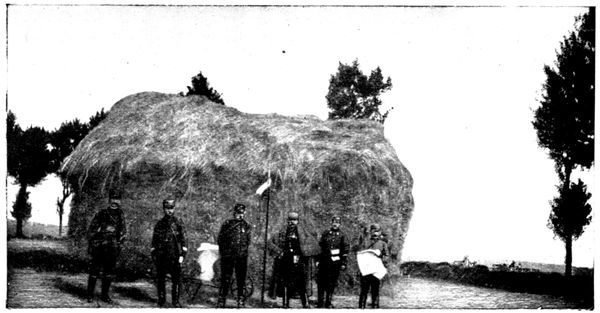

SEPTEMBER 8, 1914

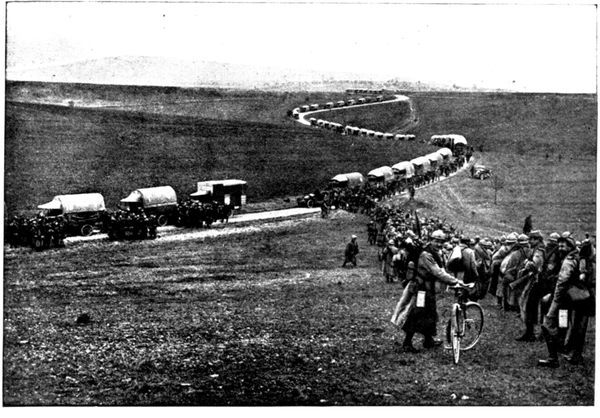

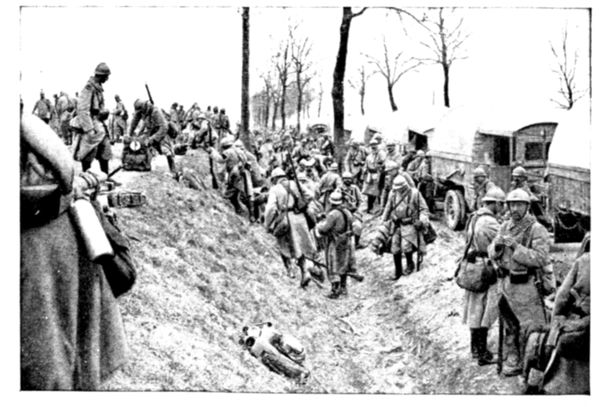

During the night of September 7-8 Gallieni, who had been following

carefully the different phases of the battle, despatched a division from Paris,

in all haste, to Maunoury's left to assist in turning the German right.

To do this with maximum rapidity, Gallieni made use of an ingenious

expedient, "a civilian's idea," as he termed it. He commandeered all the

taxicabs in Paris. Those running in the streets were held up by the police,

and the occupants made to alight. When the latter learned the reason, instead

of grumbling, they gave a rousing cheer. Eleven hundred taxis made the

journey twice during the night from Paris to the front transporting, in all,

eleven thousand men.

Unfortunately, the effect of these reinforcements was fully counterbalanced

by the troops which Von Kluck had brought up on the two previous

days from before the British front, and only the extreme tenacity and courage

of his troops enabled Maunoury to avoid being outflanked.

However, Von Kluck could not with impunity reduce his forces opposed

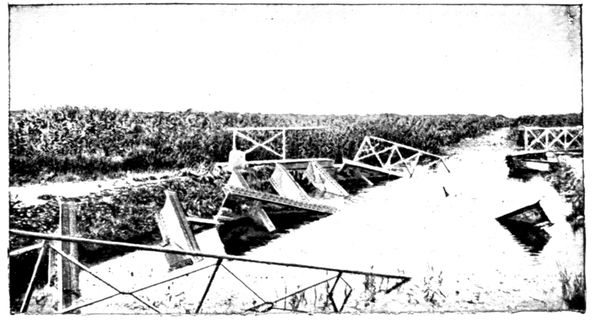

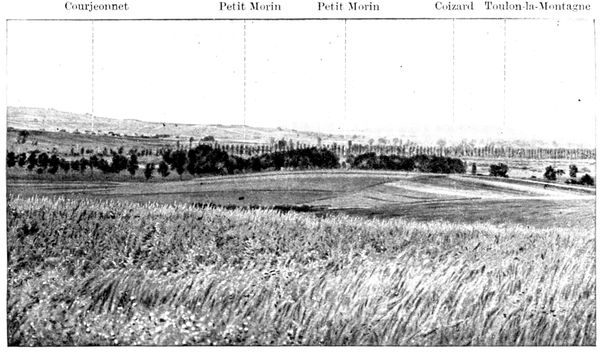

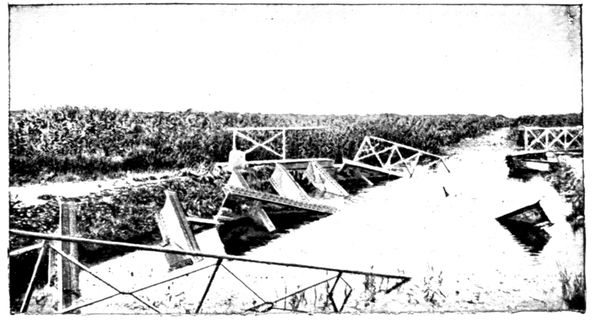

to the British. The latter pulled themselves together, crossed the Petit

Morin river and reached La Ferté-sous-Jouarre.

The danger feared by the German generals became apparent.

[Pg 11]

On this day of September

8, a German

officer wrote in his notebook:

"Caught sight of

Von Kluck. His eyes

usually so bright, were

dull. He, who was wont

to be so alert, spoke in

dejected tones. He was

absolutely depressed."

At the right of the

British army, General

Franchet d'Esperey continued

his rapid advance

and occupied the

outskirts of Montmirail.

Moreover, his troops co-operated efficiently in helping to check the violent

attacks of Von Bulow's army against Grossetti's division.

The Germans became more and more anxious, and rightly so, at the turn

events were taking on their right where Von Kluck's army was beginning

to be tightly squeezed between the armies of General Maunoury, the British

and General Franchet d'Esperey. Von Kluck was forced to retreat

and, in doing so, left exposed Von Bulow's army. The armies of Von Bulow

and Von Hausen received orders to crush Foch and break through the French

centre at all costs, so as to be able to turn Franchet d'Esperey's army on the

west, and that of Langle de Cary on the east.

The position was this: If the manœuvre succeeded, Joffre's entire plan

would fall to pieces. If, on the other hand, it failed a general retreat on the

part of the Germans would be inevitable.

Foch's army received a terrible blow. It was forced back in the centre,

and almost pierced on the right. However, Foch in no wise lost confidence,

but pronounced the situation to be 'excellent.' The fact was, he clearly

realised that these furious attacks were dictated by the desperate position

in which the Germans found themselves. He rallied his troops, hurled

them again against the Germans, but was unable to win back the ground

which he had just lost.

[Pg 12]

Von Hausen's fierce thrust also made itself

felt on Langle de Gary's left; the connection

between the latter's army and Foch's was in

great danger of being severed, and could only be

maintained by the rapid displacement of troops,

and by the intervention of a new army corps

despatched by Joffre just in time to restore the

balance.

While Von Hausen was striking on the left,

the Duke of Wurtemberg brought all his weight

to bear on Langle de Cary's right, with the

Crown Prince executing a similar manœuvre

against Sarrail's left.

The German plan was still the same, viz., to

separate the two armies and, if possible, isolate

Sarrail's army, so that the latter, attacked at the same time in the rear on

the heights above the Meuse, where the Germans had begun to bombard

the fort of Troyon, would find itself encircled and be forced to surrender.

SEPTEMBER 9, 1914

On September 9, the battle reached its culminating point along the

whole front.

Under pressure from the right wing of Maunoury's army, and before the

menacing advance of the British forces which had reached Château-Thierry,

the Germans were obliged to withdraw from both banks of the River Ourcq.

In order to make this retreat easier along the banks of the Ourcq Von

Kluck, at the end of the day, caused an extremely fierce attack to be made

against the French left, which bent beneath the shock and was almost turned.

At that time, the situation was truly extraordinary: the Germans were

already retreating, while the French, stunned by the blow they had just

received, were in anxious doubt whether the morrow would not bring them

disaster.

The struggle seemed so hopeless, that orders were asked for, in view of

a possible retreat on Paris. However, General Gallieni refused to consider

this possibility and, faithful to Joffre's instructions, gave orders to "die rather

than give way." Maunoury's left continued therefore its heroic resistance.

[Pg 13]

Von Kluck's retreat along the Ourcq left Von

Bulow's army completely unprotected, and he

was, in turn, obliged to give way before Franchet

d'Esperey's left.

The latter continued to co-operate actively in

the heroic resistance of the French centre, by

taking in the flank the enemy forces which were

furiously attacking Foch. This general became

the objective of the last and most furious attacks

of Von Bulow and Von Hausen who, realizing

that should they fail they would be forced to

continue the retreat begun on their right, decided

to make one more attempt to crush in the French

centre.

They very nearly succeeded; all along the

line, the French were forced to fall back, and the southern boundary of the

Marshes of Saint-Gond was entirely abandoned.

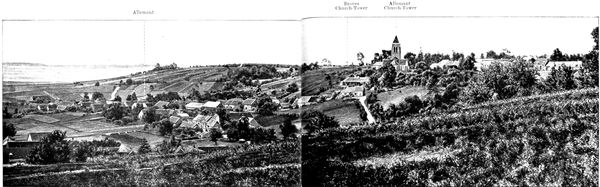

The position, to the east of Sézanne, seemed hopeless. It was there that

the loss of ground was most dangerous, and it is perhaps necessary to explain

in detail this critical phase of the battle.

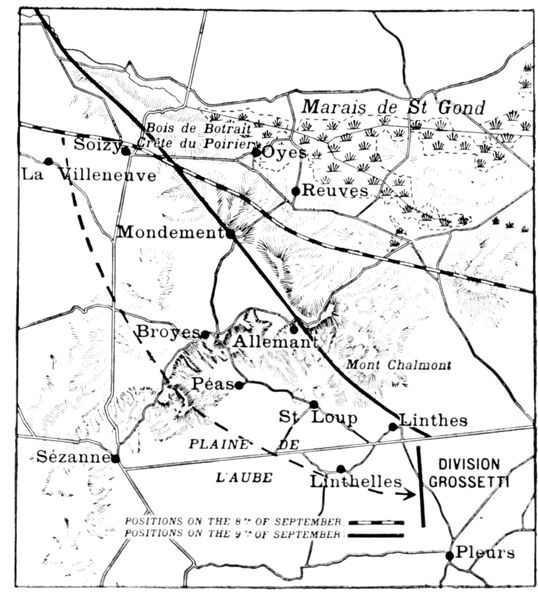

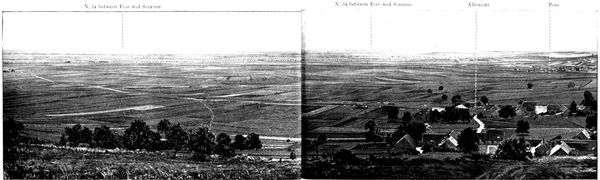

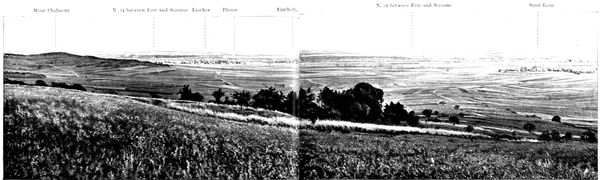

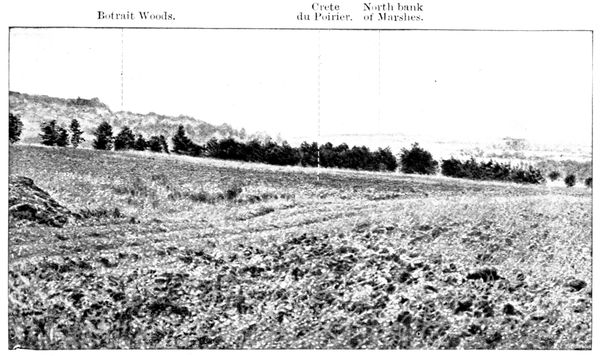

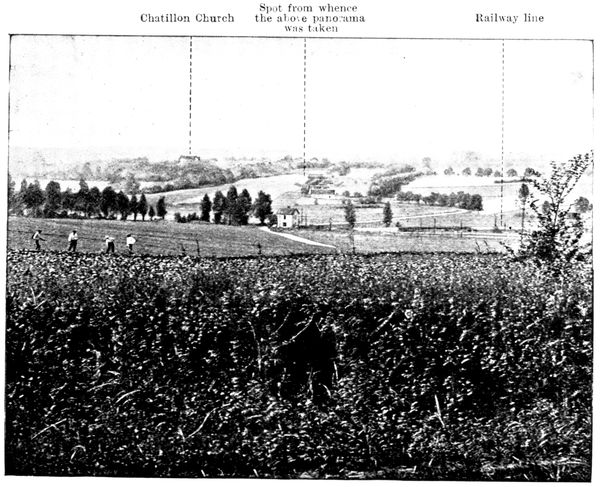

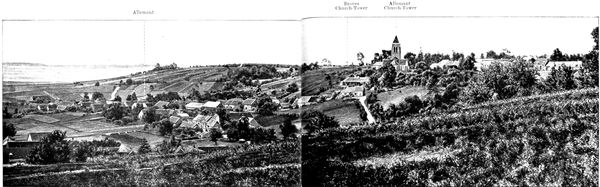

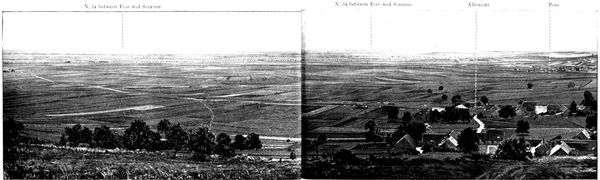

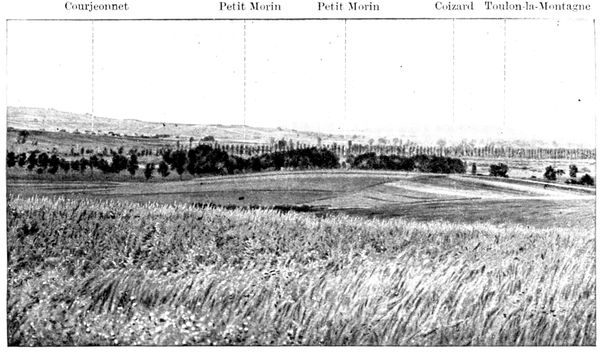

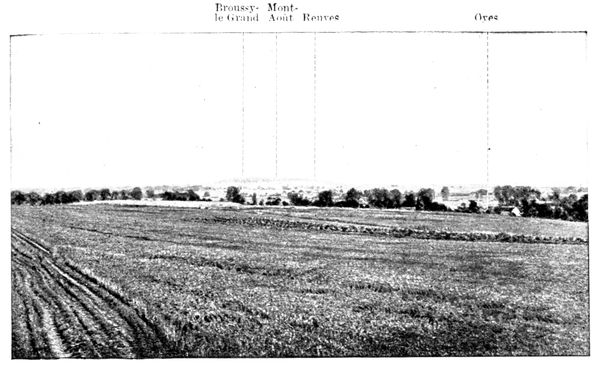

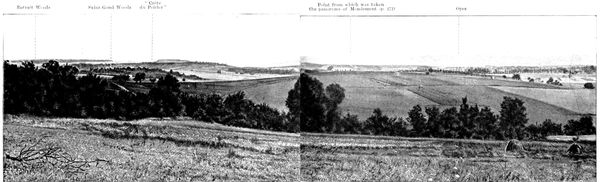

On the large-scale map below is shown the position of Foch's left and

centre on September 8 and 9.

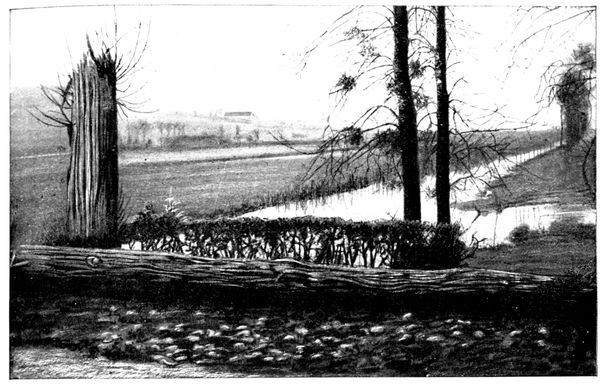

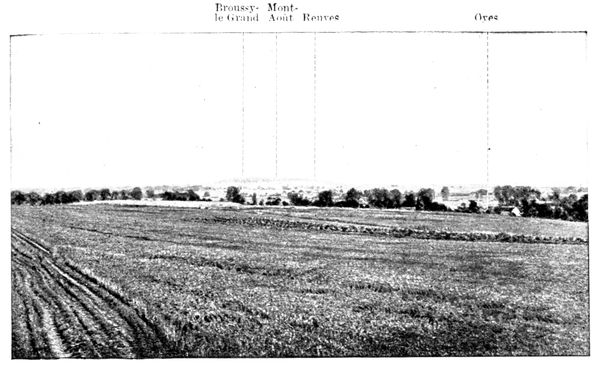

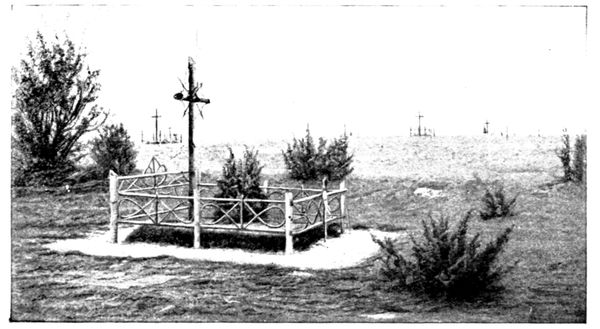

It was in the region of Villeneuve and Soisy that General Grossetti's

Division had fought so heroically for four days. Absolutely decimated, it was

replaced on the morning of the 9th by one of the neighbouring army

corps under Franchet d'Esperey. This corps advanced during the day

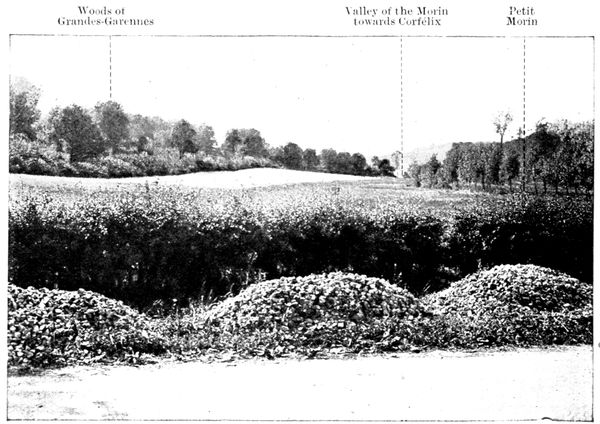

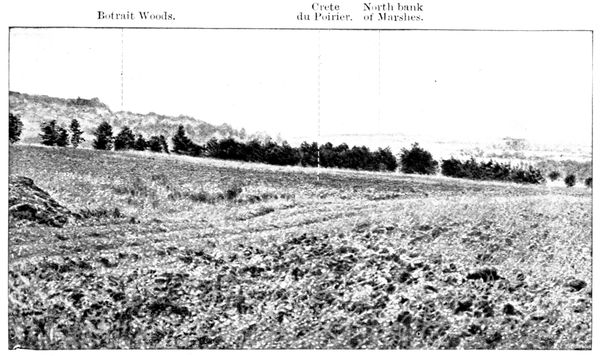

but, further to the right, the Germans forced back the French from the

Woods of Botrait and from the crest of the Poirier, capturing the heights

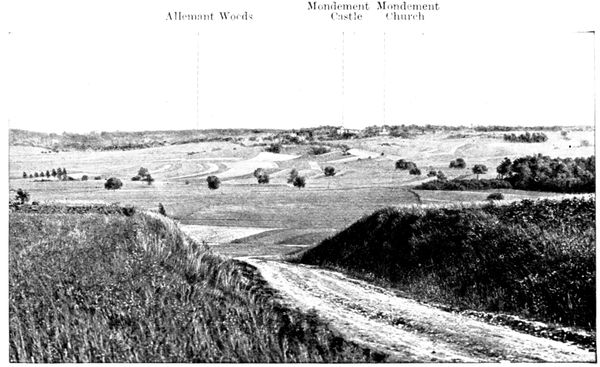

of Mondement.

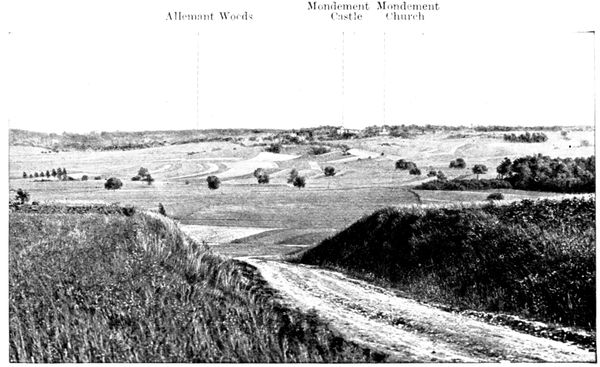

Mondement is situated on a narrow plateau, the last counterfort before

reaching the vast plain of the Aube. On the opposite side of this plateau

are to be seen the villages of Allemant and Broyes.

If the Germans, in possession of Mondement, had succeeded in reaching

these two villages on the day of the 9th, they would have attacked in the

rear those forces under Foch which were fighting in the plain. Mondement

had, therefore, to be held at all costs. Thus the battle pivoted on this

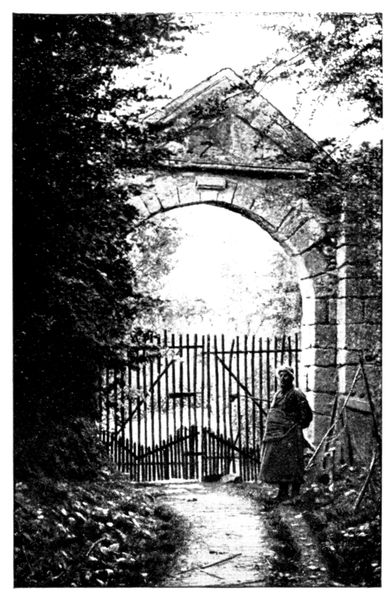

axis. In accordance with

Foch's instructions, the

Moroccan Division under

General Humbert, was

placed there and, with the

help of the 77th Infantry,

not only held its ground

but, recapturing the castle

during the day, forced

the Germans back on

the Marshes in the evening.

At the foot of the villages

of Allemant and

Broyes, the vast plain of

the Aube spreads itself

out, and it was there that

things were going badly

with Foch, the loss of

ground being serious.

The colonials under General

Humbert, who were

hanging on grimly to

the Plateau of Monde[Pg 14]ment,

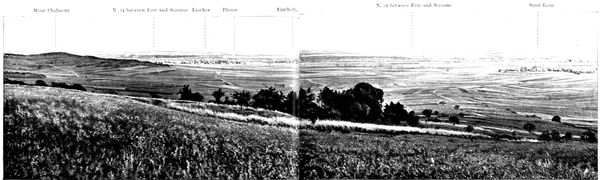

could see their comrades on the right falling

back as far as Mount Chalmont, while the enemy

fire reached successively Linthes and Pleurs.

If the centre had given way completely, the

defenders of Mondement would have been taken

in the rear, and obliged to abandon the plateau.

In other words, it would have meant complete

defeat.

To avert this terrible danger, Foch had only

Grossetti's Division which, as mentioned a few

moments ago, had been decimated by four days

of the fiercest fighting, and which he had that

morning taken from his left wing and sent to

the rear to rest.

Foch recalled this division, and hurled it

against the most critical point of his line between Linthes and Pleurs. He

hoped it would be in a position to attack about noon, but at three in the afternoon

it had not yet been reformed. These were hours of mortal suspense

along the whole front.

General Grossetti needed all his energy to reform the scattered units of his

division, and his men, who were on their way to the rear to rest, when they

were again ordered into the thick of the battle, had need of superhuman

courage to carry out the long fatiguing flank march of twelve miles, which

was to bring them that afternoon to Foch's centre.

Finally, at about four in the afternoon, Grossetti appeared on the scene and

the situation rapidly changed.

With what feelings of intense relief the defenders of Mondement must

have seen Grossetti's men moving eastwards to the attack and driving the

Germans back again behind Mount Chalmont. The enemy was literally

demoralized by this unexpected arrival of reinforcements.

The objective of Grossetti's attack was the junction of the armies of

Von Bulow and Von Hausen, viz.: the weakest point of the German front.

The German generals had at that time nothing with which to counter

this last effort of Foch's, and, realising that the battle was indeed lost, began

to make preparations for retreat.

Just as Franchet d'Esperey had supported Foch energetically on his[Pg 15]

left, so, throughout

this fateful day,

Langle de Cary helped

him not less

effectually on his

right, where he violently

attacked Von

Hausen. However,

in the centre and on

the right, the troops

of Langle de Cary

could not do more

than hold their ground

against the furious

attacks of the Duke

of Wurtemberg's army.

Sarrail, in turn, supported Langle de Cary, by operating with his left

against the flank of the German forces, which were pressing that commander.

Meanwhile, his right was in a critical position, owing to the operations in his

rear by German forces on the heights above the Meuse. In spite of the

danger, and although he had been authorized by the commander-in-chief

to withdraw his right so as to escape this menace, Sarrail clung with dogged

tenacity to Verdun: he would not abandon his position, so long as the Meuse

had not been crossed, and while there was still the slightest hope of being

able to hold out.

SEPTEMBER 10 to 13, 1914

The morning of the 10th witnessed a theatrical change of scene on the

French left, where it will be remembered Maunoury's army was in a most

critical position. After a night of anxious suspense, it was seen that the

Germans had abandoned their positions, and were retreating hastily towards

the north-east, to avoid being caught in the pincer-like jaws formed by the

Franco-British forces the previous day.

Thus Paris and France were saved, as Von Kluck's retreat carried away Von

Bulow's army with it, and Franchet d'Esperey crossed the Marne. Von[Pg 16]

Hausen's right followed suit, pursued by Foch. The troops of the former

had crossed the Marshes of St. Gond during the night to avoid disaster.

Langle de Cary precipitated the retreat of Von Hausen's army. His right,

still under heavy pressure, was however obliged to fall back. Here, the Germans

were only held up by the increasingly effectual help rendered by

Sarrail's army. The latter withstood the furious attacks of the Crown Prince

without flinching, while on the heights above the Meuse, the fort of Troyon,

the heroic defence of which has since become famous, withstood the terrible

onslaughts of the enemy forces which sought to cross the river.

It was only on the 11th that the Duke of Wurtemberg followed the retreat

begun on his right the day before, and it was only during the night of the

12th-13th that the German retreat became general.

On the 13th the Germans reached their line of resistance, and, as will be

seen on the map before you, their front extended from Soissons to Verdun,

passing by Rheims. This map also shows the positions at the beginning

of the battle.

The foregoing sketch gives a general idea of the character of this great

battle, which has been called "The Miracle of the Marne," and for the winning

of which the following factors were responsible: firmness on the part of

the commander-in-chief; the clear and well-laid plan which he caused to be

executed by highly capable army commanders working in close collaboration

with one another; and, above all, the superhuman courage and endurance of

the soldiers.

As time passes, these memorable days stand out more and more gloriously.

The study in detail of this stupendous event will continue for centuries hence,

but its main lines, which we have been at pains to trace, already stand out

clearly. They recall all the old French traditions. The clearness of the

plan, the suppleness of manœuvre, the bold use of the reserves, remind one

of the Napoleonic era. The enthusiasm which galvanized soldiers and chiefs

alike dates back to the Revolution. And going back into the remote past,

it was the remembrance of the arresting on the soil of Gaul of the great barbarian

invasions which inspired the Victory of the Marne.

[Pg 17]

TOURIST SECTION

For the greater convenience of tourists, we have divided our guide to

the Marne Battlefields into the following sub-divisions, which correspond

to the three main sectors of the battle:

1, THE OURCQ.—Visit to Chantilly, Senlis, and Meaux.

2, THE MARSHES OF SAINT-GOND.—Visit to Coulommiers, Provins,

and Sézanne.

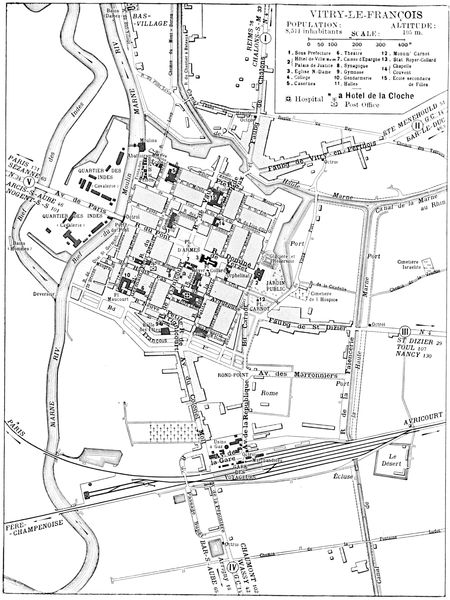

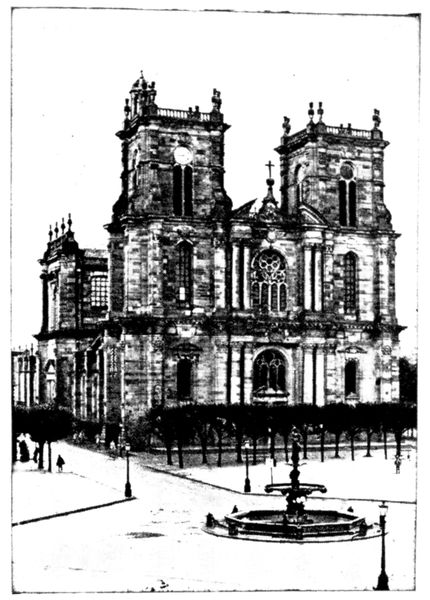

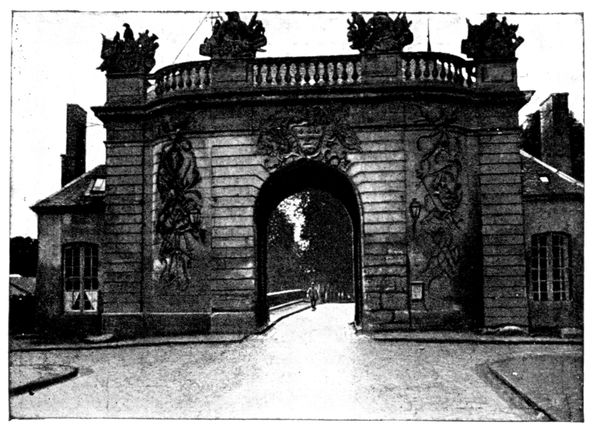

3, THE REVIGNY-PASS.—Visit to Châlons-sur-Marne, Vitry-le-François,

and Bar-le-Duc.

[Pg 18]

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

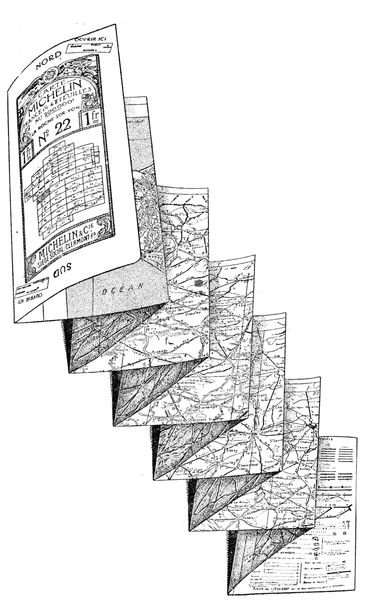

ITINERARY FOR MOTORISTS AND MOTOR-CYCLISTS

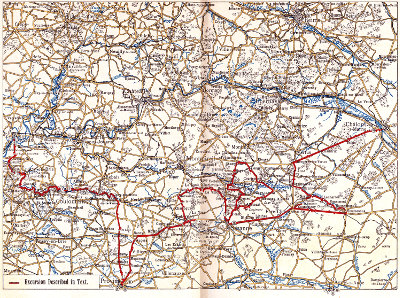

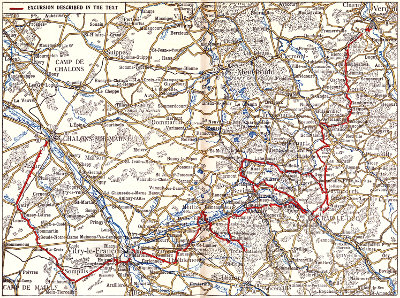

This tour is comprised in the section 11-12 of the Michelin map, Scale:

200,000 (see scale of kilometres on French map).

The circuit is about 850 km. and can be covered in six days, i.e. two days

for each part:

- Ourcq;

- Marshes of Saint-Gond;

- Pass of Revigny.

I., OURCQ.

1st day.—Leaving Paris in the morning through the Porte de la Chapelle

by N. 1 we cross Saint-Denis, then passing Pierrefitte turn to the right

by N. 16 which leads straight to Chantilly (34 km. from the gates of Paris)

through Ecouen, Le Mesnil-Aubry and Luzarches.

We visit the town (see pp. 22-36): lunch either at Chantilly (palatial

hotel) or at Senlis (good hotel) 9 km. from Chantilly; afternoon, visit Senlis

(pp. 39-67); dine sleep and at Senlis or Chantilly.

Tourists who wish to see the whole of the Castle and Park of Chantilly must

choose a Thursday, Saturday, or Sunday (see p. 31) and devote a part of the

afternoon to this visit.

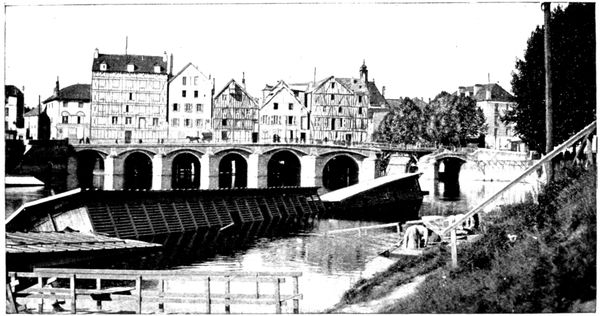

2nd day.—Leave Senlis or Chantilly in the morning and reach Meaux

by the route given on pp. 68-75. The distance from Senlis is 65 km. (by the

direct route only 37 km.); lunch at Meaux (good hotel).

Afternoon.—Do the tour of the Ourcq as indicated on pp. 84-118. This

tour may be increased from 53 to 92 km., according to the time the traveller

has at his disposal or the speed of his car.

Dine and sleep at Meaux.

Alternate routes.—Tourists who consider the second day's distance

too great, as planned above, can leave Senlis in the afternoon and thus dine

and sleep at Meaux on the first day. They can visit Meaux in the morning

of the second day, lunch there and make the tour of the Ourcq in the afternoon,

returning to dine and sleep at Meaux.

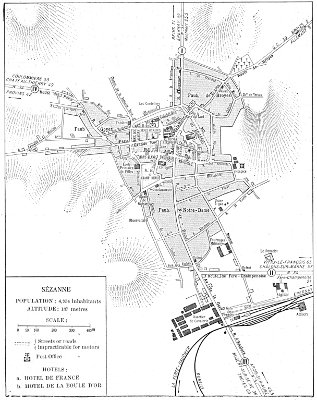

II., MARSHES OF SAINT-GOND.

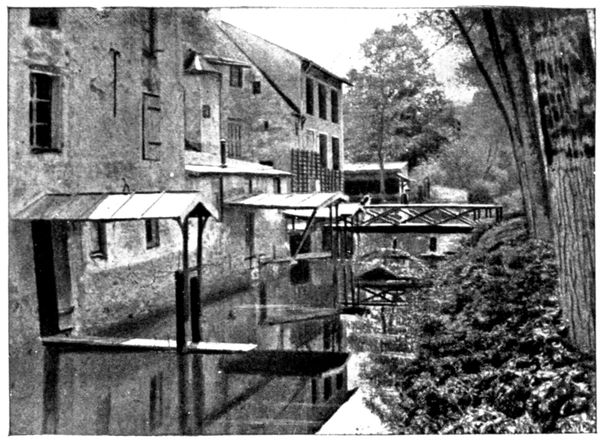

3rd day.—After mounting the course of the Grand Morin as far as La

Ferté-Gaucher via Crécy, Couilly and Coulommiers, the tourist will lunch

at Provins. In the afternoon he may visit the town, after which he will

proceed to Sézanne to pass the night.[Pg 19]

4th day.—In the morning make the tour of the Marshes of Saint-Gond.

In the afternoon proceed to Fère-Champenoise, Sommesous, ascending the

valley of the Somme and spend the night at Châlons-sur-Marne.

III., PASS OF REVIGNY (273 km.)

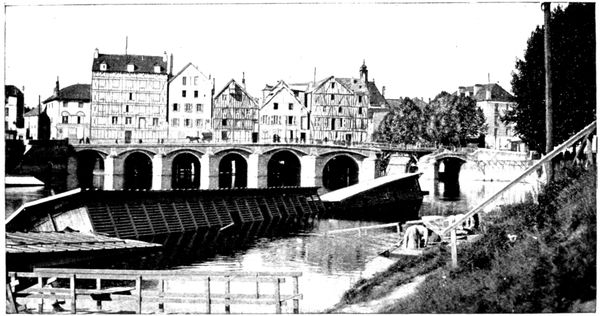

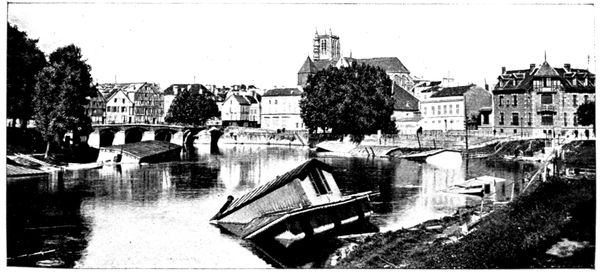

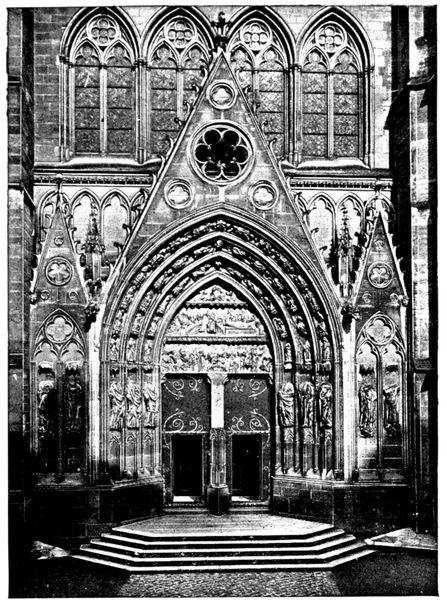

5th day.—In the morning cover the distance from Châlons to Vitry-le-François

and visit the latter town before lunch.

After lunch leave Vitry for Bar-le-Duc where the tourist can dine and

sleep.

6th day.—In the morning the tourist may visit the lower town Bar-le-Duc

and effect the circular tour which we indicate round the town. He

will come back to Bar-le-Duc for lunch.

In the afternoon the tourist will visit the upper town proceeding thence

to Verdun. The latter town and the surrounding battlefields should be

visited with the help of the separate guide which has been dedicated to

them.

IMPORTANT NOTE

For details concerning hotels and garages see insides of cover.

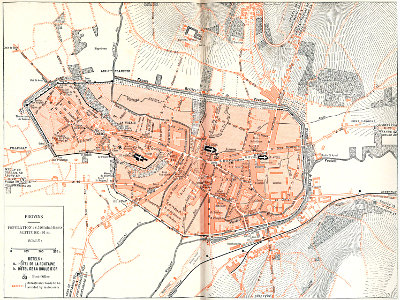

PLAN OF TOUR DESCRIBED IN THE PRESENT GUIDE

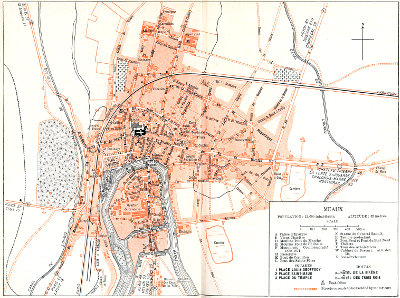

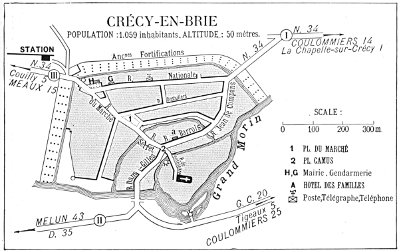

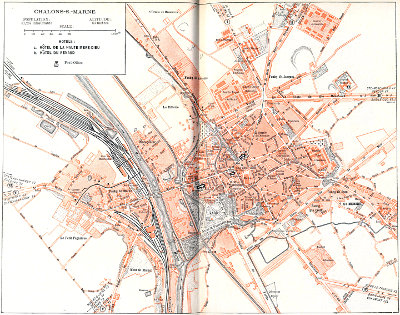

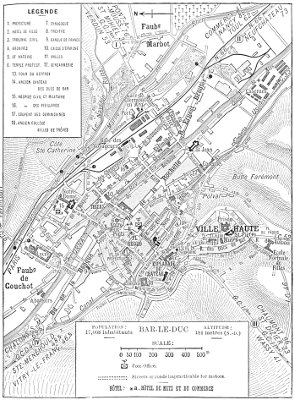

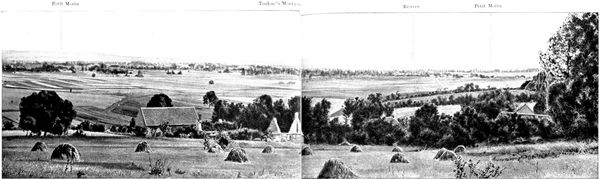

On the above plan, towns, of which a map is given in the present guide,

are shown by a circle enclosed in a small square; the large rectangles indicate

the boundaries of the coloured maps inserted in the guide, on which the

reader will be able to follow the itinerary.

[Pg 20]

I. THE OURCQ

VISIT TO THE LOCALITIES

in which were enacted the preliminary scenes of the

BATTLE OF THE OURCQ

from September 5 to 14, 1914

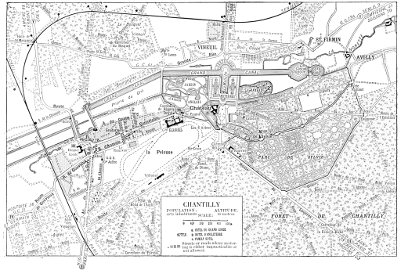

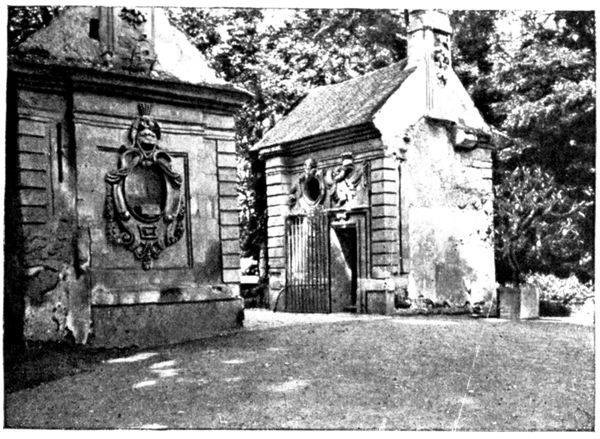

CHANTILLY

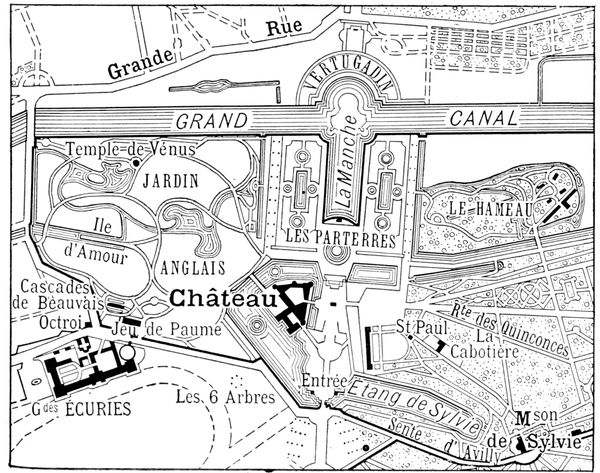

(See map on next page)

ORIGIN AND MAIN HISTORICAL FACTS

Chantilly derives its name from that of the Gallo-Roman Cantilius, who

was the first to establish himself in the locality. The Castle (a fortress during

the Middle Ages) passed to the family of Montmorency in the fifteenth century

and in the seventeenth to that of Condé. These two illustrious families

brought Chantilly to a height of splendour which made it a rival of the royal

residences.

In 1830 the Duc d'Aumale succeeded the last of the Condés and at his death

(1897) bequeathed the domain, with the Condé Museum, which he had installed

in the castle (see pp. 24-35), to the 'Institut de France.'

The town itself, built in the seventeenth century, was for a long time

dependent on the castle. In our day it has become a big centre for horse

training and racing, the great race meetings in May, July and September

attracting huge crowds.

CHANTILLY IN 1914-1916

The Germans, coming from Creil, entered Chantilly on September 3,

1914, and occupied it for several days. The mayor was at once seized as

hostage but did not suffer the same tragic fate as the Mayor of Senlis. The

troops were billeted at the castle (see p. 28).

After the victory of the Marne, Chantilly became the seat of General

Joffre's headquarters and remained so until the end of 1916.

[Pg 21]

[Pg 22]

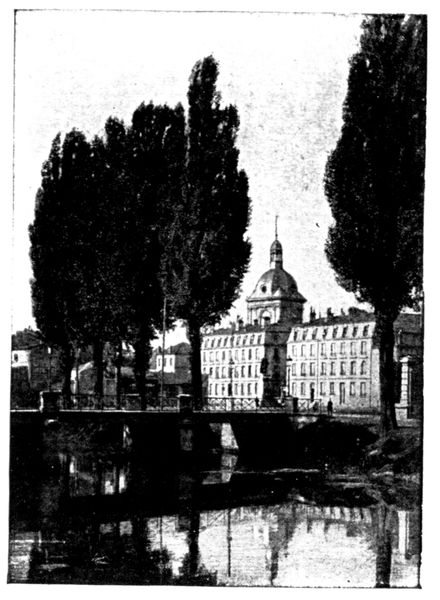

VISIT TO THE TOWN

Arriving by the Paris road the tourist will pass under the railway bridge,

then 600 yards further on turn to the right and come out on to the "Pelouse"

(Lawn). Turning round the Grand Condé Hotel on the left, he follows the

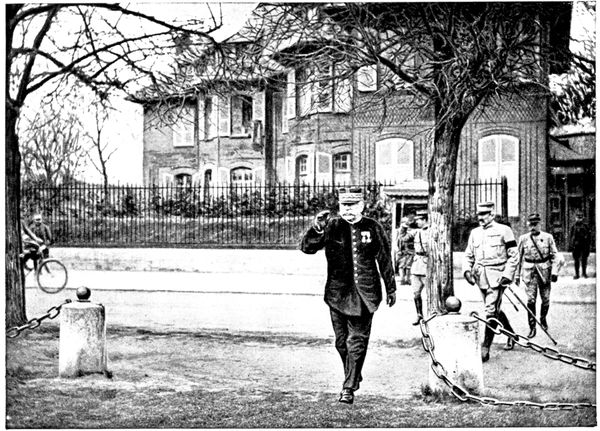

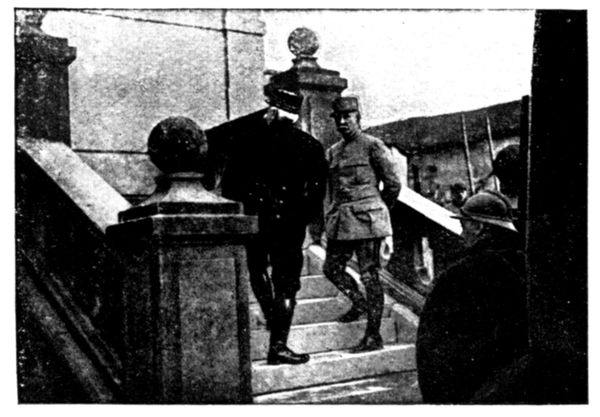

Boulevard d'Aumale as far as the Maison de Joffre, shown in the photograph

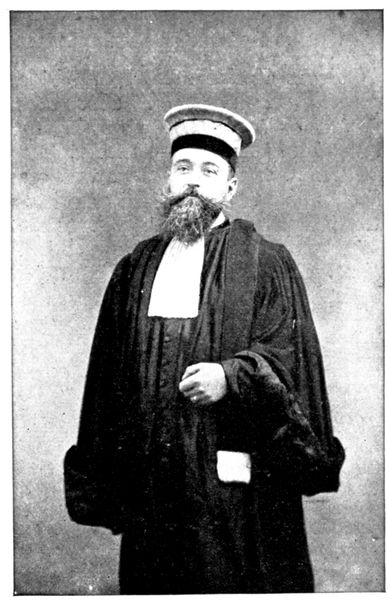

below.

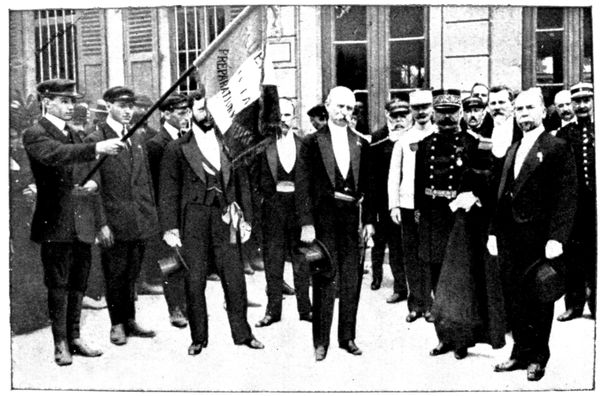

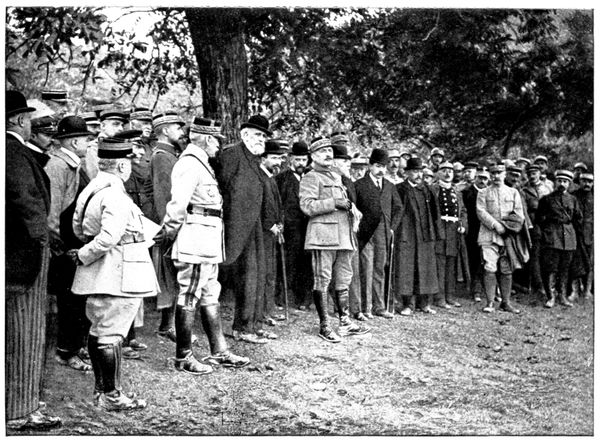

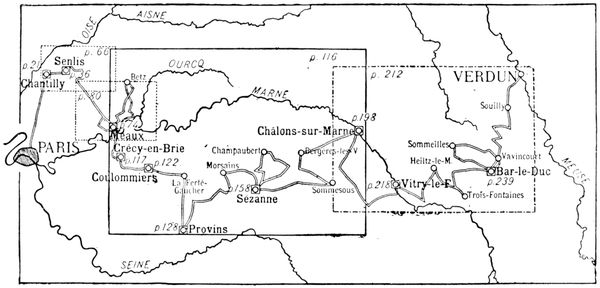

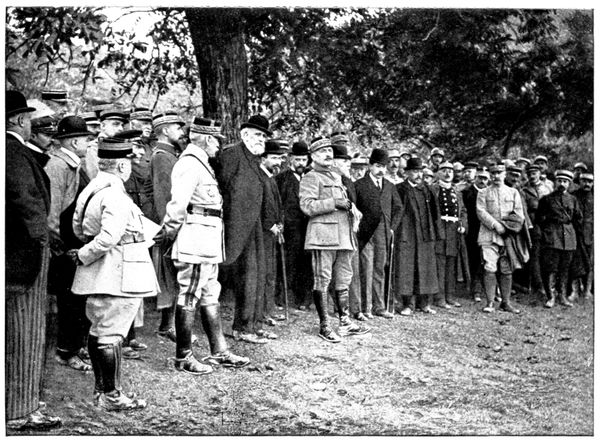

JOFFRE

LEAVING

GENERAL

HEADQUARTERS

Joffre lived here until he was made Marshal of France.

The hundreds of officers and secretaries employed in the tremendous

work incumbent on the Generalissimo were lodged in the Grand Condé

hotel, near which the tourist has just passed. In contrast with this buzzing

hive, Joffre's house seemed the embodiment of silence and meditation.

Only two orderly officers lived with the generalissimo, and his door was

strictly forbidden to all unsummoned visitors, whoever they might be.

On leaving his office Joffre had the daily relaxation of a walk in the forest

near by. It was thanks to the strict routine to which he subjected himself

that the generalissimo was able to carry the crushing weight of his responsibility

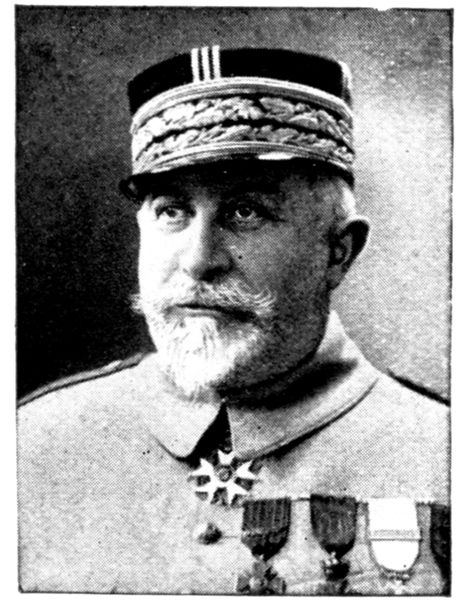

without faltering. We shall see, however, when comparing the peace

time photograph given on p. 1 with that on p. 22 that these years of war

have counted as double.

During the tragic hours of the Marne the general headquarters were first

at Bar-sur-Aube and then at Romilly. The commander-in-chief's intense

concentration of mind made him dumb and as though absent in the midst

of his colleagues, who received all his orders in writing. In a few days his

hair and moustache became perfectly white.

The Allies' grand councils of war were held in this house, which has

counted among its guests all the great actors of the war.

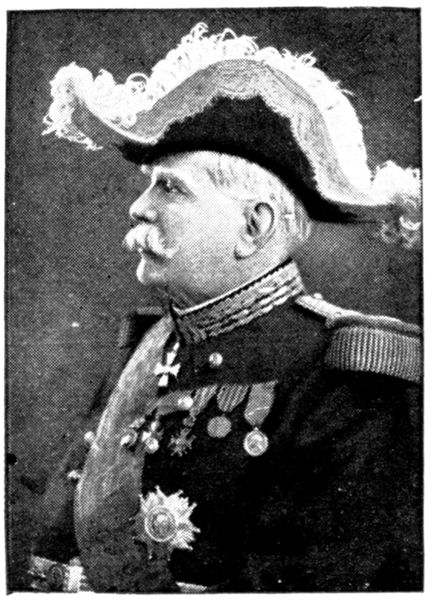

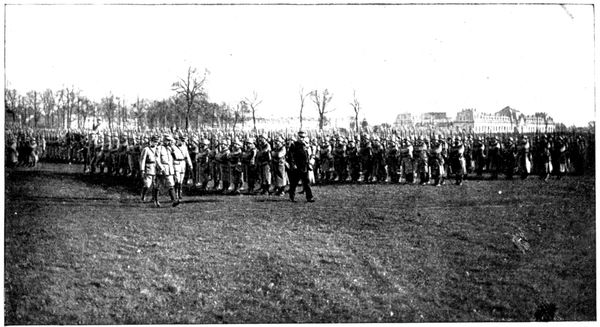

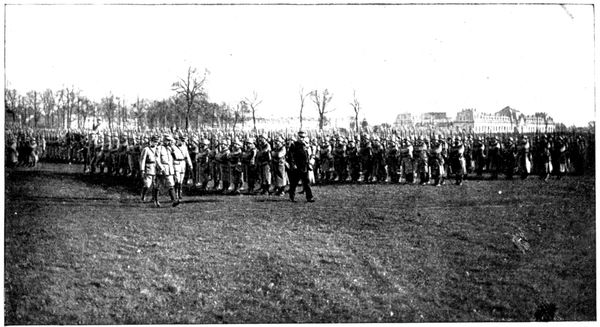

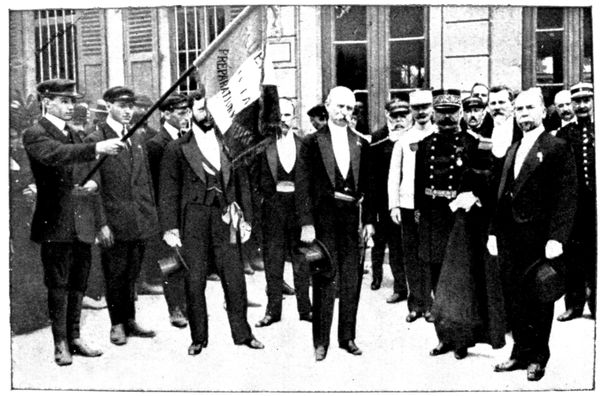

The military functions were held on the lawn. The photograph on the

next page was taken during a review.

After having seen Joffre's house we pass the few villas which separate it from

the Rue d'Aumale and bear to the right, skirting the lawn; next we turn to the left

into the Avenue de Condé, then to the right into the Rue du Connétable. In

front of the "Grandes Écuries" (great stables), which border the extreme[Pg 23]

end of the road on the right, stands the equestrian statue of the Duc d'Aumale,

by Gérome (1899).

JOFFRE

HOLDING

A REVIEW

ON THE LAWN

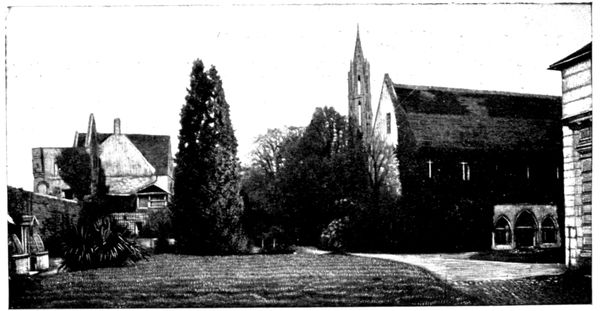

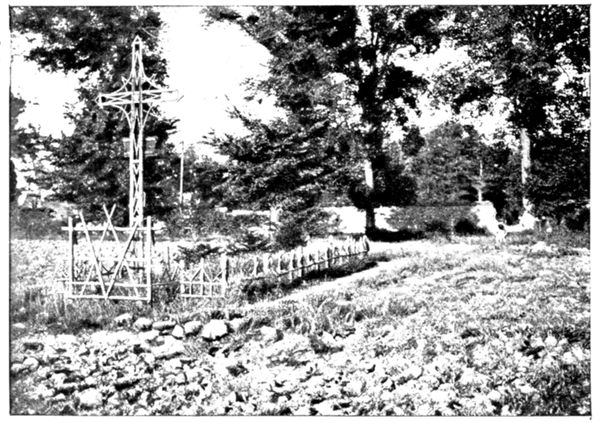

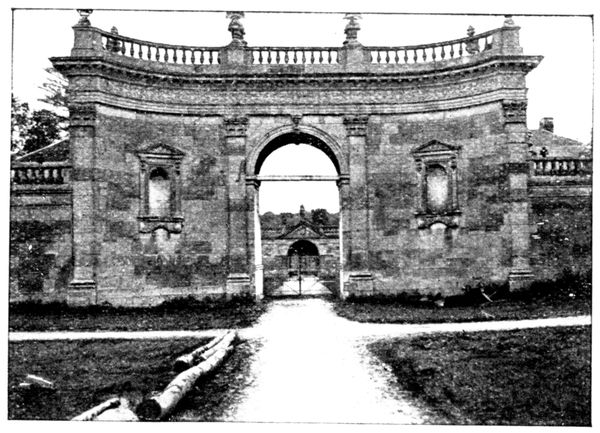

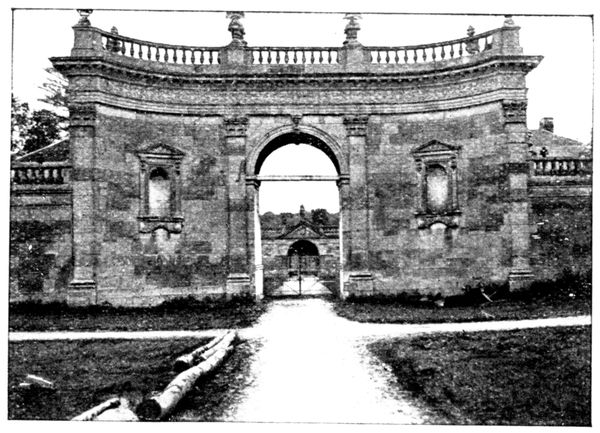

Leaving the church we turn to the right, passing through the monumental

gateway, and go towards the castle. On the lawn (still keeping to the right)

we come to the principal façade of the "Grandes Écuries", Jean Aubert's

chef-d'œuvre, built between 1719 and 1740. They are seen on the right in

the above photograph.

On the opposite side of the lawn stands a little chapel, erected in 1535,

by the high constable Anne de Montmorency, at the same time as six others

dotted here and there about Chantilly, in memory of the seven churches

of Rome which he had visited in order to obtain the indulgences pertaining

to this pilgrimage. He obtained the same grant from the Pope for the

chapels of Chantilly.

Of these only two now remain, that on the lawn—Sainte-Croix, and

another in the park—Saint-Paul.

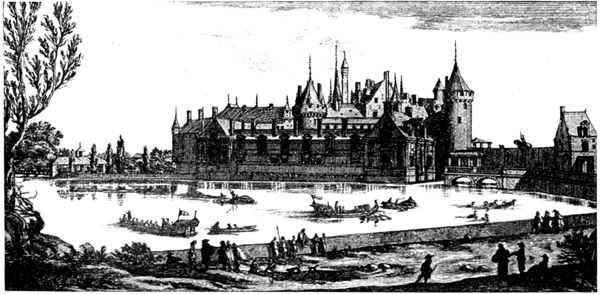

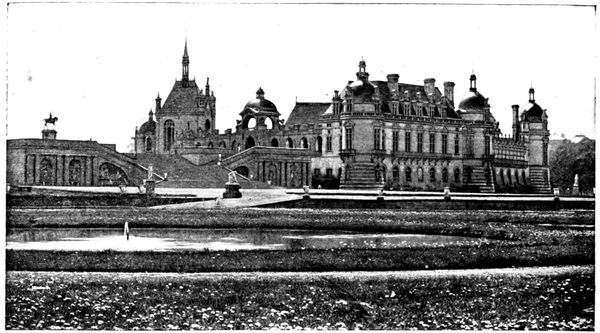

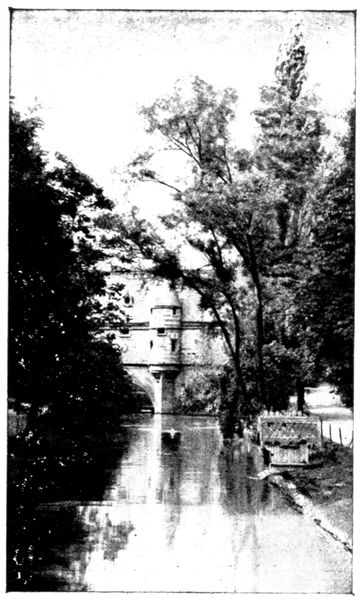

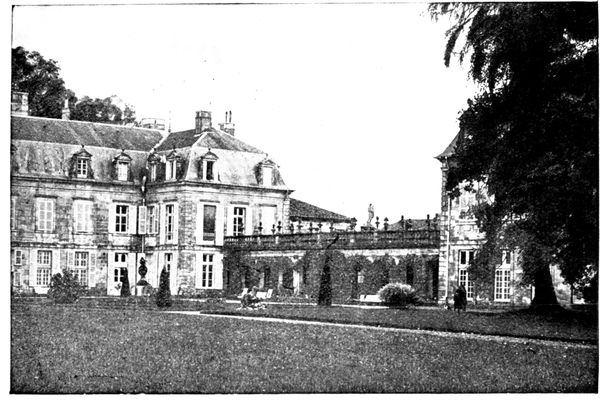

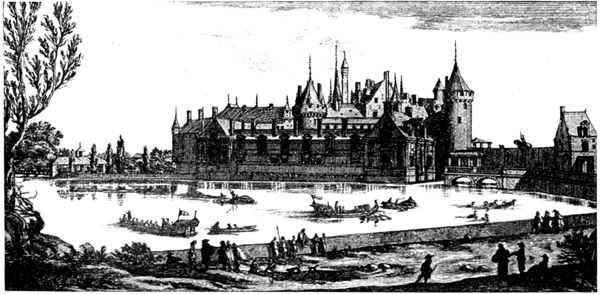

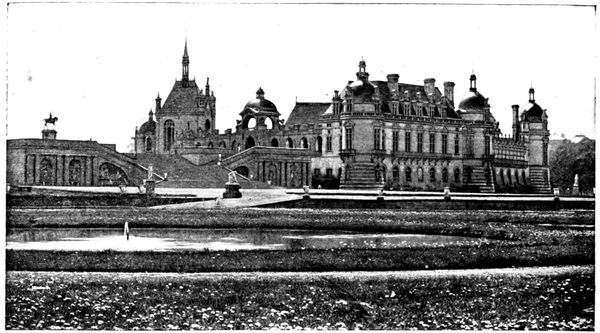

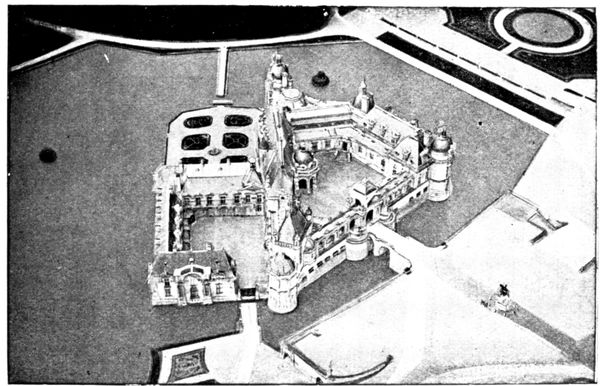

The photograph below gives a view of the whole of the castle. The little

castle dates from the sixteenth century; the big castle is the work of a contemporary

architect, Daumet, who erected it on the basement of the old dwelling,

demolished during the Revolution. The Castle of Enghien, built in the

eighteenth century, is now occupied by the guardians entrusted with its

preservation. The water surrounding the castle teems with centenarian

carp. One can get bread from the concierge and, on throwing a few crumbs

into the moat, which passes beneath the entrance bridge, watch the onrush

of the huge fish.

CASTLE OF

CHANTILLY

- Little Castle

- Chapel

- Great Castle

- The constable's Terrace

- Porter's Lodge

- Castle of Enghien

[Pg 24]

In the pages which follow we give a short historical account of the castle,

referring the tourist for further details to the extremely interesting work of

the curator, Mr. Gustave Macon: Chantilly and the Condé Museum.

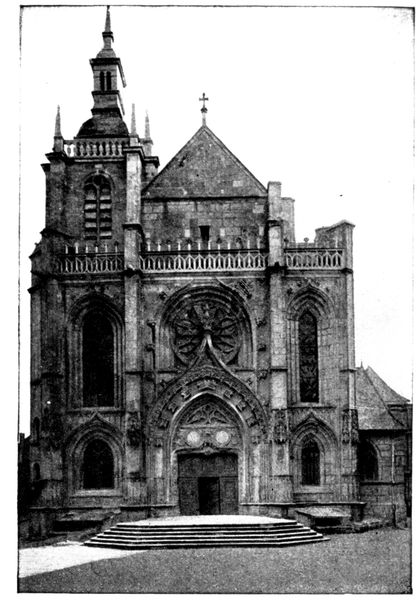

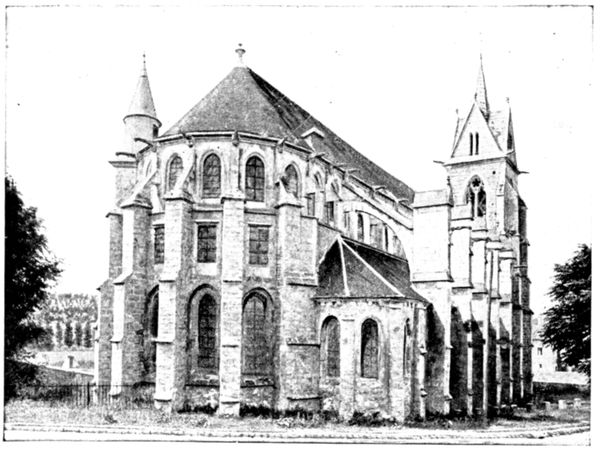

SHORT HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF THE CASTLE

In the Roman epoch Chantilly was the dwelling place of Cantilius. In the

Middle Ages it became a fortress belonging to the "Bouteiller" (cupbearer),

so named because of his hereditary functions at the court of the Capets.

(The "bouteille de France," originally in charge of the king's cellars, became

one of the greatest counsellors of the crown).

The castle then became the property of the d'Orgemonts, who rebuilt it

in the fourteenth century. In the fifteenth century it passed to the Montmorency

family. Towards 1528 the high constable Anne de Montmorency

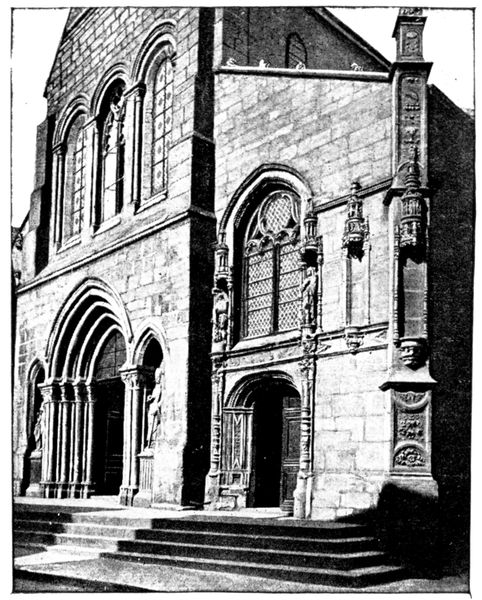

had it transformed by Pierre Chambiges. Chambiges' work no longer exists

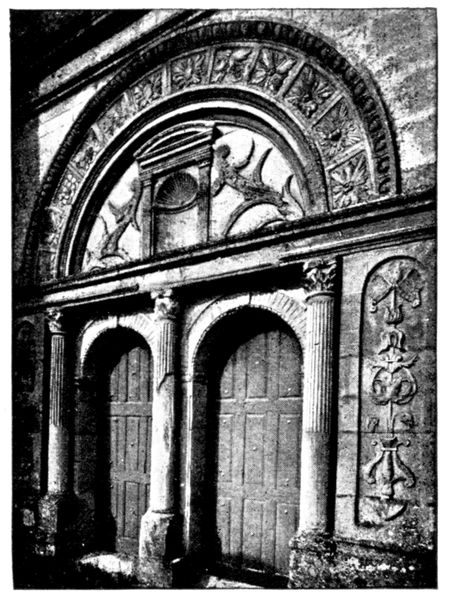

in Chantilly, but the tourist will be able to judge of his talent when he sees

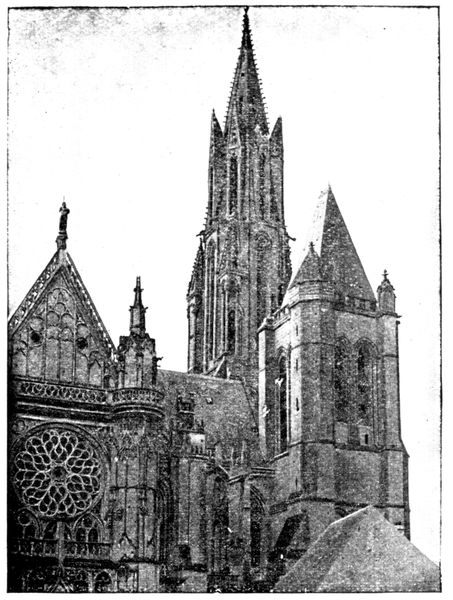

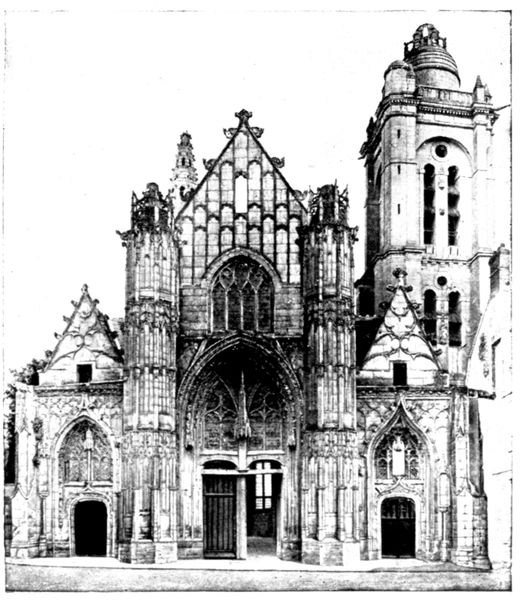

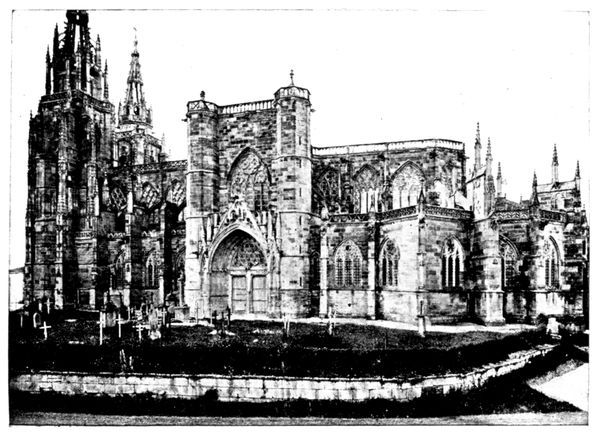

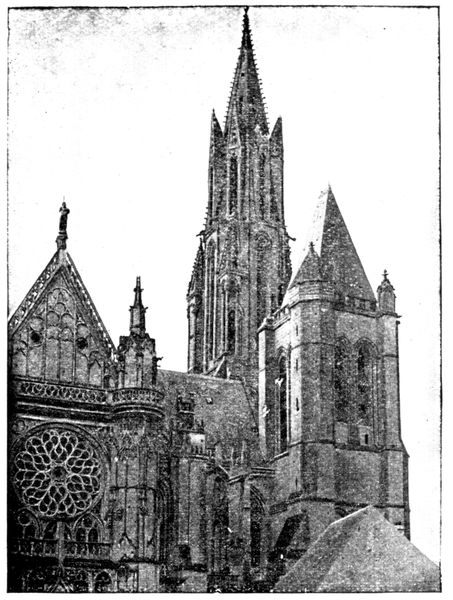

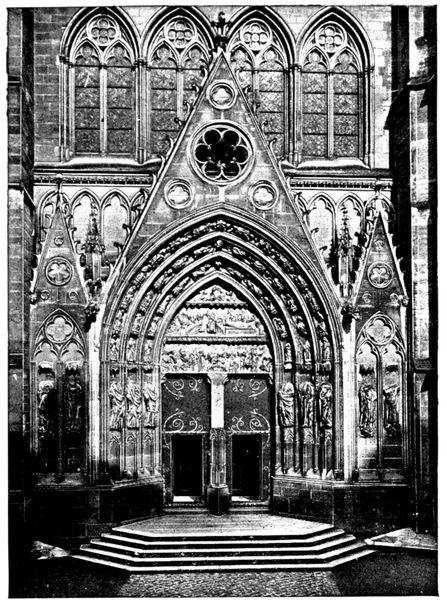

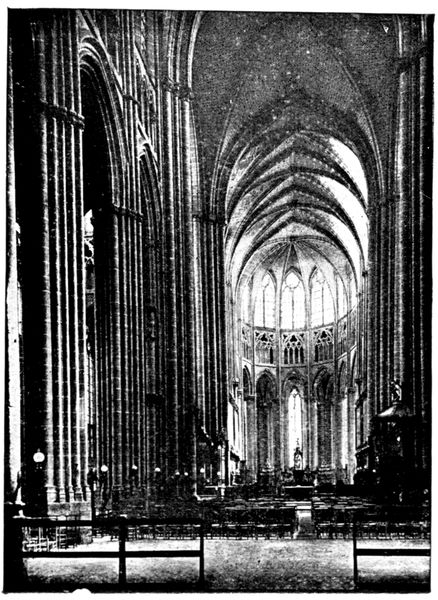

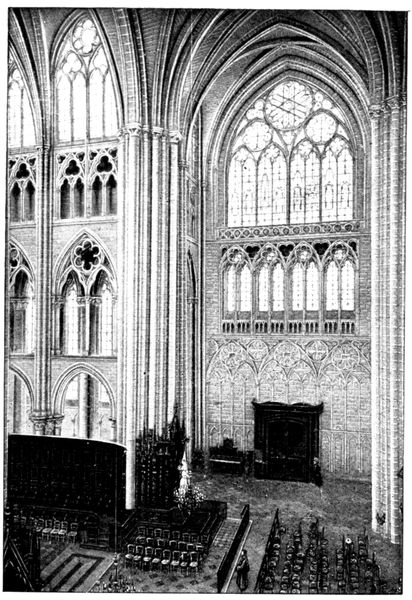

the beautiful façades of the transept of the cathedral of Senlis (p. 57). The

little castle was built thirty years later by Jean Bullant. From that time

Chantilly has been famous. Francis I. often stayed there. Charles V.

declared that he would give one of his Low Country provinces for such a

residence. Henry IV. asked his "compère," the high constable Henri, to

exchange it for any one of his royal castles. Montmorency, much embarrassed,

extricated himself from this awkward situation by answering, "Sire, the house

is yours, only let me be the lodge-keeper."

Henri II. of Montmorency, drawn into a revolt against Richelieu, died on

the scaffold in 1632. His property was confiscated and Louis XIII., attracted

by the hunting at Chantilly, kept the place for his personal use.

It was there that he drew up with his own hand the "communiqué" to

the press, concerning the taking of Corbie (1636): "The king received news,

at 4 o'clock this morning, of the surrender of Corbie. He immediately went to

church to give thanks to God, then ordered all to be ready by 2 o'clock to sing

the Te Deum, the queen and everyone else to be present, and ordered despatches

to be sent commanding thanksgiving services in all the churches of this kingdom...."

In 1643, the queen, Anne of Austria, wishing to make some recognition

for the splendid victories won by the Duc d'Enghien (the future "Grand

Condé") gave Chantilly back to his mother, Charlotte de Montmorency.

The latter, married at fifteen, had been obliged to leave France with her

young husband in 1609, to escape from the attentions of Henri IV., still

gallant despite his fifty-six years.

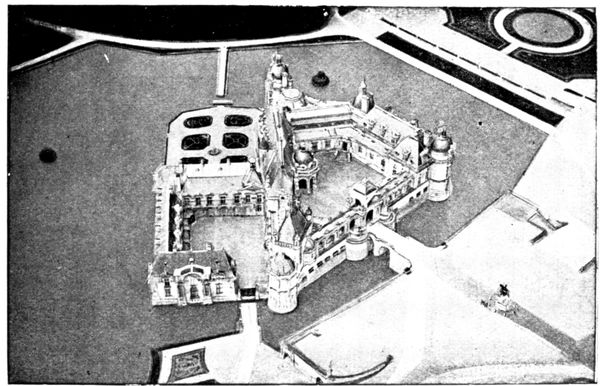

THE CASTLE

IN THE

SEVENTEENTH

CENTURY

[Pg 25]

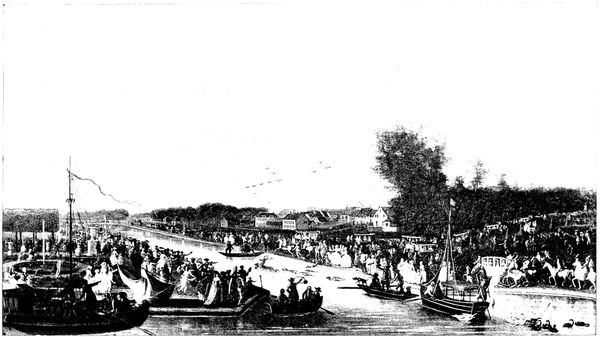

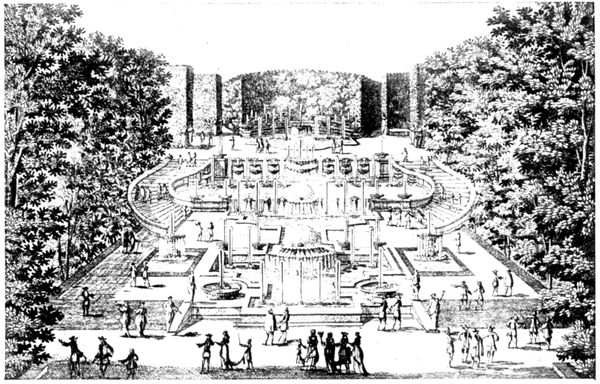

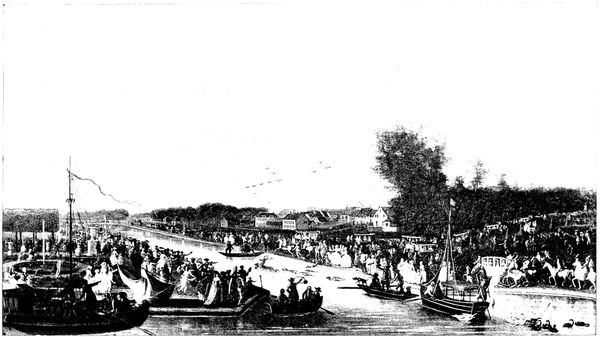

FESTIVITIES AT CHANTILLY IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY.

[Pg 26]

A gay life began again in Chantilly, interrupted in 1650 by the revolt of

Condé, his exile and the confiscation of the domain, which then returned

to Louis XIV. until the Treaty of the Pyrénées (1659). The prince then

came into his own again but for long kept aloof from public affairs and

devoted himself to the embellishment of Chantilly with the same ardour

and mastery that he formerly gave to military operations.

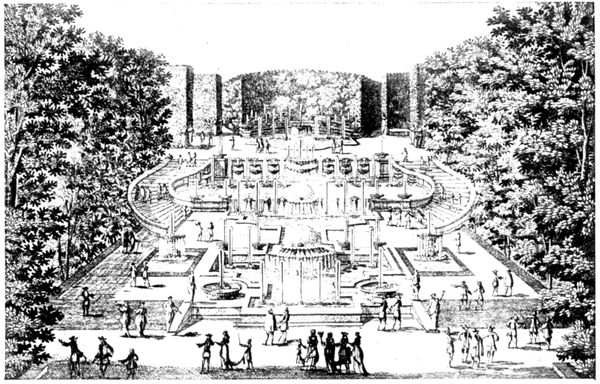

In 1662, the transformation of the park and forest was placed in the

hands of the great architect, Le Nôtre. The work continued until 1684.

The result was a masterpiece, of which a great part is still in existence, but

of which the finest features (particularly the Great Cascades which spread

over the actual site of the town) disappeared during the Revolution. Below,

we give a view of these "Jeux d'eau" (fountains), which were considered one

of the wonders of the day.

In 1671, Louis XIV. spent three days at Chantilly, with all his court.

Marvellous festivities were held on this occasion. The guests of the château

alone filled sixty large tables; all the adjoining villages were full of officers

and courtiers, boarded and lodged at the prince's expense. In one of her

letters, Mme. de Sévigné tells of the tragic death of the superintendent, Vatel,

who had the responsibility of this vast organisation. Desperate at the

thought that fish would be lacking at the king's table, he went up to his

room, leant his sword against the wall, and transfixed himself upon it.

All the great men of the seventeenth century visited Chantilly. Bossuet,

the intimate friend of the great Condé, presented to him Fénelon and La

Bruyère, who became tutor to the Prince of Condé's grandson. Molière and

his company came to play (Condé was his patron, by whose intervention

the production of Tartufe was allowed). Boileau, Racine and La Fontaine

were habitual guests.

The development of Chantilly continued under Condé's successors, and

the castle was modified by Mansart. The Duc de Bourbon caused the

"Grandes Écuries" to be built by Jean Aubert. He established the manufacture

of porcelain there (ceased in 1870), the remaining pieces of which are

greatly sought after in our day.

THE OLD

CASCADES

OF CHANTILLY

In 1722, Louis XV. stayed at Chantilly on his way back from his corona[Pg 27]tion

at Rheims. The festivities lasted four days; 60,000 bottles of wine and

55,000 lbs. of meat being consumed.

It was Prince Louis-Joseph who saw the Revolution. He had spent

enormous sums in embellishing Chantilly, besides the twenty-five million

francs which it cost him to build the Palais-Bourbon in Paris, the present seat

of the Chamber of Deputies. He erected the Castle of Enghien, named after

his grandson, the Duc d'Enghien, who was the first to inhabit it. (Early

marriages were usual in these great families: at the birth of the Duc d'Enghien

his father was sixteen years old and his grandfather thirty-six.) The Duc

d'Enghien died in 1804, shot in the moat of Vincennes.

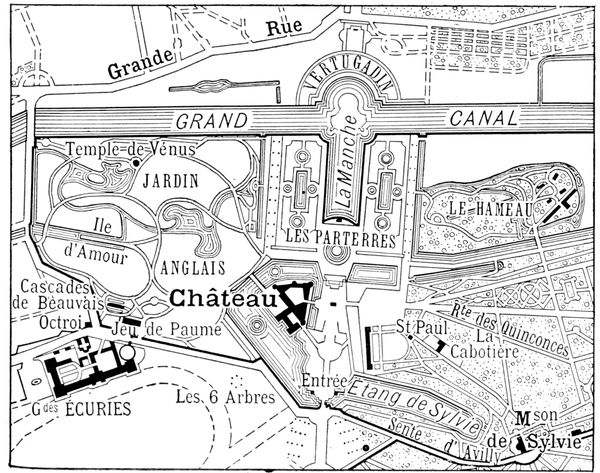

The English garden and the hamlet are due to Louis-Joseph.

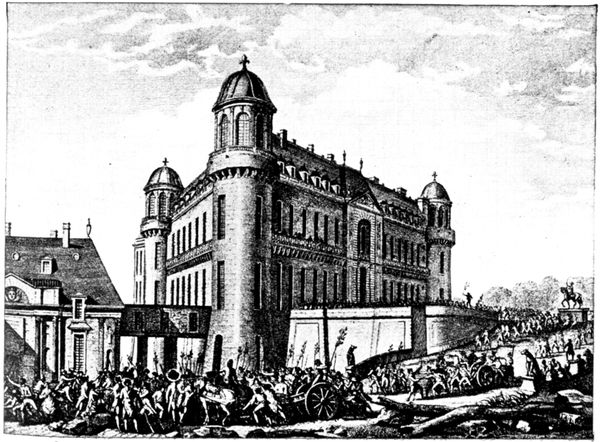

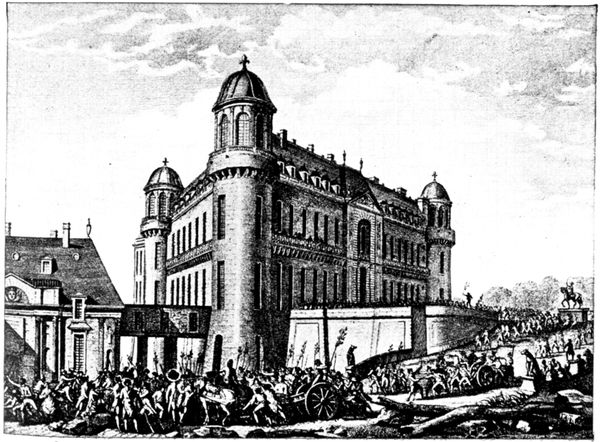

In 1789, after the Prince of Condé had gone into exile, the Parisians came

and removed the cannon from the castle (see reproduction of engraving below,

in which the castle appears as altered by Mansart). Thirty guns taken from

the enemy during the Seven Years' War, which were never used except for

firing salutes during fêtes, were brought in triumph to the Hôtel de Ville in

Paris, whence La Fayette had them sent to the arsenal.

The great cascades, the menagerie, the orangery and the theatre disappeared

during the revolutionary era.

Of the great castle nothing remained but the basement, whilst the town

grew and encroached on the park.

In 1814, the Prince de Condé returned to Chantilly and commenced the

restoration of the domain, a work continued by his son. The latter came

to a tragic end in 1830; he was found hanging from the fastening of a window

in his castle of Saint-Leu, and with him died the great family of Condé.

In his will he bequeathed Chantilly to one of his great-nephews: Henri

of Orleans, Duc d'Aumale, fifth son of King Louis-Philippe. After distinguishing

himself in the Algerian campaign, where he carried off the

Smalah of Abd-el-Kader in 1843, the Duc d'Aumale was exiled in 1848. He

established himself at Orleans House, at Twickenham, near London, where

he remained until 1871. It was during that time that he began the splendid

collections which later went to enrich the Condé Museum. On his return

to France he presided at the tribunal entrusted with the trial of Marshal

Bazaine.

THE PARISIANS

AT CHANTILLY

IN 1789

[Pg 28]

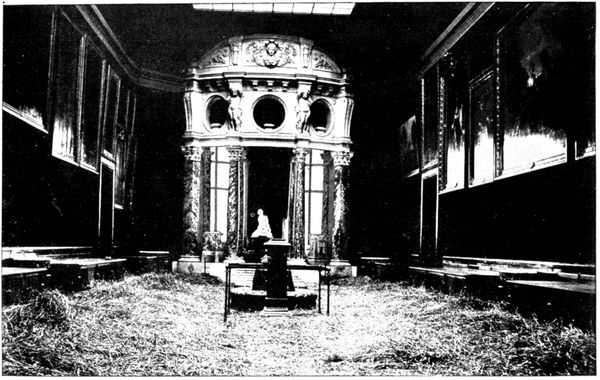

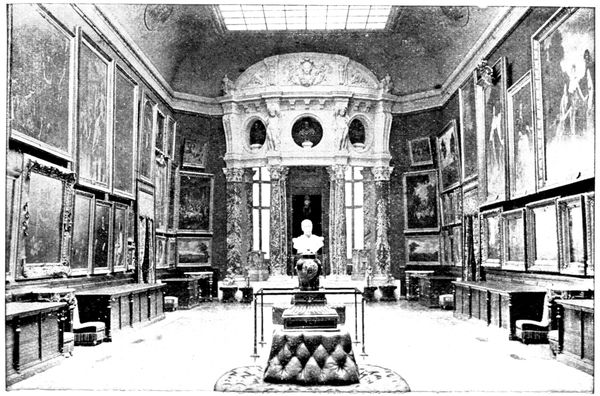

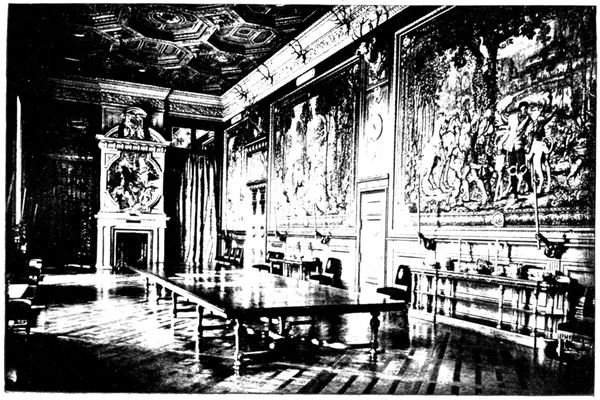

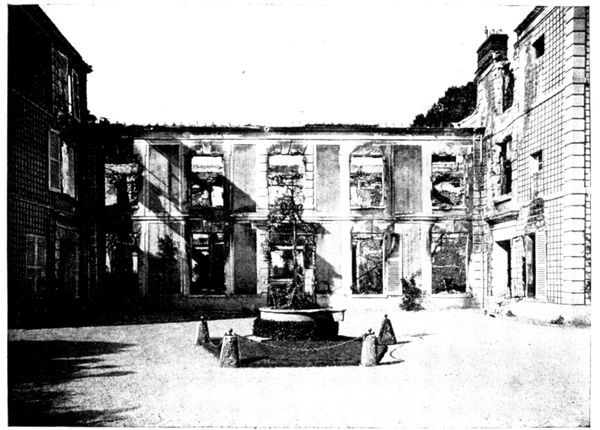

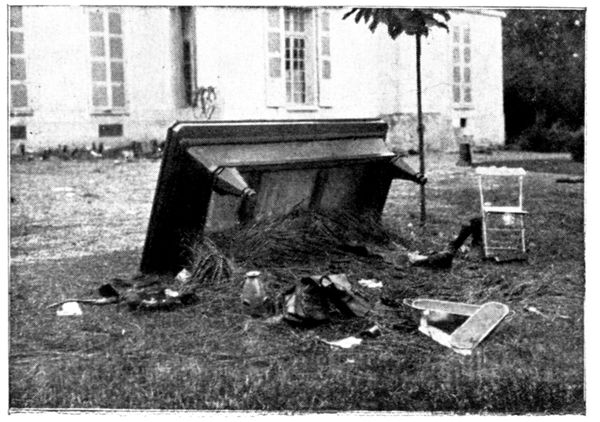

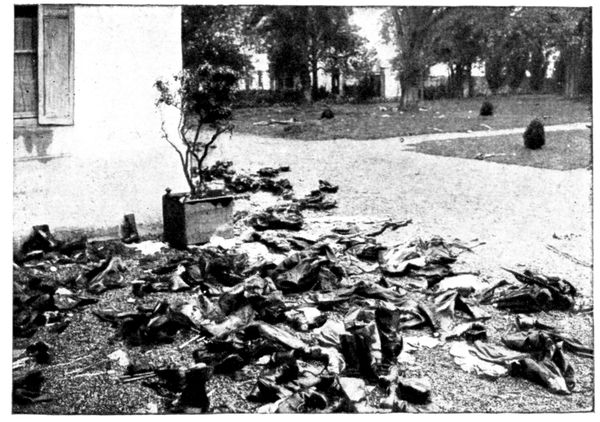

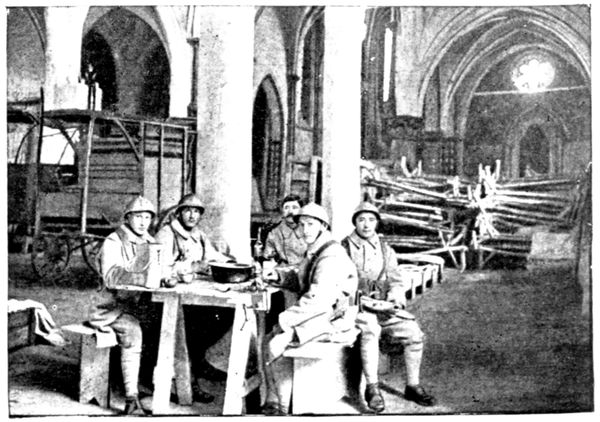

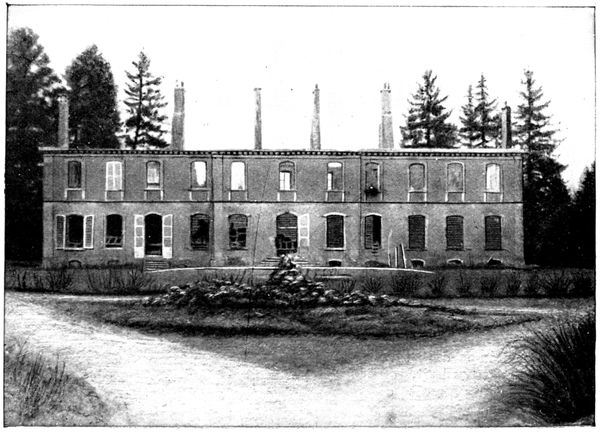

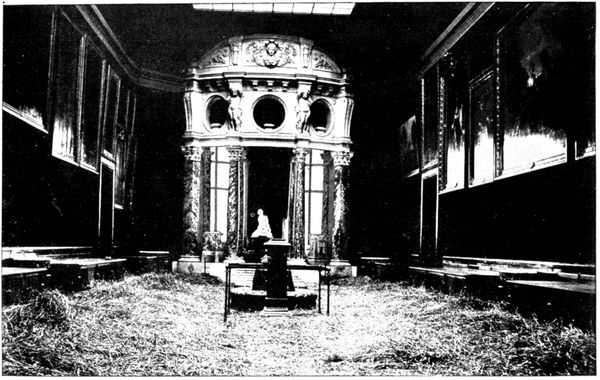

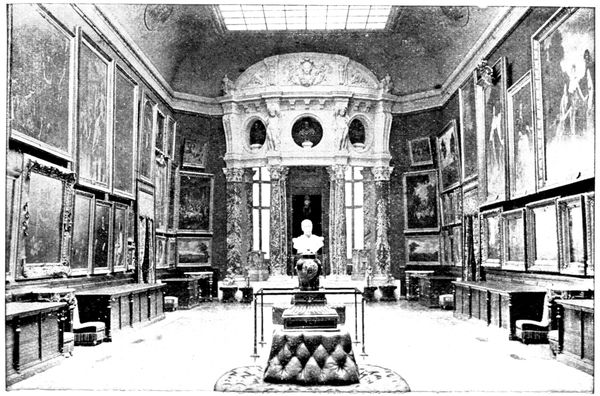

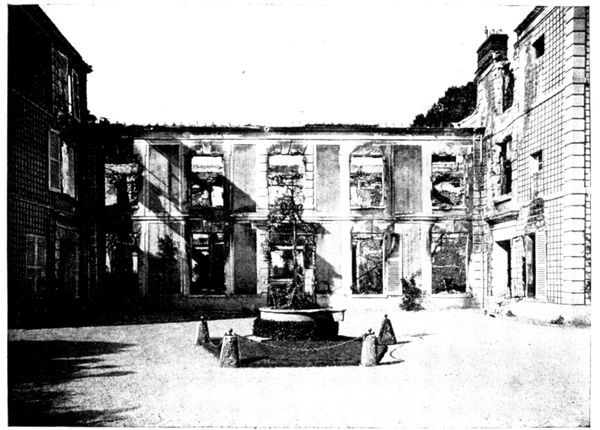

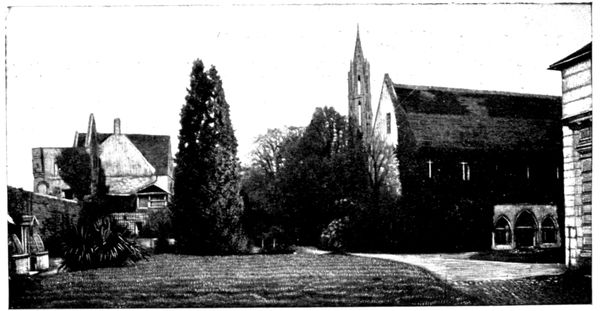

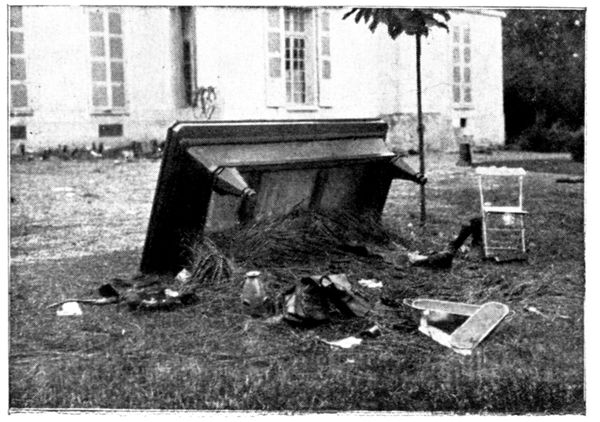

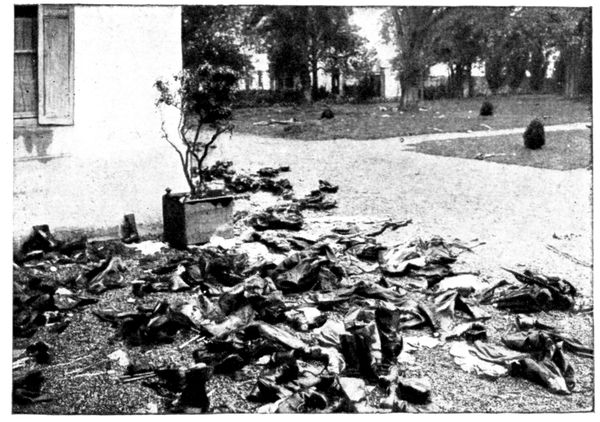

PICTURE

GALLERY

WHERE

THE GERMANS

SLEPT

(1914)

In order to house his collections, the Duc d'Aumale had the big castle

rebuilt, on plans made by the architect Daumet, from 1875 to 1882.

He died in 1897, bequeathing to the "Institut de France" the domain of

Chantilly and the Condé Museum, of which he was the founder.

The Castle in 1914

About 500 Germans stayed at the castle for twenty-four hours. These

reserve troops had not yet fought and did not take part in the battle. They

committed no excesses during their short stay. The great moral firmness

shown by the curators, Messrs. Élie Berger and Macon had great influence on

the conduct of the German soldiers. The troops were lodged in the big castle,

whilst the officers established themselves in the various suites of the small

castle.

The curators had sent the gems of the collection to Paris and sheltered as

many of the works of art as possible in the basement. This proceeding[Pg 29]

caused some ill humour on the part of the German officer in command. As

seen in the photograph (page 28) straw was spread in the rooms of the

museum, on which the Germans slept. At the end of the room Chapu's

touching Jeanne d'Arc overlooks the scene of desolation. The Germans were

much impressed by the copy of the Duc d'Aumale's tomb in the museum,

where he is represented in the uniform of a divisional general. Many gave the

military salute when crossing the room. However, this did not prevent the

commandant from warning the curators that if his troops were fired on,

the castle would be burnt and they themselves shot.

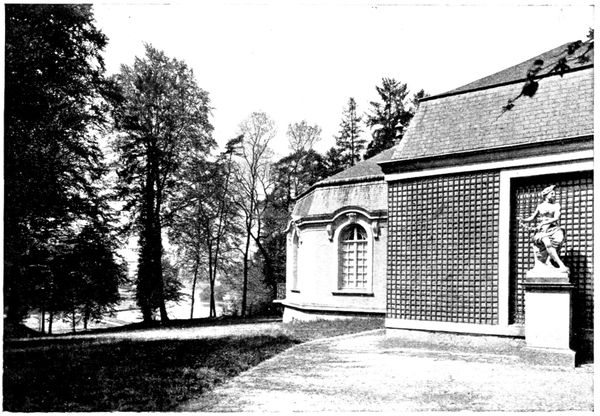

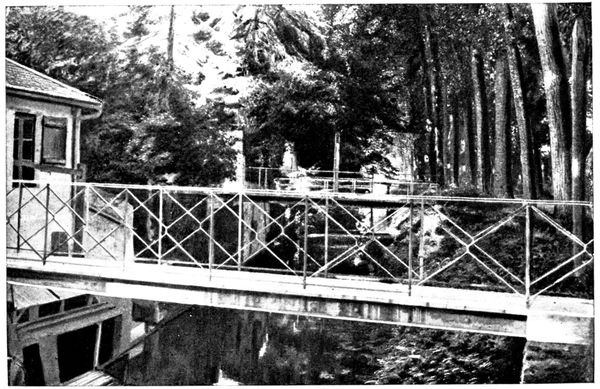

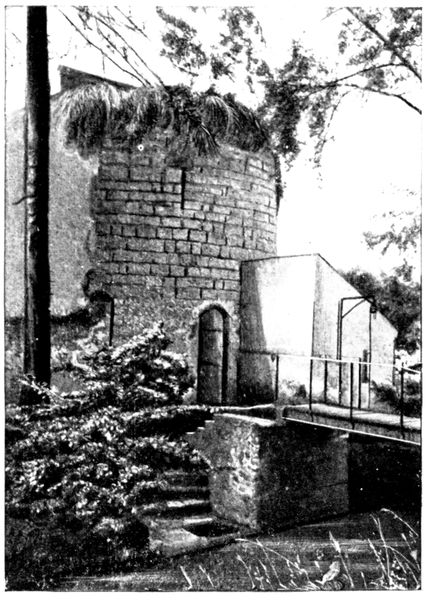

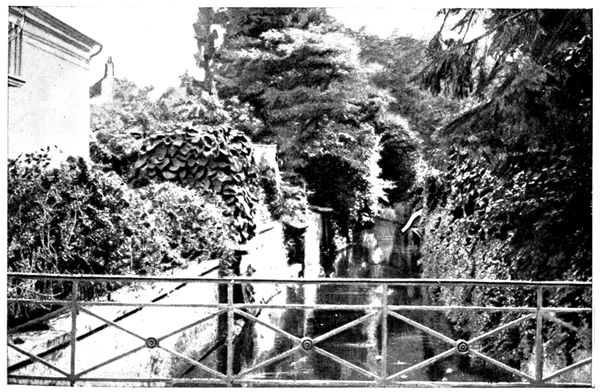

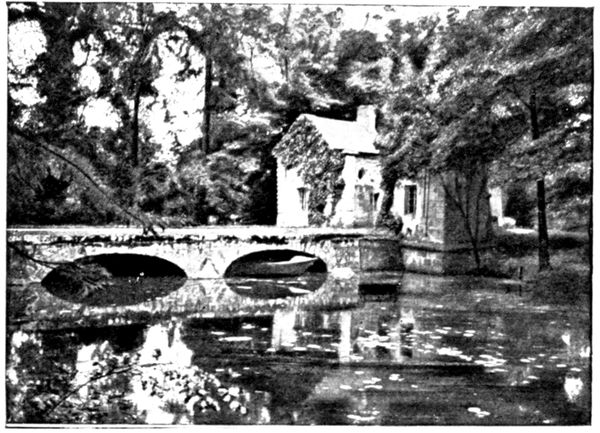

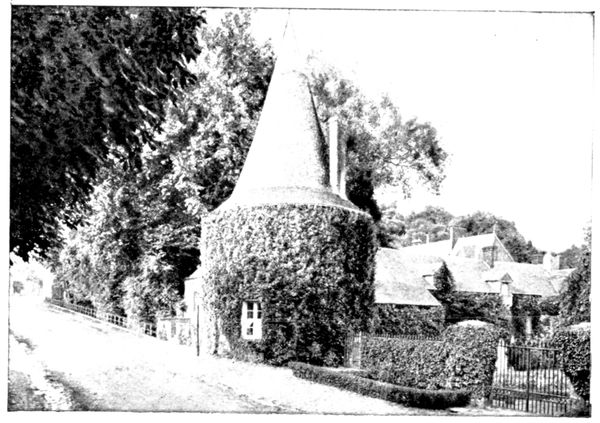

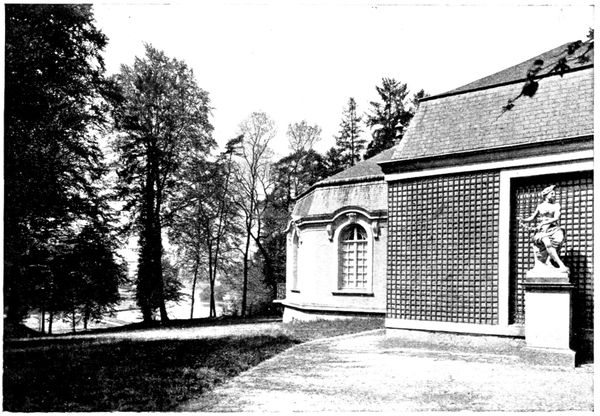

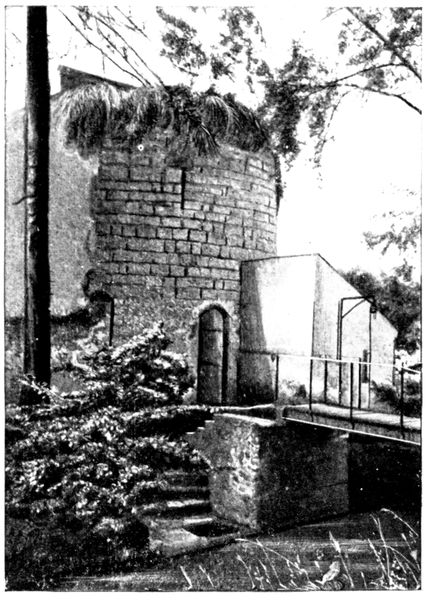

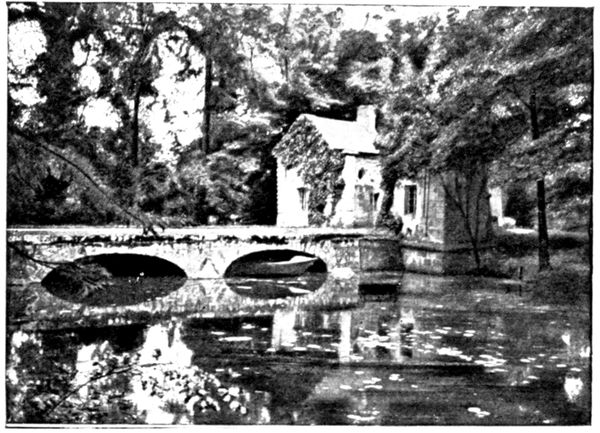

Sylvie's House

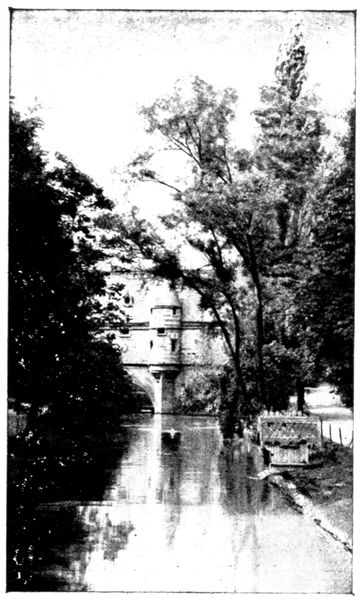

If the tourist makes this journey on a day when the castle is closed, or if he has

not time to visit it, he will at least be able to glance at the charming corner of

the park where stands Sylvie's House. He need only take the path of Avilly

(it is the road which is on the right of the main entrance) and skirt the park railings.

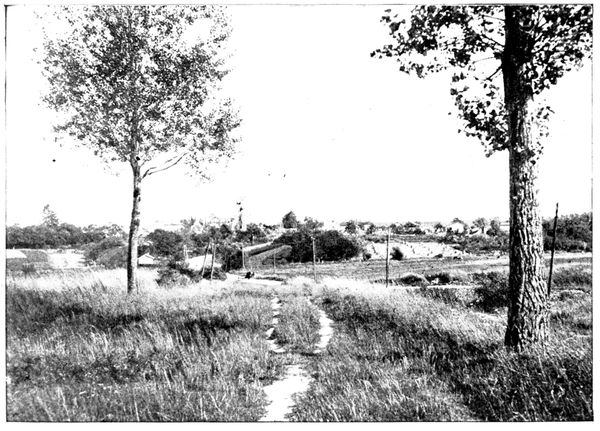

After five minutes' walk he will reach the place from where the view below is taken.

He can return to the gates by the same road.

This little shooting lodge, at first called the "Park House," was built

in 1604 by the high constable Henri de Montmorency for King Henri IV.

Sylvie is the poetical name given by Théophile de Viau to his patroness

Marie-Félicie Orsini, who in 1612, at the age of fourteen, married Henri II.

of Montmorency, aged sixteen. The poet, Théophile de Viau, persecuted

in 1623 for the licentious publication of the Parnasse Satirique, was given

shelter at Chantilly and lodged in the Park House.

Condemned to be burnt alive, he was only executed in effigy through the

intervention of the Montmorencys.

In his Odes to the House of Sylvie, he extolled the grace and goodness of

the young duchess:

Mes vers promettent à Sylvie

Ce bruit charmeur que les neveux

Nomment une seconde vie....

The wish expressed by the poet in these lines was fulfilled and the name

of Sylvie became attached to the house and park surrounding it. The great

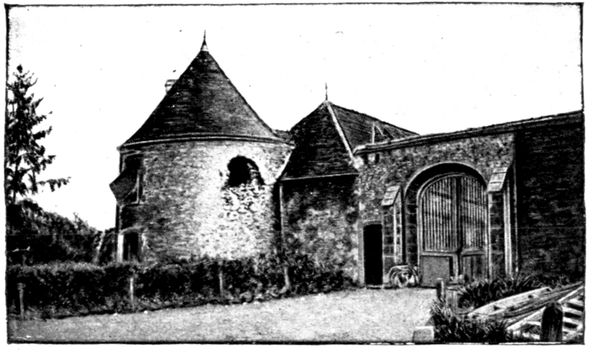

Condé rebuilt the house as it is to-day. (The rotunda seen in the photograph,

page 29, was added by the Duc d'Aumale.)

SYLVIE'S

HOUSE

AND THE PARK

[Pg 30]

In the eighteenth century Sylvie's House was the scene of the romance of

Mlle. de Clermont and Louis de Melun. The head of the house of Montmorency

objected to the marriage of his sister, Mlle. de Clermont, with this nobleman,

whose rank he considered insufficient. The young girl disregarded

this and made a secret marriage, soon ended by the tragic death of Louis de

Melun, who was killed by a stag at bay in the course of a hunt in Sylvie's

park. These various episodes in the history of Sylvie's House are recalled

in the paintings of Luc-Olivier Merson, installed by the Duc d'Aumale when

he turned the old house into a museum.

Visit to the Castle

The Castle, Sylvie's House, the Jeu de Paume, and the "Grandes-Écuries"

are open to the public from April 15 to October 14:

1, On Sundays, Thursdays and legal holidays, from 1 to 5 p.m., free;

2, On Saturdays, the same hours, one franc charged for each visitor.

The Park is open to the public all the year round on Thursdays, Sundays

and holidays: from 1 to 6 p.m., from April 15 to October 14, and till 4 p.m. for

the rest of the year.

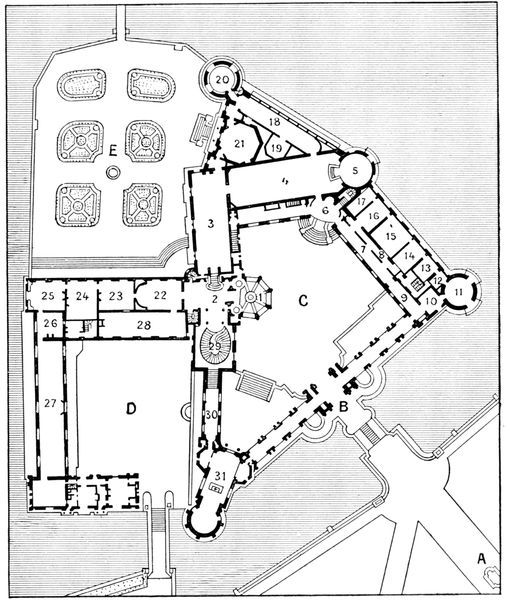

The Condé Museum is extremely interesting.

We advise tourists to obtain the guide book sold at the entrance, which gives

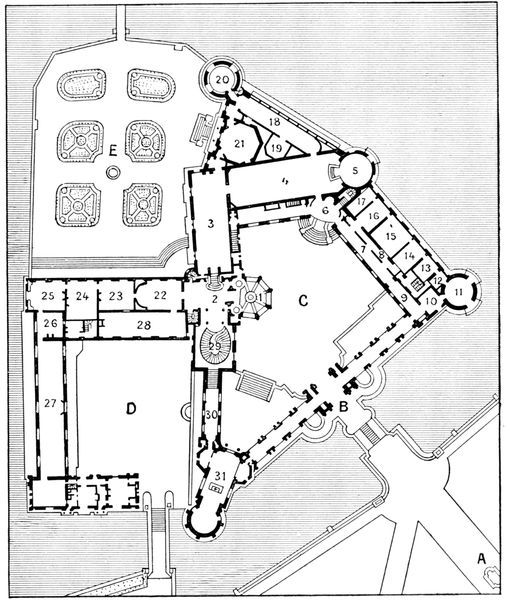

all useful information for the details of the visit. The plan (p. 31) makes it

easy to find one's way about the museum. By following the numbering in this

plan the various rooms will be seen in the order in which they are marked in the

guide book.

The several photographs which follow can give but a faint idea of the

richness and interest of the collections made by the Duc d'Aumale.

The following view shows the Gallery of the Stags, formerly the dining

room.

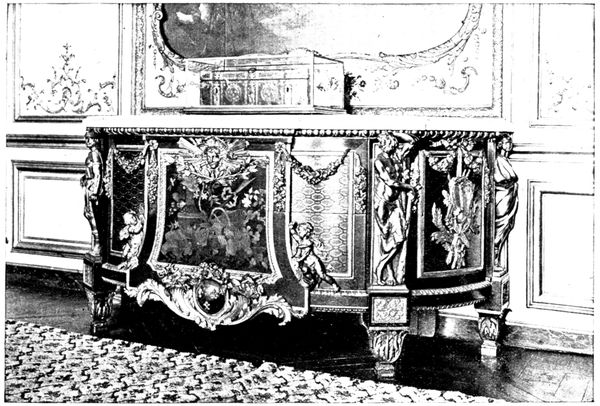

The picture on page 32 represents the magnificent carved and inlaid chest

(the work of Riesener, the great cabinet-maker), which stands in room 24

(plan p. 31).

The Duc d'Aumale gathered the gems of his collection together in the

room that he named the Santuario (No. 19 on plan, p. 31).

They are: The Virgin by Raphael, described as "of the House of Orleans,"

having belonged to that family for a very long time. This little panel,[Pg 31]

painted about the year 1506, was bought for 160,000 francs in 1869. It is

reproduced on p. 32.

The Three Graces, another small panel painted by Raphael at about the

same time as The Virgin, was bought for 625,000 francs in 1885.

Esther and Ahasuerus, panel of a marriage chest, executed by Filippino

Lippi, was bought for 85,000 francs in 1892.

Forty Miniatures by Jehan Fouquet, taken from the Book of Hours,

by Estienne Chevalier: this leading work of the French school of the

fifteenth century was acquired for the sum of 250,000 francs in 1891.

- Entrance.

- Grand Vestibule.

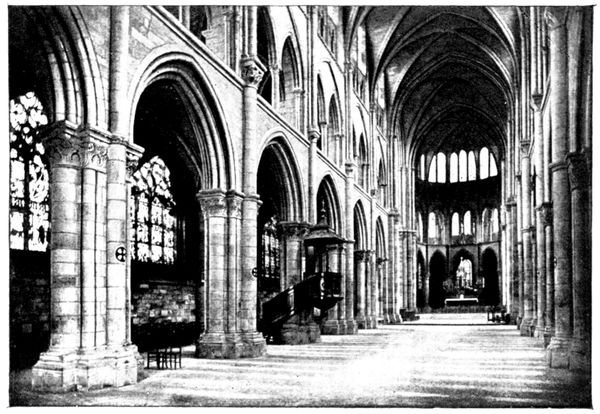

- Gallery of the Stags.

- Picture Gallery.

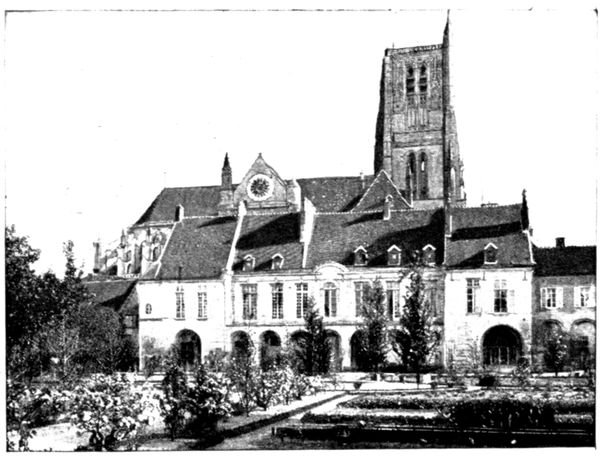

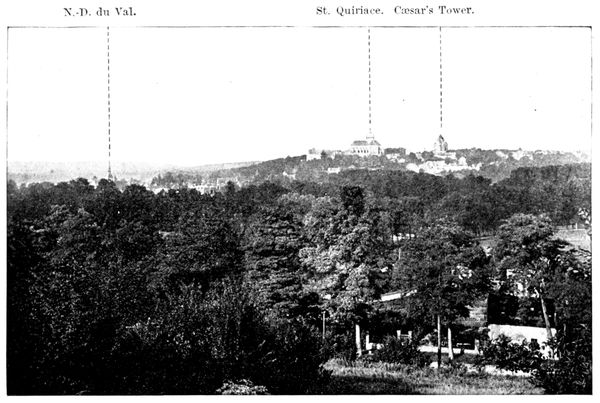

- Rotunda of the Museum (Senlis Tower).

- Vestibule of the Museum.

- Gallery of the House.

- Small Gallery of the House.

- Vestibule of House.

- The Smalah.

- The Minerva Tower (Tower of the High Constable).

- The Antiquity Room.

- Giotto Room.

- Isabelle Room.

- Orleans Room.

- Caroline Room.

- Clouet Room.

- Psyche's Gallery.

- Santuario.

- Treasure Tower.

- The Tribune.

- The Anteroom.

- Guardroom.

- La Chambre.

- The Great Study.

- The Monkey Parlour.

- The Prince's Gallery.

- Library.

- Great Staircase.

- Gallery of the Chapel.

- Chapel.

- Statue of the High Constable.

- Entrance (portcullis).

- Court of Honour.

- Court of the Little Castle.

- Flower Garden of the Aviary.

[Pg 32]

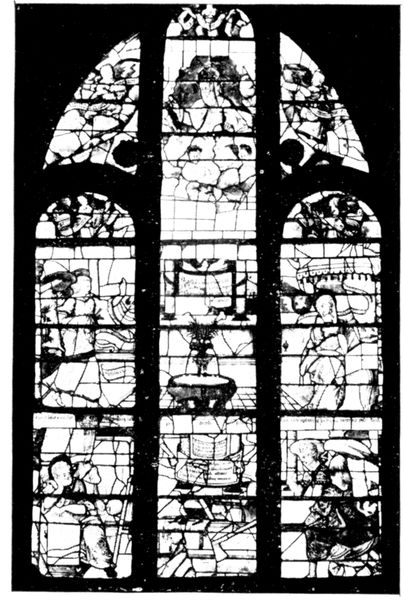

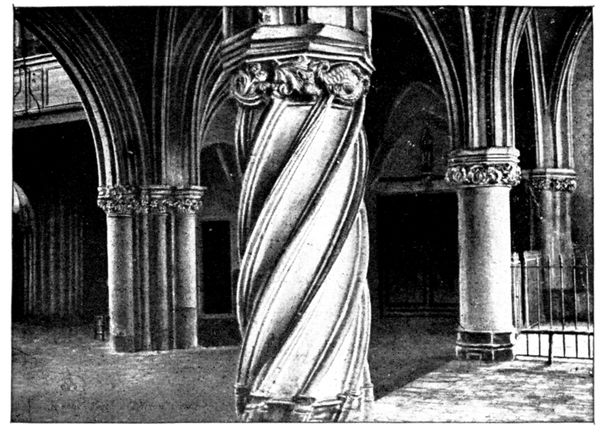

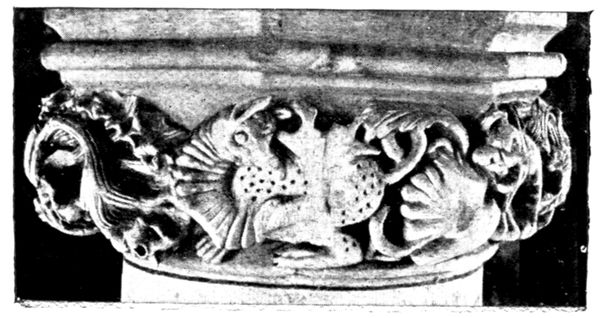

We must also mention the collection of portraits painted or drawn in

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, divided between the Gallery of the House

(7 on plan), the Clouet room (17 on plan) and the Gallery of Psyche (18 on

plan). In the Gallery of Psyche, the visitor will notice, besides the pictures,

the forty-four sixteenth century windows, representing the legend of Cupid and

Psyche. There is also a cast of the head of Henri IV.

Lovers of jewels should visit

the treasure tower (20 on

plan). Tn the Monkey Parlour

(26 on plan) will be seen

the screen painted by Huet,

representing the Monkey's

reading lesson, and on the

panels a charming eighteenth

century decoration, attributed

to the same painter.

In the Prince's Gallery

(27 on plan) the great Condé

had a series of pictures painted

representing the battles he had

fought.

In the trophy containing

his sword and pistols there

is also a flag taken in the

Battle of Rocroi in 1643. It

is the oldest standard captured

from the enemy that exists in

France.

In the middle of the gallery

stands the Table of the Vinestock,

carved out of one piece

taken from an enormous vine,

for the Connétable de Montmorency.

THE VIRGIN

OF ORLÉANS

BY RAPHAEL

[Pg 33]

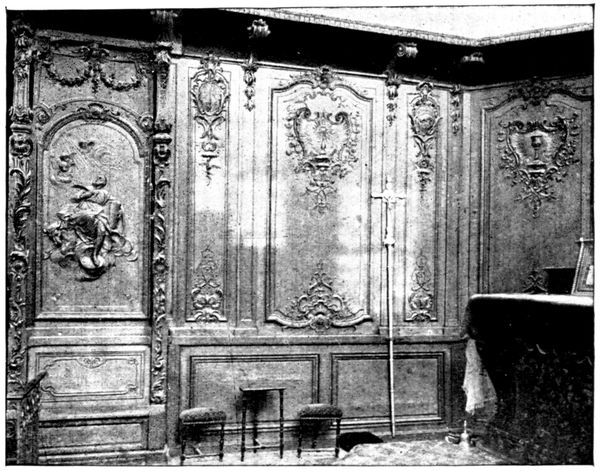

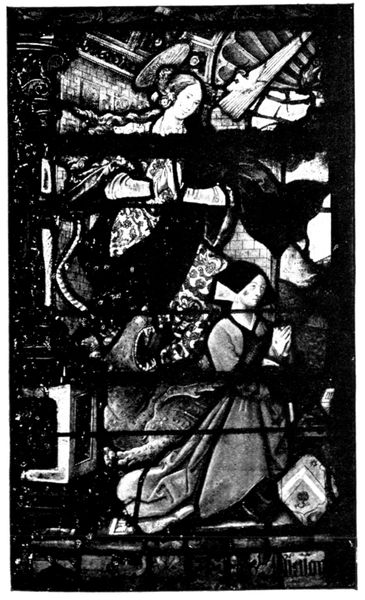

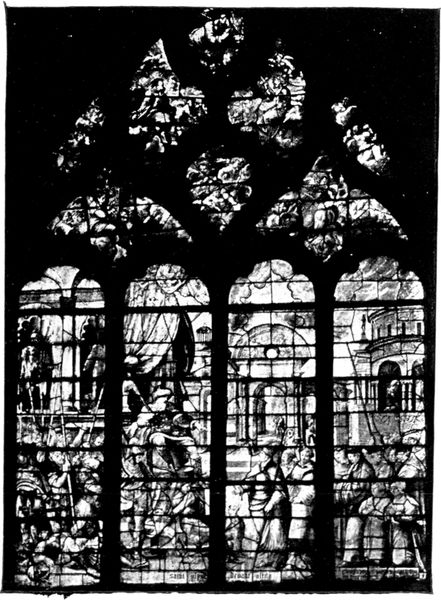

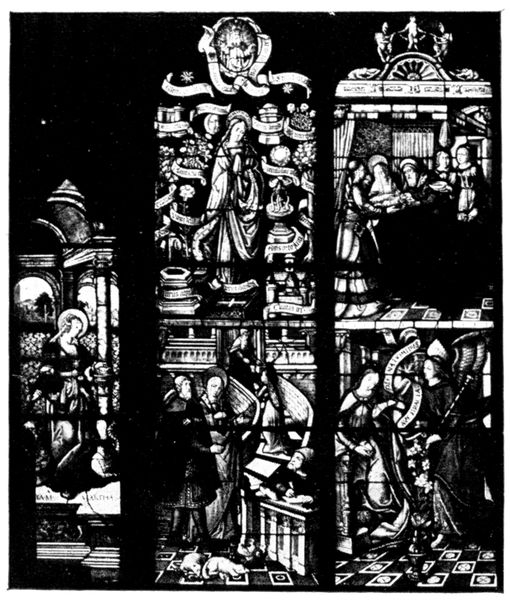

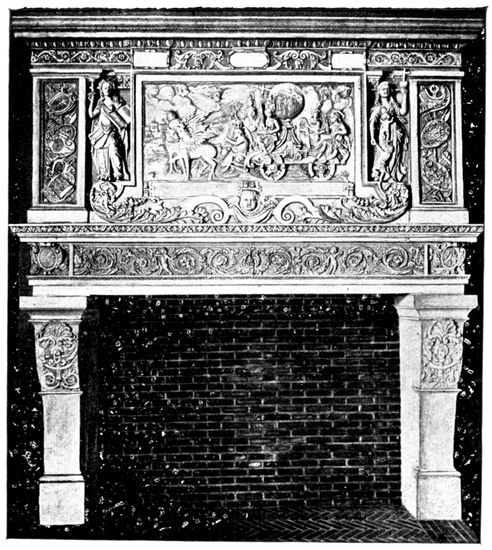

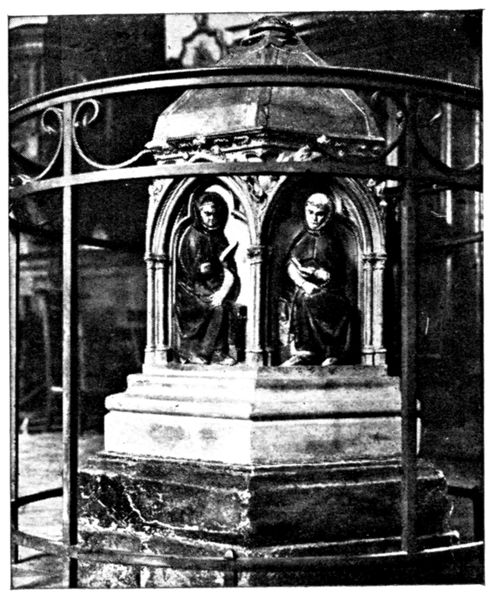

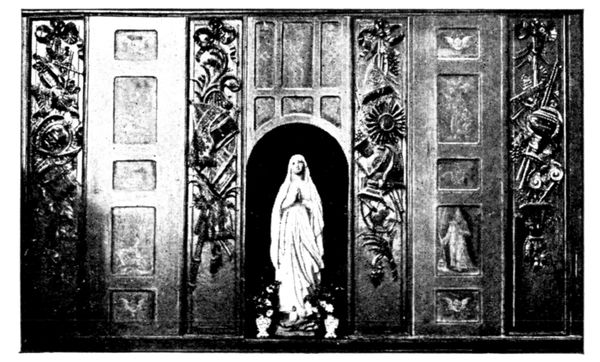

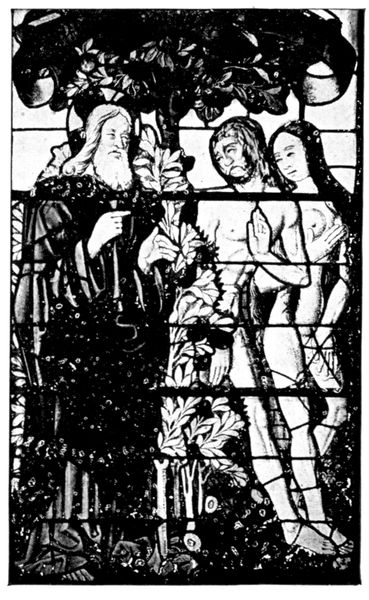

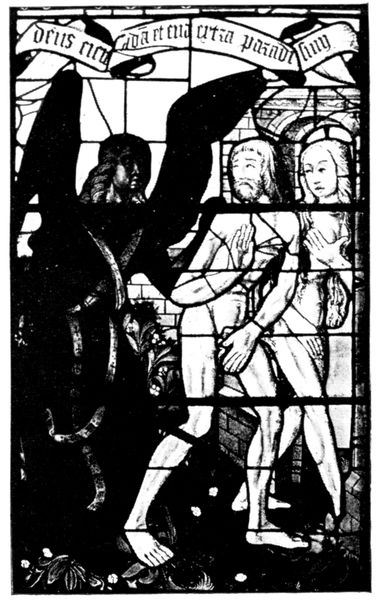

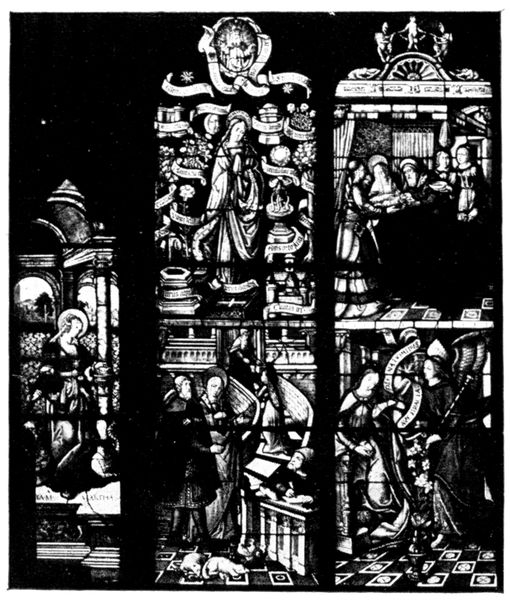

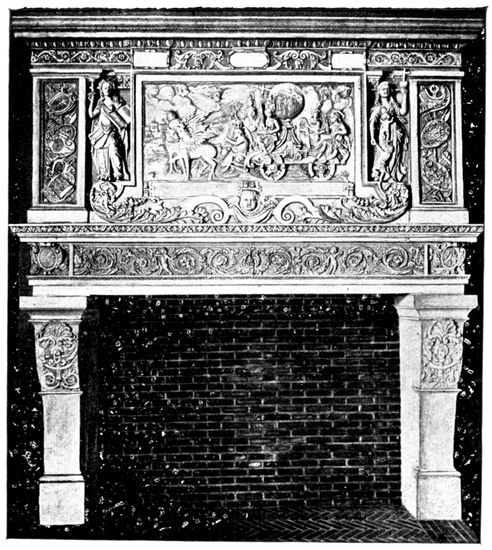

In the modern chapel (31 on plan), the Duc d'Aumale placed a beautiful

altar, carved by Jean Goujon, also some sixteenth century wainscoting and

stained glass windows taken from the chapel of the Castle of Ecouen.

In the apse stands the funeral urn which holds the hearts of the princes

of the House of Condé.

Visit to the Park

This takes from three-quarters of an hour to an hour and a quarter.

On coming out of the museum we cross the Terrasse du Connétable, in the

middle of which stands the equestrian statue of Anne de Montmorency,

by Paul Dubois (1886). Leaving the Château d'Enghien on the right we enter

the covered way by the avenue which passes before the little chapel of Saint-Paul.

Saint-Paul and Sainte-Croix are all that remain of the seven chapels

erected by Anne de Montmorency (see p. 23). A little further on, on the left,

we come to the Cabotière, a building dating from the time of Louis XIII.

It derives its name from that of the barrister Caboud, an enthusiastic amateur

horticulturist, who made a magnificent flower garden in the park for the

great Condé.

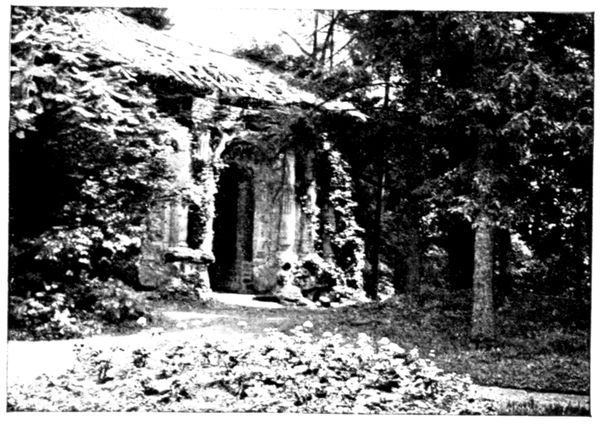

The avenue ends at Sylvie's House (see p. 29). In the interior can be

seen paintings, tapestries, pieces of furniture, and beautiful panelling of the

seventeenth century, which have been placed in the rotunda. From Sylvie's

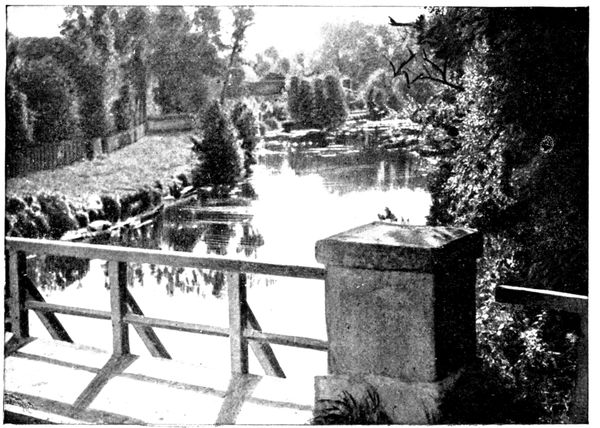

House there is a lovely view of the pond and park (see p. 29).

Leaving Sylvie's House on the right we walk about 150 yards down the path

which skirts it, then turn to the left and follow the path which leads straight to

the Hamlet (view on p. 35).

The Hamlet, which recalls that of the Petit Trianon at Versailles, dates

from 1775. At this period, under the influence of J. J. Rousseau's works,

nature and country life became the fashion, and it was the correct thing

for princes to play at peasants in miniature villages.

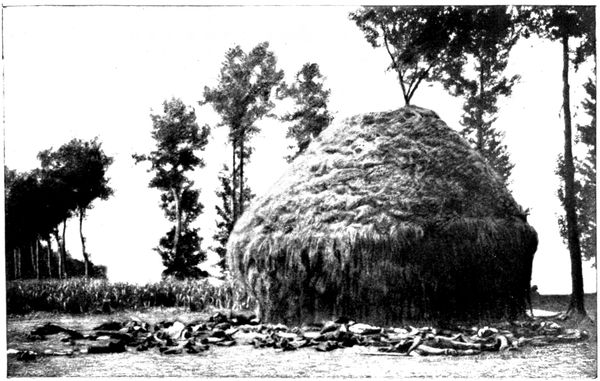

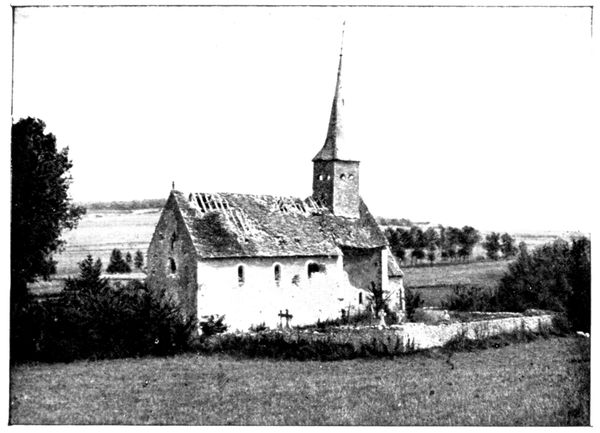

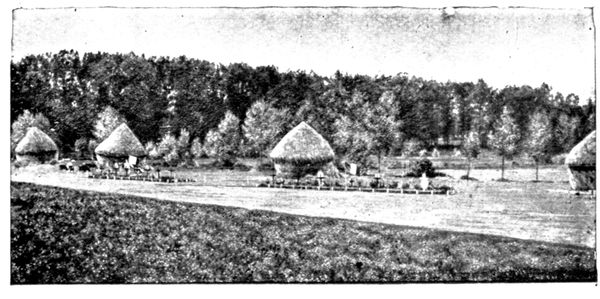

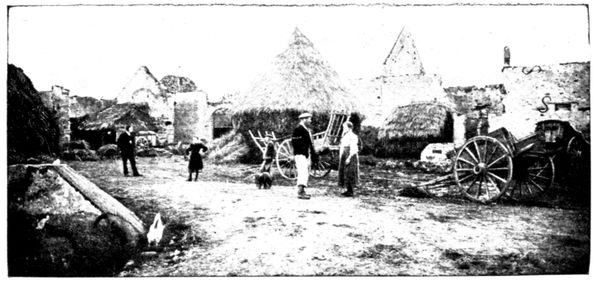

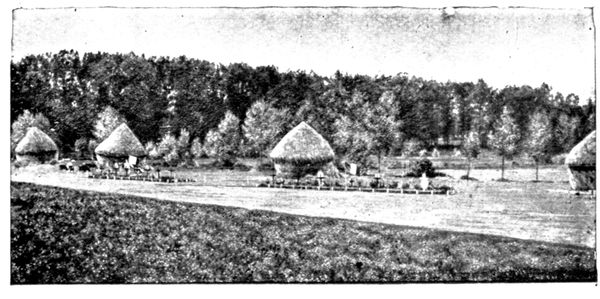

An author of the eighteenth century thus describes the Hamlet of Chantilly:

"Seven detached houses, placed without order, with thatched roofs, stand[Pg 34]

in the middle of a lawn that is always green. Here is an ancient elm, there

a well; further on a fence encloses a garden planted with vegetables and

fruit-trees; a mill, its wheel turned by the brook; in front a stable, a dairy;

one house is used as the kitchen, another is the dining-room, so decorated

as to resemble a hunting lodge. One fancies one's self in the middle of a thick

wood, the seats imitate tree-trunks, green couches and clusters of flowers

rise from the ground; a few openings made between the branches of the trees

admit the light. A third cottage serves as billiard-room, a fourth is a library.

The barn makes a large and splendid drawing-room."

THE CASTLE

SEEN FROM

THE FLOWER

GARDENS

From the time when the hamlet came into being, there was never a big

fête at Chantilly without a supper in this pretty corner of the park. Innumerable

pots de feu illuminated the thickets; on the canal the guests drifted in

gondolas to strains of dreamy music; fancy-dress fêtes were held, and the

singing and dancing continued until dawn.

The hamlet is now greatly fallen into decay, nevertheless, it is worth

a visit.

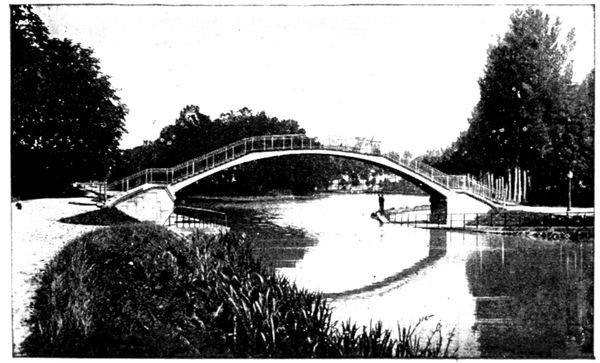

Retracing our steps we bear to the left and, having crossed, the first bridge,

follow a pretty path which brings us into the flower garden of Le Nôtre, where

we get a good view of the castle (photograph above). One can go straight

back to the entrance gates by the staircase shown in the view. It is called the

Grand Degré (great stair), and was built in 1682 by the architect Gitard.

The groups which adorn the base of the Terrasse du Connétable, on each

side of the stairs, were drawn by Le Nôtre and carved by Hardy.

This walk, from the time of leaving the museum until the return to the entrance

gates, takes about three-quarters of an hour.

If one wishes to visit the English Garden and the Jeu de Paume, which

will take about forty minutes longer, one must walk past the north front of the

castle and follow the walk which opens in the middle of the thickets.

The English Garden was laid out in 1817 to 1819 by the architect Victor

Dubois, according to the orders of the last of the Condés, just returned

from exile. The site occupied by this garden, like the ground on which

stands the town of Chantilly, belonged to the ancient park, devastated

during the Revolution.

We pass near the Temple of Venus, which shelters a Venus Callipyge

of the seventeenth century, near the Island of Love, dating from 1765 and

on which are statues of Aphrodite and Eros. In the eighteenth century the

Island of Love contained a luxurious pavilion, in which nocturnal fêtes were

held, the canals and park being illuminated. The pavilion disappeared at

the time of the Revolution.

[Pg 35]

The ancient Cascades of Beauvais that one sees before arriving at the

Jen de Paume are remnants of the old park. They were the work of

Le Nôtre.

The Jeu de Paume, constructed in 1757, is transformed into a museum.

It contains various curiosities, notably Abd-el-Kader's tent, carried away

when the Smalah was captured by the Duc d'Aumale in 1843.

After 3 p.m. one can leave the park by the gate next to the Jeu de Paume.

We come out in front of the "Grandes Écuries" of the castle and can go in

and look round them. (Enter at the side that faces the lawn.)

(Cliché André Schelcher.)

GENERAL VIEW OF THE CASTLE

[Pg 36]

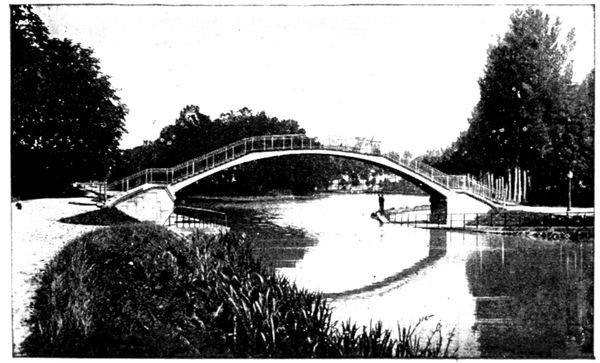

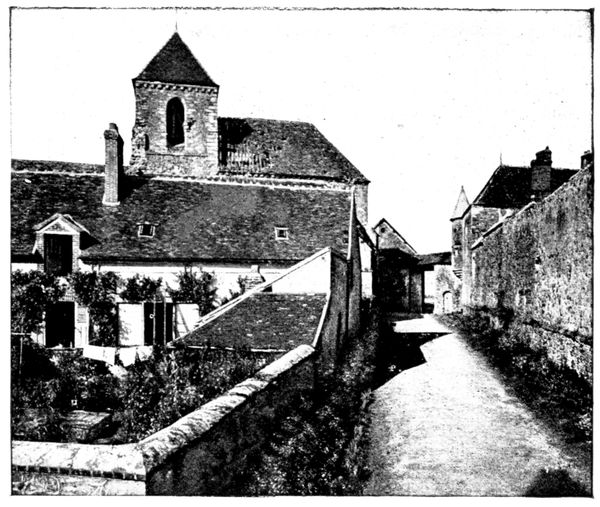

FROM CHANTILLY TO SENLIS

(9 km.)

THE CASTLE

SEEN FROM THE

ROUTE

DE VINEUIL

Returning through the monumental gateway, we cross the Rue de Connétable

and go straight on, skirting the castle park on the right. We cross the Saint-Jean

Canal, then the Great Canal, then turn to the right into the High Street of

Vineuil. On the right one soon has a beautiful vista of the castle and park

(view above).

We now go through Saint-Firmin. The church, on the left, contains in

its choir Renaissance windows which are classed as historical monuments.

From Saint-Firmin to Senlis the road is easy. We enter Senlis by the

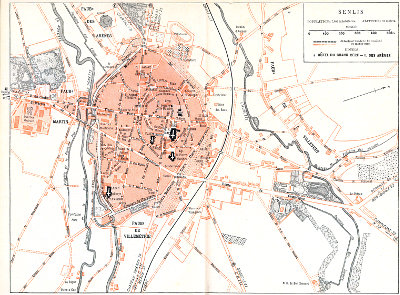

Creil Gate (see plan inserted between pp. 36-37). Turn to the left by the Avenue

Vernois and the line of boulevards to reach the station, where starts the itinerary

described further on, in Senlis.

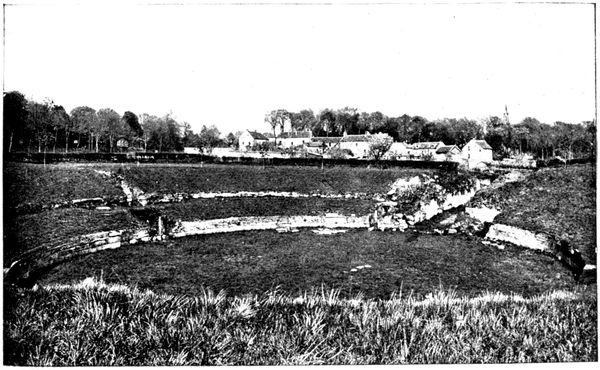

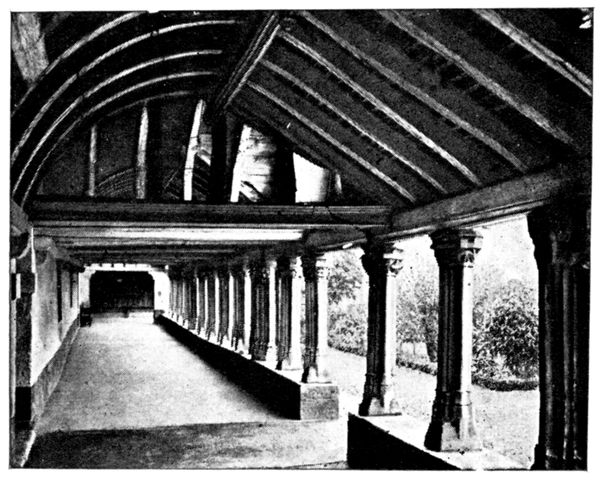

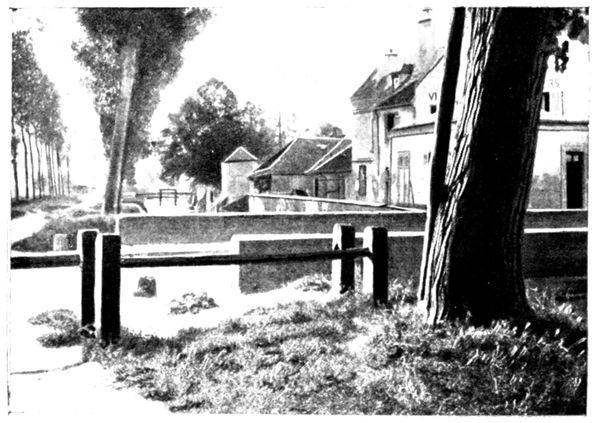

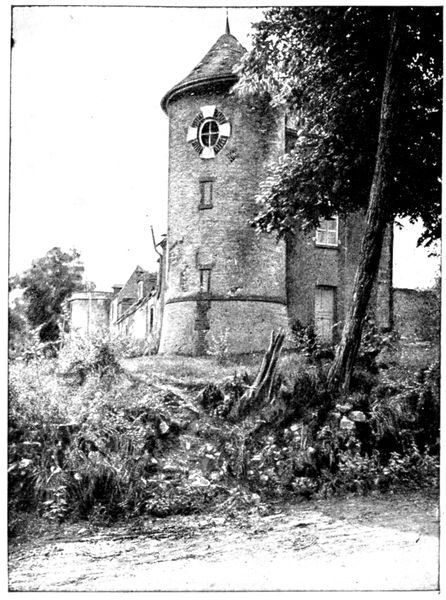

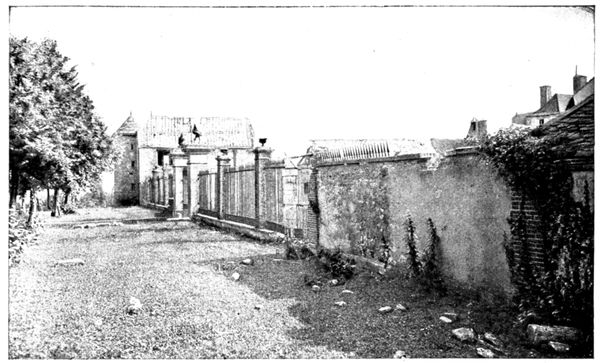

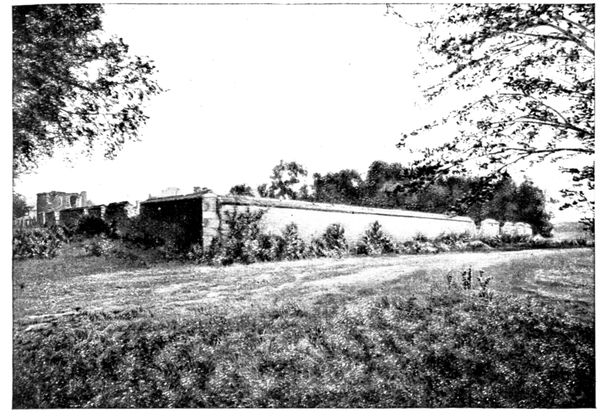

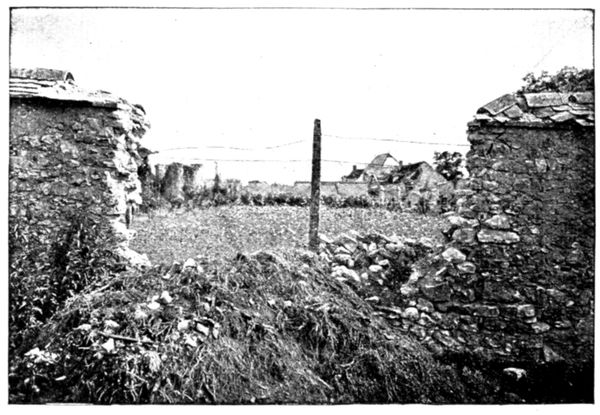

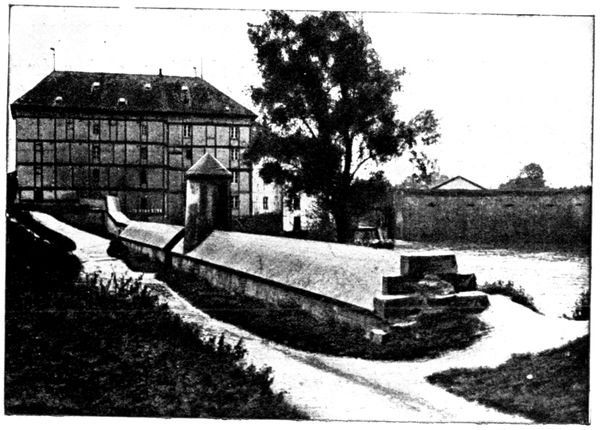

[Pg 37]

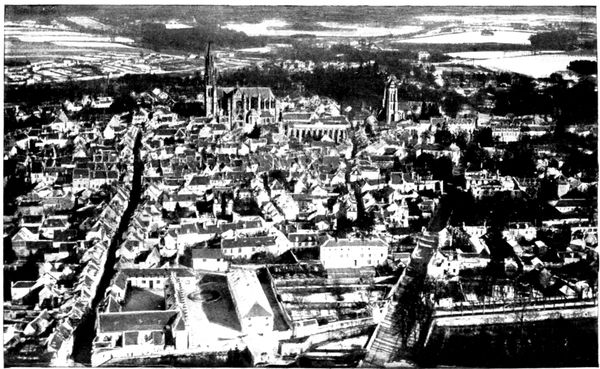

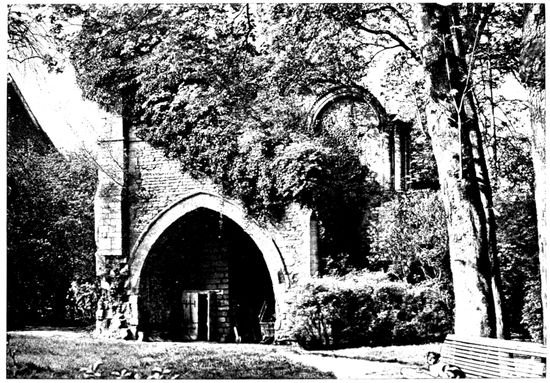

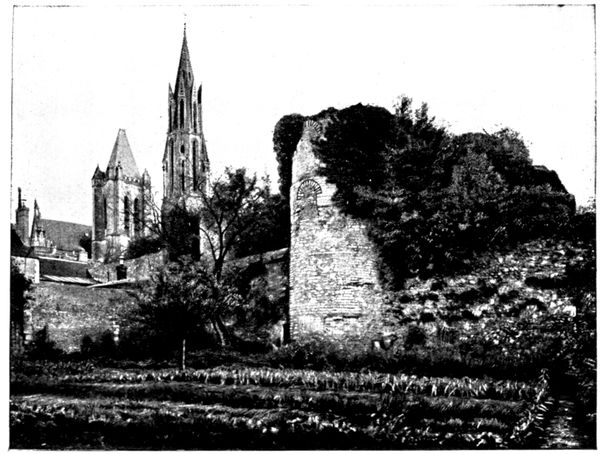

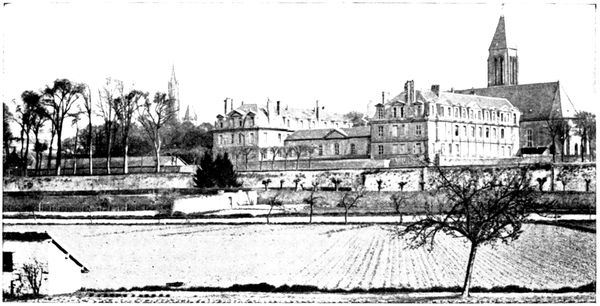

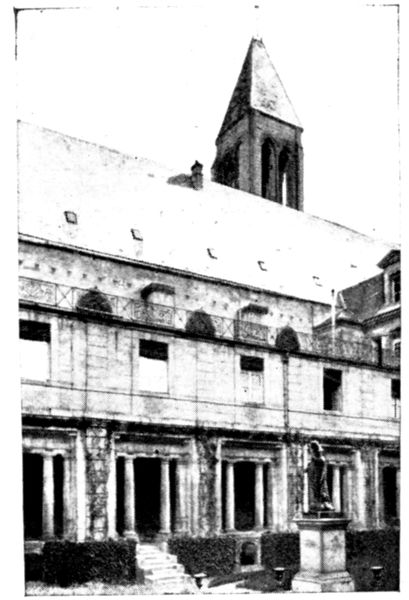

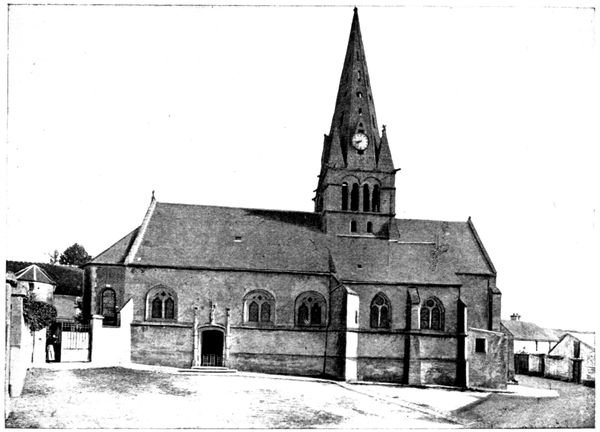

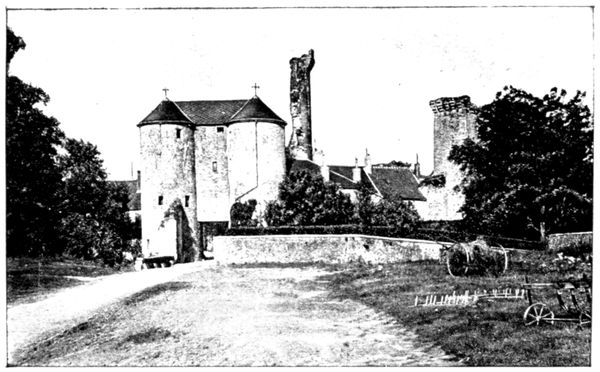

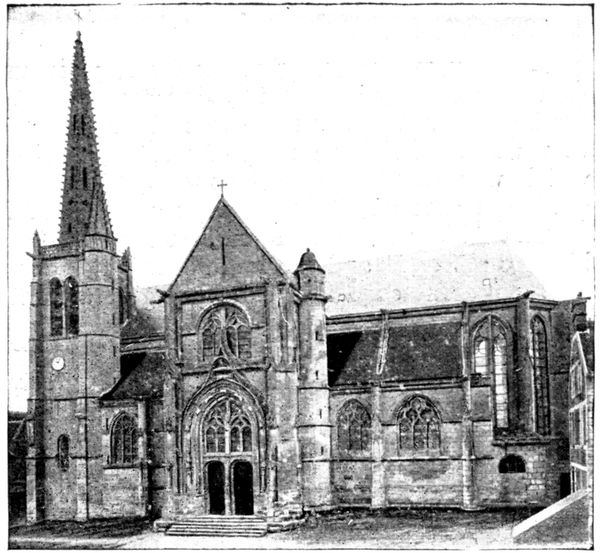

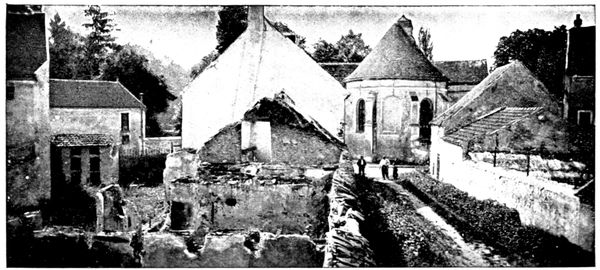

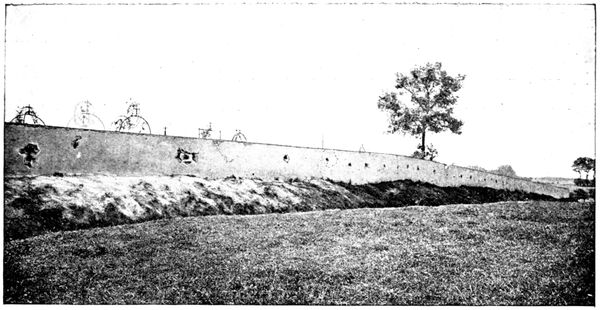

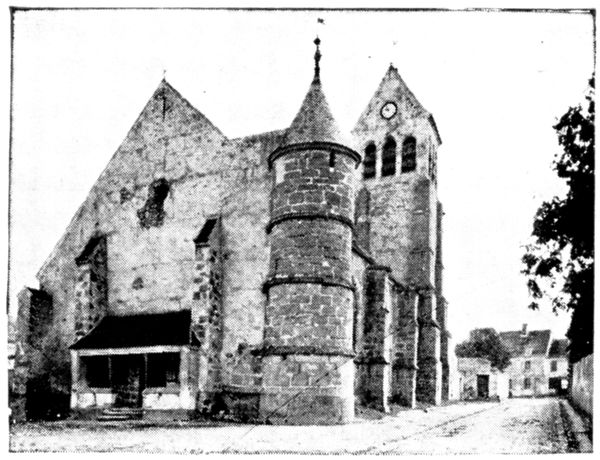

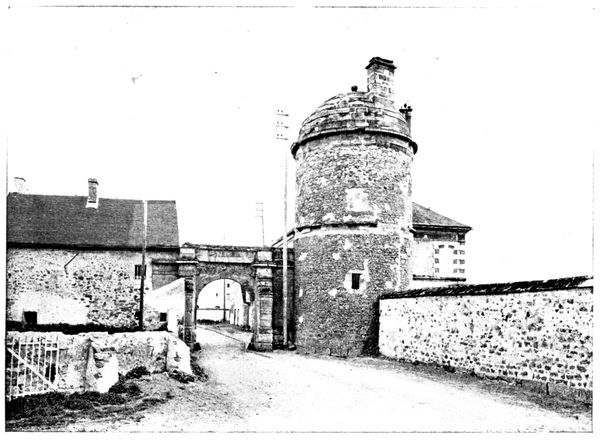

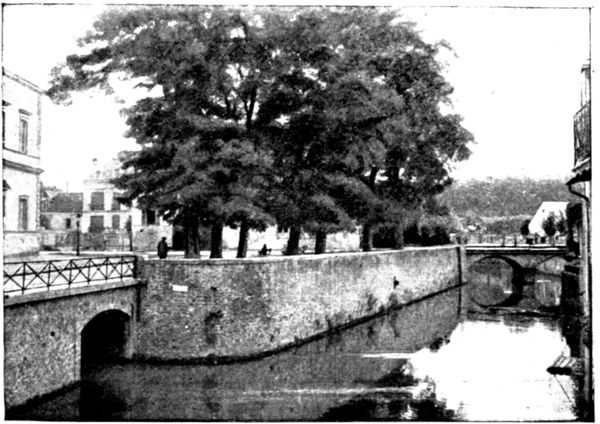

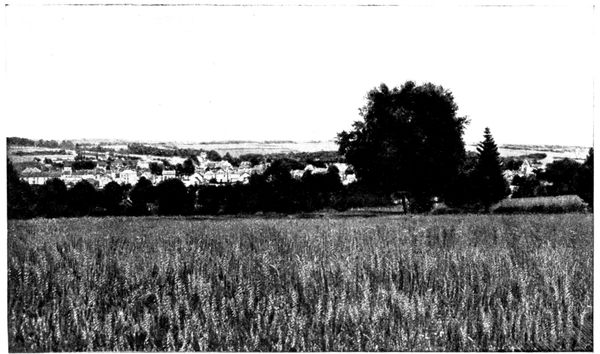

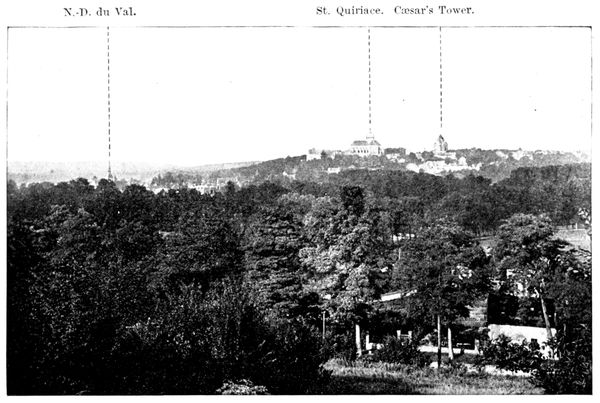

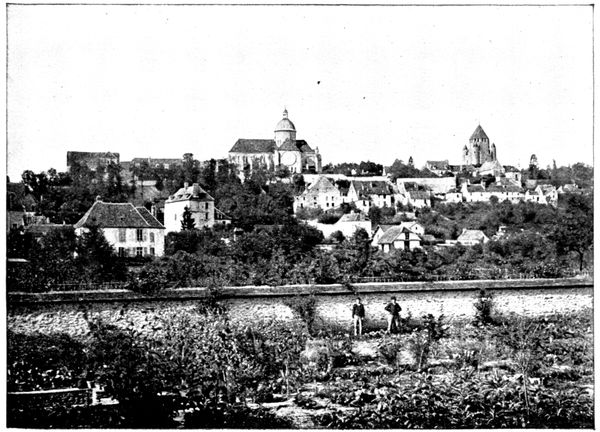

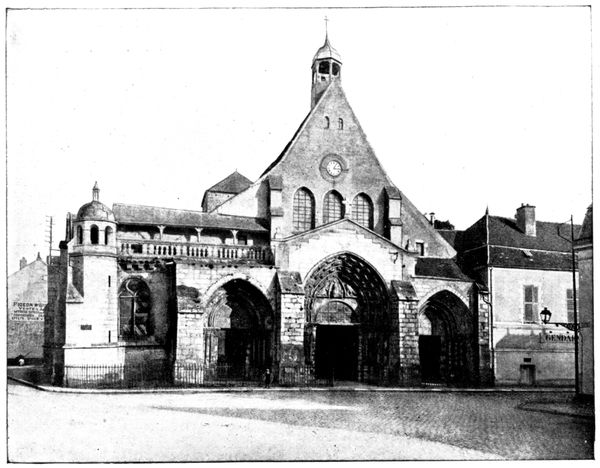

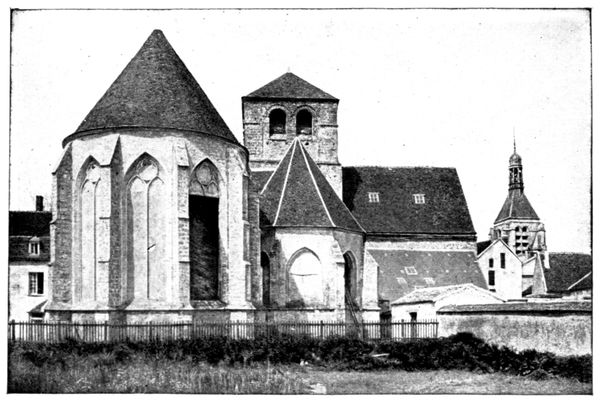

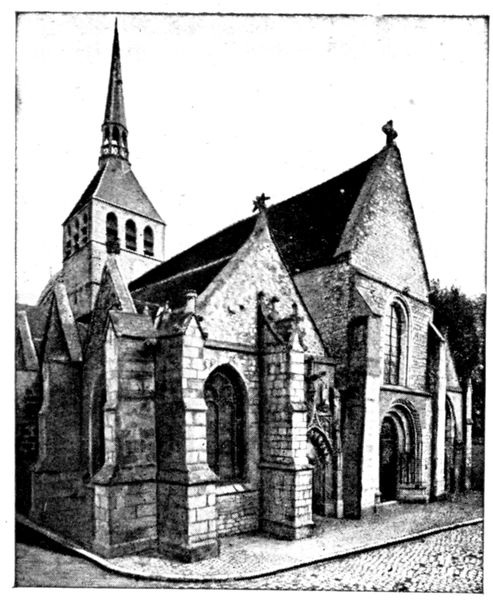

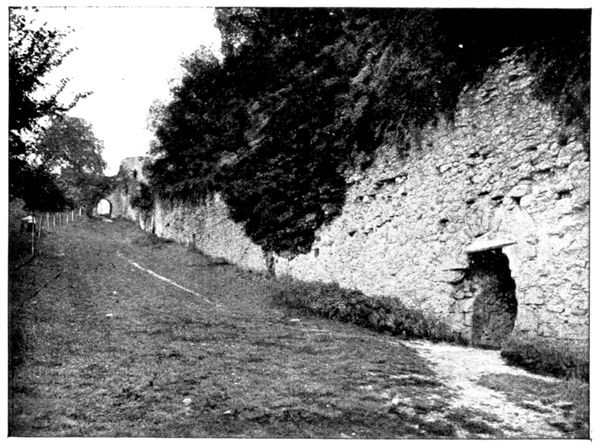

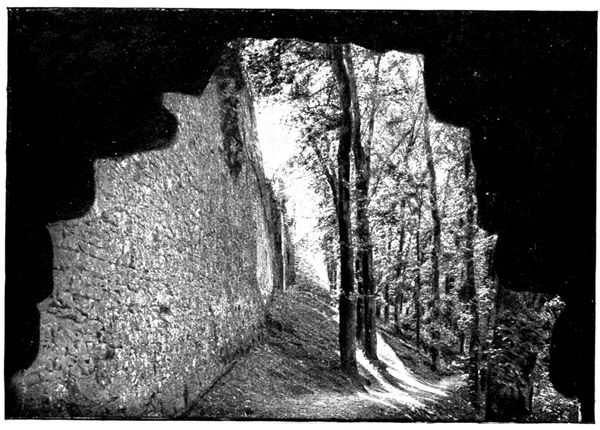

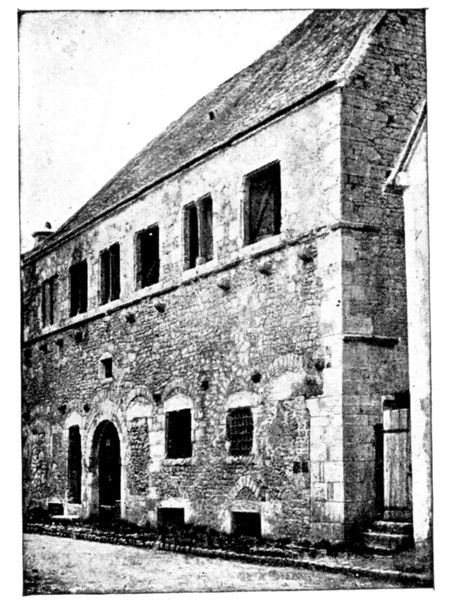

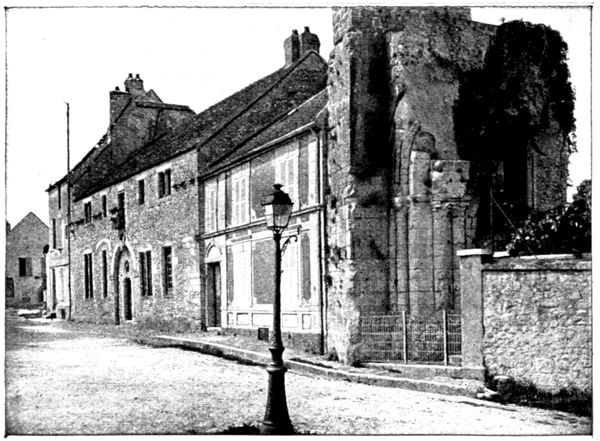

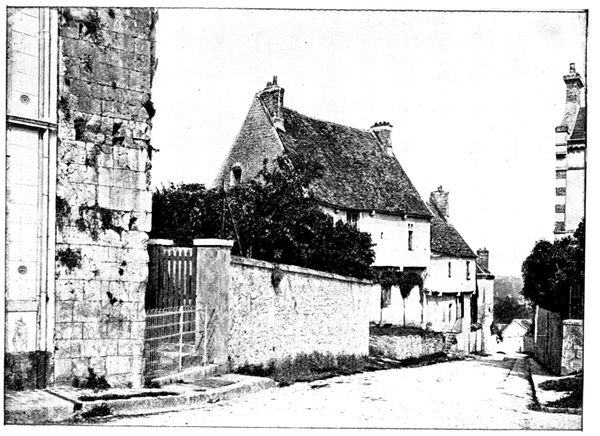

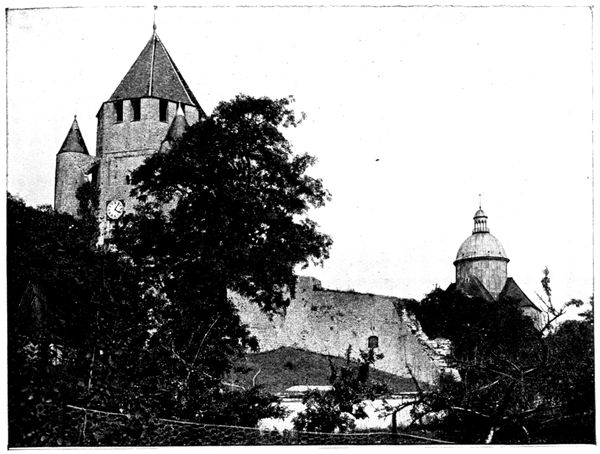

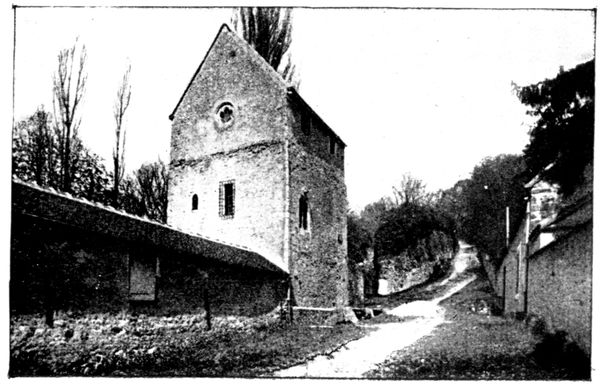

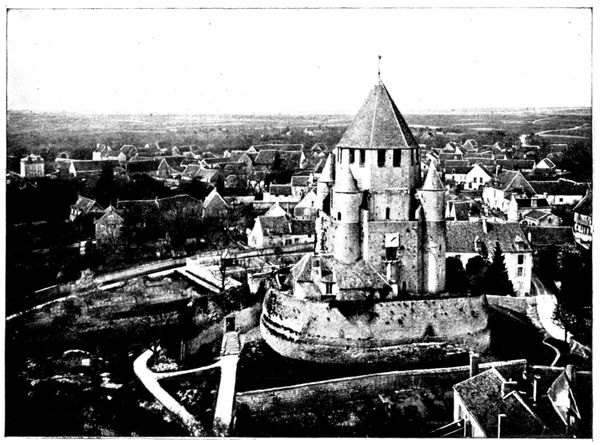

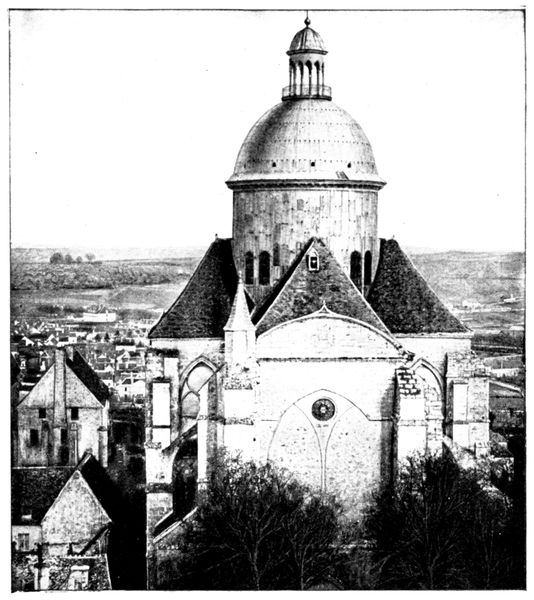

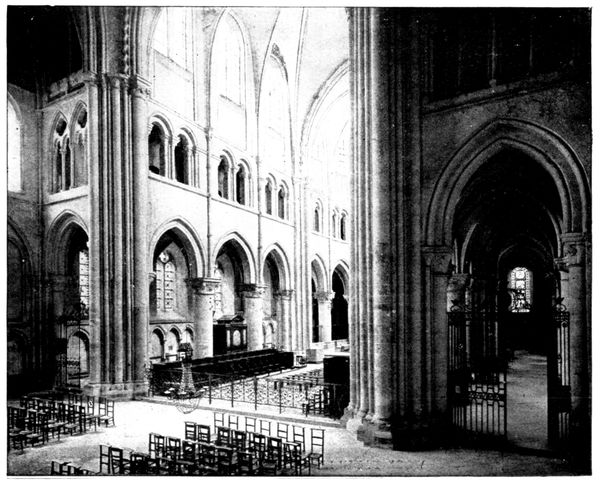

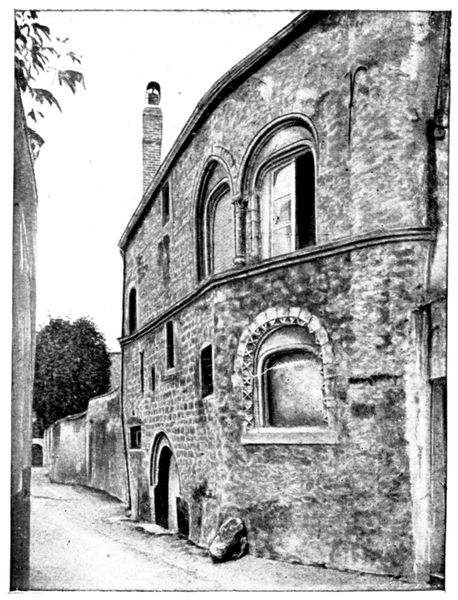

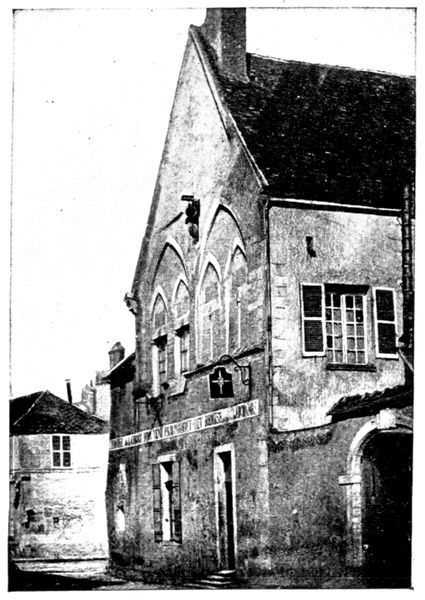

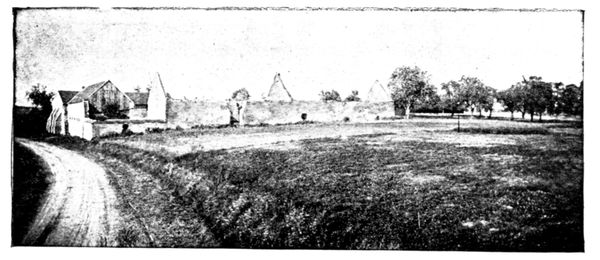

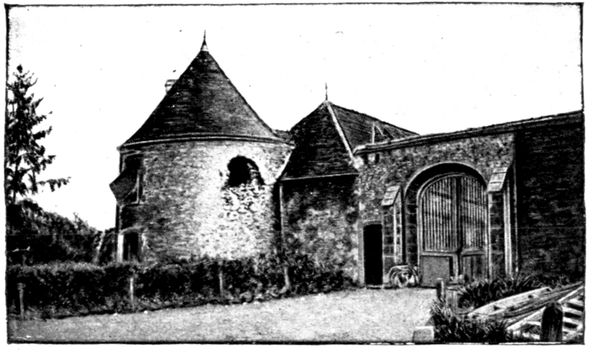

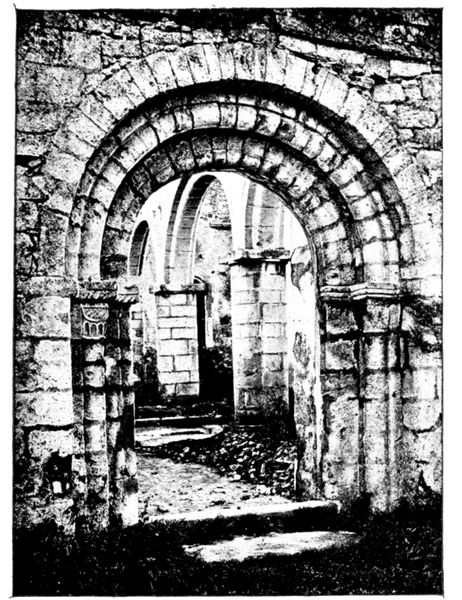

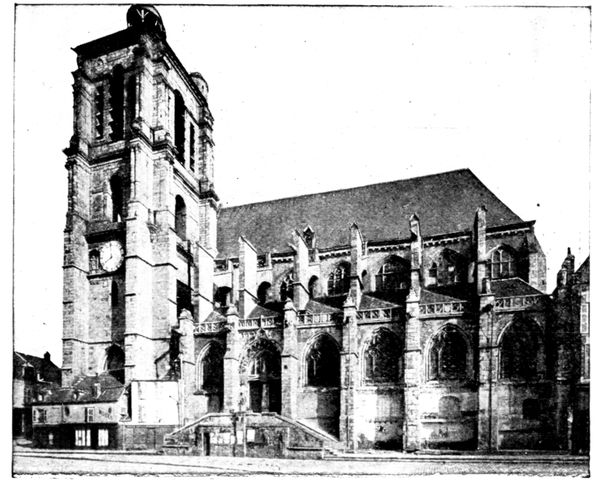

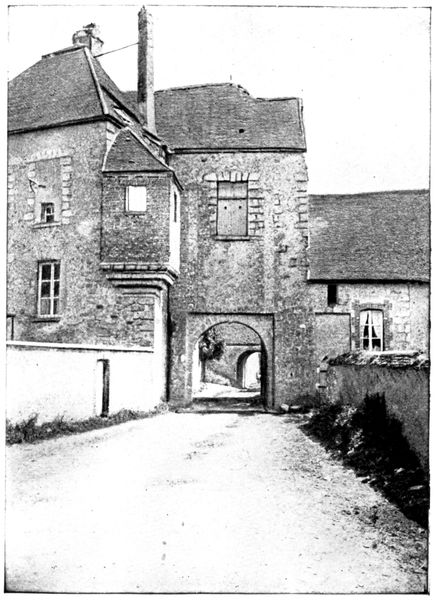

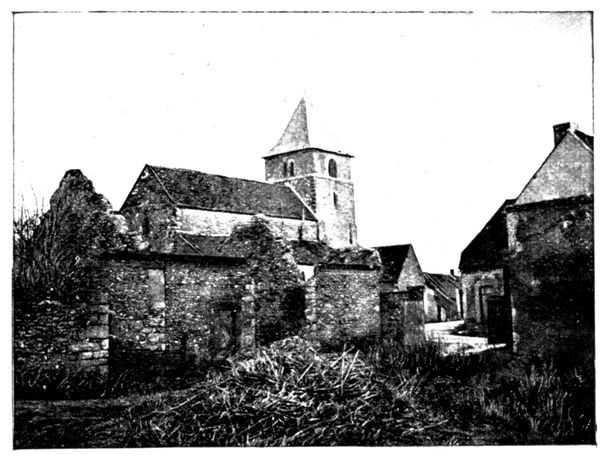

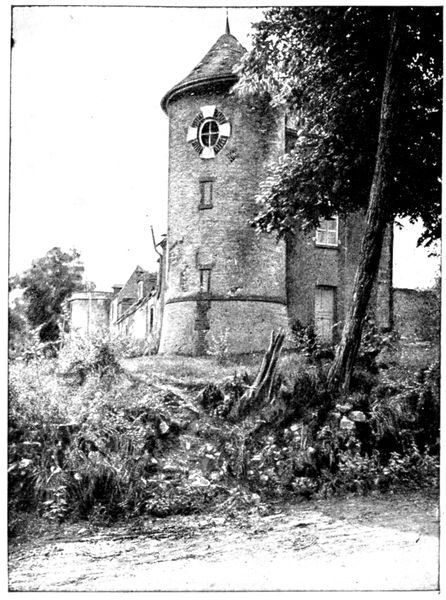

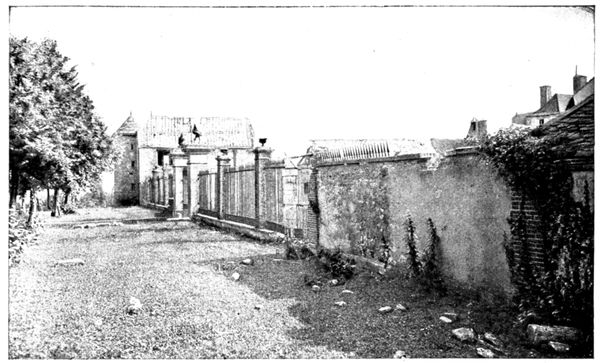

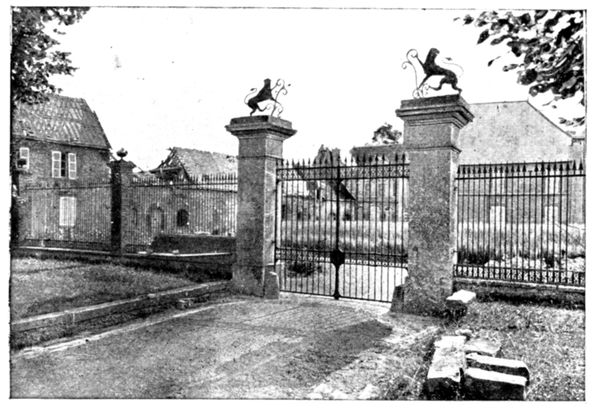

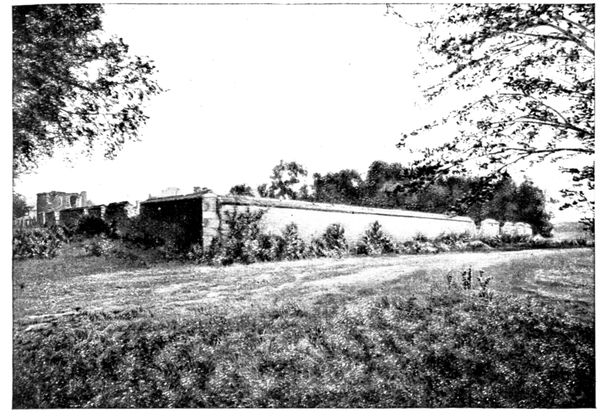

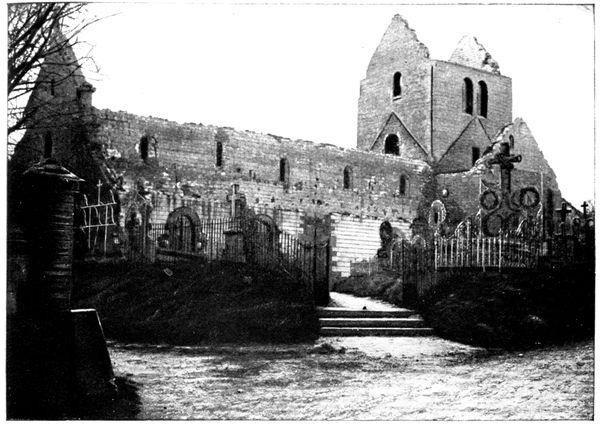

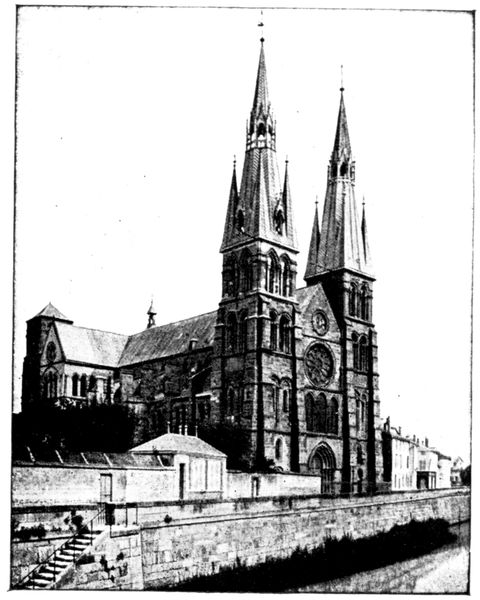

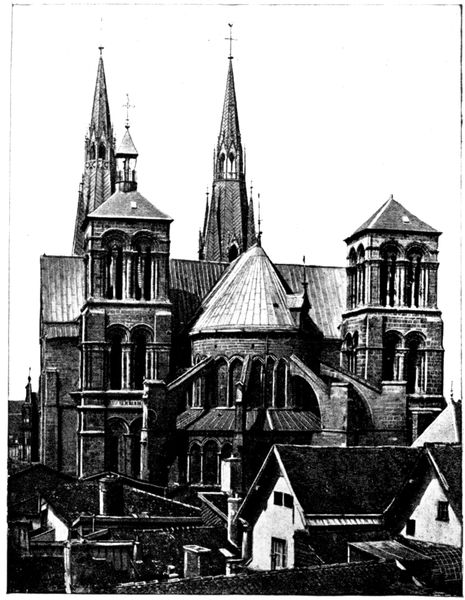

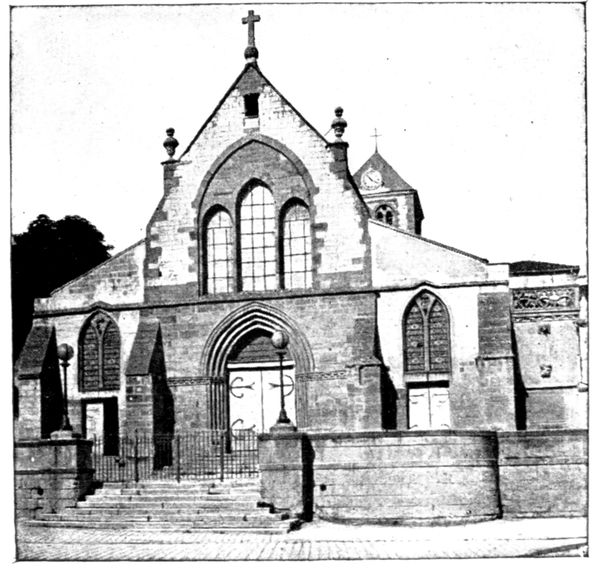

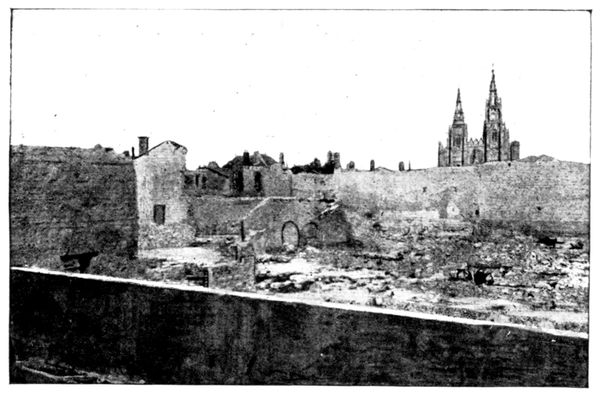

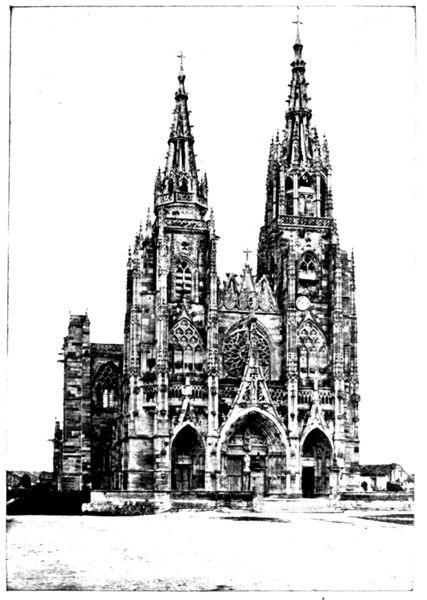

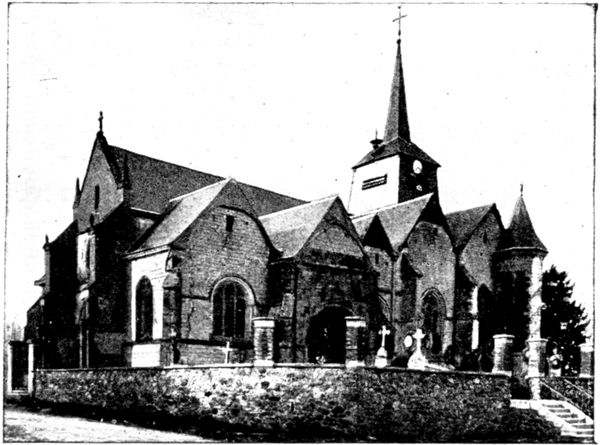

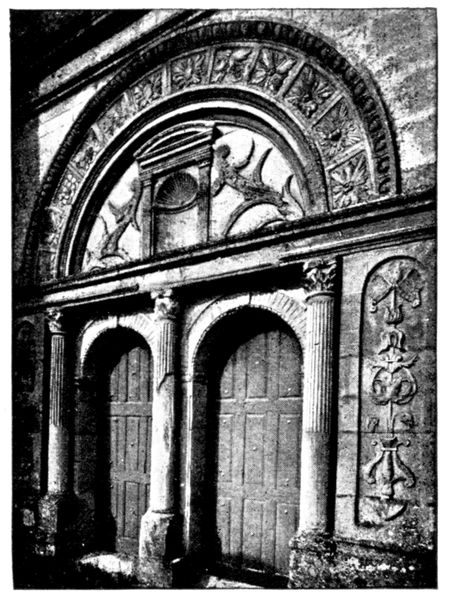

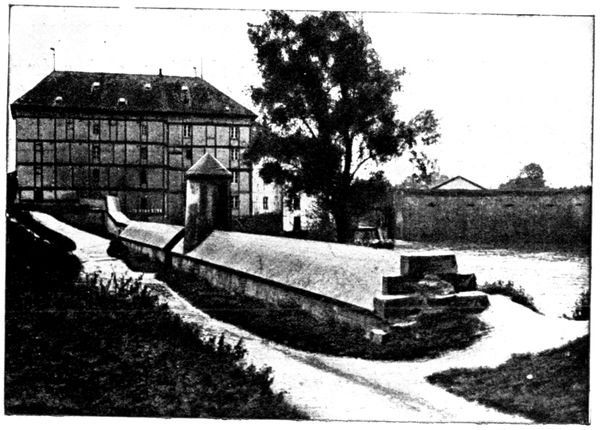

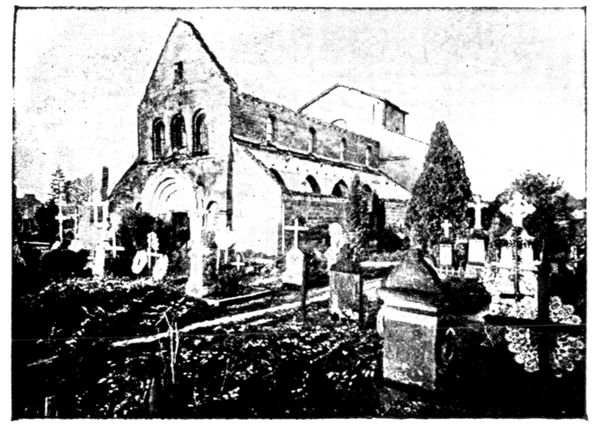

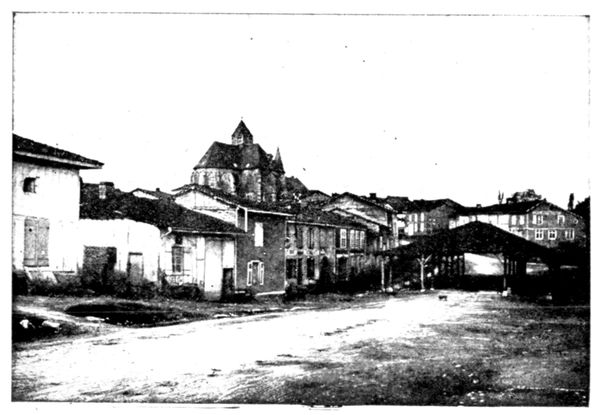

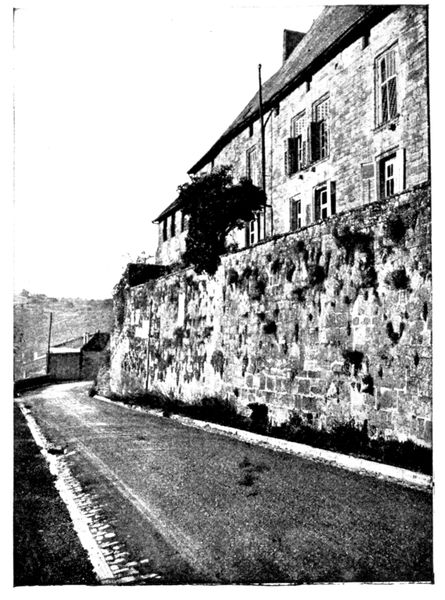

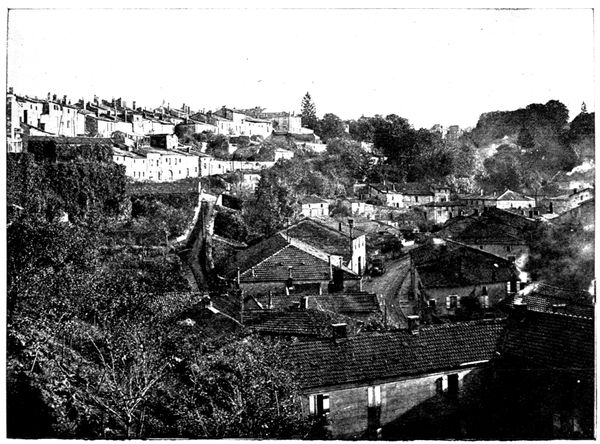

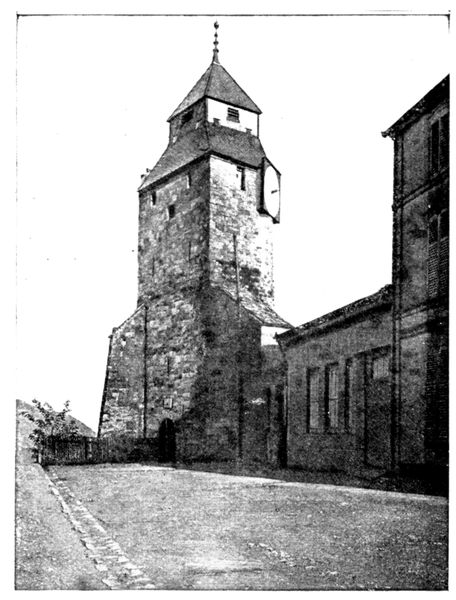

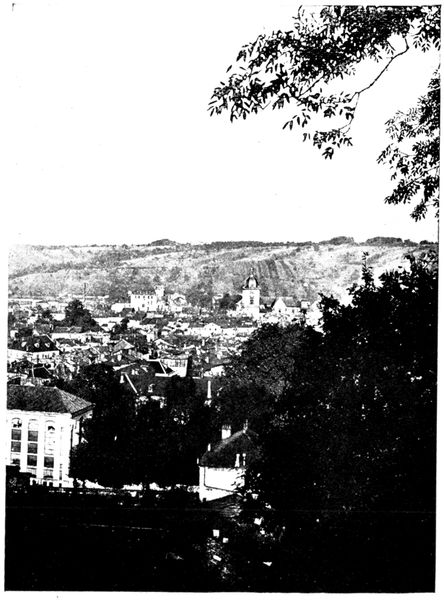

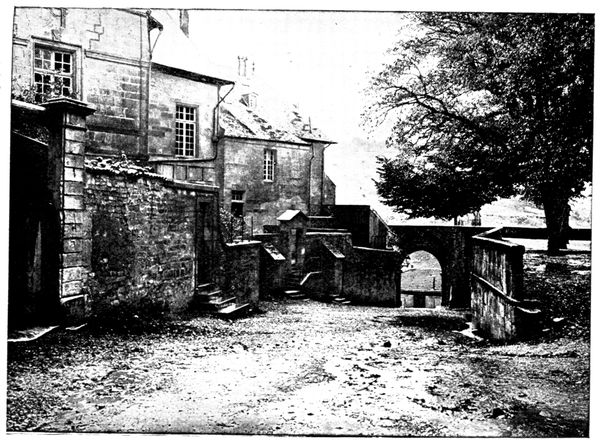

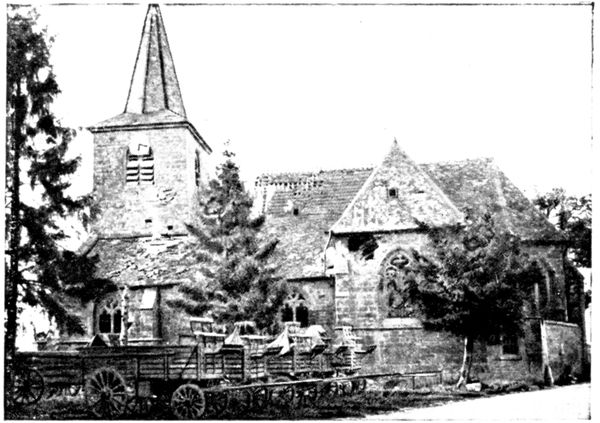

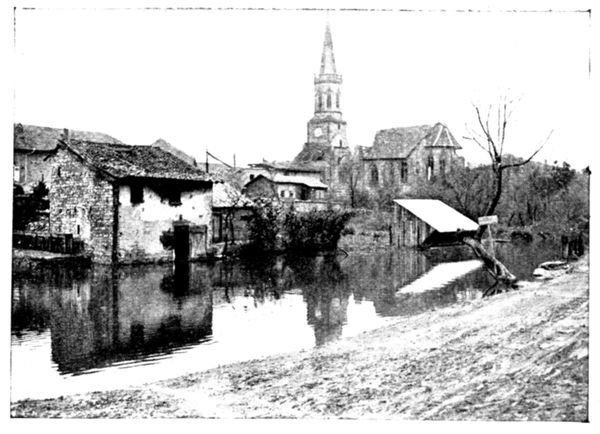

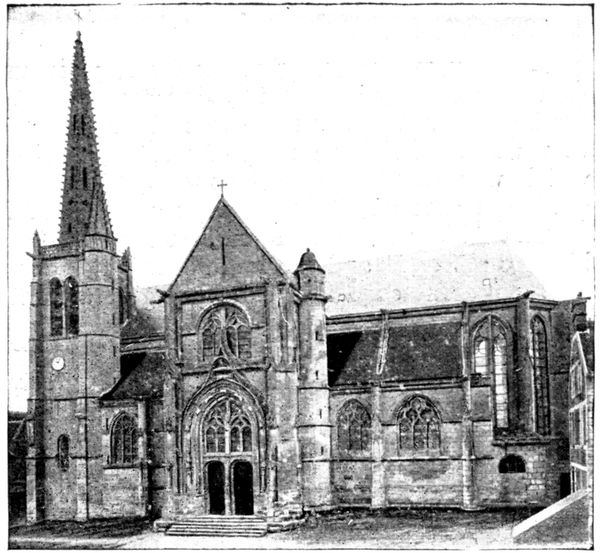

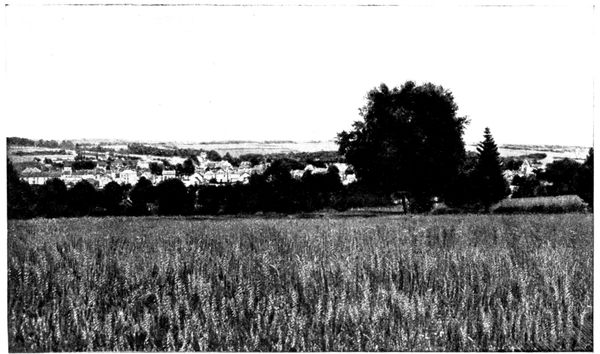

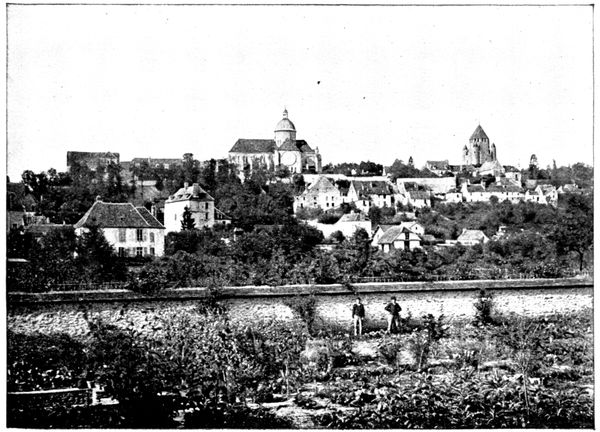

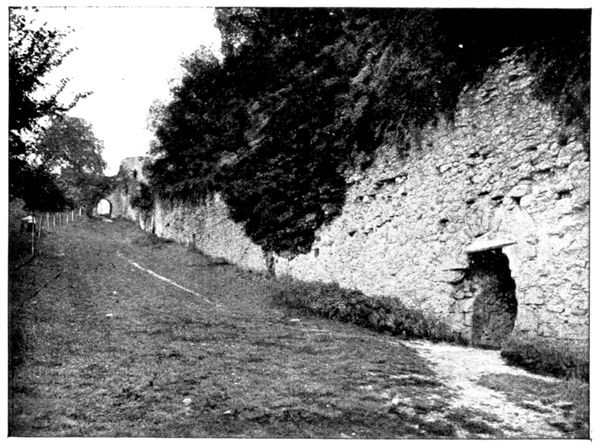

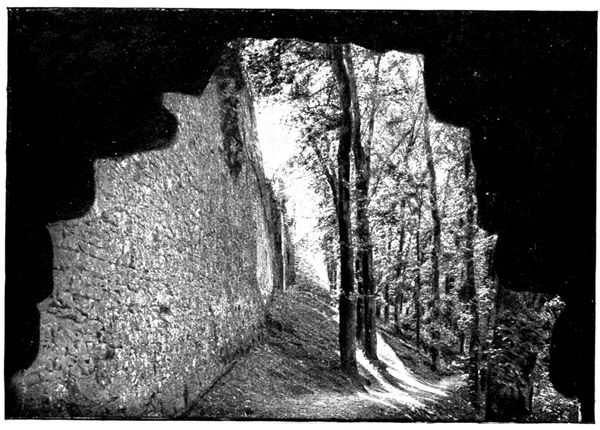

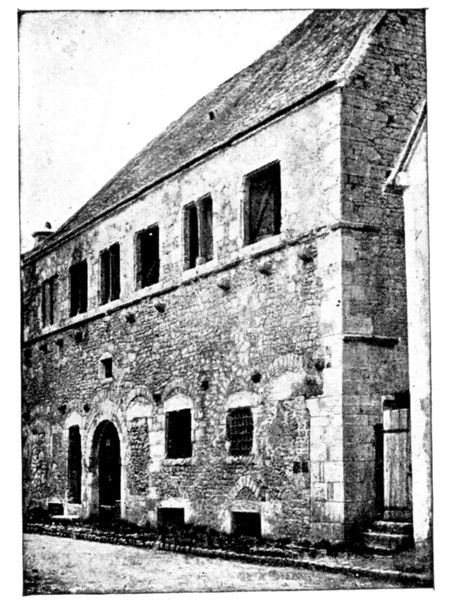

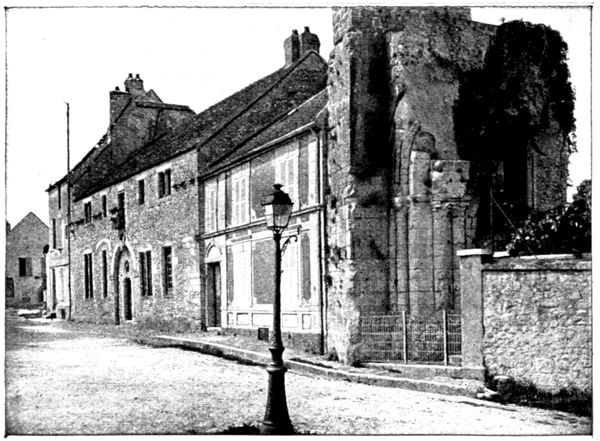

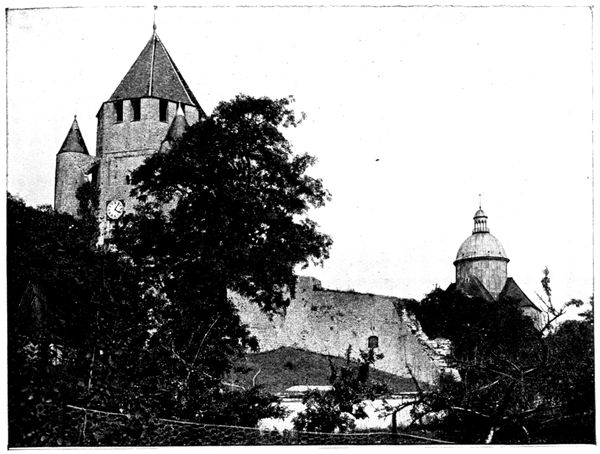

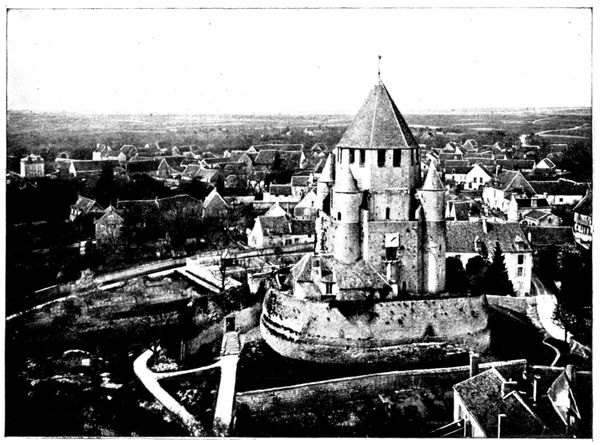

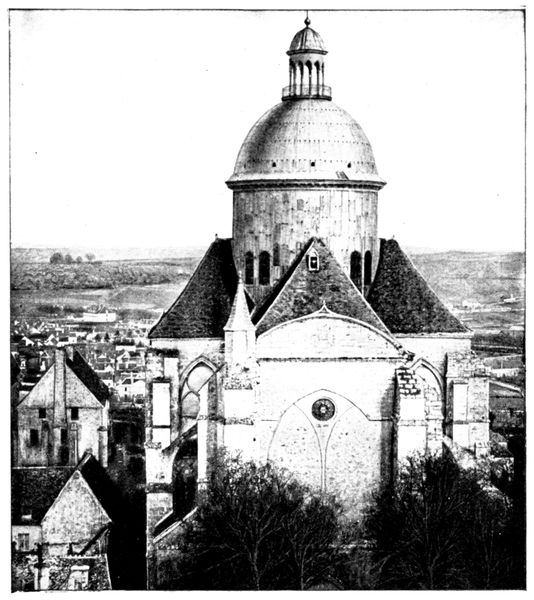

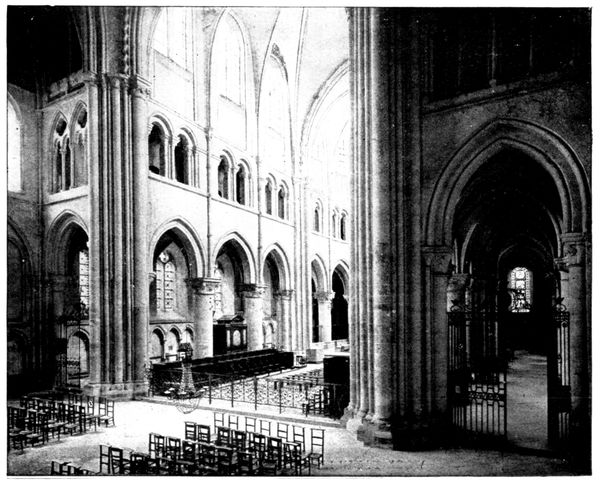

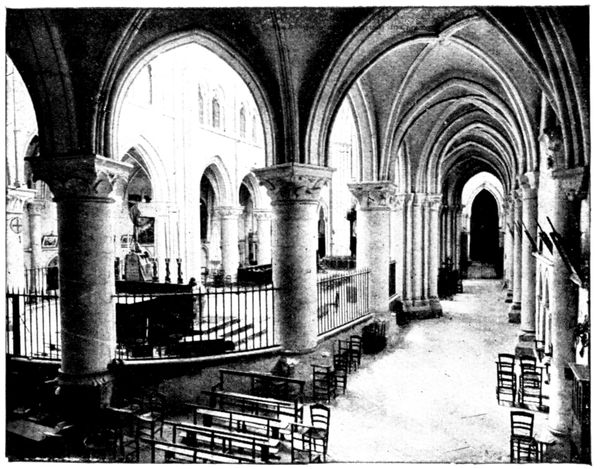

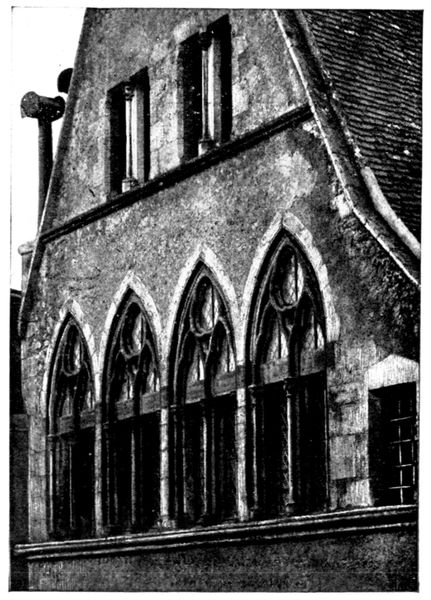

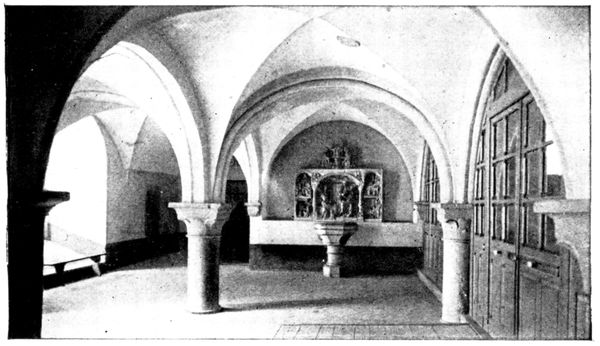

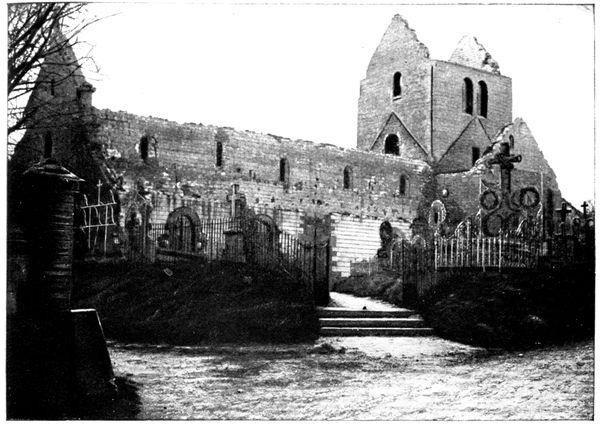

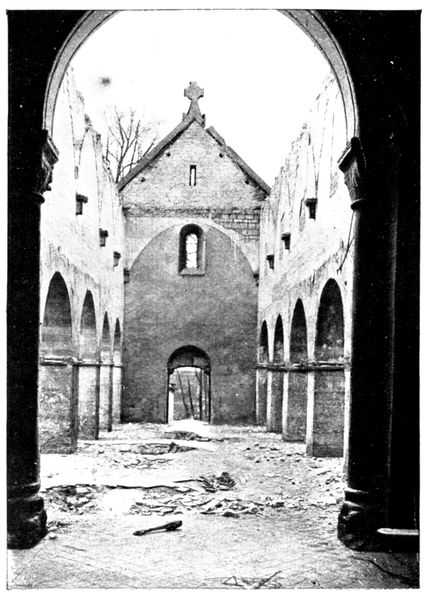

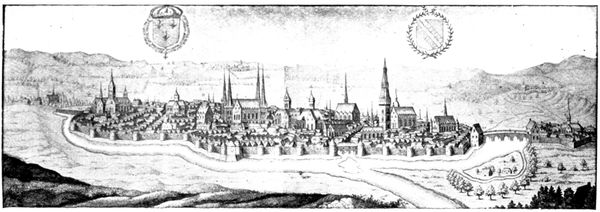

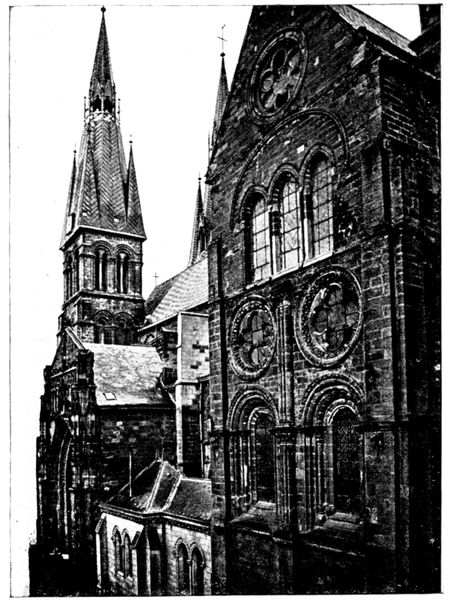

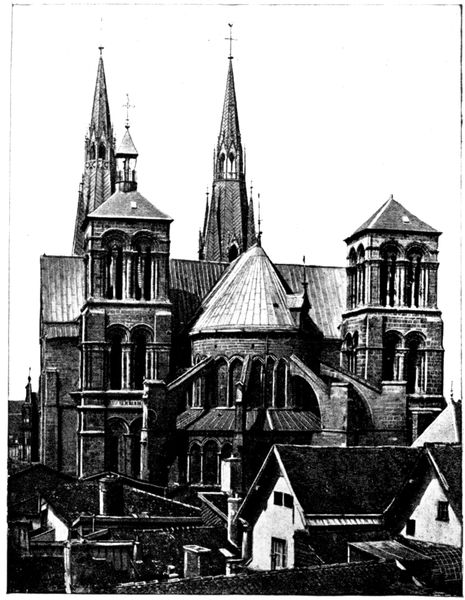

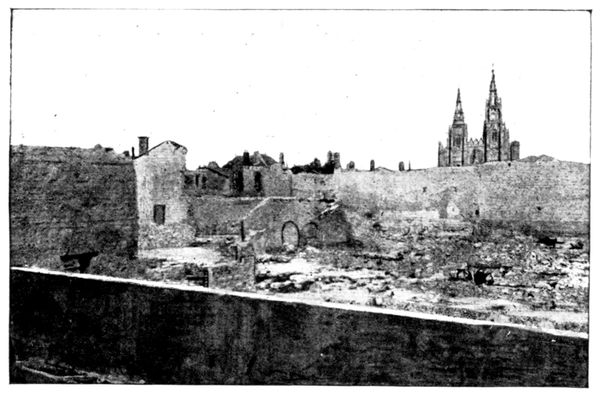

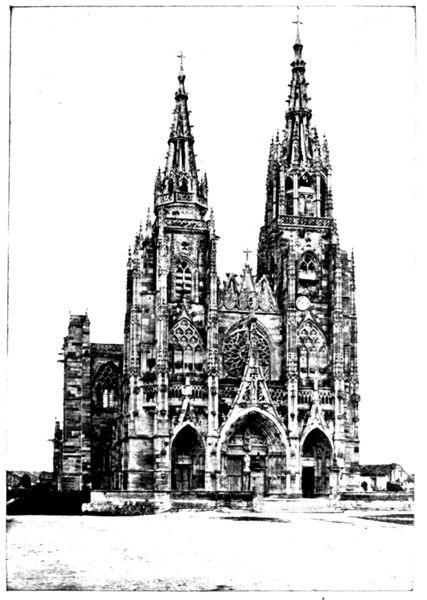

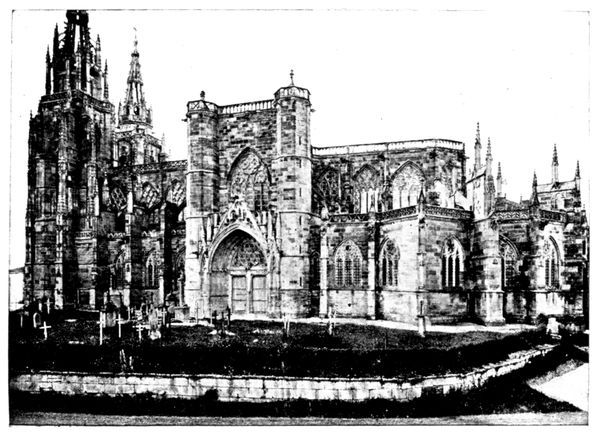

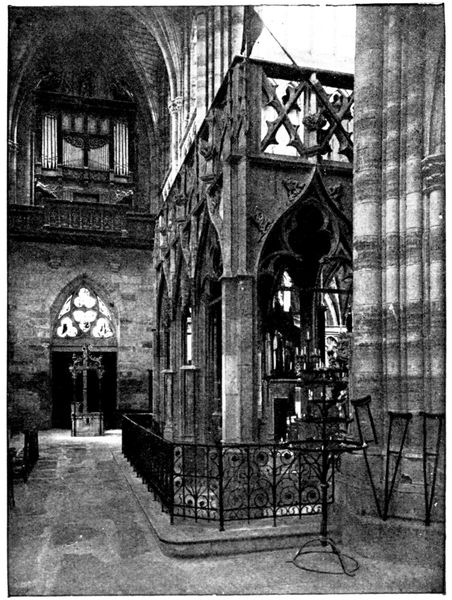

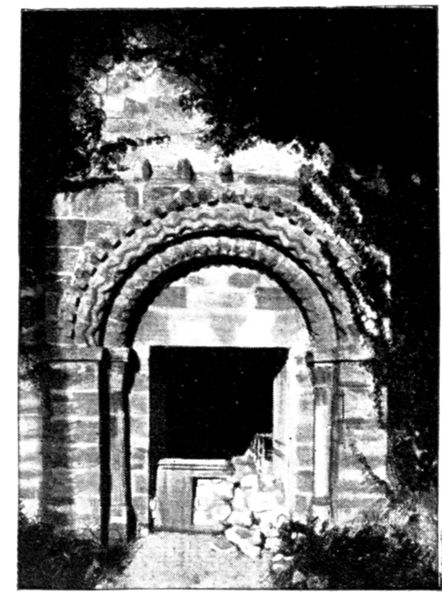

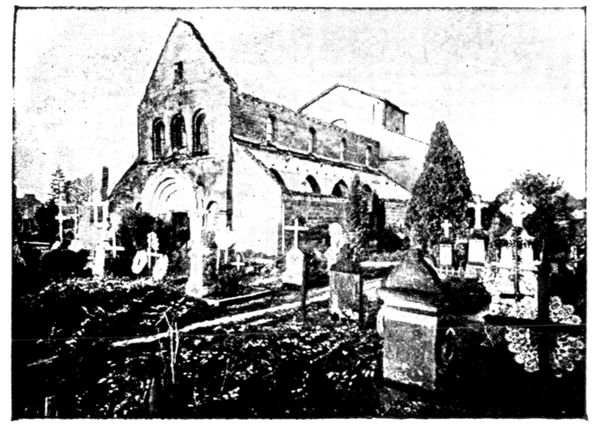

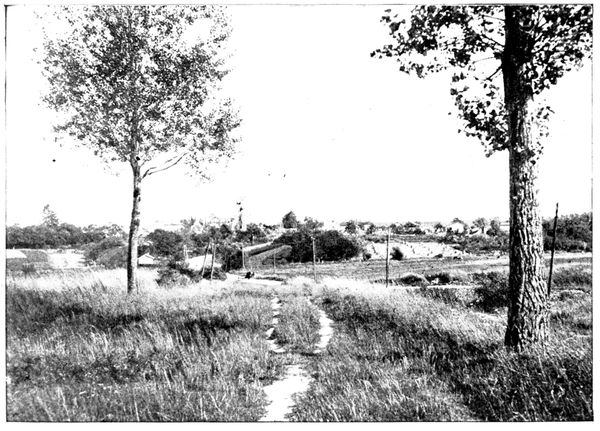

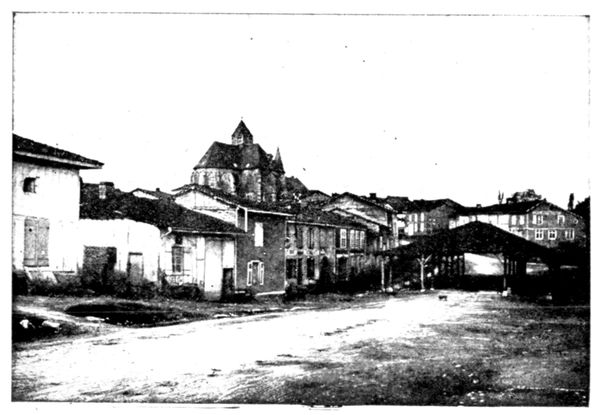

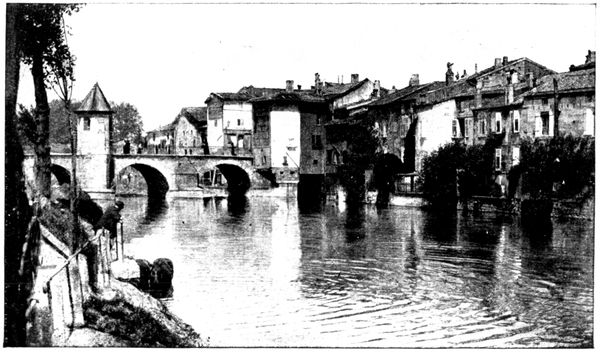

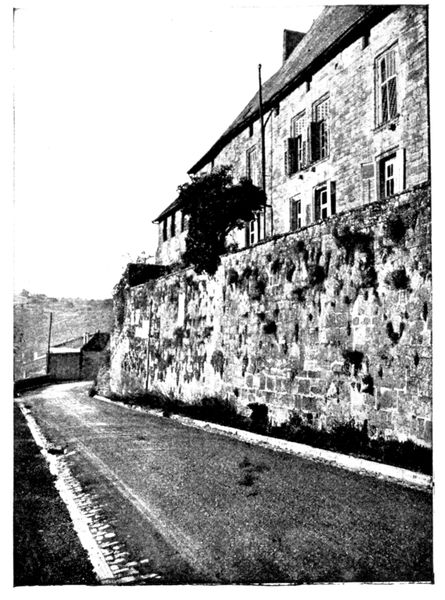

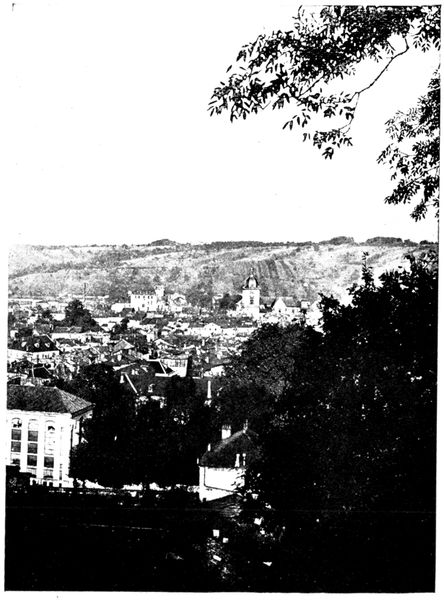

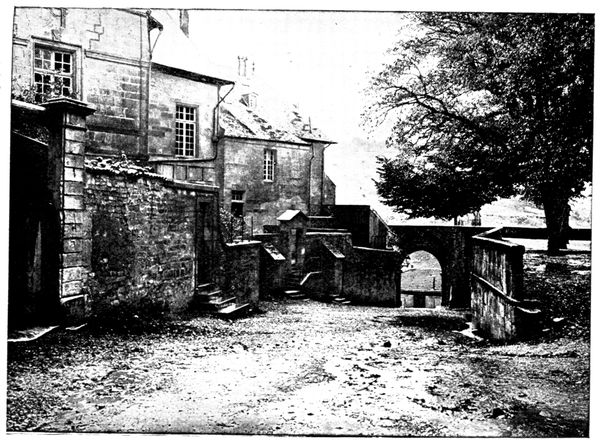

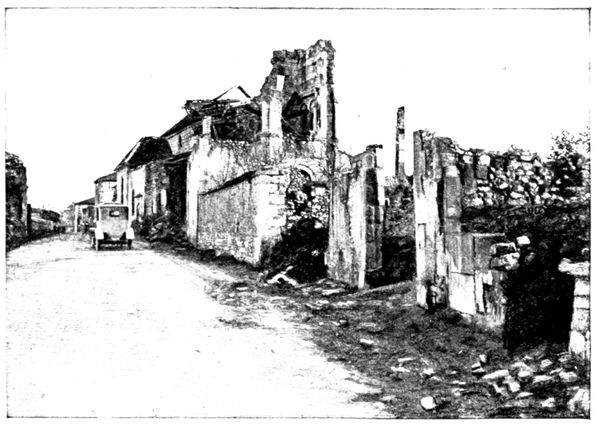

ORIGIN AND CHIEF HISTORICAL EVENTS

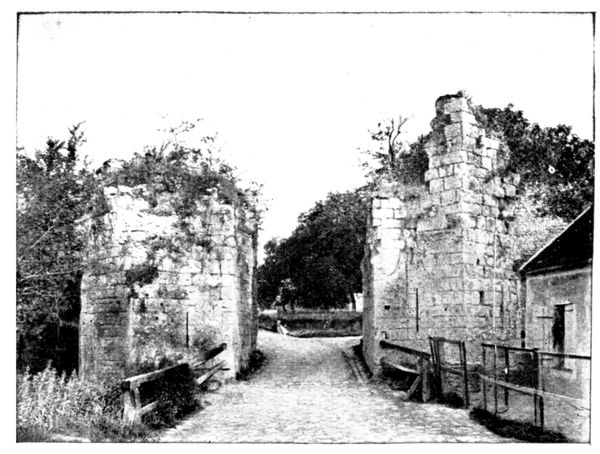

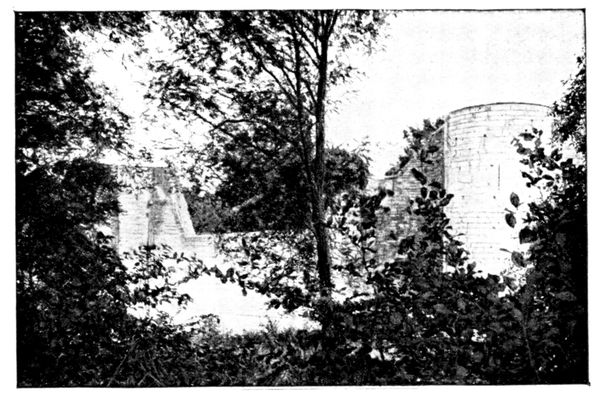

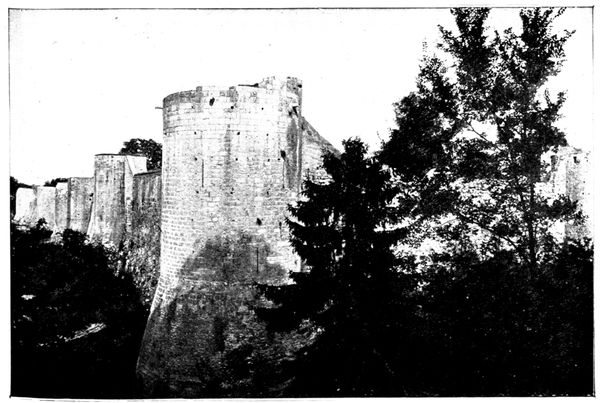

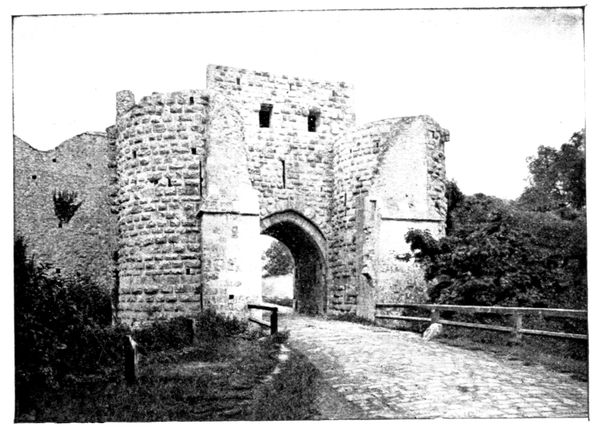

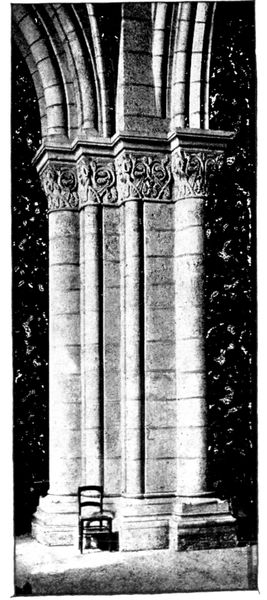

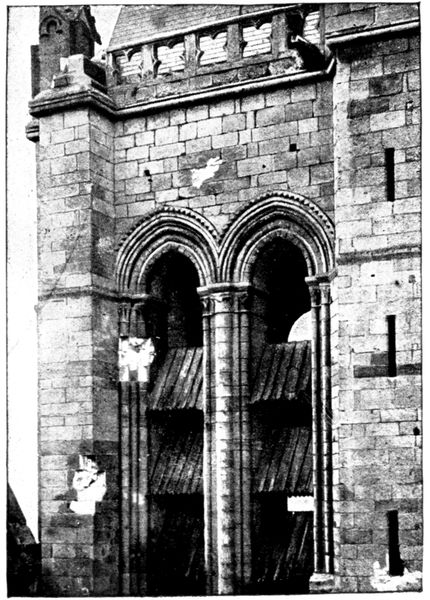

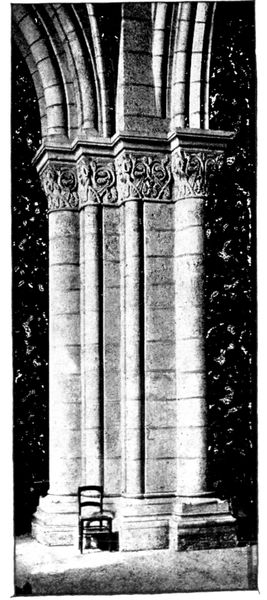

Senlis is of Gallic origin: it was the capital of the Sylvanectes. The

Romans surrounded it with fortifications, a great part of which still exist

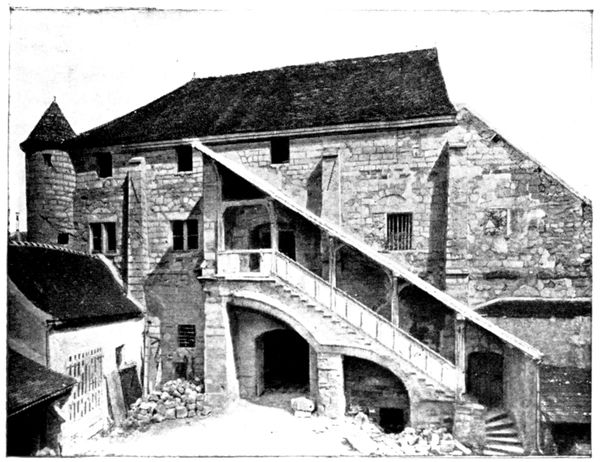

(see view below).

The first kings of France, attracted by the hunting in the surrounding

country, frequently stayed at Senlis.

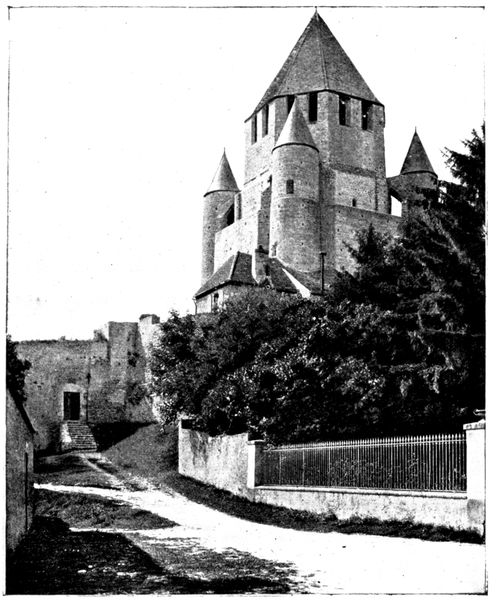

It was in Senlis Castle (see p. 61) that Hugues Capet was elected king by

the assembly of lords in 987.

The Capetians often returned to the birthplace of their dynasty and it

is to them that the town owes its chief buildings.

Taken by the peasants in the war of the Jacquerie in 1358, besieged by

the Armagnacs in 1418, it fell into the hands of the English and was delivered

by Joan of Arc in 1429. Senlis knew great vicissitudes in the fourteenth

and sixteenth centuries.

After Henri IV., who interested himself greatly in Senlis and lived in its

old castle, the kings of France gradually forsook the town in favour of

Compiègne, Fontainebleau and Versailles.

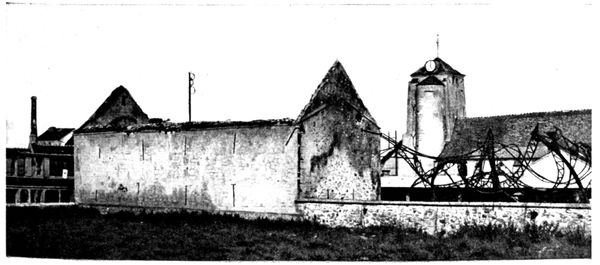

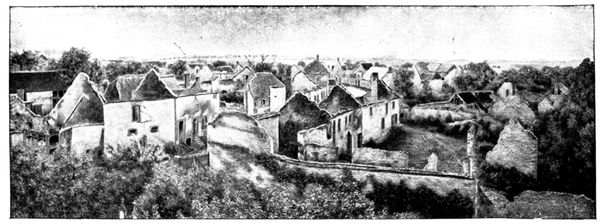

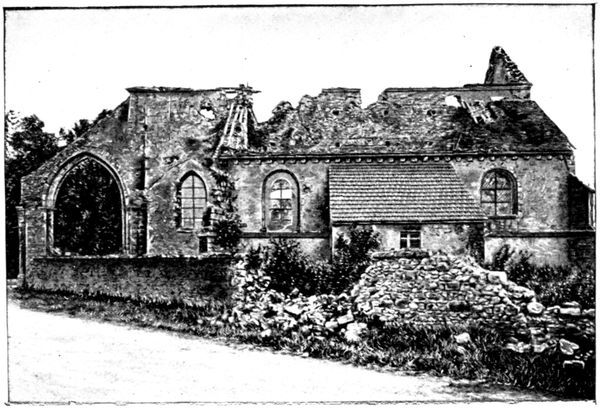

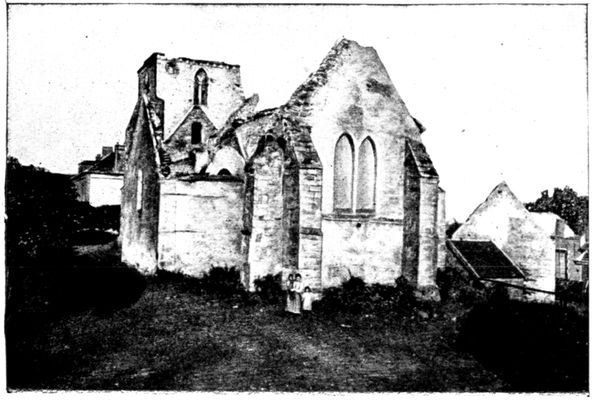

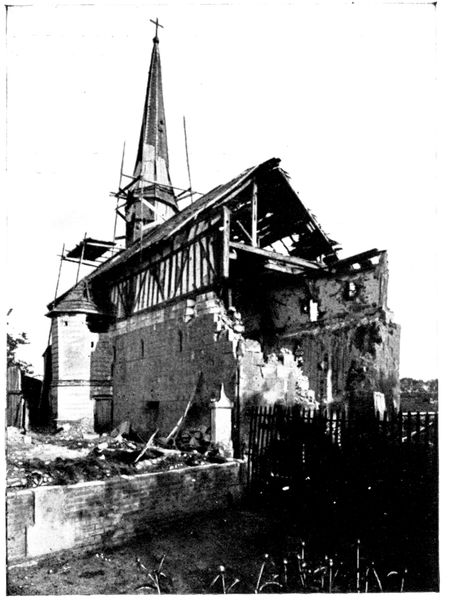

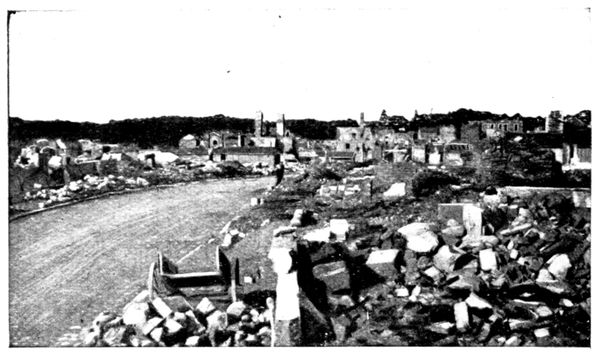

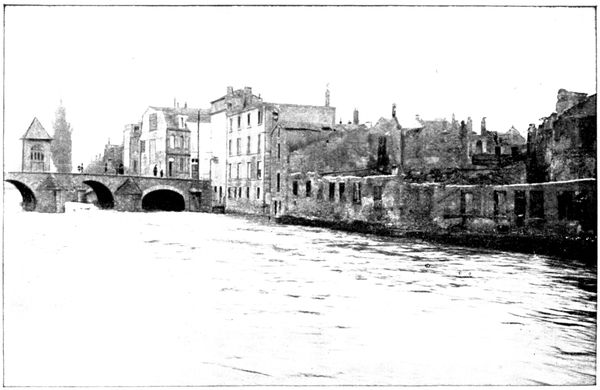

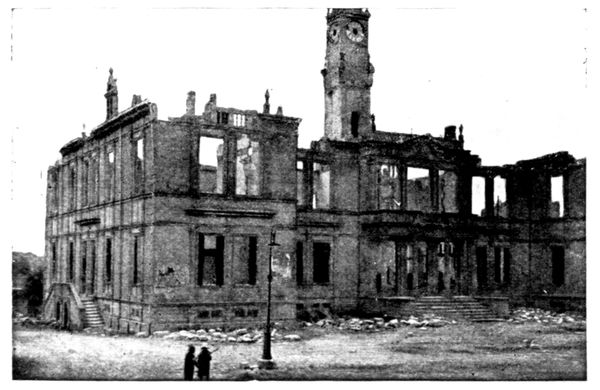

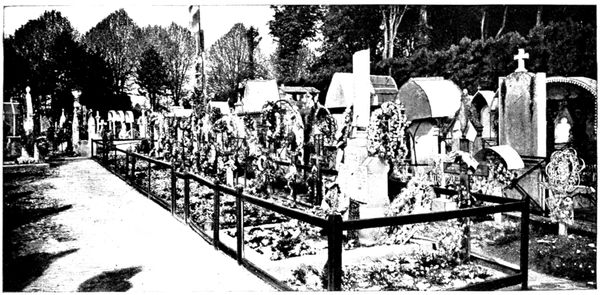

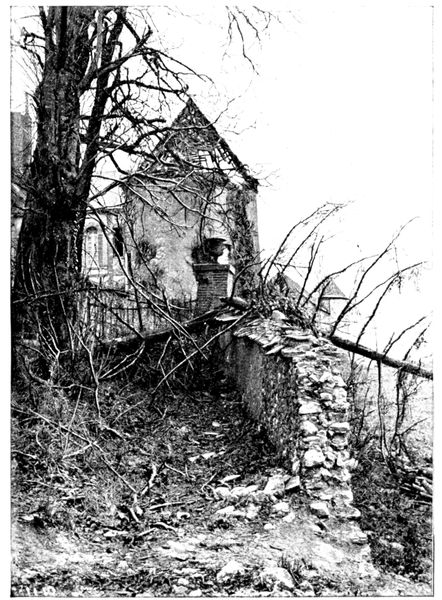

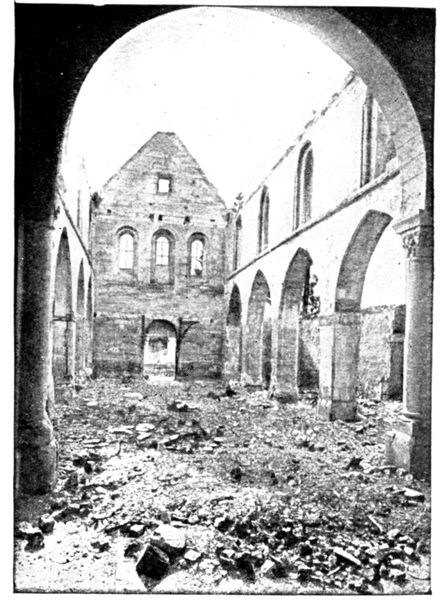

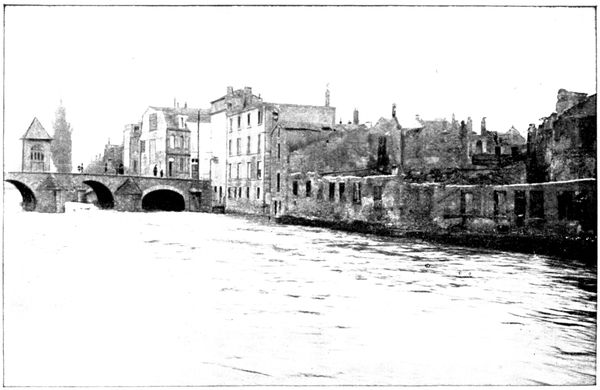

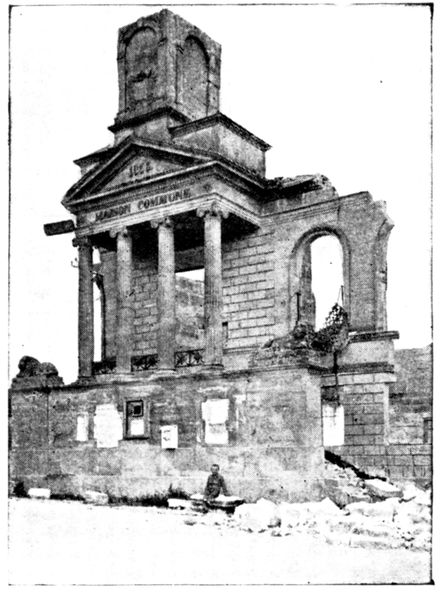

Occupied in 1871 by the Germans, it reappears in history in September

1914. The burning of the town and the summary executions which took

place there will be recalled in the course of the visit (pp. 38-52).

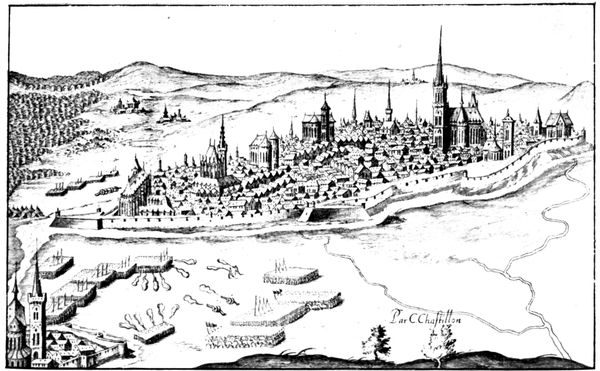

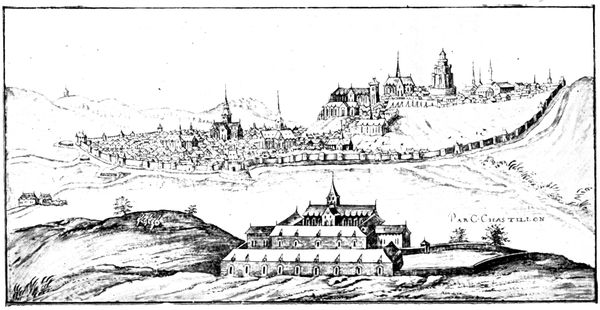

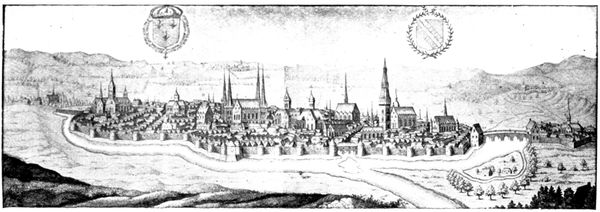

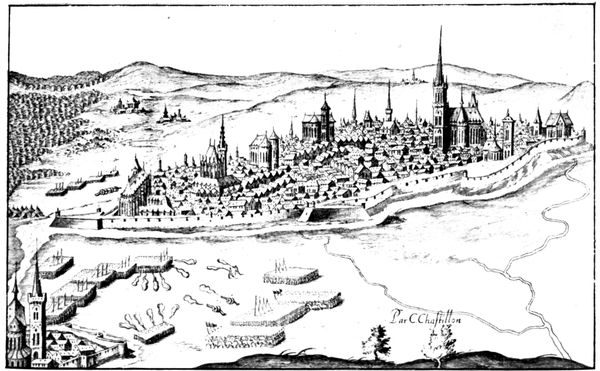

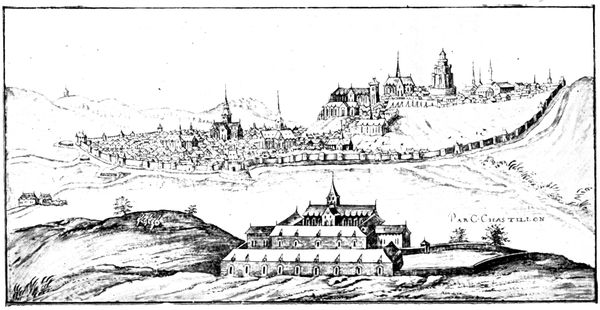

SENLIS IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

[Pg 38]

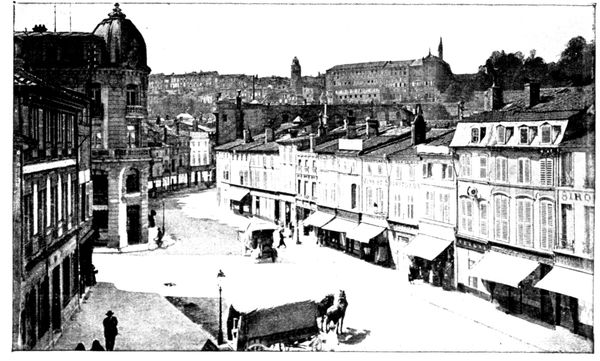

VISIT TO THE TOWN

(See plan inserted between pp. 36/37)

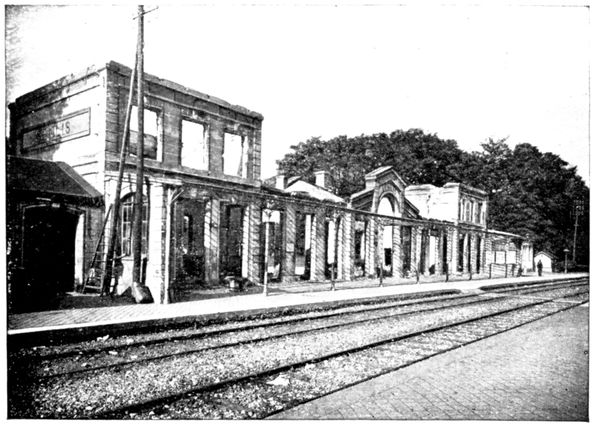

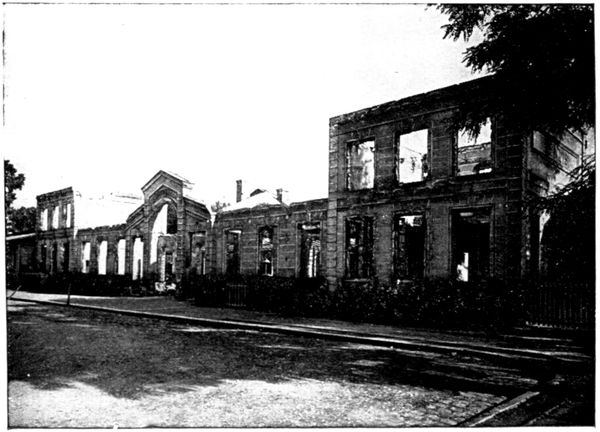

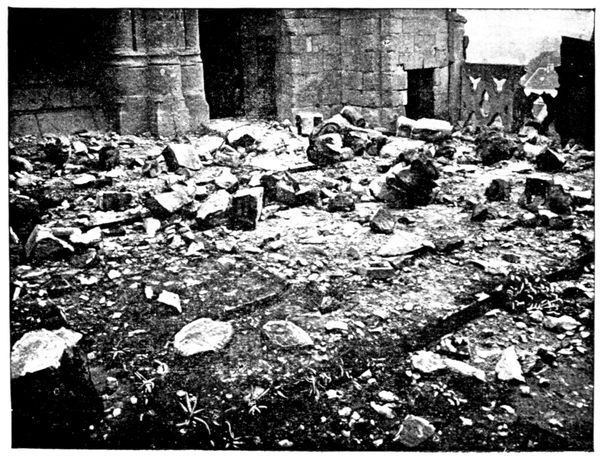

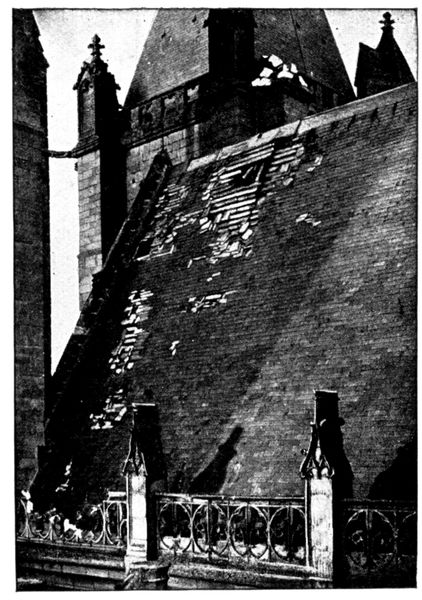

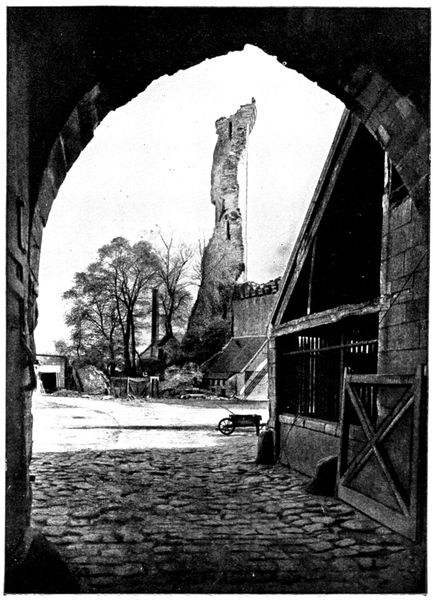

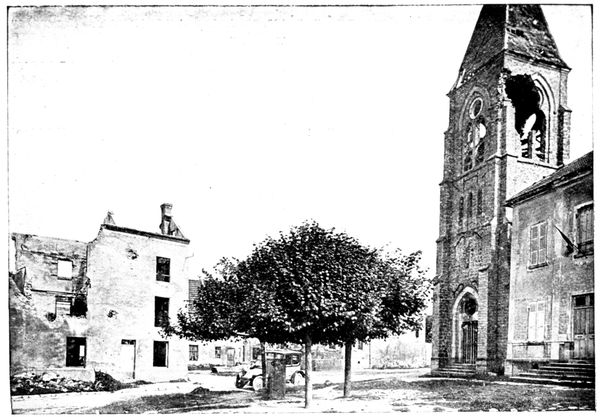

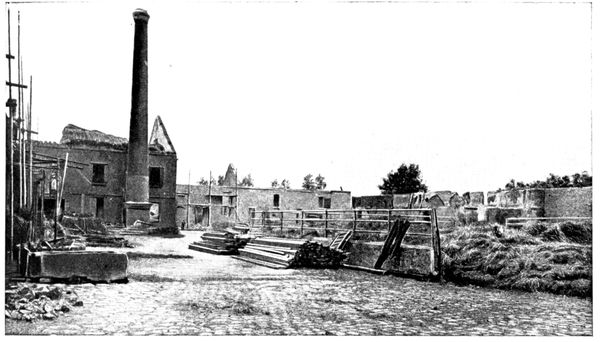

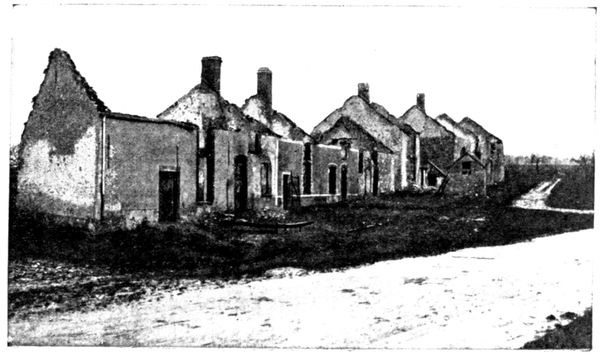

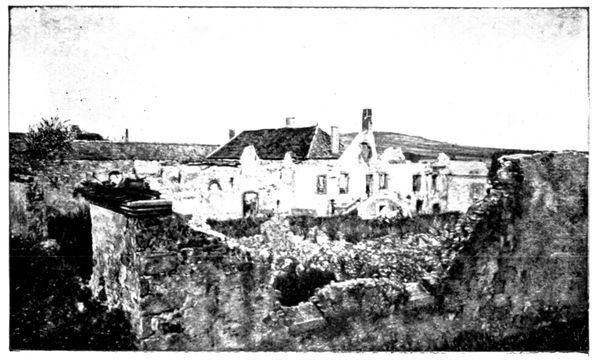

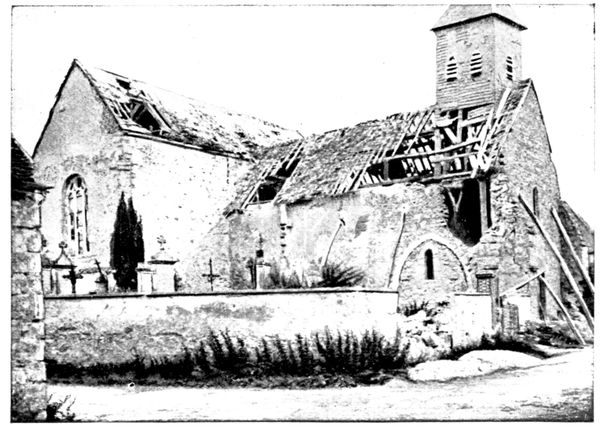

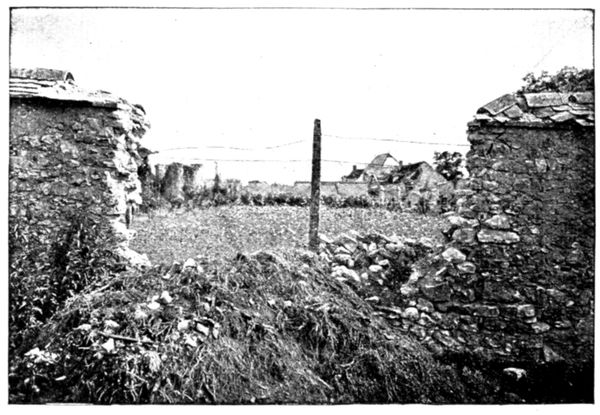

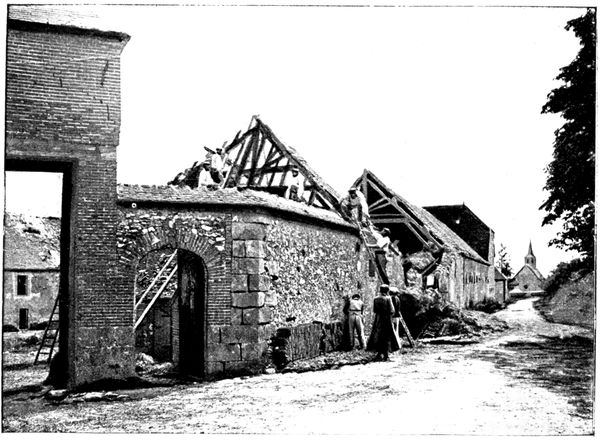

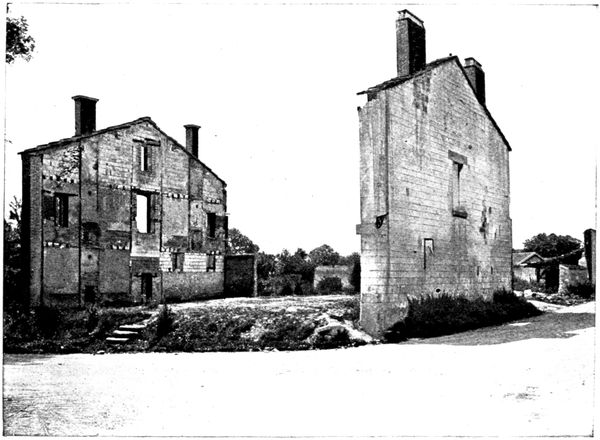

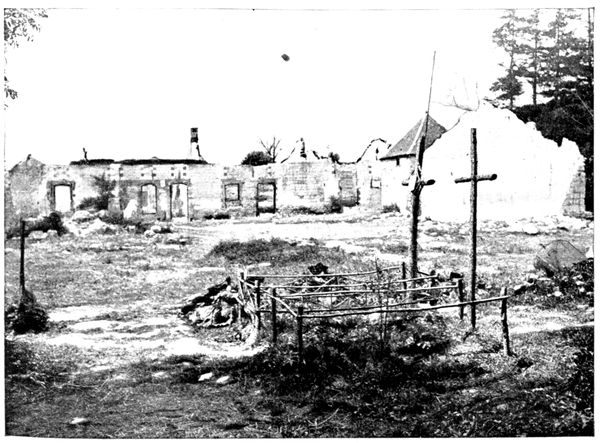

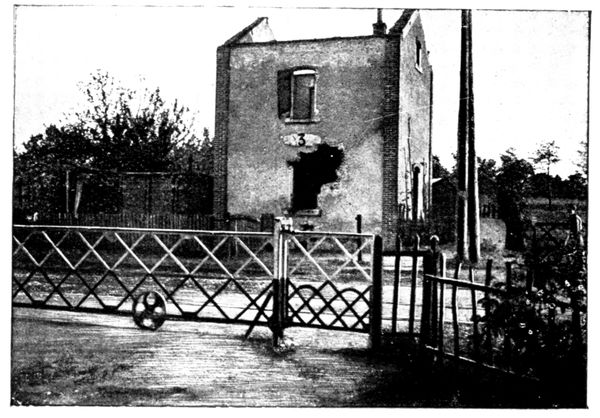

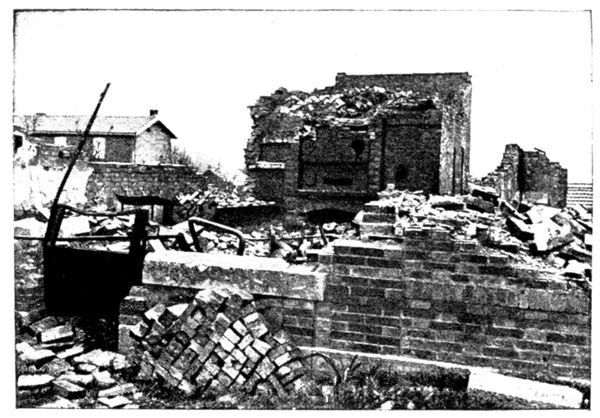

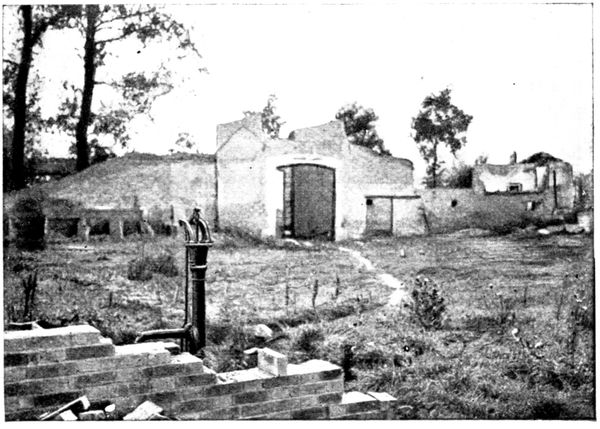

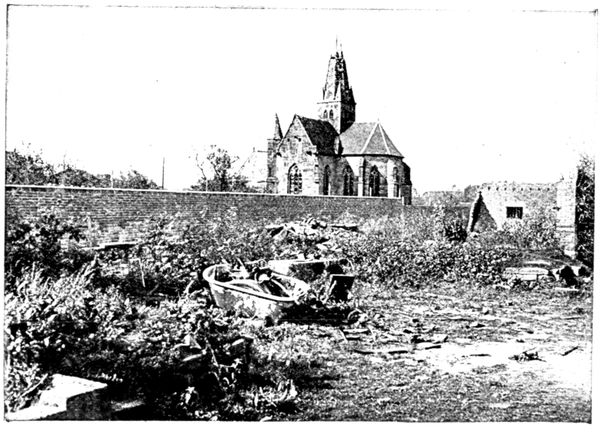

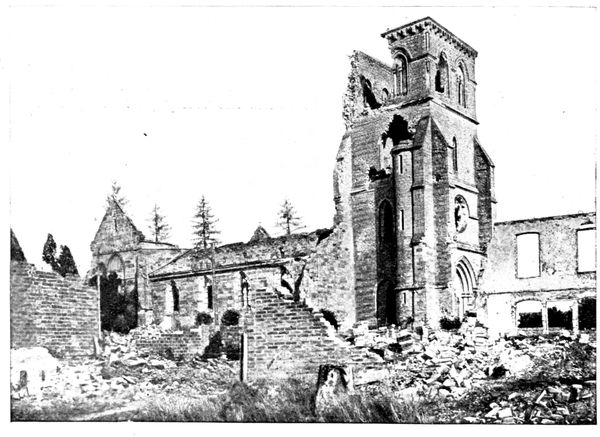

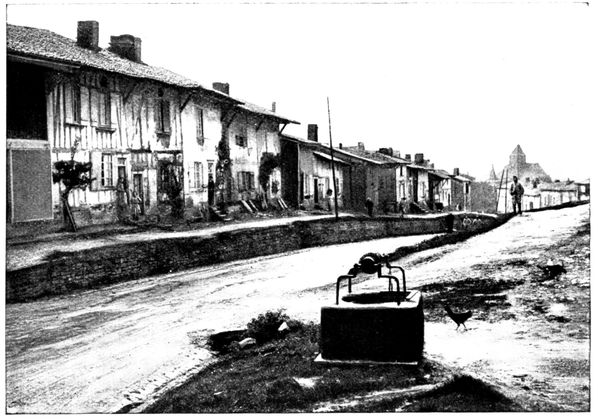

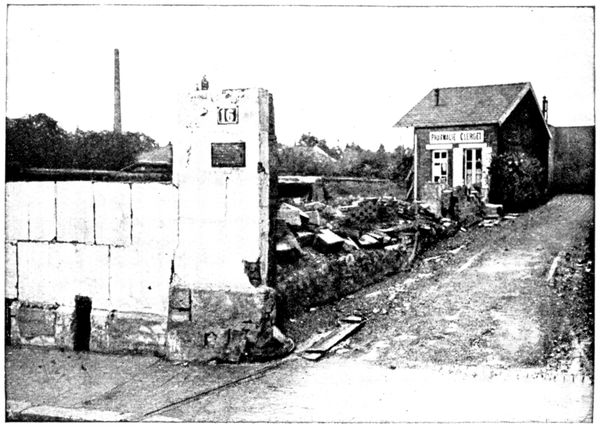

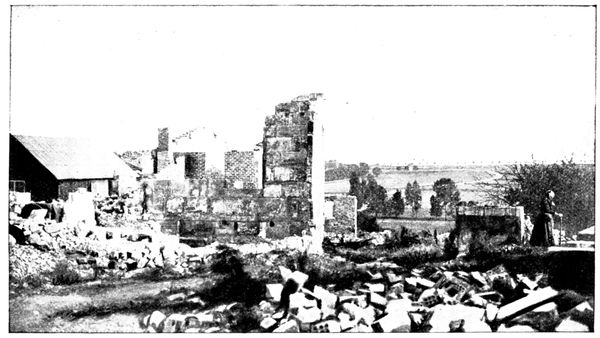

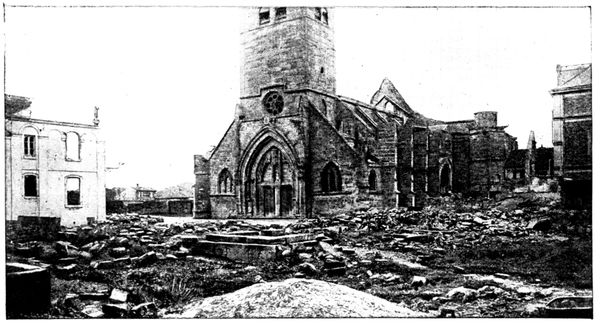

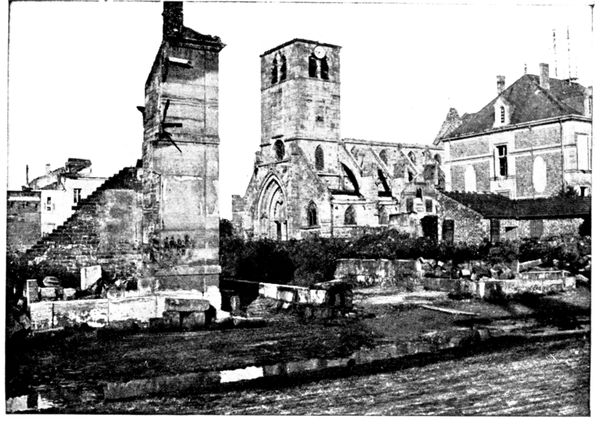

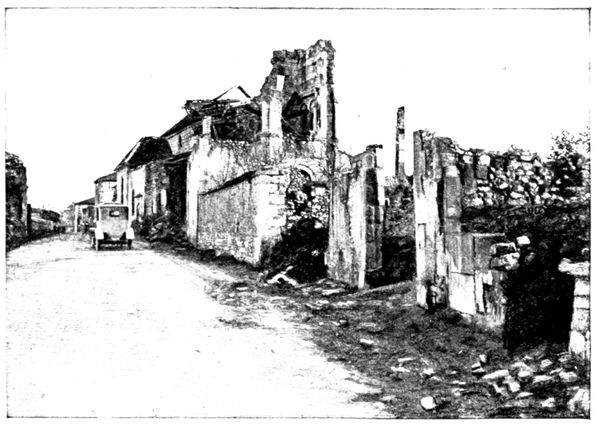

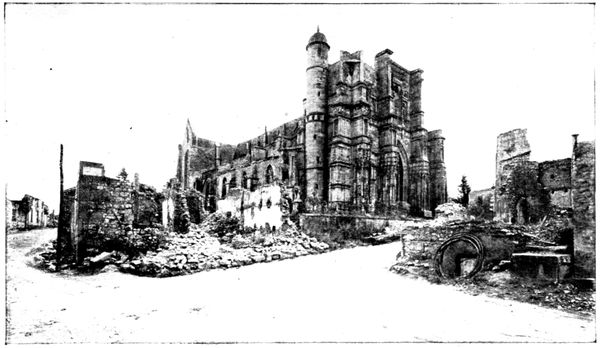

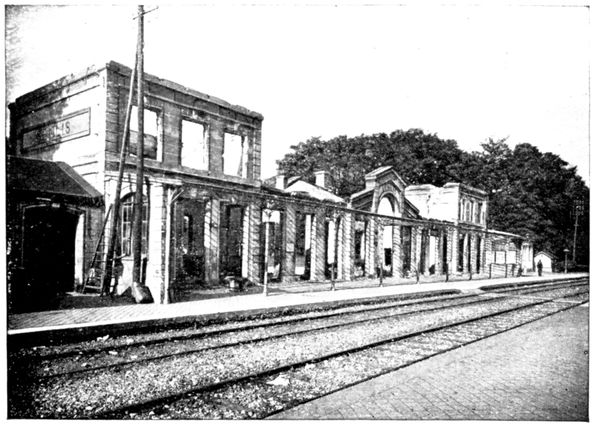

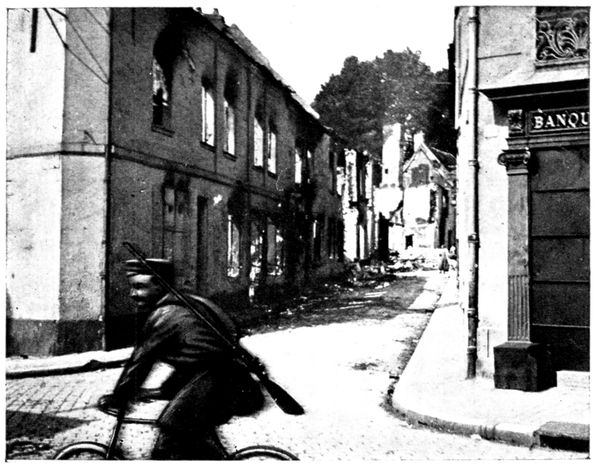

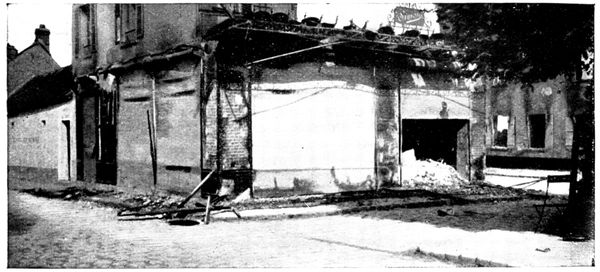

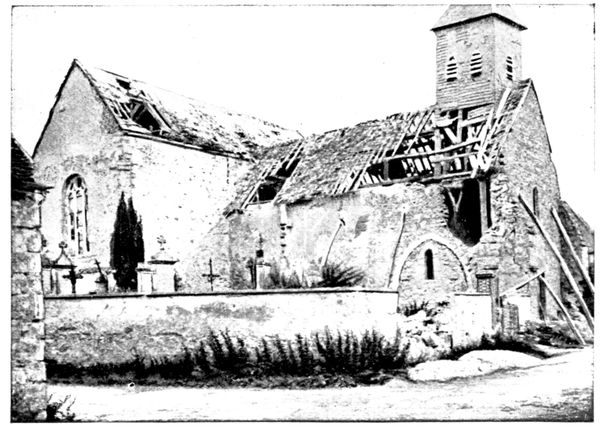

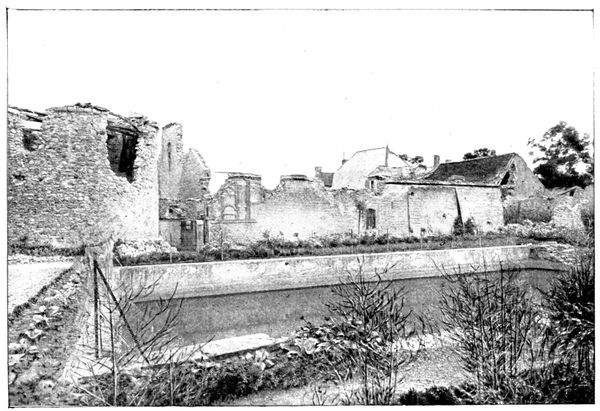

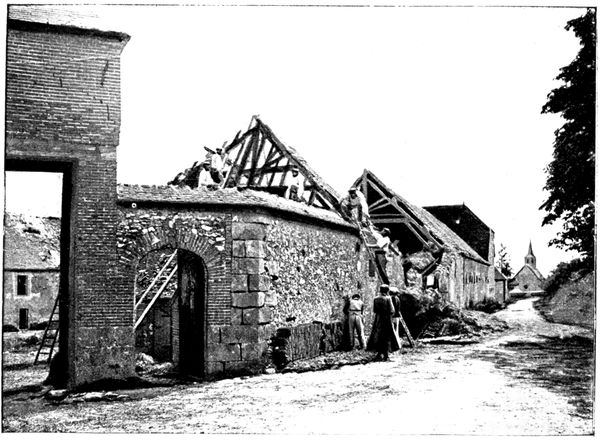

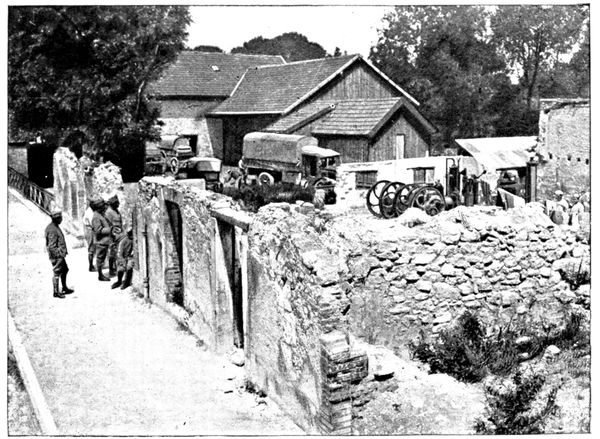

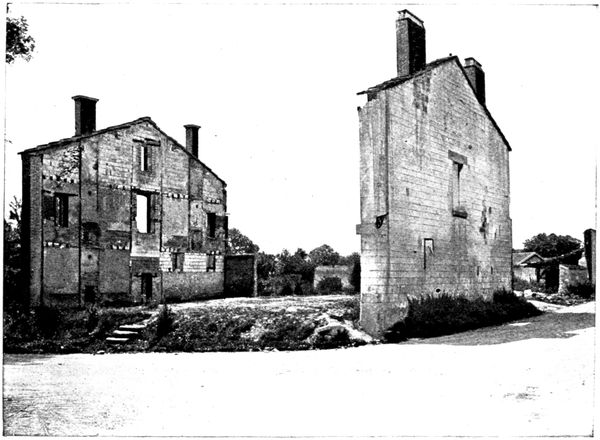

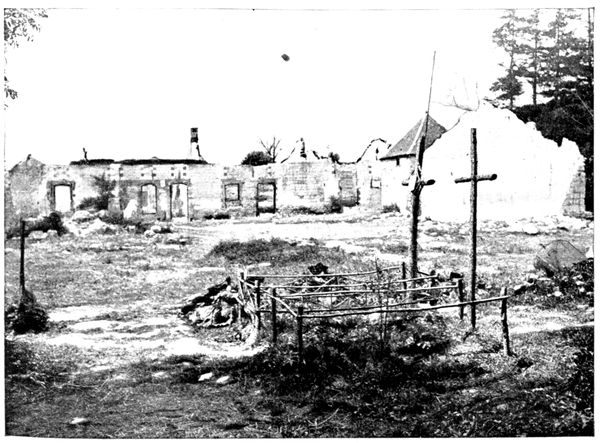

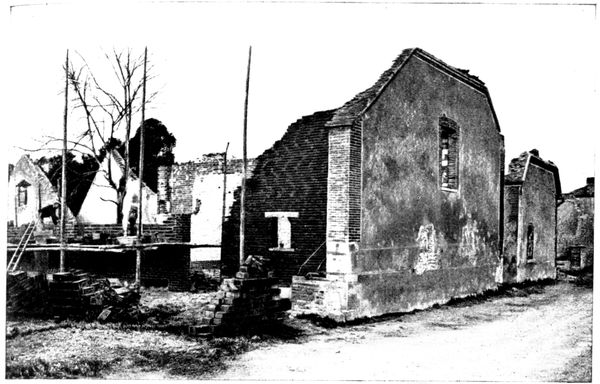

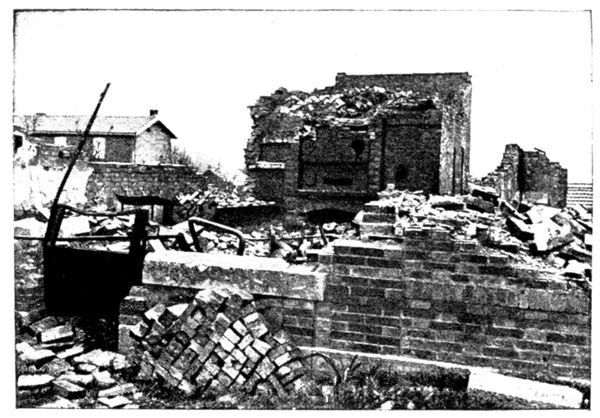

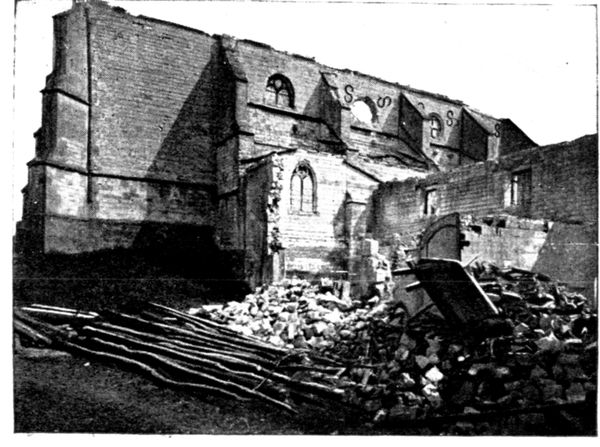

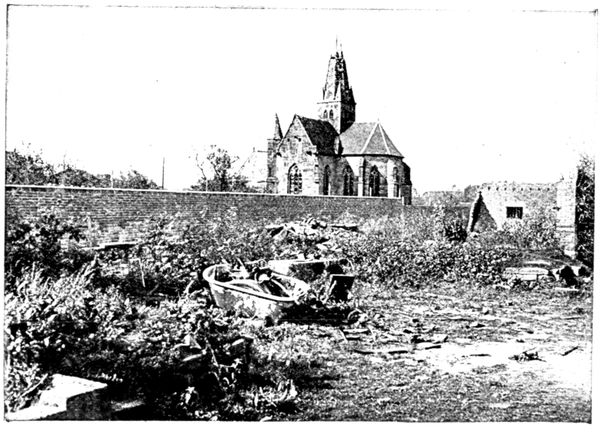

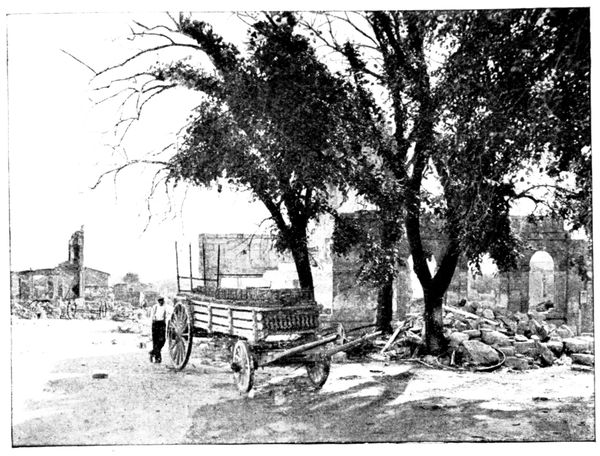

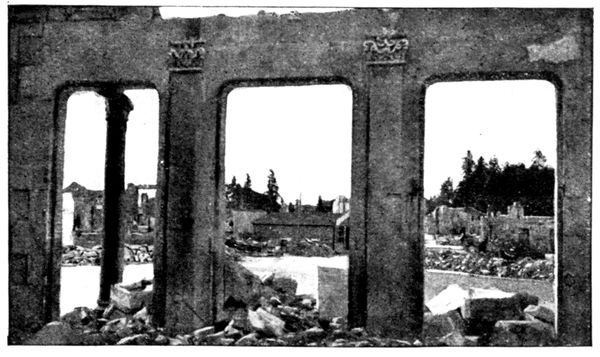

THE BURNT

STATION

(Sept. 1914)

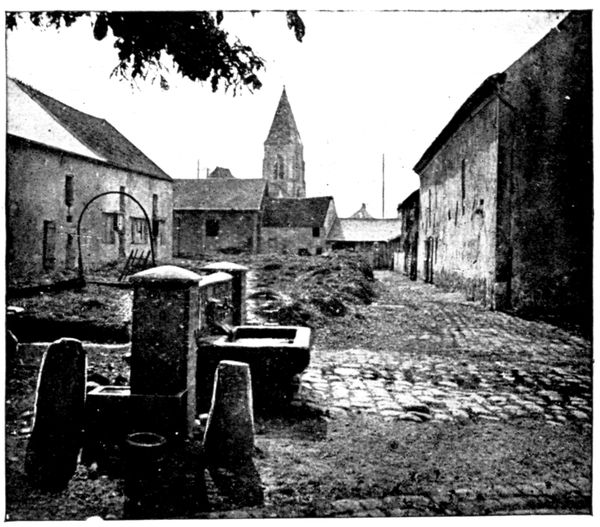

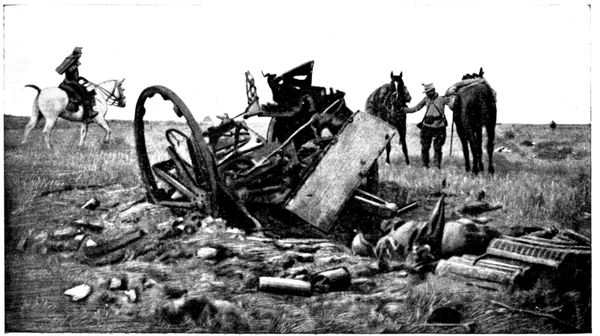

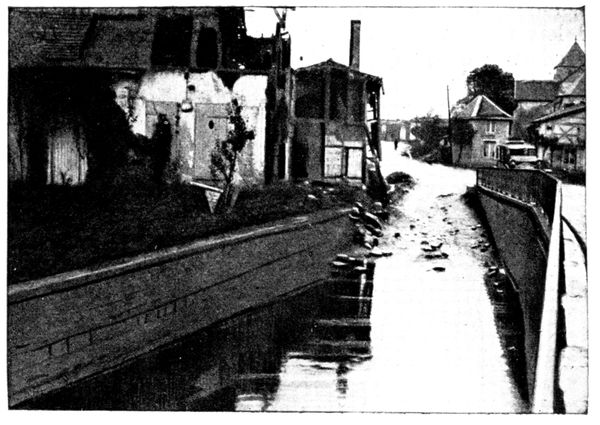

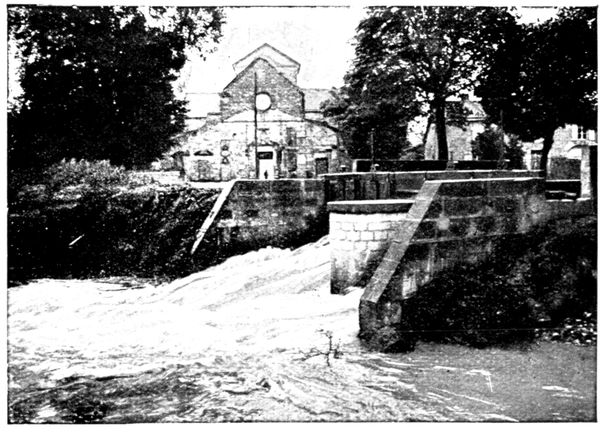

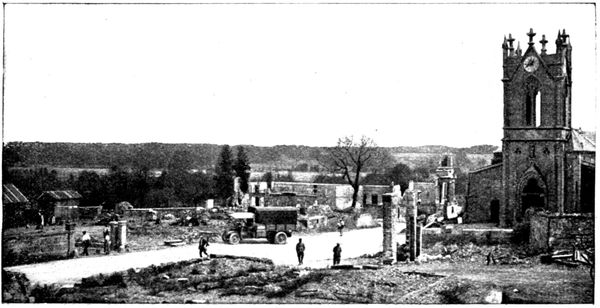

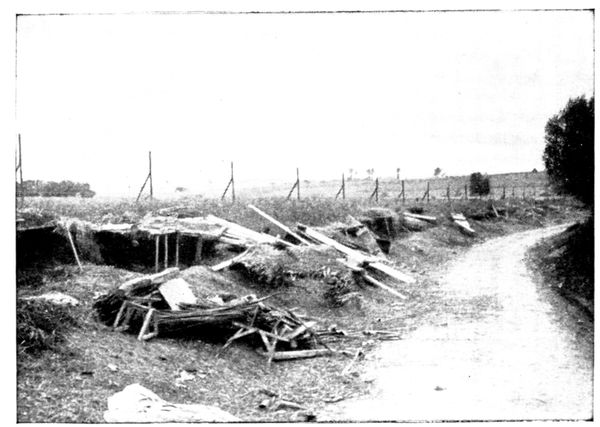

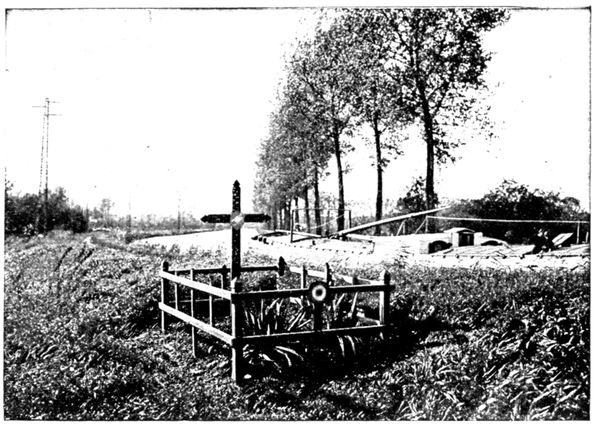

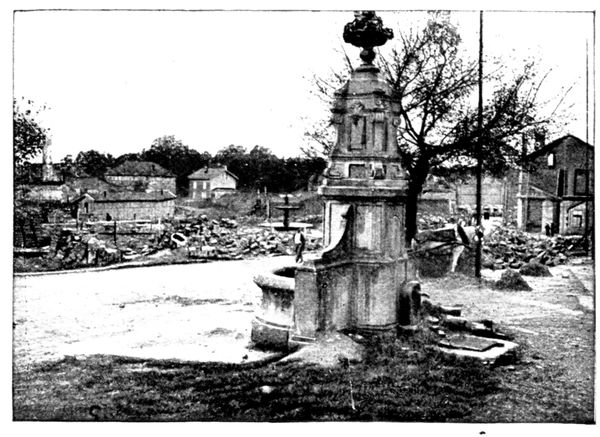

At the Station

one gets one's first

view of the havoc

done to the town

by the events of

September 1914.

It was set on fire

on the 3rd.

Follow the station

road (Avenue de la

Gare), which leads

to the Compiègne

Gate.

This is the road

by which the Germans

entered Senlis

on September 2, at

about 3 o'clock in

the afternoon.

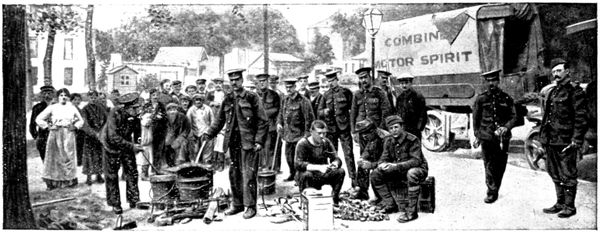

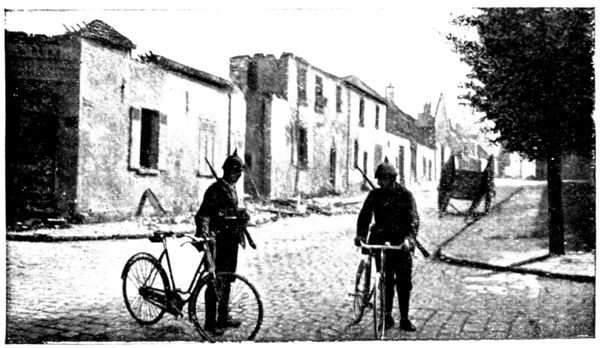

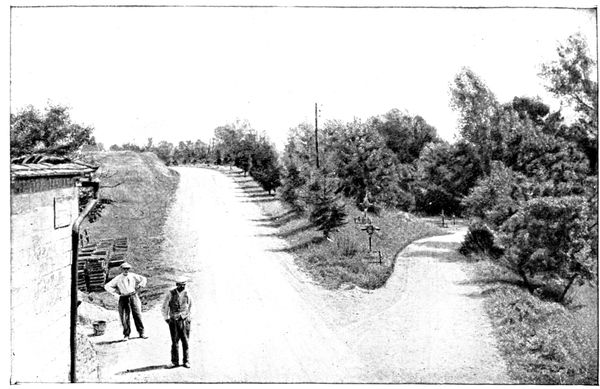

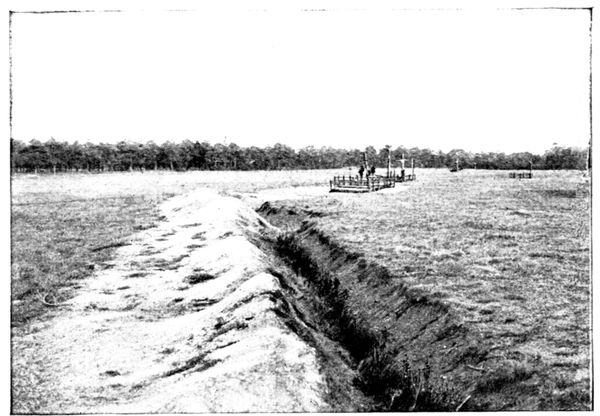

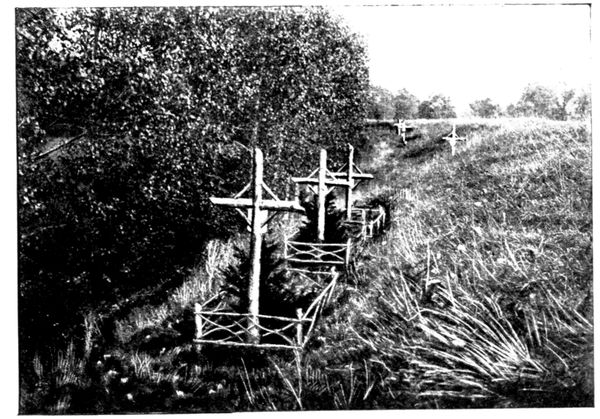

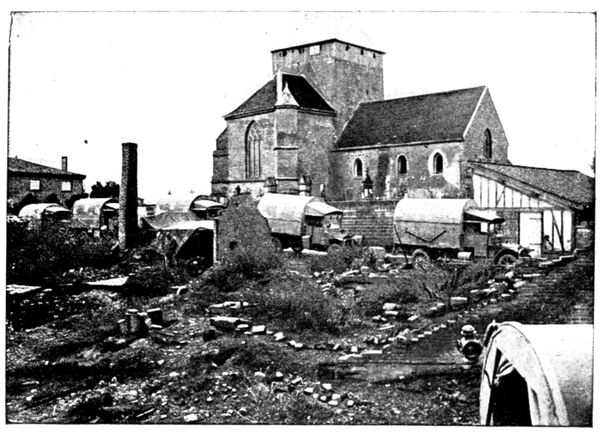

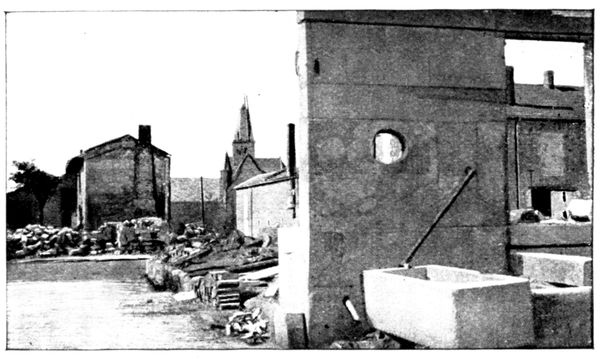

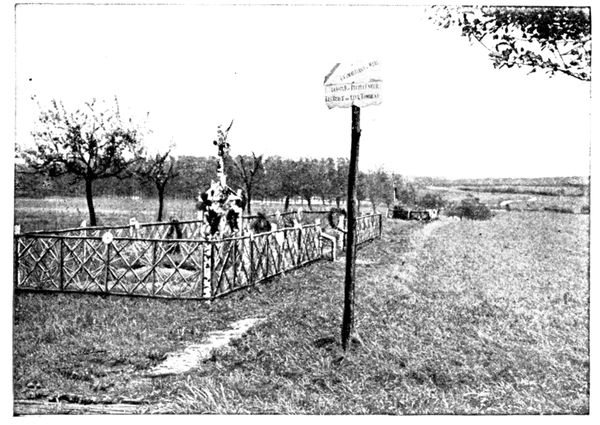

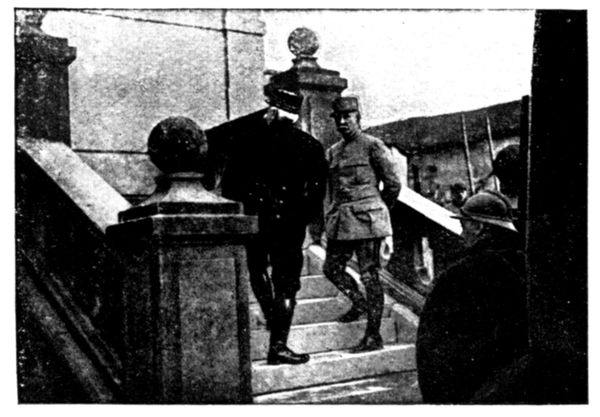

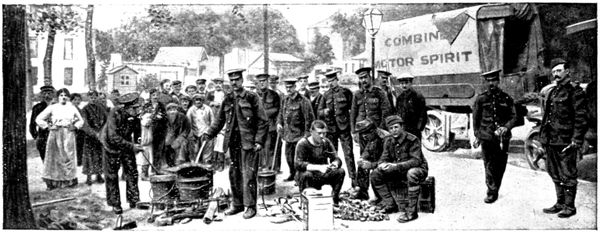

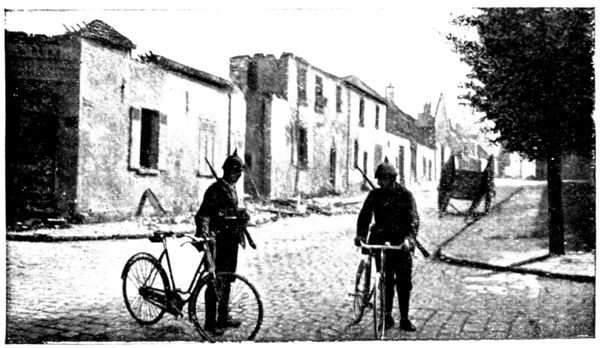

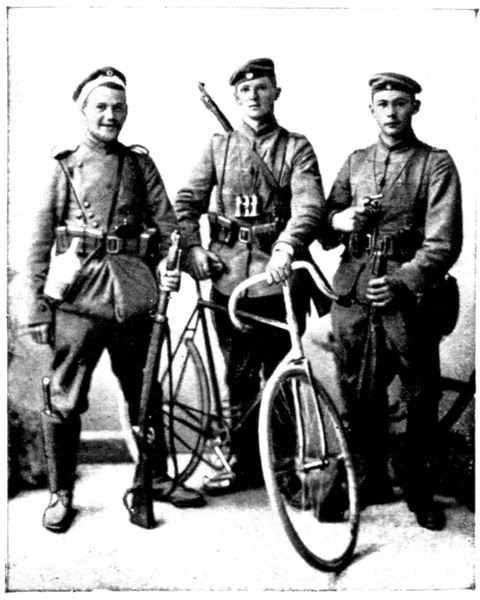

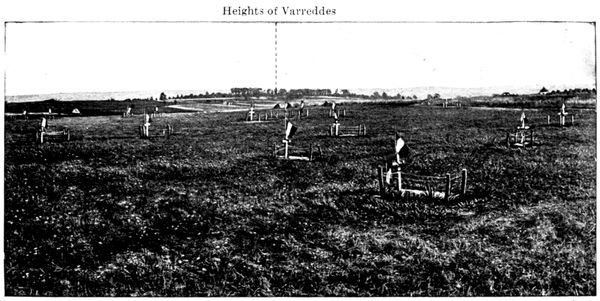

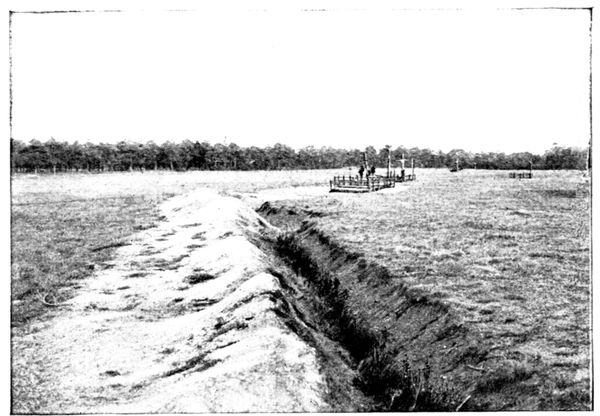

BRITISH

SOLDIERS

IN THE PLACE

DE LA GARE

(Sept. 1914)

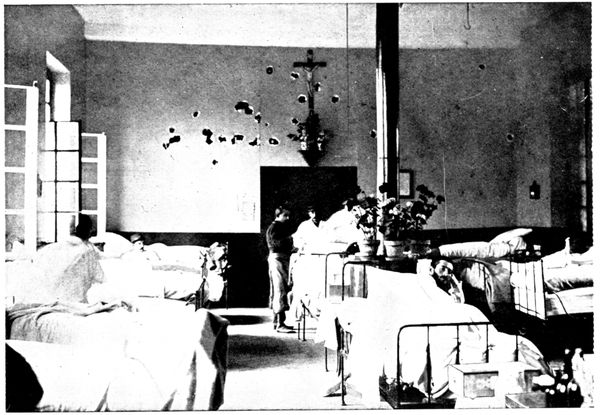

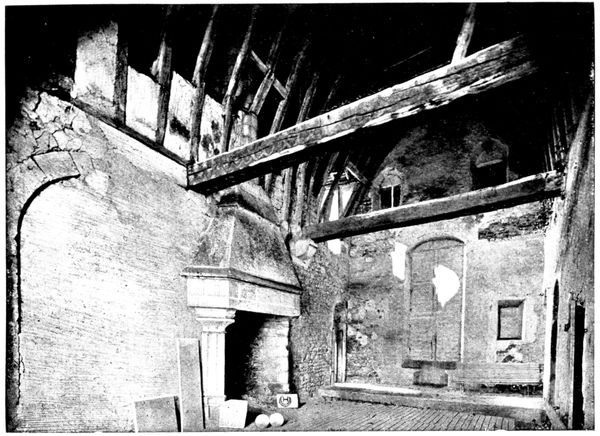

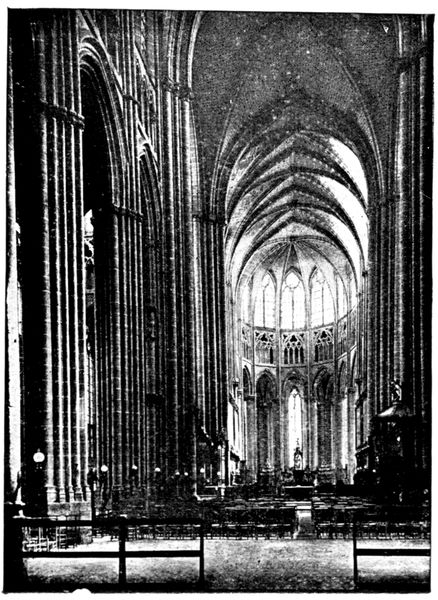

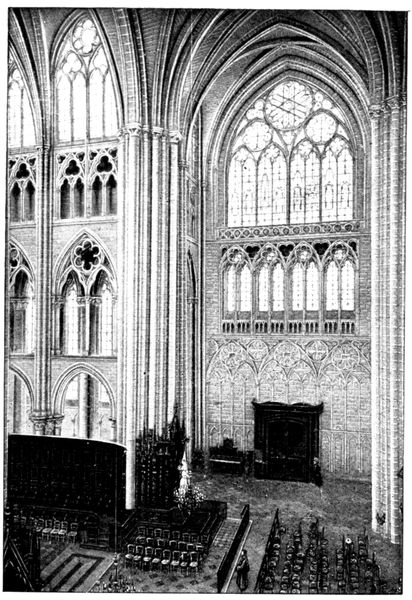

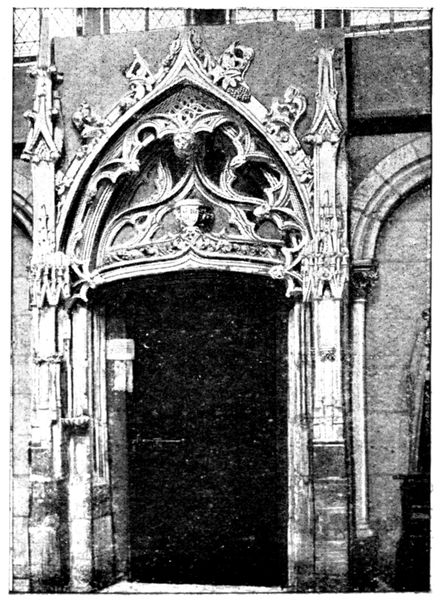

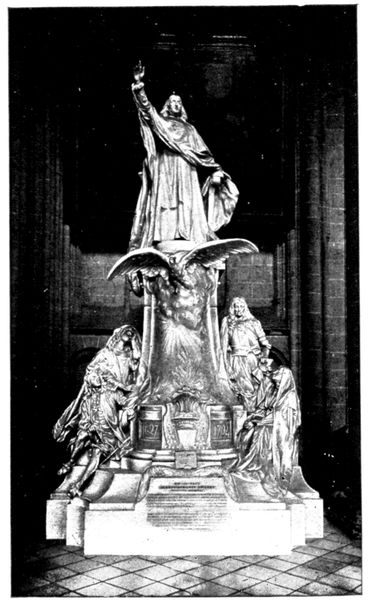

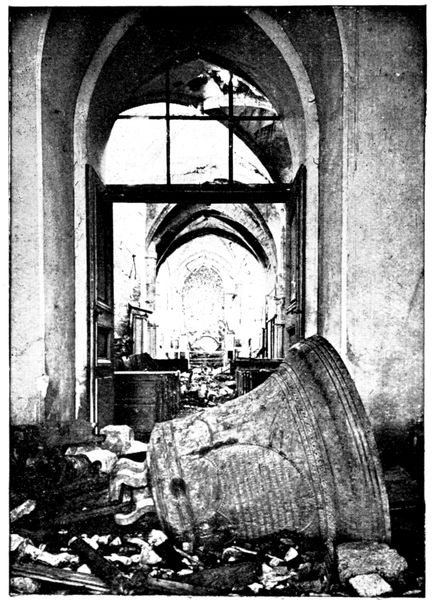

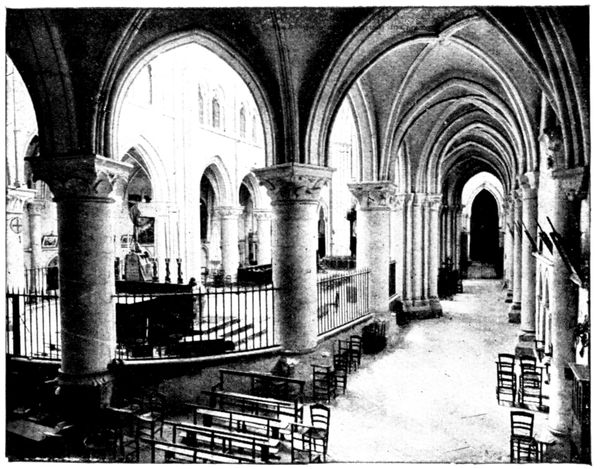

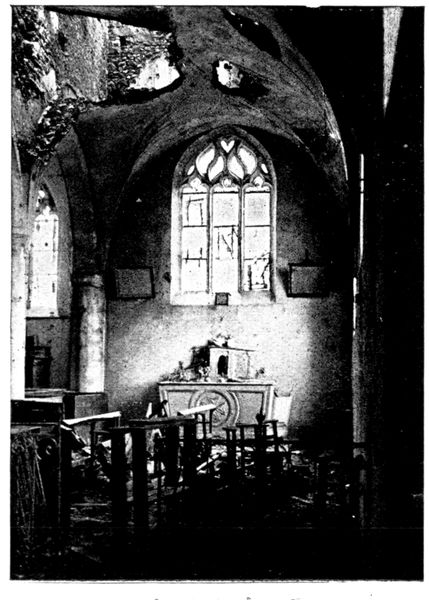

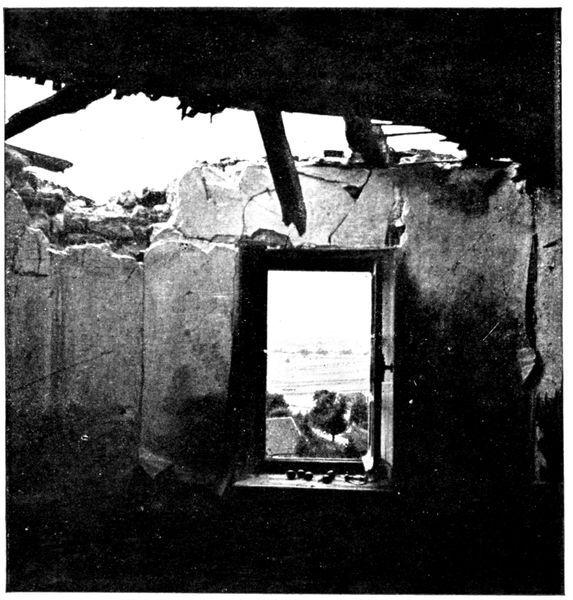

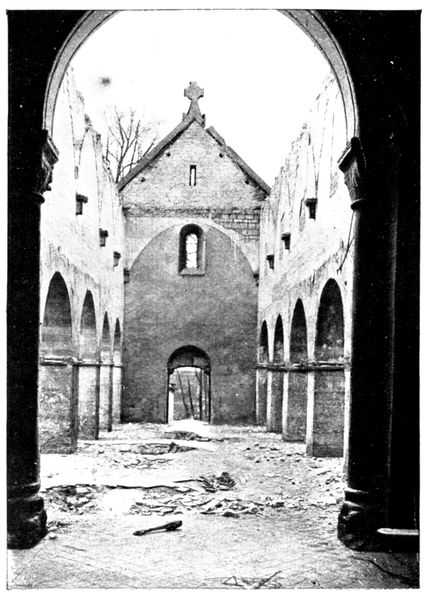

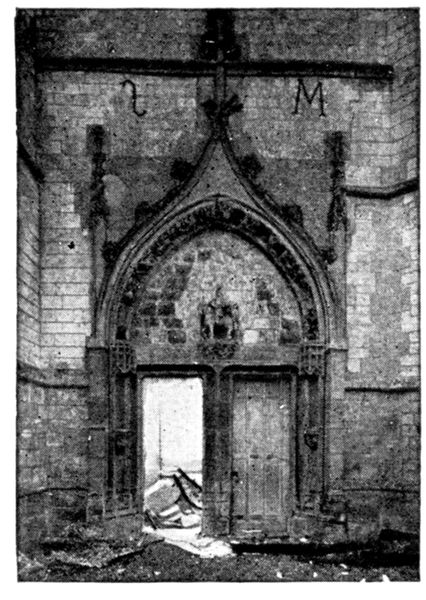

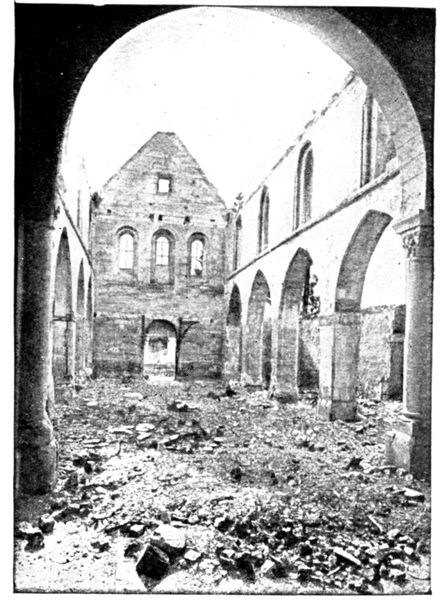

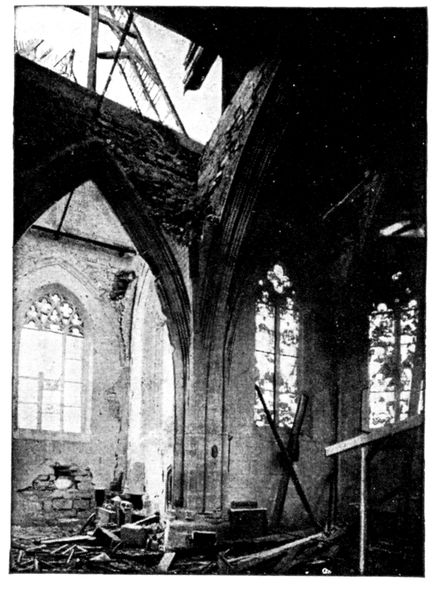

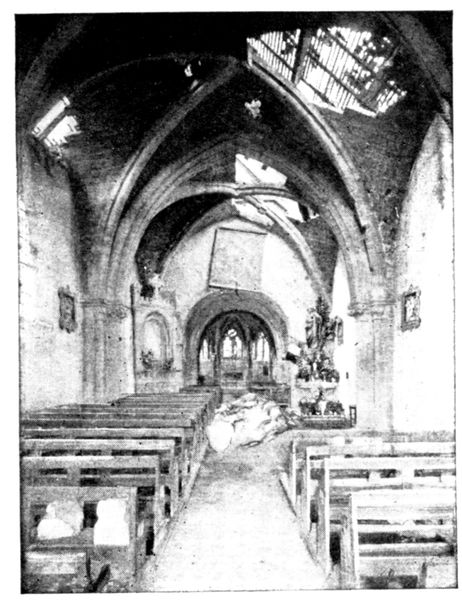

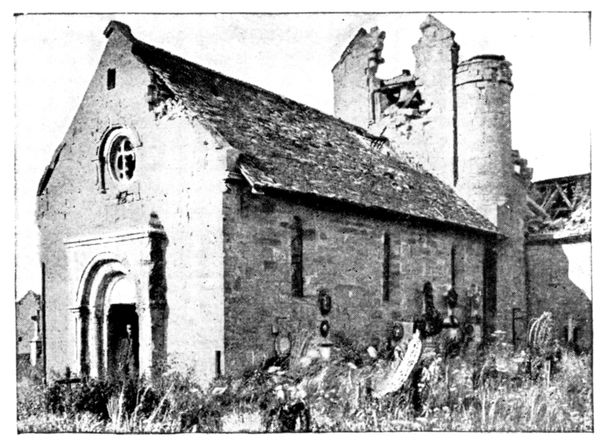

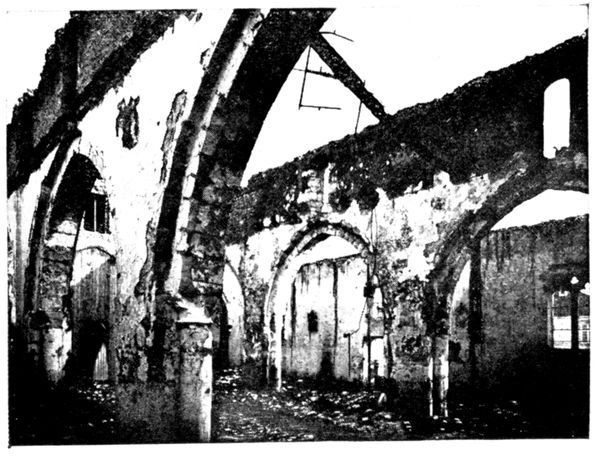

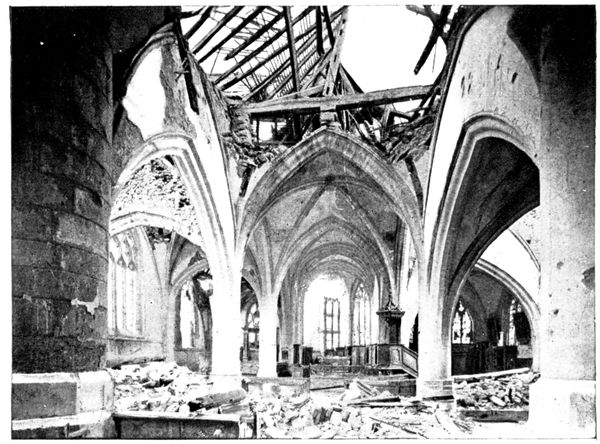

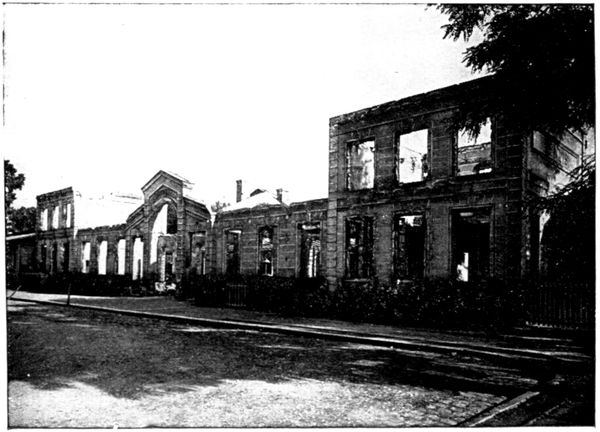

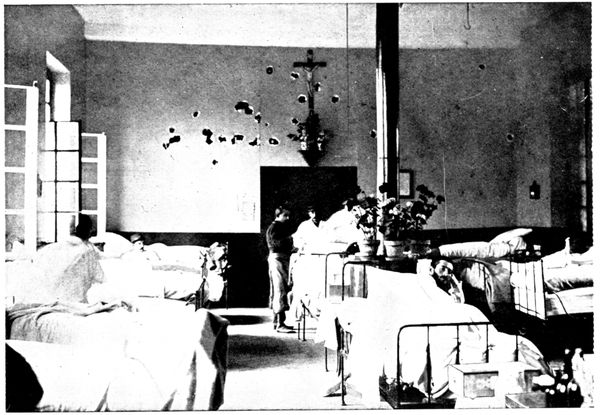

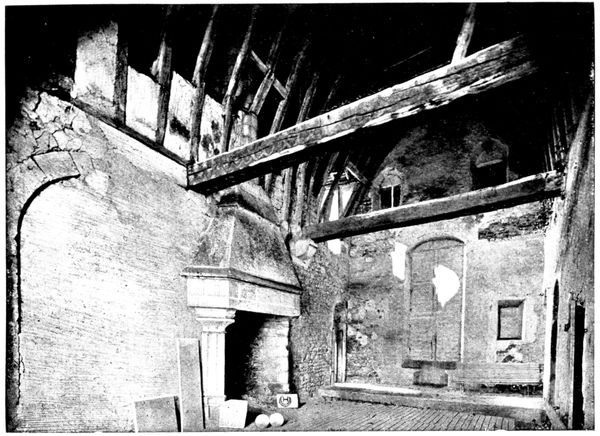

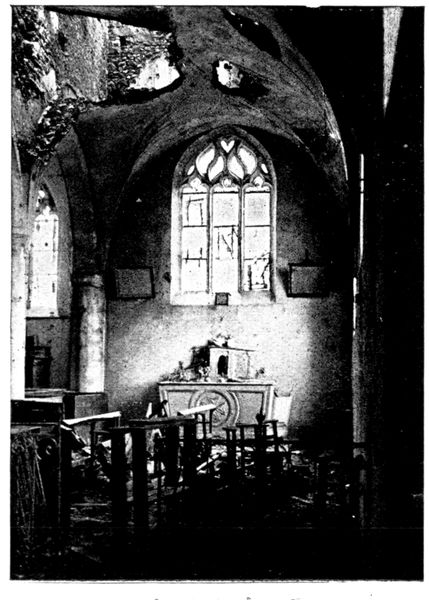

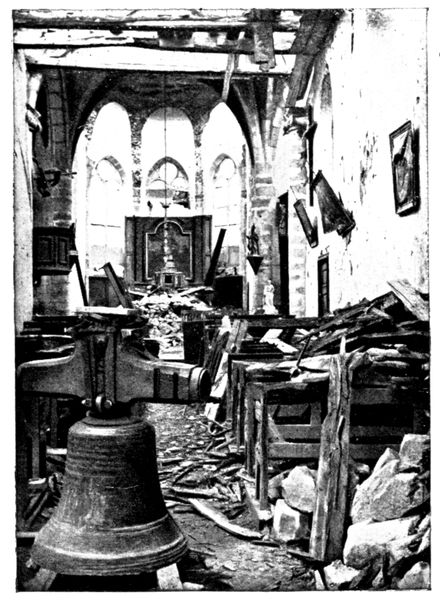

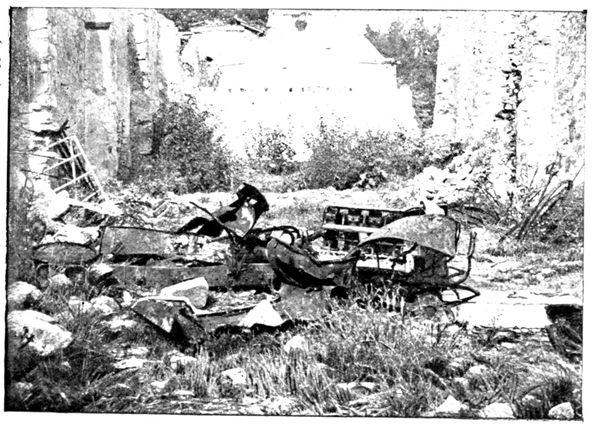

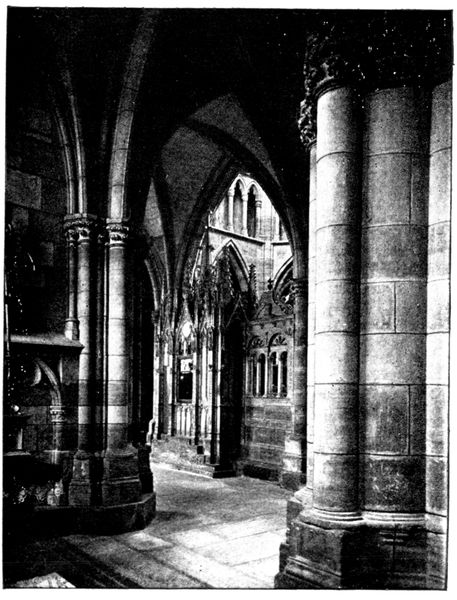

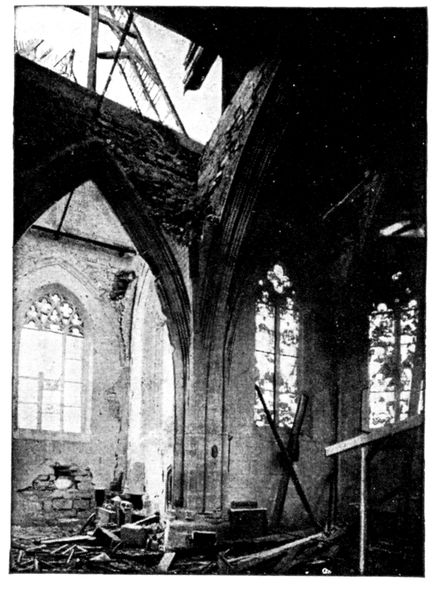

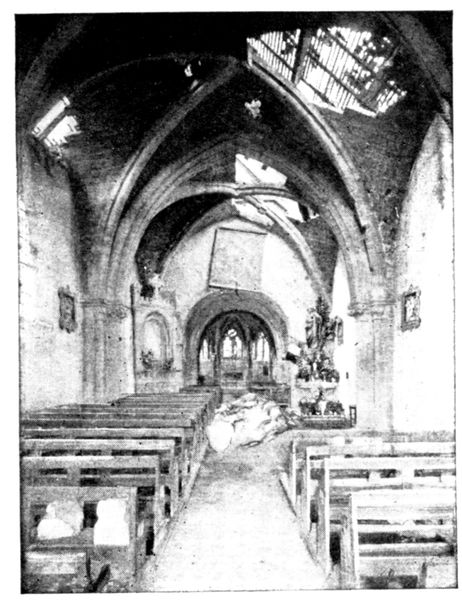

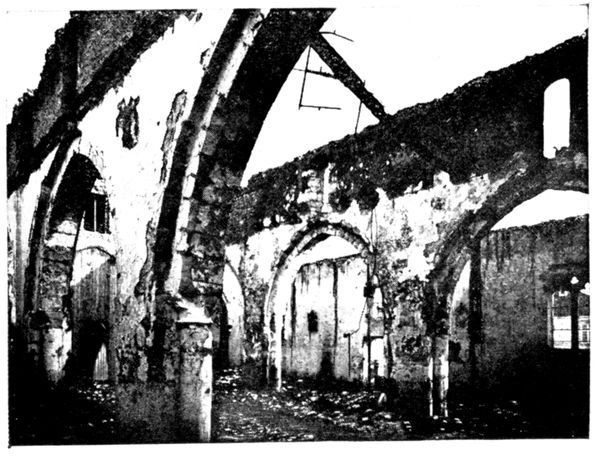

INTERIOR

OF THE BURNT

STATION

(Sept. 1914)

Whilst one part

of the advance

guard made the

tour of the town,

following the boulevards

and the

ramparts which

encircle it, other

groups descended

directly south by

the two main

streets which

cross Senlis, thus

making sure of a

thorough exploration.

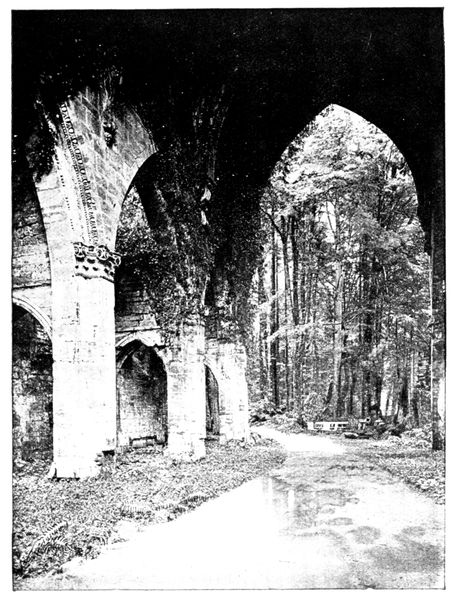

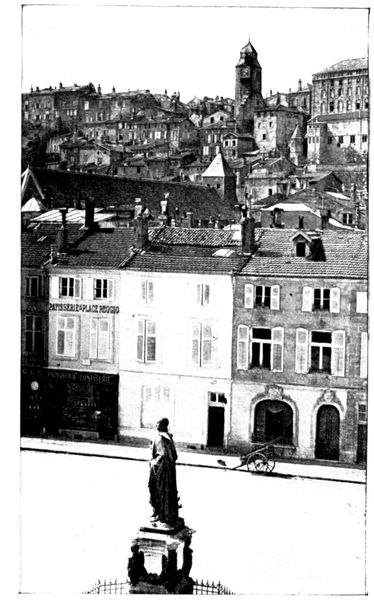

[Pg 39]

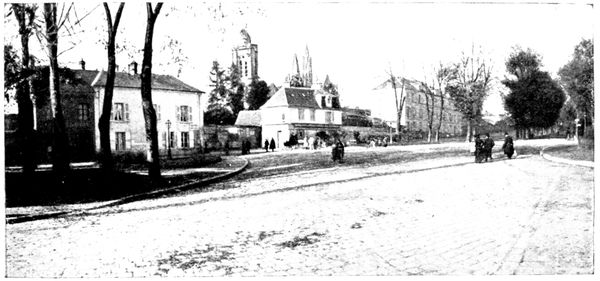

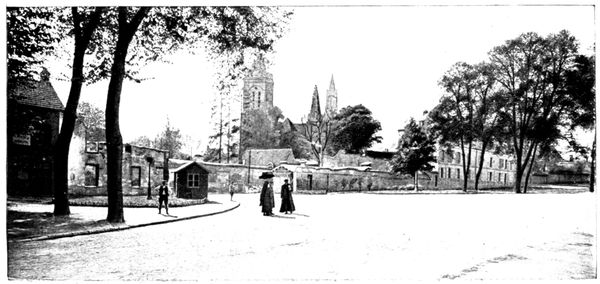

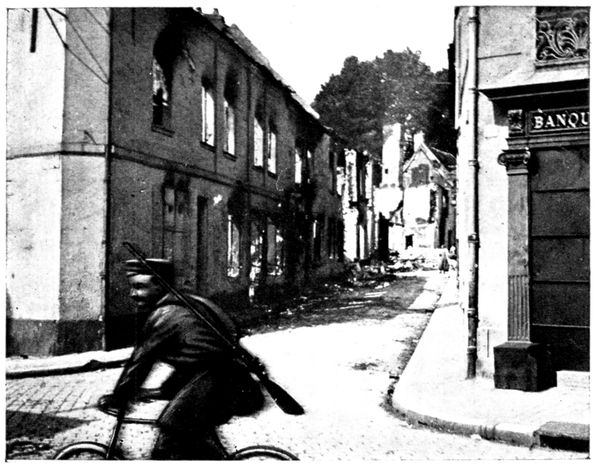

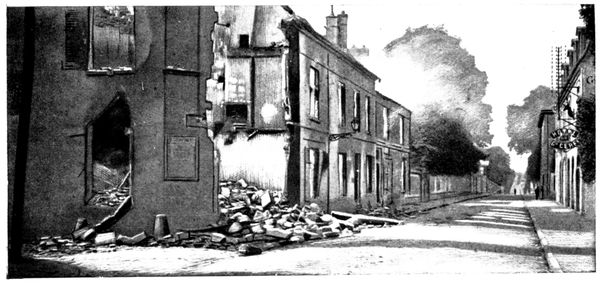

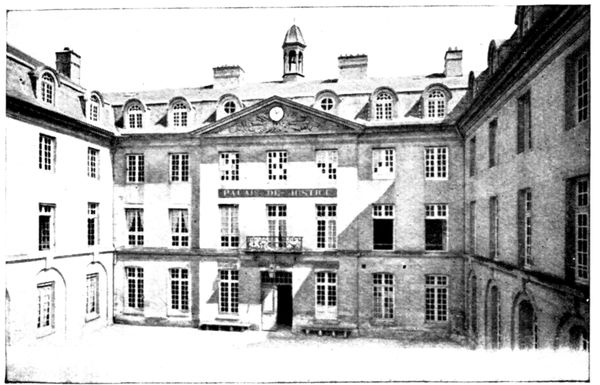

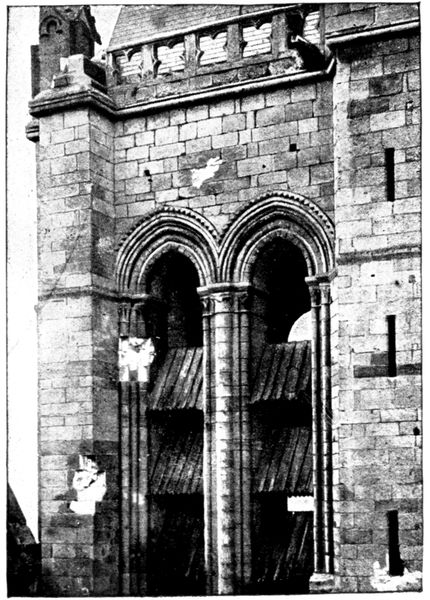

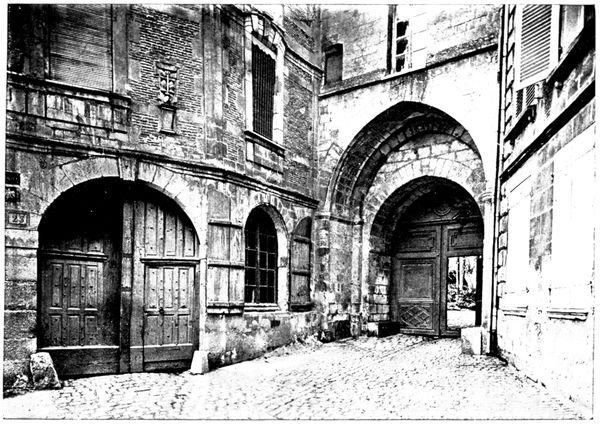

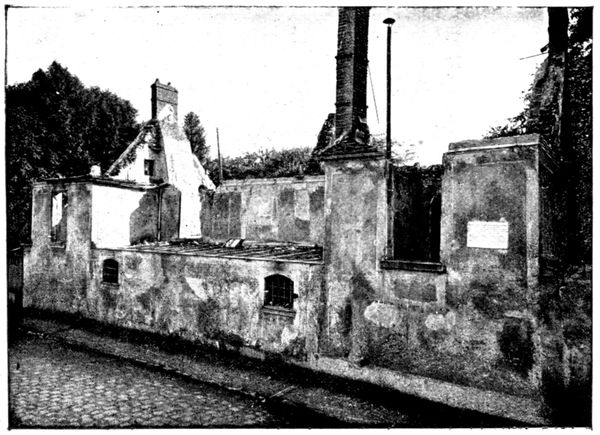

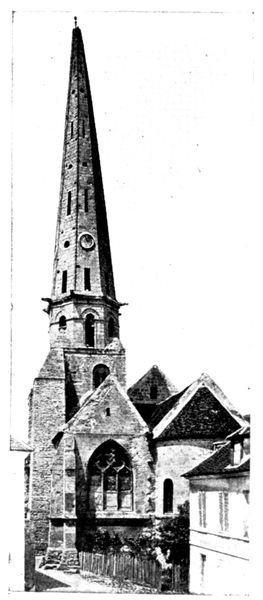

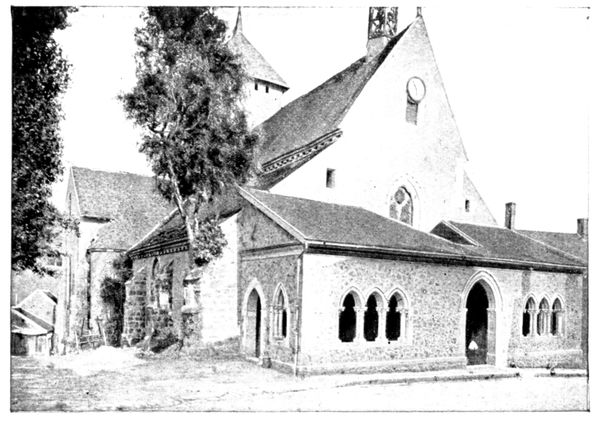

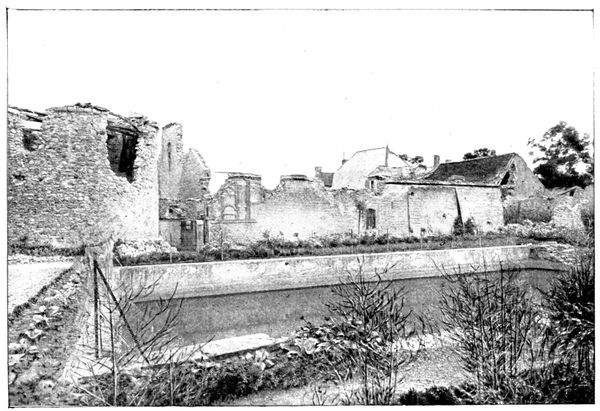

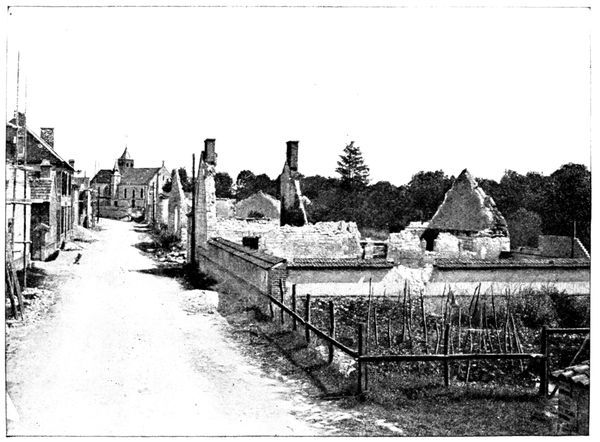

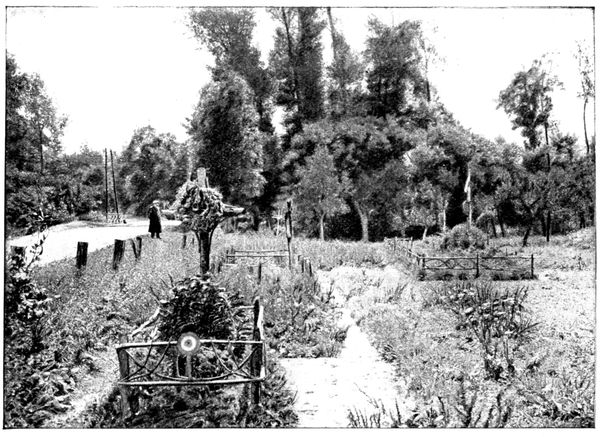

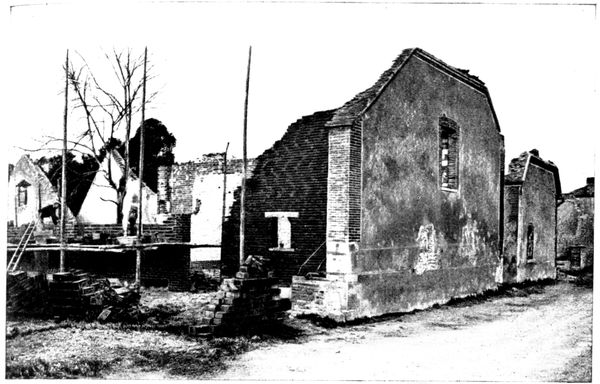

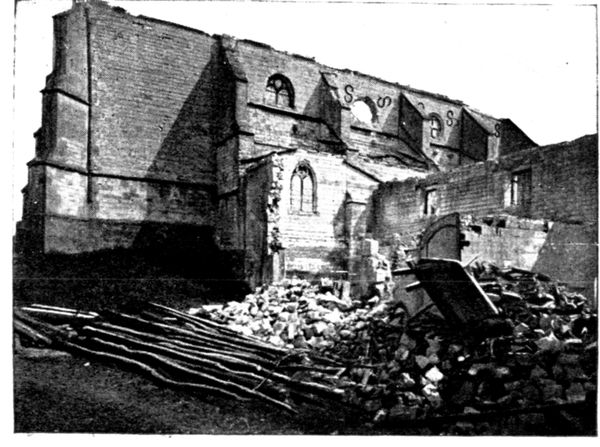

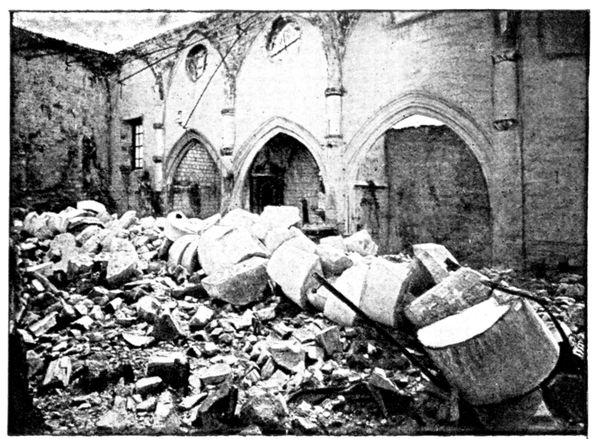

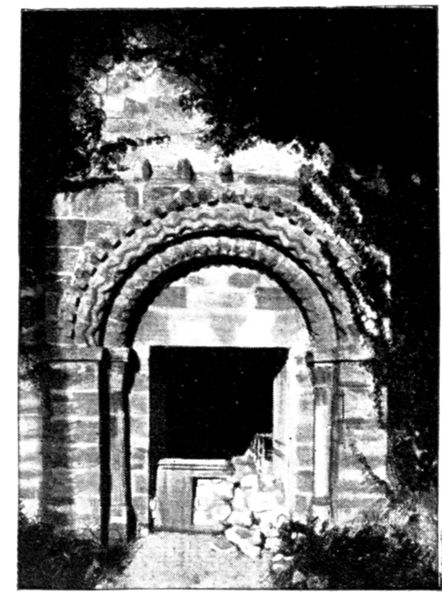

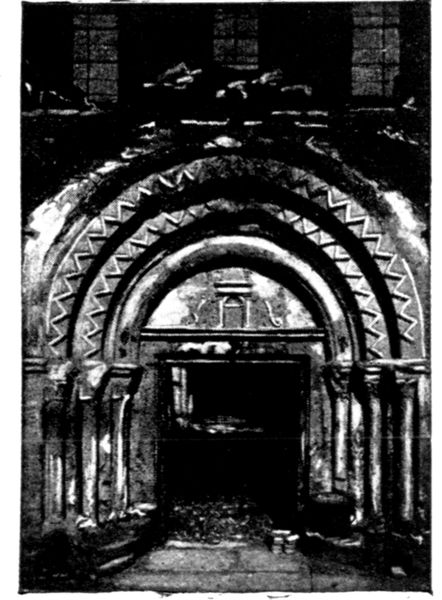

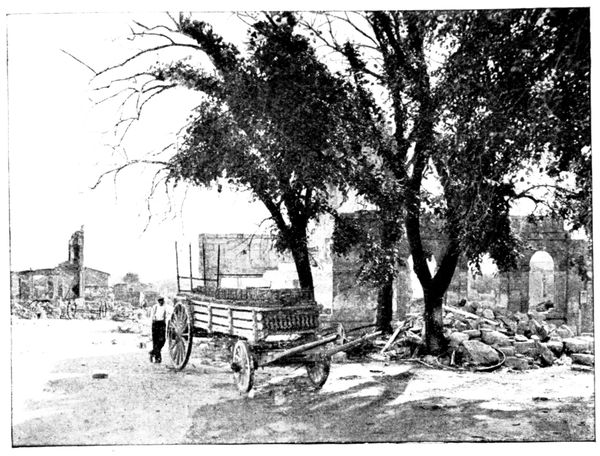

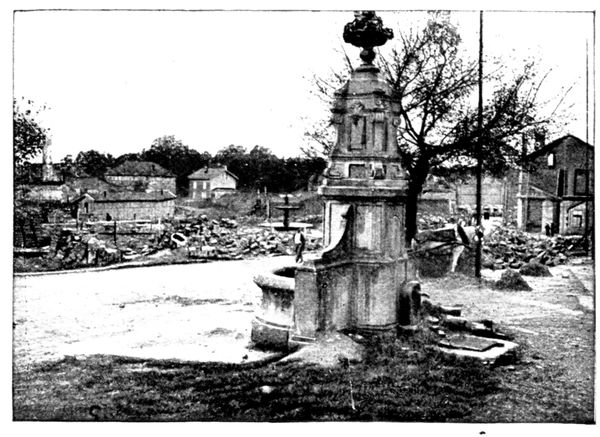

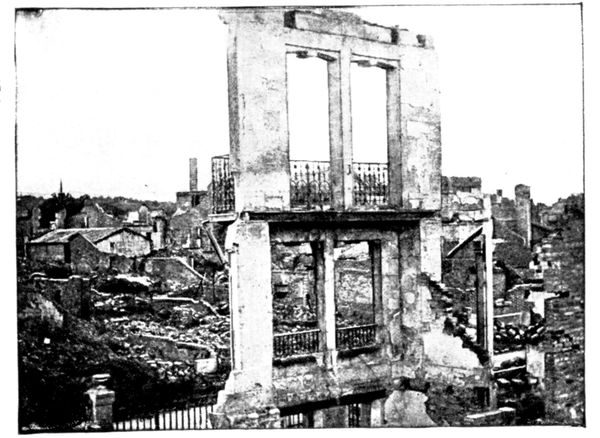

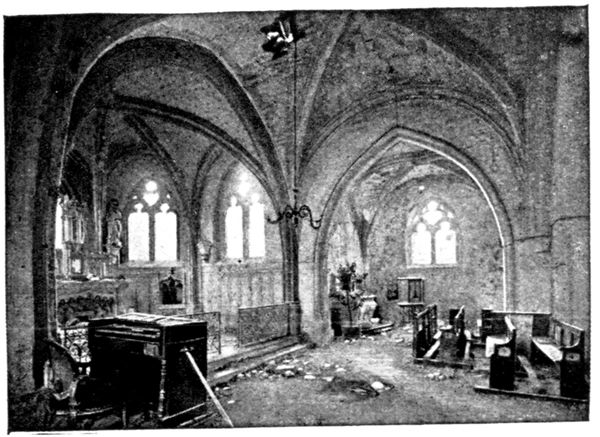

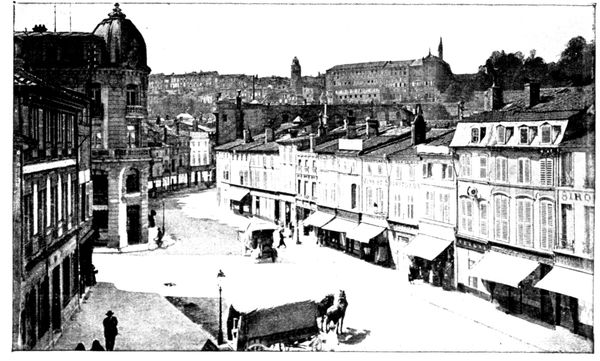

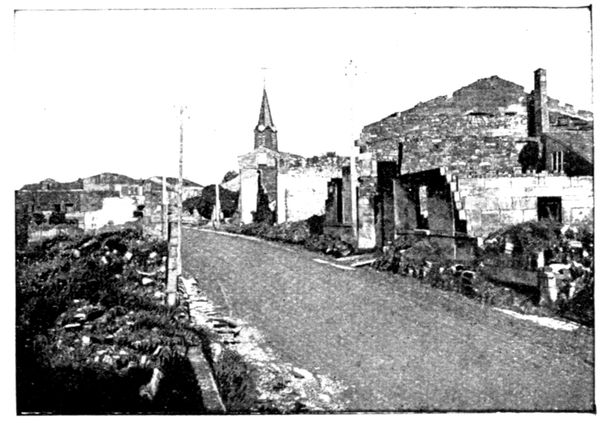

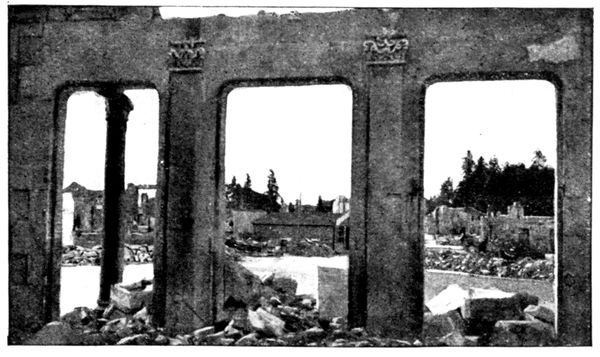

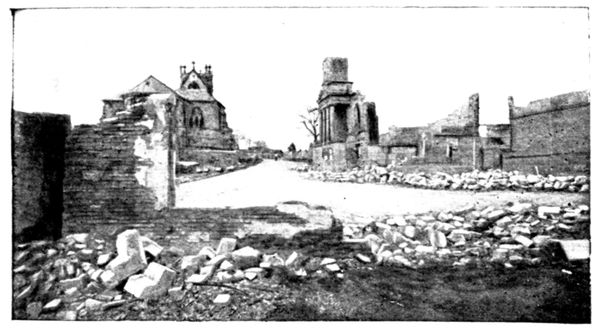

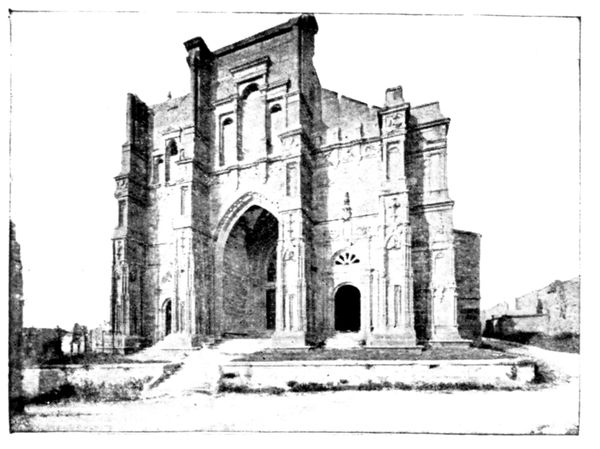

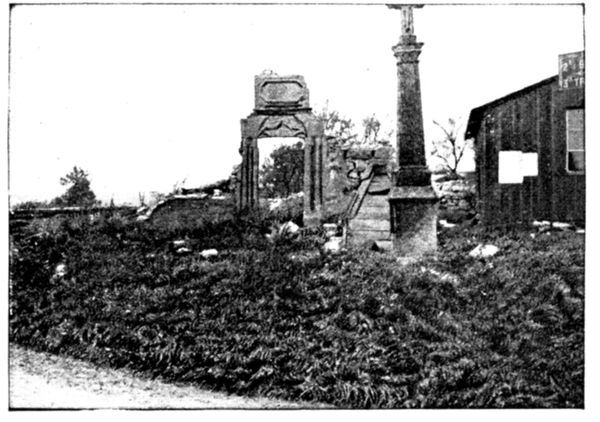

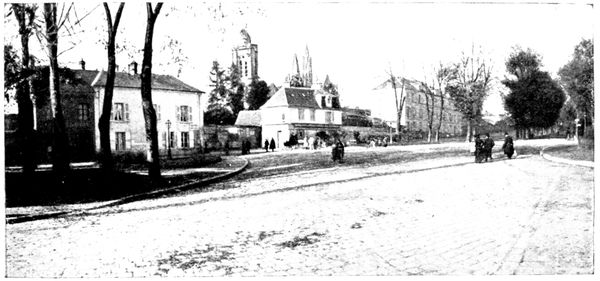

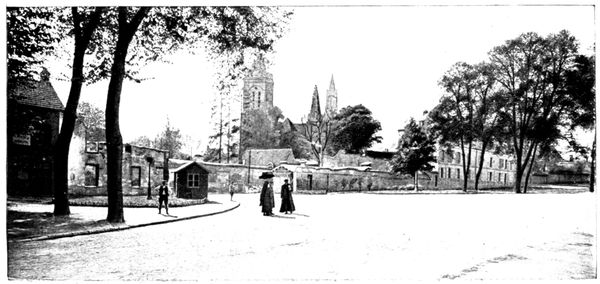

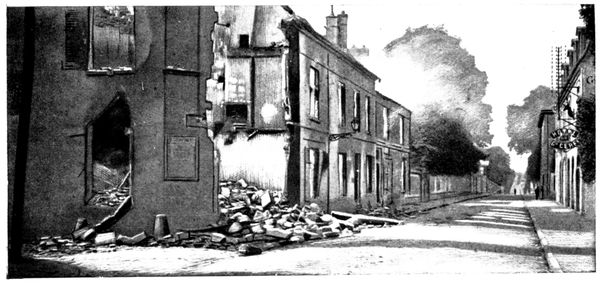

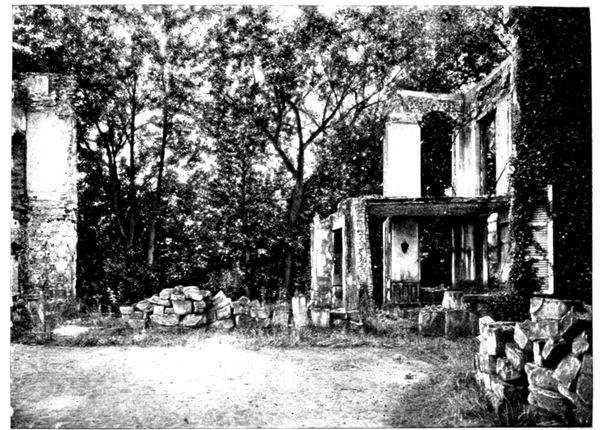

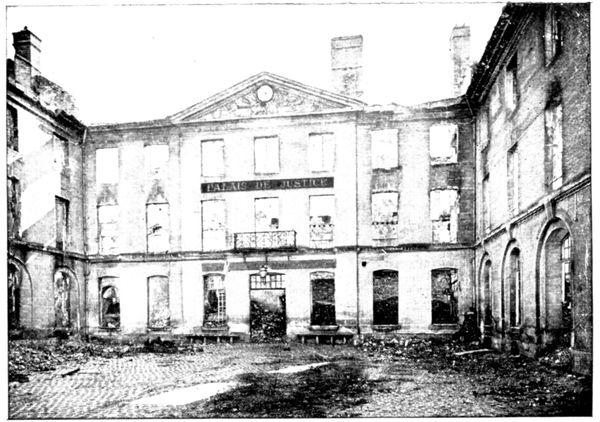

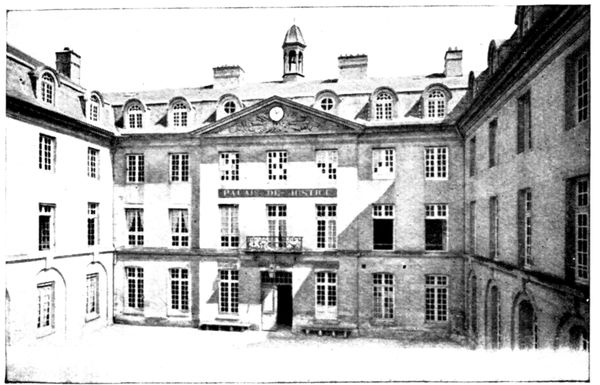

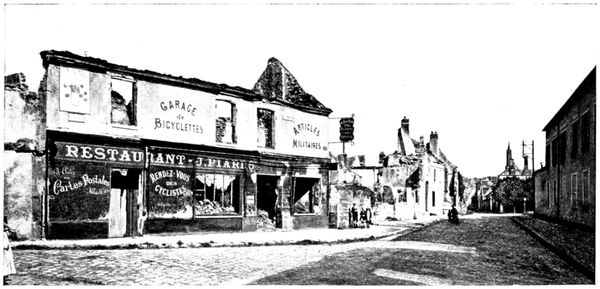

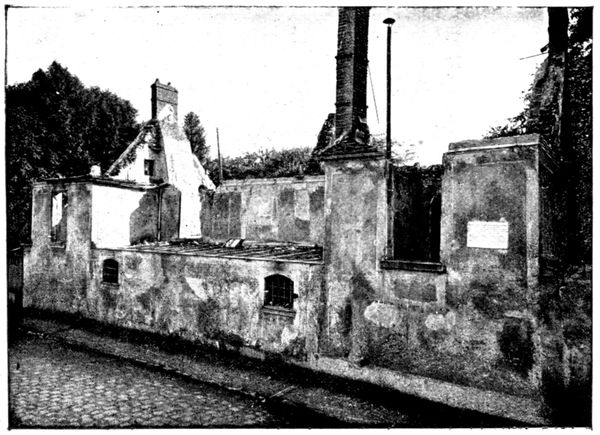

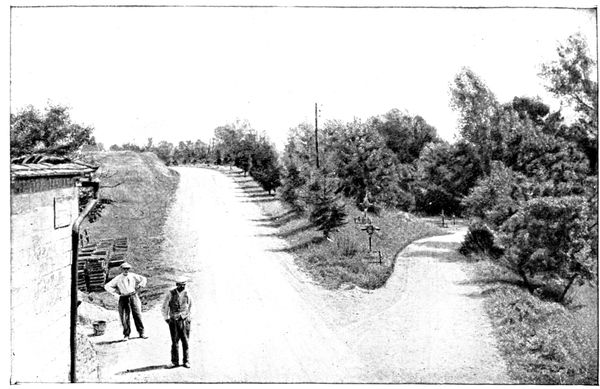

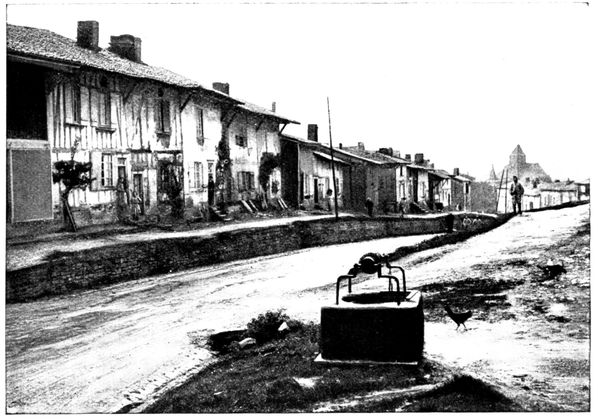

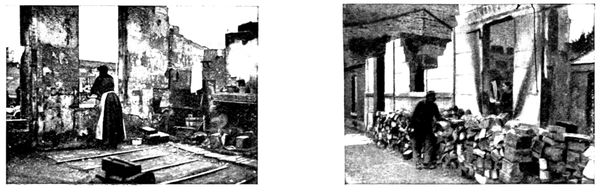

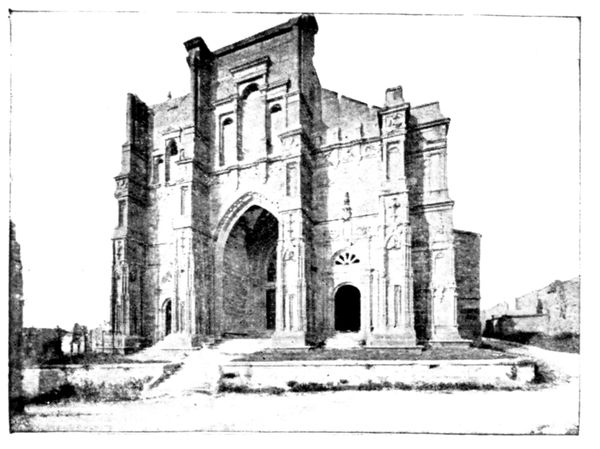

ENTRANCE

TO THE

RUE DE LA

RÉPUBLIQUE

BEFORE THE

WAR

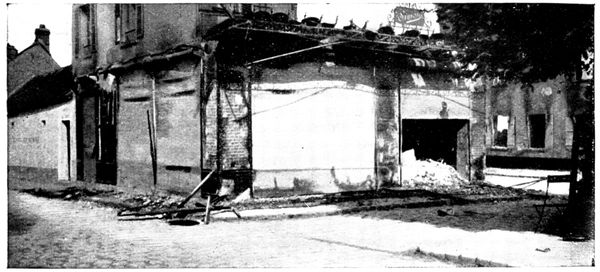

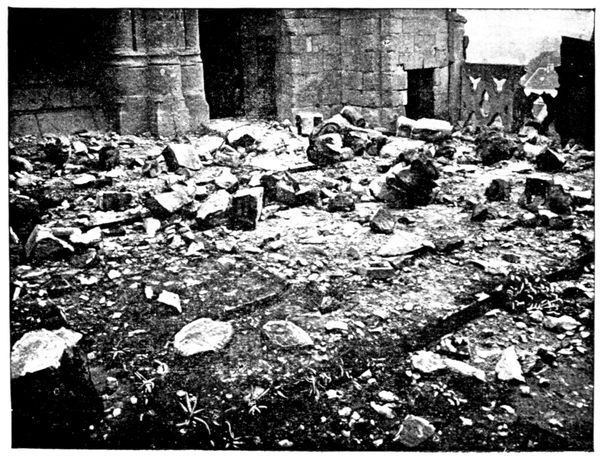

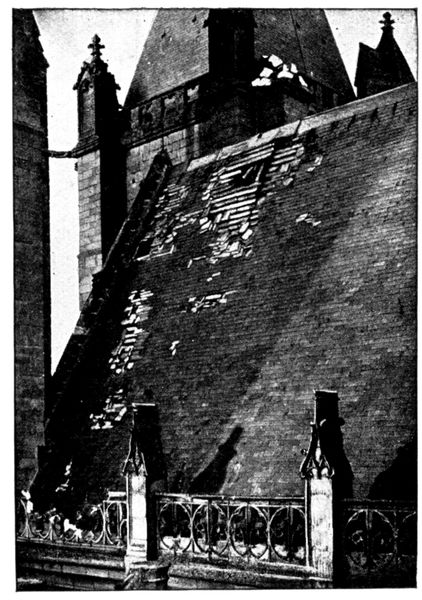

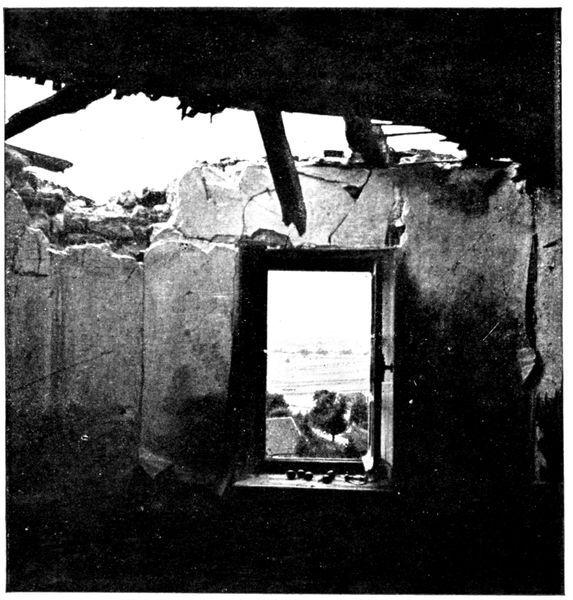

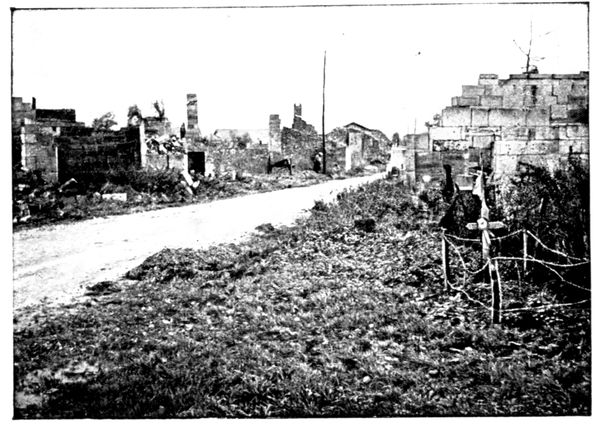

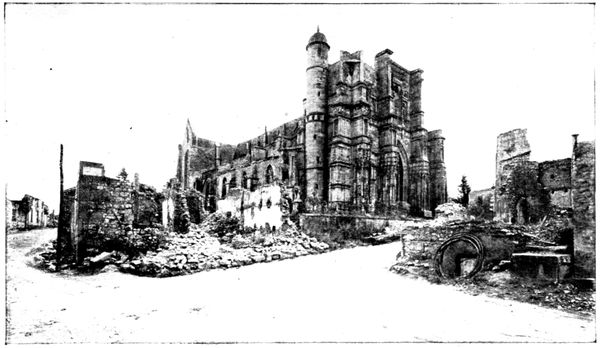

The entrance lo the Rue de la République suffered a great deal, as

is shown by the two photographs, taken before and after the fire of September

2, 1914.

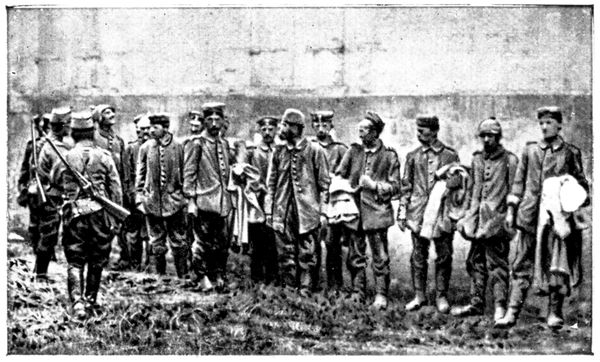

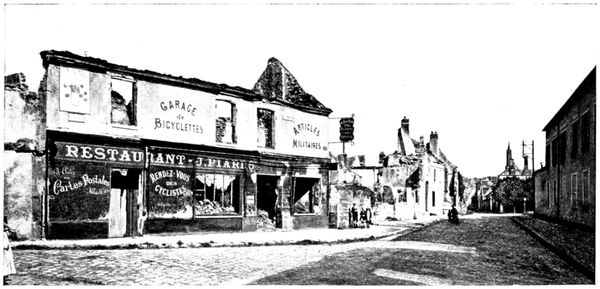

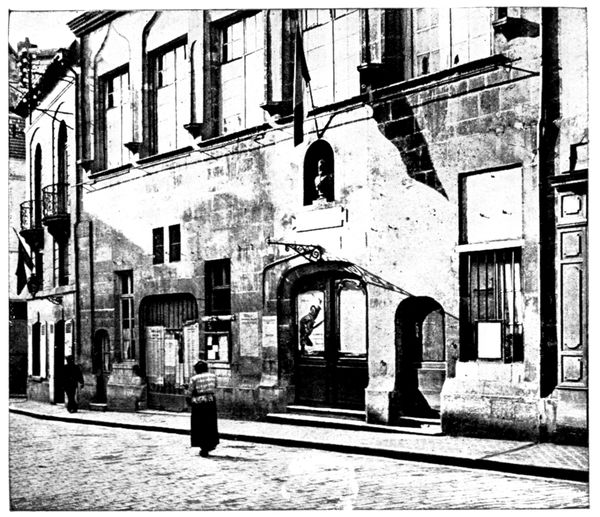

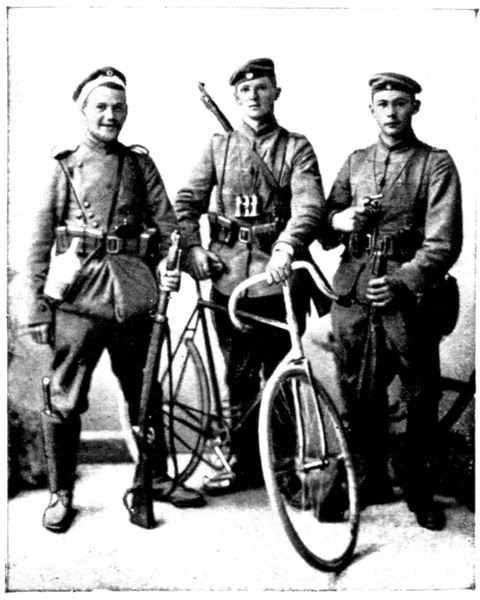

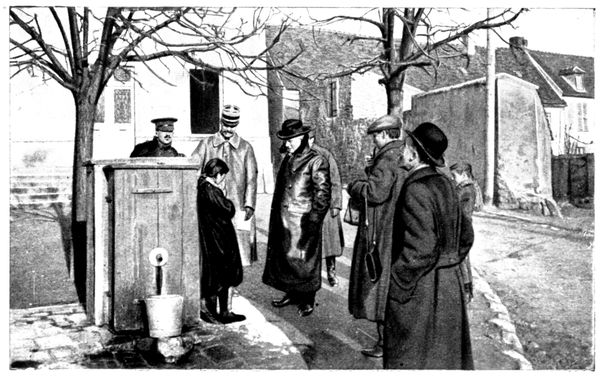

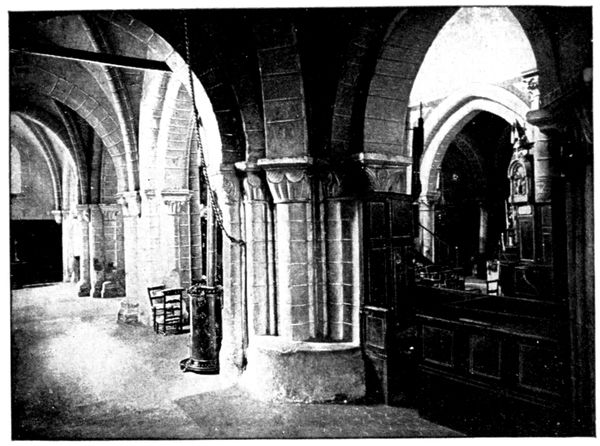

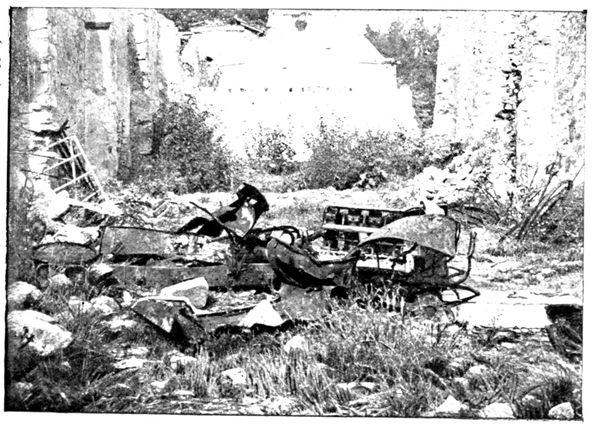

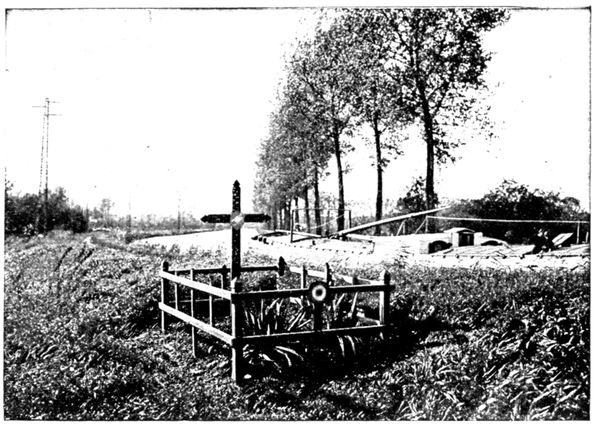

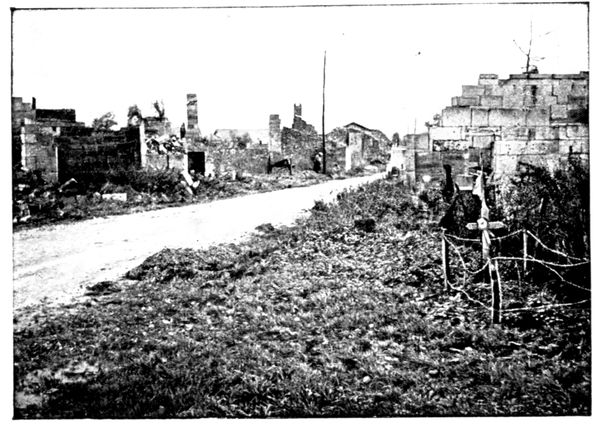

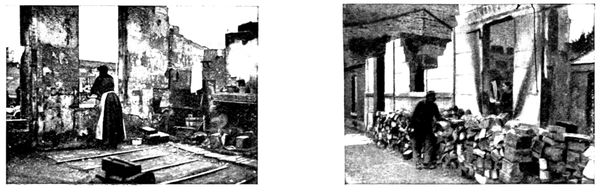

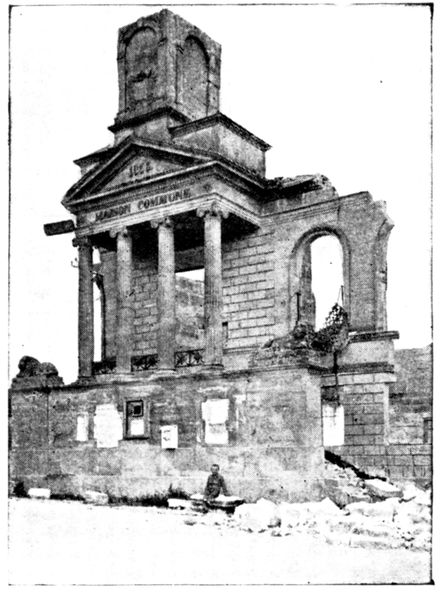

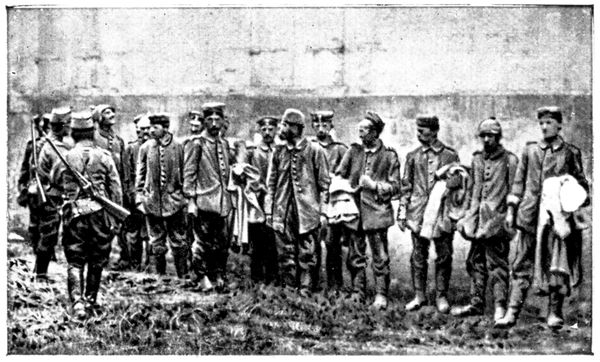

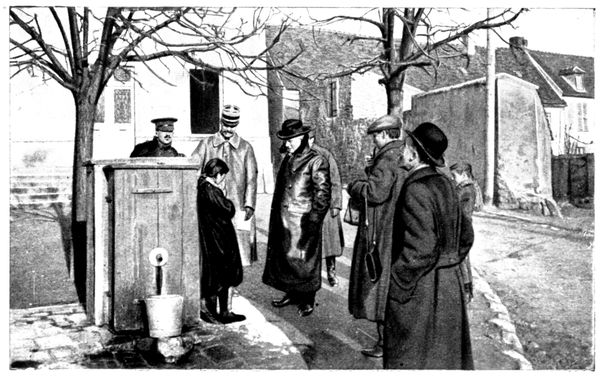

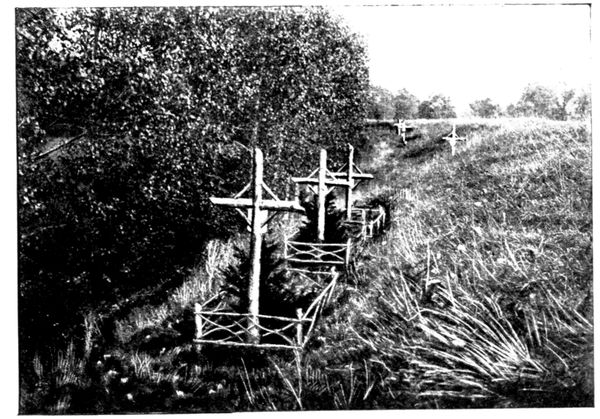

PRISONERS

IN FRONT

OF THE

GENDARMERIE

(Sept. 1914)

On the left, the toll-house is completely burnt down; in the centre, the

Hôtel du Nord and

the Restaurant Encausse

are in ruins.

The building on

the right is the

Gendarmerie.

The German prisoners

who appear

in the picture opposite

are leaning

against the wall of

these barracks.

They were the

few soldiers who,

remaining in Senlis

after the victory of

the Ourcq, were

captured by Zouaves sent from Paris in motor-cars.

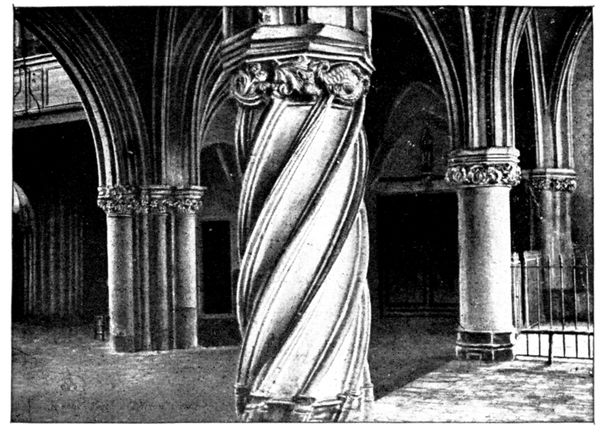

Only a few years ago the Rue de la République was called the Rue Neuve-de-Paris,

although it dated from 1753. It was made in order to spare the

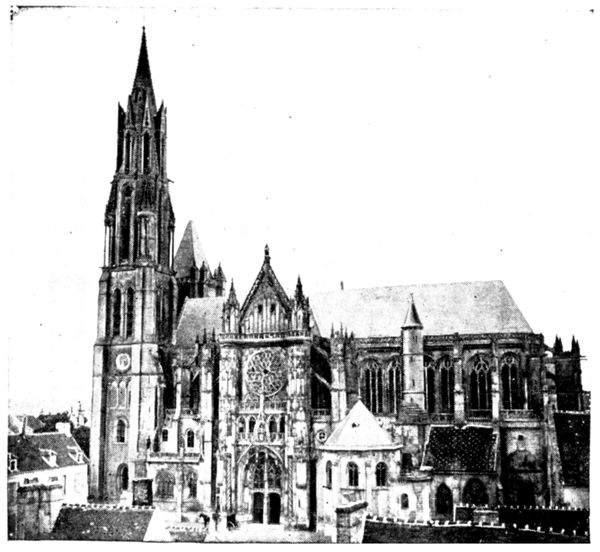

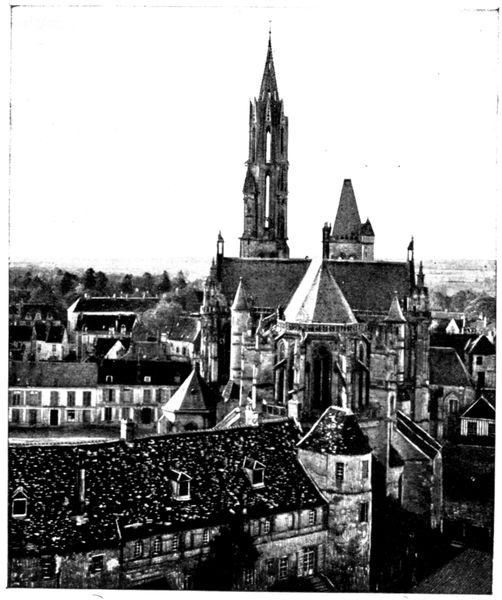

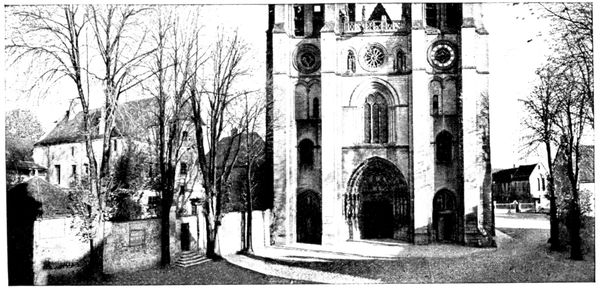

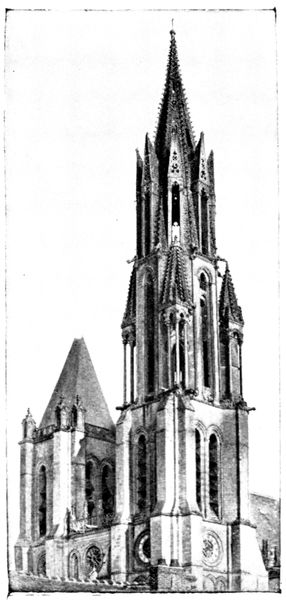

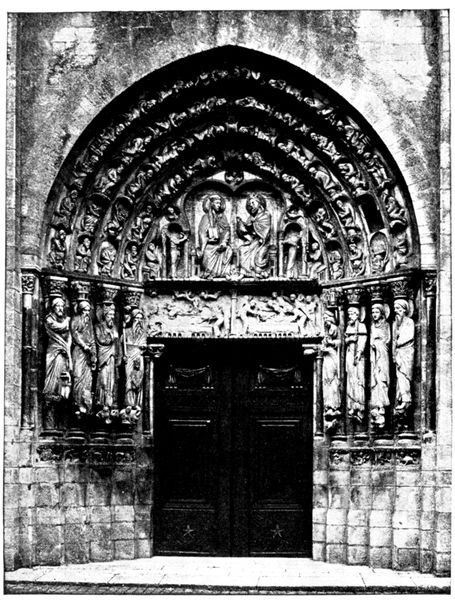

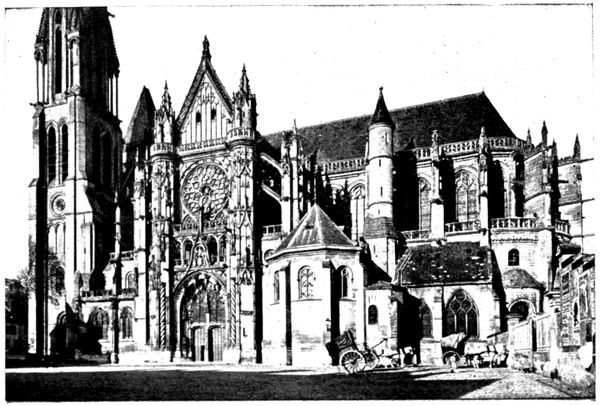

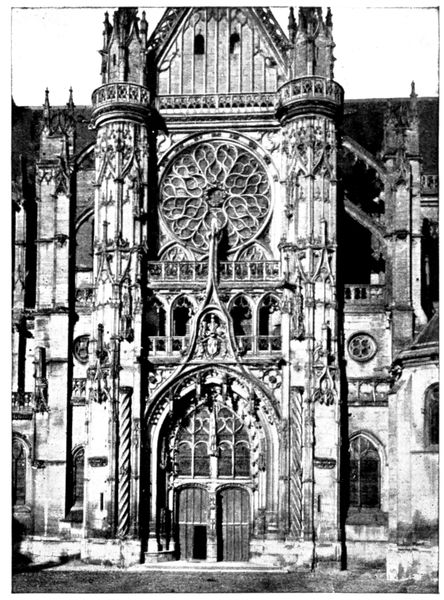

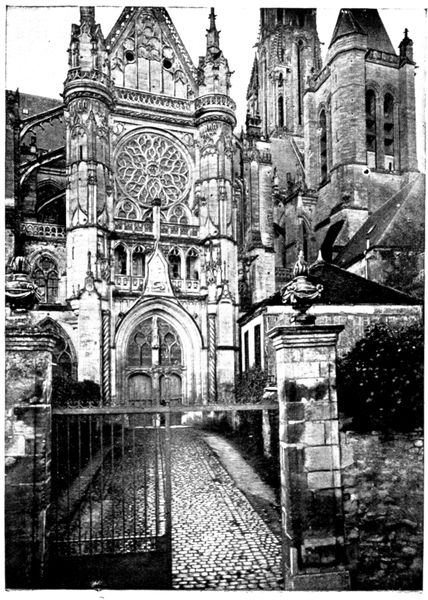

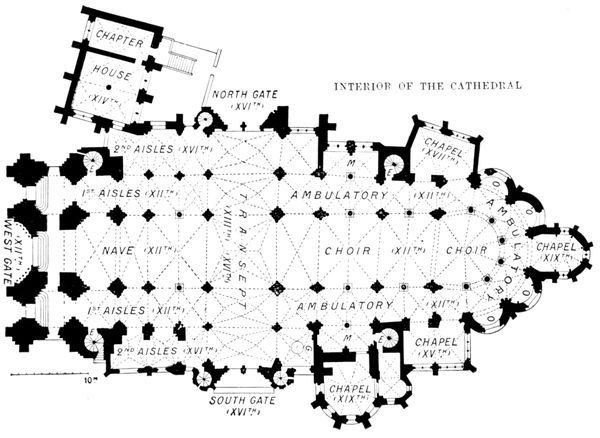

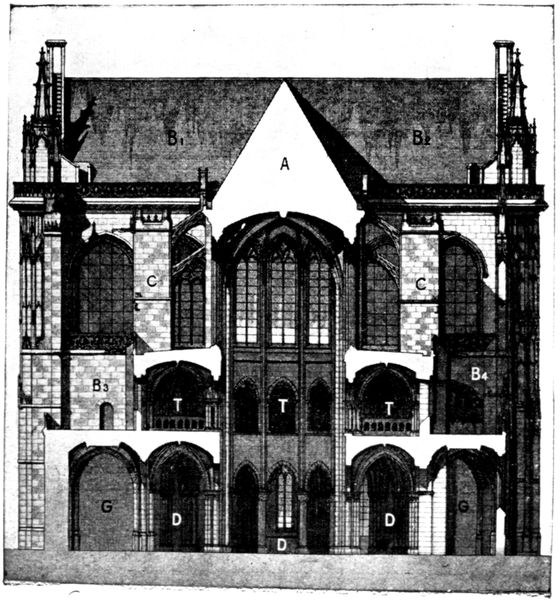

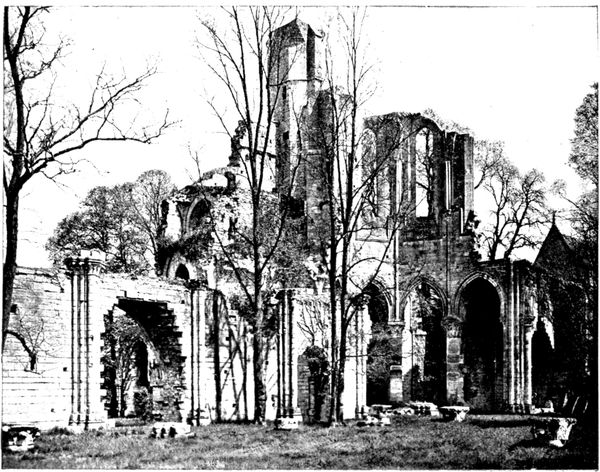

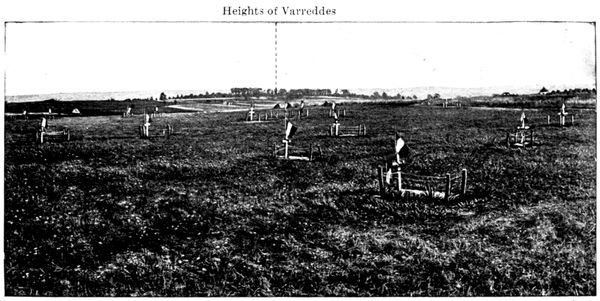

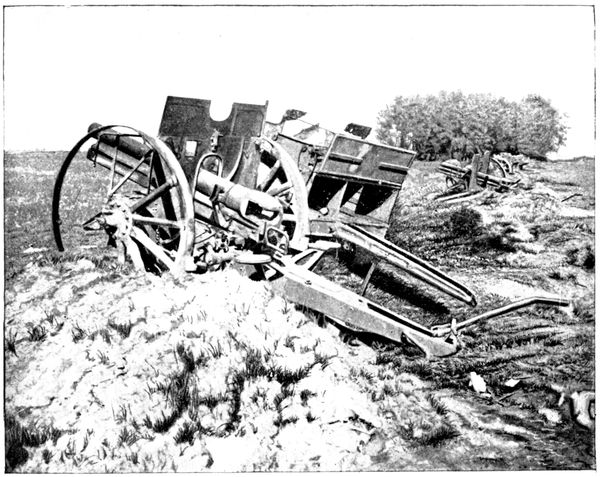

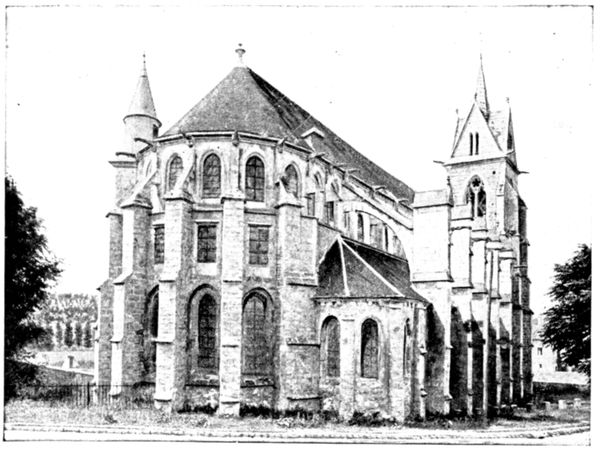

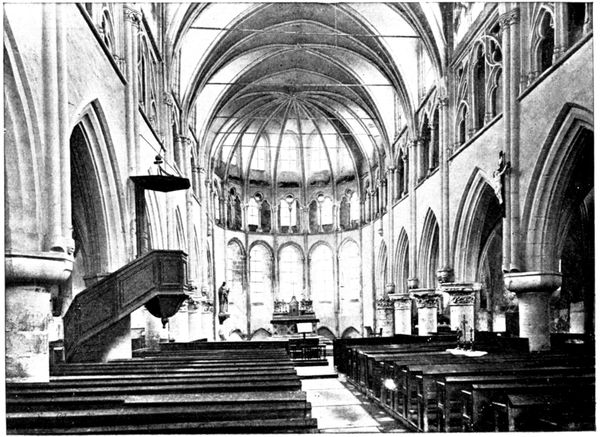

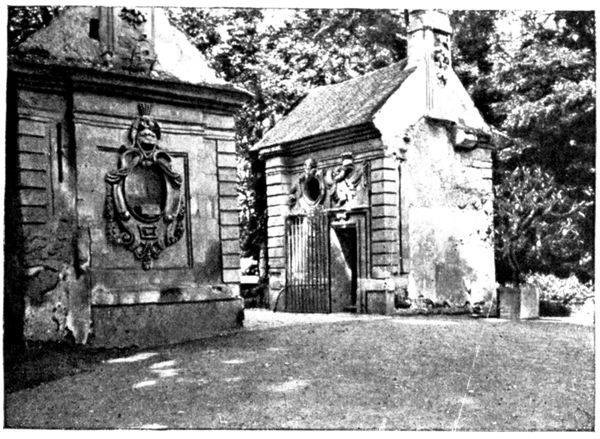

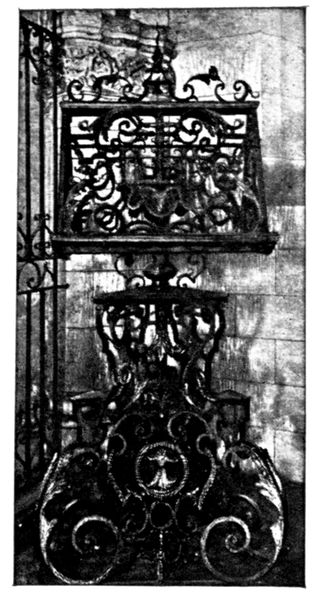

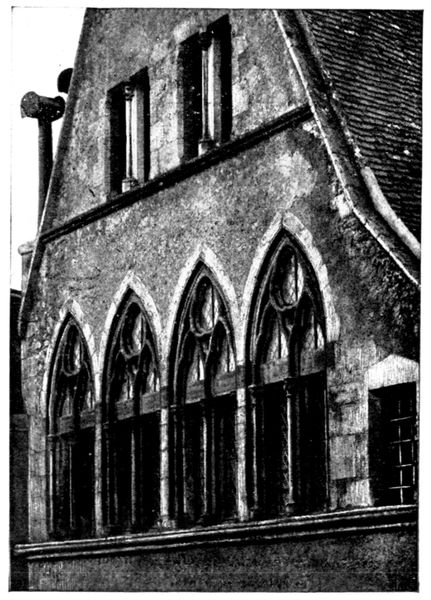

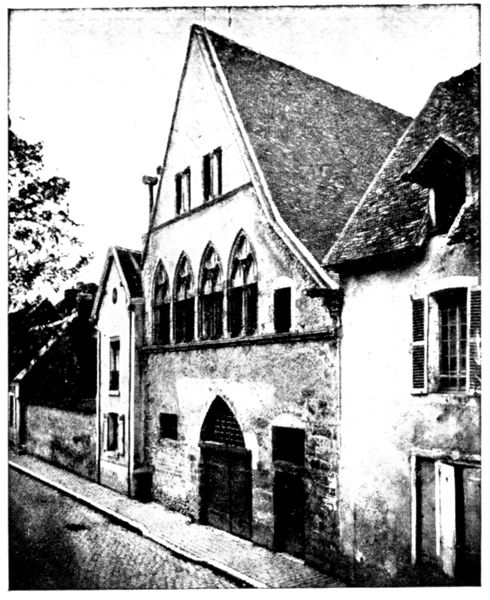

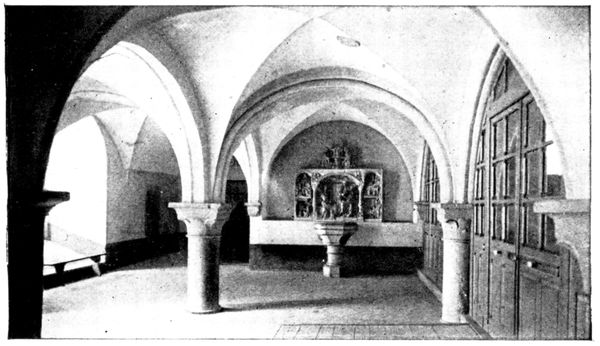

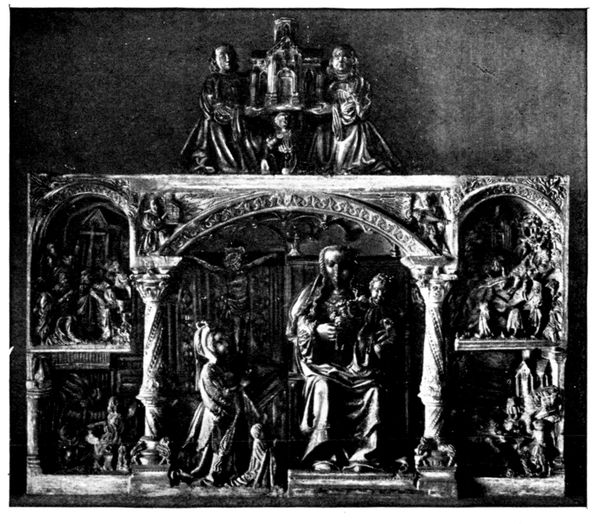

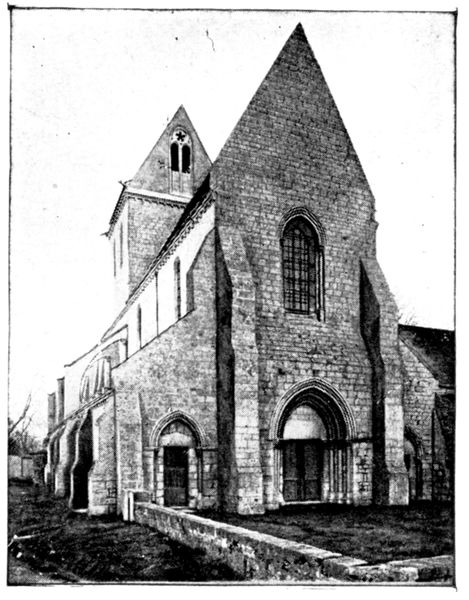

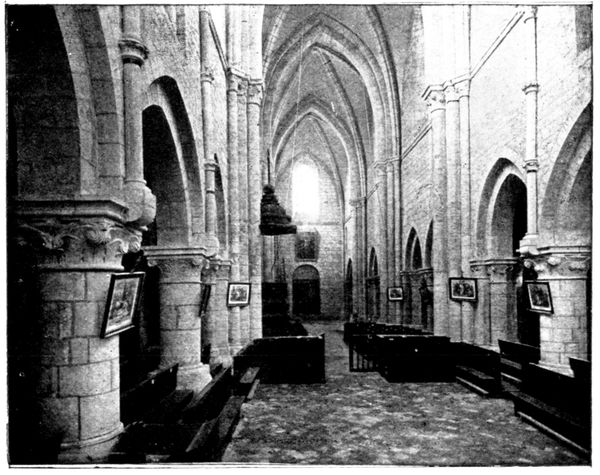

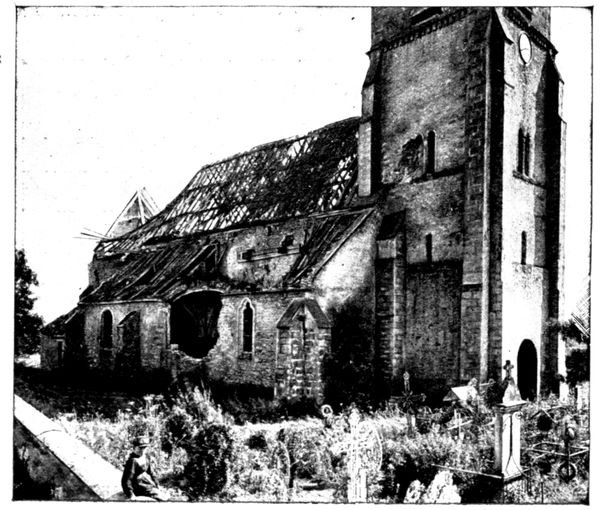

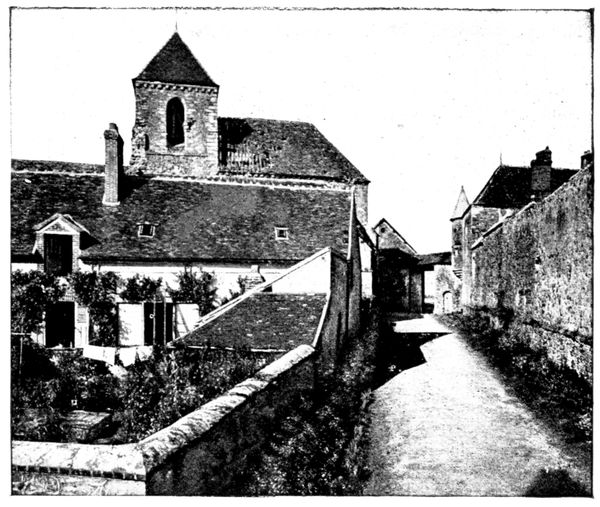

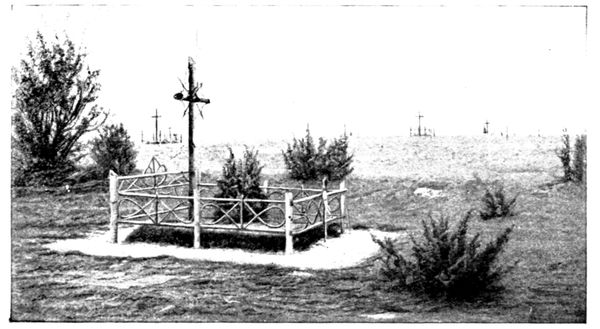

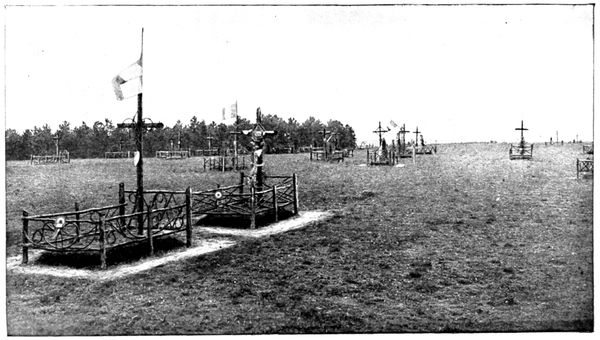

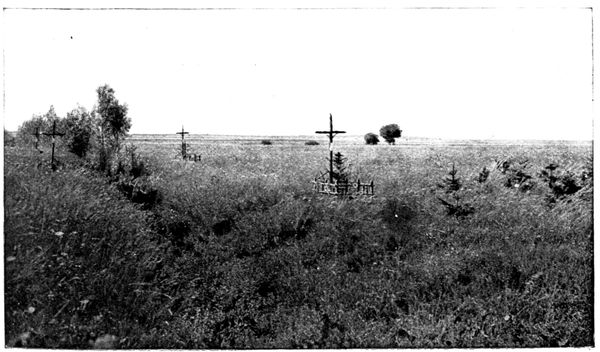

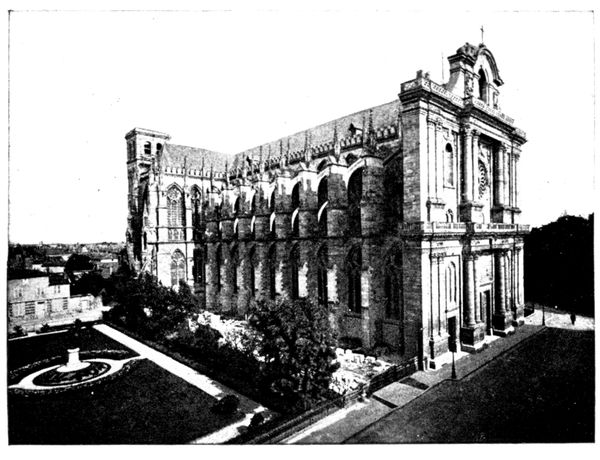

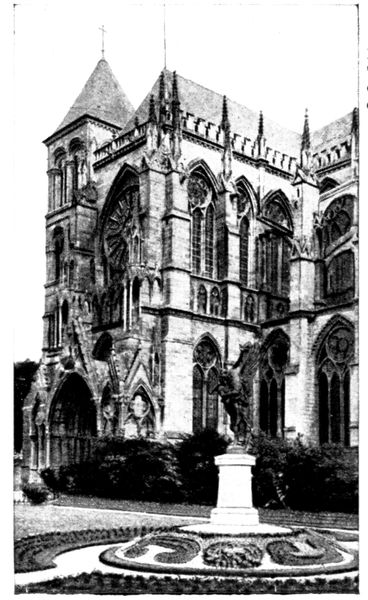

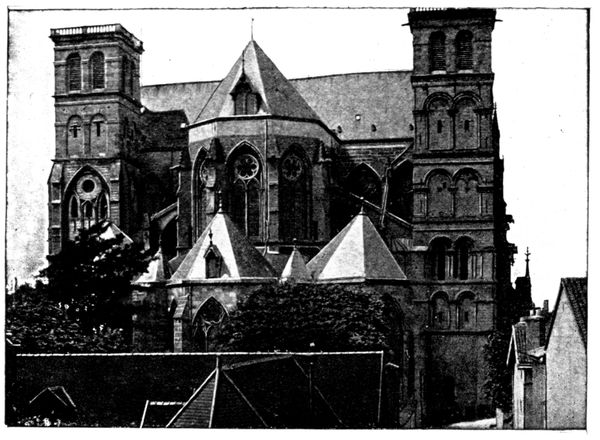

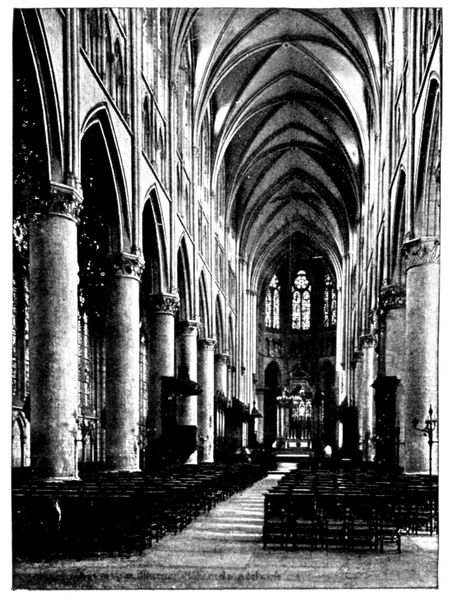

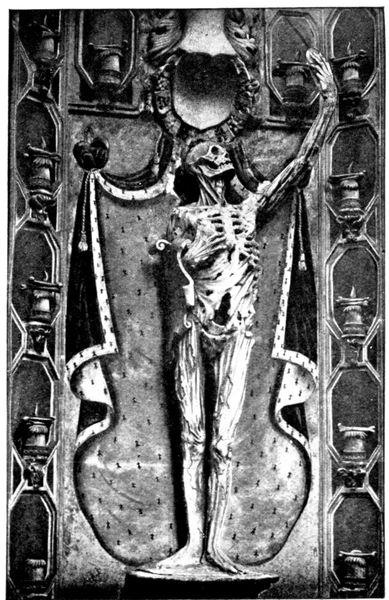

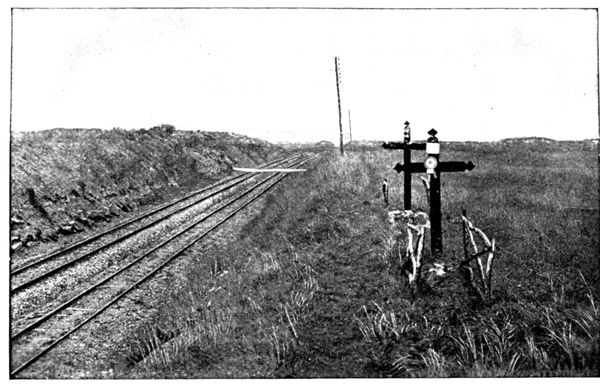

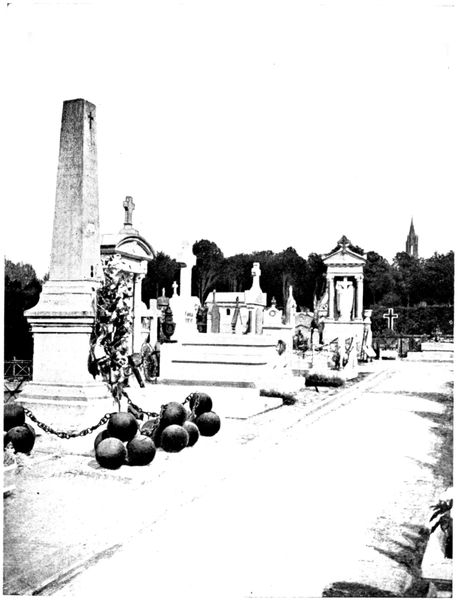

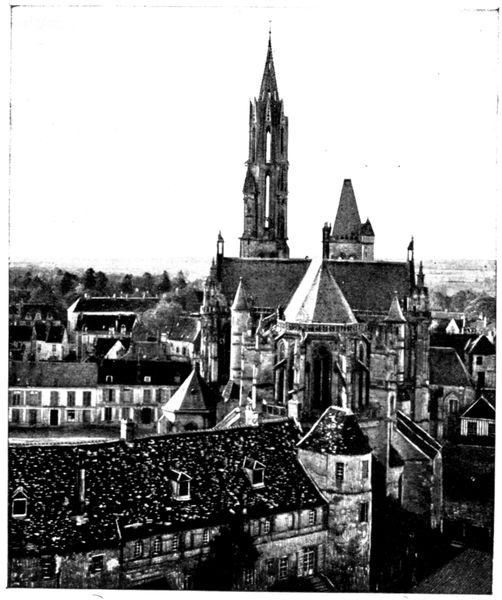

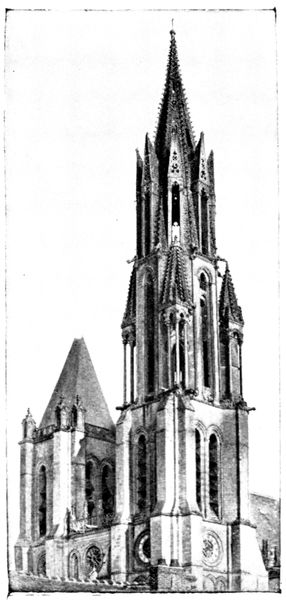

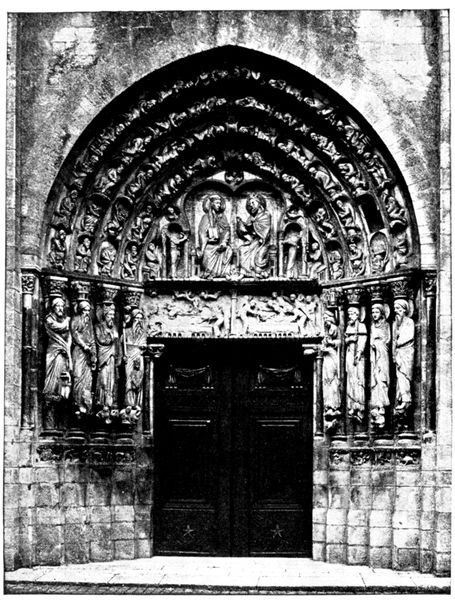

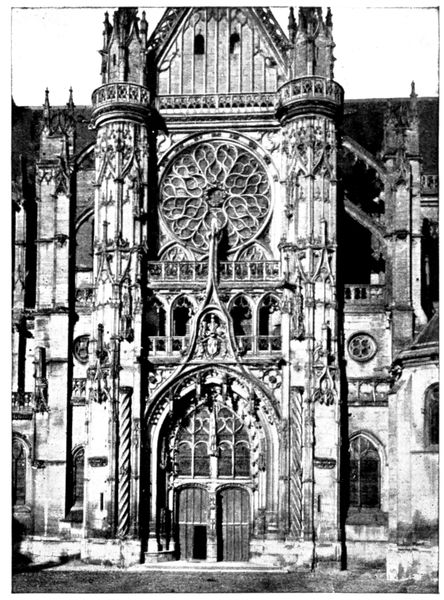

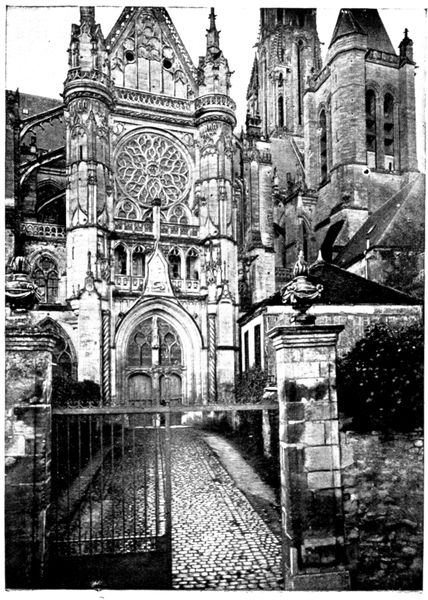

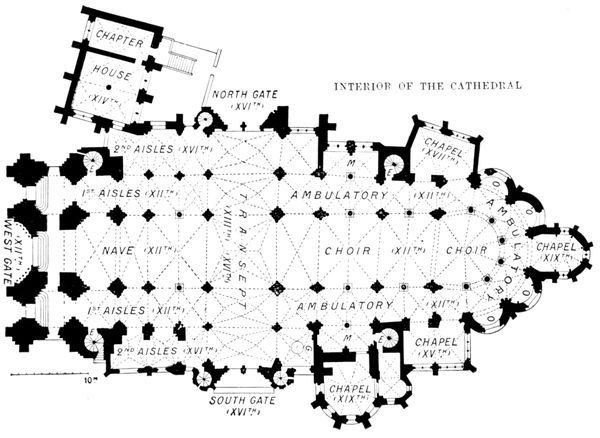

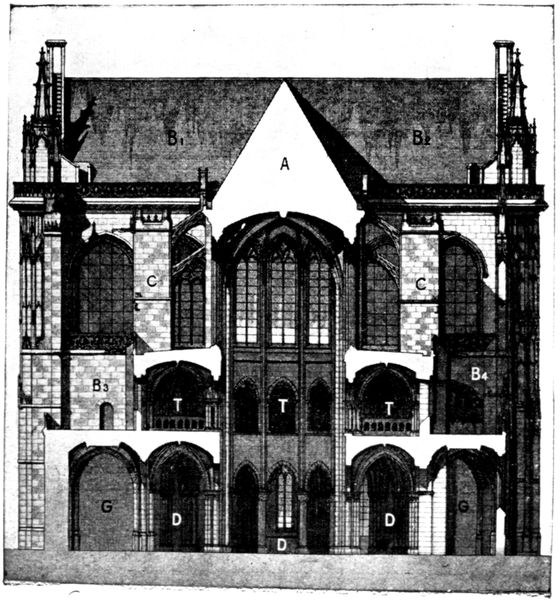

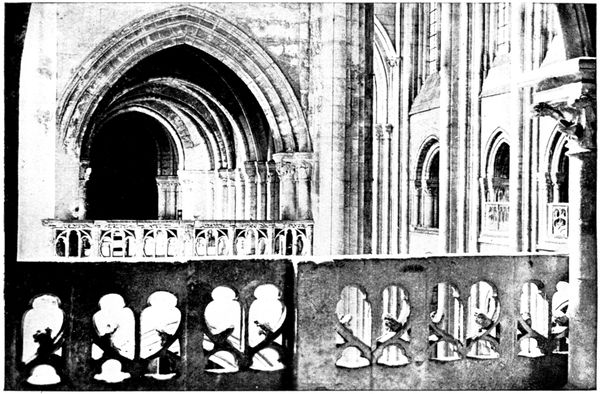

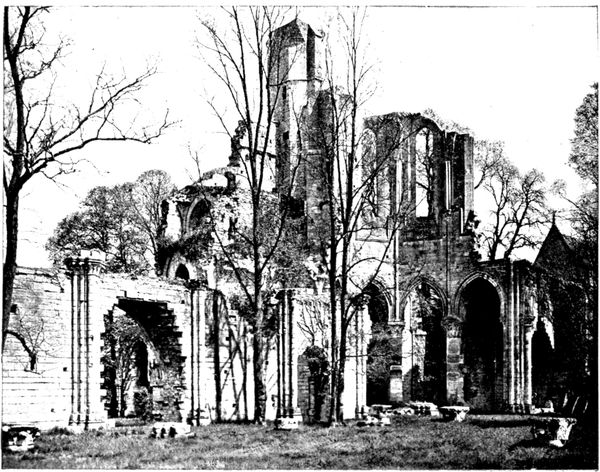

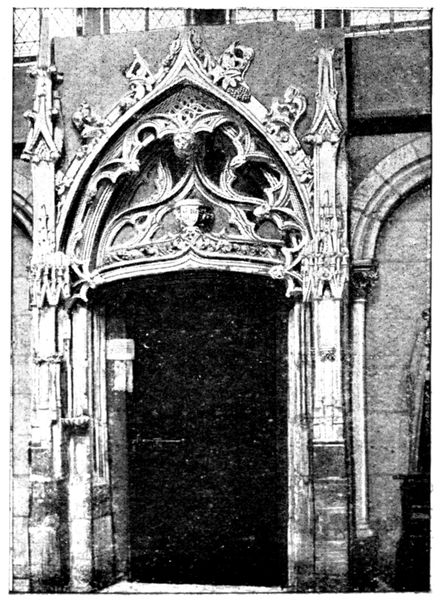

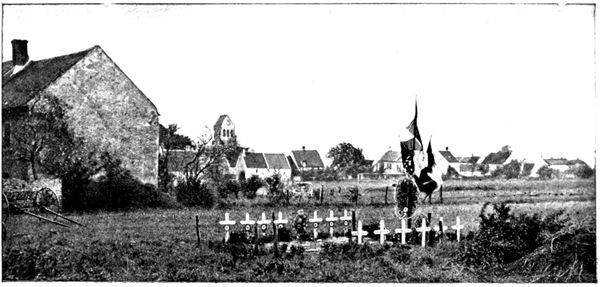

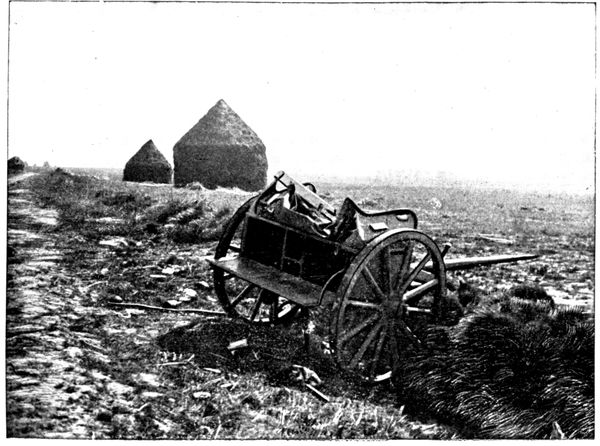

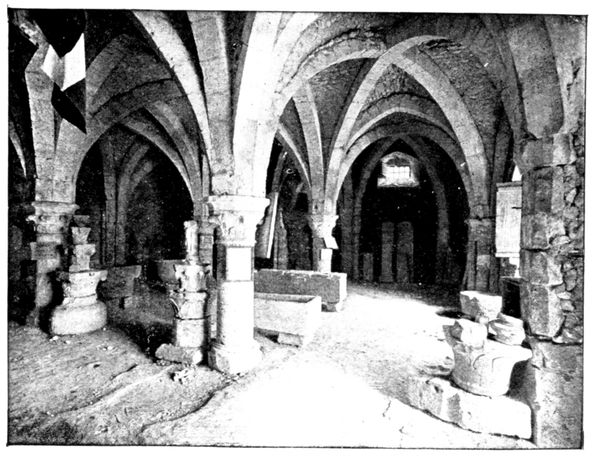

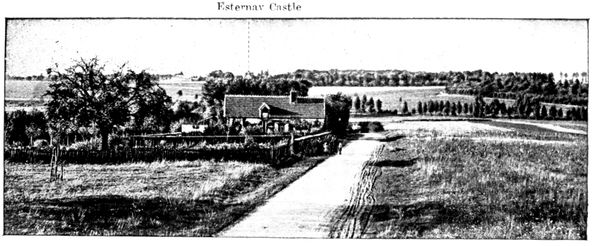

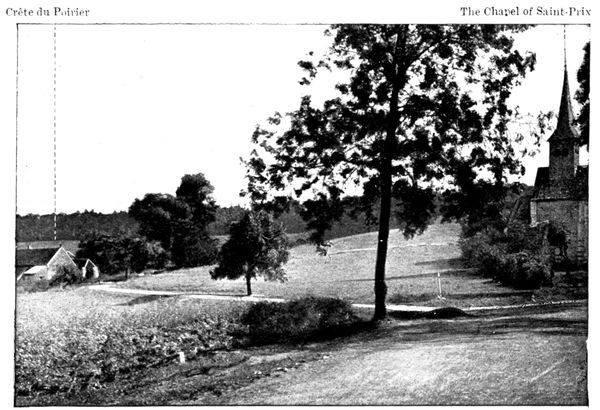

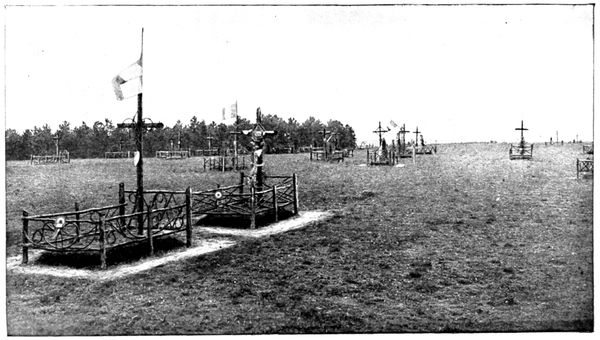

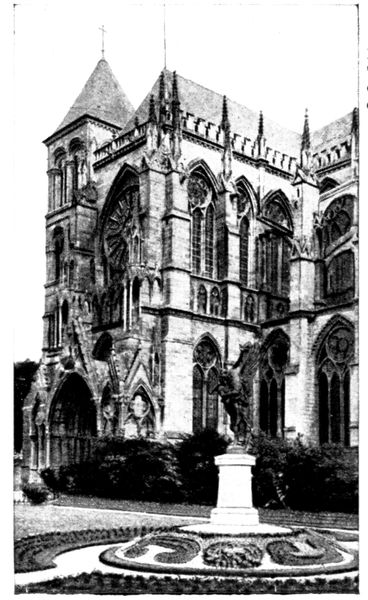

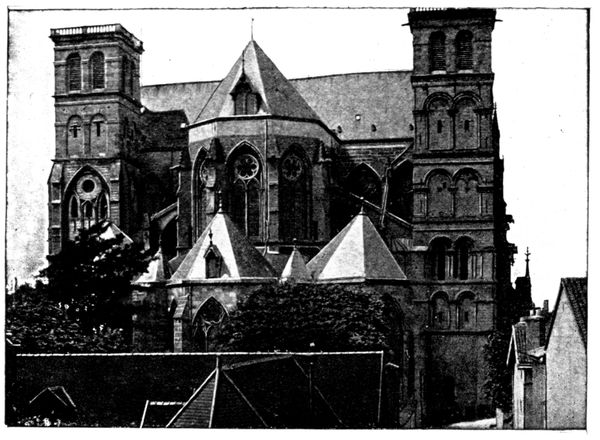

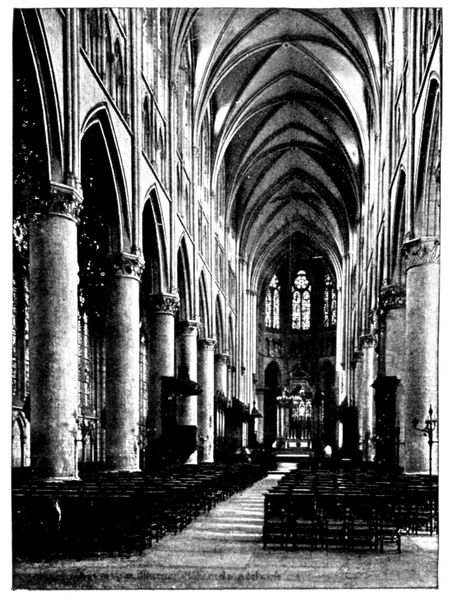

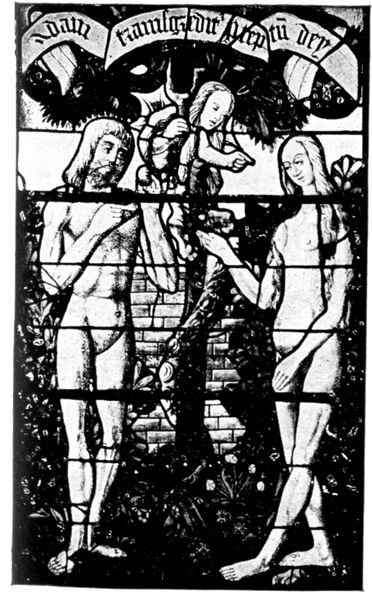

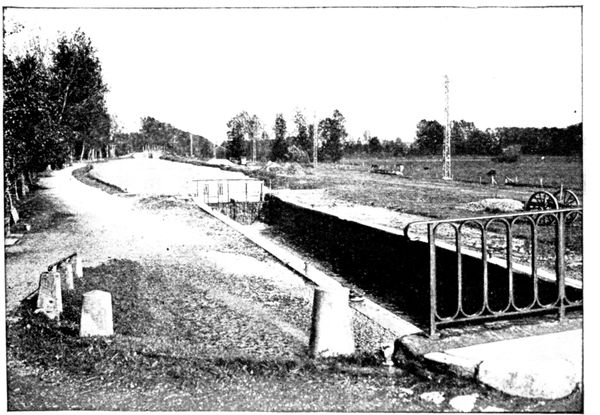

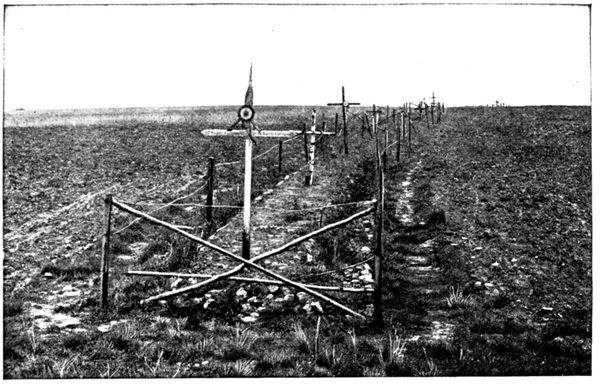

Court of Louis XV. the circuitous way and steep ascent of the old road,