LA GRANDE MADEMOISELLE

FROM A STEEL ENGRAVING

1627-1652

BY

ARVÈDE BARINE

AUTHORISED ENGLISH VERSION BY

HELEN E. MEYER

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

1902

Copyright, 1902

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

Published, November, 1902

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

La Grande Mademoiselle was one of the most original persons of her epoch, though it cannot be said that she was ever of the first order. Hers was but a small genius; there was nothing extraordinary in her character; and she had too little influence over events to have made it worth while to devote a whole volume to her history—much less to prepare for her a second chronicle—had she not been an adventurous and picturesque princess, a proud, erect figure standing in the front rank of the important personages whom Emerson called "representative."

Mademoiselle's agitated existence was a marvellous commentary on the profound transformation accomplished in the mind of France toward the close of the seventeenth century,—a transformation whose natural reaction changed the being of France.

I have tried to depict this change, whose traces are often hidden by the rapid progress of historical events, because it was neither the most salient feature of the closing century nor the result of a revolution.

Essential, of the spirit, it passed in the depths of the eager souls of the people of those tormented[iv] days. Such changes are analogous to the changes in the light of the earthly seasons. From day to day, marking dates which vary with the advancing years, the intense light of summer gives place to the wan light of autumn. So the landscape is perpetually renewed by the recurring influences of natural revolution; in like manner, the moral atmosphere of France was changed and recharged with the principles of life in the new birth; and when the long civil labour of the Fronde was ended, the nation's mind had received a new and opposite impulsion, the casual daily event wore a new aspect, the sons viewed things in a light unknown to their fathers, and even to the fathers the appearance of things had changed. Their thoughts, their feelings, their whole moral being had changed.

It is the gradual progress of this transformation that I have attempted to show the reader. I know that my enterprise is ambitious; it would have been beyond my strength had I had nothing to refer to but the Archives and the various collections of personal memoirs. But two great poets have been my guides, Corneille and Racine, both faithful interpreters of the thoughts and the feelings of their contemporaries; and they have made clear the contrast between the two distinct social epochs—between the old and the new bodies, so different, yet so closely connected.

When the Christian pessimism of Racine had—in the words of Jules Lemaître—succeeded the[v] stoical optimism of Corneille, all the conditions evolving their diverse lines of thought had changed.

The nature of La Grande Mademoiselle was exemplified in the moral revolution which gave us Phédre thirty-four years (the space of a generation) after the apparition of Pauline.

In the first part of her life,—the part depicted in this volume,—Mademoiselle was as true a type of the heroines of Corneille as any of her contemporaries. Not one of the great ladies of her world had a more ungovernable thirst for grandeur; not one of them cherished more superb scorn for the baser passions, among which Mademoiselle classed the tender sentiment of love. But, like all the others, she was forced to renounce her ideals; and not in her callow youth, when such a thing would have been natural, but when she was growing old, was she carried away by the torrent of the new thought, whose echoes we have caught through Racine.

The limited but intimately detailed and somewhat sentimental history of Mademoiselle is the history of France when Louis XIII. was old, and when young Louis—Louis XIV.—was a minor, living the happiest years of all his life.

If I seem presumptuous, let my intention be my excuse for so long soliciting the attention of my reader in favour of La Grande Mademoiselle.

CHAPTER I

PAGE

I. Gaston d'Orléans—His Marriage—His Character—II. Birth of Mademoiselle—III. The Tuileries in 1627—The Retinue of a Princess—IV. Contemporary Opinions of Education—The Education of Boys—V. The Education of Girls—VI. Mademoiselle's Childhood—Divisions of the Royal Family 1-80

I. Anne of Austria and Richelieu—Birth of Louis XIV.—II. L'Astrée and its Influence—III. Transformation of the Public Manners—The Creation of the Salon—The Hôtel de Rambouillet and Men of Letters 81-153

I. The Earliest Influences of the Theatre—II. Mademoiselle and the School of Corneille—III. Marriage Projects—IV. The Cinq-Mars Affair—Close of the Reign 154-236

I. The Regency—The Romance of Anne of Austria and Mazarin—Gaston's Second Wife—II. Mademoiselle's New Marriage Projects—III. Mademoiselle Would Be a Carmelite Nun—The Catholic Renaissance under Louis XIII. and the Regency—IV. Women Enter Politics—The Rivalry of the Two Junior Branches of the House of France—Continuation of the Royal Romance 237-327

I. The Beginning of Trouble—Paris and the Parisians in 1648—II. The Parliamentary Fronde—Mademoiselle Would Be Queen of France—III. The Fronde of the Princes and the Union of the Frondes—Projects for an Alliance with Condé—IV. La Grande Mademoiselle's Heroic Period—The Capture of Orleans—The Combat in the Faubourg Saint Antoine—The End of the Fronde—Exile 328-436

| page | |

| La Grande Mademoiselle Frontispiece | |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| Marie de Médicis | 6 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| The Château of Versailles from the Terrace | 8 |

| After the painting by J. Rigaud. | |

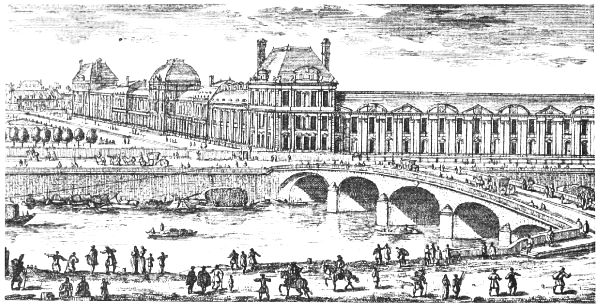

| The Tuileries from the Seine in the 16th Century | 22 |

| From a contemporary print. | |

| Madame de Sévigné | 54 |

| From an engraving of the painting by Muntz. | |

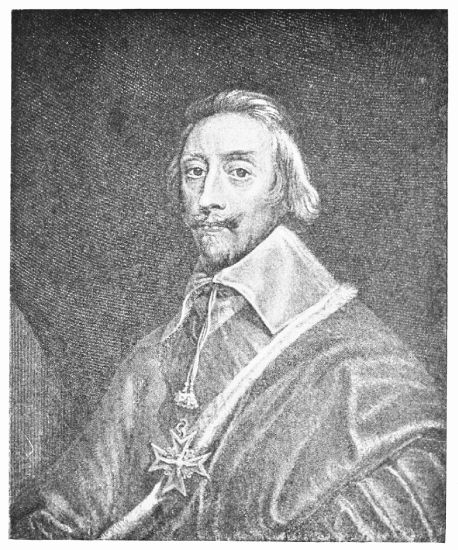

| Cardinal Richelieu | 84 |

| The Abbey of St. Germain Des-pres in the 16th Century | 110 |

| From an old print. | |

| Louis XIII., King of France and of Navarre | 152 |

| From an old print. | |

| Corneille | 168 |

| From an engraving of the painting by Lebrun. | |

| Racine | 182 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| The Hôtel de Richelieu in the 17th Century | 204 |

| From a contemporary print. | |

| A Game of Chance in the 17th Century | 210 |

| From an engraving by Sébastien Leclerc. | |

| Marquis de Cinq-Mars | 212 |

| Anne of Austria | 242 [x] |

| View of the Louvre from the Seine in the 17th Century | 254 |

| From an old print. | |

| Henriette, Duchesse d'Orléans | 258 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| St. Vincent De Paul | 292 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| Duchesse de Chevreuse | 300 |

| Cardinal Mazarin | 320 |

| Mademoiselle de Montpensier | 324 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| The Tower of Nesle | 342 |

| From a contemporary print. | |

| Cardinal de Retz | 344 |

| Madame de la Vallière | 366 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| Vicomte de Turenne | 398 |

| View of the Luxembourg (Later Called the Palais | |

| d'Orléans) in the 17th Century | 410 |

| From an old print. | |

| La Rochefoucauld | 416 |

| From a steel engraving. | |

| Prince de Condé | 420 |

| Duc d'Orléans | 422 |

I. Gaston d'Orléans—His Marriage—His Character—II. Birth of Mademoiselle—III. The Tuileries in 1627—The Retinue of a Princess—IV. Contemporary Opinions of Education—The Education of Boys—V. The Education of Girls—VI. Mademoiselle's Childhood—Divisions of the Royal Family.

In the Château of Versailles there is a full-length portrait of La Grande Mademoiselle,—so called because of her tall stature,—daughter of Gaston d'Orléans, and niece of Louis XIII. When the portrait was painted, the Princess's hair was turning grey. She was forty-five years old. Her imperious attitude and warlike mien befit the manners of the time of her youth, as they befit her Amazonian exploits in the days of the Fronde.

Her lofty bearing well accords with the adventures of the illustrious girl whom the customs and the life of her day, the plays of Corneille, and the novels of La Calprenède and of Scudéry imbued with sentiments much too pompous. The painter of the portrait had seen Mademoiselle as we have seen[2] her in her own memoirs and in the memoirs of her companions.

Nature had fitted her to play the part of the goddess in exile; and it had been her good fortune to find suitable employment for faculties which would have been obstacles in an ordinary life. To become the Minerva of Versailles, Mademoiselle had to do nothing but yield to circumstances and to float onward, borne by the current of events.

In the portrait, under the tinselled trappings the deep eyes look out gravely, earnestly; the thoughtful face is naively proud of its borrowed divinity; and just as she was pictured—serious, exalted in her assured dignity, convinced of her own high calling—she lived her life to its end, too proud to know that hers was the fashion of a bygone age, too sure of her own position to note the smiles provoked by her appearance. She ignored the fact that she had denied her pretensions by her own act (her romance with Lauzun,—an episode by far too bourgeois for the character of an Olympian goddess). She had given the lie to her assumption of divinity, but throughout the period of her romance she bore aloft her standard, and when it was all over she came forth unchanged, still vested with her classic dignity. The old Princess, who excited the ridicule of the younger generation, was, to the few surviving companions of her early years, the living evocation of the past. To them she bore the ineffaceable impression of the thought, the[3] feeling, the inspiration, the soul of France, as they had known it under Richelieu and Mazarin.

The influences that made the tall daughter of Gaston d'Orléans a romantic sentimentalist long before sentimental romanticism held any place in France, ruled the destinies of French society at large; and because of this fact, because the same influences that directed the illustrious daughter of France shaped the course of the whole French nation, the solitary figure—though it was never of a high moral order—is worthy of attention. La Grande Mademoiselle is the radiant point whose light illumines the shadows of the past in which she lived.

I

Anne-Marie-Louise d'Orléans, Duchess of Montpensier, was the daughter of Gaston of France, younger brother of King Louis XIII., and of a distant cousin of the royal family, Marie of Bourbon, Duchess of Montpensier. It would be impossible for a child to be less like her parents than was La Grande Mademoiselle. Her mother was a beautiful blond personage with the mild face of a sheep, and with a character well fitted to her face. She was very sweet and very tractable. Mademoiselle's father resembled the decadents of our own day. He was a man of sickly nerves, vacillating, weak of purpose, with a will like wax, who formed day-dreams in which he figured as a gallant and warlike knight, always on the alert, always the[4] omnipotent hero of singularly heroic exploits. He deluded himself with the idea that he was a real prince, a typical Crusader of the ancient days. In his chaotic fancy he raised altar against altar, burning incense before his purely personal and peculiar gods, taking principalities by assault, bringing the kings and all the powers of the earth into subjection, bearing down upon them with his might, and shifting them like the puppets of a chess-board. His efforts to attain the heights pictured by his imagination resulted in awkward gambols through which he lost his balance and fell, crushed by the weight of his own folly. Thus his life was a series of ludicrous but tragic burlesques.

In the seventeenth century, in flesh and blood, he was the Prince whom modern writers set in prominent places in romance, and whom they introduce to the public, deluded by the thought that he is the creature of their invention. Louis XIII. was a living and pitiable anachronism. He had inherited all the traditions of his rude ancestors. Yet, to meet the requirements of his situation, nature had accoutred him for active service with nothing but an enervated and unbalanced character. One of his most odious infamies—his first—served as a prologue to the birth of "Tall Mademoiselle." In 1626, as Louis XIII. had no child, his brother Gaston was heir-presumptive to the throne, and he was a bachelor. They who had some interest in the question were pushing him from all sides, urging him not to fetter himself by the inferior[5] marriage of a younger son. They implored him to have patience; to "wait a while"; to see if there would not be some unlooked-for opening for him in the near future. His own apparent future was promising; there was much encouragement in the fact that the King was sickly. What might not a day bring forth?—"under such conditions great changes were possible!"

Monsieur's mind laid a tenacious grasp on the idea that he must either marry a royal princess, or none at all; and he was so imbued with the thought that he must remain free to attain supreme heights that when Marie de Médicis proposed to him a marriage with the richest heiress of France, Mlle. de Montpensier, he tried to evade her offer. He encouraged Chalais's conspiracy, which was to be the means of helping him to effect his flight from Court; he permitted his friends to compromise themselves, then without a shadow of hesitation he sold them all. When the plot had been exposed, he hastily withdrew his irons from the fire by reporting everything to Richelieu and the Queen-mother. His friends tried to excuse him by saying that he had lost his head; but it was not true. His avowals as informer are on record in the archives of the Department of Foreign Affairs, and they prove that he was a man who knew very well what he was doing and why he was doing it, who worked intelligently and systematically, planning his course with matter-of-fact self-possession, selling his treason at the highest market-price of such commodities.

The 12th July, 1626, Monsieur denounced thirty of his friends, or servitors, whose only fault had lain in their devotion to his interests.

Once when Marie de Médicis reproached him for having failed to keep a certain written promise "never to think of anything tending to separate him from the King," Monsieur replied calmly that he had signed that paper but that he never had said that he would not do it,—that he "never had given a verbal promise." They then reminded him that he had "solemnly sworn several times." The young Prince replied with the same serenity, that whenever he took an oath, he did it "with a mental reservation."

The 18th, Monsieur, being in a good humour, made some strong protestations to his mother, who was in her bed. He again took up the thread of his denunciations to Richelieu without waiting to be invited to give his information. The 23d, he went to the Cardinal and told him to say that he, Monsieur, was ready to marry whenever they pleased, "if they would give him his appanage at the time of the marriage,"—after which announcement he remarked that the late M. d'Alençon had had three appanages. Monsieur sounded his seas, and spied out his land in all directions, carefully gathering data and making very minute investigations as to the King's intentions. He intimated his requirements to the Cardinal, who "sent the President, Le Coigneux, to talk over his marriage and his appanage."

MARIE DE MEDICIS

FROM A STEEL ENGRAVING

His haggling and his denunciations alternated until August 2d. Finally he obtained the duchies of Montpensier and of Chartres, the county of Blois, and pecuniary advantages which raised his income to the sum of a million livres. His vanity was allowed free play on the occasion of the signing of the contract, but this was forgiven him because he was only eighteen years old.

Monsieur had eighty French guards, all wearing casques, and bandoleers of the fine velvet of his livery. Their helmets were loaded, in front and behind, with Monsieur's initials enriched with gold. He had, also, twenty-four Swiss guards, who marched before him on Sundays and other fête days, with drums beating, though the King was still in Paris. He was fond of pomp. The lives of his friends did not weigh a feather in the balance against a few provinces and a rolling drum.

His guardian, Marshal d'Ornano, was a prisoner in Versailles, where the Court was at that time. Investigations against him were in rapid progress; but the face of the young bridegroom was wreathed with smiles when he led his bride to the altar, 5th August, 1626. As soon as he had given his consent they had hastened the marriage. The ceremony took place as best it could. It was marriage by the lightning process. There was no music, the bridegroom's habit was not new. While the cortège was on its way, two of the resplendent duchesses quarrelled over some question of precedence. To quote the Chronicles: "From words they came to blows and from blows to scratches of their skins."

This event scandalised the public, but the splendour of the fêtes effaced the memory of the regrettable incidents preceding them. While the fêtes were in progress, Monsieur exhibited a gayety which astonished the people; they were not accustomed to the open display of such indelicacy. It was known why young Chalais had been condemned to death; it was known that Monsieur had vainly demanded that he be shown some mercy. When the 19th—the day of execution—came, Monsieur saw fit to be absent. The youthful Chalais was beheaded by a second-rate executioner, who hacked at his neck with a dull sword and with an equally dull tool used by coopers. When the twentieth blow was struck, Chalais was still moaning. The people assembled to witness the execution cried out against it.

Fifteen days later Marshal d'Ornano gave proof of his accommodating amiability by dying in his prison. Others who had vital interests at stake either fled or were exiled.

THE CHATEAU OF VERSAILLES FROM THE TERRACE

AFTER THE PAINTING BY J. RIGAUD

Judging from appearances, Monsieur had had nothing to do with the condemned or the suspected. His callous levity was noted and judged according to its quality. Frequently tolerant to an extraordinary degree, the morality of the times was firm enough where the fidelity of man to master, or of master to man, was concerned. The common idea of decency exacted absolute devotion from the soldier to his chief, from servant to employer, from the gentleman to his seignior. Nor was the duty of master to man less binding. Though his creatures[9] or servants were in the wrong, though their failures numbered seventy times seven, it was the master's part to uphold, to defend, and to give them courage, to stand or to fall with them, as the leader stands with his armies. Gaston knew this; he knew that he dishonoured his own name in the eyes of France when he delivered to justice the men who had worn his colours. But he mocked at the idea of honour, shaming it, as those among our own sons—if they are unfortunate enough to resemble him—mock at the higher and broader idea of home and country,—the idea which, in our day, takes the place of all other ideas exacting an effort or a sacrifice.

It must not be supposed that Monsieur was an ordinary poltroon, bowed down by the weight of his shame, desperately feeble, a mawkish and shambling type of the effeminate adolescent; though a coward in shirking consequences he was a typical "prince": very spirited, very gay, and very brilliant; conscious of the meaning of all his actions; contented in his position,—such as he made it,—and resigned to act the part of a coward before the world.

His vivacity was extraordinary. The people marvelled at his unfailing lack of tact. Though very young, he was well grown. He was no longer a child whose nurse caught him with one hand, forcibly buttoning his apron as he struggled to run away; yet he skipped and gambolled, spinning incessantly on his high heels, his hand thrust into his pocket, his cap over his ear. In one way or in[10] another he incessantly proclaimed his presence. His sarcastic lips were always curved over his white teeth; he was always whistling.

"One can see well that he is high-born," wrote the indulgent Madame de Motteville. "His restlessness and his grimaces show it." But Madame de Motteville was not his only chronicler. Others relished his manners less. A gentleman who had lived in his (Monsieur's) house when Monsieur was very young, saw him again under Mazarin, and finding that despite his age and size he was the same peculiar being that he had been in infancy, the old gentleman turned and ran away. "Well, upon my word," he cried, "if he is not the same deuced scamp as in the days of Richelieu! I shall not salute him."

Monsieur's portraits are not calculated to contradict the impression given by his contemporaries. He is a handsome boy. The long oval face is delicately fine. The eyes are spiritual; and despite its look of self-sufficiency the whole face is infinitely charming. One of the portraits shows a certain shade of sly keenness, but as a whole the face is always indescribably attractive,—and yet as we gaze upon it we are seized by an impulse to follow the example of the old marquis, and run away without saluting. In the portrait the base soul looks out of the handsome face just as it did in life, manifesting its deplorable reality through its mask of natural beauty and intelligence. No one could say that Monsieur was a fool. Retz declared: "M. le[11] Duc d'Orléans had a fine and enlightened mind." It was the general impression that his conversation was admirable; judged by his talk he was a being of a superior order. His manners and his voice were engaging. He was an artist, very fond of pictures and rare and handsome trifles. He was skilful in engraving on metals; he loved literature; he loved to read; he was interested in new ideas and in the march of thought. He knew many curious sciences. He was a cheerful companion, easy-mannered, sprightly, easy of approach, fond of raillery, and full of his jests, but his jests were never ill-natured. Even his enemies were forced to own that he had a good disposition, and that he was naturally kind; and this was the general opinion of the strange being who was a Judas to so many of his most devoted friends.

Had Monsieur possessed but one grain of moral consciousness, and had he been free from an almost inconceivable degree of weakness and of cowardice, he would have made a fine Prince Charming. But his poltroonery and his moral debility stained the whole fabric of his life and made him a lugubrious example of spiritual infirmity. He engaged in all sorts of intrigues because he was too weak to say No, and owing to the same weakness he never honestly fulfilled an engagement.

At times he started out intending to do his duty, then when midway on his route he was seized by fear, he took the bit between his teeth, and ran, and nothing on earth could stop him. He carried[12] out his cowardice with impudence, and his villainy was artful and adroit. However base his action, he was never troubled by remorse. He was insensible to love, and devoid of any sense of honour. Having betrayed his associates, he abandoned them to their fate, then thrust his hand into his pocket, pirouetted, cut a caper, whistled a tune, and thought no more of it.

II

The third week in October the Duchess of Orleans returned to Paris. The Court was at the Louvre. The young pair, Monsieur and his wife, had their apartments in the palace, and the courtiers were not slow in finding their way to them.

Hardly had she arrived when Madame declared her pregnancy. As there was no direct heir to the crown, this event was of great importance. The people precipitated themselves toward the happy Princess who was about to give birth to a future King of France. Staid and modest though she was, her own head was turned by her condition. She paraded her hopes. It seemed to her that even then she held in her arms the son who was to take the place of a dauphin. Every one offered her prayer and acclamations; and every one hailed Monsieur as if he had been the rising sun.[1]

Monsieur asked nothing better than to play his part; he breathed the incense offered to his brilliant prospects with felicity.

Husband and wife enjoyed their importance to the full; they displayed their triumphant faces in all parts of that palace that had seen so much bitterness of spirit.

In itself, politics apart, the Louvre was not a very agreeable resting-place. On the side toward Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois its aspect was rough and gloomy. The remains of the old fortress of Philip Augustus and of Charles V. were still in existence. Opposite the Tuileries, towards the Quai, the exterior of the palace was elegant and cheerful. There the Valois and Henry IV. had begun to build the Louvre as we know it to-day.

A discordant combination of extreme refinement and of extreme coarseness made the interior of the palace one of the noisiest and dirtiest places in the world. The entrance to the palace of the King of France was like the entrance to a mill; a tumultuous crowd filled the palace from morning until night; and it was the custom of the day for individuals to be perfectly at ease in public,—no one stood on ceremony. The ebbing and flowing tide of courtiers, of business men, of countrymen, of tradesmen, and all the throngs of valets and underlings considered the stairways, the balconies, the corridors, and the places behind the doors, retreats propitious for the relief of nature.

It was a system, an immemorial servitude, existing in Vincennes and Fontainebleau as at the Louvre,—a system that was not abolished without great difficulty. In a document dated posterior to[14] 1670, mention is made of the thousand masses of all uncleanness, and the thousand insupportable stenches, "which made the Louvre a hot-bed of infection, very dangerous in time of epidemic." The great ones of earth accepted such discrepancies as fatalities; they contented themselves with ordering a sweep of the broom.

Neither Gaston nor the Princess, his wife, descended to the level of their critical surroundings. They were habituated to the peculiar features of the royal palaces; and certainly that year, in the intoxication of their prospects, they must have considered the palatial odours very acceptable.

It did not agree with their frame of mind to note that the always gloomy palace was more than usually dismal. Anne of Austria had been struck to the heart by the pregnancy of her sister-in-law. She had been married twelve years and she no longer dared to cherish the hope of an heir. She felt that she was sinking into oblivion. Her enemies had begun to insinuate that her usefulness was at an end and that she had no reason for clinging to life. The Queen of France lived so eclipsed a life that to the world she was nothing but a pretty woman with a complexion of milk and roses. The people knew that she was unhappy, and they pitied her. They never learned her true character until she became Regent. Anne of Austria was not the only one to drain the cup of bitterness that year. Louis XIII. also was jealous of the maternity of Madame. It was a part of his nature to cherish[15] evil sentiments, and his friends found some excuse for his faults in his misfortunes. Since Richelieu had attained power, Louis had succumbed to the exigencies of monarchical duty. His whole person betrayed his distress, exhaling constraint and anxiety. The most mirthful jester quailed at the sight of the long, livid face, so mournful, so expressive of the mental torment of the Prince who "knew that he was hated and who had no fondness for himself."

Louis was timid and prudish, and, like his brother, he had sick nerves. Hérouard, who was his doctor when he was a child, exhibits the young Prince as a somnambulist, who slept with eyes open, and who arose in his sleep, walking and talking in a loud voice. Louis's doctors put an end to any strength that he may have had originally. In one year Bouvard bled him forty-seven times; and during that one twelvemonth the child was given twelve different kinds of medicines and two hundred and fifteen enemas. Is it credible that after such an experience the unhappy King merited the reproach of being "obstreperous in his intercourse with the medical faculty"?

He had studied but little; he took no interest in the things that pleased the mind; his pastimes were purely animal. He liked to hunt, to work in his garden, to net pouches for fish and game, to make snares and arquebuses. He liked to make preserves, to lard meat, and to shave. Like his brother, he had one artistic quality: he loved music[16] and composed it. "This was the one smile, the only smile of a natural ingrate."

Louis XIII. was of a nature dry and hard. He detested his wife; he loved nothing on earth but his young favourites. He loved them; then, in an instant, without warning, he ceased to love them; and when he had ceased to love them he did not care what became of them,—did not care whether they lived or died. Whenever he could witness the agony of death he did so, and turned the occasion into a picnic or a pleasure trip. He enjoyed watching the grimaces of the dying. His religious devotion was sincere, but it was narrow and sterile. He was jealous and suspicious, forgetful, frivolous, incapable of applying himself to anything serious.

He had but one virtue, but that he carried to such lengths that it sufficed to embalm his memory. This virtue was the one which raised the family of Hohenzollern to power and to glory. The sombre soul of Louis XIII. was imbued with the imperious sentiment of royal duty,—the professional duty of the man designed and appointed by Divine Providence to give account to God for millions of the souls of other men. He never separated either his own advantage or his own glory from the advantage and the glory of France. He forced his brother to marry, though he knew that the birth of a nephew would ulcerate his own flesh. He harboured Richelieu with despairing resolution because he believed that France could not maintain its existence without the hated ministry. He had the[17] essential quality, the one quality which supplies the lack of other qualities, without which all other qualities, great and noble though they be, are useless before the State.

Around these chiefs of the Court buzzed a swarm of ambitious rivals and whispering intriguers all animated by one purpose, to effect the discomfiture of Richelieu. The King's health was failing. The Cardinal knew that Louis "had not two days to live"; he was seen daily, steadily advancing toward the grave. In Michelet's writings there is a striking page devoted to the "great man of business wasting his time and strength struggling against I do not know how many insects which have stung him." Marie de Médicis was the only one who united with the King in defending Richelieu in the critical winter of 1626. The Cardinal was the Queen's creature. The pair had many memories in common—and of more than one kind. Some years previous Richelieu had taken the trouble to play lover to the portly quadragenarian, and he had brought to bear upon his effort all the courage requisite for such a suit. The Court of France had looked on while the Cardinal took lessons in lute playing, because the Queen-mother, notwithstanding her age and her proportions, had had a fancy to play the lute as she had done when a little girl. Marie de Médicis had given proof that she was not insensible to such delicate attentions, and she had forgotten nothing; but the moment was approaching when Richelieu would find that it had[18] been to no purpose that he had shouldered the ridicule of France by sighing out his music at the feet of the fat Queen.

That year a stranger would have said that the Court of France had never been more gay. Fête followed fête. In the winter there were two grand ballets at the Louvre, danced by the flower of the nobility, the King at their head. Louis XIII. adored such exhibitions, though they overthrow all modern ideas of a royal majesty.

The previous winter he had invited the Bourgeoisie of Paris to the Hôtel-de-Ville to contemplate their ghastly monarch masked for the carnival, dancing his grand pas. "It is my wish," said he, "to confer honour upon the city by this action." The Bourgeoisie had accepted the invitation; man and wife had flocked to the appointed place at the appointed hour, and there they had waited from four o'clock in the afternoon until five o'clock in the morning, before the royal dancers had made their appearance. The dance had not ended until noon, when the honoured Bourgeoisie had returned to their homes.

Monsieur took his full share of all official pleasures, and he had also some pleasures of his own,—and purely personal they were. Some of them were infantine; some of them, marked by intelligence, were far in advance of the ideas of that epoch. Contemporary customs demanded that people of the world should relegate their serious affairs to the tender mercies of the professional[19] keen wits, who made it their business to attend to such questions. Gaston used to convene the chosen of his lords and gentlemen, to argue subjects of moral and political import. In discussion Monsieur bore himself very gallantly. The resources of his wit were inexhaustible, and the justice of his judgment invariably evoked applause. He was a sleep-walker, because awake or asleep he was so restless that "he could not stay long in one place."[2] But he was not always asleep when he was met in the night groping his way through the noisome alleys. He used to jump from his bed, disguise himself, and run about in the night, leading a life like that of the wretched Gérard de Nerval, lounging on foot through the little streets of Paris which were very dark and suspiciously dirty. It amused him to enter strange houses and invite himself to balls and other assemblies. His behaviour in such places is not recorded, but the gentlemen who followed him (to protect him) let it be understood that there was "nothing good in it."

Gaston of Orleans had all the traits common to those whom we call "degenerate." His chief characteristic was an active form of bare and shameless moral relaxation. He was the mainspring of many and various movements.

One day when Richelieu was present, Louis XIII. twitted the Queen with her fancies. He said that she had "wished to prevent Monsieur from marrying[20] so that she could marry him herself when she became a widow."

Anne of Austria cried out: "I should not have gained much by the change!"

(Neither would France have "gained much by the change," and it was fortunate for her that Louis was permitted to retain possession of his feeble rights.)

The child so desired by some, so envied and so dreaded by others, entered the world May 29, 1627. Instead of a dauphin it was a girl—La Grande Mademoiselle. Seven days after the child was born the mother died.

Louis XIII. gave orders for the provision of royal obsequies, and he himself sprinkled the bier with the blessed water, very grateful because Providence had not endowed him with a nephew. Anne of Austria, incognito, assisted at the funeral pomps. This act was received with various interpretations. The simple—the innocent-minded—said that it was a proof of the compassion inspired by Madame's sudden taking off; the malicious supposed that it was just as the King had said: "The Queen loved Monsieur; she rejoiced in his wife's death; she hoped to marry him when she became a widow."

The Queen was sincerely afflicted by Madame's death. She cherished an open preference for her second son, and the thought of his ambitious flight had agreeably caressed her heart.

Richelieu pronounced a few suitable words of regret for the Princess who had never meddled[21] with politics, and Monsieur did just what he might have been expected to do: he wept boisterously, immediately dried his tears, and plunged into debauchery.

The Court executed the regulation manœuvres, and came to the "about face" demanded by the circumstances. Whatever may have been the calculations made by individuals relative to the positions to be taken in order to secure the best personal results, and whatever the secret opinions may have been (as to the advantages to be drawn from the catastrophe), it was generally conceded that the little Duchess had been fortunate in being left sole possessor of the vast fortune of the late Madame her mother.

The latter had brought as marriage-portion the dominion of Dombes, the principality of Roche-sur-Yon, the duchies of Montpensier, Châtellerault, and Saint-Fargeau, with several other fine tracts of territory bearing the titles of marquisates, counties, viscounties, and baronies, with very important incomes from pensions granted by the King and by several private individuals,—in all amounting to three hundred thousand livres of income.[3]

The child succeeding to this immense inheritance was the richest heiress in Europe. As her mother had been before her, so Mademoiselle was raised in all the magnificence and luxury befitting her rank and fortune.

III

They had brought her from the Louvre to the Tuileries by the balustraded terrace along the Seine.[4]

She was lodged in the Dôme—known to the old Parisians as the pavillon d'Horloge—and in the two wings of the adjoining buildings. At that time the Tuileries had not assumed the aspect of a great barrack. They wore a look of elegance and fantastic grace before they were remodelled and aligned by rule. At its four corners the Dôme bore four pretty little towers; on the side toward the garden was a projecting portico surmounted by a terrace enclosed by a gallery. On this terrace, in time, Mademoiselle and her ladies listened to many a serenade and looked down on many a riot.

The rest of the façade (as far as the pavillon de Flore) formed a succession of angles, now jutting forward, now receding, in conformations very pleasing to the eye. The opposite wing and the pavillon de Marsan had not been built. Close at hand lay an almost unbroken country. The rear of the palace looked out upon a parterre; beyond the parterre lay a chaos from which the Carrousel was not wholly delivered until the Second Empire. There stood the famous Hôtel de Rambouillet, close to the hotel of Madame de Chevreuse, confidential friend of Anne of Austria and interested enemy of Richelieu. There were other hotels, entangled with churches, with a hospital, a "Court of Miracles," gardens, and wild lands overgrown with weeds and grasses. There were shops and stables; and away at the far end of the settlement stood the Louvre, closing the perspective.

THE TUILERIES FROM THE SEINE IN THE 16TH CENTURY

FROM A CONTEMPORARY PRINT

The Court and the city crowded together around the Bird House and the Swans' Pond, in the Dedalus and before the Echo, ogling or criticising one another. At that time the Place de la Concorde was a great, green field, called the Rabbit Warren. In one part of the field stood the King's kennels.[5] The city's limits separated the Champs-Élysées from the wild lands running down to the Seine at the point where the Pont de la Concorde now stands. This space, enclosed by the boundaries of the city, assured to the Court a park-like retreat in the green fields of the open country. The enclosure was entered by the gate of the Conférence. The celebrated "Garden of Renard" was associated with Mademoiselle's first memories. It had been taken from that part of La Garenne which lay between the gate of the Conférence[6] and the Garden of the Tuileries. Renard had been valet-de-chambre to a noble house. He was witty, pliable, complaisant to the wishes or the fancied needs of his employers, amiable, and of "easy, accommodating manners"[7]; in short, he was a[24] precursor of the Scapins and the Mascarelles of Molière. Mazarin found pleasure and profit in talking with him. Renard's garden was a bower of delights. It was the preferred trysting-place of the lordlings of the Court, and the scene of all things gallant in that gallant day.

The fair ladies of the Court frequented the place; so did the crowned queens; and there many an amorous knot was tied, and many a plot laid for the fall of many a minister.

There the men of the day gave dinners, and rolled under the table at dessert; and in the bosky glades of the garden the ladies offered their collations. There were balls, comedies, concerts, and serenades in the groves, and all the gay world met there to hear the news and to discuss it. Renard was the man of the hour, no one could live without him.

The Cours la Reine, created by Marie de Médicis, was outside of Paris. It was a broad path, fifteen hundred and forty common steps long, with a "round square," or rond-point, in its centre. In that sheltered path, the fine world, good and bad, displayed its toilets and its equipages.

Mlle. de Scudéry has given us a description of it at the hour when it was most frequented. Two of her characters entered Paris by the village of Chaillot.

Coming into the city, where Hermogène led Bélésis, one finds beside the beautiful river four great alleys, so broad, so straight, and so shaded by the great trees which form them,[25] that one could not imagine a more agreeable promenade. And this is the place where all the ladies come in the evening in little open chariots, and where all the men follow them on horseback; so that having liberty to approach either one or the other, or all of them, as they go up and down the paths they all promenade and talk together; and this is doubtless very diverting.

Hermogène and Bélésis having penetrated into the Cours,

they saw the great alleys full of little chariots, all painted and gilded; sitting in the chariots were the most beautiful ladies of Suze (Paris), and near the ladies were infinite numbers of gentlemen of quality, admirably well mounted and magnificently dressed, going and coming, saluting as they passed.

In the summer they lingered late in the Cours la Reine, and ended the evening at Renard's. Marie de Médicis and Anne of Austria were rarely absent.

Close by the Champs-Élysées lay a forest, through which the huntsman passed to hunt the wolf in the dense woods of the Bois de Boulogne. In the distance could be seen the village of Chaillot, perched on a height amidst fields and vines. Market gardens covered the quarters of Ville l'Evêque and the Chaussée d'Antin.

Mademoiselle was installed with royal magnificence at the Tuileries. In her own words: "They made my house, and they gave me an equipage much grander than any daughter of France had ever had."

Thirty years later she was still happily surrounded by the retinue provided by her far-seeing[26] guardians. Her servitors were of every grade, from the lowest, who prepared a pathway for her feet, to the highest, whose service added dignity to her presence. By investing her with her nucleus of domestic tributaries, her friends had established her importance, even in her infancy, by manifestations that could not be disputed. In that day people were obliged to attach importance to such details. But a short time had passed since brutal force had been the only recognised right; and it was the way of the world to judge the grandeur of a prince by the length and volume of his train. It was because La Grande Mademoiselle had, from earliest youth, possessed an army of squires, of courtiers, of valets, and of serving-men and serving-women—a horde beginning with the fine milord and ending with the hare-faced scullion, seen now and then in some shadowy retreat of the palace, low-browed, down-trodden, looking out with dazzled eyes upon the world of life and luxury,—it was because she had been a ruler even in her swaddling bands, that she could aspire, naturally and without overweening arrogance, to the hands of the most powerful sovereigns. "The sons of France," says a document of 1649, "are provided with just such officials as surround the King; but they are less numerous.... The Princes have officers in accordance with their revenues and in accordance with the rank that they hold in the kingdom."[8]

The same document furnishes us with details of[27] the installation of Anne of Austria. If, when we estimate the equipage of Mademoiselle, we reduce it by half of the estimate of the Queen's equipage, we fall short of the reality. Like an army in campaign, a Court ought to be sufficient unto itself, able to meet all its requirements. The upper domestic retinue of the Queen comprised more than one hundred persons, maîtres-d'hôtel or stewards, cup-bearers, carvers, secretaries, physicians, surgeons, oculists, musicians, squires, almoners, nine chaplains, "her confessor," a common confessor, and too many other kinds of employees to be enumerated. Under all these officials, each one of whom had his own especial underlings, were equal numbers of valets and of chambermaids who assured the service of the apartments. The Court cooking kept busy one hundred and fifty-nine drilled knife-sharpeners, soup-skimmers, roast-hasteners, and water-handers, or people to hand water as the cooks needed it for their mixtures. There were other servitors whose business it was to await the beck and call of their superiors,—call-boys, always waiting for signals. Then came the busy world of the stables; then fifty merchants or shop-men, and an indefinite number of artisans of all the orders of all the trades. In all there were between six and seven hundred souls, not counting the valets of the valets or the grand "charges," the officials close to the Queen, the Queen's chancellor, the chevaliers d'honneur, or gentlemen-in-waiting, the ladies in-waiting, and maids of honour.

The great and noble people were often very badly served by their hordes of servants. Madame de Motteville tells us how the ladies of the Court of Anne of Austria were nourished in the peaceful year 1644, when the Court coffers were yet full.

According to the law of etiquette, the Queen supped in solitary state. Her supper ended, we ate what was left. We ate without order or measure, in any way we could. Our only table service was her wash-cloth and the remnants of her bread. And, though this repast was very ill-organised, it was not at all disagreeable, because it had the advantage of what is called "privacy," and because of the quality and the merit of those who sometimes met there.

The most modern Courts still retain some vestiges of the Middle Ages. Louis XIII. had, or had had, four dwarfs, their salary being three hundred "tournois" or Tours livres. The King paid a man to look after his dwarfs, keep them in order, and regulate their conduct.[9]

To the day of her death, despite her exile and her misery, Marie de Médicis maintained in her service a certain Jean Gassan, who figures in her will as employed in "keeping the parrot."

When a child, Louis XIV. had two baladins. Mademoiselle had a dwarf who did not retire from her service until 1645. The registers of the Parliament (date, 10th May, 1645) contain letters patent and duly verified, by which the King accorded to "Ursule Matton, the dwarf of Mademoiselle, sole daughter of the Duke of Orleans, the power and[29] the right to establish a little market in a court behind the new meat market of Saint Honoré."[10]

Marie de Médicis completed the house and establishment of her granddaughter by giving her, for governess, a person of much virtue, wit, and merit, Madame de Saint Georges, who knew the Court thoroughly. Nevertheless Mademoiselle asserted that she had been very badly raised, thanks to the herd of flattering hirelings who thronged the Tuileries, and who no sooner surrounded her than they became insupportable.

It is a common thing [said she] to see children who are objects of respect, and whose high birth and great possessions are continually the subject of conversation, acquire sentiments of spurious glory. I so often had at my ears people who talked to me either about my riches or about my birth that I had no trouble to persuade myself that what they said was true, and I lived in a state of vanity which was very inconvenient.

While very young she had reached a degree of folly where it displeased her to have people speak of her maternal grandmother, Madame de Guise. "I used to say: 'She is my distant grandmamma; she is not Queen.'"

It does not appear that Madame Saint Georges, that person of so much merit, had done anything to neutralise evil influences.

Throughout the seventeenth century, opinions on the education of girls were very vacillating because little importance was attached to them. In[30] 1687, after all the progress accomplished through the double influence of Port Royal and Madame de Maintenon, Fénelon wrote:

Nothing is more neglected than the education of girls. Fashion and the caprices of the mothers often decide nearly everything. The education of boys is considered of eminent importance because of its bearing upon the public welfare; and while as many errors are committed in the education of boys as in the education of girls, at least it is an accepted idea that a great deal of enlightenment is required for the successful education of a boy.

It was supposed that contact with society would be sufficient to form the mind and to polish the wit of woman. In this fact lay the cause of the inequality then noticeable in women of the same class. They were more or less superior from various points of view, as they had been more or less advantageously placed to profit by their worldly lessons, by the spectacle of life, and by the conversation of honest people.

The privileged ones were women who, like Mademoiselle and her associates, had been accustomed to the social circles where the history of their times was made by the daily acts of life. Their best teachers were the men of their own class, who intrigued, conspired, fought, and died before their eyes,—often for their pleasure. The agitated and peril-fraught lives of those men, their chimeras, and their romanticism put into daily practice, were admirable lessons for the future heroines of the Fronde. To understand the pupils, we must know[31] something of their teachers. What was the process of formation of those professors of energy; in what mould was run that race of venturesome and restless cavaliers who evoked a whole generation of Amazons made in their own image? The system of the education of France of that epoch is in question, and it is worthy of a close and detailed examination.

IV

From their infancy, boys were prepared for the ardent life of their times. They were raised according to a clearly defined and fixed idea common to rich and poor, to noble and to plebeian. The object of a boy's education was to make him a man while he was still very young. The only difference in the opinions of the gentleman and of the bourgeois was this:

The gentleman believed that action was the best stimulant to action. The bourgeois thought that the finer human sentiments, the so-called "humanities," were the only sound foundations for a virile and practical education. But whatever the method used, in that day, a man entered upon life at the age when our sons are but just beginning interminable studies preliminary to their "examinations." At the age of eighteen, sixteen—even fifteen years,—the De Gassions, the La Rochefoucaulds, the Omer Talons, and the Arnauld d'Andillys had become officers, lawyers, or men of business, and in their day affairs bore little resemblance to modern[32] affairs. In our day men do not enter active life until they have been aged and fatigued by the march of years. The time of entrance upon the career of life ought not to be a matter of indifference to a people. At the age of thirty years a man no longer thinks and feels as he thought and felt at the age of twenty. His manner of making war is different; and there is even more difference in his political action. He has different ambitions. His inclinations lead him into different adventures. The moments of history, when the agitators of the nation were young men, glow with the light of no other epoch. There was then an indefinable quality in life,—an active principle, more ardent and more vital. Under Louis XIII. there were scholars to make the unhappy students of our own emasculated times die of envy. Certain examples of our modern school become bald before they rise from the benches of their college.

Jean de Gassion, Marshal of France at the age of thirty years, who "killed men" at the age of thirty-eight years (1647), was the fourth son, but not the last, of a President of Parliament at Navarre, who had raised his offspring with great care (having destined him for the career of "Letters"). The child took such advantage of his opportunities that before he was sixteen years old he was a consummate scholar. He knew several of the living languages—German, Flemish, Italian, and Spanish. Thus prepared for active life, he set out from Pau astride of his father's old horse. When he[33] had gone four or five leagues, the old horse gave out. Jean de Gassion continued his journey on foot. When he reached Savoy, they made war on him. He enlisted as common soldier, and fought so well that he was promoted cornet. When peace was declared, he was in France. He determined to go to the King of Sweden—Gustavus Adolphus,—who was said to be somewhere in Germany. De Gassion had resolved to offer the King the service of his sword, and to ask to be allowed to lead the Swedish armies. But as he had no idea of presenting himself to the King single-handed, he persuaded some fifteen or twenty cavaliers of his own regiment to go with him, and embarked with them on the Baltic Sea. And—so runs the story—he just happened to land where Gustavus Adolphus was walking along the shore.

(Such coincidences are possible only when youths are in their teens; after the age of twenty, no man need hope for similar experience.) Jean saluted the King, and addressed him in excellent Latin. He expressed his desire to be of service. The King was amused; he received the strange offer amiably, and consented to put the learned stripling to the test. And so it was that Gassion was enabled to attain to a colonelcy when he was but twenty-two years old. His early studies had stood him in good stead; had he not known his Latin, he would have missed his career. His Ciceronian harangue, poured out fluently just as the occasion demanded it, attracted the favour of a King who was, by his own might, a prince of letters.

After the King of Sweden died, Gassion returned to France. With Condé he won the battle of Rocroy, and, during the siege, died of a bullet in his head, leaving behind him the reputation of a brilliant soldier and accomplished man of letters, as virtuous as he was brave. He never wished to marry. When they spoke to him of marriage, he answered that he did not think enough of his life to offer a share of it to any one. This was an expression of pessimism far in advance of his epoch.

La Rochefoucauld, who will never be accused of having been naturally romantic, offered another example of the miracles performed by youths. Only once in his life did he play the part of Paladin. He launched himself in politics before he had a beard. When he was sixteen years old, he entered upon his grand campaign, bearing the title of "Master of the Camp."

The following year he was at Court, elbowing his way among all the parties, busily engaged in opposition to Richelieu. But his politics did not add anything to his age; he was still an adolescent, far removed from the enlightened theorist of the Maximes.

The peculiarly special savour of the springtime of life was communicated to his soul at the hour appointed by nature. In him it was impregnated by a faint perfume of heroism and of poetry. He never forgot the happiness with which for a week or more he played the fool. He was then twenty-three[35] years old. Queen Anne of Austria was in the depths of her disgrace, maltreated and persecuted by her husband and by Richelieu.

In this extremity [said Rochefoucauld], abandoned by all the world, devoid of aid, daring to confide in no one but Mademoiselle de Hautefort—and in me,—she proposed to me to abduct them both and take them to Brussels. Whatever difficulty I may have seen in such a project, I can say that it gave me more joy than I had ever had in my life. I was at an age when a man loves to do extraordinary things, and I could not think of anything that would give me more satisfaction than that: to strike the King and the Cardinal with one blow, to take the Queen from her husband and from the jealous Richelieu, and to snatch Mademoiselle de Hautefort from the King who was in love with her!

In truth the adventure would not have been an ordinary one; La Rochefoucauld assumed its duties with enthusiasm, renouncing them only when the Queen changed her mind.

Like all his fellows, La Rochefoucauld had his outburst of youth; but he fell short of its folly. Recalling his extravagant project, he said: "Youth is a continuous intoxication; it is the fever of Reason."

The memoirs of Arnauld d' Andilly tell us how the sons of the higher nobility were educated in the year 1600 and thereabout. Arnauld d' Andilly began to study Greek and Latin at home, under the supervision of a very learned father. Toward his tenth year his family thought that the moment had come to introduce into his little head the meanings and the realities of speculation. The[36] child was destined for "civil employment." His day was divided into two parts; one half was devoted to "disinterested study"; the other half to the study of things practical. So he served his apprenticeship for business by such a system that his themes and his versions lost none of their rights. His mornings were consecrated to lessons and tasks. They were long mornings; the family rose at four o'clock. The little student became a good Latinist, and even a good Hellenist. He wrote very well in French, and he was a good reader.

Ten or twelve volumes which belonged to him are still in existence, and they attest that he knew a great deal more than the graduates of our modern colleges,—though he knew nothing of the things they aim at. At eleven o'clock he closed his lexicons, bade adieu to his preceptor and to the pedagogy, bestrode his horse, and rode to Paris, to the house of one of his uncles, who had taken it upon himself to teach the boy everything that he could not learn from his books. Our forefathers carefully watched their sons' first contact with reality. They tried not to leave to chance the duties of so important an initiation; and as a general thing their supervision left ineffaceable traces. Uncle Claude de la Mothe-Arnauld, Treasurer-General of France, installed his nephew in his private cabinet and gave him various bundles of endorsed papers to decipher. The child was obliged to pick out their meaning and then render a clear analysis of it in a distinct voice. When he[37] was fifteen years old another uncle, a Supervisor of the National Finances, caused the student to "put his fist into the dough" in his own office. At sixteen years of age, "little Arnauld" was "M. Arnauld d' Andilly"; vested with office under the State, received at Court, and permitted to assist behind the chair of the King, at the Councils of Finance, so that he might hear financial arguments, and learn from the Nation's statesmen how to decide great questions. His education was not an exceptional one. The sons of the bourgeoisie were raised in like manner. Attempts to educate boys were more or less successful, according to the natural gifts of the postulants. Omer Talon, Advocate-General of the Parliament of Paris, and one of the great Parliamentary orators of the century, had pursued extensive classical studies, and "as he spoke, Latin and Greek rushed to his lips." He had "vast attainments in law," a science much more complicated in the sixteenth century than in our day. But, learned though he was, he had not lingered on the benches of his school. He was admitted to the Bar when he was eighteen years old, and "immediately began to plead and to be celebrated."

Antoine Le Maïtre, the first "Solitaire" of Port Royal, began his career by appearing in public as the best known and most important and influential lawyer in Paris when he was twenty-one years old.

Generally, the nobility sacrificed learning, which it despised, to an impatient desire to see its sons "in active life." The nobles made pages of their sons as[38] soon as they were thirteen or fourteen years old, or else sent them to the "Academy" to learn how to make proper use of a horse, to fence, to vault, and to dance.[11]

In the eyes of people of quality books and writings were the tools of plebeians; good enough for professional fine wits, or lawyers' clerks, but not fit for the nobility.

In the reign of Louis XIII.,[12] M. d'Avenal wrote thus: "Gentlemen are perfectly ignorant,—the most illustrious and the most modestly insignificant alike. In this respect, with few exceptions, there is absolute equality between them."

The Constable, De Montmorency, had the reputation of a man of sound sense, "though he had no book learning, and hardly knew how to write his own name." Many of the great lords knew no more; and this ignorance was not shameful; on the contrary it was desired, affected, gloried in, and eagerly imitated by the lesser nobility.

"I never sharpen my pen with anything but my sword," proudly declared a gentleman.

"Ah?" answered a wit; "then your bad writing does not astonish me!"

The exceptions to the rule resulted from the caprices of the fathers; and they were sometimes found where least expected. The famous Bassompierre, arbiter of fashion and flower of courtiers,[39] who, at one sitting, burned more than six thousand letters from women, who wore habits costing fourteen thousand écus, and could describe their details twenty years after he had worn them, had been very liberally educated, and according to a method which as may be imagined, was far in advance of the methods of his day. He had followed the college course until the sixteenth year of his age, he had laboured at rhetoric, logic, physics, and law, and dipped deep into Hippocrates and Aristotle. He had also studied les cas de Conscience. Then he had gone to Italy, where he had attended the best riding schools, the best fencing schools, a school of fortifications, and several princely Courts. At the age of nineteen years he was a superb cavalier and a good musician, he knew the world, and had made a very brilliant first appearance at Court.

The great Condé, General-in-Chief at the age of twenty-two years, had followed a college course at the school of Bourges, and had been "drilled" at the "Academy." He was tried by the fire of many a hard school. Wherever he went he was preceded by tart letters of instruction from his father. By his father's orders he was always received and treated as impartially as any of the lesser aspirants to education; he was severely "exercised," put on his mettle in various ways, and compelled to start out from first principles, no matter how well he knew them. When seven years old he spoke Latin fluently. When he reached the age of eleven he[40] was well grounded in rhetoric, law, mathematics, and the Italian language. He could turn a verse very prettily; and he excelled in everything athletic.

Louis XIII. applauded this deep and thorough study,—perhaps because he regretted his lost opportunities. He told people that he should "wish to have ... Monsieur the Dauphin," educated in like manner.[13]

In measure as the century advanced it began to be recognised that a nobleman could "study" without detracting from his noble dignity. Louis de Pontis, who started out as a D'Artagnan, and ended at Port Royal,[14] wished that time could be taken to instruct the youth of the nation. Answering some one who had asked his advice as to the education of two young lords of the Court, he wrote[15]:

I will begin by avowing that I do not share the sentiments of those who wish for their children only so much science as is "needed"—as they call it—"for a gentleman"; I do not see things in that light. I should demand more science.

Since science teaches man how to reason and to speak well in public, is it not necessary to men, who, by the grandeur of their birth, their employment, and their duties, may need it at any moment, and who make use of it in their numerous meetings with the enlightened of the world? There are several personages who hold that the society of virtuous and talented women expands and polishes the mind of a young cavalier more than the conversation of men of letters; but I am not of their opinion....

Notwithstanding this declaration, Pontis desired that great difference should be established between the treatment of a child training for the robes and the treatment of one training for military service. "The first ought never to end his studies; it is sufficient for the second to study until his fifteenth or sixteenth year; after that time he ought to be sent to the Academy...."

In this opinion Pontis echoed the general impression. At the time when La Grande Mademoiselle was born, the man of quality no longer had a right to be "brutal,"—in other words, to betray coarseness of nature. New customs and new manners exacted from the man of noble birth tact and good breeding, not science. But it was requisite that the nobleman's mind should be "formed" by the influence and discourse of a man of letters, so that he might be capable of judging witty and intellectual works ("works of the mind").

Marshal Montmorency,[16] son of the Constable, who "hardly knew how to write his own name," had always in his employ cultured and intellectual people, who "made verses" for him on a multitude of such subjects as it was befitting his high estate that he should know; such subjects as were calculated to give him an air of intelligence and general information. His intellectual advisers informed him what to think and what to say of the current questions of the day.[17] It was good form for great and noble houses to entertain at least one[42] autheur. As there were no public journals or reviews, the autheur took the place of literary chronicles and literary criticism. He talked of the last dramatic sketch, or of the last new novel.

It was not long before another step in advance was taken, by which every nobleman was permitted to entertain his own personal autheur, and to compose "works of the mind" for himself. But he who succumbed to the epidemic (cacoëthes scribendi), owed it to his birth and breeding to hide his malady, or to make excuses for it.

Mlle. de Scudéry puts in the mouth of Sapho (herself) in Le Grand Cyrus[18]:

Nothing is more inconvenient than to be intellectual or to be treated as if one were so, when one has a noble heart and a certain degree of birth; for I hold that it is an indubitable fact that from the moment one separates himself from the multitude, distinguishing one's self by the enlightenment of one's mind; when one acquires the reputation of having more mind than another, and of writing well enough—in prose or in verse—to be able to compose books, then, I say, one loses one half of one's nobility—if one has any—and one is not one half as important as another of the same house and of the same blood, who has not meddled with writings....

About the time this opinion saw the light, Tallemant des Réaux wrote to M. de Montausier, husband of the beautiful Julie d'Angennes, and one of the satellites of the Hôtel de Rambouillet: "He plys the trade of a man of mind too well for a man of quality—or at least he plays the part too seriously ... he has even made translations...."[43] This mention is marked by one just feature: the man who wrote, who could write, or who indulged in writing, was supposed to have judgment enough to keep him from attaching importance to his works. The fine world had regained the taste for refinement lost in the fracas of the civil wars; but in the higher classes of society was still reflected the horror of the preceding generations for pedants and for pedantry.

Ignorant or learned, half-grown boys were cast forward by their hasty education into their various careers when they had barely left the ranks of infancy. They were reckless, still in the flower of their giddy youth; but they were enthusiastic and generous. France received their high spirits very kindly. Deprived of the good humour, and stripped of the illusions furnished by the young representatives of their manhood, the times would have been too hard to be endured. The traditions of the centuries when might was the only right still weighed upon the soul of the people. One of those traditions exacted that—from his infancy—a man should be "trained to blood." A case was cited where a man had his prisoners killed by his own son,—a child ten years old. One exaction was that a man should never be conscious of the sufferings of a plebeian.

France had received a complete inheritance of inhuman ideas, which protected and maintained the remains of the savagery that ran, like a stained thread, through the national manners, just falling[44] short of rendering odious the gallant cavaliers. All that saved them from the disgust aroused by the brutal exercise of the baser "rights" was the bright ray of poetry, whose dazzling light gleamed amidst their sombre faults.

They were quarrelsome, but brave. Perchance as wild as outlaws, but devoted, gay, and loving. They were extraordinarily lively, because they were—or had been but a short time before—extraordinarily young, with a youth that is not now, nor ever shall be.

They inspired the women with their boisterous gallantry. In the higher classes the sexes led nearly the same life. They frequented the same pleasure resorts and revelled in the same joys. They met in the lanes and alleys, at the theatre (Comédie), at balls, in their walks, on the hunt, on horseback, and even in the camps. A woman of the higher classes had constantly recurring opportunities to drink in the spirit of the times. As a result the ambitious aspired to take part in public life; and they shaped their course so well, and made so much of their opportunities, that Richelieu complained of the importance of women in the State. They were seen entering politics, and conspiring like men; and they urged on the men to the extremes of folly.

Some of the noblewomen had wardrobes full of disguises; and they ran about the streets and the highways dressed as monks or as gentlemen. Among them were several who wielded the sword in duel and in war, and who rode fearlessly and[45] well. They were all handsome and courageous, and even in the abandon of their most reckless gambols they found means to preserve their delicacy and their grace. Never were women more womanly. Men adored them, trembling lest something should come about to alter their perfection. Their fear was the cause of their desperate and stubborn opposition to the idea of the education of girls, then beginning to take shape among the elder women.

I cannot say that the men were not in the wrong; but I do say that I understand and appreciate their motives. Woman, or goddess, of the order of the nobles of the time of Louis XIII., was a work of art, rare and perfect; and to tremble for her safety was but natural!

It happened that La Grande Mademoiselle came to the age to profit by instruction just when polite circles were discussing the education of girls. The governess whose duty it had been to guide her mind was caught between two opposing forces: the defendants of the ancient ignorance and the first partisans of the idea of "enlightenment for all."

V

Les Femmes Savantes might have been written under Richelieu. Philamente had not awaited the advent of Molière to protest against the ignorance and the prejudice that enslaved her sex. When the piece appeared, more than half a century had elapsed since people had quarrelled in the little[46] streets about woman's position,—what she ought to know, and what she ought not to know. But if the piece had been written long before its first appearance, the treatment of the subject could not have been the same. It would have been necessary to agree as to what woman ought to be in her home and in her social relations; and at that time they were just beginning to disagree on that very subject. Nearly all men thought that things ought to be maintained in the existing conditions. The nobles had exquisite mistresses and incomparable political allies; the bourgeois had excellent housekeepers; and to one and all alike, noble and bourgeois, it seemed that any instruction would be superfluous; that things were perfect just as they were. The majority of the women shared the opinions of the men. The minority, looking deeper into the question, saw that there might be a more serious and more intellectual way of living to which ignorance would be an obstacle; but at every turn they were met by men stubbornly determined that women should not be made to study. Such men would not admit that there could be any difference between a cultivated woman and "Savante,"—the term then used for "blue-stocking." It must be confessed that there was some justice in their judgment. For a reason which escapes me, when knowledge attempted to enter the mind of a woman it had great trouble to make conditions with nature and simplicity. It was not so easy! Even to-day certain preparations are necessary,—appointment[47] of commandants, the selection of countersigns, establishment of a picket-line—not to say a deadline. We have précieuses in our own day, and their pretensions and their grimaces have been lions in our path whenever we have attempted the higher instruction of our daughters; the truly précieuses, they who were instrumental in winning the cause of the higher education of women—they who, under the impulsion given by the Hôtel de Rambouillet, worked to purify contemporary language and manners—were not ignorant of the baleful affectation of their sisters, nor of the extent of its compromising effect upon their own efforts. Mlle. de Scudéry, who knew "nearly everything that one could know" (by which was probably meant "everything fit to be known"), and who piqued herself upon being not less modest than she was wise, could not be expected to share, or to take part in, and in the mind of the public be confounded with, the female Trissotins whose burden of ridicule she felt so keenly. She would not allow herself to resemble them in any way when she brought them forth in Grand Cyrus, where the questions now called "feminist" were discussed with great good sense.

Damophile, who affects to imitate Sapho, is only her caricature. Sapho "does not resemble a 'Savante'"; her conversation is natural, gallant, and easy (commodious).

Damophile always had five or six teachers. I believe that the least learned among them taught her astrology.

She was always writing to the men who made a profession of science. She could not make up her mind to have anything to say to people who did not know anything. Fifteen or twenty books were always to be seen on her table; and she always held one of them in her hand when any one entered the room, or when she sat there alone; and I am assured that it could be said without prevarication that one saw more books in her cabinet than she had ever read, and that at Sapho's house one saw fewer books than she had read.

More than that, Damophile used only great words, which she pronounced in a grave and imperious voice; though what she said was unimportant; and Sapho, on the contrary, used only short, common words to express admirable things. Besides that, Damophile, believing that knowledge did not accord with her family affairs, never had anything to do with domestic cares; but as to Sapho, she took pains to inform herself of everything necessary to know in order to command even the least things pertaining to the household.

Damophile not only talked as if she were reading out of a book, but she was always talking about books; and, in her ordinary conversation, she spoke as freely of unknown authors as if she were giving public lessons in some celebrated academy.

She tries ... with peculiar and strange carefulness, to let it be known how much she knows, or thinks that she knows. And that, too, the first time that a stranger sees her. And there are so many obnoxious, disagreeable, and troublesome[49] things about Damaphile, that one must acknowledge that if there is nothing more amiable nor more charming than a woman who takes pains to adorn her mind with a thousand agreeable forms of knowledge,—when she knows how to use them,—nothing is as ridiculous and as annoying as a woman who is "stupidly wise."

Mlle. de Scudéry raged when people, who had no tact, took her for a Damophile, and, meaning to compliment her, consulted her "on grammar," or "touching one of Hesiod's verses." Then the vials of her wrath were poured out upon the "Savantes" who gave the prejudiced reason for condemning the education of woman, and who provoked annoying and ridiculous misconception by their insupportable pedantry; when there were so many young girls of the best families who did not even learn their own language, and who could not make themselves understood when they took their pens in hand.

"The majority of women," said Nicanor, "seem to try to write so that people will misunderstand them, so strange is their writing and so little sequency is there in their words."

"It is certain," replied Sapho, "that there are women who speak well who write badly; and that they do write badly is purely their own fault.... Doubtless it comes from the fact that they do not like to read, or that they read without paying any attention to what they are doing, and without reflecting upon what they have read. So that although they have read the same words they use when they write, thousands and thousands of times, when they come to write they write them all wrong. And by putting some letters where other letters ought to be, they make a confused tangle which no one can distinguish unless he is well used to it."

"What you say is so true," answered Erinne, "that I saw it proved no longer ago than yesterday. I visited one of my friends, who has returned from the country, and I carried her all the letters she wrote to me while she was away, so that she might read them to me and let me know what was in them."