THE LUCY BOOKS.

BY THE

Author of the Rollo Books.

New York,

CLARK AUSTIN & CO.

205 BROADWAY.

COUSIN LUCY’S

CONVERSATIONS.

NEW YORK:

CLARK, AUSTIN & SMITH,

3 PARK ROW AND 3 ANN-STREET,

1854.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1841,

By T. H. CARTER,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

The simple delineations of the ordinary incidents and feelings which characterize childhood, that are contained in the Rollo Books, having been found to interest, and, as the author hopes, in some degree to benefit the young readers for whom they were designed,—the plan is herein extended to children of the other sex. The two first volumes of the series are Lucy’s Conversations and Lucy’s Stories. Lucy was Rollo’s cousin; and the author hopes that the history of her life and adventures may be entertaining and useful to the sisters of the boys who have honored the Rollo Books with their approval.

| Page. | |

| CONVERSATION I. | |

| The Treasury, | 9 |

| CONVERSATION II. | |

| Definitions, | 21 |

| CONVERSATION III. | |

| The Glen, | 34 |

| CONVERSATION IV. | |

| A Prisoner, | 43 |

| CONVERSATION V. | |

| Target Painting, | 51 |

| CONVERSATION VI. | |

| Midnight, | 60 |

| CONVERSATION VII. | |

| Joanna, | 75 |

| CONVERSATION VIII. | |

| Building, | 88 |

| CONVERSATION IX. | |

| Equivocation, | 103 |

| CONVERSATION X. | |

| Johnny, | 118 |

| CONVERSATION XI. | |

| Getting Lost, | 132 |

| CONVERSATION XII. | |

| Lucy’s Scholar, | 146 |

| CONVERSATION XIII. | |

| Sketching, | 159 |

| CONVERSATION XIV. | |

| Danger, | 170 |

One day in summer, when Lucy was a very little girl, she was sitting in her rocking-chair, playing keep school. She had placed several crickets and small chairs in a row for the children’s seats, and had been talking, in dialogue, for some time, pretending to hold conversations with her pupils. She heard one read and spell, and gave another directions about her writing; and she had quite a long talk with a third about the reason why she did not come to school earlier. At last Lucy, seeing the kitten come into the room, and thinking that she should like to go and play with her, told the children that she thought it was time for school to be done.

Royal, Lucy’s brother, had been sitting upon10 the steps at the front door, while Lucy was playing school; and just as she was thinking that it was time to dismiss the children, he happened to get up and come into the room. Royal was about eleven years old. When he found that Lucy was playing school, he stopped at the door a moment to listen.

“Now, children,” said Lucy, “it is time for the school to be dismissed; for I want to play with the kitten.”

Here Royal laughed aloud.

Lucy looked around, a little disturbed at Royal’s interruption. Besides, she did not like to be laughed at. She, however, said nothing in reply, but still continued to give her attention to her school. Royal walked in, and stood somewhat nearer.

“We will sing a hymn,” said Lucy, gravely.

Here Royal laughed again.

“Royal, you must not laugh,” said Lucy. “They always sing a hymn at the end of a school.” Then, making believe that she was speaking to her scholars, she said, “You may all take out your hymn-books, children.”

Lucy had a little hymn-book in her hand, and she began turning over the leaves, pretending to find a place.

11 “You may sing,” she said, at last, “the thirty-third hymn, long part, second metre.”

At this sad mismating of the words in Lucy’s announcement of the hymn, Royal found that he could contain himself no longer. He burst into loud and incontrollable fits of laughter, staggering about the room, and saying to himself, as he could catch a little breath, “Long part!—O dear me!—second metre!—O dear!”

“Royal,” said Lucy, with all the sternness she could command, “you shall not laugh.”

Royal made no reply, but tumbled over upon the sofa, holding his sides, and every minute repeating, at the intervals of the paroxysm, “Long part—second metre!—O dear me!”

“Royal,” said Lucy again, stamping with her little foot upon the carpet, “I tell you, you shall not laugh.”

Then suddenly she seized a little twig which she had by her side, and which she had provided as a rod to punish her imaginary scholars with; and, starting up, she ran towards Royal, saying, “I’ll soon make you sober with my rod.”

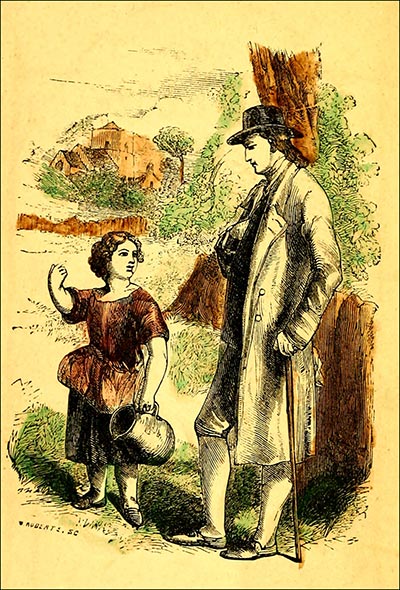

Royal immediately jumped up from the sofa, and ran off,—Lucy in hot pursuit. Royal turned into the back entry, and passed out through an open door behind, which led into a little green12 yard back of the house. There was a young lady, about seventeen years old, coming out of the garden into the little yard, with a watering-pot in her hand, just as Royal and Lucy came out of the house.

She stopped Lucy, and asked her what was the matter.

“Why, Miss Anne,” said Lucy, “Royal keeps laughing at me.”

Miss Anne looked around to see Royal. He had gone and seated himself upon a bench under an apple-tree, and seemed entirely out of breath and exhausted; though his face was still full of half-suppressed glee.

“What is the matter, Royal?” said Miss Anne.

“Why, he is laughing at my school,” said Lucy.

“No, I am not laughing at her school,” said Royal; “but she was going to give out a hymn, and she said——”

Royal could not get any further. The fit of laughter came over him again, and he lay down upon the bench, unable to give any further account of it, except to get out the words, “Long part! O dear me! What shall I do?”

13 “Royal!” exclaimed Lucy.

“Never mind him,” said Miss Anne; “let him laugh if he will, and you, come with me.”

“Why, where are you going?”

“Into my room. Come, go in with me, and I will talk with you.”

So Miss Anne took Lucy along with her into a little back bedroom. There was a window at one side, and a table, with books, and an inkstand, and a work-basket upon it. Miss Anne sat down at this window, and took her work; and Lucy came and leaned against her, and said,

“Come, Miss Anne, you said you would talk with me.”

“Well,” said Miss Anne, “there is one thing which I do not like.”

“What is it?” said Lucy.

“Why, you do not keep your treasury in order.”

“Well, that,” said Lucy, “is because I have got so many things.”

“Then I would not have so many things;—at least I would not keep them all in my treasury.”

“Well, Miss Anne, if you would only keep some of them for me,—then I could keep the rest in order.”

“What sort of things should you wish me to keep?”

14 “Why, my best things,—my tea-set, I am sure, so that I shall not lose any more of them; I have lost some of them now—one cup and two saucers; and the handle of the pitcher is broken. Royal broke it. He said he would pay me, but he never has.”

“How was he going to pay you?”

“Why, he said he would make a new nose for old Margaret. Her nose is all worn off.”

“A new nose! How could he make a new nose?” asked Miss Anne.

“O, of putty. He said he could make it of putty, and stick it on.”

“Putty!” exclaimed Miss Anne. “What a boy!”

Old Margaret was an old doll that Lucy had. She was not big enough to take very good care of a doll, and old Margaret had been tumbled about the floors and carpets until she was pretty well worn out. Still, however, Lucy always kept her, with her other playthings, in her treasury.

The place which Lucy called her treasury was a part of a closet or wardrobe, in a back entry, very near Miss Anne’s room. This closet extended down to the floor, and upwards nearly to the wall. There were two doors above, and two below. The lower part had been assigned to15 Lucy, to keep her playthings and her various treasures in; and it was called her treasury.

Her treasury was not kept in very good order. The upper shelf contained books, and the two lower, playthings. But all three of the shelves were in a state of sad disorder. And this was the reason why Miss Anne asked her about it.

“Yes, Miss Anne,” said Lucy, “that is the very difficulty, I know. I have got too many things in my treasury; and if you will keep my best things for me, then I shall have room for the rest. I’ll run and get my tea things.”

“But stop,” said Miss Anne. “It seems to me that you had better keep your best things yourself, and put the others away somewhere.”

“But where shall I put them?” asked Lucy.

“Why, you might carry them up garret, and put them in a box. Take out all the broken playthings, and the old papers, and the things of no value, and put them in a box, and then we will get Royal to nail a cover on it.”

“Well,—if I only had a box,” said Lucy.

“And then,” continued Miss Anne, “after a good while, when you have forgotten all about the box, and have got tired of your playthings in the treasury, I can say, ‘O Lucy, don’t you remember you have got a box full of playthings up in16 the garret?’ And then you can go up there, and Royal will draw out the nails, and take off the cover, and you can look them all over, and they will be new again.”

“O aunt Anne, will they be really new again?” said Lucy; “would old Margaret be new again if I should nail her up in a box?”

Lucy thought that new meant nice, and whole, and clean, like things when they are first bought at the toy-shop or bookstore.

Miss Anne laughed at this mistake; for she meant that they would be new to her; that is, that she would have forgotten pretty much how they looked, and that she would take a new and fresh interest in looking at them.

Lucy looked a little disappointed when Anne explained that this was her meaning; but she said that she would carry up some of the things to the garret, if she only had a box to put them in.

Miss Anne said that she presumed that she could find some box or old trunk up there; and she gave Lucy a basket to put the things into, that were to be carried up.

So Lucy took the basket, and carried it into the entry; and she opened the doors of her treasury, and placed the basket down upon the floor before it.

17 Then she kneeled down herself upon the carpet, and began to take a survey of the scene of confusion before her.

She took out several blocks, which were lying upon the lower shelf, and also some large sheets of paper with great letters printed upon them. Her father had given them to her to cut the letters out, and paste them into little books. Next came a saucer, with patches of red, blue, green, and yellow, all over it, made with water colors, from Miss Anne’s paint-box. She put these things into the basket, and then sat still for some minutes, not knowing what to take next. Not being able to decide herself, she went back to ask Miss Anne.

“What things do you think I had better carry away, Miss Anne?” said she. “I can’t tell very well.”

“I don’t know what things you have got there, exactly,” said Miss Anne; “but I can tell you what kind of things I should take away.”

“Well, what kind?” said Lucy.

“Why, I should take the bulky things.”

“Bulky things!” said Lucy; “what are bulky things?”

“Why, big things—those that take up a great deal of room.”

18 “Well, what other kinds of things, Miss Anne?”

“The useless things.”

“Useless?” repeated Lucy.

“Yes, those that you do not use much.”

“Well, what others?”

“All the old, broken things.”

“Well, and what else?”

“Why, I think,” replied Miss Anne, “that if you take away all those, you will then probably have room enough for the rest. At any rate, go and get a basket full of such as I have told you, and we will see how much room it makes.”

So Lucy went back, and began to take out some of the broken, and useless, and large things, and at length filled her basket full. Then she carried them in to show to Miss Anne. Miss Anne looked them over, and took out some old papers which were of no value whatever, and then told Lucy, that, if she would carry them up stairs, and put them down upon the garret floor, she would herself come up by and by, and find a box to put them in. Lucy did so, and then came down, intending to get another basket full.

As she was descending the stairs, coming down carefully from step to step, with one hand upon the banisters, and the other holding her basket, singing a little song,—her mother, who was at19 work in the parlor, heard her, and came out into the entry.

“Ah, my little Miss Lucy,” said she, “I’ve found you, have I? Just come into the parlor a minute; I want to show you something.”

Lucy’s mother smiled when she said this; and Lucy could not imagine what it was that she wanted to show her.

As soon, however, as she got into the room, her mother stopped by the door, and pointed to the little chairs and crickets which Lucy had left out upon the floor of the room, when she had dismissed her school. The rule was, that she must always put away all the chairs and furniture of every kind which she used in her play; and, when she forgot or neglected this, her punishment was, to be imprisoned for ten minutes upon a little cricket in the corner, with nothing to amuse herself with but a book. And a book was not much amusement for her; for she could not read; she only knew a few of her letters.

As soon, therefore, as she saw her mother pointing at the crickets and chairs, she began at once to excuse herself by saying,

“Well, mother, that is because I was doing something for Miss Anne.—No, it is because20 Royal made me go away from my school, before it was done.”

“Royal made you go away! how?” asked her mother.

“Why, he laughed at me, and so I ran after him; and then Miss Anne took me into her room and I forgot all about my chairs and crickets.”

“Well, I am sorry for you; but you must put them away, and then go to prison.”

So Lucy put away her crickets and chairs, and then went and took her seat in the corner where she could see the clock, and began to look over her book to find such letters as she knew, until the minute-hand had passed over two of the five-minute spaces upon the face of the clock. Then she got up and went out; and, hearing Royal’s voice in the yard, she went out to see what he was doing, and forgot all about the work she had undertaken at her treasury. Miss Anne sat in her room two hours, wondering what had become of Lucy; and finally, when she came out of her room to see about getting tea, she shut the treasury doors, and, seeing the basket upon the stairs, where Lucy had left it, she took it and put it away in its place.

A few days after this, Lucy came into Miss Anne’s room, bringing a little gray kitten in her arms. She asked Miss Anne if she would not make her a rolling mouse, for her kitten to play with.

Miss Anne had a way of unwinding a ball of yarn a little, and then fastening it with a pin, so that it would not unwind any farther. Then Lucy could take hold of the end of the yarn, and roll the ball about upon the floor, and let the kitten run after it. She called it her rolling mouse.

Miss Anne made her a mouse, and Lucy played with it for some time. At last the kitten scampered away, and Lucy could not find her. Then Anne proposed to Lucy that she should finish the work of re-arranging her treasury.

“Let me see,” said Miss Anne, “if you remember what I told you the other day. What were the kinds of things that I advised you to carry away?”

22 “Why, there were the sulky things.”

“The what!” said Miss Anne.

“No, the big things,—the big things,” said Lucy.

“The bulky things,” said Miss Anne, “not the sulky things!”

“Well, it sounded like sulky,” said Lucy; “but I thought it was not exactly that.”

“No, not exactly,—but it was not a very great mistake. I said useless things, and bulky things, and you got the sounds confounded.”

“Con— what?” said Lucy.

“Confounded,—that is, mixed together. You got the s sound of useless, instead of the b sound of bulky; but bulky and sulky mean very different things.”

“What does sulky mean? I know that bulky means big.”

“Sulkiness is a kind of ill-humor.”

“What kind?”

“Why, it is the silent kind. If a little girl, who is out of humor, complains and cries, we say she is fretful or cross; but if she goes away pouting and still, but yet plainly out of humor, they sometimes say she is sulky. A good many of your playthings are bulky; but I don’t think23 any of them are sulky, unless it be old Margaret. Does she ever get out of humor?”

“Sometimes,” said Lucy, “and then I shut her up in a corner. Would you carry old Margaret up garret?”

“Why, she takes up a good deal of room, does not she?” said Miss Anne.

“Yes,” said Lucy, “ever so much room. I cannot make her sit up, and she lies down all over my cups and saucers.”

“Then I certainly would carry her up garret.”

“And would you carry up her bonnet and shawl too?”

“Yes, all that belongs to her.”

“Then,” said Lucy, “whenever I want to play with her, I shall have to go away up garret, to get all her things.”

“Very well; you can do just as you think best.”

“Well, would you?” asked Lucy.

“I should, myself, if I were in your case; and only keep such things in my treasury as are neat, and whole, and in good order.”

“But I play with old Margaret a great deal,—almost every day,” said Lucy.

“Perhaps, then, you had better not carry her away. Do just which you think you shall like best.”

24 Lucy began to walk towards the door. She moved quite slowly, because she was uncertain whether to carry her old doll up stairs or not. Presently she turned around again, and said,

“Well, Miss Anne, which would you do?”

“I have told you that I should carry her up stairs; but I’ll tell you what you can do. You can play that she has gone away on a visit; and so let her stay up garret a few days, and then, if you find you cannot do without her, you can make believe that you must send for her to come home.”

“So I can,” said Lucy; “that will be a good plan.”

Lucy went immediately to the treasury, and took old Margaret out, and everything that belonged to her. This almost made a basket full, and she carried it off up stairs. Then she came back, and got another basket full, and another, until at last she had removed nearly half of the things; and then she thought that there would be plenty of room to keep the rest in order. And every basket full which she had carried up, she had always brought first to Miss Anne, to let her look over the things, and see whether they had better all go. Sometimes Lucy had got something in her basket which Miss Anne thought had better remain, and be kept in the treasury; and25 some of the things Miss Anne said were good for nothing at all, and had better be burnt, or thrown away, such as old papers, and some shapeless blocks, and broken bits of china ware. At last the work was all done, the basket put away, and Lucy came and sat down by Miss Anne.

“Well, Lucy,” said Miss Anne, “you have been quite industrious and persevering.”

Lucy did not know exactly what Miss Anne meant by these words; but she knew by her countenance and her tone of voice, that it was something in her praise.

“But perhaps you do not know what I mean, exactly,” she added.

“No, not exactly,” said Lucy.

“Why, a girl is industrious when she keeps steadily at work all the time, until her work is done. If you had stopped when you had got your basket half full, and had gone to playing with the things, you would not have been industrious.”

“I did, a little,—with my guinea peas,” said Lucy.

“It is best,” said Miss Anne, “when you have anything like that to do, to keep industriously at work until it is finished.”

26 “But I only wanted to look at my guinea peas a little.”

“O, I don’t think that was very wrong,” said Miss Anne. “Only it would have been a little better if you had put them back upon the shelf, and said, ‘Now, as soon as I have finished my work, then I’ll take out my guinea peas and look at them.’ You would have enjoyed looking at them more when your work was done.”

“You said that I was something else besides industrious.”

“Yes, persevering,” said Miss Anne.

“What is that?”

“Why, that is keeping on steadily at your work, and not giving it up until it is entirely finished.”

“Why, Miss Anne,” said Lucy, “I thought that was industrious.”

Here Miss Anne began to laugh, and Lucy said,

“Now, what are you laughing at, Miss Anne?” She thought that she was laughing at her.

“O, I am not laughing at you, but at my own definitions.”

“Definitions! What are definitions, Miss Anne?” said Lucy.

27 “Why, explanations of the meanings of words. You asked me what was the meaning of industrious and persevering; and I tried to explain them to you; that is, to tell you the definition of them; but I gave pretty much the same definition for both; when, in fact, they mean quite different things.”

“Then why did not you give me different definitions, Miss Anne?” said Lucy.

“It is very hard to give good definitions,” said she.

“I should not think it would be hard. I should think, if you knew what the words meant, you could just tell me.”

“I can tell you in another way,” said Miss. Anne. “Suppose a boy should be sent into the pasture to find the cow, and should look about a little while, and then come home and say that he could not find her, when he had only looked over a very small part of the pasture. He would not be persevering. Perhaps there was a brook, and some woods that he ought to go through and look beyond; but he gave up, we will suppose, and thought he would not go over the brook, but would rather come home and say that he could not find the cow. Now, a boy, in such a case, would not be persevering.”

28 “I should have liked to go over the brook,” said Lucy.

“Yes,” said Miss Anne, “no doubt; but we may suppose that he had been over it so often, that he did not care about going again,—and so he turned back and came home, without having finished his work.”

“His work?” said Lucy.

“Yes,—his duty, of looking for the cow until he found her. He was sent to find the cow, but he did not do it. He became discouraged, and gave up too easily. He did not persevere. Perhaps he kept looking about all the time, while he was in the pasture; and went into all the little groves and valleys where the cow might be hid: and so he was industrious while he was looking for the cow, but he did not persevere.

“And so you see, Lucy,” continued Miss Anne, “a person might persevere without being industrious. For once there was a girl named Julia. She had a flower-garden. She went out one morning to weed it. She pulled up some of the weeds, and then she went off to see a butterfly; and after a time she came back, and worked a little longer. Then some children came to see her; and she sat down upon a seat, and talked with them some time, and left her work. In this way,29 she kept continually stopping to play. She was not industrious.”

“And did she persevere?” asked Lucy.

“Yes,” said Miss Anne. “She persevered. For when the other children wanted her to go away with them and play, she would not. She said she did not mean to go out of the garden until she had finished weeding her flowers. So after the children had gone away, she went back to her work, and after a time she got it done. She was persevering; that is, she would not give up what she had undertaken until it was finished;—but she was not industrious; that is, she did not work all the time steadily, while she was engaged in doing it. It would have been better for her to have been industrious and persevering too, for then she would have finished her work sooner.”

As Miss Anne said these words, she heard a voice out in the yard calling to her,

“Miss Anne!”

Miss Anne looked out at the window to see who it was. It was Royal.

“Is Lucy in there with you?” asked Royal.

Miss Anne said that she was; and at the same time, Lucy, who heard Royal’s voice, ran to another window, and climbed up into a chair, so that she could look out.

30 “Lucy,” said Royal, “come out here.”

“O no,” said Lucy, “I can’t come now. Miss Anne is telling me stories.”

Royal was seated on a large, flat stone, which had been placed in a corner of the yard, under some trees, for a seat; he was cutting a stick with his knife. His cap was lying upon the stone, by his side. When Lucy said that she could not come out, he put his hand down upon his cap, and said,

“Come out and see what I’ve got under my cap.”

“What is it?” said Lucy.

“I can’t tell you; it is a secret. If you will come out, I will let you see it.”

“Do tell me what it is.”

“No,” said Royal.

“Tell me something about it,” said Lucy, “at any rate.”

“Well,” said Royal, “I will tell you one thing. It is not a bird.”

Lucy concluded that it must be some curious animal or other, if it was not a bird; and so she told Miss Anne that she believed she would go out and see, and then she would come in again directly, and hear the rest that she had to say. So she went out to see what Royal had got under his cap.

33 Miss Anne suspected that Royal had not got anything under his cap; but that it was only his contrivance to excite Lucy’s curiosity, and induce her to come out.

And this turned out to be the fact; for when Lucy went up to where Royal was sitting, and asked him what it was, he just lifted up his cap, and said, it was that monstrous, great, flat stone!

At first, Lucy was displeased, and was going directly back into the house again; but Royal told her that he was making a windmill, and that, if she would stay there and keep him company, he would let her run with it, when it was done. So Lucy concluded to remain.

Behind the house that Lucy lived in, there was a path, winding among trees, which was a very pleasant path to take a walk in. Lucy and Royal often went to take a walk there. They almost always went that way when Miss Anne could go with them, for she liked the place very much. It led to a strange sort of a place, where there were trees, and high, rocky banks, and a brook running along in the middle, with a broad plank to go across. Miss Anne called it the glen.

One morning Miss Anne told Lucy that she was going to be busy for two hours, and that after that she was going to take a walk down to the glen; and that Lucy might go with her, if she would like to go. Of course Lucy liked the plan very much. When the time arrived, they set off, going out through the garden gate. Miss Anne had a parasol in one hand and a book in the other. Lucy ran along before her, and opened the gate.

They heard a voice behind them calling out,

35 “Miss Anne, where are you going?”

They looked round. It was Royal, sitting at the window of a little room, where he used to study.

“We are going to take a walk,—down to the glen,” said Miss Anne.

“I wish you would wait for me,” said Royal, “only a few minutes; the sand is almost out.”

He meant the sand of his hour-glass; for he had an hour-glass upon the table, in his little room, to measure the time for study. He had to study one hour in the afternoon, and was not allowed to leave his room until the sand had all run out.

“No,” said Lucy, in a loud voice, calling out to Royal; “we can’t wait.”

“Perhaps we had better wait for him,” said Miss Anne, in a low voice, to Lucy. “He would like to go with us. And, besides, he can help you across the brook.”

Lucy seemed a little unwilling to wait, but on the whole she consented; and Miss Anne sat down upon a seat in the garden, while Lucy played about in the walks, until Royal came down, with his hatchet in his hand. They then walked all along together.

When they got to the glen, Miss Anne went up a winding path to a seat, where she used to36 love to sit and read. There was a beautiful prospect from it, all around. Royal and Lucy remained down in the little valley to play; but Miss Anne told them that they must not go out of her sight.

“But how can we tell,” said Royal, “what places you can see?”

“O,” said Miss Anne, “look up now and then, and if you can see me, in my seat, you will be safe. If you can see me, I can see you.”

“Come,” said Royal, “let us go down to the bridge, and go across the brook.”

The plank which Royal called a bridge, was down below the place where Miss Anne went up to her seat, and Royal and Lucy began to walk along slowly towards it.

“But I am afraid to go over that plank,” said Lucy.

“Afraid!” said Royal; “you need not be afraid; it is not dangerous.”

“I think it is dangerous,” said Lucy; “it bends a great deal.”

“Bends!” exclaimed Royal; “the bending does no harm. I will lead you over as safe as dry ground. Besides, there is something over there that I want to show you.”

“What is it?” said Lucy.

37 “O, something,” said Royal.

“I don’t believe there is anything at all,” said Lucy, “any more than there was under your cap.”

“O Lucy! there was something under my cap.”

“No, there wasn’t,” said Lucy.

“Yes, that great, flat stone.”

“In your cap, I mean,” said Lucy; “that wasn’t in your cap.”

“In!” said Royal; “that is a very different sort of a preposition.”

“I don’t know what you mean by a preposition,” said Lucy; “but I know you told me there was something in your cap, and that is what I came out to see.”

“Under, Lucy; I said under.”

“Well, you meant in; I verily believe you meant in.”

Lucy was right. Royal did indeed say under, but he meant to have her understand that there was something in his cap, and lying upon the great, flat stone.

“And so you told me a falsehood,” said Lucy.

“O Lucy!” said Royal, “I would not tell a falsehood for all the world.”

“Yes, you told me a falsehood; and now I don’t believe you about anything over the brook.38 For Miss Anne told me, one day, that when anybody told a falsehood, we must not believe them, even if they tell the truth.”

“O Lucy! Lucy!” said Royal, “I don’t believe she ever said any such a word.”

“Yes she did,” said Lucy. But Lucy said this rather hesitatingly, for she felt some doubt whether she was quoting what Miss Anne had told her, quite correctly.

Here, however, the children arrived at the bridge, and Royal was somewhat at a loss what to do. He wanted very much to go over, and to have Lucy go over too; but by his not being perfectly honest before, about what was under his cap, Lucy had lost her confidence in him, and would not believe what he said. At first he thought that if she would not go with him, he would threaten to go off and leave her. But in a moment he reflected that this would make her cry, and that would cause Miss Anne to come down from her seat, to see what was the matter, which might lead to ever so much difficulty. Besides, he thought that he had not done exactly right about the cap story, and so he determined to treat Lucy kindly.

“If I manage gently with her,” said he to himself, “she will want to come across herself pretty soon.”

39 Accordingly, when Royal got to the plank, he said,

“Well, Lucy, if you had rather stay on this side, you can. I want to go over, but I won’t go very far; and you can play about here.”

So Royal went across upon the plank; when he had got to the middle of it, he sprang up and down upon it with his whole weight, in order to show Lucy how strong it was. He then walked along by the bank, upon the other side of the brook, and began to look into the water, watching for fishes.

Lucy’s curiosity became considerably excited by what Royal was constantly saying about his fishes. First he said he saw a dozen little fishes; then, going a little farther, he saw two pretty big ones; and Lucy came down to the bank upon her side of the brook, but she could not get very near, on account of the bushes. She had a great mind to ask Royal to come and help her across, when all at once he called out very eagerly,

“O Lucy! Lucy! here is a great turtle,—a monster of a turtle, as big as the top of my head. Here he goes, paddling along over the stones.”

“Where? where?” said Lucy. “Let me see. Come and help me across, Royal.”

Royal ran back to the plank, keeping a watch40 over the turtle, as well as he could, all the time. He helped Lucy across, and then they ran up to the place, and Royal pointed into the water.

“There, Lucy! See there! A real turtle! See his tail! It is as sharp as a dagger.”

It was true. There was a real turtle resting upon the sand in a shallow place in the water. His head and his four paws were projecting out of his shell, and his long, pointed tail, like a rudder, floated in the water behind.

“Yes,” said Lucy. “I see him. I see his head.”

“Now, Lucy,” said Royal, “we must not let him get away. We must make a pen for him. I can make a pen. You stay here and watch him, while I go and get ready to make a pen.”

“How can you make it?” said Lucy.

“O, you’ll see,” said Royal; and he took up his hatchet, which he had before laid down upon the grass, and went into the bushes, and began cutting, as if he was cutting some of them down.

Lucy remained some time watching the turtle. He lay quite still, with his head partly out of the water. The sun shone upon the place, and perhaps that was the reason why he remained so still; for turtles are said to like to bask in the beams of the sun.

41 After a time, Royal came to the place with an armful of stakes, about three feet long. He threw them down upon the bank, and then began to look around for a suitable place to build his pen. He chose, at last, a place in the water, near the shore. The water there was not deep, and the bottom was sandy.

“This will be a good place,” he said to Lucy. “I will make his pen here.”

“How are you going to make it?” said Lucy.

“Why, I am going to drive these stakes down in a kind of a circle, so near together that he can’t get out between them; and they are so tall that I know he can’t get over.”

“And how are you going to get him in?” said Lucy.

“O, I shall leave one stake out, till I get him in,” answered Royal. “We can drive him in with long sticks. But you must not mind me; you must watch the turtle, or he will get away.”

So Royal began to drive the stakes. Presently Lucy said that the turtle was stirring. Royal looked, but he found he was not going away, and so he went on with his work; and before long he had a place fenced in with his stakes, about as large round as a boy’s hoop. It was42 all fenced, excepting in one place, which he left open to get the turtle through.

The two children then contrived, by means of two long sticks, which Royal cut from among the bushes, to get the turtle into his prison. The poor reptile hardly knew what to make of such treatment. He went tumbling along through the water, half pushed, half driven.

When he was fairly in, Royal drove down the last stake in the vacant space which had been left. The turtle swam about, pushing his head against the bars in several places; and when he found that he could not get out, he remained quietly in the middle.

“There,” said Royal, “that will do. Now I wish Miss Anne would come down here, and see him. I should like to see what she would say.”

Miss Anne did come down after a while; and when the children saw her descending the path, they called out to her aloud to come there and see. She came, and when she reached the bank opposite to the turtle pen, she stood still for a few minutes, looking at it, with a smile of curiosity and interest upon her face; but she did not speak a word.

After a little while, they all left the turtle, and went rambling around, among the rocks and trees. At last Royal called out to them to come to a large tree, where he was standing. He was looking up into it. Lucy ran fast; she thought it was a bird’s nest. Miss Anne came along afterwards, singing. Royal showed them a long, straight branch, which extended out horizontally from the tree, and said that it would be an excellent place to make a swing.

“So it would,” said Miss Anne, “if we only had a rope.”

“I’ve got a rope at home,” said Royal, “if Lucy would only go and get it,—while I cut off some of the small branches, which are in the way.

“Come, Lucy,” he continued, “go and get my rope. It is hanging up in the shed.”

“O no,” said Lucy; “I can’t reach it.”

“O, you can get a chair,” said Royal; “or44 Joanna will hand it to you; she will be close by, in the kitchen. Come, Lucy, go, that is a good girl; and I’ll pay you.”

“What will you give me?” said Lucy.

“O, I don’t know; but I’ll give you something.”

But Lucy did not seem quite inclined to go. She said she did not want to go so far alone; though, in fact, it was only a very short distance. Besides, she had not much confidence in Royal’s promise.

“Will you go, Lucy, if I will promise to give you something?” said Miss Anne.

“Yes,” said Lucy.

“Well, I will,” said Miss Anne; “I can’t tell you what, now, for I don’t know; but it shall be something you will like.

“But, Royal,” she added, “what shall we do for a seat in our swing?”

“Why, we must have a board—a short board, with two notches. I know how to cut them.”

“Yes, if you only had a board; but there are no boards down here. I think you had better go with Lucy, and then you can bring down a board.”

Royal said that it would take some time to saw45 off the board, and cut the notches; and, finally, they concluded to postpone making the swing until the next time they came down to the glen; and then they would bring down whatever should be necessary, with them.

As they were walking slowly along, after this, towards home, Royal said something about Lucy’s not being willing to go for his promise, as well as for Miss Anne’s,—which led to the following conversation:—

Lucy. I don’t believe you were going to give me anything at all.

Royal. O Lucy!—I was,—I certainly was.

Lucy. Then I don’t believe that it would be anything that I should like.

Royal. But I don’t see how you could tell anything about it, unless you knew what it was going to be.

Lucy. I don’t believe it would be anything; do you, Miss Anne?

Miss Anne. I don’t know anything about it. I should not think that Royal would break his promise.

Lucy. He does break his promises. He won’t mend old Margaret’s nose.

Royal. Well, Lucy, that is because my46 putty has all dried up. I am going to do it, just as soon as I can get any more putty.

Lucy. And that makes me think about the thing in your cap. I mean to ask Miss Anne if you did not tell a falsehood. He said there was something in his cap, and there was nothing in it at all. It was only on the great, flat stone.

Royal. O, under, Lucy, under. I certainly said under.

Lucy. Well, you meant in; I know you did. Wasn’t it a falsehood?

Miss Anne. Did he say in, or under?

Royal. Under, under; it was certainly under.

Miss Anne. Then I don’t think it was exactly a falsehood.

Lucy. Well, it was as bad as a falsehood, at any rate.

Royal. Was it as bad as a falsehood, Miss Anne?

Miss Anne. Let us consider a little. Lucy, what do you think? Suppose he had said that there was really something in his cap,—do you think it would have been no worse?

Lucy. I don’t know.

Miss Anne. I think it would have been worse.

Royal. Yes, a great deal worse.

47 Miss Anne. He deceived you, perhaps, but he did not tell a falsehood.

Lucy. Well, Miss Anne, and isn’t it wrong for him to deceive me?

Miss Anne. I think it was unwise, at any rate.

Royal. Why was it unwise, Miss Anne? I wanted her to come out, and I knew she would like to be out there, if she would only once come. Besides, I thought it would make her laugh when I came to lift up my cap and show her that great, flat stone.

Miss Anne. And did she laugh?

Royal. Why, not much. She said she meant to go right into the house again.

Miss Anne. Instead of being pleased with the wit, she was displeased at being imposed upon.

Royal laughed.

Miss Anne. The truth is, Royal, that, though it is rather easier, sometimes, to get along by wit than by honesty, yet you generally have to pay for it afterwards.

Royal. How do we have to pay for it?

Miss Anne. Why, Lucy has lost her confidence in you. You cannot get her to go and get a rope for you by merely promising her something, while I can. She confides in me, and not in you. She is afraid you will find some ingenious48 escape or other from fulfilling it. Wit gives anybody a present advantage, but honesty gives a lasting power; so that the influence I have over Lucy, by always being honest with her, is worth a great deal more than all you can accomplish with your contrivances. So I think you had better keep your wits and your contrivances for turtles, and always be honest with men.

Royal. Men! Lucy isn’t a man.

Miss Anne. I mean mankind—men, women, and children.

Royal. Well, about my turtle, Miss Anne. Do you think that I can keep him in his pen?

Miss Anne. Yes, unless he digs out.

Royal. Dig?—Can turtles dig much?

Miss Anne. I presume they can work into mud, and sand, and soft ground.

Royal. Then I must get a great, flat stone, and put into the bottom of his pen. He can’t dig through that.

Miss Anne. I should rather make his pen larger, and then perhaps he won’t want to get out. You might find some cove in the brook, where the water is deep, for him, and then drive your stakes in the shallow water all around it. And then, if you choose, you could extend it up upon the shore, and so let him have a walk upon the land,49 within his bounds. Then, perhaps, sometimes, when you come down to see him, you may find him up upon the grass, sunning himself.

Royal. Yes, that I shall like very much. It will take a great many stakes; but I can cut them with my hatchet. I’ll call it my turtle pasture. Perhaps I shall find some more to put in.

Lucy. I don’t think it is yours, altogether, Royal.

Royal. Why, I found him.

Lucy. Yes, but I watched him for you, or else he would have got away. I think you ought to let me own a share.

Royal. But I made the pen altogether myself.

Lucy. And I helped you drive the turtle in.

Royal. O Lucy! I don’t think you did much good.

Miss Anne. I’ll tell you what, Lucy; if Royal found the turtle and made the pen, and if you watched him and helped drive him in, then I think you ought to own about one third, and Royal two thirds.

Royal. Well.

Miss Anne. But, then, Royal, why would it not be a good plan for you to let her have as much of your share as will make hers half, and50 yours half, to pay her for the trouble you gave her by the cap story?

Royal. To pay her?

Miss Anne. Yes,—a sort of damages. Then, if you are careful not to deceive her any more, Lucy will pass over the old cases, and place confidence in you for the future.

Royal. Well, Lucy, you shall have half.

Lucy clapped her hands with delight at this concession, and soon after the children reached home. The next day, Royal and Lucy went down to see the turtle; and Royal made him a large pasture, partly in the brook and partly on the shore, and while he was doing it, Lucy remained, and kept him company.

On rainy days, Lucy sometimes found it pretty difficult to know what to do for amusement,—especially when Royal was in his little room at his studies. When Royal had finished his studies, he used to let her go out with him into the shed, or into the barn, and see what he was doing. She could generally tell whether he had gone out or not, by looking into the back entry upon his nail, to see if his cap was there. If his cap was there, she supposed that he had not gone out.

One afternoon, when it was raining pretty fast, she went twice to look at Royal’s nail, and both times found the cap still upon it. Lucy thought it must be after the time, and she wondered why he did not come down. She concluded to take his cap, and put it on, and make believe that she was a traveller.

She put the cap upon her head, and then got a pair of her father’s gloves, and put on. She also found an umbrella in the corner, and took that in her hand. When she found herself rigged, she52 thought she would go and call at Miss Anne’s door. She accordingly walked along, using her umbrella for a cane, holding it with both hands.

When she got to Miss Anne’s door, she knocked, as well as she could, with the crook upon the handle of the umbrella. Miss Anne had heard the thumping noise of the umbrella, as Lucy came along, and knew who it was; so she said, “Come in.”

Lucy opened the door and went in; the cap settled down over her eyes, so that she had to hold her head back very far to see, and the long fingers of her father’s gloves were sticking out in all directions.

“How do you, sir?” said she to Miss Anne, nodding a little, as well as she could,—“how do you, sir?”

“Pretty well, I thank you, sir; walk in, sir; I am happy to see you,” said Miss Anne.

“It is a pretty late evening, sir, I thank you, sir,” said Lucy.

“Yes, sir, I think it is,” said Miss Anne. “Is there any news to-night, sir?”

“No, sir,—not but a few, sir,” said Lucy.

Lucy looked pretty sober while this dialogue lasted; but Miss Anne could not refrain from laughing aloud at Lucy’s appearance and expressions,53 and Lucy turned round, and appeared to be going away.

“Can’t you stop longer, sir?” said Miss Anne.

“No, sir,” said Lucy. “I only wanted to ask you which is the way to London.”

Just at this moment, Lucy heard Royal’s voice in the back entry, asking Joanna if she knew what had become of his cap; and immediately she started to run back and give it to him. Finding, however, that she could not get along fast enough with the umbrella, she dropped it upon the floor, and ran along without it, calling out,

“Royal! Royal! here; come here, and look at me.”

“Now I should like to know, Miss Lucy,” said Royal, as soon as she came in sight, “who authorized you to take off my cap?”

“I’m a traveller,” said Lucy.

“A traveller!” repeated Royal; “you look like a traveller.”

He pulled his cap off from Lucy’s head, and put it upon his own; and then held up a paper which he had in his hands, to her view.

There was a frightful-looking figure of a man upon it, pretty large, with eyes, nose, and mouth, painted brown, and a bundle of sticks upon his back.

54 “What is that?” said Lucy.

“It is an Indian,” said Royal. “I painted him myself.”

“O, what an Indian!” said Lucy. “I wish you would give him to me.”

“O no,” said Royal; “it is for my target.”

“Target?” said Lucy. “What is a target?”

“A target? Why, a target is a mark to shoot at, with my bow and arrow. They almost always have Indians for targets.”

Lucy told him that she did not believe his target would stand up long enough to be shot at; but Royal said, in reply, that he was going to paste him upon a shingle, and then he could prop the shingle up so that he could shoot at it. And he asked Lucy if she would go and borrow Miss Anne’s gum arabic bottle, while he went and got the shingle.

The shingle which Royal meant was a thin, flat piece of wood, such as is used to put upon the roofs of houses.

The gum arabic bottle was a small, square bottle, containing some dissolved gum arabic, and a brush,—which was always ready for pasting.

Before Lucy got the paste, Royal came back with his shingle, and he came into Miss Anne’s room, to see what had become of Lucy; and55 Miss Anne then said he might paste it there if he pleased. So she spread a great newspaper upon the table, and put the little bottle and the Indian upon it; and Royal and Lucy brought two chairs, and sat down to the work. They found that the table was rather too high for them; and so they took the things off again, and spread the paper upon the carpet, and sat down around it. Lucy could see now a great deal better than before.

“Miss Anne,” said Lucy, “I very much wish that you would give me your gum arabic bottle, and then I could make little books, and paste pictures in them, whenever I pleased.”

“Yes,” said Miss Anne, “and that would make me ever so much trouble.”

“No, Miss Anne, I don’t think it would make you much trouble.”

“Why, when I wanted a little gum arabic, to paste something, how would I get any?”

“O, then I would lend you mine,” said Lucy.

“Yes, if you could find it.”

“O, Miss Anne, I could find it very easily; I am going to keep it in my treasury.”

“Perhaps you might put it in once or twice, but after that you would leave it about anywhere. One day I should find it upon a chair, and the next day upon a table, and the next on the floor;—that56 is the way you leave your things about the house.”

“I used to, when I was a little girl,” said Lucy, “but I don’t now.”

“How long is it since you were a little girl?” asked Miss Anne.

“O, it was before you came here. I am older now than I was when you came here; I have had a birthday since then.”

“Don’t you grow old any, except when you have a birthday?” asked Miss Anne.

Lucy did not answer this question at first, as she did not know exactly how it was; and while she was thinking of it, Miss Anne said,

“It can’t be very long, Lucy, since you learned to put things in their places, for it is not more than ten minutes since I heard you throw down an umbrella upon the entry floor, and leave it there.”

“The umbrella?—O, that was because I heard Royal calling for his cap; and so I could not wait, you know; I had to leave it there.”

“But you have passed by it once since, and I presume you did not think of such a thing as taking it up.”

Lucy had no reply to make to this statement, and she remained silent.

57 “I have got a great many little things,” continued Miss Anne, “which I don’t want myself, and which I should be very glad to give away to some little girl, for playthings, if I only knew of some one who would take care of them. I don’t want to have them scattered about the house, and lost, and destroyed.”

“O, I will take care of them, Miss Anne,” said Lucy, very eagerly, “if you will only give them to me. I certainly will. I will put them in my treasury, and keep them very safe.”

“If I were a little girl, no bigger than you,” said Miss Anne, “I should have a great cabinet of playthings and curiosities, twice as big as your treasury.”

“How should you get them?” asked Lucy.

“O, I know of a way;—but it is a secret.”

“Tell me, do, Miss Anne,” said Lucy.—“You would buy them, I suppose, with your money.”

“No,” said Miss Anne, “that is not the way I meant.”

“What way did you mean, then?” said Lucy. “I wish you would tell me.”

“Why, I should take such excellent care of everything I had, that my mother would give me58 a great many of her little curiosities, and other things, to keep.”

“Would she, do you think?”

“Yes,” said Miss Anne, “I do not doubt it. Every lady has a great many beautiful things, put away, which she does not want to use herself, but she only wants to have them kept safely. Now, I should take such good care of all such things, that my mother would be very glad to have me keep them.”

“Did you do so, when you were a little girl?” said Lucy.

“No,” said Miss Anne; “I was just as careless and foolish as you are. When I was playing with anything, and was suddenly called away, I would throw it right down, wherever I happened to be, and leave it there. Once I had a little glass dog, and I left it on the floor, where I had been playing with it, and somebody came along, and stepped upon it, and broke it to pieces.”

“And would not your mother give you things then?” asked Lucy.

“No, nothing which was of much value.—And once my uncle sent me a beautiful little doll; but my mother would not let me keep it. She kept it herself, locked up in a drawer, only sometimes she would let me have it to play with.”

59 “Why would not she let you keep it?” said Lucy.

“O, if she had, I should soon have made it look like old Margaret.”

Here Royal said he had got his Indian pasted; and he put away the gum arabic bottle, and the sheet of paper, and then he and Lucy went away.

One night, while Miss Anne was undressing Lucy, to put her to bed, she thought that her voice had a peculiar sound, somewhat different from usual. It was not hoarseness, exactly, and yet it was such a sort of sound as made Miss Anne think that Lucy had taken cold. She asked her if she had not taken cold, but Lucy said no.

Lucy slept in Miss Anne’s room, in a little trundle-bed. Late in the evening, just before Miss Anne herself went to bed, she looked at Lucy, to see if she was sleeping quietly; and she found that she was.

But in the night Miss Anne was awaked by hearing Lucy coughing with a peculiar hoarse and hollow sound, and breathing very hard. She got up, and went to her trundle-bed.

“Lucy,” said she, “what’s the matter?”

“Nothing,” said Lucy, “only I can’t breathe very well.”

Here Lucy began to cough again; and the61 cough sounded so hoarse and hollow, that Miss Anne began to be quite afraid that Lucy was really sick. She put on a loose robe, and carried her lamp out into the kitchen, and lighted it,—and then came back into her room again. She found that Lucy was no better, and so she went to call her mother.

She went with the lamp, and knocked at her door; and when she answered, Miss Anne told her that Lucy did not seem to be very well,—that she had a hoarse cough, and that she breathed hard.

“O, I’m afraid it is the croup,” she exclaimed; “let us get up immediately.”

“We will get right up, and come and see her,” said Lucy’s father.

So Miss Anne put the lamp down at their door, and went out into the kitchen to light another lamp for herself. She also opened the coals, and put a little wood upon the fire, and hung the tea-kettle upon the crane, and filled it up with water; for Miss Anne had observed that, in cases of sudden sickness, hot water was one of the things most sure to be wanted.

After a short time, Lucy’s father and mother came in. After they had been with her a few minutes, her mother said,

“Don’t you think it is the croup?”

62 “No, I hope not,” said her father; “I presume it is only quinsy; but I am not sure, and perhaps I had better go for a doctor.”

After some further consultation, they concluded that it was best to call a physician. Lucy’s mother recommended that they should call up the hired man, and send him; but her father thought that it would take some time for him to get up and get ready, and that he had better go himself.

When he had gone, they brought in some hot water, and bathed Lucy’s feet. She liked this very much; but her breathing seemed to grow rather worse than better.

“What is the croup?” said Lucy to her mother, while her feet were in the water.

“It is a kind of sickness that children have sometimes suddenly in the night; but I hope you are not going to have it.”

“No, mother,” said Lucy; “I think it is only the quinsy.”

Lucy did not know at all what the quinsy was; but her sickness did not seem to her to be any thing very bad; and so she agreed with her father that it was probably only the quinsy.

When the doctor came, he felt of Lucy’s pulse, and looked at her tongue, and listened to her breathing.

63 “Will she take ipecacuanha?” said the doctor to Lucy’s mother.

“She will take anything you prescribe, doctor,” said her father, in reply.

“Well, that’s clever,” said the doctor. “The old rule is, that the child that will take medicine is half cured already.”

So the doctor sat down at the table, and opened his saddle-bags, and took out a bottle filled with a yellowish powder, and began to take some out.

“Is it good medicine?” said Lucy, in a low voice, to her mother. She was now sitting in her mother’s lap, who was rocking her in a rocking-chair.

“Yes,” said the doctor; for he overheard Lucy’s question, and thought that he would answer it himself. “Yes, ipecacuanha is a very good medicine,—an excellent medicine.”

As he said this, he looked around, rather slyly, at Miss Anne and Lucy’s father.

“Then I shall like to take it,” said Lucy.

“He means,” said her mother, “that it is a good medicine to cure the sickness with; the taste of it is not good. It is a very disagreeable medicine to take.”

Lucy said nothing in reply to this, but she thought to herself, that she wished the doctors64 could find out some medicines that did not taste so bad.

Miss Anne received the medicine from the doctor, and prepared it in a spoon, with some water, for Lucy to take. Just before it was ready, the door opened, and Royal came in.

“Why, Royal,” said his mother, “how came you to get up?”

“I heard a noise, and I thought it was morning,” said Royal.

“Morning? no,” replied his mother; “it is midnight.”

“Midnight?” said Lucy. She was quite astonished. She did not recollect that she had ever been up at midnight before, in her life.

“Is Lucy sick?” said Royal.

“No, not very sick,” said Lucy.

Royal came and stood by the rocking-chair, and looked into Lucy’s face.

“I am sorry that you are sick,” said he. “Is there anything that I can do for you?”

Lucy hesitated a moment, and then her eye suddenly brightened up, and she said,

“Yes, Royal,—if you would only just be so good as to take my medicine for me.”

Royal laughed, and said, “O Lucy! I guess you are not very sick.”

65 In fact, Lucy was breathing pretty freely then, and there was nothing to indicate, particularly, that she was sick; unless when a paroxysm of coughing came on. Miss Anne brought her medicine to her in a great spoon, and Royal said that he presumed that the doctor would not let him take the medicine, but that, if she would take it, he would make all the faces for her.

Accordingly, while she was swallowing the medicine, she turned her eyes up towards Royal, who had stood back a little way, and she began to laugh a little at the strange grimaces which he was making. The laugh was, however, interrupted and spoiled by a universal shudder which came over her, produced by the taste of the ipecacuanha.

Immediately afterwards, Lucy’s mother said,

“Come, Royal; now I want you to go right back to bed again.”

“Well, mother,—only won’t you just let me stop a minute, to look out the door, and see how midnight looks?”

“Yes,” said she, “only run along.”

So Royal went away; and pretty soon the doctor went away too. He said that Lucy would be pretty sick for about an hour, and that after that he hoped that she would be better; and he left a66 small white powder in a little paper, which he said she might take after that time, and it would make her sleep well the rest of the night.

It was as the doctor had predicted. Lucy was quite sick for an hour, and her father and mother, and Miss Anne, all remained, and took care of her. After that, she began to be better. She breathed much more easily, and when she coughed she did not seem to be so very hoarse. Her mother was then going to carry her into her room; but Miss Anne begged them to let her stay where she was; for she said she wanted to take care of her herself.

“The doctor said he thought she would sleep quietly,” said Miss Anne; “and if she should not be so well, I will come and call you.”

“Very well,” said her mother, “we will do so. But first you may give her the powder.”

So Miss Anne took the white powder, and put it into some jelly, in a spoon; and when she had covered the powder up carefully with the jelly, she brought it to Lucy.

“Now I’ve got some good medicine for you,” said Miss Anne.

“I am glad it is good,” said Lucy.

“That is,” continued Miss Anne, “the jelly is good, and you will not taste the powder.”

67 Lucy took the jelly, and, after it, a little water; and then her mother put her into her trundle-bed. Her father and mother then bade her good night, and went away to their own room.

Miss Anne then set the chairs back in their places, and carried out all the things which had been used; and after she had got the room arranged and in order, she came to Lucy’s bedside to see if she was asleep. She was not asleep.

“Lucy,” said Miss Anne, “how do you feel now?”

“O, pretty well,” said Lucy; “at least, I am better.”

“Do you feel sleepy?”

“No,” said Lucy.

“Is there any thing you want?” asked Miss Anne.

“Why, no,—only,—I should like it,—only I don’t suppose you could very well,—but I should like it if you could hold me a little while,—and rock me.”

“O yes, I can,” said Miss Anne, “just as well as not.”

So Miss Anne took Lucy up from her bed, and wrapped a blanket about her, and sat down in her rocking-chair, to rock her. She rocked her a few minutes, and sang to her, until she68 thought she was asleep. Then she stopped singing, and she rocked slower and slower, until she gradually ceased.

A moment afterwards, Lucy said, in a mild and gentle voice,

“Miss Anne, is it midnight now?”

“It is about midnight,” said Miss Anne.

“Do you think you could just carry me to the window, and let me look out, and see how the midnight looks?—or am I too heavy?”

“No, you are not very heavy; but, then, there is nothing to see. Midnight looks just like any other part of the night.”

“Royal wanted to see it,” said Lucy, “and I should like to, too, if you would be willing to carry me.”

When a child is so patient and gentle, it is very difficult indeed to refuse them any request that they make; and Miss Anne immediately began to draw up the blanket over Lucy’s feet, preparing to go. She did not wish to have her put her feet to the floor, for fear that she might take more cold. So she carried her along to the window, although she was pretty heavy for Miss Anne to carry. Miss Anne was not very strong. 69

71 Lucy separated the two curtains with her hands, and Miss Anne carried her in between them. There was a narrow window-seat, and she rested Lucy partly upon it, so that she was less heavy to hold.

“Why, Miss Anne,” said Lucy, “isn’t it any darker than this?”

“No,” said Miss Anne; “there is a moon to-night.”

“Where?” said Lucy. “I don’t see the moon.”

“We can’t see it here; we can only see the light of it, shining on the buildings.”

“It is pretty dark in the yard,” said Lucy.

“Yes,” said Miss Anne, “the yard is in shadow.”

“What do you mean by that, Miss Anne?” asked Lucy.

“Why, the moon does not shine into the yard; the house casts a shadow all over it.”

“Then I should think,” said Lucy, “that you ought to say that the shadow is in the yard,—not the yard is in the shadow.”

Miss Anne laughed, and said,

“I did not say that the yard was in the shadow, but in shadow.”

“And is not that just the same thing?” said Lucy.

72 “Not exactly; but look at the stars over there, beyond the field.”

“Yes,” said Lucy, “there’s one pretty bright one; but there are not a great many out. I thought there would be more at midnight.”

“No,” said Miss Anne, “there are no more stars at midnight than at any other time; and to-night there are fewer than usual, because the moon shines.”

“I don’t see why there should not be just as many stars, if the moon does shine.”

“There are just as many; only we can’t see them so well.”

“Why can’t we see them?” said Lucy.

But Miss Anne told Lucy that she was rather tired of holding her at the window, and so she would carry her back, and tell her about it while she was rocking her to sleep.

“You see,” said Miss Anne, after she had sat down again, “that there are just as many stars in the sky in the daytime, as there are in the night.”

“O Miss Anne!” exclaimed Lucy, raising up her head suddenly, as if surprised; “I have looked up in the sky a great many times, and I never saw any.”

“No, we cannot see them, because the sun shines so bright.”

73 “Did you ever see any, Miss Anne?”

“No,” said she.

“Did any body ever see any?”

“No,” said Miss Anne, “I don’t know that any body ever did.”

“Then,” said Lucy, “how do they know that there are any?”

“Well—that is rather a hard question,” said Miss Anne. “But they do know; they have found out in some way or other, though I don’t know exactly how.”

“I don’t see how they can know that there are any stars there,” said Lucy, “unless somebody has seen them. I guess they only think there are some, Miss Anne,—they only think.”

“I believe I don’t know enough about it myself,” said Miss Anne, “to explain it to you,—and besides, you ought to go to sleep now. So shut up your eyes, and I will sing to you, and then, perhaps, you will go to sleep.”

Lucy obeyed, and shut up her eyes; and Miss Anne began to sing her a song. After a little while, Lucy opened her eyes, and said,

“I rather think, Miss Anne, I should like to get into my trundle-bed now. I am rather tired of sitting in your lap.”

“Very well,” said Miss Anne; “I think it will74 be better. But would not you rather have me bring the cradle in? and then you can lie down, and I can rock you all the time.”

“No,” said Lucy; “the cradle has got so short, that I can’t put my feet out straight. I had rather get into my trundle-bed.”

So Miss Anne put Lucy into the trundle-bed, and she herself took a book, and sat at her table, reading. In a short time, Lucy went to sleep; and she slept soundly until morning.

The next morning, when Lucy waked up, she found that it was very light. The curtains of the room were up, and she could see the sun shining brightly upon the trees and buildings out of doors, so that she supposed that it was pretty late. Besides, she saw that Miss Anne was not in the room; and she supposed that she had got up and gone out to breakfast.

Lucy thought that she would get up too. But then she recollected that she had been sick the night before, and that, perhaps, her mother would not be willing to have her get up.

Her next idea was, that she would call out for Miss Anne, or for her mother; but this, on reflection, she thought would make a great disturbance; for it was some distance from the room which she was in to the parlor, where she supposed they were taking breakfast.

She concluded, on the whole, to wait patiently until somebody should come; and having nothing76 else to do, she began to sing a little song, which Miss Anne had taught her. She knew only one verse, but she sang this verse two or three times over, louder and louder each time, and her voice resounded merrily through all that part of the house.

Some children cry when they wake up and find themselves alone; some call out aloud for somebody to come; and others sing. Thus there are three ways; and the singing is the best of all the three;—except, indeed, for very little children, who are not old enough to sing or to call, and who, therefore, cannot do anything but cry.

They heard Lucy’s singing in the parlor, and Miss Anne came immediately to see her. She gave her a picture-book to amuse herself with for a time, and went away again; but in about a quarter of an hour she came back, and helped her to get up and dress herself.

Her mother told her that she must not go out of doors that day, but that she might play about in any of the rooms, just as she pleased.

“But what shall I do for my breakfast?” said Lucy.

“O, I will give you some breakfast,” said Miss Anne. “How should you like to have it by yourself, upon your little table, in the kitchen?”

77 “Well,” said Lucy, “if you will let me have my own cups and saucers.”

“Your cups won’t hold enough for you to drink,—will they?”

“O, I can fill them up two or three times.”

Miss Anne said she had no objection to this plan; and she told Lucy to go and get her table ready. So Lucy went and got her little table. It was just high enough for her to sit at. Her father had made it for her, by taking a small table in the house, which had been intended for a sort of a light-stand, and sawing off the legs, so as to make it just high enough for her.

Lucy brought this little table, and also her chair; and then Miss Anne handed her a napkin for a table-cloth, and told her that she might set her table,—and that, when it was all set, she would bring her something for breakfast; and so she left Lucy, for a time, to herself.

Lucy spread the napkin upon her table, and then went and got some of her cups and saucers, and put upon it. Joanna was ironing at the great kitchen table, and Lucy went to ask her how many cups and saucers she had better set.

“I should think it would take the whole set,” said Joanna, “to hold one good cup of tea.”

78 “But I am going to fill up my cup three times, Joanna; and if that isn’t enough, I shall fill it up four times.”

“O, then,” said Joanna, “I would not have but one cup,—or at most two. I think I would have two, because you may possibly have some company.”

“I wish you would come and be my company, Joanna.”

“No, I must attend to my ironing.”

“Well,” said Lucy, as she went back to her table, “I will have two cups, at any rate, for I may have some company.”

She accordingly put on two cups and a tea-pot; also a sugar-bowl and creamer. She placed them in various ways upon the table; first trying one plan of arrangement, and then another; and when at last they were placed in the best way, she went and called Miss Anne, to tell her that she was ready for her breakfast.

Miss Anne came out, according to her promise, to give her what she was to have to eat. First, she put a little sugar in her sugar-bowl; then some milk in her cream-pitcher; then some water, pretty hot, in her tea-pot.

“Could not you let me have a little real tea?” said Lucy.

79 “O, this will taste just as well,” said Miss Anne.

“I know it will taste just as well; but it will not look just right. Real tea is not white, like water.”

“Water is not white,” said Miss Anne; “milk is white; water is very different in appearance from milk.”

“What color is water, then?” said Lucy.

“It is not of any color,” said Miss Anne. “It is what we call colorless. Now, you want to have something in your tea-pot which is colored a little, like tea,—not perfectly colorless, like water.”

Lucy said yes, that that was exactly what she wanted. So Miss Anne took her tea-pot up, and went into the closet with it, and presently came out with it again, and put it upon the table. The reason why she took all this pains to please Lucy was, because she was so gentle and pleasant; and, although she often asked for things, she was not vexed or ill-humored when they could not be given to her.

Miss Anne then cut some thin slices of bread, and divided them into square pieces, so small that they could go on a small plate, which she brought from the closet. She also gave her a80 toasting-fork with a long handle, and told her that she might toast her own bread, and then spread it with butter. She gave her a little butter upon another plate.

When all these things were arranged, Miss Anne went away, telling Lucy that she had better make her breakfast last as long as she could, for she must remember that she could not go out at all that day; and that she must therefore economize her amusements.

“Economize? What do you mean by that, Miss Anne?” said Lucy.

“Why, use them carefully, and make them last as long as you can.”

Lucy followed Miss Anne’s advice in making the amusement of sitting at her own breakfast table last as long as possible. She toasted her little slices of bread with the toasting-fork, and poured out the tea from her tea-pot. She found that it had a slight tinge of the color of tea, which Miss Anne had given it by sweetening it a little, with brown sugar. Lucy enjoyed her breakfast very much.

While she was eating it, Joanna, who was much pleased with her for being so still, and so careful not to make her any trouble, asked her if she should not like a roasted apple.

81 “Yes,” said Lucy, “very much indeed.”

“I will give you one,” said Joanna, “and show you how to roast it, if you will go and ask your mother, if she thinks it will not hurt you.”

Lucy accordingly went and asked her mother. She said it would not hurt her at all, and that she should be very glad to have Joanna get her an apple.

Joanna accordingly brought a large, rosy apple, with a stout stem. She tied a long string to the stem, and then held the apple up before the fire a minute, by means of the stem. Then she got a flat-iron, and tied the other end of the string to the flat-iron. The flat-iron she then placed upon the mantle shelf, and the string was just long enough to let the apple hang down exactly before the fire.

When it was all arranged in this way, she took up the apple, and twisted the string for some time; and then, when she let the apple down again gently to its place, the weight of it began to untwist the string, and this made the apple itself turn round quite swiftly before the fire.

Joanna also put a plate under the apple, to catch any of the juice or pulp which might fall down, and then left Lucy to watch it while it was roasting.

82 Lucy watched its revolutions for some time in silence. She observed that the apple would whirl very swiftly for a time, and then it would go slower, and slower, and slower, until, at length, she said,

“Joanna, Joanna, it is going to stop.”

But, instead of this, it happened that, just at the very instant when Lucy thought it was going to stop, all at once it began to turn the other way; and, instead of going slower and slower, it went faster and faster, until, at length, it was revolving as fast as it did before.

“O no,” said she to Joanna; “it has got a going again.”

It was indeed revolving very swiftly; but pretty soon it began to slacken its speed again;—and again Lucy thought that it was certainly going to stop. But at this time she witnessed the same phenomenon as before. It had nearly lost all its motion, and was turning around very slowly indeed, and just upon the point of stopping; and in fact it did seem to stop for an instant; but immediately it began to move in an opposite direction, very slowly at first, but afterwards faster and faster, until it was, at length, spinning around before the hot coals, as fast as ever before. Pretty soon, also, the apple began to sing; and83 Lucy concluded that it would never stop,—at least not before it would have time to be well roasted.

“It goes like Royal’s top,” said Lucy.

“Has Royal got a top?” said Joanna.

“Yes,” said Lucy, “a large humming-top. There is a hole in it. It spins very fast, only it does not go first one way and then the other, like this apple.”

“I never saw a top,” said Joanna.

“Never saw one!” exclaimed Lucy. “Did not the boys have tops when you were little?”

“No boys that I ever knew,” answered Joanna.

“Did you have a tea-set when you were a little girl?” asked Lucy.

“No,” said Joanna, “I never saw any such a tea-set, until I saw yours.”

“What kind of playthings did you have, then, when you were a little girl?”

“No playthings at all,” said Joanna; “I was a farmer’s daughter.”

“And don’t the farmers’ daughters ever have any playthings?”

“I never did, at any rate.”

“What did you do, then, for play?”

“O, I had plenty of play. When I was about as big as you, I used to build fires in the stumps.”

84 “What stumps?” said Lucy.

“Why, the stumps in the field, pretty near my father’s house. I used to pick up chips and sticks, and build fires in the hollow places in the stumps, and call them my ovens. Then, when they were all heated, I used to put a potato in, and cover it up with sand, and let it roast.”

“I wish I had some stumps to build fires in,” said Lucy. “I should like to go to your house and see them.”

“O, they are all gone now,” said Joanna. “They have gradually got burnt up, and rotted out; and now it is all a smooth, green field.”

“O, what a pity!” said Lucy. “And an’t there any more stumps anywhere?”

“Yes, in the woods, and upon the new fields. You see, when they cut down trees, they leave the stumps in the ground; and pretty soon they begin to rot; and they rot more and more, until, at last, they tumble all to pieces; and then they pile up the pieces in heaps, and burn them. Then the ground is all smooth and clear. So I used to build fires in the stumps as long as they lasted. One day my hen laid her eggs in a stump.”

“Your hen?” said Lucy; “did you have a hen?”

“Yes,” replied Joanna; “when I was a little85 older than you are, my father gave me a little yellow chicken, that was peeping, with the rest, about the yard. I used to feed her, every day, with crumbs. After a time, she grew up to be a large hen, and laid eggs. My father said that I might have all the eggs too. I used to sell them, and save the money.”

“How much money did you get?” asked Lucy.

“O, considerable. After a time, you see, I let my hen sit, and hatch some chickens.”

“Sit?” said Lucy.

“Yes; you see, after hens have laid a good many eggs, they sit upon them, to keep them warm, for two or three weeks; and, while they keep them warm, a little chicken begins to grow in every egg, and at length, after they grow strong enough, they break through the eggs and come out. So I got eleven chickens from my hen, after a time.”

“Eleven?” repeated Lucy; “were there just eleven?”

“There were twelve, but one died,” replied Joanna. “And all these chickens were hatched in a stump.”

“How did that happen?” asked Lucy.

86 “Why, the hens generally used to lay their eggs in the barn, and I used to go in, every day, to get the eggs. I carried a little basket, and I used to climb about upon the hay, and feel in the cribs; and I generally knew where all the nests were. But once I could not find my hen’s nest for several days; and at last I thought I would watch her, and see where she went. I did watch her, and I saw her go into a hollow place in a great black stump, in the corner of the yard. After she came out, I went and looked there, and I found four eggs.”