Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, December 27, 1881, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Harper's Young People, December 27, 1881

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: December 31, 2015 [EBook #50809]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE, DEC 27, 1881 ***

Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| Vol. III.—No. 113. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, December 27, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

An angel voice on Judah's plain

Announced to men a Saviour's birth:

Each Christmas sends the sweet refrain

Re-echoing wider o'er the earth.

Whence come the joys of Christmas-tide?

A Child from Heaven has given us them.

Above all thoughts let this abide:

The Christ is born in Bethlehem.

The sharp crack of a rifle startled the echoes around Judge Malcom's country home, and a big black crow dropped from the wood-pile. Out ran a little darky boy from the kitchen, followed by Aunt Dinah, his fat old grandmother.

"Now, you Jo, what you gwine to do wid dat dar crow? You better drap him like a hot potater. He's a-gwine to de Ole Scratch, whar he belongs."

But Jo had run over to the wood-pile, picked up the poor old crow, and held it to his bosom. His woollen shirt was open, and down his black skin ran the red blood of the wounded bird, down his black cheeks ran the tears, and he rocked himself to and fro in an agony of grief.

"He's done gone dead for suah," sobbed Jo. "Oh, Mas'r Harry! what made yer kill poor old 'Thus'lem?"

"I'm sorry, Jo," said a handsome lad of twelve, putting down his gun. "I didn't know it was your crow, and he made such a capital target up there on that jagged stick, I couldn't help it. Don't cry, Jo; I'll get you another much nicer pet than that. He's the most broken-down, dilapidated-looking customer I ever saw. He's blind in one eye, and no wonder Aunt Dinah named him Methuselah; he must be a thousand years old. Let the miserable thing die, Jo, and I'll give you one of my bull-pups."

"An' I'll dib oo a pet tennary, Do," lisped little Laura.

"An' I'll gib you a good lickin' ef you don't shet dat dar bawlin'," said Aunt Dinah. "Why, yer couldn't make more ob a rumpus over a pore Christian."

But entreaties or threats were of no avail. Jo thanked Master Harry for his offer of the bull-pup, and Miss Laura for hers of a canary, but he said he didn't want any more pets if 'Thus'lem died. Then he climbed the back steps to the room over the kitchen where he and Aunt Dinah slept. Taking out of an old box a checked shirt, he proceeded to tear off the tail some narrow strips. These he bound tightly about the bleeding body of the crow, and finding one leg hanging limp and useless, he cut a splinter from the box, and set the shattered limb. Then he bathed 'Thus'lem's head with water, all the while calling upon his favorite to open his eyes and look at him once more before he died.

'Thus'lem seemed to have made up his mind to look at Jo a good many more times before he died, for his best eye opened and began to blink in such a lively manner that Jo jumped up and clapped his hands with delight.

"Why, 'Thus'lem," he stammered—"why, why, yer ain't done gone, is yer? Yer's a-gwine to lib, mebbe?"

"Jes so, jes so," feebly croaked the crow.

Not that I mean to say 'Thus'lem could talk. No member of the crow family has ever been known to carry on a conversation; but as for those two words, everybody said they were plain enough when you knew what they were.

"'Clar to goodness," said Aunt Dinah, "ef dere's any kill in dat dar crow! He's been froze to deff, an' scalded to deff, an' crushed to deff, an' shot to deff, an' here he is agin, peart as a maggot. Reckon he's lived 's long 's de creation itseff, an' looked on wid dat dar crooked eye o' his'n when Noah built de ark. He's enuff to scar' de life out ob any one. Jes look at him, Mas'r Harry."

He certainly was a very queer specimen of the bird creation. His body seemed to be held together with strips of Jo's old shirt, he had only one leg to stand on, and every feather seemed to straggle in a different direction.

"He hasn't got off by de skin ob his teef for nuffin," said Aunt Dinah; "he's chock-full ob inikity, dat dar crow."

"Jes so, jes so," croaked the crow.

But Jo patted tenderly the wounded body of his favorite, and told him not to mind granny, to be a good crow, and get well and comfort the oppressed heart of his master.

"For, 'Thus'lem," said Jo, as he settled down to his potato-paring, with the bird on his shoulder, "I know you's ill-used an' pussecuted an' slanderized, an' folks don't gib yer no peace, sleepin' nor wakin'; but dat's acause you's black, 'Thus'lem, an' I's black, an' we's bofe black. Ef yer woz a lubly yaller canary ob Missy Laura's, you'd hab a mos' spreneriferous time, 'Thus'lem. You'd hab a shinin' gilt cage to lib in, an' a boss swing to swing on, an' all de lump-sugar yer could swaller down, an' Missy Laura'd call yer 'honey' an' 'sugar-plum,' an' let yer roost on her lily-white finger, an' peck out ob her lubly red lips. Oh, goodness gracious' sakes alive, 'Thus'lem!" said Jo, his eyes rolling in his head at the thoughts of such ecstasy, "ef yer woz only a yaller canary!"

But 'Thus'lem shook his head, as much as to say that he wouldn't give a rotten cherry for such felicity.

"It's a mos' drefful pity," sighed poor Jo, "dat yer looks is so mightily agin yer, 'Thus'lem; dat dar nose o' yourn bein' so drefful hooked, an' dat dar eye o' yourn so powerful skewed. But don't worry about it, 'Thus'lem; it can't be helped, yer know."

"Jes so, jes so," meekly croaked the crow.

"We'll hab to be sassyfried, 'Thus'lem, an' do de bes' we can. Don' yer smell de good tings a-cookin', 'Thus'lem? Don' yer sniff up de pies an' cookies, 'Thus'lem, an' de ginger an' spice an' all de lubly cookin', 'Thus'lem? Dat's acause it's Christmas-time, when eberybody's kinder happy, 'Thus'lem, even a pore old crow."

"Jes so, jes so," croaked the crow, and apparently a little tired of Jo's sermonizing, he limped out of his sight.

Shortly after, Master Harry entered the kitchen, and told Jo he had some very particular work for him to do.

"You see, Jo," said Harry, "Santa Claus is very busy this year, and he can't get time to provide Christmas trees for folks that have them handy. We'll have to help him a little." And winking mysteriously to Jo, he beckoned him outside, and told him the joyful news that he too was to help get the Christmas tree and greens.

It may not seem such a very pleasant thing to some people to go out in the freezing air, and hack down a lot of tough cedars, but to Jo it was simply delightful.

"Jes tink of dat dar, 'Thus'lem," he said to his crow, "'ter be sot ter work for Santy Claws himseff! 'Pears like as ef de good times is comin' for dis yere Jo, 'Thus'lem. Mas'r Harry's powerful good to bofe of us nowadays. It's a bressed Christmas dis yere, 'Thus'lem."

The fact was that Harry had determined to make up to Jo for the grief he had given him in the careless shooting of his favorite crow. He was shocked when he saw the agony his careless indifference had given Jo. He had no idea a little darky like that could feel even worse than he would if any accident should happen to one of his pets. When Harry found out that the color of Jo's skin did not hinder him from being a real boy like himself, with all a boy's appreciation, and much more than an average boy's feeling, Jo went up a good many pegs in Harry's estimation, and not having any white boys handy, he made excellent use of Jo.

There was an air of secrecy about the house that always belonged to Christmas-time. When the Judge came home from town with his pockets bulging out, and winked to his wife to follow him to an adjoining room,[Pg 131] nobody thought of prying into their secrets except 'Thus'lem; but then no one minded him.

Harry had his own secrets too, shared by nobody except Jo. He was almost too dignified to take a poor little negro like Jo into his full confidence, but there was a little package in his bureau drawer, and he was bursting to show it to somebody. It was a likeness of himself nicely inclosed in a little locket that would just fit upon his mother's gold chain.

"Don't you say anything about it, Jo."

"Not for de worl', Mas'r Harry. I'd die afore I'd reveal a solemn secret like dat dar."

"I believe you would, Jo. I think I can trust you."

Jo's heart almost burst with pride at this mark of confidence. He did not even tell 'Thus'lem, though he was sorely tempted to, as he never kept anything from his pet crow. The very next day it happened that another honor was conferred upon Jo.

Mrs. Malcom had shut herself up in her room, and when Jo brought a scuttle of coal, she did not put aside the pretty purse she was knitting, but nodded and smiled when she saw Jo looking at it.

"It's for Master Harry, Jo. When I get it done and put a few gold pieces in it, don't you think he'll like it all the better because his mother knit it?"

"Shouldn't wunner a bit ef he would, missus. My souls an' bodies! wot a Christmas this will be!"

"Don't tell him, Jo."

"I'd be chopped into bits afore I'd tell it!"

"Jo is a faithful, honest, good little fellow," said Mrs. Malcom to Harry; "we mustn't forget Jo at Christmas."

"No, indeed, mamma. Do you know what I think would please him more than anything? A pretty collar for 'Thus'lem, as he calls that old crow. Of course we'll give him clothes and things; but he'd like something of that kind for Methuselah—darkies like trinkets, you know."

"Jes so, jes so," said the crow.

Harry remembered this remark bitterly enough upon Christmas-eve, when the happy moment had at last come for him to bring forth his treasure from its hiding-place, and put it triumphantly in the hands of his mamma.

The Christmas greens were all hung, the Christmas tree was ready for Santa Claus to trim, and Jack Frost had already begun his wonderful decorations. Little Laura was fast asleep in her snug little bed; Jo had gone, whistling cheerfully, to his garret; and even 'Thus'lem had squeezed himself through the hole in the plaster that led from the main building to the room over the kitchen, and gone to roost comfortably in Jo's black bosom.

Jo looked out of the little window up to the clear cold sky. One tiny star was glimmering there.

"Pears like as ef it might be de bressed star ob Bethlehem, 'Thus'lem," said Jo; "it's de berry same hebben, 'Thus'lem, as it woz long ago."

"Jes so, jes so," sleepily croaked the crow.

In the mean while Harry had gone to get his treasure. He opened the bureau, put his hand to the accustomed place, and lo! the treasure was gone. With a trembling hand Harry tossed every article over a dozen times. He looked, as people will for missing articles, in all sorts of out-of-the-way and impossible places. At length he yielded to the fact that the locket was gone. The little treasure was lost at the one moment that it was of priceless value to him; for he could get nothing now to take its place. It was too late to secure the cheapest trinket. For the first time since he could remember he must go empty-handed on Christmas to his mother. Tears of grief, of rage, of disappointment, burst from his eyes. How in the world could it have gone? Nobody knew it was there but himself, nobody but—Jo.

"Darkies love trinkets," he muttered, bitterly. "Jo is the only living soul that could possibly have taken it."

Then he jumped upon his feet, and went down stairs.

"Oh, mamma," he faltered, "I had something for you that I know you'd like, but it's gone, it's stolen."

Then with clinched fists and streaming eyes, Harry told her of his loss.

"My dear boy," said Mrs. Malcom, "don't grieve; above all, don't lose your temper on Christmas-eve, of all times in the year. I'm just as glad as if I had the pretty picture in my hand; and as for poor Jo, if he did take it, it was from love of your dear face and ignorance of the crime he was committing. But now that you have as good as given me your present, you shall have mine."

She went into her little sitting-room and put her hand into the work-box for her purse. Only that morning she had put in the gold pieces—it ought to be an easy thing to feel them in the dark. But it was not. She lit the lamp, and even then her search was vain. The purse was gone. A serious, sad, and pained expression overshadowed her face. Nobody knew even of the existence of the purse. Nobody had seen it, nobody but—Jo.

Sighing heavily, she went back into the parlor. "Harry, my son," she said, "it is so sad to have such a thing happen upon Christmas-eve! I would not have believed it possible; even now I can scarcely credit my senses."

Then she told him all.

Harry's face lit with sudden wrath.

"Come, mamma, let's go to Jo's room. I believe he's run away with them. I don't believe he's there."

Mrs. Malcom followed Harry to the kitchen, and up the back stairs to the little garret. Her heart smote her as she saw the miserable rags upon which Dinah and Jo and 'Thus'lem were all sleeping. For Jo was there, soundly sleeping as if innocent of everything of which they thought him guilty. How cold it was in that miserable place! How the wind whistled through the unplastered beams! How scant and wretched was their bed, their covering! How wicked she had been not to look after these poor creatures who had served her so long and faithfully! The crime, the fault, was partly hers.

But Harry had shaken Jo rudely by the shoulder. The startled crow limped out of his warm black resting-place and blinked maliciously at the intruders. Jo started to his feet in surprise.

A loud chink upon the old floor was distinctly heard, and by the light of Harry's lamp could be plainly seen the lost treasures. From under the ragged quilt had fallen the locket and the purse.

"Oh, you miserable thief!" said Harry to Jo.

Jo's teeth began to chatter in his head, his eyes to roll wildly. He looked from one to the other in a dazed and bewildered way.

"Wot in de canopy's de matter?" said Aunt Dinah, rubbing her eyes.

"Matter enough," said Harry. "Jo's a mean, sneaking thief. See what he has stolen from mamma and me."

When Harry held up the little locket and the purse, it seemed as if Jo's eyes would start out of his head.

"Mas'r Harry, Mas'r Harry," he cried, "I neber fotched 'em here. I neber laid a finger on 'em; wisher may die on dis berry spot ef I did!"

The poor black had crouched upon the floor, and held up his shaking hands in entreaty. His teeth chattered in his head, and his face was overspread with that ashen hue that can make even a black skin pale.

Harry had never seen such abject misery. It blunted the edge of his rage and disappointment. "Jo, Jo," he said, "don't add lying to your other crimes. Didn't we find the things here where you had hidden them?"

"Dis beats creation!" said Aunt Dinah. "In all de bressed borned days ob my life, I neber see de like ob dis. Jes you leab him to me, Mas'r Harry. I'll wollup de trufe out ob him, ef it takes me all night."

But Mrs. Malcom stepped forward and held her hands over the poor shrinking head of the little black boy.

"No," she said, "he shall no longer be treated like a brute. I will find another way to reach his heart. Oh, Harry! oh, my son! the fault is mine. I have cared nothing for poor Jo—for his body or his soul. Our dumb, soulless animals are better cared for. I'll wait awhile, Jo; I'll go away, and leave you to think it over. By-and-by you'll remember all about it, won't you, Jo?"

Jo shook his head to and fro hopelessly. "Ef you wait until de day ob judgment, missus, I neber can 'member. It's a mos' drefful mystery how dem dar tings got here."

"Come, mother," said Harry, in disgust. "I wouldn't have had this happen for ten times the worth of the things."

"Nor I," said his mother, and they both sat sadly down to wait for the Judge, who had been detained in town. He was surprised and vexed, when he came, to find that Christmas-eve was being rapidly spoiled.

"That's the worst of these blacks, they will steal," said the Judge. "But don't you want to see my presents? They have been kept out of the reach of thieves."

The Judge took from his vest pocket a tiny jewel-box containing a ring. Mrs. Malcom had never seen a finer diamond. She quite forgot poor Jo in her delight and surprise. Then the Judge took from his other vest pocket an American watch. As he handed it over to Harry, the lad's clouded face was bright with joy.

But as the Judge was placing the ring upon his wife's finger, it suddenly slipped from his hold, and rolled away upon the floor. All three of them stooped to look for it. It seemed scarcely to have left their sight. They lifted chairs and tables, looked closely around the solid base of the Christmas tree, but the ring had vanished. Again and again they fruitlessly hunted. Tired, vexed, bewildered, they looked at each other in dismay.

"Jo is not the thief, anyway. He didn't take it."

"Who did take it?" said the Judge.

"I give it up," said Harry. "The place is bewitched."

The Judge looked blankly around the room, in utter bewilderment. Suddenly, he put his finger upon Harry's arm.

"Hush!" he said. "Be perfectly quiet. I think I've got your thief as well as mine. He's black, but he isn't Jo. Look over there in that corner; don't you see a spark of light? Don't frighten the scoundrel. I'll lay a dollar he'll make off with that ring when I give him the chance."

True enough, a black object moved slowly along the floor, and with it something that shone like a star.

The Judge softly opened the parlor door. Out hopped 'Thus'lem, with the ring in his beak.

"It's worth the risk of the diamond to clear poor Jo," said the Judge to Harry, and carefully they followed the sly old crow. Up the back stairs he limped, through the hole in the plaster he squeezed his way, and soon he was clasped to the bursting heart of his master.

"''THUS'LEM, MY PORE HEART IS 'MOS' BROKE.'"

"''THUS'LEM, MY PORE HEART IS 'MOS' BROKE.'"

"Why, why, 'Thus'lem," faltered poor Jo, "I woz afeard you'd turned agin me, an' believed all de slanderizin'. 'Pears like as ef I don' care to lib much longer, 'Thus'lem; my pore heart is 'mos' broke. Mas'r Harry he's done gone agin me, an' missus she's done gone wuss 'n Mas'r Harry; an' dem dar tings dat fell out o' my bed-quilt goes fur to show I'm a burgular, 'Thus'lem, even ef I don't know nuffin 'bout it. I s'pect I'll be put in jail; dere ain't nobody to help a pore black boy. 'Pears like as ef dat dar sky woz so fur away dat no star of Bethlehem eber shined dar—leastways for pore black people like you an' me, 'Thus'lem. Yer don' somehow tink dat yer could scrape 'long in a jail, does yer, 'Thus'lem? Yer could squeeze in an' out de bars, yer know."

"Yes, take him off to jail," said the voice of the Judge. "That's where he belongs, the rascal. 'Thus'lem's the thief, Jo. Look at him there with the ring still in his[Pg 133] beak. I've heard that crows will steal, but 'Thus'lem beats all the 'burgulars' I know."

"Jes so, jes so," chuckled the crow; and down fell the diamond ring, and rolled to the feet of the Judge.

Up jumped Jo in wonder and affright. Down he fell upon his knees, and begged harder for 'Thus'lem than he ever did for himself.

"He's on'y a pore ole crow, Mas'r Jedge, an' don' know no better. He mus' hab thought I woz mos' drefful pore, an' he'd try to help me. He won't do so no more, Mas'r Jedge. Will yer, 'Thus'lem?"

"Jes so, jes so," croaked the crow.

"He's chock-full ob inikity," said Aunt Dinah, "an' his neck ought to be twisted dis berry minute."

"We'll spare his life for Jo's sake," said the Judge, "to show him that the star of Bethlehem did shine for everybody, black or white, and our blessed Saviour had compassion upon as big a thief as his wicked old crow."

"Jes so, jes so," chuckled the crow.

So the Christmas mystery was cleared up, and everybody was thoroughly happy at last, particularly Jo, who had plenty of presents. But dearer to him than the apple of his rolling eye was the gift of Mas'r Harry's second-best watch, which made the fastest time on record, and carried Jo along into the next week in a single day.

'Thus'lem waxed old in years, sharing his master's prosperity; and I shouldn't wonder if he was alive and "chock-full ob inikity" this very day.

uring one part of the journey Steve Harrison and Murray had found the ledge along the mountain-side pretty rough travelling, but after a while they succeeded in getting out on to the comparatively smooth slope of the pine forest.

"Our only risk now is that we may meet some of their hunters up here after game. We'll push right on."

"I'll fight if it can't be helped, Murray, but I'd a good deal rather not meet anybody."

"We must find a hiding-place for the horses, and creep down into the valley on foot. I'll show you some new tricks to-day."

After searching some time, they tethered their horses[Pg 134] between two rocks, where the thickly woven vines overhead made almost a dark stable for them.

"Now, Steve, a good look up and down, and we're off."

Between them, and what could be called "the road" were many yards of tangled growth, and before they had gotten through it, Steve felt his arm gripped hard.

"Listen! Horses coming. Lie still."

A minute more and they were both willing to lie as still as mice, for they had nearly walked into the very cover chosen by Bill and his two comrades in which to wait for their intended prisoners.

They and their horses were hardly twenty feet from Steve and Murray.

Suddenly Murray whispered: "Two young squaws. The foolish things are coming right into the trap."

"Can't we help 'em?"

"They're Apache squaws, Steve."

"I don't care. I'm white."

"So am I. Tell you what, Steve— Ha! I declare!"

"What's the matter, Murray."

"One of 'em's white. Sure's you live. They sha'n't touch a hair of their heads."

The expression of Murray's face astonished Steve. It was ghastly white under all its tan and sunburn, and the wrinkles seemed twice as deep as usual, while the fire in his sunken eyes was fairly blazing.

"There's an Indian coming."

"Apache. After the squaws. Don't you hear his whoop? I suppose they'll shoot him first thing, but they won't send a bullet at the girls. They're a bad crowd. Worse than Apache Indians."

"I don't consider them white men."

"Not inside, they ain't. I'd rather be a Lipan."

The two merry, laughing girls rode by in happy ignorance of the danger that was lurking in the thicket, and Red Wolf galloped swiftly on to join them. Then the three miners, with Bill at their head, sprang out of their cover.

"Look out, boys. Don't use your rifles. Thar must be plenty more within hearin'."

"We'll have to kill the brave."

"Of course. Git close to him, though. No noise. I'd like not to give him a chance to so much as whoop."

They never dreamed of looking behind.

"They've start enough now," growled Murray. "Come on, Steve. Step like a cat. We must take them unawares. Have your tie-up ready."

The buckskin thongs which hang from the belt, or shoulder, or knee of an Indian warrior are not all put there for ornament. They are for use in tying things, and they are terribly strong.

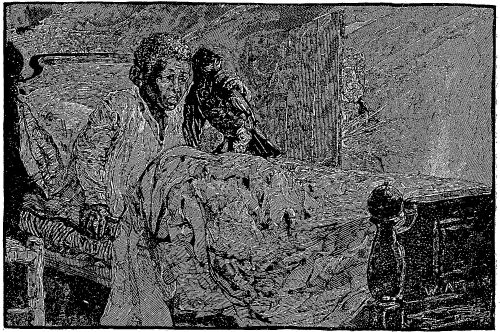

The two men saw Red Wolf join his sisters; they heard the startled cries of Rita and Ni-ha-be, the demand for their surrender, and Red Wolf's reply.

"Now, Steve, quick! Do just as I tell you."

Twang! went Ni-ha-be's bow at that instant, and the man next to Bill was raising his rifle to fire, when his arms were suddenly seized by a grasp of iron, and jerked behind him.

"Right at the elbows, Steve. Draw the loop hard. Quick!"

As the second miner turned in his tracks, he was astonished by a blow between the eyes that laid him flat.

"Give it up, boys. Don't one of ye lift a hand."

Bill could not lift his, with the arrow in his arm. The man Steve had tied could not move his elbows. The man on the ground was ruefully looking into the barrel of Murray's rifle. Besides, here was Red Wolf springing forward, with his lance in one hand and his revolver in the other. Rita held his horse, while Ni-ha-be sat upon her own, with her second arrow on the string.

"We give it up," said Bill; "but what are you fellows up to? I see. You're the two miners, and you're down on us because we jumped your claim to that thar gold ledge."

Red Wolf lowered his lance, and stuck his pistol in his belt. "Your prisoners; not mine," he said to Murray. "Glad to meet friend. Come in good time."

Murray answered, short and sharp: "Young brave, take friend's advice. Jump on horse. Take young squaws back to camp. Tell chief to ride hard. Kill pony. Get away fast."

"Who shall I tell him you are?"

"Say you don't know. Tell him I'm an enemy. Killed you. Killed young squaws. Going to kill him."

There was a sort of grim humor in Murray's face as he said that. Not only Red Wolf, but the two girls, understood it.

Steve had not said a word, but he was narrowly watching the three miners for any signs of an effort to get loose.

"It's that other one, Steve. He's watching his chance. That's it. Draw it hard. Now he won't be cutting any capers."

The expression of the miner's eyes promised the unfriendliest kind of "capers" if he should ever get an opportunity to cut them.

"It's no use, boys," said Bill. "Mister, will you jest cut this arrer close to my arm, so's I can pull it out?"

"I will in a minute. It's as good as a tie of deer-skin jest now. Watch 'em, Steve!"

He walked forward, and looked long and hard into the face of Rita.

"'THEY'D BETTER HAVE KILLED HER, LIKE THEY DID MINE.'"

"'THEY'D BETTER HAVE KILLED HER, LIKE THEY DID MINE.'"

"Too bad! too bad! They'd better have killed her, like they did mine. It's awful to think of a white girl growing up to be a squaw. Ride for your camp, young man. I'll take care of these three."

"I will send out warriors to help you. You shall see them all burned and cut to pieces."

"Oh, Rita," whispered Ni-ha-be, "they ought to be burned!"

Rita was gazing at the face of old Murray, and did not say a word in reply.

"Come," said Red Wolf; "the great chief is waiting for us."

And then he added, to Murray and Steve:

"The lodges of the Apaches are open to their friends. You will come?"

"Steve, you had better say yes. It may be a lift for you."

"I will come some day," said Steve, quickly. "I don't know when."

"The white head must come too. He has the heart of an Apache, and his hand is strong for his friends. We must go now."

He looked at the three miners for a moment, as if he disliked leaving them behind, and then he bounded upon his pony, and the two girls followed him.

"Was he not handsome, Rita?"

Ni-ha-be was thinking of Steve Harrison, but Rita replied:

"Oh, very handsome! His hair is white, and his face is wrinkled, but he is so good. He is a great warrior, too. The bad pale-face went down before him like a small boy."

"His hair is not white. It is brown. His face is not wrinkled. He is a young brave. He will be a chief."

"Oh, that other one. I hardly looked at him. I hope they will come. I want to see them again."

Red Wolf rode fast, and did not pause until he reached the very presence of Many Bears and his counsellors.

There were already signs, in all directions, that the camp was beginning to break up, as well as tokens of impatience on the face of the chief.

"Where go?" he said, angrily. "Why do young squaws ride away when they are wanted?"

Ni-ha-be was about to answer, but Red Wolf had his own story to tell first. It was eagerly listened to.

Pale-face enemies so near? Who could they be? White friends too, ready to fight for them, and send them warning of danger? That was more remarkable yet.

A trusty chief and a dozen braves were instantly ordered to dash into the pass, bring back the prisoners, and learn all they could of the friendly pale-faces.

Perhaps Steve Harrison would hardly have felt proud of the name which was given him on the instant.

The only feat the Apaches knew of his performing was the thorough manner in which he had tied up the two miners. So, for lack of any other name, they spoke of him as the "Knotted Cord." Murray was named "Send Warning." He had actually earned a "good name" among his old enemies.

Rita and Ni-ha-be were saved any further scolding. The chief was too anxious to ask questions of the "talking leaves," now he was sure of the neighborhood of danger.

"Ask about the bad pale-faces. Who are they?"

Rita took her magazines from the folds of her antelope-skin tunic with trembling hands, for she was beginning to understand that they could not tell her of things which were to be. It seemed to her in that moment that she could not remember a single word of English.

The one she opened first was not that which contained the pictures of the cavalry; but Rita's face instantly brightened. There were five or six pages, each of which contained a picture of men engaged in mining for gold.

The chief gravely turned the leaves till he came to a sketch that drew from him a sharp and sullen "Ugh!"

There were the sturdy miners, with rifles instead of picks, making a gallant charge upon a party of Indians.

"No need of talk. Great chief see for himself. No lie. I remember. Kill some of them. Rest got away. Now they come to strike the Apaches. Ugh!"

It was only a "fancy sketch"; but it must have been true to life when an Apache chief could say he had been one of the very crowd of Indians who were being shot at in the picture.

"That do. Talk more by-and-by. Big fight come."

Many Bears rapidly transformed his buffalo-hunters into "warriors." All that was needed was a chance to put on their war-paint, and a double allowance of cartridges.

When that was done, they made a formidable-looking array, and the last chance of the Lipans or any other enemies for "surprising" them was gone. Then they rode slowly on after their women and children, and the braves came back from the pass to report to Many Bears that "Send Warning, Knotted Cord, and their three prisoners had gone, no one could guess whither."

Seventy years ago a boy was born in Rochdale, England, who was destined to fill a great place in the world. His parents were Jacob and Martha Bright—people of good old Quaker stock—and they called their eldest boy simply John.

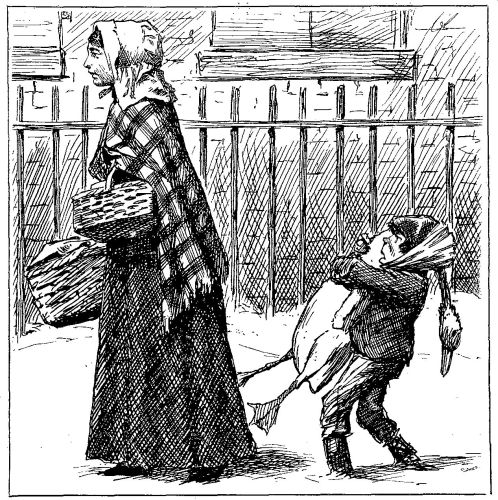

Jacob Bright was a cotton manufacturer, and both he and his wife were beloved for their charitable deeds. One Sunday Mrs. Bright and little John were walking out, and the boy wore his pair of long trousers for the first time. Of course he felt proud of them. But soon they met a poor woman with her little boy, and he was clothed in rags. Mrs. Bright stopped them, and the result of a few minutes' conversation was that the poor woman and her ragged son returned home with them, and Master John had to strip off his new suit and let the other boy put it on in place of his rags. Mrs. Bright's charity was very thorough.

At school young John was quick and industrious, but his father thought business more important than book-learning; so at fifteen the boy was placed in his father's cotton mill. Fortunately for himself and the world he did not give up learning from books when he left school, or he would not have been the great man he is.

As a boy and a young man he was a good cricketer, and all his life he has been very fond of fishing, having caught minnows and other small fish in the river that ran by his home, and salmon of forty pounds weight in Scotland and in Norway. At twenty-two years of age he began training himself in public speaking in a literary society of which he was one of the founders, and doubtless it is to this early training that he owes the honor of being the greatest of living English orators.

Mr. Bright was first elected a member of Parliament in 1843, and fourteen years later he was chosen to represent the great manufacturing town of Birmingham, which seat he still occupies.

Mr. Bright's public life has been a busy and a useful one. No man has done more for the benefit of the working classes than he, and he has never hesitated in the pursuit of the course which he felt to be the right one.

In this country the name of John Bright is justly honored, for he was the only English statesman who supported the Union without wavering during the late war between the North and the South. Six weeks ago (November 16), Mr. Bright celebrated his seventieth birthday.

The illustration, which accompanies this article is a fac-simile, so far as the drawing is concerned, of the postage stamps at present in use in one of the Dutch possessions off the coast of South America, namely, the island of Curaçoa. It represents the uniform type of the whole series, and was introduced in 1873. The head on the stamp represents King William III. of Holland.

The series consists of the following values and colors.

| 2-1/2c., bright green. |

| 3c., stone. |

| 5c., rose. |

| 10c., bright blue. |

| 25c., light brown. |

| 50c., mauve. |

The currency is in cents, one hundred of which go to the guilder, or florin. A guilder is equal to nearly forty-one cents of our money.

Curaçoa, or, as printed on the stamps, Curaçao—the "c" being sounded like "s"—is an island in the Caribbean Sea, lying off the north coast of Venezuela. It is forty miles in length from northwest to southeast, and ten miles in average breadth; the area is two hundred and twelve square miles. The island is hilly, and deficient in water, being wholly dependent upon the rains, yet, owing to the industry of the Dutch planters, considerable quantities of sugar, cotton, tobacco, and maize are raised. A peculiar variety of orange grows abundantly, and supplies an important part in the liqueur which takes its name from the island. The principal export is salt. The shores are bold, in some places deeply indented, and present several harbors, the chief one being Santa Anna, on the southwest side of the island. The narrow entrance to this harbor is protected by Fort Amsterdam and other batteries; but the harbor itself is large and secure, and is the port of the chief town, Curaçoa, or Willemstad. The population in 1875 amounted to nearly twenty-four thousand, about one-third being emancipated negroes. All belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, except about two thousand Protestants and one thousand Jews.

The island was settled by the Spaniards about 1527, was captured by the Dutch in 1634, was taken by the English[Pg 136] in 1798, and again in 1806, but was restored to the Dutch in 1814, in whose possession it has since remained. It is seldom that the name of this island is found in ordinary geographies, although stamp-collectors think it ought to be given a place.

Oh, that marvellous Christmas pie!

Fred, and Fanny, and Carl, and I

Sat up one night till the clock struck one

To plan the party; and oh, the fun

Of having a secret among us four!

(The "Queer Quadrangle" admits no more

Within its circle—or, no—its square,

I should have written, perhaps, just there.)

I can not tell you the things we said

(It's against the rules), but I'll tell instead

About the party, the pie, and all.

'Twas not, you know, like a grown-up ball,

But just a rally of all the clan,

And quite the thing for our little plan.

Thirty cousins from far and near,

With aunts and uncles were gathered here.

But I must hasten. The hour drew nigh

When Fred announced with a flourish:

"Pie!

Down the staircase, and through the hall.

This side of the supper, and free to all!

'Put in your thumb, and pull out a plum,'

But mind, the word of the hour is 'mum,'

Forward, march!"

And the march began,

Headed, of course, by Fred and Fan,

And close behind them were Carl and I—

We four were guards of the precious pie,

And sat in glory behind it, while

The others passed it in solemn file.

'Twas heaped and frosted as white as snow

In grandpa's punch-bowl—the one, you know,

He calls his "Kaga," so deep and round,

With painted dragons and golden ground.

The ice was broken by Lottie's hand

(The pie, you know, was of white sea-sand

And packed with presents), and Lottie drew

The sweetest locket of gold and blue,

And Maud a letter, and Ruth a ring,

And Will's was a fan—such a funny thing!

But my sheet is full. I will surely call,

When I get to the city, and tell you all,

And how we missed you, and how a plum

Was saved for the cousin that couldn't come.

A Merry Christmas to all of you,

With love unfailing, from

(Q. Q.)

Cousin Sue.

Oh! this is the tale of a very bad boy;

He had done all he could other folks to annoy;

Then what do you think there was found to employ

The very bad wits of this very bad boy?

On the night before Christmas, St. Nick to decoy,

Two stockings were hung by the very bad boy,

Who said to himself, "Of the sweet Christmas joy

To double my share, a trick I'll employ;

I'll watch for St. Nick—and the fun I'll enjoy—

I'll give him these stockings his time to employ;

And while he's at work," said the very bad boy,

"I'll hook from his pack just the handsomest toy."

But somehow the fun had a bit of alloy;

St. Nick got a peep at the very bad boy;

He whipped up his steeds, and he cried out, "Ahoy!

You'll get, my young lad, neither candy nor toy."

Then away went St. Nick, and he chuckled with joy,

And he left not a thing for the very bad boy.

"I just wish there wasn't any New-Year."

It was a boy—Sam Jenkins—who spoke, the time New-Year's Eve, the place Madison Avenue and Sixty-ninth Street. And what a night it was! and what a day it had been! Snow and slush all day long, and now the wind was blowing a gale across the Harlem flats, and the slush was freezing on the sidewalk, and there was not a star to be seen in all the sky.

Sam was a District Messenger boy, and had been on duty all day and all the evening, and this final call at nine o'clock, when his legs were tired, was the last ounce that broke the camel's back.

Since the noon hour he had been in a bad humor. Now he was not only tired, but cold and down-hearted, and as his foot slipped, and he just managed to save the fragile parcel he was carrying, he cried out with a spiteful voice, "I just wish there wasn't any New-Years."

Somehow Sam's ill-humor had made him very uncomfortable all the afternoon. He had had a scuffle near the office with Dick Rainey, and all about nothing, for Dick, noticing his peculiar gait, simply asked him what made his legs so heavy. He had quarrelled with the old apple woman in the little shop round the corner because she wouldn't give him two apples for three cents, when the price was two cents apiece; he had thrown a lump of ice at a poor cat shivering behind a barrel on the Third Avenue, and kicked at a wretched little dog that had sniffed up to him with his tail between his legs. Altogether Sam was in a very bad way. He didn't care for anybody or anything. Down town the gay shop windows had failed to catch his eye; the bright lights in the houses on the avenue were nothing to him. He was out with himself, and so he was out with everybody else.

I am sorry to say that when Sam had delivered his parcel he snapped up the servant for having kept him waiting so long for his ticket, although the poor girl had nothing to do with that, and that he kicked the sidewalk very hard when he again put his foot upon it. And yet he had now only to report himself at the office, and then go home.

Sam lived on one of the side streets, where the great tenement-houses loom up in long rows. It was past ten o'clock when he entered the dark hallway, and began his climb to the fourth floor. On the third floor he passed the room in which Jenny Wilson, the little lame girl, lived, and just then some one opened the door for a moment, and he heard Jenny say,

"Oh, I wonder if I will ever be well!" and "I am so tired!"

Then Sam, still cross, said to himself, "Why don't you go to sleep, then?" but in a moment he was ashamed of himself for having said it.

Bang! went the door behind him as he entered his mother's room. Without saying a word, he pitched his heavy coat into a corner, and shied his cap across the room.

"What's the matter, Sam?" asked his mother, with a kindly voice.

"Matter enough," answered Sam. "I'm tired to death. It's nothing but run, run, run all day and all night. I just wish there wasn't any New-Year's. Nobody cares for a boy. It's Sam here, and Sam there, and Sam all the time. That's because I'm a boy. I wish I was a girl—yes, I do."

His mother soothed him while he ate his supper; but the frown did not lift from his face, for there was no sunshine in his heart.

Then he went to bed—went, too, without saying his prayers. It was not long before he fell asleep, and then he dreamed.

He dreamed that he was still in New York, that he was a messenger boy, and that it was the day before New-Year's. All day long he was busy carrying messages and delivering parcels, and everybody was kind, and everybody happy. It seemed to him that it was a great thing to be a messenger boy at such a time, when every one was doing something for some one else, and he had a hand in so much of it. As he thought of this (he was going up Madison Avenue again), some one seemed to say: "Sam, you're a little fellow, but you can have a big heart if you want to. All day it's been growing bigger and bigger; now all you have to do is to keep it open, and see how much it will hold."

Then Sam laughed. He didn't know why, but he couldn't help it, he felt so good all over.

Pretty soon he came across a blind man. A dog was leading the man, but Sam helped the man over the crossing, and motioned to a butcher's cart to hold up. Then he saw a cat, half sick, lying in the gutter, and picked her up, saying, "Poor pussy!" and laid her inside the railing of a house, and asked the cook, who stood in the basement doorway, if she wouldn't give her a sop of milk. After a little he saw an old colored woman struggling along with a heavy basket of clothes, and said, "Aunty, I'm going up a few streets, and I'll take hold of the basket on this side." And so he went on up the avenue and down, and the sun was so bright and the air so pleasant, while it seemed as if he was just helping everybody. He didn't quite understand how, but kept on taking them into his heart, all the time feeling and saying, "Come in; there is still plenty of room." Soon all the poor people down in the side streets, and all the rich people up on the avenue, all the sick people in the hospital where he was yesterday, and the dreadful people he had seen down by the Tombs—why, he just thought of them all, and before he knew it they came crowding up and upon him, and he took all of them into his heart, and they didn't seem crowded a bit, for the more that came, the more room was there left. He could not understand it, but he was sure that the increase in the number only made him the happier; and as he went on thinking it over, he stretched out his arms just as wide as he could, and cried out: "Come in, all the world; come into my heart. I've plenty of room for all, for my heart grows just as fast as my love, and I just love everybody in this big, blessed world."

As Sam stretched out his arms, his mother woke him, saying, "I wish you a happy New-Year, Sam, and it's time to get up."

And Sam got up. You could tell by his face that he had had a pleasant dream, for his voice was gentle and his manner very kind, as he said, "Well, mother, I guess I was pretty cross last night, but I'm going to try and be good-natured to-day."

Then his mother said, "You were tired last night, Sam." That's the way our mothers always try and overlook our faults when we are sorry.

Sam had to go to the office for half a day, and he had a little money which he intended to spend on his presents. Before he started for home, however, he made up with Dick Rainey by dancing a jig to show that his legs were light to-day. On his way home he called in at the old apple woman's to wish her a very happy New-Year, and to take two apples at her price. He hoped to get a sight of the poor old cat and the wretched little dog, that he might show them how sorry he was, but they were gone. On the Third Avenue he bought two or three little things for his mother, and an orange, some candy, and a bright picture paper for his little sister. And as Sam thought of these friends and all his other friends, and all the poor people in the houses and on the streets, oh! how he wished he could buy something for them all, but he couldn't. But then he could love them all the same.

There is not room to tell you all that he said to his mother, and sister, and Jenny, and what a bright, happy day it was to them and to Sam. He tried hard to make it all out, but he couldn't exactly understand it. "It was a nice, queer dream," he said, "and I found out one thing by it, and that is that you can make room in your heart for just as many folks as you please, and that you can't make other folks pleasant when you are cross yourself; and I just wish that New-Year would come twenty times in a year."

Tom Fairweather sighed as he stood on the quarter-deck. "Holiday-time, indeed!" said he. "What are the holidays without snow, I'd like to know? I'd give a good deal for a real old-fashioned coasting lark to-day, but I don't believe these people ever heard of such a thing."

It was a balmy day off the island of Madeira, where Tom's ship, or rather his father's, lay. Here spring and summer reign the year round.

"Old-time coasting is what you would like, eh, Tom?" said Lieutenant Jollytarre, with a twinkle in his eye. "Ask your father to let you go ashore with me, and I'll give you a frolic that you'll not be apt to forget."

Captain Fairweather gave his consent, and they hurried off.

A ten minutes' pull took them close to the island; but this Madeira shore is so steep that it makes an uncomfortable landing for a man-of-war's boat. Another boat, one belonging to the shore men, lay off waiting for passengers. Into this Tom and the lieutenant stepped, and were rowed close to the beach by two Madeira men.

As soon as the boat's bow touched the beach, two other men standing there made fast to it one end of a rope of which the other was attached to two strong oxen. At the word these oxen started, and up glided the boat over the round smooth pebbles, so easily that Tom was astonished to find himself at the top of the bank. With a laugh he jumped out. "That was a coast up hill, sure enough," he said. "Was that what you meant?"

The lieutenant looked mysterious. "No, it wasn't. Wait a while."

"What queer narrow streets!" said Tom, as he surveyed critically Funchal, the capital of Madeira. "And what a lingo—Portuguese—only it sounds even more like gibberish than it did in Lisbon. And what a lot of peddlers! They swarm like gnats."

Mr. Jollytarre was busy buying an inlaid box of one of the peddlers referred to, and did not answer.

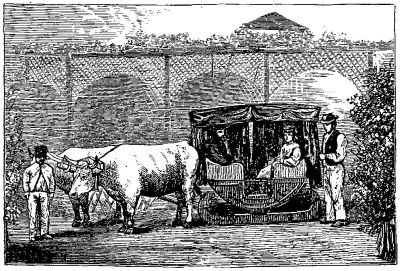

CARRIAGE DRAWN BY OXEN.

CARRIAGE DRAWN BY OXEN.

Meanwhile Tom's attention was attracted by a very odd carriage. This vehicle was drawn by oxen, and like a sleigh was set on runners, which offered less resistance than wheels would have done to the smooth round little stones of the pavement. These cobble-stones are very like the stones of the beach. The body of the carriage reminded Tom of a Sedan-chair; it seated comfortably two persons facing each other, had a top, and was draped on the sides by curtains drawn apart. Tom began to laugh, so much was he entertained by this strange equipage, whereat the lieutenant turned to see what had caught his eye.

"We might take a drive," said he, meditatively. "I want to take you to the Church of Nossa Senhora do Monte, on the top of that hill over there. What do you say, Tom?"

"I'd sooner walk," said our young friend. "I should think it would be slow work riding in an ox-cart, for that's all that amounts to, unless you choose to call it a sleigh."

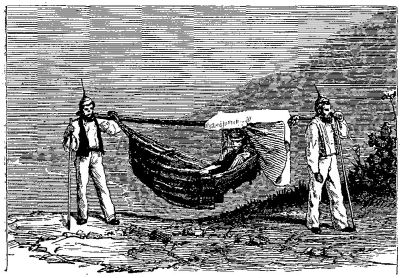

HAMMOCK-RIDING IN MADEIRA.

HAMMOCK-RIDING IN MADEIRA.

At this moment two men came slowly down the street bearing between them a pole on which was slung a curtained hammock, wherein reclined a pale sweet-faced lady.

As she passed Tom his bright face took her fancy, and she glanced at him with a smile.

"Wasn't that a beautiful lady?" he cried to Mr. Jollytarre.

"Indeed she was. But what do you think of her method of travelling? Slow as the ox-cart, eh?" Then suddenly, "Tom, I have it; we'll go on horseback." And almost in the same breath, cried, "Caballos."

The lieutenant's knowledge of Portuguese was limited, and he was obliged to make a little of it, mixed with Spanish, go a long way.

But the people about him were quick-witted, and it seemed to Tom that two horses with their two owners appeared on the scene as if by magic.

"Now, Tom," said Lieutenant Jollytarre, "you may walk if you please—I shall ride. The coasting I told you of is up there at that church. Will you take a horse?"

Tom replied by leaping into the saddle, and starting off at a slow canter.

As they rode away, the owners of the horses followed them, keeping up to the increasing pace by each clinging to his horse's tail.

This was all very well as long as they remained in the narrow streets, where a little steering was necessary; but as they left them, Tom grew impatient for a run.

"See here, now, this won't do," he called to his man. "I ain't a baby. I know how to ride. Leave go."

He slackened his pace to say this. The man slackened his pace, but did not drop the horse's tail. He grinned upon Tom, showing his even white teeth.

Tom waxed wroth. "Come now, let go," and he gave his horse a cut which started him into a gallop. The guide kept up, tugging away at the horse's tail.

"Come now, be off," cried Tom. "You keep my horse back. I say, Mr. Jollytarre, do put this into Portuguese for me. Tell this beggar I'll give him a cut if he don't let go."

"Cut away," said Mr. Jollytarre. "It won't make any difference. He understands you, but he wouldn't let go if you were to shout to him from now until doomsday. I know all about it. I've been here before."

"What does he hold it for?"

"Tom, I have often wondered. I suppose he knows. I don't. Wants to keep his horse in sight, perhaps; wants a run; likes our society. You see my fellow is doing the same thing. However, we are not going any slower in consequence. The horses are used to it. They don't mind in the least."

At this point the guides stopped both horses. They were in front of a little wine-shop half way up the hill.

The guides pulled off their caps, and urged the lieutenant to treat. This was another custom of the country, to which the lieutenant also submitted gracefully.

The waiters poured out a glassful all around.

"Take care, Tom; this is strong Madeira wine, although these people drink it almost like water. Better not do more than taste it."

"Never fear," replied Tom. "I wouldn't poison myself with the stuff. No, thank you" (to the waiter). "Drink it yourself, if you've a mind to."

"Temperance, are you?" said the lieutenant. "Well, that's a very good thing."

"I should say it was," said Tom, stoutly. "Anyway for a boy."

The rest of the road was very steep. But it was fun. Tom was sorry to reach the top, where, at the door of the church, they dismounted, and sat down to rest. The horses were led off.

When Mr. Jollytarre rose to his feet and announced that they must be going, Tom looked around for his horse in vain. Instead, two sleds approached, each pushed by two men toward our friends.

"Get on board, Tom," exclaimed the lieutenant; "that is, if you want to have the best coasting you ever had in your life. If your prejudices hold you back now, you'll regret it the longest day you live."

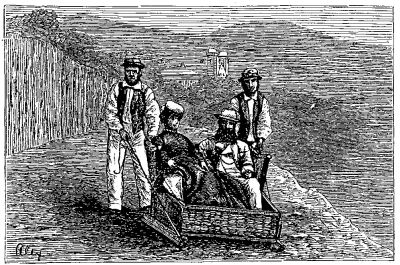

THE MOUNTAIN SLED.

THE MOUNTAIN SLED.

So saying, he scrambled into one of the sleds himself, and Tom followed his example, although still a little doubtful as to the success of the experiment. There were two thongs for steering tied to the front of each sled, which were held by the two men behind.

When everything was ready, the two sleds started together down the hill. It was like the wind. It was like chain-lightning. It was like a telegram. As they tore down the hill, they made a hissing sound like the cracking of whips. There were sudden turns in the road, beneath which lay dark and deep ravines. If Tom had known that sometimes in these wild rides persons had been hurled over the sides of such precipices, a still greater zest would have been imparted to his flying trip; for he was a thorough boy, and loved a spice of danger. However, he would have had hardly time to dwell upon this thought, for in less time than it has taken to write of it he was landed again in Funchal.

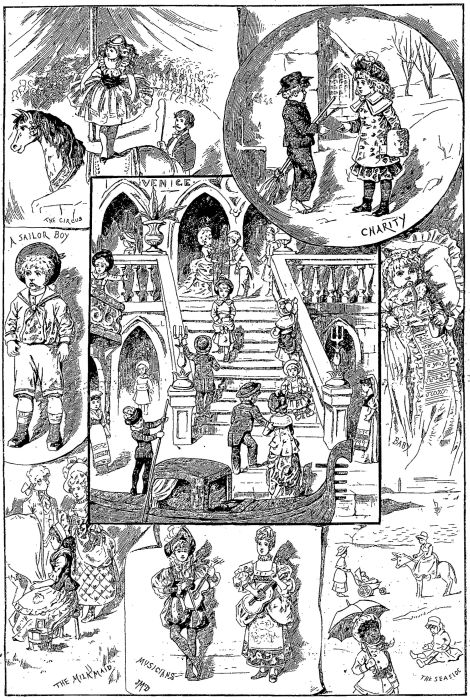

I think I can hear some little tongue ask, "Are these beautiful pictures really to be seen in the shops, or has the artist only imagined them?"

Every one of these pretty sights is taken from actual windows in New York, and for days past gay throngs of people have tiptoed and crowded close to the panes that they might assist at such dainty doll receptions.

The central scene here is a bit of Venice. There are the bridge and the stairs and the arches, and there, too, are the ladies and gentlemen coming in their gondolas to attend a reception at some grand palace.

It is almost as good as going to the circus to look at the fairy figure standing on the back of yonder spirited steed, with the rows of doll spectators in the background. I think I like it even better than the real thing, for one is sure that this little lady has never known a blow, nor an unkind word, and we are not at all easy in our minds when we are watching some poor little Queen of the Ring, and holding our breath at her wonderful leaps.

The little picture entitled "Charity" may be seen in the streets every cold day. The contrast between the child, with her golden hair and warm furs, and the barefooted boy, ragged and shivering, who sweeps the crossings, and holds out his thin hand for a penny, is true to life.

Here is Baby, as large as the one at home in the nursery, her christening dress on, to be sure, and her bottle in her hands. What comfort she is taking!

But wouldn't you rather have that sailor lad, whose jaunty air tells you that he knows every rope in the ship, and can climb the rigging like a cat?

How graceful are these musicians! and how quaint this coquettish milk-maid, who will presently give a cup of milk to the high-bred girl and boy watching her! One can take a history lesson, for just as these children are dressed were Mistress Dorothy Quincy and his Excellency John Hancock more than a hundred years ago.

Perhaps our eyes linger longest on the sea-side window, which brings back memories of the summer. There is the donkey on which Minnie used to ride; Chloe with her parasol; and the children at play on the sands, with the waves rolling in.

Well, well, we can not look all day at the shop windows, be they ever so attractive, for the holidays are full of fun and frolic, and we want to catch it all.

SCENES IN SHOP WINDOWS, NEW YORK CITY.—Drawn by Miss Jessie McDermott.

SCENES IN SHOP WINDOWS, NEW YORK CITY.—Drawn by Miss Jessie McDermott.

HAPPY NEW-YEAR!

HAPPY NEW-YEAR!

A Happy New Year to all the boys and girls who read this paper! Every mail which comes to Our Post-office Box brings us letters which we are too modest to publish, so lavish is their praise of the stories, pictures, and instructive articles which we furnish for the weekly feast of the young writers. Now, little men and women, since you like the paper so well, and enjoy it so thoroughly, let us tell you how you can give us a useful proof of your friendship. We would like you to help us extend the circulation of Harper's Young People by showing it to your friends and their parents, and asking them to subscribe for it the coming year. The more subscribers the paper shall have, the more attractive and valuable the publishers will be able to make it. That you may have the prospect of a reward for your efforts, we make the following tempting offers, to which we ask your attention.

To any boy or girl sending us at one time before March 1, 1882, the names and addresses of ten new yearly subscribers, together with the money, and referring to this offer, we will mail, postage paid, any one of the volumes mentioned in the following list:

The Boy Travellers in the Far East—Part I.—Adventures of two Youths in a Journey to Japan and China. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Ornamental Cloth, $3.

The Boy Travellers in the Far East—Part II.—Adventures of two Youths in a Journey to Siam and Java. With Descriptions of Cochin China, Cambodia, Sumatra, and the Malay Archipelago. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Ornamental Cloth, $3.

The Boy Travellers in the Far East.—Part III.—Adventures of two Youths in a Journey to Ceylon and India. With Descriptions of Borneo, the Philippine Islands, and Burmah. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Ornamental Cloth, $3.

The Story of Liberty.—Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.

Old Times in the Colonies.—Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.

The Boys of '76.—A History of the Battles of the Revolution. Copiously Illustrated. 8vo, Cloth, $3.

Here you have your choice from a beautiful little library of travel and history. Any one of these books will be a constant source of pleasure to everybody in the household.

To the boy or girl who, before March 1, 1882, shall send us the largest number of new yearly subscriptions, with the money, we further offer to present

Harper's Household Edition of Charles Dickens's Works, in 16 Volumes, handsomely bound in Cloth, in a box. Price, $22.

No collection of books is complete which does not include the works of the great English novelist, whose characters are as vivid as real flesh-and-blood people, and whose humor and pathos never lose their charm.

We feel sure that every boy and girl among our readers will be anxious to win this handsome edition of Dickens's works, which is full of exquisite illustrations by leading English and American artists.

In order that we may keep an accurate account of the number of subscriptions we receive, it will be necessary for each one, when sending a list of new subscriptions, to notify us that he or she intends to try to secure this valuable prize. Cash must accompany each order.

Harper's Young People, $1.50 a year.

Westport, California.

I have a darling doll, and it has light blue eyes and golden hair. It is a wax doll. I have no name for it. Would somebody please tell me a pretty one? I have a cunning little carriage in which I take my doll to ride. I have a little pony named Daisy, and papa bought me a saddle, so that I can ride to school. I have to go three miles through the woods, and Daisy sometimes rears up with me, but I have never yet fallen off. I received two very pretty cards at school last week. I have a pair of roller skates. When I read Augusta C.'s letter I said, "I will join you, Augusta, for I hate cats too."

Etta M.

How delightful it must be to canter to school through the woods. If Daisy is sometimes a little frisky, her mistress must keep a steady and delicate hand on the rein, sit firmly in her saddle, and often pet and caress her horse, so that she will understand that her rider is her friend. It is possible to win the affection and confidence of a horse so that it will understand nearly every word you say to it.

Why not call your dolly Katrine, or Gretchen, or Fairy, or Maud? There are many pretty names for dolls, and as you are dolly's mamma, you should not neglect the duty of naming her.

Wildwood, Catahoula Parish, Louisiana.

Several weeks ago I wrote you proposing an exchange of deer horns, leaves, and mosses, never dreaming of having so many applications for the horns—all nice offers, too. As I am at home only one day of the week—boarding from home to attend school—I could not possibly reply to all; so I decided to answer through the Post-office Box. I wish to say I think Jackson Bechler's offer would best please me, if he would only name his curiosities, and the expense of my getting them. As we have no near express office, the horns would have to be sent by boat to New Orleans; the expense from here to New Jersey would be about $1.75. I forgot in my previous letter to say that one of the horns on one point was fractured by a shot. I have three pairs, the one just mentioned the largest, which measures twenty-four inches from head to tip—that is, one shank; fifteen inches from tip to tip; four points on each shank. The second pair is a little less, but not so pretty, as they were shot before the horns hardened, and instead of making a straight point, it is somewhat contorted. The third are little beauties, which we used on the bow of our boat when we had skiff races during high water. As I had only one offer for leaves, etc., I answered by postal. I hope to hear soon from my young friends.

Marie Louise Usher.

Boston, Massachusetts.

In a recent number of Young People you said that some little New England girl could have a corner if she chose to write, and although I am not so very little, I hope I may have part of a corner in the Post-office Box.

In a letter from Viola B. a week or two ago she spoke of the names of Southern children, and afterward you said that you had seen an allusion to the same thing in a book you had read lately. Will you please tell me in what book you saw it, if you remember, as I wish to know if it is the same book I saw it in.

I agree with Miss Viola in regard to telling the age.

L. H.

The book was Homoselle, which belongs to the "No Name Series" of novels.

Knowlton, Canada.

I am a little girl six years old. The only pet I have is a little baby sister, whom I love very much. I went to a mill with papa a few weeks ago, and saw them card wool into rolls, and weave flannel. I live on a farm near Brome Lake, and there is a river runs through the pasture back of our house, and in warm weather we like to take off our shoes and stockings and go in wading. I had a little flower garden last summer. It was my very own. I had some petunias and sweet-peas, and some pretty gladioli; and I had some daisies and pansies, and sweet-williams too. My sister Connie helped me weed my garden. I have a wax doll which I often play with. Her name is May. The prettiest dress she has is a red one trimmed with fringe, and she wears a lace bib with it. Her every-day dress is gray, with little red bows all down the front of it. I have a carriage to push her around in. It was one of my Christmas presents last year. I read all the letters and most of the stories in Young People, but I can not write yet, so mamma is writing this for me. The stories I like best are "Susie Kingman's Decision," "Phil's Fairies," "Toby Tyler," and "The Cruise of the 'Ghost.'" I am tired now, so I will not write any more.

Bessie C.

Weedville, Pennsylvania.

Please may some of the boys write in defense of the cats, as well as the girls? We think Augusta would like our cat if she could see it. It is white, with large black and yellow spots. We call it Popcorn. The white for the corn that is popped, the yellow for before it is popped, and the black for that that got burned. Popcorn and our little dog Felix go fishing with us down in the woods. She can follow as well as Felix. When Felix has to be punished, he cries; then Popcorn runs up to him and licks his face, and we know she is sorry for him. We think so much of both! We had to go a mile to school last summer, and Felix would start from home about four o'clock, and meet us sometimes nearly half of the way. We wondered how he knew when to start. He would be so glad to see us, he would jump nearly as high as our heads. When we got home, Popcorn would be waiting for us on the front steps. We like Young People, and are glad Tip didn't die.

We have coaxed mamma to write this for us.

Dwight, Eddie, and Clare A.

Westmoreland County, Virginia.

One of the little correspondents said she had a three-legged cat. I want to tell you of a kitten we had which had six legs, one on either side with the toes turning backward.

Emily C. M.

Oviedo, Orange County, Florida.

I am a little boy seven years old, and live in South Florida, on Lake Jessup—a large lake in Orange County. My father has a beautiful orange grove, and some of the trees are just loaded with oranges. We also have a pine-apple grove; but the strangest thing I ever saw is a pawpaw-tree; it is bearing and blooming at the same time, and the shape of the fruit is like a musk-melon in size, and my father could get a hundred dollars for it if he were to try. I have some pets and other things, but I won't write about them now. I have been taking Young People for nearly a year.

Theodore A.

Queenstown, Maryland.

I have wished for some time to write and thank you for the great pleasure Young People gives me. I love so its coming once a week.

I wish I had something to offer little Marie Louise Usher in exchange for her deer horns. We all read her letter with so much pleasure last week. One of my uncles went, some winters ago, to look after his interests in Hope Estate, Louisiana. It adjoins Dr. Usher's residence; and Uncle George says then Marie Louise was a little girl like I am now, not more than six or seven years old. He was so pleased to read her letter, for he enjoyed his visit to the sunny South.

My subscription to Young People runs out the 11th of December, but Aunt Kate, who is going to Baltimore in a few days, will renew it for another year. I made the money myself, selling "Stowell's Evergreen Corn." I have every number of this year, not one torn or soiled, and I want to have it bound by the Baltimore News Company, where I subscribe. It was a Christmas gift this year from my two aunts.

I have a nice little girl, Clara, from an orphan asylum, who plays with and reads to me. I go to school, and do not play much with dolls, though I have eighteen. Like most of the subscribers, I have a cat, Toby; for "Toby Tyler" was the very nicest continued story I ever read.

I was in a spelling-class yesterday of a dozen or more girls and boys, and I spelled "duenna" after it had passed almost all the others. I was so "clapped" (because I am so little), I thought the school-house was on fire; so I began to cry.

I shall think it a very nice Christmas gift if you will publish my letter. Good-by, Mr. Harper.

Anna H. D.

George H. P.—Your long trip must have been very delightful. There is nothing much pleasanter in life than a boy's journey under the care of a kind and indulgent father. But your mother must have felt a little anxious about her travellers while they were enduring 500 miles of staging, bathing in Salt Lake, and venturing into other dangerous places. No doubt she was very glad indeed when you both arrived safely at home. Your exchange will duly appear.

Marian M.—The two kittens named Cenny and Tenny, after the Centennial year, in which they were born, must have been very amusing, from your description of them.

Flora S.—Carlo must be a little torment, and yet we do not wonder at your loving him dearly.

We have pleasure in giving our readers this vivid description of the cruise of the adventurous little Toby Tyler since we left her, some weeks ago, in the beautiful harbor of Norfolk, Virginia.

There is one portion of the journey of the Toby Tyler which can hardly fail to interest the readers of Young People, although they might not care much for a record of the entire voyage. The trip through the Dismal Swamp occupied nearly five days, not because the little steamer could not have passed over the thirty miles of canal sooner, but because all on board were disposed to linger where the scenery was so novel and fascinating.

We will not try to give here a lesson in geography, nor to tell the exact size, location, and characteristics of these three hundred miles of submerged forest. This letter will simply contain an account of what the passengers of the Toby Tyler saw after leaving Norfolk, sailing five miles up the Elizabeth River, and entering what is known as the Dismal Swamp Canal.

Each one had expected to see a veritable swamp, where the trees would appear to be growing in the water, and where it would be impossible to walk, even a few paces, save at the risk of sinking deep in the mud. But dismal as the swamp is, it is not quite as bad as had been imagined. To be sure, there are miles and miles of territory where one would find it impossible to walk, owing both to the water and tangle of brake and vine; but along the banks of the canal the land is not only quite as firm as elsewhere, but there are several villages, where were found children who had read of the coming of the Toby Tyler, and were watching for the little steamer.

At those points where the marshy portions of the great swamp extend fully out to the canal, hedges of cane and flags have been trained, so that one sees only the masses of verdure which seem to have been cut apart by the narrow ribbon of water on which floated great barges and steamers, past which it seemed impossible the Toby could go, from sheer lack of space.

And the water in the canal looked so very strange, because, instead of being clear, it is exactly the color of strong tea, owing to the juniper-trees, which grow in the swamp in such profusion as to discolor it. But it tastes like the purest of spring water despite its queer look, and the ships of war sailing from the Portsmouth Navy-yard carry it for drinking purposes, because it will keep sweet and fresh six or eight months.

The charm and beauty of the swamp are not to be seen as one sails through its brown water-way; if one wishes to see it in all its dismal waste, he should do as did the voyagers on the Toby, and that is, explore some of the small rivers that cross the canal by means of a boat. The one belonging to the Toby is fourteen feet long, and can sail where the water is not more than five or six inches deep; it may also interest some of your readers to know that it is named Mr. Stubbs. In this little craft the writer and the artist almost forced their way up what is known as Old River, pushing aside branches of trees and clinging vines that seemed doing their best to prevent any one from entering the retreat they guarded.

Fifty yards in from the canal it was as if one had gotten miles away from all traces of civilization; not a sound was to be heard save the hooting of an owl or the twitter of the small birds; on a log just ahead an assembly of terrapin were holding a convention, probably to protest against being considered such a delicacy in the way of food; while just beyond, under the roots of an overturned tree, could be seen the head of a small bear, that was trying to make up his mind whether it would be better to run away, or stay and find out what the intruders wanted. He concluded to leave, however, and the terrapin followed his example by rolling off the log with a great splash, thus leaving the two explorers alone in a river that seemed all trees and but little water. It was indeed a swamp, or rather a submerged forest, this river, and it was only with the greatest difficulty the little boat could be forced along. After the banks of the canal were left astern it was no longer possible to distinguish the course of this river, for it stretched out in one broad body of water, which so mingled with the swamp that no one could say it had banks, or even a channel.

Perhaps a mile was passed over by alternate rowing and pulling, and then further progress was impeded by huge trees that had fallen into the water, completely blocking the way. Ahead, astern, and on either hand could be seen the dark, shallow water, thickly studded with trees from which hung the gray trailing moss so plentiful here. No sound broke the silence, no sign of life could be seen, no traces of man anywhere. It was certainly as wild a place as can be imagined, and the two exploring it thought they had seen the most dismal portion of this wonderful swamp.

In this, however, they found they were mistaken, when, on the following day, the Toby was anchored in the main canal, and in Mr. Stubbs the party rowed up a smaller canal into the lake of the swamp—Lake Drummond. Imagine this vast swamp (for up this last canal there was no question as to the swampy nature of the place), in the heart of which is a large body of water separated from that around it by an army of tree trunks bleached to a light gray by the sun and weather. Back of this ashen-colored border the juniper and pine trees lift their heads so high that the sun only illumines the water at noonday, while at other times the shadows cast by the trees on the brown water lend to all objects a purplish hue that is at least startling when first seen. It is a strange, weird-looking place, where one involuntarily whispers, as if he feared to waken nature from its solemn repose.

To describe this body of water in the midst of the vast swamp is impossible, so strange is the sensation the visitor has when seeing it for the first time. It was early in the morning when the passengers from the Toby arrived at the lake, and it was late in the afternoon before any of them remembered that they must return to the little steamer. Then it was almost a race to get back to the yacht in order that the village of South Mills could be reached before dark.

In this attempt, however, the voyagers were unsuccessful, owing to an exciting hunt which a party of gentlemen were having after a deer. They succeeded in their murderous design, for they killed him as he attempted to swim across the canal just under the bow of the Toby.

Late that night, when the little steamer was made fast to the pier at the village that marks the southern end of the canal, the voyagers on the yacht had venison steaks for supper that were cut from the deer they had seen killed, and all hands retired, almost sad that the journey through the swamp was ended, but anticipating very much from the trip down the Pasquotank River to Albemarle Sound.

James Otis.

Howard B.—You could have no more appropriate name for your dancing club than the one you have selected, "Lads and Lasses." All sorts of pretty and tasteful trifles may be used for favors, such as little bells, rosettes, flags, stars, butterflies, sashes, pictures, and flowers. At present tiny Japanese fans, umbrellas, cups, and vases are fashionable. Flowers are always appropriate as favors. The German affords scope for individual taste, and the favors may be very simple or very costly, as circumstances may regulate the affair. But while in some cases gold or silver jewelry has been given in the way of favors, it will be better for a club of young people to confine themselves to trinkets which, while of small money value, may still be pretty enough to be kept as souvenirs of a happy evening.

Dear Postmistress,—We have had a little discussion as to the proper method of hanging our pictures, and as we can not agree, will you kindly settle the question. We have hung them about on a level with our eyes, and are satisfied that that arrangement is good. The trouble is to know the proper angle of inclination. We had the tops of the frames about four inches from the wall; but a friend came in the other evening, and deliberately told us that that was all wrong. He then made rolls of stiff paper and, with them behind the pictures, forced the top of each frame about eighteen inches from the wall. Some of the family like the effect, and some declare it hideous. Which plan is considered the correct one by those who ought to know?

Trenton.

In hanging pictures it is well to have the middle of the picture in line with the eye. Let all small pictures be as flat as possible against the wall, and for larger ones let the angle of inclination depend upon size, making it invariably as small as you can. Only for a very large picture would an angle of eighteen inches be admissible. I would advise you to take away the stiff rolls of paper, and trust to your own sense of the beautiful and becoming rather than, in this instance, to your friend's judgment.

Elsie.—Your question whether it is ever right to make other people the subject of conversation is easily answered. It is right to speak of our friends and acquaintances, if we do so kindly, and talk of their good qualities. Nothing is so mean as to speak unkindly of the absent, who can not defend themselves. Conversation, if restricted to historical facts, as you propose, would be very dull.