THE MENTOR

SERIAL No. 40

DEPARTMENT

OF FINE ARTS

By JOHN C. VAN DYKE

Professor of the History of Art, Rutgers College

THE MENTOR

SERIAL No. 40

DEPARTMENT

OF FINE ARTS

| ANGEL WITH VIOLIN | Melozzo da Forlì | MADONNA AND CHILD WITH ANGELS | Bellini |

| ANGEL CHOIR | Benozzo Gozzoli | ANGEL WITH LUTE | Carpaccio |

| ANGEL OF ANNUNCIATION | Burne-Jones | SAINT MICHAEL | Perugino |

"Paint an angel!" exclaimed Courbet (koor-bay´) the realist to a pupil who one day asked him how it should be done. "When did you ever see an angel?" The abashed pupil had to admit that he had never had the good fortune to see one. "Very well, then, you had better paint the portrait of your grandfather, whom you see every day." The advice to keep his head out of the clouds while his feet were on earth may have been needed by the pupil; but nevertheless angels have been painted time out of mind, and even such pronounced realists as Courbet and Manet (mah-nay´) have painted them. And they saw them, too; that is, they saw the pretty-faced models they turned into angels by adding enlarged pigeon wings to their shoulder blades. But they were not very spiritual angels. Realism rather scorns things spiritual, and besides religious feeling and sentiment in art passed out several centuries before the coming of the modern realists.

The early men—the Fra Angelicos, the Benozzos (ben-ots-o), the Filippinos, of the fifteenth century—believed in the Biblical scenes they painted, and sometimes stated their belief in letters of gold at the bottom of their pictures. They saw things with the eye of faith,—saw Madonnas, saints, and angels in visions, and painted them, as the evangelists wrote, by the aid of inspiration. Perhaps it was their belief, their intense feeling, that gave the fine religious sentiment to the work of these early men. Yet they did not invent or discover the angel in art. It had a more mate[2]rial and commonplace origin than in medieval belief and religious fervor.

PERUGINO: BAPTISM OF CHRIST (detail)

There were winged figures in Egyptian, Chaldean, and Assyrian art, deities of the air, goddesses of the cloud and the heavens. The Hittite and the Persian produced the winged Sphinx, and the Greek the winged Victory that flew above the advancing host and pointed the way to glory. This winged Victory of the Greeks probably suggested the Christian angel; though the immediate forerunner of the angel was found in the Cupid and Psyche of Roman art. The Christians, following the Romans, took over in their art much of the material of the old Roman world. They had to do this; for Christianity was without form in art, and the early Christians decried it as idolatrous. But later on there came a demand for telling the Bible stories in form and color, that people might see what they could not read. Then Christianity, answering the demand, took up Roman forms and gave them Christian significance. They took the Cupids of Roman art and turned them into Cherubs, and out of the winged Victories and Psyches they made ministering angels.

PERUGINO: CHERUB HEAD (detail)

The pagan form was soon forgotten in the Christian spirit, and the angels of the Gothic and early Renaissance periods developed a new meaning, a new soul. What beautiful sentiment, what profound feeling, the early painters put into the angel of the Annunciation! What a world of pathos and sadness they gave the angel seated by the tomb of Christ! What gladness and joy to the angels of the Nativity standing near the Madonna or singing the Gloria in Excelsis in the upper sky! According to tradition, the angels know neither gladness nor sadness, neither wrath nor pity. They are heavenly messengers obeying the mandates of the Most High, without emotion or feeling of any kind. But the old masters of Italy did not so regard them. They gave them human characteristics, made them emotional and sympathetic, painted them in robes of blue, of red, of gold, of white, and gave them faces and forms that were human, it is true, but as near divine as earthly thought could render them.

The red-robed angels (they were painted red of face as well as of robe) were the Seraphim, the angels of love, and nearest to God. Often with the early painters only their heads were shown, with wings crossed in front of them, sometimes with four, six, or eight wings. The blue-robed angels were the Cherubim, the angels of knowledge, and they too were shown in their heads only, with many crossed wings. They appeared in groups and halos surrounding the presence of the Father, the Son, or the Virgin. The cherubs or putti of later Italian art, so frequently seen with the Madonna and Child, are the artistic descendants of the Seraphim and Cherubim. They are seen in the large aureoles of light that surround the Madonna; for instance, in Raphael's "Sistine Madonna" and Titian's "Assumption of the Virgin." They recede into the background or come forward in clouds as the countless hosts of heaven.

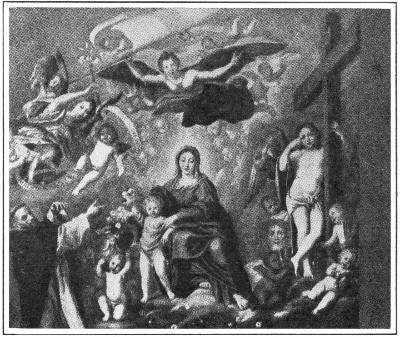

DOMENICHINO. MADONNA OF THE ROSARY (detail)

Frequently the Cherubs are given enlarged childlike or feminine forms with individual features, elongated wings, variegated colors. They are then shown hovering or standing or seated near the Madonna, and are usually playing on musical instruments—making music for the glory of the Madonna and Child. They are seen in the pictures of Bellini (bel-lee´-nee) and Carpaccio (kahr-pah´-cho) near the foot of the throne; with Melozzo da Forlì (for-lee´) they soar in the air; with Duccio (doo´-cho) and Cimabue (chee-mah-boo´-ah) they stand about the throne, dressed in rich robes, singing, playing, or worshiping. Music and color were associated in the minds of the early Italians as though both were manifestations of sentiment in art. Especially was this true at Venice,—the one great color spot in Italian art.

The angels that sang the Gloria in Excelsis, or knelt near at hand at the birth of Christ, were usually larger than the putti, girlish in form, and very beautiful of face.[4] They were dressed sometimes in colors, as with Correggio (kor-red´-jo); sometimes in gold brocades of gorgeous pattern, as with the Vivarini (vee-vahr-ee´-nee); sometimes in white and blue, as with Piero della Françesca (frahn-ches´-kah). Again, they frequently had jeweled crowns or embossed halos or peacock-eyed wings. It was the idea of the old masters to make them decoratively beautiful as well as representative of purity and truth. And they carried out this idea still further in the faces, which were always of the most lovely types they could find or imagine. To us today these angel faces are perhaps the most attractive feature of this early church art of Italy.

CORREGGIO; ANGEL GROUP (detail of fresco at Parma)

The same kind of angels, but clothed usually in white, appeared to the Shepherds, attended the Holy Family in their flight into Egypt, stood by the river bank at the baptism of Christ, were with Him in the wilderness, in the garden, at the crucifixion, watched by the tomb, and rolled away the stone from the door. Others of the angelic host appeared at times to warn Abraham, to present a message to Saint Joachim, to guide Saint Peter out of his prison. They were all ministering spirits, but without specific names.

FRA BARTOLOMMEO; MADONNA ENTHRONED (detail)

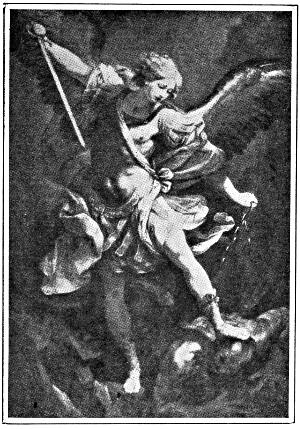

On the other hand, certain deeds to be done were given to certain angels who had definite names. These were the seven archangels. It was Michael, captain of the Hosts of Heaven, that overcame the Demon and drove him into the Bottomless Pit; it was Jophiel with the flaming sword that drove Adam and Eve out of Paradise; it was Zadkiel that stayed the hand of Abraham, and Chamuel that wrestled with Jacob. These were all archangels who appeared with their various symbols in Christian art. Uriel, guardian of the sun, is seen less[5] frequently than the others; but Raphael, the chief guardian angel, is often seen in company with Tobit, and occasionally in the pictures of the Last Judgment with Michael, blowing the dread blast of the great resurrection.

GUIDO RENI: ST. MICHAEL AND THE DEMON

But the angel Gabriel appears in art oftener than all the other angels put together. This is because he was the angel of the Annunciation and foretold the coming of Christ. He is seen a thousand times in Italian art, lilies in hand, kneeling and repeating the message to the Madonna. The theme was the most popular of all, and a thousand different types of beauty were created to impersonate Gabriel. Many of them are still existent, and some of them are the most lovely creations of the old masters.

VEROCCHIO (School of) ARCHANGEL RAPHAEL (detail)

Of course the ideal of angelic beauty varied with each painter. Each chose for a model the fairest type he could find, and each differed from his fellow. Perhaps the most popular types of angels in the early Renaissance were painted by Melozzo da Forlì. A notable group of them was painted in a cupola of the Church of the Apostles in Rome. They were angels of the Ascension, and surrounded the rising figure of Christ. The fresco afterward became so damaged that it was taken down, and some of the angels were transferred to the Sacristy of St. Peter's, where they are now to be seen. Our reproduction shows a detail of one of them,—one with a fair face, abundant hair, a halo about the head made up of golden cubes of mosaic, and large expanded wings. The figure is seen[6] slightly foreshortened, and this, with the spread wings that seem really large enough to support an angel, gives the impression of flight, or at least a hovering movement. The wings are upraised, and seem to frame the beautiful head and its halo. This upward swing of the wings is counterbalanced by the downward sweep of the drapery from the waist line. Between the upward and the downward curves is a swirling cross line, made up by the shoulder, the arm, and the violin bow. All this is shrewdly worked out, and gives force and movement to the figure. The whole composition has nobility and loftiness about it, and is not a mere sweet-faced affair of the Carlo Dolci (dol´-chee) kind.

VERONESE: ANNUNCIATION (detail)

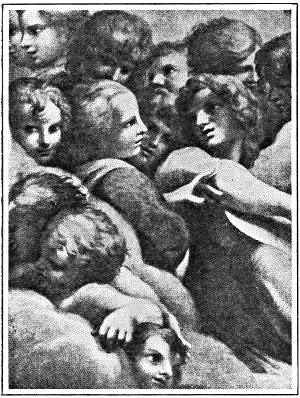

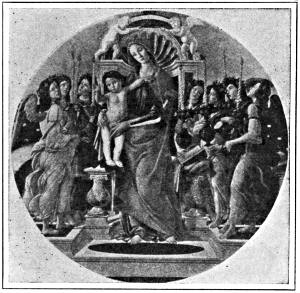

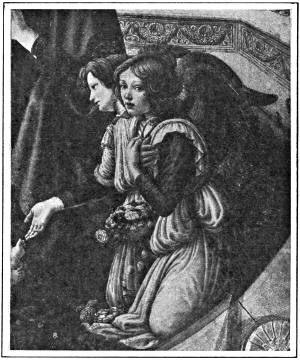

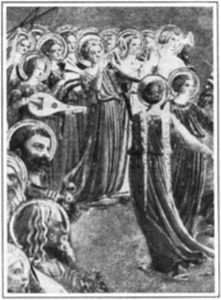

BOTTICELLI: MADONNA, CHILD, AND ANGELS

The angels of Benozzo Gozzoli (got´-so-lee) are of similar characters. They have not a particle of sweetness about them, and would never be called "pretty"; but what fine sentiment and decided individuality they have! They are part of a famous fresco in the Riccardi Palace at Florence, one of the finest and best preserved frescos in all Italy. The little chapel where they are had its walls entirely covered by Benozzo with a fresco representing the Adoration of the Kings. The gorgeous procession of the kings and their attendants (made up of portraits of the Medici and their friends, with Lorenzo the Magnificent riding as one of the kings) covers three walls of the chapel. The splendid cavalcade winds along,[7] and finally comes up to the fourth wall, where was once shown the Madonna and Child with Joseph. This group of the Holy Family has disappeared; but the band of worshiping angels is on the side wall, still intact. The angels are kneeling and standing amid flowers which one does not see at first because of the bright colors and the golden halos. What beautiful faces, naïve forms, and praying hands are here! This is sincerity in art, and true enough sentiment into the bargain. One will travel far before seeing its better.

BOTTICINI: MADONNA AND CHILD (detail of angels)

A historic and even a sentimental interest attaches to Leonardo da Vinci's (lay-o-nahrd´-o dah vin´-chee) little angel in the Baptism of Christ by Andrea Verocchio (vay-rok´-kee-o). Vasari (vah-sah´-ree) recites the story of how Verocchio, when ill perhaps, told his pupil, the young Leonardo, to finish this picture by painting in the second angel, and that Leonardo did it so well that it was superior to the other parts of the picture. "Perceiving this, Andrea resolved never again to take pencil in hand; since Leonardo, though still so young, had acquitted himself better in the art than he had done." This is a pretty story, which has been pooh-poohed and denied by recent criticism, but without reason. The angel with the profile was certainly done by a different hand than the angel with the full face. It is different from any other part of the picture, and there is every reason to believe it done by Leonardo as Vasari states. The charm of the angel, the type, the graceful contours, the light and shade, all foreshadow the later work of Leonardo. What a lovely creation, not only in face and feature, but in serenity and fine feeling!

Perugino (pay-roo-jee´-no) was in that same studio of Verocchio, a fellow pupil with Leonardo; but his angels are much weaker conceptions than Leonardo's. They are contemplative, full of wistful tenderness, lost in reverie; but they lack somewhat in mental grip. They make up for this, however, by a charming sentiment. The St. Michael, reproduced herewith,[8] shows it. He is hardly the ideal captain-general of the heavenly host, able to wield the sword in the front ranks; but on the contrary is a slight, boyish figure, full of fancy, and lost in day dreams.

FRA ANGELICO: TRUMPET-BLOWING ANGEL

In this picture he stands aloof from the figures about him, and, with his head inclined to one side, seems to be listening to the song of the angels in the upper air. The brown eyes are full of earnestness; but the round face and slight mouth have no set purpose other than to suggest sentiment and symmetry. A very pretty type, no doubt; but not a strong one. A man of power like Michelangelo could have very little sympathy with it. Indeed, he sneered at the pretty face and called Perugino a dolt and blockhead in art. That was more than Perugino could bear, and, in a rage, he brought Michelangelo before the Council of Eight on a charge of slander. But it only resulted in a laugh at Perugino's expense. His action was perhaps foolish; but his pictures are not to be laughed at. They are excellent in color, and the pretty face that Michelangelo scorned became the early model for Perugino's great pupil, Raphael.

FRA ANGELICO: CORONATION (detail)

In sweetness of type and depth of feeling, the angels of Fra Angelico are more profound than Perugino's. Besides, they seem to have more sincerity about them. The monk-painter in his cell saw visions of heavenly things, and as he saw so he recorded in art. All his faces seem filled with divine tenderness. He painted only one face, one type. His pictures show men with beards and monks[9] in cowls, and angels in flowing robes with bright wings; but there is always the same face, the same sentiment. His trumpet-blowing angels, of which there are countless copies in existence, are epitomes of this conception and sentiment. They have great purity and beauty. Fra Angelico was a man of pure thought to start with, and everything he touched reflected his purity.

FILIPPINO LIPPI: MADONNA AND ST. BERNARD (detail of angels)

SEPPI; ANGEL OF ANNUNCIATION

Filippino and Botticelli came later than Fra Angelico, and the Florence of their day had begun to draw away from medieval traditions in art in favor of more learned technical accomplishment; yet one can hardly see any waning of sentiment in the work of these men. In fact, the sentiment of Filippino is often perilously near to sentimentality, so intense and earnest is the feeling of the man. His Madonna is always on the brink of tears, and his angels are in perfect sympathy with the Madonna. Botticelli is more of an intellectual force; but he too is saturated with sentiment to a point of morbidity. His Madonnas have sad eyes, mouths that droop at the corners, hollow cheeks, and long, flowing hair. They bend before the Angel of the Annunciation like broken flowers, or agonize at the Crucifixion like lost souls. Their sentiment is intense. Nor does it vary much when Botticelli dealt with classic subjects. His Venus in her seashell, his Pallas, his Spring, all have some of the same morbidity, mingled with mystery, melancholy, tenderness, that we see in his angels surrounding the Madonna. This personal quality of the painter is very attractive, and has perhaps done more to make Botticelli popular than his fine qualities as a draftsman and a painter.

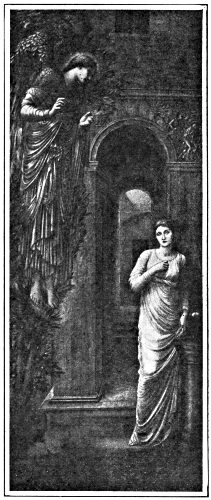

When the Preraphaelite movement started in England over half a century ago, with Rossetti, Holman-Hunt, and Millais as painters, and Ruskin for a prophet, it could think of no one better as a model to follow than Botticelli. The Botticelli look is quite apparent in the sad, rather unhealthy faces of Rossetti. This Rossetti influence was handed on to his pupil, Burne-Jones. None of the Preraphaelite ardor was abated or its sentiment lessened with Burne-Jones. Indeed, he improved upon his master both technically and sentimentally. He was a much better draftsman and colorist than Rossetti, and presented the Preraphaelite idea with greater force and effect.

BURNE-JONES: THE ANNUNCIATION

VEROCCHIO: BAPTISM (detail of Leonardo's Angel)

The Burne-Jones type had rounder, more inquiring eyes, thinner cheeks, a sadder mouth, a more willowy figure. It appears often in long, flowing hair, with swirling drapery, and dramatic action. At other times one sees it as a romantic type consumed by a fever of passionate sentiment. The Annunciation shown herewith is not a very good illustration of this. The Madonna has a dull stare in her eyes as though she was something of an invalid, and even the angel has a semi-malarious look. But the melancholy, the sadness, the morbidity, so apparent in Botticelli are also apparent here. The picture is a fine example of the painter's decorative sense. It has been put together with much skill. Notice the architecture, the passageway at back, the bas reliefs, the repeated lines of the draperies in both the Madonna and the angel. One could almost wish it in stained glass, so beautifully would it fill an upright window.

Every painter of Botticelli's rank in Italy had a score or less of followers, and among them all there was never any dearth of sentimental Madonnas and pathetic angels. Florence held no monopoly of the subject.

At Venice in the early days were Bellini and Carpaccio, who produced famous Madonnas and most lovable angels. They are different angels from those of Botticelli. In fact, they are little more than handsome children naïvely making music for the Madonna and Child. Their unconscious quality is captivating. How very childlike, in their pure faces, their golden hair, their round legs and fat little hands! The models were perhaps the painter's own children. Why not? Was not the Madonna, nine times out of ten, the painter's own wife? And how better could he depict the winged messengers of the sky than by painting them with the forms of those he loved here below? It is only a step across the world from heaven to earth, and is not love the band that unites them?

MURILLO: GUARDIAN ANGEL

SUPPLEMENTARY READING.—"Sacred and Legendary Art," Jameson; "Life of Christ in Art," Farrar; "Christian Iconography," Didron; "Angels of God," Timpson; "Angels in Art," Clement.

THE MENTOR

ISSUED SEMI-MONTHLY BY

The Mentor Association, Inc.

381 Fourth Ave., New York, N. Y.

Volume 1 Number 40

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. FOREIGN POSTAGE, SEVENTY-FIVE CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE, FIFTY CENTS EXTRA. ENTERED AT THE POST OFFICE AT NEW YORK, N. Y., AS SECOND-CLASS MATTER.

We have just received the following letter from a reader of The Mentor: "I have examined with great care and profit a copy of The Mentor just received. There is only one suggestion that I can make towards its improvement, and that is that on the back of the photogravures there should be a pronunciation scheme for all foreign names. Not everyone who reads is able to pronounce properly the Spanish, French, or Italian; particularly is this true of names and places. The pronunciation might be put in brackets right after the names, or made a sort of marginal affair."

This is the kind of letter we like to get. The suggestion is a good one. We wrote at once to the writer, saying that pronunciation would be indicated wherever foreign names were used. We have done so in the text pages of The Mentor—our readers know that. We have not been doing it in the stories printed on the back of The Mentor gravures. There was no reason for not doing it. The indication of pronunciations should accompany foreign names wherever they are used. The writer of the above has done us a real service in calling attention to the matter. We wish that readers would write to us whenever they have a suggestion that they think would add to the value and usefulness of The Mentor.

Half knowledge on any subject is not of much use. The case of a college professor comes to mind. He was very strong on what he called "completing a thought and finishing a fact." He said that as a man walked through life or looked through books he was constantly in an atmosphere of information—that facts were darting like meteors all about him. He said that the habit of mind of most people was slovenly. Such complete facts as come to their attention are perhaps absorbed. Half facts come along, and most people do not "follow them up to a finish." The habit of this professor was to carry a memorandum pad in his pocket, and whenever he would hear a statement or receive a bit of knowledge he would jot down a note and then, in some leisure moment, look the matter up in an authoritative reference book, thereby completing his information and, as he put it, "sewing it up good and tight" for future use.

The result is that that college professor knows what he knows thoroughly and accurately. He is never heard saying, as so many do when a subject is mentioned, "Oh, what about that. I have had bits of information concerning it from time to time. What does it mean?" The professor had looked up the matter when he got his first bit of information, and, as a result, he had digested the subject and in his way owned it.

We have planned The Mentor with the thought of giving members of the Association the essential information that they should have on different subjects. Everyone is not fortunate enough to have a good reference library—some are not even in touch with reference books. It is the purpose of The Mentor, therefore, to come like a good friend who is well informed and spend a few minutes a day with you, telling you in simple language about the many interesting and important things, events, and people of the world.

And you don't have to make notes as the professor did. You don't have to go looking for books of reference on the subject. The Mentor not only gives you in an interesting way the essential facts about a thing, together with illustrations, but it gives you a list of the important reference books on the subject.

ONE

Today we think of Italy as one united country. For that reason it is difficult for many of us to realize the Italy of Melozzo da Forlì's (mel-ot´-so day for-lee´) time. Then there was no union—practically no Italy. The country was rent by the strivings of many tiny principalities, each jealous of the other, each trying to outdo the other, each quick to seize an opportunity to work its neighbor harm.

Every one of the petty princes was seeking to beautify his capital city, to have his court outshine those of his rivals. If he desired to be known as a patron of art and letters, poets, architects, and philosophers were invited to associate themselves with him. Artists, like the scholars, had to rely on the favor of such princes for their living.

In later years the introduction of oil painting made easy the sending of a panel or a canvas as the gift of one lord to another. But before that time, instead of sending the painter's work, it would have been necessary to send the painter; for most of the work was done in another way. In fresco painting the artist was obliged to work directly on the wall on which the picture was to be seen when finished. Often he himself applied the wet plaster, and after smoothing it laid on the color. He had to work rapidly; for when the plaster had dried every addition or correction showed.

But before becoming sufficiently generous to give away their artist's work most of the nobles first employed their artists to decorate their own chapels or palaces for them. It was under the patronage of one of the cardinals, a nephew of Pope Pius IV, that Melozzo da Forlì painted his angels. Pius IV did not wish to be behind his neighbors in the encouragement of the fine arts. He wanted Rome to be the finest city in the world, and set about making it so. Those who wished to please him were not slow to follow his leading.

The angels reproduced in The Mentor are but a portion of the entire fresco, which showed the Ascension of Christ, and formerly decorated the dome of the Church of the Apostles at Rome. These fragments escaped destruction when the church was reconstructed in 1711. They are now in the Sacristy of Saint Peter's.

Almost nothing is known of the life of Melozzo. We should not have known when he was born if his epitaph had not recorded his age. His name indicates that he came from Forlì, a small town not far from Ravenna. His fame rests almost entirely on these fragments; but so well were they done that they give this man high rank among the artists of Italy.

TWO

Like many another painter, Benozzo Gozzoli (beñ-ot´-so got´-so-lee) owed much to his master. Fra Angelico painted beautiful angels, and his pupil seems to have learned some of his skill; for the group of Adoring Angels in the Riccardi Palace is one of the loveliest to be seen in all Italy. Early in his life Benozzo was apprenticed to Ghiberti, the sculptor of the doors of the baptistery at Florence. So splendid are they that by the Italians they are called "The Doors of Paradise." He began under a good man. But he could not have remained in that studio long; for at the age of twenty-seven we find Fra Angelico taking him with him to Rome as assistant in his work for the Pope.

Two years later Benozzo started out for himself. He worked in several of the smaller Tuscan towns, until in 1459 the death of several of the older artists of Florence opened up the way for his return to his native city.

He was not obliged to wait long; for the Medici soon called upon him for what proved to be his masterpiece. The palace of the Medici had in it a small private chapel; to Benozzo they gave the task of decorating its walls. The subject chosen was "The Adoration of the Magi." We have three letters written by Benozzo to Piero de' Medici when he was engaged upon this work. They show that he was using every effort to do his best. "I have no other thought in my heart," he writes, "but how best to perfect my work and satisfy your wishes."

The work was well done. Perhaps that is why everyone who today visits Florence feels that he must see this tiny chapel before he leaves. One steps from the busy Florentine street, through massive portals, into a courtyard. From the present we step back into the past. Climbing a stair, we reach the dim chapel, which is but little changed from the way it was left by Benozzo. It is as much a monument of his skill as it is of the munificence of the Medici.

Benozzo's success with this work insured his prosperity. He married and settled in Florence. Ten years later he moved to Pisa, where he spent sixteen years painting a series of frescos in the Campo Santo. And in that lovely, quiet place he lies buried today, near the frescos upon which he labored so faithfully.

THREE

The mother of Sir Edward Burne-Jones died when he was born. The lot of a lad without a mother is bound to be a hard one, especially if he has no brothers or sisters. His father would permit him to read only two or three books; but one of them was Æsop's Fables, and this was the boy's favorite, because it had prints in it. The child used to spend much time before the shop windows looking at the volumes he might not read. He was never very strong physically.

This course seems to have driven the boy to living in the realms of the imagination,—a training for the painter of nymphs and fairies he was to become later. Not until he was twenty-three, it is said, did Burne-Jones see a good picture.

When he went up to Oxford he formed a friendship with William Morris, a youth almost as shy as himself. They read Ruskin's "Modern Painters" together, and told each other their dreams. At London during one of the vacations he came into touch with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and on advice of this artist gave up his studies at Oxford to devote himself exclusively to the study of art. However frail Burne-Jones may have been physically, there could have been no lack of mental courage in the man who could take such a bold step as this.

His struggle was a long one and a hard one; but he was never without the help and encouragement of warm friends, Ruskin among them. He traveled to Italy. On his second trip he went with Ruskin. But with the possible exception of Botticelli, the Italian masters had little direct influence upon his work. He seems to have caught their spirit of doing things, of doing them as well as he was able, with deep sincerity of feeling.

He was one of the leading spirits of the Preraphaelites, a band of young men who hoped to regenerate art by putting into their work the simplicity and sincerity that had actuated the artists before Raphael's time.

He married in 1860, and settled on the outskirts of London. A gradually increasing host of friends began to make their way to his modest home. Burne-Jones felt that, wherever else he might be at fault, in spirit he was right. So he did not reach for the fame that makes less wise men seek short cuts, but worked steadily and carefully. His reputation increased, honors came to him, and before he died he knew that his work was being appreciated.

In 1894, four years before his death, a baronetcy was conferred upon him by Queen Victoria, and to those who knew the man and his work this was felt to be not higher than was deserved.

FOUR

The Bellini (bel-lee´-nee) family was a very artistic one. Not only Giovanni, but his brother Gentile as well, became a famous artist, and their father was a painter of note. Not to be outdone by the other members of the family, their only sister Andrea married Mantegna, the great Paduan master. Under such circumstances it is unlikely that the boy Giovanni had to overcome any parental opposition to his becoming an artist. Art must have been a part of the daily life of the entire family. At first he doubtless studied under his father's direction; but his early work shows that he was much influenced by his brother-in-law as well.

Although the two brothers, Giovanni and Gentile, worked independently, they both won distinction and were highly esteemed by the Venetians. They were commissioned to paint a series of large canvases for the Ducal Palace; but these works have since been destroyed by two fires which greatly damaged that wonderful building,—the first in 1479 and the second in 1577.

Although no longer a young man when the invention of oil painting was first brought to Venice, instead of adhering to the old traditions he set about mastering the new medium. And he succeeded too. Pupils came to him to be taught the new practice; among them Titian and Giorgione. His studio was the very dwelling place of the Genius of Painting, and from his workshop went out many of the men to whom Venetian painting owes its fame.

Painters from far and near came to visit him. Among them was Albrecht Dürer, the German master, whom Bellini received very cordially. "He is very old," wrote Dürer, "but still the best in painting." There was a waiting list of nobles who wanted him to paint their portraits.

Fine in color, and accurate in drawing to the last, he seems not to have degenerated. He must have been a man of great force and talent.

He lived to be ninety years old. He was laid to rest beside his brother, in San Giovanni e Paolo, the Westminster Abbey of Venice.

FIVE

Venice the Magnificent is never very far removed from the pictures of Vittore Carpaccio (kahr-pah´-cho). It doesn't matter whether he is painting the story of Saint Ursula at Cologne or a scene from Holy Writ, Cologne is given a very Venetian look, and the Madonna or the Saints are in Venetian costumes and brocades.

This oriental love for splendor in dress has led some writers to believe that Carpaccio must have accompanied his master Gentile Bellini to Constantinople. When the sultan desired that Venice send one of her foremost artists to paint his portrait, the commission was given to Gentile Bellini. He may have taken Carpaccio with him. The portrait Bellini painted exists today in the Layard collection, recently bequeathed to the National Gallery, London.

Although Carpaccio painted many religious pictures, he succeeded best when there was some story to be told. He gave to his pictures the charming simplicity that is the first essential of a good story-teller. Nor was he without a sense of humor. In one of his pictures telling the story of the life of Saint Jerome he shows the lion walking up to Jerome and holding out his paw in order that the troublesome thorn might be removed, while the terrified brothers of the saint are seen flying in all directions.

One of the Venetian nobles gave Carpaccio a commission to paint the portrait of a poet connected with his household. At least one of these rhymesters was to be found in the train of most of the nobles in those times. The poet was so elated that he burst forth into verse, giving Carpaccio directions to paint him with a wreath of laurel. Carpaccio painted the portrait; but, possibly at a hint from the nobleman, he substituted for the crown of laurel one of grape leaves. The poet retaliated by reviling Carpaccio in a lampoon full of abuse.

We do not know exactly when Carpaccio was born, though it is generally believed to have been in 1450, in Istria, nor just when he died. Only at Venice can an adequate conception of his work be formed. He seems never to have journeyed far from that island city.

Carpaccio's love for splendor found plenty of employment among the beauty-loving Venetians. Venice was beyond the reach of papal dictation, and religion came to be considered by them more as an opportunity for display than as a rule of conduct. Its tragic phases were not at all popular. The Crucifixion was not often painted; but the Presentation in the Temple and the Feast in the House of Simon, with their display of fine costumes, were painted again and again.

When Ruskin first went to Venice, Carpaccio's work was not at all appreciated; but, thanks to his lead in admiring its charming qualities, today Carpaccio is loved by many.

SIX

Perugino (pay-roo-jee´-no) was born in 1446 in a little town not far from Perugia. His parents were respectable people, and when he was nine years old they sent him to Perugia to be educated under one of the artists of that city. His family name was Vannucci; but like many other Italian artists he was called after the city from which he came. He grew up in Perugia; but by the time he had reached early manhood we find him at Florence, studying the frescos. According to Vasari, he became a pupil of Verocchio, and in Verocchio's studio worked side by side with Leonardo da Vinci.

It was about this time that the change from tempera to oil painting took place in Italy. Perugino and Leonardo were among the first of the artists who thoroughly mastered the new medium.

Perugino's careful work did much to increase his fame. Before he had reached the age of forty he was invited by the Pope to come to Rome. He painted several subjects for the Sistine Chapel, and his work was given a prominent place in that place. But when a later pope wished to make room for Michelangelo's "Last Judgment" Perugino's frescos were ruthlessly destroyed and the space they had occupied was filled with Michelangelo's huge composition.

Judging from his quiet, pensive Madonnas and his melancholy Saints, it might be thought that Perugino was of a saintly character too; but the records of Florence show that after his return from Rome he and a companion got into difficulties with the authorities. They were captured when lying in wait for someone against whom they had a grudge. Perugino escaped with a fine of ten florins after pleading that he had intended that the fellow should have no more than a good drubbing; but his companion, who harbored graver designs, was exiled.

Perugino's work arose steadily in public esteem. Commissions came rapidly, and he was able to choose among them. A number of the younger men came to him to be taught his method. Among them was the young Raphael, who worked with him for several years. Raphael's early work much resembles Perugino's.

Perugino married a beautiful girl many years his junior. He never tired of dressing her in rich costumes. But as he grew older he also grew miserly. When he died he left a comfortable estate for her and her three sons. He was carried off by the plague when working in one of the towns not far from Florence, at the age of seventy-eight years.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 40, SERIAL No. 40 COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

In HTML version, plate images (preceding each chapter after the Editorial) are clickable links to larger images.

Minor punctuation and printer errors repaired.