LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

NOVEMBER 1 1917

SERIAL NO. 142

THE

MENTOR

BOLIVIA

By E. M. NEWMAN

Lecturer and Traveler

DEPARTMENT OF

TRAVEL

VOLUME 5

NUMBER 18

TWENTY CENTS A COPY

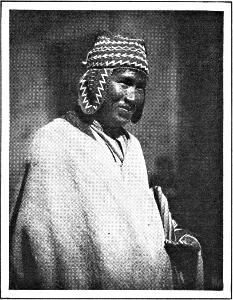

The Indian of the Bolivian plateau is still only a half-civilized man and less than half a Christian. He retains his primeval Nature worship, which groups together the spirits that dwell in mountains, rivers, and rocks with the spirits of his ancestors, revering and propitiating all as Achachilas. In the same ceremony his medicine man invokes the Christian “Dios” to favor the building of a house, or whatever he undertakes, and simultaneously invokes the Achachilas, propitiating them also by offerings, the gift made to the Earth Spirit being buried in the soil. Similarly he retains the ceremonial dances of heathendom, and has secret dancing guilds, of whose mysteries the white man can learn nothing.

His morality is what it was, in theory and practice, four centuries ago. He neither loves nor hates, but fears, the white man, and the white man neither loves nor hates, but despises him; there being some fear mingled with the contempt. Intermarriage between pure Indians and pure Europeans is very uncommon. They are held together neither by social relations nor by political, but by the need which the white landowner has for the Indian’s labor and by the power of long habit, which has made the Indian acquiesce in his subjection as a rent payer.

Neither of them ever refers to the Spanish Conquest. The white man does not honor the memory of Pizarro; to the Indian the story is too dim and distant to affect his mind. Nor is it the least remarkable feature of the situation that the mestizo, or half-breed, forms no link between the races. He prefers to speak Spanish which the Indian rarely understands. He is held to belong to the upper race, which is, for social and political purpose, though not by right of numbers, the Peruvian or Bolivian nation.

JAMES BRYCE.

From “South America, Observations and Impressions.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY E. M. NEWMAN

INCA TEMPLE OF THE SUN—ON THE SHORE OF LAKE TITICACA, BOLIVIA

ONE

With the exception of Paraguay, Bolivia is the only entirely inland State in South America. It is really a manufactured nation. When the War of Independence of that part of South America ended, the revolutionary leaders set up this country as an independent State, and gave it the name of Bolivia, in honor of Simon Bolivar, the Liberator, himself a native of Venezuela. Bolivia is bounded on the north and east by Brazil, on the south by Paraguay and Argentina, and on the west by Chile and Peru.

In its early days Bolivia was simply a part of the empire of the Incas of Peru. The story of the Incas has been given in Mentor No. 132, “Peru.” After the conquest of Peru by the Spaniards in the sixteenth century, the natives were subjected to a great deal of tyranny and oppression. They were compelled to work in the mines, and endured so many hardships and cruelties that their numbers rapidly diminished.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there were many struggles between the native-born inhabitants and their Spanish rulers. The Indian revolt in Cuzco (koos´-ko or kooth´-ko), Peru, which was led by the Inca Tupac Amaru (too´-pahk ah-mah-roo´), stirred up the Bolivian Indians to further efforts. For three months Ayoayo (ei-o-ei´-o) with 80,000 men, besieged the city of La Paz (lah pahth; local pronunciation, lah pahs´). Finally his army was dispersed and the insurrection was crushed.

Injustice had been worked not only upon the Indians, but upon the native born Spanish-Americans. These grew restless at last, and on July 16, 1809, conspirators at La Paz deposed and put into prison the governor, and then proclaimed the independence of the country. One of the leaders, Pedro Domingo Murillo (pay´-dro do-min´-go myr-ril´-o or moo-reel´-yo), was elected president. This was the first effort in South America toward democratic government. The Spanish Viceroy, however, sent a trained army which soon overcame that of the patriots. On January 29, 1810, Murillo perished on the scaffold. In the face of death, however, he exclaimed: “The torch which I have lighted shall never be extinguished.”

From then on until 1825 there was almost uninterrupted warfare. Success was equally divided at first between the Spanish and the revolutionary forces. On December 9, 1824, the Battle of Ayacucho (i-ah-koo´-cho), in lower Peru, finally ended Spanish dominion in South America. General Sucre (soo´-kray) was the victorious general. On January 29, 1825, the last Spanish authorities vacated La Paz. General Sucre and his army made a triumphal entry there on February 7, 1825. This general now assumed supreme command in upper Peru. The first national assembly met in June at the city of Chuquisaca (choo-kee-sah´-kah), now called Sucre. They decided that the part of the country hitherto known as upper Peru should be made a separate and independent nation, with the name of Bolivia. The Act of Independence bears the date of August 6, 1825.

Simon Bolivar (bo-lee´-var) was elected the first president; and Chuquisaca was made the capital under the name of Sucre. When General Bolivar arrived in the city of La Paz on August 18th, he was greeted with wild enthusiasm. He was inaugurated at Sucre in November; but resigned in January, 1826, to return to Lima (lee´-mah) in Peru.

There was no peace for the people of Bolivia yet, however. Troublous times followed, and finally came the war with Chile. This war arose over the collection of an export tax on nitrate. Chile sent troops to occupy Bolivian territory; and then Peru, linked to Bolivia by secret treaty, together with that country, declared war on Chile on April 5, 1879. Both Peru and Bolivia were entirely unprepared, and Chile was completely victorious in this war. As a result Bolivia lost what little coastline the country had previously possessed.

During the last thirty years internal dissensions in Bolivia have for the most part ceased. There was a brief time of trouble in 1898 over the question of the capital city. It had been the custom for the cities of Sucre, La Paz, Cochabamba (ko-chah-bahm´-bah), and Oruro (o-roo-ro) to take turns in being the seat of government. In December, 1898, however, the Bolivian Congress attempted to pass a law making Sucre the permanent residence of the president and cabinet. La Paz protested, and the people of the city rose in open revolt. On January 17, 1899, a battle was fought between the insurgents and the government forces. The insurgents were completely victorious. As a result, La Paz was made the real seat of government, although Sucre retains the name of capital. General Pando, (pahn´-do), commander of the revolutionary forces, was elected president. In 1903 a boundary dispute with Brazil over some rich rubber country was settled by the cession by Bolivia of a part of the province of Acre, (ah´-kray), in return for a cash payment of $10,000,000.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 5, No. 18, SERIAL No. 142

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

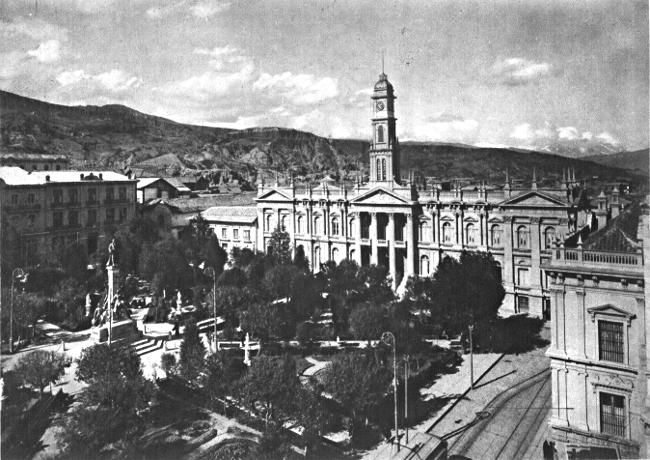

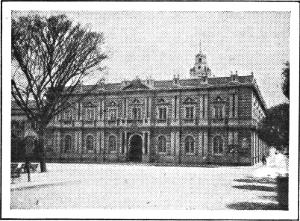

PHOTOGRAPH BY E. M. NEWMAN

HOUSE OF CONGRESS, LA PAZ, BOLIVIA

TWO

Bolivia is a centralized republic. Its government is representative in form, but to a great extent it is autocratic in effect. The Bolivian constitution was adopted on October 28, 1880, and is a model of its kind. The executive branch of the government consists of a president and two vice-presidents. They are elected by direct popular vote for a period of four years, and are ineligible for election for the next succeeding term. The president has a cabinet of six ministers: Foreign Relations and Worship, Treasury, Government and Promotion (Fomento), Justice and Industry, Public Instruction and Agriculture, War and Colonization.

The legislative branch consists of a national Congress of two houses—a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies. The Senate is composed of sixteen members, two from each department, who are elected by direct popular vote for a period of six years. The Chamber of Deputies is composed of seventy members, who are elected for a period of four years. Congress meets annually and its sessions are for sixty days, which may be extended to ninety days. All male citizens twenty-one years of age or over, who can read and write and have a fixed independent income, may vote. The number of citizens who vote, therefore, is very small, and the country is for that reason under the control of a political oligarchy.

The judiciary consists of a national supreme court, eight superior district courts, and many lower district courts. The supreme court is composed of seven justices, elected by the Chamber of Deputies.

In each department or State a prefect appointed by the president has supreme power. The government of these departments rests with the national congress.

The military forces of Bolivia include about 3,000 regulars and an enrolled force of 80,000 men. This enrolled force, however, is both unorganized and unarmed. In 1894 a conscription law was passed providing for compulsory military service for all males between the ages of twenty-one and fifty years, with two years’ actual service in the regulars for those between twenty-one and twenty-five. This law is practically a dead letter. There is a military school with sixty cadets and an arsenal at the city of La Paz. Naturally Bolivia, having no coast line, is not provided with a navy.

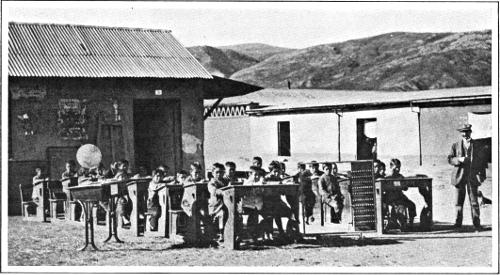

Bolivia has a free and compulsory school system, but education has made little progress there. Very few of the people can read and write. Spanish is the official language, but Quichua (kee-choo´-ah or kee´-chwah). Aymará (i-mah-rah´), and Guarani (gwah-rah´-nee) are the languages of the natives, who form a majority of the population. A great part of the Indians do not understand Spanish at all and will not learn it. The school enrollment is about one in forty-four. There are universities at Sucre, La Paz, Cochabamba, Tarija (tah-ree´-hah), Potosí (po-to-see´), Santa Cruz (san´-tah kroos), and Oruro. The university at Sucre, which dates from colonial times, and that of La Paz, are the only ones well enough equipped to merit the title.

The Constitution of Bolivia says: “The State recognizes and supports the Roman Apostolic Catholic religion, the public exercise of any other worship being prohibited, except in the colonies, where it is tolerated.” However, this toleration is extended to resident foreigners belonging to other religious sects. The Indians profess the Roman Catholic faith, but this is tinged with the superstitions of their ancestors.

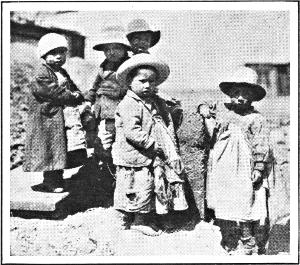

At this point it will be interesting to consider the Indians of Bolivia. The population of the country is composed of Indians and Caucasians of European origin, and a mixture of the two races, generally described as mestizos (mes-tee´zos). There is also a small percentage of Africans, descendants of the negro slaves introduced in colonial times. Naturally, the Indians are in great majority. The Bolivian Indian is essentially a farmer. Scarcely any of these Indians are educated.

Of the various tribes of Indians, the Aymaras are the most civilized. The Mojos (mo´-hos) and Chiquitos (chee-kee´-tose) tribes are peaceable and industrious. They have little ambition, and are held almost in a state of peonage. Inhabiting the southern part of the Bolivian plains are the Chiraguanos (chee-rah-gwah´-nos), a detached tribe of the Guarani race which drifted westward, to the vicinity of the Andes, long ago. They are of a superior physical and mental type, and have made a great deal of progress toward civilization. Of the wild Indians very little is known in regard to either their numbers or customs.

The mestizos, or half-breeds, sometimes called Cholos, are the connecting link between the whites and the Indians. It has been said of the mestizos that they inherit the vices of both races and the virtues of neither.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 5, No. 18, SERIAL No. 142

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

PHOTOGRAPH BY E. M. NEWMAN

A PACK TRAIN OF LLAMAS IN LA PAZ, BOLIVIA—TWILIGHT

THREE

“Imagine,” says James Bryce, “a country as big as the German and Austrian dominions put together, with a population less than that of Denmark, four-fifths of it consisting of semi-civilized or uncivilized Indians, and a few educated men of European and mixed stock, scattered here and there in half a dozen towns, none of which has more than a small number of capable citizens of that stock.” That country is Bolivia.

The popular idea of Bolivia is that it is an extremely rugged, mountainous country. In fact, only two-fifths of the total area of Bolivia is comprised within the Andine Cordilleras, which cross its southwest corner. Three-fifths of the country is composed of low, alluvial plains, great swamps and flooded bottom lands, and gently undulating forest regions. There are also considerable areas that afford rich grazing lands.

Bolivia lies wholly within the torrid zone. The only variations in temperature, therefore, are due to elevation. For this reason the country possesses every degree of temperature, from that of the tropical lowlands to the Arctic cold of the snow-capped peaks directly above.

Bolivia has many interesting animals. There are numerous species of monkeys that inhabit the forests of the tropical region, together with the puma, jaguar, wild cat, tapir, and sloth. A rare bear, the Ursus ornatus (spectacled bear) inhabits the wooded Indian foothills. The chinchilla lives in the colder plateau regions of the country. The most interesting of all the Bolivian animals, however, are the guanaco (gwah-na´ko) and its relatives, the llama (lyah´ma), alpaca (al-pak´ah) and vicuña (vi-koon´yah). These animals have the structure and habits of the African camel, but are smaller and have no hump. They are able to go without food and drink for long periods. The llama and the alpaca have been domesticated for centuries; but the guanaco and vicuña are found in a wild state only. The llama is used as a pack animal; and the alpaca is highly prized for its fine wool. The slaughter of the guanaco and the vicuña is rapidly diminishing their number.

Of birds the species in Bolivia are very numerous. The high mountains are frequented by condors and eagles of the largest size; while the American ostrich and a species of large stork inhabit the tropical plains and valleys. The common vulture is scattered throughout the whole country.

All sorts of plants, flowers and vegetation are to be found in Bolivia. Coca (a shrub of the flax family, the dry leaves of which are chewed by the native Indians as a stimulant) is one of the most important plants of the country. The most important of the forest products, however, is rubber. Sugar cane, rice, and tobacco are cultivated in the warm districts.

The most important industry in Bolivia is mining. The lofty and desert part of the country finds its only natural source of wealth in minerals. The Western Cordillera is especially rich in copper and silver, the Eastern in gold and tin. It has been said that one-third of all the world’s production of tin now comes from Bolivia. It was from the east Andine regions that the Incas obtained those vast stores of gold which so excited the Spaniards. Legend has it that the gold that the Spanish took out of the country was much less than that which the Indians buried or threw into the lakes to keep it from the conquerors.

Next to mining, stock raising is one of the chief industries of the country. Horses and, to a greater extent, cattle, are raised there. Goats and sheep are also a source of profit.

Although the agricultural resources of Bolivia are of great value, their development has been slow. Sugar cane is grown, but chiefly for the manufacture of rum. Rice is also raised, but the quantity is not great. Tobacco and coffee of fair quality grow readily. The product that receives most attention, however, is coca. This plant is highly esteemed by the natives, who chew the leaf. It is also used for medicinal purposes.

It is from her forests, however, that Bolivia derives the greatest immediate profit. The most prominent and profitable industry is that of rubber collecting. This was begun in Bolivia between 1880 and 1890. In 1903 Bolivia’s best rubber forests were transferred to Brazil, but there still remain extensive areas where good rubber is collected.

The industrial activities of the Bolivian people are still of a very primitive character. Spinning and weaving are done in the home. The Indian women are expert weavers. Other industries of some importance are the manufacture of cigars and cigarettes, soap, candles, hats, gloves, starch, cheese and pottery. The foreign trade of Bolivia is comparatively unimportant, with the exception of the products of its mines.

One difficulty that Bolivia has to contend with is the lack of transportation facilities. Railways have never been developed to any extent, but great plans are on foot to remedy this. With communications improved and extended, the future of Bolivia appears bright.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 5, No. 18, SERIAL No. 142

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

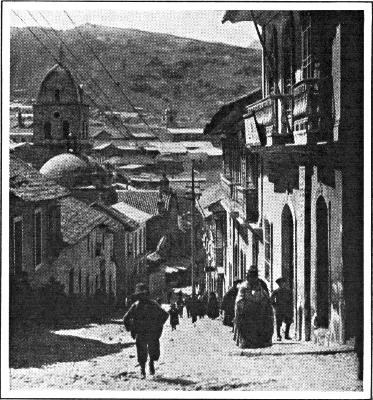

PHOTOGRAPH BY E. M. NEWMAN

LA PAZ, BOLIVIA—FROM THE RIM OF THE HEIGHTS

FOUR

La Paz (lah pahth; local pronunciation, lah pahs´) is a most unusual city. It is the highest capital city in the world—for although Sucre is the official capital, La Paz is really the capital city of Bolivia. It lies in a great mountain hollow nearly 13,000 feet above the sea. This altitude closely approaches that of Pike’s Peak; but whereas such an altitude in our country would mean perpetual snow, here it brings only a temperate climate, where flowers blossom throughout the year and the little snow that falls quickly vanishes in the morning sunlight.

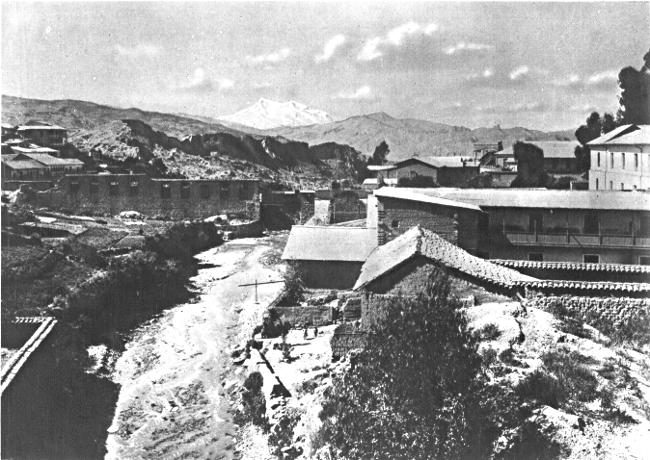

The city’s official name is La Paz de Ayacucho (eiah-koo´cho). It is built in a deeply worn valley of the Cordillera Real, which is believed to have formed an outlet of Lake Titicaca (tee-tee-kah´kah). La Paz is built on both banks of the Rio de La Paz, or Rio Chuquiapu, thirty miles southeast of Lake Titicaca. The valley in which the city lies is about ten miles long and three miles wide. It is very barren and forbidding, and its precipitous sides, gullied by rains and colored by mineral ores, rise 1,500 feet above the city. Above Illimani (eel-yee-mah´-nee) and other giant mountains of the Bolivian Cordilleras rear their snow-capped peaks. The upper edge of the valley is called the Alto de La Paz, or Heights of La Paz.

The city is surprisingly large, its population being about 80,000. Two-thirds of the population consists of Indians. They give a picturesqueness to the place, the women of the Cholos (cho´los), or half-breeds, being especially gaily attired.

The greater part of La Paz lies on the left bank of the river. Both banks rise steeply from the stream, and the streets at right angles to the river are very precipitous. All the streets are narrow, and paved with small cobblestones. The sidewalks also are so narrow that only two may go abreast. Many of the inhabitants prefer to walk in the middle of the street. The only things likely to be met are either pedestrians or llamas, the latter used in great numbers in this part of the country as pack animals.

La Paz was founded in 1548 by the Spaniard, Alonzo de Mendoza (ahlon´tho day men-do´-thah), on the site of an Indian village called Chuquiapu (choo-ku-ah´-poo). It soon became an important colony. At the end of the war of independence, in 1825, it was re-named La Paz de Ayacucho, in honor of the last decisive battle of the revolution. La Paz was then made one of the four capitals of the Bolivian republic. When the Bolivian Congress, however, attempted to designate Sucre as the permanent capital, the citizens of La Paz revolted; and by this revolution of 1898 the seat of government was permanently established there.

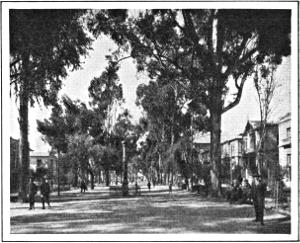

One of the most interesting parts of the city to visitors is the Alameda (ah-lah-may´-dah). This is a handsome thoroughfare, with rows of trees, shrubs and flowers. It also has a wide central walk with pools, in which are swans and goldfish. Along the Alameda are many new and rather pretty residences. Most of the houses are painted in tints of pale blue, green, yellow and strawberry, giving the street a gay and pleasing appearance.

The Plaza Murillo is so named from the patriot Pedro Domingo Murillo, who was executed there in 1810. This spot is also the place where independence was first declared in 1809. It has been the scene of many turbulent episodes. On one side of the plaza is the Government Palace, erected in 1885. This contains the offices of many state officials, and, in the upper story, the office and residence of the president and his family.

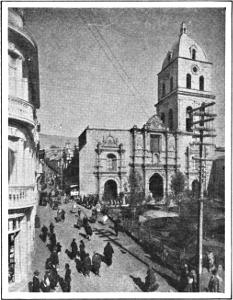

The Cathedral of La Paz, on the same side of the plaza as the Government Palace, is still in process of construction. The foundations were laid in 1843. When finished it will be one of the largest and most expensive cathedrals in South America. It is to be built in the Græco-Roman style, will have towers nearly 200 feet high, a dome the top of which will be 150 feet above the floor, and will be capable of seating 12,000 persons.

Across the corner from the Government Palace is the Hall of Congress. Another interesting spot is the market place. Here come thousands of Indians to buy and sell.

Other buildings of note are the old University of San Andrés (ahn-dres´), the Church of San Francisco, the Church of Santo Domingo, the Museum of Natural History, rich in relics of the Inca and colonial periods, the very much up-to-date theater, and the Municipal Library.

The houses of the poorer classes in La Paz are usually built with mud walls and covered with tiles. The better class dwellings, however, are constructed of stone and brick.

La Paz is an important commercial center. It is connected with the Pacific coast by the Bolivian Railway from Mollendo (mol-yen´-do), to Puno (poo´-no) and a Bolivian extension from Guaqui (gwah´-kee) to Alto de La Paz—the two lines being connected by a steamship service across Lake Titicaca. An electric railway, five miles long, runs from the Alto de La Paz to the city.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 5, No. 18, SERIAL No. 142

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

PHOTOGRAPH BY I. F. SCHEELER

STREET SCENE AND MARKET, SUCRE, BOLIVIA

FIVE

On May 25, 1809, the first city of Spanish South America revolted against the rule of Spain. That city was Sucre (soo´-kray). This town was originally the site of an Indian village called Chuquisaca (choo-kee-sah´-kah) or Chuquichaca, which means “golden bridge.” In 1538 the Spaniards under Captain Pedro Angules (pay´-dro ahn-goo´lace) settled there and called the place Charcas (chahr´-kahs) and Ciudad de la Plata (thee-oo-thath´ day lah plah´tah), but the natives always clung to the original Indian name. In time the town became the favorite residence and health resort of the rich mine owners of Potosí, some distance away. After the South Americans had won their independence, the name of Chuquisaca was changed to Sucre, in honor of the general who won the last decisive battle of the war and then became the first president of Bolivia. Since that time the city has suffered much from quarrels between the various factions of Bolivia. It is now the nominal capital of the republic, but the seat of government for Bolivia is located in La Paz. Since the government was removed there, Sucre has greatly diminished in importance.

The city is in an elevated valley, being about 8,839 feet above the sea. For this reason it has an exceptionally agreeable climate. In the vicinity are fertile valleys which provide the city markets with fruits and vegetables. The population of the city is about 25,000.

Sucre is laid out regularly. It has broad streets, a large central plaza and a public garden, or promenade, called the Prado. There are nine plazas altogether. That called the “25 de Mayo” has a stream on each side. One of these flows northward and joins the Mamoré (mah-mo-ray´) and so reaches the Amazon. The other turns southeast, going on to the Pilcomayo (peel-ko-my´-o) and at last to the estuary of La Plata (lah-plah´-tah). The Cathedral of Sucre, called the Metropolitan Cathedral, is the richest in Bolivia. It dates from 1553, and possesses an image of solid gold with a rich adornment of jewels, called “The Virgin of Guadalupe (gwah-dah-loo´-pay).” This is said to be worth a million dollars. The legislative palace of Sucre contains handsomely decorated halls; but this building is no longer occupied as such by the national government. Other important buildings are the Cabildo (kah-beel´do), or town hall; the mint, dating from 1572; the courts of justice; and the University of San Francisco Xavier (sahn frahn-this-ko zav´-ih-er; Spanish, hahvee-air´), which was founded in 1624 and has faculties of law, medicine and theology.

At the lower end of the central plaza, or Prado (prah´do) is a pretty chapel called the “Rotunda.” This was erected in 1852 by President Belzu (bale´-thoo), on the spot where an unsuccessful attempt had been made to assassinate him.

Sucre is the seat of the supreme court of Bolivia, and also of the archbishop of La Plata and Charcas, the primate of Bolivia.

The city is not a commercial one. Its only noteworthy manufacture is the “clay dumplings” which are eaten with potatoes by the inhabitants of the Bolivian uplands. In spite of being the capital of the country, it is one of its most isolated towns, because of the difficult character of the roads leading to it. It is reached from the Pacific by way of Challapata (chahl-ya-pah´tah), a station on the Antofagasta (ahn-toe-fah-gahs´-tah) and Oruro Railroad. The city will soon be connected by rail with the region of the west.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 5, No. 18, SERIAL No. 142

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

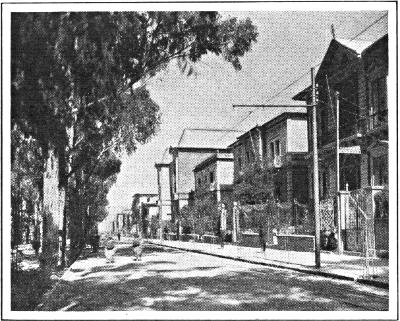

PHOTOGRAPH BY E. M. NEWMAN

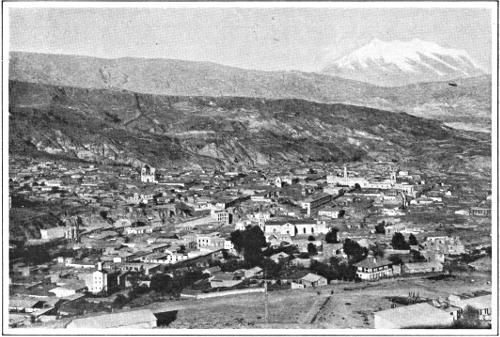

ORURO, BOLIVIA

SIX

Cochabamba (ko-chah-bahm´bah) is called the Garden City of Bolivia. It was founded in 1574 in a beautiful valley on the east side of the mountains, which are here called the Royal Range. For a time the town was known as Oropesa (o-ro-pay´sah). During the war of independence, the people of the city took an active part; the women especially distinguished themselves in an attack on the Spanish camp in 1815. Three years later some of them were put to death by the Spanish forces. In general, the isolated situation of Cochabamba has been a protection against the disorders which have from time to time upset Bolivia.

Cochabamba stands on the Rocha (ro´cha), a small tributary of the Guapai (gwah-pie´) River. Its population is about 30,000, mostly Indians and mestizos. The city is 8,400 feet above the sea, 291 miles north-northwest of Sucre, and 132 miles east-northeast of Oruro (o-roo´-ro). A newly constructed railway runs from Oruro to Cochabamba.

The climate is mild and temperate, and the surrounding country fertile and cultivated. Trade is active; and in fact the city is one of the most progressive in Bolivia, in spite of its isolated situation. It is laid out regularly and contains many attractive buildings. The city has a university and two colleges, but they are poorly equipped.

The name of the city of Potosí (po-to-see´) has become proverbial and “smacks of almost magical and unearthly wealth.” It possesses some of the most wonderful silver mines in the world. Founded in 1547, shortly after the first discovery of silver there by an Indian herder, it has since produced an enormous amount of the precious metal. One writer estimates the yield of the mines there as having been worth one billion dollars. Seven thousand mines have been started, of which seven hundred are being worked for silver and tin today. At one time the city had a population of 150,000, which has now dwindled to about 25,000.

Potosí stands on a barren terrace about 13,000 feet above sea level, and is one of the highest towns in the world. It is 47 miles southwest of Sucre in a direct line. The famous Cerro Gordo (ser´-ro gor´-do; Spanish, ther´-ro gor´-do) de Potosí rises above the town to a height of 15,381 feet, a barren, white capped mountain, honeycombed with mining shafts. The town itself is laid out regularly. A large plaza forms the center, around which are grouped various buildings, such as the government house, national college, the old “Royal Mint,” dating from 1585, and the treasury. The city has a cathedral, which in part dates from early colonial times. The water supply is derived from a system of twenty-seven artificial lakes, or reservoirs, and aqueducts constructed by the Spanish government during the years of the city’s greatest prosperity.

Oruro (o-roo´-ro) is an important mining town of about 20,000 people. During the colonial period this town was noted next to Potosí, for the richness and productiveness of its mines. The mines in the neighborhood are now worked principally, though not entirely, for tin.

Oruro is 115 miles south-southeast in a direct line from La Paz. It stands 12,250 feet above sea level, and its climate is characterized by a short, cool summer and a cold, rainy winter. Oruro is the Bolivian terminus of the Antofagasta (ahn-toe-fah-gahs´-tah) Railway, the first constructed in Bolivia. In time the city promises to be one of the most important railway centers in the country.

Oruro contains many foreign residents, and several clubs. The government palace and the university building face the principal plaza. Besides these, the city has a theater, a public library and a mineralogical museum, as well as the usual churches, hospitals and schools.

There is one other region in Bolivia that should be visited by all travelers interested in the mysterious past of the country. This region is called Tiahuanacu (tee-ah-wah-nah´-koo). It is not far from La Paz, and the ruins there were believed by Sir Clements Markham to indicate the former existence of a large city of the Incas. One huge gateway, broken and apparently not in its original position, is especially interesting. This great piece of stone is 13 feet wide, 7 feet above the ground, and 3 feet thick. It is curiously and elaborately carved. In the center is a human head, supposed to represent the creator of the universe. To this, other figures, partly human and some with heads of condors, seem to be offering worship.

Other stones in this region are remarkable for their size and for the ornamental carving that appears upon them. All the ruins are apparently of great age. It is not difficult to imagine a time when the city was the home of thousands of human beings in a very advanced stage of civilization.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR. VOL. 5, No. 18, SERIAL No. 142

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE MENTOR · DEPARTMENT OF TRAVEL

NOVEMBER 1, 1917

By E. M. NEWMAN

Lecturer and Traveler

Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the post-office at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright, 1917, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

MENTOR GRAVURES

A PACK TRAIN OF LLAMAS IN LA PAZ

LA PAZ—FROM THE RIM OF THE HEIGHTS

HOUSE OF CONGRESS LA PAZ

MENTOR GRAVURES

INCA TEMPLE OF THE SUN, ON LAKE TITICACA

ORURO

STREET SCENE AND MARKET, SUCRE

THE NATIVE BOLIVIAN INDIAN

Bolivia is another Thibet; one of the highest inhabited plateaus in the world. It is one of the richest mineral sections, as it now produces about one-third of the world’s supply of tin, and contains vast wealth in its rich copper, gold, and silver mines. Nearly ninety per cent. of its population is of Indian origin, and to this fact may be attributed its slow progress; as outside of its capital city, almost everything is still in a primitive state.

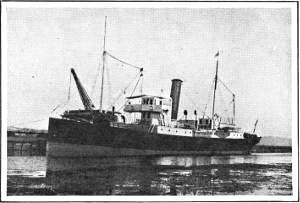

Since its last war with Chile, it has been shut off from the sea-coast; and to get to Bolivia one must now cross either Chile or Peru, which necessitates a long journey by rail; and if the entrance be by way of the Peruvian gateway, Mollendo, Lake Titicaca must also be crossed.

STEAMER ON LAKE TITICACA

The parts of this steamer were carried to the lake by rail and put together there

Lying in a valley, at an altitude of more than 12,000 feet above the level of the sea, is the Bolivian capital, La Paz, the City of Peace. It is picturesquely situated in a huge bowl, cut into the plateau; and to reach it one must descend in an electric car, 1,300 feet down the steep slope, where, at the bottom of the cup, lies a city of more than 150,000 people. In its situation, it is probably the most remarkable of all capitals. Although called the City of Peace, it has been the scene of turmoil and strife ever since the Spaniards invaded these solitudes. Rising high above the city is beautiful Illimani, one of the highest peaks of the Andes. Perpetually clad in snow, this magnificent mountain dominates the view, and is one of the most striking scenic features of Bolivia.

In the central square of La Paz rises the cathedral, which has been in process of building for forty years, and at the rate it is progressing it will probably not be completed for another century. On this same central square is the Bolivian House of Congress, nearly all of its members of Indian origin. This plaza is the center of political life, and radiating from it are the principal business thoroughfares.

Plaza San Francisco is another of the important squares of the city, and takes its name from the magnificent church, one of the most artistic structures in South America. Upon this square, at all hours of the day, there is a fascinating panorama of life; for, passing constantly, are picturesque Indians, clad in grotesque costumes, many of them driving burros or the Andean beast of burden, the llama.

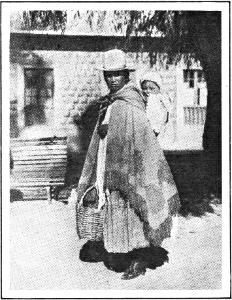

In no other city of the world are the costumes worn by Indians as elaborate as those seen in the streets of La Paz. The Cholo or half-breed is resplendent in garments of the brightest colors. The women in particular are gorgeously arrayed in silk skirts, kid boots and straw hats.

There is a curious custom which is rigidly observed. Full blooded Indians must wear felt hats, and are looked upon as inferior in social standing. The Cholos may always be distinguished by their straw hats, which are never worn by the others. Having married a Bolivian, or perhaps a white man, a Cholo woman considers herself quite a superior being. She delights in patronizing the best shops, where she seeks only the costliest silks, the gayest of shawls, and kid boots with high heels, which are imported from France or from the United States.

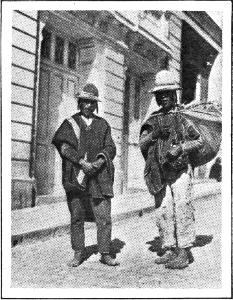

When fully attired, she is a sight to behold. Arrayed in all her finery, she promenades like a queen through the streets of the city; and yet, back of it all, the influence of blood is evident. She may dress ever so elaborately, but the old customs still cling; she still insists upon carrying her baby on her back in good old Indian fashion, and she is not averse to carrying her market basket when she goes to the market to make her purchases. Most numerous among the Indians are the Aymaras, who, unlike the Quichua Indians of Peru, are surly and inclined to hold aloof from the white man. They are seemingly indifferent to the white man’s influence. For clothing, the Aymará men wear shirts and trousers of a coarse cotton material; and over their shoulders is thrown a poncho of heavy woolen cloth. Aside from their poncho, the most attractive part of their costume is a curious woolen head-covering, beautifully embroidered with beads in gay colors. In a climate where it is always cold except at midday, these caps with their long ear-muffs are very serviceable. Women who are wives of full-blooded Indians make no pretension in the way of attire, and they accept without question their social status, which relegates them to an inferior position.

ON LAKE TITICACA

BALSA BOAT

Native making the boat of reeds

Much of the trading carried on with the Indians is done by barter; they bring their farm and garden produce to the city, and exchange it with dealers for groceries or wearing apparel. Very few of them accumulate money, and wealth is very rare.

Many of their laws are unique, and are no doubt born of tribal customs which have been handed down for generations, and yet are usually rigidly observed. If, for instance, a doctor loses seven patients, Indian law decrees that the career of the doctor must terminate, and that his life must be a forfeit for his failure to save the lives of his patients. After the Indian doctor has lost his sixth patient, he usually departs for some unknown place.

Although the Bolivian capital is overwhelmingly Indian in point of population, in appearance it is decidedly modern. Its streets are paved with cobblestones, but as a rule are clean and kept in good condition. The pavements may be rough, but it must be borne in mind that there are very few level thoroughfares; most of the streets are very hilly, and would be almost impossible to navigate were it not for the cobblestones, which permit men and beasts to maintain a foothold. Municipal laws will not permit Indians to make use of the thoroughfares for their llamas during business hours; they are brought into the city early in the morning, remaining in some patio or courtyard awaiting the evening hours, when their owners drive them home. At sunset one may see long trains of these quaint animals driven through the streets on their way back to the farms. The llama lends picturesqueness to one of the most unusual cities on the face of the globe.

LA PAZ, VIEWED FROM THE RIM—MT. ILLIMANI IN THE DISTANCE

THE EVENINGS ARE COLD IN LA PAZ

Little or no coal is burned, as it costs $60 per ton, and only the very wealthy could afford to use it. There is no wood, so few of the houses are heated. Most of the English and American residents use oil burners or electric heaters in their homes; but even the principal hotel is so cold that men usually go to dinner in their overcoats and the women enveloped in furs. Most visitors usually retire immediately after dining, as the night air is so cold that it can be endured only by those acclimated. It is no uncommon thing for a guest at the hotel to pile upon his bed all the available covering that he can obtain, including the carpet on the floor of his room.

One might imagine that Cholo women are unusually corpulent; but this is apparent only because of the fact that they don from twelve to twenty skirts. At times, contests are held between Indian belles as to which has the more gorgeous petticoats, and also the greater number. A winner is said to have displayed as many as twenty-four, disclosing a collection of brilliantly colored petticoats unequaled elsewhere for variety.

A LEADING CITIZEN

Both Bolivians and Indians are, as a rule, Catholics. On Corpus Christi day, which is religiously celebrated, there is a curious procession in which thousands of people take part, and a strange combination of Cholos, Aymaras and native Bolivians wend their way through the various thoroughfares. In this parade, the Cholo women discard their straw hats and wear their shawls instead. Most of them belong to church societies, and these organizations are indicated by ribbons worn around the neck, the color denoting the society to which the wearer belongs.

THE FAITHFUL, HARDWORKING LLAMAS

All the dignitaries of the church take part in the Corpus Christi day procession. Business is practically suspended, and the President of the Republic, accompanied by the members of the Houses of Congress and all the officials of the Government, march to the cathedral, where services are held. On various thoroughfares, altars are erected, and these are usually decorated by the members of the different ladies’ societies.

Religion has a strong hold on the people of Bolivia. One not affiliated with the church is looked upon with suspicion and becomes a social outcast. In no other country are the churches better attended.

The most attractive of the thoroughfares in the Bolivian capital is the Alameda, a wide avenue lined with trees, and having in its center a promenade. It is on this thoroughfare that the various legation buildings are situated. As usual, one may walk along this street and seek for the most unattractive building and be quite sure that it is the American legation building. Almost every government is here represented, so that the Alameda might be said to be the center of diplomatic life.

A HILLY STREET IN LA PAZ

ALAMEDA, LA PAZ

Where the foreign Legation buildings are

CHURCH OF SAN FRANCISCO, LA PAZ

La Paz is surprisingly modern in the architecture of its business structures. Most of the buildings are of brick, plastered over and painted. Many of its shops would be a credit to an American city. They are by no means mere country stores, but carry an astonishingly good class of merchandise, and many of the products of France and the United States are displayed for sale in the various shop windows. To leave the capital city, one must ascend by electric railway to the plateau, where is situated the railway depot. One may go directly south by rail all the way to Antofagasta, Chile, where steamer connections are made for Valparaiso. On this journey, one obtains a wonderful view of the back-bone of the Andes, traveling along a plateau averaging in height about 14,000 feet above sea level. The snow-clad summits of this mighty range of mountains are constantly in sight. There are few cities along the railway. Perhaps the most important of the Bolivian towns is Oruro, which is in the center of a very rich salt country, and as the railroad approaches the Chilean boundary there are rich deposits of borax and nitrate.

LOOKING DOWN THE ALAMEDA, LA PAZ

Many travelers experience all the terrors of soroche or mountain sickness when traveling on the high Bolivian plateau. The altitude is dangerous for some people, and in a few cases results fatally. One whose heart is weak should not attempt the journey, as it is trying even upon the strongest constitution, and such evidences of altitude as nose-bleed and dizzy spells afflict even those who are accustomed to high altitudes.

During the cold winter months, many Bolivians descend the eastern slope of the Andes to Sucre, which has become a favorite winter resort for diplomatic representatives. Sucre is several thousand feet lower than La Paz, and its climate is somewhat milder. Lower down, toward the Brazilian boundary, there are tropical forests and a wild, uninhabited country where disease lurks; and here are great jungles and swamps, making human habitation almost impossible except for the aboriginal tribes, which seem to be immune to the fevers that infest this low-lying country. Among other important cities in Bolivia are Potosí, and Cochabamba, where there is an American school, a branch of the American Institute of La Paz. A number of young American men and women have voluntarily left home and friends and have gone to Bolivia to teach the youth of that country. The best families send their children to the American schools, and the Bolivian boys and girls are not only taught the English language, but they are made familiar with the history of the United States. It is the ambition of many of the sons of Bolivian parents to acquire the language, so that they may make their future home in America. The American teachers are unusually capable young men and women, and the standard of efficiency that one finds in the American Institute is a credit to the young people who have made the sacrifice of leaving home and living in Bolivia.

The military system is patterned after that of Germany, as the soldiers of the country have been drilled by German officers, and their influence is plainly evident in the familiar goose-step and the various manœuvers that one may observe in military camps. The Bolivian soldiers have not the fighting qualities of the Chileans, and in past wars have proved anything but a match for their neighbors to the south.

In going from La Paz to Lake Titicaca, one travels over a level plateau, nearly three miles above the sea. Little or nothing grows at this altitude, and the few Indians living on this plain must have their food supply brought up from the valleys below on the backs of llamas. Other than mines, there is no inducement for even an Indian to make his home on this lofty plateau. There is no source of income other than working in some of the gold, silver and copper mines which abound in these altitudes.

BOLIVIAN INDIAN MOTHER

BOLIVIAN FARMERS

BOLIVIAN CHILDREN OF THE MOUNTAIN COUNTRY

Guaqui, a little town on the shores of Lake Titicaca, is the terminus of the railway. A regiment of cavalry is stationed at this port, as it in reality forms the boundary line of the country. In this little place, one obtains his final glimpse of the picturesquely attired Cholo women, as they are rarely seen outside of Bolivia. In their native country, their appearance excites no unusual interest; but even in Peru they are subjected to a certain amount of ridicule, which is displeasing to these haughty belles.

Because of the intense cold, school children are often seen seated in the open air, where they may enjoy the benefit of the warm sun. This applies largely to the smaller towns and villages, as in the larger cities the school houses are now quite comfortable.

STREET ALTAR, CORPUS CHRISTI DAY, LA PAZ

Lake Titicaca is a great inland sea, lying between the two ranges of the Cordillera, and is very high above the ocean. Its area is about one-third that of Lake Erie, and its present length is about 120 miles, while its greatest width is about 41 miles. It is, without doubt, one of the highest navigable bodies of water in the world.

Among the water plants that one sees growing in the lake is a sort of rush, which abounds in shallow water from two to six feet in depth, and rises several feet above the surface.

It is this material which the Indians, having no wood, use to construct their boats. In these apparently frail craft, propelled by sails of the same material, they traverse the lake, carrying with them two or three men, and in addition, a heavy load of merchandise.

There is considerable skill exercised in the making of the balsa, as these reed-boats are called. Centuries of experience have taught the Indians the process, which has been developed to a remarkable stage of perfection, enabling them to defy the storms which are so frequent. The short, heavy waves make navigation dangerous even for much larger boats than the native balsa.

CAPITOL BUILDING IN SUCRE

Like the waters of Lake Superior, these are too cold for the swimmer; but the lack of bathing facilities gives the Indian but little concern. The greatest depth of the lake is said to be about 600 feet. Fish are plentiful, and the few Indians who live around the shores of the lake devote themselves principally to fishing. As far as habitation is concerned, other than Puno on the Peruvian side and Guaqui on the Bolivian, there are but a few scattered villages.

OPEN-AIR SCHOOL—GUAQUI, BOLIVIA

Four steamers ply to and fro between these ports, connecting with the train service. These boats were brought from England, taken in sections by railway and put together on the shores of the lake. They are today used to transfer freight, which arrives by sea at a Peruvian or Chilean port, and is carried by rail to Puno, then across the lake to Bolivia.

ON THE STATE ROAD FROM POTOSÍ TO SUCRE

Numerous islands dot the surface of the lake. One is of real interest. It is known as Titicaca Island. It has a population of about 300, but of that number there is but one man who can read and write. In all Bolivia, only 30,000 children attend school, out of a total population of 2,000,000. The aborigines do not seem to care for education, and the Bolivians of European race are few in number.

On a small island in Lake Titicaca is the ruined Temple of the Sun, another reminder of the days of the Incas. When that empire flourished, this portion of Bolivia was also under the domination of the Inca ruler; and even today, in some parts of Bolivia, one still comes upon numerous evidences of Inca rule, such as the ruins of buildings, temples and stone images, which plainly indicate that they were the work of that remarkable, ancient people. Inaccessible as is the country, for one who can stand the journey it affords much of interest. If there were nothing more in Bolivia than the view afforded in looking down from the rim of the cup upon La Paz, this alone would tempt one to visit the country. The buildings of this city have the appearance of so many tea leaves left in the bottom of a cup, so tiny do they seem from above. Another glorious scene is that of the encircling mountains that surround Lake Titicaca, crowning it with a diadem of snow-covered peaks—a view that is unsurpassed among the world’s natural wonders.

Although Bolivia has no seaport, the country has a great network of rivers. The entire length of Bolivia’s navigable streams is about 12,000 miles. These naturally provide excellent means of transportation and communication. The Paraguay River is navigable for about 1,100 miles for steamers of from eight to ten feet draft. The Itenes has about 1,000 miles of navigable water. Another river, the Beni, is navigable for 1,000 miles for steamers of six feet draft only. Other streams, such as the Pilcomayo, Mamoré, Sara, and Paragua Rivers can accommodate light draft vessels for distances varying from 200 to 1,000 miles.

From the ocean Bolivia can be approached through the ports of Mollendo, in Peru, or Arica and Antofagasta in Chile. These are all regular ports of call of the steamers between Panama and Valparaiso. From these ports there is railroad communication to Bolivia.

CITY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, SUCRE

THE PLAZA IN SUCRE

| BOLIVIA, THE CENTRAL HIGHWAY OF SOUTH AMERICA | By M. R. Wright |

| BOLIVIA | By P. Walle |

| PLATEAU PEOPLES OF SOUTH AMERICA | By A. A. Adams |

| ACROSS THE ANDES | By C. J. Post |

| THE SOUTH AMERICANS | By W. H. Koebel |

| A SEARCH FOR THE APEX OF AMERICA | By Annie S. Peck |

| THE SOUTH AMERICAN TOUR | By Annie S. Peck |

| SOUTH AMERICA | By James Bryce |

| THE BOLIVIAN ANDES | By Sir Martin Conway |

⁂ Information concerning the above books may be had on application to the Editor of The Mentor.

Let me tell you about our daily mail. We get letters of appreciation and letters of suggestion—hundreds of both kinds. Many of them are addressed to the “Editor of The Mentor,” others to “Dear Mr. Editor”—and some to “Mr. Moffat.” I like the last form best, for I know that when a member of The Mentor Association writes in a personal way, with a message of encouragement or a valuable suggestion, The Mentor has found a real friend. I like to see the spirit of personal interest growing in our daily mail. It is the best assurance of the vitality of The Mentor Idea that we could have. Fellowship spirit is the soul of all mutual endeavor.

It is pleasing to see how close an interest some of our members take in the details of The Mentor work. The following letter came to me a day or so ago—and it is too good to keep to myself.

“My dear Mr. Moffat: When I opened the Hawaiian number of The Mentor, I was delighted to find a greeting from you on the inside of the front cover page. Now that you have moved over there, why don’t you stay? Of course, I don’t know anything about the workings of an editorial office, and it may mean a furious amount of trouble. You might have to move your desk and your whole staff, and even have to get out a new copyright, but from an outsider’s point of view the move looks easy. And to my way of thinking the front of the magazine is the place for you anyway—if you will permit me to say so. There you seem to stand as a host at the threshold, offering a welcome to guests before they enter.”

SYLVIA.

“Who is Sylvia? What is she?”—so Shakespeare and Schubert sang. And if they couldn’t tell who Sylvia was, how can I? Of one thing I feel sure: she is a faithful reader of The Mentor, for she has taken note of our goings and comings, and our varied forms of editorial expression. The notion of my being the “host” is an inviting one. It is a role that one should be proud to fill, especially when the feast to which he invites his guests is the wealth of the world’s knowledge. The thought of assuming that role, however, is a bit staggering. Thanks, Miss Sylvia, but perhaps I had better play the more generally useful part of planning, preparing and making up The Mentor feast. Your welcome to the second cover page is appreciated. I have been there many times before, however, when the page has borne no signature. No number of The Mentor appears, Miss Sylvia, without my being around somewhere. I have no preference for one particular page. I find occupation and joy on every page of The Mentor from cover to cover.

Here are some of the things that we do in reply to letters.

We answer questions in the various fields of knowledge. We look up sources of information for our readers and give them full replies. We have just mailed a letter in which answers were made to historical questions that called for a morning’s research by one of our staff.

We supply programs for reading clubs and lay out schedules for a whole season of meetings.

We supply material extracted from reference works for the benefit of members who are pursuing courses of reading.

We occasionally read essays or papers that have been prepared by members, and offer helpful editorial suggestions. Aside from club work, we lay out reading courses for private individuals who are pursuing special studies.

In some cases, where a member lives in a remote spot and cannot conveniently obtain books, we get them for the member at publisher’s prices. Occasionally, where books could not be had in the market, we have lent copies from our library.

We give full information and service in art, telling our readers where and how to get good pictures—we also give travel information.

These are but a few of the things that we do. We have a booklet in which we describe The Mentor Service. Send for it. If you have not had the benefit of our service, you will be surprised to see how wide and varied it is.

The Prize Contest Letters have been coming in fast. There are so many good ones that it will be difficult to make a choice. I am going to print extracts from some of them. A part of the first letter appears on the opposite page. It tells of The Mentor as a friend. Could there be any happier note to begin with than that? Other letters will tell of the many ways in which The Mentor is or can be made valuable in home, school and social life. The story of one reader will help another, and the sum total of the information will be of benefit to all.

W. D. Moffat

Editor

A MESSAGE FROM A MENTOR READER

“Some time ago a very neat stranger called at my home and made the hour so pleasant, that he at once became my friend. Now this friend has a permanent place in my home, and is known throughout the vicinity as ‘The Mentor.’

“The reason why so many are acquainted with this friend of mine is because of his value and usefulness manifested in every subject and service. The Mentor has a permanent personal and social value. There might be added that also of inspiration. The Mentor has a message of interest and importance. It has a voice with a true ring, that speaks, as it were, from personal experience.

“In company with this companion and friend, one may be charmed as the story of the distant past or that of unfamiliar and remote things, people and places is being unfolded. Hardly can there be found any one so generous, considerate and tactful.

“The Mentor calls twice a month to inform, enlarge the vision, to inspire and encourage old and young, men and women, in all walks of life.

“The social value is vital. Whether it be in the home or elsewhere, The Mentor furnishes food for intelligent conversation that has weight and depth. The personal value is realized more and more as the weeks come and go. Impressions are left on the mind which in time ripen into principles.

“If I wished to make a friend more friendly, I would give him The Mentor. If I had an enemy—well—I would send him The Mentor. It might make him my friend.”

The Mentor Association

ESTABLISHED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POPULAR INTEREST IN ART, LITERATURE, SCIENCE, HISTORY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL

THE MENTOR IS PUBLISHED TWICE A MONTH

BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC., AT 222 FOURTH AVENUE, NEW YORK, N. Y. SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, J. S. CAMPBELL; ASSISTANT TREASURER AND ASSISTANT SECRETARY, H. A. CROWE.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, Inc., 222 Fourth Avenue, New York, N. Y.

Statement of the ownership, management, circulation, etc., required by the Act of Congress of August 24, 1912, of The Mentor, published semi-monthly at New York, N. Y., for October 1, 1917. State of New York, County of New York. Before me, a Notary Public, in and for the State and county aforesaid, personally appeared Thomas H. Beck, who, having been duly sworn according to law, deposes and says that he is the Publisher of The Mentor, and that the following is, to the best of his knowledge and belief, a true statement of the ownership, management, etc., of the aforesaid publication for the date shown in the above caption, required by the Act of August 24, 1912, embodied in section 443, Postal Laws and Regulations, to wit: (1) That the names and addresses of the publisher, editor, managing editor, and business manager are: Publisher, Thomas H. Beck, 52 East 19th Street, New York; Editor, W. D. Moffat, 222 Fourth Avenue, New York; Managing Editor, W. D. Moffat, 222 Fourth Avenue, New York; Business Manager, Thomas H. Beck, 52 East 19th Street, New York. (2) That the owners are: American Lithographic Company, 52 East 19th Street, New York; C. Eddy, L. Ettlinger, J. P. Knapp, C. K. Mills, 52 East 19th Street, New York; M. C. Herczog, 28 West 10th Street, New York; William T. Harris, Villa Nova, Pa.; Mrs. M. E. Heppenheimer, 51 East 58th Street, New York; Emilie Schumacher, Executrix for Luise E. Schumacher and Walter L. Schumacher, Mount Vernon, N. Y.; Samuel Untermyer, 120 Broadway, New York. (3) That the known bondholders, mortgagees, and other security holders owning or holding 1 per cent. or more of total amount of bonds, mortgages, or other securities, are: None. (4) That the two paragraphs next above, giving the names of the owners, stockholders, and security holders, if any, contain not only the list of stockholders and security holders as they appear upon the books of the Company, but also, in cases where the stockholder or security holder appears upon the books of the Company as trustee or in any other fiduciary relation, the name of the person or corporation for whom such trustee is acting, is given; also that the said two paragraphs contain statements embracing affiant’s full knowledge and belief as to the circumstances and conditions under which stockholders and security holders who do not appear upon the books of the Company as trustees, hold stock and securities in a capacity other than that of a bona fide owner; and this affiant has no reason to believe that any other person, association, or corporation has any interest direct or indirect in the said stock, bonds, or other securities than as so stated by him. Thomas H. Beck, Publisher. Sworn to and subscribed before me this 18th day of September, 1917. J. S. Campbell, Notary Public, Queens County. Certificate filed in New York County. My commission expires March 30, 1918.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, Inc., 222 Fourth Avenue, New York, N. Y.

THE MENTOR

How the Mentor Club Service

Helps Clubwomen

and Women Who Wish to Organize

Literary Clubs

The success and pleasure of a woman’s club depends on the year’s program, which should be based on subjects that fascinate and interest, as well as instruct.

The planning of an interesting and helpful club program is a difficult matter, as you who have served on program committees know, and can really be done successfully only by experts.

The Mentor Club Service

Plans the Programs for Hundreds of

Clubs, Free of Charge

The Mentor Service Editors, men and women of high intellectual attainments and broad experience, will be glad at any time to help you with suggestions or a completely worked out plan for your club program, based on any desired subject. They will also supply lists of reference books for help in the preparation of club papers, and will be glad to assist further by procuring any necessary books not in your library, at cost, postage prepaid.

Remember—The

Mentor Club Service Is Free

ADDRESS ALL INQUIRIES TO

Editor, The Mentor Association

222 Fourth Avenue, New York City

MAKE THE SPARE

MOMENT COUNT