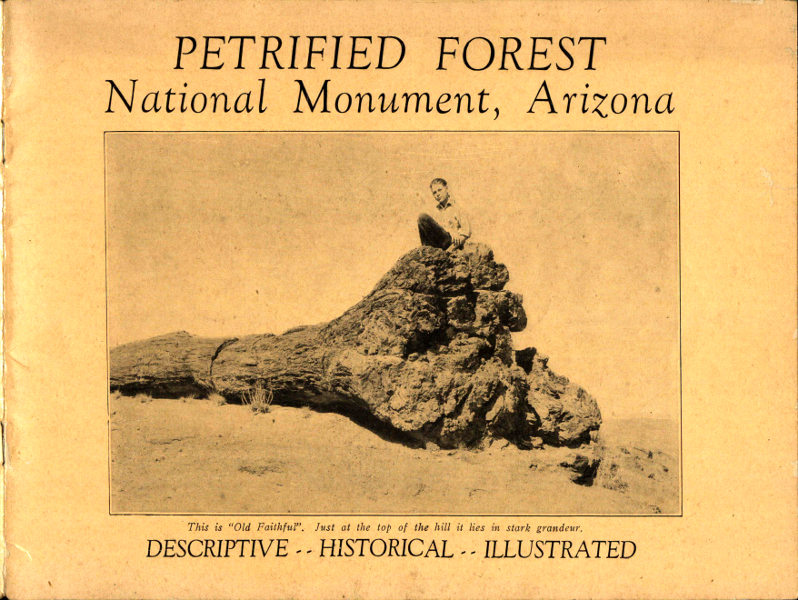

Cover Illustration:

This is “Old Faithful”. Just at the top of the hill it lies in stark grandeur.

DESCRIPTIVE—HISTORICAL—ILLUSTRATED

By

DAMA MARGARET SMITH

COPYRIGHT 1930

By Dama Margaret Smith

In Arizona, that land of mystic beauties and many wonders, lies a great tract of land that, once upon a time, was covered with waters of the sea. How many centuries ago the ocean waves sparkled and rippled over what is now the desert, no one can definitely say. But from the nature of the stratum is which great logs are embedded, and the fossilized reptiles found, it is known that they were entombed during the Triassic age, many millions of years ago.

Petrified logs are found over a wide area, more than a hundred square miles being covered with varying amounts of the “stone” trees. This fossilized “forest” is greater in area, more highly colored, and contains more petrified wood than any like deposit in the world.

Many visitors who have heard of the “forest” drive through miles of the Reservation and ask at the Museum where they can find the Petrified Forest. Inquiry discloses that they expected to find an area of standing trees, trunks merely turned to stone, branches and all. Perhaps they have seen one or more such trunks in Yellowstone National Park and think to find hundreds of them here. Yet, when they learn the story of these fallen monarchs, and catch a glimpse of the dazzling beauties of agate and carnelian, jasper and onyx, no signs of disappointment are seen. Let the visitor but leave his car to view the logs, and step by step he is led on by here a gleaming fragment of carnelian, and there the soft sheen of jasper and topaz. It is like the carpet of Fairyland.

These trees did not grow where they lie, or even within many miles of where they are found. They were carried from a long distance to this region by flood waters, and after whirling and drifting around in the inland sea then covering the land, they became waterlogged and finally sank to the bottom, where some eddy or whirlpool carried them. Here they lay for countless centuries, slowly being covered by silt and sand, while yet other logs came to rest above them. Thousands of years elapsed during this drifting and sinking into oblivion under the ooze of this Triassic Sea. And then came Old Ocean, later on in the Mesozoic Age submerging the entire region and adding its weight to the terrific pressure already brought to bear on the burial place of the giants. This pressure packed the sands to stone, and compressed the clays to shale. Already the logs were impregnated with a strong solution of silica, with iron and manganese also present, and the pressure forced it into every fiber. Atom by atom the cells of the wood were dissolved and replaced by the silica, which hardened, taking the exact shape of the cell it destroyed. While the logs were probably partly petrified before the influx of the ocean waters, a great many show that enormous pressure was brought to bear while they were yet flexible.

Some logs recently brought to light by the summer floods, are mashed almost flat, cross sections measuring eighteen inches one way and more than five feet the other.

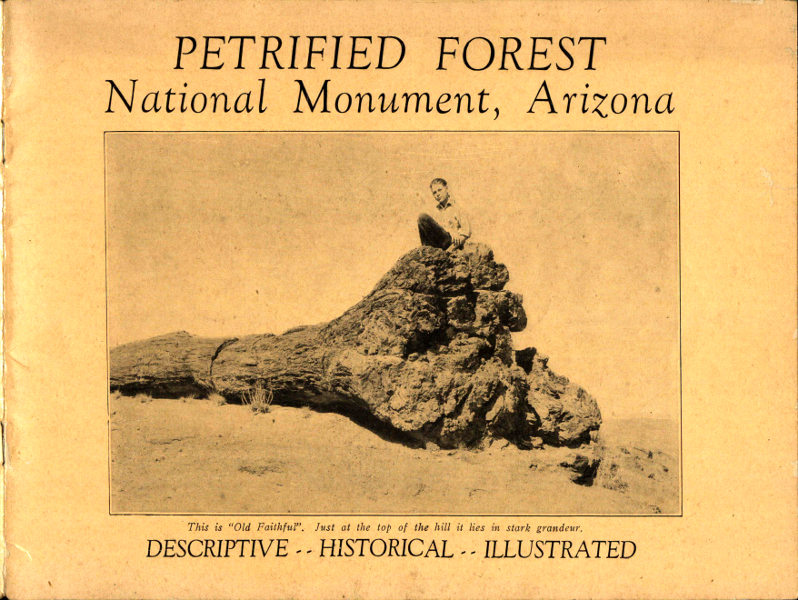

Courtesy National Park Service

Cross section of log showing natural fracture.

Nature did not slight details in this work of substitution. Even to the most minute particular the structure of the wood was replaced by the intruder. Under the microscope it is possible to identify the kind of wood represented. Dr. F. H. Knowlton has classified the major portion of these trees as belonging to a species of conebearing tree now extinct, related to the Norfolk Island Pine.

The logs lay buried for numberless centuries, but natural forces were at work bringing them to the surface again. During the Tertiary Period, a slow upheaval brought the submerged area to light. On and upward it rose, until it now lies more than a mile above the level of the ocean. Freed of its Old Man of the Sea, warmed and comforted by Arizona’s brilliant sun and searching wind, the region lay at rest.

Slowly the fingers of time, tipped with wind and rain, broke through the heavier sandstone above, and tore away the softer layers of shale and marl. Bit by bit, the covering was lifted from the buried logs, and one by one, the gem-like wonders saw the light of day. And what a glorious resurrection it was! As the support was plucked from about them, they left their sleeping places in the sandstone and marl and rolled to the levels below. Frost tore at their vitals; rain fell into the crevices and freezing there, expanded, until many of the finer logs are now merely heaps of gleaming jewels, opaline and rose, lavendar and mauve, deepest brown and softest yellow, black and purple, blue and red. In their range of color they leave the beauty lover breathless. And these colors are permanent, too, having endured through the aeons.

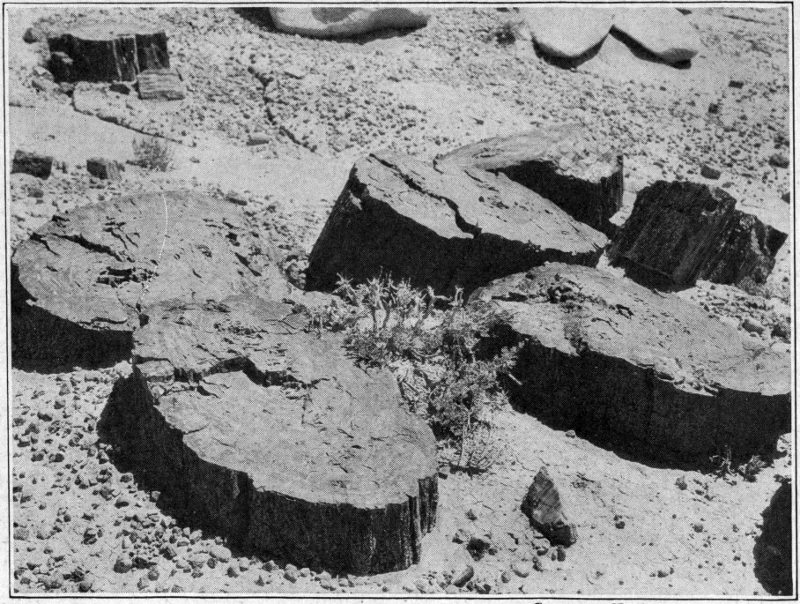

Courtesy Mrs. Adam Hanna

The most noted tree in the whole reservation. The Natural Bridge. About four feet in thickness this 111 foot log measures 44 feet between the sides of the arroyo.

“How did it happen?”

That is usually the first question asked of the rangers in the Petrified Forest.

In contact with eighty thousands or more tourists each year, there are certain questions asked so many times that one learns what the average person is most curious about in connection with these petrified trees. Here are the most popular of these questions, together with the answers, shorn of technical terms:

Why are none of the trees standing?

This is simply an exposed deposit of petrified logs that came here from a distance, as driftwood.

How were they brought here?

Probably by rivers in flood periods. This region might have been the mouth of a large river as is indicated by the crossbedded sandstone.

Why are they piled up in particular spots?

This was at one time an inland sea. The trees floated here, and were swept by whirlpools or strong currents into eddys where they became waterlogged and sank.

How long ago was that?

Men who have made a lifetime study of it, say it was from ten to forty million years ago.

What became of the sea that was here?

Gradual upheaval of the country, aided by earthquakes and volcanic action, raised this area and drained it. The Sierras were probably brought to their present height during these disturbances.

What kind of trees are they?

Mostly an extinct species of cone bearing tree. (Araucarioxylon Arizonicum.)

How big were these trees?

Some of them are now a hundred feet long, and six to eight feet in diameter. The Natural Bridge is one hundred and eleven feet long. The height of some of these trees while standing was doubtless two hundred feet or more.

Why did they turn to rock?

They did not really turn to stone. Silica and minerals in solution were forced into the wood, dissolved it, and replaced the wood cells with their own substance.

How is it polished?

By a process of grinding with carborundum and diamond dust, then rubbed with leather buffer. It approaches the diamond in hardness and an ordinary emery wheel will scarcely mark it.

What is the weight of the petrified wood?

About 200 pounds to the cubic foot. It varies.

Why can’t visitors take specimens away with them?

First: Because it is against the United States Law. After that comes consideration of future visitors to the Petrified Forest National Monument. When one reflects that there are about eighty thousand visitors here annually and that if each visitor took what pleased him, it is an unrefutable fact the best specimens would speedily disappear. A visitor would not be satisfied with one small piece. There would be the home folks to consider; the neighbor that fed the left-at-home cat, and the friend who loaned his kodak for the trip. These would all need souvenirs. It would be difficult to choose among several beautiful pieces and so a compromise would be made by taking all of them.

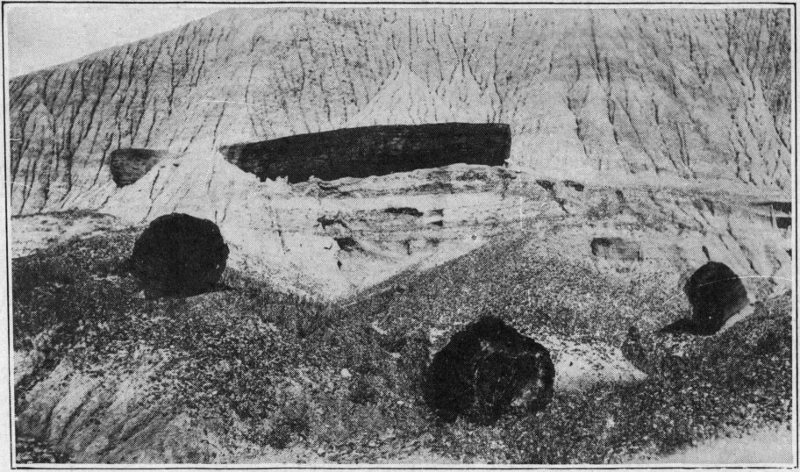

Courtesy National Park Service

They leave their sleeping places in the sides of the marl hills and roll to levels below.

What is a National Monument?

An area set aside by the President of the United States to preserve regions of scientific, historic or prehistoric interest.

What is the area of the Petrified Forest National Monument?

25,908 acres.

Who has charge of it?

The National Park Service, one of the largest and the most important bureaus of the Department of the Interior. A custodian and several Park Rangers are the immediate representatives of the Government on the Reservation.

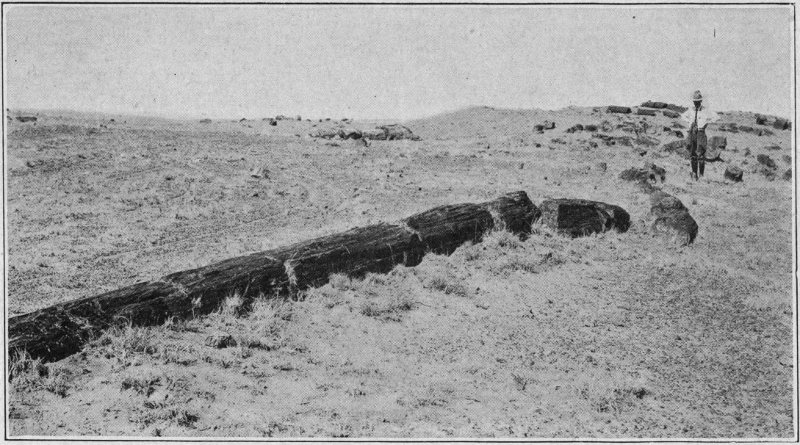

Courtesy National Park Service

As the soil slowly settles beneath these giants their weight dismembers them. In this way they were broken in the lengths we find them now.

The Rainbow Forest lies eighteen miles east of Holbrook on U. S. Highway 70, the Holbrook-Springerville Road, open and in splendid condition the year around. This Rainbow Forest area contains a greater amount of highly colored petrified wood, than any of the other “forests” included in the Reservation.

The varied and decided coloring of the logs, many of which are broken into minute chips, is so gorgeous that it has been given this name. The outstanding features of the Rainbow Forest are the logs themselves, which may be seen in all stages of preservation, some not entirely uncovered, some lying on the sides of the marl hills waiting their time to be let down by erosion, to the levels below, some almost at the top of the sandstone cap, and others in fragments at the bottoms of ravines; the Government Museum, which 7 is free to the public, located half a mile from the highway. In this building the Government has collected outstanding specimens of wood from all sections of the Reservation. These representative specimens, both polished and unpolished form an interesting exhibit. Here too, are Indian relics found in the prehistoric ruins scattered throughout the area. Many of the sections of wood here surpass the very finest Italian marble both in coloring and composition. One huge section of a log, weighing a ton, holds all the colors of the rainbow and the intermediate tints. One may trace woodland scenes, Japanese landscapes, city skylines, outlines of animals and trees in the polished surface of this tree. This specimen was shipped to Denver and polished there, and required many days of grinding with carborundum and diamond dust. No visitor fails to admire it. Another exhibit which evokes admiration is a globe about eight inches in diameter, which was turned and polished in Germany. It was originally a big knot or burl and shows swirls of color like a child’s agate marble.

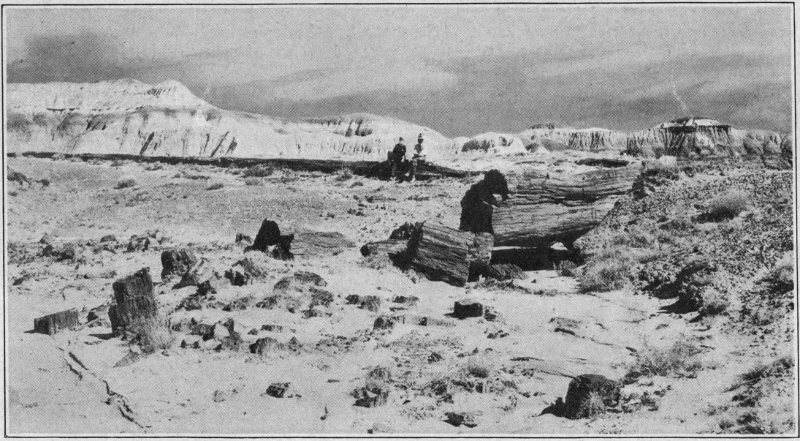

Courtesy National Park Service

Showing work of erosion. This log is becoming slowly undermined by the action of the small stream.

In this Museum are fragments of wood bearing at their clusters of topaz crystals, black crystals and beautiful purple amethysts. 8 Various explanations have been advanced as to why these gemlike formations are found in the wood. One authority says cavities in the logs caused by decay, are filled by mineral crystals, there being no wood fiber to absorb. Other geologists offer the theory that the resin and sap forced to the center formed into tangible shape by being crystalized. Be that as it may, the semi-precious stones were very much sought after, and a great jewelry concern in the East had a crew of men working in these “forests” blasting the precious work of nature to pieces in search of the jewels.

Of course this vandalism ceased abruptly when in 1906 President Roosevelt issued the proclamation which made this Reservation a National Monument.

In the Museum is a register, in which all visitors are expected to sign their names. In this book are found names from practically every civilized nation in the world.

In this Rainbow Forest is found one of the best preserved trees with the stump, that has been discovered. It is to the Petrified Forest what the Old Faithful Geyser is to Yellowstone Park. It is the tourists’ friend. This log is the favorite picture place in the entire Reservation. Here parties stop their car and visit the fallen monarch. Almost any hour of the day in pleasant weather, one can see little children playing on this big log. Here they lunch and rest, and here they pose for their photographs. The old fellow must have many happy memories collected through the ages. It lies in the sunlight at the brow of the hill, as one drops down to the Museum. Most probably before this log was broken into sections, it measured well over two hundred feet. It is now about fifty feet long, and at its thickest portion, measures six feet through. The great stump still remains as it was when some terrific storm, millions of years ago, uprooted it in its native forest. We call it “Old Faithful.”

A mile or two east of the Museum is the Third Forest. Here is a tangible sign that our far-removed forefathers admired the utility of the petrified wood, if they did not appreciate its beauty.

The ruins of quite a castle stand on the crest of a hill overlooking the plains, and one can almost visualize the first dwellers in this mystic land. See them laboriously carrying the heavy blocks of petrified wood to the top of the hill where they are laid out in orderly rows to form rooms. In the meantime, a close watch is kept that neither animal nor human enemy may creep up unheeded. The walls have fallen during the passage of time, but each foundation can be traced. Shards of broken pottery in great amounts lie at the base of the hill. We wonder if some angry housewife fired it out at her better half as he stumbled home from a prehistoric lodge room too late to please her?

Here, too, are found the workshops of arrowmakers. Chips, flaked thin as wafers, lie like bits of rainbows about the place, and show that they were broken from larger pieces by human agencies. This, we think, was done by heating the rock wood to a high temperature and then touching, lightly, the spot to be chipped with a feather dipped in water.

Leaving the Headquarters area, where the Museum is located, the visitor drives over a winding road, beautiful in its arid desert beauty, six or seven miles to reach the Second Forest. Were it my privilege to name this lovely section I should call it “The Coral Garden”. In this “forest” are many logs encrusted with coral formation. Some of them have broken apart and even the interiors are mossed with the coral, soft rose in color. The ground is covered with tiny round stones, coral colored. Here many 9 logs are filled with crystals and the range of coloring found in the chips strewn over the landscape is marvelous. Many pebbles bear the impression of seashells, and deep in the heart of a section of petrified log was found a fossilized mussel.

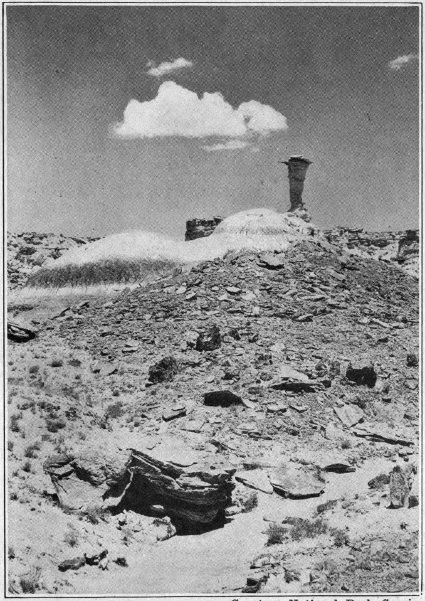

Courtesy National Park Service

At one place in the First Forest a slender column of rock rises to the height of thirty or forty feet. This is the Eagle Rock.

There is little of the sandstone cap in this area, and the logs lie in the blue-gray marl formation. Here we find larger trees in greater masses than elsewhere. Many of the trees lie piled on top of others in the coulees and small arroyos, carved out by wind and rain, during the centuries since these logs first settled there. One big tree, near the road, is mashed flat its entire length of perhaps ninety feet. Evidences of bark are plain on this particular log, and where the limbs were torn off, the grain of the wood is quite discernible. One could spend hours in this area, spellbound with the beautiful sight.

About eight miles from Headquarters, and three miles from the Second Forest, is the most noted tree in the Monument, the Natural Bridge. This sleeping giant lies where it was abandoned as a plaything by the waters that carried it here. Each end is firmly embedded in the sandstone rock, which was formerly the sand at the bottom of the sea. In the process of erosion, which finally carried away all of the material above this log, it ultimately came to lie on the surface of the ground. As the land rises somewhat to the south of it, water gathered there with the big log forming a natural dam. This water tended to soften the sandstone, and after a period of time it forced its way through under the log. Soon this became a free passage for the water, and resulted in the formation of the gorge which the prostrate trunk spans today.

The Natural Bridge log is about four feet in thickness at the largest point in sight. Part of the log is still encrusted with the sandstone which wrapped it about, before wind and rain unshrouded it. The canyon is twenty-five feet deep, and this one hundred and eleven foot log measures forty-four feet between the points at which it rests on the sides of the arroyo.

From the canyon beneath it, cedar, juniper and cottonwood trees have sprung to life and grown up to furnish shade for this comrade of another Age. They must seem mere upstarts to this old veteran!

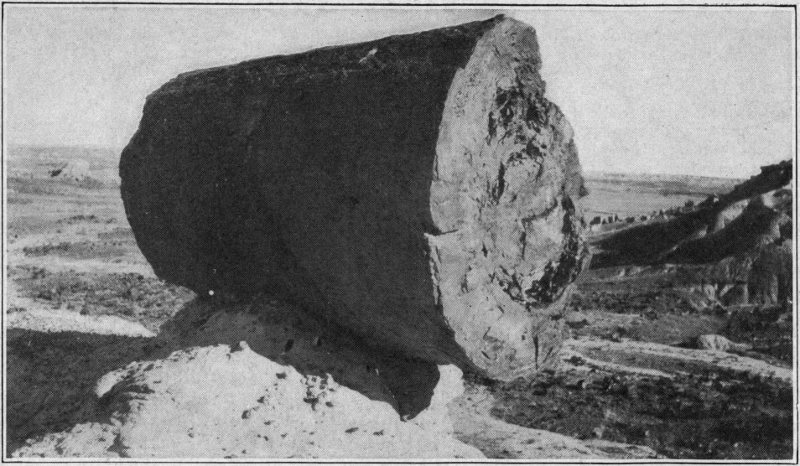

A hundred yards or so to the east, down over the rim of the mesa, is another freak of erosion, called the Pedestal Log. It is a large section, resting upon a support of sandstone, ten or fifteen feet above the level of the surrounding plain. It forms a protective cap which has kept the softer material immediately under it from washing away.

Here, again, were I choosing a suitable name for this portion of the Reservation I should not hesitate to call it “The Vandal’s Paradise”. It has been badly denuded of its finest specimens, and the big trees demolished by vandals. Here the despoiler has had full sway. Great trees are blown to atoms by searchers for the semi-precious jewels. Choice specimens have been hauled away by the carload. There was no law, other than one’s own individual decency to protect these jeweled timbers lying near Adamana, which for years was the nearest railroad station and the only entrance to the Reservation. This “forest” is located five miles south of Adamana, and is about half a mile from the Natural Bridge. It is composed of trees, which are geologically speaking, “all out of place”. That means they have all, by the work of erosion, been let down from higher levels. They are badly shattered, but, nevertheless beautiful, on account of the vivid coloring found in the fragments. Another feature of this area is the carving of the rocks into beautiful and fantastic shapes by the elements. At one place a slender column of sandstone rises to the height of twenty-five or thirty feet, and broadens at the top into a platform perhaps ten feet across. Here, for years, an eagle has nested, and the rock bears the official name of “Eagle Rock.” Quite close to this rock is the “Snow Lady”, a statuesque pillar against the background of an imposing cliff.

After an extended visit in 1889, Prof. Lester F. Ward, an eminent paleobotanist, on the staff of the United States Geological Survey, recommended that this area be made a National Park, or Reservation, in order to preserve it from destruction and oblivion. Local leaders brought pressure to bear upon their representatives in Washington, and at least one of Holbrook’s leading men, Mr. W. H. Clark, made a trip to Washington in the interest of preserving the Petrified Forest. He saw President Roosevelt in person and for half an hour talked with him concerning the reasons no action had been taken by Congress to protect the Forest. He left with the President’s assurance that something would be done. This something was a proclamation by President Roosevelt on December 8, 1906, declaring the area to be a National Monument.

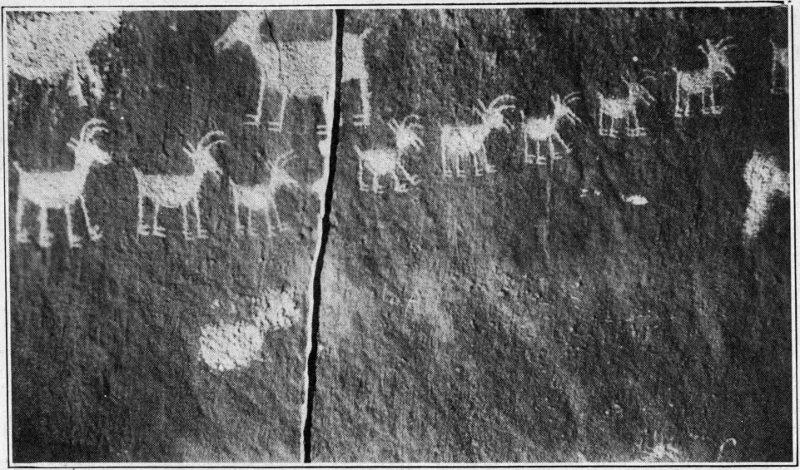

Throughout Arizona can be found traces of a vanished people. In and around the Petrified Forest, prehistoric dwellings and “picture writings” are plentiful, and of great antiquity and high development. Probably nowhere have such pictographs been so well preserved. The soft smooth sandstone was an ideal surface for the artist to work upon, and nowhere in the world, in that age, could such suitable tools be found to work with. Here at hand were sharp pointed chisels already prepared by the fracturing of wood. These chisels were hard enough to cut glass. Rounded pieces of the same material made excellent mallets. Hundreds of these have been found in the Reservation. With these rude instruments, this unknown people left for us a record of their existence graven deep in the sandstone in sheltered places. These pictures today are a lasting monument to the race that roamed this 11 region in the gone-by centuries.

These sketches depict different kinds of animals, such as antelope and mountain sheep, snakes and turtles. They are grotesque and out of proportion, but doubtless they represent, for the most part, animals that formerly roamed the western plains. Some pictures, however, represent animals that could never have been seen on land and sea, and existed only in the fevered imagination of the artist. Perhaps there were futurist artists even among those primitive men.

In one scene a herd of deer cross a plain. Near that a stork stands on attenuated legs and dangles what appears to be a baby in its bill. This is doubtless the earliest picturization of a stork’s visit. In another place a long line of human figures clasp their hands and drag one another up a steep incline. In the heart of the Reservation lies a mesa almost entirely surrounded by a steep cliff that has broken and fallen in ruins. On the huge boulders that have rolled to the desert below, there are pages and pages of history could one but read what is so plainly written. One figure stands alone disconsolately weeping. Quite monstrous tears are falling from his eyes, and just beneath his weeping figure a six inch bowl was found. Although broken in half by the passage of time with its destructive elements the piece of pottery, at least two thousand years old, was carefully restored and has an honored place in the Government Museum.

Courtesy C. J. Smith

Graven deep into the stone in sheltered places thousands of years ago, these pictures are a lasting monument to the people who roamed this region in the gone-by centuries.

On almost every mesa are the remains of ancient dwellings. There are arrowmaker’s chips and fragments of pottery, and crude colored beads that may have delighted some wee maiden with their brilliance. The pottery shows two distinct varieties, the finger-nail decorations covering the blackened bowls which seem to have served as cooking utensils, and the finer pottery, on which the black and white tracings are as startlingly vivid today, as they were so many, many centuries ago when they were drawn by the day-dreaming housewife as she sat in the sun and painted the fanciful designs.

By virtue of the Gadsden Purchase, at the close of the Mexican War, what is now Arizona came into possession of the United States. At this date, 1848, there was no record of the Petrified Forest ever having been seen by white men. In 1853 Lieut. Whipple, engaged in surveying a railroad route to the Pacific, discovered the deposits lying to the north of the present Reservation. He did not, however, discover the deposits of petrified wood south of Adamana, and there is no definite record of just when, and by whom, these “forests” were first seen. John Muir claims to have discovered the Blue Forest.

An Indian legend tells that one of their Goddesses wandered into the place which is now the Petrified Forest. She was hungry, cold and exhausted. When she saw the hundreds of logs lying around she was delighted and managed to kill a rabbit with a club, expecting to have a delicious supper. When she attempted to kindle a fire to cook her kill, the logs were wet and would not burn. In anger and her disappointment, she cursed the spot and turned the logs into stone that they might never burn.

As travel became more plentiful over the Santa Fe Railroad and across country, great amounts of the fossilized wood were carried away or destroyed, and the people of the Territory became alarmed about their unprotected treasure. In 1895 the assembly sent this Memorial to Congress.

House Memorial No. 4

TO THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN CONGRESS ASSEMBLED:

We, your memorialists, the eighteenth legislative assembly of Arizona, beg leave to represent to your honorable bodies:

FIRST: That there is in the northern part of this Territory, lying within the borders of Apache County, near the Town of Holbrook, a wonderful deposit of petrified wood commonly called the “Petrified Forest” or “Chalcedony Park”. This deposit, or forest, is unequalled for its extent, the size of the trees and the beauty and great variety of coloring found in the logs.

The country ten miles square is covered by the trunks of trees, some of which measure over two hundred feet in length and from seven to ten feet in diameter.

Ruthless curiosity seekers are destroying these huge trees and logs by blasting them in pieces in search of crystals, which are found in the center of many of them, while carloads of the limbs and smaller pieces are being shipped away to be ground up for various purposes.

SECOND: Believing that this wonderful deposit should be kept inviolate, that future generations may enjoy its beauties and study one of the most curious and interesting effects of nature’s forces,

We, your memorialists, most respectfully request that the Commissioner of the General Land Office be directed to withdraw from entry all public lands covered by this forest until a Commission, or officer appointed by your honorable body, may investigate and report 13 to you upon the advisability of taking this forest under the charge of the General Government and making a National Park or Reservation of it. * * *

J. H. Carpenter, SPEAKER A. J. Doran, PRESIDENT

Filed in the office of the Secretary of the Territory of Arizona this 11th day of February A. D. 1895, at 11 a. m.

This appeal was effective and Congress appointed Prof. Lester F. Ward to visit the Petrified Forest and make a report. The report was favorable to preservation, and acting with his usual promptness, President Theodore Roosevelt issued the proclamation which created the Petrified Forest National Monument.

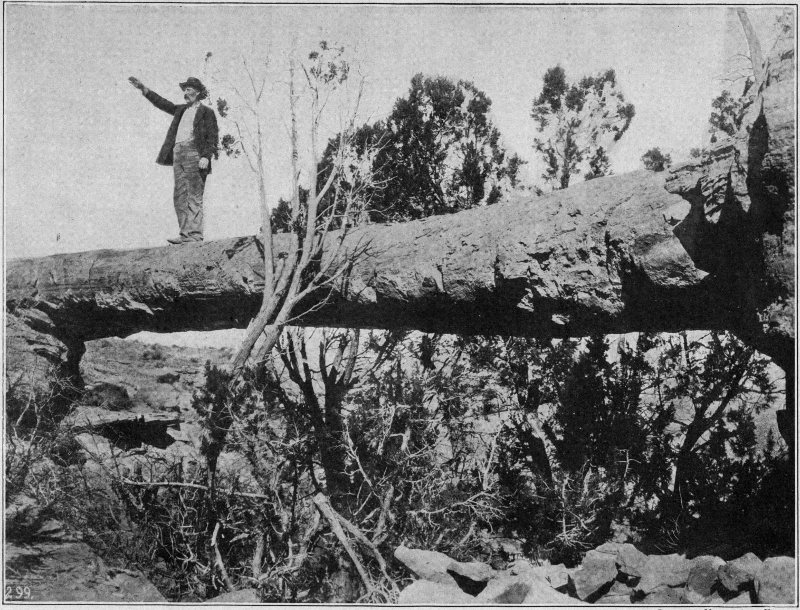

Photo by C. J. Smith

The surrounding country has washed away in the passing of years and leaves this mammoth cross section thirty feet or more above the plain.

This proclamation, in part, follows:

BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, A PROCLAMATION.

WHEREAS, it is provided by section two of the Act of Congress, approved June 8, 1906, entitled, “AN ACT FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES”, “THAT THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES IS HEREBY AUTHORIZED, IN HIS DISCRETION, TO DECLARE BY PUBLIC PROCLAMATION HISTORIC LANDMARKS, HISTORIC AND PREHISTORIC STRUCTURES, AND OTHER OBJECTS OF HISTORIC OR SCIENTIFIC INTEREST TO BE NATIONAL MONUMENTS * * *

And, whereas the mineralized remains of Mesozoic forests, commonly known as the “Petrified Forest”, in the Territory of Arizona, situated upon the public lands owned and controlled by the United States, are of the greatest scientific interest and value, and it appears that the public good would be promoted by reserving these deposits of fossilized wood as a national monument with as much land as may seem necessary for the proper protection thereof;

Now, therefore, I, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, by virtue of the power in me vested by section two of the aforesaid Act of Congress, do hereby set aside as the Petrified Forest National Monument * * *

14Warning is hereby expressly given to all unauthorized persons not to appropriate, excavate, injure, or destroy any of the mineralized forest remains hereby declared to be a National Monument or to locate or settle upon any of the lands reserved and made a part of said Monument by this proclamation.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 8th day of December, in the year of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and six and the Independence of the United States the one hundred and thirty-first.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT.

In 1911, President Taft made a new proclamation reducing the extent of the Petrified Forest National Monument to its present size of 25,908 acres.

While the Blue Forest was included in the National Monument originally it is now several miles outside the present boundary. It is from this section that much of the wood used commercially is obtained. Many find this weird formation the most interesting spot in the entire country. Miles and more miles of blue-gray mounds, varying in size, formed of the crumbling marl have been beaten and blown into a semblance of numberless haystacks. It is arduous climbing to reach the top of this Blue Forest, but the view obtained is well worth the skinned knees and twisted ankles produced by rolling shale. From the highest elevation there is a view that beggars description. One cannot put into words his feeling of desolation, of helplessness, that comes in looking over the formation. Vanishing in the distance the mounds lie in rows that grow gradually smaller and smaller until they melt into the level landscape below. On the tops of these cold, blue mounds great trees lie prone, many of them shattered and cascading their jeweled hearts down the slope....

Here great piles of splintered, colorless wood are found, looking as if the chopper had just left the scene of his labors, the chips of his day’s work lying scattered about. Again, a big tree broken open by the frost, or other agencies, discloses a lining of gleaming crystals, glittering and sparkling in the Arizona sun. Here the great dinosaur lived and died, and from his tomb fossil bones have been carried to universities far and wide. Here the phytosaurus and the stegosaurus breathed their last, and from here was taken the wicked looking upper jaw of a phytosaurus which had weathered the ravages of time and elements. This lies in a glass case in the store at Headquarters, where all may see it and be thankful such creatures roam this region no longer.

Here, the rattlesnake lies coiled in the shade of the sombre hued cones, and scarcely troubles to sound his warning when visitors intrude. Overhead a tireless buzzard hangs suspended. No other signs of life are seen in this dead gray waste, the burial plot of the Dark Ages.

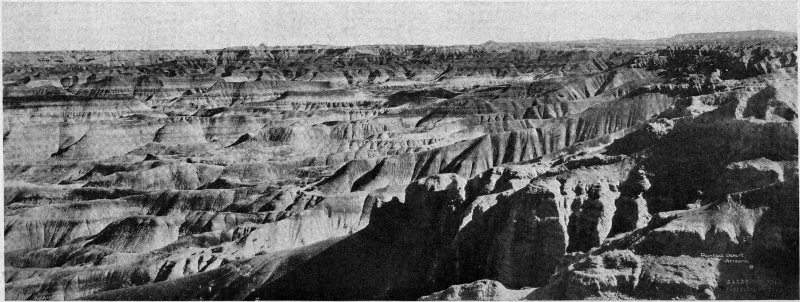

Many of the Petrified Forest visitors are intensely interested in the Painted Desert, lying only a few miles from Adamana. On U. S. Highway 66, six miles from the Rio Puerco, one comes to a sign: “Painted Desert Inn”. A mile from the highway this inn is stationed. But before reaching the building, an abrupt climb brings one to the top of the mesa, and spread out before the eyes is the world’s most magnificent palette, with the colors ready mixed,—The Painted Desert. It is a breath-taking vision that bursts on one’s sight, this “El Pintado Desierto” that Coronado stumbled upon and named in 1540. As far as one can see colors mingle and glow. From the most delicate lavendar to the deepest purple, from palest pink to flaming red, greens, browns, chocolate and blues, all the colors are here. This desert does not lie in level sandy stretches, but is formed of mounds and hills, and varying sizes of “haystacks”.

With each hour, as the light changes in the sky, so change the colors of this wonderland. It is truly the foot of the rainbow. Walk down the trail and there is the bewildered feeling that one has strayed into an immense paint factory which has just been badly wrecked! The sand underfoot is light, almost like burnt earth, but the colors are there, mixed by the Super Artist.

This Painted Desert is a fitting frame for the Petrified Forest.

The Petrified Forest is one of the most popular and accessible units of the National Park Service, open every day in the year. Westbound tourists traveling by automobile may choose between two great continental highways that will lead directly to the “Forest”.

U. S. Highway No. 66 passes on the north and tourists may enter the Forest either from Adamana or Holbrook. This highway brings the traveler by the famous Painted Desert.

U. S. Highway No. 70 on the Carlsbad-Petrified Forest-Grand Canyon Route, winds through the foothills of the White Mountains by way of Springerville, and passes through one of the most interesting sections of the Petrified Forest.

Eastbound tourists enter the Forest from Holbrook where Highways No. 66 and 70 meet.

The Santa Fe railroad, carrying The Chief, The Navajo, The California Limited and the Grand Canyon Limited runs through Holbrook and Winslow. Either east or west bound travelers on any of these trains may obtain a twenty-four hour stopover. “La Posada” at Winslow combines all the romance and fascination of the old Spanish regime with the most modern conveniences for the comfort of those wishing to make it their home while visiting surrounding attractions. From this hotel, the well known Harveycar Motor Coaches, each with its charming girl courier, conveys guests to the Petrified Forest.

For those wishing to visit the Forest and resume their journey the same day, arrangements have been made to meet eastbound Navajo No. 2, at Winslow, take the guest to “La Posada” for breakfast, drive from there to the Petrified Forest, where the most 16 interesting points, including the Museum, are visited, and then rejoin the train at Holbrook. The program is reversed with west bound tourists on Navajo No. 9. The coaches meeting the train at Holbrook make the “Petrified Forest Detour” and drive to Winslow for luncheon at the hotel, resuming train travel there. This trip affords a convenient and inexpensive means of seeing the “Forest” and is a pleasant interruption of a long train journey. Any tourist agency or Santa Fe ticket office can furnish additional information.

Rainbow Lodge, near the Museum at Headquarters of Petrified Forest, is prepared to accommodate overnight visitors. New rock cabins and food supplies are available.

A public camp ground is provided by the Government.

View of the Painted Desert, near Holbrook.

PRICE 25 CENTS

Postpaid Anywhere in United States

DAMA MARGARET SMITH

Holbrook, Arizona

PRESS OF

WINSLOW DAILY MAIL

WINSLOW, ARIZONA