The Project Gutenberg EBook of Wailing Wall, by Roger Dee This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Wailing Wall Author: Roger Dee Release Date: January 16, 2016 [EBook #50940] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WAILING WALL *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By ROGER DEE

Illustrated by ED ALEXANDER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction July 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

An enormous weapon is forcing people to keep

their troubles to themselves—it's dynamite!

Numb with the terror that had dogged him from the moment he regained consciousness and found himself naked and weaponless, Farrell had no idea how long he had been lost in the honeycombed darkness of the Hymenop dome.

The darkness and damp chill of air told him that he was far underground, possibly at the hive's lowest level. Somewhere above him, the silent audience chambers lay shrouded in lesser gloom, heavy with the dust of generations and peopled only by cryptic apian images. Outside the dome, in a bend of lazy silver river, sprawled the Sadr III village with its stoic handful of once-normal Terran colonists and, on the hillside above the village, Gibson and Stryker and Xavier would be waiting for him in the disabled Marco Four.

Waiting for him....

They might as well have been back on Terra, five hundred light-years away.

Six feet away on either side, the corridor walls curved up faintly, a flattened oval of tunneling designed for multiple alien feet, lighted for faceted eyes demanding the merest fraction of light necessary for an Earthman's vision. For two yards Farrell could see dimly, as through a heavy fog; beyond was nothing but darkness and an outlandish labyrinth of cross-branching corridors that spiraled on forever without end.

Behind him, his pursuers—human natives or Hymenop invaders, he had no way of knowing which—drew nearer with a dry minor rustling whose suggestion of imminent danger sent Farrell plunging blindly on into the maze.

—To halt, sweating, when a sound exactly similar came to him from ahead.

It was what he had feared from the beginning. He could not go on, and he could not go back.

He made out the intersecting corridor to his right, then a vague oval opening that loomed faintly grayer than the wall about it. He darted into it as into a sanctuary, and realized too late that the choice had been forced upon him.

It had been intended from the start that he should take this way. He had been herded here like a halterless beast, driven by the steady threat of action never quite realized. They had known where he was going, and why.

But there was light down there somewhere at the end of the tunnel's aimless wanderings. If, once there, he could see—

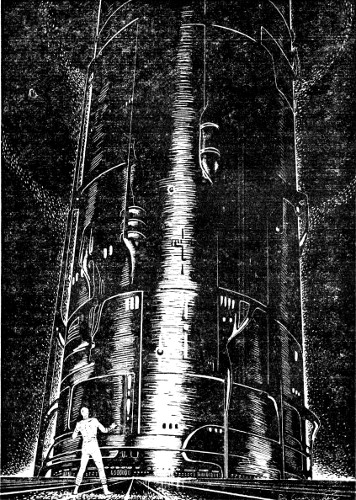

He did not find light, only a lesser darkness. The tunnel led him into a larger place whose outer reaches were lost in shadow, but whose central area held a massive cylindrical machine at once alien and familiar.

He went toward it hesitantly, confused for the moment by a paramnesiac sense of repeated experience, the specious recognition of déjà vu.

It was a Ringwave generator, and it was the thing he had ventured into the dome to find.

His confusion stemmed from its resemblance to the disabled generator aboard the Marco Four, and from the stereo-sharp associations it evoked: Gibson working over the ship's power plant, his black-browed face scowling and intent, square brown body moving with a wrestler's easy economy of motion; Stryker, bald and fat and worried, wheezing up and down the companionway from engine bay to chart room, his concern divided between Gibson's task and Farrell's long silence in the dome.

Stryker at this moment would be regretting the congenital optimism that had prompted him to send his navigator where he himself could not go. Sweating anxiety would have replaced Stryker's pontifical assurance, dried up his smug pattering of socio-psychological truisms lifted from the Colonial Reclamations Handbook....

"So far as adaptability is concerned," Stryker had said an eternal evening before, "homo sapiens can be a pretty weird species. More given to mulish paradox, perhaps, than any alien life-form we're ever likely to run across out here."

He had shifted his bulk comfortably on the grass under the Marco Four's open port, undisturbed by the busy clatter of tools inside the ship where Gibson and Xavier, the Marco's mechanical, worked over the disabled power plant. He laced his fingers across his fat paunch and peered placidly through the dusk at Farrell, who lay on his back, smoking and watching the stars grow bright in the evening sky.

"Isolate a human colony from its parent planet for two centuries, enslave it for half that time to a hegemony as foreign as the Hymenops' hive-culture before abandoning it to its own devices, and anything at all in the way of eccentric social controls can develop. But men remain basically identical, Arthur, in spite of acquired superficial changes. They are inherently incapable of evolving any system of control mechanisms that cannot be understood by other men, provided the environmental circumstances that brought that system into being are known. At bottom, these Sadr III natives are no different from ourselves. Heredity won't permit it."

Farrell, half listening, had been staring upward between the icy white brilliance of Deneb and the twin blue-and-yellow jewels of Albireo, searching for a remote twinkle of Sol. Five hundred light-years away out there, he was thinking, lay Earth. And from Earth all this gaudy alien glory was no more than another point of reference for backyard astronomers, a minor configuration casually familiar and unremarkable.

A winking of lighted windows springing up in the village downslope brought his attention back to the scattered cottages by the river, and to the great disquieting curve of the Hymenop dome that rose above them like a giant above pygmies. He sat up restlessly, the wind ruffling his hair and whirling the smoke of his cigarette away in thin flying spirals.

"You sound as smug as the Reorientation chapter you lifted that bit from," Farrell said. "But it won't apply here, Lee. The same thing happened to these people that happened to the other colonists we've found, but they don't react the same. Either those Hymenop devils warped them permanently or they're a tribe of congenital maniacs."

Stryker prodded him socratically: "Particulars?"

"When we crashed here five weeks ago, there were an even thousand natives in the village, plus or minus a few babes in arms. Since that time they've lost a hundred twenty-six members, all suicides or murders. At first the entire population turned out at sunrise and went into the dome for an hour before going to the fields; since we came, that period has shortened progressively to a few minutes. That much we've learned by observation. By direct traffic we've learned exactly nothing except that they can speak Terran Standard, but won't. What sort of system is that?"

Stryker tugged uncomfortably at the rim of white hair the years had left him. "It's a stumper for the moment, I'll admit ... if they'd only talk to us, if they'd tell us what their wants and fears and problems are, we'd know what is wrong and what to do about it. But controls forced on them by the Hymenops, or acquired since their liberation, seem to have altered their original ideology so radically that—"

"That they're plain batty," Farrell finished for him. "The whole setup is unnatural, Lee. Consider this: We sent Xavier out to meet the first native that showed up, and the native talked to him. We heard it all by monitoring; his name was Tarvil, he spoke Terran Standard, and he was amicable. Then we showed ourselves, and when he saw that we were human beings like himself and not mechanicals like Xav, he clammed up. So did everyone in the village. It worries me, Lee. If they didn't expect men to come out of the Marco, then what in God's name did they expect?"

He sat up restlessly and stubbed out his cigarette. "It's an unimportant world anyway, all ocean except for this one small continent. I think we ought to write it off and get the hell out as soon as the Marco's Ringwave is repaired."

"We can't write it off," Stryker said. "Besides reclaiming a colony, we may have added a valuable marine food source to the Federation. Arthur, you're not letting a handful of disoriented people get under your skin, are you?"

Farrell made an impatient sound and lit another cigarette. The brief flare of his lighter pierced the darkness and picked out a hurried movement a short stone's throw away, between the Marco Four and the village.

"There's one reason why I'm edgy," Farrell said. "These Sadrians may be harmless, but they make a point of posting a guard over us. There's a sentry out there in the grass flats again tonight." He turned on Stryker uneasily. "I've watched on the infra-scanner while those sentries changed shifts, and they don't speak to each other. I've tracked them back to the village, but I've never seen one of them turn in a—"

Down in the village a man screamed, a raw, tortured sound that brought both men up stiffly. A frantic drumming of running feet came to them, unmistakable across the little distance. The fleeing man came up from the dark huddle of cottages by the river and out across the grass flats, screaming.

Pursuit overtook him halfway to the ship. There was a brief scuffling, a shadowy dispersal of silent figures. After that, nothing.

"They did it again," Farrell said. "One of them tried to come up here to us. The others killed him, and who's to say what sort of twisted motive prompted them? They go to the dome together every morning, not speaking. They work all day in the fields without so much as looking at each other. But every night at least one of them tries to escape from the village and come up here—and this is what happens. We couldn't trust them, Lee, even if we could understand them!"

"It's our job to understand them," Stryker said doggedly. "Our function is to find colonies disoriented by the Hymenops and to set them straight if we can. If we can't, we call in a long-term reorientation crew, and within three generations the culture will pass again for Terran. The fact that slave colonies invariably lose their knowledge of longevity helps; they don't get it back until they're ready for it.

"I've seen some pretty foul results of Hymenop experimenting on human colonies, Arthur. There was the ninth planet of Beta Pegasi—rediscovered in 3910, I think it was—that developed a religious fixation on fertility, a mania fostered by the Hymenops to supply expendable labor for their mines. The natives stopped mining when the Hymenops gave up the invasion and went back to 70 Ophiuchi, but they were still multiplying like rabbits when we found them. They followed a cultural conviction something like that observed in Oriental races of ancient Terran history, but they didn't pursue the Oriental tradition of sacrosancts. They couldn't—there were too many of them. By the time they were found, they numbered fourteen billions and they were eating each other. Still it took only three generations to set them straight."

He took one of Farrell's cigarettes and puffed it placidly.

"For that matter, Earth had her own share of eccentric cultures. I recall reading about one that existed as late as the twentieth century and equaled anything we're likely to find here. Any society should be geared to a set of social controls designed to furnish it, as a whole with a maximum of pleasure and a minimum of discomfort, but these ancient Terrestrial Dobuans—island aborigines, as I remember it—had adjusted to their total environment in a manner exactly opposite. They reversed the norm and became a society of paranoiacs, hating each other in direct ratio to nearness of relationship. Husbands and wives detested each other, sons and fathers—"

"Now you're pulling my leg," Farrell protested. "A society like that would be too irrational to function."

"But the system worked," Stryker insisted. "It balanced well enough, as long as they were isolated. They accepted it because it was all they knew, and an abrupt reversal that negated their accustomed habits would create an impossible societal conflict. They were reoriented after the Fourth War, and succeeding generations adjusted to normal living without difficulty."

A sound from overhead made them look up. Gibson was standing in the Marco's open port.

"Conference," Gibson said in his heavy baritone, and went back inside.

They followed Gibson quickly and without question, more disturbed by the terse order than by the killing in the grass flats. Knowing Gibson, they realized that he would not have wasted even that one word unless emergency justified it.

They found him waiting in the chart room with Xavier. For the thousandth time, seeing the two together, Farrell found himself comparing them: the robot, smoothly functional from flexible gray plastoid body to featureless oval faceplate, blandly efficient, totally incapable of emotion; Gibson, short and dark and competent heavy-browed and humorless. Except for initiative, Farrell thought, the two of them could have traded identities and no one would have been able to notice any difference.

"Xav and I found our Ringwave trouble," Gibson said. "The generator is functioning, but the warp isn't going out. Something here on Sadr III is neutralizing it."

They stared at him as if he had just told them the planet was flat.

"But a Ringwave can't be stopped completely, once it is started," Stryker protested. "You'd have to dismantle it to shut it off, Gib!"

"The warping field can be damped out, though," Gibson said. "Adjacent generators operating at different phase levels will heterodyne at a frequency representing the mean variance between levels. The resulting beat-phase will be too low to maintain either field, and one or the other, or both, will blank out. If you remember, all Terran-designed power plants are set to the same phase for that reason."

"But these natives can't have a Ringwave plant!" Farrell argued. "There's only this one village on Sadr III, Gib, an insignificant little agrarian township! If they had the Ringwave, they'd be mechanized. They'd have vehicles, landing ports...."

"The Hymenops had the Ringwave," Gibson interrupted. "And they left the dome down there, the first undamaged one we've found. Figure it out for yourselves."

They digested the statement in silence. Stryker paled slowly, as if it needed time for apprehension to work its way through his fat bulk. Farrell's uneasiness, sourceless until now, grew to chill certainty.

"I think I've expected this, without realizing it, since my first flight," he said. "It stood to reason that the Hymenops would quit running somewhere, that we'd bump into them eventually out here on the fringes. Twenty thousand light-years back to 70 Ophiuchi is a long way to retreat.... Gib, do you think they're still here?"

Gibson did not shrug, but his voice seemed to. "It won't matter one way or the other unless we can clear the Marco's generator."

From another man it might have been irony. Knowing Gibson, Farrell and Stryker accepted it as a bald statement of fact.

"Then we're up against a Hymenop hive-mind," Stryker said. "And we can't run away from it. Any suggestions?"

"We'll have to find the interfering generator and stop it," Farrell offered, knowing that was the only obvious solution.

"One alternative," Gibson corrected. "If we can determine what phase-level the interfering warp uses, we may be able to adjust the Marco's generator to match it. Once they're in resonance, they won't interfere." He caught Stryker's unspoken question and answered it. "It would take a week. Maybe longer."

Stryker vetoed the alternative. "Too long. If there are Hymenops here, they won't give us that much time."

Farrell switched on the chart room scanning screen and centered it on the village downslope. Scattered cottages with dark tiled roofs and lamp-bright windows showed up clearly. Out of their undisciplined grouping swept the great hemispherical curve of the dome, glinting dully metallic in the starshine.

"Maybe we're jumping to conclusions," he said. "We've been here for five weeks without seeing a trace of Hymenops, and from what I've read of them, they'd have jumped us the minute we landed. Chances are that they left Sadr III in too great a hurry to wreck the dome, and their Ringwave power plant is still running."

"You may be right," Stryker said, brightening. "They carried the fight to us from the first skirmish, two hundred years ago, and they damned near beat us before we learned how to fight them."

He looked at Xavier's silent plastoid figure with something like affection. "We'd have lost that war without Xave's kind. We couldn't match wits with Hymenop hive-minds, any more than a swarm of grasshoppers could stand up to a colony of wasps. But we made mechanicals that could. Cybernetic brains and servo-crews, ships that thought for themselves...."

He squinted at the visiscreen with its cryptic, star-streaked dome. "But they don't think as we do. They may have left a rear guard here, or they may have boobytrapped the dome."

"One of us will have to find out which it is," Farrell said. He took a restless turn about the chart room, weighing the probabilities. "It seems to fall in my department."

Stryker stared. "You? Why?"

"Because I'm the only one who can go. Remember what Gib said about changing the Marco's Ringwave to resonate with the interfering generator? Gib can make the change; I can't. You're—"

"Too old and fat," Stryker finished for him. "And too damned slow and garrulous. You're right, of course."

They let it go at that and put Xavier on guard for the night. The mechanical was infinitely more alert and sensitive to approach than any of the crew, but the knowledge did not make Farrell's sleep the sounder.

He dozed fitfully, waking a dozen times during the night to smoke cigarettes and to speculate fruitlessly on what he might find in the dome. He was sweating out a nightmare made hideous by monstrous bees that threatened him in buzzing alien voices when Xavier's polite monotone woke him for breakfast.

Farrell was halfway down the grassy slope to the village when he realized that the Marco was still under watch. Approaching close enough for recognition, he saw that the sentry this time was Tarvil, the Sadrian who had first approached the ship. The native's glance took in Farrell's shoulder-pack of testing tools and audiphone, brushed the hand-torch and blast gun at the Terran's belt, and slid away without trace of expression.

"I'm going into the dome," Farrell said. He tried to keep the uncertainty out of his voice, and felt a rasp of irritation when he failed. "Is there a taboo against that?"

The native fell in beside him without speaking and they went down together, walking a careful ten feet apart, through dew-drenched grass flats that gleamed like fields of diamonds under the early morning sun. From the village, as they approached, straggled the inevitable exodus of adults and half-grown children, moving silently out to the fields.

"Weird beggars," Farrell said into his audiphone button. "They don't even rub elbows at work. You'd think they were afraid of being contaminated."

Stryker's voice came tinnily in his ear. "They won't seem so strange once we learn their motivations. I'm beginning to think this aloofness of theirs is a religious concomitant, Arthur, a hangover from slave-controls designed to prevent rebellion through isolation. Considering what they must have suffered under the Hymenops, it's a wonder they're even sane."

"I'll grant the religious origin," Farrell said. "But I wouldn't risk a centicredit on their sanity. I think the lot of them are nuts."

The village was not deserted, but so far as Farrell's coming was concerned, it might as well have been. The few women and children he saw on the streets ignored him—and Tarvil—completely.

He met with only one sign of interest, when a naked boy perhaps six years old stared curiously and asked something in a childish treble of the woman accompanying him. The woman answered with a single sharp word and struck the child across the face, sending him sprawling.

Farrell relayed the incident. "She said 'Quiet!' and slapped him down, Lee. They start their training early."

"Their sort of indifference couldn't be congenital," Stryker said. His tinny murmur took on a puzzled sound. "But they've been free for four generations. It's hard to believe that any forcibly implanted control mechanism could remain in effect so long."

A shadow blocked the sun, bringing a faint chill to Farrell when he looked up to see the great rounded hump of the dome looming over him.

"I'm going into the dome now," he said. "It's like all the others—no openings except at ground level, where it's riddled with them."

Tarvil did not accompany him inside. Farrell, looking back as he thumbed his hand-torch alight in the nearest entranceway, saw the native squatting on his heels and looking after him without a single trace of interest.

"I'm at ground level," Farrell said later, "in what seems to have been a storage section. Empty now, with dust everywhere except in the corridors the natives use when they come in, mornings. No sign of Hymenops yet."

Stryker's voice turned worried. "Look sharp for traps, Arthur. The place may be mined."

The upper part of the dome, Farrell knew from previous experience, would have been given over in years past to Hymenop occupation, layer after rising layer of dormitories tiered like honeycombs to conserve space. He followed a spiral ramp downward to the level immediately below surface, and felt his first excitement of discovery when he found himself in the audience chambers that, until the Marco's coming, had been the daily goal of the Sadrian natives.

The level was entirely taken up with bare ten-foot cubicles, each cramped chamber dominated by a cryptic metal-and-crystal likeness of the Hymenop head set into the metal wall opposite its corridor entrance. From either side of a circular speaking-grill, the antennae projected into the room, rasplike and alert, above faceted crystal eyes that glowed faintly in the near-darkness. The craftsmanship was faultless, stylized after a fashion alien to Farrell's imagining and personifying with disturbing realism the soulless, arrogant efficiency of the Hymenop hive-mind. To Farrell, there was about each image a brooding air of hypnotic fixity.

"Something new in Hymenop experiments," he reported to Stryker. "None of the other domes we found had anything like this. These things have some bearing on the condition of the natives, Lee—there's a path worn through the dust to every image, and I can see where the people knelt. I don't like it. I've got a hunch that whatever these damned idols were used for succeeded too well."

"They can't be idols," Stryker said. "The Hymenops would have known how hard it is to displace anthropomorphism entirely from human worship. But I think you're right about the experiment's working too well. No ordinary compulsion would have stuck so long. Periodic hypnosis? Wait, Arthur, that's an angle I want to check with Gibson...."

He was back a moment later, wheezing with excitement.

"Gib thinks I'm on the right track—periodic hypnosis. The Hymenops must have assigned a particular chamber and image to each slave. The images are mechanicals, robot mesmerists designed to keep the natives' compulsion-to-isolation renewed. Post-hypnotic suggestion kept the poor devils coming back every morning, and their children with them, even after the Hymenops pulled out. They couldn't break away until the Marco's Ringwave forced a shutdown of the dome's power plant and deactivated the images. Not that they're any better off now that they're free; they don't know how—"

Farrell never heard the rest of it. Something struck him sharply across the back of the head.

When he regained consciousness, he was naked and weaponless and lost. The rustling of approach, bodiless and dreadful in darkness, panicked him completely and sent him fleeing through a sweating eternity that brought him finally to the dome's lowest level and the Hymenop power plant.

He went hesitantly toward the shadowy bulk of the Ringwave cylinder, drawn as much now by its familiarity as driven by the terror behind him. At the base of the towering machine, he made out a control board totally unrecognizable in design, studded with dials and switches clearly intended for alien handling.

The tinny whispering of Stryker's voice in the vaultlike quiet struck him with the frightening feeling that he had gone mad.

He saw his equipment pack then, lying undamaged at the foot of the control board. Stryker's voice murmured from its audicom unit: "We're in the dome, Arthur. Where are you? What level—"

Farrell caught up the audicom, swept by a sudden wild lift of hope. "I'm at the bottom of the dome, in the Ringwave chamber. They took my gun and torch. For God's sake, hurry!"

The darkness gave up a furtive scuffling of sandaled feet, the tight breathing of many men. Someone made a whimpering sound, doglike and piteous; a Sadrian voice hissed sharply, "Quiet!"

Stryker's metallic whisper said: "We're tracking your carrier, Arthur. Use the tools they left you. They brought you there to repair the Ringwave, to give back the power that kept their images going. Keep busy!"

Farrell, only half understanding, took up his instrument case. His movement triggered a tense rustle in the darkness; the voice whimpered again, a tortured sound that rasped Farrell's nerves like a file on glass.

"Give me back my Voice. I am alone and afraid. I must have Counsel...."

Beneath the crying, Farrell felt the terror, incredibly voiced, that weighted the darkness, the horror implicit in stilled breathing, the swelling sense of outrage.

There was a soft rush of bodies, a panting and struggling. The whimpering stopped.

The instrument case slipped out of Farrell's hands. On the heels of its nerve-shattering crash against the metal floor came Stryker's voice, stronger as it came closer.

"Steady, Arthur. They'll kill you if you make a scene. We're coming, Gib and Xav and I. Don't lose your head!"

Farrell crouched back against the cold curve of the Ringwave cylinder, straining against flight with an effort that left him trembling uncontrollably. A spasm of incipient screaming seized his throat and he bit it back savagely, stifling a terror that could not be seen, grasped, fought with.

He was giving way slowly when Xavier's inflectionless voice droned out of the darkness: "Quiet. Your Counsel will be restored."

There was a sudden flood of light, unbearable after long darkness. Farrell had a failing glimpse of Gibson, square face blocked with light and shadow from the actinic flare overhead, racing toward him through a silently dispersing throng of Sadrians.

Then he passed out.

He was strapped to his couch in the chart room when he awoke. The Marco Four was already in space; on the visiscreen, Farrell could see a dwindling crescent of Sadr III, and behind it, in the black pit of space, the fiery white eye of Deneb and the pyrotechnic glowing of Albireo's blue-and-yellow twins.

"We're headed out," he said, bewildered. "What happened?"

Stryker came over and unstrapped him. Gibson, playing chess with Xavier across the chart-room plotting table, looked up briefly and went back to his gambit.

"We reset the Ringwave in the dome to phase with ours and lugged you out," Stryker explained genially. He was back in character again, his fat paunch quivering with the beginning of laughter. "We're through here. The rest is up to Reorientation."

Farrell gaped at him. "You're giving up on Sadr III?"

"We've done all we can. Those Sadrians need something that a preliminary expedition like ours can't give them. Right now they are willing victims of a rigid religious code that makes it impossible for any one of them to express his wants, hopes, ideals or misfortunes to another. Exchanging confidences, to them, is the ultimate sacrilege."

"Then they are crazy. They'd have to be, with no more opportunity for emotional catharsis than that!"

"They're not insane, they're—adapted. Those robot images you found are everything to this culture: arbiters, commercial agents, monitors and confessors all in one. They not only relay physical needs from one native to another; they listen to all problems and give solutions. They're Counselors, remember? Man's gregariousness stems largely from his need to unload his troubles on someone else. The Hymenops came up with an efficient substitute here, and the natives accepted it as the norm."

Farrell winced with sudden understanding. "No wonder the poor devils cracked up right and left. With their Ringwave dead, they might as well have been struck blind and dumb! They couldn't even get together among themselves to figure a way out."

"There you have it," Stryker said. "They knew we were responsible for their catastrophe, but they couldn't bring themselves to ask us for help because we were human beings like themselves. So they went mad one by one and committed the ultimate blasphemy of shouting their misery in public, and their fellows had to kill them or countenance sacrilege. But they'll quiet down now. They should be easy enough to handle by the time the Reorientation lads arrive."

He began to chuckle. "We left their Counselors running, but we disconnected the hypnosis-renewal circuits. They'll get only what they need from now on, which is an outlet for shifting their personal burdens. And with the post-hypnotic compulsion gone, they'll turn to closer association with each other. Human gregariousness will reassert itself. After a couple of generations, the Reorientation boys can write them off as Terran Normal and move on to the next planetary madhouse we've dug up for them."

Farrell said wonderingly, "I never thought of the need to exchange confidences as being so important. But it is; everyone does it. You and I often talk over personal concerns, and Gib—"

He broke off to study the intent pair at the chessboard, comparing Gibson's calm selfsufficiency to the mechanical's bland competence.

"There's an exception for your theory, Lee. Iron Man Gibson never gave out with a confidence in his life!"

Stryker laughed. "You may be right. How about it, Gib? Do you ever feel the need of a wailing wall?"

Gibson looked up briefly from his game, his square face unsurprised.

"Well, sure. Why not? I tell my troubles to Xavier."

When they looked at each other blankly, he added, with the nearest approach to humor that either Farrell or Stryker had ever seen in him: "It's a reciprocal arrangement. Xav confides his to me."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Wailing Wall, by Roger Dee

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WAILING WALL ***

***** This file should be named 50940-h.htm or 50940-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/0/9/4/50940/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.