| English Explorations AND Settlements IN North America 1497-1689 |

|

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA

EDITED

By JUSTIN WINSOR

LIBRARIAN OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

VOL. III

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

Copyright, 1884,

By JAMES R. OSGOOD AND COMPANY.

All rights reserved.

CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

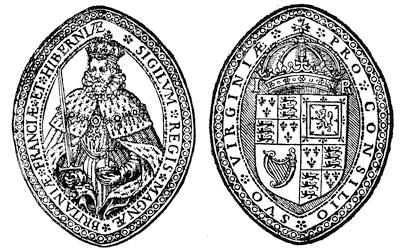

[The English arms on the title are copied from the Molineaux map, dated 1600.]

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Voyages of the Cabots. Charles Deane | 1 |

| Illustration: Sebastian Cabot, 5. | |

| Autographs: Henry VII., 1; Henry VIII., 4; Edward VI., 6; Queen Mary, 7. | |

| Critical Essay | 7 |

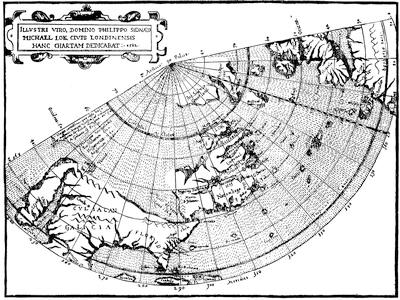

| Illustrations: La Cosa map (1500), phototype, 8, 8; Ruysch’s map (1508), 9; Orontius Fine’s map (1531), 11; Stobnicza’s map (1512), 13; Page of Peter Martyr in fac-simile, 15; Thorne’s map (1527), 17; Sebastian Cabot’s map (1544), 22; Lok’s map (1582), 40; Hakluyt-Martyr map (1587), 42; Portuguese Portolano (1514-1520), 56. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Hawkins and Drake. Edward E. Hale | 59 |

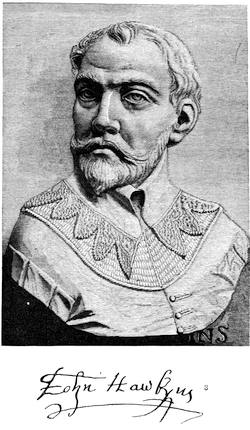

| Illustrations: John Hawkins, 61; Zaltieri’s map (1566), 67; Furlano’s map (1574), 68. | |

| Autographs: John Hawkins, 61; Francis Drake, 65. | |

| Critical Essay on Drake’s Bay | 74 |

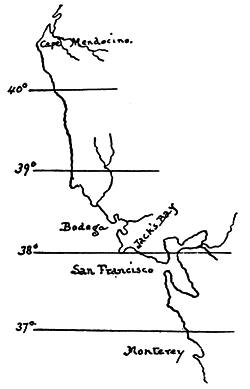

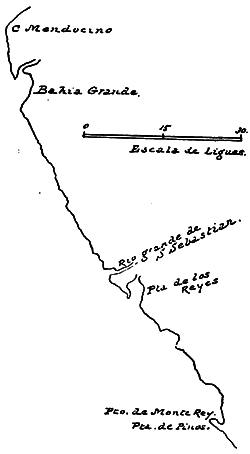

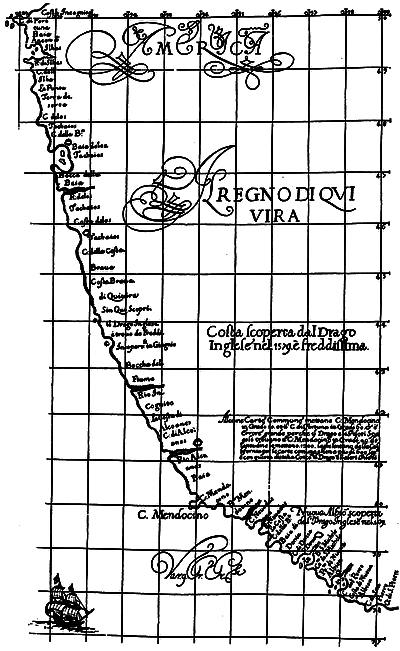

| Illustrations: Modern map of California coast, 74; Viscaino’s map (1602), 75; Dudley’s map (1646), 76, 77; Jeffreys’ sketch-map (1753), 77. | |

| Notes on the Sources of Information. The Editor | 78 |

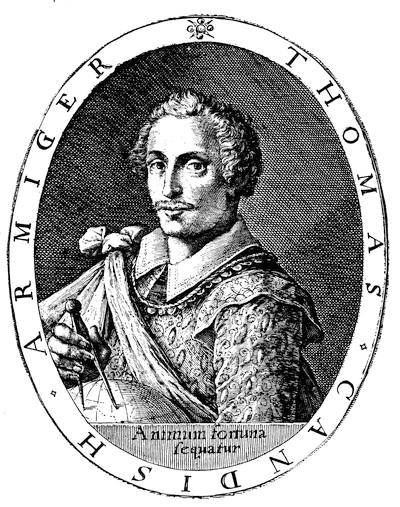

| Illustrations: Hondius’s map, 79; Portus Novæ Albionis, 80; Molineaux’s map (1600), 80; Sir Francis Drake, 81, 84; Thomas Cavendish, 83. | |

| CHAPTER III.[viii] | |

| Explorations to the North-West. Charles C. Smith | 85 |

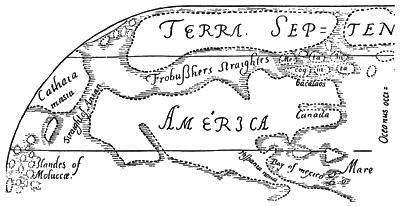

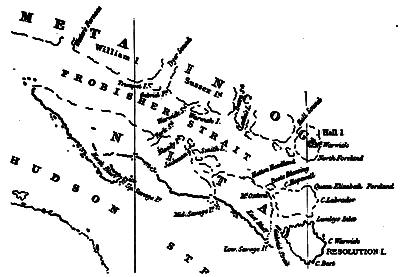

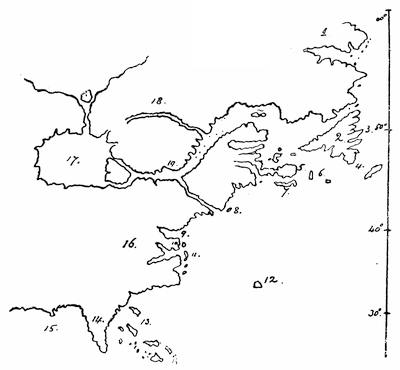

| Illustrations: Martin Frobisher, 87; Molineaux globe (1592), 90; Molineaux map (1600), 91; Sir Thomas Smith, 94; James’s map of Hudson Bay (1632), 96. | |

| Autographs: Martin Frobisher, 87; John Davis, 89; George Waymouth, 91; William Baffin, 94. | |

| Critical Essay | 97 |

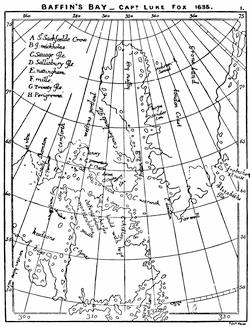

| Illustration: Luke Fox’s map of Baffin’s Bay (1635), 98. | |

| The Zeno Influence on Early Cartography; Frobisher’s and Hudson’s Voyages. The Editor | 100 |

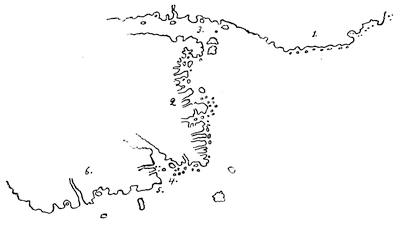

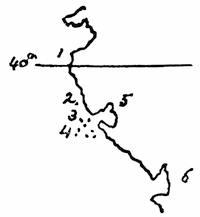

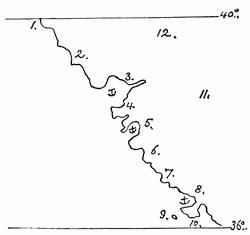

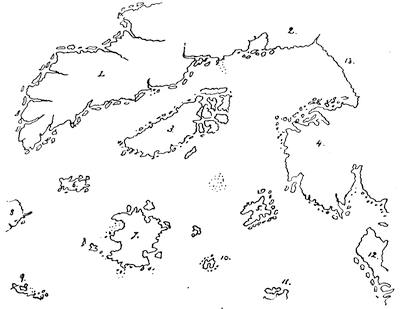

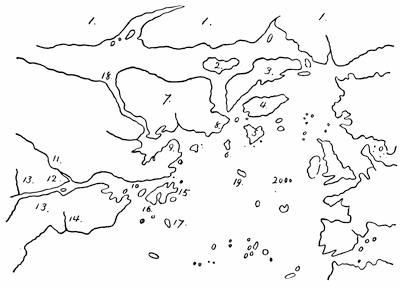

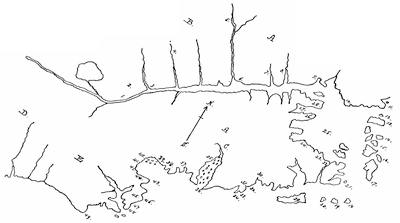

| Illustrations: The Zeno map (circa 1400), 100; map in Wolfe’s Linschoten (1598), 101; Beste’s map (1578), 102; Frobisher’s Strait, 103. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Sir Walter Ralegh: Settlements at Roanoke and Voyages to Guiana. William Wirt Henry | 105 |

| Autographs: Walter Ralegh, 105; Queen Elizabeth, 106; Ralph Lane, 110. | |

| Critical Essay | 121 |

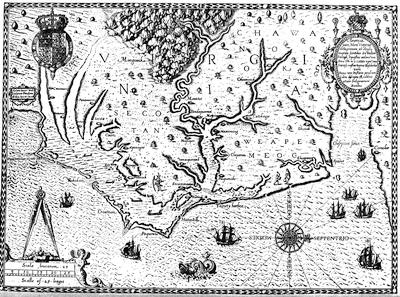

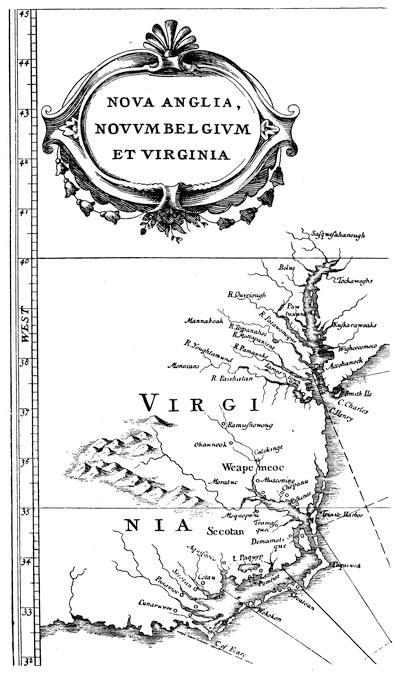

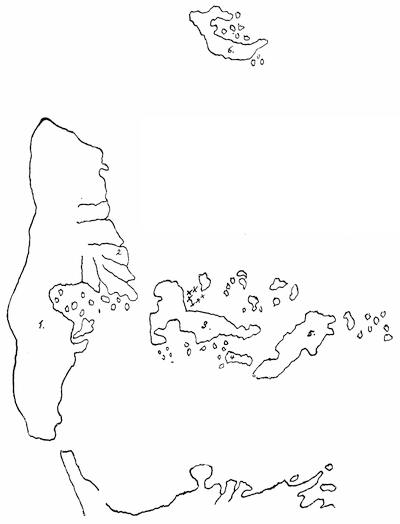

| Illustrations: White’s map in Hariot (1587), 124; De Laet’s map (1630), 125. | |

| Autograph: Francis Bacon, 121. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Virginia, 1606-1689. Robert A. Brock | 127 |

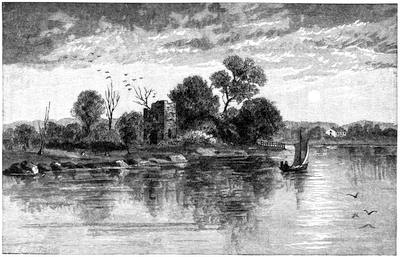

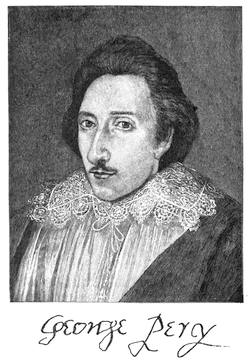

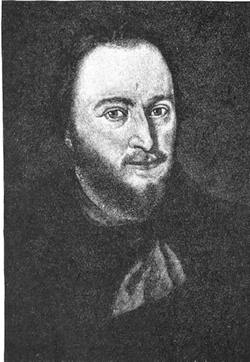

| Illustrations: Jamestown, 130; George Percy, 134; Seal of the Virginia Company, 140; Lord Delaware, 142. | |

| Autographs: King James, 127; Delaware, 133; Thomas Gates, 133; George Percy, 134; George Calvert, 146; William Berkeley, 147. | |

| Critical Essay | 153 |

| Autographs: William Strachey, 156; Delaware, 156; John Harvey, 156; John West, 164. | |

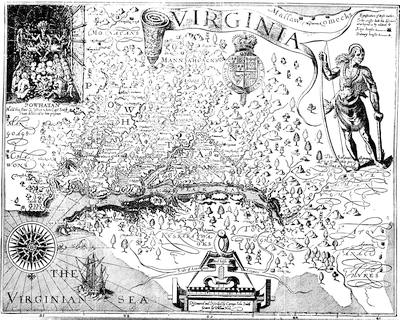

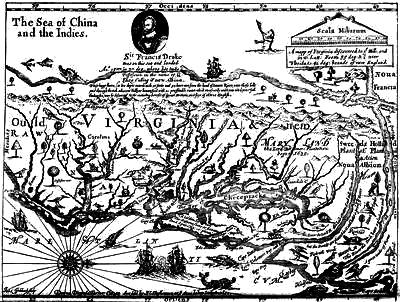

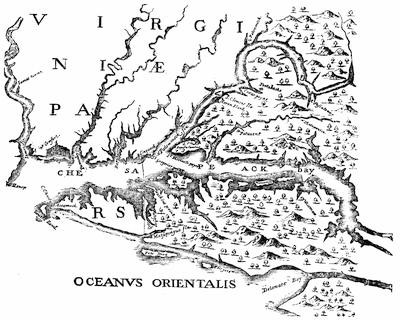

| Notes on the Maps of Virginia, etc. The Editor | 167 |

| Illustration: Smith’s map of Virginia or the Chesapeake, phototype, 167. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Norumbega and its English Explorers. Benjamin F. De Costa | 169 |

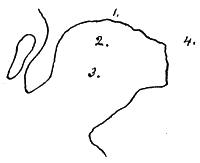

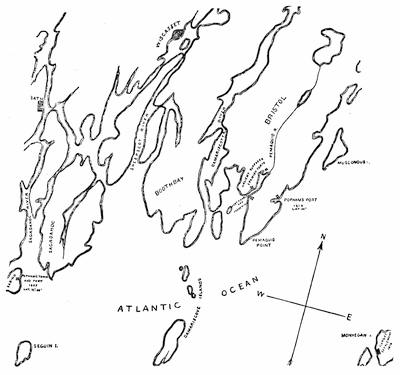

| Illustration: Map of Ancient Pemaquid, 177. | |

| Autographs: J. Popham, 175; Ferd. Gorges, 175. | |

| Critical Essay[ix] | 184 |

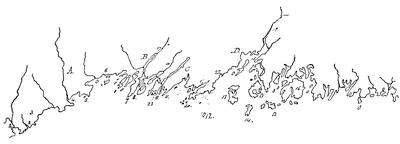

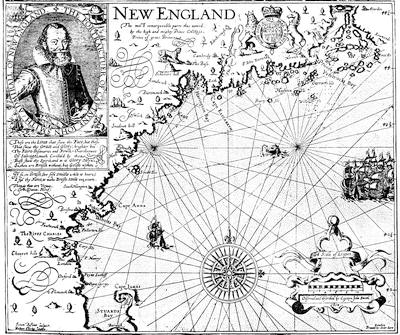

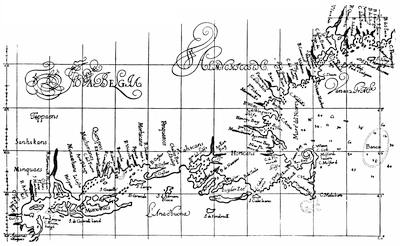

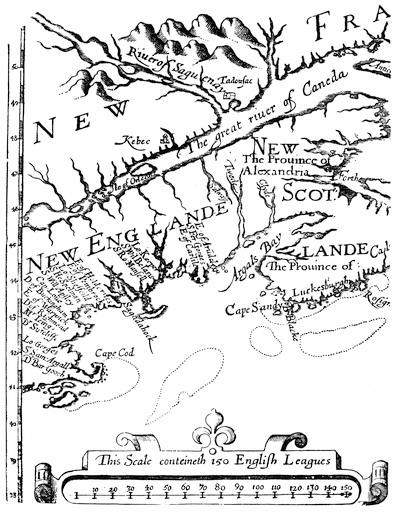

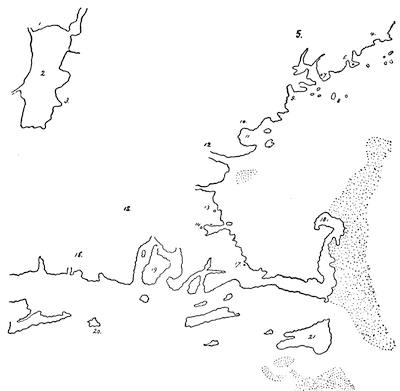

| Illustrations: Modern map of Coast of Maine, 190; Henri II. map (1543), 195; Hood’s map (1592), 197; Smith’s map of New England (1616), 198. | |

| Autographs: J. Popham, 175; Ferd. Gorges, 175. | |

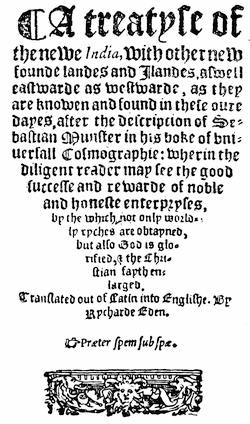

| Earliest English Publications on America, and other Notes. The Editor | 199 |

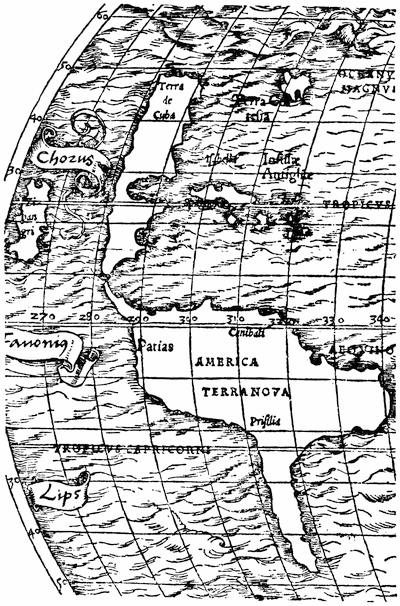

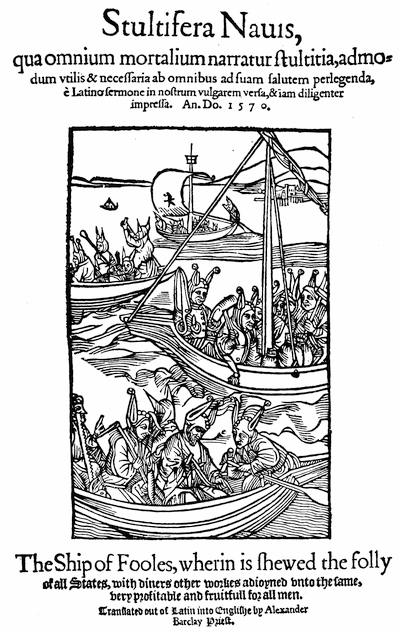

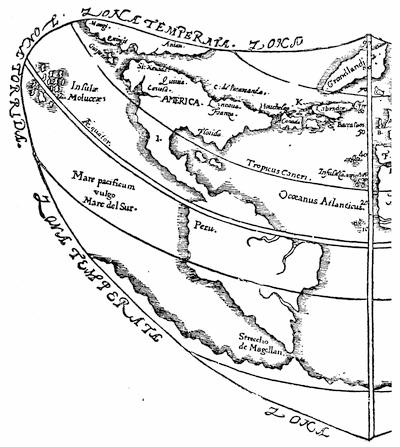

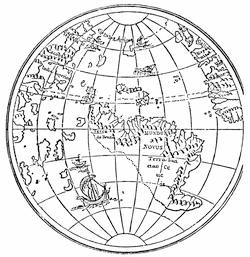

| Illustrations: Title of Eden’s Münster, 200; Münster’s map (1532), 201, (1540), 201; Title of Stultifera Nauis (1570), 202; Gilbert’s map (1576), 203; Linschoten, 206; John G. Kohl, 209; Lenox globe (1510-1512), 212; Extract from Molineaux globe (1592), 213; Frankfort globe (1515), 215; Molineaux map (1600), 216. | |

| Autographs: Humphrey Gilbert, 203; Richard Hakluyt, 204; Jul. Cæsar, 205; Ro. Cecyll, 206; John Smith, 211. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Religious Element in the Settlement of New England.—Puritans and Separatists in England. George E. Ellis | 219 |

| Critical Essay | 244 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

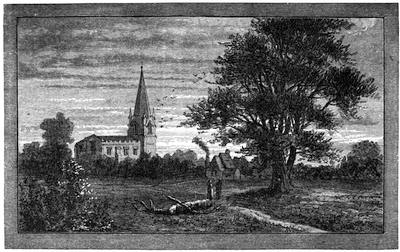

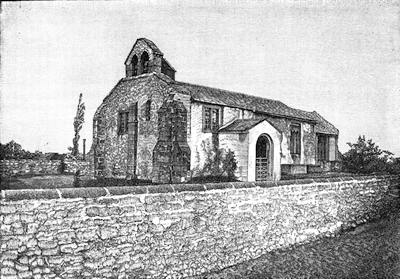

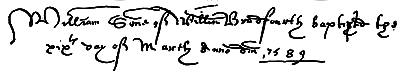

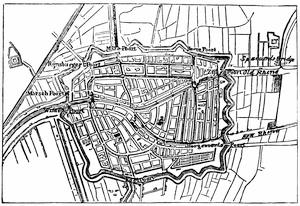

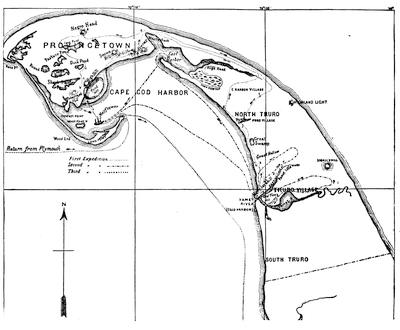

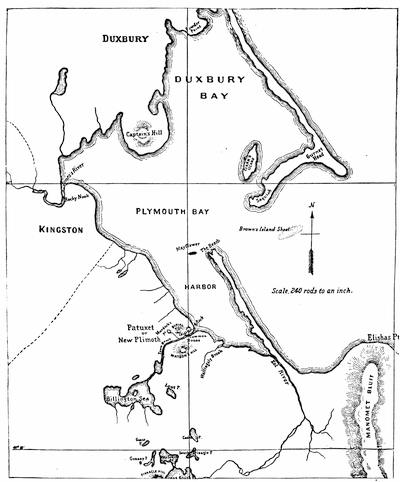

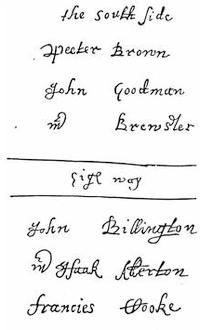

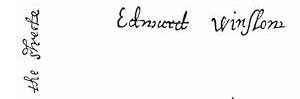

| The Pilgrim Church and Plymouth Colony. Franklin B. Dexter | 257 |

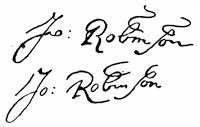

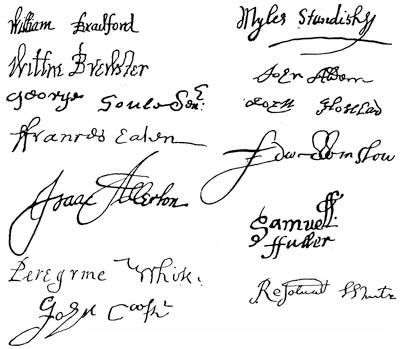

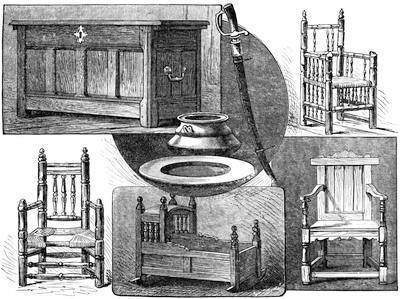

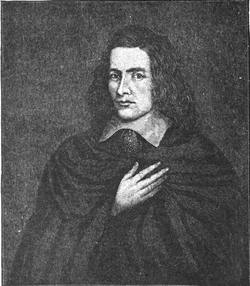

| Illustrations: Site of Scrooby Manor-House, 258; Map of Scrooby and Austerfield, 259; Austerfield church, 260; Record of William Bradford’s baptism, 260; Robinson’s House in Leyden, 262; Plan of Leyden, 263; Map of Cape Cod Harbor, 270; Map of Plymouth Harbor, 272; Historic Swords, 274; Governor Edward Winslow, 277; Pilgrim relics, 279; Governor Josiah Winslow, 282. | |

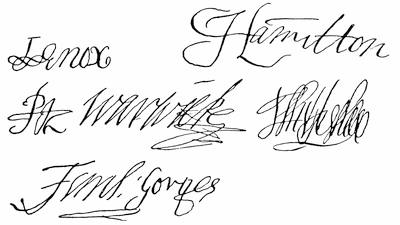

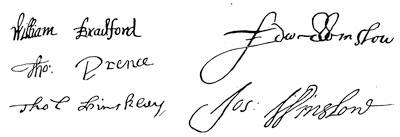

| Autographs: John Smyth, 257; John Robinson, 259; Robert Browne, 261; Francis Johnson, 261; Signatures of Mayflower Pilgrims (William Bradford, Myles Standish, William Brewster, John Alden, John Howland, Edward Winslow, George Soule, Francis Eaton, Isaac Allerton, Samuel Fuller, Peregrine White, Resolved White, John Cooke), 268; Dorothy May, 268; William Bradford, 268; Thomas Cushman, 271; Alexander Standish, 273; James Cole, senior, 273; Signers of the Patent,1621 (Hamilton, Lenox, Warwick, Sheffield, Ferdinando Gorges), 275; Governors of Plymouth Colony (William Bradford, Edward Winslow, Thomas Prence, Thomas Hinckley, Josiah Winslow), 278. | |

| Critical Essay | 283 |

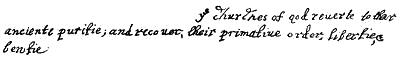

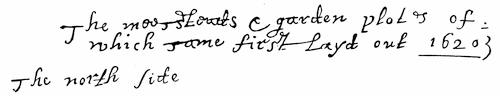

| Illustrations: Extract from Bradford’s History, 289; First page, Plymouth Records, 292. | |

| Autograph: Nathaniel Morton, 291. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| New England. Charles Deane | 295 |

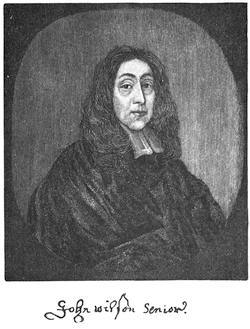

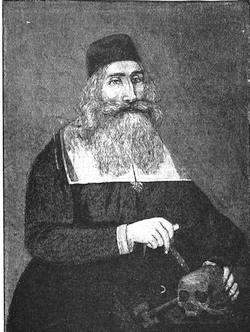

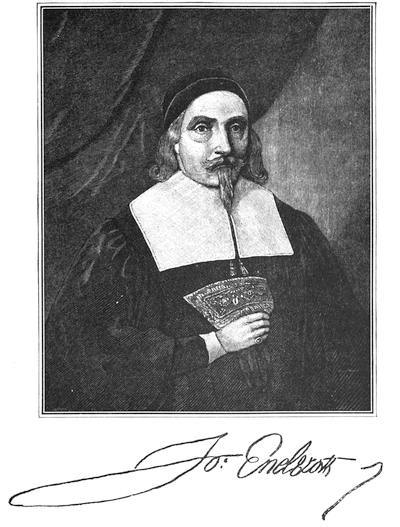

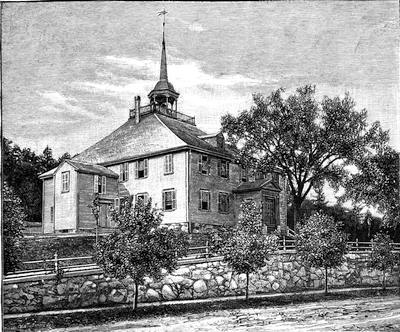

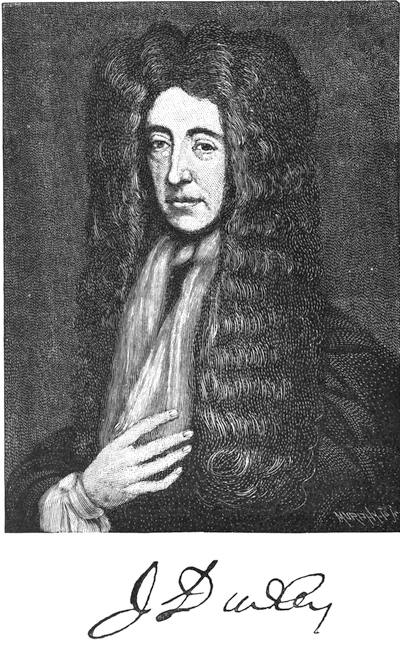

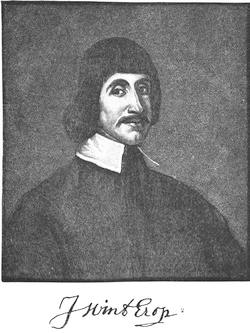

| Illustrations: Dudley’s map of New England (1646), 303; Alexander’s map (1624), 306; John Wilson, 313; Dr. John Clark, 315; John Endicott, 317; Hingham meeting-house, 319; Joseph Dudley, 320; John Winthrop of Connecticut, 331; John Davenport, 332; Map of Connecticut River (1666), 333. | |

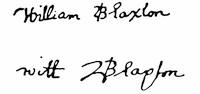

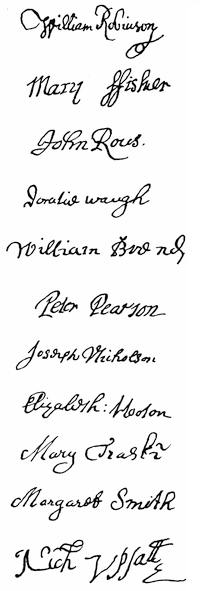

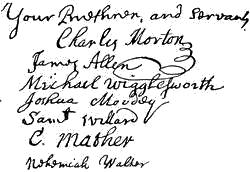

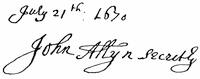

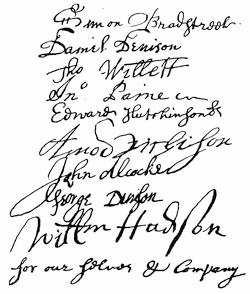

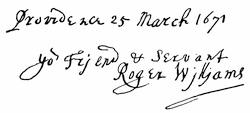

| Autographs[x]: William Blaxton, 311; Samuel Maverick, 311; Thomas Walford, 311; Mathew Cradock, 312; John Wilson, 313; Quaker autographs, 314; John Endicott, 317; Colonial ministers of 1690 (Charles Morton, James Allen, Michael Wigglesworth, Joshua Moody, Samuel Willard, Cotton Mather, Nehemiah Walter), 319; Joseph Dudley, 320; Abraham Shurt, 321; Thomas Danforth, 326; Thomas Hooker, 330; John Haynes, 331; John Winthrop, the younger, 331; John Allyn, 335; William Coddington, 336; Samuel Gorton, 336; Narragansett proprietors (Simon Bradstreet, Daniel Denison, Thomas Willett, Jno. Paine, Edward Hutchinson, Amos Richison, John Alcocke, George Denison, William Hudson), 338; Roger Williams, 339. | |

| Critical Essay | 340 |

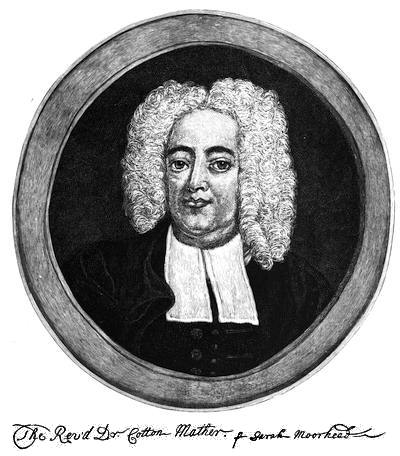

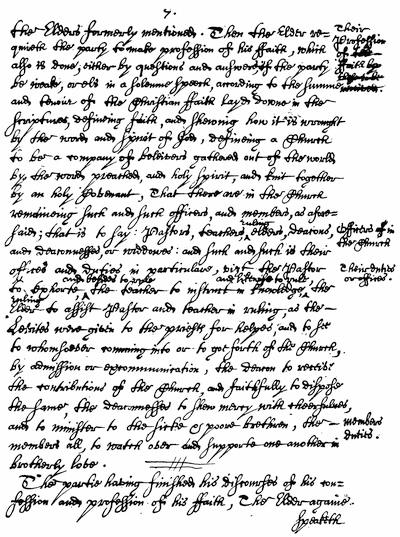

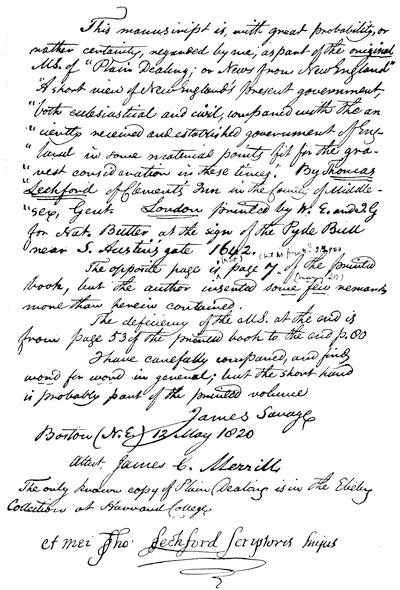

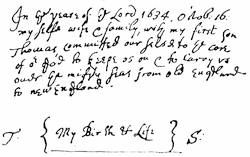

| Illustrations: Seal of the Council for New England, 342; Cotton Mather, 345; Ship of the seventeenth century, 347; Fac-simile of a page of Thomas Lechford’s Plaine Dealing, 352; James Savage’s manuscript note on Lechford, 353; Beginning of Thomas Shepard’s Autobiography, 355. | |

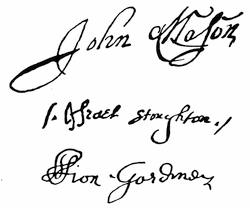

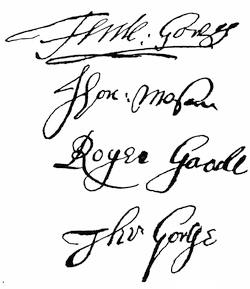

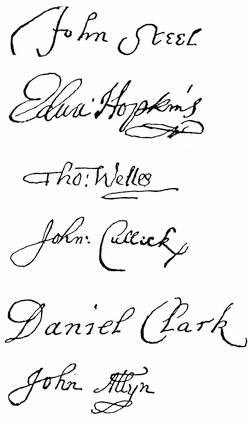

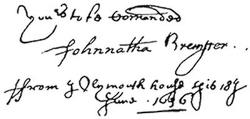

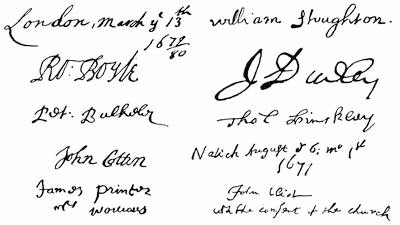

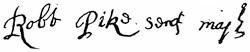

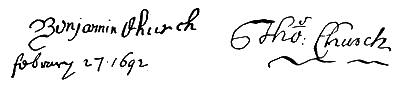

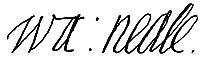

| Autographs: Leaders in Pequot war (John Mason, Israel Stoughton, Lion Gardiner), 348; Jonathan Brewster, 349; Nathaniel Ward, 350; Signatures connected with the Indian Bible (Robert Boyle, Peter Bulkley, William Stoughton, Joseph Dudley, Thomas Hinckley, John Cotton, John Eliot, James Printer), 356; Edward Johnson, 358; John Norton, 358; Edward Burrough, 359; Robert Pike, 359; Benjamin Church, 361; Thomas Church, 361; William Hubbard, 362; Walter Neale, 363; Ferdinando Gorges, 364; John Mason, 364; Roger Goode, 364; Thomas Gorges, 364; Connecticut secretaries (John Steel, Edward Hopkins, Thomas Welles, John Cullick, Daniel Clark, John Allyn), 374. | |

| Bibliographical Notes; Early Maps of New England. The Editor | 380 |

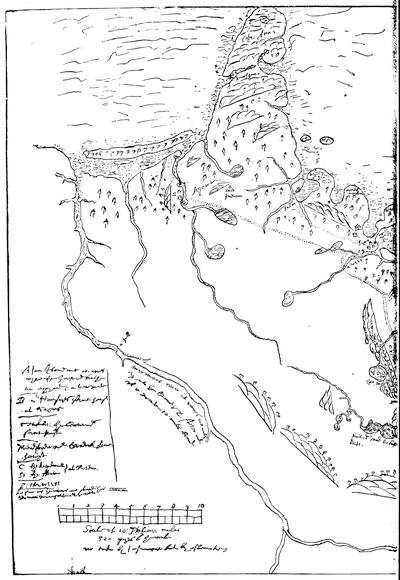

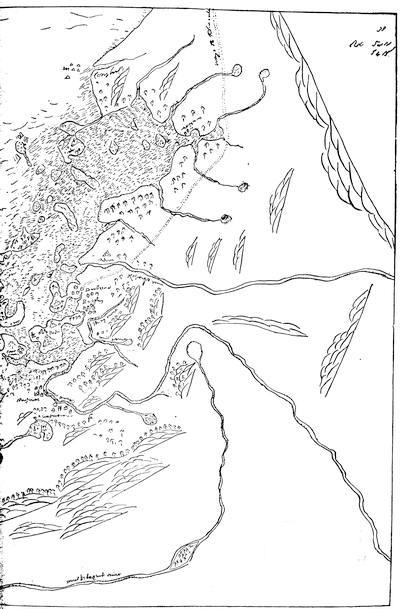

| Illustrations: Maps of New England (1650), 382, (1680), 383. | |

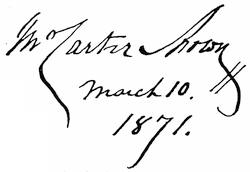

| Autograph: John Carter Brown, 381. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

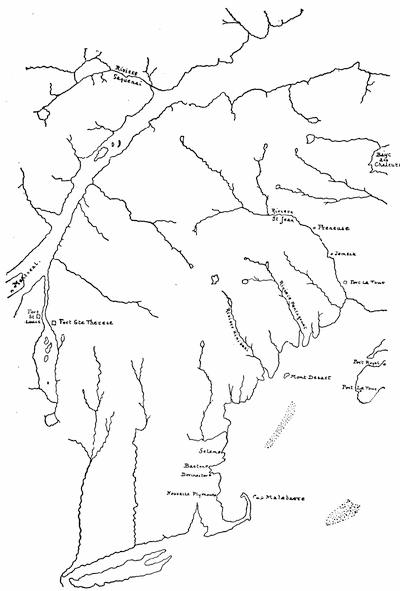

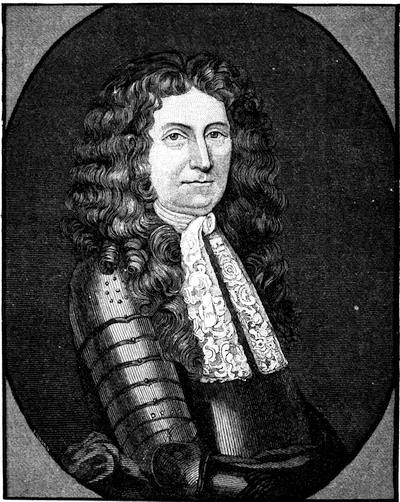

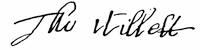

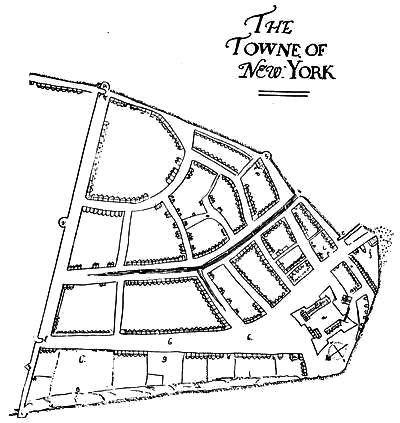

| The English in New York. John Austin Stevens | 385 |

| Illustrations: Sir Edmund Andros, 402; Great Seal of Andros, 410. | |

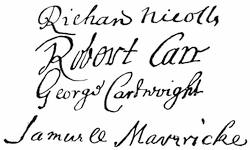

| Autographs: Commissioners (Richard Nicolls, Sir Robert Carr, George Cartwright, Samuel Maverick), 388; Francis Lovelace, 395; Thomas Dongan, 404; Jacob Leisler, 411. | |

| Critical Essay | 411 |

| Notes. The Editor | 414 |

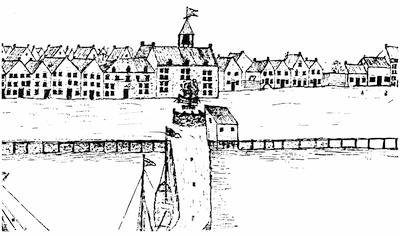

| Illustrations: View of New York (1673), 416; View of The Strand, 417; Plan of New York, 418; Stadthuys (1679), 419. | |

| Autograph: Thomas Willett, 414. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The English in East and West Jersey, 1664-1689. William A. Whitehead | 421 |

| Autographs: King James, 421; Richard Nicoll, 421; Robert Carr, 422; John Berkeley, 422; G. Carteret, 423; Philip Carteret, 424; James Bollen, 428; Edward Byllynge, 430; Gawen Laurie, 430; Nicolas Lucas, 430; Edmond Warner, 430; R. Barclay, 436; Earl of Perth, 439. | |

| Critical Essay[xi] | 449 |

| Note. The Editor | 455 |

| Illustration: Sanson’s map (1656), 456. | |

| Note on New Albion. Gregory B. Keen | 457 |

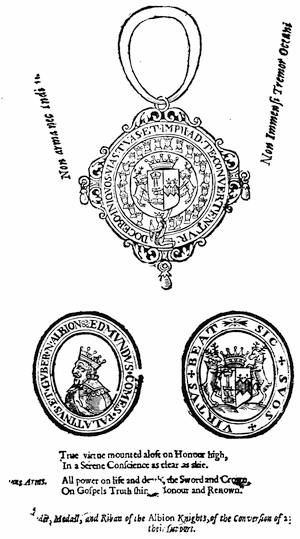

| Illustrations: Insignia of the Albion knights, 462; Farrer map of Virginia (1651), 465. | |

| Autograph: Robert Evelin, 458. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Founding of Pennsylvania. Frederick D. Stone | 469 |

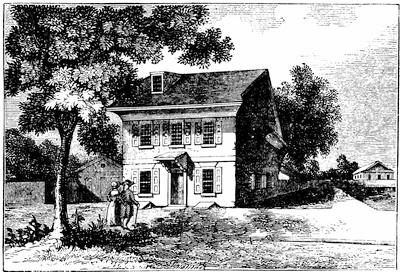

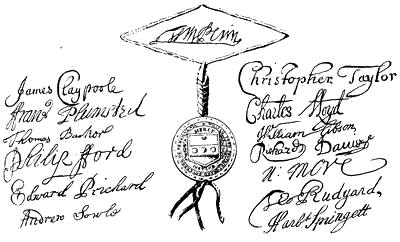

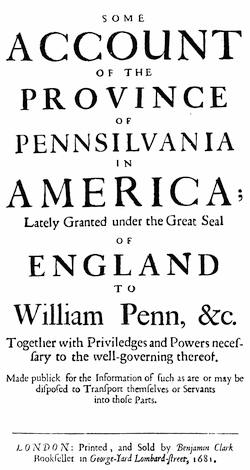

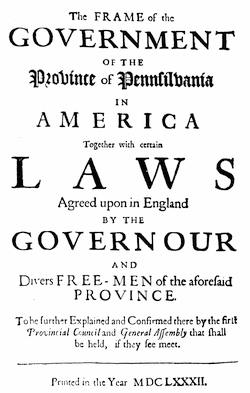

| Illustrations: George Fox, 470; William Penn, 474; Letitia Cottage, 483; Seal and Signatures to Frame of Government, 484; Slate-roof House, 492. | |

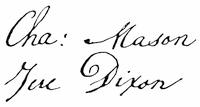

| Autographs: William Penn, 474; Thomas Wynne, 486; Charles Mason, 489; Jeremiah Dixon, 489; Thomas Lloyd, 494. | |

| Critical Essay | 495 |

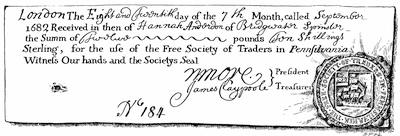

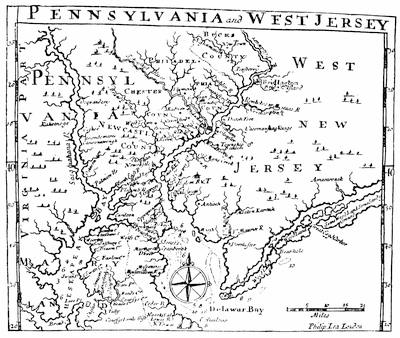

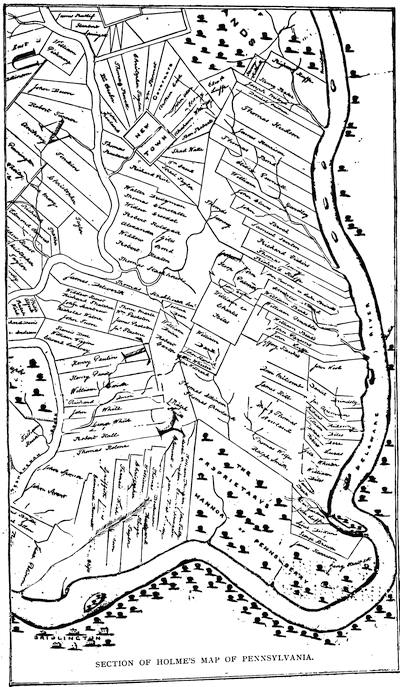

| Illustrations: Title of Some Account, etc., 496; Title of Frame of Government, 497; Receipt and Seal of Free Society of Traders, 498; Gabriel Thomas’s map (1698), 501; Seal of Pennsylvania, 511; Section of Holme’s map of Pennsylvania, 516. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The English in Maryland, 1632-1691. William T. Brantly | 517 |

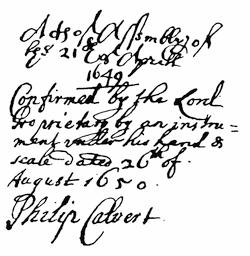

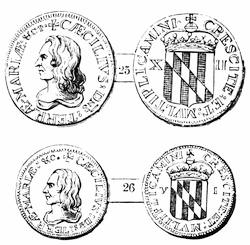

| Illustrations: George, first Lord Baltimore, 518; Baltimore arms, 520; Map of Maryland (1635), 525; Endorsement of Toleration Act, 535; Baltimore coins, 543; Cecil, second Lord Baltimore, 546. | |

| Autographs: George, first Lord Baltimore, 518; Leonard Calvert, 524; Thomas Cornwallis, 524; John Lewger, 528; Thomas Greene, 533; Margaret Brent, 533; William Stone, 534; Josias Fendall, 540; Charles Calvert, 542. | |

| Critical Essay | 553 |

| Autograph: Thomas Yong, 558. | |

| INDEX | 563 |

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

THE VOYAGES OF THE CABOTS.

BY CHARLES DEANE, LL. D.

Vice-President, Massachusetts Historical Society.

“WE derive our rights in America,” says Edmund Burke, in his Account of the European Settlements in America, “from the discovery of Sebastian Cabot, who first made the Northern Continent in 1497. The fact is sufficiently certain to establish a right to our settlements in North America.” If this distinguished writer and statesman had substituted the name of John Cabot for that of Sebastian, he would have stated the truth.

SIGN MANUAL OF HENRY VII.

John Cabot, as his name is known to English readers, or Zuan Caboto, as it is called in the Venetian dialect, the discoverer of North America, was born, probably, in Genoa or its neighborhood. His name first appears in the archives of Venice, where is a record, under the date of March 28, 1476, of his naturalization as a citizen of Venice, after the usual residence of fifteen years. He pursued successfully the study of cosmography and the practice of navigation, and at one time visited Arabia, where, at Mecca, he saw the caravans which came thither, and was told that the spices they brought were received from other hands, and that they came originally from the remotest countries of the east. Accepting the new views as to “the roundness of the earth,” as Columbus had done, he was quite disposed to put them to a practical test. With his wife, who was a Venetian woman, and his three sons, he removed to England, and took up his residence at the maritime city of Bristol. The time at which this removal took place is uncertain. In the year 1495 he laid his proposals before the king, Henry VII., who on the 5th of March, 1495/6, granted to him and his three sons, their heirs and[2] assigns a patent for the discovery of unknown lands in the eastern, western, or northern seas, with the right to occupy such territories, and to have exclusive commerce with them, paying to the King one fifth part of all the profits, and to return to the port of Bristol. The enterprise was to be “at their own proper cost and charge.” In the early part of May in the following year, 1497, Cabot set sail from Bristol with one small vessel and eighteen persons, principally of Bristol, accompanied, perhaps, by his son Sebastian; and, after sailing seven hundred leagues, discovered land on the 24th of June, which he supposed was “in the territory of the Grand Cham.” The legend, “prima tierra vista,” was inscribed on a map attributed to Sebastian Cabot, composed at a later period, at the head of the delineation of the island of Cape Breton. On the spot where he landed he planted a large cross, with the flags of England and of St. Mark, and took possession for the King of England. If the statement be true that he coasted three hundred leagues, he may have made a periplus of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, returning home through the Straits of Belle Isle. On his return he saw two islands on the starboard, but for want of provisions did not stop to examine them. He saw no human beings, but he brought home certain implements; and from these and other indications he believed that the country was inhabited. He returned in the early part of August, having been absent about three months. The discovery which he reported, and of which he made and exhibited a map and a solid globe, created a great sensation in England. The King gave him money, and also executed an agreement to pay him an annual pension, charged upon the revenues of the port of Bristol. He dressed in silk, and was called, or called himself, “the Great Admiral.” Preparations were made for another and a larger expedition, evidently for the purpose of colonization, and hopes were cherished of further important discoveries; for Cabot believed that by starting from the place already found, and coasting toward the equinoctial, he should discover the island of Cipango, the land of jewels and spices, by which they hoped to make in London a greater warehouse of spices than existed in Alexandria. His companions told marvellous stories about the abundance of fish in the waters of that coast, which might foster an enterprise that would wholly supersede the fisheries of Iceland. On the 3d of February 1497/8 the King granted to John Cabot (the sons are not named) a license to take up six ships, and to enlist as many men as should be willing to go on the new expedition. He set sail, says Hakluyt, quoting Fabian, in the beginning of May, with, it is supposed, three hundred men, and accompanied by his son Sebastian. One of the vessels put back to Ireland in distress, but the others continued on their voyage. This is the last we hear of John Cabot. His maps are lost. It is believed that Juan de la Cosa, the Spanish pilot, who in the year 1500 made a map of the Spanish and English discoveries in the New World, made use of maps of the Cabots now lost.

Sebastian Cabot, the second son of John Cabot, was born in Venice,[3] probably about the year 1473. He was early devoted to the study of cosmography, in which science his father had become a proficient, and Sebastian was largely imbued with the same spirit of enterprise; and on the removal of his father with his family to England, he lived with them at Bristol. His name first occurs in the letters patent of Henry VII., dated March 5, 1495/6, issued to John Cabot and his three sons, Lewis, Sebastian, and Sancius, and to their heirs and assigns, authorizing them to discover unknown lands. There is some reason to believe that he accompanied his father in the expedition, already mentioned, on which the first discovery of North America was made; but in none of the contemporary documents which have recently come to light respecting this voyage is Sebastian’s name mentioned as connected with it. A second expedition, as already stated, followed, and John Cabot is distinctly named as having sailed with it as its commander; but thenceforward he passes out of sight. Sebastian Cabot, without doubt, accompanied the expedition. No contemporary account of it was written, or at least published, and for the incidents of the voyage we are mainly indebted to the reports of others written at a later period, and derived originally from conversations with Sebastian Cabot himself; in all of which the father’s name, except incidentally, as having taken Sebastian to England when he was very young, is not mentioned. In these several reports but one voyage is spoken of, and that, apparently, the voyage on which the discovery of North America was made; but circumstances are narrated in them which could have taken place only on the second or a later voyage.

With a company of three hundred men, the little fleet steered its course in the direction of the northwest in search of the land of Cathay. They came to a coast running to the north, which they followed to a great distance, where they found, in the month of July, large bodies of ice floating in the water, and almost continual daylight. Failing to find the passage sought around this formidable headland, they turned their prows and, as one account says, sought refreshment at Baccalaos. Thence, coasting southwards, they ran down to about the latitude of Gibraltar, or 36° N., still in search of a passage to India, when, their provisions failing, they returned to England.

If the views expressed by John Cabot, on his return from his first voyage, had been seriously cherished, it seems strange that this expedition did not, at first, on arriving at the coast, pursue the more southerly direction, where he was confident lay the land of jewels and spices.

They landed in several places, saw the natives dressed in skins of beasts, and making use of copper. They found the fish in such great abundance that the progress of the ships was sometimes impeded. The bears, which were in great plenty, caught the fish for food,—plunging into the water, fastening their claws into them, and dragging them to the shore. The expedition was expected back by September, but it had not returned by the last of October.

There is some evidence that Sebastian Cabot, at a later period, sailed on a voyage of discovery from England in company with Sir Thomas Pert, or Spert, but which, on account of the cowardice of his companion, “took none effect.” But the enterprise is involved in doubt and obscurity.

AUTOGRAPH OF HENRY VIII.

In 1512, after the death of Henry VII., and when Henry VIII. had been three years on the throne, Sebastian Cabot entered into the service of Ferdinand, King of Spain, arriving at Seville in September of that year, where he took up his residence; and on the 20th of October was appointed “Capitan de Mar,” with an annual salary of fifty thousand maravedis.[1] Preparations for a voyage of discovery were now made, and Cabot was to depart in March, 1516, but the death of Ferdinand prevented his sailing. On the 5th of February, 1518, he was named, by Charles V., “Piloto Mayor y Exâminadór de Pilotos,” as successor of Juan de Solis, who was killed at La Plata in 1516. This office gave him an additional salary of fifty thousand maravedis; and it was soon afterwards decreed that no pilots should leave Spain for the Indies without being examined and approved by him. In 1524 he attended, not as a member but as an expert, the celebrated junta at Badajoz, which met to decide the important question of the longitude of the Moluccas,—whether they were on the Spanish or the Portuguese side of the line of demarcation which followed, by papal consent in 1494, a meridian of longitude, making a fixed division of the globe, so far as yet undefined, between Spain and Portugal. On the second day of the session, April 15, he and two others delivered an opinion on the questions involved.

In the following year an expedition to the Moluccas was projected, and under an agreement with the Emperor, executed at Madrid on the 4th of March, Sebastian Cabot was appointed its commander with the title of Captain-General. The sailing of the expedition was delayed by the intrigues of the Portuguese. In the mean time his wife, Catalina Medrano, who is again mentioned with her children a few years later, received by a royal order fifty thousand maravedis as a gratificacion. On April 3, 1526, the armada sailed from St. Lucar for the Spice Islands, intending to pass through the Straits of Magellan. It was delayed from point to point, and did not arrive on the coast until the following year, when Cabot entered the La Plata River. A feeling of disloyalty to their commander, the seeds of which had been sown from the beginning, broke out in open mutiny. He had, moreover, lost one of his vessels off the coast of Brazil. He therefore determined to proceed no farther at present, to send to the Emperor a report of the condition of affairs, and in the mean time to explore the La[5] Plata River, which had been penetrated by De Solis in 1515. He remained in that country for several years, and returned in July or August, 1530. The details of this expedition are described in another volume of this work and by another hand.

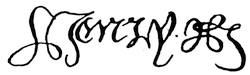

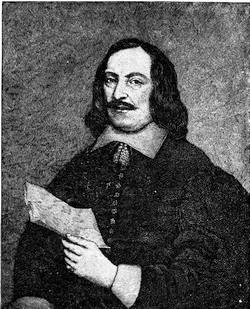

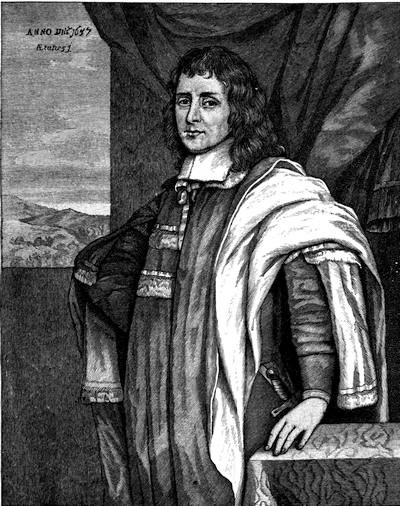

SEBASTIAN CABOT.

[This cut follows a photograph taken from the Chapman copy of the original. The original was engraved when owned by Charles J. Harford, Esq., for Seyer’s Memoirs of Bristol, 1824, vol. ii. p. 208, and a photo-reduction of that engraving appears in Nicholl’s Life of Sebastian Cabot. Other engravings have appeared in Sparks’s Amer. Biog., vol. ix. etc. See Critical Essay.—Ed.]

As might have been expected, this enterprise was regarded at home as a failure, and Cabot had made many enemies in the exercise of his legitimate authority in quelling the mutinies which had from time to time broken out among his men. Complaints were made against him on his return. Several families of those of his companions who were killed in the expedition brought suits against him, and he was arrested and imprisoned, but was liberated on bail. Public charges for misconduct in the affairs of La Plata were preferred against him; and the Council of the Indies, by an order dated from Medina del Campo, Feb. 1, 1532, condemned him to a banishment of two years to Oran, in Africa. I have seen no evidence to show that this sentence was carried into execution. Cabot, who on his return laid before the Emperor Charles V. his final report on the expedition, appears to have fully justified himself in that monarch’s esteem; for he soon resumed his duties as Pilot Major, an office which he retained till his final return to England.

Cabot made maps and globes during his residence in Spain; and a large mappe monde bearing date 1544, engraved on copper, and attributed to him, was found in Germany in 1843, and is now deposited in the National Library in Paris. This map has been the subject of much discussion. While in the employ of the Emperor, Cabot offered his services to his native country, Venice, but was unable to carry his purpose into effect. He was at last desirous of returning to England, and the Privy Council, on Oct. 9, 1547, issued a warrant for his transportation from Spain “to serve and inhabit in England.” He came over to England in that or the following year, and on Jan. 6, 1548/9, the King granted him a pension of £166 13s. 4d., to date from St. Michael’s Day preceding (September 29), “in consideration of the good and acceptable service done and to be done” by him. In 1550 the Emperor, through his ambassador in England, demanded his return to Spain, saying that Cabot was his Pilot Major under large pay, and was much needed by him,—that “he could not stand the king in any great stead, seeing he had but small practice in those seas;” but Cabot declined to return. In that same year, June 4, the King renewed to him the patent of 1495/6, and in March, 1551, gave him £200 as a special reward.

AUTOGRAPH OF EDWARD VI. OF ENGLAND.

The discovery of a passage to China by the northwest having been deemed impracticable, a company of merchants was formed in 1553 to prosecute a route by the northeast, and Cabot was made its governor. He drew up the instructions for its management, and the expedition under Willoughby was sent out, the results of which are well known. China was not reached, but a trade with Muscovy was opened through Archangel. After the accession of Mary to the Crown of England, the Emperor made another unsuccessful demand for Cabot’s return to Spain. On Feb. 6, 1555/6, what is known as the Muscovy Company was chartered, and Cabot became its[7] governor. Among the last notices preserved of this venerable man is an account, by a quaint old chronicler, of his presence at Gravesend, April 27, 1556, on board the pinnace, the “Serchthrift,” then destined for a voyage of discovery to the northeast. It is related that after Sebastian Cabot, “and divers gentlemen and gentlewomen” had “viewed our pinnace, and tasted of such cheer as we could make them aboard, they went on shore, giving to our mariners right liberal rewards; and the good old Gentleman, Master Cabota, gave to the poor most liberal alms, wishing them to pray for the good fortune and prosperous success of the ‘Serchthrift,’ our pinnace. And then at the sign of the ‘Christopher,’ he and his friends banqueted, and made me and them that were in the company great cheer; and for very joy that he had to see the towardness of our intended discovery he entered into the dance himself, amongst the rest of the young and lusty company,—which being ended, he and his friends departed most gently commending us to the governance of Almighty God.”

AUTOGRAPH OF QUEEN MARY.

Cabot’s pension, granted by the late King, was renewed to him by Queen Mary Nov. 27, 1555; but on May 27, 1557, he resigned it, and two days later a new grant was issued to him and William Worthington, jointly, of the same amount, by which he was deprived of one half his pay. This is the last official notice of Sebastian Cabot. He probably died soon afterwards, and in London. Richard Eden, the translator and compiler, attended him in his last moments, and “beckons us, with something of awe, to see him die.” He gives a touching account of the feeble and broken utterances of the dying man. Though no monument or gravestone marks his place of burial, which is unknown, his portrait is preserved, as shown on a preceding page.

CRITICAL ESSAY ON THE SOURCES OF INFORMATION.

UNLIKE the enterprises of Columbus, Vespucius, and many other navigators who wrote accounts of their voyages and discoveries at the time of their occurrence, which by the aid of the press were published to the world, the exploits of the Cabots were unchronicled. Although the fact of their voyages had been reported by jealous and watchful liegers at the English Court to the principal cabinets of the Continent, and the map of their discoveries had been made known, and this had had its influence in leading other expeditions to the northern shores of North America, the historical literature relating to the discovery of America, as preserved in print, is, for nearly twenty years after the events took place, silent as to the enterprises and even the names of the Cabots. Scarcely anything has come down to us directly from these navigators themselves, and for what we know we have hitherto been chiefly indebted to the uncertain reports, in foreign languages, of conversations originally held with Sebastian Cabot many years afterwards, and sometimes related at second and third hand. Even the year in which[8] the voyage of discovery was made was usually wrongly stated, when stated at all, and for more than two hundred years succeeding these events there was no mention made of more than one voyage.[2]

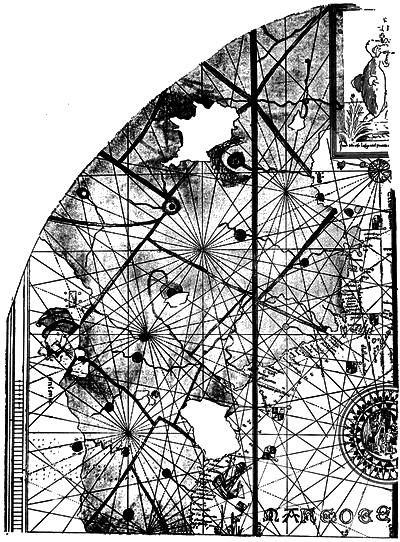

La Cosa Map. 1500. - Left side

La Cosa Map. 1500. - Right side

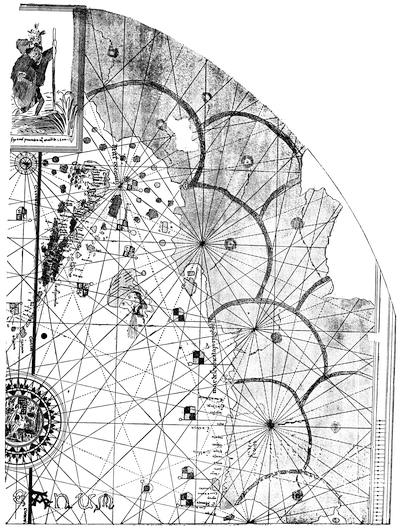

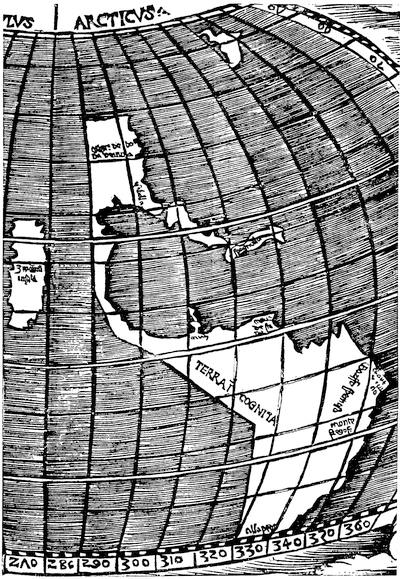

RUYSCH’S MAP, 1508.

I now ask the reader to follow me down through the sixteenth century, if no further, and examine what notices of the Cabots and their voyages we can find in the historical literature of this period; and then to examine what has recently come to light.

John Cabot had died when his son Sebastian in 1512, three years after the death of Henry VII., left England and entered into the service of the King of Spain, who gave him the title of Captain, and a liberal allowance, directing that he should reside at Seville to await orders. He there became an intimate friend of the famous Peter Martyr, the author of the Decades of the New World, or De Orbe Novo, and a volume of letters entitled Opus Epistolarum, etc., a writer too well known to need further introduction here. Through Martyr, for the first time, there was printed in 1516 an account of the voyage of the Cabots.

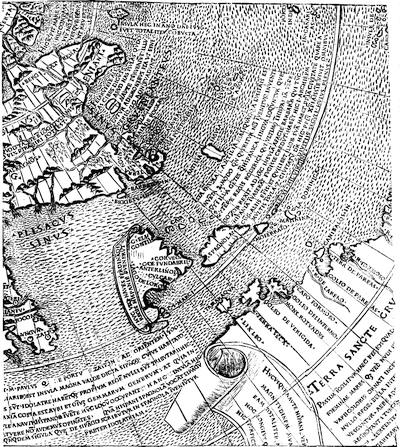

PART OF ORONTIUS FINE’S GLOBE OF 1531, REDUCED TO MERCATOR’S PROJECTION.

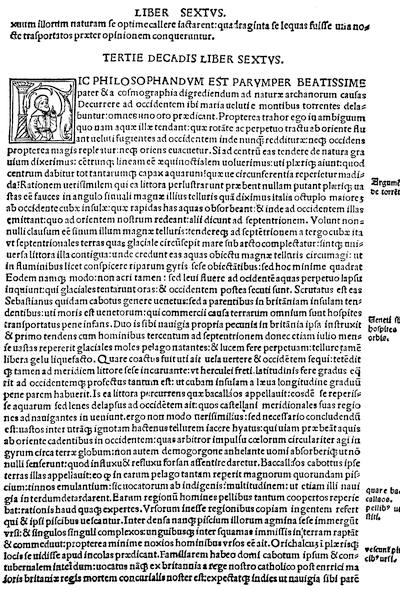

He published in that year at Alcala (Complutum), in Spain, the first three of his Decades, addressed to Pope Leo X., the second and third of which Decades had been written in 1514 and 1515.[3] In the sixth chapter of the third Decade—of which we give later a page in slightly reduced fac-simile—is the following:—

“These northern shores have been searched by one Sebastian Cabot, a Venetian born, whom, being but in manner an infant, his parents carried with them into England, having occasion to resort thither for trade of merchandise, as is the manner of the Venetians to leave no part of the world unsearched to obtain riches. He therefore furnished two ships in England at his own charges, and first with three hundred men directed his course so far towards the North Pole that even in the month of July he found monstrous heaps of ice swimming on the sea, and in manner continual daylight; yet saw he the land in that tract free from ice, which had been molten. Wherefore he was enforced to turn his sails and follow the west; so coasting still by the shore that he was thereby brought so far into the south, by reason of the land bending so much southwards that it was there almost equal in latitude with the sea Fretum Herculeum. He sailed so far towards the west that he had the island of Cuba on his left hand in manner in the same degree of longitude. As he travelled by the coasts of this great land (which he named Baccalaos) he saith that he found the like course of the waters toward the great west, but the same to run more softly and gently than the swift waters which the Spaniards found in their navigation southward.... Sebastian Cabot himself named these lands Baccalaos, because that in the seas thereabout he found so great multitudes of certain big fishes much like unto tunnies (which the inhabitants call baccallaos)[4] that they sometimes staied his ships. He also found the people of those regions covered with beasts’ skins, yet not without the use of reason. He also saith there is great plenty of bears in those regions which use to eat fish; for plunging themselves into the water, where they perceive a[14] multitude of these fishes to lie, they fasten their claws in their scales, and so draw them to land and eat them, so (as he saith) they are not noisome to men. He declareth further, that in many places of those regions he saw great plenty of laton among the inhabitants. Cabot is my very friend, whom I use familiarly, and delight to have him sometimes keep me company in mine own house. For being called out of England by the commandment of the Catholic king of Castile, after the death of Henry VII. King of England, he is now present at Court with us, looking for ships to be furnished him for the Indies, to discover this hid secret of Nature. I think that he will depart in March in the year next following, 1516, to explore it. What shall succeed your Holiness shall learn through me, if God grant me life. Some of the Spaniards deny that Cabot was the first finder of the land of Baccalaos, and affirm that he went not so far westward.”[5]

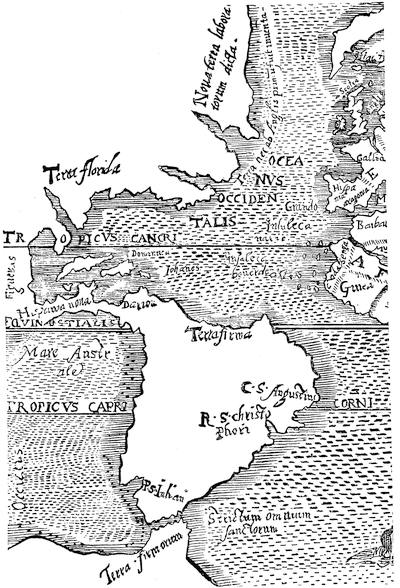

STOBNICZA’S MAP, 1512, REDUCED.

[The legends on the map even on the large scale are not clear, and Brunet, Supplement, p. 697, gives a deceptive account of them. The Carter-Brown Catalogue, p. 54, makes them thus: On North America, “Ortus de bona ventura,” and “Isabella.” Hispaniola is called “Spagnolla.” On the northern shore of South Ameica, “Arcay” and “Caput de Sta de.” On its eastern parts, “Gorffo Fremosa,” “Caput S. Crucis,” and “Monte Fregoso.” At the southern limit, “Alla pega.” The straight lines of the western coasts, as well as the words “Terra incognita,” are thought to represent an uncertainty of knowledge. The island at the west is “Zypangu insula,” or Japan. Mr. Bartlett, the editor of the Carter-Brown Catalogue, is of the opinion that the island at the north is Iceland; but it seems more in accordance with the prevailing notions of the time to call it Baccalaos. It appears in the same way on the Lenox globe, and in the circumpolar MS. map of Da Vinci (1513) in the Queen’s library at Windsor, where this island is marked “Bacalar.” The eastern coast outline of the Stobnicza map bears a certain resemblance to the Waldseemüller map which appeared in the Ptolemy of 1513, having been however engraved, but not published, in 1507, and Stobnicza may have seen it. If so, he might have intended the straight western line of North America to correspond to the marginal limit of the Ptolemy map; but he got no warrant in the latter for the happy conjecture of the western coast of the Southern Continent, nor could he find such anywhere else, so far as we know. The variations of the eastern coast do not indicate that he depended, solely at least, upon the Ptolemy map, which carries the northern cut-off of the northern continent five degrees higher. “Isabella” is transferred from Cuba to Florida, and the northeast coast of South America is very different. There are accurate fac-similes of this Ptolemy map in Varnhagen’s Premier Voyage de Vespucci, and in Stevens’s Historical and Geographical Notes, pl. ii. See the chapter on Norumbega, notes.—Ed.]

This account we may well suppose to have come primarily from Sebastian Cabot himself, and it will be noticed that his father is not mentioned as having accompanied him on the voyage. Indeed, no reference is made to the father except under the general statement that his parents took him to England while he was yet very young, pene infans. No date is given, and but one voyage is spoken of. It may be said that Peter Martyr is not here writing a history of the voyage or voyages of the Cabots; that the account is merely brought into his narrative incidentally, as it were, to illustrate a subject upon which he was then writing,—namely, on a “search” into “the secret causes of Nature,” or the reason “why the sea runneth with so swift course from the east into the west;” and that he cites the observations of Sebastian Cabot, in the region of the Baccalaos, for his immediate purpose. Richard Biddle, in his Life of Sebastian Cabot, pp. 81-90, supposes the voyage here described to be the second, that of 1498, undertaken after the death of the father, as the mention of the three hundred men taken out would imply a purpose of colonization, while the first voyage was one of discovery merely; and thinks that this view is confirmed by a subsequent reference of Martyr to Cabot’s discovery of the Baccalaos, in Decade seven, chapter two, written in 1524, where the discovery is said to have taken place “twenty-six years before,” that is, in 1498.[6]

PETER MARTYR, 1516.

A map of the world was composed in 1529 by Diego Ribero, a very able cosmographer and map-maker of Spain in the early part of the sixteenth century. It is a very interesting map, but is so well known to geographers that I need give no particular description of it here. The northern part of our coast, delineated upon it, is supposed to have been drawn from the explorations and reports of Gomez made in 1525. It was copied and printed, in its general features only, in 1534, at Venice. A superior copy in fac-simile of the original map was published by Dr. Kohl in 1860, at Weimar, in his Die beiden Æltesten General-Karten von Amerika.[7] On this map an inscription, of which the following is an English version, is placed over the territory inscribed Tierra del Labrador: “This country the English discovered, but there is nothing useful in it.” See an abridged section of the map and a description of it in Kohl’s Doc. Hist. of Maine, i. 299-307.[8]

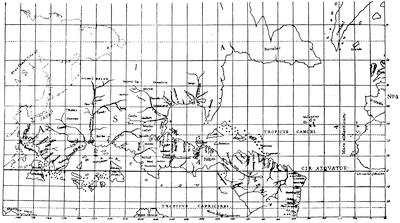

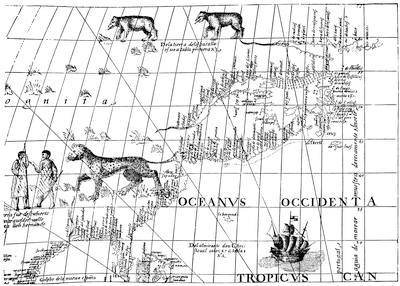

THORNE’S MAP, 1527.

In 1530, four years after Martyr’s death, there was published at Alcala (Complutum), in Spain, his eight Decades, De Orbe Novo, which included the three first published in 1516, in the last of which, the third, appeared the notice of Sebastian Cabot cited above. And it may be added here that the three Decades, including the De nuper ... repertis insulis, etc., or abridgment, so called, of the fourth Decade, printed at Basel in 1521, were reprinted together in that city in 1533. Of later editions there will be occasion to say something farther on. Martyr’s notice of Cabot was the earliest extant, and the republication of these Decades, at different places, served to keep alive the important fact of the discovery of North America under the English flag. In some of these later Decades, written in 1524 and 1525, references will be found to Sebastian Cabot and to his employment in Spain.

There was published in Latin at Argentoratum (Strasbourg), in 1532, by James Ziegler,—a Bavarian theologian, who cultivated mathematics and cosmography with success,—a book relating in part to the northern regions. Under the head of “Gronland” the author quotes Peter Martyr’s account of Sebastian Cabot’s voyage:—

“Peter Martyr of Angleria writeth in his Decades of the Spanish navigations, that Sebastian Cabot,[9] sailing from England continually towards the north, followed that course so far that he chanced upon great flakes of ice in the month of July; and diverting from thence he followed the coast by the shore, bending toward the south until he came to the clime of the island of Hispaniola above Cuba, an Island of the Cannibals. Which narration hath given me occasion to extend Gronland beyond the promontory or cape of Huitsarch to the continent or firm land of Lapponia above the castle of Wardhus; which thing I did the rather for that the reverend Archbishop of Nidrosia constantly affirmed that the sea bendeth there into the form of a crooked elbow.”

This writer evidently supposed that Cabot sailed along the east coast of Greenland, and the inference he drew from Cabot’s experience, as related by Martyr, confirmed his belief[19] that that country joined on to Lappona (Lapland),—an old notion which lasted down to the time of Willoughby,—making “one continent;” and so he represented it on his map no. 8, published in his book.[10] He places “Terra Bacallaos” on the east coast of “Gronland.” He believed that Cabot’s falling in with ice proved “that he sailed not by the main sea, but in places near unto the land, comprehending and embracing the sea in the form of a gulf.” I have copied this from Eden’s English version of Ziegler (Decades, fol. 268), in the margin of which at this place Eden says, “Cabot told me that this ice is of fresh water, and not of the sea.”[11]

There was published at Venice in 1534, in Italian, a volume in three parts; the first of which was entitled, Summario de la generale historia de l’indie occidentali cavato da libri scritti dal signor don Pietro Martyre del consiglio delle indie della maesta de l’imperadore, et da molte altre particulari relationi.[12]

This, as will be seen, purports to be a summary drawn from Peter Martyr and other sources,—“from many other private accounts.” The basis of the work is Martyr’s first three Decades, published together in Latin in 1516, the original arrangement of the author being entirely disregarded, many facts omitted, and new statements introduced for which no authority is given. By virtue of the concluding words of the quoted title, the translator or compiler appears to claim the privilege of taking the utmost liberty with the text of Martyr. For the well-known passage in the sixth chapter of the third Decade, where Martyr says that Sebastian Cabot “sed a parentibus in Britāniam insulam tendentibus, uti moris est Venetorum: qui commercii causa terrarum omnium sunt hospites transportatus pene infans” (“whom being yet but in manner an infant, his parents carried with them into England, having occasion to resort thither for trade of merchandise, as is the manner of the Venetians to leave no part of the world unsearched to obtain riches”), the Italian translator has substituted, “Costui essendo piccolo fu menato da suo padre in Inghilterra, da poi la morte del quale trouandosi ricchissimo, et di grande animo, delibero si come hauea fatto Christoforo Colombo voler anchor lui scoprire qualche nuoua parte del mōdo,” etc. (“He being a little boy was taken by his father into England, after whose death, finding himself very rich and of great ambition, he resolved to discover some new part of the world as Columbus had done”).

M. D’Avezac has given some facts which show that the editor of this Italian version of Peter Martyr, as he calls this work, was Ramusio, the celebrated editor of the Navigationi et Viaggi,[13] etc., and this work is introduced into the third volume of that publication, twenty-one years later. Mr. Brevoort has also called my attention to the fact that the woodcut of “Isola Spagnuola,” used in the early work, was introduced into the later one, which is confirmatory of the opinion that Ramusio was at least the editor of the Summario of 1534.[14]

Cabot we know was, during his residence in Spain, a correspondent of Ramusio,—at least, the latter speaks once of Cabot’s having written to him, and we shall see farther on that they were not strangers to each other,—and it is possible that this modification of Peter Martyr’s language was authorized by him. It is here stated, however, that Cabot reached only 55° north, while in the prefatory Discorso to his third volume the editor says that Cabot wrote to him many years before that he reached the latitude of 67 degrees and a half, and no explanation is given as to whether the reference is to the same voyage. A fair inference from the passage above cited from the Italian Summario would be that Sebastian Cabot planned the voyage of discovery after his father’s death, which we know[20] was not true; as it was equally untrue that the death of his father made him very rich, for the Italian envoy tells us that John Cabot was poor. Indeed, the whole language of the passage relating to Sebastian Cabot is mythical and untrustworthy, whoever may have inspired it.[15]

I now come to a map of Sebastian Cabot, bearing date 1544, as the year of its composition, a copy of which was discovered in Germany in 1843, by Von Martius, in the house of a Bavarian curate, and deposited in the following year in the National Library in Paris. It has been described at some length by M. D’Avezac, in the Bulletin de la Société de Géographie, 4 ser. xiv. 268-270, 1857. It is a large elliptical mappe monde, engraved on metal, with geographical delineations drawn upon it down to the time it was made. I saw the map in Paris in 1866. On its sides are two tables: the first, on the left, inscribed at the head “Tabula Prima;” and that on the right, “Tabula Secunda.” On these tables are seventeen legends, or inscriptions, in duplicate; that is to say, in Spanish and in Latin, the latter supposed to be a translation of the former,—each Latin legend immediately following the Spanish original and bearing the same number.[16]

After the seventeen legends in Spanish and in Latin, we come to a title or heading: “Plinio en el secund libro capitulo lxxix., escriue” (“Pliny, in the second book, chapter 79, writes”). Then follows an inscription in Spanish, no. 18, from Pliny’s Natural History, cap. lxvii., the chapter given above being an error. Four brief inscriptions, also in Spanish, numbered 19 to 22, relating to the natural productions of islands in the eastern seas, taken from other authors, complete the list. So there are twenty-two Spanish inscriptions or legends on the map,—ten on the first table and twelve on the second,—the last five of which have no Latin exemplaires; and there are no Latin inscriptions without the same text in Spanish immediately preceding.

There are no headings prefixed to the inscriptions, except the 1st, the 17th, and 18th. The first inscription, relating to the discovery of the New World by Columbus, has this title, beneath Tabula Prima, “del almirante.” The 17th—a long inscription—has this title: Retulo, del auctor conçiertas razones de la variaçion que haze il aguia del marear con la estrella del Norte (“A discourse of the author of the map, giving certain reasons for the variation of the magnetic needle in reference to the North Star”). It is also repeated in Latin over the version of the inscription in that language. The title to the 18th inscription, if it may be called a title, has already been given.

The 17th inscription begins as follows: “Sebastian Caboto, capitan y piloto mayor de la S. c. c. m. del Imperador don Carlos quinto deste nombre, y Rey nuestro sennor [21]hizo este figura extenda en plano, anno del nascimo de nrō Salvador Iesu Christo de MDXLIIII. annos, tirada por grados de latitud y longitud con sus vientos como carta de marear, imitando en parte al Ptolomeo, y en parte alos modernos descobridores, asi Espanoles como Portugueses, y parte por su padre, y por el descubierto, por donde, podras navegar como por carta de marear, teniendo respecto a luariaçion que haze el aguia,” etc. (“Sebastian Cabot, captain and pilot-major of his sacred imperial majesty, the emperor Don Carlos, the fifth of this name, and the king our lord, made this figure extended on a plane surface, in the year of the birth of our Saviour Jesus Christ, 1544, having drawn it by degrees of latitude and longitude, with the winds, as a sailing chart, following partly Ptolemy and partly the modern discoveries, Spanish and Portuguese, and partly the discovery made by his father and himself: by it you may sail as by a sea-chart, having regard to the variation of the needle,” etc.). Then follows a discussion relating to the variation of the magnetic needle, which Cabot claims first to have noticed.[17]

In the inscription, No. 8, which treats of Newfoundland, it says: “This country was discovered by John Cabot, a Venetian, and Sebastian Cabot, his son, in the year of our Lord Jesus Christ, MCCCCXCIV. [1494] on the 24th of June, in the morning, which country they called ‘primum visam’; and a large island adjacent to it they named the island of St. John, because they discovered it on the same day.”[18]

A fac-simile of this map was published in Paris by M. Jomard, in Plate XX. of his Monuments de la Géographie (begun in 1842, and issued during several years following down to 1862), but without the legends on its sides, which unquestionably belong to the map itself; for those which, on account of their length, are not included within the interior of the map, are attached to it by proper references. M. Jomard promised a separate volume of “texte explicatif,” but death prevented the accomplishment of his purpose.[19]

PART OF THE SEBASTIAN CABOT MAPPE MONDE, 1544.

If this map, with the date of its composition, is authentic, it is the first time the name of John Cabot has been introduced to our notice in any printed document, in connection with the discovery of North America. Here the name is brought in jointly with that of Sebastian Cabot, on the authority apparently of Sebastian himself. He is said to be the maker of the map, and if he did not write the legends on its sides he may be supposed not to have been ignorant of their having been placed there. As to Legend No. 8, copied above, who but Sebastian Cabot would know the facts embodied in it,—namely, that the discovery was made by both the father and the son, on the 24th of June, about five o’clock in the morning; that the land was called prima vista, or its equivalent, and that the island near by was called St. John, as the discovery was made on St. John’s Day? Whether or not Sebastian Cabot’s statement is to be implicitly relied on, in associating his own name with his father’s in the voyage of discovery, in view of the evidence which has recently come to light, the legend itself must have proceeded from him. Some additional information in the latter part of the inscription, relating to the native inhabitants, and the productions of the country, may have been gathered in the voyage of the following year. Sebastian Cabot, without doubt, was in possession of his father’s maps, on which would be inscribed by John Cabot himself the day on which the discovery was made.

Whatever opinions, therefore, historical scholars may entertain as to Sebastian Cabot’s connection with this map in its present form, or with the inscriptions upon it as a whole, all must admit that the statements embodied in No. 8, and, it may be added, in No. 17, could have been communicated by no one but Sebastian Cabot himself. The only alternative is that they are a base fabrication by a stranger. Moreover, this very map itself, or a map with these legends upon it, as we shall see farther on, was in the possession of Richard Eden, or was accessible to him; and one of its long inscriptions was translated into English, and printed in his Decades, in 1555, as from “Cabot’s own card,”—and this at a time when Cabot was living in London, and apparently on terms of intimacy with Eden. Legend No. 8 contains an important statement which is confirmed by evidence recently come to light, namely, the fact of John Cabot’s agency in the discovery of North America; and, although the name of the son is here associated with the father, it is a positive relief to find an acknowledgment from Sebastian himself of a truth that was to receive, before the close of the century, important support from the publication of the Letters Patent from the archives of the State. And this should serve to modify our estimate of the authenticity of reports purporting to come from Sebastian, in which the father is wholly ignored, and the son alone is represented as the hero. The long inscription, No. 17, contains an honorable mention of his father, as we have already seen; and in the Latin duplicate, the language in the passage which I have given in English will be seen to be even more emphatic than is expressed in the Spanish text. Indeed, in several instances in the Latin, though generally following the Spanish, so far as I have had an opportunity of observing, there are some statements of fact not to be found in the Spanish.[20] The passage already cited concludes[24] thus in the Latin: “And also from the experience and practice of long sea-service of the most excellent John Cabot, a Venetian by nation, and of my author [the map is here made to speak for itself] Sebastian his son, the most learned of all men in knowledge of the stars and the art of navigation, who have discovered a certain part of the globe for a long time hidden from our people.”[21]

Though we are not quite willing to believe that Sebastian Cabot wrote the eulogy of himself contained in this passage, yet who but he could have known of those facts concerning his father, who, we suppose, had been dead some fifty years before this map was composed?

The map itself, as a work of Sebastian Cabot, is unsatisfactory, and many of the legends on its sides are also unworthy of its alleged author. It brought forward for the first time, in Legend 8, the year 1494 as the year of the discovery of North America, which the late M. D’Avezac accepted, but which I cannot but think from undoubted evidence, to be adduced farther on, is wrong. The “terram primum visam” of the legend is inscribed on the northern part of Cape Breton, and there would seem to be no good reason for not accepting this point on the coast as Cabot’s landfall. The “y de s. Juan,” the present Prince Edward Island, is laid down on the map; and although Dr. Kohl thinks that the name was given by the French, and that Cabot may have taken it, not from his own survey, but from the French maps, I have seen no evidence of the application of the name on any map before this of Cabot. Cartier gave the name “Sainct Jean” to a cape on the west coast of Newfoundland, in 1534, discovered also on St. John’s Day; but this fact was not known, in print at least, till 1556, when the account of his first voyage was published in the third volume of Ramusio.

We find no strictly contemporaneous reference to this map, or evidence that it exerted any influence on opinions respecting the first two voyages of the Cabots; and the name of John Cabot again sinks out of sight. Dr. Kohl has called attention to the fact that the author of this map has copied the coast line of the northern shore largely from Ribero.

It may be added that the inscription No. 8, on Cabot’s map, has since its republication by Hakluyt, with an English version by him, in 1589, been regarded as containing the most definite and satisfactory statement which had appeared as to the discovery of North America, the date as to the year having been subjected to some interesting criticisms, to be referred to farther on.

In the year 1550 Ramusio issued at Venice the first volume of his celebrated collection of voyages and travels in Italian, entitled, Delle Navigationi et Viaggi, etc. This contained, in a discourse on spices, etc., the well-known report of a conversation at the villa of Hieronymo Fracastor, at Caphi, near Verona, in which the principal speaker, a most profound philosopher and mathematician, incidentally relates an interview which he had, some years before, with Sebastian Cabot at Seville. Ramusio, who was present, and tells the story himself, says he does not pretend to give the conversation precisely as he heard it, for that would require a talent beyond his; but he would try and give briefly what he could recollect of it. The substance of Cabot’s story as related, much abridged by me, is this:—

Sebastian Cabot’s father took him from Venice to London when he was very young, yet having some knowledge of the humanities, and of the sphere. His father died at the time when the news was brought of the discovery of Columbus, which caused a great talk at the court of Henry VII., and which created a great desire in him (Cabot) to attempt some great thing; and understanding, by reason of the sphere, that if he should sail by the northwest he would come to India by a shorter route, he caused the king to be informed of his idea, and the king immediately furnished him with two small ships, and all things necessary for the voyage, which was in the year 1496, in the beginning of summer. He therefore began to sail to the northwest, expecting to go to Cathay, and from thence to turn towards India, but found after some days, to his displeasure, that the land ran towards the north. He still proceeded hoping to find the passage, but found the land still continent to the 56th degree; and seeing there that the coast turned toward the east, he, in despair of finding the passage, turned back and sailed down the coast toward the equinoctial, ever hoping to find the passage, and came as far south as Florida, when, his provisions failing, he returned to England, where he found great tumults among the people, and wars in Scotland.

The volumes of Ramusio became justly celebrated throughout the literary centres of Europe, and the publication of the account of Sebastian Cabot’s discovery in the first volume attracted the attention of scholars in England. It will be noticed that Sebastian Cabot here, as well as in the account in Peter Martyr, is said to have been born in Venice, and taken to England while yet very young; yet not so young but that he had acquired some knowledge of letters, and of the sphere. He speaks here of the death of his father as occurring before the voyage of discovery was entered upon, for which he had two small ships furnished him by the king. He says that this was in the year 1496; yet he speaks of events occurring in England on his return,—great tumults among the people, and wars in Scotland,—which point to the year 1497. The latitude he reached “under our pole” was 56 degrees; and, despairing to find the passage to India, he turned back again, sailed down the coast, “and came to that part of this firm land we now call Florida.”[22] Many incidents here described could not have occurred on the voyage of discovery, as we shall see farther on.

We do not know the precise year in which the interview at Seville between this learned man and Sebastian Cabot was held, but have given some reasons below for believing that it took place about ten years before it was printed by Ramusio.[23]

I might mention here another reference to Cabot, in Ramusio’s third volume, 1556, though of a little later date. In a prefatory dedication to his excellent friend Hieronimo Fracastor,[24] at whose house the conversation related in Ramusio’s first volume took place, Ramusio under date of June 20, 1553, says that “Sebastian Cabot our countryman, a Venetian,” wrote to him many years ago that he sailed along and beyond this land of New France, at the charges of Henry VII. King of England; that he sailed a long time west and by north into the latitude of 67½ degrees, and on the 11th of June, finding still the sea open, he expected to have gone on to Cathay, and would have gone, if the mutiny of the shipmaster and mariners had not hindered him and made him return homewards from that place.[25]

I have already briefly referred to this letter, in speaking of the alleged voyage of 1516-17, contended for by Biddle (pp. 117-19), on which occasion he thinks Cabot entered Hudson Bay. This passage in Ramusio is mentioned twenty years later by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, in his tract, as we shall see farther on, principally on account of the high degree of northern latitude reached, 67½°, and where the sea was found still open.[26] As this is the only account of a voyage which describes so high an elevation reached, and an immediate return thence by reason of mutiny, some have supposed that the incidents described must have occurred on a third voyage, in company with Sir Thomas Pert. On Cabot’s map of 1544 there is inscribed a coast line trending westward, terminating at the degree of latitude named.

In 1552 Gomara’s Historia General de las Indias was published at Saragossa in Spain. In cap. xxxix., under the head of “Los Baccalaos,” he says:—

“Sebastian Cabot was the first that brought any knowledge of this land, for being in England in the days of King Henry VII. he furnished two ships at his own charges, or (as some say) at the King’s, whom he persuaded that a passage might be found to Cathay by the North Seas.... He went also to know what manner of lands those Indies were to inhabit. He had with him three[27] hundred men, and directed his course by the track of Iceland, upon the Cape of Labrador, at fifty-eight degrees (though he himself says much more), affirming that in the month of July there was such cold and heaps of ice that he durst pass no further; that the days were very long and in manner without night, and the nights very clear. Certain it is that at sixty degrees the longest day is of 18 hours. But considering the cold and the strangeness of the unknown land, he turned his course from thence to the west, refreshing themselves at Baccalaos; and following the coast of the land unto the 38th degree, he returned to England.”[27]

Francis Lopez Gomara was among the most distinguished of the historical writers of Spain. In his History of the Indies his purpose was to give a brief view of the whole range of Spanish conquest in the islands and on the American continent, as far down as about the middle of the sixteenth century. He must have known Cabot in Seville, and might have informed himself as to his early maritime enterprises, but he seems to have neglected his opportunity. His book was published after Cabot had returned to England. On one point in the above brief account, namely, as to whether the ships were furnished at the charge of Cabot, he speaks doubtfully. Peter Martyr had said that Cabot furnished two ships at his own charge, while Ramusio, in the celebrated Discorso, makes Cabot say that the king furnished them. As usual but one voyage is spoken of; and Sebastian Cabot is the only commander, and is called a Venetian. His statement contains little new, and is principally a repetition of Peter Martyr. There is added the statement that the expedition, on returning from the northern coasting, “refreshed at Baccalaos.” The degrees given, as to the latitude and longitude reached in sailing both north and south, appear to be an inference from Martyr and Ramusio. The incidents here related of course refer to the second voyage. Gomara, in his history, has other notices of Cabot during his residence in Spain at a later period, in connection with his account of the junta at Badajos, and the expedition to the La Plata.

In 1553 Richard Eden, the first English collector of voyages and travels, published in London a translation “out of Latin into English” of the fifth book of the Universal Cosmographia of Sebastian Münster, entitling it A Treatise of the Newe India,[28] etc. In the dedication of the book to the Duke of Northumberland, who had been Lord High Admiral of England under Henry VIII., Eden says, incidentally, that “King Henry VIII. about the same year of his reign [i. e. between April 1516 and April 1517], furnished and sent forth certain ships under the gouvernance of Sebastian Cabot yet living, and one Sir Thomas Pert, whose faint heart was the cause that the voyage took none effect;” and that if manly courage “had not at that time been wanting, it might happily have come to pass that that rich treasure called Perularia, which is now in Spain in the city of Sivil, and so named for that in it is kept the infinite riches brought hither from the new-found-land of Peru, might long since have been in the Tower of London, to the king’s great honor and wealth of this his realm.”

I find no notice taken of this statement of Eden, at the time, and it is only when we come down to the publication of Hakluyt’s folio, in 1589, that we see an attempt made to attach some importance to it. Although deviating a little from the chronological order of[28] this narrative, I propose here to bring together what I may have to say concerning this voyage.

Dr. Kohl[29] very properly says that this incidental remark of Eden is all the original evidence we have on this so-called expedition of Cabot in 1516, to which some modern writers attach great importance, and by which great discoveries are said to have been made under Henry VIII. Hakluyt, in his folio of 1589, p. 515, copies the language of Eden cited above, and also an abstract from a spurious Italian version of Oviedo, in Ramusio’s collections, in which that writer is made to say that a Spanish vessel in the year 1517 fell in with an English rover at the islands of St. Domingo and St. John’s in the West Indies, on their way from Brazil; and concludes that this English rover could be none other than the vessel of Cabot and Pert. But Richard Biddle,[30] nearly two hundred and fifty years after Hakluyt wrote this opinion, exploded this theory by showing that Oviedo, in his genuine work, really gave 1527 as the date of the meeting of the English vessel, as narrated. Biddle, however, still had faith in Eden’s statement that an expedition sailed from England in the year indicated, commanded by Cabot and Pert, but held that it took a northwesterly direction, and that it was on this expedition that Cabot entered Hudson Bay, and reached the high latitude of 67½ N. as mentioned by him in a letter to Ramusio;[31] in which letter Cabot says that “on the 11th of June, finding still the open sea without any manner of impediment, he thought verily by that way to have passed on still the way to Cathay, which is in the east, ... if the mutiny of the shipmaster and mariners had not hindered him, and made him to return homewards from that place.” Biddle saw a parallel in the language of Eden as to the “faint heart” of Pert, and in that of Cabot as to the “mutiny of the shipmaster and mariners;” not forgetting also similar language in a letter written by Robert Thorne to Doctor Ley, in 1527, relating to a voyage of discovery to the west, in which Thorne’s father and another merchant of Bristol, Hugh Eliot, were participants—which voyage, Mr. Biddle says, was in 1517—that, “if the mariners would then have been ruled and followed their pilots’ mind, the lands of the West Indies, from whence all the gold cometh, had been ours.”[32] Mr. Biddle forgets that in the letter of Cabot to Ramusio, cited above, the writer says that the voyage of which he is here speaking was made in the reign of Henry VII., who died in 1509, seven or eight years before the date which Biddle assigns to the alleged Cabot and Pert voyage.

Dr. Kohl, who has very learnedly and at great length examined the claims for this voyage of 1516-17,[33] has little confidence that any such expedition actually sailed. Eden says the voyage “took none effect,” which may mean that the expedition never sailed. It seems also very improbable that Cabot, so recently domiciled in Spain, where he was occupying an honorable position, should leave it all now and re-enter the service of England, by whose Government he had apparently for so many years been neglected. No English or Spanish writer mentions his leaving Spain at this time.[34]

In 1555 there appeared in London the first collection in English of the “results of that spirit of maritime enterprise which had been everywhere awakened by the discovery of America.” The book was edited by Richard Eden,—just mentioned as the translator of the fifth book of Munster, in 1553,—and consisted of translations from foreign writers, principally Latin, Spanish, and Italian, of travels by sea and land, largely relating to discoveries in the New World. The book was entitled, The Decades of the Newe Worlde or West India, etc., inasmuch as one hundred and sixty-six folios out of three hundred and seventy-four, which the book contains, consist of the first three Decades of Peter Martyr, and an epitome of the fourth Decade first issued at Basle, in 1521. Then follow abstracts of Oviedo, Gomara, Ramusio, Ziegler, Pigafeta, Munster, Bastaldus, Vespucius, and several others. Some of the voyages are original and were drawn up by Eden’s own hand. It is a very desirable book to possess; and though Eden was a clumsy editor, not always correct in his translations, and did not always make it clear whether he or his author was speaking, we are grateful to him for the book. An enthusiastic tribute is paid to Eden and his book by Richard Biddle,[35] who sets him off by an invidious comparison with Richard Hakluyt, whom he studiously depreciates. Eden was apparently a devoted Catholic, and was a spectator of the public entry of Philip and Mary into London in 1554. He says that the splendid pageant as it passed before him inspired him to enter upon some work which he might in due season offer as the result of his loyalty, and “crave for it the royal blessing.”[36] In his preface to the reader Eden gives a brief review of ancient history, and coming down to the time of the conquest of the Indies by Spain he eulogizes the conduct of that nation towards the natives, particularly in having so effectually labored for their conversion. His language is one continued eulogy of the Spaniards. He urges England to submit to King Philip, of whom he says:—

“Of his behavior in England, his enemies (which canker virtue never lacked),—they, I say, if any such yet remain,—have greatest cause to report well, yea so well, that if his natural clemency were not greater than was their unnatural indignation, they know themselves what might have followed.... Being a lion he behaved himself as a lamb, and struck not his enemy having the sword in his hand. Stoop, England, stoop, and learn to know thy lord and master, as horses and other brute beasts are taught to do!”

He earnestly desires to see the Christian religion enlarged, and urges his countrymen to follow here the example of the Spaniards in the New World. He says:—

“I am not able, with tongue or pen, to express what I conceive hereof in my mind, yet one thing I see which enforseth me to speak, and lament that the harvest is so great and the workmen so few. The Spaniards have showed a good example to all Christian nations to follow. But as God is great and wonderful in all his works, so beside the portion of land pertaining to the Spaniards (being eight times bigger than Italy, as you may read in the last book of the second Decade), and beside that which pertaineth to the Portugals, there yet remaineth another portion of that main land reaching toward the northeast, thought to be as large as the other, and not yet known but only by the sea-coasts, neither inhabited by any Christian men; whereas, nevertheless, (as writeth Gemma Phrisius) in this land there are many fair and fruitful regions, high mountains, and fair rivers, with abundance of gold, and diverse kinds of beasts. Also cities and towers so well builded, and people of such civility, that this part of the world seemeth little inferior to our Europe, if the inhabitants had received our religion. They are witty people and refuse not bartering with strangers. These regions are called Terra Florida and Regio Baccalearum or Bacchallaos, of the which you may read somewhat in this book in the voyage of that worthy old man yet living,[30] Sebastian Cabot, in the vi. book of the third Decade. But Cabot touched only in the north corner, and most barbarous part thereof, from whence he was repulsed with ice in the month of July. Nevertheless, the west and south parts of these regions have since been better searched by other, and found to be as we have said before.... How much therefore is it to be lamented, and how greatly doth it sound to the reproach of all Christendom, and especially to such as dwell nearest to these lands (as we do), being much nearer unto the same than are the Spaniards (as within xxv days sailing and less),—how much, I say, shall this sound unto our reproach and inexcusable slothfulness and negligence, both before God and the world, that so large dominions of such tractable people and pure gentiles, not being hitherto corrupted with any other false religion (and therefore the easier to be allured to embrace ours), are now known unto us, and that we have no respect neither for God’s cause nor for our own commodity, to attempt some voyages into these coasts, to do for our parts as the Spaniards have done for theirs, and not ever like sheep to haunt one trade, and to do nothing worthy memory among men or thanks before God, who may herein worthily accuse us for the slackness of our duty toward him.”

The few voyages of discovery made by the English in the first part of the sixteenth century, either by the authority of the Government or on private account, were productive of little results; and when Sebastian Cabot finally returned to England from Spain, in 1547 or 1548, his influence was engaged by sundry merchants of London, who were seeking to devise some means to check the decay of trade in the realm, by the discovery of a new outlet for the manufactured products of the nation. The result was the sending off the three vessels under Willoughby, in May, 1553, to the northeast, and finally the incorporation of the merchant adventurers, with Cabot as governor.

In Richard Eden’s long address to the reader prefixed to his translation of the fifth Book of Sebastian Münster, written probably before the Willoughby expedition had been heard from, he speaks of “the attempt to pass to Cathay by the North East, which some men doubt, as the globes represent it all land north, even to the north pole.” In his preface to his Decades, cited above, written two years later, we have seen that he urges the people of England to turn their attention in the old direction, and to take possession of the waste places still unoccupied by any Christian people; which regions be says are called Terra Florida and Regio Baccalearum. These offer a large opportunity for traffic as a remedy for the stagnation of trade under which England is suffering, and a wide field for the Christian missionary.

The reader will have noticed, in the above extract, that Eden says that Sebastian Cabot “touched only in the north corner and most barbarous part” of the region which he is urging his countrymen to take possession of, “from whence he was repulsed with ice in the month of July.”

Eden’s Decades placed before the English reader for the first time the several notices of Sebastian Cabot, of which mention has been here made; namely, by Martyr, Ramusio, Gomara, and the brief Commentary by Ziegler. And the fact that this large unoccupied territory at the west, which Eden here urges the English Government and people to take possession of, was discovered by Cabot for the English nation, could not fail in time to produce its fruit upon the English mind.

Sebastian Cabot, as we have seen, was living in England at the time Richard Eden published his book, and a very old man. Eden appears to have been on terms of acquaintance with him, if not of intimacy; and unless the infirmities of years weighed too heavily upon his faculties, Cabot might have been able to impart much information to one so curious and eager as Eden was to gather up details. Eden more than once speaks of what Sebastian Cabot told him. In the margin of folio 255, where is a report of the famous conversation concerning Sebastian Cabot, extracted from Ramusio, in which Cabot is spoken of as “a Venetian born,” Eden says: “Sebastian Cabot told me that he was born in Brystowe, and that at iiii years old he was carried with his father to Venice, and so returned again into England with his father, after certain years, wherby he was thought to have been born in Venice.” This was a bad beginning on the part of Eden as an interviewer; that is to say, the truth was not reached.

Sebastian Cabot, if he had been asked, might have told Eden much more. Why did not Eden hand in a list of questions? Why did he not submit to him a proof-sheet of the story from Ramusio, which we know contains so many errors, and ask him to correct it, so that the world might have a true account of the discovery of North America? What an excellent opportunity was lost to Cabot for printing here under the auspices of Eden all those maps and discourses which Hakluyt, at a later period, tells us were in the custody of the worshipful Master William Worthington, who was very willing to have them overseen and published, but which have never yet seen the light![37]

I have already called attention to the fact that Eden had a copy of Cabot’s map, and translated one of the legends upon it,—that relating to the River La Plata, no. vii.[38]

About this time, or perhaps a few years earlier, there was painted in England a portrait of Sebastian Cabot, supposed for many years to have been done by Holbein, whose death has usually been referred to the year 1554, though recent investigations have rendered it probable that he died eleven years before. The first notice of this portrait which I have seen is in Purchas.[39] A minute description of it, with a notice of its disappearance from Whitehall, where it hung for many years, is given by Mr. Biddle,[40] who subsequently purchased the picture in England and brought it to this country, where in 1845 it was burned with his house and contents, in Pittsburg, Pa. Two excellent copies of it, however, had fortunately been taken, one of which, by the artist Chapman, is in the gallery of the Massachusetts Historical Society,[41] and the other in that of the New York Historical Society.[42] The portrait was painted after Cabot had returned to England; and it is said, I know not on what authority, to have been painted for King Edward VI., who died in 1553. Cabot lived some five years longer. The picture represents Cabot as a very old man. It has the following inscription upon it:[43]—

Effigies· Sebastiani Caboti

Angli· Filii· Johãnis· Caboti· Vene

Ti· Militis· Avrati· Primi· Invēt

Oris· Terræ Noviæ Sub Herico Vii. Angl

Læ Rege.