|

(In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers]

clicking on this symbol (etext transcriber's note) |

BY

JAMES BALDWIN

![]()

NEW YORK CINCINNATI CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Copyright, 1897, by

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY.

SCH. READ. FIFTH YEAR.

W. P. 29

The pupil who has read the earlier numbers of this series is now prepared to study with some degree of care the peculiarities of style which distinguish the different selections in the present volume. Hence, while due attention must be given to the study of words merely as words,—that is to spelling, defining, and pronouncing,—considerable time should be occupied in observing and discussing the literary contents, the author’s manner of narrating a story, of describing an action or an appearance, of portraying emotion, of producing an impression upon the mind of the reader or the hearer. The pupils should be encouraged to seek for and point out the particular passages or expressions in each selection which are distinguished for their beauty, their truth, or their peculiar adaptability to the purpose in view. The habit should be cultivated of looking for and enjoying the admirable qualities of any literary production, and particularly of such productions as are by common consent recognized as classical.

The lessons in this volume have been selected and arranged with a view towards several ends: to interest the young reader; to cultivate a taste for the best style of literature as regards both thought and expression; to point the way to an acquaintance with good books; to appeal to the pupil’s sense of duty, and strengthen his desire to do right; to arouse patriotic feelings and a just pride in the achievements of our countrymen; and incidentally to add somewhat to the learner’s knowledge of history and science and art.

The illustrations will prove to be valuable adjuncts to the text. Spelling, defining, and punctuation should continue to receive special attention. Difficult words and idiomatic expressions should be carefully studied with the aid of the dictionary and of the Word List at the end of this volume. Persistent and systematic practice in the pronunciation of these words and of other difficult combinations of sounds will aid in training the pupils’ voices to habits of careful articulation and correct enunciation.

While literary biography can be of but little, if any, value in cultivating literary taste, it is desirable that pupils should acquire some knowledge of the writers whose productions are placed before them for study. To assist in the acquisition of this knowledge, and also to serve for ready reference, a few Biographical Notes are inserted towards the end of the volume. The brief suggestions given on page 6 should be read and commented upon at the beginning, and frequently referred to and practically applied in the lessons which follow.{4}

Acknowledgments are due to Messrs. Charles Scribner’s Sons, publishers of the works of Eugene Field, for permission to use the poem entitled “The Wanderer”; to Messrs. Houghton, Mifflin & Co., publishers of the works of H. W. Longfellow and J. G. Whittier, for the use of “The Village Blacksmith” and “The Corn Song”; and to The J. B. Lippincott Company, publishers of the poems of T. Buchanan Read, for the piece entitled “The Stranger on the Sill.”{6}

A famous writer has said that the habit of reading is one’s pass to the greatest, the purest, the most perfect pleasures that have been prepared for human beings. “But,” he continued, “you cannot acquire this habit in your old age; you cannot acquire it in middle age; you must do it now, when you are young. You must learn to read, and to like reading now, or you cannot do so when you are old.” Now, no one can derive very great pleasure or very great profit from reading unless he is able to read well. The boy or girl who stumbles over every hard word, or who is at a loss to know the meaning of this or that expression, is not likely to find much enjoyment in books. To read well to one’s self, one must be able to read aloud in such a manner as to interest and delight those who listen to him: and this is the chief reason why we have so many reading books at school, and why your teachers are so careful that you should acquire the ability to enunciate every sound distinctly, pronounce every word properly, and read every sentence readily and with a clear understanding of its meaning.

Is the reading exercise a task to you? Try to make it a pleasure. Ask yourself: What is there in this lesson that teaches me something which I did not know before? What is there in this lesson that is beautiful, or grand, or inspiring? Has the writer said anything in a manner that is particularly pleasing—in a manner that perhaps no one else would have thought to say it? What particular thought or saying, in this lesson, is so good and true that it is worth learning by heart and remembering always. Does the selection as a whole teach anything that will tend to make me wiser, or better, or stronger than before? Or is it merely a source of temporary amusement to be soon forgotten and as though it had never been? Or does it, like fine music or a noble picture, not only give present pleasure, but enlarge my capacity for enjoyment and enable me to discover and appreciate beautiful things in literature and art and nature which I would otherwise never have known?

When you have asked yourself all these questions about any selection, and have studied it carefully to find answers to them, you will be prepared to read it aloud to your teacher and your classmates; and you will be surprised to notice how much better you have read it than would have been the case had you attempted it merely as a task or as an exercise in the pronouncing of words. It is by thus always seeking to discover things instructive and beautiful and enjoyable in books, that one acquires that right habit of reading which has been spoken of as the pass to the greatest, the purest, the most perfect of pleasures.{7}

A beautiful book, and one profitable to those who read it carefully, is “Sesame and Lilies” by John Ruskin. It is beautiful because of the pleasant language and choice words in which it is written; for, of all our later writers, no one is the master of a style more pure and more delightful in its simplicity than Mr. Ruskin’s. It is profitable because of the lessons which it teaches; for it was written “to show somewhat the use and preciousness of good books, and to awaken in the minds of young people some thought of the purposes of the life into which they are entering, and the nature of the world they have to conquer.” The following{8} pertinent words concerning the choice of books have been taken mainly from its pages:

All books may be divided into two classes,—books of the hour, and books of all time. Yet it is not merely the bad book that does not last, and the good one that does. There are good books for the hour and good ones for all time; bad books for the hour and bad ones for all time.

The good book of the hour,—I do not speak of the bad ones,—is simply the useful or pleasant talk of some person printed for you. Very useful often, telling you what you need to know; very pleasant often, as a sensible friend’s present talk would be.

These bright accounts of travels, good-humored and witty discussions of questions, lively or pathetic story-telling in the form of novel: all these are books of the hour and are the peculiar possession of the present age. We ought to be entirely thankful for them, and entirely ashamed of ourselves if we make no good use of them. But we make the worst possible use, if we allow them to usurp the place of true books; for, strictly speaking, they are not books at all, but merely letters or newspapers in good print.

Our friend’s letter may be delightful, or necessary,{9} to-day; whether worth keeping or not, is to be considered. The newspaper may be entirely proper at breakfast time, but it is not reading for all day. So, though bound up in a volume, the long letter which gives you so pleasant an account of the inns and roads and weather last year at such a place, or which tells you some amusing story, or relates such and such circumstances of interest, may not be, in the real sense of the word, a book at all, nor, in the real sense, to be read.

A book is not a talked thing, but a written thing. The book of talk is printed only because its author can not speak to thousands of people at once; if he could, he would—the volume is mere multiplication of the voice. You can not talk to your friend in India; if you could, you would; you write instead; that is merely a way of carrying the voice.

But a book is written, not to multiply the voice merely, not to carry it merely, but to preserve it. The author has something to say which he perceives to be true and useful, or helpfully beautiful. So far as he knows, no one has yet said it; so far as he knows, no one can say it. He is bound to say it, clearly and in a melodious manner if he may; clearly, at all events.

In the sum of his life he finds this to be the thing, or group of things, manifest to him; this the piece of true knowledge, or sight, which his share of sunshine{10} and earth has allowed him to seize. He would set it down forever; carve it on a rock, if he could, saying, “This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate and drank and slept, loved and hated, like another; my life was as the vapor, and is not; but this I saw and knew; this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory.” That is his writing; that is a book.

Now books of this kind have been written in all ages by their greatest men—by great leaders, great statesmen, great thinkers. These are all at your choice; and life is short. You have heard as much before; yet have you measured and mapped out this short life and its possibilities? Do you know, if you read this, that you can not read that—that what you lose to-day you can not gain to-morrow?

Will you go and gossip with the housemaid, or the stableboy, when you may talk with queens and kings? Do you ask to be the companion of nobles? Make yourself noble, and you shall be. Do you long for the conversation of the wise? Learn to understand it, and you shall hear it.

Very ready we are to say of a book, “How good this is—that is just what I think!” But the right feeling is, “How strange that is! I never thought of that before, and yet I see it is true; or if I do not now, I hope I shall, some day.”

But whether you feel thus or not, at least be sure{11} that you go to the author to get at his meaning, not to find yours. And be sure also, if the author is worth anything, that you will not get at his meaning all at once; nay, that at his whole meaning you may not for a long time arrive in any wise. Not that he does not say what he means, and in strong words too; but he can not say it all, and, what is more strange, will not, but in a hidden way in order that he may be sure you want it.

When, therefore, you come to a good book, you must ask yourself, “Am I ready to work as an Australian miner would? Are my pickaxes in good order, and am I in good trim myself, my sleeves well up to the elbow, and my breath good, and my temper?” For your pickaxes are your own care, wit, and learning; your smelting furnace is your own thoughtful soul. Do not hope to get at any good author’s meaning without these tools and that fire; often you will need sharpest, finest carving, and the most careful melting, before you can gather one grain of the precious gold.

I can not, of course, tell you what to choose for your library, for every several mind needs different books; but there are some books which we all need, and which if you read as much as you ought, you will not need to have your shelves enlarged to right and left for purposes of study.{12}

If you want to understand any subject whatever, read the best book upon it you can hear of. A common book will often give you amusement, but it is only a noble book that will give you dear friends.

Avoid that class of literature which has a knowing tone; it is the most poisonous of all. Every good book, or piece of book, is full of admiration and awe; and it always leads you to reverence or love something with your whole heart.

Æson was king of Iolcus by the sea; but for all that, he was an unhappy man. For he had a stepbrother named Pelias, a fierce and lawless man who was the doer of many a fearful deed, and about whom many dark and sad tales were told. And at last Pelias drove out Æson, his stepbrother, and took the kingdom for himself, and ruled over the rich town of Iolcus by the sea.

And Æson, when he was driven out, went sadly away from the town, leading his little son by the hand; and he said to himself, “I must hide the child in the mountains, or Pelias will surely kill him, because he{13} is the heir.” So he went up from the sea across the valley, through the vineyards and the olive groves, and across a foaming torrent toward Pelion, the ancient mountain, whose brows are white with snow.

He went up and up into the mountain, over marsh and crag, and down, till the boy was tired and foot-sore, and Æson had to bear him in his arms, till he came to the mouth of a lonely cave at the foot of a mighty cliff. Above the cliff the snow wreaths hung, dripping and cracking in the sun; but at its foot, around the cave’s mouth, grew all fair flowers and herbs, as if in a garden arranged in order, each sort by itself. There they grew gayly in the sunshine, and in the spray of the torrent from above; while from the cave came a sound of music, and a man’s voice singing to the harp.

Then Æson put down the lad, and whispered:

“Fear not, but go in, and whomsoever you shall find, lay your hands upon his knees, and say, ‘In the name of the Father of gods and men, I am your guest from this day forth.’ ”

Then the lad went in without trembling, for he too was a hero’s son; but when he was within, he stopped in wonder, to listen to that magic song.

And there he saw the singer lying upon bearskins and fragrant boughs; Chiron, the ancient Centaur,{14} the wisest of all beings beneath the sky. Down to the waist he was a man; but below he was a noble horse; his white hair rolled down over his broad shoulders, and his white beard over his broad brown chest; and his eyes were wise and mild, and his forehead like a mountain wall.

And in his hands he held a harp of gold, and struck it with a golden key; and as he struck he sang till his eyes glittered, and filled all the cave with light.

And he sang of the birth of Time, and of the heavens and the dancing stars; and of the ocean, and the ether, and the fire, and the shaping of the wondrous earth. And he sang of the treasures of the hills, and the hidden jewels of the mine, and the veins of fire and metal, and the virtues of all healing herbs; and of the speech of birds, and of prophecy, and of hidden things to come.

Then he sang of health, and strength, and manhood, and a valiant heart; and of music and hunting, and wrestling, and all the games which heroes love; and of travel, and wars, and sieges, and a noble death in fight,; and then he sang of peace and plenty, and of equal justice in the land; and as he sang, the boy listened wide-eyed, and forgot his errand in the song.

And at last Chiron was silent, and called the lad{15} with a soft voice. And the lad ran trembling to him, and would have laid his hands upon his knees; but Chiron smiled, and said, “Call hither your father Æson; for I know you and all that has befallen you.”

Then Æson came in sadly, and Chiron asked him, “Why came you not yourself to me, Æson?”

And Æson said: “I thought, Chiron will pity the lad if he sees him come alone; and I wished to try whether he was fearless, and dare venture like a hero’s son. But now I entreat you, let the boy be your guest till better times, and train him among the sons of the heroes that he may become like them, strong and brave.”

And Chiron answered: “Go back in peace and bend before the storm like a prudent man. This boy shall not leave me till he has become a glory to you and to your house.”

And Æson wept over his son and went away; but the boy did not weep, so full was his fancy of that strange cave, and the Centaur, and his song, and the playfellows whom he was to see. Then Chiron put the lyre into his hands, and taught him how to play it, till the sun sank low behind the cliff, and a shout was heard outside. And then in came the sons of the heroes,—Æneas, and Hercules, and Peleus, and many another mighty name.{16}

And great Chiron leaped up joyfully, and his hoofs made the cave resound, as they shouted, “Come out, Father Chiron; come out and see our game.” And one cried, “I have killed two deer,” and another, “I took a wild cat among the crags.” And Hercules dragged a wild goat after him by its horns; and Cæneus carried a bear cub under each arm, and laughed when they scratched and bit; for neither tooth nor steel could wound him. And Chiron praised them all, each according to his deserts.

Only one walked apart and silent, Æsculapius, the{17} too wise child, with his bosom full of herbs and flowers, and round his wrist a spotted snake; he came with downcast eyes to Chiron, and whispered how he had watched the snake cast his old skin, and grow young again before his eyes, and how he had gone down into a village in the vale, and cured a dying man with a herb which he had seen a sick goat eat. And Chiron smiled and said:

“To each there has been given his own gift, and each is worthy in his place. But to this child there has been given an honor beyond all honors,—to cure while others kill.”

Then some of the lads brought in wood, and split it, and lighted a blazing fire; and others skinned the deer and quartered them, and set them to roast before the fire; and while the venison was cooking they bathed in the snow torrent, and washed away the dust and sweat. And then all ate till they could eat no more—for they had tasted nothing since the dawn—and drank of the clear spring water, for wine is not fit for growing lads. And when the remnants were put away, they all lay down upon the skins and leaves about the fire, and each took the lyre in turn, and sang and played with all his heart.

And after a while they all went out to a plot of grass at the cave’s mouth, and there they boxed, and{18} ran, and wrestled, and laughed till the stones fell from the cliffs.

Then Chiron took his lyre, and all the lads joined hands; and as he played, they danced to his measure, in and out, and round and round. There they danced hand in hand, till the night fell over land and sea, while the black glen shone with their broad white limbs, and the gleam of their golden hair.

And the lad danced with them, delighted, and then slept a wholesome sleep, upon fragrant leaves of bay, and myrtle, and marjoram, and flowers of thyme; and rose at the dawn, and bathed in the torrent, and became a schoolfellow to the heroes’ sons. And in course of time he forgot Iolcus, and Æson his father, and all his former life. But he grew strong, and brave, and cunning, upon the rocky heights of Pelion, in the keen, hungry, mountain air. And he learned to wrestle, and to box, and to hunt, and to play upon the harp; and, next, he learned to ride, for old Chiron often allowed him to mount upon his back; and he learned the virtues of all herbs, and how to cure all wounds; and Chiron called him Jason the healer, and that is his name until this day.

—From “The Heroes; or Greek Fairy Tales,” by Charles Kingsley.

In the old castle of Montargis in France, there was once a stone mantelpiece of workmanship so rare that it was talked about by the whole country. And yet it was not altogether its beauty that caused people to speak of it and remember it. It was famous rather on account of the strange scene that was carved upon it. To those who asked about its meaning, the old custodian of the castle would sometimes tell the following story.

It happened more than five hundred years ago, when this castle was new and strong, and people lived and thought in very different sort from what they do now. Among the young men of that time there was none more noble than Aubrey de Montdidier, the nephew of the Count of Montargis; and among all the knights who had favor at the royal court, there was none more brave than the young Sieur de Narsac, captain of the king’s men at arms.

Now these two men were devoted friends, and whenever their other duties allowed them, they were sure to be in each other’s company. Indeed, it was a rare thing to see either of them walking the streets of Paris alone.

“I will meet you at the tournament to-morrow,”{20} said Aubrey gayly, one evening, as he was parting from his friend.

“Yes, at the tournament to-morrow,” said De Narsac; “and be sure that you come early.”

The tournament was to be a grand affair. A gentleman from Provence was to run a tilt with a famous Burgundian knight. Both men were noted for their horsemanship and their skill with the lance. All Paris would be out to see them.

When the time came, De Narsac was at the place appointed. But Aubrey failed to appear. What could it mean? It was not at all like Aubrey to forget his promise; it was seldom that he allowed anything to keep him away from the tournament.

“Have you seen my friend Aubrey to-day?” De Narsac asked this question a hundred times. Everybody gave the same answer, and wondered what had happened.

The day passed and another day came, and still there was no news from Aubrey. De Narsac had called at his friend’s lodgings, but could learn nothing. The young man had not been seen since the morning before the tournament.

Three days passed, and still not a word. De Narsac was greatly troubled. He knew now that some accident must have happened to Aubrey. But what could it have been?{21}

Early in the morning of the fourth day he was aroused by a strange noise at his door. He dressed himself in haste and opened it. A dog was crouching there. It was a greyhound, so poor that its ribs stuck out, so weak that it could hardly stand.

De Narsac knew the animal without looking at the collar on its neck. It was Dragon, his friend Aubrey’s greyhound,—the dog who went with him whenever he walked out, the dog who was never seen save in its master’s company.

The poor creature tried to stand. His legs trembled from weakness; he swayed from side to side. He wagged his tail feebly, and tried to put his nose in De Narsac’s hand. De Narsac saw at once that he was half starved; that he had not had food for a long time.

He led the dog into his room and fed him some warm milk. He bathed the poor fellow’s nose and bloodshot eyes with cold water. “Tell me where is your master,” he said. Then he set before him a full meal that would have tempted any dog.

The greyhound ate heartily, and seemed to be much stronger. He licked De Narsac’s hands. He fondled his feet. Then he ran to the door and tried to make signs to his friend to follow him. He whined pitifully.

De Narsac understood. “You want to lead me to{22} your master, I see.” He put on his hat and went out with the dog.

Through the narrow lanes and crooked streets of the old city, Dragon led the way. At each corner he would stop and look back to make sure that De Narsac was following. He went over the long bridge—the only one that spanned the river in those days. Then he trotted out through the gate of St. Martin and into the open country beyond the walls.

In a little while the dog left the main road and took a bypath that led into the forest of Bondy. De Narsac kept his hand on his sword now, for they were on dangerous ground. The forest was a great resort for robbers and lawless men, and more than one wild and wicked deed had been enacted there.

But Dragon did not go far into the woods. He stopped suddenly near a dense thicket of briers and tangled vines. He whined as though in great distress. Then he took hold of the sleeve of De Narsac’s coat, and led him round to the other side of the thicket.

There under a low-spreading oak the grass had been trampled down; there were signs, too, of freshly turned-up earth. With moans of distress the dog stretched himself upon the ground, and with pleading eyes looked up into De Narsac’s face.{23}

“Ah, my poor fellow!” said De Narsac, “you have led me here to show me your master’s grave.” And with that he turned and hurried back to the city; but the dog would not stir from his place.

That afternoon a company of men, led by De Narsac, rode out to the forest. They found in the ground beneath the oak what they had expected—the murdered body of young Aubrey de Montdidier.

“Who could have done this foul deed?” they asked of one another; and then they wept, for they all loved Aubrey.

They made a litter of green branches, and laid the body upon it. Then, the dog following them, they carried it back to the city and buried it in the king’s cemetery. And all Paris mourned the untimely end of the brave young knight.

After this, the greyhound went to live with the young Sieur de Narsac. He followed the knight wherever he went. He slept in his room and ate from his hand. He seemed to be as much devoted to his new master as he had been to the old.

One morning they went out for a stroll through the city. The streets were crowded; for it was a holiday and all the fine people of Paris were enjoying{24} the sunlight and the fresh air. Dragon, as usual, kept close to the heels of his master.

De Narsac walked down one street and up another, meeting many of his friends, and now and then stopping to talk a little while. Suddenly, as they were passing a corner, the dog leaped forward and planted himself in front of his master. He growled fiercely; he crouched as though ready for a spring; his eyes were fixed upon some one in the crowd.

Then, before De Narsac could speak, he leaped forward upon a young man whom he had singled{25} out. The man threw up his arm to save his throat; but the quickness of the attack and the weight of the dog caused him to fall to the ground. There is no telling what might have followed had not those who were with him beaten the dog with their canes, and driven him away.

De Narsac knew the man. His name was Richard Macaire, and he belonged to the king’s bodyguard.

Never before had the greyhound been known to show anger towards any person. “What do you mean by such conduct?” asked his master as they walked homeward. Dragon’s only answer was a low growl; but it was the best that he could give. The affair had put a thought into De Narsac’s mind which he could not dismiss.

Within less than a week the thing happened again. This time Macaire was walking in the public garden. De Narsac and the dog were some distance away. But as soon as Dragon saw the man, he rushed at him. It was all that the bystanders could do to keep him from throttling Macaire. De Narsac hurried up and called him away; but the dog’s anger was fearful to see.

It was well known in Paris that Macaire and young Aubrey had not been friends. It was remembered that they had had more than one quarrel. And now the people began to talk about the dog’s{26} strange actions, and some went so far as to put this and that together.

At last the matter reached the ears of the king. He sent for De Narsac and had a long talk with him. “Come back to-morrow and bring the dog with you,” he said. “We must find out more about this strange affair.”

The next day De Narsac, with Dragon at his heels, was admitted into the king’s audience room. The king was seated in his great chair, and many knights and men at arms were standing around him. Hardly had De Narsac stepped inside when the dog leaped quickly forward. He had seen Macaire, and had singled him out from among all the rest. He sprang upon him. He would have torn him in pieces if no one had interfered.

There was now only one way to explain the matter.

“This greyhound,” said De Narsac, “is here to denounce the Chevalier Macaire as the slayer of his master, young Aubrey de Montdidier. He demands that justice be done, and that the murderer be punished for his crime.”

The Chevalier Macaire was pale and trembling. He stammered a denial of his guilt, and declared that the dog was a dangerous beast, and ought to be put out of the way. “Shall a soldier in the service{27} of the king be accused by a dog?” he cried. “Shall he be condemned on such testimony as this? I, too, demand justice.”

“Let the judgment of God decide!” cried the knights who were present.

And so the king declared that there should be a trial by the judgment of God. For in those rude times it was a very common thing to determine guilt or innocence in this way—that is, by a combat between the accuser and the accused. In such cases it was believed that God would always aid the cause of the innocent and bring about the defeat of the guilty.

The combat was to take place that very afternoon in the great common by the riverside. The king’s herald made a public announcement of it, naming the dog as the accuser and the Chevalier Macaire as the accused. A great crowd of people assembled to see this strange trial by the judgment of God.

The king and his officers were there to make sure that no injustice was done to either the man or the dog. The man was allowed to defend himself with a short stick; the dog was given a barrel into which he might run if too closely pressed.

At a signal the combat began. Macaire stood upon his guard while the dog darted swiftly around him, dodging the blows that were aimed at him, and{28} trying to get at his enemy’s throat. The man seemed to have lost all his courage. His breath came short and quick. He was trembling from head to foot.

Suddenly the dog leaped upon him and threw him to the ground. In his great terror he cried to the king for mercy, and acknowledged his guilt.

“It is the judgment of God!” cried the king.

The officers rushed in and dragged the dog away before he could harm the guilty man; and Macaire was hurried off to the punishment which his crimes deserved.

And this is the scene that was carved on the old mantelpiece in the castle of Montargis—this strange trial by the judgment of God. Is it not fitting that a dog so faithful, devoted, and brave should have his memory thus preserved in stone? He is remembered also in story and song. In France ballads have been written about him; and his strange history has been dramatized in both French and English.

One morning when Hercules was a fair-faced lad of twelve years, he was sent out to do an errand which he disliked very much. As he walked slowly along the road, his heart was full of bitter thoughts; and he murmured because others no better than himself were living in ease and pleasure, while for him there was little but labor and pain. Thinking upon these things, he came after a while to a place where two roads met; and he stopped, not quite certain which one to take.

The road on his right was hilly and rough, and there was no beauty in it or about it; but he saw that it led straight toward the blue mountains in the far distance. The road on his left was broad and smooth, with shade trees on either side, where sang thousands of beautiful birds; and it went winding in and out, through groves and green meadows, where bloomed countless flowers; but it ended in fog and mist long before reaching the wonderful mountains of blue.

While the lad stood in doubt as to which way he should go, he saw two ladies coming toward him, each by a different road. The one who came down the flowery way reached him first, and Hercules saw that she was beautiful as a summer day. Her cheeks{35} were red, her eyes sparkled, her voice was like the music of morning.

“O noble youth,” she said, “this is the road which you should choose. It will lead you into pleasant ways where there is neither toil, nor hard study, nor drudgery of any kind. Your ears shall always be delighted with sweet sounds, and your eyes with things beautiful and gay; and you need do nothing but play and enjoy the hours as they pass.”

By this time the other fair woman had drawn near, and she now spoke to the lad.

“If you take my road,” said she, “you will find that it is rocky and rough, and that it climbs many a hill and descends into many a valley and quagmire. The views which you will sometimes get from the hilltops are grand and glorious, while the deep valleys are dark and the uphill ways are toilsome; but the road leads to the blue mountains of endless fame, of which you can see faint glimpses, far away. They can not be reached without labor; for, in fact, there is nothing worth having that must not be won through toil. If you would have fruits and flowers, you must plant and care for them; if you would gain the love of your fellow-men, you must love them and suffer for them; if you would be a man, you must make yourself strong by the doing of manly deeds.”{36}

Then the boy saw that this lady, although her face seemed at first very plain, was as beautiful as the dawn, or as the flowery fields after a summer rain.

“What is your name?” he asked.

“Some call me Labor,” she answered, “but others know me as Truth.”

“And what is your name?” he asked, turning to the first lady.

“Some call me Pleasure,” said she with a smile; “but I choose to be known as the Joyous One.”

“And what can you promise me at the end if I go with you?”{37}

“I promise nothing at the end. What I give, I give at the beginning.”

“Labor,” said Hercules, “I will follow your road. I want to be strong and manly and worthy of the love of my fellows. And whether I shall ever reach the blue mountains or not, I want to have the reward of knowing that my journey has not been without some worthy aim.”

Then up rose Mrs. Cratchit, dressed out but poorly in a twice-turned gown, but brave in ribbons, which are cheap and make a goodly show for sixpence; and she laid the cloth, assisted by Belinda Cratchit, second of her daughters, also brave in ribbons; while Master Cratchit plunged a fork into the saucepan of potatoes, and getting the corner of his monstrous shirt collar (Bob’s private property, conferred upon his son and heir in honor of the day) into his mouth, rejoiced to find himself so gallantly attired, and yearned to show his linen in the fashionable Parks.

And now two smaller Cratchits, boy and girl, came tearing in, screaming that outside the baker’s they had smelt the goose, and known it for their{38} own; and basking in luxurious thoughts of sage and onion, these young Cratchits danced about the table and exalted Master Peter Cratchit to the skies, while he (not proud, although his collar nearly choked him) blew the fire, until the slow potatoes bubbling up knocked loudly at the saucepan lid to be let out and peeled.

“What has ever got your precious father then?” said Mrs. Cratchit. “And your brother, Tiny Tim! And Martha wasn’t as late last Christmas Day, by half an hour!”

“Here’s Martha, mother!” said a girl, appearing as she spoke.

“Here’s Martha, mother!” cried the two young Cratchits. “Hurrah! There’s such a goose, Martha!”

“Why, bless your heart alive, my dear, how late you are!” said Mrs. Cratchit, kissing her a dozen times, and taking off her shawl and bonnet for her with officious zeal.

“We’d a deal of work to finish up last night,” replied the girl, “and had to clear away this morning, mother!”

“Well! never mind so long as you are come,” said Mrs. Cratchit. “Sit ye down before the fire, my dear, and have a warm, Lord bless ye!”

“No, no! There’s father coming,” cried the two{39}

young Cratchits, who were everywhere at once. “Hide, Martha, hide!”

So Martha hid herself, and in came little Bob, the father, with at least three feet of comforter exclusive of the fringe hanging down before him; and his threadbare clothes darned up and brushed, to look seasonable; and Tiny Tim upon his shoulder. Alas for Tiny Tim, he bore a little crutch, and had his limbs supported by an iron frame!

“Why, where’s our Martha?” cried Bob Cratchit, looking round.

“Not coming,” said Mrs. Cratchit.

“Not coming!” said Bob, with a sudden declension in his high spirits; for he had been Tim’s blood horse all the way from church, and had come home rampant. “Not coming upon Christmas Day!”

Martha did not like to see him disappointed, if it were only in joke; so she came out prematurely from behind the closet door, and ran into his arms, while the two young Cratchits hustled Tiny Tim, and bore him off into the washhouse that he might hear the pudding singing in the copper.

“And how did little Tim behave?” asked Mrs. Cratchit, when she had rallied Bob on his credulity, and Bob had hugged his daughter to his heart’s content.

“As good as gold,” said Bob, “and better. Somehow{41} he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, who made lame beggars walk and blind men see.”

Bob’s voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool beside the fire; and while Bob, turning up his cuffs,—as if, poor fellow, they were capable of being made more shabby,—compounded some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons, and stirred it round and round and put it on the hob to simmer; Master Peter and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds; a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course—and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs. Cratchit made the gravy (ready beforehand in a little saucepan) hissing hot; Master Peter{42} mashed the potatoes with incredible vigor; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a tiny corner at the table; the two young Cratchits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on, and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs. Cratchit, looking slowly all along the carving knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast; but when she did, and when the long-expected gush of stuffing issued forth, one murmur of delight arose all round the board, and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Cratchits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried Hurrah!

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavor, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs. Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of a bone upon the dish), they hadn’t ate it all at last! Yet every one had had enough, and the youngest Cratchits, in particular, were steeped in sage and{43} onion to the eyebrows! But now the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs. Cratchit left the room alone—too nervous to bear witnesses—to take the pudding up and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the backyard and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose—a supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid. All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating house and a pastry cook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs. Cratchit entered—flushed, but smiling proudly—with the pudding like a speckled cannon ball, so hard and firm, smoking hot, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs. Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs. Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small{44} pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted, and considered perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table, and a shovel full of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Cratchit family drew round the hearth, in what Bob Cratchit called a circle, meaning half a one; and at Bob Cratchit’s elbow stood the family display of glass,—two tumblers and a custard cup without a handle.

These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done; and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and cracked noisily. Then Bob proposed: “A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!”

Which all the family reëchoed.

“God bless us every one!” said Tiny Tim, the last of all.

He sat very close to his father’s side, upon his little stool. Bob held his withered little hand in his, as if he loved the child, and wished to keep him by his side, and dreaded that he might be taken from him.

—From “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens.

And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him; and he opened his mouth and taught them, saying: Blessed are the poor in spirit; for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are they that mourn; for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek; for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness; for they shall be filled. Blessed are the merciful; for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart; for they shall see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers; for they shall be called the children of God. Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake; for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are ye when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake. Rejoice and be exceeding glad; for great is your reward in heaven.

Ye have heard that it hath been said by them of old time, Thou shalt not forswear thyself, but shalt perform unto the Lord thine oaths: but I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God’s throne: nor by the earth; for it is his foot-stool:{46} neither by Jerusalem; for it is the city of the great King.

Neither shalt thou swear by thy head, because thou canst not make one hair white or black. But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil.

Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth: but I say unto you, That ye resist not evil; but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also.

And if any man will sue thee at law, and take away thy coat, let him have thy cloak also. And whosoever shall compel thee to go a mile, go with him twain. Give to him that asketh thee, and from him that would borrow of thee turn not thou away.

Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbor and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust.

For if ye love them that love you, what reward have ye? Do not even the publicans the same? And if ye salute your brethren only, what do ye more{47} than others? Do not even the publicans so? Be ye, therefore, perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect....

Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you; for every one that asketh, receiveth; and he that seeketh, findeth; and to him that knocketh, it shall be opened. Or what man is there of you, whom if his son ask bread, will he give him a stone? Or if he ask a fish, will he give him a serpent?

If ye then, being evil know how to give good gifts unto your children, how much more shall your Father which is in heaven give good things to them that ask him? Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.

Whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock: and the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not; for it was founded upon a rock. And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand: and the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.

—From the Gospel according to St. Matthew.

In the early days of New England all the money that was used was brought from Europe. Coins of gold and silver from England were the most plentiful; but now and then one might see a doubloon, or some piece of smaller value, that had been made in Spain or Portugal. As for paper money, or bank bills, nobody had ever heard of them.

Money was so scarce that people were often obliged to barter instead of buying and selling. That is, if a lady wanted a yard of dress goods, she would perhaps exchange a basket of fruit or some vegetables for it; if a farmer wanted a pair of shoes, he might give the skin of an ox for it; if he needed nails, he might buy them with potatoes. In many places there was not money enough of any kind to pay the salaries of the ministers; and so, instead of gold or silver, they were obliged to take fish and corn and wood and anything else that the people could spare.

As the people became more numerous, and there was more trade among them, the want of money caused much inconvenience. At last, the General Court of the colony passed a law providing for the coinage of small pieces of silver—shillings, sixpences, and threepences. They also appointed Captain John Hull to be mint-master for the colony, and{49} gave him the exclusive right to make this money. It was agreed that for every twenty shillings coined by him, he was to keep one shilling to pay him for his work.

And now, all the old silver in the colony was hunted up and carried to Captain Hull’s mint. Battered silver cans and tankards, silver buckles, broken spoons, old sword hilts, and many other such curious old articles were doubtless thrown into the melting pot together. But by far the greater part of the silver consisted of bullion from the mines of South America, which the English buccaneers had taken from the Spaniards and brought to Massachusetts. All this old and new silver was melted down and coined; and the result was an immense amount of bright shillings, sixpences, and threepences. Each had the date, 1652, on one side, and the figure of a pine tree on the other; hence, the shillings were called pine-tree shillings.

When the members of the General Court saw what an immense number of coins had been made, and remembered that one shilling in every twenty was to go into the pockets of Captain John Hull, they began{50} to think that the mint-master was having the best of the bargain. They offered him a large amount, if he would but give up his claim to that twentieth shilling. But the Captain declared that he was well satisfied to let things stand as they were. And so he might be, for in a few years his money bags and his strong box were all overflowing with pine-tree shillings.

Now, the rich mint-master had a daughter whose name I do not know, but whom I will call Betsey. This daughter was a fine, hearty damsel, by no means so slender as many young ladies of our own days. She had been fed on pumpkin pies, doughnuts, Indian puddings, and other Puritan dainties, and so had grown up to be as round and plump as any lass in the colony. With this round, rosy Miss Betsey, a worthy young man, Samuel Sewell by name, fell in love; and as he was diligent in business, and a member of the church, the mint-master did not object to his taking her as his wife. “Oh, yes, you may have her,” he said in his rough way; “but you will find her a heavy enough burden.”

On the wedding day we may suppose that honest John Hull dressed himself in a plum-colored coat, all the buttons of which were made of pine-tree shillings. The buttons of his waistcoat were sixpences, and the knees of his small clothes were buttoned with silver threepences. Thus attired, he{51} sat with dignity in the huge armchair which had been brought from old England expressly for his comfort. On the other side of the room sat Miss Betsey. She was blushing with all her might, and looked like a full-blown peony or a great red apple.

There, too, was the bridegroom, dressed in a fine purple coat and gold-laced waistcoat. His hair was cropped close to his head, because Governor Endicott had forbidden any man to wear it below the ears. But he was a very personable young man; and so thought the bridesmaids and Miss Betsey herself.

When the marriage ceremony was over, Captain Hull whispered a word to two of his men servants, who immediately went out, and soon returned lugging in a large pair of scales. They were such a pair as wholesale merchants use for weighing bulky commodities; and quite a bulky commodity was now to be weighed in them.

“Daughter Betsey,” said the mint-master, “get into one side of these scales.” Miss Betsey—or Mrs. Sewell, as we must now call her—did as she was bid, like a dutiful child, without any question of why and wherefore. But what her father could mean, unless to make her husband pay for her by the pound (in which case she would have been a dear bargain), she had not the least idea.

“Now,” said honest John Hull to the servants,{52} “bring that box hither.” The box to which the mint-master pointed was a huge, square, iron-bound, oaken chest; it was big enough, my children, for three or four of you to play at hide and seek in. The servants tugged with might and main, but could not lift this enormous receptacle, and were finally obliged to drag it across the floor. Captain Hull then took a key from his girdle, unlocked the chest, and lifted its ponderous lid.

Behold! it was full to the brim of bright pine-tree shillings fresh from the mint; and Samuel Sewell began to think that his father-in-law had got possession of all the money in the Massachusetts treasury. But it was only the mint-master’s honest share of the coinage.

Then the servants, at Captain Hull’s command, heaped double handfuls of shillings into one side of the scales, while Betsey remained in the other. Jingle, jingle went the shillings, as handful after handful was thrown in, till, plump and ponderous as she was, they fairly weighed the young lady from the floor.

“There, son Sewell!” cried the honest mint-master, “take these shillings for my daughter’s portion. It is not every wife that is worth her weight in silver.”

—Adapted from “Grandfather’s Chair” by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Among all the great poems that have ever been written none are grander or more famous than the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey,” of the old Greek poet Homer. They were composed and recited nearly three thousand years ago, and yet nothing that has been written in later times has so charmed and delighted mankind. In the “Iliad” the poet tells how the Greeks made war upon Troy, and how they did brave deeds around the walls of that famed city, and faltered not till they had won the stubborn fight. In the “Odyssey” he tells how the Greek hero Ulysses or Odysseus, when the war was ended, set sail for his distant home in Ithaca; how he was driven from his course by the wind and waves; and how he was carried against his will through unknown seas and to strange, mysterious shores where no man had been before.

One of the most famous passages in the “Odyssey” is that in which Ulysses relates the story of his meeting with the one-eyed giant, Polyphemus. He tells it in this manner:{55}

When we had come to the land, we saw a cave not far from the sea. It was a lofty cave roofed over with laurels, and in it large herds of sheep and goats were used to rest. About it a high outer court was built with stones set deep in the ground, and with tall pines and oaks crowned with green leaves. In it was wont to sleep a man of monstrous size who shepherded his flocks alone and had no dealings with others, but dwelt apart in lawlessness of mind. Indeed, he was a monstrous thing, most strangely shaped; and he was unlike any man that lives by bread, but more like the wooded top of some towering hill that stands out apart and alone from others.

Then I bade the rest of my well-loved company stay close by the ship and guard it; but I chose out twelve of my bravest men and sallied forth. We bore with us a bag of corn and a great skin filled with dark sweet wine; for in my lordly heart I had a foreboding that we should meet a man, a strange, strong man who had little reason and cared nothing for the right.

Soon we came to the cave, but he was not within; he was shepherding his fat flocks in the pastures. So we went into the cave and looked around. There we saw many folds filled with lambs and kids. Each kind was penned by itself; in one fold were the{56} spring lambs, in one were the summer lambs, and in one were the younglings of the flock. On one side of the cave were baskets well laden with cheeses; and the milk pails and the bowls and the well-wrought vessels into which he milked were filled with whey.

Then my men begged me to take the cheeses and return, and afterwards to make haste and drive off the kids and lambs to the swift ship and sail without delay over the salt waves. Far better would it have been had I done as they wished; but I bade them wait and see the giant himself, for perhaps he{57} would give me gifts as a stranger’s due. Then we kindled a fire and made a burnt-offering; and we ate some of the cheeses, and sat waiting for him till he came back driving his flocks. In his arms he carried a huge load of dry wood to be used in cooking supper. This he threw down with a great noise inside the cave, and we in fear hid ourselves in the dark corners behind the rocks.

As for the giant, he drove into the wide cavern all those of his flock that he was wont to milk; but the males, both of the sheep and of the goats, he left outside in the high-walled yard. Then he lifted a huge door stone and set it in the mouth of the cave; it was a stone so weighty that two-and-twenty good, four-wheeled wagons could scarce have borne it off the ground. Then he sat down and milked the ewes and the bleating goats, each in its turn, and beneath each ewe he placed her young. After that he curdled half of the white milk and stored it in wicker baskets; and the other half he let stand in pails that he might have it for his supper.

Now, when he had done all his work busily, he kindled the fire, and as its light shone into all parts of the cave, he saw us. “Strangers, who are you?” he cried. “Whence sail you over the wet ways? Are you on some trading voyage, or do you rove as sea robbers over the briny deep?”{58}

Such were his words, and so monstrous was he and so deep was his voice that our hearts were broken within us for terror. But, for all that, I stood up and answered him, saying:

“Lo, we are Greeks, driven by all manner of winds over the great gulf of the sea. We seek our homes, but have lost our way and know not where we go. Now we have landed on this shore, and we come to thy knees, thinking perhaps that thou wilt give us a stranger’s gift, or make any present, as is the due of strangers. Think upon thy duty to the gods; for we are thy suppliants. Have regard to Jupiter, the god of the sojourner and the friend of the stranger.”

This I said, and then the giant answered me out of his pitiless heart: “Thou art indeed a foolish fellow and a stranger in this land, to think of bidding me fear the gods. We Cyclops care nothing for Jupiter, nor for any other of the gods; for we are better men than they. The fear of them will never cause me to spare either thee or thy company, unless I choose to do so.”

Then the giant sprang up and caught two of my companions, and dashed them to the ground so hard that they died before my eyes; and the earth was wet with their blood. Then he cut them into pieces, and made ready his evening meal. So he ate, as a lion of the mountains; and we wept and raised our{59} hands to Jupiter, and knew not what to do. And after the Cyclops had filled himself, he lay down among his sheep.

Then I considered in my great heart whether I should not draw my sharp sword, and stab him in the breast. But upon second thought, I held back. For I knew that we would not be able to roll away with our hands the heavy stone which the giant had set against the door, and we would then have perished in the cave. So, all night long, we crouched trembling in the darkness, and waited the coming of the day.

Now, when the rosy-fingered Dawn shone forth, the Cyclops arose and kindled the fire. Then he is milked his goodly flock, and beneath each ewe he set her lamb. When he had done all his work busily, he seized two others of my men, and made ready his morning meal. And after the meal, he moved away the great door stone, and drove his fat flocks forth from the cave; and when the last sheep had gone out, he set the stone in its place again, as one might set the lid of a quiver. Then, with a loud whoop, he turned his flocks toward the hills; but I was left shut up in the cave, and thinking what we should do to avenge ourselves.

And at last this plan seemed to me the best. Not far from the sheepfold there lay a great club of the{60} Cyclops, a club of olive wood, yet green, which he had cut to carry with him when it should be fully seasoned. Now when we looked at this stick, it seemed to us as large as the mast of a black ship of twenty oars, a wide merchant vessel that sails the vast sea. I stood by it, and cut off from it a piece some six feet in length, and set it by my men, and bade them trim it down and make it smooth; and while they did this, I stood by and sharpened it to a point. Then I took it and hardened it in the bright fire; and after that, I laid it away and hid it. And I bade my men cast lots to determine which of them should help me, when the time came, to lift the sharp and heavy stick and turn it about in the Cyclops’ eye. And the lots fell upon those whom I would have chosen, and I appointed myself to be the fifth among them.

In the evening the Cyclops came home, bringing his well-fleeced flocks; and soon he drove the beasts, each and all, into the cave, and left not one outside in the high-walled yard. Then he lifted the huge door stone, and set it in the mouth of the cave; and after that he milked the ewes and the bleating goats, all in order, and beneath each ewe he placed her young.{61}

Now when he had done all his work busily, he seized two others of my men, and made ready his supper. Then I stood before the Cyclops and spoke to him, holding in my hands a bowl of dark wine: “Cyclops, take this wine and drink it after thy feast, that thou mayest know what kind of wine it was that our good ship carried. For, indeed, I was bringing it to thee as a drink offering, if haply thou wouldst pity us and send us on our way home; but thy mad rage seems to have no bounds.”

So I spoke, and he took the cup and drank the wine; and so great was his delight that he asked me for yet a second draught.

“Kindly give me more, and tell me thy name, so that I may give thee a stranger’s gift and make thee glad.”

Thus he spoke, and again I handed him the dark wine. Three times did I hand it to him, and three times did he drink it to the dregs. But when the wine began to confuse his wits, then I spoke to him with soft words:

“O Cyclops, thou didst ask for my renowned name, and now I will tell it to thee; but do thou grant me a stranger’s gift, as thou hast promised. My name is No-man; my father and my mother and all my companions call me No-man.”

Thus I spoke, and he answered me out of his{62} pitiless heart: “I will eat thee, No-man, after I have eaten all thy fellows: that shall be thy gift.”

Then he sank down upon the ground with his face upturned; and there he lay with his great neck bent round; and sleep, that conquers all men, overcame him. Then I thrust that stake under the burning coals until the sharpened end of it grew hot; and I spoke words of comfort to my men lest they should hang back with fear. But when the bar of olive wood began to glow and was about to catch fire, even then I came nigh and drew it from the coals, and my men stood around me, and some god filled our hearts with courage.

The men seized the bar of olive wood and thrust it into the Cyclops’ eye, while I from my place aloft turned it around. As when a man bores a ship’s beam with a drill while his fellows below spin it with a strap, which they hold at either end, and the auger runs round continually: even so did we seize the fiery-pointed brand and whirl it round in his eye. And the flames singed his eyelids and brows all about, as the ball of the eye was burned away. And the Cyclops raised a great and terrible cry that made the rocks around us ring, and we fled away in fear, while he plucked the brand from his bleeding eye.

Then, maddened with pain, he cast the bar from{63} him, and called with a loud voice to the Cyclopes, his neighbors, who dwelt near him in the caves along the cliffs. And they heard his cry, and flocked together from every side, and standing outside, at the door of the cave, asked him what was the matter:

“What troubles thee, Polyphemus, that thou criest thus in the night, and wilt not let us sleep?”

The strong Cyclops whom they thus called Polyphemus, answered them from the cave: “My friends, No-man is killing me by guile, and not by force!”

And they spoke winged words to him: “If no man is mistreating thee in thy lonely cave, then it must be some sickness, sent by Jupiter, that is giving thee pain. Pray to thy father, great Neptune, and perhaps he will cure thee.”

And when they had said this they went away; and my heart within me laughed to see how my name and cunning counsel had deceived them. But the Cyclops, groaning with pain, groped with his hands, and lifted the stone from the door of the cave. Then he sat in the doorway, with arms outstretched, to lay hold of any one that might try to go out with the sheep; for he thought that I would be thus foolish. But I began to think of all kinds of plans by which we might escape; and this was the plan which seemed to me the best:{64}

The rams of the flock were thick-fleeced, beautiful, and large; and their wool was dark as the violet. These I quietly lashed together with the strong withes which the Cyclops had laid in heaps to sleep upon. I tied them together in threes: the middle one of the three was to carry a man; but the sheep on either side went only as a shield to keep him from discovery. Thus, every three sheep carried their man. As for me, I laid hold of a young ram, the best and strongest of all the flock; and I clung beneath him, face upward, grasping the wondrous fleece.

As soon as the early Dawn shone forth, the rams of the flock hastened out to the pasture, but the ewes bleated about the pens and waited to be milked. As the rams passed through the doorway, their master, sore stricken with pain, felt along their backs, and guessed not in his folly that my men were bound beneath their wooly breasts. Last of all, came the young ram cumbered with his heavy fleece, and the weight of me and my cunning. The strong Cyclops laid his hands on him and spoke to him:

“Dear ram,” he said, “pray tell me why you are the last of all to go forth from the cave. You are not wont to lag behind. Hitherto you have always been the first to pluck the tender blossoms{65} of the pasture, and you have been the first to go back to the fold at evening. But now you are the very last. Can it be that you are sorrowing for your master’s eye which a wicked man blinded when he had overcome me with wine?

“Ah, if you could feel as I—if you could speak and tell me where he is hiding to shun my wrath—then I would smite him, and my heart would be lightened of the sorrows that he has brought upon me.”

Then he sent the ram from him; and when we had gone a little way from the cave I loosed myself from under the ram, and then set my fellows free. Swiftly we drove the flock before us, and often is turned to look about, till at last we came to the ship.

Our companions greeted us with glad hearts,—us who had fled from death; and they were about to bemoan the others with tears when I forbade. I told them to make haste and take on board the well-fleeced sheep, and then sail away from that unfriendly shore. So they did as they were bidden, and when all was ready, they sat upon the benches, each man in his place, and smote the gray sea water with their oars.

But when we had not gone so far but that a man’s shout could be heard, I called to the Cyclops and taunted him:

“Cyclops, you will not eat us by main might in your hollow cave! Your evil deeds, O cruel monster, were sure to find you out; for you shamelessly ate the guests that were within your gates, and now Jupiter and the other gods have requited you as you deserved.”

Thus I spoke, and so great became his anger that he broke off the peak of a great hill and threw it at us, and it fell in front of the dark-prowed ship. And the sea rose in waves from the fall of the rock, and drove the ship quickly back to the shore. Then I caught up a long pole in my hands, and thrust the ship from off the land; and with a motion of the head, I bade them dash in with their oars, so that we might escape from our evil plight. So they bent to their oars and rowed on.

Such is the story which Ulysses told of his adventure with the giant Cyclops. Many and strange were the other adventures through which he passed before he reached his distant home; and all are related in that wonderful poem, the “Odyssey.” This poem has been often translated into the English language. Some of the translations are in the form of poetry, and of these the best are the versions by{67} George Chapman, by Alexander Pope, and by our American poet William Cullen Bryant. The best prose translation is that by Butcher and Lang—and this I have followed quite closely in the story which you have just read.

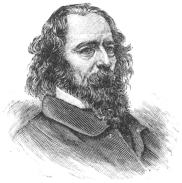

This poem, by Alfred Tennyson, was written in 1832. Considered as a picture, or as a series of pictures, its beauty is unsurpassed. The story which is here so briefly told is founded upon a touching legend connected with the romance of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Tennyson afterwards (in 1859) expanded it into the Idyll called “Elaine,” wherein he followed more closely the original narrative as related by Sir Thomas Malory.

Sir Lancelot was the strongest and bravest of the Knights of the Round Table, and for love of him Elaine, “the fair maid of Astolat,” pined away and died. But before her death she called her brother, and having dictated a letter which he was to write, she spoke thus:

“ ‘While my body is whole, let this letter be put into my right hand, and my hand bound fast with the letter until I be cold, and let me be put in a fair bed with all my richest clothes that I have about me, and so let my bed and all my rich clothes be laid with me in a chariot to the next place whereas the Thames is, and there let me be put in a barge, and but one man with me, such as ye trust to steer me thither, and that my barge be covered with black samite over and over.’... So when she was dead, the corpse and the bed and all was led the next way unto the Thames, and there all were put in a barge on the Thames, and so the man steered the barge to Westminster, and there he rowed a great while to and fro, or any man espied.”[1] At length the King and his Knights, coming down to the water side, and seeing the boat and the fair maid of Astolat, they uplifted the hapless body of Elaine, and bore it to the hall.

[1] Malory’s “King Arthur,” Book XVIII.

Let us suppose that it is summer time, that you are in the country, and that you have fixed upon a certain day for a holiday ramble. Some of you are going to gather wild flowers, some to collect pebbles, and some without any very definite aim beyond the love of the holiday and of any sport or adventure which it may bring with it.

Soon after sunrise on the eventful day you are awake, and great is your delight to find the sky clear, and the sun shining warmly. It is arranged, however, that you do not start until after breakfast time, and meanwhile you busy yourselves in getting ready all the baskets and sticks and other gear of which you are to make use during the day. But the brightness of the morning begins to get dimmed. The few clouds which were to be seen at first have grown large, and seem evidently gathering together for a storm. And sure enough, ere breakfast is well over, the first ominous big drops are seen falling.

You cling to the hope that it is only a shower which will soon be over, and you go on with the preparations for the journey notwithstanding. But the rain shows no symptom of soon ceasing. The big drops come down thicker and faster. Little pools of water begin to form in the hollows of the{80} road, and the window panes are now streaming with rain. With sad hearts you have to give up all hope of holding your excursion to-day.

It is no doubt very tantalizing to be disappointed in this way when the promised pleasure was on the very point of becoming yours. But let us see if we can not derive some compensation even from the bad weather. Late in the afternoon the sky clears a little, and the rain ceases. You are glad to get outside again, and so we all sally forth for a walk. Streams of muddy water are still coursing along the sloping roadway. If you will let me be your guide, I would advise that we should take our walk by the neighboring river. We wend our way by wet paths and green lanes, where every hedgerow is still dripping with moisture, until we gain the bridge, and see the river right beneath us. What a change this one day’s heavy rain has made! Yesterday you could almost count the stones in the channel, so small and clear was the current. But look at it now!

The water fills the channel from bank to bank, and rolls along swiftly. We can watch it for a little from the bridge. As it rushes past, innumerable leaves and twigs are seen floating on its surface. Now and then a larger branch, or even a whole tree trunk, comes down, tossing and rolling about on the{81} flood. Sheaves of straw or hay, planks of wood, pieces of wooden fence, sometimes a poor duck, unable to struggle against the current, roll past us and show how the river has risen above its banks and done damage to the farms higher up its course.

We linger for a while on the bridge, watching this unceasing tumultuous rush of water and the constant variety of objects which it carries down the channel. You think it was perhaps almost worth while to lose your holiday for the sake of seeing so grand a sight as this angry and swollen river, roaring and rushing with its full burden of dark water. Now, while the scene is still fresh before you, ask yourselves a few simple questions about it, and you will find perhaps additional reasons for not regretting the failure of the promised excursion.

In the first place, where does all this added mass of water in the river come from? You say it was the rain that brought it. Well, but how should it find its way into this broad channel? Why does not the rain run off the ground without making any river at all?

But, in the second place, where does the rain come from? In the early morning the sky was bright, then clouds appeared, and then came the rain, and you answer that it was the clouds which supplied the rain. But the clouds must have derived the water{82} from some source. How is it that clouds gather rain, and let it descend upon the earth?

In the third place, what is it which causes the river to rush on in one direction more than another? When the water was low, and you could, perhaps, almost step across the channel on the stones and gravel, the current, small though it might be, was still quite perceptible. You saw that the water was moving along the channel always from the same quarter. And now when the channel is filled with this rolling torrent of dark water, you see that the direction of the current is still the same. Can you tell why this should be?

Again, yesterday the water was clear, to-day it is dark and discolored. Take a little of this dirty-looking water home with you, and let it stand all night in a glass. To-morrow morning you will find that it is clear, and that a fine layer of mud has sunk to the bottom. It is mud, therefore, which discolors the swollen river. But where did this mud come from? Plainly, it must have something to do with the heavy rain and the flooded state of the stream.

Well, this river, whether in shallow or in flood, is always moving onward in one direction, and the mud which it bears along is carried toward the same point to which the river itself is hastening. While we sit on the bridge watching the foaming water as it{83} eddies and whirls past us, the question comes home to us—what becomes of all this vast quantity of water and mud?

Remember, now, that our river is only one of many hundreds which flow across this country, and that there are thousands more in other countries where the same thing may be seen which we have been watching to-day. They are all flooded when heavy rains come; they all flow downwards; and all of them carry more or less mud along with them.

As we walk homewards again, it will be well to put together some of the chief features of this day’s experience. We have seen that sometimes the sky is clear and blue, with the sun shining brightly and warmly in it; that sometimes clouds come across the sky, and that, when they gather thickly, rain is apt to fall. We have seen that a river flows, that it is swollen by heavy rain, and that when swollen it is apt to be muddy. In this way we have learned that there is a close connection between the sky above us and the earth under our feet. In the morning, it seemed but a little thing that clouds should be seen gathering overhead; and yet, ere evening fell, these clouds led by degrees to the flooding of the river, the sweeping down of trees and fences and farm produce; and it might even be to the destruction of bridges, the inundation of fields and{84} villages and towns, and a large destruction of human life and property.

But perhaps you live in a large town and have no opportunity of seeing such country sights as I have been describing, and in that case you may naturally enough imagine that these things cannot have much interest for you. You may learn a great deal, however, about rain and streams even in the streets of a town. Catch a little of the rain in a plate, and you will find it to be so much clear water. But look at it as it courses along the gutters. You see how muddy it is. It has swept away the loose dust worn by wheels and feet from the stones of the street, and carried it into the gutters. Each gutter thus becomes like the flooded river. You can watch, too, how chips of straw, corks, bits of wood, and other loose objects lying in the street are borne away, very much as the trunks of trees are carried by the river. Even in a town, therefore, you can see how changes in the sky lead to changes on the earth.

If you think for a little, you will recall many other illustrations of the way in which the common things of everyday life are connected together. As far back as you can remember, you have been familiar with such things as sunshine, clouds, wind, rain, rivers, frost, and snow, and they have grown so commonplace that you never think of considering about{85} them. You cannot imagine them, perhaps, as in any way different from what they are; they seem, indeed, so natural and so necessary that you may even be surprised when any one asks you to give a reason for them.

But if you had lived all your lives in a country where no rain ever fell, and if you were to be brought to such a country as this, and were to see such a storm of rain as you have been watching to-day, would it not be very strange to you, and would you not naturally enough begin to ask the meaning of it? Or suppose that a boy from some very warm part of the world were to visit this country in winter, and see for the first time snow falling, and the rivers solidly frozen over, would you be surprised if he showed great astonishment? If he asked you to tell him what snow is, and why the ground is so hard, and the air so cold, why the streams no longer flow, but have become crusted with ice—could you answer his questions?

And yet these questions relate to very common, everyday things. If you think about them, you will learn, perhaps, that the answers are not quite so easily found as you had imagined. Do not suppose that because a thing is common, it can have no interest for you. There is really nothing so common as not to deserve your attention.{86}