At Regina Trench, Vimy Ridge

From the Painting by J. Prinsep Beadle

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

GLASGOW

TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW

| MACMILLAN AND CO. LTD. | LONDON |

| THE MACMILLAN CO. | NEW YORK |

| MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA | TORONTO |

| SIMPKIN, HAMILTON AND CO. | LONDON |

| BOWES AND BOWES | CAMBRIDGE |

| DOUGLAS AND FOULIS | EDINBURGH |

| MCMXX | |

The Pipes of War

A Record of the Achievements of Pipers

of Scottish and Overseas Regiments

during the War 1914-18

BY

Brevet-Col. SIR BRUCE SETON, Bart., of Abercorn, C.B.

AND

Pipe-Major JOHN GRANT

WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY

NEIL MUNRO, BOYD CABLE, PHILIP GIBBS, and Others

GLASGOW

MACLEHOSE, JACKSON & CO.

PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY

1920

Wherever Scottish troops have fought the sound of the pipes has been heard, speaking to us of our beloved native land, bringing back to our memories the proud traditions of our race, and stimulating our spirits to fresh efforts in the cause of freedom. The cry of "The Lament" over our fallen heroes has reminded us of the undying spirit of the Scottish race, and of the sacredness of our cause.

The Pipers of Scotland may well be proud of the part they have played in this war. In the heat of battle, by the lonely grave, and during the long hours of waiting, they have called to us to show ourselves worthy of the land to which we belong. Many have fallen in the fight for liberty, but their memories remain. Their fame will inspire others to learn the pipes, and keep alive their music in the Land of the Gael.

This record of the achievements of pipers during the war of 1914-18 is not intended to be an appeal to emotionalism. It aims at showing that, in spite of the efforts of a very efficient enemy to prevent individual gallantry, in spite of the physical conditions of the modern battlefield, the pipes of war, the oldest instrument in the world, have played an even greater part in the orchestra of battle in this than they have in past campaigns.

The piper, be he Highlander, or Lowlander, or Scot from Overseas, has accomplished the impossible—not rarely and under favourable conditions, but almost as a matter of routine; and to him not Scotland only but the British Empire owes more than they have yet appreciated.

In doing so he has sacrificed himself; and Scotland—and the world—must face the fact that a large proportion of the men who played the instrument and kept alive the old traditions have completed their self-imposed task. With 500 pipers killed and 600 wounded something must be done to raise a new generation of players; it is a matter of national importance that this should be taken in hand at once, and that the sons of those who have gone should follow in the footsteps of their fathers.

This is the best tribute that can be offered to them.

The Piobaireachd Society intend to institute a Memorial School of piping for this purpose, and all profits from the sale of this book will be handed over to their fund.

The compilation of the statistical portions of the work has involved correspondence with commanding officers, pipe presidents and pipe majors of many units in the Imperial armies; to them, for their enthusiastic[viii] assistance in obtaining information, is due the credit for the mass of detail that has been made available.

To the other contributors—authors, artists and poets—is due in large measure such success as may follow the publication of this work. They have helped a cause worthy of their efforts.

It is earnestly to be hoped that Scotland will rise to the occasion. To the compilers it has been a privilege to record the achievements of men—many of them personal friends—who contributed so largely to the success of their gallant regiments.

B. S.

J. G.

| PAGE | |

| Foreword by Field-Marshal Earl Haig of Bemersyde, K.T. | v |

| Preface | vii |

| THE PIPES OF WAR. By Brevet Col. Sir Bruce Seton, Bart., of Abercorn, C.B. | |

| Introduction | 3 |

| A History of the Pipes | 9 |

| The Pipes in the War, 1914-1918 | |

| The Western Front | 18 |

| Gallipoli | 31 |

| Salonika | 33 |

| Mesopotamia | 33 |

| The Last Stage | 34 |

| Pipers in the Ranks | 35 |

| Pipers on the March | 37 |

| Pipe Tunes | 42 |

| Individual Achievements | 46 |

| Foreigners and the Pipes | 63 |

| The Pipes in Captivity | 64 |

| Military Pipe Bands and Reform | 66 |

| Regimental Records | |

| The Scots Guards | 71 |

| The Royal Scots | 73 |

| The Royal Scots Fusiliers | 82 |

| The King's Own Scottish Borderers | 86 |

| The Cameronians (The Scottish Rifles) | 91 |

| The Royal Highlanders (The Black Watch) | 96 |

| The Highland Light Infantry | 105 |

| The Seaforth Highlanders | 114 |

| The Gordon Highlanders | 124 |

| The Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders | 130 |

| The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders | 135 |

| The London Scottish | 143 |

| The Tyneside Scottish | 145 |

| [x] The Middlesex Regiment | 146 |

| The Liverpool Scottish | 147 |

| The Royal Fusiliers | 147 |

| The Argyllshire Mountain Battery | 148 |

| The Ross and Cromarty Battery | 148 |

| Miscellaneous | 148 |

| The Pipe Band of the 52nd (Lowland) Division | 149 |

| Prisoners of War Band | 150 |

| Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry | 150 |

| The Royal Highlanders of Canada | 151 |

| The 48th Highlanders of Canada | 152 |

| The Canadian Scottish | 153 |

| The Cameron Highlanders of Canada | 154 |

| The 21st Canadians | 155 |

| The 25th Canadians | 155 |

| The 29th Canadians | 156 |

| The 236th Canadians | 157 |

| The Canadian Pioneers | 158 |

| The 2nd Auckland Regiment | 158 |

| The 42nd Australians | 159 |

| The South African Scottish | 159 |

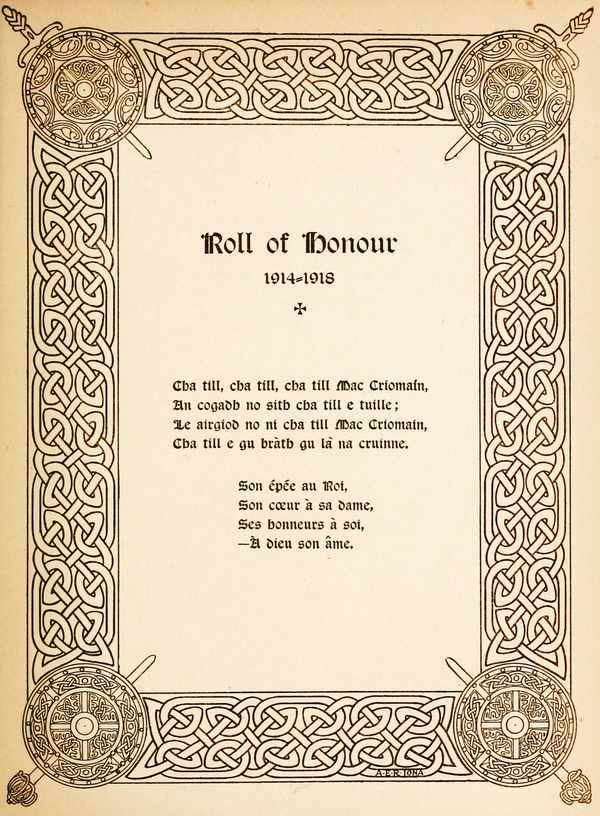

| Roll of Honour, 1914-1918 | 161 |

| Canntaireachd. By Major J. P. Grant, M.C., Yr. of Rothiemurchus | 179 |

| The Irish Pipes: their History, Development and Divergence from the Simple Highland Type. By W. H. Grattan Flood, Mus.D., K.S.G. | 191 |

| The Tuition of Young Regimental Pipers. By John Grant, Pipe Major | 195 |

| The Spirit of the Maccrimmons. By Fred. T. Macleod, F.S.A.(Scot.) | 201 |

| A Gossip about the Gordon Highlanders. By J. M. Bulloch | 219 |

| To the Lion Rampant. By Alice C. Macdonell of Keppoch | 228 |

| The Music of Battle. By Philip Gibbs | 232 |

| The Pipes in the Everyday Life of the War. By Arthur Fetterless | 239 |

| The Oldest Air in the World. By Neil Munro | 246 |

| The Pipes: Onset. By Joseph Lee, Lieut. | 255 |

| Flesh to the Eagles. By Boyd Cable | 258 |

| The Black Chanter. By Charles Laing Warr | 267 |

| The Pipes. By Edmund Candler | 286 |

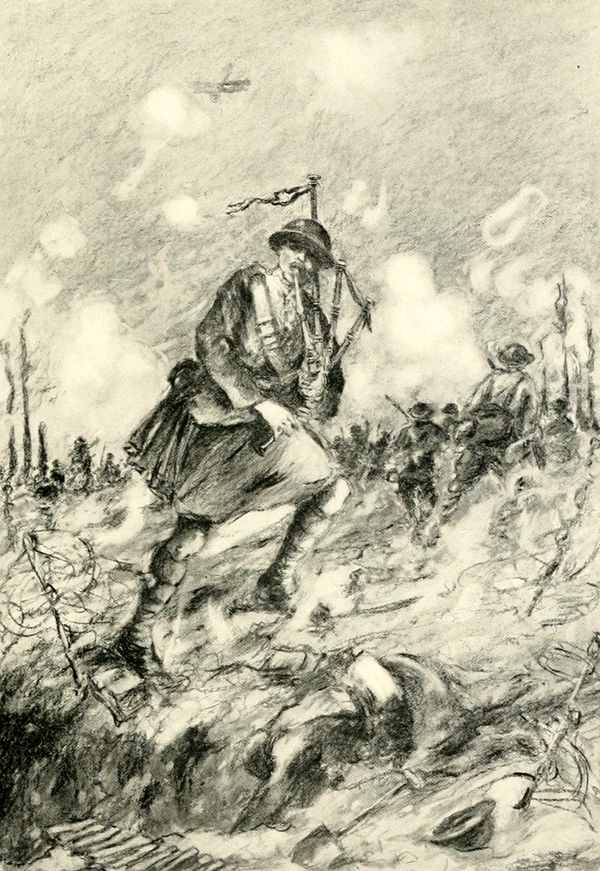

| Piper James Richardson, V.C., 16th Canadian Scottish, at Regina Trench, Vimy Ridge | Frontispiece | |

| From the Painting by J. Prinsep Beadle. | ||

| Piper Daniel Laidlaw, V.C., 7th King's Own Scottish Borderers, at Loos | Page | 24 |

| From the Drawing by Louis Weirter, R.B.A. | ||

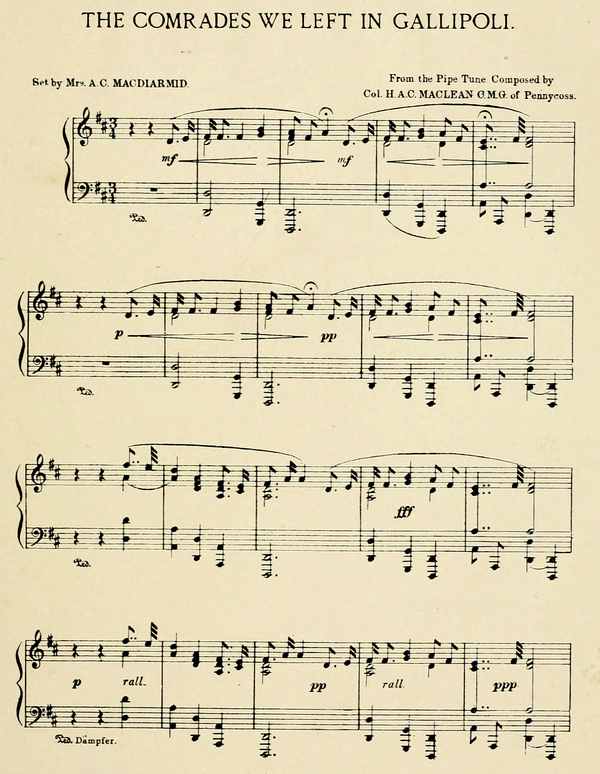

| "The Comrades we Left in Gallipoli" | " | 32 |

| From the Pipe Tune composed by Colonel H. A. C. Maclean of Pennycross, C.M.G. Set by Mrs. A. C. Macdiarmid. | ||

| Piper Kenneth Mackay, Cameron Highlanders, at Quatre-Bras | " | 64 |

| From the Painting by Lockhart Bogle, by kind permission of the Officers of the 1st Cameron Highlanders. | ||

| Pipe-Major Howarth, D.C.M., 6th Gordon Highlanders, at Neuve Chapelle | " | 120 |

| From the Painting by J. Prinsep Beadle. | ||

| Ben Buidhe, Argyllshire | " | 136 |

| From the Water-colour Drawing by George Houston, A.R.S.A. | ||

| Border of Celtic Design by Alexander Ritchie, Iona | " | 161 |

| The Pibroch | " | 208 |

| From the Painting by Lockhart Bogle. | ||

| Duniquaich, Loch Fyne | " | 248 |

| From the Water-colour Drawing by George Houston, A.R.S.A. | ||

THE PIPES OF WAR

BY

BREVET-COL. SIR BRUCE SETON, BART.

OF ABERCORN, C.B.

The history of the bagpipes as a military institution is a long and honourable one, inseparable from that of Scottish troops, Highland and Lowland, wherever they have fought, for centuries past. The strains of piob mhor have been heard all over those bloody European battlefields on which Scottish soldiers of fortune died—too often for lost causes—from the time when Buchan's force joined the Lilies of France in 1422, throughout the Hundred Years' War, in the Low Countries, in Germany, in Austria; and they have handed on a tradition which has been lived up to in the later days of the regular Scottish units of the British Army.

But memories are short; and, in the army as elsewhere, the passion for reform before the greatest war of all was threatening many old-established institutions whose utility was not immediately apparent.

And so it came about that to many observers, indeed to a considerable section of military opinion, it appeared likely that along with the kilt, the use of tartan, bonnet, doublet and other special features of the dress of Scottish regiments, the bagpipe must be regarded as a picturesque anachronism destined to disappear as the conditions of war changed and as the yearning of high military authorities for a deadly khaki uniformity of clothing and equipment became more insistent.

"Why," it has often been said, "should Scottish units find it necessary, either in peace or on active service to retain an obsolete musical instrument of their own? In days past, before the rifle had revolutionised tactics, when shooting was erratic at 100 yards' range, there might have been something to say for an instrument which experience showed to be capable of stimulating men at the psychological moment when effort was failing; but is it reasonable[4] to expect that the educated twentieth century soldier will prove to be responsive to any such stimulus—even if it were possible, under modern conditions of rifle and shell fire, to provide it?"

The reply to such a line of argument is clear enough; and its truth has been demonstrated in every action in which Scottish troops have taken part during the war.

The strength of an army depends, to an incalculable degree, on the strength not only of individual regimental esprit de corps, but of the national sentiment of its units. The retention of time-honoured territorial titles in the New Armies, instead of a soulless numbering of units, was itself due to a recognition by the authorities of the principle that the individual soldier is a better fighting man when he feels that he has to live up to an ancient and brilliant regimental record. The Rifleman, even in peace, would never voluntarily be transferred to a "red" regiment, nor does a 10th Hussar yearn for the cuirass of the Life Guardsman. When a man joins a regiment, voluntarily or compulsorily, he adopts for the whole period of his military service the customs, the prejudices, and the traditions of his unit, and is himself moulded by them in a manner which is as inexplicable as it is marked.

And if regimental esprit de corps and tradition are strong, national and territorial sentiment are stronger. In the old army, as a result of the system of recruitment, this factor was of less importance than in the, comparatively speaking, unmixed units of the new army of to-day. All our military history shows that the appeal to such national sentiment is as certain in its effects as the appeal to regimental tradition; and this war has enormously accentuated its importance.

All observers agree—and military despatches confirm the view—that the rivalry of national sentiment has proved invaluable; units, whether battalions or divisions, have literally competed for distinction for their own nationality, and have succeeded in associating particular exploits with themselves for ever. It may truly be said that behind the achievements of the 9th, 15th, 51st and 52nd and Canadian Divisions the motive impulse was national rather than merely regimental.

In the keeping alive of this national sentiment in Scottish units, their distinctive dress and, still more, the retention of the national instrument, have played an important part; and this applies with equal force to units composed of Scotsmen who have left their native land permanently or temporarily.

Throughout the war these units have more than maintained the great traditions of their past history, carrying on the records of Scottish gallantry which have been excelled by no troops in the world and equalled by few.

And so with the pipers.

How important a contributory cause they have been to the success of their battalions is recognized by all alike, men and officers—and not least by the Field Marshal Commanding in Chief. In spite of modern conditions they have, in cases too numerous to record, played the part which was normally theirs in the olden days of set battles.

To many of the men in the ranks the music of the pipes in peace time may have had no special association other than with dances and gatherings; but whenever the piper assumed his historic rôle—so long dormant—of fighting man, the inherited peculiarities of the Scottish soldier were aroused and the music made an overpowering appeal to his national sentiment.

Inherited sympathy of this kind is no doubt inexplicable—but it exists. It certainly cannot be ascribed to the Celtic strain in individuals, for we know that the bagpipe was in general use for centuries all over the Lowlands—perhaps even before it displaced the bard and the harper and became the war instrument of the Highlands. We cannot analyse what Neil Munro describes as "the tune with the river in it, the fast river and the courageous, that kens not stop nor tarry, that runs round rock and over fall with a good humour, yet no mood for anything but the way before it"; we only know that it works on some individuals and some races as no other instrument does, and we need not try to satisfy ourselves whether this is due to the flat seventh in the scale, or the ever-sounding drones, or the inherited memory it arouses.

The idea that the piper would be too conspicuous an object to be employed in his proper capacity has proved to be partly true, as indicated by the[6] casualties among them when playing; but the same argument might be applied to any other soldier in the ranks. Shells show no discrimination in their objective.

To a certain extent this objection is a sound one; but it is all a matter of relative values. Many commanding officers have expressed the opinion that at times when, on account of the all-pervading noise of the battlefield, not a note of his music could be heard by the men nearest to him, it was the actual presence of the piper that supplied the stimulus to the men; in fact, it was the piper, not his instrument, that was followed.

For obvious reasons pipers are harder to replace than the ordinary soldier, and, in trench warfare especially, most regiments have tried to keep them in relative security; but in the records of units which follow it will be seen that, when the trouble comes, the piper has always been to the fore, and "the tune with the tartan of the clan in it" has been heard again as it has for centuries past.

From the military point of view the bagpipe has the merit of accentuating national sentiment at just those moments when the stimulus is most necessary, of rousing the "mir cath," the frenzy of battle, and of rallying men when the ideal is liable to be lost sight of in the presence of the nerve shattering realities of action.

In all these ways the company pipers have justified their existence. In the discharge of a duty which may be regarded as sentimental in the highest sense of the term, they have, literally by hundreds, made the supreme sacrifice; wherever Scottish units have fought these men have exposed themselves, unhesitatingly, recklessly, playing their companies to the attack in conditions which, as regards intensity of personal risk, have never previously been experienced. Many battalions have lost all their pipers more than once, but, as long as reinforcements were available, there has never been any difficulty in getting fresh men out of the ranks or from home to take their place; and the new men have followed the old, just as heedless, as they played their comrades forward, knowing quite well that for many of them the urlar of "Baile Inneraora" or "The March[7] of the Cameron men" might suddenly change to the taorluath of "Cha till mi tuille."

The Germans at least, though they may not recognise the tune when they hear it in the streets of Cologne, appreciated the grim significance of piob mhor when "I hear the pibroch sounding, sounding" followed the lifting of the barrage.

The war also has afforded many instances of another function of the pipes in action. Charging the enemy at a foot pace through deep mud is after all but a "crowded hour of glorious life," which may or may not be completely or even partially successful, and men may have to be rallied when their nerves have given out under intolerable strain. Of this there have been several instances.

It must not, of course, be imagined that regimental pipers, during this or any other war, have been normally employed in playing their units to the attack; the whole condition of modern fighting makes this impossible in the same way and for the same reason that it has made impossible spectacular charges by battalions in line.

It would be a more accurate presentment of the case to say that the military piper, qua piper, normally exercises his functions behind the front line, in billets and on the line of march; and in this respect he resembles other army musicians whose duty—according to old Army Regulations of 300 years ago—is "to excite cheerfulness and alacrity in the soldier."

But, recognising all this, the peculiarity of the piper is that, in open fighting, when his unit has been committed to the attack, he often assumes the rôle which distinguishes him from all other musicians, and takes his place at the head of his company.

Instances of this during the war are innumerable, and those which are detailed below are but typical of what has occurred in every field of operations, and in most units which possessed pipers.

And if it is impossible to say too much of the regimental pipers of the British Army, it is equally so in the case of those of Overseas units, notably of the Canadians. From the point of view of the historian who wishes to demonstrate what pipers have done during this war, no more remarkable[8] case could be selected than that of the 16th Canadian Scottish. The pipers of this distinguished battalion won one V.C., one D.C.M., one Military Medal and Bar, and eight plain Military Medals—a record which is unique. No man was put up for a decoration unless he had played his company over the top at least twice, and no piper was ever ordered to play in action—it was left to volunteers, who, it was found, had to resort to the drawing of lots to obtain the coveted privilege of playing.

The colonel of the regiment—himself a V.C.—commenting on the casualties says: "I believe the purpose of war is to win victories, and if one can do this better by encouraging certain sentiments and traditions why shouldn't it be done? The heroic and dramatic effect of a piper stoically playing his way across the ghastly modern battlefield, altogether oblivious to danger, has an extraordinary effect on the spirit and enterprise of his comrades. His example inspires all those about him."

And so it comes to this: the method of employment of the regimental piper during this war has depended largely on opportunity—and still more on the individuality of commanding officers. Men vary within very wide limits in the price they are prepared to pay for attaining their object; and where one man will deliberately sacrifice a certain number of men to get a position, another will as deliberately avoid the sacrifice, even if it costs him his objective.

As far as pipers are concerned, the decision arrived at by commanding officers of the two schools is equally indicative of the esteem in which they hold them.

At what stages of his development primitive man discovered he could obtain musical sounds by blowing on a hollow reed we cannot now ascertain; if we could do so we could at once determine when the pipe came into existence. It is unprofitable to speculate on this point.

What we do know, however, is that men playing the pipe are portrayed in sculptures the date of which is fixed by the best authorities as about 4000 B.C., and we conclude that in Chaldaea, Egypt, Assyria and Persia at least, the pipe—but not necessarily the bagpipe—had become a recognised musical instrument.

Actual specimens of the Egyptian pipe dating back to at least 1500 B.C. are in existence, and we know that they had a reed giving a scale almost identical with the chromatic scale; they also had a drone. Such a pipe had, clearly, advanced some way on the upward development to "piob mhor."

Every stage in its evolution still persists in some country in the world, and by comparing these it is possible to trace the actual process. Thus, besides the single pipe, which is world-wide in its distribution, we have the Egyptian "arghool," which consists of a pipe "chanter" and drone lying side by side; and the later development, the "zummarah," has a bag. In India the twentieth century snake charmer has an instrument in which chanter and single drone lie side by side fixed into a small gourd with a lump of wax. The chanter has a small reed very similar to our own chanter reeds, and, although the scale differs, the sound produced is remarkably [10]similar. This instrument is essentially a single drone bagpipe, and is to be found all over India, in Yunnan and other parts of China.

Note.—The author takes this opportunity of acknowledging his indebtedness for much of the early history of the instrument to Manson's The Highland Bagpipe and Dr. Grattan Flood's The Story of the Bagpipe, both monuments of research.

It would have been more than surprising if the pipe, in some form or other, had not been used in ancient Greece and Rome. There are, in fact, very many references to it in classical literature, and by 100 A.D. we know that the "askaulos" had evolved into the bagpipe proper, and Chrysostomos speaks of a man who could "play the pipe with his mouth on the bag placed under his armpit."

Martial, Suetonius, Seneca, and other Latin writers refer to the "tibia utricularis," and there is practically no doubt that it was used as a marching instrument in the armies of Julius Caesar. A bronze showing a Roman soldier in marching order playing the utriculus has been discovered in England, and the writer Procopius refers to Roman pipe bands in this country.

But when we come to the question of the introduction of the bagpipe into the British Isles, and especially into Scotland, we are at once on highly controversial ground.

It is obvious enough that the instrument is not peculiar to the Celtic races; that it has maintained its hold on them long after its disappearance in other European nations is equally so. But who introduced it into these favoured isles, whether the Cruithne or Prydani or Picts or the later "C" Gaidheal branch of the Celtic stem—who shall say?

Some authorities—students of the subject would be a safer term—are prepared to assert that the bagpipe was introduced first into England, thence to Lowland Scotland, and only long afterwards into the Highlands; and one recent writer in the Celtic Magazine says the evidence of its association with the Scottish Gaels does not go back beyond the middle of the sixteenth century!

The matter is one of academic interest, no doubt, but there is no likelihood of its ever being settled.

Records did not exist in the ancient Highlands, and we have to turn to early Irish literature for reference to the bagpipe. In the Brehon Laws of the fifth century it is spoken of as the "cuisle"; and, although Tara's halls[11] are usually associated with the harp, it is recorded that at the assemblies which took place there in pre-Christian days it was the custom for the pipes to play at the banquets.[1]

It is possible the bagpipe was brought over from the north of Ireland, "Scotia" as it then was, on the invasion of the Highlands by Cairbre Riada, who founded the kingdom of Dalriada in Argyle in A.D. 120; or in the later great colonisation, about A.D. 506, under Lorne and Angus, the sons of Ere.

It certainly does not appear likely that the bagpipe came over from "Scotia" in the first place, unless we are to accept the view that the Scottish Celt came over by the same route; unfortunately we have very little accurate knowledge of the early history of the Highlands, and there are no local written records extant to prove—as they do in the case of Ireland—that the instrument existed in those early days. We do know that the harper and the bard were national institutions of immense antiquity in the Highlands, and that, as the bagpipe became an increasingly important feature of everyday life, they were bitterly opposed to it.

Even Latin authors, who were familiar with the bagpipe as a marching instrument in their own army, omit to refer to the existence of piob mhor in the Highlands. The Greek writer Procopius, in 530 A.D., dismisses the Highlands with the statement that "in the west the air is infectious and mortal, the ground covered with serpents, and this dreary solitude is the region of departed spirits." And so we are thrown back on tradition.

In the absence of records of the employment of the bagpipe in war in the Highlands it is to Ireland, the so-called Lowlands of Scotland and to England that we have to turn for information; at the same time we must bear in mind that evolution of the instrument itself had begun to operate, and the English and Lowland pipes were different from the variety now known as the "Highland," which has supplanted all others.

As regards Ireland it is known that the Irish troops who fought in Gascony in 1286 had pipers with them, and a drawing of their instrument appears in a manuscript of 1300 A.D. in the British Museum. There were [12]also Irish pipers at the battle of Falkirk in 1298, and they are again referred to in contemporary accounts of the battle of Creçy.

The military piper therefore goes far back into history. But it was as a social instrument that one finds most frequent reference to bagpipes of some pattern or other in the Middle Ages. There was a pipe band at the English Court in 1327, and an old inventory of 1419 shows that at the Palace of St. James' were "foure baggpypes with pypes of ivorie ... the bagge covered with purple vellat."

But, whereas the English pipes went the same way as the Continental varieties, it was otherwise in Scotland. Two institutions existed there which fostered the tradition and saved piob mhor from the fate of disappearance—the Burgh piper and the Clan piper; and by 1450 A.D. these had certainly become part of the national life.

In Edinburgh in 1487 A.D. there were three town pipers, who were paid three pence daily; one of their duties was "to accompany the toun's drummer throw toun morning and evening." In 1505 A.D. the town records of Dumbarton, Biggar, Wigton, Dumfries and Linlithgow refer to burgh pipers.

In Aberdeen in 1630 A.D. exception appears to have been taken to the custom of playing through the streets, as it is placed on record that this was to be stopped "it being an uncivill forme to be usit uithin sic a famous burghe, and being oftene found fault uith als weill be sundrie niehbouris as by strangeris." That the citizens of this "famous burghe" are peculiarly susceptible to the criticisms of "strangeris" might never have been suspected by superficial observers, and it is well that there is official testimony to the fact.

The effect of their daily music on the inhabitants of Perth was different,—or perhaps Perth was less amenable to the criticisms of "strangeris." In any case it is recorded of a burgh piper, who used to rouse the citizens at 5 a.m., that his music was "inexpressibly soothing and delightful."

At Dundee the piper played through the town "every day in the morning at four hours and every nicht at aucht hours," and was paid twelve pennies yearly by each householder.

The pipes, at least in the pre-Reformation days—were sometimes played in church; in course of time, however, piping on Sunday scandalised the authorities, religious and civil, and, in the burgh records, we find repeated instances of pipers being punished for this misdemeanour.

The burgh piper was a man of peace; the clan piper was a man of war. For many centuries he had to compete with the "clarsair," or harper, and the bard, and aroused feelings of acute hostility from the latter. In 1411 A.D. one bard, MacMhurich of Clan Ranald, wrote a poem of a most uncomplimentary nature about the bagpipes.

The recitation of the bard before battle was probably last heard at Harlaw in 1411, and the clan bards disappeared finally in 1726; the last clan harper died in 1739, and the "croistara"—the fiery cross—was sent round the clans for the last time in the '45. The last Scottish piper will pass when the Scottish race itself passes—which will certainly be the last of all.

The clan pipers were highly esteemed as musicians—from the musical point of view they, no doubt, left us far behind. The courses of training, lasting over years, at the old piping schools such as existed at Boreraig, turned a man into a piper. As Neil Munro has it: "To the make of a piper go seven years of his own learning and seven generations before; at the end of his seven years one born to it will stand at the start of knowledge, and, leaning a fond ear to the drone, he may have parley with old folks of old affairs."

One of the results of the Heritable Jurisdiction Act of 1747, which so completely altered the conditions of life in the Highlands, was the disappearance of the office of hereditary clan piper.

The tunes these men played were the old tunes we know so well; and so it has happened that in this war we find companies marching into and through machine-gun and artillery barrage and into broken French villages and through German trenches while the company piper plays the same melodies that inspired their forebears to fight their neighbours lang syne—melodies which have been heard, too, in the same part of the world in the days when Scottish troops fought for the Lilies of France against all comers.

The association of the bagpipe with military operations is probably very ancient in Scotland. Perhaps the tradition that the Menzies pipers played at Bannockburn rests on an insecure foundation, but if the Bruce had no pipers, his son David most certainly had, as witness the Exchequer Rolls. In 1549 a French writer states that "the wild Scots encouraged themselves to arms by the sound of their bagpipes"; and in 1598 Alexander Hume of Logie wrote:

"Caus michtilie the warlic nottes brake

On Heiland pipes, Scottes and Hyberniche.

Incidentally, this reference to three different kinds of pipes is interesting.

The first authentic reference to pipers in the Forces of the Crown appears to have been in 1627, when Alex. Macnaughton of Loch Fyne-side was commissioned by King Charles I. to "levie and transport twa hundredthe bowmen" for service in the French war. Writing in January 1628 to the Earl of Morton, Macnaughton says:

"As for newis from our selfis, our baggpyperis and marlit plaidis serwitt us in guid wise in the pursuit of ane man of war that hetlie followed us."

The records show that this company had a harper, "Harrie M'Gra frae Larg," and a piper, "Allester Caddell," who, in accordance with the custom of the time, had his gillie to carry his pipes for him.

Regimental pipers undoubtedly existed in the numerous bodies of Scottish troops which served at various times on the Continent. Thus, in 1586, in the "State of War" of Captain Balfour's company in the Scots Brigade in Holland, there were two drummers and a piper; and in "the worthy Scots regiment called Mackeye's" raised by Sir Donald Mackay in 1626 there was an establishment of thirty-six pipers.

Pipers are also found on the rolls of the "regiment d'Hebron"—now the Royal Scots—and to that very distinguished regiment we may safely accord the further distinction of being the first "Regular" regiment of the British Army to have pipes. The "North British Fusiliers," now one of the battalions of the Royal Scots Fusiliers, also had pipes as far back as 1678, and probably as early as 1642.

Writing in 1641, Lord Lothian said:

"I cannot out of our armie furnish you with a sober fiddler.... We are sadder and graver than ordinarie soldiers, only we are well provided with pypers. I have one for every company in my regiment, and I think they are as good as drummers."

The great Montrose had pipers in his armies, and tradition has it that, in the action of Philiphaugh in 1645, a piper stood on a small eminence and played the old Cavalier tune, "Whurry, Whigs, awa' man," until he was shot by one of Leslie's men, and fell into the "Piper's Pule" in Ettrick river.

An exactly similar incident occurred in the case of one of the pipers of Bonnie Dundee at Bothwell Brig in 1679.

At the Haughs o' Cromdale in 1690 a wounded piper climbed on to a big rock and went on playing till he died, thus setting an example which has been followed by his successors in many actions in this war. The stone on which this unknown hero stood is known to this day locally as "Clach a phiobair."

There are many such in France and elsewhere to-day.

In Wodrow's letters in 1716 there is a reference to the company pipers of the "Argyle's Highlanders": "They entered in three companies, and every company had their distinct pipers, playing three distinct springs. The first played "The Campbells are coming" ... and when they entered Dundee the people thought they had been some of Mar's men, till some of the prisoners in the Tolbooth, understanding the first spring, swung the words of it out of the windows, which mortified the Jacobites."

Again, in 1715, when Argyle's troops marched to Leith, it was stated by Cockburn (Historical MSS. Commission): "While our generals were asleep the rebels marched to Seton House, leaving the piper in the citadel to amuse."

The piper, by this time, had clearly become a recognised military institution.

In the '45 the unfortunate Sir John Cope was undoubtedly aroused by the music of piob mhor at Prestonpans, though it is doubtful whether "Hey Johnnie Cope" was composed for the occasion.

Prince Charlie had thirty-two pipers of his own, besides those belonging to the clans with him. One of these men, James Reid, was taken prisoner in the operations of 1746. He pleaded that he had not carried arms, but the Court decided that "no Highland regiment ever marched without a piper: therefore his bag pipe, in the eye of the law, was an instrument of war"—and they dealt with him accordingly.

This view was confirmed by the Disarming Act of 1747, which nearly succeeded in attaining its object of abolishing the bagpipe, the kilt, the tartan and national sentiment generally—only Regular regiments being exempted from its operation.

Penal legislation against the bagpipe was no new thing. Cromwell had tried it in Ireland, and, under William II., 600 Irish pipers and harpers were persecuted with relentless rigour. And in Ireland it succeeded.

Saxon governments have always done the piper the honour of regarding him as an exponent and supporter of national sentiment.

Even in Scotland the years between 1747 and 1782, when the iniquitous Disarming Act was repealed, were very nearly fatal to the continued existence of the bagpipe as a national institution; and it was the Regular Army which saved it—though no one could ever accuse the military authorities of unduly favouring the instrument. Even General Officers have publicly sneered at them—as when Wolfe at Quebec contemptuously refused to allow the pipes of the Fraser Highlanders to play, or when Sir Eyre Coote in 1778 described them as a "useless relic of the barbarous ages."

Both generals had to withdraw what they had said.

The opinion of the Court Martial which tried poor James Reid, that his bagpipe "was, in the eye of the law, an instrument of war," was after all as shrewd an expression of the truth as their sentence was harsh.

In later times the pipes in the army have received little official recognition. In 1858, when the King's Own Scottish Borderers applied for their pipers to be placed on the establishment, the Commander in Chief grudgingly consented "as the permission for these men is lost in time," but on condition that they were not to cost the public anything as regards their clothing.

Nor has the modern War Office shown more sympathy to an institution whose value, even on theoretical grounds, should have been recognised. The ancient and honourable title of Pipe Major has been abolished and that of "sergeant piper" has been substituted. Pipers themselves, on mobilisation, are returned to the ranks with the exception of six men. In Lowland regiments, indeed, the piper, though tolerated, is not officially recognised at all.

A bandsman may in due course become a first-class warrant officer—in one or two units, indeed, he has attained commissioned rank; but the "sergeant piper" remains a sergeant, and can hope for nothing more. This, surely, is an injustice which is remediable at small cost to the nation.

The apathy of the War Office in regard to the training of pipers as pipers is another matter which is in urgent need of reform. Commanding officers and pipe presidents are sometimes pipers themselves—though not always; it is absurd to leave to them the responsibility of training men in the art. The time has come for a thorough reform of the whole system and method of training of military pipe bands.

During the autumn[2] and winter of 1914-15 pipers, for obvious reasons, had few opportunities of attracting much attention, still less of performing their highest duty, viz. playing their companies into action. They were necessarily, on account of the extreme shortage of men, for the most part employed in the ranks; and in many of the old Regular battalions pipe bands disappeared altogether.

For a time it seemed that the critics were right, and that in warfare in the twentieth century there was no longer a place for a class of man which was destined to disappear, as the bard and the harper had done in days lang syne.

This view was widely held, and in some regiments was never modified.

But gradually, as attacks became more frequent and movements set in, and as the British Army grew stronger in numbers, the position changed, and the piper became more than an invaluable marching instrumentalist or performer at ceilidhs in billets.

The first occasion on which pipers played, or tried to play, their companies into action was at Cuinchy on 25th January 1915, when the 1st Black Watch suffered such heavy casualties in advancing through deep mud up to their knees.

It was at Neuve Chapelle in March 1915 that the company piper really had his first chance of showing what he could do, as a piper, in action. On[19] this occasion the 20th Brigade had to carry the stronghold of Moulin du Piètre, and lost very heavily; the 2nd Gordons were in the main attack and the 6th Gordons, a Territorial unit, in reserve. The 6th Gordons were called upon to support their comrades of the old Regular Army, and advanced, headed by their pipes and drums, with a rush which carried many of them beyond their objective.

From that time onwards, right up to the end of the war, pipers have repeatedly played their units into action, in spite of the unfavourable conditions resulting from modern rifle and artillery fire and gas, and have established the standard of gallantry in this respect which has been at once the admiration of all observers and an incentive to their successors to emulate them.

During the first weeks' heavy fighting, in April-May 1915, on the left of the attenuated British line of the Ypres salient, the pipers of Canadian battalions took a prominent part. In their advance on the St. Julien wood the 16th Canadians were led by their company pipers, two of whom were killed and two wounded while playing; their places were at once taken by others, who played the battalion through the German trenches at the heels of the retiring enemy to the tune "We'll tak' the guid auld way." In many subsequent actions these men distinguished themselves in the same way.

After the failure of the first attack on the German line at Rue des Bois on 9th May 1915, in the action of Richebourg-Festubert, the 1st Black Watch were played to a fresh attack by their company pipers. "With their characteristic fury they had vanished into the smoke, and the only evidence that remained was the sound of the pipes." When they reached the German trenches a piper, Andrew Wishart, stood on the parados playing until he was wounded. Another piper, W. Stewart, was awarded the D.C.M. on this occasion.

The same thing happened in the case of the 2nd Black Watch at Festubert, the companies being led by their pipers. Of these men two, Pipers Gordon and Crichton, were specially mentioned for their gallantry. The Seaforth pipers, too, suffered heavily in this as in many later actions—"Caber Feidh"[20] has often been heard along that line which looked so weak, but was too strong for the Germans.

In the action at Festubert on the 17th May the 4th Camerons got further than any other battalion, and were played in by their pipe major, J. Ross, and four pipers. These men got through untouched, though their pipes were all injured.

Later again, on 16th June 1915, when the Hooge salient was straightened by the 3rd Division, the attack was led by the 8th Brigade, and the enemy front and support lines were taken. On this occasion Pipe Major Daniel Campbell, although wounded, played his battalion, the 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers, over the top.

Dawn was just breaking when the Pipe Major scrambled out on the parapet and started playing. The men raced forward after him until stopped by uncut wire. In the hand-to-hand fighting which ensued the Pipe Major threw aside his pipes and, catching up a bayonet, joined in the attack.

It was during the Ypres fighting, where gas was first used against us, that an incident occurred of which the facts are as stated, but unfortunately it has been found impossible to get the names of the men concerned.

"The men, looking into the storm of shells that swept their course and at the awful cloud of death now almost on them, wavered, hung back—only for a moment. And who will dare to blame them?

"Two of the battalion pipers who were acting as stretcher bearers saw the situation in a moment. Dropping their stretcher they made for their dug-out and emerged a second later with their pipes. They sprang on the parapet, tore off their respirators and charged forward. Fierce and terrible the wild notes cleft the air ... after fifteen yards the pibroch ceased; the two pipers, choked and suffocated with the gas fumes, staggered and fell."[3]

Although in these earlier actions pipers had done much to maintain the traditions of the past they had never had the opportunities of distinguishing themselves that came to them during the great operations about[21] Loos in September 1915. The attack of two army corps, in which were thirty Scottish battalions, along a seven-mile front, was a chance for these men, and one of which they were not slow to avail themselves. Three pipers at least earned the title of "The piper of Loos," and one of these, Daniel Laidlaw, of the 7th King's Own Scottish Borderers, was awarded the Victoria Cross; but, in the general orgie of gallantry which characterised those operations, individual pipers in very many cases won the highest praise in their own units but escaped the official recognition they had earned.

The attack by the 28th Brigade on the Hohenzollern Redoubt was accompanied by fearful casualties; with uncut wire in front, in an atmosphere heavily laden with gas, exposed to machine-gun fire in front and flank, the 6th K.O.S.B., 10th and 11th H.L.I. and 9th Seaforths were decimated. The K.O.S.B. were played over the top by their veteran Pipe Major, Robert Mackenzie, an old soldier of forty-two years' service. He was severely wounded and died the following day.

On the right of this Brigade the 26th had better luck, as the wire was found to be more thoroughly cut. The 5th Camerons and 7th Seaforths led the way followed by the 8th Gordons and 8th Black Watch, and reached Fosse 8, where they hung on, though reduced to the strength of a single battalion.

"The heroism of the pipers was splendid. In spite of murderous fire they continued playing. At one moment, when the fire of the machine guns was so terrific that it looked as if the attack must break down, a Seaforth piper dashed forward in front of the line and started 'Caber Feidh.' The effect was instantaneous—the sorely pressed men braced themselves together and charged forward. The Germans soon got to realise the value of the pipes and tried to pick off the pipers."

In this one attack the 5th Camerons had three pipers killed and eight wounded. Further south the pipers of the 2nd and 6th Gordons led their companies in the costly attack on Hulluch and the Quarries. An officer of the Devons, on their flank, writes:

"I shall never forget those pipes.... During the charge a Gordon piper continued playing after he was down."

On the other side of the Hulluch road the 15th Division received its baptism of fire, and lost 6000 men in the two days' fighting. One of the battalions of the 46th Brigade, the 7th King's Own Scottish Borderers, afforded an admirable example of the value of the pipes in rallying men when the position is critical. The piper concerned, Daniel Laidlaw, was awarded the Victoria Cross and the Croix de Guerre. The London Gazette Notification, which does not err on the side of uncontrolled emotionalism, describes the award as follows:

"For most conspicuous bravery.... During the worst of the bombardment, when the attack was about to commence, Piper Laidlaw, seeing that his company was somewhat shaken from the effects of gas, with absolute coolness and disregard of danger, mounted the parapet, marched up and down and played his company out of the trench. The effect of his splendid example was immediate, and the company dashed out to the assault. Piper Laidlaw continued playing his pipes until he was wounded."

The evidence of eye-witnesses shows that, at the time, a cloud of gas was settling down on the trench and there was heavy machine-gun fire. Laidlaw played "Blue Bonnets over the Border," and the effect on the men was indescribable; as they followed him over the top he changed to "The Standard on the Braes of Mar." The old tune was surely never played to better purpose; and if Laidlaw's action stood alone, if he were the only piper during the war who stimulated a company at the moment when things were at their worst, surely that achievement amply supports the view that, even in the warfare of to-day, piob mhor is an instrument of war which can justify all claims made for it. As it is, Piper Laidlaw, "the Piper of Loos," stands as type of a class of men who, throughout the war, have lived up to the traditions of a great past.

Another piper of the same battalion, Douglas Taylor, being wounded and unable to play, spent thirty-six hours bringing in gassed men without relief, until he himself was dangerously wounded. Further on, the 44th Brigade—the 8th Seaforths, 7th Camerons, 9th Black Watch and 10th Gordons—made the historic charge which captured Loos and then went on, until, for want of support, they could get no further and were compelled[23] to retire. They rallied on Hill 70 round a tattered flag made out of a Cameron kilt. The battalions of this brigade were played into and beyond Loos; and, when they were widely scattered and mixed up, pipers played to rally the men of their own battalions. Among many others, Piper Charles Cameron of the 11th Argylls stood out in the open playing unconcernedly, and was thereafter known in his battalion as "the Piper of Loos."

The shattered remnants of the 15th Division were withdrawn in the evening from the blood-stained slopes of Hill 70, but the battalions were played in by their own pipers. The 9th Black Watch numbered only 100 of all ranks and one piper; the 7th Cameron pipers were practically annihilated, the 8th Seaforths lost ten, and others suffered in similar degree.

It is a far cry from Hill 70 to Scaur Donald, and they were only regimental pipers, but to these brave men the words of the old song are surely applicable.

"There let him rest in the lap of Scaur Donald,

The wind for his watcher, the mist for his shroud,

Where the green and the grey moss shall weave their wild tartan,

A covering meet for a chieftain so proud."

In the fighting subsidiary to the main action of Loos, at Mauquissart and in the neighbourhood of Neuve Chapelle, the 2nd Black Watch pipers distinguished themselves greatly. They played their companies into and beyond the first line of German trenches. One of them, A. Macdonald, stood playing on the German parapet while the position was being cleared, and then on, through a hurricane of fire, over three lines of trenches, until dangerously wounded. For this he was given the D.C.M.

Three others, J. Galloway, R. Johnstone and David Armit, did precisely the same; and yet another, David Simpson, behaved with such gallantry that he also came to be known as "the Piper of Loos," the third of the brave trio to earn that honourable title. He had already played over three lines of German trenches, and was leading towards the fourth when he was killed. Johnstone, on this occasion, played till he fell gassed.

Throughout the long succession of actions which punctuated the Somme operations in 1916, the pipes continued to be much in evidence, and refer[24]ences to them and to their effect upon the men during that bloody fighting are frequent in the contemporary reports of observers, and in private letters subsequently published. French reports also have placed on record their admiration for the company pipers of Scottish regiments. "Some of the finest work," writes one well-known French military writer, "was accomplished at the very outset by the Highlanders, who carried the trenches in lightning fashion, urged on by the inspiriting music of their pipes."

The fighting at Loos had shown, on a comparatively small scale, that the pipes, when freed from the restrictions placed upon their employment by the exigencies of trench warfare, were still capable of fulfilling their historic rôle in open fighting The gallantry of the pipers at Hulluch and Hill 70 was worthy of the units they led, and established a record which was hard to beat; but for months on end their great achievements were emulated by those of their successors in the new armies which had poured into the field.

The opening attack on the 1st July affords numerous examples of pipers playing their companies into action, and a few may be taken as representative of the whole.

In the attack by the 32nd Division the 17th H.L.I, succeeded, with a loss of over 500 men, in capturing and holding part of the Leipzig redoubt, though unsupported for a considerable time. The Commanding Officer writes:

"I told the Pipe Major to play; he at once responded, getting into a small hollow, and playing and greatly heartening the men as they lay there hanging on to the captured position. Pipe Major Gilbert showed a total disregard of danger and played as if he were on a route march. For this action he obtained the Military Medal."

In the advance on Mametz on the same day the 2nd Gordons were led by their company pipers. An officer of an English battalion in the 20th Brigade describes how "we heard their pipes play these fellows over. It sounded grand against the noise of shells, machine guns and rifle fire. I shall never forget them."

The same thing occurred later when the battalion attacked the orchards of Ginchy. On both occasions the casualties were very heavy.

At Fricourt Pipe Major David Anderson of the 15th Royal Scots stood out in front of the battalion until he was wounded, and played across shell-beaten ground under heavy fire. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

The two battalions of Tyneside Scottish were similarly played to their attack on La Boiselle and the ridge in front of it on the opening day of the battle of the Somme. A correspondent who was present says:

"The Tynesiders were on our right, and, as they got the signal to advance, I saw a piper—I think he was the Pipe Major—jump out of the trench and march straight towards the German lines. The tremendous rattle of machine-gun and rifle fire completely drowned the sound of his pipes, but he was obviously playing as though he would burst the bag, and, faintly through the roar of battle, we heard the mighty cheer his comrades gave as they swarmed after him. How he escaped I can't understand, for the ground was literally ploughed up by the hail of bullets; but he bore a charmed life, and the last glimpse I had of him as we, too, dashed out showed him still marching erect, playing on regardless of the flying bullets and of the men dropping all round him."

Of the two battalions 10 pipers were killed and 5 wounded, and Pipe Major Wilson and Piper G. Taylor both got the Military Medal. Many of these pipers, having played their companies up to the German trenches, took an active part in the fighting as bombers.

Again, at Longueval on 14th July, regimental pipers were conspicuous. As the 26th Brigade—8th Black Watch, 10th Argylls, 9th Seaforths, and 5th Camerons—commenced their advance, they were exposed to frontal and enfilading machine-gun fire, and shrapnel mowed them down; but their pipers led the way, and the men followed cheering and shouting.

"Where we were the brunt of the action fell on two New Army battalions of historic Highland regiments. Their advance was one of the most magnificent sights I have ever seen. They left their trenches at dawn, and a torrent of bullets met them. They answered immediately—with the shrill music of the pipes, and, indifferent apparently to the chaos around them, pushed steadily on towards their objective."

Describing the attack by the 10th Argylls, another observer writes:

"We came under a blistering hot fire, but the men never hesitated. In the middle of it all the pipes struck up "The Campbells are coming," and that made victory a certainty for us. We felt that whatever obstacles there barred our path they had to be overcome.... The last fight was the worst of all. It was at the extreme end of the village, where the enemy had possession of some ruined houses. They had a clear line of fire in all directions, and we were met with a murderous hail of fire. For a moment the men wavered. I doubted if they were equal to it. Then a piper sprang forward, and the strains broke out once more. The attacking line steadied and dashed at the last stronghold of the Huns. Their line snapped under our onslaught."

On this occasion the Pipe Major, Aitken, a man of sixty, was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. One of the pipers referred to in the above incident was James Dall, and his Commanding Officer considers his action in playing the regimental march at this juncture was the means of his company gaining their objective; the other was D. Wilson, who was also mentioned in despatches with Dall.

Of the attack by the 9th Seaforths a wounded officer writes:

"We swept on until we finally carried the German trench with a rousing cheer to the strain of the pipes. The heroism of the pipers was splendid. In spite of murderous fire they kept playing on. At one moment, when the fire was so terrific it looked as if the attack must break down, one of the pipers dashed forward and started playing. The change could be felt at once, the sorely pressed men gave a mighty cheer and dashed forward with new zeal."

North of Longueval the 1st Gordons made a furious attack, on the 18th July, and on this occasion they were led by their pipers.

"They were out of sight over the parapet, but we could hear at intervals their shouts of 'Scotland for ever!' and the faint strains of the pipes. Then we saw them reappear, and then came prisoners."

Similar accounts were given of the 6th and 7th Gordons. In the 6th Gordons Piper Charles Thomson had his arm blown off while playing. "The[27] gallantry of these men who wear the tartans of the old Scottish clans would seem wonderful if it were not habitual with them. Their first dash for Longueval was one of the finest exploits of the war. They were led forward by the pipers, who went with them, not only towards the German lines, but across them and into the thick of the battle.... In that September fighting the pipe major of a Gordon battalion played his men forward and then was struck below the knee; but he would not be touched by a doctor until the others had been tended. He was a giant of a man and so heavy that no stretcher could hold him, so they put him in a tarpaulin and carried him back. Then he had his leg amputated and died."[4]

On the 3rd September the 4th Black Watch were played into action and had to capture a village. According to an eye-witness:

"It was magnificent to see these men charge up the narrow street leading to the second barricade. Amid the ruined houses on each side the enemy were posted. At the moment when it was hottest the strains of the pipes were heard. The men answered with a cheer and swept steadily on over the barricade and through the ruins; and the village was ours."

Of a Seaforth battalion a similar story is told:

"The men simply raced into the storm of bullets ... at last it became too terrible for any human being to stand against it. The attacking lines melted away, the men seeking what cover could be found.... It was here that the pipers of the Seaforths had their chance. They took it. As the men advanced again to the attack they were cheered on by the strains of the pipes, which could just be heard. The men dashed through, clearing out the enemy as they went."

During the attack on Beaumont Hamel in October, as in the earlier fighting at Thiepval, the pipers of the 15th H.L.I. lost very heavily when leading their companies.

Such instances of the bravery of pipers and of the stimulus afforded by the pipes to men in action became matters of almost every-day occurrence, and, though everyone recognised the tremendous losses that were the result of their exposure, there were occasions when those losses were more[28] than compensated for at the time by the results obtained. Everywhere, at Contalmaison, Martinpuich, Pozières, Delville Wood, wherever Scottish troops were employed, their pipers played their historic rôle, and, to quote Philip Gibbs, "over the open battlefields came the music of the Scottish pipes, shrill above the noise of gunfire."

Nor were the pipers of purely Scottish regiments left to establish these records of bravery unchallenged. They had keen rivals in battalions of overseas Scots, notably the South African Scottish and the Canadians.

During the fighting for Delville Wood in July the South Africans were torn to pieces by shell fire. The remains of the battalion hung on for days, losing all their officers but the colonel. When relief came their pipers headed the blackened and weary warriors out of the wood of death.

Similarly, the 16th Canadian Scottish pipers maintained the fine reputation they had earned on the Ypres salient. When the battalion moved up to the attack on the Regina trench on 8th October, there was keen competition among the pipers as to who should be allowed to play them over. "Four pipers, Richardson, Park, M'Kellar and Paul marched ahead of the battalion with the Commanding Officer for a distance of half a mile under intense machine-gun fire and escaped scatheless. They could be heard clearly as they played 'We'll take the good old way,' and, as they passed, wounded men lying in shell holes raised themselves on their elbows and cheered them. When they got near the German line the battalion encountered uncut wire which, being unusually heavy, took some time to cut. While this was going on Piper Richardson played up and down outside the wire for twenty minutes in the face of almost certain death.... Shortly afterwards a company sergeant major was wounded, and Richardson volunteered to take him out. After he had gone he remembered he had left his pipes behind. He left the sergeant major in safety in a shell hole and returned. He was never heard of again."

This brave man was awarded a posthumous V.C., the second piper to obtain this coveted distinction. Piper Paul was subsequently given the Military Medal.

At the capture of the Vimy Ridge on 9th April, 1917, by the Canadians, the pipers of some of their battalions took a prominent part. On this occasion the 16th Canadian Scottish repeated what they had done in previous engagements, their companies being led by pipers. The pipers concerned were Pipe Major Groat and Pipers M'Gillivray, M'Nab, M'Allister, M'Kellar and Paul, and they advanced a distance of over a mile under heavy fire without any casualties. The Pipe Major was awarded the Military Medal.

Similarly the 25th Canadians had their pipers out in this action, and Piper Walter Telfer, who went on playing after being severely wounded, was given the Military Medal; Piper Brand got the same decoration.

Later on, in the fighting round Arras, a battalion of the Camerons was played to the attack:

"When the order came our men went over with right good will. It was a thrilling moment, especially when the pipes struck up the Camerons' march. I believe it was that music, at that particular moment, which made it possible for us to go through the ordeal that followed."

Once again "The March of the Cameron Men" was the undoing of an enemy which had to stand up against the Camerons; and in one part of the line, when the attack was most furiously resisted, the company piper changed his tune to the old "Piobaireachd Dhomnuil Duibh"—

"Fast they came, fast they come,

See how they gather!

Wide waves the eagle's plume

Blended with heather."

An account of the few minutes before "zero" by a piper of this battalion appeared in the Scottish Field ("Pipes of the Misty Moorland," John M'Gibbon), and affords a good example of the steadying effect of the pipes in a period of great strain on morale:

"I looked down at the company and I could see they were shaken.... I slung my rifle over my back and took up the pipes; that cheered them. I played through two or three tunes and then birled up 'Tullochgorum.' They fairly hooched it and stamped time with their feet. It was close [30]on 'zero' ... when I changed to 'The March of The Cameron Men.' Our guns burst out with drum fire behind us ... and the men jumped the parapet like deer and raced over the broken ground at the double. I kept up 'The Cameron Men.' ... I reached the parapet of the first enemy trench, when I 'stopped one' with my leg, and down I went in a heap."

The pipes were again to the front in the fighting for Hill 70 on the Lens-Loos line in August, 1917. It was surely appropriate enough that, in the advance over the very country in which so many Scottish regiments had fought, with only temporary success, two years before, the pipes should again be at the head of the units which recaptured those blood-soaked positions.

An officer, describing the advance of the 13th Royal Highlanders of Canada, says:

"Our advance was resumed and we swarmed over the top at three different points. Away to the left, which was the objective of our advance, the strains of the pipes could be heard, and across the hills, where so many Scottish lads had fallen two years ago, there burst a loud triumphant cheer as the Canadian Highlanders pressed on to complete their work."

And so it happened that the gallant lads of the 15th Division were avenged.

Opportunities for pipers continued during the later fighting in 1917-18. Records of individual companies and platoons show that on several occasions the pipes encouraged the men to further effort. In one case near Albert, a company of the Black Watch was temporarily cut off from its supports after getting into a German trench and suffered heavily; the men were crushed by superior numbers, and the prospect was black until the piper, who was present as a stretcher bearer, started playing. This had a great effect on the company, which held on to the position until reinforcements arrived.

In the fighting about Albert in August, 1918, several instances occurred of pipers playing their companies to the attack.

On the whole, however, at this stage in the war, it was being found increasingly difficult to renew the depleted ranks of the pipe bands, and most regiments were simply driven to keeping their pipers out of action as far as possible, except on special occasions. But there were still enough left of them to lead their units ever further eastward as the tide of war rolled back.

Incidents frequently occurred showing that their experience of four years' fighting had not damped the ardour of pipers in action.

On one occasion a 16th Canadian piper went into action playing on top of a tank, and was killed. At Amiens, the pipers of the 16th and 48th Highlanders of Canada played the battalions to the attack in August, 1918.

As the German defeat became increasingly apparent and the British forces drove the enemy before them, pipers again got an opportunity of leading their companies to the attack. During the fighting about Albert-Arras in August, 1918, Scottish troops were heavily engaged. Lieut. Edouard Ross, of the French interpreter staff, describes an attack by a battalion of the Black Watch in which a detachment with a piper got into the German trenches; they were all wounded, and their position was dangerous, but the piper started playing, and the sound rapidly brought reinforcements, who captured the position.

In Gallipoli, as on the Western front, pipers added lustre to their reputation; and incidents which occurred to some of them showed that they were stout fighting men even after their pipes were put out of action.

The nature of the terrain generally precluded the more spectacular duty of playing their units to the attack, and the heavy casualties in the force and the constant demand for men resulted in their being frequently employed in the ranks; nevertheless, several cases did occur of company pipers acting as such.

On 12th July, 1916, when the 6th H.L.I. captured three lines of Turkish trenches, Pipers W. Mackenzie and M'Niven played at the head of their companies; M'Niven was killed, and Mackenzie, putting down his pipes, took part in the fighting with a Turkish shovel and did great execution.

On the same day the pipers of the 7th H.L.I. led their battalion into action, and only one of them was wounded. Of these men one, Piper Kenneth MacLennan, was subsequently awarded the Distinguished Conduct[32] Medal "for playing his pipes during the attack and advancing with the line after his pipes had been shattered by shrapnel, and heartening the wounded under fire." Another, Piper Cameron, played his company over three lines of trenches, with a revolver hanging on his wrist, and earned a mention in despatches; and Piper Macfarlane played through two bayonet charges until two of his drones were blown off by shell fragments.

Writing of the fighting on 12th July, a wounded officer writes:

"The sound of the pipes undoubtedly stirred them on, a piper belonging to each of the two battalions, 5th Argylls and 7th H.L.I., having mounted the parapets of their own trenches, and there in full danger played their comrades on to victory."

In the attack on Achi Baba there was no opportunity for pipers as such, though Pipe Major Andrew Buchan played the 4th Royal Scots "over the top," and, as an officer writes: "fearless of all danger went along the line and did much to hearten the men." Buchan was killed.

Of the pipers of the 5th Royal Scots none survived the early days of the fighting on the Peninsula. An officer of the regiment wrote that they "gloriously upheld the traditions established long ago." In the Achi Baba fighting four were killed and four wounded.

Casualties in action and by disease took heavy toll of the pipers of all these battalions, and after a few months on the Peninsula the pipe bands temporarily ceased to exist.

Even before the withdrawal of the force from Gallipoli it was found that so many casualties had occurred among the pipers of the battalions engaged that the bands were well on the way to extinction. Consequently, under the able management of Colonel Maclean of Pennycross a divisional band numbering twelve pipers and six drummers—all that remained—was organised out of the wreck of the pipe bands of the 52nd Division. That band, though never sent into action, individually or collectively played frequently under shell fire; and "Hey Johnnie Cope" could be heard quite distinctly every morning in the firing line up to within a few days of the evacuation.

The divisional band served on the Desert front in Egypt, and then accompanied the Division right into Palestine, playing the leading battalion, the 4th K.O.S.B.'s, over the frontier to "Blue Bonnets over the Border."

Later on, more pipers and more Scottish units appeared; and so we find the 2nd London Scottish being played into Jerusalem, and "Dumbarton's Drums" sounding at the head of the Royal Scots as they took over the guard on the Holy Sepulchre—as is the right of "Pontius Pilate's Bodyguard."

Opportunities for the employment of pipers as such were comparatively rare in the course of the Salonika operations, for obvious reasons. At Karadzakot Zir, however, the 1st Royal Scots pipers played their companies to the attack on the village, and the C.O. reported that, in his opinion,

"It was largely due to the presence of the pipers with the leading wave that the enemy evacuated their trenches and retired in disorder."

Playing the pipes in the Golden East is a far greater effort than it is at home, and every piper who has soldiered there knows how the heat and the dryness of the atmosphere affect his bag and reeds. But the cult of piob mhor thrives east of Suez, and at least as much enthusiasm is shown by regiments stationed in India as in a home station.

And when Scottish troops were called upon to take their part in the Mesopotamia operations, we find the pipes as prominent a feature in the fighting as they were on the Western front. At Sheikh Saad on 7th January, 1916, the 1st Seaforths—the "Reismeid Caber Feidh"—were played to the attack across absolutely open ground by their Pipe Major Neil M'Kechnie and other pipers. An officer who was present describes the incident as follows:

"As we advanced over the dead flat open desert the Turks suddenly opened a very heavy fire from well concealed trenches at a range of from 600 to 800 yards. The battalion immediately advanced by rushes towards[34] the enemy's position in spite of very heavy initial losses. Foremost among the men was our acting Pipe Major, M'Kechnie, who immediately struck up the regimental charge or 'onset,' 'Cabar Feidh.'

"His fine example as well as his music had a remarkable effect on the men at such a critical moment. He was shortly afterwards wounded, and had to drop behind as the lines went on."

In the same action the 2nd Black Watch were played in by their pipers just as they had been on many previous occasions in France. In the act of playing Corpl. Piper MacNee was mortally wounded. This brave man had been wounded before at Mauquissart and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The Pipe Major, John Keith, was awarded the D.C.M. for "gallant and distinguished service throughout the operations."

For four years and a half the pipes of war played their part in the greatest war in history; in the front, under conditions in which they could never have been expected to exist at all, they have led men to victory, have rallied them when victory eluded their grasp, and have marched them back undismayed by the tortures of battle; behind the lines they have headed the long columns of Scottish troops on their way up to the furnace in which the fate of nations was cast.

But, everywhere, they expressed the ideal of the race and led men to follow causes, even causes which appeared lost ones, through to the end.

When silence fell on the 11th November, 1918, along the blasted line where rival civilisations had so long struggled for mastery, the rôle of the pipes changed, and it was no longer the "onset" that the piper was impelled to play. The consummation of long effort had been attained—and what instrument more entitled to bear witness to the fact than the one which had sounded over the blood-stained slag-heaps of Loos, the shell-swept heights of Vimy?

As the British First Army entered Valenciennes, the pipers of a historic Scottish division played through the "place" opposite the Hotel de Ville,[35] and must have awakened in the old gabled houses memories of the centuries old alliance between the Lilies of France and the Thistle.

Further east, along the roads that led to Cologne, the pipes played unceasingly, as befitted the occasion, impressing on the population that this was indeed the coming of "Scotland the Brave."

And so, over the great Rhine bridge, the pipes of the 9th and Canadian Divisions led the way, and Germany learnt at last that when piob mhor sounds "Gabhaidh sin an rathad mor"[5] it generally attains its objective.

The piper is, first and last, a fighting man; and when a regiment is mobilised it at once loses most of its pipers. Whatever the strength of the band may have been in peace time, only the "sergeant piper"—a hideous official term for the pipe major—and five "full" pipers are normally retained as such. The remainder, while acting as pipers when opportunity offers—and designated accordingly—serve in the ranks.

During this war, and notably during the early years of it, it was often found necessary to make use of full and acting pipers in some purely military capacity, i.e. either in the ranks, or as Lewis gunners, bombers, orderlies, runners or stretcher bearers. This fact accounts for many of the honours awarded to pipers, and, at the same time, for the heavy casualties among them.

It is quite impossible to do justice to individuals or units in regard to the part they played in performing such duties; for those who obtained official recognition, in some form or other, hundreds have merely had the satisfaction of playing the game, in accordance with the rules laid down by all ranks of the British army. The few examples given in this place are typical of the whole.

At Festubert in June, 1915, the pipers of the 6th Seaforths worked continuously day and night, and brought 170 casualties from the front line to the dressing station; at Loos the 9th Black Watch lost nearly all[36] their pipers when similarly engaged, and at the two actions of Loos and Neuve Chapelle the 6th Gordons had two killed and ten wounded.

Again, the 2nd Royal Scots pipers lost heavily on the Somme, and were on one occasion highly commended for bringing water up to some newly captured trenches under heavy fire.

The comments of General Sir William Birdwood in a despatch to the Australian Government, though intended to apply to Australian stretcher bearers, are very applicable to pipers acting in this capacity, whether individually or collectively:

"Where all have done so well it is very hard to differentiate, but as a class the stretcher bearers have been beyond praise. Never for a second have they flinched from going forward time after time, absolutely regardless of the fire brought against them; and I so deeply regret that they should have suffered in consequence."

Another and most hazardous class of duty, which was largely performed by pipers in some battalions, was that of "runners" or despatch carriers; this often involved crossing heavily shelled country, and has resulted in many casualties. Notable cases have occurred of men carrying despatches through intense barrages, and some have received rewards; the majority of such cases, however, have necessarily been unnoticed.

Some men appear to have specialised in this duty, e.g. Pipe Major Matheson, 1st Seaforths, who got the D.C.M. "for gallant conduct on many occasions in conveying messages under heavy fire," and Lance-Corpl. Piper Dyce, 13th Royal Highlanders of Canada, who on one occasion carried a most urgent despatch through artillery barrage when badly wounded.

In other cases pipers, individually and collectively, have done admirable service in bringing up ammunition.

Many instances of acts of heroism by individual men are detailed below.

Playing the pipes in action, though essentially the most important, is, for obvious reasons, only one of the duties of the soldier piper. Every unit of an army is not always in close touch with the enemy, and every battalion puts in a good many miles of marching in a year in conditions which are rarely ideal and very often acutely miserable. It is here that the pipes have rendered such conspicuous service as the marching instrument par excellence; and the cult of the bagpipe has spread to units and nationalities which, before the war, would never have thought it possible that the company piper would become one of their most cherished institutions.

That Irish regiments should again adopt the national instrument that had played their ancestors on to the battlefields of France in 1286 is so natural as to need no comment; but when we find English and Australian units, battalions of the United States army, and ships of His Majesty's Navy, to say nothing of field ambulances and transport units, adopting the bagpipe, no further evidence is required to substantiate its claim to be a highly important feature of modern military organisation.