Eng’d by A H Ritchie

HORACE GREELEY

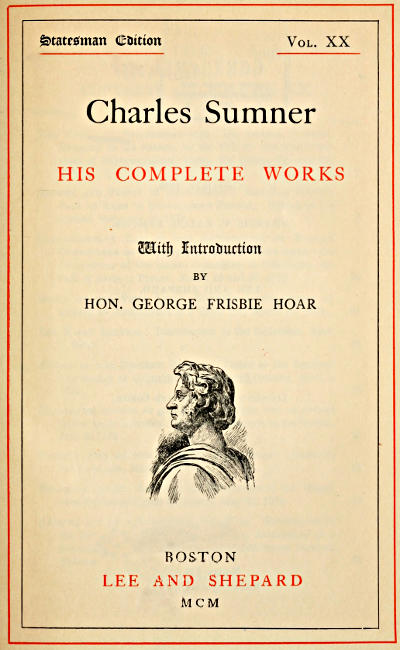

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Charles Sumner; his complete works, volume 20 (of 20), by Charles Sumner This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Charles Sumner; his complete works, volume 20 (of 20) Author: Charles Sumner Editor: George Frisbie Hoar Release Date: January 24, 2016 [EBook #51025] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHARLES SUMNER; COMPLETE WORKS, VOL 20 *** Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: in the Index, only references within this volume are hyperlinked. All other volumes are available as Project Gutenberg ebooks. A list is given at the end.

Eng’d by A H Ritchie

HORACE GREELEY

Copyright, 1883,

BY

FRANCIS V. BALCH, Executor.

Copyright, 1900,

BY

LEE AND SHEPARD.

Statesman Edition.

Limited to One Thousand Copies.

Of which this is

Norwood Press:

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

Remarks in the Senate, on the Bill for the Apportionment of Representatives among the States, January 29, 1872.

MR. PRESIDENT,—Before the vote is taken I desire to make one remark. I was struck with the suggestion of the Senator from Ohio [Mr. Sherman], the other day, with regard to the proposition which comes from the House. He reminded us that it was a House proposition, and that it was natural that the House should be allowed to regulate itself. I think there is much in that worthy of consideration. I doubt if the Senate would receive with much favor any proposition from the House especially applicable to us. I think we should be disposed to repel it. I think we should say that our experience should enable us to judge that question better than the experience of the House. And now I ask whether the experience of the House does not enable them to judge of the question of numbers better than we can judge of it? On general grounds I confess I should myself prefer a smaller House; personally I incline that way; but I am not willing on that point to set myself against the House.

Then, Sir, I cannot be insensible to the experience of other countries. I do not know whether Senators have troubled themselves on that head; but if they have not, I think it will not be uninteresting to them to have their attention called to the numbers of the great legislative bodies of the world at this moment. For instance, beginning with England, there is the upper House, the Chamber of Peers, composed of four hundred and sixty-six members; then the lower House, the House of Commons, with six hundred and fifty-eight members. We know that, practically, these members attend only in comparatively small numbers; that it is only on great questions that either House is full.

Mr. Trumbull. Did the House of Lords ever have anything like that number present?

Mr. Sumner. It has had several hundred. There are four hundred and sixty-six entitled to seats in the House of Lords.

Pass over to France. The National Assembly, sitting at Versailles at this moment, elected February 8 and July 2, 1871, consists of seven hundred and thirty-eight members.

Pass on to Prussia. The upper Chamber of the Parliament of Prussia has two hundred and sixty-seven members; the lower Chamber has four hundred and thirty-two. Now we all know that Prussia is a country where no rule of administration or of constitution is adopted lightly, and everything is considered, if I may so express myself, in the light of science.

Pass to Austria, under the recent organization. You are aware that there are two different Parliaments now in Austria,—one for what is called the cis-Leithan territories,[Pg 3] territories this side of the river Leitha; the other, trans-Leithan, or those on the other side, being the Hungarian territory. Beginning with those on this side of the river, the upper House consists of one hundred and seventy-five members: observe, it is more than twice as large as our Senate. The lower House consists of two hundred and three members: smaller than our House of Representatives. But now pass to the other side of the river and look at the Hungarian Parliament. There the upper House contains two hundred and sixty-six members, and the lower House, or Chamber of Deputies, as it is called, four hundred and thirty-eight.

Pass to Italy, a country organized under a new constitution in the light of European and American experience, liberal, and with a disposition to found its institutions on the basis of science. The Senate of Italy contains two hundred and seventy members, the Chamber of Deputies five hundred and eight.

Then pass to Spain. There the upper branch of the Cortes contains one hundred and ninety-six members, and the lower branch four hundred and sixteen.

So that you will find in all these countries,—Great Britain, France, Prussia, Austria in its two Parliaments, Italy, and Spain,—that the number adopted for the lower House is much larger than any now proposed for our House of Representatives.

I call attention to this fact because it illustrates by the experience of other nations what may be considered as a rule on this subject. At any rate, it shows that other nations are not deterred by anything in political experience from having a House with these large numbers; and this perhaps is of more value because European writers, political philosophers for successive generations,[Pg 4] have warred against large bodies. We have the famous saying of the Cardinal de Retz, that any body of men above a hundred is a mob; and that saying, coming from so consummate a statesman and wit, has passed into a proverb, doubtless affecting the judgment of many minds; and yet in the face of this testimony, and with the writings of political philosophers all inclining against numbers, we find that the actual practical experience of Europe has gone the other way. The popular branch in all these considerable countries is much more numerous than it is now proposed to make our House of Representatives.

Speech in the Senate, February 28, 1872.

February 12, 1872, Mr. Sumner introduced a resolution, with a preamble setting forth its grounds, providing,—

“That a select committee of seven be appointed to investigate all sales of ordnance stores made by the Government of the United States during the war between France and Germany; to ascertain the persons to whom such sales were made, the circumstances under which they were made, and the real parties in interest, and the sums respectively paid and received by the real parties; and that the committee have power to send for persons and papers; and that the investigation be conducted in public.”

And on his motion it was ordered to lie on the table and be printed.

On the 14th the resolution was taken up for consideration, when Mr. Sumner entered into an exposition of the matter referred to in the preamble, and of the law applicable thereto, remarking in conclusion:—

“For the first time has the United States, within my knowledge, fallen under suspicion of violating the requirement of neutrality on this subject. Such seems to be our present position. We are under suspicion. What I propose is a searching inquiry, according to the magnitude of the interests involved, to ascertain if this is without just grounds.”

Thereupon ensued a long and acrimonious debate,—toward the close of which, Mr. Sumner, on the 28th, in review of the case, spoke as follows:—

MR PRESIDENT,—Besides the unaccustomed interest which this debate excites, I cannot fail to note that it has wandered far beyond any purpose of mine, and into fields where I have no desire to follow. In a few plain remarks I shall try to bring it back to the real issue, which I hope to present without passion or prejudice. I declare only the rule of my life, when I say that nothing shall fall from me to-day which is not prompted by the love of truth and the desire for justice; but you will pardon me, if I remember that there is something on this planet higher than the Senate or any Senator, higher than any public functionary, higher than any political party: it is the good name of the American people and the purity of Government, which must be saved from scandal. In this spirit and with this aspiration I shall speak to-day.

In considering this resolution we must not forget the peculiar demands of the present moment. An aroused community in the commercial metropolis of our country has unexpectedly succeeded in overthrowing a corrupt ring by which millions of money had been sacrificed. Tammany has been vanquished. Here good Democrats vied with Republicans. The country was thrilled by the triumph, and insisted that it should be extended. Then came manifestations against abuses of the civil service generally, and especially in that other Tammany, the New York custom-house. The call for investigation at last prevailed in this Chamber, and the newspapers have been burdened since with odious details. Everybody says there must be reform, so that the Government in all its branches shall be above suspicion. The cry for reform is everywhere,—from New York to New[Pg 7] Orleans. Within a few days we hear of a great meeting, amounting to ten thousand, in the latter city, without distinction of party, calling for reform; and the demand is echoed from place to place. Reform is becoming a universal watchword.

In harmony with this cry is the appointment of a Civil-Service Commission, which has proposed mild measures looking to purity and independence in office-holders.

Amidst these transactions, occupying the attention of the country, certain facts are reported, tending to show abuses in the sale of arms at the Ordnance Office, exciting at least suspicion in that quarter; and this is aggravated by a seeming violation of neutral duties at a critical moment, when, on various grounds, the nation was bound to peculiar care. It appeared as if our neutral duties were sacrificed to money-making, if not to official jobbers. The injunction of Iago seemed to be obeyed: “Put money in thy purse.” These things were already known in Europe, especially through a notorious trial,[1] and then by a legislative inquiry, so as to become a public scandal. It was time that something should be done to remove the suspicion. This could be only by a searching investigation in such way as to satisfy all at home and abroad that there was no whitewashing.

In proportion to the magnitude of the question and the great interests involved, whether of money or neutral duty, was the corresponding responsibility on our part. Here was a case for action without delay.

Under these circumstances I brought forward the present motion. Here I acted in entire harmony with that movement, now so much applauded, which overthrew[Pg 8] Tammany, and that other movement which has exposed the Custom-House. Its object was inquiry into the sale of arms. This was the objective point. But much of this debate has turned on points merely formal, if not entirely irrelevant.

More than once it has been asserted that I am introducing “politics”; and then we have been reminded of the Presidential election, which to certain Senators is a universal prompter. I asked for reform, and the Senator from Indiana [Mr. Morton], seizing the party bugle, sounded “To arms!” But I am not tempted to follow him. I have nothing to say of the President or of the Presidential election. The Senator cannot make me depart from the rule I have laid down for myself. I introduce no “politics,” but only a question which has become urgent, affecting the civil service of the country.

Now, Sir, I have been from the beginning in favor of civil-service reform. I am the author of the first bill on that subject ever introduced into Congress, as long ago as the spring of 1864.[2] I am for a real reform that shall reach the highest as well as the lowest, and I know no better way to accomplish this beneficent result than by striving at all times for purity in the administration of Government. Therefore, when officials fall under suspicion, I should feel myself disloyal to the Government, if I did not insist on the most thorough inquiry. So I have voted in the past, so I must vote in the future. Call you this politics? Not in the ordinary sense of the term. It is only honesty and a just regard for the public weal.

Then it has been said that I am a French agent, and even a Prussian agent,—two in one. Sir, I am nothing but a Senator, whose attention was first called to this matter by a distinguished citizen not named in this debate. Since then I have obtained such information with regard to it as was open to me,—all going to develop a case for inquiry.

I should say nothing more in reply to this allegation but for the vindictive personal assault made upon a valued friend, the Marquis de Chambrun. The Senator from Missouri [Mr. Schurz] has already spoken for him; but I claim this privilege also. Besides his own merits, this gentleman is commended to Americans by his association with the two French names most cherished in our country, Lafayette and De Tocqueville. I have known him from the very day of his arrival in Washington early in the spring of 1865, and have seen him since, in unbroken friendship, almost daily. Shortly after his arrival I took him with me on a visit to Mr. Lincoln at the front, close upon the capture of Richmond. This stranger began his remarkable intimacy with American life by several days in the society of the President only one week before his death. He was by the side of the President in his last visit to a military hospital, and when he last shook hands with the soldiers; also when he made his last speech from the window of the Executive Mansion, the stranger was his guest, standing by his side. From that time down to this day of accusation his intimacies have extended beyond those of any other foreigner. His studies of our institutions have been minute and critical, being second only to those of his late friend De Tocqueville. Whether conversing on his own country or on ours, he is always at home.

If at any time the Marquis de Chambrun sustained official relations with the French Government, or was its agent, he never spoke of it to me; nor did I ever know it until the papers produced by the Senator from Iowa [Mr. Harlan]. Our conversation was always that of friends, and on topics of general interest, not of business. Though ignorant of any official relations with his own Government, I could not fail to know his close relations with members of our Government, ending in his recent employment to present our case in French for the Geneva tribunal,—an honorable and confidential service, faithfully performed.

The Senator from Indiana knew of the arms question some five months before the meeting of Congress. I did not. It was after the session began, and just before the holidays, that I first knew of it. And here my informant was not a foreigner, but, as I have already said, a distinguished citizen. The French “spy,” as he is so happily called, though with me daily, never spoke of it; nor did I speak of it to him. By-and-by the Senator from Missouri mentioned it, and then, in my desire to know the evidence affecting persons here, if any such existed, I spoke to my French friend. This was only a few days before the resolution.

Such is the history of my relations with the accused. There is nothing to disguise, nothing that I should not do again. I know no rule of senatorial duty or of patriotism which can prevent me from obtaining information of any kind from any body, especially when the object is to pursue fraud and to unmask abuse. Is not a French gentleman a competent witness? Once the black could not testify against the white, and now in some places the testimony of a Chinese is rejected. But[Pg 11] I tolerate no such exclusion. Let me welcome knowledge always, and from every quarter. “Hail, holy light!”—no matter from what star or what nation it may shine.

And this gentleman, fresh from a confidential service to our own Government, enjoying numerous intimacies with American citizens, associated with illustrious names in history and literature, and immediately connected with one of the highest functionaries of the present French Government, M. de Rémusat, Minister for Foreign Affairs, is insulted here as an “emissary” and a “spy”; nay, more, France is insulted,—for these terms are applied only to the secret agents of an enemy in time of war. But enough. To such madness of error and vindictive accusation is this defence carried!

Another charge is that I am making a case for Prussia against our own country. Oh, no! I am making a case for nobody. I simply try to relieve my country from an odious suspicion, and to advance the cause of good government. The Senator from Indiana supposes that this effort of mine, having such objects, may prejudice the Emperor of Germany against us in the arbitration of the San Juan question. The Senator does not pay a lofty compliment to that enlightened and victorious ruler. Nay, Sir, the very suggestion of the Senator is an insult to him, which he is too just to resent, but which cannot fail to excite a smile of derision. Surely the Senator was not in earnest.

The jest of the Senator, offered for argument, seems to forget that all these things are notorious in Europe, through the active press of Paris and London. Why, Sir, our own State Department furnishes official evidence that the alleged sale of arms to the French by our[Pg 12] Government is known in Berlin itself, right under the eyes of the Emperor. Our Minister there, Mr. Bancroft, in his dispatch of January 7, 1871, furnishes the following testimony from the London “Times”:—

“During the Crimean War, arms and munitions of war had been freely exported from Prussia to Russia; and recently rifled cannon and ammunition have been furnished to the French in enormous quantities, not only by private American traders, but by the War Department at Washington.”[3]

These latter words are italicized in the official publication of our Government, and thus blazoned to the world. I do not adduce them to show that the War Department did sell arms to belligerent France, but that even in Berlin the imputation upon us was known and actually reported by our Minister. If the latter made any observations on this imputation I know not; for at this point in his dispatch are those convenient asterisks which are the substitute for inconvenient revelations.

In the same spirit with the last triviality, but in the anxiety to clutch at something, it is said that the Alabama Claims are endangered by this inquiry. Very well, Sir. On this point I am clear. If these historic claims, so interesting to the American people, are to be pressed at the cost of purity in our own Government, they are not worth the terrible price. Better give them up at once. Let them all go, every dollar. “First pure, then peaceable”;[4] above all things purity. Sir, I have from the beginning insisted that England should be held to just account for her violation of international duty[Pg 13] toward us. Is that any reason why I should not also insist upon inquiry into the conduct of officials at home, to the end that the Government may be saved from reproach? Surely we shall be stronger, infinitely stronger, in demanding our own rights, if we show a determination to allow no wrong among ourselves. Our example must not be quoted against us at any time. Especially must it not be allowed to harden into precedent. But this can be prevented only by prompt correction, so that it shall be without authority. Therefore, because I would have my country irresistible in its demands, do I insist that it shall place itself above all suspicion.

The objection of Senators is too much like the old heathen cry, “Our country, right or wrong.” Unhappy words, which dethrone God and exalt the Devil! I am for our country with the aspiration that it may be always right; but I am for nothing wrong. When I hear of wrong, I insist at all hazards that it shall be made right, knowing that in this way I best serve my country and every just cause.

This same objection assumes another form, equally groundless, when it is said that I reflect upon our country and hurt its good name. Oh, no! They reflect upon our country and hurt its good name who at the first breath of suspicion fail to act. Our good name is not to be preserved by covering up anything. Not in secrecy, but in daylight, must we live. What sort of good name is that which has a cloud gathering about it? Our duty is to dispel the cloud. Especially is this the duty of the Senate. Here at least must be that honest independence which shall insist at all times upon purity in the Government, no matter what office-holders are exposed.

Again it is said that our good name cannot be compromised by these suspicions. This is a mistake. Any suspicion of wrong is a compromise, all the more serious when it concerns not only money, but the violation of neutral obligations. And the actual fact is precisely according to reason. Now while we debate, the national character is compromised at Paris, at London, at Berlin, at Geneva, where all these things are known as much as in this Chamber. But your indifference, especially after this debate, will not tend to elevate the national character either at home or abroad.

Such are some of the objections to which I reply. They are words only, as Hamlet says, “Words, words, words.” From words let us pass to things.

Mr. President, I come now to the simple question before the Senate, which I presented originally, whether there is not sufficient reason for inquiry into the sale of arms during the French and German War. I state the question thus broadly. The inquiry is into the sale of arms; and this opens two questions,—first, of international duty; and, secondly, of misfeasance in our officials, the latter involving what may be compendiously called the money question.

My object is simply to show grounds for inquiry; and I naturally begin with the rule of international duty.

In the discharge of neutral obligations a nation is bound to good faith. This is the supreme rule, to which all else is subordinate. This is the starting-point of all that is done. Without good faith neutral obligations must fail. In proportion to the character of this requirement must be the completeness of its observance. There can be no evasion, not a jot. Any evasion is a[Pg 15] breach, without the bravery of open violation. But evasion may be sometimes by closing the eyes to existing facts, or even by acting without sufficient inquiry. These things are so plain and entirely reasonable as to be self-evident.

Now nothing can be more clear than that no neutral nation is permitted to furnish arms and war material to a belligerent power. Such is a simple statement of the law. I do not cite authorities, as I did it amply on a former occasion.[5]

But there is an excellent author whom I would add to the list as worthy of consideration, especially at this moment, in view of the loose pretensions put forth in the debate. I refer to Mr. Manning, who, in his Commentaries, thus teaches neutral duty:—

“It is no interference with the right of a third party to say that he shall not carry to my enemy instruments with which I am to be attacked. Such commerce is, on the other hand, a deviation from neutrality,—or rather would be so, if it were the act of a State and not of individuals.”[6]

The distinction is obvious between what can be done by the individual and what can be done by the State. The individual may play the merchant and take the risk of capture; but the State cannot play the merchant in dealing with a belligerent. Of course, if the foreign power is at peace, there is no question; but when the power has become belligerent, then it is excluded from the market. So far as that power is concerned, all sales[Pg 16] must be suspended. The interdict is peremptory and absolute. In such a case there can be no sale knowingly without mixing in the war,—precisely as France mixed in the war of our Revolution in those muskets sent by the witty Beaumarchais, which England resented by open war.

And this undoubted principle of International Law was recognized by the Secretary of War, when he directed the Chief of Ordnance not to entertain any bids from E. Remington & Sons, who had stated that they were agents of the French Government. In giving these orders he only followed the rule of duty on which the country can stand without question or reproach; but it remains to be seen whether persons under him did not content themselves with obeying the order in letter only, breaking it in spirit. I assume that the order was given in good faith. Was it obeyed in good faith? Here we start with the admitted postulate that it was wrong to sell arms to France.

But if this cannot be done directly, it is idle to say that it can be done indirectly without a violation of good faith. If it cannot be done openly, it cannot be done privily. If it cannot be done above-board, it cannot be done clandestinely. It is idle to reject the bid of the open agent of a belligerent power and then at once accept the bid of another who may be a mere man-of-straw, unless after careful inquiry into his real character.

Nothing can be clearer than the duty of the proper officers to consider all bids in the sunlight of the conspicuous events then passing. A terrible war was convulsing the Old World. Two mighty nations were in conflict, one of which was already prostrate and disarmed. Meanwhile came bids for arms and war material[Pg 17] on a gigantic scale, on a scale absolutely unprecedented. Plainly these powerful batteries, these muskets by the hundred thousand, and these cartridges by the million were for the disarmed belligerent and nobody else. It was impossible not to see it. It is insulting to common-sense to imagine it otherwise. Who else could need arms and war material to the amount of four million dollars at once? Now it appears by the dispatches of the French Consul-General at New York, which I find in an official document, that on the 22d October, 1870, he telegraphed to the Armament Commission at Tours:—

“The prices of adjudication have been 100,000 muskets at $9.30; 40,000 at $12.30; 100,000 at $12.25; 50,000,000 cartridges at $16.30 the thousand: altogether, with the commission to Remington and the incidental expenses, more than four million dollars.”

Such gigantic purchases, made at one time, or in the space of a few days, could have but one destination. It is weakness to imagine otherwise. Obviously, plainly, unquestionably, they were for the disarmed belligerent. The telegraph each morning proclaimed the constant fearful struggle, and we all became daily spectators. In the terrible blaze, filling the heavens with lurid flame, it was impossible not to see the exact condition of the two belligerents,—Germany always victorious, France still rallying for the desperate battle. But the officials of the Ordnance Bureau saw this as plainly as the people. Therefore were they warned, so that every applicant for arms and war material on a large scale was open to just suspicion. These officials were put on their guard as much as if a notice or caveat[Pg 18] had been filed at the War Department. In neglecting that commanding notice, in overruling that unprecedented caveat, so far as to allow these enormous supplies to be forwarded to the disarmed belligerent, they failed in that proper care required by the occasion. If I said that they failed in good faith, I should only give the conclusion of law on unquestionable facts.

In the case of the Gran Para, Chief-Justice Marshall, after exposing an attempt to evade our neutral obligations by an ingenious cover, exclaimed, in words which he borrowed from an earlier period of our history, but which have been often quoted since: “This would, indeed, be a fraudulent neutrality, disgraceful to our own Government, and of which no nation would be the dupe.”[7] I forbear at present to apply these memorable words, which show with what indignant language our great Chief-Justice blasted an attempt to evade our neutral obligations. In calling it fraudulent he was not deterred by the petty cry of a false patriotism, that his judgment might affect the good name of our country. Full well he knew that national character could suffer only where fraud is maintained.

I doubt much if the true rule can be laid down in better words than those I quoted on a former occasion from the Spanish minister at Stockholm, denouncing the sale of Swedish frigates.[8] He protested against “arms and munitions furnished through intermediate speculators, under pretence of not knowing the result,” which he exhibited as an “act of hostility” and a “political scandal.” According to this excellent protest, the sale is not protected from condemnation merely by “intermediate speculators” and the[Pg 19] “pretence of not knowing the result.” And this is only according to undoubted reason. It is simply a question of good faith; and if, taking into view the circumstances of the case and the condition of the times, there is reasonable ground to believe that “intermediate speculators” are purchasing for a belligerent, then the sale cannot be made, nor will any “pretence of not knowing the result” be of avail.

In harmony with this Spanish protest is the calm statement of a Joint Committee of Congress, where this question of international duty is treated wisely. I read from the report of Mr. Jenckes on the sale of certain ironclads:—

“Perhaps the international feature of this transaction is the most grave one for the consideration of Congress. It is a matter of notorious public history that war was being carried on in the years 1865 and 1866 between the Government of Spain, on the one hand, and the Governments of Peru and Chili, on the other. During the pendency of hostilities, applications were made to obtain possession of these vessels for one of the belligerents. If the Government of the United States had been privy to any arrangement by which these vessels of war should be delivered to the agents of a belligerent, either in our own ports or upon the high seas, it would certainly have violated its international obligations. Of course, when Congress authorized the sale of these vessels, it was known that individuals had no use for them; yet it might have assumed, as in the case of the Dunderberg and the Onondaga,”—

Now mark the words, if you please,—

“that the Executive Department would take care that any individual who should purchase with a view to a resale to some foreign power would not be permitted to violate the obligations of the United States as a neutral nation.”[9]

Observe, if you please, the language employed. If the Government of the United States had been “privy” to any arrangement for the delivery of these vessels to the agents of a belligerent, it would certainly have violated its international obligations. This is undoubtedly correct. Then comes the assumption “that the Executive Department would take care that any individual who should purchase with a view to a resale to some foreign power would not be permitted to violate the obligations of the United States as a neutral nation.” Here again is the true rule. The Executive is bound to take care that there shall be no sale with a view to a resale in violation of neutral duties.

All this is so entirely reasonable, indeed so absolutely essential to the simplest performance of international duty, that I feel humbled even in stating it. The case is too clear. It is like arguing the Ten Commandments or the Multiplication Table. International Law is nothing but international morality for the guidance of nations. And be assured, Sir, that interpretation is the truest which subjects the nation most completely to the Moral Law. “Thou shalt not sell arms to a belligerent,” is a commandment addressed to nations, and to be obeyed precisely as that other commandment, “Thou shalt not steal.” No temptation of money, no proffer of cash, no chink of “the almighty dollar,” can excuse any departure from this supreme law; nor can any intervening man-of-straw have any other effect than to augment the offence by the shame of a trick.

Here, Sir, I am sensitive for my country. I can imagine no pecuniary profits, no millions poured into the Treasury, that can compensate for a departure from that international honesty which is at once the best policy and the highest duty. The dishonesty of a nation is illimitable in its operation. How true are the words,—

The demoralization is felt not at home only. Whatever any nation does is an example for other nations; whatever the Great Republic does is a testimony. I would have that testimony pure, lofty, just, so that we may welcome it when commended to ourselves; so that, indeed, it may be a glorious landmark in the history of civilization.

Therefore do I insist that international obligations, especially when war is raging, cannot be evaded, cannot be slighted, cannot be trifled with. They are not only sacred, they are sacrosanct; and whoso lays hands on them, whoso neglects them, whoso closes his eyes to their violation, is guilty of a dishonesty which, to the extent of its influence, must weaken public morals at home, while it impairs the safeguards of peace with other nations and sets ajar the very gates of War.

This question cannot be treated with levity, and waved out of sight by a doubtful story. Even if Count Bismarck, adapting himself to the situation, and anxious to avoid additional controversy, had declared in conversation that he would take these arms on the banks of the Loire,[11] this is no excuse for us. Our rule of duty is not[Pg 22] found in the courageous gayety of any foreign statesman, but in the Law of Nations, which we are bound to obey, not only for the sake of others, but for the sake of ourselves. All other nations may be silent; Count Bismarck may be taciturn; but we cannot afford to cry, “Hush!” The evil example must be corrected, and the more swiftly the better.

On this simple statement of International Law, it is evident that there must be inquiry to see if through the misfeasance of officials our Government has not in some way failed to comply with its neutral duties. Subordinates in England are charged with allowing the escape of the Alabama. Have any subordinates among us played a similar part? It is of subordinates that I speak. Has the Government suffered through them? Has their misfeasance, their jobbery, their illicit dealing, compromised our country? Is there any ring about the Ordnance Bureau through which our neutral duties have been set at nought? Here I might stop without proceeding further. The question is too grave to be blinked out of sight; it must be met on the law and the facts.

In this presentation I do not argue. The case requires a statement only. Beyond this I point to the honorable example which our country has set in times past. The equity with which we have discharged our neutral obligations has been the occasion of constant applause. Mr. Ward, the accomplished historian of the Law of Nations, and also of a treatise on the “Rights and Duties of Belligerent and Neutral Powers,” which Chancellor Kent says “exhausted all the law and learning applicable to the question,”[12] wrote in 1801, four years after Washington’s retirement:—

“Of the great trading nations, America is almost the only one that has shown consistency of principle. The firmness and thorough understanding of the Laws of Nations, which during this war [the French Revolution] she has displayed, must forever rank her high in the scale of enlightened communities.”[13]

Another English writer, Sir Robert Phillimore, author of the comprehensive work on International Law, speaks of the conduct of the United States as, “under the most trying circumstances, marked not only by a perfect consistency, but by preference for duty and right over interest and the expediency of the moment.”[14] Then again, in another place, the same English authority, after a summary of our practice and jurisprudence in seizing and condemning vessels captured in violation of neutrality, declares:—

“In these doctrines a severe, but a just, conception of the duties and rights of neutrality appears to be embodied.”[15]

An excellent French writer on International Law, Baron de Cussy, remarks, on mentioning our course with reference to a steamer purchased by Prussia in its war with Denmark in 1849,—

“It affords a genuine proof of respect for the obligations of neutrality.”[16]

American loyalty to neutral duties received the homage of the eminent orator and statesman Mr. Canning, who, from his place in Parliament, said:—

“If I wished for a guide in a system of neutrality, I should take that laid down by America in the days of the Presidency of Washington and the Secretaryship of Jefferson.”[17]

These testimonies may be fitly concluded by the words of Mr. Rush, so long our Minister in England, who records with just pride the honor accorded to our doctrines on neutral duties:—

“They are doctrines that will probably receive more and more approbation from all nations as time goes on, and continues to bring with it, as we may reasonably hope, further meliorations to the code of war. They are as replete with international wisdom as with American dignity and spirit.…

“Come what may in the future, we can never be deprived of this inheritance. It is a proud and splendid inheritance.”[18]

Such is the great and honest fame already achieved by our Republic in upholding neutral duties. No victory in our history has conferred equal renown. Surely you are not ready to forget the precious inheritance. No, Sir, let us guard it as one of the best possessions of our common country,—guard it loyally, so that it shall continue without diminution or spot. Here there must be no backward step. Not Backward, but Forward, must be our watchword in the march of civilization.

I am now brought to that other branch of the subject which concerns directly the conduct of our officials; and here my purpose is to simplify the question. Therefore I shall avoid details, which have occupied the Senate for days; and I put aside the apparent discrepancy[Pg 25] between the Annual Report of the War Department and the Annual Report of the Treasurer, which has been satisfactorily explained on this floor, so that this ground of inquiry is removed. I bring the case to certain heads, which, taken together in their mass, make it impossible for us to avoid inquiry, without leaving the Government or some of its officials exposed to serious suspicion. Now, as at the beginning, I make no accusation against any officer of our Government,—none against the President, none against the Secretary of War; but I exhibit reasons for the present proceeding.

The case naturally opens with the resolution of the Committee of the French Assembly, asking the United States “to furnish the result of the inquiry into the conduct of American officials who were suspected of participating in the purchase of arms for the French Government during the war.” This seems to have been adopted as late as February 9th last past. At least it appears in the cable dispatch of that date.[19] From this resolution three things are manifest: first, that the sale of arms by our Government is occupying the attention of the French Legislature; secondly, that American officials are suspected of participating in the purchase for the French Government; and, thirdly, that it is supposed that our Government has instituted an inquiry into the case.

This resolution is, I believe, without precedent. I recall no other instance where a foreign legislative assembly[Pg 26] has made any inquiry into the conduct of the officials of another country. If this were done in an inimical or even a critical spirit, it might, perhaps, be dismissed with indifference. But France, once in our history an all-powerful ally, is now a friendly power, with which we are in the best relations. Any movement on her part with regard to the conduct of our officials must be received according to the rules of comity and good-will. It cannot be disregarded. It ought to be anticipated. This resolution alone would justify inquiry on our part.

Passing to evidence, I come to the telegraphic dispatch of Squire, son-in-law and agent of Remington, actually addressed in French cipher to the latter in France, under date of October 8, 1870. Though brief, it is most important:—

“We have the strongest influences working for us, which will use all their efforts to succeed.”

Considering the writer of this dispatch, his family and business relations with Remington, to whom it was addressed, it is difficult to regard it except as a plain revelation of actual facts. It was important that Remington should know the precise condition of things. His son-in-law and agent telegraphs that “the strongest influences” are at work for them. What can this mean? Surely here is no broker or arms-merchant, engaged in the course of business. It is something else,—plainly something else. What? That is the point for inquiry. Mr. Squire is an American citizen. Let him be examined and cross-examined, under oath. Let him disclose what he meant by “the strongest influences.” He could not have intended to deceive his father-in-law, and puff[Pg 27] himself. He was doubtless in earnest. Did he deceive himself? On this he is a witness. But until those words are so far explained as to show that they do not point to officials, the natural inference is that it was on them that he relied,—that they were “the strongest influences” by which the job was to be carried through; for, of course, it was a job which he announced.

It cannot be doubted that this dispatch of Mr. Squire by itself alone is enough to justify inquiry. Without the resolution of the French Assembly, and without the supplementary testimony to be adduced, it throws a painful suspicion upon our officials, which should compel them to explain.

But the letter of Mr. Remington, already adduced,[20] carries this suspicion still further, by adding his positive testimony that he dealt with the Government. Before referring again to this testimony, it is important to consider the character of the witness; and here we have the authentication of the Secretary of War, who has recommended and indorsed him, in a formal paper to be used in France. Others may question the statements of Mr. Remington, but no person speaking for the Secretary will hesitate to accept them. If the testimony of the Secretary needed support, it would be found in the open declarations on this floor by the Senator from New York [Mr. Conkling], and in the following letter, which the Senator dated from the Senate Chamber during the recess, when notoriously the Senate was not in session:—

“Senate Chamber,

“Washington, D. C., November 17, 1871.

“My Dear Sir,—I learn with surprise that your personal and commercial situation and the good name of the house of Remington & Sons have been questioned. Having known your father and sons for many years, having lived within a stone-throw, so to say, of your house for a number of years, and being one of the Senators of your State, I cannot hesitate to give you my testimony relative to the accusations that have, as has been told me, been brought against you in France.

“As to what concerns personal situation, importance of affairs, success, solvency, wealth, and fidelity to the Government of the United States, your house has for a long time occupied a front rank, not only in the State of New York, but also in the Union.

“The allegation that you lack experience as a manufacturer of arms, or in anything that can, as a man of business, entitle you to respect, is, I can affirm in all sincerity, destitute of foundation, and must proceed from ignorance or malignity.

“Sincerely, your obedient servant,

“Roscoe Conkling.

“Mr. Samuel Remington.”

Thus does the Senator from New York vouch for the “good name” of Mr. Remington.

Thus introduced, thus authenticated, and thus indorsed, Mr. Remington cannot be rejected as a witness, especially when he writes an official letter to the Chairman of the French Armament Commission at Tours. You already know something of that letter, dated at New York, December 13, 1870. My present object is to show how, while announcing his large purchases of batteries, arms, and cartridges, he speaks of dealing with Government always, and not even with any intermediate agent.

Mr. Conkling. Will the Senator allow me there one moment, as he has referred to me?

Mr. Sumner. Certainly.

Mr. Conkling. He is engaged at this point, if I understand him aright, in supporting Mr. Remington in his character; and as the document from which he made the translation of my letter also contains stronger fortification in aid of the Senator and of Mr. Remington, I beg to call attention to it. The Senator might refer not only to my letter, but to letters written by Governor Hoffman, ex-Governor Horatio Seymour, Edwin D. Morgan, late a member of this body, General John A. Dix, not unknown here, and other citizens of the State of New York, who certify, I believe in somewhat stronger terms than those I employed, to the probity and standing of Mr. Remington.

Mr. Sumner. I am obliged to the Senator for the additional testimony that he bears. It only fortifies the authority of Mr. Remington, which was my object. I took the liberty of introducing the letter of the Senator, because he is among us, and had vouched for Mr. Remington personally. I gladly welcome the additional evidence which the Senator introduces. It is entirely in harmony with the case that I am presenting. I wish to show how Mr. Remington was regarded by the Senator, by the Secretary of War, and by other distinguished citizens,—so that, when he writes an official letter to the Chairman of the Arms Committee of Tours, he cannot be rejected as a witness.

The letter is long, and early in it the writer alludes to a credit from France and certain instructions with regard to it, saying:—

“This we could not do, as a considerable portion had been already paid out to the Government.”

Then coming to the purchase of breech-loading Springfield muskets, he writes:—

“The Government has never made but about seventy-five thousand, all told; and forty thousand is the greatest number they think it prudent to spare.”

In order to increase the number he proposed an exchange of his own, and here he says:—

“This question of an exchange, with the very friendly feeling I find existing to aid France, I hope to be able to procure more.”

Where was “the very friendly feeling existing to aid France”? Not among merchants, agents, or brokers. This would hardly justify the important declaration with regard to a feeling which was so efficacious.

Then comes the question of cartridges; and here the dealings with the Government become still more manifest:—

“Cartridges for these forty thousand will in a great measure require to be made, as the Government have but about three millions on hand. But the Government has consented to allow the requisite number, four hundred for each gun, to be made, and the cartridge-works have had orders, given yesterday, to increase production to the full capacity of works.”

Observe here, if you please, the part performed by the Government,—not only its consent to the manufacture, but the promptitude of this consent. This was not easily accomplished, as the well-indorsed witness testifies:—

“This question of making the cartridges at the Government works was a difficult one to get over. But it is done.”

Naturally difficult; but the agent of France overcame all obstacles. Then as to price:—

“The price the Government will charge for the guns and cartridges will be ——, or as near that as possible.”

Always “the Government”! Then comes another glimpse:—

“The forty thousand guns cannot all be shipped immediately, as they are distributed in the various arsenals throughout the country.”

That is, the Government arsenals.

Then appears one of our officials on the scene:—

“The Chief of Ordnance thinks it may take twenty to thirty days before all could be brought in.”

Then again the witness reports:—

“The Chief of Ordnance estimates the cost of the arms, including boxing and expense of freight to bring them to New York, at $20.60 currency.”

Then as to the harness:—

“The Government have not full complete sets to the extent of twenty-five hundred after selling the number required for the fifty batteries.”

Always “the Government”!

Then, after mentioning that some parts of the harness are wanting, he says:—

“I have made arrangements to have this deficiency made good by either the Government or by outside persons.”

But the Government does all it can:—

“In the mean time the Government have ordered the harness to be sent here immediately.”

Then at the close the witness says:—

“I forgot to say the Government have no Spencer rifles, having never had but a small number, and all of those you have bought.”

And he adds—

that “they have from three to four thousand transformed Springfields,” which he “may think best to take after examination,”—

showing again his intimate dealings with the Government.

Such is the testimony of Mr. Remington, the acknowledged agent of France. It is impossible to read these repeated allusions to “the Government” and “the Chief of Ordnance” without feeling that the witness was dealing directly in this quarter. If there was any middleman, he was of straw only; but a man-of-straw is nobody. If Mr. Remington’s character were not vouched so completely, if he did not appear on authentic testimony so entirely above any misrepresentation, if he were not elevated to be the model arms-dealer, this letter, with its numerous averments of relations with the Government, would be of less significance. But how can these be denied or explained without impeaching this witness?

But Mr. Remington is not without important support in his allegations. His French correspondent, M. Le Cesne, Chairman of the Armament Committee, has testified in open court that the French dealt directly with the Government. He may have been mistaken; but his testimony shows what he understood to be the case. The Senator from Missouri [Mr. Schurz] has already called attention to this testimony, which he cited from a journal enjoying great circulation on the European continent,[Pg 33] “L’Indépendance Belge.” The Senator from Vermont, [Mr. Edmunds,] not recognizing the character of this important journal, distrusted the report. But this testimony does not depend upon that journal alone. I have it in another journal, “Le Courrier des États-Unis,” of October 27, 1871, evidently copied from a Parisian journal, probably one of the law journals, where it is given according to the formal report of a trial, with question and answer:—

“The Presiding Judge. Did not this indemnity of twenty-five cents represent certain material expenses, certain disbursements, incidental expenses?

“M. Le Cesne. We could not admit these expenses; for we had an agreement with the American Federal Government, which had engaged to deliver free on board all the arms on account of France.”

Now I make no comment on this testimony except to remark that it is in entire harmony with the letter of Mr. Remington, and that beyond all doubt it was given in open court under oath, and duly reported in the trial, so as to become known generally in Europe. The position of M. Le Cesne gave it authority; for, beside his recent experience as Chairman of the Arms Committee, he is known as a former representative in the Assembly from the large town of Havre, and also a resident for twenty years in the United States. In confirmation of the value attached to this testimony, I mention that my attention was first directed to it by Hon. Gustavus Koerner, of Illinois, Minister of the United States at Madrid, under President Lincoln.

To this cumulative testimony I add that already supplied by our Minister at Berlin, under date of January 7,[Pg 34] 1871, and published by the Department of State, where it is distinctly said that “recently rifled cannon and ammunition have been furnished to the French in enormous quantities, not only by private American traders, but by the War Department at Washington.” This I have already adduced under another head.[21] It is mentioned now to show how the public knowledge of Europe was in harmony with the other evidence.

There is another piece of testimony, which serves to quicken suspicion. It is already admitted by the Secretary of War, that, after refusing Mr. Remington because he was an agent of France, bids were accepted from Thomas Richardson, who was in point of fact an attorney-at-law at Ilion, and agent and attorney of Mr. Remington. But the course of Mr. Remington, and his relations with this country attorney, are not without official illustration. Since this debate began I have received a copy of a law journal of Paris, “Le Droit, Journal des Tribunaux,” of January 18, 1872, containing the most recent judicial proceedings against the French Consul-General at New York. Here I find an official report from the acting French Consul there, addressed to the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, under date of August 25, 1871, where a fact is described which was authenticated at the Consulate, being an affidavit or deposition before a notary by a clerk of Mr. Remington, on which the report remarks:—

“This declaration establishing that this manufacturer caused the books of his house to be recopied three times, and in doing so altered the original form.”

The Report adds:—

“It is in this document that mention is made of the character, I might say criminal, which the name of Richardson appears to have assumed in the affairs of Mr. Remington.”

After remarking that the witness who has thus testified has exposed himself to the penalties of perjury, being several years of imprisonment, the Report proceeds:—

“You see from this that the operations of Mr. Remington give only too much of a glimpse of the most audacious frauds.”

Here is testimony tending at least to stimulate inquiry: Mr. Remington’s books altered three times, and the name of Richardson playing a criminal part. I quote this from an official document, and leave it.

Here, then, are six different sources of testimony, all prompting inquiry: first, the resolution of a committee of the French Assembly, showing suspicion of American officials; secondly, the cable dispatch of Squire, son-in-law and agent of Mr. Remington, declaring that “we have the strongest influences working for us, which will use all their efforts to succeed”; thirdly, the letter of Mr. Remington, reporting, in various forms and repetitions, that he is dealing with the American Government; fourthly, the testimony of M. Le Cesne, the Chairman of the French Armament Committee, made in open court and under oath, that the French “had an agreement with the American Federal Government, which had engaged to deliver free on board all the arms on account of France”; fifthly, the positive declaration of the London “Times” in the face of Europe, and reported by our Minister at Berlin, that rifled cannon and ammunition[Pg 36] had been furnished to the French in enormous quantities by the War Department at Washington; and, sixthly, the testimony of a clerk of Mr. Remington, authenticated by the French Consul-General at New York, that Mr. Remington had altered his books three times, and also speaking of the criminal character of Richardson in the affairs of Mr. Remington. On this cumulative and concurring testimony from six different sources is it not plain that there must be inquiry? The Senate cannot afford to close its eyes. The resolution of the committee of the French Assembly alone would be enough; but reinforced as it is from so many different quarters, the case is irresistible. Not to inquire is to set at defiance all rules of decency and common-sense.

To these successive reasons I add the evidence, which has been much discussed, showing a violation of the statute authorizing the sale of “the old cannon, arms, and other ordnance stores, now in possession of the War Department, which are damaged or otherwise unsuitable for the United States military service or for the militia of the United States,”[22]—inasmuch as stores were sold which were not “damaged” or “otherwise unsuitable.” I think no person can have heard the debate without admitting that here at least is something for careful investigation. The Senator from Missouri has already exposed this apparent dereliction of duty, which in its excess ended in actually disarming the country, so as to impair its defensive capacity. One of the crimes of the Cabinet of Mr. Buchanan on the eve of the Rebellion was that the North had been disarmed. It is important to consider whether, in the strange greed for[Pg 37] money or in the misfeasance of subordinates, something similar was not done when good arms were sold to France. The Chief of Ordnance, in his last Annual Report, which will be found in the Report of the Secretary of War, makes the following statement:—

“Now there are less than ten thousand breech-loading muskets in the arsenals for issue. This number of muskets is not half sufficient to supply the States with the muskets they are now entitled to receive under their apportionment of the permanent appropriation for arming and equipping the militia.”

Why, then, were breech-loading muskets exchanged for French gold? The Chief of Ordnance then proceeds:—

“This Department should, as soon as possible, be placed in a condition to fill all proper requisitions by the States upon it, and should also have on hand in store a large number of breech-loading muskets and carbines to meet any emergency that may arise.”

But these very breech-loading muskets have gone to France. The Chief of Ordnance adds:—

“Ten years ago the country felt that not less than a million of muskets should be kept in store in the arsenals.”[23]

Why was not this remembered, when the arsenals were stripped to supply France?

This important testimony speaks for itself. It is not sufficient to recount against it the arms actually in the national arsenals. The Chief of Ordnance answers the allegation by his own statements. He regrets the small number of breech-loading muskets on hand, and refers[Pg 38] as an example to the standard ten years ago, when it was felt that a million of muskets should be kept in store. It is not I who say this; it is the Chief of Ordnance.

But these several considerations, while making inquiry imperative, do not touch the money question involved. If in the asserted dealings with a belligerent power, in violation of our neutral duties, there is reason to believe corrupt practices of any kind, if there are large sums of money that seem to be unaccounted for, then is there additional ground for inquiry. Two questions are presented: first, as to the violation of neutral duties; and, secondly, as to misfeasance of subordinates involving money. In both cases the question, I repeat, is of inquiry.

I do not dwell now on the sums lost by France in this business. They are supposed to count by the million; but here I make no allegation. I allude only to what appears elsewhere.

Unquestionably there are enormous discrepancies between the sums paid by France for arms actually identified as coming from our arsenals and the sums received by our Ordnance Bureau. In different reports these discrepancies assume different forms. Not to repeat what has been said on other occasions, I introduce the report of the acting French Consul at New York, dated August 25, 1871, where, after showing that France received only 368,000 muskets and 53,000,000 cartridges, while the accounts with Mr. Remington enumerate a sum-total of 425,000 arms and 54,000,000 cartridges, it is said:—

“Whence comes this difference of 57,000 between the arms said to be sent from here and those which were received in France, if in fact the report of M. Riant signifies that they have only received a total of 368,000? How explain that there were 425,000 put on the bills of lading, and that the price of these was paid in New York?”

Now this discrepancy may be traced exclusively to French agents, so that our subordinates shall not in any way be involved; but when we consider all the circumstances of this transaction, it affords grounds of inquiry.

But there is another witness on this head, not before mentioned in this debate. I have here an extract from the official report of M. de Bellonet, the French Chargé d’Affaires at Washington, made to his Government on this very question of losses down to a certain period. His language is explicit: “The dry loss to the Treasury of France must have been about $1,500,000, or seven million francs.” This, be it remembered, is only a partial report down to a certain period. Now there is nothing in this report to charge this “dry loss” upon our officials. It may be that it was all absorbed by the intermediate agents. But taken in connection with the telegram of Squire and the abundant letter of Mr. Remington, it leaves a suspicion at least adverse to our officials.

Sir, let me be understood. I do not believe that any inquiry by any committee can give back to France any of the enormous sums she has lost. They have already gone beyond recall into the portentous mass of her terrible sacrifices destined to be an indefinite mortgage on that interesting country. Not for the sake of France or of any French claimant do I propose inquiry, but for our sake, for the sake of our own country. We read of that vast Serbonian bog “where armies whole have sunk.” It is important to know if there is any such bog anywhere about our Ordnance Office, where millions whole have sunk.

Investigation is the order of the day. Already in France, amid all the anxieties of her distracted condition, these purchases of arms have occupied much attention. As far back as last April, the “Soir,” a journal at Versailles, where the Convention was sitting, called for parliamentary inquiry. Its language was strong:—

“A parliamentary inquiry made in full day can alone establish either the culpability of some or the perfect honorableness of others.”

And the same French organ added:—

“The Chamber, in consigning this matter to its pigeonholes, refused satisfaction to an awakened public morality.”

There is, then, in France an awakened public morality, as we hope there is also in the United States, which demands investigation where there is suspicion of corrupt practices. The French Chamber has instituted inquiry.

Mr. President, as a Republic, we are bound to the most strenuous care, so that our example may not in any way suffer. If we fail, then does Republican Government everywhere feel the shock. For the sake of others as well as of ourselves must we guard our conduct. How often do I insist that we cannot at any moment, or in any transaction, forget these great responsibilities! As no man “liveth to himself,” so no nation “liveth” to itself; especially is this the condition of the Great Republic. By the very name it bears, and by its lofty dedication to the rights of human nature, is it vowed to all those things which contribute most to civilization, keeping its example always above suspicion. That great political philosopher, Montesquieu, announces that[Pg 41] the animating sentiment of Monarchy is “Honor,” but the animating sentiment of a Republic is “Virtue.”[24] I would gladly accept this flattering distinction. Therefore, in the name of that Virtue which should inspire our Government and keep it forever above all suspicion, do I move this inquiry.

On this whole matter the Senate will act as it thinks best, ordering that investigation which the case requires. For myself I have but one desire, which is, that this effort, begun in the discharge of a patriotic duty, may redound to the good of our country, and especially to the purity of the public service.

(A.) Page 15.

AUTHORITIES REFERRED TO IN SPEECH.

Wheaton, our great authority, in Lawrence’s edition, page 727, quotes Vattel as laying down the rule of neutrality:—

“To give no assistance where there is no previous stipulation to give it; nor voluntarily to furnish troops, arms, ammunition, or anything of direct use in war.”

Vattel, as quoted, then says:—

“I do not say, To give assistance equally, but, To give no assistance; for it would be absurd that a State should assist at the same time two enemies.”—Le Droit des Gens, Liv. III. ch. vii. § 104.

Another home authority, the late General Halleck, in his work on International Law, after speaking of merchants engaged[Pg 42] in selling ships and munitions of war to a belligerent, says:—

“The act is wrong in itself, and the penalty results from his violation of moral duty as well as of law. The duties imposed upon the citizens and subjects flow from exactly the same principle as those which attach to the government of neutral States.”

He then says, quoting another:—

“By these acts he makes himself personally a party to a war in which, as a neutral, he had no right to engage, and his property is justly treated as that of an enemy.”—International Law, p. 631.

Our other home authority, Professor Woolsey, in his work on International Law, section 162, says:—

“International Law does not require of the neutral sovereign that he should keep the citizen or subject within the same strict lines of neutrality which he is bound to draw for himself.”—Introduction to the Study of International Law, 2d edition, p. 270.

That is, a citizen may sell ships and arms to a belligerent and take the penalty, but the Government cannot do any such thing.

Another authority of considerable weight, Bluntschli, the German, lays down the rule as follows:—

“The neutral State must neither send troops to a belligerent, nor put ships of war at its disposal, nor furnish subsidies to aid it in making the war.

“In coming directly to the aid of one of the belligerent powers by the sending of men or war material, one takes part in the war.”—Droit International Codifié, tr. Lardy, art. 757, p. 381.

There is the true principle: “By the sending of men or war material one takes part in the war.”

But the most important illustration of this question, and the only case bearing directly on this point, which, according[Pg 43] to my recollection, has ever been diplomatically discussed, is one somewhat famous at the time, known as that of the Swedish Frigate, which will be found in the second series of “Causes Célèbres,” by Baron Charles de Martens.

It seems that in 1825, after ten years of peace, the Swedish Government conceived the idea of parting with ships, some of them more than twenty years old, as comparatively useless. A contract for their sale was made with a commercial house in London. The Spanish Government, by their minister at Stockholm, protested, on the alleged ground, that, though nominally sold to merchants, they were purchased for the revolted colonies in Mexico and South America, and in his communication, dated the 1st of July, 1825, used the following energetic language, which I translate:—

“And what would his Majesty the King of Sweden think, on the supposition of the revolt of one of his provinces,—of the kingdom of Norway for example,—if friendly and allied powers furnished the rebels with arms, munitions, a fleet even, through intermediate speculators, and under pretence of not knowing the result—

I translate literally,—

“intermediate speculators, and under pretence of not knowing the result? Informed of these preparations, would the Cabinet of Stockholm wait till the steel and the cannon furnished to its enemies had mown down its soldiers, till the vessels delivered to the rebels had annihilated its commerce and desolated its coasts, to protest against similar supplies, and to prevent them if possible? And if the protests were rejected, independently of every other measure, would it not raise its voice throughout Europe, and at the courts of all its allies, against this act of hostility, against this violation of the rights of sovereignty, and against this political scandal?”—Causes Célèbres, Tom. II. pp. 472-73.

These are strong words, but they only give expression to the feelings naturally awakened in a Power that seemed to be imperilled by such an act.

In another communication the same minister said to the Swedish Government:—

“It is the doctrine of irresponsibility which the Cabinet of Stockholm professes with regard to the sale of these war vessels, which excites the most lively representations on the part of the undersigned.”—Note of 15 July 1825: Ibid., p. 480.

Mark the words, “the doctrine of irresponsibility.” Then, again, the minister says in other words worthy of consideration at this moment:—

“The Swedish Government on this occasion, creating this new kind of commerce, determined to furnish ships of war indiscriminately to every purchaser, even to private individuals without guaranty,—establishing, as it seems to indicate, that the commercial benefits of these sales are for the State a necessity of an order superior to political considerations the most elevated, as to moral obligations the most respectable.”—Note of 9 September, 1825: Ibid., p. 486.

I ask if these words are not applicable to the present case? Did it not become the Government of the United States at this time, when making these large sales, almost gigantic, so that its suspicion was necessarily aroused, to institute inquiry into the real character of the purchaser? Was it not put on its guard? Every morning told us of war unhappily raging in Europe. Could there be doubt that these large purchases were for the benefit of one of the belligerents? Was our Government so situated that for the sake of these profits it would neglect political considerations called in this dispatch the most elevated, as moral obligations the most respectable? Was it ready to assume the responsibility characterized by the Spanish minister in a case less plain, as “an act of hostility,” a “violation of the rights of sovereignty,” a “political scandal”?

Two Protests against the Competency of the Senate Committee to Investigate the Sale of Arms to France; March 26 and 27, 1872.

March 26, 1872, Mr. Sumner appeared before the Committee to investigate the sale of arms by the United States during the French and German War, in response to a communication signed by the chairman of the Committee requesting his attendance. After reading this communication, Mr. Sumner proceeded to read and file a protest in the following terms:—

Personally, I object to no examination. Willingly would I submit to the most searching scrutiny, not only in the present case, but in all my public life. There is not an act, letter, or conversation at any time, that I would save from investigation. I make this statement, because I would not have the protest I deem it my duty to offer open to suspicion that there is anything I desire to conceal or any examination I would avoid.

But appearing before the Committee on an invitation which is in the nature of a summons, to testify in the investigation originally moved by me into the sale of[Pg 46] arms to France, I am obliged to consider my duty as a Senator. Personal inclinations, whatever they may be, cannot be my guide. I must do what belongs to a Senator under the circumstances of the case.

Before answering any questions, I am constrained to consider the competency of the Committee which has summoned me. It is of less importance what these questions may be, although there are certain obvious limitations, to which I will allude at the outset.

The examination of a Senator by a Committee of the Senate on a matter outside of the Senate, and not connected with his public duties, is sustained by precedents,—as when Mr. Seward and Mr. Wilson were examined with reference to the expedition of John Brown;[25] but any examination with regard to his public conduct, and especially with regard to a matter which he has felt it his duty to lay before the Senate in the discharge of his public duties, is of very doubtful propriety. In his public conduct a Senator acts on his responsibility, under sanction of an oath, and the Constitution declares that “for any speech or debate” he “shall not be questioned in any other place.” This inhibition, while not preventing questions of a certain character, must limit the inquiry; but the law steps forward with its own requirements, according to which it is plain that a Senator cannot be interrogated, first, with regard to his conference with other Senators on public business, and, secondly, with regard to witnesses who have confidentially communicated with him.

Referring to the most approved work on the Law of Evidence,—I mean that of Professor Greenleaf,—we[Pg 47] find under the head of “Evidence excluded from Public Policy”[26] at least four different classes of cases, which may enlighten us in determining the questions proper for Senators.

1. Communications between a lawyer and client. And are not the relations of Senators, in the discharge of their public duties, equally sacred?

2. Judges and arbitrators enjoy a similar exemption with regard to matters before them.

3. Grand jurors, embracing even the clerk and prosecuting officer, cannot be examined on matters before them.

4. Transactions between the heads of Departments and their subordinate officers are treated as confidential.

Plainly, the conferences of a Senator, in the discharge of his public duties, cannot be less protected.

This rule is equally imperative with regard to witnesses who have confidentially communicated with a Senator. Here again I quote Professor Greenleaf, who quotes the eminent English judge of the close of the last century, Lord Chief-Justice Eyre, as follows:—

“There is a rule which has universally obtained on account of its importance to the public for the detection of crimes, that those persons who are the channel by means of which that detection is made should not be unnecessarily disclosed.”[27]

Then the learned professor proceeds:—

“All were of opinion that all those questions which tend to the discovery of the channels by which the disclosure was made to the officers of justice were, upon the general principles of the convenience of public justice, to be suppressed; that all persons in that situation were protected from the discovery.”[28]

These words are explicit, and nobody can question them.

I am led to make these remarks and adduce these authorities because, perusing the testimony of Mr. Schurz, I find that he was interrogated on these very matters; and since I, too, am summoned as a witness, I desire to put on record my sense of the impropriety of such questions. It is important that they should not become a precedent. And here again I declare that I have nothing to conceal, nothing that I would not willingly give to the world under any examination and cross-examination; but I am unwilling to aid in the overthrow of a rule of law which stands on unquestionable grounds of public policy. Especially is it important in the Senate, where, without such protection, a tyrannical majority might deter a minority from originating unwelcome inquiries.

From these preliminaries I proceed to consider the competency of the present Committee. Requested as a Senator to appear before you, I deem it my duty to protest against the formation and constitution of the Committee as contrary to unquestionable requirements of Parliamentary Law; and I ask the Committee to receive this protest as my answer to their letter of invitation. I make this more readily because in my speech in the Senate, February 28, 1872, entitled “Reform and Purity in Government, Neutral Duties, Sale of Arms to Belligerent France,”[29] I have set forth what moved me to the inquiry, being grounds of suspicion, which, in my judgment, rendered the most searching inquiry by a committee friendly to inquiry absolutely necessary.

The general parliamentary rule in the appointment of special committees requires that they should be organized so as to promote the business or inquiry for which the committee is created. This requirement is according to obvious reason, and is sustained by parliamentary authorities. In familiar language, a proposition is committed to its friends and not to its enemies.

In illustration of this rule, we are told that members who have spoken directly against what is called “the body of the bill,” meaning, of course, the substance of the inquiry, are not expected to serve on the committee, but, should they be so nominated, to decline. Their presence on a committee is not unlike participation in a trial by a judge or juror interested in the result.

Very little reflection shows how natural is this rule as an instrument of justice. The friends of a measure, or the promoters of an inquiry, though in the majority on a committee, can do no more than adduce evidence that exists, so that the business cannot suffer through them,—while those unfriendly to a measure, or hostile to an inquiry, may, from lukewarmness, or neglect, or possible prejudice, fail to present the proper evidence or recognize its just value, so that the business will suffer. In legislation, plainly, those who believe an inquiry necessary are the most proper persons to conduct it, and being so, they are selected by Parliamentary Law.

This rule may be traced in the history of Parliament anterior to the settlement of our country. The ancient statement was simply that “those against the bill should not be on the committee.” The meaning of the rule is distinctly seen in historic cases, which I proceed to adduce.