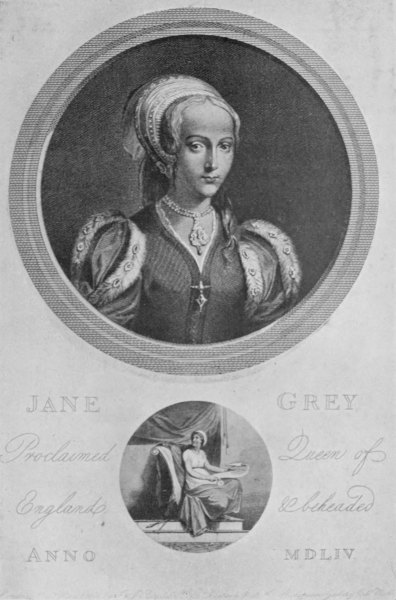

Lady Jane Grey

From a photo by Emery Walker after the picture by Lucas de Heere in the National portrait Gallery

Project Gutenberg's Lady Jane Grey and Her Times, by Ida Ashworth Taylor This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Lady Jane Grey and Her Times Author: Ida Ashworth Taylor Release Date: January 27, 2016 [EBook #51057] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LADY JANE GREY AND HER TIMES *** Produced by MWS, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

Cover created by Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

Lady Jane Grey

From a photo by Emery Walker after the picture by Lucas de Heere in the National portrait Gallery

By I. A. TAYLOR

Author of “Queen Hortense and her Friends”

“Queen Henrietta Maria,” etc.

WITH SEVENTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS

London: HUTCHINSON & CO.

Paternoster Row ![]() 1908

1908

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| The condition of Europe and England—Retrospect—Religious Affairs—A reign of terror—Cranmer in danger—Katherine Howard | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| 1546 | |

| Katherine Parr—Relations with Thomas Seymour—Married to Henry VIII.—Parties in court and country—Katherine’s position—Prince Edward | 13 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| 1546 | |

| The Marquis of Dorset and his family—Bradgate Park—Lady Jane Grey—Her relations with her cousins—Mary Tudor—Protestantism at Whitehall—Religious persecution | 24 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| 1546 | |

| Anne Askew—Her trial and execution—Katherine Parr’s danger—Plot against her—Her escape | 36 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| 1546 | |

| The King dying—The Earl of Surrey—His career and his fate—The Duke of Norfolk’s escape—Death of the King | 48 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| 1547 | |

| Triumph of the new men—Somerset made Protector—Coronation of Edward VI.—Measures of ecclesiastical reform—The Seymour brothers—Lady Jane Grey entrusted to the Admiral—The Admiral and Elizabeth—His marriage to ivKatherine | 60 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| 1547-1548 | |

| Katherine Parr’s unhappy married life—Dissensions between the Seymour brothers—The King and his uncles—The Admiral and Princess Elizabeth—Birth of Katherine’s child, and her death | 80 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| 1548 | |

| Lady Jane’s temporary return to her father—He surrenders her again to the Admiral—The terms of the bargain | 100 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| 1548-1549 | |

| Seymour and the Princess Elizabeth—His courtship—He is sent to the Tower—Elizabeth’s examinations and admissions—The execution of the Lord Admiral | 108 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| 1549-1550 | |

| The Protector’s position—Disaffection in the country—Its causes—The Duke’s arrogance—Warwick his rival—The success of his opponents—Placed in the Tower, but released—St. George’s Day at Court | 126 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| 1549-1551 | |

| Lady Jane Grey at home—Visit from Roger Ascham—The German divines—Position of Lady Jane in the theological world | 139 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| 1551-1552 | |

| An anxious tutor—Somerset’s final fall—The charges against him—His guilt or innocence—His trial and condemnation—The King’s indifference—Christmas at Greenwich—The Duke’s execution | 154 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| 1552 | |

| Northumberland and the King—Edward’s illness—Lady Jane and Mary—Mary refused permission to practise her religion—The vEmperor intervenes | 169 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| 1552 | |

| Lady Jane’s correspondence with Bullinger—Illness of the Duchess of Suffolk—Haddon’s difficulties—Ridley’s visit to Princess Mary—The English Reformers—Edward fatally ill—Lady Jane’s character and position | 178 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| 1553 | |

| The King dying—Noailles in England—Lady Jane married to Guilford Dudley—Edward’s will—Opposition of the law officers—They yield—The King’s death | 193 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| 1553 | |

| After King Edward’s death—Results to Lady Jane Grey—Northumberland’s schemes—Mary’s escape—Scene at Sion House—Lady Jane brought to the Tower—Quarrel with her husband—Her proclamation as Queen | 210 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| 1553 | |

| Lady Jane as Queen—Mary asserts her claims—The English envoys at Brussels—Mary’s popularity—Northumberland leaves London—His farewells | 225 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| 1553 | |

| Turn of the tide—Reaction in Mary’s favour in the Council—Suffolk yields—Mary proclaimed in London—Lady Jane’s deposition—She returns to Sion House | 237 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| 1553 | |

| Northumberland at bay—His capitulation—Meeting with Arundel, and arrest—Lady Jane a prisoner—Mary and Elizabeth—Mary’s visit to the Tower—London—Mary’s policy | 247 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| 1553 | |

| Trial and condemnation of Northumberland—His recantation—Final scenes—Lady Jane’s fate in the balances—A viconversation with her | 259 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| 1553 | |

| Mary’s marriage in question—Pole and Courtenay—Foreign suitors—The Prince of Spain proposed to her—Elizabeth’s attitude—Lady Jane’s letter to Hardinge—The coronation—Cranmer in the Tower—Lady Jane attainted—Letter to her father—Sentence of death—The Spanish match | 275 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| 1553-1554 | |

| Discontent at the Spanish match—Insurrections in the country—Courtenay and Elizabeth—Suffolk a rebel—General failure of the insurgents—Wyatt’s success—Marches to London—Mary’s conduct—Apprehensions in London, and at the palace—The fight—Wyatt a prisoner—Taken to the Tower | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| 1554 | |

| Lady Jane and her husband doomed—Her dispute with Feckenham—Gardiner’s sermon—Farewell messages—Last hours—Guilford Dudley’s execution—Lady Jane’s death | 311 |

| Index | 327 |

| LADY JANE GREY (Photogravure)—Frontispiece. | |

| FACING PAGE | |

| HENRY VIII. | 6 |

| KATHERINE HOWARD | 12 |

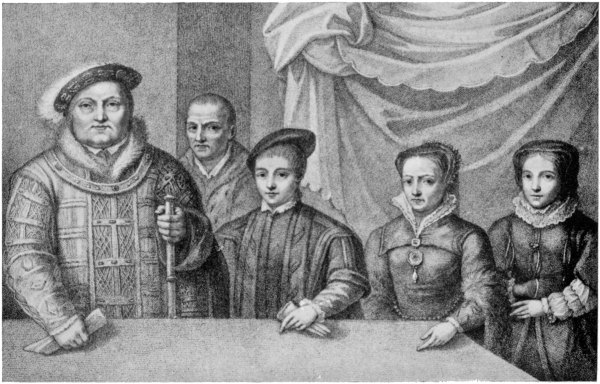

| HENRY VIII. AND HIS THREE CHILDREN | 20 |

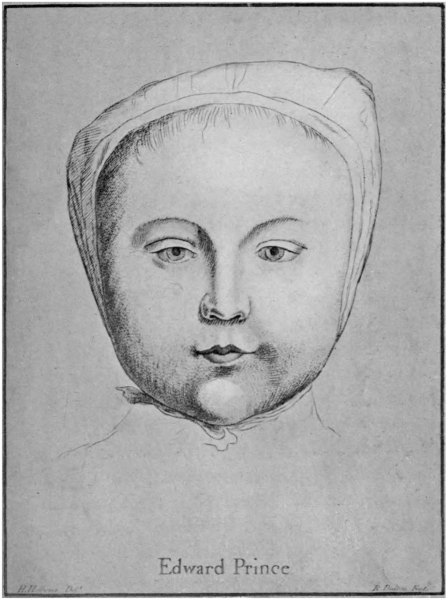

| PRINCE EDWARD, AFTERWARDS EDWARD VI. | 32 |

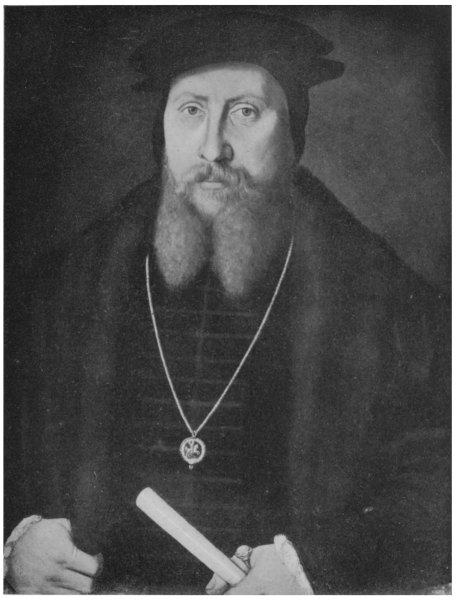

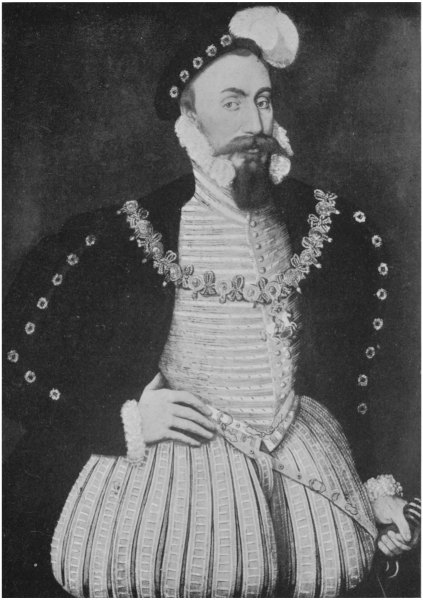

| HENRY HOWARD, EARL OF SURREY | 54 |

| KATHERINE PARR | 82 |

| WILLIAM, LORD PAGET, K.G. | 132 |

| EDWARD VI. | 136 |

| LADY JANE GREY | 142 |

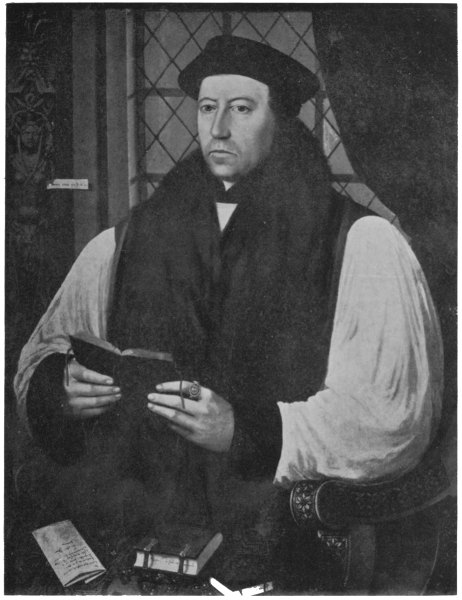

| ARCHBISHOP CRANMER | 152 |

| EDWARD SEYMOUR, DUKE OF SOMERSET, K.G. | 168 |

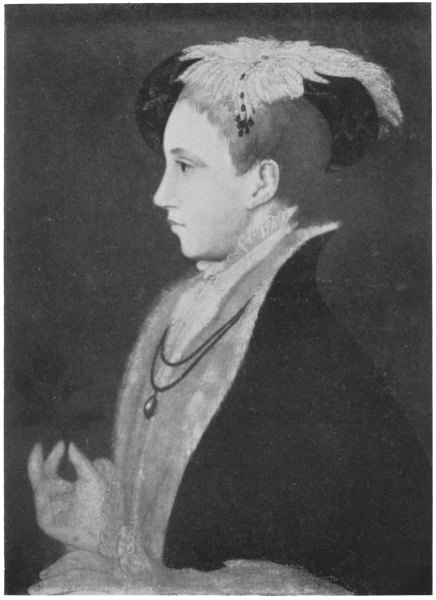

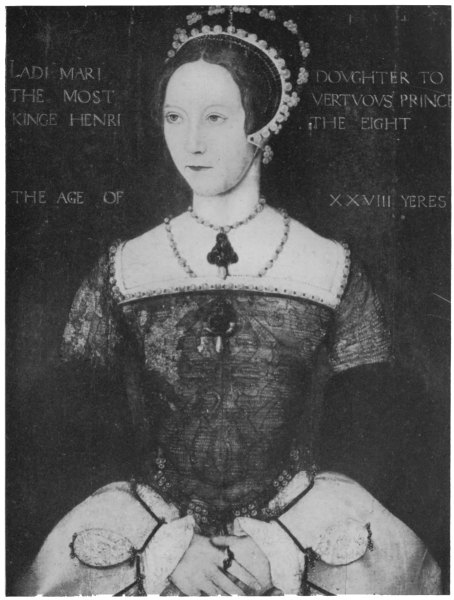

| PRINCESS MARY, AT THE AGE OF TWENTY-EIGHT | 184 |

| LADY JANE GREY | 200 |

| QUEEN ELIZABETH | 254 |

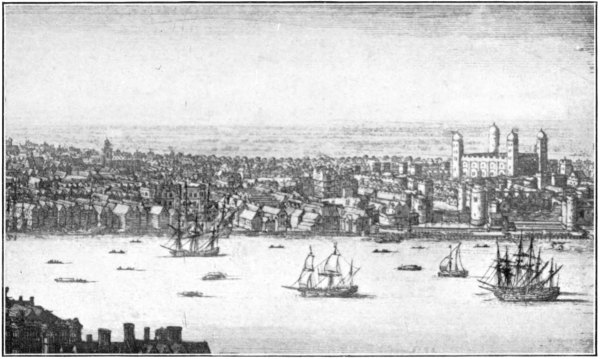

| THE TOWER OF LONDON | 284 |

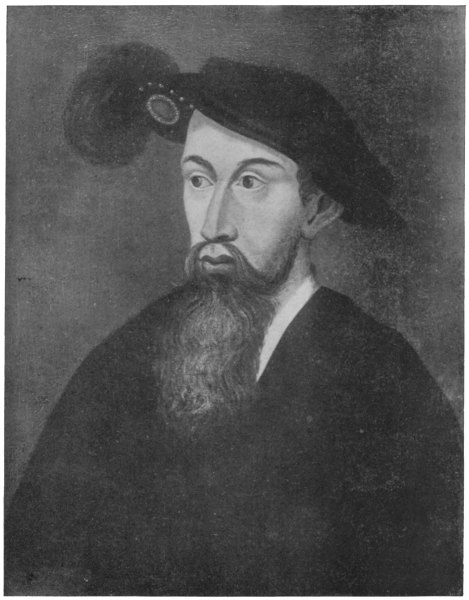

| HENRY GREY, DUKE OF SUFFOLK, K.G. | 294 |

In 1546 it must have been evident to most observers that the life of the man who had for thirty-five years been England’s ruler and tyrant—of whom Raleigh affirmed that if all the patterns of a merciless Prince had been lost in the world they might have been found in this one King—was not likely to be prolonged; and though it had been made penal to foretell the death of the sovereign, men must have been secretly looking on to the future with anxious eyes.

Of all the descendants of Henry VII. only one was male, the little Prince Edward, and in case of his death the succession would lie between his two sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, branded by successive Acts of Parliament with illegitimacy, the infant2 Queen of Scotland, whose claims were consistently ignored, and the daughters and grand-daughters of Henry VII.’s younger daughter, Mary Tudor.

The royal blood was to prove, to more than one of these, a fatal heritage. To Mary Stuart it was to bring captivity and death, and by reason of it Lady Jane Grey was to be forced to play the part of heroine in one of the most tragic episodes of the sixteenth century.

The latter part of Henry VIII.’s reign had been eventful at home and abroad. In Europe the three-cornered struggle between the Emperor Charles V., Francis of France, and Henry had been passing through various phases and vicissitudes, each of the wrestlers bidding for the support of a second of the trio, to the detriment of the third. New combinations were constantly formed as the kaleidoscope was turned; promises were lavishly made, to be broken without a scruple whensoever their breach might prove conducive to personal advantage. Religion, dragged into the political arena, was used as a party war-cry, and employed as a weapon for the destruction of public and private foes.

At home, England lay at the mercy of a King who was a law to himself and supreme arbiter of the destinies of his subjects. Only obscurity, and not always that, could ensure a man’s safety, or prevent him from falling a prey to the jealousy or hate of those amongst his enemies who had for the moment the ear3 of the sovereign. Pre-eminence in rank, or power, or intellect, was enough to give the possessor of the distinction an uneasy sense that he was marked out for destruction, that envy and malice were lying in wait to seize an opportunity to denounce him to the weak despot upon whose vanity and cowardice the adroit could play at will. Every year added its tale to the long list of victims who had met their end upon the scaffold.

For fifteen years, moreover, the country had been delivered over to the struggle carried on in the name of religion. In 1531 the King had responded to the refusal of the Pope to sanction his divorce from Katherine of Aragon by repudiating the authority of the Holy See and the assertion of his own supremacy in matters spiritual as well as temporal. Three years later Parliament, servile and subservient as Parliaments were wont to be under the Tudor Kings, had formally endorsed and confirmed the revolt.

“The third day of November,” recorded the chronicler, “the King’s Highness held the high Court of Parliament, in the which was concluded and made many and sundry good, wholesome, and godly statutes, but among all one special statute which authorised the King’s Highness to be supreme head of the Church of England, by which the Pope ... was utterly abolished out of this realm.”1

4 Since then another punishable crime was added to those, already none too few, for which a man was liable to lose his head, and the following year saw the death upon the scaffold of Fisher and of More. The execution of Anne Boleyn, by whom the match had, in some sort, been set to the mine, came next, but the step taken by the King was not to be retraced with the absence of the motive which had prompted it; and Catholics and Protestants alike had continued to suffer at the hands of an autocrat who chastised at will those who wandered from the path he pointed out, and refused to model their creed upon the prescribed pattern.

In 1546 the “Act to abolish Diversity of Opinion”—called more familiarly the Bloody Statute, and designed to conform the faith of the nation to that of the King—had been in force for seven years, a standing menace to those persons, in high or low place, who, encouraged by the King’s defiance of Rome, had been emboldened to adopt the tenets of the German Protestants. Henry had opened the floodgates; he desired to keep out the flood. The Six Articles of the Statute categorically reaffirmed the principal doctrines of the Catholic Church, and made their denial a legal offence. On the other hand the refusal to admit the royal supremacy in matters spiritual was no less penal. A reign of terror was the result.

“Is thy servant a dog?” The time-honoured5 question might have risen to the King’s lips in the days, not devoid of a brighter promise, of his youth, had the veil covering the future been withdrawn. “We mark curiously,” says a recent writer, “the regular deterioration of Henry’s character as the only checks upon his action were removed, and he progressively defied traditional authority and established standards of conduct without disaster to himself.” The Church had proved powerless to punish a defiance dictated by passion and perpetuated by vanity and cupidity; Parliaments had cringed to him in matters religious or political, courtiers and sycophants had flattered, until “there was no power on earth to hold in check the devil in the breast of Henry Tudor.”2

Such was the condition of England. Old barriers had been thrown down; new had not acquired strength; in the struggle for freedom men had cast aside moral restraint. Life was so lightly esteemed, and death invested with so little tragic importance, that a man of the position and standing of Latimer, Bishop of Worcester, when appointed to preach on the occasion of the burning of a priest, could treat the matter with a flippant levity scarcely credible at a later day.

“If it be your pleasure, as it is,” he wrote to Cromwell, “that I shall play the fool after my customary manner when Forest shall suffer, I6 would that my stage stood near unto Forest” (so that the victim might benefit by his arguments).... “If he would yet with heart return to his abjuration, I would wish his pardon, such is my foolishness.”3

Yet there was another side to the picture; here and there, amidst the din of battle and the confusion of tongues, the voice of genuine conviction was heard; and men and women were ready, at the bidding of conscience, to give up their lives in passionate loyalty to an ancient faith or to a new ideal. “And the thirtieth day of the same month,” June 1540, runs an entry in a contemporary chronicle, “was Dr. Barnes, Jerome, and Garrard, drawn from the Tower to Smithfield, and there burned for their heresies. And that same day also was drawn from the Tower with them Doctor Powell, with two other priests, and there was a gallows set up at St. Bartholomew’s Gate, and there were hanged, headed, and quartered that same day”—the offence of these last being the denial of the King’s supremacy, as that of the first had been adherence to Protestant doctrines.4

From a photo by W. Mansell & Co. after a painting by Holbein.

HENRY VIII.

No one was safe. The year 1540 had seen the fall of Cromwell, the Minister of State. “Cranmer and Cromwell,” wrote the French ambassador, “do not know where they are.”5 Cromwell at least was7 not to wait long for the certainty. For years all-powerful in the Council, he was now to fall a victim to jealous hate and the credulity of the master he had served. At his imprisonment “many lamented, but more rejoiced, ... for they banquetted and triumphed together that night, many wishing that day had been seven years before; and some, fearing that he should escape although he were imprisoned, could not be merry.”6 They need not have feared the King’s clemency. The minister had been arrested on June 10. On July 28 he was executed on Tower Hill.

If Cromwell, in spite of his services to the Crown, in spite of the need Henry had of men of his ability, was not secure, who could call themselves safe? Even Cranmer, the King’s special friend though he was, must have felt misgivings. A married man, with children, he was implicitly condemned by one of the Six Articles of the Bloody Statute, enjoining celibacy on the clergy, and was besides well known to hold Protestant views. His embittered enemy, Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, vehement in his Catholicism though pandering to the King on the subject of the royal supremacy, was minister; and his fickle master might throw the Archbishop at any moment to the wolves.

One narrow escape he had already had, when in 1544 a determined attempt had been hazarded8 to oust him from his position of trust and to convict him of his errors, and the party adverse to him in the Council had accused the Primate “most grievously” to the King of heresy. It was a bold stroke, for it was known that Henry loved him, and the triumph of his foes was the greater when they received the royal permission to commit the Lord Archbishop to the Tower on the following day, and to cause him to undergo an examination on matters of doctrine and faith. So far all had gone according to their hopes, and his enemies augured well of the result. But that night, at eleven o’clock, when Cranmer, in ignorance of the plot against him, was in bed, he received a summons to attend the King, whom he found in the gallery at Whitehall, and who made him acquainted with the action of the Council, together with his own consent that an examination should take place.

“Whether I have done well or no, what say you, my lord?” asked Henry in conclusion.

Cranmer answered warily. Knowing his master, and his jealousy of being supposed to connive at heresy, save on the one question of the Pope’s authority, he cannot have failed to recognise the gravity of the situation. He put, however, a good face upon it. The King, he said, would see that he had a fair trial—“was indifferently heard.” His bearing was that of a man secure that justice would be done him. Both he, in his heart, and the King, knew better.

9 “Oh, Lord God,” sighed Henry, “what fond simplicity have you, so to permit yourself to be imprisoned!” False witnesses would be produced, and he would be condemned.

Taking his precautions, therefore, Henry gave the Archbishop his ring—the recognised sign that the matter at issue was taken out of the hands of the Council and reserved for his personal investigation. After which sovereign and prelate parted.

When, at eight o’clock the next morning, Cranmer, in obedience to the summons he had received, arrived at the Council Chamber, his foes, insolent in their premature triumph, kept him at the door, awaiting their convenience, close upon an hour. My lord of Canterbury was become a lacquey, some one reported to the King, since he was standing among the footmen and servants. The King, comprehending what was implied, was wroth.

“Have they served my lord so?” he asked. “It is well enough; I shall talk with them by and by.”

Accordingly when Cranmer, called at length and arraigned before the Council, produced the ring—the symbol of his enemies’ discomfiture—and was brought to the royal presence that his cause might be tried by the King in person, the positions of accused and accusers were reversed. Acting, not without passion, rather as the advocate of the menaced man than as his judge, Henry received the Council10 with taunts, and in reply to their asseverations that the trial had been merely intended to conduce to the Archbishop’s greater glory, warned them against treating his friends in that fashion for the future. Cranmer, for the present, was safe.7

Protestant England rejoiced with the Protestant Archbishop. But it rejoiced in trembling. The Archbishop’s escape did not imply immunity to lesser offenders, and the severity used in administering the law is shown by the fact that a boy of fifteen was burnt for heresy—no willing martyr, but ignorant, and eager to catch at any chances of life, by casting the blame of his heresy on others. “The poor boy,” says Hall, “would have gladly said that the twelve Apostles taught it him ... such was his childish innocency and fear.”8 And England, with the strange patience of the age, looked on.

Side by side with religious persecution ran the story of the King’s domestic crimes. To go back no further, in the year 1542 Katherine Howard, Henry’s fifth wife, had met her fate, and the country had silently witnessed the pitiful and shameful spectacle. As fact after fact came to light, the tale will have been told of the beautiful, neglected child, left to her own devices and to the companionship of maid-servants in the disorderly household of her grandmother, the Duchess of Norfolk, with11 the results that might have been anticipated; of how she had suddenly become of importance when it had been perceived that the King had singled her out for favour; and of how, still “a very little girl,” as some one described her, she had been used as a pawn in the political game played by the Howard clan, and married to Henry. Only a few months after she had been promoted to her perilous dignity her doom had overtaken her; the enemies of the party to which by birth she belonged had not only made known to her husband misdeeds committed before her marriage and almost ranking as the delinquencies of a misguided child, but had hinted at more unpardonable misdemeanours of which the King’s wife had been guilty. The story of Katherine’s arraignment and condemnation will have spread through the land, with her protestations that, though not excusing the sins and follies of her youth—she was seventeen when she was done to death—she was guiltless of the action she was specially to expiate at the block; whilst men may have whispered the tale of her love for Thomas Culpeper, her cousin and playmate, whom she would have wedded had not the King stepped in between, and who had paid for her affection with his blood. “I die a Queen,” she is reported to have exclaimed upon the scaffold, “but I would rather have died the wife of Culpeper.”9 And it may have been rumoured that12 her head had fallen, not so much to vindicate the honour of the King as to set him free to form fresh ties.

However that might be, Katherine Howard had been sent to answer for her offences, or prove her innocence, at another bar, and her namesake, Katherine Parr, reigned in her stead.

From a photo by W. Mansell & Co. after a painting of the School of Holbein.

KATHERINE HOWARD.

It was now three years since Katherine Parr had replaced the unhappy child who had been her immediate predecessor. For three perilous years she had occupied—with how many fears, how many misgivings, who can tell?—the position of the King’s sixth wife. On a July day in 1543 Lady Latimer, already at thirty twice a widow, had been raised to the rank of Queen. If the ceremony was attended with no special pomp, neither had it been celebrated with the careful privacy observed with respect to some of the King’s marriages. His two daughters, Mary—approximately the same age as the bride, and who was her friend—and Elizabeth, had been present, as well as Henry’s brother-in-law, Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, and other officers of State. Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, afterwards her dangerous foe, performed the rite, in the Queen’s Closet at Hampton Court.

Sir Thomas Seymour, Hertford’s brother and14 Lord Admiral of England, was not at Hampton Court on the occasion, having been despatched on some foreign mission. More than one reason may have contributed to render his absence advisable. A wealthy and childless widow, of unblemished reputation, and belonging by birth to a race connected with the royal house, was not likely to remain long without suitors, and Lord Latimer can scarcely have been more than a month in his grave before Thomas Seymour had testified his desire to replace him and to become Katherine’s third husband. Nor does she appear to have been backward in responding to his advances.

Twice married to elderly men whose lives lay behind them, twice set free by death from her bonds, she may fairly have conceived that the time was come when she was justified in wedding, not for family or substantial reasons, not wholly perhaps, as before, in wisdom’s way, but a man she loved.

Seymour was not without attractions calculated to commend him to a woman hitherto bestowed upon husbands selected for her by others. Young and handsome, “fierce in courage, courtly in fashion, in personage stately, in voice magnificent, but somewhat empty in matter,”10 the gay sailor appears to have had little difficulty in winning the heart of a woman who, in spite of the learning, the prudence, and the piety for which she was noted, may have15 felt, as she watched her youth slip by, that she had had little good of it; and it is clear, from a letter she addressed to Seymour himself when, after Henry’s death, his suit had been successfully renewed, that she had looked forward at this earlier date to becoming his wife.

“As truly as God is God,” she then wrote, “my mind was fully bent, the other time I was at liberty, to marry you before any man I know. Howbeit God withstood my will therein most vehemently for a time, and through His grace and goodness made that possible which seemed to me most impossible; that was, made me renounce utterly mine own will and follow His most willingly. It were long to write all the processes of this matter. If I live, I shall declare it to you myself. I can say nothing, but as my Lady of Suffolk saith, ‘God is a marvellous man.’”11

Strange burdens of responsibility have ever been laid upon the duty of obedience to the will of Providence, nor does it appear clear to the casual reader why the consent of Katherine to become a Queen should have been viewed by her in the light of a sacrifice to principle. Whether her point of view was shared by her lover does not appear. It is at all events clear that both were wise enough in the world’s lore not to brave the wrath of the despot by crossing his caprice. Seymour retired16 from the field, and Katherine, perhaps sustained by the inward approval of conscience, perhaps partially comforted by a crown, accepted the dangerous distinction she was offered.

To her brother, Lord Parr, when writing to inform him of her advancement, she expressed no regret. It had pleased God, she told him, to incline the King to take her as his wife, the greatest joy and comfort that could happen to her. She desired to communicate the great news to Parr, as being the person with most cause to rejoice thereat, and added, with a suspicion of condescension, her hope that he would let her hear of his health as friendly as if she had not been called to this honour.12

Although the actual marriage had not taken place until some six months after Lord Latimer’s death, no time can have been lost in arranging it, since before her husband had been two months in the grave Henry was causing a bill for her dresses to be paid out of the Exchequer.

It was generally considered that the King had chosen well. Wriothesley, the Chancellor, was sure His Majesty had never a wife more agreeable to his heart. Gardiner had not only performed the marriage ceremony but had given away the bride. According to an old chronicle the new Queen was a woman “compleat with singular humility.”13 She17 had, at any rate, the adroitness, in her relations with the King, to assume the appearance of it, and was a well-educated, sensible, and kindly woman, “quieter than any of the young wives the King had had, and, as she knew more of the world, she always got on pleasantly with the King, and had no caprices.”14

The story of the marriage was an old one in 1546. Seymour had returned from his mission and resumed his former position at Court as the King’s brother-in-law and the uncle of his heir, and not even the Queen’s enemies—and she had enough of them and to spare—had found an excuse for calling to mind the relations once existing between the Admiral and the King’s wife. Nevertheless, and in spite of the blamelessness of her conduct, the satisfaction which had greeted the marriage was on the wane. A hard task would have awaited Queen or courtier who should have attempted to minister to the contentment of all the rival parties striving for predominance in the State and at Court, and to be adjudged the friend of the one was practically equivalent to a pledge of distrust from the other. Whitehall, like the country at large, was divided against itself by theological strife; and whilst the men faithful to the ancient creed in its entirety were inevitably in bitter opposition to the adherents of the new teachers whose headquarters were in Germany, a third party, more unscrupulous than either, was made up of the middle men who18 moulded—outwardly or inwardly—their faith upon the King’s, and would, if they could, have created a Papacy without a Pope, a Catholic Church without its corner-stone.

At Court, as elsewhere, each of these three parties were standing on their guard, ready to parry or to strike a blow when occasion arose, jealous of every success scored by their opponents. The fall of Cromwell had inspired the Catholics with hope, and, with Gardiner as Minister and Wriothesley as Chancellor, they had been in a more favourable position than for some time past at the date of the King’s last marriage. It had then been assumed that the new Queen’s influence would be employed upon their side—an expectation confirmed by her friendship with the Princess Mary. The discovery that the widow of Lord Latimer—so fervent a Catholic that he had joined in the north-country insurrection known as the Pilgrimage of Grace—had broken with her past, openly displayed her sympathy with Protestant doctrine, and, in common with the King’s nieces, was addicted to what was called the “new learning,” quickly disabused them of their hopes, rendered the Catholic party at Court her embittered enemies, and lent additional danger to what was already a perilous position by affording those at present in power a motive for removing from the King’s side a woman regarded as the advocate of innovation.

19 So far their efforts had been fruitless. Katherine still held her own. During Henry’s absence in France, whither he had gone to conduct the campaign in person, she had administered the Government, as Queen-Regent, with tact and discretion; the King loved her—as he understood love—and, what was perhaps a more important matter, she had contrived to render herself necessary to him. Wary, prudent, and pious, and notwithstanding the possession of qualities marking her out in some sort as the superior woman of her day, she was not above pandering to his love of flattery. Into her book entitled The Lamentations of a Sinner, she introduced a fulsome panegyric of the godly and learned King who had removed from his realm the veils and mists of error, and in the guise of a modern Moses had been victorious over the Roman Pharaoh. What she publicly printed she doubtless reiterated in private; and the King found the domestic incense soothing to an irritable temper, still further acerbated by disease.

By other methods she had commended herself to those who were about him open to conciliation. She had served a long apprenticeship in the art of the step-mother, both Lord Borough, her first husband, and Lord Latimer having possessed children when she married them; and her skill in dealing with the little heir to the throne and his sisters proved that she had turned her experience to good account. Her genuine kindness, not only to Mary, who had been20 her friend from the first, but to Elizabeth, ten years old at the time of the marriage, was calculated to propitiate the adherents of each; and to her good offices it was in especial due that Anne Boleyn’s daughter, hitherto kept chiefly at a distance from Court, was brought to Whitehall. The child, young as she was, was old enough to appreciate the importance of possessing a friend in her father’s wife, and the letter she addressed to her step-mother on the occasion overflowed with expressions of devotion and gratitude. To the place the Queen won in the affections of the all-important heir, the boy’s letters bear witness.

From an engraving by F. Bartolozzi after a picture by Holbein.

HENRY VIII. AND HIS THREE CHILDREN.

There is no need to assume that Katherine’s course of action was wholly dictated by interested motives. Yet in this case principle and prudence went hand in hand. Henry was becoming increasingly sick and suffering, and, with the shadow of death deepening above him, the gifts he asked of life were insensibly changing their character. His autocratic and violent temper remained the same, but peace and quiet, a soothing atmosphere of submissive affection, the absence of domestic friction, if not sufficient to ensure his wife immunity from peril, constituted her best chance of escaping the doom of her predecessors. To a selfish man the appeal must be to self-interest. This appeal Katherine consistently made and it had so far proved successful. For the rest, whether21 she suffered from terror of possible disaster or resolutely shut her eyes to what might have unnerved and rendered her unfit for the part she had to play, none can tell, any more than it can be determined whether, as she looked from the man she had married to the man she had loved, she indulged in vain regrets for the happiness of which she had caught a glimpse in those brief days when she had dreamed of a future to be shared with Thomas Seymour.

In spite, however, of her caution, in spite of the perfection with which she performed the duties of wife and nurse, by 1546 disquieting reports were afloat.

“I am confused and apprehensive,” wrote Charles V.’s ambassador from London in the February of that year, “to have to inform Your Majesty that there are rumours here of a new Queen, although I do not know how true they be.... The King shows no alteration in his behaviour towards the Queen, though I am informed that she is annoyed by the rumours.”15

With the history of the past to quicken her apprehensions, she may well have been more than “annoyed” by them. But, true or false, she could but pursue the line of conduct she had adopted, and must have turned with relief from domestic anxieties to any other matters that could22 serve to distract her mind from her precarious future. Amongst the learned ladies of a day when scholarship was becoming a fashion she occupied a foremost place, and was actively engaged in promoting educational interests. Stimulated by her step-mother’s approval, the Princess Mary had been encouraged to undertake part of the translation of Erasmus’s paraphrases of the Gospels; and Elizabeth is found sending the Queen, as a fitting offering, a translation from the Italian inscribed on vellum and entitled the Glasse of the Synneful Soule, accompanying it by the expression of a hope that, having passed through hands so learned as the Queen’s, it would come forth from them in a new form. The education of the little Prince Edward too was pushed rapidly forward, and at six years old, the year of his father’s marriage, he had been taken out of the hands of women and committed to the tuition of John Cheke and Dr. Richard Cox. These two, explains Heylyn, being equal in authority, employed themselves to his advantage in their several kinds—Dr. Cox for knowledge of divinity, philosophy, and gravity of manners, Mr. Cheke for eloquence in the Greek and Latin tongues; whilst other masters instructed the poor child in modern languages, so that in a short time he spoke French perfectly, and was able to express himself “magnificently enough” in Italian, Greek, and Spanish.16

23 His companion and playfellow was one Barnaby Fitzpatrick, to whom he clung throughout his short life with constant affection. It was Barnaby’s office to bear whatever punishment the Prince had merited—a method more successful in the case of the Prince than it might have proved with a less soft-hearted offender, since it is said that “it was not easy to affirm whether Fitzpatrick smarted more for the default of the Prince, or the Prince conceived more grief for the smart of Fitzpatrick.”17

Katherine Parr is not likely to have regretted the pressure put upon her stepson; and the boy, apologising for his simple and rude letters, adds his acknowledgments for those addressed to him by the Queen, “which do give me much comfort and encouragement to go forward in such things wherein your Grace beareth me on hand.”

The King’s latest wife was, in fact, a teacher by nature and choice, and admirably fitted to direct the studies of his son and daughters, as well as of any other children who might be brought within the sphere of her influence. That influence, it may be, had something to do with moulding the character and the destiny of a child fated to be unhappily prominent in the near future. This was Lady Jane Grey.

Amongst the households where both affairs at Court and the religious struggle distracting the country were watched with the deepest interest was that of the Marquis of Dorset, the husband of the King’s niece and father of Lady Jane Grey.

Married at eighteen to the infirm and aged Louis XII. of France, Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry VII. and friend of the luckless Katherine of Aragon, had been released by his death after less than three months of wedded life, and had lost no time in choosing a more congenial bridegroom. At Calais, on her way home, she had bestowed her hand upon “that martial and pompous gentleman,” Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who, sent by her brother to conduct her back to England, thought it well to secure his bride and to wait until the union was accomplished before obtaining the King’s consent. Of this hurried marriage the eldest child was the25 mother of Jane Grey, who thus derived her disastrous heritage of royal blood.

It was at the country home of the Dorset family, Bradgate Park, that Lady Jane had been born, in 1537. Six miles distant from the town of Leicester, and forming the south-east end of Charnwood Forest, it was a pleasant and quiet place. Over the wide park itself, seven miles in circumference, bracken grew freely; here and there bare rocks rose amidst the masses of green undergrowth, broken now and then by a solitary oak, and the unwooded expanse was covered with “wild verdure.”18

The house itself had not long been built, nor is there much remaining at the present day to show what had been its aspect at the time when Lady Jane was its inmate. Early in the eighteenth century it was destroyed by fire, tradition ascribing the catastrophe to a Lady Suffolk who, brought to her husband’s home as a bride, complained that the country was a forest and the inhabitants were brutes, and, at the suggestion of her sister, took the most certain means of ensuring a change of residence.

But if little outward trace is left of the place where the victim of state-craft and ambition was born and passed her early years, it is not a difficult matter to hazard a guess at the religious and political atmosphere of her home. Echoes of the fight carried on,26 openly or covertly, between the parties striving for predominance in the realm must have almost daily reached Bradgate, the accounts of the incidents marking the combat taking their colour from the sympathies of the master and mistress of the house, strongly enlisted upon the side of Protestantism. At Lord Dorset’s house, though with closed doors, the condition of religious affairs must have supplied constant matter for discussion; and Jane will have listened to the conversation with the eager attention of an intelligent child, piecing together the fragments she gathered up, and gradually realising, with a thrill of excitement, as she became old enough to grasp the significance of what she heard, that men and women were suffering and dying in torment for the sake of doctrines she had herself been taught as a matter of course. Serious and precocious, and already beginning an education said to have included in later years Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Chaldaic, Arabic, French, and Italian, the stories reaching her father’s house of the events taking place in London and at Court must have imprinted themselves upon her imagination at an age specially open to such impressions, and it is not unnatural that she should have grown up nurtured in the principles of polemics and apt at controversy.

Nor were edifying tales of martyrdom or of suffering for conscience’ sake the only ones to penetrate to the green and quiet precincts of Bradgate. At his niece’s house the King’s domestic affairs—27a scandal and a by-word in Europe—must have been regarded with the added interest, perhaps the sharper criticism, due to kinship. Henry was not only Lady Dorset’s sovereign, but her uncle, and she had a more personal interest than others in what Messer Barbaro, in his report to the Venetian senate, described as “this confusion of wives.”19 To keep a child ignorant was no part of the training of the day, and Jane, herself destined for a court life, no doubt had heard, as she grew older, many of the stories of terror and pity circulating throughout the country, and investing, in the eyes of those afar off, the distant city—the stage whereon most of them had been enacted—with the atmosphere of mystery and fear and excitement belonging to a place where martyrs were shedding their blood, or heretics atoning for their guilt, according as the narrators inclined to the ancient or the novel faith; where tragedies of love and hatred and revenge were being played, and men went in hourly peril of their lives.

Of this place, invested with the attraction and glamour belonging to a land of glitter and romance, Lady Jane had glimpses on the occasions when, as a near relation of the King’s, she accompanied her mother to Court, becoming for a while a sharer in the life of palaces and an actor, by reason of her strain of royal blood, in the pageant28 ever going forward at St. James’s or Whitehall;20 and though it does not appear that she was finally transferred from the guardianship of her parents to that of the Queen until after the death of Henry in the beginning of the year 1547, it is not unlikely that the book-loving child of nine may have attracted the attention of the scholarly Queen during her visits to Court and that Katherine’s belligerent Protestantism had its share in the development of the convictions which afterwards proved so strong both in life and in death.

There is at this date little trace of any connection between Jane and her cousins, the King’s children. A strong affection on the part of Edward is said to have existed, and to it has been attributed his consent to set his sisters aside in Lady Jane’s favour. “She charmed all who knew her,” says Burnet, “in particular the young King, about whom she was bred, and who had always lived with her in the familiarity of a brother.” For this statement there is no contemporary authority, and, so far as can be ascertained, intercourse between29 the two can have been but slight. Between Edward and his younger sister, on the other hand, the bond of affection was strong, their education being carried on at this time much together at Hatfield; and “a concurrence and sympathy of their natures and affections, together with the celestial bond, conformity in religion,”21 made it the more remarkable that the Prince should have afterwards agreed to set aside, in favour of his cousin, Elizabeth’s claim to the succession. It is true that in their occasional meetings the studious boy and the serious-minded little girl may have discovered that they had tastes in common, but such casual acquaintanceship can scarcely have availed to counterbalance the affection produced by close companionship and the tie of blood; and grounds for the Prince’s subsequent conduct, other than the influence and arguments of those about him, can only be matter of conjecture.

Of the relations existing between Jane and the Prince’s sisters there is little more mention; but the entry by Mary Tudor in a note-book of the gift of a gold necklace set with pearls, made “to my cousin, Jane Gray,” shows that the two had met in the course of this summer, and would seem to indicate a kindly feeling on the part of the older woman towards the unfortunate child whom, not eight years later, she was to send to the scaffold.30 Could the future have been laid bare it would perhaps not have been the victim who would have recoiled from the revelation with the greatest horror.

Although what was to follow lends a tragic significance to the juxtaposition of the names of the two cousins, there was nothing sinister about the King’s elder daughter as she filled the place at Court in which she had been reinstated at the instance of her step-mother. A gentle, brown-eyed woman, past her first youth, and bearing on her countenance the traces of sickness and sorrow and suffering, she enjoyed at this date so great a popularity as almost, according to a foreign observer, to be an object of adoration to her father’s subjects, obstinately faithful to her injured and repudiated mother. But, ameliorated as was the Princess’s condition, she had been too well acquainted, from childhood upwards, with the reverses of fortune to count over-securely upon a future depending upon her father’s caprice.

Her health was always delicate, and during the early part of the year she had been ill. By the spring, however, she had resumed her attendance at Court, and—to judge by a letter from her little wise brother, contemplating from a safe distance the dangerous pastimes of Whitehall—was taking a conspicuous part in the entertainments in fashion. Writing in Latin to his step-mother, Prince Edward besought31 her “to preserve his dear sister Mary from the enchantments of the Evil One, by beseeching her no longer to attend to foreign dances and merriments, unbecoming in a most Christian Princess”—and least of all in one for whom he expressed the wish, in the course of the same summer, that the wisdom of Esther might be hers.

It does not appear whether or not Mary took the admonitions of her nine-year-old Mentor to heart. The pleasures of court life are not likely to have exercised a perilous fascination over the Princess, her spirits clouded by the memory of her melancholy past and the uncertainty of her future, and probably represented to her a more or less wearisome part of the necessary routine of existence.

Whilst the entertainments the Prince deplored went forward at Whitehall, they were accompanied by other practices he would have wholly approved. Not only was his step-mother addicted to personal study of the Scriptures, but she had secured the services of learned men to instruct her further in them; holding private conferences with these teachers; and, especially during Lent, causing a sermon to be delivered each afternoon for her own benefit and that of any of her ladies disposed to profit by it, when the discourse frequently turned or touched upon abuses in the Church.22

It was a bold stroke, Henry’s claims to the32 position of sole arbiter on questions of doctrine considered. Nevertheless the Queen acted openly, and so far her husband had testified no dissatisfaction. Yet the practice must have served to accentuate the dividing line of theological opinion, already sufficiently marked at Court; some members of the royal household, like Princess Mary, holding aloof; others eagerly welcoming the step; the Seymours, Cranmer, and their friends looking on with approval, whilst the Howard connection, with Gardiner and Wriothesley, took note of the Queen’s imprudence, and waited and watched their opportunity to turn it to their advantage and to her destruction.

Edward Prince

From an engraving by R. Dalton after a drawing by Holbein.

PRINCE EDWARD, AFTERWARDS EDWARD VI.

Such was the internal condition of the Court. The spring had meanwhile been marked by rejoicings for the peace with foreign powers, at last concluded. On Whit-Sunday a great procession proceeded from St. Paul’s to St. Peter’s, Cornhill, accompanied by a banner, and by crosses from every parish church, the children of St. Paul’s School joining in the show. It was composed of a motley company. Bishop Bonner—as vehement in his Catholicism as Gardiner, and so much less wary in the display of his opinions that his brother of Winchester was wont at times to term him “asse”—carried the Blessed Sacrament under a canopy, with “clerks and priests and vicars and parsons”; the Lord Mayor was there in crimson velvet, the aldermen were in scarlet, and all the crafts33 in their best apparel. The occasion was worthy of the pomp displayed in honour of it, for it was—the words sound like a jest—the festival of a “Universal Peace for ever,” announced by the Mayor, standing between standard and cross, and including in the proclamation of general amity the names of the Emperor, the King of England, the French King, and all Christian Kings.23

If soldiers had for the moment consented to proclaim a truce and to name it, merrily, eternal, theologians had agreed to no like suspension of hostilities, and the perennial religious strife showed no signs of intermission.

“Sire,” wrote Admiral d’Annebaut, sent by Francis to London to ratify the peace, “I know not what to tell your Majesty as to the order given me to inform myself of the condition of religious affairs in England; except that Henry has declared himself head of the Anglican Church, and woe to whomsoever refuses to recognise him in that capacity. He has also usurped all ecclesiastical property, and destroyed all the convents. He attends Mass nevertheless daily, and permits the papal nuncio to live in London. What is strangest of all is that Catholics are there burnt as well as Lutherans and other heretics. Was anything like it ever seen?”24

34 Punishment was indeed dealt out with singular impartiality. During the spring Dr. Crome had been examined touching a sermon he had delivered against Catholic doctrine. Two or three weeks later, preaching once more at Paul’s Cross, he had boldly declared he was not there for the purpose of denying his former assertions; but a second “examination” had proved more effective, and on the Sunday following the feast of Corpus Christi he eschewed his heresies.25 “Our news here,” wrote a merchant of London to his brother on July 2, “of Dr. Crome’s canting, recanting, decanting, or rather double-canting, be this.”26 The transaction was representative of many others, which, with their undercurrent of terror, struggle, intimidation, menace, and remorse, formed a melancholy and recurrent feature of the day, the victory remaining sometimes with a man’s conscience—whatever it dictates might be—sometimes with his fears.

The King was, in fact, still endeavouring to stem the torrent he had set loose. In his speech to Parliament on Christmas Eve, 1545, after commending and thanking Lords and Commons for their loyalty and affection towards himself, he had spoken with severity of the discord and dissension prevalent in the realm; the clergy, by their sermons against each other, sowing debate and discord35 amongst the people.... “I am very sorry to know and hear how unreverently that most precious jewel, the Word of God, is disputed, rimed, sung and jangled in every ale-house and tavern ... and yet I am even as much sorry that the readers of the same follow it in doing so faintly and so coldly. For of this I am sure, that charity was never so faint amongst you, and virtuous and godly living was never less used, nor God Himself amongst Christians was never less reverenced, honoured, and served.”27

Delivered scarcely more than a year before his death, Henry’s speech was a singular commentary upon the condition of the realm, consequent upon his own policy, during the concluding years of his reign.

As the months of 1546 went by the measures taken by the King and his advisers to enforce unanimity of practice and opinion in matters of religion did not become less drastic. A great burning of books disapproved by Henry took place during the autumn, preceded in July by the condemnation and execution of a victim whose fate attracted an unusual amount of attention, the effect at Court being enhanced by the fact that the heroine of the story was personally known to the Queen and her ladies. It was indeed reported that one of the King’s special causes of displeasure was that she had been the means of imbuing his nieces—among whom was Lady Dorset, Jane Grey’s mother—as well as his wife, with heretical doctrines.

Added to the species of glamour commonly surrounding a spiritual leader, more particularly in times of persecution, Anne Askew was beautiful and young—not more than twenty-five at the time37 of her death—and the thought of her racked frame, her undaunted courage, and her final agony at the stake, may well have haunted with the horror of a night-mare those who had been her disciples, and who looked on from a distance, and with sympathy they dared not display.

There were other circumstances increasing the interest with which the melancholy drama was watched. Well born and educated, Anne had been the wife of a Lincolnshire gentleman of the name of Kyme. Their life together had been of short duration. In a period of bitter party feeling and recrimination, it is difficult to ascertain with certainty the truth on any given point; and whilst a hostile chronicler asserts that Anne left her husband in order “to gad up and down a-gospelling and gossipping where she might and ought not, but especially in London and near the Court,”28 another authority explains that Kyme had turned her out of his house upon her conversion to Protestant doctrines. Whatever might have been the origin of her mode of life, it is certain that she resumed her maiden name, and proceeded to “execute the office of an apostle.”29

Her success in her new profession made her unfortunately conspicuous, and in 1545 she was committed to Newgate, “for that she was very38 obstinate and heady in reasoning on matters of religion.” The charge, it must be confessed, is corroborated by her demeanour under examination, when the qualities of meekness and humility were markedly absent, and her replies to the interrogatories addressed to her were rather calculated to irritate than to prove conciliatory. On this first occasion, for example, asked to interpret certain passages in the Scriptures, she declined to comply with the request on the score that she would not cast pearls among swine—acorns were good enough; and, urged by Bonner to open her wound, she again refused. Her conscience was clear, she said; to lay a plaster on a whole skin might seem much folly, and the similitude of a wound appeared to her unsavoury.30

For the time she escaped; but in the course of the following year her case was again brought forward, and on this occasion she found no mercy. Her examinations, mostly reported by herself, show her as alike keen-witted and sharp-tongued, rarely at a loss for an answer, and profoundly convinced of the justice of her cause. If she was not without the genuine enjoyment of the born controversialist in the opportunity of argument and discussion, she possessed, underlying the self-assertion and confidence natural in a woman holding the position of a religious leader, a fund of indomitable heroism.39 For she must have been fully conscious of her danger. It is possible that, had she not been brought into prominence by her association with those in high places, she might again have escaped; but, apart from the grudge owed her for her influence over the King’s own kin, her attitude was almost such as to court her fate. Refusing “to sing a new song of the Lord in a strange land,” she replied to the Bishop of Winchester, when he complained that she spoke in parables, that it was best for him that she should do so. Had she shown him the open truth, he would not accept it.

“Then the Bishop said he would speak with me familiarly. I said, ‘So did Judas when he unfriendlily betrayed Christ....’ In conclusion,” she ended, in her account of the interview, “we could not agree.”

Spirited as was her bearing, and thrilling as the prisoner plainly was with all the excitement of a battle of words, it was not strange that the strain should tell upon her.

“On the Sunday,” she proceeds—and there is a pathetic contrast between the physical weakness to which she confesses and her undaunted boldness in confronting the men bent upon her destruction—“I was sore sick, thinking no less than to die.... Then was I sent to Newgate in my extremity of sickness, for in all my life I was never in such pain. Thus the Lord strengthen us in His truth. Pray, pray, pray.”

40 Her condemnation was a foregone conclusion. It followed quickly, with a subsequent visit from one Nicholas Shaxton, who, having, for his own part, made his recantation, counselled her to do the same. He spoke in vain. It were, she told him, good for him never to have been born, “with many like words.” More was to follow. If her assertion is to be believed—and there seems no valid reason to doubt it—the rack was applied “till I was nigh dead.... After that I sat two long hours reasoning with my Lord Chancellor upon the bare floor. Then was I brought into a house and laid in a bed with as weary and painful bones as ever had patient Job. I thank my God therefore.”

A scarcely credible addition is made to the story, to the effect that when the Lieutenant of the Tower had refused to put the victim to the torture a second time, the Lord Chancellor, Wriothesley, less merciful, took the office upon himself, and applied the rack with his own hands, the Lieutenant departing to report the matter to the King, “who seemed not very well to like such handling of a woman.”31 What is certain is the final scene at Smithfield, where Shaxton delivered a sermon, Anne listening, endorsing his41 words when she approved of them and correcting them “when he said amiss.”

So the shameful episode was brought to an end. The tale, penetrating even the thick walls of a palace, must have caused a thrill of horror at Whitehall, accentuated by reason of certain events going forward there about the same time.

The King’s disease was gaining upon him apace. He had become so unwieldy in bulk that the use of machinery was necessary to move him, and with the progress of his disorder his temper was becoming more and more irritable. In view of his approaching death the question of the guardianship and custody of the heir to the throne was increasing in importance and the jealousy of the rival parties was becoming more embittered. In the course of the summer the Catholics about the Court ventured on a bold stroke, directed against no less a person than the Queen.

Emboldened by the tolerance displayed by the King towards her religious practices and the preachers and teachers she gathered around her, Katherine had grown so daring as to make matters of doctrine a constant subject of conversation with Henry, urging him to complete the work he had begun, and to free the Church of England from superstition.32 Henry appears at first—though he was a man ill to argue with—to have shown singular patience under his wife’s admonitions. But daily controversy is not42 soothing to a sick man’s nerves and temper, and Katherine’s enemies, watching their opportunity, conceived that it was at hand.

Henry’s habits had been altered by illness, and it had become the Queen’s custom to wait for a summons before visiting his apartments; although on some occasions, after dinner or supper, or when she had reason to imagine she would be welcome, she repaired thither on her own initiative. But perhaps the more as she perceived that time was short, she continued her imprudent exhortations. And still her enemies, wary and silent, watched.

Henry appears—and it says much for his affection for her—to have for a time maintained the attitude of a not uncomplacent listener. On a certain day, however, when Katherine was, as usual, descanting upon questions of theology, he changed the subject abruptly, “which somewhat amazed the Queen.” Reassured by perceiving no further signs of displeasure, she talked upon other topics until the time came for the King to bid her farewell, which he did with his customary affection.

The account of what followed—Foxe being, as before, the narrator—must be accepted with reservation. Gardiner, chancing to be present, was made the recipient of his master’s irritation. It was a good hearing, the King said ironically, when women were become clerks, and a thing much to his comfort, to come in his old days to be taught by his wife.

43 Gardiner made prompt use of the opening afforded him; he had waited long for it, and it was not wasted. The Queen, he said, had forgotten herself, in arguing with a King whose virtues and whose learnedness in matters of religion were not only greater than were possessed by other princes, but exceeded those of doctors in divinity. For the Bishop and his friends it was a grievous thing to hear. Proceeding to enlarge upon the subject at length, he concluded by saying that, though he dared not declare what he knew without special warranty from the King, he and others were aware of treason cloaked in heresy. Henry, he warned him, was cherishing a serpent in his bosom.

It was risking much, but the Bishop knew to whom he spoke, and, working adroitly upon Henry’s fears and wrath, succeeded in obtaining permission to consult with his colleagues and to draw up articles by which the Queen’s life might be touched. “They thought it best to begin with such ladies as she most esteemed and were privy to all her doings—as the Lady Herbert, her sister, the Lady Lane, who was her first cousin, and the Lady Tyrwhitt, all of her privy chamber.” The plan was to accuse these ladies of the breach of the Six Articles, to search their coffers for documents or books compromising to the Queen, and, in case anything of that nature were found, to carry Katherine by night to the Tower. The King, acquainted with44 the design, appears to have given his consent, and all went on as before, Henry still encouraging, or at least not discouraging, his wife’s discourse on spiritual matters.

Time was passing; the bill of articles against the Queen had been prepared, and Henry had affixed his signature to it, whether with a deliberate intention of giving her over to her enemies, or, as some said, meaning to deter her from the study of prohibited literature—in which case, as Lord Herbert of Cherbury observes, it was “a terrible jest.”33 That Katherine herself did not regard the affair, as soon as she came to be cognisant of it, in the light of a kindly warning, is plain; for when, by a singular accident, the document containing the charges against her was dropped by one of the council and brought for her perusal, the effect upon her was such that the King’s physicians were summoned to attend her, and Henry himself, ignorant of the cause of her illness, and possibly softened by it, paid her a visit, and, hearing that she entertained fears that she had incurred his displeasure, reassured her with sweet and comfortable words, remained with her an hour, and departed.

Though Katherine had played her part well, she must have been aware that she stood on the brink of a precipice, and the ghosts of Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard warned her how little reliance45 could be placed upon the King’s fitful affection. Deciding upon a bold step, she sought his bed-chamber uninvited after supper on the following evening, attended only by her sister, Lady Herbert, and with Lady Lane,34 her cousin, to carry the candle before her. Henry, found in conversation with his attendant gentlemen, gave his wife a courteous welcome, entering at once—contrary to his custom—upon the subject of religion, as if moved by a desire of gaining instruction from her replies. Read in the light of what Katherine already knew, this new departure may well have been viewed by her with misgiving; and she hastened to disclaim the position the King appeared anxious to assign her. The inferiority of women being what it was, she said, it was for man to supply from his wisdom what they lacked. She being a silly poor woman, and his Majesty so wise, how could her judgment be of use to him, in all things her only anchor, and, next to God, her supreme head and governor on earth?

The King demurred. The attitude of submission may have struck him as unfamiliar.

“Not so, by St. Mary,” he said. “You are become a doctor, Kate, to instruct us, as we take it, and not to be instructed or directed by us.”

The plain charge elicited, it was more easy to reply to it. The King had much mistaken her,46 Katherine humbly declared. It had ever been her opinion that it was unseemly for the woman to instruct and teach her lord and husband; her place was rather to learn of him. If she had been bold to maintain opinions differing from the King’s, it had been to “minister talk”—to make conversation, in modern language—to distract him from the thought of his infirmities, as also in the hope of profiting by his learned discourse—with more of the same nature.

Henry, perhaps not sorry to be convinced, yielded to the skilful flattery thus administered.

“Is it even so, sweetheart?” he said, “and tend your arguments to no worse end? Then perfect friends we are now again,” adding, as he took her in his arms and kissed her, that her words had done him more good than news of a hundred thousand pounds.

The next day had been fixed for the Queen’s arrest. As the appointed hour approached the King sought the garden, sending for Katherine to attend him there. Accompanied by the same ladies as on the night before, the Queen obeyed the summons, and there, under the July sun, the closing scene of the serio-comic drama was played. Amused, it may be, by the anticipation of his counsellors’ discomfiture, Henry was in good spirits and “as pleasant as ever he was in his life before,” when the Chancellor, with forty of the royal guard,47 appeared, ready to take possession of the culprit. What passed between Wriothesley and his master, at a little distance from the rest of the party, could only be matter of conjecture. The Chancellor’s words, as he knelt before the angry King, were not audible to the curious bystanders, but the King’s rejoinder, “vehemently whispered,” was heard. “Knave, arrant knave, beast and fool,” were the epithets applied to the crestfallen official. After which, he was promptly dismissed.

Katherine, whether or not she divined the truth, set herself to plead Wriothesley’s cause. Ignorance, not will, was in her opinion the probable origin of what had so manifestly moved Henry to wrath. The advocacy of the intended victim softened the King’s heart even more towards her.

“Ah, poor soul,” he said, “thou little knowest how ill he deserves this grace at thy hands. On my word, sweetheart, he hath been towards thee an arrant knave, and so let him go.”35

For the moment, at least, the danger was averted, and before it recurred the despot was in his grave, and Katherine was safe. It is curious to observe that in the list of contents to the Acts and Monuments the danger of the Queen is pointed out, “and how gloriously she was preserved by her kind and loving Husband the King.”

The King was dying. So much must have been apparent to all who were in a position to judge. None, however, dared utter their thought, since it had been made an indictable offence—the act being directed against soothsayers and prophets—to foretell his death. Those who wished him well or ill, those who would if they could have cared for his soul and invited him to make his peace with God before taking his way hence, were alike constrained to be mute. Before he went to present himself at a court of justice where king and crossing-sweeper stand side by side, another judicial murder was to be accomplished, and one more victim added to the number of the accusers awaiting him there. This was the poet Earl of Surrey, heir to the Dukedom of Norfolk.

Surrey was not more than thirty. But much had been crowded, according to the fashion of the time, into his short and brilliant life. Brought up during his childhood at Windsor as the companion of the49 King’s illegitimate son, the Duke of Richmond—who subsequently married Mary Howard, his friend’s sister—Surrey had suffered many vicissitudes of fortune; had been in confinement on a suspicion of sympathy with the Pilgrimage of Grace; and in 1543 had again fallen into disgrace, charged with breaking windows in London by shooting pebbles at them. To this accusation he pleaded guilty, explaining, in a satire directed against the citizens of London, that his object had been to prepare them for the divine retribution due for their irreligion and wickedness:

He can scarcely have expected that the plea would have availed, and he expiated his offence by a short imprisonment, chiefly of importance as accentuating his hatred towards the Seymours, who were held responsible for it.36

In the course of the same year he was more worthily employed in fighting the battles of England abroad, where his conduct elicited a cordial tribute of praise from Charles V. “Our cousin, the Earl of Surrey,” wrote the Emperor to Henry, on Surrey’s return to England, would supply him with an account of all that had taken place. “We will50 therefore only add that he has given good proof in the army of whom he is the son; and that he will not fail to follow in the steps of his father and forefathers, with si gentil cœur and so much dexterity that there is no need to instruct him in aught, and you will give him no command that he does not know how to execute.”37

Two years later Surrey was in command of the English forces at Boulogne, there suffered defeat, and was, though not as an ostensible result of his failure, superseded by his rival and enemy, the Earl of Hertford, brother of the Admiral and head of the Seymour clan.

Such was the record of the man who was to fall a prey to the malice and jealousy of the opposite party in the State. His noble birth, his long descent, and his brilliant gifts, were so many causes tending to make him hated and feared; besides which, even amongst men in whom humility was a rare virtue, he was noted for his pride—“the most foolish, proud boy,” as he was once described, “that is in England.” When he came to be tried for his life those of his own house came forward to bear witness to the contempt he had displayed towards inferiors in rank, if not in power. “These new men,” he had said scornfully—it was his sister who played the part of his accuser—“these new men loved no nobility, and if God called away the King51 they should smart for it.”38 None of the King’s Council, he was reported to have declared, loved him, because they were not of noble birth, and also because he believed in the Sacrament of the Altar.39

In verse he had likewise made his sentiments clear, comparing himself, much to his advantage, with the men he hated.

It was a natural and inevitable consequence of his attitude towards them that the “new men” hated and sought the ruin of the poet who held them up publicly to scorn; and if his great popularity in the country was in some sort a shield, it was also calculated to prove perilous, by giving rise to suspicion and distrust on the part of a sovereign prone to indulge in these sentiments, and thereby to render the success of his foes more easy.

The Seymours were aware that their time was short. With the King’s approaching death the question of the guardianship of the successor to the throne was becoming daily more momentous; and when pride and vanity on the part of the Earl, together with treachery on that of friends and kin, placed a dangerous52 weapon in the hands of his opponents, they were prompt to use it.

During the summer there was nothing to serve as a presage of his fate; and so late as August he took part in the magnificent reception accorded to the French ambassadors, successfully vindicating on that occasion his right to precedence over the Earl of Hertford, with whom he was as usual at open enmity.

A new cause of quarrel had been added to the old. The Duke of Norfolk, developing, as age crept upon him, an unwonted desire for peace and amity, had lately devised a method of terminating the feud between his heir and the Seymour brothers, so powerful, by reason of their kinship to Prince Edward, in the State. Not only had he revived a project for uniting his widowed daughter, the Duchess of Richmond, to Thomas Seymour, Lord Admiral, Katherine Parr’s former lover, but had made a further proposal to cement the alliance between the rival houses by marrying three of his grandchildren to Hertford’s children.

The old man’s scheme was not destined to succeed. Whether or not the Seymours would have consented to forget ancient grudges, Surrey remained irreconcilable, flatly refusing his consent to his father’s plan. So long as he lived, he declared, no son of his should ever wed Lord Hertford’s daughter; and when his sister—perhaps not insensible to Thomas Seymour’s attractions—showed an inclination to53 yield to the Duke’s wishes, he addressed bitter taunts to her. Since Seymour was in favour with the King, he told her ironically, let her conclude the farce of a marriage, and play in England the part which had, in France, belonged to the Duchesse d’Étampes, Francis I.’s mistress.

Mary Howard did not marry the Admiral, but, possibly sharing her brother’s pride, she never forgot or forgave the insult he had offered her; and, repeating the sarcasm as if it had been advice tendered in all seriousness, did her best to damn the Earl in his day of extremity. In a contemporary Spanish chronicle further particulars, true or false, of the quarrel are added. It is there related that, grieved at the tales that had reached him of his sister’s lightness of conduct, Surrey had taken upon himself to administer a brotherly rebuke.

“Sister,” he said, “I am very sorry to hear what I do about you; and if it be true, I will never speak to you again, but will be your mortal enemy.”40

The Duchess was not a woman to accept the admonition meekly, and it was she who was to prove, in the sequel, the more dangerous foe of the two.

The offence for which Surrey nominally suffered the capital penalty seems trivial enough. According to the story told by contemporary authorities—and it suits well with his overweening pride in54 his ancient blood and royal descent—he caused a painting to be executed wherein the Norfolk arms were joined to those of the royal house, the motto Honi soit qui mal y pense being replaced by the enigmatical device Till then thus, and the whole concealed by a canvas placed above it.

From an engraving by Scriven after a painting by Holbein.

HENRY HOWARD, EARL OF SURREY.

The very fact of the secrecy observed betrays the Earl’s consciousness that he had committed an imprudence. He was guilty of a worse when, notwithstanding the terms upon which he stood with his sister, he made her his confidant in the matter. The Duchess, in her turn, informed her father of what had been done, but to the Duke’s remonstrances Surrey turned a deaf ear. His ancestors, he replied, had borne these arms, and he was much better than they. Powerless to move him, his father, reiterating his fears that it might furnish occasion for a charge of treason, begged that the affair might be kept strictly private, to which Surrey readily agreed. Both men, however, had reckoned without the woman who was daughter to the one, sister to the other. Whether, as some aver,41 the Duchess took the step of betraying her brother directly to the King, or merely corroborated the accusations preferred against him by others—Sir Richard Southwell, a friend of Surrey’s childhood, being the first to denounce him42—the matter soon became known, the55 Earl was examined at length, and by the middle of December was, with his father, lodged in the Tower on the charge of treason, the assumption of the royal arms being viewed as an implied claim to the succession to the throne, and as a menace to the little heir. Hertford and his brother were at hand to exaggerate the peril to be feared from his ambition; and the affection of the populace, who, as he was taken through the city to his place of captivity, made great lamentation,43 was not fitted to allay apprehension. A month later the Earl’s trial took place at the Guildhall, crowds filling the streets as he went by. Brought before his judges, he made so spirited a defence that Holinshed admits that “if he had tempered his answers with such modesty as he showed token of a right perfect and ready wit, his praise had been the greater”; and though neither wit nor modesty was likely to avail to save him, it was not without long deliberation that the jury agreed to declare him guilty.

Their verdict was pronounced by his implacable enemy, Hertford; being greeted by the people with “a great tumult, and it was a long while before they could be silenced, although they cried out to them to be quiet.”44

The prisoner received what was practically sentence of death in characteristic fashion. His56 enemies might have vanquished him, but he could still despise them, still assert his inborn superiority to his victors.

“Of what have you found me guilty?” he demanded. “Surely you will find no law that justifies you; but I know that the King wants to get rid of the noble blood around him, and to employ none but low people.”45

On January 19, not a week after his trial, the poet, King Henry VIII.’s latest victim, was beheaded on Tower Hill. It was not the fault of Henry’s advisers that his aged father did not follow him to the grave. To have cleared Surrey out of their path was much; but it was not enough. The Duke’s heir gone, there were many eager to share amongst themselves the Norfolk spoils; Henry was ready to send his old servant to join his son; and only the King’s death, on the very night before the day appointed for the Duke’s execution, saved him from sharing Surrey’s fate. On January 28, 1547, nine days after the Earl had been slain, Henry was dead.

The end can have taken few people by surprise. Whether it was unexpected by the King none can tell. His will was made—a will paving the way for the misfortunes of one of his kin, and preparing the scaffold upon which Lady Jane Grey was to die; since, tacitly setting aside the claims of his elder sister, Margaret of Scotland, and her heirs, he57 provided that, after his own children, Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth, the descendants of Mary Tudor, of whom Jane was, in the younger generation, the representative, should stand next in the order of succession to the throne. It was the first occasion upon which Lady Jane’s position had been explicitly defined, and was the prelude of the tragedy that was to follow. Should the unrepealed statutes declaring the King’s daughters illegitimate be permitted in the future to weigh against his present provisions in their favour, his great niece or her mother would, in the event of Prince Edward’s death, become heirs to the crown.

For Henry the opportunity of cancelling, had it been possible, the injustices of a lifetime was over. “Soon after the death of the Earl of Surrey,” writes the Spanish chronicler, “the King felt unwell; and, as he was a wise man, he called his council together, and said to them, ‘Gentlemen, I am unwell, and cannot tell when God may call me, so I wish to put my soul in order, and to reward my servants for what they have done.’”