Privately Printed

1892

Copyright, 1892,

By CHARLES H. DALTON.

All rights reserved.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

Printed by H. O. Houghton and Company.

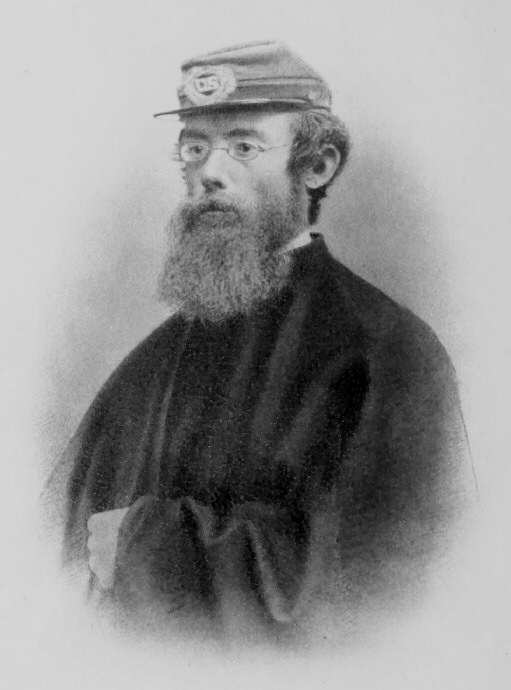

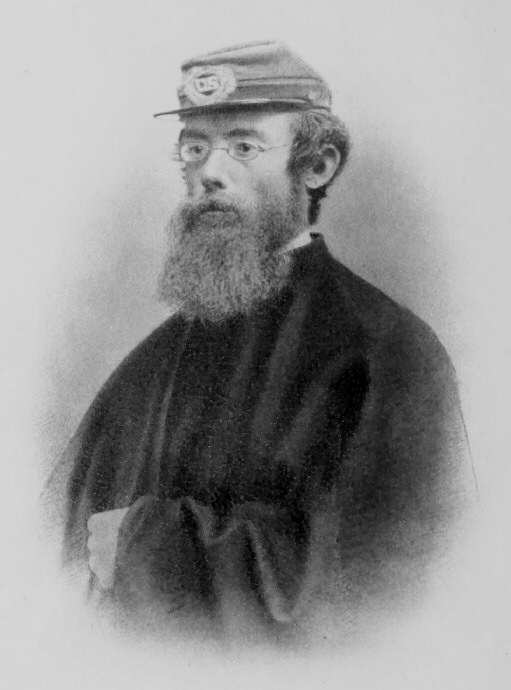

These pages are the beginning of a narrative of the personal military experience of John Call Dalton, M. D., Surgeon U. S. V., written during the last year of his life, at the request of his family, and now printed for the instruction of its younger generation.

March, 1892.

| PAGE | |

| IN WASHINGTON WITH THE SEVENTH | 5 |

| THE EXPEDITION TO PORT ROYAL | 35 |

| THE SEA ISLANDS AND FORT PULASKI | 64 |

| MILITARY HISTORY OF JOHN CALL DALTON, M. D. | 103 |

On the evening of Saturday, April 13th, 1861, the intelligence reached New York that Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, had yielded to the rebel authorities, after undergoing a bombardment of thirty-six hours. It was felt by all that this act of violence closed the door of reconciliation, and dissipated every hope of a peaceful solution for our political difficulties. Two days afterward President Lincoln issued his proclamation calling upon the states for seventy-five thousand troops to reassert the authority of the government, to "cause the laws to be duly executed," and to "repossess the forts, places, and property" which had been seized from the Union. The first object of importance was to secure the safety of the national capital; and the President had expressed a desire that one regiment from New York, already organized and[Pg 6] equipped, should be sent forward at once for that purpose.

Learning that the Seventh regiment had volunteered to meet this call, and that the assistant surgeon then attached to it had resigned the position, I applied to be taken in his place, and had the gratification to receive my appointment on Thursday the 18th. The regiment was under orders to assemble and start for Washington on the following day.

Meanwhile other states had also been exerting themselves to forward any militia regiments that could be had at short notice; and, as usual, when called upon to act, Massachusetts was the first in the field. Within three days after the President's proclamation, two regiments from that state, the Sixth and the Eighth, were on the move. The Sixth arrived in New York early on the morning of April 18th, by the N. Y. & New Haven railroad. The terminus of this road was then at Fourth Avenue and 27th Street, where I saw the regiment disembark and form in line, before proceeding on its march through the city. Its ranks had evidently been filled in some measure by new recruits, whose outfit by no means corresponded[Pg 7] altogether with the regimental uniform. There were common overcoats and slouched hats mingled with the rest. But they were a solid and serviceable looking battalion; and it was a common remark that in such an emergency it was a good thing to see the men in line with their muskets before their uniforms were ready. This regiment was followed by the Eighth Massachusetts, which passed through the city twenty-four hours later.

But at that time every one bound for Washington was too busy with his own affairs to pay much attention to the movements of others; and the morning of the 19th was filled to the last moment with indispensable preparations. Early in the afternoon the Seventh regiment assembled at its armory, which was then on the east side of Third Avenue, between Sixth and Seventh Streets. It had received within the past few days some accessions in new recruits. Its regular members reported for duty in greater numbers than usual; and when finally ready for departure it paraded nearly a thousand muskets. From the armory it was marched by companies to Lafayette Place near by, where the line was[Pg 8] formed and I took my place with the officers of the regimental staff.

Up to this time our attention had not been especially attracted to anything beyond our own immediate duties; and for a novice like myself they were occupation enough. There had been visiting friends and leave-takers at the armory, and in the adjoining streets there was the usual crowd of idlers and sight-seers about a militia parade. But when the regiment wheeled into column, and from the quiet enclosure of Lafayette Place passed into Broadway, the spectacle that met us was a revelation. From the curbstone to the top story, every building was packed with a dense mass of humanity. Men, women, and children covered the sidewalks, and occupied every window and balcony on both sides, as far as the eye could reach. The mass was alive all over with waving flags and handkerchiefs, and the cheers that came from it, right and left, filled the air with a mingled chorus of tenor and treble and falsetto voices. It was a sudden and surprising demonstration, as unlooked for as the transformation scene in a theatre. But that was hardly the beginning of it. Instead of spending itself in a short[Pg 9] outburst of welcome, it ran along with the head of the column, was taken up at every step by those in front, and only died away in the rear. As the regiment moved on past one street after another, it seemed as if at every block the crowd grew denser and the uproar more incessant. Along the entire line of march, from Lafayette Place to Cortlandt Street, there was not a rod of space that was not thronged with spectators; and all the while the same continuous cry, from innumerable throats, kept up without a moment's intermission, from beginning to end.

No one could witness such a scene without being impressed by it. It was like the act of a drama magnified in its proportions a hundred fold, and with the added difference of being a reality. The longer it continued, the more it affected the senses and the mind; until at last one almost felt as if he were marching in a dream, half dazed by the endless repetition of unaccustomed sights and sounds.

Beside that, it gave us a different idea of the city of New York. For most of us, especially those of the younger generation, it was mainly a city of immigration, offering to all comers its varied opportunities for[Pg 10] activity and enterprise. Hardly any one gave a thought to its local traditions, or believed in the existence of any unity of sentiment among its inhabitants. But now, all at once, it had risen up like an enormous family, with a single impulse of spontaneous enthusiasm, to declare that it valued loyalty and patriotism more than commerce or manufactures. The time and the occasion had brought out its latent qualities, and had given them an expression that no one could misunderstand.

When we turned from Broadway into Cortlandt Street the tumult partly subsided; but after crossing the ferry to Jersey City it began again. There were demonstrative crowds in the railroad depot, and as the train moved off they followed it with cheers that were repeated at every station on the route to Philadelphia. It did not take long to discover that transportation by railroad train, with a regiment of troops on board, was by no means a luxurious mode of traveling. With no seats to spare, many standing in the aisles, and the remaining space encumbered with arms and accoutrements, there was little opportunity for ease or comfort; and as for sleep, that was out of the[Pg 11] question. Sometime after midnight we reached Philadelphia, and were transferred to the cars for Washington, at the depot of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore railroad. But here our onward movement ceased. The train rested stationary in the depot. Expecting every moment the signal for starting, we could only wait patiently until it should come. Nevertheless the night wore away, the gray dawn found us still waiting, and no locomotive had even been coupled on to the train. What could be the cause of such delay, when everything demanded promptitude and celerity? We already knew that the Sixth Massachusetts, the pioneer regiment in advance, had been attacked the day before in the streets of Baltimore, and had only forced its way through the mob at the expense of fighting and bloodshed. Was our own march to be obstructed at the outset by a rebellious city, standing like a fortress across the route? Or were the railroad officials in sympathy with secession, and purposely hampering our movements by pretended friendship and false excuses? The Eighth Massachusetts, which had left New York some hours before us, was also in the depot, on board[Pg 12] another train, equally helpless with ourselves, and apparently with as little prospect of getting away. As daylight came, we began to straggle out of the car-house and up and down the streets of what was then a rather desolate looking neighborhood. The necessity of foraging for breakfast gave us for a while some little diversion and occupation; but that was soon over, and all the forenoon our uneasiness was on the increase. Who could tell what might be happening even then at the national capital? And thus far we had barely accomplished one third of the distance from New York to Washington. There were interviews and consultations between the field officers and the railroad authorities; and General Benjamin F. Butler, who was in command of both Massachusetts regiments, also appeared upon the scene. But for the rest of us there was little food for thought beyond rumors, doubts, and surmises. So we kept on rambling to and fro near the depot, and wondering when this thing would come to an end.

Toward noon some information began to filter through from headquarters, and we came to understand, more or less distinctly, what[Pg 13] was going on. In reality the state of affairs was this. The railroad managers were as anxious as ourselves to facilitate the transportation of the regiment; but they had no means of overcoming the difficulties of the situation. The tracks through Baltimore had been obstructed with barricades, so that the cars could not pass. Even if these should be cleared away, there was no certainty that the company could retain control of the depots and rolling stock on the other side of the city. That would depend on the coöperation of the police and perhaps of the city militia, neither of which were felt to be reliable. In fact, the Governor of Maryland and the Mayor of Baltimore had both sent despatches strongly objecting to the further passage of troops through the city in its present excited and disorderly condition. Between the Maryland state line and Baltimore there were two railroad bridges, crossing the Little Gunpowder and Bush rivers; and both these bridges had been destroyed by secessionists during the night. To repair them would need the protection of an armed force, and would be a matter of further uncertainty and delay. The object of the regiment was to reach[Pg 14] Washington at the earliest possible moment; and for that purpose the route by Baltimore was evidently impracticable.

The next accessible point was Annapolis on the Chesapeake Bay, where the grounds of the United States Naval Academy, located at the harbor, offered an additional advantage. It could be reached by either of two ways. The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore railroad runs direct from Philadelphia to the mouth of the Susquehanna river, at the head of Chesapeake Bay, where at that time there was no bridge, the cars being taken across on a steam ferry-boat, the Maryland, from one side to the other. The troops might be carried by rail to this point; and then, taking possession of the ferry-boat, might go down the bay, past the harbor of Baltimore, to Annapolis. This was the route selected by General Butler for the Eighth Massachusetts. Our commanding officer, on the other hand, Colonel Lefferts, decided to charter at once a steamer capable of taking the regiment from Philadelphia round by sea to the capes of Virginia, and so up Chesapeake Bay to Annapolis.

This was accordingly done. The regiment[Pg 15] was paraded, marched down to the pier, and embarked on the Boston, a freight and passenger steamer formerly running between Philadelphia and New York. Her capacity was just sufficient to receive so large a company with the necessary supplies; and when all were on board there was hardly more freedom of space than we had found in the railroad cars. But no more time was lost in waiting. That afternoon carried us down the river; by sunset we had entered Delaware Bay; and the next morning, which was Sunday, the 21st, we were fairly at sea, headed south for the capes of Virginia.

All that day we ploughed on over a smooth sea, with a fair wind, a bright sun and a clear sky. The scene everywhere was exhilarating; and the interest of the expedition increased every hour with the uncertainty of what lay before us. We were approaching a region where all was on the border line between loyalty and secession, and which included the most important military and naval positions in the country,—Hampton Roads, Fortress Monroe, and the Norfolk Navy Yard. Intelligence from these points was eagerly looked[Pg 16] for, and early in the afternoon, when nearing the capes, we came within hailing distance of a schooner bound north under full sail. The information she gave us was that of the destruction of Norfolk Navy Yard and its abandonment by the United States authorities. This had been done the day before by order of the navy department, to prevent the ships and ordnance falling into the hands of the rebels. It was the best thing to do in the emergency. All the ships left there had been scuttled, the guns spiked and the buildings burned; and the enemy in possession could not have made anything serviceable for aggressive purposes under at least a month. But we were ignorant of these details. We learned only that the navy yard was lost; and for anything we knew to the contrary, Hampton Roads might already be patrolled by rebel gun-boats, and even Fortress Monroe might have shared the fate of the navy yard. In that case, it would be no place for an unarmed transport, loaded with troops. As we entered Chesapeake Bay and passed by the suspicious locality, many eyes were turned in that direction; and when fairly out of reach of Hampton Roads, all felt[Pg 17] relieved that our way to Annapolis was once more clear.

That night our course lay up the Chesapeake, and at dawn on the 22d we were anchored in the harbor of Annapolis. But to the impatient and inexperienced volunteers it seemed as though the complications of our journey were to have no end. General Butler had arrived the day before from the head of the bay with the Eighth Massachusetts regiment, on the steamer Maryland; and he had rendered good service in saving the United States school ship Constitution from a threatened rebel attack by towing her out from shore toward the harbor entrance. But in doing so his own steamer had grounded on a shallow bar, where she was now lying hard and fast, with the Massachusetts troops still on board. The first thing to do was to release her, if possible, from this awkward predicament. Our vessel, the Boston, was again put under steam, and harnessed with heaving-line and hawser to the ferry-boat. Then she would go to work like a willing draught-horse, and pull this way and that for five minutes together, straining every nerve to start her clumsy load, but without effect. Her paddles only[Pg 18] brought up from the bottom such clouds of yellow foam that it made the narrow harbor look like an enormous mud-puddle; and with every new attempt we began to think that instead of floating the Maryland we should, in all likelihood, get stuck fast ourselves. Finally, much to our relief, it was decided to land the regiment and stores from the Boston, and wait for another tide to liberate the Maryland.

So, in the afternoon the regiment landed and occupied the grounds of the Naval Academy. There we found that many of the officers and cadets had left for their southern homes, to side with the rebellion. Even some of those who remained were by no means encouraging in their words or manner; they were impregnated with the doctrine of state sovereignty, as something equal or superior to that of the nation, and they had an exaggerated idea of the numbers and audacity of the insurgents who would occupy all roads and dispute every mile of our advance. One of them told me that he hoped that we would not attempt it; and declared that if we did so, not half the regiment would reach Washington alive. I shall never forget the disgust that rose in[Pg 19] my throat, at hearing a man with the uniform of the United States on his shoulders offer a welcome like that to volunteers who were trying to save the government that employed him.

The Governor of Maryland, who was then at Annapolis, also protested against any forward movement of the troops, and even against their landing. But these official fulminations had no longer any weight. It was only the physical obstacles in our way that were now to be considered. In the evening the officers gathered in council round a fire on the greensward, and it was decided to move forward at once by the most practicable route. While this was going on, General Butler joined the group and was invited to speak with the rest. The extraordinary character of this man's career from first to last, his many clever successes and preposterous failures, and the furious denunciations he has received from both friends and enemies, make it hard to say what place he will finally hold in public estimation. But the qualities he displayed on that occasion deserve the cordial recognition and gratitude of all. When he spoke, it was to the purpose. With a practical[Pg 20] insight and ready comprehension that took in the situation at a glance, he swept away in a few words the whole pretentious fabric of state rights, local supremacy, inviolability of the soil, and such like. The capital of the nation, he said, was in danger from armed rebellion. We were on our way to protect it with an armed force. That was a state of war; and it created a necessity superior to every other claim or consideration. All ordinary laws and authorities in conflict with it must be in abeyance; and, as for himself, he should lead his troops to Washington, no matter who or what might oppose his passage. More than that, he should seize upon any property or means of transportation necessary to accomplish the object, without regard to governors, mayors, or railroad companies.

I have no doubt that the Seventh regiment would have carried out its design if General Butler had not been there; but it was certain that his intellectual promptitude and directness of speech imparted new confidence to all who heard him. He struck the same chord in his written correspondence with Governor Hicks. During the day he had received from the governor a formal communication,[Pg 21] protesting against the "landing of northern troops on the soil of Maryland;"—to which he said in his reply: "These are not northern troops, they are a part of the whole militia of the United States, obeying the call of the President." Now that the question is settled, it seems plain enough. But at that time it was a great satisfaction to hear the doctrine of supreme nationality proclaimed in the terse and expressive language of General Butler.

It was intended that the regiment should march for Washington by the direct country road, a distance of about thirty miles; and much of the time next day was spent in scouring the neighborhood for horses, mules, and wagons, to serve as ambulances and for transporting the baggage and camp equipage. But in the afternoon dispatches were received from Washington, directing the troops to come, if possible, by the Annapolis branch of the Baltimore and Washington railroad, in order that this important line of communication might be kept open for future use. This was a single-track road, running twenty miles northwest from Annapolis to its junction with the Baltimore and Washington line. The depot at Annapolis[Pg 22] was closed and abandoned by the company, and the track had been disabled for some distance out of town. When General Butler, with two companies of the Eighth Massachusetts, broke open the depot, he found there a few passenger and platform cars, with only one locomotive; and that had been taken to pieces and rendered unserviceable. But the Massachusetts regiment was largely composed of mechanics, who were not only good workmen but enterprising and quick-witted. By a singular chance one of them recognized, among the fragments of the engine, a piece of machinery which he had himself helped to make; and he lost no time, with the aid of his comrades, in putting together again the disjointed limbs of the locomotive, and making it in a few hours once more fit for work. Others repaired the railroad track in the neighborhood, and before dawn on the 24th everything was ready for two companies of the Seventh to move forward as advance guard on the line of march.

Soon after daylight the whole regiment was in motion. The locomotive and a couple of platform cars were in front, carrying a howitzer with its caisson; and one or[Pg 23] two passenger and baggage cars served to carry baggage and camp equipage, and to provide for the transportation of sick or wounded. The railroad embankment, which was our only route, ran through a narrow clearing in the woods, with low hills and swampy lands alternating on either side. The day was still and warm, and a few of the men were prostrated by the unaccustomed exertion and heat. About noon we came up with the advance guard, and from that point, after a short halt, all moved on together. Missing rails and broken culverts were a constant impediment to our advance; and toward evening we came to a deep and wide watercourse, where the long trestle bridge had been burned a day or two before. But these obstacles only seemed to stimulate the volunteers. Heretofore their annoyances and disappointments had been from causes beyond their control. Now that every difficulty was within reach, they went at it with a will, and thought of nothing but how to overcome it. The ruined bridge hardly delayed them three hours. The engineer officer and his men went into the woods on each side, where a hundred busy hands were soon at work, felling trees and[Pg 24] hauling them into place; and before dark, the stream was spanned by a new bridge of rough-hewn timbers that carried the train over safely, and our march began again.

So it went on all through the night. The missing rails had often been thrown, for better concealment, into some deep pool or watercourse near by. But after a little experience, that was the very first place where they were sought for and generally found. If the search proved ineffectual, it made little difference at last; for at every siding the extra rails were taken up and carried forward on the train, to be used as they might be needed further on. So the track was made serviceable for ourselves, and left in good condition for those who were to follow. There was a line of skirmishers in front and one on each flank, to beat up the enemy, should he be there lying in wait. Once or twice a few marauders were sighted, tearing up the rails or reconnoitering our advance; but they all retreated promptly, without firing a shot or waiting for the head of the column, and none of them were even seen by the main body. That was all. The desperate resistance we were expected to meet with from swarming[Pg 25] rebels and armed guerrillas turned out to be a sham. When the advance guard about daylight occupied the village of Annapolis Junction, there was no opposition. The regiment took possession of a deserted station, and the railroad communication with Washington at last was ours.

It is remarkable how greatly the presence of an armed force conduces to friendly feeling on the part of the inhabitants. No doubt the secessionists hereabout had done their best for a few days past to prevent our ever arriving at Annapolis Junction. But now that we were there, and especially in need of a freshly cooked breakfast, there was little difficulty in obtaining one for the officers' mess. The fatigue and drowsiness that had been almost overpowering during the night, gave way like magic before the refreshing stimulus of the dawn; and the keen morning air awakened an appetite that demanded something better than pork and hardbread from the haversack. Among the neighboring farmhouses there were some quite ready to supply our wants.

Early in the forenoon a train made its appearance from the direction of Washington. It had been sent out to meet us, under[Pg 26] guard of a detachment of National Rifles, a volunteer company of the District of Columbia; and we were soon on board and under way. The cars were crowded to the utmost; but we were now nearing our destination, and every discomfort seemed a trifle. For some distance this side of Washington the road was picketed; and before long we began to see at intervals the head and shoulders of a National Rifleman, with his fresh looking uniform and glittering bayonet, peering at us over the bushes as the train went by. Finally, about noon, the city came in sight. It was Thursday, the 25th. We had been six days in getting from New York to Washington. They had been days of doubt and anxiety, of hindrances, delays, and stoppages. Every hour was precious, and yet we knew that with all possible dispatch we might still be too late. And even now, at the outskirts of the city, we could hardly help looking to see whether the flag of the nation still floated over the Capitol. The train rolled into the depot, the regiment disembarked, formed in column, marched to the White House, reported to the President, and our journey to Washington was accomplished.

There was no doubt about the sense of relief created by our arrival. After nearly a week of isolation and peril, Washington breathed more freely. The only troops there before us were the Sixth Massachusetts, a handful of regulars, and about thirty volunteer companies of the District of Columbia, mainly recent recruits. The Seventh was a full regiment, well disciplined and thoroughly equipped. What was of still more consequence, it had opened the door of Annapolis and reëstablished communication with the north. The Eighth Massachusetts arrived next day from Annapolis Junction; and within another week one more regiment from Massachusetts and four from New York followed by the same route. After that, the city of Baltimore ceased to be an obstruction, and the trains came through from Philadelphia as usual. By the middle of May there were nearly twenty-five thousand troops gathered for the defense of Washington.

For the first week after our arrival we were quartered in the Capitol building; but at the end of that time the regiment went into camp a mile or so north of the city, on Meridian Hill. This was a plateau of[Pg 28] about forty acres, admirably adapted for the purpose. It was on the direct road to Harper's Ferry, where the rebels were in possession, and would give security against incursions from that quarter. The camp was on the east side of the road, where there was a fine suburban estate, with a large, square-built mansion house and outbuildings. From the road entrance a well graded avenue led up to the house porch, which stretched its hospitable covering over the carriage way. The house was occupied by regimental headquarters and the staff officers. In front were green fields and orchards, falling away in a gentle slope toward the city; and beyond was the broad Potomac, with the Virginia shore and Arlington Heights in the distance. In the rear were the lines of company tents, and an ample parade-ground, where the regiment was reviewed every day or two by the President, the Secretary of War, the general commanding, or some other high civil or military official, who was usually as much an object of inspection to the troops as the troops were to him.

By degrees other camps began to spring up round about us. On the opposite side[Pg 29] of the road were three regiments of New Jersey volunteers, under General Runyon. A field in front of us was the daily exercise ground of a mounted battery of the regular army; and farther down, on the left, was the Twelfth regiment of New York volunteers. The Eleventh New York, under Colonel Ellsworth, was in camp below the city beyond the navy yard. This regiment was affiliated with our own through its second officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Farnham, who had been until then a lieutenant in the Seventh, and had commanded the skirmish line in the march from Annapolis.

The time was coming when the regiment would have something else to do than drilling and camp duty. Washington was saved from the danger that menaced it at the outset; and so long as the troops were there, it was secure from a sudden inroad. But it had no permanent defenses. The Potomac River was the limit of its territory. On the opposite shore the rising ground of Arlington Heights commanded all approaches from that direction; and every day, with a good spyglass, we could see the fluttering of a secession flag in the little city of Alexandria, only six or seven miles away. This was a[Pg 30] precarious situation for the seat of government and centre of military operations; and no one was surprised when it made an attempt to burst its shackles.

On the 23d of May, at midnight, the regiment was put in motion and marched down through the city, to the neighborhood of the Long Bridge. Its departure had been quiet and noiseless, as if the expedition were a secret to all but the commanding officer. It soon appeared, however, from signs that the uninitiated are not slow to comprehend, that something more was going on than the night march of the regiment. The order to halt came from other sources to our own commander. After some delay, a part of the New Jersey brigade came up from the rear and passed on in advance; and there was riding here and there of officers and messengers, going and coming in various directions. Nevertheless, everything was done in silence. Not even the occupants of the neighboring houses seemed to be awakened or disturbed; and it gave to the scene a mysterious kind of interest to feel that we were on some errand that neither friends nor enemies were to know of until it was accomplished.

Again our column was on the march, and[Pg 31] we soon found ourselves at the entrance of the Long Bridge. We passed between the two guard-houses, under the black timbers of the draw-frame, and over its three quarters of a mile of roadway to the Virginia shore. It was the first hour of a moonlight night, and half a mile farther on, at daybreak, the regiment was halted and went into bivouac on an open field by the roadside.

Not long after sunrise a horseman came clattering along the road from the direction of Alexandria, and as he galloped by toward the bridge, he flung out to us the news, "Alexandria is taken, and Colonel Ellsworth is killed."

This was one of the minor events in the early part of the war that excited a wide-spread interest, mainly from the dramatic features of the incident. The Eleventh New York had reached Alexandria by steamer, and landed there about daylight. Immediately after disembarking, Colonel Ellsworth had left his regiment, and with a small squad hastened to secure the telegraph office, to prevent communication with the south. That done, he noticed, flying above the principal hotel in the town, a secession flag. It was the flag we had seen so often[Pg 32] for the last fortnight from the direction of Washington. The colonel effected an entrance, and with his companions mounted to the roof, hauled down the flag, and brought it away with him. When about halfway down he was shot dead by the keeper of the hotel, who was lying in wait for him with a double-barreled gun. Instantly the soldier next him discharged his musket in the face of the homicide, and, driving his bayonet through his breast, hurled his body down the remaining stairway; so that within a minute both the colonel and his assailant were dead men. None of those in the hotel knew of the arrival of the regiment, and probably thought they had to do only with a few raiders from abroad.

This news of the occupation of Alexandria was our first intimation of the actual extent of the movement we were engaged in. The truth was that between midnight and dawn about 12,000 men had crossed the Potomac by the two bridges at Washington and Georgetown, beside the Eleventh regiment which went by steamer. They were to hold and fortify a defensive line extending from below Alexandria, around Arlington Heights, to the Potomac River above Georgetown;[Pg 33] comprising, when all complete, a chain of twenty-three forts, for the permanent security of the city on its southern side. Our own destination was a locality not far from our first bivouac, and where the New Jersey troops, who had gone before, were already breaking ground for the trenches.

Next day the men of the Seventh were also set to work with pick and spade and barrow, excavating the ditch and piling up the rampart along the lines laid down by the engineers. One fatigue party followed another, all doing their best, like so many ants on an ant-hill; and before night the place began to look something like a fortification. When finished it was the largest of those on the south side of the river, occupying a space of about fourteen acres. It was an inclosed bastioned work, covering the two forks of the road; one leading south to Alexandria, the other southwest toward Fairfax Court House. It defended the Long Bridge, and secured its possession for ingress and egress. It was named Fort Runyon, in honor of the general commanding the New Jersey brigade.

After a few days on the Virginia shore, the regiment was ordered back to its camp at Meridian Hill. It had been mustered into[Pg 34] service for one month, to meet an emergency which was now past. Orders for its return north were received on the 30th of May; and on the 31st it broke camp and embarked for New York, arriving there on the 1st of June. It was then mustered out of service, having been under arms forty-three days.

This was the "Washington campaign" of the Seventh regiment. It was a campaign without a battle, and the regiment was not once under fire from the enemy. Its only casualties were one man killed in camp by the accidental discharge of a musket, and another wounded in the leg by his own pistol. But it came to the front at a time when one battalion for the moment was more needed than a brigade afterward. Though mustered out as a regiment, it at once began to supply material for other organizations. Of its members in 1861, more than six hundred entered the service during the war; over fifty became regimental commanders; from twenty to thirty, brigadier-generals; and more than one reached the grade of major-general. With all this depletion, its ranks were kept tolerably full by new recruits, and it was twice afterward called into the field for temporary duty, once in 1862, and again in 1863.

After my return from Washington in 1861, I resigned my commission in the Seventh regiment, and looked for an opportunity of more permanent connection with the service.

The most attractive position which offered was that of surgeon of brigade, recently established by act of Congress; and, a medical board having been convened for the examination of candidates, I appeared before it, passed the examination, and in due time received my commission as Brigade Surgeon of Volunteers.

At that time each volunteer regiment had its surgeon and assistant surgeon, who were in general quite competent to the work they had to do. Like other regimental officers, they received their appointments and commissions from the authorities of their own state, and were permanently attached to[Pg 36] their particular regiments, without being either authorized or required to go elsewhere.

But when the volunteer army came to be organized into brigades, under command of brigadier generals with a general staff, it was found that there were no medical officers to correspond. They were needed to receive and consolidate the regimental reports, inspect the health of the commands, establish field hospitals, and perform in every way the duties of a general medical officer. Such places were filled, so far as possible, by the surgeons and assistant surgeons of the regular army. But these were too few in number to provide for the large volunteer force suddenly called into action; and for that reason the new grade of brigade surgeon was created. My commission was dated August 3, 1861.

But it was not until the first week in October that I received orders to report in Washington at army headquarters. On arriving there, I was directed to join General Viele's brigade and report for duty to that officer.

General Viele's brigade was at Annapolis. So, as soon as possible, I proceeded, with[Pg 37] my horse, baggage, and camp equipage, to Annapolis Junction, and thence, by the branch road that I had traveled with the Seventh, to Annapolis. There I found the general and his staff, quartered in the old St. John's College, a little outside the town. A locality always looks different when you are arriving and when you are going away; and, notwithstanding my brief acquaintance with Annapolis six months before, now that I was coming to it from a different direction and for another purpose, I should hardly have known it for the same place.

The building where we were quartered was a plain brick edifice, several stories in height, facing the town, with a distant view of the harbor beyond. In front was the college green, where some of the regiments were paraded for the presentation of flags. One of these presentations was made, a week after my arrival, by Governor Hicks, who had now seen his way clear to support the Union. In the rear and to the westward were the regimental camps.

It soon appeared that the troops were gathering at Annapolis in considerable force. In all, there were three brigades: General[Pg 38] Viele's, General Stevens's, and General Wright's,—the whole forming a division of a little over twelve thousand men, under command of General W. T. Sherman. In General Viele's brigade there were five regiments,—the Forty-sixth, Forty-seventh, and Forty-eighth New York, the Third New Hampshire, and Eighth Maine. This brigade was the earliest on the ground and ranked first in the division. General Stevens's was the second brigade, and General Wright's the third. Each had a brigade surgeon; and a chief medical officer, from the regular army, was attached to the staff of the division commander.

It was also claimed that we were going somewhere. Already a number of transports were in the bay, and others continued to arrive, evidently for our accommodation. Orders from the commanding general or his adjutant were dated: "Headquarters, Division E. C." These cabalistic letters were supposed to indicate in some way our future destination, though I do not remember ever seeing them, either written or printed, except as initials. After a time they were understood to mean Expeditionary Corps; but that hardly made us much wiser as to[Pg 39] how far or in what direction we were bound.

At the end of a fortnight all was ready. One by one the transports came into the harbor and took on their load of stores, artillery, ammunition, and wagons; and finally the troops embarked. Our own vessel, occupied by General Viele and his staff, was the Oriental, an iron-built ocean steamer of nine hundred tons, formerly a packet running to Havana. She also carried provisions and ordnance, and one or two companies of soldiers belonging to the brigade.

After saying good-by to Annapolis, our vessels steamed slowly together down the broad highway of the Chesapeake, past the mouth of the Potomac river, almost as broad, and the next day came to anchor in Hampton Roads. So far, our voyage was only a preliminary. We had arrived at a second rendezvous, where the remainder of the expedition was in waiting; and we now began to have an idea of its real magnitude. Grouped around us over the ample roadstead, there were war vessels of all grades and dimensions, from a steam frigate to a gunboat. Whether they were all to go with us we knew not, but the number of[Pg 40] coaling schooners lying about seemed to indicate that most of them were under sailing orders.

However, there was more waiting to be done before the final start, and we passed a week without shifting our anchorage. Not being responsible for anything outside our own brigade, we devoted ourselves mainly to cultivating the virtue of patience. Yet we could not help feeling that such a military and naval demonstration, gathered at such a point, could not long remain a secret; and that, wherever we might be bound, if it were any object to arrive without being expected, the sooner we could get away the better. For medical officers there was another cause of anxiety, which I began to appreciate almost as soon as our anchor was down. When soldiers are on land it is always possible to care for their sanitary condition. Camps can be cleansed and drained, or shifted to better ground; and the sick can be placed in hospital, or isolated at a respectable distance from the rest. But how to do this with troops confined within the narrow quarters of a ship? And what if some contagion should break out among them, like smouldering fire in a haystack?[Pg 41] Every exertion was made to keep the transports in fair condition as to cleanliness and ventilation, and to watch for the appearance of any suspicious malady. But every day made it more difficult to do the one, and added to the danger of the other. Fortunately, we got through without any serious mishap of this kind.

Meanwhile, we had some entertainment in watching our naval colleagues, and trying to learn what and who they were. They were in frequent communication with each other or with the shore; and their trim barges, with the regular dip of their oars, and a kind of scientific certainty about the way they went through the water, contrasted well with the rather sprawly fashion of our own boats and their soldier crews. The commander of the naval force was Captain Dupont.

His flagship, the Wabash, a double deck steam frigate of forty guns, was the most imposing object in view. Then came the sloops-of-war Mohican, Seminole, and Pawnee, with gunboats of various sizes, and the great transports Atlantic, Baltic, and Vanderbilt, each of about 3000 tons burden; making altogether, with the additional transports[Pg 42] and supply boats, a fleet of nearly fifty vessels.

At last the preparations were complete, and on Tuesday, October 29th, the signal for starting was given. Away from Hampton Roads, through the mouth of the Chesapeake, past the capes of Virginia, and then at sea, with prows toward the south, the stately procession moved along, every vessel in its place. The flagship led the van, with other men-of-war trailing behind, like ripples, in two diverging lines. Then came the transports in three columns, formed by the three brigades, and lastly a few gunboats brought up the rear. The vessels of the first brigade formed the right column, and as the sun went down the Virginia shore was just sinking out of sight. The weather was favorable, and every one felt pleased to see the expedition now fairly on its way.

Our progress was not very rapid. Many of the war vessels were slow-going craft, and the rest had to accommodate their speed to the leisurely rate of five or six knots. We were fully twenty-four hours in making Cape Hatteras; and, notwithstanding the bad reputation of this locality, we found there hardly enough wind and sea to be uncomfortable.[Pg 43] The main topic of talk was our destination. No one in the fleet knew what that was except the two commanders, Captain Dupont and General Sherman. The commanding officer on each vessel brought with him sealed orders, which he was not to open unless separated from the rest. But all were at liberty to guess; and in our discussions there were three objective points favored by the knowing ones; Bull's Bay on the coast of South Carolina, Port Royal entrance about a hundred miles farther down, and Fernandina in Florida. As I knew them all only as so many names on the map, and had no idea why one should be a more desirable conquest than the other, I listened for entertainment, without caring to choose between them. Our military family was made up of various elements, but all were good-natured and companionable, and promised to grow still better on acquaintance. General Viele was a graduate of West Point, and we all looked to him for information in regard to military affairs.

The order of sailing became somewhat deranged after a time, though at the end of two days we were still in sight of the flagship, with from thirty to forty others in the[Pg 44] horizon. So far, the weather had given us no trouble. But on Friday, November 1st, it began to be rough. The sky was overcast, the ship rolled and pitched, and the wind howled in a way that gave warning of worse to come. As the day wore on, there was no improvement, and before nightfall it was blowing a gale.

There is a difference between a storm and a gale of wind. A storm is disagreeable enough, with the driving rain, the lead-colored sky, the sea covered with foam, and the wet decks all going up and down hill. There is not much pleasure while that lasts. But in a gale of wind, discomfort is not what you think of. After the tempest has grown and gathered strength for five or six hours together, it begins to look threatening and wicked. The sea is a black gulf around the ship; and the great waves come rolling at her, one after the other, like troops of hungry wolves furious to swallow her up. A thousand more are behind them, and she has to fight them all, single handed, for life or death. She must keep her head steady to the front, and meet every billow as it comes without faltering or flinching; for if she loses courage or strength and falls away to[Pg 45] leeward, the next big comber will topple over her side and she will go under.

When a good ship is wrestling with such a sea, she does it almost like a living creature. She sways and settles, and rises and twists, and her beams groan and creak with the strain that is on them. But her joints hold, and she answers her helm; and the steady pulsation of her engines gives assurance of undiminished vitality and motive power. So long as she behaves in this way, you know that she is equal to the work. But what if the sea should grow yet fiercer and heavier, and buffet her with redoubled energy till she is maimed or exhausted? She is a mechanical construction, knit together with bolts and braces; and the steam from her boilers is to her the breath of life. However stanch and true, her power of resistance is limited. But in the elements there is a reserve of force and volume that is immeasurable; and when they once begin to run riot, no one can tell how severe it may become or how long it will last.

So it was on board the Oriental. All that evening the wind increased in violence. Every hour it blew harder, and the waves came faster and bigger than before. The[Pg 46] sea was no longer a highway; it was a tossing chaos of hills and valleys, sweeping toward us from the southeast with the force of the tornado, and reeling and plunging about us on every side. The ship was acting well, and showed no signs of distress thus far; but by midnight it seemed as though she had about as much as she could do. The officers and crew did their work in steady, seamanlike fashion, and among the soldiers there was no panic or bustle. Once in a while I would get up out of my berth, to look at the ship from the head of the companion way, or to go forward between decks and listen to the pounding of the sea against her bows. At one o'clock, for the first time, things were no longer growing worse; and in another hour or two it was certain that the gale had reached its height. Then I turned in for sleep, wedged myself into the berth with the blankets, and made no more inspection tours that night.

Next morning the wind had somewhat abated, though the sea was still rolling hard, under the impetus of an eighteen hours' blow. The ship was uninjured and everything on board in good condition. But where was the fleet? Of all the splendid[Pg 47] company that left Hampton Roads four days ago, only two or three were in sight, looking disconsolate enough and pitching about like eggshells. We knew afterward that two of them had gone down, one had thrown overboard her battery of eight guns to keep from foundering, and others had turned back, disabled, for Fortress Monroe. But on the whole, most of them had escaped serious damage, and, like ourselves, were again making headway toward the south. Nevertheless it was a lonely day, and at nightfall we had no more companions about us than there were in the morning.

By this time we knew our destination. The sealed orders were opened and the ship put on her course. The next day, Sunday, was bright and clear, with a smooth sea. Other vessels began to appear, moving in the same direction; and before noon we were off Port Royal entrance, with ten or eleven ships in company. Stragglers continued to come up as the time passed, and on Monday morning when the flagship arrived, there were already twenty-five or thirty sail around her.

Any land looks pleasant from the sea, when you have been knocking about for[Pg 48] some days in bad weather; and the South Carolina shore had a particularly attractive appearance for us, partly no doubt because we knew it would still be rather hard work getting there. It was ten miles away, but the mirage made it visible; and the long stretch of beaches and low sand bluffs, with their rows of pines, all sleeping in the quiet sunshine, had a kind of luxurious, semi-tropical look, at least to the imagination. Every light-house and buoy had been removed, and not a sign was left for guidance over the bar. But soon a busy little steamer was at work, sounding out the channel and placing buoys; and in the afternoon all except the deeper-draft vessels went in. We were among the first of the lot; and of those that followed, many showed the marks of their rough treatment at sea. The big sidewheel steamer, Winfield Scott, came in dismasted, and with a great patch of canvas over her bows, looking like a man with a broken head. Others had lost smoke-stacks, or stove bulwarks or wheel-houses. But when all that could get over the bar were collected inside, they still made a respectable fleet. The heavier vessels had to wait for another tide.

That was early next morning, when the Wabash came in, followed by the rest. A weather-beaten old tar was standing in her fore channels outside the bulwarks, feeling her way with lead and line; and as the great ship moved slowly by, we could hear his doleful, monotonous chant, "By the ma-ark fi-ive," telling that she was in thirty feet of water and going safely along. She passed through the fleet of transports and war vessels to her position in advance.

Meanwhile several gunboats had gone up the harbor, to learn something about the forts. They were firing away now and then, either at the enemy on shore or at the rebel gunboats hovering about beyond. We supposed that their errand was only preliminary, and felt no surprise at seeing them return after an hour or two and again quietly come to anchor. But in the afternoon, when the flagship herself got under way, we expected something more; especially as she had undergone a transformation and was now in fighting trim. Her topmasts were sent down, and all her lofty tracery of spars had disappeared. As she moved off, looking like a champion athlete stripped for the fray, every eye followed her in eager expectation.[Pg 50] Soon a puff of smoke from one of the rebel batteries, followed by the dull reverberation of the report, and then another from the opposite shore, spoke out their defiance, as if they would like nothing better than to begin hostilities at once. But there was no answering gun from the frigate. On she went, in the same leisurely fashion, as if she had seen and heard nothing. More guns from the forts, more smoke and more reverberation. Now she will surely open her ports and show these blustering rebels, at least with a shot or two, what it is to fire upon a United States frigate. But no. She seemed to pause awhile as if in doubt, then turned and came slowly back toward the fleet, followed to all appearance by the parting scoffs of the enemy. It was impossible to repress a certain feeling of chagrin at seeing the flagship apparently chased out of the harbor, on the first trial, without even firing once in reply.

That was because we had been looking at something we did not understand. After getting the reports of the gunboats, the flagship had gone up to obtain for herself a few more particulars as to the location and outline of the forts. The cannonading was[Pg 51] at too long range to do her any harm, and her expedition was meant for business, not for show.

However, the next day must find us ready; and perhaps it would be none too soon. We had now been four days, off and on, at the harbor entrance; and by this time all South Carolina knew where we were and what we had come for. Every additional twenty-four hours gave the enemy more time for preparation, without any advantage to us; and the longer the enterprise was deferred, the more difficult it would become. But the next day there was rather a high wind, with considerable sea; and accordingly matters again remained in statu quo. That was another disappointment. It seemed almost impossible that it should be so. Were these old sea-dogs, after coming six hundred miles on purpose, to be delayed in their work by a little rough water?

Well, yes. This was to be a contest between ships and forts. The forts are planted on the solid ground, and their guns are mounted on level platforms, with every angle of inclination sure and uniform. But the ships are afloat; and if rolling about with the sea, and their decks tipping this way and[Pg 52] that, their aim must be uncertain and much of their metal thrown away. Of course, a fort is not to be reduced by firing guns at it, but by having the shot penetrate where it is meant to go. Captain Dupont was a man who had come to win, not to fight a useless battle with no result; and the way he went to work after the time arrived made it plain to all that he knew equally well when to stop and when to go ahead.

On the morning of Thursday, November 7th, everything was favorable. The sea was smooth, with a gentle breeze from the northeast. About nine o'clock the war vessels began to move forward between the forts. The transports were drawn up as near as possible and yet be out of the line of fire. Our own vessel, the Oriental, was the second in position, General Sherman's being the only one in advance of us. As for myself, I climbed into the fore cross-trees, and then, seated on the reefed topsail, with my back against the foot of the topmast, I had a view that commanded the entire scene. It was a bright, clear day, with hardly a cloud on the horizon. Before us lay the broad harbor nearly two and a half miles across, guarded on each side by the enemy's earthworks.[Pg 53] On the right, at Bay Point, was Fort Beauregard, and on the left, at Hilton Head, Fort Walker, the stronger and more important of the two. A little to the north of Fort Walker was a high, two-story house, with a veranda in front, the headquarters of the rebel commander; and away beyond, moving about in the adjoining creeks, we could see the tall smoke-stacks and black smoke of the rebel gunboats, watching an opportunity to capture vessels that might be stranded or crippled, or to chase them all, should they be defeated.

And now the battle began. The naval force in a long line of fifteen ships, passed up midway between the forts, receiving and answering the fire from each. Near the head of the harbor, five or six were thrown off for a flanking squadron, to engage the rebel gunboats or enfilade the enemy's works from the north. The rest, including all the larger vessels, then turned south, and, passing slowly down in front of Fort Walker, gave her, one after the other, their heavy broadsides, turning again, after getting fairly by, to repeat the circuit. From my position I could see every shell strike. When one of them buried itself in the ramparts or plunged[Pg 54] over into the fort, its explosion would throw up a vertical column of whirling sand high in the air, followed by another almost as soon as the first had disappeared. When one from the rebel batteries burst over the ships, it appeared suddenly like a white ball of smoke against the sky, that swelled and expanded into a cloudy globe, and then slowly drifted away to leeward; while a few seconds later came the sharp detonation of the exploded shell. On both sides the conflict was unremitting, and along the whole sea-face of the fort its guns kept on belching their volleys against the fleet.

About this time we noticed on our left, close in shore, a gunboat that seemed to be engaging the fort on its own hook. It was a two-masted vessel, probably of six or seven hundred tons, but it looked hardly larger than a good sized steam tug; and on its open deck was a single big gun, firing away at the southeast angle of the fort. It was the Pocahontas. She had been kept back by the gale, and had just arrived in time to get over the bar while the fight was going on. Her commander was Captain Percival Drayton, a native of South Carolina, but one of the stanchest and most gallant officers in[Pg 55] the navy of the United States. The commander of the two forts was his brother, General Drayton, of the Confederate army, whose plantation on the island was only two or three miles away.

When looking at the new comer, I could not help thinking how much expression there may be in such inanimate things as two pieces of ordnance. The way the gun on the Pocahontas was worked certainly gave the idea of skill, determination, and persistency; while that which answered it from the fort was equally suggestive of vexation, haste, and a little apprehension. No doubt it was natural for the defenders to feel so, when, in addition to the cannonading in front and on one flank, another enemy should appear, to harass them from the opposite quarter.

Through all this hurly-burly, the movement of the war vessels was a masterpiece of concerted action. Round and round they went, following the flagship in deliberate succession, pounding at the fort with one broadside going up and with the other coming down. So far as we could see, not one of them fell out of line, or failed to do her full share in the engagement. It had been going on now nearly four hours. The fire of the[Pg 56] fort was somewhat lessened, but it was still enough to be doubtful and dangerous. One great gun in particular, on the southern half of the sea-front, kept working away with dogged energy, as if determined to inflict some deadly blow that might retrieve the fortunes of the day. After a while there seemed to be a cessation. The Wabash stood motionless before her enemy. She fired a single gun, to which there was no response. Then a boat shot out from under her quarter; and pulled straight for the shore. An officer landed, and went up the bluffs to the fort. For a moment we could see his dark figure running round the parapet, then down and out by the sally-port, and across the intervening field to the two-story house, where it disappeared in the doorway. A few moments later, at the flagstaff on the roof, a flag mounted swiftly to the top, and then, in sight of all, the stars and stripes floated out with the breeze, over the coast of South Carolina.

What followed was a kind of pandemonium. Cheers from the vessels all over the harbor, with the tooting of steam whistles and music from the regimental bands, mingled in long reiteration till every vocal[Pg 57] organ was exhausted, and the notes of the "Star-spangled Banner" had traveled over the Bay Point and back again. The transports began to move in, and were soon collected as near the beach as they could safely come. In an hour or two I went ashore with General Viele and others of his staff, to take a look at the surroundings. The fort was naturally our first object of interest. Three of its guns dismounted, with their gun-carriages standing wrong end upward, the parapet and traverses seamed with shot and shell, and the ground strewn with pieces of exploded projectiles, told of the hard struggle it had gone through. The few dead left by the enemy had been decently removed by the marines who first took possession. A day or two afterward the surgeon of the fort was found in one of the galleries, dead, and covered with sand from a bursted shell. In the rear of the fort was a stretch of open plain, also covered with fragments of shell, over which the fugitives had passed in their final rout, leaving behind arms, knapsacks, blankets, and everything that could impede their flight. Traveling over this field, half a mile or so from the fort, I came upon the body of a stout fellow, who had[Pg 58] been struck down while running for his life. There was a gaping wound in his breast, into which you might have put a quart pot; but his countenance was as serene and quiet in expression as if he had laid down by himself for a few moments' rest.

General Wright's brigade was landed that afternoon. But it was slow work, with a shelving beach and no wharf; and the rest of us postponed disembarking till the next day. When all were on shore, General Wright's command was located at and about the fort, and that of General Stevens some distance farther on, near the crossing of a tide-water creek. Our own brigade, which held the advanced position, was about two miles northwest of the creeks, on the main road from that direction. The fort at Bay Point was abandoned by the enemy without further resistance, and was occupied by a detachment from the second brigade.

I have understood that this battle made some change in current opinion as to the efficiency of ships and forts against each other. A fort, or at least an earthwork, would seem almost impregnable against artillery. It has no masonry walls to crumble or batter down. Solid shot may bury themselves[Pg 59] in its ramparts without doing the least harm; and when a shell explodes there, it only throws up a volcanic eruption of earth and sand, that settles back again nearly in the same place. The day after the battle at Hilton Head, the walls of the fort were practically as good as ever, and within a week or two its scarred outlines were all smoothed over again. On the other hand, a frigate or a sloop-of-war is vulnerable throughout. A single shot at the water line will make a leak, hot shot will set her on fire, and exploding shells may derange her machinery. Her oaken sides are a slight bulwark compared with the twenty feet of earth in the ramparts of a fort.

All this was thoroughly appreciated by the enemy, who were prepared for the attack and confident of success. Captured letters and documents showed that they had entire faith in their works and guns, and fully expected to sink the Yankee vessels and teach them a lesson for their temerity.

But in one thing ships may be superior to forts; that is, in their power of defensive action. What decides the day more than anything else is the number of guns in service and the rapidity of their fire. Ships may[Pg 60] be brought from various directions and concentrated at a given place, so that their united batteries will far outweigh the armament of a fort. At Hilton Head the Wabash alone fired, in four hours, 880 shot and shell; and from the entire fleet no less than 2000 projectiles must have been hurled upon the fort within that time. The earthwork itself may withstand this tempest, but its defenders cannot continue to work their guns. After a time their fortitude must give way under such a trial, and, as it was in Fort Walker, the moment comes at last for a final stampede. Of course, this implies that the ships are present in sufficient force and do their work in the right way.

But perhaps the victory was due, more than anything else, to the practical skill and originality of Captain Dupont. He saw at once that the work at Hilton Head was the important one, and that if that were reduced, the other would be untenable. When first leading his ships up the harbor in mid-channel, he engaged both forts at about two thousand yards distance. On making the turn and coming down again towards the south, he passed in front of Fort Walker at eight hundred yards. This distance was of his[Pg 61] own choosing, and he had the range beforehand. But the guns of the fort had to be sighted anew, in the heat and excitement of actual conflict; not an easy thing to do, even for the most experienced. After going again toward the north at longer range, he once more made the turn and repassed the fort on his way back, this time at six hundred yards. So, the vessels were always in motion, and after every turn presented themselves to the enemy at a different distance. It was this second promenade of the ships, pouring into the fort their terrific broadsides at the short distance of six hundred yards, that did the effective work of the engagement. At this time, according to nearly all the commanders' reports, the enemy's shot mostly passed over the ships, injuring only their spars and rigging. Throughout the battle none of them were struck more than ten times in the hull, none were seriously disabled, and two of them were not hit at all. Captain Dupont said afterward that he believed he had saved a hundred lives by engaging the fort at close range.

After the first rejoicings were over, there was a singular feeling of disappointment in the North at the seeming want of result from[Pg 62] the victory at Port Royal. It was expected that the troops would move at once into the interior, capture the important cities, and revolutionize the states of Georgia and South Carolina. One of the newspaper correspondents wrote home, a few days after the battle, "In three weeks we shall be in Charleston and Savannah;" and in the popular mind at that time the possession of a city seemed more important than anything else, in the way of military success. So when the months of November, December, and January passed by, without anything being done that the public could appreciate, there was no little surprise manifested at the inactivity of the army in South Carolina.

In reality the military commanders were busy from the outset. The day after the battle, Captain Gillmore, the chief engineer, made a reconnaissance to the north side of the island, and laid out there a work to control the interior water-way between Charleston and Savannah; and before the end of the month he had commenced his plans for the reduction of Fort Pulaski, which in due time were brought to a successful issue. But these movements, and others like them, were after all secondary in importance to[Pg 63] the main object of the Port Royal expedition, namely, the permanent acquisition of Port Royal itself, as an aid to the naval operations on the Atlantic coast.

The government at Washington was by this time fully alive to the magnitude of the contest and its requirements. One of the most pressing of these requirements was the blockade; which must be maintained effectively along an extensive line of coast, exposed to severe weather during a large part of the year. The vessels of the blockading squadron must be supplied with stores and coal at great inconvenience and from a long distance; and when one of them needed repairs it must be sent all the way to New York or Philadelphia to get a new topmast or chain cable. This involved much expense, long delays, and the risk of temporary inefficiency in the blockade. It was important that the fleet should have, near at hand, a capacious harbor, where store-houses and workshops might be established, and where shelter might be had for the necessary inspections and repairs. Port Royal was such a harbor; and it also served, in course of time, as a base for further military operations. It had been selected by Captain Dupont and General Sherman in joint council.

The sea islands of South Carolina and Georgia are grouped in a nearly continuous chain along the coast, between the mainland and the sea. They are flat, with only a few slight elevations here and there; and there is not, over their whole area, a single boulder, pebble, or gravel bed, nor any spot where the ledge rock comes to the surface. The soil at first seems to be sandy; but you soon discover that it has mingled with it a fine black loam and is extremely productive. It yields the "sea-island cotton," a variety of long fibre, formerly much valued for certain purposes of textile manufacture. There is no sod or turf, like that of the Northern states, but the fields not under cultivation produce a tall thin grass, which is soon trampled out of existence by passing wagons or by soldiers on the march. In the clearings are the live oak and the[Pg 65] great magnolia, both evergreen. The palmetto is also a conspicuous object, and the dwarf palmetto grows abundantly under the shadow of the pine woods. Everywhere there is a large proportion of hard-wood shrubs and trees with polished, waxy-looking, evergreen leaves.

There are many extensive plantations, where the owners often remain during a large part of the year. Their houses are not grouped in villages, but scattered at a considerable distance apart, each on its own plantation, with the negro cabins usually in long lines at the rear or on one side. The roads from one plantation to another run through the pine woods, or over the plains, bordered on each side by cotton or corn fields, and marking the only division between them. There is seldom to be seen such a thing as a rail fence, and of course never a stone wall.

Hilton Head, where we were now encamped, was one of the largest of these islands. It was twelve miles long, in a general east and west direction, and about five miles in extreme width, north and south. At its Port Royal end, the sand bluffs rose to the height of eight or ten feet above the beach, giving the name of "head" more especially[Pg 66] to this part of the island; elsewhere they were generally much lower. Along its sea-front there was a magnificent beach, ten miles long, broken only at one place by a creek fordable at half tide. At frequent intervals on this route there were marks of the slow encroachment of the sea upon the land. Often you would come upon the white, dry stump of a dead pine, standing up high above the beach on the ends of its sprawling roots, like so many corpulent spider legs. Once it grew on the low bluffs above high-water mark, as its descendants are doing now. But the sea gradually undermined its roots and washed out the soil from between them, till it gave up the ghost for want of nourishment, and in time came to be stranded here, half-way down the beach. It looked as if the tree had moved down from the bluffs toward the water, though in reality the beach had moved up past the tree. The same thing was going on all along the coast in this region. There were trees on the very edge of the bluff, with their roots toward the sea exposed and bare, but with enough still buried in the soil on the land side to hold the trunk upright and give it sap; while here and there[Pg 67] was one already losing its grip and slowly bending over toward the sea. When it has nothing more to rest on than the sands of the beach, its branches and trunk decay, but its roots and stump remain for many years whitening in the sun, like a skeleton on the plains.

The chain of islands from Port Royal toward Charleston harbor included Parry, Saint Helena, Edisto, John's and James islands; in the opposite direction, toward the Savannah river, Daufuskie, Turtle, and Jones' islands. Inside these were other smaller islands, the whole separated from each other and from the mainland by sounds and creeks, sometimes broad but oftener narrow and tortuous, through which small steamers could find an inside passage from Charleston to Savannah. This communication was of course cut off when our troops occupied Port Royal.

At Hilton Head I first made the acquaintance of the southern plantation negro. Every white inhabitant had disappeared, leaving the slaves alone in possession. Their inferior appearance, habits, and qualities, their curious lingo and strange pronunciation were in amusing contrast with those of the blacks[Pg 68] and mulattoes we had seen at the north. When I met one of them near the Jones plantation and asked him whether he belonged there, his answer was this: "No mawse, I no bene blahnx mawse Jones, I bene blahnx mawse Elliot." Not having any idea what he meant, I repeated the phrase to General Viele, who had some familiarity with the southern negro, and who gave me the interpretation as follows: "No master, I did not belong to master Jones, I belonged to master Elliot." Mr. Elliot was the owner of another plantation near by. Soon after we took possession of Hilton Head, negroes began to come in from the neighboring islands, seeking shelter and food. They generally appeared to rate themselves at the value set upon them by their former masters. One morning a young black, of the deepest dye and most cheerful expression of countenance, presented himself at brigade headquarters, and on being asked whether any others had arrived with him, he said with a delighted grin: "Yes, mawse, more 'n two hundred head o' nigger come ober las' night." Most of the field hands were of this description. But on each plantation there was usually one man[Pg 69] noticeably superior to the rest in manner and language. He was generally the leader in their religious exercises, and had the gift of the gab to no small degree; though his uncontrollable propensity to the use of long words and incongruous expressions often gave a ludicrous turn to the effect of his eloquence.

But whatever their grade of capacity or intelligence, the negroes agreed in one thing. They were well satisfied to live on the plantations, without control of their former owners, so long as the crops of the present season would supply them with food. Their liberation they knew was owing to the success of the Union troops, and they showed a much more intelligent comprehension of the causes and probable results of the war than they had been supposed to possess. But as for doing anything themselves to help it on, that did not appear to form part of their calculations. They would work for their rations when destitute, would obey when commanded as they had been accustomed, and they would aid the Union cause whenever they could do so in a passive sort of way. But we soon found that we must not look to them for anything like energetic or[Pg 70] spontaneous action. This seemed a strange indifference to a contest involving the freedom or servitude of their race, and no doubt accounted for much of the aversion afterward felt by our troops to the project of transforming some of them into soldiers.

But if we had remembered where the negroes came from, perhaps we should not have been so much surprised. Their ancestors had been brought to this country from the coast of Africa by slave-traders who had bought them there. They were slaves already, when they were taken on board ship. They had been captured in war, or seized by native marauders, who took them for the purpose of reducing them to slavery and selling them for profit. They were consequently from the least capable and least enterprising of the negro tribes in Africa; and their descendants in this country were of the same grade. If they could not resist being made slaves by other negroes, how could they be expected to take part in a war between whites, even to recover their own freedom?

Of course there were exceptions to this. In the month of May following, a boat's crew brought away from Charleston harbor the barge of the Confederate General Ripley,[Pg 71] and escaped with it to the naval vessels outside; and not long afterward the negro pilot, Robert Smalls, and his companions ran the gauntlet of the forts in the night-time with the steam-tug Planter, and delivered her safely to the blockading fleet. But these were rare instances, and nothing of the kind happened at Hilton Head.

What the sea-island negroes appeared to excel in more than anything else was handling an oar, which they did in a way quite their own. In their long, narrow "dug-outs," hollowed from the trunk of a Georgia pine, each man pulling his oar in unison with the rest, they would send the primitive craft through the water with no little velocity. In lifting and recovering the oar they had a peculiar twist of the hand and elbow that no white man could imitate; and their strange sounding boat songs seemed to give every moment a fresh impulse to the stroke. These songs had no resemblance to the half-humorous, half-sentimental "plantation melodies" known to theatre-goers at the north. They were more like religious rhapsodies in verse. At least, they had many words and phrases of a religious character; but mingled together, in a kind of incoherent chant,[Pg 72] with many others of different significance, or even none at all. It was not its meaning that gave value to the song; it was its sound and cadence. Sometimes the verse would open with a few words of extempore variation by the leader, and then the other voices would strike in with the remaining lines as usual. Oftener than not, the song was a fugue, every one of the half dozen boatmen catching up his part at the right second, and chiming in all the louder and lustier for having kept still beforehand. Once in a while the passenger would be startled at seeing an oarsman suddenly strike the one in front of him a smacking blow between the shoulders, at the same time injecting into the melody a short improvised yell, by way of stimulus and encouragement. Altogether, I have seldom witnessed a more entertaining performance than one of these semi-barbarous vocal concerts in a South Carolina dug-out.

Our brigade camp was in a large cotton-field lying across the road to the northwest. At the time of our arrival it was covered with tall, scraggy bushes, their white balls still ungathered; and for a night or two we bivouacked in the deep furrows between[Pg 73] them. But they were soon removed and the surface quickly trampled down into a serviceable parade ground, with the regimental camps extending along one side. Brigade headquarters were in advance of the parade ground, opposite the right of the line. At one end was the general's tent, fronting upon an oblong space, enclosed on its two sides by the tents of the staff officers, orderlies, and employees. Within the enclosed space was a single live-oak, under which we gathered in the evening round a fire, to smoke our pipes and talk over arrivals, reconnoissances, or projected expeditions.