LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

MARCH 1 1918

SERIAL NO. 150

THE

MENTOR

JULIUS CÆSAR

By

GEORGE WILLIS BOTSFORD

DEPARTMENT OF

BIOGRAPHY

VOLUME 6

NUMBER 2

TWENTY CENTS A COPY

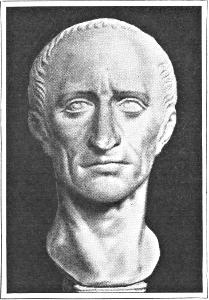

In person Cæsar was tall and slight. His features were more refined than was usual in Roman faces; the forehead was wide and high, the nose large and thin, the lips full, the eyes dark gray like an eagle’s, the neck extremely thick and sinewy. His complexion was pale. His hair was short and naturally scanty, falling off toward the end of his life and leaving him partially bald. His voice, especially when he spoke in public, was high and shrill.

His health was uniformly strong until his last year, when he became subject to epileptic fits. He was scrupulously clean in all his habits, abstemious in his food, rarely or never touching wine, and noting sobriety as the highest of qualities when describing any new people. He was an athlete in early life, admirable in all manly exercises, and especially in riding. From his boyhood it was observed of him that he was the truest of friends, that he avoided quarrels, and was most easily appeased when offended. In manner he was quiet and gentlemanlike, with the natural courtesy of high-breeding.

He was singularly careful of his soldiers. He allowed his legions rest, though he allowed none to himself. He rarely fought a battle at a disadvantage. He never exposed his men to unnecessary danger, and the loss by wear and tear in the campaigns in Gaul was exceptionally and even astonishingly slight. When a gallant action was performed, he knew by whom it had been done, and every soldier, however humble, might feel assured that if he deserved praise he would have it. The army was Cæsar’s family.

JAMES ANTHONY FROUDE

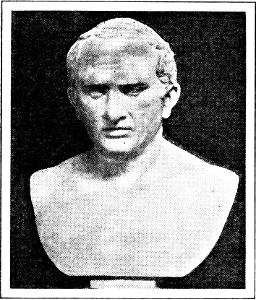

IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM, NAPLES

JULIUS CÆSAR

ONE

Gaius Julius Cæsar was born in 100 B. C. of old patrician stock. In youth he received from Greek masters the elements of their culture, including astronomy, philosophy, and rhetoric. To complete his oratorical studies he sailed for Rhodes, but on the way was taken captive by pirates and held for ransom. This mishap would have subjected him to ridicule, had he not, on his release, manned a ship and punished his captors. Returning to Rome, he entered politics, the most ambitious career open to fashionable young men. In this vocation he had to pay his respects to men of influence, plead cases at court, and render financial or other assistance to unfortunate clients; he had to call by name and compliment all whom he met, to entertain lavishly, and attend the various social functions of all classes. Above all he had to maintain a permanent coterie of supporters to act as agents in time of need.

In 68 B. C. he reached the lowest rung in the political ladder. This was the office of quæstor, who had the handling of public funds. Soon afterward as ædile, commissioner of public works and games, his magnificent entertainments won the good will of the voters, and brought about his election to the Supreme Pontificate. In this capacity he directed the state religion, and his person was esteemed sacred. It was a great political advantage. Next he was elected prætor, whose chief duty was to preside over one of the criminal courts. After a man had held the prætorship or the consulship the Senate usually appointed him as a proprætor or proconsul to the government of a province. As proprætor accordingly Cæsar governed Spain in 61-60. Returning home in the latter year, he formed a political ring, known as the First Triumvirate, with Pompey, a general who had gained splendid victories in the Orient, and Crassus, the wealthiest capitalist of the empire. This combination secured the consulship for Cæsar for the year 59. His opposition to the Senate during this year, and his legislation in the interest of the people made him very popular. As proconsul (58-50) he conquered Gaul. Meanwhile Crassus was killed in battle; and Pompey, adopting the cause of the Senate, prepared nominally to defend the Republic; in fact, to rid himself of a powerful rival. In the civil war that followed the seasoned veterans of the popular hero proved superior to the forces of the Senate, most of them hastily gathered from the farms. Thereupon the Senate, shifting about, heaped honors and triumphs upon the victor. As consul, dictator, and supreme pontiff Cæsar was virtually, though not in name, a king (49-44). The power of the aristocracy was broken, but its hatred lived and generated a plot to kill the “enemy of the Republic.” On March 15, 44, Cæsar fell, stabbed with twenty-three wounds, at the hands of erstwhile friends.

Cæsar began his career as a politician, but ended it as a statesman. His courage, clemency, and personal charm won countless friends. While costly entertainments were a political necessity, his moderation in private life earned the respect of Roman society. A blue-blooded patrician, he steadfastly championed the popular cause. This policy alienated his own class, and finally resulted in his death. His political understanding developed hand in hand with his patriotism. Better than his contemporaries, he saw the economic and social decay of the Republic, and felt that inefficiency and corruption could be eradicated in no other way than by a strong monarchy. His own supremacy he brought about with the minimum of bloodshed. When once in power he vigorously swept away the weaknesses and oppression of aristocratic rule, and laid a solid foundation for the future peace and prosperity of the empire.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6. No. 2, SERIAL No. 150

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE RIVER TIBER—IN THE TIME OF CÆSAR

TWO

Through nearly four centuries of conquest and alliance (400-44 B. C.) the Roman empire came to embrace the entire Mediterranean region. After Cæsar’s conquest of Gaul, it extended from the Atlantic to the Euphrates, from the North Sea and Alps to the Sahara. This vast area was organized into administrative divisions, called provinces. Its very size meant a heterogeneous population, scores of peoples, each with its own language and customs. In the east Greek had replaced local tongues for literary, diplomatic, and business purposes. In the west many dialects remained: for Latin, though official, was but gradually coming into universal use.

Life in the empire was mainly agricultural. Tools were simple, if not primitive; and only after a struggle could the peasant produce enough to last until the next harvest. Industries were largely domestic, carried on at home, or in small shops for local use. The eastern parts—Egypt, Asia Minor, and western Asia—were far wealthier. Here commerce and skilled industries were more flourishing, though by any modern estimate, on a small scale. As there were no machines in the modern sense, goods had to be made by hand. The imperial roads were in excellent condition but distances were long, travel was slow, and transportation expensive, save by water.

When a new territory was incorporated into the empire, it became a province. It was placed in charge of a quæstor, who controlled financial matters, and a general executive called proprætor or proconsul—both appointed annually by the imperial government. The governor commanded the army and acted as the highest judge in his territory. The province was divided into city-states, each of which retained its laws and customs, its magistrates, council, and popular assembly. They managed their local affairs, and no attempt was made to interfere in their religion. Instead of rendering military service they had to pay annual tribute. At auction the highest bidders received contracts for collecting taxes in the several cities.

Unfortunately, abuses crept into provincial rule. In the first place, Rome favored her citizens at the expense of her subjects. Native merchants were superseded by greedy speculators and traders, who, reducing the people to poverty, drove the peasants from their farms and built up vast estates of their own. The evil of “farming” taxes became intolerable, for avaricious contractors made the peasants pay far more than their due. In his year of service, too, the typical governor expected to accumulate a fortune sufficient (1) to pay political debts, (2) to bribe judges in case of prosecution, (3) to live in luxury the remainder of his life. Few governors were honest enough to check these wrongs. Furthermore, the wealthier provinces were heavily overtaxed to help pay the expense of governing the newly acquired frontier provinces, which as a rule were financial failures.

These evils Cæsar went far in remedying. He curtailed the system of “farming” taxes, and placed it under strict supervision. Thus capitalists were prevented from openly plundering the subjects. He appointed able, honest governors, and held them to account. Legionary commanders, too, appointed by him to serve under the governor, and revenue officials—his own servants and freedmen—saw that his will was everywhere enforced. The provinces, especially the poorer ones, were to be cultivated and improved. An attempt was made to equalize the burden of taxation, and the heavy drain on the eastern provinces was lessened. Lastly, in order to abolish class and national distinctions, and to weld together the empire, Cæsar allowed himself to be worshipped as a god, and adopted the policy of rapidly granting citizenship to provincials. In aiming to bring about such an empire devoid of nationality Cæsar followed the procedure of the great Alexander, and set an example for his successor, Napoleon.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6. No. 2, SERIAL No. 150

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

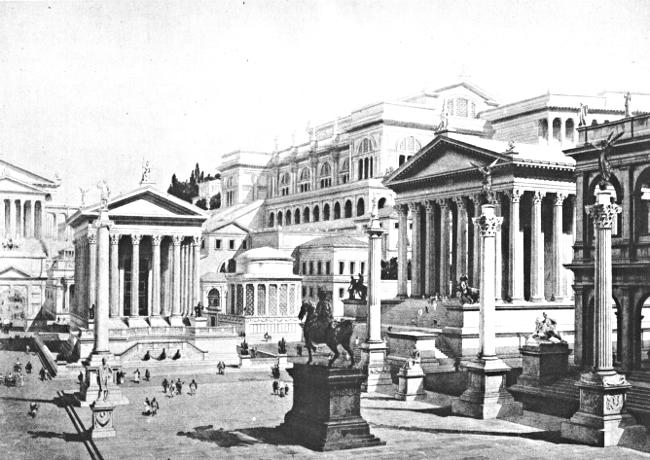

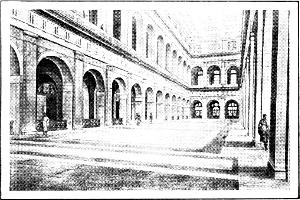

THE ROMAN FORUM—IN THE TIME OF CÆSAR

THREE

Early in his career of conquest Alexander the Great subdued Egypt and founded Alexandria (332 B. C.) This country proved the most valuable part of his vast realm, and afterward of the Roman Empire. The valley of the Nile is exceedingly fertile, well watered as it is from the river, and continually enriched by the alluvial deposits from the yearly overflow. The people were patient and laborious. For thousands of years they had toiled like slaves for their Pharaohs, whom they looked upon as gods, and who owned all the land and most of the wealth of the kingdom. Naturally Alexander usurped the property rights and the divine rights of the Pharaohs; and ultimately when Egypt fell as a kingdom, to his general, Ptolemy, the latter succeeded to all these advantages. For nearly three centuries Egypt was ruled by the dynasty thus founded, in which each king bore the name Ptolemy, inherited from his father. The king was proprietor, not only of all the land but also of the extensive industrial plants and shipping. As Alexandria was the greatest manufacturing and commercial center of the world, Ptolemy was far the wealthiest capitalist. His military and civil officers were Greeks; his soldiers were Greeks and other foreigners; so that with his complex military and administrative machine he was able to govern the Egyptians as a conquered people. In the eyes of the kings they were mere producers of wealth; the official language was Greek, and the majority of sovereigns did not take the pains to learn the native speech.

At first remarkably competent, the Ptolemies gradually declined in ability, and even before the birth of Cæsar had come to be subservient to Rome. We may imagine with what longing the greedy Roman oligarchs viewed this kingdom, and how persistent was the agitation for its conquest.

Such an object Cæsar undoubtedly had in view when he sailed against Alexandria with the pretext of settling a dispute between Ptolemy and his sister Cleopatra. This fascinating woman convinced the Roman general of the justice of her cause, and was accordingly placed on the throne. Their mutual infatuation became the gossip of Rome when she afterward visited that city. Though not beautiful, the Egyptian queen was a charming woman. A talented linguist, she could dispense with an interpreter in dealing with her subjects and with foreign princes. Fond of music, literature, and art, she made a pleasing hostess, while her gorgeous entertainments captivated her guests. She was gifted, too, with an instinct for the various paths to men’s affections; and her melodious voice and pretty ways won her desires from the strongest of rulers. This demoniac fascination, coupled with an ambition to found a great empire, made her one of the most powerful women in all history.

After Cæsar’s death Octavianus (Octavius—called Cæsar Augustus) remained at Rome, while Antony governed the eastern half of the empire. Soon he fell under the spell of Cleopatra, and gladly married her that he might become, without conquest, king of Egypt. Political motives underlay this romance: he wanted to add Egypt with its vast wealth to his domain, while she, no less ambitious, viewed the chaos at Rome as an opportunity to secure for herself Antony’s share of the empire. Octavianus saw the will of Antony bending before his consort’s superhuman fascination. Appreciating the danger to Rome, he defeated Antony in a naval battle, 31 B. C., sailed to Egypt, and with little trouble captured Alexandria. Seeing that all was lost, the royal lovers committed suicide. Thus fell the last glorious remnant of the Alexandrian kingdom. Henceforth it was but a part of the Roman world-state.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6. No. 2, SERIAL No. 150

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

ON EXHIBITION AT STERN BROS., N. Y. CITY.

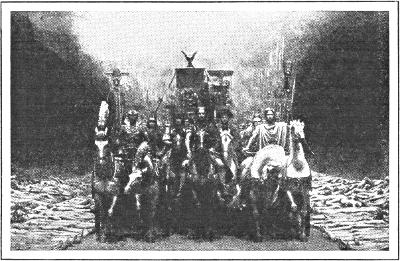

CÆSAR CROSSING THE RUBICON, by J. L. Gérôme

FOUR

Nowhere is the versatility of Julius Cæsar more clearly in evidence than in his literary accomplishments, the majority of which unfortunately have been lost. His scientific spirit is manifest in an astronomical work, “Concerning the Stars,” which we do not have, but which was doubtless connected with his reform of the calendar. As an orator Cæsar was famed for his precise use of language, good taste, and vivacious, forcible style of delivery, qualities as necessary to his political career as to success in authorship. The “Dialogue on Orators,” however, though highly praised by Cicero, has disappeared, likewise his treatise on Grammar. The world no longer has his collection of despatches and letters, many of them in cipher, or his political pamphlets against Cato, who had been eulogized as “the martyr of the Republic,” or his “Collective Sayings,” a veritable store-house of satirical witticisms, or his many poems, with the exception of a well-known criticism of Terence, the playwright.

We can only judge his varied literary talents by his “Commentaries On the Gallic War” in seven books, and “On the Civil War” in three, known to all schoolboys and college students. The former dictated amidst anxiety and distraction were intended to show his ability and courage as a general, to justify the moderation of his Gallic policy, and to forestall attacks by political opponents. Written in the third person, their modesty dispels the suspicion of egoism, yet the author knew how, without violating the truth and without boasting, to display his merits to the greatest possible advantage. The language is simple and restrained yet vigorous and clear. There are thrilling moments, for example, in the description of the ever-threatening danger of Sabinus, or the exciting escape of Cicero, when the fort of Aduatuca was endangered by a swoop of German marauders. Throughout the story the natives, with their inferior civilization, their perfidies and duplicities, are mere pigmies in the clutches of a giant. Like an irresistible force of nature, the great Roman tramples down everything in his path.

The same impassive restraint is shown in the “Civil War.” The work contains fewer thrilling events; but dramatic movements like the crossing of the Rubicon, grievances at the hands of his enemies, and his frequent overtures for peace seldom fail to awaken the reader’s sympathy. The word “commentaries,” applied to these books, signifies merely “notes,” as the author himself regarded them; but in the judgment of after ages they are model historical narratives.

From the “Commentaries,” too, we may form an estimate of Cæsar the general. In knowledge of the technical departments of warfare he has had few superiors. He knew how to enroll and organize vast numbers of raw recruits, and to transform them rapidly into trained military units. The ease with which he overcame the dangers and difficulties constantly confronting him testify to his consummate tactics and strategy. He was without a peer in practical psychology—a prime factor in successful generalship. This quality enabled him to read and understand the feelings of adversaries as well as of his own men. He possessed coolness, too, and self-control to an extraordinary degree, which served to win the confidence and affection of his troops, and to discourage panic and disaster. He was, moreover, a just critic, eager to praise, slow to blame. His inherent generosity willingly recognized and rewarded merit in officers and men. Cæsar was especially fond of his centurions—the flower of those who had risen from the ranks. Often without political or family ties, they fought and died for him alone. Though of slight physique and generally in poor health, through simple living and sheer force of will Cæsar bore many arduous campaigns, often marching on foot with his men. It was this unfailing vigor and resolution, manifesting itself in acts of heroic daring, which gave courage and moral determination to his forces.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6. No. 2, SERIAL No. 150

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

PHOTOGRAPHED FROM A PRINT

THE DEATH OF CÆSAR, by J L. Gérôme.

FIVE

The most distinguished of Cæsar’s contemporaries was Cicero. With an exceptional education, he entered politics, where, in spite of scant means and ignoble ancestry, he finally attained to the consulship, 63 B. C. Throughout his career, an ardent supporter of the Republic, he opposed the arbitrary rule of Cæsar; and in the Civil War he favored the Senatorial party. In the troubles following Cæsar’s murder Cicero heroically defended the Republic in many a brilliant oration; and in this cause he sacrificed his life. Though possessed of many noble qualities, his vacillation, artistic temperament, and supersensitiveness unfitted him for statesmanship.

Cicero’s chief claims to greatness lie in the fields of literature and philosophy. He was a poet of no mean ability. His “Orations,” with their kaleidoscopic range of mood and choice of words, are the most brilliant in the Latin language. The painstaking labor required for this supreme mastery of speech is shown in his rhetorical works. His “Letters,” written in simple style, lay bare a human heart, with all its shortcomings and aspirations, while through their wide range of topics they bring the reader into intimate touch with the spirit of the age. Of farther-reaching influence are his works on political science and philosophy. His “Republic” aims to discover the best form of government, and to examine into the foundations of national prosperity. His many philosophic writings set forth the various Greek schools of thought, especially the Platonic and the Stoic. Through the medium of a diction so perfect as to make Latin the universal language of culture for centuries to come, Cicero successfully transplanted Greek thought to Latin soil. Nor did his influence cease there; from his philosophy the Church fathers drew inspiration; and in it centuries later the scholars of the Renaissance first found the vitalizing spark of Greek culture.

Of Cæsar’s immediate associates, Cassius, Brutus, and Antony are most interesting, if only for their important rôles in Shakespeare’s “Julius Cæsar.” Though showered with offices, Cassius, a malcontent, bore a grudge against Cæsar for being his master, and began to plot against him. He found many influential men, who, jealous of Cæsar’s power, were themselves anxious to divide the spoils of government. To give the plot an air of respectability, he won over Brutus, ostensibly a student and man of letters, but at heart an unfeeling usurer. Appointed by Cæsar governor of Cisalpine Gaul and prætor, Brutus became an assassin of his benefactor.

Among the three near associates of Cæsar, Mark Antony was far the ablest, and possessed the merit of remaining faithful till the death of the benefactor. He had filled many military and civil offices with distinction, and was Cæsar’s colleague in the consulship at the time of the murder. Shortly before this event, at a public festival, Antony offered Cæsar a crown, alleging that it was from the people. Although Cæsar would gladly have welcomed any device for legitimizing his rule, he refused the kingly title because of its unpopularity.

The assassination left Antony sole consul. Having control of Cæsar’s papers and property, he skilfully used these advantages to make himself absolute. In a clever oration at the funeral he turned the feelings of the populace against the murderers, who thereupon fled from Rome. With young Octavianus (Octavius) he patched up a temporary alliance, and in combination they defeated the armies of Brutus and Cassius in the two battles of Philippi, 42 B. C. The beaten generals committed suicide, and the victors divided the empire between them, Antony taking the East and Octavianus the West. The later history of Antony is told in connection with Cleopatra.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6. No. 2, SERIAL No. 150

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

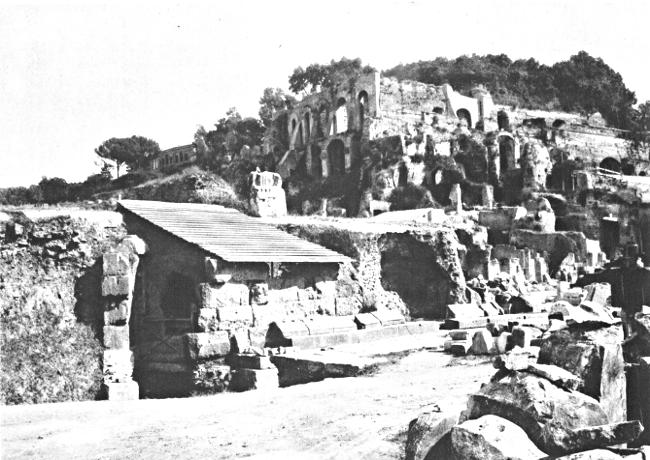

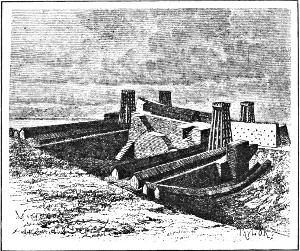

RUINS OF THE TEMPLE OF THE DEIFIED JULIUS CÆSAR—Roman Forum

SIX

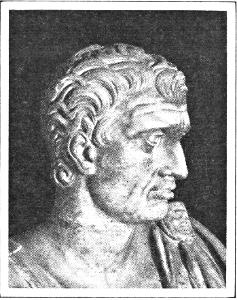

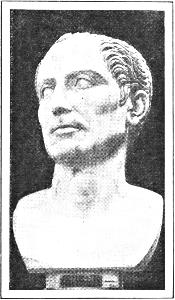

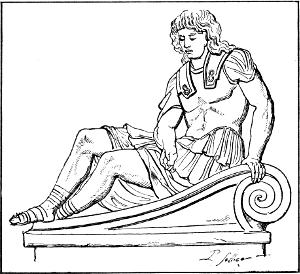

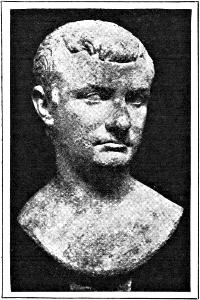

In the Rome of Cæsar Hellenic influence was active, not only in literature and philosophy, but also in art. The Roman portrait sculpture of this period reveals Greek knowledge and skill; but its essential character was determined by native tradition. The earliest Roman portraits were waxen death masks formed from a moulding over the face. Hence they were mechanically accurate but utterly devoid of animation. Though this material has perished, the visitor to the museums of Rome will find in relief many a family group in which the faces retain the mask-like quality. Only in a slighter degree does the principle apply to portrait sculpture in the round. At its best the Republican face accordingly is intensely realistic yet with no intimation of the inner spirit. Commonly the hair is indicated by parallel scratches made by firm chisel strokes. By these characteristics many busts and statues may be easily dated. It should be noticed, too, that in the Republican age the portrait heads, as distinguished from statues, include in addition to the head scarcely more than the neck, and that the bust is a gradual development during the subsequent period. With this criterion we are able to assign the Brutus of this number of The Mentor to the administration of Claudius, 41-54 A. D. In the colossal portrait of Cæsar of the National Museum at Naples the bust is a modern restoration, and we may only cherish the reasonable faith that the head is genuine, though somewhat later than his lifetime. The famous Cæsar of the British Museum, comprising head and neck, would satisfy the criterion here formulated, but fails to pass another even more important test. The indication of the pupil in the eye was not devised till after Hadrian, 117-138 A. D., and accordingly this head could be no earlier. Recently it has been suggested, with some reason, that the work is a modern study. If so, it is a great success, as it most admirably expresses the physique and the character of the famous man.

Another aid to identification is the circumstance that a colossus could represent no one but a preéminent person; and this criterion favors the Neapolitan head of Cæsar mentioned above. The colossus statue in the Conservatori Palace seems to be authentic, but was made a half century or more after his death. The face is fuller than the literary description or the coins would warrant, but the difference may well be due to idealization. The images on coins are doubtless true likenesses, but in the case of his sculptured portraits we can only deal in probabilities.

For Pompey we are in a less fortunate condition. The colossal statue in the Palazzo Spada, a detail of which is given in this number, has long passed as the image at the feet of which Cæsar met his death; but the proof is insufficient, and it seems at least as likely that it represents an emperor. Other portraits are equally uncertain. The Madrid bust of Cicero is genuine, and well represents the orator’s great intelligence with a momentary expression of scorn. The better-known Vatican head, the bust of which is modern, is also genuine and stands second in merit. For Cleopatra there are no certain sculptural portraits. The reclining woman of the Ariadne type has been mistaken for her because of the snake, as she is known to have died by the bite of an asp. The illustration is given merely because it long passed for Cleopatra and is a Greek work of rare beauty. Her true image is shown on coins.

The various reproductions of edifices are not creations of the fancy, but have been carefully worked out by archæologists from remains of buildings according to the well established principles of architecture.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6. No. 2, SERIAL No. 150

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE MENTOR · DEPARTMENT OF BIOGRAPHY

MARCH 1, 1918

By GEORGE WILLIS BOTSFORD

Late Professor of History, Columbia University. Author of “Story of Rome,” “History of Rome,” etc.

MENTOR GRAVURES

JULIUS CÆSAR

THE ROMAN FORUM IN THE TIME OF CÆSAR

THE RIVER TIBER IN THE TIME OF CÆSAR

MENTOR GRAVURES

CÆSAR CROSSING THE RUBICON

DEATH OF CÆSAR

RUINS OF THE TEMPLE OF THE DEIFIED CÆSAR

From History of Rome, by G. W. Botsford, The Macmillan Co., Publishers

JULIUS CÆSAR

Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the postoffice at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright, 1918, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

To understand the world in which Cæsar lived it is necessary first to review the growth of the Roman Empire. Four hundred years before the beginning of the Christian era Rome was a small city, an independent state, it is true, but in possession of a territory no larger than an American county. In a succession of wars lasting through a century and a third (400-264 B. C.), she gained control of the whole peninsula of Italy. In another century (264-167 B. C.), through a new series of wars, she built up an empire that nearly surrounded the Mediterranean Sea. This rapid expansion of power is one of the most notable events in the world’s history. In the present number of The Mentor, however, we are less concerned with the process of conquest than with its result. When Rome subdued a foreign state, she exercised her right of war in depriving it of a great part of its wealth, including money, land, and art treasures, not only paintings and marbles, but works of great intrinsic value in bronze, silver, and gold. These confiscations and the subsequent taxes levied by the imperial government, together with the illegal exactions of officials, tended to impoverish the world for the enrichment of Rome and of the few citizens who monopolized the offices. The conquest differentiated the freemen of the empire into three distinct classes: the few wealthy Romans, who governed the world, the masses of Roman citizens who, though in possession of the right to vote had gained no advantage by the conquest, and the subjects, barred from all share in the imperial government and greatly oppressed by its officials.

JULIUS CÆSAR

In the Capitoline Museum, Rome

Rome became a great city with a population of about a million, who had gathered from all parts of the empire. Some had come as slaves, others to seek their fortunes, while others had been driven from the surrounding districts by the pinch of poverty. As freemen could find little work in the city, there grew up a great mob of idlers, who lived in large part on food doled out to them by the state as the price of their votes.

The ruling class was represented by the Senate, which was the chief governing body. Generally the senators were the most cultured and intelligent people at Rome; but they had all the faults of a narrow plutocracy; through long enjoyment of wealth and power the class was thoroughly corrupted and enfeebled. Hence the Senate proved incapable of governing and protecting the empire and even of preventing the frequent outbreaks of anarchy in the capital.

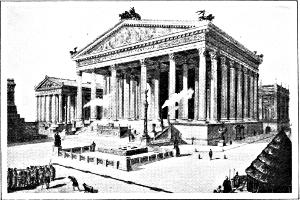

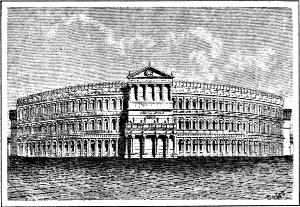

TEMPLE OF JUPITER—CAPITOLINE

As it appeared in the time of Cæsar

Such in brief was the world in which Gaius Julius Cæsar lived (100-44 B. C.) Belonging to the bluest-blooded aristocracy, he began life with all the advantages of wealth and family repute. As a boy and youth he enjoyed the best education of the time. It consisted mainly in the study and imitation of Greek writers, especially orators, in preparation for a career as public speaker and statesman. Rome had derived her civilization from Greece; and every business man or diplomatist had to speak the Greek language, which was the chief medium of communication throughout the Mediterranean world.

In company with other young aristocrats Cæsar in early life indulged in all the dissipations and vices of his class. The foppish negligence of his attire proclaimed him a rake, while exorbitant luxuries, costly entertainments, forbidden love-intrigues, gambling—in brief, the indulging of a great variety of expensive tastes—exhausted his fortune and loaded him with debts so portentous that he could never hope to pay them by legal means. Through all these immoralities he kept a sound mind and a body capable of extreme activity and endurance, though in his later years he was subject to fainting and to epileptic fits.

The clearness and quickness of his intelligence was such that he could carry on several lines of thought and keep a number of stenographers[1] occupied simultaneously with his dictations. These extraordinary mental powers enabled him to master the most complex political situations and on the battlefield to turn many a defeat into victory. For the knowledge necessary to his manifold activities he devoured the contents of a multitude of books on a great variety of subjects. He was an orator of splendid power, a writer of clear and simple Latin, a man of scientific taste, interested in the customs and character of the peoples with whom he came in contact, and in the phenomena of nature; a general with few equals in the world’s history, and a statesman variously estimated by modern historians.

[1] In that age stenography was a well-developed art, essential to the work of a secretary.

THE ROMAN FORUM (restored), northwest side

From History of Rome, by G. W. Botsford, The Macmillan Co., Publishers

A ROMAN FEAST

At the beginning of his career he cast his lot with the popular party. This policy meant little more than a preference for dealing with the Assembly rather than with the Senate. In theory the Assembly comprised all the citizens; practically it was attended by the idler members of the populace. There was no democracy; for those citizens that lived too far from Rome to attend the Assembly had no voice in the government, and the vast majority of people in the empire were subjects. It was expected that a leader of the popular party should propose to the Assembly bills for the benefit of the masses of citizens, particularly of the populace, and for checking the powers and privileges of the aristocracy.

Cæsar was by no means a believer in human equality. Speaking in early life at the funeral of an aunt, he gave the following account of his family’s genealogy: “My aunt Julia derived her lineage on her mother’s side from a race of kings, and on her father’s side from the immortal gods; for her mother’s family trace their origin to King Ancus Marcius, and her father’s to Venus, of whose stock we are a branch. We unite in our pedigree, accordingly, the sacred majesty of kings, who are the most exalted among men, and the divine majesty of gods, to whom kings themselves are subject.” Men of such pretensions could never descend to the level of peasants and artisans, nor believe that the world would benefit by popular rule.

POMPEY

In the Palazzo Spada, Rome

Through an attractive personality, political intrigue sometimes verging dangerously on conspiracy, and the lavish use of borrowed money, Cæsar rapidly made his way upward through the higher offices in the routine order. In those times the surest avenue to political power was success in military command; and for the years 61-60 B. C. Cæsar was appointed governor of “Farther Spain.” On his arrival he found his province at peace; but he managed to stir up trouble with some neighboring tribes of mountaineers who were beyond the border of the empire. After imposing upon them orders that they could not obey, he made war upon them. They had little wealth to plunder, but he took captive great numbers, whom he sold into slavery. As governor he found other ways of making money, mostly illegal; so that he was able to reward his soldiers, pay his huge debts, and have something left for the future. In this policy he acted like former governors, but with greater cleverness.

JULIUS CÆSAR

In the National Museum, Naples

Returning to Rome, he gained the Consulship, which was the highest standing office (59 B. C.) There were two consuls; and his colleague was Bibulus, a stupid person, who chanced to be a political adversary. For the first time Cæsar was in a position to display his statesmanship. Two great problems were pressing, the economic improvement of the masses throughout the empire and their protection from the greedy oppression of Roman officials. Against the obstruction of his colleague Cæsar carried a law through the Assembly for the division of large tracts of public land among the needier citizens—a measure which brought him great popularity. Although it did nothing to benefit the subjects, it was a step in the right direction. Another law, worked out in great detail, aimed to prevent officers of the empire from committing extortion upon the subjects. Though doubtless well intended, this law proved ineffective because no one in power cared to enforce it. Most of his consular year, however, he devoted to winning influential friends and to securing for himself an opportunity for further military exploits after the expiration of his Consulship. The territory placed under his government for this purpose included especially Cisalpine Gaul—substantially the Po Basin—and Narbonensis, a strip of land extending along the southern coast of Gaul, now France.

Disturbances beyond his borders gave him a pretext for war, which lasted eight years (58-50 B. C.), and which resulted in the conquest of Gaul. In accomplishing this end Cæsar employed his most brilliant generalship, including lightning-like movements and daring strategy. When we consider that he had had little experience in warfare, we must regard his achievements as marvellous. The conquest was accompanied by great cruelty to the conquered. On one occasion more than fifty thousand captives were sold into slavery; on another he beheaded the senators of a conquered community and sold all the people as slaves. At another time he massacred an entire tribe, numbering more than four hundred thousand men, women, and children. The plunder, and especially the sale of captives, brought the victor enormous wealth, a part of which he devoted to buying supporters at Rome. After overawing Gaul with terrorism he adopted a policy of conciliation, by which he won the fidelity of the survivors. Although in entering upon the conquest Cæsar had merely his own aggrandizement in mind, he must in the end have come to an appreciation of the value of the new province to the empire. Even after the vast slaughter and enslavement of the bravest Gauls, the survivors were full of vitality. The country was rich in agricultural and mineral resources, and the Rhone River formed a convenient outlet for the country’s products in the direction of Rome. This acquisition added great strength to the empire, and prepared the ground for the extension of Roman civilization into western and central Europe. The conquest was, in fact, the greatest achievement of Cæsar’s genius.

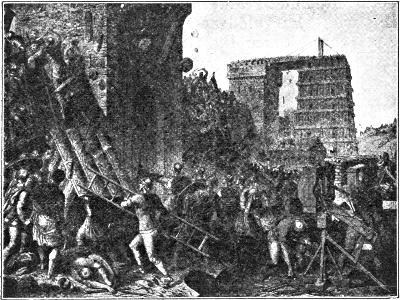

From History of Rome, by G. W. Botsford, The Macmillan Co., Publishers

WARFARE IN CÆSAR’S TIME

ROMAN LEGIONARY SOLDIER

From Duruy’s “History of Rome”

GALLIC SOLDIER

No sooner had he finished this work than he came to blows with the Senate, which feared his towering ambition. A civil war ensued (49-45 B. C.) The champion of the Senate was Pompey, who also had met with great success in war. Though in appearance the struggle was between Cæsar and the Republic, its real object was to determine which of the two leading generals should be master of the Roman world. Pompey was defeated and killed; and in the end Cæsar subdued the whole empire to his will. He ruled as Dictator, appointed to that office by the submissive Senate.

ROMAN WORKS OF APPROACH

Showing parts of a Gallic wall in which stones are intermixed with beams

During the civil war and the year following its close Cæsar gave attention to internal reforms. Humanely and prudently he forgave political offenders, and associated with himself in the government many who had fought against him in the war. He sought to reconcile old hatreds and to introduce an era of good feeling. There can be no doubt of his sympathy with the subject peoples. Those in authority in the provinces were no longer to enrich themselves and their friends by oppression, but were held strictly accountable to the Dictator. Roman citizenship was a highly-prized possession, as it meant justice and an enviable social standing to the possessor. Cæsar granted it freely to individuals and to entire communities. Obviously, his aim was the rapid equalization of all freemen of the empire.

He took especial interest in public improvements at Rome. Among these works was the completion of the temple to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva on the Capitoline Hill. The earlier temple had been destroyed by fire, and the construction of the new building required about thirty-six years. This was the largest and most stately temple in the city. Cæsar laid out a public square, named after his family the Julian Forum, in which he erected a temple to Venus Genetrix (ancestress), from whom he claimed descent. In it he placed a graceful statue of the goddess, carved by Arcesilaus, the most famous sculptor of the age. It is a remarkable example of clinging transparent drapery. In this public exhibition of his descent from a goddess Cæsar boldly displayed his egotism, which was further exalted by decrees of the Senate proclaiming him a god. It was not till after his death, however, that a temple was actually erected, at the east end of the Roman Forum, for his worship.[2] The Curia, Senate House, Cæsar began to rebuild, but its completion was left to Augustus, who named it the Curia Julia, after the Julian family, to which Cæsar, and by adoption Augustus, belonged. On the south side of the Forum he began the construction of the Basilica Julia, afterward finished by Augustus. It was a great hall intended for judicial and mercantile business. These are but a small part of the vast improvements that he planned for Rome, Italy, and the empire. The greater number remained mere schemes. To us the most interesting was the cutting of a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth, a work that has had to await the skill of the modern engineer.

[2] The temple of the deified Cæsar, the ruins of which is pictured in this number.

As supreme pontiff Cæsar was the head of the state religion and guardian of the sacred lore. In this capacity he reformed the calendar, which in his day had fallen into dire confusion. The improvement consisted essentially in the adoption of the Egyptian solar year of 365¼ days. The Julian calendar remained in force throughout the civilized world till 1582, when it was superseded by that of Pope Gregory XIII, who introduced a more exact system.

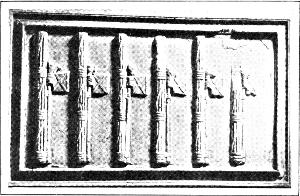

ROMAN FASCES

Bundle of rods and axe bound together and borne before emperors and other rulers as symbols of power

THE BASILICA JULIA—Roman Forum (restored)

A DENARIUS

Stamped with the head of Cæsar. A denarius was a silver coin worth about 20 cents

The Romans as a people belonged to the Mediterranean race, and the great majority, therefore, were short and dark, like the Sicilians of today. Cæsar, however, was tall and fair, with round, well-proportioned limbs and black piercing eyes. His portraits on coins and in sculpture show a spare face with a high, broad forehead inclined to baldness, representing a physique too delicate to sustain the enormous activities of his brain. To the end of his days he paid, perhaps, an excessive attention to his personal appearance, and was especially gratified when the Senate in his honor decreed him the privilege of wearing a laurel wreath; for he found it a means of covering his baldness. There was in his face and manner a frank sympathy that won the hearts of all those that came into close touch with him; and in spite of brutal conquests he developed an expression of gentleness and clemency mentioned by writers of his age.

The greatest of his contemporaries was Cicero, who by sheer energy and ability had worked his way to the highest offices, and had rescued the state from a dangerous conspiracy. Though he was a consummate political orator, Cicero’s tastes lay chiefly in the direction of literary and philosophic composition, pleasant country life, and association with intellectual men. Cæsar tried to win him as a political ally; but Cicero and those intimate associates that loved the Republic feared Cæsar’s autocratic methods and ambition. This aloofness of the intellectual class drove Cæsar to seek friends and helpers in the lower ranks of society and among his subordinate military officers. Although a few of these people served him faithfully, the great majority were incompetent to fill the offices that he gave them, and were bent only on shirking duty and enriching themselves. On such a basis no man, however great, can build up a just and efficient system of government.

CICERO

In the Vatican Museum, Rome

CICERO

In the Madrid Museum. Considered the most authentic marble portrait of the great orator

From History of Rome, by G. W. Botsford, The Macmillan Co., Publishers

POMPEY

In spite of many admirable qualities Cæsar shared fully in the moral looseness of the age, which set at naught all marriage relations. Not even his friends at Rome, nor friendly kings who gave him their hospitality, could trust their wives to his honor. With Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, he had associated in her capital; but he shocked even his dissolute countrymen by bringing her to Rome and into his own house.

POMPEY’S THEATER (restored)

First theater in Rome built of stone

That Cæsar desired absolute power, not merely for his own enjoyment but in the conviction that with it he could best serve the empire, can hardly be disputed; but whether or not he wished the kingly title no one can know. While he was in the Orient the glamor of Alexander’s achievements seems to have overcome him; and under this spell he neglected the work of improving the empire to plan the conquest of the great Parthian kingdom, Rome’s only surviving rival. In this scheme the conqueror got the better of the statesman. A motive to the new war, in itself unnecessary, was to escape from the situation at Rome—from flattery, intrigue, the incompetence of officials, from deadly though silent envy and hatred, which were making his life every day more unendurable. As the conqueror of Parthia he could overwhelm all opposition and mold the empire as clay in the potter’s hands. For the remainder of his days he could dwell serene on the pinnacle of glory; and at his death, having no son of his own, he could bequeath the regenerated world to his grandnephew Octavius, a youth of great promise whom he had adopted as a son.

CLEOPATRA

In the Vatican Museum, Rome

From all that we can learn, however, success in the Parthian war would have been a catastrophe to European civilization. In wealth and population, in the resources of war and peace, the Oriental part of the empire would have overbalanced the European. The capital would have shifted to Alexandria or farther east; and Oriental absolutism would have dominated the civilized world. Three centuries after Cæsar, autocracy was to come even to Europe. It came with its bureaucratic accompaniment to destroy the little that remained of economic strength and intellectual freedom, and to drag to ruin the decaying civilization of the ancient world.

Cæsar, however, was not destined even to set out for Parthia. On March 15 (44 B. C.), the Senate met to take the last measures preparatory to his departure. The place of session was the Senate House which Pompey had built near his theater. Scarcely had Cæsar entered and taken his seat when a throng of about sixty senators gathered round him, pretending to greet him and to offer a petition. They were conspirators who had engaged in a plot for his assassination, through no especial love for the Republic, but for various personal reasons. Many had gained office and wealth under his patronage; but in their greed for greater wealth and political glory they lost all sense of gratitude. The best among them was Marcus Brutus, in his own social circle a philosopher and an idealist, but in business a hard, relentless usurer. Caius Cassius, the brain of the conspiracy, was a plunderer of the provinces and a robber of temples, whom envy drove into the plot. By such men was Cæsar slain. It was a crime perpetrated upon the civilized world, which had to endure thirteen more years of desolating civil war (44-31 B. C.), before Octavius, the young heir to Cæsar, could gain the mastery and bring the empire to peace. This young man, known to history as Augustus, though less brilliant than his granduncle, possessed a far greater degree of practical wisdom. It was he, rather than Cæsar, who gave the Roman world an organization under which it was to enjoy more than two centuries of prosperity and happiness. Viewed in this light, the wisest act of the great Cæsar was the choice of this youth of delicately modeled features and frail body as his son and successor.

OCTAVIUS

Called “Augustus.” In the Vatican Museum, Rome

MARCUS BRUTUS

In the National Museum, Naples. Found at Pompeii

The Passing of Cæsar—“On March 15 (the Ides of March), 44 B. C., Cæsar entered the Senate Chamber and took his seat. His presence awed men, in spite of themselves, and the conspirators had determined to act at once, lest they should lose courage to act at all. He was familiar and easy of access. They gathered round him. He knew them all. There was not one from whom he had not a right to expect some sort of gratitude, and the movement suggested no suspicion. One had a story to tell him; another some favor to ask. Tullius Cimber, whom he had just made governor of Bithynia, then came close to him with some request which he was unwilling to grant. Cimber caught his gown, as if in entreaty, and dragged it from his shoulders. Cassius, who was standing behind, stabbed him in the throat. He started up with a cry, and caught Cassius’s arm. Another poinard entered his breast, giving a mortal wound. He looked round, and seeing not one friendly face, but only a ring of daggers pointing at him, he drew his gown over his head, gathered the folds about him that he might fall decently, and sank down without uttering another word. Cicero was present. Brutus, waving his dagger, shouted to Cicero, congratulating him that liberty was restored. The Senate rose with shrieks and confusion, and rushed into the Forum. The crowd outside caught the words that Cæsar was dead and scattered to their houses. The murderers, some of them bleeding from wounds which they had given one another in their eagerness, followed, crying that the tyrant was dead, and that Rome was free.”—James Anthony Froude.

THE FALLEN CONQUEROR

A reproduction of the pen drawing of the figure of Cæsar made by the painter Gérôme as a preliminary sketch for his great picture of the assassination of Cæsar

SUPPLEMENTARY READING: JULIUS CÆSAR, by G. Ferrero; JULIUS CÆSAR, a sketch, by J. A. Froude; JULIUS CÆSAR, by W. W. Fowler (Heroes of the Nations Series); JULIUS CÆSAR, by J. Abbott; LIFE OF CÆSAR, in Plutarch’s Lives.

⁂ Information concerning these books may be had on application to the Editor of The Mentor.

Copyright by Braun, Clement & Co. Original painting owned by John Wanamaker

THE CONQUERORS

This powerful painting by Pierre Fritel pictures the grim progress of the great conquerors of the world through an avenue of death lined by the victims of the world’s wars. Cæsar rides in the center—beside and behind are Tamerlane, Alexander, Attila, Charlemagne, Napoleon and other world conquerors.

It is Human Desire that makes world history—desire for conquest, possession, and control. The Conqueror of the World must have his will. He treads the peoples of the earth under his feet, and spreads ruin in his path. He knows no social distinctions—this Re-molder of Humanity. The habitations of poor and rich alike are demolished, and the treasured possessions of city and town desecrated. Monuments of revered memory are razed to the ground, and new monuments to the Conqueror are raised to the sky. Nations are subjugated; governments are revised; territory is re-assigned; new laws are made. The people bow under the yoke; the Conqueror is enthroned with pomp and ceremony, and hailed as Master of the World.

And then—something happens that saves the world for the people. Some call it the “Hand of Fate”; those that live in the faith call it the “Will of God.” But history tells us that final defeat awaits the man that aspires to be Conqueror of the World.

Tamerlane, the Tartar tyrant, called “the Scourge of God,” swept the hordes of Asia before him in world conquest. He died suddenly while preparing to invade China. Alexander of Macedon, called “the Great,” made himself master of the world of his day. He forestalled Fate by dissipating his young life away, and died broken-hearted, sighing for more worlds to conquer. Hannibal, the Carthaginian, carried the spirit of conquest across the Mediterranean to Spain, Italy, and over the Alps. He threatened Rome itself, and aspired to the overlordship of land and sea. Finally, defeated by Scipio Africanus, he was exiled to Syria, where, dishonored and deserted, he committed suicide. Julius Cæsar conquered all Gaul, and carried the standards of Rome to far-off Britain. The name of Cæsar became synonymous with conquest, so that it has been borne by successive emperors for centuries, and is, even in this day, the title of Imperialism. But Cæsar crossed the Rubicon, “and Rome was free no more.” In the very fullness of his power he was assassinated by his own senators, his friend Brutus among them.

“As he was ambitious,” said Brutus, “I slew him. There is joy for his fortune; honor for his valor; and death for his ambition.”

Napoleon Bonaparte gained leadership in France at a critical time, reconstructed her shattered institutions, and built up a military power that dominated all Europe. His ambition contemplated a personal supremacy of the Continent, with vassal nations paying tribute to his sovereignty. Beyond the bounds of Europe he carried conquest into Egypt, riding his charger to the foot of the Pyramids. But his over-weening ambition tempted him too far. As the crossing of the Rubicon sealed the fate of Cæsar, the crossing of the Niemen marked the beginning of Napoleon’s downfall. With the Grand Army of more than half a million men, he invaded Russia, penetrating as far as Moscow. In a few months, with a pitiful, broken and ragged remnant of his forces, he recrossed the Niemen, minus glory and minus the trophies of war. Soon after, Napoleon met his Waterloo, and ended his days in lonely brooding, like an eagle chained to a rock, on the desolate island of St. Helena.

Sic transit gloria mundi—“so passes away the glory of the world”; so ends the career of the Conqueror.

W. D. Moffat

Editor

Let Your Friends Share the Privilege of Membership in The Mentor Association

The Course for One Year Provides:

1—A growing library of the world’s knowledge—twenty-four numbers a year.

2—A beautiful art collection for the home—one hundred and forty-four art prints in sepia gravure and color.

3—One hundred and forty-four crisp monographs—one to accompany each Mentor Gravure.

4—A reading course throughout the year.

5—An education for all the family, under the direction of the foremost educators in this country—in art, literature, science, history, nature, and travel.

Send the names of three friends whom you wish to nominate for membership, and to whom you would like to have us send presentation copies of THE MENTOR.

The Mentor Association

ESTABLISHED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POPULAR INTEREST IN ART, LITERATURE, SCIENCE, HISTORY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL

THE MENTOR IS PUBLISHED TWICE A MONTH

BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC., AT 114 EAST 16TH STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y. SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, J. S. CAMPBELL; ASSISTANT TREASURER AND ASSISTANT SECRETARY, H. A. CROWE.

THE MENTOR

DO YOU KNOW During the past few months more than 400,000 previous issues of The Mentor have been purchased by the members of the rapidly growing Mentor Association. The idea of “Learning One Thing Every Day” is conveyed just as much through the previous issues of The Mentor, as it is through the current numbers. The foundation of The Mentor has been laid on things that are worth while, which gives them great permanent value. In reading through the list you are going to find a very large number of titles covering subjects that are of the keenest interest to you.

It would be next to impossible for you to obtain this compact information with the attractive illustrations, from any other source.

If you will make a selection at once of ten numbers that appeal to you most strongly—giving the serial numbers only (on a post-card) we will send them to you immediately—all charges paid—and send you a bill for the full amount, $2.00—which you can pay any time within 30 days. We urge you to act NOW.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, 114 East 16th Street, New York City

MAKE THE SPARE

MOMENT COUNT