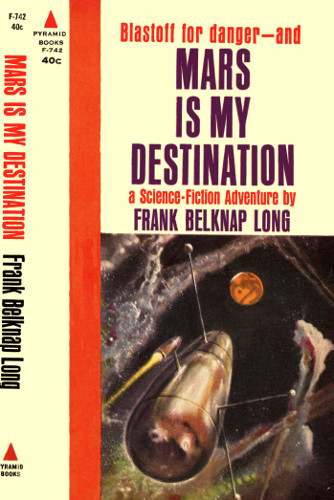

a science-fiction adventure by

FRANK BELKNAP LONG

PYRAMID BOOKS

NEW YORK

MARS IS MY DESTINATION

A Pyramid Book

First printing, June 1962

This book is fiction. No resemblance is intended between any

character herein and any person, living or dead; any such

resemblance is purely coincidental.

Copyright 1962, by Pyramid Publications, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Pyramid Books are published by Pyramid Publications, Inc.

444 Madison Avenue, New York 22, New York, U.S.A.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

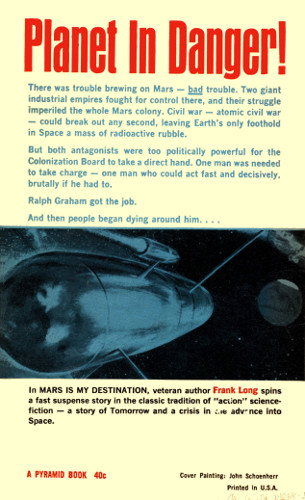

MARS

... Earth's first colony in Space. Men killed for the coveted ticket that allowed them to go there. And, once there, the killing went on....

MARS

... Ralph Graham's goal since boyhood—and he was Mars-bound with authority that put the whole planet in his pocket—if he could live long enough to assert it!

MARS

... source of incalculable wealth for humanity—and deadly danger for those who tried to get it!

MARS

... in Earth's night sky, a symbol of the god of war—in this tense novel of the future, a vivid setting for stirring action!

CONTENTS

I'd known for ten minutes that something terrible was going to happen. It was in the cards, building to a zero-count climax.

The spaceport bar was filled with a fresh, washed-clean smell, as if all the winds of space had been blowing through it. There was an autumn tang in the air as well, because it was open at both ends, and out beyond was New Chicago, with its parks and tall buildings, and the big inland sea that was Lake Michigan.

It was all right ... if you just let your mind dwell on what was outside. Men and women with their shoulders held straight and a new lift to the way they felt and thought, because Earth wasn't a closed-circuit any more. Kids in the parks pretending they were spacemen, bundled up in insulated jackets, having the time of their lives. A blue jay perched on a tree, the leaves turning red and yellow around it. A nurse in a starched white uniform pushing a perambulator, her red-gold hair whipped by the wind, a dreamy look in her eyes.

Nothing could spoil any part of that. It was there to stay and I breathed in deeply a couple of times, refusing to remember that in the turbulent, round-the-clock world of the spaceports, Death was an inveterate barhopper.

Then I did remember, because I had to. You can't bury your head in the sand to shut out ugliness for long, unless you're ostrich-minded and are willing to let your integrity go down the drain.

I didn't know what time it was and I didn't much care. I only knew that Death had come in late in the afternoon, and was hovering in stony silence at the far end of the bar.

He was there, all right, even if he had the same refractive index as the air around him and you could see right through him. The sixth-sense kind of awareness that everyone experiences at times—call it a premonition, if you wish—had started an alarm bell ringing in my mind.

It was still ringing when I raised my eyes, and knew for sure that all the furies that ever were had picked that particular time and place to hold open house.

I saw it begin to happen.

It began so suddenly it had the impact of a big, hard-knuckled fist crashing down on the spaceport bar, startling everyone, jolting even the solitary drinkers out of their private nightmares.

Actually the violence hadn't quite reached that stage. But it was a safe bet that it would in another ten or twelve seconds. And when it did there was no chain or big double lock on Earth that could keep it from terminating in bloodshed.

The tipoff was the way it started, as if a fuse had been lit that would blow the place apart. Just two voices for an instant, raised in anger, one ringing out like a pistol shot. But I knew that something was dangerously wrong the instant I caught sight of the two men who were doing the arguing.

The one whose voice had made every glass on the long bar vibrate like a tuning fork was a blond giant, six-foot-four at least and built massive around the shoulders. His shirt was open at the throat and his chest was sweat-sheened and he had the kind of outsized ruggedness that made you feel it would have taken a heavy rock-crushing machine a full half hour to flatten him out.

The other was of average height and only looked small by contrast. He was more than holding his own, however, standing up to the Viking character defiantly. His weather-beaten face was as tight as a drum, and his hair was standing straight up, as though a charge of high-voltage electricity had passed right through him.

He just happened to have unusually bristly hair, I guess. But it gave him a very weird look indeed.

I don't know why someone picked that critical moment to shout a warning, because everyone could see it was the kind of argument that couldn't be stopped by anything short of strong-armed intervention. Advice at that point could be just as dangerous as pouring kerosene on the fuse, to make it burn faster.

But someone did yell out, at the top of his lungs. "Pipe down, you two! What do you think this is, a debating society?"

It could have turned into that, all right, the deadliest kind of debating society, with the stoned contingent taking sides for no sane reason. It could have started off as a free-for-all and ended with five or six of the heaviest drinkers lying prone, with bashed-in skulls.

The barkeep made a makeshift megaphone of his two hands and added to the confusion by shouting: "Get back in line or I'll have you run right out of here. I'll show you just how tough I can get. Every time something like this happens I get blamed for it. I'm goddam sick of being in the middle."

"That's telling them, John! Need any help?"

"No, stay where you are. I can handle it."

I didn't think he could, not even if he was split down the middle into two men twice his size. I didn't think anyone could, because by this time I'd had a chance to take a long, steady, camera-eye look at the expression on the Viking character's face.

I'd seen that expression before and I knew what it meant. The Viking character was having a virulent sour grapes reaction to something Average Size had said. It had really taken hold, like a smallpox vaccination that's much too strong, and his inner torment had become just agonizing enough to send him into a towering rage.

Average Size had probably been boasting, telling everyone how lucky he was to be on the passenger list of the next Mars-bound rocket. And in a crowded spaceport bar, where Martian Colonization Board clearances are at a terrific premium, you don't indulge in that kind of talk. Not unless you have a suicide complex and are dead set on leaving the earth without traveling out into space at all.

Now things were coming to a head so fast there was no time to cheat Death of his cue. He was starting to come right out into the open, scythe swinging, punctual to the dot. I was sure of it the instant I saw the gun gleaming in the Viking character's hand and the smaller man recoiling from him, his eyes fastened on the weapon in stark terror.

Oh, you fool! I thought. Why did you provoke him? You should have expected this, you should have known. What good is a Mars clearance if you end up with a bullet in your spine?

For some strange reason the Viking character seemed in no hurry to blast. He seemed to be savoring the look of terror in Average Size's eyes, letting his fury diminish by just a little, as if by allowing a tenth of it to escape through a steam-spigot safety valve he could make more sure of his aim. It made me wonder if I couldn't still get to them in time.

The instant I realized there was still a chance I knew I'd have to try. I was in good physical trim and no man is an island when the sands are running out. I didn't want to die, but neither did Average Size and there are obligations you can't sidestep if you want to go on living with yourself.

I moved out from where I was standing and headed straight for the Viking character, keeping parallel with the long bar. I can't recall ever having moved more rapidly, and I was well past the barkeep—he was blinking and standing motionless, as white as a sheet now—when the Viking character's voice rang out for the second time.

"You think you're better than the rest of us, don't you? Sure you do. Why deny it? Who are you, who is anybody, to come in here and strut and put on airs? I'm going to let you have it, right now!"

The blast came then, sudden, deafening. They were standing so close to each other I thought for a minute the gun had misfired, for Average Size didn't stiffen or sag or change his position in any way and his face was hidden by smoke from the blast.

I should have known better, for it was a big gun with a heavy charge, and when a man is half blown apart his body can become galvanized for an instant, just as if he hasn't been hit at all. Sometimes he'll be lifted up and hurled back twenty feet and sometimes he'll just stand rigid, with the life going out of him in a rush, an instant before his knees give way and there's a terrible, welling redness to make you realize how mistaken you were about the shot going wild.

The smoke thinned out fast enough, eddying away from him in little spirals. But one quick look at him sinking down, passing into eternity with his head lolling, was all I had time for. Pandemonium was breaking loose all around me, and my only thought was to make a mad dog killer pay for what he had done before someone got between us.

Mad dog killers enrage me beyond all reason. Given enough provocation almost any man can go berserk and commit murder. But the Viking character had let a provocation that merited no more than a rebuke rip his self-control to shreds.

The naked brutality of it sickened me. Something primitive and very dangerous—or perhaps it was something super-civilized—made me out to beat him into insensibility before he could kill again. I felt like a man confronting a poisonous snake, who knows he must stamp on it or blast off its head before it can sink its fangs in his flesh.

I was not alone in feeling that way. All around me there was an angry muttering, a cursing and a shouting. If I needed support, sturdy backing, I had it. But right at that moment I didn't need it. An angry giant had come to life inside of me and we exchanged nods and understood each other.

There was a crash behind me, but I ignored it. What was harder to ignore was the barkeep straddling the bar and coming down flatfooted in the wake of two reeling drunks who were lunging for the killer with a crazy, wild look in their eyes. I didn't want them to get to him ahead of me.

He hadn't moved at all and had a frightened look on his face, as if the blast had jolted some sanity back into him and made him realize that you can't gun a man down in a crowded bar without adjusting a noose to your own throat and giving fifty men a chance to draw it tight.

The gun he'd killed with might still have saved him, if he'd swung about and started shooting up the bar. But I didn't give him a chance to recover.

I ploughed into him, wrenched the gun from him and sent him reeling back against the bar with a solidly delivered blow to the jaw, luckily aimed just right.

Then they were on him, five or six of them, and I couldn't see him for a moment.

I held the gun tightly and looked at it. It was still warm and just the feel of it sent a shiver up my spine. A gun that has just been wrenched from the hand of a killer is unlike any other weapon. There's blood on it, even if no laboratory test can bring it out.

I didn't know I'd lost anything until I looked down and saw my wallet lying on the floor at my feet. The energy I'd put into the blow had not only sent a stab of pain up my wrist to my elbow. It had jarred something loose from my inner breast pocket that had a danger-potential, right at that moment, that could have turned the tide of rage that was sweeping the bar away from the killer and straight in my direction. Some of it anyway, splitting it down the middle, causing the drunks who were divided in their minds about what he had done to change sides abruptly.

In my wallet was a perforated card, all stippled with tiny dots down one side, and it said that I was on the passenger list of the next Mars-bound rocket, and that the Martian Colonization Board clearance was of a peculiar kind ... very special.

The wallet had fallen open and the card was in plain view for anyone to read. It could be recognized by its color alone—a light shade of blue—and if anyone who felt the way the killer had done about Average Size had caught sight of it and made a grab for the wallet—

I was bending to pick it up when a voice whispered close to my ear. "Don't let anyone see that card—if you want to stay in one piece. You'd better get out of here before they start asking questions. They won't wait for the Spaceport Police to get here. Too many of them will be in trouble if they don't find out fast where everyone stands. They'll know how to go about it."

I couldn't believe it for a minute, because I hadn't seen her come in. I'd noticed two women at the bar, but not this one—it would have been impossible for me to have failed to notice so slim a waist or hips so enchantingly rounded, or the honey-blonde hair piled high, or the wide, dark-lashed eyes that were staring at me out of a face that would have made a good many men with their lives at stake forget the meaning of danger.

Even if she'd been wedged in tightly between two male escorts at the bar, I'd have noticed a part of all that. Just one glimpse of the back of her head, with the indefinable, special quality that makes beauty like that perceptible at a glance, so that you know what the whole woman will look like when she turns, would have made so deep an impression on me that not even the violence I'd participated in a moment afterwards could have blotted it from my mind.

It left me speechless for an instant. I just snatched up the wallet, put it safely back in my pocket and returned her stare in complete silence.

"Better keep the gun," she advised. "Your fingerprints are all over it now. You could clear yourself all right, considering who you are. But it would be much simpler just to toss it into Lake Michigan, especially if they decide to let him go and lie about who did the killing."

I could have wiped the gun clean and tossed it on the floor, but I knew what was in her mind. You just don't leave a murder weapon lying around in plain view when you've picked it up right after a killing. It can lead to all kinds of complications.

I nodded and stood up. "Thanks for the advice," I said, finding my voice at last. "There are enough eye-witnesses here to convict him without this, if just a few of them have a conscience."

"Don't count on it," she said. "They're angry enough to kill him right now, because they don't like to see anyone gunned down like that. But when they've had time to think it over—"

She was right, of course. There were six or seven men struggling with the killer now but there were others who weren't. A fight had started near the middle of the bar and someone was shouting: "The ugly son deserved what he got! Every man who gets a Mars clearance now has to play along with the Colonization Board! He has to turn informer and help them set a trap for anyone who gets in their way. Just depriving us of our rights doesn't satisfy them. They're scheming to get the whole Mars Colony for themselves."

It was the Big Lie—the charge that had done more damage to the Mars Colony than the shortages of food and desperately needed construction materials, and almost as much damage as the two major power conflicts and the transportation difficulties that never seemed to get solved.

I wanted to go right up to him and grab hold of him and hit him as hard as I'd hit the Viking character, because he was a killer too—a killer of the dream.

But the blonde who seemed to know all the answers and what was wise and sane and sensible was tugging at my arm and I couldn't ignore the urgency in her voice.

"Time's running out on you, Mr. Important Man. If they find out just who you are, you won't have a chance of getting out of here alive. Every one of them will be clamoring for your blood. The pity of it, the terrible pity, is that most of them hate violence as much as you do. They hate what that wild beast just did. But the Big Lie has made them hate the Colonization Board even more. Do we go?"

It came as a surprise that she was leaving with me, and that was downright idiotic, in a way. With the place in an uproar, a killer still trying to break loose and a fight under way it would have been madness for her to stay, and the two other women had vanished without stopping to talk to anyone. But in moments of stress you can overlook the obvious and wonder about it afterward.

We had to move fast and we ran into trouble when two struggling drunks got in our way. I shouldered one aside and rammed an elbow into the stomach of the other and we reached the street without being stopped by anyone who didn't want us to leave. The card was back in my pocket and not a single one of them had X-ray eyes.

In another minute or two someone would have probably remembered that I'd disarmed the Viking character and could have had a reason for the fast violent way I'd gone about it. Then I'd have been in for the kind of questioning the blonde had mentioned—a kangaroo court interrogation before the Spaceport Police could get there. And if my answers had failed to satisfy them they would have wasted no time in turning my pockets inside out.

I'd been spared all that, thanks to that same blonde. And—I didn't even know her name!

We'd been talking for twenty minutes and I still didn't know her name. She wasn't being secretive or coy or holding out on me because she didn't trust me as much as I trusted her. I just hadn't gotten around to asking her, because we were both still talking about what had happened at the bar and it was so closely tied in with what was happening in New York and London and Paris and every big city on Earth—and on Mars as well—that it dwarfed our puny selves—extra-special as the blonde's puny self happened to be from the male point of view.

I didn't know whether she was Helen or Barbara, Anne or Ruth or Tanya. I just knew that she was beautiful and that we were sipping Martinis and looking out through a wide picture window at New Chicago's lakeshore parklands enveloped in a twilight glow.

The restaurant was called the Blue Mandarin and it conformed in all respects to the picture that name conjures up—a diaphanous blue, oriental-ornate eating establishment with nothing to offer its patrons that was new, original, exciting, unique.

But there it was and there it would remain—until Lake Michigan froze solid. For the moment its artificial decor wasn't important to either of us. Only the Big Lie and what it was doing to the Martian Colonization Project.

"My father was one of the first," she said. "Do you know what it means, to stand in an empty, desolate waste, forty million miles from home, and realize you're one of the chosen few—that a city will some day grow from the seeds you've planted and nourished with your life blood?"

"I think I do," I said. "I hope I do."

"He died," she said, "when he was thirty years old, from a Martian virus they hadn't discovered how to combat until two-thirds of the first two thousand colonists succumbed to it."

"Why didn't he take you with him?" I asked. "There were no passenger restrictions then. The Colonization Board had great difficulty in finding enough volunteers."

"My mother refused to go," she said. "I'm afraid ... most women are more conservative than men. Father died alone, and five years later Mother married a man who didn't want to be one of the first ten thousand—or the first sixty thousand. He had no problem. He wasn't like the men we saw tonight."

"If every man and woman on Earth wanted to go to Mars," I said, "the Colonization Board would have no problem. A demand on so colossal a scale could not be met—in a century and a half. And laws would be passed to prevent the scheming that's taking place everywhere, the hatred and the violence. The Big Lie would not be believed."

"I know," she said. "It's when only twenty thousand can go and five million want to go that you have a problem. A little hope filters through, and the five million become envious and enraged."

I looked at her. I was feeling the glow now, the warmth creeping through the cells of my brain, the recklessness that alcohol can generate in a man with a worry that looms as big as the Big Lie, to the part of himself that isn't dedicated to combating the Lie. The ego-centered, demandingly human part, the woman-needing part, the old Adam that's in all of us.

And suddenly I found myself thinking of Paris in the Spring, and the sparkling Burgundies of France and vineyards in the dawn and what it had meant to have a woman always at my side—or almost always—and in my bed as well.

New York, flag-draped for Autumn, London in a swirling fog, the old houses, the dreaming spires, anywhere on the round green Earth where there was laughter and music and a woman to share it with....

All that had been mine for ten years. But now, like a fool, I wanted Mars as well. Mars was in my blood and I could no longer rest content with what I had.

Take it with me to Mars? And why not? It was no problem ... when you didn't have my problem. A quite simple problem, really. The woman I'd married wouldn't go with me to Mars.

She seemed to sense that I was having some kind of inward struggle, and was feeling a decided glow at the same time, for she reached out suddenly and took firm hold of my hand.

"Something's troubling you," she said. "Why don't you tell me about it while you're feeling mellow. Considering the kind of world we're living in, mellow is the best way to feel. It wears off quickly enough and next day you pay for it. But while it lasts, I believe in making the most of it. Don't you?"

Should I tell her, dared I? I might have to pay for it with a vengeance, for she'd probably think me quite mad. And I still had some old-fashioned ideas about loyalty and happened to be in love with my wife.

It was crazy, it made no sense, but that's the way it was.

I looked at the woman sitting opposite me and wondered how a man could be in love with one woman and find another so attractive that he'd been on the verge of coming right out and asking her if she'd go with him to Mars.

I looked at her blonde hair piled up high, and her pale beautiful face and wondered how it would be if I hadn't been married to Joan at all.

I shut my eyes for a moment, thinking back, remembering the quarrel I'd had with my wife that morning, the quarrel I'd tried my best to forget over four straight whiskies at the spaceport bar late in the afternoon.

It was almost as if it was taking place again, right there at the table, with another woman sitting opposite me who could not hear Joan's angry voice at all.

"I mean every word I'm saying, Ralph Graham. You either tell them you're staying right here in New Chicago or I'm divorcing you. I won't go to Mars with you—tomorrow or next year or five years from now. Is that plain?"

It was plain enough. To cushion the shock of it, and ease the pain a little I stared into the fireplace, seeing for an instant in the high-leaping flames a red desert landscape and a city that towered to the brittle stars ... white, resplendent, swimming in a light that never was on sea or land.

All right, the first Earth colony on Mars wasn't that kind of a city. It was rugged and sprawling and rowdy. It was filled with tumult and shouting, its prefabricated metal dwellings scoured and pitted by the harsh desert winds. But I liked it better that way.

I wanted to walk its crooked streets, to rejoice with its builders and creators, to be one of the first sixty thousand. With my mind and heart and blood and guts I wanted to be there before the cautious, solemn, over-serious people ruined it for the kind of man I was.

"I mean it, Ralph," Joan said. "If you go—you'll go alone. All of my friends are here, all of my roots. I won't tear myself up by the roots even for you. Much as I love you, I just won't."

It was five in the morning, and we'd been arguing half the night. In two more hours daylight would come flooding into the apartment again, and I'd probably have the worst talk-marathon hangover of my life.

I suddenly decided to go out into the cool dawn without saying another word to her, slamming the door after me to make sure she'd realize just how angry she'd made me.

I wouldn't even switch on the five A.M. news telecast or stop to take in the cat on my way out. Women and cats had a great deal in common, I told myself bitterly. They were arbitrary and stubborn and mysteriously intent on having their own way and keeping you guessing as to their real motives.

By heaven ... if I had to go alone to Mars I'd go.

So I'd really hung one on, had gone out and made a round of the lakeside bars. All morning until noon and then I'd sobered up over coffee and a sandwich and started out again early in the afternoon. It just goes to show what a quarrel like that can do to a man's nerves and peace of mind and all of his plans for the future, for I'm not even a moderately heavy drinker.

Early morning bar traveling is barbarous, a lunatic-fringe pastime, and it was the first time in my life I'd resorted to it. But resort to it I did, and as the day wore on I gravitated from the lakeside taverns toward the spaceport in slow stages, and twice in five hours reached the stage where I couldn't have passed the straight-line test. If I hadn't sobered up a little at noon I'd have reached the big, dangerous bar as high as a man can get without falling flat on his face.

The Colonization Board hadn't even tried to stop what goes on there around the clock, because there are explosive tensions and hard to uncover areas of criminality in a city as big as New Chicago it's wise to provide a safety valve for—when Mars fever is running so high practically all of us are living in the shadow of a totally unpredictable kind of violence.

If anyone had asked me toward the middle of the afternoon what was drawing me, despite all of my better instincts, in the direction of death and violence I'd have come right out and told him.

I had Mars fever too. I hated the Big Lie and all of its ramifications, knew that every charge that was being hurled at the Colonization Board was untrue. But I knew exactly how all of the tormented, desperate men felt, the ones who fought the Big Lie and still had the fever and needed to be cradled in strangeness and vastness—needed space and a new frontier to keep from feeling strapped down, walled in, prisoners in a completely new kind of torture chamber.

The restlessness was growing because Man had lived too long in a closed-circuit that had almost destroyed him. The great barrier that was no longer there had brought the world to the brink of a universal holocaust, and just knowing that it had been shattered forever was enabling men and women everywhere to lead healthier lives, set their goals higher.

There was nothing wrong with that. Only—not one man or woman in fifty thousand would see with their own eyes the rust-red plains of Mars, and the play of light and shadow on a world covered over much of its surface with wide zones of abundant vegetation. Not one in fifty thousand would have a new world to rejoice in, after the long journey through interplanetary space. A world laden with springtime scents, in the wake of the crash and thunder of the polar ice caps dissolving.

Or possibly snow piled high on a sleeping landscape, with a thaw just starting, and the prints of small furry creatures on the white blanket of snow, for the first colonists had taken animals with them.

It would take another thirty years for newer, swifter rockets to be built and the supply problem to be brought under control and the colony to outgrow its birth pangs and its tumultuous adolescence and become a white and towering city, as huge as New Chicago.

And there were some who could not wait, for whom waiting was destructive to body and mind, a kind of living death too terrible to be sanely endured.

The fingers of the woman sitting opposite me were becoming restive, tightening a little on my hand. It seemed incredible to me that I could have gone off on that kind of thinking-back tangent when I was so close to paradise.

For paradise was there, seated directly across the table from me, in that crazy twilight hour, if I'd had the courage to seize it boldly—and if I hadn't been still in love with Joan.

I could still make a stab at finding out for sure, I told myself, if I brushed aside all obstacles, if I refused to let my mind dwell on how I'd feel if something happened to Joan and I lost her forever. How could she have been so stubborn and foolish, when she was sophisticated enough to know that no man is insulated against temptation when he is lonely and despairing and paradise can be his for the taking, if he can kill just one part of himself and let the rest survive.

"What is it?" she asked. "You haven't said a word for five minutes. I'm a good listener, you know. I always have been—perhaps too good a listener."

It was the moment of truth, when I had to decide. Mars—and a woman too. Mars—and the big, important job, and the clatter and bright wonder of tremendous machines, with swiftly moving parts, whirring, blurring, dust and the stars of morning, and a woman like that in my arms.

I had to decide.

"What is it?" she asked. "Can't you tell me?"

"Someday I'll tell you," I said. "But not now. I've a feeling we'll meet again. Where and how and when I don't know, because by this time tomorrow I'll be on my way to Mars."

A pained look came into her eyes and she quickly released my hand.

"But we've just started to get acquainted," she protested. "You know nothing about me—or hardly anything. I thought—"

"It might be best not to know," I said, and I think she must have realized then just how it was, must have read the truth in my eyes, for a faint flush suffused her face and she said quickly: "All right. If that's the way it must be."

I nodded and beckoned to the waiter, hoping she wouldn't suspect how vulnerable I still was, how dangerously easy it would have been for me to alter my decision.

Ten minutes later I was alone again, with Lake Michigan glimmering at my back, and only the stars for company. And I still didn't know her name.

It happened so suddenly it would have taken me completely by surprise, if the alarm bell hadn't started ringing again in some shadowy corner of my mind. It wasn't clamorous this time, but it was loud enough to make me straighten in alarm, with every nerve alert.

I was standing by a high wall of foliage, close to the lakeside and had just started to light a cigarette. All at once, directly overhead, there was a rustling sound that was hard to mistake, for I'd heard it many times before, and it had a peculiar quality which set it apart from all other sounds.

Something was moving through the shadows above me, rustling dry leaves, slithering down toward me with a dull, mechanical buzzing.

The buzzing stopped abruptly and there was a flash of brightness, a long-drawn whining sound. I braced myself, letting my arms swing loosely at my side.

With startling swiftness something long, glistening and snakelike descended upon me and wrapped itself around my right leg just above the knee. Before I could shake it loose it contracted into a tight knot and the whining turned into a shrill scream, prolonged, ghastly. It was quite unlike the scream of an animal. There was something metallic, rasping about it, as if more than animal ferocity was giving voice to its pent-up rage in a shrill mechanical monotone.

The constriction increased and an agonizing stab of pain lanced up my thigh. I raised my right arm and brought the edge of my hand down with an abrupt, chopping motion. I chopped downward three times, not at random, but with a calculated, deadly precision, for I knew that a misdirected blow could have cost me my life.

I was in danger only for an instant, and not a very long instant at that. The damage I'd done to it caused it to release its grip on my leg, shudder convulsively and drop to the ground.

Damaged where it was most vulnerable, it writhed along the ground with groping, disjointed movements of its entire body. Tiny fragments of shattered crystal glistened in its wake, and two long wires dangled from its cone-shaped head.

Its segmented body-case glowed with a blood-red sheen as it writhed across a flat gray stone on the edge of the lakeshore embankment, and reared up for an instant like an enormous, sightlessly groping worm. Then, abruptly, all the animation went out of it, and it flattened out and lay still. Both of the optical disks which had enabled it to move swiftly through the darkness had been smashed. I was no longer in any danger and it was very pleasant just to know that.

Very pleasant indeed.

An attempt had been made on my life. There could be no blinking the fact. That little mechanical horror, with its complex interior mechanisms, had been set upon me from a distance with all of its electronic circuits clicking by remote control.

From just how great a distance I had no way of knowing. But I didn't think he'd be staying around, near enough for me to get my hands on him. Killers who made use of such gadgets usually kept their distance, and were very cautious.

But at least I knew now that I had a dangerous enemy, someone who wanted me dead. And there was nothing pleasant about that.

The human mind is a very strange instrument and it's hard to predict just how profoundly you'll be upset by an occurrence that's difficult to dismiss with a shrug.

You can either turn morbid and brood about it, or rise superior to it and pigeon-hole it, at least for the moment. By a kind of miracle I was able to pigeon-hole it, to keep it from standing in the way of what I'd made up my mind to do before I'd heard the rustling in the foliage directly overhead.

I walked back and forth for a moment, resting most of my weight on my right leg, to make sure I could keep using it without limping and when I was satisfied a long walk wouldn't be in the least painful I left the embankment with a feeling of relief and took the first turn on my left. I was pretty sure it would take me no more than twenty minutes to get back to the spaceport.

I knew that what I'd made up my mind to do wasn't going to be easy. I had to find out exactly how important a job the Colonization Board had mapped out for me on Mars. She'd called me "Mr. Important Man" because—you don't get a clearance stamped the way mine was unless there's a big undertaking in store for you which has to be handled in just the right way. The walk gave me a chance to think about it. My leg didn't trouble me at all and I was very grateful for that.... I stood for a moment just outside the spaceport's railed-off, electronically-protected launching platforms, staring up at the three-hundred-foot passenger rockets gleaming with a dull metallic luster in the moonlight, their nose-cones pointing skyward.

The New Chicago Spaceport has and always will attract sightseers, because there's no other rocket launching site on Earth that can compare with it. It's not only the largest and the most elaborately equipped. It was built to last. Fifty years from now, in 2070, say, it was a safe bet the big Mars rockets would be taking off at four-hour intervals night and day. Now they took off only twice a month and there were fifty million people in the United States alone who would have given up comfort, leisure, a well-paying job and every joy they'd ever experienced or could hope to experience on Earth to be on one of those big sky ships.

As far back as I can remember I'd hated to force a showdown with people who trusted me and believed in me. And that went double for the Martian Colonization Board, whose members were doing everything possible to keep me informed. Secrecy sometimes has to be imposed, and if you try to crack an information clamp-down prematurely you deserve to be slapped down.

But now I had no choice. I had to find out if my trip could be postponed, if I could wait one more week—a month, even—to get Joan to see things my way. And that meant I had to find out just how big a job they had lined up for me.

I had no trouble getting in to see him. There was a guard at the main entrance of the Administration Building, and when I identified myself and the massive, double-doors swung inward I had to go through it a second time, and six more times in all before I reached his private office on the twentieth floor. But you couldn't call it trouble, because all I had to do was take out my wallet and display the pale blue card that was only an incitement to violence in certain quarters.

In that massive, almost half-mile-long building, on every floor, there were guards who knew me and guards who had never set eyes on me before. But what that card stood for was treated with respect.

I'd known that building to hum with activity, to come to life with a roar. But now only one floor blazed with light and the rest of the building was as silent as a mausoleum.

It happens sometimes and when it does everyone is grateful—including the man I'd come to visit.

His private office was at the end of a long corridor in Section C 10 Y, and I knew I'd find him there, because a small circle of cold light had been glowing above the office listing board on the main floor. There was a name plate above the numbered listings—BROWN. His name wasn't Brown, of course. Or Smith, or Jones. The "Brown" was just a safety precaution—the sign and seal of immense power being modest in a genuine way and for expediency's sake as well.

No man without the kind of card I carried had ever gotten as far as that office listing board and I doubt if the most ingenious assassin would have cared to try. But it was just as well to be on the completely safe side.

A saluting guard stepped back and what was perhaps the narrowest, least impressive door in the entire building opened and closed and I found myself in his presence.

Unless you're a Gobi desert dweller or live in the precise middle of the Sahara you've seen the blue-eyed, mild-mannered little man who was Jonathan Trilling on a hundred lighted screens. In all respects but one he is the kind of man most people would go right past on the street without a second glance.

The thing that made him really not like that at all was something you couldn't pin down and analyze. If you tried, you'd get nowhere. But it was there, all right, an emanation you couldn't mistake that stamped him for what he was, radiating out from him.

Equate immense simplicity with immense power and you might come up with a part of the answer. But not all of it.

The office was stripped of all non-essentials; a hermit's cell couldn't have been barer. And it seemed to please him when my eyes swept over the almost bare desk, with just an inkwell and a single sheet of paper on it, before coming to rest on his face.

I'm pretty sure he interpreted it as an indication that I was trying to catch him up on something he took pride in, and he admired me for it, and greeted me with a chuckle.

"Well, Ralph!" he said. "I didn't expect to see you here tonight. I thought you'd be home wearing Joan's patience ragged with the kind of last-minute preparations women never seem to understand. They like to think they never forget anything. But they do. They're worse that way than we are, but just try getting them to admit it."

There was only one chair in the office and he was occupying it. I hardly expected him to get up and wave me toward it, but that's precisely what he did.

"Sit down, Ralph," he said. "I sit too much. We all do here, I guess. Can't be helped, but it doesn't give a man of fifty-five much chance to get the exercise he ought to have, if he's going to keep his weight down."

"No—don't get up for me, sir!" I said, then realized I was being unnecessarily formal.

The chair was empty and he expected me to take it. And I could see that he didn't like the "sir." He never had.

"Sit down, sit down. What is it, Ralph? Something worrying you? You'll have plenty of time for that when you get to Mars. Why start now?"

I decided to come right out with it. I favored bluntness as much as he did, and there was nothing to be gained by talking around what I'd have to ask him before I left.

"There's something I'd like to know," I said. "Is the major part of my assignment still under wraps, or could you tell me more about it—even if you'd prefer not to?"

He looked at me steadily for a moment, his lips tightening a little. "Well—I certainly haven't kept it a complete secret, Ralph. You'll get full instructions in code later on. There's naturally a reason for that. I shouldn't have to go into it, because we've discussed it at great length right here in this office."

"I realize that," I said. "But could you see your way clear to telling me much more than you have, if I can convince you that it would help me solve a problem I can't solve otherwise."

His eyebrows went up a little at that. "What kind of problem, Ralph?"

"It's as old as the hills," I said. "The really ancient kind with fossils embedded in them. It goes right back to the Old Stone Age, and maybe a lot earlier. Joan doesn't want to go to Mars. She's very stubborn, very determined about it. If I can't make her change her mind I'll have to go alone. And I guess I don't have to tell you what that would do to me. If I just had a little more time, another week or two—"

"So that's it," he said. "You want me to tell you that your assignment can be put off, that you're not really needed on Mars. We're just sending you there because we like to do whimsical things occasionally, to break the God-awful monotony of thinking about the problems the project is confronted with in a serious way."

I was startled, because I'd never known him to indulge in deliberate irony before. He had all the intellectual equipment for it, but his mind just didn't work that way.

Then I suddenly realized he was going to tell me everything I wanted to know and had just used that approach to make me a little angry and keep me alert and analytical, so that I wouldn't underestimate the seriousness of what he was about to say.

"All right, Ralph," he said. "I'll risk angering a third of the Board. I'm going to tell you exactly why the Mars Colony is in trouble, and just how tremendous your task will be. You'll be in the middle, Ralph, in the biggest clash of interests a new and growing society has ever known.

"A clash of interests can destroy any society, if they're violent enough and have powerful enough backing and the population is divided in its loyalties and lacks firm and courageous leadership.

"That's especially true if the society is on a pioneering level, with serious scarcities developing everywhere and with every man, to some extent at least, in fierce competition with his neighbors, all apart from the massive power monopolies that are in even fiercer competition among themselves.

"Don't you see, Ralph, don't you realize what that kind of cross-purpose distribution of power in a new and pioneering society can mean? When you have a three or four-way conflict, when everyone is bidding for what you've got and can't afford to sell, or what you haven't got but would like to sell, or what you can't sell for what you'd like to get?"

He smiled suddenly, for the barest instant, and then the seriously concerned look which the smile had replaced came back into his eyes. "I didn't intend that to sound facetious. It probably did, because it has a slightly humorous side to it, like most major tragedies. I'm just giving you the broad outlines now, the general situation. Frustration, bitterness, thousands of colonists who can be swayed one way or the other by corrupt pressures, self-interest, greedy power monopolies."

"But there's a more specific situation you have in mind, is that it?" I asked. "Everything you've just said is common knowledge."

Trilling nodded. "Yes—but the general situation has to be underscored. It is the crucial factor in everything that is taking place on Mars. In a more stable, and highly developed society the raw power conflict of the two major power monopolies would not take so destructive a form."

"Two?" I said. "I was under the impression—"

He waved my objection aside. "Oh, there are a dozen power combines. But only the two giants—Wendel Atomics and Endicott Fuel—have fought each other to a standstill and threaten the peace, and stability of the entire colony. I'm putting it too mildly. There's an explosive potential in that conflict that could destroy the colony overnight."

He tightened his lips and took a turn up and down the office, then came back to where I was sitting and gripped me by the shoulder. "Ralph, listen. This is vital. I'll try to sum it up as briefly as possible. You know what it cost to set up atomic generators, turbines, transmission lines, and keep utilities no city can do without in operation right here in New Chicago, in just one small section of the city? How much more do you think it costs to do the same thing on Mars? The transportation of materials alone—Have you any idea how much the total expenditures come to?"

"I guess so," I said. "I don't like to think about it."

"Who does? But we had to think about it. We had to give Wendel Atomics a thirty-year monopoly. No other power combine had sufficient monetary resources to undertake it. And we had to give Endicott Fuel the same kind of monopoly. They transport both atomic and liquid fuels at a cost that would turn your hair white."

"And now you say they're locked in a power conflict. But why? I should think Wendel Atomics would purchase all the fuel it needs directly from Endicott. And Endicott would—"

I paused, troubled.

"What would Endicott do, Ralph? It has no use for atomic generators. It isn't geared to install them, even if it could somehow absorb the terrific expense of transporting them. And that, of course, would be impossible. No combine is wealthy enough to undertake that kind of two-pronged enterprise."

"But it wouldn't have to be a two-way exchange of commodities," I said. "Not if Wendel continued to buy all of its fuel from Endicott. It would, of course, have a tendency to dwarf Endicott, make it the lesser of the two monopolies."

"It would do more than that, Ralph. It could bankrupt Endicott. You see, Wendel Atomics suddenly decided it was paying Endicott too much for the fuel it used, and cut the price it was paying in half. And Endicott could barely meet expenses."

"Good Lord," I said.

"Naturally Wendel Atomics couldn't get along without fuel," Trilling said. "And it couldn't transport fuel for its own exclusive use from Earth. The two-pronged enterprise factor again. So Endicott struck back by refusing to sell its fuel to Wendel."

"A complete stalemate, you mean?"

"Not quite, Ralph. If it were, one side or the other would have to give in eventually. Endicott seized on the bright idea of selling atomic and liquid fuel directly to the Colonists. A wildcat kind of madness. The colonists buy the fuel on margin and wait for the price to skyrocket. And every so often it does, because Wendel has to keep its generators operating. It won't buy from Endicott, but it has no choice but to buy from the colonists.

"Do you realize what such wild and dangerous wildcat speculation can do to a new, rough-and-tumble, frontier kind of society, Ralph? The colonists don't know whether they're rich or poor from one day to the next. And with all their desperate needs, their frustrations, their scrambling after scarce goods and services, their fierce competitiveness, they are at each other's throats half of the time."

"I'm beginning to get the picture," I said.

"It's a very ugly picture, Ralph. Wendel Atomics buys its fuel sporadically, cheats, steals, connives, beating the price down artificially and then sending it skyrocketing again. It has its own private police force. Translate—brutal roughnecks who know exactly how to keep the colonists in line and frighten them into selling when the fuel market sags and spending every cent they possess to buy more fuel on speculation when the price soars.

"Endicott doesn't care what happens to the colonists. It's out to make Wendel Atomics come to terms and has methods of its own to keep the colonists inflamed and reckless. The whole situation has even taken on a political cast. There are pro-Wendel colonists, who work hand in glove with the Wendel police and colonists who would willingly lay down their lives in defense of noble, altruistic Endicott. It's the right of everyone to buy fuel on speculation, isn't it?"

"I see," I said. "And my job will be to step right into the middle of all that, and try to bring order out of chaos."

Trilling didn't say anything for a moment. He just looked at me, but his gaze was not unsympathetic.

"There's something I'd like to have you hear, Ralph," he said, when the silence had lengthened between us and become almost minute-long. "We have a new, round-the-clock recording to replace the one we've been transmitting at intervals, night and day, for five years. I won't even ask you how many times you've heard it, because you travel around a lot and must have memorized it word for word. But this one is better, I think. At least, it appeals to me more. A hundred million people will hear it, starting tomorrow. It will be on every tele-screen."

He bent over his desk and removed a miniature tape-recorder from the upper right hand drawer. He set it down on the desk and clicked it on.

"Just one passage I'd like you to listen to, Ralph. Not the whole recording. This is it—"

The voice that came from the tape was a very good reading voice, one of the best I'd ever heard. The man was probably a poet. But the words themselves interested me more.

"... so bright with promise has Man's future become that all of the old animosities, the old hates, will soon seem alien to us and strange. A new world is in the making. Who can deny it? The colonization of Mars has fulfilled the deepest instincts of Man's nature, and provided scope for a growth that is as natural to him as breathing.

"The desire to know more, to explore the unknown, to reach out toward constantly expanding horizons can only be satisfied by boldly accepting what the advance of modern science has brought within our grasp. The colonization of Mars is a tribute to Man's stubborn refusal to be easily discouraged or to let mechanical difficulties, no matter how formidable, stand in his way. A tribute as well to his constructive genius, his daring and breadth of vision."

Trilling clicked the tape recorder off, returned it to his desk, and turned to face me again.

"That, Ralph, is the dream," he said. "You and I know what the reality is like. But the millions who will listen to that recording do not. They still believe—and hope."

I was silent for a moment, not quite sure how he'd take what I was going to say. I went over it in my mind, searching for just the right words. It took me a full minute to find them, but he didn't grow impatient.

"I'm not sure the Board is wise in putting out that kind of propaganda. Or any kind of propaganda. After all, we're not trying to sell Mars to anyone. We're doing something that has to be done—you might almost say we're just trying, in a very earnest way, to plug up a gap in the biggest dam that was ever built, to keep the flood waters from carrying us all to destruction."

"You're wrong, Ralph," he said. "It isn't just propaganda. A dream always has to go striding on ahead of reality. It may seem strange to you, but the reality does not frighten or discourage me. Mars is a new world and on a new world there has to be—not one, but many beginnings."

He paused an instant, then added: "That's why we're sending you to Mars, Ralph. There will have to be another beginning. It won't show too much on the surface. No matter how successful you are, for the colony will remain what it is basically—an experiment in survival. All of a new world's energy will remain, and the turbulence and the hard-to-endure disappointments. But you can help the Colonists go back, and feel the way they did when the first passenger rocket settled down on the red desert sand forty million miles from Earth and the Space Age took on a new dimension."

There was only one small window in Trilling's office. But I could see that the sky outside was still bright with stars, and the glimmer of the ceiling lamp made the metal surface above us seem to fall away and dissolve into a much wider expanse of star-studded space.

The ceiling-mirrored image of the lamp itself looked like the Sun, blazing in noonday brightness directly overhead and out beyond were galaxies and super-galaxies strung like beads on a wire across the great curve of the universe.

It was just an illusion, of course. You could see the same thing in the light-mirroring depths of a glass of wine, if you stared hard enough. But for an instant it seemed to bring bigness, vastness right into the room with us.

I was conscious of the silence again, lengthening, hanging heavy between us, as if we'd each said too much, or possibly ... not quite enough.

Then Trilling bent and removed something else from his desk. I couldn't see what it was until he set it down directly in front of me, because it was much smaller than the midget tape recorder and his hand covered it.

A flat metal box, wafer-thin, doesn't provide much scope for speculation, and I was pretty sure that the object inside was a tiny metal precision instrument or a watch or a medal even before he said: "This should make Joan change her mind, Ralph!" and snapped the box open.

The insignia caught and held the light, a two-inch silver hawk with its wings outspread. The white lining of the box made it stand out, as if it were flying through fleecy clouds high in the sky, and symboling in its flight far more than just the elevation of one man to the highest command post the Martian Colonization Board had the authority to bestow.

The significance of that finely-wrought, seldom-worn silver bird was not lost on me. In the maze of a hundred legends, a hundred witness-confirmed stories of triumph and disappointment, of heroic progress and tragic back-tracking, it had remained an important link between Earthside expectations and what was actually taking place on Mars.

Only one man could wear it at any one time, and only four men had worn it since the establishment of the colony. All four were dead now, their gravestones a white gleaming on the red desert sand a few miles north of the colony.

"Well, Ralph?" Trilling said.

I tried hard to maintain my composure, to say just the right thing, because I'd lived long enough to know there are depths beyond depths to some emotions that can't be put into words. Attempt to talk the way you feel, and you're sure to sound a little ridiculous. I was only certain of one thing. No man could wear that insignia and not feel, resting upon his shoulders, a responsibility so tremendous that whatever pride he might take in it would have to be tempered by humility—if he wanted to go on wearing it for long.

Trilling seemed aware of what was passing through my mind, for he made it easy for me. He simply smiled, snapped the box shut with a briskness that was almost casual, and handed it to me.

"You've got real massive military prestige now, Ralph," he said. "Right at the moment the Board would be gravely concerned if you wore that insignia in public. But there's nothing to prevent you from wearing it in the privacy of your own home. Later on the Board may decide you can accomplish more by coming right out and letting the colonists know there's a lion in the streets who intends to do more than just roar. A safe, protective kind of lion—dangerous only to over-ambitious men with destructive ideas."

I started to reply but he waved me to silence. "Hold on, Ralph—let me finish. You won't be wearing that insignia in public straight off. But I hope you'll have enough good sense to make the best possible use of it to overcome the first really big obstacle in your path."

He nodded. "It will be a kind of blackmail, in a way—morally reprehensible. You'll be taking advantage of something it isn't in a woman's nature to resist. But you have no choice. You've got to go to Mars and if you went alone you'd be about as useful to us as a celibate kangaroo, all packaged and ready to be sent on a journey to the taxidermist."

He seemed to realize it wouldn't have to be quite that drastic, for he grimaced wryly. "All right, all right. You could go out and find another woman and I probably could talk the Board into being the opposite of stuffy about it. But I happen to know what kind of man you are, and how you feel about Joan. I could be wrong, but I'm pretty sure she's the only woman in the world for you."

There was nothing I could say to that. I had the insignia in my inner breast pocket, and I knew that there were few obstacles it couldn't blast away on Earth or on Mars, if I kept remembering what it symbolized with Joan at my side.

I went out into the cool night again, past that long tremendous building with just one of its floors ablaze, past the big sky ships looming like sentinel ghosts on their launching pads, past winking lights and speeding cars and pedestrians walking slowly and something inside of me made me feel I'd undergone a kind of sea change, and could face whatever the future might hold without grabbing for a life-line that didn't exist.

It was a good way to feel. A man had to sink or swim without having a life-line thrown to him—if he hoped to live long enough to change things around in an important way on Mars. He had to keep his head and breast the raging currents with the sturdiest kind of overhand strokes, or be drawn down into the undertow and battered senseless against the rocks that lined the shoreline.

The change must have shown a little on the surface, in the set of my jaw or just the way I was walking, because no less than three pedestrians turned to stare at me as I went striding past them on my way to the New Chicago Underground.

I was almost at the northern entrance of the big, tree-lined square directly opposite the Administration Building when it hit me—the memory-recall, the swift emergence from its cubby-hole deep in my mind of the narrow brush I'd had with Death and hadn't even discussed with Trilling.

It had been a mistake not to discuss it, because it concerned the Board as much as it did me. Someone who knew about the insignia—or had made a shrewd guess as to just how big a job was awaiting me on Mars—had wanted me dead. The attempt on my life took on a much larger, more crucial dimension when viewed in that light.

There were three hundred million people in the United States, and if I'd been just a private citizen, with no more than my own safety at stake, I could have lost myself in that immense ocean of humanity for a week or a month and gained a brief respite. There are plenty of ways you can protect yourself against a surprise attempt on your life, if you have the time to take safety precautions. When there's a would-be assassin at large who is dead set on measuring you for a coffin you have to work the problem out carefully, with a minimum of risk.

It takes skill and psychological insight, but it can be done. You've just got to remember that an assassin is never quite normal. Even when a socio-political motivation is the governing passion of his life you're one jump ahead of him the instant you've figured out exactly how his mind works.

In fact, one of those safety precautions could have been protecting me as I crossed the square, if I hadn't let my stubborn pride stand in the way. Why hadn't I asked Trilling to provide me with armed protection?

Two alert bodyguards, trailing me on the street and down into the Underground and standing watch outside my apartment all night long—and staying fifty paces behind me until the Mars' rocket zero-count ended and the big sky ship took off with a roar ... would have given the Board the kind of reassurance they had a right to expect.

I started to turn back, then changed my mind abruptly. I'd taken just as great a risk by walking from the lakeside to the skyport right after the attack, hadn't I? And I'd be in the Underground in another three or four minutes, with people around me and—

All right. It was an out-of-focus rationalization and nothing more—an attempt to find an excuse for not turning back. But when I do something reckless for complicated reasons, when I've forged ahead despite my better judgment, I'm usually just impulsive enough to carry the folly-ball all the way across the goal line.

It was the thing I'd have to guard most against on Mars, that damnable twisted pride and impulsiveness, that taking of too much for granted when I started to do something I knew was unwise, but had an overpowering urge to carry out anyway.

Every weaving shadow beneath the double row of trees that towered on both sides of me could have cloaked a crouching figure adjusting another small mechanical killer to the deadliest possible angle of flight. But I had another reason for not wanting to go back. Trilling might fall in with the armed guard idea but I doubted it like hell. I could picture him saying instead: "Ralph, even an armed car can be blown up. You're staying under lock and key all night ... right here in the Administration Building."

I could even picture him saying much the same thing to Joan, her image bright enough on his office tele-screen to be visible from where I'd be standing: "He's not coming home tonight, Joan. We're sending an armored car to pick you up in the morning. Wait, hold on—I'll let you talk to him!"

And I could almost hear her replying: "Don't bother to send the car. I'm not going with him. Please don't think too harshly of me, please try to understand. I just can't—"

I started down the long boulevard on the far side of the square, still walking rapidly and feeling suddenly confident I'd been justified in not turning back. I could see the entrance to the Underground glimmering in the darkness a hundred feet ahead of me and there were people all around me walking in both directions. I wasn't even troubled by the feeling that everyone gets at times—that something terrible and unexpected can happen right in the midst of a crowd, if only because the presence of many people exposes you to a dangerously wide range of unpredictable human emotions.

For the barest instant, when I crossed the narrow strip of pavement directly in front of the kiosk, fear tugged at my nerves and I felt myself growing tense. But I became calm again the moment I looked around and saw that the only pedestrian within thirty feet of me was a hurrying girl with a portfolio under her arm. When she saw how intently I was staring at her she frowned and a look of annoyance came into her eyes.

Oh, for God's sake, I told myself, get rid of this nagging uncertainty, and stop behaving like a fool. If he intended to try again tonight I'd know by now. He's missed a dozen very good chances, so something must be making him super-cautious, if he hasn't keeled over just from the strain of watching me refuse to die. Killing's never easy, even for a professional. It must be a little like being cut open, watching your own blood pouring out of you, because all violence inflicts a two-way trauma ... severe enough at times to make even a mad slayer fling down his gun before going on a rampage of indiscriminate slaughter.

There were arguments I could have used to wrap it up even tighter—such as the way he'd be trapped and blasted down almost instantly if he launched another attack on me so close to the spaceport's three interlocking, hyper-sensitive security alert systems.

But I didn't even pause to weigh them, because right up to that minute I'd done very well, and the fear which had come upon me had been as brief as an autumnal flurry of wind when you're coming around a tall building at breakneck speed.

I let the girl dart past me, taking my time, and in another five seconds was descending into the big, brightly lighted cavern that was New Chicago's intercity pride.

As every school kid knows, the New Chicago Underground is six years old, and is the largest, smoothest-running transportation system in the world. It cost seven billion dollars to build and has almost as many tracks and suburban off-shoots as station guards.

It interlocks, spirals outward in a half dozen directions and circles back upon itself. In a way, it's like the serpent you see in bas-reliefs dating back three thousand years, in Babylonian and Pre-Dynastic Egyptian tombs, for instance, or on totem poles in the Northwest ... a serpent that's continually swallowing its own tail. It's the oldest archeological art-form on Earth and is supposed to symbolize Eternal Life.

But to some people at least the New Chicago Underground symbolizes something far more gloomy. If you're not careful to board just the right train you can get lost in its tomblike, spiraling immensity and feel as helpless as a wandering ghost or an experimental laboratory animal caught up in a blind maze. You can be carried fifty miles in the wrong direction and look out through the windows of a train traveling at half the speed of sound, and see a country landscape or the wide sweep of Lake Michigan five minutes after you've settled down in a comfortable chair and become absorbed in the news of the day on micro-film.

You'll stare out and the section of the city where your home is located just won't be sweeping past. You'll have to get off at the next station, perhaps twenty or thirty miles further on, ride back, and board another train. It's seldom quite as frustrating as that, but only because most of the riders have been conditioned to keep their wits about them through a nightmare kind of trial-and-error apprenticeship.

You've got to stay alert until you've boarded a train with just the right combination of numerals on its destination plate. It isn't hard to do, unless you're carrying a tiny silver hawk in a wafer-thin case, and your destination may be changed without warning and with unbelievable infamy by someone capable of great evil who would much prefer not to have you board a train at all.

I could almost picture him weaving in and out between the platform crowds—faceless so far, but quite possibly glassy-eyed with little waltzing death-heads in the depth of his pupils. An unknown human cipher intent on my destruction, refusing to be discouraged by the failure of a small mechanical killer to do the job for him.

If I'd had a strong reason to believe I actually was being followed, if he'd come right out into the open and I could have caught a glimpse of him, however brief, I'd have felt a subconscious relief that would have kept me on guard and confident. It would have given me an edge that not even the fact that I had no gun could have taken away from me.

It's the unknown and unpredictable that's unnerving, the realization that invisible eyes may be scrutinizing you from a distance and the brain behind them deciding that it would be a great mistake to let a failure of nerve or concern for the consequences interfere with what had to be done.

He wouldn't be wanting me to wear that insignia ever—on Earth or on Mars—and just knowing that made me almost miss my train as it came rushing toward me.

The train was so crowded I had to stand, but I had no complaint on that score. In a seat, with people jamming the aisle in front of me, I'd have been wedged in even more securely. In a standing position I could edge forward and back and keep an eye on the passengers who were holding fast to the horizontal support rail on both sides of me.

There were twenty-five or thirty passengers wedged into the middle section of the train, all standing in slightly cramped postures and most of them unsmiling. I knew exactly how they felt. Not being able to get a seat in an off-hour in the evening can be irritating. But right at the moment there was no room in my mind for annoyance. A slow, hard-to-pin-down uneasiness was creeping over me again, as if a pendulum were swinging back and forth somewhere close to me, ticking out a warning in rhythm—and I couldn't shut out the sound of it.

Just my over-strained nerves, of course. How could it have been anything else? I turned and looked at the man standing next to me. He was middle-aged, conservatively dressed, and had a square-jawed, rather handsome face, with a dusting of gray at his temples.

He was frowning slightly and his expression didn't change when I broke the rule of silence which was customarily observed in the Underground.

"No reason for all the seats to be gone at this hour," I said.

The crazy kind of over-exuberance mixed with peevishness that makes some people say things like that to total strangers a dozen times a day had always seemed inexcusable to me. But when you're under tension you sometimes break all the habits of rational behavior you've imposed on yourself in small matters.

My excuse was that I simply wanted to test the firmness and steadiness of my own voice, to make sure that, deep down, I wasn't nearly as apprehensive as I was beginning to feel.

"Yes, I know," the gray-templed man agreed. "It burns me up a little too. But I guess it just can't be helped at times. Operating an Underground this size must be an awful train-scheduling headache."

"Headache or not," I said. "There's no excuse for it."

He smiled abruptly, exposing large, white teeth and I noticed that there was something almost birdlike in the way his eyes lighted up. Small, black, very bright eyes they were, under short-lashed lids, and quite suddenly he made me think of a magpie alighting on a limb, taking off and alighting again, hardly able to restrain an impulse to chatter.

"What it boils down to," he said, "is the old quarrel between a pedestrian and a man in a car. Neither can understand or sympathize with the other's point of view. Fifteen million people ride this Underground every day and to them it's a poor slob's service at best. That's because they feel themselves to be the victims, at the receiving end. But you've got to remember that safety precautions pose a problem. Avoiding accidents comes first and the New Chicago Transportation System, considering its colossal size, does pretty well in that respect."

"People have been killed," I said, and could have bitten my tongue out. Why let him even suspect that I was thinking about something that wasn't tied in with his argument at all, why give him the slightest hint? The Underground's accident record was good and couldn't have justified such cynicism on my part. And just suppose he wasn't the garrulous, middle-aged business man he appeared to be—

A very sinister game can start in just that way, with everything favoring the alerted party until he lets the other know that he's on his guard and is having uneasy thoughts. That's where the danger lies, in a subconscious betrayal, a slip of the tongue that will precipitate violence faster than it would ordinarily occur.

If a killer feels that he must move swiftly, before suspicion can become a certainty, the odds shift in his favor. He has the advantage of surprise. He becomes alerted too, and necessity acts as a goad—a kind of trigger-mechanism. He'll act more quickly and decisively, without the careful planning that may prompt him to talk too much and give himself away.

He'll take risks that are dangerous and could destroy him, strike with witnesses present and all escape routes blocked. If he has to, he'll strike even in a crowded Underground train with the next station minutes away. And that kind of audacity sometimes pays off.

I told myself that I was imagining things, jumping to a completely unwarranted conclusion. The conversation of the man next to me was exactly what you'd expect from a magpie. He was carefully sidestepping all realistic appraisals of the Underground's shortcomings, trying his best to look at the problem from all sides, even if it meant being shallow and over-optimistic. He was the citizen with a smiling face, the rather likeable guy—why should one hold it against him?—who was trying his best to be fair to everybody, even if he had to burst a blood-vessel doing it.

Realizing all that made me feel less tense and part of the nightmare feeling I'd been experiencing went away. But not quite all of it and when the train passed into an unlighted tunnel and the aisle went dark apprehension began to mount in me again.

What if he was putting on an act, and wasn't the kind of man he appeared to be at all? What does a killer look like? Certainly age had nothing to do with it. He can be young or old—eighteen or seventy-five.

His appearance, his clothes? There were wild-eyed killers with "psycho" stamped all over them, and dignified, soberly-dressed men who looked no different from your next door neighbor and had criminal records a yard long, including, in all likelihood, a murder or two the Law would have a difficult time proving.

I didn't have to speculate about it. I knew, because I'd done more than my share of social research. There was nothing to prevent a man of distinction from becoming a killer, if he had a secret life that was ugly and devious and a powerful enough motive.

But now he was talking again, despite the darkness, and I was listening with my nerves on edge. I was completely in the dark as to why something about him had set the alarm bells ringing but I was sure I could hear them, very faint and distant this time, but clearly enough. It was funny. Sometimes it meant something and sometimes it didn't. I could feel that danger was hovering right at my elbow and in the end discover I'd been completely mistaken.

I hoped I was mistaken this time, but I knew there was a possibility—remote, perhaps, but dangerous to ignore—that the man who had set the small mechanical killer in motion by the Lakeside had followed me from the Administration Building into the Underground and was standing by my side.

"You take one of the really big power combines," he was saying. "Like, say, Wendel Atomics. It has its defenders and detractors, and I daresay there are quite a few people who would be happy to see its Board of Directors behind bars. I'm not defending the Wendel monopoly, understand. If I was a Martian colonist I might feel quite differently about it. But you've got to remember that when you give the go-ahead signal for a project that big you're asking fifty or a hundred key executives to do the impossible—or pretty close to the impossible."

"The impossible?" I said, trying to sound no more than mildly interested, because I didn't want him to suspect what a jolt his mention of Wendel Atomics had given me.

"Oh, yes," he went on. "That's what it boils down to. Every one of those men will be as human as you or I. They'll react in highly individual ways to every problem that comes up, every frustration, every serious interference with their private lives. You've got to remember that a man's private life is the most important thing in the world—to him personally. Every one of those fifty or a hundred men will have health worries, money worries, love life worries, every kind of worry you can think of. And on Mars worries can pile up."

"So I've heard," I said.

"Well, that's all. That sums it up. I'm simply citing Wendel as an example of what the New Chicago Transportation System is up against. I'd say, in general, that most of the directors are doing their best, when the Old Adam in them isn't in the driver's seat, to keep the trains running on schedule."

He stopped talking abruptly. I didn't think anything of it for a moment, for a loquacious man will often pause in the middle of a conversation to wonder what kind of dent he's been making on the party who's doing most of the listening. But when a full minute passed and the darkness held, and he didn't say a word, when I couldn't even hear him breathing, I began to grow uneasy.

Reach out and touch him? Well, why not? It was the simplest, quickest way of finding out whether he was still at my side and he could hardly be offended if my hand grazed his elbow in a jostling motion that would seem accidental.

It was very strange. I didn't think he was the man I'd feared he might be any longer, because of what he'd said, because he had brought Wendel Atomics into the conversation. If he'd had designs on my life giving his hand away like that would have been the height of folly. It would have been like giving me cards and spades, and a detailed history of his activities for the past five years.

It didn't take any gifted reasoning to figure that out and I didn't pride myself on it. Even a child could have done it. What disturbed me and kept me from feeling relieved was something quite different. The alarm bells were still ringing. They were still ringing.

Louder now and with a dirgelike persistence, as if I was already dead and buried. And neither a child nor a grown man could have figured that one out.

That's why I felt I had to reach out and touch him, had to start him talking again ... had to be sure he was still there at my side.

He was there, all right. He was there in the most alarming possible way, as a dead weight lurching against me, then swaying and screaming as I tried to straighten him up, and stop the terrible downward drag of his sagging body.