By MANLY BANISTER

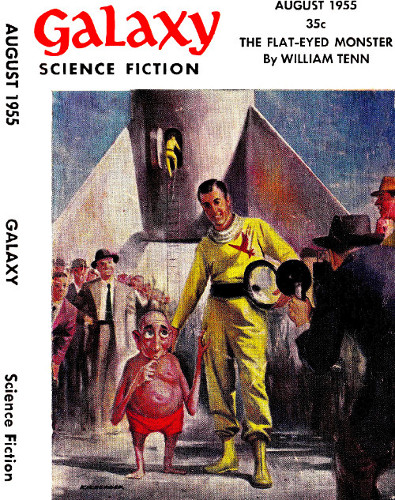

Illustrated by KOSSIN

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction August 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Except for transportation, it was absolutely

free ... but how much would the freight cost?

"It is an outrage," said Koltan of the House of Masur, "that the Earthmen land among the Thorabians!"

Zotul, youngest of the Masur brothers, stirred uneasily. Personally, he was in favor of the coming of the Earthmen to the world of Zur.

At the head of the long, shining table sat old Kalrab Masur, in his dotage, but still giving what he could of aid and comfort to the Pottery of Masur, even though nobody listened to him any more and he knew it. Around the table sat the six brothers—Koltan, eldest and Director of the Pottery; Morvan, his vice-chief; Singula, their treasurer; Thendro, sales manager; Lubiosa, export chief; and last in the rank of age, Zotul, who was responsible for affairs of design.

"Behold, my sons," said Kalrab, stroking his scanty beard. "What are these Earthmen to worry about? Remember the clay. It is our strength and our fortune. It is the muscle and bone of our trade. Earthmen may come and Earthmen may go, but clay goes on forever ... and with it, the fame and fortune of the House of Masur."

"It is a damned imposition," agreed Morvan, ignoring his father's philosophical attitude. "They could have landed just as easily here in Lor."

"The Thorabians will lick up the gravy," said Singula, whose mind ran rather to matters of financial aspect, "and leave us the grease."

By this, he seemed to imply that the Thorabians would rob the Earthmen, which the Lorians would not. The truth was that all on Zur were panting to get their hands on that marvelous ship, which was all of metal, a very scarce commodity on Zur, worth billions of ken.

Lubiosa, who had interests in Thorabia, and many agents there, kept his own counsel. His people were active in the matter and that was enough for him. He would report when the time was ripe.

"Doubtless," said Zotul unexpectedly, for the youngest at a conference was expected to keep his mouth shut and applaud the decisions of his elders, "the Earthmen used all the metal on their planet in building that ship. We cannot possibly bilk them of it; it is their only means of transport."

Such frank expression of motive was unheard of, even in the secret conclave of conference. Only the speaker's youth could account for it. The speech drew scowls from the brothers and stern rebuke from Koltan.

"When your opinion is wanted, we will ask you for it. Meantime, remember your position in the family."

Zotul bowed his head meekly, but he burned with resentment.

"Listen to the boy," said the aged father. "There is more wisdom in his head than in all the rest of you. Forget the Earthmen and think only of the clay."

Zotul did not appreciate his father's approval, for it only earned him a beating as soon as the old man went to bed. It was a common enough thing among the brothers Masur, as among everybody, to be frustrated in their desires. However, they had Zotul to take it out upon, and they did.

Still smarting, Zotul went back to his designing quarters and thought about the Earthmen. If it was impossible to hope for much in the way of metal from the Earthmen, what could one get from them? If he could figure this problem out, he might rise somewhat in the estimation of his brothers. That wouldn't take him out of the rank of scapegoat, of course, but the beatings might become fewer and less severe.

By and by, the Earthmen came to Lor, flying through the air in strange metal contraptions. They paraded through the tile-paved streets of the city, marveled here, as they had in Thorabia, at the buildings all of tile inside and out, and made a great show of themselves for all the people to see. Speeches were made through interpreters, who had much too quickly learned the tongue of the aliens; hence these left much to be desired in the way of clarity, though their sincerity was evident.

The Earthmen were going to do great things for the whole world of Zur. It required but the cooperation—an excellent word, that—of all Zurians, and many blessings would rain down from the skies. This, in effect, was what the Earthmen had to say. Zotul felt greatly cheered, for it refuted the attitude of his brothers without earning him a whaling for it.

There was also some talk going around about agreements made between the Earthmen and officials of the Lorian government, but you heard one thing one day and another the next. Accurate reporting, much less a newspaper, was unknown on Zur.

Finally, the Earthmen took off in their great, shining ship. Obviously, none had succeeded in chiseling them out of it, if, indeed, any had tried. The anti-Earthmen Faction—in any culture complex, there is always an "anti" faction to protest any movement of endeavor—crowed happily that the Earthmen were gone for good, and a good thing, too.

Such jubilation proved premature, however. One day, a fleet of ships arrived and after they had landed all over the planet, Zur was practically acrawl with Earthmen.

Immediately, the Earthmen established what they called "corporations"—Zurian trading companies under terrestrial control. The object of the visit was trade.

In spite of the fact that a terrestrial ship had landed at every Zurian city of major and minor importance, and all in a single day, it took some time for the news to spread.

The first awareness Zotul had was that, upon coming home from the pottery one evening, he found his wife Lania proudly brandishing an aluminum pot at him.

"What is that thing?" he asked curiously.

"A pot. I bought it at the market."

"Did you now? Well, take it back. Am I made of money that you spend my substance for some fool's product of precious metal? Take it back, I say!"

The pretty young wife laughed at him. "Up to your ears in clay, no wonder you hear nothing of news! The pot is very cheap. The Earthmen are selling them everywhere. They're much better than our old clay pots; they're light and easy to handle and they don't break when dropped."

"What good is it?" asked Zotul, interested. "How will it hold heat, being so light?"

"The Earthmen don't cook as we do," she explained patiently. "There is a paper with each pot that explains how it is used. And you will have to design a new ceramic stove for me to use the pots on."

"Don't be idiotic! Do you suppose Koltan would agree to produce a new type of stove when the old has sold well for centuries? Besides, why do you need a whole new stove for one little pot?"

"A dozen pots. They come in sets and are cheaper that way. And Koltan will have to produce the new stove because all the housewives are buying these pots and there will be a big demand for it. The Earthman said so."

"He did, did he? These pots are only a fad. You will soon enough go back to cooking with your old ones."

"The Earthman took them in trade—one reason why the new ones are so cheap. There isn't a pot in the house but these metal ones, and you will have to design and produce a new stove if you expect me to use them."

After he had beaten his wife thoroughly for her foolishness, Zotul stamped off in a rage and designed a new ceramic stove, one that would accommodate the terrestrial pots very well.

And Koltan put the model into production.

"Orders already are pouring in like mad," he said the next day. "It was wise of you to foresee it and have the design ready. Already, I am sorry for thinking as I did about the Earthmen. They really intend to do well by us."

The kilns of the Pottery of Masur fired day and night to keep up with the demand for the new porcelain stoves. In three years, more than a million had been made and sold by the Masurs alone, not counting the hundreds of thousands of copies turned out by competitors in every land.

In the meantime, however, more things than pots came from Earth. One was a printing press, the like of which none on Zur had ever dreamed. This, for some unknown reason and much to the disgust of the Lorians, was set up in Thorabia. Books and magazines poured from it in a fantastic stream. The populace fervidly brushed up on its scanty reading ability and bought everything available, overcome by the novelty of it. Even Zotul bought a book—a primer in the Lorian language—and learned how to read and write. The remainder of the brothers Masur, on the other hand, preferred to remain in ignorance.

Moreover, the Earthmen brought miles of copper wire—more than enough in value to buy out the governorship of any country on Zur—and set up telegraph lines from country to country and continent to continent. Within five years of the first landing of the Earthmen, every major city on the globe had a printing press, a daily newspaper, and enjoyed the instantaneous transmission of news via telegraph. And the business of the House of Masur continued to look up.

"As I have always said from the beginning," chortled Director Koltan, "this coming of the Earthmen had been a great thing for us, and especially for the House of Masur."

"You didn't think so at first," Zotul pointed out, and was immediately sorry, for Koltan turned and gave him a hiding, single-handed, for his unthinkable impertinence.

It would do no good, Zotul realized, to bring up the fact that their production of ceramic cooking pots had dropped off to about two per cent of its former volume. Of course, profits on the line of new stoves greatly overbalanced the loss, so that actually they were ahead; but their business was now dependent upon the supply of the metal pots from Earth.

About this time, plastic utensils—dishes, cups, knives, forks—made their appearance on Zur. It became very stylish to eat with the newfangled paraphernalia ... and very cheap, too, because for everything they sold, the Earthmen always took the old ware in trade. What they did with the stuff had been hard to believe at first. They destroyed it, which proved how valueless it really was.

The result of the new flood was that in the following year, the sale of Masur ceramic table service dropped to less than a tenth.

Trembling with excitement at this news from their book-keeper, Koltan called an emergency meeting. He even routed old Kalrab out of his senile stupor for the occasion, on the off chance that the old man might still have a little wit left that could be helpful.

"Note," Koltan announced in a shaky voice, "that the Earthmen undermine our business," and he read off the figures.

"Perhaps," said Zotul, "it is a good thing also, as you said before, and will result in something even better for us."

Koltan frowned, and Zotul, in fear of another beating, instantly subsided.

"They are replacing our high-quality ceramic ware with inferior terrestrial junk," Koltan went on bitterly. "It is only the glamor that sells it, of course, but before the people get the shine out of their eyes, we can be ruined."

The brothers discussed the situation for an hour, and all the while Father Kalrab sat and pulled his scanty whiskers. Seeing that they got nowhere with their wrangle, he cleared his throat and spoke up.

"My sons, you forget it is not the Earthmen themselves at the bottom of your trouble, but the things of Earth. Think of the telegraph and the newspaper, how these spread news of every shipment from Earth. The merchandise of the Earthmen is put up for sale by means of these newspapers, which also are the property of the Earthmen. The people are intrigued by these advertisements, as they are called, and flock to buy. Now, if you would pull a tooth from the kwi that bites you, you might also have advertisements of your own."

Alas for that suggestion, no newspaper would accept advertising from the House of Masur; all available space was occupied by the advertisements of the Earthmen.

In their dozenth conference since that first and fateful one, the brothers Masur decided upon drastic steps. In the meantime, several things had happened. For one, old Kalrab had passed on to his immortal rest, but this made no real difference. For another, the Earthmen had procured legal authority to prospect the planet for metals, of which they found a good deal, but they told no one on Zur of this. What they did mention was the crude oil and natural gas they discovered in the underlayers of the planet's crust. Crews of Zurians, working under supervision of the Earthmen, laid pipelines from the gas and oil regions to every major and minor city on Zur.

By the time ten years had passed since the landing of the first terrestrial ship, the Earthmen were conducting a brisk business in gas-fired ranges, furnaces and heaters ... and the Masur stove business was gone. Moreover, the Earthmen sold the Zurians their own natural gas at a nice profit and everybody was happy with the situation except the brothers Masur.

The drastic steps of the brothers applied, therefore, to making an energetic protest to the governor of Lor.

At one edge of the city, an area had been turned over to the Earthmen for a spaceport, and the great terrestrial spaceships came to it and departed from it at regular intervals. As the heirs of the House of Masur walked by on their way to see the governor, Zotul observed that much new building was taking place and wondered what it was.

"Some new devilment of the Earthmen, you can be sure," said Koltan blackly.

In fact, the Earthmen were building an assembly plant for radio receiving sets. The ship now standing on its fins upon the apron was loaded with printed circuits, resistors, variable condensers and other radio parts. This was Earth's first step toward flooding Zur with the natural follow-up in its campaign of advertising—radio programs—with commercials.

Happily for the brothers, they did not understand this at the time or they would surely have gone back to be buried in their own clay.

"I think," the governor told them, "that you gentlemen have not paused to consider the affair from all angles. You must learn to be modern—keep up with the times! We heads of government on Zur are doing all in our power to aid the Earthmen and facilitate their bringing a great, new culture that can only benefit us. See how Zur has changed in ten short years! Imagine the world of tomorrow! Why, do you know they are even bringing autos to Zur!"

The brothers were fascinated with the governor's description of these hitherto unheard-of vehicles.

"It only remains," concluded the governor, "to build highways, and the Earthmen are taking care of that."

At any rate, the brothers Masur were still able to console themselves that they had their tile business. Tile served well enough for houses and street surfacing; what better material could be devised for the new highways the governor spoke of? There was a lot of money to be made yet.

Radio stations went up all over Zur and began broadcasting. The people bought receiving sets like mad. The automobiles arrived and highways were constructed.

The last hope of the brothers was dashed. The Earthmen set up plants and began to manufacture Portland cement.

You could build a house of concrete much cheaper than with tile. Of course, since wood was scarce on Zur, it was no competition for either tile or concrete. Concrete floors were smoother, too, and the stuff made far better road surfacing.

The demand for Masur tile hit rock bottom.

The next time the brothers went to see the governor, he said, "I cannot handle such complaints as yours. I must refer you to the Merchandising Council."

"What is that?" asked Koltan.

"It is an Earthman association that deals with complaints such as yours. In the matter of material progress, we must expect some strain in the fabric of our culture. Machinery has been set up to deal with it. Here is their address; go air your troubles to them."

The business of a formal complaint was turned over by the brothers to Zotul. It took three weeks for the Earthmen to get around to calling him in, as a representative of the Pottery of Masur, for an interview.

All the brothers could no longer be spared from the plant, even for the purpose of pressing a complaint. Their days of idle wealth over, they had to get in and work with the clay with the rest of the help.

Zotul found the headquarters of the Merchandising Council as indicated on their message. He had not been this way in some time, but was not surprised to find that a number of old buildings had been torn down to make room for the concrete Council House and a roomy parking lot, paved with something called "blacktop" and jammed with an array of glittering new automobiles.

An automobile was an expense none of the brothers could afford, now that they barely eked a living from the pottery. Still, Zotul ached with desire at sight of so many shiny cars. Only a few had them and they were the envied ones of Zur.

Kent Broderick, the Earthman in charge of the Council, shook hands jovially with Zotul. That alien custom conformed with, Zotul took a better look at his host. Broderick was an affable, smiling individual with genial laugh wrinkles at his eyes. A man of middle age, dressed in the baggy costume of Zur, he looked almost like a Zurian, except for an indefinite sense of alienness about him.

"Glad to have you call on us, Mr. Masur," boomed the Earthman, clapping Zotul on the back. "Just tell us your troubles and we'll have you straightened out in no time."

All the chill recriminations and arguments Zotul had stored for this occasion were dissipated in the warmth of the Earthman's manner.

Almost apologetically, Zotul told of the encroachment that had been made upon the business of the Pottery of Masur.

"Once," he said formally, "the Masur fortune was the greatest in the world of Zur. That was before my father, the famous Kalrab Masur—Divinity protect him—departed this life to collect his greater reward. He often told us, my father did, that the clay is the flesh and bones of our culture and our fortune. Now it has been shown how prone is the flesh to corruption and how feeble the bones. We are ruined, and all because of new things coming from Earth."

Broderick stroked his shaven chin and looked sad. "Why didn't you come to me sooner? This would never have happened. But now that it has, we're going to do right by you. That is the policy of Earth—always to do right by the customer."

"Divinity witness," Zorin said, "that we ask only compensation for damages."

Broderick shook his head. "It is not possible to replace an immense fortune at this late date. As I said, you should have reported your trouble sooner. However, we can give you an opportunity to rebuild. Do you own an automobile?"

"No."

"A gas range? A gas-fired furnace? A radio?"

Zotul had to answer no to all except the radio. "My wife Lania likes the music," he explained. "I cannot afford the other things."

Broderick clucked sympathetically. One who could not afford the bargain-priced merchandise of Earth must be poor indeed.

"To begin with," he said, "I am going to make you a gift of all these luxuries you do not have." As Zotul made to protest, he cut him off with a wave of his hand. "It is the least we can do for you. Pick a car from the lot outside. I will arrange to have the other things delivered and installed in your home."

"To receive gifts," said Zotul, "incurs an obligation."

"None at all," beamed the Earthman cheerily. "Every item is given to you absolutely free—a gift from the people of Earth. All we ask is that you pay the freight charges on the items. Our purpose is not to make profit, but to spread technology and prosperity throughout the Galaxy. We have already done well on numerous worlds, but working out the full program takes time."

He chuckled deeply. "We of Earth have a saying about one of our extremely slow-moving native animals. We say, 'Slow is the tortoise, but sure.' And so with us. Our goal is a long-range one, with the motto, 'Better times with better merchandise.'"

The engaging manner of the man won Zotul's confidence. After all, it was no more than fair to pay transportation.

He said, "How much does the freight cost?"

Broderick told him.

"It may seem high," said the Earthman, "but remember that Earth is sixty-odd light-years away. After all, we are absorbing the cost of the merchandise. All you pay is the freight, which is cheap, considering the cost of operating an interstellar spaceship."

"Impossible," said Zotul drably. "Not I and all my brothers together have so much money any more."

"You don't know us of Earth very well yet, but you will. I offer you credit!"

"What is that?" asked Zotul skeptically.

"It is how the poor are enabled to enjoy all the luxuries of the rich," said Broderick, and went on to give a thumbnail sketch of the involutions and devolutions of credit, leaving out some angles that might have had a discouraging effect.

On a world where credit was a totally new concept, it was enchanting. Zotul grasped at the glittering promise with avidity. "What must I do to get credit?"

"Just sign this paper," said Broderick, "and you become part of our Easy Payment Plan."

Zotul drew back. "I have five brothers. If I took all these things for myself and nothing for them, they would beat me black and blue."

"Here." Broderick handed him a sheaf of chattel mortgages. "Have each of your brothers sign one of these, then bring them back to me. That is all there is to it."

It sounded wonderful. But how would the brothers take it? Zotul wrestled with his misgivings and the misgivings won.

"I will talk it over with them," he said. "Give me the total so I will have the figures."

The total was more than it ought to be by simple addition. Zotul pointed this out politely.

"Interest," Broderick explained. "A mere fifteen per cent. After all, you get the merchandise free. The transportation company has to be paid, so another company loans you the money to pay for the freight. This small extra sum pays the lending company for its trouble."

"I see." Zotul puzzled over it sadly. "It is too much," he said. "Our plant doesn't make enough money for us to meet the payments."

"I have a surprise for you," smiled Broderick. "Here is a contract. You will start making ceramic parts for automobile spark plugs and certain parts for radios and gas ranges. It is our policy to encourage local manufacture to help bring prices down."

"We haven't the equipment."

"We will equip your plant," beamed Broderick. "It will require only a quarter interest in your plant itself, assigned to our terrestrial company."

Zotul, anxious to possess the treasures promised by the Earthman, won over his brothers. They signed with marks and gave up a quarter interest in the Pottery of Masur. They rolled in the luxuries of Earth. These, who had never known debt before, were in it up to their ears.

The retooled plant forged ahead and profits began to look up, but the Earthmen took a fourth of them as their share in the industry.

For a year, the brothers drove their shiny new cars about on the new concrete highways the Earthmen had built. From pumps owned by a terrestrial company, they bought gas and oil that had been drawn from the crust of Zur and was sold to the Zurians at a magnificent profit. The food they ate was cooked in Earthly pots on Earth-type gas ranges, served up on metal plates that had been stamped out on Earth. In the winter, they toasted their shins before handsome gas grates, though they had gas-fired central heating.

About this time, the ships from Earth brought steam-powered electric generators. Lines went up, power was generated, and a flood of electrical gadgets and appliances hit the market. For some reason, batteries for the radios were no longer available and everybody had to buy the new radios. And who could do without a radio in this modern age?

The homes of the brothers Masur blossomed on the Easy Payment Plan. They had refrigerators, washers, driers, toasters, grills, electric fans, air-conditioning equipment and everything else Earth could possibly sell them.

"We will be forty years paying it all off," exulted Zotul, "but meantime we have the things and aren't they worth it?"

But at the end of three years, the Earthmen dropped their option. The Pottery of Masur had no more contracts. Business languished. The Earthmen, explained Broderick, had built a plant of their own because it was so much more efficient—and to lower prices, which was Earth's unswerving policy, greater and greater efficiency was demanded. Broderick was very sympathetic, but there was nothing he could do.

The introduction of television provided a further calamity. The sets were delicate and needed frequent repairs, hence were costly to own and maintain. But all Zurians who had to keep up with the latest from Earth had them. Now it was possible not only to hear about things of Earth, but to see them as they were broadcast from the video tapes.

The printing plants that turned out mortgage contracts did a lush business.

For the common people of Zur, times were good everywhere. In a decade and a half, the Earthmen had wrought magnificent changes on this backward world. As Broderick had said, the progress of the tortoise was slow, but it was extremely sure.

The brothers Masur got along in spite of dropped options. They had less money and felt the pinch of their debts more keenly, but television kept their wives and children amused and furnished an anodyne for the pangs of impoverishment.

The pottery income dropped to an impossible low, no matter how Zotul designed and the brothers produced. Their figurines and religious ikons were a drug on the market. The Earthmen made them of plastic and sold them for less.

The brothers, unable to meet the Payments that were not so Easy any more, looked up Zotul and cuffed him around reproachfully.

"You got us into this," they said, emphasizing their bitterness with fists. "Go see Broderick. Tell him we are undone and must have some contracts to continue operating."

Nursing bruises, Zotul unhappily went to the Council House again. Mr. Broderick was no longer with them, a suave assistant informed him. Would he like to see Mr. Siwicki instead? Zotul would.

Siwicki was tall, thin, dark and somber-looking. There was even a hint of toughness about the set of his jaw and the hardness of his glance.

"So you can't pay," he said, tapping his teeth with a pencil. He looked at Zotul coldly. "It is well you have come to us instead of making it necessary for us to approach you through the courts."

"I don't know what you mean," said Zotul.

"If we have to sue, we take back the merchandise and everything attached to them. That means you would lose your houses, for they are attached to the furnaces. However, it is not as bad as that—yet. We will only require you to assign the remaining three-quarters of your pottery to us."

The brothers, when they heard of this, were too stunned to think of beating Zotul, by which he assumed he had progressed a little and was somewhat comforted.

"To fail," said Koltan soberly, "is not a Masur attribute. Go to the governor and tell him what we think of this business. The House of Masur has long supported the government with heavy taxes. Now it is time for the government to do something for us."

The governor's palace was jammed with hurrying people, a scene of confusion that upset Zotul. The clerk who took his application for an interview was, he noticed only vaguely, a young Earthwoman. It was remarkable that he paid so little attention, for the female terrestrials were picked for physical assets that made Zurian men covetous and Zurian women envious.

"The governor will see you," she said sweetly. "He has been expecting you."

"Me?" marveled Zotul.

She ushered him into the magnificent private office of the governor of Lor. The man behind the desk stood up, extended his hand with a friendly smile.

"Come in, come in! I'm glad to see you again."

Zotul stared blankly. This was not the governor. This was Broderick, the Earthman.

"I—I came to see the governor," he said in confusion.

Broderick nodded agreeably. "I am the governor and I am well acquainted with your case, Mr. Masur. Shall we talk it over? Please sit down."

"I don't understand. The Earthmen...." Zotul paused, coloring. "We are about to lose our plant."

"You were about to say that the Earthmen are taking your plant away from you. That is true. Since the House of Masur was the largest and richest on Zur, it has taken a long time—the longest of all, in fact."

"What do you mean?"

"Yours is the last business on Zur to be taken over by us. We have bought you out."

"Our government...."

"Your governments belong to us, too," said Broderick. "When they could not pay for the roads, the telegraphs, the civic improvements, we took them over, just as we are taking you over."

"You mean," exclaimed Zotul, aghast, "that you Earthmen own everything on Zur?"

"Even your armies."

"But why?"

Broderick clasped his hands behind back, went to the window and stared down moodily into the street.

"You don't know what an overcrowded world is like," he said. "A street like this, with so few people and vehicles on it, would be impossible on Earth."

"But it's mobbed," protested Zotul. "It gave me a headache."

"And to us it's almost empty. The pressure of population on Earth has made us range the Galaxy for places to put our extra people. The only habitable planets, unfortunately, are populated ones. We take the least populous worlds and—well, buy them out and move in."

"And after that?"

Broderick smiled gently. "Zur will grow. Our people will intermarry with yours. The future population of Zur will be neither true Zurians nor true Earthmen, but a mixture of both."

Zotul sat in silent thought. "But you did not have to buy us out. You had the power to conquer us, even to destroy us. The whole planet could have been yours alone." He stopped in alarm. "Or am I suggesting an idea that didn't occur to you?"

"No," said Broderick, his usually smiling face almost pained with memory. "We know the history of conquest all too well. Our method causes more distress than we like to inflict, but it's better—and more sure—than war and invasion by force. Now that the unpleasant job is finished, we can repair the dislocations."

"At last I understand what you said about the tortoise."

"Slow but sure." Broderick beamed again and clapped Zotul on the shoulder. "Don't worry. You'll have your job back, the same as always, but you'll be working for us ... until the children of Earth and Zur are equal in knowledge and therefore equal partners. That's why we had to break down your caste system."

Zotul's eyes widened. "And that is why my brothers did not beat me when I failed!"

"Of course. Are you ready now to take the assignment papers for you and your brothers to sign?"

"Yes," said Zotul. "I am ready."