YES TOR

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/bookofdartmoor00bari |

A BOOK OF DARTMOOR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME

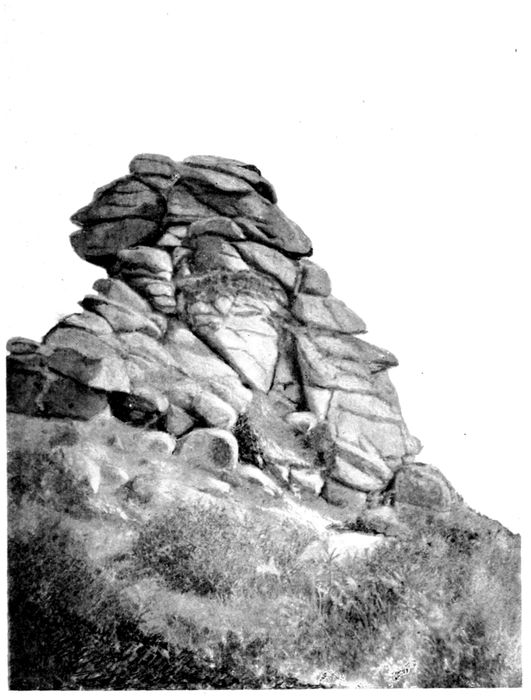

YES TOR

BY S. BARING-GOULD

WITH SIXTY ILLUSTRATIONS

SECOND EDITION

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published July 1900

Second Edition January 1907

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY UNCLE

THE LATE

THOMAS GEORGE BOND

ONE OF THE PIONEERS OF

DARTMOOR EXPLORATION

At the request of my publishers I have written A Book of Dartmoor. I had already dealt with this upland district in two chapters in my Book of the West, vol. i., "Devon." But in their opinion this wild and wondrous region deserved more particular treatment than I had been able to accord to it in the limited space at my disposal in the above-mentioned book.

I have now entered with some fulness, but by no means exhaustively, into the subject; and for those who desire a closer acquaintance with, and a more precise guide to the several points of interest on "the moor," I would indicate three works that have preceded this.

1. Mr. J. Brooking Rowe in 1896 republished the Perambulation of Dartmoor, first issued by his great-uncle, Mr. Samuel Rowe, in 1848.

The original work was written by a man whose mind was steeped in the crude archæological theories of his period. The new editor could not dispense[Pg x] with this matter, which pervaded the work, without a complete recasting of the book, and this he was reluctant to attempt. He limited himself to cautioning the reader to put no trust in these exploded theories. The result is that the reader is tripping over uncertain ground, never knowing what is to be accepted and what rejected.

2. Mr. J. H. W. Page's Exploration of Dartmoor, 1889, is admirable as a guide. The author, however, was unhappily ignorant of prehistoric archæology, and allowed himself to be led astray by the false antiquarianism that had marked the early writers. Consequently, his book is capital as a guide to what is to be seen, but eminently unreliable in its explanation of the character and age of the antiquities.

3. A capital book is Mr. W. Crossing's Amid Devonia's Alps, 1888, which is wholly free from pseudo-antiquarianism. It is brief, it is small and cheap, and an admirable handbook for pedestrians.

In no way do I desire to supersede these works. I have taken pains rather to supplement them than to step into the places occupied by their writers.

The plan I have adopted in this gossiping volume is to give a general idea of the moor and of its antiquities—the latter as interpreted by up-to-date archæologists—and then to suggest rambles made[Pg xi] from certain stations on the fringe, or in the heart of the region.

Here and there it has been inevitable that I should twice mention the same object of interest, once in the introductory portion, and again when I have to refer to it as coming within the radius of a proposed ramble.

As a boy I had an uncle, T. G. Bond, who lived near Moreton Hampstead, and who was passionately devoted to Dartmoor. He inspired me with the same love. In 1848 he presented me, as a birthday present, with Rowe's Perambulation of Dartmoor. It arrested my attention, engaged my imagination, and was to me almost as a Bible. When I obtained a holiday from my books, I mounted my pony and made for the moor. I rode over it, round it, put up at little inns, talked with the moormen, listened to their tales and songs in the evenings, and during the day sketched and planned the relics that I then fondly supposed were Druidical.

The child is father to the man. Years have rolled away. I have wandered over Europe, have rambled to Iceland, climbed the Alps, been for some years lodged among the marshes of Essex—yet nothing that I have seen has quenched in me the longing after the fresh air, and love of the wild scenery of[Pg xii] Dartmoor. There is far finer mountain scenery elsewhere, but there can be no more bracing air, and the lone upland region possesses a something of its own—a charm hard to describe, but very real—which engages for once and for ever the affections of those who have made its acquaintance. "After all said," observed my uncle to me one day, when my father had dilated on the glories of the Pyrenees, "Dartmoor is to itself, and to me—a passion." And to his memory I dedicate this volume.

My grateful thanks are due to Messrs. R. Burnard, P. F. S. Amery, J. Shortridge, and C. E. Robinson for permission to employ photographs taken by them.

S. BARING-GOULD

Lew Trenchard, Devon

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Bogs | 1 |

| II. | Tors | 14 |

| III. | The Ancient Inhabitants | 29 |

| IV. | The Antiquities | 52 |

| V. | The Freaks | 74 |

| VI. | Dead Men's Dust | 82 |

| VII. | The Camps | 97 |

| VIII. | Tin-streaming | 108 |

| IX. | Lydford | 124 |

| X. | Belstone | 144 |

| XI. | Chagford | 157 |

| XII. | Manaton | 171 |

| XIII. | Holne | 193 |

| XIV. | Ivybridge | 209 |

| XV. | Yelverton | 220 |

| XVI. | Post Bridge | 241 |

| XVII. | Princetown | 259 |

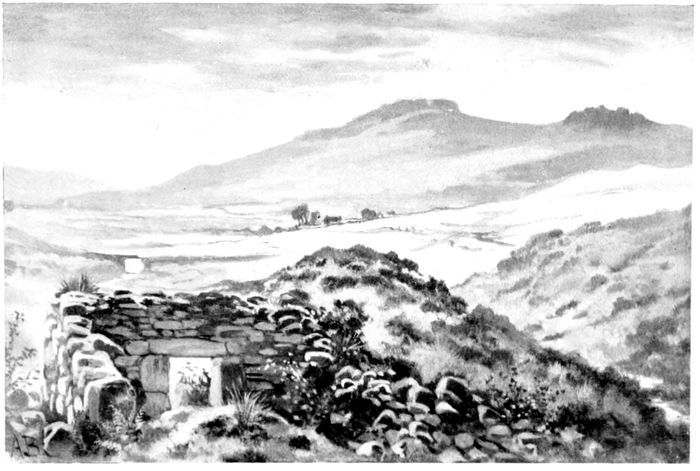

| Yes Tor | Frontispiece | |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| A Tor, showing Granite Weathering | To face page | 14 |

| From a photograph by J. Shortridge, Esq. | ||

| Vixen Tor | " | 18 |

| From a photograph by J. Shortridge, Esq. | ||

| Rocks by Hey Tor | " | 24 |

| From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| The Pedigree of a Tomb | " | 56 |

| From a drawing by S. Baring-Gould. | ||

| Stone Rows, Drizzlecombe | " | 60 |

| From a drawing by S. Baring-Gould. | ||

| The Pedigree of a Headstone | " | 64 |

| From a drawing by S. Baring-Gould. | ||

| Bowerman's Nose | " | 74 |

| From a drawing by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| Whit Tor Camp | " | 97 |

| Planned by Rev. J. K. Anderson, drawn by S. Baring-Gould. | ||

| Brent Tor | " | 102 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| Blowing-house under Black Tor | " | 108 |

| From a drawing by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| On the Lyd | " | 124 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| Hare Tor | " | 141 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| North Wyke Gate House | " | 152 |

| From a drawing by Mrs. C. L. Weekes. | ||

| Grimspound | " | 165 |

| From a photograph by C. E. Robinson, Esq.[Pg xv] | ||

| Near Manaton | " | 171 |

| From a drawing by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| Hound Tor | " | 175 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| Hey Tor Rocks | " | 176 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| Lower Tar | " | 190 |

| From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| The Cleft Rock | " | 196 |

| From a photograph by J. Amery, Esq. | ||

| Yar Tor | " | 199 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| The Dewerstone | " | 220 |

| From a drawing by E. A. Tozer, Esq. | ||

| Sheeps Tor | " | 225 |

| From a drawing by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

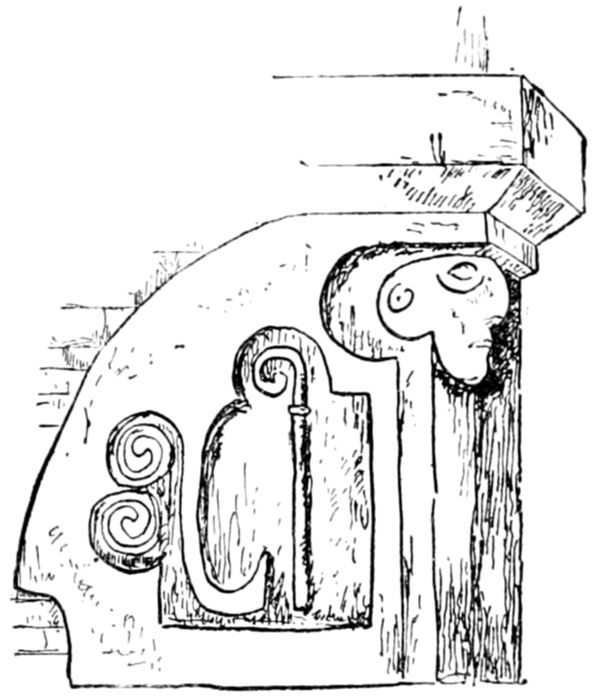

| Portion of Screen, Sheeps Tor | " | 228 |

| Drawn by F. Bligh Bond, Esq. | ||

| On the Meavy | " | 231 |

| Drawn by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

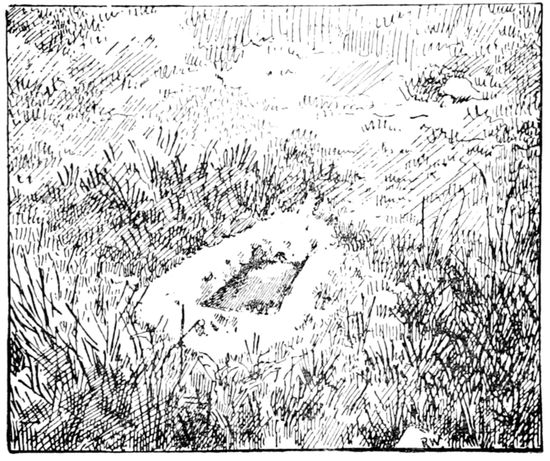

| Lake-head Kistvaen | " | 244 |

| From a photograph by R. Burnard, Esq. | ||

| Staple Tor | " | 269 |

| From a photograph by J. Shortridge, Esq. | ||

| Blowing-house on the Meavy | " | 270 |

| Drawn by A. B. Collier, Esq. | ||

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Flint Arrow-heads | 37 |

| Flint Scrapers | 45 |

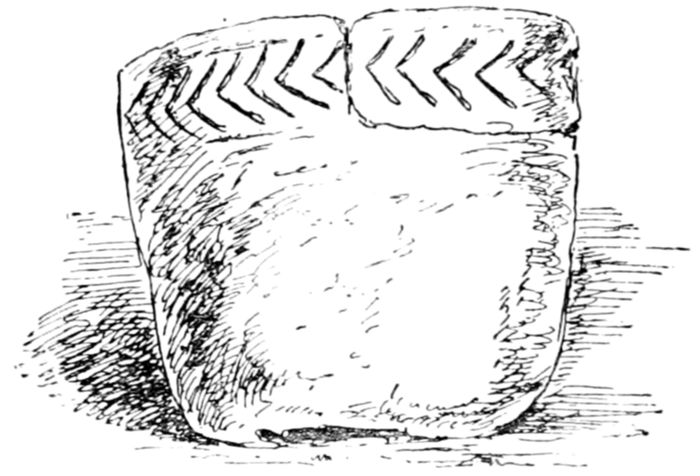

| A Cooking-pot | 46 |

| Flint Scrapers | 49 |

| Fragment of Cooking-pot | 50 |

| Cross, Whitchurch Down | 65 |

| Plan of Hut, Shapley Common | 67 |

| Hut Circle, Grimspound | 69 |

| Logan Rock. The Rugglestone, Widdecombe | 77[Pg xvi] |

| Roos Tor Logans | 79 |

| Covered Chamber, Whit Tor | 100 |

| Construction of Stone and Timber Wall | 101 |

| Tin-workings, Nillacombe | 109 |

| Mortar-stone, Okeford | 111 |

| Slag-pounding Hollows, Gobbetts | 113 |

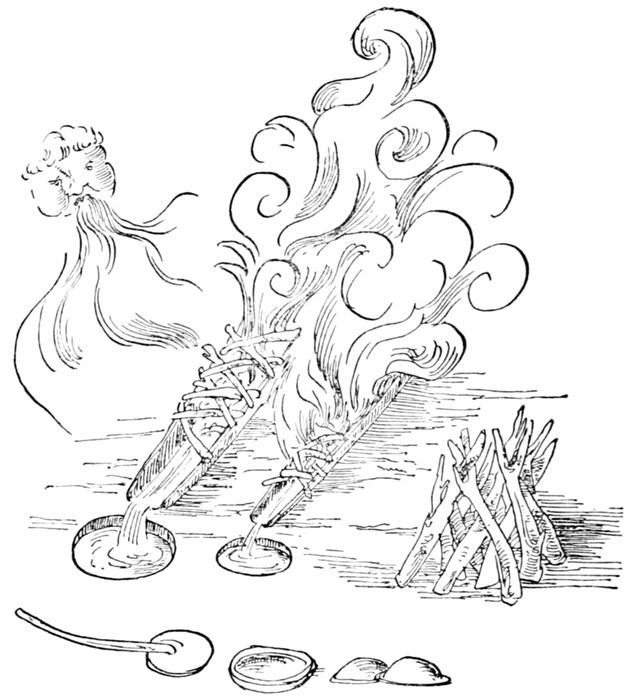

| Smelting in 1556 | 114 |

| Plan of Blowing-house, Deep Swincombe | 115 |

| Tin-mould, Deep Swincombe | 117 |

| Smelting Tin in Japan | 119 |

| A Primitive Hinge | 133 |

| Inscription on Sourton Cross | 142 |

| Inscribed Stone, Sticklepath | 150 |

| Plan of Stone Rows near Caistor Rock | 161 |

| " " Grimspound | 166 |

| " " Hut at Grimspound | 169 |

| Fragment of Pottery | 177 |

| Ornamented Pottery | 179 |

| Tom Pearce's Ghostly Mare | 191 |

| Crazing-mill Stone, Upper Gobbetts | 204 |

| Method of using the Mill-stones | 205 |

| Chancel Capital, Meavy | 237 |

| Blowing-house below Black Tor | 271 |

DARTMOOR

The rivers that flow from Dartmoor—The bogs are their cradles—A tailor lost on the moor—A man in Aune Mire—Some of the worst bogs—Cranmere Pool—How the bogs are formed—Adventure in Redmoor Bog—Bog plants—The buckbean—Sweet gale—Furze—Yellow broom—Bee-keeping.

Dartmoor proper consists of that upland region of granite, rising to nearly 2,000 feet above the sea, and actually shooting above that height at a few points, which is the nursery of many of the rivers of Devon.

The Exe, indeed, has its source in Exmoor, and it disdains to receive any affluents from Dartmoor; and the Torridge takes its rise hard by the sea at Wellcombe, within a rifle-shot of the Bristol Channel, nevertheless it makes a graceful sweep—tenders a salute—to Dartmoor, and in return receives the liberal flow of the Okement. The Otter and the Axe, being in the far east of the county, rise in the range of hills that form the natural frontier between Devon and Somerset.

But all the other considerable streams look back upon Dartmoor as their mother.

And what a mother! She sends them forth limpid and pure, full of laughter and leap, of flash and brawl. She does not discharge them laden with brown mud, as the Exe, nor turned like the waters of Egypt to blood, as the Creedy.

A prudent mother, she feeds them regularly, and with considerable deliberation. Her vast bogs act as sponges, absorbing the winter rains, and only leisurely and prudently does she administer the hoarded supply, so that the rivers never run dry in the hottest and most rainless summers.

Of bogs there are two sorts, the great parental peat deposits that cover the highland, where not too steep for them to lie, and the swamps in the bottoms formed by the oozings from the hills that have been arrested from instant discharge into the rivers by the growth of moss and water-weeds, or are checked by belts of gravel and boulder. To see the former, a visit should be made to Cranmere Pool, or to Cut Hill, or Fox Tor Mire. To get into the latter a stroll of ten minutes up a river-bank will suffice.

The existence of the great parent bogs is due either to the fact that beneath them lies the impervious granite, as a floor, somewhat concave, or to the whole rolling upland being covered, as with a quilt, with equally impervious china-clay, the fine deposit of feldspar washed from the granite in the course of ages.

In the depths of the moor the peat may be seen[Pg 3] riven like floes of ice, and the rifts are sometimes twelve to fourteen feet deep, cut through black vegetable matter, the product of decay of plants through countless generations. If the bottom be sufficiently denuded it is seen to be white and smooth as a girl's shoulder—the kaolin that underlies all.

On the hillsides, and in the bottoms, quaking-bogs may be lighted upon or tumbled into. To light upon them is easy enough, to get out of one if tumbled into is a difficult matter. They are happily small, and can be at once recognised by the vivid green pillow of moss that overlies them. This pillow is sufficiently close in texture and buoyant to support a man's weight, but it has a mischievous habit of thinning around the edge, and if the water be stepped into where this fringe is, it is quite possible for the inexperienced to go under, and be enabled at his leisure to investigate the lower surface of the covering duvet of porous moss. Whether he will be able to give to the world the benefit of his observations may be open to question.

The thing to be done by anyone who gets into such a bog is to spread his arms out—this will prevent his sinking—and if he cannot struggle out, to wait, cooling his toes in bog water, till assistance comes. It is a difficult matter to extricate horses when they flounder in, as is not infrequently the case in hunting; every plunge sends the poor beasts in deeper.

One afternoon, in the year 1851, I was in the Walkham valley above Merrivale Bridge digging into what at the time I fondly believed was a tumulus,[Pg 4] but which I subsequently discovered to be a mound thrown up for the accommodation of rabbits, when a warren was contemplated on the slope of Mis Tor.

Towards evening I was startled to see a most extraordinary object approach me—a man in a draggled, dingy, and disconsolate condition, hardly able to crawl along. When he came up to me he burst into tears, and it was some time before I could get his story from him. He was a tailor of Plymouth, who had left his home to attend the funeral of a cousin at Sampford Spiney or Walkhampton, I forget which. At that time there was no railway between Tavistock and Launceston; communication was by coach.

When the tailor, on the coach, reached Roborough Down, "'Ere you are!" said the driver. "You go along there, and you can't miss it!" indicating a direction with his whip.

So the tailor, in his glossy black suit, and with his box-hat set jauntily on his head, descended from the coach, leaped into the road, his umbrella, also black, under his arm, and with a composed countenance started along the road that had been pointed out.

Where and how he missed his way he could not explain, nor can I guess, but instead of finding himself at the house of mourning, and partaking there of cake and gin, and dropping a sympathetic tear, he got up on to Dartmoor, and got—with considerable dexterity—away from all roads.

He wandered on and on, becoming hungry, feeling the gloss go out of his new black suit, and raws[Pg 5] develop upon his top-hat as it got knocked against rocks in some of his falls.

Night set in, and, as Homer says, "all the paths were darkened"—but where the tailor found himself there were no paths to become obscured. He lay in a bog for some time, unable to extricate himself. He lost his umbrella, and finally lost his hat. His imagination conjured up frightful objects; if he did not lose his courage, it was because, as a tailor, he had none to lose.

He told me incredible tales of the large, glaring-eyed monsters that had stared at him as he lay in the bog. They were probably sheep, but as nine tailors fled when a snail put out its horns, no wonder that this solitary member of the profession was scared at a sheep.

The poor wretch had eaten nothing since the morning of the preceding day. Happily I had half a Cornish pasty with me, and I gave it him. He fell on it ravenously.

Then I showed him the way to the little inn at Merrivale Bridge, and advised him to hire a trap there and get back to Plymouth as quickly as might be.

"I solemnly swear to you, sir," said he, "nothing will ever induce me to set foot on Dartmoor again. If I chance to see it from the Hoe, sir, I'll avert my eyes. How can people think to come here for pleasure—for pleasure, sir! But there, Chinamen eat birds'-nests. There are depraved appetites among human beings, and only unwholesome-minded individuals can love Dartmoor."

There is a story told of one of the nastiest of mires on Dartmoor, that of Aune Head. A mire, by the way, is a peculiarly watery bog, that lies at the head of a river. It is its cradle, and a bog is distributed indiscriminately anywhere.

A mire cannot always be traversed in safety; much depends on the season. After a dry summer it is possible to tread where it would be death in winter or after a dropping summer.

A man is said to have been making his way through Aune Mire when he came on a top-hat reposing, brim downwards, on the sedge. He gave it a kick, whereupon a voice called out from beneath, "What be you a-doin' to my 'at?" The man replied, "Be there now a chap under'n?" "Ees, I reckon," was the reply, "and a hoss under me likewise."

There is a track through Aune Head Mire that can be taken with safety by one who knows it.

Fox Tor Mire once bore a very bad name. The only convict who really got away from Princetown and was not recaptured was last seen taking a bee-line for Fox Tor Mire. The grappling irons at the disposal of the prison authorities were insufficient for the search of the whole marshy tract. Since the mines were started at Whiteworks much has been done to drain Fox Tor Mire, and to render it safe for grazing cattle on and about it.

There is a nasty little mire at the head of Redaven Lake, between West Mill Tor and Yes Tor, and there is a choice collection of them, inviting the unwary to their chill embraces, on Cater's Beam, about the sources of the Plym and Blacklane Brook,[Pg 7] the ugliest of all occupying a pan and having no visible outlet. The Redlake mires are also disposed to be nasty in a wet season, and should be avoided at all times. Anyone having a fancy to study the mires and explore them for bog plants will find an elegant selection around Wild Tor, to be reached by ascending Taw Marsh and mounting Steeperton Tor, behind which he will find what he desires.

"On the high tableland," says Mr. William Collier, "above the slopes, even higher than many tors, are the great bogs, the sources of the rivers. The great northern bog is a vast tract of very high land, nothing but bog and sedge, with ravines down which the feeders of the rivers pour. Here may be found Cranmere Pool, which is now no pool at all, but just a small piece of bare black bog. Writers of Dartmoor guide-books have been pleased to make much of this Cranmere Pool, greatly to the advantage of the living guides, who take tourists there to stare at a small bit of black bog, and leave their cards in a receptacle provided for them. The large bog itself is of interest as the source of many rivers; but there is absolutely no interest in Cranmere Pool, which is nothing but a delusion and a snare for tourists. It was a small pool years ago, where the rain water lodged; but at Okement Head hard by a fox was run to ground, a terrier was put in, and by digging out the terrier Cranmere Pool was tapped, and has never been a pool since. So much for Cranmere Pool!

"This great northern bog, divided into two sections by Fur Tor and Fur Tor Cut, extends southwards to within a short distance of Great Mis Tor, and is a vast receptacle of rain, which it safely holds throughout the driest summer.[Pg 8] Fur Tor Cut is a passage between the north and south parts of this great bog, evidently cut artificially for a pass for cattle and men on horseback from Tay Head, or Tavy Head, to East Dart Head, forming a pass from west to east over the very wildest part of Dartmoor. Anyone can walk over the bogs; there is no danger or difficulty to a man on foot unless he gets exhausted, as some have done. But horses, bullocks, and sheep cannot cross them. A man on horseback must take care where he goes, and this Fur Tor Cut is for his accommodation."[1]

The Fur Tor Mire is not composed of black but of a horrible yellow slime. There is no peat in it, and to cross it one must leap from one tuft of coarse grass to another. The "mires" are formed in basins of the granite, which were originally lakes or tarns, and into which no streams fall bringing down detritus. They are slowly and surely filling with vegetable matter, water-weeds that rot and sink, and as this vegetable matter accumulates it contracts the area of the water surface. In the rear of the long sedge grass or bogbean creeps the heather, and a completely choked-up mire eventuates in a peat bog. Granite has a tendency to form saucer-like depressions. In the Bairischer Wald, the range dividing Bavaria from Bohemia, are a number of picturesque tarns, that look as though they occupied the craters of extinct volcanoes. This, however, is not the case; the rock is granite, but in this case the lakes are so deep that they have not as yet been filled with[Pg 9] vegetable deposit. On the Cornish moors is Dosmare Pool. This is a genuine instance of the lake in a granitic district. In Redmoor, near Fox Tor, on the same moors, we have a similar saucer, with a granitic lip, over which it discharges its superfluous water, but it is already so much choked with vegetable growth as to have become a mire. Ten thousand years hence it will be a great peat bog.

I had an adventure in Redmoor, and came nearer looking into the world beyond than has happened to me before or since. Although it occurred on the Cornish moors, it might have chanced on Dartmoor, in one of its mires, for the character of both is the same, and I was engaged in the same autumn on both sets of moors. Having been dissatisfied with the Ordnance maps of the Devon and Cornish moors, and desiring that certain omissions should be corrected, I appealed to Sir Charles Wilson, of the Survey, and he very readily sent me one of his staff, Mr. Thomas, to go over the ground with me, and fill in the particulars that deserved to be added. This was in 1891. The summer had been one of excessive rain, and the bogs were swollen to bursting. Mr. Thomas and I had been engaged, on November 5th, about Trewartha Marsh, and as the day closed in we started for the inhabited land and our lodgings at "Five Janes." But in the rapidly closing day we went out of our course, and when nearly dark found ourselves completely astray, and worst of all in a bog. We were forced to separate, and make our way as best we could, leaping from one patch of rushes or moss to another. All at once I went in[Pg 10] over my waist, and felt myself being sucked down as though an octopus had hold of me. I cried out, but Thomas could neither see me nor assist me had he been able to approach. Providentially I had a long bamboo, like an alpenstock, in my hand, and I laid this horizontally on the surface and struggled to raise myself by it. After some time, and with desperate effort, I got myself over the bamboo, and was finally able to crawl away like a lizard on my face. My watch was stopped in my waistcoat pocket, one of my gaiters torn off by the suction of the bog, and I found that for a moment I had been submerged even over one shoulder, as it was wet, and the moss clung to it.

On another occasion I went with two of my children, on a day when clouds were sweeping across the moor, over Langstone Moor. I was going to the collection of hut circles opposite Greenaball, on the shoulder of Mis Tor. Unhappily, we got into the bog at the head of Peter Tavy Brook. This is by no means a dangerous morass, but after a rainy season it is a nasty one to cross.

Simultaneously down on us came the fog, dense as cotton wool. For quite half an hour we were entangled in this absurdly insignificant bog. In getting about in a mire, the only thing to be done is to leap from one spot to another where there seems to be sufficient growth of water-plants and moss to stay one up. In doing this one loses all idea of direction, and we were, I have no doubt, forming figures of eight in our endeavours to extricate ourselves. I knew that the morass was inconsiderable in[Pg 11] extent, and that by taking a straight line it would be easy to get out of it, but in a fog it was not possible to take a bee-line. Happily, for a moment the curtain of mist lifted, and I saw on the horizon, standing up boldly, the stones of the great circle that is planted on the crest. I at once shouted to the children to follow me, and in two minutes we were on solid land.

The Dartmoor bogs may be explored for rare plants and mosses. The buckbean will be found and recognised by its three succulent sea-green leaflets, and by its delicately beautiful white flower tinged with pink, in June and July. I found it in 1861 in abundance in Iceland, where it is called Alptar colavr, the swan's clapper. About Hamburg it is known as the "flower of liberty," and grows only within the domains of the old Hanseatic Republic. In Iceland it serves a double purpose. Its thickly interwoven roots are cut and employed in square pieces like turf or felt as a protection for the backs of horses that are laden with packs. Moreover, in crossing a bog, the clever native ponies always know that they can tread safely where they see the white flower stand aloft.

The golden asphodel is common, and remarkably lovely, with its shades of yellow from the deep-tinted buds to the paler expanded flower. The sundew is everywhere that water lodges; the sweet gale has foliage of a pale yellowish green sprinkled over with dots, which are resinous glands. The berries also are sprinkled with the same glands.[Pg 12] The plant has a powerful, but fresh and pleasant, odour, which insects dislike. Country people were wont to use sprigs of it, like lavender, to put with their linen, and to hang boughs above their beds. The catkins yield a quantity of wax. The sweet gale was formerly much more abundant, and was largely employed; it went by the name of the Devonshire myrtle. When boiled, the wax rises to the surface of the water. Tapers were made of it, and were so fragrant while burning, that they were employed in sick-rooms. In Prussia, at one time, they were constantly furnished for the royal household.

The marsh helleborine, Epipactis palustris, may be gathered, and the pyramidal orchis, and butterfly and frog orchises, occasionally.

The furze—only out of bloom when Love is out of tune—keeps away from the standing water. It is the furze which is the glory of the moor, with its dazzling gold and its honey breath, fighting for existence against the farmer who fires it every year, and envelops Dartmoor in a cloud of smoke from March to June. Why should he do this instead of employing the young shoots as fodder?

I think that as Scotland has the thistle, Ireland the shamrock, and Wales the leek as their emblems, we Western men of Devon and Cornwall should adopt the furze. If we want a day, there is that of our apostle S. Petrock, on June 4th.

By the streams and rivers and on hedge-banks the yellow broom blazes, yet it cannot rival in intensity of colour and in variety of tint the magnificent furze[Pg 13] or gorse. But the latter is not a pleasant plant to walk amidst, owing to its prickles, and especial care must be observed lest it affix one of these in the knee. The spike rapidly works inwards and produces intense pain and lameness. The moment it is felt to be there, the thing to be done is immediately to extract it with a knife. From the blossoms of the furze the bees derive their aromatic honey, which makes that of Dartmoor supreme. Yet beekeeping is a difficulty there, owing to the gales, that sweep the busy insects away, so that they fail to find their direction home. Only in sheltered combes can they be kept.

The much-relished Swiss honey is a manufactured product of glycerine and pear-juice; but Dartmoor honey is the sublimated essence of ambrosial sweetness in taste and savour, drawn from no other source than the chalices of the golden furze, and compounded with no adventitious matter.

Dartmoor from a distance—Elevation—The tors—Old lake-beds—"Clitters"—The boldest tors—Luminous moss—The whortleberry—Composition of granite—Wolfram—The "forest" and its surrounding commons—Venville parishes—Encroachment of culture on the moor—The four quarters—A drift—Attempts to reclaim the moor—Flint finds—The inclosing of commons.

Seen from a distance, as for instance from Winkleigh churchyard, or from Exbourne, Dartmoor presents a stately appearance, as a ridge of blue mountains rising boldly against the sky out of rolling, richly wooded under-land.

But it is only from the north and north-west that it shows so well. From south and east it has less dignity of aspect, as the middle distance is made up of hills, as also because the heights of the encircling tors are not so considerable, nor is their outline so bold.

Indeed, the southern edge of Dartmoor is conspicuously tame. It has no abrupt and rugged heights, no chasms cleft and yawning in the range, such as those of the Okement and the Tavy and Taw. And to the east much high ground is found rising in stages to the fringe of the heather-clothed tors.

A TOR, SHOWING WEATHERING OF GRANITE

Dartmoor, consisting mainly of a great upheaved mass of granite, and of a margin of strata that have been tilted up round it, forms an elevated region some thirty-two miles from north to south and twenty from east to west. The heated granite has altered the slates in contact with it, and is itself broken through on the west side by an upward gush of molten matter which has formed Whit Tor and Brent Tor.

The greatest elevations are reached on the outskirts, and there, also, is the finest scenery. The interior consists of rolling upland. It has been likened to a sea after a storm suddenly arrested and turned to stone; but a still better resemblance, if not so romantic, is that of a dust-sheet thrown over the dining-room chairs, the backs of which resemble the tors divided from one another by easy sweeps of turf.

Most of the heights are crowned with masses of rock standing up like old castles; these, and these only, are tors.[2] Such are the worn-down stumps of vast masses of mountain formation that have disappeared. There are no lakes on or about the moor, but this was not always so. Where is now Bovey Heathfield was once a noble sheet of water fifty fathoms deep. Here have been found beds of lignite, forests that have been overwhelmed by the wash from the moor, a canoe rudely hollowed out of an oak, and a curious wooden idol was exhumed leaning against a trunk of tree that had been swallowed up in a freshet. The canoe was nine feet long. Bronze spear-heads have also been found in this ancient lake, and moulds for casting bronze instruments. A [Pg 16]representation of the idol was given in the Transactions of the Devonshire Association for 1875.

The new Plymouth Reservoir overlies an old lake-bed. Taw Marsh was also once a sheet of rippling blue water, but the detritus brought down in the weathering of what once were real mountains has filled them all up. Dartmoor at present bears the same relation to Dartmoor in the far past that the gums of an old hag bear to the pearly range she wore when a fresh girl. The granite of Dartmoor was not well stirred before it was turned out, consequently it is not homogeneous. Granite is made up of many materials: hornblende, feldspar, quartz, mica, schorl, etc. Sometimes we find white mica, sometimes black. Some granite is red, as at Trowlesworthy, and the beautiful band that crosses the Tavy at the Cleave; sometimes pink, as at Leather Tor; sometimes greenish, as above Okery Bridge; sometimes pure white, as at Mill Tor.

The granite is of very various consistency, and this has given it an appearance on the tors as if it were a sedimentary rock laid in beds. But this is its little joke to impose on the ignorant. The feature is due to the unequal hardness of the rock which causes it to weather in strata.

The fine-grained granite that occurs in dykes is called elvan, which, if easiest to work, is most liable to decay. In Cornwall the elvan of Pentewan was used for the fine church of S. Austell, and as a consequence the weather has gnawed it away, and the greater part has had to be renewed. On the other hand, the splendid elvan of Haute Vienne has supplied the[Pg 17] cathedral of Limoges with a fine-grained material that has been carved like lace, and lasts well.

The drift that swept over the land would appear to have been from west to east, with a trend to the south, as no granite has been transported, except in the river-beds to the north or west, whereas blocks have been conveyed eastward. This is in accordance with what is shown by the long ridges of clay on the west of Dartmoor, formed of the rubbing down of the slaty rocks that lie north and north-west. These bands all run north and south on the sides of hills, and in draining processes they have to be pierced from east to west. This indicates that at some period during the Glacial Age there was a wash of water from the north-west over Devon, depositing clay and transporting granite.

On the sides of the tors are what are locally termed "clitters" or "clatters" (Welsh clechr), consisting of a vast quantity of stone strewn in streams from the tors, spreading out fanlike on the slopes. These are the wreckage of the tor when far higher than it is now, i.e. of the harder portions that have not been dissolved and swept away.

"The tors—Nature's towers—are huge masses of granite on the top of the hills, which are not high enough to be called mountains, piled one upon another in Nature's own fantastic way. There may be a tor, or a group of tors, crowning an eminence, but the effect, either near or afar, is to give the hilltop a grand and imposing look. These large blocks of granite, poised on one another, some appearing as if they must fall, others piled with curious regularity—considering they are Nature's work—are the[Pg 18] prominent features in a Dartmoor landscape, and, wild as parts of Dartmoor are, the tors add a notable picturesque effect to the scene. There are very fine tors on the western side of the moor. Those on the east and south are not so fine as those on the north and west. In the centre of the moor there are also fine tors. They are, in fact, very numerous, for nearly every little hill has its granite cap, which is a tor, and every tor has its name. Some of the high hills that are tor-less are called beacons, and were doubtless used as signal beacons in times gone by. As the tors are not grouped or built with any design by Nature to attract the eye of man, they are the more attractive on that account, and one of their consequent peculiarities is that from different points of view they never appear the same. There can be no sameness in a landscape of tors when every tor changes its features according to the point of view from which you look at it. Every tor also has its heap of rock at its feet, some of them very striking jumbles of blocks of granite scattered in great confusion between the tor and the foot of the hill. Fur Tor, which is in the very wildest spot on Dartmoor, and is one of the leading tors, has a clitter of rocks on its western side as remarkable as the tor itself; Mis Tor, also on its western side, has a very fine clitter of granite; Leather Tor stands on the top of a mass of granite rocks on its east and south sides; and Hen Tor, on the south quarter, is surrounded with blocks of granite, with a hollow like the crater of a volcano, as if they had been thrown up by a great convulsion of Nature. Hen Tor is remarkable chiefly for this wonderful mass of granite blocks strewn around it. All the moor has granite boulders scattered about, but they accumulate at the feet of the tors as if for their support."[3]

VIXEN TOR

Here among the clitters, where they form caves, a search may be made for the beautiful moss Schistostega osmundacea. It has a metallic lustre like green gold, and on entering a dark place under rocks, the ground seems to be blazing with gold. In Germany the Fichtel Gebirge are of granite, and the Luchsen Berg is so called because there in the hollow under the rocks grew abundance of the moss glittering like the eyes of a lynx. The authorities of Alexanderbad have had to rail in the grottoes to prevent the gold moss from being carried off by the curious. Murray says of these retreats of the luminous moss:—

"The wonder of the place is the beautiful phosphorescence which is seen in the crannies of the rocks, and which appears and disappears according to the position of the spectator. This it is which has given rise to the fairy tales of gold and gems with which the gnomes and cobolds tantalise the poor peasants. The light resembles that of glow-worms; or, if compared to a precious stone, it is something between a chrysolite and a cat's-eye, but shining with a more metallic lustre. On picking up some of it, and bringing it to the light, nothing is found but dirt."

Professor Lloyd found that the luminous appearance was due to the presence of small crystals in the structure which reflect the light. Coleridge says:—

In 1843, when the luminosity of plants was recorded in the Proceedings of the British Association, Mr. Babington mentioned having seen in the south of England a peculiar bright appearance produced by the presence of the Schistostega pennata, a little moss which inhabited caverns and dark places: but this was objected to on the ground that the plant reflected light, and did not give it off in phosphorescence.[4]

When lighted on, it has the appearance of a handful of emeralds or aqua marine thrown into a dark hole, and is frequently associated with the bright green liverwort. Parfitt, in his Moss Flora of Devon, gives it as osmundacea, not as pennata. It was first discovered in Britain by a Mr. Newberry, on the road from Zeal to South Tawton; it is, however, to be found in a good many places, as Hound Tor, Widdecombe, Leather Tor, and in the Swincombe valley, also in a cave under Lynx Tor. If found, please to leave alone. Gathered it is invisible; the hand or knife brings away only mud.

But what all are welcome to go after is that which is abundant on every moorside—but nowhere finer than on such as have not been subjected to periodical "swaling" or burning. I refer to the whortleberry. This delicious fruit, eaten with Devonshire cream, is indeed a delicacy. A gentleman from London was visiting me one day. As he was fond of good things, I gave him whortleberry and cream. He ate it in dead silence, then leaned back in his chair,[Pg 21] looked at me with eyes full of feeling, and said, "I am thankful that I have lived to this day."

The whortleberry is a good deal used in the south of France for the adulteration and colouring of claret, whole truck-loads being imported from Germany.

There is an interesting usage in my parish, and I presume the same exists in others. On one day in summer, when the "whorts" are ripe, the mothers unite to hire waggons of the farmers, or borrow them, and go forth with their little ones to the moor. They spend the day gathering the berries, and light their fires, form their camp, and have their meals together, returning late in the evening, very sunburnt, with very purple mouths, very tired maybe, but vastly happy, and with sufficient fruit to sell to pay all expenses and leave something over.

If the reader would know what minerals are found on Dartmoor he must go elsewhere.

I have a list before me that begins thus: "Allophane, actinolite, achroite, andalusite, apatite"—but I can copy out no more. I have often found appetite on Dartmoor, but have not the slightest suspicion as to what is apatite. The list winds up with wolfram, about which I can say something. Wolfram is a mineral very generally found along with tin, and that is just the "cussedness" of it, for it spoils tin.

When tin ore is melted at a good peat fire, out runs a silver streak of metal. This is brittle as glass, because of the wolfram in it. To get rid of the wolfram the whole has to be roasted, and the operation is delicate, and must have bothered our[Pg 22] forefathers considerably. By means of this second process the wolfram, or tungsten as it is also called, is got rid of.

Now, it is a curious fact that the tin of Dartmoor is of extraordinary purity; it has little or none of this abominable wolfram associated with it, so that it is by no means improbable that the value of tin as a metal was discovered on Dartmoor, or in some as yet unknown region where it is equally unalloyed.

In Cornwall all the tin is mixed with tungsten. Now this material has been hitherto regarded as worthless; it has been sworn at by successive generations of miners since mining first began. But all at once it has leaped into importance, for it has been discovered to possess a remarkable property of hardening iron, and is now largely employed for armour-plated vessels. From being worth nothing it has risen to a rapidly rising value, as we are becoming aware that we shall have to present impenetrable sides to our Continental neighbours.

Dartmoor comprises the "forest" and the surrounding commons, as extensive together as the forest itself. "What have you got on you, little girl?" asked a good woman of a shivering child. "Please, mem, first there's a jacket, then a gownd, and then comes Oi." So with Dartmoor. First come the venville parishes, next their extensive commons, and "then comes Oi," the forest itself.

The venville parishes are all moorland parishes—Belstone, Throwleigh, Gidleigh, Chagford, North Bovey, Manaton, Widdecombe, Holne, Buckfastleigh, Dean Prior, South Brent, Shaugh, Meavy,[Pg 23] Sheeps Tor, Walkhampton, Sampford Spiney, Whitchurch, Peter Tavy, Lydford, Bridestowe, Sourton. There are others, standing like the angel of the Apocalypse, with one foot on the moorland, the other steeped in the green waves of foliage of the lowlands; such are South Tawton, Cornwood, and Tavistock. Others, again, as Lustleigh, Bridford, Moreton, Buckland-in-the-Moor, Ilsington, and Ugborough, must surely have been moorland settlements at one time, and Okehampton itself is as distinctly a moor town as is Moreton, which tells its own tale in its name. But all these have their warm envelope of arable land, groves and woods, farms and hamlets. Such have their commons, over which every householder has a right to send cattle, to take turf and stone, and, alas! with the connivance of the other householders, to inclose. This inclosing has been going on at a great rate in some of the parishes. For instance, common rights are exercised by the householders of South Zeal over an immense tract of land on the north side of Cosdon. Of late years they have put their heads together and decided, as they are few in number, to appropriate it to themselves as private property, and inclosures have proceeded at a rapid rate.

In Bridestowe there is a tract of open land on which the poor cotters have, from time immemorial, kept their cows. But they are tenants, and not householders, and have consequently no rights. The seven or eight owners have combined to inclose and sell or let for building purposes all that tract of moor, and the cotters have lost their privilege of keeping cows.[Pg 24] What we see now going on under our eyes has been going on from time immemorial. Parishes have encroached, and the genuine forest has shrunk together before them. The commons still exist, and are extensive, but they are being gradually and surely reduced. "Then comes Oi!" Look at the map and see of what the forest really consists. It surely must have been larger formerly.

On the forest itself are a certain number of "ancient tenements," thirty-five in all. These are of remote antiquity. On certainly most of them, probably on all, the plough and the hoe turn up numerous flint tools, weapons, and chips—sure proof that they were settlements in prehistoric times. These tenements are at Brimpts, Hexworthy, Huccaby, Bellever, Dunnabridge, Baberry, Pizwell, Runnage, Sherberton, Riddons, Merripit, Hartland, Broom Park, Brown Berry, and Prince Hall. These were held—and some still are—by copy of the Court Roll, and the holders are bound to do suit and service at the Court. It is customary for every holder on accession to the holding to inclose a tract of a hundred acres, and this inclosure constitutes his newtake.

The forest belongs to the Prince of Wales, but I believe has never been visited by him. Were he to do so, he would be surprised, and perhaps not a little indignant, to see how his tenants are housed. A forest does not necessarily signify a wood. It is a place for wild beasts. The origin of the word is not very clear. Lindwode says, "A Forest is a place where are wild beasts; whereas a Park is a place where they are shut in." Ockam says, "A Forest is a safe abode for wild beasts," and derives the word from feresta, i.e. a place for wild creatures. It was, in fact, a tract of uninclosed land reserved for the king to hunt in, and a chase was a similar tract reserved by the lord of the manor for his own hunting.

ROCKS NEAR HEY TOR

It is more than doubtful whether Dartmoor was ever covered with trees. No doubt there have been trees in the bottoms, and indeed oak has been taken from some of the bogs; but the charcoal found in the fire-pits of the primitive inhabitants of the moor in the Bronze Age shows that, even in the prehistoric period, the principal wood was alder, and that such oak as there was did not grow to a large size, and was mainly confined to the valleys that opened out of the moor into the lowlands. Up these, doubtless, the forest crept. Elsewhere there may have been clusters of stunted trees, of which the only relics are Piles and Wistman's Wood. There were some very fine oaks at Brimpts, and also in Okehampton Park, but these were cut down during the European war with Napoleon. After the wood at Brimpts had fallen under the axe, it was found that the cost of carriage would be so great that the timber was sold for a mere trifle, only sufficient to pay for the labour of cutting it down.

The forest is divided into four quarters, in each of which, except the western, is a pound for stray cattle. Formerly the Forest Reeve privately communicated with the venville men when he had fixed a day for a "drift," which was always some time about midsummer. Then early in the morning all[Pg 26] assembled mounted. A horn was blown through a holed stone set up on a height, and the drift began. Cattle or horses were driven to a certain point, at which stood an officer of the Duchy on a stone, and read a proclamation, after which the owners were called to claim their cattle or ponies. Venville tenants removed them without paying any fine, but all others were pounded, and their owners could not recover them without payment of a fine.

The Duchy Pound is at Dunnabridge, where is a curious old seat within the inclosure for the adjudicator of fines and costs. It is apparently a cromlech that has been removed or adapted. The Duchy now lets the quarters to the moormen, who charge a small fee for every sheep, bullock, or horse turned out on the moor not belonging to a venville man, and for this fee they accord it their protection.

A good deal of money has been expended on the reclaiming of Dartmoor. Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt, Usher of the Black Rod, was Warden of the Stannary and Steward of the Forest for George IV. when Prince of Wales. He fondly supposed that he had discovered an uncultivated land, which needed only the plough and some lime to make its virgin soil productive. He induced others to embark on the venture. Swincombe and Stannon were started to become fine farm estates. Great entrance gates were erected to where mansions were proposed to be built. But those who had leased these lands found that the draining of the bogs drained their pockets much faster than the mires, and abandoned the attempt[Pg 27] which had ruined them. Others followed. Prince's Hall was rebuilt with fine farm buildings by a Mr. Fowler from the north of England, who expended his fortune there and left a disappointed man. Before him Sir Francis Buller, who had bought Prince's Hall, planted there forty thousand trees—such as are not dead are distorted starvelings. Mr. Bennett built Archerton, near Post Bridge, and inclosed thousands of acres. He cannot have recovered a sum approaching his outlay in the sixty years of his tenancy. The fact is that Dartmoor is cut out by Nature to be a pasturage for horses, cattle, and sheep in the summer months, and for that only. In the burning and dry summers of 1893, 1897, and 1899 tens of thousands of cattle were sent there, even from so far off as Kent, where water and pasturage were scarce, and on the moor they both are ever abundant.

Tenements there must be, but they should be in the sheltered valleys, and the wide hillsides and sweeps of moor should be left severely alone. As it is, encroachments have gone on unchecked, rather have been encouraged. Every parish in Devon has a right to send cattle to the moor, excepting only Barnstaple and Totnes. But the Duchy, by allowing and favouring inclosures, is able to turn common land into private property, and that it is only too willing to do.

Happily there now exists a Dartmoor Preservation Society, which is ready to contest every attempt made in this direction. But it can do very little to protect the commons around the forest—in fact it[Pg 28] can do nothing, if the freeholders in the parishes that enjoy common rights agree together to appropriate the land to themselves—and for the poor labourer who is able to buy himself a cow it can do nothing at all, for his rights have no legal force.

[2] The Welsh twr is a tower; twrr, a heap or pile. From the same root as the Latin turris.

[3] Collier, op. cit.

Abundance of remains of primeval inhabitants—No trace of Briton or Saxon on Dartmoor—None of Palæolithic man—The Neolithic man who occupied it—Account of his migrations—His presence in Ireland, in China, in Algeria—A pastoral people—The pottery—The arrival of the Celt in Britain in two waves—The Gael—The Briton—Introduction of iron—Mode of life of the original occupants of the moor—The huts—Pounds—Cooking—Tracklines—Enormous numbers who lived on Dartmoor—A peaceable people.

Probably no other tract of land of the same extent in England contains such numerous and well-preserved remains of prehistoric antiquity as Dartmoor.

The curious feature about them is that they all belong to one period, that of the Early Bronze, when flint was used abundantly, but metal was known, and bronze was costly and valued as gold is now.

Not a trace has been found so far of the peoples who intervened between these primitive occupants and the mediæval tin-miners.

If iron was introduced a couple of centuries before the Christian era, how is it that the British inhabitants who used iron and had it in abundance have left no mark of their occupancy of Dartmoor? It can be accounted for only on the supposition that they did not value it. The woods had been thinned[Pg 30] and they preferred the lowlands, whereas in the earlier period the dense forests that clothed the country were too close a jungle and too much infested by wolves to be suitable for the habitation of a pastoral people.

That under the Roman domination the tin was worked on the moor there is no evidence to show. No Roman coins have been found there except a couple brought by French prisoners to Princetown.

It may be said that iron would corrode and disappear, whereas flint is imperishable, and bronze nearly so. But where is Roman pottery? Where is even the pottery of the Celtic period? An era is distinguished by its fictile ware. A huge gap in historic continuity is apparent. All the earthenware found on Dartmoor is either prehistoric or mediæval, probably even so late as the reign of Elizabeth.

No indication is found that the Saxons worked the tin or even drove their cattle on to the moor. In Domesday Book Dartmoor is not even mentioned. It is hard to escape the conclusion that from the close of the prehistoric period to that of our Plantagenet kings, Dartmoor was avoided as a waste, inhospitable region.

Of man in the earliest period at which he is known to have existed—the so-called Palæolithic man—not a trace has been found on Dartmoor. Probably when he lived in Britain the whole upland was clothed in snow. He has left his tools in the Brixham and Torquay caves—none in the bogs of the moor. Indeed, when these bogs have been dug into, there are not the smallest indications found of man having[Pg 31] visited the moor before the advent of what is called the Neolithic Age.

About the man of this period I must say something, as he in his day lived in countless swarms on this elevated land. He may have lived also in the valleys of the lowlands, but his traces there have been obliterated by the plough. First of all as to his personal appearance. He was dark-haired, tall, and his head was long, like that of a new-born child, or boat-shaped, a form that disappears with civilisation, and resolves itself into the long face instead of the long head.

At some period, vastly remote, a great migration of a long-headed race took place from Central Asia. It went forth in many streams. One to the east entered Japan; probably the Chinese and Anamese represent another. But we are mainly concerned with the western outpour. It traversed Syria, and Gilead and Moab are strewn with its remains, hut circles, dolmens, and menhirs identical with those on Dartmoor. Hence one branch passed into Arabia, where, to his astonishment, Mr. Palgrave lighted on replicas of Stonehenge.[5]

Another branch threw itself over the Himalayas, and covered India with identical monuments. Again another turned west; it traversed the Caspian and left innumerable traces along the northern slopes of the Caucasus. The Kuban valley is crowded with their dolmens. They occupied the Crimea, and then struck for the Baltic. That a branch had passed through Asia Minor and Greece, and constituted itself as the Etruscan power in Italy, is probable but not established. The northern stream strewed Mecklenburg and Hanover with its remains, occupied Denmark and Lower Sweden, crossed into Britain, and took complete possession of the British Isles. Other members of the same swarm skirted the Channel and crowded the plateaux and moors of Western and Central France with their megalithic remains. The same people occupied Spain and Portugal, the Balearic Isles, Corsica and Sardinia, [Pg 33]and Northern Africa, and are now represented by the Koumirs and Kabyles. To this race the name of Iberian, Ivernian, or Silurian has been given. It contributed its name to Ireland (Erin or Ierne), where it maintained itself, but was known to the conquering Gaels as the Tuatha da Danann and Firbolgs, two branches of the same stock. The name of Damnonia given to Devon is probably due to these same Danann, who were also found in the south of Scotland. When this great people reached Europe, Japan, India, Africa, before its branches had begun to ramify to east and west, to south and north, its religious doctrines and its practices had become stereotyped, and almost ineradicably ingrained into the consciousness of the entire stock.

If we desire to understand what their peculiar views were, what were the dominant ideas which directed their conduct, and which led them to erect the monuments which are marvels to us, even at the present day, we must go to China.

Let us look for a moment into China at the present day. At first sight, the Chinese strike us as being not only geographically our antipodes, but as being our opposites in every particular—mental, moral, social; in language as in ideas.

The Chinese language is without an alphabet and without a grammar. It is made up of monosyllables that acquire their significance by the position in which they are placed in a sentence. In customs the Chinese differ from us as much. In mourning they wear white; a Chinese dinner begins with the dessert and ends with the soup; a scholar, to recite[Pg 34] his lessons, turns his back on the teacher. But it is chiefly in the way in which the living and the dead are regarded as forming an indissoluble commonwealth, that the difference of ideas is most pronounced. Regard for the dead is the first obligation to a Chinese. A man of the people who is ennobled, ennobles, not his descendants, but his ancestry. The duty of the eldest son of the family is to maintain the worship of the ancestors. Denial of a sepulchre is the most awful punishment that can be inflicted; a Chinese will cheerfully commit suicide to gain a suitable tomb and cult after death. The most sacred spot on earth is the mausoleum, and that is perpetually inviolable. Consequently, if this principle could be carried out to the letter, the earth would be transformed into one vast necropolis, from the occupation of which the living would be in time entirely excluded. It is this respect for graves which stands in the way of the execution of works of public utility, such as canals and railroads; and it is the imperious obligation of maintaining the worship of ancestors that blocks conversion to Christianity. It is resentment against lack of respect shown to the dead, neglect of duty to the dead, which has provoked the massacres of Christians. A Chinese, under certain circumstances, is justified in strangling his father, but not in omitting to worship him after he has throttled him.

On the great Thibet plateau, geographically contiguous to the Chinese, and under the Empire of China, the Mongol nomads are so absolutely devoid of a grain of respect for their dead, that, without[Pg 35] the smallest scruple, they leave the corpses of their parents and children on the face of the desert, to be devoured by dogs and preyed on by vultures.

If we look at the Nile valley we see that the ancient Egyptians were dominated by the same ideas as the Chinese. To them the tomb was the habitation par excellence of the family. Of the dwelling-houses of the old Egyptians the remains are comparatively mean, but their mausoleums are palatial. The house for the living was but as a tent, to be removed; but the mansion of the dead was a dwelling-place for ever.

Not only so, but just as the ancient Egyptian supposed that the Ka, the soul, or one of the souls of the deceased, occupied the monument, tablet, or obelisk set up in memorial of the dead, so does the Chinese now hold that a soul, or emanation from the dead, enters into and dwells in the memorial set up, apart from the tomb, to his honour.

Now if we desire to discover what was the distinguishing motive in life of the long-headed Neolithic man, we shall find it in his respect for the dead; and he has stamped his mark everywhere where he has been by the stupendous tombs he has erected, at vast labour, out of unwrought stones. He cannot be better described than as the dolmen-builder; that is to say, the man who erected the family or tribal ossuaries that remain in such numbers wherever he has planted his foot.

In China, it is true, there are no dolmens, but for this there is a reason. Before the descendants of the Hundred Families who entered the Celestial Empire[Pg 36] had reached and obtained possession of mountains whence stone could be quarried, many centuries elapsed, and forced the Chinese to make shift with other material than stone, and so formed their habit of entombment without stone; but the frame of mind which, in a rocky land, would have prompted them to set up dolmens remained unchanged, and so remains to the present day.

The exploration of dolmens in Europe reveals that they were family or tribal burial-places, and were used for a long continuance of time. The dead to be laid in them were occasionally brought from a distance, as the bones show indication of having been cleaned of the flesh with flint scrapers, and to have been rearranged in an irregular and unscientific manner, a left leg being sometimes applied to a right thigh; or it may be that on the anniversary of an interment the bones of the deceased were taken out, scraped and cleaned, and then replaced.

In Algeria, and on the edge of the Sahara, are found great trilithons, that is to say, two huge upright stones, with one laid across at the top, forming doorways leading to nothing, but similar to those which are found at Stonehenge.

What was this significance?

We turn to the Chinese for an explanation, and find that to this day they erect triumphal gates—not now of stone, but of wood—in memory of and in honour of such widows as commit suicide so as to join their dear departed husbands in the world of spirits. On the other hand, our widows forget us and remarry.

FLINT ARROW-HEADS.

(Actual size.)

The dolmen-builders were people with flocks and herds, and who cultivated grain and spun yarn. Their characteristic implement is the so-called celt, in reality an axe, sometimes perforated for the reception of a handle, most commonly not. The perforation belongs to the latest stage of Neolithic civilisation. Their weapons, or tools, were first ground. In about a score of places in France polishing rocks exist, marked with the furrows made by the axe when worked to and fro upon them, and others that are smaller have been removed to museums. At Stoney-Kirk, in Wigtownshire, a grinding-stone of red sandstone, considerably hollowed by use, was found with a small, unfinished axe of Silurian schist lying upon it. In the recent[Pg 38] exploration of hut circles at Legis Tor a grindstone was found in one of the habitations, and on it an incomplete tool that was abandoned there before it was finished.

After grinding, these implements underwent laborious polishing by friction with the hand or with leather.

At the same time that these artificially smoothed tools were fabricated, flint was used, beautifully chipped and flaked, to form arrow and spear heads and swords. The arrow-heads are either leaf-shaped or tanged.

The pottery of the dolmen-builders is very rude. It is made of clay mingled with coarse fragments of stone or shell, is very thick and badly tempered; it is hand-made, and seems hardly capable of enduring exposure to a brisk fire. The vessels have usually broad mouths, with an overhanging rim like a turned-back glove-cuff, and below this the vessel rapidly slopes away. The ornamentation is constant everywhere. It consisted of zigzags, chevrons, depressions made by twisted cord, and finger-nail marks in rings round the bowls or rims. It was not till late in the Bronze Age that circles and spirals were adopted.

Celtic ornamentation is altogether different.

Whilst the long-headed dolmen-builder crept along the coast of Europe, there was growing up among the mountains and lakes of Central Europe a hardy round-headed race—the Aryan, destined to be his master. Was it through instinct of what was to be, that the Ivernian shrank from penetrating into the heart of the Continent, and clung to the seaboard?

When the dolmen-builder arrived in Britain, to the best of our knowledge, he found no one there. On the Continent, on the other hand, if he went far inland, he not only clashed with the Aryan round-heads, but also here and there stumbled on the lingering remains of the primeval Palæolithic people, who have left their remains in England in the river-drift, and in Devon in the Brixham caves and Kent's Hole.

The dolmen-builder has persisted in asserting himself. Though cranial modifications have taken place, the dusky skin, and the dark eyes and hair and somewhat squat build, have remained in the Western Isles, in Western Ireland, in Wales, and in Cornwall. It is still represented in Brittany. It is predominant in South-Western France, and is typical in Portugal.

After a lapse of time, of what duration we know not, a great wave of Aryans poured from the mountains of Central Europe, and, traversing Britain, occupied Ireland. This was the Gael. This people subjugated the Ivernian inhabitants, and rapidly mixed with them, imposing on them their tongue, except in South Wales, where the Silurian was found to have retained his individuality when conquered by Agricola in A.D. 78. But if the Gaelic invaders subjugated the Ivernians, they were in turn conquered by them, though in a different manner. The strongly marked religious ideas of the long-headed men, and their deeply rooted habit of worship of ancestors, impressed and captured the imagination of their masters, and as the races[Pg 40] became fused, the mixed race continued to build dolmens and erect other megalithic monuments once characteristic of the long-heads, often on a larger scale than before. Stonehenge and Avebury were erections of the Bronze Period, and late in it, and of the composite people.

If we look at the physique of the two races, we find a great difference between them. The Ivernian was short in stature, with a face mild in expression, oval, without high cheek-bones, and without strongly characterised supraciliary ridges. The women were all conspicuously smaller than the men, and of markedly inferior development. The conquering race was other. The lower jaw was massive and square at the chin, the molar bones prominent, and the brows heavy. The head was remarkably short, and the face expressed vigour, was coarse, and the aspect threatening. Moreover, the women were as fully developed as the men, so much so that where all the bones are not present it is not always easy to distinguish the sex of a skeleton of this race. What Tacitus says of the German women—that they are almost equal to the men both in strength and in size—applies also to these round-headed invaders of Britain; and, indeed, what we are assured of the Britons in the time of Boadicea, that it was solitum feminarum ductu bellare, shows us that the same masculine character belonged to the women of British origin. The average difference in civilised races in the stature of men and women at present is about four inches, but twice this difference is very usually found to exist between the male and[Pg 41] female skeletons of the Polished Stone Period in the long barrows. The difference is even more strikingly shown by a comparison of the male and female collar-bones; and we are able to reproduce from them in picture the Neolithic woman of the Ivernian race, with narrow chest and drooping shoulders, utterly unlike the muscular and vigorous Gaelic women who were true consorts to their men when they came over to conquer the island of Britain.

After a lapse of time the long-head began to reassert itself, and the infusion of its blood into the veins of the dominant race led to great modification of its harshness of feature. When iron was introduced into Britain, whether by peaceable means or whether by the second Aryan invasion, that of the Cymri or Britons, we do not know, but when Cæsar landed in Britain, B.C. 55, he found that iron was in general use.

The second Aryan invasion alluded to was that of the true Britons. They also came from the Alps, where they had lived on platforms constructed on the lakes. They occupied the whole of Britain proper, but not Scotland, and made but attempts to effect a landing in Ireland.

They were entirely out of sympathy with the original race and its ideas, and did not assimilate their religion and adopt their practices as had the Gaels.

The distinction between the two branches of the great Celtic family is mainly linguistic. Where the British employed the letter p, the Gael used the hard c, pronounced like k. For instance, Pen, a head,[Pg 42] in British, is Cen in Gaelic; and we can roughly tell where the population was British by noticing the place names, such as those beginning with Pen. When these were Gaels, the same headlands would begin with Cen.

and this at once decides that the inhabitants of the western peninsula were not Gaels.

From the lakes of Switzerland the Britons had brought with them their great aptitude for wattle-work. They built their houses and halls, not of stone, but of woven withies. Cæsar says that they were wont to erect enormous basket-work figures, fill them with human victims, and burn the whole as sacrifices to their gods. It is a curious coincidence that on some of the old Celtic crosses are found carved imitations of men made of wicker-work. These represent saints made of the same material and in the same manner by the same people, after they had embraced Christianity and abandoned human sacrifices.[6]

Let us try to imagine what was the mode of life of those people who raised their monuments on Dartmoor. They were pastoral, but they also certainly had some knowledge of tillage. In certain lights, hillsides on the moor show indications of having been cultivated in ridges, and this not with the plough, but with the spade. We cannot say[Pg 43] that these belong to the early population, but as they are found near their settlements it is possible that they may be traces of original cultivation. But we know from the remains of grain found in the habitations and tombs of the same people in limestone districts that they were acquainted with cereals, and their grindstones have been found on Dartmoor in their huts.

Still, grain was not the main element of their diet; they lived chiefly on milk and flesh. In the huts have been found broad vessels that were covered with round discs of slate, and it is probable that these were receptacles for milk or butter, but the milk would mainly be contained in wooden or leathern vessels. Elsewhere their spindle-whorls have been found in fair abundance; not so on Dartmoor—as yet only two have been recovered. This shows that little spinning was done, and no weights such as are used by weavers have been found. The early occupants were in the main clothed in skins.

Their huts were circular, of stone, with very frequently a shelter wall, opposed to the prevailing south-west wind, screening the door, which opened invariably to the south or south-west. The whole was roofed over by poles planted on the walls, brought together in the middle, and thatched over with rushes or heather. The walls were rarely above four feet six inches high. They are lined within with large stones, set up on end, their smooth surfaces inwards, and the stone walls were backed up with turf without, making of the huts green mounds. This gave occasion to the fairy legends[Pg 44] of the Celts, who represented the earlier population as living in mounds, which the Irish called sidi, and the people occupying them the Tuatha da Danann. As already said, this same name meets us in Damnonii, the oldest appellation for the people of Devon. They were a sociable people, clustering together for mutual protection in pounds.

These pounds are large circular inclosures, the walls probably only about four feet high, but above this was a breastwork of turf or palisading. Outside the pound were huts, perhaps of guards keeping watch.

Many of the huts have paddocks connected with them, as though these latter had been kail gardens, but some of these paddocks are large enough to have been tilled for corn. Their plough, if they used one, was no more than a crooked beam, drawn by oxen. It is possible that the numerous sharp flakes of flint that are found were employed fastened into a sort of harrow, as teeth. Their cooking was done either in pots sunk in the soil, or in holes lined with stones.

Rounded pebbles, water-worn, were amassed, and baked hot in the fire, then rolled to the "cooking-hole," in which was the meat, and layers of hot stones and meat alternated, till the hollow receptacle was full, and the whole was then covered with sods till the flesh was cooked.

The following account of the manner in which the Fiana, the Irish militia, did their cooking in pre-Christian times will illustrate this custom:—

"When they had success in hunting, it was their custom in the forenoon to send their huntsman, with what they[Pg 45] had killed, to a proper place, where there was plenty of wood and water; there they kindled great fires, into which, their way was, to throw a number of stones, where they continued till they were red hot; then they applied themselves to dig two great pits in the earth, into one of which, upon the bottom, they were wont to lay some of these hot stones as a pavement, upon them they would place the raw flesh, bound up hard in green sedge or bulrushes; over these bundles was fixed another layer of hot stones, then a quantity of flesh, and this method was observed till the pit was full. In this manner their flesh was sodden or stewed till it was fit to eat, and then they uncovered it; and, when the hole was emptied, they began their meal."[7]

FLINT SCRAPERS. (Actual size.)

Some of the huts are very large, and in these no traces of fires and no cooking-holes have been found. Adjoining them, however, are smaller huts that are so full of charcoal and peat ash and fragments of pottery that no doubt can be entertained that these were the kitchens, and the large huts were summer habitations.

COOKING-POT.

Occasionally a small hut has been found with a large hole in the centre crammed with ashes and round stones, the hole out of all proportion to the size of the hut if considered as a habitation. No reasonable doubt can be entertained that these were bath huts. The Lapps still employ the sweating-houses. They pour water over hot stones, and the steam makes them perspire profusely, whereupon they shampoo themselves or rub each other down with birch twigs.

Indeed, men wearing skin dresses are obliged to go through some such a process to keep their pores in healthy action.

It is very probable that the long tracklines that extend over hill and vale on Dartmoor indicate tribal boundaries, limits beyond which the cattle of one clan might not feed. Some of these lines, certainly of the age of the Neolithic men of the hut circles, may be traced for miles. There is one that starts apparently from the Plym at Trowlesworthy Warren, where are clusters of huts and inclosures. It follows the contour of the hills to Pen Beacon, where it curves around a collection of huts and strikes for the source of the Yealm by two pounds containing huts. That it went further is probable, but recent inclosures have led to its destruction. We cannot be sure of the age of these tracklines unless associated with habitations, as some very similar have been erected in recent times as reeves delimiting mining rights.

That the occupants of the moor at this remote period loved to play at games is shown by the numbers of little round pebbles, carefully selected, some for their bright colours, that have been found on the floors of their huts. That they used divination by the crystal is shown by clear quartz prisms having been discovered tolerably frequently. These are still employed among the Australian natives for seeing spirits and reading the future.

That these early people were monogamists is probable from the small size of their huts; they really could not have accommodated more than one wife and her little family.

That they were a gentle, peaceable people is also apparent from the rarity of weapons of war. Plenty of[Pg 48] flint scrapers are found for cleaning the hides, plenty of rubber-stones for smoothing seams, plenty of small knives for cutting up meat, but hardly a spear-head, and arrow-heads are comparatively scarce. Their most formidable camp is at Whit Tor, the soil of which is littered with flint chips. It did not, on exploration, yield a single arrow-head. The pounds were inclosed to protect the sheep and young cattle against wolves, not to save the scalps of their owners from the tomahawks of their fellow-men.

With regard to the numbers of people who lived on Dartmoor in prehistoric times, it is simply amazing to reflect upon. Tens of thousands of their habitations have been destroyed; their largest and most populous settlements, where are now the "ancient tenements," have been obliterated, yet tens of thousands remain. At Post Bridge, within a radius of half a mile, are fifteen pounds. If we give an average of twenty huts to a pound, and allow for habitations scattered about, not inclosed in a pound, and give six persons to a hut, we have at once a population, within a mile, of 2,000 persons.

FLINT SCRAPERS.

(Actual size.)

Take Whit Tor Camp. To man the wall it would require 500 men. Allow to each man five noncombatants; that gives a population of 2,500. There are pounds and clusters of hut circles in and about Whit Tor that still exist, and would have contained that population. Take the Erme valley, high up where difficult of access; the number of huts there crowded on the hill slopes is incredible. On the height is a cairn, surrounded by a ring of stones, from which leads a line of upright blocks for a distance of 10,840 feet. Allow two feet apart for the stones, that gives 5,420 stones. If, as is probable, each stone was set up by a male member of a tribe, in honour of his chief who was interred in the cairn, we are given by this calculation a population of over[Pg 50] 21,000, allowing three children and a female to each male.

FRAGMENT OF COOKING-POT.

But numerous though these occupants of the moor must have been, they must have been wretchedly poor. The vast majority of their graves yield nothing but a handful of burnt ash, not a potsherd, not a flint-chip, and the grave of a chief only a little blade of bronze as small as a modern silver pocket fruit-knife.

That they were a peaceable people I have no manner of doubt, for there are absolutely no fortified hilltops on the moor, which there assuredly would be were the denizens of that upland region in strife one with another. What camps there are may be found on the fringe, Whit Tor, Dewerstone, Hembury, Holne, Cranbrook, Halstock, as against[Pg 51] invaders. That they were a happy people I cannot doubt. They were uncivilised: and the Tree of Knowledge, under high culture, bears bitter fruit for the many and drips with tears, but it bears nuts—only for the few.