| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See https://archive.org/details/truestoriesofgre06mill |

TRUE STORIES OF THE GREAT WAR

TALES OF ADVENTURE—HEROIC DEEDS—EXPLOITS

TOLD BY THE SOLDIERS, OFFICERS, NURSES,

DIPLOMATS, EYE WITNESSES

Collected in Six Volumes

From Official and Authoritative Sources

(See Introductory to Volume I)

VOLUME VI

Editor-in-Chief

FRANCIS TREVELYAN MILLER (Litt. D., LL.D.)

Editor of The Search-Light Library

1917

REVIEW OF REVIEWS COMPANY

NEW YORK

The Board of Editors has selected for VOLUME VI this group of stories told by Soldiers and Army Officers direct from the battle-grounds of the Great War. It includes 165 episodes and personal adventures by forty-two story-tellers—"Tommies," "Boches," "Poilus," Russians, Italians, Austrians, Turks, Belgians, Scotchmen, Irishmen, Canadians, Americans—the "Best Stories of the War" gathered from the most authentic sources, according to the plan outlined in "Introductory" to Volume I. Full credit is given in every instance to the original sources.

| VOLUME VI—FORTY STORY-TELLERS—165 EPISODES | |

| "BEHIND THE GERMAN VEIL"—WITH VON HINDENBURG | 1 |

| RECORD OF A REMARKABLE WAR PILGRIMAGE | |

| Told by Count Van Maurik De Beaufort | |

| (Permission of Dodd, Mead and Company) | |

| "KITCHENER'S MOB"—ADVENTURES OF AN AMERICAN WITH | |

| THE BRITISH ARMY | 16 |

| UNCENSORED ACCOUNT OF A YOUNG VOLUNTEER | |

| Told by James Norman Hall | |

| (Permission of Houghton, Mifflin Company) | |

| "HOW BELGIUM SAVED EUROPE"—THE LITTLE KINGDOM | |

| OF HEROES | 32 |

| TRAGEDY OF THE BELGIANS | |

| Told by Dr. Charles Sarolea | |

| (Permission of J. B. Lippincott Company) | |

| THE BISHOP OF LONDON'S VISIT TO THE FRONT | 43 |

| TAKING THE MESSAGE OF CHRIST TO THE BATTLE LINES | |

| Told by The Reverend G. Vernon Smith | |

| (Permission of Longmans, Green and Company) | |

| "GRAPES OF WRATH"—WITH THE "BIG PUSH" ON THE | |

| SOMME | 52 |

| TWENTY-FOUR HOURS IN THE LIFE OF A PRIVATE | |

| SOLDIER | |

| Told by Boyd Cable | |

| (Permission of E. P. Dutton and Company) | |

| A NOVELIST AND SOLDIER ON THE BATTLE LINE | 63 |

| Told by Coningsby Dawson | |

| (Permission of John Lane Company) | |

| STORIES OF THE WAR PHOTOGRAPHERS IN BELGIUM | 81 |

| AN AMERICAN AT THE BATTLEFRONT | |

| Told by Albert Rhys Williams | |

| (Permission of E. P. Dutton and Company) | |

| TALES OF THE FIRST BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE | |

| TO FRANCE | 94 |

| IMPRESSIONS OF A SUBALTERN | |

| Told by "Casualty" (Name of Soldier Suppressed) | |

| (Permission of J. B. Lippincott Company) | |

| IN THE HANDS OF THE ENEMY—EXPERIENCES OF A PRISONER | |

| OF WAR | 104 |

| Told by Benjamin G. O'Rorke, M. A. | |

| (Permission of Longmans, Green and Company) | |

| "AT SUVLA BAY"—THE WAR AGAINST THE TURKS | 117 |

| ADVENTURES ON THE BLUE ÆGEAN SHORES | |

| Told by John Hargrave | |

| (Permission of Houghton, Mifflin Company) | |

| SEEING THE WAR THROUGH A WOMAN'S EYES | 122 |

| SOUL-STIRRING DESCRIPTION OF SCENES AMONG THE | |

| WOUNDED IN PARIS | |

| Told by (Name Suppressed) | |

| (Permission of New York American) | |

| LOST ON A SEAPLANE AND SET ADRIFT IN A MINE-FIELD | 134 |

| ADVENTURES ON THE NORTH SEA | |

| Told by a Seaplane Observer | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| HOW I HELPED TO TAKE THE TURKISH TRENCHES AT | |

| GALLIPOLI | 144 |

| AN AMERICAN BOY'S WAR ADVENTURES | |

| Told by Wilfred Raymond Doyle | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| "BIG BANG"—STORY OF AN AMERICAN ADVENTURER | 156 |

| A TALE OF THE GREAT TRENCH MORTARS | |

| Told by C. P. Thompson | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| "WITH OUR ARMY IN FLANDERS"—FIGHTING WITH TOMMY | |

| ATKINS | 165 |

| WHERE MEN HOLD RENDEZVOUS WITH DEATH | |

| Told by G. Valentine Williams | |

| (Permission of London Daily Mail) | |

| COMEDIES OF THE GREAT WAR | 176 |

| TALES OF HUMOR ON THE FIGHTING LINES | |

| Told by W. F. Martindale | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| LITTLE STORIES OF THE BIG WAR | 188 |

| UNUSUAL ANECDOTES AT FIRST HAND | |

| Told by Karl K. Kitchen in Germany | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| POGROM—THE TRAGEDY OF THE JEWS AND THE ARMENIANS | 194 |

| A MASTERFUL TALE OF THE EASTERN FRONT | |

| Told by M. C. della Grazie | |

| (Permission of New York Tribune) | |

| TALE OF THE SAVING OF PARIS | 204 |

| HOW A WOMAN'S WIT AVERTED A GREAT DISASTER | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| HOW IT FEELS TO A CLERGYMAN TO BE TORPEDOED ON | |

| A MAN-OF-WAR | 212 |

| Told by the Rev. G. H. Collier | |

| STORY OF LEON BARBESSE, SLACKER, SOLDIER, HERO | 213 |

| Told by Fred B. Pitney | |

| (Permission of New York Tribune) | |

| THE DESERTER—A BELGIAN INCIDENT | 230 |

| Told by Edward Eyre Hunt | |

| (Permission of Red Cross Magazine) | |

| GRIM HUMOR OF THE TRENCHES | 240 |

| AS SEEN BY PATRICK CORCORAN, OF THE ROYAL ENGINEERS | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| PRIVATE McTOSHER DISCOVERS LONDON | 247 |

| Told by C. Malcolm Hincks | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| RUSSIAN COUNTESS IN THE ARABIAN DESERT | 259 |

| ADVENTURES OF COUNTESS MOLITOR AS TOLD IN HER | |

| DIARY | |

| GERMAN STUDENTS TELL WHAT SHERMAN MEANT | 270 |

| THREE CONFESSIONS FROM GERMAN SOLDIERS | |

| Told by Walter Harich, Wilhelm Spengler and Willie Treller | |

| (Permission of New York Tribune) | |

| BAITING THE BOCHE—THE WIT OF THE BELGIANS | 277 |

| Told by W. F. Martindale | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| HOW SERGEANT O'LEARY WON HIS VICTORIA CROSS | 288 |

| STORY OF THE FIRST BATTALION OF THE IRISH GUARDS | |

| (Permission of New York American) | |

| STORY OF A RUSSIAN IN AN AUSTRIAN PRISON | 295 |

| AN OFFICER'S REMARKABLE EXPERIENCE | |

| (Permission of Current History) | |

| TWO WEEKS ON A SUBMARINE | 302 |

| Told by Carl List | |

| (Permission of Current History) | |

| A GERMAN BATTALION THAT PERISHED IN THE SNOW | 305 |

| Told by a Russian Officer | |

| THE FATAL WOOD—"NOT ONE SHALL BE SAVED" | 309 |

| A STORY OF VERDUN | |

| Told by Bernard St. Lawrence | |

| (Permission of Wide World Magazine) | |

| HEROISM AND PATHOS OF THE FRONT | 316 |

| Told by Lauchlan MacLean Watt | |

| AN AVIATOR'S STORY OF BOMBARDING THE ENEMY | 321 |

| Told by a French Aviator | |

| (Permission of Illustration, Paris) | |

| A DAY IN A GERMAN WAR PRISON | 325 |

| Told by Wilhelm Hegeler | |

| MURDER TRIAL OF CAPTAIN HERAIL OF FRENCH HUSSARS | 330 |

| STRANGEST EPISODE OF THE WAR | |

| Told by an Eye-Witness | |

| (Permission of New York American) | |

| HOW THEY KILLED "THE MAN WHO COULD NOT DIE" | 338 |

| Told by a Soldier Under General Cantore | |

| (Permission of New York World) | |

| HOW MLLE. DUCLOS WON THE LEGION OF HONOR | 344 |

| STORY OF A WOMAN WHO DROVE HER AUTO AT FULL | |

| SPEED INTO A GERMAN FORCE | |

| Told by an Eye-Witness | |

| (Permission of New York American) | |

| THE RUSSIAN "JOAN OF ARC'S" OWN STORY | 351 |

| Told by Mme. Alexandra Kokotseva | |

| AN ITALIAN SOLDIER'S LAST MESSAGE TO HIS MOTHER | 355 |

| Translated by Father Pasquale Maltese |

IN A PRISONERS' CAMP

Germans in a French Camp

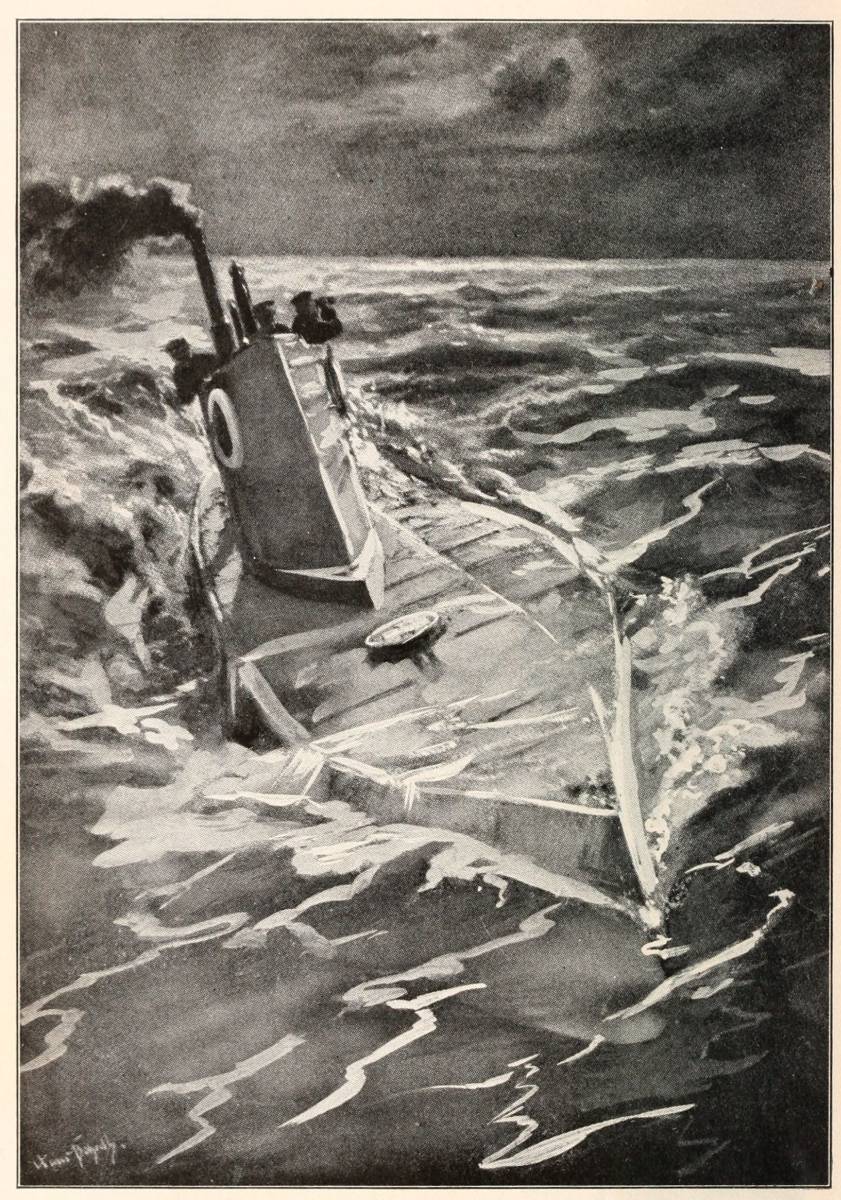

THE U-9 SPEEDING ON THE SURFACE

From a Drawing by a German Artist Published in a German Magazine

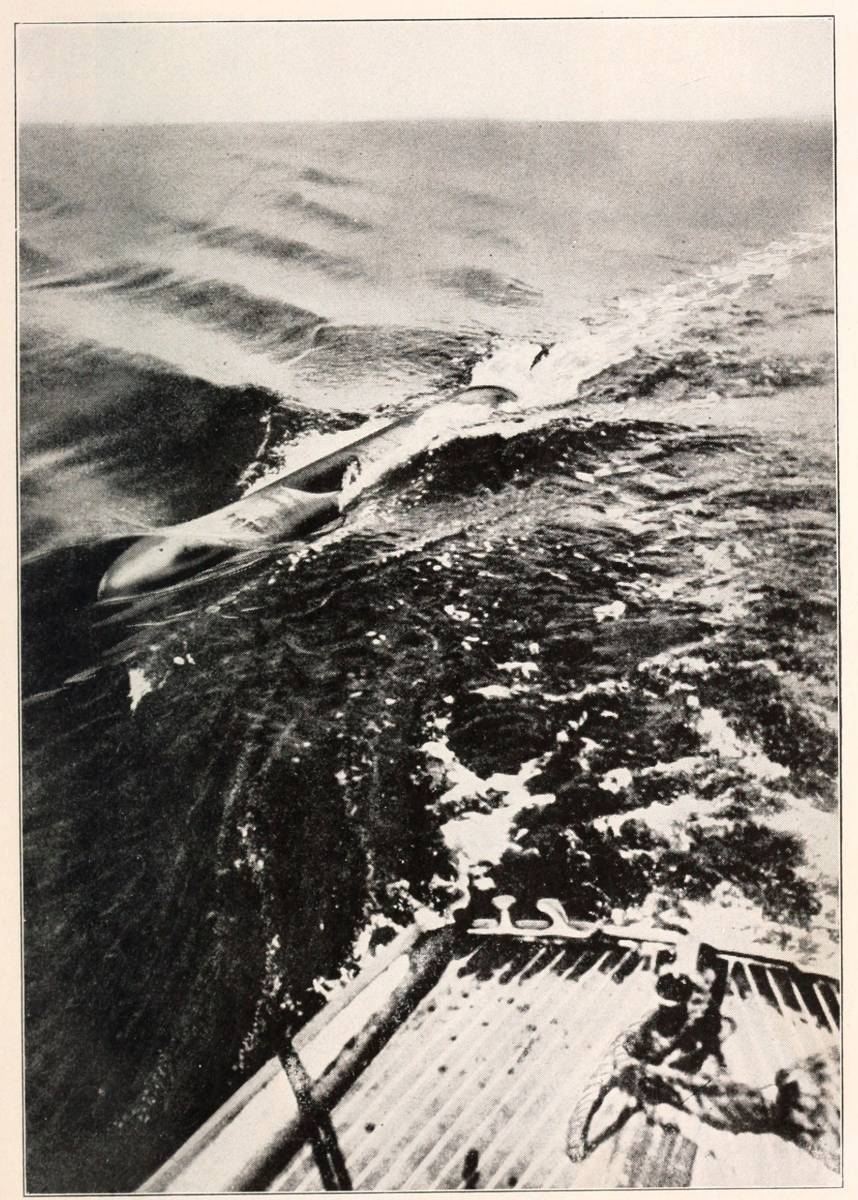

A NARROW SHAVE!

A Remarkable Photograph of a Torpedo That Missed Its Mark by a Scant Ten Feet. The Men on This Vessel, From the Stern of Which the Picture Was Made, Literally Looked Death in the Face and Watched Him Pass By.

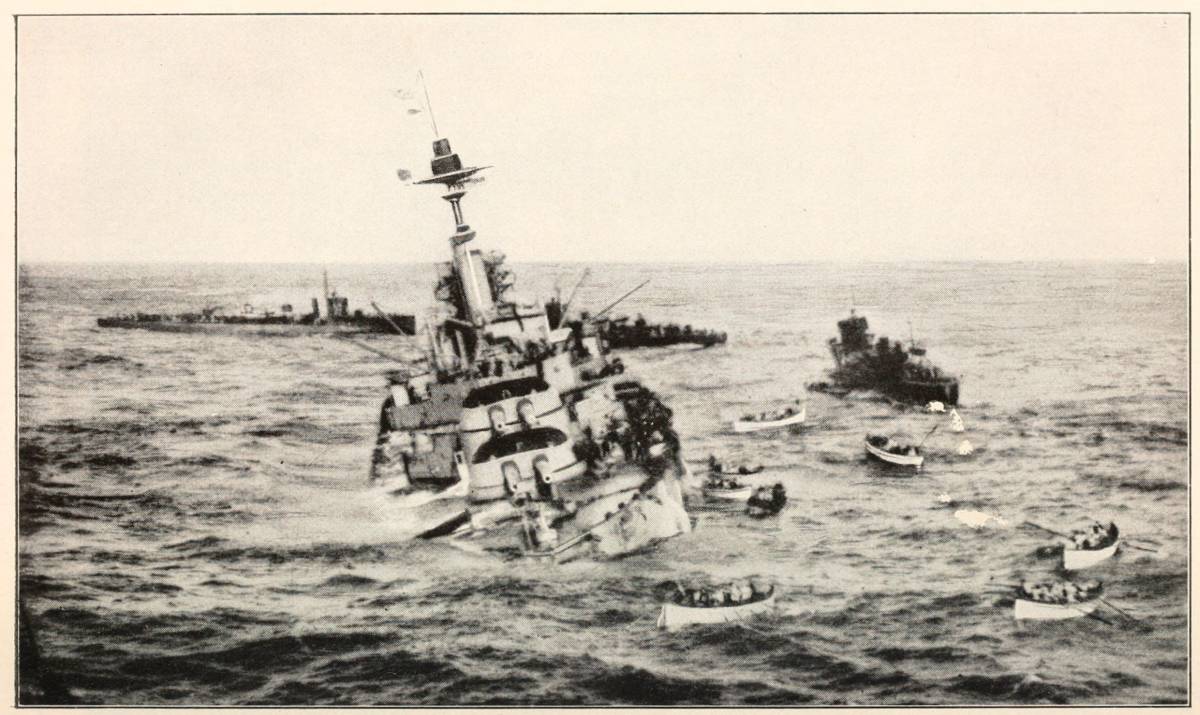

THE LAST ACT OF A SUDDEN SEA TRAGEDY

Rescuing Sailors From H. M. S. Audacious

This is the remarkable story of a titled Hollander, who was living in America at the outbreak of the War. "Europe called me," he says. "Blood will tell. I soon found myself getting restless. My sympathies with the Allies ... urged that I had no right to lag behind in making sacrifices. Before starting for the War, I applied for my first American citizenship papers. I hope to obtain my final papers shortly, after which I shall place my services at the disposal of the American Government." This Hollander was educated in Germany and recalls how in his youth he was forced to stand up in front of the class and recite five verses, each ending with: "I am a Prussian and a Prussian I will be." He later became a student at Bonn. Count De Beaufort has written a book of sensational revelations in which the German veil is lifted. With a magic passport, nothing less than a letter to Von Hindenburg from his nephew, he gained access to German headquarters and to the Eastern front in Poland and East Prussia. We here record what he thinks of Von Hindenburg from his book: "Behind the German Veil," by permission of his publishers, Dodd, Mead and Company: Copyright 1917.

[1] I—GOING TO SEE VON HINDENBURG

Yes, if the truth be told, I must say that I felt just a wee bit shaky about the knees. I wondered what view they would take of my perseverance, worthy, I am sure, of a kind reception.

I would wager that in the whole of Germany there could not be found one ... whose hair would not have stood on end at the mere suggestion of travelling to Hindenburg's headquarters without a pass. Why, he would sooner think of calling at the Palace "Unter den Linden," and of asking to interview the Kaiser.

I think I must describe to you the way I appeared at headquarters. At Allenstein I had bought, the day before, a huge portrait of Hindenburg; it must have been nearly thirty inches long.

Under one arm I carried the photograph, in my hand my letter of introduction, and in my other hand a huge umbrella, which was a local acquisition. On my face I wore that beatific, enthusiastic and very naïve expression of "the innocent abroad." I had blossomed out into that modern pest—the autographic maniac.

Army corps, headquarters, strategy and tactics were words that meant nothing to me. How could they, stupid, unmilitary foreigner that I was! It was a pure case of "Fools will enter where angels fear to tread." You may be sure that my subsequent conversation with the Staff captain confirmed the idea that I was innocent of all military knowledge, and that I probably—so he thought—did not know the difference between an army corps and a section of snipers.

Why had I come to Lötzen? Why, of course, to shake hands with the famous General, the new Napoleon; to have a little chat with him, and—last, but not least—to obtain his most priceless signature to my most priceless photograph. What? Not as easy as all that, but why? Could there be any harm in granting me those favors? Could it by the furthest stretch of imagination be considered as giving information to the enemy? What good was my letter of introduction from the General's dear nephew? Of course, I would not ask the General where[3] he had his guns hidden, and when he intended to take Petrograd, Moscow or Kieff. Oh, no; I knew enough about military matters not to ask such leading questions.

But joking apart. On showing my famous letter I had no difficulty whatsoever in entering the buildings of the General Staff. The first man I met was Hauptmann Frantz. He didn't seem a bad sort at all, and appeared rather to enjoy the joke and my "innocence," at imagining that I could walk up to Hindenburg's Eastern headquarters and say "Hello!" to the General.

He thought it was most "original," and certainly exceedingly American. Still, it got him into the right mood. "Make people smile," might be a good motto for itinerant journalists in the war zones. Few people, not excepting Germans, are so mean as to bite you with a smile on their faces. Make them laugh, and half the battle is won.

Frantz read my letter and was duly impressed. He never asked me whether I had any passes. He advised me to go to the General's house, shook hands, and wished me luck.

Phew! I was glad that my first contact with the General Staff had come off so smoothly. I had been fully prepared for stormy weather, if not for a hurricane. Cockily, I went off to Hindenburg's residence, a very modest suburban village not far from the station, and belonging to a country lawyer. There was a bit of garden in front, and at the back; the house was new, and the bricks still bright red. Across the road on two poles a wide banner was stretched, with "Willkommen" painted on it.

Two old Mecklenburger Landstrum men guarded the little wooden gate. I told them that I came from Great Headquarters, and once more produced the letter. They saluted, opened the gate, and one of them ran ahead to ring the door bell.

II—HE ENTERS THE STRANGE HOUSE

I walked up the little gravel path with here and there a patch of green dilapidated grass on either side. I remember the window curtains were of yellow plush. In the window seat stood a tall vase with artificial flowers flanked by a birdcage with two canaries. It was all very suburban, and did not look at all like the residence of such a famous man. An orderly, with his left arm thrust into a top-boot, opened the door. In a tone of voice that left no chance for the familiar War-Office question: "Have you an appointment, sir?" I inquired whether the Field-Marshal was at home, at the same time giving him my letter. The orderly peeled off his top-boot, unfastened his overalls, and slipped on his coat.

Then he carefully took my letter, holding it gingerly between thumb and third finger, so as not to leave any marks on it, and ushered me into the "Wohnzimmer," a sort of living- and dining-room combined. It was the usual German affair. A couch, a table, a huge porcelain stove, were the prominent pieces of furniture. All three were ranged against the long wall. The straight-backed chairs were covered with red plush. On the walls hung several monstrosities, near-etchings representing the effigies of the Kaiser, the Kaiserin, and, of course, of "Our" Hindenburg. There was the usual overabundance of artificial flowers and ferns so dear to the heart of every German Hausfrau.

The two canaries lived in the most elaborate homemade cage. (I understand they were the property of the "Hausfrau," not of Hindenburg!) On the table, covered with a check tablecloth, stood a bowl containing three goldfish. The floor was covered with a bright carpet, and in front of one of the doors lay a mat with "Salve" on it. Over the couch hung a photographic enlargement[5] of a middle-aged soldier leaning nonchalantly against a door on which was chalked "Kriegsjahr, 1914." Over the frame hung a wreath with a black and white ribbon, inscribed "In Memoriam," telling its eloquent story.

Behind me was a map of the Eastern front, and pinned alongside of it a caricature of a British Tommy sitting astride of a pyramid and pulling a number of strings fastened to the legs, arms and head of the Sultan, who was apparently dancing a jig.

That room impressed itself upon my memory for all time. I often dream of it.

I had waited only a few minutes when a young officer came in, who, bowing obsequiously, wished me a very formal good-morning. I took my cue from the way he bowed. He explained that the General was out in the car but was expected back before noon. Would I condescend to wait? Needless to say, I did "condescend."

I forgot to mention one point in my meditations. When I took the chance of continuing East instead of returning to Berlin, I thought there might just be a possibility that the Adjutant or Staff Officer who had spoken with von Schlieffen had entirely taken it upon himself to say "No," and that it was not unlikely that the General knew nothing whatever about my letter or my contemplated visit. If my surmise was correct, I would stand a sporting chance, because it was hardly to be expected that out of the thirty-odd officers comprising the Staff, I should run bang into the very man who had telephoned.

I soon knew that the officer in immediate attendance on Hindenburg was not aware of my contretempts at Allenstein on the previous day. Neither did he inquire after my passes. You see, they take these things for granted. Would I prefer to wait here or come in his office, where the stove was lit? Of course, I thought[6] that would be more pleasant. I thought, and am glad to say was not mistaken, that probably the young officer felt he needed some mental relaxation. This will sound strange, but I have found during my travels through Germany, that in spite of the many warnings not to talk shop, every soldier, from the humblest private to the highest General—I am sure not excepting the War Lord himself—dearly loves to expatiate on matters military, his ambitions and hopes. This one was no exception. He chatted away very merrily, and more than once I recognized points and arguments which I had read weeks ago in interviews granted by General Hindenburg to Austrian journalists. He quite imagined himself an embryo Field-Marshal.

He showed me several excellent maps, which gave every railroad line on both sides of the Polish frontier. They certainly emphasized the enormous difference and the many advantages of German versus Russian railroad communications. Many of his predictions have since come true, but most of them have not. He hinted very mysteriously, but quite unmistakably, at a prospective Russian débâcle, and predicted a separate peace with Russia before the end of 1915! "And then," he added, "we will shake up the old women at the Western front a bit and show them the 'Hindenburg method.'"

The room we were in was fitted up as an emergency staff office. There were several large tables, maps galore, a safe, a number of books that looked like ledgers and journals, six telephones and a telegraph instrument. Two non-commissioned officers were writing in a corner. In case anything important happens at night, such as an urgent despatch that demands immediate attention, everything was at hand to enable the General to issue new orders. A staff-officer and a clerk are always on duty.

I learned later on, though, that a position in that auxiliary staff-office at Hindenburg's residence is more or less of a sinecure. All despatches go first to Ludendorff, Hindenburg's Chief-of-Staff, who, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, issues orders without consulting his Chief.

III—HE STANDS BEFORE VON HINDENBURG

In the midst of a long explanation of the Russian plight, the voluble subaltern suddenly stopped short. I heard a car halt in front of the house, and a minute or two later the door of the office opened and Germany's giant idol entered. I rose and bowed. The officer and the two sergeants clicked their heels audibly, and replied to the stentorian "Morgen, meine Herren," with a brisk "Morgen, Excellence."

Hindenburg looked questions at me, but I thought I would let my young friend do the talking and act as master of ceremonies. He handed Hindenburg my letter, and introduced me as "Herr 'von' Beaufort, who has just arrived from Rome." (I had left Rome nearly three months before!) The General read his nephew's letter and then shook hands with me, assuring me of the pleasure it gave him to meet me. Of course, I was glad that he was glad, and expressed reciprocity of sentiments. I looked at him—well, for lack of a better word, I will say, with affection; you know the kind of childlike, simple admiration which expresses so much. I tried to look at him as a certain little girl would have done, who wrote: "You are like my governess: she, too, knows everything." I felt sure that that attitude was a better one than to pretend that I was overawed. That sort of homage he must receive every day. Besides, as soon as I realized[8] that he knew nothing of the telephone message from and to Allenstein, my old self-assurance had returned.

Now for my impressions of Germany's—and, as some people try to make us believe, the world's—greatest military genius. They might be summed up in two words: "Strength and cruelty." Hindenburg stands over six feet high. His whole personality radiates strength, brute, animal strength. He was, when I met him, sixty-nine years of age, but looked very much younger. His hair and moustache were still pepper and salt color. His face and forehead are deeply furrowed, which adds to his forbidding appearance. His nose and chin are prominent, but the most striking feature of the man's whole appearance are his eyes. They are steel-blue and very small, much too small for his head, which, in turn, is much too small compared with his large body. But what the eyes lacked in size they fully made up for in intensity and penetrating powers. Until I met Hindenburg I always thought that the eyes of the Mexican rebel Villa were the worst and most cruel I had ever seen. They are mild compared with those of Hindenburg. Never in all my life have I seen such hard, cruel, nay, such utterly brutal eyes as those of Hindenburg. The moment I looked at him I believed every story of refined (and unrefined) cruelty I had ever heard about him.

He has the disagreeable habit of looking at you as if he did not believe a word you said. Frequently in conversation he closes his eyes, but even then it seemed as if their steel-like sharpness pierced his eyelids. Instead of deep circles, such as, for instance, I have noticed on the Kaiser, he has big fat cushions of flesh under his eyes, which accentuate their smallness. When he closes his eyes, these cushions almost touch his bushy eyebrows and give his face a somewhat prehistoric appearance.[9] His hair, about an inch long I should judge, was brushed straight up—what the French call en brosse. The general contour of his head seemed that of a square, rounded off at the corners.

Speaking about the stories of cruelty, one or two of them may bear re-telling.

When during the heavy fighting, early in 1915, General Rennenkampf was forced to evacuate Insterburg somewhat hastily, he was unable to find transport for about fifty thousand loaves of bread. Not feeling inclined to make a present of them to the Germans, he ordered paraffin to be poured over them. When the Germans found that bread and discovered its condition, Hindenburg is reported to have been frantic with rage. The next day, after he had calmed down, he said to one of his aides: "Well, it seems to be a matter of taste. If the Russians like their bread that way, very well. Give it to the Russian prisoners."

You may feel certain that his orders were scrupulously carried out.

Another incident which they are very fond of relating in Germany is more amusing, though it also plays on their idol's cruelty.

It is a fact that both officers and men are deadly afraid of him. It is said that the great General has a special predilection for bringing the tip of his riding boots into contact with certain parts of the human anatomy. A private would far rather face day and night the Russian guns than be orderly to Hindenburg.

But one day a man came up and offered himself for the job.

"And what are you in private life?" the General snorted at him.

"At your orders, sir, I am a wild animal trainer."

IV—"WHAT VON HINDENBURG TOLD ME"

Hindenburg and I talked for about twenty minutes on various subjects—Holland, Italy, America, and, of course, the campaign.

When he tried to point out to me how all-important it was for Holland that Germany should crush England's "world-domination," I mentioned the Dutch Colonies. That really set him going. "Colonies," he shouted. "Pah! I am sick of all this talk about colonies. It would be better for people, and I am not referring to our enemies alone, to pay more attention to events in Europe. I say 'to the devil' (zum Teufel) with the colonies. Let us first safeguard our own country; the colonies will follow. It is here," and he went up to a large map of Poland hanging on the wall, and laid a hand almost as large as a medium-sized breakfast tray over the center of it—"It is here," he continued, "that European and colonial affairs will be settled and nowhere else. As far as the colonies are concerned, it will be a matter of a foot for a mile, as long as we hold large slices of enemy territory."

He spoke with great respect of the Russian soldier, but maintained that they lacked proper leaders. "It takes more than ten years to reform the morale of an officers' corps. From what I have learned, the morale of the Russian officer is to this day much the same as it was in the Russo-Japanese war. We will show you one of their ambulance trains captured near Kirbaty. It is the last word in luxury. By all means give your wounded all the comfort, all the attention you can; but I do not think that car-loads of champagne, oysters, caviare and the finest French liqueurs are necessary adjuncts to an ambulance train. The Russian soldier is splendid, but his discipline is not of the same quality as that of our men. In our armies discipline is the result of spiritual and moral training;[11] in the Russian armies discipline stands for dumb obedience. The Russian soldier remains at his post because he has been ordered to stay there, and he stands as if nailed to the spot. What Napoleon I. said still applies to-day: 'It is not sufficient to kill a Russian, you have to throw him over as well.'

"It is absurd," the General continued, "for the enemy Press to compare this campaign with that of Napoleon in 1812." Again he got up, and pointing to another map, he said: "This is what will win the war for us." The map showed the close railroad net of Eastern Germany and the paucity of permanent roads in Russia. Hindenburg is almost a crank on the subject of railroads in connection with strategy. In the early days of the war he shuffled his army corps about from one corner of Poland to the other. It is said that he transferred four army corps (160,000 men—about 600 trains) in two days from Kalish, in Western Poland, to Tannenberg, a distance of nearly two hundred miles. On some tracks the trains followed each other at intervals of six minutes.

"Our enemies reckon without two great factors unknown in Napoleon's time: railroads and German organization. Next to artillery this war means railroads, railroads, and then still more railroads. The Russians built forts; we built railroads. They would have spent their millions better if they had emulated our policy instead of spending millions on forts. For the present fortresses are of no value against modern siege guns—at least, not until another military genius such as Vauban, Brialmont, Montalembert, Coehoorn, springs up, who will be able to invent proper defensive measures against heavy howitzers.

"Another delusion under which our enemies are laboring is that of Russia's colossal supply of men. He who fights with Russia must always expect superiority[12] in numbers; but in this age of science, strategy and organization, numbers are only decisive, 'all else being equal.' The Russian forces opposed to us on this front have always been far superior in numbers to ours, but we are not afraid of that. A crowd of men fully armed and equipped does not make an army in these days."

This brought him to the subject of the British forces, more especially to Kitchener's army. "It is a great mistake to underestimate your enemy," said Hindenburg, referring to the continual slights and attacks appearing in the German Press. "I by no means underrate the thoroughness, the fighting qualities of the British soldier. England is a fighting nation, and has won her spurs on many battlefields. But to-day they are up against a different problem. Even supposing that Kitchener should be able to raise his army of several millions, where is he going to get his officers and his non-commissioned officers from? How is he going to train them, so to speak, overnight, when it has taken us several generations of uninterrupted instruction, study and work to create an efficient staff? Let me emphasize, and with all the force I can: 'Efficiency and training are everything.' There lies their difficulty. I have many officers here with me who have fought opposite the English, and all are united in their opinion that they are brave and worthy opponents; but one criticism was also unanimously made: 'Their officers often lead their men needlessly to death, either from sheer foolhardiness, but more often through inefficiency.'"

V—"WHEN I LEFT VON HINDENBURG"

Although he did not express this opinion to me personally, I have it on excellent authority that Hindenburg believes this war will last close on four years at least.[13] And the result—stalemate. He does not believe that the Allies will be able to push the Germans out of Belgium, France or Poland.

Personally, I found it impossible to get him to make any definite statement on the probable outcome and duration of the war. "Until we have gained an honorable peace," was his cryptic reply. He refused to state what, in his opinion, constituted an honorable peace. If I am to believe several of his officers—and I discussed the subject almost every day—then Hindenburg must by now be a very disappointed man. I was told that he calculated as a practical certainty on a separate peace with Russia soon after the fall of Warsaw. (I should like to point out here that this "separate peace with Russia" idea was one of the most popular and most universal topics of conversation in Germany last year.)

When Hindenburg learnt that I had come all the way from Berlin without a pass from the General Staff, he appeared very much amused; but in a quasi-serious manner he said:

"Well, you know that I ought to send you back at once, otherwise I shall risk getting the sack myself; still, as all ordinary train-service between here and Posen will be suspended for four days, the only way for you to get back is by motor-car. It would be a pity to come all the way from sunny Italy to this Siberian cold, and not see something of the men and of the hardships of a Russian winter campaign. Travelling by motor-car, you will have ample opportunity to see something of the country, and, if you feel so inclined, of the fighting as well. And then go home and tell them abroad about the insurmountable obstacles, the enormous difficulties the German has to overcome."

Hindenburg does not like the Berlin General Staff officers, and that is why he was so amused at my having got the better of them. He describes them as "drawing-room" officers, who remain safely in Berlin. With their spick and span uniforms they look askance at their mud-stained colleagues at the front. His officers, who know Hindenburg's feelings towards these gentlemen, play many a practical joke on their Berlin confrères. The latter have frequently returned from a visit to some communication trenches only to find that their car has mysteriously retreated some two or three miles ... over Polish roads.

Any one who can tell of such an experience befalling a "Salon Offizier" is sure to raise a good laugh from Hindenburg.

At the conclusion of our conversation he instructed the young A.D.C. to take me over to Headquarters and present me to Captain Cämmerer. "Tell him," and I inscribed the words that followed deeply on my mind, "to be kind to Herr Beaufort."

My introduction to Cämmerer proved to be one of those curious vagaries of fate. He was the very man who less than twenty-four hours ago had spoken with General von Schlieffen, and who had assured him how impossible it was for me to continue, and that I was to be sent back to Berlin at once!

"Beaufort, Beaufort," he sniffed once or twice before he could place me. Then suddenly he remembered. "Ah, yes, him! You are the man General von Schlieffen telephoned about yesterday? But did he not instruct you to return to Berlin?"

However, I remembered Hindenburg's injunction: "Tell Cämmerer to be kind to him," so what did I care for a mere captain?

Consequently, as they say in the moving pictures, I "registered" my most angelic smile, and sweetly said:

"Ah, yes, Captain, quite so, quite so. But, you see, I felt certain that there was some misunderstanding at this end of the wire. Probably it was not clearly explained to you that I had this very important letter of introduction to General von Hindenburg from my friend his nephew. As you see," and I waved my hand at the A.D.C., my master of ceremonies, "I was quite right in my surmise."

However that may be, you may be certain that I saw to it that when we mapped out my return journey, Cämmerer was being "kind" to me. Consequently, I spent two most interesting weeks in the German Eastern war-zones, much to the surprise and disgust of the "Drawing-room Staff" in Berlin.

(Count De Beaufort's revelations form one of the most valuable records of the war. He tells about "Spies and Spying;" "German Women;" "When I Prayed with the Kaiser;" "An Incognito Visit to the Fleet and German Naval Harbors;" "Interviews with the Leading Naval, Military and Civil Authorities in Germany"—closing with an interview that upset Berlin, caused his arrest, and as he describes it, "My Ultimate Escape Across the Baltic.")

[1] All numerals throughout this volume relate to the stories herein told—not to chapters in the original sources.

This is a glimpse of life in a battalion of one of Lord Kitchener's first armies. It gives an intimate view of the men who are so gallantly laying down their lives for England. Kitchener's Mob has become the greatest volunteer army in the history of the world—for more than three million of disciplined fighting men are united under one flag in this magnificent military organization. Their fighting has become an epic of heroism in France, Belgium, Africa and the Balkans. Some of them have seen service in India, Egypt and South Africa; they might have stepped out of any of the "Barrack-Room Ballads." The name which they bear was fastened upon them by themselves—thereby hangs a tale. Stories of their adventures have been gathered into a volume under title of "Kitchener's Mob"—and published by Houghton, Mifflin Company: Copyright, 1916, by Atlantic Monthly Company; Copyright, 1916, by James Norman Hall.

[2] I—STORY OF A YANKEE IN THE TRENCHES

With Kitchener's mob we wandered through the trenches listening to the learned discourse of the genial professors of the Parapet-etic School, storing up much useful information for future reference. I made a serious blunder when I asked one of them a question about Ypres, for I pronounced the name French fashion, which put me under suspicion as a "swanker."

"Don't try to come it, son," he said. "S'y 'Wipers.' That's wot we calls it."

Henceforth it was "Wipers" for me, although I learned that "Eeps" and "Yipps" are sanctioned by some trench authorities. I made no further mistakes of this nature, and by keeping silent about the names of the towns and villages along our front, I soon learned the accepted pronunciation of all of them. Armentières is called "Armenteers"; Balleul, "Ballyall"; Hazebrouck, "Hazy-Brook"; and what more natural than "Plug-Street," Atkinsese for Ploegsteert?

As was the case wherever I went, my accent betrayed my American birth; and again, as an American Expeditionary Force of one, I was shown many favors. Private Shorty Holloway, upon learning that I was a "Yank," offered to tell me "every bloomin' thing about the trenches that a bloke needs to know." I was only too glad to place myself under his instruction.

"Right you are!" said Shorty; "now, sit down 'ere w'ile I'm going over me shirt, an' arsk me anything yer a mind to." I began immediately by asking him what he meant by "going over" his shirt.

"Blimy! You are new to this game, mate! You mean to s'y you ain't got any graybacks?"

I confessed shamefacedly that I had not. He stripped to the waist, turned his shirt wrong side out, and laid it upon his knee.

"'Ave a look," he said proudly.

The less said about my discoveries the better for the fastidiously minded. Suffice it to say that I made my first acquaintance with members of a British Expeditionary Force which is not mentioned in official communiqués.

"Trench pets," said Shorty. Then he told me that they were not all graybacks. There is a great variety of species, but they all belong to the same parasitical family, and wage a non-discriminating warfare upon the soldiery on both sides of No-man's-Land. Germans, British, French, Belgians alike were their victims.

"You'll soon 'ave plenty," he said reassuringly; "I give you about a week to get covered with 'em. Now, wot you want to do is this: always 'ave an extra shirt in yer pack. Don't be a bloomin' ass an' sell it fer a packet o' fags like I did! An' the next time you writes to England, get some one to send you out some Keatings"—he displayed a box of grayish-colored powder. "It won't kill 'em, mind you! They ain't nothin' but fire that'll kill 'em. But Keatings tykes all the ginger out o' 'em. They ain't near so lively arter you strafe 'em with this 'ere powder."

I remembered Shorty's advice later when I became a reluctant host to a prolific colony of graybacks. For nearly six months I was never without a box of Keatings, and I was never without the need for it.

II—IN THE BARBED-WIRE "MAN-TRAPS"

Barbed wire had a new and terrible significance for me from the first day which we spent in the trenches. I could more readily understand why there had been so long a deadlock on the western front. The entanglements in front of the first line of trenches were from fifteen to twenty yards wide, the wires being twisted from post to post in such a hopeless jumble that no man could possibly get through them under fire. The posts were set firmly in the ground, but there were movable segments, every fifty or sixty yards, which could be put to one side in case an attack was to be launched against the German lines.

At certain positions there were what appeared to be openings through the wire, but these were nothing less than man-traps which have been found serviceable in case of an enemy attack. In an assault men follow the line of least resistance when they reach the barbed wire. These apparent openings are V-shaped with the open end toward the enemy. The attacking troops think they see a clear passage-way. They rush into the trap and when it is filled with struggling men machine guns are turned upon them, and, as Shorty said, "You got 'em cold."

That, at least, was the presumption. Practically, man-traps were not always a success. The intensive bombardments which precede infantry attacks play havoc with entanglements, but there is always a chance of the destruction being incomplete, as upon one occasion farther north, where, Shorty told me, a man-trap caught a whole platoon of Germans "dead to rights."

"But this is wot gives you the pip," he said. "'Ere we got three lines of trenches, all of 'em wired up so that a rat couldn't get through without scratchin' hisself to death. Fritzie's got better wire than wot we 'ave, an' more of it. An' 'e's got more machine guns, more artill'ry, more shells. They ain't any little old man-killer ever invented wot they 'aven't got more of than we 'ave. An' at 'ome they're a-s'yin', 'W'y don't they get on with it? W'y don't they smash through?' Let some of 'em come out 'ere an' 'ave a try! That's all I got to s'y."

I didn't tell Shorty that I had been, not exactly an armchair critic, but at least a barrack-room critic in England. I had wondered why British and French troops had failed to smash through. A few weeks in the trenches gave me a new viewpoint. I could only wonder at the magnificent fighting qualities of soldiers who had held their own so effectively against armies equipped and armed and munitioned as the Germans were.

After he had finished drugging his trench pets, Shorty and I made a tour of the trenches. I was much surprised at seeing how clean and comfortable they can be kept in pleasant summer weather. Men were busily at work sweeping up the walks, collecting the rubbish, which was put into sandbags hung on pegs at intervals along the fire trench. At night the refuse was taken back of the trenches and buried. Most of this work devolved upon the pioneers whose business it was to keep the trenches sanitary.

The fire trench was built in much the same way as those which we had made during our training in England. In pattern it was something like a tesselated border. For the space of five yards it ran straight, then it turned at right angles around a traverse of solid earth six feet square, then straight again for another five yards, then around another traverse, and so throughout the length of the line. Each five-yard segment, which is called a "bay," offered firing room for five men. The traverses, of course, were for the purpose of preventing enfilade fire. They also limited the execution which might be done by one shell. Even so they were not an unmixed blessing, for they were always in the way when you wanted to get anywhere in a hurry.

"An' you are in a 'urry w'en you sees a Minnie [Minnenwerfer] comin' your w'y. But you gets trench legs arter a w'ile. It'll be a funny sight to see blokes walkin' along the street in Lunnon w'en the war's over. They'll be so used to dogin' in an' out o' traverses they won't be able to go in a straight line."

III—STORIES OF SHORTY HOLLOWAY—"PROFESSOR OF TRENCHES"

As we walked through the firing-line trenches, I could quite understand the possibility of one's acquiring trench[21] legs. Five paces forward, two to the right, two to the left, two to the left again, then five to the right, and so on to Switzerland. Shorty was of the opinion that one could enter the trenches on the Channel coast and walk through to the Alps without once coming out on top of the ground. I am not in a position either to affirm or to question this statement. My own experience was confined to that part of the British front which lies between Messines in Belgium and Loos in France. There, certainly, one could walk for miles, through an intricate maze of continuous underground passages.

But the firing-line trench was neither a traffic route nor a promenade. The great bulk of inter-trench business passed through the travelling trench, about fifteen yards in rear of the fire trench and running parallel to it. The two were connected by many passageways, the chief difference between them being that the fire trench was the business district, while the traveling trench was primarily residential. Along the latter were built most of the dugouts, lavatories, and trench kitchens. The sleeping quarters for the men were not very elaborate. Recesses were made in the wall of the trench about two feet above the floor. They were not more than three feet high, so that one had to crawl in head first when going to bed. They were partitioned in the middle, and were supposed to offer accommodations for four men, two on each side. But, as Shorty said, everything depended on the ration allowance. Two men who had eaten to repletion could not hope to occupy the same apartment. One had a choice of going to bed hungry or of eating heartily and sleeping outside on the firing-bench.

"'Ere's a funny thing," he said. "W'y do you suppose they makes the dugouts open at one end?"

I had no explanation to offer.

"Crawl inside an' I'll show you."

I stood my rifle against the side of the trench and crept in.

"Now, yer supposed to be asleep," said Shorty, and with that he gave me a whack on the soles of my boots with his entrenching tool handle. I can still feel the pain of the blow.

"Stand to! Wyke up 'ere! Stand to!" he shouted, and gave me another resounding wallop.

I backed out in all haste.

"Get the idea? That's 'ow they wykes you up at stand-to, or w'en your turn comes fer sentry. Not bad, wot?"

I said that it all depended on whether one was doing the waking or the sleeping, and that, for my part, when sleeping, I would lie with my head out.

"You wouldn't if you belonged to our lot. They'd give it to you on the napper just as quick as 'it you on the feet. You ain't on to the game, that's all. Let me show you suthin'."

He crept inside and drew his knees up to his chest so that his feet were well out of reach. At his suggestion I tried to use the active service alarm clock on him, but there was not room enough in which to wield it. My feet were tingling from the effect of his blows, and I felt that the reputation for resourcefulness of Kitchener's Mob was at stake. In a moment of inspiration I seized my rifle, gave him a dig in the shins with the butt, and shouted, "Stand to, Shorty!" He came out rubbing his leg ruefully.

"You got the idea, mate," he said. "That's just wot they does w'en you tries to double-cross 'em by pullin' yer feet in. I ain't sure w'ere I likes it best, on the shins or on the feet."

This explanation of the reason for building three-sided dugouts, while not, of course, the true one, was[23] none the less interesting. And certainly, the task of arousing sleeping men for sentry duty was greatly facilitated with rows of protruding boot soles "simply arskin' to be 'it," as Shorty put it.

All of the dugouts for privates and N.C.O.s were of equal size and built on the same model, the reason being that the walls and floors, which were made of wood, and the roofs, which were of corrugated iron, were put together in sections at the headquarters of the Royal Engineers, who superintended all the work of trench construction. The material was brought up at night ready to be fitted into excavations. Furthermore, with thousands of men to house within a very limited area, space was a most important consideration. There was no room for indulging individual tastes in dugout architecture. The roofs were covered with from three to four feet of earth, which made them proof against shrapnel or shell splinters. In case of a heavy bombardment with high explosives, the men took shelter in deep and narrow "slip trenches." These were blind alley-ways leading off from the traveling trench, with room for from ten to fifteen men in each. At this part of the line there were none of the very deep shell-proof shelters, from fifteen to twenty feet below the surface of the ground, of which I had read. Most of the men seemed to be glad of this. They preferred taking their chances in an open trench during heavy shell fire.

IV—THE "SUICIDE CLUB"—A BOMBING SQUAD

Realists and Romanticists lived side by side in the traveling trench. "My Little Gray Home in the West" was the modest legend over one apartment. The "Ritz Carlton" was next door to "The Rats' Retreat," with "Vermin Villa" next door but one. "The Suicide Club" was the[24] suburban residence of some members of the bombing squad. I remarked that the bombers seemed to take rather a pessimistic view of their profession, whereupon Shorty told me that if there were any men slated for the Order of the Wooden Cross, the bombers were those unfortunate ones. In an assault they were first at the enemy's position. They had dangerous work to do even on the quietest of days. But theirs was a post of honor, and no one of them but was proud of his membership in the Suicide Club.

The officers' quarters were on a much more generous and elaborate scale than those of the men. This I gathered from Shorty's description of them, for I saw only the exteriors as we passed along the trench. Those for platoon and company commanders were built along the traveling trench. The colonel, major, and adjutant lived in a luxurious palace, about fifty yards down a communication trench. Near it was the officers' mess, a café de luxe with glass panels in the door, a cooking stove, a long wooden table, chairs,—everything, in fact, but hot and cold running water.

"You know," said Shorty, "the officers thinks they 'as to rough it, but they got it soft, I'm tellin' you! Wooden bunks to sleep in, batmen to bring 'em 'ot water fer shavin' in the mornin', all the fags they wants,——Blimy, I wonder wot they calls livin' 'igh?"

I agreed that in so far as living quarters are concerned, they were roughing it under very pleasant circumstances. However, they were not always so fortunate, as later experience proved. Here there had been little serious fighting for months and the trenches were at their best. Elsewhere the officers' dugouts were often but little better than those of the men.

The first-line trenches were connected with two lines of support or reserve trenches built in precisely the same[25] fashion, and each heavily wired. The communication trenches which joined them were from seven to eight feet deep and wide enough to permit the convenient passage of incoming and outgoing troops, and the transport of the wounded back to the field dressing stations. From the last reserve line they wound on backward through the fields until troops might leave them well out of range of rifle fire. Under Shorty's guidance I saw the field dressing stations, the dugouts for the reserve ammunition supply and the stores of bombs and hand grenades, battalion and brigade trench headquarters. We wandered from one part of the line to another through trenches, all of which were kept amazingly neat and clean. The walls were stayed with fine-mesh wire to hold the earth in place. The floors were covered with board walks carefully laid over the drains, which ran along the center of the trench and emptied into deep wells, built in recesses in the walls. I felt very much encouraged when I saw the careful provision for sanitation and drainage. On a fine June morning it seemed probable that living in ditches was not to be so unpleasant as I had imagined it. Shorty listened to my comments with a smile.

"Don't pat yerself on the back yet a w'ile, mate," he said. "They looks right enough now, but wite till you've seen 'em arter a 'eavy rain."

I had this opportunity many times during the summer and autumn. A more wretched existence than that of soldiering in wet weather could hardly be imagined. The walls of the trenches caved in in great masses. The drains filled to overflowing, and the trench walks were covered deep in mud. After a few hours of rain, dry and comfortable trenches became a quagmire, and we were kept busy for days afterward repairing the damage.

As a machine gunner I was particularly interested in[26] the construction of the machine-gun emplacements. The covered battle positions were very solidly built. The roofs were supported with immense logs or steel girders covered over with many layers of sandbags. There were two carefully concealed loopholes looking out to a flank, but none for frontal fire, as this dangerous little weapon best enjoys catching troops in enfilade owing to the rapidity and the narrow cone of its fire. Its own front is protected by the guns on its right and left. At each emplacement there was a range chart giving the ranges to all parts of the enemy's trenches, and to every prominent object both in front of and behind them, within its field of fire. When not in use the gun was kept mounted and ready for action in the battle position.

"But remember this," said Shorty, "you never fires from your battle position except in case of attack. W'en you goes out at night to 'ave a little go at Fritzie, you always tykes yer gun sommers else. If you don't, you'll 'ave Minnie an' Busy Bertha an' all the rest o' the Krupp childern comin' over to see w'ere you live."

This was a wise precaution, as we were soon to learn from experience. Machine guns are objects of special interest to the artillery, and the locality from which they are fired becomes very unhealthy for some little time thereafter.

V—AT THE "MUD LARKS'" BEAUTY SHOP

We stopped for a moment at "The Mud Larks' Hair-dressing Parlor," a very important institution if one might judge by its patronage. It was housed in a recess in the wall of the traveling trench, and was open to the sky. There I saw the latest fashion in "oversea" hair cuts. The victims sat on a ration box while the barber mowed great swaths through tangled thatch with a pair[27] of close-cutting clippers. But instead of making a complete job of it, a thick fringe of hair which resembled a misplaced scalping tuft was left for decorative purposes, just above the forehead. The effect was so grotesque that I had to invent an excuse for laughing. It was a lame one, I fear, for Shorty looked at me warningly. When we had gone on a little way he said:—

"Ain't it a proper beauty parlor? But you got to be careful about larfin'. Some o' the blokes thinks that 'edge-row is a regular ornament."

I had supposed that a daily shave was out of the question on the firing-line; but the British Tommy is nothing if not resourceful. Although water is scarce and fuel even more so, the self-respecting soldier easily surmounts difficulties, and the Gloucesters were all nice in matters pertaining to the toilet. Instead of draining their canteens of tea, they saved a few drops for shaving purposes.

"It's a bit sticky," said Shorty, "but it's 'ot, an' not 'arf bad w'en you gets used to it. Now, another thing you don't want to ferget is this: W'en yer movin' up fer yer week in the first line, always bring a bundle o' firewood with you. They ain't so much as a match-stick left in the trenches. Then you wants to be savin' of it. Don't go an use it all the first d'y or you'll 'ave to do without yer tea the rest o' the week."

I remembered his emphasis upon this point afterward when I saw men risking their lives in order to procure firewood. Without his tea Tommy was a wretched being. I do not remember a day, no matter how serious the fighting, when he did not find both the time and the means for making it.

VI—FLIES—RATS—AND DOMESTIC SCIENCE

Shorty was a Ph.D. in every subject in the curriculum, including domestic science. In preparing breakfast he gave me a practical demonstration of the art of conserving a limited resource of fuel, bringing our two canteens to a boil with a very meager handful of sticks; and while doing so he delivered an oral thesis on the best methods of food preparation. For example, there was the item of corned beef—familiarly called "bully." It was the pièce de résistance at every meal with the possible exception of breakfast, when there was usually a strip of bacon. Now, one's appetite for "bully" becomes jaded in the course of a few weeks or months. To use the German expression one doesn't eat it gern. But it is not a question of liking it. One must eat it or go hungry. Therefore, said Shorty, save carefully all of your bacon grease, and instead of eating your "bully" cold out of the tin, mix it with bread crumbs and grated cheese and fry it in the grease. He prepared some in this way, and I thought it a most delectable dish. Another way of stimulating the palate was to boil the beef in a solution of bacon grease and water, and then, while eating it, "kid yerself that it's Irish stew." This second method of taking away the curse did not appeal to me very strongly, and Shorty admitted that he practiced such self-deception with very indifferent success; for after all "bully" was "bully" in whatever form you ate it.

In addition to this staple, the daily rations consisted of bacon, bread, cheese, jam, army biscuits, tea, and sugar. Sometimes they received a tinned meat and vegetable ration, already cooked, and at welcome intervals fresh meat and potatoes were substituted for corned beef. Each man had a very generous allowance of food, a great[29] deal more, I thought, than he could possibly eat. Shorty explained this by saying that allowance was made for the amount which would be consumed by the rats and the blue-bottle flies.

There were, in fact, millions of flies. They settled in great swarms along the walls of the trenches, which were filled to the brim with warm light as soon as the sun had climbed a little way up the sky. Empty tin-lined ammunition boxes were used as cupboards for food. But of what avail were cupboards to a jam-loving and jam-fed British army living in open ditches in the summer time? Flytraps made of empty jam tins were set along the top of the parapet. As soon as one was filled, another was set in its place. But it was an unequal war against an expeditionary force of countless numbers.

"They ain't nothin' you can do," said Shorty. "They steal the jam right off yer bread."

As for the rats, speaking in the light of later experience, I can say that an army corps of Pied Pipers would not have sufficed to entice away the hordes of them that infested the trenches, living like house pets on our rations. They were great lazy animals, almost as large as cats, and so gorged with food that they could hardly move. They ran over us in the dugouts at night, and filched cheese and crackers right through the heavy waterproofed coverings of our haversacks. They squealed and fought among themselves at all hours. I think it possible that they were carrion eaters, but never, to my knowledge, did they attack living men. While they were unpleasant bedfellows, we became so accustomed to them that we were not greatly concerned about our very intimate associations.

Our course of instruction at the Parapet-etic School was brought to a close late in the evening when we shouldered our packs, bade good-bye to our friends the[30] Gloucesters, and marched back in the moonlight to our billets. I had gained an entirely new conception of trench life, of the difficulties involved in trench building, and the immense amount of material and labor needed for the work.

Americans who are interested in learning of these things at first hand will do well to make the grand tour of the trenches when the war is finished. Perhaps the thrifty continentals will seek to commercialize such advantage as misfortune as brought them, in providing favorable opportunities. Perhaps the Touring Club of France will lay out a new route, following the windings of the firing line from the Channel coast across the level fields of Flanders, over the Vosges Mountains to the borders of Switzerland. Pedestrians may wish to make the journey on foot, cooking their supper over Tommy's rusty biscuit-tin stoves, sleeping at night in the dugouts where he lay shivering with cold during the winter nights of 1914 and 1915. If there are enthusiasts who will be satisfied with only the most intimate personal view of the trenches, if there are those who would try to understand the hardships and discomforts of trench life by living it during a summer vacation, I would suggest that they remember Private Shorty Holloway's parting injunction to me:—

"Now, don't ferget, Jamie!" he said as we shook hands, "always 'ave a box o' Keatings 'andy, an' 'ang on to yer extra shirt!"

(Private Hall, of Kitchener's Mob, describes the scenes when the army was being organized for the first British expeditionary force. He tells about "The Rookies"; "The Mob in Training"; "Ordered Abroad." He describes their fights; their life under cover; their lodgings, billets and experiences in the trenches, "sitting tight."[31] It is "men of this stamp," he says, "who have the fortunes of England in their keeping. And they are called 'The Boys of the Bulldog Breed.'")

[2] All numerals relate to stories herein told—not to chapters from original sources.

Dr. Sarolea is the historian of the Belgian people in the world tragedy through which they have passed. Count D'Aviella, Belgian Secretary of State, exclaims: "I am sure no one can read these tragic pages without becoming more than ever confirmed in his conviction that we are fighting in the cause of right, of liberty, and of civilization." Dr. Sarolea has for twelve years been Belgian Consul in Scotland; he is the personal friend of His Majesty King Albert of Belgium, with whom he frequently sits in private audience. He has written a book, "How Belgium Saved Europe," which sets forth the great tragedy which places the Belgian people on the same plane with those soul stirring heroes of universal history in the Persian Wars of Greece, the Punic Wars of Rome, the Wars of Spain against the Moors, the epic of Joan of Arc, the Wars of the French Revolution—and all the outstanding and inspiring chapters in the drama of human heroism. He tells about "The Hero-King" and "The German Plot in Belgium." We here record his story on "The Destruction of Louvain," by permission of his publishers, J. B. Lippincott Company: Copyright 1915.

[3] I—STORIES OF MAD FURY IN LOUVAIN

On September 1 (1914) a procession of refugees from Louvain arrived at Malines in a frenzy of terror with the news that the town of Louvain had been set on fire by the Germans and that the whole city was a heap of ruins. The wildest stories added to the horror of the tale. It was said that there had been a wholesale massacre of men, women, and children, and that hundreds of priests, and especially Jesuits, had been singled out for murder. Many of the stories proved to be without any foundation. But when all the exaggerations had been discounted there remained a body of substantial facts that were enough to send a thrill of indignation through Europe.

Two certainties emerged from the chaos of conflicting evidence. First, there had been indiscriminate slaughter of civilians and looting of property. Secondly, the Germans, armed with incendiary fuses and obeying the order of the military authorities, had methodically burned the whole section of Louvain which extends from the station in the centre of the town, including the University and the church of St. Pierre.

Since the destruction of the hapless University town other atrocities have followed in almost daily succession, Termonde, Aerschot, Malines, Antwerp. The world has almost got accustomed to them. There has been nothing like this mad fury of destruction in the whole history of modern warfare. Rheims has outdone even Louvain, and the ruin of the Cathedral of Rheims is an even greater loss than the destruction of the old Belgian Catholic University.

Still Louvain remains the one crowning infamy. German casuistry may at least find some extenuating circumstances in the fact that Rheims was a fortified town, and that the Cathedral tower might have been used as an observation post for the French armies. For the crime of Louvain no extenuating circumstance can be urged. Louvain was undefended. It was a peaceful city of students,[34] priests, and landladies. It was in the occupation of the Germans. Its destruction, therefore, was both a wanton and a cowardly act of cruelty, and being both wanton and cruel, it will stand out as the typical atrocity of German militarism.

Only those who are familiar with the history of Belgium and Brabant, and with the history of Belgian Universities, know what Louvain and the University stood for. Founded in 1425, in the days of Petrarch, Froissart, and Chaucer, it was one of the oldest and most illustrious seats of learning in Europe. It was the seat of Pope Adrian VI, the tutor of Charles V. It still remained the most famous Catholic University in the world. It still attracted scholars from every country. It was still the nursery of Irish, English, and American priests.

And not only had Louvain 500 years of learning behind it, it was also a city with a magnificent municipal tradition. The town hall, one of the gems of Gothic architecture, was a glorious monument to that municipal tradition. By the destruction of Louvain the German soldiery have wiped out five centuries of religious and intellectual culture and of municipal freedom.

II—THE TRUTH ABOUT GERMAN ATROCITIES

Wherever the Germans have perpetrated some atrocious crime they have used the same threadbare excuse—the shooting of German soldiers by civilians. Civilians fired on German soldiers at Visé, therefore Visé was razed to the ground. The fourteen-year-old son of the Burgomaster of Aerschot killed a German officer, therefore the whole city of Aerschot had to be destroyed. Similarly, it was to avenge the murder of German soldiers that Louvain was burned. It is the civilian population of Louvain who must ultimately be held responsible.

On the face of it, the German version is an incredible invention. Louvain was in the occupation of German troops. All the arms had been handed in days before by the civil population. The authorities had posted placards recommending tranquility to the population, and warning them that any individual act of hostility would bring down instant vengeance. Those placards could still be read on the walls on the day of the destruction of Louvain. Under those circumstances, is it credible that a few peaceful citizens should have brought down destruction by their own deliberate act, which they knew would be met with instant and ruthless retribution?

But even assuming that individual Belgians had been guilty of firing on the German troops, supposing a civilian exasperated by the monstrous treatment described in the narrative of Mr. Van Ernem, the Town Treasurer. When the Belgian troops were repulsed by the enemy's crushing numbers, and the Germans had put their big guns in position on all the heights dominating the town, the Germans sent a deputation to the Burgomaster, who agreed to receive the officers to hear their proposals and conditions for occupying the town.

The German General with his état-major then came to the town hall to confer with the Burgomaster, councillors, and myself as treasurer of the town.

These were the stipulated conditions.

First: That the town should fully provide for the invaders, in consideration of which no war contributions would be exacted.

Secondly: The soldiers not billeted in private houses were to pay cash for all goods obtained; also, they were not to molest the inhabitants under any circumstances.

These stiplations, agreed to on both sides, were most scrupulously kept by the Belgians, but not by the Germans. On certain days, for example, the Germans would[36] exact 67,000 pounds of meat, and would let 20,000 pounds of it rot, although the population were suffering from hunger.

On Monday, August 24, toward 10 P. M., the Burgomaster—a respectable merchant, sixty-two years of age—was arrested in his bed, where he was lying ill. He was forced to rise and marched to the railway station, where it was demanded of him that he should provide immediately 250 warm meals and as many mattresses for the soldiers, under penalty of being shot. With admirable dispatch the inhabitants rushed to comply with the German demand. In their solicitude and pity for their aged chief, and their anxiety to save his life, they gave their own beds and their last drops of wine.

The Germans acted without the slightest consideration or regard for the faithful promises of their état-major. The troops rushed into private houses, making forcible entrances, and taking from old and young, many of the latter already orphans, whatever they fancied, paying for nothing except with paper money to be presented to the "caisse communal" at the end of the war.

The promise of exemption from contribution to a war levy was violated, like every other contract. Failing to find enough money in the treasury, the Germans in authority ordered the immediate payment of 100,000 francs.

This large sum could not be gathered from the inhabitants, and nearly all the banks had on the first warning of the approach of the enemy succeeded in transferring their funds to the National Bank.

Finally, after much bickering, the officer in command of the German troops agreed to accept 3,000 fr., to be paid the next day. But with the next morning came a further demand for 5,000 fr. The Burgomaster vigorously protested against this new exaction; but nevertheless[37] I, as treasurer of the town, was held responsible for collecting 5,000 fr. With the greatest difficulty, I succeeded in procuring 3,080 fr., and after considerable bickering this sum was accepted by the enemy, and the horrors of reprisals were delayed. The population, conscious of the terrible risk which they ran, submitted with calm resignation to the inevitable. As a functionary of the city, I can vouch for the absolutely dignified and passive attitude of the whole population of Louvain. They understood perfectly well their grave individual responsibility, and that any break of their promises would be instantly met by crushing action.

The position of affairs was minutely explained to the inhabitants in several printed proclamations, and they were personally warned by our venerable Burgomaster. Good order was so rigorously maintained that the German authorities praised the exemplary conduct of the inhabitants.

This attitude was all the more laudable because the invaders, immediately upon entering the city, liberated nine of their compatriots who had been incarcerated before the war for murder, theft, and other felonies.

III—TRUE STORIES OF "THE UNSPEAKABLE CRIME"

At last, on the Tuesday night, there took place the unspeakable crime, the shame of which can be understood only by those who followed and watched the different phases of the German occupation of Louvain.

It is a significant fact that the German wounded and sick, including their Red Cross nurses, were all removed from the hospitals. The Germans meanwhile proceeded methodically to make a last and supreme requisition, although they knew the town could not satisfy it.

Towards 6 o'clock the bugle sounded, and officers lodging in private houses left at once with arms and luggage. At the same time thousands of additional soldiers, with numerous field-pieces and cannon, marched into the town to their allotted positions. The gas factory, which had been idle, had been worked through the previous night and day by Germans, so that during this premeditated outrage the people could not take advantage of darkness to escape from the town. A further fact that proves their premeditation is that the attack took place at 8 o'clock, the exact time at which the population entered their houses in conformity with the German orders—consequently escape became well-nigh impossible. At 8.20 a full fusillade with the roar of the cannons came from all sides of the town at once.

The sky at the same time was lit up with the sinister light of fires from all quarters. The cavalry charged through the streets, sabring fugitives, while the infantry, posted on the footpaths, had their fingers on the triggers of their guns waiting for the unfortunate people to rush from the houses or appear at the windows, the soldiers complimenting each other on their marksmanship as they fired at the unhappy fugitives.

Those whose homes were not yet destroyed were ordered to quit and follow the soldiers to the railway station. There the men were separated from mothers, wives, and children, and thrown, some bound, into trains leaving in the direction of Germany.

I cannot but feel that, following the system they have inaugurated in this campaign, the Germans will use these non-combatant prisoners as human shields when they are fighting the Allies. The cruelty of these madmen surpasses all limits. They shot numbers of absolutely inoffensive people, forcing those who survived to bury their dead in the square, already encumbered with corpses[39] whose positions suggested that they had fallen with arms uplifted in token of surrender.

Others who have been allowed to live were driven past approving drunken officers by the brutal use of rifle butts, and while they were being maltreated they saw their carefully collected art and other treasures being shared out by the soldiers, the officers looking on. Those who attempted to appeal to their tormentors' better feelings were immediately shot. A few were let loose, but most of them were sent to Germany.

On Wednesday at daybreak the remaining women and children were driven out of the town—a lamentable spectacle—with uplifted arms and under the menace of bayonets and revolvers.

The day was practically calm. The destruction of the most beautiful part of the town seemed to have momentarily soothed the barbarian rage of the invaders.

On the Thursday the remnant of the Civil Guard was called up on the pretext of extinguishing the conflagration; those who demurred were chained and sent with some wounded Germans to the Fatherland. The population had to quit at a moment's notice before the final destruction.

Then, to complete their devastation, the German hordes fell back on the surrounding villages to burn them. They tracked down the men—some were shot, some made prisoners—and during many long hours they tortured the helpless women and children. This country of Eastern Brabant, so rich, so fertile, and so beautiful, is to-day a deserted charnel-house.

Why should these individual deeds have been visited on thousands of innocent and inoffensive people? Why should those deeds have been visited on monuments of brick and stone? Why should treasuries of learning and shrines of religion be destroyed? Why should the six[40] centuries of European history be destroyed because of the acts of a few patriots acting under the impulse of terror or indignation?

As I said, the whole truth cannot yet be revealed. It is difficult to disentangle the facts even from ocular witnesses, from terrorized victims who were present at the ghastly crime. I have cross-examined some of those witnesses. I have read private letters from my cousin, Professor Albert Nerincx, at present Acting-Burgomaster of Louvain, who assumed office when the civic authorities had left, and whose heroic conduct is one of the few bright spots in the tragedy. Comparing and collating all the evidence at our disposal, we may take the following version given by the Belgian Commission of Inquiry as substantially correct:

"On Tuesday evening a German corps, after receiving a check, withdrew in disorder into the town of Louvain. A German guard at the entrance of the town mistook the nature of this incursion and fired on their routed fellow-countrymen, mistaking them for Belgians.

"In spite of all denials from the authorities the Germans, in order to cover their mistake, pretended that it was the inhabitants who had fired on them, whereas the inhabitants, including the police, had been disarmed more than a week ago.

"Without inquiry, and without listening to any protests, the German Commander-in-Chief announced that the town would be immediately destroyed. The inhabitants were ordered to leave their dwellings; a party of men were made prisoners and the women and children put into trains the destination of which is unknown. Soldiers furnished with bombs set fire to all parts of the town."

IV—MURDER—LOOT—RAPINE—IN BELGIUM

An Oxford student who visited the scene of the disaster with Mr. Henry Fürst, of Exeter College, Oxford, on August 29, gives the following description of the awful picture:

"Burning houses were every moment falling into the roads; shooting was still going on. The dead and dying, burnt and burning, lay on all sides. Over some the Germans had placed sacks. I saw about half a dozen women and children. In one street I saw two little children walking hand in hand over the bodies of dead men. I have no words to describe these things. I hope people will not make too much of the saving of the Hôtel de Ville.

"The Hôtel de Ville was standing on Friday morning last, and, as we plainly saw, every effort was being made to save it from the flames. We were told by German officers that it was not to be destroyed. I have personally no doubt that it is still standing. The German officers dashing about the streets in fine motor-cars made a wonderful sight. They were well-dressed, shaven, and contented-looking; they might have been assisting at a fashionable race-meeting. The soldiers were looting everywhere; champagne, wines, boots, cigars—everything was being carried off."

But let it not be thought that Louvain was destroyed in vain. To the Belgian people it has meant more than a glorious victory. To the Germans it has been more disastrous than the most ignominious defeat. Until Louvain neutral peoples might still hesitate in their sympathies. Pacifists might still waver as to the justice of the cause. After Louvain any hesitation or doubt became impossible. The destruction of Louvain was needed to drive home the meaning of German culture. The crime of[42] Louvain branded the German rulers and the commanders of the German armies as the enemies of the human race.

The atrocities committed by the German armies have roused the indignation of both hemispheres. They have placed Germany outside the pale of civilization. They have covered the German armies with eternal infamy. In the full light of the twentieth century the German terror has outdone the deeds and wiped out the memory of the Spanish terror. We make ample allowances for wild rumors bred of panic, although in the present instance the panic caused by the mere approach of the German soldiery is in itself a most significant symptom. If the German armies had observed the laws of civilized warfare which protect the defenceless inhabitants, there would have been no need for the population to fly for their lives, and there would not be at present a million homeless exiles wandering over the high roads of Holland.

(Dr. Sarolea describes the vicissitudes of Belgian triumphants alternating with Belgian reverses, the pathetic story of brave endeavor and of suffering nobly endured in the noblest of causes. The Defense of Liège, the fall of Namur, the capture of Brussels and the beleaguering of Antwerp: the destruction of Dinant and Termonde, the bursting of the dykes of the Scheldt, the German Terror and the wholesale exodus of the stricken nation which through all time will be the favorite theme of historians and poets.)

[3] All numerals throughout this volume relate to the stories herein told—not to chapters in the original books.