President,

Hon. JAMES A. ROBERTS, New York.

First Vice-President,

Hon. GRENVILLE M. INGALSBE, Sandy Hill.

Second Vice-President,

Dr. SHERMAN WILLIAMS, Glens Falls.

Third Vice-President,

JOHN BOULTON SIMPSON, Bolton.

Treasurer,

JAMES A. HOLDEN, Glens Falls.

Secretary,

ROBERT O. BASCOM, Fort Edward.

Assistant Secretary,

FREDERICK B. RICHARDS, Ticonderoga.

| Mr. Asahel R. Wing, Fort Edward | Term Expires 1906 |

| Mr. Elmer J. West, Glens Falls | " 1906 |

| Rev. John H. Brandow, Schoharie | " 1906 |

| Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe, Sandy Hill | " 1906 |

| Col. William L. Stone, Mt. Vernon | " 1906 |

| Mr. Morris Patterson Ferris, New York | " 1906 |

| Hon. George G. Benedict, Burlington, Vt. | " 1906 |

| Hon. James A. Roberts, New York | " 1907 |

| Col. John L. Cunningham, Glens Falls | " 1907 |

| Mr. James A. Holden, Glens Falls | " 1907 |

| Mr. John Boulton Simpson, Bolton | " 1907 |

| Rev. Dr. C. Ellis Stevens, New York | " 1907 |

| Dr. Everett R. Sawyer, Sandy Hill | " 1907 |

| Mr. Elwyn Seele, Lake George | " 1907 |

| Mr. Frederick B. Richards, Ticonderoga | " 1907 |

| Mr. Howland Pell, New York | " 1907 |

| Gen. Henry E. Tremain, New York | " 1908 |

| Mr. William Wait, Kinderhook | " 1908 |

| Dr. Sherman Williams, Glens Falls | " 1908 |

| Mr. Robert O. Bascom, Fort Edward | " 1908 |

| Mr. Francis W. Halsey, New York | " 1908 |

| Mr. Harry W. Watrous, Hague | " 1908 |

| Com. John W. Moore, Bolton Landing | " 1908 |

| Rev. Dr. Joseph E. King, Fort Edward | " 1908 |

| Hon. Hugh Hastings, Albany | " 1908 |

At the Seventh Annual Meeting of the New York State Historical Association, held at Lake George on the 22d day of August, 1905, a quorum being present, the President, James A. Roberts, called the meeting to order, whereupon it was duly moved, seconded and carried, that the reading of the minutes be dispensed with.

The report of the Treasurer, James A. Holden, was read and adopted after having been approved by the auditors, Dr. Joseph E. King and the Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe.

It was further moved, seconded and carried, that the annual publication of the society be not sent to those members who are two or more years in arrears in their dues.

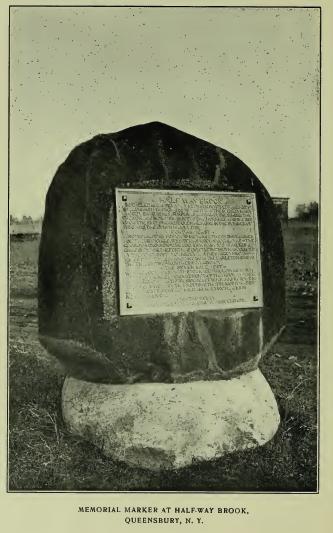

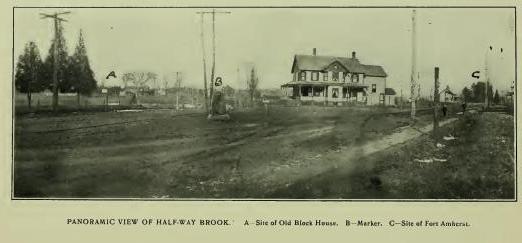

Dr. Sherman Williams, chairman of the committee on historic spots, reported orally that arrangements had been made for the erection of a boulder with a bronze tablet at Half-Way Brook, and that arrangements were in progress for marking other spots in the vicinity of Lake George. The report was accepted and the committee continued, and the committee were requested to make a written report with a historic sketch relating to the spots marked and proposed to be marked, which report together with a cut of the tablets erected and to be erected shall be published in the proceedings of the Association.

Mr. Harry W. Watrous, chairman of the committee on Fort Ticonderoga, by Mr. Grenville M. Ingalsbe reported progress.

Upon the suggestion of the chairman the following committee on Fort Ticonderoga was appointed for the ensuing year:

Mrs. Elizabeth Watrous, Mr. John Boulton Simpson, Mr. Geo. O. Knapp.

The committee on program made an oral report, which was adopted.

A vote of thanks was extended to Gen. Tremain for his very liberal gift to the Association reported by the treasurer.

A vote of thanks was extended to the committee on program.

The following new members were elected:

Alice Brooks Wyckoff, Elmira, N. Y. Hon. F. W. Hatch, N. Y. City. Hon. Albert Haight, Albany, N. Y. Hon. John Woodward, Brooklyn, N. Y. Mr. E. B. Hill, 49 Wall Street, N. Y. City. Rev. Dr. Thos. B. Slicer, N. Y. City. Mr. G. C. Lewis, Albany, N. Y. Dr. George S. Eveleth, Little Falls, N. Y. George C. Rowell, 81 Chapel Street, Albany, N. Y. Mr. James F. Smith, So. Hartford, N. Y. Mr. George Foster Peabody, Lake George, N. Y. Mr. Grenville H. Ingalsbe, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Mr. A. N. Richards, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Mr. Irwin W. Near, Hornellsville, N. Y. Mr. Archibald Stewart, Derby, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Mr. Alvaro D. Arnold, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Mr. Richard C. Tefft, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Mr. F. D. Howland, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Mr. A. W. Abrams. Mr. D. M. Alexander, Buffalo, N. Y. Mr. Philip M. Hull, Clinton, N. Y. Addie E. Hatfield, 17 Linwood Place, Utica, N. Y. George K. Hawkins, Plattsburgh, N. Y. Dr. Claude A. Horton, Glens Falls, N. Y. Dr. E. T. Horton, Whitehall, N. Y. Gen. T. S. Peck, Burlington, Vt. Myron F. Westover, Schenectady, N. Y. Dr. Wm. C. Sebring, Kingston, N. Y. Mr. Neil M. Ladd, 646 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, N. Y. Mr. J. Hervey Cook, Fishkill-on-the-Hudson, N. Y. Mr. H. L. Broughton, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Daniel L. Van Hee, Rochester, N. Y. Edmund Wetmore, 34 Pine Street, N. Y. City. Mrs. Lydia F. Upson, Glens Falls, N. Y. Mr. Daniel F. Imrie, Lake George, N. Y. Mr. James Green, Lake George, N. Y. Mr. Edwin J. Worden, Lake George, N. Y.

Dr. Sherman Williams moved that the chair appoint a committee of two to take into consideration an amendment to the constitution relating to the payment of dues.

Carried.

Whereupon the chair appointed as such committee Robert O. Bascom and James A. Holden.

Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe offered the following resolution.

Resolved, That the President be authorized to appoint a committee of three to investigate and report to the next annual meeting as to the feasibility of co-operation and of the establishment of a community of action between this association and the various other historical societies in the State, which resolution was unanimously adopted.

After some discussion, participated in by various members of the Association, it was regularly moved, seconded and carried, that a committee of three be appointed by the president upon membership, whereupon the president appointed the following committee:

Dr. Ellis C. Stevens, with power to name his associates.

The following trustees were unanimously elected by ballot for the term of three years:

Gen. Henry E. Tremain, N. Y. City; William Wait, Kinderhook, N. Y.; Dr. Sherman Williams, Glens Falls, N. Y.; Robert O. Bascom, Fort Edward, N. Y.; Francis W. Halsey, New York; Harry W. Watrous, Hague, N. Y.; Rev. Dr. Joseph E. King, Fort Edward, N. Y.; Hon. Hugh Hastings, Albany, N. Y.; Com. John W. Moore, Bolton Landing, N. Y.

Rev. Mr. Hatch and Rev. Mr. Black presented for the consideration of the Association the subject of the erection of a museum building. After some discussion it was moved, seconded and carried, that the thanks of the Association be tendered to the gentlemen for bringing the matter to the attention of the Association, after which the meeting was adjourned until two o'clock in the afternoon.

August 22d, 1905.—Afternoon Session.

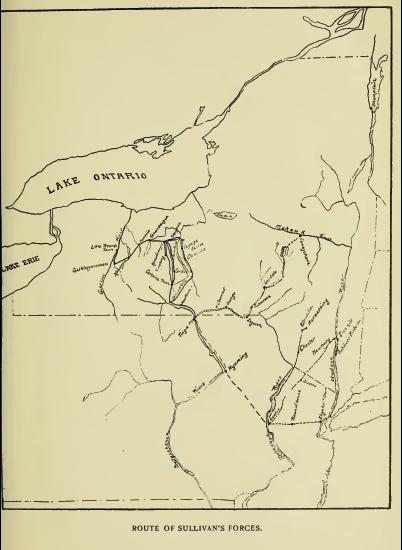

Symposium—The Sullivan Expedition.

At the adjourned session held in the afternoon August 22d, 1905, Dr. W. C. Sebring, of Kingston, read a paper entitled, "The Character of Gen. Sullivan."

A paper entitled "The Primary Cause of the Border Wars," by Francis W. Halsey, of New York, was read by the Hon. Grenville M. Ingaslsbe in the absence of Mr. Halsey.

Dr. Sherman Williams, of Glens Falls, read a monograph entitled, "The Organization of Sullivan's Expedition."

Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe read by title only a paper entitled, "A Bibliography of Sullivan's Expedition."

A paper entitled, "An Indian Civilization and its Destruction," by Col. S. W. Moulthrop, was read by the Rev. W. H. P. Hatch in the absence of Col. Moulthrop.

A paper entitled, "The Campaign," was read by William Wait, of Kinderhook, when the meeting adjourned until August 23d, at 10 o'clock A. M., at the same place.

ROBERT O. BASCOM, Secretary.

TRUSTEES' MEETING.

August 23d, 1905.

At a meeting of the Trustees of the New York State Historical Association held at Lake George on the 22d day of August, 1905, a quorum being present, the following officers were elected:

President, Hon. Jas. A. Roberts, Buffalo, N. Y. First Vice-President, Hon. G. M. Ingalsbe, Sandy Hill, N. Y. Second Vice-President, Dr. Sherman Williams, Glens Falls, N. Y. Third Vice-President, John Boulton Simpson, Bolton, N. Y. Treasurer, James A. Holden, Glens Falls, N. Y. Secretary, Robert O. Bascom, Fort Edward, N. Y. Asst. Secretary, Frederick B. Richards, Ticonderoga, N. Y.

The printing bill of E. H. Lisk was presented to the Trustees and after discussion the same was referred to the Treasurer and Secretary with power to settle the same.

The following committees were appointed:

Standing Committee on Legislation: Hon. James A. Roberts, Gen. Henry E. Tremain, Dr. Sherman Williams, Morris Patterson Ferris, Hon. Hugh Hastings. On Marking Historic Spots: Dr. Sherman Williams, Frederick B. Richards, James A. Holden, Asahel R. Wing, Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe. On Fort Ticonderoga: Mrs. Elizabeth Watrous, John Boulton Simpson, George O. Knapp. On Program: Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe, Dr. Sherman Williams, Dr. C. Ellis Stevens. On Membership: Dr. C. Ellis Stevens.

Bill of the Secretary for postage, express and sundries was thereupon audited and ordered paid, whereupon the meeting adjourned.

At a meeting of the Trustees it was moved, seconded and carried, that E. M. Ruttenber, of Newburgh, N. Y., be made an honorary member of the Association.

ROBERT O. BASCOM,

Secretary.

ASSOCIATION MEETING.

August 23d, 1905.

At the adjourned session held August 22d, a paper entitled, "Concerning the Mohawks," was read by W. Max Reid, of Amsterdam, N. Y., after which the Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe read certain hitherto unpublished letters from Gen. George Washington relating to the "Sullivan Expedition," after which a resolution was adopted requesting that Mr. Ingalsbe furnish the same for publication in the ensuing volume of the proceedings of the Association.

An address entitled, "Robert R. Livingston, the Author of the Louisiana Purchase," by Hon. D. S. Alexander, of Buffalo, N. Y., concluded the session, and after a vote of thanks to the various speakers, the meeting adjourned until two o'clock in the afternoon of the same day, at which session a paper entitled, "The Birth at Moreau of the Temperance Reformation," by Dr. Charles A. Ingraham, of Cambridge, was read.

The annual address, "The Democratic Ideal in History," by Hon. Milton Reed, of Fall River, Massachusetts, concluded the literary exercises of this meeting, and after a vote of thanks to the speakers of the afternoon the meeting adjourned sine die.

ROBERT O. BASCOM,

Secretary.

TRUSTEES' MEETING.

At a meeting of the Trustees of the New York State Historical Association, held at the Hotel Ten Eyck on the 19th day of January, 1906, in the City of Albany.

Present, Hon. James A. Roberts, President; Hon. Grenville M. Ingalsbe, First Vice-President; Dr. Sherman Williams, Second Vice-President; Hon. Hugh Hastings, Trustee; Hon. Robert O. Bascom, Secretary.

The meeting being duly called to order by the President, the semi-annual report of James A. Holden, Treasurer, was read and adopted.

The report is as follows:

SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT

of

J. A. Holden, Treasurer New York State Historical Association,

From July 1, 1905, to Jan. 18, 1906.

| RECEIPTS. | ||||

| July 1, 1905— | Cash on hand | $194.73 | ||

| Received from dues, etc. | 390.10 | |||

| $584.83 | ||||

| DISBURSEMENTS. | ||||

| Aug. 5, | E. H. Lisk, printing | $200.00 | ||

| " 5, | R. O. Bascom, postage and sundries | 27.50 | ||

| Sep. 8, | E. H. Lisk, printing | 62.25 | ||

| Sep. 7, | R. O. Bascom, postage | 23.28 | ||

| " 7, | Milton Reid, expenses | 15.31 | ||

| Nov. 8, | E. H. Lisk, printing | 31.75 | ||

| Dec. 4, | R. O. Bascom, stamps | 10.00 | ||

| " 11, | R. O. Bascom, " | 10.00 | ||

| Jan. 9, | Postage | 5.00 | ||

| 385.09 | ||||

| Cash on hand | $199.74 | |||

| ASSETS. | ||||

| Cash on hand | $199.74 | |||

| Life Membership Fund | 271.40 |

Respectfully submitted,

JAMES A. HOLDEN,

Treasurer.

The report of the committee on amendments to the Constitution was read and laid upon the table.

The report of Committee on Marking Historic Spots was read and adopted. The report is as follows:

Glens Falls, N. Y., Jan. 18, 1906.

To the Trustees of the New York State Historical Association,

Gentlemen:—I beg to report progress in regard to the work of the committee on marking Historic Spots. A good number of persons have made contributions ranging from five to fifty dollars each. A marker has been erected at Half-Way Brook and another planned for at Bloody Pond. The tablet at Half-Way Brook was made under the direction of W. J. Scales, who is also to prepare the design for the one at Bloody Pond. The marker at Half-Way Brook is a large boulder resting upon another large boulder nearly buried in the ground. The boulders are large and very hard, and the cost of cutting them to fit was unexpectedly great. Both boulders were drawn from a long distance. The cost of drawing and erecting them, and getting them ready for the tablet was about one hundred and ten dollars. This work was supervised by Mr. Henry Crandall, who had subscribed fifty dollars toward the work. When it was finished he said that if I would cancel his subscription he would meet all the expense of getting the stones in place. As this was more than twice the amount of his subscription his offer was gladly accepted. The other expenses to date have been as follows:

| For cutting a smooth face on the boulder and fitting tablet to it | $25.25 |

| For photographing the monument | 1.00 |

| Paid Mr. Scales on account | 45.00 |

| Total | $71.25 |

In the Spring it will be necessary to meet a small expense to grade the ground and seed it. We hope to have the marker at Bloody Pond in place before our next annual meeting.

Respectfully submitted,

SHERMAN WILLIAMS,

Chairman of Committee for Marking Historic Spots.

The following new members were duly elected:

The thanks of the Trustees were extended to Dr. Stevens for his services as chairman of the Committee on Membership. The Secretary and Mr. William Wait, of Kinderhook, were by motion duly carried appointed a committee on the publication of the Proceedings of the Association. The edition was fixed at 750 copies and the Secretary instructed not to send proceedings to persons who were more than four years in arrears, after which the meeting adjourned.

ROBERT O. BASCOM,

Secretary.

How the mists do gather. With the exception of Greene and Benedict Arnold, George Washington trusted Sullivan beyond any other general of the Continental army. Sullivan acquitted himself well on diverse battlefields and, though defeated, the real worth of the man shows in this, that defeat added as much prestige to his reputation as his victories. His greatness like that of Washington throve on defeat, for it can be fairly said that Washington never won a battle. And yet if you ask even those who have given time to our history as to General Sullivan, they will convey to you but the most vague impression of some minor general who sometime in the revolution made a foray on some Indians somewhere in this State.

The last scene of a drama is best remembered. The picture as the curtain falls is stamped most clearly on the memory. Sullivan was not to be an actor in the war's closing scenes, and the valor that gleams the name of Marion, the splendor of Greene's military intelligence, and the glory that is linked with the name of Washington at Yorktown were not his. Neither had he the methodical madness of Wayne, the pusillanimity of the self-seeking Gates, the recklessness of Putnam, nor the aestheistic fatalism of Ethan Allan; none of these things had Sullivan to carve his picture on men's memory.

It may not be out of place here to give a short chronology of this man's life.

He was born in Summerworth, N. H., in 1740. His parents were well-to-do emigrants from Ireland. He studied law and was a member of the first Congress, 1774. Was made Brigadier General 1775. In 1776 he superseded Arnold in Canada. Then he succeeded General Greene and was taken prisoner. He was exchanged in November. In 1777 he took part in the battle of Brandywine, Germantown, and 1778 he commanded in Rhode Island. In 1779 he led the expedition against the Indians. He then resigned from the army and took up again the practice of law. He was a member of the State constitutional convention, then he was elected a member of Congress, and in '86, '87, '89 was president of his State. Later, in 1789, he was appointed District Judge, and died in 1795 at the age of 54 years.

His personal characteristics are said to be that he was a dignified, genial and amiable man. He displayed a fine courtesy to those about him, both to his soldiers and compatriot generals.

I quote the following paragraph from A. Tiffany Norton, who I believe to be the one who has written the best account of the Indian campaign, and it is a wonder to me that one who shows so broad a grasp of history and its essential principles and the elements that make for historical research, has never written more than he has.

Norton, in his general description of Sullivan, says: "His eyes were keen and dark, his hair curly black, his form erect, his movements full of energy and grace. His height was five feet nine inches, and a slight corpulency when in his prime gave but an added grace. General Sullivan was a man of undoubted courage, warmth of temperament and independent spirit equaled only by his patriotic devotion to his country's cause and his zeal in all public affairs." Doubtless he was too impatient and outspoken and may have been deserving of some measure of blame, still his faults should not have detracted from that meed of praise to which he was justly entitled. Neither should the jealousies of his brothers in arms, which prompted them to ridicule his achievements, question his reports and detract from his hard-earned laurels, have weight with the historian. Yet such has been, in great degree, the case, and the name of Sullivan occupies a lesser space in the history of the Revolutionary struggle, than those of many others whose achievements fell far short of his in magnitude and importance. Sullivan has been made the victim of the intrigues and petty jealousies of his times, and while for this his own indiscretions may justly be blamed, the duty is none the less incumbent on the present generation to render due homage to one who is a brave soldier and a devoted, disinterested, self-sacrificing patriot. As Amory has justly said: "A friend of Washington, Greene, Lafayette, and all the noblest statesmen and generals of the war, whose esteem for him was universally known, to whom his own attachment never wavered, he will be valued for his high integrity and steadfast faith, his loyal and generous character, his enterprise and vigor in command, his readiness to assume responsibility, his courage and coolness in emergencies, his foresight for providing for all possible contingencies of campaign or battle-field, and his calmness when the results became adverse."

Could the character of Sullivan be fairly said to be that of a great man? Does he measure up to "bigness?" Remember a little man seldom does big things. Briefly, what did he do in this Indian campaign? At the beginning of the Revolution there was a democracy of six confederate states within the present boundaries of our own municipality. So strong had this democracy grown that it dominated the inhabitants of a territory of more than a million square miles. Their battle-cry was heard from the Kennebec to Lake Superior, and under the very fortifications of Quebec they annihilated the Huron.

Their orators were fit to rank with any that we have to-day. Their legends are the legends of a people whose souls were filled with poetry. Their military tactics were those of a people trained for war—successful war. Man to man, they were what no other barbarians have been, a match for the white man. They held the gateway to the West and their position made them umpires between the mighty nations of the Old World who were struggling for the possession of the New. Civilized in a sense they were, but they were barbarians too, and savages to their very heart of hearts. Rapacious, treacherous, cruel beyond belief,—they were dreaded alike by friend and foe. Their home was a terra incognita. No colonist had trodden it. From no peak had trapper looked across the profile of their land. Their numbers were unknown and could only be guessed at by their achievements—and these were terrible.

How silly of Gordon to criticize Sullivan for over-manning his expedition. Darkest Africa is better known to-day than was then the land of the Iroquois. They were re-enforced by British regulars, by fanatical Tories; they were led by white men, and one of their leaders was a thorough Indian and thoroughly educated in the white man's lore.

Among this people and into this terra incognita came Sullivan and smote them hip and thigh. He conquered them to the uttermost. He broke down the gateway to the mighty West. With a miserable commissariat, he invaded an unknown country and forever destroyed a democracy that had ruled for five hundred years.

The Indians conquered by Wayne were but a frazzle of the Six Nations united with Indians farther West.

Little men do little things, big men do big things, and great men do great things. Before Sullivan vanished

"that savage senate at the Lake, By the salt marshes, yonder in the north, Dull-visaged butchers, coarsely blanketed Squatted in a ring by their dark Council House And with strange mumery of pipes and belts Decreeing, coldly, death—forever death."

The strongest are the gentlest. It is related that having found an Indian woman too old and feeble to retreat with her people, that Sullivan left her with a plentiful supply of provisions, though, as one of the party writes, "we only had half a ration every other day ourselves."

It is not my province to put forth a brief for General Sullivan, yet that one incident cast a side-light on his character that impressed me more as to the true lovely heartiness of the man than anything I have found. Constancy to a friend is an attribute to those who approach greatness. After the Indian war Sullivan was reviled unmercifully for the devastation wrought by him in the Indian country. Out of his love for General Washington he suffered in silence, while he had in his possession General Washington's written instructions to do exactly as he had done.

Perchance for a good man some would even dare to die. But what of a man whose friendship holds so strong that he may see that which is dearer to him than life—his character—filched from him, and lest he should harm a friend, allow his enemies to do with that character as they wished.

Probably no historian ever lived who could write more wrong history than Benjamin Lossing, who accuses Sullivan of carelessness and want of vigilance as a commanding officer and mentions Bedford and Brandywine. Nothing could be farther from the truth. At Bedford he withdrew his forces because the French Navy would not support him, and it was out of the question to remain in the position he had taken up. We have John Fiske's word for it that Brandywine was a drawn battle.

Of energy he had a plenty. It is on record that after he and General Clinton united (and Clinton was no sluggard) his Division time and again out-marched that of Clinton. At one time he broke road across nine miles of swamp while Clinton following him had to camp in the middle of the morass. So difficult was the morass that the Indian spies who had been watching his advance never dreamed that he would attempt the passage of the swamp, and withdrew to their camps. So confident were the Tories and Indians, that when he emerged from the swamp their campfires were still burning.

Right here is a place to say a word about General Sullivan's veracity. After his return from conquering the Six Nations he reported that he had destroyed forty villages, and his detractors could not find but eighteen. It at last developed that when his subordinates had reported destroying a group of buildings he most naturally supposed that it was an Indian village, and so put it down in his report.

It has been said of him that he resigned from the army out of spite. Well, if he did, he was perhaps blamable. But we should remember that he was dealing with a Continental Congress of the latter years of the war, and if you search history for a thousand years you will not be able to find an aggregation of political castros equal to this same Continental Congress. The men who had made the primal congresses great had set themselves to serve the nation in other ways, and Congress had fallen to those who had some money without brains or brains without principle, or lacking both, were like our modern ones in that they loved "graft" and knew how to get it.

Sullivan was not a liar, and he himself says that his health was failing. If we care to plow through the many diaries kept by officers under him we can well believe that he told the truth, for with the spoiling of the provisions sent to the expedition most of the soldiers did suffer from chronic intestinal troubles, and it would be strange if the commander who takes the same fare as his subordinates should not suffer in the same manner.

And to back up this we must remember that even after he retired he never lost the confidence or the love of the greatest of them all, General Washington. Much has been written of General Sullivan's fallibilities, and fallibilities the greatest have.

We should remember that Sullivan was a Kelt. And through the centuries the Kelts have given us the lordliest orators and golden artists, but for tenacity of purpose no one has celebrated them.

General Sullivan when he was taken prisoner and fell under the influence of the British military power, and contrasting them with the meagerness that he had been accustomed to, for once his heart failed him and his soul sank within him, and it is no sorrow to his name to say that for the moment he thought the liberty of mankind in the Western continent was doomed.

He came from the British to us seeking peace, but after he was exchanged and in his old environment his true native Keltic courage returned and his after life was the life of an ardent patriot.

I do not think we give enough credit to the perceptions of the ignorant.

Suppose to ten thousand ignorant people this entirely hypothetical question should be stated: Around the globe is a people who for three hundred years had been fighting a tyrannical power and well nigh achieved success. Would it be right for a republic to step in and take them away from the power they were in rebellion against, and then this republic by force of arms prevent them from becoming an independent republic? State to ten thousand ignorant people this question, and they will shout with one voice "that it is not right." State this question to ten thousand college professors, and they will back and fill, debate and re-debate, and finally be fogged by their very knowledge and at last come to no conclusion at all.

It has never been sufficiently made clear that the classes fought the Revolutionary war. The educated, the elegant, the conservative, the well-to-do, in short the "better elements," were practically all with the British. While the broken, the ignorant, the discouraged, "the rabble," were the ones that won our liberty. Every single Tory that was expatriated could read and write, while I believe if the muster rolls of my own county, inhabited at that time by the educated Dutch, not one-third of those who enlisted could sign their names. So coldly did the wealthy Dutchman look upon the war that it was a common trick for him to send a slave to serve in the ranks instead of himself.

Sullivan by birth and position belonged among the former class, and yet in spite of position, broke with his own class and gladly took up the sword with the ignorant because he saw clearly that all social progress must from very necessity spring from the discontent of the Hoi Polloi. He was a true patriot for he lost his all by giving his attention to public rather than private affairs, and though respected by all and honored by his State, his last years were the years of gloom and the gathering clouds, for his life was beset by heartless creditors. The last scene is the saddest of all, for at his funeral his creditors tried to seize his body and would have done so, except that an old army general drew his pistols and drove off the bailiffs of the law. So was buried one of America's greatest patriots, a constant friend, a brave and good soldier, and a man who, take him ail in all, it is not an exaggeration to call "Great."

General Sullivan's expedition of 1779 was an immediate outcome of the massacres of Wyoming and Cherry Valley in the summer and autumn of 1778—not to mention those minor incidents of the Border Wars, which, beginning in the summer of 1777, had converted the valley of the upper Susquehanna into a land of desolation. It was a most drastic punishment that Sullivan inflicted, and such it was intended by Congress that his work should be. "The immediate objects," said Washington, in his letter of instruction to Sullivan, "are the total destruction and devastation of the Indian settlements," He added that the Indian country was "not to be merely overrun, but destroyed." If we have regard for proportions, greater losses were inflicted upon the Indians by Sullivan than were ever inflicted upon the settlements of New York by the Indians.

The expedition, however, failed completely in achieving its main purpose, which was to suppress the Indian raids. Sullivan and his army had scarcely left the Western country, when the Indian attacks were renewed and for three years were continued with a savage energy before unknown. The Indians' thirst for revenge having been thoroughly aroused, nothing could afterwards restrain their hands. Aside from the burning of German Flats and the battle of Oriskany (the latter not properly an incident of the Border Wars, since it was an integral part of the Burgoyne campaign), the injury done by the Indians to the Mohawk Valley was done subsequent to the Sullivan expedition.

In their entirety, the Border Wars constitute a phase of the Revolution of which far too little has been remembered. We may seek in vain for a territory elsewhere in the United States where so much destruction was done to non-combatants. In Tryon county alone, 12,000 farms went out of cultivation; fully two-thirds of the population either died or fled, While of the one-third who remained 300 were widows and 2,000 orphans. And yet, as I have said, the losses of the Iroquois were greater still.

But it is with the causes which led to this savage work that I am here to deal. For quite 100 years, Joseph Brant and the Tories of the Mohawk Valley, with Col. Guy and Sir John Johnson, and John and Walter Butler, at their head, were generally accepted as the original and inspiring forces in all the barbarities committed. The greater offenders, however, were men of much higher station and more ample powers—men who had never seen the valleys of the Susquehanna and the Mohawk, but who lived in London, and as members of the King's Cabinet were in direct charge of the war in America. One of them was the Earl of Dartmouth, the other Lord George Germaine; but it is to Germaine that we must ascribe the chief odium.

The administration of the Province of New York, when the Revolution began, was completely in the hands of Loyalists. New York was still a Crown colony, officials holding their appointments directly from London. Outside the official class, however, there were patriots in plenty; none of the colonies possessed more; but as New York City was completely dominated by Tory influences, so was the Mohawk Valley dominated by the Johnsons and their army of followers, in whom loyalty to England was a deep-seated sentiment and a fixed principle of conduct. Sir William Johnson had died just as the Revolution was about to begin. His successors became not only as great Loyalists as ever he had been, but, being men of smaller minds and fewer talents. They added to the sentiment of loyalty an expression of it which took the form of satanic bitterness and brute savagery. It was these men who, with their followers, became the hated Tories of the frontier of New York—men of whom in some instances, Joseph Brant said, they had been more savage than the savages themselves.

The attitude of the Indians can be best understood if we remember that they had been practically in alliance with the English of New York for a hundred years. When war began between the mother country and the colonies, or between what the Indians called "two brother nations," they were lost in amazement and tried in vain to understand it. Their own history for three hundred years had been one of peace between brother nations. "No taxation without representation" was a principle beyond their comprehension. The men who defied British soldiers in the streets of New York and Boston seemed to them exactly like the French of Canada who in the older wars had stormed English forts on the Northern Frontier, since they were engaged in war with the King of England, and the King was the Indians' powerful friend.

When the Border Wars reached their height, the frontier of New York should have been in a state of tranquility. With Burgoyne's surrender, the center of conflict was to pass away from New York and New England, and was soon to be transferred to Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina. Why then, these Border Wars in New York? In one short sentence, the whole truth may be disclosed. The ministry of George III, after long and laborious efforts, now at last had won the Indians of New York into active sympathy with their cause. For three years they had tried in vain to gain their support, and again and again had held counsels with them, but the net results had been an essentially neutral stand by the Indians.

But let us recapitulate. Soon after the battle of Lexington, Col. Guy Johnson, the official successor of Sir William, convened at his home near Amsterdam, a conference with the Indians, mostly Mohawks, and later, after the result at Bunker Hill had alarmed him anew, fled to Oswego and thence to Canada. Nearly all the Mohawk Indians went with him, as well as a domestic force of about 500 white men, mainly Scotch Highlanders, over whom he had placed in command, Col. John Butler. In July Col. Johnson reached Montreal, Where he had an interview with Sir Frederick Haldemand, who said to the Indians:

"Now is the time for you to help the King. The war has begun. Assist him now, and you will find it to your advantage. Whatever you lose during the war, the King will make up to you when peace returns."

Later in the same month, the Earl of Dartmouth, then a member of the British Cabinet, wrote from London to Col. Johnson, that it was the King's pleasure "That you lose no time in taking such steps as may induce the Indians to take up the hatchet against his Majesty's rebellious subjects in America." This letter was accompanied by a large assortment of presents for the Indians, and Col. Johnson was urged not to fail to use "the utmost diligence and activity" in accomplishing the purpose. Col. Johnson was joined in Canada in the spring of the following year by his brother-in-law, Sir John Johnson, the son and heir of Sir William. Sir John had organized a force known as the Royal Greens, composed of loyalists from the New York frontier, and mainly former tenants and dependents of his father's estate.

The Mohawks, who alone of all the Six Nations had gone to Canada, were slow to yield to the importunities of the English, in so far as taking an active part in the war was concerned. A topic of far deeper interest to them was their title to certain lands in the Mohawk and upper Susquehanna Valleys, concerning which they had failed to secure adjustments for many years. In November, 1775, Joseph Brant with other Indian chiefs, sailed for England with a view to accomplishing a settlement of this dispute. An interview took place with the Colonial Secretary, who subsequently was in direct charge of the war in America, Lord George Germaine. Brant made two speeches before Germaine, outlining the grievances of his people, and it is clear from one of them that Germaine then secured the adhesion of Brant to the English cause by promising to redress the Indian grievances after the war, and to keep for the Indians the favor and protection of the King. Thenceforth the responsibility for Indian activity in the Revolution rests mainly on Germaine. It was to him that Lord Chatham referred in a memorable speech on the American War:

"But, my lord, who is the man, that, in addition to the disgrace and mischiefs of the war, has dared to authorize and associate to our arms the tomahawk and scalping knife of the savage? To call into civilized alliance the wild and inhuman inhabitants of the woods? To delegate to the merciless Indian the defense of disputed right, and to wage the horrors of his barbarous war against our brethren? My lords, these enormities cry aloud for redress and punishment."

When the Burgoyne campaign began, Brant had arrived home. New efforts were now actively put forth to enlist the Indians in British service. A considerable company of them started south with Burgoyne, but they subsequently deserted him before a battle had been fought, or even the American army was discovered. With St. Leger a much larger force started for a descent upon the Mohawk Valley. These were in direct charge of Joseph Brant, and comprised the greater part of the efficient Mohawk force. At Oswego a counsel had been held a few weeks before, in order to enlist in British service the other "nations" of the Iroquois, who were assured that the King was a man of great power and that they should never want for food and clothing if they adhered to him. Rum, it was said, would be "as plentiful as water in Lake Ontario." Presents were made, and a bounty offered on every white man's scalp that they might take. The Senecas notably, and to some extent the Onondagas and Cayugas, thus became fired with ambition to see something of the war.

By the time St. Leger arrived at Oswego, about 700 warriors had been secured. Some of them still remained lukewarm as to fighting, but they were at last drawn into the campaign under an assurance that they need not fight themselves, but might sit by during the battle smoking their pipes, while they saw the redcoats "whip the rebels." The result was, that when a battle was imminent at Oriskany, the Indian's love of war was uppermost, and they became the most active participants in the conflict. They also became proportionately the heaviest losers and returned to their homes, not only with doleful shrieks and yells over their losses, but with a determined purpose to revenge themselves on the defenseless frontier. At what frightful cost to the Mohawk Valley they secured that revenge, the story of the ensuing four years bears ample witness.

But, as I have said, the Indians lost more. When the war was over, they had practically lost everything. Their homes were destroyed and their altars obliterated. England virtually abandoned them to the men whom they had fought as rebels, but who were now victorious patriots, the masters of imperial possessions. Nothing whatever was exacted for them in the treaty of peace. Not even their names were mentioned. Such, at the close of the war, was their pitiful state. Everything in the world that they had, had been given to a cause, not their own—the cause of an ally across the great waters, with whom they were keeping an ancient covenant chain. When at last their wide domain, among whose streams and forests for ages their race had found a home, passed forever from their control, they might have said, with a pride more just than that of Francis I., after the battle of Pavia, "All is lost save honor."

History has not done justice to the subject in telling the story of Sullivan's expedition. There are few if any equally important events in our history of which the great majority of our people know so little. It was the most important military event of 1779, fully one-third of the Continental army being engaged in it. The campaign was carried on under great difficulties, was brilliantly successful, and executed with but small loss of life. It is possible that the movement would have received more attention from the historians had the loss of life been much greater, even if the results had been of less importance.

The chief result was the practical destruction of the Iroquois Confederacy. While the Six Nations were very active on the frontier the following year, the Confederacy as an organization had received its death blow.

The massacres at Wyoming, along the New York frontier, especially in the Mohawk, Schoharie and Susquehanna valleys, had so aroused the people that the Continental Congress felt called upon to take action and on the 27th of February, 1779, passed a resolution directing Washington to take effective measures to protect the frontier.

It was decided to send a strong expedition against the Iroquois settlements, and utterly destroy their towns and crops, more especially in the territory of the Senecas and Cayugas. It was no small task to equip a large force and traverse an almost unknown, and altogether unmapped, wilderness which was wholly without roads, in the face of an active and vigilant as well as relentless foe.

The command of the expedition was tendered to General Gates because of his rank. In reply to the tender of the command General Gates wrote to Washington as follows: "Last night I had the honor of your Excellency's letter. The man who undertakes the Indian service should enjoy health and strength, requisites I do not possess. It therefore grieves me that your Excellency should offer me the only command to which I am entirely unequal. In obedience to your command I have forwarded your letter to General Sullivan."

Washington had evidently anticipated that Gates would not accept the command as he had enclosed in his letter to him a communication that was to be forwarded to Sullivan in case Gates declined the service. It was this letter to which Gates referred in his reply to Washington. No doubt it was fortunate for the country that the command of the expedition devolved upon some other person than Gates.

Washington felt somewhat hurt at the tone of the letter he received from Gates, and in a communication to the President of Congress he said, "My letter to him on the occasion I believe you will think was conceived in very candid and polite terms, and merited a different answer from the one given to it."

In his instructions to Sullivan Washington wrote as follows:

"Sir:—The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians, with their associates and adherents. The immediate object is their total destruction and devastation, and the capture of as many persons of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more."

At this time it was supposed that the expedition would reach the Indian country in the early summer, but it was not until August that the work of destruction began. Writing again of the expedition Washington said the purpose was "to cut off their settlements, destroy their crops, and inflict upon them every other mischief which time and circumstances would permit."

The purpose of the expedition was primarily to destroy the crops and villages of the Indians, after which Sullivan was to move forward and capture Niagara, if such action should prove to be practicable.

The expedition was to be made up of three divisions. The first was directly under the command of Sullivan; and the forces of which it was composed assembled at Easton, Pa., from which point they marched to Wyoming on the Susquehanna, and from there to Tioga Point. Here they waited for the second division under the command of General Clinton, who had sent an expedition into the Onondaga country, after which he was to assemble his forces at Canajoharie and march across the country to the head of Otsego Lake and then come down the Susquehanna River to join Sullivan at Tioga. The third division was under the command of Colonel Daniel Brodhead, who started from Pittsburgh, Pa. He never directly co-operated with Sullivan, but no doubt aided him by his movement. He left Pittsburgh on the 11th of August with a force of six hundred and fifty men. He followed the Allegheny river and passed up into the Seneca country, where he destroyed more than one hundred and fifty houses and about five hundred acres of corn. His presence in the southern portion of the Seneca country kept some of the Senecas from joining in the movement to oppose Sullivan and so lessened the Indian force at the battle of Newtown and possibly somewhat affected the expedition. The original intention was to have Brodhead join Sullivan at Genesee and aid in the movement against Niagara, but as for some reason no movement was made against Niagara there was no occasion for him to do more than he did, and no further attention need be given his movement as a part of the Sullivan expedition. Brodhead marched three hundred and eighty miles, destroyed houses, cornfields, and gardens, and did his part in destroying the Indian civilization.

Aside from the force of Brodhead, Sullivan's expedition was made up of four brigades. The first consisted of the First New Jersey regiment under the command of Colonel Matthias Ogden; the Second New Jersey commanded by Colonel Israel-Shreve; the Third New Jersey under Colonel Elias Dayton, and Spencer's New Jersey regiment commanded by Colonel Oliver Spencer. The brigade was under the command of Brigadier-General William Maxwell.

Brigadier-General Enoch Poor commanded the second brigade, which was made up of the First New Hampshire regiment under Colonel Joseph Cilley; the Second New Hampshire commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel George Reid; the Third New Hampshire commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Dearborn; the Sixth Massachusetts under the command of Major Daniel Whiting. The Sixth Massachusetts was at the outset a part of the fourth brigade, and the Second New York was a part of the second brigade, but the two regiments exchanged brigades in August, and from that time till the close of the expeditions were in the brigades as given in this sketch.

The third brigade was commanded by Brigadier-General Edward Hand and was composed of the Fourth Pennsylvania regiment under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel William Butler; the Eleventh Pennsylvania under Lieutenant-Colonel Hubley; the German Battalion under Major Daniel Burchardt; an artillery regiment under Colonel Thomas Proctor; Morgan's riflemen under Major James Parr; an independent rifle company under Captain Anthony Selin; the Wyoming militia under Captain John Franklin; and an independent Wyoming company under Captain Simon Spalding.

The fourth brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General James Clinton, was made up of the Second New York regiment under Colonel Philip Van Cortlandt; the Third New York under Colonel Peter Gansevoort; the Fourth New York under Colonel Frederic Weissenfels; the Fifth New York under Colonel Lewis Dubois; and the New York artillery detachment under Captain Isaac Wool.

It would be exceedingly interesting to trace the movement of each of the regiments engaged in the expedition from their place of starting to the various rallying places, but in many instances the writer has been unable to ascertain the facts after consulting all the works relating to Sullivan's expedition to be found in the State library, and other libraries, and after writing to the secretary of some of the state historical societies. Therefore the assembling of the forces constituting Sullivan's expedition will have to be treated in rather a general way.

The New Hampshire regiments apparently wintered at Soldier's Fortune, about six miles above Peekskill, as diaries of various New Hampshire officers engaged in the expedition mention marching from that point and I find no reference to any place occupied earlier. From Soldier's Fortune the New Hampshire troops, certainly the Second and Third regiments, and presumably the whole force, marched to Fishkill, a distance of seventeen miles. At this point they crossed the Hudson river to Newburgh. From that place they marched to the New Jersey line passing through Orange county. They took a route leading through New Windsor, Bethlehem, Bloomgrove Church, Chester, Warwick, and Hardiston. The distance was thirty-eight miles. From Hardiston the force marched to Easton on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware river. It passed through Sussex State House, Moravian Mills, Cara's Tavern, all these places being in the state of New Jersey. The distance from Hardiston to Easton was fifty-eight miles.

On the first of May, 1779, the Second and Fourth New York regiments left their camp near the Hudson and marched to Warwarsing in the southwestern part of Ulster county, thence to Ellenville, a few miles south of Warwarsing, then to Mamacotting (now Wurtsboro) in Sullivan county. The next day was spent in rest at Bashesland (now Westbrookville) near the Sullivan and Orange county line; from this point they marched to Port Jervis. On the 9th of May they crossed the Delaware at Decker's Ferry, and from there marched to Easton.

The New Jersey brigade had spent the previous winter at Elizabethtown, New Jersey, from which point they marched to Easton, passing through Bound Brook.

The forces which gathered at Easton marched from there to Wyoming on the Susquehanna, a distance of sixty-five miles. Nearly forty days were required to cover that distance. The way lay through thick woods and almost impassable swamps. The route took them through Hillier's Tavern, Brinker's Mills, Wind Gap, Learn's Tavern, Dogon Point, and the Great Swamp. They reached Wyoming on the 24th of June.

General Sullivan was much blamed but most unjustly so for his tardy movement. Pennsylvania had been relied upon to furnish not only a considerable body of troops but most of the supplies, but that commonwealth did not give the expedition a hearty support. The Quakers were most decidedly opposed to inflicting any punishment whatever upon the Indians. Other Pennsylvanians were offended because a New Englander had been chosen for the command instead of a Pennsylvanian. Troops were slow in coming forward. Supplies were furnished tardily and reluctantly. They were insufficient in quantity and poor in quality. The commissaries were careless and inefficient. The contractors were unscrupulous and dishonest. The authorities complained saying that Sullivan's demands were excessive and unreasonable and they threatened to prefer charges against him. However, all the testimony goes to show that the commissary department was in charge of men who were either utterly incompetent or grossly negligent of their duty. On the 23rd of June Sullivan wrote Washington saying, "more than one-third of my soldiers have not a shirt to their backs." On the 30th of July Colonel Hubbard wrote to President Reed saying, "My regiment I fear will be almost totally naked before we can possibly return. I have scarcely a coat or a blanket for every seventh man."

On the 31st of July Sullivan's army left Wyoming for Tioga Point. A fleet of more than two hundred boats and a train of nearly fifteen hundred pack horses were required to transfer the army and its equipment. Tioga Point at the junction of the Tioga and the Susquehanna rivers was reached on the 11th of August. The army had been eleven days in making sixty-five miles. The route from Wyoming led through Lackawanna (now Coxton) in Luzerne county; Quialutimuck, near Ransom Station, Luzerne county; Hunkhannock; Vanderlip's Farm (now Black Walnut) Wyoming county; Wyalusing, Standing Stone, Bradford county; Sheshhequin, Bradford county.

While waiting for Clinton Sullivan built a fort which was named in his honor, between the Tioga and Susquehanna rivers about a mile and a quarter above their junction at a point where the two streams were within a few hundred yards of each other. The center of the present village of Athens, Pa., is almost exactly at this point.

Early in the spring Clinton with the First and Third New York regiments passed up the Mohawk to Canajoharie. From this point an expedition was sent out against the Onondagas. About fifty houses were burned and nearly thirty Indians were killed and a somewhat larger number taken prisoners.

After this expedition Clinton passed from Canajoharie to the head of Otsego Lake. This was a laborious enterprise as, for a portion of the distance, roads had to be cut through an unbroken forest and there was not a good road any part of the distance. More than two hundred heavy batteaux had to be drawn across from Canajoharie, a distance of twenty miles, by oxen.

Otsego Lake, the source of the Susquehanna, is about twelve hundred feet above tide water, nine miles long with an average width of a mile. The outlet is narrow with high banks. Here Clinton built a dam and raised the water of the lake several feet, sufficient to furnish water to float his boats when the time came for a forward movement.

On the 9th of August Clinton's forces embarked and the dam was cut. The opening of the dam made very high water, flooding the flats down the river and frightening the Indians, who thought the Great Spirit was angry with them to cause the river to be flooded in August without a rain.

During his passage down the Susquehanna, Clinton destroyed Albout, a Scotch Tory settlement on the east side of the Susquehanna, about five miles above the present village of Unadilla; Conihunto, an Indian town about fourteen miles below Unadilla, on the west side of the river; Unadilla, at the junction of the Unadilla with the Susquehanna; Onoquaga, an Indian town situated on both sides of the river about twenty miles below Unadilla; Shawhiangto, a Tuscarora village near the present village of Windsor, in Broome county; Ingaren, a Tuscarora hamlet where is now the village of Great Bend; Otsiningo, sometimes called Zeringe, near the site of the present village of Chenango, on the Chenango river, four miles north of Binghamton; Choconut, on the south side of the Susquehanna at the site of the present village of Vestal, in the town of Vestal, Broome County; Owegy or Owagea, on the Owego Creek about a mile above its mouth; and Mauckatawaugum, near Barton.

On the 28th of August Clinton met a force sent out by Sullivan at a place that has since been called Union because of this meeting. It is about ten miles from Binghamton.

The two forces having joined, all was in readiness for a forward movement. The expedition which at this time had its real beginning, all the previous movements having been in the nature of organization and preparation, was a remarkable one in that it was to pass over hundreds of miles of territory of which no reliable map had ever been made, through forests where no roads had ever been cut, across swamps that were almost impassable to a single individual, with no opportunity to communicate with the rest of the world from the time they set out on their forward movement till their return, no chance to secure additional supplies, no hope of reinforcements in case of disaster, no suitable provision for the care of the sick and wounded, no chance of great glory in case of success, no hope of being excused in case of failure. It was a brave, daring, almost reckless movement. It was successful beyond all expectation, yet its story is almost unknown.

Note.—The New Hampshire troops marched from Soldier's Fortune, six miles above Peekskill, to Fishkill, crossed the Hudson to Newburgh, then across Orange County, N. Y., and northern New Jersey, to Easton on the Delaware. Some New York troops who wintered at Warwarsing in Ulster County, N. Y., passed to Easton also, going through Chester, in Orange County, and down the Delaware River The New Jersey troops who had wintered at Elizabethtown, marched to Easton from this point the united forces marched to Wyoming, on the Susquehanna River. Here they were joined by some of the Pennsylvania troops and the whole force passed up the river to Tioga Point, where they awaited the arrival of Clinton, who had gone up the Mohawk and after destroying some of the Onondaga towns crossed from Canajoharie to the head of Otsego Lake and down the Susquehanna to join Sullivan. The united forces then marched into the Indian country, going to the foot of Seneca Lake, down its east shore, thence to the foot of Canandaigua Lake, then to the foot of Honeoye Lake and across the country to head of Conesus Lake, and from there to Little Beard's Town on the Genesee. From this point the army retraced its steps. From the foot of Seneca Lake a detachment was sent up the west shore a few miles to the Indian town of Kershong. Another detachment under Colonel Dearborn went up the west side of Cayuga Lake and joined the main body at Catherine's Town, at the head of Seneca Lake. A third detachment under Colonel William Butler went up the east side of Cayuga Lake and joined the main army at Kanawaholla, not far from the present city of Corning. All these movements are indicated on the accompanying map.

Introductory Note: It is with many misgivings that this paper is submitted to the Association. When its preparation was assigned, I assumed that previous compilations had been made, and that my labors would be confined simply to their continuation. Upon investigation, however, I found that while Justin Winsor in his Hand Book of the Revolution, and in his invaluable Narrative and Critical History, and others in various works, had enumerated many titles which, though largely incomplete, would aid in the work, no definitive Bibliography of Sullivan's Expedition had ever been published.

Unfortunately, when these pages shall have been printed, this condition will still exist. I have not been able to command from the duties of an exacting profession, the time required for the preparation of a Bibliography at all satisfactory, even to myself. Moreover, the attention I have been able to bestow upon it has been that of an amateur, which in these days of highly developed scholastic specialization, is very inadequate in results. It is presented, however, with some confidence that it contains material which will aid some historical specialist of the future in the preparation of a complete Bibliography of Sullivan's Expedition.

I have made no attempt to include manuscripts, leaving that for a supplementary monograph, or to some more competent student. The location, however, of all known manuscripts relating to the Expedition is given in the various volumes to which reference is made. Neither have I included references to the general or school histories of the United States. Sullivan's Expedition is mentioned in them as an incident of more or less significance in the struggle for independence. In none of them is it given the attention to which its importance entitles it. Indeed, it is a neglected chapter of our revolutionary history. The Public Library of Boston possesses only fourteen titles referring directly to this great march into the Indian country, and that is a larger number than is reported either in the New York Public Library or in the State Library at Albany.

I desire to tender my thanks to Horace G. Wadlin, Librarian of the Boston Library, to Victor H. Paltsits, Assistant Librarian of the New York Public Library, and to Mary Childs Nerney and others of the History Division of the State Library, for many courtesies which they have extended to me.

Adams, Warren D.:

Sullivan's Expedition and the Cayugas.

Cayuga County Historical Society Collections. No. 7. 23 pp. 8 vo. Auburn. 1889.

Adler, Simon L.:

Sullivan's Campaign in Western New York, 1779.

Read before the Rochester Historical Society, January 14th, 1898. 8 pp. 8 vo. New York. 1898.

Allen, Paul:

A History of the American Revolution.

2 vols. Vol. 2. pp. 276 et seq. 8 vo. Baltimore, 1822.

Amory, Thomas Coffin:

Life of James Sullivan with selections from his writings. 2 vols. pp. 426 and 419. Portrait. Phillips, Sampson & Co., Boston. 1859.

The Military Services and Public Life of Major General John Sullivan of the American Revolutionary Army. 324 pp. Portr. 8 vo. Wiggin & Lunt, BostoN. J. Munsell, Albany, 1868.

The Military Services of John Sullivan in the American Revolution, vindicated from recent historical criticism.

Read at a meeting of the Massachusetts Historical Society, December, 1866. With additions and documents. 64 pp. 8 vo. John Wilson & Son, Cambridge. 1868.

Centennial Memoir of Major General John Sullivan, 1740-1795.

Presented at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, July 2d, 1876. 17 pp. 8 vo. Philadelphia. 1879.

Same:

The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 2. pp. 196-210.

General John Sullivan. A vindication of his Character as a Soldier and a Patriot. 56 pp. 8 vo. Morrisania, N. Y. 1867.

Memory of General John Sullivan vindicated.

Proceedings, Massachusetts Historical Society. Series I. Vol. 9. pp. 379-436.

Sullivan's Expedition against the Six Nations, 1779. Magazine American History. Vol. 4. pp. 420-427.

A Vindication of the Character of General Sullivan as a Soldier and a Patriot.

Historical Magazine. Vol. 10. Supplement VI. pp. 161.

Same:

Morrisania, N. Y. 1866.

General Sullivan's Expedition in 1779.

Proceedings, Massachusetts Historical Society. Vol. 20. pp. 88-94.

Anonymous:

An Historical Journal of the American War.

Collections, Massachusetts Historical Society. First Series. Vol. 2, pp. 175-178.

Master Sullivan of Berwick, his Ancestors and Descendants.

New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Vol. 19. pp. 289-306.

The Old Sullivan Road.

Pennsylvania Magazine. Vol. 11. p. 123.

The Old Caneadea Council House and its Last Council Fire.

Publications, Buffalo Historical Society. Vol. 6. pp. 97-123. 8 vo. Buffalo, New York.

Extracts from letters to a gentleman in Boston, dated at General Sullivan's Headquarters.

The Remembrancer or Impartial Repository of Public Events for the year 1780. Vol. 9. pp. 23-24. J. Almon, London. 1780.

The Story of Fantine Kill.

Olde Ulster, vol. 2. pp. 106-107.

Baker, William S.:

Itinery of General Washington, with notes.

Pennsylvania Magazine. Vol. 15. pp. 49-50.

Bard, Thomas R.:

Note to Lieutenant Parker's Journal.

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 27. p. 404.

Barton, William (Lieutenant in General Maxwell's New Jersey Brigade):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 3-14.

Same:

New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings. Vol. 2. pp. 22-43.

Beatty, Erkuries (Lieutenant Fourth Pennsylvania Regiment):

Journal of an Expedition to the Indian Towns, June 11, 1779.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 18-37.

Same:

Cayuga County Historical Society Collections. No. 1. p. 61-68.

Same:

Pennsylvania Archives. Second Series. Vol. 15. Portr. pp. 219-253.

Blake, Thomas (Lieutenant First New Hampshire Regiment):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 38-41.

Same:

History of the First New Hampshire Regiment in the War of the Revolution by Frederick Kidder.

Joel Munsell. Albany, 1868.

Bleeker, Captain Leonard:

The Order Book of Captain Leonard Bleeker in the Early Part of the Expedition against the Indian Settlements of Western New York in the Campaign of 1779. p. 138. 4 to.

Joseph Sabin. New York. 1865.

Board of War:

Letter to President Reed. September 9th. (Report as to progress.)

Pennsylvania Archives. First Series. Vol. 7. p. 709.

Brodhead, Daniel (Colonel Commanding Western Expedition):

Letter to Major General Sullivan, August 6th, 1779.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 307.

Report of the Expedition.

Pennsylvania Packet or the General Advertiser. Philadelphia, October 19, 1779.

Same:

Magazine of American History, Vol. 3. pp. 671-673.

Same:

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 307-309.

Brooks, Erastus:

Address. American History and American Indian Wars.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 410-423.

Bruce, Dwight H.:

Onondaga Centennial. 2 Vols. Vol. I. p. 142. 4 to. Boston, 1896.

Bryant, William Clement:

Captain Brant and the Old King. The Tragedy of Wyoming.

Publications, Buffalo Historical Society. Vol. 4. pp. 15-34. 8 vo. Buffalo, New York.

Burrowes, John (Major Fifth New Jersey Regiment):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 43-51.

Campbell, Douglass:

Address.

The Iroquois or Six Nations and New York's Indian Policy.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 457-470.

Campbell, William W.:

Annals of Tryon County or the Border Warfare of New York during the Revolution. pp. 269. p. 121 et seq. 12 mo. J. & J. Harper, New York. 1831.

The Border Warfare of New York during the Revolution, or The Annals of Tryon County.

Republication of above, pp. 396. p. 149 et seq. Baker & Scribner, New York. 1849.

Lecture on the Life and Military Services of General James Clinton.

Read before the New York Historical Society, February, 1839.

Campfield, Jabez (Surgeon Fifth New Jersey Regiment):

Diary of Dr. Jabez Campfield, Surgeon in Spencer's Regiment while attached to Sullivan's Expedition against the Indians.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 52-61.

Same:

New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings. Second Series. Vol. III. pp. 115-136.

Same:

Wyoming County (Penn.) Democrat, December 31st, 1873 to January 28th, 1874. (Five issues.)

Chapman, Isaac A.:

Wyoming Valley. A Sketch of its Early Annals.

Pittston Gazette Centennial Handbook. 1878. p. 25.

Chase, Franklin H.:

Onondaga's Soldiers of the Revolution. 8 vo. p. 48. Syracuse. 1895.

Childs, A. L.:

Poem, John Sullivan's March.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 549-552.

Clark, John S.:

Sketch of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Dearborn, Commanding Third New Hampshire Regiment, and Notes upon his Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 62-78.

Notes and Maps accompanying the Journal of Lieutenant John L. Hardenburgh.

New York Centennial Volume. pp. 116-136.

Notes upon the Journal of Thomas Grant.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 142-144.

Same:

Publications, Cayuga County Historical Society. No. 1. Auburn, 1879. pp. 71-72.

Note upon the Journal of Lieutenant Charles Nukerck.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 213-214.

Notes upon the Journal of Sergeant Major George Grant.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 113.

Clinton, George:

Papers. Sparks. MSS. No. XII. Harvard College Collections.

Congress, Journals of American, from 1774-1788.

4 vols. 8 vo. Vol. III. pp. 212, 241, 242, 346, 347, 351, 375, 389, 390, 406.

Washington, Way & Gideon. 1823.

Cook, Frederick (Secretary of State):

New York Centennial Volume.

Conover, George S. (Compiler):

Journals of the Military Expedition of Major General John Sullivan against the Six Nations of Indians in 1779, with records of Centennial Celebrations, prepared pursuant to Chapter 361, Laws of the State of New York, 1885. pp. 581. 8 vo. Maps. Portraits. Auburn, New York. 1887.

(Herein designated as New York Centennial Volume.)

Early History of Geneva, 60 pp. p. 17 et seq. 12 mo. Geneva, New York. 1879.

Craft, David:

List of Journals, Narratives, &c., of the Western Expedition, 1779.

Magazine of American History. Vol. II. pp. 673-675.

Sullivan's Centennial Historical Addresses at Elmira, Waterloo and Geneseo.

Centennial Proceedings, Waterloo Library and Historical Society, Waterloo, 1879.

Journals of the Sullivan Expedition, 1779.

Pennsylvania Magazine, p. 348.

Biographical Sketch of Major General John Sullivan.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 333-334.

Address.

A full and complete History of the Expedition against the Iroquois or Six Nations of New York in 1779, commanded by Major General John Sullivan, with Appendix, giving Loss of Men, Towns Destroyed, Washington's Instructions, and Biographical Sketches.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 336-386.

Same:

The Sullivan Campaign of 1779.

Seneca County Sullivan's Centennial, p. 90.

Biographical Sketch, Major Nicholas Fish.

New York Centennial Volume, p, 383.

Biographical Sketch, Colonel Lewis Dubois.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 384.

Biographical Sketch, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Weissenfels.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 384.

Biographical Sketch, Rev. Samuel Kirkland.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 385.

Biographical Sketch, Rev. John Gano.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 385.

Biographical Sketch, Colonel John Harper.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 386.

Biographical Sketch, Brigadier General James Clinton.

New York Centennial Volume, p. 387.

Biographical Sketch, Colonel Peter Gansevoort.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 479-480.

Biographical Sketch, Colonel Philip Van Cortlandt.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 537-538.

Craig, Neville B.:

The Olden Time.

Vol. 2. pp. 308-317. Pittsburgh. 1848.

Same:

Vol. 1. p. 308 et seq. 8 vo. Robert Clark & Co., Cincinnati. 1876.

Dana, E. L.:

Address.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 445-449.

Davis, Andrew McFarland:

Sullivan's Expedition against the Indians of New York, 1779. A letter to Justin Winsor. With the Journal of William McKendry. 45 pp. 8 vo. John Wilson & Son, Cambridge, 1886.

Same:

Proceedings, Massachusetts Historical Society. Second Series. Vol. 2. pp. 436-478. Boston. 1886.

List of Diaries relating to General Sullivan's Campaign.

Proceedings, Massachusetts Historical Society. Second Series. Vol. 2. p. 436-438.

Davis, Nathan (Private First New Hampshire Regiment):

History of the Expedition against the Five Nations commanded by General Sullivan in 1779.

Historical Magazine. Second Series. Vol. 3. pp. 198-205.

Dawson, Henry B.:

Battles of the United States. 2 Vols, Vol. I. p. 533. 4 to. New York. 1858.

Dearborn, Henry (Lieutenant Colonel Commanding Third New Hampshire Regiment):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 63-79.

Same:

Cayuga County Historical Collections. No. I. 1879.

Same:

Publications, Buffalo Historical Society. Vol. 7. p. 96. 8 vo. Buffalo, New York.

Depeyster, J. Watts:

Sullivan Centennial.

New York Mail, August 26th, 1879.

Celebrating the Anniversary of the Battle of Newtown.

New York Mail, August 29th, 1879.

The Sullivan Campaign.

New York Mail, September 15th, 1879.

Doty, Lockwood L.:

History of Livingston County. Illustrated, p. 685. pp. 113 and 151 et seq. Edward E. Doty, Geneseo.

Dwight, Timothy, S. T. D., LL. D.:

Travels in New England and New York. 4 vols. Vol. 4. p. 211. New Haven. 1822.

Edson, Obed:

Brodhead's Expedition against the Indians of the Upper Allegheny. (Contains reference to Sullivan's Expedition.)

Magazine American History. Vol. III. pp. 647-670.

Elmer, Dr. Ebenezer (Surgeon Second New Jersey Regiment):

Memoirs of an Expedition undertaken against the Savages to the westward commenced by the Hon. Major General John Sullivan, began at Easton on the Delaware (by Lieutenant Ebenezer Elmer).

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 80-85.

Same:

New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings. Vol. 2. pp. 43-50.

Elwood, Mary Cheney:

An Episode of the Sullivan Campaign and its Sequel.

(The Post-Express Printing Co.) 39 pp. 8 vo. Plates. Maps. Rochester, New York. 1904.

Farmer & Moore's Collections, Historical and Miscellaneous and Monthly Literary Journal. Vol. 2. p. 308.

Fellows, Moses (Orderly Sergeant Captain Gray's Company Third New Hampshire Regiment):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 86-91.

Fogg, Jeremiah (Paymaster and Captain (on roster) Second New Hampshire Regiment):

Journal of Major Jeremiah Fogg of Col. Poor's Regiment, New Hampshire, during the Expedition of General Sullivan in 1779 against the Western Indians.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 92-101.

Same:

News Letter Press, 1879. p. 26. Exeter, New Hampshire.

Gano, John (Brigade Chaplain General Clinton's Brigade):

A Chaplain of the Revolution.

Historical Magazine. First Series. Vol. 5. pp. 330-335

Gansevoort, Peter (Colonel Third New York Regiment):

Letter to General Sullivan.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 372-373.

Gookin, Daniel (Ensign Second New Hampshire Regiment):

Journal of March from North Hampton, N. Hampshire, in the year 1779.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 102-106.

Same:

New England Historical and Genealogical Register. Vol. XVI. pp. 27-34.

Gould, Jay:

Delaware County and the Border Wars of New York. pp. 426. p. 90 et seq. 12 mo. Roxbury. 1856.

Gordon, William, D. D.:

The History of the Rise, Progress and Establishment of the Independence of the United States.

4 Vols. Vol. 3. pp. 307-313. 8 vo. London, 1788.

Goodwin, H. C.:

Pioneer History of Cortland County. p. 456. p. 56 et seq. 12 mo. A. B. Burdick, New York. 1859.

Grant, George (Sergeant Major Third New Jersey Regiment):

A journey of the Marches, &c., completed by the Third Jersey Regiment and the rest of the Troops under the command of Major Sullivan in the Western Expedition.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 107-114.

Same:

Hazard's Register of Pennsylvania. Vol. 14. pp. 72-76.

Same:

Cayuga County Historical Collections. No. 1. 1879.

Same:

Wyoming Republican. July 16, 1834. Wilkes-Barre. 1868.

Giant, Thomas (Surveyor):

Journal.

General Sullivan's Expedition to the Genesee Country—A Journal of General Sullivan's Army after they left Wyoming.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 137-144.

Same:

Historical Magazine. First Series. Vol 6. pp. 233-273.

Same:

Cayuga County Historical Collections. No. 1. Auburn. 1879.

Statement of Distances.

Historical Magazine. Vol. 6. pp. 233-273.

Gray, Captain William:

Letter of Captain William Gray of the Fourth Pennsylvania Regiment, with a map of the Sullivan Expedition (against The Six Nations).

Pennsylvania Archives. Second Series. Vol. 15. pp. 286-290.

Greene, General Nathaniel:

Letter to Colonel Jeremiah Wadsworth.

Pennsylvania Magazine. Vol. 22. p. 211.

Greenough, Charles P.:

Roster of Officers in Sullivan's Expedition, 1779.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 315-329.

Gridley, A. D.:

History of the Town of Kirkland, New York.

New York. 1874.

Griffis, William Elliot, L. H. D.:

Address.

The History and Mythology of Sullivan's Expedition.

Proceedings Wyoming Commemorative Association, pp. 9-38. Wilkes-Barre. 1903.

New Hampshire's Part in Sullivan's Expedition of 1779.

New England Magazine, Vol. 23. pp. 355-373.

The Pathfinders of the Revolution. A Story of the Great March into the Wilderness and Lake Region of New York in 1779. Illustrated, pp. 316. 12 mo. W. A. Wilde Co., Boston.

Sullivan's Great March into the Indian Country.

The Magazine of History. Vol. II. pp. 295-311, 365-378. Vol. III. pp. 1-10.

Griffith, J. H.:

William Maxwell of New Jersey, Brigadier General in the Revolution.

New Jersey Historical Society Proceedings. Vol. 23. pp. 111-126.

Halsey, Francis W.:

Pennsylvania and New York in the Border Wars of the Revolution.

Proceedings, Wyoming Commemorative Association for the year 1898. Wilkes-Barre. 1898.

The Old New York Frontier. Illustrated, pp. 432, p. 220 et seq. 8 vo. Chas. Scribner's Sons, New York, 1901.

Hamilton, John C.:

History of the Republic of the United States of America. 2 Vols. Vol. I. pp. 543-544. 8 vo. D. Appleton & Co., New York, 1857.

Hammond, Isaac W.:

Rolls of the Soldiers of the Revolutionary War from New Hampshire.

New Hampshire State Papers. Vol. 15. (War Rolls, Vol. 2.) Concord, N. H., 1886.

Hand, General Edward:

Letter to Reed. September 25th, 1779. (Reports return of Sullivan's command.)

Pennsylvania Archives. First Series. Vol. 7. p. 715.

Hardenburgh, John L. (Lieutenant Second New York Regiment):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 116-136.

Same, with introductory notes and maps by John S. Clark and Biographical Sketch by Charles Hawley.

Cayuga County Historical Society Collections. No. 1. 8 vo. Auburn, New York, 1879.

Harding, Garrick M.:

The Sullivan Road.

Historical Record. Vol. 9. p. 101.

Hawley, Charles:

Address, Sullivan's Campaign.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 571-578.

Biographical Sketch of Lieutenant John L. Hardenburgh.

Cayuga County Historical Society Collections. No. 1. 8 vo. Auburn, New York, 1879.

Hazard, Eben:

Letter to Jeremy Belknap.

Proceedings, Massachusetts Historical Society. Fifth Series. Vol. 2. pp. 23-36.

Holmes, Abiel D. D.:

Annals of America. 2 Vols, Vol. 2, p. 301 et seq. Cambridge, Mass. 1829.

Hoops, Adam (Major. Third Aide-de-Camp to General Sullivan):

Letter to John Greig.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 310-311.

Hubbard, John N.:

Sketches of Border Adventures in the Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen.

Bath, New York, 1842.

Hubley, Colonel Adam (Lieutenant Colonel commanding Eleventh Pennsylvania Regiment):

Journal.

New York Centennial Volume, pp. 145-167.

Same:

Pennsylvania Archives. Second Series. Vol. XL (Vol. 2 of the Revolution.) pp. 11-44.

Same:

Miner's History of Wyoming. Appendix, pp. 82-104. Philadelphia, 1845.

Letter to President Reed.

Pennsylvania Archives. Second Series. Vol. VII. p. 553.