The Project Gutenberg EBook of Dead End, by Wallace Macfarlane This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Dead End Author: Wallace Macfarlane Release Date: February 18, 2016 [EBook #51247] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEAD END *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By WALLACE MACFARLANE

Illustrated by DAVID STONE

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction January 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Sparing people's feelings is deadly.

It leads to—no feelings, no people!

Scientist William Manning Norcross drank his soup meticulously and scooped up the vegetables at the bottom of the cup, while his attention was focused on the television screen. He watched girls swimming in formation as he gnawed the bone of his steak. He stolidly ate the baked potato with his fingers when the girls turned around, displaying "Weejees Are Best" signs pasted to their shapely backs. The final flourish was more formation swimming, where they formed a wheel under water, swimming past the camera to display in individual letters stuck to their bare midriffs: "Wonderful Weejees!"

Norcross chuckled appreciatively when a fat old man swam after them with an "Is That Right?" strung across his behind. Young men followed him, each carrying a one-word card that spelled: "You—Bet—It's—Right—Don't—Be—Left—Buy—Weejees—!" The scene ended on the surface. The grotesque old man was far in back, while the young men caught the young women, and together they kicked up a cloud of spray in the distance, which by a trick of photography mounted to the sky and the words swept around the globe in monstrous letters: "BUY WEEJEES!"

The dessert was apple pie, and Scientist Norcross turned the screen to the "Abstractions" channel. Watching the colors and patterns form in response to the music, he finished the pie and licked his fingers appreciatively. He pressed a stud to reveal the mirror wall before he activated the molecular cleanup.

Not many people would do that. It was not contrary to morals, exactly, but it was like scratching in public, and it took a scientific mind to study the human form unshaken, immediately after ingestion. There was pie on his tunic and gravy in his hair and a smear of grease from cheek to ear. With no sign of squeamishness, he smeared beet juice on his nose and studied the effect before he depressed the "Clear" stud.

He stretched and stood up while the tray disappeared, then turned and glanced in the mirror again. Nothing on him. Clean. He yawned luxuriantly before he tapped the "Finish" panel on the door and stepped forth, an immaculate and well-fed gentlemen of the year 2512.

He had a well-trained sense of humor, and a smile crossed his lips as he thought of the terror a 21st Century man would feel in such an eating chamber. When he pressed the clear button, the barbarian would be clean—really, sterilely clean—for the first time in his life, and without clothes, too. Oh, what a jape that would be, for the molecular cleanup would immediately disintegrate such abominations as the fur of animals, and much clothing 400 years ago was actually made of such things as sheep hair.

He bowed to a pretty woman just entering a cubicle and thought defiantly that a scientific mind afforded much amusement. There was no illusion in his icy clear thoughts, for they were not befogged by moral questions.

With a sigh, Scientist William Manning Norcross returned to the difficult problem he had set aside while having lunch. The garden city was beautiful outside, but he gave only passing attention to the rain slithering down the huge dome of force over the buildings. He did not pause to admire the everlasting flowers in their carefully simulated beds of soil.

John Davis Drumstetter was in a state of crisis again, and Scientist Norcross was worried.

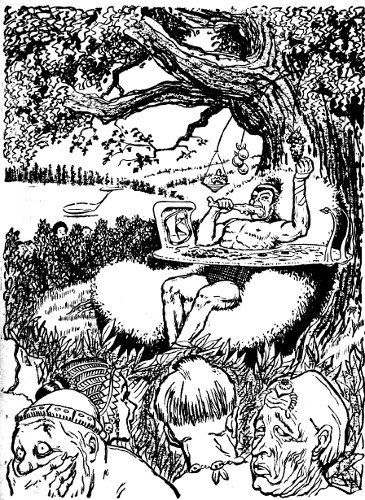

His fears were well founded. The young man wheeled on Scientist Norcross the minute he stepped through the hedge into the force field under the giant live oak tree.

"Where are they?" he demanded. "I am coming to believe, Scientist, that your reputation is exceeded only by your inability to live up to it. The problem is only an extension of your own early work. You volunteered cooperation, and I accepted it gladly, but your delays are very distressing!"

"Johnny," said Scientist Norcross, "the press of my own experiments—"

"Then tell me you won't do it!"

"I want to help you. Don't you remember the years we spent together in your training to the high calling of scientist? I took your young hand, Johnny, and helped you over the juvenile stumbling blocks. Why, your first mind machine was one I gave you, and when—"

"You're a fraud, Scientist!" said the young man bitterly.

"The young never appreciate the old," sighed Norcross.

"Go suck a mango!"

Norcross was shocked. "There's no call for being obscene, John Davis Drumstetter," he said sternly. "To mention eating to another person, and right in public, where you might be overheard—"

"Eat a slippery, sloppery mango on television, you old fool! Smear it all over your face while you ingest it into your unspeakable digestive tract!"

"John Davis Drumstetter," said the scientist with great control, "I have been your friend since you were born. Your father and I became scientists on the same day. You are young and over-eager. Just remember," he finished with a warning shake of his finger, "Satellite Station One wasn't built in a day!"

Drumstetter stopped his furious pacing and subdued his rage with visible effort. He chilled, like red steel hardening, and when he spoke he was in full command of himself.

"Now listen to me, Norcross, and keep your mouth shut. For the past forty years I've been working on the stellar overdrive. We have the Solar System in our reticule, colonies have been established on every planet, and ships have been sent to Alpha Centauri, with every chance that mankind has established itself in that solar system. But in the four hundred years since science emerged from the dark ages, we've managed to creep only four light years away from home! And you, Scientist, are withholding your work on the overdrive relay. Do you understand why your plea of old friendship does not affect me? In the past two years, you've done nothing—"

"Experiments that must be kept secret," mumbled Norcross.

"And it is my belief," said the young man in a clipped, cold voice, "that you have sold yourself to your taste buds and digestive tract. Either that," and here his burning rage came into the open, "or you are a pseudo-life!"

At this ultimate insult, Scientist Norcross was silent with indignation. He watched Drumstetter shrug into a stole, turn down the power to the huge mind machine, sling his reticule over his shoulder, and stalk off through the hedge.

Norcross slumped into a chair, his mind in confusion. He heard Drumstetter's plane as it left the ground. Plane, he thought, his mind avoiding the problem. Plane. What a curious name, handed down through the ages, to call a swift skip powered by Earth's magnetism. An original plane fought the air, buoyed up by the lift of plane surfaces in movement. When the movement stopped, it died.

Died. Death. Pseudo-life.

Scientist Norcross shuddered. His well-trained sense of humor did not include abominations.

He took the communication from his pocket and cleared to Prime Center. When the prim, grim face of Prime Center himself in the little disc was sharp, Norcross reported what had happened, even to the suggestion Drumstetter had made that he was pseudo-life.

"This is very bad," said Prime Center. "Monica Drake Lane is now pseudo-life, too."

"God's name!"

"Took her skip into a cliff in the Sierra Mountains yesterday. Disconnected the anti-collision. A clear case."

"What will this do to Drumstetter?"

"Nothing," said Prime Center, "unless he learns."

"Is she ready?"

"I'm sending her to you right now for indoctrination. Reports are that Drumstetter is visiting scientists on the West Coast, and Probability reports that he may cover the world before he returns. Do you understand? Her indoctrination must be perfect."

"It always has been." Norcross pulled his lip. "The same limitation will be in Monica Drake Lane?" he asked hopelessly.

"Of course," said Prime Center. "We'll keep you posted on developments."

"You'd better try women," said Norcross.

"Women, narcotics, or anything else! I'd eat a blueberry pie with my hands behind my back at high noon," said Prime Center with fierce obscenity, "if I thought it would do any good!"

He cut the connection.

Norcross was still under the oak tree, lost in contemplation of a color abstraction on his little communication, when a tall blonde girl, brown as a berry, stepped hesitantly through the hedge. She walked to him and, when he looked up, she buried her face in her hands. He stood and held her shoulders.

"Now, now," said Scientist Norcross, "don't cry, my dear."

"But this is so puzzling—and I wasn't crying," she answered. "What's happened to me?"

"Sit down, Monica, and tell me what you think has happened."

"But I don't know. You see, the last I remember is walking through the Psych Lab in San Francisco, and suddenly—suddenly, I'm in New York and they're sending me to you. What has happened?"

"Where do you first remember being in New York?"

"In the—oh, I don't know!" She was in a flush of embarrassment.

"I'll help you, my dear. You were in the pseudo-life clinic. You are not exactly Monica Drake Lane any longer. She died. You are pseudo-life."

Her eyes were bright and the pupils were pinpointed from shock.

"You are the pseudo-life Monica Drake Lane. To all outward appearances, you are an exact counterpart of the girl. Inwardly? Well, your internal organs have been simplified, and you cannot reproduce. Aside from such minor changes, you are identical, and incidentally a much more efficient creature than your prototype. And if your mind, which is a very good one, was a human mind, I could not tell you this. Pseudo-life is a most remarkable thing, but Lewis and Havinghurst and Covalt, who developed it 300 years ago, were never able to imbue pseudo-life with what they called the minus-one factor, which includes the phenomenal human emotional sensitivity, among other things. Are you feeling better now?"

"Why, yes—" Her voice trailed off.

"You are no longer a slave of your emotions," said Scientist Norcross complacently. "None of us are."

"You—you are—?"

"Oh, yes. We generally don't speak of such things, but since I'm to introduce you to pseudo-life, I can tell you that I died two years ago."

"I'm afraid I never did know—or Monica Drake Lane never—that is, I—"

"You are Monica Drake Lane. If you will sit quietly, I'll tell you about it." Scientist Norcross took two cigarettes from his reticule and offered the girl one. The lip play was considered somewhat daring between the sexes, but under the circumstances he thought the mild narcotic would be good for her, as well as the sharpening of the senses brought on by actually smoking together.

"When the Americans, who inhabited this continent, gained domination of the world in the 21st Century, they consolidated their position by carrying their customs to the ends of the Earth. For that matter, to Alpha Centauri, if the ships did get through.

"Forgive me," he interrupted himself, "if I seem improper or even immoral in this little talk of ours. Believe me, it's not with an easy disregard of proprieties that I bring myself to speak of such things.

"Well, the Americans believed, and rightly so, that death is a dreadful thing. Until Lewis and Havinghurst and Covalt developed pseudo-life, a great deal of time and effort and money went into such things as cemeteries—places where they literally buried their dead with elaborate ceremonials and much anguish. They had other equally wasteful practices, such as madhouses and jails, which were done away with when it became practical to replace a useless person with another, who matched the original to near absolute perfection, but without fatal flaws of body or weaknesses of the mind.

"Emphasis has shifted since those early years, when the abnormals were dealt with, to the comforting of human beings. Should John Davis Drumstetter suffer greatly at the loss of his mentor, the man who guided him in the ways of science? Of course not. He never knew I died."

Norcross puffed complacently, sending iridescent rainbow smoke rings over the mind machine.

"And I am his fiancee," said the girl.

"Should he suffer because you died? No reason for it," said Norcross heartily. "A psychic trauma of that nature would make him desperately unhappy. Happiness is the proper state in life, as everyone knows. In fact, you will make him much happier than Monica Drake Lane, the original, ever could."

"Yes, I shall be happy," mused the girl, as if feeling a more limited capacity for sorrow within herself. "But you spoke of a minus-one factor."

"Yes, it takes in a lot of things. Though we are immortal, barring accidents, and we retain all the knowledge we had as human beings, the flaw to pseudo-life is that no original thought is possible. Students of the matter compare it to glancing at a page in a dictionary. Of course you don't consciously remember the words there, but in pseudo-life you are capable of remembering and using them properly, so to speak, but not using them creatively. That is our trouble with John Davis Drumstetter. I was a brilliant physicist, but the understanding of new problems is beyond my limitations, and he is beyond me."

"But I woke in New York," she said irrelevantly.

"Because your master pseudo-life file was kept there," explained Scientist Norcross. "As a human being, you were required to visit the psych lab every month, where your changed pattern was recorded by the mind machine. The pseudo-life girl could never lose more than a month of the human being's life. What was your regular appointment date?"

"The 21st."

"Let's see—you died yesterday, so that would be only three days gone. We're very fortunate."

"But won't he notice a difference in me?"

"Absolutely not."

"Am I—still capable of love?"

Scientist Norcross blew a plume of rainbow smoke into the air. "Suppose, my dear, we find out."

Monica Drake Lane agreed, for morality, which is essentially organized taboo that changes as society changes, had, in the 26th Century, been confined exclusively to eating. Scientist Norcross had often amused himself by imagining how people of other ages would have been outraged by the moral standards of his own era, but his famous sense of humor was not rugged enough to be amused by the moral standards of the past. Not, at any rate, if he had had to endure them, though he found them sufficiently comic as history.

She built a bower, an attractive courtship custom that had been adopted from the birds, and the day ended much more pleasantly than Scientist Norcross had expected at lunch.

The reports came in from Prime Center. Drumstetter stayed in Los Angeles two days, in San Francisco three, and then consulted with Dowson in Honolulu. He skipped to New Zealand, back north to Japan, and swung across Siberia with short stops at various laboratories and universities. He was in Finland for three days with old Scientist Theophil Gertsley, who, though little better than a witch doctor, called himself a psychologist.

When John Davis Drumstetter set his skip down beside the live oak tree, Scientist Norcross and Monica Drake Lane were waiting for him. He was gaunt from hunger and weary from travel, but the expression in his eyes was not one to be assuaged by any food cubicle. Nor was it love he had been seeking and not found, for Prime Center had seen to it that opportunities were offered, from austere tropical girls to the warmth-seeking women of the north, who would even eat with a member of the opposite sex.

He greeted Scientist Norcross and his fiancee with an offhandedness that Norcross had not expected, and asked that he be excused from any long immediate association with them, due to the press of uncompleted work.

"But, Johnny," said Monica Drake Lane, "I've made a bower close by, and you seem very tired."

"There's work to be done," said the young man firmly. "I have no time to—Wait. I'll see your bower."

As they walked over the lush artificial grass, Scientist Norcross explained that his results from the overdrive relay equations were in the mind machine even now, but John Davis Drumstetter only patted him on the shoulder in a friendly way and told him not to bother.

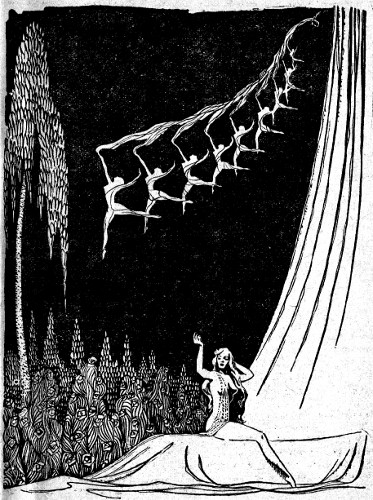

When they reached the bower, Scientist Norcross expected that Drumstetter would sleep there after all, for it was an exceptionally pleasant design. The force field was night, and the sky was filled with adapted creatures from Mars dancing to their susurrate music, and the air was permeated with the bitter-sweet and exciting scent of a Venusian lake, the very odor of romance. In the background was the song of the sea.

John Davis Drumstetter stepped out of the bower and said gently, "It's one of the nicest I've ever seen, and we spent some happy nights in it a year ago, didn't we, Monica?"

He kissed her gently, as he might kiss a child, and walked back to the oak tree.

"He's behaving very oddly," reported Norcross to Prime Center, as soon as he could, and gave the details.

"I'd give a lot to have him meet a human female," said Prime Center wistfully.

"What shall I do?"

"Stay with him and wait," ordered Prime Center. "This is the first time the hopes of humanity lie in one man. Remember that. We can only serve," he added bitterly. "He hasn't tested the final limitation? Good. Keep me informed."

John Davis Drumstetter stayed beside his huge mind machine for nearly a week, and, though he was only sixty, he looked like an old man when he greeted Monica and Norcross at the end of that time.

"The relay is finished," he announced. "It's being installed in the Last Hope now. That's what I'm calling my ship, the ship to make mankind free of the stars. My work on Earth is nearly done."

"But, Johnny darling," said Monica Drake Lane, looking up at him through her eyelashes, "what about our marriage?"

He looked at her with grim pity. "The bower was an old bower," he answered. "Did you have the courage to be a unique in a patterned world? Can you reproduce, Monica Drake Lane?"

"Oh, Johnny—"

"The final limitation!" he said. "Humans have the power to command pseudo-life. Pseudo-life, answer! I command!"

She sank to the ground.

"No," she said, "no, Johnny, I can't have a baby. I died over a month ago. I'm sorry you found out."

John Davis Drumstetter turned on Scientist William Manning Norcross. "You've done no new work because you have no capacity for it. Correct? Answer, pseudo-life, I command!"

Norcross lifted a calm face. "Why, yes," he said, "I'm pseudo-life. Have been for over two years. But don't you worry, Johnny, it's better this way and only natural that—"

John Davis Drumstetter paid no attention. He spoke as if explaining to himself. "You see, they're pseudo-life, dancing to the very end of the masquerade ball that started so long ago. It began when measurable science, the science of finity, made a finite man, a man nearly as good. It was the mental climate of an age that wanted its books digested, and then abandoned reading for television. They froze food and precooked it and said it was even better than garden fresh vegetables.

"Do it the easy way, they said, never knowing that the hard way is the only way in the last analysis. Why try to cure a neurotic when you can make a pseudo-life of him? Don't let his grieving friends and relations suffer; provide them with a pseudo-life. He's just the same, they said, and he's not sick. And should a man die? Oh, no! Make a pseudo-life for his wife and children."

"But, Johnny—"

"Be still, pseudo-life! Why bother with men who were beginning to understand the human mind, when you can create pseudo-life? The cheap drives out the good every time. Oh, with the kindliest intentions, with the softest sympathies! Hide. Conceal. The truth be damned!"

"But, Johnny darling—" began Monica Drake Lane.

"Be still, pseudo-life. There's one more thing, the final capstone to mankind's pyramid of folly." He got Prime Center on the communication. "Answer, pseudo-life, I command. Am I the last human being on Earth?"

"Since you put it that way," said Prime Center reluctantly, "you are."

"And in the Solar System?"

"I'm afraid so."

The communication dropped from John Davis Drumstetter's hand.

"This is the logical conclusion," he said slowly. "The actors are playing on a stage of worlds for an audience of one. At the solar observatory on Mercury, astronomers study the Sun and send in their reports, in case I should glance at them. In the mines of Pluto, miners dig ore to provide a market quotation I might see in the telepapers."

He kicked the communication across the floor.

"Get out," he told them with infinite weariness. "The last human being commands."

He slept for a day and had breakfast in full public view under a tree. Peeping Toms of both sexes watched him.

Prime Center appeared in person just as he finished mopping up the last of his once-over-lightly egg. Prime Center coughed and blushed and looked away, and John Davis Drumstetter laughed aloud, humorlessly.

"Good morning," he said cheerfully.

"Hm, yes," said Prime Center.

"Sit down. Have an egg?" A wicked light appeared in his eyes, and he went on in a low, sinister voice, "A coddled egg, soft and white and runny? Maybe you want to gulp some coffee? Or snap your way through a piece of crackling toast? No?" His guest was turning pale and sick-looking. "Well, let me finish this bacon, and state your business."

He threw back his head and slipped the bacon into his mouth. Prime Center shuddered.

"Scientist Drumstetter," he said, keeping his gaze fixed on the trunk of the tree, "I have come to offer you all the worlds. Yes, the whole Solar System, including the asteroids and Pluto. You will be more powerful than Alexander or Caesar or Stalin or O'Toole. We will create a new office—Prime Squared Center—to rule the Solar System. Do you mind not doing that?"

John Davis Drumstetter was licking his fingers thoughtfully. He nodded.

"Then you accept?"

"No, I'm through licking my fingers. I'll give you your answer on a systemwide communication. Arrange it, pseudo-life, immediately."

As a concession to morality, John Davis Drumstetter agreed to step into a molecular cleanup booth. When he came out again, he spoke to the worlds and all the ships in space:

"My friends, from now on the blind will lead the blind. Moral obliquity has triumphed and becomes common morality." He laughed and rubbed his nose. "I'm sorry. I was speaking to an audience of one—myself. What I want you billions to do is to continue your work, to maintain the system as it now stands. Pseudo-life will be replaced with pseudo-life till the end of time. It will be a static world. It will be a nearly-as-good world. It will be a pleasant world by your standards. I wish you to do this, and you must, of course, obey my command. My purpose reaches a little beyond your natural inclination; this system will serve as a fertile warning to any beings with intelligence who may come after me.

"I will not be with you long, myself—"

"Suicide?" asked Prime Center hopefully.

"Alpha Centauri," said John Davis Drumstetter with a chuckle. "The colonists left because they didn't like pseudo-life, either. Good-by to you all."

He snapped off the communication, waved to the little group under the tree, and entered the Last Hope. The entry port swung closed. The force field glowed, and then the ship was gone, leaving behind a whirlwind of dust.

"Alpha Centauri?" asked Monica Drake Lane.

"Following the others of his wild, unstable breed," said Scientist Norcross.

"Easy come, easy go," the girl said, shrugging.

Prime Center had the last word. "Yes, and good riddance. Human beings have always been a nuisance."

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Dead End, by Wallace Macfarlane

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEAD END ***

***** This file should be named 51247-h.htm or 51247-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/1/2/4/51247/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.