Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 31, 1895. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 844. | two dollars a year. |

In early times America was to the Spaniards a region of silver and gold, which were to be wrung from the natives and squandered in Europe; to the French and the Dutch it was a country of furs, which were to be purchased from the Indians for beads, knives, and guns, and sold across the sea at an enormous profit; to the English it was a land of homes, with liberty to think and act. Thus, while the Spaniards were delving in the mines of Mexico and Peru and freighting their argosies, and while the French couriers of the woods were steering their fur-laden canoes down the St. Lawrence, the English colonists along the Atlantic coast were cultivating the soil, making and enforcing laws, and gaining a foothold which was to remain firm long after their more restless and adventurous neighbors had vanished from the New World.

Nevertheless, the early French explorers, heedless of danger, bold and free as the Indians themselves, threading rivers and exploring lakes in their canoes, ranging through[Pg 206] limitless solitudes of forest or over interminable wastes of prairie, performed a service of the utmost value to the future nation. They mapped out the road which slower but surer feet were to follow, and if they could not organize and hold the enormous territory which they claimed, at least they prepared it for those who could.

Above the crowd of ragged and fearless adventurers who throng through the history of France's vain endeavors to found an empire in the Western World, the figure of Réné-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, towers like a statue of bronze. He was born in 1643, and was the son of a rich merchant of Rouen. A brief connection with the religious order of the Jesuits deprived him of his inheritance, and at the age of twenty-two he sailed for Canada to seek his fortune, turning his back upon the Old World, as did many another young Frenchman of gentle breeding at that time.

He was granted an estate, afterward named La Chine, near Montreal. The name of the place is a memory of the belief, long cherished by the French, that by way of the St. Lawrence, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi, a passage to the Pacific Ocean and the wealth of the East might be found. On his domain, which served as an outpost of Montreal against the incursions of the ferocious Iroquois, he lived a life of rude freedom, ruling like a young seigneur over the tenants who gathered about his stockade.

But he could not long remain quiet. The thirst for adventure was strong upon him, and, listening to the tales of his Indian visitors, he determined to explore the Ohio and the Mississippi to the "Vermilion Sea," or the Gulf of California, into which he was convinced the great river flowed. At his own expense he fitted out an expedition, and pushed boldly into the trackless wilderness.

This was the beginning of a career of hardship and danger, of successes achieved in the teeth of seemingly insurmountable obstacles and in spite of the plots of powerful enemies, with a steadfast fortitude unparalleled in the annals of discovery. La Salle's dream of reaching the Pacific was soon dispelled; but it was the nature of his mind to rear new plans on the ruins of the old. He never grew discouraged. In the presence of calamities which would have overwhelmed a less stout heart his brain was busy seeking new paths to the end he had in view.

At his first step he encountered the jealous hostility of the Jesuits, then powerful both at Quebec and Paris. To this was added the enmity of those interested in the fur trade, who feared that he would disturb their traffic; the hatred of all who had betrayed, deserted, and robbed him—no small number; and the annoyances of such as had been induced to invest in his schemes when his own resources were exhausted. While he was absent, bearing the flag of France over thousands of miles of new territory, slanderers and detractors were busy at home destroying his credit, thwarting his plans, ridiculing his hopes, and seeking to rob him of his honors. The obstacles cast in his path by nature or savage tribes were slight when compared with those reared against him by his own country men. But, unshaken in his purpose, he toiled on year after year, enduring exposure, hunger, cold, illness, and treachery, exploring the Ohio and the Illinois, and finally, in 1682, descending the Mississippi to its mouth.

This was his crowning exploit. He was now a man of middle age, inured to peril and hardship, and burdened with a heavy load of responsibility. He was stern, reserved, and self-reliant. There were few besides Tonti, his devoted lieutenant, upon whom he could rely. His followers were fickle savages or, worse still, the idle and insubordinate offscour of Europe. He had built and equipped a vessel on the lakes, and she had been sunk with her cargo. He had nearly finished another on the Illinois, when his men mutinied in his absence, and deserted. He had erected forts and planted colonies, which were destroyed or ordered abandoned by a hostile governor. He had been robbed again and again of the stores and supplies which he had transported at great cost into the wilderness, and of the furs which he sent back to Canada. At last he felt that if he was to secure for France the rich valley of the Mississippi and the boundless region drained by its tributaries, and repay his creditors through the monopoly of the trade which he hoped to establish there, he must secure the support of the King himself. Accordingly he turned toward France.

His plan found favor with Louis XIV. and his ministers. He was given four vessels, which carried, besides supplies, a hundred soldiers, mechanics and laborers, several families, a number of girls who hoped to find husbands in the new colony, and thirty volunteers. Among these last were several boys, two of them his own nephews, of whom one was destined to be the cause of his death. The expedition was to make a settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi, and organize a force to sweep the Spaniards out of New Mexico. This La Salle promised to do. At last, after so many trials and disappointments, he seemed to stand on the threshold of success.

But the dark cloud of misfortune which had so long lowered above his head reappeared when the vessels approached their destination. Numbers of the colonists fell ill on the voyage. At St. Domingo, La Salle himself was stricken down by fever, and his life was despaired of. One of his vessels was taken by Spanish pirates, and his men grew discontented and undisciplined. To cap the climax, the fleet missed the mouth of the Mississippi, and the colonists landed four hundred miles to the westward, at Matagorda Bay. There another vessel was lost while attempting to enter the harbor, and a third, which had acted as escort only, returned to France.

It did not take the unhappy pioneers long to discover that they were not on the Mississippi, and La Salle, with unabated energy, set out in search of the "fatal river." He did not find it, and on his return the last of the vessels was lost, removing all hope of escape by sea. The sufferings of the little colony were great, and La Salle formed the desperate resolution of penetrating through the wilderness to Canada for help. Some of his followers afterward escaped by this dangerous path, but he himself was never to see Canada again. On the march food ran short, and seven men were sent out to forage. Among them was a man named Duhaut, who hated La Salle, and had once deserted him. The party killed some buffaloes, and were curing the meat when one of La Salle's nephews, Moranget, who had been sent in search of them with a companion, arrived. Moranget did not lack courage, but he did lack prudence. He angered the men by finding fault with them unjustly.

Duhaut seized the opportunity, and drew four of the others into his plot. That night Moranget and his companion, with La Salle's faithful Indian servant, were murdered as they slept. The next morning, La Salle, full of anxious foreboding at his nephew's failure to return, went after him in company with a priest. Even in his defenceless condition the wretches who had resolved on his death did not dare to attack him openly. Crouched in the dry grass like savages, they awaited his coming, and shot him through the brain as he approached. Then they came out of their concealment and triumphed over the body, crying: "There thou liest, tyrant! There thou liest!"

So on the prairies of Texas perished La Salle. His name heads the list of resolute adventurers who pierced the secrets of the wilderness, and led the march of civilization across the continent. He was a man of action. When beset, as he often was, by doubts and difficulties, he saw at once what must be done, and did it without delay. Had his life been spared he would, no doubt, have rescued the colonists. Without his aid they perished miserably, Duhaut, the chief murderer, being shot down by another of the accomplices. Of all the expedition only seven, including the explorer's brother and his remaining nephew, reached Canada.

I think all little children should

Be thankful in their prayers

To God for having been so good

To make their parents theirs.

"May I go out to Blairstown on your special, Mr. Gannon?" asked Harry Sowerby, the telegraph operator at Hammonds.

"What do you want to go for, bub?" replied the superintendent of the Lexington and Danville Railroad. "It's a nasty night for travelling, and—"

"I haven't been home in two months," said the boy, eagerly. "I may not have another chance for a long time, and it's near Christmas. I can report the departure of your train to 'X' office, and then there's nothing more to be done here till 6.45 to-morrow morning."

"Come on, then," answered the superintendent. He knew that Harry Sowerby, the youngest telegraph operator on the road, was anxious to see his mother and sisters, and he knew what a lonely place Hammonds Station was.

The sounder clicked rapidly for a few moments as Harry notified the night train-despatcher at "X" office that the superintendent's special was passing westward. Then he quickly cut out the telegraph instruments, quenched the office lamp, and jumped aboard the car as it slowly rolled past the glare of the bright platform light and out into the black rain. He could not remember having ever heard such a heavy downpour. The snow that had hidden the earth for weeks was fast melting under it.

Harry Sowerby was only sixteen years old. He had been at Hammonds one year, and he was heartily tired of it. The nearest house to the station was a quarter of a mile away. He was anxious to be promoted to the train-despatcher's staff at "X" office, that mysterious place whence the orders came that governed all the trains on the road. But Mr. Gannon had put him off, telling him that he was too young.

"When you've had more experience, bub," said the big, good-natured superintendent, "maybe the dispatcher will need you. You're young yet, you know."

This was a tender point with Harry. He knew he really looked as old as most fellows of eighteen, and he felt that he had more experience at railroading than many fellows of twenty-five. Besides, if he were sent to "X," his pay would be increased to sixty-five dollars a month, and he could send his sisters to a better school.

Suddenly steam was shut off. Harry knew it by the silence with which the light train plunged forward, without a sound from the exhaust or the cylinders. Then came the sharp hissing of the air-brakes, but the train ran on unchecked. One blast of the whistle called the brakeman to the platform, where he whirled the brake-wheel swiftly, and set it up as hard as if his life depended on that one act. A grinding noise forward and a snarling from the driving-wheels told Harry's experienced ears that the engineer had "thrown her over and given her sand"—that is, he had reversed the lever and opened the sand-box, so that the driving-wheels, now turning backward, might grip the wet rails firmly.

Mr. Gannon, in his hip boots and mackintosh, was out in the snow and mud and up ahead in less than half a minute. The front of the locomotive was within thirty feet of the beginning of Williston cut. Tom Jackson had not stopped her a moment too soon. The heavy rain had washed down tons of earth and bowlders from the banks on to the track. The cut was blocked for fully thirty yards. What it was that whispered danger to the engineer he himself could not tell, but he had felt a sudden premonition that it was not safe to run through the cut.

Harry Sowerby saw the brakeman go back with a red lantern to protect the superintendent's special train from No. 576, the way freight that was due thirty minutes later. Suddenly the light flickered out. The wind and rain were too much for it. Harry knew that the same thing might happen just as the heavy freight train came along. It sickened him to think of what would follow. He thought of the train crew scattered on the snowy ground, bruised, perhaps killed.

The boy's head throbbed with excitement. If he only could do something to save the train! He had heard Ryan, the rear brakeman, say that there was not a danger torpedo on the car. He ran hopelessly up to the locomotive tender, knowing that there was none there either, but thinking that perhaps he might find something. And as he searched in the grimy tool-box he saw a long piece of heavy copper wire. There flashed across his mind the recollection of how Kline, the lineman, had once said it was possible for a "good man" to telegraph from any point on the line. Here was something worth trying.

"Bring a torch, Phil," he said to the fireman. Away he ran down the track, the coil of wire in one hand and a pair of pliers in the other. Throwing the coil around his neck and sticking the pliers in his pocket, Harry began to climb the nearest telegraph pole, while Phil helped him all he could with his free hand.

The young telegrapher soon threw his leg over the cross-arm, and braced himself securely. Fireman Phil held the flaring torch as high as he could, so that the light was only fifteen feet below the wire. The torch was so liberally soaked with petroleum that the wind could not blow it out.

Harry felt thankful when he saw, on the opposite end of the cross-arm from that which held the single telegraph line, a new glass insulator that had been placed for another line which was soon to be strung. That made his work easier. Using his pliers dexterously, he quickly spliced one end of the coil of copper wire around the wire of the telegraph line about six inches away from the cross-arm. He twined the copper wire around and around the live wire, so that it clung like a wild-grape vine tendril to a tree bough.

Then he took three turns of the copper wire around the empty insulator. Now was the trying moment. If he cut the line, would its sagging weight break his splice of copper wire? Yet if he was to carry out his plan he must separate the telegraph line into two parts, so that by bringing the ends together he could make the Morse signals. With a few nips of the pliers he cut the telegraph line, and although it fell away with a sharp snap, the copper-wire splice held it safely hung to the new insulator.

Now he was in possession of a rude but effective telegraph key. By touching the west end of the broken line, which was the jagged bit of wire that stuck up from the old insulator, against the east end of the line, which was the end of the copper wire leading back from the new insulator, he could complete the electric circuit. He tapped the end of the copper wire upon the line wire that stuck up. A tiny blue spark flashed out, and he felt sharp pains in his wet right hand as the current shot through it. But what mattered the pain? Because the current shocked him so, he felt sure that the line was "O K." Now he began tapping again. He let the wires barely touch to make dots, and held them together an instant to make dashes. He began to call up the station at Woodside, where No. 576 was due to pass within the next ten minutes. Then he held the wire ends together to receive an answer. He soon could feel the stinging, burning current bite the dots and dashes into his hand like this:

"— — — — — —— —— —— — —."

Now he telegraphed this order:

"Operator, Woodside,—Flag and hold all west-bound trains. Williston cut blockaded, and a special is stuck at east end."

He signed Mr. Gannon's name to this. Then he held the wires together while the operator telegraphed back the order, according to the railroad rules, to show that he understood. The man at Woodside was surprised at the message, but he quickly understood its importance.

Harry twisted the loose end of the copper wire around the little piece of wire that stuck up, so that the telegraph line should not be broken, and then he slid down the pole.

"They're holding all west-bound trains at Woodside!" he shouted to Phil as his feet touched the ground.

Phil gave him a congratulatory slap on the back that nearly upset him. Then Phil ran to where the superintendent and the train crew were standing, two hundred yards back of the train, trying to shield a red light and[Pg 208] keep it burning. He yelled the good news to them, and as Harry came slowly up to the little group, the crew cheered him and hugged him and told him he had saved the six lives on No. 576.

"Bub," said Mr. Gannon, as he gravely shook Harry's burned right hand, "I guess you've had enough experience to go to 'X' office. We need men as quick-witted and plucky as you in this business. I'm going to report your conduct to the directors of the road at their next meeting."

When Samuel Butler wrote

"Doubtless the pleasure is as great

Of being cheated, as to cheat,"

he afforded evidence that he had never been a conjurer.

There is a nervous strain, an excitement, in the act of cheating at conjuring that is entirely wanting when we are cheated.

For the one who does the tricks there is a fascination that has never been known to be even alleviated, but, like the proverbial brook, "goes on forever." Yet, knowing this, I propose to lure my readers to this incurable habit by teaching them the whole art and mystery of deceiving one's neighbor—in an honest way.

As an explanation of "palming," whether of coins, balls, or cards, or any of the preliminary exercises necessary in order to become a proficient conjurer, makes but dull reading, I shall postpone instruction in such finger movements until actually needed, and begin with a complete trick. I shall not content myself, however, with showing the mere bare bones of the illusions, but will present something more solid, and give such suggestions, with accompanying patter and other details, as will enable the student in what the French call "White Magic," with some practice, to perform the tricks to his own satisfaction and the delight of his audience.

At the start let me caution my readers against being too quick. The success of a sleight-of-hand trick depends on diverting the attention of the audience upon misdirection rather than on rapidity of movement. It is a fallacy that "the hand is quicker than the eye." The most accomplished conjurers this country has ever seen, men like Buatier de Kolta or the late Robert Heller, never made a rapid movement; they were deliberate. They relied more on a nimble wit, a turn of the head, a glance of the eye, a motion of the hand, and yet they successfully and artistically deceived the keenest-eyed witness of their performance.

And now to begin with our first lesson. As an opening for a performance, something that will impress an audience with your skill, there is nothing better than

The performer begins by rolling up his sleeves, and showing his hands to be empty. Yet bringing the latter together the next moment, he produces a piece of colored silk about twelve inches square, which, in spite of its diminutive size, he dignifies by the name of handkerchief.

"This," he says, holding it out, "is property number One, and here," picking up a candle from his table, "is number Two. This candle is simply the light and airy product of the chandler, and has not been tampered with by any wicked trickster since it left his hands. And yet I propose to pass into its very centre this handkerchief."

THE CANDLE.

THE CANDLE.

A narrow strip of card-board, bent into semicircular form and having a round hole cut in its centre, serves as a candlestick, and in this the candle is stood.

"You can readily see," continues the performer, "that there is absolutely no chance here to gall you—no apparatus of any kind. And now to begin."

He rolls the handkerchief between his hands, and then extending his closed right hand, while the left, also closed, goes behind his back, says: "I shall now cause the handkerchief which is in my right hand to pass invisibly into that candle. That will be a miracle, and a prerequisite for a miracle is faith. You must believe that the handkerchief is in my hand."

"But," whispers a sharp-eyed, keen-witted spectator, "the handkerchief is not there. He kept it in his left hand, and has thrust it into his coat-tail pocket."

Ah, suspicious mortal, how grievously mistaken you are! As Josh Billings has wisely said, "It's better not to know so much than to know so much that's not so." The performer opens his hand and shows that the handkerchief is still there.

Again he goes through the same manipulation, and again suspicion is aroused.

"Ah, ye of little faith!" he exclaims. "There is no need of concealing my hands for such a simple trick. See! I merely roll the handkerchief, so, between my hands"—suiting the action to the word—"and on opening them we find them empty, nothing concealed in them, and nothing up my sleeves," which he bares in proof. "Where has the handkerchief gone? It has passed, as I promised it would pass, into the candle."

"Should I cut open the candle," he goes on to say, "and in it find the missing bit of silk, you would conclude that I use a prepared candle. To prove this is not so I light the candle, and from its flame I thus extract the handkerchief." Which he does.

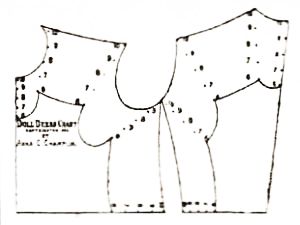

THE FALSE FINGER.

THE FALSE FINGER.

Pretty and mysterious as this trick is, it is very simple. The handkerchief which is produced from the empty hands is concealed in a hollow metal finger, which is painted a flesh-color, and is open at the lower end, where it is cut in the following shape >. This finger is placed between the second and third fingers of the left hand, and as the performer keeps all the fingers close together, and turns his hands rapidly backward and forward when showing them to be empty, it will be a keen eye indeed that will detect the apparatus. When the hands are brought together the false finger is quickly taken off, the handkerchief is pulled out and shown to the audience. In laying the handkerchief on the table the finger is placed there with it, or is retained in the hand and afterward pocketed.

Fastened to the performer's left arm, just below the elbow and under his coat sleeve, is a strong cord—a piece of fine fish-line is excellent—which passes up the sleeve, through the armholes of his vest, across his back, and down the right sleeve, where it ends in a loop placed over the right thumb. This cord is of such a length that it will only reach the thumb when the arms are held with the elbows at the hips and the forearm extended from that point. Releasing the loop from the thumb, and straightening the arms forward and slightly upward, carries the loop and anything in it well into the upper part of the sleeve. When the handkerchief is to disappear, the performer, under cover of his clasped hands, runs it through the loop, extends his arms quickly, and the handkerchief flies up the sleeve. Just here comes in a little piece of the misdirection already alluded to. The performer does not open his hands at once, but continues to rub them as if they still contained the handkerchief; then he closes the right hand and holds it well out from his body, letting the left hand fall, open, to his side. He continues for a second to work the fingers of the right hand, as though compressing the handkerchief, and finally, opening one finger after another, shows the hand empty. Next he bares his arms, but in doing so is careful to push up the left coat sleeve and turn his shirt[Pg 209] sleeve over it, so as to conceal the place at which the cord is fastened.

THE MATCH-BOX AND THREAD.

THE MATCH-BOX AND THREAD.

The production of the handkerchief from the candle is as ingenious as the rest of the trick. A duplicate handkerchief is folded as small as possible, and tied with very fine black cotton thread, to which is attached a loop of horse-hair. This is placed in one end of the cover of an ordinary parlor-match box, one of the kind that slides into its cover, like a drawer. The box, half-way open, stands on the table, the loop protruding. In picking it up to take out a match the forefinger of the left hand is run through the loop, and the act of closing the box pushes out the handkerchief, which dangles in the palm of the hand, and, as the back is kept toward the audience, is not seen. Care must be taken not to pull out the handkerchief lest the thread should break. To produce it the hands are closed quickly over the flame of the candle, extinguishing it, a sharp jerk breaks the thread, and the handkerchief appears as if pulled from the wick.

The metal finger has recently been improved on, but as the substitute requires more delicate handling, I shall defer the explanation of it for the present.

This little trick originated with De Kolta, the famous French conjurer, who, besides being the inventor of most of the tricks, great and small, exhibited by the other magicians, is an accomplished actor. In his hands it almost reaches the dignity of a work of art. Another trick of his is

The performer shows a soup plate and two small handkerchiefs, a red one and a blue, "made of raw silk," he remarks, adding, "Though the silk is raw, let us hope the trick will be well done."

That there may be no suspicion of a trap in the table, it is covered with a newspaper. The plate is laid on it, mouth down. With his arms bare to the elbow, the performer picks up one handkerchief, rolls it in his hands, and after a moment shows first his right hand empty, then the left. The second handkerchief is treated in the same way, and on lifting the plate the handkerchiefs are found under it.

Of course two sets of handkerchiefs are used, one of which is concealed in the plate by means of a double bottom. The construction of the plate is quite simple. A hole about one-eighth of an inch in diameter is drilled in the bottom at the centre. A false bottom is made of metal—zinc or tin—one side painted white to match the plate, the other covered with newspaper. Soldered to the centre on the newspaper side is a short wire, slightly hooked at the end, which passes through the hole in the plate and just catches the edge. A touch with the finger of this projecting hook dislodges the bottom. The handkerchiefs cover the wire, while the newspaper lining, matching the paper on the table, conceals the false bottom.

CHANGING THE CORD.

CHANGING THE CORD.

So much for the plate. Now for the disappearance of the handkerchiefs. For this a small black bag of some soft dull black material is used. This bag ought not to be more than an inch and three-quarters long by about the same measurement in width. In the mouth must be sewed a curtain ring about seven-eighths of an inch in diameter, and extending from the centre of one side of the bag to the centre of the other should be a loop of fine flesh-colored sewing-silk, long enough to pass over the forefinger and thumb when the former is held out from the fingers. This bag is lying on a table or hanging at the back of a chair, and is picked up with the first handkerchief. Shaking out this handkerchief, the performer pretends to gather it into his hands, in reality stuffing it into the bag by the help of his left forefinger. When completely in, he runs that finger and the left thumb through the loop, works the bag to the back of the left hand, and closes that hand. The right hand, of which the back has been toward the audience, is now turned and shown to be empty. The fingers of the left hand still keep moving, as if rolling the handkerchief into still smaller compass, and then that hand is opened and also shown empty. Almost at the same moment the tips of the right-hand fingers are laid, for an instant only, near the left palm, as if to emphasize the fact that the handkerchief has gone, but without saying a word. This brings the right forefinger about the centre of the loop, through which it passes. The hands almost immediately separate, the bag is lifted off and brought against the right palm, in which position it cannot be seen by the audience. Without calling attention to it by words, the audience are made to see that the left hand is empty, as the performer picks up the second handkerchief with it, thus showing the back and front.

The second handkerchief is now worked into the bag, which this time is left hanging from the forefinger of the right hand. This hand is opened, but the audience, though not allowed to see the palm, conclude it is empty, as it was in the case of the first handkerchief. The left hand is kept closed, as if containing the handkerchief; then it is given a sudden upward movement, as if throwing the handkerchief into space, and opened. "The handkerchiefs are gone," says the performer, "and are here." At this he touches the hook on the plate with the left forefinger, disengaging the false bottom, lifts up the plate, and reveals the duplicate handkerchiefs. These he picks up with his right hand, thus covering the bag therein concealed.

One who has not seen this trick cannot conceive the beauty of it, but if the young conjurer will follow literally the instructions here laid down, he will, with comparatively little practice, soon be able to surprise and delight his friends with it.

Mr. Adrian Plate, of New York, a most accomplished sleight-of-hand performer, who confines himself to giving drawing-room entertainments, has so far improved upon this trick that he dispenses with a prepared plate. His duplicate handkerchiefs, closely folded, are concealed beneath his table-top, and are drawn under the plate when lifting it, ostensibly to show that nothing has been smuggled under it.

There are two other very pretty handkerchief tricks easy of accomplishment, but I must reserve them for my next paper.

"Here is an account, Grandfather," said Ralph, "of a sailor who kept himself afloat at sea for ten hours with only an oar to cling to. Do you think such a thing possible?"

"Not only possible, my boy, but very probable," answered the old captain. "I once knew a sailor who swam for two hours in a heavy sea when he had not as much as a wooden toothpick to buoy him up, and if you want the yarn here it is.

"We were on our way from Cape Town to Boston, and when we reached the parallel of Bermuda we lost a man overboard in the following way: Just as evening fell, the wind that had been light all day freshened with a long-drawn-out moaning sound through the rigging, and the captain sang out to settle away royals and top-gallant sails, and to haul down the flying-jib. As it was raining heavily we all kept our oil-skins on when we went aloft. Upon reaching the cross-trees I laid out on the top-gallant yard, while a seaman named Porter kept on past me, going up to furl the royal. I had passed the gaskets around the[Pg 210] sail and was about to lay down from aloft, when something large and dark flashed by me, fetched up against the top-mast rigging, then bounded clear of the vessel, and fell into the sea. Porter had missed his footing, and was now plunging down into the ocean's depths as the ship tore rapidly onward.

"'Man overboard!' I yelled; and, seizing a backstay, I slid down on deck, repeating my warning in the descent.

"There is no cry that will nerve a seaman to greater exertion than the one that tells him a shipmate is in dire peril, and although each one worked fiercely and with the natural strength of two men, the vessel had swept fully a mile ahead before we could lay the main-yard aback and so heave the ship to. Nimble hands cast one of the lee boats adrift from her gripes, and the mate, followed by five seamen, tumbled into her, and were lowered to the water alongside.

"'I will burn a flare,' called the captain, 'so that you may keep the ship in sight!'

"Four of the sailors pulled at the long oars with powerful, sweeping strokes, while the second mate guided the little vessel back into the blackness of the night, and I stood in the bows peering ahead and sending a ringing shout of encouragement across the waters every minute or two. But not one of us expected to see poor Porter again; for although he was known as a strong swimmer, how long, we reasoned, could he keep afloat in that breaking sea, weighted down with his clothes—a suit of oil-skins, and heavy sea-boots? However, we worked as zealously as though the sight of a shipmate's struggling, drowning, beseeching face were before us. The ship had been running free when Porter fell from the yard, so to fetch the place where he had first sunk we had only to pull dead against wind and sea. The men labored at the oars until their breath was drawn in choking gasps, and the heavy oak blades were almost swept from cramped and weakened arms.

"'Cease rowing, and listen!' called the mate.

"The ceaseless washing of the waves was the only sound that reached us. The ship had continued to drift from us under the influence of the wind upon her hull and rigging, and although we could still make out the flare that was burned over her quarter, it had grown so faint with distance that it now showed only as a blot of fire far away to leeward. Then we 'darned the water,' as it is called, pulling this way and that, while all the time I sent powerful cries into the teeth of the gale. At last we gave up the search, and turned the boat's head around for the ship. Not a word was spoken, each one of us silently busy with his own gloomy thoughts, picturing a lost companion sinking down and down through the unfathomable depths of the sea, to find at last a resting-place upon the white sand and coral of the ocean's bed. Only the thump, thump of oars against rowlocks; only the incessant seething of the curling crests; only the hissing of the rain as it smote the water about us, and oars rose and fell mechanically as the boat went staggering down to where the glowworm light showed the ship to be.

"Suddenly a faint, long-away cry trembled out of the darkness.

"''Vast rowing!' shouted the mate, as he jumped excitedly to his feet. Then he put his hands to his mouth and sent an ear-splitting shout rolling across the sea. A moment later the answer came to our strained, eager ears—another cry, but fuller than the first one, as though there was heart in it.

"'Give way, my lads! bend your backs, my boys,' thundered the mate, sweeping the boat around with such a fierce pull at the yoke-lines that she laid down until the top of a comber spilled over the gunwale. Then, under the frenzied exertions of the men, we went smoking through the water at right angles to the course we had been making.

"'I see him!' I shouted. 'Cease rowing! Stern all!' And the next moment, laughing and crying, we dragged our shipmate over the rail. We pulled him into the boat, but that was all. He was as naked as on the day he came into the world. After coming to the surface from his plunge he realized that the weight of his clothes would soon drag him down; so amid the blackness, and in that jumping, tumbling sea, that broke and boiled about his head, he kicked off his boots, and one by one got rid of his garments, catching a long breath and allowing himself to sink while he pulled and tore his clinging clothes away from him. He told us that all hope of rescue by his shipmates had been given up, and that he was trying to keep himself afloat until daylight, in hopes that some vessel would pass within hail of him, when he heard the sound of oars, and gave out the cry that the mate had first heard."

The day of the Yale-Harvard meeting has come, and with it Jack Vail's chance of becoming a "'varsity man," and winning the right to wear the 'varsity Y on sweater and jersey front. What that right means none but a college man can really appreciate. Scores and scores of men spend long years in training, hoping to win the coveted honor, and out of them all only a few are chosen. To the 'varsity men more than to all others is the college honor entrusted. They personify the courage and manliness of the university, and must show themselves worthy of the trust, and the man who "makes the 'varsity" by so doing obtains the respect and consideration of the whole college world, for only one possessing unusual qualities of mind and body is chosen as worthy to join the few who represent their alma mater on track and field. And to-day, if Jack can win his race against Harvard in the annual competition for the great challenge cup, he wins his Y.

The sun rises in a cloudless sky, and the day gradually grows hotter, until, by afternoon, the last trace of heaviness has been burned out of the cinder path, and the tiers of "bleachers" are packed and jammed with cheering, sweltering college men and groups of equally enthusiastic college girls. Three of the bleachers are a mass of crimson flags, dresses, and ribbons—the Harvard "rooters," a loyal band who have come down from Cambridge to encourage their team. And now the air is shattered by volleys of cheers from the Yale tiers. Before each section stand prominent Seniors who in ordinary life bear themselves with a dignity befitting their high position in the college world, but who are now devoting every atom of the energy which has made them marked men to waving their arms and hats as leaders of the cheering, terminating each effort with a peculiarly enthusiastic bound. A triple "Rah! Rah! Rah!" from one section is followed from another by the classical "Brekity-kek-coax-coax"—a cheer adopted from Aristophanes. The cause of all the commotion is a great blue 'bus, which has just lumbered up to the training-house, a short distance from the track, with "Varsity" painted on the side. Out of this are pouring strapping hammer-throwers and shot-putters, slim distance-runners, wiry jumpers, and all the other competitors who go to make up an athletic team. And now the crimson delegation have their innings as the Harvard team file into the training-house. The Yale men are located on the ground-floor, while above them in the same house are their rivals.

In the training-house is the faint feverish smell of raw alcohol, and the sound of resounding slaps as the brawny rubbers massage divers sinewy legs. The sprinters and quarter-milers, whose events come first, are slipping into their scanty jeans and lacing up spiked shoes, every muscle quivering with that deathly nervousness which even veteran runners feel before a race.

Mike, the grim old trainer, is trotting around with a fixed smile on his face that he fondly imagines to be reassuring, answering numberless questions, encouraging this man, advising that, looking up lost articles—in short, giving backbone to the whole team by his presence. Suddenly the noise stops. The Captain of the team, a hammer-thrower with a frame like a young Hercules, has climbed upon the rubbing-table, and with a sixteen-pound[Pg 211] hammer for a gavel, is calling for silence with a series of crashing blows on the long-suffering table-top.

"Boys, in five minutes we clinch with Harvard. All I've got to say is that I am proud of every one of you. I had a good eye when I chose this team, and there isn't a man on it but's full of sand. Keep cool, grit your teeth, and go in to win, and if we get whipped Harvard'll know she's been fighting."

Bang! goes the hammer, and the customary last words are over.

"Now, boys, a good big cheer for the Cap'n," shouts Mike, hopping up and down in his excitement. And a good big cheer it is. Hardly has the last deep-throated "Rah" died away before the door opens, and a field official with a flowing badge shouts, "All out for the hundred!" and the fight between the two great rivals is on.

Jack's race, the mile run, is the next to the last event. To-day is his first great race, for it was only this season, when he won the mile at the college spring games, that Mike had recognized him as a runner worthy to compete against Harvard. And he is not seasoned enough to endure well the tremendous suspense. Very weak and nervous Mike finds him as he rushes in from the track to see if all be well.

"Sort of shaky, eh?" the latter growls, looking him over critically. "Well, I wouldn't give a cent for a man that wasn't. You'll be all right the minute the pistol goes off. Lay well back until the last ten yards!" and Mike gives Jack a little shake to emphasize his words, "The last ten yards, mind, and you'll win. You won't if you don't. Save your strength for a last jump when you hear me yell. Throw yourself forward just before you get to the tape. I'll be there to catch you. And oh, my boy, win this race and the college is yours! Why—"

But all further conversation is cut short by the precipitous entrance of the Captain. He is all adrip with perspiration, for he has just won the hammer throw.

"We win the hammer," he shouts, "and the points are a tie. Now everything depends on the mile. Harvard will take the high jump and the two hundred and twenty, and we'll get the shot and pole-vault. So it's the mile that will decide everything. They'll call it the next event, Jack. Now, boys," and he again climbs upon the table, "I think a little music will quiet Jack's nerves." And in a voice that shakes the windows he commences the college slogan: "Here's to good old Yale—drink it down! Drink it down!"

"Every man on his feet and sing!" yells Mike.

Off the beds and from retired corners rolled in blankets they stagger into the circle, even the quarter and half milers, still deathly sick from their races, add a few husky notes to the chorus. From above comes a derisive yell and the rival strains of "Fair Harvard!"

"Last call for the mile," comes through the open door.

"Now, Jack," says the Captain, "we're all looking at you."

"Remember what I told you, Jack!" shouts Mike, and then somebody else calls for a cheer for Jack Vail. So Jack goes out of the door with their voices still ringing in his ears. The three Harvard milers are already out by the start, jogging up and down the track. Jack's appearance is the signal for a burst of cheers from the Yale bleachers, and a similar roar from the Harvard adherents.

"Now, boys," remarked Dickie Arnot, Jack's chum, who is leading the cheering in front of one tier, "save your voices until Jack turns into the homestretch; then we'll ejaculate a few feeble notes just to let him know that we're here."

Jack takes a little spin down the stretch to be sure that his legs are in proper working order, and then trots back to the starting-line, where the customary ceremony between the runners takes place. Each Harvard man shakes Jack's hand, and politely expresses great pleasure at the meeting, and Jack looks each one over, and wonders how fast he can go, and withal feels a bit lonely and lost—one man against three—without his running-mate "Shorty" Farnham, who became ill a week before the games, and had to stop training.

HE CROUCHES IN THE REGULATION SPRINT START.

HE CROUCHES IN THE REGULATION SPRINT START.

"Now-boys-I-shall-tell-you-to-get-set-and-then-fire-you-off. Any-man-breaking-off-his-mark-before-the-pistol-goes-back-ten-yards," clatters the starter, jumbling the words all together, according to the time-honored custom of starters. Jack is on the extreme edge of the track furthest from the pole. So when the command "Get set" comes, he crouches in the regulation sprint start, much to the astonishment of the Harvard milers, who are standing erect, as mile-runners usually start.

"Bang!" goes the pistol, and Jack springs from his mark as if beginning a hundred-yard dash. For nearly thirty yards he sprints, and rounds in ahead of the startled Harvard men, and secures the pole. A roar from the Yale men attests their appreciation of the neat manœuvre. But now the famed team-work of the Harvard men begins. With a tremendous spurt one of them comes up from the rear, passes Jack, and secures the pole just ahead, while at the same time another man tries to run up on the outside and complete the "pocket." But Jack avoids the attempt by suddenly swerving away from the pole. Immediately the other swerves out too, and Jack is forced to run yards wide of the pole.

He tries dropping back and trailing the others. But the two drop back with him, and continue their worrying tactics. How Jack longs for the faithful "Shorty" to protect him from threatened pockets. As it is now he must either run on the outside and cover yards more than the others, or take his chances at being cramped up in a pocket until the last lap. Neither of these alternatives is to be considered for a moment, for distance-runners learn by bitter experience that the amount of energy available for a race is a fixed quantity, and that the runner who diminishes it by the tiniest extra effort will fail in the stretch. Then it is that a plan flashes into Jack's head. Two of the Harvard runners he knows are only second-rate men. The other, plodding along placidly in the rear while his two pace-makers weaken his rival, is the Harvard record-holder, the great Cowles, and the only one of three that he need fear. And no one but a miler of the first rank can stand a fast first half-mile. So away goes Jack to the front, determined to make the first half under 2.10, which will drop all but Cowles, and take his chances of resting enough in the third quarter, undisturbed by any jockeying, to gain strength for the last sprint. For Jack's strong point is his sprinting, and a waiting race his best policy. So to the utter bewilderment of his friends, who know his methods, Jack suddenly dashes to the front, takes the pole away from the Harvard leader, and is off at a tremendous pace.

"Poor old Jack's lost his head," remarks Dickie, mournfully. "Mike's often told him never to set the pace. But, boys, how about a still small cheer?" And the energetic Richard leads his band of "Assorted Howlers," as he has appropriately christened his section of the bleachers, in a rattling, shattering "Brek-e-kek-kek" cheer that could have been heard clear to the deserted campus two miles away. Only Mike appreciates the true inwardness of Jack's action, for he has seen, with many misgivings, the trained team-work of the crimson-barred runners.

"Good boy! good boy!" he chuckles, slapping his knee ecstatically. "It's the only thing left to do. Jack runs with his head more than any man I've got."

One of the Harvard pace-makers essays his old trick, and tries to sprint up past Jack, but the latter is not to be passed this time, and the quartet swing past the first quarter-post at a tremendous gait.

"Sixty-one," shouts Mike, who has been holding his watch on the race, so as to announce the time of the different quarters to Jack.

The two Harvard pace-makers are unable to hold this gait, and as Jack begins the backstretch of the second quarter at the same pace, they begin to lag, and little by little drop back. Suddenly Cowles awakens to the fact that he must depend upon his own efforts for the rest of the race, and starts after Jack at a sprinting gait. Jack hears the rapid steps close behind him, and tries a little stratagem of his own, hardly hoping that it will succeed against a veteran runner like Cowles. By slow degrees he swings out from the pole until nearly a yard away, leaving a tempting gap. By the rules, any runner passing another on the inside may be disqualified for fouling if so he interferes with the runner ahead, for the leading runner has a right to the pole, and a runner taking the inside does so at his own risk. Cowles knows the rules well, but decides to take the chance and save the two or three yards that passing on the outside would take. But just as he is almost abreast of the crafty Jack, the latter swings back to the pole, and Cowles has to stop almost short to avoid a collision, which by the rules would be blamed to him, and while his stride is broken Jack gains nearly ten yards.

Now they are at the quarter-post again, and the first half-mile has been traversed in 2.08. Jack is still leading, and by degrees sets a slower and slower pace to save himself for the final effort in the stretch. But half-way around Cowles suddenly recognizes his tactics, and with an indignant effort takes the lead with that rapid even gait which seems to devour the ground, and which so imperceptibly draws away from a following runner if so be the latter relax his efforts in the least. Ah, the bitter third quarter! when the weakness creeps up from a runner's legs breast-high, and the laboring lungs feel as if iron bands were tight around them; when the head swims, and flashes come and go before the eyes, and every effort of body and mind is concentrated in a struggle not to let the white-jersey back just ahead draw away ever so little. Past the starting-post they go, and the others are hopelessly behind. There is a tremendous roar from the Harvard men as they begin the last quarter, and Cowles draws away ever so little from Jack. But the latter grits his teeth and calls upon his numb legs, and the gap closes up again. So they run like a tandem-team, and stride by stride the last quarter lessens and lessens.

The stretch is very near, and though the pace is terrific, Jack feels that he has an atom of spirit left somewhere down in his heels. And as they turn the last corner and the homestretch looms up before them, Jack lengthens his stride a trifle, and the blue Y with two little a's on either side, which the runner who has not won a point for Yale is condemned to wear, is almost parallel with the crimson bar. A roar of cheers fills the air as the two runners come down the stretch, fighting every yard, their heads back, their eyes fixed in an unwinking stare which sees only the red line between the finish posts but forty yards away.

"COME IN—COME IN, JACK!"

"COME IN—COME IN, JACK!"

And now the band of Assorted Howlers get in their deadly work. Dickie's hat and coat are off, his collar limp, and with most marvellous gyrations he is leading his orchestra in a wonderfully constructed cheer. Finally, "Nine Jack Vails!" he whoops, "and let 'em come loud." And every Yale voice on the bleachers and grand stand joins in, and "Jack Vail! Jack Vail! Jack Vail!" they thunder. But Jack, only ten yards away from the finish, hears nothing but the sobbing gasps of the runner beside him, sees nothing but the tape and the face of Mike all working and distorted with excitement as he stands back of the judges. And suddenly out of the din, which seems somehow far away and like a dream, he hears Mike's voice, hoarse in its intensity: "It's the last ten yards, me boy! Oh, come in—come in, Jack!"

And Jack comes. With a last desperate staggering plunge he throws himself forward, and feels the blessed pressure of the parting tape that tells him the race is won.

Nothing more does Jack remember until he finds himself lying in Mike's strong arms in the training-house, while the rest of the team press up to shake his hand, and the Captain, full of joyful chuckles, kneels down, and with his penknife rips off the obnoxious a's, and the great blue Y stands forth on his jersey front—won at last.

Oh, the disheartening days that followed—the constant marching to and fro, the bitter defeats, and the hopeless feeling of being overwhelmed by superior numbers! Oh, the heart-aches and the weariness!

Once more, so to speak, George was on his native heath, for the discouraged and partly shattered army of Washington was in full retreat across the northern part of New Jersey. The men marched or, better, hurried along despondently. It was more like a rabble fleeing before the invaders than a body of fighting-men. The short enlistments were running out; dissatisfaction was everywhere; and very early one morning they had been compelled to evacuate their camp, leaving behind blankets, tents, and even their breakfasts cooking at the fire, for the British had followed them across the Hudson, and were close upon their heels. Fort Washington had been taken, and Fort Lee had been abandoned with everything it contained.

And it was growing cold; the ice had formed in the meadows, and a slight fall of snow lay melting in the muddy roads. Clothing and shoes were scarce; the inhabitants of Newark and other towns came bravely to the rescue. Yet there were many Tories who were praying already for the advance of the British, and it was rumored every day that orders would be received to resume the retreat, for recruiting had almost ceased.

These were trying times for all, but for none more so than for Lieutenant George Frothingham. By sickness and desertion his company had dwindled to scarcely thirty men. All of his gold had gone to help keep the remaining few together.

And now began the weary, weary marching once more. Discouraged and foot-sore, ragged and hungry, the patriot army retreated southward, the British so close upon their rear that oftentimes they would come in full sight, and skirmishes were frequent.

New Brunswick, Princeton, and Trenton successively fell into the hands of the enemy, and at last, on the 8th of December, Washington crossed the Delaware, and, owing to every boat being in the hands of the Americans on the southern shore, the pursuit was abandoned for the time.

Soon, however, was a victory to be given to the shivering army, and Washington was to astonish the eyes of the military world. But this is casting ahead.

"George," said Carter, one snowy afternoon—for Lieutenant Hewes had recovered from his wound and hastened to the front again—"George, to-morrow's Christmas, and although we get no plum-pudding, in my opinion there's something afoot."

"Then I trust that it may be forward," replied George; "this walking backwards in order to face the enemy tires out men's souls and courage."

The two friends were standing close to a small fire, holding out their hands to the welcome glow. In the woods about them roughly built huts showed everywhere, and before each one huddled clusters of hungry-looking men, soldiers of an army that had known nothing but defeat.

"Colonel Roberts was called to attend a council at the General's headquarters, and came back with a smile on his face. That must mean cheering news of some sort, eh?" Carter warmed to his subject. "And haven't you marked the gathering and mending of the flat-boats?"

"Yes," answered George. "It means they will cross the river. I think that it is well known that the Hessians in Trenton stay much abed this weather. But the morrow will show. I'm off to my blanket."

The boys bade each other good-night, and the fire burned low.

At daybreak the next day along the American lines everything was in the bustle of preparation for some great movement. What it was no one knew. Rations were being prepared, powder and balls distributed, the strongest men were being picked out and formed into separate companies, and the weak and sickly were distributed up and down the line of earth-works.

George awoke at the sun's first rays, and was buckling on his sword when Carter Hewes hurriedly entered the hut he shared with Captain Clarkson.

"It is Trenton surely," he whispered; "but there is a chance for us to volunteer for a service that will make the army grateful. I spoke for you as well as for myself. Was I right or not?"

"Of course you were," said George, smiling.

"Here it is," was the reply. "On the way to Trenton is an English baggage-train, eight or ten big wagons filled with stores and plunder—powder, too, perhaps. A spy, a reliable man, has just brought in the news. He says that it is lightly guarded, and that a dozen men with good horses could cross the river up above, and by fast riding intercept and burn it. The General has given his permission."

Somehow as Carter spoke he reminded George of his father, Colonel Hewes.

"I will go," he said. "But how about my Captain, and how to cross the river?"

"Captain Clarkson will be told, and there is a big flat-boat five miles up-stream that we can use. We will start when it is dark this evening." He grasped George's hand.

But it was not until midnight that everything was completed; men had to be chosen, and horses that could travel fast were scarce. But at twelve o'clock ten men, mounted and armed, started west along the river. It was not until dawn that they came across the road from Trenton to the north, for they had been forced to make a wide detour. The spy was with them; objects were growing plainer, and he pointed with his finger.

"There lies Trenton, eight miles away, and the Dutchmen all asleep," he said, "and if my judgment fails me not, our wagon-train is encamped in yonder hollow."

The ten riders crossed a field and entered a forest of small pine-trees; the snow deadened the sound of the horses. Suddenly they came to a clearing, and the guide raised his hand.

"There they are," he said. Before a small frame building ten big wagons were halted in the road. The horses were blanketed and tethered to the wheels; not a guard of any kind was to be seen.

"Hark!" exclaimed one of the troopers. A loud boom sounded from the southward.

"General Washington has crossed the river," said Carter to George, who, mounted on one of Colonel Roberts's horses, was at his elbow.

Another cannon-shot, and then a roaring of them—a constant ripple and crash of sound. Heads appeared at the windows of the frame house, a few figures ran out.

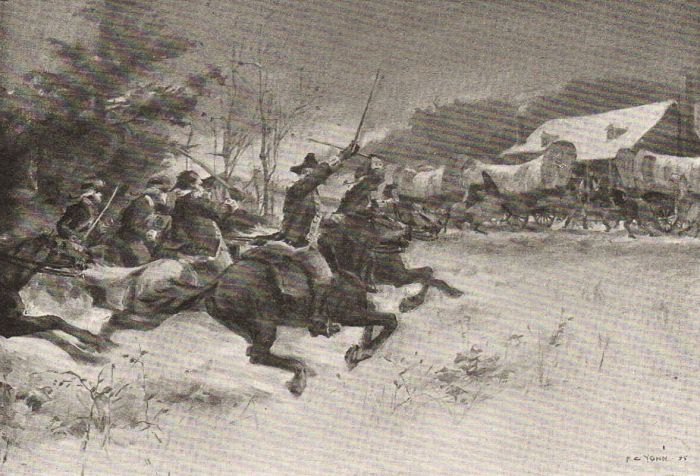

"CHARGE!" ORDERED THE CAPTAIN OF THE LITTLE PARTY.

"CHARGE!" ORDERED THE CAPTAIN OF THE LITTLE PARTY.

"Charge!" ordered the Captain of the little party.

So sudden was the attack that not a shot was fired. Then and there twenty English soldiers and a score of teamsters surrendered to ten bold Americans. They were disarmed, and penned in the frame house again.

"Don't let us burn the wagons; let us take them in," suggested George.

"Wait and see how it goes over there," said the guide. "Here! Hurry! Harness up! If they retreat, it will be along the highway. I know a wood road we can drive them into."

In a few minutes the heavy wagons had been pulled up the hill and far into the pines. The prisoners were placed underneath and guarded.

"Here comes a man on horseback," said some one from the edge of the thicket.

A dragoon, helmetless and without a coat, tore by on the road below, lashing his horse.

"Hush! Don't cheer," said Carter, sternly. "Here comes another; we have won the day."

Breathlessly the little party watched the fugitives make up the road towards Princeton, and when the last had gone, light-hearted they took their prizes up the road towards Trenton.

"There flies our flag," said Carter, as the houses came in sight. "Three cheers now, men, and with a will!"

Once more did George Frothingham shake hands with Washington.

Five days flew by, and recruits swarmed in. But the British were not idle. George was posting the guards outside of Washington's headquarters on New-Year's night, when the Commander-in-chief accompanied by his staff came walking by. The relief saluted, and the young Lieutenant caught the words, "Retreat is now impossible."

The next day the British advanced on Trenton. They did not force a battle, for it was thought that the Americans would surrender; but the latter retreated to the further side of a little creek called the Assumpinck, and here again commenced the dreary work of digging into the frozen earth, and, strange to say, the order was, "Make all the noise you can."

As soon as the darkness had settled down at night the watch-fires along the line blazed brightly in the woods. Quickly word was passed for the army, now swelled to five thousand men, to form into line. Washington again was about to astonish military eyes.

Under cover of the darkness he slipped across the creek, and marched silently northward by a road unguarded by the British. The men, looking over their shoulders, could see their own camp-fires still burning brightly behind them, for a force of men had been left there to keep them going, and pick and shovel were ringing busily.

Again the British slept on, unconscious of what was happening, and in the early morning an empty camp confronted them. But at the same time his Majesty's forces at Princeton were astonished to see well-formed bodies of troops swinging along the road toward their encampment on the hill about the college buildings.

George's company had halted, and was waiting for the word. It was a very strange sight indeed, for the command was drawn up to the side of a little brook, just across an arched stone bridge.

As the light broadened they could see coming down the road in front of them a line of red standing out brightly against the bare meadows and patches of snow. They did not seem to be afraid of the forces gathered below them in the meadow, for they did not even form a line of battle.

Everything was quiet. A rabbit jumped from a thicket, darted out and bobbed across the field. Some snow-birds twittered in the leafless branches overhead; but soon was the stillness to be broken.

"I declare, I don't think they see what they're about!" exclaimed a soldier.

The fact was, the regiment of British soldiers had taken the Americans at first for Hessians. Soon, however, they were to be undeceived, for a volley from a company off to the right warned the officers, and the Redcoats spread out across the hill-side. A body of Americans at this moment came out of a hollow and met them face to face. It was a mutual surprise, and the fighting began at once. Some horsemen galloped back in the direction of Princeton, one and a half miles or so away. Re-enforcements of the enemy were hurried down the road on a run. The detachment with which George had been standing charged up to join the hand-to-hand fighting at the front.

The battle had opened. Most of the Americans near the stone bridge were raw militia. They could not be made to fire in volleys, but each man apparently fought for himself. They had had little drilling, not having been in the affair at Trenton, and this was their first sight of blood. George saw that exhorting was of no avail. The men were full of fight, but they were not trained to listen. He sheathed his sword, and picked up a musket from the ground.

The Redcoats, advancing in their well-dressed line, came steadily on. The ranks of the militia broke and retreated; only a few stood their ground. A man on horseback rode to the front. He stood up in his stirrups, shouted, and waved his sword about his head.

"Mark ye him there on the gray horse—'tis General Mercer," a voice shouted, as the militia once more began to rally. "Stand firm! stand firm!" the officer was crying. Suddenly his steed reared, and the rider leaped up in the saddle, and, leaning across the big gray's neck, slid to the ground. The horse stumbled and fell immediately, and the General was seen almost alone, parrying the British bayonets with his sword. At last down he went before any one could reach him.

As George, for the nonce a private, was reloading his piece, he saw two soldiers draw back their muskets and plunge the bayonets into the prostrate form. A fury seized him, and with a handful of young militiamen he rushed at the red bristling line. He swung his musket by the barrel and struck to right and left. How he kept from being killed was a miracle, for men fell and shots rang all about him.

Now was the time for help, and, luckily, it came. Washington, at the head of some hurrying troops, pushed forward from the eastward, and the tide of battle turned. The British ran across the stone bridge, and many fled toward the town.

The pursuit was now kept up in two directions. Part of the American forces chased after the retreating British across the bridge toward Trenton, another detachment swept onward toward the town, where the Redcoats had taken refuge in the college buildings. The companies were mixed together by this time—Pennsylvanians, Virginians, New Jerseymen, and New-Yorkers were fighting elbow to elbow.

A strange sight that George had seen after the re-enforcements under General Washington had been hurried up kept recurring to his mind as he pressed forward. It was one of the small events that force themselves upon the mind in moments of great excitement.

The leader upon whom the fortunes of the country then depended had been regardless of all danger, and had been mixed almost with the hand-to-hand fighters, a conspicuous object on his white horse, but as yet not a ball had touched him.

Colonel Fitzgerald, one of the Irish officers attached to the American service, had ridden up to Washington as soon as the British ranks had broken. George recalled how strange it seemed. The brave Colonel's face was contorting oddly, for he was crying like a baby, the tears rolling down his cheeks, and the sobs almost preventing him from speaking.

"Thank God! thank God!" he said, "your Excellency is safe."

Washington had extended his hand, and replied, quietly, though he was touched by the congratulation, "The day is ours, Fitzgerald."

The men about had cheered as they hurried on. The sleeve of George's coat was hanging in shreds and blackened with the stain of powder. He remembered how he had grasped the muzzle of a musket, and it had seemed to go off almost in his hand. The flint of his own gun had become dislodged during its short use as a club, and was lost. He fruitlessly searched for another as he ran.

The troops of the enemy that had retreated northward had taken refuge within the walls of the historic Nassau Hall. They had smashed in windows, cut loop-holes, and had tried to get some artillery into position.

"Have you a spare flint?" George inquired of a panting figure at his side as they climbed a fence at the back of a small farm-house. The man he addressed turned. It was his fellow-clerk at Mr. Wyeth's, the man whom he had thought a chicken-heart.

"Ah, Frothingham," he said, his pale eyes alight with excitement, "I have, and you are welcome."

George grasped the hand and the extended flint together. "Bonsall," he said, "you are a brave fellow, and I have misjudged you. I must have been a nice curmudgeon in that old counting-house."

"No, no," said the other; "we didn't understand each other, and you thought I was a coward. Mayhap I was. Have you any ball about you?"

George had still some of the King's statue mementos. He handed them to his companion, who placed two or three of them in his mouth, much as a boy might marbles. The two young soldiers advanced and caught up with the line. Some scattering shots rang from the college campus. Bonsall, who was just taking aim, whirled half around, clasped one hand to his breast, and extended the other feebly before him.

"I'm shot," he said, peering blindly into the young Lieutenant's eyes.

George leaped forward and caught the dying boy; he bent over him, and placed his head on his lap.

The pale eyes opened. "Good-by, Frothingham," came the lad's voice in a weak whisper. "In my pocket, here—here."

George thrust his hand inside the threadbare coat. There was an envelope addressed to Mrs. Lucius Bonsall, New York.

"Give it to her," the poor boy said, "with love, with love."

George laid him down on the frozen earth, and now crying himself, much as the Irish Colonel had, he leaned against an elm, and aimed at the windows of Nassau Hall. A battery of artillery was playing at the bottom of the hill, and the masonry shattered from the old brown building. It was too hot for the British, and they fled across the green, down the turnpike toward New Brunswick and Rock Hill, the Americans at their heels.

"'Tis a fox chase," said a starved-looking soldier, with a grin on his unshaven face. "I heard the General say it himself. Hurrah!" Off he dashed.

George did not join in the pursuit, but finding his old friend Thomas and another soldier, they made their way back to the frozen garden, and there dug a grave, and marked the spot where poor Luke Bonsall had fallen.

George looked into the college buildings an hour or so later. Scorched with fire and littered with the remains of a cavalry occupation, vandalism had been at work. Pictures were cut and slashed, and books destroyed, and, strange to say, a cannon-ball had carried away the head of a handsome portrait of his Majesty King George.

The stay of the Continental forces here was short, for the astonished and chagrined Cornwallis was coming up from Trenton. The next day all were on the move to the northward.

George searched for his company, and helped sift the men into something of military shape. It was in horrible confusion, and had suffered many a loss. During all this time he kept thinking of Bonsall's letter, that was in his pocket next to that of his little sister's. It was not long before it was to play quite an important part in our hero's personal history.

Elated with their victories, which had revived the flagging zeal of the citizens, the army had marched to Morristown, and there sought winter-quarters.

They had only been a few days in the shelter of the town, resting from the long marches and the consequences of freezing and fighting at the same time, when Carter Hewes met George on the street.

"Roberts told me to find you," he said. "There are important orders waiting for you."

What could it mean? George furbished up the few brass buttons left on his famous coat, and walked up to the great house where a flag was flying at the top of a rough pole.

Colonel Roberts met him and took him to one side as soon as he had entered, and an aid gave him a written order, which George read hurriedly. There was no explanation; he had been detached from his company, and the whole thing was somewhat confusing. Carter Hewes was waiting at the gate, and threw his arms about his friend's shoulder as soon as he came out on the roadway.

"Is it an order for special duty or a promotion?" he inquired, much excited.

"It is the former," answered George, "but what to do I know not."

To his intense surprise he had been ordered to report to Colonel Hewes, to whom he bore despatches. And where could one suppose? At Stanham Mills! A horse was placed at his disposal; he was to start at once.

The first cabin in any part of what is now Denver, the capital of Colorado, was that of a hunter and trader, and is thought to have been an Indian's old tepee. It stood in what is now West Denver in 1857. To that neighborhood, in the early summer of 1858, came a party of Georgia men headed by a leader named Green Russell, and hunting for gold on the east slope of the Rocky Mountains. It had been said that some white men had found gold there nine years before, and that three years later some Indians also found a little. Later still a party of traders actually carried some "pay dirt" from there to their homes in Missouri. "Pay dirt," the reader should know, is any form of rock or earth or sand that contains sufficient gold to pay for working it.

Green Russell and his men arrived in June, 1858. If we stop a moment to consider these true founders of Denver, we shall see that they add a new picture to the varied, highly colored gallery of paintings that make the true pictorial history of the growth of our country. We have seen the stolid, dignified Dutchmen sail into New York Harbor with their swords, banners, queer old flint-lock guns, and quaint long pipes. We have seen the grave Puritans assemble in Massachusetts with their sober garments, their stern faces, and their muskets and Bibles carried side by side. We have seen the gorgeously dressed servants of the kings of France and Spain at their work of founding New Orleans, having their wives sent to them in ships, to make their acquaintance and be their wives after they got there. And at St. Louis we came upon the same sort of men who built up Canada—rough, brave boatmen in furs, singing and dancing, and throwing away their money that they earned in pathless forests and in savage Indian camps. When we came to study the birth of Helena, Montana, we saw upon the canvas of history the veteran gold-miner, old at the business, leaving one camp when it ceased to pay, and roaming all over the mountains, with, sharp, ferretlike eyes that saw no beauties in nature—nothing but the dull rocks and the sand in the beds of the streams where gold might be found. Rough, long-haired, bearded, dressed in whatever they could get, these "prospectors" clambered over the mountains, leaving many cities behind them that did not exist until they started them.

And now, at the birth of Denver, we see the life of the immigrants on the plains. We see the caravans of "prairie-schooners," crossing the continent like flights of brown moths, and settling a city as winged things light on a field or on a bed of flowers that offers food. They were miners, or were led by miners, but they were not yet veterans of the far Western type. They were closely followed by absolute strangers to the business—Eastern folk who wanted to pick up gold between their feet. Therefore the newest part of the picture is the life in the caravans of "prairie-schooners."

These were strong four-wheeled wagons, drawn by horses, and covered with canvas tops drawn over a series of half-hoops. In these wagons were beds, clothing, stoves, cooking and eating and drinking utensils, and women, children, and whatever invalid men there were in the train. I could not tell you fairly, in such a short article as this, a tenth part of the general experiences of the people who built up the West by travelling in these trains before the railroads came. Peril surrounded them—peril in many shapes. They were attacked by Indians. They dodged the savages, they fought them, they whipped them or were massacred. They crossed rivers and swollen streams without bridges. They crossed the plains through fearful heat or still more fearful cold. They found no water, or water unfit to drink. They fell sick, they died; cholera overtook some of them, chasing after them all the way from Asia. Their horses were stolen or died or broke down. Their food ran out. There was enough adventure in the journey to fill a lifetime—even to fill an extraordinary lifetime.

DENVER IN ITS EARLY YOUTH.

DENVER IN ITS EARLY YOUTH.

Those who reached Denver were a ragged, dust-grimed, tired-out lot, with worn horses, battered wagons, and no immediate desire except to fling themselves on the ground beside the Platte River, in the shade of the cottonwoods, and rest. Stop a moment to think of the courage and condition of those others who went all the way to Oregon! Their courage passes belief. Well, Green Russell and his Georgia men built a hut of logs, and roofed it with mud. When the rain fell it dropped on the roof as water, but it came through the roof as mud. The hut stood by that of the trader, where West Denver stands now. A third hut was built by one Ross Hutchins, and the row or street or village was called Indian Row. Gold was found in the nearby creek, and Russell took some back to Georgia to coax more of his people out to the new camp.

Then there came a party of twenty persons from Lawrence, Kansas. All of Colorado was then Kansas. These new-comers went three miles farther up the river, and washed the sand for gold at a village of their own, which they called Montana. That was in midsummer. In September of the same year, 1858, some of the Georgia men—or perhaps some outsiders—organized a town where East Denver is now, and called it St. Charles. They drew up formal organization papers, and then, not knowing what to do with them, filed them with themselves. A month later the Georgians established at Indian Row, now West Denver, formally turned that queer little pin-point on the map into a town, which they called Auraria. A store was added to the village very quickly, and one of the merchants who opened it is alive in Denver to-day. Remember that all this was only a little more than thirty years ago, when some of my readers would have called Mr. Gladstone an old man. Prince Bismarck was fifty years old when this happened.

St. Charles village was a failure, and the founders of Montana soon moved away and joined Auraria. Then came some men, such as are called "hustlers" in the West, and they went to work in mighty earnest to make a city of St. Charles. They agreed that each should build a house, and in less than fifty days (by January, 1859) there were twenty houses standing. They named the place Denver, using the name of an ex-Governor of Kansas Territory, and they gave the town a full set of officials. Then began a great rivalry between Denver and Auraria. Auraria seemed to get the business places. The merchants went there, and there Mr. William N. Byers established the first newspaper—the Rocky Mountain News. He and the[Pg 217] paper are both active to-day. But little Denver captured the express company when it came, and that ended the rivalry, for all communication with civilization was had through the express company. In 1860 the two towns became one, and were called Denver.