Project Gutenberg's Newfoundland to Cochin China, by Mrs. Howard Vincent

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Newfoundland to Cochin China

By the Golden Wave, New Nippon, and the Forbidden City

Author: Mrs. Howard Vincent

Release Date: February 23, 2016 [EBook #51280]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NEWFOUNDLAND TO COCHIN CHINA ***

Produced by Jane Robins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

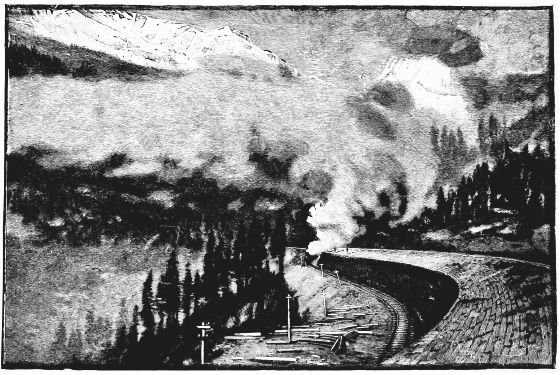

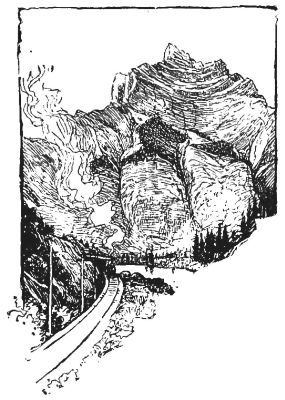

TRAIN EMERGING FROM SNOW-SHED. Page 90.

BY THE GOLDEN WAVE, NEW NIPPON,

AND THE FORBIDDEN CITY

BY

Mrs. HOWARD VINCENT

AUTHORESS OF "40,000 MILES OVER LAND AND WATER."

WITH REPORTS ON BRITISH TRADE AND INTERESTS

IN CANADA, JAPAN, AND CHINA

By Col. HOWARD VINCENT, C.B., M.P.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & COMPANY

Limited

St. Dunstan's House

Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C.

1892

[All rights reserved]

TO MY CHILD

VERA,

IN THE HOPE THAT ONE DAY SHE MAY TRAVEL

AS HER PARENTS HAVE DONE,

AND

WITH AS MUCH INSTRUCTION

AND

ENJOYMENT.

The favourable reception vouchsafed to "40,000 Miles over Land and Water" has induced me to yield to the kind wishes of many Friends and Constituents, and to record the impressions of my second circle round the world.

Ethel Gwendoline Vincent.

1, Grosvenor Square.

May 31st, 1892.

| CHAPTER I. | |

|---|---|

| Our Premier Colony | PAGE 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Maritime Provinces, and through lake and forest, to the Queen City | 21 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| By the Golden Wave to the Far West | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Canadian Rockies and the Selkirks | 70 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| To the Land of the Rising Sun | 105 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| New Nippon | 149 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| [x]The Western Capital and Inland Sea | 183 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Yellow Land | 217 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Celestial City | 247 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Forbidden City | 272 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Shanghai and Hong-Kong | 297 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Cochin China | 311 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| British and American Trade in Canada | 325 |

| British Trade with Japan | 337 |

| British Interests in China | 348 |

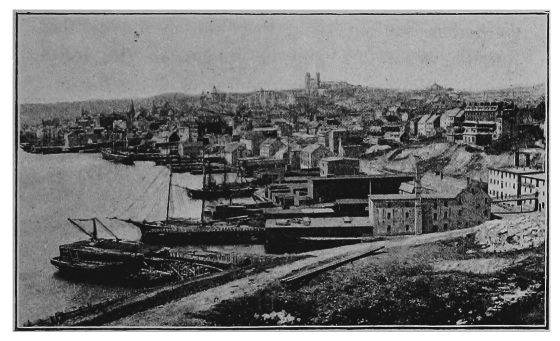

| St. John's, Newfoundland | PAGE 3 |

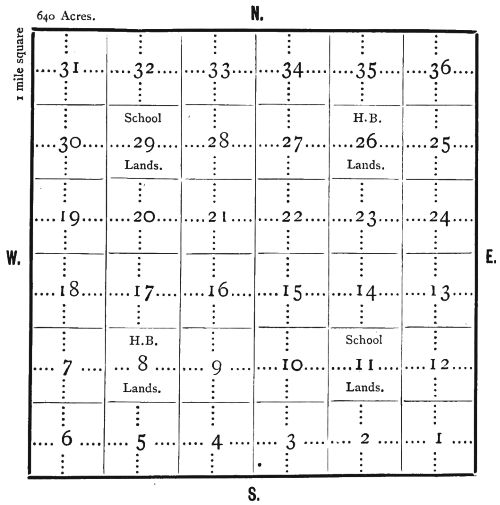

| Plan of a Manitoban Township | 53 |

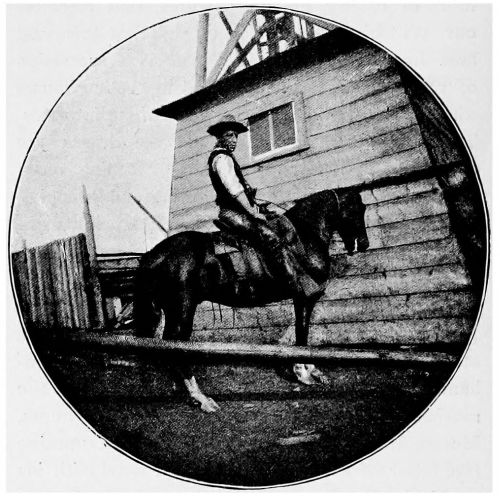

| The Ranche Pupil | 66 |

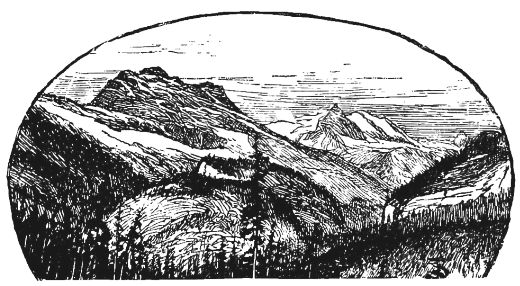

| Howe Pass | 70 |

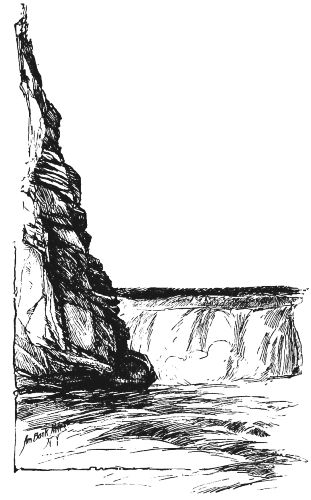

| Kananaskis Falls | 73 |

| Cascade Mountain, Banff | 74 and 75 |

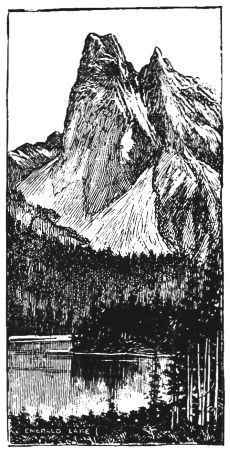

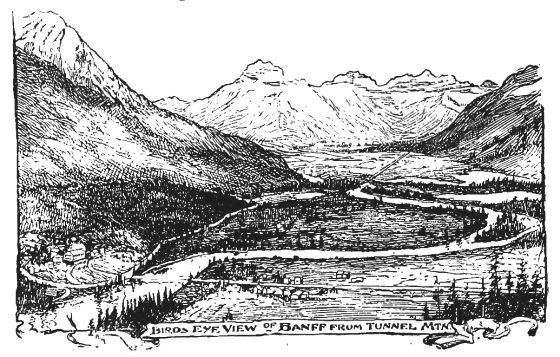

| Bird's-eye View of Banff | 77 |

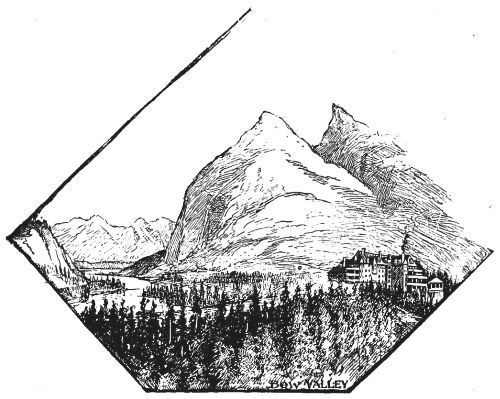

| Bow Valley | 79 |

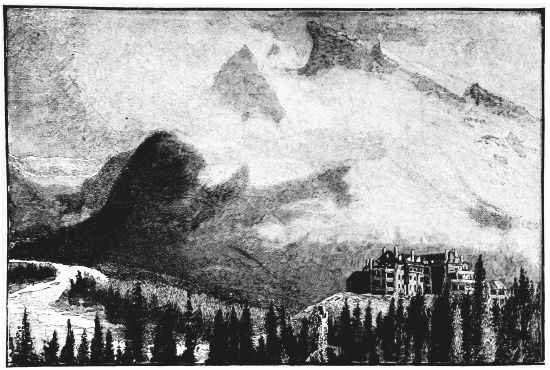

| Banff Springs Hotel, Canadian National Park | 80 |

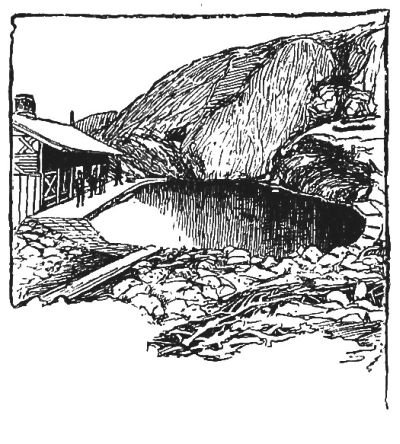

| The Pool, Hot Springs, Banff | 81 |

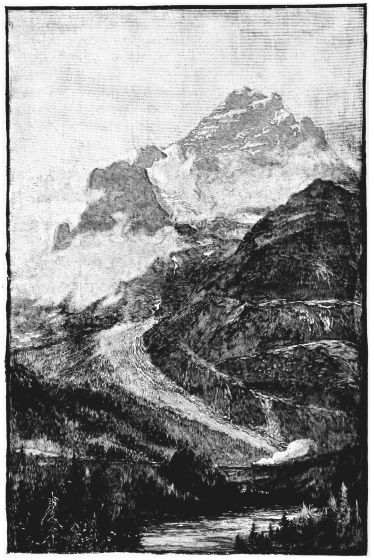

| Mount Stephen, the King of the Canadian Rockies | 85 |

| Train emerging from Snow-shed | 90 |

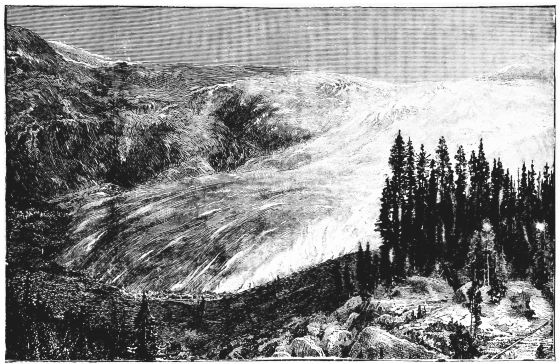

| Great Glacier, Canadian Rockies | 92 |

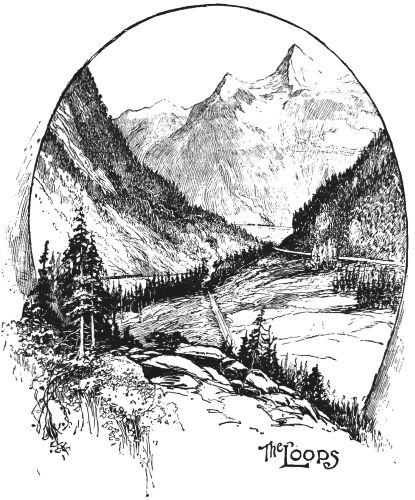

| The Loops | 94 |

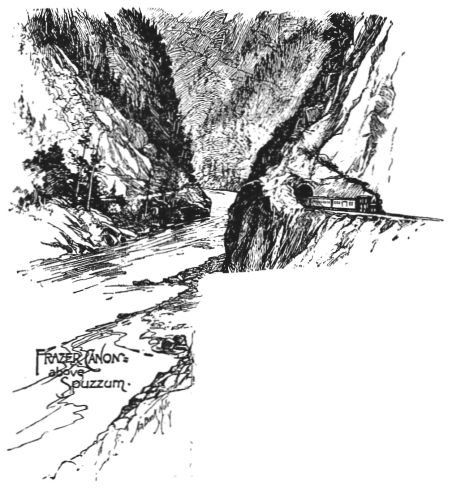

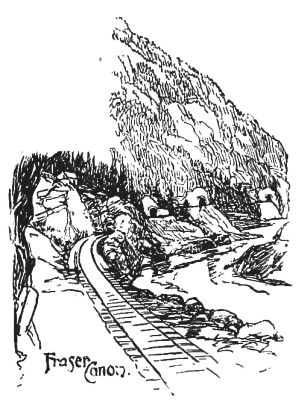

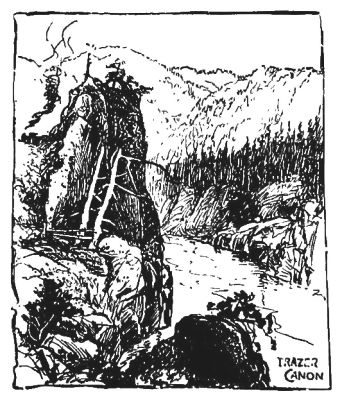

| Frazer Cañon | 97 and 98 |

| "A Little Mother" | 129 |

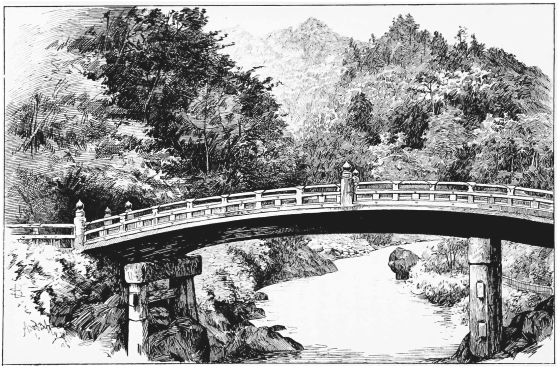

| The Red Lacquer Bridge, Nikko | 139 |

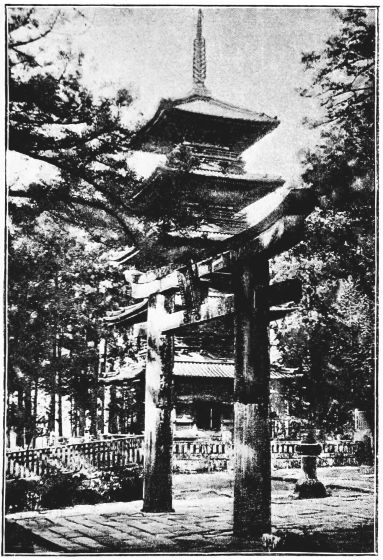

| Pagoda of the Temple at Nikko | 142 |

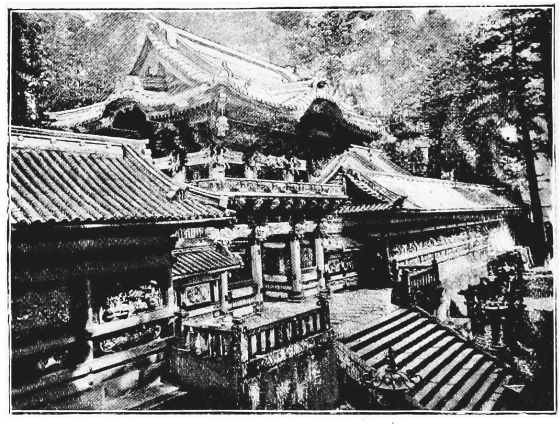

| Mausoleum of Yeyásu | 144 |

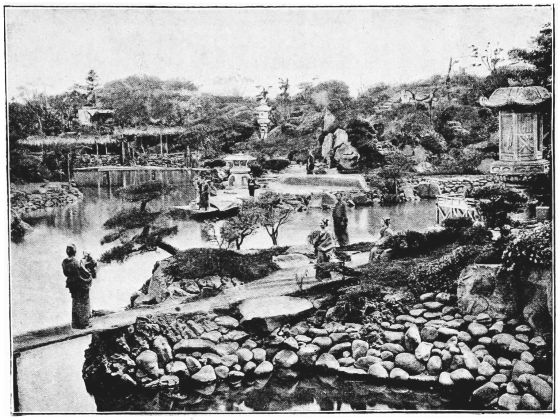

| An Imperial Garden, Tokio | 152 |

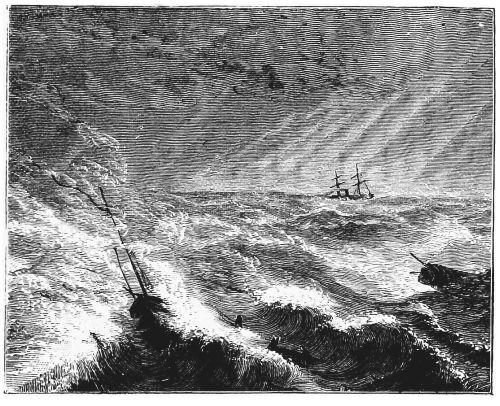

| A Typhoon | 159 |

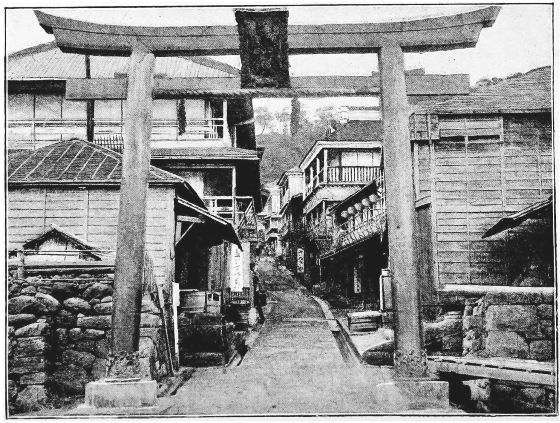

| [xii]Street of Enoshima, Japan | 163 |

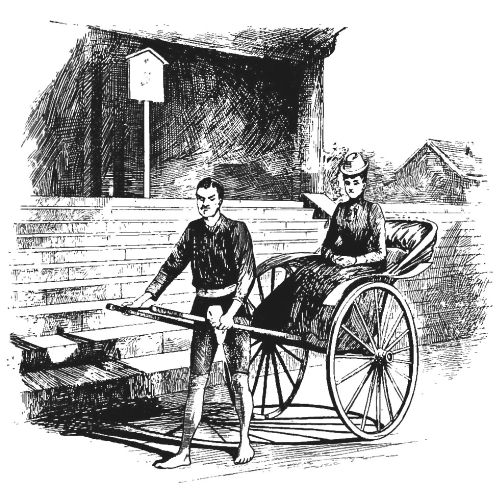

| My Carriage at Kioto | 189 |

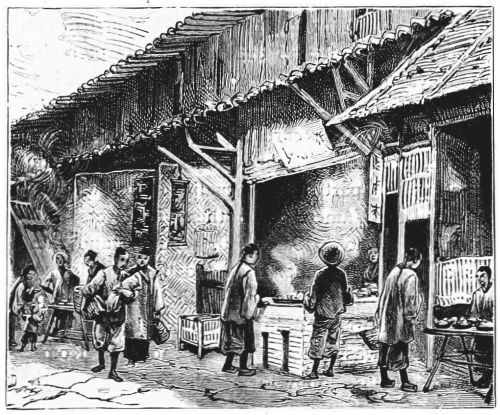

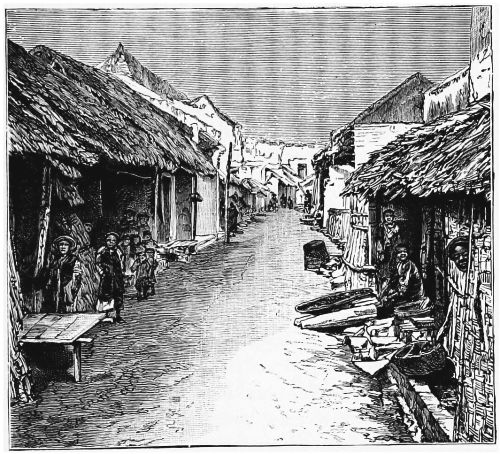

| A Chinese Street | 229 |

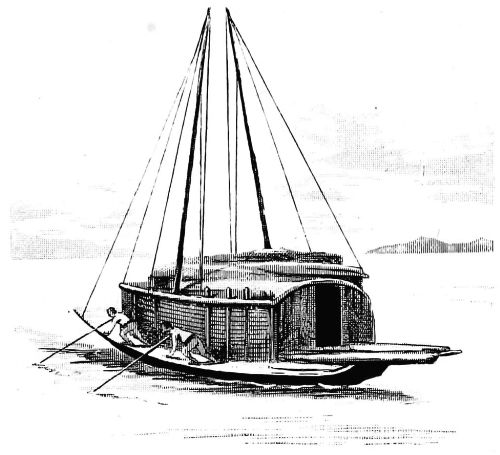

| Our Home on the Peiho | 235 |

| How I went to Peking | 241 |

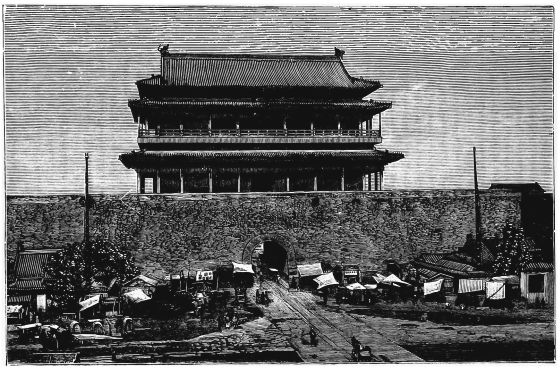

| A Gate of Peking | 250 |

| A Street in Peking | 261 |

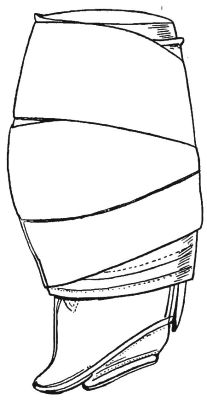

| Her Ladyship's Foot | 270 |

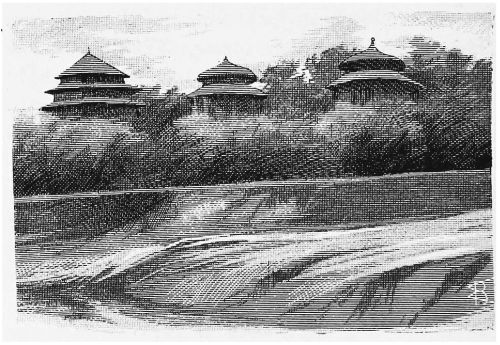

| All that is seen of the Forbidden City | 278 |

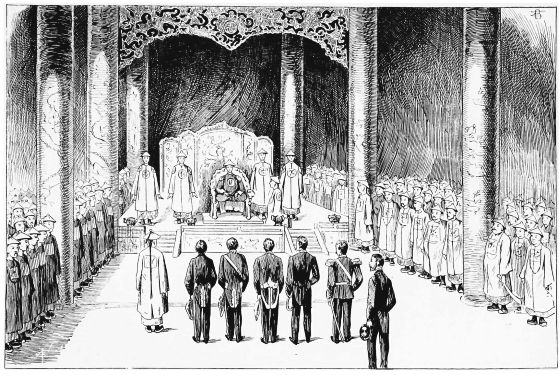

| Homage to "The Son of Heaven" | 280 |

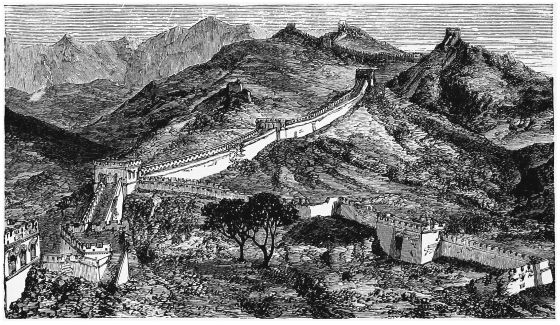

| The Great Wall | 295 |

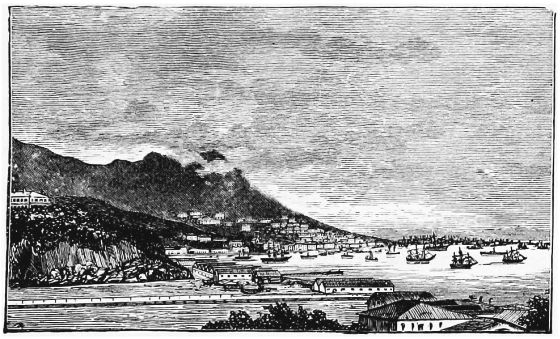

| Harbour of Hong-Kong | 305 |

| Botanical Garden, Saigon | 314 |

NEWFOUNDLAND TO

COCHIN CHINA.

Land in sight when I awake at 5 a.m., a grey streak across the oval of the port. With what intense satisfaction we gaze on the line of barren rock, which has a suspicion of green horizon on the summit of the grey cliffs, only those can picture who have been at sea for some time.

Presently we glide past Cape Race, with its neat signal station on the cliffs, and know that in a few minutes the arrival of our ship, the Nova Scotian, will be signalled at St. John's. We see a few fish-curing sheds on the tiny bays of yellow sand, and some white specks that represent cottages. They are dreary little settlements, and near them the fishing-boats pass us, returning home[2] after their rough night's work, for this is the inhospitable coast of Newfoundland, the Premier Colony of England.

As the morning wears on and the sun rises, it is a pretty scene. The great blue restless ocean, with its mighty Atlantic swell, lashing itself in spray and foam, with a long white line breaking and disappearing, re-appearing and dying against the bleak rock-bound coast. Sometimes the cliffs are formed of strata of grey lava or limestone, at others they are of rich red sandstone, colours that are intensified with the peculiar clearness of the atmosphere. Above all, there is a pure blue sky, with white clouds chasing each other and casting shadows along the coast. Now and again we pass large fishing luggers sailing swiftly by in the brisk breeze. Some have tawny orange or deep brown sails, others pure white ones, looking like wings spread in the sunlight, gliding swiftly and silently past. It is a rich bit of colouring to eyes tired and sad with the monotony of an impenetrable, all-surrounding line of sky and ocean.

The approach to St. John's is romantic. The barrier of cliffs still rises to larboard, without an apparent break or indentation, whilst they say that we shall be anchored at the wharf in ten minutes. Another scanning of the coast reveals at length two rocks rising higher than the others, with a slight fall between them. The ship ploughs[3] along broadside, and until exactly opposite this opening. With a few final plungings, and last rollings and tossings, she is brought sharply round, and we face the harbour of St. John's. The great brown rocks, sparsely sprinkled with green, rise up forbidding our entrance, and inside these is another amphitheatre of granite against which the town of St. John's is built. The line of wharves forms a black foundation. The haven where we would be lies peaceful and blue in the midst. The first sight of St. John's and the last, always include the twin red towers of the Roman Catholic Cathedral standing out on a platform above the town.

St. John's, Newfoundland.

Now we are passing immediately under the cliffs, with which we make very near acquaintance as we go through the Narrows. To add to the difficulties of this passage, there is a rock at the narrowest part called the Great Chain Rock, where in olden times a chain was fastened across the harbour to guard the entrance. Another and greater danger, a sunken rock, lies hidden under the smooth water. A gun is fired from the lofty signal station, to tell anxious hearts of the incoming mail, and with a large part of the population of St. John's on the wharf (for they always gather to greet and speed the fortnightly steamer) we land in Newfoundland.

On the kind invitation of Lady O'Brien and the Governor, we are driven by Mr. Cecil Fane, his Excellency's aide-de-camp and able secretary, to Government House. This is a handsome stone building, looking more so amongst its surroundings of wooden houses, standing above the town in its own grounds. The view from the house into the open country is charming. In the far distance a range of purple mountains. Then patches of dark pine forests, alternating with green, park-like spaces. The Roman Catholic cemetery with its wooden crosses lying on a hillside. Beneath it in a basin, the little blue lake of Quidi Vidi, which plays such an important part in the social life of St. John's. Here they yacht and boat, fish and[5] bathe in summer. In winter they use it to sleigh, skate, and toboggan on, but above all they hold their annual regatta here. It is fixed for next week, and may be called the Epsom of Newfoundland. The population from all parts of the Island gathers to see it. In olden days each merchant chief had his yacht and crew of employés, and partisanship ran high, but now the races belong to the clubs in town, such as the Temperance, Athenæum, etc.

In the afternoon the Hon. Augustus Harvey took us for a beautiful drive of twenty-eight miles across the Island. Who, seeing that bare rocky coast in the morning, would have believed that the interior of the Island could be so lovely! We drove along a good macadamized road, passing the pretty white wooden houses with red roofs and neat palings, the country residences of the merchants. Here is the one belonging to Mr. Baird of lobster fame. Each house has a flagstaff and floating flag; indeed, St. John's is called the city of flags, for everyone who is anybody possesses one, and flies it proudly when in residence. There are great clumps of purple iris growing wild by the roadside. We pass through many plantations of fir trees, junipers and larches. The great feature of Newfoundland scenery is water. It is everywhere. Flowing in rivulets, covered with reeds by the roadside, enclosed in hollows in the hills as lakes, hurrying from the mountains as a gushing[6] torrent, protesting angrily in rapids and foam against the rocks in its course. It is the great feature and the great charm, and one-third of the Island is said to be water. In one drive you may count as many as two dozen lakes.

At times, as you look round, the country reminds you of Scotland, with the purple blue mountains in the distance and the dark patches of fir trees. At others there is a marshy and barren bit of bog land, with cabins recalling the wilds of Connemara. Then some scene in the Tyrol is brought before you; high mountains and deep valleys filled with dense pine forests, a lake hidden in their midst. Frequently a chain of mountains has a similar chain of lakes winding at its base. These lakes are divided by a narrow isthmus of land, or connected by flowing streams. They are full of fish of all descriptions. If England is the paradise for horses, this is the paradise for fishermen. Other sport can be obtained by the partridge-shooting in August and September. The partridges resemble Scandinavian ptarmigan. There are also wild deer to be had by stalking the mountains forty miles in the interior.

We always think of Newfoundland as the land of fog, lobster, and cod, and know it best in connection with the breed of Newfoundland dogs. This race is degenerating and threatened with extinction, and there are scarcely any good[7] specimens of these beautiful and intelligent dogs left in the island. But I think few have any idea what extremely beautiful scenery there is, and when there is no fog, the atmosphere is remarkable for extreme dryness and clearness, giving the most vivid colouring and the sharpest delineations to the mountains.

This was the case to-day; and as we drove to the Twenty Mile Lakes, so called because they are twenty miles round, I thought I had rarely seen brighter, prettier, or more varied landscape. The water of St. John's comes from these lakes, and they claim to have the purest supply of any town in the world. Instead of being bare and desolate, the country is green and smiling. There are a few widely scattered farm-houses, but as a whole not much cultivation is attempted.

After a long ascent, we gain a glimpse of the sea. We have been driving across a narrow mainland, from the ocean to the ocean, and before us, gleaming softly in the evening sunlight, is the beautiful Bay of Conception. The surrounding cliffs are quite purple, the ocean is a golden sea broken up by green islands. Far below us is a cluster of houses, a fishing settlement, with a lobster factory and some flakes run out over the rocks. There are boats idly rocking at the quay, whilst others are catching bait for a fishing schooner, lying at anchor in the bay. They told us of one[8] of the governors who was brought here within sight of this bay to die. He thought it so beautiful. So did we. Then we drove home quickly in the dusk, late for dinner, but charmed with the island. We found Sir Terence and Lady O'Brien just arrived from a few days' cruise by the "Out-ports" on the coast. They give us wonderful descriptions of the grandeur of the scenery. The government steam yacht, in which they journeyed, will start with the judges on circuit in a few days.

Thursday, Aug. 6th.—We awoke to a lovely spring morning, with the breeze whispering amongst the trees, and the Union Jack flapping gently against the flagstaff in Government House garden. Spring has just come. Asparagus and peas are coming up in the garden, strawberries are ripening and the hay is ready to cut. We have gone back three months in our season. The climate of Newfoundland is abominable. The winter is interminably long and severe, lasting from the beginning of October to May. There are incessant fogs, which envelop everything in a cold damp pall.

Nor is the island exempt from these fogs even during its short summer. The climate is also subject to extreme and rapid changes, from heat to cold, in a few hours. The summer has been unusually delayed this year, and had we come three weeks earlier, we should have seen an iceberg in the middle of the harbour.

Newfoundland is about the size of Ireland, or one-third more. Its population is some 200,000, but of this number 28,000 live at St. John's, which is therefore the centre of all life, commercial, political and social. The remainder of the population is chiefly settled on the coast, in fishing villages called the "Out-ports", whilst the interior of the island is sparsely settled, and in some parts unexplored. The population is dwindling, and there is no immigration, of which they are jealous, as reducing the means already deficient of living, but there is emigration to Canada and the United States.

The people are of English, Scotch and Irish descent, but those from England are chiefly from the west coast and Devonshire. The Premier, Sir William Whiteway, is a Devonian. And a curious little fact exemplifies this. If you ask for cream, it is always Devonshire clotted cream that is brought.

Newfoundland was the first of England's colonial possessions. Sebastian Cabot discovered the island in 1497, and claimed it for Henry VII. With the discovery of America, all nations came forward to claim a share, but it was England and France who chiefly engaged in the fisheries, which were then a source of great wealth. Sir Gilbert Humphrey and Sir Walter Raleigh annexed the island for Queen Elizabeth. Even at that time[10] 100,000l. worth of fish were annually exported. The ships left England in March, and returned in September, and these voyages formed a nursery for English seamen. In 1635 the French obtained permission from England to dry fish on the shores of Newfoundland. This may be said to have laid the beginning of the troubles which are now so active. The island was kept in a deserted condition by the merchant adventurers up to 1729. They persuaded the authorities at home that it was uninhabitable, in order that they might retain the fishing rights in their own hands. Masters of vessels were obliged to bring back to England each soul they embarked, under penalty of 100l. When at length this tyranny gave way, a governor sent from England, and the island colonized, the fishermen were still so poor as to be in complete subjection to the merchants under the "supplying system." This baneful "truck" practice begun so long ago, continues in use unto this day, with equally evil results. The only support of the fishermen (who form the bulk of the population) is fish. Upon the result of the fishing season the year's comfort and prosperity depend. But this, to be done on a profitable scale, requires a considerable plant. There are only three classes in Newfoundland: the merchants, the planters, and the fishermen. The last class are in durance to the first, through the[11] medium of the planter. The planter obtains from the merchant the necessary outfit for the fishermen in clothes and goods, and this is sold on credit. On his return from the fisheries (the chief of which are off the Great Bank), he seizes the catch and repays himself, and the merchant, who disposes of the fish. Thus the fishermen are kept in a hopelessly poor and dependent position.

Of course, since our arrival, we have heard every side of this much-vexed Fishery Question. But at least we can now fully understand the "life-and-death" importance of the question to the island, of the curtailment of their fishery grounds by the French shore dispute. The life of the codfish and lobster is the life of the Newfoundlanders, and to lessen their catch of fish is to lower proportionately their already low standard of living. The question of the French obtaining bait and erecting lobster factories is discussed at every dinner table. Mr. Baird, by defying Sir Baldwin Walker, is called the village Hampden. They feel deeply the apparent want of sympathy of the Home Government, and indeed it cannot be easy for Her Majesty's Ministers to understand the vital interests involved in this dispute to the islanders without a personal visit to St. John's.

We should like to have visited the disputed fishing shore off the islands of St. Pierre and[12] Miquelon, but it lies 135 miles down the coast, and the only means of communication is by a fishing schooner.

We went sight-seeing in St. John's in the morning. Our first visit was to the adjacent square stone building, the House of Assembly. It is a miniature House of Commons, contained in a lofty room, with long windows. There is the Speaker's chair, the table, the ministerial and opposition benches, though the latter are only occupied by the eight members in opposition, whilst the ministerial benches boast a cohort of twenty-six, of whom all but two are said to be in receipt of an official salary. There is also a Legislative Council, or Upper House; and an Executive Council, or Cabinet, which meets weekly at Government House.

Sir William Whiteway, the Premier, returns by the next steamer from the Delegation to England, but his colleagues are here, and we meet them all.

The Roman Catholic cathedral is the next most prominent building at St. John's. Its situation on a plateau high above the town, and facing the harbour, tells in its favour. Inside the railed-off square there are four beautiful marble statues. The Cathedral is finely proportioned inside, and over the high altar there is a fine bas-relief representation of the Dying Christ. The more[13] you travel, the more struck you are with the activity of the Church of Rome in all parts of the world, and particularly in the Colonies. We found it so in Australia and New Zealand. In Eastern and Central Canada the finest buildings in the cities are the Roman Catholic cathedrals. So it is at Ottawa, at Montreal (where they are building one with a dome after the model of St. Peter's), and at Halifax. Here it is the same. One wonders whence the money comes, and whether it is true that the Roman Catholics, with no State endowment, are more generous in the support of their religion than us Protestants. We visited Bishop Power, for we hold a circular autograph letter from Cardinal Manning (my husband's godfather, now gone to his rest), written in Latin, and addressed to all the Archbishops, Bishops and Clergy of the Roman hierarchy in all parts of the globe. It ensures us a welcome from them everywhere.

We then went to the English cathedral, which lies lower down in the city, and is a fine Gothic structure designed by Sir Gilbert Scott, but it presents a sorry contrast to the other, as there is a blank where the tower should be, and, save for a few stained glass windows, it is bare and undecorated. There is a heavy debt of 20,000l. on the cathedral, to meet which several public-spirited gentlemen have banded together and insured their[14] lives in its favour. They feel that they have made sufficient sacrifices, and that having built the fabric, it must be left to their sons to decorate it.

Then we descended to Water Street. It is the principal street, lying parallel with the harbour, and a somewhat untidy and unsavoury avenue. It is a real descent to reach it, for the other streets climb up from it at right angles, and each one is a mountain to ascend. There is one cab-stand here for the whole town. The vehicles on it are of antiquated date, the seat for the driver dovetailing into a back seat for a passenger. There are frequent stand pipes ready for the fire brigade, who have stations with the horses standing ready under suspended collars, and all the new improvements. The pressure of water is so good that, with hoses attached, the jets will pass over the cathedral. Thrice already destroyed by fire, St. John's now takes all human precautions. There are several banks, a fine hotel, from without at least, but which is said to defeat its exterior promise inside, a general hospital, penitentiary, orphanages, sailors' homes, and a technical and high school. The education of the island is in a far advanced state, with compulsory and free education. The museum in the post office contains specimens of the marble, coal and gypsum found in the island. Newfoundland is rich in mineral wealth, and only requires capital for its development.

We had a heavenly afternoon for a tea picnic to Logy's Bay. Indeed the beautiful drives and expeditions seem endless, and Logy's Bay is only one of the many lovely coves and bays that indent the coast. We dip over the hill and look down on an exquisite little picture, with a blue bay surrounded by headlands of red and green cliffs, and the sea shimmering beyond. Far away on the horizon there is a gleaming white pillar. It is a floating iceberg. We wish, oh! so much, as we eat strawberries under the cliffs, that it was nearer to us.

Before we descended into Logy's Bay, we knew that it contained a fishing settlement, by the pungent odours of highly flavoured fish that ascended to us, and over the bay there are many extended flakes. These flakes are formed by rough supports made of fir poles covered with branches of fir-trees. Each codfish is split, salted and laid open on these flakes. It takes six weeks of exposure to cure the fish, and there is a good deal of labour involved. Each morning the cod must be laid out on the flake. Each evening it must be gathered in, stacked and covered with bark, to which stones are attached to keep it down. This fish is then exported to Roman Catholic countries like Spain, Brazil, Portugal, Austria and Italy, where it forms the staple of food for the poorer population on fast days. It is worth about 2d.[16] per lb. The small boats that we see outside the bay, are busy collecting bait. The bait they obtain to catch the cod are caplin, herring and squid, according to the season. We have just missed seeing a lobster factory, as they closed by law on August 5th. The factory, it appears, only consists of an open shed and a stove. As the lobsters are only worth here about three shillings per hundred, it seems that a large profit, by exporting them fresh, might be made in England.

In returning, we drove round Lake Quidi-Vidi and on reaching the top of a hill looked down on a typical fishing settlement. The granite rocks of the coast shut it into a narrow cove, through which courses a stream that finds a narrow outlet to the ocean. The wooden houses are huddled together, finding foundations on and against the rocks, whilst the flakes are run out in all directions over the stream, and men and women are hard at work splitting, salting and drying the last arrived boat-load of fish.

There was a dinner party at Government House in the evening, where we met Lady Walker, wife of Sir Baldwin Walker, Mr. Bond, Mr. Harvey, and other members of the Government, as well as Mr. Morine, the leader of the opposition. The next day was Sunday, and we experienced a sudden and disagreeable change of climate. It was bitterly cold, and we were glad of fires. But[17] we have not yet had a real Newfoundland fog.

We are in great difficulty as to how to leave the island, and find ourselves steamer-bound. That tardy line, the Allan, has a fortnightly service via Halifax to St. John's, but we shall be obliged to take a cargo boat.

Monday, August 10th.—A mid night embarkation on the Black Diamond Line s.s. Coban, from the deserted wharves of St. John's. The donkey engine is at work all night, and in the cold grey of early dawn we slipped out of the harbour. There ensued two days and nights of abject misery, only relieved by the sight of land at seven o'clock on Wednesday evening. We enter Glace Bay on the peninsula of Cape Breton. The channel entrance is so narrow that we executed some wonderful nautical manœuvres before anchoring at the wharf. We are landing on a barren shore, the chief object of interest being a coal shoot with some trucks of coal on it. We are near the great Sydney coal mines, and the country is as bleak and desolate as our Black Country. The sun is sinking, but the air is warm and moist.

We land at this uninviting place, and after some searchings amongst a half-dazed population, who seem to show surprise, mingled with resentment at our intrusion, we find a ramshackle[18] country buggy, in which to drive fourteen miles to Sydney. We are told the track is rough. The light is fast failing. There is only one narrow seat for the somewhat bulky driver and ourselves. For a moment I cannot see where I am to sit. But every second it is growing darker, and with no alternative I scrambled up, and fortunately being small, I was wedged in securely, and during the very rough drive was perhaps the less shaken. The four-year-old pony sorely tried my nerves at starting by shying, and turning sharp round—a fatal thing in these lockless buggies. Our good driver—the local constable—negotiated the worst places, the holes and rocks and frail wooden bridges, with great care, and saved us all he could. Still, we suffered severely.

We passed the two great coal mines of Sydney which supply all the coal to Newfoundland, and much to Canada. It is soft and dirty fuel. We saw the lights of the miners' cottages, and passed some of them returning with an electric lamp in their caps. On and on we drove. The twilight failed, and a pale crescent moon rose, but its dim light only added half-seen terrors to the road, as we drove through dusky pine forests and heard the rush of unseen waters, whilst the lamp of the luggage cart in advance looked like a will-o'-the-wisp dancing up and down. On and on[19] for what seemed like hours. No dwelling-places in sight, no human being seen, no sound heard, as we crossed in the darkness that isthmus of land between Glace Bay and Sydney.

After a weary while we at last saw the welcome lights of Sydney, and drove into a sleeping village, only to be told that every room in the place was full. At length a priest and a commercial traveller, fellow-passengers from the steamer, found a room, which they gave up to me. It was in a little public-house, but the bed-room was lighted by electricity!

We were up at 5 a.m., and in a torrent of rain drove to the station. The Intercolonial Railway only opened this new line from Sydney across Cape Breton eight months ago. It communicates with the magnificent harbour of Sydney and the exceedingly beautiful Bras d'Or Lakes. We travelled by the shores of several "guts," or inlets from the harbour. Then opens out the broad expanse of the lake itself, surrounded by mountains, along the foot of which we are creeping. The name Bras d'Or has such a pretty origin. When the French, in exploring Cape Breton, first saw the lake, it was autumn, and the shores were all golden in their autumnal glory; hence they called it the Golden Arm. For miles we are passing along its shores, which the waters are gently lapping under a leaden sky, and the great mountains[20] covered with fir forests, rise gloomy and forbidding on the further shore, bathed in clouds and mists. It is a beautiful, though depressing scene. The lake closes in, and its banks nearly meet at the Narrows, which the train crosses on an iron trestle bridge from one shore to the other. There is excellent fishing in this lake, and now that the railway has opened it up, it is sure to become known and largely visited.

At the Straits of Canso, the contents of the train, including passengers, are embarked on a ferry, and cross the narrow strip of sea that divides Cape Breton from the mainland of Canada. We disembark in Nova Scotia.

A long railway journey. The light streaming into the berth of a sleeper of the Intercolonial Railway awakes me, and a few minutes afterwards I emerge from between the curtains, to see the morning sun on the dancing waters of Bedford Basin, the land-locked harbour of Halifax. For about ten miles we are skirting this harbour before running into the town.

Most people would agree in thinking Halifax a charming place. There is nothing in the primitive city, with its straight, narrow streets of wooden houses, most of which require a new coat of paint, to make it so. There are few public buildings worthy of notice. But the charm lies in its position on the peninsula of land, with the deep bend in the North-west Arm on one side, and Chebuctoo Bay on the other, leading into Bedford Basin. Thus there is water on every side.

Halifax has a large official society, and takes some pride in being thought very English in its habits and ways. It owes this to being the one military station left in Canada where there are British troops, and also to its harbouring a naval station, with a resident Admiral and three war-ships at anchor in the bay. The Lieut.-Governor also resides here, and so Halifax[1] is full of official residences. Each province in Canada has a lieut.-governor, who receives the appointment for five years at the hands of the Governor-General, with a moderate salary and an official residence. He is generally some prominent and popular local man, who is thus rewarded for political services by the Premier of the day, who advises the representative of the Crown, and practically confers the post. Each province also has its local parliament, or legislature, which is independent of the Dominion Parliament, and forms its own laws of internal economy, constituting a body like our County Councils. Thus, in Canadian capitals, their public buildings always include the Parliament House, a Government House, and Ministerial offices.

In the afternoon Mr. Francklyn came and took us for a drive in the beautiful park at Point[23] Pleasant. We skirt along the blue bay, dotted with white sails, for there is a regatta in progress, until we reach the well-named Point Pleasant. This promontory is covered with a magnificent pine forest, through which wind miles of splendid roads, made by companies of the Royal Engineers when stationed here.

On one side the park is bounded by a deep inlet of the sea, running a long way inland, and which is called the North-west Arm. At a certain point there is a sunlit vista looking up this narrow bay, which is very beautiful. There are pleasant country-houses out here, in one of which Mr. Francklyn resides. It is a perfect afternoon, with warm sunshine, and a pleasant breeze whispering and sighing in the fir-trees.

Sunday, August 2nd.—In the morning I went to church at St. Paul's. This is a very old wooden building with a spire. There are the same timbers as were used for its construction in 1794, when the Hon. E. Cornwallis landed in Chebuctoo Bay with 2000 settlers. He planned this site for the church, and built it on the design sent out by the Imperial Government, which was on the model of St. Peter's, Vere Street. In 1787, when the first Bishop was appointed, he took it for his cathedral. It has taken part in all the great functions connected with the history of Halifax; and the walls are covered with mural tablets to[24] the memory of the generals and admirals who have died on the station.

We were told to go and see the public garden, which is very well laid out with carpet beds and a miniature river. The gardener is a resident of Halifax, and was sent home to England a short time ago, to model it on our London parks. In the evening we attended the Presbyterian Church to hear Principal Grant preach. He is the able, sympathetic and popular Principal of the Kingston University. The Presbyterians have a strong following, and fine churches throughout Canada, probably owing to the large number of original Scotch settlers.

From Halifax we should have gone to St. John, New Brunswick, by Annapolis, through the beautiful country celebrated by Longfellow, and called the Land of Evangeline, and across the Bay of Fundi, but there was doubt as to the hour of arrival of the steamer to be in time for a meeting of the United Empire Trade League. I must here digress a minute to explain that it was no part of our original Canadian tour to practically be "stumping" the country from Halifax to Vancouver on the subject of Imperial Preferential Trade. The meetings were thrust upon my husband, and, once begun, each city claimed its meeting in due course. Albeit, I must confess that he fell in gladly with the arrangement.[25] I may fairly say that for over six weeks in Canada, I was the victim of the United Empire Trade League.

In our schoolroom days we learnt that St. John is the capital of New Brunswick, and Halifax the capital of Nova Scotia. In the weariness of a hot study and the drowsiness of a summer afternoon, we may vaguely wonder of what use this, and much else that we learn, will ever be to us. It is pleasant now to have knowledge triumphantly vindicated, and geography by personal visits made easy.

Lying on several peninsulas formed by the river of St. John, the harbour, and the Bay of Fundi, the city is surrounded by water. You cannot be many minutes in the town without hearing of the fire of 1877, that great epoch in local history. Beginning in a blacksmith's shop, it destroyed nine miles of streets and an entire portion of the town. We were shown the one building that was left untouched in the midst of the conflagration, and for what reason no one has ever been able to ascertain. The town was rebuilt with red sandstone, granite and brick. It looks so handsome and substantial when compared to the wooden cities of Halifax and other Canadian towns.

The Mayor (Mr. Peters), the President of the Board of Trade (Mr. Robertson), met us at the station[26] and drove us about the town, and pointed out to us such public buildings as the Custom House, the hospital, the asylum for the insane, etc. My experience goes to tell that they are the same in all cities of the world. We passed rapidly from the summit of one peninsula on to the next, looking down streets that always seem to lead to water. There are pretty views from these heights of the large city, containing 40,000 inhabitants, spread out over these successions of hills, with the harbour dotted with sails below. Far away into the country, the river is seen winding amongst grey, overhanging cliffs and pine-clad mountains. They claim for it scenery as fine as the Hudson.

But the prettiest view of all is from the Cantilever Bridge. Here the wide mouth of the St. John river flows through the harbour to the sea, interrupted by rocky islands, clothed in green. They have a great curiosity here in the shape of a reversible waterfall. The tide at the mouth of the river rises and falls as much as forty feet. As the river flows seawards it is forced by the volume of water coming down the river over a ridge of rock, and forms a waterfall into the harbour at low tide. When the tide turns, the salt water is forced backwards up the river, and forms a waterfall the reverse way.

St. John was founded by the United Loyalists.[27] The other day there was a touching incident of a brave boy who went out in a storm here and saved the life of a child, perishing in the attempt. Subscriptions poured in for the erection of a public monument. They proposed to erect it on a spot we were shown, but in excavating they came upon the well-preserved coffins of twenty of these United Loyalists.

The city is the centre of a great lumber trade; 30,000 yards of timber are cut on the banks of the river annually and floated down to St. John's. They have free and undenominational education. The streets are paved with blocks of cedar. Electric light is in general and domestic use. Altogether, St. John is a most enlightened and advanced city.

We got into the "cars" at night for a long journey of two days and two nights to Toronto.

Through the State of Maine we sped at night; one of the two American total Prohibitionist States. Though saving 200 miles by this route, it seems a pity that the C. P. R. could not keep their line in Canadian territory, as, in the event of war with America, or one in which she was a neutral ally, her connections could be severed.

During this long journey of 1500 miles from Cape Breton, through the Maritime Provinces, to the more cultivated and open country of Ontario, the scenery has been beautiful but monotonous.

There are two features which repeat themselves over and over again to the eye, the ear and the senses: they are that Canada is a land of many forests, and that Canada is a land of many waters.

For many hundreds of miles we passed through the midst of these enduring spruce forests, the narrow track whose path has been roughly cleared by burning, extending with its thin thread of iron through their densest growth, lost through their trackless depths. On either side of the clearing though these, mighty forests, there is a belt of blackened stumps of grey, armless stems, where the fire has passed over them. Sometimes even there will be one green living tree left standing among the dead. And these dull grey mutilated trees look quite pathetic in their pale nakedness, leaning hither and thither, and finding support across one another, as if falling in their last agony, or lying dead and uprooted on the ground. They exercise quite a fascination as they continue for mile after mile in their dying contortions, whilst in the background there are their living brethren, so green, hardy and dense in their growth. The ground beneath is strewn with blackened snags that are partly covered with green moss and ferns, their fresh growth mingling with these dark reminiscences of man's ruthless hands. In sedgy places there are beds of waving bulrushes,[29] and sometimes a few wild flowers, such as the fox-glove, the mimosa, and the golden-rod.

Hundreds of acres of these lumber forests are on every side, and indeed, a large proportion of the Dominion is covered with these mighty stretches of pine and spruce. There are other varieties such as maple, birch and poplar, but the spruce fir is the chief growth, as it covers all the land that is not cleared or occupied by water. We see piles of ready-cut timber, stacked for transport, or cars laden with it at every station. The rivers and lakes are full of floating timber, and abandoned rafts. Frequently the whole surface of the river will be blocked with lumber, which, carried by the current, arranges itself transversely in floating down. This generally happens near a town or village. For miles away up these deep valleys, there are men busy lumbering all the summer. They cut down and strip the trees of bark and then float the lumber down to the nearest place for export. We constantly pass sawing mills where water power is used for the machinery. The bark is only useful for "kindling" or firewood. Some of the wood is crushed to pulp and used for the manufacture of paper.

Occasionally in the middle of these forests the engine will startle us with an unearthly whistle. It is a sign that we are approaching a human habitation, and in a rough clearing we pass two or three[30] wooden huts, with a potato patch mingling with the black stumps, and women and children at the door. One pities their solitary life, shut in by the impenetrable forest, and wonders how they obtain supplies. Sometimes there is a larger clearing with more attempts at farming, but where the fields, though divided off, are still a mass of charred stumps.

This work of clearing by the Eastern settler must be terribly disheartening. There is, first of all, a dense undergrowth to be hewn through and piled up ready for burning. This when dry kindles the conflagration which is to help so materially in the task. After a spell of dry weather and with the wind in the direction he wishes to clear, it must be joy to the settler to see the flames leaping up and hungrily devouring the trees. The fiercer and longer the fire lasts and the cleaner it burns, the more pleased he is, and when it dies down he must look sadly around at the trees still standing, knowing that now each one must be cut down by his own labour. Then each blackened stump and snag must be grubbed up singly. This is work done by the sweat of the brow. It is tedious, laborious and apparently endless. Occasionally you come across a beautifully cleaned piece of ground, which is pleasant to look upon, but generally the land is roughly cleared, in fact you wonder how the few cows and sheep find sufficient[31] green sustenance among such a black outlook of burnt stumps. The enormous waste of valuable timber by this rough-and-ready method of clearing seems to us reckless prodigality, but the settler surrounded by miles of similar forests cannot see it in this light.

The variety of rough wooden fences, with their ingenious inventions to save labour and time, become a source of interest. The roughest kind are formed of the roots of trees, turned on their sides, the roots forming a thorny fence. It is picturesque, untidy, but practical for its purpose, and is called a "snag" fence. Others are formed of timber stakes of every description, some with barbed wire. This, however, is too expensive to be largely used. But the prettiest of all are the snake fences. Very easy of construction, they run along in graceful zig-zags.

The land cleared, and the ground fenced off, the building of the house comes next. This is a land of lumber, and of course the house is made of wood. They are simple and easy of construction, being of one story with a door in the centre and a window on either side. The door must be covered with wire netting, for the flies in the forest amount to a pest. They are lined with planked wood inside and out, and the roof is covered with shingles or flat strips of wood nailed on like tiles. Between the outside and inside there is a lining of[32] paper tarred thickly over. This makes the house air-tight. In Canada a large proportion of the dwelling-houses are built of wood. Montreal and Toronto have streets of handsome stone houses, and in all Canadian towns the public buildings and offices in the city are of stone or brick. Still, wooden houses largely predominate throughout the Dominion. It seems curious, but arctic as the winters are, these wooden houses are more suited than stone to the climate. In the latter the mortar absorbs and gives off damp in a thaw, whilst the wooden houses are dry, air-tight and extremely comfortable. Most of the houses have furnaces in the basement, which heats the warm air in the pipes of each room, or at all events a stove in the hall. This and double windows are a necessity in the winter.

During this long journey, we are again impressed with the volume and extent of the lakes and rivers. The country is absolutely fretted with these fresh-water lakes, which are full of salmon and trout. Some are very large, like Lake Megantic, which we pass, and which is twelve miles long; or Moosehead, which is forty miles long and from one to fifteen miles broad. Others are only like large ponds. Then there are broad rivers, deep and strong; wide rivers, shallow and rapid, and mountain torrents, brown and babbling. But it is always water everywhere, still or running, silent[33] or noisy, blue or green according to its depth. If you read for a little while, or your attention is turned away from the car window, on looking up again there is sure to be more water in sight.

We now re-visited Ottawa, Montreal, and Toronto in the interests of, and for meetings of, the United Empire Trade League, after a lapse of six years. At the capital kindly, enthusiastic, and hospitable was the official and parliamentary welcome to my husband, but we heard much of the "scandals," and of the loss to the country of Sir John Macdonald. Of the former subject we weary, as of the extravagant language which fills the papers, the following being a specimen of the daily head-lines:—

"Boodle and Bungle." "The Slime of the Serpent is over Them All." "A Story of Greed, Incompetence, Extravagance and Muddle." "Another Public Works Scandal," etc.

Montreal, with its natural attractions of the St. Lawrence and the Mountain, is little changed. But Toronto has grown enormously, and is now approached through some miles of suburbs. The Torontonians claim that their "Queen City" has increased in the last few years more than any other on this Continent, not excepting any in the United States. They may well be proud of it.

On Saturday, August 22nd, we left Toronto, and five hours in the cars brought us to Owen[34] Sound. This part of the line was laid by an English engineer, who they say had never laid a railway before; it was taken over by the C.P.R. and was incorporated into their great line. It is not difficult to believe that this was the case, for the car narrowly escapes derailment by the roughness of the road.

Owen Sound is the point of departure for the C.P.R. steamers across the lakes of Huron and Superior. I think it is a preferable route to the railway, as it saves two days and two nights in the cars. The steamers are very comfortable and well arranged. They are constructed to carry a large cargo. On this voyage the cargo consists of agricultural machinery going out west for the harvest, and soon it will be the grain of the north-west which they will be carrying to the east. They have a capacity for 40,000 bushels of grain, and they are constructed in such a way that the grain can be shipped direct to and from the steamer by the grain elevator.

For several hours we steam through the Georgian Bay or southern extremity of Lake Huron. It is a pretty inlet with forested banks, and a great expanse of smooth blue water. It is difficult to realize the vast area of space covered by these Canadian lakes. Lake Huron, which we have been crossing all night, covers 28,000 square miles; Lake Superior, which we are about to enter, has[35] 30,000 square miles. Lakes Erie, Winnipeg, Michigan, and Ontario, must be added to these miniature oceans. And we are not surprised to find, that Canada claims to have one quarter of the whole of the fresh water of the globe on her surface.

The next morning the banks of Lake Huron are drawing closer together, leaving us a narrow channel staked out in the centre. We are passing a regular procession of barges. There are as many as three being towed in line, and as the passage is narrow and devious, we could shake hands in passing. Also, as we salute each one, and are saluted, with a threefold whistle, the noise is continuous and wearing. These barges are laden chiefly with lumber, but some have coal, grain, and ore.

We enter the narrow mouth of the Sault Ste. Marie River, commonly called by the Americans the "Soo." This river is the outlet between the waters of Lake Huron and Lake Superior. There is a fall of forty-two feet. It is a broad and muddy river, and on the right hand we have American soil, and on the left Canadian. Perched on the bridge in the crisp morning air, the views are very pretty. The mountains, as always, are covered with the dark blue-green of the familiar pines. The banks are clothed in brilliant green, just mellowing into yellow under autumn's golden hand. We[36] are shown a quarry of valuable variegated marble in the mountain side, which is proving inexhaustible. Then we pass the wreck of the Pontiac. She was run down by her sister ship four weeks ago, and lies helplessly across the course, her bows stove in, and the bridge and hurricane deck only above water. They are pumping her out, gallons of water pouring from her rent side.

Ten miles of this ascent of the river, and bending round a corner, we come in sight of Sault Ste. Marie. Like so many other places, the town has been created by the developing energy of the C.P.R., whose cantilever railway bridge we see crossing the river, but it is typical of the energy and "go" of the Americans, that on their side of the river there is a town, whilst on the Canadian it is only a village. At Sault Ste. Marie there are some pretty rapids which you can shoot in a canoe. Communication between the two great waterways of Lakes Superior and Huron is by a lock, where the water rises and falls sixteen feet. The lock is on the American side, but the Canadians are making a deeper one of twenty-two feet. This Soo Canal is of the greatest commercial importance. Sixty vessels, in the summer season, pass through it daily, or more, they allege, than through the Suez Canal.

There was a long procession of steamers and barges waiting on either side for their turn. It is[37] so shallow that little way can be allowed to the ships in passing in and out, and for two hours and a half we sat and were quite amused watching the skill which packed three large steam barges into this narrow canal. It must not be thought that these steam barges are like our dirty barges on the Thames or on English canals. They have a tonnage of 1500 or 2000 tons, and are as smart as white paint and polished brass can make them, being lighted, too, by electricity.

These great lakes have a complete through connection to the ocean by means of rivers, locks, and canals. Recently the whale-back boat was taken from Chicago by this route to the Atlantic and across to London. But as the commerce from the West increases, the canals will require widening and deepening. This through waterway will have an important bearing on the commercial development of Canada. Its drawback is that from November until April the lakes are frozen. We, who travel through Canada in the summer, forget what a different aspect the country assumes, when for six months of the year it is frost and snow bound.

A few hours after passing the Soo Canal, we had left the flat banks behind us, and passed out on to the ocean-like waters of Lake Superior, across which we steamed for ten hours.

At eight o'clock there is the great purple pro[38]montory of Cape Thunder in sight. It is a bold outline against the pale morning sky, clear, with a keen north wind. It shelters inside the circular bay of Thunder, with Port Arthur at its head. We pass Silver Island, where thousands of dollars' worth of silver have been raised and sunk again.

After the mine had been opened, the sea broke in, and a crib had to be constructed. The silver is there, but the difficulties in raising it seem insuperable. The whole of Cape Thunder is formed of mineral deposits.

We land at Port Arthur. It is a sad place. The C.P.R. has ruined the rising town by choosing Fort William, five miles further up the river, for its lake port. The once thriving place is deserted, the shops closing, the large hotel empty. Such is the power of a great monopoly; it creates and destroys by a stroke of the pen.

Before leaving the Alberta at Fort William, the time is put back an hour. It recedes as we travel westward, and advances for east-bound travellers. The time of the Dominion is taken from Montreal, and is numbered, for convenience and business purposes, consecutively, that is to say, they have no a.m. or p.m. to confuse their train-service, and their watches have the double numbers, and one p.m. becomes thirteen, and two p.m. fourteen, and so on. A proposition has just been made in the[39] Dominion Parliament to equalize the time, but it will not pass, at all events, this session.

Fort William was one of the advanced posts of the Hudson Bay Company. It is now a swamp laid out in streets at right angles, with wooden houses, overshadowed by some enormous grain elevators. Doubtless it has a great future before it. We wait here five long hours for the west-bound train.

Our journey to the Far West, through golden wheat, began at Fort William; from there the Canadian Pacific takes us across to the ocean.

The C.P.R., with its 2990 miles of railway, is the iron girdle that binds Canada together from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. She gives cohesion to this conglomerate whole, with its varieties of climate and production. Every mile of the line is worth a mile of gold to the country, for at every place where she lays down a station, that place becomes a town, a centre of population, civilization, and wealth to the surrounding district. This railway has been the great explorer, the great colonizer, the great wealth producer of Canada. It is the artery of the body of the Dominion.

One has constantly to remember that six or seven years ago all this country through which we are passing was an unexplored wilderness. A little band of plate-layers, headed by a surveyor,[41] true pioneers, must have forced their way through, hewing trees, blasting rock, and making the silent woods resound with the voice of civilization, occasionally coming across the track of some Indian encampment or the marks of a bear. It must have required great forethought and organization from headquarters to have the plant and stores ready to push on day by day, whilst the railway in rear acted as the pioneers' single communication with the outside world, as they plunged deeper and deeper into the forests. The average speed of construction was about five miles a day, and the greatest length laid in one day was twelve and a half miles. The portion of line between Port Arthur and Fort William was the most difficult to devise. Indeed, several times the engineers despaired. The railway is divided into divisional sections, with a superintendent at each. These again are divided into sections, with a surveyor in charge; and we frequently pass their lonely section houses. Every portion of the line is inspected once a day, the workmen using a trolly, which can be lifted on and off the track. It is a single line, and there is only one passenger train daily east and west.

The trains are very long and heavy, often consisting of eight or nine cars some eighty feet in length, weighing as much as fifty tons each. They would jump the track if lighter. Our train to-day[42] was of this length, and carried a human freight of 286 persons, exclusive of the numerous officials. The sleepers or sleeping-cars are most elegant, with their polished pine wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl, and their pale sea-green brocade hangings.

The colonist cars on these trains are excellent, and always, we noticed, well filled. They have berths like the sleeper, only with no upholstery, but the colonist can buy a mattress and pillow at Montreal for a dollar or two. They have a stove where they can cook their own provisions, and on landing from the ocean steamers they get into this car, live in it, and come as far west as they want to without change or stoppage.

From Fort William we passed through a wild, rocky country, following the line of the Kaministiquia, a shallow river scrambling over a rocky course. There are a few of these soft liquid Indian names, embodying some symbolical or romantic ideal, still left; but they are fast dying out, and the practical settler is changing them to a more prosaic but pronounceable nomenclature.

It was through this lonely district, then, unexplored by white man, that for ninety-five days Wolseley, in 1870, led his troops against the Indians. They marched 1000 miles from Fort William to Fort Garry, utilizing the waterway of the lakes and rivers where possible. At Savanne[43] we see two of his flat-bottomed boats, lying rotting in the stream near an Indian village.

We have dinner in the private car of Mr. Howland and Mr. Wilkie, the chairman and general manager of the Imperial Bank of Toronto. Seated at the end of the train, we watch the twin lines of railway uncoiling themselves in a straight line for mile after mile. An occasional section-house, a station, which is often only a wooden shed on a platform, a board with the number of the section on it, and, at long intervals, a huge red tank for watering the engine, is all we see. Night closes in on this lonely country, and we sleep in our berths, while the engine steams and pants along into the darkness, hour after hour through the long, long night.

In the cold early morning we reach Rat Portage, passing from the state of Ontario into Manitoba. Rat Portage is a wooden village of 1400 inhabitants (this is considered quite a goodly population for this sparsely-peopled country); and has the largest flour mill in Canada. It lies at the outlet of the beautiful Lake of the Woods, which is forty miles long and studded with islands.

A brake has broken and the train is divided, the first half taking on the dining-car. Hungry and impatient, the passengers wait for another to be attached, and stand on the carriage platform ready[44] to rush on board. But, as it passes, a howl of disappointed hunger goes up, for some knowing ones have jumped off the cars, and filled it before it leaves the siding.

We are still travelling through the same rock-bound country, ungainly masses of rock protruding through a scrub growth of dwarf trees. We continually pass beautiful lakes, placid sheets of water hidden away in hollows. This is succeeded by a run through some "muskeg" or black peaty bog land, where flourish rank grasses against a background of bushy poplar trees.

Thirty or forty miles from Winnipeg the country opens out and gradually assumes a prairie character. The land is quite flat now, covered with coarse yellow grasses, and sprinkled with wild flowers. It is a rich feast of colours. There are great patches of gorgeous wild sunflowers, masses of purple and white michaelmas daisies, growing more plenteously here on the open prairie, than when cultivated in our cottage gardens at home; there are bluebells and lupins, blue, pink, and white, marsh mallows, cyclamen, and acres of that weed-like growth, the golden rod. Isolated houses, becoming more frequent, tell us we are nearing Winnipeg. We cross the Red river and are in the station.

Winnipeg is the old Fort Garry settlement of the Hudson Bay Company. Twenty years ago,[45] or in 1871, population was 100, now, in 1891, it is 30,000.

The town is set down in the midst of the prairie. Main street follows the winding of the old Indian trail which takes in the deep bend of the Red river. The City Hall in this street, or "on" as the Canadians would say, is a very handsome new-looking structure. It front of it stands the column erected to the memory of the soldiers who fell in the North-West rebellion of 1870. It is surmounted by a volunteer on guard, wrapped in his fur coat, and with his fur cap on his head. The streets are paved with blocks of wood, but the foot pavements are still boarded; indeed Winnipeg is a strange mixture, with Eastern civilization meeting in this border city, the Western or rough-and-ready methods of the settler. It is only interesting on this account.

In the streets there are bullock carts bringing in cradles of hay from the prairie; sulkies, which are constructed of two wheels and a tiny board for a driver's seat; and buckboards, used for purposes of all kinds. Nor must I forget the little carts with their tandems of dogs. These are a mongrel breed, and are much used, especially in winter, when they are driven four, six, or a dozen in hand in sleighs. As we get further west, the breed of horses improves. There are country yokels with burnt faces, coarse straw hat, and flannel shirt, gazing[46] open-mouthed at the store windows, for Winnipeg is to them what London is to our country lads. Here is a family party of Indians emerging from a shop with numerous parcels, to the evident joy of the squaw. But what strikes you so much is, that you may pass from this handsome street of fine stores, straight out on to the broad expanse of prairie.

On the block of Government land stands the fine group of stone buildings of the Parliament House, together with the Ministerial offices for the Province of Manitoba, the Governor's residence, and the wooden barracks enclosed in a square. We stayed at the Clarendon Hotel, whose days are I fear numbered, as the Northern Pacific Company are just completing a magnificent red sandstone hostelry. It is shown as one of the sights of Winnipeg.

Mrs. Adams, wife of an old Royal Welsh brother-officer of my husband's, kindly took me for a drive in the afternoon. On the outskirts of the town the Assiniboine river takes a deep bend, in which there is some woodland. Trees are scarce on the prairie, and what there are—poplar, oak and maple—are all stunted in their growth from exposure to the north-west blast, which sweeps in winter across the great waste, a piercing, biting wind blowing from over acres and acres of snow. In this green belt there are many handsome[47] houses, built in an ambitious style of architecture, with towers and porticoes and balustrades. They were chiefly constructed during the great "boom" of nine years ago, a disastrous event that has left its mark. The town still suffers from the troubles which quickly followed. Families are yet living under the cloud of the financial bankruptcy which then overtook them.

In 1872, Winnipeg, with a sudden awakening, realized the immense future before her as the capital of the Far West. Land was quickly bought up. Large prices given and realized. Houses were built on a magnificent scale. Crowds flocked in from all parts of Canada to share in the coming prosperity, A complete collapse followed. The bubble had burst.

The meaning of a "boom" may be thus simply exemplified. A buys a piece of land from B, and pays half the price down as a first instalment. He sells to C at an increased price, who, in his turn, does ditto to D. At length B, the original seller, calls for payment. C and D are unable to meet the call, and are ruined in endeavouring to do so, and the land is thrown back on A, who is in the same position, and B has it thrown on his hands, and never having in the first place received full payment, is also ruined, for he has speculated with the money. All classes had taken part in this "wild land speculation," and all were involved[48] in the collapse. Houses were closed (for they could not be sold, as there were no purchasers) or are only, as we now see them, partially lived in. Winnipeg is slowly recovering from this "boom," and with the youth and energy of a young city will renew her prosperity.

Passing the ruined gateway of the old Fort Garry, we appropriately come to the Hudson Bay Store. It is contained in a large block of buildings, and is a new departure in the trade once absorbed by that great and powerful fur-trading company. They first explored the country, owned it, and kept up friendly relations with the Indians. It was one of those great trading monopolies, owned by merchants, and which have done so much for the wealth and commerce of England. The Hudson Bay Company has accomplished in a minor degree for Canada, what the East India Company did for India. This shop may truly be called the Army and Navy stores of the West, for it contains everything from brocades and Paris mantles (which are bought by the squaws) furs, carpets, groceries, to Indian blankets, pipes and bead work. In this bead work the blending of colours is exquisite. At the last Louis Riel rebellion, the wholesale department outfitted and provisioned at twenty-four hours' notice, 600 soldiers for thirty days.

We then visited the tennis club. I am impressed[49] with the immense utility of this popular game, which, if useful in England, performs a large social duty in all Canadian towns. It forms a mild daily excitement, and a meeting place for all, and is especially useful in a country where, with the impossibility of obtaining servants, entertaining is a difficult matter.

Canon O'Meara took us one morning to the outskirts of the city to see the cathedral. Lying out in the country and built of wood, it resembles a simple village church. The surrounding cemetery is full of handsome monuments, and here lie many victims of the boom. The most interesting monument is the granite sarcophagus, engraved with seven names, surrounded by laurel wreaths of the victims of the last rebellion. Their remains were brought back here to be buried, with an impressive public funeral.

We visited the Bishop of Rupert's Land in his adjoining house. He is Metropolitan of eight bishoprics, and has an enormous diocese reaching into the unexplored regions of the Mackenzie River. He has organized a college on the model of an English University, and which confers degrees.

Studying the working of the Church in Canada, one recognizes some arguments in favour of Disestablishment. In Canada there is no State endowment, and the clergy are supported by[50] voluntary contributions. This money comes partly from pew rents, and is greatly assisted by the envelope system. By this method the parishioner covenants to give a certain sum a year for the maintenance of his church, by fixed weekly Sunday instalments. He is furnished with fifty-two envelopes, on which his name is printed, and these contributions are entered in a book. There appears to be no difficulty in raising funds by these means, particularly if the clergyman is popular. If he is unpopular, or his doctrines unacceptable or extreme, he suffers by the falling off of his income. This system, moreover, has the advantage of giving every man an interest in his church. A clergyman observed that several members of his congregation appeared at church for the first time on the establishment of this envelope system. "Oh, yes," they said, in response to his remark, "we have got some stock in this concern now."

It works particularly smoothly where the bishop, adapting himself to the needs of a new country, admits the principle that those who pay must choose. They require, however, a Clergy Discipline Act as much as we do.

Mr. Robinson took us in the afternoon for a drive across the prairie to Sir Donald Smith's model farm at Silver Heights, where there are three splendid specimens of the now extinct buffalo,[51] some of the few left of those vast herds that used to roam the prairie. The farm takes its name from the adjoining wood of silver poplar trees.

C. visited the venerable French Archbishop Taché. He told him that he came out forty-six years ago, and that it took him then sixty-two days to travel from Montreal, what he can now perform in sixty-two hours. He showed the inkstand from which his uncle, the Premier of Quebec, Sir Etienne Taché, signed the Confederation Act of Canada.

Thursday, August 27th.—Before leaving Winnipeg Major Heward gave us an early inspection at the barracks of the Mounted Infantry. They are smart and well-mounted on brancho horses, reared in the west. We also inspected the chief of the three fire stations. They have a chemical steamer. In this the water is mixed with carbolic acid gas. Fire being supported by oxygen, the carbolic gas, when thrown on it, extinguishes the supply of oxygen, and with it the fire. The fire bell, in sounding, throws open the stable door and the horses trot out by themselves and place their necks under the suspended collar, which descends and is fastened by a patent bolt.

The west-bound trains all stop at Winnipeg for five hours to allow time for the colonists to visit the Railway and Dominion Land Offices, and to obtain information respecting selections of lands. The land in the North-West Provinces has now[52] been surveyed and allotted thus for twenty-four miles each side of the line. In a township of thirty-six sections of 640 acres, or one square mile to each section, the Dominion retains roughly one half, whilst the C.P.R. retains the other. There are two sections reserved for school purposes, that the value of the land may make the schools free and self-supporting, two sections for the Hudson Bay Company, and the Canada North-West Land Company have bought others. The diagram on page 53 will show the division of sections.

The station was crowded with large parties of emigrants, as many settlers leave their families here, whilst choosing their sections further west. There are bundles of bedding, tin cooking utensils, with bird cages and babies in promiscuous heaps.

As we pass out of the station we see the enormous plant and rolling stock of the C.P.R., which has here its half-way depot between Montreal and Vancouver. They have twenty miles of sidings, which are now full of plant waiting to be pressed forward, to bring down the harvest to the coast.

TOWNSHIP DIAGRAM.

The above diagram shows the manner in which the country is surveyed. It represents a township—that is, a tract of land six miles square, containing 36 sections of one mile square each. These sections are subdivided into quarter sections of 160 acres each.

We are out on the prairie at once, on that great billowy sea of brown and yellow grass; monotonous it is, and yet pleasing in its quiet, rich, monotones of colour. The virgin soil is of rich black loam. The belt of unsettled land round Winnipeg is caused by the land being held by speculators, but after that we pass many pleasant farms, clustering more thickly around Portage le Prairie, a rising town. We pass a freight train entirely composed of refrigerator cars, containing that bright pink salmon from British Columbia, which is a luxury in the east and a drug in the west. The engine[54] bears a trophy of a sheaf of corn, to show that the harvest in the west has already begun.

Out of the whole year we could not have chosen a more favourable moment for visiting the North-West, as the harvest is in full swing. We are at this moment passing through a sea of golden grain, acre after acre extending in an unbroken line to the horizon. Indeed we are told that these wheat fields form a continuous belt some forty miles deep on either side of the railway.

It would be difficult for anyone living even in the east of Canada, to realize the enormous interest shown in the crops and weather out here. For months and weeks beforehand it forms a general topic of conversation, but, as August closes in, it becomes the one and all absorbing concern. The newspapers are scanned for the daily weather reports. Warnings are telegraphed broadcast through the land. As Professor Goldwin Smith says, in his book "Canada and the Canadian Question," "Just before the harvest the weather is no commonplace topic, and a deep anxiety broods over the land."

The interests at stake are enormous, involving as they do the question to many of prosperity or ruin. One cold night, or one touch of frost may destroy the labour of a year. This year the promise is exceptional, and the prospect was bright until a week ago. Then there were ominous[55] whispers of frost. These early and late frosts are the scourge of the farmer, and the lateness of the harvest, owing to an exceptionally cold summer, increases the anxiety. Day by day, hour by hour, the temperature is discussed with earnestness, increasing with intensity as evening approaches. The other night there were people in Winnipeg going up and down Main Street all night and striking matches to look at the thermometer placed there. The interest to all was so vital that they could not rest. There are warnings published in bulletins to farmers, to light smudge fires to keep the frost from the wheat. These fires of stubble, lighted to the north or north-west of the fields, by raising the temperature two or three degrees, keep off the frost, and the dread of smutted wheat. We see these smudge fires smouldering as we pass along.

The virgin soil will yield as much as forty to fifty bushels of wheat an acre, and from fifty to sixty of oats. Manures are unknown and unwanted by these western farmers. The land has only to be "scratched with a plough," and the field will often yield a rich harvest of 500 acres of wheat. The hum of the harvest is heard in all the land, and we see for miles the golden grain waiting to be gathered, and the "reapers and binders" hard at work. This machine is an ingenious American invention, which cuts and binds at the same time. There is a string inside which is given[56] a twist, a knife comes down and cuts the strings and throws out the sheaf. It is pretty to watch the rhythmical precision with which sheaf after sheaf, thus cut and tied, is thrown out on the track of the machine. The sheaves are then piled into generous stacks and left for a fortnight to dry. Labour is at a premium throughout Canada, and machinery, chiefly of American manufacture, is more largely used than in England. Sometimes two chums will farm 200 acres alone. Nearly all this grain we see is the far-famed Manitoba No. 1 hard. It is the finest wheat in the world.

We are now approaching Brandon, which is a great wheat centre. This town has the largest grain market in Manitoba, as is shown by five elevators. "It is the distributing centre for an extensive and well settled country." We should have stayed here, but were deterred by accounts of the hotel accommodation. Then came the pleasure of an orange sunset, gilding the grain into more golden glory. We passed the celebrated Bell Farm at night where the furrows are usually four miles long, and the work is done by military organization, "ploughing by brigades, and reaping by divisions."

At five o'clock we are left cold and shivering in the just broken dawn on the prairie side at Regina. We look wistfully after the disappearing train, with the warm berths inside the car. Deceived by[57] the high-sounding designation of Capital of the North-West Provinces, we had broken our journey at Regina. There is a frontage to the line of some wooden houses and stores, which extends but a little way back, for the population of Regina is only as yet 2000. The prairie extends to the sky line on every side. It is a dreary prospect, and we are mutually depressed.

There being nothing else to do, I retire to bed for some hours—the Sheffield-born landlady giving us a true Sheffield welcome.

At one o'clock matters seem brighter, for Colonel Herchmer, commanding the Mounted Police of the North-West Territory, has kindly sent a team for us to drive two miles out across the prairie to the barracks. From the distance, the dark red buildings look quite a town, surmounted by the tower of the riding school. This force is organized on military lines, and consists of 1000 men, who maintain order over the Indian Reservations, and an area of 800 miles. Their uniform of scarlet patrol-jacket and black forage cap, with long riding-boots is extremely smart. You meet them in all parts of the North-West Provinces.

After lunching with Mrs. Herchmer, we inspected the officers' and men's mess rooms, the canteen, store room, kitchens and forge, the reading-room, bowling alley and theatre, and the guard room,[58] where we were shown the cell in which Louis Riel was kept after his capture. The force is under strict military discipline. They have a football and cricket team, and a musical ride equal to that of the Life Guards.

The horses are all "bronchos," or prairie horses, bred chiefly from Indian ponies. They cost 100 dols. to 120 dols. each, and are short and wiry. They need to be strong, for the men must be five feet eight inches in height, and measure thirty-five inches round the chest, while the Californian saddles they use are very heavy. These saddles are after the model of the Spanish South American ones, with a high pommel in front and a triangular wooden stirrup. The horses are guaranteed to go forty miles a day. There are many gentlemen in the ranks of the force, some of whom have failed in ranching and other walks of life. The wild roving life on the out-stations may be pleasant, but there is no promotion from the ranks.

A drive of two miles further out on to the prairie brought us to one of the Dominion Schools, kept for the children of the Indian Reservations. Mr. Hayter Reed, the Government Inspector, who showed us over the school, told us that they do not force the parents to give up the children, but persuade them. It is uphill work at first, civilizing and teaching English to the little brown, bright-eyed children, with lank black hair,[59] whom we saw in the schoolrooms. The bath and the wearing of boots is a severe trial to these gipsy children at first.

The Government acknowledges in the building of these schools its responsibility towards the natives. They made treaties with the Indians, giving them rations, and setting apart certain lands or Reservations for them, such as the Black Foot and the Sarcee. The Americans did the same with their Indians, but did not keep their treaties as we have done. However, like all other "indigenes," they are dying out with the advance of the white man's civilization. We drove home past Government House, and in the evening M. Royat, the Lieut.-Governor, presided over an enthusiastic meeting of the United Empire Trade League.

Since very early morning, and all through this interminably long hot day, we have been crossing the great desert prairie. Hour after hour has dragged wearily on, and still we look out from the car on to the symmetrical lines of the rolling plains.