By JIM HARMON

Illustrated by EPSTEIN

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction June 1957.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I admit it: I didn't know if I was coming or

going—but I know that if I stuck to the old

man, I was a comer ... even if he was a goner!

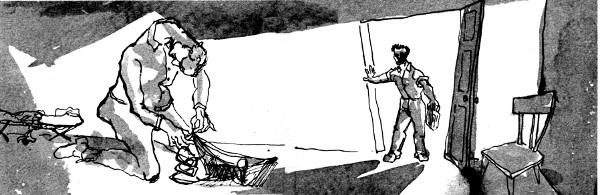

Doc had this solemn human by the throat when I caught up with him.

"Tonight," Doc was saying in his old voice that was as crackled and important as parchment, "tonight Man will reach the Moon. The golden Moon and the silver ship, symbols of greed. Tonight is the night when this is to happen."

"Sure," the man agreed severely, prying a little worriedly at Doc's arthritic fingers that were clamped on his collar. "No argument. Sure, up we go. But leave me go or, so help me, I'll fetch you one in the teeth!"

I came alongside and carefully started to lever the old man loose, one finger at a time. It had to be done this way. I had learned that during all these weeks and months. His hands looked old and crippled, but I felt they were the strongest in the world. If a half dozen winos in Seattle hadn't helped me get them loose, Doc and I would have been wanted for the murder of a North American Mountie.

It was easier this night and that made me afraid. Doc's thin frame, layered with lumpy fat, was beginning to muscle-dance against my side. One of his times was coming on him. Then at last he was free of the greasy collar of the human.

"I hope you'll forgive him, sir," I said, not meeting the man's eyes. "He's my father and very old, as you can see." I laughed inside at the absurd, easy lie. "Old events seem recent to him."

The human nodded, Adam's apple jerking in the angry neon twilight. "'Memory Jump,' you mean. All my great-grandfathers have it. But Great-great-grandmother Lupos, funny thing, is like a schoolgirl. Sharp, you know. I.... Say, the poor old guy looks sick. Want any help?"

I told the human no, thanks, and walked Doc toward the flophouse three doors down. I hoped we would make it. I didn't know what would happen if we didn't. Doc was liable to say something that might nova Sol, for all I knew.

Martians approaching the corner were sensing at Doc and me. They were just cheap tourists slumming down on Skid Row. I hated tourists and especially I hated Martian tourists because I especially hated Martians. They were aliens. They weren't men like Doc and me.

Then I realized what was about to happen. It was foolish and awful and true. I was going to have one of mine at the same time Doc was having his. That was bad. It had happened a few times right after I first found him, but now it was worse. For some undefinable reason, I felt we kept getting closer each of the times.

I tried not to think about it and helped Doc through the fly-specked flophouse doors.

The tubercular clerk looked up from the gaudy comics sections of one of those little tabloids that have the funnies a week in advance.

"Fifteen cents a bed," he said mechanically.

"We'll use one bed," I told him. "I'll give you twenty cents." I felt the round hard quarter in my pocket, sweaty hand against sticky lining.

"Fifteen cents a bed," he played it back for me.

Doc was quivering against me, his legs boneless.

"We can always make it over to the mission," I lied.

The clerk turned his upper lip as if he were going to spit. "Awright, since we ain't full up. In advance."

I placed the quarter on the desk.

"Give me a nickel."

The clerk's hand fell on the coin and slid it off into the unknown before I could move, what with holding up Doc.

"You've got your nerve," he said at me with a fine mist of dew. "Had a quarter all along and yet you Martian me down to twenty cents." He saw the look on my face. "I'll give you a room for the two bits. That's better'n a bed for twenty."

I knew I was going to need that nickel. Desperately. I reached across the desk with my free hand and hauled the scrawny human up against the register hard. I'm not as strong in my hands as Doc, but I managed.

"Give me a nickel," I said.

"What nickel?" His eyes were big, but they kept looking right at me. "You don't have any nickel. You don't have any quarter, not if I say so. Want I should call a cop and tell him you were flexing a muscle?"

I let go of him. He didn't scare me, but Doc was beginning to mumble and that did scare me. I had to get him alone.

"Where's the room?" I asked.

The room was six feet in all directions and the walls were five feet high. The other foot was finished in chicken wire. There was a wino singing on the left, a wino praying on the right, and the door didn't have any lock on it. At last, Doc and I were alone.

I laid Doc out on the gray-brown cot and put his forearm over his face to shield it some from the glare of the light bulb. I swept off all the bedbugs in sight and stepped on them heavily.

Then I dropped down into the painted stool chair and let my burning eyes rest on the obscene wall drawings just to focus them. I was so dirty, I could feel the grime grinding together all over me. My shaggy scalp still smarted from the alcohol I had stolen from a convertible's gas tank to get rid of Doc's and my cooties. Lucky that I never needed to shave and that my face was so dirty, no one would even notice that I didn't need to.

The cramp hit me and I folded out of the chair onto the littered, uncovered floor.

It stopped hurting, but I knew it would begin if I moved. I stared at a jagged cut-out nude curled against a lump of dust and lint, giving it an unreal distortion.

Doc began to mumble louder.

I knew I had to move.

I waited just a moment, savoring the painless peace. Then, finally, I moved.

I was bent double, but I got from the floor to the chair and found my notebook and orb-point in my hands. I found I couldn't focus both my mind and my eyes through the electric flashes of agony, so I concentrated on Doc's voice and trusted my hands would follow their habit pattern and construct the symbols for his words. They were suddenly distinguishable.

"Outsider ... Thoth ... Dyzan ... Seven ... Hsan ... Beyond Six, Seven, Eight ... Two boxes ... Ralston ... Richard Wentworth ... Jimmy Christopher ... Kent Allard ... Ayem ... Oh, are ... see...."

His voice rose to a meaningless wail that stretched into non-existence. The pen slid across the scribbled face of the notebook and both dropped from my numb hands. But I knew. Somehow, inside me, I knew that these words were what I had been waiting for. They told everything I needed to know to become the most powerful man in the Solar Federation.

That wasn't just an addict's dream. I knew who Doc was. When I got to thinking it was just a dream and that I was dragging this old man around North America for nothing, I remembered who he was.

I remembered that he was somebody very important whose name and work I had once known, even if now I knew him only as Doc.

Pain was a pendulum within me, swinging from low throbbing bass to high screaming tenor. I had to get out and get some. But I didn't have a nickel. Still, I had to get some.

I crawled to the door and raised myself by the knob, slick with greasy dirt. The door opened and shut—there was no lock. I shouldn't leave Doc alone, but I had to.

He was starting to cry. He didn't always do that.

I listened to him for a moment, then tested and tasted the craving that crawled through my veins. I got back inside somehow.

Doc was twisting on the cot, tears washing white streaks across his face. I shoved Doc's face up against my chest. I held onto him and let him bellow. I soothed the lanks of soiled white hair back over his lumpy skull.

He shut up at last and I laid him down again and put his arm back across his face. (You can't turn the light off and on in places like that. The old wiring will blow the bulb half the time.)

I don't remember how I got out onto the street.

She was pink and clean and her platinum hair was pulled straight back, drawing her cheek-bones tighter, straightening her wide, appealing mouth, drawing her lean, athletic, feminine body erect. She was wearing a powder-blue dress that covered all of her breasts and hips and the upper half of her legs.

The most wonderful thing about her was her perfume. Then I realized it wasn't perfume, only the scent of soap. Finally, I knew it wasn't that. It was just healthy, fresh-scrubbed skin.

I went to her at the bus stop, forcing my legs not to stagger. Nobody would help a drunk. I don't know why, but nobody will help you if they think you are blotto.

"Ma'am, could you help a man who's not had work?" I kept my eyes down. I couldn't look a human in the eye and ask for help. "Just a dime for a cup of coffee." I knew where I could get it for three cents, maybe two and a half.

I felt her looking at me. She spoke in an educated voice, one she used, perhaps, as a teacher or supervising telephone operator. "Do you want it for coffee, or to apply, or a glass or hypo of something else?"

I cringed and whined. She would expect it of me. I suddenly realized that anybody as clean as she was had to be a tourist here. I hate tourists.

"Just coffee, ma'am." She was younger than I was, so I didn't have to call her that. "A little more for food, if you could spare it."

I hadn't eaten in a day and a half, but I didn't care much.

"I'll buy you a dinner," she said carefully, "provided I can go with you and see for myself that you actually eat it."

I felt my face flushing red. "You wouldn't want to be seen with a bum like me, ma'am."

"I'll be seen with you if you really want to eat."

It was certainly unfair and probably immoral. But I had no choice whatever.

"Okay," I said, tasting bitterness over the craving.

The coffee was in a thick white cup before me on the counter. It was pale, grayish brown and steaming faintly. I picked it up in both hands to feel its warmth.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see the woman sitting on the stool beside me. She had no right to intrude. This moment should be mine, but there she sat, marring it for me, a contemptible tourist.

I gulped down the thick, dark liquid brutally. It was all I could do. The cramp flowed out of my diaphragm. I took another swallow and was able to think straight again. A third swallow and I felt—good. Not abnormally stimulated, but strong, alert, poised on the brink of exhilaration.

That was what coffee did for me.

I was a caffeine addict.

Earth-norm humans sometimes have the addiction to a slight extent, but I knew that as a Centurian I had it infinitely worse. Caffeine affected my metabolism like a pure alkaloid. The immediate effects weren't the same, but the need ran as deep.

I finished the cup. I didn't order another because I wasn't a pure sensualist. I just needed release. Sometimes, when I didn't have the price of a cup, I would look around in alleys and find cola bottles with a few drops left in them. They have a little caffeine in them—not enough, never enough, but better than nothing.

"Now what do you want to eat?" the woman asked.

I didn't look at her. She didn't know. She thought I was a human—an Earth human. I was a man, of course, not an alien like a Martian. Earthmen ran the whole Solar Federation, but I was just as good as an Earthman. With my suntan and short mane, I could pass, couldn't I? That proved it, didn't it?

"Hamburger," I said. "Well done." I knew that would probably be all they had fit to eat at a place like this. It might be horse meat, but then I didn't have the local prejudices.

I didn't look at the woman. I couldn't. But I kept remembering how clean she looked and I was aware of how clean she smelled. I was so dirty, so very dirty that I could never get clean if I bathed every hour for the rest of my life.

The hamburger was engulfed by five black-crowned, broken fingernails and raised to two rows of yellow ivory. I surrounded it like an ameba, almost in a single movement of my jaws.

Several other hamburgers followed the first. I lost count. I drank a glass of milk. I didn't want to black out on coffee with Doc waiting for me.

"Could I have a few to take with me, miss?" I pleaded.

She smiled. I caught that out of the edge of my vision, but mostly I just felt it.

"That's the first time you've called me anything but 'ma'am'," she said. "I'm not an old-maid schoolteacher, you know."

That probably meant she was a schoolteacher, though. "No, miss," I said.

"It's Miss Casey—Vivian Casey," she corrected. She was a schoolteacher, all right. No other girl would introduce herself as Miss Last Name. Then there was something in her voice....

"What's your name?" she said to me.

I choked a little on a bite of stale bun.

I had a name, of course.

Everybody has a name, and I knew if I went off somewhere quiet and thought about it, mine would come to me. Meanwhile, I would tell the girl that my name was ... Kevin O'Malley. Abruptly I realized that that was my name.

"Kevin," I told her. "John Kevin."

"Mister Kevin," she said, her words dancing with bright absurdity like waterhose mist on a summer afternoon, "I wonder if you could help me."

"Happy to, miss," I mumbled.

She pushed a white rectangle in front of me on the painted maroon bar. "What do you think of this?"

I looked at the piece of paper. It was a coupon from a magazine.

Dear Acolyte R. I. S.:

Please send me FREE of obligation, in sealed wrapper, "The Scarlet Book" revealing to me how I may gain Secret Mastery of the Universe.

Name: ........................

Address: .....................

The world disoriented itself and I was on the floor of the somber diner and Miss Vivian Casey was out of sight and scent.

There was a five dollar bill tight in my fist. The counterman was trying to pull it out.

I looked up at his stubbled face. "I had half a dozen hamburgers, a cup of coffee and a glass of milk. I want four more 'burgers to go and a pint of coffee. By your prices, that will be one sixty-five—if the lady didn't pay you."

"She didn't," he stammered. "Why do you think I was trying to get that bill out of your hand?"

I didn't say anything, just got up off the floor. After the counterman put down my change, I spread out the five dollar bill on the vacant bar, smoothing it.

I scooped up my change and walked out the door. There was no one on the sidewalk, only in the doorways.

First I opened the door on an amber world, then an azure one. Neon light was coming from the chickenwire border of the room, from a window somewhere beyond. The wino on one side of the room was singing and the one on the other side was praying, same as before. Only they had changed around—prayer came from the left, song from the right.

Doc sat on the floor in the half-darkness and he had made a thing.

My heart hammered at my lungs. I knew this last time had been different. Whatever it was was getting closer. This was the first time Doc had ever made anything. It didn't look like much, but it was a start.

He had broken the light bulb and used the filament and screw bottom. His strong hands had unraveled some of the bed "springs"—metal webbing—and fashioned them to his needs. My orb-point pen had dissolved under his touch. All of them, useless parts, were made into a meaningful whole.

I knew the thing had meaning, but when I tried to follow its design, I became lost.

I put the paper container of warm coffee and the greasy bag of hamburgers on the wooden chair, hoping the odor wouldn't bring any hungry rats out of the walls.

I knelt beside Doc.

"An order, my boy, an order," he whispered.

I didn't know what he meant. Was he suddenly trying to give me orders?

He held something out to me. It was my notebook. He had used my pen, before dismantling it, to write something. I tilted the notebook against the neon light, now red wine, now fresh grape. I read it.

"Concentrate," Doc said hoarsely. "Concentrate...."

I wondered what the words meant. Wondering takes a kind of concentration.

The words "First Edition" were what I was thinking about most.

The heavy-set man in the ornate armchair was saying, "The bullet struck me as I was pulling on my boot...."

I was kneeling on the floor of a Victorian living room. I'm quite familiar with Earth history and I recognized the period immediately.

Then I realized what I had been trying to get from Doc all these months—time travel.

A thin, sickly man was sprawled in the other chair in a rumpled dressing gown. My eyes held to his face, his pinpoint pupils and whitened nose. He was a condemned snowbird! If there was anything I hated or held in more contempt than tourists or Martians, it was a snowbird.

"My clients have occasioned singular methods of entry into these rooms," the thin man remarked, "but never before have they used instantaneous materialization."

The heavier man was half choking, half laughing. "I say—I say, I would like to see you explain this, my dear fellow."

"I have no data," the thin man answered coolly. "In such instance, one begins to twist theories into fact, or facts into theories. I must ask this unemployed, former professional man who has gone through a serious illness and is suffering a more serious addiction to tell me the place and time from which he comes."

The surprise stung. "How did you know?" I asked.

He gestured with a pale hand. "To maintain a logical approach, I must reject the supernatural. Your arrival, unless hallucinatory—and despite my voluntary use of one drug and my involuntary experiences recently with another, I must accept the evidence of my senses or retire from my profession—your arrival was then super-normal. I might say super-scientific, of a science not of my or the good doctor's time, clearly. Time travel is a familiar folk legend and I have been reading an article by the entertaining Mr. Wells. Perhaps he will expand it into one of his novels of scientific romance."

I knew who these two men were, with a tormenting doubt. "But the other—"

"Your hands, though unclean, have never seen physical labor. Your cranial construction is of a superior type, or even if you reject my theories, concentration does set the facial features. I judge you have suffered an illness because of the inhibition of your beard growth. Your over-fondness for rum or opium, perhaps, is self-evident. You are at too resilient an age to be so sunk by even an amour. Why else then would you let yourself fall into such an underfed and unsanitary state?"

He was so smug and so sure, this snowbird. I hated him. Because I couldn't trust to my own senses as he did.

"You don't exist," I said slowly, painfully. "You are fictional creations."

The doctor flushed darkly. "You give my literary agent too much credit for the addition of professional polish to my works."

The other man was filling a large, curved pipe from something that looked vaguely like an ice-skate. "Interesting. Perhaps if our visitor would tell us something of his age with special reference to the theory and practice of temporal transference, Doctor, we would be better equipped to judge whether we exist."

There was no theory or practice of time travel. I told them all I had ever heard theorized from Hindu yoga through Extra-sensory Perception to Relativity and the positron and negatron.

"Interesting." He breathed out suffocating black clouds of smoke. "Presume that the people of your time by their 'Extra-sensory Perception' have altered the past to make it as they suppose it to be. The great historical figures are made the larger than life-size that we know them. The great literary creations assume reality."

I thought of Cleopatra and Helen of Troy and wondered if they would be the goddesses of love that people imagined or the scrawny, big-nosed redhead and fading old woman of scholarship. Then I noticed the detective's hand that had been resting idly on a round brass weight of unknown sort to me. His tapered fingertips had indented the metal.

His bright eyes followed mine and he smiled faintly. "Withdrawal symptoms."

The admiration and affection for this man that had been slowly building up behind my hatred unbrinked. I remembered now that he had stopped. He was not really a snowbird.

After a time, I asked the doctor a question.

"Why, yes. I'm flattered. This is the first manuscript. Considering my professional handwriting, I recopied it more laboriously."

Accepting the sheaf of papers and not looking back at these two great and good men, I concentrated on my own time and Doc. Nothing happened. My heart raced, but I saw something dancing before me like a dust mote in sunlight and stepped toward it....

... into the effective range of Miss Casey's tiny gun.

She inclined the lethal silver toy. "Let me see those papers, Kevin."

I handed her the doctor's manuscript.

Her breath escaped slowly and loudly. "It's all right. It's all right. It exists. It's real. Not even one of the unwritten ones. I've read this myself."

Doc was lying on the cot, half his face twisted into horror.

"Don't move, Kevin," she said. "I'll have to shoot you—maybe not to kill, but painfully."

I watched her face flash blue, red, blue and knew she meant it. But I had known too much in too short a time. I had to help Doc, but there was something else.

"I just want a drink of coffee from that container on the chair," I told her.

She shook her head. "I don't know what you think it does to you."

It was getting hard for me to think. "Who are you?"

She showed me a card from her wrist purse. Vivian Casey, Constable, North American Mounted Police.

I had to help Doc. I had to have some coffee. "What do you want?"

"Listen, Kevin. Listen carefully to what I am saying. Doc found a method of time travel. It was almost a purely mathematical, topographical way divorced from modern physical sciences. He kept it secret and he wanted to make money with it. He was an idealist—he had his crusades. How can you make money with time travel?"

I didn't know whether she was asking me, but I didn't know. All I knew was that I had to help Doc and get some coffee.

"It takes money—money Doc didn't have—to make money," Miss Casey said, "even if you know what horse will come in and what stock will prosper. Besides, horse-racing and the stock market weren't a part of Doc's character. He was a scholar."

Why did she keep using the past tense in reference to Doc? It scared me. He was lying so still with the left side of his face so twisted. I needed some coffee.

"He became a book finder. He got rare editions of books and magazines for his clients in absolutely mint condition. That was all right—until he started obtaining books that did not exist."

I didn't know what all that was supposed to mean. I got to the chair, snatched up the coffee container, tore it open and gulped down the soothing liquid.

I turned toward her and threw the rest of the coffee into her face.

The coffee splashed out over her platinum hair and powder-blue dress that looked white when the neon was azure, purple when it was amber. The coffee stained and soiled and ruined, and I was fiercely glad, unreasonably happy.

I tore the gun away from her by the short barrel, not letting my filthy hands touch her scrubbed pink ones.

I pointed the gun generally at her and backed around the thing on the floor to the cot. Doc had a pulse, but it was irregular. I checked for a fever and there wasn't one. After that, I didn't know what to do.

I looked up finally and saw a Martian in or about the doorway.

"Call me Andre," the Martian said. "A common name but foreign. It should serve as a point of reference."

I had always wondered how a thing like a Martian could talk. Sometimes I wondered if they really could.

"You won't need the gun," Andre said conversationally.

"I'll keep it, thanks. What do you want?"

"I'll begin as Miss Casey did—by telling you things. Hundreds of people disappeared from North America a few months ago."

"They always do," I told him.

"They ceased to exist—as human beings—shortly after they received a book from Doc," the Martian said.

Something seemed to strike me in the back of the neck. I staggered, but managed to hold onto the gun and stand up.

"Use one of those sneaky Martian weapons again," I warned him, "and I'll kill the girl." Martians were supposed to be against the destruction of any life-form, I had read someplace. I doubted it, but it was worth a try.

"Kevin," Andre said, "why don't you take a bath?"

The Martian weapon staggered me again. I tried to say something. I tried to explain that I was so dirty that I could never get clean no matter how often I bathed. No words formed.

"But, Kevin," Andre said, "you aren't that dirty."

The blow shook the gun from my fingers. It almost fell into the thing on the floor, but at the last moment seemed to change direction and miss it.

I knew something. "I don't wash because I drink coffee."

"It's all right to drink coffee, isn't it?" he asked.

"Of course," I said, and added absurdly, "That's why I don't wash."

"You mean," Andre said slowly, ploddingly, "that if you bathed, you would be admitting that drinking coffee was in the same class as any other solitary vice that makes people wash frequently."

I was knocked to my knees.

"Kevin," the Martian said, "drinking coffee represents a major vice only in Centurian humanoids, not Earth-norm human beings. Which are you?"

Nothing came out of my gabbling mouth.

"What is Doc's full name?"

I almost fell in, but at the last instant I caught myself and said, "Doctor Kevin O'Malley, Senior."

From the bed, Doc said a word. "Son."

Then he disappeared.

I looked at that which he had made. I wondered where he had gone, in search of what.

"He didn't use that," Andre said.

So I was an Earthman, Doc's son. So my addiction to coffee was all in my mind. That didn't change anything. They say sex is all in your mind. I didn't want to be cured. I wouldn't be. Doc was gone. That was all I had now. That and the thing he left.

"The rest is simple," Andre said. "Doc O'Malley bought up all the stock in a certain ancient metaphysical order and started supplying members with certain books. Can you imagine the effect of the Book of Dyzan or the Book of Thoth or the Seven Cryptical Books of Hsan or the Necronomican itself on human beings?"

"But they don't exist," I said wearily.

"Exactly, Kevin, exactly. They have never existed any more than your Victorian detective friend. But the unconscious racial mind has reached back into time and created them. And that unconscious mind, deeper than psychology terms the subconscious, has always known about the powers of ESP, telepathy, telekinesis, precognition. Through these books, the human race can tell itself how to achieve a state of pure logic, without food, without sex, without conflict—just as Doc has achieved such a state—a little late, true. He had a powerful guilt complex, even stronger than your withdrawal, over releasing this blessing on the inhabited universe, but reason finally prevailed. He had reached a state of pure thought."

"The North American government has to have this secret, Kevin," the girl said. "You can't let it fall into the hands of the Martians."

Andre did not deny that he wanted it to fall into his hands.

I knew I could not let Doc's—Dad's—time travel thing fall into anyone's hands. I remembered that all the copies of the books had disappeared with their readers now. There must not be any more, I knew.

Miss Casey did her duty and tried to stop me with a judo hold, but I don't think her heart was in it, because I reversed and broke it.

I kicked the thing to pieces and stomped on the pieces. Maybe you can't stop the progress of science, but I knew it might be millenniums before Doc's genes and creative environment were recreated and time travel was rediscovered. Maybe we would be ready for it then. I knew we weren't now.

Miss Casey leaned against my dirty chest and cried into it. I didn't mind her touching me.

"I'm glad," she said.

Andre flowed out of the doorway with a sigh. Of relief?

I would never know. I supposed I had destroyed it because I didn't want the human race to become a thing of pure reason without purpose, direction or love, but I would never know for sure. I thought I could kick the habit—perhaps with Miss Casey's help—but I wasn't really confident.

Maybe I had destroyed the time machine because a world without material needs would not grow and roast coffee.