LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

MARCH 15 1918

SERIAL NO. 151

THE

MENTOR

THE INCAS

By

OSGOOD HARDY, M. A.

DEPARTMENT OF

HISTORY

VOLUME 6

NUMBER 3

TWENTY CENTS A COPY

The deity whose worship the Incas especially inculcated, and which they never failed to establish wherever their banners were known to penetrate, was the Sun. It was he who, in a particular manner, presided over the destinies of man; gave light and warmth to the nations, and life to the vegetable world; whom they reverenced as the father of their royal dynasty, the founder of their empire; and whose temples rose in every city and almost every village throughout the land.

Besides the Sun, the Incas acknowledged various objects of worship, in some way or other connected with this principal deity. Such was the Moon, his sister-wife; the Stars, revered as part of her heavenly train, though the fairest of them, Venus, known to the Peruvians by the name of Chasca, or the “youth with the long and curling locks,” was adored as the page of the Sun, whom he attends so closely in his rising and in his setting. They dedicated temples also to the Thunder and Lightning, in whom they recognized the Sun’s dread ministers, and to the Rainbow, whom they worshiped as a beautiful emanation of their glorious deity.

In addition to these, the subjects of the Incas enrolled among their inferior deities many objects in nature, as the elements, the winds, the earth, the air, great mountains and rivers, which impressed them with ideas of sublimity and power, or were supposed in some way or other to exercise a mysterious influence over the destinies of man.

But the worship of the Sun constituted the peculiar care of the Incas, and was the object of their lavish expenditure. The most renowned of the Peruvian temples, the pride of the capital, and the wonder of the empire, was at Cuzco, where, under the munificence of successive sovereigns, it had become so enriched that it received the name of “The Place of Gold.” It consisted of a principal building and several chapels and inferior edifices, covering a large extent of ground in the heart of the city, and completely encompassed by a wall, which, with the edifices, was all constructed of stone.

The interior of the temple was most worthy of admiration. It was literally a mine of gold. On the western wall was emblazoned a representation of the deity, consisting of a human countenance looking forth from amidst innumerable rays of light which emanated from it in every direction, in the same manner as the sun is often personified with us. The figure was engraved on a massive plate of gold of enormous dimensions, thickly powdered with emeralds and precious stones. It was so situated in front of the great eastern portal that the rays of the morning sun fell directly upon it at its rising, lighting up the whole apartment with an effulgence that seemed more than natural, and which was reflected back from the golden ornaments with which the walls and ceiling were everywhere encrusted. Gold, in the figurative language of the people, was “the tears wept by the Sun,” and every part of the interior of the temple glowed with burnished plates and studs of the precious metal.

From Prescott’s “Conquest of Peru.”

ENTRANCE TO DOMINICAN CHURCH, CUZCO, PERU

ONE

Rude and destructive as were most of the Spanish conquistadores (con-kees-tä-dõ´-rays), many of them sympathized with the conquered people, and it is from the records of their impressions that we have obtained most of what we know about the Incas. Four of these Castilian diarists whose work is most valued were soldiers. Of their number, Pedro de Cieza de Leon (pay´-dro day see´-ay-sa day lay´-on) has given us the fullest and most interesting account of the ancient Peruvians. Only a boy of fourteen was he when he embarked on the Spanish Main, and he was only nineteen when, in 1538, he joined an expedition up the valley of the Cauca (kä-oo´-kä). He commenced his chronicle in 1541, and for ten years traveled from one end of Peru to the other, writing down his impressions as he went. The first part of his journal was published in 1554. Juan de Betanzos (hwän day bay-tän´-sos), another soldier, has left us but a portion of his work. We have only the record used by Friar Gregorio de Garcia (gray-go´-rio day gar-see´-a) in the first two chapters of his “Origen (o-ree´-hen) de los Indios,” and an incomplete manuscript in the Escurial (ay-skoo-ree-al). This was edited and printed in 1880 by Jimenez de la Espada (hee-may´-nes day lä ay-spä´-dä). Betanzos’ work is valuable, as he learned the Quichua (kee´-choo-a) language and was an official interpreter. Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (pay´-dro sär-mi-ayn´-to day gäm-bo´-ä), a militant sailor, accompanied the Viceroy Toledo (to-lay´-do), and was employed by him to write a history of the Incas. Finished in 1572, it is without doubt the most authentic and reliable we possess as regards the course of events. Pedro Pizarro, a cousin of the conqueror, was also a historian of merit, finishing the “Relaciones” (rā-lä-see´-o-nays) at Arequipa (är-ay-kee´-pä) in 1571.

The writings of lawyers have been of little value, although Prescott made use of the unpublished “Relaciones” of Polo de Ondegardo (po´-lo day on-day-gär´-do), written in 1561 and 1570.

The priests were the most diligent inquirers respecting the native religion, rites, and ceremonies. Vincente de Valverde (vis-ayn´-tä day väl-vayr-day) was the first priest to come to Peru, but he stayed only a short time and wrote very little. The best known clerical author is Josef de Acosta (hos´-ayf day ä-cos´-tä), who was in Peru from 1570 to 1586, and traveled over the greater part of the country. Cristoval Molina’s (krees-to´-väl mo-lee´-nä) “Report on the Fables and Rites of the Incas,” written previous to 1584, is also valuable, for he was a master of the Quichua language. Fernando Montesinos (fayr-nän-do mon-tay-see´-nos), who, with his amazing list of kings, traced Inca ancestry back to Noah, was until recently given little consideration. But lately his work, “Ophir de España, Memorias Historiales (o-feer´ day ay-spän-yä may-mo´-ree-äs ees-tor-ee-a´-läs) y Políticos del Peru (po-lee´-tee-cos dayl pay-roo´),” written about 1644, has been given more credence, since it seems probable that much of it was based on the writings of Blas Valera (bläs vä-lay-rä). The premature death of the latter and the disposal of his valuable manuscripts is described by Markham as the most deplorable loss that Inca civilization has sustained. His work was used extensively by Garcilaso de la Vega (gär-see-lä´-so day la vay-gä), a grandnephew of the Inca Huayna Ccapac (wy´-nä k-kä´-päk). He is the most famous of all the historians, and is quoted some eighty times by Prescott.

The works of many of these authors and of others less famous are available today in English, as a result of the indefatigable efforts of Sir Clements Markham, whose translations have been published by the Hakluyt Society. There are still many interesting and valuable old manuscripts reposing in the archives of Madrid (mäd-reed´) and Seville (say-veel´-yay), which have yet to be discovered, edited, and given to the world. Of the Spanish historians who have been engaged in this work, Dr. Marcos Jimenez de la Espada is probably the best known. An excellent bibliography of Peruviana has been prepared by Markham and is published in “The History of the Incas,” Publications of the Hakluyt Society, Series II, Vol. XXII, Cambridge, England.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No 3, SERIAL No. 151

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

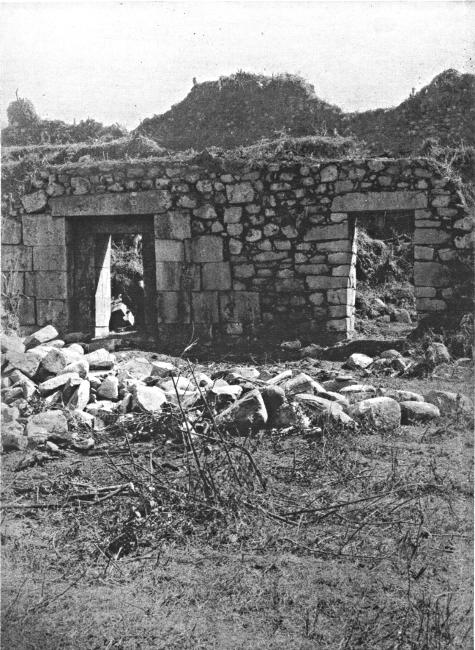

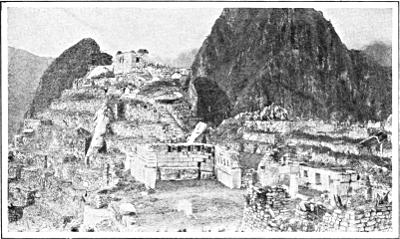

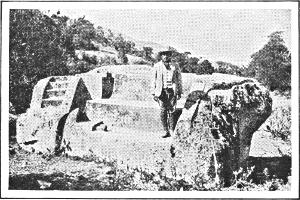

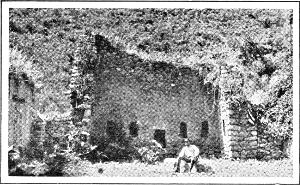

RUINS OF THE GREAT INCA TEMPLE OF VIRACCOCHA NEAR SICUANI, PERU

TWO

The Inca sovereigns about whom tradition tells us enough so that they may be considered historical personages are twelve in number. The first of these, Sinchi Rocca (seen´-chee rok-kä), or Rocca the Great, was the first ruler after the return of the Incas to Cuzco (coos´-ko) at the close of their long exile in Tampu-tocco (täm-poo-tok´-ko). He reigned from 1134-1197, according to the chronology of Dr. Gonzales de la Rosa (gon-sä-lays day lä ro´-sä), the most eminent of modern Peruvian historians. Rocca owed his position to a cleverly executed plot contrived by his mother. She dressed him in glittering gold apparel, and hid him in the Chingana (cheen-gä´-nä) Cave on Sacsahuaman (säk-sä-wä´-män) Hill. At intervals for several days excited Cuzqueñans (koos-kayn-yäns) beheld a golden vision moving on the fortress heights. Eventually, after their curiosity and fanatical credulity had been sufficiently aroused, the vision descended into the city. It gave itself over to the crowd, allowed itself to be conducted to the temple, and there proclaimed itself the adopted son of the Solar Deity. Under Rocca, the Temple of the Sun was enlarged and the city greatly improved.

There is some question among historians as to the acts of Rocca’s successors, Lloque Yupanqui (lyo´-kay yoo-pän´-kee) and Mayta Ccapac (my´-tä k-kä´-päk), who reigned from 1197-1246, and 1246-1276, respectively. Garcilaso (gär-see-lä´-so) records their conquering the Cana (kä´-nä) and Colla (kol´-yä) people in the southwest, building a Sun Temple at Hatun-Colla (ä-toom-kol´-yä), carrying on warfare along the shores of Lake Titicaca (tee-tee-kä´-kä), and Lake Aullagas (aul-yä´-gas), and on the west, going as far as Lake Parinaccochas (pär-een-äk-ko´-chäs) and Arequipa (a-ray-kee´-pä). But the majority of historians represent the first three Incas as confining themselves more or less to the Cuzco Valley, and gradually, by diplomatic means, extending their influence over the surrounding inhabitants.

Ccapac Yupanqui (yoo-pän-kee), 1276-1321, made the region to the southeast the theatre of his operations, and Garcilaso credits him with reaching Potosi (po-tos´-ee). Inca Rocca, 1321-1348, improved the water supply of Cuzco (would that he might come again), founded schools, and militariwise, attempted to penetrate the Amazonian forests. His son, Yahuar-Huaccac (yä´-wär-wäk´-käk) (weeping-blood), 1348-1370, was rather a nonentity. His name was acquired as follows, says tradition: While a child he fell into hostile hands. At the point of death he was seen to be weeping tears of blood. This so affected his enemy that he was permitted to live; he eventually escaped to his own people after a life of hardship among some shepherds.

He was followed by Uiraccocha (weer-äk-ko´-chä), 1370-1425, in whose reign occurred the invasion of the Chancas (chän´-käs). The invaders were finally driven out, chiefly through the bravery of his son, Pachacuti (päch-ä-koo´-tee), who reigned from 1425-1478. Under this rule and that of his successors, Tupac Yupanqui, 1478-1488, and Huayna Ccapac (wy´-nä k-kä´-päk), 1488-1525, the Inca dominion grew from a comparatively small confederation to the great, imperial state found by the Spaniards. Huascar (wäs´-kär), the successor of Huayna Ccapac, was overthrown and taken prisoner by his natural brother, Atahuallpa (ä-tä-wäl´-pä), about the time that Pizarro entered Peru. When the latter heard of the quarrel between the two brothers he determined to settle it. Fearful lest the decision should go against him, Atahuallpa had Huascar murdered, and this act provided Pizarro with an excuse for the execution of Atahuallpa.

After he had acquired complete control of the country, Pizarro elevated the Inca Manco (män´-co) to the throne. This proud youth soon tired of the farce and fled to the fastnesses of the Vilcabamba (veel-cä-bäm´-bä) mountains. Here he and his successors, Sayri Tupac (sigh-ree too´-päk) and Tupac-Amaru (too´-päk-ä-mä´-roo), maintained their independence until 1571, when the latter was captured by the Viceroy Toledo, brought to Cuzco, and there beheaded in the great square.

In 1781, a descendant of Tupac-Amaru bearing his name, led a revolt against the barbarous oppression of the Spaniards, only to fail and suffer torture, together with his whole family. In 1814, Pumacagua (poo-mäk-ä´-wä), also of Inca ancestry, started an abortive uprising, which, although a failure, was the beginning of the struggle which was to eventually break the power of Spain in Peru.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No 3, SERIAL No. 151

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

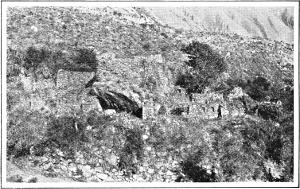

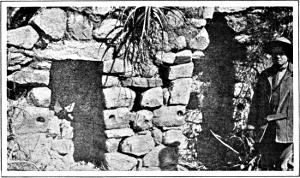

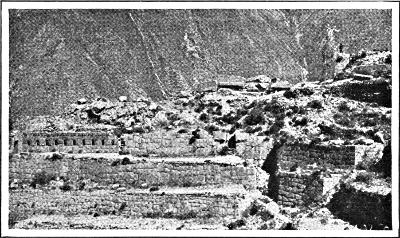

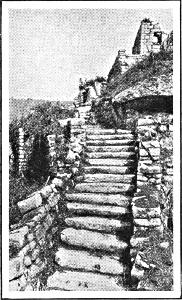

RUINS OF A TYPICAL INCA CITY

THREE

Although pacific by nature, the Incas built up their vast empire by conquest. Not one reign lacked great military campaigns, and in all of them the necessity of introducing the worship of the Sun gave rulers a pretext as plausible as the followers of Mahomet had for their great wars. Wherever it was possible, peaceful methods were employed. Persuasion, diplomacy and bribery were all tried; if these were unsuccessful, war was declared, but only after the failure of all the arts used in the acquisition of an empire by the most subtle politicians of a civilized land.

Immediately on the declaration of war, mobilization took place with extreme rapidity, for the Incas aimed early to secure such an obvious strategical advantage that their enemies would wisely surrender without a struggle. This was made possible by the remarkable series of roads constructed throughout the empire. In times of peace these served as post roads, which enabled the Incas to have surprisingly rapid intercommunication. At convenient places storehouses were located. These were always kept completely equipped, so that the mobilization of the Inca armies, which sometimes totaled 200,000 men, provided the minimum of inconvenience for the civilian population.

Contrary to the customs of some of our supposedly civilized modern nations, the Incas forbade their soldiers engaging in any unnecessary outrages, and punished such infractions of the law very severely. Even after the war had commenced, the Incas were always ready at any time to bring about peace. At the conclusion of hostilities they adopted the policy of the Romans, gaining more by clemency to the vanquished than by their victories.

As soon as the reduction of a country had been brought about, measures were taken to insure the loyalty of those newly conquered. The first step was the introduction of the worship of the Sun. No disrespect was shown to the local gods, but an acceptance of the priority of the Sun was always enforced. Often-times the peoples’ own gods were treated as hostages and removed to Cuzco. The Inca system of government was, of course, always imposed. Land was cultivated according to the well-regulated schemes of the Incas, which included fertilization, crop rotation, and careful supervision to see that the desired amount of acreage was devoted to each product. The Quichua language was enforced. The new members of the empire were assigned their particular style of clothing and hair-dressing. Roads were built to all parts of the new territories and absolute amalgamation was eventually secured.

In some instances, where the loyalty of the conquered was doubtful, a portion of them were removed, bag and baggage, to some locality where they would be surrounded by inhabitants of whose loyalty there was no question. Some of the latter were then sent to occupy the lands of the exiles.

Through successive reigns the same policy was continued. Each Inca took up the work where his predecessor had been compelled to leave it, and tried to do his share in advancing the boundaries of the empire. Each Inca’s life was a “crusade against the infidel to spread the worship of the Sun, to reclaim the benighted nations from their brutish superstitions, and to impart to them the blessings of a well-regulated government.”

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No 3, SERIAL No. 151

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

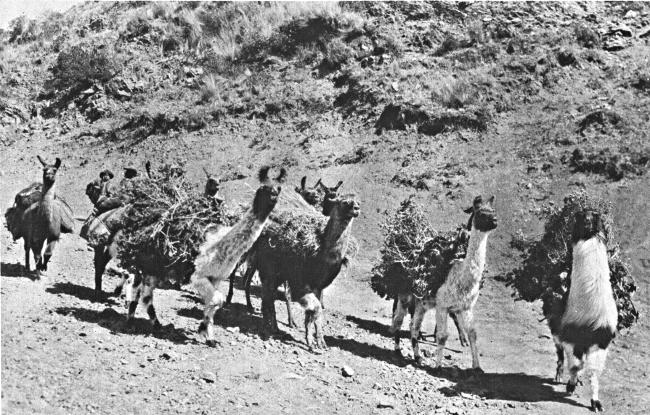

LLAMAS LADEN WITH FAGOTS COMING INTO CUZCO, PERU

FOUR

One of the greatest aids to the Incas in extending their domains was their abundant food supply: the result, largely, of the great progress they had made along agricultural lines. Although Peru is a very mountainous country, by taking advantage of every available inch of fertile ground where the climate permitted the raising of crops, they were able to carry on a system of agriculture which, in the variety of products yielded, seems truly marvelous. It is stated by Mr. O. F. Cook, of the United States Department of Agriculture, that a complete census of the plants cultivated by the ancient Peruvians would probably include between seventy and eighty species.

The most important products are the maize and the potato, one world crop of which is today more valuable than all the gold the conquering Spaniards were able to take out of the country. The cultivation of corn goes very far back, for abundant specimens have been found in ancient graves, and the type of maize that furnishes the bulk of the Peruvian crop is peculiar to that region.

Other plants familiar to us are the pineapple, the sweet potato, peanuts, beans, Lima beans, guava (gwä´-vä), alligator pears, papayas (pä-pä´-yäs), and chirimoyas (chee-ree-mo´-yäs), as well as many with which we are not familiar, as affu (äf´-foo), arracacha (är-rä-cä´-chä), tintin (teen´-teen), tomate (to-mä´-tay), purutu (poo-roo´-too), quinoa (keen´-o-ä), occa (ok´-kä), and ullucu (ool-yoo´-koo). From the dried potato a nutritious flour was made called chuña (choon´-yä), which was used to thicken stews.

The coca plant (Erythroxylon) was widely cultivated, but in the days of the Incas, if we are to believe the historians, its use was regulated by the government. Commonly used today by their modern descendants, it is alcohol’s most potent aid in the degradation of the Peruvian Indian.

We must not think, however, that the Incas were vegetarians. Although they lacked sheep, hogs and cattle, in the llama (lyämä) and alpaca they had excellent meat, as well as animals to provide them with wool, and in the case of the llama, a serviceable pack animal. The guanacos (gwä-nä´-kos) and vicuñas (vi-coo´-nyas), first cousins of the llama, were never domesticated, but were hunted in large drives superintended by representatives of the government. In the mountains there were rodents, such as the viscacha (vee-scä´-chä), chinchilla (cheen-cheel´-yä), and guinea-pigs. In the valleys there were monkeys and parrots. At the sea-shore and near the larger rivers fish were plentiful. Such excellent means of communication existed between the capital at Cuzco and the coast, that the Incas were kept constantly supplied with fresh fish.

The prevalence of both fishing and hunting is attested by the many depictions of these industries found on ceramic art objects which have been encountered by the archeologists. Hunting was carried on to such an extent, and the country in general was so intensively cultivated, that the Peruvian highlands today have less to offer the nimrod than any other section of the world equally uninhabited and desolate.

Alcoholic beverages were used, of course, but the government saw to it that their manufacture did not affect other industries. Chica (chee-cha) was made from both potatoes and maize, but the favorite brand was brewed from the molle (mol-yay) berry. Then, as today, religious feasts provided the common people with an opportunity for debauchery, but under the Incas there was less of the consequent inebriety.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No 3, SERIAL No. 151

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

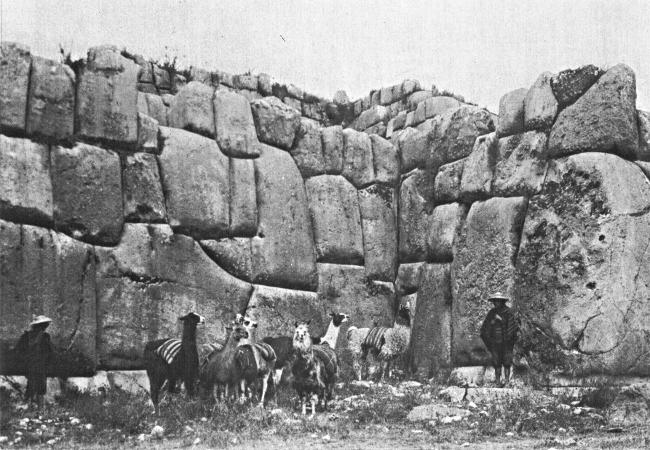

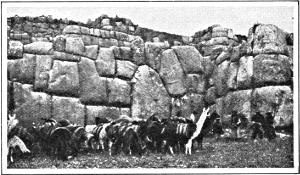

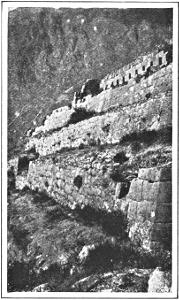

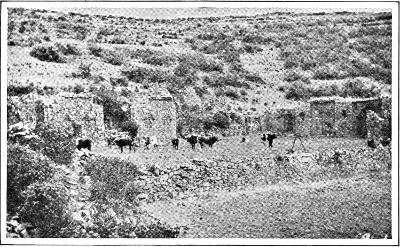

SACSAHUAMAN, THE INCAS’ GREATEST FORTRESS, CUZCO, PERU

FIVE

Together with the excellence of their governmental system and the extent of their food supply, the architecture of the ancient inhabitants of the Peruvian plateau establishes their claim to fame. Although early historians attempted to give the Incas themselves the credit for the wonderful structures to be found in Peru, it is generally believed today that most of the megalithic remains, such as Tiahuanaco, Sacsahuaman and Ollantaytambo, are the work of a people living many centuries before the Incas, whose own traditions carry them back only about 400 years prior to the coming of the Spaniards. However that may be, the ability to make equally fine structures evidently existed down to Spanish times, although in later years such work became less and less common.

There is a great uniformity in Inca architecture. In the highlands the edifices are usually built of porphyry or granite, and in the coastal regions more frequently of brick. The walls often have a thickness of several feet, but are rather low, seldom attaining more than ten or twelve feet in height. The apartments seldom open into each other—usually onto a court. The doors, which ordinarily provide the only entrance for light, are like the Egyptian, narrower at the top. The ruins at Machu Picchu (mä-choo peek´-choo) and in that vicinity are remarkable because windows are quite common in them. As the Incas had not evolved the arch, their doors, windows and niches were crowned with a lintel stone, in many cases necessarily a huge affair. Among the most interesting features of an Inca residence are these niches, probably used for shelves, perhaps for shrines, although if for that purpose there would seem to be more of them than necessary in most houses.

The fineness of the stonework is, of course, the most remarkable characteristic of the Incas’ architecture. They seemed able to fit, with equal facility, blocks of stone weighing tons and those weighing but a few pounds. Although they are not known to have used the T-square, some of their angles are very true, and when it seemed desirable, they could build a straight wall. Particularly beautiful are some of their circular structures, such as the Temple of the Sun in Cuzco.

It is probable that only the temples and palaces of the rulers were so well built, and that the common people lived in houses of mud and stone. One of the most remarkable structures in Peru, the temple of Uiraccocha (u-eer-äk-ko´-chä) at Racche (räk´-chay), shows a combination of fine stonework, and mud and stone. In addition, the upper part of these walls, which tower some thirty feet high, is of adobe (a-do´-bay) only, and centuries of weathering has done but little more damage to the sun-dried bricks than to the granite foundations.

There is something incongruous in the fact that the roofs of the buildings walled so beautifully, and often covered inside with skilfully woven tapestries and gold adornments, were commonly of thatch. The rafters were of wood, tied on to ring stones and projecting cylinder stones with maguey withes. But, although they were ignorant of iron, did not even mortise their timbers, and were content with a dingy, unlighted interior, the buildings of the Incas were adapted to the character of the climate, and the wisdom of their plan is attested by the number which still survive, while the more modern constructions of the conquerors have been buried in ruins.

Providing they escape the destructive hands of the treasure-hunting Peruvians, only a gigantic cataclysm of the earth’s surface can destroy these monuments to the stoneworking skill of Peru’s ancient inhabitants.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No 3, SERIAL No. 151

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

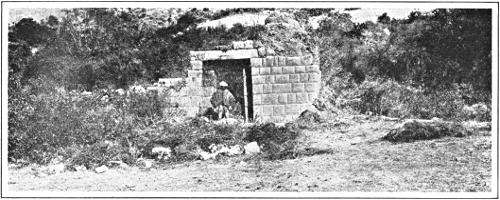

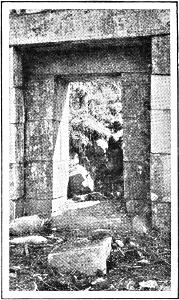

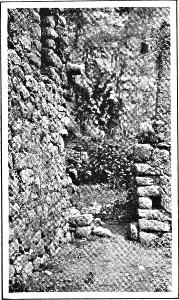

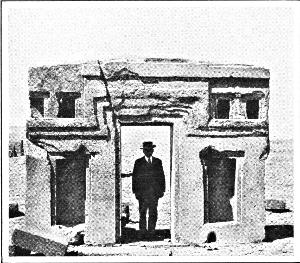

DOORWAYS IN INCA RUINS OF ROSASPATA

SIX

The location of Vitcos (veet´-kos), or Pitcos (peet´-kos), the home of the Inca Manco after he fled from Cuzco to the wilds of Vilcabamba (veel-kä-bäm´-bä), was one of the questions which students of Inca history had never answered. Arm-chair archeologists and historians had selected the site of Choqquequirau (chok-kā-kee-rä´-oo) (cradle of gold), which consists of a series of extensive ruins above the Apurimac (a-poo-ree´-mak) River near Abancay (ä-bän-ca´-ee). His visit to these ruins convinced Dr. Hiram Bingham, of Yale University (now Lieut.-Colonel Bingham), that Vitcos and Choqquequirau could not be identical.

Accordingly, in 1911 he conducted an expedition to Peru, one object of which was to find a place that would fit the descriptions of the Inca’s retreat as given by the early Spanish historians, some of whom, i.e., Father Antonio de Calancha (än-to´-nee-o day cä-län´-chä) and Baltasar de Ocampa (bäl-tä-sär´ day o-cäm´-pä), had actually visited Vitcos.

The expedition went down the Urubamba (oo-roo-bäm´-bä) Valley to the mouth of the Vilcabamba River, crossed the Chuquichaca (choo-kee-chä´-cä) Bridge, and went up the Vilcabamba Valley, finding place after place which tallied with the accounts of Ocampo (o-käm´-po) and Calancha (cä-län´-chä). Above the little town of Puquiura (poo-kee-oo´-ra) were encountered ruins now called Rosaspata (ro-säs-pä´-tä). Careful study has proved that these fit, in every detail, the description of the Inca’s last home.

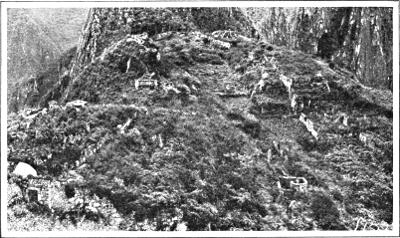

While on his way to Vitcos, Colonel Bingham was fortunate enough to discover the ruins of Machu Picchu. Although the problematical existence of these ruins had long been known, no one had ever taken the trouble to climb to the top of the ridge and make certain as to their location. In so doing, Colonel Bingham came upon ruins whose magnificent beauty alone makes them of more than ordinary interest, but doubly important is the discovery because in Machu Picchu we seem to have found at last the Tampu-tocco (tämpoo-tok´-ko) of early Inca legends.

The selection of Paccari-tampu (päk´-ka-ree-tam´-poo) as Tampu-tocco has never seemed justified. The slight similarity in name, the location of a few ruins and natural caves in that vicinity, and the non-existence of any place which had a better claim, made up the evidence to substantiate the theories of those who wished to call Paccari-tampu the cradle of the Inca race. Machu Picchu, as shown by Colonel Bingham,[1] corroborates in every detail the descriptions of Tampu-tocco given by all the historians.

[1] See The Story of Machu Picchu, by Hiram Bingham. Nat. Geo. Mag., Feb., 1915, and Vitcos, ibid., Proceedings of the Am. Antiquarian Soc., April, 1912.

In addition, it appears that Machu Picchu may also be Vilcabamba, the old, the mysterious place three days’ journey from Vitcos, to which, as told by Father Calancha, two monks were taken by the Incas while they were in that region seeking his conversion. No situation at all plausible has ever been suggested for this mythical locality. Granting that Machu Picchu is Tampu-tocco, the presence of two distinct cultures and skeleton remains, chiefly of women and effeminate men, would seem to indicate that on his retreat to Vitcos the Inca Manco made use of the wonderfully concealed first home of the Incas to provide safe retirement for the priests and priestesses of the Sun.

A very important part of the work of modern archeology lies in identifying the location of the cities and towns which have a place in Inca tradition and history. The finding of the first and last home of the Incas by Colonel Bingham’s expeditions is only the beginning of a great deal of similar work which awaits the archeologist in Peru.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 6, No 3, SERIAL No. 151

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

THE MENTOR · DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

MARCH 15, 1918

RUINS OF MAUCALLACTA, PACCARITAMBO—Near view of the gateway

By OSGOOD HARDY, M. A.

Instructor in Spanish in the Sheffield Scientific School, and Chief Assistant and Interpreter of the Peruvian Expeditions of 1914-1915, under the auspices of Yale University and the National Geographic Society

MENTOR GRAVURES

RUINS OF A TYPICAL INCA CITY · SACSAHUAMAN, THE INCAS’ GREATEST FORTRESS, CUZCO, PERU · ENTRANCE TO DOMINICAN CHURCH, CUZCO, PERU · DOORWAYS IN INCA RUINS OF ROSASPATA · LLAMAS COMING INTO CUZCO · RUINS OF THE GREAT INCA TEMPLE OF VIRACOCHA, NEAR SICUANI, PERU

NOTE.—All pictures in this Mentor are reproduced by permission of the National Geographic Society and the South American Exploration Fund of Yale University, under whose auspices the Peruvian Expeditions directed by Dr. Hiram Bingham have taken place.

NOTE ON PRONUNCIATION.—The letter “ä” with two dots above is pronounced as in “father”; the “ā” with a horizontal line above is pronounced as in “ray.”

Entered as second-class matter March 10, 1913, at the postoffice at New York, N. Y., under the act of March 3, 1879. Copyright, 1918, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

There is probably no part of the world that stimulates more curiosity in an archeologist or even in a casual traveler than that part of South America which was once inhabited by the Incas of Peru. Tiahuanaco’s (tee-ä-wane-ä´-ko) finely carved gateway and its ponderous stone platforms, Sacsahuaman’s (saks-ä-wa´-män) gigantic walls, Ollantaytambo’s (ol-yän-tie-tam´-bo) monolithic fortress, and Machu Picchu’s (mä´-choo peek´-choo) picturesque grandeur fill one with an admiration for their builders which is only equaled by the sorrow that today, over three centuries after the advent of Pizarro (pee-sä´-ro) and his conquistadores (con-kees-tä-do´-rays), we can do little more than make conjectures concerning the ancient Peruvians.

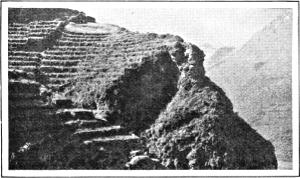

RUINS OF PATALLACTA—A Typical Inca Temple

And, furthermore, it is doubtful if we can ever go very far in solving the problem of man in the Andes. Although they made great progress in architecture, agriculture, engineering, and the science of government, the ancient Peruvians did not achieve the art of writing, nor did they even reach the stage of hieroglyphics. Their records were kept on quipus (kee-poos), variously colored strings with many different kinds of knots. These seem, however, to have been used only for accounting purposes. Thus far, the quipus in possession of our archeologists have been of no particular aid in deciphering the history of their makers. Accordingly, what we know of the Incas consists of traditions gathered together by early Spaniards, and the work of present-day students who, by modern archeological methods, are slowly bringing some light to bear on this apparently insolvable problem.

PISAC

Terraces below the principal ruins, still used for growing wheat and barley

DOORWAY

In ruins, now known as Rosaspata, but which Dr. Bingham has shown are probably those known to the Incas as “Vitcos,” the last home of the Incas

Although there are many ideas advanced as to the origin of the American aborigine, it is commonly believed that he came from northeastern Asia and gradually moved southward. Archeologists and geologists are all agreed that he arrived at the close of the glacial epoch, long after the disappearance of the prehistoric animals which Dr. Matthew described for Mentor readers some time ago. When he came to this continent he had probably already reached the higher stages of the Stone Age, and was possibly already in the Bronze Age. Just how long it has been since his arrival we cannot tell.

Although the number of traditions concerning the origin of the Inca empire is legion, the two best known are the Titicaca (tee-tee-kä´-kä) and Tampu-tocco (täm-poo-tok´-ko) legends. The former has been given us by the immortal Prescott, relying on the Commentaries of the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (gär-sil´-ä-so day lä vay-gä). From him we know there was a time when the ancient races of the continent were all plunged in deplorable barbarism. “The Sun, the grand luminary and parent of mankind, taking compassion on their degraded condition, sent two of his children, Manco Ccapac (män´-ko k-kä´-päk) and Mama Occlo (mä´-mä ok´-klo), to gather the natives into communities and teach them the arts of civilized life. The celestial pair, brother and sister, husband and wife, advanced along the high plains in the neighborhood of Lake Titicaca to about the 16th degree south. They bore with them a golden wedge, and were directed to take up their residence on the spot where the sacred emblem should without effort sink into the ground. They proceeded but a short distance—as far as the valley of Cuzco (koos´-ko), the spot indicated by the performance of the miracle; there the wedge speedily sank into the earth and disappeared forever. On this spot the children of the Sun established their residence, and laid the foundations of the city of Cuzco.”

RUINS OF PATALLACTA

Showing niches with holes for bar locks in the upper room of the temple on top of the rock

INCA FORTRESS WALL, SACSAHUAMAN

The gigantic size of the stones and the precision with which they are fitted, without mortar, bear testimony to the engineering genius of the Inca megalithic builders

The Titicaca myth, however, does not receive as much consideration today as the Tampu-tocco (täm´-poo-tok´-ko) myth. The former is characterized by the late Sir Clements Markham as an obvious invention to account for the ancient ruins and statues in the vicinity of Tiahuanaco (tee-ä-wane-ä´-ko), and on the islands of Titicaca and Koati (ko-ä´-tee). “It has no historical value,” he says, “while the Tampu-tocco myth is as certainly the outcome of a real tradition, and is the fabulous version of a distant historical event.”

CUZCO, PERU

PALACE OF THE INCA ROCCA

A large gravure picture of this massive structure will be found in The Mentor (No. 132) on “Peru”

The story is somewhat as follows. At a distance from Cuzco is a place called “Tampu-tocco” (“House of the Windows”). This was long considered to be identical with “Paccari-tampu” (päk´-kä-ree-tam´-poo) (“House of the Dawn”), but the explorations and study of Dr. Bingham have shown that the evidence is in favor of his statement that Machu Picchu is Tampu-tocco. From this locality, at a date placed by students somewhere between 950 B. C. and 200 A. D., came four brothers accompanied by four sisters. Their leader, Manco (män´-ko) (the princely), succeeded in making away with his three brothers, so that at length, on their arrival at Cuzco, where the golden rod which this Manco also carried sank into the ground, the first Inca and his sisters were able to found their kingdom without rivals. Under the leadership of Manco and his successors, sometimes known as “Pre-Megaliths,” the empire grew. In the seventeenth or nineteenth reign a change in dynasty took place, and thenceforth the megalithic monarchs, who were often distinguished and skilful astrologers and reformers, ruled with the title of Amauta (ä-mä-oo´-tä).

About 450 A. D. came the end of this dynasty. Pachacuti (pä-chä-koo´-tee) VI, a ruler of peoples on the east, south and west and subject tribes, had risen in revolt. The invaders ultimately retired, but the power of Cuzco was broken, and the ruler slain. The city was left to the priests, and the inhabitants, under a new sovereign, took refuge at Tampu-tocco, where some twenty-four princes ruled in succession. At length, when the provinces once under the control of the princes of Cuzco had relapsed into barbarism, a woman of high birth named Siyu-yacu (see´-yoo-yä´-koo), contrived a plot to place on the throne one who would initiate a bold attempt to recover the power once possessed by their forefathers. The individual selected was Siyu-yacu’s own son, Rocca (rok´-kä). The plot was successful, and Rocca, later known as Sinchi Rocca (seen´-chee rok´-kä) or the Great Rocca, was the first of the Inca sovereigns whose reign looms up clearly enough to remove it from the realm of traditions and give it a place, although slightly hazy, in history. From the accession of Rocca to the throne, about 1100 A. D., down to the murder of Tupac Amaru (too´-päk ä´-mä-roo) in 1671 by the Viceroy Francisco de Toledo (frän-sees´-ko day to-lay-do), the course of events is fairly well authenticated. It is to this period that a discussion of the Incas must necessarily be confined.

ALPACAS

A semi-domesticated animal resembling sheep, and yielding a long, fine wool, usually brown or black

GROUP OF LLAMAS IN JULIACA

When the Spaniards arrived, the little kingdom of Cuzco had already grown to an empire that extended to the equator on the north, and was bounded on the south by the River Maule (mä´-oo-lay) in southern Chile (chee´-lay). On the west it extended to the Pacific Ocean, and on the east faded away in the torrid forests of the Amazon and the rolling hills of the Argentine uplands. The Incas had succeeded in conquering the many tribes scattered over this whole region, and for the most part had enforced the use of their own language, the Quichua (kee´-choo-a). They had evolved a system of government which, expanding from that of a village community, had met the needs of a vast empire; and they had done it so gradually that the inhabitants at large had been conscious of little change save in the direction of increased prosperity and security.

MACHU PICCHU RUINS

General view, showing growth covering ruins

The Inca government was a despotism. The Inca—the chief magistrate of the dominant tribe—had absolute powers, and as a direct descendant of the Sun was also vested with sacred attributes. Surrounding him and under him were his immediate family. His official wife was his sister, and from their offspring was chosen the successor of the Inca. The elder was usually designated, although this rule was broken in several instances where the younger brother seemed more able. Next in the social scale were the nobles, or orejones (o-ray-ho´-naze), as they were called by the Spaniards. These officials wore very large earrings. The lobe of the ear was often distorted so that ornaments several inches in diameter were inserted. Under the orejones came the caracas (cä-rä´-cäs), or inspectors, who had charge of the census, the estimation of local resources, and the imposition and collection of tribute. Their work was chiefly administrative, and the actual government was left to district magistrates and judges, who acted as tax-collectors also. Finally, there were the common people. These were divided for military purposes into 10s, 100s, 1,000s, and 10,000s, and the mobilization of the Inca armies was almost Teutonic in its ease and precision.

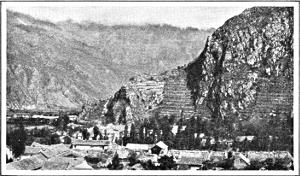

OLLANTAYTAMBO—The Town and Fortress

As might be expected, the Inca religion included the worship of many things. The priestly historians always characterize it as extremely vile; but those of Inca ancestry insist that it was remarkably pure and spiritual, consisting of only one true worship, that of the Sun. Only those that have experienced life in the Peruvian highlands and have endured the enervation of its cold altitudes can realize how certainly must the early peoples have turned to the worship of that force which alone makes life endurable or possible on the Peruvian plateau.

The places of worship were usually temples, so located as to catch the first rays of the rising sun. Huacas (wä´-käs), such as large rocks or springs, were, of course, worshiped where they were situated, and oft-times were surrounded by temples. In the case of stones, shelves or platforms were carved, on which the priests stood while making their offerings to the Sun god.

The worship was carried on by priests and mamaconas (mä-mä-ko´-näs), the latter, the priestesses, directed the lives of the virgins of the Sun. The most beautiful girls of the kingdom were gathered together from all parts of the land. The most attractive became the wives of the Inca, after they had passed through a severe training in the various feminine arts; others took the vows and became mamaconas, while the rest either became wives of the nobles or were sent back to their homes.

MACHU PICCHU

Sacred Plaza and Intihuatana Hill

OLLANTAYTAMBO—The Fortress

Many different feasts were celebrated, the most famous being those of Intip Raymi (een´-teep rye´-mee) and Situa (see´-too-a). The former was celebrated in June at the winter solstice, the object being to secure the return of the Sun. It lasted for nine days, was celebrated by all the ruling caste, and was always successful. Situa was celebrated in August, and the movable huacas were transported to Cuzco from all over the empire. There were also many feasts of local and family significance, as those of name-giving and adolescence.

The rites of worship were sacrifice, prayers, confession, and fasting. Although there has been a great deal of controversy over this point, it is generally accepted that, unlike the Mexican peoples, the Incas did not make human sacrifices. Offerings of food, libations and animal sacrifices were the customary procedure. Some of the Inca prayers which have come down to us are remarkable for their beauty and spiritual qualities. Confession was made to a priest. Fasting was usually observed by those desirous of entering some sacred spot, as at the end of a pilgrimage, and is said to have been at times of twenty days’ duration. The more famous pilgrimages were those to Pachacamac (pä-chä-kä´-mac) and Titicaca.

OLLANTAYTAMBO

Lower terrace of Fortress

“The condition of the peasant in Peru,” summarizes Mr. T. A. Joyce, “approximated nearer to the ideals of the doctrinaire socialist than in any country of the world. But it was at a price which, perhaps, the native of no other country would consent to pay. From the cradle to the grave the life of the individual was marked out for him; as he was born, so would he die, and he lived his allotted span under the ceaseless supervision of officials. His dress was fixed according to his district; he might not leave his village except at the bidding of the state, and then only for state purposes; he might not even seek a wife outside of his own community. An individual of ability might, perhaps, rise to be one of the subordinate inspectors, but the higher ranks were inexorably closed to him.”

THE CONCACHA STONE

A famous “Huaca” (meaning “holy”). The name was applied to material objects, such as rocks, etc., which were worshiped

Because of this despotism, which placed all the labor in the hands of the state, the Incas were able to achieve marvels in the way of building, road-making, irrigation works, and agricultural engineering. Inherently an agricultural people, the greatest efforts of the ancient Peruvians seem to have been exerted, not in building tombs for the dead, as did the Egyptians, but in making conditions better for the living. It is true that a great deal of labor was expended on the wonderful palaces of their rulers. Each successive Inca thought it necessary to rear an edifice for himself. But the greater part was employed for the benefit of the country as a whole, in irrigation and other projects. Water was brought many miles, and regions which today are desolate through the Spaniards’ failure to keep in repair the ditches and canals were flourishing agricultural communities in the days of the Incas. Rampant streams that threatened to destroy fertile valleys were penned within stone walls. Roads made throughout the whole dominion were useful, of course, for the transportation of troops, but especially valuable because the intershipment of crops was thereby made easy.

MACHU PICCHU

Intihuatana Hill and Stairway

As might be expected in a mountainous country, where a wide stretch of level ground is but seldom encountered, the construction of miles upon miles of terraces was necessary. “Many slopes,” writes Mr. O. F. Cook, of the United States Department of Agriculture, “have more than fifty terraces, forming huge staircases as high as the Washington Monument, resting against the lower slopes of mountains that tower thousands of feet above.”

RUINS ON KOATI ISLAND

The famous Island of the Moon

The stonework of the prehistoric builders excites the wonder and admiration of the beholder—admiration for the grand and beautiful simplicity of the Inca masonry, wonder as to the methods employed in its accomplishment. What the means were we do not know—at best we can only conjecture. The modern Indians—in fact, many of the upper class of Peruvians—prefer to explain it by magical methods, such as softening the rocks by rubbing them with the juice of some plant or fruit. Only the combined labor of hundreds of people, understanding the lever and the inclined plane, could have moved some of the huge rocks that form many of the walls. And moving them would be the easiest part of the work. How they succeeded in fitting these monoliths together, so that in places the joints are too fine for the naked eye to discern, is quite beyond the ken of the modern stone-worker. Formerly it was thought that the larger terraces were chiefly for defensive purposes; but the fact that these, as well as those more plainly agricultural in character, show the underlying strata of stones to be covered with fine agricultural soils that must have been brought from a distance, would indicate, according to some of our scientists, that these also were used to produce crops. The importance attached to agriculture can be understood from the fact that the majority of the terraces equal in fineness of masonry even the palaces of the Incas. Lacking timber, the Incas used stone as the chief building material, and, although they had not evolved the pure arch, they had learned to secure strength through the keying together of irregular blocks, and, as Dr. Bingham writes, “had developed many ingenious devices, such as lock-holes for fastening a bar back of the door; ringstones, which were inserted in the gables to enable the rafters to be tied on; and projecting cylinder stones, which could be used as points to which to tie the roof and keep it from blowing off.”

RUINS OF TORONTOY

Showing window, a projecting cylinder stone and lock-hole

Sculpture existed only in a rude form, and the decoration of Inca pottery did not equal that of the coast people. Their ceramic products are marked by simple and graceful lines, rather Grecian in effect, and of striking simplicity and utility. They had arrived at a high degree of skill in the manufacture of textiles, for the llama and alpaca provided them with excellent raw material.

Although they were unfamiliar with refined methods of heat treatment, and so were compelled to sacrifice extra hardness and strength by increasing the tin content, they had learned the art of cold working, and produced many kinds of bronze implements. Some of these were of an excellent temper, and, together with obsidian knives, were used for trepanning. Inca methods of warfare, the use of slings and war clubs, naturally caused many wounds which could be relieved only by such operations.

In war their skill was defensive rather than offensive. They built salients and re-entrant angles in their walls, and dry moats are often encountered.

They domesticated the South American camel (the llama), which enabled them to carry out engineering and agricultural works far more difficult than they could have accomplished had they been obliged to depend on human bearers. In addition to maize, potatoes, and cassava, they had many other important crops, such as pineapples, peanuts, and cotton. Great is the treasure of precious and base metals which has come, and is to come, from Peru. But that sinks into insignificance beside the value of one corn and potato crop throughout the world. And in the future it seems not at all unlikely that the Incas, famous for centuries for their system of government, their masonry, and the treasures which the Spaniards took from them, will be yet more famous for the extent to which they developed agriculture.

RUINS OF TORONTOY

The man is seated on a carved rock, probably an altar

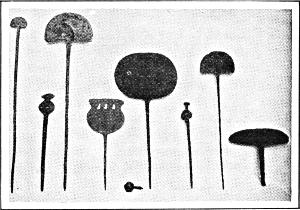

INCA IMPLEMENTS

We can do no better, in closing this account of the old Peruvian empire, than to quote from Mr. Prescott’s imperishable work, “The Conquest of Peru,” the following summary of the characteristics of Inca culture:

“Under the rule of the Incas, the meanest of the people enjoyed a far greater degree of personal comfort than was possessed by similar classes in other nations on the American continent—greater probably, than in feudal Europe. Under their scepter, the higher order of the state had made advances in many of the arts that belong to a cultivated community. By the well-sustained policy of the Incas, the rude tribes of the forest were gradually gathered within the folds of civilization, and of these materials was constructed a flourishing and populous empire, such as was to be found in no other part of America.”

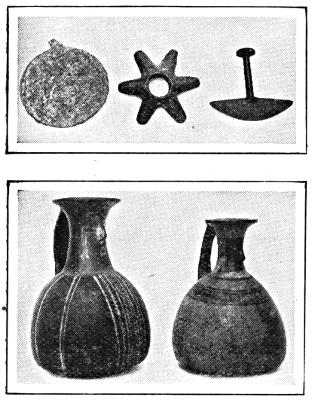

INCA POTTERY AND INSTRUMENTS

| EARLY MAN IN SOUTH AMERICA | By Ales Hrlicka |

| Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 52 | |

| HISTORY OF THE CONQUEST OF PERU | By W. H. Prescott |

| THE INCAS OF PERU | By Sir Clements R. Markham |

| SOUTH AMERICAN ARCHEOLOGY | By Thomas A. Joyce |

| STAIRCASE FARMS OF THE ANCIENTS | By O. F. Cook |

| National Geographic Magazine, Volume 29, No. 5 | |

| FURTHER EXPLORATIONS IN THE LAND OF THE INCAS | By Dr. Hiram Bingham |

| National Geographic Magazine, Volume 29, No. 5 | |

| THE STORY OF MACHU PICCHU | By Dr. Hiram Bingham |

| National Geographic Magazine, Volume 27, No. 2 |

MONOLITHIC GATEWAY AT TIAHUANACO

We are indebted to Dr. Hiram Bingham and his Peruvian Expeditions for the interesting picture material in this number of The Mentor. Dr. Bingham (Lieut.-Colonel Bingham) became interested in South America when he was in Yale University, and in 1906 he took an expedition over the historic march of Bolivar from Venezuela to Colombia. Two years later, when Colonel Bingham was appointed a delegate to the first Pan American Scientific Congress at Santiago, Chile, he went there by way of Bolivia and Peru, and, while in Peru, he visited the ruins of Choqquequirau (meaning the “cradle of gold”), said to be the last home of the Incas.

Colonel Bingham’s studies led him to think that the legend was wrong. So, in 1911, he set off to Peru, with a party of six, his objects being to hunt for “Vitcos” (the name of the last home of the Incas) and to make an ascent of Corropuna, reputed to be a rival of Aconcagua for the honor of being the highest mountain in South America. The expedition was very successful. Corropuna was scaled, and found to be somewhat lower than Aconcagua. Vitcos was found at Rosaspata and not at Choqquequirau. The reputed bottomless lake of Parinaccochas was found to be no more than four feet in depth, and, best of all, Machu Picchu was discovered.

All this was so important that the National Geographic Society decided to assist in another expedition to carry on the good work. Accordingly, the Peruvian Expedition of 1912, under the auspices of Yale University and the National Geographic Society, was sent out. It cleared the way, photographed and mapped Machu Picchu, and made many other explorations. A report of this expedition was received with so much interest, and the pictures were considered so beautiful, that the Peruvian Expedition of 1914-1915 was organized under the same auspices. This expedition accomplished a great amount of additional work in the way of map making and archeological research, collecting flora and fauna from districts previously unvisited, and determining the location of several rivers.

A vast amount of important historical material has been gathered by these expeditions, and The Mentor is very fortunate in being permitted to use photographs collected in the course of the expeditions, and in having a member of the party as author of this article. In connection with Mr. Hardy’s account of the Incas, Colonel Bingham writes to The Mentor as follows:

“Within the confines of the ancient Inca empire, the archeologist can find a field for work, which, in the beauty of its natural surroundings, and the healthfulness of its climate, together with the interest lent by the present-day inhabitants, is equal, if not superior to, any other part of the earth’s surface.

“In the past, its comparative inaccessibility has been a very great deterrent to systematic work in the regions once occupied by the Incas. Now, better steamship connections with the rest of the world, and increasing railway mileage within, have greatly lessened the transportation difficulties.

“The solution of the problem of man in the Andes has only begun, and it is to be hoped that American students will have many future opportunities to enter this field of research.”

W. D. Moffat

Editor

I want to let you know how this little ranch-woman has enjoyed her part in The Mentor Course. I would not take the influence of the pictures alone out of my family for many times the cost. I am deeply interested in all the subjects, but Nature comes first. When my husband and I ride among the whispering pines far up the sides of El Capitan or through the dainty ferns in some deep canyon, where only the tops of the dark towering firs know what the day is like, and the tiny streams slip swiftly and songfully over and through the rocks, I feel the quieting presence of God—and all the worrisome, tawdry business of life sinks down into the unimportant place where it really belongs. I wish The Mentor all profit and success in the good work it is doing in bringing people nearer to the real, big things of the world.

MRS. C. R. DEAN, Lincoln, New Mexico

The Mentor Association

ESTABLISHED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POPULAR INTEREST IN ART, LITERATURE, SCIENCE, HISTORY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL

THE MENTOR IS PUBLISHED TWICE A MONTH

BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC., AT 114-116 EAST 16TH STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y. SUBSCRIPTION, FOUR DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES TWENTY CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, J. S. CAMPBELL; ASSISTANT TREASURER AND ASSISTANT SECRETARY, H. A. CROWE.

THE MENTOR

Just a Word About Railroads and Mails

The railroads are in an unprecedented condition of congestion, and the mail trains, carrying second-class matter, are from two to eight days late in arriving at their destinations.

If you do not receive your copy of The Mentor on the day it is due, please do not take it for granted that you have been neglected. Your copy is probably being held up somewhere along the line. Wait a few days before you write us; it will save us both a great deal of trouble, and your copy will probably be delivered to you before we can reply to your letter.

We wish it were in our power to prevent this annoyance, but as we are helpless, we can only ask you to be patient and considerate.

The Mentor Association

MAKE THE SPARE

MOMENT COUNT