| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See https://archive.org/details/autobiographyofp00pettuoft |

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

As noted in the Preface, some [missing words] in the text have been added inside brackets [ ] in this edition. Many archaic and nautical terms are explained in the Footnotes.

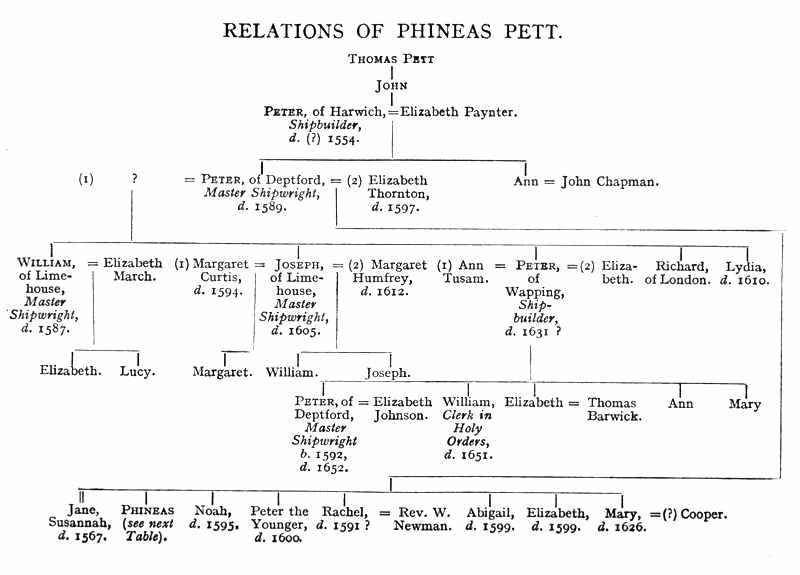

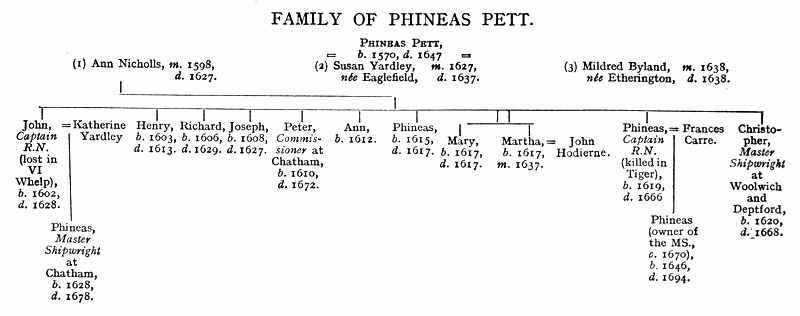

On some handheld devices the two genealogical tables are best viewed in a small font or in landscape mode. An image of each table from the original text is also provided.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

PUBLICATIONS

OF THE

NAVY RECORDS SOCIETY

Vol. LI.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF PHINEAS PETT

EDITED BY

W. G. PERRIN

PRINTED FOR THE NAVY RECORDS SOCIETY

MDCCCCXVIII

THE COUNCIL

OF THE

NAVY RECORDS SOCIETY

1917-1918

PATRON

THE KING

PRESIDENT

THE RIGHT HON. LORD GEORGE HAMILTON, G.C.S.I.

VICE-PRESIDENTS

Corbett, Sir Julian S., F.S.A.

Custance, Admiral Sir Reginald N., G.C.B., K.C.M.G., C.V.O., D.C.L.

Firth, Professor C. H., LL.D., F.B.A.

Gray, Albert, K.C., C.B.

COUNCILLORS

Atkinson, C. T.

Bethell, Admiral Hon. Sir A.E., K.C.B., K.C.M.G.

Brindley, Harold H.

Callender, Geoffrey A. R.

Dartmouth, The Earl of, K.C.B.

Desart, The Earl of, K.C.B.

Dewar, Commander Alfred C., R.N.

Gough-Calthorpe, Vice-Admiral The Hon. Sir Somerset A., K.C.B., C.V.O.

Guinness, Captain Hon. Rupert E. C., C.B., C.M.G., M.P., R.N.V.R., Ad. C.

Kenyon, Sir Frederic G., K.C.B., D.Litt., F.B.A.

Leyland, John

Marsden, R. G.

Milford Haven, Admiral The Marquess of, P.C., G.C.B., G.C.V.O., K.C.M.G., LL.D., Ad. C.

Murray, John, C.V.O.

Newbolt, Sir Henry

Ottley, Rear-Admiral Sir Charles L., K.C.M.G., C.B., M.V.O.

Parry, Sir C. Hubert, Bt., C.V.O.

Pollen, Arthur H.

Richmond, Captain Herbert W., R.N.

Robinson, Commander Charles N., R.N.

Sanderson, Lord, G.C.B., K.C.M.G., I.S.O.

Slade, Admiral Sir Edmond J. W., K.C.I.E., K.C.V.O.

Smith, Commodore Aubrey C. H., M.V.O., R.N.

Tanner, J. R., Litt.D.

SECRETARY

Lieut.-Colonel W. G. Perrin, O.B.E., R.A.F., Admiralty, S.W.

HON. TREASURER

Sir W. Graham Greene, K.C.B., Ministry of Munitions, S.W.

The Council of the Navy Records Society wish it to be distinctly understood that they are not answerable for any opinions or observations that may appear in the Society's publications. For these the responsibility rests entirely with the Editors of the several works.

The manuscript in which Phineas Pett has recorded the story of his life from his birth in 1570 to the end of September 1638, consisted originally of sixty-nine uniform quarto sheets, of which the 52nd is now lost, together with the bottom of the 14th. The handwriting is that of Phineas throughout, but marginal references on the first few pages and a note at the end—'The life of Commissioner Pett's father whose place he did enjoy'—have been added subsequently by Samuel Pepys, no doubt when he was making the transcript referred to below.

The first paragraph is written on a separate sheet, which, unlike the rest, has no writing on the back, and is followed by a series of subtraction sums of the form 1612 1570 42 giving the age of Phineas for each year from 1612 to 1640. From the differences apparent in the figures and ink it is clear that these calculations were made year by year from the time that Phineas was forty-two until he reached the age of seventy.

A close inspection of the internal construction, the handwriting, and of the ink used, leads to the conclusion that the body of the manuscript,[viii] in the form in which it has descended to us, was written up, not at short intervals, but in sections at comparatively long intervals of time. The first and largest of these, written apparently in 1612, narrates the events down to September 1610, and stops at the word 'ordered' on line 15 of page 80 below. The remainder[1] of that paragraph continues on a fresh sheet in a smaller handwriting and different ink, and from that point the ample margin of the earlier pages is abandoned and a small one ruled off with lead pencil. The top line of this page is also ruled, and from this page to the end of the writing the use of these pencil lines persists. The next break is in July 1611 (page 92), where Pett reiterates the statement that he was sent for by Prince Henry. Another break in the writing seems to occur in September 1613; and a very perceptible one, with change of ink, occurs in 1625 at 'All April' (page 134). The final section, as indicated by a further change of ink, begins in February 1631: 'The 23rd of February' (page 146). The various anachronisms observable in the text show that these sections were written up some considerable time after the events occurred. Thus, the references to 'Sir' John Pennington in 1627 and 1628 make it clear that the events of those years were not written up before 1634.

From the great accuracy of the dates given (which have been frequently tested from contemporary sources), it is clear that Phineas kept a diary in which events were recorded as they occurred, and from which the narrative was compiled. He appears to have commenced this diary on going to Chatham in June 1600, [ix]when precise dates begin to replace the vague 'about,' 'toward the end,' &c., of the earlier paragraphs.

The narrative stops abruptly in 1638, apparently with the sentence unfinished, for there is no mark of punctuation after the last word. In 1640, when the final section seems to have been written, Pett was an old man, and it is probable that, having been interrupted at this point, the fast-gathering troubles of the State diverted his mind from the subject, or left him without sufficient energy or leisure to pursue it.

It will be noticed that towards the end the composition becomes more slovenly and the omission of words more frequent, as though the task had become burdensome and the author anxious to have done with it.

Pepys copied the whole of the manuscript into the first volume of his Miscellany with the following preface:

'A Journal of Phineas Pett, Esquire, Commissioner of the Navy and father to Peter Pett, late Commissioner of the same at Chatham, viz: from his birth Ao 1570 to the arrival of the Royal Sovereign, by him then newly built, at her moorings at Chatham; transcribed from the original written all with his own hand and lent me to that purpose by his grandson Mr. Phineas, son to Captain Phineas Pett.'

The manuscript afterwards came into the possession of George Jackson, who was Secretary of the Navy Board in 1758 and Second Secretary of the Admiralty from 1766 to 1782. Sir George Duckett (he had changed his surname in 1797) died in 1822, and ten years later his library,[x] including a very valuable collection of naval manuscripts, was sold by auction. Fortunately the manuscripts were purchased by the British Museum after being bought in at the sale; the volume (No. IV) in which this manuscript was contained becoming Additional MS. 9298. A commonplace book (Additional MS. 9295) containing, among copies of various naval documents, an abbreviated version was purchased at the same time.

The copy of the autobiography most generally known is the early eighteenth-century transcript in the Harleian Collection (Harl. 6279). It is to this copy that writers usually refer, possibly because it is mentioned in the paper[2] published in Archæologia in 1796, although the garbled extracts there given are stated to have been taken 'from another copy' and seem, in fact, to have been taken from the original.[3] A further reason for the preference generally shown for the Harleian copy may be its more modern and more clerkly handwriting.

The Harleian transcript is not a good one. It contains few omissions, none of great importance, but mistranscriptions of individual words are very numerous and have reduced the text to nonsense in several places.[4] It may seem strange that writers should be content to quote passages that were evidently incorrect, without looking at another copy, which was easily to be [xi]found; but whatever the reason may be, the fact is that hitherto the original has remained unidentified as such.

The best transcript is that made by Pepys; but even he had difficulty in deciphering some of the words, although the handwriting of Pett is, on the whole, very clear and consistent.

In preparing this edition, the Pepysian and Harleian copies have been collated and the missing parts of the original made good by this means; but as the numerous inversions of form and mistakes of reading in these copies have no general interest—and are of no authority in presence of the original—there is no need to specify them in detail.

Considerable licence has been taken with the punctuation of the sentences, which is entirely without system in the original, and the spelling has been modernised in accordance with the rule of the Society, but the composition has been left otherwise untouched. Where some word is necessary to complete the sense it has been added in square brackets [ ], and the parts now missing from the original, which have been supplied from the transcripts, have been printed in italics. The legal year in England, prior to 1752, did not commence until the 25th March, and Pett usually gives his dates by this reckoning, but in one or two instances he writes as though the year had begun on 1st January and ended on 31st December. To avoid misunderstanding, it may be stated that the dates in the Introduction, headings, and notes are given according to the Julian year, commencing on 1st January.

Pett invariably wrote and signed 'Phinees' but it has been thought better to adhere to the spelling 'Phineas,' which appears from time to[xii] time in documents from 1605 onwards and has been universally adopted by modern writers.

In the Introduction an attempt has been made: first, to trace the rise of the Master Shipwright as an official of the Crown and to consider his relation to the profession of shipwrights generally; secondly, to trace the origin of the Pett family and its ramifications down to the date of Phineas' death; thirdly, to throw additional light on the events narrated in the manuscript from such original sources as are accessible. In asking the indulgence of the reader towards the evident shortcomings of this attempt, the Editor would plead that most of the work has had to be carried out under great difficulties in scanty moments of leisure. Despite the generous assistance of Mr. Vincent Redstone of Woodbridge, whose extensive knowledge of Suffolk genealogy has been brought to bear on the problem, it has not been found possible to trace the Pett family to its original location, but it is hoped that sufficient has been done to render this task more easy to some future investigator.

In conclusion the Editor has to thank many friends for the help readily given, more especially Dr. Tanner, who has read the proofs and given the Introduction the benefit of his criticism, and Mr. G. E. Manwaring, of the London Library, who has rendered invaluable help in clearing up many obscure points, and he is indebted to Mrs Scott for the loan of the MS. treatise on shipbuilding referred to in the Introduction. The Editor has also had the great advantage of discussing with Mr. L. G. Carr Laughton the technical questions raised in connexion with the Prince Royal and the Sovereign of the Seas.

December 1918.

W. G. P.

[1] Probably rewritten when the narrative was taken up again.

[2] By the Rev. S. Denne, Archæologia xii. p. 217.

[3] The words 'and ourselves to sit with the Officers' (page 144), not in the Harleian copy, are in the printed version.

[4] E.g. 'Articles' for 'Arches,' p. 14; 'enemy' for 'injury,' p. 26; 'tarried' for 'arrived,' p. 25; 'Frank Moore' for 'Tranckmore,' p. 33; 'perceived' for 'protested,' p. 61; 'care' for 'ease,' p. 104; 'Warwick,' for 'Woolwich' p. 142, &c., &c.

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | ||

| The Shipwrights | xv | |

| The Family of Pett | xlii | |

| Phineas Pett | lii | |

| The Autobiography | 1 | |

| Appendices | ||

| I. | Grant to Phineas Pett | 173 |

| II. | Petition of Shipwrights | 175 |

| III. | Charter to Shipwrights' Company (1605) | 176 |

| IV. | Charter to Shipwrights' Company (1612) | 179 |

| V. | New Building the Prince Royal | 207 |

| VI. | Petition to the Admiralty (1631) | 210 |

| VII. | Letter to Buckingham (1623) | 212 |

| VIII. | Protest against Building the Sovereign | 214 |

| IX. | Ships Built or Rebuilt by Phineas Pett | 217 |

| X. | The Arms of Pett | 218 |

| Index | 219 | |

It might be supposed that so ancient a craft as that of shipbuilding would have left some trace in contemporary records of its activities, the methods of its technique, and the personalities of those engaged in it. Yet although references to ships and shipping are frequent in the records of this country from the earliest times, and although the shipwright was a distinct class of workman at least as early as the tenth century—probably much earlier—no record of the methods in which he set about the design and construction of ships earlier than the end of the sixteenth century appears to have survived.

It may be presumed that those of our earlier kings who possessed a navy royal, and did not rely entirely on the support of the Cinque Ports and of the merchant shipping, would include among their servants some skilled man to perform the functions of a master shipwright, and if not to design, at any rate to look to the upkeep of the king's ships and to watch the construction in private yards of those intended for the royal service. But if the Clerk of the Ships, who first comes into notice in the reign of John, had any such subordinate, his existence[xvi] before the end of the reign of Henry V is not known to us. It is, however, possible that, on occasion, this duty was performed by the king's carpenters, whose principal function seems to have been to keep the woodwork of the royal castles in repair. In 1337 forty oaks required in the construction of a galley, then being built at Hull for Edward III under the superintendence of William de la Pole, a prominent merchant of that town, were supplied by the Prior of Blyth, who was directed to hand them over to William de Kelm (Kelham), the king's carpenter (carpentario nostro).[5] The accounts for this galley have not survived, and there is no means of ascertaining whether William de Kelm had anything to do with the actual construction. Another galley and a barge were at the same time being built at Lynn under Thomas and William de Melcheburn. The accounts[6] show that the master carpenter (magister carpentariorum) of the galley was John Kech, who was paid at the rate of sixpence[7] a day and had under him six carpenters at fivepence a day, six 'clynckers' at fourpence, six holders at threepence, and four labourers (servientes) at twopence halfpenny. The master carpenter of the barge was Ralph atte Grene, who received the same rate of pay as Kech. Neither Kech nor Grene appear as the King's servants.

In 1421 the 'King's servant' John Hoggekyns, 'master carpenter of the king's ships,' was granted by letters patent a pension of fourpence a day, 'because in labouring long about them he is much shaken and deteriorated in body,' [xvii]and this grant was confirmed in December of the following year on the accession of Henry VI. In 1416-18 Hoggekyns had built the Grace Dieu, 'if not the largest, probably the best equipped ship yet built in England.'[8]

With the sale of most of the royal navy on the death of Henry V, the need for a 'master carpenter of the King's Ships' must have passed away, and no trace of any further appointment of this character has been found for over a century. The construction of the Regent in 1486 was entrusted by Henry VII to the Master of the Ordnance, and it seems probable that the design of the Henri Grace à Dieu, built in 1514, was the work of the Clerk of the Ships, Robert Brygandin,[9] although the superintendence of her building was entrusted to William Bond (or Bound), who is described in 1519 as 'late clerk of the poultry, surveyor, and payer of expenses for the construction of the Henri Grace à Dieu and the three other galleys.'[10]

It is not until the later years of Henry VIII's reign that steps appear to have been taken to establish in the royal service a permanent body of men skilled in the art of shipbuilding. From the earliest times of which records exist it had been the practice to send out agents to the various ports to impress the shipwrights, caulkers, sawyers, and other workmen required for the construction and repair of ships of the Royal Navy. This system was no doubt satisfactory while the [xviii]merchant ship and the royal ship presented no essential points of difference; the latter were, indeed, often let out to hire for mercantile purposes. But when the ship-of-war began to carry a larger number of guns than the trading ship found necessary for her protection—a change that may be roughly dated from the end of the fifteenth century—the methods of construction began to diverge, and the old system of casual impressment must have tended to become less and less satisfactory; so that when Henry, after remodelling the material of the Navy, turned, at the end of his reign, to the improvement of the Administration he no doubt saw the necessity of attracting permanently to his service men capable of directing the art of shipbuilding, as applied to ships of war, in the new channels in which it was henceforth destined to run.

Up to this point, the position of the shipwright—even of the Master Shipwright—was not an exalted one. He was classed among 'servants' and 'artificers,' and his pay was made the subject of legislation expressly designed to keep the wages of those classes as low as possible. In 'Naval Accounts and Inventories of the Reign of Henry VII, 1485-8 and 1495-7,' Mr. Oppenheim has edited material which illustrates the various rates paid to shipwrights, and has pointed out that these rates of pay 'had remained practically unaltered since the days of Henry V.' An Act of Parliament of 1495[11] laid down the following scale of payments:—

| From Candlemas to Michaelmas. | ||

| With meat and drink, a day | Without meat and drink, a day | |

| Master Ship Carpenter with charge of work and men under him | 5d. | 7d. |

| Other Ship Carpenter called a Hewer | 4d. | 6d. |

| An able Clincher | 3d. | 5d. |

| Holder | 2d. | 4d. |

| Master Caulker | 4d. | 6d. |

| A mean Caulker | 3d. | 5d. |

| Caulker labouring by the tide, for as long as he may labour above water and beneath water, shall not exceed for every tide | 4d. | — |

| From Michaelmas to Candlemas. | ||

| Master Shipwright | 4d. | 6d. |

| Hewer | 3d. | 5d. |

| Able Clincher | 2½d. | 4½d. |

| Holder | 1½d. | 3d. |

| Master Caulker | 3d. | 5d. |

| A mean Caulker | 2½d. | 4½d. |

This Act was repealed in 1496, but the same scale was fixed in 1514 by an Act[12] that was not repealed until 1562.

It will be observed that the highest rate under these Acts is sevenpence a day, although in several instances in the accounts[13] referred to [xx]above a Master Shipwright was paid eightpence a day.

When Henry VIII instituted[14] the practice of granting by letters patent an annuity for life to certain shipwrights performing the duties of the office known later as 'the Master Shipwright,' he fixed the daily rate upon the basis set forth above, but it must be borne in mind that (as will be shown later) this did not represent the total emoluments of that official, who was in effect raised, both as to emoluments and status, above the class in which he had formerly been placed.

The first of the succession of officials thus established by Henry appears to have been James Baker, who by letters patent[15] dated the 20th May 1538 was granted, as from Michaelmas 1537, an annuity for life of fourpence a day, the lowest rate of a Master Shipwright, or Master Ship Carpenter as he was alternatively called by the Acts referred to. The entry in the Roll is of some interest; unlike the later grants, this grant is not based upon past services, but solely upon services which are to be rendered in the future,[16] and the authority for the letters patent is not the usual writ of privy seal, but the direct motion of the King: 'per ipsum Regem.' In December 1544 new letters patent were issued,[17] in which Baker is described as a 'Shipwright' and the annuity (annuitatem sive annualem redditum) fixed at eightpence a day. In January [xxi]of the same year, Peter Pett, 'Shipwright,' had by letters patent been granted a wage and fee (vadium et feodum) of sixpence a day for life, as from Michaelmas 1543, 'in consideration of his good and faithful service done and to be done'; from which it appears that Peter Pett was already in the royal service. It is probable that the increase in Baker's annuity was intended to mark his superior position in relation to Pett.

The official title of 'master shipwright' does not appear as yet in use, for when Baker and other shipwrights were, in the next year, sent by the Council, at the request of the Lord Admiral, to Portsmouth to examine into the decay of one of the ships there, they were simply described as 'Masters James Baker and others skilful in ships.'[18] In addition to Baker and Pett, these included John Smyth, Robert Holborn, and Richard Bull. On the 23rd April 1548 these three latter, under the designation of 'Shipwrights,' together with Richard Osborn, anchor-smith, 'had by bill signed by the King's Majesty each of them 4d. per diem in consideration of their long and good service and that they should instruct others in their feats.'[19] Smyth and Holborn were hardly in the same category as Baker and Peter Pett. They seem to have been skilled mechanics rather than constructors or designers, and are not mentioned as having 'built' a ship, though this is perhaps due to the scantiness of the surviving records; but the fact that the formality of letters patent was dispensed with in connexion with this grant is significant. Bull was, however, in May 1550 granted 12d. a day from Midsummer 1549 by letters [xxii]patent in the usual terms,[20] and since Peter Pett was not granted this higher rate until April 1558,[21] in the last year of Mary's reign, it would seem as though Bull's services were rated by Edward VI more highly than Pett's. James Baker does not seem to have long survived Henry VIII. Probably he died in 1549, and Bull received Baker's annuity, since it is not likely that an additional annuity would be created for Bull at that time, and there is no mention of any reversion in Bull's patent.

Little is known of Bull[22] or of another master shipwright 'William Stephins'[23] who is mentioned in 1553 and 1558. The latter may have been the ancestor of the Stevens[24] who built the Warspite in 1596, and contested the place of Master Shipwright with Phineas.

In 1572 Mathew Baker, son of James, succeeded to Bull's annuity. The letters patent[25] by which the grant was made are different in form from those above referred to, for Baker is first granted the office of Master Shipwright[26] with all profits and emoluments pertaining to it, which he is [xxiii]to hold in as ample a mode and form as 'a certain Richard Bull, deceased,' or any other, had held such office, and then, for the exercise of this office, he is granted the usual annuity of 12d. a day for life, as from Lady Day 1572.

In January 1584 Baker attended personally at the Exchequer and of his free will surrendered this grant in exchange for one in similar form[27] made out to himself and John Addey[28] with reversion to the longer liver. The reasons why Baker thus formally adopted Addey as his successor do not appear. However, Baker outlived him, dying in 1613, whereas Addey died in 1606 at Deptford, where he was then the Master Shipwright.

In July 1582 Peter Pett had appeared at the Exchequer and surrendered his patent of 1558, receiving in exchange a joint patent,[29] in similar terms, for himself and his eldest son, William, who was already in the royal service as a shipwright,[30] with reversion to the longer liver. William, however, died in 1587, two years before his father, so that the annuity never reverted to him. In his will he describes himself as one of her Majesty's Master Shipwrights, [xxiv]and from the reference to him in the patent above referred to it seems probable that he held the office in 1584.

In 1587 Richard Chapman received a grant[31] of the office of 'Naupegiarius,' which was to be held on similar terms (modo et forma) to those in which Peter Pett and Mathew Baker or any other held like office, but the annuity granted with it was 20d. a day, and not the usual 12d. Apparently this was an additional post created especially for Chapman, and the 20d. indicates the rise that had by that time taken place in the shipwrights' rates of pay.

In July 1590 Joseph Pett was granted 12d. a day as from Midsummer.[32] Presumably this was the annuity that had reverted to the Exchequer on the death of his father in 1589, his brother William, who had held the reversion of it, being already dead; but the patent contains no reference to this, the grant being based upon 'his good and faithful service done and to be done in building our ships.' Unlike those issued to Mathew Baker and Chapman, this patent contains no reference to office and is in the earlier form. Phineas (see p. 4) dates Joseph's succession to his father's place as Master Shipwright in 1592, but this is evidently incorrect.

In April 1592 Chapman died[33] at Deptford, and William Bright, one of the Assistant Master [xxv]Shipwrights, succeeded to his post and annuity of 20d.[34] In July 1603 Edward Stevens, who was a private shipbuilder of some importance,[35] obtained a grant by letters patent[36] in terms that differ from those hitherto noticed. In consideration of service to be rendered in the future (post-hac), he is granted an office of Master Shipwright for life—which office he is to have and exercise directly one becomes vacant, in as ample a manner as Mathew Baker, William Bright and Joseph Pett or any other had held it—together with an annuity of 20d. a day for his services. Finally the patent concludes by declaring that no one else shall be admitted to such an office until after Stevens has been duly appointed and installed. This was the patent that gave Phineas such 'great discouragement' (p. 20). It is drawn up in due form, and it is difficult to understand on what grounds it can legally have been set aside. The patent[37] granted to Phineas in 1604 did not revoke it, it was not recalled, and it would appear that it was in virtue of this same patent that Stevens was finally admitted as Master Shipwright in 1613. However, Phineas, by the all-powerful influence of the Lord High Admiral, managed to get it set aside in his favour on the death of his brother Joseph in 1605, 'by reason the fee was mistaken wherein his Majesty was abused and charged with an innovation.'[38] The 'innovation' was evidently the grant of a [xxvi]'general reversion.' It would have been interesting to see the arguments laid before the Council by Stevens when, as Phineas tells us, he contested the decision, but unfortunately all the Council Registers from 1603 to 1613 perished in the fire at Whitehall in 1618. There is little wonder that Stevens (who was an older man and had, one would imagine, superior claims) bore a grudge against Pett. Stevens appears to have been appointed as Master Shipwright in the vacancy caused by the death of Baker in 1613. In 1614 he was Master Shipwright at Portsmouth, and was in 1621 serving with Phineas as his 'fellow' Master Shipwright at Chatham, where he died, being succeeded by Henry Goddard in 1626.

On 26th April 1604 Phineas, by the assistance of the Lord High Admiral, obtained the grant by letters patent of two chances of the reversion of an annuity of 12d. a day, either that of Baker-Addey or that of his brother Joseph. His brother was the first to die, and at the end of the following year Phineas succeeded to the annuity that had been in the hands of the Petts since 1544.

It is of interest to note that the patent was not of itself sufficient to enable the patentee to enter into the office of Master Shipwright; the Lord High Admiral's warrant was also necessary. A specimen of such a warrant has been preserved in the State Papers[39] in the case of Goddard, who succeeded Stevens in 1626, having held a reversion by patent since 1620, and runs as follows:—

Whereas we have received certain knowledge of the death of Edward Stevens late one of his[xxvii] Majesty's Master Shipwrights and the necessity and importance of his Majesty's Service requireth another man to be presently entered in his place. And forasmuch as the bearer hereof Henry Goddard is authorised by his Majesty's letters patents to execute the next place of a Master Shipwright that should become void by death or otherwise. And in regard we have had good experience of the sufficiency and honesty of the said Henry Goddard and that the said place of one of his Majesty's Master Shipwrights is granted to him by his Majesty's letters patents under the great seal of England. These are therefore to will and require you to cause the said Henry Goddard to be entered one of his Majesty's Master Shipwrights with such allowances as is usual.

Hereof we require you not to fail. And for your so doing this shall be your warrant.

Dated the 16 of September 1626.

J. Coke.

To our very loving friend Peter Buck, Esq., Clerk of his Majesty's Check at Chatham or his deputy.

The Lord High Admiral's records have long since disappeared, and in the State Papers for the period with which we are concerned very few documents remain of the bulk of naval records that must once have existed. This one is therefore of considerable interest on account of the light which it throws upon the very independent position of the Lord High Admiral in relation to the Crown: it may be doubted whether any other great officer of State was in a position of such authority that he could presume to ratify a grant that had already passed the Great Seal.

At the time when Phineas became a Master Shipwright, the ordinary wages of the post, paid by the Treasurer of the Navy, were 2s. a day; to this was added the Exchequer fee or annuity[xxviii] of 12d. (or in the case of Bright 20d.) a day. Besides these Mathew Baker received a pension from the Exchequer of £40 a year granted by writ of Privy Seal, said to be 'in recompense of his service after the building of the Merhonour'; a concession that at a later period[40] was extended to Phineas. Thus, at that period, the total yearly emoluments of Mathew Baker were £94, 15s.; of Bright £66, 18s. 4d.; and of Phineas Pett £54, 15s.; while the East India Company paid Burrell, their Master Shipwright, £200. After making allowance for the difference in the value of money at the beginning of the seventeenth century and its present (or rather pre-war) value,[41] it is clear that these were inadequate emoluments for so important a post, and it is not surprising that many of the Master Shipwrights kept private shipbuilding yards,[42] while all added to their income at the expense of the Crown in ways that were very irregular and constantly gave rise to scandal. Probably none was more adept in this art than Phineas himself.

In addition to the Master Shipwrights receiving an additional allowance from the Exchequer under letters patent, who seem to have been known as the 'principal' Master Shipwrights, there were others who, although they were never fortunate enough to succeed to an Exchequer annuity, performed the duties of the post, to which, apparently, [xxix]they were admitted by warrant from the Lord High Admiral before their reversions under letters patent fell due. In this category were William Pett and Addey.

The relationship between the royal shipwrights and the commercial shipbuilders was at all times very close. Not only did the former engage freely in commercial business, but they joined the latter in attempting to regulate the shipbuilding industry of the country. An undated petition of both classes of shipwrights for incorporation occurs among the State Papers of 1578.[43] No answer seems to have been given to it, but as there is a 'brief' of a patent for shipwrights dated 1592 mentioned in the calendar of Salisbury MSS.,[44] it is clear that the proposal subsequently received consideration, although the matter did not come to fruition until thirteen years later.

All record of the steps that preceded the grant of the Charter of 1605[45] appears to be lost. It is not probable that the aged Nottingham would have moved in the matter without strong pressure from below, and we can only surmise that the officers of the company thereby incorporated were the prime movers in the agitation which led to its being granted.

It will be observed that the petition of 1578 is based upon the alleged need for regulating the pay, discipline, and training of the ordinary shipwrights, now increasing rapidly in number with the increase of the mercantile marine. The arguments for granting the Charter of 1605, as set forth in the preamble, are two: first, that [xxx]all ships, both royal and merchant, were built neither strongly nor well; secondly, that many of the shipwrights were not sufficiently skilful. The remedy proposed for this state of affairs was the formation of a corporation or trade union, of which all persons engaged in shipbuilding in England and Wales were to be compelled to become members. The government of the corporation—and therefore of the whole shipbuilding industry of the country—was placed in the hands of a Master, four Wardens, and twelve Assistants. Baker, as the most noted shipbuilder of the period, was rightly made the Master; the wardenships were divided between the remaining two master-shipwrights and two of the most prominent private shipbuilders; the twelve assistantships were divided as follows: Phineas Pett, Addey, and Apslyn, from the royal dockyards; four shipbuilders of the neighbourhood of London; and one each from Woodbridge, Ipswich, Bristol, Southampton, and Yarmouth. The omission of any representative from Hull or Newcastle is noteworthy.

No record remains to show what effect this charter had; probably very little, if one may judge from the absence of any record of complaints against it, although the documentary remains of the first ten years of James I's reign are so very scanty that no great reliance can be placed upon this argument.

In 1612 another charter[46] was sealed. The necessity for this was based on the ground of the insufficiency of the powers granted by the former charter, and no pains were spared to remedy this, so far as words could do so. The Charter of 1605 extends over five and a half membranes[xxxi] of the Patent Roll, each membrane about 30 inches long and containing 90 lines of writing. The Charter of 1612 was a portentous document; its enrolment extends from membrane 16(2) to membrane 37 and contains about 15,600 words. No possible loophole was left for any verbal quibble or evasion on the part of those who might desire to escape from its jurisdiction; the 'all and every person and persons being shipwrights or carpenters using the art or mystery of shipbuilding and making ships' of the earlier charter—sufficiently explicit, one would have thought—becomes 'all and every person and persons being shipwrights, caulkers or ship-carpenters, or in any sort using, exercising, practising, or professing the art, trade, skill or mystery of building, making, trimming, dressing, graving, launching, winding, drawing, stocking, or repairing of ships, carvels, hoys, pinnaces, crayers, ketches, lighters, boats, barges, wherries, or any other vessel or vessels whatsoever used for navigation, fishing, or transportation,' and to this is added another long clause covering accessories made of wood, from masts downward. The other clauses of the earlier charter are also expanded with the like object, and there are several new ones. Deputies were to be appointed in 'every convenient and needful place' to see that the ordinances of the Corporation were properly carried out, and to collect dues; members might be admitted who were not shipwrights; the admission of apprentices was regulated; dues were to be received on account of all ships built; the secrets of the art were to be kept from foreigners; power was given to punish those who forsook their work or became mutinous; the Corporation was granted the reversion of the post of Surveyor of Tonnage[xxxii] of new-built ships, and was to examine each new ship to see that it was properly built 'with two orlops at convenient distances, strong to carry ordnance aloft and alow, with her forcastle and half deck close for fight'; provision was to be made for the poor; and finally, no doubt on account of the extended powers granted, the ancient liberties of the Cinque Ports were expressly reserved to them.

The provision for the armament of the merchant ships is of especial interest when it is remembered that in this year the Royal Navy reached the low water mark of neglect and inefficiency, while piracy in British waters reached a high water mark of efficiency that promised the speedy extinction of the peaceful trader.

But if the general trend of the new charter was the enlargement and consolidation of the powers of the Corporation, there is one significant change that led in the opposite direction: the 'Shipwrights of England' became the 'Shipwrights of Redrith[47] in the County of Surrey,' a step so retrograde that it is difficult to imagine what possible argument could have been adduced to justify such a change: some reason, no doubt, there was, but owing to the loss of the records it has not been possible to discover it.[48] It will be observed that, although the master under the new charter was a government official, the wardens, reduced to three in number, were all private shipbuilders, and only three of the sixteen assistants were in the service of the State.

In the year following the grant of the enlarged charter, the legal position of the Corporation was [xxxiii]further strengthened by the issue of an Order in Council authorising the Master and Wardens to apprehend all persons using the art of shipbuilding contrary to the Charter, and all apprentices or journeymen departing unlawfully from their masters;[49] and by an order of the Lord High Admiral directing the apprehension of all persons who refused to conform to the regulations, and their imprisonment until they complied—'they being chiefly poor men and unable to pay a fine.'[50]

The fact that it was necessary to recapitulate two of the penal clauses of the charter throws light on the uncertain scope—possibly the illegality—of the powers intended to be conferred by it. The active life of the Corporation was one long struggle to enforce its powers and secure its rights, not only against private individuals or rival bodies, but even against the Officers of the Crown, who might well have been expected to respect the provisions of its charter. For the resistance to the Corporation did not come from 'poor men' alone. The other associated bodies of shipwrights that were in being resented interference in their own localities. The most important of these was the London Civic Company, known as the Company or Brotherhood of Free Shipwrights of London, which had been in existence as a 'trade craft' or 'guild' from an early date. It is mentioned among the Civic Companies in 1428,[51] and was in 1456 erected into a 'fraternity in the worship [xxxiv]of St. Simon and St. Jude,' and in 1483 regulations were made by it relating to apprenticeship and use of good material and workmanship.

This company held a very obscure position among the minor companies[52] of the City, and during the period in which its activities concern us it seems to have been in a very low financial condition. This, however, did not deter it from contesting the jurisdiction of the Corporation (or 'foreign' shipwrights, as it termed them, despite the fact that, owing to the growth of London, it had itself long left the boundaries of the City's Liberties, and now had its headquarters near Ratcliff Cross), and the City, not unnaturally jealous of its own special privileges, supported the opposition.

At first the efforts of the free shipwrights of the City to dispute the authority of the Corporation were unsuccessful. An attempt made in 1632 ended in the submission of the two citizens who had been put up to contest the matter, and their 'promise to be obedient to the Shipwrights of Rotherhithe, saving the freedom of the City of London';[53] a submission brought about by the fact that they were members of both companies, although they had endeavoured to deny that they were members of the Incorporated Company of Rotherhithe.[54]

A further attempt in 1637, however, by two other free shipwrights, backed again by the City Corporation, was more successful. The case was [xxxv]referred to Sir Henry Marten, the Judge of the Admiralty, who reported to the Admiralty that 'these London Shipwrights, being supported by the countenance of the City, will by no means agree to come under the King's Charter and government, and to that purpose are resolved to oppose themselves by further proceedings at law.'[55] The case was referred back to him by the Admiralty with the remark that 'You have long been acquainted with the said business and know of what importance it is to have the shipwrights kept under government, which was the ground of the grant made to the Company at Rotherhithe.'[56] Marten finally advised the Admiralty not to grant their request, 'it being a business so much importing the general good of the kingdom that all shipwrights should live under a uniform government, as now regulated by the King's charter,'[57] and the two recalcitrants were committed to the Marshalsea, where they made their submission. Nevertheless, in Oct. 1638 the matter was again brought up, coming before the newly appointed Lord High Admiral upon a petition from the City Company, and by an Order in Council of March 1639 that Company was exempted from the jurisdiction of the 'New Corporation of the Suburbs,' although, in view of the fact that 'the said Corporation of shipwrights is of so great importance for the defence of the Kingdom and is dispersed not in the suburbs only but over the whole Kingdom of England,' it was declared 'that this exception ... ought to be no encouragement to any other Society or Trade or particular persons to withdraw their obedience to the said new Corporation [xxxvi]or to make suit for the like exemption, which in no sort will be granted.'[58]

The City had won; fine words, whether in a Royal Charter or an Order in Council, were of little use without the consistent support of the authorities, and this the unfortunate Corporation never received. The attempt of the Ipswich Shipwrights in 1621 to secure its dissolution failed, but upon the motion of their member against the 'Patent of the Ship-carpenters who impose exceedingly upon builders of ships,' the House of Commons ordered that the Corporation should not demand or receive any more money by virtue of their patent until it had been brought to the Committee of Grievances and further order been taken therein by the House.[59]

Less drastic attacks on the privileges of the Company frequently succeeded. The exemption from 'land service' was ignored by the Earl Marshal and the Lord Admiral in 1628. In 1631 the King's Bench indirectly curtailed its powers by prohibiting the Lord High Admiral from proceeding in matters relating to freight, wages, and the building of ships; and two years later prohibited the Company from using its powers of arresting ships, thereby preventing the Company from getting 'their suits decided in a speedy way in the Court of Admiralty' and compelling them to 'contend with the master, who, proving poor and litigious, all that the (Company) can get, after long suit, is but the imprisonment of his body.'[60] The East Country merchants also opposed its trading privileges, and in 1634 the Company found it necessary to appeal to the Admiralty [xxxvii]for assistance in carrying out its powers in regard to the search and survey of ships, and the regulation of apprentices. In 1635, when Peter Pett was Master, the difficulties of collecting the dues of the shipwrights and the 'tonnage and poundage' granted for the support of the Corporation and its poor, became more acute than ever. After much argument and reference to Sir Henry Marten, the Master, Wardens and Assistants were told, in 1638, 'to cause their charters to be published and put in execution,' while the 'Vice-Admirals, Mayors and other Officers' were charged to assist them. In 1641 the right of freedom from impressment and from attendance on juries was again in question, and although the decision of the Lord Admiral was then favourable the troubles of the Company still continued, for in January 1642 they were petitioning the Commons for relief.

In March 1645 an Ordinance to protect the Shipwrights from impressment for land service 'on account of the importance of their trade and the decrease of qualified workmen,' was presented to the Lords by Warwick, the Lord High Admiral, and was approved by them and passed on to the Commons for concurrence, but it does not appear to have been read.[61]

In August of the following year, Warwick again reported from the Committee of the Admiralty to the Lords a 'Report and Ordinance concerning the better building of ships and granting privileges to the Shipwrights and Caulkers to be freed from Land Service,' elsewhere described as an 'Ordinance for the better regulation of the Mystery and Corporation of Shipwrights.' This[xxxviii] was agreed to and sent to the Commons, who read it a first time and ordered it to be read a second time 'on Thursday next come Sevennight,' and then dropped it.

In the meantime the Clerk and other officials of the Company, whose pay was much in arrear, were petitioning the House to take such action with the Company as would force it to meet their claims, while the Master and Wardens were complaining of individual refusals to pay assessments due to the Company.[62] This state of affairs was still in evidence in 1648, when Edward Keling, the Clerk, and the existing and late Beadles of the Company, petitioned the Lords for relief, and asked 'that the public instruments entrusted to Keling may be disposed of and he be indemnified for them.' The statement of the Wardens annexed thereto[63] explains the situation as follows: The Wardens had

consented to pay the established duties of the Corporation as directed by Order of the House, but Peter Pett and other principal members, and great dealers in that mystery, withhold and refuse to pay the duties for support of the Corporation, and so the Wardens have not the means to pay the salaries of their officers, or their house rent, to relieve the poor, to make their due surveys upon ships, or to pursue an ordinance for settlement of their government which passed the House of Peers eighteen months ago, and now remains in the House of Commons.

In June 1650 the difficulties of the Company were evidently still unrelieved, for a petition from them, together with their Charter, was referred by the Council of State to the Committee [xxxix]of the Admiralty, who were to advise with the Admiralty Judges on the matter. The result of this does not appear, but it seems probable that the Corporation shortly after ceased to exercise its functions, for a petition to the Navy Commissioners in 1672 (which shows the same old difficulties still unremedied) refers to 'the discontinuance of the exercise of this Charter in the late troublesome times.'[64]

During the earlier years of its activity the Corporation played a part of some importance in the administration of the Navy. It surveyed and reported upon the workmanship and tonnage of ships built in the royal yards, and gave advice concerning their defects—thus acting to some extent as a check upon the master shipwrights—and notices of the sale of unserviceable ships were given out at Shipwrights' Hall as well as on the Exchange. In one instance[65] it was called upon to submit a scheme 'for the mould of a ship like to prove swiftest of sail and every way best fashioned for a ship of war,' but this attempt to erect it into a board of design seems to have failed completely.

In 1683 the Corporation attempted to set its affairs on a more satisfactory basis by obtaining a new charter, surrendering the charter of 1612 in October 1684[66] and obtaining in January 1686 a warrant from James II. to renew it with additions. This was opposed by its old enemies, and nothing seems to have come of it, although the matter was under discussion until 1688, and the Masters of Trinity House in 1687, in a report [xl]to Pepys, had recommended that there should be but one Company of Shipwrights, and that all of that trade in England should be under their rule and government. The Corporation appears then to have become practically extinct, for in a report by the Navy Office, in 1690, on the method of measuring ships reference is made to the 'measurement and calculations ... formerly taken and made by the Corporation of shipwrights (when there was such a company).'[67]

In 1691[68] and 1704 the remnants of the Corporation made a final attempt at reconstruction, backed by the Admiralty, Navy Board, and Trinity House. A petition to this end came before the House of Commons in January 1705, and is recorded in the Journal[69] of the House in the following terms:

A Petition of the Master Shipwrights (who signed the same) in behalf of themselves and others, Master Shipwrights of England, was presented to the House and read: setting forth that the petitioners' predecessors were incorporated by charter in 1605, and were thereby empowered to rectify the disorders and abuses of the Shipwrights' Trade, and to furnish the Crown and Merchants with able workmen, and to bind and enrol their apprentices; but the breed of able workmen is almost lost, and for want of sufficient power to execute the good intent of their charter, the petitioners have not been in a regular method many years past to rectify the disorders amongst the shipwrights and to improve their trade; yet a Proposal of some additional heads to effect the same has been approved, and reported by the Commissioners of the Admiralty, Commissioners of the Navy, Corporation of Trinity House; and also his Royal Highness,[70] [xli]the 7th Nov. 1704, declares his opinion that it will be much for the public service to have the shipwrights incorporated by Charter, as desired by them; but in the said proposal there are some necessary clauses which cannot be made practicable and effectual without an Act of Parliament: and praying that leave be given to bring in a Bill, of regulating clauses, to be inserted in a new charter for the better breeding of Shipwrights and for the more firm and well building of ships and other vessels.

The motion to refer it to a Committee was lost, and thus went out the last spark of life of a Corporation that had struggled in vain for a hundred years to carry out the intentions of its founders.

[5] Cal. Close Rolls, 27 Jan. 1337. Rymer, Foedera, iv. 703.

[6] Exchequer Accts. 19/31.

[7] This rate was being paid in 1303.

[8] Oppenheim, The Administration of the Royal Navy, 1509-1660, p. 14.

[9] Thos. Allen, writing to the Earl of Shrewsbury in 1516, refers to 'one Brygandin son unto him that made the King's great ship.' Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. i. p. 14.

[10] Cal. S.P. Dom., May 12, 1519.

[11] 'An Act for Servants' Wages,' 11 Henry VII, c. 22.

[12] An Act concerning Artificers and Labourers, 6 Henry VIII c. 3.

[13] Op. cit., pp. 22, 153, 179, 232-3.

[14] Henry V had merely given a pension for past service to a shipwright incapable of further labours.

[15] Patent Roll 680.

[16] 'Ac in consideratione veri et fidelis servicii quod dilectus serviens noster Jacobus Baker durante vita sua impendere intendit.'

[17] Pat. Roll 704.

[18] Acts of the P.C., New Series, i. 233.

[19] Ibid., ii. p. 186.

[20] Pat. Roll 833. I cannot trace in the rolls any similar grant to Holborn or Smyth.

[21] Pat. Roll, 921.

[22] He may be the Richard Bull who was called before the Council in 1555. Acts of the P.C., v. 189.

[23] Stephins was engaged on the repair of the Lion barge in 1553, and was paid 20l. as 'the Queen's Majesty's Shipwright' for making the Leader barge in 1558. Acts of the P.C., iv. 362, and vi. 426.

[24] The difference in the spelling is no argument against this, as 'ph' and 'v' are used indifferently in the documents in this surname, Stevens' name being spelt 'Stevyns' and 'Stevins' and 'Stephens' in the rolls.

[25] Pat. Roll 1091.

[26] Officium Naupegiarii sive unius magistrorum factorum Navium et Cimbarum nostrarum.

[27] Pat. Roll 1249. The entry in Pat. Roll 1091 is vacated with an endorsement in the margin, signed by Mathew Baker and William Borough to the effect that the surrender was voluntary and in consideration of the grant to Baker and Addey.

[28] Sometimes spelt Adye, Adie, or Ady.

[29] Pat. Roll 1210. No office is mentioned; all that is conveyed is the 'annuity or annual fee of 12d. sterling a day.'

[30] Nec non in consideratione boni et fidelis servicii per præfatum Willelmum Pett Shipwright antehac impensi ac imposterum impendendi in fabricatione navium nostrarum heredum et successorum nostrorum ac in assistencia sua in causis nostris marinis.

[31] Pat. Roll 1300. In a MS. account of the 'ordinary wages and exchequer fees of his Majesty's Master Shipwrights' (Add. MS. 9299 f. 48) it is stated that this had been given in recompense for building the Ark Royal, but as this ship appears to have been originally built for Ralegh this can hardly have been the reason. The patent only speaks of 'good and faithful service done and to be done.'

[32] Pat. Roll 1342.

[33] Drake's edition of Hasted, History of Kent, p. 41.

[34] Add. MS. 9299. I have not been able to find his patent.

[35] He built the Warspite in 1596 and the Malice Scourge for the Earl of Cumberland, and in 1598 and 1600 received, in conjunction with others, the usual 'rewards' for building merchant ships (Cal. S.P. Dom., 30 July 1596, 24 Sept. 1598, 15 Jan. 1600).

[36] Pat. Roll. 1620.

[39] S.P. Dom. Chas. I, xxxv. 104. Although countersigned by Coke, this warrant is not signed by the Lord High Admiral, so presumably it is a duplicate.

[40] 11 July 1614. He does not mention this in the manuscript.

[41] Probably these amounts should be multiplied by 6.

[42] Thus in November 1591, whilst holding office as Master Shipwright, Chapman, who owned a private yard at Deptford, was paid the bounty of 5s. a ton for building the Dainty of London of 200 tons, 'as an encouragement to him and others to build like ships,' and Phineas was paid the like bounty for building the Resistance. (Cal. S.P. Dom.)

[44] Salisbury MSS. (Hist. MSS.), i. 276.

[47] Rotherhithe, where their Hall was situated.

[48] Probably it was due to the growing resistance of the City Company of Free Shipwrights.

[49] Cal. S.P. Dom., 12 July 1613.

[50] Ibid., 30 Oct. 1613.

[51] See Sharpe, Short Account of the Worshipful Company of Shipwrights. This author has made the mistake of assuming that the Charter of 1605 was granted to the City Company.

[52] It is not even mentioned in Stowe's list of sixty companies attending the Lord Mayor's Banquet in 1531.

[53] Cal. S.P. Dom., 4 Feb. 1632.

[54] Ibid., 17 June 1631. I am indebted to Mr. E. A. Ebblewhite for drawing my attention to the significance of this fact.

[55] Cal. S.P. Dom., 30 June 1637.

[56] Ibid., 10 July 1637.

[57] Ibid., 26 July 1637.

[58] Council Register, No. 50.

[59] Commons Journal, i. 563.

[60] Cal. S. P. Dom. January 21, 1633.

[61] Lords' Journal, vii. 286. Hist. MSS., Sixth Report, p. 51.

[62] Lords' Journals, viii. 232, 286; x. 403.

[63] Hist. MSS., Seventh Report, p. 40.

[64] Cal. S.P. Dom., 25 July 1672.

[65] By the Commissioners for inquiring into the State of the Navy. Cal. S.P. Dom., 22 Feb. 1627.

[66] Bodleian, Rawlinson MSS. A 177.

[67] Cal. S.P. Dom., 21 Aug. 1690.

[68] See Sutherland, Britain's Glory, or Shipbuilding Unvail'd, p. 70.

[69] Vol. xiv. p. 482.

[70] Prince George of Denmark, then Lord High Admiral.

When Thomas Heywood, in his description of the Sovereign of the Seas written in 1637, referred to the author of this manuscript as 'Captain Phineas Pett, overseer of the work, and one of the principal officers of his Majesty's navy, whose ancestors, as father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, for the space of two hundred years and upwards, have continued in the same name officers and architects in the Royal Navy,' he was, it may be presumed; recording the local tradition of the Pett family. That this tradition was strong and persistent is clear from the fact that Mansell, writing to Thomas Aylesbury[71] in 1620 to propose Peter Pett as builder of the new pinnaces; recommended him on the ground that 'his family have had the employment since Henry the Seventh's time,' while forty years later, Fuller, in his 'Worthies of England,' also referred to it in these words: 'I am credibly informed that that Mystery of Shipwrights for some descents hath been preserved successfully in Families, of whom the Petts about Chatham are of singular regard.'

This tradition, so far as it relates to the descent of the 'mystery' from generation to generation, was no doubt well founded, but there is no evidence that office under the Crown was held by any of Phineas Pett's ancestors earlier than his father, Peter.

The name 'Pett' is said by a modern writer[xliii] on the history of English surnames to be a Kentish variant of the name 'Pitt.' This would imply a Kentish origin of the family, and this supposition might seem to be strengthened by the fact that the name, as a place-name, only occurs in Kent and on the eastern border of Sussex.[72]

The fact is, however, that 'pet' is simply a Middle-English variant of the familiar word 'pit,' kin to the old Frisian 'pet,' and is found in use throughout the east coast counties from Sussex to Yorkshire, but more frequently in the South than in the North. In the 13th and 14th centuries this surname occurs in the form 'atte Pet' or 'del Pet'; i.e. 'at the pit' or 'of the pit,'[73] which indicates clearly that the bearers had, on the introduction of the hereditary surname from the 12th century onward, taken the name 'Pet'—or had it thrust upon them—because they were known as living near to a pit, and were thereby distinguished from other Walters or Adams dwelling on the heath or by the wood etc. etc. A study of the local distribution of this name in the 14th century shows that the pit in question, though it may occasionally have been a well, a sawpit, or a pitfall for wild beasts, was more usually a place where, owing to the absence of stone from the district, clay or loam had been dug in forming the walls of the rude cottages in which all but the upper strata of society then dwelt. Thus one great centre of the [xliv]Petts in Suffolk in the 13th and 14th centuries, the district between Thetford and Eye, is a heavy clayland from which stone is absent.[74] By the end of the 16th century this name, in the form 'Pet,' 'Pett,' and 'Pette' was common in Kent, Essex, Suffolk, and South Norfolk.

In 1583, Peter Pett, then Master Shipwright at Deptford, obtained a grant of arms from Herald's College. The original has unfortunately disappeared, but from the reference to it in Le Neve's 'Pedigree of the Knights'[75] it appears that he claimed descent from 'Thomas Pett of Skipton in Cumberland' through John Pett his grandfather and Peter Pett his father, who had been a shipbuilder at Harwich. The fact that there is no Skipton in Cumberland shows that this record is hardly reliable as regards the place of origin of the family. Neither of the existing Skiptons,[76] which are both in Yorkshire, remote from the sea, is likely to have given birth to a family of shipbuilders; and there is no indication that any relations of the Petts were at any time resident in Yorkshire or Cumberland. Moreover, the name was practically unknown at this period in the North.[77] In an attempt to elucidate this matter, Major Bertram Raves put forward in the 'Mariner's Mirror'[78] the suggestion 'that Thomas Pett was of Hopton,[79] in Suffolk, and that [xlv]Hopton was fudged into Skipton by the Tudor Heralds in the grant of arms to Peter Pett.... Petts about or near to Hopton at the time were yeomen or husbandmen.... The pedigree may, therefore, have seemed to need treatment.' He then goes on to show that Petts were established in the neighbouring villages of Hepworth, Wattisfield, Harling, and Walsham-le-Willows; the Petts at Wattisfield having been in the neighbourhood since the 14th century.[80] One significant fact is the letter which Peter Pett, the half-brother of Phineas, wrote to Sir Bassingbourn Gawdy[81] of Harling, in 1598, in which he apologises for his delay in visiting him and sends his remembrances to Lady Gawdy and others: it is clear from this letter that Peter was well known in the neighbourhood, and was, it may be presumed, related to the Thomas Pett living there at that time.

But it seems very doubtful whether Skipton really was a wilful substitution for, or a mis-transcription of, an original 'Hopton,' for there is no evidence that anyone of the name ever lived at Hopton, and it seems possible that some earlier Pett may have migrated to Yorkshire and his descendant John have returned to East Anglia.[82]

Of Thomas Pett nothing is known; and of John his son nothing can be stated with certainty.

In 1497 William Pette of Dunwich left by will[83] 'to my brother John Pette, my new boat and all my working tools'; a legacy that implies that the brothers were shipwrights. It is not improbable that this was the John Pett who was engaged in caulking the Regent in 1499. From the entry in the Roll[84] it is clear that John was a master workman or shipbuilder; for the sum paid him, 38l. 1s. 4d., is a fairly large amount for that period, and covered miscellaneous stores besides the caulking of the 'overlop' or deck, and the sides of the ship 'against wind and water.' Unfortunately his account, 'billam suam inde factam,' is no longer in existence. This work was possibly carried out at Portsmouth, where the Regent had been fitted for the Expedition to Scotland in 1497,[85] and where she was again undergoing repair in 1501,[86] but there would have been nothing unusual at that period, when the resources of the Portsmouth district were hardly sufficient, in entrusting such work to a shipbuilder from the eastern counties. In 1485 a master shipwright had been sent from London to Bursledon to superintend the removal of the mast of the Grace Dieu and her entry into dock,[87] and shipwrights were frequently impressed [xlvii]from East Anglia for work in Portsmouth and Southampton. The work may, however, have been carried out at Harwich, where the King's ships sometimes rode.[88]

With Peter, the son of John, we come at length upon sure ground. The will he made in March 1554 is upon record, and shows that he was possessed of a dwelling-house and shipbuilding yard at Harwich, which he bequeathed to his son Peter, the father of Phineas. Possibly he was the Peter Pett noted by Mr. Oppenheim[89] as among the shipwrights pressed from Essex and Suffolk working at Portsmouth in 1523: there can be no doubt that he was the Peter Pett of Harwich who, with other shipwrights, signed a decree of appraisement of a ship in 1540.[90]

His son Peter Pett, who died in 1589 when Master Shipwright at Deptford, entered the royal service some time before 1544, as already noted.

There is no record of the names of the earlier ships built by him, but it is known that in 1573 he built the Swiftsure and Achates, and in 1586 the Moon and Rainbow; all at Deptford. At the time of his death in 1589 he was engaged upon the Defiance and Advantage, which were completed by Joseph Pett, his second and eldest surviving son, who, as already remarked, succeeded to his place as Master Shipwright, his eldest son William Pett of Limehouse, also a Master Shipwright, who built the Greyhound in 1586, having [xlviii]died in 1587. Peter Pett was twice married, and had four sons and one daughter by his first wife, whose name is not known; and six daughters and three sons (of whom Phineas was the eldest) by his second wife, Elizabeth Thornton. These will be found set forth in the subjoined tables, which will serve to illustrate the relationship between them and the other members of the family referred to in the manuscript.

Peter Pett, towards the end of his life, had achieved a great reputation as a shipbuilder and was, as is evident from his will, a man of considerable means. He died possessed of a house at Harwich, where he had also built almshouses; a house at Deptford; land at Frating, near Colchester; the lease of a house at Chatham; and 'ground'—presumably a shipbuilding yard—at Wapping. In addition to this property, he left 20l. to the children of his son Richard;[91] 6l. 13s. 4d. to the child of his daughter Lydia; 100l. each to Phineas and his brothers Noah and Peter; and 100 marks to each of his four daughters by his second wife and to an unborn child that probably did not live. The payments to the children of his second wife were to be made on their attaining the age of twenty-four, but from the statements of Phineas on pages 12 and 13 it would appear that part of the money was embezzled by the Rev. Mr. Nunn and part retained by Phineas' brother Joseph.

Peter Pett, of Wapping, the third son of the above, carried on business as a shipbuilder in the private yard at Wapping which had been left to[xlix] him by his father. He does not appear to have held any office under the Crown, but seems to have been well known to the Lord High Admiral, for in his letter above referred to be puts off his visit to Gawdy on the ground that he has to be 'next Sunday with the Earl of Nottingham at the Court at Richmond.' In 1599 he published a poem entitled 'Time's Journey to seeke his Daughter Truth; and Truth's Letter to Fame of England's Excellencie,' which he dedicated to Nottingham. He was also the author of a sonnet in three stanzas of seven lines entitled 'All Creatures praise God.'[92]

It is not necessary for our present purpose to pursue the fortunes of this family further, but the reader who is desirous of obtaining information as to the later descendants of Peter Pett of Harwich will find it in an excellent paper in vol. x. of the 'Ancestor,' by Mr. Farnham Burke and Mr. Oswald Barron, entitled 'The Builders of the Navy: a Genealogy of the Family of Pett.'[93]

RELATIONS OF PHINEAS PETT.

[[Click here for table image.]]

| Thomas Pett | |||||||||||||||||||

| John | |||||||||||||||||||

| Peter, of Harwich, = Elizabeth Paynter. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shipbuilder, | |||||||||||||||||||

| d. (?) 1554. | |||||||||||||||||||

| (1) ? | = Peter, of Deptford, | = (2) Elizabeth | Ann = John Chapman. | ||||||||||||||||

| Master Shipwright, | Thornton, | ||||||||||||||||||

| d. 1589. | d. 1597. | ||||||||||||||||||

| William, | = Elizabeth | (1) Margaret | = Joseph, = | (2) Margaret | (1) Ann | = Peter, = | (2) Eliza- | Richard, | Lydia, | ||||||||||

| of Lime- | March. | Curtis, | of Lime- | Humfrey, | Tusam. | of | beth. | of London. | d. 1610. | ||||||||||

| house, | d. 1594. | house, | d. 1612. | Wapping, | |||||||||||||||

| Master | Master | Ship- | |||||||||||||||||

| Shipwright | Shipwright | builder | |||||||||||||||||

| d. 1587. | d. 1605. | d. 1631? | |||||||||||||||||

| Elizabeth. | Lucy. | Margaret. | William. | Joseph. | |||||||||||||||

| Peter, of = Elizabeth | William, Elizabeth = Thomas | Ann | Mary | ||||||||||||||||

| Deptford, Johnson. | Clerk in Barwick. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Master | Holy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Shipwright | Orders, | ||||||||||||||||||

| b. 1592, | d. 1651. | ||||||||||||||||||

| d. 1652. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jane, | Phineas | Noah, | Peter the | Rachel, = Rev. W. | Abigail, | Elizabeth, | Mary, = (?) Cooper. | ||||||||||||

| Susannah, | (see next | d. 1595. | Younger, | d. 1591? Newman. | d. 1599. | d. 1599. | d. 1626. | ||||||||||||

| d. 1567. | Table). | d. 1600. | |||||||||||||||||

FAMILY OF PHINEAS PETT.

[[Click here for table image.]]

| Phineas Pett, | ||||||||||||||||||||

| = b. 1570, d. 1647. = | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (1) Ann Nicholls, m. 1598, | (2) Susan Yardley, m. 1627, | (3) Mildred Byland, m. 1638, | ||||||||||||||||||

| d. 1627. | née Eaglefield, d. 1637. | née Etherington, d. 1638. | ||||||||||||||||||

| John, = Katherine | Henry, Richard, Joseph, | Peter, | Ann, | Phineas, | Phineas, = Frances | Christo- | ||||||||||||||

| Captain | Yardley | b. 1603, b. 1606, b. 1608, | Commis- | b. 1612. | b. 1615, | Captain | Carre. | pher, | ||||||||||||

| R.N. | d. 1613. d. 1629. d. 1627. | sioner at | d. 1617. | R.N. | Master | |||||||||||||||

| (lost in | Chatham, | (killed in | Shipwright | |||||||||||||||||

| VI | b. 1610, | Tiger), | at | |||||||||||||||||

| Whelp), | d. 1672. | b. 1619, | Woolwich | |||||||||||||||||

| b. 1602, | d. 1666. | and | ||||||||||||||||||

| d. 1628. | Deptford, | |||||||||||||||||||

| Phineas | b. 1620, | |||||||||||||||||||

| Phineas, | (owner of | d. 1668. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Master | the MS., | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shipwright | Mary, | Martha, = John | c. 1670), | |||||||||||||||||

| at | b. 1617, | b. 1617, Hodierne. | b. 1646, | |||||||||||||||||

| Chatham, | d. 1617. | m. 1637. | d. 1694. | |||||||||||||||||

| b. 1628, | ||||||||||||||||||||

| d. 1678. | ||||||||||||||||||||

[71] Bodleian. Clarendon State Papers, No. 166.

[72] E.g. Pett Place near Charing; Pett near Stockbury; Pett Street near Wye and Pett village near Winchelsea.

[73] E.g. Geoffrey del Pet, 1270, see Rye, Cal. of Feet of Fines for Suffolk. 'Walter de le Pet' (of Wattisfield), see Powell, A Suffolk Hundred in the year 1283; 'Adam atte Pet' (of Stonham Aspul), 'William del Pet' (of Wattisfield), see Hervey, Suffolk in 1327; 'Peter atte Pette of Shorn' (Kent) in Close Roll 1344.

[74] Mr. Redstone informs me that to this day large blocks of loam and clay are squared off in the pits of Rickinghall to form house walls.

[75] Printed by the Harleian Society.

[76] Skipton in Craven in the W. Riding and Skipton upon Swale in the N. Riding.

[77] I have only discovered one early instance of the name in Yorkshire, 'Ralph Pet' who lived in the 'Honor and Forest of Pickering' in 1314, and this, it may be observed, was on the sea coast.

[78] April 1912, p. 124.

[79] S.E. of Thetford: not the Hopton in East Suffolk.

[80] They were already there in the 13th; see note on p. xliii.

[81] Gawdy MSS. (Hist. MSS.) 405; what appears to be Pett's draft of this letter is to be found in Egerton MS. 2713.

[82] It is also possible that Thomas of Skipton did not bear the surname 'Pett.' According to Bardsley, Curiosities of Puritan Nomenclature, p. 3, 'Among the middle and lower classes these (descriptive surnames) did not become hereditary till so late as 1450 or 1500.'

[83] Ipswich Probate Court Bk. III. f. 202.

[84] Ac xxxviijli. xvjd. tam super novas iact' (? jacturas) et le calkynge de le Overlope navis regis vocatae le Regent quam pro le calkynge anti ventum et aquam ejusdem navis ac aliis necessariis pro eadem nave fiendis et providendis per manus Johannis Pett ut prius per billam suam inde factam plenius apparet datam xiij die Novembris Ao xvo Regis Henrici vijmo.. P.R.O. E. 405 (80).

[85] Naval Accounts and Inventories of Henry VII., N.R.S., Vol. viii.

[86] P.R.O. Augmentation Office Misc. Bk., 317, f. 236.

[87] N.R.S., vol. viii. pp. liv, 222.

[88] In 1487, Thomas Rogers, clerk of the King's ships, was paid xxvis. viijd. for his expenses in going to Harwich, and victualling the King's ships there. See Material Illustrative of the Reign of Henry VII, vol. ii. p. 143.

[89] Administration, p. 74.

[90] P.R.O., H.C.A. 7 (1), 'probos viros Petrum Pette et Johannem Moptye villae Harewici (and two others) fabros lignarios, anglice shipwrights.'

[91] Richard Pett of London, gent. (elsewhere described as 'unus valettorum regis') in 1593 sold his share of the property at Deptford to his brother Peter Pett, of Wapping. This property had been bought by his father in 1566.

[92] Printed by the Parker Society in Select Poetry, vol. ii. p. 386.

[93] The following errors may be noted: p. 149, the name 'Marcy' should be 'March'; p. 151, the William Pett who petitioned the Admiralty in 1631, was not the son of Joseph but a much older man, apparently belonging to another branch of the family; p. 157, the dates of the death of Phineas' second wife and of his third marriage are antedated by a year; p. 158, the date 'July' was an error of the Harl. transcriber; the dates of birth and death of Phineas, junior, are incorrect; p. 172, Joseph Pett of Chatham was not the son of Phineas, but of Joseph of Limehouse, and he was born in 1592 not 1608.

From the care that had been taken to provide for his education, and from the fact that it was only at the 'instant persuasion' of his mother that he was 'contented' to be apprenticed as a shipwright, it may be inferred that Phineas had been destined for the Church or the Law, and that Peter Pett did not propose that his son should follow in his own footsteps. The peculiarity[94] of the name chosen for him (which no doubt refers, not to the disobedient son of Eli, but to 'Phinehas, the son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron the priest,' who received 'the covenant of an everlasting priesthood')[95] gives rise to the surmise that his parents had intended him for the Church, but whatever the intention may have been, it was certainly abandoned on the death of his father.

Phineas does not seem to have profited greatly from his studies at Cambridge. He was hardly a master of English; possibly he had a good knowledge of Latin, for the influence of the Latin idiom is to be seen in almost all his periods; but the fact that he had subsequently to practise 'cyphering' in the evenings does not imply any great acquirements in mathematics, even of the very elementary forms which at that period were sufficient for the solution of the few problems arising in connection with the design of ships. [liii]Nevertheless, he received the degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1592 and that of Master in 1595.

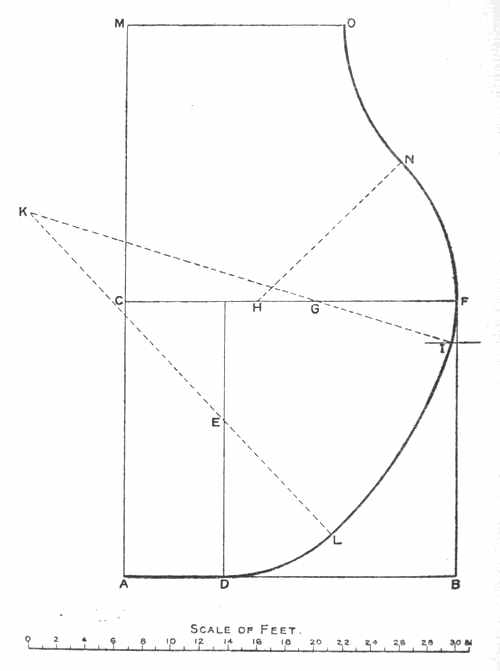

If the statement that he spent the two years of his apprenticeship to Chapman 'to very little purpose' is to be accepted literally, it would seem that the misfortunes that subsequently befell him must have aroused latent energies and filled him with determination to master the details of his future profession when he returned to England in 1594. His voyage to the Levant and subsequent employment as an ordinary workman under his brother Joseph no doubt gave him a practical acquaintance with ships that enabled him to profit greatly by the instruction of Mathew Baker, although apparently this only extended over the winter of 1595-6. Pett's confession that it was from Baker that he received his 'greatest lights,' written, as it must have been, after he had found Baker an 'envious enemy' and an 'old adversary to my name and family,' indicates how great that assistance was. This is borne out by a letter[96] which he wrote to Baker in April 1603, in order to deprecate the old man's wrath, which had been aroused when Phineas, then Assistant Master Shipwright at Chatham, commenced work on the Answer. The letter was partially destroyed by the fire which damaged the Cottonian Library in 1731, but fortunately Pepys had copied it in his Miscellanea.[97]