Walter S. Colls, Ph. Sc.

Project Gutenberg's A Queen of Tears, vol. 1 of 2, by William Henry Wilkins

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: A Queen of Tears, vol. 1 of 2

Caroline Matilda, Queen of Denmark and Norway and Princess

of Great Britain and Ireland

Author: William Henry Wilkins

Release Date: March 5, 2016 [EBook #51368]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A QUEEN OF TEARS, VOL. 1 OF 2 ***

Produced by Emmanuel Ackerman, University of California

Libraries, Microsoft (scanning) and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A QUEEN OF TEARS

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

THE LOVE OF AN UNCROWNED QUEEN:

SOPHIE DOROTHEA, CONSORT OF GEORGE I., AND HER CORRESPONDENCE WITH PHILIP CHRISTOPHER, COUNT KONIGSMARCK.

New and Revised Edition.

With 24 Portraits and Illustrations.

8vo, 12s. 6d. net.

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.,

LONDON, NEW YORK AND BOMBAY.

CAROLINE MATILDA, QUEEN OF DENMARK AND NORWAY AND PRINCESS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND

BY

W. H. WILKINS

M.A., F.S.A.

Author of “The Love of an Uncrowned Queen,” and “Caroline the Illustrious, Queen Consort of George II.”

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

IN TWO VOLUMES

Vol. I.

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1904

Some years ago, when visiting Celle in connection with a book I was writing on Sophie Dorothea, The Love of an Uncrowned Queen, I found, in an unfrequented garden outside the town, a grey marble monument of unusual beauty. Around the base ran an inscription to the effect that it was erected in loving memory of Caroline Matilda, Queen of Denmark and Norway, Princess of Great Britain and Ireland, who died at Celle in 1775, at the age of twenty-three years. To this may be traced the origin of this book, for until I saw the monument I had not heard of this English Princess—a sister of George III. The only excuse to be offered for this ignorance is that it is shared by the great majority of Englishmen. For though the romantic story of Caroline Matilda is known to every Dane—she is the Mary Stuart of Danish history—her name is almost forgotten in the land of her birth, and this despite the fact that little more than a century ago her imprisonment nearly led to a war between England and Denmark.

Inquiry soon revealed the full measure of my ignorance. The dramatic tale of Queen Caroline[Pg vi] Matilda and her unhappy love for Struensee, her Prime Minister, has been told in Danish, German, French and English in a variety of ways. Apart from history and biography, it has formed the theme of novels and plays, and even of an opera. The most trustworthy works on the Queen and Struensee are written in Danish, a language not widely read. In English nothing of importance has been written about her for half a century,[1] and, owing to the fact that many documents, then inaccessible, have since become available, the books are necessarily incomplete, and most of them untrustworthy. Moreover, they have been long out of print.

[1] I except Dr. A. W. Ward’s contribution to the Dictionary of National Biography, but this is necessarily brief. A list of the books which have been written about the Queen in different languages will be found in the Appendix.

My object, therefore, in writing this book has been to tell once more the story of this forgotten “daughter of England” in the light of recent historical research. I may claim to have broken fresh ground. The despatches of Titley, Cosby, Gunning, Keith and Woodford (British Ministers at Copenhagen, 1764-1775) and others, quoted in this book, are here published for the first time in any language. They yield authoritative information concerning the Queen’s brief reign at the Danish court, and the character of the personages who took part, directly or indirectly, in the palace revolution of 1772. Even Professor E. Holm, of Copenhagen, in his admirable work, Danmark-Norges Historie (published in 1902), vol. iv. of which deals with the Matilda-Struensee[Pg vii] period, is ignorant of these important despatches, which I found two years ago in the State Paper Office, London. To these are added many documents from the Royal Archives at Copenhagen; most of them, it is true, have been published in the Danish, but they are unknown to English readers. I have also, in connection with this book, more than once visited Denmark, and have had access to the Royal Archives at Copenhagen, and to the palaces in which the Queen lived during her unhappy life at the Danish court. I have followed her to Kronborg, where she was imprisoned, and to Celle, in Germany, where she died in exile. My researches at this latter place may serve to throw light on the closing (and little-known) years of the Queen’s brief life. She rests at Celle by the side of her ancestress, Sophie Dorothea, whose life in many ways closely resembled her own.

A word of explanation is perhaps necessary for the first few chapters of this book. In all the biographies of Caroline Matilda written in any language, her life in England before her marriage has received scant consideration, probably on account of her extreme youth. As her parentage and education were largely responsible for the mistakes of her later years, I have sketched, with some detail, the characters of her father and mother, and her early environment. This plan has enabled me to describe briefly the English court from the death of Queen Caroline to the accession of George III., and so to form a link with my other books on the House of Hanover.

My thanks are due to Miss Hermione Ramsden for kindly translating for me sundry documents from the Danish; to Mr. Louis Bobé, of Copenhagen, for much interesting information; and to the Editor of the Nineteenth Century and After for allowing me to re-publish certain passages from an article I recently contributed to that review on Augusta, Princess of Wales. I must also thank the Earl of Wharncliffe for permitting me to reproduce the picture of Lord Bute at Wortley Hall, and Count Kielmansegg for similar permission with regard to the portrait of Madame de Walmoden at Gülzow.

W. H. WILKINS.

November, 1903.

| page | |

|---|---|

| Preface | v |

| Contents | ix |

| List of Illustrations | xi |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Birth and Parentage | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Childhood and Youth | 19 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Betrothal | 35 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Training of a King | 52 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| “The Northern Scamp” | 70 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Matilda’s Arrival in Denmark | 84 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Mariage à la Mode | 106 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| At the Court of Denmark | 124 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Birth of a Prince | 138 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Christian VII. in England | 152 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| [Pg x]The Prodigal’s Return | 175 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Struensee | 193 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Tempter | 209 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Queen’s Folly | 228 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Fall of Bernstorff | 251 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Queen and Empress | 265 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Reformer | 280 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Order of Matilda | 303 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Dictator | 328 |

| Transcriber’s Note |

| Queen Matilda (Photogravure). From the Painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1766 | Frontispiece |

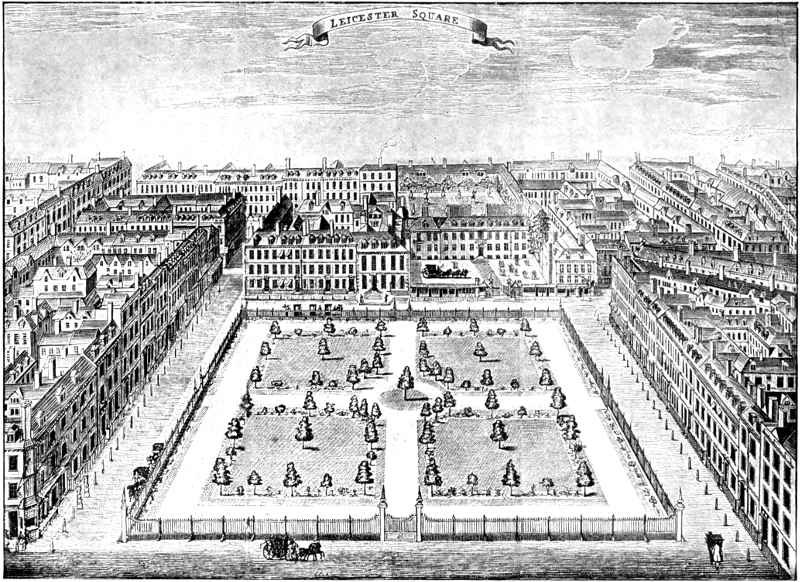

| Leicester House, where Queen Matilda was Born | Facing page 4 |

| Frederick, Prince of Wales, Father of Queen Matilda. From the Painting by J. B. Vanloo at Warwick Castle, by permission of the Earl of Warwick | " " 14 |

| Madame de Walmoden, Countess of Yarmouth. From the Painting at Gülzow by permission of Count Kielmansegg | " " 24 |

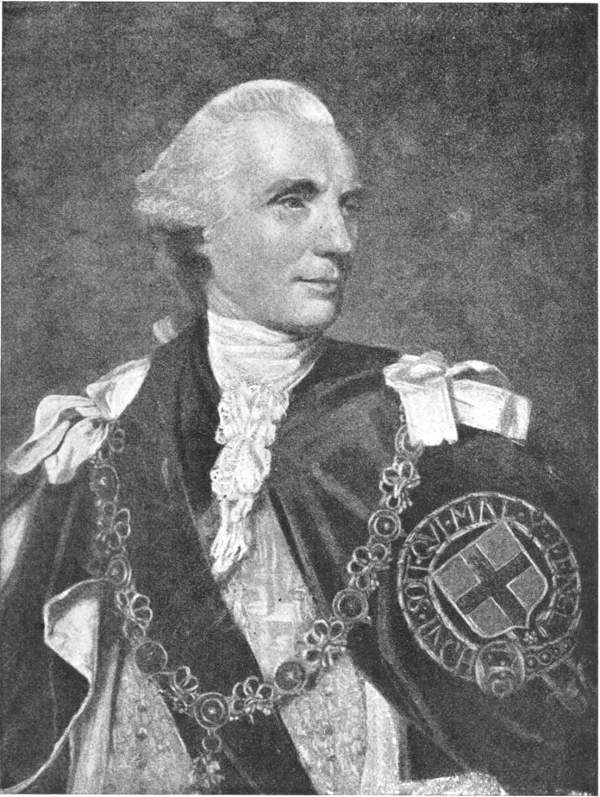

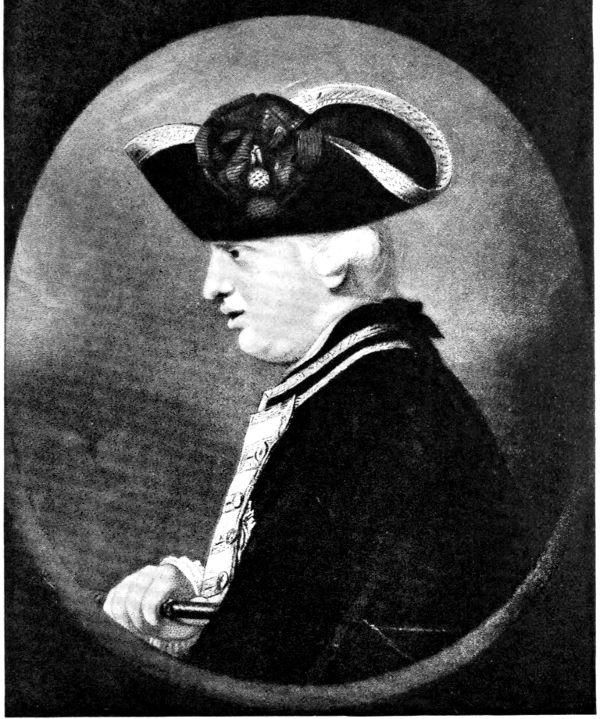

| John, Earl of Bute. From the Painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds at Wortley Hall, by permission of the Earl of Wharncliffe | " " 36 |

| The Elder Children of Frederick and Augusta, Prince and Princess of Wales, Playing in Kew Gardens. From a Painting, temp. 1750 | " " 50 |

| Queen Louise, Consort of Frederick V. of Denmark and Daughter of George II. of England. From a Painting by Pilo in the Frederiksborg Palace | " " 62 |

| King Christian VII. From the Painting by P. Wichman, 1766 | " " 76 |

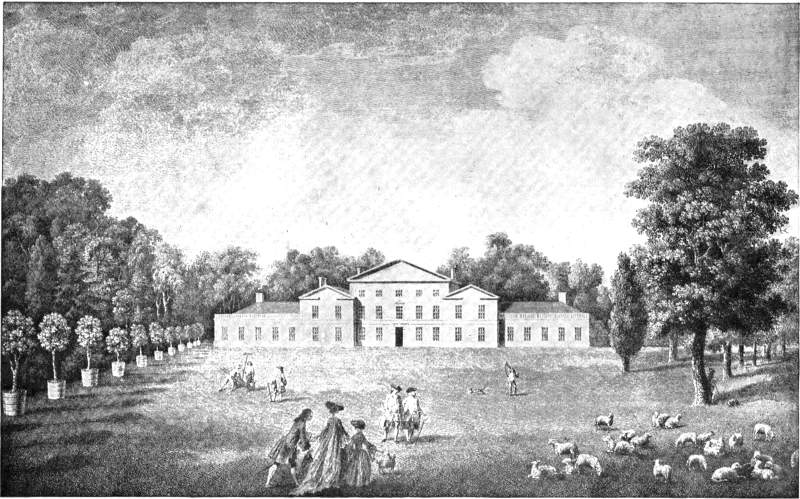

| Kew Palace, where Queen Matilda passed much of her Girlhood. From an Engraving, temp. 1751 | " " 90 |

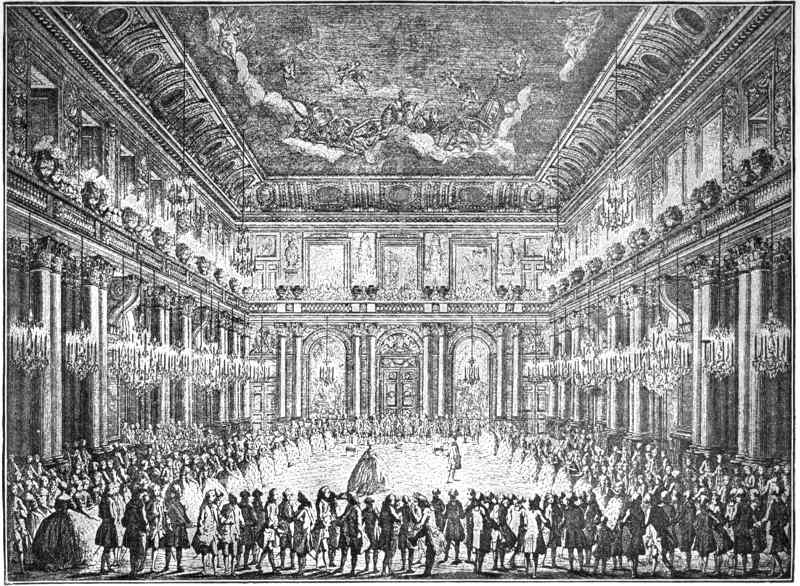

| The Marriage Ball of Christian VII. and Queen Matilda in the Christiansborg Palace. From a Contemporary Print | " " 104 |

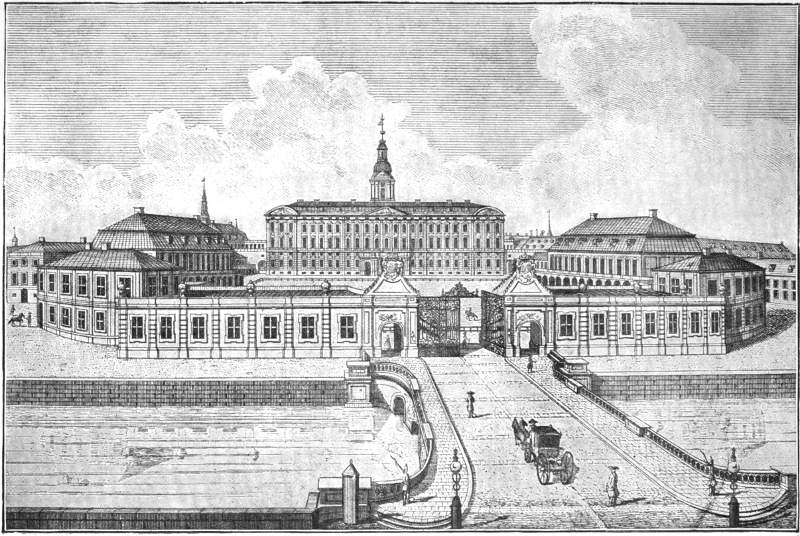

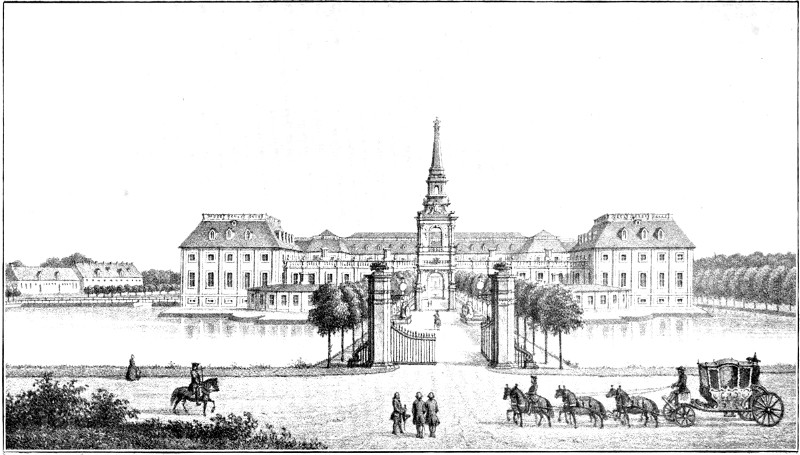

| The Christiansborg Palace, Copenhagen. From an Old Print, temp. 1768 | [Pg xii]" " 120 |

| Edward, Duke of York, Brother of Queen Matilda. From the Painting by G. H. Every | " " 132 |

| Queen Matilda Receiving the Congratulations of the Court on the Birth of the Crown Prince Frederick. From a Contemporary Print | " " 142 |

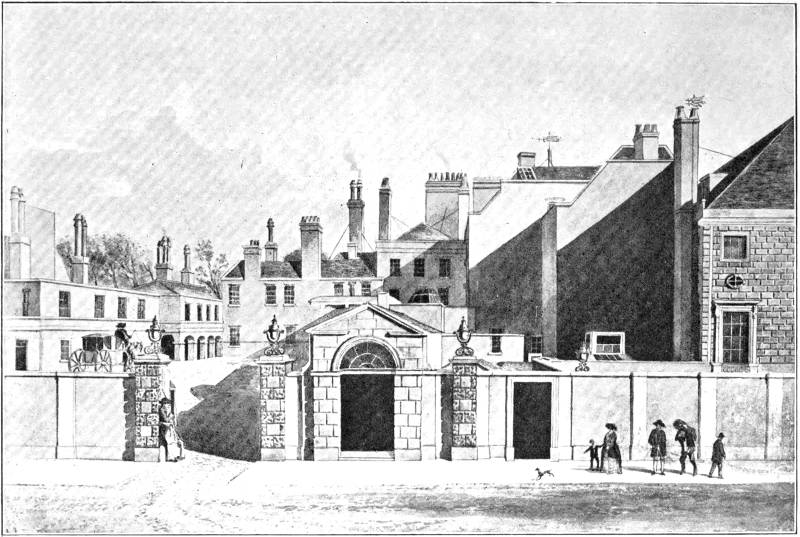

| Carlton House, Pall Mall, the Residence of the Princess-Dowager of Wales. From a Print, temp. 1765 | " " 156 |

| The Masked Ball given by Christian VII. at the Opera House, Haymarket. From the “Gentleman’s Magazine,” 1768 | " " 172 |

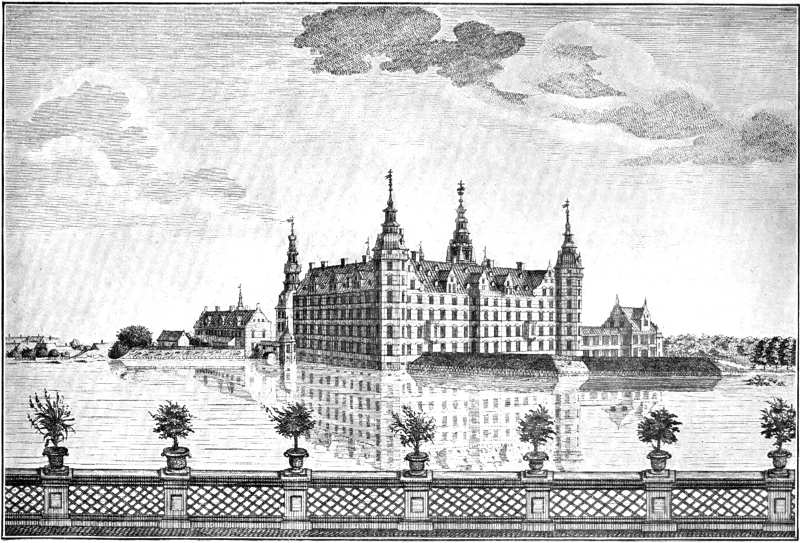

| The Palace of Frederiksborg, from the Garden Terrace. From an Engraving, temp. 1768 | " " 180 |

| William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, Brother of Queen Matilda. From the Painting by H. W. Hamilton, 1771 | " " 190 |

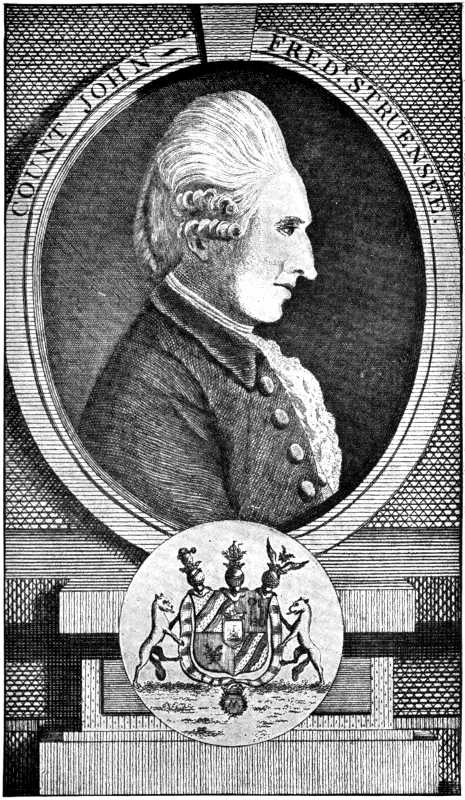

| Struensee. From an Engraving, 1771 | " " 206 |

| Queen Sophia Magdalena, Grandmother of Christian VII. | " " 226 |

| Augusta, Princess of Wales, Mother of Queen Matilda. After a Painting by F. B. Vanloo | " " 244 |

| George III., Brother of Queen Matilda. From a Painting by Allan Ramsay (1767) in the National Portrait Gallery | " " 264 |

| The Frederiksberg Palace, near Copenhagen. From a Print, temp. 1770 | " " 282 |

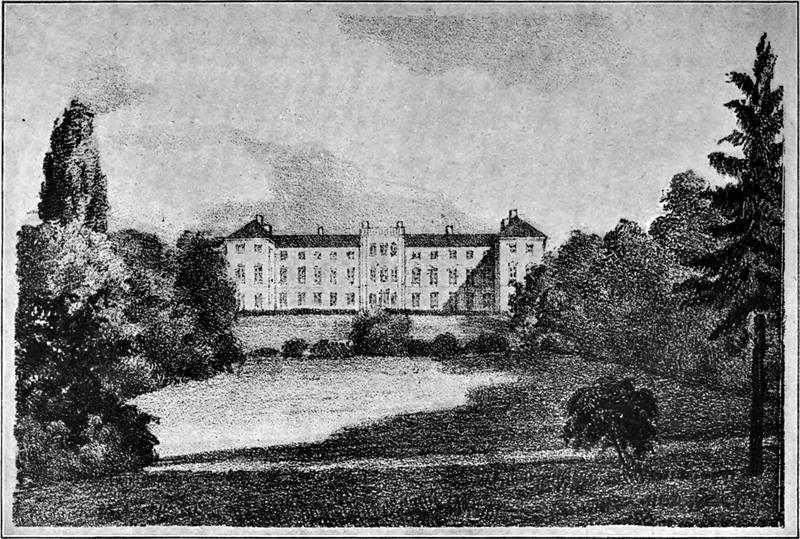

| The Palace of Hirschholm. Temp. 1770 | " " 304 |

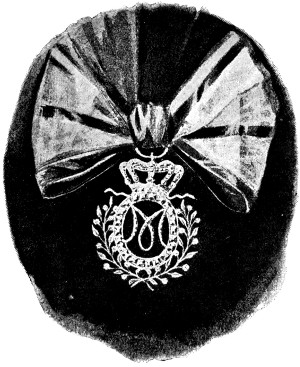

| Two Relics of Queen Matilda in the Rosenborg Castle, Copenhagen. (1) The Insignia of the Order of Matilda; (2) The Wedding Goblet | " " 330 |

| Queen Matilda and her Son, the Crown Prince of Denmark. From the Painting at the Rosenborg, Copenhagen | " " 348 |

BIRTH AND PARENTAGE.

1751.

Caroline Matilda, Queen of Denmark and Norway, Princess of Great Britain and Ireland (a sister of George III.), was born at Leicester House, London, on Thursday, July 22, 1751. She was the ninth and youngest child of Frederick Prince of Wales and of his wife Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, and came into the world a little more than four months after her father’s death. There is a Scandinavian superstition to the effect that children born fatherless are heirs to misfortune. The life of this “Queen of Tears” would seem to illustrate its truth.

Caroline Matilda inherited many of her father’s qualities, notably his warm, emotional temperament, his desire to please and his open-handed liberality. Both in appearance and disposition she resembled her father much more than her mother. Some account of this Prince is therefore necessary for a right understanding of his daughter’s character, for, though she was born after his death, the silent forces of heredity influenced her life.

Frederick Prince of Wales was the elder son[Pg 2] of George II. and of his consort Caroline of Ansbach. He was born in Hanover during the reign of Queen Anne, when the prospects of his family to succeed to the crown of England were doubtful, and he did not come to England until he was in his twenty-second year and his father had reigned two years. He came against the will of the King and Queen, whose cherished wish was that their younger son William Duke of Cumberland should succeed to the English throne, and the elder remain in Hanover. The unkindness with which Frederick was treated by his father had the effect of driving him into opposition to the court and the government. He had inherited from his mother many of the graces that go to captivate the multitude, and he soon became popular. Every cast-off minister, every discontented politician, sought the Prince of Wales, and found in him a ready weapon to harass the government and wound the King. The Prince had undoubted grievances, such as his restricted allowance and the postponement of his marriage to a suitable princess. For some years after Frederick’s arrival in England the King managed to evade the question of the marriage, but at last, owing chiefly to the clamour of the opposition, he reluctantly arranged a match between the Prince of Wales and Augusta, daughter of the reigning Duke of Saxe-Gotha.

The bride-elect landed at Greenwich in April, 1736, and, two days after her arrival, was married[Pg 3] to Frederick at the Chapel Royal, St. James’s. The Princess was only seventeen years of age and could not speak a word of English. She was tall and slender, with an oval face, regular features, bright, intelligent eyes, and an abundance of light-brown hair. Frederick’s marriage did not make him on better terms with his parents, and in this family quarrel the Princess, who soon showed that she possessed more than usual discretion, sided with her husband. The disputes between the King and the Prince of Wales culminated in an open act of revolt on the part of the latter, when, with incredible folly, he carried off his wife, on the point of her first lying-in, from Hampton Court to St. James’s. Half an hour after her arrival in London the Princess was delivered of a girl child, Augusta, who later in life became Duchess of Brunswick. The King was furious at this insubordination, and as soon as the Princess was sufficiently recovered to be moved, he sent his son a message ordering him to quit St. James’s with all his household. The Prince and Princess went to Kew, where they had a country house; and for a temporary London residence (while Carlton House, which the Prince had bought, was being repaired) they took Norfolk House, St. James’s Square.

A few weeks after this rupture the illustrious Queen Caroline died, to the great grief of the King and the nation. Her death widened the breach in the royal family, for the King considered that his son’s undutiful conduct had hastened his mother’s[Pg 4] death. Frederick now ranged himself in open opposition to the King and the government, and gathered around him the malcontent politicians, who saw in Walpole’s fall, or Frederick’s accession to the throne, their only chance of rising to power. The following year, 1738, a son and heir (afterwards George III.) was born to the Prince and Princess of Wales at Norfolk House. This event strengthened the position of the Prince, especially as the King’s health was reported to be failing.

Frederick removed his household to Leicester House in Leicester Fields. It was here, eleven years later, that his posthumous daughter Caroline Matilda was born. Leicester House was built by the Earl of Leicester in the reign of James I. There was a field before it in those days, but a square was subsequently built around the field, and Leicester House occupied the north-east corner of what was then Leicester Fields, but is now known as Leicester Square. It was a large and spacious house, with a courtyard in front, and the state rooms were admirably adapted for receptions and levees, but as a residence it was not so satisfactory. Frederick chiefly made use of Carlton House and Kew for his family life, and kept Leicester House for entertaining. His court there offered a curious parallel to the one his father had held within the same walls in the reign of George I., when the heir to the throne was also at variance with the King. Again Leicester House became the rallying place of the opposition, again its walls echoed with the sound[Pg 5] of music and dance, again there flocked to its assemblies ladies of beauty and fashion, elegant beaux, brilliant wits, politicians and pamphleteers. Frederick’s intelligence has been much abused, but he was intelligent enough to gather around him at this time much of what was best in the social life of the day, and his efforts were ably seconded by his clever and graceful wife.

After the fall of Walpole several of the Prince’s friends took office, and a formal, though by no means cordial, reconciliation was patched up between the King and the Heir Apparent, but there was always veiled hostility between them, and from time to time their differences threatened to become acute. For instance, after the Jacobite rising the Prince of Wales disapproved of the severities of his brother, the Duke of Cumberland, “the butcher of Culloden,” and showed his displeasure in no unequivocal manner. When the Jacobite peers were condemned to death the Prince and Princess interceded for them, in one case with success. Lady Cromartie, after petitioning the King in vain for her husband’s life, made a personal appeal, as a wife and mother, to the Princess of Wales, and brought her four children to plead with her as well. The Princess said nothing, but, with evident emotion, summoned her own children and placed them beside her. This she followed by praying the King for Cromartie’s life, and her prayer was granted.

After the reconciliation the Prince and Princess[Pg 6] of Wales occasionally attended St. James’s, but since the death of Queen Caroline the court of George II. had lost its brilliancy and become both gross and dull, in this respect contrasting unfavourably with Leicester House. Grossness and dulness were characteristic of the courts of our first two Hanoverian kings, but whatever complaint might be brought against Leicester House, the society there was far livelier and more refined than that which assembled at St. James’s. The popular grievance against Leicester House was that it was too French. France was just then very unpopular in England, and the British public did not like the French tastes of the Prince of Wales—the masques imitated from Versailles, the French plays acted by French players and the petits soupers. High play also took place at Leicester House, but the Princess did her best to discourage this. In the other frivolities which her husband loved she acquiesced, more for the sake of keeping her influence over him than because she liked them. Her tastes were simple, and her tendencies puritanical.

At Kew the Prince and Princess of Wales led a quieter life, and here the influence of the Princess was in the ascendant. Kew House was an old-fashioned, low, rambling house, which the Prince had taken on a long lease from the Capel family. The great beauty of Kew lay in its extensive garden, which was improved and enlarged by Frederick. He built there orangeries and hothouses after the fashion of Herrenhausen, and filled them with[Pg 7] exotics. Both Frederick and his wife had a love of gardening, and often worked with their children in the grounds, and dug, weeded and planted to their hearts’ content. Sometimes they would compel their guests to lend a hand as well. Bubb Dodington tells how he went down to Kew on a visit, accompanied by several lords and ladies, and they were promptly set to work in the garden, probably to their disgust. Dodington’s diary contains the following entries:—

“1750, February 27.—Worked in the new walk at Kew.

“1750, February 28.—All of us, men, women and children, worked at the same place. A cold dinner.”[2]

[2] Bubb Dodington’s Diary, edition 1784.

It was like Frederick’s monkeyish humour to make the portly and pompous Dodington work in his garden; no doubt he hugely enjoyed the sight. The Prince’s amusements were varied, if we may judge from the following account by Dodington:—

“1750, June 28.—Lady Middlesex, Lord Bathurst, Mr. Breton and I waited on their Royal Highnesses to Spitalfields to see the manufactory of silk, and to Mr. Carr’s shop in the morning. In the afternoon the same company, with Lady Torrington in waiting, went in private coaches to Norwood Forest to see a settlement of gypsies. We returned and went to Bettesworth the conjurer, in hackney coaches. Not finding him we went in search of the little Dutchman, but were disappointed;[Pg 8] and concluded the particularities of this day by supping with Mrs. Cannon, the Princess’s midwife.”[3]

[3] Bubb Dodington’s Diary, edition 1784.

These, it must be admitted, were not very intellectual amusements. On the other hand it stands to Frederick’s credit that he chose as his personal friends some of the ablest men of the day, and found delight and recreation in their society. Between him and Bolingbroke there existed the warmest sympathy. When Bolingbroke came back to England after Walpole’s fall, he renewed his friendship with Frederick, and often paced with him and the Princess through the gardens and shrubberies of their favourite Kew, while he waxed eloquent over the tyranny of the Whig oligarchy, which kept the King in thrall, and held up before them his ideal of a patriot king. Both the Prince and Princess listened eagerly to Bolingbroke’s theories, and in after years the Princess instilled them into the mind of her eldest son. Chesterfield and Sir William Wyndham also came to Kew sometimes, and here Frederick and Augusta exhibited with just pride their flower-beds to Pope, who wrote of his patron—

The Prince not only sought the society of men of letters, but made some attempts at authorship himself. His verse was not very remarkable; the best perhaps was the poem addressed to the Princess beginning:—

and so on through five stanzas of praise of Augusta’s charms, until:

Perhaps it was of these lines that the Prince once asked Lord Poulett his opinion. “Sir,” replied that astute courtier, “they are worthy of your Royal Highness.”

Notwithstanding his admiration of his wife, Frederick was not faithful to her. But it may be doubted whether, after his marriage, he indulged in any serious intrigue, and his flirtations were probably only tributes offered to the shrine of gallantry after the fashion of the day. In every other respect he was a good husband. He was also a devoted father, a kind master to his servants, and a true friend. In his public life he always professed a love of liberty. To a deputation of Quakers he once delivered the following answer: “As I am a friend to liberty in general, and to toleration in particular, I wish you may meet with all proper favour, but, for myself, I never gave my vote in parliament, and to influence my friends, or direct my servants, in theirs, does not become my station. To leave them entirely to their own consciences and understandings, is a rule I have hitherto prescribed to myself, and purpose through life to[Pg 10] observe.” “May it please the Prince of Wales,” rejoined the Quaker at the head of the deputation, “I am greatly affected with thy excellent notions of liberty, and am more pleased with the answer thou hast given us, than if thou hadst granted our request.”

Frederick avowed a great love for the country over which he one day hoped to reign; and, though French in his tastes rather than English, he did all in his power to encourage the national sentiment. For instance, it is recorded on one of his birthdays: “There was a very splendid appearance of the nobility and gentry and their ladies at Leicester House, and his Royal Highness observing some lords to wear French stuffs, immediately ordered the Duke of Chandos, his Groom of the Stole, to acquaint them, and his servants in general, that after that day he should be greatly displeased to see them appear in any French manufacture”.[4]

[4] The Annual Register, January, 1748.

Moreover, he instilled in the minds of his children the loftiest sentiments of patriotism. In view of the German predilections of his father and grandfather the training which Frederick gave his children, especially his eldest son, had much to do in after years with reconciling the Tory and Jacobite malcontents to the established dynasty. The wounds occasioned by the rising of 1745 were still bleeding, but the battle of Culloden had extinguished for ever the hopes of the Stuarts, and many of their adherents were casting about for a pretext of acquiescing in the inevitable. These[Pg 11] Frederick met more than half way. He was not born in England (neither was Charles Edward), but his children were, and he taught them to consider themselves Englishmen and not Germans, and to love the land of their birth. His English sentiments appear again and again in his letters and speeches. They crop up in some verses which he wrote for his children to recite at their dramatic performances. On one occasion the piece selected for representation was Addison’s play of Cato, in which Prince George, Prince Edward, and the Princesses Augusta and Elizabeth took part. Frederick wrote a prologue and an epilogue; the prologue was spoken by Prince George. After a panegyric on liberty the future King went on to say:—

There came an echo of this early teaching years later when George III. wrote into the text of his first speech to parliament the memorable words: “Born and educated in this country, I glory in the name of Briton”.

In the epilogue spoken by Prince Edward similar sentiments were expressed:—

[5] Prince Edward, Duke of York, became a Vice-Admiral of the Blue.

We get many pleasant glimpses, in contemporary letters and memoirs, of the domestic felicity of the royal household at Kew and Leicester House; of games of baseball and “push pin,” with the children in the winter, of gardening and cricket in the summer, and of little plays, sometimes composed by the Prince, staged by the Princess and acted by their sons and daughters all the year round. “The Prince’s family,” Lady Hervey writes, “is an example of innocent and cheerful amusement,”[6] and her testimony is corroborated on all sides.

[6] Lady Hervey’s Letters.

Frederick Prince of Wales died suddenly on March 20, 1751, to the great grief of his wife and children, and the consternation of his political adherents. The Prince had been suffering from a chill, but no one thought that there was any danger. On the eighth day of his illness, in the evening, he was sitting up in bed, listening to the performance of Desnoyers, the violinist, when he was seized with a violent fit of coughing. He put his hand upon his heart and cried, “Je sens la mort!” The Princess, who was in the room, flew to her husband’s assistance, but before she could reach his side he was dead. Later it was shown that the immediate cause of death was the break[Pg 13]ing of an abscess in his side, which had been caused by a blow from a cricket ball a few weeks before. Cricket had been recently introduced into England, and Frederick was one of the first to encourage the game, which soon became national. He often played in matches at Cliveden and Kew.

No Prince has been more maligned than Frederick Prince of Wales, and none on less foundation. He opposed Walpole and the Whig domination, and therefore the Whig pamphleteers of the time, and Whig historians since, have poured on him the vials of their wrath, and contemptuously dismissed him as half fool and half rogue. But the utmost that can be proved against him is that he was frivolous, and unduly fond of gambling and gallantry. These failings were common to the age, and in his case they were largely due to his neglected youth. Badly educated, disliked by his parents, to whom he grew up almost a stranger, and surrounded from the day of his arrival in England by malcontents, parasites and flatterers, it would have needed a much stronger man than Frederick to resist the evil influences around him. His public utterances, and there is no real ground for doubting their sincerity, go to show that he was a prince of liberal and enlightened views, a friend of peace and a lover of England. It is probable that, had he been spared to ascend the throne, he would have made a better king than either his father or grandfather. It is possible that he would have made a better king than his son, for, though he was by no[Pg 14] means so good a man, he was more pliant, more tolerant, and far less obstinate. Speculation is idle in such matters, but it is unlikely, if Frederick had been on the throne instead of George III., that he would have encouraged the policy which lost us our American colonies. Dying when he did, all that can be said of Frederick politically is that he never had a fair chance. Keeping the mean between two extreme parties in the state he was made the butt of both, but the fact remains that he attracted to his side some of the ablest among the moderate men who cared little for party and much for the state. Certainly nothing in his life justified the bitter Jacobite epigram circulated shortly after his death:—

George II. was playing cards when the news of his son’s death was brought to him. He turned very pale and said nothing for a minute; then he rose, whispered to Lady Yarmouth, “Fritz ist todt,” and quitted the room. But he sent that same night a message of condolence to the bereaved widow.

The death of her husband was a great blow to Augusta Princess of Wales. Suddenly deprived of the prospect of becoming Queen of England, she found herself, at the age of thirty-two, left a widow with eight young children and expecting shortly to give birth to another. Her situation excited great commiseration, and among the people the dead Prince was generally regretted, for despite his follies he was known to be kindly and humane. Elegies were cried about the streets, and very common exclamations were: “Oh, that it were his brother!” “Oh, that it were the Butcher!” Still it cannot be pretended that Frederick was deeply mourned. A conversation was overheard between two workmen, who were putting up the hatchment over the gate at Leicester House, which fairly voiced the popular sentiment: “He has left a great many small children,” said one. “Aye,” replied the other, “and what is worse, they belong to our parish.”

Contrary to expectation the King behaved with great kindness to his daughter-in-law, and a few days after her bereavement paid her a visit in person. He refused the chair of state placed for him, seated himself on the sofa beside the Princess, and at the sight of her sorrow was so much moved as to shed tears. When the Princess Augusta, his eldest granddaughter, came forward to kiss his hand, he took her in his arms and embraced her. To his grandsons the King said: “Be brave boys, be obedient to your mother, and endeavour to do credit to the high station in which you are born”. He who[Pg 16] had never acted the tender father delighted in playing “the tender grandfather”.[7]

[7] Vide Horace Walpole’s Reign of George II.

A month after his father’s death Prince George was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, but the young Prince, though always respectful, never entertained any affectionate feelings for his grandfather. This may have been due, in part, to the unforgiving spirit with which the old King followed his son even to the tomb. Frederick’s funeral was shorn of almost every circumstance of state. No princes of the blood and no important members of the government attended, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey “without either anthem or organ”. Of the few faithful friends who attended the last rites, Dodington writes: “There was not the attention to order the board of green cloth to provide them a bit of bread; and these gentlemen of the first rank and distinction, in discharge of their last sad duty to a loved, and loving, master, were forced to bespeak a great, cold dinner from a common tavern in the neighbourhood; at three o’clock, indeed, they vouchsafed to think of a dinner and ordered one, but the disgrace was complete—the tavern dinner was paid for and given to the poor”.[8]

[8] Dodington’s Diary, April 13, O.S., 1751, edition 1784.

Some five months after Frederick’s death his widow gave birth to a princess, the subject of this book. Dodington thus records the event, which, except in the London Gazette, was barely noticed by the journals of the day:—

“On Wednesday, the Princess walked in Carlton Gardens, supped and went to bed very well; she was taken ill about six o’clock on Thursday morning, and about eight was delivered of a Princess. Both well.”[9]

[9] Dodington’s Diary, July 13, O.S., 1751, edition 1784.

The advent of this daughter was hardly an occasion for rejoicing. Apart from the melancholy circumstances of her birth, her widowed mother had already a young and numerous family,[10] several of whom were far from strong, and all, with the exception of her eldest son, the heir presumptive to the throne, unprovided for.

[10] Table. See next page.

Eleven days after her birth the Princess was baptised at Leicester House by Dr. Hayter, Bishop of Norwich, and given the names of Caroline Matilda, the first being after her grandmother, the second harking back to our Norman queens. Except in official documents she was always known by the latter name, and it is the one therefore that will be used in speaking of her throughout this book. The infant had three sponsors, her aunt the Princess Caroline (represented by proxy), her eldest sister the Princess Augusta, and her eldest brother the Prince of Wales. In the case of the godfather the sponsorship was no mere form, for George III. stood in the light of guardian to his sister all through her life.

Table Showing the Children of Frederick and Augusta, Prince and Princess of Wales, and also the Descent of His Majesty King Edward VII. from Frederick Prince of Wales.

| Frederick Prince of Wales (son of George II. and Caroline of Ansbach). |

Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (daughter of Frederick II. Duke of Saxe-Gotha). | ||||||||||||

| —Augusta, b. 1737, d. 1813, m. Charles William Duke of Brunswick, and had issue among others | |||||||||||||

| Caroline, Consort of George IV., who had issue | |||||||||||||

| Princess Charlotte, d. in childbirth, 1817. | |||||||||||||

| —George III., b. 1738, d. 1820, m. Charlotte Princess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and had issue among others | |||||||||||||

| Edward Duke of Kent | |||||||||||||

| Queen Victoria | |||||||||||||

| King Edward VII. | |||||||||||||

| —Edward Duke of York, b. 1738, d. 1767, unmarried. | |||||||||||||

| —Elizabeth, b. 1739, d. 1759, unmarried. | |||||||||||||

| —William Henry Duke of Gloucester, b. 1743, d. 1805, m. Maria Countess Dowager Waldegrave, illegitimate dau. of Sir Edward Walpole, and had issue among others | |||||||||||||

| William Frederick Duke of Gloucester, m. Mary, dau. of George III., no issue. | |||||||||||||

| —Henry Frederick Duke of Cumberland b. 1745, d. 1790, m. Anne, dau. of Lord Irnham, afterwards Earl of Carlhampton, and widow of Andrew Horton, no issue. | |||||||||||||

| —Louisa Anne, b. 1748, d. 1768, unmarried. | |||||||||||||

| —Frederick William, b. 1750, d. 1765, unmarried. | |||||||||||||

| —CAROLINE MATILDA, b. July 11, 1751, m. 1766, Christian VII., King of Denmark, d. 1775, and had issue | |||||||||||||

| Frederick VI., King of Denmark, d. 1839, and Louise Augusta, Duchess of Augustenburg, d. 1843. | |||||||||||||

CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH.

1751-1760.

The early years of the Princess Matilda were passed at Carlton House and Kew. After her husband’s death the Princess-Dowager of Wales, as she was called, resided for the most part in London at Carlton House. She used Leicester House on state occasions, and kept it chiefly for her two elder sons who lived there with their tutors. Carlton House was a stately building fronting St. James’s Park with an entrance in Pall Mall. It was built by a Lord Carlton in the reign of Queen Anne, and was sold in 1732 to Frederick Prince of Wales. The great feature of Carlton House was its beautiful garden, which extended along the Mall as far as Marlborough House, and was laid out on the same plan as Pope’s famous garden at Twickenham. There were smooth lawns, fine trees and winding walks, and bowers, grottoes and statuary abounded. This garden gave Carlton House a great advantage over Leicester House in the matter of privacy, and was of benefit to the children.

Cliveden, near Maidenhead, and Park Place,[Pg 20] Henley-on-Thames, two country places, owned, or leased, by Frederick were given up, but the Princess retained her favourite house at Kew, and sent her younger children down there as much as possible. The greater part of Matilda’s childhood was spent there, and Kew and its gardens are more associated with her memory than any other place in England. The Princess-Dowager encouraged in all her children simplicity of living, love of fresh air and healthy exercise. Each of the little princes and princesses was allotted at Kew a small plot of ground wherein to dig and plant. Gardening was Matilda’s favourite amusement, and in one of the earliest of her letters she writes to a girl friend:—

“Since you left Richmond I have much improved my little plot in our garden at Kew, and have become quite proficient in my knowledge of exotics. I often miss your company, not only for your lively chat, but for your approbation of my horticultural embellishments.... You know we [the royal children] have but a narrow circle of amusements, which we can sometimes vary but never enlarge.”[11]

[11] The authenticity of this letter is doubtful. It first appeared in a work entitled Memoirs of an Unfortunate Queen, interspersed with letters written by Herself to several of her Illustrious Relatives and Friends, published 1776, soon after Matilda’s death. Some of the letters may be genuine, others are undoubtedly spurious.

The Princess was better educated than the majority of English ladies of her time, many of whom could do little more than read and write (but seldom could spell) with the addition of a few superficial accomplishments. Matilda was a fair[Pg 21] linguist, she could speak and write French well, and had a smattering of Italian. Like her brothers and sisters she committed to memory long passages from English classics, and recited them with fluency and expression. She had a great love of music, and played on the harpsichord, and sang in a sweet and pleasing voice. She was thoroughly trained in “deportment,” and danced to perfection. She was a pretty, graceful girl, not awkward, even at the most awkward age, and early gave promise of beauty. She rejoiced in an affectionate, generous disposition and a bright and happy temperament. She stood in awe of her mother, but she was devoted to her brothers and sisters, especially to her eldest sister, Princess Augusta.

This Princess was the one who was suddenly hurried into the world on a July night at St. James’s Palace. She was fourteen years of age when Matilda was born, and was a woman before her youngest sister ceased to be a child, so that she stood to her in the place of friend and counsellor. Augusta had not the beauty of Matilda, but she was a comely maiden with regular features, well-shaped figure, pleasant smile, and general animation. She was the best educated of the family. This was largely due to her thirst for knowledge. She read widely, and interested herself in the political and social questions of the day to a degree unusual with princesses of her age. She was sharp and quick-witted, and in her childhood precocious beyond her years. “La! Sir Robert,” she pertly exclaimed,[Pg 22] when only seven years of age, to Sir Robert Rich, whom she had mistaken for Sir Robert Walpole, “what has become of your blue string and your big belly?” Sir “Blue-string” was one of the Tory nicknames for Walpole, and in the caricatures of the time his corpulence was an endless subject of ridicule. Her parents, instead of reprimanding her, laughed at her pleasantries, with the result that they often found her inconveniently frank and troublesome. After Frederick’s death her mother, who had no wish to have a grown-up daughter too soon, kept her in the background as much as possible, a treatment which the lively Augusta secretly resented.

Matilda’s other sisters, the Princesses Elizabeth and Louisa Anne, were nearer her in age and were much more tractable than Augusta. They both suffered from ill-health. Her eldest brother George Prince of Wales was a silent youth, shy and retiring, and not demonstrative in any way. Edward, her second brother, afterwards Duke of York, was livelier and was always a favourite with his sister. Her three youngest brothers, William Henry, afterwards Duke of Gloucester, Henry Frederick, later Duke of Cumberland, and Frederick William (who died at the age of fifteen), were her chief playmates, for they were nearer her in age. The children of Frederick Prince of Wales and Augusta had one characteristic in common; clever or stupid, lively or dull, sickly or strong in health, they were all affectionate and fond of one another. Quarrels were[Pg 23] rare, and the brothers and sisters united in loving and spoiling the pet of the family, pretty, bright little Matilda.

For eighteen months after her husband’s death the Princess-Dowager of Wales remained in closest retirement. At the end of that time she reappeared in public and attended court, where, by the King’s command, she received the same honours as had been paid to the late Queen Caroline. She was also made guardian of her eldest son, in case of the King’s demise during the Prince of Wales’ minority. William Duke of Cumberland bitterly resented this appointment as a personal affront, and declared to his friends that he now felt his own insignificance, and wished the name of William could be blotted out of the English annals. It increased his jealousy of his sister-in-law, and she, on her part, made no secret of her inveterate dislike of him. Her children were taught to regard their uncle as a monster because of his cruelties at Culloden, and he complained to the Princess-Dowager of the “base and villainous insinuations” which had poisoned their minds against him.

The Princess-Dowager of Wales rarely attended St. James’s except on ceremonial occasions. Nominally George II.’s court, for the last twenty years of his reign, was presided over by the King’s eldest unmarried daughter, Princess Amelia, or Emily, a princess who, as years went on, lost her good looks as well as her manners. She became deaf and short-sighted, and was chiefly known for her sharp tongue[Pg 24] and her love of scandal and high play. She had no influence with the King, and her unamiable characteristics made her unpopular with the courtiers, who treated her as a person of no importance. In reality the dame regnante at St. James’s was Madame de Walmoden, Countess of Yarmouth, who had been the King’s mistress at Hanover. He brought her over to England the year after Queen Caroline’s death, lodged her in the palace, created her a peeress, and gave her a pension. In her youth the Walmoden had been a great beauty, but as she advanced in years she became exceedingly stout. Ministers, peers, politicians, place-hunters of all kinds, even bishops and Church dignitaries, paid their court to her. She accepted all this homage for what it was worth, but though she now and then obtained a place for a favourite, she very wisely abstained from meddling in English politics, which she did not understand, and chiefly occupied herself in amassing wealth.

Lady Yarmouth was the last instance of a mistress of the King of England who received a peerage. Her title did not give her much prestige, and her presence at court did not add to its lustre. During her ten years’ reign Queen Caroline had set an example of virtue and decorum, which was not forgotten, and the presence of a recognised mistress standing in her place was resented by many of the wives of the high nobility. Some of these ladies abstained from going to St. James’s on principle, others, and these the more numerous, because the[Pg 25] assemblies there had become insufferably dull and tedious. If the court had been conducted on the lavish scale which marked the reigns of the Stuarts, if beauty, wit and brilliancy had met together, some slight lapses from the strict path of virtue might have been overlooked. But a court, which was at once vicious and dull, was impossible.

The Princess-Dowager of Wales, who prided herself on the propriety of her conduct and the ordered regularity of her household, was the most conspicuous absentee, and though she now and then attended St. James’s as in duty bound, she never took her daughters to court, but declared that the society there would contaminate them. She rarely, if ever, honoured the mansions of the nobility with a visit, and her appearances in public were few and far between. She lived a life of strict seclusion, which her children shared. During the ten years that elapsed between Frederick’s death and George III.’s accession to the throne, the Princess-Dowager was little more than a name to the outer world; the time had not come when the veil of privacy was to be rudely torn from her domestic life, and the publicity from which she shrank turned on her with its most pitiless glare.

The policy of the Princess was to keep in the background as much as possible and devote herself wholly to the care and education of her numerous family. She did her duty (or what she conceived to be her duty) to her children to the utmost in her power, and in her stern, undemon[Pg 26]strative way there is no doubt that she loved them. She ruled her household with a rod of iron, her children feared and obeyed, but it could hardly be said that they loved her. Despite her high sense of duty, almsgiving and charity, the Princess-Dowager was not a lovable woman. Her temperament was cold and austere, her religion was tinged with puritanism, and her views were strict and narrow. She had many of the virtues associated with the Roman matron. There was only one flaw in the armour of the royal widow’s reputation, and this her enemies were quick to note. That flaw was her friendship with Lord Bute.

John, third Earl of Bute, had been a favourite of Frederick Prince of Wales. He owed his introduction to the Prince to an accident which, slight though it was, served to lay the foundations of his future political career. He was watching a cricket match at Cliveden when a heavy shower of rain came on. The Prince, who had been playing, withdrew to a tent and proposed a game of whist until the weather should clear. At first nobody could be found to take a fourth hand, but presently one of the Prince’s suite espied Bute and asked him to complete the party. The Prince was so much pleased with his new acquaintance that he invited him to Kew, and gave him a post in his household. Bute soon improved his opportunities, and the Princess also extended to him her confidence and friendship; perhaps she found in his cold, proud temperament and narrow[Pg 27] views some affinity with her own character and beliefs. Frederick rather encouraged this friendship than otherwise. He was very much attached to his excellent and virtuous wife, but no doubt her serious way of looking at things wearied his more frivolous nature occasionally. According to the scandalous gossip of Horace Walpole: “Her simple husband when he took up the character of the regent’s gallantry had forced an air of intrigue even upon his wife. When he affected to retire into gloomy allées of Kew with Lady Middlesex, he used to bid the Princess walk with Lord Bute. As soon as the Prince was dead, they walked more and more, in honour of his memory.”[12]

[12] Memoirs of George II., vol. ii.; see also Wraxall’s Hist. Memoirs, vol. ii.

At the corrupt court of George II., where the correct conduct of the Princess was resented as a tacit affront, the intimacy between the Princess and Lord Bute was soon whispered into an intrigue. Once at a fancy dress ball during the lifetime of Frederick when the Princess was present, the beautiful Miss Chudleigh appeared as Iphigenia and so lightly clad as to be almost in a state of nudity. The Princess threw a shawl over the young lady’s bosom, and sharply rebuked her for her bad taste in appearing in so improper a guise. “Altesse,” retorted Miss Chudleigh, in no wise abashed, “vous savez, chacun a son but.” The impertinent witticism ran like wildfire round the court, and henceforth the names of the Princess and Lord Bute were associated[Pg 28] together in a scandalous suggestion, which had nothing to warrant it at the time beyond the fact that the Princess treated Lord Bute as an intimate friend.

After Frederick’s death the scandal grew, for the Princess was very unpopular with the Walmoden and her circle, and they delighted to have the chance of painting her as bad as themselves. Yet Bute was some years older than the Princess. He was married to a beautiful wife, the only daughter and heiress of Edward Wortley Montagu, by whom he had a large family, and he was devoted to his wife and children. He was a man of high principle, and lived a clean life in an age of uncleanness. Lady Hervey writes of him: “He has always been a good husband, an excellent father, a man of truth and sentiments above the common run of men”. Bute was not a great man, but his abilities were above the average, and he possessed considerable force of character. He acquired complete ascendency in the household of the Princess-Dowager, and exercised unbounded influence over the young Prince of Wales. Princess Augusta and Prince Edward disliked him, and secretly resented his presence and his interference in family matters. The other children were too young to understand, but Lord Bute was a factor which made itself felt in the daily life of them all, and not a welcome one. Life had become appreciably duller with the royal children since their father’s death. Gone were the little plays and masquerades, the singers and dancers. Gone were[Pg 29] the picnics and the children’s parties. Even the cards were stopped, and the utmost the Princess-Dowager would allow was a modest game of comet. The children suspected Lord Bute of aiding and abetting their mother in her Spartan treatment of them, and disliked him accordingly.

The Princess-Dowager had need of a friend and counsellor, whether Lord Bute was the wisest choice she could have made or not. She was quite alone in the world, and had to fight against many intrigues. She was not a woman to make friendships quickly, and she disliked the society of her own sex. Thus it came about that in the secluded life she led, except for the members of her household, two persons only were admitted to Carlton House and Kew. One was Lord Bute, the other Bubb Dodington.

Bubb Dodington, whose diary we have quoted before, was a wealthy parvenu whose ambition in life was to become peer. Walpole had refused him his coveted desire, and he therefore attached himself to Frederick Prince of Wales, who borrowed money from him, and invented a post in his household for his benefit. As far as it was possible for Dodington to be attached to any one, he seems to have been attached to his “Master,” as he calls him. After Frederick’s death, when, to use his own phrase, “there was little prospect of his doing any good at Leicester House,” he again courted the favour of the government. But he retained a sentimental attachment to his master’s widow, or (for he was a born intriguer) he wished to keep in touch with[Pg 30] the young Prince of Wales. In either case he was careful not to break off his friendship with the Princess-Dowager, and often waited upon her at Carlton House. The Princess, though she did not wholly trust him, clung to him as a friend of her husband’s. He was useful as a link with the outer world, he could retail to her all the political gossip of the day, and she, in turn, could make him the medium of her views, for she knew what she told him in apparent confidence would be retailed to all the town before the day was over. Dodington was an inveterate gossip, and his vanity was too much flattered by being made the confidant of the Princess-Dowager for him to conceal the fact. Moreover, he was wealthy, and a shrewd man of business. The Princess sorely needed advice in money matters, for her dower was only £50,000 a year, and out of that sum she had to keep up Leicester House, Carlton House and Kew, educate and maintain her numerous family, and to pay off by instalments her husband’s debts—a task which she voluntarily took upon herself, though it crippled her financially for years. She did all so well that her economy was a triumph of management.

From Dodington’s diary we get glimpses of the domestic life of the Princess-Dowager and her children after her husband’s death. For instance, he writes: “The Princess sent for me to attend her between eight and nine o’clock. I went to Leicester House expecting a small company, or little musick, but found nobody but her Royal Highness. She[Pg 31] made me draw a stool and sit by the fireside. Soon after came in the Prince of Wales, and Prince Edward, and then the Lady Augusta, all in an undress, and took their stools and sat round the fire with us. We continued talking of familiar occurrences till between ten and eleven, with the ease and unreservedness and unconstraint as if one had dropped into a sister’s house that had a family to pass the evening. It is much to be wished that the Prince conversed familiarly with more people of a certain knowledge of the world.”[13]

[13] Dodington’s Diary, Nov. 17, 1753, edition 1784.

This last point Dodington ventured to press upon the Princess more than once, for it was a matter of general complaint that she kept her children so strictly and so secluded from the world. They had no companions or playmates of their own age besides themselves, for the Princess declared that “the young people of quality were so ill-educated and so very vicious that they frightened her.... Such was the universal profligacy ... such the character and conduct of the young people of distinction that she was really afraid to have them near her children. She should be even in more pain for her daughters than her sons, for the behaviour of the women was indecent, low, and much against their own interests by making themselves so cheap.”[14]

[14] Dodington’s Diary, edition 1784.

We have dwelt thus on Augusta Princess of Wales not only because she was the mother of Princess[Pg 32] Matilda, but because so little is known of her. The scandalous tales of Whig pamphleteers, and the ill-natured gossip of her arch-maligner Horace Walpole cannot be accepted without considerable reserve. No adequate memoir has ever been written of this Princess. Yet she was the mother of a king whose reign was one of the longest and most eventful in English history, and the training she gave her eldest son moulded his character, formed his views and influenced his policy. It influenced also, though in a lesser degree, the life of her youngest daughter. Matilda inherited certain qualities from her father, but in her early education and environment she owed everything to her mother. To the strict seclusion in which she was brought up by this stern mother, who won her children’s respect but never their confidence, and to her utter ignorance of the world and its temptations (more particularly those likely to assail one destined to occupy an exalted position), may be traced to some extent the mistakes of her later years.

There were breaks in the children’s circle at Carlton House and Kew. Prince Frederick William died in 1765 at the age of fifteen, and Princess Elizabeth in 1759 at the age of nineteen. Of the first nothing is recorded, of the latter Horace Walpole quaintly writes: “We have lost another princess, Lady Elizabeth. She died of an inflammation in her bowels in two days. Her figure was so very unfortunate, that it would have been difficult for her to be happy, but her parts and[Pg 33] application were extraordinary. I saw her act in Cato at eight years old when she could not stand alone, but was forced to lean against the side scene. She had been so unhealthy, that at that age she had not been taught to read, but had learned the part of Lucia by hearing the others studying their parts. She went to her father and mother, and begged she might act; they put her off as gently as they could; she desired leave to repeat her part, and, when she did, it was with so much sense that there was no denying her.”[15]

[15] Walpole’s Letters, vol. iii., edition 1857.

The following year a life of much greater importance in the royal family came to a close. George II. died at Kensington Palace on October 25, 1760, in the seventy-seventh year of his age, under circumstances which have always been surrounded by a certain amount of mystery. The version generally received is as follows: The King rose in the morning at his usual hour, drank his chocolate, and retired to an adjoining apartment. Presently his German valet heard a groan and the sound of a heavy fall; he rushed into the room and found the King lying insensible on the floor with the blood trickling from his forehead, where he had struck himself against a bureau in falling. The valet ran to Lady Yarmouth, but the mistress had some sense of the fitness of things, and desired that the Princess Amelia should be sent for. She arrived to find her father quite dead. His death was due to heart disease and was instantaneous.

George II. was buried in Henry VII.’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey. His last wishes were fulfilled to the letter. He had desired that one of the sides of Queen Caroline’s coffin (who had predeceased him by twenty-three years) should be removed and the corresponding side of his own coffin should be taken away, so that his body might lie side by side with hers, and in death they should not be divided. This touching injunction was piously carried out by command of his grandson, who now succeeded him as King George III.

THE BETROTHAL.

1760-1765.

The accession of George III. to the throne made at first little difference in the lives of his brothers and sisters, especially of the younger ones. It made a difference in their position, for they became brothers and sisters of the reigning king, and the public interest in them was quickened. But they remained under the control of the Princess-Dowager, and continued to live with her in the seclusion of Carlton House and Kew.

The Princess-Dowager’s dominion was not confined to her younger children, for she continued to exercise unbounded sway over the youthful monarch. He held his accession council at her residence at Carlton House, and there he delivered his first speech—not the composition of his ministers, who imagined they saw in it the hand of the Princess-Dowager and Lord Bute. “My Lord Bute,” said the King to the Duke of Newcastle, his Prime Minister, “is your very good friend, he will tell you all my thoughts.” Again in his first speech to Parliament the King wrote with his own hand the words, to which we have already alluded: “Born and educated[Pg 36] in this country, I glory in the name of Briton”. Ministers affected to find in all this an unconstitutional exercise of the royal prerogative, and the Whig oligarchy trembled lest its domination should be overthrown.

Hitherto the influence of the Princess-Dowager with her eldest son, and the intimate friendship that existed between her and Lord Bute, had been known only to the few, but now the Whigs found in these things weapons ready to their hands, and they did not scruple to use them. They instigated their agents in the press and in Parliament, and a fierce clamour was raised against the Princess as a threatener of popular liberties. Her name, linked with Lord Bute’s, was flung to the mob; placards with the words “No Petticoat Government!” “No Scottish Favourite!” were affixed to the walls of Westminster Hall, and thousands of vile pamphlets and indecent ballads were circulated among the populace. Even the King was insulted. “Like a new Sultan,” wrote Lord Chesterfield, “he is dragged out of the seraglio by the Princess and Lord Bute, and placed upon the throne.” The mob translated this into the vulgar tongue, and one day, when the King was going in a sedan chair to pay his usual visit to his mother, a voice from the crowd asked him, amid shouts and jeers, whether he was “going to suck”.

The Princess-Dowager was unmoved by the popular clamour, and her influence over the young King remained unshaken; indeed it was rather[Pg 37] strengthened, for his sense of chivalry was roused by the coarse insults heaped upon his mother. Lord Bute continued to pay his visits to Carlton House as before, the only difference made was that, to avoid the insults of the mob, his visits were paid less openly. The chair of one of the Princess’s maids of honour was often sent of an evening to Bute’s house in South Audley Street, and he was conveyed in it, with the curtains close drawn, to Carlton House, and admitted by a side entrance to the Princess’s presence. These precautions, though natural enough under the circumstances, were unwise, for before long the stealthy visits leaked out, and the worst construction was placed upon them.

In the first year of the King’s reign the supremacy of the Princess-Dowager was threatened by an attachment the monarch had formed for the beautiful Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of the second Duke of Richmond. But the house of Lennox was a great Whig house, and its members were ambitious and aspiring, therefore the Princess-Dowager and Bute determined to prevent the marriage. That they succeeded is a matter of history. Lady Sarah’s hopes came to an end with the announcement of the King’s betrothal to Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. The announcement was not popular, for the nation was weary of royal alliances with the petty courts of Germany. But the Princess-Dowager had made confidential inquiries. She was told that Charlotte, who was very young, was dutiful and obedient, and no doubt thought that she would[Pg 38] prove a cipher in her hands. In this the Princess-Dowager was sadly mistaken. Lady Sarah Lennox, or an earlier candidate for the honour, a Princess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, would have been pliable in comparison with Charlotte of Mecklenburg, who, on her arrival, showed herself to be a shrewd, self-possessed young woman, with a tart tongue, and a full sense of the importance of her position. Charlotte soon became jealous of her mother-in-law’s influence over the King. Her relations with her sisters-in-law also were never cordial, and with the Princess Augusta she was soon at open feud.

George III. and Charlotte were married at the Chapel Royal, St. James’s Palace, on September 8, 1761, and a fortnight later were crowned in Westminster Abbey. The Princess Matilda, then ten years of age, witnessed her brother’s wedding, but unofficially, from a private pew. Her first public appearance was made at the coronation, when we find her following the Princess-Dowager in a procession from the House of Lords to Westminster Abbey. A platform, carpeted with blue baize and covered by an awning, had been erected across Palace Yard to the south door of the Abbey, and over this platform the Princess-Dowager and all her children passed, except the King, who was to be crowned, and Prince Edward and Princess Augusta, who were in their Majesties’ procession.

“The Princess-Dowager of Wales,” it is written, “was led by the hand by Prince William Henry, dressed in white and silver. Her train, which was[Pg 39] of silk, was cut short, and therefore not borne by any person, and her hair flowed down her shoulders in hanging curls. She had no cap, but only a circlet of diamonds. The rest of the princes and princesses, her Highness’s children, followed in order of their age: Prince Henry Frederick, also in white and silver, handing his sister Princess Louisa Anne, dressed in a slip with hanging sleeves. Prince Frederick William, likewise in white and silver, handing his youngest sister, the Princess Matilda, dressed also in a slip with hanging sleeves. Both the young princesses had their hair combed upwards, which was contrived to lie flat at the back of their heads in an elegant taste.”[16]

[16] The Annual Register, September 22, 1761.

For some time after George III.’s marriage the Princess-Dowager and Bute continued to be all-powerful with the King. The aged Prime Minister, the Duke of Newcastle, clung to office as long as he could, but at last was forced to resign, and in 1762 Lord Bute became Prime Minister. The Princess-Dowager’s hand was very visible throughout Bute’s brief administration; her enemy the Duke of Devonshire, “the Prince of the Whigs,” as she styled him, was ignominiously dismissed from office, and his name struck off the list of privy councillors. Other great Whig Lords, who had slighted or opposed her, were treated in a similar manner. Peace was made with France on lines the Princess-Dowager had indicated before her son came to the throne, and a still greater triumph, the peace was approved[Pg 40] by a large majority in Parliament, despite the opposition of the Whig Lords. “Now,” cried the Princess exultingly, “now, my son is King of England!” It was her hour of triumph.

But though the Whigs were defeated in Parliament, they took their revenge outside. The ignorant mob was told that the peace was the first step towards despotism, the despotism of the Princess-Dowager and her led-captain Bute, and the torrent of abuse swelled in volume. One evening when the Princess was present at the play, at a performance of Cibber’s comedy, The Careless Husband, the whole house rose when one of the actresses spoke the following lines: “Have a care, Madam, an undeserving favourite has been the ruin of many a prince’s empire”. The hoots and insults from the gallery were so great that the Princess drew the curtains of her box and quitted the house. Nor was this all. In Wilkes’s periodical, The North Briton, appeared an essay in which, under the suggestive names of Queen Isabella and her paramour “the gentle Mortimer,” the writer attacked the Princess-Dowager and the Prime Minister. Again, in a caricature entitled “The Royal Dupe,” the young King was depicted as sleeping in his mother’s lap, while Bute was stealing his sceptre, and Fox picking his pocket. In Almon’s Political Register there appeared a gross frontispiece, in which the Earl of Bute figured as secretly entering the bedchamber of the Princess-Dowager; a widow’s lozenge with the royal arms[Pg 41] hung over the bed, to enforce the identity. Worst of all, one night, when the popular fury had been inflamed to its height, a noisy mob paraded under the windows of Carlton House, carrying a gallows from which hung a jack-boot and a petticoat which they afterwards burned (the first a miserable pun on the name of John Earl of Bute, and the second to signify the King’s mother). The Princess-Dowager heard the uproar from within and learned the cause from her frightened household. She alone remained calm. “Poor deluded people, how I pity them,” she said, “they will know better some day.”

What her children thought of all this is not precisely recorded, but it would seem that the King stood alone among them in the sympathy and support he gave to his mother. Prince Edward, Duke of York, and the Princess Augusta were openly hostile to Lord Bute. Prince Edward declared that he suffered “a thousand mortifications” because of him. Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, was sullenly resentful, and even Prince Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland, made sarcastic remarks. What Matilda thought there is no means of knowing; she was too young to understand, but children are quick-witted, and since her favourite brother, Edward, and her favourite sister, Augusta, felt so strongly on the subject, she probably shared their prejudices. There is little doubt that the mysterious intimacy between the Princess-Dowager and Lord Bute was the cause of much ill-feeling between her and her[Pg 42] children, and had the effect of weakening her authority over them and of losing their respect. Years after, when she had occasion to remonstrate with Matilda, her daughter retorted with a bitter allusion to Lord Bute.

The Princess Augusta had inherited her mother’s love of dabbling in politics, and as her views were strongly opposed to those of the Princess-Dowager the result did not conduce to the domestic harmony of Carlton House. The Princess Augusta, of all the royal children, had suffered most from the intimacy between her mother and Lord Bute. Horace Walpole wrote of her some time before: “Lady Augusta, now a woman grown, was, to facilitate some privacy for the Princess, dismissed from supping with her mother, and sent back to cheese-cakes with her little sister Elizabeth, on the pretence that meat at night would fatten her too much”.[17] Augusta secretly resented the cheese-cakes, but she was then too young to show open mutiny. Now that she had grown older she became bolder. She was the King’s eldest sister, and felt that she was entitled to a mind of her own. Therefore, with her brother, the Duke of York, she openly denounced Lord Bute and all his works, and lavished admiration on his great rival, Pitt. This was a little too much for the Princess-Dowager, who feared that Augusta would contaminate the minds of her younger brothers and sisters. She resolved therefore to marry her to some foreign[Pg 43] husband, and thus remove her from the sphere of her present political activities. Moreover, it was quite time that Augusta was married. She had completed her twenty-sixth year and her youthful beauty was on the wane. “Lady Augusta,” writes Horace Walpole, “is not handsome, but tall enough and not ill-made, with the German whiteness of hair and complexion so remarkable in the royal family, and with their precipitate yet thick Westphalian accent.”[18]

[17] Memoirs of the Reign of George III., vol. iii.

[18] Ibid.

Augusta might have married before, but she was extremely English in her tastes, and had a great objection to leaving the land of her birth. Neither her mother nor her brother would entertain the idea of an English alliance, and so at last they arranged a marriage between her and Charles William Ferdinand, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, a famous soldier, and the favourite nephew of Frederick the Great. The Prince arrived in England in January, 1764. He had never seen his bride before he came, not even her portrait, but when he saw her he expressed himself charmed, adding that if he had not been pleased with her he should have returned to Brunswick without a wife. Augusta, equally frank, said that she would certainly have refused to marry him if she had found him unsatisfactory. They were married in the great council chamber of St. James’s Palace with little ceremony. The bride’s presents were few and meagre, and Augusta declared that Queen[Pg 44] Charlotte even grudged her the diamonds which formed the King’s wedding gift. Four days after the marriage a civic deputation waited upon the pair at Leicester House, and presented an address of congratulation. Princess Matilda was present, and stood at the right hand of her mother.

The King did not like the popularity of his brother-in-law, and therefore hurried the departure of the newly wed couple. The Princess of Brunswick shed bitter tears on leaving her native land. The day she left she spent the whole morning at Leicester House saying good-bye to her friends, and frequently appeared at the windows that the people outside might see her. More than once the Princess threw open the window and kissed her hand to the crowd. It was very tempestuous weather when the Prince and Princess set out on their long journey to Brunswick, and after they had put to sea rumours reached London that their yacht had gone down in the storm; but, though they were for a time in great danger, eventually they landed and reached Brunswick safely.

The marriage of the Princess Augusta was soon followed by the betrothal of her youngest sister. The Princess Matilda was only in her thirteenth year. But though too young to be married, her mother and the King, her brother, did not think it too soon to make arrangements for her betrothal.

The reigning King of Denmark and Norway, Frederick V., for some years had wished to bind more closely the ties which already existed between[Pg 45] him and the English royal family. The late Queen of Denmark, Queen Louise, was the youngest daughter of King George II. She had married Frederick V., and had borne him a son and daughters. After her death the King of Denmark cherished an affectionate remembrance of his Queen and a liking for the country whence she came. He therefore approached the old King, George II., with the suggestion of a marriage in the years to come between his son, the Crown Prince Christian, then an infant, and one of the daughters of Frederick Prince of Wales. After George II.’s death the idea of this alliance was again broached to George III. through the medium of Titley,[19] the English envoy at Copenhagen.

[19] Walter Titley, whose name occurs frequently in the negotiations of this marriage, was born in 1700 of a Staffordshire family. He was educated at Westminster and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took a distinguished degree. He entered the diplomatic service in 1728 and became chargé d’affaires at Copenhagen in the absence of Lord Glenorchy. In 1730 he was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary. In 1733 Richard Bentley, the famous master of Trinity College, Cambridge, offered him the physic fellowship of the College. Titley accepted it, resigned his diplomatic appointment, but found that he had become so much attached to his life at Copenhagen that he was unable to leave it. The King of Denmark, with whom he was a great favourite, urged him to stay, and the Government at home were unwilling to lose a valuable public servant who possessed a unique knowledge of the tortuous politics of the northern kingdom. So Titley resumed his post and held it for the remainder of his life. He died at Copenhagen in February, 1768.

The King, after consultation with his mother, put forward his second surviving sister, the Princess Louisa Anne (who was about the same age as the Crown Prince Christian), as a suitable bride. But[Pg 46] Bothmar, the Danish envoy in London, reported to the court of Copenhagen that Louisa Anne, though talented and amiable, was very delicate, and he suggested that the King of Denmark should ask for the Princess Matilda instead. This Princess was the beauty of the family, and her lively disposition and love of outdoor exercise seemed to show that she had a strong constitution. George III. demurred a little at first, on account of his sister’s extreme youth, but after some pour-parlers he gave his consent, and the King of Denmark sent orders to Bothmar to demand formally the hand of the Princess Matilda in marriage for his son the Crown Prince. At the same time Bernstorff, the Danish Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs,[20] wrote to Titley, acquainting him with the proposed alliance, but asking him to keep the matter a profound secret until all preliminaries were arranged.[21]

[20] Count Johan Hartvig Ernst Bernstorff was a Hanoverian by birth, and a grandson of Bernstorff of Hanover and Celle, Minister of George I. He early entered the service of Denmark, and represented his adopted country as envoy at the courts of St. James’s and Versailles. When he left the diplomatic service he became Minister of State for Foreign Affairs at Copenhagen, and filled other important posts. Finally he became Count and Prime Minister. He must not be confounded with Count Andreas Peter Bernstorff, his nephew, who was later Prime Minister of Denmark under Frederick VI.

[21] Sa Majesté, qui se souvient toujours avec plaisir et avec la bienveillance la plus distinguée, de vos sentiments pour sa personne, et pour l’union des deux familles royales, m’a commandé de vous faire cette confidence; mais elle m’ordonne en même temps de vous prier de la tenir entièrement secrète, jusqu’a ce qu’on soit convenu de part et d’autre de l’engagement et de sa publication. (Bernstorff to Titley, August 18, 1764.)

A few days later Titley wrote home to Lord[Pg 47] Sandwich: “I received from Baron Bernstorff (by the King of Denmark’s command) a very obliging letter acquainting me with the agreeable and important commission which had been sent that same day to Count Bothmar in London.... The amiable character of the Prince of Denmark is universally acknowledged here, so that the union appearing perfectly suitable, and equally desirable on both sides, I hope soon to have an opportunity of congratulating you, my Lord, upon its being unalterably fixed and settled.”[22]

[22] Titley’s despatch to Lord Sandwich, Copenhagen, August 29, 1764.

Within the next few months everything was arranged except the question of the Princess’s dower, which had to be voted by Parliament. In the meantime a preliminary treaty between the King of Denmark and the King of Great Britain was drafted and signed in London by Lord Sandwich on the one part and Bothmar on the other. This was in the autumn, when Parliament was not sitting, but the Danish Government stipulated that the announcement of the marriage was not to be delayed beyond the next session of Parliament, though the marriage itself, on account of the extreme youth of both parties, would be deferred for a few years.

Accordingly, at the opening of Parliament on January 10, 1765, George III. in his speech from the throne said:—

“I have now the satisfaction to inform you that[Pg 48] I have agreed with my good brother the King of Denmark to cement the union which has long subsisted between the two crowns by the marriage of the Prince Royal of Denmark with my sister the Princess Caroline Matilda, which is to be solemnised as soon as their respective ages will admit”.

In the address to the throne Parliament replied to the effect that the proposed marriage was most pleasing to them, as it would tend to strengthen the ancient alliance between the crowns of Great Britain and Denmark, and “thereby add security to the Protestant religion”.[23]

[23] Presumably the alliance would strengthen the Protestant religion by weakening the influence of Roman Catholic France at Copenhagen. It must be borne in mind that Denmark was then a much larger and more important country than it is now. Norway had not broken away from the union, and Denmark had not been robbed of the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein by Prussia.