Frontispiece

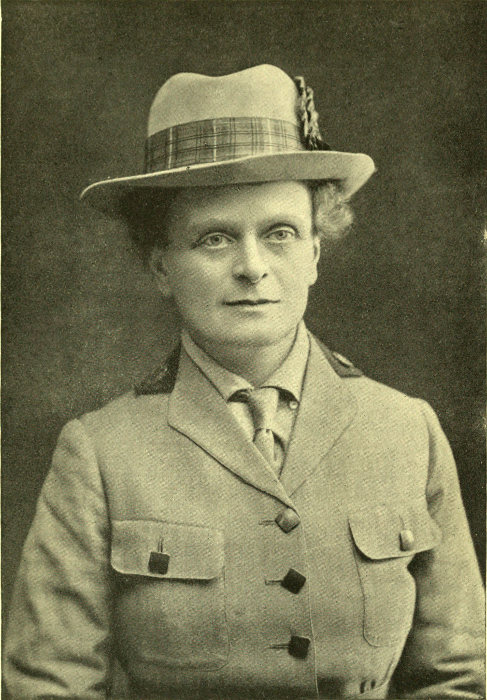

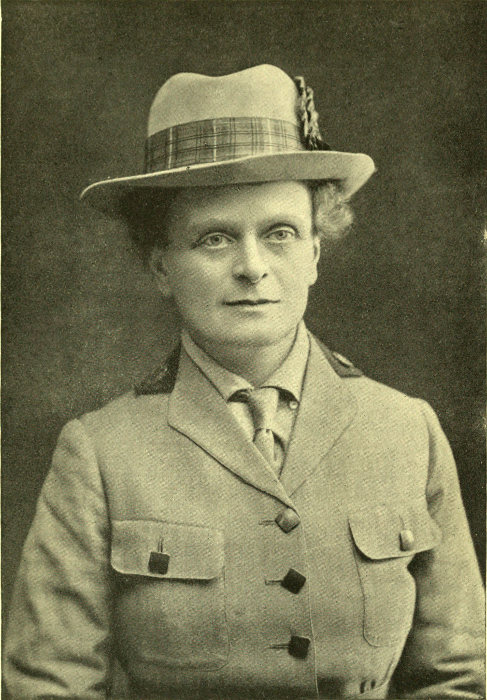

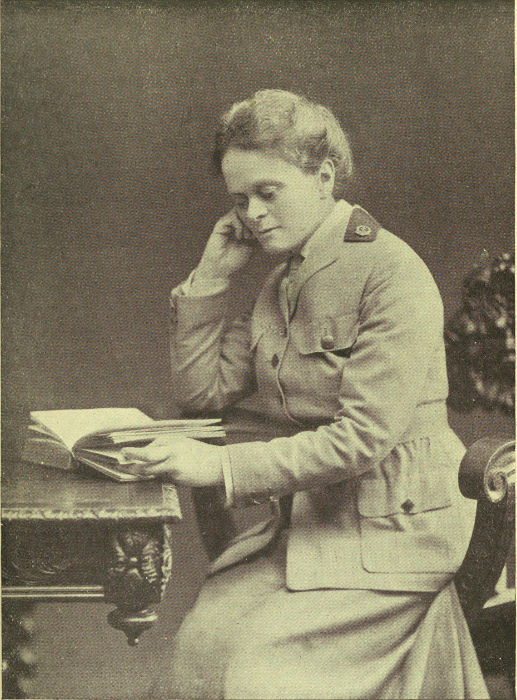

DR. ELSIE INGLIS

DR. ELSIE INGLIS, 1916

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/drelsieinglis00balfuoft |

Notes about the transcription can be found at the end of the book.

DR. ELSIE INGLIS

DR. ELSIE INGLIS, 1916

DR. ELSIE INGLIS

BY

LADY FRANCES BALFOUR

AUTHOR OF ‘THE LIFE OF LADY VICTORIA CAMPBELL’

‘LIFE AND LETTERS OF REV. JAMES MACGREGOR, D.D.’

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO

TO

SERBIA

AND THE

SCOTTISH WOMEN’S HOSPITALS

THAT SERVED AND LOVED

THEIR BRETHREN

1914–1917

‘In your patience possess ye your souls.’

The story of Elsie Inglis needs little introduction. From first to last she was the woman nobly planned. She achieved what she did because she was ready when the opportunity came. Consistently she had lived her life, doing whatever her hand found to do with all her might, and ever following the light. She had the spirit of her nation and of her race: the spirit of courageous adventure, the love of liberty, and equal freedom for all people.

If this memoir represents her faithfully, it is because it has been written among her own family and kindred. Every letter or story of her is part of a consistent whole. Transparently honest, warmly affectioned to all, the record could hardly err if, following exactly her footprints in the sands of time, it presents a portrait of one of old Scotia’s truest daughters. I owe manifold thanks to her sisters, her friends, her patients, above all, to her Units, for the help they have given me in what has[viii] been a labour of love and growing respect. She, being dead, yet speaketh; and, while we thank our God for every remembrance of her, we hope that those who are her living memorials, the patients in the Hospice, and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, will not be forgotten by those who read and pass on the pilgrim way.

The design for the book cover has been drawn by Dr. Inglis’ countryman, Mr. Anning Bell. It is the emblem of her nation and of the S.W.H.

F. B.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| INGLIS OF KINGSMILLS, INVERNESS-SHIRE | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| ELSIE MAUD INGLIS | 17 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE LADDER OF LEARNING | 27 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE STUDENT DAYS | 40 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| LONDON AND DUBLIN | 59 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| POLITICAL ENFRANCHISEMENT AND NATIONAL POLITICS | 82 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE PROFESSION AND THE FAITH | 111 |

| CHAPTER VIII[x] | |

| WAR AND THE SCOTTISH WOMEN | 137 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| SERBIA | 162 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| RUSSIA | 191 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| THE MOORINGS CUT | 234 |

Among the records of the family from whom Elsie Inglis was descended there are letters which date back to 1740. In that year the property of Kingsmills, Inverness-shire, was in the hands of Hugh Inglis. He had three sons, George, Alexander, and William. George inherited Kingsmills, and the Inglis now in Inverness are descended from him. Alexander, the great-grandfather of Elsie, married Mary Deas, and about 1780 emigrated to Carolina, leaving his four children to be educated in Scotland, in charge of his brother, William Inglis. The portrait of Alexander, in the dress of the period, has the characteristic features of the race descended from him. The face is stamped[2] with the impress of a resolute, fearless character, one who was likely to leave his mark on any country in which he took up his abode. There is an account of the property and estates of Alexander Inglis of Charleston ‘merchant in his own right.’ The account sets forth how the estates are confiscated on account of the loyalty of the said Alexander, and his adherence to, and support of the British Government and constitution.

In the schedule of property there occur, in close relation, these items: 125 head of black cattle, £125; 69 slaves at £60 a head, £4140; a pew, No. 31 in St. Michael’s Church, Charleston, £150; 11 house negroes, £700; and a library of well-chosen books, at a much lower figure. Alexander never lost sight of the four children left in his native land. In 1784 he congratulates his son David on being Dux of his class, and says that he prays constantly for him.

ALEXANDER INGLIS (d. 1791)

GREAT-GRANDFATHER OF DR. ELSIE INGLIS

Mary Deas, Alexander Inglis’ wife, through her ancestor Sir David Dundas, was a direct descendant of Robert the Bruce. All that is known of her life is contained in the undated obituary notice of the American newspaper of the day:—

‘The several duties of her station in life she discharged as became the good Christian, supporting with[3] exemplary fortitude the late trying separation from her family.’

Alexander’s restless and adventurous life was soon to have a violent end.

After their mother’s death, the three daughters must have joined their father in America. One of them, Katherine, whose face has been immortalised by Raeburn, writes to her brother David, who had been left in Scotland, to inform him of the death of their father in a duel.

MRS. ROBERTSON, née KATHERINE INGLIS

GREAT-AUNT OF DR. ELSIE INGLIS

(Portrait by Raeburn)

The letter which Alexander Inglis wrote to be given to his children, should he fall in the duel, is as fresh and clear as on the day when it was written:—

‘My dear, dear Children,—If ever you receive this letter it will be after my death. You were present this morning when I received the grossest insult that could be offered me—and such as I little expected from the young man who dared to offer it. Could the epithets which in his passion he ventured to make use of be properly applied to me—I would not wish to live another hour, but as a man of honour, and the natural guardian and protector of everything that is dear and valuable to myself and to you, I have no alternative left, but that of demanding reparation for the injury I have received. If I fall—I do so in defence of that honour, which is dearer to me than[4] life. May that great, gracious and good Being, who is the protector of innocence, and the sure rewarder of goodness, bless, preserve and keep you.—I am, my dear, dear children, your affectionate father,

‘Alexr. Inglis.

‘Charleston,

‘Tuesday evening, 29 March 1791.’

The letter is addressed by name to the four children.

Katherine writes to her brother David in the following May:—

‘In what manner, my dearest brother, shall I relate to you the melancholy event that has befallen us. Our dear parent, the best of fathers, is no more. How shall I go on? Alas! you will hear too soon by whose hand he fell; therefore I will not distress you with the particulars of his death. The second day of our dear father’s illness he called us to his bedside, when he told us he had left a letter for us three and his dear boy which would explain all things. Judge if you are able, my dear brother, what must have been our thoughts on this sad occasion to see our only dear parent tortured with the most excruciating pains and breathing his last. We were all of us too young, my brother, to experience the heavy loss we met with when our dear mother died, we had then a good father to supply our wants. I have always thought the Almighty kind to all His creatures, but more so in this particular that He seldom deprives us of one friend without raising[5] another to comfort us. My dear sisters and self are at present staying with good Mrs. Jamieson, who is indeed a truly amiable woman. I am sure you will regard her for your sisters’ sakes. You are happily placed, my brother, under the care of kind uncles and aunts who will no doubt (as they ever have done) prove all you have lost. How happy would it make me in my present situation to be among my friends in Scotland, but as that is impossible for some time I must endeavour to be as happy as I can. My kind duty to uncle and aunts.—I am, my dearest brother, your truly affectionate sister,

‘Katherine Inglis.’

Thus closes the chapter of Alexander Inglis and Mary Deas, his wife, both ‘long, long ago at rest’ in the land of their exile, both bearing the separation with fortitude, and the one rendering his children fatherless rather than live insulted by some nameless and graceless youth.

David Inglis grew up in charge of the kind Uncle William, and endeared himself to his adopted father. He also was to fare to dominions beyond the sea, and he carried the name of Inglis to India, where he went in 1798 as writer to the East India Company.

Uncle William followed him with the usual good advice. In a letter he tells David he expects him[6] to make a fortune in India that will give him ‘£3000 a year, that being the lowest sum on which it is possible to live in comfort.’

David’s life was a more adventurous one than that which usually falls to a writer. He went through the Mahratta War in 1803. He left India in 1812. On applying for a sick certificate, the resolution of Council, dated 1811, draws the attention of the Honourable Company to his services, ‘most particularly when selected to receive charge of the territorial cessions of the Peshwa under the Treaty of Bassein in the year 1803, displaying in the execution of that delicate and difficult mission, proofs of judgment and talents with moderation and firmness combined, which averted the necessity of having recourse to coercive measures, accomplished the peaceable transfer of a valuable territory, and conciliated those whose power and consequence were annihilated or abridged by the important change he so happily effected.’ David Inglis seems to have roamed through India, always seeking new worlds to conquer, and confident in his own powers to achieve.

One of the Napoleonic invasion scares alarmed the Company, and David, with two companions, was sent out on a cruising expedition to see if they[7] could sight the enemy’s fleet. As long as he wrote from India, his letters bear the stamp of a man full of vital energy and resource.

The only thing he did not accomplish while in the service of the Company was the fortune of £3000 a year.

He entered a business firm in Bombay and there made enough to be able to keep a wife. In 1806 he married Martha Money, whose father was a partner in the firm. They came home in 1812, and all their younger children were born in England at Walthamstow, the home of the Money family. One of the descendants, who has read the letters of these three brothers and their families, makes this comment on them:—

‘The letters are pervaded with a sense of activity, and of wandering. Each one entering into any pursuit that came to hand. All the family were travellers. There are letters from aunts in Gibraltar and many other airts.

‘The extraordinary thing in all the letters, whether they were written by an Inglis, a Deas, or a Money, is the pervading note of strong religious faith. They not only refer to religion, but often, in truly Scottish fashion they enter on long theological dissertations. David Inglis, Elsie’s grandfather, when he was settled in England gave missionary addresses. Two of these[8] exist, and must have taken fully an hour to read. Even the restless Alexander in Carolina, and the “whirlwind” David in India scarcely ever write a letter without a reference to some religious topic. You get the impression of strong breezy men sure of themselves, and finding the world a great playground.’

John, the second youngest son of David and Martha Inglis, was born in 1820. His mother being English, there entered with her some of the douce Saxon disposition and ways. Though the call of the blood was to cast his lot in India, John, or as he was generally called David, appears first as a student. His tutor, the Rev. Dr. Niblock, wrote a report of him as he was passing out of his hands to Haileybury. Mrs. Inglis notes on the letter: ‘Dr. Niblock is esteemed one of the best Greek scholars in England, and his Greek Grammar is the one in use in Eton.’

‘Of Master David Inglis I can speak with pleasure and pride almost unmixed. I can only loudly express how I regret that I have not the finishing of such a boy, for I feel, and shall ever feel, that he is mine. He has long begun to do what few boys do till they are leaving, or have left, school, viz. to think. I shall long cherish the hope, that as I laid the foundation, so shall I have the power and pleasure of crowning my own and other’s labours. He will make a fine fellow and be a comfort to his parents, and an honour to his tutor.’

John Inglis received a nomination for Haileybury College from one of the directors of the East India Company, and went there as a student in 1839. There he was noted as a cricketer and a good horseman, and also for his reading. He knew Shakespeare almost by heart, and could tell where to find any quotation from his works. On leaving Haileybury he sailed for Calcutta, and was there for two years learning the language. He went as assistant magistrate to Agra. He married in 1846, and in 1847 he was transferred to the newly-acquired province of the Punjab. He was sent as magistrate to Sealkote, remaining there till 1856. He then brought his family home on three years’ furlough. With the outbreak of the Mutiny all civilians were recalled, and he returned[10] to India in 1858. He was sent to Bareilly to take part in the suppression of the Mutiny, and was attached to the force under General Jones. He was present at the action at Najibabad, with the recapture of Bareilly, and the pacification of the province of Rohilcund. He remained in the province ten years till 1868, and during those years he rose to be Commissioner of Rohilcund. In 1868 he was made a member of the Board of Revenue in the North-West Provinces. As a member of the Legislative Council of India, he moved, in 1873, to Calcutta. From 1875 to 1877 he was Chief Commissioner of Oude.

The position Inglis made for himself in India, in yet early life, is to be gauged by a letter written in 1846 by Sir Frederick Currie, who was then Commissioner of Lahore. He had married Mrs. Inglis’ sister Katherine.

‘We have applied to Mr. Thomasen (Lieutenant-Governor of the N.W.P.) for young civilians for the work which is now before us, and we must take several with us into the Punjab. One whom he strongly recommends is Inglis at Agra. I will copy what he says about him. Sir Henry Hardinge (the Governor-General) has not seen the letter yet. “Another man who might suit you is Inglis at Agra; an assistant on £400, acting as joint magistrate which gives him[11] one hundred more. Active, energetic, conciliating to natives, fine-tempered, and thoroughly honest in all his works. I am not sure that he is not as good a man as you can have. I shall be glad to hear that you send for him.”’

The letter was addressed to Inglis’ eighteen-year-old bride, and Sir Frederick goes on:—

‘Shall I send for him or not? I am almost sure I should have done so, had I not heard of your getting hold of his heart. We don’t want heartless men, but really you have no right to keep such a man from us. At the present moment, however, for your sake, little darling, I won’t take him from his present work, but if, after the honeymoon, he would prefer active and stirring employment, with the prospect of distinction, to the light-winged toys of feathered cupid, I dare say I shall be able to find an opening for him.’

Mr. Inglis’ wife was Harriet Louis Thompson, one of nine daughters. Her father was one of the first Indian civilians in the old company’s days. All of the nine sisters married men in the Indian Civil, with the exception of one who married an army officer. Harriet came out to her parents in India when she was seventeen, and she married in her eighteenth year. She must have been a girl of marked character and ability. She met her future husband at a dance in her father’s house,[12] and she appears to have been the first to introduce the waltz into India. She was a fine rider, and often drove tandem in India. She must have had a steady nerve, for her letters are full of various adventures in camp and tiger-haunted jungles, and most of them narrate the presence of one of her infants who was accompanying the parents on their routine of Indian official life.

Her daughter says of her:—

‘She was deeply religious. Some years after their marriage, when she must have been a little over thirty and was alone in England with the six elder children, she started and ran most successfully a large working-men’s club in Southampton. Such a thing was not as common as it is to-day. There she lectured on Sunday evenings on religious subjects to the crowded hall of men.’

In the perfectly happy home of the Inglis family in India, the Indian ayah was one of the household in love and service to those she served. Mrs. Simson has supplied some memories of this faithful retainer:—

‘The early days, the nursery days in the life of a family, are always looked back upon with loving interest, and many of us can trace to them many sweet and helpful influences. So it was with our[13] early days, though the nursery was in India, and the dear nurse who lives in our memories was an Indian. Her name was Sona (Gold). She came into our family when the eldest of us was born, and remained one of the household for more than thirty years. Her husband came with her, and in later years three of her sons were table servants. Sona came home with us in 1857, and remained in England till the beginning of 1858. It was a sign of great attachment to us, for she left her own family away up in the Punjab, and fared out in the long sea voyage, into a strange country and among new peoples. She made friends wherever she was, and her stay in England was a great help to her in after life. When I returned to India after my school life at home, I found the dear nurse of my childhood days installed again as nurse to the little sisters and brother I found there.

‘She was a sweet, gentle woman, and we never learnt anything but kind, gentle ways from her. By the time I returned she was recognised by the whole compound of servants as one to be looked up to and respected. She became a Christian and was baptized in 1877, but long before she made profession of her faith by baptism she lived a consistent Christian life. My dear mother’s influence was strong with her, and she was a reader of the Bible. One of my earliest recollections is our reading together the fourteenth chapter of St. John.

‘She died some years after we had all settled in Scotland. My parents left her, with a small pension for life, in charge of the missionaries at Lucknow.[14] When she died, they wrote to us saying that old Sona had been one of the pillars of the Indian Christian Church in Lucknow.

‘We look forward with a sure and certain hope to our reunion in the home of many mansions, with her, around whom our hearts still cling with love and affection.’

In 1856 Mr. Inglis resolved to come home on furlough, accompanied by Mrs. Inglis, and what was called ‘the first family,’ namely, the six boys and one girl born to them in India. It was a formidable journey to accomplish even without children, and one writes, ‘How mother stood it all I cannot imagine.’ They came down from the Punjab to Calcutta trekking in dâk garris. It took four months to reach Calcutta by this means of progression, and another four months to come home by the Cape. The wonderful ayah, Sona, was a great help in the toilsome journey when they brought the children back to England. Mrs. Inglis was soon to have her first parting with her husband. When they landed in England, news of the outbreak of the Mutiny met them, and Mr. Inglis returned almost at once to take his place beside John Lawrence. Together they fought through the Mutiny, and then he worked under[15] him. Inglis was one of John Lawrence’s men in the great settling of the Punjab which followed on that period of stress and strain in the Empire of India. His own district was Bareilly, and the house where he lived in Sealkote is still known as Inglis Sahib ke koti (Inglis Sahib’s house). His children remember the thrilling stories he used to tell them of these great days, and of the great men who made their history.

His admiration was unbounded for those northern races of India. He loved and respected them, and they, in their turn, gave him unbounded confidence and affection. ‘Every bit as good as an Englishman,’ was a phrase often on his lips when speaking of the fine Sikhs and Punjabis and Rajpoots.

Englishwomen were not allowed in India during this period, and Mrs. Inglis had to remain in Southampton with her six children and their ayah. It was then that she found work in her leisure time for the work she did in the Men’s Club.

In 1863, when life in India had resumed its normal course, Mrs. Inglis rejoined her husband, leaving the children she had brought back at home.

It must have taken all the ‘fortitude’ that Mary Deas had shown long before in Carolina to face this separation. There was no prospect of[16] the running backwards and forwards, which steam was so soon to develop, and to draw the dominions into closer bonds. Letters took months to pass, and no cable carried the messages of life and death across ‘the white-lipped seas.’ Again, one of the survivors says: ‘I always felt even as a child, and am sure of it now, she left her heart behind with the six elder children. What it must have meant to a woman of her deep nature, I cannot imagine.’ The decision was made, and Mr. Inglis was to have the great reward of her return to him, after his seven years of strenuous and anxious loneliness. The boys were sent, three of them to Eton, and two more to Uppingham and to Rugby. Amy Inglis the daughter was left with friends. Relatives were not lacking in this large clan and its branches, and the children were ‘looked after’ by them. We owe much of our knowledge of ‘the second little family,’ which were to comfort the parents in India, by the correspondence concerning them with the dearly-loved children left in the homelands.

‘Lo, children are an heritage of the Lord: and the fruit of the womb is His reward. As arrows are in the hand of the mighty man, so are children of the youth. Happy is the man that hath his quiver full of them; they shall not be ashamed, but they shall speak with the enemies in the gate.’

Naini Tal, Aug. 16, 1864.

‘My darling Amy,—Thank God, I am able to tell you that your dearest mother, and your little sister who was born this morning are well. Aunt Ellen thinks that baby is very like your dearest mother, but I do not see the resemblance at present. I hope I may by and by. We could not form a better wish for her, than that she may grow up like her dear mother in every respect. Old Sona is quite delighted to have another baby to look after again. She took possession of her the moment she was born, as she has done with all of you. The nurse says she is a very strong and healthy baby. I wish to tell you as early as possible the good news of God’s great mercy and goodness towards us in having brought your dearest mother safely through this trial.’

Mrs. Inglis writes a long account of Elsie at a month old, and says she is supposed to have a temper, as she makes herself heard all over the house, and strongly objects to being brought indoors and put into her cradle.

In October she writes how the two babies, her own and Aunt Ellen’s little boy, had been taken to church to be baptized, the one by the name of Elsie Maude, the other Cyril Powney. Both children were thriving, and no one would know that there were two babies in the house. ‘Elsie always stares very hard at papa when he comes to speak to her, as if she did not quite know what to make of his black beard, something different to what she is accustomed to see, but she generally ends by laughing at him’—the first notice of that radiant friendship in which father and daughter were to journey together in a happy pilgrimage through life.

Elsie had early to make long driving expeditions with her parents, and her mother reports her as ‘accommodating herself to circumstances, watching the trees, sleeping under them, and the jolliest little traveller I ever saw.’

In December 1864 Mrs. Inglis reports their return from camp:—

‘It has been most extraordinarily warm for the time of year, and there has been very little rain during the whole twelvemonth. People attribute it to the wonderful comet which has been visible in the southern hemisphere. Elsie is very well, but she is a very little thing with a very wee face. She has a famous pair of large blue eyes, and it is quite remarkable how she looks about her and seems to observe everything. She lies in her bed at night in the dark and talks away out loud in her own little language, and little voice, and she is always ready for a laugh.’

Later on Mrs. Inglis writes: ‘I think she is one of the most intelligent babies I ever met with.’

Every letter descriptive of the dark, blue-eyed baby with the fast growing light hair, speaks of the smile ready for every one who speaks to her, and the hearty laughs which seem to have been one of her earliest characteristics.

One journey tried Elsie’s philosophy of taking life as she found it. Mrs. Inglis writes to her daughter:—

Naini Tal, 1865.

‘We came in palkies from Beharin to a place called Jeslie, half way up the hill to Naini Tal, and were about ten hours in the palkies. I had arranged to have Elsie with me in my palkie, but the little monkey did not like being away from Sona, and then the strangeness of the whole proceedings bewildered her,[20] and the noise of the bearers seemed to frighten her, so I was obliged to make her over to Sona. She went to sleep after a little while. As we came near the hills it became cold and a wind got up, and then Papa brought her back to me, for we did not quite like her being in Sona’s doolie, which was not so well protected as mine. She had become more reconciled to the disagreeables of dâk travelling by that time. We reached our house about nine o’clock yesterday morning. The change from the dried-up hot plains is very pleasant. You may imagine how often I longed for the railroad and our civilised English way of travelling.’

Mrs. Shaw M‘Laren, the companion sister of Elsie, and to whom her correspondence always refers, has written down some memories of the happy childhood days in India. The year was divided between the plains and the hills of India. Elsie was born in August 1864, at Naini Tal, one of the most beautiful hill stations in the Himalayas. From the verandah, where much of the day was spent, the view was across the masses of ‘huddled hills’ to the ranges crowned by the everlasting snows. An outlook of silent and majestic stillness, and one which could not fail to influence such a spirit as shone out in the always wonderful eyes of Elsie. She grew up with the vision of the glory of the earthly dominion, and it gave a new[21] meaning to the kingdom of the things of the spirit.

‘All our childhood is full of remembrances of “Father.” He never forgot our birthdays; however hot it was down in the scorched plains, when the day came round, if we were up in the hills, a large parcel would arrive from him. His very presence was joy and strength when he came to us at Naini Tal. What a remembrance there is of early walks and early breakfasts with him and the three of us. The table was spread in the verandah between six and seven. Father made three cups of cocoa, one for each of us, and then the glorious walk! Three ponies followed behind, each with their attendant grooms, and two or three red-coated chaprasis, father stopping all along the road to talk to every native who wished to speak to him, while we three ran about, laughing and interested in everything. Then, at night, the shouting for him after we were in bed and father’s step bounding up the stair in Calcutta, or coming along the matted floor of our hill home. All order and quietness flung to the winds while he said good night to us.

‘It was always understood that Elsie and he were special chums, but that never made any jealousy. Father was always just! The three cups of cocoa were exactly the same in quality and quantity. We got equal shares of his right and his left hand in our walks, but Elsie and he were comrades, inseparables from the day of her birth.

‘In the background of our lives there was always the quiet strong mother, whose eyes and smile live on through the years. Every morning before the breakfast and walk, there were five minutes when we sat in front of her in a row on little chairs in her room and read the scripture verses in turn, and then knelt in a straight, quiet row and repeated the prayers after her. Only once can I remember father being angry with any of us, and that was when one of us ventured to hesitate in instant obedience to some wish of hers. I still see the room in which it happened, and the thunder in his voice is with me still.’

Both Mr. and Mrs. Inglis belonged to the Anglican Church, though they never hesitated to go to any denomination where they found the best spiritual life. In later life in Edinburgh, they were connected with the Free Church of Scotland. To again quote from his daughter: ‘His religious outlook was magnificently broad and beautiful, and his belief in God simple and profound. His devotion to our mother is a thing impossible to speak about, but we all feel that in some intangible way it influenced and beautified our childhood.’

In 1870 Mrs. Inglis writes of the lessons of Elsie and her sister Eva. ‘The governess, Mrs. Marwood, is successful as a teacher; it comes easy enough to Elsie to learn, and she delights in stories[23] being told her. Every morning after their early morning walk, and while their baths are being got ready, their mother says they come to her to say their prayers and learn their Bible lesson.’ There are two letters more or less composed by Elsie and written by her father. In as far as they were dictated by herself, they take stock of independent ways, and the spirit of the Pharisee is early developed in the courts of the Lord’s House, as she manages not to fall asleep all the time, while the weaker little sister slumbers and sleeps.

Eva, the sleepy sister, has some further reminiscences of these nursery days:—

‘We had forty dolls! Elsie decreed once that they should all have measles—so days were spent by us three painting little red dots all over the forty faces and the forty pairs of arms and legs. She was the doctor and prescribed gruesome drugs which we had to administer. Then it was decreed that they should slowly recover, so each day so many spots were washed off until the epidemic was wiped out!

‘Another time one of the forty dolls was lost! Maria was small and ugly, but much loved, and the search for her was tremendous, but unsuccessful. The younger sister gave it up. After all there were plenty other dolls—never mind Maria! But Elsie stuck to it. Maria must be found. Father would find her when[24] he came home from Kutcherry in the evening, if nobody else could. So father was told with many tears of Maria’s disappearance. He agreed—Maria must be found. The next day all the enormous staff of Indian servants, numbering all told about thirty or so, were had up in a row and told that unless Maria was found sixpence would be cut from each servant’s pay for interminable months! What a search ensued! and Maria came to light within half an hour—in the pocket of one of the dresses of her little mistress found by one of the ayahs! Her mistress declared at the time, and always maintained with undiminished certainty, that she had first been put there, and then found by the ayah in question during that half-hour’s search!’

These reminiscences have more of interest than just the picture of the little child who was to carry on the early manifestations of a keen interest in life. A smile, surely one of the clouds of glory she trailed from heaven, and carried back untarnished by the tragedies of a stricken earth; they are chiefly valuable in the signs of a steadfast, independent will. The interest of all Elsie’s early development lay in the comradeship with a father whose wide benevolence and understanding love was to be the guide and helper in his daughter’s career. Not for the first time in the history of outstanding lives, the daughter has been the[25] friend, and not the subjugated child of a selfish and dominant parent.

The date of Elsie’s birth was in the dawn of the movement which believed it possible that women could have a mind and a brain of their own, and that the freedom of the one and the cultivation of the other was not a menace to the possessive rights of the family, or the ruin of society at large. Thousands of women born at the same date were instructed that the aim of their lives must be to see to the creature comforts of their male parent, and when he was taken from them, to believe it right that he had neither educated them, nor made provision for the certain old age and spinsterdom which lay before the majority.

There have been many parents who gave their daughters no reason to call them blessed, when they were left alone unprovided with gear or education. In all periods of family history, such instances as Mr. Inglis’ outlook for his daughters is uncommon. He desired for them equal opportunities, and the best and highest education. He gave them the best of his mind, not its dregs, and a comradeship which made a rare and happy entrance for them into life’s daily toil and struggle. The father asked for nothing but their love, and[26] he had his own unselfish devotion returned to him a hundredfold.

It must have been a great joy to him to watch the unfolding of talent and great gifts in this daughter who was always ‘his comrade.’ He could not live to see the end of a career so blessed, so rich in womanly grace and sustaining service, but he knew he had spared no good thing he could bring into her life, and when her mission was fulfilled, then, those who read and inwardly digest these pages will feel that she first learnt the secret of service to mankind in the home of her father.

After Mr. Inglis had been Chief Commissioner of Oude, he decided to retire from his long and arduous service. Had he been given the Lieutenant-Governorship of the North-West, as was expected by some in the service, he would probably have accepted it and remained longer in India. He was not in sympathy with Lord Lytton’s Afghan policy, and that would naturally alter his desire for further employment.

As with his father before him, his work was highly appreciated by those he served. Lord Lytton, the Viceroy, in a letter to Lord Salisbury,[28] then Secretary of State for India, writes, February 1876:—

‘During the short period of my own official tenure I have met with much valuable assistance from Mr. Inglis, both as a member of my Legislative Council, and also as officiating Commissioner in Oudh, more especially as regards the amalgamation of Oudh with the N.W. Provinces. Of his character and abilities I have formed so high an opinion that had there been an available vacancy I should have been glad to secure to my government his continued services.’

Two of Mr. Inglis’ sons had settled in Tasmania, and it was decided to go there before bringing home the younger members of his family. The eldest daughter, Mrs. Simson, was now married and settled in Edinburgh, and the Inglis determined to make their home in that city.

Two years were spent in Hobart settling the two sons on the land. Mrs. M‘Laren says:—

‘When in Tasmania, Elsie and I went to a very good school. Miss Knott, the head-mistress, had come out from Cheltenham College for Girls. Here in the days when such things were practically unknown, Elsie, backed by Miss Knott, instituted ‘school colours.’ They were very primitive, not beautiful hatbands, but two inches of blue and white ribbon sewn on to a[29] safety pin, and worn on the lapel of our coats. How proud we were of them.’

Mr. Inglis, writing to his daughter in Edinburgh, says of their school life:—

‘Elsie has done very well, she is in the second class and last week got up to second in the class.

‘We are all in a whirl having to sort and send off our boxes, some round the Cape, some to Melbourne, and some to go with us.’

Mrs. Inglis, on board the Durham homeward bound, writes:—

‘Elsie has found occupation for herself in helping to nurse sick children, and look after turbulent boys who trouble everybody on board, and a baby of seven months old is an especial favourite with her. Eva has met with a bosom friend in a little girl named Pearly Macmillan, without whom she would have collapsed altogether. Our vessel is not a fast one, but we have been only five instead of six weeks getting to Suez.’

The family took a house at 70 Bruntsfield Place, and the two girls were soon at school. Mrs. M‘Laren says:—

‘Elsie and I used to go daily to the Charlotte Square Institution, which used in those days to be the Edinburgh school for girls. Mr. Oliphant was headmaster. Father never approved of the Scotch custom of children[30] walking long distances to school, and we used to be sent every morning in a cab. The other day, when telling the story of the S.W.H.’s to a large audience of working women in Edinburgh, one woman said to me, “My husband is a prood man the day! He tells everybody how he used to drive Dr. Inglis to school every morning when she was a girl.”’

Of her school life in Edinburgh, Miss Wright gives these memories:—

‘I remember quite distinctly when the girls of 23 Charlotte Square were told that two girls from Tasmania were coming to the school, and a certain feeling of surprise that the said girls were just like ordinary mortals, though the big, earnest brows and the quaint hair parted in the middle and done up in plaits fastened up at the back of the head were certainly not ordinary. Elsie was put in a higher English class than I was in, and though I knew her, I did not know her very well.

‘A friend has a story of a question going round the class, she thinks Clive or Warren Hastings was the subject of the lesson, and the question was what one would do if a calumny were spread about one. “Deny it,” one girl answered. “Fight it,” another. Still the teacher went on asking. “Live it down,” said Elsie. “Right, Miss Inglis.” My friend writes, “The question I cannot remember, it was the bright confident smile with the answer, and Mr. Hossack’s delighted wave to the top of the class that abides in my memory.”

‘I always think a very characteristic story of Elsie is her asking that the school might have permission to play in Charlotte Square gardens. In those days no one thought of providing fresh air exercise for girls except by walks, and tennis was just coming in. Elsie had the courage (to us schoolgirls it seemed the extraordinary courage) to confront the three directors of the school and ask if we might be allowed to play in the gardens of the Square. The three directors together were to us the most formidable and awe-inspiring body, though separately they were amiable and estimable men!

‘The answer was we might play in the gardens if the neighbouring proprietors would give their consent, and the heroic Elsie, with I think one other girl, actually went round to each house in the Square and asked consent of the owner.

‘In those days the inhabitants of Charlotte Square were very select and exclusive indeed, and we all felt it was a brave thing to do. Elsie gained her point, and the girls played at certain hours in the Square till a regular playing field was arranged.’

Her sister Eva reports that the first answer of the directors was enough for the rest of the school. But Elsie, undaunted, interviewed each of the three directors herself. After every bell in Charlotte Square had been rung and all interviewed, she returned from this great expedition triumphant.[32] All had consented, so the damsels interned from nine to three were given the gardens, and the grim, dull, palisaded square must have suddenly been made to blossom like the rose. Would that some follower of Elsie Inglis even now might ring the door bells and get the gates unlocked to the rising generation. Elsie’s companion or companions in this first attempt to influence those in authority have been spoken of as ‘her first unit.’

Elsie was, for a time, joint editor of the Edina, a school magazine of the ordinary type. Her great achievement was in making it pay, which, it is recorded, no other editor was able to do. There are various editorial anxieties alluded to in her correspondence with her father. The memories quoted take us further than school days, but they find a fitting place here.

‘Our more intimate acquaintance came after Mrs. Inglis’ death and when Elsie was thinking of and beginning her medical work. In 1888 six of us girls who had been at the same school started the “Six Sincere Students Society,” which met in one house. The first year we read and discussed Emerson’s Essays on “Self-Reliance and Heroism.” I am pretty sure it was Elsie who suggested those Essays. Also, Helps,[33] and Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy. I have a note on this “two very hot discussions as to what Culture means, and if it is sufficiently powerful to regenerate the world. Culture of the masses and also of women largely gone into.”

‘This very friendly and happy society lasted on till 1891, when it was enlarged and became a Debating Society. I find Elsie taking up such subjects as “That our modern civilisation is a development not a degeneration.” “That character is formed in a busy life rather than in solitude.” Papers on Henry Drummond’s Ascent of Man, and on the “Ethics of War.”

‘Always associated with Elsie in those days I think of her father, and no biography of her will be true which does not emphasise the beautiful and deep love and sympathy between Elsie and Mr. Inglis. He used to meet us girls as if we were his intellectual equals, and would discuss problems and answer our questions with the utmost cordiality and appreciation of our point of view, and always there was the feeling of the entire understanding and fellowship between father and daughter.

‘She was a keen croquet player, and tolerated no frivolity when a stroke either at croquet or golf were in the balance. She was fond of long walks with Mr. Inglis, and then by herself, and time never hung on her hands in holiday time, she was always serene and happy.’

It was decided that Elsie should go to school in[34] Paris in September 1882—a decision not lightly made; and Mr. Inglis writes after her departure:—

‘I do not think I could have borne to part with you, my darling, did I not feel the assurance that in doing so we are following the Lord’s guidance. Your dear mother and I both made it the subject of earnest prayer, and I feel we have been guided to do what was best for you; and we shall see this when the weary time is over, and we have got you back again with us.

‘When I return to Edinburgh, I feel that I shall have no one to find out my Psalms for me, or to cut my Spectator, that we shall have no more discussions regarding the essays of Mr. Fraser, and no more anxieties about the forthcoming number of the Edina. The nine months will pass quickly.’

Elsie’s letters from Paris have not been preserved, but the ones from her father show the alert intelligence and interest in all she was reporting. Of the events at home and abroad, Mr. Inglis writes to her of the Suez Canal, the bringing to justice of the Phœnix Park murderers, the great snowstorm at home, and the Channel Tunnel. Mrs. Inglis writes with maternal scepticism on some passing events: ‘I cannot imagine you making the body of your dress. I think there would not be many carnivals if you had to make the dresses yourselves.’ Mr. Inglis, equally sceptical,[35] has a more satisfactory solution for dressmaking. ‘I hope you have more than one dinner frock, two or three, and let them be pretty ones.’ Mrs. Inglis, commenting on Elsie’s description of Gambetta’s funeral, says: ‘He is a loss to France. Poor France, she always seems to me like a vessel without a helm driven about just where the winds take it. She has no sound Christian principle to guide her. So different from our highly favoured England.’

Mr. Inglis’ letters are full of the courteous consideration for Elsie and for others which marked all the way of his life, and made him the man greatly beloved, in whatever sphere he moved. Punch and the Spectator went from him every week, and he writes: ‘I hope there was nothing in that number of Punch you gave M. Survelle to study while you were finishing your breakfast to hurt his feelings as a Frenchman. Punch has not been very complimentary to them of late.’ And when Elsie’s sense of humour had been moved by a saying of her gouvernante, Mr. Inglis writes, desirous of a very free correspondence with home, but—

‘I fear if I send your letter to Eva, at school, that your remark about Miss —— proposal to go down to[36] the lower flat of your house, because the Earl of Anglesea once lived there, may be repeated and ultimately reach her with exaggerations, as those things always do, and may cause unpleasant feelings.’

There must have been some exhibition of British independence, and in dealing with it Mr. Inglis reminds Elsie of a day in India ‘when you went off for a walk by yourself, and we all thought you were lost, and all the Thampanies and chaprasies and everybody were searching for you all over the hill.’ One later episode was not on a hillside, and except for les demoiselles in Paris, equally harmless.

‘Jan. 1883.

‘I can quite sympathise with you, my darling, in the annoyance you feel at not having told Miss Brown of your having walked home part of the way from Madame M—— last Wednesday. It would have been far better if you had told her, as you wished to do, what had happened. Concealment is always wrong, and very often turns what was originally only a trifle into a serious matter. In this case, I don’t suppose Miss B. could have said much if you had told her, though she may be seriously angry if it comes to her knowledge hereafter. If she does hear of it, you had better tell her that you told me all about it, and that I advised you, under the circumstances, as you had not told her at the time, and that as by doing so now you[37] could only get the others into trouble, not to say anything about it; but keep clear of these things for the future, my darling.’

When the end came here, in this life, one of her school-fellows wrote:—

‘Elsie has been and is such a world-wide inspiration to all who knew her. One more can testify to the blessedness of her friendship. Ever since the Paris days of ’83 her strong loving help was ready in difficult times, and such wonderfully strengthening comfort in sorrow.’

The Paris education ended in the summer of 1883, and Miss Brown, who conducted and lived with the seven girls who went out with her from England, writes after their departure:—

‘I cannot tell you how much I felt when you all disappeared, and how sad it was to go back to look at your deserted places. I cannot at all realise that you are now all separated, and that we may never meet again on earth. May we meet often at the throne of grace, and remember each other there. It is nice to have a French maid to keep up the conversations, and if you will read French aloud, even to yourself, it is of use.’

Paris was, no doubt, an education in itself, but the perennial hope of fond parents that languages[38] and music are in the air of the continent, were once again disappointed in Elsie. She was timber-tuned in ear and tongue, and though she would always say her mind in any vehicle for thought, the accent and the grammar strayed along truly British lines. Her eldest niece supplies a note on her music:—

‘She was still a schoolgirl when they returned from Tasmania. At that time she was learning music at school. I thought her a wonderful performer on the piano, but afterwards her musical capabilities became a family joke which no one enjoyed more than herself. She had two “pieces” which she could play by heart, of the regular arpeggio drawing-room style, and these always had to be performed at any family function as one of the standing entertainments.’

Elsie returned from Paris, the days of the schoolgirlhood left behind. Her character was formed, and she had the sense of latent powers. She had not been long at home when her mother died of a virulent attack of scarlet fever, and Mr. Inglis lost the lodestar of his loving nature. ‘From that day Elsie shouldered all father’s burdens, and they two went on together until his death.’

In her desk, when it was opened, these ‘Resolutions’ were found. They are written in pencil,[39] and belong to the date when she became the stay and comfort of her father’s remaining years:—

‘I must give up dreaming,—making stories.

‘I must give up getting cross.

‘I must devote my mind more to the housekeeping.

‘I must be more thorough in everything.

‘I must be truthful.

‘The bottom of the whole evil is the habit of dreaming, which must be given up. So help me, God.

‘Elsie Inglis.’

‘I remember well the day Elsie came in and, sitting down beside father, divulged her plan of “going in for medicine.” I still see and hear him, taking it all so perfectly calmly and naturally, and setting to work at once to overcome the difficulties which were in the way, for even then all was not plain sailing for the woman who desired to study medicine.’ So writes Mrs. M‘Laren, looking back on the days when the future doctor recognised her vocation and ministry. If it had been a profession of ‘plain sailing,’ the adventurous spirit would probably not have embarked in that particular vessel. The seas had only just been charted, and not every shoal had been marked. In the midst[41] of them Elsie’s bark was to have its hairbreadth escapes. The University Commission decided that women should not be excluded any longer from receiving degrees owing to their sex. The writer recollects the description given of the discussion by the late Sir Arthur Mitchell, K.C.B., one of the most enlightened minds of the age in which he lived and achieved so much. He, and one or more of his colleagues, presented the Commissioners with the following problem: ‘Why not? On what theory or doctrine was it just or beneficent to exclude women from University degrees?’ There came no answer, for logic cannot be altogether ignored by a University Commission, so, without opposition or blare of trumpets, the Scottish Universities opened their degrees to all students. It was of good omen that the Commission sat in high Dunedin, under that rock bastion where Margaret, saint and queen, was the most learned member of the Scottish nation in the age in which she reigned.

Dr. Jex Blake had founded the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, and it was there that Elsie received her first medical teaching. Everything was still in its initial stages, and every step in the higher education of women had to be[42] fought and won, against the forces of obscurantism and professional jealousy.

University Commissions might issue reports, but the working out of them was left in the hands of men who were determined to exclude women from the medical profession.

Clinical teaching could only be carried on in a few hospitals. Anatomy was learnt under the most discouraging circumstances. Mixed classes were, and still are, refused. Extra-mural teaching became complicated, on the one hand, by the extra fees which were wrung from women students, and by the careless and perfunctory teaching accorded by the twice-paid profession. Professors gave the off-scourings of their minds, the least valuable of their subjects, and their unpunctual attendance to all that stood for female students. It will hardly be believed that the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh refused to admit women to clinical teaching in the wards, until they had raised seven hundred pounds to furnish two wards in which, and in which alone, they might work. To these two wards, with their selected cases, they are still confined, with the exception of one or two other less important subjects. Medicals rarely belong to the moneyed classes, and very few women can[43] command the money demanded of the medical course, and that women should have raised at once the tax thus put upon them by the Royal Infirmary is an illustration of how keenly and bravely they fought through all the disabilities laid upon them.

Women had always staunch friends among the doctors. The names of many of them are written in gold in the story of the opening of the profession to women. It has been observed that St. Paul had the note of all great minds, a passion to share his knowledge of a great salvation, with both Jews and Gentiles. That test of greatness was not conspicuous in the majority of the medical profession at the time when Elsie Inglis came as a learner to the gates of medical science. That kingdom, like most others, had to suffer violence ere she was to be known as the good physician in her native city and in those of the allied nations.

There are no letters extant from Elsie concerning her time with Dr. Jex Blake. After Mrs. Inglis’ death, Mr. Inglis decided to leave their home at Bruntsfield, and the family moved to rooms in Melville Street. Here Elsie was with her father, and carried on her studies from his house. It was not an altogether happy start, and very soon she had occasion to differ profoundly with[44] Dr. Jex Blake in her management of the school. Two of the students failed to observe the discipline imposed by Dr. Jex Blake, and she expelled them from the school. Any high-handed act of injustice always roused Elsie to keen and concentrated resistance. A lawsuit was brought against Dr. Jex Blake, and it was successful, proving in its course that the treatment of the students had been without justification.

Looking back on this period of the difficult task of opening the higher education to women, it is easy to see the defects of many of those engaged in the struggle. The attitude towards women was so intolerably unjust that many of the pioneers became embittered in soul, and had in their bearing to friends or opponents an air which was often provocative of misunderstanding. They did not always receive from the younger generation for whom they had fought that forbearance that must be always extended to ‘the old guard,’ whose scars and defects are but the blemishes of a hardly-contested battle. Success often makes people autocratic, and those who benefit from the success, and suffer under the overbearing spirit engendered, forget their great gains in the galling sensation of being ridden over rough-shod. It is[45] an episode on which it is now unnecessary to dwell, and Dr. Inglis would always have been the first to render homage to the great pioneer work of Dr. Jex Blake.

Through it all Elsie was living in the presence chamber of her father’s chivalrous, high-minded outlook. Whatever action she took then, must have had his approval, and it was from him that she received that keen sense of equal justice for all.

These student years threw them more than ever together. On Sundays they worshipped in the morning in Free St. George’s Church, and in the evening in the Episcopal Cathedral. Mr. Inglis was a great walker, and Elsie said, ‘I learnt to walk when I used to take those long walks with father, after mother died.’ Then she would explain how you should walk. ‘Your whole body should go into it, and not just your feet.’

Of these student days her niece, Evelyn Simson, says:—

‘When she was about eighteen she began to wear a bonnet on Sunday. She was the last girl in our connection to wear one. My Aunt Eva who is two years younger never did, so I think the fashion must have changed just then. I remember thinking how very grown up she must be.’

Another niece writes:—

‘At the time when it became the fashion for girls to wear their hair short, when she went out one day, and came home with a closely-cropped head, I bitterly resented the loss of Aunt Elsie’s beautiful shining fair hair, which had been a real glory to her face. She herself was most delighted with the new style, especially with the saving of trouble in hairdressing.

‘She only allowed her hair to grow long again because she thought it was better for a woman doctor to dress well and as becomingly as possible. This opinion only grew as she became older, and had been longer in the profession; in her student days she rather prided herself on not caring about personal appearance, and she dressed very badly.

‘Her sense of fairplay was very strong. Once in college there was an opposition aroused to the Student Christian Union, and a report was spread that the students belonging to it were neglecting their college work. It happened to be the time for the class examinations, and the lists were posted on the College notice-board. The next morning, the initials C.U. were found printed opposite the names of all the students who belonged to the Christian Union, and, as these happened to head the list in most instances, the unfair report was effectually silenced. No one knew who had initialed the list; it was some time afterwards I discovered it had been Aunt Elsie.

‘She was a beautiful needlewoman. She embroidered and made entirely herself two lovely little flannel[47] garments for her first grand-nephew, in the midst of her busy life, then filled to overflowing with the work of her growing practice, and of her suffrage activities.

‘The babies as they arrived in the families met with her special love. In her short summer holidays with any of us, the children were her great delight.

‘She was a great believer in an open-air life. One summer she took three of us a short walking tour from Callander, and we did enjoy it. We tramped over the hills, and finally arrived at Crianlarich, only to find the hotel crammed and no sleeping accommodation. She would take no refusal, and persuaded the manager to let us sleep on mattresses in the drawing-room, which added to the adventures of our trip.

‘On the way she entertained us with tales of her college life, and imbued us with our first enthusiasm for the women’s cause.

‘When I myself began to study medicine, no one could have been more enthusiastically encouraging, and even through the stormy and somewhat depressing times of the early career of the Medical College for Women, Edinburgh, her faith and vision never faltered, and she helped us all to hold on courageously.’

In 1891 Elsie went to Glasgow to take the examination for the Triple Qualification at the Medical School there. She could not then take surgery in Edinburgh, and the facilities for[48] clinical teaching were all more favourable in Glasgow.

It was probably better for her to be away from all the difficulties connected with the opening of the second School of Medicine for Women in Edinburgh. The one founded by Dr. Jex Blake was the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, and the one promoted by Elsie Inglis and other women students was known as the Medical College for Women. ‘It was with the fortunes of this school that she was more closely associated,’ writes Dr. Beatrice Russell.

In Glasgow she resided at the Y.W.C.A. Hostel. Her father did not wish her to live alone in lodgings, and she accommodated herself very willingly to the conditions under which she had to live. Miss Grant, the superintendent, became her warm friend. Elsie’s absence from home enabled her to give a vivid picture of her life in her daily letters to her father.

‘Glasgow, Feb. 4, 1891.

‘It was not nice seeing you go off and being left all alone. After I have finished this letter I am going to set to work. It seems there are twelve or fourteen girls boarding here, and there are regular rules. Miss Grant told me if I did not like some of them to speak to her, but I am not going to be such a goose as that.[49] One rule is you are to make your own bed, which she did not think I could do! But I said I could make it beautifully. I would much rather do what all the others do. Well, I arranged my room, and it is as neat as a new pin. Then we walked up to the hospital, to the dispensary; we were there till 4.30, as there were thirty-six patients, and thirty-one of them new.

‘I am most comfortable here, and I am going to work like anything. I told Miss Barclay so, and she said, “Oh goodness, we shall all have to look out for our laurels!”’

‘Feb. 7, ’91.

‘Mary Sinclair says it is no good going to the dispensaries on Saturday, as there are no students there, and the doctors don’t take the trouble to teach. I went to Dr. MacEwan’s wards this morning. I was the first there, so he let me help him with an operation; then I went over to Dr. Anderson’s.

‘Feb. 9.

‘This morning I spent the whole time in Dr. MacEwan’s wards. He put me through my facings. I could not think what he meant, he asked me so many questions. It seems it is his way of greeting a new student. Some of them cannot bear him, but I think he is really nice, though he can be abominably sarcastic, and he is a first-rate surgeon and capital teacher.

‘To-day, it was the medical jurists and the police officers he was down on, and he told story after story of how they work by red tape, according to the text-books. He said that, while he was casualty surgeon,[50] one police officer said to him that it was no good having him there, for he never would try to make the medical evidence fit in with the evidence they had collected. Once they brought in a woman stabbed in her wrist, and said they had caught the man who had done it running away, and he had a knife. Dr. MacEwan said the cut had been done by glass and not by a knife, so they could not convict the man, and there was an awful row over it. Some of them went down to the alley where it had happened, and sure enough there was a pane of glass smashed right through the centre. When the woman knew she was found out, she confessed she had done it herself. The moral he impressed on us was to examine your patient before you hear the story.

‘A. is beginning to get headaches and not sleep at night. I am thankful to say that is not one of my tricks. Miss G. is getting unhappy about her, and is going to send up beef-tea every evening. She offered me some, but I like my glass of milk much better. I am taking my tonic and my tramp regularly, so I ought to keep well. I am quite disgusted when girls break down through working too hard. They must remember they are not as strong as men, and then they do idiotic things, such as taking no exercise, into the bargain.

‘Dr. MacEwan asked us to-day to get the first stray £20,000 we could for him, as he wants to build a proper private hospital. So I said he should have the second £20,000 I came across, as I wanted the first to build and endow a woman’s College in Edinburgh.[51] He said he thought that would be great waste; there should not be separate colleges. “If women are going to be doctors, equal with the men, they should go to the same school.” I said I quite agreed with him, but when they won’t admit you, what are you to do? “Leave them alone,” he said; “they will admit you in time,” and he thought outside colleges would only delay that.

‘This morning in Dr. MacEwan’s wards a very curious case came in. Some of us tried to draw it, never thinking he would see us, and suddenly he swooped round and insisted on seeing every one of the scribbles. He has eyes, I believe, in the back of his head and ears everywhere. He forgot, I thought, to have the ligature taken off a leg he was operating on, and I said so in the lowest whisper to M. S. About five minutes afterwards, he calmly looked straight over to us, and said, “Now, we’ll take off the ligature!”

‘I went round this morning and saw a few of my patients. I found one woman up who ought to have been in bed. I discovered she had been up all night because her husband came in tipsy about eleven o’clock. He was lying there asleep on the bed. I think he ought to have been horse-whipped, and when I have the vote I shall vote that all men who turn their wives and families out of doors at eleven o’clock at night, especially when the wife is ill, shall be horse-whipped. And, if they make the excuse that they were tipsy, I should give them double. They would very soon learn to behave themselves.

‘As to the father of the cherubs you ask about, his family does not seem to lie very heavily on his mind. He is not in work just now, and apparently is very often out of work. One cannot take things seriously in that house.

‘In the house over the Clyde I saw the funniest sight. It is an Irish house, as dirty as a pig-sty, and there are about ten children. When I got there, at least six of the children were in the room, and half of them without a particle of clothing. They were sitting about on the table and on the floor like little cherubs with black faces. I burst out laughing when I saw them, and they all joined in most heartily, including the mother, though not one of them saw the joke, for they came and stood just as they were round me in a ring to see the baby washed. Suddenly, the cherubs began to disappear and ragged children to appear instead. I looked round to see who was dressing them, but there was no one there. They just slipped on their little black frocks, without a thing on underneath, and departed to the street as soon as the baby was washed.

‘Three women with broken legs have come in. I don’t believe so many women have ever broken their legs together in one day before! One of them is a shirt finisher. She sews on the buttons and puts in the gores at the rate of 4½d. a dozen shirts. We know the shop, and they sell the shirts at 4s. 6d. each. Of course, political economy is quite true, but I hope that shopkeeper, if ever he comes back to this earth, will be a woman and have to finish shirts at 4½d. a dozen, and[53] then he’ll see the other side of the question. I told the woman it was her own fault for taking such small wages, at which she seemed amused. It is funny the stimulating effect a big school has on a hospital. The Royal here is nearly as big and quite as rich as the Edinburgh Royal, but there is no pretence that they really are in their teaching and arrangements the third hospital in the kingdom, as they are in size. The London Hospital is the biggest, and then comes Edinburgh, and this is the third. Guy’s and Bart.’s, that one hears so much about, are quite small in comparison, but they have big medical schools attached. The doctors seem to lie on their oars if they don’t have to teach.

‘Feb. 1892.

‘I thought the Emperor of Germany’s speech the most impertinent piece of self-glorification I ever met with. Steed’s egotism is perfect humility beside it. He and his house are the chosen instruments of “our supreme Lord,” and anybody who does not approve of what he does had better clear out of Germany. As you say, Makomet and Luther and all the great epoch-makers had a great belief in themselves and their mission, but the German Emperor will have to give some further proof of his divine commission (beyond a supreme belief in himself) before I, for one, will give in my submission. I never read such a speech. I think it was perfectly blasphemous.

‘The Herald has an article about wild women. It evidently thinks St. Andrews has opened the flood-gates,[54] and now there is the deluge. St. Andrews has done very well—degrees and mixed classes from next October. Don’t you think our Court might send a memorial to the University Court about medical degrees? It is splendid having Sir William Muir on our side, and I believe the bulk of the Senators are all right—they only want a little shove.’

In Glasgow the women students had to encounter the opposition to ‘mixed classes,’ and the fight centred in the Infirmary. It would have been more honest to have promulgated the decision of the Managers before the women students had paid their fees for the full course of medical tuition.

Elsie, in her letters, describes the toughly fought contest, and the final victory won by the help of the just and enlightened leaders in the medical world. ‘So here is another fight,’ writes the student, with a sigh of only a half regret! It was too good a fight, and the backers were too strong for the women students not to win their undoubted rights. Through all the chaffing and laughter, one perceives the thread of a resolute purpose, and Elsie’s great gift, the unconquerable facing of ‘the Hill Difficulty.’ True, the baffled and puzzled enemy often played into their hands, as when Dr. T., driven to extremity in a weak moment,[55] threatened to prevent their attendance by ‘physical force.’ The threat armed the students with yet another legal grievance. Elsie describes on one occasion in her haste going into a ward where Dr. Gemmel, one of the ‘mixed’ objectors, was demonstrating. She perceived her mistake, and retreated, not before receiving a smile from her enemy. The now Sir William MacEwan enjoyed the fight quite as much as his women students; and if to-day he notes the achievements of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, he may count as his own some of their success in the profession in which he has achieved so worthy a name. The dispute went on until at length an exhausted foe laid down its weapons, and the redoubtable Dr. T. conveyed the intimation that the women students might go to any of the classes—and a benison on them!

The faction fight, like many another in the brave days of old, roared and clattered down the paved causeways of Glasgow. Dr. T., in his gate-house, must have wished his petticoat foes many times away and above the pass. If he, or any of the obstructionists of that day survive, we know that they belong to a sect that needs no repentance. They may, however, note with self-complacency that their action trained on a generation[56] skilled in the contest of fighting for democratic rights in the realm of knowledge. It is a birthright to enter into that gateway, and the keys are given to all who possess the understanding mind and reverent attitude towards all truth.

‘Nov. 1891.

‘Those old wretches, the Infirmary Managers, have reared their heads again, and now have decided that we are not to go to mixed classes, and we have been tearing all over the wards seeing all sorts of people about it. I went to Dr. K.’s this morning—all right. Crossing the quadrangle, a porter rushed at me and said, “Dr. T. wants to see all the lady students at the gate-house.” I remarked to Miss M., “I am certainly not going to trot after Dr. T. for casual messages like that. He can put up a notice if he wants me.” We were going upstairs to Dr. R. when another porter ran up and said, “Dr. T. is in his office. He would be much obliged if you would speak to him.” So we laughed, and said that was more polite anyhow, and went into the office. So he hummed and hawed, looked everywhere except at us, and then said the Infirmary Managers said we were not to go to mixed classes. So I promptly said, “Then I shall come for my fees to-morrow,” and walked out of the room. I was angry. I went straight back to Dr. K., who said he was awfuly sorry and angry, and he would see Dr. T., but he was afraid he could do nothing.

‘So here is another fight. But you see we cannot be beat here, for the same reason that we cannot beat[57] them in Edinburgh. Were the managers, managers a hundred times over, they cannot turn Mr. MacEwan off.

‘The Glasgow Herald had an article the other day, saying there was a radical change in the country, and that no one was taking any notice of it, and no one knew where it was to land us. This was the draft ordinance of the Commissioners which actually put the education of women on the same footing as that of men, and, worse still, seemed to countenance mixed classes. The G. H. seems to think this is the beginning of the end, and will necessarily lead to woman’s suffrage, and it will probably land them in the pulpit; because if they are ordinary University students they may compete for any of the bursaries, and many bursaries can only be held on condition that the holder means to enter the Church! You never read such an article, and it was not the least a joke but sober earnest.

‘I saw Dr. P. about my surgery. The chief reason I tried to get that prize was to pay for those things and not worry you about them. I want to pass awfully well, as it tells all one’s life through, and I mean to be very successful!

‘Dr. B. has the most absurd way of agreeing with everything you say. He asked me what I would do with a finger. I thought it was past all mending and said, “Amputate it.” “Quite so, quite so,” he said solemnly, “but we’ll dress it to-day with such and such a thing.” There were two or three other cases in which I recommended desperate measures, in which he agreed, but did not follow. Finally, he asked Mr. B. what he[58] would do with a swelling. Mr. B. hesitated. I said, “Open it.” Whereupon he went off into fits of laughter, and proclaimed to the whole room my prescriptions, and said I would make a first-rate surgeon for I was afraid of nothing.

‘It is one thing to recommend treatment to another person and another to do it yourself.

‘Queen Margaret is to be taken into the University, not affiliated, but made an integral part of the University and the lecturers appointed again by the Senators. That means that the Glasgow degrees in everything are to be given from October, Arts, Medicine, Science, and Theology. The “decrees of the primordial protoplasm,” that Sir James Crichton-Browne knows all about, are being reversed right and left, and not only by the Senatus Academicus of St. Andrews!’

The remaining letters are filled with all the hopes and fears of the examined. Mr. MacEwan tells her she will pass ‘with one hand,’ and Elsie has the usual moan over a defective memory, and the certainties that she will be asked all the questions to which she has no answering key. The evidences of hard and conscientious study abound, and, after she had counted the days and rejoined her father, she found she had passed through the heavy ordeal with great success, and, having thus qualified, could pass on to yet unconquered realms of experience and service.

‘We take up the task eternal and the burden and the lesson, Pioneers, O Pioneers.’—Walt Whitman.

After completing her clinical work in Glasgow, and passing the examination for the Triple Qualification in 1892, it was decided that Elsie should go to London and work as house-surgeon in the new Hospital for Women in the Euston Road. In 1916 that hospital kept its jubilee year, and when Elsie went to work there it had been established for nearly thirty years. Its story contains the record of the leading names among women doctors. In the commemorative prayer of Bishop Paget, an especial thanksgiving was made ‘for the good example of those now at rest, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Sophia Jex Blake, of good work done by women doctors throughout the whole world, and[60] now especially of the high trust and great responsibility committed to women doctors in this hour of need.’ The hearts of many present went over the washing seas, to the lands wasted by fire and sword, and to the leader of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, who had gained her earliest surgical experience in the wards of the first hospital founded by the first woman doctor, and standing for the new principle that women can practise the healing art.

Elsie Inglis took up her work with keen energy and a happy power of combining work with varied interests. In the active months of her residence she resolutely ‘tramped’ London, attended most of the outstanding churches, and was a great sermon taster of ministers ranging from Boyd Carpenter to Father Maturin. Innumerable relatives and friends tempted her to lawn tennis and the theatres. She had a keen eye to all the humours of the staff, and formed her own opinions on patients and doctors with her usual independence of judgment.

Elsie’s letters to her father were detailed and written daily. Only a very small selection can be quoted, but every one of them is instinct with a buoyant outlook, and they are full of the joy of service.

It is interesting to read in these letters her descriptions of the work of Dr. Garrett Anderson, and then to read Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson’s speech on her mother at the jubilee of the hospital. ‘I shall never forget her at Victoria Station on the day when the Women’s Hospital Corps was leaving England for France, early in September 1914. She was quite an old woman, her life’s work done, but the light of battle was in her eyes, and she said, “Had I been twenty years younger I would have been taking you myself.” Just twenty-one years before the war broke down the last of the barriers against women’s work as doctors, Elsie Inglis entered the New Hospital for Women, to learn with that staff of women doctors who had achieved so much under conditions so full of difficulties and discouragements.

‘New Hospital for Women,