| THE English and French In North America 1689-1763 |

|

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA

EDITED

By JUSTIN WINSOR

LIBRARIAN OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

VOL. V

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

Copyright, 1887,

By HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

All rights reserved.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

[The cut on the title shows the medal struck to commemorate the fall of Quebec.]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Canada and Louisiana. Andrew McFarland Davis | 1 |

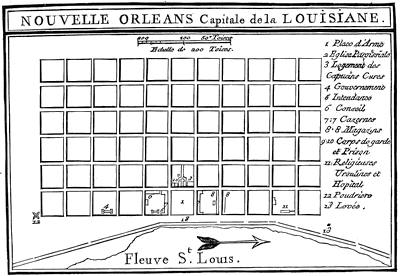

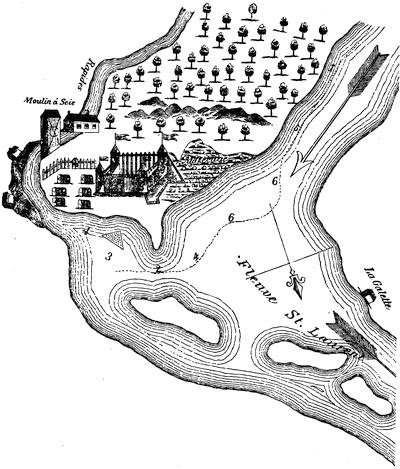

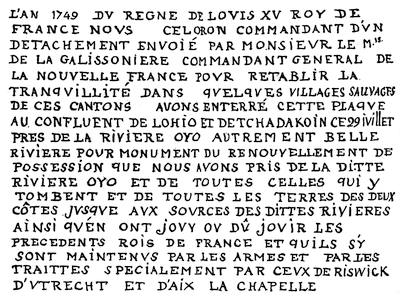

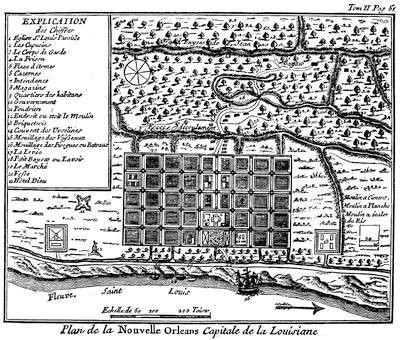

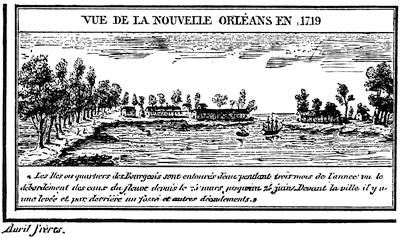

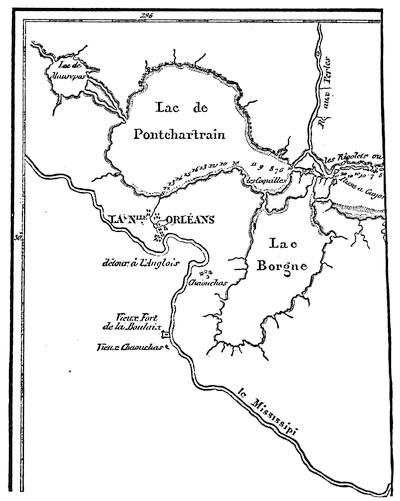

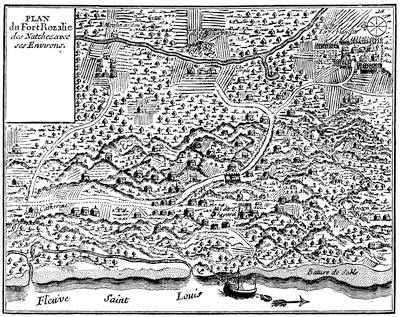

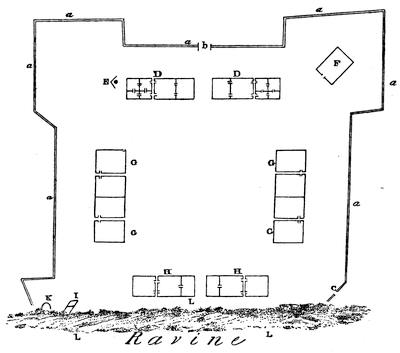

| Illustrations: La Présentation, 3; Autograph of Callières, 4; of Vaudreuil, 5; of Beauharnois, 7; of La Jonquière and of La Galissonière, 8; One of Céloron’s Plates, 9; Portrait of Lemoyne d’Iberville, with Autograph, 15; Environs du Mississipi (1700), 22; Portrait of Bienville, with Autograph, 26; Autograph of Lamothe, 29; of Lepinay, 31; Fac-simile of Bill of the Banque Royale, 34; Plans of New Orleans, 37, 38; View of New Orleans, 39; Map of the Mississippi, near New Orleans, 41; Fort Rosalie and Environs, 47; Plan of Fort Chartres, 54; Autograph of Vaudreuil, 57. | |

| Critical Essay | 63 |

| Illustrations: Autograph of La Harpe, 63; Portrait of Charlevoix, with Autograph, 64; Autograph of Le Page, 65; Map of the Mouths of the Mississippi, 66; Autograph of De Vergennes, 67; Coxe’s Map of Carolana, 70. | |

| Editorial Notes | 75 |

| Illustrations: Portrait of John Law, 75; his Autograph, 76. | |

| CARTOGRAPHY OF LOUISIANA AND THE MISSISSIPPI BASIN UNDER THE FRENCH DOMINATION. The Editor | 79 |

| Illustrations: Map of Louisiana, in Dumont, 82; Huske’s Map (1755), 84; Map of Louisiana, by Le Page du Pratz, 86. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

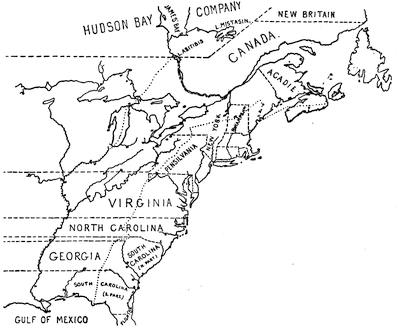

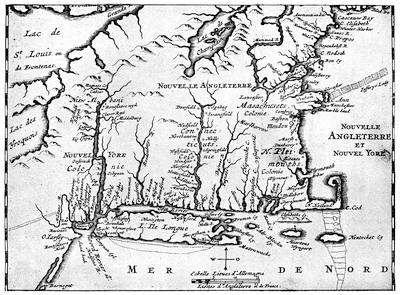

| New England, 1689-1763. The Editor | 87 |

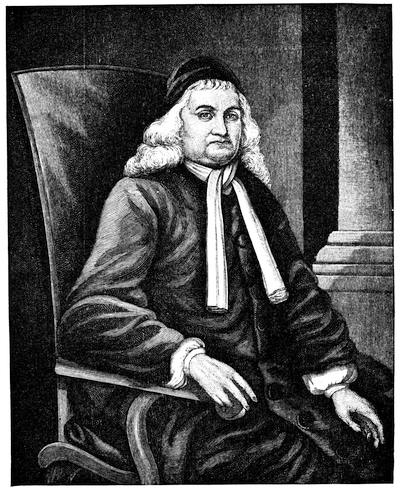

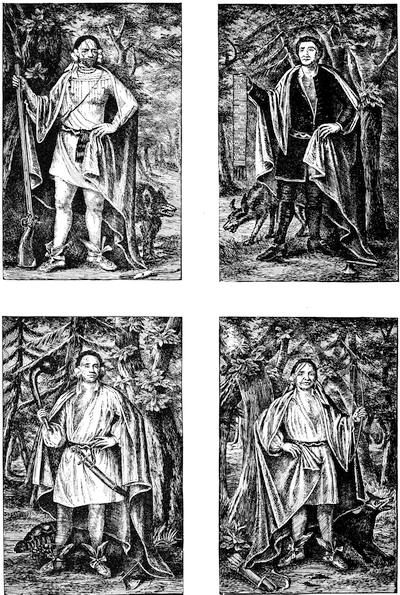

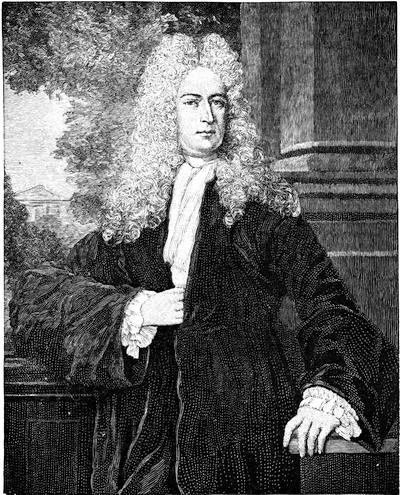

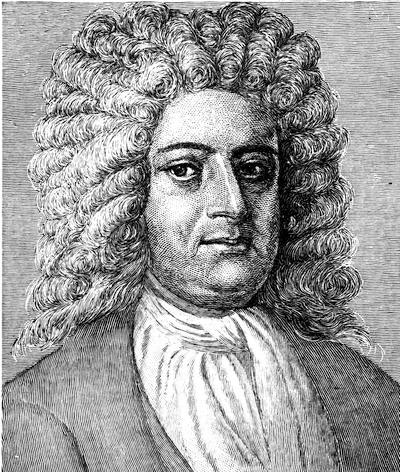

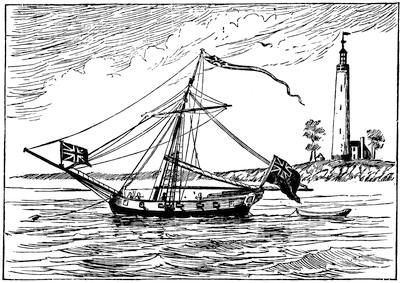

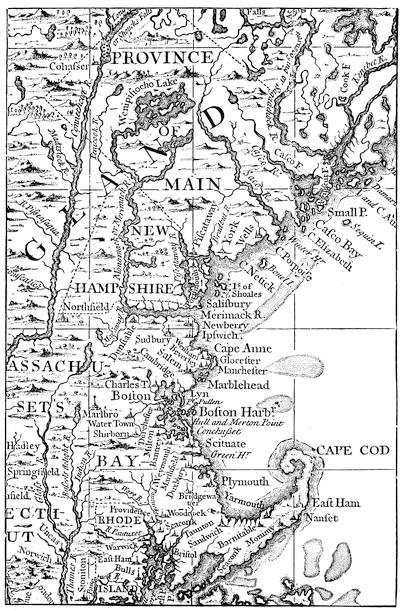

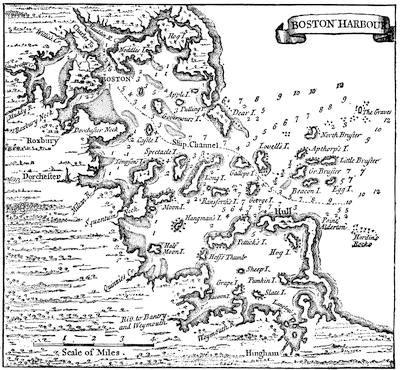

| Illustrations: Map of New England (1688), 88; Elisha Cooke, the Elder, 89; Seal of Massachusetts Province, 93; Bellomont, 97; Samuel Sewall, 100; Hertel, Seigneur de Rouville, 106; The Four Maquas (Indians), opp. 107; Draft of Boston Harbor, opp. 108; Ground Plan of Castle William, opp. 108; British Soldiers (1701-1714), 109; Gurdon Saltonstall, with Autograph, 112; William Dummer, 114; Jeremiah Dummer, 115; Elisha Cooke, the Younger, [iv]117; Thomas Prince, 122; Boston Light and Province Sloop, 123; Increase Mather, 125; Mather Byles, 128; George II., 130; Popple’s Map of New England, 134; An English Fleet, 136; Benjamin Pollard, 138; Autograph of Benning Wentworth, 139; Portrait and Autograph of George Berkeley, 140; William Shirley, 142; Popple’s Chart of Boston Harbor, 143. | |

| Critical Essay. The Editor | 156 |

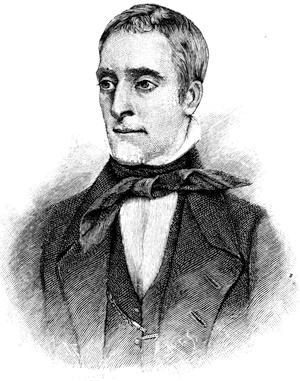

| Illustrations: Hannah Adams, 160; John Gorham Palfrey, 161. | |

| Editorial Notes | 164 |

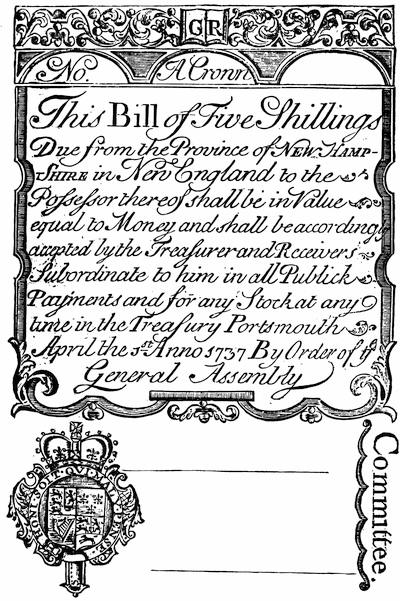

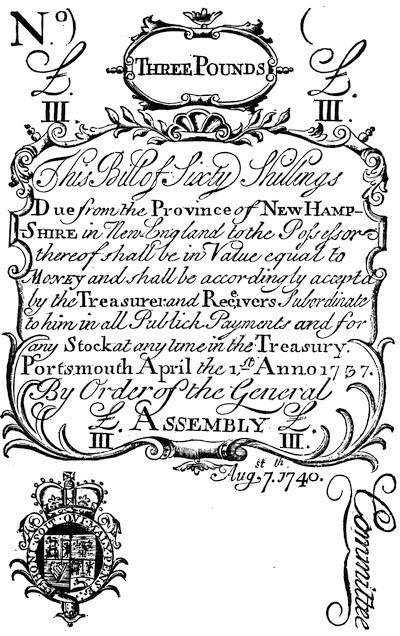

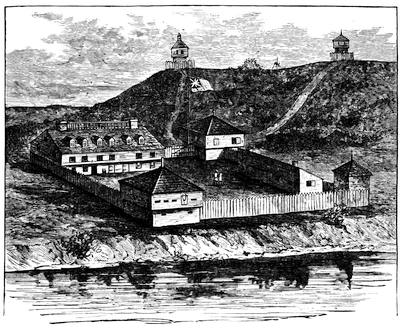

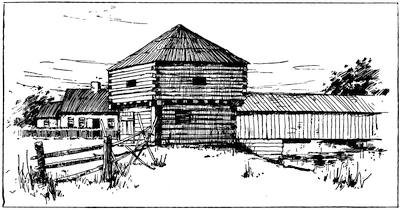

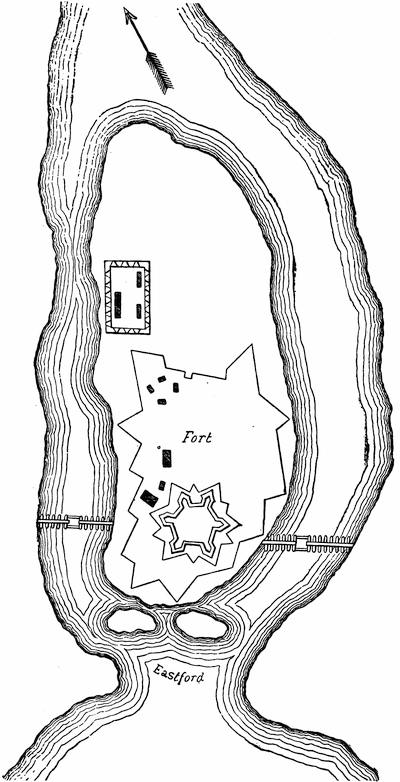

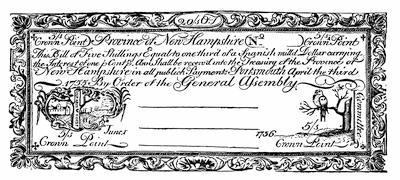

| Illustrations: Rhode Island Twelve-Pence Bill, 172; Rhode Island Three-Shillings Bill, 173; New Hampshire Five-Shillings Bill, 174; New Hampshire Three-Pounds Bill, 175; Plan of Fort Halifax, 182; Autograph of Wm. Lithgow, 182; of Jabez Bradbury, 183; Flanker of Fort Halifax, 183; Restoration of Fort Halifax, 184; Block House (1714), 185; Plans of Fort Anson, 187. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Middle Colonies. Berthold Fernow | 189 |

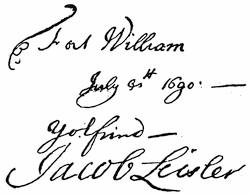

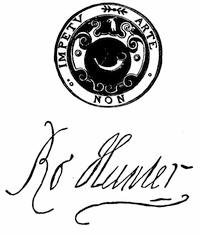

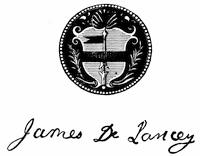

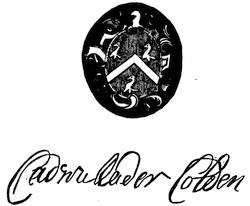

| Illustrations: Autograph of Jacob Leisler, 189; of Lord Cornbury, 192; of Governor Fletcher, with Seal, 194; of Lovelace, 196; of Governor Hunter, with Seal, 196; of Rip van Dam, 198; of Governor Clinton, with Seal, 202; of Governor James De Lancey, with Seal, 205; of Governor Cadwallader Colden, with Seal, 206; of Governor Robert Monckton, with Seal, 206. | |

| Critical Essay. (Manuscript sources, by Mr. Fernow) | 231 |

| (Cartography and Boundaries of the Middle Colonies, by Mr. Fernow and the Editor) | 233 |

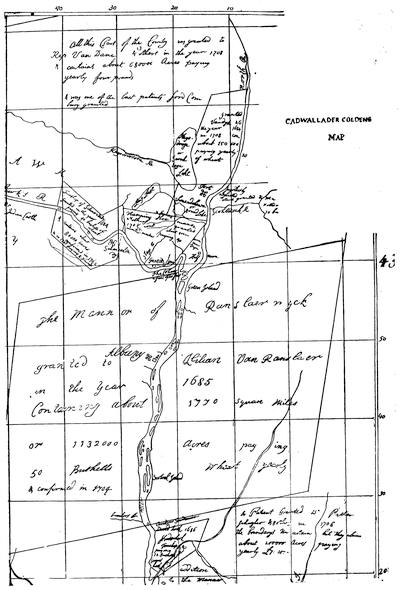

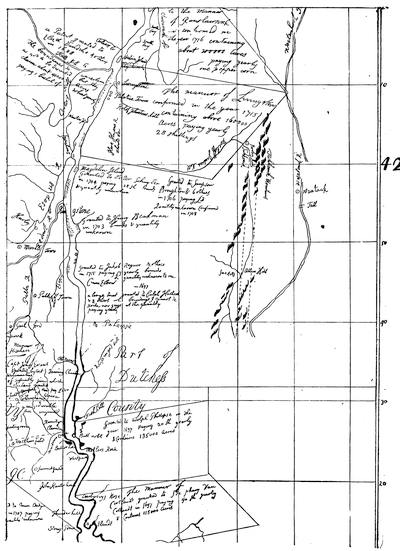

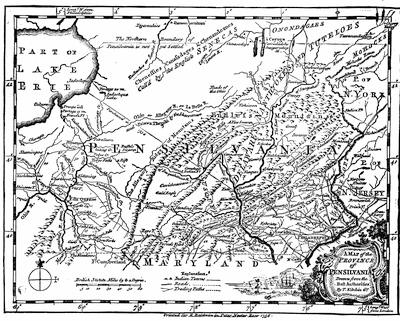

| Illustrations: Cadwallader Colden’s Map in fac-simile, 237; Map of Pennsylvania (1756), 239. | |

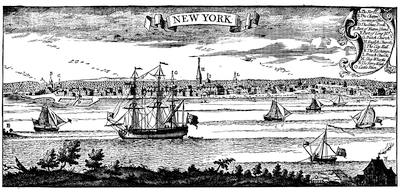

| Editorial Notes | 240 |

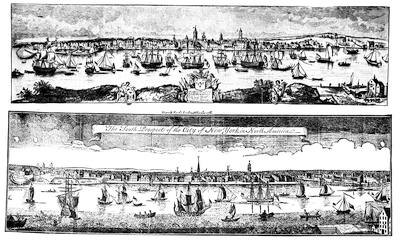

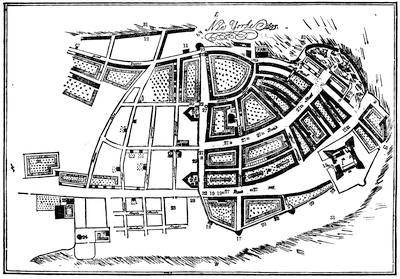

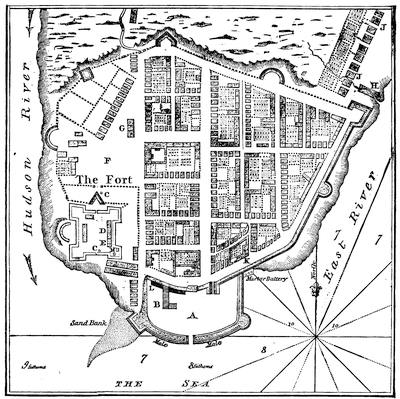

| Illustrations: Autograph of Daniel Horsmanden, 242; Views of New York (1732), 250; (1746), 251; (1761), 251; Plans of New York City (1695), 253; of New York and Perth Amboy Harbor (1732), 254; of New York (1755), 255; (1763), 256; (1764, by Bellin), 257; Heap’s East Prospect of Philadelphia (1754-1761), 258. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Maryland and Virginia. The Editor | 259 |

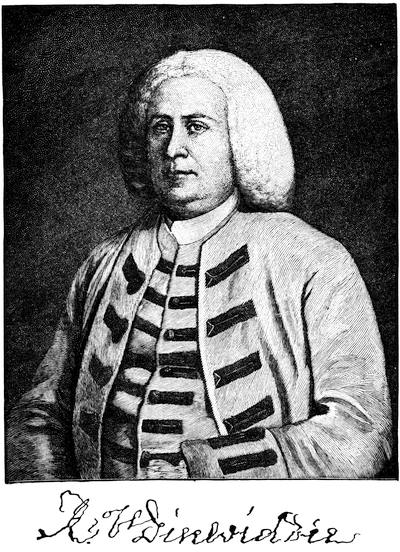

| Illustrations: Frederick, Lord Baltimore, 262; Alexander Spotswood, 266; Robert Dinwiddie, with Autograph, 269. | |

| Critical Essay | 270 |

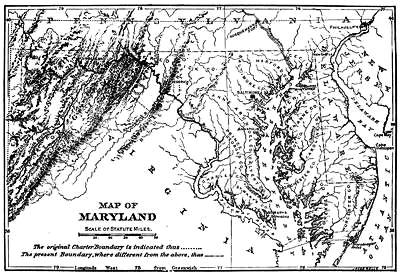

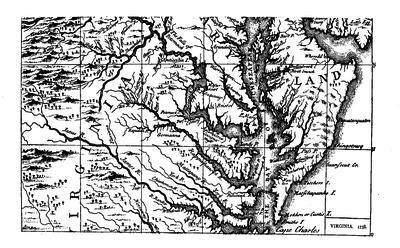

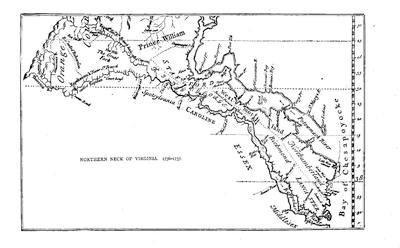

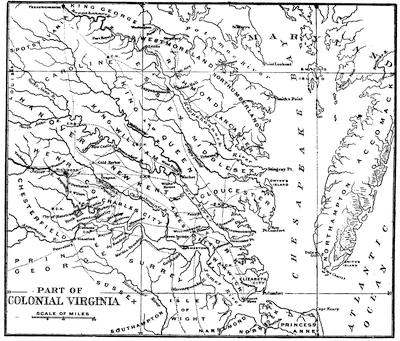

| Illustrations: Map of Maryland, opp. 273; Map of Virginia (1738), 274; William Byrd, 275; Map of Northern Neck of Virginia (1736-1737), 277; William and Mary College, 279; Autograph of Hugh Jones, 280; Map of Part of Colonial Virginia, opp. 280; Fac-simile of Title of Apostolic Charity, by Thomas Bray (1700), 283. | |

| CHAPTER V.[v] | |

| The Carolinas. William J. Rivers | 285 |

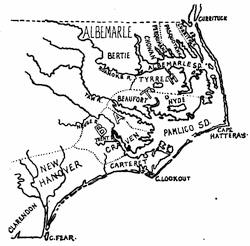

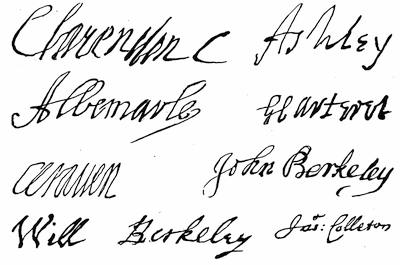

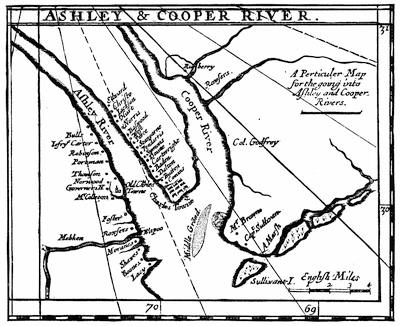

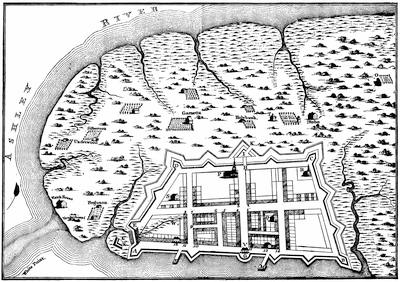

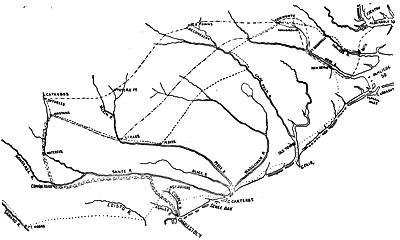

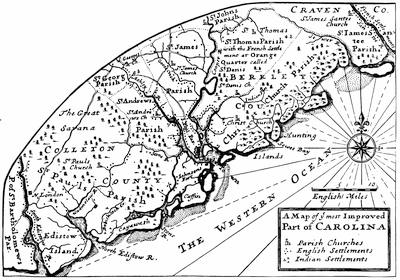

| Illustrations: Map of North Carolina (1663-1729), 285; Autographs of the Lords Proprietors (Clarendon, Ashley, Albemarle, G. Carteret, Craven, John Berkeley, Will. Berkeley, James Colleton), 287; Map of Cooper and Ashley Rivers, 315; Plan of Charlestown, S. C. (1732), 330; View of Charlestown (1742), 331. | |

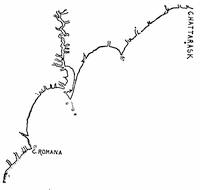

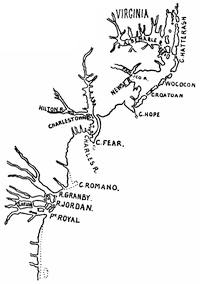

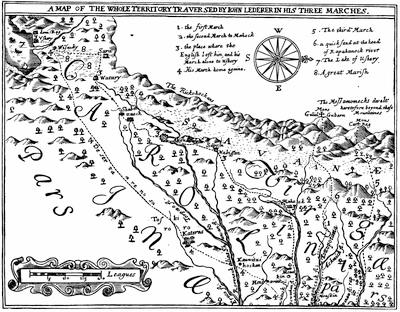

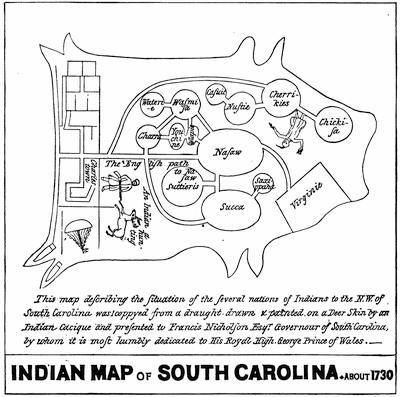

| Critical Essay. The Editor | 335 |

| Illustrations: Autograph of John Locke, 336; Shapley’s Sketch-Map of the Carolina Coast (1662), 337; Map (1666), 338; Lederer’s Map (1669-1670), 339; Morden’s Map (1687), 341; Plan of Charlestown (1704), 343; Autographs of John Archdale and John Oldmixon, 344; Carolina War-Map (1711-1715), 346; Indian Map of South Carolina (1730), 349; Moll’s Map of Carolina (1730), 351; Autograph of George Chalmers, 353. | |

| NOTE ON THE LATER HISTORIES OF CAROLINA. The Editor | 354 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The English Colonization of Georgia, 1733-1752. Charles C. Jones, Jr. | 357 |

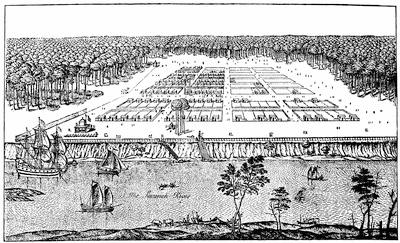

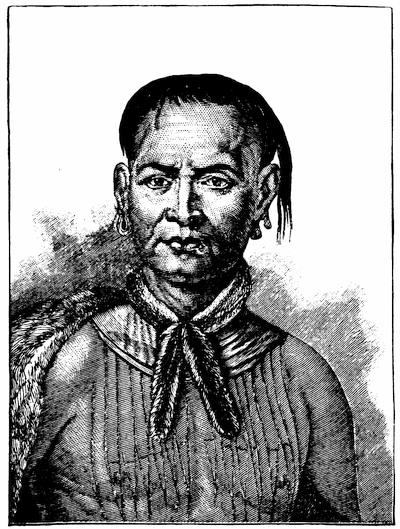

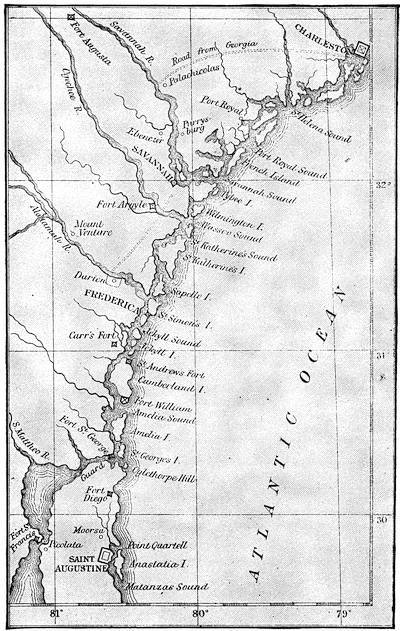

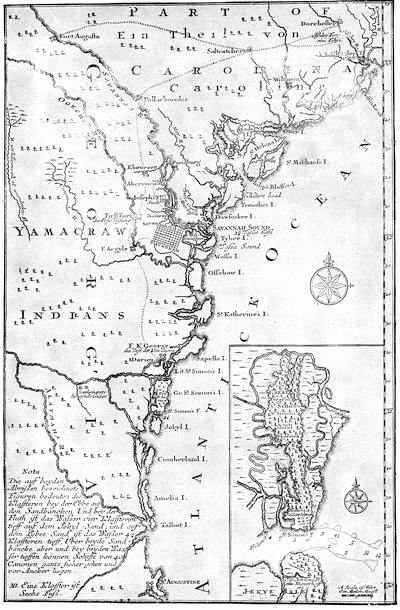

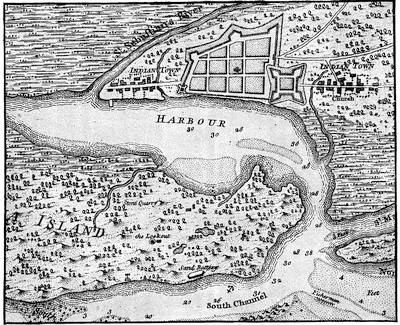

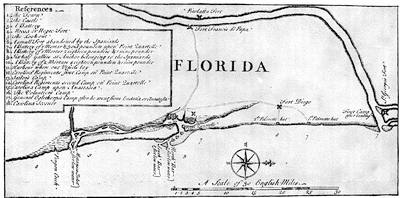

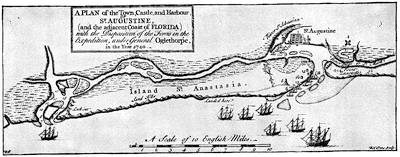

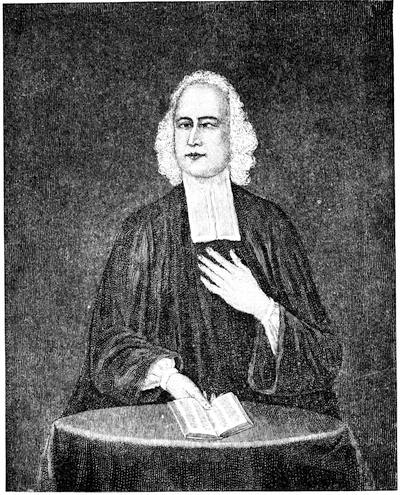

| Illustrations: General Oglethorpe, 362; Map of South Carolina and Georgia (1733), 365; Early View of Savannah, 368; Tomo-chi-chi Mico, 371; Map of the County of Savannah (Urlsperger), 373; Map of Coast Settlements before 1743, 375; Map of Coast from St. Augustine to Charlestown, S. C., with Map of Simon’s Island (Urlsperger), 379; Plan of St. Augustine (1763), 381; Map of Coast of Florida (1742), 382; Map of Harbor and Town of St. Augustine (1742), 383; Whitefield, 388. | |

| Critical Essay | 392 |

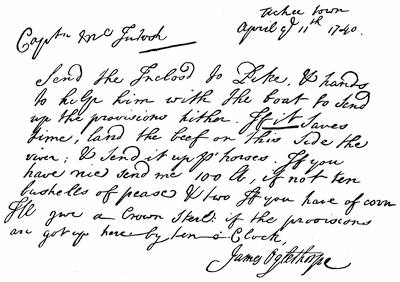

| Illustration: Handwriting of Oglethorpe, 393. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Wars on the Seaboard: Acadia and Cape Breton. Charles C. Smith | 407 |

| Illustration: A French Frigate, 412. | |

| Critical Essay | 418 |

| AUTHORITIES ON THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WARS OF NEW ENGLAND AND ACADIA, 1688-1763. The Editor | 420 |

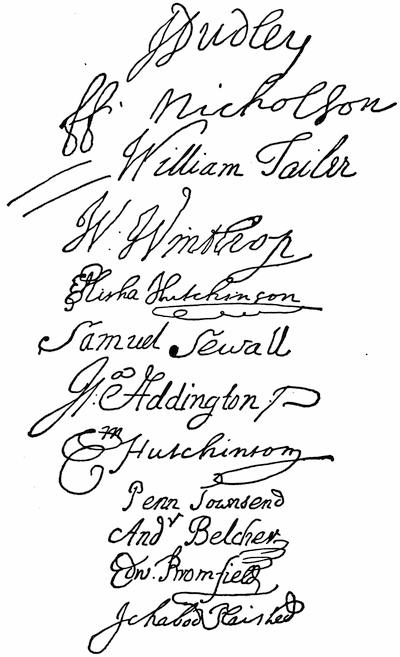

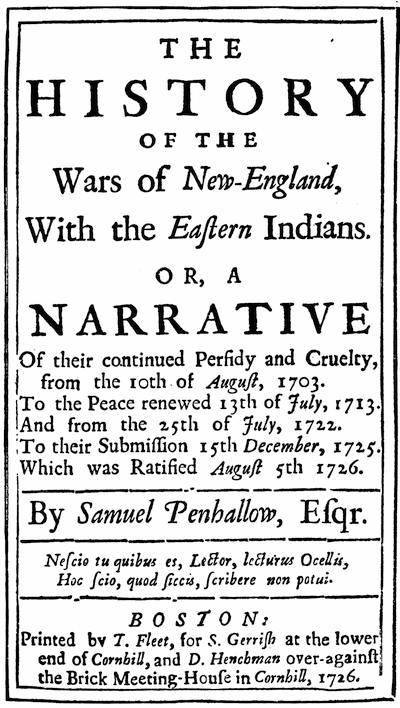

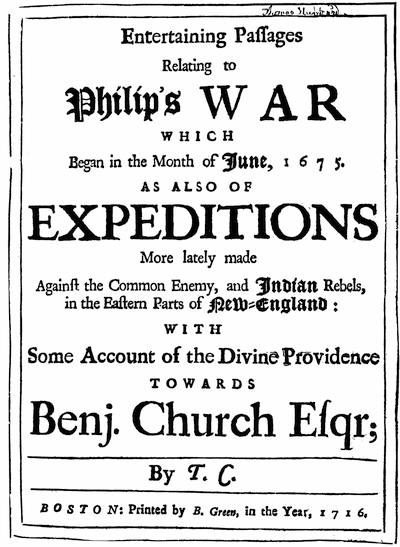

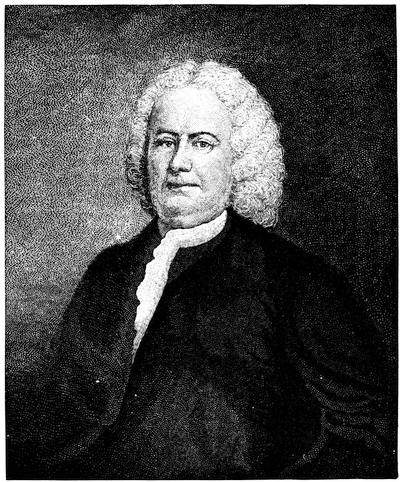

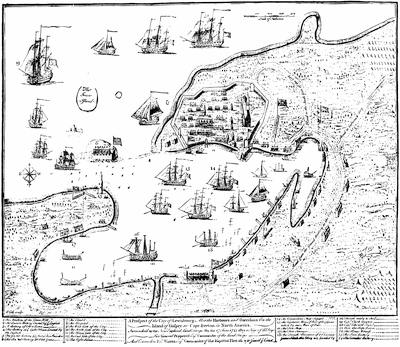

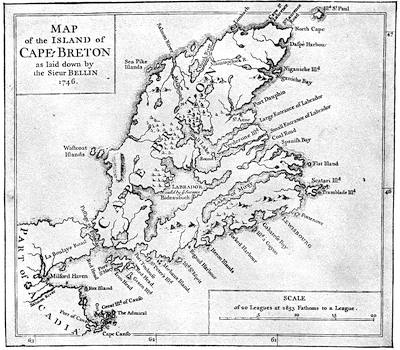

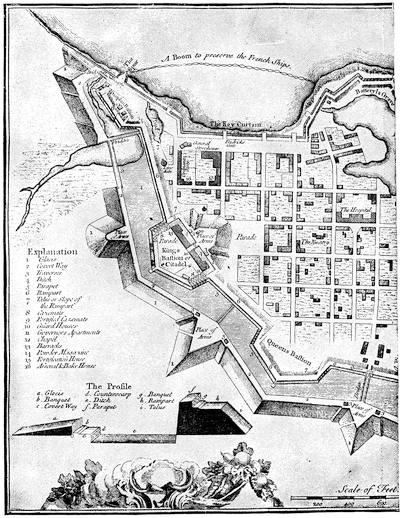

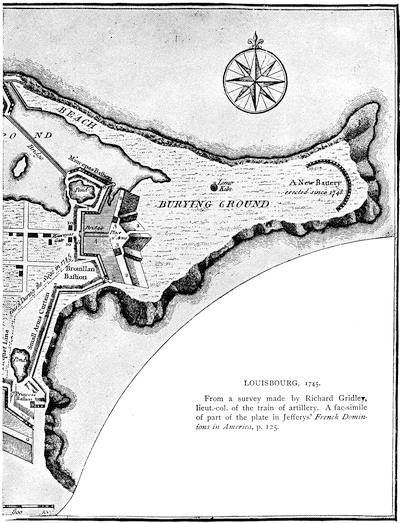

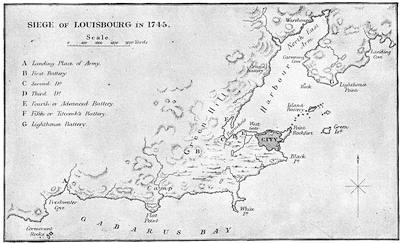

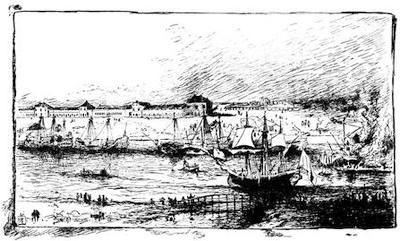

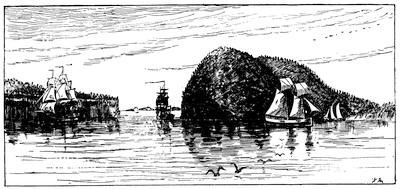

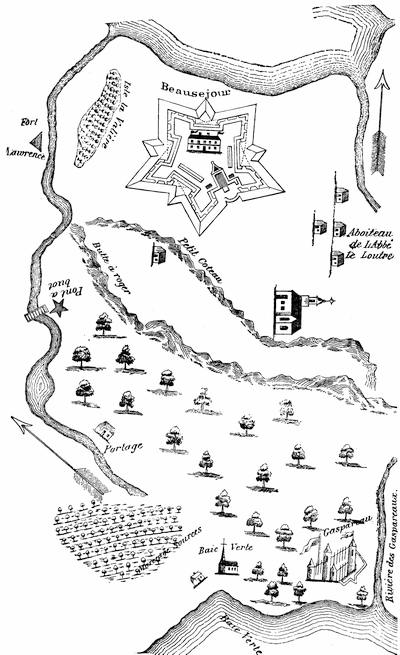

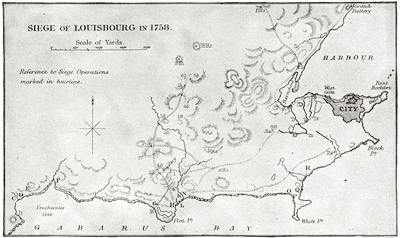

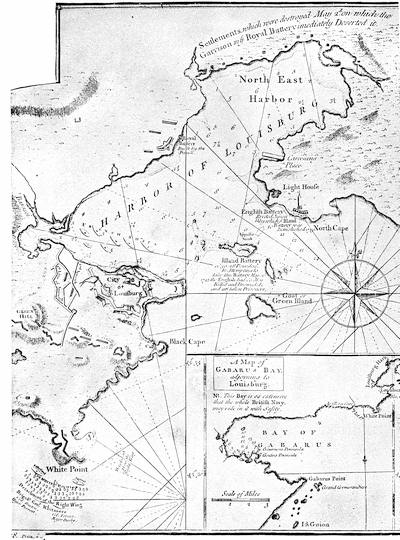

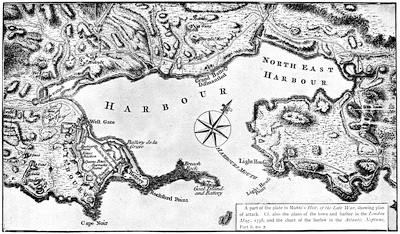

| Illustrations: Autographs of John Gyles, 421; of Francis Nicholson and Samuel Vetch, 422; View of Annapolis Royal, 423; Autographs of Vaudreuil, 424; of the Signers of the Conference, January 16, 1713-14 (J. Dudley, Francis Nicholson, William Tailer, W. Winthrop, Elisha Hutchinson, Samuel Sewall, J. Addington, Em. Hutchinson, Penn Townsend, Andrew Belcher, Edw. Bromfield, Ichabod Plaisted), 425; Fac-simile of the Title of Penhallow’s History [vi](1726), 426; of Church’s Entertaining Passages (1716), 427; Bellin’s Map of Port Royal, 428; View of Gut of Annapolis, 429; Autograph of Thomas Westbrook, 430; of John Lovewell, 431; Plan of Lovewell’s Fight, 433; Autographs of R. Auchmuty and W. Vaughan, 434; Portrait of Sir William Pepperrell, with Autograph, 435; his Arms, 436; Autographs of Edward Tyng and John Rous, 437; Gibson’s Picture of the Siege of Louisbourg, fac-simile, opp. 437; Autograph of Peter Warren, 439; of Richard Gridley, 440; Bellin’s Map of Cape Breton (1746), 440; Gridley’s Plan of Louisbourg (1745), 441, 442, 443; Plan of Attack on Louisbourg (1745), 444; Map of the Siege (1745), 445; Pepperrell’s Plan of the Siege (1745), 446; View of Louisbourg, 447; Plan of Island Battery, 448; View of the Entrance of Mines Basin, 449; View of Cape Baptist, 449; Autograph of Paul Mascarene, 450; Plan of Forts Beauséjour and Gaspereau, 451; Autograph of Charles Lawrence, 452; Map of Fort Beauséjour and Adjacent Country, 453; Colonel Monckton, with Autograph, 454; Autograph of John Winslow, 455; his Portrait, 456; Autograph of Colonel Murray, 460; Admiral Boscawen, with Autograph, 464; Map of Siege of Louisbourg (1758), 465; Views of Louisbourg and Harbor, 466; Portrait of General Wolfe, 467; Plan of Siege of Louisbourg (1758), 468, 469; Plan of the Attack, 470. | |

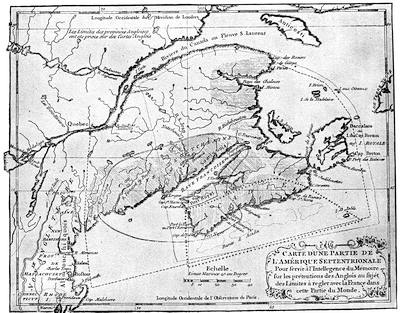

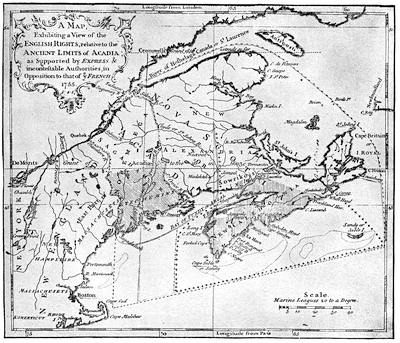

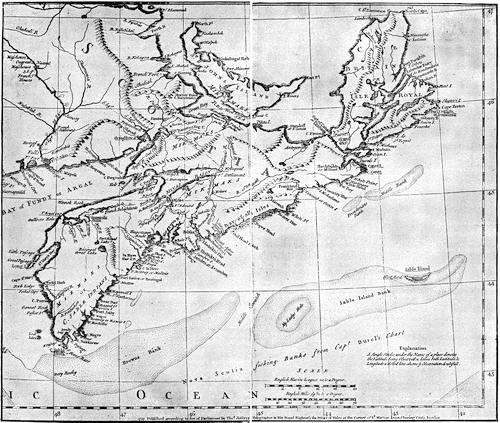

| MAPS AND BOUNDS OF ACADIA. The Editor | 472 |

| Illustrations: Lahontan’s Map of Acadia, 473; Map of the French Claim (1755), 478; of the English Claim (1755), 479; Jefferys’ Map of Nova Scotia, 480-481. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Struggle for the Great Valleys of North America. The Editor | 483 |

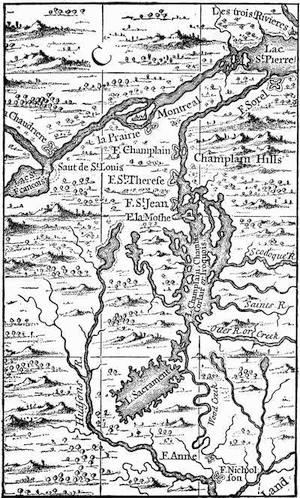

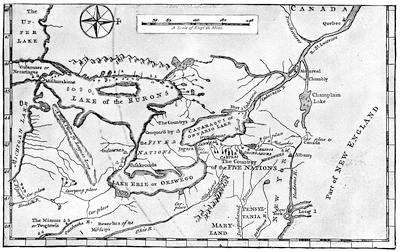

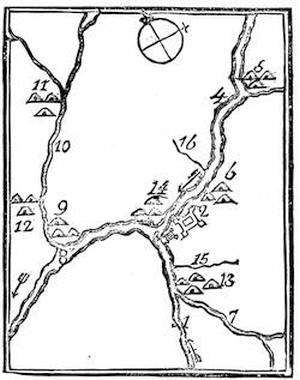

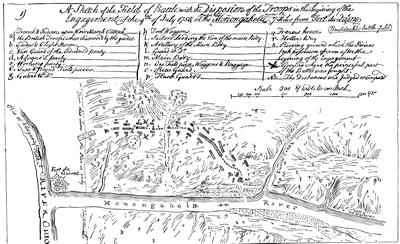

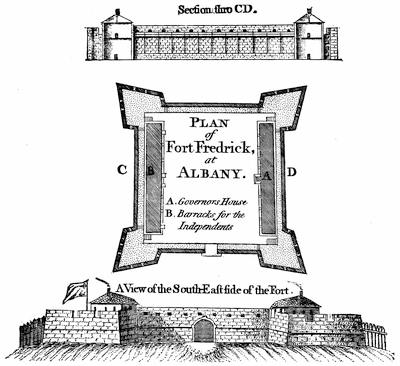

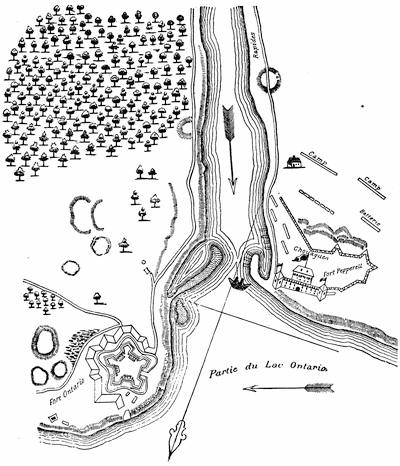

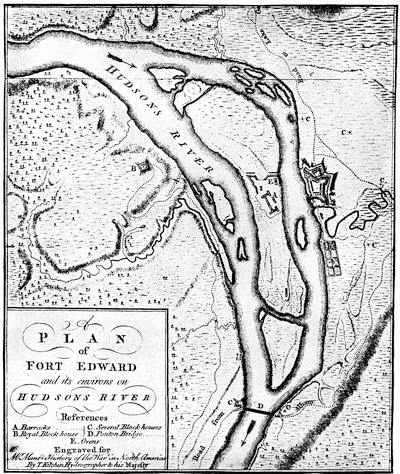

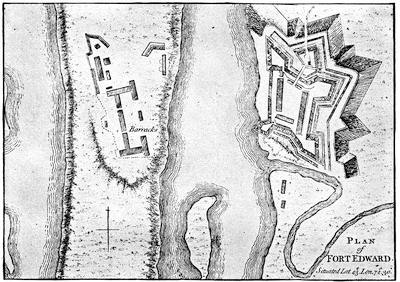

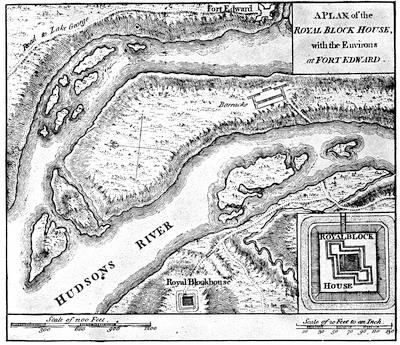

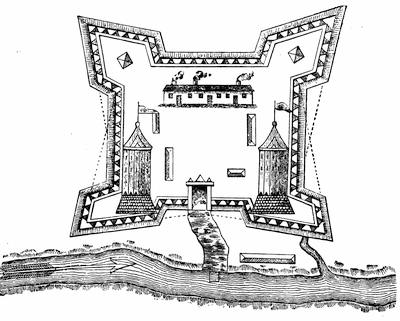

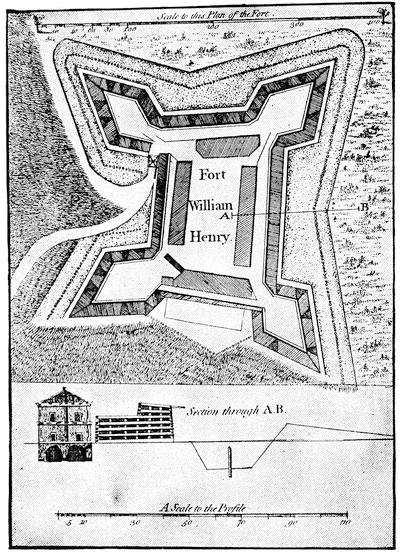

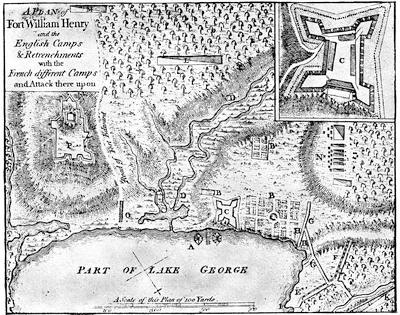

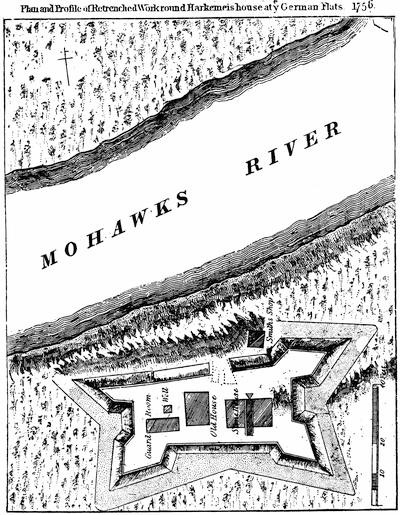

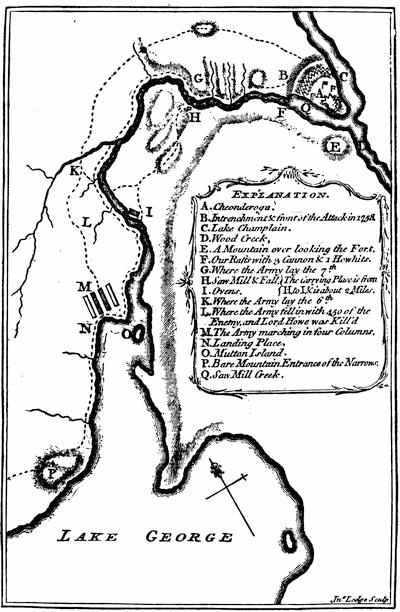

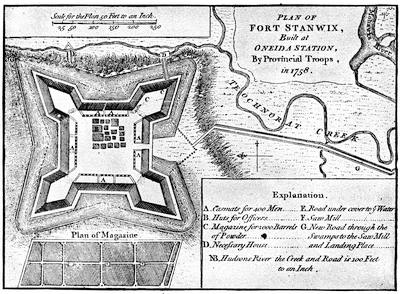

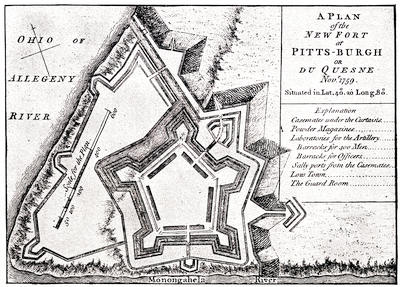

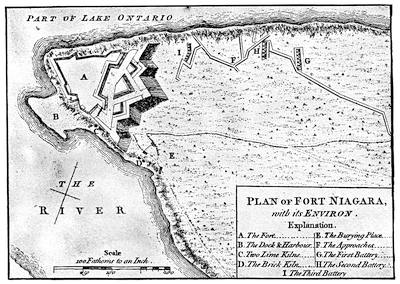

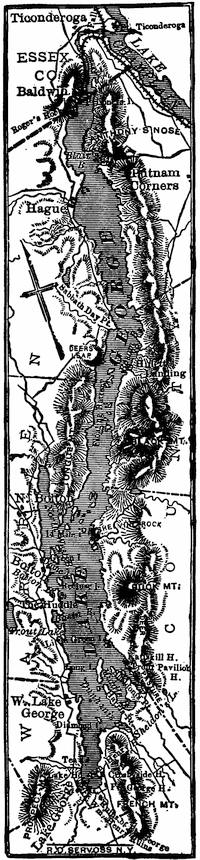

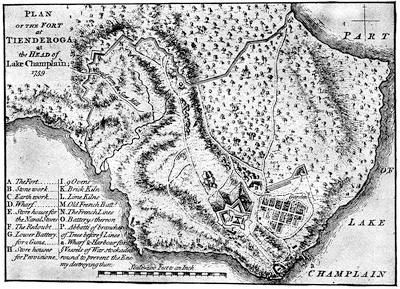

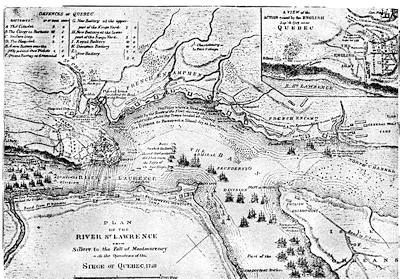

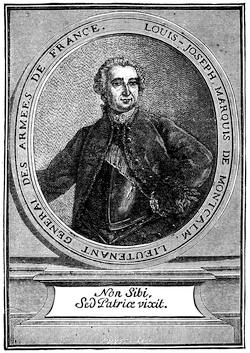

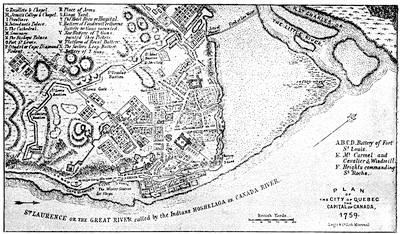

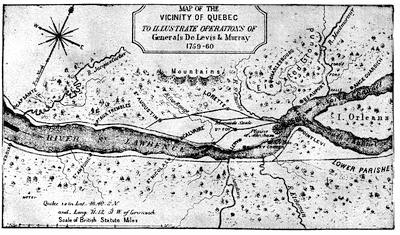

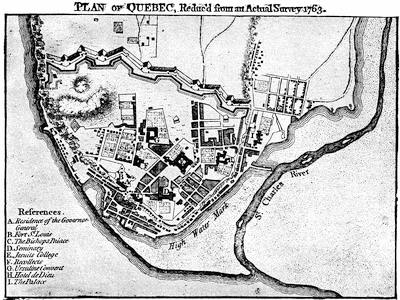

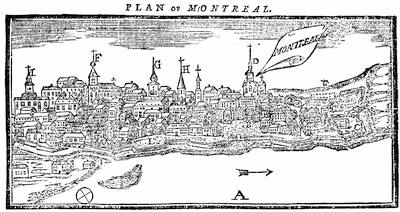

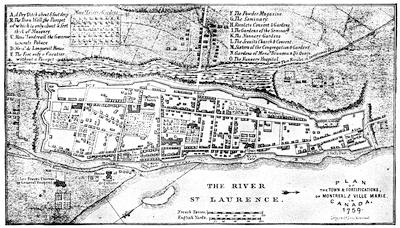

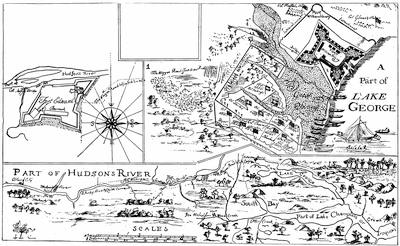

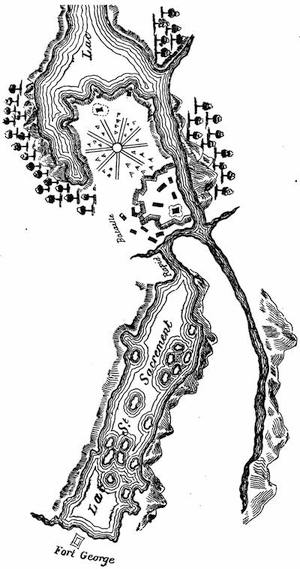

| Illustrations: French Soldier (1700), 484; British Infantry Soldier (1725), 485; Popple’s Map of Lakes Champlain and George (1732), 486; View of Quebec (1732), 488; British Footguard (1745), 489; French Soldier (1745), 489; Colden’s Map of the Region of the Great Lakes, 491; Autographs of Duquesne, 492; of Contrecœur, 493; of Jumonville, 493; of Villiers, 494; French Soldiers (1755), 497; Map of Fort Duquesne and Vicinity, 497; Contemporary Plan of Braddock’s Defeat, 499; Autograph of Sir William Johnson, 502; his Portrait, 503; Autograph of Montcalm, 505; Portraits of Lord Loudon, 506, 507; Plan of Albany, 508; Plan of Fort Frederick at Albany, 509; Autograph of Loudon, 510; The Forts at Oswego, 511; Fort Edward and Vicinity, 512, 513, 514; Fort St. Jean, 515; Fort William Henry, 516; View of the Site of Fort William Henry, 517; Plan of Attack on Fort William Henry, 518; Fort at German Flats, 519; Autograph of James Abercromby, 521; Lord Howe, 522; View of Ticonderoga, 523; Plan of Attack on Ticonderoga (1758), 524; Fort Frontenac, 525; Mante’s Map of Lake George, 526; Autograph of Jeff. Amherst, 527; Fort Stanwix, 528; Autographs of Generals Forbes and Vaudreuil, 530; Portrait of General Amherst, 531; Fort Pitt, 532; The New Fort Pitt, 533; Fort Niagara, 534; Fort George on Lake George, 535; Modern Map of Lake George, 536; Plan of Ticonderoga, 537; of Crown Point, 537; View of the Ruins of Crown Point, 538; Plan of Isle-aux-Noix, 539; Portrait of General Wolfe, 541; Plan of the Siege of Quebec (1759), 542; Contemporary Plan of Quebec, 543; Bougainville, 546; British Soldiers, 547; Montcalm, 548; Plan of Quebec as Surrendered, 549; View of Heights of Abraham, with Wolfe’s Monument, 551; Map of the Campaign of Lévis and Murray, 552; Plan of Quebec (1763), 553; View of Montreal (1761), 554; Plans of Montreal (1763, 1758 ), 555, 556; Map of Routes to Canada (1755-1763), 557; Robert Rogers, 558. | |

| Critical Essay[vii] | 560 |

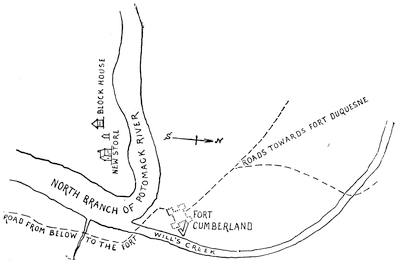

| Illustrations: French Soldiers (1710), 562; Bonnecamp’s Map, 569; Fort Cumberland and Vicinity, 577; Contemporary Map of Dieskau’s Campaign, 585; Clement’s Plan of the Battle of Lake George, 586; Map of Forts George and Ticonderoga (1749-1760), 588; Crown Point Currency of New Hampshire, 590; General Townshend, 607. | |

| Notes | 611 |

| Illustrations: Autograph of William Smith, 618; Portrait of Garneau, 619; of James Grahame, 620. | |

| INDEX | 623 |

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

CANADA AND LOUISIANA.

BY ANDREW McFARLAND DAVIS,

American Antiquarian Society.

THE story of the French occupation in America is not that of a people slowly moulding itself into a nation. In France there was no state but the king; in Canada there could be none but the governor. Events cluster around the lives of individuals. According to the discretion of the leaders the prospects of the colony rise and fall. Stories of the machinations of priests at Quebec and at Montreal, of their heroic sufferings at the hands of the Hurons and the Iroquois, and of individual deeds of valor performed by soldiers, fill the pages of the record. The prosperity of the colony rested upon the fate of a single industry,—the trade in peltries. In pursuit of this, the hardy trader braved the danger from lurking savage, shot the boiling rapids of the river in his light bark canoe, ventured upon the broad bosom of the treacherous lake, and patiently endured sufferings from cold in winter and from the myriad forms of insect life which infest the forests in summer. To him the hazard of the adventure was as attractive as the promised reward. The sturdy agriculturist planted his seed each year in dread lest the fierce war-cry of the Iroquois should sound in his ear, and the sharp, sudden attack drive him from his work. He reaped his harvest with urgent haste, ever expectant of interruption from the same source, always doubtful as to the result until the crop was fairly housed. The brief season of the Canadian summer, the weary winter, the hazards of the crop, the feudal tenure of the soil,—all conspired to make the life of the farmer full of hardship and barren of promise. The sons of the early settlers drifted to the woods as independent hunters and traders. The parent State across the water, which undertook to say who might trade, and[2] where and how the traffic should be carried on, looked upon this way of living as piratical. To suppress the crime, edicts were promulgated from Versailles and threats were thundered from Quebec. Still, the temptation to engage in what Parkman calls the “hardy, adventurous, lawless, fascinating fur-trade” was much greater than to enter upon the dull monotony of ploughing, sowing, and reaping. The Iroquois, alike the enemies of farmer and of trader, bestowed their malice impartially upon the two callings, so that the risk was fairly divided. It was not surprising that the life of the fur-trader “proved more attractive, absorbed the enterprise of the colony, and drained the life-sap from other branches of commerce.” It was inevitable, with the young men wandering off to the woods, and with the farmers habitually harassed during both seed-time and harvest, that the colony should at times be unable to produce even grain enough for its own use, and that there should occasionally be actual suffering from lack of food. It often happened that the services of all the strong men were required to bear arms in the field, and that there remained upon the farms only old men, women, and children to reap the harvest. Under such circumstances want was sure to follow during the winter months. Such was the condition of affairs in 1700. The grim figure of Frontenac had passed finally from the stage of Canadian politics. On his return, in 1689, he had found the name of Frenchman a mockery and a taunt.[1] The Iroquois sounded their threats under the very walls of the French forts. When, in 1698, the old warrior died, he was again their “Onontio,” and they were his children. The account of what he had done during those years was the history of Canada for the time. His vigorous measures had restored the self-respect of his countrymen, and had inspired with wholesome fear the wily savages who threatened the natural path of his fur-trade. The tax upon the people, however, had been frightful. A French population of less than twelve thousand had been called upon to defend a frontier of hundreds of miles against the attacks of a jealous and warlike confederacy of Indians, who, in addition to their own sagacious views upon the policy of maintaining these wars, were inspired thereto by the great rival of France behind them.

To the friendship which circumstances cemented between the English and the Iroquois, the alliance between the French and the other tribes was no fair offset. From the day when Champlain joined the Algonquins and aided them to defeat their enemies near the site of Ticonderoga, the hostility of the great Confederacy had borne an important part in the history of Canada. Apart from this traditional enmity, the interests of the Confederacy rested with the English, and not with the French. If the Iroquois permitted the Indians of the Northwest to negotiate with the French, and interposed no obstacle to the transportation of peltries from the upper lakes to Montreal and Quebec, they would forfeit all the commercial benefits which belonged to their geographical position. Thus their natural tendency was to join with the English. The value of neutrality was[3] plain to their leaders; nevertheless, much of the time they were the willing agents of the English in keeping alive the chronic border war.

LA PRÉSENTATION.

[After a plan in the contemporary Mémoires sur le Canada, 1749-1760, published by the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (réimpression), 1873, p. 13.—Ed.]

Nearly all the Indian tribes understood that the conditions of trade were better with the English than with the French; but the personal influence of the French with their allies was powerful enough partially to overcome this advantage of their rivals. This influence was exercised not only[4] through missionaries,[2] but was also felt through the national characteristics of the French themselves, which were strongly in harmony with the spirit of forest life. The Canadian bushrangers appropriated the ways and the customs of the natives. They were often adopted into the tribes, and when this was done, their advice in council was listened to with respect. They married freely into the Indian nations with whom they were thrown; and the offspring of these marriages, scattered through the forests of the Northwest, were conspicuous among hunters and traders for their skill and courage. “It has been supposed for a long while,” says one of the officers of the colony, “that to civilize the savages it was necessary to bring them in contact with the French. We have every reason to recognize the fact that we were mistaken. Those who have come in contact with us have not become French, while the French who frequent the wilds have become savages.” Prisoners held by the Indians often concealed themselves rather than return to civilized life, when their surrender was provided for by a treaty of peace.[3]

Powerful as these influences had proved with the allies of the French, no person realized more keenly than M. de Callières, the successor of Frontenac, how incompetent they were to overcome the natural drift of the Iroquois to the English. He it was who had urged at Versailles the policy of carrying the war into the province of New York as the only means of ridding Canada of the periodic invasions of the Iroquois.[4] He had joined with Frontenac in urging upon the astute monarch who had tried the experiment of using Iroquois as galley-slaves, the impolicy of abandoning the posts at Michilimakinac and at St. Joseph. His appointment was recognized as suitable, not only by the colonists, but also by Charlevoix, who tells us that “from the beginning he had acquired great influence over the savages, who recognized in him a man exact in the performance of his word, and who insisted that others should adhere to promises given to him.” He saw accomplished what Frontenac had labored for,—a peace with the Iroquois in which the allied tribes were included. The Hurons, the Ottawas, the Abenakis, and the converted Iroquois having accepted the terms of the peace, the Governor-General, the Intendant, the Governor of Montreal, and the ecclesiastical authorities signed a provisional treaty on the 8th of September, 1700. In 1703, while the Governor still commanded the confidence of his countrymen, his career was cut short by death.

The reins of government now fell into the hands of Philippe de Vaudreuil, who retained the position of governor until his death. During the entire period of his administration Canada was free from the horrors of Indian invasion. By his adroit management, with the aid of Canadians adopted by the tribes, and of missionaries, the Iroquois were held in check. The scene in which startled villagers were roused from their midnight slumber by the fierce war-whoop, the report of the musket, and the light of burning dwellings, was transferred from the Valley of the St. Lawrence to New England. Upon Vaudreuil must rest the responsibility for the attacks upon Deerfield in 1704 and Haverhill in 1708, and for the horrors of the Abenakis war. The pious Canadians, fortified by a brief preliminary invocation of Divine aid, rushed upon the little settlements and perpetrated cruelties of the same class with those which characterized the brutal attacks of the Iroquois upon the villages in Canada. The cruel policy of maintaining the alliance with the Abenakis, and at the same time securing quiet in Canada by encouraging raids upon the defenceless towns of New England, not only left a stain upon the reputation of Vaudreuil, but it also hastened the end of French power in America by convincing the growing, prosperous, and powerful colonies known as New England that the only path to permanent peace lay through the downfall of French rule in Canada.[5]

Aroused to action by Canadian raids, the New England colonies increased their contributions to the military expeditions by way of Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence, which had become and remained, until Wolfe’s success obviated their necessity, the recognized method of attack on Canada. During Vaudreuil’s time these expeditions were singularly unfortunate. Some extraneous incident protected Quebec each year.[6] It is not strange that such disasters to the English were looked upon by the pious French as a special manifestation of the interest taken in Canada by the Deity. Thanks were given in all parts of the colony to God, who had thus directly saved the province, and special fêtes were celebrated in honor of Notre Dame des Victoires.

The total population of Canada at this time was not far from eighteen thousand. The English colonies counted over four hundred thousand inhabitants. The French Governor, in a despatch to M. de Pontchartrain, called attention, in 1714, to the great disproportion of strength between the French and English settlements, and added that there could be little doubt that on the occasion of the first rupture the English would make a powerful effort to get possession of Canada. The English colonies were in themselves strong enough easily to have overthrown the French in America. In addition, they were supported by the Home Government; while Louis XIV., defeated, humiliated, baffled at every turn, was compelled supinely[6] to witness these extraordinary efforts to wrest from him the colonies in which he had taken such personal interest. Well might the devout Canadian offer up thanks for his deliverance from the defeat which had seemed inevitable! Well might he ascribe it to an interposition of Divine Providence in his behalf! Under the circumstances we need not be surprised that a learned prelate should chronicle the fact that the Baron de Longueuil, before leaving Montreal in command of a detachment of troops, “received from M. de Belmont, grand vicaire, a flag around which that celebrated recluse, Mlle. Le Ber, had embroidered a prayer to the Holy Virgin,” nor that it should have been noticed that on the very day on which was finished “a nine days’ devotion to Notre Dame de Pitié,” the news of the wreck of Sir Hovenden Walker’s fleet reached Quebec.[7] Such coincidences appeal to the imagination. Their record, amid the dry facts of history, shows the value which was attached to what Parkman impatiently terms this “incessant supernaturalism.” To us, the skilful diplomacy of Vaudreuil, the intelligent influence of Joncaire (the adopted brother of the Senecas), the powerful aid of the missionaries, the stupid obstinacy of Sir Hovenden Walker, and certain coincidences of military movements in Europe at periods critical for Canada, explain much more satisfactorily the escape of Canada from subjection to the English during the period of the wars of the Spanish Succession.

Although Vaudreuil could influence the Iroquois to remain at peace, he could not prevent an outbreak of the Outagamis at Detroit. This, however, was easily suppressed. The nominal control of the trade of the Northwest remained with the French; but the value of this control was much reduced by the amount of actual traffic which drifted to Albany and New York, drawn thither by the superior commercial inducements offered by the English.

The treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, established the cession of Acadia to the English by its “ancient limits.” When the French saw that the English pretension to claim by these words all the territory between the St. Lawrence River and the ocean, was sure to cut them off by water from their colony at Quebec, in case of another war, they on their part confined such “ancient limits” to the peninsula now called Nova Scotia. France, to strengthen the means of maintaining her interpretation, founded the fortress and naval station of Louisbourg.

About the same time the French also determined to strengthen the fortifications of Quebec and Montreal; and in 1721 Joncaire established a post among the Senecas at Niagara.[8]

In 1725 Vaudreuil died. Ferland curtly says that the Governor’s wife was the man of the family; but so far as the record shows, the preservation[7] of Canada to France during the earlier part of his administration was largely due to his vigilance and discretion. Great judgment and skill were shown in dealing with the Indians. A letter of remonstrance from Peter Schuyler bears witness that contemporary judgment condemned his policy in raiding upon the New England colonies; but in forming our estimate of his character we must remember that the French believed that similar atrocities, committed by the Iroquois in the Valley of the St. Lawrence, were instigated by the English.

The administration[9] of M. de Beauharnois, his successor, who arrived in the colony in 1726, was not conspicuous. He appears to have been personally popular, and to have appreciated fairly the needs of Canada. The Iroquois were no longer hostile. The days of the martyrdom of the Brebeufs and the Lallemands were over.[10] In the Far West a company of traders founded a settlement at the foot of Lake Pepin, which they called Fort Beauharnois. As the trade with the Valley of the Mississippi developed, routes of travel began to be defined. Three of these were especially used,—one by way of Lake Erie, the Maumee, and the Wabash, and then down the Ohio; another by way of Lake Michigan, the Chicago River, a portage to the Illinois, and down that river; a third by way of Green Bay, Fox River, and the Wisconsin,—all three being independent of La Salle’s route from the foot of Lake Michigan to the Kankakee and Illinois rivers.[11] By special orders from France, Joncaire’s post at Niagara had been regularly fortified. The importance of this movement had been fully appreciated by the English. As an offset to that post, a trading establishment had been opened at Oswego; and now that a fort was built at Niagara, Oswego was garrisoned. The French in turn constructed a fort at Crown Point, which threatened Oswego, New York, and New England.

The prolonged peace permitted considerable progress in the development of the agricultural resources of the country. Commerce was extended as much as the absurd system of farming out the posts, and the trading privileges retained by the governors, would permit. Postal arrangements were established between Montreal and Quebec in 1721. The population at that time was estimated at twenty-five thousand. Notwithstanding the[8] evident difficulty experienced in taking care of what country the French then nominally possessed, M. Varenne de Vérendrye in 1731 fitted out an expedition to seek for the “Sea of the West,”[12] and actually penetrated to Lake Winnipeg.

The foundations of society were violently disturbed during this administration by a quarrel which began in a contest over the right to bury a dead bishop. Governor, Intendant, council, and clergy took part. “Happily,” says a writer to whom both Church and State were dear, “M. de Beauharnois did not wish to take violent measures to make the Intendant obey him, otherwise we might have seen repeated the scandalous scenes of the evil days of Frontenac.”

After the fall of Louisbourg, in 1745, Beauharnois was recalled, and Admiral de la Jonquière was commissioned as his successor; but he did not then succeed in reaching his post. It is told in a later chapter how D’Anville’s fleet, on which he was embarked, was scattered in 1746; and when he again sailed, the next year, with other ships, an English fleet captured him and bore him to London.

In consequence of this, Comte de la Galissonière was appointed Governor of Canada in 1747. His term of office was brief; but he made his mark as one of the most intelligent of those who had been called upon to administer the affairs of this government. He proceeded at once to fortify the scattered posts from Lake Superior to Lake Ontario. He forwarded to France a scheme for colonizing the Valley of the Ohio; and in order to protect the claims of France to this vast region, he sent out an expedition,[13] with instructions to bury at certain stated points leaden plates upon which were cut an assertion of these claims. These instructions were fully carried out, and depositions establishing the facts were executed and transmitted to France. He notified the Governor of Pennsylvania of the steps which had been taken, and requested him to prevent his people from trading beyond the Alleghanies,[14][9] as orders had been given to seize any English merchants found trading there. An endeavor was made to establish at Bay Verte a settlement which should offset the growing importance of Halifax, founded by the English. The minister warmly supported La Galissonière in this, and made him a liberal money allowance in aid of the plan. While busily engaged upon this scheme, he was recalled. Before leaving, he prepared for his successor a statement of the condition of the colony and its needs.[15]

FAC-SIMILE OF ONE OF CÉLORON’S PLATES, 1749.

[Reduced from the fac-simile given in the Pennsylvania Archives, second series, vi. 80. Of some of these plates which have been found, see accounts in Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, i. 62, and Dinwiddie Papers, i. 95, published by the Virginia Historical Society. Cf. also Appendix A to the Mémoires sur le Canada depuis 1749 jusqu’à 1760, published by the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, 1873 (réimpression).—Ed.]

By the terms of the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, France in 1748 acquired possession of Louisbourg. La Jonquière, who was at the same time liberated, and who in 1749 assumed the government under his original appointment, did not agree with the Acadian policy of his predecessor. He feared the consequences of an armed collision with the English in Nova Scotia, which this course was likely to precipitate. This caution on his part brought down upon him a reprimand from Louis XV. and positive orders to[10] carry out La Galissonière’s programme. In pursuance of these instructions, the neck of the peninsula, which according to the French claim formed the boundary of Acadia, was fortified. The conservatism of the English officer prevented a conflict. In 1750, avoiding the territory in dispute, the English fortified upon ground admitted to be within their own lines, and watched events. On the approach of the English, the unfortunate inhabitants of Beaubassin abandoned their homes and sought protection under the French flag.

Notwithstanding the claims to the Valley of the Ohio put forth by the French, the English Government in 1750 granted to a company six hundred thousand acres of land in that region; and English colonial governors continued to issue permits to trade in the disputed territory. Following the instructions of the Court, as suggested by La Galissonière, English traders were arrested, and sent to France as prisoners. The English, by way of reprisal, seized French traders found in the same region.[16] The treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had provided for a commission to adjust the boundaries between the French and the English possessions. By the terms of the treaty, affairs were to remain unchanged until the commission could determine the boundaries between the colonies. Events did not stand still during the deliberations of the commission; and the doubt whether every act along the border was a violation of the treaty hung over the heads of the colonists like the dispute as to the boundaries of Acadia, which was a constant threat of war. The situation all along the Acadian frontier and in the Valley of the Ohio was now full of peril. To add to the difficulty of the crisis in Canada, the flagrant corruption of the Intendant Bigot, with whom the Governor was in close communication, created distrust and dissatisfaction. Charges of nepotism and corruption were made against La Jonquière. The proud old man demanded his recall; but before he could appear at Court to answer the charges, chagrin and mortification caused his wounds to open, and he died on the 17th of May, 1752. Thereupon the government fell to the Baron de Longueuil till a new governor could arrive.

Bigot, whose name, according to Garneau, will hereafter be associated with all the misfortunes of France upon this continent, was Intendant at Louisbourg at the time of its fall. Dissatisfaction with him on the part of the soldiers at not receiving their pay was alleged as an explanation of[11] their mutinous behavior. He was afterward attached to the unfortunate fleet which was sent out to recapture the place. Later his baneful influence shortened the days and tarnished the reputation of La Jonquière.

In July, 1752, the Marquis Duquesne de Menneville assumed charge of the government, under instructions to pursue the policy suggested by La Galissonière. He immediately held a review of the troops and militia. At that time the number of inhabitants capable of bearing arms was about thirteen thousand. There existed a line of military posts from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi, composed of Quebec, Montreal, Ogdensburg, Kingston, Toronto, Detroit, the Miami River, St. Joseph, Chicago, and Fort Chartres. The same year that Duquesne was installed, he took preliminary steps toward forwarding troops to occupy the Valley of the Ohio, and in 1753 these steps were followed by the actual occupation in force of that region. Another line of military posts was erected, with the intention of preventing the English from trading in that valley and of asserting the right of the French to the possession of the tributaries of the Mississippi. This line began at Niagara, and ultimately comprehended Erie, French Creek,[17] Venango, and Fort Duquesne. All these posts were armed, provisioned, and garrisoned.

All French writers agree in calling the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle a mere truce. If the sessions of the commissioners appointed to determine the boundaries upon the ante-bellum basis had resulted in aught else than bulky volumes,[18] their decision would have been practically forestalled by the French in thus taking possession of all the territory in dispute. To this, however, France was impelled by the necessities of the situation. Unless she could assume and maintain this position, the rapidly increasing population of the English colonies threatened to overflow into the Valley of the Ohio; and the danger was also imminent that the French might be dispossessed from the southern tributaries of the St. Lawrence. Once in possession, English occupation would be permanent. The aggressive spirit of La Galissonière had led him to recommend these active military operations, which, while they tended to provoke collision, could hardly fail to check the movement of colonization which threatened the region in dispute. On the Acadian peninsula the troops had come face to face without bloodshed. The firmness of the French commander in asserting his right to occupy the territory in question, the prudence of the English officer, the support given to the French cause by the patriotic Acadians, the military weakness of the English in Nova Scotia,—all conspired to cause the English to submit to the offensive bearing of the French, and to avoid in that locality the impending collision. It was, however, a mere postponement[12] in time and transfer of scene. The gauntlet thrown down at the mouth of the St. Lawrence was to be taken up at the headwaters of the Ohio.

The story of the interference of Lieutenant-Governor Dinwiddie; of George Washington’s lonely journey in 1753 across the mountains with Dinwiddie’s letter; of the perilous tramp back in midwinter with Saint-Pierre’s reply; of the return next season with a body of troops; of the collision with the detachment of the French under Jumonville; of the little fort which Washington erected, and called Fort Necessity, where he was besieged and compelled to capitulate; of the unfortunate articles of capitulation which he then signed,—the story of all these events is familiar to readers of our colonial history; but it is equally a portion of the history of Canada.[19] The act of Dinwiddie in precipitating a collision between the armed forces of the colonies and those of France was the first step in the war which was to result in driving the French from the North American continent. The first actual bloodshed was when the men under Washington met what was claimed by the French to be a mere armed escort accompanying Jumonville to an interview with the English. He who was to act so important a part in the war of the American Revolution was, by some strange fatality, the one who was in command in this backwoods skirmish. In itself the event was insignificant; but the blow once struck, the question how the war was to be carried on had to be met. The relations of the colonies to the mother country, and the possibility of a confederation for the purpose of consolidating the military power and adjusting the expenses, were necessarily subjects of thought and discussion which tended toward co-operative movements dangerous to the parent State. Thus in its after-consequences that collision was fraught with importance. Bancroft says it “kindled the first great war of revolution.”

The collision which had taken place could not have been much longer postponed. The English colonies had grown much more rapidly than the French. They were more prosperous. There was a spirit of enterprise among them which was difficult to crush. They could not tamely see themselves hemmed in upon the Atlantic coast and cut off from access to the interior of the continent by a colony whose inhabitants did not count a tenth part of their own numbers, and with whom hostility seemed an hereditary necessity. It mattered not whether the rights of discovery and prior occupation, asserted by the French, constituted, according to the law of nations, a title more or less sound than that which the English claimed through Indian tribes whom the French had by treaty recognized as British subjects. The title held by the strongest side would be better than the title based upon international law. Events had already anticipated politics. The importance of the Ohio Valley to the English colonies as an outlet to their growing population had been forced upon their attention.[13] To the French, who were just becoming accustomed to its use as a highway for communication between Canada and Louisiana, the growth of the latter colony was a daily instruction as to its value.

The Louisiana which thus helped to bring the French face to face with their great rivals was described by Charlevoix as “the name which M. de La Salle gave to that portion of the country watered by the Mississippi which lies below the River Illinois.” This definition limits Louisiana to the Valley of the Mississippi; but the French cartographers of the middle of the eighteenth century put no boundary to the pretensions of their country in the vague regions of the West, concerning which tradition, story, and fable were the only sources of information for their charts. The claims of France to this indefinite territory were, however, considered of sufficient importance to be noticed in the document on the Northwestern Boundary question which forms the basis of Greenhow’s History of Oregon and California. The French were not disturbed by the pretensions of Spain to a large part of the same territory, although based upon the discovery of the Mississippi by De Soto and the actual occupation of Florida. Neither were the charters of those English colonies, which granted territory from the Atlantic to the Pacific, regarded as constituting valid claims to this region. France had not deliberately set out to establish a colony here. It was only after they were convinced at Versailles that Coxe, the claimant of the grant of “Carolana,” was in earnest in his attempts to colonize the banks of the Mississippi by way of its mouth, that this determination was reached. As late as the 8th of April, 1699, the Minister of the Marine wrote: “I begin by telling you that the King does not intend at present to form an establishment at the mouth of the Mississippi, but only to complete the discovery in order to hinder the English from taking possession there.” The same summer Pontchartrain told the Governor of Santo Domingo[20] that the “King would not attempt to occupy the country unless the advantages to be derived from it should appear to be certain.” La Salle’s expedition in 1682 had reached the mouth of the river. His Majesty had acquiesced in it without enthusiasm, and with no conviction of the possible value of the discovery. He had, indeed, stated that “he did not think that the explorations which the Canadians were anxious to make would be of much advantage. He wished, however, that La Salle’s should be pushed to a conclusion, so that he might judge whether it would be of any use.”

The presence of La Salle in Paris after he had accomplished the journey down the river had fired the imagination of the old King, and visions of Spanish conquests and of gold and silver within easy reach had made him listen readily to a scheme for colonization, and consent to fitting out an expedition by sea. When the hopes which had accompanied the discoverer on his outward voyage gave place to accounts of the disasters[14] which had pursued his expedition, it would seem that the old doubts as to the value of the Mississippi returned.[21] It was at this time that Henri de Tonty, most faithful of followers, asked that he might be appointed to pursue the discoveries of his old leader.[22] Tonty was doomed to disappointment. His influence at Court was not strong enough to secure the position which he desired. In 1697[23] the attention of the Minister of the Marine was called by Sieur Argoud to a proposition made by Sieur de Rémonville to form a company for the same purpose. The memorial of Argoud vouches for Rémonville as a friend of La Salle, sets forth at length the advantages to be gained by the expedition, explains in detail its needs, and gives a complete scheme for the formation of the proposed company. From lack of faith or lack of influence this proposition also failed. It required the prestige of Iberville’s name, brought to bear in the same direction, to carry the conviction necessary for success.

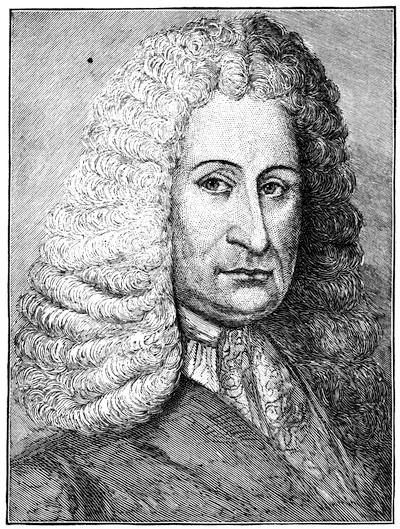

Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville was a native of Canada. He was born on the 16th of July, 1661,[24] and was reared to a life of adventure. His name and the names of his brothers, under the titles of their seigniories, are associated with all the perilous adventure of the day in their native land. They were looked upon by the Onondagas as brothers and protectors, and their counsel was always received with respect. Maricourt, who was several times employed upon important missions to the Iroquois, was known among them under the symbolic name of Taouistaouisse, or “little bird which is always in motion.” In 1697, when Iberville urged upon the minister the arguments which suggested themselves to him in favor of an expedition in search of the mouth of the Mississippi, he had already gained distinction in the Valley of the St. Lawrence, upon the shores of the Atlantic, and on the waters of Hudson’s Bay.[25] The tales of his wonderful successes on land and on sea tax the credulity of the reader; and were it not for the concurrence of testimony, doubts would creep in as to their truth. It seemed as if the young men of the Le Moyne family felt that with the death of Frontenac the days of romance and adventure had ended in Canada; that for the time being, at least, diplomacy was to succeed daring, and thoughts of trade at Quebec and Montreal were to take the place of plans for the capture of Boston and New York. To them the possibility of collision with Spaniards or Englishmen was an inducement rather than a drawback. Here perhaps, in explorations on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, courage and audacity might find those rewards and honors for which the opportunity was fast disappearing in Canada. Inspired[15] by such sentiments, the enthusiasm of Iberville overcame the reserve of the King. The grandeur of the scheme began to attract his attention. It was clear that the French had not only anticipated the English in getting possession of the upper waters of the great river, but their boats had navigated its current from source to mouth.

[This follows an engraving in Margry, vol. iv. J. M. Lemoine (Maple Leaves, 2d series, 1873, p. 1) styles him “The Cid of New France.”—Ed.]

If they could establish themselves at its entrance, and were able to control its navigation, they could hold the whole valley. Associated with these thoughts were hopes of mines in the distant regions of the upper Mississippi which might contribute to France wealth equal to that which Spain had drawn from Mexico. Visions of pearl-fisheries in the Gulf, and wild notions as to the[16] value of buffalo-wool, aided Iberville in his task of convincing the Court of the advantages to be derived from his proposed voyage.

In June, 1698, two armed vessels were designated for the expedition,—the “Badine,” which was put under the command of Iberville, and the “Marin,” under the Chevalier de Surgères. The correspondence between the Minister of the Marine and Iberville during the period of preparation shows that the Court earnestly endeavored to forward the enterprise.

Rumors were rife that summer at Rochelle that an expedition was fitting out at London[26] for the purpose of establishing a colony of French Protestants on the banks of the Mississippi. On the 18th of June Iberville wrote to the Minister to warn him of the fact. He had turned aside as a joke, he says, the rumors that his expedition was bound to the Mississippi, and he suggests that orders be sent him to proceed to the River Amazon, with which he could lay such stories at rest and deceive the English as to his movements. The instructions with which he was provided allege that he was selected for the command because of his previous record. He was left free to prosecute his search for the mouth of the river according to his own views. After he should have found it, he was to fortify some spot which should command its entrance. He was to prevent, at all hazards, any other nation from making a landing there. Should he find that be had been anticipated in the discovery, still he was to effect a landing if possible; and in case of inability to do so, he was to make a careful examination of affairs and report.

On the morning of the 24th of October, 1698,[27] the “Badine” and the “Marin” sailed from Brest, at which port they had put in after leaving Rochelle. They were accompanied by two transports, which formed a part of the expedition. The two frigates and one of the transports arrived at Santo Domingo on the 4th of December. The other transport arrived ten days after. The frigate “François,” under Chasteaumorand, was here added to the fleet as an escort to the American coast. On the 31st of December they sailed from Santo Domingo, and on the 23d of January, 1699, at half-past four in the evening, land was seen distant eight leagues to the northeast. In the evening fires were observed on shore. Pursuing a course parallel with the coast, they sailed to the westward by day and anchored each night. The shore was carefully reconnoitred with small[17] boats as they proceeded, and a record of the soundings was kept, of sufficient accuracy to give an idea of the approach to the coast. On the 26th they were abreast of Pensacola,[28] where they found two Spanish vessels at anchor, and the port in possession of an armed Spanish force, with whom they communicated. Still following the coast to the westward, they anchored on the 31st off the mouth of the Mobile River. Here they remained for several days, examining the coast and the islands. They called one of these islands Massacre Island, on account of the large number of human bones which they found upon it. Not satisfied with the roadstead, they worked along the coast, sounding and reconnoitring; and on the 10th of February came to anchor at a spot where the shelter of some islands furnished a safe roadstead. Preparations were at once begun for the work of exploration, and on the 13th Iberville left the ships for the mainland in a boat with eleven men. He was accompanied by his brother Bienville with two men in a bark canoe which formed part of their equipment. His first effort was to establish friendly relations with the natives. He had some difficulty in communicating with them, as his party was mistaken for Spaniards, with whom the Indians were not on good terms. His knowledge of Indian ways taught him how to conquer this difficulty. Leaving his brother and two Canadians as hostages in their hands, he succeeded on the 16th in getting some of the natives to come on board his ship, where he entertained them by firing off his cannons. On the 17th he returned to the spot where he had left his brother, and found him carrying on friendly converse with natives who belonged to tribes then living upon the banks of the Mississippi. The bark canoe puzzled them; and they asked if the party came from the upper Mississippi, which in their language they called the “Malbanchia.” Iberville made an appointment with these Indians to return with them to the river, and was himself at the rendezvous at the appointed time; but they failed him. Being satisfied now that he was near the mouth of the Mississippi, and that he had nothing to fear from the English, he told Chasteaumorand that he could return to Santo Domingo with the “François.” On the 21st that vessel sailed for the islands.

On the 27th the party which was to enter the mouth of the river left the ships. They had two boats, which they speak of as biscayennes, and two bark canoes. Iberville was accompanied by his brother Bienville, midshipman on the “Badine;” Sauvolle, enseigne de vaisseau on the “Marin;” the Récollet father Anastase, who had been with La Salle; and a party of men,—stated by himself in one place at thirty-three, and in another at forty-eight.[29]

On the afternoon of the 2d of March, 1699, they entered the river,—the Malbanchia of the Indians, the Palissado of the Spaniards, the Mississippi of to-day.

After a careful examination of the mouth of the river, at that time apparently in flood, Iberville set his little party at the hard work which was now before them, of stemming the current in their progress up the stream. His search was now directed toward identifying the river, by comparison with the published descriptions of Hennepin, and also by means of information contained in the Journal of Joutel,[30] which had been submitted to him in manuscript by Pontchartrain. At the distance, according to observations of the sun, of sixty-four leagues from the mouth of the river, he reached the village of the Bayagoulas, some of whom he had already seen. At this point his last doubt about the identity of the river was dissipated; for he met a chief of the Mougoulachas clothed in a cloak of blue serge, which he said was given to him by Tonty. With rare facility, Iberville had already picked up enough of the language of these Indians to communicate with them; and Bienville, who had brought a native up the river in his canoe, could speak the language passably well. “We talked much of what Tonty had done while there; of the route that he took and of the Quinipissas, who, they said, lived in seven villages, distant an eight days’ journey to the northeast of this village by land.” The Indians drew rude maps of the river and the country, showing that when Tonty left them he had gone up to the Oumas, and that going and coming he had passed this spot. They knew nothing of any other branch of the river. These things did not agree with Hennepin’s account, the truth of which Iberville began to suspect. He says that he knew that the Récollet father had told barefaced lies about Canada and Hudson’s Bay in his Relation, yet it seemed incredible that he should have undertaken to deceive all France on these points. However that might be, Iberville realized that the first test to be applied to his own reports would be comparison with other sources of information; and having failed to find the village of the Quinipissas and the island in the river, he must by further evidence establish the truth or the falsity of Hennepin’s account. This was embarrassing. The “Marin” was short of provisions, Surgères was anxious to return, the position for the settlement had not yet been selected, and the labor of rowing against the current was hard on the men, while the progress was very slow. Anxious as Iberville was to return, the reasons for obtaining further proof that he was on the Mississippi, with which to convince doubters in France, overcame his desires, and he kept on his course up the river. On the 20th he reached the village of the Oumas, and was gratified to learn that the memory of Tonty’s visit, and of the many presents which he had distributed, was still fresh in the minds of the natives. Iberville was now, according to his reckoning, about one hundred leagues up the river. He had been able to[19] procure for his party only Indian corn in addition to the ship’s provisions with which they started. His men were weary. All the testimony that he could procure concurred to show that the route by which Tonty came and went was the same as that which he himself had pursued, and that the division of the river into two channels was a myth.[31] With bitterness of spirit he inveighs against the Récollet, whose “false accounts had deceived every one. Time had been consumed, the enterprise hindered, and the men of the party had suffered in the search after purely imaginary things.” And yet, if we may accept the record of his Journal, this visit to the village of the Oumas was the means of his tracing the most valuable piece of evidence of French explorations in this vicinity which could have been produced. “The Bayagoulas,” he says, “seeing that I persisted in wishing to search for the fork and also insisted that Tonty had not passed by there, explained to me that he had left with the chief of the Mougoulachas a writing enclosed for some man who was to come from the sea, which was similar to one that I myself had left with them.” The urgency of the situation compelled Iberville’s return to the ships. On his way back he completed the circuit of the island on which New Orleans was afterward built, by going through the river named after himself and through Lake Pontchartrain. The party which accompanied him consisted of four men, and they travelled in two canoes. The two boats proceeded down the Mississippi, with orders to procure the letter from the Mougoulachas and to sound the passes at the mouth of the river.

On the 31st both expeditions reached the ships. Iberville had the satisfaction of receiving from the hands of his brother[32] the letter which Tonty had left for La Salle, bearing date, “At the village of the Quinipissas, April 20, 1685.”[33] The contents of the letter were of little moment, but its possession was of great value to Iberville. The doubts of the incredulous must yield to proof of this nature. Here was Tonty’s account of his trip down the river, of his search along the coast for traces of his old leader, and of his reluctant conclusion that his mission was a failure. In the midst of the clouds of treachery which obscure the last days of La Salle, the form of Tonty looms up, the image of steadfast friendship and genuine devotion. “Although,” he says, “we have neither heard news nor seen signs of you, I do not despair that God will grant success to your undertakings. I wish it with all my heart; for you have no more faithful follower than myself, who would sacrifice everything to find you.”

After his return to the ships, Iberville hastened to choose a spot for a fortification. In this he experienced great difficulty; but he finally selected Biloxi, where a defence of wood was rapidly constructed and by courtesy called a fort. A garrison of seventy men and six boys was landed, with stores, guns, and ammunition. Sauvolle, enseigne de vaisseau du roy,[20] “a discreet young man of merit,” was placed in command. Bienville, “my brother,” then eighteen years old, was left second in rank, as lieutenant du roy. The main object of the expedition was accomplished. The “Badine” and the “Marin” set sail for France on the 3d of May, 1699. For Iberville, as he sailed on the homeward passage, there was the task, especially difficult for him, of preparing a written report of his success. For Sauvolle and the little colony left behind, there was the hard problem to solve, how they should manage with scant provisions and with no prospect of future supply. So serious was this question that in a few days a transport was sent to Santo Domingo for food. This done, they set to work exploring the neighborhood and cultivating the friendship of the neighboring tribes of Indians. To add to their discomforts, while still short of provisions they were visited by two Canadian missionaries who were stationed among the Tonicas and Taensas in the Mississippi Valley. The visitors had floated down the river in canoes, having eighteen men in all in their company, and arrived at Biloxi in the month of July. Ten days they had lived in their canoes, and during the trip from the mouth of the river to Biloxi their sufferings for fresh water had been intense. Such was the price paid to satisfy their craving for a sight of their compatriots who were founding a settlement at the mouth of the river. On the 15th of September, while Bienville was reconnoitring the river at a distance of about twenty-three leagues from its mouth, he was astonished by the sight of an armed English ship of twelve guns.[34] This was one of the fleet despatched by Coxe, the claimant of the grant from the English Government of the province of Carolana.[35] The rumor concerning which Iberville had written to the Minister the year before had proved true. Bienville found no difficulty in persuading the captain that he was anticipated, that the country was already in possession of the French, and that he had better abandon any attempt to make a landing. The English captain yielded; but not without a threat of intention to return, and an assertion of prior English discovery. The bend in the river where this occurred was named English Turn. The French refugees, unable to secure homes in the Mississippi Valley under the English flag, petitioned to be permitted to do so as French citizens.[36] The most Christian King was not fond of Protestant colonists, and replied that he had not chased heretics out of his kingdom to create a republic for them in America. Charlevoix states that the same refugees renewed their offers to the Duke of Orleans when regent, who also, rejected them.

Iberville, who had been sent out a second time, arrived at Biloxi Dec. 7, 1699. This time his instructions were, to examine the discoveries made by Sauvolle and Bienville during his absence, and report[21] thereon. He was to bring back samples of buffalo-wool, of pearls, and of ores.[37] He was to report on the products of the country, and to see whether the native women and children could be made use of to rear silk-worms. An attempt to propagate buffaloes was ordered to be made at the fort. His report was to determine the question whether the establishment should be continued or abandoned.[38] Sauvolle was confirmed as “Commandant of the Fort of the Bay of Biloxi and its environs,” and Bienville as lieutenant du roy. Bienville’s report about the English ship showed the importance of fortifying the entrance of the river. A spot was selected about eighteen leagues from the mouth, and a fort was laid out. While they were engaged in its construction Tonty arrived. He had made his final trip down the river, from curiosity to see what was going on at its mouth.[39]

The colony was now fairly established, and, notwithstanding the reluctance of the King, was to remain. Bienville retained his position as second in rank, but was stationed at the post on the river. Surgères was despatched to France. Iberville himself, before his return, made a trip up the river to visit the Natchez and the Taensas. He was shocked, while with the latter tribe, at the sacrifice of the lives of several infants on the occasion of the temple being struck by lightning. He reported that the plants and trees that he had brought from France were doing well, but that the sugar-canes from the islands did not put forth shoots.

With the return of Iberville to France, in the spring of 1700, the romantic interest which has attached to his person while engaged in these preliminary explorations ceases, and we no longer watch his movements with the same care. His third voyage, which occupied from the fall of 1701 to the summer of 1702, was devoid of interest. On this occasion he anchored his fleet at Pensacola, proceeding afterward with one of his vessels to Mobile. A period of inaction in the affairs of the colony follows, coincident with the war of the Spanish Succession, during which the settlement languished, and its history can be told in few words. Free transportation from France to Louisiana was granted to a few unfortunate women and children, relatives of colonists. Some Canadians with Indian wives came down the river with their families. Thus a semblance of a settlement was formed. Bienville succeeded to the command, death having removed Sauvolle from his misery in the fall of 1701. The vitality of the wretched troops was almost equally sapped, whether stationed at the fort on the spongy foothold by the river side, or on the glaring sands of the gently sloping beach at Biloxi. Fishing, hunting, searching for pearls, and fitting out expeditions to discover imaginary mines occupied the time and the thoughts of the miserable colonists; while the sages across the water still pressed upon their attention the possibility of developing the trade in buffalo-wool, on which they built their hopes of the future of the colony. Agriculture was totally neglected; but hunting-parties[22] and embassies to Indians explored the region now covered by the States of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee.

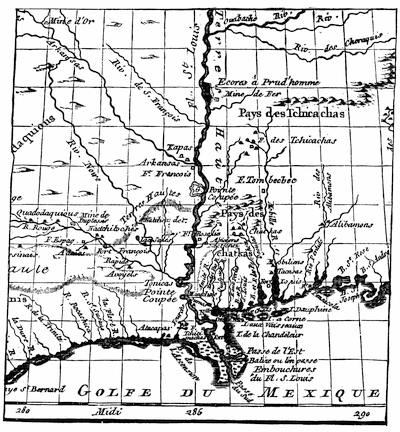

ENVIRONS DU MISSISSIPI, 1700.

[This is figure 3 of plate i. in R. Thomassy’s Géologie pratique de la Louisiane (1860), called “Carte des environs du Mississipi (envoyée à Paris en 1700).” He describes it (p. 208) as belonging to the Archives Scientifiques, and thinks it a good record of the topography as Iberville understood it. The material of this map and of another, likewise preserved in the Archives Scientifiques de la Marine, are held by Thomassy (p. 209) to have been unskilfully combined by M. de Fer in his Les Costes aux environs de la Rivière de Misisipi, 1701.

Thomassy also noted (p. 215) in the Dépôt des Cartes de la Marine, and found in the Bibliothèque Nationale, a copy of a map by Le Blond de la Tour of the mouths of the Mississippi in 1722, Entrée du Mississipi en 1722, avec un projet de fort, of which Thomassy gives a reproduction (pl. iii. fig. 1), and he considers it a map of the first importance in tracing the changes which the river has made in its bed. He next notes and depicts (pl. iii. fig. 2) a Plan particulier de l’embouchure du fleuve Saint-Louis, which was drawn at New Orleans, May 29, 1724, and is signed “De Pauger, Royal Engineer.” It assists one in tracing the early changes, being on the same scale as La Tour’s map.—Ed.]

Le Sueur[23] explored the upper Mississippi in search of mines. In 1700 Bienville and Saint-Denys scoured the Red River country in search of Spaniards, but saw none. In 1701 Saint-Denys was gone for six months on a trip to the same region, with the same result.[40] The records of these expeditions and the Relations of the fathers have preserved for us a knowledge of the country as it then was, and of the various tribes which then inhabited the Valley of the Mississippi. From them we obtain descriptions of the curious temples of the Natchez and Taensas; of the perpetual fire preserved in them; of the custom of offering as a sacrifice the first-fruits of the chase and the field; of the arbitrary despotism of their grand chief, or Sun; of the curious hereditary aristocracy transmitted through the female Suns;[41] of the strange custom of sacrificing human lives on the death of a Grand Sun. To be selected to accompany the chief to the other world was a privilege as well as a duty; to avoid its performance when through ties of blood or from other cause the selection was involuntary, was a disgrace and a dishonor.

We find records of the presence of no less than four of the Le Moyne brothers,—Iberville, Bienville, Sérigny, and Chateauguay. Iberville was rewarded in 1699 by appointment as chevalier of the Order of St. Louis; in 1702 by promotion to the position of capitaine de vaisseau; and in 1703 he was appointed commander-in-chief of the colony, which Pontchartrain in his official announcement calls “the colony of Mississippi.” These honors did not quite meet his expectations. He wanted a concession, with the title of count; the privilege of sending a ship to Guinea for negroes; a lead mine; in short, he wanted a number of things. He bore within his frame the seeds of disease contracted in the south; and in 1706, while employed upon a naval expedition against the English, he succumbed at Havana to an attack of yellow fever. With him departed much of the life and hope of the colony. Supplies, which during his life had never been abundant, were now sure to be scarce; and we begin to find in the records of the colony the monotonous, reiterated complaints of scarcity of provisions. These wails are occasionally relieved by accounts of courtesies exchanged with the Spanish settlements at Pensacola and St. Augustine.[24] The war of the Spanish Succession had brought Spain and France close together. The Spanish forts stood in the pathway of the English and protected Biloxi. When the Spanish commander called for help, Bienville responded with men and ammunition; and when starvation fairly stared the struggling Spanish settlement in the face, he shared with them his scant food. They in turn reciprocated, and a regular debit and credit account of these favors was kept, which was occasionally adjusted by commissioners thereto duly appointed. So few were the materials of which histories are ordinarily composed, during these years of torpor and inaction, that one of the historians of that time thus epitomizes a period of over a year: “During the rest of this year and all of the next nothing new happened except the arrival of some brigantines from Martinique, Rochelle, and Santo Domingo, which brought provisions and drinks which they found it easy to dispose of.”

France was too deeply engaged in the struggle with England to forward many emigrants. Canada could furnish but a scant population for the scattered settlements from Cape Breton to the Mississippi. The hardy adventurers who had accompanied Iberville in his search for the mouth of the Mississippi, and the families which had drifted down from Illinois, were as many as could be procured from her, and more than she could spare. The unaccustomed heat of the climate and the fatal fevers which lurked in the Southern swamps told upon the health of the Canadians, and sickness thinned their ranks. In the midst of the pressure of impending disasters which threatened the declining years of the most Christian King, the tardy enthusiasm in behalf of the colony, which his belief in its pearls and its buffalo-wool had aroused, caused him to spare from the resources of a bankrupt kingdom the means to equip and forward to the colony a vessel laden with supplies and bearing seventy-five soldiers and four priests. The tax upon the kingdom for even so feeble a contribution was enough to be felt at such a time; but the result was hardly worth the effort. The vessel arrived in July, 1704, during a period of sickness. Half of her crew died. To assist in navigating her back to France twenty soldiers were furnished. During the month of September the prevailing epidemic carried off the brave Tonty and thirty of the newly arrived soldiers. Given seventy-five soldiers as an increase to the force of a colony, which in 1701 was reported to number only one hundred and fifty persons, deduct twenty required to work the ship back, and thirty more for death within six weeks after arrival, and the net result which we obtain is not favorable for the rapid growth of the settlement. The same ship, in addition to supplies, soldiers, and priests, brought other cargo; namely, two Gray Sisters, four families of artisans, and twenty-three poor girls. The “poor girls” were all married to the resident Canadians within thirty days. With the exception of the visit of a frigate in 1701, and the arrival of a store-ship in 1703, this vessel is the only arrival outside of Iberville’s expeditions which is recorded in the Journal historique up to that date. The wars and[25] rumors of wars between the Indians soon disclosed a state of things at the South which in some of its features resembled the situation at the North. The Cherokees and Chickasaws were so placed geographically that they came in contact with English traders from Carolina and Virginia. Penicaut, when on his way up the river with Le Sueur, met one of these enterprising merchants among the Arkansas, of whom he says, “We found an English trader here who was of great assistance in obtaining provisions for us, as our stock was rapidly declining.” Le Sueur says, “I asked him who sent him here. He showed me a passport from the governor of Carolina, who, he said, claimed to be master of the river.” Thus English traders were here stumbling-blocks to the French precisely as they had been farther north. Their influence appears to have been used in stirring up the Indians to hostile acts, just as in New York the Iroquois were incited to attack the Canadians. The Choctaws, a powerful tribe, were on the whole friendly to the French. The wars in Louisiana were not so disastrous to the French as the raids of the Five Nations had proved in the Valley of the St. Lawrence. The vengeance of the Chickasaws was easily sated with a few Choctaw scalps, and perhaps with the capture of a few Indian women and children whom they could sell to the English settlers in Carolina as slaves. Hence the number of French lives lost in these attacks was insignificant.

The territory of Louisiana was no more vague and indefinite than its form of government. Even its name was long in doubt. It was indifferently spoken of as Louisiana or Mississippi in many despatches. Sauvolle was left as commander of the post when Iberville returned to France after his first voyage. In this office he was confirmed, and Bienville succeeded to the same position. True, the post was the colony then, but when Iberville was in Louisiana it was he who negotiated with the Indians; it was he of whom the Company of Canada complained for interfering with the trade in beaver-skins; it was he whom the Court evidently looked upon as the head of the colony even before he was formally appointed to the chief command. This chaotic state of affairs not only produced confusion, but it engendered jealousies and fostered quarrels. The Company of Canada found fault with Iberville for interfering with the beaver trade. The Governor of Canada claimed that Louisiana should be brought under his jurisdiction. Iberville insisted that the boundaries should be defined; and complained that the Canadians belittled him with the Indians when the two colonies clashed, by contrasting Canadian liberality with his poverty.

This follows an engraving given in Margry’s collection, vol. v. Other engravings, evidently from the same original, but different in expression, are in Shea’s Charlevoix, vol. i. etc.

Le Sueur, who by express orders had accompanied Iberville on his second voyage, was holding a fort on the upper Mississippi at the same time that “Juchereau de Saint-Denys,[42] lieutenant-général de la juridiction de Montréal,” was granted permission to proceed from Canada with twenty-four men to the Mississippi,[43] there to establish tanneries and to[27] mine for lead and copper. One Nicolas de la Salle, a purser in the naval service, was sent over to perform the duties of commissaire. The office of commissaire-ordonnateur was the equivalent of the intendant,—a counterpoise to the governor and a spy upon his actions. La Salle’s relation to this office was apparently the same as Bienville’s to the position of governor. A purser performed the duties of commissaire; a midshipman, those of commanding officer. Of course La Salle’s presence in the colony could only breed trouble; and we find him reporting that “Iberville, Bienville, and Chateauguay, the three brothers, are thieves and knaves capable of all sorts of misdeeds.” Bienville, on his part, complains that “M. de la Salle, purser, would not give Chateauguay pay for services performed by order of the minister.” This state of affairs needed amendment. Iberville had never reported in the colony after his appointment in 1703 as commander-in-chief. Bienville had continued at the actual head of affairs. In February, 1708, it was ascertained in the colony that M. de Muys had started from France to supersede Bienville, but had died on the way.

M. Diron d’Artaguette, who had been appointed commissaire-ordonnateur,[44] with orders to examine into the conduct of the officers of the colony and to report upon the condition of its affairs, arrived in Mobile in February, 1708. An attempt had apparently been made to organize Louisiana on the same system as prevailed in the other colonies. Artaguette made his investigation, and returned to France in 1711. During his brief stay the monotony of the record had been varied by the raid of an English privateer upon Dauphin (formerly Massacre) Island, where a settlement had been made in 1707 and fortified in 1709. The peripatetic capital had been driven, by the manifest unfitness of the situation, from Biloxi to a point on the Mobile River, from which it was now compelled by floods to move to higher lands eight leagues from the mouth of the river. No variation was rung upon the chronic complaint of scarcity of provisions. The frequent changes in the position of headquarters, lack of faith in the permanence of the establishment, and the severe attacks of fever endured each year by many of the settlers, discouraged those who might otherwise have given their attention to agriculture. To meet this difficulty, Bienville proposed to send Indians to the islands, there to be exchanged for negroes. If his plan had met with approval, perhaps he might have made the colony self-supporting, and thus have avoided in 1710 the scandal of subsisting his men by scattering them among the very savages whom he wished to sell into slavery. It is not to be wondered at that the growth of the colony under these circumstances was very slow. In 1701 the number of inhabitants was stated at one hundred and fifty. In 1708 La Salle reported the population as composed of a garrison of one hundred and twenty-two persons, including priests, workmen, and boys;[28] seventy-seven inhabitants, men, women, and children; and eighty Indian slaves. In 1712 there were four hundred persons, including twenty negroes. Some of the colonists had accumulated a little property, and Bienville reported that he was obliged to watch them lest they should go away.

On the 14th day of September, 1712, and of his reign the seventieth year, Louis, by the grace of God king of France and Navarre, granted to Sieur Antony Crozat the exclusive right to trade in all the lands possessed by him and bounded by New Mexico and by the lands of the English of Carolina; in all the establishments, ports, havens, rivers, and principally the port and haven of the Isle of Dauphin, heretofore called Massacre, the River St. Louis, heretofore called the Mississippi, from the edge of the sea as far as the Illinois, together with the River of St. Philip, heretofore called the Missouri, and of the St. Jerome, heretofore called the Ouabache, with all the countries, territories, lakes within land, and the rivers which fall directly or indirectly into that part of the River St. Louis. Louisiana thus defined was to remain a separate colony, subordinate, however, to the Government of New France. The exclusive grant of trade was to last for fifteen years. Mines were granted in perpetuity subject to a royalty, and to forfeiture if abandoned. Lands could be taken for settlement, manufactures, or for cultivation; but if abandoned they reverted to the Crown. It was provided in Article XIV., “if for the farms and plantations which the said Sieur Crozat wishes to carry on he finds it desirable to have some negroes in the said country of Louisiana, he may send a ship each year to trade for them directly on the coast of Guinea, taking a permit from the Guinea Company so to do. He may sell these negroes to the inhabitants of the colony of Louisiana, and we forbid all other companies and persons whatsoever, under any pretence whatsoever, to introduce any negroes or traffic for them in the said country, nor shall the said Crozat carry any negroes elsewhere.”