RAWLINSON

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

RAWLINSON

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME I—PROLEGOMENA; EGYPT, MESOPOTAMIA

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1905

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

New York, U. S. A.

The Historians’ History of the World is in one sense of the word a compilation, but it is a compilation of unique character. The main bulk of the work is made up of direct quotations from authorities, cited with scrupulous exactness; but so novel is our method of handling this material that the casual reader might scan chapter after chapter without suspecting that the whole is not the work of a single writer. Yet every quotation, whatever its length, is explicitly credited to its source, and the reader who wishes to know the names of the authors and works quoted may constantly satisfy his curiosity without the slightest difficulty. The key to identification of authorities is found in the unobtrusive reference letters (called by the printer “superior letters”), such as b, c, d, which are scattered through the text. These reference letters refer in each case to a “Brief Reference-List” at the end of the book, where, chapter by chapter, author and work are named. Should any work be quoted more than once in a chapter, the same reference letter is used to identify that work in each case.

The reference letters are used in two ways: they are either (1) placed at the end of a sentence, in which case they designate an actual quotation, or (2) they are placed against the name of an author, in which case they designate an authority cited but not necessarily quoted. Each reference letter at the end of a sentence refers to all the matter that precedes it back to the last similarly placed reference letter. The quotation thus designated may be of any length,—a few sentences or many pages. This quotation may contain reference letters of the second type just explained, but, if so, these may be altogether disregarded in determining the limits of the quotation; the context will make it clear that there is no change of authorship. On the other hand, however continuous the narrative may seem, a reference letter at the end of a sentence must always be understood to divide one quotation from another.

All this may seem a trifle complex as told here, but it will be found admirably simple and effective in practice. The reader has but to make the experiment, to find that he can trace the authorship of every line of the work without the slightest difficulty. It may be well to add, however, that the reference letter a is reserved for editorial matter, and that, very exceptionally, this letter is used in combination with another letter, as ab, ac, ad, to give credit for matter that has been editorially adapted, but not quoted verbatim. It is perhaps hardly necessary to explain that direct quotations, such as go to make up the bulk of our work, are often given in an abbreviated form through the omission of matter that is redundant or, for any reason, inadmissible. The necessity for such change is obvious, since otherwise the varied materials could not possibly be made to harmonise or to meet the needs of our space. But, beyond this, no liberty whatever is taken with matter presented as a direct quotation. Where editorial modification is thought necessary, the use of reference letters makes such modification feasible without introducing the slightest ambiguity. We repeat that every line of the work is ascribed to its proper source with the utmost fidelity. Any matter not otherwise accredited—as, for example, various introductions, chronologies, bibliographies, and the like—will be understood to be editorial. Brackets also indicate editorial matter.

| VOLUME I | |

| PART I. PROLEGOMENA | |

| BOOK I. HISTORY, HISTORIANS, AND THE WRITING OF HISTORIES | |

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Some General Considerations | 1 |

| The oriental period, 2. The classical historians, 3. The mediæval and modern histories, 4. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Materials for the Writing of History | 5 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Methods of the Historians | 9 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| World Histories | 13 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Present History | 22 |

| BOOK II. A GLIMPSE INTO THE PREHISTORIC PERIOD | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Introductory | 32 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Cosmogony—Ancient and Modern Ideas as to the Origin of the World | 33 |

| [xii]CHAPTER III | |

| Cosmology and Geography—Ancient and Modern Ideas | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Antiquity of the Earth and of Man | 40 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Races of Man and the Aryan Question | 43 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| On Prehistoric Culture | 45 |

| Language, 44. Clothing and housing of prehistoric man, 46. The use of fire, 46. Implements of peace and war, 47. The domestication of animals, 47. Agriculture, 48. Government, 49. The arts of painting, sculpture, and decorative architecture, 50. The art of writing, 50. | |

| PART II. EGYPT | |

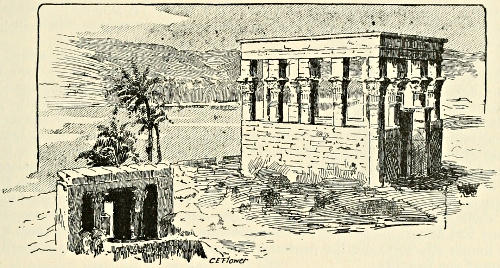

| Introductory Essay. Egypt as a World Influence. By Dr. Adolf Erman | 57 |

| Egyptian History in Outline (4400-332 B.C.) | 65 |

| CHAPTER I | |

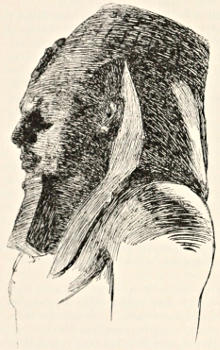

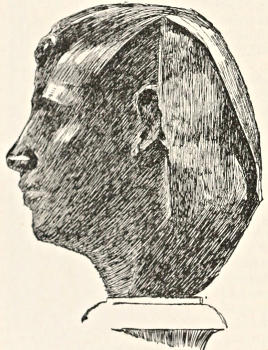

| The Egyptian Race and its Origin | 77 |

| The country and its inhabitants, 81. Prehistoric Egypt, 88. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Old Memphis Kingdom (ca. 4400-2700 B.C.) | 90 |

| The first dynasty, 90. The second dynasty, 92. The third dynasty, 92. The pyramid dynasty, 93. A modern account of the pyramids, 95. The builders of the pyramids, 98. The beautiful Nitocris, 104. | |

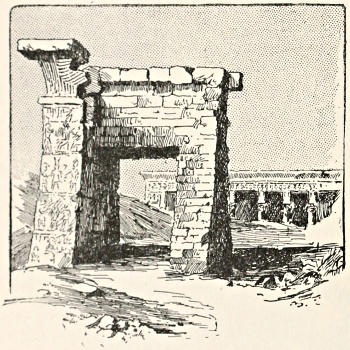

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Old Theban Kingdom (ca. 2700-1635 B.C.) | 106 |

| The eleventh dynasty, 106. The voyage to Punt, 108. The twelfth dynasty, 110. Monuments of the twelfth dynasty; a classical view, 113. The ruins of Karnak, 115. The fall of the Theban kingdom, 117. The foreign rule, 118. The Hyksos rule; the seventeenth dynasty, 121. | |

| [xiii]CHAPTER IV | |

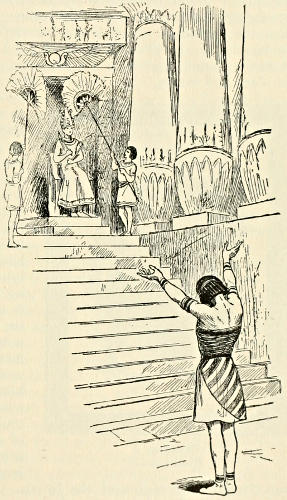

| The Restoration (ca. 1635-1365 B.C.) | 126 |

| Eighteenth dynasty, 126. The Hyksos expulsion: Aahmes and his successors, 127. Tehutimes II; Queen Hatshepsu, 133. Triumphs of Tehutimes III; his successors, 136. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Nineteenth Dynasty (ca. 1365-1285 B.C.) | 141 |

| King Seti, 142. Ramses (II) the Great, 144. The war-poem of Pentaur, 148. The kingdom of the Kheta and the nineteenth dynasty, 150. Death of Ramses II, 153. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Finding of the Royal Mummies | 155 |

| How came these monarchs here? 157. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Period of Decay (Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties: ca. 1285-655 B.C.) | 162 |

| Meneptah, 162. From Setnekht to Ramses VIII and Meri-Amen Meri-Tmu, 166. The sorrows of a soldier, 170. Egypt under the dominion of mercenaries, 171. The Ethiopian conquest, 174. Table of contemporaneous dynasties, 179. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Closing Scenes (Twenty-sixth To Thirty-first Dynasties: 655-322 B.C.) | 180 |

| Psamthek, 180. The good king Sabach (Shabak) and Psammetichus, 184. The restoration in Egypt, 185. The Persian conquest and the end of Egyptian autonomy, 188. The atrocities of Cambyses, 191. | |

| CHAPTER IX | |

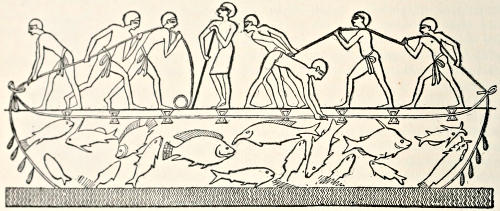

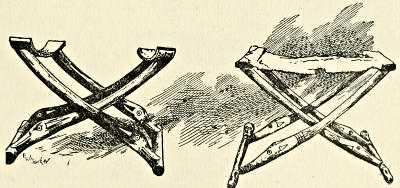

| Manners and Customs of the Egyptians | 196 |

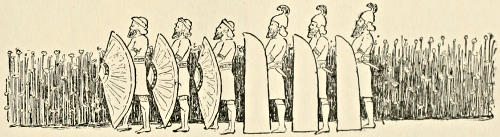

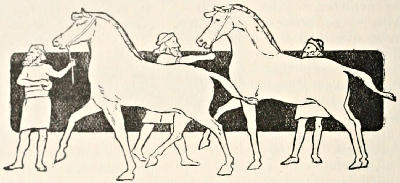

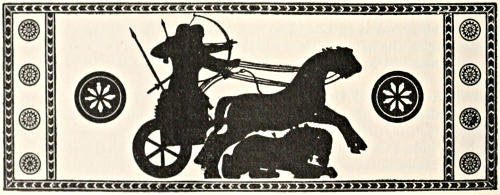

| The position of the king, 198. Weapons of war, 202. Battle methods, 205. Social customs, 208. The Egyptians as seen by Herodotus, 212. Homes of the people, 216. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

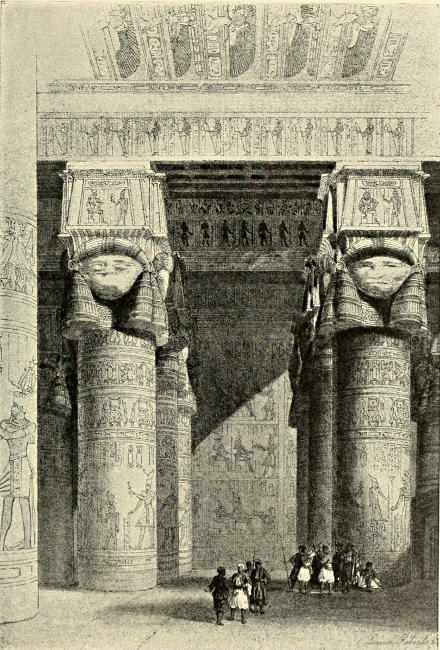

| The Egyptian Religion | 219 |

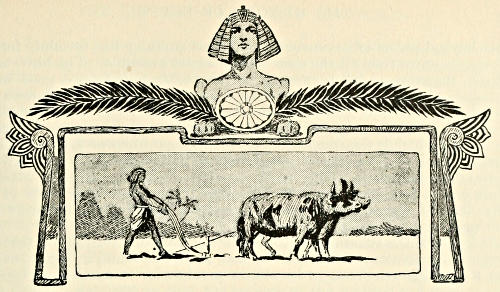

| Religious festivals and offerings, 222. Gifts and riches of temples, 225. Diodorus on animal worship, 228. A modern account of the worship of Apis, the sacred bull, 232. The methods of embalming the dead, 236. | |

| [xiv]CHAPTER XI | |

| Egyptian Culture | 240 |

| The hieroglyphics, 249. “By what characters, pictures, and images the learned Egyptians expressed the mysteries of their mindes,” 250. The riddle of the sphinx, 251. Literature, 257. The Castaway: a tale of the twelfth dynasty, 260. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Concluding Summary of Egyptian History | 263 |

| APPENDIX A | |

| Classical Traditions | 267 |

| Another ancient account of the Nile, 273. A Greek view of the origins of Egyptian history, 278. | |

| APPENDIX B | |

| The Problem of Egyptian Chronology | 287 |

| Manetho’s table of the Egyptian dynasties, 291. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 293 |

| A General Bibliography of Egyptian History | 295 |

| PART III. MESOPOTAMIA | |

| Introductory Essay. The Relations of Babylonia with other Semitic Countries. By Joseph Halévy | 309 |

| Mesopotamian History in Outline (6000-538 B.C.) | 318 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Land and People | 337 |

| The land, 338. Original peoples of Babylon: the Sumerians, 342. The Semitic Babylonians, 344. The original home of the Babylonian Semite, 347. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Old Babylonian History (ca. 4500-745 B.C.) | 349 |

| The beginnings of history, 351. The rulers of Shirpurla, 351. Kings of Kish and Gishban, 356. The first dynasty of Ur, 359. Kings of Agade, 360. The kings of Ur, 363. Accession of a south Arabian dynasty, 363. The Kassite dynasty, 364. Assyrian conquest of Babylon, 364. | |

| [xv]CHAPTER III | |

| The Rise of Assyria (ca. 3000-726 B.C.) | 366 |

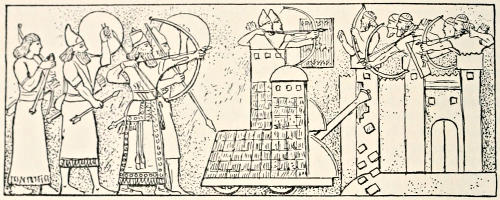

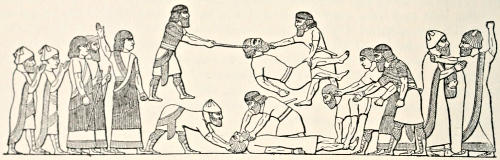

| Land and people, 369. Assyrian capitals: Asshur and Nineveh, 371. The rise of Assyria, 372. The first great Assyrian conqueror, 377. The reign and cruelty of Asshurnazirpal, 380. Shalmaneser II and his successors, 387. Tiglathpileser III, 391. Shalmaneser IV, 395. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Four Generations of Assyrian Greatness (722-626 B.C.) | 397 |

| Sennacherib, 403. Esarhaddon and Asshurbanapal, 416. Esarhaddon’s reign, 419. Asshurbanapal’s early years, 425. The Brothers’ War, 431. The last wars of Asshurbanapal, 434. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Decline and Fall of Assyria (626-606 B.C.) | 438 |

| Last years and fall of the Assyrian Empire, 440. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Renascence and Fall of Babylon (555-538 B.C.) | 446 |

| Contemporary chronology, 448. Nabopolassar and Nebuchadrezzar, 449. The followers of Nebuchadrezzar, 453. The reign of Nabonidus, 455. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Manners and Customs of Babylonia-Assyria | 460 |

| War methods, 460. Our sources, 461. Assyrian war costumes and war methods, 468. The arts of peace in Babylonia-Assyria, 472. Babylon and its customs described by an eye-witness, 473. A later classical account of Babylon, 479. The commerce of the Babylonians, 484. Ships among the Assyrians, 491. Laws of the Babylonians and Assyrians, 494. Sale of a slave, 496. Sale of a house, 497. The code of Khammurabi, 498. The discovery of the code, 498. Miscellaneous regulations, 501. Regulations concerning slaves, 502. Provisions concerning robbery, 502. Concerning leases and tillage, 503. Concerning canals, 504. Commerce, debt, 504. Domestic legislation, divorce, inheritance, 505. Laws concerning adoption, 509. Laws of recompense, 509. Regulations concerning physicians and veterinary surgeons, 510. Illegal branding of slaves, 510. Regulations concerning builders, 511. Regulations concerning shipping, 511. Regulations concerning the hiring of animals, farming, wages, etc., 511. Regulations concerning the buying of slaves, 513. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians | 515 |

| The Assyrian story of the creation, 520. The Babylonian religion, 521. The epic of Gilgamish, 525. Ishtar’s descent into Hades, 530. | |

| [xvi]CHAPTER IX | |

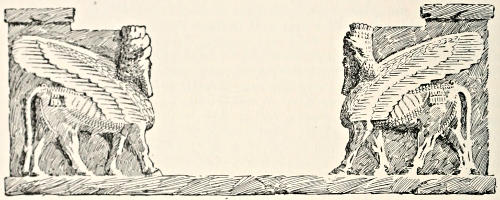

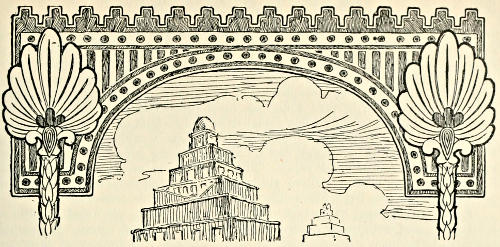

| Babylonian and Assyrian Culture | 534 |

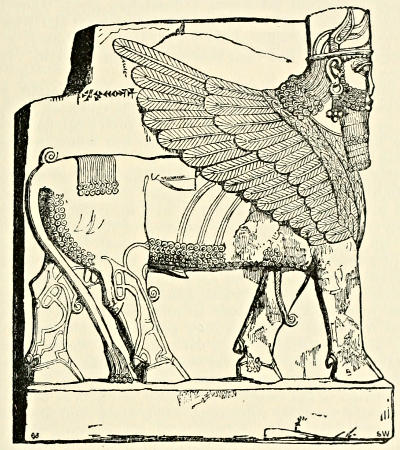

| Literature and science, 536. Epistolary literature, 539. Art, 543. Assyrian art, 552. Assyrian sculpture and the evolution of art, 558. A classical estimate of Chaldean philosophy and astrology, 563. The Babylonian year, 565. The Babylonian day and its division into hours, 566. Assyrian science, 567. | |

| APPENDIX A | |

| Classical Traditions | 571 |

| The Creation and the Flood, described by Polyhistor, 573. Other classical fragments: of the Chaldean kings, 575. Of the Chaldean kings and the deluge, 576. Of the tower of Babel, 577. Of Abraham, 577. Of Nabonassar, 577. Of the destruction of the Jewish Temple, 577. Of Nebuchadrezzar, 577. Of the Chaldean kings after Nebuchadrezzar, 578. Of the feast of Sacea, 579. A fragment of Megasthenes concerning Nebuchadrezzar, 579. Ninus and Semiramis, 580. Semiramis builds a great city, 584. Semiramis begins a career of conquest, 588. Semiramis invades India, 589. Another view of Semiramis, 593. Reign of Ninyas to Sardanapalus, 594. The destruction of Nineveh, 598. | |

| APPENDIX B | |

| Excavations in Mesopotamia and Their Results | 600 |

| The ruins of Nineveh and M. Botta’s first discovery, 600. Layard’s discoveries at Nineveh, 604. Later discoveries in Babylonia and Assyria, 610. The results of the excavations, 612. Treasures from Nineveh, 613. The library of a king of Nineveh, 618. How the Assyrian books were read, 623. | |

| Brief Reference-list of Authorities by Chapters | 627 |

| A General Bibliography of Mesopotamian History | 629 |

Broadly speaking, the historians of all recorded ages seem to have had the same general aims. They appear always to seek either to glorify something or somebody, or to entertain and instruct their readers. The observed variety in historical compositions arises not from difference in general motive, but from varying interpretations of the relative status of these objects, and from differing judgments as to the manner of thing likely to produce these ends, combined, of course, with varying skill in literary composition, and varying degrees of freedom of action.

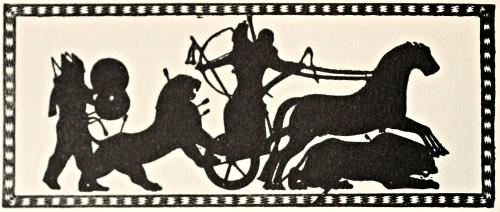

As to freedom of selective judgment, the earliest historians whose records are known to us exercised practically none at all. Their task was to glorify the particular monarch who commanded them to write. The records of a Ramses, a Sennacherib, or a Darius tell only of the successful campaigns, in which the opponent is so much as mentioned only in contrast with the prowess of the victor.

With these earliest historians, therefore, the ends of historical composition were met in the simplest way, by reciting the deeds, real or alleged, of a king, as Ramses, Sennacherib, or David; or of the gods, as Osiris, or Ishtar, or Yahveh. As to entertainment and instruction, the reader was expected to be overawed by the recital of mighty deeds, and to draw the conclusion that it would be well for him to do homage to the glorified monarch, human or divine.

A little later, in what may be termed the classical period, the historians had attained to a somewhat freer position and wider vision, and they sought to glorify heroes who were neither gods nor kings, but the representatives of the people in a more popular sense. Thus the Iliad dwells upon the achievements of Achilles and Ajax and Hector rather than upon the deeds of Menelaus and Priam, the opposing kings. Hitherto the deeds of all these heroes would simply have been transferred to the credit of the king. Now the individual of lesser rank is to have a hearing. Moreover, the state itself is now considered apart from its particular ruler. The histories of Herodotus, of Xenophon, of Thucydides, of Polybius, in effect make for the glorification, not of individuals, but of peoples.

This shift from the purely egoistic to the altruistic standpoint marks a long step. The writer now has much more clearly in view the idea of entertaining, without frightening, his reader; and he thinks to instruct in matters pertaining to good citizenship and communal morality rather than in deference to kings and gods. In so doing the historian marks the progress of civilisation of the Greek and early Roman periods.

In the mediæval time there is a strong reaction. To frighten becomes again a method of attacking the consciousness; to glorify the gods and heroes a chief aim. As was the case in the Egyptian and Persian and Indian periods of degeneration, the early monotheism has given way to polytheism. Hagiology largely takes the place of secular history. A constantly growing company of saints demands attention and veneration. To glorify these, to show the futility of all human action that does not make for such glorification, became again an aim of the historian. But this influence is by no means altogether dominant; and, though there is no such list of historians worthy to be remembered as existed in the classical period, yet such names appear as those of Einhard, the biographer of Charlemagne; De Joinville, the panegyrist of Saint Louis; Villani, Froissart, and Monstrelet, the chroniclers; and Comines, Machiavelli, and Guicciardini.

In the modern period the gods have been more or less disbanded, the heroes modified, even the kings subordinated. We hear much talk of the “philosophy” of history, even of the “science” of history. Common sense and the critical spirit are supposed to hold sway everywhere. Yet, after all, it would be too much to suppose that any historian even of the most modern school has written entirely without prejudice of race, of station, or of religion. And in any event the same ideals, generally stated, are before the historian of to-day that have actuated his predecessors—to glorify something or somebody, though it be, perhaps, a principle and not a person; and to entertain and instruct his readers.

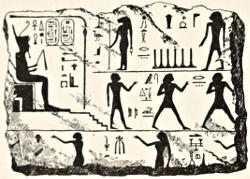

The earliest historians whose writings have come down to us are the authors of the records on the monuments of Egypt and of Mesopotamia. We shall see later on that these records, made in languages a knowledge of which has only been recovered in the past century, are full of historical interest because of the facts they narrate, and the insight they give us into the life of their times. For the moment, however, we are only concerned with the method of their construction. They are parts of records dating from many centuries before the beginning of the Christian era. Their authors are utterly unknown by name. The narrative is, indeed, in some cases, couched in the first person, but it is not to be supposed from this that the alleged writer—who, of course, is the king whose deeds are glorified—is the actual composer of the narrative. The actual scribes, mere adjuncts of the royal ménage, never dreamed of putting their own names on record beside those of their royal masters. Yet their work has preserved to future generations the names of kings that otherwise would have been absolutely forgotten. For example, Tehutimes III of Egypt and Asshurbanapal of Assyria, two of the most powerful monarchs of antiquity, had ceased to be remembered even by name several centuries before the dawn of our era, and for two thousand years no human being knew that such persons had ever existed. Yet now, thanks to the monuments, their deeds are almost as fully known to us as the deeds of an Alexander or a Cæsar.

There is, indeed, one regard in which these most ancient historical records have an advantage over more recent works. They were for the most part graven in stone or stamped in clay that was burned to stonelike hardness, and they have come down to us with the assurances of authenticity which must always be lacking in many compositions of more recent periods. The Babylonian and Assyrian records lay buried with the ruins of cities whose very location had been forgotten for ages. The most recent of these records had been seen by no human eye for more than two thousand years. Their unnamed authors seem thus to speak to us directly across the centuries. However these earliest of historians may have dreamed of immortality for their work, they can hardly have hoped to speak to eager audiences in regions far beyond the limits of their world, twenty-five centuries after the very nation to which they belonged had vanished from the earth, and the language in which they wrote had ceased to be known to men. Yet that unique glory was reserved for them.

It requires but a glance at the historians of the classical period to see how altered is the point of view from which they write. Here we have no longer men commanded by a monarch, or impelled by religious fervour to glorify a single person or epoch or country to the utter exclusion of everything else. We have bounded from insularity of view to universality. Even the Homeric legends deal with the events of two continents and of several countries. Herodotus and Diodorus make the writing of their histories a life-work. They travel from one country to another, and familiarise themselves with their subject as much as possible at first hand. They mingle with the scholars of many lands, and listen to their recitals of the annals of their respective peoples. They weigh and consider, though in a quite different mental balance from that which an historian uses in our day. They spend thirty, forty, years in composing their books. From them, then, we have, not simple chronicles of a single event, but universal histories. These are in many ways different from the universal histories of our own time; but in their frank, human way of looking out upon the world, they have a charm that is quite their own. In their interest for the general reader, they have perhaps never been excelled. And in their citation of fact and fable they become a storehouse upon which succeeding generations of historians have drawn to this day.

There are other historians of the period no less remarkable, some of them even superior, from some points of view, to these masters. The names of Thucydides, Xenophon, Polybius among the Greeks, of Tacitus, Livy, Cæsar among the Romans, to go no farther, are as familiar to every cultivated mind of our own day as the names of Gibbon, Macaulay, or Bancroft. Several of these were men who participated in the events they described, and, confining themselves to limited periods, treated these periods in such masterly fashion, with such breadth of view and discriminating judgment, that their verdicts have weight with all succeeding generations of historians. Thucydides, writing in the fifth century B.C., is regarded, even in our critical age, as a matchless writer of history. An oft-repeated tale relates that Macaulay despaired of ever equalling him, though feeling that he might hope to duplicate the work of any other historian. Polybius and Tacitus are mentioned with respect by the most exacting investigators. Clearly, then, this was a culminating epoch in the writing of histories.

We have seen that in the classical period the brief space of half a dozen generations saw a cluster of great histories written. No such intellectual activity in this direction marked the mediæval period. Now for the space of more than a thousand years there was no work produced that could bear a moment’s comparison with the great productions of the earlier periods. One theme was now dominant in the Western world, and the intellects that might have produced histories of broad scope under other circumstances contented themselves with harping on the one string. So we have ecclesiastical records in place of histories.

In due time the reaction came, but it was long before the influence of the dominant spirit was made subordinate to a saner view. Indeed, scarcely before our own generation, since the classical period, have historians been able to cast a clear and unbiased glance across the entire field of history.

Toward the middle of the eighteenth century a school of secular historians with broad views and high aims again arose. Now once more men sought to write world histories not dominated by a single idea. The first great exponents of the movement were Gibbon and Hume in England, Schlozzer and Müller in Germany. They have had a host of followers, of whom the greater number have been Germans.

The attitude of these modern writers is philosophical; they are disposed to recognise in the bald facts of human existence an importance commensurate solely with the lessons they can teach for the betterment of humanity. In this modern view, each fact must be correlated with a multitude of other facts before its true significance can be perceived. Events are, in this view, meaningless unless we know something of the human motives that led to their enactment. The task of the historian is to search for causes, to endeavour to build up from the lessons of history a true philosophy of living. It is really no different a task, as already pointed out, from that which such ancient writers as Polybius had very prominently in view; but there is an emphasis upon this phase of the subject in our time that it did not generally receive in the earlier age. In other words, the philosophy of history of our time is a more conscious philosophy. For a century past the phrase, “philosophy of history,” has been current, and it has been the custom for men who were not primarily historians to discourse on the subject. Latterly, following again the current of the times, we have come to speak even of the “science” of history; indeed, in Germany in particular, history to-day claims unchallenged position as a true science. The word “science” is a very flexible term, yet there are those who deny that it may be properly applied, as yet at any rate, to our aggregation of knowledge of historical facts. The question resolves itself into a matter of definition, the solution of which is not particularly important.

The essential thing is that the modern historical investigator is fully actuated by the spirit of scientific accuracy and impartiality. And since impartiality depends very largely upon breadth of view, it results rather curiously that the minute investigations of the specialist make indirectly for the comprehensive view of the World Historian. Professor Freeman well expressed the idea when he said:

“My position is that in all our studies of history and language—and the study of language, besides all that it is in other ways, is one most important branch of the study of history—we must cast away all distinctions of ‘ancient’ and ‘modern,’ of ‘dead’ and ‘living,’ and must boldly grapple with the great fact of the unity of history. As man is the same in all ages, the history of man is one in all ages. No language, no period of history, can be understood in its fullness; none can be clothed with its highest interest and its highest profit, if it be looked at wholly in itself, without reference to its bearing on those other languages, those other periods of history, which join with it to make up the great whole of human, or at least of Aryan and European, being.”

Such a position as this, assumed by one of the most minute searchers among modern historians, is highly interesting as illustrative of a reactionary tendency which will probably characterise the historical work of the near future. Hair-splitting analysis having been carried to its limits of refinement, there will probably come a reaction in the direction of a more comprehensive study of historical events in their wider relations. The work of the specialist, after all, is really important only when it furnishes material for wider generalisations. All minute workers in the fields of biology, geology, and the allied sciences, in the first half of the nineteenth century were unconsciously gathering material which, interesting in itself, became of real importance chiefly in so far as it ultimately aided in elucidating the great generalisation of Darwin. Perhaps the minute historians of to-day are in similar position.

The special worker, imbued with enthusiasm for his subject, is apt to forget the real insignificance of his labours. Entire epochs are dominated by the idea of microscopic research, and the workers even come to suppose that microscopic analysis is in itself an end; whereas, rightly considered, it is only the means to an end. We are just passing through such an epoch as regards historical investigation. But, as just suggested, it seems probable that we are approaching a new epoch when the work of the specialist will be subordinated to its true purpose, while at the same time proving its real value as a means to the proper end of historical studies—the comprehension of the world-historical relations of events.

It is obvious that the materials for the writing of history consist for the most part of written records. It is true that all manner of monuments, including the ruins of buried cities, remains of ancient walls and highways, and all other traces of a former civilisation, must be allotted their share as records to guide the investigator in his attempt to reconstruct past conditions. But for anything like a definite presentation of the events of by-gone days, it is absolutely essential, as Sir George Cornewall Lewis pointed out in great detail, to have access to contemporary written records, either at first hand, or through the medium of copyists, in case the original records themselves have been destroyed. Lewis reached the conclusion, as the result of his exhaustive examination of the credibility of early Roman history, that a tradition of a past event is hardly transmitted orally from generation to generation with anything like accuracy of detail for more than a century.

Theoretically, then, no accurate history could ever be constructed of events covering a longer period than about four generations before the introduction of writing. In actual practice the scope of the strictly historic view of man’s progress is confined to very much narrower limits than this, for the simple reason that the earliest written records that might otherwise serve[6] to give us glimpses of remote history have very rarely been preserved. The destruction of ancient inscriptions with the lapse of centuries has led to a great deal of difference of opinion as to the time when the art of writing was introduced among various nations. In reference to the Greeks in particular, the dispute has been ardently waged, many scholars contending that the art of writing was little practised in Greece until the sixth century B.C.

Later discoveries, in particular a knowledge of the inscription on the statue of Ramses at Abu Simbel, have made it clear that the earlier estimates were much too conservative, and it now seems probable that the Greeks had been acquainted with the art of writing for several, or perhaps many, centuries before the one previously fixed upon. It is not to be supposed, however, that the practice of the art of writing was universal in that early day. On the other hand, it was doubtless very exceptional indeed for the average individual to be able to write, and such difficulties as the lack of writing material stood in the way of composition until a relatively late period. But whether the art of writing was much or little practised in the early days does not greatly matter so far as the present-day historian is concerned, since practically all specimens of early writing in Greece disappeared in the course of succeeding ages. No fragment of any book proper, no scrap of parchment or papyrus, no single waxen tablet, from the soil of classic Greece has been preserved to us.

The Greek authors are known to us only through the efforts of successive generations of copyists; and, with the exception of a comparatively small number of Egyptian papyri, there is almost nothing in existence representing the literature of classical Greece that is older than the middle ages. There are, to be sure, considerable numbers of monumental inscriptions dating from classical times. These have the highest interest for the archæologist, but in the aggregate they give but meagre glimpses into the history of antiquity. If we were dependent upon these records for all that we know of Greek history, the entire story of that people might be told, as far as we could ever hope to learn it, in a few pages.

The case is somewhat different with Egypt and with Mesopotamia, since the climate of the former and the resistant character of the writing materials employed by the latter have permitted the modern world to receive direct messages that, under other circumstances, must inevitably have been lost. But even here the historical records are neither so abundant nor so comprehensive in their scope as might have been hoped. History-writing, in anything like a comprehensive meaning of the words, is a relatively modern art. The nearest approach to it among the nations of remote antiquity got no farther than the recording of the personal deeds of individual kings. Such records, indeed, are excellent materials for history, but they hardly constitute history by themselves. The entire lists of Egyptian inscriptions, so far as known, suffice merely to give glimpses of Egyptian history; and if the Mesopotamian records are, in this regard, somewhat more satisfactory, it is only in reference to a comparatively brief period of later Assyrian history that they can be said to have anything like comprehensiveness. As to the other nations of Oriental antiquity,—Indians, Persians, Syrians, the inhabitants of Asia Minor,—the entire sum of the monumental records that have been transmitted to us amounts to nothing more than a scattered series of vague suggestions.

In the classical world Rome is but little better off than Greece in this regard. As to both these countries, we depend for our knowledge almost[7] exclusively upon the works of historians of a relatively late period. Before Herodotus, who lived in the fifth century B.C., there is almost no consecutive history proper of Greece; and despite all the efforts of archæologists, records of Roman progress scarcely suffice to push back the prehistoric veil beyond the time of the banishment of the kings. Indeed, even for a century or two after this event transpired, the would-be historian finds himself still on very treacherous ground. The reason for this is that there were no contemporary historians in Rome in this early period; and until such contemporary chroniclers appear, no secure record of history is possible.

Once it became the fashion to write chronicles of events, the custom rapidly spread and took a fixed hold upon the people. From the day of Herodotus there was no dearth of Greek historians, and after Polybius there is an unbroken series of Roman chroniclers.

Had all the writings of these various workers been preserved to us, we should have abundant material for reconstructing the history of the entire later classical epoch in much detail; but, unfortunately, the historian worked with perishable materials. An individual papyrus or parchment roll could hardly be expected on the average to be preserved for more than a few generations, and unless copies had been made of it in the meantime, the record that it contained must inevitably be lost. Such has been the fate of the great mass of historical writings, no less than of productions in other fields of literature.

Many of the fragments of ancient writers have come down to us through rather curious channels. In the later age of Rome it became the fashion to make anthologies and compilations, and it is through such collections that the majority of classical authors are known. One of the most curious of these anthologies is that made by Athenæus about the beginning of the third century A.D. This author called his work Deipnosophistæ, or the Feast of the Learned. He attempted to give it a somewhat artistic form, making it ostensibly a dialogue in which the sayings of a company of diners were related to a friend who was not present at the banquet. The diners were supposed to have introduced quotations from the classical writers, so that the book is chiefly made up of such quotations. The work has not come down to us quite in its entirety, but, even so, no fewer than eight hundred authors and twenty-five hundred different works are represented in the anthology. Of these authors about seven hundred are known exclusively through the excerpts of Athenæus.

Two or three centuries later another Greek named Stobæus compiled a set of extracts from the Greek writers of all accessible periods prior to his own. The number of authors quoted in this anthology is more than five hundred, and here again the major part of them are quite unknown to us except through this single source. Yet another collection of excerpts was made in the latter part of the ninth century by Photius, patriarch of Constantinople, who made excerpts from about 280 authors with whose works he had familiarised himself through miscellaneous reading. In addition to these works of individual compilers there were two or three anthologies compiled in the Byzantine period, including an important collection of fragments of the Greek poets which is still extant under the title of The Greek Anthology, and the elaborate set of encyclopædias made under the direction of Constantine Porphyrogenitus. But for such collections as these, supplemented by the biographical notices of such workers as Suidas, and by fragments that have come to us through a few other channels, it would scarcely have been conceived that so many authors had[8] written in the entire period of Grecian activity, since only a fraction of this number are represented by complete works that have come down to us. Such facts as these give an inkling as to the mental activity of the old-time author, while pointing a useful lesson as to the perishability of human works. In this age of easy multiplying of books through printing, one is prone to forget how precarious must have been the existence of a manuscript of the elder day. It was a long, laborious task to produce an edition of a single copy of any extended work, and each successive duplication was precisely as slow and as difficult as the first. Under these circumstances no doubt a very considerable proportion of books were never duplicated at all, and the circulation of a very large additional number most likely was limited to two or three copies. It was only works which were early recognised as having an unusual intrinsic interest or value that stood any reasonable chance of being copied often enough to insure preservation through many succeeding generations.

As one considers the field of extant manuscripts, one is led naturally to reflect on the quality of work that was likely thus to insure perpetuity, and the more we consider the subject, limiting the view for our present purpose to historical compositions, the more clear it becomes that the one prime quality that gave a lease of life to the composition of an author was the quality of human interest. In other words, such historical compositions as were works of art, rather than such as depended upon other merits, were the ones which successive generations of copyists reproduced, and which ultimately were enabled to pass the final ordeal imposed by the monks of the middle ages, who made palimpsests of many an author deserving a better fate. The upshot of this process of the survival of the fittest was that all Greek would-be historians prior to Herodotus were allowed to sink into oblivion, causing Herodotus himself to stand out as apparently the absolute creator of a new art. In point of fact, could we know the whole truth, it would doubtless appear that there was no real revolution of method effected by the writings of Herodotus. He surpassed all of his predecessors in such a measure that the future copyist saw no necessity for preserving any work but the one, since this one practically covered the field of all the rest. It is, perhaps, an ill method of phrasing, to say that these copyists saw no reason for preserving those earlier manuscripts. There was no thought in their minds of the preservation of one book and the destruction of another; they merely copied the work which interested them, or which they believed would interest the book-buying public. The disappearance of the works not copied was a mere negative result, about which no one directly concerned himself.

The proof of the value of the work of Herodotus is found in the fact that it has come down to us entire in numerous copies, something that can be said of only three or four other considerable historical compositions of the entire classical period; two others of this select company being Thucydides and Xenophon, both of whom were contemporaries of Herodotus, though considerably younger, and therefore, properly enough, counted as belonging to the next generation. Of the other Greek historians, the biographical works of Plutarch, the works of Strabo and Pausanius, which are geographical rather than strictly historical, and the Life of Alexander the Great by Arrian, are the sole ones of the large number undoubtedly written that have come down to us intact. A survey of the Roman historians furnishes an even more striking illustration, for here no one of the great historical works has been preserved in its entirety. Livy’s monumental work is entire as to the earlier books, which treat of the mythical and half-mythical period of Roman development;[9] but the parts of it that treated of later Roman history, concerning which the author could have spoken, and probably did speak, with first-hand knowledge, are almost entirely lost. In other words, the copyists of the middle ages preserved the least valuable portion of Livy, doubtless because they found the hero tales of mythical Rome more interesting than the matter-of-fact recitals of the events of the later republic and the early empire. We can hardly suppose that Livy detailed the events of the later period with less art than characterised his earlier work, but different conditions were imposed upon him. He had now to deal with much fuller records than hitherto, and no doubt he treated many subjects that seemed important to him, simply because they were near at hand, but which another generation found tiresome and not worth the trouble of copying. Thus we see emphasised again the salient point that the interesting story rather than the important historical narrative proved itself most fit for preservation in the estimate of posterity.

Of the other great historians of Rome, Tacitus, Dionysius, Dion Cassius, Polybius, have all fared rather worse than Livy, although a few briefer masterpieces, like the two histories of Sallust and the Gallic Wars of Cæsar, and such biographies as the “Lives” of Suetonius and Cornelius Nepos, were able to fight their way through the middle ages and gain the safe shelter of the printing-press without material loss.

But perhaps the most suggestive example of all is furnished by the brief world history of Justin, which, if not quite entire, has been preserved as to its main structure in various manuscripts. This work is an artistic epitome of a large, and in its day authoritative, history of the world, written by Trogus Pompeius. Justin, when a student in Rome in the day of the early Cæsars, was led to make an epitome of this work, seemingly as proof to his friends in the provinces that he was not wasting his time. He did his task so well that future generations saw no reason to trouble themselves with the prolixities of the original work, but were content to copy and re-copy the epitome, pointing the moral that brevity, next to artistic excellence, is the surest road to permanent remembrance for the historian,—a lesson which many modern writers have overlooked to their disadvantage.

It is a curious fact, a seeming paradox, that the first two great histories ever written—the histories, namely, of Herodotus and Thucydides—should stand out pre-eminently as types of two utterly different methods of historical writing. Herodotus, “the Father of History,” wrote with the obvious intention to entertain. There is no great logicality of sequence in his use of materials; he simply rambles on from one subject to another with little regard for chronology, but with the obvious intention everywhere to tell all the good stories that he has learned in the course of his journeyings. It would be going much too far to say that there is no method in his collocation of materials, but what method he has is quite generally overshadowed and obscured in the course of presentation. Thus, for example, he is writing the history of the Persian wars, and he has reached that time in the history of Persia when Cambyses comes to the throne and prepares to invade Egypt. The mention of Egypt gives him, as it were, the cue for an utterly[10] new discourse, which he elaborates to the extent of an entire book, detailing all that he has learned of Egypt itself, its history, its people, and their manners and customs, without, for the most part, referring in any way whatever to Cambyses. He returns to the Persian king ultimately, to be sure, and takes up his story regardless of the digression, and seemingly quite oblivious of any incongruity in the fact of having introduced very much more extraneous matter in reference to Egypt than the entire subject matter proper of the Persian Empire. The method of Herodotus was justified by the results. There is every reason to believe that he was enormously popular in his own time,—as popularity went in those days,—and he has held that popularity throughout all succeeding generations. But it has been said of him often enough that this work is hardly a history in the narrower sense of the word; it is a pleasing collection of tales, in which no very close attempt is made to discriminate between fact and fiction, the prime motive being to entertain the reader. As such, the work of Herodotus stands at the head of a class which has been represented by here and there a striking example throughout all succeeding times.

Xenophon’s Anabasis, detailing the story of Cyrus the Younger and his ten thousand Greek allies, is essentially a history of the same type. It differs radically, to be sure, from Herodotus, in that it holds with the closest consistency to a single narrative, scarcely giving the barest glimpses into any other field than that directly connected with the story of the ten thousand. But it is like Herodotus in the prime essential that its motive is to entertain the reader by the citation of the incidents of a venturesome enterprise. Xenophon does indeed pause at the beginning of the second book long enough to pronounce a eulogy upon the character of Cyrus,—a eulogy that is distinctly the biased estimate of a friend, rather than the calm judgment of a critical historian. But this aside, Xenophon, philosopher though he is, concerns himself not at all with the philosophy of the subject in hand. He quite ignores the immoral features of the rebellion of Cyrus against his brother. Indeed, it seems never to occur to him that this fratricidal enterprise has any reprehensible features, or could be considered in any light other than that of a commendable proceeding of which a throne was the legitimate goal. Doubtless the very fact of this banishment of the philosophical from the work of Xenophon has been one source of its great popularity, for, as every one knows, Xenophon shares with Herodotus the credit of being the most widely read of classical authors. It would be quite aside from the present purpose to emphasise the opinion that the intrinsic merit of Xenophon’s work does not fully justify this popularity. It suffices here to note the fact that this famous work of the successor of Herodotus belongs essentially to the same class with the work of the master himself.

Of the Roman historians doubtless the one most similar to Herodotus in general aim was Livy. The author of the most famous history of Rome does not indeed make any such excursions into the history of outlying nations, as did Herodotus, but he details the history of his own people with an eye always to the literary, rather than to the strictly historical, side; transmitting to us in their best form that series of beautiful legends with which all succeeding generations have been obliged to content themselves in lieu of history proper. There is little of philosophical thought, little of search for motives, in such history-writing as this. It is essentially the art of the story-teller applied to the facts and fables of history.

Returning now to Thucydides, we have illustrated, as has been said, an utterly different plan and motive. Thucydides does indeed tell the story[11] of the Peloponnesian War; tells it, moreover, with such wealth of detail as no other historian of antiquity exceeded, and few approached. But in addition to narrating the plain facts, Thucydides searches always for the motives. He gives us an insight into the causes of events as he conceives them. He is obviously thinking more of this phase of the subject than of the mere recital of the facts themselves. It is the philosophy of history, rather than the story of history, that appeals to him, and that he wishes to make patent to the reader.

Only two or three other writers of the entire classical period whose works have come down to us followed Thucydides with any considerable measure of success in this attempt to write history philosophically; the two most prominent exponents of this method being the Greek Polybius, who told the story of Rome’s rise to world power, and Tacitus, the famous author of the Roman Annals and of the earliest history of the German people. These three examples—Thucydides, Polybius, and Tacitus—stand out at once in refutation of a claim which might otherwise be made that philosophical, or, if one prefers, didactic, historical composition is essentially a modern product. But for these exceptions one might be disposed to make a sweeping generalisation to the effect that the old-time history was a collection of tales intended to entertain the reader, and that the strictly modern historical method aims at instruction rather than at entertainment. Such generalisations, however, assuming, as they do, that the entire trend of human thought has fundamentally changed within historical times, are sure to be faulty. Quite possibly it may be true to say that the earliest historians tended as a class to write entertaining narratives rather than philosophical histories; and to say, on the other hand, that nineteenth century historians as a class have reversed the order of motives: but it must not be forgotten that our judgment here is based upon a mere fragment of the entire output of ancient historians. We have already noticed, in another connection, that the names of some hundreds of Greek writers have been preserved to us solely through a single anthological collection or two; and now, speaking of the historical works, it must be remembered that a vast number of these have perished altogether. Whole companies of historians are known to us only by name, and there is every reason to suppose that considerable other companies that once existed and wrote works of greater or less importance have not left us even this memento. The scattered fragments of Greek historical works that have come down to us, dissociated from any considerable part of their original context, fill three large volumes of the famous Didot collection of Greek classics, as edited by K. O. Müller; some hundreds of authors being represented.

We have noted that all the predecessors of Herodotus were blotted out, chiefly, perhaps, by the excellence of the work of Herodotus himself. Similarly the entire histories of Alexander the Great, written by his associates and contemporaries and his successors of the ensuing century, have without exception perished utterly.

Doubtless the excellence of the work of Arrian, which summarised and attempted to harmonise the contents of the more important preceding histories of Alexander, was responsible for the final elimination of the latter. One can hardly refer too often to that intellectual gantlet of the middle ages, which all classical literature was called upon to pass, and from which only here and there a work emerged. It is almost pathetic to consider the number of works that made their way heroically almost through this gantlet, only to succumb just before achieving the goal. One knows,[12] for example, that there was a work of Theopompus on later Grecian affairs, in fifty odd books, which was extant in the ninth century, as proved by the summary of its contents made then by a monk, but of which no single line is in existence to-day. Even the works that have come down to us in a less fragmentary condition have not usually been preserved entire in any single manuscript, but, as presented to us now, are patched together from various fragments, preserved often in widely separated collections. The explanation is that the copying of a manuscript of great length was a somewhat heroic task, and that hence the copyist would often content himself with excerpting a single book from a work which he would gladly have reproduced entire but for the labour involved.

The point of all this in our present connection is that we know the historians of antiquity very imperfectly, and that hence we are almost sure to misjudge them as a class when we attempt generalisations concerning them. In the very nature of the case, the historian who told a good story in a pleasing style stood a far better chance of being perpetuated through the efforts of copyists, than did the philosophical historian, however profound, who put forward his theories at the expense of the narrative proper. Making all due allowance for this, however, it can hardly be in doubt that the last century and a half has seen a remarkable development of the scientific spirit in its application to the work of the historian, and that the average historical work of the nineteenth century is philosophically on a far higher plane than the average historical work of antiquity. If we were to attempt to characterise the most recent phases of historical composition, we should, perhaps, not go far afield in saying that in regard to history-writing, as in regard to many other subjects, this is pre-eminently the age of specialists. In recent years no historical work could hope for any large measure of recognition among historians, unless it were based upon personal investigation of the most remote sources bearing upon the period that could be made accessible. The recent period has been pre-eminently a time of the searching out of obscure or forgotten records; the unburying of old letters and state papers; the delving into hitherto neglected archives; and the critical analysis of the conflicting statements of alleged authorities previously accessible.

The work began prominently—if any intellectual movement may properly be said to have an explicit beginning—with Gibbon and Niebuhr; it was continued by Grote and Mommsen and George Cornewall Lewis and Clinton, and the host of more recent workers, whose specific labours will claim our attention as we proceed. Naturally enough, since each generation of specialists builds upon the labours of all preceding generations, the work has become more and more minute and hair-splitting with each succeeding decade. Gibbon, specialist though he was, covered a period of a thousand years of European history, and left scarcely anything untouched that falls properly within that period. Niebuhr specialised on the few centuries of early Roman history, but his comprehensive view reached out also to Greece and to the Orient, and he was accounted a master over the whole range of ancient history. Mommsen’s efforts have followed the Roman Republic and Empire throughout the length and breadth of its wide domains, and over the whole period of its existence, as well as into all the ramifications of its political, commercial, and social life.

But there has been a tendency among most recent workers to confine their attention to a narrower field. Macaulay’s History of England attempts the really detailed history of only about seventeen years. Carlyle devotes six large volumes to the History of Frederick the Great, and such authorities as[13] Freeman and Stubbs and Gardiner and Gairdner gave years of patient research to the investigation of single periods of English history. The obvious result of all this minute and laborious effort is the piling up of a mass of more or less incoördinate details as to the crude facts of history, which only the specialist in each particular field can hope to master, and the remoter bearings of which in their relations to world history are not always clearly appreciable. It is rarely given to the same mind to have a taste or a capacity at once for minute research and for broad and accurate generalisation. Therefore much of the work of the specialist, admirable in its kind, must still be regarded rather as crude material than as a finished product. It is the work of the world historian to attempt to mass this crude material, to visualise it in its relations to other similar masses, and to build with it a unified structure of history, in which each portion shall appear in its proper relations to all the rest.

Let us turn for a moment to the work of the world historians of the past, and glance at the results of their various efforts to weld the individual history of men and of nations into a comprehensive history of mankind.

No historian worthy of the name can narrate the events even of a limited period without at least an inferential reference to the world-historic import of these events. Just in proportion as one fails to take a sweeping general view, the force of his facts is weakened; any narrow period of history, on which the attention is fixed, assumes, for the time being, a disproportionate interest, and is necessarily seen quite out of perspective. It is only when the limited period is considered in reference to other periods that it can be made to assume anything like its proper status. Something of this has been understood by all writers from the earliest times, and accordingly we find that very few of the ancient authors failed to take at least a sweeping view of contemporaneous events, even when detailing specifically the incidents of a restricted period; and often, as in the case of Herodotus, the space devoted to the history of events not strictly cognate to the main story is quite out of proportion to that reserved for the main story itself. Thus in a certain sense the history of Herodotus is a world history, inasmuch as it deals more or less comprehensively with practically all nations known to the Greeks of that time. Thucydides, as we have seen, confines himself much more closely to a precise text; yet even he devotes an introductory book to a summary of the past history of the Greeks as a preparation for the full understanding of the Peloponnesian War.

But, after all, a somewhat sharp distinction should be drawn between histories such as these, which ostensibly describe the incidents of a particular period, and more comprehensive treatises, which set the explicit task of dealing with the history of all nations in all times.

Of the works of this latter class,—World Histories proper,—the oldest one that has come down to us is at the same time probably the most comprehensive in scope, and the most extensive in point of matter, of any that was written in ancient times. This is the so-called Historical Library of Diodorus the Sicilian. Diodorus was a Greek, a native of Sicily, who lived during the time of Julius Cæsar and of Augustus. He set himself the explicit task of[14] writing a comprehensive history of the world, and he devoted thirty years to the accomplishment of this task. This history, as originally written, comprised forty books, which treated of the entire history of mankind from the earliest times to the age of Augustus. Diodorus recognised the vagueness of early chronology, and he made no attempt to estimate the exact age of the world, but he computes the time covered by what he considers the historic period proper, in the following terms:

“According to Apollodorus, we have accounted fourscore years from the Trojan War to the return of Heraclides: from thence to the first olympiad, three hundred and twenty-eight years, computing the times from the Lacedæmonian kings: from the first olympiad to the beginning of the Gallic War (where our history ends) are seven hundred and thirty years: so that our whole work (comprehended in forty books) is an history which takes in the affairs of eleven hundred and thirty-eight years, besides those times that preceded the Trojan War.”

In his preface Diodorus further explains the exact scope of his work and the precise division in the books in the following words:

“Our first six books comprehend the affairs and mythologies of the ages before the Trojan War, of which the three first contain the barbarian, and the next following almost all the Grecian antiquities. In the eleven next after these, we have given an account of what has been done in every place from the time of the Trojan War till the death of Alexander. In the three and twenty books following, we have set forth all other things and affairs, till the beginning of the war the Romans made upon the Gauls; at which time Julius Cæsar, the emperor (who upon the account of his great achievements was surnamed Divus), having subdued the warlike nations of the Gauls, enlarged the Roman Empire, as far as to the British Isles; whose first acts fall in with the first year of the hundred and eightieth olympiad, when Herodes was chief magistrate at Athens. But as to the limitations of times contained in the work, we have not bound those things that happened before the Trojan War within any certain limits, because we could not find any foundation whereon to rely with any certainty.”

Of these forty books only fifteen have come down to us intact, namely, the first five, which carry down the history only to the Trojan wars, and books eleven to twenty, which cover the period from the invasion of Greece by Xerxes to the subjugation of Greece by the Romans. The remaining books are represented by considerable fragments, which, however, even in the aggregate, are insignificant in bulk as compared with the fifteen books that are preserved entire.

Considering the time when it was written, this work of Diodorus was really an extraordinary production, though there has been a tendency on the part of the modern critic to dwell rather upon its defects than its merits. It has indeed become quite the fashion to speak of Diodorus as a weak-minded, prejudiced person, who gathered together materials for history from all sources indiscriminately, and gave them to the world, true and false together, quite unsifted by criticism. Such an estimate, however, does Diodorus a very great injustice, as the briefest perusal of his work must suffice to demonstrate. Indeed, it is perhaps not saying too much to assert that one would be nearer the truth were he to accept an estimate by Pliny, who affirms that Diodorus was the first of the Greeks who wrote seriously and avoided trifles. That Diodorus did write seriously, his work clearly testifies; that he largely avoided trifles, is shown by the mass of matter which he crowded into a comparatively small space; and that he was far from[15] using his materials without exercising selective judgment, should be evident to any one who scans these materials themselves. It is quite true that he made many mistakes. He sometimes accepted as fact what was only fable, his chronologies are not always secure, his narratives of events not always photographically accurate. But consider the task he had set himself. He was endeavouring to write a history of the entire world so far as known in his day and generation, including within the scope of his narrative all the leading events of all the nations of the globe as known in that day. No man can perform such a task, even in this day of multiplied records and edited authorities, without making mistakes.

Whoever attempts to write history philosophically is brought, sooner or later, face to face with the fact that all historical records are woven through and through with fiction. To separate the threads of truth from the threads of fable is the task of critical judgment. It will be perfectly clear to any one who considers the case, that in making such selection the historian of any generation must be biased and influenced by the prejudices and preconceptions of his time. From such prejudices and preconceptions Diodorus was, of course, not free. He looked out upon the world with eyes of the first century B.C., not with eyes of the twentieth century A.D. That century, no less than this,—perhaps not more than this,—was an age of faith and superstition; but the faith of that time was not the faith of this time; the superstitions of the Greek and Roman were not our superstitions. They were a credulous people; we are a credulous people: but the exact type of their credulity differed in many ways from the type of our credulity.

In judging Diodorus, then, one must judge him as a Roman of the first century B.C., not as a European of the twentieth century A.D. And if we bear this in mind, we shall find, after scanning his pages, that Diodorus was by no means marked among his fellows by simple credulity of the unquestioning type which accepts whatever is told it without subjecting it to criticism. Diodorus, to be sure, tells us fabulous tales as to the origin of the world and the creation of its various peoples; but he explicitly forewarns us that he tells these tales, not as matters of his own belief, but in order to make an historical record of the opinions current among the different nations themselves as to their own origin.

These tales seem to us fabulous, grotesque, absurd; but we have no reason to doubt that many of them seemed equally mythical to Diodorus himself; and modern criticism should not forget that there is one other myth tale of the creation of the world and the origin of a particular race, which, had Diodorus known it, he would doubtless have narrated with the rest, and viewed with the same scepticism which he shows towards the others, as being fabulous, grotesque, and absurd, but which would have been accepted by the critics of all Christendom, in every age prior to our own, as the authentic historical record of the actual creation of the earth, and as the true account of its chosen people.

In a word, modern criticism should bear in mind, when reproaching Diodorus and others like him for their credulity, that the accepted faith of nineteenth-century Europe would have seemed to Diodorus as absurd and fabulous and mythical as any tale which he has to tell us can seem to the twentieth-century critic.

And as to the mistakes of Diodorus in the more strictly historical portions of his narrative, these also must be viewed with a certain toleration by every candid critic when he reflects upon the vast preponderance of those[16] cases in which the records of Diodorus are worthy of the fullest credence. In considering these matters, it is very easy, indeed, to generate myths that befog our view of the true status of an ancient author. Thus, for example, it was once traditional to regard Thucydides as the most candid, just, and impartial historian who has ever lived; but it can hardly be in doubt that the real reason why this estimate has grown up about the name of Thucydides is the fact that, as Professor Mahaffy points out, Thucydides is the sole authority for the history of most of the period of which he treats. It has even been admitted by Müller that in the early portion of the first chapter of Thucydides, where he treats on Grecian history in general, and up to the Peloponnesian War, he does not manifest the same impartiality which distinguishes him in the later portions of his narrative. But it is precisely in this earlier chapter that Thucydides deals with events that are recorded by other historians. It is here, and for the most part here alone, that his story can be checked by data from other authors. Could we similarly check the story of the Peloponnesian War in general, it can hardly be in doubt that we should come across at least some discrepancies which would have tended materially to modify the almost idolatrous estimate of Thucydides that came to be, and long continued to be, unquestionably associated with his name.

Making the application of this thought to Diodorus, it is evident at once that the historian of a limited period of antiquity lays himself open to no such range of comparison as he who undertakes to write the history of the entire world. In the very nature of the case, such a writer pits himself against the whole company of specialists; and, after all, it is hardly surprising, should it be susceptible of proof, that in several, or all, fields there are specialists whose accuracy excels the accuracy of Diodorus in each particular field. Surely the comprehensiveness of his task must count for something in the estimate, and, when all this is taken into consideration, it may fairly be repeated that the general estimate of modern criticism has done but scant justice to the author of the first attempt ever made to write a complete and comprehensive history of the world.

Moreover, it must not be forgotten that in his use of authorities Diodorus sometimes showed a selective judgment that is entitled to the fullest praise. A notable instance is found in his treatment of that period of Grecian history following the Peloponnesian War, when the Spartans and the Thebans were contending for supremacy. It was treated by Xenophon in his Hellenica, and as Xenophon was actual witness of many of the events which he describes, the presumption would be that his authority for the period might be considered incontestable. But in point of fact, Xenophon, philosopher though he was and pupil of Socrates, was not above the influence of personal prejudice. He was a friend of Agesilaus, and his admiration for that hero, as well as his fondness for the Spartans in general, prejudiced his narrative to such an extent that he did very scant justice to the merits of the great Epaminondas. Indeed, were we to trust to Xenophon alone, the world never would have had in later times anything like a just appreciation of the merits of the great Theban, and since Xenophon’s account of this period is the only contemporary one that has been preserved, it was a rare chance, indeed, that preserved to posterity a just appreciation of the greatest of the Thebans, whom some critics are wont to consider the greatest of all the Greeks; and it is Diodorus whom we must thank for doing this historic justice to a great man whose merits might otherwise have been obscured by the personal prejudice of a contemporary historian.

Diodorus, in treating this period, chose as his authority, not Xenophon, but Aphorus. Just how he came to this decision is not known; it suffices that the decision was a good one. None but a prejudiced critic can doubt that in many other cases his judgment was equally perspicuous in selecting among divergent accounts the one of greatest verisimilitude.

A part of the relative neglect which has fallen to the lot of Diodorus may be ascribed to the manner of his handling. He threw his work into the form of annals, in which a chronological idea was predominant. He gives the history of a nation in a given year, and then turns aside to other nations, to follow the fortunes of each in turn over the same period. Necessarily, under such a treatment, the whole plan lacks continuity. One must break from one subject to another, must turn from Assyria to Egypt, from Greece to Rome, in order to follow the story through constantly broken chapters. Naturally, under such treatment, the reader’s interest flags. From a popular standpoint, such a treatment is clearly a mistake.

The plan of Herodotus, which took up the story of each nation, and carried it through a long period uninterruptedly, has many advantages; is infinitely more artistic. It is chiefly due to this treatment, rather than the actual phrasing of his story, that Herodotus has gained so much more universal fame than Diodorus; for in those parts of his history in which he does attempt a continuous narrative, Diodorus shows much skill as a story-teller. In the earlier portion of his work, that portion which, fortunately, has in the main been preserved to us, when dealing with what he regards as the fabulous history of the nations prior to the establishment of a fixed chronology, his narrative runs on continuously, suggesting in many ways that of the Father of History. It was so with his treatment of early Egypt, and with his even more interesting history of ancient Assyria. These parts alone of his work serve to make him one of the most important authors of antiquity whose writings have been preserved to us, and we shall have occasion to draw largely upon him for the history of this period.

What has just been said about the attitude of modern critics toward Diodorus must not be taken to imply that this earliest of great world historians has, on the whole, failed of an appreciative audience. The facts of the case amply refute such a supposition as this. An author writes to be read, and in the last resort the only valid criterion as to the value of his work is found in the preservation or neglect of that work by successive generations of readers.

Tested by this standard, very few of the ancient writers have obtained such a measure of appreciation as has been accorded to Diodorus. Something like three-fourths of what he wrote has been lost, it is true; but in fairly estimating the import of this, one must consider the bulk of what remains. The briefest comparison supplies us with some very interesting data. It appears that, of the entire series of the predecessors of Diodorus, no single historian has left us anything like a comparable bulk of extant matter. Only one predecessor in any field of literature, namely, Aristotle, greatly exceeds him in this regard, and a single other writer, Plato, about equals him. Turning to the contemporaries of Diodorus and to his successors in the use of the Greek language, a similar result is shown. A single writer exceeds him in output. This is Plutarch, the biographer and philosopher rather than historian proper. No other Greek writer in any field equals Diodorus, though two historians, Dion Cassius and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, are within hailing distance. When one reflects on the actual labour implied by the preservation of any manuscript throughout the long[18] generations of the middle ages, these data speak volumes for the aggregate judgment passed upon the work of Diodorus by posterity. Of the long list of Greek historians,—a list mounting far into the hundreds, as proved by fragmentary remains,—only three as ancient as Diodorus have fared better than he, these three being Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon. But the entire bulk of the works of these three writers does not so very greatly exceed the bulk of the extant writings of Diodorus. The works of Herodotus and Thucydides together do not comprise more matter than is contained in books eleven to twenty of Diodorus, which are preserved en bloc.

It would, of course, be absurd to imply that the mere bulk of the manuscripts preserved before the age of printing is a test of the value of an ancient author’s work; but, on the other hand, bearing in mind always the labour employed in the production of a single copy of a large work, it would be equally absurd to deny that the bulk of manuscripts has a certain bearing upon the value of the matter which they preserve. No doubt many a scribe would be deterred from starting out to copy manuscript by the great bulk of the work, and where he had no great preference, would be influenced by this alone to choose a smaller book. Again, doubtless many a scribe wearied of his task in the case of the more ponderous works, and gave it up after copying a few books. This common-sense explanation no doubt accounts for the fact that quite generally the earlier books rather than the later ones of works that have come down to us in a fragmentary condition are the ones preserved. Had Herodotus and Thucydides written forty books instead of eight or nine, it is very unlikely that even their genius would have sufficed to preserve the entire number. The case of Livy, whose work, despite the beauty of its style, has come down to us so sadly mutilated, sufficiently sustains this supposition. It is nothing against the merit of Diodorus, then, to reflect that half his work is lost; the wonder is rather that so much of it has been preserved.

We have dwelt thus at length upon the work of Diodorus because it is a work that may be taken as in many ways representative of world histories in general. Certainly it was by far the greatest world history produced in antiquity, of the exact merits of which we have any present means of judging. Indeed, there is only one other world history that has come down to us, and this, the work of Justin, is in itself only an abridgment of the writing of another author, Trogus Pompeius. Considering when it was written, this work of Trogus, if we may judge from the abridgment, was an admirable production, and the abridgment itself is of great value in throwing light on some periods that otherwise are not well covered by extant documents. As a whole, however, it is a compendium of history rather than a comprehensive work like that of Diodorus. Of the works of the other world historians of antiquity it is impossible to speak with any measure of certainty. Polybius accredited Aphorus with being the only man who had written a world history before his day. It is known that Aphorus lived in the fifth century B.C., and that he was a fellow-pupil of another historian, Theopompus, in the famous school of Isocrates at Athens; but his work is only known to us through inadequate fragments and the indirect quotations of other authors. The same is true of the works of Theopompus just referred to, and of Timæus, another Greek whose writing had something of world historic comprehensiveness. But, even had these works been preserved, it may well be doubted whether any one of them would compare favourably with the great history of Diodorus, which must stand out for all time as the greatest illustration of the writing of world history in antiquity.

Diodorus, as we have seen, brought his work down to the time of the Gallic wars of Cæsar. There are references in his writing which imply that he lived well into the time of Augustus. He probably died not long before the beginning of the Christian era.