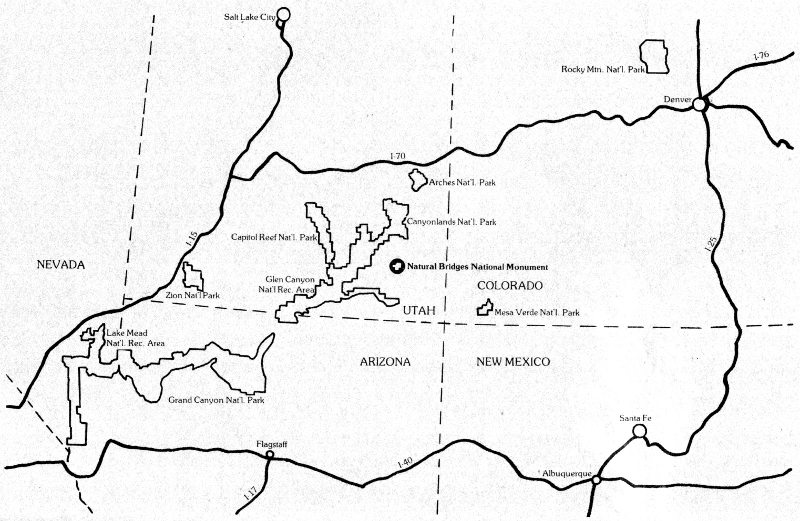

book designed and produced by visual communication center inc. denver, colorado

Published by the Canyonlands Natural History Association, an independent, non-profit corporation organized to complement the educational and environmental programs of the National Park Service.

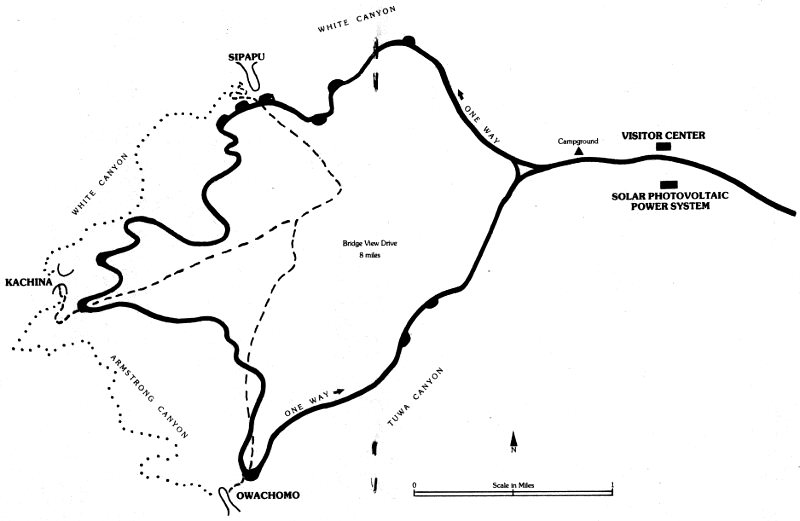

Visitor Center

Welcome to Natural Bridges National Monument. We hope you can take the time to enjoy a relaxed, leisurely visit to the area and that this Guide will help you to do so. If you are like most visitors, you came here specifically to see the three great bridges. If that is all that you want to do, you can get through the area in less than two hours.

We suggest, however, that you plan on spending more time here (if that’s possible in your situation). There are more things here to see and do, and more ways to look at the bridges, than you may have realized. You have invested time and money to get here and you will gain a better return on those investments if you can take a bit more time to visit the Monument.

As you drive along the road, you will occasionally find small parking areas with numbered posts that look like this:

The numbers on the posts refer to numbered sections of this Guide, and each section starts off something like this:

In the above example 4. is the stop number; this is the fourth stop on the trip, 1.7 is the distance (miles) from the previous stop, (4.8) is the mileage from the start of trip at the Visitor Center, and boldface words are the name of the stop.

Some sites are not described in the Guide; there are parking places without numbered posts. There are scenic views or other points of interest at these places, but we thought we’d leave some sites for you to “do your own thing,” if you wish.

At any stop, numbered or not, you must exercise care for your own and your children’s safety and you must be reasonable in your use of the park. There are many unfenced cliffs you can fall off, rocks you can trip over, and other natural hazards that could injure or kill you. We will remind you now and then about them, but we can’t protect you from every hazard. You have to do your part, too. Being reasonable in using the park involves things like not throwing rocks off cliffs (there may be someone below you), not entering or climbing on prehistoric ruins, not defacing things, and stuff like that.

Actually, if you and the Monument are both undamaged by your visit, we should all be very pleased that you chose to come here today.

Your visit to the bridges really begins in the Visitor Center. If you look over the exhibits, attend the slide program, and ask the Information Desk Ranger any questions you may have, you will have begun to collect data that should make the entire trip more pleasant. Then, with the preliminaries taken care of, step out the back door and walk to your right. From that point you and this guide are on your own.

HAVE A NICE DAY!

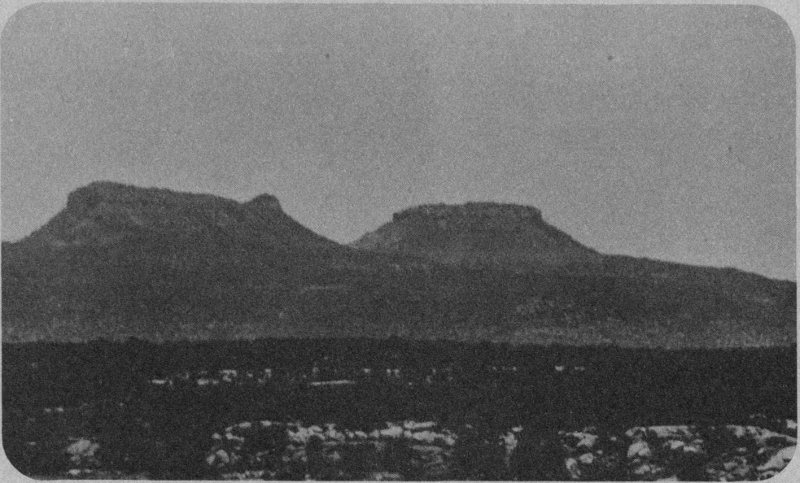

Bears Ears

The two buttes rising above Elk Ridge on the skyline are called the Bears Ears. If you have ever looked at a bear at all closely, you may wonder why the buttes are called Bears Ears. Well, we wonder about that sometimes, too, for they don’t look at all like the ears of a bear. “Bears Ears” is the officially approved name, but that name was bestowed by someone looking at the buttes from another angle. Seen from one point of view, physical features may appear completely different than from another point of view. Ideas are like that, too, in many cases. If we can look at things (including ideas) from a different point of view, we may better understand them.

So, we have tried to arrange this Guide in a way that allows you to experiment with a few things that you did not intend to do. The great majority of visitors here drive in, look at the three bridges and then drive out. You can still do that, of course, but this booklet suggests some additional things which we hope will add to your enjoyment of the Monument.

The first stop along the road is 1.4 miles from here.

This is another of those different point of view things. The guy who named this was looking at it from upper White Canyon. From that point of view (the opposite of yours) the resemblance to ancient Egyptian figures make the name quite reasonable, whereas from this side it makes no sense at all.

The light-colored, nearly white rock all over the place is Cedar Mesa Sandstone, a relatively hard, fine-grained rock. Scattered through it are thin layers of dark red shale rock which is much softer because it contains a lot of muddy silt. The softer red beds erode, or wear away, much more quickly than the hard white rock.

The long black or dark streaks on the rocks are desert varnish, a common occurrence here which we’ll explain at a later stop.

Sphinx Rock

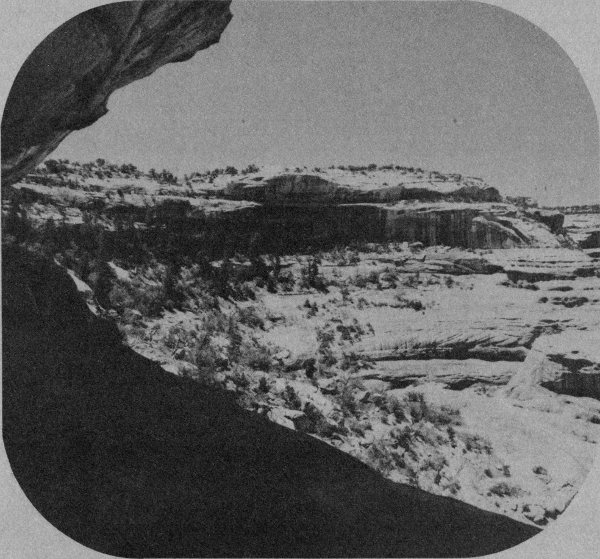

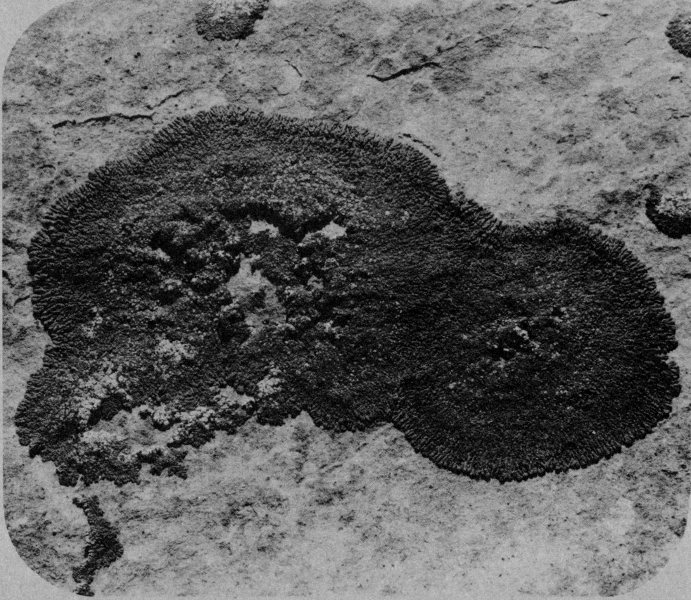

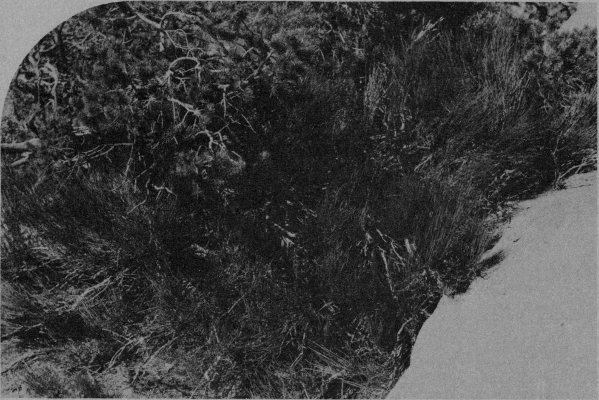

This is a nice place to try a different point of view. You came here to see the bridges, but at this stop why not get out and look at some other things of interest. You have to be careful scrambling over the rocks (the little arrow signs mark a fairly good route) and when you get out near the clifftop be very cautious, but there’s a beautiful view of the canyon. You can also see cryptogamic crust: a dark brown or black crusty layer on the soil, it is actually a very delicate plant community. DON’T WALK ON IT! Hop from rock to rock or follow the little drainages of bare sand. The cryptogamic soil is a combination of algae, fungi, lichens, and other odd plants, all dependent upon each other for some factor necessary to their lives.

Cryptogamic Crust; Detail

Douglas Fir

You will see a lot of it in the Monument; be careful not to damage it. A single footstep can destroy 25, 50 or 100 years of growth.

Ravens are a frequent sight in the canyon, flying or soaring along the cliffs. Big and black, they are readily recognized. More often, their throaty croaking call is heard and that’s easy to recognize, too.

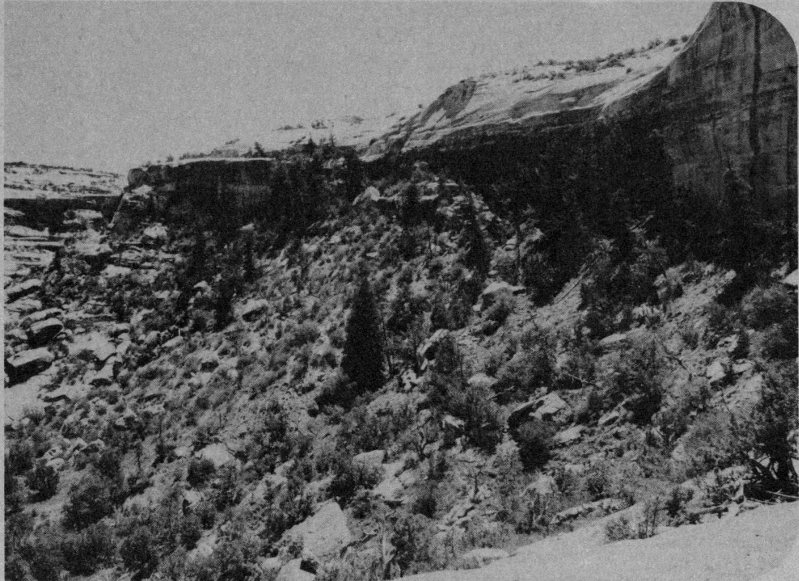

As you look along the canyon sides (not down in the bottom), note the trees on the slope and ledges—they’re different. Different from the stocky pinyon and juniper on top and different from the leafy green cottonwoods in the bottom. The tall, Christmas-tree-shaped evergreens are douglasfir. See any on the other side of the canyon? How about that? Why do they grow on only one side of the canyon?

This is another different point of view. You’ve come only a little way, you look at the same things (plus a few new ones), but it’s different.

Lichens

Lichens: Patches of color, bright or somber, like a thin crust on the rock. Blue, black, orange, red, brown, green, yellow and other colors. These represent another odd plant community. Lichens are a lot tougher than the cryptogamic crust, but it seems a shame to walk on them. They are algae and fungi that live intertwined lives. Neither can live alone; each is utterly dependent upon the other. Such things are called “symbiotic” or “symbiotes.” Incidentally, you’re a symbiote, too, in a way.

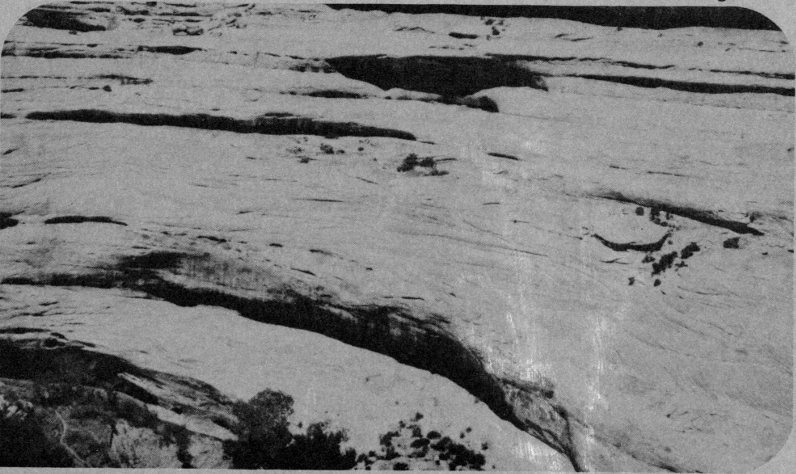

Crossbedding

“Crossbedding” is all over the place, and you can see it all through the Monument in cliffs, exposed rock faces of many kinds, boulders, etc. It is the numerous groups of thin layers of rock intersecting at odd angles. They are the result of wind-blown sands drifting across the landscape—a very different landscape than that you see. The Cedar Mesa Sandstone is largely made up of sands that drifted here in great dunes. The loose grains were later covered by more sediments, cemented 10 together by other minerals, and are now being uncovered and worn away by erosion. With each step, you free grains of sand that have been locked in place for about 180 million years. Those grains will now move on, eventually to come to rest and again become frozen in time. Rub the sandstone with your hand and feel the sand grains break loose.

There is an Indian ruin across the canyon. Can you see it?

The douglasfir community grows on the more shaded side of the canyon, for it cannot tolerate the hotter and drier environments on the sunny side or on the mesa top. In fact, the tops of most douglasfir growing near the cliff rise only to the level of the cliff top. Many have dead tops even with the cliffs edge. Hot dry winds from the mesa apparently kill the tops of these mountain forest trees, but we’re not really sure that’s the reason for the dead tops. Can you think of a better one?

Douglas Fir

Natural bridges are often described in terms like young, mature, and old, but the words have nothing to do with age in years. A “young” bridge has a great, massive span above a relatively small hole. An “old” bridge has a very thin span over a relatively large opening. A “mature” bridge is intermediate between young and old. The same terms can be used to describe natural arches—which form in a very different manner than do bridges. Remember, the terms reflect stages of development, not age in years (a mature bridge could be older in years than an old bridge!). Sipapu is mature.

Sipapu Bridge

You came here to see bridges and you got a good view of one at the last stop. Here is an outstanding opportunity for another, but different, view of that bridge. Two different views, in fact.

A trail starts here, proceeds about halfway down into the canyon and out along a ledge to an outstanding view of this beautiful, graceful bridge. It’s a fairly easy walk with guard rails, metal stairs, and other aids. You have to climb one short ladder. You can see an ancient Indian ruin, may learn quite a bit about the douglasfir community, and will get an excellent chance to photograph the bridge. You can walk out and back in about half an hour, but you may find that you want to take longer.

About halfway to the viewpoint, another trail takes off and goes right down into the canyon. DO NOT take that route unless you’re prepared for a much more ambitious hike. You need good footwear (like boots with a good sole for rock), drinking water in warm or hot weather, and plenty of time (allow 2-3 hours at least). It’s a nice trip and you’ll never really appreciate how huge this bridge is unless you stand under it, but we do not recommend the hike unless you are physically fit and properly prepared.

SPECIAL WARNING: When you make a trip into any canyon in this part of the country, beware of flash floods. Even if the weather is fine where you are, be on the lookout for thunderstorms or heavy rain upstream from your location. If it’s raining upstream, or if great towering clouds are building up, STAY OUT OF THE STREAMBED in the bottom of the canyon. NEVER CAMP in or next to a streambed in this region, even if it is dry. If you get caught by a healthy flash flood, you’re dead.

The following lettered paragraphs are coordinated with numbered stakes along the trail to the viewpoint. They help explain features as you see them. If you are not taking advantage of the different points of view here, turn to page 16. (It’s OK to read the trail guide even if you don’t take the walk.)

6

A

How’s this for a different point of

view? It used to be, when people

wanted to do what you are doing, that

they scrambled out on the rocks,

crawled across these logs and climbed

down the tree. That was the only way

down the cliff. Now you gain access

via the stairs, which cost a few

thousand of your tax dollars. Your

dollars, remember, not just

“Government funds.”

Now, some folks say we ruined the trip, that it’s no fun anymore. Others say we should have built wooden stairs, not metal. Some think this is fine and a few want nothing less than an elevator or tram. What do you think?

How does the difficulty of getting to a place affect your feeling for that place? How does it affect your opinion of the people who will not (we don’t mean those who can not) do what you are doing right now?

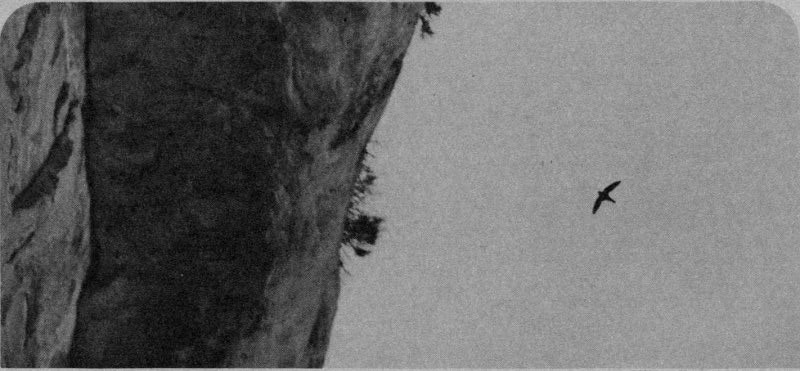

White Throated Swifts

6

B

A thousand years ago this

summer, a man stood where you

now stand and he watched the white

throated swifts sweep in and out of

cracks in the cliff above you. He didn’t

know they were white throated swifts

nor did he care. His main interest was

to see if any baby birds had fallen

from their nests into the pile of

manure. Many do, each year, and the

occupants of this land used any food

they could find.

In that 1,000 years, nearly a thousand generations of swifts have come and gone. Each year they return, nest in the cracks, wing their way through the canyons catching insects, and produce a new generation from the stuff of their environment. A thousand generations have passed; the swifts are still here. There are neither more nor less than the previous owner of the land watched a thousand years ago, and a thousand generations have left the environment ready for a thousand more. What of us—of Man?

Less than 50 generations of man have passed since the day your predecessor watched the birds from this point. Our numbers have increased to many times the number there were then and each of us uses many times as much from our environment.

Today we endure shortages of food, services and materials. Twenty-five years from now there will be twice as many of us. What will become of us? In fact, come to think of it, what became of the guy who watched the birds 1,000 years ago?

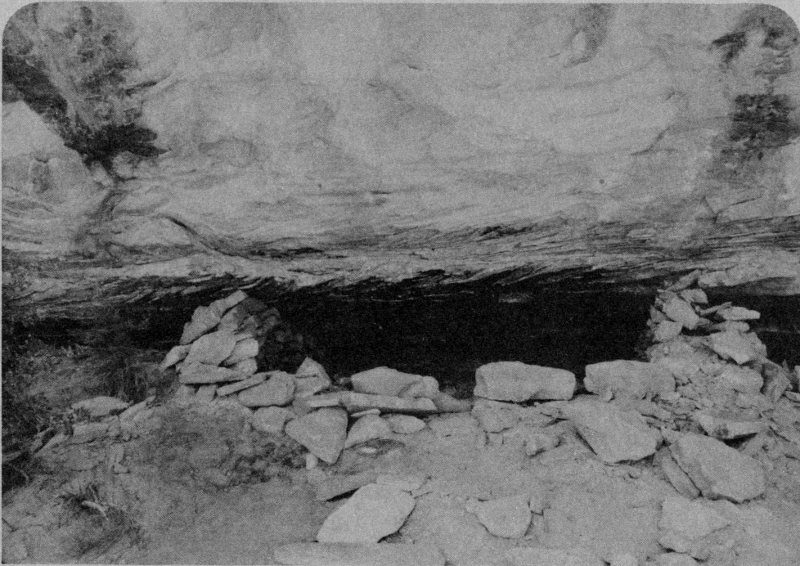

6

C

A few minutes ago we wrote of a

previous owner of this land who

gathered dead birds. Well, this is his

house. It may not look like much now

(and probably didn’t look an awful lot

better then), but it has become a little

rundown after 1,000 (800, or

whatever) years. He may have been

quite proud of it (it’s bigger than most)

14

and he built it all himself. No planes,

trains, barges, boats, trucks, or even

wheelbarrows. In fact, no wheels! A

family of Anasazis could have anything

they wanted, just so long as they

could get it by themselves.

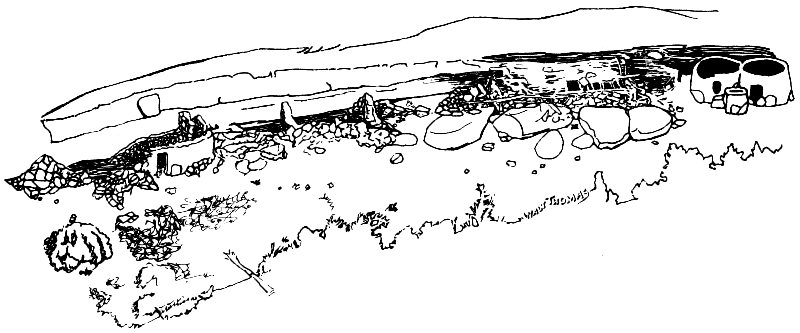

Anasazi Home

Please do not enter the ruin. In doing so, you can easily and innocently damage it. What we call “innocent vandalism” probably results in more irreparable damage than is caused by deliberate vandals.

The Anasazis probably did a little farming down in the canyon, growing and storing some corn, beans and squash. They gathered wild fruits and seeds and made fiber from native plants. They apparently led a difficult life, and probably ate anything they could get: lizards, snakes, birds, mice, squirrels, rabbits, and rarely a deer or bighorn sheep. Some scientists say they also ate each other, but we don’t know if this is true.

But the Anasazi lived within certain environmental limitations, just as we do. They needed food, water, fuel, and other resources, just as we do.

There came a time, about 700 years ago, when the environment here changed just a little. Annual rainfall patterns changed, there was a serious drought, and other factors may have 15 contributed. Whatever the reasons, the Anasazi world changed and Man could no longer survive here. Man, ancient or modern, can adapt to a certain range of environmental change. There are limits to adaptability, though, and if the changes exceed those limits, Man must move to a more suitable place or die. The Anasazi moved.

Your environment is changing very rapidly and the changes are world wide. Where will you move to?

6

D

Here it is, Sipapu. In Hopi Indian

legend, the Sipapu is a passage

between two very different worlds.

Some visitors see a similarity here.

Beneath your feet and all around you

is a world of slickrock: nearly barren

expanses of sandstone. But through

the Sipapu you can see a world of

vegetation: a softer, less harsh, more

pleasant world. One can almost

imagine that the Sipapu is a gateway

to another world.

As you go back up the trail to your car, consider again the different points of view along the trail.

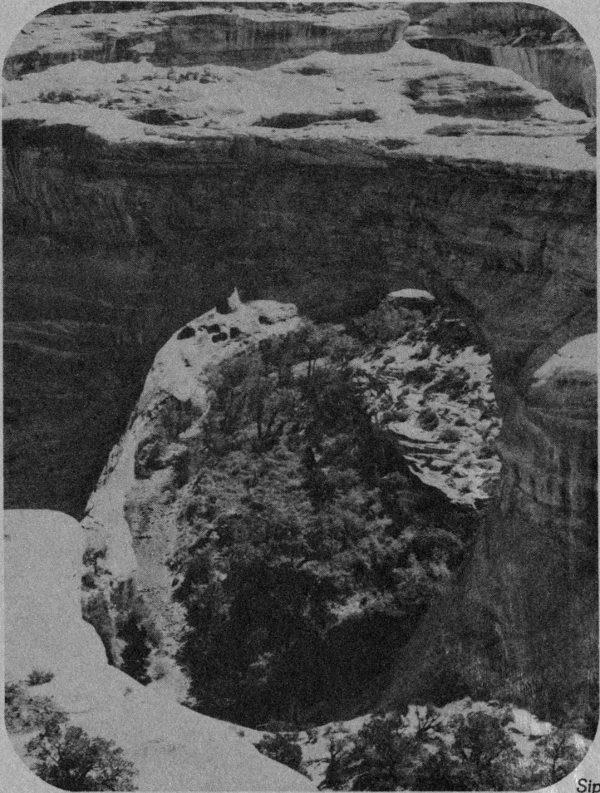

Sipapu Bridge

Now here’s an opportunity to adopt a truly different point of view: as different as it could be. We’d like you to be an Indian. Even if you already are an Indian, this walk will offer a different point of view because we want you to be an Anasazi Indian of about 800 years ago.

The trail is easy and has few hazards. Of course, you always have to exercise reasonable caution on trails or in any unfamiliar environment, but the main thing to beware of on this walk is the cliffs further out on the trail. There are abrupt, unfenced drop-offs and you and the kids have to be careful around them.

If you take the trail, try to put yourself in the place of a man of 800 years ago. We know you can’t simply forget your own rich heritage, but try for a brief period to set it aside, try to look at the things about you from a different point of view.

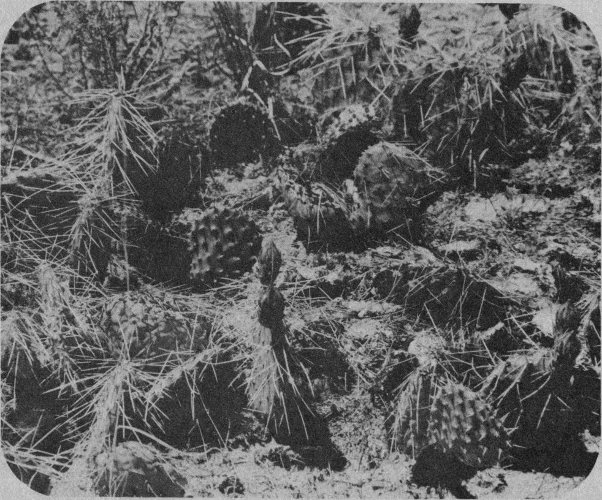

7

A

Na’va produces tangy, tart fruits

in good seasons. I like it; it’s one

of the few really tasty things in my

diet. You can eat the rest of the

cactus, too, after you scorch it, but I

don’t like it very much.

Prickly pear cactus

7

B

Mo’hu is a good plant. We eat

the seed pods, which usually

have tasty grubs in them. My woman

braids or twists the leaf fibers and

makes the nets, cords, and other

things a man needs. Mo’vi, the bottom

of the plant, helps make me clean

when I wash with it and cleans me

inside when I eat it.

7

C

Ersvi in hot water makes a drink I

take when my belly hurts or to

cure sickness. Many of us, mostly the

children, die from bellyaches and

fevers, but our medicine always makes

me well—or it has so far, anyway.

7

D

Na’shu is a really good tree, for

you can use it for many things.

The timber is good building material,

and the big seeds are good to eat

18

when the cones ripen and open.

Some years there are many of them,

and then the women need not work

so long for a supply.

7

E

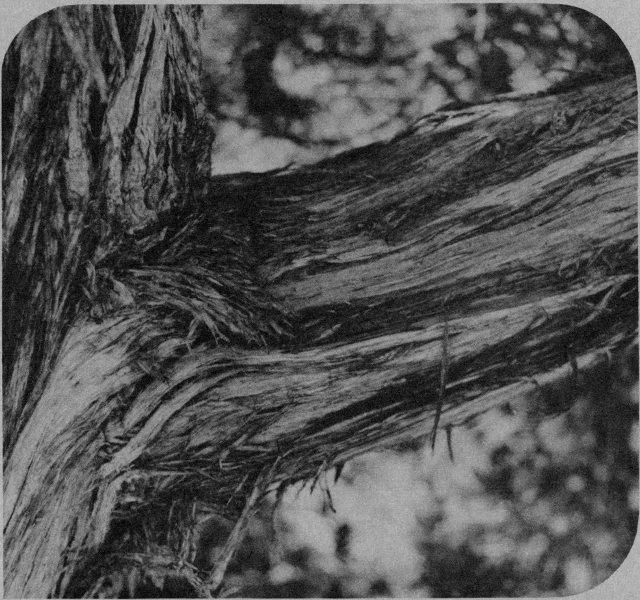

Ho’taki is another very good tree,

like Na’shu. We pull the long,

shaggy, coarse ho’lpe from the trunk

and branches to line our roofs.

Shredded very fine, it’s useful for

lining our baby’s clothes and my

woman needs it sometimes. I use the

wood for roof beams, too.

7

F

Owa’si, the rock flowers, are the

food of my war gods. We do not

eat them.

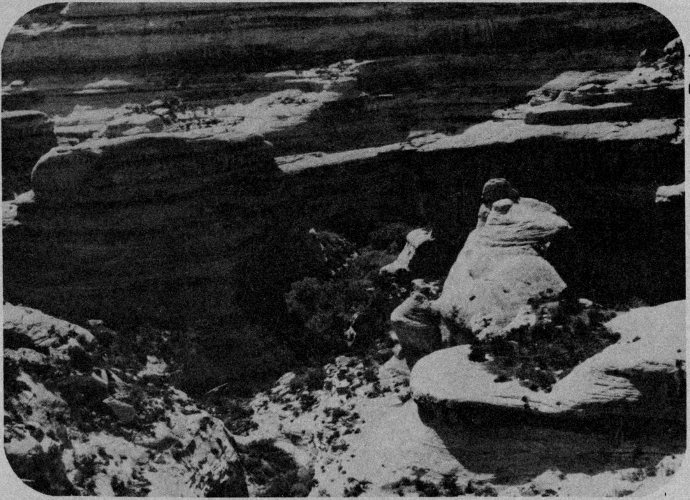

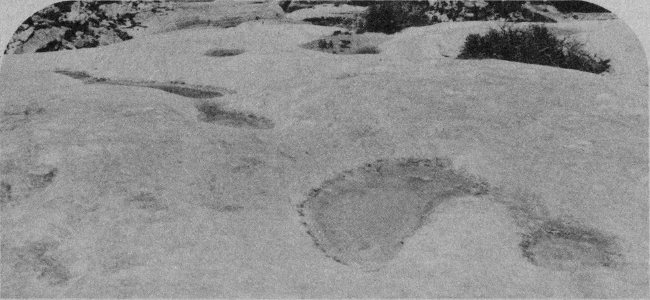

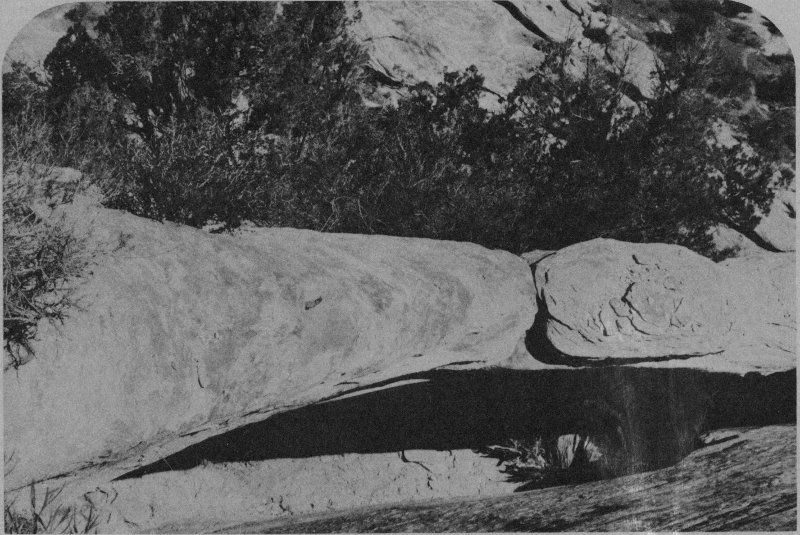

Potholes

7

G

I drink water from little pools like

these, sometimes when I have no

other water. The water often tastes

funny and has bugs in it. The deer,

bighorn sheep, and other animals

drink from these pools, too, when

there is any water.

7

H

Almost always, I can find lizards

in places like this. Even in winter,

on warm days, they come out and lie

on sunny rocks. Some years, when

our food is gone in late winter and

early spring, I eat them—but there

isn’t much meat on them.

7

I

There is our home! When I’m

hunting up here, I like to look

down at our village. It is a good place

to live. The sun shines under the cliff

in winter, warming the whole village,

but the cliff shades our houses in

summer.

The fields along the canyon floor have good crops most years, and our storage bins are usually full at the end of summer.

Well, I must leave you now, for I have much to do before dark. Good hunting!

You have come out here trying to see the world from the Anasazi point of view, we hope, but as you return you may wish to consider a 20th century point of view.

The 800-year-old buildings across the canyon and 500 feet below are called Horse Collar Ruin. It is a village of several homes, two kivas (ceremonial and religious building used by men only), and numerous storage bins. It may have been home for about 30 people. The brush covered flats along the stream were probably farmed, producing corn, beans, and other storable crops. Many other food sources were used; native plants and animals were eaten and provided numerous necessary “side products.” Hides, bone, horn, feather, bark, wood, etc., were the raw materials for many tools, implements and supplies.

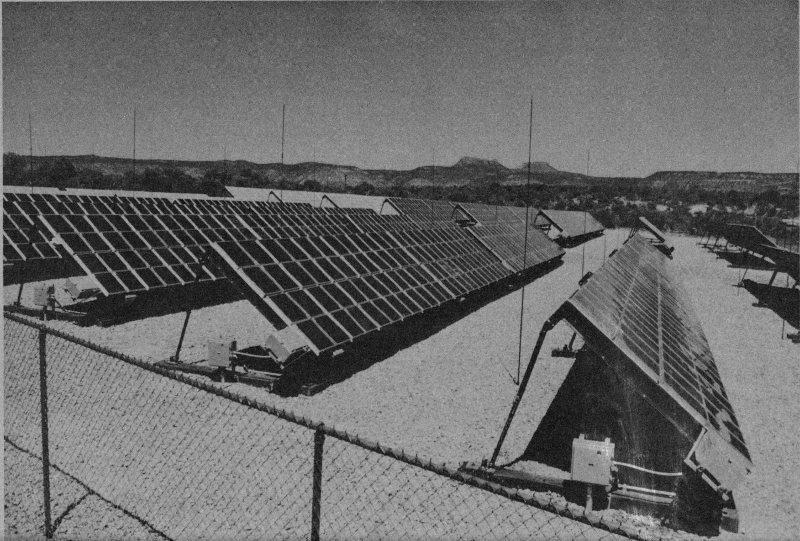

Anasazi villages were often located so as to be bathed in winter sunshine and shaded in summer. A somewhat more technological use of the sun’s energy provides most of the electricity used in the Monument today.

Horse Collar Ruin

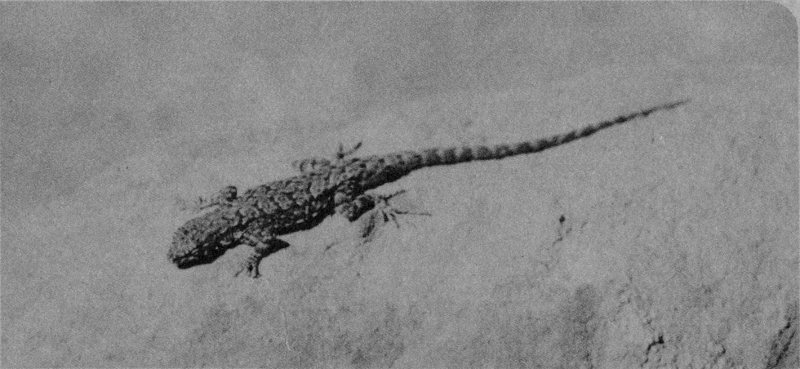

Lizard

7

H

You may see lizards just about

anywhere in the park. The more

common varieties in slickrock areas

like this are whiptails (very sleek,

streamlined; tail much longer than

body), eastern fence lizard (rough;

spiny; blue patches on throat and

belly), side-blotched lizard (long tail;

spiny; blue patch behind front legs).

7

G

Potholes, or rock pools, are a

common feature of flat sandstone

beds. Some reach great size and depth

and not all the steps in their development

are understood. Once a slight

depression is formed by erosion, it

holds water for a while after each rain.

The moisture dissolves some cement

and encourages more rapid erosion,

thus deepening the depression. The

depression thus holds water longer,

and so grows faster. Wind may sweep

away the loosened sand grains when

the pothole is dry.

7

F

Lichens are a “symbiotic” plant

association, as you may

remember. An alga and fungus grow

together, each providing to the other

an element necessary to life. Neither

can live alone; each is dependent

upon the other.

Lichens are rather effective agents of erosion, which seems a bit surprising for a thin crust on the rocks, but it’s true. Like most plants, lichens tend to make the immediate area more acid. The “cement” that holds sand grains together to make sandstone here is very susceptible to acid. The lichens create acid conditions, the acid dissolves the cement, and the sand grains are freed to blow or wash away. And that is what “erosion” is all about.

7

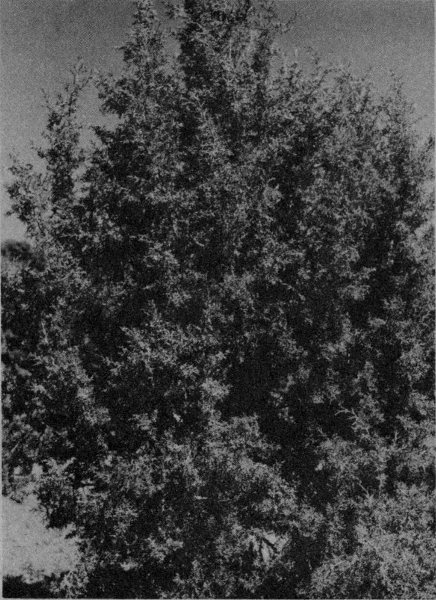

E

Juniper [Juniperus

osteosperma]. Various species of

juniper are common in the arid

southwest. As you climb from desert

grasslands to higher elevations, the

junipers are usually the first trees you

see. With pinyon pine, they often

form a dense “pigmy forest” of short,

burly trees. At slightly higher elevations,

where it is a little cooler and

moister, ponderosa pine and other

trees replace the pinyon-juniper. The

tiny scale-like needles on the twigs,

and abundant bluish berries make

junipers easy to identify.

Juniper

SIDE TRIP: This side trail will take you up to a knoll where you will have a 360 degree view of the Monument. It is the only place on your tour where you can gain such a view.

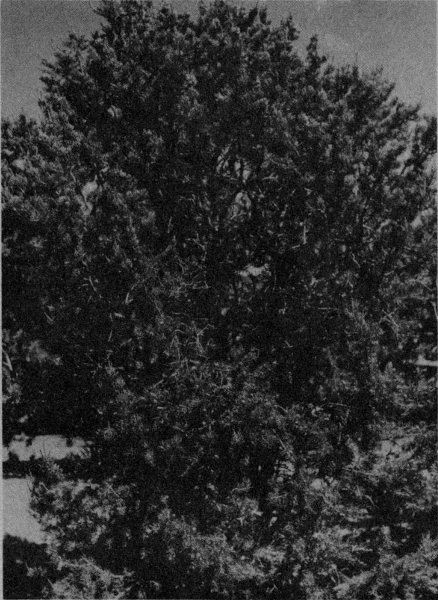

Pinyon

7

D

Pinyon [Pinus edulis]. Usually

found growing with junipers in the

pinyon-juniper woodland or pygmy

forest. Under ideal conditions, pinyon

may grow into quite respectable trees!

The seeds are still used as a staple diet

item by Southwestern Indians. As

pinyon “nuts,” they also find their way

into gourmet and specialty food shops.

The inconspicuous flowers appear in

spring and the cones mature a year

and a half later, in the fall.

Mormon Tea

7

C

Mormon tea [Ephedra viridis].

Used by Indians and pioneers as

a stimulant and medicine, the

beverage is still used as a spring tonic

by many.

Ephedra is really kind of a neat plant. Like most desert plants, it has evolved methods of conserving water. For one thing, it has no leaves. Look at it closely—it’s all stem. Plants can lose a lot of water from their leaves and many desert plants have leaves modified to reduce water loss, but Mormon tea has dispensed with leaves entirely (Well, almost entirely: they get very tiny ones in the spring, which soon fall off). Plants usually need green leaves to produce food, but Ephedra has many green stems that carry out that function.

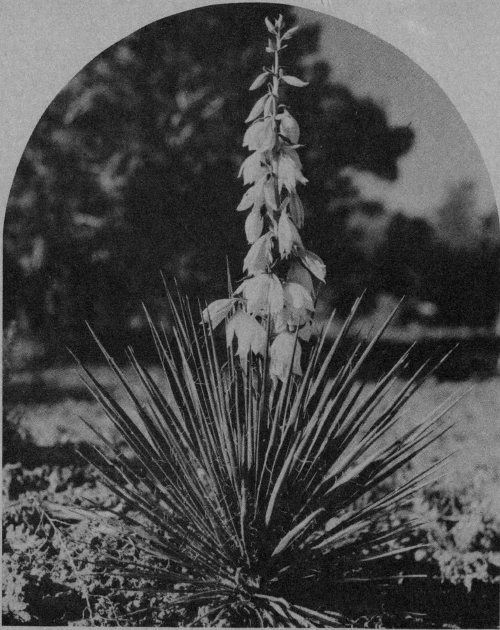

Yucca

7

B

Yucca [Yucca brevifolia]. The

yuccas are very common

throughout the Southwest, from low

desert to mountains. There are many

species, but they share one great

peculiarity. They are symbiotic with a

little white moth, the Pronuba.

Female Pronubas live in the blossoms. After mating, the moth collects a ball of yucca pollen and jams it onto the stigma (female part) of the flower. Yucca pollen is heavy and sticky; it doesn’t float around in the wind. Other insects do not transport it. The Pronuba insures that the plant will produce seeds by fertilizing the blossom and then she lays eggs in the base of the flower where the seeds will grow. The larvae that hatch from her eggs eat many seeds, but a lot of the seeds mature, too. The moth will not lay her eggs anywhere else.

The Pronuba must have yuccas to reproduce. The yuccas must have Pronubas to reproduce. Neither can get along without the other.

7

A

Prickly pear cactus [Opuntia].

Like all desert cactus, these are

well adapted to the arid environment.

Like Ephedra, cactus are all stem,

have no leaves, and the stems (or

“pads”) contain green chlorophyll, the

critically important element in food

production. Cactus spines are

modified leaves that serve as effective

protection, but are not functional food

producers. When moisture is

abundant, cactus pads get plump and

smooth. During extended dry spells,

the pads shrink and wrinkle as the

plant uses the stored water. How has

the weather been around here

recently? Look at the cactus and you

can tell!

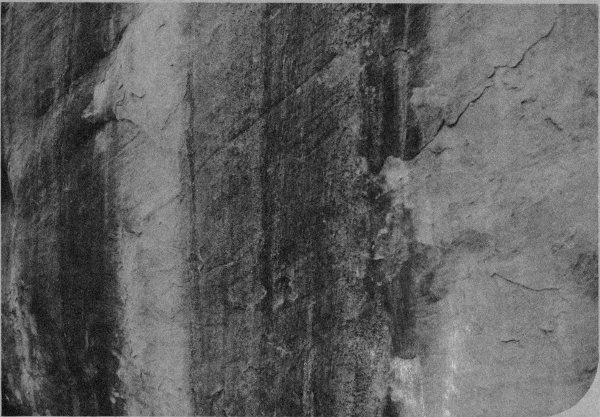

You won’t get a very good view of Kachina Bridge here, but you will find it much easier to understand how bridges are formed if you walk out to the canyon rim. There is no trail, but it’s an easy walk without unusual hazards other than the ever present cliffs. Remember, DON’T WALK ON THE CRYPTOGAMIC CRUST!

Desert Varnish

Desert varnish, the dark streaks on the canyon walls, is common in arid areas such as this. Each time the rock gets wet, some moisture is absorbed by the rock. Water actually seeps into tiny spaces between the grains of sand. Later, the moisture is drawn out of the rock and evaporated by hot, dry air. While inside the sandstone, however, the water dissolves minute amounts of minerals like iron and manganese. When the water comes to the rock surface and evaporates, the minerals come with it—but the 28 minerals do not evaporate. They accumulate on the surface of the rock over thousands of years, slowly forming a very thin dark crust.

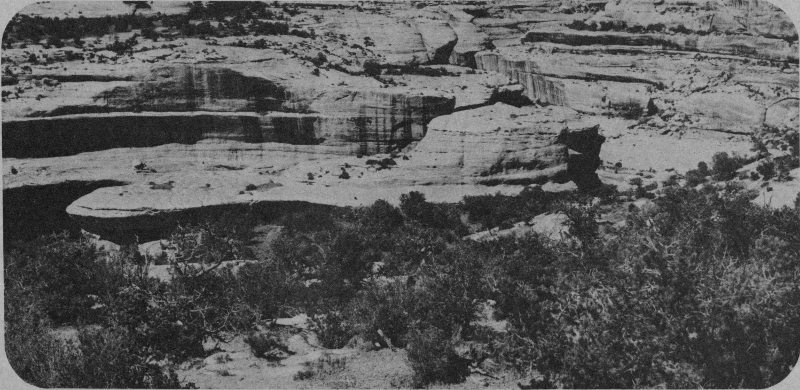

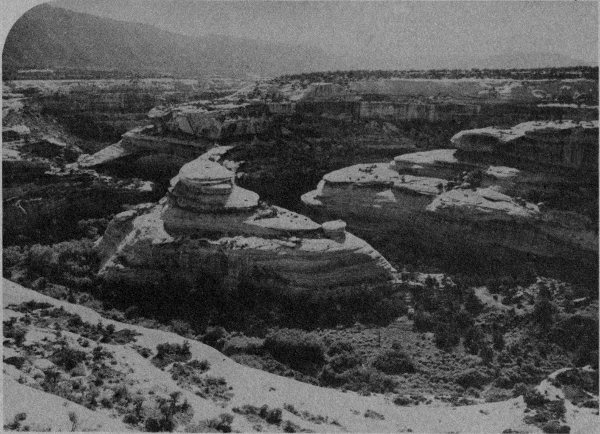

White Canyon

Notice the long, curving, fairly level valley right below you. This is an important part of the bridge formation story, for that valley was the stream channel before Kachina Bridge was formed. The stream now flows through the hole under the bridge, of course, but before there was a hole the water had to run around this side of the mass of rock that now forms the bridge. Every time White Canyon flooded (which is every time it rained very much), the stream cut a little deeper into the base of the rock and most of the cutting took place right where the stream was forced to turn toward you. As flood waters roared around this curving valley, the shape of the canyon also threw them against the downstream side of the obstructing wall of rock, so that the stream was eating into both sides of a fairly thin wall. It eventually ate right through the obstruction, and from then on the stream followed the shorter, straighter route. Continued erosion enlarged the opening and cut the channel deeper into the canyon. Downcutting of the new channel left this old channel high and dry. And there it sits!

Actually, the water coming down Armstrong Canyon (on the left) also contributed to bridge development, but we’ll get into that at a later stop.

Kachina Bridge

Kachina is an excellent example of a young bridge. The thick, heavy span crosses a relatively small opening. The span and abutments are massive, not slim and graceful.

Pictographs

Below the bridge are ancient pictographs (drawings on stone) that some people felt represented or at least looked like the Hopi Indian gods called Kachinas. So the original name was discarded and “Kachina” was substituted.

As at the other bridges, there is a very nice little trail down into the canyon. The trail is in good condition, you can walk it without special equipment, and it isn’t especially strenuous. It is a bit steep, so coming back on a hot day you may find the trip can be tedious. If the weather is fairly warm or hot today, you may also want to take water. An hour or hour and a half is adequate time to allow for the trip—unless you fool around a lot.

9

A

The Monument landscape is

typified by hundreds of ledges and

shelves separating the cliffs. Nearly all

the canyon walls are lined with such

ledges. That is because the rather hard

Cedar Mesa sandstone is seamed with

many thin layers of relatively soft rock.

The softer material erodes very much

faster, and as it wears away, the rock

above and below it is also exposed to

the elements. As a deep horizontal

crevice develops, support for the rock

above it is removed and chunks

eventually fall out. In time, a wide

ledge (or shelf, or bench, or whatever)

forms.

All of the above is happening here, right in front of you. This isn’t just an interesting formation, it’s a dynamic, continuing process that is changing the landscape.

9

B

The canyon coming around the

corner on your left is Armstrong

Canyon. It joins White Canyon on

your right. In front of you is a waterfall

(or it would be there if any water was

flowing) above a deep, narrow plunge

pool. This type of thing is often called

a “nick point,” and it is evidence of

some abrupt change in the canyon’s

development. In this case, that change

was probably formation of Kachina

Bridge, which changed the gradient,

or steepness, of the stream. The

water, rushing over the lip and

plunging into the pool, quarries out a

hollow under the lip. In time the lip

breaks off, the waterfall moves back a

few feet, and the process goes on. A

similar, but somewhat larger nick point

is Niagara Falls.

If the canyon is dry today, it may be a little difficult to believe the explanation. If you could be here just after a heavy rain, when the flood thunders over the rocks at a rate of thousands of gallons each second, you would find the whole thing more believable.

Nick Point

Little Arch

9

C

This little arch (it’s not a bridge)

may not win prizes for size, but it is

very handy for helping explain bridge

or arch growth. A bridge is first

formed by the action of running water,

but much of its subsequent growth is

like development of an arch. Water

seeps into tiny cracks, freezes in

winter, and pries flakes or blocks of

stone loose. Alternate heat and cold

causes rock to expand and contract

and that opens little cracks, causes

tension, etc. If the rock has natural

planes in it, it may break away along

those lines.

If you look at the underside and sides of this little arch, you can see evidence of these processes. Please don’t “help nature along” by prying pieces loose.

This arch may not have been here very many centuries, but it is a very “old” arch. Thin and delicate, the fragile span over a relatively huge opening is near the end of its life.

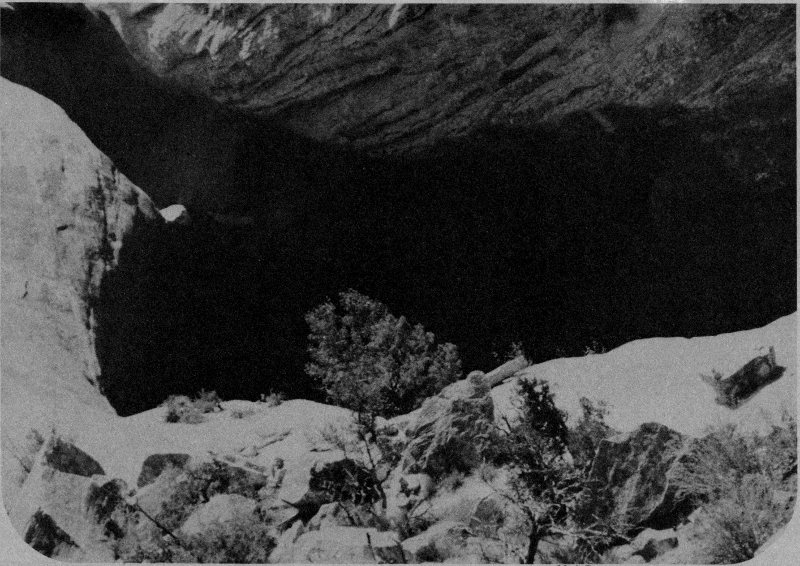

9

D

Back when we explained bridge

formation and abandoned

meanders, we said Armstrong

Canyon’s run-off played an important

role in Kachina’s development and

that we would explain it “later.”

Well, now is later. Before the opening was formed, while White Canyon run-off came around the channel on your right, Armstrong Canyon run-off flowed down the channel from your left and rushed right against the rock wall that once existed where the opening now is. Flood waters roaring down Armstrong would rush out its mouth, cross the White Canyon streambed, and smash into that rock wall. Floods carry great loads of sediment: sand, gravel, pebbles, rocks and boulders. These are the teeth of a flood, the sand and boulders. They are the agents of erosion that bang, smash and batter any obstruction. It is a bit like a liquid saw with stone teeth. It’s an act of violence, a cataclysm, a ripping and tearing. There really isn’t anything nice or gentle about it, but it’s a great way to undercut rock walls and gnaw holes in them!

And that is precisely what it did.

Well, that’s about enough for a while. You are more than halfway through the Monument and we’ve been telling you what to see, do, and think entirely long enough. Go now, and just enjoy the rest of this lovely walk. Walk the trail in leisure and peace. At the bridge are ancient ruins and irreplaceable prehistoric rock art. Let them speak to you, respect them, and consider your long gone predecessors here. Consider your place here, too, and the role you play in our beautiful little world.

BEWARE! And go cautiously, for there are spirits here that will make you part of this land and forever call you back!

Ancient Ruins and Rock Art

Owachomo is a lovely bridge. Long, thin, flat; a fragile old bridge nearing its logical and inevitable end: collapse. The opening grows very slowly under an old bridge. The opening widens as the bridge abutments wear away and the overhead span (the bridge itself) becomes thinner and thinner, one grain of sand at a time.

The walk down to this bridge is the easiest of all. You can be down and back in a half hour (as usual, we recommend that you take longer). It is not strenuous, compared with the other two, and it offers some nice insights about bridges. In other words, here’s another different point of view. Owachomo is sort of a different kind of natural bridge, for it was formed differently than the others. We’ll explain that when you get down there.

10

A

We haven’t said very much about

wildlife here, mostly because you

aren’t likely to see much of it. Here

however, you can see the work of a

porcupine. Porcupines like to eat

pinyon bark at times, and this pinyon

must be pretty tasty. The large rodents

gnaw at the tree to get at the

nutritious inner bark, and may in time

kill the tree by girdling it. The inner

bark carries needed food and water

between roots and leaves (both up

and down), and if all the lifelines

between the top and bottom of the

tree are severed, the top will die.

No, we don’t try to “protect” the tree from porcupines. We call this a natural area, and that means it is an area where we try to let natural events proceed without the interference of man. That isn’t just “protection” of things, it’s protection of a system. It just means that if the porcupine wants to eat the pinyon, let him do it. It doesn’t mean the porcupine is “worth” more than the pine, nor vice versa. Each has its own place, its own life, and its own interactions with the rest of the world. Just like you do!

10

B

This is a good place to consider

Owachomo’s origin and

evolution.

Run-off from a large area used to flow down the little canyon (Tuwa Canyon) in front of you, along the base of a rock fin, and into Armstrong Canyon behind you to your right. Owachomo did not exist; there was no natural bridge at that time. Flood waters rushing down this side of the fin ate into the base of the fin and flood waters of Armstrong Canyon ate into the other side. A hole developed in the fin, creating the bridge and allowing Tuwa’s run-off a shorter route to Armstrong.

So, Owachomo was formed by the action of two separate streams, and that makes it different from Kachina and Sipapu (and most other natural bridges we know about).

Owachomo Bridge

Erosion is a continuing, dynamic process; however, stream channels gradually change. The run-off from Tuwa no longer flows through the little canyon in front of you because there is now a deeper canyon on the other side of the bridge fin.

10

C

Passing the “Unmaintained Trail”

sign isn’t like abandoning all

hope, but it does mean that the trail

may be harder to follow and that we

don’t do as much to protect or help

you. Some hikers continue from here

and go all the way back to Sipapu via

the canyon’s trail. Many people start at

Sipapu and come out this way (which

is a lot easier), but a few start here

and go back. It isn’t really a terribly

difficult hike, either way, and it is a lot

of fun.

Owachomo must once have looked like Kachina—massive, solid, strong. Later, it was more like Sipapu—graceful and well balanced. Now it looks only like itself and the even more fragile Landscape Arch in Arches National Park.

At some time soon, one more grain will fall, a crack will race through the stone, and the bridge will be a heap of rubble in the canyon. We’ll probably run around and yell a lot when it happens, while the sand grains will quietly continue to break free and begin the next phase of their existence.

If you decide to walk on under the bridge, look behind the left abutment. There, a thin bed of the softer red stone has eroded back under the harder stuff of which the bridge is made. As erosion eats into the red-bed, removing support from the abutment, the future of the bridge becomes less and less secure. Frankly, we always feel a little nervous standing under it (where you are now) because it might collapse ... now!

As you return to your car, be aware that you may hear the death roar of Owachomo. The final, critical grain of sand may slip out of place, a bird may land on the bridge, or one of your military jets may pass at supersonic speed. However it happens, Owachomo must someday fall. And its billions of sand grains must continue their journey to another resting place, and that’s the way it ought to be.

To your right, across what appears as a fairly level stretch of pinyon-juniper forest, the Cedar Mesa sandstone is cut, slashed, incised, and divided by a bewildering complex of canyons. Slightly to the left of the “flats,” Maverick Point, Bears Ears, and long Elk Ridge (named by and for three cowboys with the initials E, L, and K, if you’d like another point of view!) form the skyline. Bears Ears, by the way, was named by Spanish explorers far to the south, from which point they look just like a bear peeking over the ridge.

If sunset is imminent, stay right here. Sunsets are sometimes very spectacular here.

Now go, and travel in peace, comfort and safety. Come again when the Canyon Country calls, if you can, but remember always that it remains here waiting, free, beautiful and untamed.

If you have questions about this magnificent land, stop at the Visitor Center. The men and women of the National Park Service will be greatly pleased to talk with you of this and the 300 other areas they serve for you and your children. And their children. And theirs.

Sunset Point

Solar Photovoltaic Power System

Most of the electricity used in the Monument is produced by converting sunlight directly into electricity. The process seems a little bit like magic, but it really does work. The system here is a demonstration of the feasibility of supplying small, remotely located communities with electricity without using fossil fuels to produce it. This process is liable to become very widely used within a decade, so the Natural Bridges installation is sort of a peek into the future. Exhibits and information leaflet explain the system in detail.