This cover was produced by the transcriber

and remains in the public domain.

This cover was produced by the transcriber

and remains in the public domain.

FRONTISPIECE.

In the beautiful vale of Ravensworth, is situated a commodious farm house: the proprietors treat all their domestic animals with humanity, and provide every possible convenience for them. The poultry yard is large and clean, at the bottom of it runs a clear brook, in which you may always see a number of ducks and geese sporting.

One day, as an old speckled hen was scratching up some grubs for her numerous family, one of her chicks came running up to her. Oh, mother, pray do go and kill the young bantam cock! Why? replied the mother. Oh! he has behaved to me worse than ever any chicken behaved to another, and I will be revenged; I know I cannot fight him myself, but I hope you will. Not till I know how he has offended. Why, I had just scratched up a fine fat worm, and was cackling with delight, thinking what a nice feast I should have, when the nasty little bantum came, snatched it from me, ran away with it, and eat it, even before my face.

Doubtless he has behaved very improperly, replied the old hen; but that is no reason you should; the best way of revenging yourself, is to take no notice of him, or ever play with him again; instead of wasting your time in quarrelling, search for another. What! and not punish him for so very unjust an action! did you ever hear of any thing so shameful before? Oh yes, many things. I should like to hear one of them. Well, my dear, I have no objection; but as it is so very hot, it would be better to go under the shade of the laburnum, and I will then relate to you the chief occurrences of my eventful life. The old hen then walked stately on, followed by her chickens; and having got upon a stone, to be a little higher than her audience, the young ones ranged themselves round her, and she began as follows:

I was hatched with six more in a large nest, formed by my mother; as soon as we broke the shell, she carefully threw out every thing she thought would hurt our tender bodies, spread her warm wings over us, and prattled us to sleep: when we awoke, we complained of hunger; she immediately went forth in search of food, but, alas! we never saw her more.

There chanced to be a large strange dog in the yard, my mother thinking he came to destroy us, flew at him, the contest was unequal, the dog provoked, seized my mother by the neck, and strangled her.

We lay cold and comfortless, wondering what had become of our parent. Before night, two of my brothers died; and we should all soon have shared their fate, had not a little girl, the farmer's daughter, found us: she took us to the fire, and fed us with a little warm milk and bread, which revived us; she then wrapped us up in flannel, and put us in a little basket, which she put in the chimney corner. She fed us very regularly; but I suppose not with proper food, as all my poor sisters and brothers died, probably I was stronger than they. My little mistress grew very fond of me, as I would eat out of her hand, and when she called chickee, would run to her.

As I grew large, I was very troublesome in flying upon the tables, and pecking at every thing; many severe blows I got from the farmer and his servants; who always ended by saying, if that troublesome fowl is not sent into the poultry yard, it shall certainly be killed; but my mistress always begged that I might stay a little longer, for she feared the other fowls would drive me away.

And indeed I had not endeavoured to make friends of any of them; but when the door was open, and I could see them, I insulted them, with calling out, poor creatures! you are obliged to work hard all day, and can scarcely get enough to eat, while I am fed plentifully with the greatest dainties, and have nothing to do but amuse myself. An old hen who had been a friend of my mother's, offered to supply her place, in teaching me how to scratch for myself; but I rejected her kind advice with disdain.

Nursing the chicken.

At last my young mistress could keep me no longer, her father insisted that I should either be killed, or go with the rest of my species, and setting open the door they fairly hunted me out.

Now it was my turn to experience mortification: numbers had been witnesses of my disgraceful exit, and taunted me with, so her ladyship is obliged to come among the working people; I suppose food will come flying to her, as she is of too much consequence to work; I wonder if her claws are differently made to ours?

In the evening, when the servant came to scatter corn, I was very hungry, and thought that would be a nice treat for me; but, alas! coarse as the food was, it was denied me; no one would suffer me to partake, but flew at, and pecked me whenever I attempted it, saying, no, no, mistress, you shall have none of this, we who have done our duty, may be rewarded; but what have you done? nothing. Thus was I driven from society, a thousand times did I wish that I had never known any other pleasure than the rest, and that my mistress had not nursed me so tenderly; but she did it from kindness, and I shall ever respect her memory.

One morning I was rudely seized, and put with several more into a small wicker basket, to be taken to market: my sensations upon that occasion, no words can describe; to the market we came, and were exposed for sale.

Putting the hen into the basket.

Numbers came to inquire our price, I was lifted up, and pricked, and pulled about, to see whether I was fat; but the distress I had of late been in, had made me very thin, I was therefore always thrown down again, with this observation, why, what a bag of bones this hussey is, I would not have her if you would give her to me.

All my companions were sold, and I remained till night tired and hungry. Towards the close of the market, when the people were preparing to return home, a little girl passed by me with a piece of bread in her hand; urged by hunger I pecked at it, and when she patted me, though my poor sides were all over bruises, I would not appear as if she hurt me, but rubbed my head against her hand; she seemed much delighted with me, crying out, Oh! what a nice tame little creature, how I wish you were mine, but I fear I have not money enough to buy you. Why what can you give? (said the man who brought me from the farm.) I have but one shilling; but I will give you all that. Very well, you shall have it then, for I am sure there is not any use in taking it back.

Little Ann, my new mistress, took me directly home; her mother lived in a thatched cottage, and was very poor: when she heard Ann had given all her money for me, she was very angry. Oh dear mother! you know it will soon lay eggs, which we can sell, and get chickens besides. You foolish girl, you cannot get both, what do you intend to feed it with? and we have no place to keep it in. Oh, we can keep it very well in the wood house, I will put up a perch for it, we will give it some crumbs to night, and to morrow it will provide for itself.

Purchasing the hen.

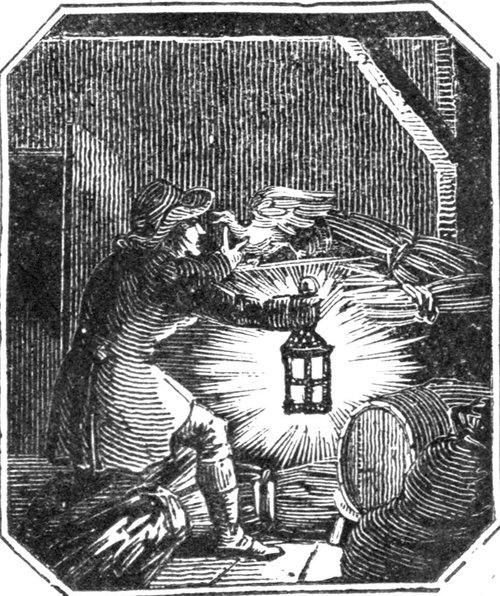

I accordingly had a good supper and went to rest in a clay hovel, very different to what I had been accustomed to, but I thought how much worse my situation might have been; my fatigue and anxiety soon put me into a sound sleep, from which I was awakened, by being violently laid hold of. When I opened my eyes, I saw a great ugly man who held a sack and lanthorn in his hand. Oh! oh! mistress hen, I did not expect such luck, you will be a nice addition to my stock: he then threw me into the sack, which he flung over his shoulder, and walked a considerable way; this mode of carrying me, together with my sore bruises, produced such violent pain, that I grew quite insensible; when I recovered, I found myself confined with several of my fellow creatures in a large hen-coop, they told me they had all been stolen by the same man, some had been torn from their children, husbands, or parents. I asked for what purpose. What! can you be ignorant that he intends taking us to market to be killed, and eaten? At the thought of being exposed in my present miserable condition to be handled by the multitude, my blood froze in my veins.

Stealing the hen.

I passed about a week in this coop; we were well fed, as our keeper wished to make us fat. One night we were alarmed with a tremendous noise, I turned to inquire the cause, when I saw the brave white cock trembling like a chick: oh! said he, give yourselves over now, nothing can save us from destruction, we shall all be devoured; no sooner had he said this, but a large fox entered; Oh! my children, how can I describe the horrors of the bloody scene which followed, even at this distance of time, the recollection draws tears from my eyes; I alone remained of all my companions; he was advancing to me, when some noise in the yard frightened him, and he ran away, leaving me more dead than alive with fright.

After he had been gone some time, I considered that if I stayed where I was, in a few days I should be taken to market: the board which the fox had broken down, offered the way to escape; but where was I to go to, how should I know the way to the cottage of Ann? but the market was worse to my imagination than any other thing. I went through the opening, flew down, and found myself in the open road, I ran as fast as possible, only stopping to take breath, or a mouthful of food; many frights had I before night, from dogs, boys, &c. As the sun was setting, I came to a fine large garden, with a high wall round it; I flew to the top, and not seeing any person in it, I thought I would look out for some grubs, or worms, in a fine bed of newly turned up mould, and then go to rest upon one of the trees; I had scarcely began my search, when I found in the ground some very pleasant tasted seeds, which I began to devour, when I received a blow upon my wing from a stone, and looking up, I beheld the gardener coming forward in a furious passion. So I have now discovered who it is that scratches up all my seeds; but these are the last you shall ever taste, believe me; saying this, he seized me in the most brutal manner. I screamed violently; by this time, another man came up, and said, Why, Thomas, what will you do with it? if it had been a cock, you might have had fine sport with it, in throwing sticks at it. And why can't I at a hen, pray? Oh, why nobody ever does. Well then, I will be the first to throw; I will take her to the village, tie her to a stake, and the boys shall have a throw for a halfpenny a piece.

While they were carrying me away, a lovely looking boy asked them what they were going to do with me. To make a cock-shye. Master, what is that? To throw sticks at it till it is killed. Oh, heavens! you surely are jesting, you cannot have so much barbarity? As to that, it has had the barbarity to eat up my seeds, to repay me for them, the nasty creature shall pay its life.

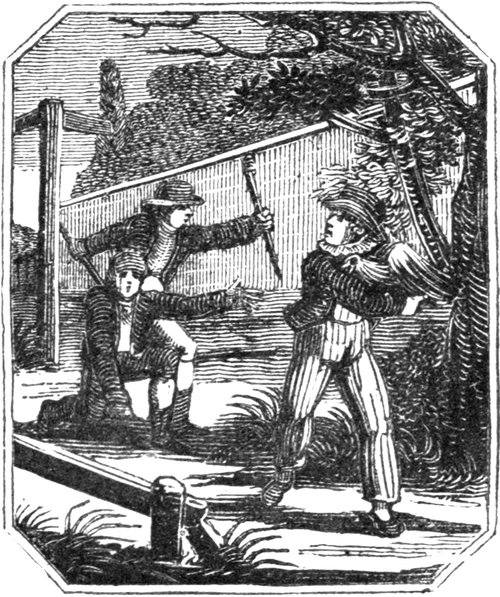

The young gentleman, whose name was Augustus Manly, entreated that he might purchase me, and offered half a crown; but the man determined I should have a few blows, and tied me to the stake, when Augustus seeming to be inspired with more than ordinary courage, threw down his half crown, and lifting me from the ground, when the barbarous gardeners were not looking, ran off with me in his arms: the men could not overtake him by running, but were cowardly enough to throw a stone, which struck me on the breast; but by the care of this humane boy, I soon entirely recovered.

Taking away the hen.

My master was a pupil in a very large school; the house in which he boarded, accommodated twelve more, but none so kind as himself; many slight injuries I received, but I considered how much worse my lot had been, and felicitated myself accordingly; but too soon I felt the most acute torments.

My master was often laughed at by the other boys for his fondness for me: I loved him so much, that whenever he came into the yard, I ran to meet him, would feed out of his hand, or fly upon his shoulder, but this I would never do to any other boy, and by this I suppose it was which made them hate me.

One day two of them came into the garden to read, the story they fixed upon was, unfortunately for me, that cruel one of Diogenes stripping a cock of all its feathers, and throwing it into the middle of the school where Plato was instructing his disciples; crying, 'there is Plato's man for you.' They laughed heartily at this, and one of them cried out, Oh! the most admirable thought has struck me! let us serve Manly's hen in the same way, and when he is in bed to night, we will open the door, and throw it at him, and cry out, 'there is Manly's lady for you.' This was highly approved of, and I was accordingly seized, and stripped of my feathers. Oh! Dickey, was not this far more unjust than the young bantum's taking your worm from you? that could give you no pain, but the tortures I endured, no one can possibly imagine; the blood flowed copiously, the skin was torn from the flesh, I wished for death to put an end to my torments, but that was denied.

At night they fulfilled their intention, my benefactor was truly distressed to see my miserable condition, and taking me to the mistress of the house, and implored her assistance to cure me; she wished to have me killed instantly, but that he would not consent to. As she was a humane woman, she endeavoured to cure me; and got some oil, which she carefully rubbed over me, and I was kept in a place where these wicked boys could not come to me. I had the pleasure of hearing that these boys had been expelled from the school, the greatest disgrace that could befall them.

It was long before I was entirely recovered; the next holidays Augustus determined to take me home with him, and leave me in charge of his amiable sister, whom he knew would nurse me tenderly. There I may say I was perfectly happy for some time. I became a mother, and had the delight of seeing my children beloved by Augustus and his sister.

Once, owing to the carelessness of a servant, I hatched some duck eggs, I did not perceive the mistake, till taking my chickens (as I thought them) out, to teach them to scratch, they all ran towards the water; in vain I called after them to stop, that they would be drowned if they attempted to go in; deaf to my entreaties, they threw themselves in, I came to the pond in all the agonies of despair, expecting to see all my precious little ones dead; but, to my astonishment, they were all swimming merrily. A duck with whom I was intimate (for I made it a rule to treat all the domestic fowls with civility) came up and assured me she would take care of my young charge while they were on the water, and teach them to swim.

Soon after, Augustus intended giving a supper to some of his friends, and it was proposed that each one should bring his favourite dish; Charles Mellish, Manly's cousin, was staying with him, he was a boy of an ardent temper, and would do any thing by way of frolic, or what he called fun; from the time this supper was proposed, he determined his dish should differ from every other persons, he accordingly procured from the cook a large pie dish and cover, and when the party assembled, he came into the poultry yard, seized me, and in spite of my peeking and scratching, forced me into it, covered me over with leaves, and placed the lid on; when he entered the parlour, I heard a number of little voices say, I wonder what Charles has got. He replied, something different to any one else I think; but before I let you see what it is, I must make an agreement that if it is different, every one of the ladies shall give me a kiss; but if any other person ever thought of bringing the same, every one in the room shall have the liberty to give me a slap on the face. This being agreed to, he set the dish upon the table, and took off the lid; I, who had been sadly cramped, immediately flew out, to the great astonishment of all present. I suppose master Charles received the reward from the ladies, but of that I did not wait to be witness; but ran out of the room as fast as possible.

Charles's dish.

Not long after, I was again seized by the same gentleman, who having discovered that miss Manly, and a party of her friends were assembled round a small fire, telling terrible stories of ghosts and murders, resolved to frighten them; he placed a ladder by the side of the chimney, and mounting it, put me in at the top. I was glad to escape from him, so I flew down the chimney, carrying the soot with me, which suddenly put out the fire; and when I entered the room, the most terrible screams were heard from all quarters; the servants soon came in with lights, to know what misfortune had happened, to occasion such an uproar. I had hidden myself in a corner of the room; one of the young ladies said it must be a ghost, that they had been sitting very quietly, when suddenly they heard a tremendous noise, the fire was extinguished in an instant, that a thick cloud of smoke followed, and a great black thing, the shape of which she could not distinguish, knocked against her face, and threw her down. By this time, Charles had joined them, and hearing such exaggerated stories, burst into a hearty laugh. You may laugh, said one of the ladies, but had you been here when it happened, you would have been as frightened as we were, it could not be fancy, for see the fire is out, and what a strong smell of sulphur is in the room.

The fright.

What would you think of me, if I discovered the cause of this wonderful affair? I should think you very clever indeed. Well then, give me a candle and I will soon find the ghost; he then took one off the table and by its assistance, soon discovered poor me sitting disconsolate under the table; at this the whole party joined in a hearty laugh; except myself, who had got some soot in my eyes, which made them very painful. Augustus took me in his arms, my poor hen, said he, you have had many strange adventures, and if you should ever take it into your head to write them (for all animals write their lives now-a-days), you shall make good mention of me, for I will now give you a good supper after your troubles.

At the idea of a hen's writing her adventures, the party was highly diverted; no, said they, that can never be, as a domestic fowl can know nothing out of the poultry yard, and that would never be worth reading; but I think, my children, that some of the adventures I have gone through, are almost as wonderful as those of cats and dogs, which I hear are published in little books: talking of cats, I once had a severe combat with one of them, in which I nearly lost one of my eyes, and had many feathers torn off: as to dogs, I was always afraid of approaching them, remembering the melancholy fate of my poor mother.

One time, when the family was paying a visit, orders were sent to the servant to fatten one of the fowls, then kill it, and send it to a poor neighbour who was sick; I was the one pitched upon, and was confined in a little coop, where I could scarcely turn round, much less take that exercise which is necessary to health, my confinement was still more distressing, when looking out, I could see all my companions enjoying themselves, how I longed to join in their sports.

I loathed the quantities of food brought me, and would freely have given a saucer full of delicious white bread softened with cream, for the delight of scratching up a worm for myself; but though I had no appetite I ate, because I had nothing else to do; and that being such voluptuous food, soon made me excessively fat, which caused me much pain, as I could scarcely breathe. I look forward with joy to the time, when the murderer's knife would end my miseries; the day was fixed.

On the morning of that day, to my astonishment, I saw Augustus enter the yard, he had returned from his visit much sooner than was expected: when I saw him, I thought of all his kindness, and wished to hear him speak once more before I died; for which purpose, I called as intelligibly as I could to him; at last I had the pleasure of hearing him say, what can be the matter with that poor hen which is confined, I never heard so pitiful a cry! Upon seeing it was his old favourite, Oh! my poor bird, said he, were you so near being killed; but I am very glad I have come in time to save you; saying this, he opened the door, and gave me liberty, that greatest of all blessings.

I was expressing, in my language, my thanks, when Susan entered with her knife; Oh! Susan, how could you think of killing this my favourite? Pray sir, how should I know which you please to call your favourite? All hens are alike to me, I caught the one which was nearest to me, and as it is now fattened, we must have it, and you may take another favourite. No, this one you shall never kill; it is cruel to destroy any, but this which knows me so well, and is so tame, I never will have it killed; so saying, he carried me away, leaving Sue in a great passion.

Soon after, my young master had to go to a boarding school, near London; his mamma accompanied him, and shut up her house; what was to be done with me, engaged much of his thoughts; at last he determined to place me here, with this worthy farmer, till his return.

Saving the hen.

I must say I have experienced much kindness, but I never can like any mortal so well as my dear Augustus; he will, when he returns, be grown almost a man, but his kind heart must ever be the same.

I anticipate the greatest pleasure from introducing my children to him, and I hope, when he comes, and I point him out to you, you will all behave with propriety to him. Yes, that we will, dear mother, how we long to see him; but I hope you have not finished your adventures, exclaimed Dickey (the little chicken who had been so angry about his worm) I should never be tired of hearing you. But I hope, my child, you have obtained more than entertainment; do you still think I should kill the bantum? Oh no! no, if I never meet with any greater troubles, I shall be a happy bird indeed; how trifling it must have appeared to you.

I wish, said the mother, you could all be advised, to look upon the present evils as trifling, by considering that at this present moment, there are thousands of our species suffering the most dreadful tortures; it is our duty to contribute as much as possible to general happiness, by forbearance and patience.

When I first came to this farm, I determined to make friends not only of my own species, but of the ducks, geese, and pigeons; and I have succeeded, by small acts of civility; and I am persuaded, there is not a fowl in the yard, but would oblige me, if it could; I shall now take you to the mother of the bantum, who is a modest young hen, whom I had once an opportunity of obliging, and I am sure when she hears of the improper behaviour of her son, she will punish him.

As the good mother imagined the young bantum was punished, after which he made apology to Dickey, they were afterwards very great friends; the chickens, by adhering strictly to their mother's advice, passed through life with ease and comfort to themselves, and were respected by all who knew them.

I hope a little history may not be quite unprofitable to children; who, by giving way a little to each other's caprices, will have more happiness themselves, and be more loved by their companions.

In the happy period of the golden age, when all the celestial inhabitants descended to the earth, and conversed familiarly with mortals, amongst the most cherished of the heavenly powers were twins, the offspring of Jupiter, Love and Joy. Wherever they appeared, the flowers sprung up beneath their feet, the sun shone with a brighter radiance, and all nature seemed embellished by their presence. They were inseparable companions, and their growing attachment was favoured by Jupiter, who had decreed that a lasting union should be solemnized between them as soon as they were arrived at maturer years. But in the mean time the sons of men deviated from their native innocence; Vice and Ruin overran the earth with giant strides; and Astrea, with her train of celestial visitants forsook their polluted abodes. Love alone remained, having been stolen away by Hope, who was his nurse, and conveyed by her to the forests of Arcadia, where he was brought up among the shepherds. But Jupiter assigned him a different partner, and commanded him to espouse Sorrow, the daughter of Até. He complied with reluctance; for her features were harsh and disagreeable, her eyes sunk, her forehead contracted into perpetual wrinkles; and her temples were covered with a wreath of cypress and wormwood. From this union sprung a virgin, in whom might be traced a strong resemblance to both her parents; but the sullen and unamiable features of her mother were so mixed and blended with the sweetness of her father, that her countenance, though mournful, was highly pleasing. The maids and shepherds of the neighbouring plains gathered round, and called her Pity. A red-breast was observed to build in the cabin where she was born; and while she was yet an infant, a dove pursued by a hawk flew into her bosom. This nymph had a dejected appearance, but so soft and gentle a mien, that she was beloved to a degree of enthusiasm. Her voice was low and plaintive, but inexpressibly sweet; and she loved to lie for hours together on the banks of some wild and melancholy stream, singing to her lute.--She taught men to weep, for she took a strange delight in tears; and often, when the virgins of the hamlet were assembled at their evening sports, she would steal in amongst them, and captivate their hearts by her tales of charming sadness. She wore on her head a garland composed of her father's myrtles, twisted with her mother's cypress.

Pity was commanded by Jupiter to follow the steps of her mother through the world, dropping balm into the wounds she made, and binding up the hearts she had broken. She goes with her hair loose, her bosom bare and throbbing, her garments torn by briars, and her feet bleeding with the roughness of the path. The nymph is mortal, for her mother is so; and when she has filled her destined course upon the earth, they shall both expire together, and Love be again united to Joy, his immortal and long-betrothed bride.

Prince Arthur was nephew to John, King of England, and had a stronger title by his birthright to the crown, than his uncle, being the son of Geoffrey, John's elder brother. The power of innocence is strikingly displayed in the influence it had over the mind of Hubert, who had devoted himself to be the guilty instrument of John's injustice and cruelty, had not the feelings of humanity and nature wrought too powerfully to permit him to execute his wicked design.

Hubert. Heat me these irons, and be sure keep within call: when I stamp with my foot, come in, and bind the boy that will be with me, fast to the chair. Take heed, and listen to my call.

Attendant. I hope you have authority for what you do.

Hub. Obey my orders, and let me have none of your scruples; for the present retire! Young lad, come here, I have something to say to you.

Arthur. Good morrow, Hubert.

Hub. Good morrow, little prince.

Arth. You look sad, good Hubert.

Hub. To say truth, I am not very happy.

Arth. Heaven take pity on me! I think nobody should be sad but I. Were I but out of prison, and a shepherd's boy, I could be cheerful all day long; nay, even here I could be happy, were I not afraid my uncle intends me harm. I fear him, and he fears me. Is it my fault that I was Geoffrey's son? Oh! that I were but your son, so you would but love me, Hubert.

Hub. If I listen to his innocent prattle, I shall awaken that compassion I have taken so much pains to stifle; therefore I will lose no time.

Arth. Are you ill, Hubert? you look very pale; if you were ill, I would attend you night and day, would watch by you, and show how much I love you.

Hub. How his words affect me! he shakes my resolution, but I will be firm, and smother these womanish feelings. Arthur, read that paper.

Arth. (Reads). Alas! alas! and will you burn out both my eyes?

Hub. I must and will.

Arth. Can you be so cruel? I have always loved you tenderly, have behaved to you as if I had been your son, watched your very looks, obeyed your orders, attended you when you were sick, and rejoiced at every symptom of recovery. Can you have the heart to put my eyes out? which never did, nor never shall, frown upon you.

Hub. I have sworn to do it, and must not break my oath.

Arth. It is better to break a wicked promise than to keep it. Had you a child you fondly loved, think what you would suffer to have him treated thus? My innocence should plead for me. I could not have believed that Hubert had been so hard-hearted.

Hub. Come in (Stamps, the attendants come in with cords, irons, &c.), do as I bid you.

Arth. Oh! save me, Hubert, save me. The fierce looks of these bloody men terrify me to death.

Hub. Give me the irons, I say, and bind him here.

Arth. Alas! you need not be so rough, there is no occasion to bind me. I will be as gentle as a lamb, if you will but send these men away. I will not stir nor make a noise, whatever pain you put me to.

Hub. Withdraw, and leave me alone with him.

Atten. I am glad to be rid of such a business.

Arth. Alas! then I have driven away my friend, let him come back, that he may plead for me.

Hub. Come, boy, prepare yourself.

Arth. Will nothing avail me?

Hub. Nothing; prepare.

Arth. Oh! Hubert, that a gnat would fly in your eye, that you might feel the pain so small a thing would cause; perhaps that might move your sympathy, and lead you to consider what I must suffer.

Hub. How ill you keep your promise, be silent.

Arth. Forgive me, Hubert, if I try to move you; you once were tender and compassionate, and you will be happier from yielding to these gentle dispositions, than from all the wealth and honours my uncle can bestow.

Hub. Well, your innocence has unnerved my firmest resolution. I am subdued, and will not touch your eyes for all the treasures of your uncle's crown. Yet have I sworn, and fully purposed to have performed----.

Arth. O, now you look like Hubert! Before you were disguised.

Hub. Hush, be quiet; I must conceal you from your uncle's vengeance till I have an opportunity of escaping with you to a foreign country, where we shall be secure from his resentment. For your sake I resign all my hopes of preferment, and incur the danger of my life, should I be taken whilst in your uncle's territories; but, poverty with innocence, is infinitely preferable to a crown with a guilty conscience. Fear nothing, but retire; not India's wealth should bribe me to injure you.

Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy, taking a walk one evening at Bruges, found in the public square a man laying on the ground, where he was soundly asleep. He had him taken up, and carried to his palace, where, after they had stripped him of his rags, and put on him a fine shirt, and a nightcap, placed him in one of the prince's beds. This drunkard was much surprized, when he awoke, to find himself in a beautiful alcove, surrounded by officers more richly dressed the one than the other. They asked him, what suit his highness wished to put on that day? This demand completed his confusion; but after a thousand positive assurances he gave them, that he was but a poor cobbler, and not at all a prince, he resolved quietly to bear all the honours they loaded him with,--suffered them to dress him, appeared in public,--heard mass in the Ducal chapel, and kissed the mass-book,--in a word, they made him perform all the usual ceremonies: he went to a sumptuous table, then to cards, to the walk, and other entertainments. After supper they gave him a ball. The good man having never found himself at a like feast, took freely the wine they offered to him, and so abundantly that he got brave and drunk. It was then the catastrophe of the comedy was brought about. Whilst he was sleeping himself sober, the duke had him clothed again with his rags, and carried back to the place from whence he had been taken at first. After having passed there all night in a sound sleep, he awoke, and went home to relate to his wife, as a dream of his, what in effect had really happened to him.

1. Punctuation has been normalized.

2. Variations in spelling hyphenation and accentuation were maintained.