The Ontario Readers.

THIRD READER.

AUTHORIZED FOR USE IN THE PUBLIC SCHOOLS

OF ONTARIO BY THE MINISTER OF

EDUCATION.

TORONTO:

THE W. J. GAGE COMPANY (Limited).

Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada in the Office of the Minister of Agriculture by the Minister of Education for Ontario, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and eighty-five.

The plan of the Third Reader is the same as that of the Second, with the exception that a few historical lessons have been introduced, and two lessons which may serve as an introduction to Physical Science. The botanical lessons supplement those given in the Second Reader. These, and the lessons on Canadian trees, and all lessons relating to things in nature, should be made the subjects of conversation between the teacher and his class, and should form a basis for scientific instruction. The pupils should be led to study nature directly. To this end they should be required to obtain (wherever possible) the natural objects which are described in the lessons, and to examine them, and to form opinions for themselves concerning them.

Similarly, every lesson should form the subject of conversation—before reading, during the progress of the reading, and after reading:—the teacher eliciting from his pupils clear statements of their knowledge of it, correcting any wrong notions they may have of it, throwing them back upon their own experience or reading, and leading them to observe, compare, and judge, and to state in words the results of their observations, comparisons, and judgments. Some of these statements should be written on the blackboard, and then be made the subject of critical conversation; others might be written by the pupils at their desks, and afterwards be reviewed in class. In this incidental teaching, it should be the teacher’s aim to develop the previous imperfect knowledge of the pupils concerning a lesson into a full and complete knowledge. This can best be effected by judicious questioning and conversation.

The illustrations of the lessons, as in the Second Reader, are intended to aid the pupils in obtaining real conceptions of the ideas involved in the lessons. Children vary greatly in capacity for imagination. It is essential, however, to the proper understanding of a lesson, and hence to the proper reading of it, that a child be able to imagine the persons, actions, objects, described in it. The illustrations will aid in developing this power of imagination, and the teacher by his questions and appropriate criticisms, and by a judicious use of his own greater knowledge and experience, will aid still more in developing it.

In the poetry great care has been taken to select not only such pieces as children can easily comprehend, but also such as are in themselves good literature. Many old favorites have been retained, their worth as reading lessons having been proved with generations of school children. In the reading of poetry the teacher must constantly assure himself that the pupils clearly understand what they read. Children have a natural ear for[4] rhythm, and a fondness for rhyme. Hence they easily learn to read verse being insensibly charmed by its melody. But they cannot, with equal facility, comprehend the poetical meanings, the terse expressions, and the inverted constructions, with which verse abounds. Much more time, therefore, should be spent by the teacher, in poetry than in prose, in eliciting from his pupils the meanings of words, phrases, and sentences. He should not rest satisfied until the pupils can substitute for every more important word, phrase, and sentence of a poem, an equivalent of their own finding. He must be certain too that they understand the substitutions which they offer. Conversation and questioning will here, as elsewhere in school work, help him in effecting his purpose.

The exercises which are put at the end of some of the lessons are intended merely as examples of exercises which the teacher can himself prepare for all the lessons. Methods of using these have been described in the Preface to the Second Reader. In the Word Exercises, many of the words have been re-spelled phonetically to indicate their pronunciation. This too is merely an example of what may be done with all words. Pupils should be taught to pick out the silent letters in words, and to indicate the true phonetic equivalents of the “orthographical expedients,” as they are called, by which vowel sounds are often indicated. For example, in neighbour, g, h, and either o or u are silent, and ei does duty for ā; so that the pronunciation of the word may be indicated by nā’bor or nā’bur. It will be a useful exercise for the pupils sometimes to write out in this way, on the blackboard, the phonetic spelling of the irregularly spelled words which occur in their lessons, alongside of their common spelling. Practice will soon give facility in doing this. It is believed that by such practice the orthography of irregularly spelled words will be more easily remembered, and accuracy of pronunciation more readily gained.

To aid in securing accuracy of pronunciation, a short chapter on Orthoëpy has been prefixed to the reading lessons. The statements in it are to form a basis for lessons to be given by the teacher to the pupils in conversation. Orthoëpy is acquired only by constant attention to utterance. Carefulness in enunciation must first become a habit. The correct pronunciation of individual words will then be gained by the imitation of those who speak correctly, or reference to a dictionary. It is true that in the pronunciation of many words, authorities differ widely; hence dogmatism in pronunciation is to be avoided. Notwithstanding this, no one can hope to become a correct speaker without the careful study of a dictionary. The teacher should see that the system of sound-marking adopted by the dictionary in use in his school, is understood by his pupils, so that they may consult it intelligently.

(The Titles of the Selections in Poetry are printed in Italics.)

| Name. | Page. |

|---|---|

| Addison, Joseph | 200 |

| Alexander, Cecil Frances | 240 |

| Allen, Elizabeth Akers | 192 |

| Andersen, Hans Christian | 36, 136 |

| Audubon, John James | 152 |

| Baker, Sir Samuel White | 173 |

| Blackie, John Stuart | 58 |

| Brown, James | 202, 210 |

| Browning, Robert | 141 |

| Bryant, William Cullen | 227 |

| Campbell, Thomas | 127 |

| Cary, Alice | 162 |

| Cook, Eliza | 44, 68 |

| Cooper, James Fenimore | 165 |

| Cowper, William | 272 |

| [8]Cunningham, Allan | 51 |

| Dickens, Charles | 11, 46, 93, 97 |

| Dodge, Mary Mapes | 78 |

| Emerson, Ralph Waldo | 20 |

| Figuier, Louis | 223 |

| Frankenstein, Gustavus | 229, 235, 257 |

| Franklin, Benjamin | 130 |

| Froude, James Anthony | 71 |

| Gustafson, Zadel Barnes | 149 |

| Hawthorne, Nathaniel | 216, 243, 264 |

| Heber, Reginald | 187 |

| Hemans, Felicia Dorothea | 16 |

| Howitt, Mary | 115 |

| Hunt, Leigh | 45 |

| Keble, John | 81 |

| Kingsley, Charles | 38 |

| Lacoste, Marie | 156 |

| Larcom, Lucy | 101 |

| Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth | 74, 171 |

| Lover, Samuel | 109 |

| Lushington, Henry | 221 |

| Mackay, Charles | 86, 88 |

| Macleod, Norman | 155 |

| Michelet, Jules | 158 |

| Montgomery, James | 177 |

| Moore, Thomas | 73 |

| McGee, Thomas D’Arcy | 122 |

| Norton, Hon. Caroline Elizabeth Sarah | 207 |

| Procter, Bryan Waller (Barry Cornwall) | 94 |

| Sangster, Charles | 110 |

| Southey, Robert | 60, 133 |

| Swain, Charles | 96 |

| Tennyson, Alfred (Lord Tennyson) | 132, 157, 233, 250, 255, 261 |

| Trowbridge, John Townsend | 33 |

| White, Henry Kirke | 129, 148 |

| Whittier, John Greenleaf | 103 |

| Wolfe, Charles | 214 |

| Wordsworth, William | 21, 27, 52 |

1. Orthoëpy or Correct Pronunciation, is the utterance of words with their right sounds and accents, as sanctioned by the best usage. It depends principally upon Articulation, Syllabication, and Accentuation.

2. Articulation is the distinct utterance of the elementary vowel and consonant sounds of the language, whether separate, or combined into syllables and words. In pronouncing a word its elementary sounds should be correctly articulated.

3. The more common faults in articulation are:—

(1) Omitting a vowel sound, or substituting one vowel sound for another, in an unaccented syllable. Of all faults in pronunciation probably this is the commonest. As a rule it results from carelessness in utterance. Examples of it are:—pronouncing—arithmetic, ’rithmetic; library, līb’ry; literature, lit’rature; geography, j’ography; barrel, barr’l; below, b’low; family, fam’ly; violent, vi’lent; history, hist’ry; memory, mem’ry; regular, reg’lar; usual, ūzh’al; alwāys, alwŭz; afford, ŭfford; abundant, abundŭnt; eatable, eatŭble; America, Ameriky; childrĕn, childrin; modĕst, modŭst; commandment, commandmŭnt; judgment, judgmŭnt; moment, momŭnt; kindness, kindniss; gospĕl, gospil; pockĕt, pockit; ēmotion, immotion; charĭty, charŭty; opposĭte, oppozŭt; potatō, pŭtatĕh; patriŏt, patriŭt; ōbedience, ŭbediĕnce; accūrāte, ak’er-ĭt; particūlar, partikĭlĕr.

(2) Substituting one vowel sound for another in an accented syllable or a one-syllabled word. This fault may result, not from carelessness, but from want of knowledge, for the correct pronunciation of the vowel sounds of words must be learned from some correct speaker, or from a dictionary. Examples of this fault are:—pronouncing—āte, ĕt; cătch, kĕtch; săt, sŏt; găther, gĕther; băde, bāde; was, wŭz; father, făther or fawther; says (sĕz), sāz; get, git; kettle, kĭttle; deaf (dĕf), deef; creek, crick; rinse, rĕnse; bŏnnet, bŭnnet; bosom, bŭzum; frŏm, frum; just, jĕst; shut, shĕt; new (nū), noo; dūty, dooty; redūce, redooce; because, bekŭz; saucy, sāssy; point, pīnt; instead, instĭd; route, (rōōt), rout.

(3) Omitting a consonant sound, or substituting one consonant sound for another; as in pronouncing—yeast, ’east; February, Feb’uary; and, an’; old, ōl’; acts, ac’s; slept, slep’; depths, dep’s; fields, fiel’s; winds, win’s; breadths, bre’ths; twelfth, twel’th or twelf’; asked (askt), as’t; mostly, mōs’ly; swiftly, swif’ly; government, gover’ment; Arctic, Ar’tic; products, produc’s; consists, consis’; commands, comman’s; morning, mornin; strength, strenth; length, lenth; shrink, srink; shrill, srill; height, hīth; Asia (A’she-a), A’zhe-a; chimney, chimbly; covetous (cŭv’ĕt-ŭs), cŭv’e-chŭs; fortūne, forchin.

(4) Introducing in the pronunciation of a word a sound that does not belong to it; as in pronouncing—drown, drownd; drowned, drownded; often (of’n), of´ten; epistle, (e-pis´l), e-pis´tel; elm, el´um; film, fil´um; height, hīt’th; grievous, grēv´i-us; mischievous (mis´chĭv-us), mis-chēv´i-us; column, col´yum; once (wŭns), wŭnst; across, acrost.

(5) Misusing the sound of r; as in pronouncing—Maria, Mariar; idea, idear; widow, widder; meadow, medder; farm, far-r-m; warm, war-r-m; war, wa’; door, do-ah; garden, gä’den; card, cä’d; warm, wä’m; forth, fo’th; hundred, hunderd; children, childern.

(6) Misusing the aspirate (h); as in pronouncing—happy, ’appy; apples, happles; whence, wence; which, wich; what, wot; whirl, wirl.

4. Syllabication (in Orthoëpy) is the correct formation of syllables in pronouncing words. A syllable is a sound, or a combination of sounds, uttered by a single impulse of the voice, and constituting a word or a part of a word. A word has as many syllables as it has separate vowel sounds. When words are uttered so that their vowel sounds are clearly and correctly articulated, they will be properly syllabified.

5. Accentuation is the correct placing of accent in uttering words. Accent is a superior stress or force of voice upon certain syllables of words which distinguishes them from the other syllables. In uttering a word of more than one syllable, one of the syllables receives a greater stress in pronunciation than the others, and is said to be accented, or to have the accent. Some words have more than one syllable accented, as con´fla-gra´´tion, in-com´pre-hen´si-bil´´ity; but one syllable is always more strongly accented than the others, and is said to have the main or primary accent. Accentuation, like the other elements of orthoëpy, is fixed by usage; that is, by the practice of those who are recognized as correct speakers.

6. In the pronunciation of a word care should be taken to give to the vowels their proper sounds, to place the accent upon the right syllable, and to sound the consonants distinctly. The tendency to drop consonant sounds, and to pronounce indistinctly or incorrectly the vowel sounds of unaccented syllables, should be carefully guarded against. The distinction between syllables should be carefully made, and especially, the distinction between separate words. Carelessness in this respect may make the meanings of sentences uncertain. For example:

He saw two beggars steal, may sound as, He sought to beg or steal;

He had two small eggs, may sound as, He had two small legs; and

Can there be an aim more lofty? as, Can there be a name more lofty?

This blending of the sounds of words is prevented, partly by distinctly uttering the sounds of their initial letters, but chiefly by distinctly uttering and slightly dwelling upon the sounds of their final letters.

King Henry I. went over to Normandy with his son Prince William and a great retinue, to have the prince acknowledged as his successor, and to contract a marriage between him and the daughter of the Count of Anjou. Both these things were triumphantly done, with great show and rejoicing; and on the 25th of November, in the year 1120, the whole retinue prepared to embark, for the voyage home.

On that day, there came to the king, Fitz-Stephen, a sea-captain, and said, “My liege, my father served your father all his life, upon the sea. He steered the ship with the golden boy upon the prow, in which your father sailed to conquer England. I have a fair vessel in the harbor here, called The White Ship, manned by fifty sailors of renown. I pray you, Sire, to let your servant have the honor of steering you in The White Ship to England.”

“I am sorry, friend,” replied the king, “that my ship is already chosen, and that I cannot, therefore, sail with the son of the man who served my father. But the prince and his company shall go along with you in the fair[12] White Ship, manned by the fifty sailors of renown.” An hour or two afterward, the king set sail in the vessel he had chosen, accompanied by other vessels, and, sailing all night with a fair and gentle wind, arrived upon the coast of England in the morning. While it was yet night, the people in some of these ships heard a faint, wild cry come over the sea, and wondered what it was.

Now, the prince was a dissolute young man of eighteen, who bore no love to the English, and who had declared[13] that when he came to the throne he would yoke them to the plough like oxen. He went aboard The White Ship with one hundred and forty youthful nobles like himself, among whom were eighteen noble ladies of the highest rank. All this gay company, with their servants and the fifty sailors, made three hundred souls aboard the fair White Ship.

“Give three casks of wine, Fitz-Stephen,” said the prince, “to the fifty sailors of renown. My father the king has sailed out of the harbor. What time is there to make merry here, and yet reach England with the rest?”

“Prince,” said Fitz-Stephen, “before morning my fifty and The White Ship shall overtake the swiftest vessel in attendance on your father the king if we sail at midnight.” Then the prince commanded to make merry; and the sailors drank out the three casks of wine, and the prince and all the noble company danced in the moonlight on the deck of The White Ship.

When, at last, she shot out of the harbor, there was not a sober seaman on board. But the sails were all set and the oars all going merrily. Fitz-Stephen had the helm. The gay young nobles and the beautiful ladies, wrapped in mantles of various bright colors to protect them from the cold, talked, laughed, and sang. The prince encouraged the fifty sailors to row yet harder, for the honor of The White Ship.

Crash! A terrific cry broke from three hundred hearts. It was the cry the people in the distant vessels of the king heard faintly on the water. The White Ship had struck upon a rock,—was filling,—going down! Fitz-Stephen[14] hurried the prince into a boat with some few nobles. “Push off,” he whispered, “and row to the land. It is not far, and the sea is smooth. The rest of us must die.” But as they rowed fast away from the sinking ship, the prince heard the voice of his sister calling for help. He never in his life had been so good as he was then. He cried in agony, “Row back at any risk! I cannot bear to leave her!”

They rowed back. As the prince held out his arm to catch his sister, such numbers leaped into the boat that it was overset. And in the same instant The White Ship went down. Only two men floated. They both clung to the mainyard of the ship, which had broken from the mast and now supported them. One asked the other who he was. He replied, “I am a nobleman,—Godfrey by name, son of Gilbert. And you?”—“I am a poor butcher of Rouen,” was the answer. Then they said together, “Lord be merciful to us both!” and tried to encourage each other as they drifted in the cold, benumbing sea on that unfortunate November night.

By and by another man came swimming toward them, whom they knew, when he pushed aside his long wet hair, to be Fitz-Stephen. “Where is the prince?” said he. “Gone, gone!” the two cried together. “Neither he, nor his brother, nor his sister, nor the king’s niece, nor her brother, nor any one of all the brave three hundred, noble or commoner, except us three, has risen above the water!” Fitz-Stephen, with a ghastly face, cried, “Woe! woe to me!” and sank to the bottom.

The other two clung to the yard for some hours. At[15] length the young noble said faintly, “I am exhausted, and chilled with the cold, and can hold no longer. Farewell, good friend! God preserve you!” So he dropped and sank; and, of all the brilliant crowd, the poor butcher of Rouen alone was saved. In the morning some fishermen saw him floating in his sheep-skin coat, and got him into their boat,—the sole relator of the dismal tale.

For three days no one dared to carry the intelligence to the king. At length they sent into his presence a little boy, who, weeping bitterly and falling at his feet, told him that The White Ship was lost with all on board. The king fell to the ground like a dead man, and never, never afterward was seen to smile.

1. Great retinue.—2. Contract a marriage.—3. Sailors of renown.—4. Fair wind.—5. To make merry.—6. Sails were set.—7. Oars going merrily.—8. Terrific cry.—9. Encourage each other.—10. Benumbing sea.—11. Ghastly face.—12. Brilliant crowd.—13. Sole relator of the dismal tale.—14. Carry the intelligence.

Casabianca, a boy about thirteen years old, son of the Admiral of the French fleet, remained at his post, in the Battle of the Nile, after his ship, the “Orient,” had caught fire, and after all the guns had been abandoned. He perished in the explosion of the vessel, when the flames reached the powder magazine.

1. Battle’s wreck.—2. To rule the storm.—3. A creature of heroic blood.—4. Lay unconscious of his son.—5. Booming shots.—6. Lone post of death.—7. Brave despair.—8. Wreathing fires.—9. Wrapped in wild splendor.—10. Gallant child.—11. Streamed like banners.—12. Fair pennon.—13. Noblest thing.—14. Faithful heart.

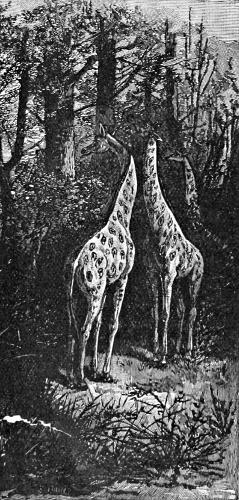

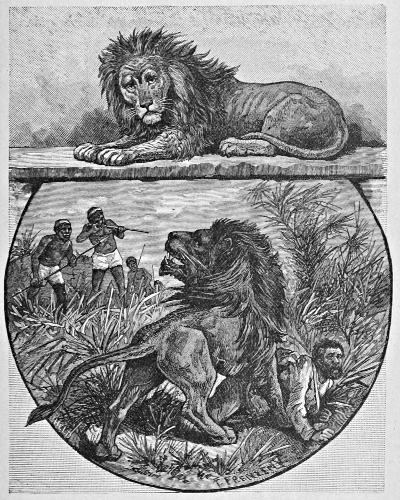

There are few sights more pleasing than a herd of tall, graceful giraffes. With their heads reaching a height of from twelve to eighteen feet, they move about in small herds on the open plains of Africa, eating the tender twigs and leaves of the mimosa and other trees.

The legs of a large giraffe are about nine feet long and its neck nearly six feet; while its body measures only seven feet in length and slopes rapidly from the neck to the tail. The graceful appearance of the giraffe is increased by the beauty of its skin, which is orange red in color, and mottled with dark spots. Its long tail has at the end a tuft of thick hair, which serves the purpose of keeping off the flies and stinging insects, so plentiful in the hot climate of Africa.

Its tongue is very wonderful. It is from thirteen to seventeen inches in length, is slender and pointed, and is capable of being moved in so many ways, that it is almost as useful to the giraffe as the trunk is to the elephant.

The horns of the giraffe are very short and covered with skin. At the ends there are tufts of short hair. The animal has divided hoofs somewhat resembling those of the ox.

The head of the giraffe is small, and its eyes large and mild looking. These eyes are set in such a way that the animal can see a great deal of what is behind it, without turning its head. In addition to its wonderful power of sight, the giraffe can scent danger from a great distance; so that there is no animal more difficult of approach.

Strange to relate, the giraffe has no voice. In London, some years ago, two giraffes were burned to death in their stables, when the slightest sound would have given notice of their danger, and have saved their lives.

The giraffe is naturally both gentle and timid, and he will always try to avoid danger by flight. It is when running that he exposes his only ungraceful point. He runs swiftly, but since he moves his fore and hind legs on each side at the same time, the movement gives him a very awkward gait. But though timid, he will, when overtaken, turn even upon the lion or panther, and defend himself successfully by powerful kicks with his strong legs.

The natives of Africa capture the giraffe in pitfalls, which are deep holes covered over with branches of trees and dirt. When captured, the giraffe can be tamed, and during its captivity it gives scarcely any trouble.

Fifty years ago, but little was known about the giraffe in America or Europe. Now it is to be found in menageries and the public gardens of large cities. The giraffe thrives in captivity and seems to be well satisfied with a diet of corn and hay. It is a source of great satisfaction to those who admire this beautiful animal, that there is nothing to prevent it from living in a climate so different from that of its African home.

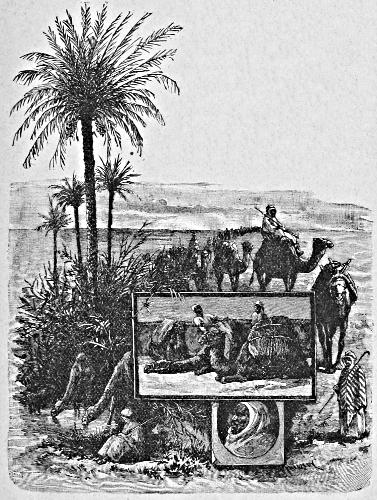

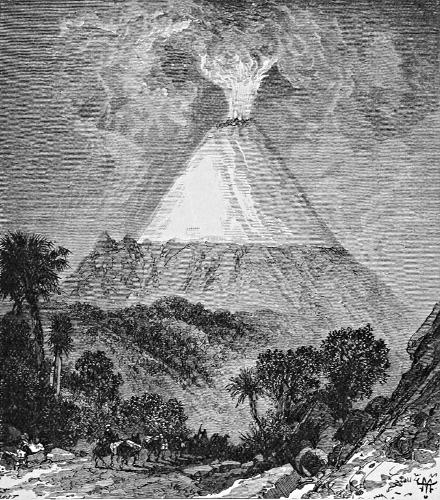

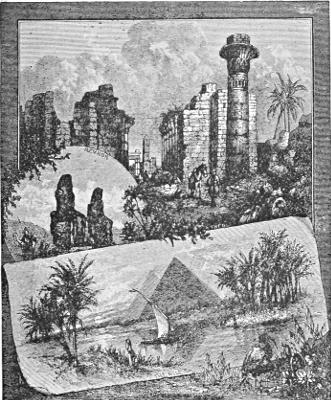

In Asia and in Africa there are vast plains of sand, upon which no grass grows, and through which no river runs. These plains are as smooth as the ocean unmoved by waves. As far as the eye can reach, nothing is to be seen but sand. In the middle of the day when the sun is hottest, the sand dazzles the eyes of the traveller, as if there were a sun beneath the sand as well as one above.

Here and there, but many miles apart, are green spots consisting of bushes, trees, and grass, growing around a small pool or spring of water. These green spots are called oases. Here the tired traveller can find food and shade, and can sleep awhile, sheltered from the blazing sun.

How do you think the traveller crosses these burning plains? Not in carriages, nor on horseback, nor in railroad trains, but on the backs of tall, long-necked, humpbacked camels.

Even if you have seen camels alive, or pictures of them, you will still be glad to learn more about these very useful animals.

The camel lives on grass, and the dry short herbage, which is found on the edges of the desert. While travelling in the desert, it is fed upon dates and barley. It is able to eat a great deal of food at a time and to drink enough water to last some days. By this means, it can go for a long time without food, and travel long distances without stopping to eat or drink. The camel has a curious lump of fat on the top of its back called a “hump.” One kind of camel has two humps. One purpose of these humps,[25] is to supply the camel with strength, when it has neither food nor water, and would otherwise die from want.

The foot of the camel is a wonderful thing. It is broad, and has a soft pad at the bottom, which keeps it from sinking in the yielding sand, when the camel crosses the arid deserts.

The camel with two humps on its back is much larger and stronger than the camel with one hump. The one-humped[26] camel is known as the Arabian camel or dromedary. Asia is the home of the camel, but numbers of them are used in Africa and other parts of the world. The camel is trained to kneel down to receive its load, and to let its master get on its back. The camel can smell water at a great distance. When its rider is nearly dead from thirst, and water is near, he can tell it by the greater speed at which the camel begins to travel.

The camel is often called the “ship of the desert.” As the desert is like a sea, and the green spots upon it like islands, so is the camel like a ship, that can carry the traveller from one point to another, quickly and safely. But even with his faithful camel, the traveller does not care to cross the desert alone. The difficulties of keeping in the right track, and the fear of wild Arabs, make it much safer for a number of travellers to cross the desert together.

Travellers take with them camel-drivers and men who know the way, to look after the beasts when they stop for the night. These men light the fires, cook the food, and fill the large skin-bottles with water when they come to a spring. The travellers, camels, and camel-drivers, together, form what is called a caravan.

1. Crossed the wild.—2. Solitary child.—3. Sweetest thing.—4. Minster clock.—5. Snapped a fagot-band.—6. Plied his work.—7. Not blither is the mountain roe.—8. Wanton stroke.—9. Disperse the powdery snow.—10. Wretched parents.—11. Sound nor sight.—12. Spied the print.—13. Tracked them on.—14. Lonesome wild.—15. Trips along.—16. Solitary song.

The Emperor Alexander, while travelling in Western Russia, came one day to a small town of which he knew very little; so, when he found that he must change horses, he thought that he would look around and see what the town was like.

Alone, habited in a plain military coat, without any mark of his high rank, he wandered through the place until he came to the end of the road that he had been following. There he paused, not knowing which way to turn; for two paths were before him,—one to the right and one to the left.

Alexander saw a man standing at the door of a house; and, going up to him, the Emperor said, “My friend, can you tell me which of these two roads I must take to get to Kalouga?” The man, who was in full military dress, was smoking a pipe with an air of dignity almost ridiculous. Astonished that so plain-looking a traveller should dare to speak to him with familiarity, the smoker answered shortly, “To the right.”

“Pardon!” said the Emperor. “Another word, if you please.”—“What?” was the haughty reply.—“Permit me to ask you a question,” continued the Emperor. “What is your grade in the army?”—“Guess.” And the pipe blazed away furiously.—“Lieutenant?” said the amused Alexander.—“Up!” came proudly from the smoker’s lips.—“Captain?”—“Higher.”—“Major?”—“At last!” was the lofty response. The Emperor bowed low in the presence of such greatness.

“Now, in my turn,” said the major, with the grand air that he thought fit to assume in addressing a humble inferior, “what are you, if you please?”—“Guess,” answered Alexander.—“Lieutenant?”—“Up!”—“Captain?”—“Higher.”—“Major?”—“Go on.”—“Colonel?”—“Again.”

The smoker took his pipe from his mouth: “Your Excellency is, then, General?” The grand air was fast disappearing.—“You are coming near it.”—The major put his hand to his cap: “Then your Highness is Field-Marshal?”

By this time the grand air had taken flight, and the officer, so pompous a moment before, looked as if the[32] steady gaze and the quiet voice of the traveller had reduced him to the last stage of fear.—“Once more, my good major,” said Alexander.—“His Imperial Majesty?” exclaimed the man, in surprise and terror, letting his pipe drop from his trembling fingers.—“His very self,” answered the Emperor; and he smiled at the wonderful change in the major’s face and manner.

“Ah, Sire, pardon me!” cried the officer, falling on his knees,—“pardon me!”—“And what is there to pardon?” said Alexander, with real, simple dignity. “My friend, you have done me no harm. I asked you which road I should take, and you told me. Thanks!”

But the major never forgot the lesson. If, in later years, he was tempted to be rude or haughty to his so-called inferiors, there rose at once in his mind a picture of a well-remembered scene, in which his pride of power had brought such shame upon him. Two soldiers in a quiet country-town made but an every-day picture, after all; but what a difference there had been between the pompous manner of the petty officer and the natural, courteous dignity of the Emperor of all the Russias!

1. Habited in a plain military coat.—2. Air of dignity.—3. Speak with familiarity.—4. Answered shortly.—5. Haughty reply.—6. Lofty response.—7. Steady gaze.—8. Exclaimed in surprise.—9. Simple dignity.—10. Pompous manner.—11. Petty officer.—12. Natural dignity.

1. Arrived safe and sound.—2. Stifled air.—3. Bustle and glare.—4. Money is king.—5. Fashion is queen.—6. Raking and scraping.—7. Days of worry.—8. Simple ways.—9. Sweet content.—10. Sees the corn in tassel.—11. Buckwheat blowing.—12. Look their thanks.—13. The doves light round him.

It was New Year’s Eve, and a cold, snowy evening. On this night, a poor little girl walked along the street with naked feet, benumbed with cold, and carrying in her hand a bundle of matches, which she had been trying all day to sell, but in vain; no one had given her a single penny. The snow fell fast upon her pretty yellow hair and her bare neck; but she did not mind that. She looked wistfully at the bright lights which shone from every window as she passed along; she could smell the nice roast goose, and she longed to taste it: it was New Year’s Eve!

Wearied and faint she laid herself down in a corner of the street, and drew her little legs under her to keep herself warm. She could not go home, for her father would scold her for not having sold any matches; and, even if she were there, she would still be cold, for the house was but poorly protected, and the wind whistled through many a chink in the roof and walls. She thought she would try and warm her cold fingers by lighting one of the matches; she drew one out, struck it against the wall, and immediately a bright, clear flame streamed from it, like a little candle.

The little girl looked at the flame, and she saw before her a beautiful brass stove with a nice warm fire in it! She stretched out her feet to warm them,—when, lo, the match went out; in a moment the stove and fire vanished; she sat again in the cold night, with the burnt match in her hand.

She struck another; the flame blazed on the opposite wall, and she saw through it into a room where a table was laid out with handsome dishes,—roast goose, and other nice things were there,—and, what was still more extraordinary, she saw the goose jump from the dish, knife, and fork, and all, and come running towards her. But again the match went out; and nothing but the dark wall and the cold street were to be seen.

The little girl drew another match; and, as soon as it struck a light, she saw a most beautiful Christmas tree, much larger and more splendid than any she had ever seen before. A vast number of lighted candles hung among the branches; and a multitude of pretty variegated pictures, like those in the shops, met her eyes. The girl lifted up her little hands in rapture at the sight; but again the match fell; and in the same moment one of the blazing candles shot through the sky, like a falling star, and fell at her feet. “Now some one dies,” cried she; for she had been told by her good old grandmother, that when a star falls, a soul returns to God.

Again she struck; and, behold, a bright light shone round about her, and in the midst of it stood her kind grandmother, looking calmly and smilingly upon her.

“Dear grandmother,” said she, “take me, oh take me! You will be gone from me when the match goes out, like the bright stove, the nice supper, and the Christmas tree;” and saying this, she struck all the rest of the matches at once, which made a light round her almost like day. And now the good grandmother smiled still more sweetly upon her; she lifted her up in her arms,[38] and they soared together, far, far away; where there was no longer any cold, or hunger, or pain,—they were in Paradise!

But the poor little match-girl was still in the corner of the street, in the cold New Year’s morning. She was frozen to death, and a bundle of burnt matches lay beside her. People said, “She has been trying to warm herself, poor thing!” But ah, they knew not what glorious things she had seen; they knew not into what joys she had entered—nor how happy she was on this festival of the New Year!

1. Benumbed with cold.—2. She did not mind that.—3. Looked wistfully.—4. Wearied and faint.—5. Poorly protected.—6. A clear flame streamed from it.—7. A table was laid out.—8. In rapture at the sight.—9. Soared far away.—10. Glorious things.

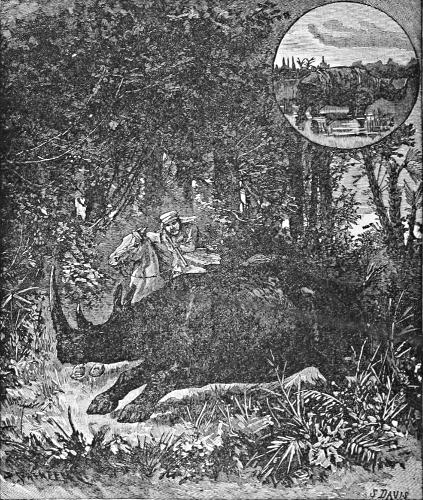

Next to the mighty elephant, the rhinoceros is the largest and strongest of animals. There are several species of the rhinoceros, some of which are found in Asia, and others in different parts of Africa.

In the latter country there are four varieties,—the black rhinoceros, having a single horn; a black species, having two horns; the long-horned white rhinoceros; and the common white species, which has a short, stubby horn.

The largest of the African species is the long-horned, white, or square-nosed rhinoceros. When full grown, it sometimes measures eighteen feet in length, and about as many feet around the body. Its horn frequently grows to the length of thirty inches.

The black rhinoceros, although much smaller than the white, and seldom having a horn over eighteen inches long, is far more ferocious than the white species, and possesses a wonderful degree of strength.

The form of the rhinoceros is clumsy, and its appearance dull and heavy. The limbs are thick and powerful, and each foot has three toes, which are covered with broad, hoof-like nails. The tail is small; the head very long and large. Taken altogether, there are few—if any—animals that compare with the rhinoceros in ugliness. The eyes are set in such a manner that the animal can not see anything exactly in front of it; but the senses of hearing and smelling are so keen that sight is not required to detect an enemy, whether it be man or beast. The skin of the African rhinoceros is smooth, and has only a[41] few scattering hairs here and there. It is, however, very thick and tough, and can resist the force of a rifle-ball except when it is fired from a very short distance.

The largest known species of the rhinoceros is found in Asia. It lives chiefly in the marshy jungles, and on the banks of lakes and rivers, in India. Some of this species are over five feet in height, and have horns three feet in length and eighteen inches around the base. Unlike that of the African rhinoceros, the skin of the Asiatic species is not smooth, but lies in thick folds upon the body, forming flaps which can be lifted with the hand.

The food of the rhinoceros consists of roots, and the young branches and leaves of trees and shrubs. It ploughs up the roots with the aid of its horn, and gathers the branches and leaves with its upper lip, which is long and pointed, and with it rolls its food together before placing it in its mouth. The flesh of the rhinoceros is good to eat; and its strong, thick skin is made by the natives into shields, whips, and other articles.

Though clumsy, and apparently very stupid, the rhinoceros is a very active animal when attacked or otherwise alarmed. It is very fierce and savage,—so much so, that the natives dread it more than they do the lion. In hunting the rhinoceros, it is dangerous for a man to fire at one, unless he is mounted upon a swift horse, and can easily reach some place of safety. When attacking an enemy, the rhinoceros lowers its head and rushes forward like an angry bull. Though it may not see the object of its attack, its sense of smell is so acute that it knows when the enemy is reached. Then begins a furious tossing of[42] the head, and if its powerful horn strikes the foe, a terrible wound is the result. When wounded itself, the rhinoceros loses all sense of fear, and charges again and again, with such desperate fury, that the enemy is almost always overcome.

A famous traveller in South Africa relates the following[43] incident that happened during one of his hunting excursions:

“Having proceeded about two miles, I came upon a black rhinoceros, feeding within fifty yards of me. I fired from my saddle, and sent a bullet in behind his shoulder, upon which he rushed forward, blowing like a grampus, and then stood looking about him. Presently he started off, and I followed. I expected that he would come to bay, but it seems a rhinoceros never does that,—a fact I did not know at that time. Suddenly he fell flat upon the ground; but soon recovering his feet, he resumed his course as if nothing had happened.

“I spurred on my horse, dashed ahead, and rode right in his path. Upon this, the hideous monster charged me in the most resolute manner, blowing loudly through his nostrils. Although I quickly turned about, he followed me at such a furious pace for several hundred yards, with his horrid, horny snout within a few yards of my horse’s tail, that I thought my destruction was certain. The animal, however, suddenly turned and ran in another direction. I had now become so excited with the incident, that I determined to give him one more shot any way. Nerving my horse again, I made another dash after the rhinoceros, and coming up pretty close to him, I again fired, though with little effect, the ball striking some thick portion of the skin and doing no harm. Not caring to run the chance of the huge brute again charging me, and believing that my rifle-ball was not powerful enough to kill him, I determined to give up the pursuit, and accordingly let him run off while I returned to the camp.”

At two-and-thirty years of age, in the year 1199, John became king of England. His pretty little nephew, Arthur, had the best claim to the throne; but John seized the treasure, and made fine promises to the nobility, and got himself crowned at Westminster within a few weeks after his brother Richard’s death. I doubt whether the crown could possibly have been put upon the head of a meaner coward, or a more detestable villain, if the country had been searched from end to end to find him out.

The French king, Philip, refused to acknowledge the right of John to his new dignity, and declared in favor of Arthur. You must not suppose that he had any generosity of feeling for the fatherless boy; it merely suited his ambitious schemes to oppose the king of England. So John and the French king went to war about Arthur.

He was a handsome boy, at that time only twelve years old. He was not born when his father, Geoffrey, had his brains trampled out at the tournament; and, besides the misfortune of never having known a father’s guidance and protection, he had the additional misfortune to have a foolish mother (Constance by name), lately married to her third husband. She took Arthur, upon John’s accession, to the French king, who pretended to be very much his friend, and made him a knight, and promised him his daughter in marriage; but who cared so little about him in reality, that, finding it his interest to make peace[47] with King John for a time, he did so without the least consideration for the poor little prince, and heartlessly sacrificed all his interests.

Young Arthur, for two years afterwards, lived quietly, and in the course of that time his mother died. But the French king, then finding it his interest to quarrel with King John again, made Arthur his pretence, and invited the orphan boy to court. “You know your rights, prince,” said the French king, “and you would like to be a king. Is it not so?” “Truly,” said Prince Arthur, “I should greatly like to be a king!” “Then,” said Philip, “you shall have two hundred gentlemen who are knights of mine, and with them you shall go to win back the provinces belonging to you, of which your uncle, the usurping king of England, has taken possession. I myself, meanwhile, will head a force against him in Normandy.”

Prince Arthur went to attack the town of Mirebeau, because his grandmother, Eleanor, was living there, and because his knights said, “Prince, if you can take her prisoner, you will be able to bring the king your uncle to terms!” But she was not to be easily taken. She was old enough by this time—eighty; but she was as full of stratagem as she was full of years and wickedness. Receiving intelligence of young Arthur’s approach, she shut herself up in a high tower, and encouraged her soldiers to defend it like men. Prince Arthur with his little army besieged the high tower. King John, hearing how matters stood, came up to the rescue with his army. So here was a strange family party! The boy-prince besieging his grandmother, and his uncle besieging him!

This position of affairs did not last long. One summer night, King John, by treachery, got his men into the town, surprised Prince Arthur’s force, took two hundred of his knights, and seized the prince himself in his bed. The knights were put in heavy irons, and driven away in open carts, drawn by bullocks, to various dungeons, where they were most inhumanly treated, and where some of them were starved to death. Prince Arthur was sent to the Castle of Falaise.

One day, while he was in prison at that castle, mournfully thinking it strange that one so young should be in so much trouble, and looking out of the small window in the deep, dark wall, at the summer sky and the birds, the door was softly opened, and he saw his uncle, the king, standing in the shadow of the archway, looking very grim.

“Arthur,” said the king, with his wicked eyes more on the stone floor than on his nephew, “will you not trust to the gentleness, the friendship, and the truthfulness of your loving uncle?” “I will tell my loving uncle that,” replied the boy, “when he does me right. Let him restore to me my kingdom of England, and then come to me and ask the question.” The king looked at him and went out. “Keep that boy a close prisoner,” said he to the warden of the castle. Then the king took secret counsel with the worst of his nobles, how the prince was to be got rid of. Some said, “Put out his eyes and keep him in prison, as Robert of Normandy was kept.” Others said, “Have him stabbed.” Others, “Have him poisoned.”

King John feeling that in any case, whatever was done afterwards, it would be a satisfaction to his mind to have[49] those handsome eyes burnt out, that had looked at him so proudly, while his own royal eyes were blinking at the stone floor, sent certain ruffians to Falaise to blind the boy with red-hot irons. But Arthur so pathetically entreated them, and shed such piteous tears, and so appealed to Hubert de Bourg (or Burgh), the warden of the castle, who had a love for him, and was a merciful, tender man, that Hubert could not bear it. To his eternal honor, he prevented the torture from being performed; and, at his own risk sent the savages away.

The chafed and disappointed king bethought himself of the stabbing suggestion next; and, with his shuffling manner and his cruel face, proposed it to one William de Bray. “I am a gentleman, and not an executioner,” said William de Bray, and left the presence with disdain. But it was not difficult for a king to hire a murderer in those days. King John found one for his money, and sent him down to the castle of Falaise. “On what errand dost thou come?” said Hubert to this fellow. “To despatch young Arthur,” he returned. “Go back to him who sent thee,” answered Hubert, “and say that I will do it!”

King John, very well knowing that Hubert would never do it, but that he evasively sent this reply to save the prince or gain time, despatched messengers to convey the young prisoner to the castle of Rouen. Arthur was soon forced from the kind Hubert—of whom he had never stood in greater need than then—carried away by night, and lodged in his new prison; where, through his grated window, he could hear the deep waters of the river Seine rippling against the stone wall below.

One dark night, as he lay sleeping, dreaming, perhaps, of rescue by those unfortunate gentlemen who were obscurely suffering and dying in his cause, he was roused, and bidden by his jailor to come down the staircase to the foot of the tower. He hurriedly dressed himself, and obeyed. When they came to the bottom of the winding-stairs, the jailor trod upon his torch, and put it out. Then Arthur, in the darkness, was hurriedly drawn into a solitary boat; and in that boat he found his uncle and one other man.

He knelt to them, and prayed them not to murder him. Deaf to his entreaties, they stabbed him, and sank his body in the river with heavy stones. When the spring morning broke, the tower-door was closed, the boat was gone, the river sparkled on its way, and never more was any trace of the poor boy beheld by mortal eyes.

1. Detestable villain.—2. Declared in favor of Arthur.—3. Ambitious schemes.—4. Heartlessly sacrificed his interests.—5. Full of stratagem.—6. Inhumanly treated.—7. Took secret counsel.—8. Arthur pathetically entreated.—9. The chafed and disappointed king.—10. To despatch Arthur.—11. Evasively sent this reply.—12. He prayed them.—13. Solitary boat.

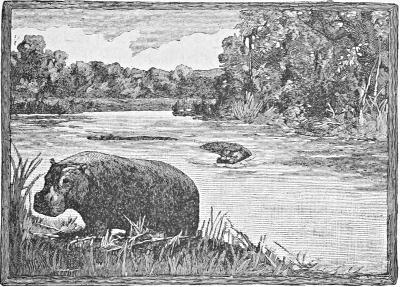

Of all the ugly-looking animals the hippopotamus is certainly one of the ugliest. Its name means the river-horse, and was given it because it is generally found either in rivers or their neighborhood, but the hippopotamus is nothing like a horse, either in its form or its habits.

Though it rarely exceeds five feet in height, it is of vast bulk, and, when full grown, will weigh, it is said, as much as four or five oxen. The head is of enormous size, and provided with a mouth of alarming width. The skin, which is of a dark color and thinly covered with short white hairs, is, in places, nearly two inches thick. The feet are large and divided into four parts, each of which is protected by a hoof.

The hippopotamus lives entirely upon vegetable food, of which it eats vast quantities, as much as six bushels of[56] grass having been found in its stomach. But it is not so much the amount of food which it consumes, as what it destroys, that makes the African dread its visits to the standing crops. Its body is so huge and its legs are so short that it tramples down far more than it eats. It is provided with a tremendous array of teeth, some of which weigh from five to eight pounds. With these it cuts down the grass and shrubs on which it lives as if they were mown with a scythe.

The hippopotamus, in spite of its awkward form, is an excellent swimmer and diver, and can remain under water for as much as ten minutes. During the first few months of its life the young hippopotamus is carried upon its mother’s neck. When born it is not much larger than a terrier dog.

The hippopotamus is caught in various ways. Sometimes several pitfalls, having sharp stakes at the bottom, are dug across the path which it pursues. In the darkness of the night it falls into one of these, and is impaled on the stakes. This is a very cruel mode of capture, and it is to be hoped that the natives who employ it, soon put the poor animal out of its misery. It is not easy to shoot it fatally, for, once it is alarmed, it does not readily show itself. It just pushes up its nostrils above the water to take in air, often selecting for this purpose some spot where the reeds conceal its movements, and then sinks again. Sometimes the hippopotamus is harpooned like a whale. As soon as it is struck with the harpoon the hunters fasten the line round a neighboring tree, and so hold their prey tight until it is despatched.[57] Or, if there is no time for them to get to land, they throw the line, with a buoy attached to it, into the water. The hippopotamus is then pursued in canoes, and every time it rises to the surface it is pierced with javelins, until, at length, it dies from loss of blood. This is dangerous sport, for it sometimes turns upon the hunters and crushes in or capsizes their canoes. Once a hippopotamus, whose calf had been speared on the previous day, attacked a boat in which was Dr. Livingstone. She struck it with such violence that the forepart was lifted clean out of the water, one of the negro boatmen was thrown into the river, and the whole crew were forced to jump ashore.

Between the skin and the flesh is a layer of fat, which is considered a great delicacy. The flesh also is very good eating. The hide is made into shields, whips, and walking-sticks. The teeth yield a beautiful white ivory, which is much valued on account of its never losing color.

1. Either in its form or its habits.—2. Rarely exceeds.—3. Vast bulk.—4. Alarming width.—5. Lives entirely upon vegetable food.—6. Food which it consumes.—7. Tremendous array.—8. Awkward form.—9. Impaled on the stakes.—10. Cruel mode of capture.—11. Shoot it fatally.—12. The reeds conceal its movements.—13. The hunters fasten the line.—14. Dangerous sport.—15. Capsizes their canoes.—16. Lifted clean out of the water.—17. Considered a delicacy.

King Edward I. of England, commonly known as “Longshanks,” nearly conquered Scotland. It was from no lack of spirit or energy that he did not quite complete his troublesome task, but he died a little too soon. On his death-bed he called his pretty, spiritless son to him, and made him promise to carry on the war; he then ordered that his bones should be wrapped up in a bull’s hide, and carried at the head of the army in future campaigns against the Scots. Edward II. soon forgot his promise to his father, and spent his time in dissipation among his favorites, and allowed the resolute Scots to recover Scotland.

Good James, Lord Douglas, was a very wise man in his day. He may not have had long shanks, but he had a very long head, as you shall presently see. He was one of the[64] hardest foes with which the two Edwards had to contend, and his long head proved quite too powerful for the second Edward, who, in his single campaign against the Scots, lost at Bannockburn nearly all that his father had gained.

The tall Scottish castle of Roxburgh stood near the border, lifting its grim turrets above the Teviot and the Tweed. When the Black Douglas, as Lord James was called, had recovered castle after castle from the English, he desired to gain this stronghold, and determined to accomplish his wish. But he knew it could be taken only by surprise, and a very wily affair it must be. He had outwitted the English so many times that they were sharply on the look out for him.

How could it be done?

’Tis an old Yule-log story, and you shall be told.

Near the castle was a gloomy old forest, called Jedburgh. Here, just as the first days of spring began to kindle in the sunrise and the sunsets, and warm the frosty hills, Black Douglas concealed sixty picked men.

It was Shrove-tide, and Fasten’s Eve, immediately before the great Church fast of Lent, was to be celebrated with song and harp and a great blaze of light, and free offerings of wine in the great hall of the castle. The garrison was to have leave for merry-making and indulging in drunken wassail.

The sun had gone down in the red sky, and the long, deep shadow began to fall on Jedburgh woods, the river, the hills, and valleys. An officer’s wife had retired from the great hall, where all was preparation for the merry-making, to the high battlements of the castle, in order to[65] quiet her little child and put it to rest. The sentinel, from time to time, paced near her. She began to sing:—

She saw some strange objects moving across the level ground in the distance. They greatly puzzled her. They did not travel quite like animals, but they seemed to have four legs.

“What are those queer-looking things yonder?” she asked of the sentinel as he drew near.

“They are Farmer Asher’s cattle,” said the soldier, straining his eyes to discern the outlines of the long figures in the shadows. “The good man is making merry to-night, and has forgotten to bring in his oxen; lucky ’twill be if they do not fall a prey to the Black Douglas.”

So sure was he that the objects were cattle, that he ceased to watch them longer.

The woman’s eye, however, followed the queer-looking cattle for some time, until they seemed to disappear under the outer works of the castle. Then feeling quite at ease, she thought she would sing again. Spring was in the evening air; and, perhaps, it was the joyousness of spring which made her sing.

Now, the name of the Black Douglas had become so terrible to the English that it was used to frighten the children, who, when they misbehaved, were told that the Black Douglas would get them. The little ditty I have quoted must have been very quieting to good children in those alarming times.

So the good woman sang cheerily:—

“Do not be so sure of that,” said a husky voice close beside her, and a mail-gloved hand fell solidly upon her shoulder. She was dreadfully frightened, for she knew from the appearance of the man he must be the Black Douglas.

The Scots came leaping over the walls. The garrison was merry making below, and, almost before the disarmed revellers had any warning, the Black Douglas was in the midst of them. The old stronghold was taken, and many of the garrison were put to the sword; but the Black Douglas spared the woman and the child, who probably never afterwards felt quite so sure about the little ditty:—

Douglas had caused his picked men to approach the castle by walking on their hands and knees, with long black cloaks thrown over their bodies, and their ladders and weapons concealed under their cloaks. The men thus presented very nearly the appearance of a herd of cattle in the deep shadows, and completely deceived the sentinel, who was probably thinking more of the music and dancing below, than of the watchful enemy who had been haunting the gloomy woods of Jedburgh.

The Black Douglas, or “Good James, Lord Douglas,” as he was called by the Scots, fought, as you will afterwards[67] read, with King Robert Bruce at Bannockburn. One lovely June day, in the far-gone year of 1329, King Robert lay dying. He called Douglas to his bedside, and told him that it had been one of the dearest wishes of his heart to go to the Holy Land, and recover Jerusalem from the Infidels; but since he could not go, he wished him to embalm his heart after his death, and carry it to the Holy City, and deposit it in the Holy Sepulchre.

Douglas had the heart of Bruce embalmed and enclosed in a silver case, and wore it on a silver chain about his neck. He set out for Jerusalem, but resolved first to visit Spain and engage in the war waged against the Moorish king of Granada. He fell in Andalusia, in battle. Just before his death he threw the silver casket into the thickest of the fight, exclaiming, “Heart of Bruce, I follow thee or die!”

His dead body was found beside the casket, and the heart of Bruce was brought back to Scotland and deposited in the ivy-clad Abbey of Melrose.

Douglas was a real hero, and few things more engaging than his exploits were ever told under the holly and mistletoe, or in the warm Christmas light of the old Scottish Yule-logs.

1. Lonely mood.—2. His heart was beginning to sink.—3. Low despair.—4. Silken clew.—5. Ceiling dome.—6. Bruce could not divine.—7. Strong endeavor.—8. Slipping sprawl.—9. Bruce braced his mind.—10. Con over this strain.

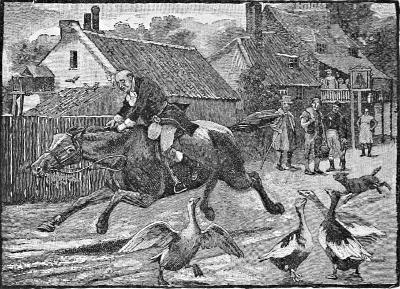

A Farmer, whose poultry-yard had suffered severely from the foxes, succeeded at last in catching one in a trap.

“Ah, you rascal!” said he, as he saw him struggling, “I’ll teach you to steal my fat geese. You shall hang on the tree yonder, and your brothers shall see what comes of thieving.”

The Farmer was twisting a halter to do what he had threatened, when the Fox, whose tongue had helped him in hard pinches before, thought there could be no harm in trying if it might not do him one more good turn.

“You will hang me,” he said, “to frighten my brother foxes. On the word of a fox they won’t care a rabbit-skin for it; they’ll come and look at me, but you may depend upon it, they will dine at your expense before they go home again!”

“Then I shall hang you for yourself, as a rogue and a rascal,” said the Farmer.

“I am only what Nature, or whatever you call the thing, chose to make me,” the Fox answered; “I didn’t make myself.”

“You stole my geese,” said the man.

“Why did Nature make me like geese, then?” said the Fox. “Live and let live; give me my share and I won’t touch yours; but you keep them all to yourself.”

“I don’t understand your fine talk,” answered the Farmer; “but I know that you are a thief, and that you deserve to be hanged.”

His head is too thick to let me catch him so, thought the Fox; I wonder if his heart is any softer. “You are taking away the life of a fellow-creature,” he said; “that’s a responsibility,—it is a curious thing that life, and who knows what comes after it? You say I am a rogue; I say I am not; but at any rate I ought not to be hanged, for if I am not, I don’t deserve it; and if I am, you should give me time to repent.” I have him now, thought the Fox; let him get out if he can.

“Why, what would you have me do with you?” said the man.

“My notion is, that you should let me go, and give me a lamb, or a goose or two, every month, and then I could live without stealing; but perhaps you know better than I, and I am a rogue; my education may have been neglected; you should shut me up, and take care of me, and teach me. Who knows but in the end I may turn into a dog?”

“Very pretty,” said the Farmer; “we have dogs enough, and more, too, than we can take care of, without you. No, no, Master Fox; I have caught you, and you shall swing, whatever is the logic of it. There will be one rogue less in the world, any how.”

“It is mere hate and unchristian vengeance,” said the Fox.

“No, friend,” the Farmer answered, “I don’t hate you, and I don’t want to revenge myself[73] on you; but you and I can’t get on together, and I think I am of more importance than you. If nettles and thistles grow in my cabbage-garden, I don’t try and persuade them to grow into cabbages. I just dig them up. I don’t hate them; but I feel somehow that they mustn’t hinder me with my cabbage, and that I must put them away; and so, my poor friend, I am sorry for you, but I am afraid you must swing.”

[Written on the river Ottawa in the summer of 1804.]

1. To bear him company.—2. Fairy flax.—3. Veering flaw.—4. Spanish Main.—5. The moon had a golden ring.—6. Scornful laugh.—7. I can weather the roughest gale.—8. Stinging blast.—9. Rock-bound coast.—10. In distress.—11. Gleaming light.—12. Stiff and stark.—13. Norman’s Woe.—14. Fitful gusts.—15. By the board.—16. Whooping billow.

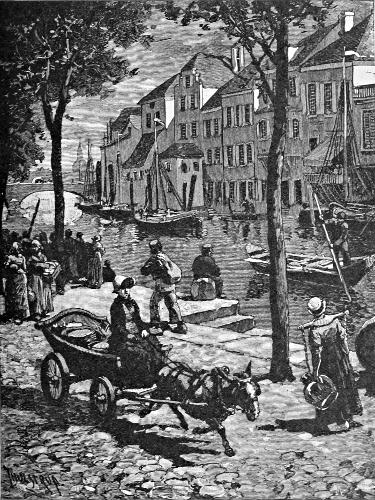

Dutch cities seem, at first sight, to be a bewildering jumble of houses, bridges, churches, and ships, sprouting into masts, steeples, and trees. In some cities boats are hitched, like horses, to their owners’ door-posts, and receive their freight from the upper windows.

Mothers scream to their children not to swing on the garden gate for fear they may be drowned. Water roads are more frequent in Holland than common roads and railroads; water fences, in the form of lazy green ditches, enclose pleasure-ground, farm, and garden.

Sometimes fine green hedges are seen; but wooden fences, such as we have, are rarely met with in Holland. As for stone fences, a Hollander would lift his hands with astonishment at the very idea. There is no stone there, excepting those great, masses of rock that have been brought from other lands, to strengthen and protect the coast. All the small stones or pebbles, if there ever were any, seem to be imprisoned in pavements or quite melted away. Boys, with strong, quick arms, may grow from aprons to full beards, without ever finding one to start the water-rings, or set the rabbits flying.

The water-roads are nothing less than canals crossing the country in every direction. These are of all sizes, from the great North Holland Ship Canal, which is the wonder of the world, to those which a boy can leap. Water-omnibuses constantly ply up and down these roads for the conveyance of passengers; and water-drays[79] are used for carrying fuel and merchandise.

Instead of green country lanes, green canals stretch from field to barn, and from barn to garden; and the farms are merely great lakes pumped dry. Some of the[80] busiest streets are water, while many of the country roads are paved with brick. The city boats, with their rounded sterns, gilded bows, and gayly-painted sides, are unlike any others under the sun; a Dutch waggon, with its funny little crooked pole, is a perfect mystery of mysteries.

One thing is clear, you may think that the inhabitants need never be thirsty. But no, Odd-land is true to itself still. With the sea pushing to get in, and the lakes struggling to get out, and the overflowing canals, rivers, and ditches, in many districts there is no water that is fit to swallow. Our poor Hollanders must go dry, or send far inland for that precious fluid, older than Adam, yet young as the morning dew. Sometimes, indeed, the inhabitants can swallow a shower, when they are provided with any means of catching it; but generally they are like the sailors told of in a famous poem, who saw

Great flapping windmills all over the country make it look as if flocks of huge sea-birds were just settling upon it. Everywhere one sees the funniest trees, bobbed into all sorts of odd shapes, with their trunks painted a dazzling white, yellow, or red.

Horses are often yoked three abreast. Men, women and children go clattering about in wooden shoes with loose heels.

Husbands and wives lovingly harness themselves side by side on the bank of the canal and drag their produce to market.

In the dark forests of Russia, where the snow lies on the ground for eight months in the year, wolves roam about in countless troops; and it is a fearful thing for the traveller, especially if night overtakes him, to hear their famished howlings as they approach nearer and nearer to him.

A Russian nobleman, with his wife and a young daughter, was travelling in a sleigh over a bleak plain. About nightfall they reached an inn, and the nobleman called for a relay of horses to go on. The innkeeper begged him not to proceed. “There is danger ahead,” said he: “the wolves are out.” The traveller thought the object of the man was to keep him as a guest for the night, and, saying it was too early in the season for wolves, ordered the horses to be put to. In spite of the repeated warnings of the landlord, the party proceeded on their way.

The driver was a serf who had been born on the nobleman’s estate, and who loved his master as he loved his life. The sleigh sped swiftly over the hard snow, and there seemed no signs of danger. The moon began to shed her light, so that the road seemed like polished silver.

Suddenly the little girl said to her father, “What is that strange, dull sound I heard just now?” Her father replied, “Nothing but the wind sighing through the trees.”

The child shut her eyes, and kept still for a while; but in a few minutes, with a face pale with fear, she turned to her father, and said, “Surely that is not the wind: I hear it again; do you not hear it too? Listen!” The nobleman listened, and far, far away in the distance behind him, but distinct enough in the clear, frosty air, he heard a sound of which he knew the meaning, though those who were with him did not.

Whispering to the serf, he said, “They are after us. Get ready your musket and pistols; I will do the same.[84] We may yet escape. Drive on! drive on!”

The man drove wildly on; but nearer, ever nearer, came the mournful howling which the child had first heard. It was perfectly clear to the nobleman that a pack of wolves had got scent, and was in pursuit of them. Meanwhile he tried to calm the anxious fears of his wife and child.

At last the baying of the wolves was distinctly heard, and he said to his servant, “When they come up with us, single you out the leader, and fire. I will single out the next; and, as soon as one falls, the rest will stop to devour him. That will be some delay, at least.”

By this time they could see the pack fast approaching, with their long, measured tread. A large dog-wolf was the leader. The nobleman and the serf singled out two, and these fell. The pack immediately turned on their fallen comrades, and soon tore them to pieces. The taste of blood only made the others advance with more fury, and they were soon again baying at the sleigh. Again the nobleman and his servant fired. Two other wolves fell, and were instantly devoured. But the next post-house was still far distant.

The nobleman then cried to the post-boy, “Let one of the horses loose, that we may gain a little more time.” This was done, and the horse was left on the road. In a few minutes they heard the loud shrieks of the poor animal as the wolves tore him down. The remaining horses were urged to their utmost speed, but again the pack was in full pursuit. Another horse was cut loose, and he soon shared the fate of his fellow.

At length the servant said to his master, “I have served you since I was a child, and I love you as I love[85] my own life. It is clear to me that we can not all reach the post-house alive. I am quite prepared, and I ask you to let me die for you.”

“No, no!” cried the master, “we will live together or die together. You must not, must not!”

But the servant had made up his mind; he was fully resolved. “I shall leave my wife and children to you; you will be a father to them: you have been a father to me. When the wolves next reach us, I will jump down, and do my best to delay their progress.”

The sleigh glides on as fast as the two remaining horses can drag it. The wolves are close on their track, and almost up with them. But what sound now rings out sharp and loud? It is the discharge of the servant’s pistol. At the same instant he leaps from his seat, and falls a prey to the wolves! But meanwhile the post-house is reached, and the family is safe.

On the spot where the wolves had pulled to pieces the devoted servant, there now stands a large wooden cross, erected by the nobleman. It bears this inscription: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

1. Heroic serf.—2. Famished howlings.—3. Bleak plain.—4. A relay of horses.—5. Ordered the horses to be put to.—6. Repeated warnings.—7. The moon began to shed her light.—8. Pack of wolves.—9. Had got scent of them.—10. To calm the anxious fears.—11. Baying at the sleigh.—12. Instantly devoured.—13. Fully resolved.—14. To delay their progress.

1. Large of heart.—2. Small estate.—3. Drain a glass.—4. Children’s early words.—5. False pretence.—6. Common sense.—7.—Open face without guile.—8. Selfish knave.—9. Contented slave.—10. Simple song.—11. Awakes emotions strong.—12. Constant whine.—13. Survey the world.—14. Excuse the faults.—15. Scorn my health.—16. Sell my soul for wealth.—17. Sunny side.—18. Conscience clear.—19. Manage to exist.

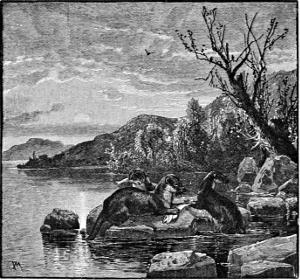

The otter resembles land animals in shape, hair, and general conformation, and the aquatic tribes in its manner of living and in its webbed toes, which assist it in swimming. It swims even faster than it runs, and can overtake fishes in their own element.

It is found in all parts of the world,—on tropical islands, in America, and on the bleak coasts of Alaska and Siberia. It is one of the great weasel family, as active and cunning in the water, as its land relations are in the field, or in the farm-yard.

The fish-otter—which is found around lakes and rivers in Canada, in the United States, in South America, and in wild parts of Europe—is a famous fisher. Its home is in the water, but it can travel over the land with wonderful swiftness, although its paws are webbed.

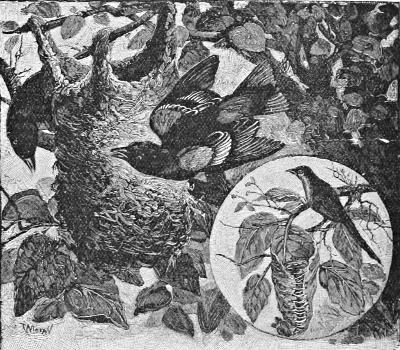

It is very fond of sliding down hill. On the slopes by ponds and rivers, it enjoys itself in a very odd fashion. It lies with its fore-feet bent backward, and pushes itself forward with its hind-feet, going down the snowy or muddy slope with as much pleasure as if it were a schoolboy “coasting.” A number of fish-otters thus amusing themselves must present a very ludicrous sight.

These furry little quadrupeds can stay a long time under water, swimming swiftly and without noise; so that the fish they follow seldom escape them. If the prey is small, the otters do not trouble themselves to go far with it, but bite off the most delicate morsels and throw the rest away. When they catch a large fish, however, they drag it ashore and feed upon it at their leisure. When fish are not plentiful enough, the otters, grown bold from necessity, will attack ducks or any other waterfowl within reach. They are so strong, and bite so fiercely, that the animals they pursue may well regard them with terror.

Their habitations are really safe hiding-places. They burrow under the ground, and make the entrance of their “nest” under water; so that no land-enemies can pursue them: certainly, no water-foe can follow them into the hollow made by them in the bank. This proves that the crafty nature of the weasel is not wanting in the otter.

They dig upward four or five feet, or even more; and at the end of the tunnel they make a little room, which they[92] line with moss and grass, for the comfort of the baby-otters. This underground room has no need of windows; but it does need ventilation, and a minute air-hole, leading, like a chimney, to the surface of the earth, is an important part of otter house-building.

When taken young, otters can be tamed and taught to catch fish for their masters, being trained to hunt as dogs are trained for the chase. “I have seen one,” says Goldsmith, “go to a gentleman’s pond at the word of command, drive up the fish into a corner, and, having seized upon the largest, bring it off in its mouth to its master.”

Otters differ very much in size and color. Fish-otters are from two to three feet long, and sea-otters—the largest of the family—are somewhat longer. These sea-otters are very much prized for their soft, glossy, black fur. Some of the species, however are white, with a yellow tinge; others are dark-brown, with yellow spots under the throat. No doubt all of you have seen caps, and gloves, and other coverings made of the soft, warm fur of the otter.

1. General conformation.—2. Aquatic tribes.—3. Bleak coast.—4. Wild parts.—5. Odd fashion.—6. Ludicrous sight.—7. Furry quadrupeds.—8. Delicate morsels.—9. Crafty nature.—10. Minute air-hole.—11. Differ in size.—12. Much prized.

There was once a child, and he strolled about a good deal, and thought of a number of things. He had a sister, who was a child too, and his constant companion. These two used to wonder all day long. They wondered at the beauty of the flowers; they wondered at the height and blueness of the sky; they wondered at the goodness and the power of God, who made the lovely world.

They used to say to one another sometimes, “Supposing all the children upon earth were to die, would the flowers, and the water, and the sky be sorry?” They believed they would be sorry. “For,” said they, “the buds are the children of the flowers, and the little playful streams that gambol down the hillsides are the children of the water; and the smallest bright specks, playing at hide-and-seek in the sky all night, must surely be the children of the stars; and they would all be grieved to see their playmates, the children of men, no more.”

There was one clear-shining star that used to come out in the sky before the rest, near the church spire, above the graves. It was larger and more beautiful, they thought, than all the others, and every night they watched for it, standing hand in hand at a window. Whoever saw it first cried out, “I see the star!” And often they cried out both together, knowing so well when it would rise, and where. So they grew to be such friends with it, that,[98] before lying down on their beds, they always looked out once again, to bid it good-night; and when they were turning round to sleep they used to say, “God bless the star!”

But while she was still very young—oh, very, very young!—the sister drooped, and came to be so weak, that she could no longer stand at the window at night; and then the child looked sadly out by himself, and when he saw the star, turned round and said to the patient, pale face on the bed, “I see the star!” and then a smile would come upon the face, and a little, weak voice used to say, “God bless my brother and the star!”

And so the time came, all too soon! when the child looked out alone, and when there was no face on the bed; and when there was a little grave among the graves, not there before; and when the star made long rays down towards him, as he saw it through his tears.

Now, these rays were so bright, and they seemed to make such a shining way from earth to heaven, that when the child went to his solitary bed, he dreamed about the star; and dreamed that, lying where he was, he saw a train of people taken up that sparkling road by angels. And the star, opening, showed him a great world of light, where many more such angels waited to receive him.

All these angels, who were waiting, turned their beaming eyes upon the people who were carried up into the star; and some came out from the long rows in which they stood, and fell upon the people’s necks, and kissed them tenderly, and went away with them down avenues of light, and were so happy in their company, that, lying in his bed, he wept for joy.

But there were many angels who did not go with them, and among them one he knew. The patient face that once had lain upon the bed was glorified and radiant, but his heart found out his sister among all the host. His sister’s angel lingered near the entrance of the star, and said to the leader among those who had brought the people thither, “Is my brother come?” And he said, “No.” She was turning hopefully away, when the child stretched out his arms, and cried, “O sister, I am here! Take me!” And then she turned her beaming eyes upon him, and it was night; and the star was shining into the room, making long rays down towards him, as he saw it through his tears. From that hour forth, the child looked out upon the star as on the Home he was to go to when his time should come; and he thought that he did not belong to the earth alone, but to the star too, because of his sister’s angel gone before. There was a baby born to be a brother to the child; and while he was so little that he never yet had spoken a word, he stretched his tiny form out on the bed, and died.

Again the child dreamed of the opened star, and of the company of angels, and the train of people, and the rows of angels, with their beaming eyes all turned upon those people’s faces. Said his sister’s angel to the leader, “Is my brother come?” And he said, “Not that one, but another.” As the child beheld his brother’s angel in her arms, he cried, “O sister, I am here! Take me!” And she turned and smiled upon him, and the star was shining.

He grew to be a young man, and was busy at his[100] books, when an old servant came to him, and said, “Thy mother is no more. I bring her blessing on her darling son!” Again at night he saw the star, and all the former company. Said his sister’s angel to the leader, “Is my brother come?” And he said, “Thy mother!” A mighty cry of joy went forth through all the star, because the mother was reunited to her two children. And he stretched out his arms, and cried, “O mother, sister, and brother, I am here! Take me!” And they answered him, “Not yet,” and the star was shining.

He grew to be a man, whose hair was turning gray, and he was sitting in his chair by the fireside, heavy with grief, and with his face bedewed with tears, when the star opened once again. Said his sister’s angel to the leader, “Is my brother come?” And he said, “Nay, but his maiden daughter.” And the man who had been the child saw his daughter, newly lost to him, a celestial creature among those three, and he said, “My daughter’s head is on my sister’s bosom, and her arm is round my mother’s neck, and at her feet there is the baby of old time, and I can bear the parting from her—God be praised!” And the star was shining.

Thus the child came to be an old man, and his face was wrinkled, and his steps were slow, and his back was bent. And one night, as he lay upon his bed, his children standing around, he cried, as he had cried so long ago, “I see the star!” They whispered to one another, “He is dying.” And he said, “I am. My age is falling from me like a garment, and I move towards the star as a child. And, O my Father, now I thank Thee that it has so often opened, to receive those dear ones who await me!” And[101] the star was shining; and it shines upon his grave.

1. In a mournful muse.—2. Her heart’s adrift.—3. Hale and clever.—4. Skies aglow.—5. No tear her wasted cheek bedews.—6. Old with watching.—7. Bleach the ragged shore.—8. Silently chase.—9. Twenty seasons.—10. Hopeless Hannah.

There are few animals that can teach us more useful lessons than the beaver.

They are very timid animals. If we went to places where they are common, it would be very difficult to find them and see what they do.