By WILLIAM W. STUART

Illustrated by RITTER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine April 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

She was a wonderful wife—sweet, pretty,

loving—but she would keep littering up

the house with her old, used-up bodies!

I

So help me, I'm not really a fiend, a monstrous murderer or a Bluebeard. I am not, truly, even a mad scientist bucking for a billing to top Frankenstein's. My knowledge of science ends with the Sunday magazine section of the paper. As for the bodies of all those women the front pages claim I butchered and buried somewhat carelessly out by the garage, all that is just—well, just an illusion of sorts.

Equally illusory, I am hoping, is my reservation for a sure seat, next performance, in the electric chair which now seems so certain after the merest formality of a trial.

Actually I am, or was, nothing but a very normal, average—upper middle average, that is—sort of a guy. I have always been friendly, sociable, kindly, lovable to a fault. So how did lovable, kindly old I happen to get into such a bloody mess?

I simply helped a little old lady cross the street. That's all.

All right, I admit I was old for Boy Scout work. But the poor old bat did look mighty confused and baffled, standing there on the corner of York and Grand Avenue, looking vaguely around.

So, "What the hell," I said to myself; and, to her, "Can I help you, Madam?" I had to cross the street anyway. Traffic being what it was, I figured I'd feel a little safer with her for company. It was silly, of course, to think that a poor old lady on my arm would ever inhibit the Grand Avenue throughway traffic but I tried it. Good job I did, too.

It was an early fall afternoon, a bit before rush hour. I had knocked off work early. It was too nice a day for work and besides the managing editor had fired me again. I had nothing better to do, so I thought I'd wander over to Maxim's for a drink or two. Then, on the corner, I found the old lady.

She was a pretty sad-looking old lady. Matter of fact she was—just standing there, not even trying—the worst-looking old lady I ever saw. She looked, to put it kindly, like a three-day corpse that had made it the hard way after a century of poor health. First I thought, hell, I'll give the old bag of misery a boost, shove her under a bus or something. It would be the decent, kindly thing to do.

I spoke, tentatively. She half-turned and looked up at me from her witch's crouch. The eyes in the beak-nosed, ravaged ruin of a face were big, luminous, a glowing green. They clearly belonged elsewhere and there was a lost, appealing look in them. There was a demand there, too.

"I—uh—that is, would you care to cross with me, Madam?" I asked her.

She took my arm. There was a moment's lull in the wake of a screaming prowl car. I muttered a word of prayer and we were off the curb. The old hag was surprisingly quick. It looked as though we were going to make it. Then, three-quarters across, I came down with a rubber heel in an oil slick just as a roaring, grinding cement-mixer truck was coming down on me like an avalanche. My feet went up. I gave the old witch a shove clear and shut my eyes for fear the coming sight of smeared blood and guts—my own—would make me sick.

And then, instead of a prone, cringing heap on the pavement sweating out the ten-to-one odds against all those wheels missing me, I was airborne. Cable-strong arms caught and lifted me. We were racing down field, elusive, unstoppable, all the way—touchdown.

So there we were, safe on the sidewalk. Traffic on the freeway, gaping at us, was chaos as the frail, doddering little old lady put me down. Me, I was never any extra large size. But still, a touch under six feet, maybe a little too friendly with beer and rich desserts—say, 210 pounds—I had considered myself a little big for convenient carrying about.

This was something new in little old ladies.

I stared down at her. She wasn't even breathing hard. In fact I couldn't tell if she was breathing at all. "Madam," I said, "my sincere thanks and admiration. I wonder now. If you're not late for practice with the Bears or something, perhaps we could go someplace and talk?" I couldn't guess what, but there was for sure some sort of a story here. If I could get something hot for the Sunday magazine, I'd have my job back.

The old crone looked up at me with those oddly out of place, compelling eyes of hers. "You will listen to me? You will help?"

"Madam, help you don't need. But listen, yes. This is my great talent. I will be happy to listen to you."

I thought a quiet booth and a couple of cold ones in Maxim's would be nice. No. She wondered in a different, quavering old voice, if greater privacy might not be better. "What I have to tell you, young man, may be difficult for you to grasp. It may be necessary to show you some things."

"Uh." She wasn't the type of doll I favored taking home for a sociable evening but it wouldn't have seemed mannerly to say no to the look of appeal in her eyes. "All right."

We went on over to the parking lot and I drove her to the very comfortable home out in Oakdale that Uncle John and Aunt Belle turned over to me when they rolled off to see the world from their house trailer a year and a half back. Of course they dropped anchor in Petersburg and haven't budged since, but I guess it gives them the footloose feeling they were looking for. And I have the house, which is quite a pleasant little place.

I think Aunt Belle figured giving me the house would offset my own dubious attributes so that some nice girl might just possibly marry and make something of me. But I kept a picture on my bureau of Uncle John, standing by the sink in his apron, and was still holding out.

Well, the old bat didn't clue me in on anything on the drive out there in my car. We chatted along the way, mostly her asking the questions, me answering. She was just a visitor to the town, she said. She wanted to find out all about it—with ten thousand nonsensical questions.

I parked in the drive and we went in. While she settled down on the sofa I went to the bar, my addition to the home furnishings, to fix a drink; wondered if there might still be any tea knocking around; thought better of that and mixed two drinks. Then I turned back toward her.

"Now," I said, "tell me."

"Well," announced that ravaged wreck of an old woman, "the fact is that I am from another world."

"Oh, hell," I said, "how did you come in? By saucer or by broom?" It was a mean remark, I suppose. Not kindly. Even so, the way she took it seemed all out of proportion. The old bat's face suddenly went slack. She slumped over sideways on the sofa, those big, green eyes open, staring, empty. There was no need to go check for a pulse or heartbeat. She was plainly, revoltingly dead.

"Ugh!" I said and tossed off one of the two drinks I was holding. It seemed the thing to do.

"Do not be alarmed," said an apparent voice. "I am really perfectly all right. I have simply left that poor vehicle I was using. I had thought, wrongly it now seems, that communication with you chemically powered life forms might be easier if I too were concealed within one such structure."

The voice actually wasn't so much a voice as a voice impression. It came from a point in the air above the body on the sofa. And it did make an impression. It came through in a rush of meanings, too loud somehow, almost overpowering.

I looked toward the point of origin. That's what it was, as near as anything, a tiny pin-point of intense, green-gold light. It was too intense; I had to turn my eyes away. My head started to ache. I felt and knew that, whatever species this might be, my visitor was a female of it. She was, at the moment, horribly overbearing. She was communicating effectively, enthusiastically, but unclearly and it wasn't easy. Not on me, anyway. My mind was swamped with a mass of concepts, jabber and ideas, like all the women's clubs of the world talking at once.

I groaned and staggered back against the bar. "All right," I yelled, "all right, I believe you. You come from another world. You are an amazing, wonderful girl and I am proud to entertain you. But please—go back to being an old woman, or something I can handle."

The ravaged old crone's eyes glowed again. She blinked and sat up. "Please don't shout so. I can hear you," she remarked primly.

I drained the other drink and put both glasses back on the bar. "Ugh. Uh, that's better. But who—where—what—?"

"Please do stop and think a minute," the old witch told me. "If you will simply use that electro-chemical mental equipment of yours, you will find that I have already given you the answers to those questions about who and what I am and where I come from."

"Nonsense." But then it came to me that she had. I just hadn't taken time to sort any of it out.

I tried sorting. Much of it remained fuzzy, I suppose because some aspects were so far outside the range of anything known to me. She was, the way I got it, a life form based on something approximating atomic energy. She came from a dwarf star out someplace, I couldn't quite place it, out Orion way I think. Sure, the entire concept was beyond me and completely alien. And yet, oddly, in a lot of ways it was like old home week. This was a kind of life totally different from ours in all structure and development; and yet their kind of thought, their relationship to their world and their social organization, seemed weirdly familiar. They had work, recreation, social organization. They reproduced by some sort of polarity business I didn't get then and still don't; but it required mating and it certainly seemed a fair approximation of sex.

They had arts based on forms and shaped patterns of energy. I don't get it. She said it compared to our literature, music and painting and I take her word for it. "Only," as she later explained a touch wistfully, "terribly, terribly decadent in the present era."

There was their problem. Their social structure and individuals alike seemed, at last, to be losing all vitality. The birth rate dropped. Culture declined. They had, fairly recently by their standards, discovered the possibility of freeing themselves from their sun and travelling through space. But, while they found planets with chemical life forms like us not uncommon in space, they had found no form comparable to their own. Outside contacts, they had thought, might stimulate and re-vitalize their society. But, of course, where there is life there is politics. They had developed many and bitter differences of opinion regarding the feasibility or value of any attempt to communicate with chemical life forms. There was a party for, a party against and several favoring an agonizing reappraisal of the position whatever it might turn out to be. Nothing was done. And that, in due course, had brought me my lone lady visitor.

The "communication" party decided to take action in spite of the absence of official sanction. They worked cautiously, in secret. Specially selected representatives with certain exceptional kinds and degrees of sensitivity were made ready. Necessary energy supplies for distant space travel were carefully hoarded. Chances of anything coming of it were considered slim but ... there was the horrible old hag sitting on my sofa, looking hopefully up at me out of great, youthfully glowing green eyes.

Anyway, that's the way the thing shaped up in my mind. And it seemed plenty hard to believe.

"Must I come out and show you again?"

"No," I said quickly. "Oh, no, please don't. I'm convinced."

"Or will be," she remarked cryptically. "Good. This now proves that at least one level of communication between us is possible. This is promising. It could mark the beginning of a relationship which may be most stimulating for both life forms."

Well, it was startling at least, I would have to admit that. "Speaking of forms," I said, "You sure picked an ugly one there. Why?"

"Oh? But I am only now beginning to understand your standards of attraction. I took this structure—" she pointed one gnarled, knotty hand at herself—"because in my own form no one seemed willing to listen or accept me logically. They only yelled that I was an A-bomb or a short circuit or lightning, or else simply pretended they didn't see me at all. So I took this body, making only a few small internal repairs and improvements. But then, until you came along, no one would stop long enough to listen to me."

"Hum. Where'd you get it?"

"I picked it up at one of your places for them to die. What you call the cold room at the County Hospital. There was, I admit, some confusion."

That I could believe.

"You are not nearly as different from us in mental processes and customs as I should have thought. Such an intriguing life form, with such amusing complications. Just strange enough to be exciting. Come over here and sit by me."

She beckoned coyly, like a flirtatious girl, and winked one youthfully glowing eye at me. The effect, in that ruin of a face, was appalling. I stayed where I was.

"Oh," she said in a hurt tone, "you don't like me? And you seemed so attractively receptive at first. How can we communicate completely on your plane if you are to be so aloof?" She stopped and seemed to concentrate a moment. I felt as if something gave my thoughts a brisk stirring with a long swizzle stick.

"Damn it," I snapped, "quit that, you hear me? You've got to stop messing around in my mind. It's an outrageous invasion of—"

"All right, all right," she said. "I won't do it again, I promise. Unless—well, never mind." A typically feminine-type promise. "But now I see that it is simply this body that offends you. Except for this, you are quite ready to love me."

That was putting it a little strongly. I had to admit though, that she was a pretty interesting proposition.

"It is odd to attach such importance to form. A chemical life characteristic, I suppose. I do note that your own structure has its—well. There is no reason for this present form of mine being a problem between us. I shall simply change it."

"Oh?" Like changing a dress, she made it sound. It wasn't quite that easy.

"You must make it clear to me what sort of body you prefer. Oh, I see. That tall, widely curved one with the red hair. Yes, I see the image ... my ... and so lightly clad. Very well. I will have this body for you."

She was reading my mind again, the back corner section where I was keeping a few brightly descriptive memos on Venus de Lite, that luscious, languorous, long-legged new stripper-exotic dancer downtown at the Roma. "That," I told her, not without a touch of wistful regret, "is a live body. You cannot take live bodies. And stop reading my mind."

"I'm sorry. I won't do it again." She kept saying that; and doing it just the same. "I shall not have to take the original body. I can simply duplicate it."

"How could you do that?"

"It should not be difficult. The elements in the structure are common enough here and in readily modified forms. The body organization is complex, true, and not particularly efficient in many respects. However, the patterns can be readily traced and duplicated. It is a simple question of the application of energy to chemical matter. So now you must take me to observe this body which has such attraction for you."

II

That as it turned out, was the toughest part. I did what I could, trying to fix the horrible old witch up in an outfit from one of Aunt Belle's old trunks and a few rather elementary cosmetics. The end result was that, instead of looking like a plain old witch, she seemed a scandalously depraved, probably drunken old witch. The Roma, in a long history dating back to prohibition days, has seen all kinds and conditions. But I don't doubt we were one of the damnedest looking couples on record.

"This—uh—this is my Grandma," I told the few, nastily grinning acquaintances I couldn't duck on our way into the joint. "Grandma is just up on a little visit from Lower Dogpatch. Excuse us, would you? Grandma needs a double shot quick."

That seemed unarguable. We finally settled at a small table off by the swinging doors to the kitchen and sat there through one floor show. "All right," said my old witch, as Venus closed the set with her final frenzy in the blue spotlight, "I have the pattern. There are a number of differences there from the picture in your mind. The age, the chemicals applied."

Venus went off to vigorous applause. The club lights came up and the M.C. stumbled out to favor us with his version of The Gent's Room Joe Miller. I considered. The more beautiful-looking the doll, I suppose, the greater the probable degree of illusion. "Where you find discrepancies," I told my old witch, "be guided by my imagination. Right?"

"All rightie," she remarked brightly, patting my hand on the table as she favored me with what I would estimate as one of history's lewdest winks. I noted a mutter of contempt from surrounding tables. "Shall I go ahead? Perhaps you'd better close your eyes," she said, "I—"

"No, not here!" I grabbed her arm and dragged her to her feet. Neighbor tables gave us their full attention and the muttering took on an ominous tone. "Come on. For pity's sake, let's get on home." I wasn't exactly convinced this proposition was going to work out; but a crowded nightclub was no place for her to try it.

"Graverobber!" was one of the indignant remarks that caught my ear as I dragged the harridan out. She giggled. The female, species immaterial, seems to have a sense of humor ranging from the Pollyanna-like to the graveyard ghoulish—missing nearly every point between.

She was quiet and thoughtful on the ride back home. So was I, pondering the doubtful status of my reputation around town and my sanity.

In the house, she was brisk and businesslike. She got me to help her stack a bunch of canned goods and junk from the refrigerator on the kitchen table—"Just for convenience." She remarked domestically, "It would have saved your fuel and power if I had made the change at the other place. I must draw heavily on the power that runs into this house. I must, you understand, conserve my own supply."

"Perfectly all right. Be my guest." The whole thing had a sort of dream quality to it by then. You know how it is in dreams sometimes? The action and story lines are fantastic. You know the whole thing must be nonsense. You could, by an effort of will, wake up and end it. And yet you go along with the thing just to see how the foolishness will turn out. That is the way I felt then.

"Oh yes, one more detail," said my witch. "What about the eyes? I found nothing about the color of the eyes in your largely imaginary mental picture of the cheap floozy in that second-rate saloon."

Already she was not only speaking the language but thinking the thoughts like a native female. The eyes. Hmm. I guess my mental film strips of Venus had kind of skipped past facial close-ups. "Why don't you just keep the same eyes you have now?" I suggested.

"Good," she said. "They are my own design. Here goes. Close your eyes; there may be some glare."

I closed my eyes. For a moment there was nothing. Then, for about a second, say, there was an intense, flaring glare that shone reddish through my closed lids. Then it was dark.

"All righty," said a sweet-soft voice, ending in a little, half-breathless giggle. "Now you can look."

I looked.

Trouble was, it was still dark. No lights. All I could see by the faint light of a half moon filtering in the kitchen window was a dim figure standing by the table.

Fact was, I found later, a sudden power surge on the main line outside the house blew a transformer and blacked out the whole blinking suburb.

I snapped out my lighter and flicked it on. Well now, indeed! There, half shy, half not so shy and wearing the same negligible costume as in her final number at the Roma, was Venus, constructed just exactly the way she should have been.

"The way I built me," she said, and giggled, "to your very explicit order. So now what are you going to—"

I wouldn't say that I am notably more impetuous than the next man. That was just an impetuous situation. I let the lighter go and grabbed her. "Ah," I remember her saying softly, "now we can truly begin to communicate."

I can say with every reasonable assurance that we did so most effectively. Alien she was, but she was also a lovely girl, my own dream girl. Or girls. What man of any imagination at all is a totally monogamous dreamer? Anyway, she was unarguably lovely, loving, uniquely adaptable, generally sweet. And if, once her frequently unfathomable mind was made up, she had the determination of seven dedicated devils—well, she was female and probably no worse than some billion local girls. My little atom-powered space girl had a lot more built-in compensating factors.

But that's as it developed. That night, naturally, was largely devoted to communication. Luckily, having been fired, I didn't need to worry about getting up to go to work.

Along about eleven or so the next morning she bounced out of bed, bright, beautiful and lively. I dragged on down to the kitchen with her to see if we could put together a breakfast from whatever staples she hadn't found it necessary to incorporate into new construction. By the kitchen table I stumbled over the most ravaged, deadest looking corpse I ever hope to see. It was, of course, the unlamented body of the original witch, lying just where it had dropped the evening before.

"Look, hon, what about this?"

She shrugged quite charmingly, in spite of the tentlike dimensions of Aunt Belle's nightgown. "What about it?"

"Well, why didn't you use the—uh—material there, instead of all the groceries?"

Another shrug. "I wanted something fresh."

She had a point. I couldn't argue. I never could, when she turned those big green eyes of hers on me, full power. "Yeah," I said. "Only what are we going to do with it?"

"What do your kind do with old bodies here?"

"Mostly we bury them."

"All right then."

That was unassailable feminine logic. All right. So I'd bury it.

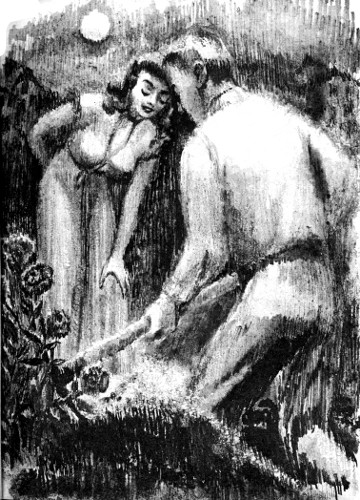

That night, by the eerie light of the waning moon, I went at it with Uncle John's pick and shovel and buried the old witch's body next to Aunt Belle's rose bushes by the garage. My bright, new-incarnation girl lounged around and chatted sociably. Everything still had quite a dreamlike quality; the corpse was a final, nightmare touch. But even so, I was beginning to wonder a bit about things; such things as, specifically, where we went from there.

"Star-doll-baby—" well, hell, there are times when a man has to use terms like that to communicate with the female—"you aren't going to vanish all of a sudden and leave me now, are you? Ugh!" That was a heavy shovel and thick clay. "What are our plans?"

"Sil-ly. I understand your custom now. We are going to be married, of course. Then we shall see. There is no hurry. I have, by your standards, plenty of time. I must assimilate and learn to understand you and your fascinating life-form. We shall live together and be man and wife. As I have said, your species and mine may derive much benefit from this intermingling."

That, if I understood her correctly, sounded fine to me. It was the best proposal I'd had yet. And surely it would have been poor hospitality to a lonely little girl some light-years away from home for me to have refused. "This is terribly sudden," I told her. "Uf! That ought to be enough of a hole for as wizened up a little old body as that ... yes, darling, I will marry you. Who's going to earn us a living?"

III

I climbed out of the hole and kissed her and, in time, we did manage to get the old woman buried.

The next day we applied for our license. Three days later we were married—so far as I know, an interstellar first. The job or money problem, as it turned out, was no problem. Her first thought was the direct, female approach to the problem. She could simply make it out of old newspapers whenever we needed some, as she had the body. She made some to show me.

"Well now," I told her, "it does seem the simplest way, I admit. But the government is pretty jealous of its ability to print money. It likes to think that nobody else can do the job just right."

I was afraid this might be one of her stubborn points but it wasn't. Government restrictions, bureaucracy and red tape were things she had no trouble understanding. "It is the same way back home with power and energy rations," she told me. "You have no idea the difficulty we had in building up the capital supply necessary for my trip here. So I suppose we must find another way. Don't you already have some of this money? Or couldn't you manage to borrow some?"

I had $37.62 in my checking account, but the house was in my name. I borrowed five grand. I invested. I was probably the most successful investor since old King Midas developed his touch. If I sank a buck in land, oil would turn up within the week, and if it turned out to be a geologically inexplicable tiny pocket the next week—that would be after I had unloaded. Stocks, commodities, it made no difference. The money rolled in. We had the touch. Paid our taxes, too, but she had a way with tax loopholes that gave the district collector a nervous breakdown.

We traveled, but we kept the old house. We always came back to it for sentimental reasons. We spent a lot of time in libraries, museums. We went to shows and concerts. Anything that was going, we went to it. She had a contagious interest that she communicated to—not to say forced on—me; and if some of the operas and symphonies we caught seemed to my elemental musical taste to run a little long and loud, I had my compensations. And a lot more than most; our adjustments were not all one-sided.

Example: We made a tour of Europe. Now, I always was a fine, loving husband to her. Completely faithful. But—well, there was a dark-haired, laughing, button-cute little chick who sang Spanish songs in English with an Italian accent in a little place on the Riviera. I didn't make a pass. I didn't even speak to her. But I have to admit that, as a strictly idle fancy, she did cross my mind once or twice.

"Hah!" my tall, statuesque, beautiful red-haired wife snorted at me one evening after we were back home. She was sitting listening to hi-fi, some of the very long-hair music that she called "the second most fascinating development of your kind." I was just sitting, maybe dozing a bit.

"So!" She gave it full-force, wifely indignation. "You sit there and you smile on me—and all the time you are thinking of this cheap, female, singing bullfighter you have seen two times. You have two times me in your mind!"

Already she was talking with just the accent that chick had used.

"Now look here," I protested, "you promised not to go prowling through my mind. A man is entitled to a little privacy!"

"How can you think so of this other woman? You don't—" sob—"love me any more!"

Women! That's the way trying to argue with them goes. You are always on the defensive.

"Aw now, Star-hon-baby," I said, "honestly, it was just a passing thought. I only—"

"I know what sort of thought it was! Very well." She got up and stalked off to the kitchen. I didn't get what she was up to, not even when I heard her banging temperishly about out there.

When there was a sudden flash and the lights blinked out, the idea hit me. I was scared. What if she had gone back, left me? I dashed to the kitchen. Just through the swinging door, I tripped over a body and fell into the kitchen table. Had she—? Then I heard a charming, slightly accented little giggle.

I didn't bother with my lighter. I reached out, caught her, pulled my sweet little dark-haired baby to me and kissed her. "Honey-doll, believe me—I do love you. No matter who you are, I love you!"

I meant every word of it, too. That was a brand of accommodation you will never get from any local girl.

The next night I had to dig a new grave out by the garage—a bigger one this time, for a big, beautiful, long-legged, red-haired body. Funny thing. Contrary to general belief, none of this ever seemed to do anything for the roses by the garage. They had done poorly ever since Aunt Belle left and they kept on doing poorly. Well, no matter. Six months later it was the little brunette's turn to go and we went back to red hair. When I say my wife was all women to me, I mean it.

The last model was medium height, Titian shade hair, not spectacular but cute, very companionable, very lovable, beautifully built, built to last. She was some builder, my wife, and she did a lot of fine construction work for me.

One night, back along about the third week of our marriage, I got to feeling lousy—sniffles, headache, no appetite.

It was no dramatic plague; just a typical, nasty case of flu. I used to get them every fall and winter. I mixed myself a couple of hot lemon and's, and explained it to my (tall, red headed) wife. "Oh, yes," she said. "I see."

I had an idea she took another quick prowl through my mind but I felt too sick to complain. "I'm going to bed," I told her. I went.

Oddly enough, instead of putting in a restless night, I slept like a log. When I woke up the next morning, I felt great. In fact, as I burst into a spontaneous and very tuneful chorus of Body and Soul in the shower, it came to me that I had never in my life felt so well. When I looked in the mirror to shave, it seemed to me I was even looking better.

Later that day I was up on the roof putting up a TV aerial. I hadn't ever bothered with TV, but she wanted to learn all about even that. I put up the aerial. Then I fell off the roof. I dropped twelve feet, landing on my left arm and shoulder on hard-packed lawn. Then I got up and dusted myself off. No damage. I was all right.

"Clumsy," she said to me from the porch.

"No," I said. "Damn it, there was this loose shingle up there. It slipped right out from under me and—anyway, you might at least be a little sympathetic. It's a wonder I didn't break my arm. In fact, I can't understand why I didn't."

"Nothing broke because of the improvements I made in you last night."

"What?"

"Darling," she said, "I made a few improvements. Of course, you were very attractive, lover. Perfectly charming. But structurally, really, you were a most imperfect mechanism. So now that I have made a study of these bodies your people use, I ... rebuilt you."

"Oh? Oh! Now, look here! Who in hell said you could?"

It did, at the time, seem pretty damned officious. I was sore. However, I had to admit that the changes she made worked out rather well. A strong, light metallic alloy seems to make much better bones than can be made of calcium. General immunity to disease was desirable, I couldn't deny. My re-wired nervous system and modified muscular structure were as pleasant to work with as they were efficient. I was a new man.

Of course, every woman always wants to make a finer specimen of whatever slob she marries. Only I had the luck to get the one who knew how to do the job properly—from the inside out, rather than by simply peck, peck, pecking away at the outside.

It was all as near perfect as a marriage can be. I have no complaints now—and very few even then. She had built me to last a couple of centuries. I was ready and willing to string along with her all the way.

But it never does work out that way, does it?

What happened to us, as it does to most, was that at the end of the third year she got pregnant. A very ordinary female trait, you may say, and not ordinarily surprising. No. Except that she was no ordinary female.

We were in bed one night—our last night as it turned out—when she told me.

"Darling," she said, and kissed me. "I have something to tell you."

"Haw?" I was sort of sleepy.

"I've been hoping and hoping it would happen, but I wasn't sure it could."

"Ha? Whatsat?"

"Darling, we—are going to become parents."

"What?" I was awake then. "We're going to have a baby? Why, that's great. Wonderful! Do you think he'll take after me?" As I thought it over, it seemed something of a problem. What would the heredity be? In fact, how could it be?

"Never mind, darling," she said quietly—sadly, I like to think, as I look back on it. "That's woman's work, you know. Just leave the details to me."

I kissed her. We were very loving and tender. I went to sleep, and dreamed all night long that I was Siamese twins in a fratricidal finish fight over my model wife.

IV

I woke up by daylight to a horrible, icy, lost and separated feeling, as though part of me had really died. I reached out my hand for reassurance—and I yelled.

That sweet, soft-curved body in the bed next to me was cold and dead.

"Please! don't be frightened. It's all right. Really, it's all right." That was a voice that wasn't a voice again, as back in the beginning. It was familiar and at the same time new. It wasn't all right! I looked up, over the bed. There were not one but two tiny, blinding-bright pinpoints of light.

"What? Who?"

"Father," they said, "we are your children."

They were certainly not my idea of it.

"No. Oh, no! Star-baby, where are you?"

"Here. We were she. Now she plus you has become us. She has divided and now we are two, the children of you and she."

"Nonsense. Quit the double talk and give it to me straight!" Double talk it was. But if it was nonsense, it was an unhappy sort of nonsense I couldn't get around.

Coming slightly out of shock, I tried arguing and got nowhere. I never won any arguments from their mother either. I was convinced in spite of myself that this was the simple, brutal truth. It was the way of reproduction of her form of life. My alien wife had divided, to become two half-alien offspring.

I felt lousy. I didn't want two bright, pin-point kids. I wanted my wife. "But look, why couldn't one of you—"

"Why, father!" I got it in a tone of shocked horror. "Such a thing would be positively incestuous. No. We must go now. This is what mother-we came here for—to mix and to re-vitalize her-our people by the addition of a fresh, new stream of life force."

"You mean me?" It was flattering to think my stock would invigorate the population of a sun, but it was no cure for the loneliness in which I was lost. "You are going back across space—and leave me here alone?"

"Yes, father. We must leave at once."

"Oh, now, wait just one radiating little minute! You say I'm your father. Well, I forbid—"

Weary patience. "Now, father, please."

"But—will you come back sometime?"

"Certainly. With the success of her-our mission, we hope the factions back home will unite in a policy of further interchange. We and others of our family will come. Soon, we hope. It could even prove possible to find a way of converting you to our own form, so that later you may return with us."

"But look—"

But that was it. A few more words and, "Goodby, father," they said, putting a reasonable amount of regret into it—even though I know damned well they were itching to get going. "And do take care of yourself."

They were gone. I was alone. No big, lush and lovely wife; no button-cute little brunette wife; no gay, lively, companionable, loving Titian-haired wife. No wife at all.

I had never been so alone. Nothing but me. What was I to do?

Well, there was only one possible thing to do, and I did it. I got drunk. I hung one on. It was a beauty. Sometime in the course of the following night I held a tearful wake out by the garage and I buried my wife's last body. That, I recognize, was thoughtless. I could and should have called doctors and undertakers to tell me there was no life left in the body, and then let them do the digging for me in a more formal, costly manner. But, for one thing, I was drunk. For another, I guess I'd just sort of gotten into the habit of doing it the other way.

Much too early the next day—like about 2:30 in the afternoon—the doorbell rang. I was totally despondent, nursing my sorrow and a fat hangover with a cold beer and some of my Star-baby's more heavily long-hair, hi-fi selections.

I let the bell ring for a while. Then I let somebody pound on the door for a bit. But that got to be hard on my headache so I went to the door.

There was Mrs. Schmerler, from next door, who used to be a real biddy-buddy of my Aunt Belle's. There were a couple of hard-eyed cops with her, too. They all pushed right on in.

"Celebrating something, Mac?" inquired cop number one, while Mrs. Schmerler and the other glared suspiciously about.

"No," I said, too miserable to think. "Not celebrating, mourning. Just lost my wife, and kids, too."

"He never had any children!" said Mrs. Schmerler. "Only women. And a great deal too many of the cheap tarts. What his poor, dear Aunt Belle, as saintly a woman as ever lived, would say.... Why don't you ask him what he was digging for—digging and yowling Star dust—out there by his garage last night? And not the first time, neither!"

The sudden realization of what could be turned up out there by the garage—and how that would look to the unsympathetic and non-credulous eyes of the law—hit me. I opened and closed my mouth three or four times like an unwell goldfish. Nothing came out except a miasma of alcohol. Mrs. Schmerler gaped at me with delighted shock, indignation and horror. It was the great moment of her life.

The cops stepped in—not aggressively, more big-brotherly—and took a good, firm grip on my arm.

I won't go into the rest of all that. They got a squad and they dug. They took me in. I wouldn't talk. They locked me up. Cell block bookies quoted 50-1, no takers, I would make the death cell. The way I felt, I didn't care. The newspapers went wild. Things had been slow since the election. All my old pals from my working days on the paper were making a buck with special "Even then there was something frighteningly different about him" feature stories.

The next day, as my hangover faded and I got to thinking things over, my outlook changed. It was no time for me to give up. I would get a lawyer.

I walked over to rattle my cell door for a bit. "Hey! Hey there, guard. Come here a minute, huh?"

He came. "So? Is our Bluebeard softening up? Want to make a statement?"

"Uh-uh. Not me. I just want to ask a question. Those bodies, are they going to autopsy them?"

"Not yet. Today."

"Well, look—"

I had a little trouble persuading him, but I got him to take down all the data I could remember on the first one, the old hag. There would be records on her at the County Hospital. They'd never make any charge worse than body-snatching stick on that one.

The others? I chuckled. I was imagining the medical officers' expressions when they ran into those stainless-steel bones, plastic circulatory system, metallic wiring and the assorted other little innovations that my wife—my late wife—had installed in her body-building exercises. That would give them something to think about.

So—that's my story; all of it up to now. I'm still here in my cool little cell, and I am damned lonesome. But I am not scared. I figure I have about four different kinds of insurance.

In the first place, the way I am built now, with all the improvements in structure and durability she put into me, I doubt they could electrocute me. I'd probably just short the equipment out. A thing like that would make me quite a scientific curiosity, no doubt; but not, at least, a dead one.

Second, there are my investments and the way the money has piled up. You know and I know perfectly well that they just don't ever send a million bucks plus to any electric chair.

Besides, third place, while I have no doubt I can be convicted of something, I don't see how it could be murder. I wouldn't be surprised to see me get sent to the loony bin. I won't much mind that. I have nothing to do but wait anyway.

And, in the fourth place, which is what I am waiting for, there are my children—hers and mine. They are coming back. Soon, I hope. Not alone, I hope. "Tell them back there," was the last thing I said before they left, "tell them I want a girl just like the girl that married your dear old dad."

I admit it's a poor thing for a man to have to send his kids to do his courting for him—but at least mine are pretty exceptional children. Much better informed than most, too. They should bring me back a new bride. They've got to.

Somehow I kind of have a feeling now that a blonde—maybe a tall, willowy, statuesquely stacked type—might be nice for a while. After that, I don't know. I'll have to think it over. The waiting is what is going to be tough.

Kids aren't really undependable today. Are they?