The Project Gutenberg EBook of Stand Pat, by David A. Curtis

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Stand Pat

Poker Stories from the Mississippi

Author: David A. Curtis

Illustrator: Henry Roth

Release Date: April 14, 2016 [EBook #51760]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STAND PAT ***

Produced by deaurider, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

S T A N D P A T

By

D a v i d A. C u r t i s

Illustrated by

H e n r y R o t h

B o s t o n

![]() L. C. P A G E &

L. C. P A G E &

C O M P A N Y

![]() Mdccccvi

Mdccccvi

Copyright, 1900, 1901, 1902

By the Sun Printing and Publishing Association

———

Copyright, 1906

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

———

All rights reserved

First Impression, May, 1906

Colonial Press

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U. S. A.

The things that I saw, that seemed worthy of note, I have set down without prejudice to the little town of Brownsville, which has grown since I was there. Let no citizen of the place pursue me vindictively because I found him less interesting than Stumpy. And let no one’s civic pride suffer because I noted in the town only what seemed to me picturesque. I have no quarrel with Brownsville. I got away from there. What I saw while there seems worth the telling. Much of it I have told in the Sunday Sun. That, and more will be found in this book.

David A. Curtis.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A New Poker Deck | 1 |

| II. | Three Kings | 11 |

| III. | Finish of the One-eyed Man | 23 |

| IV. | Looking for Gallagher | 37 |

| V. | Stumpy’s Dilemma | 53 |

| VI. | Gallagher’s Return | 67 |

| VII. | Gallagher Stripped | 80 |

| VIII. | A Trial of Skill | 93 |

| IX. | A Social Call | 103 |

| X. | Stumpy Violates Etiquette | 115 |

| XI. | The New Poker Rule Made in Arkansas | 128 |

| XII. | A Stranger and Fond of Poker | 143 |

| XIII. | On Hand Just Once | 155 |

| XIV. | It Was a Great Deal | 168 |

| XV. | He Sat in with a V | 183 |

| XVI. | His Queer System | 198 |

| XVII. | An Extra Ace | 213 |

| XVIII. | Played by the Book | 227 |

| XIX. | Only One Sure Way to Win | 243 |

| XX. | Kenney’s Royal Flush | 253 |

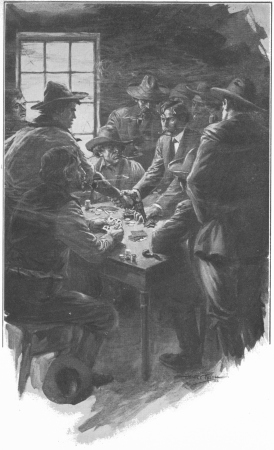

It was with entire unanimity, though without haste or undue excitement, that the male population of Brownsville emerged from the various buildings on the street when the hoarse whistle of the Rosa Lee was heard at about five o’clock one afternoon in June of 1881. The feminine portion of the community was seldom in evidence, but such glimpses as a stranger might enjoy were to be had at the same time, for the women came to their doors and looked out, listlessly, indeed, but with as much interest as they ever displayed in anything short of a fight such as occasionally disturbed the normal quietude of the place.

It was noticeable that the men who came{2} forth and who made their way toward the landing all paused at the barroom near the wharf. There was ample time to attend to such business as the boat might bring, for she would not arrive for half an hour, at least, and the barroom was handily located for a meeting-place.

No great amount of money had been squandered on the decorations of this particular temple of Bacchus, but such furniture as was deemed essential had been provided, and the main piece of it, outside of the bar itself, was a circular table about four feet in diameter, covered with what had once been green baize. It had suffered long from rough usage, but was still serviceable.

Around this table, as the citizens of Brownsville straggled in, they saw four men sitting with cards in their hands and chips in front of them. One was Long Mike, whose nickname was no mark of disrespect, since he was the richest and most influential man in town, but whose enormous height and general appearance made it{3} impossible to call him anything else, once the nickname was uttered. Wherefore, his surname, if he had one, had been by general consent, forgotten.

Another was Gallagher, his foreman. A third was a man with one eye only, who dealt cards with singular deftness, and was never known to do any manual labour.

And the fourth was a short, but very thick man, usually known as Stumpy, because of his figure. His hair was of a vivid and gorgeous red colour, and he had no quarrel on the ground of nationality with either Gallagher or Long Mike.

The game was not a big one. People seldom played for very large stakes in Brownsville, except on occasions when strangers came to town, when sometimes there would be real gambling, for Long Mike had sporting proclivities, as well as means, and the one-eyed man had never been known to decline any sort of proposition involving a game of chance.

This afternoon they were playing a dime limit, but with as much spirit as if the game{4} was for blood, and they had just called on Sam, the bartender, for a new deck of cards.

“I’ll have time to take in about three more pots,” said Long Mike, “afore the boat lands, so I’ll make ’em as large as I can,” and he opened the jack-pot for the limit.

“Well, ye may take three pots,” said Stumpy, who came next, “but I’m thinkin’ ye’ll not take this wan. Av ye do, ye’ll get more than that.” And he boosted it the limit.

The one-eyed man said nothing—he never wasted words—but he put up thirty cents.

“Here’s where I get a chanst o’ pickin’ up money,” said Gallagher, who was dealing. And he put up forty cents.

“Once more,” said Long Mike. And he raised again.

“As often as ye like,” said Stumpy, and his forty cents went in promptly.

The one-eyed man also raised it, and Gallagher fairly whooped with joy at the{5} opportunity he had to make it ten more to play.

“I reckon it’s no good givin’ yez b’yes good advice,” said Long Mike as it came his turn again. “The best thing I can do for yez’ll be to take your money. Yez may learn that way, when to lay down.” And once more he raised it the limit.

“It’s all right y’ are,” said Stumpy. “Sure it’s downright dishonest to be lettin’ thim play furder. Let’s kape thim out.” And he raised again.

But the others wouldn’t be kept out. The one-eyed man raised, and Gallagher, getting his turn again, said:

“I’ll give yez all warnin’. I’ll raise this pot ivery toime it cooms to me. Kape on now. Ruin yersel’s av ye loike.” And his money went in with a bang.

Long Mike looked puzzled.

“Sure yez ahl must have straights or flushes or such trash, an’ guns wudn’t kape yez out. Wudn’t it be best to take off the limit? We’re losin’ time this way and th’ boat’ll be in soon. What d’ yez say?{6}”

“That’d suit me fine,” said Stumpy. “I have yez all bated a mile, an’ the sooner I get th’ money the betther for me.”

“Take it off,” said the one-eyed man, and Gallagher, who had been growing more and more excited, declared that his pile would go on his hand in one bet.

“Well,” said Long Mike, “it’s five dollars more I’ll make it.” And he put up the money.

“I have siventeen dollars an’ fifty cents here,” said Stumpy, producing an old wallet and counting out the bills. The odd half-dollar he fished out of his pocket, and placing the whole amount in the middle of the table, together with a few chips that he still had left, he said: “That’s my pile. Av yez want to see my hand, ye’ll match thot.”

The one-eyed man was as quiet as ever, but he carefully counted out the equivalent of Stumpy’s bet, and added ten dollars to it, shoving the entire sum into the pot.

Not even at that was Gallagher daunted, but after exploring his pockets carefully he declared he was all in with about twelve dollars.{7} He made bigger wages than Stumpy, but spent his money more freely.

Long Mike said nothing until he had carefully portioned out the pot, putting the share in which Gallagher had an interest in one pile, and that which Stumpy expected to win in another. Then he made good, up to the amount of the one-eyed man’s wager, and raised him twenty dollars.

That worthy appeared entirely undisturbed. All the chips on the table were already in the pot, and he produced a small roll of bills from an inside pocket which he proceeded to count. Finding some sixty dollars in it, he threw it all on the table.

Long Mike covered it, and raised one hundred dollars.

“Well,” said the one-eyed man, “I reckon that will be about enough till after the draw,” and he made good.

“How many?” said Gallagher, as he picked up the deck.

“Well, ye moight give me wan,” said Long Mike, with ostentatious indifference.{8} And when Gallagher dealt it to him, he let it lie face down.

“These’ll do me,” said Stumpy, and it was observable that the ring of confidence was lacking in the tone of his voice.

The one-eyed man skinned his cards carefully before calling for any, and for just one instant an expression of bewilderment might have been noted on his face, but after a moment’s hesitation he also called for one card.

As a matter of fact he had discovered that two of his queens were clubs, but he had quickly resolved to say nothing and trust to the chance of the others not noticing it.

“Well,” said Gallagher, “I’ll take wan messilf, just to kape yez company,” and he dealt himself one.

“It’s your bet,” he said to Long Mike, who then picked up the card he had drawn.

When he saw it his eyes seemed to bulge out suddenly, and his mouth opened wide with astonishment.

“Pfwat the divil!” he exclaimed, and then he burst out laughing so loudly that no one paid any attention to the toot-toot-{9}toot of the Rosa Lee’s whistle, which, had they heard it, would have told them that the boat was approaching the landing.

The others looked in wonder while he laughed—all but the one-eyed man, who seemed to have an inkling of the truth, and he grinned, though rather sorrowfully, as if he thought of the money he had felt sure of winning.

“Well, b’yes, yez can’t bate that hand, anyhow,” said Long Mike as soon as he could speak, and he threw down five aces.

They all stared—Stumpy the hardest of all. Then he joined in the laugh.

“Sure there do be aces to burn in thot pack,” he said. “I have two of thim me own silf, wid three kings.” And he showed them down.

“Sure I have you bate, anyhow,” said Gallagher, who was as surprised as any one else, but who seemed to cherish the idea of winning something, somehow. “I have four jacks,” and he showed them, but they were all red.

“Let’s have a look at the deck,” said the{10} one-eyed man, and he spread the cards out, face up.

A most surprising number of face cards remained, despite the eleven that had been distributed in the deal, and there was a conspicuous absence of small cards.

“Wat sort of a divil’s game is this, I don’t know?” asked Stumpy.

The one-eyed man picked up the case that had held the deck, from the corner where it had been thrown, and read the word “Pinochle” on it.

“It’s a game the Dutchmen play in the East,” he said. “I’ve heard of it, but I’ve never seen it played. But it does give a man good poker hands, doesn’t it?”

There was nothing to do but divide the pot, and by the time each man had drawn down his money the Rosa Lee was screeching a continuous toot for rousters to catch her lines, and the barroom was quickly emptied.{11}

After the river was frozen up and the boats could no longer ply the upper Mississippi, the only approach to Brownsville from the other river towns was by the stage-sleigh that came from La Crosse. This crossed three times a week each way, and occasionally brought some stranger to the town, though why a stranger should come, unless he arrived on a boat that would presently carry him farther along on his way, was a thing Brownsville could not readily understand.

It was therefore with mild surprise that the citizens of the place saw one Jack Britton jump out of the low box sleigh one evening in the middle of winter. Nothing was said to him when he alighted. It was not{12} Brownsville’s way to greet newcomers with enthusiasm.

But such of the citizens as happened to be near lined up expectantly in front of Sam’s bar, when Mr. Britton, after stamping his feet a few times, and thrashing his arms across his chest to get his blood in circulation, entered the barroom and walked over to the stove to warm his fingers.

After he had stood there for a few minutes, and had, presumably, recovered from the chill of the long ride, he stepped up to the bar and called for some whiskey. His manner was that of a man who is immersed in thought, and for the moment he seemed not to observe that there were others present.

Sam produced a bottle and a glass and set them on the bar, and Mr. Britton poured out a drink for a grown man. He did not know it, or it seemed as if he did not, but the eyes of the community were fixed upon him.

That is, eyes belonging to some eight or nine representative citizens of Brownsville were so fixed, and for one critical moment{13} there appeared to be a strong probability that Mr. Britton would fail to establish himself on any footing which would entitle him to favourable consideration.

In some mysterious way he became aware of this without anything being said. Being, as he was, the focus of eight distinct glares of surprise, he became aware that something was wrong, and, pausing in the very act of lifting his glass, he looked slowly around, and then said, heartily enough:

“Excuse me, gentlemen. Won’t you join me?”

They would and they did, and it remained possible for Mr. Britton to make a good impression. The mere fact that he was unusual would not, of itself, damn him hopelessly, but the curious behaviour of a man who would come so near a fatal breach of etiquette in apparent unconsciousness, was enough to raise a doubt, and while the doubt remained Brownsville was not likely to make overtures.

Jim Bixby, the stage-driver, had swallowed his liquor and gone outside to attend{14} to his horses, and, after an interchange of glances among some of the others in the room, Larry Hennessy slouched out through the door and was lost to sight.

Making his way to the stable, where Bixby was rubbing his horses down, he stood for a few moments looking on. Presently he said:

“Thot mon inside, yonder. Is he a La Crosse man, I don’t know?”

Bixby finished with one horse and began on the other before he answered. Then he said:

“He’s on’y been around f’r about a week. Come f’m somewheres East. Been playin’ cards a good bit in Russell’s place. Left kind o’ sudden. Didn’t hear much about it, but they was some kind of a mix-up in a game last night. Didn’t have nothin’ to say comin’ over.”

This marvel of succinctness being duly absorbed by Hennessy and reported to the community in a much enlarged form, was sufficient to prepare Brownsville for the campaign which Mr. Jack Britton entered upon forthwith.{15}

Having once shaken off the preoccupied and abstracted air which he wore when he arrived in town, he developed into a jovial, free-handed man of convivial tendencies, though sparing in his own consumption of Sam’s liquor, and was accepted readily enough as a nomad whose occupation was that of a professional gambler.

It might have been supposed, because of certain previous experiences, that Brownsville would be reluctant to afford Mr. Britton an opportunity to exercise his skill, but Brownsville, in some respects, was like the rest of the world, and Long Mike and McCarthy were both resident in the place.

“Sure, I do be thinkin’ that McCarthy can play more poker an’ win less money than any other mon in Iowa,” said Stumpy, when he came into the barroom that night and found a game in progress, as he had, indeed, shrewdly suspected would be the case.

Long Mike was also in the game, but Long Mike sometimes won, having remarkable streaks of luck, such as McCarthy never seemed to get. And the one-eyed man was{16} playing, too, so that there was really no reason to suppose that the stranger was the only man at the table who understood all the tricks of the game.

Hennessy had bought a stack of chips, and even Stumpy, though he was a prudent man usually, was soon interested enough to ask for a hand. As there was no objection, he took the sixth seat.

It cost him only five dollars for a stack, and as the game was table stakes, there was a chance for him either to go broke speedily, or to win considerable money. At first, it seemed likely that he might do the latter, for the very first hand he picked up had three kings.

Long Mike was dealing and it was Hennessy’s age, so Stumpy had first say, he having sat down between Hennessy and McCarthy.

“I’ll play,” he said, throwing in his red chip with the two whites that Hennessy had put up for an ante.

McCarthy played also. It was to be expected that he would, for it was as hard for{17} him to stay out as it was to win. The one-eyed man came in, Britton raised it, and Long Mike and Hennessy laid down.

“Sure I’ll raise that,” said Stumpy, making it one dollar more.

McCarthy swore, but even his optimism was not enough to induce him to see a double raise on two nines, and he threw down his cards. The one-eyed man and Britton both made good, however, and they called for cards.

Stumpy took two, which proved to be a small pair. The one-eyed man took one, and Britton stood pat.

Stumpy threw in a white chip, being sure of a raise, but the one-eyed man dropped. He had not bettered his two pairs. Britton raised it one dollar, and Stumpy pushed all his chips forward. A king full seemed worth backing, and, when Britton called, he showed them down triumphantly.

“Give me another stack,” was all that Britton said as he threw down his cards.

It may have been part of his plan to lose at first, and in any case the loss was not heavy{18} enough to daunt him, but he smiled as cheerfully as if he had won.

There was no play on Hennessy’s deal, and a jack-pot was made. Stumpy dealt next and caught three kings again.

No one opened until it came to him and he put up the size of the pot, hardly expecting any stayers. Britton, however, came in, taking a chance on a red and a black eight, and Long Mike decided to speculate on a four flush.

Neither of them bettered, and Stumpy showed his kings and took the pot.

“Lucky cards,” said Britton, and no other comment was made.

Again there was no play and another jack-pot was made. It was not opened for two deals, but when the cards came to Long Mike in turn, Stumpy was fairly amazed to find that once more he had three kings.

It did not look right, and if it had been Britton’s deal he would have hesitated about playing them, but Long Mike was above suspicion, so he opened the pot with cheerful confidence.{19}

Again Britton was among those who came in, McCarthy and Long Mike both finding enough to justify a play, but they all took three excepting Stumpy, and he was quite easy in his mind when he bet two dollars. Britton was the only one to call, and he said, with a laugh:

“I’ve a notion to raise you, but maybe you have them three kings again.”

“I have,” said Stumpy, and scooped the pot again.

They all stared, but Britton was the only one to speak.

“If I was you,” he said, in a nasty way, “I wouldn’t play them kings so frequent. You might get beat on ’em next.”

Now there are men to whom a remark of this sort may be made without immediate trouble, but such men are not Irishmen of the peculiar redness as to hair and beard that Stumpy had. He flared in an instant.

“Oi’ll play thim cards whiniver Oi do be gettin’ thim to play,” he said, with great heat. “An’ if ony gintleman i’ th’ room, f’m La Crosse or any other place, has anything{20} to say, Oi’d loike t’ hear what it is.”

“Oh, well,” said Britton, “I said what I had to say. It don’t look well for any man to hold three kings all the time.”

“Av it’s a question o’ looks,” said Stumpy, very coolly, but with evident wrath, “Oi don’t loike th’ looks o’ that nose you do be carryin’ round wid youse.”

Britton looked around, but seeing that no one else at the table was likely to side with him in case of trouble, he controlled himself with an effort.

“ ‘Tain’t as good-lookin’ as I’d like to have it,” he said, with a forced laugh, “but it’s the only one—”

“An’ Oi do be thinkin’,” interrupted Stumpy, “it ud look a dom sight betther av it was longer.”

“Perhaps it would,” said Britton, still reluctant to accept the quarrel, “but—”

“But nothin’,” shouted Stumpy, reaching over and grasping the feature he had mentioned. “Maybe pullin’ it a little moight{21} do it good.” And he gave it a mighty tweak.

Two things only were possible after that, in Brownsville, and unfortunately for Mr. Britton he chose the wrong one. A stand-up fight with nature’s weapons would have established him as a person worthy of consideration, even though he had been well licked, but he was not in the habit of fighting in that fashion, and he reached for his gun.

It was an unlucky movement. Long Mike sat next to him, and as they all rose to their feet in the excitement, the big man seized him by the wrist and the neck, and shaking him as a dog shakes a rat, he exclaimed:

“Ye’ll pull no gun in Brownsville, ye double-jointed spalpeen, ye. An’ ye’ll understhand that any gintlemon in this town that wants to play kings, can play as many as he loikes, an’ as often as he loikes. An’ the loikes o’ yez can get back to La Crosse whin ye loike.”

And after he had shaken Britton sufficiently, he threw him into the corner of the room.{22}

When the stage-sleigh was well out on the frozen river surface next day, Jim Bixby turned to his passenger and said, briefly:

“Them fellers in Brownsville kind o’ stands by each other most generally.”

But the passenger made no reply.{23}

The one-eyed man sat playing solitaire at a table in the extreme rear of the barroom. This particular room was not the only place in Brownsville where liquor could be had by those bibulously inclined, for whiskey was recognized as one of the staples. There were few of the citizens of the place who allowed themselves to remain destitute of a domestic supply, and there was none so inhospitable as to refuse to share what he had with even a casual passer-by who cared to stop, but the room in which the one-eyed man sat, on this occasion, was known as the barroom. Brownsville was too small a place to encourage competition unduly.

There was the usual crowd in the room, it being early in the evening, and a river boat being expected soon. It was not every{24} time a boat arrived that anybody came ashore to stay, but sometimes it happened that somebody would do so, and, even if it didn’t, there was usually some freight to be landed, and while the roustabouts were bringing that off, the boat would have to stay.

On such occasions, the barroom, being handy to the landing, became not only the social centre of Brownsville, but also the news exchange where all the available intelligence of the happenings of the outside world was to be obtained. It was not that Brownsville cared specially what the outside happenings might be, or might not be, but there was more or less excitement to be had by conversing with strangers who might stroll ashore for even a few minutes, and Brownsville craved excitement.

The usual crowd was unusually noisy this evening. Long Mike, the labour contractor, who had organized a trust in handling of freight, and owned eight mules, representing a goodly proportion of his accumulated capital, had been drinking more than usual ever since the landing of the last boat, and, after{25} his fashion when he drank, his voice was being overworked. Moreover, the small crowd of able-bodied men who were enjoying his hospitality had all of them opinions of their own which they were anxious to express, and so, though Sam, the bartender, was a man of few words, there was no lack of conversation.

The one-eyed man did not drink, and as there was an ill-defined popular prejudice against him, partly for that reason, no one paid much attention to him, or to his game of solitaire.

Suddenly somebody called Long Mike a liar. Opinions differed when the matter was afterward discussed, as to who the person was. Some of them said it was Stumpy, but the only reason why they thought so, as they were obliged to admit when the statement was questioned, was that Stumpy was Irish and also red-headed, and a red-headed Irishman was always liable to make a bad break. Others thought that Gallagher had spoken the word, and this seemed more probable, for Gallagher was of a morose temper at{26} best, and utterly reckless when in his cups. But Gallagher denied it, and nobody excepting the man who spoke ever knew who it was that uttered the word. Several persons were talking at the time, but there was no doubt that somebody exclaimed, “You’re a liar!”

At the word the one-eyed man disappeared under the table at which he had been playing. Had the door been nearer to him, or had there been a window in the rear of the room, there is little doubt that he would have gone outside, but the door was the only available exit, and it would have taken two or three seconds for him to reach that. Two or three seconds form an appreciable interval of time.

The tendency of most persons to shoot too high, rather than too low, is well known to everybody who has had experience in such matters, and the course of action pursued by the one-eyed man in getting under the table is the one generally approved. He never carried a gun himself, and moreover, while he did not distinctly approve of the use{27} of the expression that had been applied to Long Mike, he had sufficient sympathy with the thought expressed to restrain him from any impulse toward resenting it on Mike’s behalf.

The fusilade, though it was furious, was brief. Five revolvers were emptied, and as three of them were seven-shooters, while the other two had only five chambers each, it was readily reckoned up that thirty-one shots were fired. Considering the size of the room, which was not great, and the fact that there were fifteen or sixteen persons present, it seemed a little remarkable that no one was hurt, but after the first volley Sam came out from behind the bar and interfered gently, but firmly, with Long Mike, who was trying in a fumbling sort of way to reload his pistol.

“Put that away,” said Sam, “or I’ll brain you where you stand.”

Long Mike looked at him and then at the bung-starter which he held poised ready for use, and forthwith put his pistol back in his pocket. Being unable, in the confusion of words which followed, to determine who{28} it was that had insulted him, he burst out crying and invited all hands to drink at his expense.

There was a prompt response to the invitation by everybody but the one-eyed man, who had resumed his game of solitaire, and Sam was juggling his glasses with his usual skill when the whistle of the Rosa Lee was heard from the river. Three minutes later Sam and the one-eyed man were alone in the room.

“The boys is pretty lively to-night,” said Sam, but the one-eyed man only grunted.

“I heer’d Jim Wharton was comin’ down the river this week,” said Sam, cheerfully insistent upon conversation. “ ‘Twouldn’t be none surprisin’ if he was on the Rosa Lee.”

The one-eyed man grunted again, but his eye gleamed, and after a moment he said, slowly: “Well, he’ll find me ready for him.” But he kept on playing solitaire as if he had no active interest in anything outside of his game.

Neither did he seem to be paying attention to any outside happening, when, after{29} the noise of considerable confusion outdoors, the crowd came straggling back into the barroom. It was not the same crowd, for the Rosa Lee had brought a considerable load of freight, and Long Mike, though insufficiently sober to bear himself with dignity in social affairs, was not too drunk to attend to business, and he remained outside attending to it. Several of his men, who had been with him in the barroom on terms of equality, were now working for dear life while he stood talking to them with all the emphasis of an army teamster addressing a balky span of mules.

There were several strangers in the incoming party, though, and the room was even more crowded than before. The boat was not likely to start again for an hour or more, and a number of passengers were stretching their legs. Among the newcomers was a tall, swarthy fellow who swaggered like a lumberman, but was dressed like a dandy, and who looked around as he entered as if in search of some familiar face. With him were three others, as well dressed as he,{30} but all of them having the indescribable appearance and manner which marked them as “professional sports”—in other words, gamblers—and all being of the type that was common along the Mississippi River years ago.

The one-eyed man did not look up, but he showed no mark of surprise when the tall stranger, having first called for a bottle of wine, which he shared with his three companions, left them standing at the bar and strolled over toward the card-table.

“Howd’ye, George,” he said, quietly enough, but with a curious suggestion of inquiry in his tone.

“Howd’ye, Jim,” was the one-eyed man’s response.

He did not even look up from his game, and so far as his voice or manner indicated, he was utterly indifferent to the fact of the other man’s presence. He kept on laying down the cards with no show of emotion of any kind, but a close observer might have noticed that he made two mistakes in his play during the short while that the other stood{31} looking on in silence. Presumably the other was a close observer. Gamblers mostly are.

Presently the newcomer spoke again:

“Bygones is bygones, ain’t they, George?” he said.

“Yes,” said the player, for the first time looking straight at his questioner, and speaking very slowly. “Yes, I reckon bygones is bygones. Anyway, my eye is gone.”

“Well, it was a fair fight, George?” said the tall man.

“Yes, it was a fair enough fight,” said the one-eyed man. “If it hadn’t been. I’d ha’ looked you up an’ killed you, ’fore now.”

“So I reckon,” said Wharton; “you was always quick for a fight, George, an’ I don’t remember as I ever shirked one that was coming my way, did I?”

“No, that’s right enough,” said the one-eyed man, indifferently. Then there was another silence and the one-eyed man resumed his game. Presently Wharton spoke again.

“Well,” he said, “I reckon there’s no grudge between us on account of the fight.{32} You talk fair enough, an’ I hain’t nothin’ to say, but there’s another thing that ain’t settled. What do you say to that?”

“What is it?” asked the one-eyed man, shortly.

“There’s a matter o’ seven hundred dollars o’ mine that you got away with in that last game. I called your play crooked an’ I couldn’t prove it, so I don’t hold it against you that you pulled a knife, but I want that money. I hain’t fool enough to think you’re goin’ to hand it over, but I’ll play you a freeze-out for one thousand dollars right now. If I lose, I’ll take back what I said an’ couldn’t prove. If I win I’m satisfied. But God help you if you don’t play straight an’ I do catch you.”

“That kind o’ talk is cheap,” said the one-eyed man, contemptuously. “I don’t reckon the Almighty’s goin’ to help anybody much if he’s caught cheatin’ along the Mississippi River, but you can say your prayers now, Jim Wharton, if you think o’ makin’ any breaks at me, like you did once. I’ll play you the freeze-out, an’ what’s more, I’ll win{33} your money unless you’ve learned to play poker since I seen you last. If it’s play, I’ll play you, an’ if it’s fight, I’ll fight you to the finish.”

Neither man had raised his voice; they were too much in earnest for that. So no one in the room had seemed to pay attention to them. When the one-eyed man called to Sam, however, to bring him cards and chips for the game, a number of bystanders came up to look on, and among them were the three men who came in with Wharton. A looker-on might have thought that they were expecting an invitation to join the game, but none was given, and they said nothing.

The chips were counted out, the two thousand dollars placed in Sam’s hands as payment, and the new deck of cards ripped open and shuffled, and the two men cut for the deal, which fell to Wharton.

It was a fruitless deal, for, finding nothing in his hand, he threw in a red chip to cover the two white ones that the one-eyed man had anted, and declared a jack-pot. The one-eyed man made good and took the cards.{34} As he shuffled and dealt them, the other watched him keenly, but evidently saw nothing wrong, though it was impossible not to see, from the way his fingers moved, that he was dexterous to a degree in their use.

In four or five hands neither man held openers. Then Wharton caught aces, opened the pot, and took it down, the one-eyed man having nothing.

“Your first pot. It’s a bad sign for you, Jim,” he said, jeeringly.

“All right,” said Wharton, “I’ll take all the pots that come. The first is as good as any.”

But for the next twenty minutes it almost seemed that the superstition was to be upheld. Wharton won no more, and the one-eyed man was four hundred dollars ahead when there came a struggle on Wharton’s deal.

Catching two pairs, he made it ten dollars to play, and the one-eyed man promptly raised it ten. Wharton made good and the one-eyed man drew two cards.

It was evident enough that he had threes,{35} having raised back before the draw, so Wharton, instead of standing pat, as he had thought of doing, took one. It proved to be a jack to his jacks up, and, as afterward appeared, the one-eyed man got a pair with his three sevens.

It was Wharton’s bet and he put up a hundred dollars.

“As much more as you have,” said the one-eyed man, pushing his blue chips forward.

“I call you,” said Wharton, and they counted the piles. Wharton had almost six hundred left, so the show-down put him ahead in the game.

“Good dealing,” said the one-eyed man, coolly, as he picked up the deck, but Wharton made no answer. Instead, he watched the deal more narrowly than ever. Something he saw seemed to interest him greatly.

The one-eyed man bet after the draw, but Wharton refused to see him, and he scooped the pot. Then Wharton took the cards.

Running them over rapidly, face down, he threw three cards to one side. Then, picking{36} up the three, he examined their backs carefully and exclaimed with an oath: “By the marks on them I reckon they’re all alike. Maybe they’re aces.”

It was done as quickly as lightning flashes, and he threw down the three cards, face up, before any one had fairly realized what he was doing. They were all aces.

Both men sprang to their feet on the instant, and as they rose Wharton drew a revolver and the one-eyed man a knife.

The revolver spoke as the man with the knife rushed around the table, and, with a yell, he stumbled forward, stabbing viciously at the other as he fell on the floor. Wharton dodged quickly, but not quickly enough to avoid a bad cut in the arm, and shifting his pistol to his left hand, he stood ready to shoot again.

There was no need, however, of another shot.{37}

Brownsville was disturbed. It can hardly be said that the industries of the place were interrupted, for there were no industries in Brownsville that were liable to interruption, except at such times as one of the river steamboats was lying at the levee, either loading or unloading.

Outside of Brownsville the prairie stretched indefinitely to the north, west, and south, and there were persons who cultivated the soil with a minimum of labour and obtained a maximum of results, and so far as planting, harvesting, and marketing the products constituted an industry, these persons were industrious.

Inside the town, people mostly sat around. Except, as aforesaid, when there was a boat at the levee.{38}

To a stranger no visible signs of disturbance would have been apparent. Looking up and down the long street that constituted the main portion of Brownsville, he might have noticed that there were no women to be seen, but the feminine fraction of the population, insignificant in number, was at no time obtrusive.

Such social functions as were in vogue with the female sex consisted mostly of long-range conversations between women who stood, each at her own door, or leaned out, each at her own window. And the subject-matter of these conversations would have been totally devoid of interest to the stranger.

At the moment when the action of this tale was about to begin, there was no sound of conversation, nor appearance of a petticoat. There was, instead, an ominous hush, though the stranger might not have recognized the omen.

It was yet early in the forenoon, and the only interruption to the unwonted silence of the morning had come from a crash in Long{39} Mike’s house half-way up the street. It was such a noise as might have been made by an angry man who should survey his breakfast-table, and, finding nothing on it to his liking, should upset it with such violence as to send some of the dishes against the walls of the room and others through the front window.

The strained attention of Brownsville had caught no further sound for half an hour, and though at every other door but his and one other, men stood as if prepared for observation or action, as the case might be, they had heard nothing further, nor seen anything.

Suddenly Long Mike’s door flew open. What force impelled it cannot be stated positively, but Stumpy, whose house was almost opposite, saw the recumbent figure of a man several feet back from the doorway, where it might have fallen after an energetic kick and a sudden recoil.

Slowly and with evident effort the man arose to his feet, and after some minutes stepped uncertainly forward. Steadying{40} himself by the lintels, he gazed out, as if dubious of the result of further effort.

Up and down the street he looked for a long time, with as much earnestness as was compatible with a confusion of ideas that seemed to be buzzing around his head, seeking entrance as bees might endeavour to enter a sealed hive.

Presently his eyes fell on the one doorway, not far from his own, where no man stood. The faces he saw at the other doors were all mistily familiar to him, but he gave no sign of recognition, and no man spoke to him. The alert but motionless figures might have been graven images, so far as any emotion could be detected, and they stirred him not.

But the empty doorway fixed his unsteady look. His eye cleared, and with a mighty lurch he sallied forth, saying nothing when he started but gurgitating violently as he strove to arouse his vocal organs to action.

“Mother of Moses!” muttered Stumpy, grimly observant. “He’s lookin’ for Gallagher. Now if Gallagher was home what{41} a broth of a shindy there’d be! Saints be! but it’s good he’s took a sneak.”

Deviously, and with many pauses and new starts, Long Mike made his way toward Gallagher’s house. Arriving in front of it he paused, and cleared his throat with a yell, the like of which Brownsville had never heard, save from the exhaust-pipe of some steamboat.

Following this came a monstrous cataract of vituperation, Homeric in strength, Gargantuan in explicit epithets, shameless in profanity, and seemingly endless in continuance, but bibulously uncertain as to its exact purport. The general tenor of it seemed to indicate a strong desire for a personal encounter with one Gallagher.

When, after a long period of this, silence ensued, Long Mike waited for awhile, but no answer came. The door remained closed, and no sign of life came from within. Standing forward at length, he raised his foot, and Gallagher’s door flew in.

“Glory be!” muttered Stumpy again, “it’s little use he has for latches and locks{42} the mornin’. And it’s little good Gallagher’ll get of his furniture from now.”

This last statement was undeniably true, for Long Mike, finding no living being in the house, seized a chair and painstakingly demolished everything destructible on the premises. Then he came out, and after whooping wildly a few times at the uttermost pitch of his powerful voice, made his way slowly and crookedly to the barroom. And after him, one by one, the heads of the households in Brownsville came slowly.

Now Gallagher, as all Brownsville knew, was Long Mike’s foreman, and Long Mike’s ownership of all the mules in Brownsville was hardly more absolute than his proprietorship in all the available human labour of the place, and, moreover, the imperious character that had enabled him to conquer his position in the community made him its autocrat.

The reflected glory of such a man, to be enjoyed by one fortunate enough to be his foreman, would be enough for any ordinary person, but Gallagher was not ordinary.{43} Debarred by nature from the possibility of attaining the highest eminence, he was still covetous of distinction, and the satisfaction he derived from the hearty hatred of the men he tyrannized over, was poisoned by the reflection that the good-natured giant who tyrannized over him held him in contempt.

Because of these things there was frequent friction between the two. Gallagher could extract more work from a mule or a man than any one else, and Long Mike valued him accordingly. Nevertheless, there were times when the foreman’s unruly tongue would so stir up the temper of his employer as to secure his immediate discharge. Having little confidence in anything that Long Mike said, Gallagher would proceed with his work, serenely indifferent to his dismissal, and would collect his wages as usual at the close of the week.

It had happened, however, that ever since the night when the one-eyed man had suddenly perished in a controversy with one Wharton, which controversy touched on{44} points of etiquette appertaining to the game of draw-poker, Long Mike had been unable to steady his nerves, despite his persistent efforts to do so by a liberal use of the one specific in which he had faith. Being unusually irritable, therefore, he had resented Gallagher’s latest impertinence more bitterly than usual, and, in addition to discharging him, had attempted also to kill him.

This he would undoubtedly have succeeded in doing with his bare hands, for he had the strength of seven men, but, fortunately for the foreman, there was considerable uncertainty in his movements, and his intended victim had eluded him by a quick movement which was continued in a panicky flight. The flight had taken him across the gangplank of the Pride of the River, just as the deck-hands were hauling it aboard, and he had gone down the river on the boat, a fact not yet known to his employer.

There was a Mrs. Gallagher, but she had found refuge with a sympathetic neighbour, and took no part in the events of the day.

In the barroom there was an atmosphere{45} of doubtful expectancy. Just what Long Mike would do when he found his rage balked in the direction of Gallagher, no one could tell, and in truth none was anxious to see. The consequences of any fresh accession of fury might be decidedly unpleasant.

It was therefore with considerable anxiety that the crowd listened for Sam’s answer, Sam being the bartender, when Long Mike questioned him.

“Where is that man Gallagher?” he demanded, thickly.

“I’m lookin’ for him every minute,” said Sam, in a matter-of-fact way, as he placed bottles and glasses on the bar. No order had been given, but Long Mike’s ways were known, and a round of drinks at his expense seemed to be an appropriate ceremony.

The due performance of this engrossed the general attention for a few minutes, and then Long Mike again demanded to know where Gallagher was.

“I’m lookin’ for him every minute,” said Sam in the same tone as before. And to the{46} same question, repeated at irregular intervals for the next quarter of an hour, he replied in the same words.

After each answer Long Mike stood, apparently satisfied, looking as steadily as he was able to do toward the door, with the evident expectation of seeing his foe appear, but abstaining from speech. Slowly, however, he seemed to gather the idea that he was being trifled with, and presently he said, with a violent hiccough:

“Where is that man Gallagher?”

“I’m lookin’ for him every minute,” said Sam, imperturbably.

Long Mike turned and look at him with a scowl.

“Ye said that before,” he exclaimed.

“I was lookin’ for him before,” said Sam.

This seemed to divert the big man’s mind to a new channel of thought, and he pondered it awhile, uncertain whether to laugh or be angry.

At length he leaned over the bar and shook a huge forefinger in Sam’s face.

“You’re a fool,” he said, and glared.{47}

Sam made no reply, but Stumpy, judging that something must be done, interposed:

“Ye’ll all have a drink with me,” he said.

Ordinarily this form of speech was unchallenged by any critic in Brownsville, and Long Mike was possibly the one citizen least likely to offer any objection, but on this occasion he turned to the speaker, and, shaking his forefinger at him, exclaimed again:

“You’re a fool.”

Stumpy stepped back a little. Long Mike faced the crowd and said with additional emphasis:

“You’re all fools.” Then he broke out with a roar of fury. “Will ye tell me where is that man Gallagher?” but no man dared make answer.

“In just about a minute, now,” said Joe Thorp in an undertone to his nearest neighbour, “there’ll be a ten-acre fight in this here barroom if nothin’ ain’t done to get the old man’s mind off’n Gallagher.”

“I reckon you’re about right,” replied Jim Hunnewell, “but there ain’t nobody here as cares about fightin’ ’cept him. An’ when{48} he’s loaded, he’d a heap rather fight than do anything else, ’thouten it’s play poker.”

“That’s the idee,” exclaimed Thorp, struck with an inspiration. Then, raising his voice, he continued: “Who’ll play a game of poker? Speak up, quick, you chump,” he whispered, and Hunnewell spoke.

“I will,” he said, eagerly.

“And I,” “And I,” “And I,” said Baxter and Wilson and Cosgrove almost as quickly. They had caught the whispered words, and appreciated the emergency.

“Give us the chips, Sam,” called Thorp, bustling toward the card-table in the rear of the room. “Will you take a hand, Mike?” he added, carelessly, as the others followed him with more noise than seemed necessary.

Long Mike considered the matter for a moment, but, finding that he no longer held public attention, he wavered and then said:

“I will.”

“It’s like picking his pockets,” said Cosgrove, with some compunction, as they all{49} took their seats. Even in Brownsville the code prohibits playing with a man who is hopelessly drunk if he happens to be your neighbour and friend.

“Isn’t it better than to have him kill somebody before he sobers up?” said Thorp, and the argument was sufficient for all of them.

But the picking of Long Mike’s pockets did not proceed with any alarming speed. They played the usual game, table stakes, and each man took five dollars in chips at the start. The first pot was a jack.

Cosgrove dealt. Thorp passed. Baxter passed. Wilson opened it for a dollar and a half. Hunnewell threw down. Long Mike raised it two dollars. Cosgrove stayed. Thorp stayed and Wilson stayed.

When they came to draw cards, Thorp took one, Wilson took two, and Long Mike was found to be fast asleep. They roused him with some difficulty, and after scanning his cards with every appearance of dissatisfaction, he called for four. Cosgrove took three.{50}

Wilson bet a white chip. Long Mike chipped. Cosgrove shoved in his pile, having caught a third ace. The others all stayed, and Wilson showed three tens. Thorp had a small straight, and Long Mike had a king-high flush.

It was quick action and called for another jack. As three of the conspirators bought more chips, they consoled themselves as well as they could with the thought that sheer luck like that seldom comes to one player frequently in one sitting.

This time Baxter opened it under the guns. Wilson passed. Hunnewell raised it one dollar on a small straight. Long Mike stayed on a pair of deuces. Cosgrove and Thorp laid down and Baxter saw the raise, having kings up.

In the draw Long Mike caught the three aces Cosgrove had had the deal before. After Baxter and Hunnewell had bought again, there was fifty-five dollars on the table, of which over thirty was in Long Mike’s pile.

In the next deal he caught nothing and{51} promptly went to sleep again. They woke him up in time to look at his next hand, and that failed also to interest him. In the following deal, however, he caught three sevens.

It had been his ante, and the money had been put up out of his pile without waking him, but even under existing circumstances no one cared to go so far as to play his hand for him, the more especially as they all had pretty good cards and saw his raise when he made it two dollars to play.

Catching the fourth seven in the draw, he made good on two raises that had been made before it came to him, and threw in five dollars more. Thorp and Wilson both called for their piles, one having a flush and the other a full.

Just what might have happened in a few hands more it is impossible to say, for the whistle of the Prairie Belle startled the crowd as she steamed up to the levee, and Long Mike staggered to his feet, stuffing his winnings in his pockets as he rose. Neither{52} whiskey nor poker was potent to hold him when there was business to be done.

As he stepped unsteadily into the open air, Sam heard him asking of the wide, wide world, “Where is that man Gallagher?{53}”

The only thing stirring on the levee at Brownsville on Sunday morning, usually, was a small dog belonging to Stumpy. It was of record that when Stumpy arrived at Brownsville with his dog Peter, bringing their entire earthly possessions wrapped in a large red handkerchief, Peter came across the gangplank first, being in hot pursuit of a rat. The rat escaped, finding its way into a crevice near the edge of the water, and the most of Peter’s spare time for the two years that had elapsed since then had been spent near that crevice. No sign of the rat had ever been discovered, but Peter’s faith was abiding.

It was possibly characteristic of the breed of Peter, which was considered in Brownsville to be some sort of terrier—and it was{54} certainly characteristic of Peter that he did not sit down by the crevice to watch for that rat, but ran back and forth continually, barking, meanwhile, with cheerful disregard of the effort involved. He did not wag his tail, being possessed of a totally insufficient amount of tail to be wagged. “Sure his tail was never cut off,” Stumpy used to say, “it was drove in.” But he wagged the entire hinder portion of his body, as he ran, with an enthusiasm that frequently sent two of his legs high in the air.

While he was engaged in this fashion one otherwise peaceful Sabbath day, his master appeared in view, and the two were soon in conversation.

“Thim two spalpeens that kim off the boat last night, I’m thinkin’, is goin’ to do up the town, I do’ know,” said Stumpy, whose habit it was to discuss matters with Peter when he found them too difficult to understand easily.

Peter looked at him anxiously, but finding that Stumpy had paused for reflection, he barked once, and waited.

“That’s just it,” said Stumpy, eagerly.{55} “The divil’s own cousin cudn’t tell if they was Mormon missionaries or retail grocers on a holiday trip. If it was down the river, now, they’d be cotton factors maybe, but whhat’d a cotton factor be doin’ in Brownsville, I do’ know. An’ the drink! Glory be, but they’re divils for drink. An’ Long Mike on’y a week after the last wan.”

This last remark called for no explanation in Brownsville, where Long Mike’s sprees were events in municipal history. Peter whined lugubriously.

“An’ it’s right ye are, Peter,” said Stumpy. “If he starts in again now there’ll be an end. Didn’t he wipe out Gallagher’s place from door to door, wid the glory o’ drink in him, two weeks ago? It’s none too peaceful at the best, that Brownsville is, but wid him drunk it’s hell. An’ it’s drunk he’ll be again if thim two strangers stays. An’ I do be thinkin’, Peter, that if he’s drunk again afore the change o’ the moon, he’ll sober up in the life everlastin’.”

At this Peter howled long and loud, and Stumpy lapsed into silence.{56}

To them presently appeared Sam. The exigencies of business required Sam’s presence in the barroom, as a usual thing, regardless of the day, or time of day, he being the only dispenser of potable necessities in Brownsville, but the stress of Saturday nights was commonly followed by an interval of calm on Sabbath mornings, and his custom was to go abroad for air on those occasions.

Seating himself on a piece of driftwood, he chewed the end of his cigar for a time, and then observed: “It was a large night.”

“It was,” said Stumpy. “Is thim two strangers stayin’ here long, I don’t know?” Stumpy’s brogue defied spelling.

“They’ll be dead if they do,” said Sam. “I’ve saw wild men afore, but I never seen two men try to pull up the Mississippi River by the roots.”

“If it was thim ’ud die,” said Stumpy, gloomily. “An’ Hennessy. We c’d do widout Hennessy an’ wan or more others. But I do be thinkin’ Long Mike is off again.”

“Looks like it,” said Sam.

Just then the report of a pistol-shot rang

out, and Peter leaped in the air. He was not hurt, but the bullet had struck between his fore paws, and he was frightened.

Stumpy turned like a flash. The two strangers were approaching, laughing heartily, and one of them was about to shoot again. Stumpy was a small man, probably a foot shorter than either of the newcomers, but his hair was very red. He sprang to his feet.

“That’s my dog,” he said, pulling off his coat, and the man who was poising his revolver lowered it.

“No offence, friend,” he said, pleasantly. “I just wanted to see the dog dance.”

“Dance, is it?” shouted Stumpy, in a fine rage. “That dog’s no circus. If it’s dancin’ ye want, I’ll dance, but it’s on your ugly face it’ll be, wid you on the flat o’ your back.” And he squared off in excellent style.

“There, there,” said the big man, soothingly, “I’ll not fight you, and I’ll not bother your dog, if it’s yours. Come and have a drink.”

It was not easy to placate the little Irishman,{58} but the two strangers finally accomplished it, and the entire party went over to the barroom. Peter, however, refused to enter the place, and showed his teeth viciously when the sportive pistol-player, whose name was Carruthers, offered to pat his head by way of apology.

As the day wore on, the male population of Brownsville, one by one, appeared in the barroom, and Carruthers and his mate, Hopper, played the part of hosts with great assiduity, so that the general condition of hilarity that had prevailed on Saturday night, but which had been greatly modified in the early morning hours, was fully reëstablished before nightfall.

The two men told about themselves without reserve, and there seemed to be no reason to doubt their story. They were sports, they said, frankly, it being fully understood that the word sport was a mere euphemism for professional gambler, and, having “made a killing” in La Crosse a few days before, they were enjoying a trip down the river with the ultimate purpose of getting into a{59} big game at Vicksburg or New Orleans. Things being too slow to suit them on the boat on which they started, they had stopped off at the first landing-place to wait for another. Being thus in Brownsville, they proposed to enjoy themselves as heartily as possible, so what was the matter with all hands having another drink?

Whatever latent prejudice there was in the minds of Stumpy and one or two others who recognized an element of peril in the situation, was of little force against the popular enthusiasm the two strangers evoked by their liberality. Being men of seemingly unlimited capacity themselves, they soon discovered that Brownsville had also a few mighty drinkers, and, while now and again some less gifted man dropped out of the bout and made his uncertain way to some hiding-place, there were others on whom even Sam’s brands of red liquors had no appreciable effect.

Long Mike, indeed, seemed in his element. Glass for glass with anybody and everybody he tossed off his tipple as if it were filtered{60} water, and his eye grew brighter, his hand steadier, and his tongue more nimble with each potation, so that only those who knew the awful cumulative effect drink had on him when his limit was actually reached, could realize that the commercial standing of Brownsville was at stake, for without Long Mike there was no head to the community, and no prospect of carrying on any business of importance. Therefore Stumpy—and others—had misgivings.

Not all the boats that ply the Mississippi stop at Brownsville, and the intervals at which some do stop are uncertain, so that Carruthers and Hopper had no means of calculating the length of their stay. It did not appear to trouble them much, but toward evening, no boat having appeared, and none being expected that night, Carruthers remarked, casually, that he could wish for a little excitement.

“Your liquor is all right,” he said, “and your society here is pleasant enough to suit anybody, but don’t you ever do anything in Brownsville?{61}”

“We had a cock-fight here last month,” said Hennessy, “but there’s only one cock in town now. That was Gallagher’s afore Gallagher lit out, but even if he was to come home there’s no way o’ fightin’ one cock. That is, there’s no way I know on, ’thouten you put him front of a lookin’-glass,” he added, with a foolish laugh that no one echoed.

“Don’t nobody ever play poker here?” asked Hopper.

“I knowed it,” said Stumpy, under his breath, to Sam, who nodded understandingly.

People did play poker in Brownsville, quite a number of them, but they had a wholesome respect for travelling sports, realizing that the domestic variety of the game was by no means up to the standard established on the boats by gentlemen who made a business of playing. Liquor, however, played the mischief with Long Mike’s bump of caution, and he was fond of poker anyhow.

It turned out as Stumpy feared, and as{62} Hopper expressed his disdain of a limit game, and nobody else was strong enough to put up a hundred dollars, Long Mike was presently engaged in playing table stakes with the two sports, each of the three having produced that sum.

“It’s not the hundred’ll break him,” said Stumpy, while Sam was getting the chips and cards, “but he’ll buy and buy, by and by, till the divil himself couldn’t save him.”

And this was the prevailing opinion among the score or more of men who clustered around to watch the game. No man, however, cared to raise his voice in protest. It would hardly have been done in any case, for a wholesome respect obtains on the Mississippi River for the right of the individual to go to the devil in his own chosen way, but, in the case of Long Mike, there was an additional feeling that he would make it extremely uncomfortable for any one who might presume to remonstrate with him for anything.

The game was not, at first, a notable one. No particularly sensational play marked the{63} loss of Long Mike’s first hundred, though it went pretty fast, and with the second hundred he managed to secure some good pots, so that he ran up, almost even, for a few moments. But a series of losses reduced his pile again to less than forty dollars, when he caught a flush against Hopper’s full house, and called on Sam for two hundred more in chips.

It was evident, then, that he had the fever, and Stumpy groaned in spirit. There was no telling what the end would be, but he felt that it was among the possibilities for Long Mike to ruin himself in an hour or two, and his ruin would be disastrous to more than one in the room.

Suddenly he saw something which set his brain in a whirl. If he could have been positive and could have given proof, he would have declared that he saw Hopper deal himself a card from the bottom of the deck. He knew, however, what the accusation of cheating would mean, and he hesitated. Possibly he might have been mistaken, he thought, and anyhow it would be{64} his word against one other’s. It was altogether uncertain what the result would be.

He watched the game, however, even more keenly than before, determined to speak, regardless of consequences, if he should see anything he was sure of. What he did not notice was that Carruthers had seen the gasp of astonishment that he had himself been unconscious of, and was watching him carefully. He stood opposite where Carruthers sat.

Presently there came a jack-pot that Hopper opened for five dollars. Carruthers passed, but did not immediately throw his cards on the table. Long Mike raised it ten dollars, it being his deal. Hopper came back at him with ten more, and Long Mike stayed.

Hopper called for two cards, and, as he did so, Stumpy distinctly saw Carruthers show Hopper his hand as he threw it on the table in the discard. One of the five was an ace, and Stumpy saw it.

Watching Hopper as he moved to pick up the cards dealt to him in the draw, he{65} saw further that Hopper took one of them and one from the discarded pile. It was deftly done, but he was certain this time.

Long Mike stood pat, and when Hopper pushed his whole pile forward, Long Mike called him for all he had in front of him, a hundred and odd dollars. Then he showed a pat straight and Hopper showed four aces.

“Hold on!” shouted Stumpy. “There’s foul play here. That—” and then he paused.

Every man in the room was looking at him, and he was the only one who saw the muzzle of Carruther’s pistol just above the edge of the table. It was pointed directly at him, and the barrel looked to him as large around as a nail-keg.

It was not necessary to explain to him that Carruthers had the drop on him. Moreover, he knew that if he tried to finish his sentence he would be shot before he got the words out. It was small wonder he paused.

Nobody spoke for a moment, Stumpy for the excellent reason just stated, and the others because of their surprise. Then Carruthers{66} said: “Evidently the gentleman never saw four aces held before. Is that what you meant when you spoke of foul play?”

Still all eyes were on Stumpy. No one else had seen the revolver, but he knew that on his answer depended the question whether Carruthers should shoot or not. Drops of sweat came out on his forehead. He drew a long breath.

Then he saw something else, and he answered Carruthers curiously.

“Yes-s-s,” he said, prolonging the word into a curious hiss which he knew that Peter understood.

At the instant that Carruthers, with an evil smile, was relaxing his aim, a small, brown dog landed on his shoulders and fastened his teeth in his throat.

No man was ever able to recall all the details of the mix-up that followed, but after two badly damaged strangers had departed from Brownsville on the next boat, Stumpy observed to Sam: “Sure, it would ha’ been betther to kill thim, I don’t know.{67}”

When Gallagher came back to Brownsville he did not expect to be met at the steamboat-landing by a delegation of citizens eager to welcome his return. There was no thought in his mind of having to listen to an address of eulogy and being obliged to reply with a few or a great many well-chosen remarks.

The idea of a brass band and a display of fireworks tooting and blazing in his honour had never entered his head. The most he hoped for was to be able to sneak across the gangplank unnoticed, and to make his way under the friendly obscurity of darkness, in case it should happen to be after nightfall, along the edge of the levee to the neighbourhood of his own house, where he might remain in seclusion until such time as he{68} should learn what the disposition of the community might be, and more especially what Long Mike’s attitude toward him was.

The recollection of all the circumstances attending his departure from Brownsville was sufficiently vivid in his mind to fill him with apprehension, and the utmost caution seemed absolutely necessary when he determined to return. He recalled distinctly that, after he had tried Long Mike’s temper to the point at which further endurance became impossible, that usually good-natured person became suddenly furious with rage, and not only discharged him from his employ—that, Gallagher was accustomed to—but strove earnestly to preclude the possibility of hiring him again, by the simple but effective expedient of killing him.

It should be said that Long Mike seldom attempted to kill anybody. Murder was not his habit, he being usually a tolerant person, albeit he required a full equivalent of labour in return for the wages he paid.

On such occasions, however, as he had deemed serious enough to demand extreme{69} action, he had never been known to fail to get his man, until Gallagher had eluded him by a flight that took him far from Brownsville. Some months had elapsed since then, but Gallagher had no means of knowing whether his boss’s wrath had cooled or not.

The caution he displayed in eluding observation when he went ashore from the river boat was not, therefore, uncalled for. Knowing the ground perfectly, even in the darkness, he picked his way carefully to the door of his own house, but before lifting the latch he stopped and listened, as one who was in great doubt. As he continued to listen he passed through many phases and degrees of doubt, perplexity, and amazement.

It was his own house beyond a question, but many things had happened since his sudden departure. Long Mike was impetuous, but not devoid of generous impulses, or of a prejudice in favour of fair play. When he realized that he had wrought injustice to Mrs. Gallagher in the fervour of his pursuit of her husband, he had taken effective{70} and characteristic measures to remedy the wrong.

This was largely due to the personality of Stumpy, whose Irish blood boiled on slight provocation, and who entertained no fear, even of his boss, when he was moved to remonstrate against any happening which failed to comport with his ideas of propriety. Stumpy it was who said:

“Sure, it was a blackguard’s thrick to lave Misthress Gallagher widout a bed to lie on, or a shtove or a taable to her back.”

“Did Gallagher do that?” demanded Long Mike, indignantly.

“He did not,” said Stumpy, “but there’s them that did.”

“Who did it?” asked Long Mike.

“It was yoursilf,” said Stumpy, and stood immediately on the defensive.

The look of blank astonishment that Long Mike gave at the accusation was at least presumptive proof that he did not realize his offence, and seeing it, Stumpy’s wrath was somewhat assuaged. It did not right{71} the wrong, however, and Stumpy wanted that done.

“It was whin ye was lukkin’ f’r Gallagher,” he explained. “Belike ye was confused wid the rage that was in ye, an’ maybe a thrifle o’ liquor, too, but ye found his house, an’ him not bein’ there, by the mercy o’ God, ye smashed, and smashed, an’ there’s nothin’ left.”

“Did I, now?” said Long Mike, and he chuckled, whereat Stumpy’s wrath blazed up again.

“Ye did,” he said, briefly, “an’ ’twas a blackguard act for to lave a lone woman deshtitoot.”

“Aisy now, Stumpy, aisy now,” said Long Mike, good-naturedly. “Av that pirut, Gallagher, has left his woman deshtitoot—”

“ ‘Twas you drove him away,” interrupted Stumpy.

“Yis, an’ a good job. Av he cooms back, I’ll break ivery dommed bone in his body,” exclaimed Long Mike, with sudden fury. “But I’ll have no woman suffer in Brownsville, Stumpy. Av that dirty pirut lift her{72} deshtitoot, as ye say, she’ll be took care of. Mind that.”

Taken care of, she had been, in Brownsville fashion. New furniture had replaced the stuff that Long Mike destroyed, and, as the house contained two rooms, or one more than Mrs. Gallagher required to live in, the sporting element of Brownsville had established the custom of using her extra space for a card-room.

Whenever a game was in progress, the good lady retired to her own apartment, but after the players had departed she always found that the kitty, established for her benefit, remained on the table. And inasmuch as the income she derived from this source was much larger, and no more irregular, than that which she enjoyed from Gallagher, it had come about that she no longer felt any very keen anxiety for his return.

All this was, of course, unknown to Gallagher, as he listened, and his surprise at the unexpected sounds he heard was natural enough.

One Harrison had been in Brownsville{73} for two or three days, in company with his side partner, Davis, the two being on one of their occasional business trips down the Mississippi Valley. They had been known to play in some of the principal cities, but for the most part they preferred the smaller places, being of the variety of sports commonly known as crossroads gamblers, and Brownsville was one of their favourite stopping-places.

They had at first been inclined to question the use of a private house for their purposes, but after the circumstances were explained, they had acquiesced readily enough, and on this occasion they were sitting in.

Long Mike was there. It would have taken more than one Gatling gun to keep him out of a game when one was in progress and he was in the neighbourhood. McCarthy had a hand also, and Billy Flynn.

McCarthy was a character. He loved the game of poker with a fervour that would have made him a large winner if he could only have learned how to play the game. As it was, he only sat in at such times as{74} he had sufficient money saved up from his wages to buy a stack. And he never sat long.

Flynn was a good player, and Long Mike was better than the average, but neither of them knew enough of the game to detect the peculiarities of play that gave Harrison and Davis a large percentage in their favour.

They had been playing for half an hour, and only the remnants of his stack remained to McCarthy, when he caught a king full, pat, on Flynn’s deal. It was a jack-pot, and Harrison, having first say, opened it for the size of it, which was a dollar and a quarter. The game was a small one.

McCarthy raised it all he had, which was about seven dollars more, and the others all laid down, including the opener, who showed jacks. McCarthy took down his two dollars and a quarter winnings, and proceeded to make the only additional blunder that was possible under the circumstances. He showed his hand and exulted in his winning.

It was nobody’s business to instruct him, and the others smiled grimly as Harrison{75} took the cards to deal. He was impatient at the smallness and the slowness of the game and made ready for a killing.

Shuffling with extra care, he dealt good hands to everybody, making sure of the aces at the bottom of the deck that he could utilize in the draw. It would have been pitiful, had there been anybody there to see, to note the way in which everybody backed his cards, and the fact that Harrison’s full of tens on aces scooped the pot.

McCarthy was out of it, and Flynn and Long Mike had to buy again, but they were brave, if foolish, and being well supplied with money, they played on. McCarthy sat by watching. The fascination held him, even though he could play no longer.

Suddenly he saw that which made his eyelids contract and his jaw set itself like a bulldog’s. He said nothing at the moment, but watched carefully until it came Harrison’s turn to deal again. Then he leaned a little forward and looked a little more intently.

Again it was a jack-pot, and Long Mike{76} opened it. Davis and Flynn dropped, but Harrison raised it, and Long Mike stayed. When it came to the draw he called for one card, and McCarthy spoke up.

“If it’s two pairs ye’re drawin’ to, you’d better split ’em an’ draw three cards,” he said, and Long Mike stared at him in amazement.

“An’ what for should I do that, I don’t know?” he said, but Harrison broke in with an oath and an angry:

“What do you mean?”

“I mean,” said McCarthy, very distinctly, “that you’ve stacked the cards and—”

Further than that he did not speak, for Harrison’s gun was out and almost in position before McCarthy could grapple him and seize his wrist. At the same moment Flynn grabbed the pistol itself and strove to wrench it from his fingers.

Even with two men holding him, and they were both powerful men, the gambler struggled mightily, and for a moment seemed about to wrench himself free. The three were all over the room.{77}

It was harder to keep Long Mike out of a fight than to drag him away from a bar or poker game. Moreover, though he held McCarthy in contempt as a gambler, he knew him for a man who spoke the truth, and leaping to his feet he started forward.

Davis, however, sprang up at the same instant, and, stretching out his foot, he tripped the big man and threw him headlong on the floor. Drawing a knife from his belt, he threw himself on the prostrate form and raised his arm for a blow. In the excitement nobody noticed that the door had been opened.

“Whurroo!” said Gallagher, and threw himself into the fray.

There was no time to find a weapon, and he carried none, but he was handy with his feet, and a well-directed kick not only lamed Davis’s elbow for a week, but knocked the knife from his hand half-way across the room. It would have been between Long Mike’s ribs but for the kick. Disarmed and disabled, the desperado was no match for the two men, one of whom was grappling{78} him from beneath while the other was continuing to kick from above.

At this moment the pistol went off and Gallagher fell to the floor. Flynn had got possession of the weapon, but it had been discharged in the transfer and Gallagher’s head was directly in line. Having it, however, Flynn used it promptly and stunned Harrison with a single blow, practically ending the shindy, for Long Mike made short work of Davis when he realized the situation.

“Is he kilt?” he inquired, anxiously, as Flynn and McCarthy bent over Gallagher. “Sure he saved my life when this blackguard was shtickin’ me like a pig.”

“I think he is,” said McCarthy. “There’s a hole in his head the size of a shtove door.”

But the bullet had glanced, and Gallagher was only stunned. Sitting up a moment later he said:

“Will ye’s all get out o’ my house? I have confidential affairs to discuss wid Misthress Gallagher.{79}”

“We will,” said the three friends, as they departed, dragging the gamblers with them.

Then the other door opened.

“Is it you, Pat?” said a female voice.

“It is,” said Gallagher, “an’ I’d like my supper. But first ye’ll give me a bit o’ a wet rag till I wipe my head.{80}”

“Sure I do be thinkin’ it’s like playin’ lotthery,” said Stumpy, as he sat one day in meditative mood near the steamboat-landing with Deaf Dan. It was a hot afternoon and there had been a long, sociable silence between them when Stumpy yawned and shot off his comparison. It was uttered in stentorian tones, for none could converse otherwise with Deaf Dan.

“As bein’ how?” inquired Deaf Dan. “Who’s a lotthery?”

“All of us,” said Stumpy. “Iv’ry marnin’ we do put in, loike the suckers that buys thim little printed bits o’ paper wid a big number on ’em, an’ lies. An’ thin we set around, like bumps on a log, waitin’ for to see what the drawin’ ’ll be, the same as thim same suckers does. Mostly it’s blanks. Sildom{81} it is that anythin’ happens in Brownsville. But now an’ again, some wan’ll dhraw a proize. Maybe it’s a chanst at th’ red liquor, an’ maybe it’s a shindy, an’ sometimes it’s a game of dhraw-poker, but annyhow it’s a proize, such as it may be.”

“It’s right y’ are,” said Deaf Dan. “An’ lately it’s all blanks. Sure, there’s nothin’ do be doin’ in th’ place since the night that Gallagher got back.”

“Sure, that was a fine foight,” said Stumpy.

“They tell me that same,” responded Deaf Dan, “but Gallagher an’—Howly mother o’ Moses, phwat’s that?”

“That” appeared at first to be a procession of two, emerging with great suddenness from the door of the barroom, but, as Deaf Dan and Stumpy rose to get a better view of the proceedings, the two who first appeared were followed by a straggling crowd of others, all eagerly intent on observation, so that presently the entire male population of Brownsville was assembled on the levee, looking with interest to see the outcome of{82} what seemed to be a personal difficulty between two prominent citizens. Last of all to appear was Sam, the bartender, whose appearance on his doorstep was indisputable evidence that there was no one remaining inside.

The leading figure in the procession was Gallagher, and judging from the earnestness with which he was moving, it was easily to be understood that he was desirous of putting as much vacant space as possible between himself and the second advancing figure. He might almost be said to be flying, rather than fleeing. And every ounce of force at his command was devoted to the effort to keep in the lead, so that, although his mouth was open, he emitted no sound.

His pursuer, on the other hand, though he was no less resolute in his endeavour to cover the ground quickly, was devoting a part of his strength to the loud utterance of many words. For the most part, these words savoured of profanity, too enthusiastic to be well chosen, but sufficiently impassioned to be exceedingly impressive. There{83} was no questioning the fact that Long Mike had lost his temper again, and small doubt that he would do bodily harm to his foreman if he should succeed in getting near enough to lay hands upon him.