HARPER’S

STORY BOOKS

No. 1

BRUNO.

DECEMBER, 1854.

PRICE 25 Cts

HARPER & BROTHERS

FRANKLIN SQUARE, NEW YORK.

HARPER’S

STORY BOOKS

No. 1

BRUNO.

DECEMBER, 1854.

PRICE 25 Cts

HARPER & BROTHERS

FRANKLIN SQUARE, NEW YORK.

“Bruno forgives him, and why should not I?” said Hiram.

HARPER’S STORY BOOKS.

A SERIES OF NARRATIVES, DIALOGUES, BIOGRAPHIES, AND TALES,

FOR THE INSTRUCTION AND ENTERTAINMENT

OF THE YOUNG.

BY

JACOB ABBOT.

Embellished with

NUMEROUS AND BEAUTIFUL ENGRAVINGS.

BRUNO;

OR,

LESSONS OF FIDELITY, PATIENCE, AND SELF-DENIAL

Taught by a Dog.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS.

Entered, according to an Act of Congress, in the year

one thousand eight hundred and fifty-four, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

in the Clerk’s Office for the Southern District of New York.

The present volume is the first of a proposed monthly series of story books for the young.

The publishers of the series, in view of the great improvements which have been made within a few years past in the means and appliances of the typographical art, and of the accumulation of their own facilities and resources, not only for the manufacture of such books in an attractive form, and the embellishment of them with every variety of illustration, but also for the circulation of them in the widest manner throughout the land, find that they are in a condition to make a monthly communication of this kind to a very large number of families, and under auspices far more favorable than would have been possible at any former period. They have accordingly resolved on undertaking the work, and they have intrusted to the writer of this notice the charge of preparing the volumes.

The books, though called story books, are not intended to be works of amusement merely to those who may receive them, but of substantial instruction. The successive volumes will comprise[viii] a great variety, both in respect to the subjects which they treat, and to the form and manner in which the subjects will be presented; but the end and aim of all will be to impart useful knowledge, to develop the thinking and reasoning powers, to teach a correct and discriminating use of language, to present models of good conduct for imitation, and bad examples to be shunned, to explain and enforce the highest principles of moral duty, and, above all, to awaken and cherish the spirit of humble and unobtrusive, but heartfelt piety. The writer is aware of the great responsibility which devolves upon him, in being thus admitted into many thousands of families with monthly messages of counsel and instruction to the children, which he has the opportunity, through the artistic and mechanical resources placed at his disposal, to clothe in a form that will be calculated to open to him a very easy access to their attention, their confidence, and their hearts. He can only say that he will make every exertion in his power faithfully to fulfill his trust.

Jacob Abbott.

New York, 1854.

In the night, a hunter, who lived in a cottage among the Alps, heard a howling.

“Hark!” said he, “I heard a howling.”

His wife raised her head from the pillow to listen, and one of the two children, who were lying in a little bed in the corner of the room, listened too. The other child was asleep.

“It is a wolf,” said the hunter.

“In the morning,” said the hunter, “I will take my spear, and my sheath-knife, and Bruno, and go and see if I can not kill him.”

Bruno was the hunter’s dog.

The hunter and his wife, and the child that was awake, listened a little longer to the howling of the wolf, and then, when at length the sounds died away, they all went to sleep.

In the morning the hunter took his spear, and his sheath-knife, and his hunting-horn besides, and then, calling Bruno to follow him, went off among the rocks and mountains to find the wolf.

While he was climbing up the mountains by a steep and narrow path, he thought he saw something black moving among the rocks at a great distance across the valley. He stopped to look at it. He looked at it very intently.

At first he thought it was the wolf. But it was not the wolf.

Then he thought it was a man. So he blew a loud and long blast with his horn. He thought that if the moving thing which he saw were another man, he would answer by blowing his horn, and that then, perhaps, he would come and help the hunter hunt the wolf. He listened, but he heard no reply. He heard nothing but echoes.

By-and-by he came to a stream of water. It was a torrent, flowing wildly among the rocks and bushes.

“Bruno,” said the hunter, “how shall we get across this torrent?”

Bruno stood upon a rock, looking at the torrent very earnestly, but he did not speak.

“Bruno,” said the hunter again, “how shall we get across this torrent?”

Bruno barked.

The hunter then walked along for some distance on the margin of the stream, and presently came to a place where there was a log lying across it. So he and Bruno went over on the log. Bruno ran over at once. The hunter was at first a little afraid to go, but at last he ventured. He got across in safety. Here the hunter stopped a few minutes to rest.

He then went on up the mountain. At last Bruno began to bark and to run on forward, looking excited and wild. He saw the wolf. The hunter hastened forward after him, brandishing his spear. The wolf was in a solitary place, high up among the rocks. He was gnawing some bones. He was gaunt and hungry. Bruno attacked him, but the wolf was larger and stronger than he, and threw him back with great violence against the ground. The dog howled with pain and terror.

Picture of the combat.

The man thrust the spear at the wolf’s mouth, but the ferocious beast evaded the blow, and seized the shaft of the spear between his teeth. Then the great combat came on. Very soon the dog sprang up and seized the wolf by the throat, and held him down, and finally the man killed him with his spear.

Then he took his horn from his belt, and blew a long and loud blast in token of victory.

He took the skin of the wolf, and carried it home. The fur was long, and gray in color. The hunter tanned and dressed the skin, and made it soft like leather. He spread it down upon the floor before the fire in his cottage, and his children played upon it. Bruno was accustomed to lie upon it in the evening. He would lie quietly there for a long time, looking into the fire, and thinking of the combat he had with the savage monster that originally wore the skin, at the time when he fought him on the mountains, and helped the hunter kill him.

The hunter and the hunter’s children liked Bruno very much before, but they liked him more than ever after his combat with the wolf.

Some wild animals are so ferocious and strong that it requires several dogs to attack and conquer them. Such animals are found generally in remote and uninhabited districts, among forests and mountains, or in countries inhabited by savages.

The wild boar is one of the most terrible of these animals. He has long tusks projecting from his jaws. These serve him as weapons in attacking his enemies, whether dogs or men. He roams in a solitary manner among the mountains, and though he is very fierce and savage in his disposition, he will seldom molest any one who does not molest him. If, when he is passing along through the forests, he sees a man, he pays no regard to him, but[17] goes on in his own way. If, however, when he is attacked by dogs, and is running through the forest to make his escape, he meets a man in his way, he thinks the man is the hunter that has set the dogs upon him, or at least that he is his enemy. So he rushes upon him with terrible fury, and kills him—sometimes with a single blow—and then, trampling over the dead body, goes on bounding through the thickets to escape from the dogs.

Picture of a fight.

Wild boars often have dreadful combats with each other. In this engraving we have a representation of such a fight. The weapons with which they fight are sharp tusks growing out of the under jaw. With these tusks they can inflict dreadful wounds.

Savages, when they attack the wild boar, arm themselves with spears, and station themselves at different places in the forest, where they think the boar will pass. Sometimes they hide themselves in thickets, so as to be ready to come out suddenly and attack the boar when the dogs have seized him.

Picture of the combat.

Here is a picture of such a combat. The dogs have pursued the boar through the woods until he begins to be exhausted with fatigue and terror. Still, he fights them very desperately. One he has thrown down. He has wounded him with his tusks. The dog is crying out with pain and fright. There are three other dogs besides the one who is wounded. They are endeavoring to seize and hold the boar, while one of the hunters is thrusting the iron point of his spear into him. Two other hunters are coming out of a thicket near by to join in the attack. One of them looks as if he were afraid of the boar. He has good reason to be afraid.

These hunters[19] are savages. They are nearly naked. One of them is clothed with a skin. I suppose, by the claws, that it is a lion’s skin. He hunted and killed the lion, perhaps, in the same way that he is now hunting and killing the boar.

Savages use the skins of beasts for clothing because they do not know how to spin and weave.

But we must now go back to Bruno, the Alpine hunter’s dog that killed the wolf, and who used afterward to sleep before the fire in the hunter’s cottage on the skin.

Bruno’s master lived among the Alps. The Alps are very lofty mountains in Switzerland and Savoy.

The upper portions of these mountains are very rocky and wild. There are crags, and precipices, and immense chasms among them, where it is very dangerous for any one to go. The hunters, however, climb up among these rocks and precipices to hunt the chamois, which is a small animal, much like a goat in form and character. He has small black horns, the tips of which turn back.

The chamois climbs up among the highest rocks and precipices to feed upon the grass which grows there in the little nooks and corners. The chamois hunters climb up these after him. They take guns with them, in order to shoot the chamois when they see one. But sometimes it is difficult for them to get the game when they have killed it, as we see in this engraving. The hunters[20] were on one side of a chasm and the chamois on the other, and though he has fallen dead upon the rocks, they can not easily reach him. One of the hunters is leaning across the chasm, and is attempting to get hold of the carcass with his right hand. With his left hand he grasps the rock to keep himself from falling. If his hand should slip, he would go headlong down into an awful abyss.

Picture of the chamois hunters on the Alps.

The other hunter is coming up the rock to help his comrade.[21] He has his gun across his shoulder. Both the hunters have ornamented their hats with flowers.

The chamois lies upon the rock where he has fallen. We can see his black horns, with the tips turned backward.

In the summer season, the valleys among these Alpine mountains are very delightful. The lower slopes of them are adorned with forests of fir and pine, which alternate with smooth, green pasturages, where ramble and feed great numbers of sheep and cows. Below are rich and beautiful valleys, with fields full of flowers, and cottages, and pretty little gardens, and every thing else that can make a country pleasant to see and to play in. There are no noxious or hurtful animals in these valleys, so that there is no danger in rambling about any where in them, either in the fields or in the groves. They must take care of the wet places, and of the thorns that hide among the roses, but beyond these dangers there is nothing to fear. In these valleys, therefore, the youngest children can go into the thickets to play or to gather flowers without any danger or fear; for there are no wild beasts, or noxious animals, or poisonous plants there, or any thing else that can injure them.

Children at play.

Thus the country of the Alps is very pleasant in summer, but in winter it is cold and stormy, and all the roads and fields, especially[22] in the higher portions of the country, are buried up in snow. Still, the people who live there must go out in winter, and sometimes they are overtaken by storms, and perish in the cold.

Once Bruno saved his master’s life when he was thus overtaken in a storm. The baby was sick, and the hunter thought he would go down in the valley to get some medicine for him. The baby was in a cradle. His grandmother took care of him and rocked him. His mother was at work about the room, feeling very anxious and unhappy. The hunter himself, who had come in tired from his work a short time before, was sitting in a comfortable easy-chair which stood in the corner by the fire. The head of the cradle was near the chair where the hunter was sitting.[1]

“George,” said the hunter’s wife, “I wish you would look at the baby.”

George leaned forward over the head of the cradle, and looked down upon the baby.

“Poor little thing!” said he.

“What shall we do?” said his wife. As she said this she came to the cradle, and, bending down over it, she moved the baby’s head a little, so as to place it in a more comfortable position. The baby was very pale, and his eyes were shut. As soon as he felt his mother’s hand upon his cheek, he opened his eyes, but immediately shut them again. He was too sick to look very long even at his mother.

“Poor little thing!” said George again.[23] “He is very sick. I must go to the village and get some medicine from the doctor.”

“Oh no!” said his wife. “You can not go to the village to-night. It is a dreadful storm.”

“Yes,” said the hunter, “I know it is.”

“The snow is very deep, and it is drifting more and more,” said his wife. “It will be entirely dark before you get home, and you will lose your way, and perish in the snow.”

The hunter did not say any thing. He knew very well that there would be great danger in going out on such a night.

“You will get lost in the snow, and die,” continued his wife, “if you attempt to go.”

“And baby will die, perhaps, if I stay at home,” said the hunter.

The hunter’s wife was in a state of great perplexity and distress. It was hard to decide between the life of her husband and that of her child. While the parents were hesitating and looking into the cradle, the babe opened its eyes, and, seeing its father and mother there, tried to put out its little hands to them as if for help, but finding itself too weak to hold them up, it let them drop again, and began to cry.

“Poor little thing!” said the hunter. “I’ll go—I’ll go.”

The mother made no more objection. She could not resist the mute appeal of the poor helpless babe. So she brought her husband his coat and cap, and forced her reluctant mind to consent to his going.

It was strange, was it not, that she should be willing to risk the life of her husband, who was all the world to her, whose labor was her life, whose strength was her protection, whose companionship was her solace and support, for the sake of that helpless and useless baby?

It was strange, too, was it not, that the hunter himself, who was already almost exhausted by the cold and exposure that he had suffered during the day, should be willing to go forth again into the storm, for a child that had never done any thing for him, and was utterly unable to do any thing for him now? Besides, by saving the child’s life, he was only compelling himself to work the harder, to procure food and clothing for him while he was growing up to be a man.

What was the baby’s name?

His name was Jooly.

At least they called him Jooly. His real name was Julien.

When the hunter was all ready to go, he came to the cradle, and, putting his great rough and shaggy hand upon the baby’s wrist, he said,

“Poor little Jooly! I will get the doctor himself to come and see you, if I can.”

So he opened the door and went out, leaving Jooly’s grandmother rocking the cradle, and his mother at work about the room as before.

When the hunter had gone out and shut the door, he went along the side of the house till he came to a small door leading to his cow-house, which was a sort of small barn.

He opened the door of the cow-house and called out “Bruno!”

Bruno, who was asleep at this time in his bed, in a box half filled with straw, started up on hearing his master’s voice, and, leaping over the side of the box, came to his master in the storm.

Bruno was glad to be called. And yet it was a dark and stormy night. The wind was blowing, and the snow was driving terribly.[25] On the other hand, the bed where he had been lying was warm and comfortable. The cow was near him for company. He was enjoying, too, a very refreshing sleep, dreaming of races and frolics with other dogs on a pretty green. All this repose and comfort were disturbed. Still, Bruno was glad. He perceived at once that an unexpected emergency had occurred, and that some important duty was to be performed. Bruno had no desire to lead a useless life. He was always proud and happy when he had any duty to perform, and the more important and responsible the duty was, the more proud and happy it made him. He cared nothing at all for any discomfort, fatigue, or exposure that it might bring upon him.

Some boys are very different from Bruno in this respect. They do not share his noble nature. They never like duty. All they like is ease, comfort, and pleasure. When any unexpected emergency occurs, and they are called to duty, they go to their work with great reluctance, and with many murmurings and repinings, as if to do duty were an irksome task. I would give a great deal more for a dog like Bruno than for such a boy.

Bruno and his master took the road which led to the village. The hunter led the way, and Bruno followed. The road was steep and narrow, and in many places the ground was so buried in snow that the way was very difficult to find. Sometimes the snow was very soft and deep, and the hunter would sink into it so far that he could scarcely advance at all. At such times Bruno, being lighter and stronger, would wallow on through the drift, and then look back to his master, and wait for him to come, and then go back to him again, looking all the time at the hunter with an[26] expression of animation and hope upon his countenance, and wagging his tail, as if he were endeavoring to cheer and encourage him. This action had the effect, at any rate, of encouragement. It cheered the hunter on; and so, in due time, they both arrived safely at the village.

The doctor concluded, after hearing all about the case, that it would not be best for him to go up the mountain; but he gave the hunter some medicine for the baby.

The medicine was put in a phial, and the hunter put the phial in his pocket. When all was ready, the hunter set out again on his return home.

It was much harder going up than it had been to come down. The road was very steep. The snow, too, was getting deeper every hour. Besides, it was now dark, and it was more difficult than ever to find the way.

At last, when the hunter had got pretty near his own cottage again, his strength began to fail. He staggered on a little farther, and then he sank down exhausted into the snow. Bruno leaped about him, and rubbed his head against his master’s cheek, and barked, and wagged his tail, and did every thing in his power to encourage his master to rise and make another effort. At length he succeeded.

“Yes,” said the hunter, “I’ll get up, and try again.”

So he rose and staggered feebly on a little farther. He looked about him, but he could not tell where he was. He began to feel that he was lost. Now, whenever a man gets really lost, either in the woods or in the snow, a feeling of great perplexity and bewilderment generally comes over his mind, which almost wholly[27] deprives him of the use of his faculties. The feeling is very much like that which one experiences when half awake. You do not know where you are, or what you want, or where you want to go. Sometimes you scarcely seem to know who you are. The hunter began to be thus bewildered. Then it was bitter cold, and he began to be benumbed and stupefied.

Intense cold almost always produces a stupefying effect, when one has been long exposed to it. The hunter knew very well that he must not yield to such a feeling as this, and so he forced himself to make a new effort. But the snow seemed to grow deeper and deeper, and it was very hard for him to make his way through it. It was freshly fallen, and, consequently, it was very light and soft, and the hunter sank down in it very far. If he had had snow shoes, he could have walked upon the top of it; but he had no snow shoes.

At last he became very tired.

“Bruno,” said he, “I must lie down here and rest a little, before I can go on any further.”

But Bruno, when he saw his master preparing to lie down, jumped about him, and barked, and seemed very uneasy. Just then the hunter saw before him a deep black hole. He looked down, and saw that it was water. Instead of being in the road, he was going over some deep pit filled with water, covered, except in one place, with ice and snow. He perceived that he had had a very narrow escape from falling into this water, and he now felt more bewildered and lost than ever. He contrived to get by the dangerous hole, feeling his way with a stick, and then he sank down in the snow among the rocks, and gave up in despair.

And yet the house was very near. The chimney and the gable end of it could just be distinguished in the distance through the falling snow. Bruno knew this, and he was extremely distressed that his master should give up when so near reaching home. He lay down in the snow by the side of his master, and putting his paw over his arm, to encourage him and keep him from absolute despair, he turned his head toward the house, and barked loud and long, again and again, in hopes of bringing somebody to the rescue.

In the picture you can see the hunter lying in the snow, with Bruno over him. His cap has fallen off, and is half buried. His stick, too, lies on the snow near his cap. That was a stick that he got to feel down into the hole in[29] the ice with, in order to ascertain how deep the water was, and to find his way around it. The rocks around the place are covered with snow, and the branches of the trees are white with it.

It is extremely dangerous to lie down to sleep in the snow in a storm like this. People that do so usually never wake again. They think, always, that they only wish to rest themselves, and sleep a few minutes, and that then they will be refreshed, and be ready to proceed on their journey. But they are deceived. The drowsiness is produced, not by the fatigue, but by the cold. They are beginning to freeze, and the freezing benumbs all their sensations. The drowsiness is the effect of the benumbing of the brain.

Sometimes, when several persons are traveling together in cold and storms, one of their number, who may perhaps be more delicate than the rest, and who feels the cold more sensibly, wishes very much to stop a few minutes to lie down and rest, and he begs his companions to allow him to do so. But they, if they are wise, will not consent. Then he sometimes declares that he will stop, at any rate, even if they do not consent. Then they declare that he shall not, and they take hold of his shoulders and arms to pull him along. Then he gets angry, and attempts to resist them. The excitement of this quarrel warms him a little, and restores in some degree his sensibility, and so he goes on, and his life is saved. Then he is very grateful to them for having disregarded his remonstrances and resistance, and for compelling him to proceed.[2]

[2] Children, in the same way, often complain very strenuously of what their parents and teachers require of them, and resist and contend against it as long as they can; and then, if their parents persevere, they are afterward, when they come to perceive the benefit of it, very grateful.

But now we must return to the story.

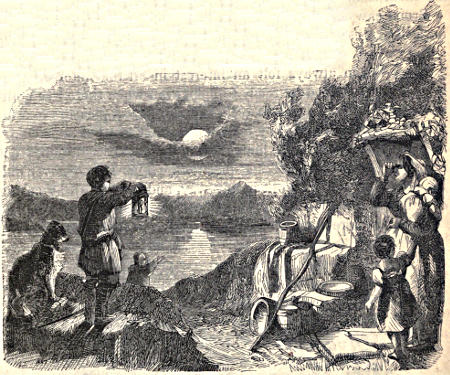

The hunter’s family heard the barking in the house. They all immediately went to the door. One of the children opened the door. The gusts of wind blew the snow in her face, and blinded her. She leaned back against the door, and wiped the snow from her face and eyes with her apron. Her grandmother came to the door with a light, but the wind blew it out in an instant. Her mother came too, and for a moment little Jooly was left alone.

“It is my husband!” she exclaimed. “He is dying in the snow! Mercy upon us! What will become of us?

“Give me the cordial,” said she. “Quick!”

So saying, she turned to the shelves which you see in the picture near where she is standing, and hastily taking down a bottle containing a cordial, which was always kept there ready to be used on such occasions, she rushed out of the house. She shut the door after her as she went, charging the rest, with her last words, to take good care of little Jooly.

Of course, those that were left in the cottage were all in a state of great distress and anxiety while she was gone—all except two, Jooly and the puss. Jooly was asleep in the cradle. The puss was not asleep, but was crouched very quietly before the fire in a warm and bright place near the grandmother’s chair. She was looking at the fire, and at the kettle which was boiling upon it, and wondering whether they would give her a piece of the meat by-and-by that was boiling in the kettle for the hunter’s supper.

When the hunter felt the mouth of the cordial bottle pressed gently to his lips, and heard his wife’s voice calling to him, he opened his eyes and revived a little. The taste of the cordial revived him still more. He was now able to rise, and when he was told how near home he was, he felt so cheered and encouraged by the intelligence that he became quite strong. The company in the house were soon overjoyed at hearing voices at the door, and on opening it, the hunter, his wife, and Bruno all came safely in.

Jooly took the medicine which his father brought him, and soon got well.

Here is a picture of Bruno lying on the wolf-skin, and resting from his toils.

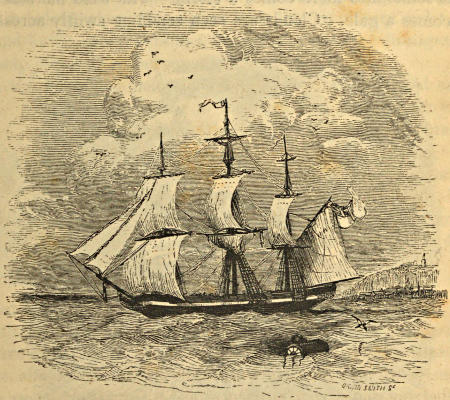

The hunter, Bruno’s master, emigrated to America, and when he went, he sold Bruno to another man. A great many people from Europe emigrate to America.

To emigrate means to move from one country to another. The people in Europe come from all parts of the interior down to the sea-shore, and there embark in great ships to cross the Atlantic Ocean. A great many come in the same ship. While they are at sea, if the weather is pleasant, these passengers come up upon the deck, and have a very comfortable time. But when it is cold and stormy, they have to stay below, and they become sick, and are very miserable. They can not stay on deck at such times on account of the sea, which washes over the ships, and often keeps the decks wet from stem to stern.

When the emigrants land in America, some of them remain in the cities, and get work there if they can. Others go to the West to buy land.

Opposite you see a farmer’s family in England setting out for America. The young girl who stands with her hands joined together is named Esther. That is her father who is standing behind her. Her mother and her grandmother are in the wagon. Esther’s mother has an infant in her arms, and her grandmother is holding a young child. Both these children are Esther’s brothers. Their names are George and Benny. The baby’s name is Benny.

The farmer’s family. The farewell.

Esther has two aunts—both very kind to her. One of her aunts is going to America, but the other—her aunt Lucy—is to remain behind. They are bidding each other good-by. The one who has a bonnet on her head is the one that is going. We can tell[34] who are going on the journey by their having hats or bonnets on. Esther’s aunt Lucy, who has no bonnet on, is to remain. When the wagon goes away, she will go into the house again, very sorrowful.

The farmer has provided a covered wagon for the journey, so as to protect his wife, and his mother, and his sister, and his children from the cold wind and from the rain. But they will not go all the way in this wagon. They will go to the sea-shore in the wagon, and then they will embark on board a ship, to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

We can see the ship, all ready and waiting, in the background of the picture, on the right. There will be a great many other families on board the ship, all going to America. There will be sailors, too, to navigate the ship and to manage the sails.

The voyage which the emigrants have to take is very long. It is three thousand miles from England to America, and it takes oftentimes many weeks to accomplish the transit. Sometimes during the voyage the breeze is light, and the water is smooth, and the ship glides very pleasantly and prosperously on its way. Then the emigrants pass their time very agreeably. They come up upon the decks, they look out upon the water, they talk, they sew, they play with the children—they enjoy, in fact, almost as many comforts and pleasures as if they were at home on land.

Opposite is a picture of the ship sailing along very smoothly, in[35] pleasant weather, at the commencement of the voyage. The cliff in the background, on the right, is part of the English shore, which the ship is just leaving. There is a light-house upon the cliff, and a town on the shore below.

The emigrant ship setting sail. Smooth sea.

The wind is fair, and the water is smooth. The emigrants are out upon the decks. We can see their heads above the bulwarks.

The object in the foreground, floating in the water, is a buoy. It is placed there to mark a rock or a shoal. It is secured by an anchor.

Thus, when the weather is fair, the emigrants pass their time very pleasantly. They amuse themselves on the decks by day, and at night they go down into the cabins, which are below the deck of the ship, and there they sleep.

The ship in a storm. Great danger. Heavy seas.

But sometimes there comes a storm. The wind increases till it becomes a gale. Clouds are seen scudding swiftly across the sky. Immense billows, rolling heavily, dash against the ship, or chase each other furiously across the wide expanse of the water,[37] breaking every where into foam and spray. The winds howl fearfully in the rigging, and sometimes a sail is burst from its fastenings by the violence of it, and flaps its tattered fragments in the air with the sound of thunder.

While the storm continues, the poor emigrants are obliged to remain below, where they spend their time in misery and terror. By-and-by the storm subsides, the sailors repair the damages, and the ship proceeds on her voyage.

In the engraving below we see the ship far advanced on her way. She is drawing near to the American shore. The sea is smooth, the wind is fair, and she is pressing rapidly onward.

On the left is seen another vessel, and on the right two more, far in the offing.

The emigrants on board the ship are rejoiced to believe that their voyage is drawing toward the end.

When the farmer and his family have landed in America, they will take another wagon, and go back into the country till they come to the place where they are going to have their farm. There they will cut down the trees of the forest, and build a house of logs. Then they will plow the ground, and sow the seeds, and make the farm. By-and-by they will gain enough by their industry to build a better house, and to fit it with convenient and comfortable furniture, and thenceforward they will live in plenty and happiness.

All this time they will take great care of George and Benny, so that they shall not come to any harm. They will keep them warm[38] in the wagon, and they will watch over them on board the ship, and carry them in their arms when they walk up the hills, in journeying in America, and make a warm bed for them in their house, and take a great deal of pains to have always plenty of good bread for them to eat, and warm milk for them to drink. They will suffer, themselves, continual toil, privation, and fatigue, but they will be very careful not to let the children suffer any thing if they can possibly help it.

By-and-by, when Benny and George grow up, they will find that their father lives upon a fine farm, with a good house and good furniture, and with every comfort around them. They will hardly know how much care and pains their father, and mother, and grandmother took to save them from all suffering, and to provide for them a comfortable and happy home. How ungrateful it would be in them to be unkind or disobedient to their father, and mother, and grandmother, when they grow up.

Sometimes, when a man is intending to emigrate to America, he goes first himself alone, in order to see the country, and choose a place to live in, and buy a farm, intending afterward to come back for his family. He does not take them with him at first, for he does not know what he should do with his wife and all his young children while he is traveling from place to place to view the land.

He bids his wife and children good-by. Picture of it.

When the emigrant goes first alone in this way, leaving his[39] family at home, the parting is very sorrowful. His poor wife is almost broken-hearted. She gathers her little children around her, and clasps them in her arms, fearing that some mischief may befall their father when he is far away, and that they may never[40] see him again. The man attempts to comfort her by saying that it will not be long before he comes back, and that then they shall never more be separated. His oldest boy stands holding his father’s staff, and almost wishing that he was going to accompany him. He turns away his face to hide his tears. As for the dog, he sees that his master is going away, and he is very earnestly desirous to go too. In fact, they know he would go if he were left at liberty, and so they chain him to a post to keep him at home.

It is a hard thing for a wife and a mother that her husband should thus go away and leave her, to make so long a voyage, and to encounter so many difficulties and dangers, knowing, as she does, that it is uncertain whether he will ever live to return. She bears the pain of this parting out of love to her children. She thinks that their father will find some better and happier home for them in the New World, where they can live in greater plenty, and where, when they grow up, and become men and women, they will be better provided for than they were in their native land.

In the distance, in the engraving, we see the ship in which this man is going to sail. We see a company of emigrants, too, down the road, going to embark. There is one child walking alone behind her father and mother, who seems too young to set out on such a voyage.

Bruno belonged to several different masters in the course of his life. He was always sorry to leave his old master when the changes were made, but then he yielded to the necessity of the case in these emergencies with a degree of composure and self-control, which, in a man, would have been considered quite philosophical.

The hunter of the Alps, whose life Bruno had saved, resolved at the time that he would never part with him.

“I would not sell him,” said he, “for a thousand francs.”

They reckon sums of money by francs in Switzerland. A franc is a silver coin. About five of them make a dollar.

However, notwithstanding this resolution, the hunter found himself at last forced to sell his dog. He had concluded to emigrate to America. He found, on making proper inquiry and calculation, that it would cost a considerable sum of money to take Bruno with him across the ocean. In the first place, he would have to pay not a little for his passage. Then, besides, it would cost a good deal to feed him on the way, both while on board the ship and during his progress across the country. The hunter reflected that all the money which he should thus pay for the dog would be so much taken from the food, and clothing, and other comforts of his wife and children. Just at this time a traveler came by who offered to buy the dog, and promised always to take most excellent[42] care of him. So the hunter sold him, and the traveler took him away.

Bruno was very unwilling at first to go away with the stranger. But the hunter ordered him to get into the gentleman’s carriage, and he obeyed. He looked out behind the carriage as they drove away, and wondered what it all could mean. He could not understand it; but as it was always a rule with him to submit contentedly to what could not be helped, he soon ceased to trouble himself about the matter, and so, lying down in the carriage, he went to sleep. He did not wake up for several hours afterward.

The traveler conveyed the dog home with him to England, and kept him a long time. He made a kennel for him in the corner of the yard. Here Bruno lived several years in great peace and plenty.

At length the gentleman was going away from home again on a long tour, and as there was nobody to be left at home to take an interest in Bruno, he put him under the charge, during his absence, of a boy named Lorenzo, who lived in a large house on the banks of a stream near his estate. Lorenzo liked Bruno very much, and took excellent care of him.[3]

[3] The house where Lorenzo lived was a large double house, of a very peculiar form. There is a picture of it on page 58.

There was a grove of tall trees near the house where Lorenzo lived, which contained the nests of thousands of rooks. Rooks are large black birds, very much like crows. Bruno used to lie in the yard where Lorenzo kept him, and watch the rooks for hours together.

The encampment of gipsies.

In a solitary place near where Lorenzo lived there was an encampment of gipsies. Gipsies live much like Indians. They wander about England in small bands, getting money by begging, and selling baskets, and they build little temporary huts from time to time in solitary places, where they live for a while, and[44] then, breaking up their encampment, they wander on till they find another place, where they encamp again.

Sometimes, when they can not get money enough by begging and selling baskets, they will steal. They show a great deal of ingenuity in the plans they devise for stealing. In fact, they are very adroit and cunning in every thing they undertake.

At one time Lorenzo’s father went away, and one of the gipsies, named Murphy, resolved to take that opportunity to steal something from the house.

“We can get in,” said he to his comrade, “very easily, in the night, by the back door, and get the silver bowl. We can melt the bowl, and sell it for four or five sovereigns.”

The silver bowl which Murphy referred to was one which had been given to Lorenzo by his uncle when he was a baby. Lorenzo’s name was engraved upon the side of it.

Lorenzo used his bowl to eat his bread and milk from every night for supper. It was kept on a shelf in a closet opening from the kitchen. Murphy had seen it put there once or twice, when he had been in the kitchen at night, selling baskets.

“We can get that bowl just as well as not,” said Murphy, “when the man is away.”

“There’s a big dog there,” said his comrade.

“Yes,” said Murphy, “but I’ll manage the dog.”

“How will you manage him?” asked his comrade.

“I’ll try coaxing and flattery first,” said Murphy. “If that don’t do, I’ll try threatening; if threatening won’t do, I’ll try bribing; and if he won’t be bribed, I’ll poison him.”

That night, about twelve o’clock, Murphy crept stealthily round[45] to a back gate which led into the yard behind the house where Lorenzo lived. The instant that Bruno heard the noise, he sprang up, and went bounding down the path till he came to the gate. As soon as he saw the gipsy, he began to bark very vociferously.

Lorenzo was asleep at this time; but as his room was on the back side of the house, and his window was open, he heard the barking. So he got up and went to the window, and called out,

“Bruno, what’s the matter?”

Bruno was at some distance from the house, and did not hear Lorenzo’s voice. He was watching Murphy.

Murphy immediately began to coax and cajole the dog, calling him “Nice fellow,” and “Good dog,” and “Poor Bruno,” speaking all the time in a very friendly and affectionate tone to him. Bruno, however, had sense enough to know that there was something wrong in such a man being seen prowling about the house at that time of night, and he refused to be quieted. He went on barking louder than ever.

“Bruno!” said Lorenzo, calling louder, “what’s the matter? Come back to your house, and be quiet.”

Murphy thought he heard a voice, and, peeping through a crack in the fence, he saw Lorenzo standing at the window. The moon shone upon his white night-gown, so that he could be seen very distinctly.

As soon as Murphy saw him, he crept away into a thicket, and disappeared. Bruno, after waiting a little time to be sure that the man had really gone, turned about, and came back to the house. When he saw Lorenzo, he began to wag his tail. He would have told him about the gipsy if he had been able to speak.

“Go to bed, Bruno,” said he, “and not be keeping us awake, barking at the moon this time of night.”

So Bruno went into his house, and Lorenzo to his bed.

The next night, Murphy, finding that Bruno could not be coaxed away from his duty by flattery, concluded to try what virtue there might be in threats and scolding. So he came armed with a club and stones. As soon as he got near the gate, Bruno, as he had expected, took the alarm, and came bounding down the path again to see who was there.

As soon as he saw Murphy, he set up a loud and violent barking as before.

“Down, Bruno, down!” exclaimed Murphy, in a stern and angry voice. “Stop that noise, or I’ll break your head.”

So saying, he brandished his club, and then stooped down to pick up one of the stones which he had brought, and which he had laid down on the ground where he was standing, so as to have them all ready.

Bruno, instead of being intimidated and silenced by these demonstrations, barked louder than ever.

Lorenzo jumped out of bed and came to the window.

“Bruno!” said he, calling out loud, “what’s the matter? There’s nothing there. Come back to your house, and be still.”

The gipsy, finding that Bruno did not fear his clubs and stones, and hearing Lorenzo’s voice again moreover, went back into the thicket. Bruno waited until he was sure that he was really gone, and then returned slowly up the pathway to the house.

“Go to bed, Bruno,” said Lorenzo,[47] “and not be keeping us awake, barking at the moon this time of night.”

So Bruno and Lorenzo both went to bed again.

The next night Murphy came again, with two or three pieces of meat in his hands.

“I’ll bribe him,” said he. “He likes meat.”

Bruno, on hearing the sound of Murphy’s footsteps, leaped out of his bed, and ran down the path as before. As soon as he saw the gipsy again, he began to bark. Murphy threw a piece of meat toward him, expecting that, as soon as Bruno saw it, he would stop barking at once, and go to eating it greedily. But Bruno paid no attention to the offered bribe. He kept his eyes fixed closely on the gipsy, and barked away as loud as ever.

Lorenzo, hearing the sound, was awakened from his sleep, and getting up as before, he came to the window.

“Bruno,” said he, “what is the matter now? Come back to your house, and go to bed, and be quiet.”

Murphy, finding that the house was alarmed again, and that Bruno would not take the bribe that he offered him, crept away back into the thicket, and disappeared.

“I’ll poison him to-morrow night,” said he—“the savage cur!”

Accordingly, the next evening, a little before sunset, he put some poison in a piece of meat, and having wrapped it up in paper, he put it in his pocket. He then went openly to the house where Lorenzo lived, with some baskets on his arm for sale. When he entered the yard, he took the meat out of the paper, and secretly threw it into Bruno’s house. Bruno was not there at the time. He had gone away with Lorenzo.

Murphy then went into the kitchen, and remained there some time, talking about his baskets. When he came out, he found[48] Lorenzo shutting up Bruno in his house, and putting a board up before the door.

“What are you doing, Lorenzo?” said the gipsy.

“I am shutting Bruno up,” said Lorenzo. “He makes such a barking in the night that we can not sleep.”

“That’s right,” replied the gipsy. So he went away, saying to himself, as he went down the pathway, “He won’t bark much more, I think, after he has eaten the supper I have put in there for him.”

Bruno wondered what the reason was that Lorenzo was shutting him up so closely. He little thought it was on account of his vigilance and fidelity in watching the house. He had, however, nothing to do but to submit. So, when Lorenzo had finished fastening the door, and had gone away, he lay down in a corner of his apartment, extended his paws out before him, rested his chin upon them, and prepared to shut his eyes and go to sleep.

His eyes, however, before he had shut them, fell upon the piece of meat which Murphy had thrown in there for him. So he got up again, and went toward it.

He smelt of it. He at once perceived the smell of the gipsy upon it. Any thing that a man handles, or even touches, retains for a time a scent, which, though we can not perceive it is very sensible to a dog. Thus a dog can follow the track of a man over a road by the scent which his footsteps leave upon the ground. He can even single out a particular track from among a multitude of others on the same ground, each scent being apparently different in character from all the rest.

In this way Bruno perceived that the meat which he found in[49] his house had been handled by the same man that he had barked at so many times at midnight at the foot of the pathway. This made him suspicious of it. He thought that that man must be a bad man, and he did not consider it prudent to have any thing to do with bad men or any of their gifts. So he left the meat where it was, and went back into his corner.

His first thought in reflecting on the situation in which he found himself placed was, that since Lorenzo had forbidden him so sternly and positively to bark in the night, and had shut him up so close a prisoner, he would give up all care or concern about the premises, and let the robber, if it was a robber, do what he pleased. But then, on more sober reflection, he perceived that Lorenzo must have acted under some mistake in doing as he had done, and that it was very foolish in him to cherish a feeling of resentment on account of it.

“The wrong doings of other people,” thought he to himself, “are no reason why I should neglect my duty. I will watch, even if I am shut up.”

So he lay listening very carefully. When all was still, he fell into a light slumber now and then; but the least sound without caused him to prick up his ears and open one eye, until he was satisfied that the noise he heard was nothing but the wind. Thus things went on till midnight.

About midnight he heard a sound. He raised his head and listened. It seemed like the sound of footsteps going through the yard. He started up, and put his head close to the door. He heard the footsteps going up close to the house. He began to bark very loud and violently. The robbers opened the door with[50] a false key, and went into the house. Bruno barked louder and louder. He crowded hard against the door, trying to get it open. He moaned and whined, and then barked again louder than ever.

Lorenzo came to the window.

“Bruno,” said he, “what a plague you are! Lie down, and go to sleep.”

Bruno, hearing Lorenzo’s voice, barked again with all the energy that he possessed.

“Bruno,” said Lorenzo, very sternly, “if you don’t lie down and be still, to-morrow night I’ll tie your mouth up.”

Murphy was now in the house, and all was still. He had got the silver bowl, and was waiting for Lorenzo to go to bed. Bruno listened attentively, but not hearing any more sounds, ceased to bark. Presently Lorenzo went away from the window back to his bed, and lay down. Bruno watched some time longer, and then he went and lay down too.

In about half an hour, Murphy began slowly and stealthily to creep out of the house. He walked on tiptoe. For a time he made no noise. He had the bowl in one hand, and his shoes in the other. He had taken off his shoes, so as not to make any noise in walking. Bruno heard him, however, as he was going by, and, starting up, he began to bark again. But Murphy hastened on, and the yard was accordingly soon entirely still. Bruno listened a long time, but, hearing no more noise, he finally lay down again in his corner as before.

Murphy crept away into the thicket, and so went home to his encampment, wondering why Bruno had not been killed by the poison.

“I put in poison enough,” said he to himself, “for half a dozen dogs. What could be the reason it did not take effect?”

When the people of the house came down into the kitchen the next morning, they found that the door was wide open, and the silver bowl was gone.

What became of the silver bowl will be related in another story. I will only add here that gipsies have various other modes of obtaining money dishonestly besides stealing. One of these modes is by pretending to tell fortunes. Here is a picture of a gipsy endeavoring to persuade an innocent country boy to have his fortune told. She wishes him to give her some money. The boy wears a frock. He is dressed very neatly. He looks as if he were half persuaded to give the gipsy his money. He might, however, just as well throw it away.

On the night when Lorenzo’s silver bowl was stolen by the gipsy, all the family, except Lorenzo, were asleep, and none of them knew aught about the theft which had been committed until the following morning. Lorenzo got up that morning before any body else in the house, as was his usual custom, and, when he was dressed, he looked out at the window.

“Ah!” said he, “now I recollect; Bruno is fastened up in his house. I will go the first thing and let him out.”

So Lorenzo hastened down stairs into the kitchen, in order to go out into the yard. He was surprised, when he got there, to find the kitchen door open.

“Ah!” said he to himself, “how came this door open? I did not know that any body was up. It must be that Almira is up, and has gone out to get a pail of water.”

Lorenzo went out to Bruno’s house, and took down the board by which he had fastened the door. Then he opened the door. The moment that the door was opened Bruno sprang out. He was very glad to be released from his imprisonment. He leaped up about Lorenzo’s knees a little at first, to express his joy, and then ran off, and began smelling about the yard.

He found the traces of Murphy’s steps, and, as soon as he perceived them, he began to bark. He followed them to the kitchen door, and thence into the house, barking all the time, and looking very much excited.

“Bruno,” said Lorenzo, “what is the matter with you?”

Bruno went to the door of the closet where the bowl had been kept. The door was open a little way. Bruno insinuated his nose into the crevice, and so pushing the door open, he went in. As soon as he was in he began to bark again.

“Bruno!” exclaimed Lorenzo, “what is the matter with you?”

Bruno looked up on the shelf where the bowl was usually placed, and barked louder than ever.

“Where’s my bowl?” exclaimed Lorenzo, looking at the vacant place, and beginning to feel alarmed. “Where’s my bowl?”

He spoke in a tone of great astonishment and alarm. He looked about on all the shelves; the bowl was nowhere to be seen.

“Where can my bowl be gone to?” said he, more and more frightened. He went out of the closet into the kitchen, and looked all about there for his bowl. Of course, his search was vain. Bruno followed him all the time, barking incessantly, and looking up very eagerly into Lorenzo’s face with an appearance of great excitement.

“Bruno,” said Lorenzo, “you know something about it, I am sure, if you could only tell.”

Lorenzo, however, did not yet suspect that his bowl had been stolen. He presumed that his mother had put it away in some other place, and that, when she came down, it would readily be found again. So he went out into the yard, and sat on a stone step, and went to work to finish a wind-mill he had begun the day before.

By-and-by his mother came down; and as soon as she had heard Lorenzo’s story about the bowl, and learned, too, that the outer[54] door had been found open when Lorenzo first came down stairs, she immediately expressed the opinion that the bowl had been stolen.

“Some thief has been breaking into the house,” said she, “I’ve no doubt, and has stolen it.”

“Stolen it!” exclaimed Lorenzo.

“Yes,” replied his mother; “I’ve no doubt of it.”

So saying, she went into the closet again, to see if she could discover any traces of the thieves there. But she could not. Every thing seemed to have remained undisturbed, just as she had left it the night before, except that the bowl was missing.

“Somebody has been in and stolen it,” said she, “most assuredly.”

Bruno, who had followed Lorenzo and his mother into the room, was standing up at this time upon his hind legs, with his paws upon the edge of the shelf, and he now began to bark loudly, by way of expressing his concurrence in this opinion.

“Seize him, Bruno!” said Lorenzo. “Seize him!”

Bruno, on hearing this command, began smelling about the floor, and barking more eagerly than ever.

“Bruno smells his tracks, I verily believe,” said Lorenzo, speaking to his mother. Then, addressing Bruno again, he clapped his hands together and pointed to the ground, saying,

“Go seek him, Bruno! seek him!”

Bruno began immediately to follow the scent of Murphy’s footsteps along the floor, out from the closet into the kitchen, and from the kitchen into the yard; he ran along the path a little way, and then made a wide circuit over the grass, at a place where Murphy[55] had gone round to get as far as possible away from Bruno’s house. He then came back into the path again, smelling as he ran, and thence passed out through the gate; here, keeping his nose still close to the ground, he went on faster and faster, until he entered the thicket and disappeared.

Lorenzo did not pay particular attention to these motions. He had given Bruno the order, “Seek him!” rather from habit than any thing else, and without any idea that Bruno would really follow the tracks of the thief. Accordingly, when Bruno ran off down the yard, he imagined that he had gone away somewhere to play a little while, and that he would soon come back.

“He’ll be sure to come back pretty soon,” said he, “to get his breakfast.”

But Bruno did not come back to breakfast. Lorenzo waited an hour after breakfast, and still he did not come.

He waited two hours longer, and still he did not come.

Where was Bruno all this time? He was at the camp of the gipsies, watching at the place where Murphy had hid the stolen bowl.

When he followed the gipsy’s tracks into the thicket, he perceived the scent more and more distinctly as he went on, and this encouraged him to proceed. Lorenzo had said “Seek him!” and this Bruno understood as an order that he should follow the track until he found the man, and finding him, that he should keep watch at the place till Lorenzo or some one from the family should come. Accordingly, when he arrived at the camp, he followed the scent round to the back end of a little low hut, where Murphy had hidden the bowl. The gipsy had dug a hole in the ground, and buried[56] the bowl in it, out of sight, intending in a day or two to dig it up and melt it. Bruno found the place where the bowl was buried, but he could not dig it up himself, so he determined to wait there and watch until some one should come. He accordingly squatted down upon the grass, near the place where the gipsies were seated around their fire, and commenced his watch.[4]

There were two gipsy women sitting by the fire. There was also a man sitting near by. Murphy was standing up near the entrance of the tent when Bruno came. He was telling the other gipsies about the bowl. He had a long stick in his hand, and Bruno saw this, and concluded that it was best for him to keep quiet until some one should come.

“I had the greatest trouble with Bruno,” said Murphy. “He barked at me whenever he saw me, and nothing would quiet him. But he is getting acquainted now. See, he has come here of his own accord.”

“You said you were going to poison him,” remarked the other man.

“Yes,” replied Murphy. “I did put some poisoned meat in his house, but he did not eat it. I expect he smelled the poison.”

The hours of the day passed on, and Lorenzo wondered more and more what could have become of his dog. At last he resolved to go and look him up.

“Mother,” said he, “I am going to see if I can find out what’s become of Bruno.”

“I would rather that you would find out what’s become of your bowl,” said his mother.

“Why, mother,” said Lorenzo, “Bruno is worth a great deal more than the bowl.”

“That may be,” replied his mother, “but there is much less danger of his being lost.”

Lorenzo walked slowly away from the house, pondering with much perplexity the double loss he had incurred.

“I can not do any thing,” he said, “to get back the bowl, but I can look about for Bruno, and if I find him, that’s all I can do. I must leave it for father to decide what is to be done about the bowl, when he comes home.”

So Lorenzo came out from his father’s house, and after hesitating for some minutes which way to go, he was at length decided by seeing a boy coming across the fields at a distance with a fishing-pole on his shoulder.

“Perhaps that boy has seen him somewhere,” said he. “I’ll go and ask him. And, at any rate, I should like to know who the boy is, and whether he has caught any fish.”

So Lorenzo turned in the direction where he saw the boy. He walked under some tall elm-trees, and then passed a small flock of sheep that were lying on the grass in the field. He looked carefully among them to see if Bruno was there, but he was not. After passing the sheep, he walked along on the margin of a broad and shallow stream of water. There were two geese floating quietly upon the surface of this water, near where the sheep were lying upon the shore. These geese floated quietly upon the water, like vessels riding at anchor. Lorenzo was convinced that they had not seen any thing of Bruno for some time. If they had, they would not have been so composed.

Lorenzo walked on toward the boy. He met him at a place where the path approached near the margin of the water. There was some tall grass on the brink. Three ducks were swimming near. The ducks turned away when they saw the boys coming, and sailed gracefully out toward the middle of the stream.

Lorenzo meets Frank going a fishing.

Lorenzo, when he drew near the boy, perceived that it was an acquaintance of his, named Frank. Frank had a long fishing-pole in one hand, with a basket containing his dinner in the other.

“Frank,” said Lorenzo,[59] “where are you going?”

“I am going a fishing,” said Frank. “Go with me.”

“No,” said Lorenzo, “I am looking for Bruno.”

“I know where he is,” said Frank.

“Where?” asked Lorenzo.

“I saw him a little while ago at the gipsies’ camp, down in the glen. He was lying down there quietly by the gipsies’ fire.”

“What a dog!” said Lorenzo. “Here I have been wondering what had become of him all the morning. He has run away, I suppose, because I shut him up last night.”

“What made you shut him up?” asked Frank.

“Oh, because he made such a barking every night,” replied Lorenzo. “We could not sleep.”

“He is still enough now,” said Frank. “He is lying down very quietly with the gipsies.”

Lorenzo then asked Frank some questions about his fishing, and afterward walked on. Before long he came to a stile, where there was a path leading to a field. He got over the stile, and followed the path until at last he came to the gipsies’ encampment.

There he found Bruno lying quietly on the ground, at a little distance from the fire. As soon as he came in sight of him, he called him. “Bruno! Bruno!” said he.

Bruno looked up, and, seeing Lorenzo, ran to meet him, but immediately returned to the camp, whining, and barking, and seeming very uneasy. He, however, soon became quiet again, for he knew very well, or seemed to know, that it would require more of a man than Lorenzo to take the bowl away from the gipsies, and, consequently, that he must wait there quietly till somebody else should come.

“Bruno,” said Lorenzo, speaking very sternly, “come home!”

Bruno paid no attention to this command, but, after smelling about the ground a little, and running to and fro uneasily, lay down again where he was before.

“Bruno!” said Lorenzo, stamping with his foot.

“Won’t your dog obey you?” said Murphy.

“No,” said Lorenzo. “I wish you would take a stick, and drive him along.”

Now the gipsies did not wish to have the dog go away. They preferred that he should stay with them, and be their dog. They had no idea that he was there to watch over the stolen bowl.

“Don’t drive him away,” said one of the gipsy women, speaking in a low tone, so that Lorenzo could not hear.

“I’ll only make believe,” said Murphy.

So Murphy took up a little stick, and threw it at the dog, saying, “Go home, Bruno!”

Bruno paid no heed to this demonstration.

Lorenzo then advanced to where Bruno was lying, and attempted to pull him along, but Bruno would not come. He would not even get up from the ground.

“I’ll make you come,” said Lorenzo. So he took hold of him by the neck and the ears, and began to pull him. Bruno uttered a low growl.

“Oh, dear me!” said Lorenzo, “what shall I do?”

In fact, he was beginning to grow desperate. So he looked about among the bushes for a stick, and when he had found one sufficient for his purpose, he came to Bruno, and said, in a very stern voice,

“Now, Bruno, go home!”

Bruno did not move.

“Bruno,” repeated Lorenzo, in a thundering voice, and brandishing his stick over Bruno’s head, “GO HOME!”

Bruno, afraid of being beaten with the stick, jumped up, and ran off into the bushes. Lorenzo followed him, and attempted to drive him toward the path that led toward home. But he could accomplish nothing. The dog darted to and fro in the thickets, keeping well out of the way of Lorenzo’s stick, but evincing a most obstinate determination not to go home. On the contrary, in all his dodgings to and fro, he took care to keep as near as possible to the spot where the bowl was buried.

At last Lorenzo gave up in despair, and concluded to go back to the house, and wait till his father got home.

His father returned about the middle of the afternoon, and Lorenzo immediately told him of the double loss which he had met with. He explained all the circumstances connected with the loss of the bowl, and described Bruno’s strange behavior. His father listened in silence. He immediately suspected that the gipsies had taken the bowl, and that Bruno had traced it to them. So he sent for some officers and a warrant, and went to the camp.

As soon as Bruno saw the men coming, he seemed to be overjoyed. He jumped up, and ran to meet them, and then, running back to the camp again, he barked, and leaped about in great excitement. The men followed him, and he led them round behind the hut, and there he began digging into the ground with his paws. The men took a shovel which was there, one belonging to the gipsies, and began to dig. In a short time they came[62] to a flat stone, and, on taking up the stone, they found the bowl under it.

Bruno seemed overjoyed. He leaped and jumped about for a minute or two when he saw the bowl come out from its hiding-place, and raced round and round the man who held the bowl, and then ran away home to find Lorenzo. The officers, in the mean time, went off hastily in pursuit of Murphy, who had made his escape while they had been digging up the bowl.

Bruno was quite a large dog. There are a great many different kinds of dogs. Some are large, others are small. Some are irritable and fierce, others are good-natured and gentle. Some are stout and massive in form, others are slender and delicate. Some are distinguished for their strength, others for their fleetness, and others still for their beauty. Some are very affectionate, others are sagacious, others are playful and cunning. Thus dogs differ from each other not only in form and size, but in their disposition and character as well.

Some dogs are very intelligent, others are less so, and even among intelligent dogs there is a great difference in respect to the modes in which their intelligence manifests itself. Some dogs naturally love the water, and can be taught very easily to swim and dive, and perform other aquatic exploits. Others are afraid of the water, and can never be taught to like it; but they are excellent hunters, and go into the fields with their masters, and[63] find the game. They run to and fro about the field that their master goes into, until they see a bird, and then they stop suddenly, and remain motionless till their master comes and shoots the bird. As soon as they hear the report of the gun, they run to get the game. Sometimes quite small dogs are very intelligent indeed, though of course they have not so much strength as large dogs.

The little parlor dogs.

In the above engraving we see several small dogs playing in a parlor. The ladies are amusing themselves with flowers that they are arranging, and the dogs are playing upon the carpet at their feet.

There are three dogs in all. Two of them are playing together near the foreground, on the left. The other is alone.

Bruno was a large dog. He was a very large dog indeed.[64] When other dogs were playing around him, he would look down upon them with an air of great condescension and dignity. He was, however, very kind to them. They would jump upon him, and play around him, but he never did them any harm.

Bruno among his companions.

Bruno was a very faithful dog. In the summer, when the farmer,[65] his master (at a time when he belonged to a farmer), went into the field to his work in the morning, he would sometimes take his dinner with him in a tin pail, and he would put the pail down under a tree by the side of a little brook, and then, pointing to it, would say to Bruno,

“Bruno, watch!”

So Bruno would take his place by the side of the pail, and remain there watching faithfully all the morning. Sometimes he would become very hungry before his master came back, but, though he knew that there was meat in the pail, and that there was nothing to cover it but a cloth, he would never touch it. If he was thirsty, he would go down to the brook and drink, turning his head continually as he went, and while he was drinking, to see that no one came near the pail. Then at noon, when his master came for his dinner, Bruno would be rejoiced to see him. He would run out to meet him with great delight. He would then sit down before his master, and look up into his face while he was eating his dinner, and his master would give him pieces of bread and meat from time to time, to reward him for his fidelity.

Bruno was kind and gentle as well as faithful. If any body came through the field while he was watching his master’s dinner, or any thing else that had been intrusted to his charge, he would not, as some fierce and ill-tempered dogs are apt to do, fly at them and bite them at once, but he would wait to see if they were going to pass by peaceably. If they were, he would not molest them. If they came near to whatever he was set to guard, he would growl a little, to give them a gentle warning. If they came nearer still, he would growl louder; but he would never bite them[66] unless they actually attempted to seize and take away his trust. Thus he was considerate and kind as well as faithful.

Some dogs, though faithful, are very fierce. They are sometimes trained to be fierce when they are employed to watch against thieves, in order that they may attack the thieves furiously. To make them more fierce, their masters never play with them, but keep them chained up near their kennels, and do not give them too much to eat. Wild animals are always more ferocious while hungry.

The hungry watch-dog.

Here is a picture of a fierce watch-dog, set to watch against thieves. He is kept hungry, in some degree, all the time, to make[67] him more ferocious. He looks hollow and gaunt. There is a pan upon the ground, from which his master feeds him, but he has eaten up all that it contained, and he wants more. This makes him watchful. If he had eaten too much, he would probably now be lying asleep in his kennel. The kennel is a small house, with a door in front, where the dog goes in and out. There is straw upon the floor of the kennel. The dog was lying down upon the floor of his kennel, when he thought he heard a noise. He sprang up from his place, came out of the door, and has now stopped to listen. He is listening and watching very attentively, and is all ready to spring. The thief is coming; we can see him climbing over the gate. He is coming softly. He thinks no one hears. A moment more, and the dog will spring out upon him, and perhaps seize him by the throat, and hold him till men come and take him prisoner.

This dog is chained during the day, but his chain is unhooked at night, so as to leave him at liberty. By day he can do no harm, and yet the children who live in the neighborhood are afraid to go near his kennel, he barks so ferociously when he hears a noise; besides, they think it possible that, by some accident, his chain may get unfastened.

This dog’s name is Tiger. Bruno was not such a dog as Tiger. He was vigilant and faithful, but then he was gentle and kind.

Bruno’s master, the farmer, had a son named Antonio. That is, his name was properly Antonio, though they commonly called him Tony.

Tony was very different from Bruno in his character. He was as faithless and remiss in all his duties as Bruno was trusty and[68] true. When his father set him at work in the field, instead of remaining, like Bruno, at his post, and discharging his duty, he would take the first opportunity, as soon as his father was out of sight, to go away and play. Sometimes, when Bruno was upon his watch, Tony would attempt to entice him away. He would throw sticks and stones across the brook, and attempt to make Bruno go and fetch them. But Bruno would resist all these temptations, and remain immovable at his post.

It might be supposed that it would be very tiresome for Bruno to remain so many hours lying under a tree, watching a pail, with nothing to do and nothing to amuse him, and that, consequently, he would always endeavor to escape from the duty. We might suppose that, when he saw the farmer’s wife taking down the pail from its shelf, and preparing to put the farmer’s dinner in it, he would immediately run away, and hide himself under the barn, or among the currant-bushes in the garden, or resort to some other scheme to make his escape from such a duty. But, in fact, he used to do exactly the contrary of this. As soon as he saw that his master was preparing to go into the field, he would leap about with great delight. He would run into the house, and take his place by the door of the closet where the tin pail was usually kept. He would stand there until the farmer’s wife came for the pail, and then he would follow her and watch her while she was preparing the dinner and putting it into the pail, and then would run along, with every appearance of satisfaction and joy, by the side of his master, as he went into the field, and finally take his place by the side of the pail, as if he were pleased with the duty, and proud of the trust that was thus committed to him.

In fact, he was really proud of it. He liked to be employed, and to prove himself useful. With Tony it was the reverse. He adopted all sorts of schemes and maneuvers to avoid the performance of any duty. When he had reason to suppose that any work was to be done in which his aid was to be required, he would take his fishing-line, immediately after breakfast, and steal secretly away out of the back door, and go down to a brook which was near his father’s house, and there—hiding himself in some secluded place among the bushes, where he thought they could not find him—he would sit down upon a stone and go to fishing. If he heard a sound as of his father’s voice calling him, he would make a rustling of the leaves, or some other similar noise, so as to prevent his hearing whether his father was calling to him or not. Thus his father was obliged to do without him. And though his father would reprove him very seriously, when he came home at noon, for thus going away, Tony would pretend that he did not know that his father wanted him, and that he did not hear him when he called.

One evening in the spring, Tony heard his father say that he was going to plow a certain piece of ground the following day, and he supposed that he should be wanted to ride the horse. His father was accustomed to plow such land as that field by means of a yoke of oxen, and a horse in front of them; and by having Tony to ride the horse, he could generally manage to get along without any driver for the oxen, as the oxen in that case had nothing to do but to follow on where the horse led the way. But if Tony was not there to ride the horse, then it was necessary for the farmer to have his man Thomas with him, to drive the horse[70] and the oxen. There was no way, therefore, by which Tony could be so useful to his father as by thus assisting in this work of plowing; for, by so doing, he saved the time of Thomas, who could then be employed the whole day in other fields, planting, or hoeing, or making fence, or doing any other farm-work which at that season of the year required to be done.

Accordingly, when Tony understood that this was the plan of work for the following day, he stole away from the house immediately after breakfast, and ran out into the garden. He had previously put his fishing-line, and other necessary apparatus for fishing, upon a certain bench there was in an arbor. He now took these things, and then went down through the garden to a back gate, which led into a wood beyond. He looked around from time to time as he went on, to see if any one at the house was observing him. He saw no one; so he escaped safely into the wood, without being called back, or even seen.

He felt glad when he found that he had thus made his escape—glad, but not happy. It is quite possible to be glad, and yet to be not at all happy. Tony felt guilty. He knew that he was doing very wrong; and the feeling that we are doing wrong always makes us miserable, whatever may be the pleasure that we seek.

There was a wild and solitary road which led through the wood. Tony went on through this road, with his fishing-pole over his shoulder, and his box of bait in his hand. He wore a frock, like a plowman’s frock, over his dress. It was one which his mother had made for him. This frock was a light and cool garment, and Tony liked to wear it very much.

When Tony had got so far that he thought there was no danger[71] of his being called back, and the interest which he had felt in making his escape began to subside, as the work had been accomplished, he paused, and began to reflect upon what he was doing.

“I have a great mind to go back, after all,” he said, “and help my father.”

So he turned round, and began to walk slowly back toward the house.

“No, I won’t,” said he again; “I will go a fishing.”

So he turned again, and began to walk on.

“At any rate,” he added, speaking to himself all the time, “I will go a fishing for a while, and then, perhaps, I will go back and help my father.”

So Tony went on in the path until at length he came to a place where there was a gateway leading into a dark and secluded wood. The wood was very dark and secluded indeed, and Tony thought that the path through it must lead to some very retired and solitary place, where nobody could find him.

“I presume there is a brook, too, somewhere in that wood,” he added, “where I can fish.”

The gate was fastened, but there was a short length of fence on the left-hand side of it, formed of only two rails, and these were so far apart that Tony could easily creep through between them. So he crept through, and went into the wood.

He rambled about in the wood for some time, following various[72] paths that he found there, until at length he came to a brook. He was quite rejoiced to find the brook, and he immediately began fishing in it. He followed the bank of this brook for nearly a mile, going, of course, farther and farther into the wood all the time. He caught a few small fishes at some places, while at others he caught none. He was, however, restless and dissatisfied in mind. Again and again he wished that he had not come away from home, and he was continually on the point of resolving to return. He thought, however, that his father would have brought Thomas into the field, and commenced his plowing long before then, and that, consequently, it would do no good to return.

While he was sitting thus, with a disconsolate air, upon a large stone by the side of the brook, fishing in a dark and deep place, where he hoped that there might be some trout, he suddenly saw a large gray squirrel. He immediately dropped his fishing-pole, and ran to see where the squirrel would go. In fact, he had some faint and vague idea that there might, by some possibility, be a way to catch him.