Project Gutenberg's The Old Soak, and Hail And Farewell, by Don Marquis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Old Soak, and Hail And Farewell Author: Don Marquis Illustrator: Sterling Patterson Release Date: May 1, 2016 [EBook #51920] Last Updated: March 13, 2018 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE OLD SOAK *** Produced by David Widger from page images generously provided by the Internet Archive

The author thanks the Publishers of the New York Sun, in which the following sketches and verses originally appeared, for permission to reissue them in book form.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE—Introducing the Old Soak

CHAPTER TWO—Beginning the Old Soak's History of the Rum Demon

CHAPTER THREE—Liquor and Hennery Simms

CHAPTER FOUR—The Old Soak's History—The Barroom as an Educative

CHAPTER FIVE—Look Out For Crime Waves!

CHAPTER SIX—Continuing the Old Soak's History—The Barroom and the Arts

CHAPTER SEVEN—An Argument With the Old Woman

CHAPTER EIGHT—The Old Soak's History—More Evils of Prohibition

CHAPTER NINE—Preparing for Christmas

CHAPTER TEN—Continuing the History—the Old Soak Fears for the Growing

CHAPTER ELEVEN—Jabe Potter's Optimism

CHAPTER TWELVE—More of the History—As It Used to Be of a Morning

CHAPTER THIRTEEN—Peace and Contentment

CHAPTER FOURTEEN—Continuing the History of the Rum Demon—Unfermented

CHAPTER FIFTEEN—Political Talk

CHAPTER SIXTEEN—The History Continued—Prohibition and Winter Weather

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN—The Old Soak Finds a Way

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN—The History Continued—the Barroom's Good Influence

CHAPTER NINETEEN—A House Divided

CHAPTER TWENTY—Continuing the History of the Rum Demon—the Barroom and

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE—Sympathy Wanted

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO—The History of the Rum Demon Concluded—Prohibition

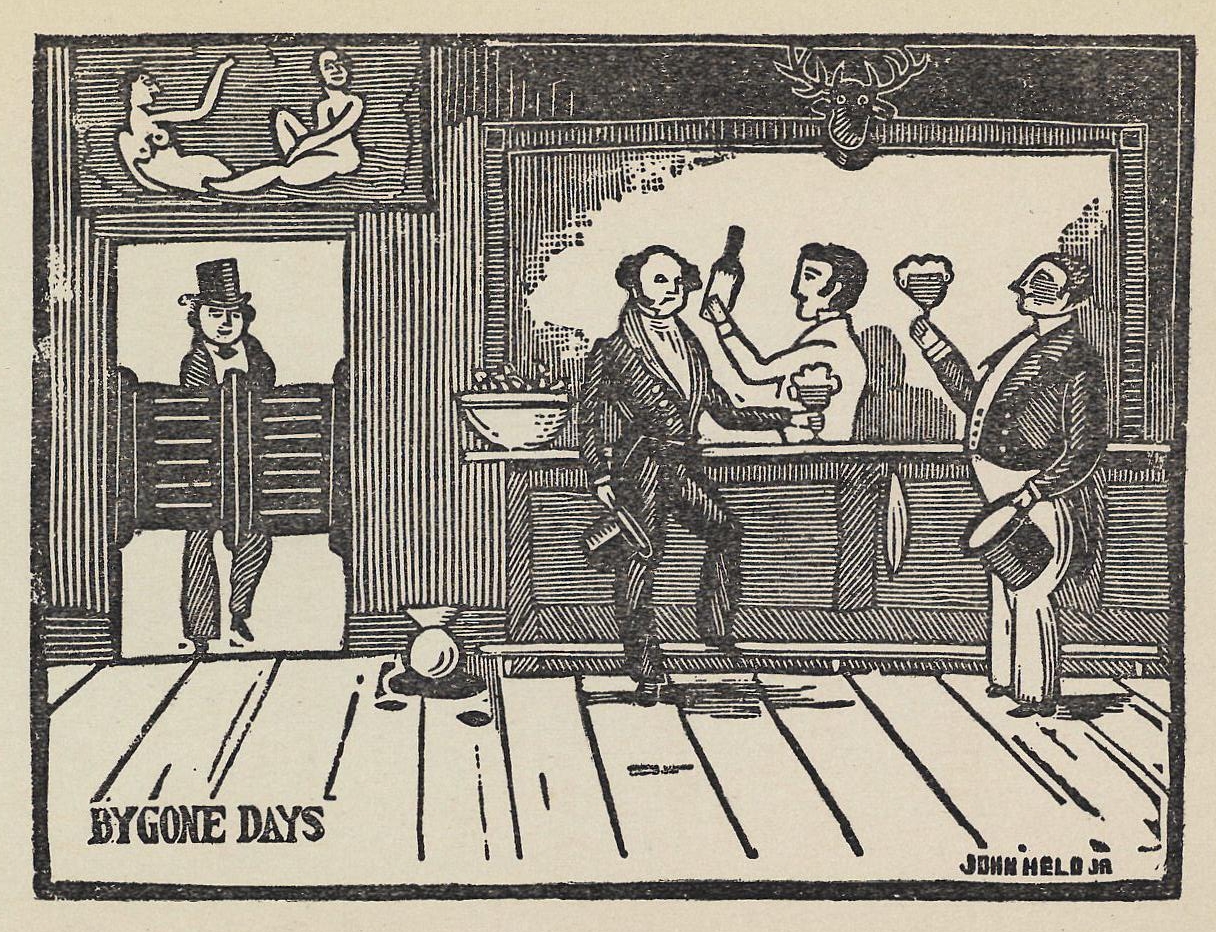

XI—THERE WERE GIANTS IN THE OLD DAYS

XII—IN AN OLD-TIME TAVERN BOOTH

XVII—THE BATTLE OF THE KEYHOLES

XXVI—CHANT ROYAL OF THE DEJECTED DIPSOMANIAC

OUR friend, the Old Soak, came in from his home in Flatbush to see us not long ago, in anything but a jovial mood.

“I see that some persons think there is still hope for a liberal interpretation of the law so that beer and light wines may be sold,” said we.

“Hope,” said he, moodily, “is a fine thing, but it don't gurgle none when you pour it out of a bottle. Hope is all right, and so is Faith... but what I would like to see is a little Charity.

“As far as Hope is concerned, I'd rather have Despair combined with a case of Bourbon liquor than all the Hope in the world by itself.

“Hope is what these here fellows has got that is tryin' to make their own with a tea-kettle and a piece of hose. That's awful stuff, that is. There's a friend of mine made some of that stuff and he was scared of it, and he thinks before he drinks any he will try some of it onto a dumb beast.

“But there ain't no dumb beast anywheres handy, so he feeds some of it to his wife's parrot. That there parrot was the only parrot I ever knowed of that wasn't named Polly. It was named Peter, and was supposed to be a gentleman parrot for the last eight or ten years. But whether it was or not, after it drank some of that there home-made hootch Peter went and laid an egg.

“That there home-made stuff ain't anything to trifle with.

“It's like amateur theatricals. Amateur theatricals is all right for an occupation for them that hasn't got anything to do nor nowhere to go, but they cause useless agony to an audience. Home-made booze may be all right to take the grease spots out of the rugs with, but it ain't for the human stomach to drink. Home-made booze is either a farce with no serious kick to it, or else a tragedy with an unhappy ending. No, sir, as soon as what is left has been drank I will kiss good-bye to the shores of this land of holiness and suffering and go to some country where the vegetation just naturally works itself up into liquor in a professional manner, and end my days in contentment and iniquity.

“Unless,” he continued, with a faint gleam of hope, “the smuggling business develops into what it ought to. And it may. There's some friends of mine already picked out a likely spot on the shores of Long Island and dug a hole in the sand that kegs might wash into if they was throwed from passing vessels. They've hoisted friendly signals, but so far nothing has been throwed overboard.”

He had a little of the right sort on his hip, and after refreshing himself, he announced:

“I'm writing a diary. A diary of the past. A kind of gol-dinged autobiography of what me and Old King Booze done before he went into the grave and took one of my feet with him.

“In just a little while now there won't be any one in this here broad land of ours, speaking of it geographically, that knows what an old-fashioned barroom was like. They'll meet up with the word, future generations of posterity will, and wonder and wonder and wonder just what a saloon could have resembled, and they will cudgel their brains in vain, as the poet says.

“Often in my own perusal of reading matter I run onto institutions that I would like to know more of. But no one ever set down and described 'em because everyone knowed all about them in the time when the writing was done. Often I thought I would 'a' liked to knowed all about them Hanging Gardens of Babylon, for instance, and who was hanged in 'em and what for; but nobody ever described 'em, as fur as I know.”

“Have you got any of it written?” we asked him. “Here's the start of it,” said he.

We present it just as the Old Soak penned it.

I WILL hereinunder set down nothing but what is the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so help me God. Well, in the old days, before everybody got so gosh-amighty good, barrooms was so frequent that nobody thought of setting down their scenery and habits.

Usually you went into it by a pair of swinging doors that met in the middle and didn't go full length up, so you could see over the top of the door, and if any one was to come into one door you didn't want to have talk with or anything you could see him and have a chance to gravitate out the door at the other end of the barroom while he was getting in. But you couldn't see into the windows of them as a habitual custom, because who could tell whether a customer's family was going to pass by and glance in. Well, in your heart you knew you was doing nothing to be ashamed of, but all families even in the good old days contained some prohibition relations. The Good Book says that flies in the ointment send forth a smell to heaven. Well, you felt more private like with the windows fixed thataway. They was painted, soaped, and some stained glassed.

It had its good sides and it had its bad sides, but I will say I have been completely out of touch, just as much as if I was a native of some hot country, with all kinds of morality and religions of all sorts, ever since the barrooms was shut up. From childhood's earliest hours religion has been one of my favourite studies, and I never let a week pass without I get down on my knees some time or another and pray about something any more than I would let a week pass without I washed all over. It was early recollections of a good woman that kept me religious, and I hope I do not have to say anything further to this gang. Well, in spite of my religion I never went to church none. Because it ain't reasonable to suppose that a man could keep awake. He thinks, “What if I should nod,” and he does. So that always throwed me back onto the barrooms for my religion.

Well, then, the first thing you know when you are up by the free lunch counter eating some of that delicatessen in comes a girl and says to contribute to the cause. Well, “What cause are you?” you ask her. Well, she says, Salvation Army or the Volunteers, or what not, and so forth, as the case may be, or maybe she was boosting for some of these new religions that gets out a paper and these girls go around and sell it for ten cents, which they always set a date for the world coming to an end. Well, then, you got a line on her religion, and you was ashamed not to give her a quarter, for you had spent a dollar for drinks already that morning. And then all through the day there was other religions come in, one after another, or maybe the same religion over and over again.

Well, then, you kept in touch with religions and it made a better man out of you, and along about evening time when you figured on going home you felt like it wouldn't be right to tell any pervarications to your wife about how you come to be so late, so you just said over the phone: “I am starting right away. I stopped into Ed's place to play a game of pool after work and met a fellow I used to know. I couldn't get away from him and I was too thoughtful of you to insist for him to come home to dinner so he insisted I ought to have a drink with him for old time's sake.” And if it hadn't been for being in contact with different religions all day you would of lied outright to your wife and felt mean as a dog about it when she found you out.

Well, then, it needs no further proof that the abolishment of the saloon has taken away the common people's religions from them, but it is my message to tell just what the barrooms was like and not to criticize the laws of the land, even when they are dam-foolish as so many of them are. So I will confine myself to describing the barroom and the rum demon.

Well, I never saw much rum drunk in the places where I hung out. Sometimes some baccardy into a cocktail, but for my part cocktails always struck me as wicked. The good book says that the Lord started the people right but that men had made many adventures. Well, then, I took mine straight for the most part, except when I needed some special kind of a pick-up in the morning.

And the good book says not to tarry long over the wine cup, and I never done that, neither, except a little Rhine wine in the summer time, but mostly took mine straight.

Well, then, to come down to describing these phantom places over which the raven says nevermore but the posterity of the future may wish to have its own say so about. Well, there was a long counter always kept wiped off, not like these here sticky soda-water counters which the boys and girls back of them always look sticky, too, and their sleeves look sticky and the glasses is sticky, but in a decent barroom the counter was kept swiped off clean and selfrespectable.

And there was a brass rail with cuspidors near to it, if you wanted to cuspidate it was handy right there, and there's no place to hawk and cuspidate in these here soda-water dives. Not that I ever been in them much. All that stuff rots the lining of your stomach. As far as I am concerned, being the posterity of a lot of Scotch ancestors, I never liked soft stuff in my insides.

I never drunk nothing but whiskey for comfort and pleasure, and I never took no medicine in my life except calomel, and I always held to the Presbyterian religion as my favourite religion because those three things has got some kick when took inside of you.

Well, then, to get down to telling just what these places was like, it would surprise this generation of posterity how genteel some of them was. Which I will come down to in my next chapter. Well, I will close this chapter.

I NEVER could see liquor drinking as a bad habit,” said the Old Soak, “though I admit fair and free it will lead to bad habits if it ain't watched.

“In these here remarks of mine, I aim to tell the truth, and nothing but the truth, so help me Jehorsophat, as the good book says.

“One feller I knowed whose liquor drinking led to bad habits was my old friend Hennery Simms.

“Every time Hennery got anyways jingled he used to fall downstairs, and he fell down so often that it got to be a habit and you couldn't call it nothing else. He thought he had to.

“One time late at night I was going over to Brooklyn on the subway, and I seen one of these here escalators with Hennery onto it moving upwards, only Hennery wasn't riding on his feet, he was riding on the spine of his back.

“And when he got to the top of the thing and it skated him out onto the level, what does Hennery do but pitch himself onto it again, head first, and again he was carried up.

“After I seen him do that three or four times I rode up to where Hennery was floundering at and I ast him what was he doing.

“'I'm falling downstairs,' says Hennery.

“'What you doing that fur?' I says.

“'I'm drunk, ain't I?' says Hennery. 'You old fool, you knows I always falls downstairs when I'm drunk.'

“'How many times you goin' to fall down these here stairs?' I ast him.

“'I ain't fell down these here stairs once yet,' says Hennery, 'though I must of tried to a dozen times. I been tryin' to fall down these here stairs ever since dusk set in, but they's something wrong about 'em.

“'If I didn't know I was drunk, I would swear these here stairs was movin'.'

'“They be movin',' I tells him.

“'You go about your business,' he says, 'and don't mock a man that's doing the best he can. In course they ain't movin'.

“'They only looks like they was movin' to me because I'm drunk. You can't fool me.'

“And I left him still tryin' to fall down them stairs, and still bein' carried up again. Which, as I remarked at first, only goes to show that drink will lead to habits if it ain't watched, even when it ain't a habit itself.”

“Do you have any more of your History of the Rum Demon written?” we asked him.

“Uh-huh,” said he, and left us the second installment.

WELL, as I said in my first installment, some 'of them barrooms was such genteel places they would surprise you if you had got the idea that they was all gems of iniquity and wickedness with the bartenders mostly in clean collars and their hair slicked, not like so many of these soda-water places, where the hair is stringy.

Well, this is for future generations of posterity that will have never saw a saloon, and the whole truth is to be set down, so help me God, and I will say that it took a good deal of sweeping sometimes to keep the floor clean and often the free lunch was approached with one fork for several people, especially the beans. Well, it has been three or four years even before that Eighteenth Commandment passed since free lunch was what it once was. And some barrooms was under par. But I am speaking of the average good class barroom, where you would take your own children or grandchildren, as the case may be.

They was some very kind-hearted places among them where if a man had spent all his money already for his own good they would refuse to let him have anything more to drink until maybe someone set them up for him.

But to get down to brass tacks and describe what they looked like more thoroughly I will say they was always attractive to me with those long expensive mirrors and brass fixtures like a scene of elegance and grandeur out of the Old Testament where it tells of Solomon in all his glory. And if a gent would forget to be genteel after he took too much and his money was all spent and imbue himself with loud talk or rough language and maybe want to hit somebody and there was none of his friends there to take charge of him often I have seen such throwed out on their ear, for the better class places always aimed to be decent and orderly and never to have an indecent reputation for loudness and roughhouseness.

Well, I will say I have not kept up with politics like I used to since the barrooms was vanished. My eyes ain't what they used to be and the newspapers are different from each other so who can tell what to believe, but in the old days you could keep in touch with politics in the barrooms. It made a better citizen out of you for every man ought to vote for what his consciousness tells him is right and to abide in politics by his consciousness.

Well, closing the barroom has shut off my chance to be imbued with political dope and who to bet on in the next election and I am not so good a citizen as before the saloons was closed. I would not know who to bet on in any election but I used to get straight tips and in that way took an interest in politics which a man is scarcely to be called an American citizen unless he does.

Well I see everywhere where all the doctors and science sharks says to keep in touch with outdoor sports if you want to keep young. I used to know all about all those outdoor sports and who the Giants had bought and what they paid for him and who was the best pitcher and what the dope was on tomorrow's entries at Havana, but all that is taken away from me now the saloons is closed and I got no chance to get into touch with outdoor sports and I feel it in my health. Some of these days the Prohibition aliments will wake up and see they have ruined the country but then it will be too late. Taking the sports away from a nation is not going to do it any good when the next war comes along if one does.

Well, I promised I would describe more what they looked like. I will tackle that in the next chapter, so I will bring this installment to a close.

THEY'RE going to take our tobacco next, are they?” said the Old Soak. “Well, me, I won't struggle none! I ain't fit to struggle. I'm licked; my heart's broke. They can come and take my blood if they want it, and all I'll do is ask 'em whether they'll have it a drop at a time, or the whole concerns in a bucket.

“All I say is: Watch out for Crime Waves! I don't threaten nobody, I just predict. If you ever waked up about 1 o'clock in the morning, two or three miles from a store, and that store likely closed, and no neighbour near by, and the snow drifting the roads shut, and wanted a smoke, and there wasn't a single crumb of tobacco nowheres in the house, you know what I mean. You go and look for old cigar and cigarette butts to crumble into your pipe, and there ain't none. You go through all your clothes for little mites of tobacco that have maybe jolted into your pockets, and there ain't none. Your summer clothes is packed away into the bottom of a trunk somewheres, and you wake your wife to find the key to the trunk, and you get the clothes and there ain't no tobacco in them pockets, either.

“And then you and your wife has words. And you sit and suffer and cuss and chew the stem of your empty pipe. By 3 in the morning there ain't no customary crime known you wouldn't commit. By 4 o'clock you begin to think of new crimes, and how you'd like to commit them and then make up comic songs about 'em and go and sing them songs at the funerals of them you've slew.

“Hark to me: If tobacco goes next, there'll be a crime wave! Take away a man's booze, and he dies, or embraces dope or religion, or goes abroad, or makes it at home, or drinks varnish, or gets philosophical or something. But tobacco! No, sir! There ain't any substitute. Why, the only way they're getting away with this booze thing now is because millions and millions of shattered nerves is solacing and soothing theirselves with tobacco.

“I'm mild, myself. I won't explode. I'm getting my booze. I know where there's plenty of it. My heart's broke to see the saloons closed, and I'm licked by the overwhelming righteous... but I won't suffer any personal for a long time yet. But there's them that will. And on top of everything else, tobacco is to go! All right, take it—but I say solemn and warningly: Look Out For Crime Waves!

“The godly and the righteous can push us wicked persons just so far, but worms will turn. Look at the Garden of Eden! The mammal of iniquity ain't never yet been completely abolished. Look at the history of the world—every once in a while it has always looked as if the pious and the uplifter was going to bring in the millennium, with bells on it—but something has always happened just in time and the mammal of unrighteousness has come into his own again. I ain't threatening; I just predict—-Look Out For Crime Waves!

“As for me, I may never see Satan come back home. I'm old. I ain't long for this weary land of purity and this vale of tears and virtue. I'll soon be in a place where the godly cease from troubling and the wicked are at rest. But I got children and grandchildren that'll fight against the millennium to the last gasp, if I know the breed, and I'm going to pass on full of hope and trust and calm belief.

“Here,” concluded the Old Soak, unscrewing the top of his pocket flask, “here is to the mammal of unrighteousness!”

He deposited on our desk the next installment of his History.

WELL, I promised to describe what the saloon that has been banished was like so that future generations of posterity will know what it was like they never having seen one. And maybe being curious, which I would give a good deal to know how they got all their animals into the ark only nobody that was on the spot thought to write it down and figure the room for the stalls and cages and when it comes to that how did they train animals to talk in those days like Balaam and his ass, and Moses knocking the water out of the rocks always interested me.

Which I will tell the truth, so help me. It used to be this way: some had tables and some did not. But I never was much of a one for tables, for if you set down your legs don't tell you anything about how you are standing it till you get up and find you have went further than you intended, but if you stand up your legs gives you a warning from time to time you better not have but one more.

Well, I will tell the truth. And one thing is the treating habit was a great evil. They would come too fast, and you would take a light drink like Rhine wine whilst they was coming too fast and that way use up considerable room that you could of had more advantage from if you had saved it for something important.

Well, the good book says to beware of wine and evil communications corrupts a good many. Well, what I always wanted was that warm feeling that started about the equator and spread gentle all over you till you loved your neighbour as the good book says and wine never had the efficiency for me.

Well, I will say even if the treating habit was a great evil it is an ill wind that blows nobody any good. Well, I promised to come down to brass tacks and describe what the old-time barroom looked like. Some of the old timers had sawdust on the floor, which I never cared much for that as it never looked genteel to me and almost anything might be mixed into it.

I will tell the whole truth, so help me. And another kick I got is about business advantages. Which you used to be lined up by the bar five or six of you and suppose you was in the real estate business or something a fellow would say he had an idea that such and such a section would be going to have a boom and that started you figuring on it. Well, I missed a lot of business opportunities like that since the barroom has been vanished. What can a country expect if it destroys all chances a man has got to get ahead in business? The next time they ask us for business as usual to win a war with this country will find out something about closing up all chances a man has to get tips on their business chances.

Well, the good book says to laugh and grow fat and since the barroom has been taken away, what chance you got to hear any new stories I would like to know. Well, so help me, I said I would tell the truth, and the truth is some of them stories was not fit to offer up along with your prayers, but at the same time you got acquainted with some right up-to-date fellows. Well, what I want to know is how could you blame a country for turning into Bolshevisitors if all chance for sociability is shut off by the government from the plain people?

Well, the better class of them had pictures on the walls, and since they been taken away what chance has a busy man like me got to go to a museum and see all them works of art hand painted by artists and looking as slick and shiny as one of these here circus lithographs. Well, a country wants to look out what it is doing when it shuts off from the plain people all the chance to educate itself in the high arts and hand painting. Some of the frames by themselves must of been worth a good deal of money.

The Good Book says you shalt not live by bread alone and if you ain't got a chance to educate your self in the high arts or nothing after a while this country will get to the place where all the foreign countries will laugh at us for we won't know good hand painting when we see it. Well, they was a story to all them hand paintings, and often when business was slack I used to talk with Ed the bartender about them paintings and what did he suppose they was about.

What chance have I got to go and buy a box to set in every night at the Metropolitan Opera House I would like to know and hear singing. Well, the good book says not to have anything to do with a man that ain't got any music in his soul and the right kind of a crowd in the right kind of a barroom could all get to singing together and furnish me with music.

A government that takes away all its music like that from the plain people had better watch out. Some of these days there will be another big war and what will they do without music. I always been fond of music and there ain't anywhere I can go that it sounds the same sort of warmed up and friendly and careless. Let alone taking away my chance to meet up with different religions taking away my music has been a big blow to me.

Well, I will tell the truth so help me, it was a nice place to drop into on a rainy day; you don't want to be setting down at home on a rainy day, reading your Bible all the time. But since they been closed I had to do a lot of reading to get through the day somehow and the wife is too busy to talk to me and the rest of the family is at work or somewheres.

Well, another evil is I been doing too much reading and that will rot out your brains unless of course it is the good book and you get kind of mixed up with all them revelations and things. And you get tired figuring out almanacs and the book with 1,000 drummer's jokes in it don't sound so good in print as when a fellow tells them to you and I never was much of a one for novels. What I like is books about something you could maybe know about yourself and maybe some of them old-time wonders of the world with explanations of how they was made. But nobody that was on the spot took the trouble to explain a lot of them things which is why I am setting down what the barroom was like so help me.

Well, in the next chapter I will describe it some more or future generations will have no notion of them without the Constitution of the United States changes its mind and comes to its census again.

THE Old Woman and me had quite an argument last Sunday,” said the Old Soak. “It ended up with her turning a saucepan full of hot peas onto my bald spot, which ain't no way to treat garden truck, with the cost of things what they be.

“But I won one of these here moral victories, even if she did get the best of me and chase me out of the house.

“It all come about over some pie we had for dinner on Sunday. It looked like mince pie to me when she set it on the table, and I says to her why don't she make some rhubarb pie or apple pie or something, for this is a hell of a time of year to be having mince pie. And mince pie ain't no good anyhow unless you put a shot of brandy or hard cider into it. She knows I orter be careful what I put into my stomach, which is all to the bad since I can't get the right kind of drink any more, and I told her so.

“'Well, then,' says she, 'this ain't mince pie. This is raisin pie.'

“'Raisin pie!' I says, and I was shocked and scandalized. 'Raisin pie! Good lord, woman, are you crazy? You don't mean to say you've went and took hundreds and hundreds of good raisins and went and wasted them thataway by puttin' 'em in a pie! It's the most extravagant thing I ever hearn tell on! Ain't you got sense enough to know that in these days raisins ain't something you eat?'

'“Well, what are they, then?' she says.

'“Raisins, I told her, 'is something you make hootch out of, and you know I'm reduced to makin' my own stuff these days. And yet here you be, puttin' at least a quart of good raisins into a gosh-darned pie!'

“Well, one word led to another, and, as I said, she hit me with the peas. But I got away with that pie. I won the moral victory. I got that pie fermentin' now, in the bottom of a cask full of grape and berry juice and other truck I picked up here and there. No, sir, there ain't goin' to be no raisins wasted around my house by eatin' of 'em in this here time of need!”

The Old Soak was silent a moment, and then he said: “This here installment of my diary of booze takes up that very point of quarrellin' with the Old Woman.”

WELL, another kick I got on the abvolition of ' the barroom is the fact that you got to stay around home so much and that naturally leads to having a row with your wife.

When there was barrooms my wife used to jaw me every time I come home anyways lit up and I just let her jaw me and there wasn't any row for I figured better let her get away with it who knows maybe she thinks she is right about it.

But now I stick around home a good deal of the time and it leads to words.

Well, she says to me, why don't you go and get a job of work of some kind.

Well, I tell her, mind your own business I always been a good pervider ain't I. You have got five or six children working for you ain't you and a man that pervides his wife with five or six children to work for her is not going to listen to no back talk.

Well, she says, you ought to be ashamed to loaf around home all the time.

Well, I says, I'm thinking up a big business deal but that's the way with women they never understand they got to keep their mouth shut and give a man peace and quiet to do his thinking in so he can make them a good living all they think about is newfangled ways to spend the money after he has slaved himself half to death making it.

Well, she says, I ain't seen you slaving any lately.

Well, I tells her, I done all my hard slaving when I was young and I got a little money coming in right along from them two houses I own, and I ain't going to work myself into the grave for no extravagant woman, and me with a heart pappitation you can hear half a mile on a clear day.

Well, she says, what rent money them two houses brings in don't any more than pay for the booze you drink.

Well, I says, you Prohibitionists done that to me. You went and made it plumb impossible to get good liquor for any reasonable price. That there rent money used to pay for three times the booze I drink.

Well, she says, you oughta get a job.

If I was to tie myself down to a job, I tells her, what chance would I have to trade and dicker around and make little turnovers, let alone thinking up this big business deal I am working on.

You are a liar, she said, and if I knowed where your whiskey was hid I'd bust every bottle and what kind of a business deal are you thinking up.

It is an invention I says to her and you mind your own business just because I have stood for you intrupting me for forty years is no sign I am going to stand for it forty years more.

You can quit any time she says and good riddance the children will keep me and there will be one less to cook for besides being ashamed of you before all my own friends and the nice people the children know.

Well, I said, here I set turning over the leaves of the Bible and you attack me that way and me trying to think up a business deal to buy you an automobile and the pappitation in my heart that bad it shakes the chair I am setting in and if a man with one foot in the grave can't get any peace and quiet to read his Bible in his own home against the time he is going to cash in then I will say that Prohibition has brought this country to a pretty pass.

Well, she says, what is that pappitation from but all the liquor you drunk.

It is from my constitution, I says, as the doctor will tell you if it hadn't been for a little mite of stimulant now and then I would of cashed in long ago and you would now have the life insurance money.

Well, she says, what kind of an invention is this you claim you are thinking up all the time?

Yes, I says, I would see myself telling you, wouldn't I and you blabbing it the next time a lot of them church women meets at our house and some old church deacon getting hold of it and getting rich off of it and me wandering the streets in destitution with the rain running down often my beard and the end of my nose because you and the children cast me into the street.

Well, she says, where is that thousand dollars that my uncle Lemuel willed to me and I give it to you for one of them inventions nearly thirty years ago and never seen hide nor hair on it since then.

Well, I says, that thousand dollars is gone and it went the same way as that money I loaned to your cousin Dan when he failed in business and would of starved to death him and his family if I hadn't come across with the cash that is where that thousand dollars is.

Well, that's the way it goes, until I get tired of trying to make her see any sense and sneak out to where my stuff is hid and fill me a pint bottle for my hip pocket and go and find a friend somewheres.

And in just that way Prohibition is breaking up millions and millions of homes every day.

CHRISTMAS,” said the Old Soak, “will soon be here. But me, I ain't going to look at it. I ain't got the heart to face it. I'm going to crawl off and make arrangements to go to sleep on the twenty-third of December and not wake up until the second of January.

“Them that is in favour of a denaturized Christmas won't be interfered with by me. I got no grudge against them. But I won't intrude any on them, either. They can pass through the holidays in an orgy of sobriety, and I'll be all alone in my own little room, with my memories and a case of Bourbon to bear me up.

“I never could look on Christmas with the naked eye. It makes me so darned sad, Christmas does. There's the kids... I used to give 'em presents, and my tendency was to weep as I give them. 'Poor little rascals,' I said to myself, 'they think life is going to be just one Christmas tree after another, but it ain't.' And then I'd think of all the Christmases past I had spent with good friends, and how they was all gone, or on their way. And I'd think of all the poor folks on Christmas, and how the efforts made for them at that season was only a drop in the bucket to what they'd need the year around. And along about December twenty-third I always got so downhearted and sentimental and discouraged about the whole darned universe I nearly died with melancholy.

“In years past, the remedy was at hand. A few drinks and I could look even Christmas in the face. A few more and I'd stand under the mistletoe and sing, 'God rest ye merry, gentlemen.' And by the night of Christmas day I had kidded myself into thinking I liked it, and wanted to keep it up for a week.

“But this Christmas there ain't going to be any general iniquity used to season the grand religious festival with, except among a few of us Old Soaks that has it laid away. I ain't got the heart to look on all the melancholy critters that will be remembering the drinks they had last year. And I ain't going to trot my own feelings out and make 'em public, neither. No, sir. Me, I'm going to hibernate like a bear that goes to sleep with his thumb in his mouth. Only it won't be a thumb I have in my mouth. My house will be full of children and grandchildren, and there will be a passel of my wife's relations that has always boosted for Prohibition, but any of 'em ain't going to see the old man. I won't mingle in any of them debilitated festivities. I ain't any Old Scrooge, but I respect the memory of the old-time Christmas, and I'm going to have mine all by myself, the melancholy part of it that comes first, and the cure for the melancholy. This country ain't worthy to share in my kind of a Christmas, and I ain't so much as going to stick my head out of the window and let it smell my breath till after the holidays is over. I got presents for all of 'em, but none of 'em is to be allowed to open the old man's door and poke any presents into his room for him. They ain't worthy to give me presents, the people in general in this country ain't, and I won't take none from them. They might 'a' got together and stopped this Prohibition thing before it got such a start, but they didn't have the gumption. I've seceded, I have. And if any of my wife's Prohibition relations comes sniffin' and smellin' around my door, where I've locked myself in, I'll put a bullet through the door. You hear me! And I'll know who's sniffin', too, for I can tell a Prohibitionist sniff as fur as I can hear it.

“I got a bar of my own all fixed up in my bedroom and there's going to be a hot water kettle near by it and a bowl of this here Tom and Jerry setting onto it as big as life.

“And every time I wake up I'll crawl out of bed and say to myself: 'Better have just one more.'

“'Well, now,' myself will say to me, 'just one! I really hadn't orter have that one; I've had so many—but just one goes.'

“And then we'll mix it right solemn and pour in the hot water, standing there in front of the bar, with our foot onto the railing, me and myself together, and myself will say to me:

“'Well, old scout, you better have another afore you go. It's gettin' right like holiday weather outside.'

“'I hadn't really orter,' I will say to myself again, 'but it's a long time to next holidays, ain't it, old scout? And here's all the appurtenances of the season to you, and may it sing through your digestive ornaments like a Christmas carol. Another one, Ed.'

“And then I'll skip around behind the bar and play I was Ed, the bartender, and say, 'Are they too sweet for you, sir?'

“And then I'll play I was myself again and say, 'No, they ain't, Ed. They're just right. Ask that feller down by the end of the bar, Ed, to join us. I know him, but I forget his name.'

“And then I'll play I was the feller and say I hadn't orter have another but I will, for it's always fair weather when good fellows gets together.

“And then me and myself and that other feller will have three more, because each one of us wants to buy one, and then Ed the bartender will say to have one on the house. And then I'll go to sleep again and hibernate some more. And don't you call me out of that there room till along about noon on the second day of January. I'll be alone in there with my joy and my grief and all them memories.”

ANOTHER thing wrong with Prohibition that will one day make them sorry they passed that commandment onto the constitution is the way it will bring liquor in front of the growing children and if the children learns to drink it too young what will become of this country I would like to know when the next war comes along.

I guess they didn't think of that, all these here wise Johnnies when they passed that law.

When you used to get all you wanted in a barroom you went there for it and the children didn't see you and they couldn't go into them places and it wasn't sticking around under the children's noses at home all the time making them ask Pa what do you need with so much of that medicine and can I have some Pa.

But now you have it at home and it is sticking under their noses all the time and the chances are millions and millions of children will learn to drink too soon just because it is sticking under their noses all the time and that is what Prohibition is doing for this country for everyone knows if they drink it too soon it will stunt their growths.

It is a great responsibility to bring up children right and Godfearing and be sure they say their lay me down to sleep every night like the Good Book says they should, and what I want to know is why this government don't help the parents and fathers with all them responsibilities instead of being a stumbling block in their way and putting liquor in the home where the growing children will smell it all the time and if they smell it they will want some of it.

Of course a young feller has got to learn to drink some time but there is such a thing as learning too young and it stunts their growth and the good book says keep it out of the mouths of babes and sucklings.

Maybe a little beer is all right if a baby is puny to fatten him up but I never give my children any hard liquor till they had their growth and I got no use for a government that turns in and puts liquor in the home to make drunkards out of the little innocent children.

Maybe if a child has got a cold a little whiskey is good for him and what is left in the bottom of the glass when their dad is done with it if they put some sugar and water in it and play they are like Pa won't hurt none of them any and will help make them so they can hold their share when they get growed up, but that is different from forcing it down their poor little innocent throats all the time and every day, which is what that Prohibition commandment amounts to.

I knowed a child once in a fambly where they thought it was smart to let him have some hard liquor and he growed up with goggle eyes and all rickety from it and took to smoking these here cheap cigarettes and it was a shame as any person with any heart a tall would have said and does this government want the whole future generation of posterity to grow up goggle eyed and rickety like that by forcing liquor into the home and where will they get their strong soldiers from in the next war.

I will say they got no conscience to do a thing like that to the whole passel of children waiting to grow up and go to be soldiers.

It is enough to make any honest man stop and think and his heart bleed when he thinks of all them millions and millions of innocent children and the way they are being ruined with liquor in the home and maybe helping their daddies make it with yeast and raisins and things and cornmeal in the cellar.

I teached my boys to drink in the barroom just as fast as they growed up and teached them to tell good liquor from bad liquor and not to mix their drinks and not to go in for fancy drinks and to drink along with me for a comfort for my old age and a father had ought to make chums of his boys like that and give them the right example and they stay close to him and he knows what they are thinking about and can give them good advice and my boys has been a comfort to me.

My boys is all growed up, but what worries me is the millions and millions of little children that is going to learn to drink too young.

Well, in my next chapter I promise to get down to brass tacks and tell just exactly what those barrooms was like that has been vanished.

NO, SIR,” said the Old Soak, “I ain't got so darned much left. It may get me through a year, and it may run me only about ten months.

“But I don't want so much as I use to, for some reason. In course, no gentleman of the old school figgers on less than a quart a day, but there has been times when I exceeded that there limit. Looking back on them times, I don't know whether to be glad or sorry. It's a satisfaction to remember that I had the liquor, but it's a grief to know I won't never have that same liquor again.

“But at a quart a day, if I'm careful, and don't give any parties to new acquaintances that is took sudden with a love and admiration for me, I'll toddle along fer ten or twelve months yet. And by that time, something or other will happen in my favour; you see if it don't. Either the country will backslide into iniquity again in spots; or else somebody will die and leave me an island down near Cuba; or else Old Jabe Potter, my friend out on Long Island I told you of, will get his smuggling works started into operation.

“Fact is, Old Jabe is already set, and his smuggling works is ready to operate right now, only there don't seem to be nothin' to smuggle, Jabe says. He's got one of these here gasolene boats, and he goes out and makes signals to the ocean liners to and from Europe, but they ain't onto Jabe's signals, or something. I tell him he's got to make arrangements in advance with some of them transatlantic bartenders, for they don't know what he's driving at. 'Well,' Jabe says, 'you'd think they could tell by my looks I'm thirsty, wouldn't you?' Jabe, he's romantic and optimistic; but them notions of his is all right if they was only organized.”

He paused a while, refreshed himself from his pocket flask, and then took up another line of enquiry.

“What I would like to know,” he said, “is what mean folks is going to blame their meanness onto, now that booze is gone. It used to be a good excuse for a lot of people that wasn't worth nothin', and knowed it, and acted ornery... booze was the answer, everybody said. If they did anything they hadn't orter, people said they was all right except when they had a drink or two, but a drink or two changed their entire disposition, and the drink orter be blamed, and not them. My own observation and belief leads me to remark that them kind of folks was less ornery and mean when they had booze than when they didn't have it.

“Well, I notice in myself a kind of a habit growing up to blame everything onto Prohibition, just as Prohibitionists used to blame everything onto booze. I want to be fair to the drys, and I will say that neither Prohibition nor booze has much to do with making a mean man mean. I want to be fair to the drys, so as to show them up; they ain't fair to me, and when I'm fair to them it shows how superior I be.”

WELL, I promised I would tell just what those vanished barrooms was like, and I will tell the truth, so help me.

One thing that I can't get used to going without is that long brass railing where you would rest your feet, and I have got one of them fixed up in my own bedroom now so when I get tired setting down I can go and stand up and rest my feet one at a time.

Well, you would come in in the morning and you would say, Ed, I ain't feeling so good this morning.

I wonder what could the matter be, Ed says, though he has got a pretty good idea of what it could be all the time. But he's too kind hearted to let on.

I don't know, you says to Ed, I guess I am smoking too much lately. When you left here last night, Ed says, you seemed to be feeling all right, maybe what you got is a little touch of this here influenza.

It ain't influenza, Ed, you says to him, it is them heavy cigars we was all smoking in here last night. I swallered too much of that smoke, Ed, and I got a headache this morning and my stomach feels kind o' like it was a democratic stomach all surrounded by republican voters, and a lot of that tobacco must of got into my eyes and I feel so rotten this morning that when my wife said are you going downtown without your breakfast I just said to her Hell and walked out to dodge a row because I could see she was bad tempered this morning.

What would you say to a little absinthe, says Ed, sympathetic and helpful, a cocktail or frappy.

No, says you, if you was to say what I used to say, I leave that there stuff to these here young cigarettesmoking squirts, which it always tasted like paregoric to me.

Yes, sir, Ed says, it is one of them foreign things, and how about a milk punch, it is sometimes soothing when a person has smoked too much.

No, Ed, you says, a milk punch is too much like vittles and I can't stand the idea of vittles.

Yes, sir, Ed used to say, you are right, sir, how about a gin fizz. A gin fizz will bring back your stomach to life right gradual, sir, and not with a shock like being raised from the dead.

Ed, you says to him, or leastways I always used to say, a silver fizz is too gentle, and one of them golden fizzes, with the yellow of an egg in it, has got the same objections as a milk punch, it is too much like vittles.

Yes, sir, Ed says, I think you are right about vittles. I can understand how you feel about not wanting vittles in the early part of the day. And that makes you love Ed, for you meet a lot of people who can't understand that. There ain't no sympathy and understanding left in the world since bartenders was abolished.

How about an old-fashioned whiskey cocktail, says Ed.

You feel he is getting nearer to it, and you tell him so, but it don't seem just like the right thing yet.

And then Ed sees you ain't never going to be satisfied with nothing till after it is into you and he takes the matter into his own hands.

I know what is the matter with you, he says, and what you want, and he mixes you up a whiskey sour and you get a little cross and say it helped some but there was too much sugar in it and not to put so much sugar in the next one.

And by the time you drink the third one, somewhere away down deep inside of you there is a warm spot wakes up and kind of smiles.

And that is your soul has waked up.

And you sort of wish you hadn't been so mean with your wife when you left home, and you look around and see a friend and have one with him and your soul says to you away down deep inside of you for all you know about them old Bible stories they may be true after all and maybe there is a God and kind of feel glad there may be one, and if your friend says let's go and have some breakfast you are surprised to find out you could eat an egg if it ain't too soft or ain't too done.

Well, I promised, so help me, I would tell the truth about them barrooms that has perished away, and the truth I will tell, and the truth with me used to be that more than likely it wasn't really cigars that used to get me feeling that way in the mornings, and I will take up a different part of the subject in my next chapter.

PROHIBITION,” said the Old Soak, “is doing more harm than you can see with the naked eye. Formerly when a man called up and told his wife that he was detained at his office by an unexpected caller on business just as he was starting home his wife knew he had stopped to take three or four balls with the boys on the corner and thought very little about it. Now she wonders if that unexpected caller could have been a lady.

“When a man came home late with the smell of liquor on his breath he knew he was in bad, but he knew just how bad in he was. Now everything is uncertainty and guesswork everywhere, and intellects is cracking under strains on all sides.

“It must 'a' been the same way back in the historic days of iniquity and antiquity, when the Roman Empire switched all of a sudden from being heathen to being Christian; everybody had to be good all of a sudden, and only a few had learnt how; and everybody that hadn't quite succeeded in turning Christian went around for a while wondering if everybody else was as gosh-darned Christian as they let on to be. I know a lot of people now that says they're on the wagon, but I'd hate to go so sound asleep in a street car that I wouldn't wake up if they tried to pull my flask out of my pocket. I don't struggle none trying to be good, myself. I'm a dipsomaniac, and I know it, and I'm contented to be that way.

“Years ago I used to struggle, and think maybe I would quit drinking some time, and it kept me unhappy. But as soon as I come right out and acknowledged Booze as my boss and master, and set him up and crowned him king, a great peace fell onto me, and I ceased to struggle, and I been happy and contented and full of love for my fellow men ever since. There ain't nothing like finding out which gang you belong to and sticking to your own crowd consistent. If I had only been brought up to be a drunkard when I was young I would 'a' settled into it natural and been saved a lot of worry and struggle and uncertainty. But there was years when I fit against it, from time to time, and it kept me unsettled and discontented, and I wasted a lot of good time trying to keep sober when I might 'a' been drunk and cheerful, radiating joy and happiness into the world and being of some use to my fellow men. But I s'pose everybody thinks if they had their life to live over again they'd do different, and the main thing is to reach peace and contentment toward the end, as I have reached it.”

WELL, as I said in my last chapter, it is time for me to get down to brass tacks and describe just what those barrooms that has been vanished was like so that future generations of posterity will know what they missed, and to tell the truth in all particulars, so help me.

Some of them was that arted up with hand paintings that if you had all them paintings in your home you would feel proud of yourself, like Solomon in all his glory, and would feel like you was living in the midst of a high art museum, and the shining brass cuspidores to spit in and the brass rail and all them shiny glasses and bottles and mirrors made up a scene of grandeur and glory like the good book mentions and you would think you was King Faro of Egypt, if you lived in the midst of all that or Job in all his riches before the itch broke out on him.

Well, speaking of the Good Book, my wife has always been more or less of a prohibitionist in order to show me that she is independent of me, and one day one of these here church friends of hers tries to tell me all the liquor that was drinked in the Bible wasn't nothing but unfermented grape juice.

Yes, it was, I said, don't you believe it was, like hell it was. You go and get your testament and see where King Solomon talks about the stuff that makes the heart merry and then go and swill yourself with grape juice and see if you could get the way he was when he wrote eat, drink, and be merry for tomorrow ye die. And how about the time them two women came to him with that one child and both claimed that it was hern and he says to the officer on duty, let me see that there sword of yourn for a minute I'll darned soon see who this kid belongs to. And verily the officer drawed his sword and the King he heaved it up and was about to cut the kid in two when one of the women says to stop unhand him King and not do the rash act it is the other woman's yew lamb and let her have it, it being her own all the time and her one yew lamb and her preferring to see the other woman grab it off than have half of it.

Well, says the King, half a loaf is better than no bread, but with infants it is different, take the child, it is yours woman, and go and sin no more.

Well, now, I ask you, was King Solomon drinking the unfermented juice of the grape when he got that there hunch, or was he not? I will say he was not. Them radical and righteous ideas never come to a man when he is cold sober. He has got to have a shot of something moving around under his belt before he gets thataway.

And how about them Bible hangovers, I said to this here church person. Man and boy I been a student of the Bible from cover to cover for a good many years now and I never seen a book with more evidences of hangovers and katzenjammers into it. How about that there book that says vanity, vanity, all is vanity. Well, I ask you, did you ever get that way in the morning after you had spent the night before drinking the unfermented juice of the grape.

That there Book of Exclusiastics is just one long howl from the next morning head. Things seem right, says old Exclusiastic, and they look right; but if you bite into them they don't taste right, or words to that effect. And you stick around awhile, says old man Exclusiastic, and you'll darned soon see they ain't nothing right nowhere and never will be again. Moreover, says he, I was wrong when I used to think things was right; there ain't never anything anywhere been all right and I was all wrong when I was a young feller and used to think things was right and the wrongest thing about the whole business is the darned fools like I used to be who go around saying things is all right, and the sum and substance of everything is vanity, says he, vanity, vanity, all is vanity.

You could tell some folks that that there old Exclusiastic was writing as the result of unfermented grape juice, but a man with any experience of his own knows a good deal better and what kind of a taste was in his mouth. You can't tell an old Bible reader like me anything about this unfermented stuff. The trouble with these here church people is that too many of them ain't never read the Bible, or if they did read it they read it with the idea that it was saying something else like they wanted it to say.

I always stuck to the Bible in spite of the church folks and I always will for it has got some kick into it. There is three things in the world I always stick to, the Bible and hard liquor and calomel, for they has got the kick to them. You can have all your light wines and unfermented stuff and all your pretty new-thought religions and all your new-fangled medicines you want to, but for me I will stick to the Old Testament and corn whiskey and calomel like my forefathers done before me. You can't pull any of that unfermented stuff on me and get away with it.

THE Old Soak came in to see us during the recent Presidential campaign.

“What I expected has come to pass,” he said, sorrowfully. “This here Cox that everybody hoped was a Wet Prohibitionist ain't that at all. He ain't nothin' but a Dry Liquor Man. I been a Republican ever sense the days of Abraham Lincoln, but I had an idee this year I was goin' to have fer to leave the old party flat on account o' rumours I hearn that this here Cox was comin' out for liquor. My conscience is Republican, but my religion is liquor; an' I would of voted agin any conscience fer the sake o' my religion. But I ain't goin' to be compelled fer to make that sacrifice. I'd ruther vote fer an outan'-out Prohibitionist than one of these here fellers that gits the word passed private to the wets that they'll be a stick in the lemonade, and gets the word passed private to the drys that what he means is nothin' but a stick o' pep'mint candy. They ain't no hope fer liquor in public life no more; it has become a question fer the home. As fur es my own private stock is concerned, it mostly ain't. But I got a grand idee workin' up. My old woman's got a niece who's come to live with us, an' I'm tryin' to marry that there gal to a revenue agent. I see by the papers they are always trackin' down a couple thousand gallons somewheres or other, and I don't hear no glass crashin' nowheres to indicate where them bottles is bein' busted. I wants somebody in the fambly that will take me along on some of these here raids I read about.”

WELL, when I seen all them men shovelling snow and ice in the streets and no place to go for a drink and maybe one of them spring thaws coming along soon now which they are always full of these here la grip germs I says to myself them Prohibitionists think they have done something pretty smart but they got another think coming to them.

I never been much of a hand to kick against the weather. As a fact, I use to like all kinds of weather as it come along.

You went into a place and you said to Ed it looks like one of them cold rains is going to start up pretty soon, Ed.

Yes, sir, Ed says, it is pretty raw. The wind is rawring. What will you have?

Well, I use to say, I was wondering about a little Scotch with boiling water into it and a lump of butter and a lump of sugar into it I knowed a fellow used to treat himself thataway one time.

No, sir, says Ed, I wouldn't advise anything like that sir, it will get you sweating inside of you all around your stomach and lungs and then you will go out and swallow some cold damp air and take one of them inside colds, sir, and it may run into new-monia or this here pellicanitis.

Well, Ed, I don't want to ketch none of them germs, you would say to him, and how about some rock and rye.

You better stick to straight rye and leave out the rock. When you was in here a little bit ago you was drinking straight rye and you don't want to be mixing them too much, says Ed.

And no sooner said than done.

Or maybe it was summer time and a hot day and you would say to Ed I wonder how many people is getting sun struck to-day, Ed.

A good many says Ed they drink too much cold water and it gets to them.

I am glad I don't have to go out into the awful heat, you would say.

The main thing is to keep your pores open says Ed for if you stop the presspiration that means a sun stroke. The main thing is to encourage the presspiration to sweat itself out of you.

I think you are right Ed you says and I was wondering about some beer.

No, sir, not for you, says Ed, I wouldn't advise no beer. You put these here temperance drinks like beer and sassperiller into your stomach, sir, and it takes up a lot of room you will wish you had later in the day. For some people I would say beer wouldn't do no harm, sir, but I should say, sir, that it was the wrong thing for you.

One of them long silver fizzes with ice shook up into it would sound nice to my ears as it went down my oozlygoozlum you would say to Ed.

Ed he is kind of lazy with the heat and he don't want to shake it up so he says to you on a hot day like this you are taking chances with your life every time you put ice drinks into you and he says what's the matter with that rye you been drinking all the early part of the day that is the best thing to keep the presspiration coming out of your sweat pores.

Well, no sooner said than done.

The number of times them old-fashioned bartenders has saved my life summer and winter with good advice is as too numerous to mention as is the stars in the sky and their name is legend as the good book says.

In them days when there was a barroom on every corner and sometimes four barrooms on every four corners I never cared about the weather at all for I knowed no matter what the weather was I could keep my health safe.

If you was to look out the barroom window and see a sudden change in the weather you could make a sudden change and switch to some other kind of drink and keep yourself protected from them sudden changes.

But in these days when a sudden change in the weather comes what protection have you got I would like to know. You are running the risks of them sudden changes all the time day and night, and no chance to change your drink to meet them with for you are lucky if you have one kind of liquor let alone all the different kinds of ingredients you used to ornament your digestion with.

Nowadays when the weather ain't just right I have to stay home in my own room up to the top of the house where I got that little bar rigged up where I wait on myself and staying to home all the time ain't any too good for me.

It don't give me a chance to get any outdoor exercise, staying at home don't and a man needs outdoor exercise if he is going to keep his health.

That is another thing Prohibition has done to me: it has took away all my chance for outdoor exercise.

I reckon them Prohibitionists will be satisfied when they got everybody's health broke down on account of them sudden changes in the weather and nobody getting any outdoor exercise any more.

YES, sir; yes, sir!” said the Old Soak, with a happy smile on his face. “I've done found out the way to beat the game—! Ask me no questions, and I'll tell ye no lies as to how I done it.

“Ye see this here bottle, do ye? Kentucky Bourbon, and nothin' else. Bottled in bond, an' there's plenty more where that comes from.—Ask me no questions, and I'll enrich ye with no misinformations!—Ye see that there little car parked out there by the curbstone, do ye? Well, sir, that there car is my car, and under the back seat of it is twelve quarts of this here stuff!—And it ain't home brewed, neither; it's some of the best liquor you ever throwed your lips over!—How do I do it?—Don't ply me with no questions, and I won't bring you no false witnesses!

“Notice these here new clothes of mine? Well, sir, that there suit's a bargain.—It only cost me two cases of rye.—I got three new suits like that to home, an' I'm figgerin' on buying one of these here low neck an' short sleeve dress suits for to wear to banquets this winter.—They's a whole passel o' folks would like to give me banquets this cornin' season.—How do I do it?—Ask me no questions, and I'll give you no back talk!

“If you was to come out to the house, I'd interduce ye to quite a lot of good liquor.—Can't drink no more, huh?—Ain't ye got a friend ye could bring?—I'd like to have ye meet my son-in-law.

“Yes, sir; yes, sir! Daughter was married two months ago. The youngest one. Her and her husband is makin' their home with us temporary.—I'm tryin' to persuade of 'em to stop to our house permanent.—Yes, sir, my son-in-law, he is one of these here revenooers.—Well, so long!—I gotto see an old friend o' mine that lives up to the Bronx this afternoon.—He ain't had a real drink fer nigh onto three months, he tells me.—I'm headin' a rescue party into them there regions.

“Yes, sir; yes, sir! I figger my daughter married well!—Bring up yer kids in the way they should go like the Good Book says, and Providence will do the rest.—Henry, that's my son-in-law, is figgerin' mebby he can get my son Jim made a revenooer, too.—Ask me no questions, an I'll give away no fambly secrets!”

ANOTHER thing I miss in regard to all them vanished barrooms being closed up is kind feeling about respect to the old especially to parents and them that has departed.

Where is the younger generations of posterity going to learn how to be kind hearted about home and mother now that the barrooms is all closed up I would like to know?

It used to be that a lot of fellows would get all tanked up of an afternoon or evening and in the right sort of a place they would get to singing songs.

All them songs about home and mother and to treat her right now that her hair had turned gray. I never was much of a one to sing myself especially unless I had a few drinks into me.

But whether I helped sing them or not all them songs would make a better man of me. You stand up to a bar or sit down at a table and listen to them songs for two or three hours and if you are any kind of a man at all you will wish you had always done the right thing and now that all them songs about home and mother has been took away from me I ain't the man I used to be at all.

I feel myself going down hill because my softer emotions and feelings ain't never stirred up by nothing any more.

Well, this Eighteenth Commandment is going to make a hard-hearted country out of this here country. Nobody is never going to think as much of home and mother as they used to. And I guess them prohibitionists won't feel so smart when they see all them old ladies with gray hair flung out onto the streets in the rainy weather just because nobody would pay the mortgage off. Lots of times when I was a young feller after hearing them songs for awhile I would say to myself I will set right down and write a letter to my mother, I ain't wrote her for five or six months. And when I got older after she passed on I used to say to myself some of these days I will have to make a visit to the old home place and take a look around there.

But all them softer feelings has been took away from me now and what I would like to know is how is the younger generation going to grow up. Hard hearted, that is how.

Some of these here fine days I may be cast out into the street myself with the rain drops dripping down offen my hat brim into my eyebrows just because nobody won't pay a mortgage and it has got to be a hard-hearted country.

I hope none of them there smart alick Prohis will be flung out onto the street thataway. Because they got no friends would pay off their mortgages and they would just naturally be destituted to death. I ain't hard hearted like they be and I hope that don't happen to none of them. But if it ever did they would find out a few things.

In my next chapter I will get down to brass tacks and give a true description of them barrooms that has perished off the face of the earth.

THE Old Soak has been looking rather well for some time; he seems prosperous and happy, for the most part, and contented with the quantity and quality of the hootch he has been gettin'. But yesterday he dropped in to see us with just the slightest shade of gloom on his features. We asked him about it.

“It's that there son of mine,” he says. “He's too young to know enough to let well enough alone, like the Good Book says to do. They's a lot of these young fellers you can't learn nothing to.

“This yere son-in-lawr of mine I been tellin' you about, that is a revenooer, got my son made into a revenooer, too. And it ain't long before my son gits jest as good an automobile as the one my son-in-lawr's been drivin'. And joy out to our house has been unconcerned, with everyone exceptin' the Ol' Woman, and she's been prayin' agin the rest of the fambly.

“But this yere son o' mine, he gets too much hootch under his belt one day, and he gets into this yere brand-new automobile of his'n and he starts onto one of these yere raids. Which would of been all right, bein' as it's what a revenooer is for, if he had only used a leetle bit o' jedgment. But the young has got a lot to learn, and babes and striplings, the Good Book says, jest naturally has their dam fool streaks.

“This yere raid my son goes onto turns out all wrong. For whilst he is pinchin' who does he pinch in the gang of wicked sinners but that there son-in-lawr of mine, the revenooer as got him his job, said son-in-lawr bein' off duty and pickled hisself at the time.

“So this here son-in-lawr of mine, he mighty nigh loses of his job as a revenooer, bein' took up in one of the raids he was legally supposed to be startin' himself, and they was quite a fuss about it, so I understand, and the thing was finally settled with a compromise—it wasn't my son-in-lawr lost his job, but they compromised it and fired my son out'n his job.

“But now my son, he has went and got sore at my son-in-lawr, and he says unless he gits his job back as a revernooer he will tell all he knows.

“So my house is a house that is sided against itself, like the Good Book says, and every member of the fambly has took sides one way or the other 'twixt my son and my son-in-lawr, and the Ol' Woman is agin both on 'em, and agin me, too—a-prayin' an' a-prayin' an' a-prayin'.

“'You went and prayed for years an' years so as to get prohibish'n,' I tells her; 'an' now you got it—you got more on it than any woman I knows, for it's come right into your own home. An' now you got it you ain't satisfied with it—there you be onto your marrow bones prayin' agin the revenooers.'

“I s'pose I was too hifalutin' an' ambitious, wantin' to keep two members of my fambly into the revenooer job. And as long as my son-in-lawr stays into office and continues to make his home with me I won't have no kick cornin', but will take my hootch in thankfulness and humility, like the Good Book says to do, eatin', drinkin' an' bein' merry. This yere leetle cloud of gloom what you notice is due to the Ol' Woman's prayers. I cain't help but feel she is goin' direct agin Scripter and her husband's best intrusts.”

ANOTHER thing about those barrooms that has been vanished forever is the fact that most of them was right polite sort of places if a fellow edged up to the bar and knocked over your glass of whiskey or something like that he would say, O excuse me stranger and you would say sure, but look where in hell you are going to after this.

Sure he would say no offence meant. No offence taken you would say to him. Have one with me he would say.

No sooner said than done.

But nowadays all you see and hear is bad manners and impoliteness with people hustling and bumping into each other on the subways and stepping on each other and women and children amongst them and nobody ever begging anybody's pardon and hard feelings everywhere.

The trouble is everybody is sore and wanting a drink all the time and there is no place where the younger generation is going to learn good manners now that the barrooms is gone. What is the young fellows just growing up to manhood going to do for their manners now that the barrooms is closed, is what I want to know.

It used to be you would get onto a subway train and there would be two or three women standing up and you would be setting down and there would be three or four drinks under your belt and you would be feeling good and you would say to yourself am I a gentleman or ain't I a gentleman.

You're damned right I am a gentleman, you would say to yourself, here, lady, you set down, and don't let any of these here bums roust you out of that seat.

If any of these here bums tries to roust you out of that seat I will put a tin ear onto them.

That's the kind of a gentleman I am, lady, they would have a hell of a time, lady, getting your seat away from you with me here.

And she seen you was a gentleman and she smiled at you and you hung onto a strap and felt good.

But nowadays there ain't no manners, with no place to get a drink or anything.

You are setting in the subway and a lady comes in and has nowheres to set, and you say to yourself let some of these other guys get up and give her a seat.

And you think a while and you say to yourself I'll bet she is a Prohibitionist anyhow. Let her stand up. She has got to learn you can't have any manners with the barrooms all closed and everything.

Well, that's another thing closing the barroom has done. It has took away all the manners this town ever had.

In my next chapter I will get down to brass tacks and tell just what those barrooms was like for the benefit of future posterity that has never seen one.

YES,” said the Old Soak, “I get plenty of hootch nowadays. My son is back into the revenoo business, and my son-in-lawr is with it, too. I gets plenty of whiskey. I've got some into me, and I've got some onto my hip, and I know where I'm going to get some more when that's gone.”

And he sighed.

“Why so gloomy, then?” we asked. “You should be radiating a Falstaffian joviality. You should be as merry as the merry, merry villagers in an opera on the Duke's birthday. But on the contrary, you shake from out your condor wings unutterable wo, as E. A. Poe has it. Wherefore?”

“I miss,” he said, “the next mornin' sympathy... the next mornin' ministration. Any one can get drunk under the auspices of Prohibition, but it takes the right kind of barkeep fur to get you sober agin and make you like it.

“Where is the next morning barkeep? He ain't. He was wise as a serpent and gentle as a dove like the Good Book says. He knowed right off what ailed you, at 11 o'clock on a cloudy morning, and what was good for it. A little of this, out of the long green bottle, and a little of that, and some ice tinklin' in it, and the white of an egg mebby, and... oh, you know! One of them, and there was salve onto the sore spot of your soul. Two of them and you began to forgive yourself. Three of them, and you could hear about breakfast; you could look an egg into the eye.

“And he never asked no question about your past, that barkeep didn't. He didn't need to. He knowed. He seen last night's history in this morning's footnote. He was kind. 'Feel a little better now, sir?' he'd ask. 'Two or three of them is enough, sir, if you ask me. Get your breakfast, now, sir, and you'll be quite O. K. Yes, sir, I learned to mix them in New Orleans...' You talked to him, and he let you. He was like a mother's knee to a three-year-old that's bumped his head, the old-fashioned barkeep was.

“But now, he ain't. Now, when you get up, Gloom stands on one side of you and Conscience on the other, and Remorse is feeding lines of both of 'em.

“'Well,' says Gloom, 'this is a fine, cheerful morning, this is! This is about as full of sunshine as the insides of the whale that drank Jonah.'

“'It is,' says Remorse, 'and then some. Conscience and me feels so bad about it that we're gonna jump off the dock together.'

“'I ain't, neither,' says Conscience. 'I'm gonna save myself for the worst. The worst is yet to come. And I want to be here when it comes.'

“'I ain't gonna be here when it comes,' says Gloom. 'I'm going over to the Aquarium and rent myself out for a fish.'

“Just then,” went on the Old Soak, “a strange party sticks his head in at the door and says, 'Never again!' “'Who be you?' says Gloom. 'I'm Repentance,' says the buttinski, 'and I calls on you guys to mend your ways!'

“And Gloom, he looks at the hard liquor left in the bottom of the bottle, and at the sky, and at the door of the closed-up barroom across the street, and he says, 'It can't be done without some uplift. I need soothing words, and an educated hand.'

“'We got what's coming to us,' says Remorse. 'And there's more of it coming,' says Conscience. 'Better quit!' says Repentance. 'I ain't gonna quit,' says Gloom, 'without the right kind of a drink to quit on. I ain't never yet quit without the right kind of a drink to quit on, and I'm not going to start any innovations on a rotten day like this.'

“Well,” went on the Old Soak, “you sits on the edge of your bed and you listen to these yere guys talking, and you think how right all of them is, and you wonder whether it's any use getting up, and you think of all the barkeeps you used to know, and after a while you suck an orange and think of one of them long silver fizzes with frost on the glass and charity and loving-kindness in its heart, like Ed used to shake up,—you think of it so hard you well-nigh taste it, and then the meerage fades away and you ain't nothin' but a camel in the desert again with a humpbacked taste in your mouth.

“Yes, sir,” said the Old Soak, “I can get all the booze I want, but I can't get sympathy. What a man needs in the morning is a kind heart for to comfort him, and a strong arm to lean on. Anybody can give me good advice, but it don't soothe me any; what I want is a quick friend in a white apron, wise as a bishop and gentle as a nurse.