TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

HE MAY HAVE FOUND ANOTHER HARE”

TOMMY SMITH’S

ANIMALS

BY

EDMUND SELOUS

WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS BY

G. W. ORD

TWELFTH EDITION

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

| First Published | October | 1899 |

| Second Edition | December | 1900 |

| Third Edition | December | 1902 |

| Fourth Edition | September | 1905 |

| Fifth Edition | April | 1906 |

| Sixth Edition | September | 1906 |

| Seventh Edition | January | 1907 |

| Eighth Edition | April | 1907 |

| Ninth Edition | November | 1907 |

| Tenth Edition | May | 1908 |

| Eleventh Edition | September | 1909 |

| Twelfth Edition | September | 1912 |

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE MEETING | 1 |

| II. | THE FROG AND THE TOAD | 11 |

| III. | THE ROOK | 25 |

| IV. | THE RAT | 39 |

| V. | THE HARE | 54 |

| VI. | THE GRASS-SNAKE AND ADDER | 74 |

| VII. | THE PEEWIT | 96 |

| VIII. | THE MOLE | 115 |

| IX. | THE WOODPIGEON | 143 |

| X. | THE SQUIRREL | 166 |

| XI. | THE BARN-OWL | 187 |

| XII. | THE LEAVE-TAKING | 205 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| “HE MAY HAVE FOUND ANOTHER HARE” | Frontispiece |

| “THAT IS WHY I AM SO WISE” | 9 |

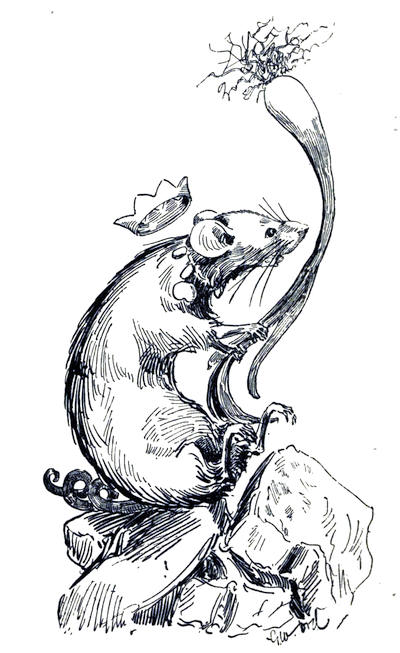

| “I SHALL KEEP AWAKE TILL THE RAT COMES” | 39 |

| PAT, PAT, PAT. “DO YOU HEAR?” | 41 |

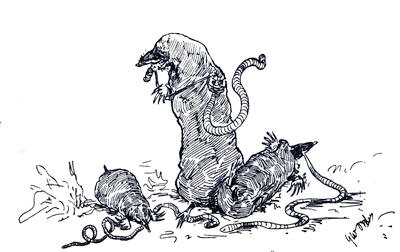

| “BITE HIM!” | 51 |

| “ALL HAPPY (EXCEPT THE HARE)” | 63 |

| “THERE ARE THREE FROGS IN MY STOMACH AT THIS MOMENT” | 79 |

| “WE MOLES ARE VERY HEROIC” | 141 |

TOMMY SMITH’S ANIMALS

CHAPTER I.

THE MEETING

“The owl calls a meeting, and has an idea:

They all think it good, though it SOUNDS rather queer.”

THERE was once a little boy, named Tommy Smith, who was very cruel to animals, because nobody had taught him that it was wrong to be so. He would throw stones at the birds as they sat in the trees or hedges; and if he did not hit them, that was only because they were too quick for him, and flew away as soon as they saw the stone coming. But he always meant to hit them—yes, and to kill them too,—which made it every bit as bad as if he really had killed them. Then, if he saw a rat, he would make his dog run after it, and if the poor thing tried to escape by running down a hole, he and the dog together would dig it out, and then the dog[2] would bite it with his sharp teeth until it was quite dead. It never seemed to occur to this boy that the poor rat had done him no harm, and that it might be the father or mother of some little baby rats, who would now die of hunger. Even if the rat got away, he would whip the dog for not catching it, yet the dog had done his best; for, of course, dogs must do what their masters tell them, and cannot know any better. It was just the same with hares or rabbits, squirrels, rooks, or partridges. Indeed, this boy could not see any animal playing about, and doing no harm, without trying to frighten it or to hurt it.

When the spring came, and the birds began to build their nests, and to lay their pretty eggs in them, then it is dreadful to think how cruel this Tommy Smith was. He would look about amongst the trees and bushes, and when he had found a nest, he would take all the eggs that were in it, and not leave even one for the poor mother bird to sit on when she came back. Indeed, he would often tear down the nest too, after he had taken the eggs. Perhaps you will wonder what he did with these eggs.[3] Well, when he had brought them home and shown them to his father and mother, who never thought of scolding him, or to his little brothers and sisters (for he was the eldest of the family), he would throw them away, and think no more about them. If he had left them in the nest, then out of each pretty little egg would have come a pretty little bird. But now, for every egg he had taken away, there was one bird less to sing in the woods in the spring and summer.

At last this boy became such a nuisance to all the animals round about, that they determined to punish him in some way or other. They thought the first thing to do was for all of them to meet together and have a good talk about it. In a wood, not far off, there was a nice open space where the ground was smooth and covered with moss. Here they all agreed to come one fine night, for they thought it would be nice and quiet then, and that nobody would disturb them, as, perhaps, they might do in the daytime.

So, as soon as the moon rose, they began to assemble, and I wish you could have been there too, to see them all come, sometimes[4] one at a time, and sometimes two or three together.

The rat was one of the first to arrive, and then came the hare and the rabbit arm in arm, for they knew each other well, and were very good friends. The frog was late, for he had had a good way to hop from the nearest pond, where he lived, so that his cousin, the toad, who was slower, but lived nearer, got there before him. The snake had no need to make a journey at all, for he lived under a bush just on the edge of the open space. All the little birds, too, had gone to roost in the trees and bushes close by, so as to be ready in good time; and, when the moon rose, they drew out their heads from under their wings, and were wide awake in a moment. The rook and the partridge, and other large birds, were there as well, and the squirrel sat with his tail over his head, on the branch of a small fir tree. Then there were weasels, and lizards, and hedgehogs, and slow-worms, and many other animals besides.

In fact, if you had seen them all together, you would have wondered how one little boy could have found time to plague and[5] worry so many different creatures. But you must remember that even a very little boy can do a great deal of mischief. Perhaps there were some animals there that little Tommy Smith had not hurt, because he had not yet seen them, but these came because they knew he would hurt them as soon as he could; and, besides, they were angry because their friends and companions had been ill-treated by him.

At last it seemed as if there was nobody else to come, and that everything was ready. Still, they seemed waiting for something, and all at once a great owl came swooping down, and settled on a large mole-hill which was just in the middle of the open space. Now, the owl, as perhaps you know, is a very wise bird, and, for this reason, all the other animals had chosen him to be the chief at their meeting, and to decide what was best to be done, in case they should not agree amongst themselves. He at once showed how wise he was, by saying that before he gave his own opinion he would hear what everybody else had to say. Then everybody began to talk at once, and there was a great hubbub, until the owl said that[6] only one should speak at a time, and that the hare had better begin, because he was the largest of all the animals there.

So the hare stood up, and said he thought the best way to punish Tommy Smith was for every one of them to do him what harm he could. For his part, he was only a timid animal, and not at all accustomed to hurt people. Still, he had very sharp teeth, and he thought he might be able to jump as high as Tommy Smith’s face and give him a good bite on the cheek or ear, and then run off so quickly that nobody could catch him. The rabbit spoke next, and said that he was just as timid as the hare, and not so strong or so swift. All he could do was to go on digging holes, and he hoped that some day Tommy Smith would fall into one of them. The hedgehog then got up, and said he would hide himself in one of these holes and put up his prickles for Tommy Smith to fall on. This would be sure to hurt him, and perhaps it might even put one of his eyes out. The rat thought it would be better if the hedgehog were to get into Tommy Smith’s bed, so as to prick him all over when he was[7] undressed; but the hedgehog would not agree to this, as he did not understand houses, and thought he would be sure to be caught if he went into one.

“Well, then,” said the rat, “if you are afraid I will go myself, for I know the way about, and am not at all frightened. In the middle of the night, when it is quite dark, and when Tommy Smith is fast asleep, I will creep up the stairs and into his room, and then I can run up the counterpane to the foot of his bed and bite his toes.”

“Why his toes?” said the weasel. “I can do much better than that, and if you will only show me the way into his room, I will bite the veins of his throat, and then he will soon bleed to death.”

“That would be taking too much trouble,” said the adder, coming from under his bush. “You all know that my bite is poisonous. Well, I know where this bad boy goes out walking, so I will just hide myself somewhere near, and when he comes by I will spring out and bite his ankle. Then he will soon die.”

The birds, too, had different things to suggest. Some said they would scratch[8] Tommy Smith’s face with their claws, and others that they would peck his eyes out. The frog wanted to hop down his throat and choke him, and the lizard was ready to crawl up his back and tickle him, if they thought that would do any good.

At length, when everyone else had spoken, the owl called for silence, and then he gave his own opinion in these words:—“I have now heard what every animal has had to say, and I have no doubt that we could easily hurt this boy very much, or perhaps even kill him, if we really tried to. But would it not be a better plan, first to see if we cannot make little Tommy Smith a better boy? Many little boys are unkind to animals because they know nothing about them, and think that they are stupid and useless. If they knew how clever we all of us really are, and what a lot of good we do, I do not think they would be unkind to us any more. I am sure that they would then have quite a friendly feeling towards us. But they cannot know this without being taught. Tommy Smith’s father and mother ought, of course, to teach him, but as they will not do so, why should not we teach him ourselves? To do this, we shall have to speak to him in his own language, as he does not understand ours; but that is not such a difficult matter to us animals. I myself can speak it quite well when I want to, for I often sit on the trees near old houses at night, or even on the houses themselves, and I can hear the conversations coming up through the chimneys. That is why I am so wise. So I can easily teach all of you enough of it to make you able to talk to a little boy. My idea, then, is to teach little Tommy Smith before we begin to punish him, and it will be quite as easy to do the one as the other. Only let the next animal that he is going to kill or throw stones at, call out to him, and tell him not to do so. This will surprise him so much that he will be sure to leave off, and then each of us can tell him something about ourselves in turn. In this way he will get such a high idea of all of us, that he will never annoy us any more, but treat us with great respect for the future.”

“THAT IS WHY I AM SO WISE”

All the other animals thought this was a very clever idea of the owl’s, and they agreed to do what he said, before trying[10] anything else. So they begged him to begin teaching them the little-boy language at once (all except the rat, for he knew it too), so that they should lose no time. This the owl was quite ready to do, and he taught them so well, and they all learnt so quickly, that when little Tommy Smith got up next morning to have his breakfast, there was hardly an animal in the whole country that was not able to talk to him.

CHAPTER II.

THE FROG AND THE TOAD

“Tommy Smith takes a turn in the garden next day,

And he finds the frog ready with something to say.”

AS soon as he had had his breakfast, Tommy Smith went out into the garden. It had been raining a little, and the first thing he saw was a large yellow frog sitting on the wet grass. Tommy Smith had a stick in his hand, and he at once lifted it up over his shoulder.

“Don’t hit me,” said the frog. “That would be a very wicked thing to do.”

Tommy Smith was so surprised to hear a frog speak that he dropped his stick and stood with both his eyes wide open for several seconds.

“Why do you want to kill me?” said the frog.

Tommy Smith thought he must say something, so he answered, “Because you are a nasty, stupid frog.”

“I don’t know what you mean by calling me nasty,” said the frog. “Look[12] at my bright smooth skin, how nice and clean it is—cleaner than your own face, I daresay, although it is not long since you have washed it. As for my being stupid, you see that I can speak your language, although you cannot speak mine; and there are lots of other things which I am able to do, but you are not. I think I can catch a fly better than you can.”

By this time it seemed to Tommy Smith as if it was quite natural to be talking to an animal, so he said, “I never thought that a frog could catch a fly.”

“You shall see,” said the frog. And as he spoke a fly settled on a blade of grass just in front of him. Then all at once a pink streak seemed to shoot out of the frog’s mouth; back it came again—snap! His mouth, which had been wide open, was shut once more, and the fly was nowhere to be seen.

“Have you caught it?” said Tommy Smith.

“Yes,” said the frog, “and swallowed it too.”

“But how did you do it?” said Tommy Smith; “and what was that funny pink thing that came out of your mouth?”

“That was my tongue,” the frog answered.

“Your tongue!” cried Tommy Smith. “But it looked so funny—not at all like my own tongue.”

“No,” said the frog. “My tongue is quite different to yours, and I do not use it in the same way. Hold out your hand so that I can hop into it, and then I will show you all about it.”

Tommy Smith did as he was told, and—plop! there was the frog sitting in his hand. He at once opened his mouth, which was a very wide one, and allowed Tommy Smith to look at his tongue. What a funny tongue it was! It seemed to be turned backwards, for the tip, which was forked, instead of being just inside the lips as it is with us, was right down the throat, whilst the root of it was where the tip of our tongue is.

“But how do you use a tongue like that?” said Tommy Smith.

“Put the tip of your forefinger against your thumb,” said the frog; “only, first, you must turn your hand so that the back of it is towards the ground, and the palm upwards.” Tommy Smith did so.[14] “Now shoot your finger back as hard as you can.” Tommy Smith did this too. “That,” said the frog, “is the way I shoot my tongue out of my mouth when I want to catch a fly. Like this”—and he shot it out again. “You see it flies out like the lash of a whip, and my aim is so good that it always hits what I want it to, whether it is a fly or any other insect. Then I bring it back, just as you would bring your finger back to your thumb again, or as the lash of a whip flies back when you jerk the handle. The tip of it goes right down my throat where it was before, and the fly goes down with it.”

“But why does the fly stay on your tongue?” said Tommy Smith. “Why doesn’t it fly away?”

“It would if it could, of course,” said the frog; “but it can’t. My tongue, you see, is sticky—just feel it,—and so whatever it touches sticks to it, and comes back with it, if it isn’t too large.”

“Well, it is very curious,” said Tommy Smith. “But when you said you could catch a fly, I did not know that you were going to eat it too. Then, do you like flies? and do you eat them every day?”

“I eat them when I can get them,” said the frog; “but I like them better at night than in the daytime, if only I can catch them asleep. You eat during the day, and go to sleep at night. That is because you are a little boy. I am a frog, and we frogs like to be quiet in the daytime, and come out to feed when it is dark. We eat all sorts of insects—beetles, and flies, and moths, and caterpillars, and we eat slugs as well, and that is why we are so useful.”

“Useful?” cried Tommy Smith. “Oh, I don’t believe that! I am sure that a frog can be of no use to anybody.”

“If you were a gardener you would think differently,” said the frog; “at least, if you were not a very ignorant one. Have I not told you that I eat slugs and insects, and do you not know that slugs and insects eat the leaves of the flowers and vegetables in your garden? Have you never seen your father or his gardener pouring something over his rose-trees to kill the insects upon them? Now, I eat a great many insects in a single night, and I am only one of the frogs in your garden. There are others there besides me. If we[16] were all to be killed, your father would find it much more difficult to have nice roses, and he would lose other flowers too, for there are insects which do harm to all of them. As for the slugs, if you will go out some night with a lantern, you may see them feeding on some of the handsomest plants, with your own eyes. That is to say, unless one of us frogs has been there; for if we have, you will not see any. Then you have seen caterpillars feeding on the cabbages. Well, I feed on those caterpillars. So always remember that the boy who kills a frog, does harm to his father’s garden.”

“I don’t want to do that,” said Tommy Smith; “so, if what you say is true”—

“You can find it in a natural history book, if you look,” said the frog; “but I ought to know best myself. And I can tell you this, that when a frog speaks to a little boy, he always speaks the truth.”

“Well, then,” said Tommy Smith, “I will never hurt a frog again.”

How pleased the poor frog was when he heard that. He gave a great hop out of Tommy Smith’s hand, and came down upon the grass again, and then he hopped[17] about for a little while, jumping higher each time than the time before. “Frogs always speak the truth,” he said,—“when they speak to little boys. And now, perhaps, you would like to learn something more about me. Ask me any question you like, and I will answer it, because of what you have just promised.”

This puzzled Tommy Smith a little, because he did not know where to begin, but at last he said, “You seem to me a very big frog. Were you always as big as you are now?”

“Why, of course not,” said the frog, “a frog grows up just as much as a little boy does. I was once so small that you would hardly have been able to see me. But, besides being smaller, I was quite a different shape to what I am now. I had no legs at all, but instead of them I had a long tail, with which I used to swim about in the water, so that I was much more like a fish than a frog, and many people would have thought that I was a fish.”

“That sounds very funny,” said Tommy Smith.

“But were not you once much smaller than you are now?” said the frog.

“Oh yes!” Tommy Smith answered, “but however small I was, I was always a little boy, and had hands and feet, just as I have now.”

“With you it is different,” said the frog; “but there are some animals who are one thing when they are born, but change into another as they grow older. It is so with us frogs, and, if you listen, I will tell you all about it.”

“Go on,” said Tommy Smith, “I should like to hear very much.”

“In the nice warm weather,” the frog continued, “we hop about the country, and then we like to come into gardens. But in the winter we go to ponds and ditches and bury ourselves in the mud at the bottom, and go to sleep there. In the early spring, when the weather begins to get a little warmer, we come up again, and then the mother frog lays a lot of eggs, which float about in the water, and look like a great ball of jelly. After a time, out of each egg there comes a tiny little brown thing, and directly it comes out, it begins to swim about in the water, as well as if it had had swimming lessons, although, of course, it has never had any. It soon[19] grows bigger, and then you can see that it has a large round head and a long tail, but you cannot see any legs. But, as it goes on growing, a small pair of hind legs come out, one on each side of the tail, and then every day the tail gets smaller and the hind legs larger. Still there are no front legs yet, but at last these come too. The tail is now quite short, and the head and body begin to look like a frog’s head and body, which they did not do before, and they go on looking more and more like one, until, at last, the little brown thing with a tail, that swam about like a fish in the water, has changed into a little baby frog, that hops about on the land. Then this little baby frog grows larger and larger, until, at last, he becomes a fine fat frog, as big and as handsome as I am.”

“It all seems very curious,” said little Tommy Smith; “and I never knew anything about it before.”

“That is because nobody ever told you,” said the frog, “and you have never thought of finding out for yourself. But have you not passed by ponds in the spring time and seen those little brown things with[20] tails that I have been telling you about swimming about in them?”

“Oh yes, I have!” said Tommy Smith; “but I always thought that those were tadpoles.”

“They are tadpoles,” said the frog, “but they are young frogs for all that. A little tadpole grows into a big frog, just as a little boy grows into a big man. So you see, what a funny life mine has been, and what a lot of curious things have happened to me.”

“Yes, you have had a funny life, Mr. Frog,” said Tommy Smith, “and I think it is very interesting. But is there any other clever thing you can do besides catching flies? I can catch flies myself, but I do it with my hand instead of with my tongue.”

“I can change my skin,” said the frog, “and that is something which you cannot do.”

“No,” said Tommy Smith; “and I do not believe you can do it either. I think you are only laughing at me.”

“Well,” said the frog, “as it happens, my skin fits me quite comfortably now, and is not at all too tight, so I do not want[21] to change it yet. But I have a cousin—a toad—who is quite ready to have a new one. He lives a little way off, in the shrubbery; so if you would like to see how he does it, I can bring you to him. He is very good natured, like myself, and if you will only promise to leave off hurting him, as well as me, he will be very pleased to show you, I am sure. I must tell you, too, that he is almost as useful in a garden as I am, for he lives on the same things, and catches flies and slugs just as I do.”

“Then isn’t he quite as useful?” said Tommy Smith; but as the frog didn’t seem to hear, he went on with—“Then I will not hurt him any more than I will you.”

“Come along, then,” said the frog; and he began to hop in front of the little boy until they came to the shrubbery, where, in the mould beside a laurel bush, there sat a great, solemn-looking toad.

“I have brought someone to see you,” said the frog. “This is little Tommy Smith, who used to be such a bad boy, and kill every animal he saw; but now he has promised not to hurt either of us.”

“I am glad to hear it,” answered the toad, “and I hope he will soon learn to leave other creatures alone too. Well, what is it he wants?”

“He wants to see you change your skin,” said the frog.

“He had better look at me, then,” said the toad, “for that is just what I am doing.”

Tommy Smith bent down to look, and then he saw that the toad was wriggling about in rather a funny way, as if he was a little uncomfortable. He noticed, too, that his skin had split along the back, and it seemed to be wrinkling up and getting loose all over him, although it had been too tight before. This loose skin was dirty and old-looking, but underneath it, where it was split, Tommy Smith could see a nice new one that looked ever so much better. The more the toad wriggled, the looser the old skin got, and it was soon plain that he was wriggling himself out of it, just as you might wriggle your hand out of an old glove. At last he had got right out of it, and there lay the old skin on the ground.

“You see,” said the frog, “that is how[23] we change our skin, just as you would change a suit of clothes. Does he not look handsome in his new one?”

“Very handsome—for a toad,” said Tommy Smith. (The toad only heard the first two words of this, so he was very pleased.) “But what is he doing with his old skin, now that he has got it off?”

“If you wait a little, you will see,” said the frog.

All this time the toad was pushing his old skin backwards and forwards with his two front feet, and he kept on doing this until, at last, he had rolled it up into a sort of ball. Then all at once he opened his great wide mouth and swallowed the ball, just as if it had been a large pill.

Tommy Smith was so surprised that he could hardly believe his eyes. “He has swallowed his own skin!” he cried.

“Of course I have,” said the toad; “and the best thing to do with it, I think. I always like to be tidy, and not to leave things lying about. Now, good-morning,” and he began to crawl away, for he was not an idle toad, but had business to attend to.

“And I have something to see about,[24]” said the frog, “so I will say good-bye, too, for the present. But remember what you have promised—never to hurt a frog or a toad;” and, with two or three great hops, he was out of sight.

Tommy Smith stood thinking about it all for some time, and then he ran into the house to tell everybody all the wonderful things he had learnt about frogs and toads, and to beg them never to kill any, because they do good in the garden.

CHAPTER III.

THE ROOK

“The rook gives advice which we must not neglect.

I hope that his CAWS will produce an effect.”

IT was a nice, fine afternoon, and Tommy Smith was just going out for a little walk. He thought he would take his little terrier dog with him, so he called, “Pincher! Pincher!” But Pincher was not there, so he had to go without him. He was very sorry for this, for when he had got a little way from the house, what should run across the road but a rat, which sat down just inside the hedge and looked at him. “What a pity,” he said out loud. “It’s no use my trying to catch him alone, for he’s sure to get away; but if Pincher had been with me, we would have hunted him down together.”

“Then you would have done very wrong,” said the rat, as he peeped at little Tommy Smith through the hedge. “You are a naughty boy yourself, and you teach Pincher to be a naughty dog.”

“What!” said Tommy Smith; “then can you talk as well as the frog and toad?”

“Of course I can,” the rat answered; “and I think if I were to talk to you for a little while as they did, you would not wish to hurt me any more either. I am sure I am just as clever as a frog or a toad.”

“Can you change your skin like them?” said Tommy Smith.

“My skin never wants changing,” said the rat; “but there are many other things I can do which are quite as clever as that.”

“Well, do some of them,” said Tommy Smith.

“I will,” said the rat, “but not now. I can do things much better at night, and I prefer being indoors. To-night, when everybody is in bed and asleep, and the house is quiet, I will come to your room and wake you up. We can talk without being disturbed then, and I will soon teach you what a clever animal I am.”

“I wonder what you will have to tell me,” said Tommy Smith. “But say what you will, I believe that rats were only made to be killed.”

The rat looked very angry. “They have[27] as much right to be alive as little boys have,” he said. “But good-bye for the present,” and he scampered away.

Tommy Smith walked on, and when he had gone some little way, he saw a number of rooks walking about a field. There was a haystack in the field, and he thought that perhaps if he were to get behind it and wait there for a little while, some of the rooks would come near enough for him to throw a stone at them. So he put several stones in his pocket, and then, with one in his hand, he began to walk towards the haystack. When he got there, he sat down behind it, and peeped cautiously round the corner. Yes, the rooks were still there, and some of them were coming nearer. “Oh,” thought Tommy Smith (but I think he must have thought it aloud), “I have only to wait a little while, and then, perhaps, I shall be able to kill one.”

“For shame!” said a voice close to him.

Tommy Smith looked all about, but he saw no one. “Who was that?” he said.

“Oh, fie!” said the voice. “What? kill a poor rook? What a wicked, wicked thing to do!”

Tommy Smith thought that there must be someone on the other side of the haystack,[28] so he went there to see; but he found no one. Then he walked all round it, but nobody was there. But the rooks had seen him as he went round the haystack, and they all flew away. Then the same voice (it was rather a hoarse one) said, “Ah! now they are gone; so you will not be able to kill any of them.”

“Who are you?” said Tommy Smith. “I hear you, but I cannot see anybody;” and, indeed, he began to feel rather frightened.

“If I show myself, will you promise not to hurt me?” said the hoarse voice.

“Yes, I will,” said Tommy Smith.

“Very well, then. Throw away that stone you have in your hand, and the ones in your pocket as well.”

Tommy Smith did this, and then, what should he see, standing on the very top of the haystack, but a large black rook. “Why, where were you?” he said. “I did not see you there when I looked.”

“No,” the rook said; “I hid myself under a little loose hay, for I did not want a stone thrown at me. I saw you coming, and I knew very well what you wanted to do, so I thought I would wait till you came,[29] and then give you a good talking to. And, indeed, a naughty boy like you, who wants to kill rooks, ought to be scolded.”

“I don’t see why it is so naughty,” answered Tommy Smith; “I have always thrown stones at the rooks, and nobody has ever told me not to.”

“That is just why I have come to tell you how wrong it is,” said the rook. “Would you like anybody to throw stones at you?”

Tommy Smith had to confess that he would not like that at all.

“Then, do you not know,” the rook went on, looking very grave, “that you ought to do the same to other people that you would like other people to do to you? Have not your father and mother taught you that?”

“Oh yes, they have,” said Tommy Smith; “but I don’t think they meant animals.”

“They ought to have meant them,” said the rook, “whether they did or not, for animals have feelings as well as human beings. If you are kind to them, they are happy; but if you are unkind to them and hurt them, then they are unhappy. An animal, you know, is a living being like[30] yourself, and surely it is better to make any living being happy than to make it unhappy.”

Tommy Smith looked rather ashamed when he heard this, and did not quite know what to say. He thought the rook spoke as if he were preaching a sermon, and then he remembered having heard some old country people talk of “Parson Rook.” Still, what he said seemed to be sensible, and all he could say, at last, as an answer was, “Oh, it’s all very well, but you know you rooks do a great deal of harm.”

“That shows how little you know about us,” answered the rook. “We do not do harm, but good; and if the farmers knew how much good we did them, they would think us their best friends.”

“Why, what good do you do them?” said Tommy Smith. “I always thought that you ate their corn.”

“Perhaps we may eat a little of it,” the rook said; “that is only fair, for if it were not for us, the farmer would have very little corn or anything else. I am sure, at least, that he would have scarcely any potatoes.”

“Oh! but why wouldn’t he?” said Tommy Smith.

“I will explain it to you,” said the rook. “So now listen, because you are going to learn something. There is an insect which you must often have seen, for it is very common in the springtime. It is about the size of a very large humble-bee, and it has wings too, but you would not think it had at first, for they are hidden under a pair of smooth, brown covers, which are called shards. In the daytime it sits upon a tree or a bush, or sometimes you may see it crawling along a dusty road. But in the evening it begins to fly about with a humming noise. This insect is called the cockchafer. The mother cockchafer lays her eggs in the ground, and, after a few weeks, there comes out of each egg something which you would not think was a cockchafer at all, because it is so different. It has a yellow head and a long white body, which is bent at the end in the shape of a hook. On the front part of its body it has three pairs of legs, like a caterpillar’s, only they are very small; but behind, it has no legs at all. It has a very strong pair of jaws, and with these it cuts through the roots of the grass and corn and wheat under which it lies, for these are the things[32] on which it feeds. There is hardly anything which the farmer plants, and would like to see grow, that this grub or caterpillar (for that is what it is) does not eat and destroy; but what it likes best of all is the potato.

“The cockchafer-grub lies in the ground for four years before it turns into a real cockchafer, and all this time it keeps growing larger and larger; and, of course, the larger it grows, the more it eats and the more harm it does. Now if there were no one to kill this great, greedy thing, I don’t know what the farmers would do, for all their crops would be spoilt. But we rooks kill them, and eat them too, for they are very nice, and we like them very much. We eat them for breakfast, and dinner, and supper, so you can think what a lot of them we eat in the day. When you see us walking about over the fields, we are looking for these great white things, and, whenever we give a dig into the ground with our beaks, you may be almost sure that we have either found one of them or something else which does harm too. When the fields are ploughed, a great many grubs and worms are turned up by[33] the ploughshare, and then you may see us following the plough, and walking along in the furrow it has made, so as to pick up all we can get. So think what a lot of good we must do, and remember that the boy who kills a rook is doing harm to somebody’s corn, or wheat, or potatoes.”

“I do not want to do that,” said Tommy Smith.

“Of course not,” said the rook; “so you must not throw stones at us any more.”

“I won’t, then,” said Tommy Smith. “But why do the farmers shoot you, if you do them so much good?”

“You may well ask,” the rook answered. “They ought to be ashamed of themselves. I will tell you something about that. Once upon a time some farmers thought they would kill us all because we stole their corn; so they all went out together with their guns, and whenever they saw any of us, they fired at us and killed us, until, at last, there was not a rook left in the whole country; for all those that had not been shot had flown away. The farmers were so glad, for they thought that next year they would have a much better harvest. But they were quite wrong, for,[34] instead of having a better harvest, they had hardly any harvest at all. The slugs and the caterpillars, and, above all, the great, hungry cockchafer-grubs, had eaten almost everything up; for, you see, there were no hungry rooks to eat them. The little corn we used to take from the farmers they could very well have spared, but now, without us, they found that they had lost much more than they could spare. Then the farmers saw how foolish they had been, and they were very sorry, and did all they could to get the rooks to come back again; and when they did come back, they took care not to shoot them any more.”

Tommy Smith was very interested in this story which the rook told him, and he was just going to ask where it all happened, and whether it was near where he lived or a long way away, when the rook said, “Well, I must be flapping” (just as an old gentleman might say, “Well, I must be jogging”); “there is a meeting this afternoon which I ought to attend.”

“A meeting!” Tommy Smith said, feeling quite surprised.

“Certainly,” replied the rook. “Why not? I belong to a civilised community,[35] so, of course, there are meetings. I should be sorry not to go to some of them.”

It seemed very funny to Tommy Smith that birds should have meetings as well as men. “But, perhaps,” he thought, “it is not quite the same kind of thing.” Only he didn’t like to say this, in case the rook should be offended, so he only asked, “What sort of a meeting is it that you are going to, Mr. Rook?”

“A very important one,” the rook answered. “It is a meeting to try someone who is accused of having done something wrong.”

“Why, then, it is a trial,” said Tommy Smith. “But do rooks have trials?”

“Of course,” said the rook. “Have I not just said that we are a civilised community? We are not wild birds. Amongst civilised people, when someone is accused of doing wrong, he is tried for it, is he not?”

“Oh yes!” said Tommy Smith. “If he is a man, he is.”

“If he is a man, men try him,” said the rook; “but if he is a rook, rooks do.”

“But what do you do if you find him guilty?” said Tommy Smith.

“Why, we punish him, to be sure,” said the rook; “and if he has been very wicked, we peck him to death.”

“Oh, but that is very cruel,” said Tommy Smith. He forgot that he had seen innocent rooks shot without thinking it cruel at all.

“Not more cruel than hanging a man,” the rook answered. “Do you think it is?” and Tommy Smith couldn’t say that he did. He thought he would very much like to see this trial that the rook was going to. “Oh, Mr. Rook,” he said, “do let me go with you.” But the rook said, “Oh no! that would never do. No men are allowed at our trials. There are no rooks at yours, you know.”

“No,” said Tommy Smith; “but that is because”—

“Never mind why it is,” interrupted the rook; “no doubt there is some good reason, and we have our reasons too. We could not try a rook properly if we thought a man was watching us. It would make us nervous. Sometimes (but not very often) a man has watched us without our knowing it, and then he has told everybody about our wonderful[37] trials. But people have not believed him; and other men, who sit at home and see very little, and only believe what they see, have written to say it was all nonsense. But now, when they tell you it is all nonsense, you will not believe them, because a rook himself has told you it is all true.”

“Oh yes, and I believe it,” said Tommy Smith. “But do tell me what the rook you are going to try has done.”

“I cannot tell you that till we have tried him,” said the rook, “for perhaps it may not be true after all. As yet, I do not even know what he is accused of. Perhaps it is of stealing the sticks from another rook’s nest to make his own with. Perhaps it is of something even worse than that. But this you may be sure of, that if we do peck him to death, it will be because he has behaved himself in a manner totally unworthy of a rook. Now I really must go, or I shall be late. Good-bye,—and, let me see, I think you promised never to throw stones at rooks again.”

“Oh no!” said Tommy Smith, “I promise not to.”

“Or to shoot us when you grow up,” said the rook, just turning his head round as he was preparing to fly.

“Oh no! indeed, I won’t,” said Tommy Smith; and the rook flew away with a loud caw of pleasure.

“I SHALL KEEP AWAKE TILL THE RAT COMES”

CHAPTER IV.

THE RAT

“The rat is a king. Tommy Smith has a peep

At his palace: but is he awake or asleep?”

“I SEE you,” said the rat, as Tommy Smith passed through the yard of his father’s house. “I see you, but it is not the right time yet. Wait till to-night.”

So all that day Tommy Smith kept thinking of what the rat had promised; and when his bedtime came, instead of wanting to stay up longer, as he usually did, he was quite pleased to go, and went upstairs without making any fuss. “Now,” thought he, as he made himself nice and snug in bed, “I shall keep awake till the rat comes. I am not at all sleepy. I can see the branch of the cedar tree by the window shaking in the wind, and I can hear the clock ticking on the staircase. ‘Tick, tick—tick, tick,’—I wonder if it gets tired of saying that all day long, and all night long, too, without ever once stopping,—unless they don’t[40] wind it up. ‘Tick, tick—tick, tick.’ If I keep on counting it, I shan’t go to sleep. ‘Tick, tick—tick, tick—tick, tick—tick—squeak!’”

“What was that?” said Tommy Smith, as he sat up in bed. “That wasn’t the clock;” and then, all at once, the old clock on the stairs struck one. “One? Then it must be wrong. When I got into bed it was only”—

“It is quite right,” said a squeaky little voice close to Tommy Smith’s ear, “I don’t know what time it was when you got into bed, but you have been asleep for a good many hours; and now it is one in the morning, which is what I call a nice, comfortable time.”

“I suppose you are the rat,” said Tommy Smith, rubbing his eyes.

“Yes, I am,” the same voice answered. “But it is too dark for you to see me here. Get up, and put on some of your clothes, and then we will come down to the kitchen. The fire is not quite out, and you can put a few more sticks on it. Then you will be able to see me as well as I can see you now, and we can talk together comfortably.”

PAT, PAT, PAT. “DO YOU HEAR?”

“But can you see in the dark?” said Tommy Smith, whilst he sat on the bed and began to put on his stockings.

“Oh yes,” the rat answered; “just as well as I can in the light.”

“I wish I could,” said Tommy Smith, “for I can’t see you at all.”

“Of course not,” said the rat. “So, you see, it has not taken a very long time to find out something which I can do, but you can’t. Well, you are ready now, so come along. You will be able to follow me, for I will pat the floor just in front of you with my tail,—and that is another thing which you couldn’t do, even if you were to try for a very long time.”

“Because I haven’t got a tail,” said Tommy Smith.

“That is one reason,” the rat answered; “but you can’t be sure you could do it even if you had one. It might be too short, you know. Now, come along.” Pat, pat, pat. “Do you hear?”

Tommy Smith heard quite plainly, and he followed the rat through the door, and down the stairs, and right into the kitchen. The fire was still alight, as the rat had said.[42] There were some sticks lying in the fender, and Tommy Smith put some of them on to make it burn up. Then there was a blaze of light, and he could see the rat sitting up on his hind legs, and holding his front paws close to the bars so as to warm them.

“Now,” the rat said, “we will begin at once. I promised to show you that I could do some clever things as well as the frog and toad. Do you see that bottle of oil standing there on the dresser?”

“Oh yes, I see it,” said Tommy Smith.

“Well,” the rat went on, “I should like to taste a little of it. But how do you suppose I am to get at it?”

“Why, by knocking it over,” said Tommy Smith at once. “That is the only way that I can see.”

“Fie!” said the rat. “That may be your way of drinking oil, but I should be ashamed to make such a mess. I am a rat, and I like to do things in a proper manner.”

Tommy Smith felt a little offended at this, and he said, “I never knock a bottle over when I want to get oil or anything else out of it, for I am a little boy, and[43] have a pair of hands to lift it up with, and pour what is in it out of it. But you have no hands, and you cannot get your head into it, because the neck is too narrow, and your tongue is not long enough to reach down to where the oil is. So I don’t see what you can do, unless you knock it over.”

“Fie!” said the rat again. “Well, you shall soon see what I can do.” And almost as he said this, he was on the dresser, and from there he gave a little jump on to the window-sill, and sat down, with his long tail hanging over the edge of it. Now the neck of the bottle came almost up to the edge of the window-sill, and the rat’s tail was as long as the bottle.

“Oh, I see!” cried Tommy Smith.

“You will in a minute,” said the rat, and he drew up his tail, and began to feel about with the tip of it till he had got it right inside the mouth of the bottle. Then he let it down again until it was dipped more than an inch deep into the oil at the bottom—for the bottle was not quite half full.

“Oh, how clever!” cried Tommy Smith, clapping his hands.

“I should think so,” said the rat, as he drew out his tail, and then, putting the end of it to his mouth, he began to lick off the delicious oil. “You say that I have not a pair of hands,” he went on. “That is true, but you see I have a tail, and I make it do just as well.”

“So you do,” said Tommy Smith; “and I see that you are a very clever animal indeed.”

“We are clever in many other ways besides that,” said the rat. “Oil, you know, is not the only thing which we care about. We like eggs for breakfast, just as much as you do, and when we find any, we take them to our holes, even if they are a long way off. Now, how do you think we do that?”

“Let me see,” said Tommy Smith. “You have no hands, and I don’t think you could carry an egg in your tail. I think you must push it in front of you with your nose and paws.”

“Oh, we can do that, of course,” said the rat, “but it takes so long, and, besides, the eggs might get broken. We have better ways than that. Sometimes, if there are a great many of us, we all sit in a row, and[45] pass the eggs along from one to the other in our fore-paws. But we have another way which is cleverer still, and as there is a basket of eggs in that cupboard there, I don’t mind showing it you; for, between ourselves, when we do that trick, we like to have a little boy in the kitchen at nights to look at us. But, first, I must call a friend of mine.” The rat then gave rather a loud squeak, and out another rat came running; but Tommy Smith didn’t see where it came from.

“What is it?” said the second rat.

“Oh, I want to show little Tommy Smith how we carry eggs about,” said the first rat.

“Very well,” said the second rat. “Come along.” And they both scampered into the cupboard together. (The door of the cupboard was half open. I think it ought to have been shut.)

Very soon the two rats came out again, but whatever do you think they were doing? Why, one of them was on his back, and the other one was dragging him along the floor by his tail, which he had in his mouth. But what was that white thing which the rat who was being dragged[46] along was holding? Was it an egg? Yes, indeed it was; and he was holding it very tightly with all his four feet, so that it was pressed up against his body, and didn’t slip at all.

Tommy Smith could hardly believe his eyes. “Is that how you do it?” he cried. “I see. One rat holds the egg, and the other pulls him along by the tail.”

“Of course he does,” said the rat. “He pulls him and the egg too.”

“Well,” Tommy Smith said, “of all the clever things I have ever seen, I think that is the cleverest. But where are you going with it?”

Yes, it was easy to ask, but there was no one to answer him; for both the little rats were gone all of a sudden,—and, what is more, the egg was gone too. “That will be one egg less for breakfast,” thought Tommy Smith to himself. “I wonder that I didn’t think of that before. Ah, Mr. Rat,” he called out, “you may be very clever, but you are a thief, for all that. That egg which you have just taken away belongs to me. I mean it belongs to my father and mother. I call that stealing.”

“Oh, do you?” said the rat, for he had[47] come out of his hole again. “Then just let me ask you one question. Who laid that egg?”

“Why, the hen did, of course,” answered Tommy Smith.

“Oh, did she?” said the rat. “Then I suppose your father, or someone else, took it away from her, and I call that stealing.”

“Oh no,” said Tommy Smith; “I don’t think it is.”

“Don’t you?” said the rat. “Well, you had better ask the hen what she thinks. I feel sure she would agree with me.”

Tommy Smith felt certain that the rat was wrong, and that the egg had not been stolen. Still, he thought he had better not ask the hen; and, whilst he was considering what he should say, the rat went on with—“There are other things we rats do which are quite as clever as what you have just seen. But, perhaps, if I were to show them you, you would make some other rude remark about stealing.”

“Perhaps I should,” Tommy Smith answered; “and, besides, I feel very sleepy, and should like to go upstairs to bed again.”

As he said this, he yawned, and looked[48] straight into the fire; but, dear me, what was happening there? The coals in it seemed to be getting larger and larger, till they looked like the sides of great red mountains, and the spaces between them were like great caves, so deep that Tommy Smith could not see to the bottom of them. In and out of these caves, and all down the sides of the red mountains, hundreds of rats were running, and they all met each other in the centre of—what? Not of the fireplace. Of course not, for they would have been burnt. Nor of the kitchen either. There was no kitchen now. It had all disappeared. It was in the centre of a great hall, or amphitheatre, that Tommy Smith stood now; and when he looked round him, he saw only those great rugged mountains, which seemed to make its walls on every side. He looked up but he could see nothing. There was neither sun, nor moon, nor stars, yet everything was lit up with a strange light, which seemed to Tommy Smith like the red glow of the fire, though he couldn’t see the fire any more. It had gone with the kitchen.

“Where am I?” he cried.

“In the great underground store-cupboard of the rats,” said a voice close beside him; and, looking round, he saw the same rat who had come up into his bedroom, and taken him down to the kitchen, and shown him his clever tricks.

Yes, he was the same rat,—but how different he looked! On his head was a yellow crown, which was either of gold, or else it must have been cut out of a cheese-paring; and in his right fore-paw he held his sceptre, which looked exactly like a delicate spring-onion. He had a necklace of the finest peas round his neck, from which a lovely green bean hung as a pendant upon his breast, and his tail was twisted into beautiful rings. “I am the king of the rats,” he said, “and all the other rats are my subjects. Those great caves which you see in the sides of the mountains are so many passages that lead into all the kitchens of the world. Through them we bring all the good things that we find in the kitchens, and larders, and pantries, and then we feast on them here in our own palace; for a rat’s palace is his store-cupboard. See!” And with this the rat king struck his sceptre on the[50] ground, and at once all the rats left off scampering about, and formed themselves into a great many long lines, which stretched from the mouths of all the caves right into the very middle of that wonderful place. There they all sat upright, side by side, waiting to be told what to do. Then the king of the rats waved his sceptre three times round his head, and called out, “Supper.” Immediately all kinds of things that are good for rats to eat, such as bits of cheese, scraps of bread or toast, beans, onions, bacon, potatoes, apples, biscuits,—everything of that kind that you can possibly think of (besides some things that you can’t possibly think of), began to pour out from all the great caves, and to fly like lightning from rat to rat down all the long lines. One rat seized something in his fore-paws and passed it on to another, and that one to the next, so quickly that it made Tommy Smith quite giddy to look at it; and he hardly knew what was happening, till all at once there was an immense heap of provisions piled up in the very centre of the floor. Then the king of the rats climbed up to the top of the heap, and called out, “Take your places,” and in a moment all the other rats came scampering up, and sat in a large circle round the great heap of provisions. “Begin!” said the king; and every rat made a leap forward, and fixed his teeth into the first piece of bread, or cheese, or toast, or bacon, that he could get hold of, and there was such a noise of nibbling, and gnawing, and scratching, and squeaking. Tommy Smith was quite frightened, and put his fingers to his ears.

“BITE HIM!”

“What are you doing that for?” said the king of the rats. “Didn’t you hear me tell you to begin?”

“But I don’t want to begin,” said Tommy Smith.

“Why not?” said the king; and all the other rats stopped eating, and said, “Why not?”

“Because I don’t like eating in the night,” Tommy Smith answered; “and, besides, I can’t eat what rats eat.”

At this there was a great commotion, and the king of the rats cried out, “Bite him!” in a very loud and shrill voice.

Oh, how fast little Tommy Smith ran! “The caves!” he thought. “They lead to[52] all the kitchens of the world, so one of them must lead to ours.” He got to one, but the rats were close behind him. He could see their eyes shining in the dark as he looked back. “Oh dear!” he said; “I shall be caught. It’s getting narrower and narrower, and, of course, it must be a rat’s hole at the other end. Ah, there! I’m stuck, and I shall be bitten all over.” As he said this, he kicked and squeezed as hard as he could, and, to his great surprise, he found that the sides of the rat-hole were quite soft—in fact, they felt very like bedclothes; and the next moment his head was on his own pillow, and the old clock on the staircase struck two.

“Well, good-night,” said a squeaky little voice, that he seemed to have heard before. “If you will go to sleep, I can’t help it, but I think the way in which little boys turn night into day is quite dreadful.”

The next time Tommy Smith heard the old clock on the stairs, it was striking eight, so, of course, it was broad daylight, and high time to get up. “What a funny dream I have had,” he said, as he rubbed his eyes; “or did the rat really come, as he said he would?” Then, after thinking[53] a little, he said to himself, “Rats are certainly very clever animals, and I don’t think I’ll kill another, even if they do steal a few things. At anyrate, I won’t hurt them until they hurt me.”

CHAPTER V.

THE HARE

“When you’ve read through this chapter, I’m sure you’ll declare

That you hate everybody who hunts the poor hare.”

WHAT a beautiful day it was!

How bright the sun shone, and how pleasantly the birds were singing,—for it was the lovely season of spring. All the air was full of melody, so that it seemed to Tommy Smith as if he had somehow got inside a very large musical box, which would keep on playing. And so he had, really, only it was Nature’s great musical box,—the music was immortal, and the works were alive.

Far up in the sky the lark was doing his very best to please little Tommy Smith and everybody else, for he made whoever heard him feel happier than they had felt before. But what was little Tommy Smith doing to show how grateful he was to the bird that gave him so much pleasure? Why, I am sorry to say that he was trying to find the poor[55] lark’s nest, so that he might take away the eggs which were in it,—those eggs which the mother lark had been taking so much trouble to keep warm, so that little baby larks might come out of them, which she meant to feed and take care of till they were grown up, and could fly and sing like herself. It was the thought of those eggs, and of the mother bird sitting upon them, which made the lark himself sing so gladly up in the air, for, when he looked down, he fancied he could see them; and he knew that there was someone waiting for him there who would be glad to see him again, when he came down to roost. But Tommy Smith did not think of this, for nobody had talked to him about it. All he thought of was how he could get the eggs, so that he could take them away with him, and show them to other boys.

Ah! what was that? How gracefully the cowslips waved, and up went a lark into the sky; and as he rose he seemed to shake a song out of his wings. Tommy Smith thought there was sure to be a nest close to where he had risen, so he went to look; but before he had got to the[56] place, away went something—something brown like a lark, but ever so much larger, and, instead of flying, it galloped along over the ground; so, you see, it was not a bird at all. What was it? Tommy Smith knew well enough, for he had often seen such an animal before. “Ha!” he cried. “Puss! puss! A hare! a hare!” and he sent the stick which he had in his hand whizzing after it; but, I am glad to say, he did not hit it.

The hare did not seem so very frightened. Perhaps he knew that he could run away faster than any stick thrown by a little boy could come after him. At anyrate, before he had gone far, he stopped, and then he turned round, and raised himself right up, almost on his hind legs, and looked back at Tommy Smith.

“Well,” he said, as Tommy Smith came up; “you see you cannot catch me.”

“No,” said Tommy Smith—he was getting quite accustomed to having talks with animals,—“you run too quickly.”

“For my part,” said the hare, “I wonder how any little boy who has a kind heart can like to tease and frighten a poor, timid[57] animal who is persecuted in so many ways as I am.”

“What do you mean by ‘persecuted’?” said Tommy Smith. “That is a word which I don’t understand. It is too long for me.”

“It is a great pity,” the hare went on, “that a little boy should always be doing something which he does not know the word for. To ‘persecute’ people is to be very cruel to them, and whenever you hurt, or annoy, or frighten, or ill-treat any of us animals, then you are persecuting us.”

“If I had known that,” said Tommy Smith, “I would not have done it.”

“Then you mustn’t do it any more,” said the hare; “and especially not to me, because I have so many enemies who are always trying to injure me.”

“Why, what enemies have you?” said Tommy Smith.

“Plenty,” the hare said. “First, there is that wicked animal the fox, who is always ready to kill and eat me whenever he has the chance. He is very cunning, and, as he knows he cannot run fast enough to catch me, he tries all sorts of ways to pounce upon me when I am[58] not expecting it. Sometimes he will wait by a hole in the hedge that he has seen me go through, and when I come to it again, he springs out and seizes me with his teeth and kills me, for he is much stronger than I am. Then sometimes one fox will chase me past a place where another fox is hiding, and then the fox that was hiding jumps out at me, and they both eat me together.”

“How wicked!” said Tommy Smith.

“Is it not?” said the hare. “And then there is that horrid little creature the weasel. He follows me about till he catches me, and then he bites me in the throat, so that I bleed to death.”

“That is horrid of him,” said Tommy Smith. “But there is one thing which I cannot understand. The weasel does not go so very fast, and you can run faster than a horse. I am sure that if you were to run away, he would never be able to catch you.”

“You don’t know what it is,” said the hare. “That odious little animal follows me about, and never leaves off. You see, wherever I go I leave a smell behind me.”

“Do you?” said Tommy Smith. “That[59] seems very funny. Why, I am close to you, and I don’t smell anything.”

“Little boys cannot smell nearly as well as animals,” said the hare. “However, I don’t quite understand it myself, for I am sure I am as clean as any animal can be, and there is nothing nasty about me; and yet whenever my feet touch the ground, they leave a smell upon it. That is my scent; but other animals have their scent too as well as I, so I needn’t mind about it. Now the weasel has a very good nose, so that he is able to follow the scent that I have left on the ground, until he comes to where I am; and, besides, when I know that that cruel little animal is following me, I get so frightened that I cannot run away, as I would from you, or from a fox, or a dog. And so he comes up and kills me.”

“Poor hare!” said Tommy Smith. “I feel very sorry for you. I am afraid that you are not clever like other animals, or else you would escape and get away more often. The rat would run down a hole, I am sure, and so would the rabbit. I have often seen him do it.”

“Pray do not compare me to the rabbit,[60]” said the hare. “I have twice as much sense as he has, and I can tell you that you make a great mistake if you think I am not clever, for I am very clever indeed, as I will soon show you. If you will follow me a few steps, I will take you to the place where I was lying when you frightened me out of it. See, here it is. Look how nicely the grass is pressed downward and bent back on each side, so that it makes a pretty little bower for me to rest in when I am tired of running about. That is better, I think, than a mere hole in the ground; and, for my part, I look upon burrowing as a very foolish habit. I prefer fresh air, and I think that it is much nicer to see all about one than to live in the dark. This little bower of mine is what people call my form, and I am so fond of it that, however often I am driven away, I always come back to it again. And now, how do you think I get into this form of mine? I have told you that wherever I go I leave a scent upon the ground, so if I just came to my form and walked into it, any animal that crossed my scent would[61] be able to follow it till he came to where I was. Now, what do you think I do to prevent this?”

“I don’t know,” said Tommy Smith, after he had thought a little; “I don’t see how you can prevent it, for you must come to your form on your feet,—you cannot fly.”

“No,” said the hare; “but I can jump. Look!” And he gave several leaps into the air, which made Tommy Smith clap his hands and call out, “Bravo! how well you do it!”

“Now,” said the hare, “when I am coming back to my form, I leap first to this side and then to that side, and then I make a very big jump indeed, and down I come in my own house. Of course, by doing this, I make it much more difficult for a fox or a weasel to smell where I have been, for it is only where my feet touch the ground that I leave my scent upon it.”

“Ah, I see,” cried Tommy Smith; “so, when you make long jumps, your feet will not touch the ground at so many places as they would if you only just ran along it.”

“Of course not,” said the hare.

“And then there will not be so many[62] places for a dog or a fox to smell where you have been,” said Tommy Smith.

“Not nearly so many,” said the hare; “that is the reason why I do it. I hope you think that quite as clever as just running down a hole, which is what the rat and the rabbit do.”

“I think it very clever, indeed,” said Tommy Smith; “and I see now that you are a clever animal.”

“I have other ways of escaping when I am chased,” the hare went on; “and I think, when you have heard them, you will confess they are quite as clever as anything which that conceited animal, the rat, has shown you. As to the rabbit, I say nothing. He is a relation of mine, and we have always been friendly. But the brains are not on his side of the family.”

“Please go on, Mr. Hare,” said Tommy Smith. “I should like to hear all you can tell me.”

ALL HAPPY (EXCEPT THE HARE)

“Well,” the hare said, “I have told you about the fox and the weasel, but they are not my only enemies. I have others—horses and dogs, and, worst of all, hard-hearted men and women, who ride the horses, and teach the dogs to run after me, and to catch me. It is a pretty sight to see them all meet together in some field or lane. First one rides up, and then another, until there are quite a number. They laugh and talk whilst they wait for the huntsman to come with his pack of hounds. All are merry and light-hearted; even the horses neigh, they are in such spirits. Does it not seem funny that one creature’s wretchedness should make so many creatures happy? And there are women—ladies, some of them quite young, and so pretty—like angels. I have seen them smile as if they could not hurt any living thing. You would have thought that they had come to stroke me, instead of to hunt me to death. But I know better. They are not to be trusted. They have soft cheeks, and soft eyes, and soft looks, but their hearts are hard.

“At last, up comes the huntsman, in his green coat and black velvet cap. He cracks his whip, and the dogs leap and bark around him—such a noise! I hear it all as I lie crouched in my form, and my heart beats with terror. But I cannot lie there long, for now they are coming towards me. I start up, and run for my life. Away I go, one poor, timid animal, who[64] never hurt anyone, and after me come men and women, boys and girls, horses and dogs, all happy, and all thinking it the finest thing in the world to hunt and to kill—a hare.”

“Are the dogs greyhounds?” said Tommy Smith.

“No,” answered the hare; “the dogs I am talking about now are not greyhounds, but beagles. They hunt me by scent, but the greyhound hunts me by sight, for he runs so fast that he can always see me.”

“Does he run as fast as you do?” asked Tommy Smith.

“Yes, indeed,” said the hare; “he runs much faster, but he does not always catch me, for all that. When he is close behind me, I stop all of a sudden, and crouch flat on the ground. The greyhound cannot stop himself so quickly, for he is not so clever as I am. He runs right over me, and it is several seconds before he can turn round again. But I turn round as soon as he has passed me, and then I run as fast as I can the other way, so that, when he starts after me again, he is a good way behind. When he catches up to me, I do the same thing again. This clever trick of mine is[65] called doubling, and I am so proud of it, for if it was not for that, the greyhound would catch me directly.”

“Then does he never catch you?” said Tommy Smith.

“He never has yet,” said the hare. “But I have other ways of getting away from him, as well as from other dogs, and I will tell you some of them. Sometimes I run under a gate. The dogs are too big to do this, so they are obliged to jump over it. Then, when they are near me, on the other side I double, in the way I told you, run as fast as I can back to the gate, and go under it again. Of course they have to jump over it a second time, and in this way I keep running under the gate and making them jump over it until they are quite tired, for, of course, it is more tiring to jump over anything than only to run under it. At last, when they are too tired to run any more, I slip quietly through a hedge and gallop away.”

“Bravo!” cried Tommy Smith.

The hare looked very pleased, and said, “I see that you are not at all a stupid boy, so I will tell you something else. Now, supposing you were being chased across[66] the fields by a lot of dogs, and you were to come to a flock of sheep, what would you do?”

Tommy Smith thought a little, and then he said, “I think I should call out to the shepherd and ask him to help me.”

“Yes, and I daresay he would help you,” said the hare, “for he would remember the time when he was a little boy, and he would feel sorry for you. But he would not feel sorry for me, who am only a little hare (he was never that, you know). He would throw his stick at me, as you did, and then he would do all he could to help the dogs to catch me. No, it is not the shepherd that I should ask to help me, but the sheep—they are so gentle,—and when I came to them I should run right into the middle of them, and then the dogs would not be able to find me.”

“But would not the dogs follow you in amongst the sheep and catch you there?” said Tommy Smith.

“No,” said the hare, “they would not be able to; for the flock would keep together, so that the dogs could only run round the outside of it. But I should[67] keep right in the middle, and wherever the sheep went, I should go with them; I could run between their feet, you know. Besides, the dogs would not be able to see me amongst so many sheep.”

“No,” said Tommy Smith. “But could not they still follow you by your scent?”

“No, indeed, they could not,” said the hare; “for, you see, sheep have a stronger scent than I have, and they would put down their feet just in the very place where I had put down mine, and then their scent would hide mine. So, you see, by hiding amongst a flock of sheep I should save my life, for the dogs would not be able either to see me, or smell me, or to follow me, even if they could.”

“Have you ever done it?” said Tommy Smith.

“Oh yes!” said the hare; “and there is something else which I have done. Sometimes when the dogs were chasing me, I have run to where I knew another hare was sitting, and I have pushed that hare out of his place, so that the dogs have followed him instead of me. I sat down where he had been sitting, and they all went by without finding it out.”

“Well,” said Tommy Smith, “that may have been very clever, but I don’t think it was at all kind to the other hare.”

The hare looked a little surprised at this, as if he had not thought of it before. “One hare should help another, you know,” he said; “and, besides, I daresay the dogs did not catch him after all. He may have found another hare.”

Tommy Smith was just beginning with “Oh, but”—when the hare said, “Never mind!” rather impatiently, and then he continued, “And now I am going to tell you something which will show you that, although I am not a large or a fierce animal, I can sometimes be revenged on those who injure me, though they are larger and fiercer than myself.”

“Oh, do tell me,” said Tommy Smith, for the hare had paused a little, and seemed to be thinking.

“Ah!” he began again; “how well I remember it. I was very nearly caught that time. How fast the greyhounds ran, and how close behind me they were! What could I do to get away? I had gone up steep hills to tire them; and I had tired them, but then I had tired[69] myself still more. I had run up one side of a hedge and down the other, so that they should not see me, and then I had gone through the roughest and thorniest part of that hedge, in hopes that they would not be able to follow. But they had kept close after me all the time, and now they were just at my heels. Then I doubled. Oh, how close I lay on the ground as the greyhounds leaped over me! I saw their white teeth, and their glaring eyes, and their red tongues lolling out of their great open mouths. But they had missed me, and I was saved for a little while. But where was I to run to next? There were no hedges now; no woods, or hills, or rocky ground, nothing but smooth level grass, which is just what greyhounds love to race over. Was there no escape? Yes. What was that long line far away where the green grass ended and the blue sky began? White birds were wheeling above it, and, from beneath, came a sound as though a giant were whispering. That was the sound of the sea, and the long line meeting the sky was the line of the cliffs. Oh, if I could reach it! But, first, I had to double—once—twice—three times;[70] over me they flew, and off I darted again. And now the line grew nearer, the white birds looked larger as they sailed in the air, and the whispering sound was changing to a moan—to a roar. Yes, I was close to it now, but the greyhounds were just behind me, and their hot breath blew upon my fur. They had caught me! No. On the very edge of the cliffs I doubled once more, and once more they went over me.”

“And over the cliffs?” said Tommy Smith.

“Yes,” said the hare; “over me, and over the cliffs as well. Something hid the sky for a moment,—a dark cloud passed above me. Then the sky was clear again; and there were no greyhounds now. Over and over, down, down, down they went, and were dashed to pieces on the black rocks, and drowned in the white waves. I know they were, for I peeped over the edge and saw it. You may ask the seagulls, if you like. They saw it too.”

“Were they all drowned?” said Tommy Smith.

“Yes, all,” said the hare.

“And were you glad?” he asked, for it seemed to him very dreadful.

“Well,” the hare said, “I was glad to escape, of course, and so would you have been. But yet I could not help feeling sorry for the poor dogs, because they had been taught to chase me, and it was not their fault. Do you know who I should have liked to see fall over the cliffs instead of them?”

“Who?” said Tommy Smith.

“The cruel, hard-hearted men who taught them,” said the hare. “It is they who ought to have been drowned, and I am very sorry that they were not.”

“You poor hare!” said Tommy Smith, as he stroked its soft fur, and played with its long, pretty ears. “It is very hard that you should always be hunted, and I do think that you are very badly treated. But what clever ways you have of escaping! Do you know, I think you are the cleverest animal I have had a talk with yet, and I like you very much.”

“Ah! it is all very well to say that now,” said the hare. “But who was it that threw a stick at me?”

“I never will again,” said Tommy Smith. “You know you jumped up all of a sudden, so that I had no time to think.[72] But I did not come out on purpose to throw it at you. I only wanted to find a lark’s nest, so as to get the eggs.”

When the hare heard that, I cannot tell you how sad and grieved he looked. “What!” he said. “Would you take the poor lark’s eggs away, and make it unhappy? No, no; if you really like me, as you say you do, you must promise me not to do anything so cruel as that. The lark is the best friend I have. He sings to me as I lie in my form, and consoles me for all my troubles. His voice cheers me too, when I am being chased by the dogs, for he always seems to be saying, ‘You will get away; I know you will get away.’ Then sometimes he comes down to roost quite close to me, and we talk to each other. He tells me what it is like up above the clouds, and I tell him all that has been going on down here. He has his trials too, for there are hawks that try to catch him, just as there are greyhounds that try to catch me; so we sit and comfort each other. Promise me never to be unkind to my friend the lark.”

“I won’t hurt him,” said Tommy Smith. “And if ever I find his nest with eggs in[73] it, I will only just look at them and leave them there.”

“Oh, thank you,” the hare said; “and you won’t hurt me either?”

“No, indeed, I won’t,” said Tommy Smith. “Do you know, I begin to think that it would be better not to hurt any animal.”

“Oh, much better!” said the hare, as he skipped gladly away. “Except the fox,—and the weasel, you may hurt him—if you can catch him.” He said that, of course, because he was a hare, and felt prejudiced. You must not think I agree with him. Only a critic or a silly person would think that.

CHAPTER VI.

THE GRASS-SNAKE AND ADDER

“Tommy Smith has a talk with the grass-snake, and then

With the adder: they’re both as conceited as men.”

WHEN Tommy Smith had said good-bye to the hare, he thought he would walk home through some woods which were not far off. So off he set towards them, and as he went along he said to himself, “I know there are a great many animals that live in the woods. Now I wonder which of them will be the first to have a talk with me. Let me see. The pigeon and the squirrel both live there, for I have often seen them together on the same tree. And then there is the—” Good gracious! What was that just gliding out from under a bush? Tommy Smith gave a start and a jump, and well he might, for it was a large snake, perhaps three feet long. He was so surprised that, at first, he didn’t quite know what to do, and before he had made up his mind, it was too late to do anything,[75] for the snake had wriggled away into another bush. “It was an adder,” said Tommy Smith out loud. “That, at least, is an animal which I ought to kill, because it is poisonous.”

“I beg your pardon,” said a sharp, hissing voice. “I am not an adder, and I am not poisonous.”

Tommy Smith looked all about, but he could see nothing. Still, he felt sure that it must be the snake who had spoken, because the voice came from the very centre of the bush into which he had seen it go. So he answered, “Of course it is very easy for you to say that, but everybody knows that snakes are poisonous, and, if you are not a snake, I should just like to know what you are.”

“I did not say that I was not a snake,” said the voice again. “Of course I am, but I am not an adder for all that. There are two different kinds of snakes in this country. One is the adder, which is poisonous, and the other is the grass-snake, which is quite harmless. Now I am the grass-snake, so if you had killed me, you would have done something very[76] wrong, for you would have killed a poor harmless animal.”

“Well,” said Tommy Smith, “if that is true, I am glad I didn’t kill you. But are you quite sure?”

“If you don’t believe me,” said the snake, “you must get some good book of natural history, and there you will find it mentioned that we grass-snakes are quite harmless. It is the great superiority which our family have always had over that of the adder. People may call him a ‘poisonous reptile,’ but they cannot speak of us in that way. If they were to, they would only show their ignorance.”

“But how am I to know which is one and which is the other?” asked Tommy Smith.

“You will not find that very difficult,” the grass-snake answered; “and if you will promise not to hurt me, I will come out from where I am and show you.”

Of course Tommy Smith promised (you see he was getting a much better boy to animals than he used to be), and directly he had, the snake came gliding out from under the bush, and lay on the ground[77] just at his feet. “Now”, he said, “to begin with, I am a good deal longer than an adder. I should just like to see the adder that was three feet long, and I am an inch longer than that. No, indeed! Whenever you see such a fine, long snake as I am, you may be sure that it is a nice grass-snake, and not a nasty adder.”

“I won’t forget that,” said Tommy Smith. “But, I suppose, snakes grow like other animals. How should I be able to tell you from an adder if I were to meet you before you were three feet long?”