Transcriber Note

Table of Contents added.

A THRILLING NARRATIVE

OF

THE MINNESOTA MASSACRE

AND THE

SIOUX WAR OF 1862-63

GRAPHIC ACCOUNTS OF THE

SIEGE OF FORT RIDGELY, BATTLES OF BIRCH COOLIE, WOOD

LAKE, BIG MOUND, STONY LAKE, DEAD BUFFALO

LAKE AND MISSOURI RIVER.

ILLUSTRATED.

CHICAGO:

A. P. CONNOLLY, Publisher,

PAST COMMANDER U. S. GRANT POST, NO. 28, G. A. R.

DEPARTMENT OF ILLINOIS.

Copyright 1896, by

A. P. CONNOLLY

CHICAGO.

DONOHUE & HENNEBERRY, PRINTERS AND BINDERS, CHICAGO.

Thirty-four years ago and Minnesota was in an unusual state of excitement. The great War of the Rebellion was on and many of her sons were in the Union army “at the front.” In addition, the Sioux Indian outbreak occurred and troops were hurriedly sent to the frontier. Company A, Sixth Minnesota Infantry, and detachments from other companies were sent out to bury the victims of the Indians. This duty performed, they rested from their labors and in an unguarded hour, they, too, were surrounded by the victorious Indians and suffered greatly in killed and wounded at Birch Coolie, Minnesota, on September 2 and 3, 1862. The men who gave up their lives at this historic place, have been remembered by the state in the erection of a beautiful monument to their memory and the names inscribed thereon are as follows:

John College, sergeant, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Wm. Irvine, sergeant, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Wm. M. Cobb, corporal, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Cornelius Coyle, private, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

George Coulter, private, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Chauncey L. King, private, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Henry Rolleau, private, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Wm. Russell, private, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Henry Whetsler, private, Company A, Sixth Minnesota.

Benj. S. Terry, sergeant, Company G, Sixth Minnesota.

F. C. W. Renneken, corporal, Company G, Sixth Minnesota.

Robert Baxter, sergeant, Mounted Rangers.

Richard Gibbons, corporal, Mounted Rangers.

To these, knowing them all personally and well, I fraternally and reverentially inscribe this book.

“We are coming, Father Abraham, SIX HUNDRED THOUSAND MORE!”

This was in response to the President’s appeal for men to go to the front, and the vast levies this called for made men turn pale and maidens tremble.

The Union army was being defeated, and its ranks depleted by disease and expiration of terms of service—the enemy was victorious and defiant, and foreign powers were wavering. In England aristocracy wanted a confederacy—the Commoners wanted an undivided Union. The North responded to the appeal, mothers gave up their sons, wives their husbands, maidens their lovers, and six hundred thousand “boys in blue” marched away.

In August, 1862, I enlisted to serve Uncle Sam for “three years or during the war.” In January, 1865, I reenlisted to serve another term; but the happy termination of the conflict made it unnecessary. I do not write this boastingly, but proudly. There are periods in our lives we wish to emphasize and with me this is the period in my life.

The years from 1861 to 1865—memorable for all time, I look back to now as a dream. The echo of the first gun on Sumter startled the world. Men stood aghast and buckling on the sword and shouldering the musket they marched away. Brave men from the North met brave men from the South, and, as the clash of arms resounded throughout our once happy land, the Nations of the World with bated breath watched the destinies of this Republic.

After four years of arbitration on many sanguinary « 6 » fields, we decided at Appomattox to live in harmony under one flag. The soldiers are satisfied—“the Blue and the Gray” have joined hands; but the politicians, or at least some of them, seem to be unaware that the war is over, and still drag us into the controversy.

“The Boys in Blue?” Why, that was in 1866, and this is 1896—thirty years after we had fulfilled our contract and turned over the goods; and was ever work better done?

Then we could have anything we wanted; now we are “Old Soldiers” and it is 16 to 1 against us when there is work to do. A new generation has arisen, and the men of 1861 to 1865 are out of “the swim,” unless their vote is wanted. We generally vote right. We were safe to trust in “the dark days” and we can be trusted now; but Young America is in the front rank and we must submit.

The soldier was a queer “critter” and could adapt himself to any circumstance. He could cook, wash dishes, preach, pray, fight, build bridges, build railroads, scale mountains, dig wells, dig canals, edit papers, eat three square meals a day or go without and find fault; and so with this experience of years,—the eventful years of 1861 and 1865 before me, when the door is shut and I am no longer effective and cannot very well retire—to the poor-house, have concluded to write a book. I am not so important a character as either Grant, Sherman, Sheridan or Logan; but I did my share toward making them great. I’ll never have a monument erected to my memory unless I pay for it myself; but my conscience is clear, for I served more than three years in Uncle Sam’s army and I have never regretted it and have no apologies to make. I did not go for pay, bounty or pension, although I got both the former when I did enlist and am living in the enjoyment « 7 » of the latter now. I would not like to say how much my pension is, but it is not one hundred a month by “a large majority”—and so, I have concluded, upon the whole, to profit by a portion of my experience in the great “Sioux War” in Minnesota and Dakota in 1862 (for I campaigned both North and South) and write a book and thus “stand off” the wolf in my old age.

When peace was declared, the great armies were ordered home and the “Boys in Blue” became citizens again. The majority of us have passed over the hill-top and are going down the western slope of life, leaving our comrades by the wayside. In a few years more there will be but a corporal’s guard left and “the place that knows us now will know us no more forever.” The poor-house will catch some and the Soldiers’ Home others; but the bread of charity can never be so sweet and palatable as is that derived from one’s own earnings,—hence this little book of personal experiences and exciting events of these exciting years—1862 and 1863. In it I deal in facts and personal experiences, and the experiences of others who passed through the trying ordeal, as narrated to me. As one grows old, memory in some sense is unreliable. It cannot hold on as it once did. The recollection of the incidents of youth remains, while the more recent occurrences have often but a slender hold on our memories; often creeps in touching dates, but the recollections of August, 1862, and the months that followed, are indeed vivid; the impress is so indelibly graven on our memories that time has not effaced them.

The characters spoken of I knew personally, some for years; the locations were familiar to me, the buildings homely as they appear, are correct in size and in style « 8 » of architecture and some of them I helped to build. The narrative is as I would relate to you, were we at one of our “Camp Fires.” It is turning back the pages of memory, but in the mental review it seems but yesterday that the sad events occurred.

A. P. CONNOLLY.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | General Remarks—Death of Dr. Weiser. | 11 |

| II. | St. Paul and Minneapolis in 1836 and 1896—Father Hennepin. | 14 |

| III. | A Pathetic Chapter—Captain Chittenden’s Minnehaha. | 20 |

| IV. | Origin of Indians—Captain Carver—Sitting Bull. | 27 |

| V. | Fort Snelling. | 33 |

| VI. | The Alarm. | 38 |

| VII. | Some of the Causes of the War. | 43 |

| VIII. | Little Crow at Devil’s Lake. | 50 |

| IX. | Fort Ridgely Besieged. | 63 |

| X. | Siege of New Ulm. | 67 |

| XI. | Col. Flandreau in Command. | 75 |

| XII. | Mrs. Eastlick and Family. | 78 |

| XIII. | The Missionaries—Their Escape. | 85 |

| XIV. | The Indian Pow-wow. | 87 |

| XV. | Gov. Sibley Appointed Commander. | 97 |

| XVI. | March to Fort Ridgely. | 103 |

| XVII. | Burial of Capt. Marsh and Men. | 106 |

| XVIII. | Battle of Birch Coolie. | 112 |

| XIX. | Birch Coolie Continued. | 118 |

| XX. | Battle of Wood Lake. | 128 |

| XXI. | Camp Release. | 139 |

| XXII. | The Indian Prisoners—The Trial. | 146 |

| XXIII. | Capture of Renegade Bands—Midnight March. | 153 |

| XXIV. | Homeward Bound. | 156 |

| XXV. | Protests—President Lincoln’s Order For the Execution. | 163 |

| XXVI. | The Execution—The Night Before. | 169 |

| XXVII. | Squaws Take Leave of Their Husbands. | 176 |

| XXVIII. | Capture and Release of Joe Brown’s Indian Family. | 178 |

| XXIX. | Governor Ramsey and Hole-in-the-Day. | 185 |

| XXX. | Chaska—George Spencer—Chaska’s Death—The “Moscow” Expedition. | 190 |

| XXXI. | The “Moscow” Expedition. | 195 |

| XXXII. | Campaign of 1863—Camp Pope. | 199 |

| XXXIII. | “Forward March.” | 205 |

| XXXIV. | Burning Prairie—Fighting Fire. | 209 |

| XXXV. | Death of Little Crow. | 211 |

| XXXVI. | Little Crow, Jr.—His Capture. | 218 |

| XXXVII. | Camp Atchison—George A. Brackett’s Adventure—Lieutenant Freeman’s Death. | 221 |

| XXXVIII. | Battle of Big Mound. | 232 |

| XXXIX. | Battle of Dead Buffalo Lake. | 237 |

| XL. | Battle of Stony Lake—Capture of a Teton—Death of Lieutenant Beaver. | 241 |

| XLI. | Homeward Bound. | 252 |

| XLII. | The Campaign of 1864. | 257 |

| XLIII. | The Battle of the Bad Lands. | 261 |

| XLIV. | Conclusion. | 271 |

GENERAL REMARKS—DEATH OF DR. WEISER.

Historians have written, orators have spoken and poets have sung of the heroism and bravery of the great Union army and navy that from 1861 to 1865 followed the leadership of Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, Logan, Thomas, McPherson, Farragut and Porter from Bull Run to Appomattox, and from Atlanta to the sea; and after their work was done and well done, returned to their homes to receive the plaudits of a grateful country.

More than thirty years have elapsed since these trying, melancholy times. The question that then called the volunteer army into existence has been settled, and the great commanders have gone to their rewards. We bow our heads in submission to the mandate of the King of Kings, as with sorrow and pleasure we read the grateful tributes paid to the memories of the heroes on land and on sea,—the names made illustrious by valorous achievements, and that have become household words, engraven on our memories; and we think of them as comrades who await us “on fame’s eternal camping ground.”

Since the war, other questions have arisen to claim our attention, and this book treats of another momentous theme. The Indian question has often, indeed too often, been uppermost in the minds of the people. We have had the World’s Fair, the Four Hundredth Anniversary of the discovery of America, the recollection of which is still fresh in our memories. Now we have politics and « 12 » doubtless have passed through one of the most exciting political campaigns of our day and generation; but, let us take a retrospective view, and go back thirty years; look at some of the causes leading up to the Indian war of 1862; make a campaign with me as we march over twelve hundred miles into an almost unknown land and defeat the Indians in several sanguinary battles, liberate four hundred captive women and children, try, convict and hang thirty-nine Indians for participating in the murder of thousands of unsuspecting white settlers, and if, upon our return, you are not satisfied, I hope you will in the kindness of your heart forgive me for taking you on this (at the time) perilous journey.

I will say to my comrades who campaigned solely in the South, that my experience, both North and South, leads me to believe there is no comparison. In the South we fought foemen worthy of our steel,—soldiers who were manly enough to acknowledge defeat, and magnanimous enough to respect the defeat of their opponents. Not so with the redskins. Their tactics were of the skulking kind; their object scalps, and not glory. They never acknowledged defeat, had no respect for a fallen foe, and gratified their natural propensity for blood. Meeting them in battle there was but one choice,—fight, and one result only, if unsuccessful,—certain death. They knew what the flag of truce meant (cessation of hostilities), but had not a proper respect for it. They felt safe in coming to us with this time-honored symbol of protection, because they knew we would respect it. We did not feel safe in going to them under like circumstances, because there were those among them who smothered every honorable impulse to gratify a spirit of revenge and hatred. As an illustration « 13 » of this I will state, that just after the battle of the Big Mound in 1863, we met a delegation of Indians with a flag of truce, and while the interpreter was talking to them and telling them what the General desired, and some soldiers were giving them tobacco and crackers, Dr. Weiser, surgeon of the Second Minnesota Cavalry, having on his full uniform as major, tempted a villainous fellow, who thinking, from the uniform, that it was General Sibley, our commander, jumped up, and before his intention could be understood, shot him through the back, killing him instantly. Treachery of this stamp does not of course apply to all the members of all tribes and benighted people; for I suppose even in the jungles of Africa, where tribes of black men live who have never heard of a white man, we could find some endowed with human instincts, who would protect those whom the fortunes of war or exploration might cast among them. We found some Indians who were exceptions to the alleged general rule—cruel. The battles we fought were fierce, escapes miraculous, personal experiences wonderful and the liberation of the captives a bright chapter in the history of events in this exciting year.

ST. PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS IN 1836 AND 1896—FATHER HENNEPIN.

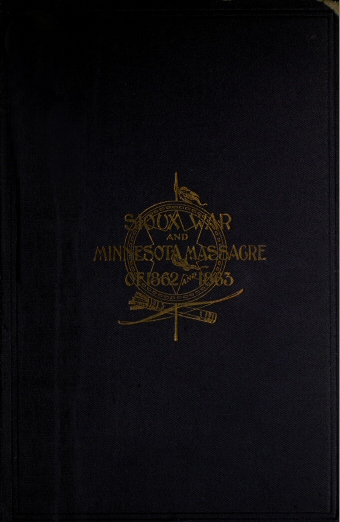

As St. Paul, Minnesota, is our starting point, we will pause for a little and cultivate the acquaintance of her people. The picture represents St. Paul and Minneapolis about as we suppose they were previous to 1838, and before a white man gazed upon the natural beauties of our great country. In the picture you see “one of the first families,” in fact it is the first family, and a healthy, dirty-looking lot they are. They had evidently heard that a stranger had “come to town” and the neighbors came in to lend a hand in “receiving” the distinguished guest. The Indian kid on the left hand, with his hair a la Paderewski, was probably playing marbles with young Dirty-Face-Afraid-of-Soap-and-Water in the back yard, when his mother whooped for him to come. He looks mad about it. They all have on their Sunday clothes and are speculating as to whether it is best to get acquainted with the forerunner of civilization or not. Their liberties had never been abridged. The Indians came and went at will, never dreaming that the day was approaching when civilization would force them to “move on.” As early as 1819 white people were in Minnesota, ’tis true, but this was when Fort St. Anthony was first garrisoned.

One of the “First Families” of St. Paul in 1835.

One of the “First Families” of St. Paul in 1835.

Anterior to this, however, a zealous Franciscan priest, Father Hennepin, ascended the Mississippi, by oar, impelled on by its beautiful scenery, and in August, 1680, he stood upon the brink of the river near where Fort Snelling now is, and erected the cross of his church and probably was the first to proclaim to the red man the glad tidings of “Peace on earth, good will to man.” He pointed them to the cross as the emblem of liberty from superstition, but they in their ignorance did not heed his peaceful coming, but made him their captive, holding him thus for six months, during which time he so completely gained their confidence as to cause them to liberate him, and his name is still remembered reverentially by them.

Father Hennepin named the Falls of St. Anthony after his patron saint, and was the first white man to look upon its beauties and listen to the music of Minnehaha, as her crystal water rolled over the cliffs and went rippling through the grasses and flowers on its merry way to the bosom of the “Father of Waters.”

Minnehaha, beautiful in sunshine and in shadow; in rain-shower and in snow-storm—for ages has your laughter greeted the ear of the ardent Indian lover. Here Hiawatha, outstripping all competitors in his love-race, wooed his Minnehaha and in triumph carried her away to his far-off Ojibway home. The Indians loved this spot and as they camped upon its banks and smoked the peace pipe “as a signal to the nations,” dreamed only of peace and plenty. The Great Spirit was good to them; but the evil day was approaching, invisible yet, then a speck on the horizon, but the cloud grew and the “pale face” was among them. Sorrowfully they bid farewell forever to their beautiful “Laughing Water.”

In these early days it was almost beyond the comprehension of man that two populous cities should spring up as have St. Paul and Minneapolis, and Pierre Parrant, the first settler at St. Paul, little dreamed that the “Twin Cities,” with a population variously estimated at from 200,000 to 225,000, would greet the eye of the astonished beholder in 1896. They sprang into existence and grew apace; they met with reverses, as all cities do, but the indomitable energy of the men who started out to carve for themselves a fortune, achieved their end, and their children are now enjoying the fruits of their labor.

There is no city in America that can boast an avenue equal to Summit avenue in St. Paul, with its many beautiful residences ranging in cost from $25,000 to $350,000. Notably among these palatial homes is that of James J. Hill, the railroad king of the Northwest. His is a palace set on a hill, built in the old English style, situated on an eminence overlooking the river and the bluffs beyond. The grounds without and the art treasures within are equal to those of any home in our country, and such as are found only in homes of culture where money in plenty is always at hand to gratify every desire.

The avenue winds along the bluff, and the outlook up and down the river calls forth exclamations of delight from those who can see beauty in our natural American scenery. In the springtime, when the trees are in their fresh green garb, and budding forth, and in the autumn when the days are hazy and short, when the sere of months has painted the foliage in variegated colors, and it begins to fall, the picture as unfolded to the beholder standing on the bluffs is delighting, enchanting.

The urban and interurban facilities for transport from « 19 » city to city are the best in the world, and is the successful result of years of observation and laborious effort on the part of the honorable Thomas Lowry, the street railway magnate; and the many bridges spanning the “Father of Waters” at either end of the line give evidence of the ability of the business men of the two cities to compass anything within reason.

Minneapolis, the “flour city,” noted for its broad streets and palatial homes nestling among the trees; its magnificent public library building with its well-filled shelves of book treasures; its expensive and beautiful public buildings and business blocks; its far-famed exposition building, and its great cluster of mammoth flouring mills that astonish the world, are the pride of every Minnesotian. Even the “Father of Waters” laughs as he leaps over the rocks and, winding in and out, drives this world of machinery that grinds up wheat—not by the car-load, but by the train-load, and—“Pillsbury’s Best”—long since a national pride, has become a familiar international brand because it can be found in all the great marts of the world. What a transformation since 1638! Father Hennepin, no doubt, looks down from the battlements of Heaven in amazement at the change; and the poor Indians, who had been wont to roam about here, unhindered, have long since, in sorrow, fled away nearer to the setting sun; but alas! he returned and left the imprint of his aroused savage nature.

A PATHETIC CHAPTER—CAPTAIN CHITTENDEN’S MINNEHAHA.

In August, 1862, what do we see? Homes, beautiful prairie homes of yesterday, to-day have sunken out of sight, buried in their own ashes; the wife of an early love has been overtaken and compelled to submit to the unholy passion of her cruel captor; the prattling tongues of the innocents have been silenced in sudden death, and reason dethroned. A most pathetic case was that of Charles Nelson, a Swede. The day previous, his dwelling had been burned to the ground, his daughter outraged, the head of his wife, Lela, cleft by the tomahawk, and while seeking to save himself, he saw, for a moment, his two sons, Hans and Otto, rushing through the corn-field with the Indians in swift pursuit. Returning with the troops under Colonel McPhail, and passing by the ruins of his home, he gazed about him wildly, and closing the gate of the garden, asked: “When will it be safe to return?” His reason was gone!

This pathetic scene witnessed by so many who yet live to remember it, was made a chapter entitled, “The Maniac,” in a work from the pen of Mrs. Harriet E. McConkey, published soon after it occurred.

Captain Chittenden, of Colonel McPhail’s command, while sitting a few days after, under the Falls of Minnehaha, embodied in verse this wonderful tragedy, giving to the world the following lines:

ORIGIN OF INDIANS—CAPTAIN CARVER—SITTING BULL.

There is something wonderfully interesting about the origin of the Indians. Different writers have different theories; John McIntosh, who is an interesting and very exhaustive writer on this subject, says they can date their origin back to the time of the flood, and that Magog, the second son of Japhet, is the real fountain head. Our North American Indians, however, were first heard of authentically from Father Hennepin, who so early came among them.

At a later date, about 1766, Jonathan Carver, a British subject and a captain in the army, made a visit of adventure to this almost unknown and interesting country. The Sioux were then very powerful and occupied the country about St. Anthony Falls, and west of the Mississippi, and south, taking in a portion of what now is the State of Iowa.

The country to the north and northeast was owned by the Chippewas. The Sioux then, as later, were a very war-like nation, and at the time of Captain Carver’s advent among them were at war with the Chippewas, their hated foes. Captain Carver came among them as a peace-maker; « 28 » his diplomacy and genial spirit prevailed, and the hatchet was buried. For these good offices, the Indians ceded to him a large tract of land, extending from the Falls of St. Anthony to the foot of Lake Pipin; thence east one hundred miles; thence north and west to the place of beginning—a most magnificent domain, truly, and which in Europe would call for nothing less than a king to supervise its destinies.

A writer, Hon. W. S. Bryant, of St. Paul, Minnesota, on this subject, says: “That at a later period, after Captain Carver’s death, congress was petitioned by others than his heirs, to confirm the Indian deed, and among the papers produced in support of the claim, was a copy of an instrument purporting to have been executed at Lake Traverse, on the 17th day of February, 1821, by four Indians who called themselves chiefs and warriors of the Uandowessies—the Sioux. They declare that their fathers did grant to Captain Jonathan Carver this vast tract of land and that there is among their people a traditional record of the same. This writing is signed by Ouekien Tangah, Tashachpi Tainche, Kache Noberie and Petite Corbeau (Little Crow).” This “Petite” is undoubtedly the father of Little Crow, who figures in this narrative as the leader in the massacre.

Captain Carver’s claim has never been recognized, although the instrument transferring this large tract of land to him by the Indians was in existence and in St. Paul less than twenty-five years ago. It has since been destroyed and the possessors of these valuable acres can rest themselves in peace.

In 1862 the red man’s ambition was inflamed, and in his desire to repossess himself of his lost patrimony, he « 29 » seeks redress of his wrongs in bloody war. Fort Snelling at the junction of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers was the rallying point for the soldiers and we produce a picture of it as it appeared then and give something of its history from its first establishment up to date.

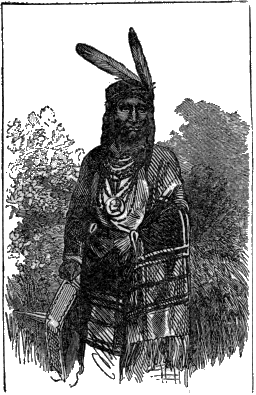

The great Sioux or Dakotah nation at one time embraced the Uncapapas, Assinaboines, Mandans, Crows, Winnebagoes, Osages, Kansas, Kappaws, Ottoes, Missourias, Iowas, Omahas, Poncas, Nez Perces, Arrickarees, Minnetarees, Arkansas, Tetons, Yanktons, Yanktonais, and the Pawnees. It was a most powerful nation and under favorable conditions could withstand the encroachments of our modern civilization. The Ahahaways and Unktokas are spoken of as two lost tribes. The Unktokas are said to have lived in “Wiskonsan,” south of the St. Croix and were supposed to have been destroyed by the Iowas about the commencement of the present century. The Ahahaways, a branch of the Crows, lived on the Upper Missouri, but were lost—annihilated by disease, natural causes and war. The Uncapapa tribe were from the Missouri, and Sitting Bull, whose picture appears, although not an hereditary chief, was a strong man among them. He was for a time their Medicine Man and counselor. He was shrewd and a forceful diplomat; he was a pronounced hater of the whites, and has earned notoriety throughout the country as the leader of five thousand warriors, who annihilated General Custer and his command at the Little Big Horn in 1876. After the massacre, this huge Indian camp was broken up, and Bull, with more than one thousand warriors retreated into the British possessions, from whence he made frequent raids upon American soil. His band constantly suffered depletion until, in the summer of « 30 » 1881, he had but one hundred and sixty followers remaining. These he surrendered to Lieutenant-Colonel Brotherton, at Fort Buford, and with them was sent as a prisoner to Fort Randall, Dakota. He was married four times, and had a large family. He was not engaged in the Sioux war of 1862, but being a chief of that nation and an important Indian character, I introduce him. He has gone to the happy hunting ground, some years since, through the treachery of the Indian police, who were sent out to capture him.

FORT SNELLING.

FROM E. D. NEILL’S RECOLLECTIONS.

On the 10th of February, 1819, John C. Calhoun, then secretary of war, issued an order for the Fifth regiment of infantry to rendezvous at Detroit, preparatory to proceeding to the Mississippi to garrison or establish military posts, and the headquarters of the regiment was directed to be at the fort to be located at the mouth of the Minnesota river.

It was not until the 17th of September that Lieutenant-Colonel Leavenworth, with a detachment of troops, reached this point. A cantonment was first established at New Hope, near Mendota, and not far from the ferry. During the winter of 1819-20, forty soldiers died from scurvy.

On the 5th of May, 1819, Colonel Leavenworth crossed the river and established a summer camp, but his relations with the Indian agent were not as harmonious as they might have been, and Colonel Josiah Snelling arrived and relieved him. On the 10th of September, the cornerstone of Fort St. Anthony was laid; the barracks at first were of logs.

During the summer of 1820 a party of Sisseton Sioux killed on the Missouri Isadore Poupon, a half-breed, and Joseph Andrews, a Canadian, two men in the employ of the fur company. As soon as the information reached the agent, Major Taliaferro, trade with the Sioux was interdicted until the guilty were surrendered. Finding that « 34 » they were deprived of blankets, powder and tobacco, a council was held at Big Stone Lake, and one of the murderers, and the aged father of another, agreed to go down and surrender themselves.

On the 12th of November, escorted by friends and relatives, they approached the post. Halting for a brief period, they formed and marched in solemn procession to the center of the parade ground. In the advance was a Sisseton, bearing a British flag; next came the murderer, and the old man who had offered himself as an atonement for his son, their arms pinioned, and large wooden splinters thrust through the flesh above the elbow, indicating their contempt for pain; and in the rear followed friends chanting the death-song. After burning the British flag in front of the sentinels of the fort, they formally delivered the prisoners. The murderer was sent under guard to St. Louis, and the old man detained as a hostage.

The first white women in Minnesota were the wives of the officers of Fort St. Anthony. The first steamer to arrive at the new fort was the Virginia, commanded by Captain Crawford. The event was so notable that she was greeted by a salute from the fort.

In 1824, General Scott, on a tour of inspection, visited Fort St. Anthony, and suggested that the name be changed to Fort Snelling, in honor of Colonel Snelling, its first commander. Upon this suggestion of General Scott and for the reason assigned, the war department made the change and historic Fort Snelling took its place among the defenses of the nation; and from this date up to 1861, was garrisoned by regulars, who were quartered here to keep in check the Indians who were ever on the alert for an excuse to avenge themselves on the white settlers.

Author’s Note.

When visiting Fort Snelling during the occasion of the holding of the National Encampment of the Grand Army of the Republic in St. Paul in September, 1896, I found such a change.

The old stone quarters for the use of the rank and file during the war days were there, it is true, but are being used for purposes other than accommodating the soldiers. I found my old squad room, but the old associations were gone; the memories of the war days crowded upon me, and I thought of the boys whose names and faces I remembered well, but they are dead and scattered over the land. Some few were there, and we went over our war history, and in the recital, recalled the names of our comrades who have been finally “mustered out” and have gone beyond the river.

The present commandant of the beautiful new fort is Colonel John H. Page of the Third United States Infantry. This officer has been continuously in the service since April, 1861. He was a private in Company A, First Illinois Artillery, and went through all the campaigning of this command until the close of the war, when he received an appointment in the Regular Establishment, and as Captain was placed on recruiting service in Chicago.

His advancement in his regiment has been phenomenal, and to be called to the command of a regiment of so renowned a record as has the Third Infantry, is an honor to any man, no matter where he won his spurs.

Colonel Page is a Comrade of U. S. Grant Post No. 28, Grand Army of the Republic, Department of Illinois, and is also a Companion of the Loyal Legion. He has an interesting family who live with him in the enjoyment of his well-earned laurels.

In 1861, and from that to 1866, the scene underwent a wondrous change, and volunteers instead of regulars became its occupants. All the Minnesota volunteers rendezvoused here preparatory to taking the field. Some years after the war the department determined to make this historic place one of the permanent forts, and commenced a series of improvements. Now it is one of the finest within the boundary of our country, and we find the grounds, 1,500 acres in extent, beautifully laid out, and extensive buildings with all the modern improvements erected for the accommodation of Uncle Sam’s soldiers.

The present post structures consist of an executive building, 93x64 feet, of Milwaukee brick, two stories and a basement, heated by furnaces and with good water supply. It contains offices for the commanding general and department staff. The officers’ quarters: a row of thirteen brick buildings with all the modern improvements, hot and cold water, and a frame stable for each building. Minnesota Row: Six double one-story frame buildings, affording twelve sets of quarters for clerks and employes. Brick Row: A two-story brick building, 123x31 feet, with cellars, having sixteen suites of two rooms each, for unmarried general service clerks and employes. Quartermaster’s employes have a one-story brick building, 147x30 feet, containing eight sets of quarters of two rooms each, also a mess-house, one story brick, 58x25 feet, containing a kitchen and dining room, with cellar 30x12 feet. Engineer’s quarters, school house, quartermaster’s corrals, brick stables, blacksmith shops, frame carriage house, granary and hay-house, ice house, etc., good water works, sewer system, and electric lights.

THE ALARM.

The Indians! The Indians are coming!

How the cry rang out and struck terror to the hearts of the bravest. It brought to mind the stories of early days, of this great Republic, when the east was but sparsely settled, and the great west an unknown country, with the Indian monarch of all he surveyed. The vast prairies, with their great herds of buffalo were like the trackless seas; the waving forests, dark and limitless; mountain ranges—the Alleghanies, the Rockies and the Sierra Nevadas, towering above the clouds; the countless lakes—fresh and salt, hot and cold; the great inland seas; the gigantic water falls, and the laughing waters; the immense rivers, little rivulets at the mountain source, accumulating as they flowed on in their immensity, as silently and sullenly they wend their way to the sea; the rocky glens and great canyons, the wonder of all the world. It was in the early day of our Republic, when the hardy pioneer took his little family and out in the wilderness sought a new home; a time when the Indian, jealous of the white man’s encroachment, and possessor by right of previous occupation, of this limitless, rich and wonderful empire, when great and powerful Indian nations—The Delawares, the Hurons, the Floridas, and other tribes in their native splendor and independence, said to the pale face, “Thus far shalt thou go, and no farther.” The terror-stricken people were obliged to flee to places of safety, or succumb to the tomahawk; and on throughout the Seminole, the Black Hawk and other wars, including the great Minnesota Massacre of 1862.

Reader accompany me. The atmosphere is surcharged with excitement, and the whole country is terror-stricken. The southland is drenched in blood, and the earth trembles under the tread of marching thousands.

The eyes of the nation are turned in that direction, and the whole civilized world is interested in the greatest civil war of the world’s history. The levies from the states are enormous, and the stalwarts, by regiments and brigades, respond to the call for “Six Hundred Thousand more.”

The loyal people of the frontier have long since ceased to look upon the Indians as enemies, and tearfully urge their husbands and sons to rally to the colors in the South. What is taking place in the land of the Dakotahs?

Their empire is fading away, their power is on the wane, their game is scarce, and they look with disgust and disfavor upon their unnatural environments. In poetry and in prose we have read of them in their natural way of living. They have been wronged; their vast empire has slipped away from them; they laugh, they scowl and run from tribe to tribe; they have put on the war-paint and broken the pipe of peace; with brandishing tomahawk and glistening scalping knife they are on the trail of the innocent.

“Turn out, the regulars are coming!” were the ringing words of Paul Revere, as he, in mad haste, on April 18, « 42 » 1775, on foaming steed, rode through the lowlands of Middlesex; so, too, are the unsuspecting people in Minnesota aroused by the cry of a courier, who, riding along at a break-neck speed shouts: “The Indians, the Indians are coming!” All nature is aglow; the sun rises from his eastern bed and spreads his warm, benign rays over this prairie land, and its happy occupants, as this terrific sound rings out on the morning air, are aroused and the cry: “Come over and help us” from the affrighted families, as they forsake their homes and flee for their lives, speeds on its way to ears that listen and heed their earnest, heart-piercing not, of despair, for the “Boys in Blue” respond.

The people had been warned by friendly Indians that the fire brands would soon be applied; and that once started, none could tell where it would end. They were implored to take heed and prepare for the worst; but unsuspecting, they had been so long among their Indian friends, they could not believe that treachery would bury all feelings of friendship; but alas! thousands were slain.

Go with me into their country and witness the sad results of a misguided people, and note how there was a division in their camp. The hot young bloods, ever ready for adventure and bloody adventure at that, had dragged their nation into an unnecessary war and the older men and conservative men with sorrowful hearts counselled together how best to extricate themselves and protect the lives of those who were prisoners among them. The campaign of 1862 is on.

SOME OF THE CAUSES OF THE WAR.

Lo! the poor Indian, has absorbed much of the people’s attention and vast sums of Uncle Sam’s money; and being a participant in the great Sioux war of 1862, what I write deals with facts and not fiction, as we progress from Fort Snelling, Minnesota, to “Camp Release,” where we found and released over four hundred white captives. But I will digress for a time and look into the causes leading up to this cruel Sioux war that cost so many lives and so much treasure. There is a great diversity of opinion on this question, and while not particularly in love with the Indian, I have not the temerity to criticise the Almighty because he puts his impress white upon some, and red upon others; neither shall I sit in judgment and say there are no good Indians—except dead ones. The Indian question proper is of too great a magnitude to analyze and treat with intelligence in this little book; but in the abstract, and before we enter upon the active campaign against them, let us look at it and see if the blame does not to a great extent rest more with the government than it does with these people. The Indians came from we know not where—legends have been written and tradition mentions them as among the earliest known possessors of this great western world. The biologist speculates, and « 44 » it is a matter of grave doubt as to their origin. Certain it is, that as far back as the time of Columbus they were found here, and we read nothing in the early history of the voyages of this wonderful navigator to convince us that the Indians were treacherous;—indeed we would rather incline to the opposite opinion. The racial war began with the conquest of the Spaniards. In their primitive condition, the Indians were possessed of a harmless superstition—they knew no one but of their kind; knew nothing of another world; knew nothing of any other continent in this world. When they discovered the white men and the ships with their sails spread, they looked upon the former as supernatural beings and the ships as great monsters with wings. Civilization and the Indian nature are incompatible and evidences of this were soon apparent. The ways of the Europeans were of course unknown to them. They were innocent of the white man’s avaricious propensities and the practice of “give and take” (and generally more take than give) was early inaugurated by the sailors of Columbus and the nefarious practice has been played by a certain class of Americans ever since. Soon their suspicions were aroused and friendly intercourse gave place to wars of extermination. The Indian began to look upon the white man as his natural enemy; fighting ensued; tribes became extinct; territory was ceded, and abandoned. Soon after American Independence had been declared, the Indians became the wards of the nation. The government, instead of treating them as wards and children, has uniformly allowed them to settle their own disputes in their own peculiar and savage way, and has looked upon the bloody feuds among the different tribes much as Plug « 45 » Uglies and Thugs do a disreputable slugging match or dog-fight. A writer says:

“If they are wards of the nation, why not take them under the strong arm of the law and deal with them as with others who break the law? Make an effort to civilize, and if civilization exterminates them it will be an honorable death,—to the nation at least. Send missionaries among them instead of thieving traders; implements of peace, rather than weapons of war; Bibles instead of scalping knives; religious tracts instead of war paint; make an effort to Christianize instead of encouraging them in their savagery and laziness; such a course would receive the commendation and acquiescence of the Christian world.”

There is not a sensible, unprejudiced man in America to-day, who gives the matter thought, but knows that the broken treaties and dishonest dealing with the Indians are a disgrace to this nation; and the impress of injustice is deeply and justly engraven upon the savage mind. The lesson taught by observation was that lying was no disgrace, adultery no sin, and theft no crime. This they learned from educated white men who had been sent to them as the representatives of the government; and these educated gentlemen (?) looked upon the Indian as common property, and to filch him of his money by dishonest practices, a pleasant pastime. The Indian woman did not escape his lecherous eye and if his base proposals were rejected, he had other means to resort to to enable him to accomplish his base desire. These wards were only Indians and why respect their feelings? “Sow the wind and reap the whirlwind.” The whirlwind came and oh, the sad results!

The Indians were circumscribed in their hunting grounds by the onward march of civilization which crowded them on every side and their only possible hope « 46 » from starvation, was in the fidelity with which a great nation kept its pledges. ’Tis true, money was appropriated by the government for this purpose, but it is equally true that gamblers and thieving traders set up fictitious claims and the Indians came out in debt and their poor families were left to starve. Hungry, exasperated and utterly powerless to help themselves, they resolved on savage vengeance when the propitious time arrived.

“The villainy you teach me I will execute,” became a living, bloody issue. This did not apply alone to the Sioux nation, but to the Chippewas as well. These people have always been friends of the whites, and have uniformly counselled peace; but broken pledges and impositions filled the friendly ones with sorrow, and the others with anger. The commissioners, no doubt, rectified the wrong as soon as it was brought to their notice, but the Indians were plucked all the same and had sense enough to know it. Our country is cursed with politicians—the statesmen seem to have disappeared; but, the politician grows like rank weeds and the desire for “boodle” permeates our municipal, state and national affairs. Our Indian system has presented a fat field so long as these wards of the nation submitted to being fleeced by unprincipled agents and their gambling friends, but at last, the poor Indian is aroused to the enormity of the imposition and the innocent whites had to suffer. In some instances the vengeance of God followed the unscrupulous agent and the scalping knife in the hand of the injured Indian was made the instrument whereby this retribution came.

There has been a great deal said of Indian warriors—we have read of them in poetry and in prose and of the beautiful Indian maiden as well. The Sioux warriors are « 47 » tall, athletic, fine looking men, and those who have not been degraded by the earlier and rougher frontier white man, or had their intellects destroyed by the white man’s fire-water, possess minds of a high order and can reason with a correctness that would astonish our best scholars and put to blush many of our so-called statesmen, and entirely put to rout a majority of the men who, by the grace of men’s votes hold down Congressional chairs. Yet they are called savages and are associated in our minds with tomahawks and scalping knives. Few regard them as reasoning creatures and some even think they are not endowed by their Creator with souls. Good men are sending Bibles to all parts of the world, sermons are preached in behalf of our fellow-creatures who are perishing in regions known only to us by name; yet here within easy reach, but a few miles from civilization, surrounded by churches and schools and all the moral influences abounding in Christian society; here, in a country endowed with every advantage that God can bestow, are perishing, body and soul, our countrymen—perishing from disease, starvation and intemperance and all the evils incident to their unhappy condition. I have no apology to make for the savage atrocities of any people, be they heathen or Christian, or pretended Christian; and we can point to pages of history where the outrages perpetrated by the soldiers of so-called Christian nations, under the sanction of their governments, would cause the angels to weep. Look at bleeding Armenia, the victim of the lecherous Turk, who has satiated his brutal, bestial nature in the blood and innocency of tens of thousands of men, women and children; and yet, the Christian nations of the world look on with indifference at these atrocities and pray: "Oh, Lord, « 48 » pour out Thy blessings on us and protect us while we are unmindful of the appeals of mothers and daughters in poor Armenia!”

This royal, lecherous, murderous Turk, instead of being dethroned and held to a strict accountability for the horrible butcheries, and worse than butcheries, going on within his kingdom and for which he, and he alone, is responsible, is held in place by Christian and civilized nations for fear that some one shall, in the partition of his unholy empire, get a bigger slice than is its equitable share.

The “sick man” has been allowed for the last half century to commit the most outrageous crimes against an inoffensive, honest, progressive, and law-abiding people, and no vigorous protest has gone out against it. Shall we, then, mercilessly condemn the poor Indians because, driven from pillar to post, with the government pushing in front and hostile tribes and starvation in their rear, they have in vain striven for a bare existence? Whole families have starved while the fathers were away on their hunt for game. Through hunger and disease powerful tribes have become but a mere band of vagabonds.

America, as she listens to the dying wail of the red man, driven from the forests of his childhood and the graves of his fathers, cannot afford to throw stones; but rather let her redeem her broken pledges to these helpless, benighted, savage children, and grant them the protection they have the right to expect, nay, demand.

“I will wash my hands in innocency” will not suffice. Let the government make amends, and in the future mete out to the dishonest agent such a measure of punishment as will strike terror to him and restore the confidence of « 49 » the Indians who think they have been unjustly dealt with. But to my theme.

The year of which I write was a time in St. Paul when the Indian was almost one’s next door neighbor,—a time when trading between St. Paul and Winnipeg was carried on principally by half-breeds, and the mode of transportation the crude Red river cart, which is made entirely of wood,—not a scrap of iron in its whole make-up. The team they used was one ox to a cart, and the creak of this long half-breed train, as it wended its way over the trackless country, could be heard twice a year as it came down to the settlements laden with furs to exchange for supplies for families, and hunting purposes. It was at a time when the hostile bands of Sioux met bands of Chippewas, and in the immediate vicinity engaged in deadly conflict, while little attention was paid to their feuds by the whites or the government at Washington.

LITTLE CROW AT DEVIL’S LAKE.

It was in August, 1861, on the western border of Devil’s Lake, Dakota, there sat an old Indian chief in the shade of his wigwam, preparing a fresh supply of kinnikinnick.

The mantle of evening was veiling the sky as this old chief worked and the events of the past were crowding his memory. He muses alone at the close of the day, while the wild bird skims away on its homeward course and the gathering gloom of eventide causes a sigh to escape his breast, as many sweet pictures of past happy years “come flitting again with their hopes and their fears.” The embers of the fire have gone out and he and his dog alone are resting on the banks of the lake after the day’s hunt; and, as he muses, he wanders back to the time when in legend lore the Indian owned the Western world; the hills and the valleys, the vast plains and their abundance, the rivers, the lakes and the mountains were his; great herds of buffalo wended their way undisturbed by the white hunter; on every hand abundance met his gaze, and the proud Red Man with untainted blood, and an eye filled with fire, looked out toward the four points of the compass, and, with beating heart, thanked the Great Spirit for this goodly heritage. To disturb his dream the white man came, and as the years rolled on, step by step, pressed him back;—civilization brought its cunning and greed for money-getting. A generous government, perhaps too confiding, allowed unprincipled men to rob and crowd, and crowd and rob, until the Mississippi is reached and the farther West is portioned out to him for his future residence. The influx of whites from Europe and the rapidly increasing population demand more room, and another move is planned by the government for the Indians, until they are crowding upon the borders of unfriendly tribes.

This old chief of whom we speak awoke from his meditative dream, and in imagination we see him with shaded eyes looking afar off toward the mountain. He beholds a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand; he strains his eye, and eagerly looks, for he sees within the pent-up environments of this cloud all the hatred and revenge with which his savage race is endowed. The cloud that is gathering is not an imaginative one, but it will burst in time upon the heads of guilty and innocent alike; and the old chief chuckles as he thinks of the scalps he will take from the hated whites, and the great renown, and wonderful power yet in store for him. His runners go out visiting other bands and tell what the old chief expects. They give their assent to it, and as they talk and speculate, they too, become imbued with a spirit of revenge and a desire to gain back the rich heritage their fathers once held in possession for them, but which has passed from their control. They are not educated, it is true, but nature has endowed them with intelligence enough to understand that their fathers had bartered away an empire, and in exchange had taken a limited country, illy adapted to their wants and « 54 » crude, uncivilized habits. This old chief’s mind is made up, and we will meet him again—aye! on fields of blood and carnage.

The government had acted in good faith, and had supplied the Indians with material for building small brick houses, furnishing, in addition to money payments and clothing, farming implements and all things necessary to enable them to support themselves on their fertile farms; and missionaries, also, were among them, and competent teachers, ready to give the young people, as they grew up, an education, to enable them to better their condition and take on the habits and language of the white settlers.

But the devil among the Indians, as among the whites, finds “some mischief still for idle hands to do;” gamblers and other unprincipled men followed the agents, hob-nobbed with them, and laid their plans to “hold-up and bunko” the Indians, who, filled with fire-water and a passion for gambling, soon found themselves stripped of money, ponies and blankets, with nothing in view but a long, cold, dreary winter and starvation. A gambler could kill an Indian and all he had to fear was an Indian’s vengeance (for the civil law never took cognizance of the crime); but if an Indian, filled with rum, remorse and revenge, killed a gambler, he was punished to the full extent of the law. In this one thing the injustice was so apparent that even an Indian could see it; and he made up his mind that when the time came he would even up the account. The savage Indians were intelligent enough to know that in these transactions it was the old story of the handle on the jug—all on one side.

Those of the “friendlies” who were Christianized and civilized were anxious to bury forever all remains of savagery « 55 » and become citizens of the nation, and if the government had placed honorable men over them to administer the law, their influence would have been felt, and in time the leaven of law and order, would have leavened the whole Sioux nation. The various treaties that had been made with them by the government did not seem to satisfy the majority, and whether there was any just cause for this dissatisfaction I do not propose to discuss; but, that a hostile feeling did exist was apparent, as subsequent events proved.

The provisions of the treaties for periodical money payments, although carried out with substantial honesty, failed to fulfill the exaggerated expectations of the Indians; and these matters of irritation added fuel to the fire of hostility, which always has, and always will exist between a civilized and a barbarous nation, when brought into immediate contact; and especially has this been the case where the savages were proud, brave and lordly warriors, who looked with supreme contempt upon all civilized methods of obtaining a living, and who felt amply able to defend themselves and avenge their wrongs. Nothing special has been discovered to have taken place other than the general dissatisfaction referred to, to which the outbreak of 1862 can be immediately attributed. This outbreak was charged to emissaries from the Confederates of the South, but there was no foundation for these allegations. The main reason was that the Indians were hungry and angry; they had become restless, and busy-bodies among them had instilled within them the idea that the great war in the South was drawing off able-bodied men and leaving the women and children at home helpless. Some of the ambitious chiefs thought it a good opportunity « 56 » to regain their lost country and exalt themselves in the eyes of their people. The most ambitious of the lot was Little Crow, the old chief we saw sitting in the shade of his wigwam on Devil’s Lake. He was a wily old fox and knew how to enlist the braves on his side. After the battles of Birch Coolie and Wood Lake, Minnesota, in September, 1862, he deserted his warriors, and was discovered one day down in the settlements picking berries upon which to subsist. Refusing to surrender, he was shot, and in his death the whites were relieved of an implacable foe, and the Indians deprived of an intrepid and daring leader.

There was nothing about the agencies up to August 18, 1862, to indicate that the Indians intended, or even thought, of an attack. Everything had an appearance of quiet and security. On the 17th of August, however, a small party of Indians appeared at Acton, Minnesota, and murdered several settlers, but it was not generally thought that they left the agency with this in mind; this killing was an afterthought, a diversion; but, on the news of these murders reaching the Indians at the Upper Agency on the 18th, open hostilities were at once commenced and the whites and traders indiscriminately murdered. George Spencer was the only white man in the stores who escaped with his life. He was twice wounded, however, and running upstairs in the loft hid himself away and remained concealed until the Indians, thinking no more white people remained, left the place, when an old squaw took Spencer to her home and kept him until his fast friend, Chaska, came and took him under his protection. The picture of Spencer is taken from an old-time photograph.

The missionaries residing a short distance above the Yellow Medicine, and their people, with a few others, were notified by friendly disposed Indians, and to the number of about forty made their escape to Hutchinson, Minnesota. Similar events occurred at the Lower Agency on the same day, when nearly all the traders were butchered, and several who got away before the general massacre commenced were killed before reaching Fort Ridgely, thirteen miles below, or the other places of safety to which they were fleeing. All the buildings at both agencies « 58 » were destroyed, but such property as was valuable to the Indians was carried off.

The news of the outbreak reached Fort Ridgely about 8 o’clock a. m. on the 18th of August through the arrival of a team from the Lower Agency, which brought a citizen badly wounded, but no details. Captain John F. Marsh, of the Fifth Minnesota, with eighty-five men, was holding the fort, and upon the news reaching him he transferred his command of the fort to Lieutenant Gere and with forty-five men started for the scene of hostilities. He had a full supply of ammunition, and with a six-mule team left the fort at 9 a. m. on the 18th of August, full of courage and anxious to get to the relief of the panic-stricken people. On the march up, evidences of the Indians’ bloody work soon appeared, for bodies were found by the roadside of those who had recently been murdered, one of whom was Dr. Humphrey, surgeon at the agency. On reaching the vicinity of the ferry no Indians were in sight except one on the opposite side of the river, who endeavored to induce the soldiers to cross. A dense chaparral bordered the river on the agency side and tall grass covered the bottom land on the side where the troops were stationed. From various signs, suspicions were aroused of the presence of Indians, and the suspicions proved correct, for without a moment’s notice, Indians in great numbers sprang up on all sides of the troops and opened a deadly fire. About half of the men were instantly killed. Finding themselves surrounded, desperate hand-to-hand encounters occurred, with varying results, and the remnant of the command made a point down the river about two miles from the ferry, Captain Marsh being among the number. They evidently attempted to cross, but Captain « 59 » Marsh was drowned in the effort, and only thirteen of his command escaped and reached the fort alive. Captain Marsh, in his excitement, may have erred in judgment and deemed it more his duty to attack than retreat; but the great odds of five hundred Indians to forty-five soldiers was too great and the captain and his brave men paid the penalty. He was young, brave and ambitious and knew but little of the Indians’ tactics in war; but he no doubt believed he was doing his duty in advancing rather than retreating, and his countrymen will hold his memory and the memory of those who gave up their lives with him in warmer esteem than they would had he adopted the more prudent course of retracing his steps.

At a later date, in 1876, it will be remembered, the brave Custer was led into a similar trap, and of the five companies of the Seventh United States cavalry and their intrepid commanders only one was left to tell the tale.

After having massacred the people at the agencies, the Indians at once sent out marauding parties in all directions and covered the country from the northeast as far as Glencoe, Hutchinson and St. Peter, Minnesota, and as far south as Spirit Lake, Iowa. In their trail was to be found their deadly work of murder and devastation, for at least one thousand men, women and children were found brutally butchered, houses burned, and beautiful farms laid waste. The settlers, being accustomed to the friendly visits of these Indians, were taken completely unawares and were given no opportunity for defense.

Major Thomas Galbraith, the Sioux agent, had raised a company known as the Renville Rangers, and was expecting to report at Fort Snelling for muster and orders to proceed south to join one of the Minnesota commands; « 60 » but upon his arrival at St. Peter, on the evening of August 18, he learned the news of the outbreak at the agencies, and immediately retraced his steps, returning to Fort Ridgely, where he arrived on the 19th. On the same day Lieutenant Sheehan, of the Fifth Minnesota Infantry, with fifty men, arrived also, in obedience to a dispatch received from Captain Marsh, who commanded the post at Fort Ridgely. Lieutenant Sheehan, in enthusiasm and appearance, resembled General Sheridan. He was young and ambitious, and entered into this important work with such vim as to inspire his men to deeds of heroic valor. Upon receipt of Captain Marsh’s dispatch ordering him to return at once, as “The Indians are raising hell at the Lower Agency!” he so inspired his men so as to make the forced march of forty-two miles in nine hours and a half, and he did not arrive a minute too soon. After Captain Marsh’s death he became the ranking officer at Fort Ridgely, and the mantle of authority could not fall on more deserving shoulders. His command consisted of Companies B and C of the Fifth Minnesota, 100 men; Renville Rangers, 50 men; with several men of other organizations, including Sergeant John Jones (afterwards captain of artillery), and quite a number of citizen refugees, and a party that had been sent up by the Indian agent with the money to pay the Indians at the agency.

FORT RIDGELY BESIEGED.

Fort Ridgely was a fort in name only. It was not built for defense, but was simply a collection of buildings built around a square facing inwards. The commandant’s quarters, and those of the officers, also, were two-story structures of wood, while the men’s barracks of two stories and the commissary storehouse were stone, and into these the families of the officers and soldiers and the refugee families were placed during the siege. On the 20th of August, 1862, about 3 p. m., an attack was made upon the fort by a large body of Indians, who stealthily came down the ravines and surrounded it. The first intimation the people and the garrison had of their proximity was a volley from the hostile muskets pouring between the openings of the buildings. The sudden onslaught caused great consternation, but order was soon restored.

Sergeant Jones, of the battery, who had seen service in the British army, as well as in our own regular army, in attempting to turn his guns on the Indians found to his utter astonishment that the pieces had been tampered with by some of the half-breeds belonging to the Renville Rangers who had deserted to the enemy. They had spiked the guns by ramming old rags into them. The sergeant soon made them serviceable, however, and brought his « 64 » pieces to bear upon the Indians in such an effective way as to teach them a lesson in artillery practice they did not forget. The “rotten balls,” as they termed the shells, fell thick and fast among them, and the havoc was so great that they withdrew out of range to hold a council of war and recover from their surprise. The fight lasted, however, for three hours, with a loss to the garrison of three killed and eighteen wounded. On the morning of Thursday, the 21st of August, the attack was renewed by the Indians, and they made a second attack in the afternoon, but with less force and earnestness and but little damage to the garrison. The soldiers were on the alert and the night was an anxious one, for the signs from the hostiles indicated that they were making preparations for a further attempt to capture the fort. During the night barricades were placed at all open spaces between the buildings, and the little garrison band instructed, each man’s duty specified, and directions given to the women and children, who were placed in the stone barracks, to lie low so as not to be harmed by bullets coming in at the windows. On Friday, the 22d, Little Crow, the then Sioux commander in chief, had the fort surrounded by 650 warriors whom he had brought down from the agency. He had them concealed in the ravines which surrounded the fort, and endeavored by sending a few of the warriors out on the open prairie to draw the garrison out from the fort, but fortunately there were men there who had previously had experience in Indian warfare, and the scheme of this wily old Indian fox did not work. Little Crow, finding it useless to further maneuver in this way, ordered an attack. The showers of bullets continued for seven long hours, or until about 7 p. m., but the attack was courageously and bitterly « 65 » opposed by the infantry, and this, together with the skillfully handled artillery by Sergeant Jones, saved the garrison for another day. The Indians sought shelter behind and in the outlying wooden buildings, but well directed shells from the battery fired these buildings and routed the Indians, who in turn made various attempts by means of fire arrows to ignite the wooden buildings of the fort proper. But for the daring and vigilance of the troops the enemy would have succeeded in their purpose. The Indians lost heavily in this engagement, while the loss to the troops was one killed and seven wounded. Lieutenant Sheehan, the commander of the post, was a man of true grit, and he was ably assisted by Lieutenant Gorman of the Renville Rangers, and Sergeants Jones and McGrau of the battery. Every man was a hero and did his whole duty. Surrounded as they were by hundreds of bloodthirsty savages, this little band was all that stood between the hundreds of women and children refugees and certain death, or worse than death! Besides, the government storehouses were filled with army supplies, and about $75,000 in gold, with which they intended making an annuity payment to these same Indians.

The water supply being cut off, the soldiers and all the people, especially the wounded, suffered severely, but Post Surgeon Mueller and his noble wife heroically responded to the urgent calls of the wounded sufferers irrespective of danger. Mrs. Mueller was a lovely woman of the heroic type. During the siege, in addition to caring for the wounded, she made coffee, and in the night frequently visited all the men who were on guard and plentifully supplied them with this exhilarating beverage. An incident in relation to her also is, that during the siege the Indians « 66 » had sheltered themselves behind a haystack and from it were doing deadly work. Sergeant Jones could not bring his twenty-four pounder to bear on them without exposing his men too much, unless he fired directly through a building that stood in the way. This house was built as they are on the plantations in the South, with a broad hall running from the front porch clear through to the rear. In the rear of this hall were rough double doors, closed principally in winter time to keep the snow from driving through. The sergeant had them closed and then brought his piece around in front, and the Indians away back of the house could not see what the maneuvering was. He crept up and attached a rope to the handle of the door, and looking through the cracks got the range and then sighted his gun. Mrs. Mueller, sheltered and out of harm’s way, held the end of the attached rope. The signal for her to pull open the doors was given by Sergeant Jones, and this signal was the dropping of a handkerchief. When the signal came, with good nerve, she pulled the rope and open flew the doors. Immediately the gunner pulled the lanyard and the shell with lighted fuse landed in the haystacks, which were at once set fire to and the Indians dislodged. This lady died at her post, beloved by all who knew her, and a grateful government has erected an expensive monument over her remains, which lie buried in the soldiers’ cemetery at Fort Ridgely, where, with hundreds of others whose pathway to the grave was smoothed by her motherly hands, they will remain until the great reveille on the resurrection dawn.

CHAPTER X.

SIEGE OF NEW ULM.

Little Crow, finding himself baffled in his attempt to capture the fort, and learning from his scouts that Colonel Sibley was on his way with two regiments to relieve the garrison, concentrated all his forces and proceeded to New « 68 » Ulm, about thirteen miles distant, which he intended to wipe out the next morning. Here, again, he was disappointed. The hero of New Ulm was Hon. Charles E. Flandreau, who deserves more than a passing notice. By profession he is a lawyer, and at this time was a judge on the bench, and is now enjoying a lucrative practice in St. Paul. By nature he is an organizer and a leader, and to his intrepid bravery and wise judgment New Ulm and her inhabitants owe their salvation from the savagery of Little Crow and his bloodthirsty followers. He had received the news of the outbreak at his home near St. Peter in the early morning of August 19, and at once decided what should be done to save the people.

His duty to wife and children was apparent, and to place them in safety was his first thought, which he did by taking them to St. Peter. He then issued a call for volunteers, and in response to this soon found himself surrounded by men who needed no second bidding, for the very air was freighted with the terror of the situation. Armed with guns of any and all descriptions, with bottles of powder, boxes of caps and pockets filled with bullets, one hundred and twenty men, determined on revenge, pressed forward to meet this terrible foe.

Where should they go? Rumors came from all directions, and one was that Fort Ridgely was being besieged and had probably already fallen. Their eyes also turned toward New Ulm, which was but thirteen miles distant and in an absolutely unprotected condition. Its affrighted people were at the mercy of this relentless enemy. The work Judge Flandreau performed in perfecting an organization was masterful, for the men who flocked in and offered their services he could not control in a military « 69 » sense, because they were not enlisted. The emergency was very great and it was necessary to do the right thing and at the right time and to strike hard and deadly blows, and trusted men were sent forward to scout and report. Hon. Henry A. Swift, afterwards governor of Minnesota, rendered good service in company with William G. Hayden as they scouted the country in a buggy. It was a novel way to scout, but horses were too scarce to allow a horse to each. An advance guard was sent forward about noon, and an hour later the balance of the command was in motion, eagerly pushing forward and anxious to meet the enemy wherever he might be found. The advance guard which Flandreau sent out to determine whether Fort Ridgely or New Ulm should be the objective point had not yet been heard from, and, that no time might be lost, he determined that he would push forward to New Ulm, and if that village was safe he would turn his attention to Ridgely. He found his guard at New Ulm, and they had been largely reinforced by other men who came in to help protect the place. They arrived just in time to assist in repelling an attack of about two hundred Indians, who had suddenly surrounded the little village. Before the arrival of Flandreau and his command they could see the burning houses in the distance, and by this they knew that the work of devastation had commenced, and the forced march was kept up. The rain was pouring in torrents, and yet they had made thirty-two miles in seven hours and reached the place about 8 o’clock in the evening.

The next day reinforcements continued to come in from various points until the little army of occupation numbered three hundred effective and determined men. A « 70 » council of war was called and a line of defense determined upon by throwing up barricades in nearly all the streets.

The situation was a very grave one and it was soon apparent that a one-man power was necessary—that a guiding mind must control the actions of this hastily gathered army of raw material; and to this end, Judge Flandreau was declared generalissimo, and subsequent events proved that the selection was a most judicious one. In a few days subsequent to this he received a commission as colonel from Governor Ramsey and was placed in command of all irregular troops. There were fifty companies reported to him all told; some were mounted and others were not. His district extended from New Ulm, Minnesota, to Sioux City, Iowa. It was a most important command, and Colonel Flandreau proved himself a hero as well as a competent organizer. He is so modest about it even to-day that he rarely refers to it.

A provost guard was at once established, order inaugurated, defenses strengthened and confidence partially restored. Nothing serious transpired until Saturday morning at about 9 o’clock, when 650 Indians, who had been so handsomely repulsed at Fort Ridgely, thirteen miles above, made a determined assault upon the town, driving in the pickets. The lines faltered for a time, but soon rallied and steadily held the enemy at bay. The Indians had surrounded the town and commenced firing the buildings, and the conflagration was soon raging on both sides of the main street in the lower part of the town, and the total destruction of the place seemed inevitable. It was necessary to dislodge the enemy in some way, so a squad of fifty men was ordered out to charge down the burning street, and the Indians were driven out. The soldiers then « 71 » burned everything and the battle was won. The desperate character of the fighting may be judged when we find the casualties to be ten men killed and fifty wounded in about an hour and a half, and this out of a much depleted force, for out of the little army of three hundred men, seventy-five who had been sent under Lieutenant Huey to guard the ferry were cut off and forced to retreat towards St. Peter. Before reaching this place, however, they met reinforcements and returned to the attack. The Indians now, in turn, seeing quite a reinforcement coming, thought it wise to retreat, and drew off to the northward, in the direction of the fort, and disappeared.

The little town of New Ulm at this time contained from 1,200 to 1,500 non-combatants, consisting of women and children, refugees and unarmed citizens, every individual of whom would have been massacred if it had not been for this brave band of men under the command of Colonel Flandreau. Not knowing what the retreat of the Indians indicated, the uncertainty and scarcity of provisions, the pestilence to be feared from stench and exposure, all combined to bring about the decision to evacuate the town and try to reach Mankato. In order to do this a train was made up, into which were loaded the women and children and about eighty wounded men. It was a sad sight to witness this enforced breaking up of home ties, homes burned and farms and gardens laid waste, loved ones dead and wounded, and this one of the inevitable results of an unnecessary and unprovoked war. The march to Mankato was without special incident. Especially fortunate was this little train of escaping people in not meeting any wandering party of hostile Indians.

The first day about half the distance from Mankato to St. Peter was covered; the main column was pushed on to its final destination, it being the intention of Colonel Flandreau to return with a portion of his command to New Ulm, or remain where they were, so as to keep a force between the Indians and the settlements. But the men of his command, not having heard a word from their families for over a week, felt apprehensive and refused to return or remain, holding that the protection of their families was paramount to all other considerations. It must be remembered that these men were not soldiers, but had demonstrated their willingness to fight when necessary, and they did fight, and left many of their comrades dead and wounded on the battlefield. The train that had been sent forward arrived in Mankato on the 25th of August, and the balance of the command reached the town on the day following, when the men sought their homes.

The stubborn resistance the Indians met with at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm caused them to withdraw to their own country, and this temporary lull in hostilities enabled the whites to more thoroughly organize, and the troops to prepare for a campaign up into the Yellow Medicine country, where it was known a large number of captives were held.

COL. FLANDREAU IN COMMAND.

While the exciting events narrated in the previous chapters were taking place other portions of the state were preparing for defense. At Forest City, Hutchinson, Glencoe, and even as far south as St. Paul and Minneapolis, men were rapidly organizing for home protection. In addition to the Sioux, the Chippewas and Winnebagoes were becoming affected and seemed anxious for a pretext to don the paint and take the warpath. Colonel Flandreau having received his commission as colonel from Governor Ramsey, with authority to take command of the Blue Earth country extending from New Ulm to the Iowa line, embracing the western and southwestern frontier of the state, proceeded at once to properly organize troops, commission officers, and do everything in his power as a military officer to give protection to the citizens. The Colonel established his headquarters at South Bend and the home guards came pouring in, reporting for duty, and squads that had been raised and mustered into the volunteer service, but had not yet joined their commands, were organized into companies, and the Colonel soon found himself surrounded by quite an army of good men, well officered, and with a determination to do their whole duty. This was done by establishing a cordon of military posts so as to inspire confidence and prevent an exodus of the people. Any one « 76 » who has not been through the ordeal of an Indian insurrection can form no idea of the terrible apprehension that takes possession of a defenseless and non-combatant people under such circumstances.