| France | Holland | Norway |

|---|---|---|

| COMTE A. DeCHAMBURE 37, Rue Bergere Paris |

TECHNISCH BUREAU VAN LEENT Nassaukade 17 Ryswyk |

OTTO PLATOU Skovveien 39 Christiania |

| Italy | Japan | |

| GEORGES BREITTMAYER 20, Rue Taitbout Paris |

F. P. CAMPERIO Via Bagutta 24 Milan |

MITSUI & CO., LTD. Tokyo |

| Sweden | ||

| F. J. DELVES 20, Rue Taitbout Paris |

GRAHAM BROS. Stockholm |

MITSUBISHI ZOSEN KAISHA, LTD. Tokyo (For Ship Stabilizer) |

| Spain | Denmark | Chili, Peru & Bolivia |

| F. WEYDMANN Victoria 2 Madrid |

C. KNUDSEN 11 Kobmagagade Copenhagen |

WESSEL DUVAL & CO. 25 Broad Street New York |

HEN the earth was thrown off from the sun and commenced rotating about its own axis, there was developed a force generated by the earth’s rotation. For countless centuries this force has been at work, but no one has ever been able to harness it to serve the purposes of man. But now, through the efforts of Foucault, Hopkins, Sperry, and other noted scientists, this force has been put to work. It serves to direct a thousand ships in their courses.

Of course, this is not the only force which has been used to guide ships. Since 1297 A.D. mariners have used magnetic attraction as the force by which to guide their vessels. For centuries seafaring men sailed only in wooden ships, and were therefore satisfied with the magnetic compass. Then came steam and steel. Navigation then instead of being a hit or miss game of chance became the exact art of directing a ship by the shortest possible course in the quickest possible time.

Now that ships cost millions of dollars to build and thousands of dollars per day to operate, time has become the most essential element in navigation. The development of ships from the sailing vessel to the ocean greyhound has been one of the marvels of modern times. But the development of the magnetic compass has not kept pace with the development of the ships which rely upon it. Many of the great trans-Atlantic liners are guided by practically the same type of compass as that which Columbus used on the Santa Maria. The compass on the wooden Santa Maria pointed to magnetic north with a fair degree of accuracy, but the compass on the steel greyhounds must contend with many distractions.

For years magnetic compass designers spent their efforts to produce

compensating devices that would annul the effects of all external

influences, so that the magnetic compass would be free to indicate only

the direction of the earth’s magnetic lines. Very little has been done

to improve the compass itself—it still depends upon the attraction of

the Magnetic North Pole. The Sperry Gyro-Compass differs in principle

from any other compass. It is not magnetic. It derives its directive

force, not from magnetic attraction, but from the earth’s

rotation.

There is certainly a crying need for this new type of compass. A ship now-a-days costs millions of dollars and carries cargoes usually equal in value to that of the ship. It has been estimated that inaccuracies in navigation attending the use of the magnetic compass cause a yearly loss of ships to the value of $70,000,000. No estimate can possibly be made on the value of lives lost on these ships.

Millions of dollars are spent each year on charts, lighthouses, buoys, geodetic and hydrographic surveys, and on compilation of notices to mariners. Notwithstanding all of these, ships must ultimately depend upon their compasses for their safety and efficiency of navigation.

Inaccuracies in navigation can be eliminated by the use of a reliable compass. The Sperry Gyro-Compass puts the earth to work. It utilizes a force which is as unvarying as the law of gravity, a force that cannot be interfered with by any other influence.

Any wheel rotating at a high speed about its own axis, and free to place itself in any plane, is called a Gyroscope. The Gyroscope is the instrument which utilizes the earth’s rotation as a force to direct the course of ships.

Suppose you were to place such a small wheel supported by its axis upon a larger wheel which also is revolving. The rotation of the larger wheel would so influence the smaller wheel that its axis would point in the same direction as the axis of the larger wheel. Why this is the case does not concern us here. Let it suffice that the larger wheel will cause the smaller wheel to behave in this manner. This is in accordance with a natural law. This law operates as unfailingly as the law which causes an unsupported body to fall to the ground.

Suppose the larger wheel happens to be the earth, which in reality is a revolving wheel. Suppose further, the small wheel is a Sperry Gyro-Compass. In accordance with this natural law just outlined the smaller wheel, or Gyro-Compass, will point its axis in the same direction as the axis of the earth, or, in other words, to the true or geographical North Pole. This explanation of the principle of gyroscopic motion is necessarily crude. The principle itself has been established beyond any reasonable doubt. It can be proved by mathematics to the satisfaction of the most exacting scientist and has been demonstrated, throughout the navies of the world, to practical seamen.

The final result is that we have

a principle which enables us to construct

an instrument which will place

itself in the true geographic north and

south meridian, and that it responds

to no influence or impulse other than

the earth’s unvarying rotation.

HE purpose of a compass

is to indicate direction. The relative

position of the North Pole to any point on the earth’s surface is

called North. We figure all direction from this conception. This

geographical North Pole is called the True North. About 800 miles

from this True North Pole is a spot which has a strange magnetic

attraction. The needle of the magnetic compass, if undisturbed by

local influences, points to this spot, and not to the True North Pole.

This spot is called the Magnetic North Pole. This mysterious attractive spot is not

stationary. It moves about from year to year within a wide

circle.

Inasmuch as the navigator must refer to True North, he must determine the angle or variation between True North and Magnetic North as indicated by his magnetic compass. This determination is made comparatively easy by using charts which express in degrees the difference between Magnetic North and True North for any point on the earth’s surface.

Such a chart is shown in Figure 3. Also on each chart used by a navigator for a particular locality there is marked a compass rose in which is recorded the variation for that exact spot as of a certain date, and in addition the rate at which the variation changes annually, Figure 4.

Navigation along a coast line where sights can be taken on buoys or lighthouses is simple, and is termed “piloting.” This, of course, can be done without the aid of a compass.

Upon getting to open sea the mariner checks

his position in a similar manner, by observing

the position of his ship in relation to the position

of the sun, moon or stars. Between observations

the position of a ship is determined by “dead

reckoning.” The distance it has traveled from

the last known position is measured by the ship’s

log and the direction is indicated by the compass.

Very often for days at a time, owing to weather

conditions, it is impossible to get an observation

or sight on a celestial body. During this run the

navigator is dependent entirely upon the compass.

The slightest error in the compass, due to

variation or deviation, in such circumstances

will cause the ship to be miles out of its course,

and the actual position will be far from the

calculated position.

F you were to conceive of a compass which would be free from all the

troubles and errors found in most compasses, which would relieve

you of all the worry and care the present compass requires, a compass

which would be accurate and reliable, a compass which would

be the Ideal Compass under all conditions, you would undoubtedly

conceive of a compass that had the following

characteristics:

Let us compare the Magnetic Compass with the Sperry Gyro-Compass and determine which more nearly approaches the Ideal Compass.

The Magnetic Compass does not point to True North, it points to Magnetic North, which is about 800 miles from the True North Pole.

The Sperry Gyro-Compass, which is not a Magnetic Compass, and is not affected by a magnetism of any sort, and derives its directive force from the earth’s rotation, points True North. It does not point to the Magnetic North Pole.

Every time a ship’s course is laid or changed, or its position noted, the navigator must make and apply calculations to correct the errors caused by variation of the earth’s magnetic fields, and deviation due to local conditions about the ship. Mistakes are frequently made in applying the correction factors by applying them to the wrong side. An error is thus introduced, which in magnitude is twice the correction factor. Instances are reported of ships being 200 miles out of their courses as a result.

The Gyro-Compass requires no corrections since it is undisturbed by variations or any local magnetic conditions. The reading indicated by the Sperry Gyro-Compass is not approximate—it is absolutely and immediately correct. It is not necessary to correct the course every few hours for variation—the navigator is freed from the necessity of making calculations.

After the navigator has made calculations for the deviation errors of the Magnetic Compass, they must be applied by means of manipulating the soft iron globes and compensating magnets. This is an operation requiring such a high degree of skill that only trained men called Compass Adjusters are qualified for the work.

The occasional turning of a thumb nut is the only compensation necessary in the use of a Sperry Gyro-Compass. No tables or curves are required. The ship’s Navigating Officer makes this adjustment with ease.

Each time a compass is compensated it is necessary to check the compensation by checking the deviation on various headings. This may be done by the use of deflector magnets. A more exact method is to swing the ship in a circle while bearings are taken of a known object on land and the deviation noted on various headings. The sun is often taken as a reference point for this purpose.

It is never necessary to swing ship or to correct the Gyro-Compass for either variation or deviation of any kind. Where a Gyro-Compass and a magnetic compass are both used on a ship, the ship may be swung to correct the magnetic compass—the Gyro-Compass furnishing true headings. The time required is thereby materially shortened.

When a steel ship is building a subpermanent magnetism is induced in its keel, hull, and plates. It causes a compass deviation classed as “semicircular.” This deviation must be compensated for.

As a ship moves through the earth’s magnetic fields in its varying quantities and directions, a temporary and varying magnetism is induced in the soft iron of the ship. The resultant deviation is classed as “quadrantal,” and must be compensated for.

The Sperry is not a Magnetic Compass. Hammering, riveting, and moving through magnetic fields may induce magnetism in the ship, but will have no effect upon the Sperry Gyro-Compass.

There is no condition of the ship or cargo for which the Gyro-Compass must be corrected.

Change in the character or disposition of the cargo of the ship causes a change in the magnetic fields surrounding the compass. These changes must be compensated for.

The Sperry Gyro-Compass is not affected by any cargo. A cargo of iron ore has no more effect upon it than a cargo of cotton. You could even carry a load of strong magnets without causing the slightest deviation.

Changes in the temperature of the stack, due to shifting of the wind and force of draft, vary its magnetic characteristics. Consequently the Magnetic Compass is affected.

Temperature changes do not influence the Sperry Gyro-Compass.

No matter what the conditions are that change the magnetic characteristics of the stack, ship or cargo, they cannot affect the Gyro-Compass, as it has nothing whatever to do with magnetism.

Another error, called heeling error, is caused by the change in the disposition of the material of the ship with reference to the compass. It is brought about when the ship rolls. For example, a ship heading on a northerly course would, if rolled to port, place all magnetic material of the ship to the eastward of the compass. This pulls the north end of the compass to the eastward. The action and effect would be just opposite to this on a roll to the starboard. The result is that the needle is caused to oscillate in either direction. The helmsman in his attempt to keep “on” will cause the ship to traverse a sinuous course.

The card and needle of the magnetic compass are placed in a bowl filled with a liquid. The purpose in so doing is to make the action of the card somewhat sluggish, so that it will not follow very slight magnetic distractions or ship movements. Every time the course of the ship is changed the sluggish action, due to adhesion between the bowl, liquid and card, pulls the compass off the meridian. Official test has shown that from three to four minutes are required for the compass to overcome this “lag.” The “lag” is somewhat less in the dry card compass.

Not only is the Sperry Gyro-Compass unaffected by magnetic conditions, resulting from the heeling error, but before being placed upon the ship it is tested for days under conditions simulating the motion of the ship in the most severe storm.

A ship steered by the Gyro-Compass traverses a straight line course; the Gyro-Compass does not oscillate with the rolling of the ship. It is not necessary for the helmsman to use as much helm to keep the ship on her course. A great saving is made in the use of the steering engine.

There is no “lag” in the Sperry Gyro-Compass, because it does not leave the meridian, no matter which way or how quickly the ship may turn or zig-zag. Exhaustive tests have been conducted on compasses installed on torpedo boat destroyers. Even when zig-zagging at top speed in heavy seas the Gyro-Compass shows no “lag.”

Traveling the straight line course instead of the sinuous course, ships equipped with the Sperry Gyro-Compass have saved from one to ten per cent in time over the average schedule time required to cover their courses when steering by the magnetic compass.

Due to magnetic storms and any number of other causes the magnetic compass may at any time be distracted so that it does not indicate correctly. Disturbances are extraneous and their direction and magnitude cannot be determined. The navigator is constantly subject to the feeling that his compass may not be accurate—that he cannot depend on it.

About the only thing that will cause an error in the Gyro-Compass is the failure of the electrical power supply. Should this contingency occur an electric bell warns the navigator. Any disturbances must originate with the master compass and can be quickly and accurately located.

The Sperry Gyro-Compass unfailingly points True North under all conditions of weather, ship or cargo. It relieves the navigator of calculation of errors, and tiresome compass compensations. It makes a great saving in time required to “swing ship.” The Sperry Gyro-Compass is, therefore, the Ideal Compass.

URING the construction of a steel ship it is usual to build it on ways the direction of which lie in the East-West line. Should the ways be placed in a North-South line the riveting on the keel and plates tends to help the molecules of metal to place themselves parallel to the magnetic lines of force, and magnetize the metal. When placed in the East-West line the molecules of metal in the plates are at right angles to the magnetic lines of force, and are not as easily magnetized. The use of the Gyro-Compass eliminates the necessity of placing the ways in the East-West line.

After a large ship has been launched, and during the fitting out period, it is often necessary to have it swung end for end in order to neutralize or equalize the magnetism induced by the earth’s magnetic field. To swing a large ship end for end costs anywhere from one thousand ($1000) to three thousand ($3000) dollars. The Gyro-Compass is unaffected by any magnetic phenomena, and is so dependable that it makes the swinging of the ship unnecessary.

In constructing a ship it is customary to make all metal parts within approximately ten (10) feet of the magnetic-compass stand of bronze, brass or other non-magnetic material. The proximity of magnetic metals seriously affects the accuracy of the compass. All electric leads are run so as to clear the vicinity of the compass, as the magnetic fields set up by such conductors seriously influence the compass needle. Actual experience is on record that the total installation cost of the Sperry Gyro-Compass has been saved many times over by the elimination of special metals and special run of electric leads.

Before starting on a long voyage, especially with a new ship using

the magnetic compass, it is customary to swing the ship through a

complete circle to check deviation. To swing ship it is first necessary

to pick out a suitable object on land having a known bearing to the

ship. This object is used as a reference point. If at sea observations

are taken on the sun. The ship is then swung through 360 degrees,

stopping usually on each 15-degree heading, and noting the deviation.

A table is made up showing the deviation on each of these headings.

An attempt is then made to so adjust or manipulate the compensating

magnets to eliminate the error found. The ship must then again be

swung through 360 degrees, stopping at headings as before to check the

applied compensation.

On some ships it is the custom to check the deviation by the deflector magnet method. The ship in this case is put on a certain heading and a magnet placed to one side of the compass and the deviation noted. The same magnet is then placed at an equal distance to the opposite side and the deviation noted. The difference, if any, between the readings is the deviation on that particular course.

With either method of checking for deviation, considerable time is used. It is not

necessary to check for deviation or apply any compensation to the Gyro-Compass, as it

is not magnetic. In fact the Gyro-Compass has nothing

whatever to do with magnetism.

When at sea the Gyro-Compass affords the means of keeping to the straight-line, true course. The line A B, Figure 5, shows the straight-line course from the port of New York to the port of Liverpool. The line A C E B shows, with exaggeration, the actual course steered due to compass and other errors. At the point E the ship’s position was checked by observation of a celestial body. The line E B represents the new course set to bring the ship to her destination. This is an occurrence which sometimes happens not once but often during a voyage.

It is evident that a loss of time is involved when the ship leaves her straight line course. The inherent accuracy of the Sperry Gyro-Compass enables the ship to keep to the straight line course, and also to steer directly on true courses.

By keeping on a straight line course the ship is enabled to make

a good many more miles on the same number of revolutions or turns of

the propeller. Under exactly the same weather conditions a 16,000 ton

liner made 370 miles in 24 hours at an average of 86.95 revolutions per

minute per mile when steered by a magnetic compass, and the same liner

made 377 miles with 85.61 revolutions per minute per mile when steered

by the Gyro-Compass. This saving amounts to easily $50 per day for this

ship. During her eleven-day voyage she saved $550. At this rate of

saving the Gyro-Compass equipment is soon paid

for.

The Sperry Gyro-Compass does not oscillate with the rolling of the ship, or in other words, has no heeling error. The use of the helm is greatly diminished. Records show that on one trans-Atlantic liner a saving of 24 percent in the revolutions of the steering engine, when steered by Gyro-Compass, was effected. One of the largest trans-Atlantic liners reports that but one-third of the helm is used when the ship is steered by Gyro-Compass.

This saving in the use of the steering engine gives actual proof that the ship navigated by a Gyro-Compass steers a straight line course. It further proves that the ship does not divert its slip-stream as often—the power output of the main engines is thereby reduced.

Records taken on a well-known passenger liner show that in making her regular trip between New York and Jacksonville, Florida, she saved more than two hours due to steering by a Sperry Gyro-Compass. A saving of 3,410 turns of her propeller was also effected. These savings were made even with much greater than the usual draft.

Records taken by means of the Sperry Recording Compass show that when the helmsman is given a certain course he can keep the ship one and one-half degrees nearer the course when steering by the Gyro-Compass than when steering by magnetic compass.

The Gyro-Compass can make great savings in money both in construction and operation of the ship. These factors are perhaps trivial when compared with the safety factor introduced by the use of the Sperry Gyro-Compass.

Due to the elimination of the many uncertainties of the magnetic compass, insurance companies are favorably disposed toward the use of the Sperry Gyro-Compass, which ultimately will result in a reduction of insurance rates.

The use of the Sperry Gyro-Compass eliminates inaccuracies due to navigation, thereby saving time, insuring the ship, the cargo, and the lives of passengers and crew.

Sperry Gyro-Compasses are operating on many of the world’s largest and fastest passenger liners and cargo ships. These ships are making savings every day of fuel used and time required to make their courses. The navigators using these compasses find that they can come very much nearer their calculated positions when steering by the Gyro-Compass. The Gyro-Compass makes the art of navigation more exact.

The Sperry Gyro-Compass is the only one to

pass the service tests in the world’s

navies.

HE equipment which applies the principle set forth in a practical way consists of:

The function of each piece of equipment and its relation to other parts is shown on pages 22 and 23.

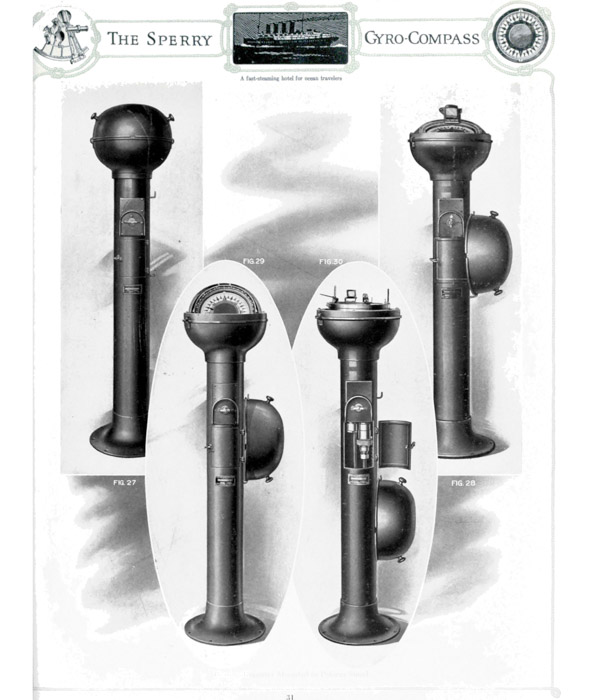

The Master Gyro-Compass is contained within a binnacle stand, with glass dome top.

As shown in the photographs and sectional view, the twin gyro-wheels are supported from a frame-work which is in turn set in gimbal rings. The outer gimbal ring is attached to the binnacle stand by means of a number of supporting springs. The springs are provided for protecting the compass against sudden jars and vibrations. Figure 18 shows a photograph of the top view, while the wheels are shown from below in Figure 16.

A diagrammatic representation of the Sperry Gyro-Compass is shown in plan view in Figure 17. The elevation, or side view, is shown in Figure 15. These drawings show the working parts of the Gyro-Compass. Each of the twin gyro-wheels is enclosed in a case, which is in turn suspended from the main frame and spider.

The wheels are spun at a high

speed in unison by means of electricity.

The force of the earth’s

rotation combines with the force

resulting from the rotating wheels.

The resultant action of these two

forces is that both wheels turn their

axes directly into, or parallel with,

the earth’s north and south meridian.

The compass card, of course, also

turns and indicates direction by comparing

the stationary “lubber line,”

representing the ship’s head, with

the compass card.

| Figure 6. Control Panel. | Figure 8. Master Compass. | Figure 9. Storage Battery. |

| Figure 7. Motor Generator. |

| Figure 10. Repeater on Steering Stand. | Figure 11. Repeater, Bulkhead Type. | Figure 12. Bearing Repeater in Pelorus Stand. |

A single gyro-wheel would constitute a satisfactory stationary, or “land compass.” On shipboard the roll, yaw and pitch of the ship would impose additional duty on a single wheel. It would have to point not only True North, but also offset the effect of the sea. One of the two wheels is arranged to always point True North, while its twin wheel opposes and neutralizes all influences other than the force of the earth’s rotation. The force of both wheels is utilized in seeking the meridian.

The Master Gyro-Compass is a marvel of mechanical perfection and ruggedness. Every rotating or revolving part moves upon special bearings to reduce friction. It should be noted also that the gyro-wheels do not directly operate the compass card. The compass card is turned by a small electric motor (Azimuth Motor), Figure 17. The slightest change in position between the wheels and card operates the “trolley” or electrical contact, which controls the Azimuth Motor. The card is made to “shadow” the wheels. The follow-up is so close that the card frame has been called the “phantom.”

An electrical transmitter, Figure 17, is operated by

the movement of the card. This transmitter is the means by which the repeaters are

kept in unison with the movements of the Master Gyro-Compass, and made to show the

exact reading at any instant. Again the Azimuth Motor furnishes the very slight

amount of power required to operate this

device.

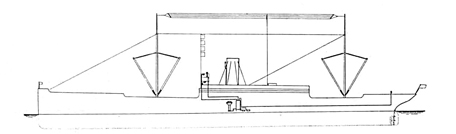

The Master Compass is placed near the center of the ship at the water line. At

this point the effect of rolling is at a minimum. It is, however, not necessary to place it

exactly at this position. Figure 13 shows the approximate location of the various

pieces of equipment aboard ship.

A familiar application of the repeater principle is that used in hotels and public buildings, where a number of repeater clocks are operated from one master instrument. Likewise, the repeater used upon the bridge, the bearing repeater, and the one at the after steering station, are all operated by electricity in perfect unison with the Master Gyro-Compass and show the exact reading of the Master at any instant. Repeaters are operated by a small electric motor within each case, controlled by the transmitter at the Master Gyro. In designing the repeaters particular attention has been given to the electrical circuits so as to make all connections water, spray and condensation proof. Stuffing tubes of improved design are used at all outlets and entrances.

A miniature electric lamp within the repeater supplies the necessary illumination of the dial. The illumination can be brightened or dimmed by turning the switch handle on the face of the terminal box.

The repeaters are supplied in three styles:

Special stands or fixtures can be supplied if necessary.

A metal “non-reflection” cover is supplied which can be fitted to either the bridge or the after steering repeaters. The cover has adjustable doors and a hood. Its object is to exclude all light from the top glass of the repeater except at the lubber’s line. No light will be reflected into the eyes of the helmsman. The doors can be closed until a very small sector of the repeater dial appears at the lubber’s line. Experience has proved that it is easier to watch and concentrate when only a small portion of the dial is visible. A magnifying glass can be used in conjunction with the cover so that the repeater indication can be read at a distance.

The bridge and after steering repeaters are mounted on adjustable brackets. The position of the repeater can be changed so as to allow a full face view of the dial from almost any angle.

The bearing repeater is of great aid to the navigator. The repeater is mounted within the stand and, of course, shows the exact reading of the Master Compass. In taking a bearing on a distant object or a sun azimuth it is not necessary to first set the “dumb” compass to correspond with the main compass. A constant true indication is afforded.

Installation of the bearing repeater can be

made in such a position on the upper bridge so

that it may be used for steering from that

position as well as for taking bearings. A special

pelorus stand cover can be supplied with windows

to allow steering with the cover on, so as to protect

the repeater from spray and the

weather.

An improved design of azimuth circle is furnished which fits directly over the top of the repeater. Figures 24 and 26, on page 30, show the azimuth circle and bearing repeater in use, taking a bearing on a distant object, and on the sun respectively. This azimuth circle is so constructed as to bring the object, the spirit level and dial within the field of vision concurrently. The bearing can be taken with great accuracy. There is no possibility of the Master Compass changing its position while the pelorus is in use. Such an occurrence is not uncommon when using the ordinary pelorus or “dummy” compass.

An additional graduated ring, Figure 25, is supplied for placing under the azimuth circle so that in case the Gyro-Compass is not operating such, for instance, as when the ship is at anchor, the pelorus can still be used as a “dumb” compass. The main compass setting is made upon the ring, and the azimuth circle used in the usual manner.

The bearing repeater can be furnished with any one of three kinds of azimuth circles. The Ritchie circle is usually supplied. The purchaser also has the option of choosing either the Sperry circle or the Kelvin Azimuth Mirror.

The compass control-panel provides a means for controlling the various electrical parts of the Gyro-Compass, the storage battery, motor-generator and ship’s supply current. It is very compact, neat, and of good appearance. It receives electrical power from the ship’s mains and distributes it to the motor-generator set, Master Compass and repeater.

The switch panel is made up of black ebony asbestos, mounted upon angle iron. The panel is usually mounted with its back near the bulkheads, but so hinged as to admit of access to its rear.

The Motor-Generator supplied is an efficient and exceptionally reliable piece of equipment. Its purpose is to convert the ship’s supply current into electricity of the characteristics used in spinning the gyro-wheels and operating the repeaters.

The complete failure of

the electrical plant aboard a

modern ship is an event of

rare occurrence. If, however,

such a contingency

should occur, provision has

been made for it in the Gyro-Compass equipment by

supplying a storage battery of sufficient capacity to

operate the entire equipment for a period of two hours.

The battery is so connected electrically as to keep

itself in a charged condition while the compass is

operating under normal conditions.

An outstanding feature of the Gyro-Compass is that it makes possible the recording of the actual courses steered by a vessel. The recording compass is connected to the electrical circuits like a repeater and follows the movements of the Master Compass. It not only indicates the heading at any instant, but also makes a graphic record on a chart. Radial lines on the chart represent the various courses. Concentric circles represent time—each small division five minutes—each large division one hour.

The dial on which the chart is mounted turns

with the movements of the master compass bringing

the correct course under the marking point. As the

time advances a line is marked on the chart showing the exact course steered at a

definite time. On starting, the marking arm is at the inner edge, clockwork moves

it toward the outer edge with uniform motion.

The chart shown in Figure 32 forms a valuable record. It was taken on a ship at

a time a radio call was received from a burning

oil tanker. Being within the distance

defined by law, the ship was legally, as well

as morally bound to proceed to the distressed

ship. The chart shows that the

course was altered to go to the tanker’s aid.

It also showed the exact time, thereby

establishing proof as to the fulfillment of

the obligation. A few minutes later another

radio call advised that the fire aboard the

tanker was extinguished. The chart shows

that the course was again altered to bring

the vessel back on her original given course.

The chart further shows the actual courses steered in holding the ship on its given course. It shows just how efficiently each helmsman handles the ship. It provides an excellent method of training helmsmen to use less helm, effecting a saving by less frequent use of the steering engine.

The recording compass is a great aid to the Captain and Navigator in improving the navigating efficiency of the ship.

The recording compass can be supplied as a part of the Gyro-Compass equipment—its additional cost is small when compared to the saving and benefits derived from its use.

The operation of the Sperry Gyro-Compass is made easy by making all parts as simple as possible.

In starting the equipment it is necessary to turn but one switch. The twin wheels immediately start spinning and will in a short time come up to the normal speed.

After the speed has been attained, a short time is allowed for the wheels to cause their axes to “settle,” or, in other words, to seek and hold the meridian.

In case of failure of the ship’s supply, or other trouble, an audible signal immediately gives indication that something is wrong. This is a decided improvement over the ordinary compass, as no indication is afforded of the presence of factors which cause errors in its reading.

All of the greatest commercial aids require some care, such, for instance, as the telephone, typewriter, adding machine, duplicating machine and so on.

The magnetic compasses aboard ship receive especially watchful attention, to see that they are not meddled or tampered with. As a rule the entire ship’s crew, including the youngest apprentice, knows that the compass must in no way be handled.

It should be remembered that the Sperry

Gyro-Compass is a mechanical compass. Although

the very best materials, design and skill

enter into its construction, it is still liable to

failure. Even with that possibility, it is so

superior to the magnetic compass that it more

than justifies its installation use. In the same

way the electric light, although liable to failure,

is vastly superior to the old oil lamp. The oil

lamps are seldom used, yet they are carried

aboard ships for the contingency which might

happen. Similarly a failure of the electric or

hydraulic steering gear may necessitate the

temporary use of the inefficient hand-steering

gear.

Fig. 33. Repeater at After Steering Station. Fig. 35. Repeater on Wing of Upper Bridge. Fig. 34. Bearing Repeater on top of Wheel-house.

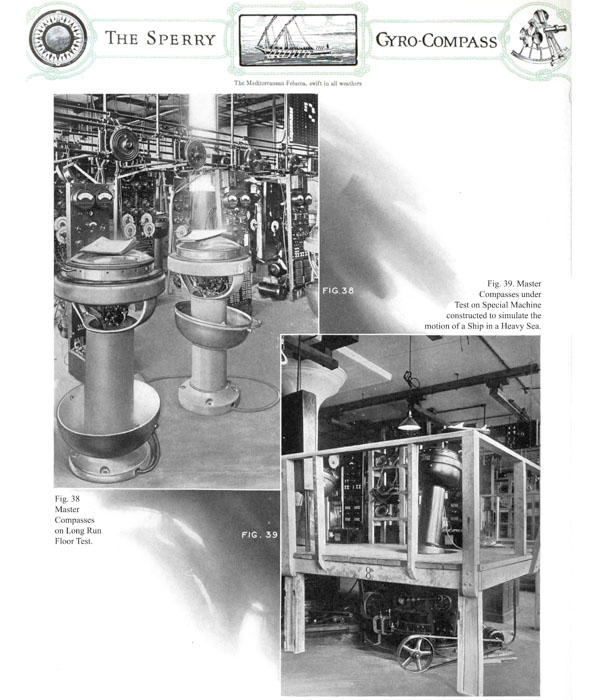

Fig. 38. Master Compasses on Long Run Floor Test. Fig. 39. Master Compasses under Test on Special Machine constructed to simulate the motion of a Ship in a Heavy Sea.

HEN a Gyro-Compass is sold the interest of The Sperry Gyroscope Company does not cease. Our interest in our customer is only beginning. An experienced service engineer installs every Sperry Gyro-Compass. This engineer is also available to make the first trip with the compass in order to assure its proper operation. After installation the Sperry Service Engineers are available in every large port in the world to come aboard and inspect, clean, repair and overhaul the Gyro-Compass equipment so as to keep it in first class operating condition. A radiogram sent to any of the Sperry Service Stations will bring a Service Engineer to meet your ship. During the first year there is no charge. After this period a reasonable charge is made for the service. Such a charge is similar to that at present made by compass-adjusters.

A list of the Sperry Representatives is given on the title page of this book.

The Sperry Gyro-Compass is an instrument of precision. From the work done by the Gyro-Compass and the objects accomplished it would be natural to class it as a scientific instrument. It is, however, more than that for the reason that it has been made strong and sturdy for operation under the most severe conditions at sea. The most expert and skilled workmanship is required to combine strength and precision, such as found in the Gyro-Compass. The Sperry organization prides itself upon having the best workmen that can be obtained for their respective vocations.

The materials used are the very best obtainable. The rigid and inflexible set of purchasing specifications insures receiving the best materials.

A well organized inspection force passes upon

all material upon its receipt, and through the

various manufacturing stages to the final

product.

Each Sperry Gyro-Compass is on test for several days. During this time it is put through every devisable test to simulate the conditions under which it will have to operate. Figures 38 and 39 show a compass mounted on a stand which is operated by means of motor driven gears, cams, etc., so as to reproduce the roll, pitch and yaw of a ship at sea. Absolute accuracy of the Master Compass and all repeaters while operating under this condition is required.

The purchaser is thereby assured that the compass to be installed upon his ship will have had all manufacturing inaccuracies or so-called “kinks” worked out. A record of the test accompanies each compass.

Special care is taken in packing the Gyro-Compass for shipment. Experience gained from the shipment of hundreds of compasses has devised means whereby to insure the safe arrival of all parts so that installation will not be delayed.

In order that no injury may result to any parts, the Gyro-Compass is unpacked under the supervision of the Sperry Service Engineer.

The Sperry Service Organization is one which serves in all parts of the world. A corps of Service Engineers, having special training at the factory in all departments relating to the Gyro-Compass, are available in nearly every large port of the world. These engineers are ready to come aboard your ship, to clean, adjust and overhaul the Gyro-Compass, thus relieving the navigator of all care other than the actual use of the Gyro-Compass.

During the war we had Service Engineers in every port where the ships of the Navy

were likely to call. Our men have been in many of the naval actions and have been

able to render very considerable service on many

unusual occasions. For example, it

was desired to place an equipment on a British ship which was on her way to the Dardanelles.

The Admiralty instructed us by telegram to have an equipment and a Service

Engineer meet the ship at the British

Naval Station at Malta in the

Mediterranean. By sending the

equipment with our Service Engineer

via a passenger train to the south of

Italy and via destroyer to Malta we

were able to meet the ship there on

the day she arrived. The ship was

able to stay only twenty-four hours,

and as it took about four days to install the equipment,

our engineer

remained on board and finished the

work while the ship was enroute from

Malta to the Dardanelles.

This ship, the Inflexible, arrived at the Dardanelles just in time to join in the first naval action directed against the land batteries. During the first part of the engagement our engineer remained with the Master Compass which was installed near the dynamo room. When he saw that it was functioning properly he left it to go on deck and view the action, the effects of which he had become aware of, as a number of shells from the land batteries had hit the ship. Almost immediately after he arrived on deck a torpedo struck the ship directly under the compartment where the Gyro-Compass was located, killing every man in that compartment. Although badly damaged the ship was able to get out of range of the land batteries and reach the naval base near the Dardanelles.

The Gyro-Compass was, of course, almost totally destroyed. Shortly after the action ended our engineer was enabled to get ashore on a Greek island via one of the British destroyers. This island had a telegraph station which he used to cable us that “Equipment No. 286 is under four feet of water,” and that we should have another equipment ready to replace it. We took this telegram to the Admiralty who authorized us to have another equipment prepared to meet this ship at Gibraltar. This we did, again sending a Service Engineer who met the ship at Gibraltar, on her way back to England to be repaired and refitted.

The Sperry Service Organization stands ready to help all ships equipped with a Gyro-Compass at all times, even in emergencies such as those experienced by naval vessels.

At the time of the battle of Coronel on the west coast of

South America, H. M. S. Invincible was being overhauled

at the Portsmouth Dockyard in England. She was immediately

ordered with one other large British ship to South American

waters under the command of Admiral Sturdee, to re-enforce

the British fleet, and then to find and destroy the German

ships which had defeated the British at the battle of

Coronel. When the overhaul of the Invincible was completed

and she was ready to leave the docks, it was at first planned

to delay sailing until the ship could be swung and the

magnetic compasses compensated. It was decided, however,

that although the compasses were badly in need of adjustment

it was necessary to save every minute in order to reach

South American waters before the German ships could find

and destroy the British ships remaining in those waters.

The Invincible therefore sailed without adjusting her

magnetic compasses and navigated entirely by the Sperry

Gyro-Compass from Portsmouth to the Falkland Islands. When

an azimuth was finally taken the magnetic compass was found

to be out about 22 degrees. The Invincible arrived at the

Falkland Islands just in time to coal before the German fleet

appeared. If H. M. S. Invincible had not had a Gyro-Compass

the probabilities are that she would not have reached the

Falkland Islands in time to win the battle which took place

almost immediately upon her arrival.

Figure 49 shows a British submarine, a sister ship of the E-11, that entered the Sea of Marmora through the Dardanelles for the purpose of destroying Turkish and German shipping. The E-11 put a torpedo right into Constantinople harbor. The Second Officer of the E-11 in relating this exploit, stated that they steered by the “Sperry” all the way in and out. His remark was that, “It never let me down.”

In this exploit, and many others of a similar nature, the Gyro-Compass was used for all navigation. These extremely daring and hazardous operations would not have been possible without this instrument.

A similar British submarine left Harwich on the east coast of England, and during a period of three weeks made seven patrol trips, and without once seeing the sun, finally returned to Harwich and picked up the buoy at the mouth of the harbor without the least difficulty. The navigation in this case was carried out entirely by the Gyro-Compass.

Figure 54 is a photograph of H. M. S. Lion, the flagship of Admiral Beatty in the battle of Jutland. This ship was provided with the Sperry Gyro-Compass equipment early in the war. During the Jutland engagement a fire broke out in a magazine of the Lion immediately below the two Master Compasses which were located in one compartment. It became so hot that the lead sheathing was melted off the electric cables and one of the Gyro-Compasses was heated until its parts fused. Notwithstanding this same heat the other compass functioned throughout the entire action. Of the ships engaged in the battle of Jutland practically all except the destroyers were equipped with the Gyro-Compass. Every one of them performed perfectly throughout the action except in the case of the Lion on which one was destroyed by fire.

Hundreds of Sperry Gyro-Compasses are veterans of many

battles and encounters under heavy gunfire and adverse

conditions.

40. R. M. S Bergensfjord. 41. R. M. S. Aquitania. 42. S. S. Lenape. 43. S. S. Conneaut. 44. Yacht Lyndonia.

45. U.S.S. Pennsylvania—© E. Muller, Jr. 46. U.S.S. Bush. 47. H.M.S. Invincible—© Underwood & Underwood. 48. R. F. La Marsellaise—© Underwood & Underwood. 49. H.M. Submarine E-11—© Underwood & Underwood.

50. H. I. M. S. Kongo—© Underwood & Underwood. 51. H. M. S. Conte di Cavour—© Underwood & Underwood. 52. U. S. S. Delaware—First Ship to Carry Gyro-Compass. 53. H. M. S. Queen Elizabeth—© Western Newspaper Union. 54. H. M. S. Lion—© Underwood & Underwood.

NEW YORK.

It gives me very great pleasure to inform you that my Company has received from Their Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, under date 20th July, the following words of commendation:―

“I am to add an expression of Their Lordships’ appreciation of the valuable assistance rendered to the Admiralty by your Company since the outbreak of War, in your very prompt and efficient execution of the important work entrusted to you”.

I might mention that this was the first recommendation given to a private Firm by the British Admiralty for fifteen years, and had to be concurred in by no less than thirty-seven Government Officials.

Original spelling and grammar are generally retained. Illustrations are moved from inside paragraphs to between paragraphs.

Page 21. The second and third list items under the heading "The Sperry Gyro-Compass Equipment" were incorrectly labeled "3." and "2.", in that order. These labels were corrected.