Two Hundred and fifty Copies of this Work have

been Printed on Hand-made Paper for Private

Circulation Only among Members of the

Brovan Society, and Twenty-five for the

Editors. None of these Copies is

for Sale. The Society Pledges

itself Never to Reprint nor to

Re-issue in any form. Of

the Brovan Society’s

Issue, this Copy

is Number:

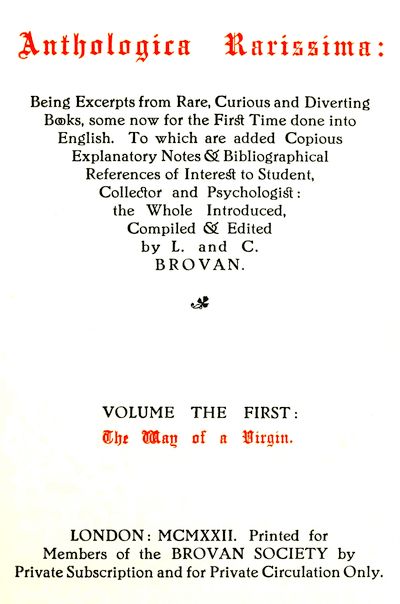

Anthologica Rarissima:

Being Excerpts from Rare, Curious and Diverting

Books, some now for the First Time done into

English. To which are added Copious

Explanatory Notes & Bibliographical

References of Interest to Student,

Collector and Psychologist:

the Whole Introduced,

Compiled & Edited

by L. and C.

BROVAN.

VOLUME THE FIRST:

The Way of a Virgin.

LONDON: MCMXXII. Printed for

Members of the BROVAN SOCIETY by

Private Subscription and for Private Circulation Only.

v

With the publication of its Records, under the title of ANTHOLOGICA RARISSIMA, the Brovan Society, which has been formed to carry out research work into the less-known and more curious folk-lore and literature of Europe and the Orient, takes leave to explain its aims and aspirations.

There exists in the literature of all countries a multitude of books not usually accorded public circulation. Yet these books contain some of the most life-like and diverting material ever fashioned by human pen. Their contents have stood the test of time and taste, and to-day, though publicly ignored, they are privately applauded. The trend of these books is, in the main, erotic, or so frank asvi to relegate them to the category of improper or “privately printed.” Some have never come under the hands of an English translator: others in such limited editions as to make their existence negligible so far as the average student is concerned.

Anthologica Rarissima is a modest attempt to remedy this state of affairs. In a series of volumes the editors will put before their readers the cream of what is tantamount to a small library, and a library not often seen on the book-lover’s shelves. Herein will be found, set out in plain English, curious and diverting extracts from some of the world’s most remarkable works. The text will be literal and unexpurgated. Nothing of interest to the student of folk-lore, psychology and literature will be omitted or glossed over, for the editors believe that a classic castrated is a classic spoilt. The Records throughout will be enriched by copious notes and valuable bibliographical references.

vii

So far as the compilers are aware, no similar anthology exists in the English tongue. It purports to put within reach of the student and bibliophile comprehensive and representative excerpts from writers, the possession of whose works would entail time and expense beyond the means of many collectors.

At present it is impossible to give a full list of the authors from whom we shall quote. Mention of such names as those of Sir Richard Burton, Casanova, Aretino, the Marquis de Sade, Wilkes, Boccaccio, Bandello, Masuccio, Straparola, Rabelais, Lucian, Apuleius, Aristophanes, Sinistrari, Nicolas Chorier, Poggio, J. S. Farmer, John Payne, La Fontaine, Chaucer, Brantôme, Sellon, Pisanus Fraxi, Payne Knight, Havelock Ellis, Bloch, Huhner, Forel and Kraft-Ebing, will give some idea of the work contemplated. Special attention will be paid to the less-known folk-lore of Europe and the Orient, as portrayed in those remarkable books, Kruptadia, Untrodden Fields of Anthropology,viii The Kama Sutra, The Ananga Ranga, The Perfumed Garden, The Old Man Young Again, Les Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles, Ethnology of the Sixth Sense, The Book of Exposition, Priapeia, Genital Laws, Marriage Ceremonies and Priapic Rites, and Des Divinités Génératrices.

Anthologica Rarissima, for reasons which will seem as regrettable as absurd to the student and collector, must ever be a privately printed work; its tone, though erotic, is in no sense pornographic. The extracts have been selected with care, and always with an eye to artistry and bibliographical value. The complete issue, extending to many volumes, will form an unique collection in the English tongue of a type of literature far too little known in this country.

The subject of our first volume—virginity and its treatment in fable, conte, and legend—is far from exhausted in these pages. It will be necessary to devote another Record to the theme at a laterix date. Meanwhile, we have in preparation Vol. 2: “The Way of a Priest,” Vol. 3: “The Way of a Wife,” Vol. 4: “The Way of a Husband,” and Vol. 5: “The Way of Love.” This last, culled from such authorities as Ovid, Martial, Catullus, Aretino, Forberg, Veniero, and the authors of The Kama Sutra, The Perfumed Garden, and The Ananga Ranga, should prove the most complete treatise on the Ars Amandi ever published in the English language.

In conclusion, we can only reiterate what was said at the outset—that this work is the outcome of a project to give the English student and collector the cream of a rare and remarkable literature.

We wish to lay special emphasis on the literal nature of our text, having often sacrificed style to preserve it. When translating from French, where an English translation already existed, we have never failed to compare and work upon the two versions for the composition of our extract.

x

Les Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles is a case in point, the old French text and Mr. R. B. Douglas’ English translation both being utilised in our Record. The same applies to Casanova; each line of his Memoirs, as existing in the privately printed English translation, has been closely compared with Garnier’s French text; while Aretino’s Dialogues will be scrutinised in no fewer than three languages. Our aim throughout has been to put before the reader a rendering in English which most exactly approximates to the original work of the author in question.

THE EDITORS.

xi

| Page. | ||

| FOREWORD. | v. | |

| VIRGINITY AND ITS TRADITIONS. | xix. | |

| THE ENCHANTED RING: | ||

| Of a Young Husband who Sought to Redeem his Yard from Pawn, and of the Divers Adventures that Befell him in his Quest. | 1 | |

| VARIANT: | ||

| Of a Tailor who Consented to Sin with a certain Woman who Admired his Proportions; and how they Fared. | 10 | |

| THE INSTRUMENT: | ||

| Of a Young Girl who Desired her Lover to Buy a Better Instrument, which she Enjoyed, Lost and Found again. | 13 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE INSTRUMENT. | 16 | |

| THE TIMOROUS FIANCÉE: | ||

| Of a Maid who would Wed None save Ivan the No-Yard; and how they were Wed, after which she first Hired, then Bought, a Good Yard from Ivan’s Uncle. | 17xii | |

| EXCURSUS to THE ENCHANTED RING, THE INSTRUMENT, and THE TIMOROUS FIANCÉE. | 22 | |

| ADVENTURES WITH HEDVIGE AND HELÈNE AT GENEVA: | ||

| Of an Adventure with two Charming Cousins, one of whom Desired to know why a Deity could not Impregnate a Woman; and how the Hero of our Story gave Demonstration of Theological and other Matters. | 24 | |

| EXCURSUS to ADVENTURES WITH HEDVIGE AND HELÈNE. | 37 | |

| THE DAMSEL AND THE PRINCE: | ||

| Of a Young Lady, who, being Enamoured of a Prince, Sendeth for one of his Chaplains, and with him Entereth into a Plot which Bringeth the Affair to the Desired Issue. | 42 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE DAMSEL AND THE PRINCE. | 49 | |

| THE PENITENT NUN: | ||

| Of a Nun, who Strove to Flee the Shafts of Love; how she Succeeded; and how certain Young Nuns Received her Counsel. | 52xiii | |

| BEYOND THE MARK: | ||

| Of a Shepherd who Made an Agreement with a Shepherdess that he should Mount upon her; and how he Kept that Agreement. | 53 | |

| THE DEVIL IN HELL: | ||

| Of a Young Maid, who, Turning Hermit, was Taught by a Monk to Put the Devil in Hell; and how she found Much Pleasure therein. | 56 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE DEVIL IN HELL. | 63 | |

| THE WEDDING NIGHT OF JEAN THE FOOL: | ||

| Of a Young Husband who thought his Wife would Give him a Chicken on their Wedding Night; and how he Learned in what Fashion he must Comport himself to have that Chicken. | 65 | |

| THE MAIDEN WELL GUARDED: | ||

| Of a Maid who had been most Strictly Enjoined to Guard her Maidenhead; and how a Youth Restored it to her when she Lost it. | 69 | |

| VARIANT: | ||

| Of one Coypeau, who Securely Sewed up a Damsel’s Maidenhead with his own Thread. | 72xiv | |

| TALE OF KAMAR AL-ZAMAN: | ||

| Of a Prince and a Princess who became Acquainted in Strange Circumstances; of their Loves, Separation, Re-union, and divers Remarkable Happenings. | 74 | |

| EXCURSUS to the TALE OF KAMAR AL-ZAMAN. | 92 | |

| THE FOOL: | ||

| Of a Young Man who would fain have Wed, yet Contrived to Satisfy his Wish without Marriage. | 101 | |

| “OH MOTHER, ROGER WITH HIS KISSES”: | ||

| Of the Emotions of an Innocent Virgin when Wooed Boisterously by her Swain. | 103 | |

| FOOLISH FEAR: | ||

| Of a Virgin Wife who did not Understand the Business of Marriage; and how the Parties went to Law, and what Ensued therefrom. | 104 | |

| THE PRINCESS WHO PISSETH OVER THE HAYCOCKS: | ||

| Of a King’s Daughter, the Like of whom was not Seen Elsewhere on Earth; and how she was Cured of her Ways by a Young Peasant, divers Physicians and Charlatans having Failed in the Task. | 111xv | |

| THE COMB: | ||

| Of a Pope’s Daughter who was “Combed” by a Peasant; and how the Comb was Lost and Found again, together with other Strange and Delightsome Happenings. | 116 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE PRINCESS WHO PISSETH OVER THE HAYCOCKS and THE COMB. | 121 | |

| THE SKIRMISH: | ||

| Of a Virgin who, on her Marriage Eve, told a Wedded Friend of the Recent and Disturbing Conduct of her Fiancé. | 124 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE SKIRMISH. | 132 | |

| THE NIGHTINGALE: | ||

| Of a Maid who would fain Hear the Nightingale Sing; and how she Made it Sing many Times and even Held it in her Hand. | 134 | |

| THE PIKE’S HEAD: | ||

| Of a Young Virgin who Played a Trick on a Youth; and how the Youth, from Fear of being “Bitten,” was for some Time Ignorant of the Pleasures of Marriage. | 142xvi | |

| THE LOVELY NUN AND HER YOUNG BOARDER: | ||

| Of a Lovely Young Virgin, who was of an Inquisitive Turn of Mind, and Proved herself an Apt Pupil in the School of Love. | 147 | |

| JOHN AND JOAN: | ||

| Of a Serving Wench who sent her Fellow Servant to Buy her a Steel; and how she Fared thereafter. | 158 | |

| THE HUSBAND AS DOCTOR: | ||

| Of a Young Squire who, when he Married, had never Mounted a Christian Creature; of the Means found to Instruct him; and how, on a Sudden, he Wept at a great Feast shortly after he had been Instructed. | 162 | |

| THE PRIEST AND THE LABOURER: | ||

| Of a Priest’s two Daughters who were Tricked by a Labourer; and of divers Strange and Diverting Happenings thereafter. | 171 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE PRIEST AND THE LABOURER. | 178xvii | |

| THE TWO LOVERS AND THE TWO SISTERS: | ||

| Of two Cavaliers who became Enamoured of two Sisters; and how they found Enjoyment of their Love, albeit in Strange Fashion but none the less Pleasant. | 179 | |

| THE BURNING YARD: | ||

| Of a Maid who would not Suffer a Youth to Pleasure her, since, so she Alleged, he had a Burning Yard. | 188 | |

| TAKE TIME BY THE FORELOCK: | ||

| Of a Young Virgin Wife who was Paid back in her own Coin by her Husband. | 190 | |

| EXCURSUS to TAKE TIME BY THE FORELOCK. | 192 | |

| FIRST MEETING BETWEEN A YOUTH AND HIS FIANCÉE: | ||

| Of a Maid and a Youth who held Pleasant Converse in a Coach-house; and of divers Experiments and Discoveries they made there. | 193 | |

| THE BREAKER OF EGGS: | ||

| Of a certain Wench who had Eggs in her Belly, which were Broken for her by an Obliging Youth. | 195 | |

| EXCURSUS to THE BREAKER OF EGGS. | 198 | |

xviii

xix

xx

VIRGINITY AND ITS TRADITIONS.

HORACE, I., xxiii.

xxi

In devoting a volume to the romance and folk-lore of Virginity, it may not be inappropriate first to examine the psychology of a word and a quality as magical as they are misused.

What is virginity? Is it the possession intact of that delicate piece of membrane, the poets’ ‘flos virginitatis,’ or is it some indescribable, intangible attribute in no sense dependent on physical perfection? Does it imply abstention from and ignorance of all sexual pleasures, or must it be a chastity which falls little short of stupid, even criminal, innocence?

To us moderns, blessed (or cursed) with a smattering of science, woman is virginal just as long as we know or believe her to be, physical qualities notwithstanding. By the poet of the past, the romanticist, the mediæval lover, and the ignorant, physical as well as spiritual proofs were probably required or expected. To them, virginity was something tangible; to us it is not.

Nor is the reason far to seek. For while Havelock Ellis, the greatest authority on sexual psychology the world has known, describes the hymen as having acquired in human estimation a spiritual value which has made it far more than a part of the feminine body, ... “something that gives woman all her worth and dignity, ... her marketxxii value,” he goes on to point out that the presence or absence of the hymen is no real test of virginity.

“There are many ways,” he writes, (Studies in the Psychology of Sex: Philadelphia, 1914: vol. 5: Erotic Symbolism), “in which the hymen may be destroyed apart from coïtus.... On the other hand, integrity of the hymen is no proof of virginity, apart from the obvious fact that there may be intercourse without penetration.... The hymen may be of a yielding or folding type, so that complete penetration may take place and yet the hymen be afterwards found unruptured. It occasionally happens that the hymen is found intact at the end of pregnancy.”1

And while the foregoing is the exception rather than the rule, it goes far to prove the fallibility of the physical, tangible test.

To most of us, virginity is a quality supposedly prized at all times and by all races. This is far from the case. As Havelock Ellis points out, (op. cit.), virginity is not usually of any value among peoples who are entirely primitive. “Indeed, even in the classic civilisation which we inherit,” he writes, “it is easy to show that the virgin and the admiration for virginity are of late growth; the virgin goddesses were not originally virgins in our modern sense. Diana was the many-breasted patroness of childbirth before she became the chaste and solitary huntress, for the earliest distinction would appear to have been simply between the woman who was attached to a man and the woman who followed an earlier rule ofxxiii freedom and independence; it was a later notion to suppose that the latter women were debarred from sexual intercourse.”

A French Army Surgeon, Dr. Jacobus X—, (Untrodden Fields of Anthropology: Charles Carrington: Paris, 1898), has some interesting remarks on the subject, and we offer no apology for reproducing them at length. Writing on the “Unimportance of the signs of virginity in the negress,” he says:—

“The Negroes of Senegal do not attach, as the Arabs do, considerable importance to the presence of the real signs of virginity in young girls.... The non-existence of the material proofs of virginity seldom give rise to any complaint on the part of the husband.... Moreover, the size of the virile member of the Negro2 renders it difficult for him to detect any trick. The black bride, on the wedding night, shows herself expert in the art of simulating the struggles of an expiring virginity, and it is considered good taste for the girls to require almost to be raped. The least innocent young women are often the most clever at this game.

“Thus, throughout nearly all Senegal, the European, who has a taste for maidenheads, can easily be satisfied, provided he is willing to pay the price.3 At St. Louis women of ill-fame procure young xxiv girls, who bear the significant name of the ‘unpierced,’4 and vary from eight or nine years to the nubile age. It is even easier to obtain a young girl before she is nubile than afterwards, on account of the certainty of her not bearing any children. The price is within the range of all purses, according to quality, and you can have a negro girl, warranted ‘unpierced’ (belonging to the category of domestic slaves), for the modest sum of from eight to sixteen shillings. Of course, the respectable matron pockets half this sum for her honorarium....

“ ... The ‘unpierced’ soon lose their right to the title when they have to do with a Toubab, but, on account of the size of their genital parts, the loss of their maidenhead is not such a serious affair for them as it would be for a little French girl who was not yet nubile. I have never remarked in a little negress, who had been deflowered by a White, the valvular inflammation, which, with us, is noticed as the result of premature copulation before the parts are sufficiently developed.... If the reader will remember that the European, who is below the average dimensions in regard to his penis, is like a little boy in proportion to the negress of ten or twelve years old, it is not difficult to imagine that the negress he has deflowered can entirely take in the yard of the White, the dimensions of which are much less than that ofxxv the adult black.

“ ... When the girl has to do later with a negro husband, an astringent lotion will render the bride a pseudo-virgin. The deceived husband, not having the anatomical knowledge necessary to assure himself of the real existence of the signs of virginity, feels a difficulty in copulating, and is far from suspecting any trick.5

“Does not much the same kind of thing prevail also in Europe? How many girls who have been deflowered get married without their husband ever suspecting anything, although he has not the same physical disadvantages that the black has to prevent his seeing through the trick? Is it to thisxxvi amorous blindness that the Greeks and Romans alluded when they represented Cupid with a bandage over his eyes? One is almost tempted to believe it.

“ ... In opposition to those who exact the virginity of the bride, there are others who attach no importance whatever to it.... The ancient Egyptians used to make an incision in the hymen previous to marriage, and St. Athanasius relates that among the Phœnicians a slave of the bridegroom was charged by him to deflower the bride.6 The Caraib Indians attached no value to virginity, and only the daughters of the higher classes were shut up during two years previous to marriage.

“It appears that among the Chibcha Indians in Central America virginity is not at all esteemed; it was considered to be a proof that the maiden had never been able to inspire love.

“In ancient Peru the old maids were the objects of high esteem. There were sacred virgins called ‘Wives of the Sun,’ somewhat similar to the Roman vestals.7 (The nuns of the present day, do xxvii they not style themselves the ‘Spouses of Christ’?). They made a vow of perpetual chastity.... It is also said they were buried alive when they happened to break their vow of chastity, unless indeed they could prove having conceived, not from a man, but from the sun.

“Several authors worthy of credence assure us that these vestals were guarded by eunuchs. The temple at Cuzco had one thousand virgins, that of Caranqua two hundred. It would appear, however, that the virginity of these vestals was not so very sacred after all, for the Inca Kings used to choose from among them concubines for themselves or for theirxxviii principal vassals and favourite friends.

“Marco Polo narrates how young girls were exposed by their mothers on the public highway in order that travellers might freely make use of them.8 A young girl was expected to have at least twenty presents earned by such prostitutions before she could hope to find a husband. This did not prevent them from being very virtuous after marriage, nor their virtue from being much appreciated.9

“Waitz assures us that in several countries ofxxix Africa a young girl is preferred for wife when she has made herself remarked by several amours and by much fecundity. (C.f. Havelock Ellis, op. cit., vol.6: ‘Equally unsound is the notion that the virgin bride brings her husband at marriage an important capital which is consumed in the first act of intercourse and can never be recovered. That is a notion which has survived into civilisation, but it belongs to barbarism and not to civilisation. So far as it has any validity it lies within a sphere of erotic perversity which cannot be taken into consideration in an estimation of moral values. For most men, however, in any case, whether they realise it or not, the woman who has been initiated into the mysteries of love has a higher erotic value than the virgin,10 and there need be no anxiety on this ground concerning the wife who has lost her virginity.’)

“It was impossible,” continues Dr. Jacobus X—, “ever to find the signs of virginity among the Machacura women in Brazil, and Feldner explains the reason thus:—

xxx

“‘Among them a virgin is never to be found, for this reason: that the mother from her daughter’s tenderest years endeavours with the utmost care to remove all tightness of the vagina and obstacle therein. With this end in view, the leaf of a tree folded in the shape of a funnel is held in the right hand, then while the index finger is introduced into the genital parts and worked to and fro, warm water is admitted by means of the funnel.’ (Journey Across Brazil, 1828.)

“Among the Sakalaves in Madagascar the young girls deflower themselves, when the parents have not previously seen to this necessary preparation for marriage.

“Among the Balanti of Senegambia, one of the most degraded races in Africa, the girls cannot find a husband until they have been deflowered by their King, who often exacts costly presents from his female subjects for putting them in condition to be able to marry.

“Barth, (1856), in describing Adamad, says that the chief of the Bagoli used to lie the first night with the daughters of the Fulba, a people under his sway. Similar facts are related of the aborigines of Brazil and of the Kinipeto Esquimaux.

“Demosthenes informs us that there was a celebrated Greek hetaira, named Mæra, who had seven slaves whom she called her daughters, so that being supposed to be free a higher price was paid for their favours. She sold their virginity five or six times over, and ended by selling the whole lot together.

“The god Mutinus, Mutunus or Tutunus of ancient Rome used to have the new brides come and sit upon his knees, as if to offer him their virginity.xxxi St. Augustine says: ‘In the celebration of nuptials the newly wed bride used to be bidden sit on the shaft of Priapus.’ Lactantius gives more precise details: ‘And Mutunus, in whose shameful lap brides sit, in order that the god may appear to have gathered the first-fruits of their virginity.’ It appears, however, that this offering was not merely symbolical, for when they had become wives, they used to return to the favourite deity to pray for fecundity.11

“Arnobius also asks: ‘Is it Tutunus, on whose huge organs and bristling tool you think it an auspicious and desirable thing that your matrons should be mounted?’

“Pertunda was another hermaphrodite divinity that St. Augustine maliciously proposed rather to name the Deus Pretundus (who strikes first); it was carried on to the nuptial bed to aid the bridegroom: ‘Pertunda stands there ready in the bed-chamber for the aid of husbands excavating the virgin pit.’ (Arnobius.)

“The Kondadgis (Ceylon), the Cambodgians, and other peoples charged their priests with the defloration of their brides.

“Jager communicated to the Berlin Anthropological Society a passage from Gemelli Cancri,xxxii which mentions a stupratio officialis12 practised at a certain period among the Bisayos of the Philippine Islands: ‘There is no known example of a custom so barbarous as that which had been there established, of having public officials, and even paid very dearly, to take the virginity of young girls, the same being considered to be an obstacle to the pleasures of the husband. As a fact there no longer exists any trace of this infamous practice since the establishment of the Spanish rule, ... but even to-day a Bisayo feels vexed to find his wife safe from suspicion, because he concludes, that not having excited the desire of anyone, she must have some bad quality which will prevent him from being happy with her.’

“On the Malabar Coast, also, there were Brahmins whose only religious office was to gather the virgin flower of young girls. These latter used to pay them for it, without which they could not find husbands. The King of Calicut himself used to grant the right of the first night to a Brahmin; the King of Tamassat grants it to the first stranger who arrives in the town; whereas the King of Campa reserves to himself the jus primæ noctis13 for all the marriages in the kingdom. (De Gubernatis, Histoire des voyageurs italiens aux Indes Orientales: Livourne, 1875.)

xxxiii

“Warthema says that the King of Calicut, when he took a wife, chose the most worthy and learned Brahmin to deflower the maiden; for this service he received from 400 to 500 crowns. At Tenasserim fathers used to beg of their daughters to allow themselves to be deflowered by Christians or Mohammedans.

“Pascal de Andagoya, who visited Nicaragua between 1514 and 1522, says that it was usual for a grand-priest to lie during the first night with the bride, and Oviedo, (1535), speaking of the Acovacks and other American nations, relates that the wife, in order that the marriage should be happy, passed the first nuptial night with the priest or piache, and Gomarra, (1551), relates the same thing of the inhabitants of Cumana.

“In Europe, young girls who are not very virtuous, and who have studied all the various forms of flirtation, are most generally passed off as virgins when they marry. Even when it does not really exist, there are many ways by which a virginity—which perhaps has been sold over and over again by expert and clever procuresses—can be simulated. A little time before going to the nuptial bed, the girl inserts into her vagina a few drops of pigeon’s blood; or in some cases she selects for her wedding day the last day of menstruation. A sponge, skilfully placed, allows the blood to flow at the moment of thexxxiv catastrophe, when a sudden ‘Oh!’ announces to the unsuspecting husband that the temple has been violated for the first time, and that the veil of the sanctum sanctorum has really been rent by him. Add also to these methods injections so astringent that, at the required time, they will give to a prostitute, whose gap has been widened by a thousand customers, a tightness greater than that of a real virgin.”

The more one examines the question, the more one is convinced that virginity or chastity has come to be regarded as a spiritual and moral asset only in civilised, or comparatively civilised, society. “In considering the moral quality of chastity among savages,” writes Havelock Ellis (Studies in the Psychology of Sex, vol. 6, p. 147), “we must carefully separate that chastity which among semi-primitive peoples is exclusively imposed upon women. This has no moral quality whatever, for it is not exercised as a useful discipline, but merely enforced in order to heighten the economic and erotic value of women.

“Many authorities believe that the regard for women as property furnishes the true reason for the widespread insistence on virginity in brides. Thus A. B. Ellis, speaking of the West Coast of Africa (Yoruba Speaking Peoples, pp. 183 et seq.), says that girls of good class are betrothed as mere children, and are carefully guarded from men, while girls of lower class are seldom betrothed, and may lead any life they choose.”

Virginity in woman, it seems, has been set on a pedestal unsupported by history, science, or investigation. It is obviously the outcome of man’s desire, when he buys or acquires, to obtain unsoiled goods. Comes a time, however, when the value ofxxxv these so-called unsoiled goods grows questionable. Something virgin, in terms of common sense, is not necessarily something valuable; here enters the thinking, and, ultimately, the erotic, element. Let a man fall to asking why he demands virginity, and he will speedily begin to realise that it is the last thing he requires. Virginity spells ignorance, awkwardness and obstacles; maturity means understanding and co-operation. Thus, by easy stages, we reach the conclusion, mentioned by Havelock Ellis and quoted above, that for most men, whether they realise it or not, the love-wise woman has a greater erotic value than the virgin.14

xxxvi

Quoting Westermarck (History of Human Marriage), he goes on to refer to the fact that the seduction of an unmarried girl “is chiefly, if not exclusively, regarded as an offence against the parents or family of the girl,” and there is no indication that it is ever held by savages that any wrong has been done to the woman herself.

“Westermarck realises at the same time,” adds Havelock Ellis, “that the preference given to virgins has also a biological basis in the instinctive masculine feeling of jealousy in regard to women who have had intercourse with other men, and especially in the erotic charm for men of the emotional state of shyness which accompanies virginity.”

Here, in all probability, are the most powerful reasons for the value placed on virginity; each reason, too, is highly practical. Who among us truly wants to share his most treasured possession? And the shy charm of virginity ‘neath the attack of the amorous lover is as undeniable as it is indescribable. Hence the virgin’s lure for the old and worn-out roué, who finds in her shrinking reluctance a stimulant to his erotic prowess which sympathy, boldness, even lewdness, have no power to furnish. That quaint old book, “Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure,” (London, 1780), gives a typical account of the attempt and failure of an aged rake to ravish the then virginal heroine of the story.15

xxxvii

At certain times and with certain peoples the virgin maid has been fenced about with all manner of safeguards up to the very hour of her marriage; but have these and other peoples ever troubled to preserve the virginity of their daughters as they were at pains to guard the chastity of their wives? What nation ever inflicted that ghastly contrivance, the Girdle of Chastity, upon its virgin daughters? This bar to erotic pleasure was reserved exclusively for the potentially froward wife.

xxxviii

Originating in the woollen band worn by the Spartan virgins16—a garment removed for the first time by the husband on the wedding night—these Girdles of Chastity, with their padlocks and keys, were undoubtedly in use in the fourteenth or fifteenth century, and in use for an unmistakable purpose. “The first to employ this apparatus,” says Dr. Jacobus X—(Ethnology of the Sixth Sense: Charles Carrington: Paris, 1899), “was Francis of Tarrara, Provost of Padua in the fourteenth century. It was a belt having a central piece made of ivory, with a barbed narrow slit down the middle, which was passed between the legs and fixed there by lock and key. A specimen of this safety apparatus is to be seen actually at the Musée de Cluny in Paris.”

Dr. Caufeynon, the great authority on the subject, believes, however, that these girdles only date from the Renaissance.17 In his remarkable littlexxxix work, La Ceinture de Chasteté (Paris, 1904), which contains numerous engravings and photographic designs, he gives an illustration of the specimen in the Musée de Cluny. Quoting Brantôme (Lives of Fair and Gallant Ladies), he adds:—

“In the time of Henry the king there lived an ironmonger who brought to the fair of St. Germain a dozen of certain machines to bridle the parts of women; they were fashioned of iron and went round like a girdle, and went below and were closed with a key. So cleverly were they fashioned that it was not possible for the women, when once bridled, to arrive at the sweet pleasure, there being but a few small holes in it for pissing.

“‘Tis said there were five or six jealous husbands, who bought these machines and bridled their wives with them in such fashion that they might well have said ‘Farewell, happy time,’ had there not been one who bethought her of applying to a locksmith very skilled in his art, to whom she showed the machine, her own, her husband being then out in the fields; and he applied his mind so well to the matter that he made for her a false key, with which the lady opened or closed the machine at any time and when she willed.

“The husband never discovered aught to say on the matter; and the lady gave herself up to her own good pleasure, despite her foolish, jealous, cuckold husband, being ever able to live in the freedom of cuckoldom. But the wicked locksmith who fashioned the false key tasted of it all; and he did well, so they say, for he was the first to taste of it.

“They say, too, that there were many gallant and honest gentlemen of the court who threatenedxl that ironmonger with death did he ever presume to carry about such merchandise; so much so that he was afraid and returned no more and threw away all the rest, and no more was heard of. Wherein he was wise, for it were enough to lose half the world, for want of any body to people it, through such bridles, clasps and fastenings of a nature abominable and detestable and enemies to human multiplication.”

The troubadour Guillaume de Machault speaks of a key given to him by Agnes of Navarre; this key was obviously intended to unlock a girdle of chastity. Nicolas Chorier, in his erotic Dialogues of Luisa Sigea (Paris: Isidore Liseux, 1890), mentions the apparatus. Although the existence of such girdles has often been denied, “the presence of many undoubted specimens in several of the most important museums of Europe,” says Dr. Jacobus X—(Ethnology of the Sixth Sense), “places their authenticity beyond all doubt. This custom existed more particularly during the time of the Crusades, ... but a very curious instance is mentioned as having occurred as late as the middle of the eighteenth century, for it is recorded that the advocate Feydeau pleaded before the supreme court of Montpellier on behalf of a woman who accused her husband of making her undergo this shameful treatment. (Petition against the introduction of padlocks or girdles of chastity, Montpellier, 1750.)”

All this only goes to show that virginity and chastity are two very different things, and that the latter was obviously of more account than the former in the eyes of mediæval man. Much the same obtains to-day. To a certain extent we seek to preserve the virginity of our daughters; but is there any limit toxli the precautions with which a jealous husband will fence about his wife? In short, virginity concerns alone her who loses it; is any man’s for the taking. Chastity is another person’s property.

This slight survey of virginity would be incomplete without a reference to the operation of infibulation18—the artificial adhesion of the labia majora by means of a ring or stitches with a view to the prevention of sexual intercourse. Kisch, (The Sexual Life of Woman: translated by M. Eden Paul: London: Wm. Heinemann), quotes the authority of Ploss-Bartels for saying that this operation is practised by many savage peoples, among them the Bedschas, the Gallas, the Somalis, the inhabitants of Harrar, at Massaua, etc.

“The purpose of this practise,” he adds, “is to preserve the chastity of the girls until marriage, when the reverse operative procedure is undertaken. If the husband goes away on a journey, in many cases the operation of infibulation is once more performed upon his wives. Slave-dealers also make use of this operation so as to prevent their slaves from becoming pregnant. It is reported, however, that the operation does not invariably produce the desired effect.”

Nothing we have said or quoted, however, can alter the fact that virginity has been and willxlii always be a certain asset in civilised or semi-civilised communities. There is a romance attached to the term which neither cynicism nor materialism can kill. Incidentally, there is a strong business side to the question. Who, as we said before, wants to feel that his dearest possession has been shared by others? Who, in more modern parlance, wants damaged goods?

While life lasts, the virgin maid will lure the normal lover, common sense and cold facts notwithstanding. What the poet sang and the amorous swain coveted in those by-gone times of pomp and paganism, in the days of chivalry, and even in that dreary early Victorian era, will be sung and coveted centuries hence. Science, new discoveries, new theories, new ideals, new conditions, cannot oust human nature, our undeniable birthright. The sanctity and value of virginity are traditions; and, as Havelock Ellis says, in that singularly beautiful postscript to his Studies, “there can be no world without traditions; neither can there be any life without movement. As Heracleitus knew at the outset of modern philosophy, we cannot bathe twice in the same stream, though, as we know to-day, the stream still flows in an unending circle. There is never a moment when the new dawn is not breaking over the earth, and never a moment when the sunset ceases to die. It is well to greet serenely even the first glimmer of the dawn when we see it, not hastening toward it with undue speed, nor leaving the sunset without gratitude for the dying light that once was dawn.

“In the moral world we are ourselves the light-bearers, and the cosmic process is in us made flesh. For a brief space it is granted to us, if we will,xliii to enlighten the darkness that surrounds our path. As in the ancient torch-race, which seemed to Lucretius to be the symbol of all life, we press forward torch in hand along the course. Soon from behind comes the runner who will outpace us. All our skill lies in giving into his hand the living torch, bright and unflickering, as we ourselves disappear in the darkness.”

Beautiful words, and fitting monument to a man who gave thirty years of his life to the production of a work that will live for all time. Hardly applicable to our present theme some, perhaps, will say. We take leave to differ. In the relations between man and woman all life is epitomised. Each bears the torch, and the race they run is the life they lead. To almost all is granted the chance to hand on the torch in living, breathing prototype.

Let us recognise new conditions, new ideas; let us welcome, examine and weigh them, that none may say we do not ‘greet serenely the dawn.’ But let us also remember that theory cannot oust fact, nor materialism human nature.

Down the ages man has altered in custom and habit, but in his spiritual essence not at all. Save for local and racial differences, humanity has shared the same passions of pain, sorrow, happiness, anger, laughter and lust throughout all time. Human nature alone does not change; our birthright is immutable. Human nature ever has, and ever will, set store by virginity. It has become a tradition. And without tradition, as the great psychologist has truly told us, there is no world.

1

THE WAY OF A VIRGIN.

In a certain reign, in a certain kingdom, there lived once on a time three peasant brethren, who quarrelled among themselves and divided up their goods; they did not share equally, and the division gave much to the elder brethren but very little to the youngest.

All three were young lads. They went forth together into the courtyard, saying one to the other:

“‘Tis time for us to wed.”

“‘Tis well enough for ye,” quoth the youngest brother. “Ye are rich, and the rich can marry. But what may I do? I am poor. I have not even a log of wood to my name. All I have for a fortune is a yard which reacheth to my knees!”

On this very moment there chanced to pass a merchant’s daughter, who overheard these words and said to herself:

“Ah! that I might have this young man for a husband! He hath a yard that reacheth to his very knees!”

The two elder brethren married; the youngest remained single.

2

The merchant’s daughter, back in her home, had no thought in her head but to wed the young peasant; several rich merchants sought her hand in marriage, but she would have none of them.

“I will wed with none save this young man,” quoth she.

Her father and mother sought to dissuade her. “What art thinking on, foolish one?” said they. “Come back to thy senses! Why wouldst wed with a poor peasant?”

“Concern not yourselves with that!” answered she. “‘Tis not ye who will have to live with him!”

The merchant’s daughter came to an understanding with the matchmaker, and dispatched her to tell the young man to come without fail and ask her hand in marriage. The matchmaker went to see him, saying:

“Hearken, oh! my little dove. Why standest there gaping? Go ask in marriage the merchant’s daughter. She hath awaited thee this long time, and will wed thee with joy.”

The young man swiftly apparelled himself, donned a new smock-frock, took his new hat, and hied him forthwith to the house of the merchant to ask his daughter’s hand in marriage. When the merchant’s daughter perceived him, when she recognised that it was indeed he whose yard reached to his knees, she fell to asking her father and mother for their blessing on a union indissoluble.

On the wedding night she went to bed with her husband, and perceived that he had but a little yard, smaller even than a finger.

“Oh! thou scoundrel!” she cried. “Thou boastest ownership of a yard reaching to thy knees!3 What hast done with it?”

“Dear wife, thou knowest that I was a bachelor, and very poor; when I resolved to marry, I had neither gold nor aught else to enable me so to do. So I have pledged my yard.”20

“And for what sum hast thou pledged thy yard?”

“But for little—for fifty roubles.”

“Good. On the morrow I will go seek my mother, I will beg money of her, and thou wilt go without fail to recover thy yard. If thou dost not buy it back, enter not the house!”

She waited until morn, then ran swiftly in search of her mother, saying:

“Grant me a favour, little mother. Give me fifty roubles. I have sore need of them.”

“But tell me why thou hast need of them.”

“See, little mother. My husband had a yard which reached to his knees. When we desired to marry, he knew not where to find the money, the poor man, and he hath pledged his yard for fifty roubles. Now my husband hath but a tiny yard, even smaller than a finger. ‘Tis of the utmost necessity, therefore, to buy back his ancient yard.”

The mother, understanding the need, drew fifty roubles from her purse, and gave them to her daughter. The latter returned to her home and gave the money to her husband, saying:

“Go! Run now swiftly to buy back thine ancient yard, in order that strangers may not make use of it!”

The young man took the money and went forth, eyes downcast. Where might he turn now?4 Where find for his wife such a yard? Best leave it to chance.

He went forward, now swiftly, now slowly, and at length he encountered an aged woman.

“Good day, good woman.”

“Good day, good man. Whither goest thou at this pace?”

“Ah, good woman—would thou knewest—would thou didst know my sorrow—would I might tell thee whither I go!”

“Tell me thy sorrow, little dove. Perchance I can come to thine aid.”

“I am shamed to tell it thee.”

“Fear not, have no shame. Speak boldly.”

“Ah, well, see here, good woman. I had boasted of having a yard that reached to my knees; a merchant’s daughter, who had heard this, espoused me, but when she lay with me on our wedding night and perceived that I had but a little yard, smaller than a finger, she cried out and asked what I had done with my great yard. I told her that I had pledged it for fifty roubles; she gave me the money and bade me buy it back without fail; otherwise, I might not show myself again at my home. And I know not how to satisfy my little dove.”

The aged woman made answer to him:

“Give me thy money,” said she, “and I will find a remedy for thy sorrow.”

Forthwith he drew the fifty roubles from his pocket and gave them to her; the aged woman handed to him a ring.

“Come, take this ring,” quoth she. “Put it only on thy finger nail.”

The young man took the ring, and scarce had5 he put it on his finger nail ere his yard stretched itself a cubit’s length.

“Well, what of it?” asked the aged woman. “Doth thy yard reach to thy knees?”

“Yea, good woman. It reacheth even below my knees.”

“Now, my little dove, pass the ring down thy whole finger.”

He passed the ring over his entire finger, and his yard lengthened out even unto seven versts.21

“Ah! good woman! where shall I lodge it? It will bring me ill fortune with my wife.”

“Thrust up the ring to thy finger nail; thy yard will be but a cubit’s span. This for thy guidance—pay attention and never put the ring beyond thy finger nail.”

He thanked the aged woman, and retook the road homeward; and as he journeyed he rejoiced in that he need not appear before his wife with empty hands.

But as he went, he felt a desire to eat. Going aside, he seated himself not far from the road at the foot of a burdock, drew biscuits from his wallet, dipped them in water, and fell to eating. Anon, desire to slumber o’er-came him; he lay down, belly uppermost, and played with the ring. He put it upon his finger nail, and his yard rose to the height of a cubit’s span; he pressed his whole finger through the ring, and his yard rose to a height of seven versts; he removed the ring, and his yard became small as before. He examined and re-examined the ring, and thus he fell asleep. But he forgot to conceal the ring,6 which rested upon his belly.

There chanced to pass in a carriage a lord and his wife. The lord saw, not far from the road, a peasant aslumbering, and upon his belly glittered a ring, as it were a live coal in the sun. He stopped the horses, saying to his lackey:

“Approach the peasant, take the ring, and bring it to me.”

Straightway the lackey ran to the peasant, and carried back the ring to the lord. And these went on their way.

The lord admired the ring.

“Look thou, my dear loved one,” said he to his wife. “What a superb ring! Behold! I put it upon my finger.” And he passed it down his whole finger.

Straightway his yard reached out, o’erturned the coachman from his box seat, struck one of the mares right beneath the tail, pushed aside the animal, and caused the carriage to go ahead of it.22

The lady beheld what misfortune had befallen, was greatly affrighted, and cried with all her force to the lackey, saying:

“Run most swiftly to the peasant and lead him hither!”

The lackey sped amain to the peasant and aroused him, saying:

“Come swiftly, my little peasant, to my master!”

The peasant sought his ring.

“A curse on thee! Thou hast taken my ring!”

7

“Seek not,” said the lackey. “Come to my master. He hath thy ring, which hath caused us a great fuss.”

The peasant ran to the carriage. Quoth the lord to him:

“Pardon me, but come to my aid in my misfortune!”

“What wilt give me, lord?”

“Here are one hundred roubles.”

“Give me two hundred and I will deliver thee.”

The lord drew two hundred roubles from his pocket, the peasant took the money, and withdrew the ring from the lord’s finger, whereat the yard vanished as if by magic, and there was left to the lord but his former little instrument.

The lord went his way, and the peasant hied him homeward with the ring. His wife was at the window and saw him come; she ran to meet him.

“Hast brought it back?” asked she.

“I have.”

“Show it me!”

“Come within the chamber. I cannot show it thee outside.”

They entered the chamber, nor did the wife cease to repeat: “Show it me! Show it me!”

He placed the ring on his finger-nail, and his yard lengthened a cubit’s span; then he drew off his drawers, saying: “Behold, wife!”

The wife fell on his neck.

“My dear little husband, here is truly an instrument that will be better in our house than with strangers. Come swiftly and eat; then we will to bed and make trial of it.”

8

Forthwith she put upon the table all manner of meats and beverages, and they fell to eating and drinking. Having feasted, they betook themselves to bed. When he had pierced his wife with this yard, she, for three whole days, was ever peering ‘neath his garment; it seemed to her that the yard was ever thrusting between her legs.

She went to pay a visit to her mother, what time her husband hied him to the garden and lay down ‘neath an apple tree.

“Well,” asked the mother of her daughter, “have ye bought back the yard?”

“We have bought it back, little mother.”

And the mother had but one thought: to steal away, profiting by her daughter’s visit, to run to the house of her son-in-law, and to make trial of his great yard.

And while the daughter chattered, the mother came to the house of the son-in-law and sped into the garden. The son-in-law was aslumbering; the ring was on his finger nail, and his yard stood erect to the height of a cubit’s span.

“I will mount upon his yard,” said the good mother to herself.

And she mounted, in sooth, upon the yard, and balanced herself thereon.

But, by ill fortune, the ring slipped to the base of the finger of the son-in-law what time he slept, and the yard raised the good mother to the height of seven versts.

The daughter perceived that her mother had gone forth, she divined the reason, and hastened to return home. In her house there was no one. She went into the garden, and what saw she? Her9 husband aslumbering, his yard raised to a vast height, and, all in the clouds, the good mother, scarce visible; and she, when the wind blew, turned upon the yard as though upon a stake.

What to do? How remove her mother from off the yard?

A great crowd had come together; they discussed; they proferred counsel. Said some: there is naught for it but to take a hatchet and cut the yard. Said others: no, ‘tis a bad plan. Why lose two souls? For as soon as the yard is cut, the woman will fall and kill herself. ‘Tis better to pray to God that perchance by some miracle the old woman will disentangle herself from it.

During this time the son-in-law awoke, and perceived that his ring had descended to the base of his finger, that his yard raised itself towards the sky to a height of seven versts, and that it nailed him solidly to the earth, in such wise that he could not turn upon his other side.

He withdrew very softly the ring from his finger; his yard descended to the height of a cubit’s span; and the son-in-law saw his mother-in-law suspended upon it.

“How camest thou there, little mother?”

“Pardon, my little son-in-law. I will not do it any more!”

10

Once on a time a tailor possessed a magic ring; as soon as he put it upon his finger, his yard assumed an extraordinary development. It fell out that he went to work at the house of a woman; by nature he was gay and given to jesting, and when he lay down to slumber he neglected always to cover his genitals.

The woman observed that he had a yard of great proportions; desirous of sampling the power of such an instrument, she summoned the tailor to her chamber.

“Hearken,” quoth she to him. “Consent to sin once with me.”

“Why not, madam? But only on one condition—that thou dost not fart! If thou dost fart, thou shalt pay me three hundred roubles.”

“Very good,” answered she.

They betook themselves to bed; the good woman took all possible precautions not to expel wind during the sexual act; she instructed her chambermaid to seek a large onion, to thrust this into her fundament, and to hold it there with both hands. These orders were carried out minutely, but at the first assault delivered by the tailor upon the woman, the onion was violently expelled and struck the chambermaid11 with such force that she was killed outright!

The woman lost her three hundred roubles; the tailor pocketed this sum and hied him homeward. Having journeyed some distance, he felt a desire to slumber and lay down in a field. He placed the ring upon his finger and his yard stretched to the length of one verst. As he lay thus, slumber o’ertook him, and whilst he slept came seven starving wolves, which devoured the greater part of his yard. He awoke as if naught had chanced,23 took the ring from his finger, put it in his pocket, and pursued his way.

Came night, and the tailor entered the house of a peasant. Now this peasant had married a young woman who had a liking for well-membered men. The guest went to sleep in the courtyard, leaving his yard exposed. Perceiving it, the peasant’s wife felt a great desire; raising her robe, she coupled with the tailor.

“Good,” quoth he to himself; and he placed the ring on his finger, and his yard rose little by little to the height of one verst. But when the wife perceived herself so far from the earth, all desire to futter left her, and she clung with both hands to this strange support in mid-air.

Beholding the peril that beset the wretched woman, her neighbours and relations fell to praying for the safety of both. But the tailor gently withdrew the ring from his finger; gradually the dimensions of his member decreased, and, when it reached but to a small height, the woman jumped to earth.

“Ah! insatiable coynte,” quoth the tailor12 to her. “It had been thy death had they cut my yard.”24

13

Once on a time a youth, wishing to become a smith, quitted his village and hired himself as an apprentice to a farrier. His master was a busy man, all the beds in his house being filled by his workmen, and when evening came he was sore pressed to find sleeping quarters for his apprentice. Reflecting long, he thus finally argued:—

“In each bed are several persons; my daughter alone hath one to herself. With her will I put the youth to sleep. His parents are good people, and I have known him from boyhood. There is no danger.”

When these two were in bed together, the youth began to caress the daughter, a maid nigh unto sixteen years, and since she did not repulse him, he lost no time in showing her how one makes love. The daughter found the business very much to her liking, and Pierre (for so the apprentice was named) gave her several lessons in this pretty game. She did not tire, and wished that the play might last the whole night long; but Pierre, awearied, would fain have slept. Anon, when he began to grow drowsy, she pinched him and snuggled up to him; but he did not respond to her allurements.

14

“Pierre,” said she, “dost play no more with thine implement?”

“No—’tis used up,” quoth Pierre.

“‘Tis a pity,” said the girl. “Why is it not more solid? Would it cost much to have another?”

“Yea—at least three or four hundred francs.”

“I myself have not that sum; but I know where my father keepeth his money, and on the morrow I will give thee the wherewithal to procure another. What dost thou call it?”

“‘Tis called an ‘instrument’,”26 quoth Pierre.

In the morning the girl, taking her father’s money, gave it to the apprentice, who hied him to the town and made pretence of buying another instrument; and when night came, he played on his instrument to the infinite satisfaction of the girl.

On the morrow the apprentice received a letter, wherein he learned that his mother lay ill and desired to see him. He started on his journey forthwith. Anon the girl appeared, and not seeing the apprentice, inquired:

“Where is Pierre?”

And they answered her that he was gone and would return no more. Whereat she sped after him, and when she perceived him afar off, cried out:—

“Pierre! Pierre! At least leave me the instrument!”

15

Pierre, who was in a field at the moment, wrenched up a big turnip, and casting it into a swamp at the feet of the girl, cried out:—

“Take it—’tis there!”

And while the girl sought the instrument, he continued on his way.

With both her eyes she looked, but of Pierre’s instrument could perceive no vestige. Anon she sat down on the edge of the swamp and gave herself up to tears. Presently there chanced to pass the vicar, who made inquiry as to the cause of her grief.

“Oh! thy reverence!” she made answer. “The instrument hath fallen in the swamp and I cannot recover it. A sad pity, for ‘tis a precious instrument and cost three or four hundred francs.”

“Let us both seek,” quoth the vicar. “I will aid thee.”

He tucked up his gown, and both fell to seeking in the swamp, which was somewhat deep. Anon the girl turned her head, and perceiving the vicar with his garments tucked up above his hips, cried out:—

“Ah! thy reverence! No need for further search! ‘Tis thou who hast the instrument ‘twixt thy legs!”

16

A variant of the foregoing story, (The Instrument), is to be found in Le Moyen de Parvenir (Béroalde de Verville). The editors of Kruptadia draw attention to it, quoting the following extract:—

The simpleton husband Hauteroue, while futtering his wife, remarked:—

“What a labour it is, my love!”

“I am not surprised,” quoth she. “Thou dost work with a bad implement.”

“I should have a better had I the money.”

“Let not that hinder thee; I will give thee the money on the morrow.”

When the husband received his money, he set out to enjoy himself; then he went to bed with his wife, whom he pleasured well.

“Ho! my love!” said she. “This implement is as good as the one thou hadst. But, love, what hast done with the other?”

“I have thrown it away, my love.”

“Bah! Thou hast made a great mistake. ‘Twould have served for my mother!”

17

Two young girls held converse together. Quoth one:

“Like thee, little one, I, too, will never marry.”

“And why should we marry against our will?” said the other. “We have no masters.”

“Hast seen, little one, that instrument with which men make trial upon us?”

“I have seen it.”

“And is it not huge?”

“Little one, it is assuredly of the size of an arm!”

“One would never come out of it alive.”

“Come, I will tickle thee with a straw.”

“That also hurteth me.”

The foolish one lay down, and the wiser fell to tickling her with a straw. “Ah! that hurteth!” she repeated.

Now the father of one of the young girls forced her to take a husband; she waited two nights, then went to see her young friend.

“Good day, little one,” she said.

The latter besought her to relate forthwith what had befallen.

18

“Ah!” answered the young wife. “Had I known, had I truly known the business, I had not listened to my father or my mother. I thought to lose my life, and my tongue hung from my mouth a foot in length.”

The young friend was so affrighted that she had no wish to speak further of fiancés.

“I will wed with none,” quoth she. “And if my father seeks to employ violence, 1 will espouse, for form’s sake, the first bachelor I encounter.”

Now there was in the same village a young lad and a very poor. None would give him a seemly maid in marriage, and he did not desire an ill; by chance he overheard the conversation of the young girls.

“Wait,” thought he to himself. “I will play a trick on that one. At a suitable moment I will say that I have no yard.”

Came a day when the young girl went to mass; she beheld the lad leading his horse, thin and unshod, to the watering place; the poor beast went limping, and the young girl laughed. They came to a steep slope; the mare climbed with difficulty, then fell and rolled on her back. The lad was annoyed, seized the mare by her tail, and fell to beating her without pity, saying:

“Get up! Thou wilt flay all the skin off thyself!”

“Why beatest thou the horse, brigand?” asked the young girl.

The lad lifted the tail, looked at it and said:

“And what should I do? Futter her? But I have no yard.”

When the girl heard his words, she pissed19 herself with joy, saying:

“Behold! the good God hath sent me a fiancé after my liking!”

She returned to her house, sat down in a secluded corner, and fell to pouting. Presently all the family seated themselves at table, calling on her to come, but she replied in anger:

“I will not!”

“Come, Douniouchka,” said the mother. “What art thinking of? Tell me.”

The father intervened.

“Why dost pout? Perchance thou dost desire to wed? Thou wouldst wed with this one and not with that?” The young girl had but one idea in her head: to wed Ivan the No-Yard.

“I will wed,” she replied, “neither this one nor that. An it please ye or not, I will wed Ivan.”

“What sayest thou, little fool? Art enraged, or hast lost thy reason? Thou wouldst share thy life with him?”

“He is my destiny. Seek not to marry me to another, else I will drown or strangle myself.”

Hitherto the old father had not honoured the poverty-stricken Ivan with so much as a look, but now he went himself to the lad to make him release his daughter. He approached. Ivan was seated, repairing an old hempen shoe.

“Good day, Ivanouchka.”

“Good day, old man.”

“What dost thou?”

“I seek to mend my hempen shoes.”

“Shoes? Thou hast need of new boots.”

“Since I have with difficulty amassed fifteen20 copeks to buy these shoes, where shall I find money to purchase boots?”

“And why dost thou not marry, Vania?”

“Who would give me his daughter?”

“I, if thou wilt! Kiss me on the mouth.”

And they came to an understanding.

At the rich man’s house there was no lack of beer and brandy. The girl and the lad were wed forthwith, high feast was held, and then the best man conducted the young people to their sleeping chamber and put them to bed. One knows the sequel. Ivan pierced the young girl till she bled and there was a road by which he might travel.

“What a blockhead, what a fool I have been!” thought Dounuka. “What have I done? How much better had I taken one richly-endowed! But where hath he found this yard? I will question him.”

And she questioned him, saying:

“Hearken, Ivanouchka. Where hast got this yard?”

“I have hired it from mine uncle for one night.”

“Ah! my little dove! Beg it of him for yet another night.”

A second night passed and she said to him again:

“Little dove! Beg of thine uncle if he will not sell thee the yard outright. But bargain well.”

“Good. One can always bargain.”

He went to the house of his grandsire, came to an understanding with him,28 and returned to his home.

21

“Well, what of it?” asked his wife.

“What can I say?” answered the lad. “There was no bargaining with him. We must give him three hundred roubles or he will not yield us the yard. And where may we get this sum?”

“Ah, well. Return and beg him to hire thee the yard for yet another night. To-morrow I ask my father for the money, and we will buy the yard outright.”

“Nay—go thyself and ask it of him. In sooth, I dare not.”

She went to the uncle’s house, entered his apartment, prayed to heaven, and bowed, saying:

“Good day, mine uncle.”

“Thou art welcome. What good news hast thou?”

“See, mine uncle, I am shamed to speak, but ‘twould be a sin an I kept silent. Lend thy yard to Ivan for a night.”

The relative took counsel with himself, shook his head, and said:

“It can be lent, but care must be taken of a yard belonging to another.”

“We will take care of it, uncle. I swear by the Cross. And to-morrow, without fail, we will buy it outright of thee.”

“Go, then, and send Ivan to me.”

She bowed to the earth and left the house.

On the morrow she went to seek her father, asked of him three hundred roubles for her husband, and bought for herself a good yard.

22

Each of the three foregoing stories is remarkable for the fact that it contains the same naïve idea—the possibility of purchasing a male “implement.” The idea is fairly common in folk-lore stories of virginity, but, almost always, results in a highly humorous situation. It is a crude but very effective method of depicting the ignorance, even stupidity, of a virgin girl. It also affords the story-teller an opportunity of an indirect reference to a favourite theme—the erotic tendency of women once their sexual senses are aroused.29

One episode of The Enchanted Ring (the remarkable qualities of the young man’s penis when adorned with the ring) can hardly fail to recall “The Night of Power,” (Sir Richard F. Burton’s Thousand Nights and a Night), wherein the husband’s organs undergo rapid and wonderful transformation. This tale is described by Sir Richard Burton as “the grossest and most brutal satire on the sex, suggesting that a woman would prefer an additional inch of23 penis to anything this world or the next can offer her.” One cannot help noting, none the less, the indecent anxiety of the mother-in-law, in our story from Kruptadia, to sample the mighty yard of the newly-returned husband.30

24

Casanova makes the acquaintance of two charming cousins, Hedvige and Helène, at Geneva. After sundry meetings, at which theology and sexual matters are discussed in a frank and amusing fashion, Casanova gets the chance to take his two charmers for a stroll in the garden where they can be sure of immunity from interruption. Casanova’s opportunity occurs as a result of Hedvige’s desire to know why a deity could not impregnate a woman, a male acquaintance having said that he could not with propriety expound such mysteries to her. Casanova gladly agrees to make the matter clear, adding, however, that he must be allowed to speak quite plainly. The text continues:

Yea, speak clearly,” quoth Hedvige, “for none can hear us; but I am forced to confess that I am cognisant of the formation of man only in theory and by lecture. True, I have seen statues, but I have never seen and still less have I25 examined real32 man. And thou, Helène?”

“I have never desired so to do.”

“Why not? ‘Tis good to know all.”

“Well, my charming Hedvige,” said I, “thy theologian wished to tell thee that Jesus was not capable of erection.”

“What is that?”

“Give me thy hand.”

“I feel it and I can picture it; for, without this natural phenomenon, man could not impregnate his consort. And this foolish theologian pretendeth that it is an imperfection!”

“Yea, for this phenomenon springeth from desire, for ‘tis very true that it would not have worked in me, sweet Hedvige, had I not found thee charming and had not what I had seen of thee given me the most seductive idea of the beauties I see not. Tell me frankly if, after feeling this rigidity of mine, thou dost not experience an agreeable sensation?”

“I confess it; ‘tis precisely where thou pressest. Dost not feel as I, my dear Helène, an itching and a longing on likening to the very true discourse given to us by this gentleman?”

“Yea, I feel it, but I feel it very often, without any discourse exciting it.”

“And then,” quoth I, “Nature forceth thee to appease it thus?”

“Not at all.”

“Oh, that it were so, Hedvige! Even in sleep one’s hand strayeth there by instinct; and, lacking this easement, I have read that we should suffer terrible maladies.”

26

And whilst we continued this philosophical converse, which the youthful theologian sustained with an authoritative tone, and which brought a look of voluptuousness to the lovely complexion of her cousin, we came to the edge of a fine pool where one descended by a marble staircase to bathe. Although it was chilly, our heads were warm, and it came to me to propose to the maidens that they put their feet in the water, assuring them that it would do them good and, if they permitted me, that I would count it an honour to remove their shoes and stockings.

“Come,” said Hedvige, “I like the project well.”

“I, too,” said Helène.

“Seat yourselves, ladies, on the first stair.”

Behold them, then, seated, and thy servant, on the fourth stair, busy unshoeing them, what time he extolled the beauty of their legs and made pretence to be incurious at the moment to see higher than the knee. Then, having gone down to the water, they had perforce to lift their garments, and in this business I encouraged them.

“Ah, well,” remarked Hedvige, “men also have thighs.”

Helène, who would have felt shame to show less courage than her cousin, did not hang back.

“Come, my charming naiads,” quoth I, “‘tis enough. Ye will catch cold if ye remain for long in the water.”

They reascended the staircase backwards, ever holding up their robes lest they might wet them; and it fell to me to dry their limbs with all the handkerchiefs that I possessed. This pleasant task permitted me to see and touch everything at my leisure,27 and the reader will scarce need my word to affirm that I made the best of my opportunity. The pretty niece (Hedvige) declared that I was too curious, but Helène let me have my way with an air so tender and so languid that I was hard pressed not to push the matter further. In the end, having again put on their shoes and stockings, I told them that I was enchanted to have viewed the secret charms of the two most lovely ladies in Geneva.

“What effect hath it on thee?” asked Hedvige of me.

“I dare not tell ye to look, but feel, both of ye.”

“Bathe thou thyself also.”

“Impossible. The business is too long for a man.”

“But we have yet two full hours to remain here without fear of interruption from anyone.”

This response caused me to see the happiness that awaited me; but I did not think fit to expose myself to an illness by entering the water in the state in which I was. Seeing a summer-house not far off and assured that M. Tronchin would have left it open, I took my two beauties by the arm and led them thither, not letting them guess, however, my intentions.

The summer-house was full of vases of pot pourri, pretty engravings, and so forth; but what I valued most was a large and lovely divan, fit for repose and for pleasure. There, seated ‘twixt these two beauties and lavishing caresses upon them, I said that I desired to show them that which they had never seen, at the same time exposing to their gaze the principal agent of humanity. They raised themselves to admire it, and then, taking the hand of each28 one of them, I procured for them a considerable pleasure; but, in the course of this labour, an abundant emission on my part caused them great amazement.

“‘Tis its speech,” said I. “The speech of the great creator of men.”

“‘Tis delicious!” cried Helène, laughing at the term ‘speech.’

“I, too, have the power of speech,” said Hedvige, “and I will show it thee, if thou wilt wait a moment.”

“Put thyself in my hands, sweet Hedvige. I will spare thee the trouble of making it come thyself, and I will do it better than thee.”

“I well believe it. But I have never done that with a man.”

“Nor I,” said Helène.

When they had placed themselves directly before me, their arms enlaced, I made them swoon away afresh. Then, having seated ourselves, what time my hand strayed all over their charms, I let them divert themselves at their leisure, till in the end I moistened their palms with a second emission of the natural moisture, which they examined curiously on their fingers.

Having once again put ourselves in a state of decency, we passed yet another half hour in exchanging kisses, after which I told them that they had rendered me partially happy, but, to make the work perfect, that I hoped they would devise a means of granting me their first favours. Then I showed them those preservative sachets which the English have invented in order to rid the fair sex of all fear.29 These little “purses,”33 the use of which I explained to them, excited their admiration, and Hedvige said to her cousin that she would give thought to the matter. Become intimate friends and in good case to become even better, we took our way towards the house, where we found Helène’s mother and the minister walking by the edge of the lake....

Follows now the description of a dinner at which Casanova, Hedvige and Helène are present. The text continues:

Helène shone in solving the questions put to her by the company. M. de Ximenes begged her to justify as best she might our first mother, who had deceived her husband by causing him to eat the fatal apple.

“Eve,” quoth she, “deceived not her husband; she did but cajole him into eating it in the hope of giving him one more perfection. Moreover, Eve had not received the prohibition from God but from Adam; in her act there was seduction, not deceit; in all probability her womanly sense did not let her regard the prohibition as serious.” ...

... Another lady then asked her if one might believe the history of the apple to be symbolical. Hedvige answered:

“I think not, since it could only be a symbol of sexual union, and ‘tis established that such was not consummated ‘twixt Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.”

“On this point the learned differ.”

30

“So much the worse for them, madam; the Scripture is plain enough. ‘Tis written in the first verse of the fourth chapter that Adam knew Eve after his expulsion from their terrestrial paradise, and that in consequence she conceived Cain.”

“Yea, but the verse sayeth not that Adam did not know her before, and, consequently, he might so have done.”

“This I cannot allow, for had he known her before she would have conceived; ‘twere foolish to suppose that two creatures, who had just quitted God’s hands, and were, in consequence, as nigh perfect as is possible, could consummate the act of generation with no result.”

The conversation now becomes very theological and controversial, and we take leave to omit it.

... After dinner ... I went apart with Helène, who told me that her cousin and the pastor would sup with her mother on the following day.

“Hedvige,” she added, “will stay and sleep with me, as is ever her custom when she cometh with her uncle to sup. It remaineth to be seen if thou art willing to hide in a spot I will show thee to-morrow at eleven of the clock, in order to pass the night with us. Call on my mother at that hour to-morrow, and I will find means of showing thee the spot....”

... In the morning I paid the mother a visit, and as Helène was escorting me out, she showed me a closed door ‘twixt the two stairs.

“At seven hours of the clock,” said she, “thou will find it open, and when thou art within, put on the bolt. Take care lest any see thee as thou enter the house.”

31

Casanova, in due course, takes up his position in the hiding place, and during his long wait for the two charmers, gives himself up to reflection on his past. The text continues:

... In my long and profligate career, during which I have turned the heads of several hundreds of ladies, I have grown familiar with all methods of seduction; but it hath ever been my guiding principle never to press my attack against novices or those in whom prejudices were likely to prove an obstacle, save in the presence of another woman. Timidity, I soon discovered, maketh a girl averse from seduction; in company with another girl she is easily conquered; the weakness of one bringeth on the fall of the other.

Fathers and mothers are of contrary opinion, but they err. They will not trust their daughter to take a walk or go to a ball with a young man, but no difficulty is made if she hath another girl with her. I repeat—they err; if the young man hath the requisite skill, their daughter is lost. A sense of false shame hindereth them from making a determined resistance to seduction, but, the first step taken, the fall cometh inevitably and rapidly. One girl, granting some small favour, straightway maketh her friend grant a much greater, thereby to hide her own blushes; and if the seducer be clever at his trade, the youthful innocent will soon have travelled too far to be able to draw back. In addition, the more innocent the girl, the greater her ignorance of seduction’s methods. Ere she hath time to think, pleasure doth attract her, curiosity draweth her yet a little further, and opportunity doth the rest.

For example, ‘twere possible I had been able to seduce Hedvige without Helène, but I am assured32 I had never succeeded with Helène had she not seen her cousin grant me certain licenses what time she took liberties with me—practices which she thought, doubtless, contrary to the modesty and decorum of a respectable young woman.... I desire what I say to be a warning to fathers and mothers, and to secure me a place in their esteem, at any rate.

Shortly after the pastor had gone I heard three light knocks on my prison door. I opened it, and a hand soft as satin grasped mine. My whole being quivered. ‘Twas Helène’s hand, and that happy moment had already repaid me for my long waiting.

“Follow me softly,” she said, in a low voice; but scarce had she closed the door ere I, in my impatience, clasped her tenderly in my arms, and caused her to feel the effect which her mere presence had produced on me, what time I assured myself of her docility.

“Be prudent, my friend,” said she to me, “and come softly upstairs.”

I followed her as best I might in the darkness, she leading me along a gallery into a room without light, the door of which she closed behind us, and thence into a lighted chamber, wherein was Hedvige, well nigh in a state of nudity. She came to me with open arms on the instant she saw me, and, embracing me ardently, signified her appreciation of my patience in my weary prison.

“Divine Hedvige,” quoth I, “had I not loved thee madly, I had not stayed one fourth of an hour in that dismal cell; but for thy sake I would readily pass hours there daily till I quit this spot. But let us lose no time. To bed!”

33

“Do ye twain get to bed,” quoth Helène. “I will couch on the divan.”

“Oh!” cried Hedvige. “Think not so. Our fate must be exactly equal.”