These volumes are most respectfully inscribed. If the efforts of the writer to illustrate more fully and minutely than has hitherto been done, the most interesting portion of American history, in its immediate connection with the large and populous State of which The Patroon has so long been one of the most distinguished citizens, shall be so fortunate as to merit the regard, and receive the approbation, of one so excellently qualified to judge of its interest and value, there will be nothing left unsatisfied to the ambition and the hopes of

His friend and servant, THE AUTHOR.

Birth and parentage—Discussion of the doubts cast upon his origin—Visit of Mohawk chiefs to Queen Anne—Evidence of Brant's descent from one of those—Digression from the main subject, and Extracts from the private and official journals of Sir William Johnson—Connexion between Sir William and the family of Brant—Incidental references to the old French war—Illustrations of Indian proceedings, speeches, &c.—Brant's parentage satisfactorily established—Takes the field in the Campaign of Lake George (1765.)—Is engaged at the conquest of Niagara (1759.)—Efforts of Sir William Johnson to civilize the Indians—Brant is sent, with other Indian youths, to the Moor Charity School, at Lebanon—Leaves school—Anecdote—Is engaged on public business by Sir William—As an Interpreter for the Missionaries—Again takes the field, in the wars against Pontiac—Intended massacre at Detroit—Ultimate overthrow of Pontiac—First marriage of Brant—Entertains the Missionaries—Again employed on public business—Death of his wife—Engages with Mr. Stewart in translating the Scriptures—Marries again—Has serious religious impressions—Selects a bosom friend and confidant, after the Indian custom—Death of his friend—His grief, and refusal to choose another friend.

Page 1

Early symptoms of disaffection at Boston—Origin of the Revolutionary War—First blood shed in 1770—Stirring eloquence of Joseph Warren—Feelings of Sir William Johnson—His influence with the Indians and Germans, and his unpleasant position—Last visit of Sir William to England—His death—Mysterious circumstances attending it—Suspicions of suicide unjust—His son, Sir John Johnson, succeeds to his title and estates—His son-in-law, Col. Guy Johnson, to his office as superintendent General of the Indians—Early life of Sir John—Joseph Brant appointed Secretary to Guy Johnson—Influence of the Johnson family—Revolutionary symptoms in County, fomented by the proceedings in New England—First meeting of Tryon County Whigs—Declaration of Rights—First meeting of Congress—Effect of its proceedings—in England—Tardiness of Provincial legislature of New-York—Spirit of the people—Notes of preparation in Massachusetts, &c.—Overt acts of rebellion in several States—Indians exasperated by the Virginia borderers in 1774—Melancholy story of Logan—Campaign of Lord Dunmore and Colonel Lewis—Battle of the Kanhawa—Speech of Logan—Its authenticity questioned—Peace of Chilicothe—Unhappy feeling of the Indians.

29

Unyielding course of the parent Government—Efforts of the Earl of Chatham unavailing—Address to the Crown from New-York—Leslie's Expedition to Salem—Affair of Lexington—Unwise movements of Tryon County loyalists—Reaction—Public meetings—The Sammons family—Interference of the Johnsons—Quarrel at Caughnawaga—Spirited indications at Cherry Valley—Counteracting efforts of the Johnsons among their retainers—Intrigues with the Indians—Massachusetts attempts the same—Correspondence with the Stockbridge Indians—Letter to Mr. Kirkland—His removal by Guy Johnson—Neutrality of the Oneidas—Intercepted despatch from Brant to the Oneidas—Apprehensions of Guy Johnson—Correspondence—Farther precautions of the Committees—Reverence for the Laws—Letter of Guy Johnson to the Committees of Albany and Schenectady—Substance of the reply.

49

Council of the Mohawk chiefs at Guy Park—A second council called by Johnson at Cosby's Manor—Proceeds thither with his retinue—First full meeting of Tryon County Committee—Correspondence with Guy Johnson—No council held—Johnson proceeds farther West, accompanied by his family and most of the Indians—Consequent apprehensions of the people—Communication from Massachusetts Congress—Ticonderoga and Crown Point taken by Ethan Allen—Skenesborough and St. Johns surprised—Farther proceedings in Massachusetts—Battle of Bunker Hill—Death of Warren—Council with the Oneidas and Tuscaroras at German Flats—Speech to the Indians—Subsequent council with the Oneidas—Conduct of the people toward Guy Johnson—Speech to, and reply of Oneidas—Guy Johnson moves westwardly to Ontario—His letter to the Provincial Congress of New-York—Holds a great Indian council at the West—Unfavourable influence upon the dispositions of the Indians—Causes of their partiality for the English—Great, but groundless alarm of the people—Guy Johnson, with Brant and the Indian warriors, descends the St. Lawrence to Montreal—Council there—Sir Guy Carleton and Gen. Haldimand complete the work of winning the Indians over to the cause of the Crown.

Page 71

Meeting of the second Continental Congress—Measures of defence—Declaration—National fast—Organization of an Indian department—Address to the Six Nations—Council called at Albany—Preliminary consultation at German Flats—Speeches of the Oneidas and others—Adjourn to Albany—Brief interview with the commissioners—Conference and interchange of speeches with the Albanians—Proceedings of the grand council—Speeches of the commissioners—Replies of the Indians—Conclusion of the grand council—Resumption of the conference with the Albanians—Speech of the Albany Committee—Reply of the Indians—Disclosures of Guy Johnson's proceedings at Oswego—Close of the proceedings—Epidemic among the Indians—Small benefit resulting from the council—Proceedings in Tryon County resumed—Doubtful position of New-York—Symptoms of disaffection to the cause of the people—Sir John Johnson—Sheriff White deposed by the people—The royal authorities superseded by appointments from the people—Affray at Johnstown—First gun fired at Sampson Sammons—White recommissioned by Tryon—His flight—Labors of the Committee—Opposition of the Tories—Designs of Sir John Johnson and Sir Guy Carleton—Letter and deputation to Sir John—Prisoners for political offences sent to gaol—Letter from Provincial Congress—Mohawks commence fighting at St. Johns—Speech of the Canajoharies in explanation—Indians apply for release of prisoners—Review of the progress of the Revolution in other parts of the Colonies—Proceedings of Parliament—Burning of Falmouth—Descent upon Canada—Ethan Allen taken—Arnold's expedition—Siege of Quebec—Fall of Montgomery—Caughnawaga and Delaware Indians.

91

Lord Dunmore—Glance at the South—Suspicious conduct of Sir John Johnson—Conduct of the Tories in Tryon County—Gen. Schuyler directed by Congress to march into that County and disarm the Tories—Preliminary mission to the Lower Mohawks—Message to them—Their displeasure and reply—March of Schuyler—Meets the Indians at Schenectady—Interview and speeches—Advance of Schuyler—Letter to Sir John Johnson—Interview—Negotiations of capitulation—Terms proposed—Schuyler advances to Caughnawaga—Joined by Tryon County Militia—Farther correspondence with Sir John—Interview with the Indian mediators—Terms of surrender adjusted—Schuyler marches to Johnstown—Sir John, his household, and the Highlanders, disarmed—Troops scour the country to bring in the loyalists—Disappointment as to the supposed Tory Depot of warlike munitions—Return of Schuyler to Albany—Resolution of Congress—Additional trouble with Sir John—Preparations for his seizure—Expedition of Col. Dayton—Flight of the Baronet and his partisans to Canada—Their sufferings—And subsequent conduct—How the violation of his parole was considered.

119

History of Brant resumed—Advanced to the chieftaincy of the Confederacy—Mode of appointing chiefs and sachems—Embarks for England—Arrives in London—Received with marked consideration—Becomes acquainted with James Boswell and others—Agrees to espouse the Royal cause, and returns to America—Steals through the country to Canada—Curious supposed letter to President Wheelock—Battle of the Cedars—Cowardice of Major Butterfield—Outrages of the Indians—Story of Capt. McKinstry, who was saved from the stake by Brant—Indignation of Washington, the people, and Congress—Resolutions of retaliation—Mutual complaints of treatment of prisoners—Murder of Gen. Gordon—Indignation at the outrage—Indian deputation at Philadelphia—Speech to them—Congress resolves upon the employment of an Indian force—Schuyler opposed—Review of the incidents of the war elsewhere—Destitution of the Army—Evacuation of Boston by the English—Disastrous termination of the Canadian campaign—Deplorable condition of the army—Humanity of Sir Guy Carleton—Glance at the South—Declaration of Independence—Spirit of Tryon County—Cherry Valley—Fortifications at Fort Stanwix—American army moves to New-York—Arrival of the British fleet and army—Battle of Long-Island—Washington evacuates New-York—Battle of White Plains—Retreats across New-Jersey—Followed by Cornwallis—Defeat of Arnold on Lake Champlain—Fall of Rhode Island—Battle of Trenton.

Page 147

Continuation of movements in New Jersey—Extinguishment of the council-fire at Onondaga—Tryon County—Colonel Harper's mission to Oghkwaga—The Harper family—Adventure at the Johnstone settlement—Capture of Good Peter and his party—Thayendanegea crosses from Canada to Oghkwaga—Interview with the Rev. Mr. Johnstone—Doubtful course of Brant—Feverish situation of the people—Expedition of General Herkimer to Unadilla—Remarkable meeting between Herkimer and Brant—Meditated act of treachery—Wariness of the chief—Meeting abruptly terminated—Ended in a storm—Brant draws off to Oswego—Grand council there—The Indians generally join the Royal standard—Approach of Brant upon Cherry Valley—How defeated—Death of Lieutenant Wormwood.

175

British preparations for the prosecution of the war—Indications at the North—Doubtful position and conduct of General Howe—Embarrassing to the Americans—Intercepted correspondence—General Howe sails to the Chesapeake—Enters Philadelphia in triumph—Burgoyne approaches from the North—Indian policy—Sir Guy Carleton—False estimates of the strength of Ticonderoga—Burgoyne arrives at Crown Point—Feasts the Indians—Invests Ticonderoga—Carries the outworks—Fortifies Sugar Hill—The fortress evacuated by St. Clair—Retreat of the Americans—Battles near Skenesborough and at Fort Ann—Burgoyne enters the valley of the Hudson—Schuyler, without means, retreats from Fort Edward—Terror of the people—Cruelties of the Indians—Story of Miss McCrea—General flight of the population—Mrs. Ann Eliza Bleecker—Heroism of Mrs. Schuyler—Attempted assassination of General Schuyler.

195

Expedition against the Mohawk Valley from Oswego—Despondency of the people in Tryon County—Letter of John Jay—Arrest of several of the disaffected—Flight of others to Canada—Schuyler's complaints of the cowardice of the people—Great discouragements—Proclamation of General Herkimer—Letter from Thomas Spencer—St. Leger's approach—Caution and plan of his march—Diary of Lieut. Bird—Fort Stanwix invested—Colonel Gansevoort takes command—Its deplorable condition—Gansevoort joined by Willett—Story of Captain Gregg—Situation of the garrison—Arrival of St. Leger—His proclamation—Burgoyne's affairs becoming critical—Affair of Bennington—General Herkimer, with the Tryon County militia, advances to the relief of Gansevoort—Battle of Oriskany—Bloody upon both sides—Unexampled bravery of Captain Gardenier—Major Watts—Dissatisfaction of the Indians—Sortie and success of Colonel Willett—Death and character of General Herkimer.

209

Siege of Fort Schuyler continued—Forced letter from prisoners to Col. Gansevoort—St. Leger summons the garrison to surrender—Refusal of Gansevoort—Appeal of Sir John Johnson to the people of Tryon County—Secret expedition of Colonel Willett and Major Stockwell—Schuyler orders Arnold to the relief of Gansevoort—Willett proceeds to Albany—Arrest of Walter Butler, and others, at German Flats—Tried and convicted as a spy—Reprieved—Sent to Albany—Escapes—Arnold's proclamation—Advance of the besiegers—Uneasiness of the garrison—Sudden flight of St. Leger and his forces—Stratagem of Arnold—Story of Hon-Yost Schuyler—Merriment and mischief of the Indians—Arrival of Arnold at the Fort—The spoils of victory—Public estimation of Gansevoort's services—Address to his soldiers—His promotion—Address of his officers.

Page 249

Recurrence to the invasion of Burgoyne—General Schuyler again superseded by Gates—Causes of this injustice—Battle of Stillwater—Both armies entrench—Battle and victory of Behmus's Heights—Funeral of General Frazer—Retreat of Burgoyne—Difficulties increasing upon him—His capitulation—Meeting of Burgoyne and Gates—Deportment of Gates toward Gen. Washington—Noble conduct of Gen. Schuyler.

265

Sir Henry Clinton's attempt to co-operate with Burgoyne—Storming of Forts Clinton and Montgomery—Burning of Æsopus—Review of military operations elsewhere—Expedition to Peekskill—Of Gov. Tryon to Danbury—Progress of Sir William Howe in Pennsylvania—Battle of Brandywine—Massacre of the Paoli—Battle of Germantown—Death of Count Donop—Murder of Captain Deitz and family at Berne—John Taylor—Lady Johnson ordered to leave Albany—Exasperation of Sir John—Attempts to abduct Mr. Taylor—An Indian and white man bribed to assassinate General Schuyler—Fresh alarms in Tryon County—Address of Congress to the Six Nations—The appeal produces no effect—Articles of confederation—Close of the year.

280

Treaty of alliance with France—Policy of France—Incidents of the Winter—Projected expedition against St Johns—Lafayette appointed to the command of the North—Failure of the enterprise for lack of means—Disappointment and chagrin of Lafayette—Unpleasant indications respecting the Western Indians—Indian council at Johnstown—Attended by Lafayette—Its proceedings—And result—Reward offered for Major Carleton—Letter of Lafayette—He retires from the Northern Department—Return of the loyalists for their families—Unopposed—Their aggressions—Prisoners carried into Canada—Their fate—Re-appearance of Brant at Oghkwaga and Unadilla—Anecdote of Brant—Comparative cruelty of the Tories and Indians—Murder of a family—Exposed situation of the people—Captain McKean—Sends a challenge to Brant—Burning of Springfield—First battle in Schoharie.

298

The story of Wyoming—Glance at its history—Bloody battle between the Shawanese and Delawares—Count Zinzendorf—Conflicting Indian claims and titles—Rival land companies of Connecticut and Pennsylvania—Murder of Tadeusund—The first Connecticut Colony destroyed by the Indians—Controversy respecting their titles—Rival Colonies planted in Wyoming—The civil wars of Wyoming—Bold adventure of Captain Ogden—Fierce passions of the people—The Connecticut settlers prevail—Growth of the settlements—Annexed to Connecticut—Breaking out of the Revolution—The inhabitants, stimulated by previous hatred, take sides—Arrest of suspected persons in January—Sent to Hartford—Evil consequences—The enemy appear upon the outskirts of the settlements in the Spring—Invasion by Colonel John Butler and the Indians—Colonel Zebulon Butler prepares to oppose them—Two of the forts taken—Colonel Z. Butler marches to encounter the enemy—Battle of Wyoming—The Americans defeated—The flight and massacre—Fort Wyoming besieged—Timidity of the garrison—Zebulon Butler's authority not sustained—He escapes from the fort—Colonel Denniston forced to capitulate—Destruction of the Valley—Barbarities of the Tories—Brant not in the expedition—Catharine Montour—Flight of the fugitives—Expedition of Colonel Hartley up the Susquehanna—Colonel Zebulon Butler repossesses himself of Wyoming, and rebuilds the fort—Indian skirmishes—Close of the history of Wyoming.

Page 318

Evacuation of Philadelphia by Sir Henry Clinton—Followed through New Jersey by Washington—Battle of Monmouth—Conduct and arrest of General Lee—Retreat of the enemy—Arrival of the French fleet—Combined attack of the Americans and French upon the British army of Rhode Island—British fleet escapes from Count D'Estaing—Battle of Rhode Island—Failure of the expedition-Projected campaigns against the Indians—Captains Pipe and White-Eyes—McKee and Girty—General McIntosh ordered against the Sandusky towns—Irruption of Brant into Cobleskill—Of McDonald into the Schoharie settlements—Pusillanimity of Colonel Vrooman—Bravery of Colonel Harper—His expedition to Albany—Captivity of Mr. Sawyer—Slays six Indians and escapes—Colonel William Butler sent to Schoharie—Morgan's rifle corps—Daring adventures of Murphy and Elerson—Death of Service, a noted Tory—Murphy's subsequent adventures—Affairs at Fort Schuyler—Alarming number of desertions—Destruction of Andros-town by the Indians—Conflagration of the German Flats—Expedition of Colonel William Butler from Schoharie to Unadllla and Oghkwaga.

343

Walter N. Butler—His flight from Albany, bent on revenge—The Great Tree—Hostile indications among the Senecas and Cayugas—Premonitions of an attack by Butler and Brant upon Cherry Valley—Discredited by Colonel Alden—Scouts sent out and captured—Surprise of the town—Massacre and burning—Death of Colonel Alden—Families of Mr. Wells, Mr. Dunlop, and others—Brutality of the Tories—Family of Mr. Mitchell—The monster Newberry—Departure of the enemy with their captives—A night of gloom—Women and children sent back—Letter of Butler to Gen. Schuyler—Murder of Mrs. Campbell's mother—Vindication of Brant—Interesting incident—Brant's opinion of Capt. McKean—Colonel John Butler laments the conduct of his son—Letter of General James Clinton to Walter Butler—Letter of Butler in reply—Molly Brant—Particulars of Mrs. Campbell's captivity—Feast of thanksgiving for their victory—The great feast of the White Dogs—Return of Walter Butler from Quebec—Col. Butler negotiates with the Indians for Mrs. Campbell—She goes to Niagara—Catharine Montour and her sons—Mrs. Campbell finds her children—Descends the St. Lawrence to Montreal—Meets Mrs. Butler—Arrives at Albany, and is joined by her husband—Grand campaign projected—Jacob Helmer and others sent privately to Johnstown for the iron chest of Sir John—Execution of Helmer—Arrival of British Commissioners—Not received—Exchange of Ministers with France—Incidents of the war elsewhere for the year.

369

Indian siege of Fort Laurens—Successful stratagems—Flight of the pack-horses—The fort abandoned—Projected enterprise from Detroit—Gov. Hamilton captured at St. Vincent by Col. Clarke—Projects of Brant—Uneasiness in the West of New-York—Deliberations of the Oneidas and Onondagas—Brant's projects defeated—Treachery of the Onondagas—Colonel Van Schaick marches to lay waste their towns—Instructions of General Clinton—Passage of Wood Creek and Oneida Lake—Advance upon the Indian towns—Their destruction—Return of the expedition to Fort Schuyler—Mission of the Oneidas to Fort Schuyler in behalf of the Onondagas—Speech of Good Peter—Reply of Colonel Van Schaick—Irruption of Tories and Indians into the lower Mohawk country—Stone Arabia—Defence of his house by Captain Richer—The Indians in Schoharie—General Clinton traverses the Mohawk valley—McClellan's expedition to Oswegatchie—Unsuccessful—Irruption of the Onondagas into Cobleskill—Defeat of the Americans—The settlement destroyed—Murders in the neighborhood of Fort Pitt—Irruptions of Tories into Warwasing—Invasion of Minisink—Battle near the Delaware—Massacre of the Orange County militia—Battle with the Shawanese.

396

It is related by Æsop, that a forester once meeting with a lion, they traveled together for a time, and conversed amicably without much differing in opinion. At length a dispute happening to arise upon the question of superiority between their respective races, the former, in the absence of a better argument, pointed to a monument, on which was sculptured, in marble, the statue of a man striding over the body of a vanquished lion. "If this," said the lion, "is all you have to say, let us be the sculptors, and you will see the lion striding over the vanquished man."

The moral of this fable should ever be borne in mind when contemplating the character of that brave and ill-used race of men, now melting away before the Anglo-Saxons like the snow beneath a vertical sun—the aboriginals of America. The Indians are no sculptors. No monuments of their own art commend to future ages the events of the past. No Indian pen traces the history of their tribes and nations, or records the deeds of their warriors and chiefs—their prowess and their wrongs. Their spoilers have been their historians; and although a reluctant assent has been awarded to some of the nobler traits of their nature, yet, without yielding a due allowance for the peculiarities of their situation, the Indian character has been presented with singular uniformity as being cold, cruel, morose, and revengeful; unrelieved by any of those varying traits and characteristics, those lights and shadows, which are admitted in respect to other people no less wild and uncivilized than they.

Without pausing to reflect that, even when most cruel, they have been practising the trade of war—always dreadful—as much in conformity to their own usages and laws, as have their more civilized antagonists, the white historian has drawn them with the characteristics of demons. Forgetting that the second of the Hebrew monarchs did not scruple to saw his prisoners with saws, and harrow them with harrows of iron; forgetful, likewise, of the scenes at Smithfield, under the direction of our own British ancestors; the historians of the poor untutored Indians, almost with one accord, have denounced them as monsters sui generis—of unparalleled and unapproachable barbarity; as though the summary tomahawk were worse than the iron tortures of the harrow, and the torch of the Mohawk hotter than the faggots of Queen Mary.

Nor does it seem to have occurred to the "pale-faced" writers, that the identical cruelties, the records and descriptions of which enter so largely into the composition of the earlier volumes of American history, were not barbarities in the estimation of those who practised them. The scalp-lock was an emblem of chivalry. Every warrior, in shaving his head for battle, was careful to leave the lock of defiance upon his crown, as for the bravado, "Take it if you can." The stake and the torture were identified with their rude notions of the power of endurance. They were inflicted upon captives of their own race, as well as upon the whites; and with their own braves these trials were courted, to enable the sufferer to exhibit the courage and fortitude with which they could be borne—the proud scorn with which all the pain that a foe might inflict, could be endured.

But they fell upon slumbering hamlets in the night, and massacred defenceless women and children! This, again, was their own mode of warfare, as honourable in their estimation as the more courteous methods of committing wholesale murder, laid down in the books.

But of one enormity they were ever innocent. Whatever degree of personal hardship and suffering their female captives were compelled to endure, their persons were never dishonoured by violence; a fact which can be predicated, we apprehend, of no other victorious soldiery that ever lived.

In regard, moreover, to the countless acts of cruelty alleged to have been perpetrated by the savages, it must still be borne in mind that the Indians have not been the sculptors—the Indians have had no writer to relate their own side of the story. There has been none "to weep for Logan!" while his wrongs have been unrecorded. The annals of man, probably, do not attest a more kindly reception of intruding foreigners, than was given to the Pilgrims landing at Plymouth, by the faithful Massassoit, and the tribes under his jurisdiction. Nor did the forest kings take up arms until they but too clearly saw, that either their visitors or themselves, must be driven from the soil which was their own—the fee of which was derived from the Great Spirit. And the nation is yet to be discovered that will not fight for their homes, the graves of their fathers, and their family altars. Cruel they were, in the prosecution of their contests; but it would require the aggregate of a large number of predatory incursions and isolated burnings, to balance the awful scene of conflagration and blood, which at once extinguished the power of Sassacus, and the brave and indomitable Narragansets over whom he reigned. No! until it is forgotten, that by some Christians in infant Massachusetts it was held to be right to kill Indians as the agents and familiars of Azazel; until the early records of even tolerant Connecticut, which disclose the fact that the Indians were seized by the Puritans, transported to the British West Indies, and sold as slaves, are lost; until the Amazon and La Plata shall have washed away the bloody history of the Spanish American conquest; and until the fact that Cortez stretched the unhappy Guatimozin naked upon a bed of burning coals, is proved to be a fiction, let not the American Indian be pronounced the most cruel of men!

If, then, the moral of the fable is thus applicable to aboriginal history in general, it is equally so in regard to very many of their chiefs, whose names have been forgotten, or only known to be detested. Peculiar circumstances have given prominence, and fame of a certain description, to some few of the forest chieftains, as in the instances of Powhatan in the south, the mighty Philip in the east, and the great Pontiac of the north-west. But there have been many others, equal, perhaps, in courage, and skill, and energy, to the distinguished chiefs just mentioned, whose names have been steeped in infamy in their preservation, because "the lions are no sculptors." They have been described as ruthless butchers of women and children, without one redeeming quality save those of animal courage and indifference to pain; while it is not unlikely, that were the actual truth known, their characters, for all the high qualities of the soldier, might sustain an advantageous comparison with those of half the warriors of equal rank in Christendom. Of this class was a prominent subject of the present volume, whose name was terrible in every American ear during the war of Independence, and was long afterward associated with every thing bloody, ferocious, and hateful. It is even within our own day, that the name of Brant [FN-1] would chill the young blood by its very sound, and cause the lisping child to cling closer to the knee of its mother. As the master spirit of the Indians engaged in the British service during the war of the Revolution, not only were all the border massacres charged directly upon him, but upon his head fell the public maledictions for every individual act of atrocity which marked that sanguinary contest, whether committed by Indians, or Tories, or by the exasperated regular soldiery of the foe. In many instances great injustice was done to him, as in regard to the affair of Wyoming, in connexion with which his name has been used by every preceding annalist who has written upon the subject; while it has, moreover, for the same cause, been consigned to infamy, deep and foul, in the deathless song of Campbell. In other cases again, the Indians of the Six Nations, in common with their chief, were loaded with execrations for atrocities of which all were alike innocent—because the deeds recorded were never committed—it having been the policy of the public writers, and those in authority, not only to magnify actual occurrences, but sometimes, when these were wanting, to draw upon their imaginations for accounts of such deeds of ferocity and blood, as might best serve to keep alive the strongest feelings of indignation against the parent country, and likewise induce the people to take the field for revenge, if not driven thither by the nobler impulse of patriotism. [FN-2]

[FN-1] Almost invariably written Brandt in the books, even in despite of his own orthography, which was uniformly Brant.

[FN-2] See Appendix A—the well-known scalp-story of Dr. Franklin—long believed, and recently revived and included in several works of authentic history.

Such deliberate fictions, for political purposes, as that by Dr. Franklin, just referred to, were probably rare; but the investigations into which the author has been led, in the preparation of the present work, have satisfied him, that from other causes, much of exaggeration and falsehood has obtained a permanent footing in American history. Most historians of that period, English and American, wrote too near the time when the events they were describing occurred, for a dispassionate investigation of truth; and other writers who have succeeded, have too often been content to follow in the beaten track, without incurring the labour of diligent and calm inquiry. Reference has been made above to the affair of Wyoming, concerning which, to this day, the world has been abused with monstrous fictions—with tales of horrors never enacted. The original causes of this historical inaccuracy are very obvious. As already remarked, our histories were written at too early a day; when the authors, or those supplying the materials, had, as it were, but just emerged from the conflict. Their passions had not yet become cooled, and they wrote under feelings and prejudices which could not but influence minds governed even by the best intentions. The crude, verbal reports of the day—tales of hear-say, coloured by fancy and aggravated by fear,—not only found their way into the newspapers, but into the journals of military officers. These, with all the disadvantages incident to flying rumors, increasing in size and enormity with every repetition, were used too often, it is apprehended, without farther examination, as authentic materials for history. Of this class of works was the Military Journal of Dr. James Thatcher, first published in 1823, and immediately recognized as historical authority. Now, so far as the author speaks of events occurring within his own knowledge, and under his own personal observation, the authority is good. None can be better. But the worthy army surgeon did not by any means confine his diary to facts and occurrences of that description. On the contrary, his journal is a general record of incidents and transactions occurring in almost every camp, and at every point of hostilities, as the reports floated from mouth to mouth through the division of the army where the journalist happened to be engaged, or as they reached him through the newspapers. Hence the present author has found the Doctor's journal a very unsafe authority in regard to facts, of which the Doctor was not a spectator or directly cognizant. Even the diligent care of Marshall did not prevent his measurably falling into the same errors, in the first edition of his Life of Washington, with regard to Wyoming; and it was not until more than a quarter of a century afterward, when his late revised edition of that great work was about to appear, that, by the assistance of Mr. Charles Miner, an intelligent resident of Wilkesbarre, the readers of that eminent historian were correctly informed touching the revolutionary tragedy in that valley. Nor even then was the correction entire, inasmuch as the name of Brant was still retained, as the leader of the Indians on that fearful occasion. Nor were the exaggerations in regard to the invasion of Wyoming greater than were those connected with the irruption into, and destruction of, Cherry Valley, as the reader will discover in the course of the ensuing pages. Indeed, the writer, in the preparation of materials for this work, has encountered so much that is false recorded in history as sober verity, that he has at times been disposed almost to universal scepticism in regard to uninspired narration.

In conclusion of this Introduction, a short history of the origin of the present work may not be impertinent. It was the fortune of the author to spend several of his early years, and commence his public life, in the valley of the Mohawk—than which the country scarce affords a more beautiful region. The lower section of this valley was entered by the Dutch traders, and settlements were commenced, originally at Schenectady, very soon after the first fort was built at Albany, then called Fort Orange, by Henry Christiaens in 1614. The Dutch gradually pushed their settlements up the Mohawk on the rich bottom lands of the river, as far as Caughnawaga. Beyond that line, and especially in the upper section of the valley west of the Little Falls, and embracing the broad and beautiful garden of the whole district known as the German Flats, the first white settlers introduced were Germans—being a division of the Palatinates, who emigrated to America early in the eighteenth century, under the patronage of Queen Anne. Three thousand Germans came over at the time referred to, about the year 1709, a portion of whom settled in Pennsylvania. The residue ascended the Hudson to a place called East Camp, now in the county of Columbia. From thence they found their way into the rich valley of the Schoharie-kill, about the year 1713, and thence to the German Flats, of which they were in possession as early as 1720. The first colony, planting themselves in Schoharie, consisted of between forty and fifty families. Some disagreements soon after arising among them, twelve of these families separated from their companions; and, pushing farther westward beyond the Little Falls, planted themselves down upon the rich alluvial Flats at the confluence of the West Canada Creek and the Mohawk.

At the time of its discovery, that valley was occupied by the Mohawk Indians, the head of the extended confederacy of the Five Nations—the Iroquois of the French, and the Romans, as Doctor Colden has denominated them, of the New World. Of this confederacy, the Mohawks were the head or leading nation, as they were also the fiercest. [FN] The Five Nations early attached themselves to the English, and were consequently often engaged in hostilities with the French of Canada, and especially with the Hurons and Adirondacks or Algonquins—powerful nations in alliance with the Canadians. Another consequence was, that the Mohawk valley, and indeed the whole country inhabited by the Five Nations, were the theatre of successive wars, from the discovery down to the close of the war of the American Revolution. There is, therefore, no section of the United States so rich in historical incident, as the valley of the Mohawk and the contiguous territory at the west.

[FN] "I have been told by old men in New England, who remembered the time when the Mohawks made war on their Indians (the Mohicans), that as soon as a single Mohawk was discovered in their country, their Indians raised a cry from hill to hill, A Mohawk! A Mohawk! upon which they all fled, like sheep before wolves, without attempting to make the least resistance or defence on their side; and that the poor New England Indians immediately ran to the Christian houses, and the Mohawks often pursued them so closely, that they entered along with them, and knocked their brains out in the presence of the people of the house." [Colden's Six Nations.] The excellent Heckewelder, in his paramount affection for the Lenni Lenape, enters into a long argument to disprove Colden upon this point; maintaining that the Mohawks were never of more terrific fame than the Delawares. The authorities, however, are against the good Moravian missionary, to which the writer may add the weight of the following incident, of comparatively recent occurrence:—Some ten or twelve years ago, a wandering Mohawk had straggled away from the ancient home of his tribe, as far as the State of Maine, and presented himself, one day, in the streets of a small town not far from the Penobscot river. Indian forms and faces were not strangers in this little community, there being a remnant of the Penobscots yet existing in the neighbourhood, who were in the habit of visiting the place, four or five times a year, for the purchase of such necessaries as their means could command. It happened that a party of them had come in on the very day of the Mohawk's arrival; and as he was lounging through the street, he came suddenly upon them in turning a corner. The recognition, on their part, was instantaneous, and was evidently accompanied by emotions of alarm and distrust. "Mohawk, Mohawk," was muttered by one and another, and so long as he remained in sight, their eyes were fixed upon him with an evident expression of uneasiness. As for the Mohawk, he condescended only to give them a passing glance, and went on his way with the same lounging, indifferent step that he had exhibited from the first. He was a superb-looking fellow, of about 25, full six feet in height, and could easily have demolished three or four of the dwarfish and effeminate Penobscots.

At the time of the author's residence in the Mohawk country, the materials of that history, especially that portion of them connected with events subsequent to the conquest of Canada by Great Britain, were for the most part ungathered. The events of the war of the Revolution, which nowhere else raged so furiously, and was nowhere else marked with such bitter and entire desolation, were then fresh in the recollections of the people; and many a time and oft were the recitals listened to with thrilling interest, and laid up in the store-house of memory, as among the richest of its traditionary treasures. Nor was the interest of these verbal narratives diminished by visiting the sites of the old fortifications, strolling over the battle-fields, and noting the shot-holes in the walls of such houses as had stood out the contest, and the marks of cannon balls upon the trunks of trees yet remaining on fields which had been scenes of bloody strife.

Several years afterward it occurred to the author to undertake a task which he ought to have commenced years before, viz. the composition of a historical memoir of the Mohawk Valley, which would embody those written and unwritten materials of history, now fast disappearing by the death of the actors in the scenes to be described, and the loss of papers and manuscripts, of which such reckless destruction is allowed in this country. In the progress of thought and investigation upon the subject, it was soon determined to embrace in the proposed memoir some biographical account of the Great Chief of the Six Nations, Joseph Brant—Thayendanegea; but there was yet another distinguished name, whose history and fame were intimately connected with the Mohawks, and whose character has neither been justly described nor well understood. The reader will probably anticipate the name, Sir William Johnson. By this time it was apparent that the work, if executed, must be more extended than had originally been contemplated; and a few slight preparations were made for its commencement ten years ago.

It was some time in the year 1829 that the design was abandoned. Calling upon his venerable friend Chancellor Kent, one morning, for the purpose of borrowing a rare volume of a still rarer history of the old French war of 1755-'63, the author was informed that his design had been anticipated by William W. Campbell, Esq., a young gentleman of promise who was just coming to the bar—a native of the country to be occupied as historic ground—and whose work was then nearly ready for the press. Under these circumstances, the project of the author was at once relinquished.

Mr. Campbell's book—"Annals of Tryon County,"—made its appearance in 1831; and was at once found valuable for its facts, and creditable alike to the industry and talents of an author, who, although then so young, possessed the enterprise to undertake the necessary labour, and the ambition to inscribe his name upon the roll of American historians. Still, the work was not a substitute for that which the author had proposed; its object was a more limited history, both of time and territory, than had been entertained in respect of the present work. Mr. Campbell's Annals, with the exception of a very few brief and partial sketches, embraced the history only of the war of the Revolution in that particular section of country, and had little to do with biography. The design of the author, enlarged by reflection and research, now began to comprehend a history of the Six Nations, and their wars with the French, Hurons, or Wyandots, and Adirondacks; the settlement of the country by the pale faces; a history of the French War, so far as that memorable contest was connected with the Indians and colony of New-York; together, or rather blended, with the Lives of Sir William Johnson and Joseph Brant. A work of this description seemed to be a desideratum in American history; and in the autumn of 1832, preparations for the undertaking were resumed, with what success will in part be seen in the sequel.

In the prosecution of the preliminary labour, efforts were made to procure materials from the survivors of the family of Sir William Johnson, residing in the Canadas. These efforts have thus far been attended with but partial success. From one of the grandsons, however, Mr. Archibald Johnson, a valuable manuscript volume has been procured, containing the private diary of Sir William during the Niagara campaign of 1759, in which General Prideaux fell, leaving the command of the army to the baronet, whose efforts were crowned with brilliant success. From among the papers of the late Lieut. Governor of New-York, John Taylor, in possession of his daughter, Mrs. Cooper, the author has fortunately obtained the manuscript of Sir William's official diary for the years 1757, 1758, and a part of the year 1759, together with a small parcel of other papers and letters. A few of the baronet's letters and papers are also yet extant, in the archives of the state at Albany. All these will afford materials for his proposed biography, and for other historical illustrations, of high value. Many of the baronet's papers were destroyed in the war of the Revolution; and many others, it is ascertained, are only to be found in England—to which country a special visit will probably be necessary for their consultation.

It will readily be perceived, that the proposed work embraces two epochs, between which there is a very natural, and even necessary, division. The first embraces the early history referred to, with a history of the French war, and the country, to the death of Sir William Johnson. The second division embraces the life of Joseph Brant, and the revolutionary, Indian, and Tory wars of the northern and western part of the State of New-York; and although anticipated, to a considerable extent, by Mr. Campbell, still the author entered the field of investigation with as much spirit as though it had not been historically traversed before. In the course of his labours he has visited the Mohawk Valley three several times with no other object. Ascertaining, moreover, that the venerable Major Thomas Sammons, of Johnstown, himself, with his father and two brothers, an efficient actor in the scenes of the Revolution, had for many years been collecting historical materials in that region, the author applied to him; and was so fortunate as not only to procure his collections, but to induce the old gentleman to re-enter the field of inquiry. By his assistance a large body of facts and statements, taken down in writing during the last thirty years, from the lips of surviving officers and soldiers, has been obtained for the present work. These documents have added largely to the most authentic materials of history, enabling the author to bring out many new and interesting facts, and to correct divers errors in the works of preceding writers, who have superficially occupied the same ground. In addition to these, the few remaining papers of the brave old General Herkimer, who fell at Oriskany in 1777, have been placed at the disposal of the author, by his nephew, John Herkimer, Esq. Still the work of Mr. Campbell has been found of great use, and by consent has been liberally drawn upon. In regard to some transactions, it was, indeed, almost the only authority; as in the cases of Cherry Valley, some of the transactions in the Schoharie Valley, and the exploits of Colonel Harper.

But this is not all. The author has visited Upper Canada, and Montreal and Quebec, in search of materials. Most luckily for the cause of historic truth, and the reputation of Joseph Brant, during his Canadian researches he became apprised of the fact, that the old Mohawk chief, himself a man of a pretty good English education, had left a large mass of manuscripts, consisting of his own speeches, delivered on many and various occasions, and a great number of letters addressed to him; together with copies of his own letters in reply, which he had preserved with equal industry and care. These papers were in the keeping of his youngest daughter, a lady of high respectability, aboriginal though she be, and eligibly married to William Johnson Kerr, Esq. of Wellington Square, Upper Canada. It was obvious that those papers must prove a rich mine for exploration; and an application from the author, through his friend the Hon. Marshall S. Bidwell, of Toronto, was most readily responded to by Mr. and Mrs. Kerr. The papers, it is true, were less connected than had been hoped; and by hundreds of references and allusions contained therein, it is obvious that large numbers of letters, journals, and speeches have been lost—past recovery. Still, those which remain have proved of great assistance and rare value.

To the kindness of Charles A. Clinton, Esq. the author has been indebted for access to the private papers of General James Clinton, his grandfather. In the composition of one portion of the present volume, these papers have been found of vast importance. General James Clinton was the father of the late illustrious De Witt Clinton, and the brother of Governor George Clinton. He was much in command in the northern department, and it was under his conduct that the celebrated descent of the Susquehanna was performed in 1779. His own letters, and those of his correspondents, have been of material assistance, not only in relation to that campaign, but upon various other points of history. It was among these papers that the letters of Walter N. Butler, respecting the affairs of Cherry Valley and Wyoming, were discovered.

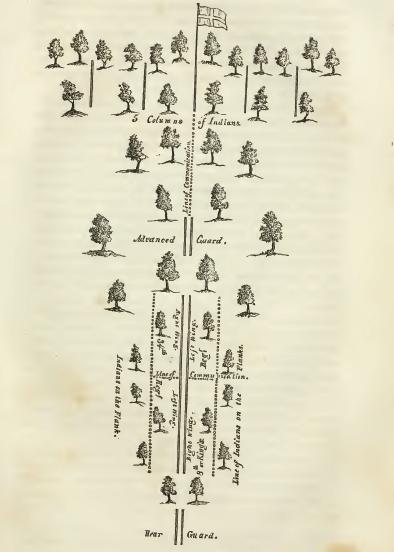

In connexion with the history of the expedition of Sullivan and Clinton, just referred to, the author has likewise been favoured with the manuscript diary of the venerable Captain Theodosius Fowler of this city, who was an active officer during the whole campaign. In addition to the valuable memoranda contained in this diary, Capt. Fowler has preserved a drawing of the order of march adopted in ascending the Chemung, after the junction of the two armies, and also a plan of the great battle fought at Newtown by Sullivan, against the Indians and Tories commanded by Brant and Sir John Johnson; both of which drawings have been engraved, and will be found in the Appendix.

In the winter of 1775-'76, an expedition was conducted from Albany into Tryon County, for the purpose of disarming the Tories and arresting Sir John Johnson, of the particulars of which very little has hitherto been known. On application to the family of General Schuyler, it was ascertained that his letter books for that period were lost. After much inquiry, the necessary documents were obtained from Peter Force, Esq. at Washington.

The author has likewise been indebted to General Peter B. Porter, of Black Rock, for some valuable information respecting the character and some of the actions of Brant. General Porter was an early emigrant into the western part of the State, as an agent for the great landholder, Oliver Phelps; and the execution of his duties brought him into frequent intercourse with many of the chiefs and sachems of the Indians. Among these he became intimately acquainted with the Mohawk chief, between whom and himself a written correspondence was occasionally maintained for several years. Unfortunately, however, that correspondence, with other communications in his hand-writing, which Gen. Porter had taken some pains to preserve, was destroyed by one of the incursions of the enemy across the Niagara during the last war. Still, the General has supplied the author with several important reminiscences respecting the old chief, and one transaction of thrilling interest, heretofore entirely unknown.

A friend of the author, a highly respectable and intelligent octogenarian, Samuel Woodruff, Esq., of Windsor, Connecticut, made a visit to Brant at the Grand River Settlement, in the summer of 1797, and remained with him several days, in the enjoyment of frequent and full conversations upon many subjects. Mr. Woodruff has obligingly furnished a dozen pages or more of instructive notes and memoranda of those conversations, which have been freely used. The author is likewise under obligations to Professor Marsh of Burlington College, (Vt.) a connexion, by marriage, of the Wheelock family, for several of Brant's original letters; and also to Thomas Morris, Esq., of New-York, who knew the chief well, and was several years in correspondence with him, for the same favour. Mr. Campbell has, moreover, supplied several documents of value, obtained by him after the publication of his own book.

Having, by the acquisition of these and other papers, procured all the materials that appeared to remain, or, at least, all that were accessible, while the documentary papers for the first division of the work were yet very incomplete, the author, like Botta, in his promised complete history of Italy, has been compelled to write the latter portion of the work first. In the execution of this task, he had supposed that the bulk of his labour would cease with the close of the war of the Revolution, or at most, that some fifteen or twenty pages, sketching rapidly the latter years of the life of Thayendanegea, would be all that was necessary. Far otherwise was the fact. When the author came to examine the papers of Brant, nearly all of which were connected with his career subsequent to that contest, it was found that his life and actions had been intimately associated with the Indian and Canadian politics of more than twenty years after the treaty of peace; that a succession of Indian Congresses were held by the nations of the great lakes, in all which he was one of the master spirits; that he was directly or indirectly engaged in the wars between the United States and Indians from 1789 to 1795, during which the bloody campaigns of Harmar, St. Clair, and Wayne, took place; and that he acted an important part in the affair of the North-Western posts, so long retained by Great Britain after the treaty of peace. This discovery compelled the writer to enter upon a new and altogether unexpected field of research. Many difficulties were encountered in the composition of this branch of the work, arising from various causes and circumstances. The conflicting relations of the United States, the Indians, and the Canadians, together with the peculiar and sometimes apparently equivocal position in which the Mohawk chief—the subject of the biography—stood in regard to them all; the more than diplomatic caution with which the British officers managed the double game which it suited their policy to play so long; the broken character of the written materials obtained by the author; and the necessity of supplying many links in the chain of events from circumstantial evidence and the unwritten records of Indian diplomacy; all combined to render the matters to be elucidated, exceedingly complicated, intricate, and difficult of clear explanation. But tangled as was the web, the author has endeavoured to unravel he materials, and weave them into a narrative of consistency and truth. The result of these labours is embodied in the second part of the present work; and unless the author has over-estimated both the interest and the importance of this portion of American history, the contribution now made will be most acceptable to the reader.

In addition to the matters here indicated, a pretty full account of the life of Brant, after the close of the Indian wars, is given, by no means barren either of incident or anecdote; and the whole is concluded by some interesting particulars respecting the family of the chief, giving their personal history down to the present day.

It may possibly be objected by some—those especially who are apt to form opinions without much reflection—that the author has indulged rather liberally, not only in the use of public speeches and documents, but also in the transcription of private letters. To this he would reply, that in his view, his course in that respect adds essentially to the value of the work; and had it not been for the unexpected size to which the volumes have attained, those quotations would have been made with still greater freedom. For instance, in regard to the interesting proceedings at the last Grand Council of the Six Nations held in Albany, it was the original intention of the author, long as they are, to insert them in the text; and so the matter was at first arranged. The ancient Council Fire of the Six Nations was always kept burning at Onondaga, the central nation of the confederacy. But from the time of the alliance between the Six Nations and the English, the fires of the united councils of the two powers were kindled at Albany. There, according to the Indian figure of speech, the big tree was planted, to which the chain of friendship was made fast. But with the close of the Great Council held there in the summer of 1775, that fire, which had so long been burning, was extinguished. It was the last Indian congress ever held at the ancient Dutch capital. It took place at a most important crisis, and its proceedings were both of an important and an interesting character. Nor, until now, have those proceedings ever been published entire. Indeed, it is believed that no part of them was ever in print, until very recently a portion of the manuscript was discovered, and inserted in that invaluable collection, the papers of the Massachusetts Historical Society. That manuscript, however, was very defective and incomplete, and chance alone has enabled the author to supply the deficiency. It happened, during one of his visits to the office of the Secretary of State last year, in search of documents, that he discovered, among some ancient, loose, and neglected papers, several sheets of Indian treaty proceedings, which were of themselves very imperfect. Supposing, however, that they might possibly be of use at some time, he caused them to be transcribed. Most luckily, on examining them in connexion with the publication of the Massachusetts collection, they were found exactly to supply the deficiencies of the latter. The result is, that the papers appear now for the first time entire; a portion of them, however, from their great length, having been transferred to the Appendix.

In regard to the use of speeches and letters, moreover, the author, after much consideration, has adopted the plan, as far as possible, of allowing the actors in the scenes described to tell their own stories. This is a method of historical, and especially of biographical, writing, which is coming more into favour than formerly. Marshall adopts it to a considerable extent, and very effectively, in the Life of Washington. The instructive and admirable life of that noblest of England's naval warriors, Lord Collingwood, was constructed upon this plan. So, also, with Moore's Life of Byron. Taylor's Life of Cowper, one of the most useful as well as interesting lives that have been written of that most melancholy and yet most delightful of English bards, is composed almost entirely from the poet's own correspondence. Lockhart's captivating Memoirs of the peerless Scott, now in course of publication, have been constructed upon the basis of the mighty minstrel's own letters. And it is upon the same principle that the author has quoted so largely from the letters and speeches of Joseph Brant, and several of his distinguished correspondents; among whom, the reader who has only heard of "the monster Brant" as a savage once leading the Mohawks abroad upon scalping parties, will probably be surprised to learn, were numbered many gentlemen of rank and standing in Church and State, both in England and America.

An able English writer [FN] has recently opened a very interesting discussion, upon the great advantages of thus using letters and manuscripts in the composition of history. Speaking of the maxim that "history is philosophy teaching by example," he remarks:—"In morals, all depends upon circumstances. An example, whether real or fictitious, can teach us nothing, if it contains only dry facts. The mischief of a great many histories, and those of no mean account, is, that they are quite contented with giving an agreeable narration of naked facts, from which we can gather nothing beyond the facts themselves. To the chronicler, the murder of Thomas A' Becket is the murder of Becket, and it is nothing more. To what quarter, then, are we to look for the magic by which we may make the dry bones live again? We answer, unhesitatingly, to the letters of the day, if there be any. We say so, not because they will contain any elaborate description of the feelings, or expose' of the views, of the age to which they belong, but because they must be written, to a great extent, in the spirit of the age in which their writers lived. The events of the day—the writers' feelings toward their neighbours, and their neighbours' feelings toward them—their comments on the ordinary course of things around them; these are precious records for all who wish to study mankind and morals in history; for these things, and these alone, can enable us fully to appreciate the temper and spirit in which the acts commemorated in history were done. . . . It is very true that some historians profess to use letters, and that some have actually used them in a small degree; but, considering their great value, they have never been used as they deserved; and, in very many cases, their existence seems to be hardly known to historians themselves." It is in accordance with these views, that letters and speeches have been so copiously used in the present work; although it is not supposed that the correspondence of a burly chieftain of the forest, or the bluff partisan officers of a wilderness border, can in any respect be compared with Cowper's polished models of epistolary writing, or with those of Scott or Byron, or those of Lady Mary Wortley Montague, of Peter of Blois or John of Salisbury. They are nevertheless valuable in themselves, both as historical records and as illustrations of character. Of the speeches, and sketches of speeches, embodied in this work, together with the narratives given of the occasions which called them forth, it may be added that they are all memorials of a people,—once a noble race—numerous and powerful—now fast disappearing from the face of the earth—a beautiful portion of the earth—once their own! These memorials it was one of the chief purposes of the author to gather up and preserve.

[FN] London Quarterly Review, No. cxvi.—Art. on Upcott's Collection of Original Letters, Manuscripts, and State Papers.

The plan of the work, especially of the first and larger portion of it, may perhaps in some respects disappoint the reader, though, it is hoped, not unfavourably. It has been the object of the author to render it not only a local, but, to a certain extent, a brief general history of the War of the Revolution. Thus, while it is a particular history, ample in its details, of the belligerent events occurring at the west of Albany, the author has from time to time introduced brief sketches of contemporaneous events occurring in other parts of the country. By this means, bird's-eye glimpses have been presented, for the most part in the proper order of time, of all the principal military operations of the whole contest. In order, moreover, to the better understanding of the incipient revolutionary movements in the Mohawk country, (then Tryon County,) a rapid view is given of the same description of movements elsewhere. The proceedings of that county were, of course, connected with, and dependent upon, those of New England, especially of Boston—the head, and heart, and soul of the rebellion, in its origin and its earlier stages. Hence a summary review of the measures directly, though by degrees, leading to the revolt of the Colonies, has not been deemed out of place, in its proper chronological position. And as all the Indian history of the Revolutionary war at the north, the west, and the south, has been written out in full, by the incidental sketches of other events and campaigns marking the contest, the work may be considered in the three-fold view of local, general, and biographical; the whole somewhat relieved, from time to time, if not enlivened, by individual narratives—tales of captivity and suffering—of daring adventures and bold exploits.

Several weeks after the preceding pages had been stereotyped, but before any considerable progress had been made in printing the body of the work, the author was so fortunate as to obtain a large accession of valuable materials from General Peter Gansevoort, of Albany, embracing the extensive correspondence of his father, the late General Gansevoort, better known in history as "the hero of Fort Stanwix." These papers, embracing those captured by him from the British General St. Leger, have been found of great importance in the progress of the work, and will add materially to its completeness and its value.

A few words respecting the embellishments of these volumes. The frontispiece of each volume presents an elegantly engraved portrait of the brave and wary Mohawk, who forms the principal biographical figure of the work, taken at different periods of his life. The Chief sat for his picture several times in England; once, at the request of Boswell, in 1776, but to what artist is not mentioned. He likewise sat, during the same visit, to the celebrated portrait and historical painter, George Romney, for the Earl of Warwick. He was again painted in England, in 1786, for the Duke of Northumberland; and a fourth time, during the same visit, in order to present his likeness in miniature to his eldest daughter. His last sitting was to the late Mr. Ezra Ames of Albany, at the request of the late John Caldwell, Esq. of that city. This was about the year 1805, and the likeness is pronounced the best ever taken of Captain Brant. The author's valued friend Catlin has made a very faithful copy of this portrait, which has been beautifully engraved by Mr. A. Dick, a well-known and skillful artist of New-York. This picture, as latest in the order of time, will be found at the head of the second volume. The inscription of this plate is a facsimile of the old chief's signature, from a letter written by him to the Duke of Northumberland not long before his death. The author has another picture of the elder Brant, of which he may be pardoned for giving some account. Being at Catskill, in the Summer of 1833, the author discovered, in the possession of his friend, Mr. Van Bergen, some odd volumes of the London Magazine of 1776, in one of which he accidentally found an engraving of Brant, from the portrait taken for Boswell, in the gala costume of the Chief as he appeared at Court. The countenance of this picture, however, was dull, and comparatively unmeaning. On his visit to Upper Canada, in September, 1836, the chieftain's daughter, Mrs. Kerr, showed him a head of her father in a gold locket, which was full of character and energy—with an eye like the eagle's. Having procured this locket, and placed it, together with the engraving referred to, in the hands of Mr. N. Rogers, that eminent artist has produced a very spirited and beautiful picture, which was painted expressly to be engraved for this work. Before it was placed in the hands of the artist, however, Mr. Chapman, an artist of New-York, returning from a visit to England, brought with him a superb print of Brant, taken from the Earl of Warwick's picture by Romney. As this print not only presents more of the figure of the chief than either of the others, and possesses withal more character and spirit, it has been adopted for the work in lieu of that painted by Mr. Rogers. The engraving has also been well executed by Dick, and stands in front of the first volume. The picture by Catlin is the war-chief of the forest in the full maturity of years. The other is the Indian courtier in London. This first volume also contains a finely engraved portrait of General Gansevoort, by Prudhomme, from a portrait by Stuart. It is a fine specimen of the gentleman of the Revolutionary era.

But these are not all the pictorial illustrations. In the completion of the life of Brant, it has been deemed proper to add some account of his family subsequent to his decease. The law of official inheritance among the Six Nations will be found peculiar to that people, the descent being through the female line. Joseph Brant was himself the principal War-chief of the Six Nations; and his third wife, who at his decease was left a young widow, was, in her own right, the representative of the sovereignty of the Confederacy, in whom alone was vested the power of naming, from among her own children, or, in default of a child of her own, from the next of kin, a principal civil and military chief. On the death of her husband, therefore, she selected as his successor her youngest son, John Brant, then a lad of seven years old. He grew up a noble fellow, both in courage and character, as the reader will ascertain before he closes the second volume. During the author's visit to the Brant House in Upper Canada, he saw a portrait of the young chief, then recently deceased, which, though painted by a country artist, and, as a whole, a very bad picture, was nevertheless pronounced by Mr. and Mrs. Kerr to be very correct, so far as the figure and likeness were concerned. Obtaining this portrait from Canada last Autumn, it was placed in the hands of Mr. Hoxie, who has produced the excellent picture which has been well engraved by Mr. Parker, and will be found in the second volume. As the young chief went first upon the war-path in the Niagara campaigns of 1812-15, the idea of embodying a section of the great cataract in the back-ground of the picture was exceedingly appropriate.

As the name of the celebrated Red Jacket appears frequently in the second volume, a likeness of him has been added, from a painting by Weir, beautifully engraved by Hatch. In addition to all which is the finely engraved title-page, designed, engraved, and presented to the author, by his estimable friend Mr. A. Rawdon.

In addition to these illustrations, another has been added, the character of which is striking and its history curious. It is the sketch of a scene at a conference with the Indians at Buffalo Creek, in the year 1793, held by Beverley Randolph, General Benjamin Lincoln, and Colonel Timothy Pickering, in the presence of a number of the British officers then stationed upon that frontier. Messrs. Randolph, Lincoln, and Pickering were on a pacific mission, accompanied, at the request of the Indians, by a number of Quakers. The sketch of that conference was drawn by a British officer, Col. Pilkington, and taken to Europe. In 1819 it was presented to an American gentleman of the name of Henry, at Gibraltar, and by him given to the Massachusetts Historical Society. The sketch is drawn with the taste and science of a master of the art; the grouping is fine, and the likenesses are excellent. As the history of the mission of those gentleman forms an interesting chapter in the present work, this sketch has been deemed an appropriate accompaniment.

In addition to the acknowledgments already made in the preceding pages, the author is under obligations, to a greater or less extent, to many other individuals, for hints, suggestions, and the collection of materials. Among these he takes pleasure in naming the Hon. Lewis Cass, late Secretary of War, and now Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary near the Court of St. Cloud; General Dix, Secretary of the State of New-York, and Mr. Archibald Campbell, his deputy; General Morgan Lewis; Major James Cochran, of Oswego, and also his Lady, who was the youngest daughter of General Schuyler; Major William Popham, who was an aid-de-camp to General James Clinton; Samuel S. Lush, Esq., and S. De Witt Bloodgood, Esq. of Albany; James D. Bemis, Esq. of Canandaigua; Lauren Ford and George H. Feeter, Esquires, of Little Falls; Giles F. Yates, Esq. of Schenectady; William Forsyth, Esq. of Quebec; and the Rev. Mr. Lape, formerly of Johnstown, and now of Athens, N. Y.

With these preliminary explanations, the work is committed to the public, in the belief that, although it might, of course, have been better executed by an abler hand with a mind less distracted by other pressing and important duties, it will, nevertheless, be found a substantial addition to the stock of American history.

WILLIAM L. STONE. New-York, March, 1838.

Birth and parentage—Discussion of the doubts cast upon his origin—Visit of Mohawk chiefs to Queen Anne—Evidence of Brant's descent from one of those—Digression from the main subject, and Extracts from the private and official journals of Sir William Johnson—Connexion between Sir William and the family of Brant—Incidental references to the old French war—Illustrations of Indian proceedings, speeches, &c.—Brant's parentage satisfactorily established—Takes the field in the Campaign of Lake George (1765.)—Is engaged at the conquest of Niagara (1759.)—Efforts of Sir William Johnson to civilize the Indians—Brant is sent, with other Indian youths, to the Moor Charity School, at Lebanon—Leaves school—Anecdote—Is engaged on public business by Sir William—As an Interpreter for the Missionaries—Again takes the field, in the wars against Pontiac—Intended massacre at Detroit—Ultimate overthrow of Pontiac—First marriage of Brant—Entertains the Missionaries—Again employed on public business—Death of his wife—Engages with Mr. Stewart in translating the Scriptures—Marries again—Has serious religious impressions—Selects a bosom friend and confidant, after the Indian custom—Death of his friend—His grief, and refusal to choose another friend.

The birth and parentage of Joseph Brant, or, more correctly, of Thayendanegea—for such was his real name—have been involved in uncertainty, by the conflicting accounts that have been published concerning him. The Indians have no herald's college in which the lineage of their great men can be traced, or parish registers of marriages and births, by which a son can ascertain his paternity. Ancestral glory and shame are therefore only reflected darkly through the dim twilight of tradition. By some authors, Thayendanegea has been called a half-breed. By others he has been pronounced a Shawanese by parentage, and only a Mohawk by adoption. Some historians have spoken of him as a son of Sir William Johnson; [FN] while others again have allowed him the honour of Mohawk blood, but denied that he was descended from a chief.

[FN] Several authors have suggested that Brant was the son of the Baronet. Drake, in his useful compilation, "The Book of the Indians," states that he had been so informed by no less an authority than Jared Sparks. Drake himself calls him an Onondaga of the Mohawk Tribe!

Nearly twenty years ago, a brief account of the life and character of this remarkable man was published in the Christian Recorder, at Kingston, in the province of Upper Canada. In that memoir it was stated that Thayendanegea was born on the banks of the Ohio, whither his parents had emigrated from the valley of the Mohawk, and where they are said to have sojourned several years. "His mother at length returned with two children—Mary, who lived with Sir William Johnson, and Joseph, the subject of this memoir. Nothing was known of Brant's father among the Mohawks. Soon after the return of this family to Canajoharie, the mother married a respectable Indian called Carrihogo, or News-Carrier, whose Christian name was Barnet or Bernard; but, by way of contraction, he went by the name of Brant." Hence it is argued that the lad, who was in future to become not only a distinguished war-chief, but a statesman, and the associate of the chivalry and nobility of England, having thus been introduced into the family of that name, was first known by the distinctive appellation of "Brant's Joseph" and in process of time, by inversion, "Joseph Brant." [FN]

[FN] Christian Register, 1819, Vol. I. No. 3, published at Kingston, (U. C.) and edited by the Rev. Doctor, now the Honourable and Venerable Archdeacon Strachan, of Toronto. The sketches referred to were written by Dr. Strachan, upon information received by him many years before, from the Rev. Dr. Stewart, formerly a missionary in the Mohawk Valley, and father of the present Archdeacon Stewart of Kingston.

There is an approximation to the truth in this relation, and it is in part sustained by the existing family tradition. The facts are these: the Six Nations had carried their arms far to the west and south, and the whole country south of the lakes was claimed by them, to a certain extent of supervisory jurisdiction, by the right of conquest. To the Ohio and Sandusky country they asserted a stronger and more peremptory claim, extending to the right of soil—at least on the lake shore as far as Presque Isle. From their associations in that country, it had become usual among the Six Nations, especially the Mohawks, to make temporary removals to the west during the hunting seasons, and one or more of those families would frequently remain abroad, among the Miamis, the Hurons, and Wyandots, for a longer or shorter period, as they chose. One of the consequences of this intercommunication, was the numerous family alliances existing between the Six Nations and others at the west—the Wyandots, in particular.

It was while his parents were abroad upon one of those hunting excursions, that Thayendanegea was born, in the year 1742, on the banks of the Ohio. The home of his family was at the Canajoharie Castle—the central of the three Castles of the Mohawks, in their native valley. His father's name was Tehowaghwengaraghkwin, a full-blooded Mohawk of the Wolf Tribe. [FN] Thayendanegea was very young when his father died. His mother married a second time to a Mohawk; and the family tradition at present, is, that the name of Brant was acquired in the manner assumed by the publication already cited. There is reason to doubt the accuracy of this tradition, however, since it is believed that there was an Indian family, of some consequence and extent, bearing the English name of Brant. Indeed, from the extracts presently to be introduced from the recently discovered manuscripts of Sir William Johnson, it may be questioned whether Tehowaghwengaraghkwin, and an old chief, called by Sir William sometimes Brant, and at others Nickus Brant, were not one and the same person.

[FN] Each of the original Five Nations was divided into three tribes—the Tortoise, the Bear, and the Wolf. The subject of the present memoir was of the latter. According to David Cusick, a Tuscarora, who has written a tract respecting the history of the ancient Five Nations, the laws of the confederation required that the Onondagas should provide the King, and the Mohawks a great War-Chief.

The denial that he was a born chief, is likewise believed to be incorrect. It is very true, that among the Six Nations, chieftainship was not necessarily obtained by inheritance. But in regard to Thayendanegea, there is no doubt that he was of noble blood. The London Magazine for July, 1776, contains a sketch of him, probably furnished by Boswell, with whom he was intimate during his first visit to England in 1775-'76. In that account it is affirmed as a fact without question, that he was the grandson of one of the five sachems who visited England, and excited so much attention in the British capital, in 1710, during the reign of Queen Anne. Of those chiefs, two were of the Muhhekaneew, or River Indians, and three were Mohawks—one of whom was chief of the Canajoharie clan. [FN-1] Thayendanegea was of the latter clan; and as there is reason to believe that his father was a sachem, there can be little doubt of the correctness of the London publication, in claiming for him direct descent from the Canajoharie chief who visited the British court at the time above mentioned. But there is other evidence to sustain the assumption. In the Life of the first President Wheelock, by the Rev. Messrs. McClure and Parish, it is asserted that the father of Joseph Brant "was sachem of the Mohawks, after the death of the famous King Hendrick." The intimacy for a long time existing between the family of Brant and the Wheelocks, father and sons, renders this authority, in the absence of unwritten testimony still more authentic, very good; and as Hendrick fell in 1755, when Thayendanegea was thirteen years of age, the tradition of the early death of his father, and his consequent assumption of a new name, is essentially weakened. Mrs. Grant, of Laggan, who in early life was a resident of Albany, and intimately acquainted with the domestic relations of Sir William Johnson, speaks of the sister of young Thayendanegea, who was intimately associated in the family of the Baronet, as "the daughter of a sachem." [FN-2]

[FN-1] These five sachems, or Indian kings, as they were called, were taken to England by Colonel Schuyler. Their arrival in London created a great sensation, not only in the capital, but throughout the kingdom. The populace followed them wherever they went. The Court was at that time in mourning for the death of the Prince of Denmark, and the chiefs were dressed in black under-clothes, after the English manner; but, instead of a blanket, they had each a scarlet-ingrain cloth mantle, edged with gold, thrown over all their other clothes. This dress was directed by the dressers of the play-house, and given by the Queen. A more than ordinary solemnity attended the audience they had of her Majesty. They were conducted to St. James's in two coaches by Sir Charles Cotterel, and introduced to the royal presence by the Duke of Shrewsbury, then Lord Chamberlain. [Smith's History.] Oldmixon has preserved the speech delivered by them on the occasion, and several historians record the visit. Sir Richard Steele mentions these chiefs in the Tatler of May 13, 1710, They were also made the subject of a number of the Spectator, by Addison.

[FN-2] "Memoirs of an American Lady," chap, xxxix.