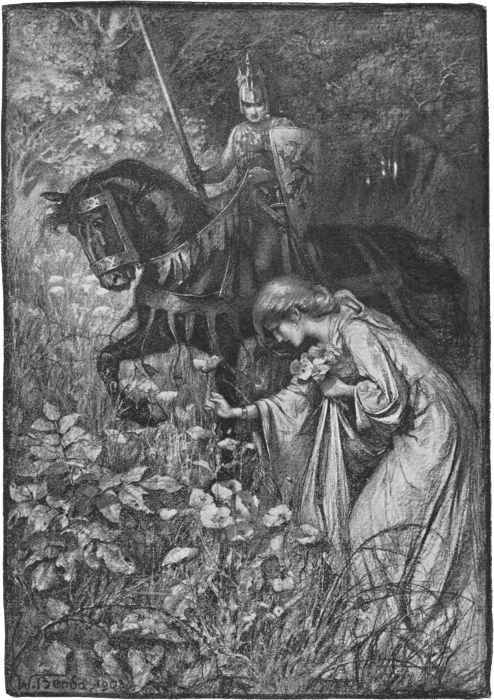

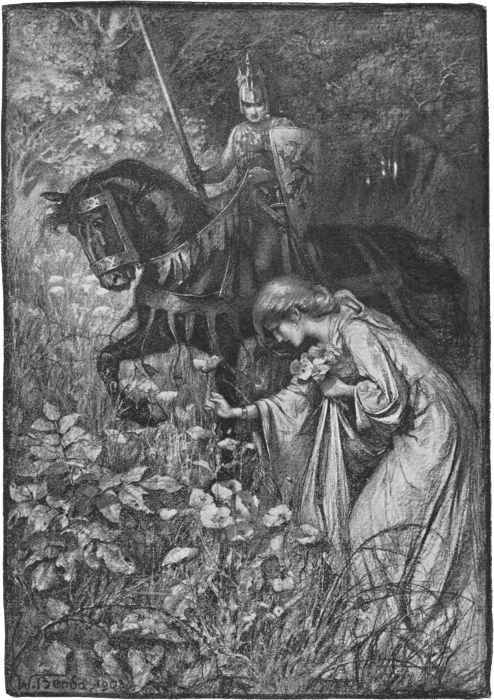

“PELLEAS WATCHED HER AS HER GREY GOWN WENT AMID THE GREEN AND RED”

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Uther and Igraine, by Warwick Deeping This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Uther and Igraine Author: Warwick Deeping Illustrator: W. Benda Release Date: May 23, 2016 [EBook #52139] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK UTHER AND IGRAINE *** Produced by Christopher Wright and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

UTHER AND IGRAINE

“PELLEAS WATCHED HER AS HER GREY GOWN WENT AMID THE GREEN AND RED”

BY

WARWICK DEEPING

ILLUSTRATED BY W. BENDA

NEW YORK

THE OUTLOOK COMPANY

1903

Copyright, 1903, by

THE OUTLOOK COMPANY.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Published October, 1903.

To

MAUDE MERRILL

WITH THE AUTHOR’S HOMAGE

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| BOOK I | |

| The Way to Winchester | 1 |

| BOOK II | |

| Gorlois | 93 |

| BOOK III | |

| The War in Wales | 199 |

| BOOK IV | |

| Tintagel | 325 |

THE WAY TO WINCHESTER

Beneath the dark cornices of a thicket of wind-stunted pines stood a small company of women looking out into the hastening night. The half light of evening lay over the scene, rolling wood and valley into a misty mass, while the horizon stood curbed by a belt of imminent clouds. In the western vault, a vast rent in the wall of grey gave out a blaze of transient gold that slanted like a spear-shaft to a sullen sea.

A wind cried restlessly amid the trees, gusty at intervals, but tuning its mood to a desolate and constant moan. There was an expression of despair on the face of the west. The woods were full of a vague woe, and of troubled breathing. The trees seemed to sway to one another, to fling strange words with a tossing of hair, and outstretched hands. The furze in the valley—swept and harrowed—undulated like a green lagoon.

The women upon the hill were garbed after the fashion of grey nuns. Their gowns stood out blankly against the ascetic trunks of the pines. They were huddled together in a group, like sheep under a thorn hedge when storms threaten. The dark ovals of their hoods were turned towards the south, where the white patch of a sail showed vaguely through the gathering grey.

Between the hill and the cliffs lay a valley, threaded by a meagre stream, that quavered through pastures. A mist hung there despite the wind. Folded by a circle of oaks rose the grey walls of an ecclesiastical building of no inconsiderable size, while the mournful clangour of a bell came up upon the wind, with a vague sound as of voices chanting.[4] Valley, stream, and abbey were rapidly melting into the indefinite background of the night.

Suddenly a snarling murmur seemed to swell the plaining of the bell. A dark mass that was moving through the meadows beneath like a herd of kine broke into a fringe of hurrying specks that dissolved into the shadows of the circle of oaks. The bell still continued to toll, while the women beneath the pines shivered and drew closer together as though for warmth and comfort. There was not one among them who had not grasped the full significance of the sinister sound that had come to them from the valley. A novice, taller than her sisters, stood forward from the group, as though eager to catch the first evidence of the deed that was to be done on that drear evening. She held up a hand to those behind her, in mute appeal to them to listen. The bell had ceased pulsing. In its stead sounded a faint eerie whimper, an occasional shrill cry that seemed to leap out of silence like a bubble from a pool where death has been.

The women were shaken from their strained vigilance as by a wind. The utter grey of the hour seemed to stifle them. Some were on their knees, praying and weeping; one had fainted, and lay huddled against the trunk of a pine. It was such a tragedy as was often played in those days of disruption and despair, for Rome—the decrepit Saturn of history—had fallen from empire to a tottering dotage. Her colonies—those Titans of the past—still quivered beneath the doom piled upon them by the Teuton. In Britain, the cry of a nation had gone out blindly into the night. Vortigern had perished in the flames of Genorium. Reculbuum, RhutupiŠ, and Durovernum had fallen. The fair fields of Kent were open to the pirate; while Aurelius, stout soldier-king, gathered spear and shield to remedy the need of Britain.

The women upon the hill were but the creatures of destiny. Realism had touched them with cynical finger. The barbarians had come shorewards that day in their ships,[5] and at the first breathing of the news the abbey dependants had fled, leaving nun and novice to the mercies of the moment. It had become a matter of flight or martyrdom. Certain fervent women had chosen to remain beside their abbess in the abbey chapel, to await with vesper chant and bell the coming of sword and saexe. Those more frail of spirit had fled with the novices from the valley, and now knelt numb with a tense terror on the brow of that windswept hill, watching fearfully for the abbey’s doom. They could imagine what was passing in the shadowy chapel where they had so often worshipped. The face of the Madonna would be gazing placidly on death—and on more than death. It was all very swift—very terrible. Thenceforward cloister and garden were theirs no more.

A red gleam started suddenly from the black mass in the valley. The nuns gripped hands and watched, while the gleam became a glare that poured steadily above the dark outline of the oaks. A long flame leapt up like a red finger above the trees. The belfry of the chapel rose blackly from a circlet of fire, and gilded smoke rolled away nebulously into the night. The barbarians had set torch to the place. The abbey of Avangel went up in flame.

The tall novice who had been kneeling in advance of the main company rose to her feet, and turned to those who still watched and prayed under the pines. The girl’s hood had fallen back; the hair that should have been primly coifed rolled down in billowy bronze upon her shoulders. There was infinite pride on the wistful face—a certain scorn for the frailer folk who wept and found sustenance in prayer. The girl’s eyes shone largely even in the meagre light under the trees, and there was a straight courage about her lips. She approached and spoke to the women who knelt and watched the burning abbey in a cataleptic stupor.

“Will you kneel all night?” she said.

The words were scourges in their purpose. Several of the nuns looked up from the flames in the valley.

“Shame on you, worldling!” said one of thin and thankless[6] visage; “down on your knees, brat, and pray for the dead.”

The novice gave a curt, low laugh. The reproofs of a year rankled in her like bitter herbs.

“Let the dead bury their dead,” quoth she. “I am for life and the living.”

“Shame, shame!” came the ready response. “May the Mother of Mercy melt your proud heart, and punish you for your sins. You are bad to the core.”

“Shame or no shame,” said the girl, “my heart can grieve for death as well as thine, Sister Claudia; and now the abbey’s burnt, you may couch here and scold till dawn if you will. You may scold the heathen when they come to butcher you all. I warrant they will give such a beauty short shrift.”

The lean nun ventured no answer. She had been worsted before by this rebellious tongue, and had discovered expediency in silence. Several of the women had risen, and were thronging round the novice Igraine, querulous and fearful. Implicit faith, though pious and admirable in the extreme, neither pointed a path nor provided a lantern. Southwards lay the sea and the barbarians; the purlieus of Andredswold came down to touch the ocean. There was night in the sky; no refuge within miles, and wild folk enough in the world to make travelling sufficiently perilous. Moreover, the day’s deed had harried the women’s emotions into a condition of vibrating panic. The unknown seemed to hem them in, to smother as with a cloak. They were like children who fear to stir in the dark, and shrink from impalpable nothingness as though a strange hand waited to grip them to some spiritual torture. As it was, they were fluttering among the pines like birds who fear the falcon.

“It grows dark,” said one.

“Let Claudia pray for us.”

“Igraine, you are wiser in the world than we!”

“Truth,” said the girl, “you may bide and snivel with Claudia if you will. I am for Anderida through the woods.”

“But the woods,” said a child with wide, dark eyes, “the woods are fearful at night.”

“They are kinder than the heathen,” said Igraine, taking the girl’s hand. “Come with me; I will mother you.”

Even as she spoke the novice saw a point of fire disjoint itself from the dark circle of the oaks below. Another and another followed it, and began to jerk hither and thither in the meadows. The dashes of flame gradually took a northern trend, as though the torch-bearers were for ascending the long slope that idled up to the ragged thicket of pines. She turned without further vigil, and made the most of her tidings in an appeal to the women under the trees.

“Look yonder,” she said, pointing into the valley. “Let Sister Claudia say whether she will wait till those torches come over the hill.”

There was instant hubbub among the nuns. Cooped as they had been within the mothering arms of the Church, peril found them utterly impotent when self-reliance and natural instinct were needed to shepherd them from danger. The night seemed to sweep like a wheel with the burning pyre in the meadows for axle. The torches were moving hither and thither in fantastic fashion, as though the men who bore them were doubling right and left in the dark, like hounds casting about for a scent. The sight was sinister, and stirred the women to renewed panic.

“Igraine, help us,” came the cry.

Even tyranny is welcome in times of peril. Witless, resourceless, they gathered about her in a dumb stupor. Even Claudia lost her greed for martyrdom and became human. They were all eager enough for the forest now, and hungry for a leader. Igraine stood up among them like a tall figure of hope. Her eyes were on the east, where a weird glow above the tree tops told her that the moon was rising.

“See,” she said, "we shall have light upon our way. There is a bridle-path through the wold here that goes[8] north, and touches the road from Durovernum. I am going by that path, follow who will."

“We will follow Igraine,” came the answer.

North, east, and west lay Andredswold, sinister as a sea at night. The hill, tangled with gorse and bracken, and sapped by burrows, dipped to it gradually like an outjutting of the land. To the east they could see a wide tangle of pines latticing the light of the moon. It was dark, and the ground more than dubious to the feet. The women, nine in all, herded close on Igraine, who walked like an Eastern shepherdess with the sheep following in her track. First came Claudia, who had held sway over the linen, with Malt, the stout cellaress, next Elaine and Lily, twin sisters, two nuns, and two novices. There was much stumbling, much clutching at one another in the dark; but, thanks to holy terror, their progress was in measure ungracefully speedy.

The girl Igraine led with a keen gleam in her eyes and a queer cheerfulness upon her face, as she stepped out blithely for the dark mass where the wold began. Her sojourn in the abbey had been brief and stormy, a curt attempt at discipline that had failed most nobly. One might as well have sought to hem in spring with winter as to curb desire that leapt towards greenness and the dawn like joy. She had ever thought more of a net for her hair than of her rosary. The little pool in the pleasaunce had served her as her mirror, casting back a full face set with amber shadowed eyes, and a bosom more attuned to passion than to dreams of quiet sanctity. She had been the wayward child of the abbey flock, flooded with homilies, surrendered to eternal penances, yet holding her own in a fair worldly fashion that left the good women of the place wholly to leeward.

Thrust out into the world again she took to the wild like a fox to the woodland, while her more tractable comrades were like caged doves baffled by unaccustomed freedom. Matins, complines, vespers were no more. Cold[9] stone arched no more to tomb her fancies. Above stretched the free dome of the sky; around, the wilderness free and untainted; in lieu of psalms she heard the gathering cry of the wind, and the great voice of the forest at night.

In due course they came to where a dark mass betokened the rampart thickets of the wold, rising like a wall across the sky. Igraine hoped for the track, and found it running like a white fillet about the brow of a wood. They followed till it thrust into the trees, a thin thread in the shadows. As they went, great oaks overreached them with sinuous limbs. The vault was fretted innumerably with the faint overdome of the sky. Now and again a solitary star glimmered through. To the women that place seemed like an interminable cavern, where grotto on grotto dwindled away into oblivious gloom. But for the track’s narrow comfort, Igraine and her company would have been impotent indeed.

The prospect was sad for these folk who had lived for peace, and had tuned their lives to placid chants and the balm of prayer. In Britain Christ was worshipped and the Cross adored, yet abbeys were burnt, and children martyred, and strong towns given over to sack and fire. Truth seemed to taunt them with the apparent impotence of their creed. The abbess Gratia had often said that Britain, for its sloth and sin, deserved to meet the scourge of war, and here were her words exampled by her own stark death. The nuns talked of the state of the land, as they plodded on through the night. There was no soul among them that had not been grossly stirred by the fate that had overtaken Avangel, Gratia, and her more zealous nuns. It was but natural that a cry for vengeance should have gained voice in the hearts of these outcast women, and that a certain querulous bitterness should have found tongue against those in power.

Igraine, walking in the van, listened to their words, and laughed with some scorn in her heart.

“You are very wise, all of you,” she said presently over[10] her shoulder. “You speak of war and disruption as though the whole kingdom were in the dust. True, Kent is lost, the heathen have burnt defenceless places on the coast, and have stormed a few towns. The abbey of Avangel is not all Britain. Have we not Aurelius and the great Uther? Our folk will gather head anon, and push these whelps into the sea.”

“God grant it,” said Claudia, with a smirk heavenward.

“We need a man,” quoth Igraine.

“Perhaps you will find him, pert one.”

“Peril will,” said the girl; “there is no hero when there is no dragon or giant in need of the sword. Britain will find her knight ere long.”

“Lud,” said Malt, the cellaress, “I wish I could find my supper.”

Thereat they all laughed, Igraine as heartily as any.

“Perhaps Claudia will pray for manna dew,” she said.

“Scoffer!”

“It will be cranberries, and bread and water, till better seasons come. I have heard that there are wild grapes in the wold.”

“Bread!” quoth Malt; “did some kind soul say bread?”

“I have a small loaf here under my habit.”

“Ah, Igraine, girl, I would chant twenty psalms for a morsel of that loaf.”

“Chant away, sister. Begin on the ‘Attendite, popule.’ I believe it is one of the longest.”

“Don’t trifle with a hungry wretch.”

“The psalms, Malt, or not a crust.”

“Keep it yourself, greedy hussy; I can go without.”

“We will share it, all of us, presently,” said the girl, “unless Malt wants to eat the whole.”

They held on under the ban of night, following the track like Theseus did his thread. At times the path struck out into a patch of open ground, covered with scrub and bracken, or bristling thick with furze. Igraine had never seen such timid folk as these nuns from Avangel. If a stick cracked[11] they would start, huddle together, and vow they heard footsteps. They mistook an owl’s hoot for a heathen cry, and a night-jar’s creaking note made them swear they caught the chafe of steel. Once they suffered a most shrewd fright. They drove a herd of red deer from cover, and the rush and tumultuous sound of their galloping created a most holy panic among the women. It was some time before Igraine could get them on the march again.

As the night wore on they began to lag from sheer weariness. Two or three were feeble as sickly children, and the abbey life had done little for the body, though it had done much to deform the mind. Igraine had to turn tyrant in very earnest. She knew the women looked to her for courage and guidance, and that they would be hopeless without her stronger mind to lead them. She put this knowledge to effect, and held it like a lash over their weakly spirits.

Igraine found abundant scope for her ingenuity. When they voted a halt for rest, she vowed she would hold on alone and leave them. The threat made the whole company trail after her like sheep. When they grumbled, she told tales of the savagery and lust of the heathen, and made their fears ache more lustily than did their feet. By such devices she kept them to it for the greater portion of the night, knowing that the shrewdest kindness lay in seeming harshness, and that to humour them was but mistaken pity.

At last—heathen or no heathen—they would go no further. It was some hours before dawn. The trees had thinned, and through more open colonnades they looked out on what appeared to be a grass-grown valley sleeping peacefully under the moon. A great cedar grew near, a pyramid of gloom. Malt, the cellaress, grumbling and groaning, crept under its shadows, and commended Igraine to purgatorial fire. The rest, limp and spiritless, vowed they would rather die than take another step. Huddling together under the branches, they were soon half of them asleep in an ecstasy of weariness. Igraine, seeing further[12] effort useless, surrendered to the inevitable, and lay down herself to sleep under the tree.

Day came with an essential stealth. The great trees stood without a rustling leaf, in a stupor of silence. A vast hush held as though the wold knelt at orisons. Soon ripple on ripple of light surged from the hymning east, and the night was not.

The sleep of the women from Avangel had proved but brief and fitful, couched as they had been under so strange a roof. They were all awake under the cedar. Igraine, standing under its green ledges, listened to their monotonous talk as they rehearsed their plight dismally under the shade. The nun Claudia’s voice was still raised weakly in pious fashion; she had learnt to ape saintliness all her life, and it was a mere habit with her. The cellaress’s red face was in no measure placid; hunger had dissipated her patience like an ague, and she found comfort in grumbling. The younger women were less voluble, as age and custom behoved them to be. Unnaturally bred, they were like images of wax, capable only of receiving the impress of the minds about them. Such a woman as Malt owed her individuality solely to the superlative cravings of the flesh.

About them rose the slopes of a valley, set tier on tier with trees, nebulous, silent in the now hurrying light. Grassland, moist and spangled, lay dew-heavy in the lap of the valley, with the track curling drearily into a further tunnel of green.

Igraine, scanning the trees and the stretch of grassland, found on a sudden something to hold her gaze. On the southern side of the valley the walls of a building showed vaguely through the trees. It was so well screened that a transient glance would have passed over the line of foliage[13] without discovering the white glimmer of stone. She pointed it out to her companions, who were quickly up from under the cedar at the thought of the meal and the material comforts such a forest habitation might provide. They were soon deep in the tall grass, their habits wet to the knee with dew, as they held across the valley for the manor amid the trees.

The place gathered distinctness as they approached. Two horns of woodland jutted out—enclosing and holding it jealously from the track through the valley. There were outhouses packed away under the trees. A garden held it on the north. The building itself was modelled somewhat after the fashion of a Roman villa, with a porch—whitely pillared—leading from a terrace fringed with flowers.

The silence of the place impressed itself upon Igraine and the women as they drew near from the meadowlands. The manor seemed lifeless as the woods that circled it. There were no cattle—no servants to be seen, not even a hound to bay warning on the threshold. Passing over a small stone bridge, they went up an avenue of cypresses that led primly to the garden and the terrace. They halted at the steps leading to the portico. The garden, broken in places, and somewhat unkempt, glistened with colour in the early sun; terrace and portico were void and silent; the whole manor seemed utterly asleep.

The women halted by the stairway, and looked dubiously into one another’s faces. There was something sinister about the place—a prophetic hush that seemed to stand with finger on lip and bid the curious forbear. After their march over the meadows, and considering the hungry plight they were in, it seemed more than unreasonable to turn away without a word. None the less, they all hesitated, beckoning each to her fellow to set foot first in this house of silence. Igraine, seeing their indecision, took the initiative as usual, and began to climb the steps that led to the portico. Claudia and the rest followed her in a body.

Within the portico the carved doors were wide. The sun streamed down through a latticed roof into a peristylum, where flowers grew, and a pool shone silverly. There were statues at the angles; one had been thrown down, and lay half buried in a mass of flowers. The place looked wholly deserted, though, by the orderly mood of court and garden, it could not have been long since human hands had tended it.

The women gathered together about the little font in the centre of the peristylum, and debated together in low tones. They were still but half at ease with the place, and quite ready to suspect some sudden development. The house had a scent of tragedy about it that was far from comforting.

Said Malt, “I should judge, sisters, that the folk have fled, and that we are to be sustained by the hand of grace. Come and search.”

Claudia demurred a moment.

“Is it lawful,” quoth she, “to possess one’s self of food and raiment in a strange and empty house?”

“Nonsense,” said the cellaress with a sniff.

“But, Malt, I never stole a crust in my life.”

“Better learn the craft, then. King David stole the shewbread.”

“It was given him of the priests.”

“Tut, sister, then are we wiser than David; we can thieve with our own hands. I say this house is God-sent for our need. May I stifle if I err.”

“Malt is right,” said Igraine, laughing; “let us deprive the barbarians of a pie or a crucifix.”

“Aye,” chimed Malt, “want makes thieving honest. Jubilate Deo. I’m for the pantry.”

A colonnade enclosed the peristylum on every quarter. Beneath the shadows cast by the architrave and roof, showed the portals of the various chambers. Igraine led the way. The first room that they essayed appeared to have been a sleeping apartment, for there were beds in it, the bedding[15] lying disordered and fallen upon the floor as though there had been a struggle, or a sudden wild flight. It was a woman’s chamber, judging by its mirror of steel, and the articles that were scattered on floor and table. The next room proved to be a species of parlour or living-room. A meal had been spread upon the table, and left untouched. Platter and drinking cups were there, a dish of cakes, a joint on a great charger, bread, olives, fruit, and wine. Armour hung on the walls, with mirrors of steel, and paintings upon panels of wood.

The women made themselves speedily welcome after the trials of the night. Each was enticed by some special object, and character leaked out queerly in the choosing. Malt ran for a beaker of wine; the cakes were pilfered by the younger folk; Claudia—whispering of Saxon desecration—possessed herself with an obeisance of a little silver cross that hung upon the wall. Igraine took down a bow, a quiver of arrows, and a sheathed hunting knife; she slung the quiver over her shoulder, and strapped the knife to her girdle. The clear kiss of morning had sharpened the hunger of a night, and the meal spread in that woodland manor proved very comforting to the fugitives from Avangel.

Satisfied, they passed out to explore the rooms as yet unvisited. A fine curiosity led them, for they were like children who probe the dark places of a ruin. The eastern chambers gave no greater revealings than did those upon the west. The kitchen quarters were empty and soundless, though there was a joint upon the spit that hung over the ashes of a spent fire. It seemed more than likely that the inmates had fled in fear of the barbarians, leaving the house in the early hours of some previous dawn.

As yet they had not visited a room whose door opened upon the southern quarter of the peristyle. Judging by its portal, it promised to be a greater chamber than any of the preceding, probably the banqueting or guest room. The door stood ajar, giving view of a frescoed wall within.

Malt, who had waxed jovial since her communion with the tankard, pushed the door open, and went frankly into the half light of a great chamber. She came to an abrupt halt on the threshold, with a fat hand quavering the symbol of a cross in the air. The women crowded the doorway, and looked in over the cellaress’s stout shoulders.

In a gilded chair in the centre of the room sat the figure of a man. His hands were clenched upon the lion-headed arms of the siege, and his chin bowed down upon his breast. He was clad in purple; there were rings upon his fingers, and his brow was bound with a band of gold. At his feet crouched a great wolf-hound, motionless, dead.

The women in the doorway stared on the scene in silence. The man in the chair might have been thought asleep save for a certain stark look—a bleak immobility that contradicted the possibility of life. Here they had stumbled on tragedy with a vengeance. The mute face of death lurked in the shadows, and the vast mystery of life seemed about them like a cold vapour. It was a sudden change from sunlight into shade.

Igraine pushed past Malt, and ventured close to the crouching hound. Bending down, she looked into the dead man’s face. It was pinched and grey, but young, none the less, and bearing even in death a certain sensuous haughtiness and dissolute beauty. The man had been dark, with hair turbulent and lustrous. In his bosom glinted the silver pommel of a knife, and there were stains upon cloak and tessellated pavement. Clasped in one hand was a small cross of gold that looked as though it had been plucked from a chain or necklet, and held gripped in the death agony. The wolf-hound had been thrust through the body with a sword.

“Hum,” said Malt, with a sniff,—“Christian work here. And a comely fellow, too—more’s the pity. Look at the rings on his fingers; I wonder whether I might take one for prayer money? It would buy candles.”

Igraine was still looking at the dead man with strange awe in her heart.

“Keep off,” she said, thrusting off Malt; “the man has been stabbed.”

“Well, haven’t I eyes too, hussy?”

Claudia came in, white and quavering, with her crucifix up.

“Poor wretch!” said she; “can’t we bury him?”

“Bury him!” cried Malt.

“Yes, sister.”

“Thanks, no. It would spoil my dinner.”

Claudia gave a sudden scream, and jumped back, holding her skirts up.

“There’s blood on the floor! Holy mother! did the dog move?”

“Move!” quoth Malt, giving the brute a kick; “what a mouse you are, Claudia.”

“Are you sure the man’s dead?”

“Dead, and cold,” said Igraine, touching his cheek, and drawing away with a shiver. “Come away, the place makes my flesh creep. Shut the door, Malt. Let us leave him so.”

The women from Avangel had seen enough of the manor in the forest. Certainly, it held nothing more perilous than a corpse, perched stiffly in a gilded chair; but the dead man seemed to exert a sinister influence upon the spirits of the company, and to stifle any desire for a further sojourn in the place. Folk with murder fresh upon their hands might still be within the purlieus of the valley. The women thought of the glooms of the forest, and of the strong walls of Anderida, and discovered a very lively desire to be free of Andredswold, and the threats of the unknown.

They left the man sitting in his chair, with the hound at his feet, and went to gather food for the day’s journey. Bread they took, and meat, and bound them in a sheet, while Malt filled a flask with wine, and bestowed it at her girdle. Igraine still had her bow, shafts, and hunting knife. Before sallying, they remembered the dead. It was Igraine’s[18] thought. They went and stood before the door of the great chamber, sang a hymn, and said a prayer. Then they left the place, and held on into the forest.

Nothing befell them on their way that morning. It was noon before they struck the road from Durovernum to Anderida, a straight and serious highway that went whitely amid wastes of scrub, thickets, and dark knolls of trees. The women were glad of its honest comfort, and blessed the Romans who had wrought the road of old. Later in the day they neared the sea again. Between masses of trees, and over the slopes, they caught glimpses of the blue plain that touched the sky. From a little hill that gave broader view, they saw the white sails of ships that were ploughing westward with a temperate wind. They took them for the galleys of the Saxons, and the thought hurried them on their way the more.

Presently they came to a mild declivity, with a broken toll-house standing by the roadside, and two horsemen on the watch there, as the distant galleys swept over the sea towards the west. The men belonged to the royal forces in Anderida. They were reticent in measure, and in no optimistic mood. They told how the heathen had swept the coast, how their ships had ventured even to Vectis, to burn, slay, and martyr. The women learnt that Andred’s town was some ten miles distant. There was little likelihood, so the men said, of their getting within the walls that night, for the place was in dread of siege, and was shut up like a rock after dusk.

Igraine and the nuns elected, none the less, to hold upon their way. Despite their weariness, the women preferred to push on and gain ground, rather than to lag and lose courage. For all they knew, the Saxons might be soon ashore, ready to raid and slay in their very path. They left the soldiers at the toll-house, and went downhill into a long valley.

Possibly they had gone a mile or more when they heard the sound of galloping coming in their wake. On the slope of the hill they had left, they could see a distant wave of[19] dust curling down the road like smoke. The two men from Andred’s town were coming on at a gallop. They were very soon within bowshot, but gave no hint of halting. Thundering on, they drew level with the women, shouted as they went by, and held on fast,—dust and spume flying.

“God’s curse upon the cravens,” said Malt, the cellaress.

Cravens they were in sense; yet the men had reason on their side, and the women were left staring at the diminishing fringe of dust. There was much frankness in the phenomenon, a curt hint that carried emphasis, and advised action. “To the woods,” it said; “to the woods, good souls, and that quickly.”

The road ran through the flats at that place, with marsh and meadowland on either hand. Further westward, the wold thrust forth a finger from the north to touch the highway. Southward, scrub and grassland swept away to the sea. It was when looking southwards that the nuns from Avangel discovered the stark truth of the soldier’s warning. Against the skyline could be seen a number of jerking specks, moving fast over the open land, and holding north-west as though to touch the road. They were the figures of men riding.

The outjutting of woodland that rolled down to edge the highway was a quarter of a mile from where the women stood. A bleak line of roadway parted them from the mazy refuge of the wold. They started away at a run; Igraine and another novice dragging the nun Claudia between them. The display was neither Olympic nor graceful; it would have been ridiculous but for the stern need that inspired it. Igraine and her fellows made the best of the highway. In the west, the wold seemed to stretch an arm to them like a mother.

The heathen raiders were coming fast over the marshes. Igraine, dragging the panting Claudia by the hand, looked back and took measure of the chase. There were some score at the gallop three furlongs or more away, with others on foot, holding on to stirrups, running and leaping like[20] madmen. The girl caught their wild, burly look even at that distance. They were hallooing one to another, tossing axe and spear—making a race of it, like huntsmen at full pelt. Possibly there was sport in hounding a company of women, with the chance of spoil and something more brutish to entice.

Igraine and her flock were struggling on for very life. Their feet seemed weighted with the shackles of an impotent fear, while every yard of the white road appeared three to them as they ran. How they anguished and prayed for the shadows of the wood. A frail nun, winded and lagging, began to scream like a hare when the hounds are hard on her haunches. Another minute, and the trees seemed to stride down to them with green-bosomed kindness. A wild scramble through a shallow dyke brought them to bracken and a tangled barrier about the hem of the wood. Then they were amid the sleek, solemn trunks of a beech wood, scurrying up a shadowed aisle with the dull thudding of the nearing gallop in their ears.

It was borne in upon Igraine’s reason as she ran that the trees would barely save them from the purpose of pursuit. The women—limp, witless, dazed by danger—could hardly hold on fast enough to gain the deeper mazes of the place, and the sanctuary the wold could give. Unless the pursuit could be broken for a season, the whole company would fall to the net of the heathen, and only the Virgin knew what might befall them in that solitary place. Sacrifice flashed into the girl’s vision—a sudden ecstasy of courage, like hot flame. These abbey folk had been none too gentle with her. None the less she would essay to save them.

She cast Claudia’s hand aside, and turned away abruptly from the rest. They wavered, looking at her as though for guidance, too flurried for sane measures. Igraine waved them on, with a certain pride in her that seemed to chant the triumph song of death.

“What will you do, girl? Are you mad?”

“Go!” was all she said. “Perhaps you will pray for me as for Gratia the abbess.”

“They will kill you!”

“Better one than all.”

They wavered, unwilling to be wholly selfish despite their fear and the sounding of pursuit. There shone a fine light on the girl’s face as they beheld her—tyrannical even in heroism. Her look awed them and made them ashamed; yet they obeyed her, and like so many winging birds they fled away into the green shadows.

Igraine watched them a moment, saw the grey flicker of their gowns go amid the trees, and then turned to front her fortune. Pursing her lips into a queer smile, she took post behind a tree bole, and waited with an arrow fitted to her string. She heard a sluthering babel as the men reined in, with much shouting, on the forest’s margin. They were very near now. Even as she peered round her tree trunk a figure on foot flashed into the grass ride, and came on at the trot. The bow snapped, the arrow streaked the shadows, and hummed cheerily into the man’s thigh. Igraine had not hunted for nothing. A second fellow edged into view, and took the point in his shoulder. Igraine darted back some forty paces and waited for more.

In this fashion—slipping from tree to tree, and edging north-west—she held them for a furlong or more. The end came soon with an empty quiver. The wood seemed full of armed men; they were too speedy for her, too near to her for flight. She threw the empty quiver at her feet, with the bow athwart it, put a hand in the breast of her habit, and waited. It was not for long. A man ran out from behind a tree and came to a curt halt fronting her.

He was young, burly, with a great tangle of hair, and a yellow beard that bristled like a hound’s collar. A naked sword was in his hand, a buckler strapped between his shoulders. He laughed when he saw the girl—the coarse laugh of a Teuton—and came some paces nearer to her, staring in her face. She was very rich and comely in a way[22] foreign to the fellow’s fancy. There was that in his eyes that said as much. He laughed again, with a guttural oath, and stretched out a hand to grip the girl’s shoulder.

An instant shimmer of steel, and Igraine had smitten him above the golden torque that ringed his throat. Life rushed out in a red fountain. He went back from her with a stagger, clutching at the place, and cursing. As the blood ebbed he dropped to his knees, and thence fell slantwise against a tree. He had found death in that stroke.

A hand closed on the girl’s wrist. The knife that had been turned towards her own heart was smitten away and spurned to a distance. There were men all about her—ogrish folk, moustachioed, jerkined in skins, bare armed, bare legged. Igraine stood like a statue—impotent—frozen into a species of apathy. The bearded faces thronged her, gaped at her with a gross solemnity. She had no glance for them, but thought only of the man twitching in the death trance. The wood seemed full of gruff voices, of grotesque words mouthed through hair.

Then the barbaric circle rippled and parted. A rugged-faced old man with white hair and beard came forward slowly. There was a tense silence over the throng as the old man stood and looked at the figure at his feet. There were shadows on the earl’s face, and his hands shook, for the smitten man was his son.

Out of silence grew clamour. Hands were raised, fingers pointed, a sword was poised tentatively above the girl’s head. The wood seemed full of bearded and grotesque wrath, and the hollow aisles rang with the clash of sword on buckler. But age was not for sudden violence, though the blood of youth ebbed on the grass. The old man pointed to a tree, spoke briefly, quietly, and the rough warriors obeyed him.

They stripped Igraine, cast her clothes at her feet, and bound her to the trunk of the tree with their girdles. Then they took up the body of the dead man, and so departed into the forest.

It was well towards evening when the men disappeared into the wood, leaving the girl bound naked to the tree. The day was calm and tranquil, with the mood of June on the wind, and a benign sky above. Igraine’s hair had fallen from its band, and now hung in bronze masses well-nigh to her knees, covering her as with a cloak. Her habit, shift, and sandals lay close beside her on the grass. The barbarians had robbed her of nothing, according to their old earl’s wishes. She was simply bound there, and left unscathed.

When the men were gone, and she began to realise what had passed, she felt a flush spread from face to ankle, a glow of shame that was keen as fire. Her whole body seemed rosily flaked with blushes. The very trees had eyes, and the wind seemed to whisper mischief. There were none to see, none to wonder, and yet she felt like Eve in Eden when knowledge had smitten the pure flesh with gradual shame. Though the place was solitary as a dry planet, her aspen fancy peopled it with life. She could still see the heavy-jowled barbaric faces staring at her like the malign masks of a dream.

The west was already prophetic of night. There was the golden glow of the decline through the billowy foliage of the trees, and the shadows were very still and reverent, for the day was passing. A beam of gold slanted down upon Igraine’s breast, and slowly died there amid her hair. The west flamed and faded, the east grew blind. Soon the day was not.

Igraine watched the light faint above the trees, wondering in her heart what might befall her before another sun could set. She had tried her bonds, and had found them lacking sympathy in that they were staunch as strength could make them. She was cramped, too, and began to long for the hated habit that had trailed the galleries of Avangel, and had brought such scorn into her discontented heart. There[24] was no hope for it. She was pilloried there, bound body, wrist, and ankle. Philosophy alone remained to her, a poor enough cloak to the soul, still worse for things tangible.

Her plight gave her ample time for meditation. There were many chances open to her, and even in mere possibilities fate had her at a vantage. In the first place, she might starve, or other unsavoury folk find her, and her second state be worse than her first. Then there were wolves in the wold; or country people might find and release her, or even Claudia and the women might return and see how she had fared. There was little comfort in this last thought. She shrewdly guessed that the abbey folk would not stop till they happened on a stone wall, or the heathen took them. Lastly, the road was at no very great distance, and she might hear perchance if any one passed that way.

Presently the moon rose upon Andredswold with a stupendous splendour. The veil of night seemed dusted with silver as it swept from her tiar of stars. Innumerable glimmering eyes starred the foliage of the beeches. Vague lights streamed down and netted the shadows with mysterious magic. Here and there a tree trunk stood like a ghost, splashed with a phosphor tunic.

The wilderness was soundless, the billowy bastions of the trees unruffled by a breath. The hush seemed vast, irrefutable, supreme. Not a leaf sighed, not a wind wandered in its sleep. The great trees stood in a silver stupor, and dreamt of the moon. The solemn aisles were still as Thebes at midnight; the smooth boles of the beeches like ebony beneath canopies of jet.

The scene held Igraine in wonder. There was a mystery about a moonlit forest that never lessened for her. The vasty void of the night, untainted by a sound, seemed like eternity unfolded above her ken. She forgot her plight for the time, and took to dreaming, such dreams as the warm fancy of the young heart loves to remember. Perhaps beneath such a benediction she thought of a pavilion set amid water lilies, and a boy who had looked at her with boyish[25] eyes. Yet these were childish things. They lost substance before the chafing of the cords that bound her to the tree.

Presently she began to sing softly to herself for the cheating of monotony. She was growing cold and hungry, too, despite all the magic of the place, and the hours seemed to drag like a homily. Then with a gradual stealthiness the creeping fear of death and the unknown began to steal in and cramp even her buoyant courage. It was vain for her to put the peril from her, and to trust to day and the succour that she vowed in her heart must come. Dread smote into her more cynically than did the night air. What might be her end? To hang there parched, starved, delirious till life left her; to hang there still, a loathsome, livid thing, rotting like a cloak. To be torn and fed upon by birds. She knew the region was as solitary as death, and that the heathen had emptied it of the living. The picture grew upon her distraught imagination till she feared to look on it lest it should be the lurid truth.

It was about midnight, and she was beginning to quake with cold, when a sound stumbled suddenly out of silence, and set her listening. It dwindled and grew again, came nearer, became rhythmic, and ringing in the keen air. Igraine soon had no doubts as to its nature. It was the steady smite of hoofs on the high-road, the rhythm of a horse walking.

Now was her chance if she dared risk the character of the rider. Doubts flashed before her a moment, hovered, and then merged into decision. Better to risk the unknown, she thought, than tempt starvation tied to the tree. She made her choice and acted.

“Help, there! Help!”

The words went like silver through the woods. Igraine, listening hungrily, strained forward at her bonds to catch the answer that might come to her. The sound of hoofs ceased, and gave place to silence. Possibly the rider was in doubt as to the testimony of his own hearing. Igraine called again, and again waited.

Stillness held. Then there was a stir, and a crackling as of trampled brushwood, followed by the snort of a horse and the thrill of steel. The sounds came nearer, with the deadened tramp of hoofs for an underchant. Igraine, full of hope and fear, of doubt and gratitude, kept calling for his guidance. Presently a cry came back to her in turn.

“By the holy cross, who are you that calls?”

“A woman,” she cried in turn, “bound here by the heathen.”

“Where?”

“Here, in a grass ride, tied to a tree.”

The words that had come to her were very welcome, heralding, as they did, a friend, at least in race, and there was a manly depth in the voice, too, that gave her comfort. She saw a glimmer of steel in the shadows of the wood as man and horse drew into being from the darkness. Moonlight played fitfully upon them, weaving silver gleams amid a smoke of gloom, making a white mist about the man’s great horse. A single ray burnt and blazed like a halo about the rider’s casque, and his spear-point flickered like a star beneath the vaultings of the trees. He had halted, a solitary figure wrapped round with night, and rendered grand and wizard by the misty web of the moon.

The sight was pathetic enough, yet infinitely fair. Light streamed through, and fell full upon the tree where Igraine stood. The girl’s limbs were white and luminous against the dark bosom of the beech, and her rich hair fell about her like mist. As for the strange rider, he could at least claim the inspiration accorded to a Christian. The servant of the Galilean has, like Constantine, a symbol in the sky, prophetic in all need, generous of all guidance. The Cross is a perpetual Delphi oracular on trivial matters as on the destinies of kingdoms. The man dismounted, knelt for a moment with sword held before him, and then rose and strode to the tree with shield held before his face.

Igraine was looking at the figure in armour, kindly,[27] redly, from amid the masses of her hair. The small noblenesses of his bearing towards her had won her trust with a flush of gratitude. The man saw only the white feet like marble amid the moss as he cut the thongs where they circled the tree. The bands fell, he saw the white feet flicker, a trail of hair waving under his shield. Then he turned on his heel without a word, and went to tether his horse.

The interlude was as considerate as courtesy had intended. Igraine darted for her habit with a rapturous sigh. When the man turned leisurely again, a tall girl met him, cloaked in grey, with her hair still hanging about her, and sandals on her feet.

“Mother Virgin, a nun!”

The words seemed sudden as an echo. Igraine bent her head to hide the half-abashed, half-smiling look upon her face. It had been thus at Avangel. Nun and novice had worn like habits, and there had been nothing to distinguish them save the final solemn vow. The man’s notions were plainly celibate, and, with a sudden twinkling inspiration, she fancied they should bide so. It would make matters smoother for them both, she thought.

“My prayers are yours, daily, for this service,” she said.

The man bent his head to her.

“I am thankful, madame,” he answered, “that I should have been so good fortuned as to be able to befriend you. How came you by such evil hazard?”

“I was of Avangel,” she said.

“You speak as of the past,” quoth he, with a keen look.

“Avangel was burnt and sacked but yesterday,” she said. “Many of the nuns were martyred; some few escaped. I was made captive here, and bound to this tree by the heathen.”

Igraine could see the man’s face darken even in the moonlight, as though pain and wrath held mute confederacy there. He crossed himself, and then stood[28] with both hands on the pommel of his sword, stately and statuesque.

“And the Lady Gratia?” he said.

“Dead, I fear.”

A half-heard groan seemed to come from the man’s helmet. He bent his head into the shadows and stood stiff and silent as though smitten into thought. Presently he seemed to remember himself, Igraine, and the occasion.

“And yourself, madame?” he said, with a twinge of tenderness in his voice.

The girl blushed, and nearly stammered.

“I am unscathed,” she hastened to say, “thanks to heaven. I am safe and whole as if I had spent the day in a convent cell. My name is Igraine, if you would know it. I fear I have told you heavy tidings.”

The man turned his face to the sky like one who looks into other worlds.

“It is nothing,” he said, gazing into the night; “nothing but what we must look for in these stark days. Our altars smoke, our blood is spilt, and yet we still pray. Yet may I be cursed, and cursed again, if I do not dye my sword for this.”

There was a sudden bleak fierceness in his voice that betrayed his fibre and the strong thoughts that were stirring in his heart that moment. His face looked almost fanatical in the cold gloom, gaunt, heavy-jawed, lion-like. Igraine watched this thunder-cloud of thought and passion in silence, thinking she would meet the man in the wrack of life rather as friend than as foe. The brief mood seemed to pass, or at least to lose expression. Again, there was that in the kindness of his face that made the girl feel beneath the eye of a brother.

“You will ride with me?” he asked.

Igraine hesitated a moment.

“I was for Anderida,” she said, “and it is only three leagues distant. Now that I am free I can go through the wold alone, for I am no child.”

“An insult to my manhood,” said the stranger.

“But the heathen are everywhere, and I should but cumber you.”

“Madame, you talk like a fool.”

There was a sheer sincerity about the speech that pleased Igraine. His spirit seemed to overtop hers, and to silence argument. Proud heart! yet without thought of debate she gave way in the most placid manner, and was content to be shepherded.

“I might walk at your stirrup,” she said meekly.

The man seemed to ponder. He merely looked at her with dark, solemn eyes, showing a quiet disregard for her humility.

“Listen to me,” he said, “you, a woman, must not attempt Anderida alone. The town will be beleaguered, or I am no prophet. To Anderida I cannot go, for I have folk at Winchester who wait my coming. If you can put trust in me, and will ride with me to Winchester, you will find harbour there.”

She considered a moment.

“Winchester,” she said, “yes, and most certainly I trust you.”

The man stretched out a hand to her with a smile.

“God willing,” he said, “I will bear you safe to the place. As for your frocks and vows, they must follow necessity, and pocket their pride. It will not damn you to ride before a man.”

“I trow not,” she said, with a little laugh that seemed to make the leaves quiver. So they took horse together, and rode out from the beech wood into the moonlight.

When they were clear of the solemn beeches, and saw the road white as white before them, Igraine began to tell the man of the doom of Avangel, and the great end made by[30] Gratia the abbess. The knight had folded his red cloak and spread it for her comfort. Her tale seemed very welcome to him despite its grievous humour, and he questioned her much concerning Gratia, her goodness and her charity. Now it had been well known in Avangel that Gratia had come of noble and excellent descent, and seeing that this stranger had been familiar with her in the past, Igraine guessed shrewdly that he himself was of some ancient and goodly stock. To tell the truth, she was very curious concerning him, and it was not long before she found a speech ready to her tongue likely to draw some confession from his lips.

“I have promised to pray for you,” she said, “and pray for you I will, seeing that you have done me so great a blessing to-night. When I bow to the Virgin and the Saints, what name may I remember?”

The man did not look at her, for her face was in the shadow of her hood and his clear and white in the light of the moon.

“To some I am known as Sir Pelleas,” he said.

“And to me?”

“As Sir Pelleas, if it please you, madame.”

Igraine understood that she was to be pleased with the name, whether she liked it or not.

“Then for Sir Pelleas I will pray,” she said, “and may my gratitude avail him.”

There was silence for a space, broken by the rhythmic play of hoofs upon the road, and the dull jar of steel. Igraine was meditating further catechism, adapting her questions for the knowledge she wished for.

“You ride errant,” she said presently.

“I ride alone, madame.”

“The wold is a rude region set thick with perils.”

“Very true,” quoth the man.

“Perhaps you are a venturesome spirit.”

“I believe that I am often as careful as death.”

Igraine made her culminating suggestion.

“Some high deed must have been in your heart,” she said, “or probably you would not have risked so much.”

The man Pelleas did not even look at her. She felt the bridle-arm that half held her tighten unconsciously, as though he were steeling himself against her curiosity.

“Madame,” he said very gravely, “every man’s business should be for his own heart, and I do not know that I have any need to share the right or wrong of mine with others. It is a grand thing to be able to keep one’s own counsel. It is enough for you to know my name.”

Igraine none the less was not a bit abashed.

“There is one thing I would hear,” she said, “and that is how you came to know of the abbess Gratia.”

For the moment the man looked black, and his lips were stern—

“You may know if you wish,” he said.

“Well?”

“Madame, the Lady Gratia was my mother.”

Igraine felt a flood of sudden shame burst redly into her heart. Gratia was the man’s mother, and she had been plying him with questions, cruelly curious. She caught a short, shallow breath, and hung her head, shrinking like a prodigal.

“Set me down,” she said. “I am not worthy to ride with you.”

“Pardon me,” quoth the man; “you did not think, not knowing I was in pain.”

“Set me down,” was all she said; “set me down—set me down.”

The man Pelleas changed his tone.

“Madame,” he said, with a sudden gentleness that made her desire to weep, “I have forgiven you. What, then, does it matter?”

Igraine hung her head.

“I am altogether ashamed,” she said.

She drew her hood well over her face, and took her[32] reproof to heart like a veritable penitent. Even religious solemnities make little change in the notorious weaknesses of woman. Igraine was angry, not only for having blundered clumsily against the man’s sorrow, but also because of the somewhat graceless part she seemed to have played after the deliverance he had vouchsafed her. As yet her character seemed to have lost honour fast by mere brief contrast with the man’s.

Pelleas meanwhile rode with eyes watching the wan stretch of road to the west. On either hand the woods rose up like nebulous hills bowelled by tunnelled mysteries of gloom. He had turned his horse to the grass beside the roadway, so that the tramp of hoofs should fall muffled on the air. Igraine, close against his steeled breast, with his bridle-arm about her, looked into his face from the shadows of her hood, and found much to initiate her liking.

If she loved strength, it was there. If she desired the grand reserve of silent vigour, it was there also. The deeply caverned eyes watching through the night seemed dark with a quiet destiny. The large, finely moulded face, gaunt and white in its meditative repose, seemed fit to front the ruins of a stricken land. It was the face of a man who had watched and striven, who had followed truth like a shadow, and had found the light of life in the heavens. There was bitterness there, pain, and the ghost of a sad desire that had pleaded with death. The face would have seemed morose, but for a certain something that made its shadows kind.

Instinctively, as she watched the mask of thought beneath the dark arch of his open casque, she felt that he had memories in his heart at that moment. His thoughts were not for her, however much she pitied him or longed to tell him of her shame and sympathy. Nothing could come into that sad session of remembrances, save the soul of the man and the memories of his mother. That he was grieving deeply Igraine knew well. His was a strong nature that brooded in silence, and felt the more; it must[33] be a terrible thing, she thought, to have the martyrdom of a mother haunting the heart like a fell dream at night.

Slipping from such a reverie, the turmoil and weariness of the past days returned to take their tribute. Despite the strangeness of the night, Igraine began to feel sleepy as a tired child. The magnetic calm of the man beside her seemed to lull to slumber, while the motion of the ride cradled her the more. The noise of hoofs, the dull clink of scabbard against spur or harness, grew faint and faint. The woods seemed to swim into a mist of silver. She saw, as in a dream, the strong face above her staring calmly into the night, the long spear poised heavenwards. Her head was on the man’s shoulder. With scarcely a thought she was asleep.

It was then that Pelleas discovered the girl heavy in his arms, and looked down to find her sleeping, with hood fallen and a white face turned peacefully to his. Strangely enough, the sorrow that had taken him seemed to make his senses vibrate strongly to the more human things of life. The supple warmth of the girl’s slim body crept up the sinews of his arm like a subtle flame. From her half-parted lips the sigh of her breathing came into his bosom. Over his harness clouded her hair, and her two hands had fastened themselves upon his sword-belt with a restful trust.

The man bent his head and watched her in some awe. Her lips were like autumn fruit fed wistfully on moonlight. To Pelleas, woman was still wonderful, a creature to be touched with reverence and soft delight. The drab, the scold, and the harlot had failed to debase the ideals of a staunch spirit, and the fair flesh at his breast was as full of mystery as a woman could be.

He took his fill of gazing, feeling half ashamed of the deed, and half dreading lest Igraine should wake suddenly and look deeply into his eyes. He felt his flesh creep with magic when she stirred or sighed, or when the hands upon his belt twitched in their slumber. Pelleas had seen stark things of late, burnt hamlets, priests slaughtered and churches[34] in flames, children dead in the trampled places of the slain. He had ridden where smoke ebbed heavenwards, and blood clotted the green grass. Now this ride beneath the quiet eyes of night, with the bosomed silence of the woods around, and this lily plucked from death in his arms, seemed like a passage of calm after a page of tempest. Little wonder that he looked long into the girl’s face, and thrilled to the soft sway of her bosom. He thanked God in his heart that he had plucked her blemishless from gradual death. It was even thus, he thought, that a good soldier should ride into Paradise bearing the soul of the woman he loved.

Igraine stirred little in her sleep. “Poor child,” thought Pelleas, “she has suffered much, has feared death, and is weary. Let her sleep the night through if she can.” So he drew the cloak gently about her, said his prayers in his heart, and, holding as much as possible under the shadows of the trees, kept watch patiently on the track before him.

All that night Pelleas rode, thinking of his mother, with the girl sleeping in his arms. He saw the moon go down in the west, while the grey mist of the hour before dawn made the forest gaunt like an abode of the dead. He heard the birds wake in brake and thicket. He saw the red deer scamper, frightened into the glooms, and the rabbits scurrying amid the bracken. When the east mellowed he found himself in fair meadowlands lying locked in the depths of the wold, where flowers were thick as on some rich tapestry, and where the scent of dawn was as the incense of many temples. With a calm sorrow for the dead he rode on, threading the meadowland, till the girl woke and looked up into his face with a little sigh. Then he smiled at her half sadly, and wished her good-morning.

Igraine, wide-eyed, looked round in a daze.

“Day?” she said, “and meadows? It was moonlight when I fell asleep.”

“It has dawned an hour or more.”

“Then I have slept the night through? You must be tired to death, and stiff with holding me.”

“Not so,” said Pelleas.

“I am sorry that I have been selfish,” she said. “I was asleep before I could think. Have you ridden all night?”

“Of course,” quoth he, with a smile, “and not a soul have I seen. I have been watching your face and the moon.”

Igraine coloured slightly, and looked sideways at him from under her long lashes. Her sleep had chastened her, and she felt blithe as a bird, and ready to sing. Putting the man’s scarlet cloak from her, she shook her hair from her shoulders, and sprang lightly from her seat to the grass.

“I will run at your side awhile,” she said, “and so rest you. Perhaps you will halt presently, and sleep an hour or two under a tree. I can watch and keep guard with your sword.”

Pelleas smiled down at her like the sun from behind a cloud.

“Not yet,” he said; “a soldier needs no sleep for a week, and I feel lusty as Christopher. We will go awhile before breakfast, if it please you. There is a stream near where I can water my horse, and we can make a meal from such stuff as I have. When you are tired, tell me, and I will mount you here again.”

She nodded at him gravely. Grass and flowers were well-nigh to her waist. Her gown shook showers of dew from the feathery hay. Foxgloves rose like purple rods amid the snow webs of the wild daisy. Tangled domes of dogrose and honeysuckle lined the white track, and there were countless harebells lying like a deep blue haze under the green shadows of the grass.

Presently they came to where red poppies grew thickly in the golden meads. Igraine ran in among them, and began to make a great posy, while Pelleas watched her as her grey gown went amid the green and red. In due course she came back to him holding her flowers in her bosom.

“Scarlet is your colour,” she said, “and these are the flowers of sleep and of dreams for those that grieve. Hold them in the hollow of your shield for me.”

Pelleas obeyed her mutely. She began to sing a soft slumberous dirge while she walked beside the great black horse and plaited the flowers into its mane. The man watched her with a kind of wondering pain. The song seemed to wake echoes in him, like sea surges wake in the caverns of a cliff. He understood Igraine’s grace to him, and was grateful in his heart.

“How long were you mewed in Avangel?” he said, presently.

“Long enough,” quoth she, betwixt her singing, “to learn to love life.”

“So I should judge,” said Pelleas, curtly.

His tone disenchanted her. She threw the rest of the flowers aside, and walked quietly beside him, looking up with a frank seriousness into his face.

“I was placed there by my parents,” she said, by way of explanation, “and against my will, for I had no hope in me to be a nun. But the times were wild, and my father—a solemn soul—thought for the best.”

“But your novitiate. You had your choice.”

“I had my choice,” she answered vaguely. “Did ever a woman choose for the best? Avangel was no place for me.”

Pelleas eyed her somewhat sadly from his higher vantage. “The nun’s is a sorry life,” he said, “when her thoughts fly over the convent walls.”

A level kindness in the words seemed to loose her tongue like magic. Twelve long months had her sympathies been outraged, and her young desires crushed by the heel of a so-called godliness. Never had so kind a chance for the outpouring of her discontent come to her. Women love an honest grumble. In a moment all her bitterness found ready flight into the man’s ears.

“I hated it!” she said, "I hated it! Avangel had no hold on me. What were vigils, penitences, and long prayers to a girl? They made us kneel on stone, and sleep on boards. The chapel bell seemed to ring every minute of the day; we had vile food, and no liberty. It was Saint This, Saint[37] That, from morning till night. We saw no men. We might never dress our hair; and, believe me, there were no mirrors. I had to go to a little pool in the garden to see my face.

“And they were so dull,—so dismal. No one ever laughed; no one ever told romances; all our legends were of pious things in petticoats. And what was the use of it all? Was any one ever a jot the better? I used to get into my cell and stamp. I felt like a corpse in a charnel-house, and the whole world seemed dead.”

Pelleas scanned her half smilingly, half sadly.

“I am sorry for your heart,” he said.

“Sorry! You needs must be when you are a soldier, with life in your ears like a clarion cry.”

“Life is a sorry ballad, Sister Igraine, unless we remember the Cross.”

“Ah, yes, I have all the saints in mind—dear souls; but then, Sir Pelleas, one cannot live on one’s knees. I was made to laugh and twinkle, and if such is sin, then a sorry nun am I.”

“You misunderstand me,” said the man. “I would that a Christian held his course over the world, with a great cross set in the west to lead him. He can laugh and joy as he goes, sleep like the good, and take the fruits of life in his time. Yet ever above him should be the glory of the cross, to chasten, purge, and purify. There is no sin in living merrily if we live well, but to plot for pleasure is to lose it. Look at the sun; there is no need for us to be ever on our knees to him, yet we know well it would be a sorry world without his comfort.”

“Ah,” she said, with a little gesture. “I see you are too devout for me, despite my habit. Take me up again, Sir Pelleas, and I will ride with you, though I may not argue.”

Pelleas halted his horse, and she was soon in the saddle before him, somewhat subdued and pensive in contrast to her former vivacity. The man believed her a nun, and she had a character to play. Well, when she wearied of it,[38] which would probably be soon, she could tell him and so end the matter. It was not long before they came to the ford across the stream Pelleas had spoken of. It was a green spot shut in by thorn trees, and here they made a halt as the knight had purposed.

Before the meal Pelleas knelt by the stream and prayed. Igraine, seeing him so devout, did likewise, though her eyes were more on the man than on heaven. Her thoughts never got above the clouds. When they were at their meal of meat and bread, with a horn of water from the stream, she talked yet further of her life at Avangel, and the meagre blessing it had been to her. It was while she talked thus that she saw something about the man’s person that fired her memory, and set her thinking of the journey of yesterday.

Pelleas was wearing a gold chain that bore a cross hanging above the left breast, but with no cross over the right. Looking more keenly, Igraine saw a broken link still hanging from the right portion of the chain. Instinctively her thoughts fled back to the silent manor in the wood, and the dead man seated stiffly in the great carved chair.

Without duly weighing the possible gravity of her words, she began to tell Pelleas of the incident.

“Yesterday,” she said, “I saw a strange thing as we fled through the wold. We came to a villa, and, seeking food there, found it deserted, save for a dead man seated in a chair, and stricken in the breast. The dead man had a small gold cross clutched in his fingers, and there was a dead hound at his feet.”

The man gave her a keen look from the depths of his dark eyes, and then glanced at the broken chain.

“You see that I have lost a cross,” he said.

Igraine nodded.

“Your reason can read the rest.”

She nodded again.

“There is nothing like the truth.”

Igraine stared at the man in some astonishment. He was cold as a frost, and there was no shadow of discomfort[39] on his strong face. Knowledge had come to her so sharply that she had no answer for him at the moment. Yet there stood a sublime certainty in her heart that this violent deed was deserving of absolute approval, so soon had her faith in him become like steel.

“The man deserved death,” she said presently, with a curt and ingenuous confidence.

Pelleas eyed her curiously.

“How should you know?” he asked.

“I have faith in you,” was all she said.

Pelleas smiled, despite the subject.

“No man deserved death better.”

“And so you slew him.”

He nodded without looking at her, and she could see still the embers of wrath in his eyes.

“I slew him in his own manor, finding him alone, and ready to justify himself with lies. Honour does not love such deeds; but what would you?—Britain is free of a viper.”

“And you have blood on your hand.”

He winced slightly, and glanced at his fingers as though she had not spoken in metaphor.

“All is blood in these days,” he said.

“And what think you of such laws?” she ventured, with a supreme reaching after the requirements of her Order. “What of the Cross?”

“There was blood upon it.”

“But the blood of self-sacrifice.”

Her words moved him more than she had purposed. His dark face flushed, and light kindled in his eyes as though the basal tenets of his life had been called in question. He glowed like a man whose very creed is threatened. Igraine watched the fire rising in him with a secret pleasure,—the love of a woman for the hot courage of a man.

“Listen to me,” he said strongly; "which think you is the worthier life: to dream in a stone cell mewed from the world like a weak weed in a cellar, or to go forth with a[40] red heart and a mellow honour; to strive and smite for the weak and the wounded; to right the wrong; to avenge the fatherless? Choose and declare."

“Choose,” she said, with a shrill laugh and a kindling colour, “truth, and I will. Away with the rosary; give me the sword.”

Like a wild echo to her human choice came the distant cry of a horn borne hollowly over the sleeping meadows. Both heard it and started. The great war-horse, grazing near by, tossed his head, snorted, and stood listening with ears twitching and head to the east. Pelleas rose up and scanned the road from under his hand, with the girl Igraine beside him.

“A Saxon horn,” he said laconically; “the heathen are in the woods.”

As they watched, looking down betwixt two thorn trees, a faint puff of dust rose on the road far to the east, and hung like a diminutive cloud over the meadows. This danger signal counselled the pair. Pelleas caught his horse and sprang to selle; Igraine clambered by his stirrup, and was lifted to her seat before him. Pelleas slung his shield forward, and loosened his sword.

“If it comes to battle,” he said, “I will set you down, and you must hide in the meadows or woods, while I fight. You would but cumber me, and be in great peril here. Rest assured, though, that I shall not desert you while I live.”

With that he turned his horse to the road, and halted, gazing down amid the placid fields to where the little cloud of dust had hinted at life. It was there still, only larger, and sounded on by the distant triple canter of horses at the gallop. Pelleas and Igraine could see three mounted figures coming up the road amid a white haze, moving fast, as[41] though pressed by some as yet unseen enemy. It was soon evident to Pelleas and the girl that one of the fugitives was a woman.

“We will abide them,” said the man, “and learn their peril. We shall be stronger, too, for company, and may succour one another if it comes to smiting. Look! yonder comes the heathen pack.”

A second and larger cloud of dust had appeared, a mile or less beyond the first. Pelleas watched it awhile, and then turned and began riding at a trot towards the west, so that the three fugitives should overtake him. He bade Igraine keep watch over his shoulder while he scanned the meadows before them for sign of peril or of friendly harbour.

“Have no fear, child,” he said; “I could vow, by these fields, that there is a manor near. I trust confidently that we shall find refuge.”

Igraine smiled at him.

“I am no coward,” she said.

“That is well spoken.”

“I would, though, that you would give me your dagger, so that, if things come to an evil pass, I shall know how to quit myself.”

“My dagger!” he said, with a sudden stare. “I left it in the man’s heart in Andredswold.”

“Ah!” said Igraine; “then I must do without.”

The dull thunder of the nearing gallop came up to them—a stirring sound, full of terse life and eager hazard. Pelleas spurred to a canter, while Igraine’s hair blew about his face and helmet as they began to meet the kiss of the wind. She clung fast to him with both hands, and told what was passing on the road in their rear.

“How they ride,” she said; “a tangle of dust and whirling hoofs. There is a lady in blue on a white horse, with an armed man on either flank. They are very near now. I can see the heathen far away over the meadows. They are galloping, too, in a smoke of dust. Our folk will be with us soon.”

In a minute the lady and her men were hurtling close in Pelleas’s wake. He spurred to a gallop in turn, and bade Igraine wave them on to his side. The three were soon with them, stride for stride. The girl on the white horse drew up on Pelleas’s right flank. She was habited in blue and silver—a flaxen-haired damosel, with the round face of a child. Seemingly she was possessed of little hardihood, for her mouth was a red streak in a waste of white, and her blue eyes so full of fear that Igraine pitied her. She cried shrilly to Pelleas, her voice rising above the din like the cry of a frightened bird.

“The heathen!” she cried.

“Many?” shouted the man.

“Two score or more. There is a strong manor near. If we gain it we may live.”

“How far?”

“Not a mile over the meadows.”

“Lead on,” said Pelleas; “we will follow as we may.”

The damosel on the white horse turned from the road, and headed southwards over the meadows, with her men galloping beside her. The long grass swayed, water-like, before them, its summer seed flying like a mist of dew. Wood and pasture slid back on either hand. The ground seemed to rise and fall before them as a sea, while rocks here and there thrust up bluff noses in the grass like great lizards stirred by the hurtling thunder of the gallop.

On they went, with white spume on breast and bridle; leaping, swerving where rough ground showed. To Igraine the ride was life indeed, bringing back many a whistling gallop from the past. She felt her heart in her leaping to the horse’s stride. Now and again she took a sly look at Pelleas’s face, finding it calm and vigilant—the face of a man whose thought ran a silent course unruffled by the breeze of peril. She felt his bridle-arm staunchly about her like a girdle of steel. Although she could see the dust gathering thickly on the distant road, she felt blithe as a[43] new bride in the man’s company, and there was no fear at all in her thought.

The grassland began to slope gradually towards the south. A quavering screech of joy came back to them from the woman riding in the van. Pelleas spoke his first word during the gallop.

“Courage,” he said. “Southwards lies our refuge.”

Igraine looked over his shoulder, and saw how their flight tended down the flank of a gentle hill into the lap of a fair valley. The grass stretch was broken by great trees—oaks, beeches, and huge, corniced cedars. Down in the green hollow below them a mere shone with the soul of the sky steeped in its quiet waters. It was ringed with trailing willows, and an island held its centre, piled with green shadows and the grey shape of a fair manor. The place looked as peaceful as sleep in the eye of the morning.

The woman on the white horse bade one of her men take his bugle-horn and blow a summons thereon to rouse the folk upon the island. Twice the summons sounded down over the water, but there was no answering stir to be marked about the house or garden. The place was smokeless, lifeless, silent. Like many another home, its hearths were cold for fear of the barbarian sword.

As they held downhill, Igraine wove the matter through her thought like swift silk through a shuttle.

“Should there be no boat,” she said, giving voice to her misgivings, “what can you do for us?”

“We must swim for it,” said Pelleas, keenly.

“It is a broad, fair water, and the horse cannot bear us both.”

“He shall, if needs be.”

She felt that the brute would, after Pelleas had spoken so. She patted the arched black neck, and smiled at the sky as they came down to the mere’s edge at a canter. The water was lapping softly at the sedges amid a blaze of marsh marigolds and purple flags, the surface gleaming[44] like glass in the sun. Half a score water-hens went winging from the reeds, and skimming low and fast towards the island. A heron rose from the shallows, and laboured heavenwards with legs trailing.