By PERCY F. WESTERMAN

|

|---|

The Dispatch-Riders: The Adventures of Two British Motor-cyclists with the Belgian Forces.

"No boy will find a dull page in Mr. Westerman's story." —Bookman. |

The Sea-girt Fortress: A Story of Heligoland.

"Mr. Westerman has provided a story of breathless excitement, and boys of all ages will read it with avidity." —Athenaeum. |

Rounding up the Raider: A Naval Story of the Great War. |

The Fight for Constantinople: A Tale of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

"Breathless adventures crowd into this thrilling story.... It teems with enthralling episodes and vivid word-pictures." —British Weekly. "The reader sits absolutely spellbound to the end of the story." —Sheffield Daily Telegraph. |

Captured at Tripoli: A Tale of Adventure.

"We cannot imagine a better gift-book than this to put into the hands of the youthful book-lover, either as a prize or present." —Schoolmaster. |

The Quest of the "Golden Hope": A Seventeenth-century Story of Adventure.

"The boy who is not satisfied with this crowded story must be peculiarly hard to please." —Liverpool Courier. |

A Lad of Grit: A Story of Restoration Times.

"The tale is well written, and has a good deal of variety in the scenes and persons." —Globe. |

| CHAP. | |

| I. | Laddie's Warning |

| II. | Held Up by a U-Boat |

| III. | The Bomb in the Hold |

| IV. | A Night on the Neutral Ground |

| V. | The Encounter with a Spy |

| VI. | The Dummy Periscope |

| VII. | Rammed |

| VIII. | "In the Ditch" |

| IX. | A Midnight Expedition |

| X. | How the Landing Party Fared |

| XI. | Osborne's Capture |

| XII. | The Turkish Biplane |

| XIII. | The "Sunderbund's" Life-boat |

| XIV. | Submarined |

| XV. | Castaways on a Hostile Shore |

| XVI. | 'Twixt U-Boat and Arabs |

| XVII. | The Whaler's Voyage |

| XVIII. | In the Nick of Time |

| XIX. | Misunderstandings |

| XX. | The Desert Wireless Station |

| XXI. | "A Proper Lash Up" |

| XXII. | The Fouled Propellers |

| XXIII. | Driven to Destruction |

| XXIV. | The Chase of the Felucca |

| XXV. | An Unknown Antagonist |

| XXVI. | Reunited |

| XXVII. | A Daring Operation |

| XXVIII. | Osborne's Reward |

"What a rotten night!"

With this well-expressed remark Sub-lieutenant Webb gained the head of the bridge-ladder of H.M. armed merchant-cruiser Portchester Castle.

Contrasted with the brightness of his comfortable cabin the blackness of the night seemed impenetrable. The horned moon, already well down in the western sky, was almost hidden by a rapidly drifting patch of mottled clouds of sufficient density to obscure its pale rays. Slapping viciously against the ship's starboard side were the surging rollers of the Bay of Biscay. With a succession of heavy thuds the waves broke against the vessel's hull, recoiling in masses of phosphorescent foam and at the same time sending clouds of spindrift flying across the lofty bridge. The Portchester Castle was forty-eight hours out from England, bound for patrol duties in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was by no means her first trip to that inland sea. In pre-war days, under a different name, she had been making regular pleasure trips under the auspices of a touring agency. It had been said that her skipper could find his way practically blindfold into any of the better-known Mediterranean ports, so long had he been on this particular service.

But the outbreak of the Great War had changed all that. Taken over by the Admiralty, the former liner-yacht had been rapidly and efficaciously adapted to her new rôle. Her palatial cabin fittings had been ruthlessly scrapped. The dazzling white enamel had been hidden under a coat of neutral grey. Her bluff funnels were disguised with "wash" of the same dingy hue. Light armour protected her vital parts; quick-firing guns of hard-hitting power were mounted on the decks that previously had been given over to pleasure-seeking tourists. In short, the Portchester Castle was now a swift and formidable unit of the British Navy.

Four years had made a marked difference in the appearance of Tom Webb, formerly Tenderfoot of the Sea Scouts' yacht Petrel. Thanks to his preliminary training in the rudiments of seamanship and navigation acquired in the little ketch yacht, Webb had had no difficulty in being accepted for service in the trawler patrol soon after the outbreak of hostilities.

It was now that his Sea Scout training bore fruit. Self-reliant, and willing to undertake the most arduous tasks with the utmost good humour and alacrity, he quickly gained the goodwill of his superiors.

Two years in the North Sea in the trawler Zealous gave him plenty of experience and adventure, until the trawler came to an untimely end in an encounter with some German torpedo-boats, but not before she had sent one of them to the bottom. The outcome of this little "scrap", as far as Tom Webb was concerned, was that the ex-Tenderfoot was given a commission as Acting Sub-lieutenant, R.N.R., and appointed to the armed merchant-cruiser Portchester Castle.

It required a fair effort on Webb's part to carry out one portion of the Scout's creed and "keep smiling" as he mounted the bridge in this particular middle watch. Turning out of a comfortable bunk to do duty in an exposed, spray-swept post was not a matter of choice but of obligation.

Still dazed by the sudden transition from the electric light 'tween decks to the intense blackness of the night, Webb could just discern the figure of the Sub he was about to relieve.

"Mornin', Haynes!"

"Wish you well of it, my festive," was Dick Haynes's rejoinder. "Nothing to report. Here's the course. You ought to sight the Spanish coast in an hour or so. Well, so long, and good luck!"

The relieved Sub-lieutenant vanished down the bridge-ladder. Webb, muffled in his greatcoat, satisfied himself that the quartermasters were acquainted with the correct compass course, and received the usual report: "Screened light's burning, sir, and all's well."

This done he took up his position on the lee side of the bridge and, sheltered by the storm-dodger, gazed fixedly in the direction of the swelter of black water ahead of the labouring ship.

Slowly the minutes sped. The Portchester Castle, steaming at seventeen knots, rolled and plunged through the long waves without so much as the distant navigation lights of another vessel to break the monotony of the night. Yet the utmost vigilance was necessary. The safety of the ship depended upon the sharp eyes of the two look-out men on the fo'c'sle, and the alertness of the junior watch-keeper on the bridge. To the ordinary risk of collision was added another danger, for hostile submarines had been reported making for the Mediterranean, and were reasonably expected to take a very similar course to that followed by the British armed merchant-cruiser.

The "Rules of the Road for Preventing Collision at Sea" reduced the former danger to a minimum, provided an efficient watch were maintained; against the mad dogs of the sea—the German submarines, who never hesitated to torpedo at sight anything afloat regardless of her nationality—the ship had to take her chances, and trust to Providence and a quick use of the helm to avoid the deadly torpedo, should the phosphorescent swell in the wake of the weapon betray its approach.

A faint click, barely perceptible above the howling of the wind and the swish of the waves, attracted Webb's attention. The officer of the watch had switched off the light in the chart-house before emerging, lest a stray beam should betray the vessel to a lurking foe.

Presently the door opened and a tall, broad-shouldered man appeared, his outlines just discernible in the faint light; for the moon, now soon on the point of setting, was momentarily unobscured.

"Hallo, Tom!" he exclaimed. "What do you think of the Bay, eh?"

The speaker was Lieutenant Jack Osborne, R.N.R., for the time being officer of the watch. He, too, had good reason to be thankful for his early training as a Sea Scout on the yacht Petrel. The outbreak of war found him at Shanghai—a Third Officer on one of the liners of the Royal British and Pacific Steamship Company's fleet. Within two hours of the receipt of the mobilization telegram, Osborne was on board a vessel bound for Vancouver, en route for home by the Canadian Pacific. Twelve months' sea service procured him his promotion as lieutenant, R.N.R., and when the Portchester Castle was commissioned he found that one of his brother officers was his former Sea Scout chum, Tom Webb.

"An improvement on the North Sea in winter," replied Webb optimistically. "And it will be a jolly sight warmer when we get to the Mediterranean."

"You haven't been abroad before?" asked Osborne.

"Strictly speaking—no," replied the Sub. "I've been within sight of Iceland a few times, and don't want to see it again; but I have never set foot ashore. You remember—— Hallo! What's that?"

He gave an involuntary start as something gripped his left hand with a gentle yet firm hold.

Osborne smiled.

"You're a bit jumpy," he said. "Come, this won't do; it's only Laddie. He's always with me on the bridge, you know."

"Hope he hasn't mistaken my hand for a piece of raw beef-steak," remarked Webb, disengaging his hand from the jaws of a large dog. "I'm not afraid of dogs, you know, Osborne, but for the moment I wondered what was up."

"Only his way of showing friendliness," explained the Lieutenant. "I've had him on board ever since he was a pup. He's only fourteen months old now."

"I haven't seen him before."

"No, I kept him ashore while we were commissioning, and he generally keeps down below for the first twenty-four hours at sea. He'll be a pal to you, Webb; almost as much as Cinders. Well, I'll leave him with you. Stop there, Laddie, there's a good dog. Call me directly you sight Cape Villano light, Webb. Keep it well on the port bow; we're off a tricky coast, you know."

Left alone the Sub stooped and patted the silky hair of the sheep-dog's head. Webb was one of those fellows to whom most dogs take at sight. This animal was no exception to the general rule.

Laddie was a large bob-tailed sheep-dog standing more than two feet from the ground—or rather, deck—and powerfully built. Even in the dim light Webb noticed one peculiarity. The animal's eyes were of a turquoise-blue colour and gleamed in the dark like those of a cat.

Suddenly the animal bounded to the weather side of the bridge and, placing his front paws on the guard-rail, gave vent to three deep, angry barks.

"What's the matter, old boy?" asked Webb, peering in vain to ascertain the cause of the dog's excitability.

Hearing his pet's warning bark Lieutenant Osborne was on the bridge in a trice. One glance at Laddie was sufficient.

"Action stations!" he roared in stentorian tones; then, "Hard-a-port, quartermaster!"

Even as the spokes of the steam steering-gear revolved rapidly under the helmsman's hands, the guns' crews, who had been fitfully dozing beside their weapons, manned the quick-firers, while the search-lights with their carbons sizzling were trained outboard, ready at the word of command to unscreen and throw their dazzling rays upon the surface of the waves.

Listing heavily to port as she turned rapidly on her helm, the Portchester Castle just missed by a few yards an ever-diverging double track of foam that contrasted vividly with the inky blackness of the water.

By a few seconds the British vessel had escaped destruction from a torpedo fired from a lurking hostile submarine.

"Hard-a-starboard!" roared Osborne. In the vivid glare of the now unmasked searchlights he had detected a short spar-like object projecting a couple of feet or more above the waves. Almost at the same time three of the Portchester Castle's quick-firers united in a loud roar, their projectiles knocking up tall clouds of foam in the vicinity of the supposed periscope ere they ricochetted a mile or so away.

Dipping in the trough of an enormous roller the slight target was lost to sight. Whether hit by the shell the young lieutenant could not determine. In any case he meant to try and ram the skulking foe.

Round swung the armed liner and, steadying on her helm, bore down upon the spot where the submarine was supposed to be lurking. No slight jarring shock announced the successful issue of her attempt.

"Missed her, I'm afraid, Mr. Osborne," exclaimed a deep voice.

The Lieutenant turned and found himself confronted by the Captain, who, aroused from his slumbers, had appeared on the bridge dressed only in pyjamas, a greatcoat, and carpet slippers.

"And fortunately she missed us, sir," replied Osborne. "The wake of the torpedo was close under our stern."

"Did anyone sight her?"

"The dog, sir," said the Lieutenant. "He began barking at something. I immediately hurried up to see what was amiss, and ordered the helm to be ported."

"Then your wall-eyed pet has done us a good turn," observed Captain Staggles grimly. He was a keen disciplinarian, and did not altogether approve of a dog being brought on board. It was only on Osborne's earnest request that the skipper had relented, and then only on the condition that the animal must be got rid of should he give trouble.

Osborne had run the risk. To lose his pet would be nothing short of a calamity, but such was his confidence in Laddie that he had brought him on board; and now, within a few hours of leaving port, the sheep-dog had gained distinction.

"Suppose the brute's got second sight," remarked the Captain. "Well, carry on, Mr. Osborne, and put the ship on her former course. Call for more speed—the sooner we get away from this particular danger zone the better, since we can do nothing on a night like this. See that a wireless is sent reporting the presence and position of the U-boat."

Having steadied the vessel and dispatched a signalman to the wireless room, Osborne rejoined Webb, who was methodically examining the surface of the sea with his night glasses. Already the search-lights had been switched off and the guns cleaned and secured.

"A close shave," remarked Webb. "I thought she'd bagged us that time. It was fortunate that Laddie gave us warning."

"Fortunate in a double sense," added Osborne. "The skipper will be more favourably disposed towards Laddie after this. I've nothing to say against the Captain (wouldn't if I had, you understand). From what I know of him he's a jolly smart skipper, but I fancy he doesn't cotton on to animals."

"He ought to as far as Laddie is concerned, after this," said the Sub. "It is a perfect mystery to me how the dog spotted the submarine. I'll swear he did. He was so excited that I thought he was going to jump over the rail."

Just then a signalman ran up the bridge-ladder and tendered a writing-pad to the officer of the watch.

"'S.O.S.' call, sir," he explained. "Sparks can't make head or tail of it, in a manner of speaking. He's jotted it down just as it was received."

Osborne took the message and retired into the chart-room. At a glance he discovered that the message was partly in International Code and partly in Spanish, or a language closely approaching it. An intimate knowledge of the ports of the Pacific coast of South America had enabled Osborne to understand a good many words in Spanish. He could therefore make a fair translation of the appeal for aid.

"It's a message from a Portuguese merchantman—the Douro," he explained to Webb. "She is being pursued by a German submarine. She gives her position. We're thirty miles to the nor'nor'-east. Inform Captain Staggles," he added, addressing the signalman.

In a very short space of time the Captain again appeared on the bridge.

"It will be daybreak before we sight her," he observed when Osborne had made his report. "You didn't acknowledge the signal, I hope?"

"No, sir."

"That's good. Sorry to keep Senhor Portuguese on tenterhooks, but if we wirelessed him the strafed Hun might pick up the message. We must try and catch the U-boat on the hop. Pass the word for the look-out to keep his eyes well skinned."

The Captain leant over the for'ard guard-rail of the lofty bridge. Beneath lurked two greatcoated figures sheltering under the lee side of the deckhouse from the driving spray.

"Bos'n's mate!" shouted Captain Staggles.

"Ay, ay, sir."

"Pipe General Quarters."

The shrill trills of the whistle brought the watch below surging on deck. Already by some mysterious means the news had spread along the lower deck. Taking into consideration the fact that the ship had been but newly commissioned, there was little fault to be found with the way in which the men responded to the call.

In the engine-room the staff had risen nobly to the Captain's request to "whack her up". Quickly speed was increased to twenty knots as the Portchester Castle hastened on her errand of succour to the harassed Portuguese merchantman.

"I shouldn't be surprised if we are too late," remarked Captain Staggles. "That wireless will most certainly be picked up by the Portuguese destroyer flotilla patrolling the Tagus. They'll be on the spot before us, I fancy."

Lieutenant Osborne did not reply. He had good cause to think otherwise, but he kept his thoughts to himself. Nevertheless he was glad when the skipper expressed his intention of "carrying on" in the direction of the pursued tramp.

With daybreak came the sound of distant intermittent gun-fire. For five minutes the cannonade was maintained, and then an ominous silence. In addition the hitherto constant wireless appeals for aid ceased abruptly.

"They've got her, I'm afraid," remarked Webb to his chum and brother officer as the twain searched the horizon with their binoculars.

"Not a sign of her," began Osborne.

"Sail ahead, sir," reported the masthead man, who from his point of vantage could command a far greater distance than the officers on the bridge.

"Where does she bear?" shouted Osborne.

"Two points on the port bow, sir," was the prompt reply.

In anxious suspense officers and crew waited for the Portuguese vessel to come within range of vision. Quickly the daylight grew brighter. A slight mist that hung around in low, ill-defined patches began to lift. The sea, still high, rendered it difficult to locate a vessel at any considerable distance from the British auxiliary cruiser.

Presently Osborne went to the voice-tube communicating with the engine-room. His observant eye had noticed that the Portchester Castle's funnels were throwing out considerable volumes of smoke. Since it was imperative that she should conceal her approach until the last possible moment, he requested the Engineer-lieutenant to exercise a little more care in the stokeholds. A minute or two later the black volumes of smoke gave place to a thin haze of bluish vapour.

"There she is!" exclaimed Webb. "By Jove, they've bagged her! She's hove-to."

The tramp, a vessel of about 2000 tons, was lying motionless and showing almost broadside on to the oncoming Portchester Castle. As yet there was no sign of the pursuing submarine.

By the aid of the binoculars the British officers could just discern the red and green mercantile ensign of Portugal being slowly lowered from the vessel's ensign-staff. The Douro had surrendered: would the Portchester Castle be in time to save her from being sunk, or merely able to witness her final plunge, and experience the mortification of finding that the lawless U-boat had submerged into comparative safety?

For some seconds the silence on board the Portchester Castle was broken only by the swish of the water against her bows, the muffled thud of the propeller shaftings, and the clear incisive tones of the range-finding officer as the distance rapidly and visibly decreased betwixt the ship and the supposed position of the German submarine.

Presently, upon the rounded crest of a roller appeared the elongated conning-tower and a portion of the deck of the U-boat. She was forging gently ahead, and was just drawing clear of the bows of the Douro.

The situation was a delicate one. If the German commander's attention were wholly centred upon his capture it might be possible that the submarine would increase her distance sufficiently to enable the Portchester Castle to send a shell into her without risk to the Portuguese vessel. If, on the other hand, the approaching succourer were sighted by the Huns, the submarine would have time to go astern, close hatches under the lee of the Douro, and dive.

Five thousand yards.

A uniformed figure appeared above the poop-rail of the captured tramp. The officers of the British vessel, keeping him under observation by means of the powerful glasses, could see him gesticulating to the submarine. The latter began to lose way before going astern.

Now or never. A gap of barely fifty yards lay betwixt captor and prize. At the word of command the gun-layers of the two for'ard quick-firers bent over their sights. The two reports sounded as one as the projectiles screeched on their errand of destruction.

One shell hurtled within a few feet of the top of the conning-tower, sweeping away both periscopes in its career. The other struck the raised platform in the wake of the conning-tower, exploded, tearing a jagged hole in the hull plating. Before the smoke had time to clear away the U-boat had vanished for all time, only a smother of foam and a series of ever-widening concentric circles of iridescent oil marking her ocean bed.

Viewed from the deck of the Portchester Castle there could be no doubt as to the fate of the modern pirate. Simultaneously a deafening cheer burst from the throats of the British crew. It was a feat to be proud of, sending a hostile submarine to her last account before the Portchester Castle was three days out of port.

When within signalling distance of the Douro the latter rehoisted her colours and made the "NC" signal, "Immediate assistance required".

"Perhaps the Huns have already begun to scuttle her," remarked Tom Webb. "Although I can't detect any sign of a list."

"We'll soon find out," replied Osborne. "Pipe away the cutter," he ordered, in response to a sign from the skipper.

Quickly the falls were manned, the boat's crew, fully armed, scrambling into the boat as it still swung from the davits. Sub-lieutenant Webb, being the officer in charge, dropped into the stern-sheets.

"Lower away."

With a resounding smack the cutter renewed a touching acquaintance with the water. The falls were disengaged, and, to Webb's encouraging order, "Give way, lads!" the boat drew clear of the now almost stationary ship, which was within a couple of cables' lengths of the Douro.

"Wonder what's wrong?" thought Webb, for there were still no signs that the Portuguese vessel had sustained damage. She was rolling heavily in the seaway. Her engines being stopped, she had fallen off in the trough of the sea.

Rounding under her stern the Sub brought the cutter under the lee of the tramp. The bowman dexterously caught a coil of rope thrown by a seaman on the Douro's deck. The trouble was how to board without staving in the cutter's planks against the heaving, rusty sides of the tramp.

The Douro had not come off unscathed in her flight from the German submarine. Under her quarter, and about three feet above the water-line, were a couple of shell-holes. Fortunately the projectiles had failed to burst, otherwise the tramp would not be still afloat. The missiles had partly demolished the wheel-house and played havoc with the bridge, as the shattered woodwork and the debris that littered the deck bore witness. Two of the crew had been slain and three wounded, as a result of being unable to lift a hand in self-defence, yet the Portuguese skipper had held gallantly on his way until a sliver of steel from one of the shells had penetrated the main steam-pipe and had rendered the Douro incapable of further flight.

A Jacob's ladder—a flexible wire arrangement with wooden rungs—had been lowered from the tramp's side. At one moment its bottommost end was swaying far from the vessel's water-line; at another it was pinned hard against her side according to the roll of the ship. Boarding was a difficult—nay, dangerous—business.

Standing with his feet wide apart on the stern-sheets grating, Webb awaited his opportunity. Then he became aware that his boot was touching something soft and endowed with life. To his surprise he found Laddie crouching under the seat.

Evidently the sheep-dog was under the impression that the boat was bound for the shore. He had contrived to leap into the cutter as it was on the point of being lowered, and, although the Sub had not noticed him, the boat's crew had seen and had winked at the presence of the canine stowaway.

"All right, my boy," thought Webb as he made a spring for the swinging ladder. "There you'll have to stop, I fancy. Now you're properly dished."

But the young officer was mistaken. Laddie waited until the last of the boarding party had gained the deck of the Douro, then, knowingly biding his time until the tramp had rolled away from the boat, he made a spring at the ladder and gained the deck.

"Good morning, senhor!" exclaimed the Portuguese skipper in very good English as he greeted the British boarding officer. "We are grateful for your assistance. Another five minutes and the Douro no more would be. I offer my respects to the brave representative of our ancient ally."

"Thank you, senhor capitan," replied Tom with a bow, for he was determined not to be outdone in courtesy by the grateful Portuguese skipper. "Yes, we have sent that submarine to Davy Jones, I fancy. But I have to convey the compliments of Captain Staggles of His Majesty's armed merchant-cruiser Portchester Castle, and to offer you any assistance that lies in our power. You have the 'NC' signal flying, I see."

"Yes," replied the skipper, grinning broadly and shrugging his shoulders in a manner peculiar to dwellers in southern climes. "The trouble, senhor, is this: down below in the fore-hold are six Germans—men sent on board from the submarine to place explosives in the hold. They are armed, we are not. Can you get them out for us?"

"Well, that's a cool request," soliloquized Webb. "The old chap wants us to act the part of the cat, and hook the monkey's chestnuts out of the fire. All in a day's work, I suppose."

He glanced at the Portuguese skipper, who was anxiously awaiting the Sub's reply.

"It seems to me a simple matter," said Tom, "to clap on the hatches and carry them into the Tagus. We'll have to tow you, I suppose. There are several of your war-ships off Belem, and I fancy they'll be only too glad of a chance to collar a few Huns."

The captain of the Douro shook his head.

"Senhor, you do not quite understand. These pirates are armed. We are not. Moreover they threaten to blow up the ship."

"Very good," decided the Sub. "Unship the hatches. Stand by, men; take cover until we find out what these rascals intend doing. Laddie, you imp of mischief, keep to heel."

The dog obeyed, reluctantly. Already he had his suspicions that there was danger. His instinct prompted him to bound forward and grapple with the foe.

Deftly the fore hatchway cover was drawn aside. A ray of brilliant sunshine penetrating the narrow opening played with a pendulum-like movement into the dark recesses as the vessel rolled from side to side. The Sub deemed it safe to show himself, since the eyes of the imprisoned Huns were likely to be dazzled by the sudden glare.

"Now then!" he shouted sternly. "Do you surrender?"

"Nein," was the guttural reply; "we vos stop here. If you attempt to damage us do, den we der ship sink."

"All right, please yourself," rejoined Webb coolly. "Only remember, you'll be cooped up under hatches, and I need not remind you that it's a mighty unpleasant death, and you have only yourselves to blame for the consequences of your rash decision."

The trapped Huns conversed amongst themselves for some moments. Apparently their spokesman had been impressed by the Sub's view of the situation, and was communicating the news to his fellows.

"Don't hurry on our account," continued Webb cheerfully. "The odds are that we shall get to the Mediterranean before your submarine. But please do make up your minds."

"You vos our lives spare?" enquired the Hun spokesman anxiously.

"Of course; you will be treated as prisoners of war," replied the young officer promptly.

"Every von of us?"

"Yes, every man jack of you."

"Goot; den we surrender make."

One by one five Germans stumbled up the ladder, each man raising his hands high above his head as he appeared above the coaming. Mistrust was written upon their brutal-looking faces until they found that no attempt was made to harm them. Then their demeanour became insolently defiant towards the smiling young officer.

Webb stepped aside and conferred with the Portuguese captain. The latter nodded his head emphatically.

"Si, senhor; there were six," he declared.

The smile vanished from Webb's face.

"Which of you speak English?" he enquired of the five prisoners.

"Me," replied the man who had tendered the surrender. "Before der war I vos in der English merchantship——"

"Never mind about what you were," said Webb. "The point is: six of you boarded this vessel. There are only five on deck. How about it?"

"We tell you all about it when in the boat we vos," declared the spokesman, glancing over the side at the waiting cutter.

"You'll tell me now," corrected the Sub with unmistakable firmness. "Otherwise I'll have you put in irons."

For a brief instant the Hun hesitated.

"Der six man, Hans, below is," he explained. "He vos stop and light a bomb. Ach! You vos do nodings. You promise make to all our lives spare."

The Sub realized that he had been done. It was up to him to do his best, even at the risk of his life, to prevent the destruction of the ship. It was obviously unfair to risk the lives of his men in a task that, but for his precipitate pledge, need never have been undertaken.

"Keep those fellows on deck under close arrest. The boarding party will remain here," he exclaimed, addressing the coxswain petty officer of the cutter. "I'm going below."

Without hesitation Webb descended the ladder into the gloomy depths of the fore hold. Groping until his feet touched the iron floor, he waited while his eyes grew accustomed to the dim light. The place was crowded with cargo, for the most part tiers of barrels. Fore and aft ran a narrow space, terminating at the transverse steel bulkheads.

A faint hissing sound was borne to his ears. For'ard a splutter of dim reddish sparks told him that already the time-fuse had been lighted; but the Hun responsible for the firing of the bomb had not yet bolted for the deck. Was it possible that he was going to throw away his life in a useless act of revenge upon the Douro? Or was the time-fuse of sufficient length for him to remain in the hold for several minutes before making a dash for safety?

In any case the Sub had no time to debate upon the situation. His chief concern was to save the ship. Unhesitatingly he made his way towards the hissing fuse.

"Tamped" by means of a bale of cotton, the bomb had been placed against the curved tapering side of the ship. Only a few inches of the fuse was visible. It seemed a matter of a few seconds before the powerful explosive would be detonated.

Placing his boot upon the ignited tape, Webb severed the fuse. As he knelt there, in order to make certain that the sparks were thoroughly extinguished, a pair of powerful hands gripped him from behind. The desperate Hun, hitherto hidden in the after part of the hold, had thrown himself upon the young officer.

Taken by surprise, although he had been prepared for a frontal attack, Webb found himself stretched upon his back with a burly Teuton kneeling on his chest. The Hun's left hand was pressed over the Sub's mouth, thus effectually preventing him from making a sound, while with his right the fellow groped for the severed portion of the fuse, which, released from the pressure of Webb's boot, had again burst into a splutter of angry sparks.

For a seemingly interminable time Webb struggled desperately yet unavailingly. Slowly yet surely the relentless pressure on his chest was telling. Multitudes of lights flashed before his eyes; vainly he gasped for breath, writhing frantically to refill his lungs with air. Dimly he wondered why his men had not come to his assistance. His mind was too confused to remember that it was by his express order that he had forbidden anyone to accompany him upon his hazardous enterprise.

Suddenly the Hun gave vent to a yell of terror. His grasp relaxed. Again he yelled, this time the scream trailing off into a muffled, choking sob. A savage and determined snarl gave the half-dazed Tom an inkling of the identity of his rescuer. It was Laddie.

Unseen and unheard by the Sub the sheep-dog had followed him down the ladder. Eager to face the danger, yet fearing to pass his master's chum, the dog had lurked in the darkness until the German had launched his treacherous attack. In reality the seemingly long interval during which Webb was at the mercy of his assailant was but a few seconds, for with a bound Laddie flew at the Hun's neck.

At the first contact of the animal's teeth in the back of his neck the Hun had yelled. An instant later Laddie had shifted his grip, and was savagely worrying the German's throat. Vainly the man strove to throw off his four-footed enemy. Laddie was not to be denied.

Hearing the sound of the encounter, and guessing rightly that their young officer was in danger, several of the cutter's crew swarmed down into the fore hold. They were barely in time to save the German from death. Even then the dog was reluctant to relax his jaws.

Once more the still fizzling portion of the severed fuse was extinguished. The prisoner was hauled unceremoniously out of the hold, while Webb was assisted to the deck, where in the open air he soon recovered sufficiently to direct operations.

"They're signalling, sir," reported the coxswain, indicating the Portchester Castle, which now lay about a quarter of a mile on the port beam of the Douro. "They want to know what the delay is for."

"Tell them that the vessel's engines are disabled, that an attempt has been made to destroy her by means of bombs, and that we have six prisoners. Ask instructions how to proceed."

A signalman perched upon the guard-rail of the Douro's shattered bridge quickly sent the message. After a brief interval came the order:

"Cutter to be recalled. Bring off prisoners. Inform commanding officer of Douro that we propose to take her in tow."

Without resistance the six Huns were bundled into the boat. The Hun who had attacked Webb in the hold was now quite incapable of so doing, even had he been inclined. With a bandage applied to his lacerated throat he crouched in the stern-sheets, anxiously watching with ill-concealed terror Laddie's fierce-looking blue eyes.

The Portuguese skipper was profuse in his expressions of thanks when Sub-lieutenant Webb took his departure. For the time being all danger was at an end. There was every reason to believe that the Douro would in safety make her destination.

"Very good, carry on," was Captain Staggles's stereotyped remark after Tom had made his report. The Sub saluted and went aft, wondering dimly what manner of man his new skipper could be, since his spoken expression of the Sub's conduct was limited to four words.

For the next twelve hours the Portchester Castle towed the crippled Douro. Late in the afternoon the latter was taken over by a couple of tugs that had been summoned from the Tagus by wireless. Free to resume her interrupted voyage, the British armed merchantman acknowledged the dip of the Portuguese ensign, and was soon reeling off the miles that separated her from Gibraltar.

"Game for a jaunt into Spanish territory, old man?" enquired Osborne, indicating the hilly ground across the blue waters of the bay. "There's a boat leaving for Algeciras in half an hour."

The Portchester Castle lay off the New Mole at Gibraltar. She had coaled and had taken in stores. A few minor defects were being made good, and she was awaiting orders to proceed. Leave had been given to the starboard watch that afternoon, and, having nothing in the way of duty to perform, Osborne had made a tempting suggestion to his chum Tom Webb.

"Rather, I'm on," replied the Sub. "There's leave for officers till eight bells, I believe."

"Yes, but we'll have to be back well before that time," observed Osborne. "The gates of the fortress close at sunset, remember."

Tom Webb during the last few days had made good use of his time at Gib., but, he argued, being ashore on that bold, rocky promontory was not exactly being abroad. He was still on British territory. Hence his eagerness to set foot upon foreign soil.

Soon the two chums, in undress uniforms, were picking their way through the narrow streets of Gibraltar, dodging among the motley crowd that comprises the populace of the place—Spaniards, Greeks, Moors, Arabs, and "Rock Scorps", with a liberal leavening of British seamen, marines, and soldiers.

"That fellow seems to take a lot of interest in us," remarked Webb as the two officers found themselves on board the little steamer bound for Algeciras.

"Let him," declared Osborne inconsequently. He had had too long an acquaintance with foreign ports to trouble about the curious looks and attentions of the inhabitants. "Which one do you refer to? That Spaniard with the piebald side-whiskers?"

"No, the johnny leaning against the ventilator," replied the Sub. "Looks as if he wants a permanent prop, and his hands seem sewn up in his pockets."

Osborne glanced over his shoulder. Instantly the individual in question feigned interest in the smoke issuing from the steamer's funnel, until the effort of craning his neck was too much of a physical strain, and he again looked curiously at the two naval officers.

He was a man of about thirty, full-faced and of a sleek and oily complexion. His dark chestnut hair was closely cropped. He sported a tuft of side-whiskers on each cheek and a heavy moustache. His costume consisted of a dirty white shirt, ill-cut trousers, and straw-plaited shoes round his waist was a gaudily coloured scarf that might or might not have hidden a knife. On the back of his head he wore a broad-rimmed straw hat with a band of vivid yellow, into which was stuck a bunch of peacock's feathers.

"A picturesque-looking villain!" commented Webb.

"A typical Spaniard, that's all," Osborne reassured him. "We'll have a few dozen of 'em crowding round directly we land, you know. Every man jack will offer his services as a guide, philosopher, and friend."

Apparently the fellow thought it worth while to take time by the forelock, since his interest in the British officers was reciprocated. Removing his hands from his pockets he came forward, and giving an elaborate sweep with his hat he tendered a dirty piece of pasteboard.

"My card, señores!" he exclaimed. "At your service. Show you everyzing in Algeciras. Blow me tight, I will."

The last sentence, of which he seemed particularly proud, had been picked up from a British Tommy. The Spaniard considered it to be the hall-mark of correct English.

Osborne took the proffered card. On it was printed: "Alfonzo y Guzman Perez, Qualified Guide and Interpreter".

"We don't require a guide," said Osborne.

Señor Perez smiled benignly.

"P'raps ze senores get into ze mischief wizout a Spanish caballero who through misfortune is obliged to accept ze monies for his services. You officers are from ze war-ship Paragon?"

"No, from the——" began Webb. Then he brought himself up with a round turn.

"From ze——?" repeated the Spaniard. But Tom was not to be caught napping a second time.

"Sorry, Señor Perez," interrupted Osborne firmly. "We don't want you. Nothing doing this trip."

The steamer was now making fast to the little pier. Without paying further attention to the over-attentive Spaniard the young officers landed, and, as Osborne had foretold, were surrounded by a mob of frantically gesticulating natives.

"Not much of a place," declared Webb. "Horribly dirty, in fact. Can't we get out into the country?"

"We could," replied his chum. "In fact we could give the steamer a miss on the return journey."

"How?"

"By walking round the Bay and getting back to Gib. by means of the Neutral Ground. It's a tidy step, but we've heaps of time."

"Good idea!" declared Webb enthusiastically. "Let's get along out of this."

By degrees the mob of undesirables diminished. The pace set by two mad Englishmen was far too hot. A few, however, still hung on, their appeals for alms giving place to abuse at the callousness of the British officers.

"Wish we had Laddie with us," remarked Webb. "He'd soon make the crowd take to their heels."

"Couldn't be done," said Osborne. "I thought of it, but there are the local quarantine restrictions to be taken into consideration. Also, there'd be a risk of the dog being shot by the Spanish Customs guards on the Neutral Ground. They're dead nuts on dogs."

"Why?" asked Tom.

"Because dogs are largely used by smugglers to run contraband into Gib. Of course, I'm sorry, but it can't be helped."

At last the Spaniards dropped behind and the chums were free of any embarrassing society. They, too, were glad to ease down, for the day was extremely sultry. There were bunches of delicious grapes to be had without let or hindrance, and altogether the two chums were beginning to enjoy themselves.

"How much farther?" enquired Tom at length.

Osborne consulted his watch.

"By Jove, we must look sharp!" he said. "We've a tidy step yet. In fact, we haven't got as far as Mayorga."

The road, hitherto by no means good, had deteriorated into a rough track. Progress, too, was impeded by several inlets, which meant considerable detours inland. Consequently it was late in the afternoon when, hot and tired, the young officers limped into the village of Mayorga, some five miles from the "Lines" of Gibraltar.

"I vote we get a carriage of sorts," suggested Osborne. "We'll be properly dished if we don't. My heel's galled, and it's still some way to go."

Making the best of his limited knowledge of Spanish, Osborne contrived to hire, for the sum of five pesetas, a ramshackle conveyance with solid wooden wheels and drawn by a couple of oxen. It was the only vehicle available, but the villainous-looking driver assured his hirers that it was a swift means of transport.

The cart set off in excellent style—"Under forced draught," Osborne explained—but before it was clear of the village the swaying, jolting conveyance had settled down to a funeral pace. When Osborne expostulated, the driver stopped to offer a lengthy explanation of the dangerous character of the road, promising to make up for the lost time directly the comparatively level Neutral Ground was reached.

Anxiously the Lieutenant consulted his watch, glanced at the setting sun, and mentally measured the distance between him and the frowning Rock, which appeared much nearer than it actually was.

Suddenly the cart gave an extra heavy lurch. The oxen stumbled; while, to the accompaniment of a rending crash and the angry oaths of the driver, the off-side wheel was wrenched from its axle. The next instant Osborne and Webb found themselves lying in the long rank grass by the side of the cart-track.

"Excelsior, old bird!" exclaimed the Lieutenant as the twain recovered their feet. "Look alive, there's no time to be lost!"

Paying the Spaniard his five pesetas, although he had not completed his part of the contract, the two officers hastened towards their goal, regardless of the forcible demands of the driver that his late fares would contribute towards the damage done to the crazy vehicle.

Nearer and nearer came the "Lines", until the Neutral Ground was less than four hundred yards away. Then, to the chums' consternation, a gun boomed forth in the still evening air. It was the signal that until daybreak the gates of Gibraltar were closed so that none should enter or depart.

"A fine old business!" declared Osborne. "It's no use going on. We'd stand a chance of being fired upon by the Spanish guards, and a still greater one of being winged by the British sentries. They were alert enough in pre-war days, and you can bet your bottom dollar that they'll be doubly sharp now."

"Suppose the best thing to do is to return to Mayorga and get a bed at the inn," suggested Webb. "My word, there'll be a row for overstaying our leave!"

"No Spanish inn for me," said the Lieutenant with conviction. "Verminous holes, that's what they are. No, we'll camp out, and imagine it's the good old Scout days."

"Might do worse," agreed Tom with his cheery smile. "So the sooner we pitch upon a suitable spot the better. It will be dark in another ten minutes."

The site selected was a sandy hollow fringed with long coarse grass, and open to the east. In that direction lay the Mediterranean, its shores being separated from the officers' bivouac by a distance of about twenty yards. To the south the summit of the towering heights of the Rock could just be discerned, above the ridge of sand that enclosed the hollow on three sides.

Thoroughly tired with their exertions, the chums were soon fast asleep. Then Webb awoke with a start and a stifled exclamation on his lips. It seemed as if he had slept but a few minutes. In reality six hours had elapsed.

He could hear voices conferring in undertones—voices unfamiliar, and speaking in a foreign language.

For some moments Webb lay still. He remembered where he was, and that it was not at all strange for men to be conversing in an unknown tongue. What he remarked was the fact that they should choose an isolated spot in the small hours of the morning to engage upon what was evidently a secret confabulation.

Cautiously the Sub raised himself on his elbows and peered through the long grass. In the bright starlight he made a strange discovery. There were three men: two in the uniform that bore a strong resemblance to that of the British Navy; the third was none other than the chums' would-be philosopher and guide, Señor Alfonzo y Guzman Perez.

With hardly a sound Sub-lieutenant Webb made his way to the side of his sleeping chum, and roused him effectually and silently by the simple expedient of grasping him firmly by the hand.

"'Ssh!" cautioned Tom.

Side by side the two officers crawled to a place of vantage from which the three men could be kept under observation.

"By Jove!" thought Osborne. "Two German officers and our old pal Alfonzo. Jabbering away in German, too; and I don't understand the lingo. Now if they were to try Spanish——"

"Ach, friend Georgeos Hymettus!" exclaimed the senior Hun officer in execrable English. "Your German a disgrace is. You kultur have neglected. We confused are in your explanations. Therefore, since we talk not Spanish nor Greek it will be more easy to talk in der accursed English. You say you no haf der list of ships?"

"No," replied Perez, or, to give him his true name, Hymettus. "It no safe. Me no trust ze writing. Carry all here," and he tapped his forehead significantly. "S'pose me caught and nodings found in ze writing. Zen, nodings doin' as ze Englise say."

Thereupon, with great fidelity the Greek spy named the British war-ships on the station and their probable destinations. One exception was the Portchester Castle. Either the name had slipped his memory, or else he was ignorant of her presence in the Bay of Gibraltar. He then proceeded to detail the names of British and foreign merchantmen at Gib. and their probable date of departure, which information the Germans jotted down in a notebook.

An off-shore wind, rustling across the sand-dunes, rendered a considerable portion of the following conversation inaudible, but the chums could see that a sum of paper money changed hands.

"U-boat officers!" whispered Webb, taking advantage of the hush of the grass. "Game to tackle them?"

"Yes, I'm game," replied Osborne, "but it can't be done yet. I'll explain later. Steady!"

The spy and the Huns were on the point of separating.

"Till Friday," cautioned the senior German officer. "Meanwhile tell Gonales dat we be off Alminecar on Wednesday, an' dat we vos have more petrol. Leben Sie wohl, Georgeos. Do not from dis place move make until twenty minutes."

The Huns moved off diagonally in the direction of the shore. Before they had gone very far two greatcoated seamen jumped to their feet and saluted. Osborne, then, was wise in not attempting to tackle the officers, since there were members of the submarine's boat's crew within easy hailing distance. Silently the Germans pushed off in a collapsible canvas boat, and were rowed seaward until they were lost to sight and hearing of the British officers.

True to his instructions, Georgeos Hymettus remained at the spot where he had parted with his uniformed confederates. He was stealthily counting the notes he had received as the price of his espionage, as if to make sure that he had not been cheated by his Teutonic paymasters. Rapidly Osborne revolved the situation in his mind. With the assistance of his chum the capture of the solitary spy ought to present no special difficulties; but, having laid him by the heels, the question arose, what could they do with him? The spy was in Spanish territory, and, if the facts became known, his arrest constituted a breach of neutrality. Again, between them and the Neutral Ground were the Spanish Lines, through which it would be almost a matter of impossibility to conduct the captive without detection by the Civil Guards. On the other hand it would be a thankless task to give the Greek over to the Spanish authorities. Not only would it mean delay, when it was imperative that Osborne and his chum should return to the ship as soon as practicable, but the chances were that the Spanish officials would refuse to keep the fellow under arrest, since he had been merely engaged in conversation with two subjects of a friendly power. In Spain, especially in the southern part, the officials are notoriously pro-German, having succumbed to the wiles and pecuniary charms of the Hun agents.

"I'll risk it," decided the Lieutenant. "Even if we don't succeed in planting him down in Gib. it will give him a rare fright."

He pointed towards the unsuspecting Greek. Webb nodded. Stealthily the twain advanced, treading on the soft sand and avoiding contact with the dry driftwood that abounded in the grass.

Without warning Georgeos Hymettus turned and saw two forms approaching through the gloom of the starlit night. He took to his heels, doubtless imagining that he was about to be attacked by some of the numerous robbers who, under the guise of beggars, infest the countryside.

Swift of foot though the Greek might be, the two Englishmen were swifter. Before the fugitive had covered a hundred yards he realized that escape by means of flight seemed hopeless.

He was almost on the point of stopping and feigning surrender when Osborne's foot tripped over a projecting stone, sending the Lieutenant sprawling in the grass. Webb, springing aside to avoid the prostrate form of his chum, shouted to the spy to give in.

Promptly the Greek held both hands, with the fingers outspread, high above his head.

"That's sensible," declared Tom, and incautiously he turned to see how his companion was progressing. Like a flash of lightning the spy's right hand sought his voluminous sash, and grasping a long, keen-bladed knife he slashed viciously at the Sub's chest.

Springing backwards Webb avoided what would otherwise have been a fatal blow. As it was, the sharp steel ripped his coat from lapel to waist, while so much energy had Georgeos put into the blow that his arm swung outwards behind him.

The Sub was quick to counter. Throwing himself upon the ground, he gripped his antagonist by the ankles. With a crash the fellow measured his length on his back, while Webb, following up the attack, seized him by the throat.

Over and over the two rolled, Hymettus striking blindly with his knife, while Tom, shifting one hand, strove to pin the spy's right arm to his side and render him incapable of dealing further dangerous, but fortunately ineffectual, blows.

By this time Osborne had regained his feet, and was awaiting an opportunity of coming to his chum's assistance. It was no easy matter, for in the starlight it was hard to distinguish betwixt friend and foe as they writhed and rolled in a close embrace.

The glint of steel prompted Osborne to take the risk. At any chance moment a thrust might bury the weapon in Webb's body. Both combatants were obviously becoming exhausted. Their quick breaths sounded like those of a pair of dogs spent after running a long distance, while, in addition, the Greek was snarling like a wild beast.

Grasping a favourable moment, Osborne took a flying kick at the knife as for a brief instant it paused in mid-air. The weapon flew a dozen yards, the bright blade twirling and scintillating in the dim light ere it vanished from sight in the soft sand.

With the loss of the weapon the Greek ceased to offer resistance. Upon that knife he had relied to win clear; it was the mainstay of his defence.

"What you was do?" he whined in broken English, for he had already recognized his assailants. "Me harmless Spanish caballero."

"We'll see about that," retorted Osborne. "The question is: are you coming quietly or are you not?"

"Where?" asked the spy.

"To Gibraltar."

"What for ze reason?"

The Lieutenant thought it best to ignore the question. With Webb's assistance he set the spy upon his feet, securely bound his arms behind his back by means of his shawl, and, cutting off a portion of the latter, effectually gagged the prisoner.

Osborne listened intently. There was nothing to show that the Spanish Civil Guards had been alarmed by the noise of the struggle. Everything seemed quiet. There was a fair chance of being able to pass the captive through the Spanish Lines without detection, especially as it was now close upon dawn and the sentries apt, in consequence, to relax their vigilance.

All went well until the two officers and their prisoner were within fifty yards of one of the guard-houses that mark the termination of Spanish territory and the commencement of the Neutral Ground. There were no signs of any of the sentries; and Osborne was beginning to congratulate himself upon the successful issue of his attempt, when a cock-hatted, gaudily uniformed man sprung seemingly from the ground.

Levelling his rifle he called upon the British officers to halt, following up this order by a warning shout to others of his comrades within the block-house.

"It's all right," declared Osborne in his halting Spanish. "We're bringing back a deserter."

"Do not be in a hurry," was the exasperating reply. "Have you any papers bearing the Alcalde's signature for the prisoner's removal?"

The thought flashed across the Lieutenant's mind that it was more than likely that none of the Spanish guards could read. Education in Spain, he remembered, is in a very backward state, barely ten per cent of the population being able to read or write. As president of the mess on board the Portchester Castle he had in his possession several receipted bills. The most imposing of these he produced for the Civil Guard's inspection. At the same time he noticed that others of the Spaniards were about to remove the gag from the spy's mouth.

"Get them to hang on a minute, old man," he exclaimed, addressing Webb. Then tendering the document to the inquisitive soldier, he ostentatiously displayed a handful of coins.

The natural cupidity of the man was unable to resist the bait. "Palm oil" would have done the trick had not the spy contrived at that moment to slip the bonds that secured his wrists. With a deft movement he produced the bundle of English Treasury notes that had been paid him by the German submarine officers, at the same time fumbling with the knot that held his gag in position.

Before Webb, whose attention had been centred upon restraining the rest of the Civil Guards, could prevent it, the spy had freed himself from the gag, and was protesting in voluble Spanish that he was an Andalusian who had been kidnapped by English brigands.

Hopelessly outbidden, for the Greek was doling out pound notes in a most lavish fashion, Osborne realized that he had been beaten at his own game. The climax came when Georgeos Hymettus scattered a handful of paper money in the dim light, and while the Spanish troops were scrambling for the spoil he took to his heels.

Since it was useless to follow, Osborne and Webb watched him till he vanished in the darkness. Then silently they waited until the morning gun from the citadel announced that the fortress of Gibraltar was open until the setting of the sun.

"A pretty pickle!" remarked Osborne. "Nothing done, your undress uniform ripped to ribbons, the spy gone, and we ourselves have to face the music for having overstayed our leave. Rotten, I call it!"

"Don't know so much about that'," remarked Webb, the cheery optimist. "We've discovered something that will be of interest to the authorities, and, after all, we've had quite an exciting adventure. Some night, eh, what?"

Captain Staggles interviewed the two delinquents separately. The skipper was one of those men who are apt to bluster and browbeat whenever occasion offered. It was his idea of imparting discipline. Popularity he scoffed at. He was, in short, one of a fortunately rare type of officer of the old school, who at the outbreak of the war had been once more employed on the active list. To his disappointment Captain Staggles had not received a shore appointment, owing to a lack of sufficient influence; and after filling various stopgap billets he had been given the armed merchant-cruiser Portchester Castle, whose complement consisted entirely of Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve officers and men.

Unfortunately Captain Staggles did not possess sufficient sagacity to realize that there must be a difference between a crew, trained for years in proper Navy fashion, and a body of men drawn from the merchant service. In both cases good material was present, but one had been developed to meet certain requirements, the other had not.

"The point is," thundered Captain Staggles to Jack Osborne; "the point is, sir, you had to be on duty on board. You were not. You, instead, try to bamboozle me with some cock-and-bull yarn about a spy. Now, what have you got to say?"

"I take it, sir, that you insinuate I'm not speaking the truth," said Osborne quietly, controlling his indignation with a strong effort. "And that without giving me an opportunity of proving my statement."

"I take it, sir," mimicked the skipper, "that you don't realize that you've overstayed your leave?"

"Unfortunately, no, sir," replied Osborne. "It was my fault entirely that Mr. Webb was in the same predicament."

"Very well," exclaimed Captain Staggles, raising his voice to a regular roar. "Now, don't do it again. Clear out, sir."

"But concerning the spy, sir?" began the Lieutenant.

"Don't want to hear any more about it," bellowed the skipper. "Thank your lucky stars you've got off so lightly. Leave my cabin, sir."

Osborne saluted and withdrew. On the half-deck he encountered Webb, who was awaiting his turn "on the carpet".

"Reprimanded," announced Osborne laconically. "The captain won't listen to my explanation. Better luck, old man."

But Sub-lieutenant Webb fared no better. His attempt to throw a light upon the night's work met with an equally curt reception.

"I believe the skipper's been drinking," said Webb to his chum after his interview.

"Since you mention it, I agree," said Osborne gravely. "I've known it for some time, but I didn't like to give my chief away. We've struck hard lines in the matter of a skipper, Tom. You see, our temporal future lies entirely in his hands. If he sends in an unfavourable report upon our conduct and abilities, we're done as far as the Service is concerned. There is no appeal. However, we must carry on and do our duty."

Osborne had previously said that Captain Staggles was a keen officer. He had been; but retirement had blunted his zest and rusted his abilities. Still rankling under the mistaken idea of injustice at having been refused a shore appointment, the skipper had lost interest in his work. He was content to rely mainly upon the stereotyped order "Carry on", and a non-committal "Very good" when addressing his subordinate officers. His formerly active brain, fuddled by intemperance, was no longer capable of controlling the destinies of a ship's company. Had he been permitted to remain in command the result might have been fatal to the efficiency of the ship. Fortunately it was otherwise.

By some means the story of the adventure of Osborne and his chum reached the ears of the Senior Naval Officer on the Station. He immediately applied for a report from Captain Staggles, and the latter had to admit that he knew nothing of the details of the occurrence. The result was that Osborne and Webb were sent for, and, under severe cross-examination, had to reveal the facts of their interview with their commanding officer, and how the latter had refused to hear the report concerning the spy.

Two hours later Captain Staggles was ordered to undergo a medical examination and, found unfit for duty, was sent to hospital; the Lieutenant-commander of the Portchester Castle was given temporary command pending a fresh appointment from the Admiralty.

Jimmy M'Bride, Captain Staggles's successor, was a man of totally different character and disposition. There was a humorous side to his nature that the former skipper lacked. He knew his job thoroughly, regarding the men under him as something different from mere machines. He expected a high standard—and got it; not by aggressive methods, but by example. He was always ready to consider a grievance, but woe betide the incautious man who attempted to impose upon him.

Already precious time had been lost, but M'Bride delayed no longer in acting upon the information that Osborne and Webb had gained from the Greek spy. Since the Portchester Castle had not figured in the list of ships supplied to the kapitan of the German submarine, the armed merchant-cruiser was detailed to take the place of a large tramp, the s.s. Two-Step, which was under orders for Marseilles.

Just before sundown the Portchester Castle was, roughly, twenty miles east of Gibraltar. It was a calm, glorious evening. Not a ripple disturbed the placid surface of the Mediterranean, save the long, ever-diverging swell in the wake of the slowly moving vessel, for in the rôle of merchant-man the Portchester Castle was steaming at a bare fifteen knots. Three miles away and broad on the starboard beam was the tramp, flying the red ensign. Already by means of the International Code she had "made her number". Her course was approximately parallel to that of the Portchester Castle, although her speed was less by a good five knots.

"Spot anything?" enquired Osborne of his chum, as Webb kept his binoculars focused at something almost midway and ahead of the two vessels.

"Yes," replied the Sub. "A periscope, or I'm a greenhorn. Here you are, Osborne, right in line with the foremast shrouds."

"By Jove, you're right!" assented the Lieutenant. "I can see it distinctly. Now who is she going for—the Two-Step or us?"

"The Two-Step, I fancy," replied Webb. "It looks to me as if the U-boat's periscope is trained in that direction."

Quickly the guns were manned. A warning signal, "'Ware submarine on your port bow", was sent to the tramp. The suppressed excitement grew as the Portchester Castle drew nearer to her as yet unsuspecting foe.

M'Bride was on the bridge at the time. Deliberately he delayed the order to open fire. The gun-layer could, he knew, easily knock away that pole-like object, but that was not enough. The U-boat, even when deprived of her "eyes", could dive and seek shelter until the danger had passed. Not until the submarine showed herself above the surface could a "knock-out" blow be delivered, unless the Portchester Castle could approach and ram her antagonist before the latter had time to submerge to a sufficient depth.

"Look!" exclaimed Osborne. "She's actually going to attempt to ram. Well, of all the cool cheek!"

The Lieutenant was correct in his assertion, for the plucky tramp, starboarding helm, was bearing down upon the vertical spar that denoted the presence of the otherwise hidden danger.

This manoeuvre interested Webb hardly at all. His attention was centred upon the periscope. For some time he had been keeping it under observation through his marine glasses. There was something fishy about it. He had seen partly submerged periscopes before, and they had never behaved in that erratic fashion.

This one was stationary as regards direction. No feather-like spray denoted its passage through the water. It certainly was not forging ahead. It was, however, rolling erratically, its centre of semi-rotation being but a few inches beneath the surface. The periscope of a submarine, if it were inclining in a vertical plane at all, would have a very different movement, protruding as it was from the comparatively huge hull of the vessel.

"It's a dummy periscope," he announced.

"Sure of it, Mr. Webb?" asked Captain M'Bride.

"Positive, sir."

The skipper of the Portchester Castle did not hesitate. A warning blast from the armed merchant-cruiser's syren was followed by the peremptory signal, "Go astern instantly", while the white ensign hoisted aft imparted the necessary authority to the Two-Step.

An exchange of signals followed, with the result that the tramp forged ahead once more, and, altering her course slightly, passed quite a couple of cables' lengths from the sinister spar that bobbed lazily above the sea.

"And there are half a dozen destroyers leaving Gib. to-day," remarked Captain M'Bride. "If they had sighted this decoy one of them would have gone at it like a bull at a gate. We must risk it, I suppose. Away first cutter's and whaler's crews!"

The Portchester Castle had to slow down to enable the boats to be lowered. This in itself was a risky operation, since it was quite possible that a real hostile submarine might be lurking in the vicinity, awaiting the opportunity to discharge a torpedo at the almost stationary target afforded by the armed merchantman. Nevertheless the risk had to be undertaken. It fell within the scope of the duties of the Royal Navy in its gigantic task of rendering the maritime highways as safe as possible for the sea-borne commerce of Britain, her Allies, and of neutral nations.

Tom Webb was in charge of the cutter, his brother Sub-lieutenant, Dicky Haynes, having command of the whaler. The moment the two boats cast off, the Portchester Castle pelted off at full speed, maintaining an erratic course to minimize possible danger until the two Sub-lieutenants had carried out their hazardous investigations.

Each boat had two hundred yards of grass rope trailing astern, the other ends being made fast to the bight of a flexible steel wire, which, by means of a couple of buoys, was permitted to sink to a depth of one fathom beneath the surface. Steadily the boats approached the dummy periscope, the cutter passing it to port and the whaler to starboard at a distance of twenty yards.

Presently Webb glanced astern. The towed buoys were now quite close to the upright spar.

"Give way for all you're worth, lads!" he ordered, while Haynes shouted a similar encouragement to the whaler's crew.

The strain on the grass rope increased. Then with a terrific roar a column of water shot two hundred feet into the air from the spot where the dummy periscope had been.

"We're much too knowing birds to be caught by that sort of chaff," remarked a member of the cutter's crew. The man was right. Had any passing vessel rammed the tempting-looking periscope she would have found herself bumping over a couple of mines that, with fiendish ingenuity, the Huns had lashed to the decoy in the hope that an inquisitive foe would be sent to the bottom. The trick was an old one, but it added to the complication of perils which the British seamen have to face hourly in the frequently underrated task of preserving the millions of inhabitants of the United Kingdom from the horrors of famine.

The echoes of the explosion had scarce died away when the Portchester Castle turned and steamed back to pick up her two boats. She was still about two miles off, and nearly three times that distance from the receding Two-Step.

The crews of the cutter and the whaler were busily engaged in coiling away the undamaged grass ropes. The connecting span had, of course, been blown to bits by the detonation. Both boats had to be baled out, for a quantity of water hurled skywards by the exploded mines had fallen into the little craft. Webb's command was flooded to a depth of a couple of inches over the bottom boards, while the whaler had considerably more water in her.

"Look astern, sir!" exclaimed the coxswain of the cutter.

The Sub glanced across his shoulder. The sea in the vicinity had now almost regained its mirror-like aspect, but in the direction indicated by the petty officer its surface was rippled by a tell-tale swell, as if some large object were moving slowly at a considerable depth.

"Stand by, lads!" ordered Webb. "Oars!"

The blades had barely touched the water when, at a distance of less than five yards from the cutter, appeared the twin periscopes of a submarine—this time the genuine article.

The U-boat, for such she was, had been lurking in the vicinity of the decoy. Her kapitan had seen the approach of the Portchester Castle and the tramp, and feeling confident that the booby periscope would be noticed, had remained to watch the effect of the Englanders' curiosity.

On hearing the explosion he wrongly concluded that the experiment had not been a successful one, as far as the inquisitive vessel was concerned; and after a brief interval he ordered the U-boat to the surface, with the intention of gloating over the sinking of yet another strafed English ship.

"Back port—pull starboard!" ordered Webb.

Almost in her own length the cutter swung round until she lay broadside on to the appearing periscopes, which were still forging ahead and momentarily showing higher and higher above the surface.

Drawing his revolver the Sub took steady aim at almost point-blank range. It was practically impossible to miss. The mirrors on the top of the periscope were shattered. The next instant, the foremost metal pipe of the now blinded submarine was grinding against the cutter's gunwale.

"Cutter ahoy!" shouted Haynes.

The whaler was now a hundred yards off, and the cutter lay between her and the still submerged U-boat. Haynes had heard the double report of the revolver shots, and was at a loss to account for Webb's seemingly inexplicable act.

"Come alongside as hard as you can!" shouted Webb; then addressing the bowman of the cutter he ordered: "A couple of hitches with your painter, man."

The bowman acted promptly. In a few seconds the cutter had swung round and was being urged at a steady rate through the water with her painter made fast to the foremost of the damaged periscopes.

Haynes, too, had now grasped the situation. The whaler, urged at the greatest speed by the rowers, was quickly on the spot. Her painter was then secured to the aftermost periscope.

The two Subs were now keenly on the alert for further developments. The point to consider was whether the U-boat would attempt to continue to ascend, or make a frantic effort to submerge completely. In the former case both boats would have to be trimmed by the head to counteract the lifting power of the invisible submarine; in the latter case all hands, with the exception of the bowman, would have to crowd aft in order to impart the greatest buoyancy to the for'ard portion of the boats.

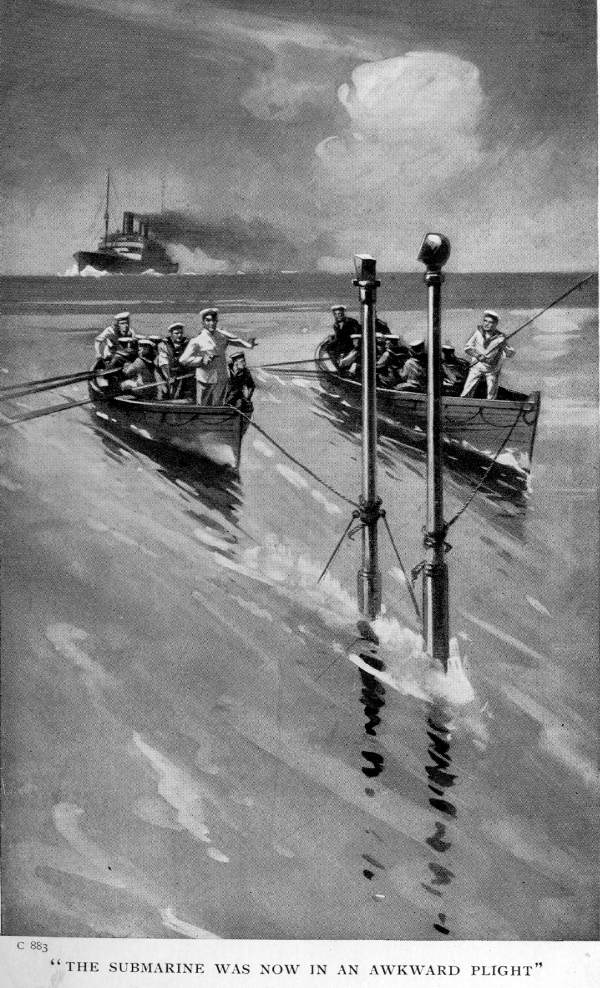

The submarine was now in an awkward plight. In spite of the fact that her displacement was something in the neighbourhood of six hundred tons she had little reserve of buoyancy, represented by the weight of water in her ballast tanks. Against this she was hampered by the two boats, the cutter weighing a little over a ton without her crew and gear, and the whaler supplying a dead weight of nearly half that of her consort.

The U-boat dare not rise. To do so, even if she were capable of the fact with the two "millstones" literally hanging round her neck, she would be running an unknown risk, since she was unaware of the nature of the obstruction. Nor could she dive with safety. Before she could admit sufficient water ballast to make her heavy enough to swamp the two boats, the strain would wrench the periscopes from the submarine's hull. In spite of the intricate valves, the wrench imparted to her mechanism would make it an impossibility to prevent quantities of water entering the interior, and send the U-boat down for good and all.

"We've got her, old man!" explained Haynes joyously.

"And she's got us, too," replied Webb. "Sort of marine game of beggar my neighbour."

Haynes was certainly right, and so was his brother officer. Until the Portchester Castle arrived to render assistance the struggle looked like being a dead heat, unless——

Yes, Webb knew that there was an "unless"—a mighty unpleasant one. There was a possibility that the U-boat's skipper would not surrender. Rather he would explode the war-heads of the torpedoes still within the hull, and send the submarine to instant destruction, at the same time involving the annihilation of the two boats and their crews.

At all costs Webb determined to "stand fast", but it was with mingled feelings of elation and apprehension that he regarded the shadowy outlines of his "capture", as the enormous hull showed dimly at twelve feet beneath the surface. Air bubbles broke upon the slightly agitated waves as the U-boat strove either to "sound" or break away and rise awash. At intervals her twin screws churned the water, sometimes going ahead and sometimes astern, with the result that the cutter and the whaler crashed gunwale to gunwale half a dozen times in twice as many minutes. Only the skilful and strenuous endeavours of their crews prevented the strongly-built sides from collapsing like shattered egg-shells.

All this while the Portchester Castle was bearing down upon the boats. Captain M'Bride knew that something unusual was taking place. The erratic movements of the two craft told him that, but he was at a loss to understand the reason.

"Cutter ahoy!" came a hail through a megaphone from the armed merchantman's bridge.

"What are you foul of?"

One of the boat's crew, producing two handflags, dexterously balanced himself upon one of the thwarts.

"Hooked a submarine, sir," he reported.

"How does she lie?" was the skipper's next question.

"Bows away from you, sir; her stern's swinging on to your port bow."

This knowledge was of importance, for, although the U-boat was blind, it was just possible that her crew might discharge a torpedo on the off chance of the missile getting home.

"Stand by to cast off roundly," came the next order from the Portchester Castle. "I'm going to ram her aft."

"Now for it," thought Tom Webb. "If we're not in the ditch within the next fifty seconds I'll be very much mistaken."

The Sub had barely expressed himself thus, when with a quivering jerk the U-boat shot above the surface, exposing the whole of the after part of the conning-tower, although the fore part was still beneath the surface. She was so down by the head that the blades of her stern hydroplanes were visible. Realizing that it was touch-and-go, the German skipper had released the emergency metal keel with which these craft are equipped.

Owing to their short painters, the cutter and the whaler were swung in close alongside the rounded hull, their bows hoisted clear of the water by the terrific strain upon their bow ropes.

Several of their crews had been flung upon the bottom boards and stern-sheets, while streams of water from the U-boat's deck threatened to swamp the frail craft alongside.

Instantly the after hatch of the submarine was flung open, and, headed by a stout, fair-haired leutnant, the German crew armed with revolvers began to pour through the narrow opening on to the U-boat's decks.

There was no indication on their part of a wish to surrender. It was evidently going to be a hand-to-hand scrap 'twixt British and Germans.

The submarine's officer had taken in part of the situation at a glance. Shouting to a couple of hands to cut the painters, he led the rest of the men in a headlong rush towards the two boats, the Huns opening a hot but erratic fire from their small-arms. Unfortunately for him the leutnant had not noticed in his haste the Portchester Castle's approach, until a warning shout from one of the Germans revealed the immediate danger.

The attack stopped immediately. Throwing down their revolvers the Huns raised their hands above their heads, shouting "Mercy, kamerad!" at the fullest pitch of their lungs, some directing their appeal towards the British seamen in the boats, others towards the vengeful merchant-cruiser.

"Cast off!" shouted Webb. "Back, men, for all you're worth."

Deftly the bowman of the cutter severed the painter. With a flop the boat's bows slid down the bulging sides of the submarine, and, backed by the vigorous efforts of half a dozen rowers, drew away from the doomed pirate.