ON THE

VARIOUS FORCES OF NATURE.

WORKS by RICHARD A. PROCTOR.

EASY STAR LESSONS. With Star Maps for Every Night in the Year, Drawings of the Constellations, &c. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

FLOWERS OF THE SKY. With 55 Illustrations. Small crown 8vo, cloth extra, 3s. 6d.

SATURN AND ITS SYSTEM. Revised Edition, with 13 Steel Plates. Demy 8vo, cloth extra, 10s. 6d.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE STUDIES. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

MYSTERIES OF TIME AND SPACE. With Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

THE UNIVERSE OF SUNS, and other Science Gleanings. With Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

WAGES AND WANTS OF SCIENCE WORKERS. Crown 8vo, 1s. 6d.

By Dr. ANDREW WILSON, F.R.S.E.

CHAPTERS ON EVOLUTION: A Popular History of the Darwinian and Allied Theories of Development. Second Edition, with 259 Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

LEAVES FROM A NATURALIST’S NOTE-BOOK. Post 8vo, cloth limp, 2s. 6d.

LEISURE-TIME STUDIES, chiefly Biological. Third Edition, with a New Preface and Numerous Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

STUDIES IN LIFE AND SENSE. With numerous Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra. 6s.

COMMON ACCIDENTS AND HOW TO TREAT THEM. With Illustrations. Crown 8vo, 1s.; cloth, 1s. 6d.

GLIMPSES OF NATURE. With 35 Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 3s. 6d.

By Dr. J. E. TAYLOR, F.L.S.

THE SAGACITY AND MORALITY OF PLANTS: A Sketch of the Life and Conduct of the Vegetable Kingdom. With Coloured Frontispiece and 100 Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

OUR COMMON BRITISH FOSSILS, and Where to Find Them. A Handbook for Students. With over 300 Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

THE PLAYTIME NATURALIST. With 366 Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 5s.

By GRANT ALLEN.

THE EVOLUTIONIST AT LARGE. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

COLIN CLOUT’S CALENDAR. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

By W. MATTIEU WILLIAMS, F.R.A.S.

SCIENCE IN SHORT CHAPTERS. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 7s. 6d.

A SIMPLE TREATISE ON HEAT. With Illustrations. Crown 8vo, cloth limp, 2s. 6d.

THE CHEMISTRY OF COOKERY. Crown 8vo, cloth extra, 6s.

By Sir DAVID BREWSTER.

MORE WORLDS THAN ONE: The Creed of the Philosopher and the Hope of the Christian. With Plates. Post 8vo, cloth extra, 4s. 6d.

THE MARTYRS OF SCIENCE: Lives of Galileo, Tycho Brahe, and Kepler. With Portraits. Post 8vo, cloth extra, 4s. 6d.

LETTERS ON NATURAL MAGIC. A new Edition, with numerous Illustrations, and Chapters on Additional Phenomena of Natural Magic, by J. A. Smith. Post 8vo, cloth extra, 4s. 6d.

By MICHAEL FARADAY.

THE CHEMICAL HISTORY OF A CANDLE. With Illustrations. Edited by William Crookes, F.C.S. Post 8vo, cloth extra, 4s. 6d.

ON THE VARIOUS FORCES OF NATURE, and their Relations to each other. With numerous Illustrations. Edited by William Crookes, F.C.S. Post 8vo, cloth extra, 4s. 6d.

LONDON: CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

A COURSE OF LECTURES DELIVERED BEFORE A JUVENILE

AUDIENCE AT THE ROYAL INSTITUTION

BY MICHAEL FARADAY, D.C.L., F.R.S.

EDITED BY

WILLIAM CROOKES, F.C.S.

A NEW EDITION, WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

London:

CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

1894.

5

Which was first, Matter or Force? If we think on this question, we shall find that we are unable to conceive of matter without force, or of force without matter. When God created the elements of which the earth is composed, He created certain wondrous forces, which are set free, and become evident when matter acts on matter. All these forces, with many differences, have much in common, and if one is set free, it will immediately endeavour to free its companions. Thus, heat will enable us to eliminate light, electricity, magnetism, and chemical6 action; chemical action will educe light, electricity, and heat. In this way we find that all the forces in nature tend to form mutually dependent systems; and as the motion of one star affects another, so force in action liberates and renders evident forces previously tranquil.

We say tranquil, and yet the word is almost without meaning in the Cosmos.—Where do we find tranquillity? The sea, the seat of animal, vegetable, and mineral changes, is at war with the earth, and the air lends itself to the strife. The globe, the scene of perpetual intestine change, is, as a mass, acting on, and acted on, by the other planets of our system, and the very system itself is changing its place in space, under the influence of a known force springing from an unknown centre.

7

For many years the English public had the privilege of listening to the discourses and speculations of Professor Faraday, at the Royal Institution, on Matter and Forces; and it is not too much to say that no lecturer on Physical Science, since the time of Sir Humphrey Davy, was ever listened to with more delight. The pleasure which all derived from the expositions of Faraday was of a somewhat different kind from that produced by any other philosopher whose lectures we have attended. It was partially derived from his extreme dexterity as an operator: with him we had no chance of apologies for an unsuccessful experiment—no hanging fire in the midst of a series of brilliant demonstrations, producing that depressing tendency akin to the pain felt by an audience at a false note from a vocalist.8 All was a sparkling stream of eloquence and experimental illustration. We would have defied a chemist loving his science, no matter how often he might himself have repeated an experiment, to feel uninterested when seeing it done by Faraday.

The present publication presents one or two points of interest. In the first place, the Lectures were especially intended for young persons, and are therefore as free as possible from technicalities; and in the second place, they are printed as they were spoken, verbatim et literatim. A careful and skilful reporter took them down; and the manuscript, as deciphered from his notes, was subsequently most carefully corrected by the Editor as regards any scientific points which were not9 clear to the short-hand writer; hence all that is different arises solely from the impossibility, alas! of conveying the manner as well as the matter of the Lecturer.

May the readers of these Lectures derive one-tenth of the pleasure and instruction from their perusal which they gave to those who had the happiness of hearing them!

W. CROOKES.

[Pg 10]

[Pg 11]

| LECTURE I. | |

| PAGE | |

| THE FORCE OF GRAVITATION, | 13 |

| LECTURE II. | |

| GRAVITATION—COHESION, | 44 |

| LECTURE III. | |

| COHESION—CHEMICAL AFFINITY, | 72 |

| LECTURE IV. | |

| CHEMICAL AFFINITY—HEAT, | 99 |

| LECTURE V. | |

| MAGNETISM—ELECTRICITY, | 122 |

| LECTURE VI. | |

| THE CORRELATION OF THE PHYSICAL FORCES, | 147 |

| LIGHT-HOUSE ILLUMINATION—THE ELECTRIC LIGHT, | 173 |

| NOTES, | 195 |

| Book Catalogue | |

[Pg 12]

[Pg 13]

THE

VARIOUS FORCES OF NATURE.

It grieves me much to think that I may have been a cause of disturbance in your Christmas arrangements1, for nothing is more satisfactory to my mind than to perform what I undertake; but such things are not always left in our own power, and we must submit to circumstances as they are appointed. I will to-day do my best, and will ask you to bear with me if I am unable to give more than a few words; and as a substitute, I will endeavour to make the illustrations of the sense I try to express as full as possible; and if we find by the end of this lecture that we may be justified in continuing them, thinking that next week our power shall be greater,—why, then,14 with submission to you, we will take such course as you may think fit,—either to go on, or discontinue them; and although I now feel much weakened by the pressure of illness (a mere cold) upon me, both in facility of expression and clearness of thought, I shall here claim, as I always have done on these occasions, the right of addressing myself to the younger members of the audience. And for this purpose, therefore, unfitted as it may seem for an elderly infirm man to do so, I will return to second childhood and become, as it were, young again amongst the young.

Let us now consider, for a little while, how wonderfully we stand upon this world. Here it is we are born, bred, and live, and yet we view these things with an almost entire absence of wonder to ourselves respecting the way in which all this happens. So small, indeed, is our wonder, that we are never taken by surprise; and I do think that, to a young person of ten, fifteen, or twenty years of age, perhaps the first sight of a cataract or a mountain would occasion him more surprise than he had ever felt con15cerning the means of his own existence,—how he came here; how he lives; by what means he stands upright; and through what means he moves about from place to place. Hence, we come into this world, we live, and depart from it, without our thoughts being called specifically to consider how all this takes place; and were it not for the exertions of some few inquiring minds, who have looked into these things and ascertained the very beautiful laws and conditions by which we do live and stand upon the earth, we should hardly be aware that there was anything wonderful in it. These inquiries, which have occupied philosophers from the earliest days, when they first began to find out the laws by which we grow, and exist, and enjoy ourselves, up to the present time, have shewn us that all this was effected in consequence of the existence of certain forces, or abilities to do things, or powers, that are so common that nothing can be more so; for nothing is commoner than the wonderful powers by which we are enabled to stand upright—they are essential to our existence every moment.

16

It is my purpose to-day to make you acquainted with some of these powers; not the vital ones, but some of the more elementary, and, what we call, physical powers: and, in the outset, what can I do to bring to your minds a notion of neither more nor less than that which I mean by the word power, or force? Suppose I take this sheet of paper, and place it upright on one edge, resting against a support before me (as the roughest possible illustration of something to be disturbed), and suppose I then pull this piece of string which is attached to it. I pull the paper over. I have therefore brought into use a power of doing so—the power of my hand carried on through this string in a way which is very remarkable when we come to analyse it; and it is by means of these powers conjointly (for there are several powers here employed) that I pull the paper over. Again, if I give it a push upon the other side, I bring into play a power, but a very different exertion of power from the former; or, if I take now this bit of shell-lac [a stick of shell-lac about 12 inches long and 1½ in diameter] and rub it with flannel, and17 hold it an inch or so in front of the upper part of this upright sheet, the paper is immediately moved towards the shell-lac, and by now drawing the latter away, the paper falls over without having been touched by anything. You see—in the first illustration I produced an effect than which nothing could be commoner—I pull it over now, not by means of that string or the pull of my hand, but by some action in the shell-lac. The shell-lac, therefore, has a power wherewith it acts upon the sheet of paper; and as an illustration of the exercise of another kind of power, I might use gunpowder with which to throw it over.

Now, I want you to endeavour to comprehend that when I am speaking of a power or force, I am speaking of that which I used just now to pull over this piece of paper. I will not embarrass you at present with the name of that power, but it is clear there was a something in the shell-lac which acted by attraction, and pulled the paper over; this, then, is one of those things which we call power, or force; and you will now be able to recognise it as such in whatever form I shew it to you. We are18 not to suppose that there are so very many different powers; on the contrary, it is wonderful to think how few are the powers by which all the phenomena of nature are governed. There is an illustration of another kind of power in that lamp; there is a power of heat—a power of doing something, but not the same power as that which pulled the paper over: and so, by degrees, we find that there are certain other powers (not many) in the various bodies around us. And thus, beginning with the simplest experiments of pushing and pulling, I shall gradually proceed to distinguish these powers one from the other, and compare the way in which they combine together. This world upon which we stand (and we have not much need to travel out of the world for illustrations of our subject; but the mind of man is not confined like the matter of his body, and thus he may and does travel outwards; for wherever his sight can pierce, there his observations can penetrate) is pretty nearly a round globe, having its surface disposed in a manner of which this terrestrial globe by my side is a rough model; so much is land and19 so much is water, and by looking at it here we see in a sort of map or picture how the world is formed upon its surface. Then, when we come to examine further, I refer you to this sectional diagram of the geological strata of the earth, in which there is a more elaborate view of what is beneath the surface of our globe. And when we come to dig into or examine it (as man does for his own instruction and advantage, in a variety of ways), we see that it is made up of different kinds of matter, subject to a very few powers, and all disposed in this strange and wonderful way, which gives to man a history—and such a history—as to what there is in those veins, in those rocks, the ores, the water springs, the atmosphere around, and all varieties of material substances, held together by means of forces in one great mass, 8,000 miles in diameter, that the mind is overwhelmed in contemplation of the wonderful history related by these strata (some of which are fine and thin like sheets of paper),—all formed in succession by the forces of which I have spoken.

I now shall try to help your attention to what20 I may say by directing, to-day, our thoughts to one kind of power. You see what I mean by the term matter—any of these things that I can lay hold of with the hand, or in a bag (for I may take hold of the air by enclosing it in a bag)—they are all portions of matter with which we have to deal at present, generally or particularly, as I may require to illustrate my subject. Here is the sort of matter which we call water,—it is there ice [pointing to a block of ice upon the table], there water [pointing to the water boiling in a flask], here vapour—you see it issuing out from the top [of the flask]. Do not suppose that that ice and that water are two entirely different things, or that the steam rising in bubbles and ascending in vapour there is absolutely different from the fluid water. It may be different in some particulars, having reference to the amounts of power which it contains; but it is the same, nevertheless, as the great ocean of water around our globe, and I employ it here for the sake of illustration, because if we look into it we shall find that it supplies us with examples of all the powers to which I shall have to refer. For in21stance, here is water—it is heavy; but let us examine it with regard to the amount of its heaviness, or its gravity. I have before me a little glass vessel and scales [nearly equipoised scales, one of which contained a half-pint glass vessel], and the glass vessel is at present the lighter of the two; but if I now take some water and pour it in, you see that that side of the scales immediately goes down; that shews you (using common language, which I will not suppose for the present you have hitherto applied very strictly) that it is heavy: and if I put this additional weight into the opposite scale, I should not wonder if this vessel would hold water enough to weigh it down. [The Lecturer poured more water into the jar, which again went down.] Why do I hold the bottle above the vessel to pour the water into it? You will say, because experience has taught me that it is necessary. I do it for a better reason—because it is a law of nature that the water should fall towards the earth, and therefore the very means which I use to cause the water to enter the vessel are those which will carry the whole body of water down. That power is what we call22 gravity, and you see there [pointing to the scales] a good deal of water gravitating towards the earth. Now here [exhibiting a small piece of platinum2] is another thing which gravitates towards the earth as much as the whole of that water. See what a little there is of it—that little thing is heavier than so much water [placing the metal in opposite scales to the water]. What a wonderful thing it is to see that it requires so much water as that [a half-pint vessel full] to fall towards the earth, compared with the little mass of substance I have here! And again, if I take this metal [a bar of aluminium3 about eight times the bulk of the platinum], we find the water will balance that as well as it did the platinum; so that we get, even in the very outset, an example of what we want to understand by the words forces or powers.

I have spoken of water, and first of all of its property of falling downwards. You know very well how the oceans surround the globe—how they fall round the surface, giving roundness to it, clothing it like a garment; but, besides that, there are other properties of water. Here,23 for instance, is some quick-lime, and if I add some water to it, you will find another power or property in the water.4 It is now very hot, it is steaming up, and I could perhaps light phosphorus or a lucifer match with it. Now, that could not happen without a force in the water to produce the result; but that force is entirely distinct from its power of falling to the earth. Again, here is another substance [some anhydrous sulphate of copper5] which will illustrate another kind of power. [The Lecturer here poured some water over the white sulphate of copper, which immediately became blue, evolving considerable heat at the same time.] Here is the same water, with a substance which heats nearly as much as the lime does; but see how differently. So great indeed is this heat in the case of lime, that it is sufficient sometimes (as you see here) to set wood on fire; and this explains what we have sometimes heard, of barges laden with quick-lime taking fire in the middle of the river, in consequence of this power of heat brought into play by a leakage of the water into the barge. You see how strangely different subjects for our con24sideration arise, when we come to think over these various matters,—the power of heat evolved by acting upon lime with water, and the power which water has of turning this salt of copper from white to blue.

I want you now to understand the nature of the most simple exertion of this power of matter called weight, or gravity. Bodies are heavy—you saw that in the case of water when I placed it in the balance. Here I have what we call a weight [an iron half cwt.]—a thing called a weight, because in it the exercise of that power of pressing downwards is especially used for the purposes of weighing; and I have also one of these little inflated india-rubber bladders, which are very beautiful although very common (most beautiful things are common), and I am going to put the weight upon it, to give you a sort of illustration of the downward pressure of the iron, and of the power which the air possesses of resisting that pressure. It may burst, but we must try to avoid that [During the last few observations the Lecturer had succeeded in placing the half cwt. in a state of quiescence upon the inflated india-rubber25 ball, which consequently assumed a shape very much resembling a flat cheese with round edges.] There you see a bubble of air bearing half a hundred weight, and you must conceive for yourselves what a wonderful power there must be to pull this weight downwards, to sink it thus in the ball of air.

Let me now give you another illustration of this power. You know what a pendulum is. I have one here (fig. 1), and if I set it swinging, it will continue to swing to and fro. Now, I wonder whether you can tell me why that body oscillates to and fro—that pendulum bob as it is sometimes called. Observe, if I hold the straight stick horizontally, as high as the position of the balls at the two ends of its journey26 you see that the ball is in a higher position at the two extremities than it is when in the middle. Starting from one end of the stick, the ball falls towards the centre; and then rising again to the opposite end, it constantly tries to fall to the lowest point, swinging and vibrating most beautifully, and with wonderful properties in other respects—the time of its vibration, and so on—but concerning which we will not now trouble ourselves.

If a gold leaf, or piece of thread, or any other substance, were hung where this ball is, it would swing to and fro in the same manner, and in the same time too. Do not be startled at this statement: I repeat, in the same manner and in the same time; and you will see by and by how this is. Now, that power which caused the water to descend in the balance—which made the iron weight press upon and flatten the bubble of air—which caused the swinging to and fro of the pendulum,—that power is entirely due to the attraction which there is between the falling body and the earth. Let us be slow and careful to comprehend this. It is not that the earth has any particular attraction towards27 bodies which fall to it, but, that all these bodies possess an attraction, every one towards the other. It is not that the earth has any special power which these balls themselves have not; for just as much power as the earth has to attract these two balls [dropping two ivory balls], just so much power have they in proportion to their bulks to draw themselves one to the other; and the only reason why they fall so quickly to the earth is owing to its greater size. Now, if I were to place these two balls near together, I should not be able, by the most delicate arrangement of apparatus, to make you, or myself, sensible that these balls did attract one another: and yet we know that such is the case, because, if instead of taking a small ivory ball, we take a mountain, and put a ball like this near it, we find that, owing to the vast size of the mountain, as compared with the billiard ball, the latter is drawn slightly towards it; shewing clearly that an attraction does exist, just as it did between the shell-lac which I rubbed and the piece of paper which was overturned by it.

Now, it is not very easy to make these things28 quite clear at the outset, and I must take care not to leave anything unexplained as I proceed; and, therefore, I must make you clearly understand that all bodies are attracted to the earth, or, to use a more learned term, gravitate. You will not mind my using this word; for when I say that this penny-piece gravitates, I mean nothing more nor less than that it falls towards the earth, and if not intercepted, it would go on falling, falling, until it arrived at what we call the centre of gravity of the earth, which I will explain to you by and by.

I want you to understand that this property of gravitation is never lost, that every substance possesses it, that there is never any change in the quantity of it; and, first of all, I will take as illustration a piece of marble. Now this marble has weight—as you will see if I put it in these scales; it weighs the balance down, and if I take it off, the balance goes back again and resumes its equilibrium. I can decompose this marble and change it, in the same manner as I can change ice into water and water into steam. I can convert a part of it into its own steam easily, and shew you that this steam from29 the marble has the property of remaining in the same place at common temperatures, which water-steam has not. If I add a little liquid to the marble, and decompose it6, I get that which you see—[the Lecturer here put several lumps of marble into a glass jar, and poured water and then acid over them; the carbonic acid immediately commenced to escape with considerable effervescence]—the appearance of boiling, which is only the separation of one part of the marble from another. Now this [marble] steam, and that [water] steam, and all other steams gravitate, just like any other substance does—they all are attracted the one towards the other, and all fall towards the earth; and what30 I want you to see is, that this steam gravitates. I have here (fig. 2) a large vessel placed upon a balance, and the moment I pour this steam into it, you see that the steam gravitates. Just watch the index, and see whether it tilts over or not. [The Lecturer here poured the carbonic acid out of the glass in which it was being generated into the vessel suspended on the balance, when the gravitation of the carbonic acid was at once apparent.] Look how it is going down. How pretty that is! I poured nothing in but the invisible steam, or vapour, or gas which came from the marble, but you see that part of the marble, although it has taken the shape of air, still gravitates as it did before. Now, will it weigh down that bit of paper? [Placing a piece of paper in the opposite scale.] Yes, more than that; it nearly weighs down this bit of paper. [Placing another piece of paper in.] And thus you see that other forms of matter besides solids and liquids tend to fall to the earth; and, therefore, you will accept from me the fact—that all things gravitate, whatever may be their form or condition. Now here is another chemical test which is very31 readily applied. [Some of the carbonic acid was poured from one vessel into another, and its presence in the latter shewn by introducing into it a lighted taper, which was immediately extinguished.] You see from this result also that it gravitates. All these experiments shew you that, tried by the balance, tried by pouring like water from one vessel to another, this steam, or vapour, or gas, is, like all other things, attracted to the earth.

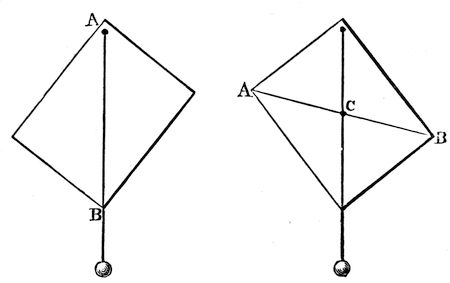

There is another point I want in the next place to draw your attention to. I have here a quantity of shot; each of these falls separately, and each has its own gravitating power, as you perceive when I let them fall loosely on a sheet of paper. If I put them into a bottle, I collect them together as one mass; and philosophers have discovered that there is a certain point in the middle of the whole collection of shots that may be considered as the one point in which all their gravitating power is centred, and that point they call the centre of gravity: it is not at all a bad name, and rather a short one—the centre of gravity. Now suppose I take a sheet of pasteboard, or any other thing easily dealt32 with, and run a bradawl through it at one corner A (fig. 3), and Mr. Anderson hold that up in his hand before us, and I then take a piece of thread and an ivory ball, and hang that upon the awl—then the centre of gravity of both the pasteboard and the ball and string are as near as they can get to the centre of the earth; that is to say, the whole of the attracting power of the earth is, as it were, centred in a single point of the cardboard—and this point is exactly below the point of suspension. All I have to do, therefore, is to draw a line, A B, corresponding with the string, and we shall find that the centre of gravity is33 somewhere in that line. But where? To find that out, all we have to do is to take another place for the awl (fig. 4), hang the plumb-line, and make the same experiment, and there [at the point C] is the centre of gravity—there where the two lines which I have traced cross each other; and if I take that pasteboard, and make a hole with the bradawl through it at that point, you will see that it will be supported in any position in which it may be placed. Now, knowing that, what do I do when I try to stand upon one leg? Do you not see that I push myself over to the left side, and quietly take up the right leg, and thus bring some central point in my body over this left leg. What is that point which I throw over? You will know at once that it is the centre of gravity—that point in me where the whole gravitating force of my body is centred, and which I thus bring in a line over my foot.

Here is a toy I happened to see the other day, which will, I think, serve to illustrate our subject very well. That toy ought to lie something in this manner (fig. 5); and would do so if it were uniform in substance. But you34 see it does not; it will get up again. And now philosophy comes to our aid; and I am perfectly sure, without looking inside the figure, that there is some arrangement by which the centre of gravity is at the lowest point when the image is standing upright; and we may be certain, when I am tilting it over (see fig. 6), that I am lifting up the centre of gravity (a), and raising it from the earth. All this is effected by putting a piece of lead inside the lower part of the image, and making the base of large curvature; and there you have the whole secret. But what will happen if I try to make the figure stand upon a sharp point? You observe, I must get that point exactly under the centre of gravity, or it will fall over thus [endeavouring unsuccessfully to balance it]; and this you see35 is a difficult matter—I cannot make it stand steadily. But if I embarrass this poor old lady with a world of trouble, and hang this wire with bullets at each end about her neck, it is very evident that, owing to there being those balls of lead hanging down on either side, in addition to the lead inside, I have lowered the centre of gravity, and now she will stand upon this point (fig. 7); and what is more, she proves the truth of our philosophy by standing sideways.

I remember an experiment which puzzled36 me very much when a boy. I read it in a conjuring book, and this was how the problem was put to us: “How,” as the book said, “how to hang a pail of water, by means of a stick, upon the side of a table” (fig. 8). Now, I have here a table, a piece of stick, and a pail, and the proposition is, how can that pail be hung to the edge of this table? It is to be done; and can you at all anticipate what arrangement I shall make to enable me to succeed? Why, this. I take a stick, and put it in the pail between the bottom and the horizontal piece of wood, and thus give it a stiff handle—and there it is; and what37 is more, the more water I put into the pail the better it will hang. It is very true that before I quite succeeded I had the misfortune to push the bottoms of several pails out; but here it is hanging firmly (fig. 9), and you now see how you can hang up the pail in the way which the conjuring books require.

Again, if you are really so inclined (and I do hope all of you are), you will find a great deal of philosophy in this [holding up a cork and a pointed thin stick about a foot long]. Do not refer to your toy-books, and say you have seen that before. Answer me rather, if I ask you have you understood it before?38 It is an experiment which appeared very wonderful to me when I was a boy; I used to take a piece of cork (and I remember, I thought at first that it was very important that it should be cut out in the shape of a man; but by degrees I got rid of that idea), and the problem was to balance it on the point of a stick. Now, you will see I have only to place two sharp-pointed sticks one on each side, and give it wings, thus, and you will find this beautiful condition fulfilled.

We come now to another point:—All bodies, whether heavy or light, fall to the earth by this force which we call gravity. By obser39vation, moreover, we see that bodies do not occupy the same time in falling. I think you will be able to see that this piece of paper and that ivory ball fall with different velocities to the table [dropping them]; and if, again, I take a feather and an ivory ball, and let them fall, you see they reach the table or earth at different times—that is to say, the ball falls faster than the feather. Now, that should not be so, for all bodies do fall equally fast to the earth. There are one or two beautiful points included in that statement. First of all, it is manifest that an ounce, or a pound, or a ton, or a thousand tons, all fall equally fast, no one faster than another: here are two balls of lead, a very light one and a very heavy one, and you perceive they both fall to the earth in the same time. Now, if I were to put into a little bag a number of these balls sufficient to make up a bulk equal to the large one, they would also fall in the same time; for if an avalanche fall from the mountains, the rocks, snow and ice, together falling towards the earth, fall with the same velocity, whatever be their size.

40

I cannot take a better illustration of this than that of gold leaf, because it brings before us the reason of this apparent difference in the time of the fall. Here is a piece of gold-leaf. Now, if I take a lump of gold and this gold-leaf, and let them fall through the air together, you see that the lump of gold—the sovereign, or coin—will fall much faster than the gold leaf. But why? They are both gold, whether sovereign or gold-leaf. Why should they not fall to the earth with the same quickness? They would do so, but that the air around our globe interferes very much where we have the piece of gold so extended and enlarged as to offer much obstruction on falling through it. I will, however, shew you that gold-leaf does fall as fast when the resistance of the air is excluded—for if I take a piece of gold-leaf and hang it in the centre of a bottle, so that the gold, and the bottle, and the air within shall all have an equal chance of falling, then the gold-leaf will fall as fast as anything else. And if I suspend the bottle containing the gold-leaf to a string, and set it oscillating like a pendulum, I may make it41 vibrate as hard as I please, and the gold-leaf will not be disturbed, but will swing as steadily as a piece of iron would do; and I might even swing it round my head with any degree of force, and it would remain undisturbed. Or I can try another kind of experiment:—if I raise the gold-leaf in this way [pulling the bottle up to the ceiling of the theatre by means of a cord and pulley, and then suddenly letting it fall to within a few inches of the lecture-table], and allow it then to fall from the ceiling downwards (I will put something beneath to catch it, supposing I should be maladroit), you will perceive that the gold-leaf is not in the least disturbed. The resistance of the air having been avoided, the glass bottle and gold-leaf all fall exactly in the same time.

Here is another illustration,—I have hung a piece of gold-leaf in the upper part of this long glass vessel, and I have the means, by a little arrangement at the top, of letting the gold-leaf loose. Before we let it loose we will remove the air by means of an air pump, and while that is being done, let me shew you another experiment of the same kind.42 Take a penny-piece, or a half-crown, and a round piece of paper a trifle smaller in diameter than the coin, and try them, side by side, to see whether they fall at the same time [dropping them]. You see they do not—the penny-piece goes down first. But, now place this paper flat on the top of the coin, so that it shall not meet with any resistance from the air, and upon then dropping them you see they do both fall in the same time [exhibiting the effect]. I dare say, if I were to put this piece of gold-leaf, instead of the paper, on the coin, it would do as well. It is very difficult to lay the gold-leaf so flat that the air shall not get under it and lift it up in falling, and I am rather doubtful as to the success of this, because the gold-leaf is puckery; but will risk the experiment. There they go together! [letting them fall] and you see at once that they both reach the table at the same moment.

We have now pumped the air out of the vessel, and you will perceive that the gold-leaf will fall as quickly in this vacuum as the coin does in the air. I am now going to let it loose, and you must watch to see how rapidly it falls.43 There! [letting the gold loose] there it is, falling as gold should fall.

I am sorry to see our time for parting is drawing so near. As we proceed, I intend to write upon the board behind me certain words, so as to recall to your minds what we have already examined—and I put the word Forces as a heading; and I will then add, beneath, the names of the special forces according to the order in which we consider them: and although I fear that I have not sufficiently pointed out to you the more important circumstances connected with this force of Gravitation, especially the law which governs its attraction (for which, I think, I must take up a little time at our next meeting), still I will put that word on the board, and hope you will now remember that we have in some degree considered the force of gravitation—that force which causes all bodies to attract each other when they are at sensible distances apart, and tends to draw them together.

44

Do me the favour to pay me as much attention as you did at our last meeting, and I shall not repent of that which I have proposed to undertake. It will be impossible for us to consider the Laws of Nature, and what they effect, unless we now and then give our sole attention, so as to obtain a clear idea upon the subject. Give me now that attention, and then, I trust, we shall not part without your knowing something about those Laws, and the manner in which they act. You recollect, upon the last occasion, I explained that all bodies attracted each other, and that this power we called gravitation. I told you that when we brought these two bodies [two equal sized ivory balls suspended by threads] near together, they attracted each other, and that we might suppose that the whole power of45 this attraction was exerted between their respective centres of gravity; and furthermore, you learned from me, that if, instead of a small ball, I took a larger one, like that [changing one of the balls for a much larger one], there was much more of this attraction exerted; or, if I made this ball larger and larger, until, if it were possible, it became as large as the Earth itself—or, I might take the Earth itself as the large ball—that then the attraction would become so powerful as to cause them to rush together in this manner [dropping the ivory ball]. You sit there upright, and I stand upright here, because we keep our centres of gravity properly balanced with respect to the earth; and I need not tell you that on the other side of this world the people are standing and moving about with their feet towards our feet, in a reversed position as compared with us, and all by means of this power of gravitation to the centre of the earth.

I must not, however, leave the subject of gravitation, without telling you something about its laws and regularity; and first, as regards its power with respect to the distance that bodies46 are apart. If I take one of these balls and place it within an inch of the other, they attract each other with a certain power. If I hold it at a greater distance off, they attract with less power; and if I hold it at a greater distance still, their attraction is still less. Now this fact is of the greatest consequence; for, knowing this law, philosophers have discovered most wonderful things. You know that there is a planet, Uranus, revolving round the sun with us, but eighteen hundred millions of miles off; and because there is another planet as far off as three thousand millions of miles, this law of attraction, or gravitation, still holds good—and philosophers actually discovered this latter planet, Neptune, by reason of the effects of its attraction at this overwhelming distance. Now I want you clearly to understand what this law is. They say (and they are right) that two bodies attract each other inversely as the square of the distance—a sad jumble of words until you understand them; but I think we shall soon comprehend what this law is, and what is the meaning of the “inverse square of the distance.”

47

I have here (fig. 11) a lamp A, shining most intensely upon this disc, B, C, D; and this light acts as a sun by which I can get a shadow from this little screen, B F (merely a square piece of card), which, as you know, when I place it close to the large screen, just shadows as much of it as is exactly equal to its own size. But now let me take this card E, which is equal to the other one in size, and place it midway between the lamp and the screen: now look at the size of the shadow B D—it is four times the original size. Here, then, comes the “inverse square of the distance.” This distance, A E, is one, and that distance, A B, is two; but that size E being48 one, this size B D of shadow is four instead of two, which is the square of the distance; and, if I put the screen at one-third of the distance from the lamp, the shadow on the large screen would be nine times the size. Again, if I hold this screen here, at B F, a certain amount of light falls on it; and if I hold it nearer the lamp at E, more light shines upon it. And you see at once how much—exactly the quantity which I have shut off from the part of this screen, B D, now in shadow; moreover, you see that if I put a single screen here, at G, by the side of the shadow, it can only receive one-fourth of the proportion of light which is obstructed. That, then, is what is meant by the inverse of the square of the distance. This screen E is the brightest, because it is the nearest; and there is the whole secret of this curious expression, inversely as the square of the distance. Now, if you cannot perfectly recollect this when you go home, get a candle and throw a shadow of something—your profile, if you like—on the wall, and then recede or advance, and you will find that your shadow is exactly in proportion to the square of the distance you49 are off the wall; and then if you consider how much light shines on you at one distance, and how much at another, you get the inverse accordingly. So it is as regards the attraction of these two balls—they attract according to the square of the distance, inversely. I want you to try and remember these words, and then you will be able to go into all the calculations of astronomers as to the planets and other bodies, and tell why they move so fast, and why they go round the sun without falling into it, and be prepared to enter upon many other interesting inquiries of the like nature.

Let us now leave this subject which I have written upon the board under the word Force—Gravitation—and go a step further. All bodies attract each other at sensible distances. I shewed you the electric attraction on the last occasion (though I did not call it so); that attracts at a distance: and in order to make our progress a little more gradual, suppose I take a few iron particles [dropping some small fragments of iron on the table]. There, I have already told you that in all cases where bodies fall, it is the particles that are attracted. You50 may consider these then as separate particles magnified, so as to be evident to your sight; they are loose from each other—they all gravitate—they all fall to the earth—for the force of gravitation never fails. Now, I have here a centre of power which I will not name at present, and when these particles are placed upon it, see what an attraction they have for each other.

Here I have an arch of iron filings (fig. 12) regularly built up like an iron bridge, because I have put them within a sphere of action which will cause them to attract each other. See!—I could let a mouse run through it, and yet if I try to do the same thing with them here [on51 the table], they do not attract each other at all. It is that [the magnet] which makes them hold together. Now, just as these iron particles hold together in the form of an elliptical bridge, so do the different particles of iron which constitute this nail hold together and make it one. And here is a bar of iron—why, it is only because the different parts of this iron are so wrought as to keep close together by the attraction between the particles that it is held together in one mass. It is kept together, in fact, merely by the attraction of one particle to another, and that is the point I want now to illustrate. If I take a piece of flint and strike it with a hammer, and break it thus [breaking off a piece of the flint], I have done nothing more than separate the particles which compose these two pieces so far apart, that their attraction is too weak to cause them to hold together, and it is only for that reason that there are now two pieces in the place of one. I will shew you an experiment to prove that this attraction does still exist in those particles, for here is a piece of glass (for what was true of the flint and the bar of iron is true of the piece of glass, and is true of52 every other solid—they are all held together in the lump by the attraction between their parts), and I can shew you the attraction between its separate particles; for if I take these portions of glass, which I have reduced to very fine powder, you see that I can actually build them up into a solid wall by pressure between two flat surfaces. The power which I thus have of building up this wall is due to the attraction of the particles, forming as it were the cement which holds them together; and so in this case, where I have taken no very great pains to bring the particles together, you see perhaps a couple of ounces of finely-pounded glass standing as an upright wall. Is not this attraction most wonderful? That bar of iron one inch square has such power of attraction in its particles—giving to it such strength—that it will hold up twenty tons weight before the little set of particles in the small space, equal to one division across which it can be pulled apart, will separate. In this manner suspension bridges and chains are held together by the attraction of their particles; and I am going to make an experiment which will shew53 how strong is this attraction of the particles. [The Lecturer here placed his foot on a loop of wire fastened to a support above, and swung with his whole weight resting upon it for some moments.] You see while hanging here all my weight is supported by these little particles of the wire, just as in pantomimes they sometimes suspend gentlemen and damsels.

How can we make this attraction of the particles a little more simple? There are many things which if brought together properly will shew this attraction. Here is a boy’s experiment (and I like a boy’s experiment). Get a tobacco-pipe, fill it with lead, melt it, and then pour it out upon a stone, and thus get a clean piece of lead (this is a better plan than scraping it—scraping alters the condition of the surface of the lead). I have here some pieces of lead which I melted this morning for the sake of making them clean. Now these pieces of lead hang together by the attraction of their particles; and if I press these two separate pieces close together, so as to bring their particles within the sphere of attraction, you will see how soon they become one. I have merely to give54 them a good squeeze, and draw the upper piece slightly round at the same time, and here they are as one, and all the bending and twisting I can give them will not separate them again: I have joined the lead together, not with solder, but simply by means of the attraction of the particles.

This, however, is not the best way of bringing those particles together—we have many better plans than that; and I will shew you one that will do very well for juvenile experiments. There is some alum crystallised very beautifully by nature (for all things are far more beautiful in their natural than their artificial form), and here I have some of the same alum broken into fine powder. In it I have destroyed that force of which I have placed the name on this board—Cohesion, or the attraction exerted between the particles of bodies to hold them together. Now I am going to shew you that if we take this powdered alum and some hot water, and mix them together, I shall dissolve the alum—all the particles will be separated by the water far more completely than they are here in the powder; but then, being in the water, they will55 have the opportunity as it cools (for that is the condition which favours their coalescence) of uniting together again and forming one mass.7

Now, having brought the alum into solution, I will pour it into this glass basin, and you will, to-morrow, find that those particles of alum which I have put into the water, and so separated that they are no longer solid, will, as the water cools, come together and cohere, and by to-morrow morning we shall have a great deal of the alum crystallised out—that is to say, come back to the solid form. [The Lecturer here poured a little of the hot solution of alum into the glass dish, and when the latter had thus been made warm, the remainder of the solution was added.] I am now doing that which I advise you to do if you use a glass vessel, namely, warming it slowly and gradually; and in repeating this experiment, do as I do—pour the liquid out gently, leaving all the dirt behind in the basin: and remember that the more carefully and quietly you make this experiment at home, the better the crystals. To-morrow you will see the particles of alum drawn together; and56 if I put two pieces of coke in some part of the solution (the coke ought first to be washed very clean, and dried), you will find to-morrow that we shall have a beautiful crystallisation over the coke, making it exactly resemble a natural mineral.

Now, how curiously our ideas expand by watching these conditions of the attraction of cohesion!—how many new phenomena it gives us beyond those of the attraction of gravitation! See how it gives us great strength. The things we deal with in building up the structures on the earth are of strength (we use iron, stone, and other things of great strength); and only think that all those structures you have about you—think of the “Great Eastern,” if you please, which is of such size and power as to be almost more than man can manage—are the result of this power of cohesion and attraction.

I have here a body in which I believe you will see a change taking place in its condition of cohesion at the moment it is made. It is at first yellow, it then becomes a fine crimson red. Just watch when I pour these two liquids together—both colourless as water. [The57 Lecturer here mixed together solutions of perchloride of mercury and iodide of potassium, when a yellow precipitate of biniodide of mercury fell down, which almost immediately became crimson red.] Now, there is a substance which is very beautiful, but see how it is changing colour. It was reddish-yellow at first, but it has now become red.8 I have previously prepared a little of this red substance, which you see formed in the liquid, and have put some of it upon paper. [Exhibiting several sheets of paper coated with scarlet biniodide of mercury.9] There it is—the same substance spread upon paper; and there, too, is the same substance; and here is some more of it [exhibiting a piece of paper as large as the other sheets, but having only very little red colour on it, the greater part being yellow], a little more of it, you will say. Do not be mistaken; there is as much upon the surface of one of these pieces of paper as upon the other. What you see yellow is the same thing as the red body, only the attraction of cohesion is in a certain degree changed; for I will take this red body, and apply heat to it (you may perhaps see a little smoke arise,58 but that is of no consequence), and if you look at it, it will first of all darken—but see, how it is becoming yellow. I have now made it all yellow, and what is more, it will remain so; but if I take any hard substance, and rub the yellow part with it, it will immediately go back again to the red condition. [Exhibiting the experiment.] There it is. You see the red is not put back, but brought back by the change in the substance. Now [warming it over the spirit lamp] here it is becoming yellow again, and that is all because its attraction of cohesion is changed. And what will you say to me when I tell you that this piece of common charcoal is just the same thing, only differently calesced, as the diamonds which you wear? (I have put a specimen outside of a piece of straw which was charred in a particular way—it is just like black lead.) Now, this charred straw, this charcoal, and these diamonds, are all of them the same substance, changed but in their properties as respects the force of cohesion.

Here is a piece of glass [producing a piece of plate-glass about two inches square]—(I shall59 want this afterwards to look to and examine its internal condition)—and here is some of the same sort of glass differing only in its power of cohesion, because while yet melted it has been dropped into cold water [exhibiting a “Prince Rupert’s drop”.10 (fig. 13)]; and if I take one of these little tear-like pieces and break off ever so little from the point, the whole will at once burst and fall to pieces. I will now break off a piece of this. [The Lecturer nipped off a small piece from the end of one of the Rupert’s drops, whereupon the whole immediately fell to pieces.] There! you see the solid glass has suddenly become powder—and more than that, it has knocked a hole in the glass vessel in which it was held. I can shew the effect better in this bottle of water; and it is very likely the whole bottle will go. [A 6-oz. vial was filled with water, and a Rupert’s drop placed in it, with the point of the tail just projecting out; upon breaking the tip off, the drop burst, and the shock being transmitted through the water to the sides of the bottle, shattered the latter to pieces.]

Here is another form of the same kind of60 experiment. I have here some more glass which has not been annealed [showing some thick glass vessels11 (fig. 14)], and if I take one of these glass vessels and drop a piece of pounded glass into it (or I will take some of these small pieces of rock crystal—they have the advantage of being harder than glass), and so make the least scratch upon the inside, the whole bottle will break to pieces,—it cannot hold together. [The Lecturer here dropped a small fragment of rock crystal into one of these glass vessels, when the bottom immediately came out and fell upon the plate.] There! it goes through, just as it would through a sieve.

Now, I have shewn you these things for the purpose of bringing your minds to see that bodies are not merely held together by this61 power of cohesion, but that they are held together in very curious ways. And suppose I take some things that are held together by this force, and examine them more minutely. I will first take a bit of glass, and if I give it a blow with a hammer, I shall just break it to pieces. You saw how it was in the case of the flint when I broke the piece off; a piece of a similar kind would come off, just as you would expect; and if I were to break it up still more, it would be as you have seen, simply a collection of small particles of no definite shape or form. But supposing I take some other thing, this stone for instance (fig. 15) [taking a piece of mica12], and if I hammer this stone, I may batter it a great deal before I can break it up. I may even bend it without breaking it; that is to say, I may bend it in one particular direction without breaking it much, although I feel in my hands that I am doing it some injury. But now, if I take it by the edges, I find that it breaks up into leaf after leaf in a most extraordinary manner. Why should it break up like that? Not because all stones do, or all crystals; for there is some salt (fig. 16)—you62 know what common salt is13: here is a piece of this salt which by natural circumstances has had its particles so brought together that they have been allowed free opportunity of combining or coalescing; and you shall see what happens if I take this piece of salt and break it. It does not break as flint did, or as the mica did, but with a clean sharp angle and exact surfaces, beautiful and glittering as diamonds [breaking it by gentle blows with a hammer]; there is a square prism which I may break up into a square cube. You see these fragments are all square—one side may be longer than the other, but they will only split up so as to form square or oblong pieces with cubical sides. Now, I go a little further, and I find another stone (fig. 17) [Iceland, or calc-spar]14,63 which I may break in a similar way, but not with the same result. Here is a piece which I have broken off, and you see there are plain surfaces perfectly regular with respect to each other; but it is not cubical—it is what we call a rhomboid. It still breaks in three directions most beautifully and regularly, with polished surfaces, but with sloping sides, not like the salt. Why not? It is very manifest that this is owing to the attraction of the particles, one for the other, being less in the direction in which they give way than in other directions. I have on the table before me a number of little bits of calcareous spar, and I recommend each of you to take a piece home, and then you can take a knife and try to divide it in the direction of any of the surfaces already existing. You will be able to do it at once; but if you try to cut it across the crystals, you cannot—by hammering, you may bruise and break it up—but you can only divide it into these beautiful little rhomboids.

Now I want you to understand a little more how this is—and for this purpose I am going to use the electric light again. You see, we64 cannot look into the middle of a body like this piece of glass. We perceive the outside form, and the inside form, and we look through it; but we cannot well find out how these forms become so: and I want you, therefore, to take a lesson in the way in which we use a ray of light for the purpose of seeing what is in the interior of bodies. Light is a thing which is, so to say, attracted by every substance that gravitates (and we do not know anything that does not). All matter affects light more or less by what we may consider as a kind of attraction, and I have arranged (fig. 18) a very simple experiment upon the floor of the room for the purpose of illustrating this. I have put into that basin a few things which those who are in the body of the theatre will not be able to see, and I am going to make use of this power, which matter possesses, of attracting a ray of light. If Mr. Anderson pours some water, gently and steadily, into the basin, the water will attract the rays of light downwards, and the piece of silver and the sealing-wax will appear to rise up into the sight of those who were before not high enough to see over65 the side of the basin to its bottom. [Mr. Anderson here poured water into the basin, and upon the Lecturer asking whether any body could see the silver and sealing-wax, he was answered by a general affirmative.] Now, I suppose that everybody can see that they are not at all disturbed, whilst from the way they appear to have risen up, you would imagine the bottom of the basin and the articles in it were two inches thick, although they are only one of our small silver dishes and a piece of sealing-wax which I have put there. The light which now goes to you from that piece of silver was obstructed by the edge of the basin, when there was no water there, and you were unable to see anything of it; but when we poured in water, the rays were attracted down by it, over the edge66 of the basin, and you were thus enabled to see the articles at the bottom.

I have shewn you this experiment first, so that you might understand how glass attracts light, and might then see how other substances, like rock-salt and calcareous spar, mica, and other stones, would affect the light; and, if Dr. Tyndall will be good enough to let us use his light again, we will first of all shew you how it may be bent by a piece of glass (fig. 19). [The electric lamp was again lit, and the beam of parallel rays of light which it emitted was bent about and decomposed by means of the prism.] Now, here you see, if I send the light through this piece of plain glass, A, it goes straight through, without being bent, unless the glass be held obliquely, and then the phenomenon becomes more complicated;67 but if I take this piece of glass, B [a prism], you see it will shew a very different effect. It no longer goes to that wall, but it is bent to this screen, C; and how much more beautiful it is now [throwing the prismatic spectrum on the screen]. This ray of light is bent out of its course by the attraction of the glass upon it. And you see I can turn and twist the rays to and fro, in different parts of the room, just as I please. Now it goes there, now here. [The Lecturer projected the prismatic spectrum about the theatre.] Here I have the rays once more bent on to the screen, and you see how wonderfully and beautifully that piece of glass not only bends the light by virtue of its attraction, but actually splits it up into different colours. Now, I want you to understand that this piece of glass [the prism] being perfectly uniform in its internal structure, tells us about the action of these other bodies which are not uniform—which do not merely cohere, but also have within them, in different parts, different degrees of cohesion, and thus attract and bend the light with varying powers. We will now let the light pass through one or two of these things68 which I just now shewed you broke so curiously; and, first of all, I will take a piece of mica. Here, you see, is our ray of light. We have first to make it what we call polarised; but about that you need not trouble yourselves—it is only to make our illustration more clear. Here, then, we have our polarised ray of light, and I can so adjust it as to make the screen upon which it is shining either light or dark, although I have nothing in the course of this ray of light but what is perfectly transparent [turning the analyser round]. I will now make it so that it is quite dark; and we will, in the first instance, put a piece of common glass into the polarised ray, so as to shew you that it does not enable the light to get through. You see the screen remains dark. The glass then, internally, has no effect upon the light. [The glass was removed, and a piece of mica introduced.] Now, there is the mica which we split up so curiously into leaf after leaf, and see how that enables the light to pass through to the screen, and how, as Dr. Tyndall turns it round in his hand, you have those different colours, pink, and purple,69 and green, coming and going most beautifully—not that the mica is more transparent than the glass, but because of the different manner in which its particles are arranged by the force of cohesion.

Now we will see how calcareous spar acts upon this light,—that stone which split up into rhombs, and of which you are each of you going to take a little piece home. [The mica was removed, and a piece of calc-spar introduced at A.] See how that turns the light round and round, and produces these rings and that black cross (fig. 20). Look at those colours—are they not most beautiful for you and for me?—for I enjoy these things as much as you do. In what a wonderful manner they70 open out to us the internal arrangement of the particles of this calcareous spar by the force of cohesion.

And now I will shew you another experiment. Here is that piece of glass which before had no action upon the light. You shall see what it will do when we apply pressure to it. Here, then, we have our ray of polarised light, and I will first of all shew you that the glass has no effect upon it in its ordinary state,—when I place it in the course of the light, the screen still remains dark. Now, Dr. Tyndall will press that bit of glass between three little points, one point against two, so as to bring a strain upon the parts, and you will see what a curious effect that has. [Upon the screen two white dots gradually appeared.] Ah! these points shew the position of the strain—in these parts the force of cohesion is being exerted in a different degree to what it is in the other parts, and hence it allows the light to pass through. How beautiful that is—how it makes the light come through some parts, and leaves it dark in others, and all because we weaken the force of cohesion between particle and particle.71 Whether you have this mechanical power of straining, or whether we take other means, we get the same result; and, indeed, I will shew you by another experiment that if we heat the glass in one part, it will alter its internal structure, and produce a similar effect. Here is a piece of common glass, and if I insert this in the path of the polarised ray, I believe it will do nothing. There is the common glass [introducing it]—no light passes through—the screen remains quite dark; but I am going to warm this glass in the lamp, and you know yourselves that when you pour warm water upon glass you put a strain upon it sufficient to break it sometimes—something like there was in the case of the Prince Rupert’s drops. [The glass was warmed in the spirit-lamp, and again placed across the ray of light.] Now you see how beautifully the light goes through those parts which are hot, making dark and light lines just as the crystal did, and all because of the alteration I have effected in its internal condition; for these dark and light parts are a proof of the presence of forces acting and dragging in different directions within the solid mass.

72

We will first return for a few minutes to one of the experiments made yesterday. You remember what we put together on that occasion—powdered alum and warm water; here is one of the basins then used. Nothing has been done to it since; but you will find on examining it, that it no longer contains any powder, but a multitude of beautiful crystals. Here also are the pieces of coke which I put into the other basin—they have a fine mass of crystals about them. That other basin I will leave as it is. I will not pour the water from it, because it will shew you that the particles of alum have done something more than merely crystallise together. They have pushed the dirty matter from them, laying it around the outside or outer edge of the lower crystals—squeezed out as it were by the strong attrac73tion which the particles of alum have for each other.

And now for another experiment. We have already gained a knowledge of the manner in which the particles of bodies—of solid bodies—attract each other, and we have learnt that it makes calcareous spar, alum, and so forth, crystallise in these regular forms. Now, let me gradually lead your minds to a knowledge of the means we possess of making this attraction alter a little in its force; either of increasing, or diminishing, or apparently of destroying it altogether. I will take this piece of iron [a rod of iron about two feet long, and a quarter of an inch in diameter], it has at present a great deal of strength, due to its attraction of cohesion; but if Mr. Anderson will make part of this red-hot in the fire, we shall then find that it will become soft, just as sealing-wax will when heated, and we shall also find that the more it is heated the softer it becomes. Ah! but what does soft mean? Why, that the attraction between the particles is so weakened that it is no longer sufficient to resist the power we bring to bear upon it. [Mr. Anderson74 handed to the Lecturer the iron rod, with one end red-hot, which he shewed could be easily twisted about with a pair of pliers.] You see, I now find no difficulty in bending this end about as I like; whereas I cannot bend the cold part at all. And you know how the smith takes a piece of iron and heats it, in order to render it soft for his purpose: he acts upon our principle of lessening the adhesion of the particles, although he is not exactly acquainted with the terms by which we express it.

And now we have another point to examine; and this water is again a very good substance to take as an illustration (as philosophers we call it all water, even though it be in the form of ice or steam). Why is this water hard? [pointing to a block of ice] because the attraction of the particles to each other is sufficient to make them retain their places in opposition to force applied to it. But what happens when we make the ice warm? Why, in that case we diminish to such a large extent the power of attraction that the solid substance is destroyed altogether. Let me illustrate this: I will take75 a red-hot ball of iron [Mr. Anderson, by means of a pair of tongs, handed to the Lecturer a red-hot ball of iron, about two inches in diameter], because it will serve as a convenient source of heat [placing the red-hot iron in the centre of the block of ice]. You see I am now melting the ice where the iron touches it. You see the iron sinking into it, and while part of the solid water is becoming liquid, the heat of the ball is rapidly going off. A certain part of the water is actually rising in steam—the attraction of some of the particles is so much diminished that they cannot even hold together in the liquid form, but escape as vapour. At the same time, you see I cannot melt all this ice by the heat contained in this ball. In the course of a very short time I shall find it will have become quite cold.

Here is the water which we have produced by destroying some of the attraction which existed between the particles of the ice,—for below a certain temperature the particles of water increase in their mutual attraction, and become ice; and above a certain temperature the attraction decreases, and the water becomes76 steam. And exactly the same thing happens with platinum, and nearly every substance in nature; if the temperature is increased to a certain point, it becomes liquid, and a further increase converts it into a gas. Is it not a glorious thing for us to look at the sea, the rivers, and so forth, and to know that this same body in the northern regions is all solid ice and icebergs, while here, in a warmer climate, it has its attraction of cohesion so much diminished as to be liquid water. Well, in diminishing this force of attraction between the particles of ice, we made use of another force, namely, that of heat; and I want you now to understand that this force of heat is always concerned when water passes from the solid to the liquid state. If I melt ice in other ways, I cannot do without heat (for we have the means of making ice liquid without heat; that is to say, without using heat as a direct cause). Suppose, for illustration, I make a vessel out of this piece of tinfoil [bending the foil up into the shape of a dish]. I am making it metallic, because I want the heat which I am about to deal with to pass readily through it; and I am going77 to pour a little water on this board, and then place the tin vessel on it. Now if I put some of this ice into the metal dish, and then proceed to make it liquid by any of the various means we have at our command, it still must take the necessary quantity of heat from something, and in this case it will take the heat from the tray, and from the water underneath, and from the other things round about. Well, a little salt added to the ice has the power of causing it to melt, and we shall very shortly see the mixture become quite fluid, and you will then find that the water beneath will be frozen—frozen, because it has been forced to give up that heat which is necessary to keep it in the liquid state, to the ice on becoming liquid. I remember once, when I was a boy, hearing of a trick in a country alehouse; the point was how to melt ice in a quart-pot by the fire, and freeze it to the stool. Well, the way they did it was this: they put some pounded ice in a pewter pot and added some salt to it, and the consequence was, that when the salt was mixed with it, the ice in the pot melted (they did not tell me anything about the salt, and they78 set the pot by the fire, just to make the result more mysterious), and in a short time the pot and the stool were frozen together, as we shall very shortly find it to be the case here. And all because salt has the power of lessening the attraction between the particles of ice. Here you see the tin dish is frozen to the board—I can even lift this little stool up by it.

This experiment cannot, I think, fail to impress upon your minds the fact, that whenever a solid body loses some of that force of attraction by means of which it remains solid, heat is absorbed; and if, on the other hand, we convert a liquid into a solid, e.g., water into ice, a corresponding amount of heat is given out. I have an experiment shewing this to be the case.79 Here (fig. 21) is a bulb, A, filled with air, the tube from which dips into some coloured liquid in the vessel B. And I dare say you know that if I put my hand on the bulb A, and warm it, the coloured liquid which is now standing in the tube at C will travel forward. Now we have discovered a means, by great care and research into the properties of various bodies, of preparing a solution of a salt15 which, if shaken or disturbed, will at once become a solid; and as I explained to you just now (for what is true of water is true of every other liquid), by reason of its becoming solid, heat is evolved, and I can make this evident to you by pouring it over this bulb;—there! it is becoming solid, and look at the coloured liquid, how it is being driven down the tube, and how it is bubbling out through the water at the end; and so we learn this beautiful law of our philosophy, that whenever we diminish the attraction of cohesion, we absorb heat—and whenever we increase that attraction, heat is evolved. This, then, is a great step in advance, for you have learned a great deal in addition to the mere circumstance that particles attract80 each other. But you must not now suppose that because they are liquid they have lost their attraction of cohesion; for here is the fluid mercury, and if I pour it from one vessel into another, I find that it will form a stream from the bottle down to the glass—a continuous rod of fluid mercury, the particles of which have attraction sufficient to make them hold together all the way through the air down to the glass itself; and if I pour water quietly from a jug, I can cause it to run in a continuous stream in the same manner. Again, let me put a little water on this piece of plate-glass, and then take another plate of glass and put it on the water; there! the upper plate is quite free to move, gliding about on the lower one from side to side; and yet, if I take hold of the upper plate and lift it up straight, the cohesion is so great that the lower one is held up by it. See how it runs about as I move the upper one! and this is all owing to the strong attraction of the particles of the water. Let me shew you another experiment. If I take a little soap and water—not that the soap makes the particles of the water more adhesive one for the other81 but it certainly has the power of continuing in a better manner the attraction of the particles (and let me advise you, when about to experiment with soap-bubbles, to take care to have everything clean and soapy). I will now blow a bubble; and that I may be able to talk and blow a bubble too, I will take a plate with a little of the soapsuds in it, and will just soap the edges of the pipe, and blow a bubble on to the plate. Now, there is our bubble. Why does it hold together in this manner? Why, because the water of which it is composed has an attraction of particle for particle,—so great, indeed, that it gives to this bubble the very power of an india-rubber ball; for you see, if I introduce one end of this glass tube into the bubble, that it has the power of contracting so powerfully as to force enough air through the tube to blow out a light (fig. 22)—the light is blown out. And look! see how the bubble is disappearing, see how it is getting smaller and smaller.

There are twenty other experiments I might shew you to illustrate this power of cohesion of the particles of liquids. For instance, what82 would you propose to me if, having lost the stopper out of this alcohol bottle, I should want to close it speedily with something near at hand. Well, a bit of paper would not do, but a piece of linen cloth would, or some of this cotton wool which I have here. I will put a tuft of it into the neck of the alcohol bottle, and you see, when I turn it upside down, that it is perfectly well stoppered, so far as the alcohol is concerned; the air can pass through, but the alcohol cannot. And if I were to take an oil vessel, this plan would do equally well, for in former times they used to send us oil from Italy in flasks stoppered only with cotton wool (at the present time the cotton is put in after the oil has arrived here, but formerly it used to be sent so stoppered). Now, if it were not for the particles of liquid cohering together, this alcohol would run83 out; and if I had time, I could have shewn you a vessel with the top, bottom, and sides altogether formed like a sieve, and yet it would hold water, owing to this cohesion.