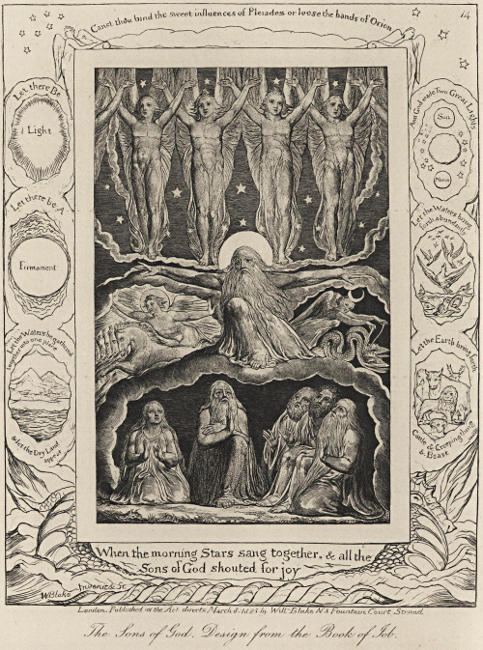

London. Published as the Act directs March 8. 1823 by Willm Blake N3 Fountain Court Strand

The Sons of God. Design from the Book of Job.

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/gri_33125007593565 |

Images outlined in blue are clickable for larger versions.

London. Published as the Act directs March 8. 1823 by Willm Blake N3 Fountain Court Strand

The Sons of God. Design from the Book of Job.

WILLIAM BLAKE

PAINTER AND POET

By

RICHARD GARNETT, LL.D.

Keeper of the Printed Books in the British Museum

LONDON

SEELEY AND CO. LIMITED, ESSEX STREET, STRAND

NEW YORK, MACMILLAN AND CO.

1895

| PLATES | |

| PAGE | |

| The Sons of God. From the Book of Job | Frontispiece |

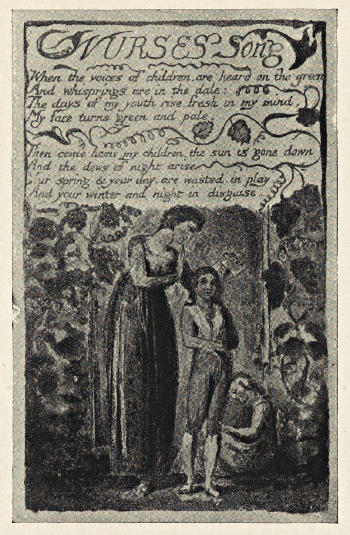

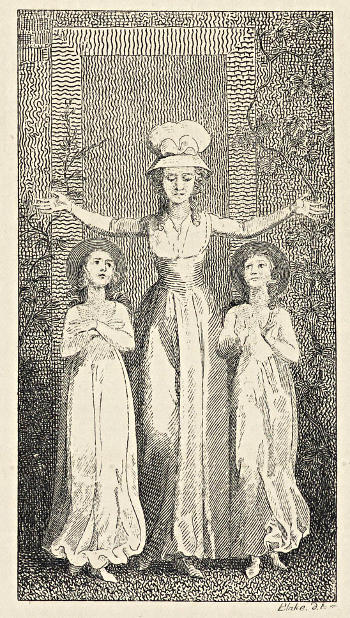

| The Lamb, and Infant Joy. Songs of Innocence | to face 20 |

| The Fly, and the Tiger. Songs of Experience | ” ” 24 |

| The Book of Thel, title-page. In facsimile by W. Griggs | ” ” 33 |

| ” ”page vi.” ” | ” ” 36 |

| America, page | ” ” 42 |

| ” page | ” ” 48 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT | |

| Morning, or Glad Day. From an engraving by W. Blake | 11 |

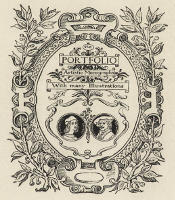

| Illustration from “David Simple.” Engraved by W. Blake after T. Stothard, R.A. | 17 |

| From a coloured copy of the “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” British Museum | 22 |

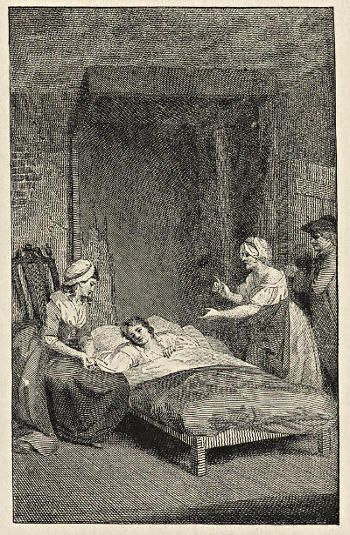

| Frontispiece of Mary Wollstonecraft’s “Stories” | 24 |

| Page of Young’s “Night Thoughts.” Illustrated by W. Blake | 26 |

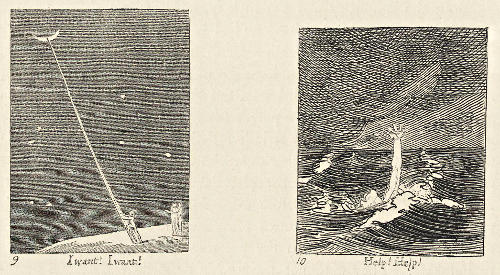

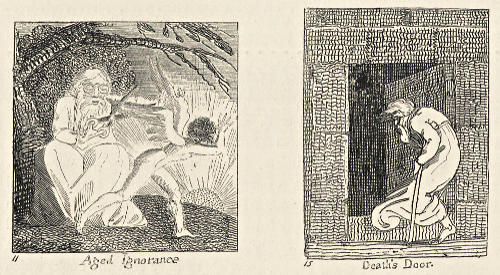

| I want! I want!—Help! Help!—Aged Ignorance!—Death’s Door | 28 |

| Design from the “Book of Urizen.” By W. Blake | 34 |

| The Ancient of Days setting a Compass to the Earth. From a water-colour drawing by W. Blake. British Museum | 39 |

| Sweeping the Parlour in the Interpreter’s House | 40 |

| Design from “Milton.” By W. Blake | 47[4] |

| Portrait of William Blake. From the engraving by L. Schiavonetti, after T. Phillips, R.A. | 50 |

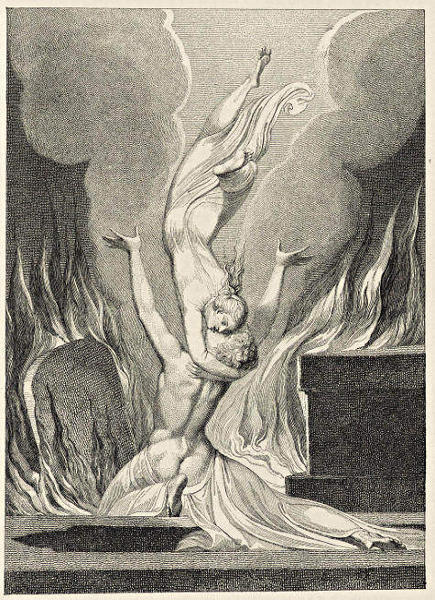

| The Reunion of Soul and Body. From Blair’s “Grave,” illustrated by W. Blake | 53 |

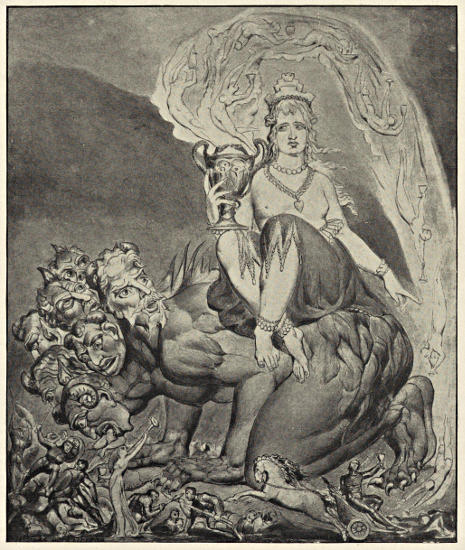

| The Babylonian Woman on the Seven-headed Beast. From a water-colour drawing by W. Blake. British Museum | 55 |

| Portrait of Wilson Lowry. By John Linnell. Engraved by Blake and Linnell | 61 |

| The Resurrection of the Dead. From a water-colour drawing by W. Blake. British Museum | 63 |

| Woodcut from Thornton’s Pastoral | 64 |

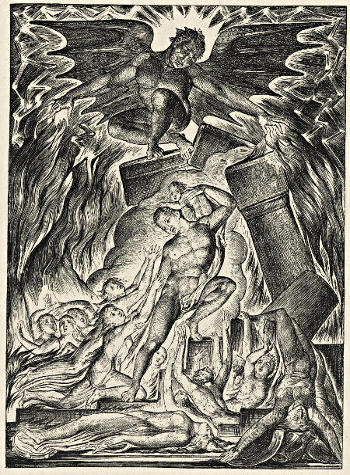

| The Destruction of Job’s Sons and Daughters. From the “Book of Job.” By W. Blake | 67 |

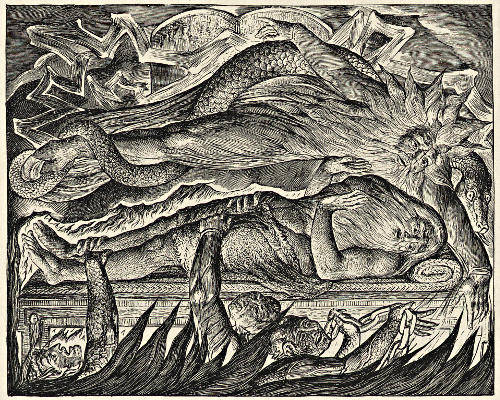

| With dreams upon my bed thou scarest me. From the “Book of Job.” By W. Blake | 69 |

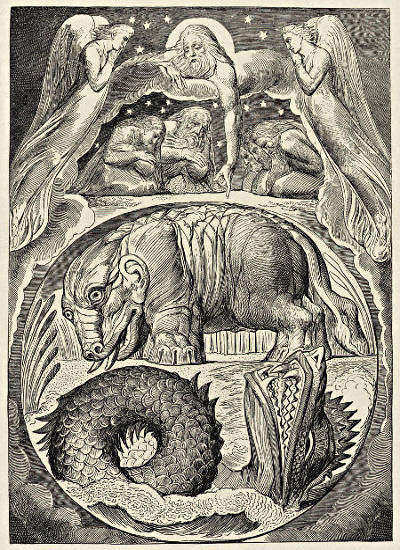

| Behemoth and Leviathan. From the “Book of Job.” By W. Blake | 71 |

Preliminary observations—Blake’s Birth—Education—Marriage—Early Poems—Drawings and Engravings.

The position of William Blake among artists is exceptional. Of no other painter of like distinction, save Dante Rossetti, can it be said that his fame as a poet has fully rivalled his fame as a painter; much less that, in the opinion of some, his fame as a seer ought to have exceeded both. Many painters, from Reynolds downwards, have written admirably upon art; in some instances, notably Haydon’s, the worth of their precepts greatly exceeds that of their performance. But, Rossetti always excepted, perhaps no other painter of great distinction, save Michael Angelo alone, has achieved high renown in poetry, and the compass of Michael Angelo’s poetical work is infinitesimal in comparison with his work as an artist. Again, the literary achievements of an Angelo or a Reynolds admit of clear separation from their performances as artists. The critic who approaches them from the artistic side may, if he pleases, omit the literary side entirely from consideration. This is impossible with Blake, for not only do the artistic and the poetical monuments of his genius nearly balance each other in merit and in their claim upon the attention of posterity, but they are the offspring of the same creative impulse, and are indissolubly fused together by the process adopted for their execution. A study of Blake, therefore, must include more literary discussion than would be allowable in a monograph on any other artist. The poet and painter in Blake, moreover, are but manifestations of the[6] more comprehensive character of seer, which suggests inquiries alien to both these arts; while the personal character of the man is so fascinating, and his intellectual character so perplexing, that the investigation of either of them might afford, and often has afforded, material for a prolonged discussion. In the following pages it will be our object, whenever compelled to quit the safe ground of biographical narrative, to subordinate all else to the consideration of Blake as an artist; but the Blake of the brush is too emphatically the Blake of the pen to be long dissociated from him, and neither can be detached from the background of abnormal visionary faculty.

From a certain point of view, artists may be regarded as divisible into three classes: those who regard the material world as an unquestionable solid reality, whose accurate representation is the one mission of Art; those to whom it is a mere hieroglyphic of an essential existence transcending it; and those who, uniting the two conceptions, are at the same time idealists and realists. The greatest artists generally belong to the latter class, and with reason, for a literal adherence to matter of fact almost implies defect of imagination; while an extravagant idealism may be, to say the least, a convenient excuse for defects of technical skill. It is difficult to know whether to class the works of the very greatest artists as realistic or idealistic. Take Albert Dürer’s Melancholia. It is a hieroglyph, a symbol, an expression of something too intense to be put into words; a delineation of what the painter beheld with the inner eye alone. Yet every detail is as correct and true to fact as the most uninspired Dutchman could have made it. Take Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, and observe how separate details which the artist may have actually noticed, are combined into a whole which has never been beheld, save by the spiritual vision, since the last thyrsus was brandished by the last Mænad. Yet, though the creators of such scenes are the greatest, some realists, such as Velasquez, have in virtue of surpassing technical execution asserted a nearly equal rank. The case is different when we come to the enthusiasts and visionaries, whose art is wholly symbolic, who have given us little that can be enjoyed as art for art’s sake, without reference to the ideas of which it is made the vehicle. In many very interesting artists, such as Wiertz and Calvert and Vedder, and in many isolated works of great[7] masters, such as Giorgione’s Venetian Pastoral, the feeling is so much in excess of the execution—admirable as this may be—that the result is rather a poem than a picture. But only one artist who has deliberately made himself the prophet of this tendency, who has avowedly and defiantly discarded all purpose from his works save that of spiritual suggestiveness, seems to have ever been admitted as a candidate for very high artistic honours, and he is our countryman, William Blake.

This circumstance alone should render Blake an interesting object of study, even for those who can see no merit in his works: indeed, the less the merit the more remarkable the phenomenon. He is, moreover, a most peculiar and enigmatical character, both intellectually and morally. As an art critic he is of all the most dogmatic, trenchant, and revolutionary. As a poet, were nineteen-twentieths of his compositions to be discarded as rubbish, lyrics would remain not only exquisite in themselves, but possessing the incommunicable and Sapphic quality that a single stanza, even a single phrase, would often suffice to make the writer immortal. The question of his sanity is as well adapted to furnish the world with an interminable subject of discussion as the execution of Charles I. or the assassination of Cæsar. Finally, it is very significant that while no man ever wilfully put more obstacles into the way of his success than Blake, whether as artist, thinker, or poet, and he did in fact succeed in condemning himself to poverty and obscurity, the verdict of his contemporaries is now so far reversed that the drawings which a kind friend overpaid, as he thought, at fifty guineas, are worth a thousand pounds.

What manner of man was he to whose shade the world has made this practical apology?

William Blake was born on November 28th,[1] 1757, at 28, Broad Street, Golden Square. By a singular coincidence this was the very year which a still more celebrated mystic, Swedenborg, had announced as that of the Last Judgment in a spiritual sense, which was by no means to preclude the world from going on in externals pretty much as usual. Blake’s father, James Blake, was a hosier in moderately prosperous circumstances, whose father is stated by Blake’s most elaborate commentators, Messrs. [8]Ellis and Yeats, to have been originally named O’Neil, and to have assumed his wife’s name as a means of escape from pecuniary difficulties. This wife, however, was not the mother of James. This genealogy is not supported by any strong authority, and is at variance with another, also indifferently supported, according to which the artist’s family were connected with the admiral’s. We must leave the question where we find it, merely remarking that Blake’s parents were certainly Protestants, and that we can detect no specifically Irish trait in his character or his works. He had three brothers—one, James, mild and unassuming like his father; another, Robert, who died young, apparently with more affinity to William; the third, John, a scapegrace. There was also a sister who never married, and is described as a thorough gentlewoman, reserved and proud. None of the family except William and Robert seem to have shown any artistic talent. With William it must have been precocious, for, ere he had attained the age of ten, his father, who as a small tradesman might rather have been expected to have thwarted the boy’s inclinations, placed him at “Mr. Pars’ drawing school in the Strand.” Here he learned to draw from plaster casts—the life was denied him—and with the aid of his father and a friendly auctioneer collected prints, then to be picked up cheap, showing from the very first, as he afterwards related, a complete independence of the pseudo-classic taste of the day. At four he had had his first vision, when “God put his forehead to the window, which set him screaming.” At eight or ten he saw a tree filled with angels, and angelic figures walking among haymakers. “The child is father to the man.”

At the age of fourteen Blake was apprenticed to the engraver Basire. Ryland had been thought of, but Blake, according to a story which he must have narrated, but may not improbably have imagined, demurred, declaring that the fashionable engraver looked as if he would one day be hanged, as he actually was. Basire’s practice lay chiefly in engraving antiquities, and the last five years of Blake’s apprenticeship were chiefly spent in drawing tombs and architectural details in Westminster Abbey a most advantageous discipline, which imbued his mind with the Gothic spirit, an influence already in the air, evincing itself in Götz von Berlichingens, Rowley Poems, Percy Relics, and Castles of Otranto; and, by directing him to English history and Shakespeare, powerfully[9] stimulated and felicitously guided the poetical genius of which he was shortly to give proof. He drew, Malkin tells us, the monuments of kings and queens in every point of view he could catch, frequently standing on them. The heads he considered as portraits, and all the ornaments appeared as miracles of art to his Gothicised imagination. Nor could a better environment for a mystic be desired than the venerable and generally solitary temple, “the height, the space, the gloom, the glory,” with its music, its memories, and its constant sense of the presence of the dead. The bent of his mind at the time is shown by his first engraving, Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion, copied, as he states, from a scarce Italian print. If this was indeed the case, it may be queried whether the title at least was not his—Joseph, according to the legend, having been the first missionary to Britain. The original, if original there was, certainly was not the work of Michael Angelo, to whom Blake chose to attribute it. Scarcely was he out of his articles than he produced (1779) two engravings from the history of England, The Penance of Jane Shore and King Edward and Queen Eleanor. These were after two water-colour drawings, selected from a much greater number with which he had amused the leisure hours of his apprenticeship. Mr. Gilchrist says that these and other works of the period have little of the peculiar Blakean quality, except the striking design Morning, or Glad Day, dated 1780, a facsimile of which is given here. This, indeed, is Blake all over, and would have made an excellent frontispiece for the poems with which he was about to herald the dawn of a new era in English poetry, though in all probability designed as an illustration of the lines in Romeo and Juliet;

A naked Apollo-like figure, wearing the dawn for a halo, in whom one fancifully traces a resemblance to Goethe, alights throbbing with joy and victory on the peak of a mountain, while the waning moon, as would seem, sets behind him, and a winged beetle scuds away.

The poems to which reference has been made had meanwhile been slowly accumulating; if the language of the advertisement which heralded their publication is to be taken literally, they were now complete. Before appearing as a poet, however, Blake had to undergo his[10] probation as a lover. He became enamoured of a pretty girl variously called Polly or Clara Woods. She rejected him. He fell into a melancholy, and was sent to Richmond for change of air. There he lodged with a nursery gardener named Boucher. The daughter of the house, Catherine, had been frequently asked whom she would like to marry, and had always replied that she had not seen the man. Coming on the night of Blake’s arrival into the room where he was sitting with the rest of the family, she grew faint from the presentiment that she beheld her destined husband. On subsequently hearing of his disappointment with Clara Woods, she told him that she pitied, and he told her that he loved. They were married on August 18, 1782, Blake having, it is said, proved their mutual constancy by refraining from seeing her for a year, while he was toiling to save enough to render their marriage not utterly imprudent. His first care afterwards was to teach her to read and write, to which he afterwards added enough of the pictorial art to enable her to colour his drawings. A more devoted wife never lived, though her devotion wore in the eyes of strangers an aspect of formality, and was always tinged with awe.

Poetical Sketches, 1783, were the first-fruits of Blake’s genius, composed, as asserted in the advertisement prefixed by his friends, between 1768 and 1777.[2] They are the only examples of his literary work devoid of artistic illustration; we ought not, consequently, to spend much time upon them, yet they are the most memorable of his works, for they are nothing short of miraculous, and alone among his productions mark an era. For a hundred and thirty years English poetry had been mainly artificial, the product of conscious effort ranging down from the superb art of Paradise Lost to the prettinesses of Pope’s imitators, but seldom or never wearing the aspect of a spontaneous growth. This young obscure engraver was the first to show that it was still possible to sing as the bird sings; he and no other was the morning star which announced the new day of English poetry. Had even the verses been of inferior quality, such inspiration would have sufficed for fame, but Blake is as exquisite as original, and warbles such nightingale notes as England had not heard since Andrew Marvell forsook song for satire. The songs of Dryden, indeed, have great merit, but how they savour of the study compared with the artless melody of a strain like this!

This is such a song as Marlowe might have written, but for a delicate eighteenth-century suggestion in the style, whose aroma is not quite that of the Elizabethan era. It is none the less one of the pieces which none but Blake could have produced. The characteristics of his style, indeed, are much less apparent in this early volume than in his subsequent productions. They are most conspicuous in the Mad Song, but a more pleasing if less intense example is the following:

SONG.

Not the least remarkable of the Poetical Sketches are “Samson” and other short pieces in blank verse. They are marvellously Tennysonian; if imitation there was, it obviously was not on Blake’s part. Who would have hesitated to ascribe these lines, addressed to the Evening Star, to the Laureate?

Even more marvellous than the sentiment is the metre, which cannot be judged by a short passage. Well might it be said, “Thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent, and revealed them unto babes,” when the secret of melodious blank verse, withheld since the Civil War from all the highly cultured and in many respects highly gifted bards of England, is disclosed on the sudden to this half-educated young man. It is exemplified on a larger scale by the accompanying fragments of an intended tragedy on Edward the Third, which proves two things: first, that Blake was destitute of all dramatic faculty; secondly, that, notwithstanding, few have so thoroughly assimilated Shakespeare. Shakespeare stands almost alone among great poets in having had hardly any direct imitators. Every one, of course, has profited by the study of his art; but those most deeply indebted to him in this respect have felt the least disposed to reproduce his style. The reason is evident. Other writers are partial, Shakespeare is universal; the model is too vast for study. A deliberate imitation of Shakespeare would assuredly be a failure: imitation is only practicable when it is not deliberate but unconscious, the effluence of a mind so saturated with Shakespeare that it can for the time only express itself in Shakespearian numbers, and think under Shakespearian forms. Blake must have been in such a situation when he attempted Edward the Third, the direct fruit[14] of his roamings among the regal tombs in the Abbey with Shakespeare’s historical plays in his hand. The drama is childish, but the feeling approaches Shakespeare as nearly as Keats’s early poems approach Spenser. The imitation, being spontaneous and unsought, is never senile, but every line reveals a youth whose soul is with Shakespeare, though his body may be in Golden Square. Yet the reproduction of Shakespeare’s manner is never so exact as to conceal the fact that the poet is writing in the eighteenth and not in the sixteenth century. The following passage may serve as an example both of the closeness of Blake’s affinity with Shakespeare and of the nuances of difference that serve to vindicate his originality.

This is beautiful description, sentiment and metre, but these beauties sum up the attractions of Blake’s dramatic fragment. The dramatic element is wanting, there is no action. This deficiency runs through his whole work, pictorial as well as literary, and explains why one capable of such sublime conceptions was nevertheless incapable of taking rank with the Miltons and Michael Angelos. His productions are full of tremendous scenes, the strivings and agonies of colossal unearthly powers realised by his own mind with a vividness which proves the intensity of his conceptions. Yet he seldom impresses the beholder with any sentiment of awe or terror. The cause is not solely the fantastic character of these conceptions, for the effect is the same when he deals with mankind, and represents it in the most thrilling crises of which humanity is capable. His representation of the plague, for instance, engraved in Gilchrist’s biography, excites strong interest and curiosity, but nothing of the shuddering dismay with which we should view such a[15] scene in actual life, and which is so powerfully conveyed in such works as Géricault’s Wreck of the Medusa and Poole’s Solomon Eagle. The reason seems to be that Blake was not only a visionary but also a mystic, and that mysticism is hardly compatible with tragic passion. The visionary, as in the instances of Dante and Bunyan, may realise every detail of his ideal conceptions with the force of actual perception, but it is the very essence of the mystic’s creed that things are not what they seem, and the man who knows himself to be depicting a hieroglyphic will never grasp his subject with the force of him who feels that he is dealing with a concrete reality. The Hindoos are a nation of mystics who regard existence as an illusion, and their art labours under the same defects as Blake’s; their drama especially, with all the charm of lovely arabesque, makes nothing of the strongest situations, save when these are of the pathetic order. For although the mystic cannot be exciting, he can be tender: and while Blake’s efforts at the delineation of frantic passion or overwhelming catastrophes usually (there are exceptions) leave us unmoved, nothing can be more pathetic than some of his delineations, such, for example, as the famous illustration to Blair, of an old man approaching the grave.

It seems almost strange that verses, as contrary to the spirit of the age that gave them birth as prophetic of the ideals of the age to come, should have found friends willing to defray their cost. If, however, it is true that Flaxman was among these friends, Blake had met with one congenial spirit. A clergyman named Matthews, incumbent of Percy Chapel, Charlotte Street, is mentioned as another patron, and as the writer of the well-meaning but too apologetic preface. Through him Blake seems to have become acquainted with Flaxman. To the few then able to appreciate the poems, they might well have seemed indicative of a great poetical career, for they are exactly the sweet, wild, untaught, prelusive music wherewith youth, as yet unschooled by criticism and unawakened to its really profound problems, is wont to essay its art. Why was it that Blake, though rivalling these early attempts in his Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, never progressed further; and in by far the greater part of his subsequent poetry went off altogether upon a wrong track, so far at least as concerned poetry? Partly, we think, because his mind was almost entirely deficient in the plastic element. He could[16] reproduce a scene ready depicted for him, as in his illustrations to Job; he could embody a solitary thought with exquisite beauty, whether in poetry or in painting; but he could not combine his ideas into a whole. His faculty was purely lyrical, and when this evanescent endowment forsook him, devoid as he was of all plastic literary power, he had no Oenone or Ulysses to replace his Claribels and Eleanores. His verse became a mere accompaniment of his pictorial art, and harmonising with its vagueness and obscurity, necessarily lacked the symmetry with which a colourist can dispense, but which is essential to a poet. Even more remarkable than the music of Blake’s early verses, unparalleled in their age, is the fact, vouched for by J. T. Smith, the biographer of Nollekens and Keeper of Prints at the British Museum, that he had composed tunes for them, which he could only repeat by ear from his ignorance of musical notation. Some of these, Smith says, were exquisitely beautiful.

At the appearance of the Poetical Sketches (1783), Blake had for a year been a married man, and was actively striving to make a living as an engraver. Most of his work of this nature at this time was executed after Stothard. It cannot be disputed that this graceful artist largely influenced Blake’s style in its more idyllic aspects; whether, as he was afterwards inclined to assert, Stothard’s invention owed something to him is not easy to determine. In 1784 he lost his father, a mild, pious man, who had well performed his duty to his son. Blake’s elder brother James took his business, and the artist, who had probably inherited some little property, returned from Green Street to Broad Street, and, establishing himself next door to his brother, launched into speculation as a print-seller in partnership with a former fellow apprentice named Parker, taking his brother Robert as a gratuitous pupil. In 1785 he sent four drawings to the Academy. Three, illustrative of the story of Joseph, were shown in the International Exhibition of 1862, and are described by Gilchrist as “full of soft tranquil beauty, specimens of Blake’s earlier style; a very different one from that of his later and better-known works.” This is probably as much as to say that he then wrought much under the influence of Stothard, after whom he engraved the subject from David Simple given here; for the earlier design illustrative of the passage in Romeo and Juliet is characteristically Blakean. Mr. Gilchrist adds,[17] “the design is correct and blameless, not to say tame (for Blake), the colour full, harmonious and sober.” Mr. Rossetti says that the figure of Joseph, in the third drawing, “is especially pure and impulsive.”

Illustration from “David Simple.” Engraved by W. Blake after T. Stothard, R.A.

In 1787 Blake’s experiment in print-selling came to an end, through disagreements, it is said, with his partner; but as neither appears to have afterwards pursued the calling, it is probable that it had never been profitable. Parker obtained some distinction as an engraver, chiefly after Stothard, and died in 1805. In February, 1787, Blake had sustained a severe loss in the death of his brother and pupil Robert. Blake himself nursed the patient for some weeks, and when at last the end[18] came, it is not surprising that he should have beheld his brother’s spirit “arise and clap its hands for joy.” Not long after, as he asserted, the spirit appeared to him in a dream, and revealed to him that process of printing from copper plates which, as we shall see, had the most decisive influence upon his work as an artist. Writing to Hayley in 1800, he says, “Thirteen years ago I lost a brother, and with his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the spirit, and see him in remembrance in the regions of my imagination. I hear his advice, and even now write from his dictate.” “The ruins of Time,” he finely subjoins, “build mansions in Eternity.”

From this time Blake’s sole assistant was his wife, whom he carefully instructed, and who tinted many of the coloured drawings which henceforth form the more characteristic portion of his work. After giving up his business as a print-seller, he removed from Broad Street to 28, Poland Street. Messrs. Ellis and Yeats conjecture that this may have been to escape the blighting influence of his commercial brother next door, but it is more probable that his venture had impoverished him, and that he was obliged to give up housekeeping.

Blake’s Technical Methods—“Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience”—Life in Poland Street and in Lambeth—Mystical Poetry and Art.

It was during his residence in Poland Street that Blake first appeared in that mingled character of poet and painter which marks him off so conspicuously from other painters and other poets. Painting has often been made the handmaid of poetry; it was Blake’s idea, without infringing upon this relationship, to make poetry no less the handmaid of painting by employing his verse, engraved and beautified with colour, to enhance the artistic value of his designs, as well as to provide them with the needful basis of subject. The same principle may probably be recognised in those Oriental scrolls where the graceful labour of the scribe is as distinctly a work of art as the illustration of the miniaturist; but of these Blake can have known nothing. Necessity was with him the mother of invention. Since the appearance of Poetical Sketches he had written much that he desired to publish—but how to pay for printing? So severely had he suffered by his unfortunate commercial adventure that when at length, as he firmly believed, the new process by which his song and his design could be facsimiled together was revealed by his brother’s spirit in a dream, a half-crown was the only coin his wife and he possessed between them in the world. One shilling and tenpence of this was laid out in providing the necessary materials.

The technical method to which Blake now resorted is thus described by Mr. Gilchrist:[20] “It was quite an original one. It consisted of a species of engraving in relief, both words and designs. The verse was written and the designs and marginal embellishments outlined on the copper with an impervious liquid, probably the ordinary stopping-out varnish of engravers. Then all the white parts or lights, the remainder of the plate that is, were eaten away with aquafortis or other acid, so that the outline of letter and design was left prominent, as in stereotype. From these plates he printed off in any tint, yellow, brown, blue, required to be the prevailing or ground colour in his facsimiles; red he used for the letterpress. The page was then coloured up by hand in imitation of the original drawing with more or less variety of detail in the local hues. He ground and mixed his water-colours himself on a piece of statuary marble, after a method of his own, with common carpenter’s glue diluted. The colours he used were few and simple: indigo, cobalt, gamboge, vermilion, Frankfort-black freely, ultramarine rarely, chrome not at all. These he applied with a camel’s-hair brush, not with a sable, which he disliked. He taught Mrs. Blake to take off the impressions with care and delicacy, which such plates signally needed; and also to help in tinting them from his drawings with right artistic feeling; in all of which tasks she, to her honour, much delighted. The size of the plates was small, for the sake of economising copper, something under five inches by three. The number of engraved pages in the Songs of Innocence alone was twenty-seven. They were done up in boards by Mrs. Blake’s hand, forming a small octavo; so that the poet and his wife did everything in making the book, writing, designing, printing, engraving,—everything except manufacturing the paper; the very ink, or colour rather, they did make. Never before, surely, was a man so literally the author of his own book.”

The total effect of this process is tersely expressed by Mr. Rossetti, “The art is made to permeate the poetry.” It resulted in the publication of Songs of Innocence in 1789, two years after its discovery or revelation. Other productions, of that weird and symbolic character in which Blake came more and more to delight, followed in quick succession. These will claim copious notice, but for the present we may pass on to Songs of Experience, produced in 1794, so much of a companion volume to Songs of Innocence that the two are usually found within the same cover. Neither attracted much attention at the time. Charles Lamb says: “I have heard of his poems, but have never seen them.” He is, however, acquainted with “Tiger, tiger,” which he pronounces “glorious.” The price of the two sets when issued together was from thirty shillings to two guineas—an illustration of the material service which Art can render[21] to Poetry when it is considered that, published simply as poems, they would in that age have found no purchasers at eighteenpence. This price was nevertheless absurdly below their real value, and was enhanced even during the artist’s lifetime. It came to be five guineas, and late in his life friends, from the munificent Sir Thomas Lawrence downwards, would commission sets tinted by himself at from ten to twenty guineas as a veiled charity.

Of the poems and illustrations in Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience Gilchrist justly declares that their warp and woof are formed in one texture, and that to treat of them separately is like pulling up a daisy by the roots out of the green sward in which it springs. One essential characteristic inspires them both, and may be defined as childish fearlessness, the innocent courage of the infant who puts his hand upon the serpent and the cockatrice. Any one but Blake would have feared to publish designs and verses apparently so verging upon the trivial, and which indeed would have been trivial—and worse, affected—if the emanation of almost any other brain, or the execution of almost any other hand. Being his, their sincerity is beyond question, and they are a valuable psychological document as establishing the possibility of a man of genius and passion reaching thirty with the simplicity of a child. Hardly anything else in literature or art, unless some thought in Shakespeare, so powerfully conveys the impression of a pure elemental force, something absolutely spontaneous, innocent of all contact with and all influence from the refinements of culture. They certainly are not as a rule powerful, and contrast forcibly with the lurid and gigantic conceptions which if we did not remember that the same Dante depicted The Tower of Famine and Matilda gathering Flowers, we could scarcely believe to have proceeded from the same mind. Their impressiveness proceeds from a different source; their primitive innocence and simplicity, and the rebuke which they seem to administer to artifice and refinement. Even great artists and inspired poets, suddenly confronted with such pure unassuming nature, may be supposed to feel as the disciples must have felt when the Master set the little child among them. No more characteristic examples could have been given than “The Lamb” and “Infant Joy” from Songs of Innocence, and “The Fly” and “The Tiger” from Songs of Experience selected for reproduction here from an[22] uncoloured copy in the library of the British Museum. There is frequently a great difference in the colouring of the copies. That in the Museum Print Room is in full rich colour, while others are very lightly and delicately tinted.

From a coloured copy of the “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” British Museum.

It is of course much easier to convey an idea of the merits of Blake’s verse than of his painting, for the former loses nothing by transcription, and the latter everything. The merit of the latter, too, is a variable quantity, depending much upon the execution of the coloured plates. The uncoloured are but phantoms of Blake’s ideas. The general characteristics of his art in these books may be described as caressing[23] tenderness and gentle grace, evinced in elegant human figures, frequently drooping like willows or recumbent like river deities, and in sinuous stems and delicate sprays, often as profuse as delicate. The foliated ornament in “On Another’s Sorrow,” for instance, seems like a living thing, and would almost speak without the aid of the accompanying verse. The figures usually are too small to impress by themselves, and rather seem subsidiary parts of the general design than the dominant factors. They mingle with the inanimate nature portrayed, as one note of a multitudinous concert blends with another. Yet “The Little Girl Found” tells its story by itself powerfully enough; and the innocent Bacchanalianism of the chorus in the “Laughing Song” is conveyed with truly Lyæan spirit and energy.

The prevalent cheerfulness of the Songs of Innocence is of course modified in Songs of Experience. The keynote of the former is admirably struck in the introductory poem:—

Frontispiece of Mary Wollstonecraft’s “Stories.”

This incarnate enigma among men could manifestly be as transparent as crystal when he knew exactly what he wished to say—a remark which may not be useless to the student of his mystical and prophetical writings. The character of Songs of Experience, published in 1794, when he had attained the age so often fatal to men of genius, is conveyed more symbolically, yet intelligibly, in “The Angel”:—

Generally speaking, the Songs of Experience may be said to answer to their title. They exhibit an awakening of thought and an occupation with metaphysical problems alien to the Songs of Innocence. Such a stanza as this shows that Blake’s mind had been busy:—

These ideas, however, are always conveyed, as in the remainder of the poem quoted, through the medium of a concrete fact represented by the poet. Perhaps the finest example of this fusion of imagination and thought is this stanza of the most striking and best known of all the poems, “The Tiger”:—

An evident, though probably unconscious, reminiscence of “When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy,” and like it for that extreme closeness to the inmost essence of things which the author of the Book of Job enjoyed in virtue of the primitive simplicity of his age and environment, and Blake through a childlike temperament little short of preternatural in an age like ours. It may be added, that although the pieces in Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience are of very unequal degrees of poetical merit, none want the infallible mark of inspired poetry—spontaneous, inimitable melody.

Both the simplicity and the melody, however, are absent from the remarkable works with which Blake had been occupying himself during the interval between the publication of the two series of his songs, which, with their successors, have given him a peculiar and unique reputation in their own weird way, but could not by themselves have given him the reputation of a poet. Blake’s plain prose, as we shall see, is much more effective. In a strictly artistic point of view, nevertheless, these compositions reveal higher capacities than would have been inferred from the idyllic beauty of the pictorial accompaniments of Songs of Innocence and Experience. Before discussing these it will be convenient to relate the chief circumstances of Blake’s life during the period of their production, and up to the remarkable episode of his migration to Felpham. They were not memorable or striking, but one of them had considerable influence upon his development. In 1791 he was employed by Johnson, the Liberal publisher of St. Paul’s Churchyard, and as such a minor light of his time, to illustrate Mary Wollstonecraft’s Tales for Children with six plates, both designed and engraved by him, one of which accompanies this essay. They are much in the manner of Stothard. This commission brought Blake as a guest to Johnson’s house, where he became acquainted with a republican coterie—Mary Wollstonecraft, Godwin, Paine, Holcroft, Fuseli—with whose political opinions he harmonised well, though totally dissimilar in temperament from all of them, except Fuseli, who gave him several tokens of interest and friendship. These acquaintanceships, and the excitement of the times, led Blake to indite, and, which is more extraordinary, Johnson to publish, the first of an intended series of seven poetical books on the French Revolution. This, Gilchrist tells us, was a thin quarto, without illustrations, published without Blake’s name, and priced at a shilling. Gilchrist probably derived this information from a catalogue, for he carefully avoids claiming to have seen the book, which seems to have also escaped the researches of all Blake’s other biographers. It must be feared that it is entirely lost. Gilchrist must, however, have known something more of it if his assertion that the other six books[28] were actually written but not printed, “events taking a different turn from the anticipated one,” is based upon anything besides conjecture.

9 I want! I want! 10 Help! Help!

11 Aged Ignorance. 15 Death’s Door.

In 1793 Blake removed from Poland Street to Hercules Buildings, Lambeth, then a row of suburban cottages with little gardens. Here he engraved his friend Flaxman’s designs for the Odyssey, to replace plates engraved by Piroli and lost in the voyage from Italy, whence Flaxman[29] had returned after seven years’ absence. In 1795 he designed three illustrations for Stanley’s translation of Burger’s “Lenore,” and in 1796 executed a much more important work, 537 drawings for an edition of Young’s Night Thoughts projected by a publisher named Edwards. Forty-three were engraved and published in 1797, but the undertaking was carried no further for want of encouragement, and the designs, after remaining long in the publisher’s family, eventually came into the hands of Mr. Bain of the Haymarket, who is still the possessor. The most important are described by Mr. Frederic Shields in the appendix to the second volume of Gilchrist’s biography. Mr. Shields’ descriptions are so fascinating[3] that from them alone one would be inclined to rate the drawings very high: but Mr. Gilchrist thinks these ill adapted for the special purpose of book illustration which they were destined to subserve, and reminds us that the absence of colour is a grave loss. Blake is said to have been paid only a guinea a plate for the forty-three engravings, on which he worked for a year. The Lambeth period, however, seems not to have been an unprosperous one, for he had many pupils. Several curious anecdotes of it were related after his death on the alleged authority of Mrs. Blake, but their truth seems doubtful. It is certain that during this period he met with the most constant of his patrons, Mr. Thomas Butts, who for nearly thirty years continued a steady buyer of his drawings, and but for whom he would probably have fallen into absolute distress.

It is now time to speak of the literary works—“pictured poesy,” like the woven poesy of The Witch of Atlas—produced during this period. In 1789, the year of publication of the Songs of Innocence, the series opens with Thel. In 1790 comes The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; in 1793, The Gates of Paradise, The Vision of the Daughters of Albion, and America; in 1794, Europe, A Prophecy, and Urizen; in 1795, The Song of Los, and The Book of Ahaniah. In 1797 Blake seems to have written, or to have begun to write, the mystical poem ultimately entitled Vala, never published by him, and more than fifty years after his death found [30]in Linnell’s possession in such a state of confusion that it took Messrs. Ellis and Yeats days to arrange the MS., which they fondly deem to be now in proper order. It is printed in the third volume of their work on Blake. Tiriel is undated, but would seem to be nearly contemporary with Thel.

The Gates of Paradise constitutes an exception to the general spirit of the works of this period, the accompanying text, though mystical enough, being lyrical and not epical. The seventeen beautiful designs, emblematical of the incidents necessarily associated with human nature, are well described by Allan Cunningham as “a sort of devout dream, equally wild and lovely.”

The merits of this remarkable series of works will always be a matter of controversy. “Whether,” as Blake himself says, “whether this is Jerusalem or Babylon, we know not.” It must be so, for they are purely subjective, there is no objective criterion; they admit of comparison with nothing, and can be tested by no recognised rules. In the whole compass of human creation there is perhaps hardly anything so distinctively an emanation of the mind that gave it birth. Visions they undoubtedly are, and, as Messrs. Ellis and Yeats well say, they are manifestly not the production of a pretender to visionary powers. Whatever Blake has here put down, pictorially or poetically, is evidently a record of something actually discerned by the inner eye. This, however, leaves the question of their value still open. To the pictorial part, indeed, almost all are agreed in attaching a certain value, though the warmth of appreciation is widely graduated. But literary estimation is not only discrepant but hostile; some deem them revelation, others rhapsody. The one thing certain is the general tendency towards Pantheism which Mr. Swinburne has made the theme of an elaborate essay. To us they seem an exemplification of the truth that no man can serve two masters. Blake had great gifts, both as poet and artist, and he aspired not only to employ both, but to combine both in the same work. At first this was practicable, but soon the artistic faculty grew while the poetical dwindled. Not only did the visible speech of painting become more important to him than the viewless accents of verse, but his poetry became infected with the artistic method. He allowed a latitude to his language which he ought to have reserved for his form and colour, and became as hieroglyphic[31] in a speech where hieroglyphs are illegitimate as in one where they are permissible. This is proved by the fact that the decline in the purity of poetical form and in the perspicuity of poetical language proceed pari passu. Thel, the earliest, is also both the most luminous and the most musical of these pieces. Could Blake have schooled himself to have written such blank verse as he had already produced in Edward the Third and Samson, Thel would have been a very fine poem. Even as it is its lax, rambling semi-prose is full of delicate modulations:

In every succeeding production, however, there is less of metrical beauty, and thought and expression grow continually more and more amorphous. Blake may not improbably have been influenced by Ossian, whose supposed poems were popular in his day, and from whom some of his proper names, such as Usthona, seem to have been adopted. Many then deemed that Ossian had demonstrated form to be a mere accident of poetry instead of, as in truth it is, an indissoluble portion of its essence. There is certainly a strong family resemblance between Blake’s shadowy conceptions and Ossian’s misty sublimities. On the other hand, he may be credited with having made a distinguished disciple in Walt Whitman, who would not, we think, have written as he did if Blake had never existed. What was pardonable in one so utterly devoid of the sentiment of beautiful form as Whitman, was less so in one so exquisitely gifted as Blake. Both derive some advantages from their laxity, especially the poet of Democracy, but both suffer from the inability of poetry, divorced from metrical form, to take a serious hold upon the memory. One reads and admires, and by and by the sensation is of the passage of a great procession of horsemen and footmen and banners, but no distinct impression of a single countenance.

The general effect of these strange works upon the average mind is correctly expressed by Gilchrist, when he says, speaking of Europe:[32] “It is hard to trace out any distinct subject, any plan or purpose, or to determine whether it mainly relates to the past, the present, or things to come. And yet its incoherence has a grandeur about it as of the utterance of a man whose eyes are fixed on strange and awful sights, invisible to bystanders.” What, then, did Blake suppose himself to behold? Messrs. Ellis and Yeats have devoted an entire volume of their three-volume work on Blake to the exposition of his visions. Their comment is often highly suggestive, but it is seldom convincing. When the right interpretation of a symbol has been found, it is usually self-evident. Not so with their explanations, which appear neither demonstrably wrong nor demonstrably right. Not that Blake talked aimless nonsense; we are conscious of a general drift of thought in some particular direction which seems to us to offer a general affinity to the thought of the ancient Gnostics. It would be interesting if some competent person would endeavour to determine whether the resemblance goes any deeper than externals. Blake certainly knew nothing of the Gnostics at first hand, nor is it probable that he could have gained any knowledge of them from the mystical writers he did study, Behmen and Swedenborg. But similar tendencies will frequently incarnate themselves in individuals at widely remote periods of the world’s history without evidence of direct filiation. Even so exceptional a personage as Blake cannot be considered apart from his age, and his age, among its other aspects, was one of mesmerism and illuminism. The superficial resemblance of his writings to those of the Gnostics is certainly remarkable. Both embody their imaginations in concrete forms; both construct elaborate cosmogonies and obscure myths; both create hierarchies of principalities and powers, and equip their spiritual potentates with sonorous appellations; both disparage matter and its Demiurgus. “I fear,” said Blake to Robinson, “that Wordsworth loves nature, and nature is the work of the devil. The devil is in us as far as we are nature.” The chief visible difference, that the Gnostics’ philosophy tends to asceticism, and Blake’s to enjoyment, may perhaps be explained by the consideration that he was a poet, and that they were philosophers and divines. Perhaps the best preparation for any student of Blake who might wish to investigate this subject further would be to read the article in the Dictionary of Christian Biography upon the Pistis Sophia, the only Gnostic book that has come down to us, and one which Blake would have delighted in illustrating. The Gnostic belief in the all-importance of the[33] transcendent knowledge which comes of immediate perception (γνῶσις) reappears in him with singular intensity. “Men are admitted into heaven,” he says, “not because they have curbed and governed their passions, or have no passions, but because they have cultivated their understandings. The fool shall not enter into heaven, let him be ever so holy.” Nothing in Blake, perhaps, is so Gnostic as the strange poem, The Everlasting Gospel, first published by Mr. Rossetti, though many things in it would have shocked the Gnostics.

The strictly literary criticism of Blake’s mystical books may be almost confined to the Book of Thel, for this alone possesses sufficient symmetry to allow a judgment to be formed upon it as a whole. The others are like quagmires occasionally gay with brilliant flowers; but Thel, though its purpose may be obscure, is at all events coherent, with a beginning and an end. Thel, “youngest daughter of the Seraphim,” roves through the lower world lamenting the mortality of beautiful things, including her own. All things with which she discourses offer her consolation, but to no purpose. At last she enters the realm of Death himself.

The effect of the voice of sorrow upon Thel is answerable to that of the spider upon little Miss Muffet. This abrupt conclusion injures the effect of a piece which otherwise may be compared to a strain of soothing music, suggestive of many things, but giving definite expression to none. Messrs. Ellis and Yeats, however, have no difficulty in assigning a meaning. Thel, according to them, is “the pure spiritual essence,” her grief is the dread of incarnation, and her ultimate flight is a return “to the land of pure unembodied innocence from whence she came.” Yet her forsaking this land is represented as her own act, and it is difficult to see[34] how she could have “led round her sunny flocks” in it if she had not been embodied while she inhabited it. At the same time, if Messrs. Ellis and Yeats are right, no interpretation of Blake can be disproved by any inconsistency that it may seem to involve. “The surface,” they say, “is perpetually, as it were, giving way before one, and revealing another surface below it, and that again dissolves when we try to study it. The making of religions melts into the making of the earth, and that fades away into some allegory of the rising and the setting of the sun. It is all like a great cloud full of stars and shapes, through which the eye seeks a boundary in vain.”

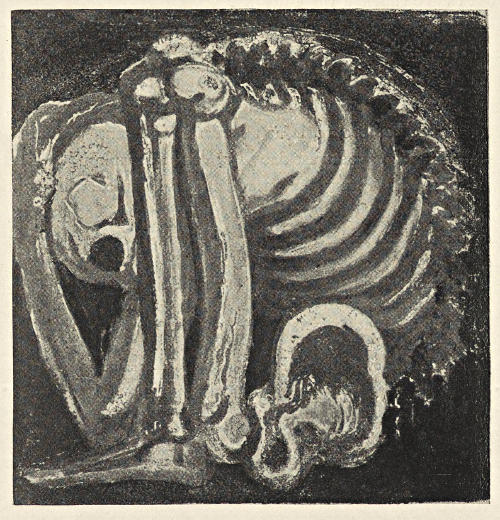

Design from the “Book of Urizen.” By W. Blake.

Mr. Yeats, putting his interpretation of Blake’s symbolism more tersely into the preface to his excellent edition of the Poetical Works, describes it as shadowing forth the endless conflict between the Imagination[35] and the Reason, which, we may add, the Gnostics would have expressed as the strife between the Supreme Deity and the god of this world, the very phrase which Mr. Yeats himself uses in describing Urizen, Blake’s Evil Genius, “the maker of dead law and blind negation,” contrasted as the Gnostics would have contrasted him with Los, the deity of the living world. Blake, therefore, has points of contact with the representatives of the French Revolution on one side, and with Coleridge on the other. Mr. Yeats’s interpretation is in itself coherent and plausible, but the question whether it can be fairly deduced from Blake himself is one on which few are entitled to pronounce, and the causes of Blake’s obscurity are not so visible as its consequences. To us, as already said, much of it appears to arise from his imperfect discrimination between the provinces of speech and of painting. His discourse frequently seems a hieroglyphic which would have been more intelligible if it could have been expressed in the manner proper to hieroglyphics by pictorial representation. As Mr. Smetham says of some of the designs, “Thought cannot fathom the secret of their power, and yet the power is there.” It seems evident that the poem, when a complete lyric, generally preceded the picture in Blake’s mind, and that the latter must usually be taken as a gloss, in which he seeks to illustrate by means of visible representation what he was conscious of having left obscure by verbal expression. The exquisite song of the Sunflower, for example, certainly existed before the very slight accompanying illustration.

The first of these stanzas is perfectly clear: the second requires no interpretation to a poetical mind, but will not bear construing strictly, and its comprehension is certainly assisted by the slight fugitive design lightly traced around the border. Generally the pictorial illustration of Blake’s thought is much more elaborate, but in Songs of Innocence and[36] Experience it almost always seems to have grown out of the poem. In the less inspired Prophetical Books, on the other hand, the pictorial representation, even when present only to the artist’s mind, seems to have frequently suggested or modified the text. An example may be adduced from The Book of Thel.

Blake had noted the external likeness of the convolutions of the ear to the convolutions of a whirlpool; therefore the ear shall be described as actually being what it superficially resembles, and because the whirlpool sucks in ships, the ear shall suck in creations. It must also be remembered that Blake’s belief that his works were given him by inspiration prevented his revising them, and that they were stereotyped by the method of their publication. No considerable productions of the human mind, it is probable, so nearly approach the character of absolutely extemporaneous utterances.

Before passing from the literary to the artistic expression of Blake’s genius in these books, something must be said of the remarkable appendix to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell entitled Proverbs of Hell. These are a number of aphoristic sayings, impregnated with Blake’s peculiarities of thought and expression, but for the most part so shrewd and pithy as to demonstrate the author’s sanity, at least at this time of his life. The following are some of the more striking:—

These are not the scintillations of reason which may occasionally illumine the chaos of a madman’s brain, but bespeak a core of good[37] sense quite inconsistent with general mental disturbance, though sufficiently compatible with delusion on particular subjects. With incomparable art, Shakespeare has imparted a touch of wildness to Hamlet’s shrewdest sayings; but Blake speaks rather as Polonius would have spoken if it had been possible for Polonius to speak in tropes.

From the difficult subject of the interpretation of Blake’s mystical designs we pass with satisfaction to the artistic qualities of the designs themselves. On this point there is an approximation to unanimity. To some the sublime, to others the grotesque, may seem to preponderate, but all will allow them to be among the most remarkable and original series of conceptions that ever emanated from a mortal brain. To whatever exceptions they may be liable, it enlarges one’s apprehension of the compass of human faculties to know that human faculties have been adequate to their production. They may be ranked with the most imaginative passages of Paradise Lost, and of Byron’s Cain as an endeavour of the mind to project itself beyond the visible and tangible, and to create for itself new worlds of grandeur and of gloom in height and abyss and interstellar space. Wonderful indeed is the range of imagination displayed, even though we cannot shut our eyes to some palpable repetitions. In the opinion, however, of even so sympathetic a critic as Dr. Wilkinson, Blake deserves censure for having degenerated into mere monstrosity. “Of the worst aspect of Blake’s genius,” he says, “it is painful to speak. In his Prophecies of America, his Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and a host of unpublished drawings, earth-born might has banished the heavenlier elements of art, and exists combined with all that is monstrous and diabolical. The effect of these delineations is greatly heightened by the antiquity which is engraven on the faces of those who do and suffer in them. We have the impression that we are looking down into the hells of the ancient people, the Anakim, the Nephilim, and the Rephaim. Their human forms are gigantic petrifactions, from which the fires of lust and intense selfish passion have long dissipated what was animal and vital, leaving stony limbs and countenances expressive of despair and stupid cruelty.” We, on the other hand, should rather criticise Blake for having failed to be as appalling as he meant to be. His power, as it seems to us, consisted rather in the vivid imagination than in the[38] actual rendering of scenes of awe and horror. Far inferior artists have produced more thrilling effects of this sort with much simpler means. It would be wrong to say that his visions appear unreal, but they do appear at a remove from reality, a world seen through a glass darkly, its phantasm rather than its portrait. This, however, only applies to the inventions of Blake’s own brain, which, if we may judge by the moderate development of the back head in Deville’s cast, lacked the force of the animal propensities requisite for the portrayal of cruelty and horror. He could render the conceptions of others with startling force—witness the impressive delineation reproduced by us of the Architect of the Universe at work with his compasses; and the simple pencil outline of Nebuchadnezzar in Mr. Rossetti’s book, engraved by Gilchrist, where the human quadruped creeps away with an expression of overwhelming and horror-stricken dismay. This power of interpretation was to find yet finer expression in the illustration of the Book of Job.

Blake’s technical defects are indicated by Messrs. Ellis and Yeats as consisting mainly in imperfect treatment of the human form from want of anatomical knowledge. He had always disliked that close study of the life which alone could have made him an able draughtsman; it “obliterated” him, he said, and had resolved to quarrel with almost all the artists from whom he might have learned. It must be remembered in his excuse that consummate colouring and consummate draughtsmanship are seldom found associated. Those who may feel disappointed with the reproductions of Blake’s mystical designs must also remember that these are but shadows of the artist’s thought, which needed for its full effect the application of colour by his own hand. “Much,” says Dante Rossetti, “which seems unaccountably rugged and incomplete is softened by the sweet, liquid, rainbow tints of the coloured copies into mysterious brilliancy.” The effect thus obtained may perhaps be best shown by Mr. Gilchrist’s eloquent description of the illuminated drawings in Lord Crewe’s copy of America. “Turning over the leaves, it is sometimes like an increase of daylight in the retina, so fair and open is the effect of particular pages. The skies of sapphire, or gold, rayed with hues of sunset, against which stand out leaf or blossom, or pendent branch, gay with bright-plumaged birds; the strips of emerald sward below, gemmed with flower and lizard, and enamelled[39] snake, refresh the eye continually. Some of the illustrations are of a more sombre kind. There is one in which a little corpse, white as snow, lies gleaming on the floor of a green over-arching cave, which close inspection proves to be a field of wheat, whose slender interlacing stalks, bowed by the full ear and by a gentle breeze, bend over the dead infant. The delicate network of stalks, which is carried up one side of the page, the main picture being at the bottom, and the subdued yet vivid green light shed over the whole, produce a lovely decorative effect. Decorative effect is, in fact, never lost sight of, even where the motive of the design is ghastly or terrible.” Whatever the imperfections of Blake’s peculiar sphere, it was his sphere, and probably the only department of art in which he could have obtained greatness even if his technical accomplishment had been as complete as it was the reverse. When painting on more orthodox lines he is often surprisingly tame and conventional. How remote he was from the inane when he could revel in his own conceptions may, notwithstanding the tremendous disadvantages inherent in reproduction, be judged from the illustrations to his mystical books selected for this monograph, the frontispiece and Plate IV. of Thel, and the two subjects from America.

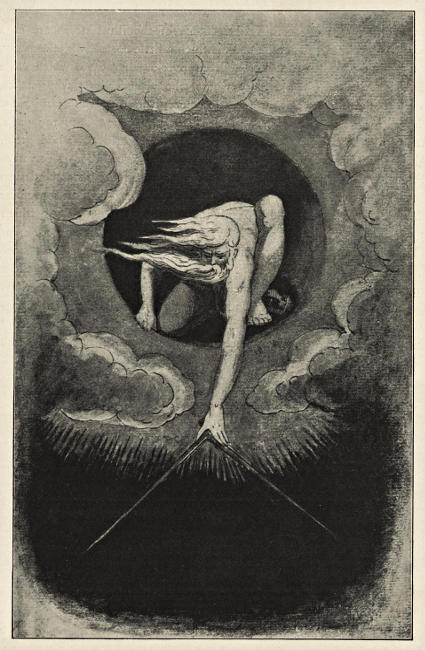

The Ancient of Days setting a Compass to the Earth. From a water-colour drawing by W. Blake. British Museum.

Blake’s removal to Felpham—Intercourse with Hayley—Return to London—“Jerusalem”—Connection with Cromek—Illustrations of Blair’s “Grave”—Illustration of Chaucer’s “Canterbury Pilgrims”—Exhibition of his Works and “Descriptive Catalogue.”

Blake was now about to make a change in his external environment, which would have been momentous to any artist whose themes had been less exclusively discerned by the inner eye. It is an extraordinary fact, but there is absolutely no evidence that the poet who “made a rural pen” had as yet ever seen the country beyond the immediate neighbourhood of London. It is vain to speculate upon the precise modification which might have been wrought in his genius by rural nurture or foreign travel. Now he was actually to become a denizen of the country for some years. An introduction from Flaxman had made him acquainted with William Hayley, a Sussex squire and scholar, now chiefly remembered as his patron and the biographer of Cowper, but esteemed in his own day as one of the best representatives of English poetry at what seemed the period of its deepest decrepitude, though he is unaccountably omitted in Porson’s catalogue of the bards of the epoch.[4] Hayley, having lost his son, a pupil of Flaxman, and his friend Cowper within a week of each other in the spring of 1800, resolved to solace his grief by writing Cowper’s life, and suggested that Blake should live near him during the progress of the work to execute the engravings by which it was to be illustrated. In August, 1800, Blake removed from Lambeth to Felpham, near Bognor, on the Sussex coast, where Hayley occupied a marine villa, his own residence at Eastham being let on account of [42]the embarrassment of his affairs. The cottage was not provided by him for Blake, but the rent was paid by Blake himself. The change from Lambeth to a beautiful country of groves, meadows, and cornfields, with sails in the distance,

affected Blake with enthusiastic delight. “Felpham,” he wrote to Flaxman, “is a sweet place for study, because it is more spiritual than London. Heaven opens here on all sides her golden gates; her windows are not obstructed by vapours; voices of celestial inhabitants are more distinctly heard, and their forms more distinctly seen, and my cottage is also a shadow of their houses.” He continues: “I am more famed in Heaven for my works than I could well conceive. In my brain are studies and chambers with books and pictures of old, which I wrote and painted in ages of eternity before my mortal life; and those works are the delight and study of archangels. Why then should I be anxious about the riches or fame of mortality?” It is clear that, notwithstanding his theories of the deadness of the material creation, Blake valued natural beauty as an instrument for bringing him into more intimate connection with the visionary world. At first the desired effect was fully produced. Blake began to compose, or rather, according to his own account, to take down from supernatural dictation the Jerusalem, the most important in some respects of his mystical writings. Walking by the shore—the very shore where Cary was afterwards to encounter Coleridge—he habitually met Moses and the Prophets, Homer, Dante, and Milton. “All,” he said, “majestic shadows, gray but luminous, and superior to the common height.” A description so fine, that some may be inclined to deem it something more than a mere fancy. Unfortunately he also fell in with a fairies’ funeral, a stumbling-block to the most resolute faith. By and by, however, the dampness of the cottage proved provocative of rheumatism, and, which was much more disastrous, the mental climate proved unsympathetic. Hayley’s patronage of so strange a creature as he must have thought Blake does him the highest honour. He appears throughout, not only as a very kind man, but, what is less usual in a literary personage,[43] a very patient one. He actually instructed Blake in Greek. His kindness and patience did not, however, render him any the better poet; he was an elegant dilettante at the best, and Blake must have chafed at the obligation under which he felt himself to illustrate his verses. One ballad of some merit, however, “Little Tom the Sailor,” inspired Blake with a striking if somewhat rude design, and he adorned Hayley’s library with ideal portraits of illustrious authors. The engraving work which he had to execute for Hayley’s life of Cowper was also little to his taste, but there seems no valid reason to charge him with neglect of it. His own self-reproach, indeed, ran in quite a different channel: he accused himself most seriously of unfaithfulness to his high vocation as a revealer and interpreter of spiritual things. Absence from town led him to write frequently to his friend and patron Butts, and these letters are invaluable indications not only of the frame of his mind at the time, but of its general habit. “I labour,” he says, “incessantly, I accomplish not one-half of what I intend, because my abstract folly hurries me often away while I am at work, carrying me over mountains and valleys, which are not real, into a land of abstraction where spectres of the dead wander. This I endeavour to prevent; I, with my whole might, chain my feet to the world of duty and reality. But in vain! the faster I bind, the lighter is the ballast; for I, so far from being bound down, take the world with me in my flights, and often it seems lighter than a ball of wool rolled by the wind.… If we fear to do the dictates of our angels, and tremble at the tasks set before us, if we refuse to do spiritual acts because of natural fears or natural desires, who can describe the dismal torments of such a state?… Though I have been very unhappy, I am so no longer. I have travelled through perils and darkness not unlike a champion. I have conquered and shall go on conquering. Nothing can withstand the fury of my course among the stars of God and in the abysses of the accuser.” In plain English Hayley strongly advised Blake to give up his mystical poetry and design and devote himself solely to engraving, and Blake looked upon the advice as a suggestion of the adversary. We do not know what Hayley said. If he thought that one of the Poetical Sketches or the Songs of Innocence was worth many pages of Urizen apart from the illustrations,[44] he had reason for what he thought. But Blake’s lyrical gift had all but forsaken him; he was incapable of emitting “wood-notes wild,” and the only way in which he could give literary expression to the inspiration by which he justly deemed himself visited was through his rhythmical form, which to Hayley may well have seemed monstrous. It is highly probable that the pictorial part of Blake’s work found no more favour with Hayley than the poetical; at all events it is very certain that he greatly preferred his engraving, and wished Blake to follow the art by which he had the best prospect of providing for himself. Johnson and Fuseli, by Blake’s own admission, had given the same advice; and an obscure line in one of his rather undignified and splenetic epigrams against his well-intentioned friend may be interpreted as meaning that Hayley had tried to bring his wife’s influence to bear upon him for this end. In any case he lost temper with Hayley, and wrote to Butts (July, 1803): “Mr. Hayley approves of my designs as little as he does of my poems, and I have been forced to insist on his leaving me in both to my own self-will; for I am determined to be no longer pestered with his genteel ignorance and polite disapprobation. I know myself both poet and painter, and it is not his affected contempt that can move to anything but a more assiduous pursuit of both arts.” Two months afterwards he returned to London, but on better terms with Hayley; partly on account of the latter’s generous conduct in providing for his defence against a charge of using seditious language, trumped up against him by a soldier whom he had turned out of his garden. “Perhaps,” he wrote to Butts, “this was suffered to give opportunity to those whom I doubted to clear themselves of all imputation.” The case was tried in January, 1804, and terminated in Blake’s triumphant acquittal. An old man who had attended the trial as a youth said that he remembered nothing of it except Blake’s flashing eye.

The engravings executed by Blake for Hayley during his residence at Felpham were six for the life and letters of Cowper; four original designs for ballads by Hayley, including “Poor Tom,” and six engravings after Maria T. Flaxman for Hayley’s Triumphs of Temper. He did some work for Hayley after his return to town—engravings for the Life of Romney, and original designs for Hayley’s Ballads on Animals—and[45] corresponded with him in a friendly spirit, but the intimacy gradually died away.

Blake was profoundly influenced by his residence at Felpham in one respect; he became acquainted with opposition, and distinctly realised a power antagonistic to his aspirations. He was thus stung into self-assertion, and became hostile to the artists whose aims and methods he was unable to reconcile with his ideas. The first hints of this attitude appear in the praises he bestows upon the work of his own which chiefly occupied him at Felpham, the Jerusalem. “I may praise it,” he says, “since I dare not pretend to be any other than the secretary; the authors are in eternity. I consider it as the grandest poem that this world contains. Allegory addressed to the intellectual powers, while it is altogether hidden from the corporeal understanding, is my definition of the most sublime poetry.” Blake’s allegory so effectually eludes both the reason and the understanding that Messrs. Ellis and Yeats frankly tell us that it is not for a moment to be supposed that their own elaborate interpretation will convey any idea to the mind unless it is read conjointly with the poem; and if such is the commentary what must the text be? If they are right the confusion is greatly increased by a wrong arrangement, and by the numerous interpolations which Blake subsequently introduced into the poem, which, though nominally issued in 1804, was not, they think, actually completed until about 1820. It suffers from being nearer prose than any of his former books. “When this verse was dictated to me,” he says, “I considered a monotonous cadence, like that used by Milton, Shakespeare, and all writers of English blank verse, derived from the modern bondage of rhyming, to be a necessary and indispensable part of the verse. But I soon found that in the mouth of a true orator such monotony was not only awkward, but as much a bondage as rhyme itself.” What can be said of the ears that could find Shakespeare’s and Milton’s blank verse monotonous? The truth is that Blake’s originally exquisite perception of harmony had waned with his lyrical faculty, and he scoffs at what he is no longer able to produce. Yet the general grandiose effect of Jerusalem is undeniable. Little as we can attach any definite idea to it, it simultaneously awes and soothes like one of the great inarticulate voices of nature, the booming of the billows, or[46] the whisper of the winds in the wood. Occasionally we encounter some beautiful little vignette like this:—

This seems an illustration of what we have said of the dependence of Blake’s poetry upon his pictorial imagination, for it is clearly nothing but a magnificent expansion of the midsummer night idyl of the glowworm shining for her mate, “with her little drop of moonlight,” as Beddoes beautifully says.

In artistic merit Jerusalem is fully equal to any of Blake’s works. There is less of the grotesque than in the others, and even more of the impressive. Much, however, depends upon the colouring, which varies greatly in different copies. Mr. Gilchrist warns us that it cannot be judged aright if we have not seen the “incomparable” copy in the possession of Lord Crewe. “It is printed in a warm reddish-brown, the exact colour of a very fine photograph; and the broken blending of the deeper lines with the more tender shadows—all sanded over with a sort of golden mist peculiar to Blake’s mode of execution—makes still more striking the resemblance to the then undiscovered handling of Nature herself.” The general character of the design is excellently described by Gilchrist. “The subjects are vague and mystic as the poem itself. Female figures lie among waves full of reflected stars: a strange human image, with a swan’s head and wings, floats on water in a kneeling attitude and drinks; lovers embrace in an open water-lily; an eagle-headed creature sits and contemplates the sun; serpent-women are coiled with serpents; Assyrian-looking, human-visaged bulls are seen yoked to the plough or the chariot; rocks swallow or vomit forth human forms, or appear to amalgamate with them; angels cross each other over wheels of flame; and flames and hurrying figures wreathe and wind among the lines.” It may indeed, like Blake’s other productions of the kind, be[47] described as a gigantic arabesque, imbued with a passion and pathos not elsewhere attempted in this branch of art.

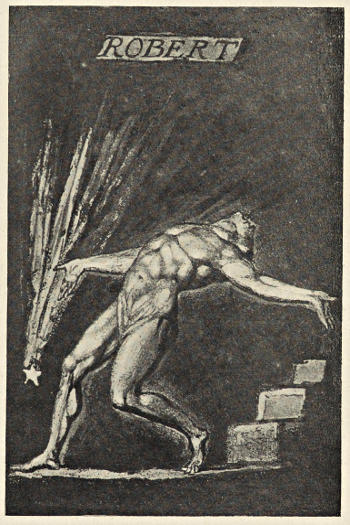

Design from “Milton.” By W. Blake.

The subject of Milton, from which one of our illustrations is selected, is, in Mr. Swinburne’s words, the incarnation and descent into earth and hell of Milton, who represents redemption by inspiration. Something similar, as we have seen, is the idea of Blake’s fine mystical book, Thel,[48] and the pilgrimage through a lower sphere is also found in the oldest Assyrian poetry. The book, like Jerusalem, is dated 1804, but, like its companion, must have been composed at Felpham. Nothing save actual and present contact with country scenes could have inspired such a passage as this, the crown of all Blake’s unrhymed poetry:—

Such a passage shows how greatly Blake might have gained as a poet had he been more intimate with external nature. Very splendid lines might be quoted from “Milton,” such as “A cloudy heaven mingled with stormy seas in loudest ruin,” but they are glowing light upon a black core of obscurity. Mr. Housman’s judgment applies to it as to all the works of its class. “They are the sign chiefly of a beautiful nature wasted for lack of equipment in formulating disputatively what grew out of his better work with all the thoughtlessness and glory of a flower.”[5]

Several lyrical poems printed in Blake’s works may be assigned to this date. Some, such as “The Crystal Cabinet” and “The Mental Traveller,” are extremely mystical; others, such as “Mary,” are of simply human interest; others, such as “Auguries of Innocence,” seem little remote from nonsense. “The Everlasting Gospel” expresses his profoundest ideas with startling crudity. None are wholly unmelodious,[49] but the old bewitching melody has gone from all, unless from the lines introductory to “Milton”:—

Portrait of William Blake. From the engraving by L. Schiavonetti, after T. Phillips, R.A.