Transcriber’s Note

Text on cover added by Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

By HENRY CURWEN.

“In these days, ten ordinary histories of kings and courtiers were well exchanged

against the tenth part of one good History of Booksellers.”—Thomas Carlyle.

WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

London:

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

“History” has been aptly termed the “essence of innumerable biographies;” and this surely justifies us in the selection of our title; but in inditing a volume to be issued in a cheap and popular form, it was manifestly impossible to trace the careers of all the eminent members, ancient and modern, of a Trade so widely extended; had we, indeed, possessed all possible leisure for research, every available material, and a space thoroughly unlimited, it is most probable that the result would have been distinguished chiefly for its bulk, tediousness, and monotony. It was resolved, therefore, in the first planning of the volume, to primarily trace the origin and growth of the Bookselling and Publishing Trades up to a comparatively modern period; and then to select, for fuller treatment, the most typical English representatives of each one of the various branches into which a natural division of labour had subdivided the whole. And, by this plan, it is believed that, while some firms at present growing into eminence may have been omitted, or have received but scant acknowledgment,vi no one Publisher or Bookseller, whose spirit and labours have as yet had time to justify a claim to a niche in the “History of Booksellers,” has been altogether passed over. In the course of our “History,” too, we have been necessarily concerned with the manner of the “equipping and furnishing” of nearly every great work in our literature. So that, while on the one hand we have related the lives of a body of men singularly thrifty, able, industrious, and persevering—in some few cases singularly venturesome, liberal, and kindly-hearted—we have on the other, by our comparative view, tried to throw a fresh, at all events a concentrated, light upon the interesting story of literary struggle.

No work of the kind has ever previously been attempted, and this fact must be an apology for some, at least, of our shortcomings.

H. C.

November, 1873.

| PAGE | |

| THE BOOKSELLERS OF OLDEN TIMES | 9 |

| THE LONGMAN FAMILY Classical and Educational Literature. |

79 |

| CONSTABLE, CADELL, AND BLACK The “Edinburgh Review,” “Waverley Novels,” and “Encyclopædia Britannica.” |

110 |

| JOHN MURRAY Belles-Lettres and Travels. |

159 |

| WILLIAM BLACKWOOD “Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.” |

199 |

| CHAMBERS, KNIGHT, AND CASSELL Literature for the People. |

234 |

| HENRY COLBURN Three-Volume Novels and Light Literature. |

279 |

| THE RIVINGTONS, THE PARKERS, AND JAMES NISBET Religious Literature. |

296 |

| BUTTERWORTH AND CHURCHILL Technical Literature. |

333 |

| EDWARD MOXON Poetical Literature. |

347 |

| KELLY AND VIRTUE The “Number” Trade. |

363viii |

| THOMAS TEGG Book-Auctioneering and the “Remainder Trade.” |

379 |

| THOMAS NELSON Children’s Literature and “Book-Manufacturing.” |

399 |

| SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, AND CO. Collecting for the Country Trade. |

412 |

| CHARLES EDWARD MUDIE The Lending Library. |

421 |

| W. H. SMITH AND SON Railway Literature. |

433 |

| PROVINCIAL BOOKSELLERS York: Gent and Burdekin. Newcastle: Goading, Bryson, Bewick, and Charnley. Glasgow: Fowlis and Collins. Liverpool: Johnson. Dublin: Duffy. Derby: Mozley, Richardson, and Bemrose. Manchester: Harrop, Barker, Timperley, and the Heywoods. Birmingham: Hutton, Baskerville, and “The Educational Trading Co.” Exeter: Brice. Bristol: Cottle. |

441 |

Long ages before the European invention of the art of printing, long even before the encroaching masses of Huns and Visigoths rolled the wave of civilization backward for a thousand years, the honourable trades, of which we aim to be in some degree the chroniclers, had their representatives and their patrons. Without going back to the libraries of Egypt—a subject fertile enough in the pages of mythical history—or to the manuscript-engrossers and sellers of Ancient Greece—though by their labours much of the world’s best poetry, philosophy, and wit was garnered for a dozen centuries, like wheat ears in a mummy’s tomb, to be scattered to the four winds of heaven, when the Mahometans seized upon Constantinople, thenceforth to fructify afresh, and, in connection with the art of printing, as if the old world and the new clasped hands upon promise of a better time, to be mainly instrumental in the “revival of letters”—it will be sufficient for our present purpose to know that there were in Rome, at the time of the Empire, many publishing firms, who, if they could not altogether rival the magnates of Albemarle Street and the “Row,” issued books at least as good, and, paradoxical10 as it may seem, at least as cheaply as their modern brethren.

To the sauntering Roman of the Augustan age literature was an essential; never, probably, till quite modern times was education—the education, at all events, that supplies a capability to read and write—so widely spread. The taste thus created was gratified in many ways. If the Romans had no Mudie, they possessed public libraries, thrown freely open to all. They had public recitations, at which unpublished and ambitious writers could find an audience; over which, too, sometimes great emperors presided, while poets, with a world-wide reputation, read aloud their favourite verses. They had newspapers, the subject-matter of which was wonderfully like our own. The principal journal, entitled Acta Diurna, was compiled under the sanction of the government, and hung up in some place of frequent resort for the benefit of the multitude, and was probably copied for the private accommodation of the wealthy. All public events of importance were chronicled here; the reporters, termed actuarii, furnished abstracts of the proceedings in the law courts and at public assemblies; there was a list of births, deaths, and marriages; and we are informed that the one article of news in which the Acta Diurna particularly abounded was that of reports of trials for divorce. Juvenal tells us that the women were all agog for deluges, earthquakes, and other horrors, and that the wine-merchants and traders used to invent false news in order to affect their various markets. But, in addition to all these means for gratifying the Roman taste for reading, every respectable house possessed a library, and among the better classes the slave-readers (anagnostæ) and the slave-transcribers (librarii) were11 almost as indispensable as cooks and scullions. At first we find that these slaves were employed in making copies of celebrated books for their masters; but gradually the natural division of labour produced a separate class of publishers. Atticus, the Moxon of the period, and an author of similar calibre, saw an opening for his energies in the production of copies of favourite authors upon a large scale. He employed a number of slaves to copy from dictation simultaneously, and was thus able to multiply books as quickly as they were demanded. His success speedily finding imitators, among whom were Tryphon and Dorus, publishing became a recognized trade. The public they appealed to was not a small one. Martial, Ovid, and Propertius speak of their works as being known all the world over; that young and old, women and girls, in Rome and in the provinces, in Britain and in Gaul, read their verses. “Every one,” says Martial, “has me in his pocket, every one has me in his hands.”

Horace speaks of the repugnance he felt at seeing his works in the hands of the vulgar. And Pliny writes that Regulus is mourning ostentatiously for the loss of his son, and no one weeps like him—luget ut nemo. “He composes an oration which he is not content with publicly reciting in Rome, but must needs enrich the provinces with a thousand copies of it.”

School-books, too, an important item in publishing eyes, were in demand at Rome: Juvenal says that “the verses which the boy has just conned over at his desk12 he stands up to repeat,” and Persius tells us that poets were ambitious to be read in the schools; while Nero, in his vanity, gave special command that his verses should be placed in the hands of the students.

Thus, altogether, there must have been a large book-buying public, and this fact is still further strengthened by the cheapness of the books produced. M. Geraud1 concludes that the prices were lower than in our own day. According to Martial the first book of his Epigrams was to be bought, neatly bound, for five denarii (nearly three shillings), but in a cheaper binding for the people it cost six to ten sestertii (a shilling to eighteenpence); his thirteenth book of Epigrams was sold for four sestertii (about eightpence), and half that price would, he says, have left a fair profit (Epig. xiii. 3). He tells us, moreover, that it would only require one hour to copy the whole of the second book,

This book contains five hundred and forty verses, and though he may be speaking with poetical licence, the system of abbreviations did undoubtedly considerably lessen the labour of transcribing, and it would be quite possible, by employing a number of transcribers simultaneously, to produce an edition of such a work in one day.

In Rome, therefore, we see that from the employment of slave labour—and some thousands of slaves were engaged in this work of transcribing—books were both plentiful and cheap.2

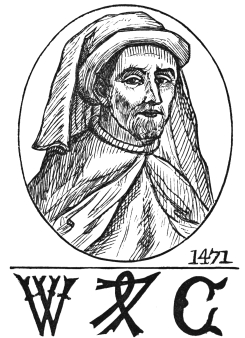

William Caxton. The first printer at Westminster.

1410–1491.

Caxton’s Monogram.

(Facsimile from his Works.)

13 In the Middle Ages this state of things was entirely altered. Men were too busy in giving and receiving blows, in oppressing and being oppressed, to have the slightest leisure for book-learning. Slaves, such as then existed, were valued for far different things than reading and writing; and even their masters’ kings, princes, lords, and other fighting dignitaries, would have regarded a quill-pen, in their mail-gloved hands, as a very foolish and unmanly weapon. There was absolutely no public to which bookmakers could have appealed, and the art of transcribing was confined entirely to a few monks, whose time hung heavily upon their hands; and, as a natural result, writers became, as Odofredi says, “no longer writers but painters,” and books were changed into elaborate works of art. Nor was this luxurious illumination confined to Bibles and Missals; the very law-books were resplendent, and a writer in the twelfth century complains that in Paris the Professor of Jurisprudence required two or three desks to support his copy of Ulpian, gorgeous with golden letters. No wonder that Erasmus says of the Secunda Secundea that “no man can carry it about, much less get it into his head.”

At first there was no trade whatever in books, but gradually a system of barter sprung up between the monks of various monasteries; and with the foundation of the Universities a regular class of copyists was established to supply the wants of scholars and professors, and this improvement was greatly fostered by the invention of paper.

The booksellers of this period were called Stationarii, either from the practice of stationing themselves at booths or stalls in the streets (in contradistinction14 to the itinerant vendors) or from the other meaning of the Latin term statio, which is, Crevier tells us, entrepôt or depository, and he adds that the booksellers did little else than furnish a place of deposit, where private persons could send their manuscripts for sale. In addition to this, indeed as their chief trade, they sent out books to be read, at exorbitant prices, not in volumes, but in detached parts, according to the estimation in which the authors were held.

In Paris, where the trade of these stationarii was best developed, a statute regarding them was published in 1275, by which they were compelled to take the oath of allegiance once a year, or, at most, once every two years. They were forbidden by this same statute to purchase the books placed in their hands until they had been publicly exposed for sale for at least a month; the purchase money was to be handed over direct to the proprietor, and the bookseller’s commission was not to exceed one or two per cent. In addition to the stationarii, there were in Paris several pedlars or stall-keepers, also under University control, who were only permitted to exhibit their wares under the free heavens, or beneath the porches of churches where the schools were occasionally kept. The portal at the north end of the cross aisle in Rouen Cathedral is still called le Portail des Libraires.

Wynkyn de Worde. 1493–1534. The second printer at Westminster.

(From a drawing by Fathorne.)

In England the first stationers were probably themselves the engrossers of what they sold, when the learning and literature of the country demanded as the chief food A B C’s and Paternosters, Aves and Creeds, Graces and Amens. Such was the employment of our earliest stationers, as the names of their15 favourite haunts—Paternoster Row, Amen Corner, and Ave Maria Lane—bear ample witness; while the term stationer soon became synonymous with bookseller, and, in connection with the Stationers’ Company, of no little importance, as we shall soon see, in our own bookselling annals.

In 1292, the bookselling corporation of Paris consisted of twenty-four copyists, seventeen bookbinders, nineteen parchment makers, thirteen illuminators, and eight simple dealers in manuscripts. But at the time when printing was first introduced upwards of six thousand people are said to have subsisted by copying and illuminating manuscripts—a fact that, even if exaggerated, says something for the gradual advancement of learning.

The European invention of printing, which here can only be mentioned; the diffusion of Greek manuscripts and the ancient wisdom contained therein, consequent upon the capture of Constantinople by the Turks; the discovery of America; and, finally, the German and English religious Reformations, were so many rapid and connected strides in favour of knowledge and progress. All properly-constituted conservative minds were shocked that so many new lights should be allowed to stream in upon the world, and every conceivable let and hindrance was called up in opposition. Royal prerogatives were exercised, Papal bulls were issued, and satirists (soi-disant) were bitter. A French poet of this period, sneering at the invention of printing, and the discovery of the New World by Columbus, says of the press, in language conveyed by the following doggerel:—

In spite of this feeling against the popularization of learning and the spread of education—a feeling not quite dead yet, if we may trust the evidence of a few good old Tory speakers on the evil effects (forgery, larceny, and all possible violation of the ten commandments) of popular education—a feeling perhaps subsiding, for a country gentleman of the old school told us recently that he “would wish every working man to read the Bible—the Bible only—and that with difficulty”—a progressive sign—the world was too well aware of the good to be gathered from the furtherance of these novelties to willingly let them die, and though the battle was from the first a hard one, it has been, from first to last, a winning battle.

It will be essential throughout this chapter, and indeed throughout the whole work, to bear in mind that it was not till quite modern times that a separate class was formed to buy copyrights, to employ printers, and to sell the books wholesale, to which their names were affixed on the title-pages—to be in fact, in the modern acceptation of the word, Publishers. There was no such class among the old booksellers; but they had to do everything for themselves, to construct the types, presses, and other essentials for printing, to bind the sheets when printed, and finally, when the17 books were manufactured, to sell them to the general public. For long, many of the booksellers had printing offices; they all, of course, kept shops, at which not only printed books but stationery was retailed; bookbinders were not unfrequent among them; and, to very recent times, they were the chief proprietors of newspapers, a branch of the trade that appears, from some modern instances, to be again falling in their direction.

In England the printing press found a sure asylum, but at first the books printed were very few in number and the issue of each book small. The works produced by Caxton consisted almost entirely of translations. “Divers famous clerks and learned men,” says one of the early printers, “translated and made many noble works into our English tongue. Whereby there was much more plenty and abundance of English used than there was in times past.” Wynkyn de Worde followed closely in his master’s footsteps; but soon a new source of employment for the press was discovered, and De Worde turned his attention to the production of Accidences, Lucidaries, Orchards of Words, Promptuaries for Little Children, and the like. With the Reformation came of course a great demand for Bibles, and, between the years 1526 and 1600, so great was the rush for this new supply of hitherto forbidden knowledge that we have no less than three hundred and twenty-six editions, or parts of editions, of the English Bible.

In the “Typographical Antiquities” of Ames and Herbert are recorded the names of three hundred and fifty printers in England and Scotland, who flourished between 1474 and 1600. Though these “printers” were also booksellers, their history belongs more18 properly to the annals of printing. We will, therefore, confine ourselves to a preliminary account of the Stationers’ Company, and then enter forthwith upon such biographical sketches as our space will allow, of the men who may be regarded, if not uniformly in the modern sense as publishers, at any rate as the representative booksellers of old London.

The “Stationers or Text-writers who wrote and sold all sorts of books then in use” were first formed into a guild in the year 1403, by the authority of the Lord Mayor and Court of Aldermen, and possessed ordinances made for the good government of their fellowship; and thus constituted they assembled regularly in their first hall in Milk Street under the government of a master and two wardens; but no privilege or charter has ever been discovered, under which, at that period, they acted as a corporate body. The Company had, however, no control over printed books until they received their first charter from Mary and Philip on 4th May 1557. The object of the charter is thus set forth in the preamble: “Know ye that we, considering and manifestly perceiving that several seditious and heretical books, both in verse and prose, are daily published, stamped and printed, by divers scandalous, schismatical, and heretical persons, not only exciting our subjects and liege-men to sedition and disobedience against us, our crown and dignity; but also to the renewal and propagating very great and detestable heresies against the faith and sound Catholic doctrine of Holy Mother the Church; and being willing to provide a proper remedy in this case,” &c. The powers granted to the Company by this charter were, verbally, absolute. Not only were they to search out, seize, and destroy books19 printed in contravention of the monopoly, or against the faith and sound Catholic doctrine of Holy Mother Church; but they might seize, take away, have, burn, or convert to their own use, whatever they should think was printed contrary to the form of any statute, act, or proclamation, made or to be made. And this charter renewed by Elizabeth in 1588, amplified by Charles II. in 1684, and confirmed by William and Mary in 1690, is still virtually in existence. It is scarcely strange that such enormous powers as these were but little respected; indeed Queen Elizabeth herself was one of the first to invade their privileges, and she granted the following, among other monopolies, away from the Stationers’ Company:—

(This last had his printing office in Moorgate Street, ornamented with the motto, “Arise, for it is Day!”)

The Stationers’ Company, sorely damaged in trade by the sudden and almost entire loss of their privileges, petitioned the Queen, representing that they were subject to certain levies, that they supplied when called upon a number of armed men, and that they expected to derive some benefit when they20 underwent these liabilities. As a reply they were severely reprimanded for daring to question the Queen’s prerogative, upon which they petitioned again, but more humbly, that they might at least be placed on an equal footing with the interlopers, and be permitted to print something or other. Her Majesty was shortly pleased to sanction an arrangement by which they were to possess the exclusive right of printing and selling psalters, primers, almanacs, and books tending to the same purpose—the A B C’s, the Little Catechism, Nowell’s English and Latin Catechisms, &c.

Ward, and Wolf a fishmonger, however, disputed the power of the Company, declaring it to be lawful, according to the written law of the land, for any printer to print all books; and when the Master and Wardens of the Company went to search Ward’s house, preparatory to seizing, burning, or conveying away his books, they were ignominiously defeated by his wife. The Lord Treasurer likewise sent commissioners thither, “but they, too, could bring him to nothing.”

Learning from this how useless the tremendous powers conferred upon them by their charter really were, the Stationers’ Company took a wiser course and subscribed £15,000 to print the books in which they had the exclusive property.

The “entry” of copies at Stationers’ Hall was commenced in 1558, but without the delivery of any books, and these entries seem originally to have been intended by the booksellers of the Company to make known to each other their respective copyrights, and to act as advertisements of the works thus entered. Half a century later, Sir Thomas Bodley was appointed21 librarian at Oxford, and so great was his zeal for obtaining books that he persuaded the Company of Stationers in London to give him a copy of every book that was printed, and this voluntary offering was rendered compulsory by the celebrated Licensing Act of 1663, which prohibited the publication of any book unless licensed by the Lord Chamberlain, and entered in the Stationers’ Registers, and which fixed the number of copies to be presented gratis at three. In the reign of William and Mary the liberty of the press was restored, but in the new Act the door was unfortunately thrown open to infractions of literary property by clandestine editions of books, and in the following reign the property of copyright was secured for fourteen years, though the perpetuity of copyright was still vulgarly believed in, and, by the better class of booksellers, still respected. The number of compulsory presentation copies was gradually increased to eleven, forming a very heavy tax upon expensive books, and was only in our own times reduced to five. At present the registration of books at Stationers’ Hall is quite independent of the presentations, which are still compulsory. The fee for the registration or assignment of a copyright is five shillings.

By the end of the last century all the privileges and monopolies of the Company had been shredded away till they had nothing left but the right to publish a common Latin primer and almanacs. In 1775 J. Carnan,3 an enterprizing tradesman, questioning the legality of the latter monopoly, published an22 almanac on his own account, and defended himself against an action brought by the Company in which the monopoly was declared worthless. As, however, the Company still paid the Universities for the lease of the sole right to publish almanacs, they endeavoured to recover their privilege by Act of Parliament, but were defeated by Erskine in a memorable speech, who showed that, while supposed to be protectors of the order and the decencies of the press, the Company had not only entirely omitted to exercise their duties, but that, even in using their privileges, they had, to increase their revenue, printed, in the “Poor Robin’s” and other almanacs, the most revolting indecencies; and the question was decided against them.

John Day or Daye. “A famous printer. He lived over Aldgate.”

1522–1584.

The “earliest men of letters”—if we accept the word in its modern meaning of those who earn their bread by their pens—were the dramatists; but the publication of their plays was a mere appendix to the acting thereof, and Shakespeare never drew a penny from the printing of his works. The Elizabethan dramatists—the Greenes and Marlowes—led a life of wretchedness only paralleled later on by the annals of Grub Street. As the use of the printing press expanded, however, a race of authors by profession sprang into existence. At the time of the Commonwealth James Howell, author of the “Epistolæ Ho-elianæ,” who was thrown into the Fleet prison, appears to have made his bread by scribbling for the booksellers; Thomas Fuller, also, was among the first, as well as the quaintest, hack-writers; he observes, in the preface to his “Worthies,” that no stationers have hitherto lost by him. His “Holy State” was reprinted four times before the Restoration, but the publisher continued to describe the last two impressions, on the23 title-page, as only the third edition, as if he were unwilling that the extent of the popularity should be known—a fact probably unprecedented. But still the great writers had either private means, or lived on the patronage of rank and wealth; for the reward of a successful book in those days did not lie in so much hard cash from one’s publisher, but in hopes of favour and places from the great. The famous agreement between Milton and Samuel Simmons, a printer, is one of the earliest authenticated agreements of copy money being given for an original work; it was executed on April 27th, 1667, and disposes of the copyright of “Paradise Lost” for the present sum of five pounds, and five pounds more when 1300 copies of the first impression should be sold in retail, and the like sum at the end of the second and third editions, to be accounted as aforesaid; and that (each of) the said first three impressions shall not exceed fifteen books or volumes of the said manuscript. The price of the small quarto edition was three shillings in a plain binding. Probably, as Sir Walter Scott remarks, the trade had no very good bargain of it, for the first impression of the poem does not seem to have been sold off before the expiration of seven years, nor till the bookseller (in accordance with a practice nor confined solely to that age) had given it five new title-pages. The second five pounds was received by Milton, and in 1680, for the present sum of eight pounds, his widow resigned all further right in the copyright, and thus the poem was sold for eighteen pounds instead of the stipulated twenty. The whole transaction must be regarded rather as an entire novelty, than as an example of a bookseller’s meanness—a view too often unjustly taken.

24 The first “eminent man of letters” was Dryden, who serves us as a connecting link between those who earned their livelihood by writing for the stage and those who earned it by working for the booksellers, and the first “eminent publisher” was Jacob Tonson, his bookseller. Dryden, like his predecessors, commenced life as a dramatist, but in his times plays acquired a marketable value elsewhere than on the stage. Before Tonson started, Dryden’s works—almost entirely plays—were sold by Herringman, the chief bookseller in London, says Mr. Peter Cunningham, before Tonson’s time; but now only remembered because Dryden lodged at his house, taking his money out in kind, as authors then often did.

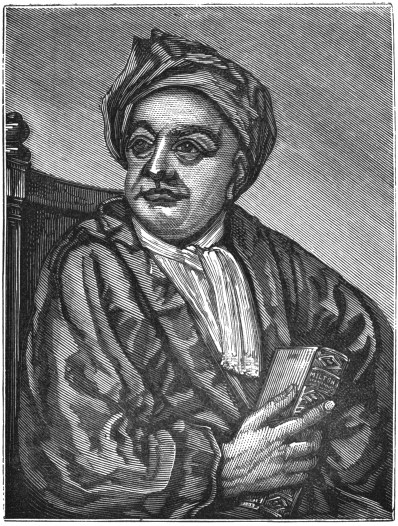

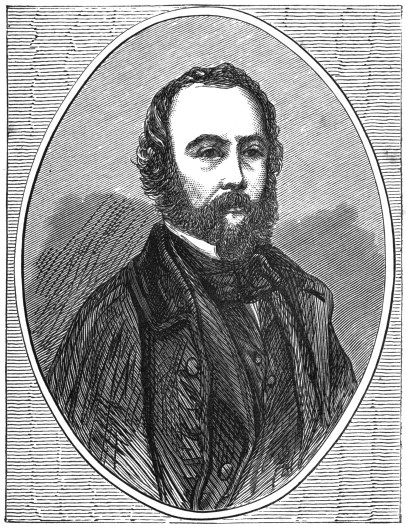

Jacob Tonson.

1656–1736.

(From the Portrait by Kneller.)

Jacob Tonson, born in 1656, was the son of a barber-surgeon in Holborn, who died when his two sons were both very young, leaving them each a hundred pounds to be paid them on their coming of age. The two lads resolved to become printers and booksellers, and, at fourteen, Jacob was apprenticed to Thomas Barnet. After serving the usual term of seven years he was admitted to the freedom of the Stationers’ Company, and immediately commenced business with his small capital at the Judge’s House, in Chancery Lane, close to the corner of Fleet Street. Like many other publishers he began trade by selling second-hand books and those produced by other firms, but he soon issued plays on his own account; finding, however, that the works of Otway and Tate, which were among his first attempts, had no very extensive sale, he boldly made a bid for Dryden’s next play, but the twenty pounds required by the author was too great a venture for his small capital, so “Troilus and Cressida; or Truth found too Late,” was published conjointly by25 Tonson and Levalle in 1679. This connection with Dryden, which lasted till the poet’s death, was of only less importance to the furtherance of Tonson’s fortune than a bargain concluded four years later with Brabazon Aylmer for one-half of his interest in the “Paradise Lost,” which Dryden told him was one of the greatest poems England had ever produced. Still he waited four years before he ventured to publish, and then only by the safe method of subscription, and in 1788 the folio edition came out, and by the sale of this and future editions Tonson was, according to Disraeli, enabled to keep his carriage. The other moiety of the copyright was subsequently purchased. There is a pleasant description of Tonson, in these early days, in a short poem by Rowe:—

From John Dunton, the bookseller, we get the following description:—“He was bookseller to the famous Dryden, and is himself a very good judge of persons and authors; and, as there is nobody more competently qualified to give their opinion upon another, so there is none who does it with a more severe exactness, or with less partiality; for, to do Mr. Tonson justice, he speaks his mind upon all occasions, and will flatter nobody.”

Not only did Tonson first make “Paradise Lost” popular, but some years afterwards he was the first bookseller to throw Shakespeare open to a reading public.

26 Then, as now, however, the works in most urgent demand were “novelties,” and with these Dryden supplied his publisher as fast almost as pen could drive upon paper. From the correspondence between Dryden and Tonson, printed in Scott’s edition of the poet’s works, they seem to have been privately on very friendly terms, falling out only when agreements were to be signed or payments to be made. Tonson was at this time publishing what are sometimes known as Tonson’s, sometimes as Dryden’s, Miscellany Poems, written, so the title-pages averred, by the “most eminent hands.” Apropos of this, Pope writes, “Jacob creates poets as kings create knights, not for their honour, but for their money. I can be satisfied with a bare saving gain without being thought an eminent hand.” The first volume of the “Miscellany” was published in 1684, and the second in the following year, and of this second, Dryden writes, after thanking the bookseller for two melons—“since we are to have nothing but new, I am resolved we shall have nothing but good, whomever we disoblige.” The third “Miscellany” was published in 1693, and Tonson sends an earnest letter of remonstrance anent the amount of “copy” received of the translation of Ovid:—“You may please, sir, to remember that upon my first proposal about the third ‘Miscellany,’ I offered fifty pounds, and talked of several authors without naming Ovid. You asked if it should not be guineas, and said I should not repent it; upon which I immediately complied, and left it wholly to you what, and for the quantity too; and I declare it was the furthest in the world from my thoughts that by leaving it to you I should have the less.” He proceeds to show that Dryden had sold a previous, though recent translation27 to another bookseller at the rate of 1518 lines for forty guineas, while he adds, “all that I have for fifty guineas are but 1446; so that if I have no more, I pay ten guineas above forty, and have 72 lines less for fifty in proportion. I own, if you don’t think fit to add something more, I must submit; ’tis wholly at your choice, for I left it entirely to you; but I believe you cannot imagine I expected so little; for you were pleased to use me much kindlier in Juvenal, which is not reckoned so easy to translate as Ovid. Sir, I humbly beg your pardon for this long letter, and, upon my word, I had rather have your good will than any man’s alive.”

These were hard times for Dryden, for through the change of government he had been deprived of the laureateship, and it is little likely that Tonson ever received his additional lines or recovered his money. Frequent at this period were the bickerings between them. On one occasion, the bookseller having refused to advance a sum of money, the poet forwarded the following triplet with the significant message, “Tell the dog that he who wrote these lines can write more:”—

The descriptive hint is said to have been successful. On another occasion, when Bolingbroke was visiting Dryden, they heard a footstep. “This,” said Dryden, “is Tonson; you will take care not to depart before he goes away; for I have not completed the sheet which I promised him; and, if you leave me unprotected, I shall suffer all the rudeness to which resentment28 can prompt his tongue.” And yet, almost at this period, we find Dryden writing, “I am much ashamed of myself that I am so much behindhand with you in kindness.”

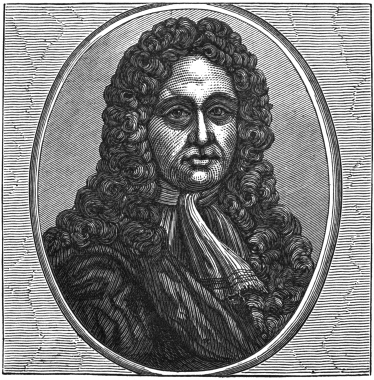

John Dunton.

1659–1733.

Dryden’s translations of the classics had been most successful in selling off the “Miscellanies” very rapidly, and Tonson now induced the author, by the offer of very liberal terms, to commence a translation of Virgil. As usual, the preliminary terms were to be settled in a tavern—a custom between authors and booksellers that seems to have been universal. “Be ready,” writes Dryden, “with the price of paper, and of the books. No matter for any dinner; for that is a charge to you, and I care not for it. Mr. Congreve may be with us as a common friend.” There were two classes of subscribers, the first of whom paid five guineas each, and were individually honoured with the dedication of a plate, with their arms engraved underneath; the second class paid two guineas only. The first class numbered 101, and the second 250, and the money thus received, minus the expense of the engravings, was handed over to Dryden, who received in addition from Tonson fifty guineas a book for the Georgics and Æneid, and probably the same for the Pastorals collectively. But the price actually charged to the subscribers of the second class appears to have been exorbitant, and reduced the amount of Dryden’s profits to about twelve or thirteen hundred pounds—still a very large sum in those days. Frequent, however, were the disputes between them during the progress of the work. The currency at this time was terribly deteriorated. In October, 1695, the poet writes, “I expect fifty pounds in good silver: not such as I have had formerly. I am not29 obliged to take gold, neither will I; nor stay for it beyond four-and-twenty hours after it is due.” Good silver, however, was very scarce, and was at a premium of forty per cent; so after a year’s wrangling he had to put up with the fate of all who then sold labour for money. “The Notes and Queries,” continues Dryden, perhaps as a gibe at Jacob’s parsimony, “shall be short; because you shall get the more by saving paper.” Again he attacks him, this time half playfully:—“Upon trial I find all of your trade are sharpers, and you not more than others; therefore I have not wholly left you.” Tonson all along wished to dedicate the work to King William, but Dryden, a staunch Tory, would not yield a tittle of his political principles, so the bookseller consoled himself by slyly ordering all the pictures of Æneas in the engravings to be drawn with William’s characteristic hooked nose; a manœuvre that gave rise to the following:—

In December, 1699, Dryden finished his last work, the “Fables,” for which “ten thousand verses” he was paid the sum of two hundred and fifty guineas, with fifty more to be added at the beginning of the second impression. In this volume was included his Ode to St. Cecilia, which had first been performed at the Music Feast kept in Stationers’ Hall, on the 22nd of November, 1697.

30 In 1700 the poet died, but Tonson was by this time in affluent circumstances.

About the date of Dryden’s death, probably before it, as his portrait was included among the other members, the famous Kit-Cat Club was founded by Tonson. Various are the derivations of the club. The most circumstantial account of its origin is given by the scurrilous writer, Ned Ward, in his “Secret History of Clubs.” It was established, he says, “by an amphibious mortal, chief merchant to the Muses, to inveigle new profitable chaps, who, having more wit than experience, put but a slender value as yet upon their maiden performances.” (Tonson must have been a rare publisher if he found “new chaps” to be in any way profitable.) With the usual custom of the times, Tonson was always ready to give his author, especially upon concluding a bargain, wherewithal to drink, but he now proposed to add pastry in the shape of mutton pies, and, according to Ward, promises to make the meeting weekly, provided his clients would give him the first refusal of their productions. This generous proposal was very readily agreed to by the whole poetic class, and the cook’s name being Christopher, called for brevity Kit, and his sign the Cat and Fiddle, they very merrily derived a quaint denomination from puss and her master, and from thence called themselves the Kit-Cat Club. According to Arbuthnot, their toasting-glasses had verses upon them in honour of “old cats and young kits,” and many of these toasts were printed in Tonson’s fifth “Miscellany.” At first they met in Shire Lane, (Ward says Gray’s Inn Lane), and subsequently at the Fountain Tavern in the Strand. In a short time the chief men of letters having joined the club,31 “many of the quality grew fond of sharing the everlasting honour that was likely to crown the poetical society.” Sir Godfrey Kneller, himself a member, painted portraits of all the members, commencing with the Duke of Somerset, and these were hung round the club-room at Tonson’s country house at Water Oakeley, where the members of the club were in after-times wont to meet. The tone of the club-room became decidedly political, and interesting as it is, our space forbids us to do more than give the following lines from “Faction Displayed” (1705), which, by-the-way, quotes Dryden’s threatening triplet, already alluded to:—

By this time Tonson had taken his nephew into partnership, had left his old shop in Chancery Lane, and changed his sign from the “Judge’s Head” to the “Shakespeare’s Head;” and he and his descendants had certainly a right to the latter symbol, for the editions of Rowe, Pope, Theobald, Warburton, Johnson, and Capell, were all associated with their name. The following schedule of the prices paid to the various editors possesses some bibliographical interest:—

| £ | s. | d. | |

| Rowe | 36 | 10 | 0 |

| Hughes | 28 | 7 | 0 |

| Pope | 217 | 12 | 0 |

| Fenton | 30 | 14 | 0 |

| Gay | 35 | 17 | 6 |

| Whalley | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Theobald | 652 | 10 | 0 |

| Warburton | 500 | 0 | 0 |

| Capell | 300 | 0 | 0 |

| Dr. Johnson, for 1st edition. | 375 | 0 | 0 |

| ” for 2nd edition. | 100 | 0 | 0 |

Upon Dryden’s death Tonson had looked round anxiously for a likely successor, and had made humble overtures to Pope, and in his later “Miscellanies” appeared some of Pope’s earliest writings; but Pope soon deserted to Tonson’s only rival—Bernard Lintot, who also opposed him in an offer to publish a work of Dr. Young’s. The poet answered both letters the same morning, but unfortunately cross-directed them: in the one intended for Tonson he said that Lintot was so great a scoundrel that printing with him was out of the question, and in Lintot’s that Tonson was an old rascal.

Jacob Tonson died in 1736, and is reported on his death-bed to have said—“I wish I had the world to begin again, because then I should have died worth a hundred thousand pounds, whereas now I die worth only eighty thousand;”—a very improbable story, for, in spite of Dryden’s complaints, Tonson seems to have been a generous man for the times, and to have fully earned his title of the “prince of booksellers.” His nephew died a few months before this, and was succeeded by his son, Jacob Tonson the third, who carried on the business in the same shop opposite Catherine Street in the Strand, until his removal33 across the road, only a short time before his death. He died in 1767, when the time-honoured name was erased from the list of booksellers.

Bernard Lintot, or, as he originally wrote his name, Barnaby Lintott, was the son of a Sussex yeoman, and commenced business as a bookseller at the sign of the Cross Keys, between the Temple Gates, in the year 1700. He is thus characterized by John Dunton—“He lately published a collection of Tragic Tales, &c., by which I perceive he is angry with the world, and scorns it into the bargain; and I cannot blame him: for D’Urfey (his author) both treats and esteems it as it deserves; too hard a task for those whom it flatters; or perhaps for Bernard himself, should the world ever change its humour and grin upon him. However, to do Mr. Lintot justice, he is a man of very good principles, and I dare engage will never want an author of Sol-fa,4 so long as the play-house will encourage his comedies.” The world, however, did grin upon him, for in 1712 he set up a “Miscellany” intended to rival Tonson’s, and here appeared the first sketch of the “Rape of the Lock,” and this introduction to Pope was to turn out of as much importance in his fortunes as the previous connection with Dryden had been to Tonson.

A memorandum-book, preserved by Nichols, contains an exact account of the money paid by Lintot to his various authors. Here are the receipts for Pope’s entire works:—

| £ | s. | d. | |

| 1712, Feb. 19. Statius, first book; Vertumnus and Pomona | 16 | 2 | 6 |

| 1712, March 21. First edition of the Rape | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 1712, April 9. To a Lady presenting Voiture upon Silence to the author of a Poem called Successio | 3 | 16 | 6 |

| 1712–13, Feb. 23. Windsor Forest | 32 | 5 | 0 |

| 1713, July 22. Ode on St. Cecilia’s Day | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| 1714, Feb. 20. Additions to the Rape | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| 1715, Feb. 1. Temple of Fame | 32 | 5 | 0 |

| 1715, April 31. Key to the Lock | 10 | 15 | 0 |

| 1716, July 17. Essay on Criticism | 15 | 0 | 0 |

In 1712 Pope, mindful of Dryden’s success, commenced his translation of Homer, and in 1714 Lintot, equally mindful probably of the profits Tonson had derived from Virgil, made a splendid offer for its publication. He agreed to provide at his own expense all the subscription and presentation copies, and in addition to pay the author two hundred pounds per volume. The Homer was to consist of six quarto volumes, to be delivered to subscribers, as completed, at a guinea a volume, and through the unremitting labours of the poet’s literary and political friends, six hundred and fifty-four copies were delivered at the original rate, and Pope realized altogether the munificent sum of five thousand, three hundred and twenty pounds, four shillings.

It was probably just after the publication of the first volume, in August, 1714, that Pope wrote his exquisitely humorous letter to the Earl of Burlington, describing a journey to Oxford, made in company with Lintot. “My lord, if your mare could speak, she would give an account of what extraordinary company she had on the road; which since she cannot do, I will.” Lintot had heard that Pope was “designed for Oxford, the seat of the Muses, and would, as my bookseller, by all means accompany me thither.... Mr. Lintot began in this manner: ‘Now,35 damn them, what if they should put it in the newspapers, how you and I went together to Oxford? What would I care? If I should go down into Sussex, they would say I was gone to the Speaker. But what of that? If my son were but big enough to go on with the business, by God! I would keep as good company as old Jacob.’... As Mr. Lintot was talking I observed he sat uneasy on his saddle, for which I expressed some solicitude. ‘’Tis nothing,’ says he; ‘I can bear it well enough, but since we have the day before us, methinks it would be very pleasant for you to rest awhile under the woods.’ When we alighted, ‘See here, what a mighty pretty Horace I have in my pocket! what if you amused yourself by turning an ode, till we mount again? Lord, if you pleased, what a clever Miscellany might you make at leisure hours.’ ‘Perhaps I may,’ said I, ‘if we ride on; the motion is an aid to my fancy, a round trot very much awakens my spirits; then jog on apace, and I’ll think as hard as I can.’

“Silence ensued for a full hour, after which Mr. Lintot tugged the reins, stopped short and broke out, ‘Well, sir, how far have you gone?’ I answered, ‘Seven miles.’ ‘Zounds, sir,’ said Lintot, ‘I thought you had done seven stanzas. Oldworth, in a ramble round Wimbleton hill, would translate a whole ode in half this time. I’ll say that for Oldworth (though I lost by his Sir Timothy’s), he translates an ode of Horace the quickest of any man in England. I remember Dr. King would write verses in a tavern three hours after he could not speak; and there’s Sir Richard, in that rambling old chariot of his, between Fleet ditch and St. Giles’s pound shall make half a job.’ ‘Pray, Mr. Lintot,’ said I, ‘now you talk of36 translators, what is your method of managing them?’ ‘Sir,’ replied he, ‘those are the saddest pack of rogues in the world; in a hungry fit, they’ll swear they understand all the languages in the universe. I have known one of them take down a Greek book upon my counter and cry, Ay, this is Hebrew. I must read it from the latter end. My God! I can never be sure of those fellows, for I neither understand Greek, Latin, French nor Italian myself.’ ‘Pray tell me next how you deal with the critics.’ ‘Sir’, said he, ‘nothing more easy. I can silence the most formidable of them; the rich ones for a sheet a-piece of the blotted manuscript, which costs me nothing; they’ll go about to their acquaintance and pretend they had it from the author, who submitted to their correction: this has given some of them such an air, that in time they come to be consulted with, and dictated to as the top critic of the town. As for the poor critics, I’ll give you one instance of my management, by which you may guess at the rest. A lean man, that looks like a very good scholar, came to me t’other day; he turned over your Homer, shook his head, shrugged up his shoulders, and pished at every line of it. One would wonder, says he, at the strange presumption of some men; Homer is no such easy task, that every stripling, every versifier—He was going on, when my wife called to dinner. ‘Sir,’ said I, ‘will you please to eat a piece of beef with me?’ ‘Mr. Lintot,’ said he, ‘I am sorry you should be at the expense of this great book; I am really concerned on your account.’ ‘Sir, I am much obliged to you; if you can dine upon a piece of beef, together with a slice of pudding.’ ‘Mr. Lintot, I do not say but Mr. Pope, if he would condescend to advise with men of learning—’ ‘Sir, the37 pudding is on the table, if you please to go in.’ My critic complies, he comes to a taste of your poetry, and tells me in the same breath that the book is commendable and the pudding excellent. These, my lord, are a few traits by which you may discern the genius of Mr. Lintot, which I have chosen for the subject of a letter. I dropt him as soon as I got to Oxford.”

Pope’s Iliad took longer in coming out than was expected. Gay writes facetiously, “Mr. Pope’s Homer is retarded by the great rains that have fallen of late, which causes the sheets to be long a-drying.” However, in 1718, the six volumes had been completely delivered to the subscribers, and three days afterwards Tonson announced, as a rival, the first book of Homer’s Iliad, translated by Mr. Tickell. “I send the book,” writes Lintot to Pope, “to divert an hour, it is already condemned here; and the malice and juggle at Button’s (for Addison had assisted Tickell in the attempted rivalry) is the conversation of those who have spare moments from politics.”

Lintot intended to reimburse his expenses by a cheap edition, but here he was anticipated by the piratical dealers, who caused a cheap edition to be published in Holland; a nefarious proceeding that Lintot met by bringing out a duodecimo edition at half-a-crown a volume, “finely printed from an Elzevir letter.”

The Odyssey was published in 1725, likewise by subscription, and Pope gained nearly three thousand pounds by the transaction, avowing, however, that he had only “undertaken” the translation, and had been assisted by friends; and “undertaker Pope” became a favourite byword among his many unfriendly38 contemporaries. Lintot was, however, disappointed with his share of the profits, and, pretending to have found something invalid in the agreement, threatened a suit in Chancery. Pope denied this, quarrelled, and finally left him, and turned his rancour to good account in the pages of the Dunciad.

By this time Lintot’s fortunes were firmly assured. Pope was, says Mr. Singer, “at first apprehensive that the contract (for the Iliad) might ruin Lintot, and endeavoured to dissuade him from thinking any more of it. The event, however, proved quite the reverse. The success of the work was so unparalleled as to at once enrich the bookseller, and prove a productive estate to his family,” and he must have certainly been progressing when Humphrey Walden, custodian of the Earl of Oxford’s heraldic manuscripts, made, in 1726, the following entry in his diary: “Young Mr. Lintot, the bookseller, came inquiring after arms, as belonging to his father, mother and other relations, who now, it seems, want to turn gentlefolks. I could find none of their names.” “Young Mr. Lintot” was Bernard’s son and successor—Henry.

There was scarcely a writer of eminence in the “Augustan Era,” whose name is not to be found in Lintot’s little account book of moneys paid. In 1730, however, he appears to have relinquished his business and retired to Horsham in Sussex, for which county he was nominated High Sheriff, in November, 1735, an honour which he did not live to enjoy, and which was consequently transferred to his son. Henry Lintot died in 1758, leaving £45,000 to his only daughter, Catherine.

Edmund Curll is, perhaps, as a name, better known to casual readers than any other bookseller of this39 period, and it is not a little comforting to find that the obloquy with which he has ever been associated was richly merited. He was born in the west of England, and after passing through several menial capacities, became a bookseller’s assistant, and then kept a stall in the purlieus of Covent Garden. The year of his birth is unknown, and the writer of a contemporary memoir, The Life and Writings of E. C—l, who prophesied that “if he go on in the paths of glory he has hitherto trod,” his name would appear in the Newgate Calendar, has unluckily been deceived. He appears to have first commenced publishing in the year 1708, and to have combined that honourable task with the vending of quack pills and powders for the afflicted. The first book he published was An Explication of a Famous Passage in the Dialogue of St. Justin Martyr with Typhon, concerning the Immortality of Human Souls, bearing the date of 1708; and, curiously enough, religious books formed in aftertime a very large portion of his stock, side by side, of course, with the most filthy and ribald works that have ever been issued.

In 1716 began his quarrel with Pope, originating as far as we know in the publication of the Court Poems, the advertisement of which said that the coffee-house critics assigned them either to a Lady of Quality, Mr. Gay, or the translator of Homer. It is not clear now whether Pope was really annoyed by the appearance of the volume, or whether he had first secretly promoted it, and then endeavoured to divert suspicion. At all events, he had a meeting with Curll at the “Swan Tavern,” in Fleet Street, where, writes the bookseller, “My brother, Lintot, drank his half-pint of old hock, Mr. Pope his half-pint of sack, and I the40 same quantity of an emetic powder; but no threatenings past. Mr. Pope, indeed, said that no satire should be printed (tho’ he has now changed his mind). I answered that they should not be wrote, for if they were they would be printed.” Curll, on entering the tavern, declared he had been poisoned, and for months the town was amused with broadsides and pamphlets relative to the affair. Pope afterwards published his version of the story in his Miscellanies; the “Full and True Account” is, however, as gross and unquotable as Curll’s own worst publication.

Later on in the same year the bookseller fell into a fresh scrape. A Latin discourse had been pronounced at the funeral of Robert South by the captain of Westminster School, and Curll, thinking it would be readily purchased by the public,

and thereby aroused the anger of the Westminster scholars, who enticed him into Dean’s Yard on the pretence of giving him a more perfect copy; there, he met with a college salutation, for he was first presented with the ceremony of the blanket, in which, “when the skeleton had been well shook, he was carried in triumph to the school, and, after receiving a mathematical construction for his false concords, he was re-conducted to Dean’s Yard, and on his knees asking pardon of the aforesaid Mr. Barber (the captain whose Latin he had murdered) for his offence, he was kicked out of the yard, and left to the huzzas of the rabble.”

No sooner was Curll out of one scrape than he fell into another; for, still in this same year, he was summoned41 to the bar of the House of Lords for printing and publishing a paper entitled An Account of the Trial of the Earl of Winton, a breach of the standing orders of the House. However, having received kneeling a reprimand from the Lord Chancellor, he was dismissed upon payment of the fees.

While the authorities were quick enough to punish any violation of their own peculiar privileges, they were graciously pleased to wink at the perpetual offences Curll was committing against public morals, for Curll was a strong politician on the safe party side, and in his political publications had in view the interests of the government. However, he was attacked on all sides by public opinion and the press. Mist’s Weekly Journal for April 5, 1718, contained a very strong article on the “Sin of Curllicism.” “There is indeed but one bookseller eminent among us for this abomination, and from him the crime takes its just denomination of Curllicism. The fellow is a contemptible wretch a thousand ways; he is odious in his person, scandalous in his fame; ... more beastly, insufferable books have been published by this one offender than in thirty years before by all the nation.” Curll, “the Dauntless,” did not long remain in silence, and his reply is characteristically outspoken, for the writer was never a coward. “Your superannuated letter-writer was never more out than when he asserted that Curllicism was but of four years’ standing. Poor wretch! he is but a novice in chronology;” and then, after threatening the journalist with the terrors of an outraged government, he concludes “in the words of a late eminent controvertist, the Dean of Chichester.”

Curll was fond of the dignitaries of the Church, and42 endeavoured to play a shrewd trick upon one of them; he sent a copy of Lord Rochester’s Poems (certainly not the most innocent book he published) to Dr. Robinson, Bishop of London, with a tender of his duty, and a request that his lordship would please to revise the interleaved volume as he thought fit; but the bishop, not to be caught, “smiled” and said, “I am told that Mr. Curll is a shrewd man, and should I revise the book you have brought me, he would publish it as approved by me.”5

Public dissatisfaction seems to have been expressed more forcibly against Curll than heretofore, and to have taken the form of a remonstrance to government, for he published The Humble Representation of Edmund Curll, Bookseller and Citizen of London, containing Five Books complained of to the Secretary. As the books were eminently of a nature requiring an apology, we cannot do more than give their titles: 1. The Translation of Meibomius and Tractatus de Hermaphroditis; 2. Venus in the Cloister; 3. Ebrietatis Encomium; 4. Three New Poems, viz. Family Duty, The Curious Wife, and Buckingham House; and 5. De Secretis Mulierum. At last the government did interfere, as we learn from a notice in Boyer’s Political State, Nov. 1725:—

“On Nov. 30, 1725, Curll, a bookseller in the Strand, was tried at the King’s Bench Bar, Westminster, and convicted of printing and publishing several obscene and immodest books, greatly tending to the corruption and depravation of manners, particularly one translated from a Latin treatise entitled De Usu Flagrorum in Re Venereâ; and another from a French43 book called La Religieuse en Chemise.” In the indictment Curll is thus accurately summed up: homo iniquus et sceleratus ac nequiter machinans et intendens bonos mores subditorum hujus regni corrumpere et eos ad nequitiam inducere; and in the State Trials we read the following report of the sentence:—

“This Edmund Curll stood in the pillory at Charing Cross, but was not pelted or used ill; for being an artful, cunning (though wicked) fellow, he had contrived to have printed papers dispersed all about Charing Cross, telling the people how he stood there for vindicating the memory of Queen Anne.”

It does, in fact, appear that he received three sentences at once, and that not until Feb. 12, 1728. For publishing the Nun in her Smock, and the treatise De Usu Flagrorum, he was sentenced to pay a fine of twenty-five marks each, and to enter into recognizances of £100 for his good behaviour for one year; but for publishing the Memoirs of John Ker of Kersland, Esq. (a political offence), he was fined twenty marks, and ordered to stand in the pillory for the space of one hour.6

In 1729 Curll was again pilloried—this time by Pope in the Dunciad, in connection with Tonson and Lintot:

And finally Curll stumbles into an unsavoury pool:—

In reference to Curll there is a note to this passage, “He carried the trade many lengths beyond what it ever before had arrived at; he was the envy and admiration of all his profession. He possessed himself of a command over all authors whatever; he caused them to write what he pleased; they could not call their very names their own. He was not only famous among them; he was taken notice of by the state, the church, and the law, and received particular marks of distinction from each.”

We have no space to discuss the vexed question as to how the letters of Pope published by Curll came into his hands—the discussion would occupy a volume and remain a moot question after all. But we are disposed to believe with Johnson and Disraeli that “being inclined to print his own letters, and not45 knowing how to do so without the imputation of vanity, what in this country has been done very rarely, he contrives an appearance of compulsion; that when he could complain that his letters were surreptitiously published, he might decently and defensively publish them himself.” The letters at all events were genuine, and Pope in a feigned or real indignation caused Curll to be brought for a third time (the second had been for publishing the Duke of Buckingham’s words) before the bar of the House of Lords for disobeying its standard rules; but on examination the book was not found to contain any letters from a peer, and Curll was dismissed, and boldly continued the publication till five volumes had been issued.

In spite, or perhaps on account of the unblushing effrontery with which he run amuck at everything and everybody, Curll was a successful man, as his repeated removals to better and better premises plainly testifies. Over his best shop in Covent Garden he erected the Bible as a sign. He has had many apologists, among others worthy John Nichols, as deserving commendation for his industry in preserving our national remains, but the scavenger, when he gathers his daily filth, lays little claim to doing a meritorious action, he only works unpleasantly for his daily bread; and it has been the repeated cry of publishers, even in our own times, in reproducing an immoral book, that they were wishing only for the preservation of something rare and curious. It were not well that any book once written should ever die,—that any one link in the vast chain of human thought should ever be irrecoverably lost, but the publisher of such a book must, at least, bear the same penalty of stigma as the author, for he has not46 even the author’s self-vanity as an excuse, but only the still more wretched plea of mercenary motive. We will conclude our notice of Curll by an extract from “John Buncle,” by Thomas Amory, who knew him personally and well. “Curll was in person very tall and thin—an ungainly, awkward, white-faced man. His eyes were a light gray—large, projecting, goggle, and purblind. He was splay-footed and baker-kneed.... He was a debauchee to the last degree, and so injurious to society, that by filling his translations with wretched notes, forged letters, and bad pictures, he raised the price of a four-shilling book to ten. Thus, in particular, he managed Burnet’s ‘Archæology.’ And when I told him he was very culpable in this and other articles he sold, his answer was, ‘What would I have him do? He was a bookseller;—his translators, in pay, lay three in a bed at the Pewter Platter Inn, in Holborn, and he and they were for ever at work deceiving the public.’ He, likewise, printed the lewdest things. He lost his ears for the ‘Nun in her Smock’ and another thing. As to drink, he was too fond of money to spend any in making himself happy that way; but, at another’s expense, he would drink every day till he was quite blind and as incapable of self-motion as a block. This was Edmund Curll. But he died at last as great a penitent, I think, in the year 1748 (it was 1747), as ever expired. I mention this to his honour.”7

47 Thomas Guy, more eminent certainly as a very successful money-maker, and a generous benefactor to charitable institutions, than as a bookseller, was born in Horsley-down, the son of a coal-heaver and lighterman. The year of his birth is uncertain, but in 1660, he was bound apprentice to John Clarke, bookseller, in the porch of Mercers’ Chapel, and, in 1668, having been admitted a liveryman of the Stationers’ Company, he opened a small shop in “Stock Market” (the site of the present Mansion House, then a fruit and flower market, where, also, offenders against the law were punished) with a stock-in-trade worth above £200. From the first, Guy’s chief business seems to have been in Bibles, for Maitland, his biographer relates, “The English Bibles, printed in this kingdom, being very bad, both in the letter and the paper, occasioned divers of the booksellers in this city to encourage the printing thereof in Holland, with curious types and fine paper, and imported vast numbers of the same to their no small advantage. Mr. Guy, soon becoming acquainted with this profitable commerce, became a large dealer therein.” As early as Queen Elizabeth’s time, the privilege of printing Bibles had been conferred on the Queen’s (or King’s) printer, conjointly, of course, with the two Universities, and the effect of this prolonged monopoly resulted, not only in exorbitant prices, but in great typographical carelessness, and, says Thomas Fuller, under the quaint heading of “Fye for Shame,” “what is but carelessness in other books is impiety in setting forth of the Bible.” Many of the errors were curious;—the printers in Charles I.’s reign had been heavily fined for issuing an edition in which, the word “not” being omitted, the seventh,48 commandment had been rendered a positive, instead of a negative injunction. The Spectator wickedly suggests that, judging from the morals of the day, very many copies must have got abroad into continuous use. In the Bible of 1653, moreover, the printers allowed “know ye not that the unrighteous shall inherit the kingdom of God” to stand uncorrected. However, the Universities and the King’s printer still possessed the monopoly, and this new trade of good cheap Bibles “proving not only very detrimental to the public revenues, but likewise to the King’s printer, all ways and means were devised to quash the same, which, being vigorously put in execution, the booksellers, by frequent seizures and prosecutions, became so great sufferers, that they judged a further pursuit thereof inconsistent with their interests.” Defeated in this manner, Guy cautiously induced the University of Oxford to contract with him for an assignment of their privilege, and not only obtained type from Holland, and printed the Bible in London, but was, later on, in 1681, according to Dunton, a partner with Parker in printing the Bible, at Oxford (Parker could have been no connection of the famous publishing family).

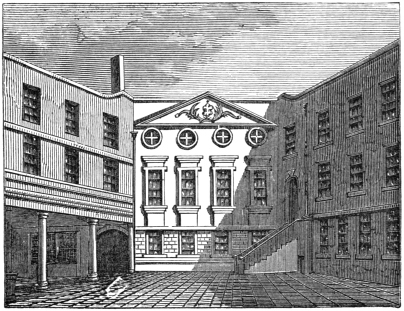

Thomas Guy, founder of Guy’s Hospital. 1644–1724.

(From the statue by J. Bacon, R.A.)

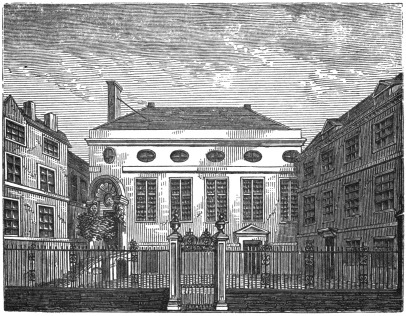

Guy’s Hospital.

(Bird’s-eye view from a Print, 1738.)

Guy seems to have contracted in his early days very frugal and personally pernicious habits. According to Nichols, he is said to have dined every day at his counter, “with no other table-cloth than an old newspaper,” and if the “Intelligence” or the “Newes” of that period really served him for a cloth, the dish that contained his meat must have been uncommonly small. “He was also,” it is added, “as little nice in his apparel.” It was probably, too, in the commencement of his career, that, looking round for a tidy and49 inexpensive helpmate, he asked his servant-maid to become his wife. The girl, of course, was delighted, but, alas! presumed too much upon her influence over her careful lover; seeing that the paviours who were repairing the street, in front of the house (an order was issued, in 1671, to every householder to pave the street in front of his dwelling, “for the breadth of six feet at least from the foundation”) had neglected a broken place, she called their attention to it, but they told her that Guy had carefully marked a particular stone, beyond which they were not to go. “Well,” said the girl, “do you mend it; tell him I bade you, and I know he will not be angry.” When Guy saw the extra charge in the bill, however, he at once renounced his matrimonial scheme.

The Bible trade proved prosperous, and Guy, ready for any lucrative and safe investment for his money, speculated in Government securities, and, according to Nichols and Maitland, acquired the “bulk of his fortune” by purchasing seaman’s tickets; but the practice of paying the royal sailors by ticket does not seem to have existed later than the year 1684; so that if he dealt in them at all it must have been a very early period in his career, when it appears unlikely that he would have had much spare cash to invest. Maitland adds “as well as in Government securities, and this was probably the manner in which the ‘bulk of his fortune’ was really acquired.”

That his finances were in a healthy condition, is apparent, from his appearance in Parliament as member for Tamworth, from 1695 to 1707. According to Maitland, “as he was a man of unbounded charity, and universal benevolence, so he was likewise a good patron of liberty, and the rights of his fellow-subjects;50 which, to his great honour, he strenuously asserted in divers parliaments.” An honourable testimony to his character, supported also by Dunton: “Thomas Guy, of Lombard-street, makes an eminent figure in the Company of Stationers, having been chosen sheriff of London, and paid the fine.... He is a man of strong reason, and can talk very much to the purpose on any subject you can propose. He is truly charitable.”

Throughout his life, he was very kind to his relatives, lending money when needed to help some, and pensioning others. To charities, whose purpose was pure benevolence, apart from sectarian motive, his purse was ever open, and St. Thomas’s Hospital and the Stationers’ Company were largely indebted to his generosity.

In his latter days, Guy was able to multiply his fortune many fold. The South Sea Company was a good investment for a wary, cool-headed business man, and he became an original holder in the stock. “It no sooner received,” says Maitland, “the sanction of Parliament, than the national creditors from all parts came crowding to subscribe into the said company the several sums due to them from the government, by which great run, £100 of the Company’s stock, that before was sold at £120 (at which time, Mr. Guy was possessed of £45,500 of the said stock) gradually arose to above £1,050. Mr. Guy wisely considering that the great use of the stock was owing to the iniquitous management of a few, prudently began to sell out his stock at about £300 (for that which probably at first did not cost him about £50 or £60) and continued selling till it arose to about £600 when he disposed of the last of his property51 in the said company,” and then the terrible panic came.

He was between seventy and eighty years of age when he determined to devote his fortune to building and endowing a hospital which should bear his name, and, dying in 1724, he lived just long enough to see the walls roofed in. The cost of building “Guy’s Hospital” amounted to £18,793, and he left £219,499 as endowment. At Tamworth, his mother’s birthplace, which he represented in Parliament for many years, he erected alms-houses and a library. Christ’s Hospital received £400 a year for ever, and, after many gifts to public charities, he directed that the balance of his fortune, amounting to about £80,000, should be divided among all who could prove themselves in any degree related to him. Guy’s noble philanthropy would be unequalled in bookselling annals, but that Edinburgh, happily boasting of a Donaldson, can rival London in the generosity of a bookseller.

We have had occasion to quote several times from “Dunton’s Characters;” and, as the author was himself a bookseller, and was, moreover, the only contemporary writer who thought it worth his while to preserve any continuous record of the bookselling fraternity, we must give him a passing notice here. John Dunton, the son of a clergyman, was born in 1689, and, after passing through a disorderly apprenticeship, commenced bookselling “in half a shop, a warehouse, and a fashionable chamber.” “Printing,” he says, “was the uppermost in my thoughts, and hackney authors began to ply me with specimens as earnestly and with as much passion and concern as the waterman do passengers with oars and sculls.”

Having some private capital he went ahead merrily,52 printing six hundred books, of which he repented only of seven, and these he recommends all who possess to burn forthwith. Somewhat erratic in his habits he went to America to recover a debt of £500, consoling his wife, “dear Iris,” through whom he became connected with Wesley’s father, by sending her sixty letters in one ship. Here he stayed for nearly a twelvemonth, pleasantly viewing the country at his leisure, and cultivating a platonic friendship with maids and widows. At his return he found his business disordered, and sought to make amends by another voyage to Holland. By this time he had pretty nearly dissipated his capital, but luckily came “into possession of a considerable estate” through the death of a cousin. “The world,” he says, “now smiled on me, and I have humble servants enough among the stationers, booksellers, printers, and binders.”

Of all his publications, the only one that attained any fame was the “Athenian Mercury,” which reached twenty volumes. His three literary associates in this work were Samuel Wesley, Richard Sault, and Dr. John Norris, and with his aid they resolved all “nice and curious questions in prose and verse,” concerning physic, philosophy, love, &c. They were afterwards reprinted in four volumes, under the title of the Athenian Oracle, and form a curious picture of the wants, manners, and opinions of the age; but the work is, perhaps, chiefly to be remembered as one of the earliest periodicals not professing to contain “news.”

Dunton now, finding that he did not make much money by bookselling in London, went over to Dublin for six months with a cargo of books and53 started as auctioneer, naturally falling foul of the Irish booksellers, whom he dressed off in a tract entitled “The Dublin Scuffle.” He returned to England complacently believing that he had done more service to learning by his auctions “than any single man that had come into Ireland these hundred years.”

In London, however, he was by this time so involved in commercial difficulties, that he was fain to give up bookselling altogether, and take to bookmaking instead; and his pen was so indefatigable that he soon bid fair to be the author of as many volumes as he had published. The book that concerns us most here is the “Life and Errors of John Dunton, written by himself in Solitude,” in which is included the “Lives and Characters of a Thousand Persons now living in London.” In this latter part he was obliged, “out of mere gratitude,” “to draw the characters of the most eminent of the profession in the three kingdoms;” consequently we find some half-dozen lines of “character” given to every bookseller of his time in London, “gratitude” compelling him, however, to be almost invariably laudatory; the other parts of the “three kingdoms” are thus summarily and easily dealt with, “Of three hundred booksellers now trading in country towns, I know not of one knave or a blockhead amongst them all.” The book, however rambling and incoherent, contains much worth preservation, and is not unpleasant desultory reading.

Dunton’s own “character” has been preserved elsewhere than in his Life and Confessions. Warburton describes him as “an auction bookseller and an abusive scribbler;” Disraeli, “as a crack-brain,54 scribbling bookseller, who boasted that he had a thousand projects, fancied he had methodised six hundred, and was ruined by the fifty he executed.” His greatest project, by the way, was intended “to extirpate lewdness from London.” “Armed with a constable’s staff, and accompanied by a clerical companion, he sallied forth in the evening, and followed the wretched prostitutes home to a tavern, where every effort was used to win the erring fair to the paths of virtue; but these he observes were perilous adventures, as the cyprians exerted every art to lead him astray in the height of his spiritual exhortations.”

There is something so Quixotic about his schemes, so complacent about his marvellous self-vanity, that we are really grieved when we find him ending his life, as most “projectors” do, with Dying Groans from the Fleet Prison; or, a Last Shift for Life. Shortly after this, in 1733, his teeming brain and his eager pen were at rest for ever.

Another bookseller, also a “man of letters,” but of very different calibre from poor John Dunton, must have a niche here, not because he was eminent as a publisher, but because he was, taken altogether, the most famous man who has ever stood behind a bookseller’s counter. One of our greatest novelists, his general life is so well known, that we will only treat here of his bookselling career. Samuel Richardson, born in 1689, was the son of a joiner in Derbyshire; a quiet shy boy, he became the confident and love-letter writer of the girls in his neighbourhood, gaining thereby his wonderful knowledge of womankind. Fond of books, and longing for opportunities of study, he was, at the age of sixteen, apprenticed to John55 Wilde, of Stationers’ Hall, but his master, though styling him the “pillar of his house,” grudged him, he says, “every hour that tended not to his profit.” So Richardson used to sit up half the night over his books, careful at that time to burn only his own candles. On the termination of his apprenticeship, he became a journeyman and corrector of the press, and six years later commenced business in an obscure court in Fleet-street, where he filled up his leisure hours by compiling indices, and writing prefaces and what he terms “honest dedications” for the booksellers.

Through his industry and perseverance his business became much extended, and he was selected by Wharton to print the True Briton; but, after the publication of the sixth number, he would not allow his name to appear, and consequently escaped the results of the ensuing prosecution. Through the friendly interest of Mr. Speaker Onslow he printed the first edition of the Journal of the House of Commons, completed in twenty-six folio volumes, for which, after long and vexatious delays, he received upwards of £3000. He also printed from 1736 to 1737 the Daily Journal, and in 1738 the Daily Gazette.

In 1740 Mr. Rivington and Mr. Osborne proposed that he should write for them a little volume of letters, which resulted in his first novel Pamela, the publication of which will be treated in our account of the Rivingtons. This was followed by Clarissa, one of the few books from which it is absolutely impossible to steal away, when once the dread of its size has been overcome. Though famous now as the first great novelist who had written in the English tongue,56 Richardson was not then above his daily work. He writes to his friend Mr. Defreval, “You know how my business engages me. You know by what snatches of time I write, that I may not neglect that, and that I may preserve that independency which is the comfort of my life. I never sought out of myself for patrons. My own industry and God’s providence have been my sole reliance.” In 1754, he was, to the great honour of the members, chosen master of the Stationers’ Company, the only fear of his friends being that he would not play the gourmand well. “I cannot,” writes Edwards, “but figure to myself the miserable example you will set at the head of their loaded tables, unless you have two stout jaw-workers for your wardens, and a good hungry court of assistants.”

Samuel Richardson, Bookseller and Novelist. 1689–1761.

(From a Picture by Chamberlin.)