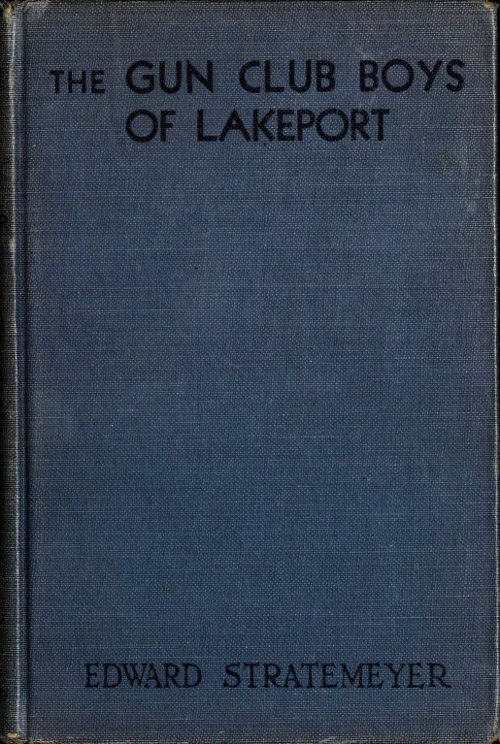

The old hunter was at hand

LAKEPORT SERIES

By EDWARD STRATEMEYER

Author of “The Baseball Boys of Lakeport,” “Dave Porter at Oak Hall,” “Old Glory Series,” “Pan-American Series,” Etc.

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO.

Copyright, 1904, by A. S. Barnes & Co., under the Title

“The Island Camp.”

Copyright, 1908, by Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

This story is a complete tale in itself, and it also forms the first volume of a series to be devoted to sport in the forest, on the water, and on the athletic field.

My object in writing this tale was two-fold: first, to present to the boys a story which would please them, and, second, to give my young readers an insight into Nature as presented in the depths of the forest during the winter.

The young hunters of Lakeport are no different from thousands of other youths of to-day. Although they do some brave deeds, they are no heroes in the accepted sense of that term, and at certain times they get scared just as others might under similar circumstances. They are light-hearted and full of fun, and not above playing some odd practical jokes upon each other. In the old and experienced hunter, who goes with them on this never-to-be-forgotten outing, they find a companion exactly to their liking, and one who teaches them not a few “points” about hunting that are worth knowing.

The scene of this tale is laid in one of our eastern states. A few years ago small game of all kinds was plentiful there, and deer, moose, and even bears, could also be laid low. But some of the larger animals are fast disappearing, and it is now only a question of time when they will be wiped out altogether. This seems a great pity; but the march of the lumberman and the progress of the farmer cannot be stayed.

Edward Stratemeyer.

“How many miles have we still to go, Harry?”

“I think about four,” answered Harry Westmore, as he looked around him on the country road he and his brother were traveling. “I must say, I didn’t think the walk would be such a long one, did you?”

“No, I thought we’d be back home before this,” came from Joe Westmore. “I wish we could find some sort of a signboard. For all we know, we may be on the wrong road.”

“There used to be signboards on all of these roads, but I heard Joel Runnell tell that some tramps had torn them down and used them for firewood.”

“Yes, they did it for that, and I guess they took ’em down so that folks could miss their way, too. Those tramps are not above waylaying folks and making them give up all they’ve got in their pockets.”

“I believe you there. But since Sheriff Clowes rounded up about a dozen of ’em last month they have kept themselves scarce. Phew! How the wind blows!”

“Yes, and how the snow is coming down! If we are not careful, we’ll not get home at all. I hadn’t any idea it was going to snow when we left home.”

“I’m afraid if we don’t get home by dark mother will worry about us.”

“Oh, she knows we are old enough to take care of ourselves. If it snows too hard we can seek shelter at the next farmhouse we come to and wait until it clears off.”

The two Westmore boys, of whom Joe was the older by a year and a day, had left their home at Lakeport early that morning for a long tramp into the country after some late fall nuts which a friend had told them were plentiful at a locality known as Glasby’s Hill. They knew the Hill was a long way off, but had not expected such a journey to get to it. The bridge was down over one of the country streams and this had necessitated a walk of over a mile to another bridge, and here the road was not near as good as that on which they had been traveling. Then, after the nuts were found and two fair-sized bags gathered, it had begun to snow and blow, until now the wind was sailing by them at a great rate and the snow was coming down so fast that it threatened to obliterate the landscape around them.

The Westmore family were six in number, Mr. Horace Westmore and his wife, the boys just introduced, and two younger children named Laura and Bessie. Mr. Westmore was a flour and feed dealer, and had the principal establishment of that kind in Lakeport, at the lower end of Pine Lake. While the merchant was not rich, he was fairly well-to-do, and the family moved in the best society that the lake district afforded. On Mrs. Westmore’s side there had once been much wealth, but an unexpected turn of fortune had left her father almost penniless at his death. There was a rumor that the dead man had left to his daughter the rights to a valuable tract of land located at the head of the lake, but though Mr. Westmore tried his best he could not establish any such claim. The land was there, held by a miserly real estate dealer of Brookside named Hiram Skeetles; but Skeetles declared that the property was his own, free and clear, and that Mrs. Westmore’s father had never had any right to it whatsoever.

“What’s mine is mine, and don’t ye go for to forgit it!” Hiram Skeetles had snarled, during his last interview with Horace Westmore on the subject. “Ye ain’t got nary a slip o’ paper to show it ever belonged to Henry Anderson. I don’t want ye to bother me no more. If ye do, I’ll have the law on ye!” And Mr. Westmore had come away feeling that the case was decidedly a hopeless one.

“It’s a shame mother and father can’t bring old Skeetles to time,” had been Joe’s comment, when he heard of the interview. “I wouldn’t trust that old skinflint to do the square thing.”

“Nor I,” had come from Harry. “But if Grandfather Anderson had any deeds or other papers what did he do with them?”

“I’m sure I don’t know. Mother said she saw some papers once—years ago, when she was a young girl—but she never saw them after that,” had been Joe’s comment; and there the subject had been dropped.

With their bags of nuts over their shoulders the two boys continued to trudge along in the direction of home. The loads had not seemed heavy at starting, but now each bag was a dead weight that grew harder to carry at every step.

“Let us rest for awhile,” said Joe, at length. “I must have a chance to get my wind.”

“Isn’t there wind enough flying around loose,” returned his brother, with a faint grin. “Just open your mouth wide and you’ll gather in pure, unadulterated ozone by the barrelful.”

“It’s the wind that’s taking my wind, Harry. I feel as if I’d been rowing a two-mile race, or just made a home run on the baseball field.”

“Or a touchdown on the gridiron, eh? Say, but that last game of football with the Fordhams was great, wasn’t it?”

The two boys had moved on a few steps further, and now, through the flying snow, caught sight of a dilapidated barn standing close to the roadway.

“Hurrah! here’s a shelter, made to order!” cried Joe. “Let us go in and take a quarter of an hour’s rest.”

“Yes, and eat a few of the nuts,” added Harry. “My! but ain’t I hungry. I’m going to eat all there is on the table when I get home.”

“Then you wouldn’t refuse a mince pie right now, would you?”

At this question Harry gave a mock groan. “Please don’t mention it! You’ll give me palpitation of the heart. If you’ve got a mince pie tucked away in your vest pocket, trot it out.”

“Wish I had. But stop talking and come into the barn. It isn’t a first-class hotel, but it’s a hundred per cent. better than nothing, with a fraction added.”

Like many a similar structure, the old barn had no door or window on the road side, so they had to go around to the back to get in. As they turned the corner of the building they caught sight of two men who stood in the tumble-down doorway. The men were rough-looking individuals and shabbily dressed, and when they saw them the lads came to a halt.

“Hullo, who are you?” demanded one of the men, who possessed a head of tangled red hair and an equally tangled red beard.

“We were traveling on the road and came around here for a little shelter from the storm,” answered Joe. He did not like the appearance of the two tramps—for such they were—and neither did Harry.

At the explanation the tramp muttered something which the two boys did not catch. At the same time a third tramp came forth from the barn, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand.

“Maybe they’re from that farm back here,” he said, with a jerk of his head over the shoulder. “I believe there was a couple o’ boys up there.”

“No, we’re not from any farm,” answered Harry. “We come from Lakeport.”

“What have ye in them bags?” put in the tramp who had not yet spoken.

“Nuts. We have been out nutting.”

“Humph! Thought as how nuts was all gone by this time.”

“We heard of a spot that hadn’t been visited,” said Joe. He looked at his brother significantly. “Guess we had better be moving on.”

“Oh, don’t hurry yourselves, gents,” came quickly from the tramp with the red and tangled beard. “Come in an’ rest all yer please. We’re keepin’ open house to-day,” and he gave a low laugh.

“Thank you, but we haven’t a great deal of time to spare,” said Harry. “Come, Joe,” he went on, and started to move toward the roadway once more.

He had scarcely taken two steps when the tramp with the red beard caught him by the shoulder.

“Don’t go,” he said pointedly. “Come in an’ warm up. We’ve got a bit o’ a fire in there.”

“A fire?” queried Harry, not knowing what else to say. “Aren’t you afraid you’ll burn the barn down?”

“Not much! Even if she went, the buildin’ ain’t worth much. Come on in.”

The tramp had a firm grip on Harry’s arm by this time and now the other two got between Joe and the roadway.

It must be confessed that the two lads were much dismayed. As already noted, they knew that folks in that neighborhood had been waylaid by tramps in the past, and they now felt that a similar experience was in store for them. How to get out of such a dilemma was a serious question.

“We don’t want to stop with you,” said Joe, as sharply as he could, although his heart beat violently. “Let me pass, please.”

“But we ain’t goin’ to let yer pass just yet, young feller,” said one of the tramps. “Come on in an’ be sociable.”

“We don’t mean for to hurt ye!” put in another. “So don’t git scart. If ye belong down to Lakeport we’ll treat yer right.”

“We don’t wish to stay, I tell you,” went on Joe. “Let me pass, do you hear?”

“And let me go, too,” added Harry. He tried to twist himself loose but could not, for the tramp was strong and had a good clutch.

“Peppery youngsters,” drawled the tramp with the red hair. “Got to teach ’em manners, I guess. Shove ’em into the barn, boys. There don’t seem to be nobuddy else around, an’ it looks like we had run up against a real good thing!”

“Do you mean to say that you intend to rob us?” cried Joe, as he struggled to free himself from the man who had him by the collar.

“Rob yer? Who said anything ’bout robbin’ yer? We’re honest men, we are! Come on inside, an’ behave yerself!”

And with this Joe was shoved toward the barn door. He tried to struggle, but it was useless. Using brute force the tramps almost pitched him inside, and Harry followed in a similar manner. Then the tramp with the red beard set up the broken-down door before the opening and stood on guard with a club in his hand.

It was a situation which no boy would care to confront, and as Joe and Harry looked from one brutal face to another, their hearts sank within them. They could see at a glance that the tramps were among the worst of their class and would hesitate at little or nothing to accomplish their ends.

To one side of the barn, where the flooring had rotted away, a fire was burning, the smoke drifting forth through a broken-out window and the numerous holes in the roof. Beside the fire lay the remains of two chickens, which the tramps had probably stolen from some farmer’s hen-roost. Three soda water bottles were also on the floor, but there was no telling what they had contained, since all were empty. But as the breath of each tramp smelt strongly of liquor, it is safe to say that the bottles had contained—at least one of them—something stronger than a temperance drink.

“See here, you haven’t any right to treat us in this fashion,” said Joe, as soon as he could recover from the attack which had been made upon him.

“You ain’t got no right to call us thieves,” was the answer, and the speaker leered in a knowing manner at his fellows.

“That’s it,” spoke up another of the tramps. “It’s a downright insult to honest men like us.”

“Thet’s wot it is,” came from the third tramp. “Boys, yer ought to ’polergize.”

“I want you to let us go,” went on Joe.

“Right away,” put in Harry. “If you don’t——”

“If we don’t,—what?” demanded the tramp who stood guard with the club.

“It may be the worse for you, that’s all.”

At this all three of the tramps set up a low laugh. Then the fellow at the doorway called one of the others to his side and whispered something in his ear.

“Dat’s all right, Noxy; but I don’t care to go until I see wot we strike,” answered the man addressed.

“Oh, you’ll get your fair share, Stump,” was the answer, but Stump refused to leave even when urged a second time.

“Say, just you tell us wot time it is,” put in the other tramp, who went by the name of Muley. He had noticed that Joe carried a watch—a silver affair, given to him by his father on his last birthday.

“It’s time you let us go,” answered Joe. He understood perfectly well what the fellow was after.

He had scarcely spoken when Muley stepped forward and grabbed the watch chain. The watch came with it, and despite Joe’s clutch for his property it was quickly transferred to the tramp’s possession.

“Give me that watch!”

“They are nothing but robbers!” burst out Harry. “Joe, let us get out right away!”

Unable to pass the tramp at the doorway, Harry made for one of the barn windows, and feeling it would be useless to argue just then about the timepiece, Joe followed his brother.

“Hi, stop ’em!” roared Stump. “Don’t let ’em get away!”

Instantly all three of the tramps went after the two lads. Muley was the quickest of the number and in a trice he had placed himself in front of the window.

“Not so fast!” he sang out. “We want what you have in your pockets first!”

Cut off from escape by the window, the two boys turned around. They now saw that the doorway was unguarded, and ran for the opening with all speed. Harry reached the door first and tumbled it aside, and both ran into the open.

“Stop!” yelled Noxy. “Stop, or we’ll fix ye!” And then, his foot catching in a loose board of the flooring, he pitched headlong, and Stump and Muley came down on top of him.

“Run, Harry, run, or they’ll catch us sure!” cried Joe.

Harry needed no urging, and in a minute the two lads were on the roadway once again and running harder than they had ever done in any footrace. For the moment they forgot how tired they had been, and fear possibly gave them additional strength.

“Ar—are the—they coming?” panted Harry, after quarter of a mile had been covered.

“I don’t—don’t know!” puffed his brother. “Do—don’t se—see anything of ’em.”

“What mean rascals, Joe!”

“Yes, they ought to be in jail!”

The boys continued to run, but as nobody appeared to be following they gradually slackened their pace and at length came to a halt.

“Joe, I’m almost ready to drop.”

“So am I, but we had better not stop here. Let us keep on until we reach some farmhouse. I’m going to get back my watch and chain if I can.”

“And the nuts. Think of losing them after all the trouble we had in gathering them.”

“Yes, Harry, but the watch and chain are worth more than the nuts. If you’ll remember, they were my birthday present from father.”

“Oh, we’ve got to get back the watch and chain. Come on—the sooner we find a farmhouse and get assistance the better. More than likely those tramps won’t stay at the barn very long.”

Scarcely able to drag one foot after the other, the two Westmore boys continued on their way. The snow had now stopped coming down, yet the keen fall wind was as sharp as ever. But presently the wind shifted and then they made better progress.

“I see a farmhouse!” cried Harry, a little later.

“Not much of a place,” returned his brother. “Yet we may get help there,—who knows?”

When the cottage—it was no more than that—was reached, Joe knocked loudly on the door.

“Who is there?” came in a shrill voice from inside.

“Two boys,” answered Joe. “We want help, for some tramps have robbed us.”

“I can’t help you. The tramps robbed me, too—stole two of my best chickens. I’m an old man and I must watch my property. You go to Neighbor Dugan’s—he’ll help you, maybe.”

“Where is Dugan’s place?”

“Down the road a spell. Keep right on an’ you can’t miss it.” And that was all the boys could get out of the occupant of the cottage.

“He must be a crabbed old chap,” was Harry’s comment, as they resumed their weary tramp.

“Well, an old man can’t do much, especially if he is living all alone. I suppose he’s afraid to leave his place for fear the tramps will visit it during his absence,” and in this surmise Joe was correct.

Fortunately the farm belonging to Andy Dugan was not far distant. The farmer was a whole-souled Irishman and both boys had met him on more than one occasion at Mr. Westmore’s store.

“Sure, an’ where did you b’ys spring from?” said Dugan, on opening the door. “’Tis a likely walk ye are from town.”

“We’ve been out for some nuts, over to Glasby’s Hill,” answered Harry.

“Ah now, so ye’ve got there before me, eh? I didn’t know ’twas known there was nuts there.”

“Mr. Dugan, we want your help,” put in Joe, quickly.

“Phat for, Joe—to help carry home the nuts? Where’s the bags?”

“We met some tramps, and——”

“Tramps? On this road ag’in?” Andy Dugan was all attention and his face grew sober. “Tell me about thim at onct!”

The boys entered the farmhouse, where were collected the Dugan family, consisting of Mrs. Dugan, who weighed about two hundred and fifty pounds, and seven children, including three half-grown sons. All listened with close attention to what the Westmore boys had to relate.

“Th’ schamps!” cried Andy Dugan. “Sure an’ they should be in the town jail! An’ was the watch an’ chain worth much?”

“Twelve or fifteen dollars. And a birthday present, too.”

“I’ll go after thim, that I will. Pat, git me gun, and you go an’ take yer own gun, too—an’, Teddy, git the pistol, an’ see if it’s after bein’ loaded. We’ll tache thim scallywags a lisson, so we will!”

“That’s the talk, Mr. Dugan!” said Joe, brightening. “But you’ll have to hurry, or they’ll be gone.”

“I’ll hurry all I can, lad. But phat about you? You’re too tired to walk back, ain’t ye?”

“Lit thim roide the mare, Andy,” came from Mrs. Dugan. “Th’ mare wants exercise annyway.”

“So they shall, Caddy,” answered the husband, and one of the smaller boys of the family was sent to bring the mare forth.

In less than ten minutes the party was ready to set out, Andy Dugan and his son Pat with guns, Teddy, who boasted of a face that was nothing but a mass of freckles, with the pistol, and Joe and Harry, on the mare’s back, with clubs.

The mare was rather a frisky creature, and both boys had all they could do to make her walk along as they wished.

“She’s been in the sthable too long,” explained Andy Dugan. “She wants a run av a couple o’ miles to take the dancin’ out av her heels.”

“Well, she mustn’t run now,” said Harry, who had no desire to reach the old barn before the others could come up.

The wind was gradually going down, so journeying along the road was more agreeable than it had been. When they passed the little cottage they saw the old man peeping from behind a window shutter at them.

“He’s a quare sthick, so he is,” said Andy Dugan. “But, as he is afther lavin’ us alone, we lave him alone.”

The party advanced upon the barn boldly and when they were within a hundred yards of the structure, Joe and Harry urged the mare ahead. Up flew the rear hoofs of the steed and away she went pell-mell along the road.

“Whoa! whoa!” roared Joe. “Whoa, I say!”

But the mare did not intend to whoa, and reaching the barn, she flew by like a meteor, much to the combined chagrin of the riders. Joe was in front, holding the reins, and Harry in the rear, with his arms about his brother’s waist. Both kept bouncing up and down like twin rubber balls.

“Do stop her, Joe!”

“Whoa!” repeated Joe. “Whoa! Confound the mare, she won’t listen to me!”

“She is running away with us!”

“Well, if she is, I can’t help it.”

“Pull in on the reins.”

“That’s what I am doing—just as hard as I can.”

“Hi! hi!” came in Andy Dugan’s voice. “Phy don’t ye sthop? Ain’t this the barn ye was afther spakin’ about?”

“Yes!” yelled back Joe. “But your mare won’t stop!”

“Hit her on th’ head wid yer fist!” screamed Pat Dugan.

“I don’t believe that will stop her,” said Harry.

“Perhaps it will, if she’s used to it,” said his brother, and an instant later landed a blow straight between the mare’s ears.

Up went the creature’s hind quarters in a twinkling and over her head shot the two boys, to land in the snow and brushwood beside the roadway. Then the mare shied to one side and pranced down the road, and soon a turn hid her from view.

“B’ys! b’ys! Are ye after bein’ hurted?”

It was Andy Dugan who asked the question, as he came rushing to Joe and Harry’s assistance and helped to set them on their feet.

“I—I guess I’m all right, Mr. Dugan,” panted Harry. “But I—I thought my neck was broken at first!”

“So did I,” put in Joe. His left hand was scratched but otherwise he was unharmed.

“Oh, father, the mare’s run away!” chimed in Teddy Dugan. “We won’t never git her back anymore!”

“Hould yer tongue!” answered the parent. “She’ll come back as soon as it’s feedin’ time, don’t worry.”

“Oh, father, are you sure?”

“To be course I am. Didn’t she run away twice before, an’ come back that same way, Teddy? Come on after thim tramps an’ let the mare take care av hersilf.”

“We’ve made noise enough to bring the tramps out—if they’re still in the barn,” was Joe’s comment. “I believe they’ve gone.”

“Exactly my opinion,” answered Harry.

Advancing boldly to the doorway of the barn, Andy Dugan pointed his gun and cried:

“Come out av there, ye rascals! Sure an’ it won’t do ye any good to hide!”

To this demand no answer was returned, and a moment of painful silence followed.

“Are ye comin’ out or not?” went on Dugan the elder. “Answer me.”

“How can they answer, father, if they ain’t there?” put in Teddy Dugan, with a broad smile on his freckled face.

To this query the father made no reply, but advancing cautiously, he gazed into the barn and then stepped inside.

“Are they there, Mr. Dugan?” queried Joe.

“If they are, they’re mighty good at hidin’.”

“Let us make a search,” said Harry. “Pat, you remain on guard outside.”

“That I will,” answered Pat. “Run ’em out here till I shoot ’em first, an’ have ’em arrested afterwards!”

The barn was speedily searched, but the tramps had taken their departure, and soon they discovered the track of the rascals, leading across the fields to another road.

“I believe they left almost as soon as we did,” said Joe. “They knew we’d come back with help.”

“Shall we follow?” asked Harry.

“Av course,” replied Andy Dugan.

“It’s getting rather dark,” went on Joe. “I’m afraid they have given us the slip.”

The matter was talked over, and it was decided that all of the Dugans should go forward, and Joe and Harry were to follow if they could find the mare. If not, they were to tramp back to the Dugan homestead and await news.

Half an hour was spent by the two boys in looking for the runaway steed, and by that time both could hardly walk.

“I wish I was at the Dugan house this instant,” said Harry.

“Ditto myself, Harry. And I wish I had my watch and chain back. Did you notice, the tramps didn’t touch the bags of nuts.”

“I guess they were too excited to remember them. Maybe they thought we’d come back quicker than we did.”

The boys rested for awhile at the barn, and then, with their bags of nuts on their shoulders, set out on the roadway once again.

“Tired out, are ye,” said Mrs. Dugan, on seeing them. “Where are the others?”

They told their story, to which she listened with many a nod of her head.

“The ould b’y take that mare!” she cried. “Sure an’ didn’t she run away wid me wance an’ nearly scare me to death, so she did. Andy must trade her th’ furst chanct he gits.”

She had prepared a hot supper and invited the boys to sit down, which they did willingly, for, as Harry expressed it, “they were hollow clear down to their shoes.”

The meal was just finished when one of the little children, who was at the window gazing into the oncoming darkness, set up a shout:

“There’s Kitty now!”

“Who’s Kitty?” asked Joe.

“Sure an it’s the mare. She’s walkin’ in the yard just as if nothin’ had happened at all!”

The youngster was right, and by the time the boys were outside the mare was standing meekly by the barn door, waiting to be put in her stall.

“Now ain’t she aggravatin’?” came from Mrs. Dugan. “Ye can’t bate her when she looks loike that, can ye? Poor Kitty! It’s a fool thing that ye are entoirely!” And she hurried out, opened the stable and let the mare find her proper place inside. “Fer sech a thrick, ye’ll git only half yer supper this night,” she added, shaking her fist at the animal.

The boys knew that they would be expected home, and waited anxiously for news of the Dugans. Fully an hour and a half passed, before they came back, worn out and downcast.

“They give us the shlip,” said Andy Dugan. “They came around be the lake road an’ thet’s the last we could find av thim.”

“And I guess that’s the last of my watch,” added Joe, soberly.

Andy Dugan had a faithful old horse in his stable and this animal he harnessed to his family carriage, an old affair that had seen far better days.

“Ye can drive yerselves home,” he said. “An’ leave the turnout at Bennett’s stable. Tell him I’ll call for it to-morrow.”

“Thank you, Mr. Dugan,” said Joe. “We’ll settle for the keeping, and get father to pay you——”

“That’s all right, Joe. I want no pay. Your father is a fri’nd av mine. I’m sorry we didn’t catch the thramps, that’s all,” was Andy Dugan’s reply.

It was not until nine o’clock at night that Joe and Harry drove into the town of Lakeport. All the stores were closed, but the livery stable was still open, and there they left the horse and carriage, as Andy Dugan had directed. It was but a short walk from the stable to the house.

“I thought you would be back to supper,” said Mrs. Westmore, when they entered. “I kept everything hot for over an hour.”

“We’ve had an adventure, mother,” answered Joe, and as the family gathered around he told his story.

“Oh, Joe, weren’t you awfully scared!” cried Laura.

“I don’t like tramps at all!” piped in little Bessie.

“This is certainly an outrage,” said Mr. Westmore. “So the Dugans could find no trace of them after they got on the lake road?”

“No.”

“I must have one of the constables look into this, and I’ll notify Sheriff Clowes, too.”

“You can be thankful that the tramps did not injure you,” said Mrs. Westmore, with a shudder.

“Yes, I am thankful for that,” said Harry.

“So am I, mother,” added Joe. “Just the same, I’m downright sorry to lose that watch and chain.”

“Perhaps we’ll get on the track of it. If not, we’ll have to see what we can do about getting you another,” added the fond mother.

The fact that Joe and Harry had been held up by tramps was speedily noised around the town, and for the next few days the authorities and several other people did what they could to locate the evildoers. But the tramps had made good their escape, and, for the time being nothing more was heard from them. But they were destined to turn up again, and in a most unexpected fashion, as the pages to follow will testify.

Joe and Harry had many friends in Lakeport, boys who went to school with them, and who played with them on the local baseball and football teams. All of these were interested in the “hold-up,” as they called it, and anxious to see the tramps captured.

“Glad it wasn’t me,” said one of the lads.

“I’ve got a gold watch—one my uncle left when he died.”

“Why didn’t you punch their heads?” questioned another, who had quite a reputation as an all-around athlete. “That is what I should have done.”

“Yes, and maybe got killed for doing it,” came from a third. “Joe and Harry were sharp enough to escape with whole skins, and that is where they showed their levelheadedness.”

The adventure had happened on Saturday, and Monday found the boys at school as usual. They were so anxious to get news concerning the tramps that they could scarcely learn their lessons, but as day after day went by without news, this feeling wore away; and presently the incident was almost forgotten.

It was customary at Lakeport to close the schools for about a month around the winter holidays and all of the pupils counted the days to when the vacation would begin. At last the time came, and with a whoop, Joe, Harry, and several dozen other lads rushed forth, not to return until near the end of January.

“And now for Christmas!” cried Joe. Deep down in his heart he was wondering if he would get another watch and chain.

Ice had already formed on Pine Lake, but just before Christmas it began to snow and blow heavily, so that skating was out of the question. This put something of a damper on the lads and they went around feeling somewhat blue.

Christmas morning dawned bright and fair. The ground was covered with over a foot of snow, and the merry jingle of sleighbells filled the air.

As may be surmised the Westmore boys were up early. There were many presents to be given and received, and it was a time of great surprises and not a little joy.

What pleased Joe most of all was the new watch he received. It was decidedly better than the first watch had been, and so was the chain better than the other.

“Just what I wanted!” he declared. “It tops all the presents—not but what I like them, too,” he added, hastily.

Harry had slipped off without the others noticing. Now he came back, his face aglow with enthusiasm.

“Oh, Joe, what do you think?” he cried. “The wind has swept Pine Lake as clean as a whistle.”

“If that’s the case, Harry, we can go skating this morning instead of waiting until after dinner. But how do you know the ice on the lake is clear?”

“Didn’t I just come from there?” Harry held up a shining pair of nickel-plated skates. “Couldn’t resist trying ’em, you know. Say, it was just all right of Uncle Maurice to give each of us a pair, wasn’t it?”

“It certainly was,” returned Joe. “But I rather think I love that double-barreled shotgun a little better. I am fairly aching to give it a trial on a bird or a rabbit, or something larger.”

“Well, as for that, I don’t go back on the camera Aunt Laura sent up from New York. Fred Rush was telling me it was a very good one, and he ought to know, for he has had four.”

“What did Fred get for Christmas’?”

“A shotgun something like yours, a big bobsled, some books, and a whole lot of other things. One book is on camping out, and he is just crazy to go. He says a fellow could camp out up at Pine Island, and have a bang-up time.”

“To be sure!” ejaculated Joe, enthusiastically. “Just the thing! If he goes I’m going, too!”

“You don’t know yet if father will let you go. He says no boy should go hunting without some old hunter with him.”

“I’m seventeen,” answered Joe, drawing himself up to his full height; he was rather tall for his age. “And Fred is almost as old. I reckon we could take care of ourselves.”

“If I went I’d like to take my camera,” said Harry. “I was reading an article in the paper the other day about how to hunt game with a snap-shot machine. That would just suit me. Think of what a famous collection of pictures I might get—wild turkeys, deer and maybe a bear——”

“If you met a bear I don’t think you’d stand to take his photograph. I’ll wager you’d leg it for all you were worth—or else shoot at him. But come on. If skating is so good there is no use of our wasting time here talking,” concluded Joe, as he moved off.

Lakeport was a thriving town with a large number of inhabitants. Early as it was many people were out, and nearly every passer-by was greeted with a liberal dose of snowballs, for the lads of this down-East town were as fun-loving as are boys anywhere, and to leave a “good mark” slip past unnoticed was considered nothing short of a crime.

When Joe and Harry reached the lake front they found a crowd of fully fifty men and boys, with a fair sprinkling of girls, engaged in skating and in ice-boating. The majority of the people were in the vicinity of the steamboat dock, for this was at the end of the main street, and a great “hanging-out” spot during the summer. But others were skating up the lake shore, and a few were following Dan Marcy’s new ice yacht, Silver Queen, as she tacked along on her way to the west shore, where an arm of the lake encircled the lower end of Pine Island.

“Marcy’s going to try to beat the lake record,” Joe heard one boy call to another. “He says his new boat has got to knock the spots out of anything that ever sailed on the lake, or he’ll chop her up for firewood.”

“Well, she’ll have to hum along if she beats the time made by the old Whizzer last winter,” came from the other boy. “She sailed from the big pine to Hallett’s Point in exactly four minutes and ten seconds. My, but didn’t she scoot along!”

It took but a few minutes for Joe and Harry to don their skates. As they left the shore they ran into Fred Rush, who was swinging along as if his very life depended upon it.

“Hello, so you fellows have come down at last!” sang out Fred, who was short and stout, and as full of fun as a lad can be. “Thought you had made up your mind to go to bed again, or stay home and look for more Christmas presents. Been having dead loads of fun—had a race and come in second best, got knocked down twice, slipped on the ice over yonder, and got a wet foot in a hole some fellow cut, and Jerry Little hit me in the shin with his hockey stick. Say, but you fellows are positively missing the time of your lives.”

“I want to miss it, if I’m going to have all those things happen to me,” returned Joe, dryly. Then he added: “Harry tells me you got a double-barreled shotgun almost like mine. How do you like it?”

“Like it? Say, that gun is the greatest thing that ever happened. I tried it just before I came down to skate—fired both barrels at once, because I didn’t have time to fire ’em separately. It knocked me flat, and a snowbank was all that saved my life. But she’s a dandy. I’m going to bring down a bear with that gun before the winter is over, you see if I don’t.”

“How are you going to do it?” put in Harry. “Offer to let the animal shoot off the gun, and kill him that way?”

“Don’t you make fun of me, Harry. You’ll see the bear sooner or later, mark the remark.”

The three boys skated off, hand in hand, with Fred in the center. The fun-loving youth was the only son of the town hardware dealer, and he and the Westmore lads had grown up together from childhood. At school Fred had proved himself far from being a dunce, but by some manner of means he was almost constantly in “hot water;” why, nobody could explain.

“Let Fred Rush pick up a poker, and he’ll get the hot end in his hand,” said one of the girls one day, and this remark came close to hitting the nail squarely on the head. Yet with all his trials and tribulations Fred rarely lost his temper, and he was always ready to promise better things for the future.

The boys skated a good half mile up the lake shore. At this point they met several girls, and one of them, Cora Runnell, asked Joe if he would fix her skate for her.

“Certainly I will,” replied the youth, and on the instant he was kneeling on the ice and adjusting a clamp that had become wedged fast to the shoe plate of the skate. Cora was the daughter of an old hunter and trapper of that vicinity, and as he worked Joe asked her what her father was doing.

“He isn’t doing anything just now,” was the girl’s answer. “He was out acting as a guide for a party of New York sportsmen, but they went back to the city last week.”

“Did you hear him say anything about game?”

“Yes, he said the season was a very good one. The party got six deer over at Rawson Hill and a moose at Bender’s, and any quantity of small game. I think pa’s going out alone in a day or two—just to see what he can bring down for the market at Brookside.”

“I wish he’d take me along. I’ve got a new double-barreled shotgun that I want to try the worst way.”

“And I’ve got one, too,” broke in Fred. “I’m sure we could bring down lots of game between us.”

Cora Runnell looked at the stout youth, and began to giggle. “Oh, dear, if you went along I guess pa’d have to hide behind a tree when you took your turn at shooting.”

“Whoop, you’re discovered, Fred!” burst out Harry. “Cora must have heard how you shot off both barrels at once, and——”

“Oh, I can shoot straight enough,” came doggedly from Fred. “Just you give me the chance and see.”

“Well, you’ll have to see pa about going out with him,” answered Cora, and then started to skate after her girl friends, who had moved off a minute before, and were getting farther and farther away.

“Hi, there!” came suddenly in a shout from the lake shore. “Beware of the ice boat!”

“The ice boat?” repeated Harry. “Where—— Oh!”

He glanced up the lake, and saw the Silver Queen coming along as swiftly as the stiff breeze could drive the craft over the glassy surface. The ice boat was headed directly for the three boys, but now the course was shifted slightly, and the craft pointed fairly and squarely for the spot where Cora Runnell was skating along, all unconscious of her danger.

“By gracious, Dan Marcy will run Cora down!” ejaculated Fred. He raised his voice to a yell. “Stop! stop! you crazy fool! Do you want to kill somebody?”

“Save my girl!” came from the shore. “Cora! Cora! Look out for the ice boat!” But the girl did not heed the warning, and now the ice boat, coming as swiftly as ever, was almost on top of her. Then the girl happened to glance back. She gave a scream, tried to turn, but slipped, and then sank in a heap directly in the track of the oncoming danger.

It was a moment of extreme peril, and the heart of more than one onlooker seemed to stop beating. The ice boat was a heavy affair, with runners of steel, and a blow from that bow, coming at such a speed, would be like a blow from a rushing locomotive. It looked as if Cora Runnell was doomed.

But as all of the others stood helpless with surprise and consternation, Joe Westmore dashed forward with a speed that astonished even himself. He fairly flew over the ice, directly for Cora, and, reaching the fallen girl, caught her by the left hand.

“Quick! we must get out of the way!” he cried, and without waiting to raise her to her feet he dragged her over the smooth ice a distance of four or five yards. Then the Silver Queen whizzed past, sending a little drift of snow whirling over them.

“Git out of the way!” came rather indistinctly from Dan Marcy. “Can’t you see I’m trying to beat the record?” And then he passed out of hearing.

“Are you hurt?” questioned Joe, as he assisted the bewildered girl to her feet.

“I—I guess not, Joe,” she stammered. “But, oh! what a narrow escape!” And Cora shuddered.

“Dan Marcy ought to be locked up for such reckless sailing.”

“I think so myself.” Cora paused for a moment. “It was awfully good of you to help me as you did,” she went on, gratefully.

By this time the others were coming up, and the story of the peril and escape had to be told many times. Among the first to arrive was Joel Runnell, Cora’s father, who had shouted the warning from the shore. He had been out hunting, and carried an old-fashioned shotgun and a game bag full of birds.

“Not hurt, eh?” he said, anxiously. “Thank fortune for that! Who was sailing that boat?” And when told, he said he would settle with Marcy before the day was done. “Can’t none of ’em hurt my girl without hearing from me,” he added.

The excitement soon died down, and the skaters scattered in various directions. In the meantime, to avoid being questioned about the affair, Dan Marcy, who was a burly fellow of twenty, and a good deal of a bully, turned his ice boat about, and went sailing up the lake once more.

Some of the lads on the lake were out for a game of snap the whip, and Joe, Harry and Fred readily joined in this sport. At the third snap, Fred was placed on the end of the line.

“Oh, but we won’t do a thing to Fred,” whispered one of the boys, and word was sent along to make this snap an extra sharp one.

“You can’t rattle me!” sang out Fred, as the skating became faster and faster. “I’m here every time, I am. Let her go, everybody, whoop!” And then he had to stop talking, for he could no longer keep up. The line broke, and like a flash Fred spun around, lost his footing, and turned over and over, to bring up in a big snowbank on the shore.

“Hello, Fred, where are you bound?” sang out Harry.

“Where—where am I bound?” spluttered the stout youth, as he emerged and cleaned the snow from out of his collar and sleeves. “I don’t know.” He paused to catch his breath. “Reckon I’m in training for a trip to the North Pole.”

Half an hour later found the Westmore boys at home for dinner. There was something of a family gathering this Christmas day, mostly elderly people, so neither Joe nor Harry had a chance to speak to their father about the hunting trip they had in mind. Everybody was in the best of humor, and the table fairly bent beneath the load of good things placed upon it—turkey with cranberry sauce, potatoes, onions, squash, celery, and then followed pumpkin and mince pies, and nuts and raisins, until neither of the boys could eat a mouthful more. Both voted that Christmas dinner “just boss,” and the other folks agreed with them.

The middle of the afternoon found the lads at the lake again. It had clouded over once more, and they were afraid that another fall of snow might stop skating for several weeks, if not for the balance of the season.

“We want to take the good of it while it lasts,” said Harry.

Dan Marcy was again out on his ice boat, and Joe and Harry, accompanied by Fred, followed the craft to a cove on the west shore. There seemed to be something the matter with the sail of the Silver Queen, and Marcy ran the craft into a snowbank for repairs.

“Say, what do you want around here?” demanded Dan Marcy, as soon as he caught sight of the Westmore boys. His face wore an ugly look, and his tone of voice was far from pleasant.

“I don’t know as that is any of your business, Dan Marcy,” returned Joe.

“Ain’t it? We’ll see. I understand you’ve been telling folks that I tried to run into you and that Runnell girl on purpose.”

“You didn’t take much care to keep your ice boat out of the way.”

“It was your business to keep out of the way. You knew I was trying to beat the record?”

“Do you own the lake?” came from Harry.

“Maybe you’ve got a mortgage on the ice?” put in Fred.

Now the year before, Dan Marcy had been in the ice business, and had made a failure of it, and this remark caused him to look more ugly than ever.

“See here, for two pins I’d pitch into the lot of you, and give you a sound thrashing!” he roared.

“Would you?” came sharply from Joe. “Sorry I haven’t the pins.”

“I’ll give you an order on our servant girl for two clothespins, if they’ll do,” put in Fred.

“Then you want that thrashing, do you?” growled Dan Marcy; but as he looked at the three sturdy lads he made no movement to begin the encounter.

“If anybody needs a thrashing it is you, for trying to run down Cora Runnell,” said Joe. “It was a mean piece of business, and you know it as well as we do.”

“You shut up, Joe Westmore!” Marcy picked up a hammer with which he had been driving one of the blocks of the sail. “Say another word, and I’ll crack you with this!” He advanced so threateningly that Joe fell back a few steps. As he did this, a form appeared on the lake shore, and an instant later Dan Marcy felt himself caught by the collar and hurled flat on his back.

“I reckon as how this is my quarrel,” came in the high-pitched voice of Joel Runnell. “I’ve been looking for you for the past hour, Dan Marcy. I’ll teach you to run down my girl. If it hadn’t a-been for Joe Westmore she might have been killed.”

“Let go!” roared Marcy, and scrambled to his feet, red with rage. He rushed at the old hunter with the hammer raised as if to strike, but before he could land a blow, Joe caught hold of the tool and wrenched it from his grasp.

“Give me that hammer! Do you hear? I want that hammer!” went on the bully. Then he found himself on his back a second time, with his nose bleeding profusely from a blow Joel Runnell had delivered.

“Have you had enough?” demanded the old hunter, wrathfully. “Have you? If not, I’ll give you some more in double-quick order.”

“Don’t—don’t hit me again,” gasped Dan Marcy. All his courage seemed to desert him. “It ain’t fair to fight four to one, nohow!”

“I can take care of you alone,” retorted Joel Runnell, quickly. “I asked you if you had had enough. Come, what do you say?” And the old hunter held up his clinched fists.

“I—I don’t want to fight.”

“That means that you back down. All right. After this you let my girl alone—and let these lads alone, too. If you don’t, you’ll hear from me in a way you won’t like.”

There was an awkward pause, and Dan Marcy wiped the blood from his face, and shoved off on his ice boat.

“We’ll see about this some other time,” he called out when at a safe distance. “I shan’t forget it, mind that!”

“He’s a bully if there ever was one,” observed Harry.

“And a coward into the bargain,” put in Joel Runnell. “Watch out for him, or he may play you foul.”

“I certainly shall watch him after this,” said Joe.

“We’re glad you came along,” came from Fred. “We want to ask you something about hunting. I’ve got a new double-barreled shotgun and so has Joe, and we want to go out somewhere and try for big game.”

“And I’ve got a new camera, and I want to get some pictures of live game,” added Harry.

“You can’t get any big game around Lakeport. If you want anything worth while you’ll have to go out for several days or a week.”

“We’re willing to go out as long as our folks will let us,” explained Harry. “We haven’t said much about it yet, for we wanted to see you.”

“We thought you might like to take us out, or rather go with us,” came from Joe. “If you’d go with us we’d pay the expenses of the trip, and give you your full share of whatever game we managed to bring down.”

At this Joel Runnell’s gray eyes twinkled. He loved boys, and knew the lads before him very well. All the powder and shot he used came from Mr. Rush’s hardware establishment, and his flour from the Westmore mill, and he was always given his own time in which to pay for the articles. Moreover, he was not the one to forget the service Joe had rendered his daughter.

“I’ll go out with you willingly,” he said. “I’ll show you all the big game I can, and what you bring down shall be yours.”

“Hurrah! It’s settled!” cried Fred, throwing up his cap. “We’ll have just the best time that ever was!”

“Where do you want to go to?”

“I was thinking of camping out up on Pine Island,” answered Harry. “But of course we have got to see my father about it first.”

“Pine Island is a nice place. There is an old lodge up there—put up five years ago by some hunting men from Boston. It’s a little out of repair, but we could fix it up, and then use that as a base of supplies.”

“Just the thing!” said Joe, enthusiastically. “If we liked it would you stay out with us for two or three weeks?”

“To be sure. There is a little game on the island, and we could easily skate to shore when we wished. When do you want to go?”

“As soon as we get permission,” said Harry. “We’ll find out about it to-morrow.”

After that the boys could talk of nothing but the proposed outing and what they hoped to bring down in the way of game. Harry wanted pictures worse than he wanted to bring down game; nevertheless, he said he would take along a gun and a pistol. “Then I can snapshot my bear first, and shoot him afterward,” he said.

It was not until the day after Christmas that the Westmore lads got a chance to speak to their parents about what was uppermost in their minds. At first Mrs. Westmore was inclined to demur, but her husband said the outing might do their sons some good.

“And they couldn’t go out with a better fellow than Joel Runnell,” added Mr. Westmore. “They’ll be as safe with him as they would be with me.”

As soon as it was settled that they were really to go, Harry rushed over to Fred’s house. Fred had already received permission to go, and now all they had to settle on was the time for their departure and what was to be taken along. Christmas had fallen on Thursday, and it was decided to leave home on the following Monday morning, weather permitting. As to the stores to be taken along, that was to be left largely to the judgment of Joel Runnell and to Mr. Westmore, who also knew a good bit about hunting and life in camp.

“Boys, we’ve got to organize a club,” said Joe, as they were talking the matter over, and getting one thing and another ready for the trip.

“Just the thing!” shouted Fred. “Let us organize by all means.”

“What shall we call ourselves?” queried Harry. “The Outdoor Trio.”

“Or the Forest Wanderers,” came from Joe.

“Bosh!” interrupted Fred. “We’re going out with guns. You’ve got to put a gun in the name.”

“How will Young Gunners do?”

“Gun Boys of Lakeport.”

“Young Hunters of the Lake.”

“Bull’s-eye Boys.”

“Yes, but if we can’t make any bull’s-eyes, what then?”

There was a general hubbub and then a momentary silence.

“I’ve got it,” said Joe. “Let us call ourselves The Gun Club. That’s a neat name.”

“Hurrah for the Lakeport Gun Club!” shouted Fred. “Three cheers and a tiger! Sis-boom-ah! Who stole the cheese?”

There was a general laugh, in the midst of which Laura Westmore came up.

“Gracious sake! what a noise you’re making! What is it all about?”

“We’ve just organized the Gun Club of Lakeport,” answered Harry.

“Indeed. And who is president, who is vice president, who is secretary, and who is treasurer?”

At this the three lads looked glum for a moment. Then Joe made a profound bow to his sister.

“Madam, we scarcely need so many officers,” he said, sweetly. “We’ll elect a leader and a treasurer, and that will be sufficient. You can be the secretary—to write up our minutes after we get home and tell you what happened.”

“I move we make Joe leader,” said Fred.

“Second the commotion,” responded Harry, gravely. “’Tis put and carried instanter. Mr. Joseph Westmore is elected to the high and dignified office of president, etc., of the Gun Club of Lakeport. The president will kindly deliver his speech of acceptance at the schoolhouse during next summer’s vacation. He can treat with doughnuts——”

“Just as soon as his sister consents to bake them for him,” finished Fred.

At this Laura burst out laughing. “I’ll treat to doughnuts on one condition,” she said.

“Condition granted,” cried Fred. “What is it?”

“That you make me an honorary member of the club.”

“Put and carried, madam, put and carried before you mentioned it. That makes you the secretary sure.”

And Laura accepted the position, and the boys got their doughnuts ere the meeting broke up.

The news soon spread that the Gun Club of Lakeport had been organized. Many boys who possessed guns asked if they could join, and half a dozen were taken in. But of these none could go on the outing as planned, although they said they would try to join the others just as soon as they could get away.

“I’ll tell you one thing I am going to take along,” said Harry. “That is a pair of snowshoes.”

“Right you are,” returned Fred. “Never had so much fun in my life as when I first put on those things. I thought I knew it all, and went sailing down a slide about a mile a minute, until one shoe got caught in a bush, and then I flew through the air for about ’steen yards and landed on my head kerbang! Oh, they are heaps of fun—when somebody else wears ’em.”

It was decided that all should take snowshoes. In addition they were to take their firearms, plenty of powder and shot, a complete set of camp cooking utensils and dishes, some coffee, sugar, condensed milk, flour, bacon, salt pork, beans and potatoes, salt and pepper, and half a dozen other things for the table. Mr. Rush likewise provided a small case of medicines and a good lantern, and from the Westmore household came the necessary blankets. Each lad was warmly dressed, and carried a change of underwear.

“It is going to be no easy work transporting that load to Pine Island,” observed Harry, gazing at the stores as they lay in a heap on the barn floor at his parents’ place.

“We are to take two low sleds,” answered Fred. “We have one and Joel Runnell will furnish the other.”

The sleds were brought around Saturday morning, and by afternoon everything was properly loaded. Joel Runnell examined the new shotguns with care and pronounced each weapon a very good one.

“And I hope you have lots of sport with ’em,” he added.

Late Saturday evening Harry was sent from home to the mill to bring over a sack of buck-wheat flour his mother desired. On his way he passed Fred’s home, and the latter readily agreed to accompany his chum on the errand.

The promise of more snow had not yet been fulfilled, and the night was a clear one, with the sky filled with countless stars.

“I only hope it stays clear,” said Fred. “That is, until we reach the lodge on the island. After that I don’t care what happens.”

“It might not be so jolly to be snowed in—if we run short of provisions, Fred.”

“Oh, old Runnell will be sure to keep the larder full. He told me that the woods are full of wild turkeys and rabbits.”

Having procured the sack of flour and placed it on a hand sled, the lads started on the return. On the way they had to pass a small clump of trees, back of which was located the district schoolhouse. As they paused to rest in the shadow of the trees they noted two men standing in the entryway of the schoolhouse conversing earnestly.

“Wonder who those men are?” said Harry.

“It’s queer they should be there at this hour,” returned Fred. “Perhaps they are up to no good.”

“They wouldn’t get much if they robbed the place,” laughed Harry. “A lot of worn-out books and a stove that isn’t worth two dollars as old iron.”

“Let’s go a little closer, and see who they are anyway.”

This was agreed to, and both boys stole along through the trees, and up to the side of the entryway. From this point they could not see the men, but could hear them talking in earnest tones, now high and then very low.

“It ain’t fair to be askin’ me fer money all the time,” they heard one man say. “I reckoned as how I’d settled in full with ye long ago.”

“It ain’t so, Hiram Skeetles,” was the reply in Dan Marcy’s voice. “I did you a big service, and what you’ve paid ain’t half of what I ought to have.”

“It’s more’n you ought to have. Them papers wasn’t of no account, anyway.”

“Maybe—but you were mighty anxious to get ’em when——” And the boys did not catch what followed.

“And that’s the reason,” came presently from Hiram Skeetles.

“Do you mean to say you lost ’em?” demanded Dan Marcy.

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“One day when I was sailin’ down the lake in Jack Lasher’s sloop. We got ketched by a squall that drove us high and dry on Pine Island. I jumped to keep from getting hurt on the rocks, and when we got off after the storm my big pocketbook with everything in it was gone.”

“Humph!” came in a sniff from Dan Marcy. “Do you expect me to believe any such fish story? Not much! I want fifty dollars, and I am bound to have it.”

A long wrangle followed, in which the bully threatened to expose Hiram Skeetles. This angered the real estate dealer from Brookside exceedingly.

“If you’re a natural born idiot, expose me,” he cried. “But you’ll have to expose yourself fust.”

Dan Marcy persisted, and at last obtained ten dollars. Then the men prepared to separate, and in a few minutes more each was gone.

“Now what do you make of that?” questioned Fred.

“I hardly know what to make of it,” replied Harry. “But I am going to tell my father about this just as soon as I get home.”

Harry was as good as his word, and Horace Westmore listened attentively to what his son had to relate.

“It is certainly very mysterious,” said Mr. Westmore. “The papers that were mentioned may have been those which your grandfather once possessed—those which showed that he was the owner of the land at the upper end of the lake which Skeetles declares is his property. Then again the papers may be something entirely different.”

“I think we ought to watch Dan Marcy, father.”

“Yes, I’ll certainly watch him after this.”

“You haven’t been able to do much about the land, have you?”

“I can’t do a thing without the papers—the lawyers have told me so.”

“If old Skeetles lost them we couldn’t make him give them up, even on a search warrant.”

“That is true. But they may not have been lost even though he said so. He may have them hidden away where nobody can find them,” concluded Mr. Westmore.

Sunday passed quietly enough, the lads attending church with their families, and also going to Sunday school in the afternoon. In the evening Joel Runnell dropped in on the Westmores to see that everything was ready for an early start the next morning.

“Funny thing happened to me,” said the old hunter. “I was over to the tavern Saturday night, and met Hiram Skeetles there. He asked me how matters were going, and I mentioned that I was to take you fellows up to Pine Island for a hunt. He got terribly excited, and said you had no right to go up there.”

“Had no right?” questioned Joe. “Why not?”

“He claims that Pine Island belongs to his family, being a part of the old Crawley estate. But I told him that old Crawley didn’t leave the island to him, and he had better mind his own business,” went on Joel Runnell. “We had some hot words, and he flew out of the tavern madder nor a hornet.”

“Can he stop us, do you think?”

“He shan’t stop me, and I shall protect you boys. Crawley was only a fourth-handed relation of his, and the property is in the courts, and has been for three years. At the most, Skeetles ain’t got more’n a sixth interest in it. Sheriff Cowles is taking care of it.”

This news made the boys wonder if Hiram Skeetles would really try to prevent their going to the island, but when the time came to start on the trip the real estate dealer was nowhere to be seen.

“Gone back to Brookside,” said a neighbor. “He got word to come at once.”

Down at the lake there were a dozen or more friends to see them off, including Cora Runnell, who came to say good-by to her father. The start was made on skates, and it was an easy matter to drag the two heavily loaded sleds over the smooth ice.

“Good-by, boys; take good care of yourselves,” said Mr. Westmore.

“Don’t let a big buck or a bear kill you,” said Mr. Rush to Fred, and then with a laugh and a final handshake the hunting tour was begun.

As the party moved up the lake they noticed that the Silver Queen was nowhere in sight. Dan Marcy had failed to break the record with his new ice boat and had hauled her over to a carpenter shop for alterations.

“I don’t believe he is doing a stroke of regular work,” observed Joe. “If he keeps on he will become a regular town loafer. He has already gone through all the money, his folks left him.”

There was no sunshine, but otherwise the atmosphere was clear, and as the wind was at their backs they made rapid progress in the direction of Pine Island. The lodge which Joel Runnell had mentioned was situated near the upper shore, so that they would have to skirt the island for over a mile before reaching the spot.

Inside of an hour they had passed out of sight of Lakeport, and now came to a small island called the Triangle, for such was its general shape. Above the Triangle the lake narrowed for the distance of half a mile, and here the snow had drifted in numerous ridges from a foot to a yard high.

“This isn’t so nice,” observed Harry, as they tugged at the ropes of the sleds.

“I’ll go ahead and break the way,” said Joel Runnell, and then he continued, suddenly, “There is your chance!”

“Chance for what?” asked Harry.

“Chance for wild turkeys. They’ve just settled in the woods on the upper end of the Triangle.”

“Hurrah!” shouted Joe. “Where is my gun?”

He had it out in an instant, and Fred and Harry followed suit—the latter forgetting all about his precious camera in the excitement.

“You can go it alone this time,” said the old hunter. “Show me what you can do. I’ll watch the traps.”

In a moment they were off, and five minutes of hard skating brought them to the shore of the Triangle. Here they took off their skates, and then plunged into the snow-laden thickets.

“Make no noise!” whispered Joe, who was in advance. “Wild turkeys are hard to get close to.”

“Oh, I know that,” came from Fred. “I’ve tried it more than half a dozen times.”

As silently as ghosts the three young hunters flitted through the woods, each with his gun before him, ready for instant use.

Presently they saw a little clearing ahead, and Joe called a halt. They listened intently and heard the turkeys moving from one tree to another.

“Now then, watch out—and be careful how you shoot,” cautioned Joe, and moved out into the open.

A second later he caught sight of a turkey, and blazed away. The aim was true, and the game came down with a flutter. Then Harry’s gun rang out, followed by a shot from Fred. Two more turkeys had been hit, but neither was killed.

“They mustn’t get away!” cried Fred, excitedly, and blazed away once more. But his aim was wild, and the turkey was soon lost among the trees in the distance.

Harry was more fortunate, and his second shot landed the game dead at his feet. Joe tried for a second turkey, but without success.

“Never mind, two are not so bad,” said Harry, “It’s a pity you didn’t get yours,” he went on, to Fred.

“Oh, I’ll get something next time, you see if I don’t,” replied the stout youth. “I don’t care for small game, anyway. A deer or a bear is what I am after.”

“Well, I hope you get all you want of deer and bear,” put in Joe; and then they hastened to rejoin Joel Runnell, and resume the journey.

“Got two, did you?” came from Joel Runnell, when the party came up. “That’s a good deal better than I looked for.”

“I hit a third, but it got away from me,” said Fred.

“You mustn’t mind that. I’ve seen young gunners go out more than once and not bring a thing down,” returned the old hunter.

Once more the journey up the lake was resumed, and an hour later they came in sight of Pine Island; a long narrow strip of land, located half a mile off the western shore. The island lay low at either end, with a hill about a hundred feet high in the middle. On the hill there was a patch of trees that gave to the place its name, and trees of other varieties lined the shores, interspersed here and there with brushwood. There were half a dozen little coves along the eastern shore, and two small creeks near the southern extremity.

As the party drew closer to the island they saw that all the trees were heavily laden with snow, and many of the bushes were covered.

“Pretty well snowed up, isn’t it?” remarked Joe.

“I’m going to take a picture of the island,” said Harry, and proceeded to get out his camera, which was a compact affair, taking film pictures four by five inches in size.

“Is the light strong enough?” questioned Joe. “I thought you had to have sunlight for a snapshot.”

“I’ll give it a time exposure, Joe.”

“Fred, how long do you think it ought to have?”

“About ten seconds with a medium stop,” was the reply.

The camera was set on the top of one of the sleds and properly pointed, and Joe timed the exposure. Then Harry turned the film roll around for picture number two.

“That’s a good bit easier than a plate camera,” came from Joel Runnell. “I once went out with a man who had that sort. His plates weighed an awful lot, and he was always in trouble trying to find some dark place where he could fill his holders.”

“This camera loads in daylight; so I’ll not have any trouble that way,” said Harry. “And I can take six pictures before I have to put in a new roll of films.”

It was high noon when the upper end of Pine Island was gained. All of the party were hungry, but it was decided to move on to the lodge before getting dinner.

The lodge set back about a hundred feet from the edge of a cove, and ten minutes more of walking over the ice and through the deep snow brought them in sight of the building. It was a rough affair of logs, twenty by thirty feet in size, with a rude chimney at one end. There was a door and two windows, and the ruins of a tiny porch. Over all the snow lay to a depth of a foot or more.

“I’ve got a name for this place,” said Joe. “I don’t think anything could be more appropriate than that of Snow Lodge.”

“That fits it exactly!” cried Fred. “Snow Lodge it is, eh, Harry?”

“Yes, that’s all right,” was the answer; and Snow Lodge it was from that moment forth.

There had been a padlock on the door, but this was broken off, so they had no difficulty in getting inside. They found the lodge divided into two apartments, one with bunks for sleeping purposes, and the other, where the fireplace was, for a living-room. Through an open window and through several holes in the roof the snow had sifted, and covered the flooring as with a carpet of white.

“We’ll have to clean up first of all,” said Joe. “No use of bringing in our traps until then.”

“Our first job is to clean off the roof and mend that,” came from Joe Runnell. “Then we’ll be ready for the next storm when it comes. After that we can clean up inside and cut some firewood.”

“But dinner——” began Fred.

“I’ll cook the turkeys and some potatoes while the others fix the room,” said Harry.

This was agreed to, and soon they had a fire blazing away in front of the lodge. To dry-pick the turkeys was not so easy, and all the small feathers had to be singed off. But Harry knew his business, and soon there was an appetizing odor floating to the noses of those on the roof of the lodge.

The young hunters thought the outing great sport, and while on the roof Joe and Fred got to snowballing each other. As a consequence, Joe received one snowball in his ear, and Fred, losing his balance, rolled from the roof into a snowbank behind the lodge.

“Hi! hi! let up there!” roared old Runnell. “This isn’t the play hour, lads. Work first and play afterward.”

“It’s no play to go headfirst in that snowbank,” grumbled Fred. “I’m as cold as an icicle!”

“All hands to dinner!” shouted Harry. “Don’t wait—come while everything is hot!”

“Right you are!” came from Joe, as he took a flying leap from the roof to the side of the fire. “Phew! but that turkey smells good, and so do the potatoes and coffee!”

They were soon eating with the appetite that comes only from hours spent in the open air in winter. Everything tasted “extra good,” as Fred put it, and they spent a good hour around the fire, picking the turkey bones clean. The turkeys had not been large, so that the meat was extra tender and sweet.

The roof of the lodge had been thoroughly cleaned, and now the boys were set to work to clean out the interior, and to start a fire in the open fireplace. In the meantime Joel Runnell procured some long strips of bark, and nailed these over the holes he had discovered. Over the broken-out window they fastened a flap of strong, but thin, white canvas in such a manner that it could be pushed aside when not wanted, and secured firmly during the night or when a storm was on.

The roaring fire soon dried out the interior of the building, and made it exceedingly comfortable. The boys found several more cracks in the sides, and nailed bark over these.

“Now for some firewood and pine boughs for the bunks, and then we can consider ourselves at home,” said Joel Runnell. “I know cutting firewood isn’t sport, but it’s all a part of the outing.”

“Oh, I shan’t mind that a bit,” replied Joe, and the others said the same.

Several small pine trees were handy, and from these old Runnell cut the softest of the boughs, and the boys arranged them in the bunks, after first drying them slightly before the fire. Over the boughs were spread the blankets brought along, and this furnished each with a bed, which, if not as comfortable as that at home, was still very good.

“It will beat sleeping on a hard board all hollow,” said Harry.

Next came the firewood; and this was stacked up close to the door of the lodge, while a fair portion was piled up in the living-room, for use when a heavy storm was on. Each of the boys chopped until his back fairly ached, but no one complained. It was so different, chopping wood for an outing instead of in the back yard at home!

“And now for something for supper and for breakfast,” said Joel Runnell, as the last stick was flung on the woodpile. “Supposing we divide our efforts. Joe can go with me into the woods on a hunt, while Fred and Harry can chop a hole in the ice on the lake, and try their luck at fishing.”

“Just the thing!” cried Fred. “Wait and see the pickerel I haul in.”

“And the fish I catch,” added Harry.

“Will we have to lock up the lodge?” asked Joe.

“Hardly,” answered the old hunter. “I don’t believe there is anybody, but ourselves inside of five miles of this spot.”

The guns were ready, and Joel Runnell and Joe soon set off, for the short winter day was drawing to a close, and there was no time to lose. But the fishing outfits had still to be unpacked, and the boys had to find bait, so it was half an hour later before Fred and Harry could get away.

Arriving at the lake shore, the two would-be fishermen selected a spot that they thought looked favorable, and began to cut their hole. As the ice was fully sixteen inches thick this was no easy task. But at last the sharp ax cut through, and then it was an easy matter to make the hole large enough for both to try their luck.

“I’ll wager a potato that I get the first bite,” observed Harry, as he threw in.

“What odds are you giving on that bet?” came from Fred.

“I didn’t think you were such small potatoes as to ask odds,” was the quick answer; and then both lads laughed.

Fishing proved to be slow work, and both boys became very cold before Fred felt something on his line.

“Hurrah, I’ve got a bite!” he shouted. “Here is where I win that potato!” And he hauled in rapidly.

“Be careful that you don’t lose your fish,” cautioned Harry. “We can’t afford to lose anything just now.”

“Huh! don’t you think I know how to fish?” grunted Fred, and hauled in as rapidly as before. But then the game appeared to hold back, and he hardly knew what to do.

“Coming in hard,” he said, slowly. “I think——. Ah, I’ve got him now! Here he comes!” And then the catch did come—a bit of brushwood, with several dead weeds clinging to it.

“That’s a real fine fish,” said Harry, dryly. “What do you suppose he’d weigh, in his own scales?”

“Oh, give us a rest!”

“The potato is yours, Fred. You can eat it for supper, along with that fine catch.”

“If you say another word, I’ll pitch you into the hole!”

“I never saw a fish exactly like that one. Is it a stickleback, or a hand-warmer?”

Fred did not answer, and Harry said no more, seeing that his chum did not relish the joke. Both baited up afresh, and this time Fred got a real bite, and landed a pickerel weighing close to a pound.

“Now you’re doing something!” cried Harry, heartily. “I’ll give in, you are the best fisherman, after all.”

“It was blind luck, Harry. You may——You’ve got a bite!”

Harry did have a bite, and the strain on the line told that his catch was a heavy one. He had to play his catch a little. Then it came up—a fine lake bass twice the size of the pickerel.

After this the sport continued steadily, until the young fishermen had fourteen fish to their credit. In the meantime it had grown quite dark, and the air was filled with softly falling snowflakes.

“I wonder if the others have got back to the lodge yet?” said Fred.

“It is not likely, Fred. That last shot we heard came from almost on top of the hill.”

“I hope they’ve had good luck. It looks now as if we wouldn’t be able to do much to-morrow.”

“Oh, this storm may not last. The wind isn’t in the right direction. We may—Hark!”

The boys stopped short in their talk, and both listened intently. From a distance they could hear a faint cry:

“Help! help!”

“It is Joe!” ejaculated Harry. “He is in trouble. We must go and see what is wrong!”

And throwing down his line and his fish he bounded in the direction of the cry for assistance, with Fred at his heels.

We must go back to the time when Joe and old Runnell started away from Snow Lodge to see what game they could bring down for the next meal or two.

“We haven’t any time to waste,” said the old hunter, as they moved along. “In an hour it will be too dark to shoot at a distance.”

“Shall we take snowshoes along?” asked the youth.

“Not worth while, lad. We’ll try those in the big forest over on the mainland later on.”

The lodge was soon left behind, and old Runnell led the way through some brushwood that skirted the base of the hill.

“There ought to be some rabbits around here,” he said, and had scarcely spoken, when two rabbits popped into view. Bang! went his gun, and both were brought low by the scattering shot.

“Gracious! but you were quick about that!” cried Joe, enthusiastically.

“You don’t want to wait in hunting, Joe. Be sure of what you are shooting at, and then let drive as quick as you can pull trigger.”

On they went, and a few rods farther scared up two other rabbits. Joe now tried his luck, Joel Runnell not firing on purpose. One of the rabbits fell dead, while the other was so badly lamed that Joe caught and killed him with ease.

“Good enough! Now we are even!” exclaimed the old hunter.

“Do you think we shall find any large game here?”

“Hardly. If a deer was near by he’d slide away in jig time as soon as he heard those shots. The most we can hope for are rabbits and birds.”

“I see a squirrel!” cried Joe, a little later.

“Watch where he goes,” returned the old hunter. “Ah, there’s his tree.”

Joe took aim, and the squirrel was brought down just as he was entering his hole. The tree was not a tall one, and Joel Runnell prepared to climb it.

“What are you going to do that for?” asked the youth.

“For the nuts, Joe. They’ll make fine eating during the evenings around the fire.”

It was an easy matter to clean out the hole in the tree—after they had made sure that no other animals were inside. From the place they obtained several quarts of hickory and other nuts, all of which Joel Runnell poured into the game bag he had brought along.

“This is easier than picking ’em from the trees,” he remarked. “And that squirrel will never need them now.”

By the time the top of the hill was gained, it was almost dark, and the snow had begun to fall. At this point they scared up half a dozen birds, and brought down four. Joel Runnell also caught sight of a fox, but the beast got away before he could fire on it.

“We may as well be getting back,” said the old hunter. “It is too dark to look for more game.”

“Suppose we separate?” suggested Joe. “I can take to the right, and you can go to the left. Perhaps one or the other will spot something before we get back to the lodge.”

This was agreed to, and soon Joe found himself alone. As he hurried on as fast as the deep snow permitted, he heard Joel Runnell fire his gun twice in succession.

“He has seen something,” thought the youth. “Hope I have equal luck.”

He was still on high ground when he came to something of a gully. Here the rocks had been swept bare by the wind. As he leaped the gully something sprang up directly in front of him.

What the animal was Joe could not make out. But the unexpected appearance of the beast startled the young hunter, and he leaped back in astonishment. In doing this he missed his footing, and the next instant found himself rolling over the edge of the gully to a snow-covered shelf ten feet below.

“Help! help!” he cried, not once, but half a dozen times.

He had dropped his gun, and was now trying his best to cling fast to the slippery shelf. But his hold was by no means a good one, and he found himself slipping, slipping, slipping, until with a yell he went down, and down, into the darkness and snow far below.

In the meantime, not only Harry and Fred, but also Joel Runnell were hurrying to his assistance. But the darkness and the falling snow made the advance of the three slow. They came together long before the edge of the gully was reached.

“Hello!” cried the old hunter. “Was that Joe calling?”

“It must have been,” answered Harry. “But where is he?”

“He wasn’t with me. When we started back to the lodge we separated. I just shot another brace of squirrels, when I heard him yell.”