TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—The transcriber of this project created the book cover image using the front cover of the original book. The image is placed in the public domain.

So soon as we got into the street, we met the Turtle and the Pelican, walking arm-in-arm, and each smoking a cigarette.— Page 151.

Wallypugland.

ADVENTURES IN

WALLYPUG-LAND

By G. E. FARROW

AUTHOR OF “THE WALLYPUG OF WHY,”

“THE WALLYPUG IN

LONDON,” ETC.

WITH FIFTY-SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY ALAN WRIGHT

A. L. BURT COMPANY, PUBLISHERS,

52-58 Duane Street, New York.

DEDICATED

TO

LIONEL

ADVENTURES IN WALLYPUG-LAND.

PREFACE.

My dear little Friends,

I have again to thank you for the many kind and delightful letters which I have received from all parts of the world, and I cannot tell you how happy I am to find that I have succeeded so well in pleasing you with my stories.

What am I to say to the little boy who wrote, and begged “that, if the Wallypug came to stay with me again, would I please invite him too?” or to the other dear little fellow who came to me with tears in his eyes, to tell me that some superior grown-up person had informed him that “there[10] never was a Wallypug, and it was all just a pack of nonsense”; that “Girlie never went to Why at all, and that in fact there was no such place in existence”?

I can only regretfully admit that, sooner or later as we grow up to be men and women, there are bound to be many fond illusions which are one by one ruthlessly dispelled, and that many of the dreams and thoughts which, in our younger days, we cherish most dearly, the hard, matter-of-fact world will always persist in describing as “a pack of nonsense.” However, for many of us fortunately, this tiresome time has not yet arrived, and for the present we will refuse to give up our poor dear Wallypug—for whom I declare I have as great an affection and regard, as the most enthusiastic of my young readers.

You will see that in the following story I have described my own experiences during a recent visit to the remarkable land over which His Majesty[11] reigns as a “kind of king”, and I may tell you that, amongst all of the extraordinary creatures that I met there, there was not one who expressed the slightest doubt as to the reality of what was happening; while for my own part, I should as soon think of doubting the existence of the fairies themselves, as of the simple, kind-hearted, little Wallypug.

There now! I hope that I have given quite a clear and lucid explanation, and one which will prevent you from being made unhappy by any doubts which may arise in your mind as to the possibility, or probability, of this story. Please don’t forget to write to me again during the coming year.

Believing me to be as ever,

Your affectionate Friend,

G. E. FARROW.

CONTENTS.

| Adventures in Wallypugland. | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | How I Went to Why | 13 |

| II. | A Strange Welcome | 29 |

| III. | A Terrible Night | 40 |

| IV. | Late for Breakfast | 50 |

| V. | The Trial | 62 |

| VI. | His Majesty is Deposed | 74 |

| VII. | Foiled | 83 |

| VIII. | The Little Blue People | 94 |

| IX. | The Wallypug Recovers his Crown | 103 |

| X. | The Home of Ho-Lor | 116 |

| XI. | The Why and Wer-Har-Wei Railway | 131 |

| XII. | Back Again at Why | 145 |

| XIII. | A New State of Affairs | 155 |

| XIV. | “Good for the Complexion” | 165 |

| XV. | “Wallypug’s Blush Limited” | 175 |

| XVI. | “Au Revoir” | 187 |

| The Blue Dwarfs | 197 | |

MR. NOBODY.

CHAPTER I.

HOW I WENT TO WHY.

For some time past I have been the guest of his Majesty the Wallypug at his palace in the mysterious kingdom of Why—a country so remarkable that even now I am only just beginning to get used to my strange surroundings and stranger neighbors. Imagine, if you can, a place where all of the animals not only talk, but take an[14] active part in the government of the land, a place where one is as likely as not to receive an invitation to an evening party from an ostrich, or is expected to escort an elderly rhinoceros in to dinner; where it is quite an everyday occurrence to be called upon by a hen with a brood of young chickens just as you are sitting down to tea, and be expected to take a lively interest in her account of how the youngest chick passed through its latest attack of the “pip.”

In such a country, the unexpected is always happening, and I am continually being startled in the streets at being addressed by some dangerous-looking quadruped, or an impertinent bird, for I must say that as a class the birds are the most insolent of all the inhabitants of this strange land. There is in particular one old crow, a most objectionable personage, and a cockatoo who is really the most violent and ill-natured bird that I have ever been acquainted with.

She takes a very active interest in Parliamentary affairs, and is a strong supporter of woman’s wrongs.

“Every woman has her wrongs,” she declares, “and if she hasn’t she ought to have.”

You will naturally wish to know how I reached this strange country, and will, no doubt, be surprised when I tell you how the journey was accomplished.

One morning a few weeks since, I received a letter from his Majesty the Wallypug asking me to visit him at his palace at Why, in order to assist him in establishing some of our social customs and methods of government, which he had so greatly admired during his visit to England, and which he was desirous of imitating in his own land. A little packet was enclosed in the letter, bearing the words, “The shortest way to Why. This side up with anxiety.” “Well,” I thought, “I suppose they mean ‘This side up with care,[16]’” and was proceeding very carefully to open the packet when a gust of wind rushed in at the window, and blowing open the paper wrapper, scattered the contents—a little white powder—in all directions. Some particles flew up into my eyes, and caused them to smart so violently that I was obliged to close them for some time till the pain had gone, and when I opened them again, what do you think? I was no longer in my study at home, but out on a kind of heath in the brilliant sunshine, and apparently miles from a house of any kind. A finger-post stood a little way in front of me, and I could see that three roads met just here. Anxiously I hurried up to the post to see where I was. One arm pointed, “To Nowhere.” “And I certainly don’t want to go there,” I thought; the other one was inscribed, “To Somewhere,” which was decidedly a little better, but the third one said, “To Everywhere Else.”

“THAT’S NOT MUCH USE.”

“And, good gracious me,” I thought, “that’s not much use, for I don’t know in the least now which of the last two roads to take.” I was puzzling my brain as to what was the best thing to be done, when I happened to look down the road leading to “Nowhere,” and saw a curious-looking[18] little person running towards me. He had an enormous head, and apparently his arms and legs were attached to it, for I could see no trace of a body. He was flourishing something in his hand as he ran along, and as soon as he came closer I discovered that it was his card which he handed to me with a polite bow and an extensive smile, as soon as he got near enough to do so.

“MR. NOBODY,

No. 1 NONESUCH-STREET,

NOWHERE,”

is what I read.

The little man was still smiling and bowing, so I held out my hand and said:

“How do you do, sir? I am very pleased to make your acquaintance. Perhaps you can be good enough to tell me—”

The little man nodded violently.

“To tell me where I am,” I continued.

Mr. Nobody looked very wise, and after a few moments’ thought smiled and nodded more violently than ever, and simply pointed his finger at me.

“Yes, yes,” I cried, rather impatiently; “of course I know that I’m here, but what I want to know is, what place is this?”

The little fellow knitted his brows, and looked very thoughtful, and finally staring at me sorrowfully, he slowly shook his head.

“You don’t know?” I inquired.

He shook his head again.

“Dear me, this is very sad; the poor man is evidently dumb,” I said, half aloud.

Mr. Nobody must have heard me, for he nodded violently, then resuming his former smile, he bowed again, and turning on his heels ran back in the direction of Nowhere, stopping every now and then to turn around and nod and smile and wave his hand.

“What a remarkable little person,” I was just saying, when I heard a voice above my head calling out:

“Man! man!”

I looked up and saw a large crow perched on the finger-post. He had a newspaper in one claw, and was gravely regarding me over the tops of his spectacles.

“Well! what are you staring at?” he remarked as soon as he caught my eye.

“Well, really,” I began.

“Haven’t you ever seen a crow before?” he interrupted.

“Of course I have,” I answered rather angrily, for my surprise at hearing him talk was fast giving way to indignation at his insolent tone and manner.

“Very well, then, what do you want to stand there gaping at me in that absurd way for?” said the bird. “What did he say to you?” he[21] continued, jerking his head in the direction in which Mr. Nobody had disappeared.

“Nothing,” I replied.

“Very well, then, what was it?” he asked.

“What do you mean?” said I.

“Why, stupid, you said Nobody and nothing, didn’t you, and as two negatives make an affirmative that means he must have said something.”

“I’m afraid I don’t quite understand,” I said.

“Ignorant ostrich!” remarked the crow contemptuously.

“Look here,” I cried, getting very indignant, “I will not be spoken to like that by a mere bird!”

“Oh, really! Who do you think you are, pray, you ridiculous biped? Where’s your hat?”

I was too indignant to answer, and though I should have liked to have asked the name of the place I was at, I determined not to hold any further conversation with the insolent bird, and[22] walked away in the direction of “Somewhere,” pursued by the sound of mocking laughter from the crow.

“WHERE’S YOUR HAT?”

I had not gone far, however, before I perceived a curious kind of carriage coming towards me. It was a sort of rickshaw, and was drawn by a kangaroo, who was jerking it along behind him. A large ape sat inside, hugging a carpet bag, and holding on to the dashboard with his toes.

“Let’s pass him with withering contempt,” I heard one of them say.

“All right,” was the reply. “Drive on.”

“I say, Man,” called out the Ape, as they passed, “we’re not taking the slightest notice of you.”

“Oh, aren’t you? Well, I’m sure I don’t care,” I replied rather crossly.

The Kangaroo stopped and stared at me in amazement, and the Ape got out of the rickshaw and came towards me, looking very indignant.

“Do you know who I am?” he asked, striking an attitude.

“No, I don’t,” I replied, “and what’s more, I don’t care.”

“But I’m a person of consequence,” he gasped.

“You are only an ape or a monkey,” I said firmly.

“Oh! I can clearly see that you don’t know me,” remarked the Ape pityingly. “I’m Oom Hi.”

“Indeed,” I said unconcernedly. “I am afraid I’ve never heard of you.”

“Never heard of Oom Hi,” cried the Ape. “Why, I am the inventor of Broncho.”

“What’s that?” I asked. “Good gracious! what ignorance,” said the Ape; “here, go and fetch my bag,” he whispered to the Kangaroo, who ran back to the rickshaw and returned with the carpet bag.

“This,” continued Oom Hi, taking out a bottle, “is the article; it is called ‘Broncho,’ and is excellent for coughs, colds, and affections of the throat; you will notice that each bottle bears a label stating that the mixture is prepared according to my own formula, and bears my signature; none other is genuine without it. The Wallypug, when he returned from England and heard that I had invented it, declared that I must be a literary genius.”

“There,” continued Oom Hi, taking out the bottle, “is the article; it is called ‘Broncho.’”—Page 24.

Wallypugland.

“A what!” I exclaimed.

“A literary genius,” repeated the Ape, smirking complacently.

“Why, what on earth has cough mixture to do with literature?” I inquired.

“I don’t know, I’m sure,” admitted Oom Hi, “but the Wallypug said that in England any one who invented anything of that sort was supposed to possess great literary talent.”

“The Wallypug!” I exclaimed, suddenly remembering. “Am I anywhere near his Kingdom of Why, then?”

“Of course you are; it’s only about a mile or two down the road. Are you going there?” inquired Oom Hi.

“Well, yes,” I answered. “I’ve had an invitation from his Majesty, and should rather like to go there, as I’m so near.”

“His Majesty; he—he—he, that’s good,” laughed the Kangaroo. “Do you call the Wallypug ‘his Majesty’?” he asked.

“Of course,” I replied, “he is a king, isn’t he?”

“A kind of king,” corrected Oom Hi. “You don’t catch us calling him ‘your Majesty,’ I can tell you though, one animal is as good as another here, and if anything, a little better. If you are going to Why, we may as well go back with you, and give you a lift in the rickshaw.”

“You’re very kind,” I said, gratefully.

“Not at all, not at all; jump in,” said Oom Hi.

“Hold on a moment,” said the Kangaroo. “It’s his turn to pull, you know.”

“Of course, of course,” said the Ape, getting into the vehicle; “put him in the shafts!”

“What do you mean?” I expostulated.

“Your turn to pull the rickshaw, you know;[27] we always take turns, and as I have been dragging it for some time it’s your turn now.”

“But I’m not going to pull that thing with you two animals in it. I never heard of such a thing,” I declared.

“Who are you calling an animal?” demanded the Kangaroo, sulkily. “You’re one yourself, aren’t you?”

“Well, I suppose I am,” I admitted. “But I’m not going to draw that thing, all the same.”

“Oh, get in, get in; don’t make a fuss. I suppose I shall have to take a turn myself,” said Oom Hi, grasping the handles, and the Kangaroo and myself having taken our seats we were soon traveling down the road. The Kangaroo turned out to be a very pleasant companion after all, and when he found out that I came from England told me all about his brother, who was a professional boxer, and had been to London and made his fortune as the Boxing Kangaroo. He was[28] quite delighted when I told him that I had seen notices of his performance in the papers. We soon came in sight of a walled city, which Oom Hi, turning around, informed me was Why. And on reaching the gate he gave the rickshaw in charge of an old turtle, who came waddling up, and each of the animals taking one of my arms, I was led in triumph through the city gates to the Wallypug’s palace, several creatures, including a motherly-looking goose and a little gosling, taking a lively interest in my progress, while a giraffe in a very high collar craned his neck through a port-hole to try and get a glimpse of us as we passed under the portcullis.

CHAPTER II.

A STRANGE WELCOME.

WE soon reached the Wallypug’s palace, which stood in a large park in the center of the city of Why. I had been very interested in noticing the curious architecture in the streets as we passed along, but was scarcely prepared to find the palace such a very remarkable place. It was a long, low, rambling building, built in a most singular style, with all[30] sorts of curious towers and gables at every point.

Oom Hi and the Kangaroo saw me as far as the entrance, and then took their departure, saying that they would see me again another day, and I walked up the stone steps, to what I imagined to be the principal door, alone. To my great surprise, however, I found that, instead of being[31] the way in, it was nothing more or less than a huge jam-pot, with a very large label on it marked “Strawberry Jam,” while above it were the words, “When is a door not a door?” “When is a door not a door?” I repeated, vaguely conscious of having heard the question before.

“SOLD AGAIN! SERVE YOU RIGHT!”

“Ha—ha—ha,” laughed a mocking voice at the bottom of the steps, and looking down I saw an enormous Cockatoo with a Paisley shawl over her shoulders and walking with the aid of a crutched stick.

“Sold again, were you? Serve you right,” she cried. “When is a door not a door? Pooh! fancy not knowing that old chestnut. Why! when it’s a jar, of course, stupid. Bah!”

“It’s a very absurd practical joke, that’s all that I can say,” I remarked, crossly, walking down the steps again. “Perhaps you can tell me how I am going to get into this remarkable place.”

“Humph! Perhaps I can and perhaps I won’t,” said the Cockatoo. “I dare say it’s a better place than you came from, anyhow. You’re not the first man that has come down here with his superior airs and graces, grumbling and finding fault with this, that, and the other; but we’ll soon take the conceit out of you, I can tell you. Where’s your hat?”

This was the second creature that had asked me this question, and really they threw so much scorn and contempt into the inquiry that one would imagine that it was a most disgraceful offense to be without a head covering.

I thought the most dignified thing to do under the circumstances was to take no further notice of the bird, and was quietly walking away when the Cockatoo screamed out again, “Where’s your hat? Where’s your hat? Where’s your hat?” each time louder and louder, till the last inquiry ended in a perfect shriek.

“Don’t be so ridiculous,” I cried. “I’ve left it at home, if you must know.”

“Down with the hatters!” screamed the Cockatoo irrelevantly, “Down with the Wallypug! Down with men without hats! Down with everybody and everything!” and the wretched bird danced about like a demented fury.

At the sound of all this commotion a number of windows in the upper stories of the palace were thrown open, and curious heads were popped out to see what was the matter. Among them and immediately over my head, I noticed the Doctor-in-Law.

“Oh! it’s you, is it, kicking up all this fuss?” he remarked as soon as he recognized me.

“Well, really!” I replied, “I think you might have the politeness to say ‘How do you do?’ considering that it is some months since we met.”

“Oh, do you indeed?” said the Doctor-in-Law,[34] contemptuously. “Well, supposing I don’t care one way or another. Where’s your hat?”

“DOWN WITH THE DOCTOR-IN-LAW.”

Before I could answer the Cockatoo had screamed out “Down with the Doctor-in-Law!” and the irate little man had replied by throwing a book at her head out of the palace window.

“I saw his Majesty, the Wallypug himself, running across the lawn towards me, with both hands stretched out in welcome.”— Page 35.

Wallypugland.

I was thoroughly disgusted at this behavior and at the strange reception that I was receiving, and had fully determined to try and find some way of getting home again, when, happening to turn round, I saw his Majesty the Wallypug himself running across the lawn towards me, with both hands stretched out in welcome, and his kind little face beaming with good nature.

“How d’ye do? How d’ye do?” he cried. “So pleased to see you. Didn’t expect you quite so soon, though. Come along—this way.” And his Majesty led me to another entrance, and through a large square hall hung with tapestry and many quaint pieces of old-fashioned armor, to a door marked “His Majesty the Wallypug. Strictly private.” I noticed, in passing, that the words, “His Majesty” had been partly painted out, and “What cheek!” written above them. Once inside[36] the door, the Wallypug motioned me to a chair, and said, in a mysterious whisper,

“I’m so glad you came before she returned; there’s so much I want to tell you.”

“Who do you mean?” I asked.

“Sh—Madame—er, my sister-in-law,” he replied, with a sigh.

“Your sister-in-law!” I exclaimed. “Why, I didn’t know you were married.”

“Neither am I,” said his Majesty, with a puzzled frown. “That’s the awkward part about it.”

“But how on earth can you possibly have a sister-in-law, unless you have a wife or a married brother?” I asked.

“Well, I’ve never quite been able to understand how they make it out,” said the poor Wallypug, sorrowfully; “but I believe it is something mixed up with the Deceased Wife’s Sister’s Bill, and the fact that my uncle, The Grand Mochar[37] of Gamboza, was married twice. Anyhow, when I returned from London I found this lady, who says that she is my sister-in-law, established here in the palace; and—and—” his Majesty sank his voice to a whisper, “she rules me with a rod of iron.”

I had no time to make further inquiries, for just then the door opened, and a majestic-looking person sailed into the room, and after looking me up and down with elevated eyebrows, pointed her finger at me, and said, in a stern voice:

“And who is this person, pray?”

“Oh, this,” said his Majesty, smiling nervously, and bringing me forward, “is the gentleman who was so kind to us in London, you know. Allow me to present him, Mr. Er—er——”

“I hope you have not been picking up any undesirable acquaintances, Wallypug,” interrupted his Majesty’s Sister-in-Law severely. “I don’t like the look of him at all.”

“I’m sorry, madame, that my appearance doesn’t please you,” I interposed, feeling rather nettled; “perhaps under the circumstances I had better——”

“I DON’T APPROVE OF YOU IN THE LEAST,” SAID THE SISTER-IN-LAW.

“You had better do as you are bid and speak[39] when you are spoken to,” remarked the lady grimly. “Where’s your hat?”

“I haven’t one,” I replied, rather abruptly, I am afraid, but I was getting quite tired of this continual cross-questioning; “and really I don’t see that it’s of the slightest consequence,” I ventured to add.

“Oh! don’t you,” said his Majesty’s Sister-in-Law, with a sarcastic smile. “Well, that’s one of the many points upon which we shall disagree. Now, look here, I may tell you at once that I don’t approve of you in the least; still, as you are here now you had better remain; but mind, no putting on parts or giving yourself airs and graces, or I shall have something to say to you. Do you understand?” And with a severe glance at me, the lady folded her arms and stalked out of the room, leaving his Majesty and myself staring blankly at one another.

CHAPTER III.

A TERRIBLE NIGHT.

My reception at Why had been such a very peculiar one that I had fully made up my mind to return home at once, but his Majesty the Wallypug begged me so earnestly to stay with him, at any rate for a few days, that I determined, out of friendship to him, to put up as best I could with that extraordinary person the Sister-in-Law, and the rest of the creatures, and remain, in order to help him if possible to establish his position at Why on a firmer basis.

So I took possession of a suite of rooms in the west wing of the palace, near his Majesty’s private apartments, and we spent a very pleasant evening together in my sitting-room, playing[41] draughts till bedtime, when his Majesty left me to myself, promising that he would show me around the palace grounds the first thing in the morning.

After he had gone, there being a bright wood fire burning in my bedroom, I drew a high-backed easy-chair up to the old-fashioned fireplace, and made myself comfortable for a little while before retiring for the night.

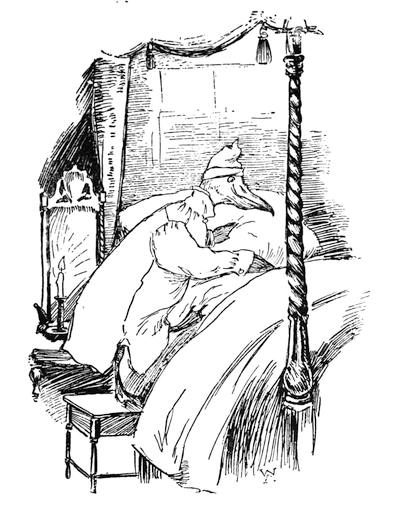

My bedroom was a large, old-fashioned apartment, with a low ceiling and curiously carved oak wainscoting, and I watched the firelight flickering, and casting all sorts of odd shadows in the dark corners, till I must have fallen asleep, for I remember awaking with a start, at hearing a crash in the corridor outside my bedroom door. A muttered exclamation, and a Pelican, carrying a bedroom candlestick marched in, and carefully fastened the door behind him.

“Great clumsy things—I can’t think who can[42] have left them there,” he grumbled, sitting down and rubbing one foot against the other, as though in pain. And I suddenly came to the conclusion that he must have stumbled over my boots, which I had stood just outside the door, in order that they might be cleaned for the morning.

The Pelican had not noticed me in my high-backed chair, and, being rather curious to see what he was up to, I kept perfectly still.

Going over to a clothes press, which stood in one corner of the room, the bird drew forth a long white night-gown and a nightcap; these he proceeded solemnly to array himself in, and then, getting up on a chair, he turned back the bedclothes with his enormous beak, and was just about to hop into bed, when I thought that it was time for me to interfere.

“Here! I say, what are you up to?” I called out in a stern voice.

“He turned back the bedclothes with his enormous beak, and was just about to hop into bed.”— Page 42.

Wallypugland.

“Oh—h-h! Ah—h-h! There’s a man in my room!” screamed the Pelican, evidently greatly alarmed. “Murder! Fire! Police! Thieves!”

“Hold your tongue!” I commanded. “What do you mean by making all that noise at this time of night, and what are you doing in my room?”

“Your room, indeed!” gasped the bird; “my room you mean, you featherless biped, you!”

“Look here!” I remarked, going up to the Pelican, and shaking him till his beak rattled again. “Don’t you talk to me like that, my good bird, for I won’t put up with it.” You see I was getting tired of being treated so contemptuously by all of these creatures, and was determined to put a stop to it, somehow.

“But it is my room. Let me go, I say!” screamed the bird, struggling to get free, and dabbing at me viciously with his great beak.

“It is not your room,” I maintained; “and[44] what is more, you are not going to stay here,” and I pushed the creature towards the door.

“We’ll soon see all about that,” shouted the Pelican, wrenching himself from my grasp, and rushing at me with his beak wide open, and his wings outstretched.

He was an enormous bird, and I had a great struggle with him. We went banging about the room, knocking over the furniture and making a terrible racket. At last, however, I managed to get him near the door, and giving a terrific shove I pushed him outside, and, pulling the door to, quickly turned the key.

I could hear Mr. Pelican slipping and stumbling about on the highly polished floor of the corridor outside, and muttering indignantly. Presently he came to the door, and banging with his beak, he cried, “Look here! this is beyond a joke—let me in, I say—where do you suppose I am going to sleep?”

“Anywhere you like except here,” I replied, feeling that I had got the best of it. “Go and perch or roost, or whatever you call it, on the banisters, or sleep on the mat if you like—I don’t care what you do!”

“Impertinent wretch!” yelled the bird. “You only wait till the morning. I’ll pay you out;” and I could hear him muttering and mumbling in an angry way as he waddled down the corridor to seek some other resting-place. “What ridiculous nonsense it is,” I thought, as I tumbled into bed shortly after this little episode; “these creatures giving themselves such airs. No wonder the Wallypug is such a meek little person if he has been subjected to this sort of treatment all his life.” And pondering over the best method of altering the extraordinary state of affairs, I dropped off to sleep.

I do not know how long it may have been after this, but a terrific din, this time in the courtyard[46] below my window, caused me once more to jump from my bed in alarm. I could hear a most unearthly yelling going on, a babel of voices, and occasionally a resounding crash as though something hollow had been violently struck.

HE WAS INTERRUPTED BY A SHOWER OF MISSILES.

Pushing open the latticed windows I saw in the moonlight a little man dressed in a complete suit of armor with an enormous shield, like a dishcover,[47] arranged over his head, playing the guitar, and endeavoring to sing to its accompaniment. He was continually interrupted, however, by a shower of missiles thrown from all of the windows overlooking the courtyard, out of which angry heads of animals and other occupants of the palace were thrust; he was surrounded by a miscellaneous collection of articles which had evidently been thrown at him, and some of them, had it not been for his suit of armor and the erection over his head, would have caused him considerable injury.

THE MUSICIAN TOOK TO HIS HEELS AND FLED.

He did not seem to mind them in the least, though, and continued singing amid a perfect storm of boots, brushes, and bottles, as though he was quite accustomed to such treatment: and it was only when an irate figure, which somehow reminded me of his Majesty’s Sister-in-Law, clad in white garments and flourishing a pair of tongs, appeared in the courtyard, that he took to his heels and fled, pursued by the white-robed apparition, till both disappeared beneath an archway at the farther end of the courtyard. Most of the windows were thereupon closed, and the disturbed occupants of the palace returned to their rest. I was just about to close my lattice too, when I caught sight of a familiar figure at the[49] adjoining window. It was my old friend A. Fish, Esq.

“Oh! id’s you iz id,” he cried. “You have cub thed, I heard that you were egspegded.”

“Yes, here I am,” I replied. “How are you? How is your cold?”

“Oh, id’s quide cured, thags; dote you dotice how butch better I speak?”

“I’m very glad to hear it, I’m sure,” I replied, waiving the question and trying to keep solemn. “What’s all this row about?”

“Oh! thad’s the troubadour, up to his old gabes agaid; he’s ad awful dusadce. I’ll tell you aboud hib in the bordig—good dight.” And A. Fish, Esq., disappeared from view.

CHAPTER IV.

LATE FOR BREAKFAST.

I awoke very early in the morning, just as it was daylight, and being unable to get to sleep again amid my strange surroundings, I arose and crept down-stairs as noiselessly as possible, intending to go for a long walk before breakfast.

At the bottom of the stairs I came upon a strange-looking white object, which, upon closer inspection, turned out to be the Pelican, asleep on the floor.

He was not sleeping as any respectable bird would have done, with his head tucked under his wing; but was lying stretched out on a rug in the hall, with his head resting on a cushion. His[51] enormous beak was wide open, and he was snoring violently, and muttering uneasily in his sleep.

THE PELICAN WAS SNORING VIOLENTLY.

I did not disturb him for fear lest he should make a noise; but hurrying past him I made my way to the hall door, which after a little difficulty I succeeded in unfastening. An ancient-looking turtle with a white apron was busily cleaning the steps, and started violently as I made my appearance at the door.

“Bless my shell and fins!” he muttered; “what’s the creature wandering about this time of the morning for; they’ll be getting up in the[52] middle of the night next. Just mind where you’re treading, please!” he called out. “The steps have been cleaned, and I don’t want to have to do them all over again.”

I managed to get down without doing much damage, and then remarked pleasantly:

“Good morning; have you——”

“No, I haven’t,” interrupted the Turtle snappishly; “and what’s more, I don’t want to.”

“What do you mean?” I inquired, in surprise.

“Soap!” was the reply.

“I don’t understand you,” I exclaimed.

“You’re an advertisement for somebody’s soap, aren’t you?” asked the Turtle.

“Certainly not,” I replied, indignantly.

“Your first remark sounded very much like it,” said the Turtle suspiciously. “‘Good morning, have you used——’”

“I wasn’t going to say that at all,” I interrupted.[53] “I was merely going to ask if you could oblige me with a light.”

“Oh, that’s another thing entirely,” said the Turtle, handing me some matches from his waistcoat pocket, and accepting a cigarette in return. “But really we have got so sick of those advertisement catchwords since the Doctor-in-Law returned from London with agencies for all sorts of things, that we hate the very sound of them. We are continually being told to ‘Call a spade a spade,’ which will be ‘grateful and comforting’ to ‘an ox in a teacup’ who is ‘worth a guinea a box,’ and who ‘won’t be happy till he gets it.’”

“It must be very trying,” I murmured sympathetically.

“Oh, it is,” remarked the Turtle. “Well,” he continued in a business-like tone, “I’m sorry you can’t stop—good morning.”

“I didn’t say anything about going,” I ejaculated.

“Oh, didn’t you? Well, I did then,” said the Turtle emphatically. “Move on, please!”

“You’re very rude,” I remarked.

“Think so?” said the Turtle pleasantly. “That’s all right then—good-by,” and he flopped down on his knees and resumed his scrubbing.

THE TURTLE FLOPPED DOWN ON HIS KNEES AND RESUMED HIS SCRUBBING.

There was nothing for me to do but to walk on, and seeing a quaint-looking old rose garden in the distance, I decided to go over and explore.

I was walking slowly along the path leading to[55] it, when I heard a curious clattering noise behind me, and turning around I beheld the Troubadour, still in his armor, dragging a large standard rosebush along the ground.

“As if it were not enough,” he grumbled, “to be maltreated as I am every night, without having all this trouble every morning. I declare it is enough to make you throw stones at your grandfather.”

“What’s the matter?” I ventured to ask of the little man.

“Matter?” was the reply. “Why, these wretched rosebushes, they will get out their beds at night, and wander about. I happened to leave the gate open last night, and this one got out, and goodness knows where he would have been by this time if I hadn’t caught him meandering about near the Palace.”

“Why! I’ve never heard of such a thing as a rosebush walking about,” I exclaimed in surprise.

“IN YOU GO!”

“Never heard of a——. Absurd!” declared the Troubadour, incredulously. “Of course they do. That’s what you have hedges and fences around the gardens for, isn’t it? Why, you can’t have been in a garden at night-time, or you wouldn’t talk such nonsense. All the plants are allowed to leave their beds at midnight. They are expected to be back again by daylight, though, and not go wandering about goodness knows where like this beauty,” and he shook the rosebush violently.

“In you go,” he continued, digging a hole with the point of his mailed foot, and sticking the rosebush into it.

“Hullo!” he exclaimed, going up to another one, at the foot of which were some broken twigs and crumpled leaves. “You’ve been fighting, have you? I say, it’s really too bad!”

“But what does it matter to you?” I inquired. “It’s very sad, no doubt, but I don’t see why you should upset yourself so greatly about it.”

“Well, you see,” was the reply, “I’m the head gardener here as well as Troubadour, and so am responsible for all these things. I do troubing as an extra,” he explained. “Three shillings a week and my armor. Little enough, isn’t it, considering the risk?”

“Well, the office certainly does not seem overpopular, judging from last night,” I laughed. “Who were you serenading?”

“Oh, any one,” was the reply. “I give it to them in turns. If any one offends me in the daytime I pay them out at night, see?

“I serenaded the Sister-in-Law mostly, but I shall give that up. She doesn’t play fair. I don’t mind people shying things at me in the least, for you see I’m pretty well protected; but when it comes to chivying me round the garden with a[58] pair of tongs, it’s more than I bargained for. Look out! Here comes the Wallypug,” he continued.

Sure enough his Majesty was walking down the path, attended by A. Fish, Esq., who was wearing a cap and gown and carrying a huge book.

“Ah! good morning—good morning,” cried his Majesty, hurrying towards me. “I’d no idea you were out and about so early. I’m just having my usual morning lesson.”

“Yes,” said A. Fish, Esq., smiling, and offering me a fin. “Ever sidse I god rid of by cold I’ve been teaching the Wallypug elocutiod. We have ad ‘our every bordig before breakfast, ad he’s geddig on spledidly.”

“I’m sure his Majesty is to be congratulated on having so admirable an instructor,” I remarked, politely, if not very truthfully.

“His Majesty was walking down the path, attended by A. Fish, Esq., who was wearing a cap and gown and carrying a huge book.”— Page 58.

Wallypugland.

“Thags,” said A. Fish, Esq., looking very pleased. “I say, Wallypug, recide that liddle thig frob Richard III., jusd to show hib how well you cad do id, will you? You doe thad thig begiddidg ’Ad ’orse, ad ’orse, by kigdob for ad ’orse.’”

“Yes, go on, Wallypug!” chimed in the Troubadour, indulgently.

“Oh, I don’t know,” said his Majesty, simpering nervously. “I’m afraid I should break down.”

“Doe you wondt, doe you wondt,” said A. Fish, Esq. “Cub alog, try id.”

So his Majesty stood up, with his hands folded in front of him, and was just about to begin, when a bell in a cupola on the top of the palace began to ring violently.

“Good gracious, the breakfast bell! We shall be late,” cried the Wallypug, anxiously grasping my hand and beginning to run towards the palace.

A. Fish, Esq., also shuffled along behind us as[60] quickly as possible, taking three or four wriggling steps, and then giving a funny little hop with his tail, till, puffing and out of breath, we arrived at the palace just as the bell stopped ringing.

His Majesty hastily rearranged his disordered crown, and led the way into the dining hall.

A turtle carrying a large dish just inside the door whispered warningly to the Wallypug as we entered, “Look out! You’re going to catch it,” and hurried away.

A good many creatures were seated at the table which ran down the center of the room, and at the head of which his Majesty’s Sister-in-Law presided, with a steaming urn before her. The Doctor-in-Law occupied a seat near by, and I heard him remark:

“They are two minutes late, madame. I hope you are not going to overlook it,” to which the lady replied, grimly, “You leave that to me.”

“Sit there,” she remarked coldly, motioning me to a vacant seat, and the Wallypug and A. Fish, Esq., subsided into the two other unoccupied chairs on the other side of the table.

CHAPTER V.

THE TRIAL.

For a moment nobody spoke. The Wallypug sat back in a huddled heap in his chair, looking up into Madame’s face with a scared expression. A. Fish unconcernedly began to eat some steaming porridge from a plate in front of him—and I sat still and waited events.

A band of musicians in the gallery at the end of the hall were playing somewhat discordantly, till Madame turned around and called out in an angry voice:

“Just stop that noise, will you? I can’t hear myself speak.”

“STOP THAT NOISE!”

The musicians immediately left off playing with the exception of an old hippopotamus, playing a brass instrument, who being deaf, and very near-sighted, had neither heard what had been said nor observed that the others had stopped. With his eyes fixed on the music stand in front[64] of him, he kept up a long discordant tootling on his own account, gravely beating time with his head and one foot.

His Majesty’s Sister-in-Law turned around furiously once or twice, and then seeing that the creature did not leave off, she threw a teacup at his head, and followed it up with the sugar basin.

The latter hit him, and hastily dropping his instrument, he looked over the top of his spectacles in surprise.

Perceiving that the others had left off playing, he apparently realized what had happened, and meekly murmuring, “I beg your pardon,” he leaned forward with one foot up to his ear, to hear what was going on.

“I’m waiting to know what you have to say for yourselves,” resumed Madame, addressing the Wallypug and myself.

“The traid was late, add there was a fog od[65] the lide,” explained A. Fish, Esq., mendaciously, with his mouth full of hot porridge.

“A likely story!” said the good lady sarcastically. “A very convenient excuse, I must say; but that train’s been late too many times recently to suit me. I don’t believe a word of what you are saying.”

“If I might venture a suggestion,” said the Doctor-in-Law, sweetly, “I would advise that they should all be mulcted in heavy fines, and I will willingly undertake the collection of the money for a trifling consideration.”

“It’s too serious a matter for a fine,” said the Madame severely. “What do you mean by it?” she demanded, glaring at me furiously.

“Well, I’m sure we are all very sorry,” I remarked, “but I really do not see that being two minutes late for breakfast is such a dreadful affair after all.”

“Oh! you don’t, don’t you?” said the Sister-in-Law,[66] working herself up into a terrible state of excitement; “Well, I do, then. Do you suppose that you are going to do just as you please here? Do you think that I am going to allow myself to be brow-beaten and imposed upon by a mere man——”

“Who hasn’t a hat to his back,” interposed the Doctor-in-Law, spitefully.

“Hold your tongue,” said the Sister-in-Law. “I’m dealing with him now. Do you suppose,” she went on, “that I am to be openly defied by a ridiculous Wallypug and a person with a cold in his head?”

“I’b sure I havn’d,” declared A. Fish, Esq., indignantly. “By code’s beed cured this last bunth or bore.”

“Humph, sounds like it, doesn’t it?” said the lady, tauntingly. “However, we’ll soon settle this matter. We’ll have a public meeting, and see who’s to be master, you or I.”

“Hooray, public meeting! Public meeting!” shouted all the creatures excitedly.

“Yes, and at once,” said the Sister-in-Law impressively, getting up and leaving the table, regardless of the fact that scarcely anybody had as yet had any breakfast.

The rest of the creatures followed her out of the room.

When they had quite disappeared and the Wallypug, A. Fish, Esq., and myself were left alone, I thought that we might as well help ourselves to some breakfast. So I poured out some of the coffee, which we found excellent, and had just succeeded in persuading his Majesty to try a little bread and butter, when some crocodiles appeared at the door and announced: “You are commanded to attend the trial at once.”

“What trial?” I asked.

“Your own,” was the reply. “You and the[68] Wallypug are to be tried for ‘Contempt of Sister-in-Law,’ and A. Fish, Esq., is subpœnaed as a witness.”

“Oh, dear! Oh, dear!” said the poor Wallypug, wringing his hands. “I know what that means. Whatever shall we do?”

“Dever bide, old chap. I do the best I cad to get you off,” said A. Fish, Esq. “Cub alog, it will odly bake badders worse to delay.”

So we allowed ourselves to be taken in charge by the crocodiles, and led to the Public Hall, his Majesty and myself being loaded with chains.

We found the Sister-in-Law and the Doctor-in-Law seated at the judges’ bench when we entered. The Sister-in-Law wore a judge’s red robe, and a long, flowing wig under her usual head-dress, and the Doctor-in-Law was provided with a slate, pencil, and sponge.

“SILENCE IN COURT!”

SCREAMED THE OSTRICH.

We were conducted to a kind of dock on one side of the bench, and on the other side appeared what afterwards transpired to be the witness box. The body of the hall was crowded with animals, craning their necks to catch a glimpse of us.

“Silence in court,” screamed out a gaily-dressed ostrich, and the trial began.

“We’ll take the man creature first,” said the Sister-in-Law, regarding me contemptuously. “Now then, speak up! What have you got to say for yourself?”

“There appears to be—” I began.

“Silence in court,” shouted the ostrich, who was evidently an official.

“Surely I may be allowed to explain,” I protested.

“Silence in court,” shouted the bird again.

I gave it up and remained silent. “Call the first witness,” remarked the Sister-in-Law impatiently, and the Turtle, whom I had seen cleaning the steps in the morning, walked briskly up into the witness-box.

“Well, Turtle, what do you know about this man?” was the first question.

“So please your Importance, I was cleaning my steps very early this morning, when the prisoner opened the door in a stealthy manner and crept out very quietly. ‘Ho!’ thinks I, ‘this ’ere man’s up to no good,’ and so I keeps him in conversation a little while, but his language—oh!—and what with one thing and another and noticing that he hadn’t a hat, I told him he had better move on. I saw him walk over to the rose garden and afterwards join the Wallypug and Mr. Fish. I think that’s all, except—ahem—that I missed a small piece of soap.”

“Soap?” said the Doctor-in-Law, elevating his eyebrows. “This is important—er—er—what kind of soap?”

“Yellow,” said the Turtle. “Fourpence a pound.”

“Hum!” said the Doctor-in-Law, “very mysterious, but not at all surprising from what I know of this person—call the next witness.”

The next witness was the Cockatoo, who scrambled into the box in a great fluster.

“He’s a story-teller, and a pickpocket, and a backbiter, and a fibber, and a bottle-washer,” she screamed excitedly, “and a heartless deceiver, and an organ-grinder, so there!” And she danced out of the witness-box again excitedly, muttering, “Down with him, down with him, the wretch,” all the way back to her seat.

“Ah, that will about settle him, I fancy,” remarked the Doctor-in-Law, putting down some figures on his slate and counting them up.

“What are you doing?” demanded the Sister-in-Law.

“Summing up,” was the reply. “The judges always sum up in England, you know; that’s thirty-two pounds he owes. Shall I collect it?”

“Wait a minute till I pass the sentence,” said the Sister-in-Law.

“Prisoner at the bar,” she continued, “you have since your arrival here been given every latitude.”

“And longitude,” interrupted the Doctor-in-Law.

“And have taken advantage of the fact to disobey the laws of the land in every possible way. You have heard the evidence against you, and I may say more clear proof could not have been given. It appears that you are a thoroughly worthless character, and it is with great pleasure I order you to be imprisoned in the deepest[73] dungeon beneath the castle moat, and fined thirty-two pounds and costs.”

Then pointing to me tragically, she called out, “Officers! take away that Bauble!” And I was immediately seized by two of the crocodiles, preparatory to being taken below.

CHAPTER VI.

HIS MAJESTY IS DEPOSED.

“Stop a minute!” cried Madame, as I was being led away. “We may as well settle the Wallypug’s affair at the same time and get rid of them both at once. Put the creature into the dock.”

His Majesty was hustled forward, looking very nervous and white, as he stood trembling at the bar, while Madame regarded him fiercely.

“Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?” she demanded.

“Ye-e-s!” stammered his Majesty, though what the poor little fellow had to be ashamed of was more than I could tell.

“I should think so, indeed,” commented the lady. “Now then, call the first witness.”

The first witness was A. Fish, Esq., who coughed importantly as he stepped up into the box with a jaunty air. “Let’s see, what’s your name?” asked the Doctor-in-Law, with a supercilious stare. Now, this was absurd, for, of course, he knew as well as I did what the Fish’s name was; but as I heard him whisper to Madame, the judges in England always pretend not to know anything, and he was doing the same.

“By dabe is A. Fish, you doe thadt well edough,” was the answer.

“Don’t be impertinent, or I shall commit you for contempt,” said the Doctor-in-Law, severely. “Now then—ah—you are a reptile of some sort, I believe, are you not?”

“Certainly dot!” was indignant reply.

“Oh! I thought you were. Er—what do you do for a living?”

“I’b a teacher of elocutiod add a lecturer,” said A. Fish, Esq., importantly.

“Oh! indeed. Teacher of elocution, are you? And how many pupils have you, pray?”

“Well, ad presend I’ve odly wud,” replied A. Fish, Esq., “and that the Wallypug.”

“Oh! the Wallypug’s a pupil of yours, is he? I suppose you find him very stupid, don’t you?”

“Doe, I don’t!” said A. Fish, Esq., loyally. “He’s a very clever pupil, ad he’s gettig od splendidly with his recitig.”

“Oh! is he, indeed; and what do you teach him, may I ask?”

“I’ve taught hib ‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star,’ ad ‘Billy’s dead ad gone to glory,’ ad several other things frob Shakespeare.”

“Shakespeare? hum—ha—Shakespeare? I seem to have heard the name before. Who is he?”

“A great poet, born in England in 1564, m’lud,” explained one of the Crocodiles.

“Really! He must be getting quite an old man by now,” said the Doctor-in-Law, vaguely.

“He’s dead,” said A. Fish, Esq., solemnly.

“Dear me! poor fellow! what did he die of?”

“Don’t ask such a lot of silly questions,” interrupted the Sister-in-Law, impatiently; “get on with the business. What has A. Fish to say on behalf of the Wallypug? that is the question.”

“He’s gettig od very dicely with his recitig,” insisted A. Fish, Esq. “He was repeatig a speech from Richard III. to us this bordig whed the breakfast bell rang, ad that’s why we were late at table.”

“Oh! that’s the reason, is it?” said the Sister-in-Law. “Bah! I’ve no patience with a man at his time of life repeating poetry. Positively childish, I call it. What was the rubbish?” she demanded, turning to the Wallypug.

“A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse,” began his Majesty, feebly.

“What!” shrieked the Sister-in-Law, starting up from her seat. “Say that again!”

“‘A-a horse, a horse, my-my kingdom for a horse,’” stammered the Wallypug, nervously.

“Traitor! Monster!” cried the Sister-in-Law furiously. “Hear him!” she screamed. “He actually has the effrontery to tell us to our faces that he is willing to sell the whole of this kingdom for a horse. Oh! it is too much! the heartless creature! Oh-h!” and the lady sank back and gasped hysterically. At this there was a terrible uproar in the court—the animals stood up on the seats, frantically gesticulating and crying: “Traitor!” “Down with the Wallypug!” “Off with his head!” “Banish him!” “Send him to jail!” while above all could be heard the Cockatoo screaming:

“I told you so. I told you so! Down with the Wallypug! Off with his crown! Dance on his sceptre, and kick his orb round the town.”

The poor Wallypug threw himself on his knees and called out imploringly, “It’s all a mistake,” and I tried in vain to make myself heard above the uproar.

“TRAITOR! MONSTER!” “OFF WITH HIS HEAD!”

The whole assembly seemed to have taken leave of their senses, and for a few moments the utmost confusion prevailed. The creatures nearest to the Wallypug seemed as though they would tear him to pieces in their fury, and if it had not been for[80] his jailers, the Crocodiles, I am convinced they would have done him some injury. “This is outrageous,” I managed to shout at last. “You are making all this disturbance for nothing. What the Wallypug said was merely a quotation from one of Shakespeare’s plays.”

“Oh, it’s all very well to try and blame it on to poor Shakespeare, when you know very well he’s dead and can’t defend himself,” was Madame’s reply. “That’s your artfulness. I’ve no doubt you are quite as bad as the Wallypug himself, and probably put him up to it.”

“Yes. Down with him! Down with the hatless traitor!” screamed the Cockatoo.

And despite our protests the Wallypug and myself were loaded with chains and marched off by the Crocodiles, his Majesty having first been robbed of his crown, sceptre, and orb, and other insignia of Royalty by the Doctor-in-Law, who hadn’t a kind word to say for his old sovereign,[81] and who seemed positively to rejoice at his Majesty’s downfall. I was highly indignant with his heartless ingratitude, but could do positively nothing, while all of my protests were drowned in the babel of sounds made by the furious creatures in the body of the court.

THE WALLYPUG WAS LOADED WITH CHAINS AND MARCHED OFF BY THE CROCODILES.

After being taken from the dock I was marched off in one direction and his Majesty in another, and the last view I had of the Wallypug was that[82] of the poor little fellow being limply dragged along by two Crocodiles in the direction of the dungeons. I was conducted to the top room of a tower, in an unfrequented part of the palace, and there left to my reflections, without any one to speak to for the remainder of the day.

Towards the evening I heard some shouting at the bottom of the tower, and looking out as well as I could through the barred window, I saw the Doctor-in-Law rushing about with a packet of newspapers under one arm—and heard him calling out, in a loud voice, “Special edition! Arrest of the Wallypug! Shocking discovery! The Wallypug a traitor! Sister-in-Law prostrate with excitement! The Hatless Man implicated!” He was doing a roaring trade, as nearly everybody was buying papers of him, and excited groups of animals were standing about eagerly discussing what was evidently the cause of a tremendous sensation in the kingdom of Why.

“I saw the Doctor-in-Law rushing about with a packet of newspapers under one arm, calling out in a loud voice, ‘Special edition! Arrest of the Wallypug!’”— Page 82.

Wallypugland.

CHAPTER VII.

FOILED!

I stood at the barred window for some time, watching the Doctor-in-Law rushing about with his papers, and then started back as a huge and disreputable-looking black Crow settled on the stone ledge outside.

I soon recognized him as being the bird who had behaved so impertinently to me on my first arrival at Why.

“Well!” he exclaimed, squeezing himself through the iron bars, and staring at me over the tops of his spectacles. “You have got yourself into a pretty muddle now, I must say. I should think you are thoroughly ashamed of yourself, aren’t you?”

“Indeed, I’m not,” I replied. “I’m not conscious of having done anything to be ashamed of, and as for that trial, why it was a mere farce, and perfectly absurd,” and I laughed heartily at the recollection of it.

“H’m! I’m glad you find it so amusing,” remarked the bird sententiously. “You won’t be so light-hearted about it to-morrow if they treat you as the papers say they purpose doing.”

“Why, what do they intend to do then?” I exclaimed, my curiosity thoroughly aroused.

“Execute you,” said the Crow solemnly. “And serve you jolly well right, too.”

“What nonsense!” I cried, “they can’t execute me for doing nothing.”

“Oh, you think so, do you? Didn’t you instigate the Wallypug to become a traitor, and sell the kingdom for the sake of a horse?” said the Crow, referring to his paper.

“Certainly not!” I cried emphatically.

“Well, they say you did, anyhow,” said the Crow, “and they intend to chop off your head and the Wallypug’s too. It won’t matter you not having a hat then,” he continued grimly.

“But you don’t mean it, surely!” I exclaimed. “They certainly can’t be so ridiculous as to treat the affair seriously.”

“Well, you see,” said the bird, “things without doubt look very black against you. In the first place what did you want to come here at all for?”

“I’m sure I wish I hadn’t,” I remarked.

“Just so! So does every one else,” said the Crow rudely. “Then, when you did come, you were without a hat, which is in itself a very suspicious circumstance.”

“Why?” I interrupted.

“Respectable people don’t go gadding about without hats,” said the bird contemptuously, turning up his beak. “And then, the first morning[86] after your arrival you must needs go prowling about the grounds before any one else was up.”

“WHAT ARE YOU GOING TO LEAVE ME IN YOUR WILL?”

“What are you going to leave me in your will?” he continued insinuatingly.

“Nothing at all,” I declared. “And besides, I’m not going to make a will. I don’t intend to let them kill me without a good struggle, I can tell you.”

“H’m, you might as well let me have your watch and chain. It will only go to the Doctor-in-Law if you don’t. He is sure to want to grab everything. I expect he will want to seize the throne when the Wallypug is executed. I saw him just now trying on the crown, and smirking and capering about in front of the looking-glass.”

“The Doctor-in-Law is an odious little monster,” I exclaimed.

“Oh, very well,” cried the Crow, wriggling through the bars, “I’ll just go and tell him what you say. I’ve no doubt he will be delighted to hear your opinion of him—and perhaps it will induce him to add something to your punishment. I hope so, I’m sure—ha—ha!”

And the wretched ill-omened bird flew away laughing derisively.

I could not help feeling rather uncomfortable at the turn which events had taken, for there was no knowing to what lengths the extraordinary[88] inhabitants of this remarkable place might go, and if it had really been decided that the poor Wallypug and myself should be executed on the morrow, then there was no time to be lost in our efforts to effect an escape.

I was puzzling over the matter, and wondering what was best to be done, when I heard a bell ringing at the other end of the apartment.

“Ting-a-ling-a-ling-a-ling,” for all the world like the ring of a telephone call bell.

I ran across the room, and sure enough, there was a telephone fitted up in the far corner. I hastily put the receiver to my ears, and heard a squeaky voice inquiring:

“Are you there? Are you 987654321?”

“Yes,” I called out, for I thought that I might as well be this number as any other.

“Well,” the voice replied, in an agitated way, “Aunt Kesiah has done it at last.”

“What?” I shouted.

“Proposed to the curate, and so all those slippers will be wasted. Don’t you think we had better—”

But I rang off and stopped the connection, for I felt sure that the communication was not intended for me.

Presently there was another ring at the bell, and this time I found myself connected with the exchange. I knew that it was the exchange, because they were all quarreling so.

“It was all your fault!” “No it wasn’t.” “Yes it was.” “Well, you know A. Fish, Esq., is 13,579—so there.” “Yes, and he wanted to be connected with the West Tower in the Palace.”

“Connect me with 13,579, please,” I called.

And a moment or two afterwards I heard a well-known voice sounding through the instrument, and I knew that A. Fish, Esq., was at the other end.

“Are you there?” he cried.

“Yes; what is it?” I asked.

“There isn’t a biddit to spare,” he gasped; “lift up the loose stode dear the fireplace, ad you will find a secret staircase leadig to the dudgeod, where the Wallypug is ibprisod; hurry for your life, he has discovered a way of escape.”

I dropped the receiver, and flew to the fireplace. Yes, sure enough, there was the loose stone that A. Fish, Esq., had spoken of, and having raised it with some difficulty I found a narrow spiral staircase beneath, leading down into mysterious depths.

I plunged into the darkness, and after walking round and round, and down and down, for a considerable time I saw a faint light at the other end. I hurried forward as quickly as I could, and found myself in a dimly-lighted dungeon. The Wallypug was here alone, and was busily cramming everything he could lay his hands on into an enormous carpet-bag.

“Thank goodness, you have come!” he exclaimed, in a terrible fluster, when he saw me. “I was afraid you would be too late. We must escape at once if we would save our necks. Fortunately, I have just remembered that this dungeon is connected with the shute which the late Wallypug had constructed between here and Ling Choo, in China, which is on the other side of the world—it is enormously long and very steep, but quite safe—we must use it in order to get away. We are to be executed in the morning if we stay here, so I am informed; therefore, we must lose no time. I have just finished packing up. Ah! What’s that?” he exclaimed, listening intently.

“Quick! they are coming!” he cried, as sounds were heard in the passage outside the dungeon door; and touching a spring, an enormous opening appeared in the wall. His Majesty gave me a sudden push, which sent me sprawling on to a[92] smooth and very steep incline, and jumping down himself, we slid rapidly away into the unknown.

WE SLID RAPIDLY DOWN THE SHUTE.

That we were only just in time was evidenced by the cries of rage and disappointment which pursued us from the dungeon, as the Doctor-in-Law[93] and the other creatures saw us escape from their clutches, and we could hear the Cockatoo’s shrill cries grow fainter and fainter as we sped swiftly down the shute towards Ling Choo.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE LITTLE BLUE PEOPLE.

Down, and down, and down we flew, quicker and quicker each moment. The shute was as smooth as glass, and grew steeper than ever as we descended. His Majesty was a little way behind me, but the terrific rate at which we were traveling made it impossible for us to hold any conversation. Once or twice I shouted out something to him, but receiving no reply I soon gave that up. The attitude in which I was slipping down the shute was a most uncomfortable one, but after a considerable time I managed to turn over on to my back, and eventually to twist around, till, at any rate, I was traveling feet foremost, which was some slight consolation, although[95] naturally I was dreadfully concerned as to what was to be our fate at the other end of our journey. “Slipping along at this rate,” I thought, “we shall probably be smashed to a jelly when we do arrive at the bottom. At any rate I shall, for the Wallypug and the carpet-bag are bound to descend upon my devoted head.”

By and by I began to grow very hungry, and then came another dismal thought. Supposing this extraordinary trip continued for any length of time, how should we get on for food?

We seemed to be traveling through a kind of tunnel, with very smooth walls on either side. The Wallypug had said that we were bound for China, and that that country was on the other side of the world. If so, then we were in for a pretty long journey. I twisted my head around, and tried to get a glimpse of his Majesty, who was only a few yards above me. I could see that he was struggling to get something out of the[96] carpet-bag, and a few minutes afterwards a little packet of sandwiches came whizzing past my head. I managed to catch it as it fell upon the highly-polished boards by stretching out one leg just in time to prevent it from slipping too far.

I COULD SEE HE WAS STRUGGLING TO GET SOMETHING OUT OF THE CARPET-BAG.

The sandwiches were very good, and I enjoyed them immensely, and for a few moments almost forgot our strange surroundings. I was soon,[97] however, recalled to a sense of our condition by the fact that we suddenly emerged from the tunnel into broad daylight, the shute apparently descending the steep sides of a high mountain. As soon as my eyes became accustomed to the light I noticed, to my great surprise, that everything in this new country was of a deep rich blue color. The rocks on the mountain side, the strange-looking trees, and even the birds—of which I could see several flying about—were all of the same unusual tint.

I had hardly noticed this fact, as we flew down the side of the mountain, when I felt myself suddenly pulled up with a jerk, and lifted high into the air in a most unaccountable manner, and when, after a moment or two, I recovered from the shock, I found that both the Wallypug and myself were suspended from a line at the end of two long fishing-rods which were fastened into a quaint little bridge crossing the shute.

There we hung, dangling and bobbing about in front of each other in the most ridiculous way, the dear Wallypug still clinging to his carpet-bag with one hand, while in the other he clutched a half-eaten sandwich. I shall never forget his Majesty’s surprised expression when he found himself hanging up the air in this unexpected way.

“Like being a bird, isn’t it?” he remarked when at last he found a voice.

“H’m, not much,” I replied. “I feel more like a fish at the end of this line. I wish some one would come and help us off. There’s a hook, or something, sticking into my shoulder, and it hurts no end.” You see there was evidently something at the end of the lines which had caught into our clothes, and the hook, or whatever it was, just touched my shoulder. It did not hurt very much, but just enough to make me feel uncomfortable.

“I wonder where we are,” said the Wallypug, looking about him. “What a funny colour everything is, to be sure.”— Page 98.

Wallypugland.

“I wonder where we are,” said the Wallypug, looking about him. “What a funny color everything is, to be sure.”

“Yes, isn’t it?” I replied. And truly it was a most remarkable scene. There was a curious little kind of temple in the distance and a number of most extraordinary-looking trees; and these, and the grass, and, in fact, everything that could be seen, were of a bright blue tint.

“I know what those trees are called,” said the Wallypug, pointing to some remarkable looking ones, with a lot of large blue globes on the branches instead of leaves.

“What?” I asked.

“Gombobble trees,” said his Majesty. “I’ve seen pictures of them before.”

“Where?” I asked, more for the sake of something to say than for anything else.

“On our willow-pattern plates at home,” said his Majesty. “There were those and the wiggle-woggely trees, you know.”

“I wonder,” he continued speculatively, “if by any chance we are there.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“I wonder if this is the place which is shown on the willow-pattern plates,” said his Majesty.

Before I could reply we heard an excited exclamation from the bank, and turning around as well as we could we saw two curious little blue people dressed in flowing blue costumes.

“Oh!” they exclaimed, when they saw us, throwing up their hands in a comical little way, “we’ve caught something. What funny things! What are they?”

“I wonder if they bite,” cried the shorter of the two.

“Do you bite, you funny things, you?” cried the other, shaking her head at us.

“No, of course not,” said the Wallypug. “Help us to get down, will you, please?”

“Not yet,” said both of the little blue creatures,[101] shaking their heads simultaneously. “What are your names?”

“OH!” THEY EXCLAIMED, “WHAT ARE THEY?”

“I’m the Wallypug,” explained his Majesty graciously, “and this gentleman is——”

“He, he, he! He, he, he! He, he, he!” giggled[102] the little blue people. “They’re Wallypugs. Two great big fat Wallypugs. Oh, oh! what funny things. Let’s go and fetch Ho-lor.” And they ran off as fast as their little blue legs would carry them.

CHAPTER IX.

THE WALLYPUG RECOVERS HIS CROWN.

His Majesty and myself stared at each other in dismay. Our position was growing more and more uncomfortable every moment, and, added to this, I had a growing impression that the rods to which we were attached would sooner or later break with our weight.

“Well! I do think that they might have helped us off the hooks, at any rate,” grumbled his Majesty, discontentedly.

“So do I,” I rejoined, and was about to add something else when my attention was attracted to the peculiar behavior of the two blue birds which we had previously noticed circling about over our heads.

They were wheeling round and round in a most eccentric manner, and as they drew closer we could see that they were as singular in appearance as they were in their manner.

“Why, they’ve got ever so many wings!” cried his Majesty in surprise.

“Go away!” he shouted, as one of them fluttered past his face. The birds, however, were not to be got rid of so easily, and, uttering shrill little cries, they hovered about over his Majesty’s head, every now and then making a vicious dart at the sandwich which he still held in one hand.

“Oh! take them away!—take them away!” he shouted, dropping his carpet-bag in alarm, and evidently forgetting that I was as incapable as he was of driving them off.

“Throw your sandwich away!” I shouted; “it’s that they are after, I believe.”

His Majesty did so, and we soon had the satisfaction[105] of seeing the birds squabbling over it on the bank at the side of the shute.

“GO AWAY!” SHOUTED HIS MAJESTY.

“Fortunate I tied my bag to the string of my cloak, wasn’t it?” remarked the Wallypug, when they had gone. “I should have lost it else. Oh,[106] look! What’s that coming down the shute?” he cried, as something suddenly came rolling and bounding down the steep incline.

“O—o—o—h!” he continued delightedly, as it stopped, caught in the mouth of the carpet-bag which, attached to the cord of his Majesty’s cloak, dangled down the shute. “Why, it’s my crown! They must have thought that I wanted it, and sent it down after me. How very kind of them. Wasn’t it?”

I had my own opinions on the subject, and held my peace, for I felt quite sure that it was not through any intentional kindness that the crown had found its way to its proper owner.

His Majesty very carefully drew up the carpet-bag with its precious burden, and soon had the intense satisfaction of putting the crown of Why on his royal head once more.

“Oh!” he cried with a little sigh of satisfaction, “it does seem nice to have it on again. I’m afraid[107] that I should soon have caught a cold in my head, like A. Fish, Esq., if I had gone without it much longer.”

A LONG LINE OF CREATURES WAS

COMING DOWN THE SHUTE.

“Gracious!” he cried, pointing excitedly towards the top of the shute, “there’s something else coming down! Why it’s the Doctor-in-Law and Madame. Oh!—and the Cockatoo—and—the Rabbit and the Mole. Bless me! if the whole of Why isn’t coming along.”

It was quite true; attached to a strong rope a long line of creatures[108] was coming down the shute, the Doctor-in-Law leading the way.

He soon caught sight of us dangling at the end of our rods, and calling out “Halt!” in a loud voice, he pulled at the rope as a sign that they were to stop. This signal was passed along by the others, and the Cockatoo, who was attached to the rope in a very uncomfortable manner, gave a loud “squ-a-a-k” as the sudden jerk caused it to tighten about her neck.

The signal, however, managed somehow to reach those at the other end, for the procession suddenly came to a standstill.

“Oh, there you are then!” called out the Doctor-in-Law in a severe voice. “Thought you had escaped us, I suppose.”

The Cockatoo, in a voice choking with rage, and the tightened rope, shrieked out, “Down with the traitors!” while the Rabbit passed the word along, “It’s all right. We’ve found them.”

“Just you come down and tie yourself to this rope at once!” called out Madame, glaring fiercely at the Wallypug.

“Shan’t!” shouted his Majesty defiantly, pushing his crown further on to his head.

“What!” screamed the good lady, in a terrible passion. “Do you dare to rebel?”

“Yes, I do,” called out his Majesty bravely. “I don’t believe you are my sister-in-law at all, and I’m not going back to Why to be snubbed and ill-treated for you or any one else—so there. You can’t get at me, hanging up here, and I don’t mean to get down till you’re gone. Yah!”

“Oh, we’ll soon see all about that,” called out the Doctor-in-Law, working himself to the edge of the shute, and trying to climb up the steep sides of the bank.

We watched his endeavors with considerable anxiety, for if he did succeed in getting on to the bank, it would be an easy matter for him to get[110] at us, by means of the bridge. The rope, however, by which he was attached to the Sister-in-Law was not sufficiently long to enable him to do this, and while he was unfastening it there was a sudden cry in the direction of the tunnel, and a moment afterwards, screaming, kicking, and struggling, the whole party rapidly disappeared down the shute.

The rope had given way!

“He, he, he! Ha, ha!” laughed his Majesty, as the huddled mass vanished in the distance. “What a lark! Oh what a muddle they will be in when they reach the bottom.”

I tried to imagine what would be the result, and came to the conclusion that, uncomfortable as I was in my present position, I would rather be where I was than attached to the rope with the others.

In the meantime the little blue people, their curiosity evidently aroused by the noise, were[111] hurrying towards us as quickly as possible, bringing with them a very stout blue person, who was waddling along, being alternately pushed and pulled by the others in their eagerness to reach us.

“See, there they are!” cried the little lady whose name we afterwards found out was Gra-Shus. “Oh my! Aren’t they a funny color?”

“Shall we get them down?” asked the other, whose name was Mi-Hy.

The little fat man regarded us critically, and said nothing for a moment or two, then he nodded his head violently.

“You’re sure you won’t bite?” said Mi-Hy, looking up into my face.

“No, of course not. Don’t be silly,” I replied.

Thereupon, after a great deal of pulling and pushing on the part of Mi-Hy and Gra-Shus, the rods to which we were attached were swung around, and the Wallypug and myself alighted, one on either side of the bank.

His Majesty smoothed his rumpled garments, and, adjusting his crown to a more becoming angle, positively swaggered across the bridge to where the three little blue people stood in a line to receive us.

“This is Ho-Lor,” said Mi-Hy, pushing the little fat man forward, while Gra-Shus bashfully hid behind the ample folds of his gorgeous blue skirts.

“How do you do?” asked his Majesty graciously.

“Do what?” asked Ho-Lor, smilingly.

“I mean, how are you?” explained the Wallypug.

“You mean what am I, I suppose?” said the little man, putting on a puzzled expression.

“No, I don’t,” said the Wallypug. “I mean just what I say—How are you?”

“But I don’t understand,” replied Ho-Lor. “How am I what?”

“His Majesty the Wallypug of Why,” I explained, “wishes to say, that he hopes you are quite well.”

His Majesty swaggered across the bridge to where the three little blue people stood in a line to receive us.— Page 112.

Wallypugland.

“Oh! I beg your pardon” said Ho-Lor. “How very stupid of me. But you know, the fact is, we get such a lot of foreigners down here, and they do ask such funny questions. A Frenchman we caught the other day actually asked me how I carried myself. Wasn’t it rude of him—considering my weight too?”

“You’re a Wallypug, too, aren’t you?” asked Gra-Shus, looking smilingly up into my face.

“Oh, no!” I replied; “I am only his Majesty’s guest.”

“His Majesty! Do you mean that?” said Mi-Hy, pointing to the Wallypug.

The Wallypug drew himself up with an air of offended dignity.

“I am not a ‘that’; I’m a kind of a king,” he explained, in a tone of remonstrance.

“O-ooh!” exclaimed the little blue people, falling[114] down on their knees and bowing their foreheads to the ground, with their hands stretched out before them. “Pray forgive us, Majestuous Wallypug, we thought you were only an ordinary person. You see we’ve never caught a king before. Oh! don’t chop our heads off, will you?”

“PRAY FORGIVE US,” EXCLAIMED THE BLUE PEOPLE.

“Of course not,” said his Majesty, kindly.

“But kings always chop off people’s heads, don’t they?” cried the little people, anxiously.

“Oh dear no,” said the Wallypug.

“Get up; or you’ll spoil your clothes. Could we have a cup of tea, please? We are rather fatigued with our long journey.”

The little blue people immediately jumped up and led the way to where behind a clump of curious blue trees the quaintest little boat you could possibly imagine was moored against the bank. A blue lake stretched as far as the eye could reach, and a number of little islands were dotted about it. On one, a little larger than the rest, a quaint little blue pagoda could be seen.

CHAPTER X.

THE HOME OF HO-LOR.

“I live over there,” said Ho-Lor with pride, pointing to the island with the pagoda on it. “Mi-Hy shall row us across, and Gra-Shus shall make us some tea.”

“Oh! yes,” said Gra-Shus clapping her hands. “And we’ll show Mr. Majesty Wallypug our beautiful pet dog—won’t we?”

It was impossible not to be interested in these quaint and simple-minded little folk, and after we had all stepped into the little boat and Mi-Hy had pushed off, his Majesty was soon chatting affably with Ho-Lor, who explained that he was a mandarin of the Blue Button, and ninety-eighth-cousin-twice-removed to the Emperor of China.

We soon reached the opposite bank, and his Majesty having been ceremoniously assisted out of the boat, we ascended a slight hill, and soon found ourselves before Ho-Lor’s residence. To our great surprise we found that it exactly resembled the building so familiar to all who have seen a willow-pattern plate.

The tall pillars at the portico, the quaintly-shaped curly roofs, the little zig-zag fence running along the path, and the curious trees, all seemed to be old friends—while two little islands, one of which was connected to the mainland by a quaint bridge, completed the picture.

The two birds, which had by this time finished squabbling about the sandwich, were billing and cooing over our heads, and the sight of them seemed suddenly to convince us of the identity of the spot.

“Why, this must be the land of the Willow-pattern plate,” cried his Majesty excitedly.

“Yes, it is,” admitted Ho-Lor. “Don’t you think it is a very pretty spot?”

“Charming,” declared the Wallypug; “I have often wanted to come here.”

“The real name of the place,” said Ho-Lor, “is Wer-har-wei, and it is a portion of China; but come, you must see our little dog; I can hear that Mi-Hy has gone to fetch him.”

“His name is Kis-Smee,” said Gra-Shus, “and he is such a dear old thing. We’ve had him ever since he was a puppy.”